User login

Selecting therapies in moderate to severe inflammatory bowel disease: Key factors in decision making

Despite new advances in treatment, head to head clinical trials, which are considered the gold standard when comparing therapies, remain limited. Other comparative effectiveness studies and network meta-analyses are the currently available substitutes to guide decision making.1

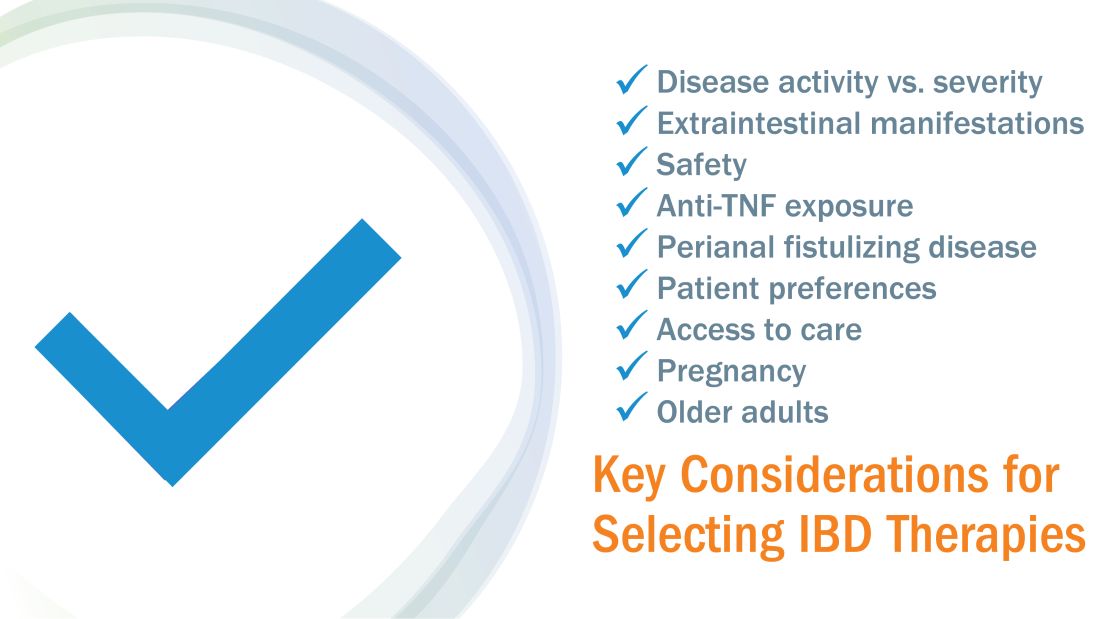

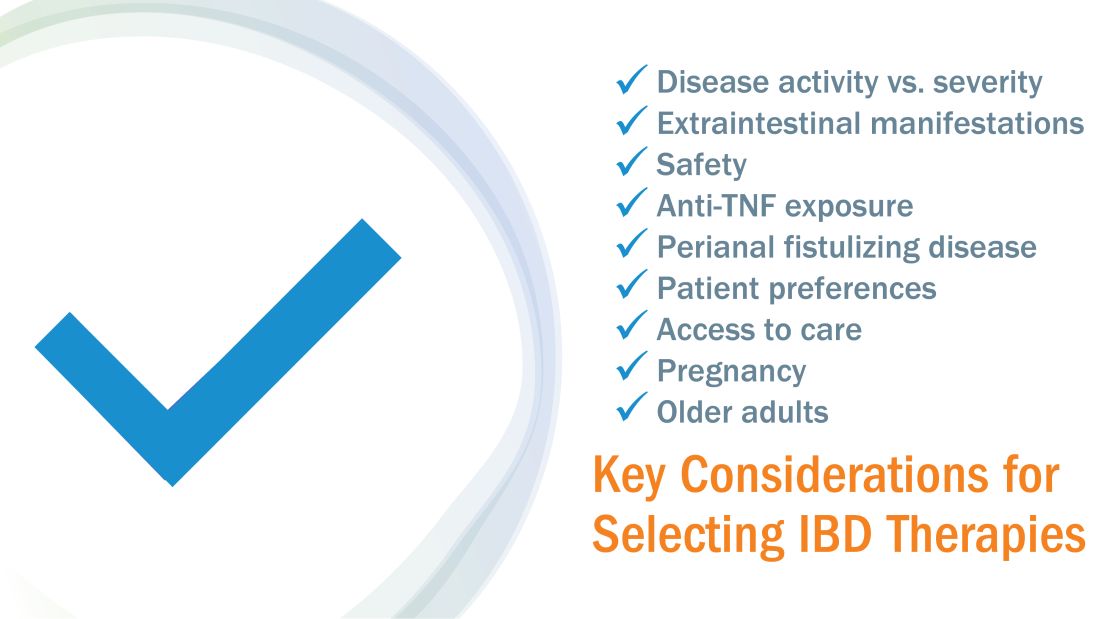

While efficacy is often considered first when choosing a drug, other critical factors play a role in tailoring a treatment plan. This article focuses on key considerations to help guide clinical decision making when treating patients with moderate to severe IBD (Figure 1).

Disease activity versus severity

Both disease activity and disease severity should be considered when evaluating a patient for treatment. Disease activity is a cross-sectional view of one’s signs and symptoms which can vary visit to visit. Standardized indices measure disease activity in both Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC).2,3 Disease severity encompasses the overall prognosis of disease over time and includes factors such as the presence or absence of high risk features, prior medication exposure, history of surgery, hospitalizations and the impact on quality of life.4

