User login

Recurrent Bleeding in Small-Intestinal Angiodysplasia Reduced by Thalidomide

, according to results of a new placebo-controlled trial.

At 1 year follow-up, thalidomide doses of 100 mg/day and 50 mg/day outperformed placebo in reducing by at least 50% the number of bleeding episodes, compared with the year prior to treatment, according to the study published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

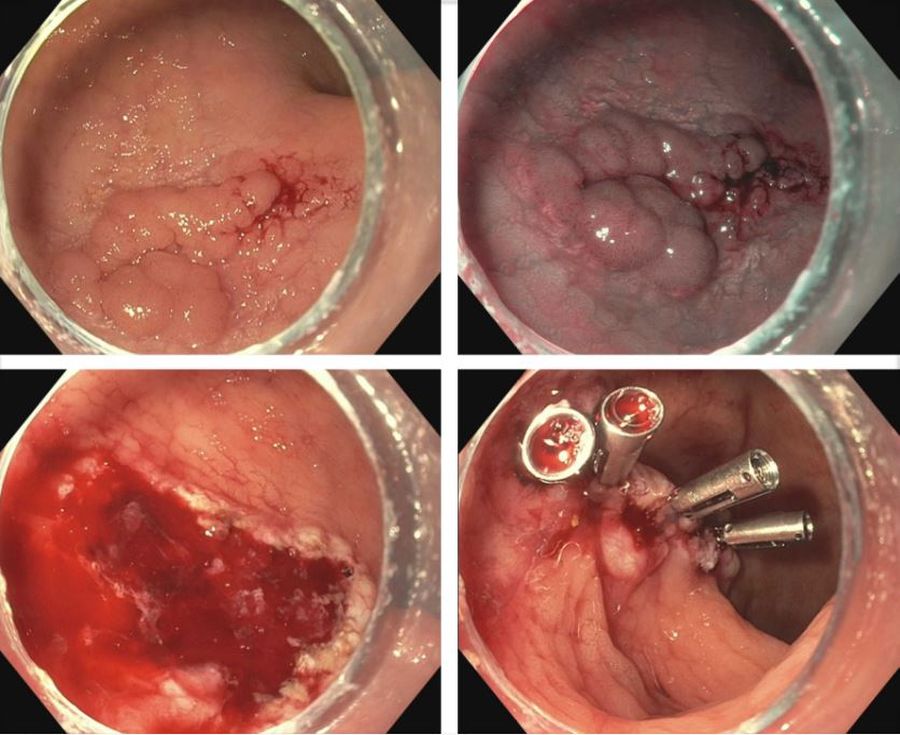

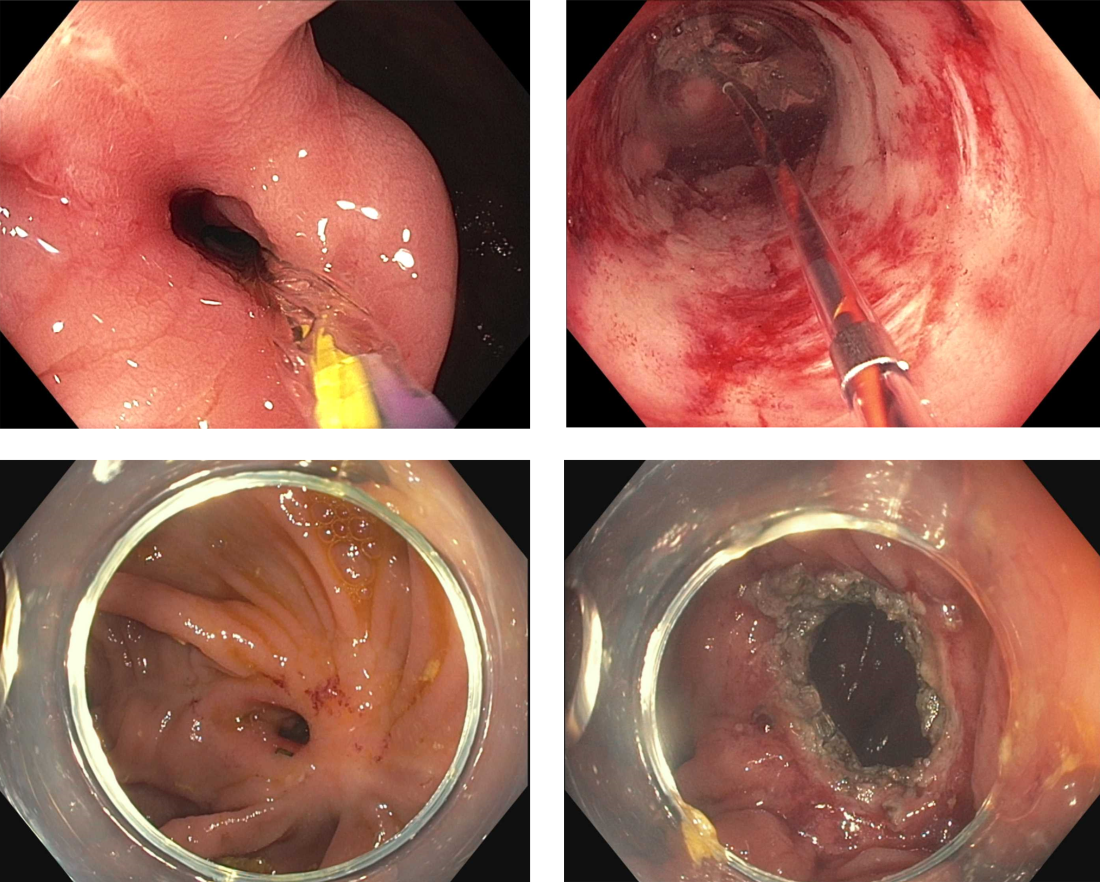

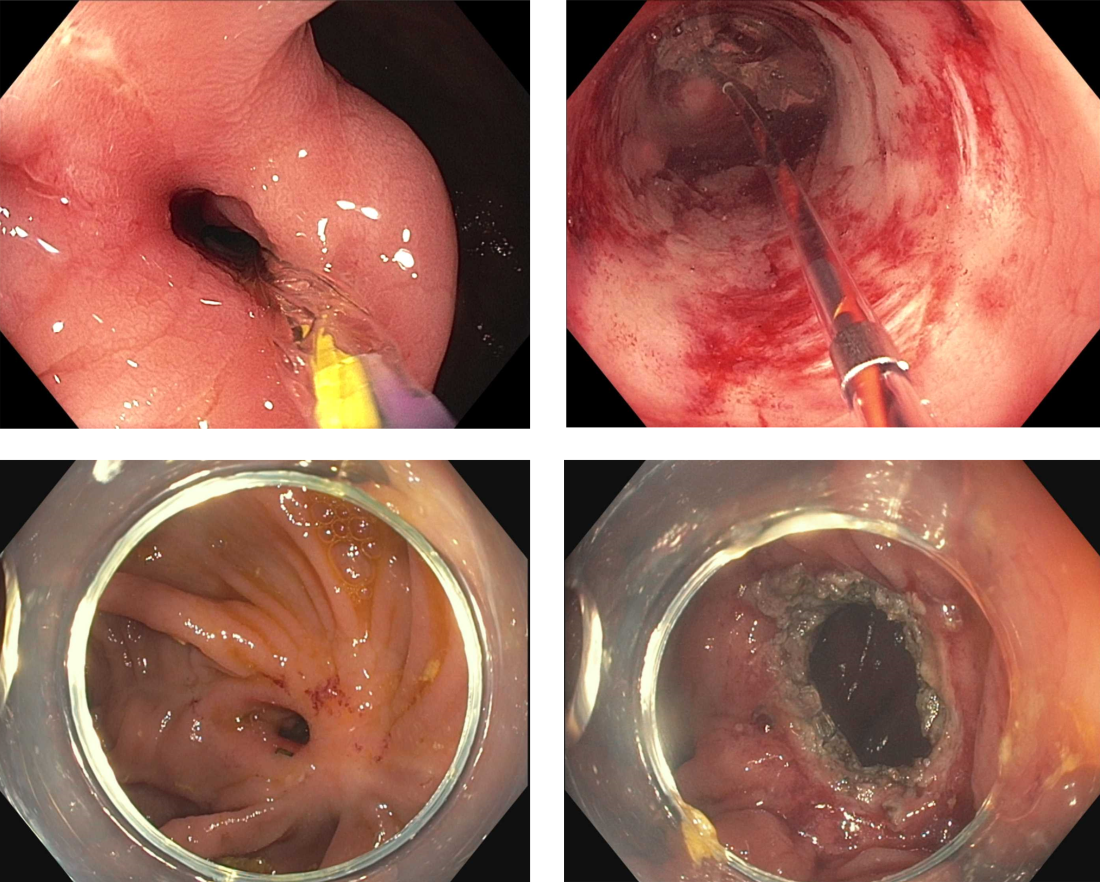

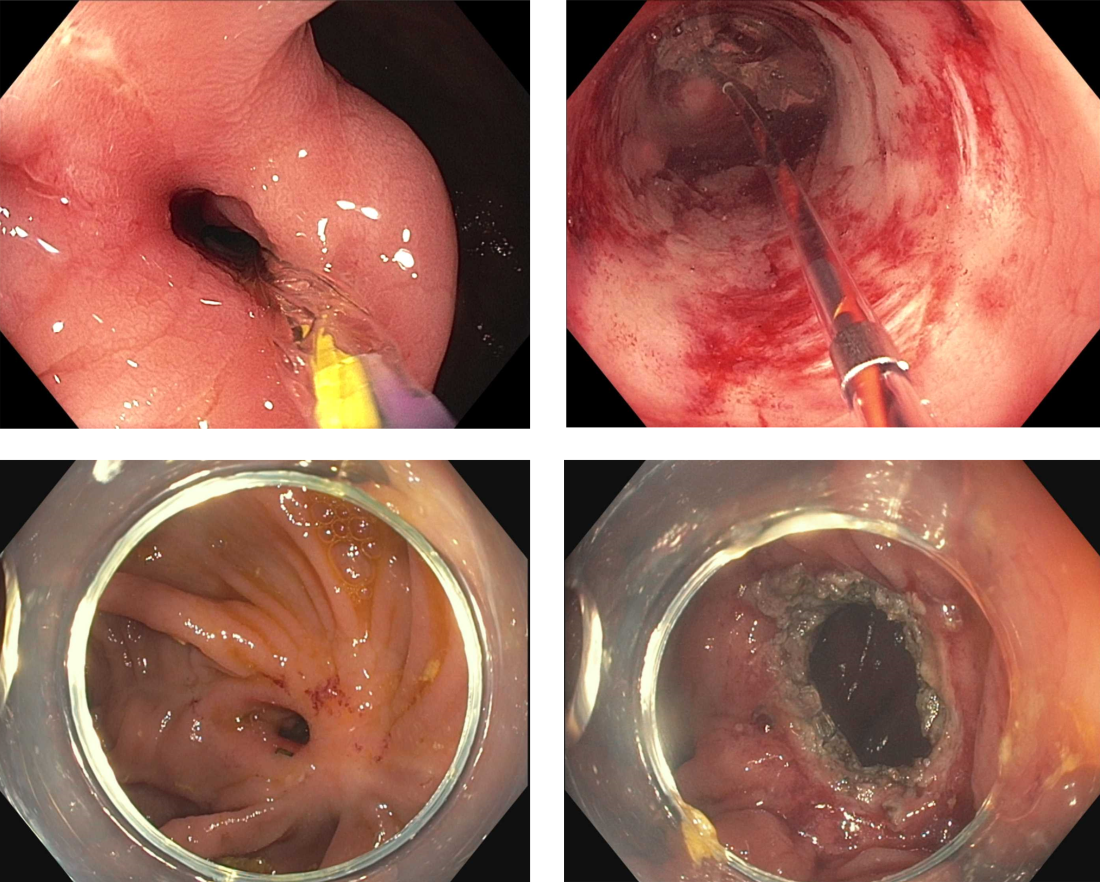

SIA, an increasingly recognized cause of repeat obscure gastrointestinal bleeding and iron-deficiency anemia, is a distinct vascular abnormality in the mucosa and submucosa characterized by focal accumulation of ectatic vessels. It is the most common cause of small intestine bleeding, especially among patients older than 50.

There is a high unmet need among patients with SIA for an effective and relatively safe oral medication, given substantial recurrent bleeding risks following endoscopic or surgical procedures, and only observational studies suggest treatment with somatostatin and octreotide, noted senior author Zhizheng Ge, MD, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China.

SIA is characterized by dilated and tortuous arterial or venous capillaries between thin-walled and immature veins and capillaries without a smooth-muscle layer. Its pathologic process involves chronic hypoxia and vessel sprouting.

Dr. Ge and colleagues postulated that thalidomide’s ability to decrease the expression of proangiogenic factors and angiogenesis would have a long-lasting ameliorating effect on bleeding episodes of angiodysplasia, and thus a continued benefit with respect to bleeding cessation. Their previous small, single-center, open-label, randomized controlled trial of thalidomide for SIA showed a benefit, but it required larger confirmatory trials.

For their current trial, the researchers explored whether a short treatment period, selected to avoid treatment nonadherence, could have a long-term effect. They randomly assigned on a 1:1:1 basis 150 patients with recurrent SIA-related bleeding, defined as at least four episodes during the previous year, to an oral daily dose of 100 mg of thalidomide, 50 mg of thalidomide, or placebo for 4 months.

The patients (median age, 62.2 years; 88% aged 50 years or older) were followed for at least 1 year after treatment. The trial was conducted at 10 sites in China.

The primary endpoint was effective response, defined as a reduction of at least 50% in the number of bleeding episodes in the year following thalidomide treatment, compared with the number in the year before treatment. Bleeding was defined as the presence of overt bleeding or a positive fecal occult blood test.

The percentages of patients with effective response at 1-year follow-up were 68.6% in the 100-mg thalidomide group, 51% in the 50-mg thalidomide group, and 16% in the placebo group.

Among secondary endpoints, the incidence of rebleeding during the 4-month treatment period was 27.5% (14 of 51 patients) in the 100-mg thalidomide group, 42.9% (21 of 49 patients) in the 50-mg thalidomide group, and 90% (45 of 50 patients) in the placebo group. The percentage of patients who received a blood transfusion during the 1-year follow-up period were 17.6% in the 100-mg thalidomide group, 24.5% in the 50-mg thalidomide group, and 62% in the placebo group.

Cessation of bleeding, defined by two consecutive negative fecal occult blood tests on different days, during 1 year of follow-up was observed in 44 patients: 26 (51%) of patients in the 100-mg thalidomide group, 16 (32.7%) in the 50-mg thalidomide group, and 2 (4%) in the placebo group. The authors urge further exploration of the duration of benefit and the efficacy of longer courses of treatment.

Adverse events, all grade 1 or 2, resolved after treatment of symptoms, completion of treatment, or discontinuation of thalidomide or placebo.

Retreatment May Be Necessary

In an accompanying editorial, Loren Laine, MD, chief of the section of digestive diseases, internal medicine, and medical chief, digestive health, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, affirmed the authors’ conclusions and commended the quality of evidence they provided.

“Their results suggest that thalidomide may be disease-modifying, with efficacy persisting after discontinuation,” wrote Dr. Laine, also a Yale professor of medicine and digestive diseases.

While thalidomide effectively prevented rebleeding for 42 patients during the year after therapy was stopped, suggesting an alteration of angiodysplasias, rebleeding during the subsequent 3-27 months occurred among 20 of those patients, Dr. Laine noted. That finding, “suggests that retreatment will be needed,” although the appropriate duration of treatment before retreatment and the duration of retreatment remain unclear, he added.

The study’s reliance on bleeding episodes that were defined by positive fecal occult blood tests, which may be clinically unimportant, is a weakness in the trial, Dr. Laine wrote.

Despite the study’s positive findings, clinicians may still prefer somatostatin analogues because of their potential for better safety and, with once-monthly injections versus daily thalidomide pills, their likelihood for better adherence, Dr. Laine wrote. “[They] will reserve thalidomide for use in patients who have continued bleeding or side effects with somatostatin analogues,” he added.

