User login

Androgenetic Alopecia: What Works?

When it comes to selecting medical treatments for androgenetic alopecia (AGA), patients and practitioners alike want to know, “What works?” The ideal AGA treatment is one that meets 4 criteria: highly effective, safe, affordable, and easy to use. To date, there is no known treatment for AGA that meets all these criteria. Some therapies are more effective than others, but there are no treatments at present that are able to completely and permanently reverse the condition. Some treatments are safer, some are less expensive, and some are easier to use than others. In the end, the treatment that the patient chooses is influenced not only by its known effectiveness but also by the value that the patient places on the other 3 categories—safety, affordability, and ease of use. Therefore, shared decision-making between patient and practitioner is central to the selection of specific AGA treatments.

Effectiveness: Some Treatments Work Better Than Others

Of the nearly 2 dozen medical treatments for AGA, some have been found to be more effective than others. Whether a given treatment should be considered a bona fide AGA therapy—and then whether to position it as a first-line, second-line, or third-line agent—depends on the answers to 3 fundamental questions:

- Does the treatment truly help patients with AGA?

- How effective is this treatment?

- How safe is it?

Does the Treatment Truly Help Patients?—Surprisingly, it is not always straightforward to confirm that a given treatment helps patients with AGA. Does oral finasteride help female AGA? Yes and no: Finasteride 1 mg is ineffective in the treatment of female AGA, but higher doses such as 2.5 or 5 mg likely have benefit.1,2 Does topical minoxidil help AGA? Yes and no: Minoxidil 5% is ineffective in the treatment of a male with Hamilton-Norwood stage VII AGA but often is helpful in earlier stages of the condition.

One of the best ways to determine if a treatment really helps AGA is to evaluate how it performs in the setting of a well-conducted, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. These types of clinical trials have been performed for many known AGA treatments and give us some of the best evidence that a treatment truly works. The AGA treatments with the highest-quality evidence (level 1) are topical minoxidil, oral finasteride, and oral dutasteride for male AGA and topical minoxidil for female AGA.

How Effective Is This Treatment?—Patients are particularly interested to know whether a given treatment has the potential to notably restore hair density. It is one thing to know that use of the treatment might slightly improve hair density and another to know that it could potentially lead to dramatic improvement. In addition, patients want to know whether a specific treatment they are considering is more (or less) likely to improve their hair density compared to another treatment.

Advanced statistical methods such as the network meta-analysis are increasingly being used to understand how individual treatments from different studies compare. Two recent studies have provided us with powerful data on the relative efficacy of minoxidil and 5α-reductase inhibitors in the treatment of both male and female AGA.2,3 A 2022 network meta-analysis of male AGA ranked treatment efficacy from most to least effective: oral dutasteride 0.5 mg, oral finasteride 5 mg, oral minoxidil 5 mg, oral finasteride 1 mg, and topical minoxidil 5%.3 Similarly, a 2023 network meta-analysis of female AGA ranked treatment efficacy from most to least effective: oral 5 mg finasteride, minoxidil solution 5% twice daily, oral minoxidil 1 mg, and minoxidil foam 5% once daily.2 We are not yet able to rank all known treatments for AGA.

Things We Tend to Ignore: Quality of Data, Long-term Results, Nonresponders, and Study Populations—There are a few caveats for anyone treating AGA. First, the quality of published AGA studies is highly variable and many are of low quality. The highest-quality evidence (level 1) for male AGA comes from studies of minoxidil solution/foam 5% twice daily, oral finasteride 1 mg, and oral dutasteride 0.5 mg. For female AGA, the highest-quality evidence is for topical minoxidil—either 5% foam once daily or 2% solution twice daily. Lower-quality studies limit conclusions and the ability to properly compare treatments.

Second, long-term data are nonexistent for most of our AGA treatments. The exceptions include finasteride, dutasteride, and topical minoxidil, which have reasonably adequate long-term studies.4-6 However, most other treatments have been evaluated only through short-term studies. It is tempting to assume that results from a 24-week study can be used to infer how a patient might respond when using the same treatment over the course of many decades; however, making these assumptions would be unwise.

Third, most AGA treatments help improve hair density in only a proportion of patients who decide to use the given treatment. There usually is one subgroup of patients for whom the treatment does not seem to help much at all and one subgroup for whom the treatment halts further hair loss but does not regrow hair. For example, in the case of finasteride treatment of male AGA, approximately 10% of patients do not seem to respond to treatment at all, and another 50% seem to be able to halt further loss but never achieve hair regrowth.7 In an analysis of 12 studies with 3927 male patients, Mella et al8 showed that 5.6 patients needed to be treated short term and 3.4 patients needed to be treated long term for 1 patient to perceive an improvement in the hair. It is clear that many males who use finasteride will not see evidence of hair regrowth. This same general concept applies for all available treatments and is important to remember if a patient with AGA decides to start 2 new treatments simultaneously. Consider the 34-year-old man who starts oral minoxidil and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) for AGA. At his follow-up appointment 9 months later, the patient reports improved hair density and wants to know what contributed to the improvement: the oral minoxidil, the PRP, or both? Many practitioners would believe that both treatments likely provided some degree of benefit—but in reality, that represents a flaw in logic. If 2 hair loss treatments are started at exactly the same time, it is impossible to know the relative benefit of each treatment and whether one might not be helping at all. Combination therapies are still common in my practice and highly encouraged, but my personal preference is to stagger start dates whenever possible so I can determine each treatment’s contribution to the patient’s final outcome.

Finally, when evaluating what works for AGA, we need to define the specific patient subpopulation, as the available data are less robust for some patient groups than others. We have limited data in children and adolescents with AGA, as well as limited comparative data across different racial backgrounds, body mass indices, and underlying health issues. For example, data on the most effective strategies to treat female AGA in the setting of polycystic ovary syndrome, premature menopause, and other endocrine disorders are lacking.

Which Treatments Also Have Good Safety?—The treatment that a patient ultimately selects also depends on its actual or perceived safety. Patients have vastly different levels of risk tolerance. Some patients would much rather start a less effective treatment if they believe that the chances of experiencing treatment-related adverse effects would be lower. In general, topical and injectable treatments tend to have fewer adverse effects than oral therapies. Long-term safety data generally are lacking for many hair-loss therapies. A limited number of studies of topical minoxidil include data up to 5 years,4 and some studies of oral finasteride and oral dutasteride include patients who used these medications for up to 10 years.5,6

So Then, What Works?