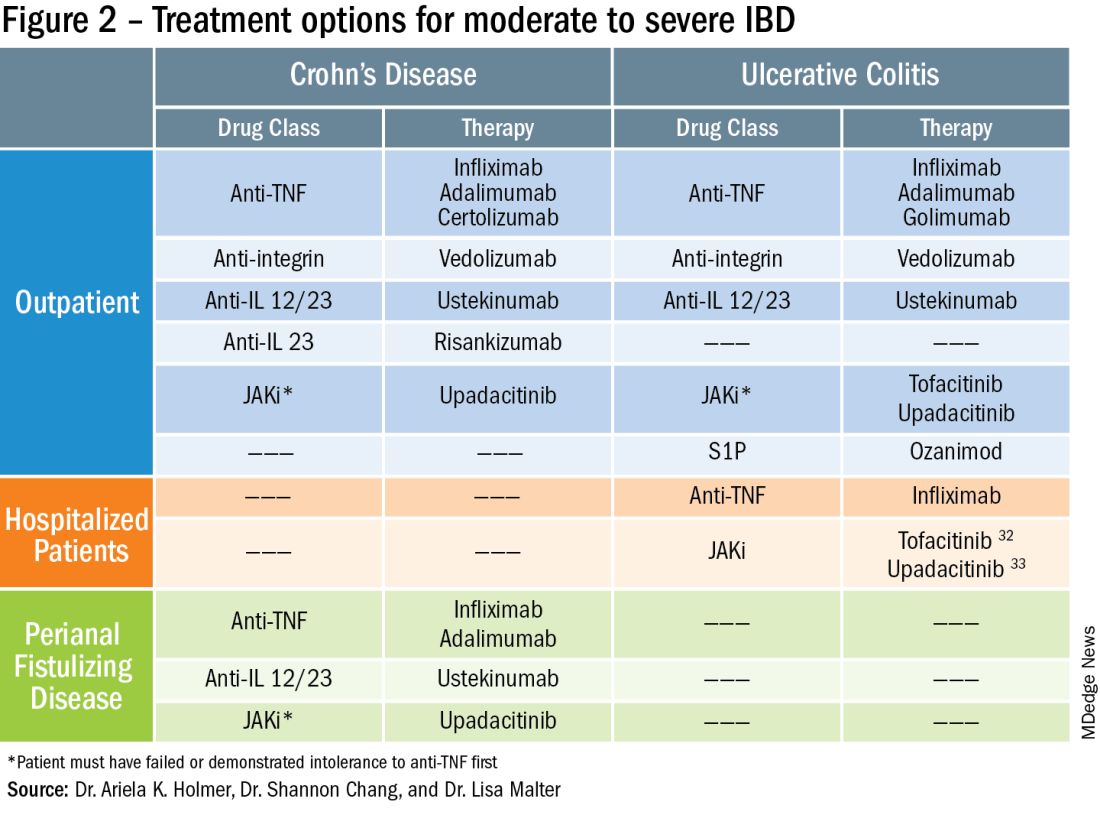

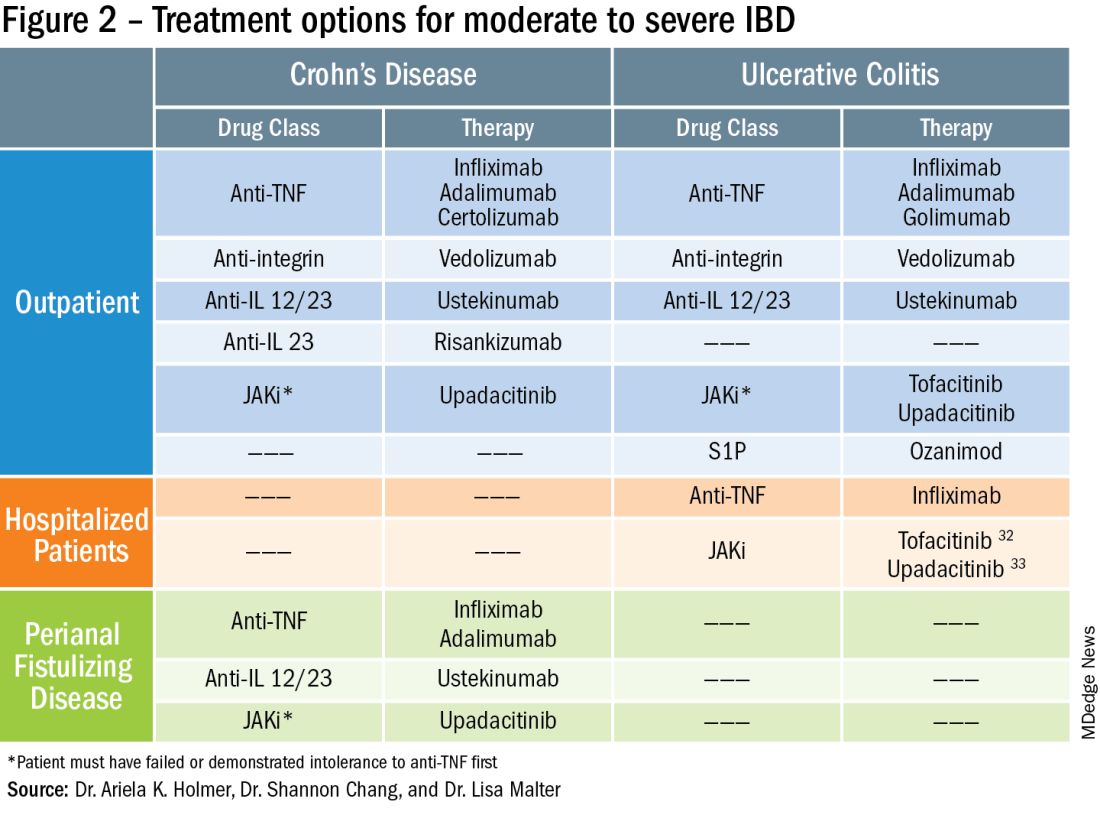

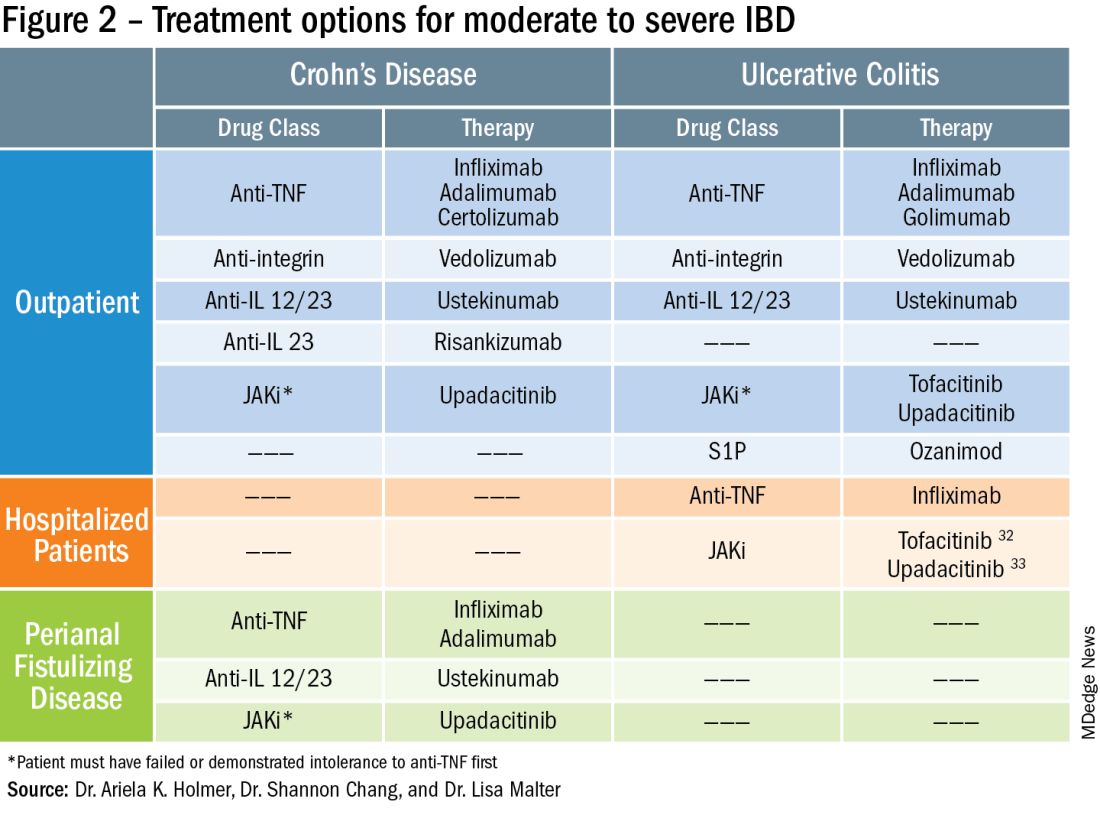

To prevent disease complications, the goals of treatment should be aimed at both reducing active symptoms (disease activity) but also healing mucosal inflammation, preventing disease progression (disease severity) and downstream sequelae including cancer, hospitalization or surgery.5 Determining the best treatment option takes disease activity and severity into account, in addition to the other key factors listed below (Figure 2).

Extraintestinal manifestations

Inflammation of organs outside of the gastrointestinal tract is common and can occur in up to 50% of patients with IBD.6 The most prevalent extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) involve the skin and joints, which will be the primary focus in this article. We will also focus on treatment options with the most evidence supporting their use. Peripheral arthritis is often associated with intestinal inflammation, and treatment of underlying IBD can simultaneously improve joint symptoms. Conversely, axial spondyloarthritis does not commonly parallel intestinal inflammation. Anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents including infliximab and adalimumab are effective for the treatment of both peripheral and axial disease.6

Ustekinumab, an interleukin (IL)-12/23 inhibitor, may be effective for peripheral arthritis, however is ineffective for the treatment of axial spondyloarthritis.6 Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors which include tofacitinib and upadacitinib are oral small molecules used to treat peripheral and axial spondyloarthritis and have more recently been approved for moderate to severe IBD.6,7

Erythema nodosum (EN) and pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) are skin manifestations seen in patients with IBD. EN appears as subcutaneous nodules and parallels intestinal inflammation, while PG consists of violaceous, ulcerated plaques, and presents with more significant pain. Anti-TNFs are effective for both EN and PG, with infliximab being the only biologic studied in a randomized control trial of patients with PG.8 In addition, small case reports have described some benefit from ustekinumab and upadacitinib in the treatment of PG.9,10

Safety

