User login

Tackling Inflammatory and Infectious Nail Disorders in Children

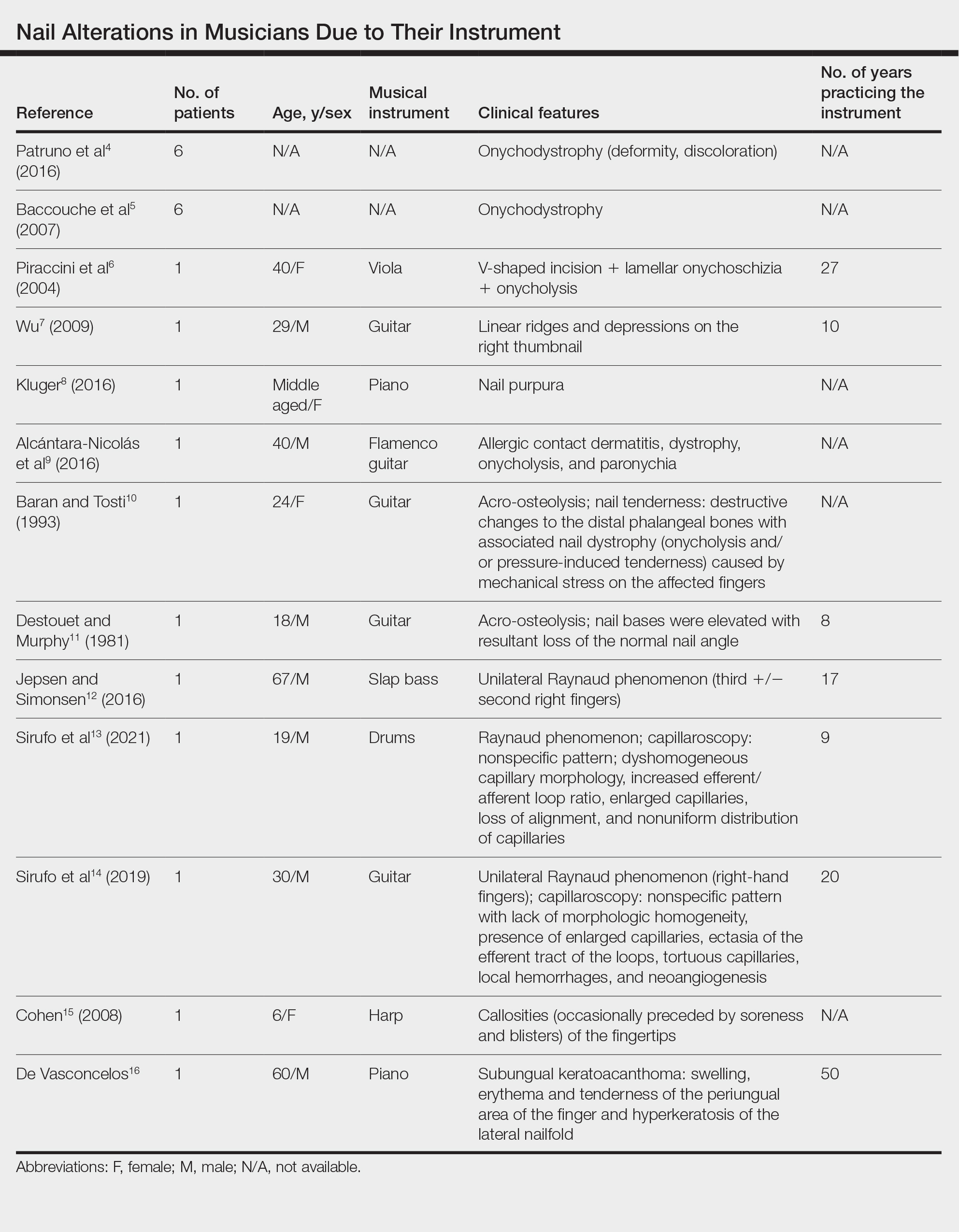

Nail disorders are common among pediatric patients but often are underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed because of their unique disease manifestations. These conditions may severely impact quality of life. There are few nail disease clinical trials that include children. Consequently, most treatment recommendations are based on case series and expert consensus recommendations. We review inflammatory and infectious nail disorders in pediatric patients. By describing characteristics, clinical manifestations, and management approaches for these conditions, we aim to provide guidance to dermatologists in their diagnosis and treatment.

INFLAMMATORY NAIL DISORDERS

Nail Psoriasis

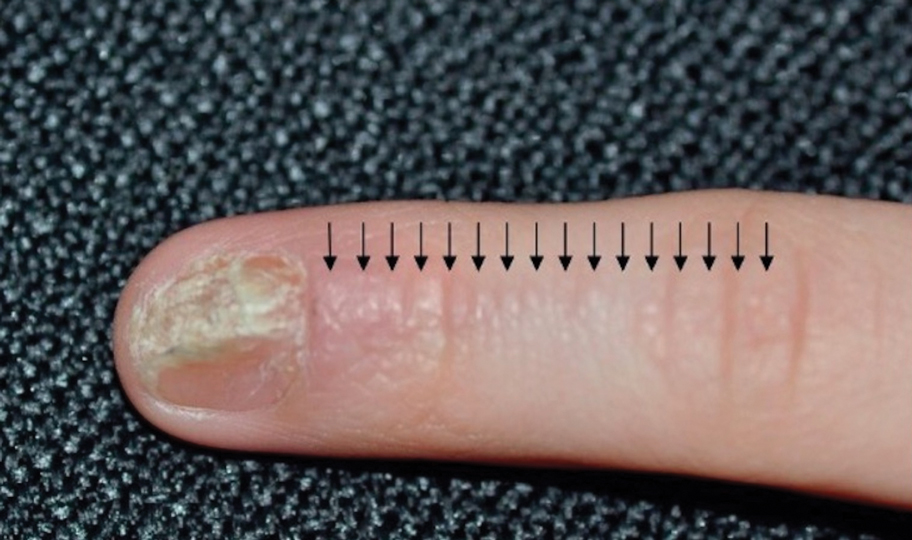

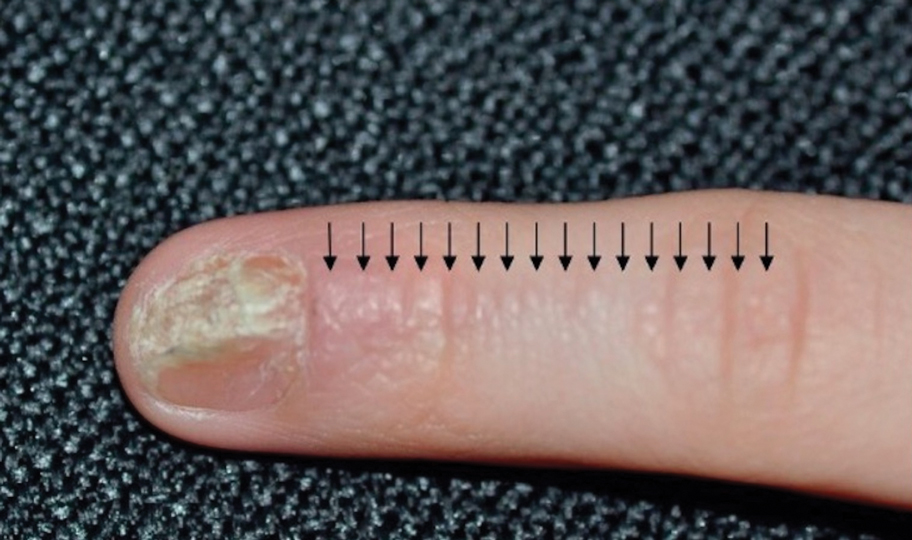

Nail involvement in children with psoriasis is common, with prevalence estimates ranging from 17% to 39.2%.1 Nail matrix psoriasis may manifest with pitting (large irregular pits) and leukonychia as well as chromonychia and nail plate crumbling. Onycholysis, oil drop spots (salmon patches), and subungual hyperkeratosis can be seen in nail bed psoriasis. Nail pitting is the most frequently observed clinical finding (Figure 1).2,3 In a cross-sectional multicenter study of 313 children with cutaneous psoriasis in France, nail findings were present in 101 patients (32.3%). There were associations between nail findings and presence of psoriatic arthritis (P=.03), palmoplantar psoriasis (P<.001), and severity of psoriatic disease, defined as use of systemic treatment with phototherapy (psoralen plus UVA, UVB), traditional systemic treatment (acitretin, methotrexate, cyclosporine), or a biologic (P=.003).4

