User login

PCOS: Laser, Light Therapy Helpful for Hirsutism

BY DEEPA VARMA

TOPLINE:

, according to the results of a systematic review.

METHODOLOGY:

- Hirsutism, which affects 70%-80% of women with PCOS, is frequently marginalized as a cosmetic issue by healthcare providers, despite its significant psychological repercussions, including diminished self-esteem, reduced quality of life, and heightened depression.

- The 2023 international evidence-based PCOS guideline considers managing hirsutism a priority in women with PCOS.

- Researchers reviewed six studies (four randomized controlled trials and two cohort studies), which included 423 patients with PCOS who underwent laser or light-based hair reduction therapies, published through 2022.

- The studies evaluated the alexandrite laser, diode laser, and intense pulsed light (IPL) therapy, with and without pharmacological treatments. The main outcomes were hirsutism severity, psychological outcome, and adverse events.

TAKEAWAY:

- Alexandrite laser (wavelength, 755 nm) showed effective hair reduction and improved patient satisfaction (one study); high-fluence treatment yielded better outcomes than low-fluence treatment (one study). Alexandrite laser 755 nm also showed longer hair-free intervals and greater hair reduction than IPL therapy at 650-1000 nm (one study).

- Combined IPL (600 nm) and metformin therapy improved hirsutism and hair count reduction compared with IPL alone, but with more side effects (one study).

- Diode laser treatments (810 nm) with combined oral contraceptives improved hirsutism and related quality of life measures compared with diode laser alone or with metformin (one study).

- Comparing two diode lasers (wavelengths, 810 nm), low-fluence, high repetition laser showed superior hair width reduction and lower pain scores than high fluence, low-repetition laser (one study).

IN PRACTICE:

Laser and light treatments alone or combined with other treatments have demonstrated “encouraging results in reducing hirsutism severity, enhancing psychological well-being, and improving overall quality of life for affected individuals,” the authors wrote, noting that additional high-quality trials evaluating these treatments, which include more patients with different skin tones, are needed.

SOURCE:

The first author of the review is Katrina Tan, MD, Monash Health, Department of Dermatology, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, and it was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Limitations include low certainty of evidence because of the observational nature of some of the studies, the small number of studies, and underrepresentation of darker skin types, limiting generalizability.

DISCLOSURES:

The review is part of an update to the PCOS guideline, which was funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council through various organizations. Several authors reported receiving grants and personal fees outside this work. Dr. Tan was a member of the 2023 PCOS guideline evidence team. Other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

BY DEEPA VARMA

TOPLINE:

, according to the results of a systematic review.

METHODOLOGY:

- Hirsutism, which affects 70%-80% of women with PCOS, is frequently marginalized as a cosmetic issue by healthcare providers, despite its significant psychological repercussions, including diminished self-esteem, reduced quality of life, and heightened depression.

- The 2023 international evidence-based PCOS guideline considers managing hirsutism a priority in women with PCOS.

- Researchers reviewed six studies (four randomized controlled trials and two cohort studies), which included 423 patients with PCOS who underwent laser or light-based hair reduction therapies, published through 2022.

- The studies evaluated the alexandrite laser, diode laser, and intense pulsed light (IPL) therapy, with and without pharmacological treatments. The main outcomes were hirsutism severity, psychological outcome, and adverse events.

TAKEAWAY:

- Alexandrite laser (wavelength, 755 nm) showed effective hair reduction and improved patient satisfaction (one study); high-fluence treatment yielded better outcomes than low-fluence treatment (one study). Alexandrite laser 755 nm also showed longer hair-free intervals and greater hair reduction than IPL therapy at 650-1000 nm (one study).

- Combined IPL (600 nm) and metformin therapy improved hirsutism and hair count reduction compared with IPL alone, but with more side effects (one study).

- Diode laser treatments (810 nm) with combined oral contraceptives improved hirsutism and related quality of life measures compared with diode laser alone or with metformin (one study).

- Comparing two diode lasers (wavelengths, 810 nm), low-fluence, high repetition laser showed superior hair width reduction and lower pain scores than high fluence, low-repetition laser (one study).

IN PRACTICE:

Laser and light treatments alone or combined with other treatments have demonstrated “encouraging results in reducing hirsutism severity, enhancing psychological well-being, and improving overall quality of life for affected individuals,” the authors wrote, noting that additional high-quality trials evaluating these treatments, which include more patients with different skin tones, are needed.

SOURCE:

The first author of the review is Katrina Tan, MD, Monash Health, Department of Dermatology, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, and it was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Limitations include low certainty of evidence because of the observational nature of some of the studies, the small number of studies, and underrepresentation of darker skin types, limiting generalizability.

DISCLOSURES:

The review is part of an update to the PCOS guideline, which was funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council through various organizations. Several authors reported receiving grants and personal fees outside this work. Dr. Tan was a member of the 2023 PCOS guideline evidence team. Other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

BY DEEPA VARMA

TOPLINE:

, according to the results of a systematic review.

METHODOLOGY:

- Hirsutism, which affects 70%-80% of women with PCOS, is frequently marginalized as a cosmetic issue by healthcare providers, despite its significant psychological repercussions, including diminished self-esteem, reduced quality of life, and heightened depression.

- The 2023 international evidence-based PCOS guideline considers managing hirsutism a priority in women with PCOS.

- Researchers reviewed six studies (four randomized controlled trials and two cohort studies), which included 423 patients with PCOS who underwent laser or light-based hair reduction therapies, published through 2022.

- The studies evaluated the alexandrite laser, diode laser, and intense pulsed light (IPL) therapy, with and without pharmacological treatments. The main outcomes were hirsutism severity, psychological outcome, and adverse events.

TAKEAWAY:

- Alexandrite laser (wavelength, 755 nm) showed effective hair reduction and improved patient satisfaction (one study); high-fluence treatment yielded better outcomes than low-fluence treatment (one study). Alexandrite laser 755 nm also showed longer hair-free intervals and greater hair reduction than IPL therapy at 650-1000 nm (one study).

- Combined IPL (600 nm) and metformin therapy improved hirsutism and hair count reduction compared with IPL alone, but with more side effects (one study).

- Diode laser treatments (810 nm) with combined oral contraceptives improved hirsutism and related quality of life measures compared with diode laser alone or with metformin (one study).

- Comparing two diode lasers (wavelengths, 810 nm), low-fluence, high repetition laser showed superior hair width reduction and lower pain scores than high fluence, low-repetition laser (one study).

IN PRACTICE:

Laser and light treatments alone or combined with other treatments have demonstrated “encouraging results in reducing hirsutism severity, enhancing psychological well-being, and improving overall quality of life for affected individuals,” the authors wrote, noting that additional high-quality trials evaluating these treatments, which include more patients with different skin tones, are needed.

SOURCE:

The first author of the review is Katrina Tan, MD, Monash Health, Department of Dermatology, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, and it was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

LIMITATIONS:

Limitations include low certainty of evidence because of the observational nature of some of the studies, the small number of studies, and underrepresentation of darker skin types, limiting generalizability.

DISCLOSURES:

The review is part of an update to the PCOS guideline, which was funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council through various organizations. Several authors reported receiving grants and personal fees outside this work. Dr. Tan was a member of the 2023 PCOS guideline evidence team. Other authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Consensus Statement Aims to Guide Use of Low-Dose Oral Minoxidil for Hair Loss

SAN DIEGO — .

Those are among the key recommendations that resulted from a modified eDelphi consensus of experts who convened to develop guidelines for LDOM prescribing and monitoring.

“Topical minoxidil is safe, effective, over-the-counter, and FDA-approved to treat the most common form of hair loss, androgenetic alopecia,” one of the study authors, Jennifer Fu, MD, a dermatologist who directs the Hair Disorders Clinic at the University of California, San Francisco, told this news organization following the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. The results of the expert consensus were presented during a poster session at the meeting. “It is often used off label for other types of hair loss, yet clinicians who treat hair loss know that patient compliance with topical minoxidil can be poor for a variety of reasons,” she said. “Patients report that it can be difficult to apply and complicate hair styling. For many patients, topical minoxidil can be drying or cause irritant or allergic contact reactions.”

LDOM has become a popular alternative for patients for whom topical minoxidil is logistically challenging, irritating, or ineffective, she continued. Although oral minoxidil is no longer a first-line antihypertensive agent given the risk of cardiovascular adverse effects at higher antihypertensive dosing (10-40 mg daily), a growing number of small studies have documented the use of LDOM at doses ranging from 0.25 mg to 5 mg daily as a safe, effective option for various types of hair loss.

“Given the current absence of larger trials on this topic, our research group identified a need for expert-based guidelines for prescribing and monitoring LDOM use in hair loss patients,” Dr. Fu said. “Our goal was to provide clinicians who treat hair loss patients a road map for using LDOM effectively, maximizing hair growth, and minimizing potential cardiovascular adverse effects.”

Arriving at a Consensus

The process involved 43 hair loss specialists from 12 countries with an average of 6.29 years of experience with LDOM for hair loss, who participated in a multi-round modified Delphi process. They considered questions that addressed LDOM safety, efficacy, dosing, and monitoring for hair loss, and consensus was reached if at least 70% of participants indicated “agree” or “strongly agree” on a five-point Likert scale. Round 1 consisted of 180 open-ended, multiple-choice, or Likert-scale questions, while round 2 involved 121 Likert-scale questions, round 3 consisted of 16 Likert-scale questions, and round 4 included 11 Likert-scale questions. In all, 94 items achieved Likert-scale consensus.

Specifically, experts on the panel found a direct benefit of LDOM for androgenetic alopecia, age-related patterned thinning, alopecia areata, telogen effluvium, traction alopecia, persistent chemotherapy-induced alopecia, and endocrine therapy-induced alopecia. They found a supportive benefit of LDOM for lichen planopilaris, frontal fibrosing alopecia, central centrifugal alopecia, and fibrosing alopecia in a patterned distribution.

“LDOM can be considered when topical minoxidil is more expensive, logistically challenging, has plateaued in efficacy, results in undesirable product residue/skin irritation,” or exacerbates inflammatory processes (ie eczema, psoriasis), they added.

Contraindications to LDOM listed in the consensus recommendations include hypersensitivity to minoxidil, significant drug-drug interactions with LDOM, a history of pericardial effusion/tamponade, pericarditis, heart failure, pulmonary hypertension associated with mitral stenosis, pheochromocytoma, and pregnancy/breastfeeding. Cited precautions of LDOM use include a history of tachycardia or arrhythmia, hypotension, renal impairment, and being on dialysis.

Dr. Fu and colleagues noted that the earliest time point at which LDOM should be expected to demonstrate efficacy is 3-6 months. “Baseline testing is not routine but may be considered in case of identified precautions,” they wrote. They also noted that LDOM can possibly be co-administered with beta-blockers with a specialty consultation, and with spironolactone in biologic female or transgender female patients with hirsutism, acne, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and with lower extremity and facial edema.

According to the consensus statement, the most frequently prescribed LDOM dosing regimen in adult females aged 18 years and older includes a starting dose of 1.25 mg daily, with a dosing range between 0.625 mg and 5 mg daily. For adult males, the most frequently prescribed dosing regimen is a starting dose of 2.5 daily, with a dosing range between 1.25 mg and 5 mg daily. The most frequently prescribed LDOM dosing regimen in adolescent females aged 12-17 years is a starting dose of 0.625 mg daily, with a dosing range of 0.625 to 2.5 mg daily. For adolescent males, the recommended regimen is a starting dose of 1.25 mg daily, with a dosing range of 1.25 mg to 5 mg daily.

“We hope that this consensus statement will guide our colleagues who would like to use LDOM to treat hair loss in their adult and adolescent patients,” Dr. Fu told this news organization. “These recommendations may be used to inform clinical practice until additional evidence-based data becomes available.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the effort, including the fact that the expert panel was underrepresented in treating hair loss in pediatric patients, “and therefore failed to reach consensus on LDOM pediatric use and dosing,” she said. “We encourage our pediatric dermatology colleagues to further research LDOM in pediatric patients.”

In an interview, Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, associate professor of clinical dermatology, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, who was asked to comment, but was not involved with the work, characterized the consensus as a “helpful, concise reference guide for dermatologists.”

The advantages of the study are the standardized methods used, “and the experience of the panel,” she said. “Study limitations include the response rate, which was less than 60%, and the risk of potential side effects are not stratified by age, sex, or comorbidities,” she added.

Dr. Fu disclosed that she is a consultant to Pfizer. Dr. Lipner reported having no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO — .

Those are among the key recommendations that resulted from a modified eDelphi consensus of experts who convened to develop guidelines for LDOM prescribing and monitoring.

“Topical minoxidil is safe, effective, over-the-counter, and FDA-approved to treat the most common form of hair loss, androgenetic alopecia,” one of the study authors, Jennifer Fu, MD, a dermatologist who directs the Hair Disorders Clinic at the University of California, San Francisco, told this news organization following the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. The results of the expert consensus were presented during a poster session at the meeting. “It is often used off label for other types of hair loss, yet clinicians who treat hair loss know that patient compliance with topical minoxidil can be poor for a variety of reasons,” she said. “Patients report that it can be difficult to apply and complicate hair styling. For many patients, topical minoxidil can be drying or cause irritant or allergic contact reactions.”

LDOM has become a popular alternative for patients for whom topical minoxidil is logistically challenging, irritating, or ineffective, she continued. Although oral minoxidil is no longer a first-line antihypertensive agent given the risk of cardiovascular adverse effects at higher antihypertensive dosing (10-40 mg daily), a growing number of small studies have documented the use of LDOM at doses ranging from 0.25 mg to 5 mg daily as a safe, effective option for various types of hair loss.