The safety of IBD therapies is a key consideration and often the most important factor to patients when choosing a treatment option. It is important to note that untreated disease is associated with significant morbidity, and should be weighed when discussing risks of medications with patients. In general, anti-TNFs and JAK inhibitors may be associated with an increased risk of infection and malignancy, while ustekinumab, vedolizumab, risankizumab and ozanimod offer a more favorable safety profile.11 In large registries and observational studies, infliximab was associated with up to a two times greater risk of serious infection as compared to nonbiologic medications, with the most common infections being pneumonia, sepsis and herpes zoster.12 JAK inhibitors are associated with an increased risk of herpes zoster infection, with a dose dependent effect seen in the maintenance clinical trials with tofacitinib.7

Ozanimod may be associated with atrioventricular conduction delays and bradycardia, however long-term safety data has reported a low incidence of serious cardiac related adverse events.13 Overall, though risks of infection may vary with different therapies, other consistent risk factors associated with greater rates of serious infection include prolonged corticosteroid use, combination therapy with thiopurines, and disease severity. Anti-TNFs have also been associated with a somewhat increased risk of lymphoma, increased when used in combination with thiopurines. Reassuringly, however, in patients with a prior history of cancer, anti-TNFs and non-TNF biologics have not been found to increase the risk of new or recurrent cancer.14

Ultimately, in patients with a prior history of cancer, the choice of biologic or small molecule should be made in collaboration with a patient’s oncologist.

Anti-TNF exposure

Anti-TNFs were the first available biologics for the treatment of IBD. After the approval of vedolizumab in 2014, the first non-TNF biologic, many patients enrolled in clinical trials thereafter had already tried and failed anti-TNFs. In general, exposure to anti-TNFs may reduce the efficacy of a future biologic. In patients treated with vedolizumab, endoscopic and clinical outcomes were negatively impacted by prior anti-TNF exposure.15 However, in VARSITY, a head-to-head clinical trial where 20% of patients with UC were previously exposed to anti-TNFs other than adalimumab, vedolizumab had significantly higher rates of clinical remission and endoscopic improvement compared to adalimumab.16 Clinical remission rates with tofacitinib were not impacted by exposure to anti-TNF treatment, and similar findings were observed with ustekinumab.7,17 Risankizumab, a newly approved selective anti-IL23, also does not appear to be impacted by prior anti-TNF exposure by demonstrating similar rates of clinical remission regardless of biologic exposure status.18 Therefore, in patients with prior history of anti-TNF use, consideration of ustekinumab, risankizumab or JAK inhibitors as second line agents may be more favorable as compared to vedolizumab.