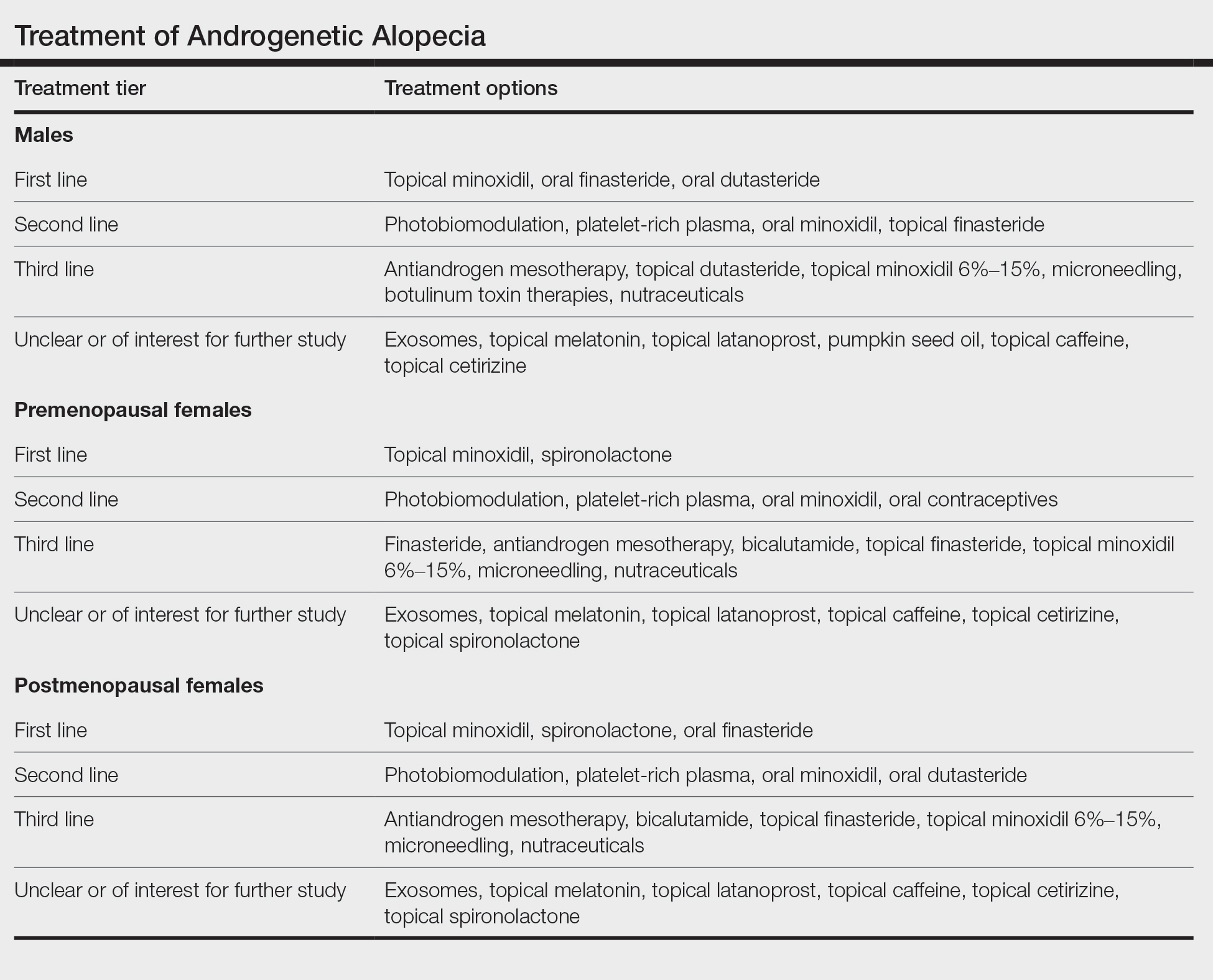

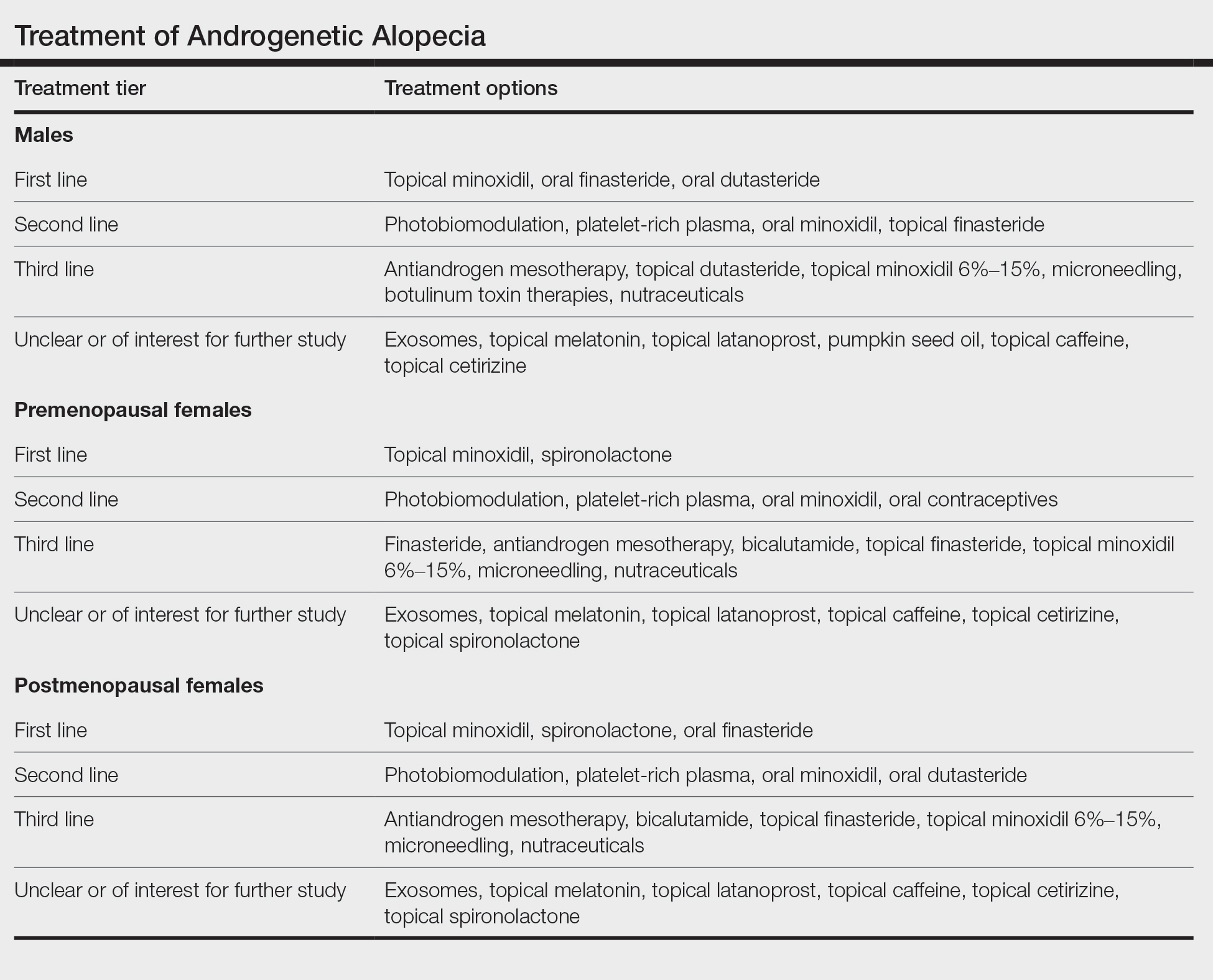

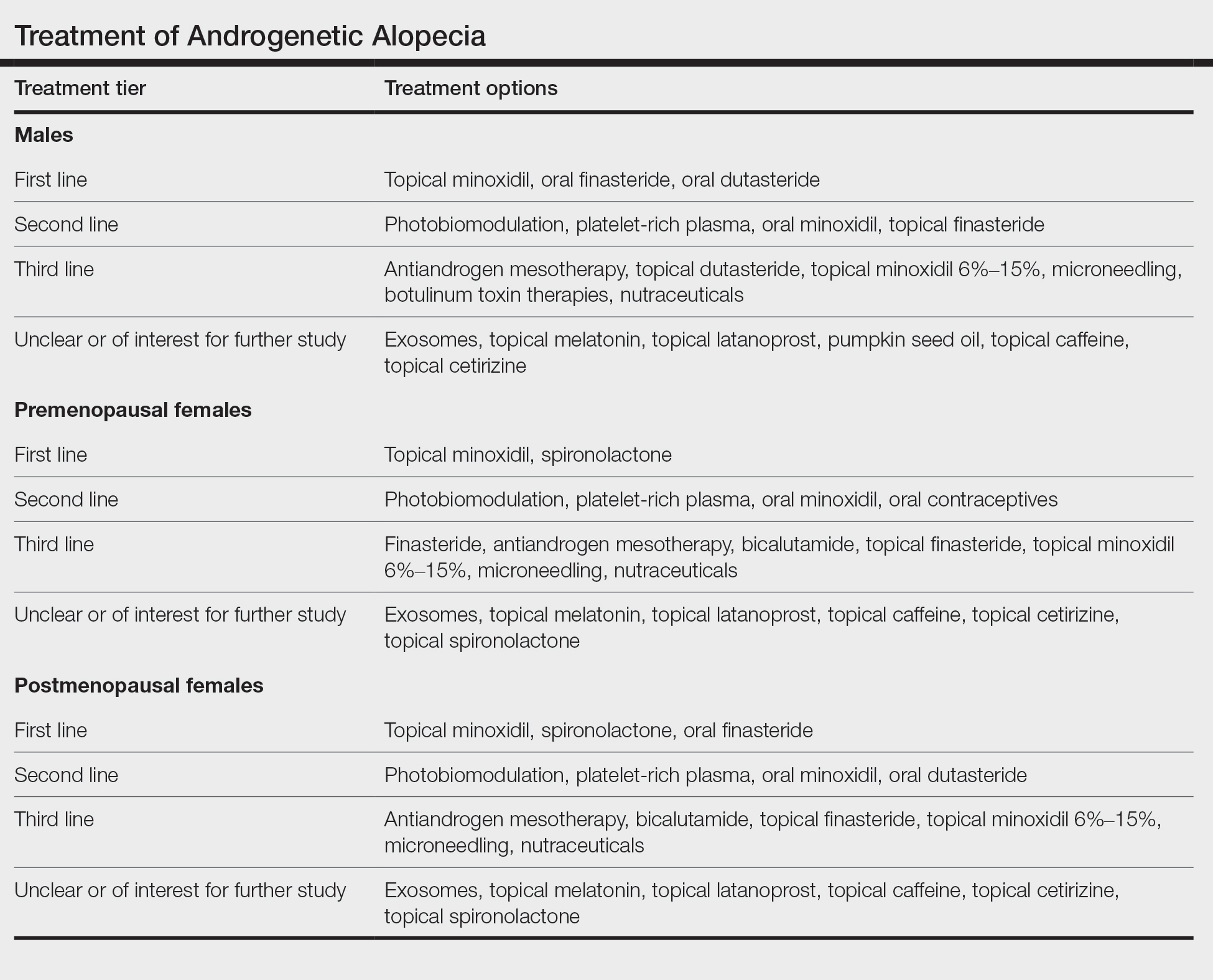

The Table shows treatments for AGA and how I prioritize starting them in my own clinic. First-line treatment options often include those with level 1 evidence but also may include those with less-robust evidence plus a good history (over many years) of safety, affordability, ease of use, and effectiveness (eg, spironolactone and finasteride for female-pattern hair loss).

• Male AGA: I consider topical minoxidil, oral finasteride, and oral dutasteride as first-line agents, and low-level laser, PRP, oral minoxidil, and topical finasteride as second-line agents. Only topical minoxidil and oral finasteride are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for AGA in males; laser devices are FDA cleared.

• Premenopausal females with AGA: I use topical minoxidil and spironolactone as first-line agents. Low-level laser, PRP, oral minoxidil, and oral contraceptives are helpful second-line agents. Only topical minoxidil is FDA approved in women. I consider all treatments, with the exception of low-level laser, to be contraindicated in pregnancy.

• Postmenopausal females with AGA: I consider topical minoxidil, spironolactone, and oral finasteride as first-line agents. Low-level laser, PRP, oral minoxidil, and oral dutasteride are helpful second-line agents.

When choosing an initial treatment plan, I generally will start with one or more first-line options. I will then add or replace with remaining first-line options or a second-line option after 6 to 12 months depending on how well the patient responds to the first-line options. Patients who do not wish to use first-line options or have contraindications begin with second-line options. Third-line options are best reserved for patients who do not respond to or do not wish to use first- and second-line options.

Experts differ in opinion as to what constitutes a first-line treatment option and what constitutes a second- or third-line option. For example, some increasingly consider oral minoxidil to be a first-line option for AGA.9 In my opinion, the lack of high-quality comparative, randomized, controlled trials and long-term safety data keep oral minoxidil reserved as a respectable second-line option. Similarly, some experts reserve oral dutasteride as a second-line option for AGA.10 In my opinion, the data now are of the highest-quality evidence (level 1)9 to support placing oral dutasteride in the tier of first-line treatments.

Shared decision-making using an evidence-based approach is ultimately what connects patients with treatment plans that offer a good chance of helping to improve hair loss.

- Price VH, Roberts JL, Hordinsky M, et al. Lack of efficacy of finasteride in postmenopausal women with androgenetic alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(5 pt 1):768-776. doi:10.1067/mjd.2000.107953

- Gupta AK, Bamimore MA, Foley KA. Efficacy of non-surgical treatments for androgenetic alopecia in men and women: a systematic review with network meta-analyses, and an assessment of evidence quality. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:62-72. doi:10.1080/09546634.2020.1749547

- Gupta AK, Wang T, Bamimore MA, et al. The relative effect of monotherapy with 5-alpha reductase inhibitors and minoxidil for female pattern hair loss: a network meta-analysis study [published online June 29, 2023]. J Cosmet Dermatol. doi:10.1111/jocd.15910

- Olsen EA, Weiner MS, Amara IA, et al. Five-year follow-up of men with androgenetic alopecia treated with topical minoxidil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:64.

- Choi G-S, Sim W-Y, Kang H, et al. Long-term effectiveness and safety of dutasteride versus finasteride in patients with male androgenic alopecia in South Korea: a multicentre chart review study. Ann Dermatol. 2022;34:349-359. doi:10.5021/ad.22.027

- Rossi A, Cantisani C, Scarnò M, et al. Finasteride, 1 mg daily administration on male androgenetic alopecia in different age groups: 10-year follow-up. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:455-461.