Somatostatin is rarely used in the treatment of SIA bleeding in China, where thalidomide is relatively easy to obtain and is being used clinically, Dr. Ge told this news organization in response to Dr. Laine’s editorial. “The clinical application of thalidomide has been taken up in other [Chinese] hospitals that have seen our research,” he added.

Future research may include randomized controlled trials of somatostatin, since Chinese experience with it is so limited, Dr. Ge said. “We would want to compare efficacy, safety, feasibility and cost-effectiveness between somatostatin and thalidomide,” he added.

The study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and a grant from the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission, Gaofeng Clinical Medicine. The author disclosures can be found with the original article.

, according to results of a new placebo-controlled trial.

At 1 year follow-up, thalidomide doses of 100 mg/day and 50 mg/day outperformed placebo in reducing by at least 50% the number of bleeding episodes, compared with the year prior to treatment, according to the study published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

SIA, an increasingly recognized cause of repeat obscure gastrointestinal bleeding and iron-deficiency anemia, is a distinct vascular abnormality in the mucosa and submucosa characterized by focal accumulation of ectatic vessels. It is the most common cause of small intestine bleeding, especially among patients older than 50.

There is a high unmet need among patients with SIA for an effective and relatively safe oral medication, given substantial recurrent bleeding risks following endoscopic or surgical procedures, and only observational studies suggest treatment with somatostatin and octreotide, noted senior author Zhizheng Ge, MD, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China.

SIA is characterized by dilated and tortuous arterial or venous capillaries between thin-walled and immature veins and capillaries without a smooth-muscle layer. Its pathologic process involves chronic hypoxia and vessel sprouting.

Dr. Ge and colleagues postulated that thalidomide’s ability to decrease the expression of proangiogenic factors and angiogenesis would have a long-lasting ameliorating effect on bleeding episodes of angiodysplasia, and thus a continued benefit with respect to bleeding cessation. Their previous small, single-center, open-label, randomized controlled trial of thalidomide for SIA showed a benefit, but it required larger confirmatory trials.

For their current trial, the researchers explored whether a short treatment period, selected to avoid treatment nonadherence, could have a long-term effect. They randomly assigned on a 1:1:1 basis 150 patients with recurrent SIA-related bleeding, defined as at least four episodes during the previous year, to an oral daily dose of 100 mg of thalidomide, 50 mg of thalidomide, or placebo for 4 months.

The patients (median age, 62.2 years; 88% aged 50 years or older) were followed for at least 1 year after treatment. The trial was conducted at 10 sites in China.

The primary endpoint was effective response, defined as a reduction of at least 50% in the number of bleeding episodes in the year following thalidomide treatment, compared with the number in the year before treatment. Bleeding was defined as the presence of overt bleeding or a positive fecal occult blood test.

The percentages of patients with effective response at 1-year follow-up were 68.6% in the 100-mg thalidomide group, 51% in the 50-mg thalidomide group, and 16% in the placebo group.

Among secondary endpoints, the incidence of rebleeding during the 4-month treatment period was 27.5% (14 of 51 patients) in the 100-mg thalidomide group, 42.9% (21 of 49 patients) in the 50-mg thalidomide group, and 90% (45 of 50 patients) in the placebo group. The percentage of patients who received a blood transfusion during the 1-year follow-up period were 17.6% in the 100-mg thalidomide group, 24.5% in the 50-mg thalidomide group, and 62% in the placebo group.

Cessation of bleeding, defined by two consecutive negative fecal occult blood tests on different days, during 1 year of follow-up was observed in 44 patients: 26 (51%) of patients in the 100-mg thalidomide group, 16 (32.7%) in the 50-mg thalidomide group, and 2 (4%) in the placebo group. The authors urge further exploration of the duration of benefit and the efficacy of longer courses of treatment.

Adverse events, all grade 1 or 2, resolved after treatment of symptoms, completion of treatment, or discontinuation of thalidomide or placebo.

Retreatment May Be Necessary

In an accompanying editorial, Loren Laine, MD, chief of the section of digestive diseases, internal medicine, and medical chief, digestive health, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, affirmed the authors’ conclusions and commended the quality of evidence they provided.

“Their results suggest that thalidomide may be disease-modifying, with efficacy persisting after discontinuation,” wrote Dr. Laine, also a Yale professor of medicine and digestive diseases.

While thalidomide effectively prevented rebleeding for 42 patients during the year after therapy was stopped, suggesting an alteration of angiodysplasias, rebleeding during the subsequent 3-27 months occurred among 20 of those patients, Dr. Laine noted. That finding, “suggests that retreatment will be needed,” although the appropriate duration of treatment before retreatment and the duration of retreatment remain unclear, he added.

The study’s reliance on bleeding episodes that were defined by positive fecal occult blood tests, which may be clinically unimportant, is a weakness in the trial, Dr. Laine wrote.