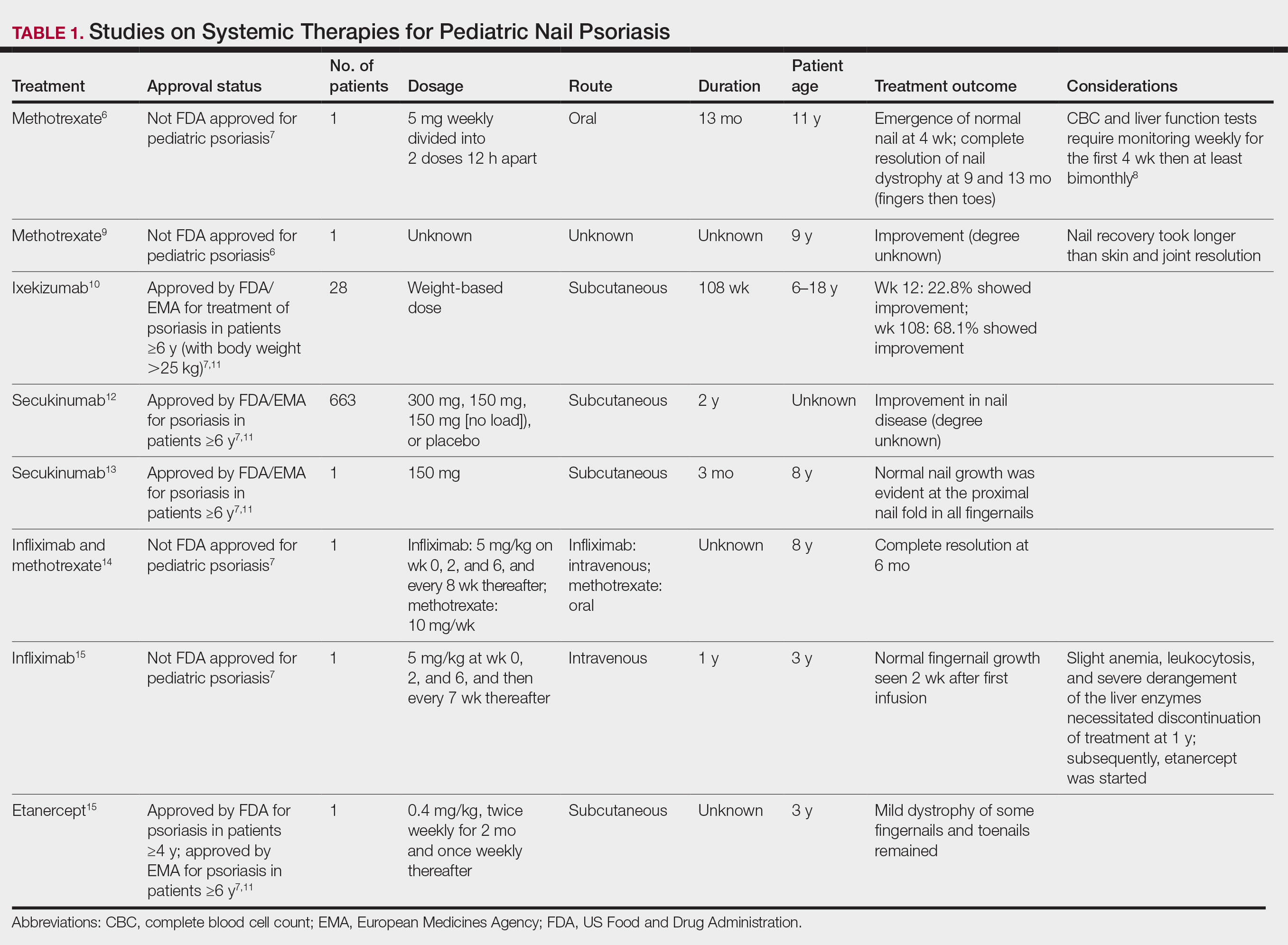

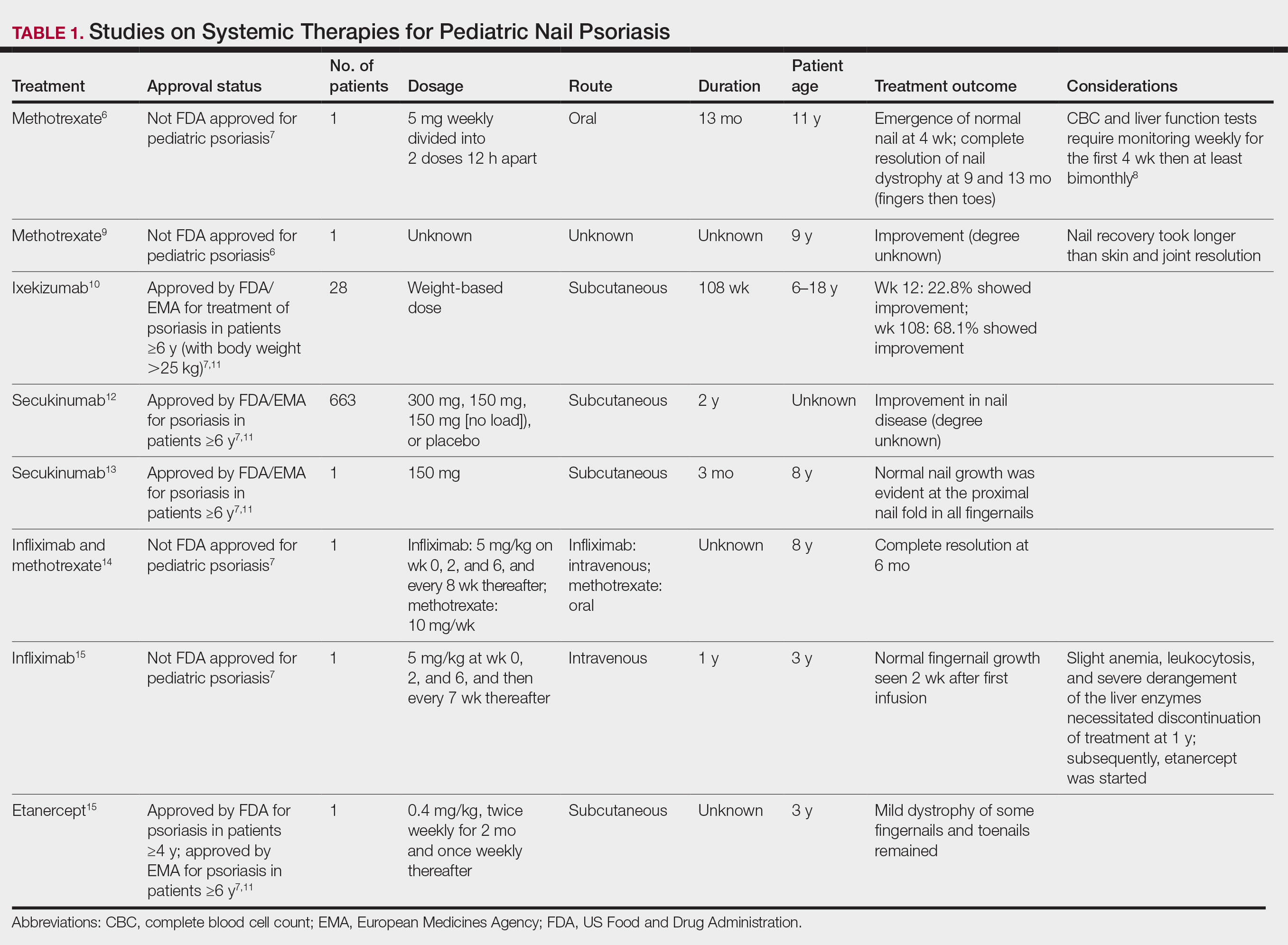

Topical steroids and vitamin D analogues may be used with or without occlusion and may be efficacious.5 Several case reports describe systemic treatments for psoriasis in children, including methotrexate, acitretin, and apremilast (approved for children 6 years and older for plaque psoriasis by the US Food and Drug Administration [FDA]).2 There are 5 biologic drugs currently approved for the treatment of pediatric psoriasis—adalimumab, etanercept, ustekinumab, secukinumab, ixekizumab—and 6 drugs currently undergoing phase 3 studies—brodalumab, guselkumab, risankizumab, tildrakizumab, certolizumab pegol, and deucravacitinib (Table 1).6-15 Adalimumab is specifically approved for moderate to severe nail psoriasis in adults 18 years and older.

Intralesional steroid injections are sometimes useful in the management of nail matrix psoriasis; however, appropriate patient selection is critical due to the pain associated with the procedure. In a prospective study of 16 children (age range, 9–17 years) with nail psoriasis treated with intralesional triamcinolone (ILTAC) 2.5 to 5 mg/mL every 4 to 8 weeks for a minimum of 3 to 6 months, 9 patients achieved resolution and 6 had improvement of clinical findings.16 Local adverse events were mild, including injection-site pain (66%), subungual hematoma (n=1), Beau lines (n=1), proximal nail fold hypopigmentation (n=2), and proximal nail fold atrophy (n=2). Because the proximal nail fold in children is thinner than in adults, there may be an increased risk for nail fold hypopigmentation and atrophy in children. Therefore, a maximum ILTAC concentration of 2.5 mg/mL with 0.2 mL maximum volume per nail per session is recommended for children younger than 15 years.16

Nail Lichen Planus

Nail lichen planus (NLP) is uncommon in children, with few biopsy-proven cases documented in the literature.17 Common clinical findings are onychorrhexis, nail plate thinning, fissuring, splitting, and atrophy with koilonychia.5 Although pterygium development (irreversible nail matrix scarring) is uncommon in pediatric patients, NLP can be progressive and may cause irreversible destruction of the nail matrix and subsequent nail loss, warranting therapeutic intervention.18

Treatment of NLP may be difficult, as there are no options that work in all patients. Current literature supports the use of systemic corticosteroids or ILTAC for the treatment of NLP; however, recurrence rates can be high. According to an expert consensus paper on NLP treatment, ILTAC may be injected in a concentration of 2.5, 5, or 10 mg/mL according to disease severity.19 In severe or resistant cases, intramuscular (IM) triamcinolone may be considered, especially if more than 3 nails are affected. A dosage of 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/mo for at least 3 to 6 months is recommended for both children and adults, with 1 mg/kg/mo recommended in the active treatment phase (first 2–3 months).19 In a retrospective review of 5 pediatric patients with NLP treated with IM triamcinolone 0.5 mg/kg/mo, 3 patients had resolution and 2 improved with treatment.20 In a prospective study of 10 children with NLP, IM triamcinolone at a dosage of 0.5 to 1 mg/kg every 30 days for 3 to 6 months resulted in resolution of nail findings in 9 patients.17 In a prospective study of 14 pediatric patients with NLP treated with 2.5 to 5 mg/mL of ILTAC, 10 achieved resolution and 3 improved.16

Intralesional triamcinolone injections may be better suited for teenagers compared to younger children who may be more apprehensive of needles. To minimize pain, it is recommended to inject ILTAC slowly at room temperature, with use of “talkesthesia” and vibration devices, 1% lidocaine, or ethyl chloride spray.18

Trachyonychia

Trachyonychia is characterized by the presence of sandpaperlike nails. It manifests with brittle thin nails with longitudinal ridging, onychoschizia, and thickened hyperkeratotic cuticles. Trachyonychia typically involves multiple nails, with a peak age of onset between 3 and 12 years.21,22 There are 2 variants: the opaque type with rough longitudinal ridging, and the shiny variant with opalescent nails and pits that reflect light. The opaque variant is more common and is associated with psoriasis, whereas the shiny variant is less common and is associated with alopecia areata.23 Although most cases are idiopathic, some are associated with psoriasis and alopecia areata, as previously noted, as well as atopic dermatitis (AD) and lichen planus.22,24

Fortunately, trachyonychia does not lead to permanent nail damage or pterygium, making treatment primarily focused on addressing functional and cosmetic concerns.24 Spontaneous resolution occurs in approximately 50% of patients. In a prospective study of 11 patients with idiopathic trachyonychia, there was partial improvement in 5 of 9 patients treated with topical steroids, 1 with only petrolatum, and 1 with vitamin supplements. Complete resolution was reported in 1 patient treated with topical steroids.25 Because trachyonychia often is self-resolving, no treatment is required and a conservative approach is strongly recommended.26 Treatment options include topical corticosteroids, tazarotene, and 5-fluorouracil. Intralesional triamcinolone, systemic cyclosporine, retinoids, systemic corticosteroids, and tofacitinib have been described in case reports, though none of these have been shown to be 100% efficacious.24

Nail Lichen Striatus

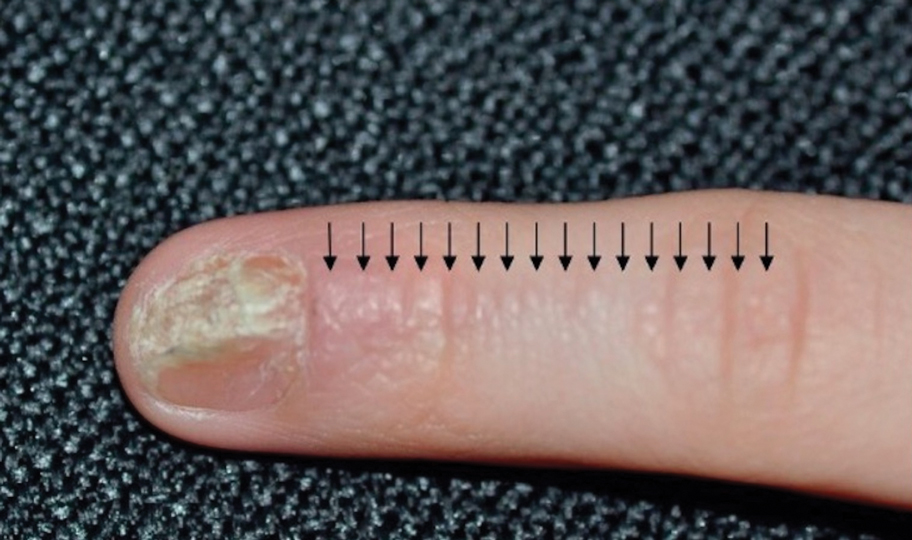

Lichen striatus involving the nail is uncommon and is characterized by onycholysis, longitudinal ridging, splitting, and fraying, as well as what appears to be a subungual tumor. It can encompass the entire nail or may be isolated to a portion of the nail (Figure 2). Usually, a Blaschko-linear array of flesh-colored papules on the more proximal digit directly adjacent to the nail dystrophy will be seen, though nail findings can occur in isolation.27-29 The underlying pathophysiology is not clear; however, one hypothesis is that a triggering event, such as trauma, induces the expression of antigens that elicit a self-limiting immune-mediated response by CD8 T lymphocytes.30

Generally, nail lichen striatus spontaneously resolves in 1 to 2 years without treatment. In a prospective study of 5 patients with nail lichen striatus, the median time to resolution was 22.6 months (range, 10–30 months).31 Topical steroids may be used for pruritus. In one case report, a 3-year-old boy with nail lichen striatus of 4 months’ duration was treated with tacrolimus ointment 0.03% daily for 3 months.28

Nail AD

Nail changes with AD may be more common in adults than children or are underreported. In a study of 777 adults with AD, nail dystrophy was present in 124 patients (16%), whereas in a study of 250 pediatric patients with AD (aged 0-2 years), nail dystrophy was present in only 4 patients.32,33

Periungual inflammation from AD causes the nail changes.34 In a cross-sectional study of 24 pediatric patients with nail dystrophy due to AD, transverse grooves (Beau lines) were present in 25% (6/24), nail pitting in 16.7% (4/24), koilonychia in 16.7% (4/24), trachyonychia in 12.5% (3/24), leukonychia in 12.5% (3/24), brachyonychia in 8.3% (2/24), melanonychia in 8.3% (2/24), onychomadesis in 8.3% (2/24), onychoschizia in 8.3% (2/24), and onycholysis in 8.3% (2/24). There was an association between disease severity and presence of toenail dystrophy (P=.03).35

Topical steroids with or without occlusion can be used to treat nail changes. Although there is limited literature describing the treatment of nail AD in children, a 61-year-old man with nail changes associated with AD achieved resolution with 3 months of treatment with dupilumab.36 Anecdotally, most patients will improve with usual cutaneous AD management.

INFECTIOUS NAIL DISORDERS

Viral Infections

Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease—Hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) is a common childhood viral infection caused by various enteroviruses, most commonly coxsackievirus A16, with the A6 variant causing more severe disease. Fever and painful vesicles involving the oral mucosa as well as palms and soles give the disease its name. Nail changes are common. In a prospective study involving 130 patients with laboratory-confirmed coxsackievirus CA6 serotype infection, 37% developed onychomadesis vs only 5% of 145 cases with non-CA6 enterovirus infection who developed nail findings. There was an association between CA6 infection and presence of nail changes (P<.001).37

Findings ranging from transverse grooves (Beau lines) to complete nail shedding (onychomadesis)(Figure 3) may be seen.38,39 Nail findings in HFMD are due to transient inhibition of nail growth and present approximately 3 to 6 weeks after infection.40 Onychomadesis is seen in 30% to 68% of patients with HFMD.37,41,42 Nail findings in HFMD spontaneously resolve with nail growth (2–3 mm per month for fingernails and 1 mm per month for toenails) and do not require specific treatment. Although the appearance of nail changes associated with HFMD can be disturbing, dermatologists can reassure children and their parents that the nails will resolve with the next cycle of growth.

Kawasaki Disease—Kawasaki disease (KD) is a vasculitis primarily affecting children and infants. Although the specific pathogen and pathophysiology is not entirely clear, clinical observations have suggested an infectious cause, most likely a virus.43 In Japan, more than 15,000 cases of KD are documented annually, while approximately 4200 cases are seen in the United States.44 In a prospective study from 1984 to 1990, 4 of 26 (15.4%) patients with KD presented with nail manifestations during the late acute phase or early convalescent phase of disease. There were no significant associations between nail dystrophy and severity of KD, such as coronary artery aneurysm.45

Nail changes reported in children with KD include onychomadesis, onycholysis, orange-brown chromonychia, splinter hemorrhages, Beau lines, and pincer nails. In a review of nail changes associated with KD from 1980 to 2021, orange-brown transverse chromonychia, which may evolve into transverse leukonychia, was the most common nail finding reported, occurring in 17 of 31 (54.8%) patients.44 It has been hypothesized that nail changes may result from blood flow disturbance due to the underlying vasculitis.46 Nail changes appear several weeks after the onset of fever and are self-limited. Resolution occurs with nail growth, with no treatment required.

FUNGAL INFECTIONS

Onychomycosis

Onychomycosis is a fungal infection of the nails that occurs in 0.2% to 5.5% of pediatric patients, and its prevalence may be increasing, which may be due to environmental factors or increased rates of diabetes mellitus and obesity in the pediatric population.47 Onychomycosis represents 15.5% of nail dystrophies in pediatric patients.48 Some dermatologists treat presumptive onychomycosis without confirmation; however, we do not recommend that approach. Because the differential is broad and the duration of treatment is long, mycologic examination (potassium hydroxide preparation, fungal culture, polymerase chain reaction, and/or histopathology) should be obtained to confirm onychomycosis prior to initiation of antifungal management. Family members of affected individuals should be evaluated and treated, if indicated, for onychomycosis and tinea pedis, as household transmission is common.

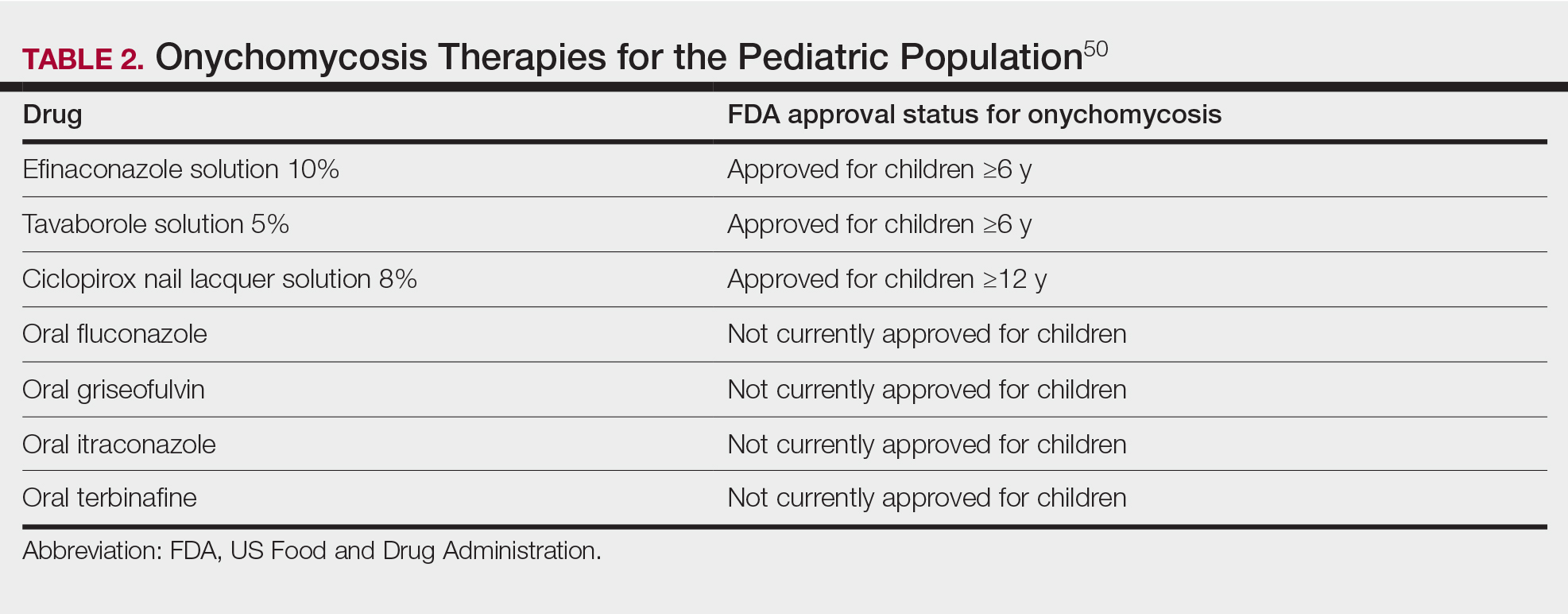

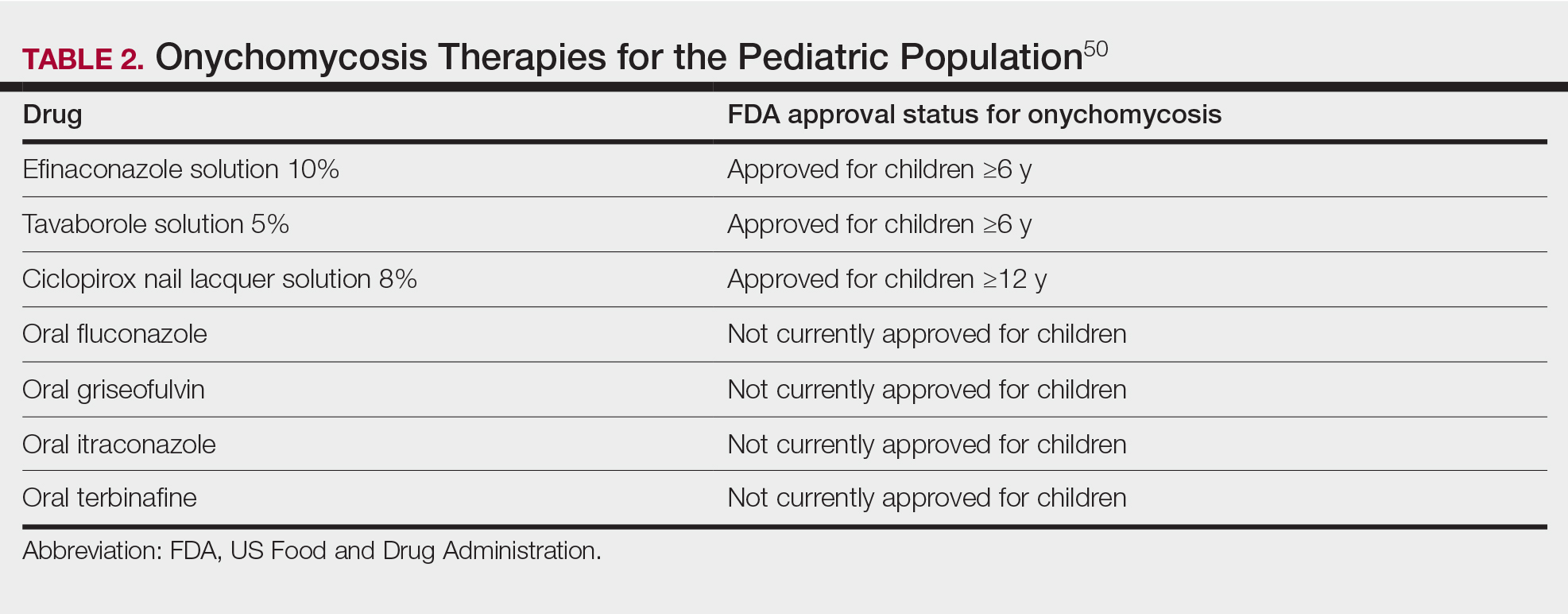

Currently, there are 2 topical FDA-approved treatments for pediatric onychomycosis in children 6 years and older (Table 2).49,50 There is a discussion of the need for confirmatory testing for onychomycosis in children, particularly when systemic treatment is prescribed. In a retrospective review of 269 pediatric patients with onychomycosis prescribed terbinafine, 53.5% (n=144) underwent laboratory monitoring of liver function and complete blood cell counts, and 12.5% had grade 1 laboratory abnormalities either prior to (12/144 [8.3%]) or during (6/144 [4.2%]) therapy.51 Baseline transaminase monitoring is recommended, though subsequent routine laboratory monitoring in healthy children may have limited utility with associated increased costs, incidental findings, and patient discomfort and likely is not needed.51

Pediatric onychomycosis responds better to topical therapy than adult disease, and pediatric patients do not always require systemic treatment.52 Ciclopirox is not FDA approved for the treatment of pediatric onychomycosis, but in a 32-week clinical trial of ciclopirox lacquer 8% use in 40 patients, 77% (27/35) of treated patients achieved mycologic cure. Overall, 71% of treated patients (25/35) vs 22% (2/9) of controls achieved efficacy (defined as investigator global assessment score of 2 or lower).52 In an open-label, single-arm clinical trial assessing tavaborole solution 5% applied once daily for 48 weeks for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis in pediatric patients (aged 6–17 years), 36.2% (20/55) of patients achieved mycologic cure, and 8.5% (5/55) achieved complete cure at week 52 with mild or minimal adverse effects.53 In an open-label, phase 4 study of the safety and efficacy of efinaconazole solution 10% applied once daily for 48 weeks in pediatric patients (aged 6 to 16 years) (n=60), 65% (35/60) achieved mycologic cure, 42% (25/60) achieved clinical cure, and 40% (24/60) achieved complete cure at 52 weeks. The most common adverse effects of efinaconazole were local and included ingrown toenail (1/60), application-site dermatitis (1/60), application-site vesicles (1/60), and application-site pain (1/60).54

In a systematic review of systemic antifungals for onychomycosis in 151 pediatric patients, itraconazole, fluconazole, griseofulvin, and terbinafine resulted in complete cure rates similar to those of the adult population, with excellent safety profiles.55 Depending on the situation, initiation of treatment with topical medications followed by addition of systemic antifungal agents only if needed may be an appropriate course of action.