- Kaufman KD, Olsen EA, Whiting D, et al. Finasteride in the treatment of men with androgenetic alopecia. Finasteride Male Pattern Hair Loss Study Group. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(4 pt 1):578-89. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70007-6

- Mella JM, Perret MC, Manzotti M, et al. Efficacy and safety offinasteride therapy for androgenetic alopecia: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1141-1150. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.256

- Vañó-Galván S, Fernandez-Crehuet P, Garnacho G, et al; Spanish Trichology Research Group. Recommendations on the clinical management of androgenetic alopecia: a consensus statement from the Spanish Trichology Group of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venererology (AEDV). Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2023 Oct 25:S0001-7310(23)00844-X. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2023.10.013. Online ahead of print.

- Kanti V, Messenger A, Dobos G, et al. Evidence-based (S3) guideline for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in women and in men - short version. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:11-22. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14624

When it comes to selecting medical treatments for androgenetic alopecia (AGA), patients and practitioners alike want to know, “What works?” The ideal AGA treatment is one that meets 4 criteria: highly effective, safe, affordable, and easy to use. To date, there is no known treatment for AGA that meets all these criteria. Some therapies are more effective than others, but there are no treatments at present that are able to completely and permanently reverse the condition. Some treatments are safer, some are less expensive, and some are easier to use than others. In the end, the treatment that the patient chooses is influenced not only by its known effectiveness but also by the value that the patient places on the other 3 categories—safety, affordability, and ease of use. Therefore, shared decision-making between patient and practitioner is central to the selection of specific AGA treatments.

Effectiveness: Some Treatments Work Better Than Others

Of the nearly 2 dozen medical treatments for AGA, some have been found to be more effective than others. Whether a given treatment should be considered a bona fide AGA therapy—and then whether to position it as a first-line, second-line, or third-line agent—depends on the answers to 3 fundamental questions:

- Does the treatment truly help patients with AGA?

- How effective is this treatment?

- How safe is it?

Does the Treatment Truly Help Patients?—Surprisingly, it is not always straightforward to confirm that a given treatment helps patients with AGA. Does oral finasteride help female AGA? Yes and no: Finasteride 1 mg is ineffective in the treatment of female AGA, but higher doses such as 2.5 or 5 mg likely have benefit.1,2 Does topical minoxidil help AGA? Yes and no: Minoxidil 5% is ineffective in the treatment of a male with Hamilton-Norwood stage VII AGA but often is helpful in earlier stages of the condition.

One of the best ways to determine if a treatment really helps AGA is to evaluate how it performs in the setting of a well-conducted, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. These types of clinical trials have been performed for many known AGA treatments and give us some of the best evidence that a treatment truly works. The AGA treatments with the highest-quality evidence (level 1) are topical minoxidil, oral finasteride, and oral dutasteride for male AGA and topical minoxidil for female AGA.

How Effective Is This Treatment?—Patients are particularly interested to know whether a given treatment has the potential to notably restore hair density. It is one thing to know that use of the treatment might slightly improve hair density and another to know that it could potentially lead to dramatic improvement. In addition, patients want to know whether a specific treatment they are considering is more (or less) likely to improve their hair density compared to another treatment.

Advanced statistical methods such as the network meta-analysis are increasingly being used to understand how individual treatments from different studies compare. Two recent studies have provided us with powerful data on the relative efficacy of minoxidil and 5α-reductase inhibitors in the treatment of both male and female AGA.2,3 A 2022 network meta-analysis of male AGA ranked treatment efficacy from most to least effective: oral dutasteride 0.5 mg, oral finasteride 5 mg, oral minoxidil 5 mg, oral finasteride 1 mg, and topical minoxidil 5%.3 Similarly, a 2023 network meta-analysis of female AGA ranked treatment efficacy from most to least effective: oral 5 mg finasteride, minoxidil solution 5% twice daily, oral minoxidil 1 mg, and minoxidil foam 5% once daily.2 We are not yet able to rank all known treatments for AGA.

Things We Tend to Ignore: Quality of Data, Long-term Results, Nonresponders, and Study Populations—There are a few caveats for anyone treating AGA. First, the quality of published AGA studies is highly variable and many are of low quality. The highest-quality evidence (level 1) for male AGA comes from studies of minoxidil solution/foam 5% twice daily, oral finasteride 1 mg, and oral dutasteride 0.5 mg. For female AGA, the highest-quality evidence is for topical minoxidil—either 5% foam once daily or 2% solution twice daily. Lower-quality studies limit conclusions and the ability to properly compare treatments.

Second, long-term data are nonexistent for most of our AGA treatments. The exceptions include finasteride, dutasteride, and topical minoxidil, which have reasonably adequate long-term studies.4-6 However, most other treatments have been evaluated only through short-term studies. It is tempting to assume that results from a 24-week study can be used to infer how a patient might respond when using the same treatment over the course of many decades; however, making these assumptions would be unwise.

Third, most AGA treatments help improve hair density in only a proportion of patients who decide to use the given treatment. There usually is one subgroup of patients for whom the treatment does not seem to help much at all and one subgroup for whom the treatment halts further hair loss but does not regrow hair. For example, in the case of finasteride treatment of male AGA, approximately 10% of patients do not seem to respond to treatment at all, and another 50% seem to be able to halt further loss but never achieve hair regrowth.7 In an analysis of 12 studies with 3927 male patients, Mella et al8 showed that 5.6 patients needed to be treated short term and 3.4 patients needed to be treated long term for 1 patient to perceive an improvement in the hair. It is clear that many males who use finasteride will not see evidence of hair regrowth. This same general concept applies for all available treatments and is important to remember if a patient with AGA decides to start 2 new treatments simultaneously. Consider the 34-year-old man who starts oral minoxidil and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) for AGA. At his follow-up appointment 9 months later, the patient reports improved hair density and wants to know what contributed to the improvement: the oral minoxidil, the PRP, or both? Many practitioners would believe that both treatments likely provided some degree of benefit—but in reality, that represents a flaw in logic. If 2 hair loss treatments are started at exactly the same time, it is impossible to know the relative benefit of each treatment and whether one might not be helping at all. Combination therapies are still common in my practice and highly encouraged, but my personal preference is to stagger start dates whenever possible so I can determine each treatment’s contribution to the patient’s final outcome.

Finally, when evaluating what works for AGA, we need to define the specific patient subpopulation, as the available data are less robust for some patient groups than others. We have limited data in children and adolescents with AGA, as well as limited comparative data across different racial backgrounds, body mass indices, and underlying health issues. For example, data on the most effective strategies to treat female AGA in the setting of polycystic ovary syndrome, premature menopause, and other endocrine disorders are lacking.

Which Treatments Also Have Good Safety?—The treatment that a patient ultimately selects also depends on its actual or perceived safety. Patients have vastly different levels of risk tolerance. Some patients would much rather start a less effective treatment if they believe that the chances of experiencing treatment-related adverse effects would be lower. In general, topical and injectable treatments tend to have fewer adverse effects than oral therapies. Long-term safety data generally are lacking for many hair-loss therapies. A limited number of studies of topical minoxidil include data up to 5 years,4 and some studies of oral finasteride and oral dutasteride include patients who used these medications for up to 10 years.5,6

So Then, What Works?

The Table shows treatments for AGA and how I prioritize starting them in my own clinic. First-line treatment options often include those with level 1 evidence but also may include those with less-robust evidence plus a good history (over many years) of safety, affordability, ease of use, and effectiveness (eg, spironolactone and finasteride for female-pattern hair loss).

• Male AGA: I consider topical minoxidil, oral finasteride, and oral dutasteride as first-line agents, and low-level laser, PRP, oral minoxidil, and topical finasteride as second-line agents. Only topical minoxidil and oral finasteride are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for AGA in males; laser devices are FDA cleared.

• Premenopausal females with AGA: I use topical minoxidil and spironolactone as first-line agents. Low-level laser, PRP, oral minoxidil, and oral contraceptives are helpful second-line agents. Only topical minoxidil is FDA approved in women. I consider all treatments, with the exception of low-level laser, to be contraindicated in pregnancy.

• Postmenopausal females with AGA: I consider topical minoxidil, spironolactone, and oral finasteride as first-line agents. Low-level laser, PRP, oral minoxidil, and oral dutasteride are helpful second-line agents.

When choosing an initial treatment plan, I generally will start with one or more first-line options. I will then add or replace with remaining first-line options or a second-line option after 6 to 12 months depending on how well the patient responds to the first-line options. Patients who do not wish to use first-line options or have contraindications begin with second-line options. Third-line options are best reserved for patients who do not respond to or do not wish to use first- and second-line options.

Experts differ in opinion as to what constitutes a first-line treatment option and what constitutes a second- or third-line option. For example, some increasingly consider oral minoxidil to be a first-line option for AGA.9 In my opinion, the lack of high-quality comparative, randomized, controlled trials and long-term safety data keep oral minoxidil reserved as a respectable second-line option. Similarly, some experts reserve oral dutasteride as a second-line option for AGA.10 In my opinion, the data now are of the highest-quality evidence (level 1)9 to support placing oral dutasteride in the tier of first-line treatments.

Shared decision-making using an evidence-based approach is ultimately what connects patients with treatment plans that offer a good chance of helping to improve hair loss.

When it comes to selecting medical treatments for androgenetic alopecia (AGA), patients and practitioners alike want to know, “What works?” The ideal AGA treatment is one that meets 4 criteria: highly effective, safe, affordable, and easy to use. To date, there is no known treatment for AGA that meets all these criteria. Some therapies are more effective than others, but there are no treatments at present that are able to completely and permanently reverse the condition. Some treatments are safer, some are less expensive, and some are easier to use than others. In the end, the treatment that the patient chooses is influenced not only by its known effectiveness but also by the value that the patient places on the other 3 categories—safety, affordability, and ease of use. Therefore, shared decision-making between patient and practitioner is central to the selection of specific AGA treatments.

Effectiveness: Some Treatments Work Better Than Others

Of the nearly 2 dozen medical treatments for AGA, some have been found to be more effective than others. Whether a given treatment should be considered a bona fide AGA therapy—and then whether to position it as a first-line, second-line, or third-line agent—depends on the answers to 3 fundamental questions:

- Does the treatment truly help patients with AGA?

- How effective is this treatment?

- How safe is it?

Does the Treatment Truly Help Patients?—Surprisingly, it is not always straightforward to confirm that a given treatment helps patients with AGA. Does oral finasteride help female AGA? Yes and no: Finasteride 1 mg is ineffective in the treatment of female AGA, but higher doses such as 2.5 or 5 mg likely have benefit.1,2 Does topical minoxidil help AGA? Yes and no: Minoxidil 5% is ineffective in the treatment of a male with Hamilton-Norwood stage VII AGA but often is helpful in earlier stages of the condition.