Despite the study’s positive findings, clinicians may still prefer somatostatin analogues because of their potential for better safety and, with once-monthly injections versus daily thalidomide pills, their likelihood for better adherence, Dr. Laine wrote. “[They] will reserve thalidomide for use in patients who have continued bleeding or side effects with somatostatin analogues,” he added.

Somatostatin is rarely used in the treatment of SIA bleeding in China, where thalidomide is relatively easy to obtain and is being used clinically, Dr. Ge told this news organization in response to Dr. Laine’s editorial. “The clinical application of thalidomide has been taken up in other [Chinese] hospitals that have seen our research,” he added.

Future research may include randomized controlled trials of somatostatin, since Chinese experience with it is so limited, Dr. Ge said. “We would want to compare efficacy, safety, feasibility and cost-effectiveness between somatostatin and thalidomide,” he added.

The study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and a grant from the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission, Gaofeng Clinical Medicine. The author disclosures can be found with the original article.

, according to results of a new placebo-controlled trial.

At 1 year follow-up, thalidomide doses of 100 mg/day and 50 mg/day outperformed placebo in reducing by at least 50% the number of bleeding episodes, compared with the year prior to treatment, according to the study published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

SIA, an increasingly recognized cause of repeat obscure gastrointestinal bleeding and iron-deficiency anemia, is a distinct vascular abnormality in the mucosa and submucosa characterized by focal accumulation of ectatic vessels. It is the most common cause of small intestine bleeding, especially among patients older than 50.

There is a high unmet need among patients with SIA for an effective and relatively safe oral medication, given substantial recurrent bleeding risks following endoscopic or surgical procedures, and only observational studies suggest treatment with somatostatin and octreotide, noted senior author Zhizheng Ge, MD, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China.

SIA is characterized by dilated and tortuous arterial or venous capillaries between thin-walled and immature veins and capillaries without a smooth-muscle layer. Its pathologic process involves chronic hypoxia and vessel sprouting.

Dr. Ge and colleagues postulated that thalidomide’s ability to decrease the expression of proangiogenic factors and angiogenesis would have a long-lasting ameliorating effect on bleeding episodes of angiodysplasia, and thus a continued benefit with respect to bleeding cessation. Their previous small, single-center, open-label, randomized controlled trial of thalidomide for SIA showed a benefit, but it required larger confirmatory trials.

For their current trial, the researchers explored whether a short treatment period, selected to avoid treatment nonadherence, could have a long-term effect. They randomly assigned on a 1:1:1 basis 150 patients with recurrent SIA-related bleeding, defined as at least four episodes during the previous year, to an oral daily dose of 100 mg of thalidomide, 50 mg of thalidomide, or placebo for 4 months.

The patients (median age, 62.2 years; 88% aged 50 years or older) were followed for at least 1 year after treatment. The trial was conducted at 10 sites in China.

The primary endpoint was effective response, defined as a reduction of at least 50% in the number of bleeding episodes in the year following thalidomide treatment, compared with the number in the year before treatment. Bleeding was defined as the presence of overt bleeding or a positive fecal occult blood test.

The percentages of patients with effective response at 1-year follow-up were 68.6% in the 100-mg thalidomide group, 51% in the 50-mg thalidomide group, and 16% in the placebo group.

Among secondary endpoints, the incidence of rebleeding during the 4-month treatment period was 27.5% (14 of 51 patients) in the 100-mg thalidomide group, 42.9% (21 of 49 patients) in the 50-mg thalidomide group, and 90% (45 of 50 patients) in the placebo group. The percentage of patients who received a blood transfusion during the 1-year follow-up period were 17.6% in the 100-mg thalidomide group, 24.5% in the 50-mg thalidomide group, and 62% in the placebo group.

Cessation of bleeding, defined by two consecutive negative fecal occult blood tests on different days, during 1 year of follow-up was observed in 44 patients: 26 (51%) of patients in the 100-mg thalidomide group, 16 (32.7%) in the 50-mg thalidomide group, and 2 (4%) in the placebo group. The authors urge further exploration of the duration of benefit and the efficacy of longer courses of treatment.

Adverse events, all grade 1 or 2, resolved after treatment of symptoms, completion of treatment, or discontinuation of thalidomide or placebo.

Retreatment May Be Necessary

In an accompanying editorial, Loren Laine, MD, chief of the section of digestive diseases, internal medicine, and medical chief, digestive health, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, affirmed the authors’ conclusions and commended the quality of evidence they provided.

“Their results suggest that thalidomide may be disease-modifying, with efficacy persisting after discontinuation,” wrote Dr. Laine, also a Yale professor of medicine and digestive diseases.

While thalidomide effectively prevented rebleeding for 42 patients during the year after therapy was stopped, suggesting an alteration of angiodysplasias, rebleeding during the subsequent 3-27 months occurred among 20 of those patients, Dr. Laine noted. That finding, “suggests that retreatment will be needed,” although the appropriate duration of treatment before retreatment and the duration of retreatment remain unclear, he added.

The study’s reliance on bleeding episodes that were defined by positive fecal occult blood tests, which may be clinically unimportant, is a weakness in the trial, Dr. Laine wrote.

Despite the study’s positive findings, clinicians may still prefer somatostatin analogues because of their potential for better safety and, with once-monthly injections versus daily thalidomide pills, their likelihood for better adherence, Dr. Laine wrote. “[They] will reserve thalidomide for use in patients who have continued bleeding or side effects with somatostatin analogues,” he added.

Somatostatin is rarely used in the treatment of SIA bleeding in China, where thalidomide is relatively easy to obtain and is being used clinically, Dr. Ge told this news organization in response to Dr. Laine’s editorial. “The clinical application of thalidomide has been taken up in other [Chinese] hospitals that have seen our research,” he added.

Future research may include randomized controlled trials of somatostatin, since Chinese experience with it is so limited, Dr. Ge said. “We would want to compare efficacy, safety, feasibility and cost-effectiveness between somatostatin and thalidomide,” he added.

The study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and a grant from the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission, Gaofeng Clinical Medicine. The author disclosures can be found with the original article.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Caring for LGBTQ+ Patients with IBD

Cases

Patient 1: 55-year-old cis-male, who identifies as gay, has ulcerative colitis that has been refractory to multiple biologic therapies. His provider recommends a total proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis (TPC with IPAA), but the patient has questions regarding sexual function following surgery. Specifically, he is wondering when, or if, he can resume receptive anal intercourse. How would you counsel him?

Patient 2: 25-year-old, trans-female, status-post vaginoplasty with use of sigmoid colon and with well-controlled ulcerative colitis, presents with vaginal discharge, weight loss, and rectal bleeding. How do you explain what has happened to her? During your discussion, she also asks you why her chart continues to use her “dead name.” How do you respond?

Patient 3: 32-year-old, cis-female, G2P2, who identifies as a lesbian, has active ulcerative colitis. She wants to discuss medical or surgical therapy and future pregnancies. How would you counsel her?

Many gastroenterologists would likely know how to address patient 3’s concerns, but the concerns of patients 1 and 2 often go unaddressed or dismissed. Numerous studies and surveys have been conducted on patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), but the focus of these studies has always been through a heteronormative cisgender lens. The focus of many studies is on fertility or sexual health and function in cisgender, heteronormative individuals.1-3 In the last few years, however, there has been increasing awareness of the health disparities, stigma, and discrimination that sexual and gender minorities (SGM) experience.4-6 For the purposes of this discussion, individuals within the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, intersex, and asexual (LGBTQIA+) community will be referred to as SGM. We recognize that even this exhaustive listing above does not acknowledge the full spectrum of diversity within the SGM community.

Clinical Care/Competency for SGM with IBD is Lacking

Almost 10% of the US population identifies as some form of SGM, and that number can be higher within the younger generations.4 SGM patients tend to delay or avoid seeking health care due to concern for provider mistreatment or lack of regard for their individual concerns. Additionally, there are several gaps in clinical knowledge about caring for SGM individuals. Little is known regarding the incidence or prevalence of IBD in SGM populations, but it is perceived to be similar to cisgender heterosexual individuals. Furthermore, as Newman et al. highlighted in their systematic review published in May 2023, there is a lack of guidance regarding sexual activity in the setting of IBD in SGM individuals.5 There is also a significant lack of knowledge on the impact of gender-affirming care on the natural history and treatments of IBD in transgender and gender non-conforming (TGNC) individuals. This can impact providers’ comfort and competence in caring for TGNC individuals.

Another important point to make is that the SGM community still faces discrimination due to sexual orientation or gender identity to this day, which impacts the quality and delivery of their care.7 Culturally-competent care should include care that is free from stigma, implicit and explicit biases, and discrimination. In 2011, an Institute of Medicine report documented, among other issues, provider discomfort in delivering care to SGM patients.8 While SGM individuals prefer a provider who acknowledges their sexual orientation and gender identity and treats them with the dignity and respect they deserve, many SGM individuals share valid concerns regarding their safety, which impact their desire to disclose their identity to health care providers.9 This certainly can have an impact on the quality of care they receive, including important health maintenance milestones and cancer screenings.10

An internal survey at our institution of providers (nurses, physician assistants, surgeons, and physicians) found that among 85 responders, 70% have cared for SGM who have undergone TPC with ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA). Of these, 75% did not ask about sexual orientation or practices before pouch formation (though almost all of them agreed it would be important to ask). A total of 55% were comfortable in discussing SGM-related concerns; 53% did not feel comfortable discussing sexual orientation or practices; and in particular when it came to anoreceptive intercourse (ARI), 73% did not feel confident discussing recommendations.11

All of these issues highlight the importance of developing curricula that focus on reducing implicit and explicit biases towards SGM individuals and increasing the competence of providers to take care of SGM individuals in a safe space.