Perianal fistulizing disease

Perianal fistulizing disease can affect up to one-third of patients with CD and significantly impact a patient’s quality of life.19 The most robust data for the treatment of perianal fistulizing disease includes the use of infliximab with up to one-third of patients on maintenance therapy achieving complete resolution of fistula drainage. While no head-to-head trials compare combination therapy with infliximab plus immunomodulators versus infliximab alone for this indication specifically, one observational study demonstrated higher rates of fistula closure with combination therapy as compared to infliximab mono-therapy.19 In a post hoc analysis, higher infliximab concentrations at week 14 were associated with greater fistula response and remission rates.20 In patients with perianal disease, ustekinumab and vedolizumab may also be an effective treatment option by promoting resolution of fistula drainage.21

More recently, emerging data demonstrate that upadacitinib may be an excellent option as a second-line treatment for perianal disease in patients who have failed anti-TNF therapy. Use of upadacitinib was associated with greater rates of complete resolution of fistula drainage and higher rates of external fistula closure (Figure 2).22 Lastly, as an alternative to medical therapy, mesenchymal stem cell therapy has also shown to improve fistula drainage and improve external fistula openings in patients with CD.23 Stem cell therapy is only available through clinical trials at this time.

Patient preferences

Overall, data are lacking for evaluating patient preferences in treatment options for IBD especially with the recent increase in therapeutic options. One survey demonstrated that patient preferences were most impacted by the possibility of improving abdominal pain, with patients accepting additional risk of treatment side effects in order to reduce their abdominal pain.24 An oral route of administration and improving fatigue and bowel urgency were similarly important to patients. Patient preferences can also be highly variable with some valuing avoidance of corticosteroid use while others valuing avoidance of symptoms or risks of medication side effects and surgery. It is important to tailor the discussion on treatment strategies to each individual patient and inquire about the patient’s lifestyle, medical history, and value system, which may impact their treatment preferences utilizing shared decision making.

Access to treatment including the role of social determinants of health

The expanded therapeutic armamentarium has the potential to help patients achieve the current goals of care in IBD. However, these medications are not available to all patients due to numerous barriers including step therapy payer policies, prohibitive costs, insurance prior authorizations, and the role of social determinants of health and proximity to IBD expertise.25 While clinicians work with patients to determine the best treatment option, more often than not, the decision lies with the insurance payer. Step therapy is the protocol used by insurance companies that requires patients to try a lower-cost medication and fail to respond before they approve the originally requested treatment. This can lead to treatment delays, progression of disease, and disease complications. The option to incorporate the use of biosimilars, currently available for anti-TNFs, and other biologics in the near future, will reduce cost and potentially increase access.26 Additionally, working with a clinical pharmacist to navigate access and utilize patient assistance programs may help overcome cost related barriers to treatment and prevent delays in care.

Socioeconomic status has been shown to impact IBD disease outcomes, and compliance rates in treatment vary depending on race and ethnicity.27 Certain racial and ethnic groups remain vulnerable and may require additional support to achieve treatment goals. For example, disparities in health literacy in patients with IBD have been demonstrated with older black men at risk.28 Additionally, the patient’s proximity to their health care facility may impact treatment options. Most IBD centers are located in metropolitan areas and numerous “IBD deserts” exist, potentially limiting therapies for patients from more remote/rural settings.29 Access to treatment and the interplay of social determinants of health can have a large role in therapy selection.

Special considerations: Pregnancy and older adults

Certain patient populations warrant special consideration when approaching treatment strategies. Pregnancy in IBD will not be addressed in full depth in this article, however a key takeaway is that planning is critical and providers should emphasize the importance of steroid-free clinical remission for at least 3 months before conception.30 Additionally, biologic use during pregnancy has not been shown to increase adverse fetal outcomes, thus should be continued to minimize disease flare. Newer novel small molecules are generally avoided during pregnancy due to limited available safety data.

Older adults are the largest growing patient population with IBD. Frailty, or a state of decreased reserve, is more commonly observed in older patients and has been shown to increase adverse events including hospitalization and mortaility.31 Ultimately reducing polypharmacy, ensuring adequate nutrition, minimizing corticosteroid exposure and avoiding undertreatment of active IBD are all key in optimizing outcomes in an older patient with IBD.

Conclusion

When discussing treatment options with patients with IBD, it is important to individualize care and share the decision-making process with patients. Goals include improving symptoms and quality of life while working to achieve the goal of healing intestinal inflammation. In summary, this article can serve as a guide to clinicians for key factors in decision making when selecting therapies in moderate to severe IBD.

Dr. Holmer is a gastroenterologist with NYU Langone Health specializing in inflammatory bowel disease. Dr. Chang is director of clinical operations for the NYU Langone Health Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center. Dr. Malter is director of education for the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at NYU Langone Health and director of the inflammatory bowel disease program at Bellevue Hospital Center. Follow Dr. Holmer on X (formerly Twitter) at @HolmerMd and Dr. Chang @shannonchangmd. Dr. Holmer disclosed affiliations with Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, and AvevoRx. Dr. Chang disclosed affiliations with Pfizer and Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr. Malter disclosed receiving educational grants form Abbvie, Janssen, Pfizer and Takeda, and serving on the advisory boards of AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celltrion, Janssen, Merck, and Takeda.

References

1. Chang S et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023 Aug 24. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002485.