One of the best ways to determine if a treatment really helps AGA is to evaluate how it performs in the setting of a well-conducted, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. These types of clinical trials have been performed for many known AGA treatments and give us some of the best evidence that a treatment truly works. The AGA treatments with the highest-quality evidence (level 1) are topical minoxidil, oral finasteride, and oral dutasteride for male AGA and topical minoxidil for female AGA.

How Effective Is This Treatment?—Patients are particularly interested to know whether a given treatment has the potential to notably restore hair density. It is one thing to know that use of the treatment might slightly improve hair density and another to know that it could potentially lead to dramatic improvement. In addition, patients want to know whether a specific treatment they are considering is more (or less) likely to improve their hair density compared to another treatment.

Advanced statistical methods such as the network meta-analysis are increasingly being used to understand how individual treatments from different studies compare. Two recent studies have provided us with powerful data on the relative efficacy of minoxidil and 5α-reductase inhibitors in the treatment of both male and female AGA.2,3 A 2022 network meta-analysis of male AGA ranked treatment efficacy from most to least effective: oral dutasteride 0.5 mg, oral finasteride 5 mg, oral minoxidil 5 mg, oral finasteride 1 mg, and topical minoxidil 5%.3 Similarly, a 2023 network meta-analysis of female AGA ranked treatment efficacy from most to least effective: oral 5 mg finasteride, minoxidil solution 5% twice daily, oral minoxidil 1 mg, and minoxidil foam 5% once daily.2 We are not yet able to rank all known treatments for AGA.

Things We Tend to Ignore: Quality of Data, Long-term Results, Nonresponders, and Study Populations—There are a few caveats for anyone treating AGA. First, the quality of published AGA studies is highly variable and many are of low quality. The highest-quality evidence (level 1) for male AGA comes from studies of minoxidil solution/foam 5% twice daily, oral finasteride 1 mg, and oral dutasteride 0.5 mg. For female AGA, the highest-quality evidence is for topical minoxidil—either 5% foam once daily or 2% solution twice daily. Lower-quality studies limit conclusions and the ability to properly compare treatments.

Second, long-term data are nonexistent for most of our AGA treatments. The exceptions include finasteride, dutasteride, and topical minoxidil, which have reasonably adequate long-term studies.4-6 However, most other treatments have been evaluated only through short-term studies. It is tempting to assume that results from a 24-week study can be used to infer how a patient might respond when using the same treatment over the course of many decades; however, making these assumptions would be unwise.

Third, most AGA treatments help improve hair density in only a proportion of patients who decide to use the given treatment. There usually is one subgroup of patients for whom the treatment does not seem to help much at all and one subgroup for whom the treatment halts further hair loss but does not regrow hair. For example, in the case of finasteride treatment of male AGA, approximately 10% of patients do not seem to respond to treatment at all, and another 50% seem to be able to halt further loss but never achieve hair regrowth.7 In an analysis of 12 studies with 3927 male patients, Mella et al8 showed that 5.6 patients needed to be treated short term and 3.4 patients needed to be treated long term for 1 patient to perceive an improvement in the hair. It is clear that many males who use finasteride will not see evidence of hair regrowth. This same general concept applies for all available treatments and is important to remember if a patient with AGA decides to start 2 new treatments simultaneously. Consider the 34-year-old man who starts oral minoxidil and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) for AGA. At his follow-up appointment 9 months later, the patient reports improved hair density and wants to know what contributed to the improvement: the oral minoxidil, the PRP, or both? Many practitioners would believe that both treatments likely provided some degree of benefit—but in reality, that represents a flaw in logic. If 2 hair loss treatments are started at exactly the same time, it is impossible to know the relative benefit of each treatment and whether one might not be helping at all. Combination therapies are still common in my practice and highly encouraged, but my personal preference is to stagger start dates whenever possible so I can determine each treatment’s contribution to the patient’s final outcome.

Finally, when evaluating what works for AGA, we need to define the specific patient subpopulation, as the available data are less robust for some patient groups than others. We have limited data in children and adolescents with AGA, as well as limited comparative data across different racial backgrounds, body mass indices, and underlying health issues. For example, data on the most effective strategies to treat female AGA in the setting of polycystic ovary syndrome, premature menopause, and other endocrine disorders are lacking.

Which Treatments Also Have Good Safety?—The treatment that a patient ultimately selects also depends on its actual or perceived safety. Patients have vastly different levels of risk tolerance. Some patients would much rather start a less effective treatment if they believe that the chances of experiencing treatment-related adverse effects would be lower. In general, topical and injectable treatments tend to have fewer adverse effects than oral therapies. Long-term safety data generally are lacking for many hair-loss therapies. A limited number of studies of topical minoxidil include data up to 5 years,4 and some studies of oral finasteride and oral dutasteride include patients who used these medications for up to 10 years.5,6

So Then, What Works?

The Table shows treatments for AGA and how I prioritize starting them in my own clinic. First-line treatment options often include those with level 1 evidence but also may include those with less-robust evidence plus a good history (over many years) of safety, affordability, ease of use, and effectiveness (eg, spironolactone and finasteride for female-pattern hair loss).

• Male AGA: I consider topical minoxidil, oral finasteride, and oral dutasteride as first-line agents, and low-level laser, PRP, oral minoxidil, and topical finasteride as second-line agents. Only topical minoxidil and oral finasteride are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for AGA in males; laser devices are FDA cleared.

• Premenopausal females with AGA: I use topical minoxidil and spironolactone as first-line agents. Low-level laser, PRP, oral minoxidil, and oral contraceptives are helpful second-line agents. Only topical minoxidil is FDA approved in women. I consider all treatments, with the exception of low-level laser, to be contraindicated in pregnancy.

• Postmenopausal females with AGA: I consider topical minoxidil, spironolactone, and oral finasteride as first-line agents. Low-level laser, PRP, oral minoxidil, and oral dutasteride are helpful second-line agents.

When choosing an initial treatment plan, I generally will start with one or more first-line options. I will then add or replace with remaining first-line options or a second-line option after 6 to 12 months depending on how well the patient responds to the first-line options. Patients who do not wish to use first-line options or have contraindications begin with second-line options. Third-line options are best reserved for patients who do not respond to or do not wish to use first- and second-line options.

Experts differ in opinion as to what constitutes a first-line treatment option and what constitutes a second- or third-line option. For example, some increasingly consider oral minoxidil to be a first-line option for AGA.9 In my opinion, the lack of high-quality comparative, randomized, controlled trials and long-term safety data keep oral minoxidil reserved as a respectable second-line option. Similarly, some experts reserve oral dutasteride as a second-line option for AGA.10 In my opinion, the data now are of the highest-quality evidence (level 1)9 to support placing oral dutasteride in the tier of first-line treatments.

Shared decision-making using an evidence-based approach is ultimately what connects patients with treatment plans that offer a good chance of helping to improve hair loss.

- Price VH, Roberts JL, Hordinsky M, et al. Lack of efficacy of finasteride in postmenopausal women with androgenetic alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(5 pt 1):768-776. doi:10.1067/mjd.2000.107953

- Gupta AK, Bamimore MA, Foley KA. Efficacy of non-surgical treatments for androgenetic alopecia in men and women: a systematic review with network meta-analyses, and an assessment of evidence quality. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:62-72. doi:10.1080/09546634.2020.1749547

- Gupta AK, Wang T, Bamimore MA, et al. The relative effect of monotherapy with 5-alpha reductase inhibitors and minoxidil for female pattern hair loss: a network meta-analysis study [published online June 29, 2023]. J Cosmet Dermatol. doi:10.1111/jocd.15910

- Olsen EA, Weiner MS, Amara IA, et al. Five-year follow-up of men with androgenetic alopecia treated with topical minoxidil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:64.

- Choi G-S, Sim W-Y, Kang H, et al. Long-term effectiveness and safety of dutasteride versus finasteride in patients with male androgenic alopecia in South Korea: a multicentre chart review study. Ann Dermatol. 2022;34:349-359. doi:10.5021/ad.22.027

- Rossi A, Cantisani C, Scarnò M, et al. Finasteride, 1 mg daily administration on male androgenetic alopecia in different age groups: 10-year follow-up. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:455-461.

- Kaufman KD, Olsen EA, Whiting D, et al. Finasteride in the treatment of men with androgenetic alopecia. Finasteride Male Pattern Hair Loss Study Group. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(4 pt 1):578-89. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70007-6

- Mella JM, Perret MC, Manzotti M, et al. Efficacy and safety offinasteride therapy for androgenetic alopecia: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1141-1150. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.256

- Vañó-Galván S, Fernandez-Crehuet P, Garnacho G, et al; Spanish Trichology Research Group. Recommendations on the clinical management of androgenetic alopecia: a consensus statement from the Spanish Trichology Group of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venererology (AEDV). Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2023 Oct 25:S0001-7310(23)00844-X. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2023.10.013. Online ahead of print.

- Kanti V, Messenger A, Dobos G, et al. Evidence-based (S3) guideline for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in women and in men - short version. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:11-22. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14624

- Price VH, Roberts JL, Hordinsky M, et al. Lack of efficacy of finasteride in postmenopausal women with androgenetic alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(5 pt 1):768-776. doi:10.1067/mjd.2000.107953

- Gupta AK, Bamimore MA, Foley KA. Efficacy of non-surgical treatments for androgenetic alopecia in men and women: a systematic review with network meta-analyses, and an assessment of evidence quality. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:62-72. doi:10.1080/09546634.2020.1749547

- Gupta AK, Wang T, Bamimore MA, et al. The relative effect of monotherapy with 5-alpha reductase inhibitors and minoxidil for female pattern hair loss: a network meta-analysis study [published online June 29, 2023]. J Cosmet Dermatol. doi:10.1111/jocd.15910

- Olsen EA, Weiner MS, Amara IA, et al. Five-year follow-up of men with androgenetic alopecia treated with topical minoxidil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:64.

- Choi G-S, Sim W-Y, Kang H, et al. Long-term effectiveness and safety of dutasteride versus finasteride in patients with male androgenic alopecia in South Korea: a multicentre chart review study. Ann Dermatol. 2022;34:349-359. doi:10.5021/ad.22.027

- Rossi A, Cantisani C, Scarnò M, et al. Finasteride, 1 mg daily administration on male androgenetic alopecia in different age groups: 10-year follow-up. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:455-461.

- Kaufman KD, Olsen EA, Whiting D, et al. Finasteride in the treatment of men with androgenetic alopecia. Finasteride Male Pattern Hair Loss Study Group. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39(4 pt 1):578-89. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70007-6

- Mella JM, Perret MC, Manzotti M, et al. Efficacy and safety offinasteride therapy for androgenetic alopecia: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1141-1150. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2010.256

- Vañó-Galván S, Fernandez-Crehuet P, Garnacho G, et al; Spanish Trichology Research Group. Recommendations on the clinical management of androgenetic alopecia: a consensus statement from the Spanish Trichology Group of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venererology (AEDV). Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2023 Oct 25:S0001-7310(23)00844-X. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2023.10.013. Online ahead of print.