Additionally, it further justifies the need for ethical research that focuses on the needs of SGM individuals to guide evidence-based approaches to care. Given the implicit and explicit heterosexism and transphobia in society and many health care systems, Rainbows in Gastro was formed as an advocacy group for SGM patients, trainees, and staff in gastroenterology and hepatology.4

Research in SGM and IBD is lacking

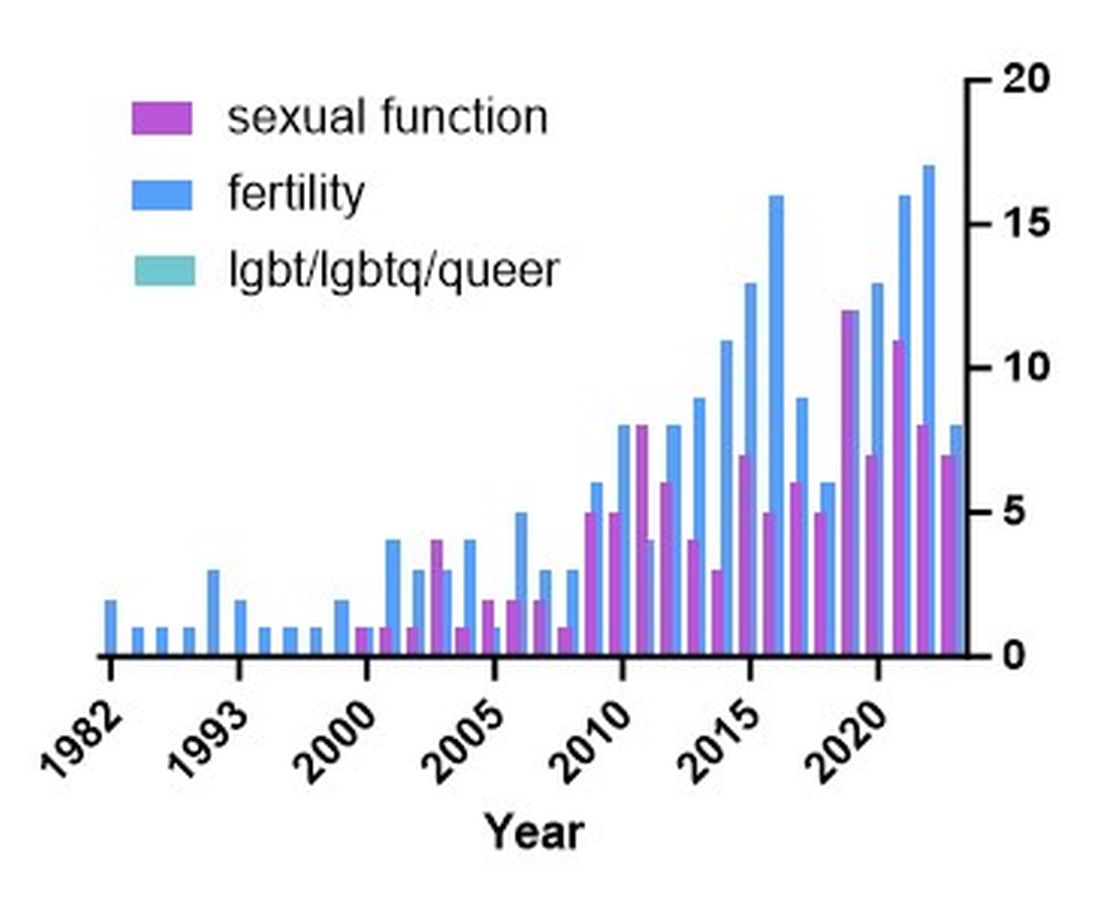

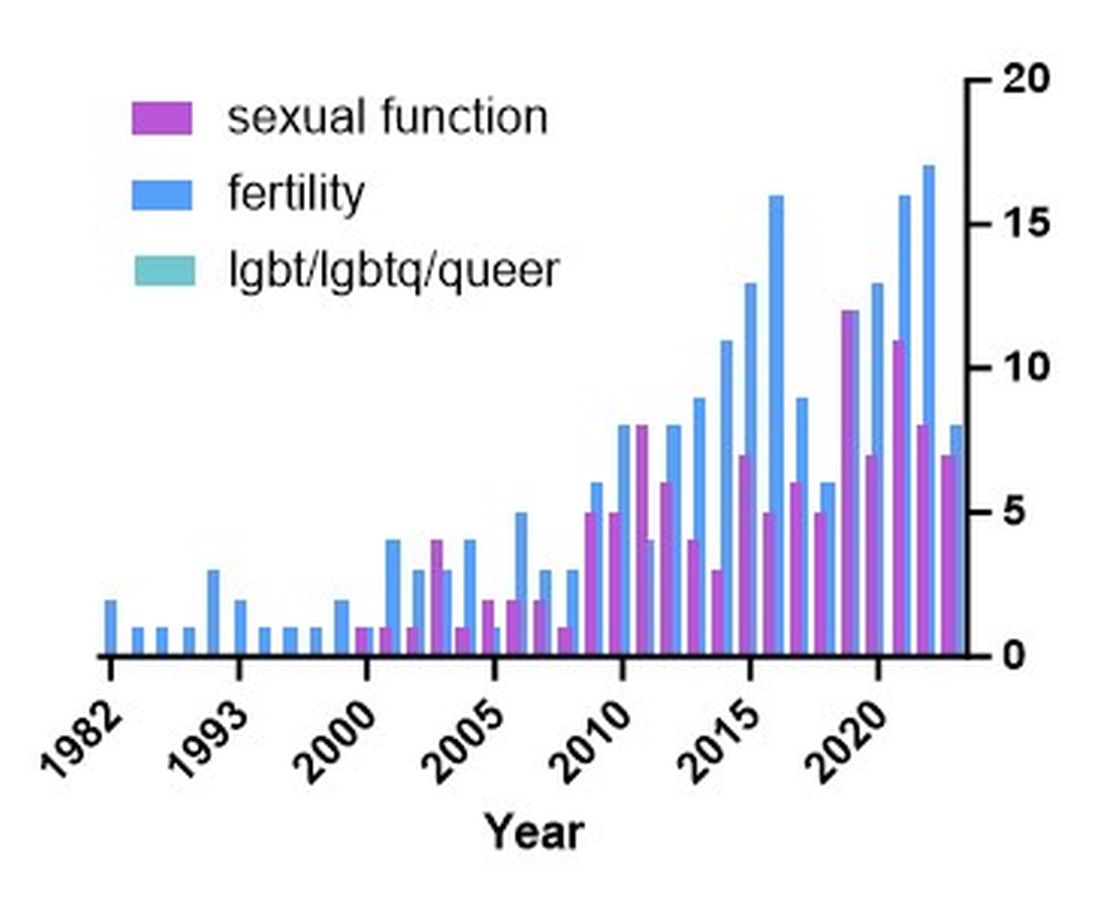

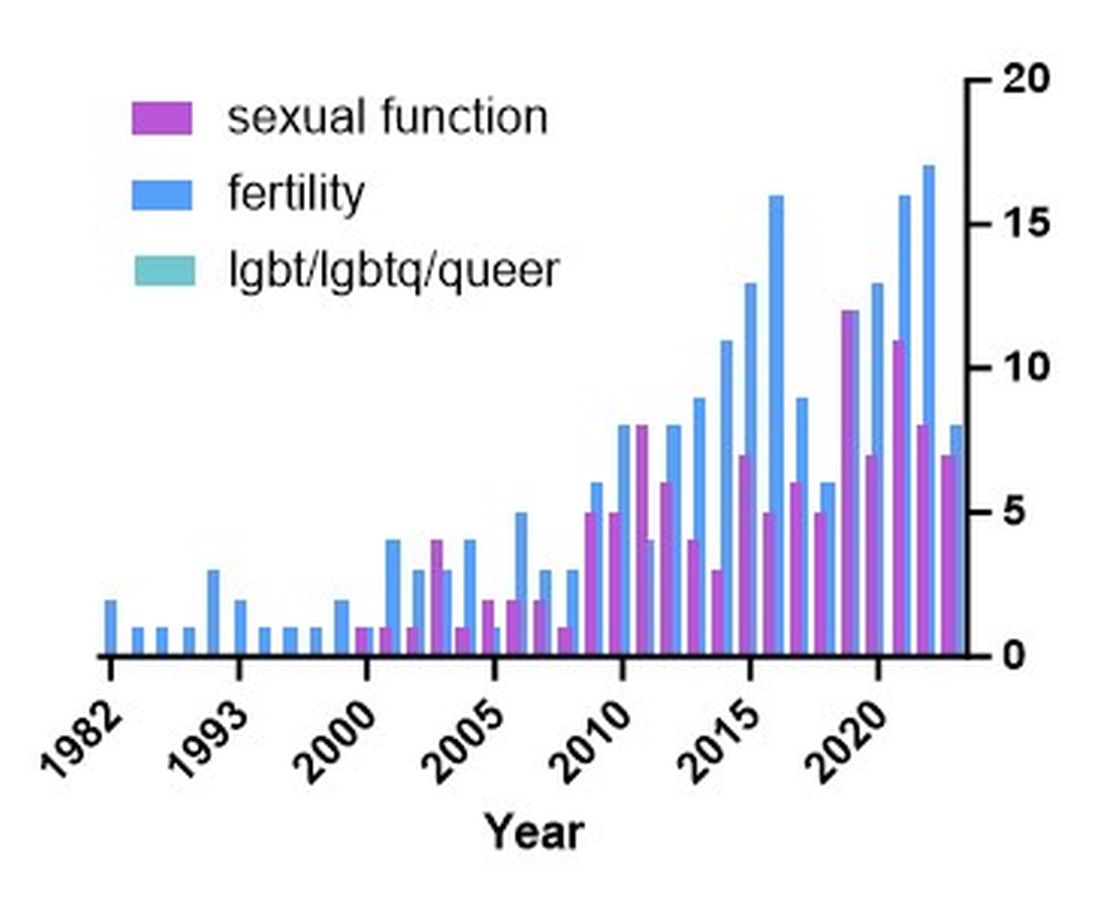

There are additional needs for research in IBD and how it pertains to the needs of SGM individuals. Figure 1 highlights the lack of PubMed results for the search terms “IBD + LGBT,” “IBD + LGBTQ,” or “IBD + queer.” In contrast, the search terms “IBD + fertility” and “IBD + sexual dysfunction” generate many results. Even a systemic review conducted by Newman et al. of multiple databases in 2022 found only seven articles that demonstrated appropriately performed studies on SGM patients with IBD.5 This highlights the significant dearth of research in the realm of SGM health in IBD.

Newman and colleagues have recently published research considerations for SGM individuals. They highlighted the need to include understanding the “unique combination of psychosocial, biomedical, and legal experiences” that results in different needs and outcomes. There were several areas identified, including minority stress, which comes from existence of being SGM, especially as transgender individuals face increasing legal challenges in a variety of settings, not just healthcare.6 In a retrospective chart review investigating social determinants of health in SGM-IBD populations,12 36% of patients reported some level of social isolation, and almost 50% reported some level of stress. A total of 40% of them self-reported some perceived level of risk with respect to employment, and 17% reported depression. Given that this was a chart review and not a strict questionnaire, this study was certainly limited, and we would hypothesize that these numbers are therefore underestimating the true proportion of SGM-IBD patients who deal with employment concerns, social isolation, or psychological distress.