BACTERIAL INFECTIONS

Acute Paronychia

Acute paronychia is a nail-fold infection that develops after the protective nail barrier has been compromised.56 In children, thumb-sucking, nail-biting, frequent oral manipulation of the digits, and poor skin hygiene are risk factors. Acute paronychia also may develop in association with congenital malalignment of the great toenails.57

Clinical manifestations include localized pain, erythema, and nail fold edema (Figure 4). Purulent material and abscess formation may ensue. Staphylococcus aureus as well as methicillin-resistant S aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes are classically the most common causes of acute paronychia. Treatment of paronychia is based on severity. In mild cases, warm soaks with topical antibiotics are indicated. Oral antibiotics should be prescribed for more severe presentations. If there is no improvement after 48 hours, surgical drainage is required to facilitate healing.56

FINAL THOUGHTS

Inflammatory and infectious nail disorders in children are relatively common and may impact the physical and emotional well-being of young patients. By understanding the distinctive features of these nail disorders in pediatric patients, dermatologists can provide anticipatory guidance and informed treatment options to children and their parents. Further research is needed to expand our understanding of pediatric nail disorders and create targeted therapeutic interventions, particularly for NLP and psoriasis.

- Uber M, Carvalho VO, Abagge KT, et al. Clinical features and nail clippings in 52 children with psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:202-207. doi:10.1111/pde.13402

- Plachouri KM, Mulita F, Georgiou S. Management of pediatric nail psoriasis. Cutis. 2021;108:292-294. doi:10.12788/cutis.0386

- Smith RJ, Rubin AI. Pediatric nail disorders: a review. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2020;32:506-515. doi:10.1097/mop.0000000000000921

- Pourchot D, Bodemer C, Phan A, et al. Nail psoriasis: a systematic evaluation in 313 children with psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:58-63. doi:10.1111/pde.13028

- Richert B, André J. Nail disorders in children: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:101-112. doi:10.2165/11537110-000000000-00000

- Lee JYY. Severe 20-nail psoriasis successfully treated by low dose methotrexate. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:8.

- Nogueira M, Paller AS, Torres T. Targeted therapy for pediatric psoriasis. Paediatr Drugs. May 2021;23:203-212. doi:10.1007/s40272-021-00443-5

- Hanoodi M, Mittal M. Methotrexate. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 16, 2023. Accessed July 1, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556114/

- Teran CG, Teran-Escalera CN, Balderrama C. A severe case of erythrodermic psoriasis associated with advanced nail and joint manifestations: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:179. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-4-179

- Paller AS, Seyger MMB, Magariños GA, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of up to 108 weeks of ixekizumab in pediatric patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: the IXORA-PEDS randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:533-541. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0655

- Diotallevi F, Simonetti O, Rizzetto G, et al. Biological treatments for pediatric psoriasis: state of the art and future perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:11128. doi:10.3390/ijms231911128

- Nash P, Mease PJ, Kirkham B, et al. Secukinumab provides sustained improvement in nail psoriasis, signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis and low rate of radiographic progression in patients with concomitant nail involvement: 2-year results from the Phase III FUTURE 5 study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2022;40:952-959. doi:10.55563/clinexprheumatol/3nuz51

- Wells LE, Evans T, Hilton R, et al. Use of secukinumab in a pediatric patient leads to significant improvement in nail psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:384-385. doi:10.1111/pde.13767

- Watabe D, Endoh K, Maeda F, et al. Childhood-onset psoriaticonycho-pachydermo-periostitis treated successfully with infliximab. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:506-508. doi:10.1684/ejd.2015.2616

- Pereira TM, Vieira AP, Fernandes JC, et al. Anti-TNF-alpha therapy in childhood pustular psoriasis. Dermatology. 2006;213:350-352. doi:10.1159/000096202

- Iorizzo M, Gioia Di Chiacchio N, Di Chiacchio N, et al. Intralesional steroid injections for inflammatory nail dystrophies in the pediatric population. Pediatr Dermatol. 2023;40:759-761. doi:10.1111/pde.15295

- Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Cambiaghi S, et al. Nail lichen planus in children: clinical features, response to treatment, and long-term follow-up. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1027-1032.

- Lipner SR. Nail lichen planus: a true nail emergency. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:e177-e178. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.065

- Iorizzo M, Tosti A, Starace M, et al. Isolated nail lichen planus: an expert consensus on treatment of the classical form. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1717-1723. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.056

- Piraccini BM, Saccani E, Starace M, et al. Nail lichen planus: response to treatment and long term follow-up. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:489-496. doi:10.1684/ejd.2010.0952

- Mahajan R, Kaushik A, De D, et al. Pediatric trachyonychia- a retrospective study of 17 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2021;66:689-690. doi:10.4103/ijd.ijd_42_21

- Leung AKC, Leong KF, Barankin B. Trachyonychia. J Pediatr. 2020;216:239-239.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.08.034

- Haber JS, Chairatchaneeboon M, Rubin AI. Trachyonychia: review and update on clinical aspects, histology, and therapy. Skin Appendage Disord. 2017;2:109-115. doi:10.1159/000449063

- Jacobsen AA, Tosti A. Trachyonychia and twenty-nail dystrophy: a comprehensive review and discussion of diagnostic accuracy. Skin Appendage Disord. 2016;2:7-13. doi:10.1159/000445544

- Kumar MG, Ciliberto H, Bayliss SJ. Long-term follow-up of pediatric trachyonychia. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:198-200. doi:10.1111/pde.12427

- Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Iorizzo M. Trachyonychia and related disorders: evaluation and treatment plans. Dermatolog Ther. 2002;15:121-125. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8019.2002.01511.x

- Leung AKC, Leong KF, Barankin B. Lichen striatus with nail involvement in a 6-year-old boy. Case Rep Pediatr. 2020;2020:1494760. doi:10.1155/2020/1494760

- Kim GW, Kim SH, Seo SH, et al. Lichen striatus with nail abnormality successfully treated with tacrolimus ointment. J Dermatol. 2009;36:616-617. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00720.x

- Iorizzo M, Rubin AI, Starace M. Nail lichen striatus: is dermoscopy useful for the diagnosis? Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:859-863. doi:10.1111/pde.13916

- Karp DL, Cohen BA. Onychodystrophy in lichen striatus. Pediatr Dermatol. 1993;10:359-361. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.1993.tb00399.x

- Tosti A, Peluso AM, Misciali C, et al. Nail lichen striatus: clinical features and long-term follow-up of five patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(6, pt 1):908-913. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(97)80270-8

- Simpson EL, Thompson MM, Hanifin JM. Prevalence and morphology of hand eczema in patients with atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2006;17:123-127. doi:10.2310/6620.2006.06005

- Sarifakioglu E, Yilmaz AE, Gorpelioglu C. Nail alterations in 250 infant patients: a clinical study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:741-744. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02592.x

- Milanesi N, D’Erme AM, Gola M. Nail improvement during alitretinoin treatment: three case reports and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:533-536. doi:10.1111/ced.12584

- Chung BY, Choi YW, Kim HO, et al. Nail dystrophy in patients with atopic dermatitis and its association with disease severity. Ann Dermatol. 2019;31:121-126. doi:10.5021/ad.2019.31.2.121

- Navarro-Triviño FJ, Vega-Castillo JJ, Ruiz-Villaverde R. Nail changes successfully treated with dupilumab in a patient with severe atopic dermatitis. Australas J Dermatol. 2021;62:e468-e469. doi:10.1111/ajd.13633

- Wei SH, Huang YP, Liu MC, et al. An outbreak of coxsackievirus A6 hand, foot, and mouth disease associated with onychomadesis in Taiwan, 2010. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:346. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-11-346

- Shin JY, Cho BK, Park HJ. A clinical study of nail changes occurring secondary to hand-foot-mouth disease: onychomadesis and Beau’s lines. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:280-283. doi:10.5021/ad.2014.26.2.280

- Verma S, Singal A. Nail changes in hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD). Indian Dermatol Online J. 2021;12:656-657. doi:10.4103 /idoj.IDOJ_271_20

- Giordano LMC, de la Fuente LA, Lorca JMB, et al. Onychomadesis secondary to hand-foot-mouth disease: a frequent manifestation and cause of concern for parents. Article in Spanish. Rev Chil Pediatr. 2018;89:380-383. doi:10.4067/s0370-41062018005000203

- Justino MCA, da SMD, Souza MF, et al. Atypical hand-foot-mouth disease in Belém, Amazon region, northern Brazil, with detection of coxsackievirus A6. J Clin Virol. 2020;126:104307. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104307

- Cheng FF, Zhang BB, Cao ML, et al. Clinical characteristics of 68 children with atypical hand, foot, and mouth disease caused by coxsackievirus A6: a single-center retrospective analysis. Transl Pediatr. 2022;11:1502-1509. doi:10.21037/tp-22-352

- Nagata S. Causes of Kawasaki disease-from past to present. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:18. doi:10.3389/fped.2019.00018

- Mitsuishi T, Miyata K, Ando A, et al. Characteristic nail lesions in Kawasaki disease: case series and literature review. J Dermatol. 2022;49:232-238. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.16276

- Lindsley CB. Nail-bed lines in Kawasaki disease. Am J Dis Child. 1992;146:659-660. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1992.02160180017005

- Matsumura O, Nakagishi Y. Pincer nails upon convalescence from Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr. 2022;246:279. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.03.002

- Solís-Arias MP, García-Romero MT. Onychomycosis in children. a review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:123-130. doi:10.1111/ijd.13392

- Gupta AK, Mays RR, Versteeg SG, et al. Onychomycosis in children: safety and efficacy of antifungal agents. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:552-559. doi:10.1111/pde.13561

- 49. Gupta AK, Venkataraman M, Shear NH, et al. Labeled use of efinaconazole topical solution 10% in treating onychomycosis in children and a review of the management of pediatric onychomycosis. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13613. doi:10.1111/dth.13613

- Falotico JM, Lipner SR. Updated perspectives on the diagnosis and management of onychomycosis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2022;15:1933-1957. doi:10.2147/ccid.S362635

- Patel D, Castelo-Soccio LA, Rubin AI, et al. Laboratory monitoring during systemic terbinafine therapy for pediatric onychomycosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:1326-1327. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.4483

- Friedlander SF, Chan YC, Chan YH, et al. Onychomycosis does not always require systemic treatment for cure: a trial using topical therapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:316-322. doi:10.1111/pde.12064

- Rich P, Spellman M, Purohit V, et al. Tavaborole 5% topical solution for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis in pediatric patients: results from a phase 4 open-label study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:190-195.

- Gupta AK, Venkataraman M, Abramovits W, et al. JUBLIA (efinaconazole 10% solution) in the treatment of pediatric onychomycosis. Skinmed. 2021;19:206-210.

- Gupta AK, Paquet M. Systemic antifungals to treat onychomycosis in children: a systematic review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:294-302. doi:10.1111/pde.12048

- Leggit JC. Acute and chronic paronychia. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96:44-51.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Congenital malalignment of the great toenails with acute paronychia. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:e288-e289.doi:10.1111/pde.12924

Nail disorders are common among pediatric patients but often are underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed because of their unique disease manifestations. These conditions may severely impact quality of life. There are few nail disease clinical trials that include children. Consequently, most treatment recommendations are based on case series and expert consensus recommendations. We review inflammatory and infectious nail disorders in pediatric patients. By describing characteristics, clinical manifestations, and management approaches for these conditions, we aim to provide guidance to dermatologists in their diagnosis and treatment.

INFLAMMATORY NAIL DISORDERS

Nail Psoriasis

Nail involvement in children with psoriasis is common, with prevalence estimates ranging from 17% to 39.2%.1 Nail matrix psoriasis may manifest with pitting (large irregular pits) and leukonychia as well as chromonychia and nail plate crumbling. Onycholysis, oil drop spots (salmon patches), and subungual hyperkeratosis can be seen in nail bed psoriasis. Nail pitting is the most frequently observed clinical finding (Figure 1).2,3 In a cross-sectional multicenter study of 313 children with cutaneous psoriasis in France, nail findings were present in 101 patients (32.3%). There were associations between nail findings and presence of psoriatic arthritis (P=.03), palmoplantar psoriasis (P<.001), and severity of psoriatic disease, defined as use of systemic treatment with phototherapy (psoralen plus UVA, UVB), traditional systemic treatment (acitretin, methotrexate, cyclosporine), or a biologic (P=.003).4

Topical steroids and vitamin D analogues may be used with or without occlusion and may be efficacious.5 Several case reports describe systemic treatments for psoriasis in children, including methotrexate, acitretin, and apremilast (approved for children 6 years and older for plaque psoriasis by the US Food and Drug Administration [FDA]).2 There are 5 biologic drugs currently approved for the treatment of pediatric psoriasis—adalimumab, etanercept, ustekinumab, secukinumab, ixekizumab—and 6 drugs currently undergoing phase 3 studies—brodalumab, guselkumab, risankizumab, tildrakizumab, certolizumab pegol, and deucravacitinib (Table 1).6-15 Adalimumab is specifically approved for moderate to severe nail psoriasis in adults 18 years and older.

Intralesional steroid injections are sometimes useful in the management of nail matrix psoriasis; however, appropriate patient selection is critical due to the pain associated with the procedure. In a prospective study of 16 children (age range, 9–17 years) with nail psoriasis treated with intralesional triamcinolone (ILTAC) 2.5 to 5 mg/mL every 4 to 8 weeks for a minimum of 3 to 6 months, 9 patients achieved resolution and 6 had improvement of clinical findings.16 Local adverse events were mild, including injection-site pain (66%), subungual hematoma (n=1), Beau lines (n=1), proximal nail fold hypopigmentation (n=2), and proximal nail fold atrophy (n=2). Because the proximal nail fold in children is thinner than in adults, there may be an increased risk for nail fold hypopigmentation and atrophy in children. Therefore, a maximum ILTAC concentration of 2.5 mg/mL with 0.2 mL maximum volume per nail per session is recommended for children younger than 15 years.16

Nail Lichen Planus

Nail lichen planus (NLP) is uncommon in children, with few biopsy-proven cases documented in the literature.17 Common clinical findings are onychorrhexis, nail plate thinning, fissuring, splitting, and atrophy with koilonychia.5 Although pterygium development (irreversible nail matrix scarring) is uncommon in pediatric patients, NLP can be progressive and may cause irreversible destruction of the nail matrix and subsequent nail loss, warranting therapeutic intervention.18

Treatment of NLP may be difficult, as there are no options that work in all patients. Current literature supports the use of systemic corticosteroids or ILTAC for the treatment of NLP; however, recurrence rates can be high. According to an expert consensus paper on NLP treatment, ILTAC may be injected in a concentration of 2.5, 5, or 10 mg/mL according to disease severity.19 In severe or resistant cases, intramuscular (IM) triamcinolone may be considered, especially if more than 3 nails are affected. A dosage of 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/mo for at least 3 to 6 months is recommended for both children and adults, with 1 mg/kg/mo recommended in the active treatment phase (first 2–3 months).19 In a retrospective review of 5 pediatric patients with NLP treated with IM triamcinolone 0.5 mg/kg/mo, 3 patients had resolution and 2 improved with treatment.20 In a prospective study of 10 children with NLP, IM triamcinolone at a dosage of 0.5 to 1 mg/kg every 30 days for 3 to 6 months resulted in resolution of nail findings in 9 patients.17 In a prospective study of 14 pediatric patients with NLP treated with 2.5 to 5 mg/mL of ILTAC, 10 achieved resolution and 3 improved.16

Intralesional triamcinolone injections may be better suited for teenagers compared to younger children who may be more apprehensive of needles. To minimize pain, it is recommended to inject ILTAC slowly at room temperature, with use of “talkesthesia” and vibration devices, 1% lidocaine, or ethyl chloride spray.18

Trachyonychia

Trachyonychia is characterized by the presence of sandpaperlike nails. It manifests with brittle thin nails with longitudinal ridging, onychoschizia, and thickened hyperkeratotic cuticles. Trachyonychia typically involves multiple nails, with a peak age of onset between 3 and 12 years.21,22 There are 2 variants: the opaque type with rough longitudinal ridging, and the shiny variant with opalescent nails and pits that reflect light. The opaque variant is more common and is associated with psoriasis, whereas the shiny variant is less common and is associated with alopecia areata.23 Although most cases are idiopathic, some are associated with psoriasis and alopecia areata, as previously noted, as well as atopic dermatitis (AD) and lichen planus.22,24

Fortunately, trachyonychia does not lead to permanent nail damage or pterygium, making treatment primarily focused on addressing functional and cosmetic concerns.24 Spontaneous resolution occurs in approximately 50% of patients. In a prospective study of 11 patients with idiopathic trachyonychia, there was partial improvement in 5 of 9 patients treated with topical steroids, 1 with only petrolatum, and 1 with vitamin supplements. Complete resolution was reported in 1 patient treated with topical steroids.25 Because trachyonychia often is self-resolving, no treatment is required and a conservative approach is strongly recommended.26 Treatment options include topical corticosteroids, tazarotene, and 5-fluorouracil. Intralesional triamcinolone, systemic cyclosporine, retinoids, systemic corticosteroids, and tofacitinib have been described in case reports, though none of these have been shown to be 100% efficacious.24

Nail Lichen Striatus

Lichen striatus involving the nail is uncommon and is characterized by onycholysis, longitudinal ridging, splitting, and fraying, as well as what appears to be a subungual tumor. It can encompass the entire nail or may be isolated to a portion of the nail (Figure 2). Usually, a Blaschko-linear array of flesh-colored papules on the more proximal digit directly adjacent to the nail dystrophy will be seen, though nail findings can occur in isolation.27-29 The underlying pathophysiology is not clear; however, one hypothesis is that a triggering event, such as trauma, induces the expression of antigens that elicit a self-limiting immune-mediated response by CD8 T lymphocytes.30

Generally, nail lichen striatus spontaneously resolves in 1 to 2 years without treatment. In a prospective study of 5 patients with nail lichen striatus, the median time to resolution was 22.6 months (range, 10–30 months).31 Topical steroids may be used for pruritus. In one case report, a 3-year-old boy with nail lichen striatus of 4 months’ duration was treated with tacrolimus ointment 0.03% daily for 3 months.28

Nail AD

Nail changes with AD may be more common in adults than children or are underreported. In a study of 777 adults with AD, nail dystrophy was present in 124 patients (16%), whereas in a study of 250 pediatric patients with AD (aged 0-2 years), nail dystrophy was present in only 4 patients.32,33

Periungual inflammation from AD causes the nail changes.34 In a cross-sectional study of 24 pediatric patients with nail dystrophy due to AD, transverse grooves (Beau lines) were present in 25% (6/24), nail pitting in 16.7% (4/24), koilonychia in 16.7% (4/24), trachyonychia in 12.5% (3/24), leukonychia in 12.5% (3/24), brachyonychia in 8.3% (2/24), melanonychia in 8.3% (2/24), onychomadesis in 8.3% (2/24), onychoschizia in 8.3% (2/24), and onycholysis in 8.3% (2/24). There was an association between disease severity and presence of toenail dystrophy (P=.03).35

Topical steroids with or without occlusion can be used to treat nail changes. Although there is limited literature describing the treatment of nail AD in children, a 61-year-old man with nail changes associated with AD achieved resolution with 3 months of treatment with dupilumab.36 Anecdotally, most patients will improve with usual cutaneous AD management.

INFECTIOUS NAIL DISORDERS

Viral Infections

Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease—Hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) is a common childhood viral infection caused by various enteroviruses, most commonly coxsackievirus A16, with the A6 variant causing more severe disease. Fever and painful vesicles involving the oral mucosa as well as palms and soles give the disease its name. Nail changes are common. In a prospective study involving 130 patients with laboratory-confirmed coxsackievirus CA6 serotype infection, 37% developed onychomadesis vs only 5% of 145 cases with non-CA6 enterovirus infection who developed nail findings. There was an association between CA6 infection and presence of nail changes (P<.001).37

Findings ranging from transverse grooves (Beau lines) to complete nail shedding (onychomadesis)(Figure 3) may be seen.38,39 Nail findings in HFMD are due to transient inhibition of nail growth and present approximately 3 to 6 weeks after infection.40 Onychomadesis is seen in 30% to 68% of patients with HFMD.37,41,42 Nail findings in HFMD spontaneously resolve with nail growth (2–3 mm per month for fingernails and 1 mm per month for toenails) and do not require specific treatment. Although the appearance of nail changes associated with HFMD can be disturbing, dermatologists can reassure children and their parents that the nails will resolve with the next cycle of growth.

Kawasaki Disease—Kawasaki disease (KD) is a vasculitis primarily affecting children and infants. Although the specific pathogen and pathophysiology is not entirely clear, clinical observations have suggested an infectious cause, most likely a virus.43 In Japan, more than 15,000 cases of KD are documented annually, while approximately 4200 cases are seen in the United States.44 In a prospective study from 1984 to 1990, 4 of 26 (15.4%) patients with KD presented with nail manifestations during the late acute phase or early convalescent phase of disease. There were no significant associations between nail dystrophy and severity of KD, such as coronary artery aneurysm.45

Nail changes reported in children with KD include onychomadesis, onycholysis, orange-brown chromonychia, splinter hemorrhages, Beau lines, and pincer nails. In a review of nail changes associated with KD from 1980 to 2021, orange-brown transverse chromonychia, which may evolve into transverse leukonychia, was the most common nail finding reported, occurring in 17 of 31 (54.8%) patients.44 It has been hypothesized that nail changes may result from blood flow disturbance due to the underlying vasculitis.46 Nail changes appear several weeks after the onset of fever and are self-limited. Resolution occurs with nail growth, with no treatment required.

FUNGAL INFECTIONS

Onychomycosis

Onychomycosis is a fungal infection of the nails that occurs in 0.2% to 5.5% of pediatric patients, and its prevalence may be increasing, which may be due to environmental factors or increased rates of diabetes mellitus and obesity in the pediatric population.47 Onychomycosis represents 15.5% of nail dystrophies in pediatric patients.48 Some dermatologists treat presumptive onychomycosis without confirmation; however, we do not recommend that approach. Because the differential is broad and the duration of treatment is long, mycologic examination (potassium hydroxide preparation, fungal culture, polymerase chain reaction, and/or histopathology) should be obtained to confirm onychomycosis prior to initiation of antifungal management. Family members of affected individuals should be evaluated and treated, if indicated, for onychomycosis and tinea pedis, as household transmission is common.

Currently, there are 2 topical FDA-approved treatments for pediatric onychomycosis in children 6 years and older (Table 2).49,50 There is a discussion of the need for confirmatory testing for onychomycosis in children, particularly when systemic treatment is prescribed. In a retrospective review of 269 pediatric patients with onychomycosis prescribed terbinafine, 53.5% (n=144) underwent laboratory monitoring of liver function and complete blood cell counts, and 12.5% had grade 1 laboratory abnormalities either prior to (12/144 [8.3%]) or during (6/144 [4.2%]) therapy.51 Baseline transaminase monitoring is recommended, though subsequent routine laboratory monitoring in healthy children may have limited utility with associated increased costs, incidental findings, and patient discomfort and likely is not needed.51

Pediatric onychomycosis responds better to topical therapy than adult disease, and pediatric patients do not always require systemic treatment.52 Ciclopirox is not FDA approved for the treatment of pediatric onychomycosis, but in a 32-week clinical trial of ciclopirox lacquer 8% use in 40 patients, 77% (27/35) of treated patients achieved mycologic cure. Overall, 71% of treated patients (25/35) vs 22% (2/9) of controls achieved efficacy (defined as investigator global assessment score of 2 or lower).52 In an open-label, single-arm clinical trial assessing tavaborole solution 5% applied once daily for 48 weeks for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis in pediatric patients (aged 6–17 years), 36.2% (20/55) of patients achieved mycologic cure, and 8.5% (5/55) achieved complete cure at week 52 with mild or minimal adverse effects.53 In an open-label, phase 4 study of the safety and efficacy of efinaconazole solution 10% applied once daily for 48 weeks in pediatric patients (aged 6 to 16 years) (n=60), 65% (35/60) achieved mycologic cure, 42% (25/60) achieved clinical cure, and 40% (24/60) achieved complete cure at 52 weeks. The most common adverse effects of efinaconazole were local and included ingrown toenail (1/60), application-site dermatitis (1/60), application-site vesicles (1/60), and application-site pain (1/60).54

In a systematic review of systemic antifungals for onychomycosis in 151 pediatric patients, itraconazole, fluconazole, griseofulvin, and terbinafine resulted in complete cure rates similar to those of the adult population, with excellent safety profiles.55 Depending on the situation, initiation of treatment with topical medications followed by addition of systemic antifungal agents only if needed may be an appropriate course of action.

BACTERIAL INFECTIONS

Acute Paronychia

Acute paronychia is a nail-fold infection that develops after the protective nail barrier has been compromised.56 In children, thumb-sucking, nail-biting, frequent oral manipulation of the digits, and poor skin hygiene are risk factors. Acute paronychia also may develop in association with congenital malalignment of the great toenails.57

Clinical manifestations include localized pain, erythema, and nail fold edema (Figure 4). Purulent material and abscess formation may ensue. Staphylococcus aureus as well as methicillin-resistant S aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes are classically the most common causes of acute paronychia. Treatment of paronychia is based on severity. In mild cases, warm soaks with topical antibiotics are indicated. Oral antibiotics should be prescribed for more severe presentations. If there is no improvement after 48 hours, surgical drainage is required to facilitate healing.56

FINAL THOUGHTS

Inflammatory and infectious nail disorders in children are relatively common and may impact the physical and emotional well-being of young patients. By understanding the distinctive features of these nail disorders in pediatric patients, dermatologists can provide anticipatory guidance and informed treatment options to children and their parents. Further research is needed to expand our understanding of pediatric nail disorders and create targeted therapeutic interventions, particularly for NLP and psoriasis.

Nail disorders are common among pediatric patients but often are underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed because of their unique disease manifestations. These conditions may severely impact quality of life. There are few nail disease clinical trials that include children. Consequently, most treatment recommendations are based on case series and expert consensus recommendations. We review inflammatory and infectious nail disorders in pediatric patients. By describing characteristics, clinical manifestations, and management approaches for these conditions, we aim to provide guidance to dermatologists in their diagnosis and treatment.

INFLAMMATORY NAIL DISORDERS

Nail Psoriasis

Nail involvement in children with psoriasis is common, with prevalence estimates ranging from 17% to 39.2%.1 Nail matrix psoriasis may manifest with pitting (large irregular pits) and leukonychia as well as chromonychia and nail plate crumbling. Onycholysis, oil drop spots (salmon patches), and subungual hyperkeratosis can be seen in nail bed psoriasis. Nail pitting is the most frequently observed clinical finding (Figure 1).2,3 In a cross-sectional multicenter study of 313 children with cutaneous psoriasis in France, nail findings were present in 101 patients (32.3%). There were associations between nail findings and presence of psoriatic arthritis (P=.03), palmoplantar psoriasis (P<.001), and severity of psoriatic disease, defined as use of systemic treatment with phototherapy (psoralen plus UVA, UVB), traditional systemic treatment (acitretin, methotrexate, cyclosporine), or a biologic (P=.003).4

Topical steroids and vitamin D analogues may be used with or without occlusion and may be efficacious.5 Several case reports describe systemic treatments for psoriasis in children, including methotrexate, acitretin, and apremilast (approved for children 6 years and older for plaque psoriasis by the US Food and Drug Administration [FDA]).2 There are 5 biologic drugs currently approved for the treatment of pediatric psoriasis—adalimumab, etanercept, ustekinumab, secukinumab, ixekizumab—and 6 drugs currently undergoing phase 3 studies—brodalumab, guselkumab, risankizumab, tildrakizumab, certolizumab pegol, and deucravacitinib (Table 1).6-15 Adalimumab is specifically approved for moderate to severe nail psoriasis in adults 18 years and older.

Intralesional steroid injections are sometimes useful in the management of nail matrix psoriasis; however, appropriate patient selection is critical due to the pain associated with the procedure. In a prospective study of 16 children (age range, 9–17 years) with nail psoriasis treated with intralesional triamcinolone (ILTAC) 2.5 to 5 mg/mL every 4 to 8 weeks for a minimum of 3 to 6 months, 9 patients achieved resolution and 6 had improvement of clinical findings.16 Local adverse events were mild, including injection-site pain (66%), subungual hematoma (n=1), Beau lines (n=1), proximal nail fold hypopigmentation (n=2), and proximal nail fold atrophy (n=2). Because the proximal nail fold in children is thinner than in adults, there may be an increased risk for nail fold hypopigmentation and atrophy in children. Therefore, a maximum ILTAC concentration of 2.5 mg/mL with 0.2 mL maximum volume per nail per session is recommended for children younger than 15 years.16

Nail Lichen Planus

Nail lichen planus (NLP) is uncommon in children, with few biopsy-proven cases documented in the literature.17 Common clinical findings are onychorrhexis, nail plate thinning, fissuring, splitting, and atrophy with koilonychia.5 Although pterygium development (irreversible nail matrix scarring) is uncommon in pediatric patients, NLP can be progressive and may cause irreversible destruction of the nail matrix and subsequent nail loss, warranting therapeutic intervention.18

Treatment of NLP may be difficult, as there are no options that work in all patients. Current literature supports the use of systemic corticosteroids or ILTAC for the treatment of NLP; however, recurrence rates can be high. According to an expert consensus paper on NLP treatment, ILTAC may be injected in a concentration of 2.5, 5, or 10 mg/mL according to disease severity.19 In severe or resistant cases, intramuscular (IM) triamcinolone may be considered, especially if more than 3 nails are affected. A dosage of 0.5 to 1 mg/kg/mo for at least 3 to 6 months is recommended for both children and adults, with 1 mg/kg/mo recommended in the active treatment phase (first 2–3 months).19 In a retrospective review of 5 pediatric patients with NLP treated with IM triamcinolone 0.5 mg/kg/mo, 3 patients had resolution and 2 improved with treatment.20 In a prospective study of 10 children with NLP, IM triamcinolone at a dosage of 0.5 to 1 mg/kg every 30 days for 3 to 6 months resulted in resolution of nail findings in 9 patients.17 In a prospective study of 14 pediatric patients with NLP treated with 2.5 to 5 mg/mL of ILTAC, 10 achieved resolution and 3 improved.16

Intralesional triamcinolone injections may be better suited for teenagers compared to younger children who may be more apprehensive of needles. To minimize pain, it is recommended to inject ILTAC slowly at room temperature, with use of “talkesthesia” and vibration devices, 1% lidocaine, or ethyl chloride spray.18

Trachyonychia

Trachyonychia is characterized by the presence of sandpaperlike nails. It manifests with brittle thin nails with longitudinal ridging, onychoschizia, and thickened hyperkeratotic cuticles. Trachyonychia typically involves multiple nails, with a peak age of onset between 3 and 12 years.21,22 There are 2 variants: the opaque type with rough longitudinal ridging, and the shiny variant with opalescent nails and pits that reflect light. The opaque variant is more common and is associated with psoriasis, whereas the shiny variant is less common and is associated with alopecia areata.23 Although most cases are idiopathic, some are associated with psoriasis and alopecia areata, as previously noted, as well as atopic dermatitis (AD) and lichen planus.22,24

Fortunately, trachyonychia does not lead to permanent nail damage or pterygium, making treatment primarily focused on addressing functional and cosmetic concerns.24 Spontaneous resolution occurs in approximately 50% of patients. In a prospective study of 11 patients with idiopathic trachyonychia, there was partial improvement in 5 of 9 patients treated with topical steroids, 1 with only petrolatum, and 1 with vitamin supplements. Complete resolution was reported in 1 patient treated with topical steroids.25 Because trachyonychia often is self-resolving, no treatment is required and a conservative approach is strongly recommended.26 Treatment options include topical corticosteroids, tazarotene, and 5-fluorouracil. Intralesional triamcinolone, systemic cyclosporine, retinoids, systemic corticosteroids, and tofacitinib have been described in case reports, though none of these have been shown to be 100% efficacious.24

Nail Lichen Striatus

Lichen striatus involving the nail is uncommon and is characterized by onycholysis, longitudinal ridging, splitting, and fraying, as well as what appears to be a subungual tumor. It can encompass the entire nail or may be isolated to a portion of the nail (Figure 2). Usually, a Blaschko-linear array of flesh-colored papules on the more proximal digit directly adjacent to the nail dystrophy will be seen, though nail findings can occur in isolation.27-29 The underlying pathophysiology is not clear; however, one hypothesis is that a triggering event, such as trauma, induces the expression of antigens that elicit a self-limiting immune-mediated response by CD8 T lymphocytes.30

Generally, nail lichen striatus spontaneously resolves in 1 to 2 years without treatment. In a prospective study of 5 patients with nail lichen striatus, the median time to resolution was 22.6 months (range, 10–30 months).31 Topical steroids may be used for pruritus. In one case report, a 3-year-old boy with nail lichen striatus of 4 months’ duration was treated with tacrolimus ointment 0.03% daily for 3 months.28

Nail AD

Nail changes with AD may be more common in adults than children or are underreported. In a study of 777 adults with AD, nail dystrophy was present in 124 patients (16%), whereas in a study of 250 pediatric patients with AD (aged 0-2 years), nail dystrophy was present in only 4 patients.32,33

Periungual inflammation from AD causes the nail changes.34 In a cross-sectional study of 24 pediatric patients with nail dystrophy due to AD, transverse grooves (Beau lines) were present in 25% (6/24), nail pitting in 16.7% (4/24), koilonychia in 16.7% (4/24), trachyonychia in 12.5% (3/24), leukonychia in 12.5% (3/24), brachyonychia in 8.3% (2/24), melanonychia in 8.3% (2/24), onychomadesis in 8.3% (2/24), onychoschizia in 8.3% (2/24), and onycholysis in 8.3% (2/24). There was an association between disease severity and presence of toenail dystrophy (P=.03).35

Topical steroids with or without occlusion can be used to treat nail changes. Although there is limited literature describing the treatment of nail AD in children, a 61-year-old man with nail changes associated with AD achieved resolution with 3 months of treatment with dupilumab.36 Anecdotally, most patients will improve with usual cutaneous AD management.

INFECTIOUS NAIL DISORDERS

Viral Infections

Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease—Hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) is a common childhood viral infection caused by various enteroviruses, most commonly coxsackievirus A16, with the A6 variant causing more severe disease. Fever and painful vesicles involving the oral mucosa as well as palms and soles give the disease its name. Nail changes are common. In a prospective study involving 130 patients with laboratory-confirmed coxsackievirus CA6 serotype infection, 37% developed onychomadesis vs only 5% of 145 cases with non-CA6 enterovirus infection who developed nail findings. There was an association between CA6 infection and presence of nail changes (P<.001).37

Findings ranging from transverse grooves (Beau lines) to complete nail shedding (onychomadesis)(Figure 3) may be seen.38,39 Nail findings in HFMD are due to transient inhibition of nail growth and present approximately 3 to 6 weeks after infection.40 Onychomadesis is seen in 30% to 68% of patients with HFMD.37,41,42 Nail findings in HFMD spontaneously resolve with nail growth (2–3 mm per month for fingernails and 1 mm per month for toenails) and do not require specific treatment. Although the appearance of nail changes associated with HFMD can be disturbing, dermatologists can reassure children and their parents that the nails will resolve with the next cycle of growth.

Kawasaki Disease—Kawasaki disease (KD) is a vasculitis primarily affecting children and infants. Although the specific pathogen and pathophysiology is not entirely clear, clinical observations have suggested an infectious cause, most likely a virus.43 In Japan, more than 15,000 cases of KD are documented annually, while approximately 4200 cases are seen in the United States.44 In a prospective study from 1984 to 1990, 4 of 26 (15.4%) patients with KD presented with nail manifestations during the late acute phase or early convalescent phase of disease. There were no significant associations between nail dystrophy and severity of KD, such as coronary artery aneurysm.45

Nail changes reported in children with KD include onychomadesis, onycholysis, orange-brown chromonychia, splinter hemorrhages, Beau lines, and pincer nails. In a review of nail changes associated with KD from 1980 to 2021, orange-brown transverse chromonychia, which may evolve into transverse leukonychia, was the most common nail finding reported, occurring in 17 of 31 (54.8%) patients.44 It has been hypothesized that nail changes may result from blood flow disturbance due to the underlying vasculitis.46 Nail changes appear several weeks after the onset of fever and are self-limited. Resolution occurs with nail growth, with no treatment required.

FUNGAL INFECTIONS

Onychomycosis

Onychomycosis is a fungal infection of the nails that occurs in 0.2% to 5.5% of pediatric patients, and its prevalence may be increasing, which may be due to environmental factors or increased rates of diabetes mellitus and obesity in the pediatric population.47 Onychomycosis represents 15.5% of nail dystrophies in pediatric patients.48 Some dermatologists treat presumptive onychomycosis without confirmation; however, we do not recommend that approach. Because the differential is broad and the duration of treatment is long, mycologic examination (potassium hydroxide preparation, fungal culture, polymerase chain reaction, and/or histopathology) should be obtained to confirm onychomycosis prior to initiation of antifungal management. Family members of affected individuals should be evaluated and treated, if indicated, for onychomycosis and tinea pedis, as household transmission is common.

Currently, there are 2 topical FDA-approved treatments for pediatric onychomycosis in children 6 years and older (Table 2).49,50 There is a discussion of the need for confirmatory testing for onychomycosis in children, particularly when systemic treatment is prescribed. In a retrospective review of 269 pediatric patients with onychomycosis prescribed terbinafine, 53.5% (n=144) underwent laboratory monitoring of liver function and complete blood cell counts, and 12.5% had grade 1 laboratory abnormalities either prior to (12/144 [8.3%]) or during (6/144 [4.2%]) therapy.51 Baseline transaminase monitoring is recommended, though subsequent routine laboratory monitoring in healthy children may have limited utility with associated increased costs, incidental findings, and patient discomfort and likely is not needed.51

Pediatric onychomycosis responds better to topical therapy than adult disease, and pediatric patients do not always require systemic treatment.52 Ciclopirox is not FDA approved for the treatment of pediatric onychomycosis, but in a 32-week clinical trial of ciclopirox lacquer 8% use in 40 patients, 77% (27/35) of treated patients achieved mycologic cure. Overall, 71% of treated patients (25/35) vs 22% (2/9) of controls achieved efficacy (defined as investigator global assessment score of 2 or lower).52 In an open-label, single-arm clinical trial assessing tavaborole solution 5% applied once daily for 48 weeks for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis in pediatric patients (aged 6–17 years), 36.2% (20/55) of patients achieved mycologic cure, and 8.5% (5/55) achieved complete cure at week 52 with mild or minimal adverse effects.53 In an open-label, phase 4 study of the safety and efficacy of efinaconazole solution 10% applied once daily for 48 weeks in pediatric patients (aged 6 to 16 years) (n=60), 65% (35/60) achieved mycologic cure, 42% (25/60) achieved clinical cure, and 40% (24/60) achieved complete cure at 52 weeks. The most common adverse effects of efinaconazole were local and included ingrown toenail (1/60), application-site dermatitis (1/60), application-site vesicles (1/60), and application-site pain (1/60).54

In a systematic review of systemic antifungals for onychomycosis in 151 pediatric patients, itraconazole, fluconazole, griseofulvin, and terbinafine resulted in complete cure rates similar to those of the adult population, with excellent safety profiles.55 Depending on the situation, initiation of treatment with topical medications followed by addition of systemic antifungal agents only if needed may be an appropriate course of action.

BACTERIAL INFECTIONS

Acute Paronychia

Acute paronychia is a nail-fold infection that develops after the protective nail barrier has been compromised.56 In children, thumb-sucking, nail-biting, frequent oral manipulation of the digits, and poor skin hygiene are risk factors. Acute paronychia also may develop in association with congenital malalignment of the great toenails.57

Clinical manifestations include localized pain, erythema, and nail fold edema (Figure 4). Purulent material and abscess formation may ensue. Staphylococcus aureus as well as methicillin-resistant S aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes are classically the most common causes of acute paronychia. Treatment of paronychia is based on severity. In mild cases, warm soaks with topical antibiotics are indicated. Oral antibiotics should be prescribed for more severe presentations. If there is no improvement after 48 hours, surgical drainage is required to facilitate healing.56

FINAL THOUGHTS

Inflammatory and infectious nail disorders in children are relatively common and may impact the physical and emotional well-being of young patients. By understanding the distinctive features of these nail disorders in pediatric patients, dermatologists can provide anticipatory guidance and informed treatment options to children and their parents. Further research is needed to expand our understanding of pediatric nail disorders and create targeted therapeutic interventions, particularly for NLP and psoriasis.

- Uber M, Carvalho VO, Abagge KT, et al. Clinical features and nail clippings in 52 children with psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:202-207. doi:10.1111/pde.13402

- Plachouri KM, Mulita F, Georgiou S. Management of pediatric nail psoriasis. Cutis. 2021;108:292-294. doi:10.12788/cutis.0386

- Smith RJ, Rubin AI. Pediatric nail disorders: a review. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2020;32:506-515. doi:10.1097/mop.0000000000000921

- Pourchot D, Bodemer C, Phan A, et al. Nail psoriasis: a systematic evaluation in 313 children with psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:58-63. doi:10.1111/pde.13028

- Richert B, André J. Nail disorders in children: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:101-112. doi:10.2165/11537110-000000000-00000

- Lee JYY. Severe 20-nail psoriasis successfully treated by low dose methotrexate. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:8.

- Nogueira M, Paller AS, Torres T. Targeted therapy for pediatric psoriasis. Paediatr Drugs. May 2021;23:203-212. doi:10.1007/s40272-021-00443-5

- Hanoodi M, Mittal M. Methotrexate. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 16, 2023. Accessed July 1, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556114/

- Teran CG, Teran-Escalera CN, Balderrama C. A severe case of erythrodermic psoriasis associated with advanced nail and joint manifestations: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:179. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-4-179

- Paller AS, Seyger MMB, Magariños GA, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of up to 108 weeks of ixekizumab in pediatric patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: the IXORA-PEDS randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:533-541. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0655

- Diotallevi F, Simonetti O, Rizzetto G, et al. Biological treatments for pediatric psoriasis: state of the art and future perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:11128. doi:10.3390/ijms231911128

- Nash P, Mease PJ, Kirkham B, et al. Secukinumab provides sustained improvement in nail psoriasis, signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis and low rate of radiographic progression in patients with concomitant nail involvement: 2-year results from the Phase III FUTURE 5 study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2022;40:952-959. doi:10.55563/clinexprheumatol/3nuz51

- Wells LE, Evans T, Hilton R, et al. Use of secukinumab in a pediatric patient leads to significant improvement in nail psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:384-385. doi:10.1111/pde.13767

- Watabe D, Endoh K, Maeda F, et al. Childhood-onset psoriaticonycho-pachydermo-periostitis treated successfully with infliximab. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:506-508. doi:10.1684/ejd.2015.2616

- Pereira TM, Vieira AP, Fernandes JC, et al. Anti-TNF-alpha therapy in childhood pustular psoriasis. Dermatology. 2006;213:350-352. doi:10.1159/000096202

- Iorizzo M, Gioia Di Chiacchio N, Di Chiacchio N, et al. Intralesional steroid injections for inflammatory nail dystrophies in the pediatric population. Pediatr Dermatol. 2023;40:759-761. doi:10.1111/pde.15295

- Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Cambiaghi S, et al. Nail lichen planus in children: clinical features, response to treatment, and long-term follow-up. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1027-1032.

- Lipner SR. Nail lichen planus: a true nail emergency. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:e177-e178. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.065

- Iorizzo M, Tosti A, Starace M, et al. Isolated nail lichen planus: an expert consensus on treatment of the classical form. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1717-1723. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.056

- Piraccini BM, Saccani E, Starace M, et al. Nail lichen planus: response to treatment and long term follow-up. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:489-496. doi:10.1684/ejd.2010.0952

- Mahajan R, Kaushik A, De D, et al. Pediatric trachyonychia- a retrospective study of 17 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2021;66:689-690. doi:10.4103/ijd.ijd_42_21

- Leung AKC, Leong KF, Barankin B. Trachyonychia. J Pediatr. 2020;216:239-239.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.08.034

- Haber JS, Chairatchaneeboon M, Rubin AI. Trachyonychia: review and update on clinical aspects, histology, and therapy. Skin Appendage Disord. 2017;2:109-115. doi:10.1159/000449063

- Jacobsen AA, Tosti A. Trachyonychia and twenty-nail dystrophy: a comprehensive review and discussion of diagnostic accuracy. Skin Appendage Disord. 2016;2:7-13. doi:10.1159/000445544

- Kumar MG, Ciliberto H, Bayliss SJ. Long-term follow-up of pediatric trachyonychia. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:198-200. doi:10.1111/pde.12427

- Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Iorizzo M. Trachyonychia and related disorders: evaluation and treatment plans. Dermatolog Ther. 2002;15:121-125. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8019.2002.01511.x

- Leung AKC, Leong KF, Barankin B. Lichen striatus with nail involvement in a 6-year-old boy. Case Rep Pediatr. 2020;2020:1494760. doi:10.1155/2020/1494760

- Kim GW, Kim SH, Seo SH, et al. Lichen striatus with nail abnormality successfully treated with tacrolimus ointment. J Dermatol. 2009;36:616-617. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00720.x

- Iorizzo M, Rubin AI, Starace M. Nail lichen striatus: is dermoscopy useful for the diagnosis? Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:859-863. doi:10.1111/pde.13916

- Karp DL, Cohen BA. Onychodystrophy in lichen striatus. Pediatr Dermatol. 1993;10:359-361. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.1993.tb00399.x

- Tosti A, Peluso AM, Misciali C, et al. Nail lichen striatus: clinical features and long-term follow-up of five patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(6, pt 1):908-913. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(97)80270-8

- Simpson EL, Thompson MM, Hanifin JM. Prevalence and morphology of hand eczema in patients with atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2006;17:123-127. doi:10.2310/6620.2006.06005

- Sarifakioglu E, Yilmaz AE, Gorpelioglu C. Nail alterations in 250 infant patients: a clinical study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:741-744. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02592.x

- Milanesi N, D’Erme AM, Gola M. Nail improvement during alitretinoin treatment: three case reports and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:533-536. doi:10.1111/ced.12584

- Chung BY, Choi YW, Kim HO, et al. Nail dystrophy in patients with atopic dermatitis and its association with disease severity. Ann Dermatol. 2019;31:121-126. doi:10.5021/ad.2019.31.2.121

- Navarro-Triviño FJ, Vega-Castillo JJ, Ruiz-Villaverde R. Nail changes successfully treated with dupilumab in a patient with severe atopic dermatitis. Australas J Dermatol. 2021;62:e468-e469. doi:10.1111/ajd.13633

- Wei SH, Huang YP, Liu MC, et al. An outbreak of coxsackievirus A6 hand, foot, and mouth disease associated with onychomadesis in Taiwan, 2010. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:346. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-11-346

- Shin JY, Cho BK, Park HJ. A clinical study of nail changes occurring secondary to hand-foot-mouth disease: onychomadesis and Beau’s lines. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:280-283. doi:10.5021/ad.2014.26.2.280

- Verma S, Singal A. Nail changes in hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD). Indian Dermatol Online J. 2021;12:656-657. doi:10.4103 /idoj.IDOJ_271_20

- Giordano LMC, de la Fuente LA, Lorca JMB, et al. Onychomadesis secondary to hand-foot-mouth disease: a frequent manifestation and cause of concern for parents. Article in Spanish. Rev Chil Pediatr. 2018;89:380-383. doi:10.4067/s0370-41062018005000203

- Justino MCA, da SMD, Souza MF, et al. Atypical hand-foot-mouth disease in Belém, Amazon region, northern Brazil, with detection of coxsackievirus A6. J Clin Virol. 2020;126:104307. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104307

- Cheng FF, Zhang BB, Cao ML, et al. Clinical characteristics of 68 children with atypical hand, foot, and mouth disease caused by coxsackievirus A6: a single-center retrospective analysis. Transl Pediatr. 2022;11:1502-1509. doi:10.21037/tp-22-352

- Nagata S. Causes of Kawasaki disease-from past to present. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:18. doi:10.3389/fped.2019.00018

- Mitsuishi T, Miyata K, Ando A, et al. Characteristic nail lesions in Kawasaki disease: case series and literature review. J Dermatol. 2022;49:232-238. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.16276

- Lindsley CB. Nail-bed lines in Kawasaki disease. Am J Dis Child. 1992;146:659-660. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1992.02160180017005

- Matsumura O, Nakagishi Y. Pincer nails upon convalescence from Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr. 2022;246:279. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2022.03.002

- Solís-Arias MP, García-Romero MT. Onychomycosis in children. a review. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:123-130. doi:10.1111/ijd.13392

- Gupta AK, Mays RR, Versteeg SG, et al. Onychomycosis in children: safety and efficacy of antifungal agents. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:552-559. doi:10.1111/pde.13561

- 49. Gupta AK, Venkataraman M, Shear NH, et al. Labeled use of efinaconazole topical solution 10% in treating onychomycosis in children and a review of the management of pediatric onychomycosis. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33:e13613. doi:10.1111/dth.13613

- Falotico JM, Lipner SR. Updated perspectives on the diagnosis and management of onychomycosis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2022;15:1933-1957. doi:10.2147/ccid.S362635

- Patel D, Castelo-Soccio LA, Rubin AI, et al. Laboratory monitoring during systemic terbinafine therapy for pediatric onychomycosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:1326-1327. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.4483

- Friedlander SF, Chan YC, Chan YH, et al. Onychomycosis does not always require systemic treatment for cure: a trial using topical therapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:316-322. doi:10.1111/pde.12064

- Rich P, Spellman M, Purohit V, et al. Tavaborole 5% topical solution for the treatment of toenail onychomycosis in pediatric patients: results from a phase 4 open-label study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:190-195.

- Gupta AK, Venkataraman M, Abramovits W, et al. JUBLIA (efinaconazole 10% solution) in the treatment of pediatric onychomycosis. Skinmed. 2021;19:206-210.

- Gupta AK, Paquet M. Systemic antifungals to treat onychomycosis in children: a systematic review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:294-302. doi:10.1111/pde.12048

- Leggit JC. Acute and chronic paronychia. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96:44-51.

- Lipner SR, Scher RK. Congenital malalignment of the great toenails with acute paronychia. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:e288-e289.doi:10.1111/pde.12924

- Uber M, Carvalho VO, Abagge KT, et al. Clinical features and nail clippings in 52 children with psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:202-207. doi:10.1111/pde.13402

- Plachouri KM, Mulita F, Georgiou S. Management of pediatric nail psoriasis. Cutis. 2021;108:292-294. doi:10.12788/cutis.0386

- Smith RJ, Rubin AI. Pediatric nail disorders: a review. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2020;32:506-515. doi:10.1097/mop.0000000000000921

- Pourchot D, Bodemer C, Phan A, et al. Nail psoriasis: a systematic evaluation in 313 children with psoriasis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:58-63. doi:10.1111/pde.13028

- Richert B, André J. Nail disorders in children: diagnosis and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:101-112. doi:10.2165/11537110-000000000-00000

- Lee JYY. Severe 20-nail psoriasis successfully treated by low dose methotrexate. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:8.

- Nogueira M, Paller AS, Torres T. Targeted therapy for pediatric psoriasis. Paediatr Drugs. May 2021;23:203-212. doi:10.1007/s40272-021-00443-5

- Hanoodi M, Mittal M. Methotrexate. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 16, 2023. Accessed July 1, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556114/

- Teran CG, Teran-Escalera CN, Balderrama C. A severe case of erythrodermic psoriasis associated with advanced nail and joint manifestations: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:179. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-4-179

- Paller AS, Seyger MMB, Magariños GA, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of up to 108 weeks of ixekizumab in pediatric patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: the IXORA-PEDS randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:533-541. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0655

- Diotallevi F, Simonetti O, Rizzetto G, et al. Biological treatments for pediatric psoriasis: state of the art and future perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:11128. doi:10.3390/ijms231911128

- Nash P, Mease PJ, Kirkham B, et al. Secukinumab provides sustained improvement in nail psoriasis, signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis and low rate of radiographic progression in patients with concomitant nail involvement: 2-year results from the Phase III FUTURE 5 study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2022;40:952-959. doi:10.55563/clinexprheumatol/3nuz51

- Wells LE, Evans T, Hilton R, et al. Use of secukinumab in a pediatric patient leads to significant improvement in nail psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:384-385. doi:10.1111/pde.13767

- Watabe D, Endoh K, Maeda F, et al. Childhood-onset psoriaticonycho-pachydermo-periostitis treated successfully with infliximab. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:506-508. doi:10.1684/ejd.2015.2616

- Pereira TM, Vieira AP, Fernandes JC, et al. Anti-TNF-alpha therapy in childhood pustular psoriasis. Dermatology. 2006;213:350-352. doi:10.1159/000096202

- Iorizzo M, Gioia Di Chiacchio N, Di Chiacchio N, et al. Intralesional steroid injections for inflammatory nail dystrophies in the pediatric population. Pediatr Dermatol. 2023;40:759-761. doi:10.1111/pde.15295

- Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Cambiaghi S, et al. Nail lichen planus in children: clinical features, response to treatment, and long-term follow-up. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:1027-1032.

- Lipner SR. Nail lichen planus: a true nail emergency. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:e177-e178. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.065

- Iorizzo M, Tosti A, Starace M, et al. Isolated nail lichen planus: an expert consensus on treatment of the classical form. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1717-1723. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.056

- Piraccini BM, Saccani E, Starace M, et al. Nail lichen planus: response to treatment and long term follow-up. Eur J Dermatol. 2010;20:489-496. doi:10.1684/ejd.2010.0952

- Mahajan R, Kaushik A, De D, et al. Pediatric trachyonychia- a retrospective study of 17 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2021;66:689-690. doi:10.4103/ijd.ijd_42_21

- Leung AKC, Leong KF, Barankin B. Trachyonychia. J Pediatr. 2020;216:239-239.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.08.034

- Haber JS, Chairatchaneeboon M, Rubin AI. Trachyonychia: review and update on clinical aspects, histology, and therapy. Skin Appendage Disord. 2017;2:109-115. doi:10.1159/000449063

- Jacobsen AA, Tosti A. Trachyonychia and twenty-nail dystrophy: a comprehensive review and discussion of diagnostic accuracy. Skin Appendage Disord. 2016;2:7-13. doi:10.1159/000445544

- Kumar MG, Ciliberto H, Bayliss SJ. Long-term follow-up of pediatric trachyonychia. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:198-200. doi:10.1111/pde.12427

- Tosti A, Piraccini BM, Iorizzo M. Trachyonychia and related disorders: evaluation and treatment plans. Dermatolog Ther. 2002;15:121-125. doi:10.1046/j.1529-8019.2002.01511.x

- Leung AKC, Leong KF, Barankin B. Lichen striatus with nail involvement in a 6-year-old boy. Case Rep Pediatr. 2020;2020:1494760. doi:10.1155/2020/1494760

- Kim GW, Kim SH, Seo SH, et al. Lichen striatus with nail abnormality successfully treated with tacrolimus ointment. J Dermatol. 2009;36:616-617. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00720.x

- Iorizzo M, Rubin AI, Starace M. Nail lichen striatus: is dermoscopy useful for the diagnosis? Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:859-863. doi:10.1111/pde.13916

- Karp DL, Cohen BA. Onychodystrophy in lichen striatus. Pediatr Dermatol. 1993;10:359-361. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.1993.tb00399.x

- Tosti A, Peluso AM, Misciali C, et al. Nail lichen striatus: clinical features and long-term follow-up of five patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(6, pt 1):908-913. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(97)80270-8

- Simpson EL, Thompson MM, Hanifin JM. Prevalence and morphology of hand eczema in patients with atopic dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2006;17:123-127. doi:10.2310/6620.2006.06005

- Sarifakioglu E, Yilmaz AE, Gorpelioglu C. Nail alterations in 250 infant patients: a clinical study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:741-744. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02592.x

- Milanesi N, D’Erme AM, Gola M. Nail improvement during alitretinoin treatment: three case reports and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:533-536. doi:10.1111/ced.12584

- Chung BY, Choi YW, Kim HO, et al. Nail dystrophy in patients with atopic dermatitis and its association with disease severity. Ann Dermatol. 2019;31:121-126. doi:10.5021/ad.2019.31.2.121

- Navarro-Triviño FJ, Vega-Castillo JJ, Ruiz-Villaverde R. Nail changes successfully treated with dupilumab in a patient with severe atopic dermatitis. Australas J Dermatol. 2021;62:e468-e469. doi:10.1111/ajd.13633

- Wei SH, Huang YP, Liu MC, et al. An outbreak of coxsackievirus A6 hand, foot, and mouth disease associated with onychomadesis in Taiwan, 2010. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:346. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-11-346

- Shin JY, Cho BK, Park HJ. A clinical study of nail changes occurring secondary to hand-foot-mouth disease: onychomadesis and Beau’s lines. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:280-283. doi:10.5021/ad.2014.26.2.280

- Verma S, Singal A. Nail changes in hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD). Indian Dermatol Online J. 2021;12:656-657. doi:10.4103 /idoj.IDOJ_271_20