- Kanti V, Messenger A, Dobos G, et al. Evidence-based (S3) guideline for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in women and in men - short version. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:11-22. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14624

US Dermatologic Drug Approvals Rose Between 2012 and 2022

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Only five new drugs for diseases treated mostly by dermatologists were approved by the FDA between 1999 and 2009.

- In a cross-sectional analysis to characterize the frequency and degree of innovation of dermatologic drugs approved more recently, researchers identified new and supplemental dermatologic drugs approved between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2022, from FDA lists, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services CenterWatch, and peer-reviewed articles.

- They used five proxy measures to estimate each drug’s degree of innovation: FDA designation (first in class, advance in class, or addition to class), independent clinical usefulness ratings, and benefit ratings by health technology assessment organizations.

TAKEAWAY:

- The study authors identified 52 new drug applications and 26 supplemental new indications approved by the FDA for dermatologic indications between 2012 and 2022.

- Of the 52 new drugs, the researchers categorized 11 (21%) as first in class and 13 (25%) as first in indication.

- An analysis of benefit ratings available for 38 of the drugs showed that 15 (39%) were rated as being clinically useful or having high added therapeutic benefit.

- Of the 10 supplemental new indications with ratings by any organization, 3 (30%) were rated as clinically useful or having high added therapeutic benefit.

IN PRACTICE:

While innovative drug development in dermatology may have increased, “these findings also highlight opportunities to develop more truly innovative dermatologic agents, particularly for diseases with unmet therapeutic need,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

First author Samir Kamat, MD, of the Medical Education Department at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, and corresponding author Ravi Gupta, MD, MSHP, of the Internal Medicine Division at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, led the research. The study was published online as a research letter on December 20, 2023, in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

They include the use of individual indications to assess clinical usefulness and benefit ratings. Many drugs, particularly supplemental indications, lacked such ratings. Reformulations of already marketed drugs or indications were not included.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Kamat and Dr. Gupta had no relevant disclosures. Three coauthors reported having received financial support outside of the submitted work.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Only five new drugs for diseases treated mostly by dermatologists were approved by the FDA between 1999 and 2009.

- In a cross-sectional analysis to characterize the frequency and degree of innovation of dermatologic drugs approved more recently, researchers identified new and supplemental dermatologic drugs approved between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2022, from FDA lists, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services CenterWatch, and peer-reviewed articles.

- They used five proxy measures to estimate each drug’s degree of innovation: FDA designation (first in class, advance in class, or addition to class), independent clinical usefulness ratings, and benefit ratings by health technology assessment organizations.

TAKEAWAY:

- The study authors identified 52 new drug applications and 26 supplemental new indications approved by the FDA for dermatologic indications between 2012 and 2022.

- Of the 52 new drugs, the researchers categorized 11 (21%) as first in class and 13 (25%) as first in indication.

- An analysis of benefit ratings available for 38 of the drugs showed that 15 (39%) were rated as being clinically useful or having high added therapeutic benefit.

- Of the 10 supplemental new indications with ratings by any organization, 3 (30%) were rated as clinically useful or having high added therapeutic benefit.

IN PRACTICE:

While innovative drug development in dermatology may have increased, “these findings also highlight opportunities to develop more truly innovative dermatologic agents, particularly for diseases with unmet therapeutic need,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

First author Samir Kamat, MD, of the Medical Education Department at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, and corresponding author Ravi Gupta, MD, MSHP, of the Internal Medicine Division at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, led the research. The study was published online as a research letter on December 20, 2023, in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

They include the use of individual indications to assess clinical usefulness and benefit ratings. Many drugs, particularly supplemental indications, lacked such ratings. Reformulations of already marketed drugs or indications were not included.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Kamat and Dr. Gupta had no relevant disclosures. Three coauthors reported having received financial support outside of the submitted work.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Only five new drugs for diseases treated mostly by dermatologists were approved by the FDA between 1999 and 2009.

- In a cross-sectional analysis to characterize the frequency and degree of innovation of dermatologic drugs approved more recently, researchers identified new and supplemental dermatologic drugs approved between January 1, 2012, and December 31, 2022, from FDA lists, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services CenterWatch, and peer-reviewed articles.

- They used five proxy measures to estimate each drug’s degree of innovation: FDA designation (first in class, advance in class, or addition to class), independent clinical usefulness ratings, and benefit ratings by health technology assessment organizations.

TAKEAWAY:

- The study authors identified 52 new drug applications and 26 supplemental new indications approved by the FDA for dermatologic indications between 2012 and 2022.

- Of the 52 new drugs, the researchers categorized 11 (21%) as first in class and 13 (25%) as first in indication.

- An analysis of benefit ratings available for 38 of the drugs showed that 15 (39%) were rated as being clinically useful or having high added therapeutic benefit.

- Of the 10 supplemental new indications with ratings by any organization, 3 (30%) were rated as clinically useful or having high added therapeutic benefit.

IN PRACTICE:

While innovative drug development in dermatology may have increased, “these findings also highlight opportunities to develop more truly innovative dermatologic agents, particularly for diseases with unmet therapeutic need,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

First author Samir Kamat, MD, of the Medical Education Department at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, and corresponding author Ravi Gupta, MD, MSHP, of the Internal Medicine Division at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, led the research. The study was published online as a research letter on December 20, 2023, in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

They include the use of individual indications to assess clinical usefulness and benefit ratings. Many drugs, particularly supplemental indications, lacked such ratings. Reformulations of already marketed drugs or indications were not included.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. Kamat and Dr. Gupta had no relevant disclosures. Three coauthors reported having received financial support outside of the submitted work.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Navigating Hair Loss in Medical School: Experiences of 2 Young Black Women

As medical students, we often assume we are exempt from the diagnoses we learn about. During the first 2 years of medical school, we learn about alopecia as a condition that may be associated with stress, hormonal imbalances, nutrient deficiencies, and aging. However, our curricula do not explore the subtypes, psychosocial impact, or even the overwhelming number of Black women who are disproportionately affected by alopecia. For Black women, hair is a colossal part of their cultural identity, learning from a young age how to nurture and style natural coils. It becomes devastating when women begin to lose them.

The diagnosis of alopecia subtypes in Black women has been explored in the literature; however, understanding the unique experiences of young Black women is an important part of patient care, as alopecia often is destructive to the patient’s self-image. Therefore, it is important to shed light on these experiences so others feel empowered and supported in their journeys. Herein, we share the experiences of 2 authors (J.D. and C.A.V.O.)—both young Black women—who navigated unexpected hair loss in medical school.

Jewell’s Story

During my first year of medical school, I noticed my hair was shedding more than usual, and my ponytail was not as thick as it once was. I also had an area in my crown that was abnormally thin. My parents suggested that it was a consequence of stress, but I knew something was not right. With only 1 Black dermatologist within 2 hours of Nashville, Tennessee, I remember worrying about seeing a dermatologist who did not understand Black hair. I still scheduled an appointment, but I remember debating if I should straighten my hair or wear my naturally curly Afro. The first dermatologist I saw diagnosed me with seborrheic dermatitis—without even examining my scalp. She told me that I had a “full head of hair” and that I had nothing to worry about. I was unconvinced. Weeks later, I met with another dermatologist who took the time to listen to my concerns. After a scalp biopsy and laboratory work, she diagnosed me with telogen effluvium and androgenetic alopecia. Months later, I had the opportunity to visit the Black dermatologist, and she diagnosed me with central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. I am grateful for the earlier dermatologists I saw, but I finally feel at ease with my diagnosis and treatment plan after being seen by the latter.

Chidubem’s Story

From a young age, I was conditioned to think my hair was thick, unmanageable, and a nuisance. I grew accustomed to people yanking on my hair, and my gentle whispers of “this hurts” and “the braid is too tight” being ignored. That continued into adulthood. While studying for the US Medical Licensing Examination, I noticed a burning sensation on my scalp. I decided to ignore it. However, as the days progressed, the slight burning sensation turned into intense burning and itching. I still ignored it. Not only did I lack the funds for a dermatology appointment, but my licensing examination was approaching, and it was more important than anything related to my hair. After the examination, I eventually made an appointment with my primary care physician, who attributed my symptoms to the stressors of medical school. “I think you are having migraines,” she told me. So, I continued to ignore my symptoms. A year passed, and a hair braider pointed out that I had 2 well-defined bald patches on my scalp. I remember feeling angry and confused as to how I missed those findings. I could no longer ignore it—it bothered me less when no one else knew about it. I quickly made a dermatology appointment. Although I opted out of a biopsy, we decided to treat my hair loss empirically, and I have experienced drastic improvement.

Final Thoughts

We are 2 Black women living more than 500 miles away from each other at different medical institutions, yet we share the same experience, which many other women unfortunately face alone. It is not uncommon for us to feel unheard, dismissed, or misdiagnosed. We write this for the Black woman sorting through the feelings of confusion and shock as she traces the hairless spot on her scalp. We write this for the medical student ignoring their symptoms until after their examination. We even write this for any nondermatologists uncomfortable with diagnosing and treating textured hair. To improve patient satisfaction and overall health outcomes, physicians must approach patients with both knowledge and cultural competency. Most importantly, dermatologists (and other physicians) should be appropriately trained in not only the structural differences of textured hair but also the unique practices and beliefs among Black women in relation to their hair.

Acknowledgments—Jewell Dinkins is the inaugural recipient of the Janssen–Skin of Color Research Fellowship at Howard University (Washington, DC), and Chidubem A.V. Okeke is the inaugural recipient of the Women’s Dermatologic Society–La Roche-Posay dermatology fellowship at Howard University.

As medical students, we often assume we are exempt from the diagnoses we learn about. During the first 2 years of medical school, we learn about alopecia as a condition that may be associated with stress, hormonal imbalances, nutrient deficiencies, and aging. However, our curricula do not explore the subtypes, psychosocial impact, or even the overwhelming number of Black women who are disproportionately affected by alopecia. For Black women, hair is a colossal part of their cultural identity, learning from a young age how to nurture and style natural coils. It becomes devastating when women begin to lose them.

The diagnosis of alopecia subtypes in Black women has been explored in the literature; however, understanding the unique experiences of young Black women is an important part of patient care, as alopecia often is destructive to the patient’s self-image. Therefore, it is important to shed light on these experiences so others feel empowered and supported in their journeys. Herein, we share the experiences of 2 authors (J.D. and C.A.V.O.)—both young Black women—who navigated unexpected hair loss in medical school.