What Next? Back to the Patients

Circling back to our patients from the introduction, how would you counsel each of them? In patient 1’s case, we would inform him that pelvic surgery can increase the risk for sexual dysfunction, such as erectile dysfunction. He additionally would be advised during a staged TPC with IPAA, he may experience issues with body image. However, should he desire to participate in receptive anal intercourse after completion of his surgeries, the general recommendation would be to wait at least 6 months and with proven remission. It should further be noted that these are not formalized recommendations, only highlighting the need for more research and consensus on standards of care for SGM patients. He should finally be told that because he has ulcerative colitis, removal of the colon does not remove the risk for future intestinal involvement such as possible pouchitis.

In patient 2’s case, she is likely experiencing diversion vaginitis related to use of her colon for her neo-vagina. She should undergo colonoscopy and vaginoscopy in addition to standard work-up for her known ulcerative colitis.13 Management should be done in a multidisciplinary approach between the IBD provider, gynecologist, and gender-affirming provider. The electronic medical record should be updated to reflect the patient’s preferred name, pronouns, and gender identity, and her medical records, including automated clinical reports, should be updated accordingly.

As for patient 3, she would be counseled according to well-documented guidelines on pregnancy and IBD, including risks of medications (such as Jak inhibitors or methotrexate) versus the risk of uncontrolled IBD during pregnancy.1

Regardless of a patient’s gender identity or sexual orientation, patient-centered, culturally competent, and sensitive care should be provided. At Mayo Clinic in Rochester, we started one of the first Pride in IBD Clinics, which focuses on the care of SGM individuals with IBD. Our focus is to address the needs of patients who belong to the SGM community in a wholistic approach within a safe space (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pYa_zYaCA6M; https://www.mayoclinic.org/departments-centers/inflammatory-bowel-disease-clinic/overview/ovc-20357763). Our process of developing the clinic included training all staff on proper communication and cultural sensitivity for the SGM community.

Furthermore, providing welcoming and affirming signs of inclusivity for SGM individuals at the provider’s office — including but not limited to rainbow progressive flags, gender-neutral bathroom signs, or pronoun pins on provider identification badges (see Figure 2) — are usually appreciated by patients. Ensuring that patient education materials do not assume gender (for example, using the term “parents” rather than “mother and father”) and using gender neutral terms on intake forms is very important. Inclusive communication includes providers introducing themselves by preferred name and pronouns, asking the patients to introduce themselves, and welcoming them to share their pronouns. These simple actions can provide an atmosphere of safety for SGM patients, which would serve to enhance the quality of care we can provide for them.

For Resources and Further Reading: CDC,14 the Fenway Institute’s National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center,15 and US Department of Health and Human Services.16

Dr. Chiang and Dr. Chedid are both in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. Dr. Chedid is also with the Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery, Mayo Clinic. Neither of the authors have any relevant conflicts of interest. They are on X, formerly Twitter: @dr_davidchiang , @VictorChedidMD .

CITATIONS

1. Mahadevan U et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in pregnancy clinical care pathway: A report from the American Gastroenterological Association IBD Parenthood Project Working Group. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1508-24.

2. Pires F et al. A survey on the impact of IBD in sexual health: Into intimacy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e32279.

3. Mules TC et al. The impact of disease activity on sexual and erectile dysfunction in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29:1244-54.

4. Duong N et al. Overcoming disparities for sexual and gender minority patients and providers in gastroenterology and hepatology: Introduction to Rainbows in Gastro. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:299-301.

5. Newman KL et al. A systematic review of inflammatory bowel disease epidemiology and health outcomes in sexual and gender minority individuals. Gastroenterology. 2023;164:866-71.

6. Newman KL et al. Research considerations in Digestive and liver disease in transgender and gender-diverse populations. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:523-28 e1.

7. Velez C et al. Digestive health in sexual and gender minority populations. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117:865-75.

8. Medicine Io. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press, 2011.

9. Austin EL. Sexual orientation disclosure to health care providers among urban and non-urban southern lesbians. Women Health. 2013;53:41-55.

10. Oladeru OT et al. Breast and cervical cancer screening disparities in transgender people. Am J Clin Oncol. 2022;45:116-21.

11. Vinsard DG et al. Healthcare providers’ perspectives on anoreceptive intercourse in sexual and gender minorities with ileal pouch anal anastomosis. Digestive Disease Week (DDW). Chicago, IL, 2023.

12. Ghusn W et al. Social determinants of health in LGBTQIA+ patients with inflammatory bowel disease. American College of Gastroenterology (ACG). Charlotte, NC, 2022.

13. Grasman ME et al. Neovaginal sparing in a transgender woman with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:e73-4.

14. Prevention CfDCa. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health — https://www.cdc.gov/lgbthealth/index.htm.

15. Institute TF. National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center — https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/.

16. Services UDoHaH. LGBTQI+ Resources — https://www.hhs.gov/programs/topic-sites/lgbtqi/resources/index.html.

Cases

Patient 1: 55-year-old cis-male, who identifies as gay, has ulcerative colitis that has been refractory to multiple biologic therapies. His provider recommends a total proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis (TPC with IPAA), but the patient has questions regarding sexual function following surgery. Specifically, he is wondering when, or if, he can resume receptive anal intercourse. How would you counsel him?

Patient 2: 25-year-old, trans-female, status-post vaginoplasty with use of sigmoid colon and with well-controlled ulcerative colitis, presents with vaginal discharge, weight loss, and rectal bleeding. How do you explain what has happened to her? During your discussion, she also asks you why her chart continues to use her “dead name.” How do you respond?

Patient 3: 32-year-old, cis-female, G2P2, who identifies as a lesbian, has active ulcerative colitis. She wants to discuss medical or surgical therapy and future pregnancies. How would you counsel her?

Many gastroenterologists would likely know how to address patient 3’s concerns, but the concerns of patients 1 and 2 often go unaddressed or dismissed. Numerous studies and surveys have been conducted on patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), but the focus of these studies has always been through a heteronormative cisgender lens. The focus of many studies is on fertility or sexual health and function in cisgender, heteronormative individuals.1-3 In the last few years, however, there has been increasing awareness of the health disparities, stigma, and discrimination that sexual and gender minorities (SGM) experience.4-6 For the purposes of this discussion, individuals within the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, intersex, and asexual (LGBTQIA+) community will be referred to as SGM. We recognize that even this exhaustive listing above does not acknowledge the full spectrum of diversity within the SGM community.

Clinical Care/Competency for SGM with IBD is Lacking

Almost 10% of the US population identifies as some form of SGM, and that number can be higher within the younger generations.4 SGM patients tend to delay or avoid seeking health care due to concern for provider mistreatment or lack of regard for their individual concerns. Additionally, there are several gaps in clinical knowledge about caring for SGM individuals. Little is known regarding the incidence or prevalence of IBD in SGM populations, but it is perceived to be similar to cisgender heterosexual individuals. Furthermore, as Newman et al. highlighted in their systematic review published in May 2023, there is a lack of guidance regarding sexual activity in the setting of IBD in SGM individuals.5 There is also a significant lack of knowledge on the impact of gender-affirming care on the natural history and treatments of IBD in transgender and gender non-conforming (TGNC) individuals. This can impact providers’ comfort and competence in caring for TGNC individuals.

Another important point to make is that the SGM community still faces discrimination due to sexual orientation or gender identity to this day, which impacts the quality and delivery of their care.7 Culturally-competent care should include care that is free from stigma, implicit and explicit biases, and discrimination. In 2011, an Institute of Medicine report documented, among other issues, provider discomfort in delivering care to SGM patients.8 While SGM individuals prefer a provider who acknowledges their sexual orientation and gender identity and treats them with the dignity and respect they deserve, many SGM individuals share valid concerns regarding their safety, which impact their desire to disclose their identity to health care providers.9 This certainly can have an impact on the quality of care they receive, including important health maintenance milestones and cancer screenings.10

An internal survey at our institution of providers (nurses, physician assistants, surgeons, and physicians) found that among 85 responders, 70% have cared for SGM who have undergone TPC with ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA). Of these, 75% did not ask about sexual orientation or practices before pouch formation (though almost all of them agreed it would be important to ask). A total of 55% were comfortable in discussing SGM-related concerns; 53% did not feel comfortable discussing sexual orientation or practices; and in particular when it came to anoreceptive intercourse (ARI), 73% did not feel confident discussing recommendations.11

All of these issues highlight the importance of developing curricula that focus on reducing implicit and explicit biases towards SGM individuals and increasing the competence of providers to take care of SGM individuals in a safe space.

Additionally, it further justifies the need for ethical research that focuses on the needs of SGM individuals to guide evidence-based approaches to care. Given the implicit and explicit heterosexism and transphobia in society and many health care systems, Rainbows in Gastro was formed as an advocacy group for SGM patients, trainees, and staff in gastroenterology and hepatology.4

Research in SGM and IBD is lacking

There are additional needs for research in IBD and how it pertains to the needs of SGM individuals. Figure 1 highlights the lack of PubMed results for the search terms “IBD + LGBT,” “IBD + LGBTQ,” or “IBD + queer.” In contrast, the search terms “IBD + fertility” and “IBD + sexual dysfunction” generate many results. Even a systemic review conducted by Newman et al. of multiple databases in 2022 found only seven articles that demonstrated appropriately performed studies on SGM patients with IBD.5 This highlights the significant dearth of research in the realm of SGM health in IBD.

Newman and colleagues have recently published research considerations for SGM individuals. They highlighted the need to include understanding the “unique combination of psychosocial, biomedical, and legal experiences” that results in different needs and outcomes. There were several areas identified, including minority stress, which comes from existence of being SGM, especially as transgender individuals face increasing legal challenges in a variety of settings, not just healthcare.6 In a retrospective chart review investigating social determinants of health in SGM-IBD populations,12 36% of patients reported some level of social isolation, and almost 50% reported some level of stress. A total of 40% of them self-reported some perceived level of risk with respect to employment, and 17% reported depression. Given that this was a chart review and not a strict questionnaire, this study was certainly limited, and we would hypothesize that these numbers are therefore underestimating the true proportion of SGM-IBD patients who deal with employment concerns, social isolation, or psychological distress.