2. Harvey RF et al. The Lancet. 1980;1:514.

3. Lewis JD et al. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2008;14:1660-1666.

4. Siegel CA et al. Gut. 2018;67(2):244-54.

5. Peyrin-Biroulet L et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1324-38

6. Rogler G et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1118-32.

7. Sandborn WJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1723-36.

8. Brooklyn TN et al. Gut. 2006;55:505-9.

9. Fahmy M et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:794-5.

10. Van Eycken L et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;37:89-91.

11. Lasa JS et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:161-70.

12. Lichtenstein GR et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:490-501.

13. Long MD et al. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:S-5-S-6.

14. Holmer AK et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.2023;21:1598-1606.e5.

15. Sands BE et al. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:618-27.e3.

16. Sands BE et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1215-26.

17. Sands BE et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1201-14.

18. D’Haens G et al. Lancet. 2022;399:2015-30.

19. Bouguen G et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:975-81.e1-4.

20. Papamichael K et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:1007-14.

21. Shehab M et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29:367-75.

22. Colombel JF et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:i620-i623.

23. Garcia-Olmo D et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022;65:713-20.

24. Louis E et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:231-9.

25. Rubin DT et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:224-32.

26. Gulacsi L et al. Curr Med Chem. 2019;26:259-69.

27. Cai Q et al. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:545.

28. Dos Santos Marques IC et al. Crohns Colitis 360. 2020 Oct;2(4):otaa076.

29. Deepak P et al. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:11-15.

30. Mahadevan U et al. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1508-24.

31. Faye AS et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28:126-32.

32. Berinstein JA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:2112-20.e1.

33. Levine J et al. Gastroenterology. 2023;164:S103-S104.

Despite new advances in treatment, head to head clinical trials, which are considered the gold standard when comparing therapies, remain limited. Other comparative effectiveness studies and network meta-analyses are the currently available substitutes to guide decision making.1

While efficacy is often considered first when choosing a drug, other critical factors play a role in tailoring a treatment plan. This article focuses on key considerations to help guide clinical decision making when treating patients with moderate to severe IBD (Figure 1).

Disease activity versus severity

Both disease activity and disease severity should be considered when evaluating a patient for treatment. Disease activity is a cross-sectional view of one’s signs and symptoms which can vary visit to visit. Standardized indices measure disease activity in both Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC).2,3 Disease severity encompasses the overall prognosis of disease over time and includes factors such as the presence or absence of high risk features, prior medication exposure, history of surgery, hospitalizations and the impact on quality of life.4

To prevent disease complications, the goals of treatment should be aimed at both reducing active symptoms (disease activity) but also healing mucosal inflammation, preventing disease progression (disease severity) and downstream sequelae including cancer, hospitalization or surgery.5 Determining the best treatment option takes disease activity and severity into account, in addition to the other key factors listed below (Figure 2).

Extraintestinal manifestations

Inflammation of organs outside of the gastrointestinal tract is common and can occur in up to 50% of patients with IBD.6 The most prevalent extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) involve the skin and joints, which will be the primary focus in this article. We will also focus on treatment options with the most evidence supporting their use. Peripheral arthritis is often associated with intestinal inflammation, and treatment of underlying IBD can simultaneously improve joint symptoms. Conversely, axial spondyloarthritis does not commonly parallel intestinal inflammation. Anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents including infliximab and adalimumab are effective for the treatment of both peripheral and axial disease.6

Ustekinumab, an interleukin (IL)-12/23 inhibitor, may be effective for peripheral arthritis, however is ineffective for the treatment of axial spondyloarthritis.6 Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors which include tofacitinib and upadacitinib are oral small molecules used to treat peripheral and axial spondyloarthritis and have more recently been approved for moderate to severe IBD.6,7

Erythema nodosum (EN) and pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) are skin manifestations seen in patients with IBD. EN appears as subcutaneous nodules and parallels intestinal inflammation, while PG consists of violaceous, ulcerated plaques, and presents with more significant pain. Anti-TNFs are effective for both EN and PG, with infliximab being the only biologic studied in a randomized control trial of patients with PG.8 In addition, small case reports have described some benefit from ustekinumab and upadacitinib in the treatment of PG.9,10

Safety

The safety of IBD therapies is a key consideration and often the most important factor to patients when choosing a treatment option. It is important to note that untreated disease is associated with significant morbidity, and should be weighed when discussing risks of medications with patients. In general, anti-TNFs and JAK inhibitors may be associated with an increased risk of infection and malignancy, while ustekinumab, vedolizumab, risankizumab and ozanimod offer a more favorable safety profile.11 In large registries and observational studies, infliximab was associated with up to a two times greater risk of serious infection as compared to nonbiologic medications, with the most common infections being pneumonia, sepsis and herpes zoster.12 JAK inhibitors are associated with an increased risk of herpes zoster infection, with a dose dependent effect seen in the maintenance clinical trials with tofacitinib.7

Ozanimod may be associated with atrioventricular conduction delays and bradycardia, however long-term safety data has reported a low incidence of serious cardiac related adverse events.13 Overall, though risks of infection may vary with different therapies, other consistent risk factors associated with greater rates of serious infection include prolonged corticosteroid use, combination therapy with thiopurines, and disease severity. Anti-TNFs have also been associated with a somewhat increased risk of lymphoma, increased when used in combination with thiopurines. Reassuringly, however, in patients with a prior history of cancer, anti-TNFs and non-TNF biologics have not been found to increase the risk of new or recurrent cancer.14

Ultimately, in patients with a prior history of cancer, the choice of biologic or small molecule should be made in collaboration with a patient’s oncologist.

Anti-TNF exposure

Anti-TNFs were the first available biologics for the treatment of IBD. After the approval of vedolizumab in 2014, the first non-TNF biologic, many patients enrolled in clinical trials thereafter had already tried and failed anti-TNFs. In general, exposure to anti-TNFs may reduce the efficacy of a future biologic. In patients treated with vedolizumab, endoscopic and clinical outcomes were negatively impacted by prior anti-TNF exposure.15 However, in VARSITY, a head-to-head clinical trial where 20% of patients with UC were previously exposed to anti-TNFs other than adalimumab, vedolizumab had significantly higher rates of clinical remission and endoscopic improvement compared to adalimumab.16 Clinical remission rates with tofacitinib were not impacted by exposure to anti-TNF treatment, and similar findings were observed with ustekinumab.7,17 Risankizumab, a newly approved selective anti-IL23, also does not appear to be impacted by prior anti-TNF exposure by demonstrating similar rates of clinical remission regardless of biologic exposure status.18 Therefore, in patients with prior history of anti-TNF use, consideration of ustekinumab, risankizumab or JAK inhibitors as second line agents may be more favorable as compared to vedolizumab.