Jewell’s Story

During my first year of medical school, I noticed my hair was shedding more than usual, and my ponytail was not as thick as it once was. I also had an area in my crown that was abnormally thin. My parents suggested that it was a consequence of stress, but I knew something was not right. With only 1 Black dermatologist within 2 hours of Nashville, Tennessee, I remember worrying about seeing a dermatologist who did not understand Black hair. I still scheduled an appointment, but I remember debating if I should straighten my hair or wear my naturally curly Afro. The first dermatologist I saw diagnosed me with seborrheic dermatitis—without even examining my scalp. She told me that I had a “full head of hair” and that I had nothing to worry about. I was unconvinced. Weeks later, I met with another dermatologist who took the time to listen to my concerns. After a scalp biopsy and laboratory work, she diagnosed me with telogen effluvium and androgenetic alopecia. Months later, I had the opportunity to visit the Black dermatologist, and she diagnosed me with central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. I am grateful for the earlier dermatologists I saw, but I finally feel at ease with my diagnosis and treatment plan after being seen by the latter.

Chidubem’s Story

From a young age, I was conditioned to think my hair was thick, unmanageable, and a nuisance. I grew accustomed to people yanking on my hair, and my gentle whispers of “this hurts” and “the braid is too tight” being ignored. That continued into adulthood. While studying for the US Medical Licensing Examination, I noticed a burning sensation on my scalp. I decided to ignore it. However, as the days progressed, the slight burning sensation turned into intense burning and itching. I still ignored it. Not only did I lack the funds for a dermatology appointment, but my licensing examination was approaching, and it was more important than anything related to my hair. After the examination, I eventually made an appointment with my primary care physician, who attributed my symptoms to the stressors of medical school. “I think you are having migraines,” she told me. So, I continued to ignore my symptoms. A year passed, and a hair braider pointed out that I had 2 well-defined bald patches on my scalp. I remember feeling angry and confused as to how I missed those findings. I could no longer ignore it—it bothered me less when no one else knew about it. I quickly made a dermatology appointment. Although I opted out of a biopsy, we decided to treat my hair loss empirically, and I have experienced drastic improvement.

Final Thoughts

We are 2 Black women living more than 500 miles away from each other at different medical institutions, yet we share the same experience, which many other women unfortunately face alone. It is not uncommon for us to feel unheard, dismissed, or misdiagnosed. We write this for the Black woman sorting through the feelings of confusion and shock as she traces the hairless spot on her scalp. We write this for the medical student ignoring their symptoms until after their examination. We even write this for any nondermatologists uncomfortable with diagnosing and treating textured hair. To improve patient satisfaction and overall health outcomes, physicians must approach patients with both knowledge and cultural competency. Most importantly, dermatologists (and other physicians) should be appropriately trained in not only the structural differences of textured hair but also the unique practices and beliefs among Black women in relation to their hair.

Acknowledgments—Jewell Dinkins is the inaugural recipient of the Janssen–Skin of Color Research Fellowship at Howard University (Washington, DC), and Chidubem A.V. Okeke is the inaugural recipient of the Women’s Dermatologic Society–La Roche-Posay dermatology fellowship at Howard University.

As medical students, we often assume we are exempt from the diagnoses we learn about. During the first 2 years of medical school, we learn about alopecia as a condition that may be associated with stress, hormonal imbalances, nutrient deficiencies, and aging. However, our curricula do not explore the subtypes, psychosocial impact, or even the overwhelming number of Black women who are disproportionately affected by alopecia. For Black women, hair is a colossal part of their cultural identity, learning from a young age how to nurture and style natural coils. It becomes devastating when women begin to lose them.

The diagnosis of alopecia subtypes in Black women has been explored in the literature; however, understanding the unique experiences of young Black women is an important part of patient care, as alopecia often is destructive to the patient’s self-image. Therefore, it is important to shed light on these experiences so others feel empowered and supported in their journeys. Herein, we share the experiences of 2 authors (J.D. and C.A.V.O.)—both young Black women—who navigated unexpected hair loss in medical school.

Jewell’s Story

During my first year of medical school, I noticed my hair was shedding more than usual, and my ponytail was not as thick as it once was. I also had an area in my crown that was abnormally thin. My parents suggested that it was a consequence of stress, but I knew something was not right. With only 1 Black dermatologist within 2 hours of Nashville, Tennessee, I remember worrying about seeing a dermatologist who did not understand Black hair. I still scheduled an appointment, but I remember debating if I should straighten my hair or wear my naturally curly Afro. The first dermatologist I saw diagnosed me with seborrheic dermatitis—without even examining my scalp. She told me that I had a “full head of hair” and that I had nothing to worry about. I was unconvinced. Weeks later, I met with another dermatologist who took the time to listen to my concerns. After a scalp biopsy and laboratory work, she diagnosed me with telogen effluvium and androgenetic alopecia. Months later, I had the opportunity to visit the Black dermatologist, and she diagnosed me with central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. I am grateful for the earlier dermatologists I saw, but I finally feel at ease with my diagnosis and treatment plan after being seen by the latter.

Chidubem’s Story

From a young age, I was conditioned to think my hair was thick, unmanageable, and a nuisance. I grew accustomed to people yanking on my hair, and my gentle whispers of “this hurts” and “the braid is too tight” being ignored. That continued into adulthood. While studying for the US Medical Licensing Examination, I noticed a burning sensation on my scalp. I decided to ignore it. However, as the days progressed, the slight burning sensation turned into intense burning and itching. I still ignored it. Not only did I lack the funds for a dermatology appointment, but my licensing examination was approaching, and it was more important than anything related to my hair. After the examination, I eventually made an appointment with my primary care physician, who attributed my symptoms to the stressors of medical school. “I think you are having migraines,” she told me. So, I continued to ignore my symptoms. A year passed, and a hair braider pointed out that I had 2 well-defined bald patches on my scalp. I remember feeling angry and confused as to how I missed those findings. I could no longer ignore it—it bothered me less when no one else knew about it. I quickly made a dermatology appointment. Although I opted out of a biopsy, we decided to treat my hair loss empirically, and I have experienced drastic improvement.

Final Thoughts

We are 2 Black women living more than 500 miles away from each other at different medical institutions, yet we share the same experience, which many other women unfortunately face alone. It is not uncommon for us to feel unheard, dismissed, or misdiagnosed. We write this for the Black woman sorting through the feelings of confusion and shock as she traces the hairless spot on her scalp. We write this for the medical student ignoring their symptoms until after their examination. We even write this for any nondermatologists uncomfortable with diagnosing and treating textured hair. To improve patient satisfaction and overall health outcomes, physicians must approach patients with both knowledge and cultural competency. Most importantly, dermatologists (and other physicians) should be appropriately trained in not only the structural differences of textured hair but also the unique practices and beliefs among Black women in relation to their hair.

Acknowledgments—Jewell Dinkins is the inaugural recipient of the Janssen–Skin of Color Research Fellowship at Howard University (Washington, DC), and Chidubem A.V. Okeke is the inaugural recipient of the Women’s Dermatologic Society–La Roche-Posay dermatology fellowship at Howard University.

Practice Points

- Hair loss is a common dermatologic concern among Black women and can represent a diagnostic challenge to dermatologists who may not be familiar with textured hair.

- Dermatologists should practice cultural sensitivity and provide relevant recommendations to Black patients dealing with hair loss.

Pilot study educates barbers about pseudofolliculitis barbae

A .

The results were published in a research letter in JAMA Dermatology. “Educating barbers on dermatologic conditions that disproportionately affect Black males and establishing referral services between barbers and dermatologists could serve as plausible interventions,” the authors wrote.

PFB — or “razor bumps” in layman’s terms — is a chronic, inflammatory follicular disorder, which can occur in any racial group, but primarily affects Black men, noted the corresponding author of the study, Xavier Rice, MD, a dermatology resident at Washington University in Saint Louis, Missouri. PFB manifests as bumps and pustules or nodules along the beard line and are painful, he said in an interview. “They tend to leave scars once they resolve,” and impair the ability to shave, he noted.

In some communities, Black men may see their barbers more often than primary care doctors or dermatologists, “so if you equip the barbers with the knowledge to recognize the disease, make recommendations on how to prevent and to treat, and also form some allyship with barbers and dermatologists, then we can get referrals for people, especially the ones with severe disease,” he said. A lot of the barbers in the study said that “they didn’t receive much education on how to properly address it [PFB] and they had a lot of miseducation about what actually caused it,” added Dr. Rice, who was a medical student at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, when the study was conducted.

Study involved 40 barbers

For the study, Dr. Rice and his coauthors surveyed 40 barbers in the Houston, Texas, area; 39 were Black and one was Hispanic; 75% were men and 25% were women. Most (90%) said that at least 60% of their clients were Black. Between January and April 2022, the barbers received questionnaires before and after participating in a session that involved a review of a comprehensive educational brochure with information on the recognition, cause, prevention, and treatment of PFB, which they then kept for reference and to provide to clients as needed. “Common myths and nuanced home remedies from barber experience were also addressed,” the authors wrote.

No more than 2 weeks after the information session, each barber completed a posttest questionnaire.

Based on their responses to pretest questions, 39 of the 40 barbers understood that Black men were the group most impacted by PFB and that a person with severe PFB should see a physician. In the pretest survey, 12 barbers (30%) correctly recognized a photo of PFB, which increased to 39 (97.5%) in the posttest survey. In the pretest survey, two barbers (5%) identified laser hair removal as the most effective treatment for PFB, compared with 37 (92.5%) in the posttest survey.

Overall, the mean percentage of correct scores out of 20 questions was 54.8% in the pretest survey, increasing to 91% in the posttest survey (P <.001).

Limitations of the studies included heterogeneity in the survey response options that potentially could have introduced bias, the authors wrote. Another was that since there is a lack of evidence for ideal treatment strategies for PFB, there may have been some uncertainty among the correct answers for the survey that might have contributed to variability in responses. “Further research and implementation of these interventions are needed in efforts to improve health outcomes,” they added.

“Barbers can serve as allies in referral services,” Dr. Rice said in the interview. “They can be the first line for a number of diseases that are related to hair.”

Part of his role as a dermatologist, he added, includes going into a community with “boots on the ground” and talking to people who will see these patients “because access to care, presentation to big hospital systems can be challenging.”

Dr. Rice and the other study authors had no not report any financial disclosures.

A .

The results were published in a research letter in JAMA Dermatology. “Educating barbers on dermatologic conditions that disproportionately affect Black males and establishing referral services between barbers and dermatologists could serve as plausible interventions,” the authors wrote.