What Next? Back to the Patients

Circling back to our patients from the introduction, how would you counsel each of them? In patient 1’s case, we would inform him that pelvic surgery can increase the risk for sexual dysfunction, such as erectile dysfunction. He additionally would be advised during a staged TPC with IPAA, he may experience issues with body image. However, should he desire to participate in receptive anal intercourse after completion of his surgeries, the general recommendation would be to wait at least 6 months and with proven remission. It should further be noted that these are not formalized recommendations, only highlighting the need for more research and consensus on standards of care for SGM patients. He should finally be told that because he has ulcerative colitis, removal of the colon does not remove the risk for future intestinal involvement such as possible pouchitis.

In patient 2’s case, she is likely experiencing diversion vaginitis related to use of her colon for her neo-vagina. She should undergo colonoscopy and vaginoscopy in addition to standard work-up for her known ulcerative colitis.13 Management should be done in a multidisciplinary approach between the IBD provider, gynecologist, and gender-affirming provider. The electronic medical record should be updated to reflect the patient’s preferred name, pronouns, and gender identity, and her medical records, including automated clinical reports, should be updated accordingly.

As for patient 3, she would be counseled according to well-documented guidelines on pregnancy and IBD, including risks of medications (such as Jak inhibitors or methotrexate) versus the risk of uncontrolled IBD during pregnancy.1

Regardless of a patient’s gender identity or sexual orientation, patient-centered, culturally competent, and sensitive care should be provided. At Mayo Clinic in Rochester, we started one of the first Pride in IBD Clinics, which focuses on the care of SGM individuals with IBD. Our focus is to address the needs of patients who belong to the SGM community in a wholistic approach within a safe space (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pYa_zYaCA6M; https://www.mayoclinic.org/departments-centers/inflammatory-bowel-disease-clinic/overview/ovc-20357763). Our process of developing the clinic included training all staff on proper communication and cultural sensitivity for the SGM community.

Furthermore, providing welcoming and affirming signs of inclusivity for SGM individuals at the provider’s office — including but not limited to rainbow progressive flags, gender-neutral bathroom signs, or pronoun pins on provider identification badges (see Figure 2) — are usually appreciated by patients. Ensuring that patient education materials do not assume gender (for example, using the term “parents” rather than “mother and father”) and using gender neutral terms on intake forms is very important. Inclusive communication includes providers introducing themselves by preferred name and pronouns, asking the patients to introduce themselves, and welcoming them to share their pronouns. These simple actions can provide an atmosphere of safety for SGM patients, which would serve to enhance the quality of care we can provide for them.

For Resources and Further Reading: CDC,14 the Fenway Institute’s National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center,15 and US Department of Health and Human Services.16

Dr. Chiang and Dr. Chedid are both in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. Dr. Chedid is also with the Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery, Mayo Clinic. Neither of the authors have any relevant conflicts of interest. They are on X, formerly Twitter: @dr_davidchiang , @VictorChedidMD .

CITATIONS

1. Mahadevan U et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in pregnancy clinical care pathway: A report from the American Gastroenterological Association IBD Parenthood Project Working Group. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1508-24.

2. Pires F et al. A survey on the impact of IBD in sexual health: Into intimacy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e32279.

3. Mules TC et al. The impact of disease activity on sexual and erectile dysfunction in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29:1244-54.

4. Duong N et al. Overcoming disparities for sexual and gender minority patients and providers in gastroenterology and hepatology: Introduction to Rainbows in Gastro. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:299-301.

5. Newman KL et al. A systematic review of inflammatory bowel disease epidemiology and health outcomes in sexual and gender minority individuals. Gastroenterology. 2023;164:866-71.

6. Newman KL et al. Research considerations in Digestive and liver disease in transgender and gender-diverse populations. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:523-28 e1.

7. Velez C et al. Digestive health in sexual and gender minority populations. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117:865-75.

8. Medicine Io. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press, 2011.

9. Austin EL. Sexual orientation disclosure to health care providers among urban and non-urban southern lesbians. Women Health. 2013;53:41-55.

10. Oladeru OT et al. Breast and cervical cancer screening disparities in transgender people. Am J Clin Oncol. 2022;45:116-21.

11. Vinsard DG et al. Healthcare providers’ perspectives on anoreceptive intercourse in sexual and gender minorities with ileal pouch anal anastomosis. Digestive Disease Week (DDW). Chicago, IL, 2023.

12. Ghusn W et al. Social determinants of health in LGBTQIA+ patients with inflammatory bowel disease. American College of Gastroenterology (ACG). Charlotte, NC, 2022.

13. Grasman ME et al. Neovaginal sparing in a transgender woman with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:e73-4.

14. Prevention CfDCa. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health — https://www.cdc.gov/lgbthealth/index.htm.

15. Institute TF. National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center — https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/.

16. Services UDoHaH. LGBTQI+ Resources — https://www.hhs.gov/programs/topic-sites/lgbtqi/resources/index.html.

Cases

Patient 1: 55-year-old cis-male, who identifies as gay, has ulcerative colitis that has been refractory to multiple biologic therapies. His provider recommends a total proctocolectomy with ileal pouch anal anastomosis (TPC with IPAA), but the patient has questions regarding sexual function following surgery. Specifically, he is wondering when, or if, he can resume receptive anal intercourse. How would you counsel him?

Patient 2: 25-year-old, trans-female, status-post vaginoplasty with use of sigmoid colon and with well-controlled ulcerative colitis, presents with vaginal discharge, weight loss, and rectal bleeding. How do you explain what has happened to her? During your discussion, she also asks you why her chart continues to use her “dead name.” How do you respond?

Patient 3: 32-year-old, cis-female, G2P2, who identifies as a lesbian, has active ulcerative colitis. She wants to discuss medical or surgical therapy and future pregnancies. How would you counsel her?

Many gastroenterologists would likely know how to address patient 3’s concerns, but the concerns of patients 1 and 2 often go unaddressed or dismissed. Numerous studies and surveys have been conducted on patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), but the focus of these studies has always been through a heteronormative cisgender lens. The focus of many studies is on fertility or sexual health and function in cisgender, heteronormative individuals.1-3 In the last few years, however, there has been increasing awareness of the health disparities, stigma, and discrimination that sexual and gender minorities (SGM) experience.4-6 For the purposes of this discussion, individuals within the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, intersex, and asexual (LGBTQIA+) community will be referred to as SGM. We recognize that even this exhaustive listing above does not acknowledge the full spectrum of diversity within the SGM community.

Clinical Care/Competency for SGM with IBD is Lacking

Almost 10% of the US population identifies as some form of SGM, and that number can be higher within the younger generations.4 SGM patients tend to delay or avoid seeking health care due to concern for provider mistreatment or lack of regard for their individual concerns. Additionally, there are several gaps in clinical knowledge about caring for SGM individuals. Little is known regarding the incidence or prevalence of IBD in SGM populations, but it is perceived to be similar to cisgender heterosexual individuals. Furthermore, as Newman et al. highlighted in their systematic review published in May 2023, there is a lack of guidance regarding sexual activity in the setting of IBD in SGM individuals.5 There is also a significant lack of knowledge on the impact of gender-affirming care on the natural history and treatments of IBD in transgender and gender non-conforming (TGNC) individuals. This can impact providers’ comfort and competence in caring for TGNC individuals.

Another important point to make is that the SGM community still faces discrimination due to sexual orientation or gender identity to this day, which impacts the quality and delivery of their care.7 Culturally-competent care should include care that is free from stigma, implicit and explicit biases, and discrimination. In 2011, an Institute of Medicine report documented, among other issues, provider discomfort in delivering care to SGM patients.8 While SGM individuals prefer a provider who acknowledges their sexual orientation and gender identity and treats them with the dignity and respect they deserve, many SGM individuals share valid concerns regarding their safety, which impact their desire to disclose their identity to health care providers.9 This certainly can have an impact on the quality of care they receive, including important health maintenance milestones and cancer screenings.10

An internal survey at our institution of providers (nurses, physician assistants, surgeons, and physicians) found that among 85 responders, 70% have cared for SGM who have undergone TPC with ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA). Of these, 75% did not ask about sexual orientation or practices before pouch formation (though almost all of them agreed it would be important to ask). A total of 55% were comfortable in discussing SGM-related concerns; 53% did not feel comfortable discussing sexual orientation or practices; and in particular when it came to anoreceptive intercourse (ARI), 73% did not feel confident discussing recommendations.11

All of these issues highlight the importance of developing curricula that focus on reducing implicit and explicit biases towards SGM individuals and increasing the competence of providers to take care of SGM individuals in a safe space.

Additionally, it further justifies the need for ethical research that focuses on the needs of SGM individuals to guide evidence-based approaches to care. Given the implicit and explicit heterosexism and transphobia in society and many health care systems, Rainbows in Gastro was formed as an advocacy group for SGM patients, trainees, and staff in gastroenterology and hepatology.4

Research in SGM and IBD is lacking

There are additional needs for research in IBD and how it pertains to the needs of SGM individuals. Figure 1 highlights the lack of PubMed results for the search terms “IBD + LGBT,” “IBD + LGBTQ,” or “IBD + queer.” In contrast, the search terms “IBD + fertility” and “IBD + sexual dysfunction” generate many results. Even a systemic review conducted by Newman et al. of multiple databases in 2022 found only seven articles that demonstrated appropriately performed studies on SGM patients with IBD.5 This highlights the significant dearth of research in the realm of SGM health in IBD.

Newman and colleagues have recently published research considerations for SGM individuals. They highlighted the need to include understanding the “unique combination of psychosocial, biomedical, and legal experiences” that results in different needs and outcomes. There were several areas identified, including minority stress, which comes from existence of being SGM, especially as transgender individuals face increasing legal challenges in a variety of settings, not just healthcare.6 In a retrospective chart review investigating social determinants of health in SGM-IBD populations,12 36% of patients reported some level of social isolation, and almost 50% reported some level of stress. A total of 40% of them self-reported some perceived level of risk with respect to employment, and 17% reported depression. Given that this was a chart review and not a strict questionnaire, this study was certainly limited, and we would hypothesize that these numbers are therefore underestimating the true proportion of SGM-IBD patients who deal with employment concerns, social isolation, or psychological distress.