“Given the current absence of larger trials on this topic, our research group identified a need for expert-based guidelines for prescribing and monitoring LDOM use in hair loss patients,” Dr. Fu said. “Our goal was to provide clinicians who treat hair loss patients a road map for using LDOM effectively, maximizing hair growth, and minimizing potential cardiovascular adverse effects.”

Arriving at a Consensus

The process involved 43 hair loss specialists from 12 countries with an average of 6.29 years of experience with LDOM for hair loss, who participated in a multi-round modified Delphi process. They considered questions that addressed LDOM safety, efficacy, dosing, and monitoring for hair loss, and consensus was reached if at least 70% of participants indicated “agree” or “strongly agree” on a five-point Likert scale. Round 1 consisted of 180 open-ended, multiple-choice, or Likert-scale questions, while round 2 involved 121 Likert-scale questions, round 3 consisted of 16 Likert-scale questions, and round 4 included 11 Likert-scale questions. In all, 94 items achieved Likert-scale consensus.

Specifically, experts on the panel found a direct benefit of LDOM for androgenetic alopecia, age-related patterned thinning, alopecia areata, telogen effluvium, traction alopecia, persistent chemotherapy-induced alopecia, and endocrine therapy-induced alopecia. They found a supportive benefit of LDOM for lichen planopilaris, frontal fibrosing alopecia, central centrifugal alopecia, and fibrosing alopecia in a patterned distribution.

“LDOM can be considered when topical minoxidil is more expensive, logistically challenging, has plateaued in efficacy, results in undesirable product residue/skin irritation,” or exacerbates inflammatory processes (ie eczema, psoriasis), they added.

Contraindications to LDOM listed in the consensus recommendations include hypersensitivity to minoxidil, significant drug-drug interactions with LDOM, a history of pericardial effusion/tamponade, pericarditis, heart failure, pulmonary hypertension associated with mitral stenosis, pheochromocytoma, and pregnancy/breastfeeding. Cited precautions of LDOM use include a history of tachycardia or arrhythmia, hypotension, renal impairment, and being on dialysis.

Dr. Fu and colleagues noted that the earliest time point at which LDOM should be expected to demonstrate efficacy is 3-6 months. “Baseline testing is not routine but may be considered in case of identified precautions,” they wrote. They also noted that LDOM can possibly be co-administered with beta-blockers with a specialty consultation, and with spironolactone in biologic female or transgender female patients with hirsutism, acne, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and with lower extremity and facial edema.

According to the consensus statement, the most frequently prescribed LDOM dosing regimen in adult females aged 18 years and older includes a starting dose of 1.25 mg daily, with a dosing range between 0.625 mg and 5 mg daily. For adult males, the most frequently prescribed dosing regimen is a starting dose of 2.5 daily, with a dosing range between 1.25 mg and 5 mg daily. The most frequently prescribed LDOM dosing regimen in adolescent females aged 12-17 years is a starting dose of 0.625 mg daily, with a dosing range of 0.625 to 2.5 mg daily. For adolescent males, the recommended regimen is a starting dose of 1.25 mg daily, with a dosing range of 1.25 mg to 5 mg daily.

“We hope that this consensus statement will guide our colleagues who would like to use LDOM to treat hair loss in their adult and adolescent patients,” Dr. Fu told this news organization. “These recommendations may be used to inform clinical practice until additional evidence-based data becomes available.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the effort, including the fact that the expert panel was underrepresented in treating hair loss in pediatric patients, “and therefore failed to reach consensus on LDOM pediatric use and dosing,” she said. “We encourage our pediatric dermatology colleagues to further research LDOM in pediatric patients.”

In an interview, Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, associate professor of clinical dermatology, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, who was asked to comment, but was not involved with the work, characterized the consensus as a “helpful, concise reference guide for dermatologists.”

The advantages of the study are the standardized methods used, “and the experience of the panel,” she said. “Study limitations include the response rate, which was less than 60%, and the risk of potential side effects are not stratified by age, sex, or comorbidities,” she added.

Dr. Fu disclosed that she is a consultant to Pfizer. Dr. Lipner reported having no relevant disclosures.

SAN DIEGO — .

Those are among the key recommendations that resulted from a modified eDelphi consensus of experts who convened to develop guidelines for LDOM prescribing and monitoring.

“Topical minoxidil is safe, effective, over-the-counter, and FDA-approved to treat the most common form of hair loss, androgenetic alopecia,” one of the study authors, Jennifer Fu, MD, a dermatologist who directs the Hair Disorders Clinic at the University of California, San Francisco, told this news organization following the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology. The results of the expert consensus were presented during a poster session at the meeting. “It is often used off label for other types of hair loss, yet clinicians who treat hair loss know that patient compliance with topical minoxidil can be poor for a variety of reasons,” she said. “Patients report that it can be difficult to apply and complicate hair styling. For many patients, topical minoxidil can be drying or cause irritant or allergic contact reactions.”

LDOM has become a popular alternative for patients for whom topical minoxidil is logistically challenging, irritating, or ineffective, she continued. Although oral minoxidil is no longer a first-line antihypertensive agent given the risk of cardiovascular adverse effects at higher antihypertensive dosing (10-40 mg daily), a growing number of small studies have documented the use of LDOM at doses ranging from 0.25 mg to 5 mg daily as a safe, effective option for various types of hair loss.

“Given the current absence of larger trials on this topic, our research group identified a need for expert-based guidelines for prescribing and monitoring LDOM use in hair loss patients,” Dr. Fu said. “Our goal was to provide clinicians who treat hair loss patients a road map for using LDOM effectively, maximizing hair growth, and minimizing potential cardiovascular adverse effects.”

Arriving at a Consensus

The process involved 43 hair loss specialists from 12 countries with an average of 6.29 years of experience with LDOM for hair loss, who participated in a multi-round modified Delphi process. They considered questions that addressed LDOM safety, efficacy, dosing, and monitoring for hair loss, and consensus was reached if at least 70% of participants indicated “agree” or “strongly agree” on a five-point Likert scale. Round 1 consisted of 180 open-ended, multiple-choice, or Likert-scale questions, while round 2 involved 121 Likert-scale questions, round 3 consisted of 16 Likert-scale questions, and round 4 included 11 Likert-scale questions. In all, 94 items achieved Likert-scale consensus.

Specifically, experts on the panel found a direct benefit of LDOM for androgenetic alopecia, age-related patterned thinning, alopecia areata, telogen effluvium, traction alopecia, persistent chemotherapy-induced alopecia, and endocrine therapy-induced alopecia. They found a supportive benefit of LDOM for lichen planopilaris, frontal fibrosing alopecia, central centrifugal alopecia, and fibrosing alopecia in a patterned distribution.

“LDOM can be considered when topical minoxidil is more expensive, logistically challenging, has plateaued in efficacy, results in undesirable product residue/skin irritation,” or exacerbates inflammatory processes (ie eczema, psoriasis), they added.

Contraindications to LDOM listed in the consensus recommendations include hypersensitivity to minoxidil, significant drug-drug interactions with LDOM, a history of pericardial effusion/tamponade, pericarditis, heart failure, pulmonary hypertension associated with mitral stenosis, pheochromocytoma, and pregnancy/breastfeeding. Cited precautions of LDOM use include a history of tachycardia or arrhythmia, hypotension, renal impairment, and being on dialysis.

Dr. Fu and colleagues noted that the earliest time point at which LDOM should be expected to demonstrate efficacy is 3-6 months. “Baseline testing is not routine but may be considered in case of identified precautions,” they wrote. They also noted that LDOM can possibly be co-administered with beta-blockers with a specialty consultation, and with spironolactone in biologic female or transgender female patients with hirsutism, acne, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and with lower extremity and facial edema.

According to the consensus statement, the most frequently prescribed LDOM dosing regimen in adult females aged 18 years and older includes a starting dose of 1.25 mg daily, with a dosing range between 0.625 mg and 5 mg daily. For adult males, the most frequently prescribed dosing regimen is a starting dose of 2.5 daily, with a dosing range between 1.25 mg and 5 mg daily. The most frequently prescribed LDOM dosing regimen in adolescent females aged 12-17 years is a starting dose of 0.625 mg daily, with a dosing range of 0.625 to 2.5 mg daily. For adolescent males, the recommended regimen is a starting dose of 1.25 mg daily, with a dosing range of 1.25 mg to 5 mg daily.

“We hope that this consensus statement will guide our colleagues who would like to use LDOM to treat hair loss in their adult and adolescent patients,” Dr. Fu told this news organization. “These recommendations may be used to inform clinical practice until additional evidence-based data becomes available.”

She acknowledged certain limitations of the effort, including the fact that the expert panel was underrepresented in treating hair loss in pediatric patients, “and therefore failed to reach consensus on LDOM pediatric use and dosing,” she said. “We encourage our pediatric dermatology colleagues to further research LDOM in pediatric patients.”

In an interview, Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, associate professor of clinical dermatology, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, who was asked to comment, but was not involved with the work, characterized the consensus as a “helpful, concise reference guide for dermatologists.”

The advantages of the study are the standardized methods used, “and the experience of the panel,” she said. “Study limitations include the response rate, which was less than 60%, and the risk of potential side effects are not stratified by age, sex, or comorbidities,” she added.

Dr. Fu disclosed that she is a consultant to Pfizer. Dr. Lipner reported having no relevant disclosures.

FROM AAD 2024

Alopecia Areata: Late Responses Complicate Definition of JAK Inhibitor Failure

SAN DIEGO — , according to late breaker data presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Although the majority respond within months, response curves have so far climbed for as long as patients are followed, allowing many with disappointing early results to catch up, according to Rodney D. Sinclair, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of Melbourne, Australia.

His remarks were derived specifically from new long-term follow-up with baricitinib, the first JAK inhibitor approved for AA, but the pattern appears to be similar with ritlecitinib, the only other JAK inhibitor approved for AA, and for several if not all JAK inhibitors in phase 3 AA trials.

“We have had patients on baricitinib where not much was happening at 18 months, but now, at 4 years, they have a SALT score of zero,” Dr. Sinclair reported

A Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score of 0 signifies complete hair regrowth. On a scale with a maximum score of 100 (complete hair loss), a SALT score of 20 or less, signaling clinical success, has been a primary endpoint in many JAK inhibitor trials, including those conducted with baricitinib.

Providing the most recent analysis in patients with severe AA participating in the phase 3 BRAVE-AA1 and BRAVE-AA2 trials of baricitinib, which were published together in 2022, Dr. Sinclair broke the data down into responders, mixed responders, and nonresponders at 52 weeks. The proportion of patients who responded with even longer follow-up were then tallied.

In the as-observed responses over time, the trajectory of response continued to climb through 76 weeks of follow-up in all three groups.

Relative to the 44.5% rate of overall response (SALT ≤ 20 ) at 52 weeks, there was some further growth in every group maintained on JAK inhibitor therapy over longer follow-up. In Dr. Sinclair’s late breaking analysis, this did not include nonresponders, who stopped therapy by week 52, but 78.4% of the combined responders and mixed responders who remained on treatment had reached treatment success at 76 weeks.

Response Curves Climb More Slowly With Severe Alopecia

While improvement in SALT scores was even seen in nonresponders over time as long as they remained on therapy, Dr. Sinclair reported that response curves tended to climb more slowly in those with more severe alopecia at baseline. Yet, they still climbed. For example, 28.1% of those with a baseline SALT score of 95 to 100 had reached treatment success at week 52, but the proportion had climbed to 35.4% by week 76.

The response curves climbed more quickly among those with a SALT score between 50 and 95 at baseline than among those with more severe alopecia, but the differences in SALT scores at 52 weeks and 76 weeks among patients in this range of baseline SALT scores were small.

Basically, “those with a SALT score of 94 did just as well as those with a SALT score of 51 when followed long-term,” he said, noting that this was among several findings that confounded expectations.

Duration of AA was found to be an important prognostic factor, with 4 years emerging as a general threshold separating those with a diminished likelihood of benefit relative to those with a shorter AA duration.

“When the duration of AA is more than 4 years, the response to any JAK inhibitor seems to fall off a cliff,” Dr. Sinclair said.

To clarify this observation, Dr. Sinclair made an analogy between acute and chronic urticaria. Chronicity appears to change the pathophysiology of both urticaria and AA, making durable remissions more difficult to achieve if the inflammatory response was persistently upregulated, he said.

The delayed responses in some patients “suggests that it is not enough to control inflammation for the hair to regrow. You actually have to activate the hair to grow as well as treat the inflammation,” Dr. Sinclair said.

This heterogeneity that has been observed in the speed of AA response to JAK inhibitors might be explained at least in part by the individual differences in hair growth activation. For ritlecitinib, the only other JAK inhibitor approved for AA to date, 62% were categorized as responders in the registration ALLEGRO trials, but only 44% were early responders, meaning SALT scores of ≤ 20 by week 24, according to a summary published last year. Of the remaining 16%, 11% were middle responders, meaning a SALT score of ≤ 20 reached at week 48, and 6% were late responders, meaning a SALT score of ≤ 20 reached at week 96.

In the context of late breaking 68-week data with deuruxolitinib, an oral JAK inhibitor currently under FDA review for treating moderate to severe AA, presented in the same AAD session as Dr. Sinclair’s baricitinib data, Brett King, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, described similar long-term response curves. At 24 weeks, the SALT ≤ 20 response was achieved in 34.9% of patients, but climbed to 62.8% with continuous therapy over 68 weeks.

The difference between AA and most other inflammatory conditions treated with a JAK inhibitor is that “it takes time to treat,” Dr. King said.

Time Factor Is Important for Response

“What we are learning is that patients keep getting better over time,” Dr. Sinclair said. Asked specifically how long he would treat a patient before giving up, he acknowledged that he used to consider 6 months adequate, but that he has now changed his mind.

“It might be that even 2 years is too short,” he said, although he conceded that a trial of therapy for this long “might be an issue for third-part payers.”

Asked to comment, Melissa Piliang, MD, chair of the department of dermatology at the Cleveland Clinic, agreed with the principle that early responses are not necessarily predictive of complete response.

“In my clinical experience, 6 months is not long enough to assess response,” she told this news organization. “Some patients have hair growth after 18 months to 2 years” of treatment. Additional studies to identify the characteristics and predictors of late response, she said, “would be very helpful, as would trials allowing multiple therapies to simulate real-world practice.”

Like Dr. Sinclair, Dr. Piliang is interested in the possibility of combining a JAK inhibitor with another therapy aimed specially at promoting hair regrowth.

“Using a secondary therapy to stimulate regrowth as an addition to an anti-inflammatory medicine like a JAK inhibitor might speed up response in some patients,” she speculated. Dr. Sinclair reports financial relationships with more than 30 pharmaceutical companies, including Eli Lilly, the manufacturer of baricitinib. Dr. King reports financial relationships with multiple companies, including Concert Pharmaceuticals (consultant and investigator), the manufacturer of deuruxolitinib. Dr. Piliang reports financial relationships with Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and Proctor & Gamble.

SAN DIEGO — , according to late breaker data presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Although the majority respond within months, response curves have so far climbed for as long as patients are followed, allowing many with disappointing early results to catch up, according to Rodney D. Sinclair, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of Melbourne, Australia.

His remarks were derived specifically from new long-term follow-up with baricitinib, the first JAK inhibitor approved for AA, but the pattern appears to be similar with ritlecitinib, the only other JAK inhibitor approved for AA, and for several if not all JAK inhibitors in phase 3 AA trials.

“We have had patients on baricitinib where not much was happening at 18 months, but now, at 4 years, they have a SALT score of zero,” Dr. Sinclair reported

A Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score of 0 signifies complete hair regrowth. On a scale with a maximum score of 100 (complete hair loss), a SALT score of 20 or less, signaling clinical success, has been a primary endpoint in many JAK inhibitor trials, including those conducted with baricitinib.

Providing the most recent analysis in patients with severe AA participating in the phase 3 BRAVE-AA1 and BRAVE-AA2 trials of baricitinib, which were published together in 2022, Dr. Sinclair broke the data down into responders, mixed responders, and nonresponders at 52 weeks. The proportion of patients who responded with even longer follow-up were then tallied.

In the as-observed responses over time, the trajectory of response continued to climb through 76 weeks of follow-up in all three groups.

Relative to the 44.5% rate of overall response (SALT ≤ 20 ) at 52 weeks, there was some further growth in every group maintained on JAK inhibitor therapy over longer follow-up. In Dr. Sinclair’s late breaking analysis, this did not include nonresponders, who stopped therapy by week 52, but 78.4% of the combined responders and mixed responders who remained on treatment had reached treatment success at 76 weeks.

Response Curves Climb More Slowly With Severe Alopecia

While improvement in SALT scores was even seen in nonresponders over time as long as they remained on therapy, Dr. Sinclair reported that response curves tended to climb more slowly in those with more severe alopecia at baseline. Yet, they still climbed. For example, 28.1% of those with a baseline SALT score of 95 to 100 had reached treatment success at week 52, but the proportion had climbed to 35.4% by week 76.

The response curves climbed more quickly among those with a SALT score between 50 and 95 at baseline than among those with more severe alopecia, but the differences in SALT scores at 52 weeks and 76 weeks among patients in this range of baseline SALT scores were small.

Basically, “those with a SALT score of 94 did just as well as those with a SALT score of 51 when followed long-term,” he said, noting that this was among several findings that confounded expectations.

Duration of AA was found to be an important prognostic factor, with 4 years emerging as a general threshold separating those with a diminished likelihood of benefit relative to those with a shorter AA duration.

“When the duration of AA is more than 4 years, the response to any JAK inhibitor seems to fall off a cliff,” Dr. Sinclair said.

To clarify this observation, Dr. Sinclair made an analogy between acute and chronic urticaria. Chronicity appears to change the pathophysiology of both urticaria and AA, making durable remissions more difficult to achieve if the inflammatory response was persistently upregulated, he said.

The delayed responses in some patients “suggests that it is not enough to control inflammation for the hair to regrow. You actually have to activate the hair to grow as well as treat the inflammation,” Dr. Sinclair said.

This heterogeneity that has been observed in the speed of AA response to JAK inhibitors might be explained at least in part by the individual differences in hair growth activation. For ritlecitinib, the only other JAK inhibitor approved for AA to date, 62% were categorized as responders in the registration ALLEGRO trials, but only 44% were early responders, meaning SALT scores of ≤ 20 by week 24, according to a summary published last year. Of the remaining 16%, 11% were middle responders, meaning a SALT score of ≤ 20 reached at week 48, and 6% were late responders, meaning a SALT score of ≤ 20 reached at week 96.

In the context of late breaking 68-week data with deuruxolitinib, an oral JAK inhibitor currently under FDA review for treating moderate to severe AA, presented in the same AAD session as Dr. Sinclair’s baricitinib data, Brett King, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, described similar long-term response curves. At 24 weeks, the SALT ≤ 20 response was achieved in 34.9% of patients, but climbed to 62.8% with continuous therapy over 68 weeks.

The difference between AA and most other inflammatory conditions treated with a JAK inhibitor is that “it takes time to treat,” Dr. King said.

Time Factor Is Important for Response

“What we are learning is that patients keep getting better over time,” Dr. Sinclair said. Asked specifically how long he would treat a patient before giving up, he acknowledged that he used to consider 6 months adequate, but that he has now changed his mind.

“It might be that even 2 years is too short,” he said, although he conceded that a trial of therapy for this long “might be an issue for third-part payers.”

Asked to comment, Melissa Piliang, MD, chair of the department of dermatology at the Cleveland Clinic, agreed with the principle that early responses are not necessarily predictive of complete response.

“In my clinical experience, 6 months is not long enough to assess response,” she told this news organization. “Some patients have hair growth after 18 months to 2 years” of treatment. Additional studies to identify the characteristics and predictors of late response, she said, “would be very helpful, as would trials allowing multiple therapies to simulate real-world practice.”

Like Dr. Sinclair, Dr. Piliang is interested in the possibility of combining a JAK inhibitor with another therapy aimed specially at promoting hair regrowth.

“Using a secondary therapy to stimulate regrowth as an addition to an anti-inflammatory medicine like a JAK inhibitor might speed up response in some patients,” she speculated. Dr. Sinclair reports financial relationships with more than 30 pharmaceutical companies, including Eli Lilly, the manufacturer of baricitinib. Dr. King reports financial relationships with multiple companies, including Concert Pharmaceuticals (consultant and investigator), the manufacturer of deuruxolitinib. Dr. Piliang reports financial relationships with Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and Proctor & Gamble.

SAN DIEGO — , according to late breaker data presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Although the majority respond within months, response curves have so far climbed for as long as patients are followed, allowing many with disappointing early results to catch up, according to Rodney D. Sinclair, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of Melbourne, Australia.

His remarks were derived specifically from new long-term follow-up with baricitinib, the first JAK inhibitor approved for AA, but the pattern appears to be similar with ritlecitinib, the only other JAK inhibitor approved for AA, and for several if not all JAK inhibitors in phase 3 AA trials.

“We have had patients on baricitinib where not much was happening at 18 months, but now, at 4 years, they have a SALT score of zero,” Dr. Sinclair reported

A Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score of 0 signifies complete hair regrowth. On a scale with a maximum score of 100 (complete hair loss), a SALT score of 20 or less, signaling clinical success, has been a primary endpoint in many JAK inhibitor trials, including those conducted with baricitinib.

Providing the most recent analysis in patients with severe AA participating in the phase 3 BRAVE-AA1 and BRAVE-AA2 trials of baricitinib, which were published together in 2022, Dr. Sinclair broke the data down into responders, mixed responders, and nonresponders at 52 weeks. The proportion of patients who responded with even longer follow-up were then tallied.

In the as-observed responses over time, the trajectory of response continued to climb through 76 weeks of follow-up in all three groups.

Relative to the 44.5% rate of overall response (SALT ≤ 20 ) at 52 weeks, there was some further growth in every group maintained on JAK inhibitor therapy over longer follow-up. In Dr. Sinclair’s late breaking analysis, this did not include nonresponders, who stopped therapy by week 52, but 78.4% of the combined responders and mixed responders who remained on treatment had reached treatment success at 76 weeks.

Response Curves Climb More Slowly With Severe Alopecia

While improvement in SALT scores was even seen in nonresponders over time as long as they remained on therapy, Dr. Sinclair reported that response curves tended to climb more slowly in those with more severe alopecia at baseline. Yet, they still climbed. For example, 28.1% of those with a baseline SALT score of 95 to 100 had reached treatment success at week 52, but the proportion had climbed to 35.4% by week 76.

The response curves climbed more quickly among those with a SALT score between 50 and 95 at baseline than among those with more severe alopecia, but the differences in SALT scores at 52 weeks and 76 weeks among patients in this range of baseline SALT scores were small.

Basically, “those with a SALT score of 94 did just as well as those with a SALT score of 51 when followed long-term,” he said, noting that this was among several findings that confounded expectations.

Duration of AA was found to be an important prognostic factor, with 4 years emerging as a general threshold separating those with a diminished likelihood of benefit relative to those with a shorter AA duration.

“When the duration of AA is more than 4 years, the response to any JAK inhibitor seems to fall off a cliff,” Dr. Sinclair said.

To clarify this observation, Dr. Sinclair made an analogy between acute and chronic urticaria. Chronicity appears to change the pathophysiology of both urticaria and AA, making durable remissions more difficult to achieve if the inflammatory response was persistently upregulated, he said.

The delayed responses in some patients “suggests that it is not enough to control inflammation for the hair to regrow. You actually have to activate the hair to grow as well as treat the inflammation,” Dr. Sinclair said.

This heterogeneity that has been observed in the speed of AA response to JAK inhibitors might be explained at least in part by the individual differences in hair growth activation. For ritlecitinib, the only other JAK inhibitor approved for AA to date, 62% were categorized as responders in the registration ALLEGRO trials, but only 44% were early responders, meaning SALT scores of ≤ 20 by week 24, according to a summary published last year. Of the remaining 16%, 11% were middle responders, meaning a SALT score of ≤ 20 reached at week 48, and 6% were late responders, meaning a SALT score of ≤ 20 reached at week 96.

In the context of late breaking 68-week data with deuruxolitinib, an oral JAK inhibitor currently under FDA review for treating moderate to severe AA, presented in the same AAD session as Dr. Sinclair’s baricitinib data, Brett King, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, described similar long-term response curves. At 24 weeks, the SALT ≤ 20 response was achieved in 34.9% of patients, but climbed to 62.8% with continuous therapy over 68 weeks.

The difference between AA and most other inflammatory conditions treated with a JAK inhibitor is that “it takes time to treat,” Dr. King said.

Time Factor Is Important for Response

“What we are learning is that patients keep getting better over time,” Dr. Sinclair said. Asked specifically how long he would treat a patient before giving up, he acknowledged that he used to consider 6 months adequate, but that he has now changed his mind.

“It might be that even 2 years is too short,” he said, although he conceded that a trial of therapy for this long “might be an issue for third-part payers.”

Asked to comment, Melissa Piliang, MD, chair of the department of dermatology at the Cleveland Clinic, agreed with the principle that early responses are not necessarily predictive of complete response.

“In my clinical experience, 6 months is not long enough to assess response,” she told this news organization. “Some patients have hair growth after 18 months to 2 years” of treatment. Additional studies to identify the characteristics and predictors of late response, she said, “would be very helpful, as would trials allowing multiple therapies to simulate real-world practice.”

Like Dr. Sinclair, Dr. Piliang is interested in the possibility of combining a JAK inhibitor with another therapy aimed specially at promoting hair regrowth.

“Using a secondary therapy to stimulate regrowth as an addition to an anti-inflammatory medicine like a JAK inhibitor might speed up response in some patients,” she speculated. Dr. Sinclair reports financial relationships with more than 30 pharmaceutical companies, including Eli Lilly, the manufacturer of baricitinib. Dr. King reports financial relationships with multiple companies, including Concert Pharmaceuticals (consultant and investigator), the manufacturer of deuruxolitinib. Dr. Piliang reports financial relationships with Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and Proctor & Gamble.

FROM AAD 2024

Androgenetic Alopecia: Study Finds Efficacy of Topical and Oral Minoxidil Similar

Oral minoxidil, 5 mg once a day, “did not demonstrate superiority” over topical minoxidil, 5%, applied twice a day, after 24 weeks, reported Mariana Alvares Penha, MD, of the department of dermatology at São Paulo State University, in Botucatu, Brazil, and coauthors. Their randomized, controlled, double-blind study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

Topical minoxidil is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for androgenetic alopecia (AGA), but there has been increasing interest worldwide in the use of low-dose oral minoxidil, a vasodilator approved as an antihypertensive, as an alternative treatment.

The trial “is important information that’s never been elucidated before,” Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview. The data, he added, can be used to reassure patients who do not want to take the oral form of the drug that a topical is just as effective.

“This study does let us counsel patients better and really give them the evidence,” said Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, associate professor of clinical dermatology at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, who was also asked to comment on the results.

Both Dr. Lipner and Dr. Friedman said the study was well-designed.

The investigators enrolled 90 men aged 18-55; 68 completed the trial. Most had mild to moderate AGA. Men were excluded if they had received treatment for alopecia in the previous 6 months, a history of hair transplant, cardiopathy, nephropathy, dermatoses involving the scalp, any clinical conditions causing hair loss, or hypersensitivity to minoxidil.

They were randomized to receive either 5 mg of oral minoxidil a day, plus a placebo solution to apply to the scalp, or topical minoxidil solution (5%) applied twice a day plus placebo capsules. They were told to take a capsule at bedtime and to apply 1 mL of the solution to dry hair in the morning and at night.

The final analysis included 35 men in the topical group and 33 in the oral group (mean age, 36.6 years). Seven people in the topical group and 11 in the oral group were not able to attend the final appointment at 24 weeks. Three additional patients in the topical group dropped out for insomnia, hair shedding, and scalp eczema, while one dropped out of the oral group because of headache.

At 24 weeks, the percentage increase in terminal hair density in the oral minoxidil group was 27% higher (P = .005) in the vertex and 13% higher (P = .15) in the frontal scalp, compared with the topical-treated group.

Total hair density increased by 2% in the oral group compared with topical treatment in the vertex and decreased by 0.2% in the frontal area compared with topical treatment. None of these differences were statistically significant.

Three dermatologists blinded to the treatments, who analyzed photographs, determined that 60% of the men in the oral group and 48% in the topical group had clinical improvement in the frontal area, which was not statistically significant. More orally-treated patients had improvement in the vertex area: 70% compared with 46% of those on topical treatment (P = .04).

Hypertrichosis, Headache

Of the original 90 patients in the trial, more men taking oral minoxidil had hypertrichosis: 49% compared with 25% in the topical formulation group. Headache was also more common among those on oral minoxidil: six cases (14%) vs. one case (2%) among those on topical minoxidil. There was no difference in mean arterial blood pressure or resting heart rate between the two groups. Transient hair loss was more common with topical treatment, but it was not significant.

Dr. Friedman said that the study results would not change how he practices, but that it would give him data to use to inform patients who do not want to take oral minoxidil. He generally prescribes the oral form, unless patients do not want to take it or there is a medical contraindication, which he said is rare.

“I personally think oral is superior to topical,” mainly “because the patient’s actually using it,” said Dr. Friedman. “They’re more likely to take a pill a day versus apply something topically twice a day,” he added.

Both Dr. Lipner and Dr. Friedman said that they doubted that individuals could — or would want to — follow the twice-daily topical regimen used in the trial.

“In real life, not in the clinical trial scenario, it may be very hard for patients to comply with putting on the topical minoxidil twice a day or even once a day,” Dr. Lipner said.

However, she continues to prescribe more topical minoxidil than oral, because she believes “there’s less potential for side effects.” For patients who can adhere to the topical regimen, the study shows that they will get results, said Dr. Lipner.

Dr. Friedman, however, said that for patients who are looking at a lifetime of medication, “an oral will always win out on a topical to the scalp from an adherence perspective.”

The study was supported by the Brazilian Dermatology Society Support Fund. Dr. Penha reported receiving grants from the fund; no other disclosures were reported. Dr. Friedman and Dr. Lipner reported no conflicts related to minoxidil.

Oral minoxidil, 5 mg once a day, “did not demonstrate superiority” over topical minoxidil, 5%, applied twice a day, after 24 weeks, reported Mariana Alvares Penha, MD, of the department of dermatology at São Paulo State University, in Botucatu, Brazil, and coauthors. Their randomized, controlled, double-blind study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

Topical minoxidil is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for androgenetic alopecia (AGA), but there has been increasing interest worldwide in the use of low-dose oral minoxidil, a vasodilator approved as an antihypertensive, as an alternative treatment.

The trial “is important information that’s never been elucidated before,” Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview. The data, he added, can be used to reassure patients who do not want to take the oral form of the drug that a topical is just as effective.

“This study does let us counsel patients better and really give them the evidence,” said Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, associate professor of clinical dermatology at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, who was also asked to comment on the results.

Both Dr. Lipner and Dr. Friedman said the study was well-designed.

The investigators enrolled 90 men aged 18-55; 68 completed the trial. Most had mild to moderate AGA. Men were excluded if they had received treatment for alopecia in the previous 6 months, a history of hair transplant, cardiopathy, nephropathy, dermatoses involving the scalp, any clinical conditions causing hair loss, or hypersensitivity to minoxidil.

They were randomized to receive either 5 mg of oral minoxidil a day, plus a placebo solution to apply to the scalp, or topical minoxidil solution (5%) applied twice a day plus placebo capsules. They were told to take a capsule at bedtime and to apply 1 mL of the solution to dry hair in the morning and at night.

The final analysis included 35 men in the topical group and 33 in the oral group (mean age, 36.6 years). Seven people in the topical group and 11 in the oral group were not able to attend the final appointment at 24 weeks. Three additional patients in the topical group dropped out for insomnia, hair shedding, and scalp eczema, while one dropped out of the oral group because of headache.

At 24 weeks, the percentage increase in terminal hair density in the oral minoxidil group was 27% higher (P = .005) in the vertex and 13% higher (P = .15) in the frontal scalp, compared with the topical-treated group.

Total hair density increased by 2% in the oral group compared with topical treatment in the vertex and decreased by 0.2% in the frontal area compared with topical treatment. None of these differences were statistically significant.

Three dermatologists blinded to the treatments, who analyzed photographs, determined that 60% of the men in the oral group and 48% in the topical group had clinical improvement in the frontal area, which was not statistically significant. More orally-treated patients had improvement in the vertex area: 70% compared with 46% of those on topical treatment (P = .04).

Hypertrichosis, Headache

Of the original 90 patients in the trial, more men taking oral minoxidil had hypertrichosis: 49% compared with 25% in the topical formulation group. Headache was also more common among those on oral minoxidil: six cases (14%) vs. one case (2%) among those on topical minoxidil. There was no difference in mean arterial blood pressure or resting heart rate between the two groups. Transient hair loss was more common with topical treatment, but it was not significant.

Dr. Friedman said that the study results would not change how he practices, but that it would give him data to use to inform patients who do not want to take oral minoxidil. He generally prescribes the oral form, unless patients do not want to take it or there is a medical contraindication, which he said is rare.

“I personally think oral is superior to topical,” mainly “because the patient’s actually using it,” said Dr. Friedman. “They’re more likely to take a pill a day versus apply something topically twice a day,” he added.

Both Dr. Lipner and Dr. Friedman said that they doubted that individuals could — or would want to — follow the twice-daily topical regimen used in the trial.

“In real life, not in the clinical trial scenario, it may be very hard for patients to comply with putting on the topical minoxidil twice a day or even once a day,” Dr. Lipner said.

However, she continues to prescribe more topical minoxidil than oral, because she believes “there’s less potential for side effects.” For patients who can adhere to the topical regimen, the study shows that they will get results, said Dr. Lipner.

Dr. Friedman, however, said that for patients who are looking at a lifetime of medication, “an oral will always win out on a topical to the scalp from an adherence perspective.”

The study was supported by the Brazilian Dermatology Society Support Fund. Dr. Penha reported receiving grants from the fund; no other disclosures were reported. Dr. Friedman and Dr. Lipner reported no conflicts related to minoxidil.

Oral minoxidil, 5 mg once a day, “did not demonstrate superiority” over topical minoxidil, 5%, applied twice a day, after 24 weeks, reported Mariana Alvares Penha, MD, of the department of dermatology at São Paulo State University, in Botucatu, Brazil, and coauthors. Their randomized, controlled, double-blind study was published online in JAMA Dermatology.

Topical minoxidil is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for androgenetic alopecia (AGA), but there has been increasing interest worldwide in the use of low-dose oral minoxidil, a vasodilator approved as an antihypertensive, as an alternative treatment.

The trial “is important information that’s never been elucidated before,” Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview. The data, he added, can be used to reassure patients who do not want to take the oral form of the drug that a topical is just as effective.

“This study does let us counsel patients better and really give them the evidence,” said Shari Lipner, MD, PhD, associate professor of clinical dermatology at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, who was also asked to comment on the results.

Both Dr. Lipner and Dr. Friedman said the study was well-designed.

The investigators enrolled 90 men aged 18-55; 68 completed the trial. Most had mild to moderate AGA. Men were excluded if they had received treatment for alopecia in the previous 6 months, a history of hair transplant, cardiopathy, nephropathy, dermatoses involving the scalp, any clinical conditions causing hair loss, or hypersensitivity to minoxidil.

They were randomized to receive either 5 mg of oral minoxidil a day, plus a placebo solution to apply to the scalp, or topical minoxidil solution (5%) applied twice a day plus placebo capsules. They were told to take a capsule at bedtime and to apply 1 mL of the solution to dry hair in the morning and at night.

The final analysis included 35 men in the topical group and 33 in the oral group (mean age, 36.6 years). Seven people in the topical group and 11 in the oral group were not able to attend the final appointment at 24 weeks. Three additional patients in the topical group dropped out for insomnia, hair shedding, and scalp eczema, while one dropped out of the oral group because of headache.

At 24 weeks, the percentage increase in terminal hair density in the oral minoxidil group was 27% higher (P = .005) in the vertex and 13% higher (P = .15) in the frontal scalp, compared with the topical-treated group.

Total hair density increased by 2% in the oral group compared with topical treatment in the vertex and decreased by 0.2% in the frontal area compared with topical treatment. None of these differences were statistically significant.

Three dermatologists blinded to the treatments, who analyzed photographs, determined that 60% of the men in the oral group and 48% in the topical group had clinical improvement in the frontal area, which was not statistically significant. More orally-treated patients had improvement in the vertex area: 70% compared with 46% of those on topical treatment (P = .04).

Hypertrichosis, Headache

Of the original 90 patients in the trial, more men taking oral minoxidil had hypertrichosis: 49% compared with 25% in the topical formulation group. Headache was also more common among those on oral minoxidil: six cases (14%) vs. one case (2%) among those on topical minoxidil. There was no difference in mean arterial blood pressure or resting heart rate between the two groups. Transient hair loss was more common with topical treatment, but it was not significant.

Dr. Friedman said that the study results would not change how he practices, but that it would give him data to use to inform patients who do not want to take oral minoxidil. He generally prescribes the oral form, unless patients do not want to take it or there is a medical contraindication, which he said is rare.

“I personally think oral is superior to topical,” mainly “because the patient’s actually using it,” said Dr. Friedman. “They’re more likely to take a pill a day versus apply something topically twice a day,” he added.

Both Dr. Lipner and Dr. Friedman said that they doubted that individuals could — or would want to — follow the twice-daily topical regimen used in the trial.

“In real life, not in the clinical trial scenario, it may be very hard for patients to comply with putting on the topical minoxidil twice a day or even once a day,” Dr. Lipner said.

However, she continues to prescribe more topical minoxidil than oral, because she believes “there’s less potential for side effects.” For patients who can adhere to the topical regimen, the study shows that they will get results, said Dr. Lipner.

Dr. Friedman, however, said that for patients who are looking at a lifetime of medication, “an oral will always win out on a topical to the scalp from an adherence perspective.”

The study was supported by the Brazilian Dermatology Society Support Fund. Dr. Penha reported receiving grants from the fund; no other disclosures were reported. Dr. Friedman and Dr. Lipner reported no conflicts related to minoxidil.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Enhancing Cosmetic and Functional Improvement of Recalcitrant Nail Lichen Planus With Resin Nail

Practice Gap

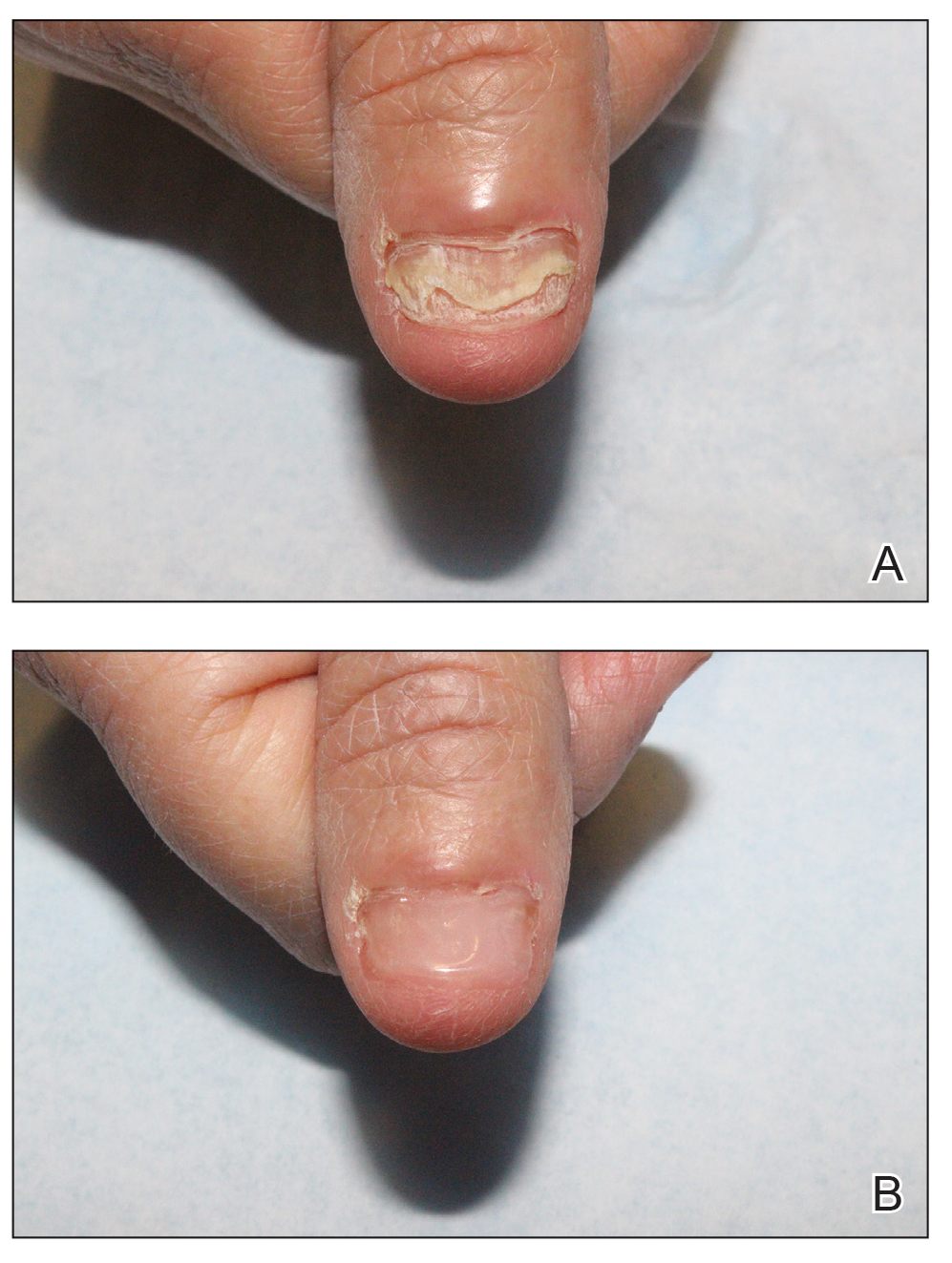

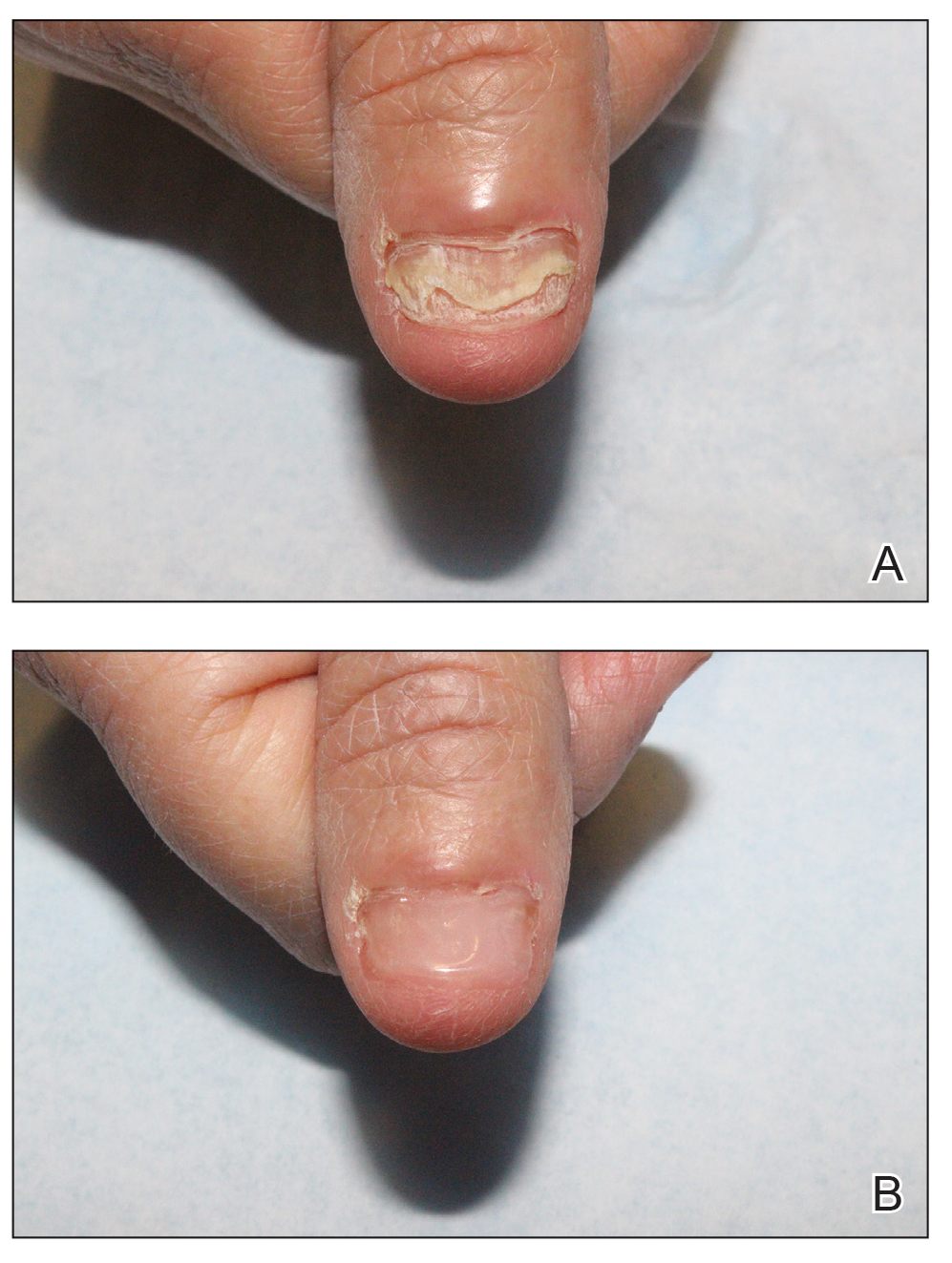

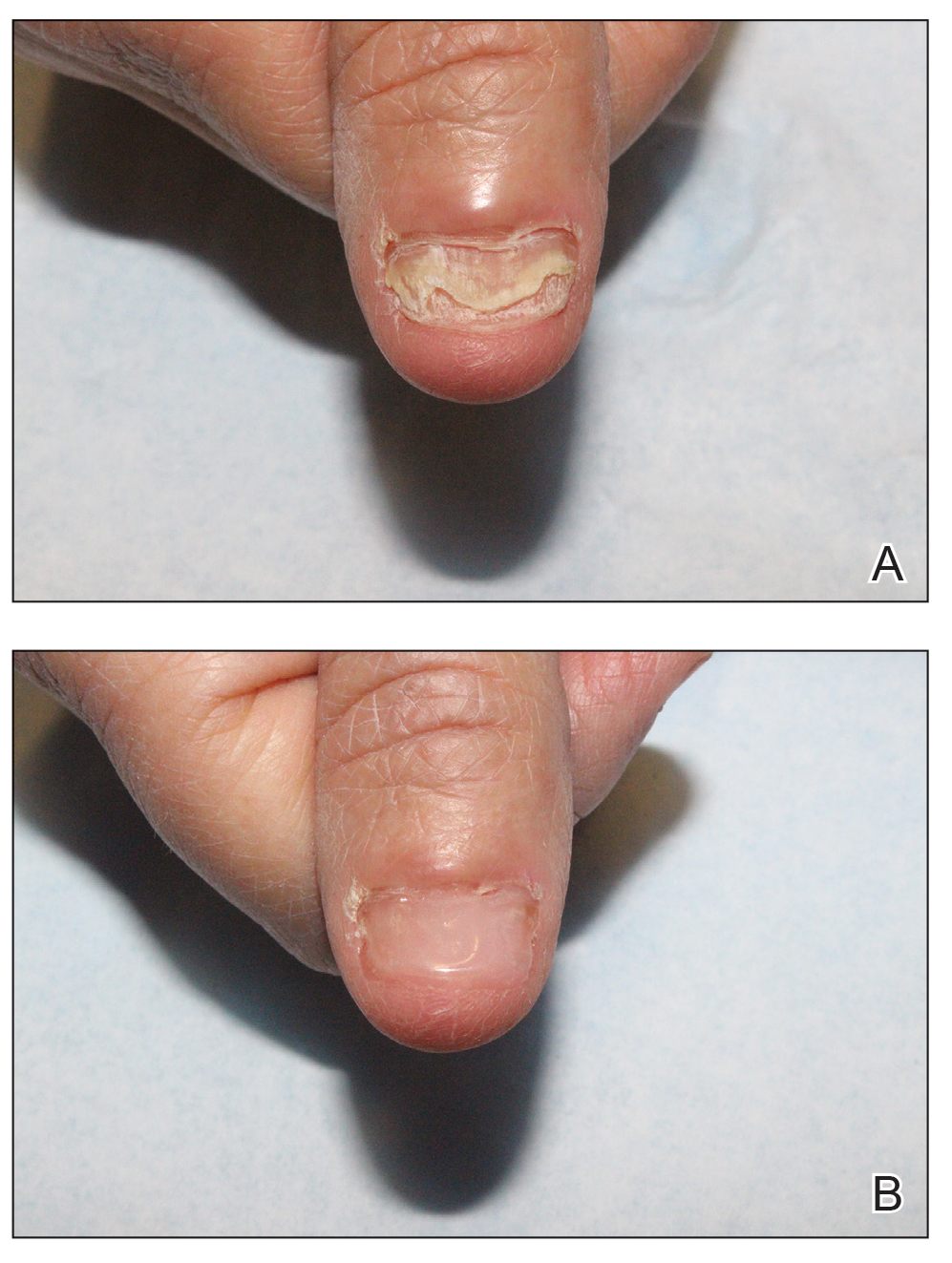

Lichen planus (LP)—a chronic inflammatory disorder affecting the nails—is prevalent in 10% to 15% of patients and is more common in the fingernails than toenails. Clinical manifestation includes longitudinal ridges, nail plate atrophy, and splitting, which all contribute to cosmetic disfigurement and difficulty with functionality. Quality of life and daily activities may be impacted profoundly.1 First-line therapies include intralesional and systemic corticosteroids; however, efficacy is limited and recurrence is common.1,2 Lichen planus is one of the few conditions that may cause permanent and debilitating nail loss.

Tools

A resin nail can be used to improve cosmetic appearance and functionality in patients with recalcitrant nail LP. The composite resin creates a flexible nonporous nail and allows the underlying natural nail to grow. Application of resin nails has been used for toenail onychodystrophies to improve cosmesis and functionality but has not been reported for fingernails. The resin typically lasts 6 to 8 weeks on toenails.

The Technique

Application of a resin nail involves several steps (see video online). First, the affected nail should be debrided and a bonding agent applied. Next, multiple layers of resin are applied until the patient’s desired thickness is achieved (typically 2 layers), followed by a sealing agent. Finally, the nail is cured with UV light. We recommend applying sunscreen to the hand(s) prior to curing with UV light. The liquid resin allows the nail to be customized to the patient’s desired length and shape. The overall procedure takes approximately 20 minutes for a single nail.

We applied resin nail to the thumbnail of a 46-year-old woman with recalcitrant isolated nail LP of 7 years’ duration (Figure). She previously had difficulties performing everyday activities, and the resin improved her functionality. She also was pleased with the cosmetic appearance. After 2 weeks, the resin started falling off with corresponding natural nail growth. The patient denied any adverse events.

Practice Implications

Resin nail application may serve as a temporary solution to improve cosmesis and functionality in patients with recalcitrant nail LP. As shown in our patient, the resin may fall off faster on the fingernails than the toenails, likely because of the faster growth rate of fingernails and more frequent exposure from daily activities. Further studies of resin nail application for the fingernails are needed to establish duration in patients with varying levels of activity (eg, washing dishes, woodworking).

Because the resin nail may be removed easily at any time, resin nail application does not interfere with treatments such as intralesional steroid injections. For patients using a topical medication regimen, the resin nail may be applied slightly distal to the cuticle so that the medication can still be applied by the proximal nail fold of the underlying natural nail.

The resin nail should be kept short and removed after 2 to 4 weeks for the fingernails and 6 to 8 weeks for the toenails to examine the underlying natural nail. Patients may go about their daily activities with the resin nail, including applying nail polish to the resin nail, bathing, and swimming. Resin nail application may complement medical treatments and improve quality of life for patients with nail LP.

- Gupta MK, Lipner SR. Review of nail lichen planus: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:221-230. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.12.002

- Iorizzo M, Tosti A, Starace M, et al. Isolated nail lichen planus: an expert consensus on treatment of the classical form. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1717-1723. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.056

Practice Gap

Lichen planus (LP)—a chronic inflammatory disorder affecting the nails—is prevalent in 10% to 15% of patients and is more common in the fingernails than toenails. Clinical manifestation includes longitudinal ridges, nail plate atrophy, and splitting, which all contribute to cosmetic disfigurement and difficulty with functionality. Quality of life and daily activities may be impacted profoundly.1 First-line therapies include intralesional and systemic corticosteroids; however, efficacy is limited and recurrence is common.1,2 Lichen planus is one of the few conditions that may cause permanent and debilitating nail loss.

Tools

A resin nail can be used to improve cosmetic appearance and functionality in patients with recalcitrant nail LP. The composite resin creates a flexible nonporous nail and allows the underlying natural nail to grow. Application of resin nails has been used for toenail onychodystrophies to improve cosmesis and functionality but has not been reported for fingernails. The resin typically lasts 6 to 8 weeks on toenails.

The Technique

Application of a resin nail involves several steps (see video online). First, the affected nail should be debrided and a bonding agent applied. Next, multiple layers of resin are applied until the patient’s desired thickness is achieved (typically 2 layers), followed by a sealing agent. Finally, the nail is cured with UV light. We recommend applying sunscreen to the hand(s) prior to curing with UV light. The liquid resin allows the nail to be customized to the patient’s desired length and shape. The overall procedure takes approximately 20 minutes for a single nail.

We applied resin nail to the thumbnail of a 46-year-old woman with recalcitrant isolated nail LP of 7 years’ duration (Figure). She previously had difficulties performing everyday activities, and the resin improved her functionality. She also was pleased with the cosmetic appearance. After 2 weeks, the resin started falling off with corresponding natural nail growth. The patient denied any adverse events.

Practice Implications

Resin nail application may serve as a temporary solution to improve cosmesis and functionality in patients with recalcitrant nail LP. As shown in our patient, the resin may fall off faster on the fingernails than the toenails, likely because of the faster growth rate of fingernails and more frequent exposure from daily activities. Further studies of resin nail application for the fingernails are needed to establish duration in patients with varying levels of activity (eg, washing dishes, woodworking).

Because the resin nail may be removed easily at any time, resin nail application does not interfere with treatments such as intralesional steroid injections. For patients using a topical medication regimen, the resin nail may be applied slightly distal to the cuticle so that the medication can still be applied by the proximal nail fold of the underlying natural nail.

The resin nail should be kept short and removed after 2 to 4 weeks for the fingernails and 6 to 8 weeks for the toenails to examine the underlying natural nail. Patients may go about their daily activities with the resin nail, including applying nail polish to the resin nail, bathing, and swimming. Resin nail application may complement medical treatments and improve quality of life for patients with nail LP.

Practice Gap

Lichen planus (LP)—a chronic inflammatory disorder affecting the nails—is prevalent in 10% to 15% of patients and is more common in the fingernails than toenails. Clinical manifestation includes longitudinal ridges, nail plate atrophy, and splitting, which all contribute to cosmetic disfigurement and difficulty with functionality. Quality of life and daily activities may be impacted profoundly.1 First-line therapies include intralesional and systemic corticosteroids; however, efficacy is limited and recurrence is common.1,2 Lichen planus is one of the few conditions that may cause permanent and debilitating nail loss.

Tools

A resin nail can be used to improve cosmetic appearance and functionality in patients with recalcitrant nail LP. The composite resin creates a flexible nonporous nail and allows the underlying natural nail to grow. Application of resin nails has been used for toenail onychodystrophies to improve cosmesis and functionality but has not been reported for fingernails. The resin typically lasts 6 to 8 weeks on toenails.

The Technique

Application of a resin nail involves several steps (see video online). First, the affected nail should be debrided and a bonding agent applied. Next, multiple layers of resin are applied until the patient’s desired thickness is achieved (typically 2 layers), followed by a sealing agent. Finally, the nail is cured with UV light. We recommend applying sunscreen to the hand(s) prior to curing with UV light. The liquid resin allows the nail to be customized to the patient’s desired length and shape. The overall procedure takes approximately 20 minutes for a single nail.

We applied resin nail to the thumbnail of a 46-year-old woman with recalcitrant isolated nail LP of 7 years’ duration (Figure). She previously had difficulties performing everyday activities, and the resin improved her functionality. She also was pleased with the cosmetic appearance. After 2 weeks, the resin started falling off with corresponding natural nail growth. The patient denied any adverse events.

Practice Implications

Resin nail application may serve as a temporary solution to improve cosmesis and functionality in patients with recalcitrant nail LP. As shown in our patient, the resin may fall off faster on the fingernails than the toenails, likely because of the faster growth rate of fingernails and more frequent exposure from daily activities. Further studies of resin nail application for the fingernails are needed to establish duration in patients with varying levels of activity (eg, washing dishes, woodworking).

Because the resin nail may be removed easily at any time, resin nail application does not interfere with treatments such as intralesional steroid injections. For patients using a topical medication regimen, the resin nail may be applied slightly distal to the cuticle so that the medication can still be applied by the proximal nail fold of the underlying natural nail.

The resin nail should be kept short and removed after 2 to 4 weeks for the fingernails and 6 to 8 weeks for the toenails to examine the underlying natural nail. Patients may go about their daily activities with the resin nail, including applying nail polish to the resin nail, bathing, and swimming. Resin nail application may complement medical treatments and improve quality of life for patients with nail LP.

- Gupta MK, Lipner SR. Review of nail lichen planus: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:221-230. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.12.002

- Iorizzo M, Tosti A, Starace M, et al. Isolated nail lichen planus: an expert consensus on treatment of the classical form. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1717-1723. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.056

- Gupta MK, Lipner SR. Review of nail lichen planus: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39:221-230. doi:10.1016/j.det.2020.12.002

- Iorizzo M, Tosti A, Starace M, et al. Isolated nail lichen planus: an expert consensus on treatment of the classical form. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1717-1723. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.056

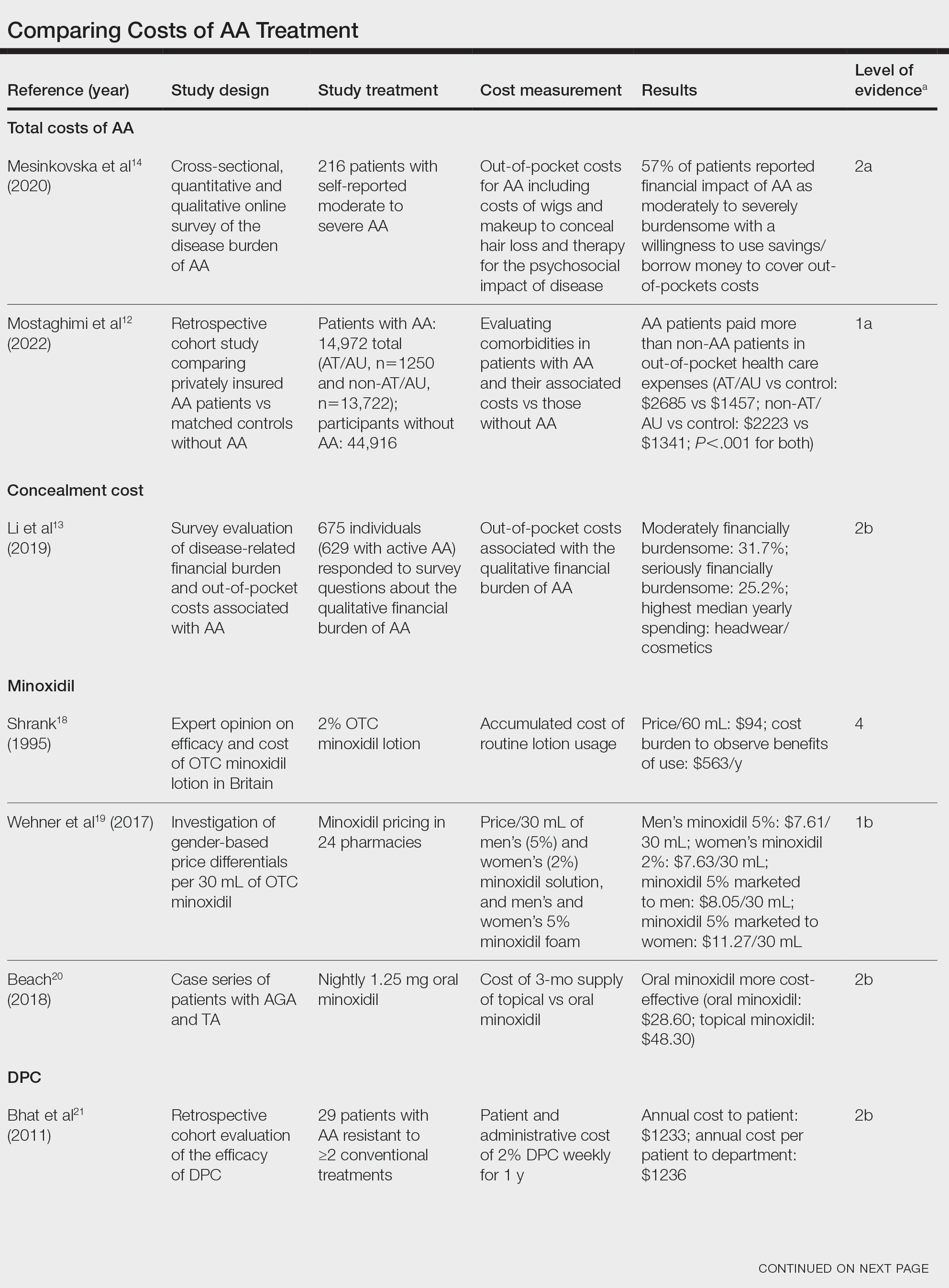

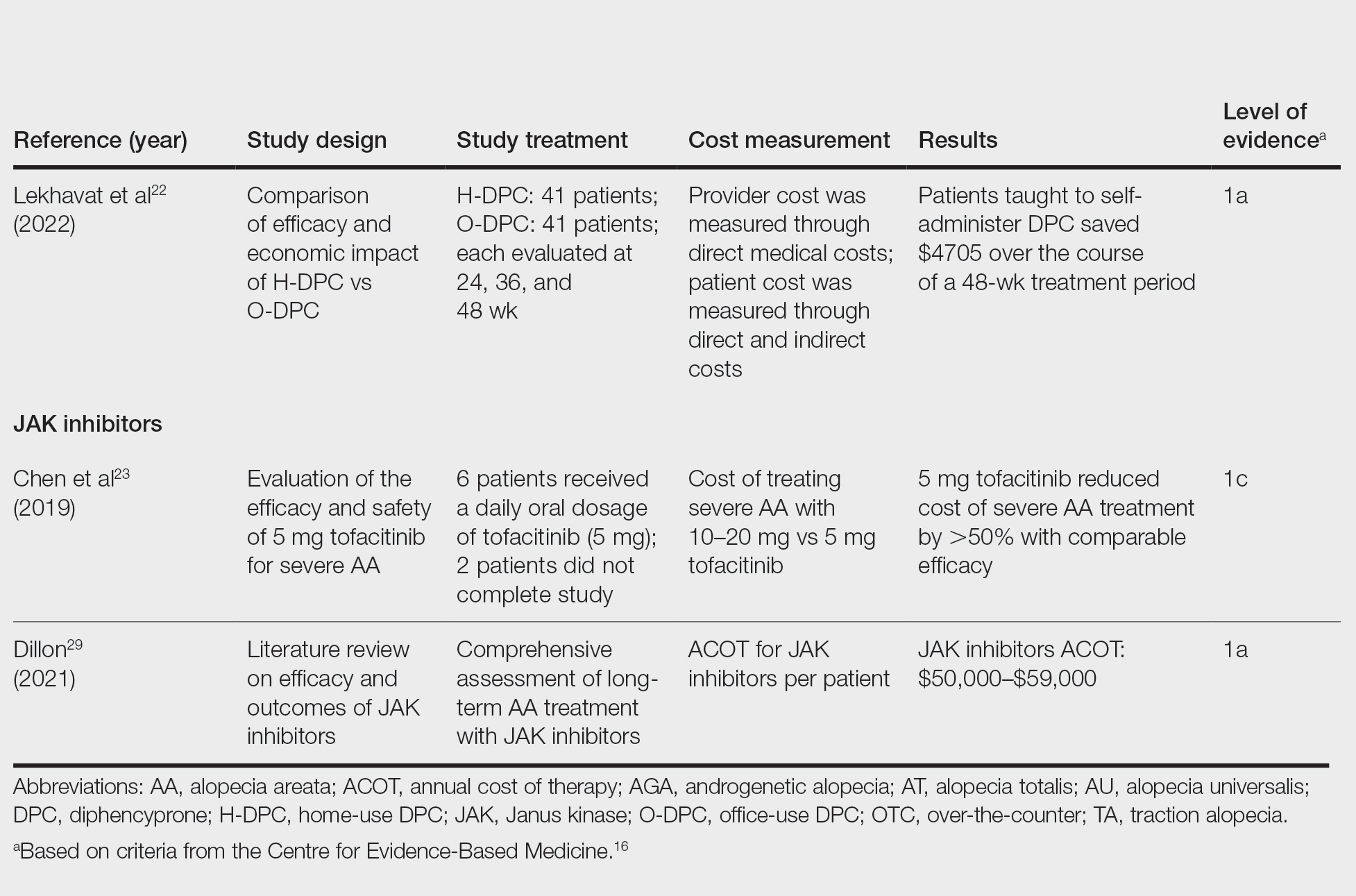

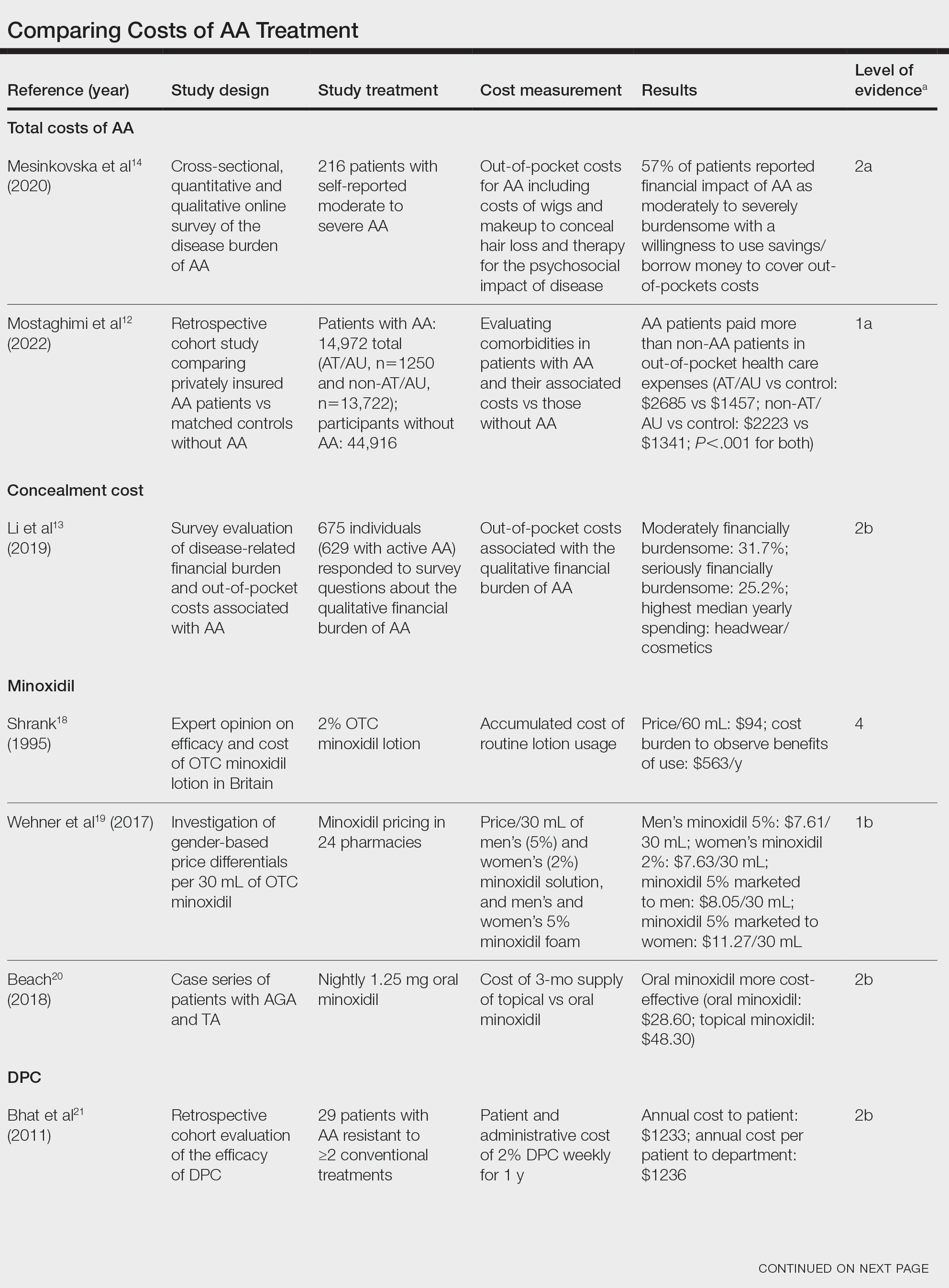

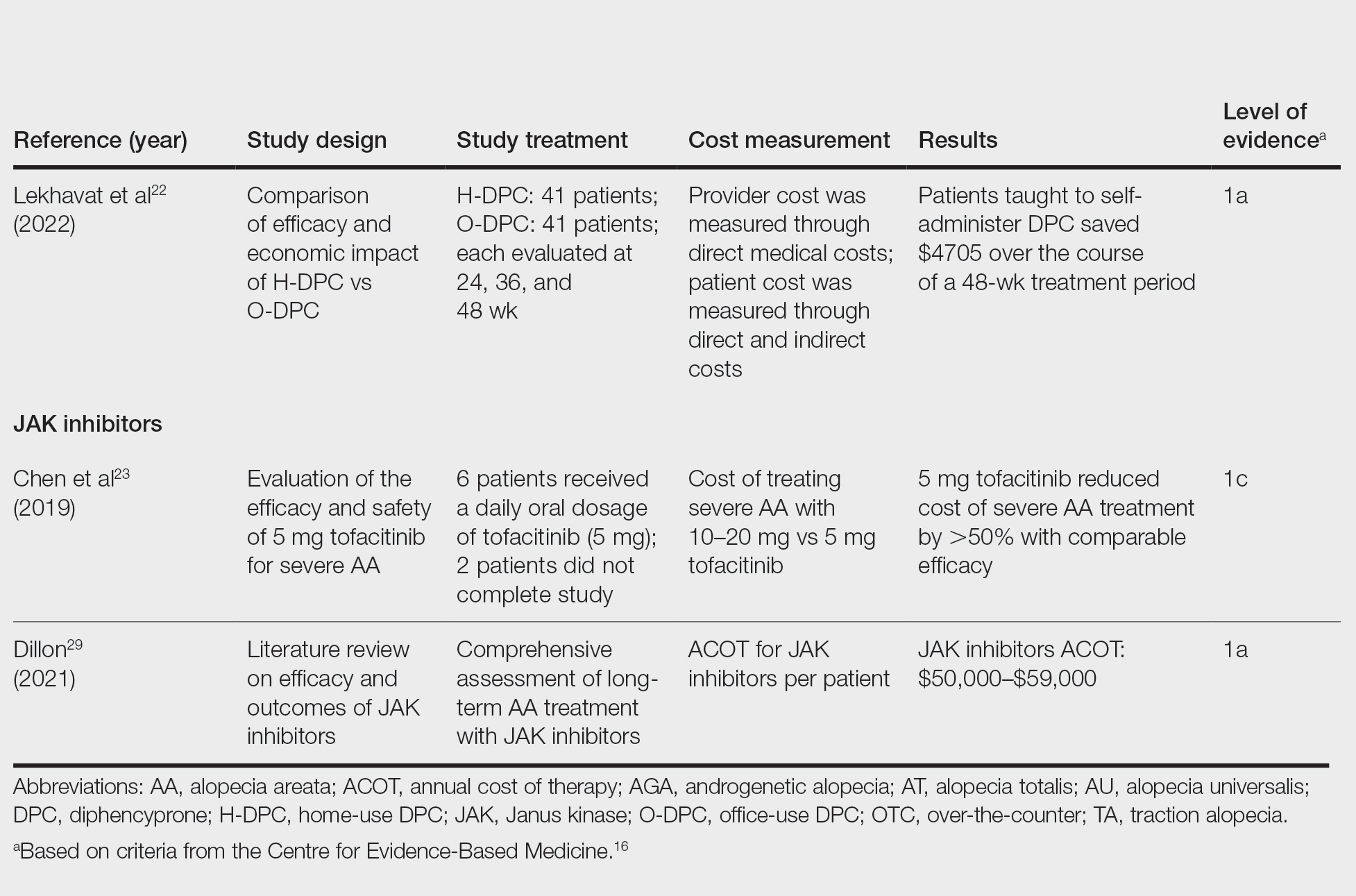

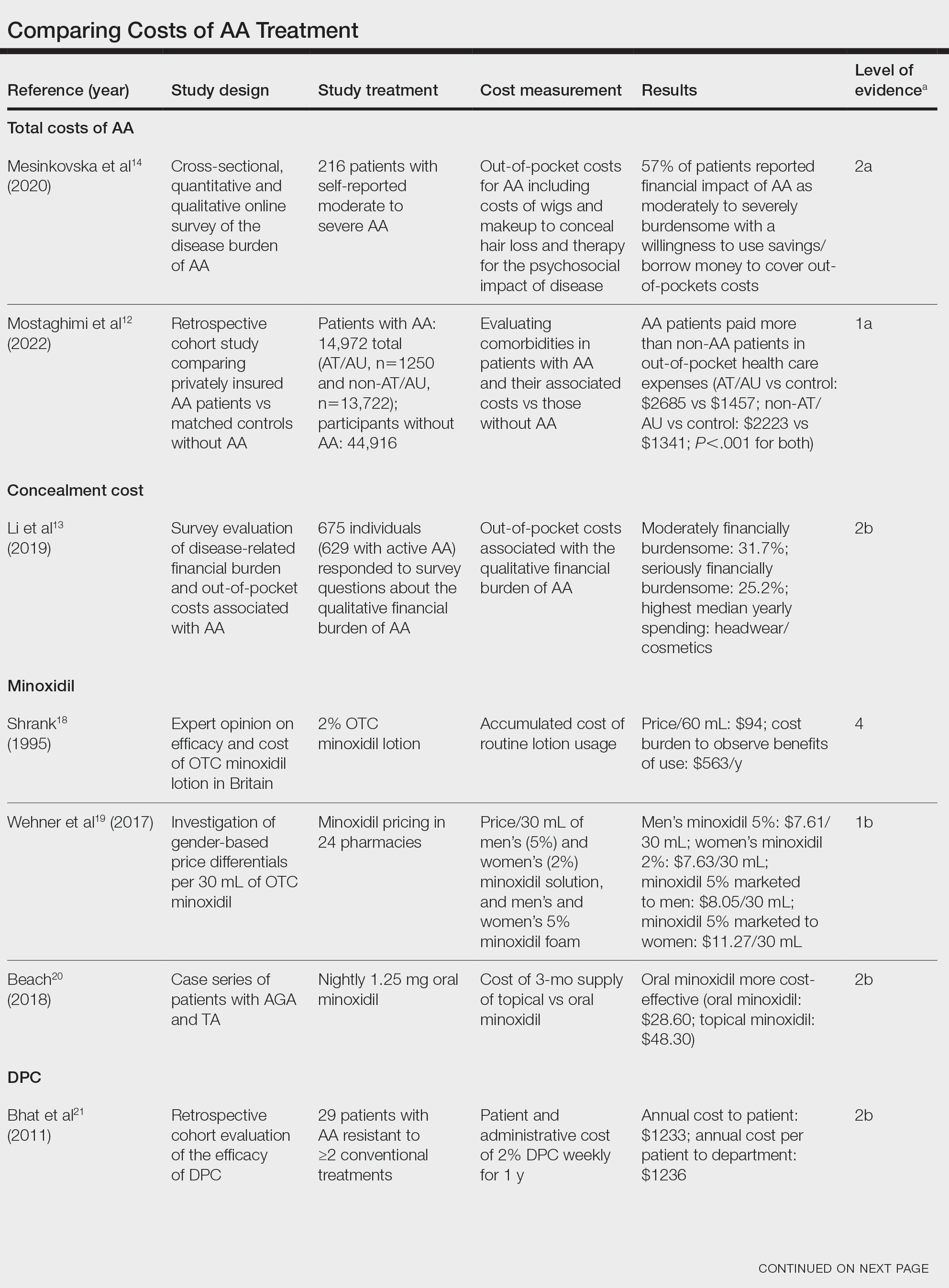

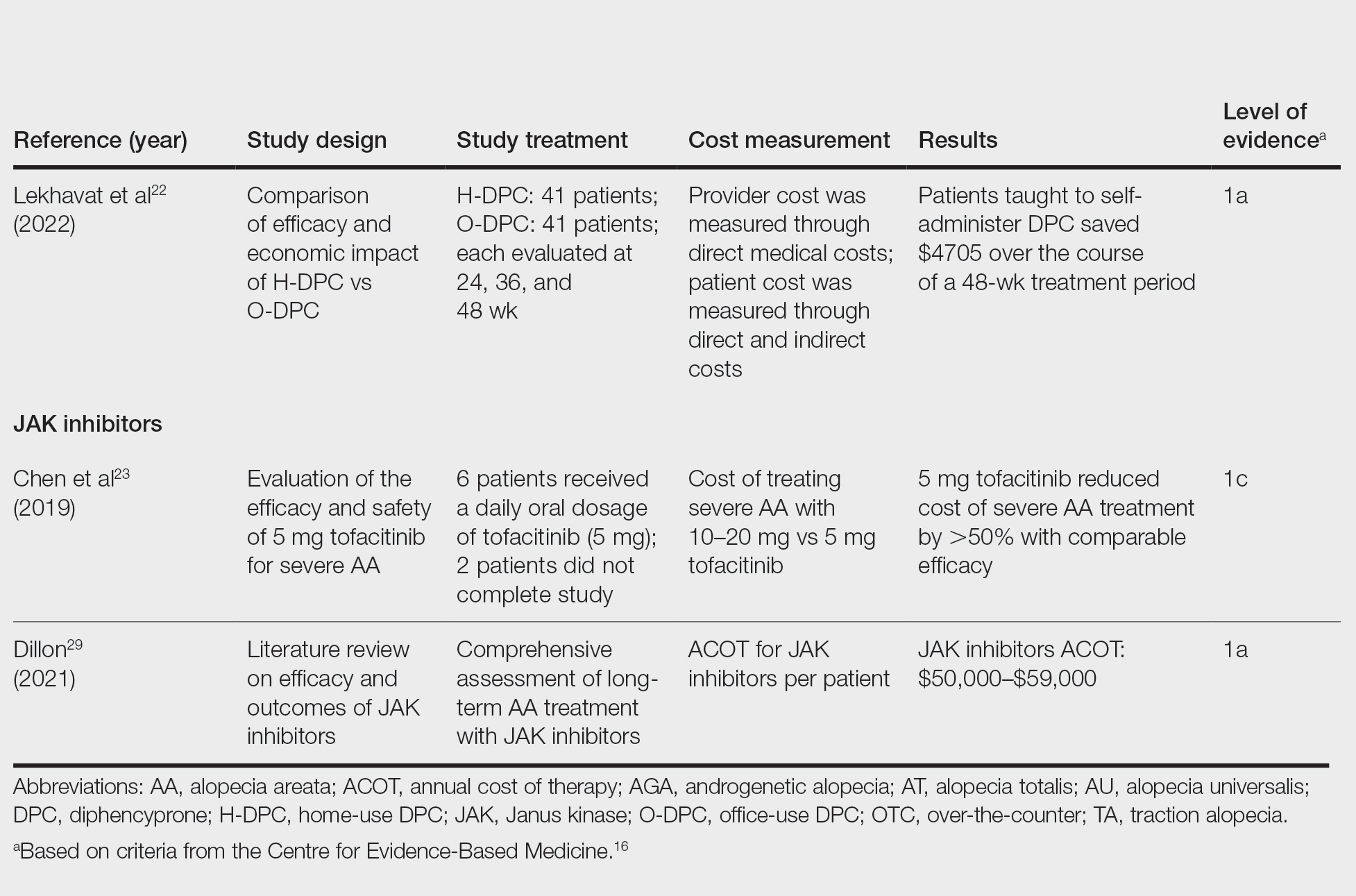

Evaluating the Cost Burden of Alopecia Areata Treatment: A Comprehensive Review for Dermatologists

Alopecia areata (AA) affects 4.5 million individuals in the United States, with 66% younger than 30 years.1,2 Inflammation causes hair loss in well-circumscribed, nonscarring patches on the body with a predilection for the scalp.3-6 The disease can devastate a patient’s self-esteem, in turn reducing quality of life.1,7 Alopecia areata is an autoimmune T-cell–mediated disease in which hair follicles lose their immune privilege.8-10 Several specific mechanisms in the cytokine interactions between T cells and the hair follicle have been discovered, revealing the Janus kinase–signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT) pathway as pivotal in the pathogenesis of the disease and leading to the use of JAK inhibitors for treatment.11

There is no cure for AA, and the condition is managed with prolonged medical treatments and cosmetic therapies.2 Although some patients may be able to manage the annual cost, the cumulative cost of AA treatment can be burdensome.12 This cumulative cost may increase if newer, potentially expensive treatments become the standard of care. Patients with AA report dipping into their savings (41.3%) and cutting back on food or clothing expenses (33.9%) to account for the cost of alopecia treatment. Although prior estimates of the annual out-of-pocket cost of AA treatments range from $1354 to $2685, the cost burden of individual therapies is poorly understood.12-14

Patients who must juggle expensive medical bills with basic living expenses may be lost to follow-up or fall into treatment nonadherence.15 Other patients’ out-of-pocket costs may be manageable, but the costs to the health care system may compromise care in other ways. We conducted a literature review of the recommended therapies for AA based on American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines to identify the costs of alopecia treatment and consolidate the available data for the practicing dermatologist.