PFB — or “razor bumps” in layman’s terms — is a chronic, inflammatory follicular disorder, which can occur in any racial group, but primarily affects Black men, noted the corresponding author of the study, Xavier Rice, MD, a dermatology resident at Washington University in Saint Louis, Missouri. PFB manifests as bumps and pustules or nodules along the beard line and are painful, he said in an interview. “They tend to leave scars once they resolve,” and impair the ability to shave, he noted.

In some communities, Black men may see their barbers more often than primary care doctors or dermatologists, “so if you equip the barbers with the knowledge to recognize the disease, make recommendations on how to prevent and to treat, and also form some allyship with barbers and dermatologists, then we can get referrals for people, especially the ones with severe disease,” he said. A lot of the barbers in the study said that “they didn’t receive much education on how to properly address it [PFB] and they had a lot of miseducation about what actually caused it,” added Dr. Rice, who was a medical student at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, when the study was conducted.

Study involved 40 barbers

For the study, Dr. Rice and his coauthors surveyed 40 barbers in the Houston, Texas, area; 39 were Black and one was Hispanic; 75% were men and 25% were women. Most (90%) said that at least 60% of their clients were Black. Between January and April 2022, the barbers received questionnaires before and after participating in a session that involved a review of a comprehensive educational brochure with information on the recognition, cause, prevention, and treatment of PFB, which they then kept for reference and to provide to clients as needed. “Common myths and nuanced home remedies from barber experience were also addressed,” the authors wrote.

No more than 2 weeks after the information session, each barber completed a posttest questionnaire.

Based on their responses to pretest questions, 39 of the 40 barbers understood that Black men were the group most impacted by PFB and that a person with severe PFB should see a physician. In the pretest survey, 12 barbers (30%) correctly recognized a photo of PFB, which increased to 39 (97.5%) in the posttest survey. In the pretest survey, two barbers (5%) identified laser hair removal as the most effective treatment for PFB, compared with 37 (92.5%) in the posttest survey.

Overall, the mean percentage of correct scores out of 20 questions was 54.8% in the pretest survey, increasing to 91% in the posttest survey (P <.001).

Limitations of the studies included heterogeneity in the survey response options that potentially could have introduced bias, the authors wrote. Another was that since there is a lack of evidence for ideal treatment strategies for PFB, there may have been some uncertainty among the correct answers for the survey that might have contributed to variability in responses. “Further research and implementation of these interventions are needed in efforts to improve health outcomes,” they added.

“Barbers can serve as allies in referral services,” Dr. Rice said in the interview. “They can be the first line for a number of diseases that are related to hair.”

Part of his role as a dermatologist, he added, includes going into a community with “boots on the ground” and talking to people who will see these patients “because access to care, presentation to big hospital systems can be challenging.”

Dr. Rice and the other study authors had no not report any financial disclosures.

A .

The results were published in a research letter in JAMA Dermatology. “Educating barbers on dermatologic conditions that disproportionately affect Black males and establishing referral services between barbers and dermatologists could serve as plausible interventions,” the authors wrote.

PFB — or “razor bumps” in layman’s terms — is a chronic, inflammatory follicular disorder, which can occur in any racial group, but primarily affects Black men, noted the corresponding author of the study, Xavier Rice, MD, a dermatology resident at Washington University in Saint Louis, Missouri. PFB manifests as bumps and pustules or nodules along the beard line and are painful, he said in an interview. “They tend to leave scars once they resolve,” and impair the ability to shave, he noted.

In some communities, Black men may see their barbers more often than primary care doctors or dermatologists, “so if you equip the barbers with the knowledge to recognize the disease, make recommendations on how to prevent and to treat, and also form some allyship with barbers and dermatologists, then we can get referrals for people, especially the ones with severe disease,” he said. A lot of the barbers in the study said that “they didn’t receive much education on how to properly address it [PFB] and they had a lot of miseducation about what actually caused it,” added Dr. Rice, who was a medical student at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, when the study was conducted.

Study involved 40 barbers

For the study, Dr. Rice and his coauthors surveyed 40 barbers in the Houston, Texas, area; 39 were Black and one was Hispanic; 75% were men and 25% were women. Most (90%) said that at least 60% of their clients were Black. Between January and April 2022, the barbers received questionnaires before and after participating in a session that involved a review of a comprehensive educational brochure with information on the recognition, cause, prevention, and treatment of PFB, which they then kept for reference and to provide to clients as needed. “Common myths and nuanced home remedies from barber experience were also addressed,” the authors wrote.

No more than 2 weeks after the information session, each barber completed a posttest questionnaire.

Based on their responses to pretest questions, 39 of the 40 barbers understood that Black men were the group most impacted by PFB and that a person with severe PFB should see a physician. In the pretest survey, 12 barbers (30%) correctly recognized a photo of PFB, which increased to 39 (97.5%) in the posttest survey. In the pretest survey, two barbers (5%) identified laser hair removal as the most effective treatment for PFB, compared with 37 (92.5%) in the posttest survey.

Overall, the mean percentage of correct scores out of 20 questions was 54.8% in the pretest survey, increasing to 91% in the posttest survey (P <.001).

Limitations of the studies included heterogeneity in the survey response options that potentially could have introduced bias, the authors wrote. Another was that since there is a lack of evidence for ideal treatment strategies for PFB, there may have been some uncertainty among the correct answers for the survey that might have contributed to variability in responses. “Further research and implementation of these interventions are needed in efforts to improve health outcomes,” they added.

“Barbers can serve as allies in referral services,” Dr. Rice said in the interview. “They can be the first line for a number of diseases that are related to hair.”

Part of his role as a dermatologist, he added, includes going into a community with “boots on the ground” and talking to people who will see these patients “because access to care, presentation to big hospital systems can be challenging.”

Dr. Rice and the other study authors had no not report any financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Treatment and Current Policies on Pseudofolliculitis Barbae in the US Military

Pseudofolliculitis barbae (PFB)(also referred to as razor bumps) is a skin disease of the face and neck caused by shaving and remains prevalent in the US Military. As the sharpened ends of curly hair strands penetrate back into the epidermis, they can trigger inflammatory reactions, leading to papules and pustules as well as hyperpigmentation and scarring.1 Although anyone with thick curly hair can develop PFB, Black individuals are disproportionately affected, with 45% to 83% reporting PFB symptoms compared with 18% of White individuals.2 In this article, we review the treatments and current policies on PFB in the military.

Treatment Options

Shaving Guidelines—Daily shaving remains the grooming standard for US service members who are encouraged to follow prescribed grooming techniques to prevent mild cases of PFB, defined as having “few, scattered papules with scant hair growth of the beard area,” according to the technical bulletin of the US Army, which provides the most detailed guidelines among the branches.3 The bulletin recommends hydrating the face with warm water, followed by a preshave lotion and shaving with a single pass superiorly to inferiorly. Following shaving, postrazor hydration lotion is recommended. Single-bladed razors are preferred, as there is less trauma to existing PFB and less potential for hair retraction under the epidermis, though multibladed razors can be used with adequate preshave and postrazor hydration.4 Shaving can be undertaken in the evening to ensure adequate time for preshave preparation and postshave hydration. Waterless shaving uses waterless soaps or lotions containing α-hydroxy acid just prior to shaving in lieu of preshaving and postshaving procedures.4

Topical Medications—For PFB cases that are recalcitrant to management by changes in shaving, topical retinoids are commonly prescribed, as they reduce follicular hyperkeratosis that may lead to PFB.5 The Army medical bulletin recommends a pea-sized amount of tretinoin cream or gel 0.025%, 0.05%, or 0.1% for moderate cases, defined as “heavier beard growth, more scattered papules, no evidence of pustules or denudation.”3 Adapalene cream 0.1% may be used instead of tretinoin for sensitive skin. Oral doxycycline or topical benzoyl peroxide–clindamycin may be added for secondary bacterial skin infections. Clinical trials have demonstrated that combination benzoyl peroxide–clindamycin significantly reduces papules and pustules in up to 63% of patients with PFB (P<.029).6 Azelaic acid can be prescribed for prominent postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. The bulletin also suggests depilatories such as barium sulfide to obtund the hair ends and make them less likely to re-enter the skin surface, though it notes low compliance rates due to strong sulfur odor, messy application, and irritation and reactions to ingredients in the preparations.4