What Next? Back to the Patients

Circling back to our patients from the introduction, how would you counsel each of them? In patient 1’s case, we would inform him that pelvic surgery can increase the risk for sexual dysfunction, such as erectile dysfunction. He additionally would be advised during a staged TPC with IPAA, he may experience issues with body image. However, should he desire to participate in receptive anal intercourse after completion of his surgeries, the general recommendation would be to wait at least 6 months and with proven remission. It should further be noted that these are not formalized recommendations, only highlighting the need for more research and consensus on standards of care for SGM patients. He should finally be told that because he has ulcerative colitis, removal of the colon does not remove the risk for future intestinal involvement such as possible pouchitis.

In patient 2’s case, she is likely experiencing diversion vaginitis related to use of her colon for her neo-vagina. She should undergo colonoscopy and vaginoscopy in addition to standard work-up for her known ulcerative colitis.13 Management should be done in a multidisciplinary approach between the IBD provider, gynecologist, and gender-affirming provider. The electronic medical record should be updated to reflect the patient’s preferred name, pronouns, and gender identity, and her medical records, including automated clinical reports, should be updated accordingly.

As for patient 3, she would be counseled according to well-documented guidelines on pregnancy and IBD, including risks of medications (such as Jak inhibitors or methotrexate) versus the risk of uncontrolled IBD during pregnancy.1

Regardless of a patient’s gender identity or sexual orientation, patient-centered, culturally competent, and sensitive care should be provided. At Mayo Clinic in Rochester, we started one of the first Pride in IBD Clinics, which focuses on the care of SGM individuals with IBD. Our focus is to address the needs of patients who belong to the SGM community in a wholistic approach within a safe space (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pYa_zYaCA6M; https://www.mayoclinic.org/departments-centers/inflammatory-bowel-disease-clinic/overview/ovc-20357763). Our process of developing the clinic included training all staff on proper communication and cultural sensitivity for the SGM community.

Furthermore, providing welcoming and affirming signs of inclusivity for SGM individuals at the provider’s office — including but not limited to rainbow progressive flags, gender-neutral bathroom signs, or pronoun pins on provider identification badges (see Figure 2) — are usually appreciated by patients. Ensuring that patient education materials do not assume gender (for example, using the term “parents” rather than “mother and father”) and using gender neutral terms on intake forms is very important. Inclusive communication includes providers introducing themselves by preferred name and pronouns, asking the patients to introduce themselves, and welcoming them to share their pronouns. These simple actions can provide an atmosphere of safety for SGM patients, which would serve to enhance the quality of care we can provide for them.

For Resources and Further Reading: CDC,14 the Fenway Institute’s National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center,15 and US Department of Health and Human Services.16

Dr. Chiang and Dr. Chedid are both in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. Dr. Chedid is also with the Robert D. and Patricia E. Kern Center for the Science of Health Care Delivery, Mayo Clinic. Neither of the authors have any relevant conflicts of interest. They are on X, formerly Twitter: @dr_davidchiang , @VictorChedidMD .

CITATIONS

1. Mahadevan U et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in pregnancy clinical care pathway: A report from the American Gastroenterological Association IBD Parenthood Project Working Group. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1508-24.

2. Pires F et al. A survey on the impact of IBD in sexual health: Into intimacy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e32279.

3. Mules TC et al. The impact of disease activity on sexual and erectile dysfunction in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29:1244-54.

4. Duong N et al. Overcoming disparities for sexual and gender minority patients and providers in gastroenterology and hepatology: Introduction to Rainbows in Gastro. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:299-301.

5. Newman KL et al. A systematic review of inflammatory bowel disease epidemiology and health outcomes in sexual and gender minority individuals. Gastroenterology. 2023;164:866-71.

6. Newman KL et al. Research considerations in Digestive and liver disease in transgender and gender-diverse populations. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:523-28 e1.

7. Velez C et al. Digestive health in sexual and gender minority populations. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117:865-75.

8. Medicine Io. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press, 2011.

9. Austin EL. Sexual orientation disclosure to health care providers among urban and non-urban southern lesbians. Women Health. 2013;53:41-55.

10. Oladeru OT et al. Breast and cervical cancer screening disparities in transgender people. Am J Clin Oncol. 2022;45:116-21.

11. Vinsard DG et al. Healthcare providers’ perspectives on anoreceptive intercourse in sexual and gender minorities with ileal pouch anal anastomosis. Digestive Disease Week (DDW). Chicago, IL, 2023.

12. Ghusn W et al. Social determinants of health in LGBTQIA+ patients with inflammatory bowel disease. American College of Gastroenterology (ACG). Charlotte, NC, 2022.

13. Grasman ME et al. Neovaginal sparing in a transgender woman with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:e73-4.

14. Prevention CfDCa. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health — https://www.cdc.gov/lgbthealth/index.htm.

15. Institute TF. National LGBTQIA+ Health Education Center — https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/.

16. Services UDoHaH. LGBTQI+ Resources — https://www.hhs.gov/programs/topic-sites/lgbtqi/resources/index.html.

Real-world evidence: Early ileocecal resection outperforms anti-TNF therapy for Crohn’s disease

These findings add weight to previously reported data from the LIR!C trial, suggesting that ileocecal resection should be considered a first-line treatment option for CD, reported principal investigator Kristine H. Allin, MD, PhD, of Aalborg University, Copenhagen.

“The LIR!C randomized clinical trial has demonstrated comparable quality of life with ileocecal resection and infliximab as a first-line treatment for limited, nonstricturing ileocecal CD at 1 year of follow-up, and improved outcomes with ileocecal resection on retrospective analysis of long-term follow-up data,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology. “However, in the real world, the long-term impact of early ileocecal resection for CD, compared with medical therapy, remains largely unexplored.”

To gather these real-world data, the investigators turned to the Danish National Patient Registry and the Danish National Prescription Registry, which included 1,279 individuals diagnosed with CD between 2003 and 2018 who received anti-TNF therapy or underwent ileocecal resection within 1 year of diagnosis. Within this group, slightly less than half underwent ileocecal resection (45.4%) while the remainder (54.6%) received anti-TNF therapy.

The primary outcome was a composite of one or more events: perianal CD, CD-related surgery, systemic corticosteroid exposure, and CD-related hospitalization. Secondary analyses evaluated the relative risks of these same four events as independent entities.

Multifactor-adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression analysis revealed that patients who underwent ileocecal resection had a 33% lower risk of the composite outcome compared with those who received anti-TNF therapy (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.67; 95% CI, 0.54-0.83).

In the secondary analyses, which examined risks for each component of the composite outcome, the surgery group had a significantly lower risk of CD-related surgery (aHR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.39-0.80) and corticosteroid exposure (aHR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.54-0.92), but not perianal CD or CD-related hospitalization.

After 5 years, half of the patients (49.7%) who underwent ileocecal resection were not receiving any treatment for CD. At the same timepoint, a slightly lower percentage of this group (46.3%) had started immunomodulator therapy, while 16.8% started anti-TNF therapy. Just 1.8% of these patients required a second intestinal resection.

“To our knowledge, these are the first real-world data in a population-based cohort with long-term follow-up of early ileocecal resection compared with anti-TNF therapy for newly diagnosed ileal and ileocecal CD,” the investigators wrote. “These data suggest that ileocecal resection may have a role as first-line therapy in Crohn’s disease management and challenge the current paradigm of reserving surgery for complicated Crohn’s disease refractory or intolerant to medications.”

Corresponding author Manasi Agrawal, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, suggested that “validation of our findings in external cohorts [is needed], and understanding of factors associated with improved outcomes following ileocecal resection.”

For clinicians and patients choosing between first-line anti-TNF therapy versus ileocecal resection using currently available evidence, Dr. Agrawal suggested that a variety of factors need to be considered, including disease location, extent of terminal ileum involved, presence of complications such as stricture, fistula, comorbid conditions, access to biologics, financial considerations, and patient preferences.

Benjamin Cohen, MD, staff physician and co-section head and clinical director for inflammatory bowel diseases in the department of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at Cleveland Clinic, called this “an important study” because it offers the first real-world evidence to support the findings from the LIR!C trial.

Dr. Cohen agreed with Dr. Agrawal that more work is needed to determine which patients benefit most from early ileocecal resection, although he suggested that known risk factors for worse outcomes — such as early age at diagnosis, penetrating features of disease, or perianal disease — may increase strength of surgical candidacy.

Still, based on the “fairly strong” body of data now available, he suggested that all patients should be educated about first-line ileocecal resection, as it is “reasonable” approach.

“It’s always important to present surgery as a treatment option,” Dr. Cohen said in an interview. “We don’t want to think of surgery as a last resort, or a failure, because that really colors it in a negative light, and then that ultimately impacts patients’ quality of life, and their perception of outcomes.”

The study was supported by the Danish National Research Foundation. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest. Dr. Cohen disclosed consulting and speaking honoraria from AbbVie.

These findings add weight to previously reported data from the LIR!C trial, suggesting that ileocecal resection should be considered a first-line treatment option for CD, reported principal investigator Kristine H. Allin, MD, PhD, of Aalborg University, Copenhagen.

“The LIR!C randomized clinical trial has demonstrated comparable quality of life with ileocecal resection and infliximab as a first-line treatment for limited, nonstricturing ileocecal CD at 1 year of follow-up, and improved outcomes with ileocecal resection on retrospective analysis of long-term follow-up data,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology. “However, in the real world, the long-term impact of early ileocecal resection for CD, compared with medical therapy, remains largely unexplored.”

To gather these real-world data, the investigators turned to the Danish National Patient Registry and the Danish National Prescription Registry, which included 1,279 individuals diagnosed with CD between 2003 and 2018 who received anti-TNF therapy or underwent ileocecal resection within 1 year of diagnosis. Within this group, slightly less than half underwent ileocecal resection (45.4%) while the remainder (54.6%) received anti-TNF therapy.

The primary outcome was a composite of one or more events: perianal CD, CD-related surgery, systemic corticosteroid exposure, and CD-related hospitalization. Secondary analyses evaluated the relative risks of these same four events as independent entities.

Multifactor-adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression analysis revealed that patients who underwent ileocecal resection had a 33% lower risk of the composite outcome compared with those who received anti-TNF therapy (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.67; 95% CI, 0.54-0.83).

In the secondary analyses, which examined risks for each component of the composite outcome, the surgery group had a significantly lower risk of CD-related surgery (aHR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.39-0.80) and corticosteroid exposure (aHR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.54-0.92), but not perianal CD or CD-related hospitalization.

After 5 years, half of the patients (49.7%) who underwent ileocecal resection were not receiving any treatment for CD. At the same timepoint, a slightly lower percentage of this group (46.3%) had started immunomodulator therapy, while 16.8% started anti-TNF therapy. Just 1.8% of these patients required a second intestinal resection.