Perianal fistulizing disease

Perianal fistulizing disease can affect up to one-third of patients with CD and significantly impact a patient’s quality of life.19 The most robust data for the treatment of perianal fistulizing disease includes the use of infliximab with up to one-third of patients on maintenance therapy achieving complete resolution of fistula drainage. While no head-to-head trials compare combination therapy with infliximab plus immunomodulators versus infliximab alone for this indication specifically, one observational study demonstrated higher rates of fistula closure with combination therapy as compared to infliximab mono-therapy.19 In a post hoc analysis, higher infliximab concentrations at week 14 were associated with greater fistula response and remission rates.20 In patients with perianal disease, ustekinumab and vedolizumab may also be an effective treatment option by promoting resolution of fistula drainage.21

More recently, emerging data demonstrate that upadacitinib may be an excellent option as a second-line treatment for perianal disease in patients who have failed anti-TNF therapy. Use of upadacitinib was associated with greater rates of complete resolution of fistula drainage and higher rates of external fistula closure (Figure 2).22 Lastly, as an alternative to medical therapy, mesenchymal stem cell therapy has also shown to improve fistula drainage and improve external fistula openings in patients with CD.23 Stem cell therapy is only available through clinical trials at this time.

Patient preferences

Overall, data are lacking for evaluating patient preferences in treatment options for IBD especially with the recent increase in therapeutic options. One survey demonstrated that patient preferences were most impacted by the possibility of improving abdominal pain, with patients accepting additional risk of treatment side effects in order to reduce their abdominal pain.24 An oral route of administration and improving fatigue and bowel urgency were similarly important to patients. Patient preferences can also be highly variable with some valuing avoidance of corticosteroid use while others valuing avoidance of symptoms or risks of medication side effects and surgery. It is important to tailor the discussion on treatment strategies to each individual patient and inquire about the patient’s lifestyle, medical history, and value system, which may impact their treatment preferences utilizing shared decision making.

Access to treatment including the role of social determinants of health

The expanded therapeutic armamentarium has the potential to help patients achieve the current goals of care in IBD. However, these medications are not available to all patients due to numerous barriers including step therapy payer policies, prohibitive costs, insurance prior authorizations, and the role of social determinants of health and proximity to IBD expertise.25 While clinicians work with patients to determine the best treatment option, more often than not, the decision lies with the insurance payer. Step therapy is the protocol used by insurance companies that requires patients to try a lower-cost medication and fail to respond before they approve the originally requested treatment. This can lead to treatment delays, progression of disease, and disease complications. The option to incorporate the use of biosimilars, currently available for anti-TNFs, and other biologics in the near future, will reduce cost and potentially increase access.26 Additionally, working with a clinical pharmacist to navigate access and utilize patient assistance programs may help overcome cost related barriers to treatment and prevent delays in care.

Socioeconomic status has been shown to impact IBD disease outcomes, and compliance rates in treatment vary depending on race and ethnicity.27 Certain racial and ethnic groups remain vulnerable and may require additional support to achieve treatment goals. For example, disparities in health literacy in patients with IBD have been demonstrated with older black men at risk.28 Additionally, the patient’s proximity to their health care facility may impact treatment options. Most IBD centers are located in metropolitan areas and numerous “IBD deserts” exist, potentially limiting therapies for patients from more remote/rural settings.29 Access to treatment and the interplay of social determinants of health can have a large role in therapy selection.

Special considerations: Pregnancy and older adults

Certain patient populations warrant special consideration when approaching treatment strategies. Pregnancy in IBD will not be addressed in full depth in this article, however a key takeaway is that planning is critical and providers should emphasize the importance of steroid-free clinical remission for at least 3 months before conception.30 Additionally, biologic use during pregnancy has not been shown to increase adverse fetal outcomes, thus should be continued to minimize disease flare. Newer novel small molecules are generally avoided during pregnancy due to limited available safety data.

Older adults are the largest growing patient population with IBD. Frailty, or a state of decreased reserve, is more commonly observed in older patients and has been shown to increase adverse events including hospitalization and mortaility.31 Ultimately reducing polypharmacy, ensuring adequate nutrition, minimizing corticosteroid exposure and avoiding undertreatment of active IBD are all key in optimizing outcomes in an older patient with IBD.

Conclusion

When discussing treatment options with patients with IBD, it is important to individualize care and share the decision-making process with patients. Goals include improving symptoms and quality of life while working to achieve the goal of healing intestinal inflammation. In summary, this article can serve as a guide to clinicians for key factors in decision making when selecting therapies in moderate to severe IBD.

Dr. Holmer is a gastroenterologist with NYU Langone Health specializing in inflammatory bowel disease. Dr. Chang is director of clinical operations for the NYU Langone Health Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center. Dr. Malter is director of education for the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at NYU Langone Health and director of the inflammatory bowel disease program at Bellevue Hospital Center. Follow Dr. Holmer on X (formerly Twitter) at @HolmerMd and Dr. Chang @shannonchangmd. Dr. Holmer disclosed affiliations with Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, and AvevoRx. Dr. Chang disclosed affiliations with Pfizer and Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr. Malter disclosed receiving educational grants form Abbvie, Janssen, Pfizer and Takeda, and serving on the advisory boards of AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celltrion, Janssen, Merck, and Takeda.

References

1. Chang S et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023 Aug 24. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002485.

2. Harvey RF et al. The Lancet. 1980;1:514.

3. Lewis JD et al. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2008;14:1660-1666.

4. Siegel CA et al. Gut. 2018;67(2):244-54.

5. Peyrin-Biroulet L et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1324-38

6. Rogler G et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1118-32.

7. Sandborn WJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1723-36.

8. Brooklyn TN et al. Gut. 2006;55:505-9.

9. Fahmy M et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:794-5.

10. Van Eycken L et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;37:89-91.

11. Lasa JS et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:161-70.

12. Lichtenstein GR et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:490-501.

13. Long MD et al. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:S-5-S-6.

14. Holmer AK et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.2023;21:1598-1606.e5.

15. Sands BE et al. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:618-27.e3.

16. Sands BE et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1215-26.

17. Sands BE et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1201-14.

18. D’Haens G et al. Lancet. 2022;399:2015-30.

19. Bouguen G et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:975-81.e1-4.

20. Papamichael K et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:1007-14.

21. Shehab M et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29:367-75.

22. Colombel JF et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:i620-i623.

23. Garcia-Olmo D et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022;65:713-20.

24. Louis E et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:231-9.

25. Rubin DT et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:224-32.

26. Gulacsi L et al. Curr Med Chem. 2019;26:259-69.

27. Cai Q et al. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:545.

28. Dos Santos Marques IC et al. Crohns Colitis 360. 2020 Oct;2(4):otaa076.

29. Deepak P et al. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:11-15.

30. Mahadevan U et al. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1508-24.

31. Faye AS et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28:126-32.

32. Berinstein JA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:2112-20.e1.

33. Levine J et al. Gastroenterology. 2023;164:S103-S104.

Despite new advances in treatment, head to head clinical trials, which are considered the gold standard when comparing therapies, remain limited. Other comparative effectiveness studies and network meta-analyses are the currently available substitutes to guide decision making.1

While efficacy is often considered first when choosing a drug, other critical factors play a role in tailoring a treatment plan. This article focuses on key considerations to help guide clinical decision making when treating patients with moderate to severe IBD (Figure 1).

Disease activity versus severity

Both disease activity and disease severity should be considered when evaluating a patient for treatment. Disease activity is a cross-sectional view of one’s signs and symptoms which can vary visit to visit. Standardized indices measure disease activity in both Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC).2,3 Disease severity encompasses the overall prognosis of disease over time and includes factors such as the presence or absence of high risk features, prior medication exposure, history of surgery, hospitalizations and the impact on quality of life.4

To prevent disease complications, the goals of treatment should be aimed at both reducing active symptoms (disease activity) but also healing mucosal inflammation, preventing disease progression (disease severity) and downstream sequelae including cancer, hospitalization or surgery.5 Determining the best treatment option takes disease activity and severity into account, in addition to the other key factors listed below (Figure 2).

Extraintestinal manifestations

Inflammation of organs outside of the gastrointestinal tract is common and can occur in up to 50% of patients with IBD.6 The most prevalent extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) involve the skin and joints, which will be the primary focus in this article. We will also focus on treatment options with the most evidence supporting their use. Peripheral arthritis is often associated with intestinal inflammation, and treatment of underlying IBD can simultaneously improve joint symptoms. Conversely, axial spondyloarthritis does not commonly parallel intestinal inflammation. Anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents including infliximab and adalimumab are effective for the treatment of both peripheral and axial disease.6

Ustekinumab, an interleukin (IL)-12/23 inhibitor, may be effective for peripheral arthritis, however is ineffective for the treatment of axial spondyloarthritis.6 Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors which include tofacitinib and upadacitinib are oral small molecules used to treat peripheral and axial spondyloarthritis and have more recently been approved for moderate to severe IBD.6,7

Erythema nodosum (EN) and pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) are skin manifestations seen in patients with IBD. EN appears as subcutaneous nodules and parallels intestinal inflammation, while PG consists of violaceous, ulcerated plaques, and presents with more significant pain. Anti-TNFs are effective for both EN and PG, with infliximab being the only biologic studied in a randomized control trial of patients with PG.8 In addition, small case reports have described some benefit from ustekinumab and upadacitinib in the treatment of PG.9,10

Safety

The safety of IBD therapies is a key consideration and often the most important factor to patients when choosing a treatment option. It is important to note that untreated disease is associated with significant morbidity, and should be weighed when discussing risks of medications with patients. In general, anti-TNFs and JAK inhibitors may be associated with an increased risk of infection and malignancy, while ustekinumab, vedolizumab, risankizumab and ozanimod offer a more favorable safety profile.11 In large registries and observational studies, infliximab was associated with up to a two times greater risk of serious infection as compared to nonbiologic medications, with the most common infections being pneumonia, sepsis and herpes zoster.12 JAK inhibitors are associated with an increased risk of herpes zoster infection, with a dose dependent effect seen in the maintenance clinical trials with tofacitinib.7

Ozanimod may be associated with atrioventricular conduction delays and bradycardia, however long-term safety data has reported a low incidence of serious cardiac related adverse events.13 Overall, though risks of infection may vary with different therapies, other consistent risk factors associated with greater rates of serious infection include prolonged corticosteroid use, combination therapy with thiopurines, and disease severity. Anti-TNFs have also been associated with a somewhat increased risk of lymphoma, increased when used in combination with thiopurines. Reassuringly, however, in patients with a prior history of cancer, anti-TNFs and non-TNF biologics have not been found to increase the risk of new or recurrent cancer.14

Ultimately, in patients with a prior history of cancer, the choice of biologic or small molecule should be made in collaboration with a patient’s oncologist.

Anti-TNF exposure

Anti-TNFs were the first available biologics for the treatment of IBD. After the approval of vedolizumab in 2014, the first non-TNF biologic, many patients enrolled in clinical trials thereafter had already tried and failed anti-TNFs. In general, exposure to anti-TNFs may reduce the efficacy of a future biologic. In patients treated with vedolizumab, endoscopic and clinical outcomes were negatively impacted by prior anti-TNF exposure.15 However, in VARSITY, a head-to-head clinical trial where 20% of patients with UC were previously exposed to anti-TNFs other than adalimumab, vedolizumab had significantly higher rates of clinical remission and endoscopic improvement compared to adalimumab.16 Clinical remission rates with tofacitinib were not impacted by exposure to anti-TNF treatment, and similar findings were observed with ustekinumab.7,17 Risankizumab, a newly approved selective anti-IL23, also does not appear to be impacted by prior anti-TNF exposure by demonstrating similar rates of clinical remission regardless of biologic exposure status.18 Therefore, in patients with prior history of anti-TNF use, consideration of ustekinumab, risankizumab or JAK inhibitors as second line agents may be more favorable as compared to vedolizumab.

Perianal fistulizing disease

Perianal fistulizing disease can affect up to one-third of patients with CD and significantly impact a patient’s quality of life.19 The most robust data for the treatment of perianal fistulizing disease includes the use of infliximab with up to one-third of patients on maintenance therapy achieving complete resolution of fistula drainage. While no head-to-head trials compare combination therapy with infliximab plus immunomodulators versus infliximab alone for this indication specifically, one observational study demonstrated higher rates of fistula closure with combination therapy as compared to infliximab mono-therapy.19 In a post hoc analysis, higher infliximab concentrations at week 14 were associated with greater fistula response and remission rates.20 In patients with perianal disease, ustekinumab and vedolizumab may also be an effective treatment option by promoting resolution of fistula drainage.21

More recently, emerging data demonstrate that upadacitinib may be an excellent option as a second-line treatment for perianal disease in patients who have failed anti-TNF therapy. Use of upadacitinib was associated with greater rates of complete resolution of fistula drainage and higher rates of external fistula closure (Figure 2).22 Lastly, as an alternative to medical therapy, mesenchymal stem cell therapy has also shown to improve fistula drainage and improve external fistula openings in patients with CD.23 Stem cell therapy is only available through clinical trials at this time.