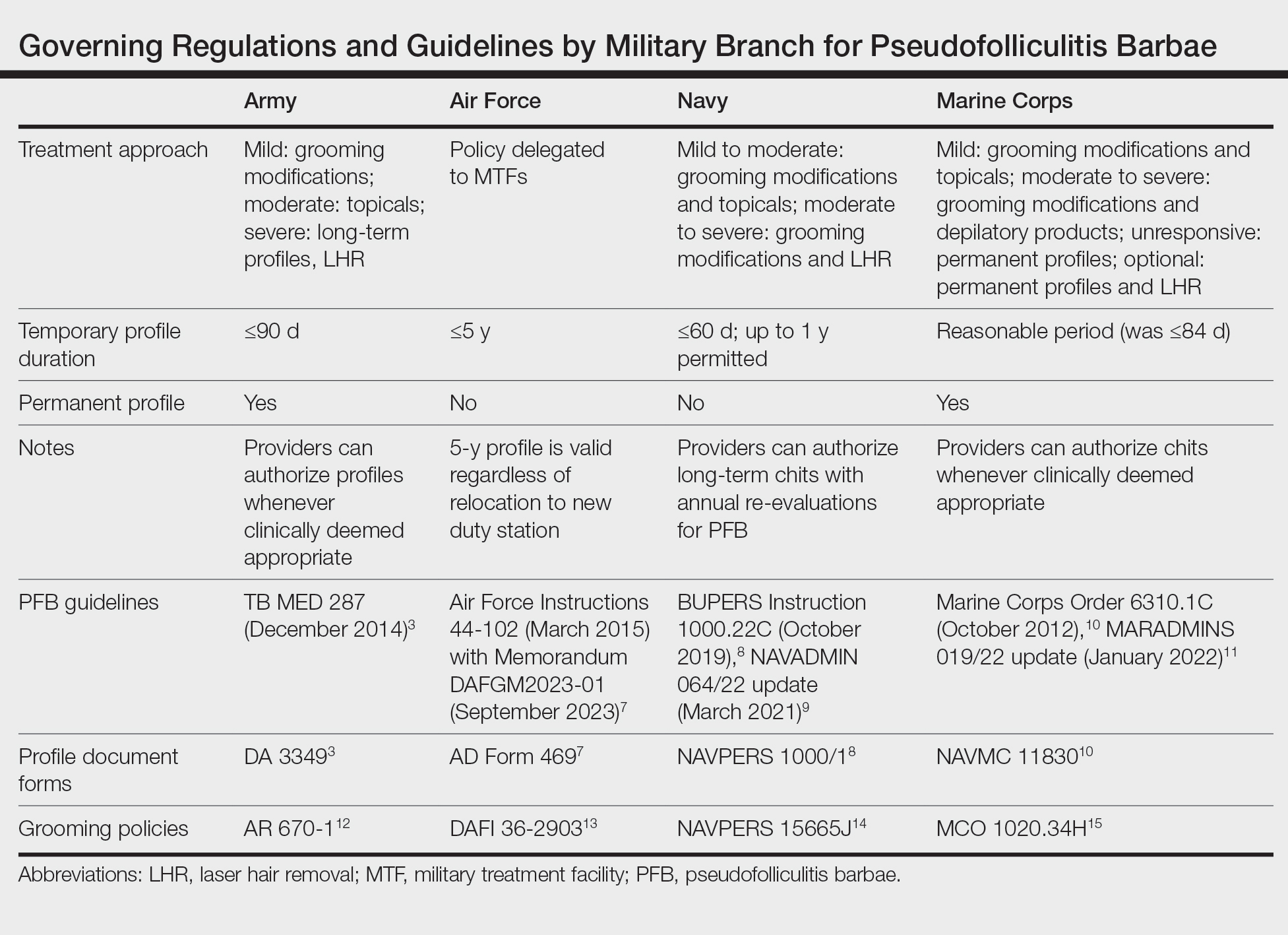

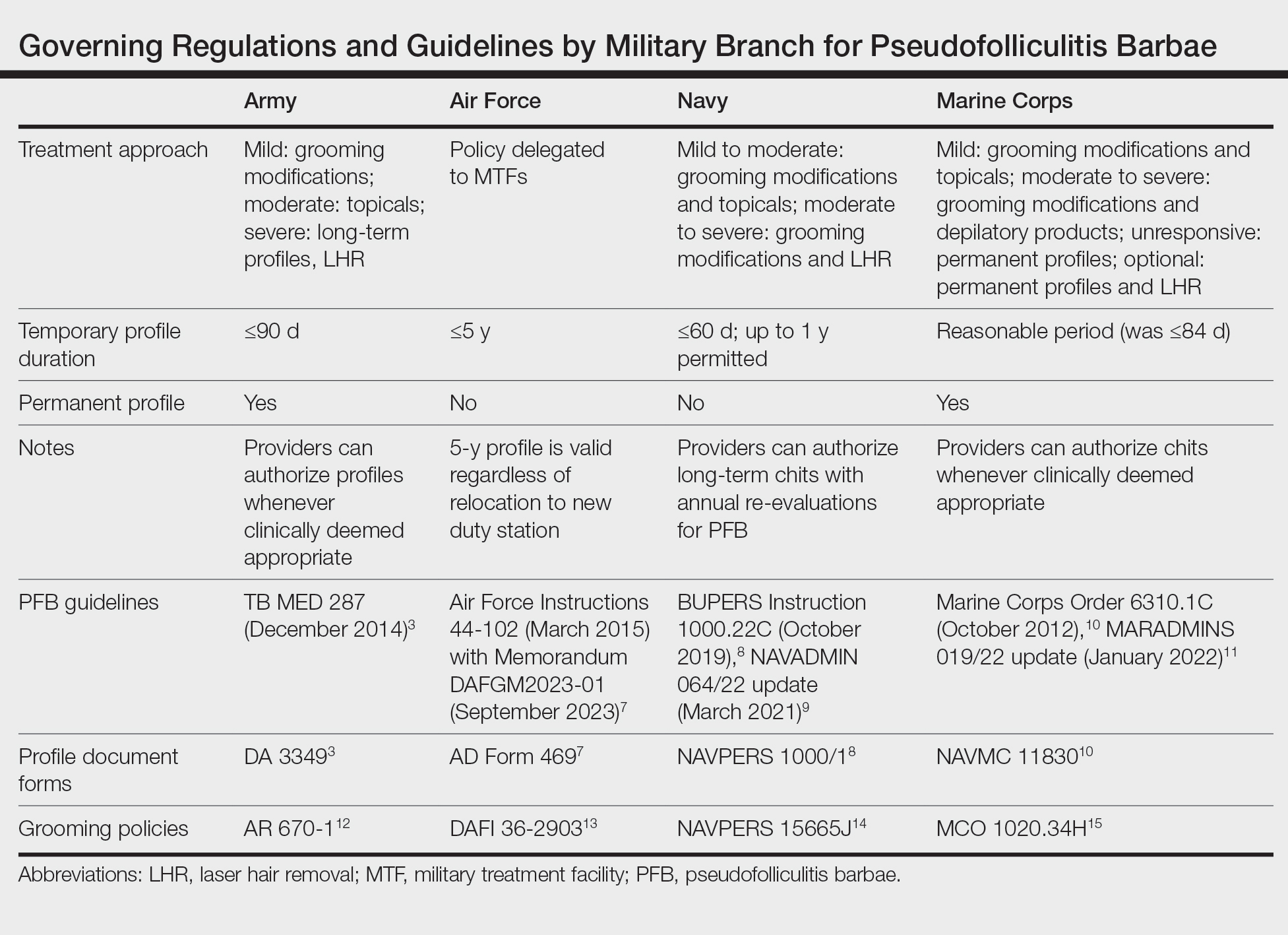

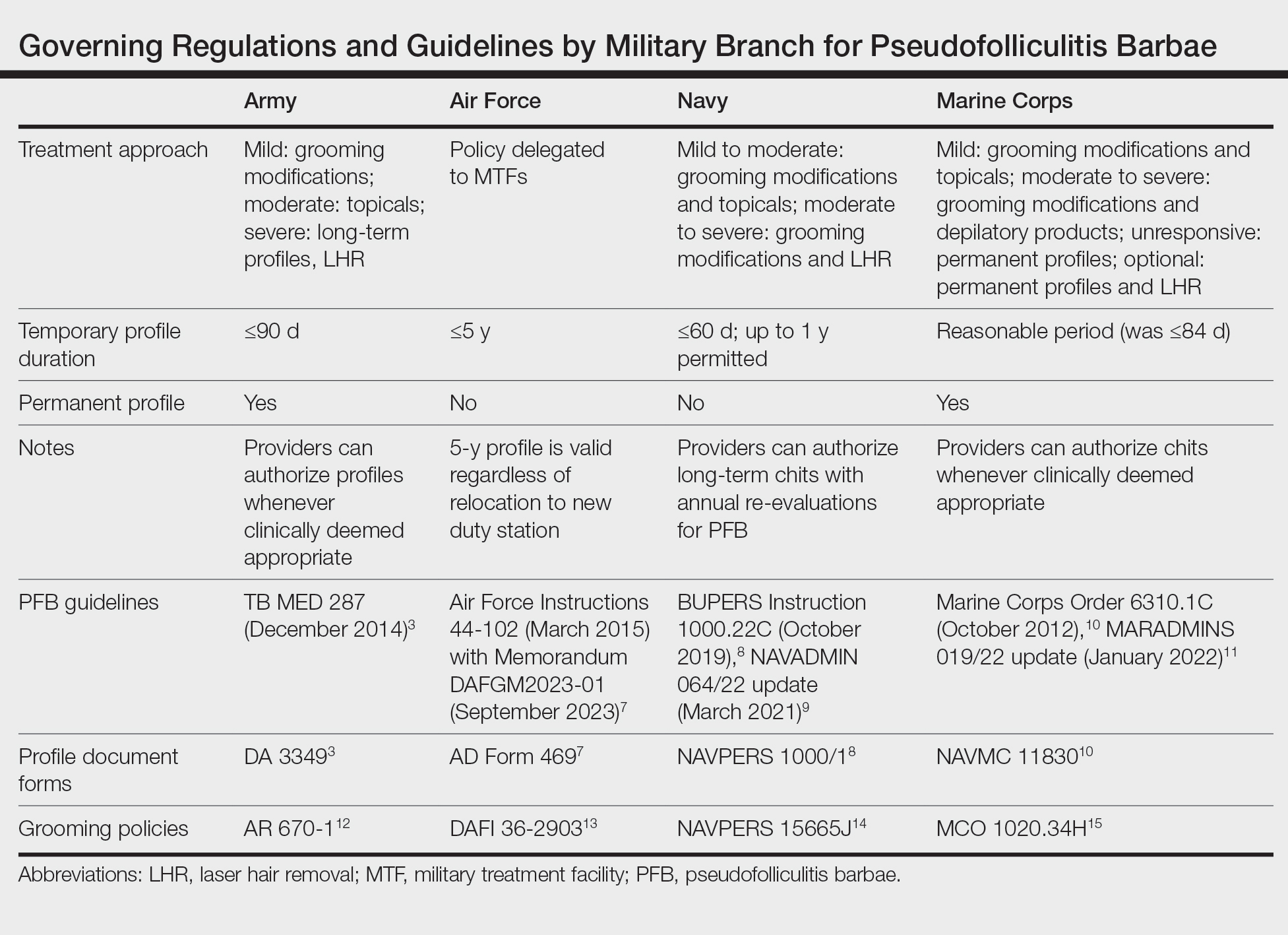

Shaving Waivers and Laser Hair Removal—The definitive treatment of PFB is to not shave, and a shaving waiver or laser hair removal (LHR) are the best options for severe PFB or PFB refractory to other treatments. A shaving waiver (or shaving profile) allows for growth of up to 0.25 inches of facial hair with maintenance of the length using clippers. The shaving profile typically is issued by the referring primary care manager (PCM) but also can be recommended by a dermatologist. Each military branch implements different regulations on shaving profiles, which complicates care delivery at joint-service military treatment facilities (MTFs). The Table provides guidelines that govern the management of PFB by the US Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps. The issuance and duration of shaving waivers vary by service.

Laser hair removal therapy uses high-wavelength lasers that largely bypass the melanocyte-containing basal layer and selectively target hair follicles located deeper in the skin, which results in precise hair reduction with relative sparing of the epidermis.16 Clinical trials at military clinics have demonstrated that treatments with the 1064-nm long-pulse Nd:YAG laser generally are safe and effective in impeding hair growth in Fitzpatrick skin types IV, V, and VI.17 This laser, along with the Alexandrite 755-nm long-pulse laser for Fitzpatrick skin types I to III, is widely available and used for LHR at MTFs that house dermatologists. Eflornithine cream 13.9%, which is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to treat hirsutism, can be used as monotherapy for treatment of PFB and has a synergistic depilatory effect in PFB patients when used in conjunction with LHR.18,19 Laser hair removal treatments can induce a permanent change in facial hair density and pattern of growth. Side effects and complications of LHR include discomfort during treatment and, in rare instances, blistering and dyspigmentation of the skin as well as paradoxical hair growth.17