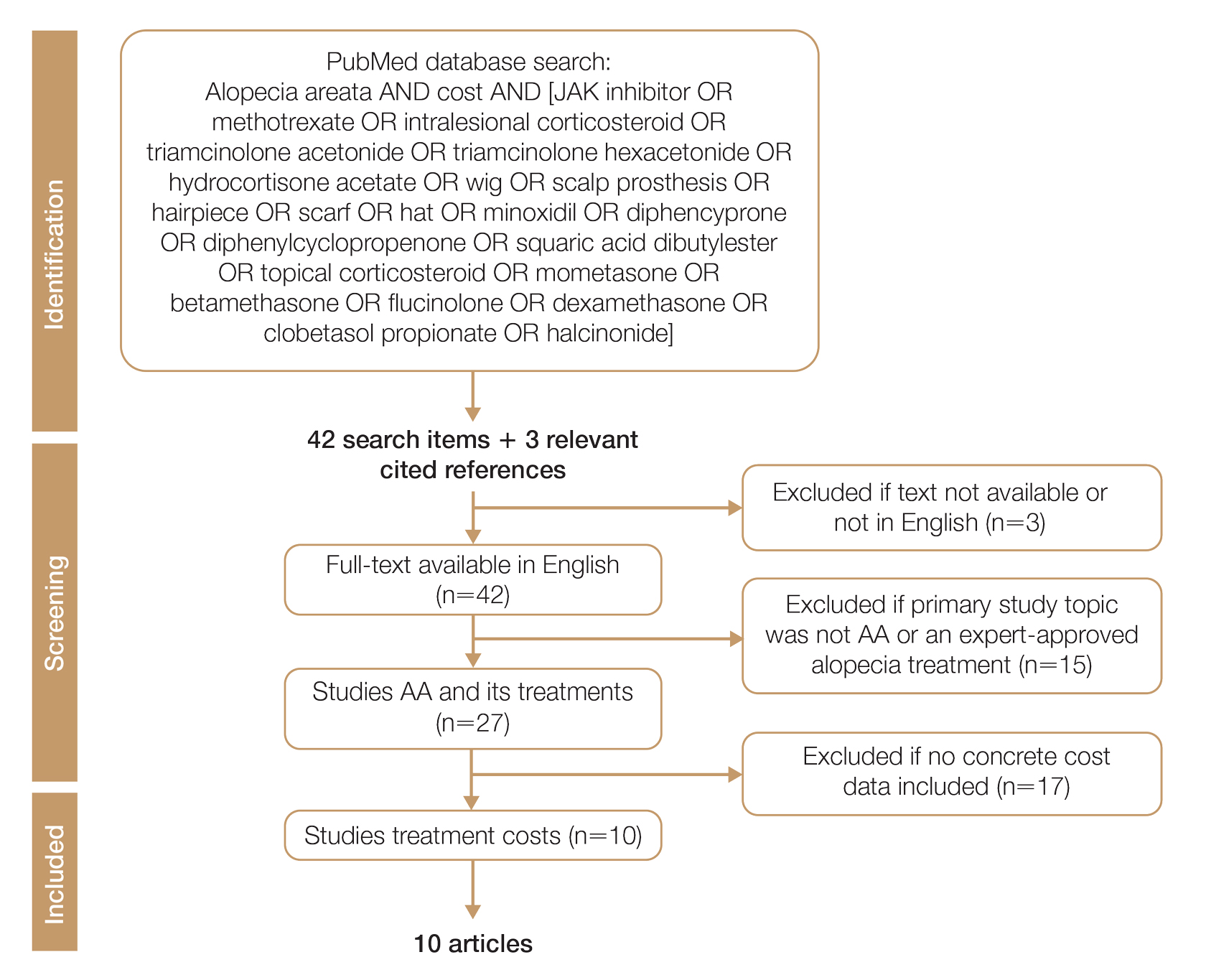

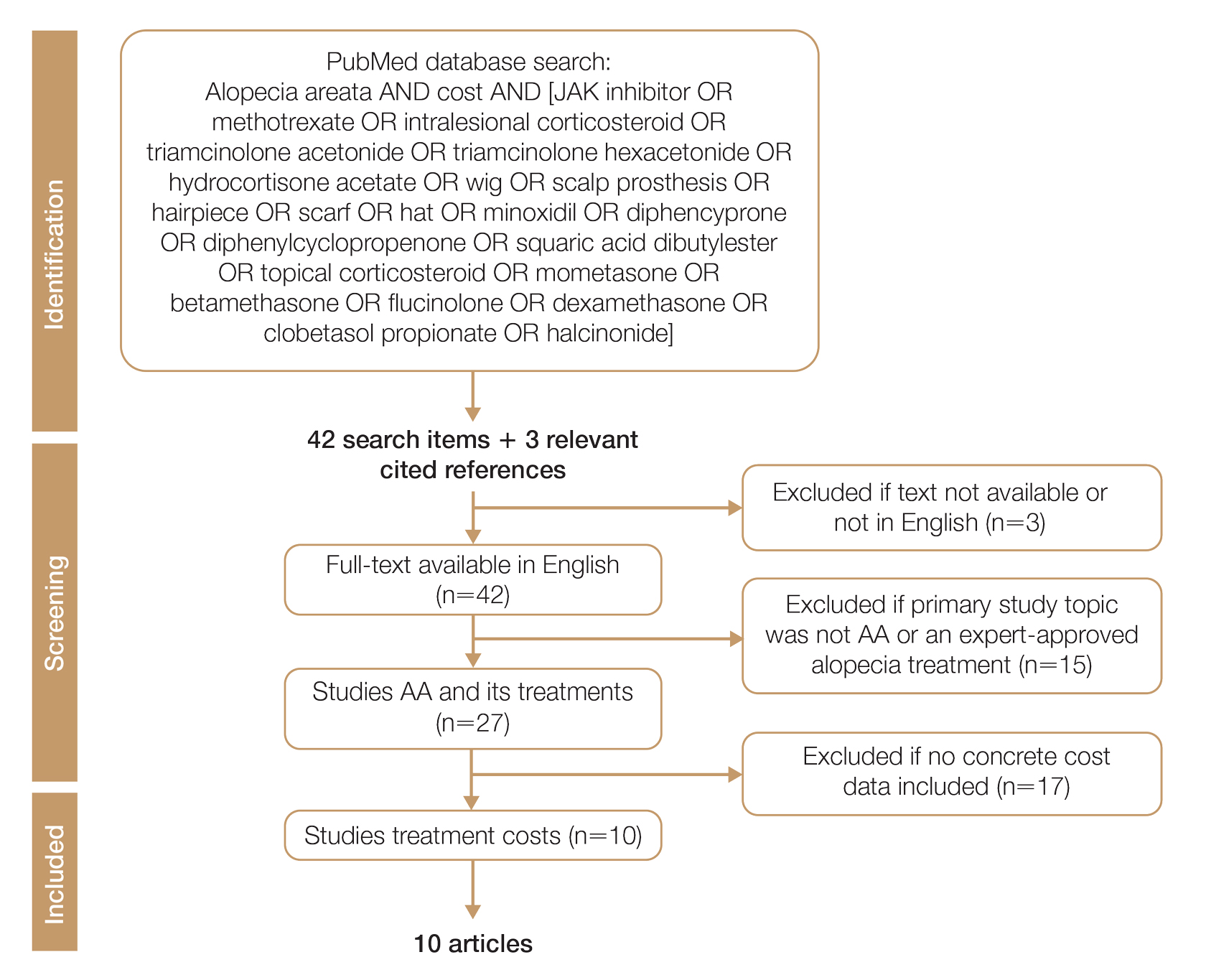

Methods

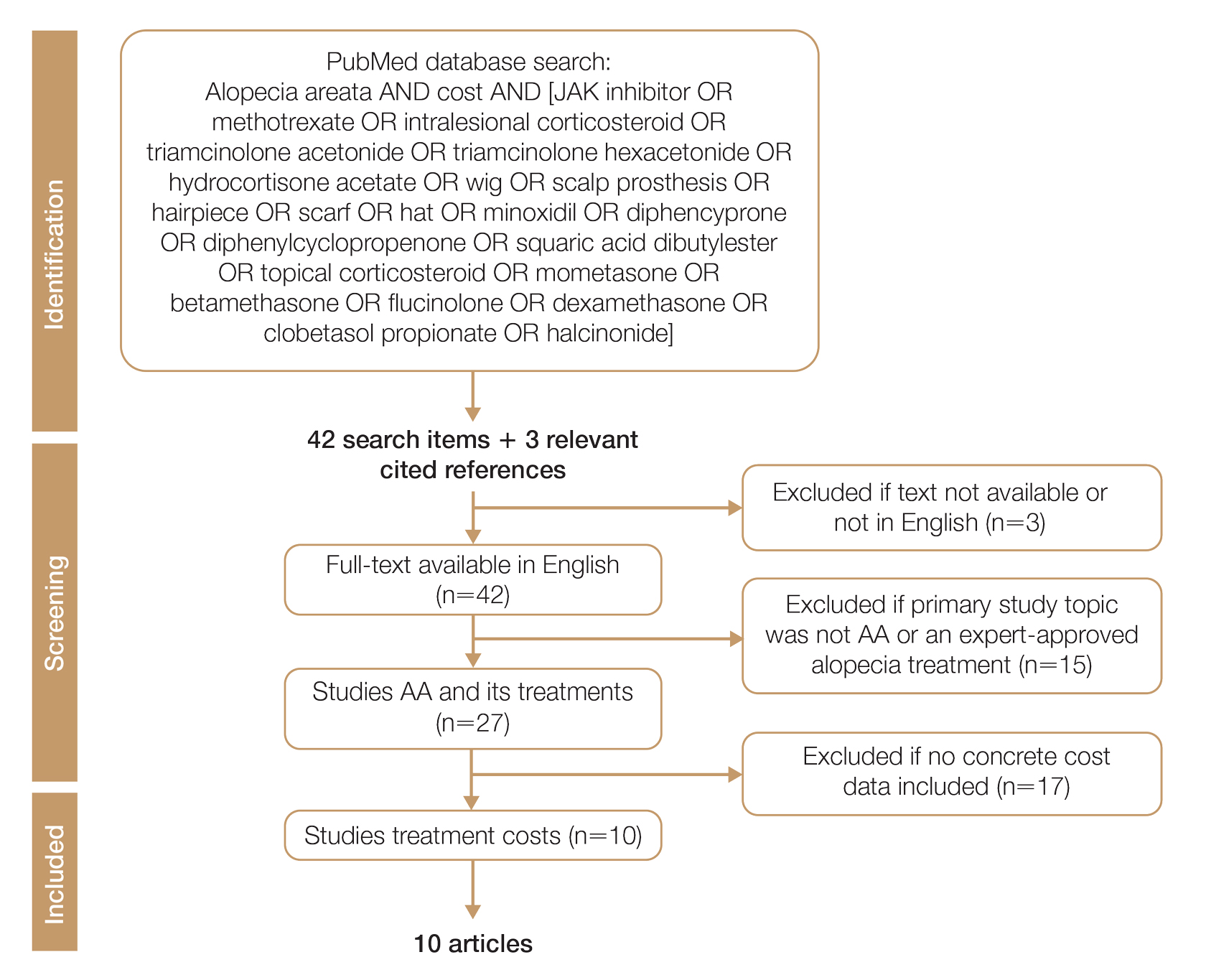

We conducted a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE through September 15, 2022, using the terms alopecia and cost plus one of the treatments (n=21) identified by the AAD2 for the treatment of AA (Figure). The reference lists of included articles were reviewed to identify other potentially relevant studies. Forty-five articles were identified.