Patient preferences

Overall, data are lacking for evaluating patient preferences in treatment options for IBD especially with the recent increase in therapeutic options. One survey demonstrated that patient preferences were most impacted by the possibility of improving abdominal pain, with patients accepting additional risk of treatment side effects in order to reduce their abdominal pain.24 An oral route of administration and improving fatigue and bowel urgency were similarly important to patients. Patient preferences can also be highly variable with some valuing avoidance of corticosteroid use while others valuing avoidance of symptoms or risks of medication side effects and surgery. It is important to tailor the discussion on treatment strategies to each individual patient and inquire about the patient’s lifestyle, medical history, and value system, which may impact their treatment preferences utilizing shared decision making.

Access to treatment including the role of social determinants of health

The expanded therapeutic armamentarium has the potential to help patients achieve the current goals of care in IBD. However, these medications are not available to all patients due to numerous barriers including step therapy payer policies, prohibitive costs, insurance prior authorizations, and the role of social determinants of health and proximity to IBD expertise.25 While clinicians work with patients to determine the best treatment option, more often than not, the decision lies with the insurance payer. Step therapy is the protocol used by insurance companies that requires patients to try a lower-cost medication and fail to respond before they approve the originally requested treatment. This can lead to treatment delays, progression of disease, and disease complications. The option to incorporate the use of biosimilars, currently available for anti-TNFs, and other biologics in the near future, will reduce cost and potentially increase access.26 Additionally, working with a clinical pharmacist to navigate access and utilize patient assistance programs may help overcome cost related barriers to treatment and prevent delays in care.

Socioeconomic status has been shown to impact IBD disease outcomes, and compliance rates in treatment vary depending on race and ethnicity.27 Certain racial and ethnic groups remain vulnerable and may require additional support to achieve treatment goals. For example, disparities in health literacy in patients with IBD have been demonstrated with older black men at risk.28 Additionally, the patient’s proximity to their health care facility may impact treatment options. Most IBD centers are located in metropolitan areas and numerous “IBD deserts” exist, potentially limiting therapies for patients from more remote/rural settings.29 Access to treatment and the interplay of social determinants of health can have a large role in therapy selection.

Special considerations: Pregnancy and older adults

Certain patient populations warrant special consideration when approaching treatment strategies. Pregnancy in IBD will not be addressed in full depth in this article, however a key takeaway is that planning is critical and providers should emphasize the importance of steroid-free clinical remission for at least 3 months before conception.30 Additionally, biologic use during pregnancy has not been shown to increase adverse fetal outcomes, thus should be continued to minimize disease flare. Newer novel small molecules are generally avoided during pregnancy due to limited available safety data.

Older adults are the largest growing patient population with IBD. Frailty, or a state of decreased reserve, is more commonly observed in older patients and has been shown to increase adverse events including hospitalization and mortaility.31 Ultimately reducing polypharmacy, ensuring adequate nutrition, minimizing corticosteroid exposure and avoiding undertreatment of active IBD are all key in optimizing outcomes in an older patient with IBD.

Conclusion

When discussing treatment options with patients with IBD, it is important to individualize care and share the decision-making process with patients. Goals include improving symptoms and quality of life while working to achieve the goal of healing intestinal inflammation. In summary, this article can serve as a guide to clinicians for key factors in decision making when selecting therapies in moderate to severe IBD.

Dr. Holmer is a gastroenterologist with NYU Langone Health specializing in inflammatory bowel disease. Dr. Chang is director of clinical operations for the NYU Langone Health Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center. Dr. Malter is director of education for the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at NYU Langone Health and director of the inflammatory bowel disease program at Bellevue Hospital Center. Follow Dr. Holmer on X (formerly Twitter) at @HolmerMd and Dr. Chang @shannonchangmd. Dr. Holmer disclosed affiliations with Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, and AvevoRx. Dr. Chang disclosed affiliations with Pfizer and Bristol Myers Squibb. Dr. Malter disclosed receiving educational grants form Abbvie, Janssen, Pfizer and Takeda, and serving on the advisory boards of AbbVie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celltrion, Janssen, Merck, and Takeda.

References

1. Chang S et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2023 Aug 24. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002485.

2. Harvey RF et al. The Lancet. 1980;1:514.

3. Lewis JD et al. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2008;14:1660-1666.

4. Siegel CA et al. Gut. 2018;67(2):244-54.

5. Peyrin-Biroulet L et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1324-38

6. Rogler G et al. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1118-32.

7. Sandborn WJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1723-36.

8. Brooklyn TN et al. Gut. 2006;55:505-9.

9. Fahmy M et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:794-5.

10. Van Eycken L et al. JAAD Case Rep. 2023;37:89-91.

11. Lasa JS et al. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:161-70.

12. Lichtenstein GR et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:490-501.

13. Long MD et al. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:S-5-S-6.

14. Holmer AK et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.2023;21:1598-1606.e5.

15. Sands BE et al. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:618-27.e3.

16. Sands BE et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1215-26.

17. Sands BE et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1201-14.

18. D’Haens G et al. Lancet. 2022;399:2015-30.

19. Bouguen G et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:975-81.e1-4.

20. Papamichael K et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:1007-14.

21. Shehab M et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29:367-75.

22. Colombel JF et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:i620-i623.

23. Garcia-Olmo D et al. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022;65:713-20.

24. Louis E et al. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17:231-9.

25. Rubin DT et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:224-32.

26. Gulacsi L et al. Curr Med Chem. 2019;26:259-69.

27. Cai Q et al. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:545.

28. Dos Santos Marques IC et al. Crohns Colitis 360. 2020 Oct;2(4):otaa076.

29. Deepak P et al. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:11-15.

30. Mahadevan U et al. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1508-24.

31. Faye AS et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28:126-32.

32. Berinstein JA et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:2112-20.e1.

33. Levine J et al. Gastroenterology. 2023;164:S103-S104.