“To our knowledge, these are the first real-world data in a population-based cohort with long-term follow-up of early ileocecal resection compared with anti-TNF therapy for newly diagnosed ileal and ileocecal CD,” the investigators wrote. “These data suggest that ileocecal resection may have a role as first-line therapy in Crohn’s disease management and challenge the current paradigm of reserving surgery for complicated Crohn’s disease refractory or intolerant to medications.”

Corresponding author Manasi Agrawal, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, suggested that “validation of our findings in external cohorts [is needed], and understanding of factors associated with improved outcomes following ileocecal resection.”

For clinicians and patients choosing between first-line anti-TNF therapy versus ileocecal resection using currently available evidence, Dr. Agrawal suggested that a variety of factors need to be considered, including disease location, extent of terminal ileum involved, presence of complications such as stricture, fistula, comorbid conditions, access to biologics, financial considerations, and patient preferences.

Benjamin Cohen, MD, staff physician and co-section head and clinical director for inflammatory bowel diseases in the department of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at Cleveland Clinic, called this “an important study” because it offers the first real-world evidence to support the findings from the LIR!C trial.

Dr. Cohen agreed with Dr. Agrawal that more work is needed to determine which patients benefit most from early ileocecal resection, although he suggested that known risk factors for worse outcomes — such as early age at diagnosis, penetrating features of disease, or perianal disease — may increase strength of surgical candidacy.

Still, based on the “fairly strong” body of data now available, he suggested that all patients should be educated about first-line ileocecal resection, as it is “reasonable” approach.

“It’s always important to present surgery as a treatment option,” Dr. Cohen said in an interview. “We don’t want to think of surgery as a last resort, or a failure, because that really colors it in a negative light, and then that ultimately impacts patients’ quality of life, and their perception of outcomes.”

The study was supported by the Danish National Research Foundation. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest. Dr. Cohen disclosed consulting and speaking honoraria from AbbVie.

These findings add weight to previously reported data from the LIR!C trial, suggesting that ileocecal resection should be considered a first-line treatment option for CD, reported principal investigator Kristine H. Allin, MD, PhD, of Aalborg University, Copenhagen.

“The LIR!C randomized clinical trial has demonstrated comparable quality of life with ileocecal resection and infliximab as a first-line treatment for limited, nonstricturing ileocecal CD at 1 year of follow-up, and improved outcomes with ileocecal resection on retrospective analysis of long-term follow-up data,” the investigators wrote in Gastroenterology. “However, in the real world, the long-term impact of early ileocecal resection for CD, compared with medical therapy, remains largely unexplored.”

To gather these real-world data, the investigators turned to the Danish National Patient Registry and the Danish National Prescription Registry, which included 1,279 individuals diagnosed with CD between 2003 and 2018 who received anti-TNF therapy or underwent ileocecal resection within 1 year of diagnosis. Within this group, slightly less than half underwent ileocecal resection (45.4%) while the remainder (54.6%) received anti-TNF therapy.

The primary outcome was a composite of one or more events: perianal CD, CD-related surgery, systemic corticosteroid exposure, and CD-related hospitalization. Secondary analyses evaluated the relative risks of these same four events as independent entities.

Multifactor-adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression analysis revealed that patients who underwent ileocecal resection had a 33% lower risk of the composite outcome compared with those who received anti-TNF therapy (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.67; 95% CI, 0.54-0.83).

In the secondary analyses, which examined risks for each component of the composite outcome, the surgery group had a significantly lower risk of CD-related surgery (aHR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.39-0.80) and corticosteroid exposure (aHR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.54-0.92), but not perianal CD or CD-related hospitalization.

After 5 years, half of the patients (49.7%) who underwent ileocecal resection were not receiving any treatment for CD. At the same timepoint, a slightly lower percentage of this group (46.3%) had started immunomodulator therapy, while 16.8% started anti-TNF therapy. Just 1.8% of these patients required a second intestinal resection.

“To our knowledge, these are the first real-world data in a population-based cohort with long-term follow-up of early ileocecal resection compared with anti-TNF therapy for newly diagnosed ileal and ileocecal CD,” the investigators wrote. “These data suggest that ileocecal resection may have a role as first-line therapy in Crohn’s disease management and challenge the current paradigm of reserving surgery for complicated Crohn’s disease refractory or intolerant to medications.”

Corresponding author Manasi Agrawal, MD, of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, suggested that “validation of our findings in external cohorts [is needed], and understanding of factors associated with improved outcomes following ileocecal resection.”

For clinicians and patients choosing between first-line anti-TNF therapy versus ileocecal resection using currently available evidence, Dr. Agrawal suggested that a variety of factors need to be considered, including disease location, extent of terminal ileum involved, presence of complications such as stricture, fistula, comorbid conditions, access to biologics, financial considerations, and patient preferences.

Benjamin Cohen, MD, staff physician and co-section head and clinical director for inflammatory bowel diseases in the department of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at Cleveland Clinic, called this “an important study” because it offers the first real-world evidence to support the findings from the LIR!C trial.

Dr. Cohen agreed with Dr. Agrawal that more work is needed to determine which patients benefit most from early ileocecal resection, although he suggested that known risk factors for worse outcomes — such as early age at diagnosis, penetrating features of disease, or perianal disease — may increase strength of surgical candidacy.

Still, based on the “fairly strong” body of data now available, he suggested that all patients should be educated about first-line ileocecal resection, as it is “reasonable” approach.

“It’s always important to present surgery as a treatment option,” Dr. Cohen said in an interview. “We don’t want to think of surgery as a last resort, or a failure, because that really colors it in a negative light, and then that ultimately impacts patients’ quality of life, and their perception of outcomes.”

The study was supported by the Danish National Research Foundation. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest. Dr. Cohen disclosed consulting and speaking honoraria from AbbVie.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

AGA clinical practice guideline affirms role of biomarkers in Crohn’s disease management

, offering the most specific evidence-based recommendations yet for the use of fecal calprotectin (FCP) and serum C-reactive protein (CRP) in assessing disease activity.

Repeated monitoring with endoscopy allows for an objective assessment of inflammation and mucosal healing compared with symptoms alone. However, relying solely on endoscopy to guide management is an approach “limited by cost and resource utilization, invasiveness, and reduced patient acceptability,” wrote guideline authors on behalf of the AGA Clinical Guidelines Committee. The guideline was published online Nov. 17 in Gastroenterology.

“Use of biomarkers is no longer considered experimental and should be an integral part of IBD care and monitoring,” said Ashwin Ananthakrishnan, MBBS, MPH, a gastroenterologist with Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and first author of the guideline. “We need further studies to define their optimal longitudinal use, but at a given time point, there is now abundant evidence that biomarkers provide significant incremental benefit over symptoms alone in assessing a patient’s status.”

Using evidence from randomized controlled trials and observational studies, and applying it to common clinical scenarios, there are conditional recommendations on the use of biomarkers in patients with established, diagnosed disease who were asymptomatic, symptomatic, or in surgically induced remission. Those recommendations, laid out in a detailed Clinical Decision Support Tool, include the following:

For asymptomatic patients: Check CRP and FCP every 6-12 months. Patients with normal levels, and who have endoscopically confirmed remission within the last 3 years without any subsequent change in symptoms or treatment, need not undergo endoscopy and can be followed with biomarker and clinical checks alone. If CRP or FCP are elevated (defined as CRP ≥ 5 mg/L, FCP ≥ 150 mcg/g), consider repeating biomarkers and/or performing endoscopic assessment of disease activity before adjusting treatment.

For mildly symptomatic patients: Role of biomarker testing may be limited and endoscopic or radiologic assessment may be required to assess active inflammation given the higher rate of false positive and false negative results with biomarkers in this population.

For patients with more severe symptoms: Elevated CRP or FCP can be used to guide treatment adjustment without endoscopic confirmation in certain situations. Normal levels may be false negative and should be confirmed by endoscopic assessment of disease activity.

For patients in surgically induced remission with a low likelihood of recurrence: FCP levels below 50 mcg/g can be used in lieu of routine endoscopic assessment within the first year after surgery. Higher FCP levels should prompt endoscopic assessment.

For patients in surgically induced remission with a high risk of recurrence: Do not rely on biomarkers. Perform endoscopic assessment.

All recommendations were deemed of low to moderate certainty based on results from randomized clinical trials and observational studies that utilized these biomarkers in patients with Crohn’s disease. Citing a dearth of quality evidence, the guideline authors determined they could not make recommendations on the use of a third proprietary biomarker — the endoscopic healing index (EHI).

Recent AGA Clinical Practice Guidelines on the role of biomarkers in ulcerative colitis, published in March, also support a strong role for fecal and blood biomarkers, determining when these can be used to avoid unneeded endoscopic assessments. However, in patients with Crohn’s disease, symptoms correlate less well with endoscopic activity.

As a result, “biomarker performance was acceptable only in asymptomatic individuals who had recently confirmed endoscopic remission; in those without recent endoscopic assessment, test performance was suboptimal.” In addition, the weaker correlation between symptoms and endoscopic activity in Crohn’s “reduced the utility of biomarker measurement to infer disease activity in those with mild symptoms.”

The guidelines were fully funded by the AGA Institute. The authors disclosed a number of potential conflicts of interest, including receiving research grants, as well as consulting and speaking fees, from pharmaceutical companies.

, offering the most specific evidence-based recommendations yet for the use of fecal calprotectin (FCP) and serum C-reactive protein (CRP) in assessing disease activity.

Repeated monitoring with endoscopy allows for an objective assessment of inflammation and mucosal healing compared with symptoms alone. However, relying solely on endoscopy to guide management is an approach “limited by cost and resource utilization, invasiveness, and reduced patient acceptability,” wrote guideline authors on behalf of the AGA Clinical Guidelines Committee. The guideline was published online Nov. 17 in Gastroenterology.

“Use of biomarkers is no longer considered experimental and should be an integral part of IBD care and monitoring,” said Ashwin Ananthakrishnan, MBBS, MPH, a gastroenterologist with Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and first author of the guideline. “We need further studies to define their optimal longitudinal use, but at a given time point, there is now abundant evidence that biomarkers provide significant incremental benefit over symptoms alone in assessing a patient’s status.”

Using evidence from randomized controlled trials and observational studies, and applying it to common clinical scenarios, there are conditional recommendations on the use of biomarkers in patients with established, diagnosed disease who were asymptomatic, symptomatic, or in surgically induced remission. Those recommendations, laid out in a detailed Clinical Decision Support Tool, include the following: