User login

Sacral nerve stimulation may aid female sexual dysfunction

Sacral nerve stimulation (SNS) is a therapeutic procedure that could be used to help women with sexual dysfunction. However, the benefits of this method in this indication should still be reviewed in high-quality studies with sexual function as the primary endpoint, Erik Allemeyer, MD, PhD, a proctologist at the Niels Stensen Clinics in Georgsmarienhütte, Germany, and colleagues wrote in a recent journal article.

The World Health Organization defines sexual health as physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being in relation to sexuality. There are extensive investigations that verify the considerable importance of sexual function on a person’s quality of life. It therefore follows that therapy may be required if an individual is experiencing sexual dysfunction.

According to the authors, there are diverse data on the frequency of sexual dysfunction in women, in part because of heterogeneous definitions. The prevalence ranges between 26% and 91%. The estimated prevalence of orgasm difficulties in particular ranges from 16% to 25%. Sexual dysfunction can therefore be said to be a clinically significant problem.

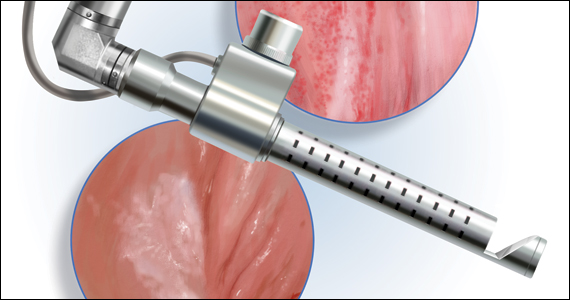

It was recently discovered that SNS, which has only been used for other conditions so far, could also be an option for women with sexual dysfunction. According to Dr. Allemeyer and coauthors, SNS was first described in 1988 as a therapeutic alternative for patients with neurogenic bladder and has been approved in Europe since 1994. As a minimally invasive therapy for urge incontinence, idiopathic pelvic pain, and for nonobstructive urinary retention, SNS can now be used to treat a wide spectrum of conditions in urology and urogynecology. After the successful stimulation treatment of fecal incontinence was first described in 1995, the procedure has also been used in coloproctology.

Tested before implantation

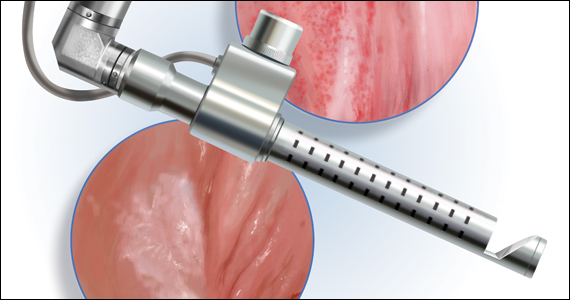

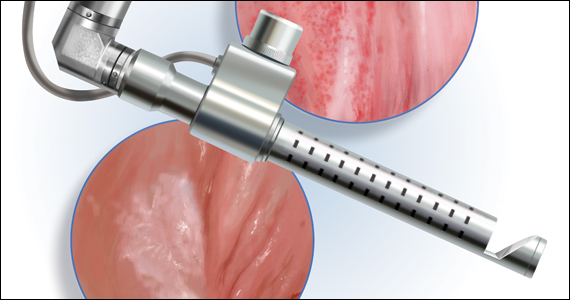

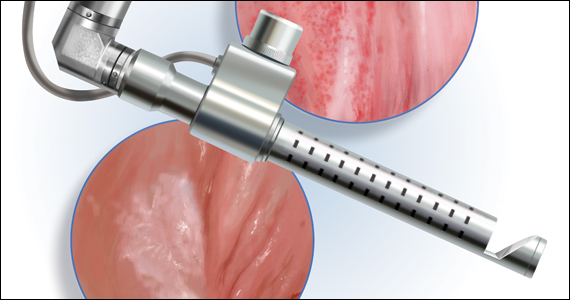

In SNS, sacral nerve roots (S3 and S4) are permanently stimulated via a percutaneously implanted electrode. At first, the effect is reviewed using a test electrode and an external impulse generator over a period of a few weeks. Only if the test stimulation significantly alleviates symptoms can the indication for full implantation be issued, wrote the authors.

The positive effects on sexual function could be seen, even in the early years of stimulation therapy, when it was used for urinary and fecal incontinence as well as for idiopathic pelvic pain, they added. They have now summarized and discussed the current state of research on the potential effects of SNS on women’s sexual function in a literature review.

Systematic study analysis

To do this, they analyzed 16 studies, which included a total of 662 women, that reviewed the effect of SNS on sexual function when the treatment was being used in other indications. The overwhelming majority of data relates to urologic indications for SNS (such as overactive bladder, chronic retention, and idiopathic pelvic pain). In contrast, the SNS indication was rarely issued for fecal incontinence (9.1% of SNS indications or 61 patients). The most often used tool to assess the effect is the validated Female Sexual Function Index. The indicators covered in this index are “desire,” “arousal,” “lubrication,” “orgasm,” and “satisfaction.”

According to Dr. Allemeyer and coauthors, the analysis revealed evidence of significantly improved sexual function. It was unclear, however, whether this improvement was a primary or secondary effect of the SNS. All the original works and reviews expressly indicated that there was no proof of a primary effect of SNS on sexual function.

The mode of action of SNS and the immediate anatomic and physiologic link between the functions of urination, urinary incontinence, pelvic pain, fecal incontinence, and sexual function suggest a possible primary effect of SNS on sexual function, wrote the authors. However, no investigations use sexual function as the primary outcome parameter of SNS. This outcome should be reviewed in high-quality studies with sexual function as the primary endpoint.

An experimental therapy

According to Dr. Allemeyer and colleagues, two practical conclusions can be drawn from the study data available to date:

A possible primary effect of SNS on sexual function should be reviewed in high-quality, prospective studies that include detailed analyses of the different aspects of sexual dysfunction in both sexes.

An offer for trial-based SNS for sexual dysfunction should be made only at experienced sites with a multidisciplinary team of sex therapists and medical specialists and only after available therapy options have been exhausted and initially only within systematic studies.

This article was translated from Univadis Germany and a version appeared on Medscape.com.

Sacral nerve stimulation (SNS) is a therapeutic procedure that could be used to help women with sexual dysfunction. However, the benefits of this method in this indication should still be reviewed in high-quality studies with sexual function as the primary endpoint, Erik Allemeyer, MD, PhD, a proctologist at the Niels Stensen Clinics in Georgsmarienhütte, Germany, and colleagues wrote in a recent journal article.

The World Health Organization defines sexual health as physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being in relation to sexuality. There are extensive investigations that verify the considerable importance of sexual function on a person’s quality of life. It therefore follows that therapy may be required if an individual is experiencing sexual dysfunction.

According to the authors, there are diverse data on the frequency of sexual dysfunction in women, in part because of heterogeneous definitions. The prevalence ranges between 26% and 91%. The estimated prevalence of orgasm difficulties in particular ranges from 16% to 25%. Sexual dysfunction can therefore be said to be a clinically significant problem.

It was recently discovered that SNS, which has only been used for other conditions so far, could also be an option for women with sexual dysfunction. According to Dr. Allemeyer and coauthors, SNS was first described in 1988 as a therapeutic alternative for patients with neurogenic bladder and has been approved in Europe since 1994. As a minimally invasive therapy for urge incontinence, idiopathic pelvic pain, and for nonobstructive urinary retention, SNS can now be used to treat a wide spectrum of conditions in urology and urogynecology. After the successful stimulation treatment of fecal incontinence was first described in 1995, the procedure has also been used in coloproctology.

Tested before implantation

In SNS, sacral nerve roots (S3 and S4) are permanently stimulated via a percutaneously implanted electrode. At first, the effect is reviewed using a test electrode and an external impulse generator over a period of a few weeks. Only if the test stimulation significantly alleviates symptoms can the indication for full implantation be issued, wrote the authors.

The positive effects on sexual function could be seen, even in the early years of stimulation therapy, when it was used for urinary and fecal incontinence as well as for idiopathic pelvic pain, they added. They have now summarized and discussed the current state of research on the potential effects of SNS on women’s sexual function in a literature review.

Systematic study analysis

To do this, they analyzed 16 studies, which included a total of 662 women, that reviewed the effect of SNS on sexual function when the treatment was being used in other indications. The overwhelming majority of data relates to urologic indications for SNS (such as overactive bladder, chronic retention, and idiopathic pelvic pain). In contrast, the SNS indication was rarely issued for fecal incontinence (9.1% of SNS indications or 61 patients). The most often used tool to assess the effect is the validated Female Sexual Function Index. The indicators covered in this index are “desire,” “arousal,” “lubrication,” “orgasm,” and “satisfaction.”

According to Dr. Allemeyer and coauthors, the analysis revealed evidence of significantly improved sexual function. It was unclear, however, whether this improvement was a primary or secondary effect of the SNS. All the original works and reviews expressly indicated that there was no proof of a primary effect of SNS on sexual function.

The mode of action of SNS and the immediate anatomic and physiologic link between the functions of urination, urinary incontinence, pelvic pain, fecal incontinence, and sexual function suggest a possible primary effect of SNS on sexual function, wrote the authors. However, no investigations use sexual function as the primary outcome parameter of SNS. This outcome should be reviewed in high-quality studies with sexual function as the primary endpoint.

An experimental therapy

According to Dr. Allemeyer and colleagues, two practical conclusions can be drawn from the study data available to date:

A possible primary effect of SNS on sexual function should be reviewed in high-quality, prospective studies that include detailed analyses of the different aspects of sexual dysfunction in both sexes.

An offer for trial-based SNS for sexual dysfunction should be made only at experienced sites with a multidisciplinary team of sex therapists and medical specialists and only after available therapy options have been exhausted and initially only within systematic studies.

This article was translated from Univadis Germany and a version appeared on Medscape.com.

Sacral nerve stimulation (SNS) is a therapeutic procedure that could be used to help women with sexual dysfunction. However, the benefits of this method in this indication should still be reviewed in high-quality studies with sexual function as the primary endpoint, Erik Allemeyer, MD, PhD, a proctologist at the Niels Stensen Clinics in Georgsmarienhütte, Germany, and colleagues wrote in a recent journal article.

The World Health Organization defines sexual health as physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being in relation to sexuality. There are extensive investigations that verify the considerable importance of sexual function on a person’s quality of life. It therefore follows that therapy may be required if an individual is experiencing sexual dysfunction.

According to the authors, there are diverse data on the frequency of sexual dysfunction in women, in part because of heterogeneous definitions. The prevalence ranges between 26% and 91%. The estimated prevalence of orgasm difficulties in particular ranges from 16% to 25%. Sexual dysfunction can therefore be said to be a clinically significant problem.

It was recently discovered that SNS, which has only been used for other conditions so far, could also be an option for women with sexual dysfunction. According to Dr. Allemeyer and coauthors, SNS was first described in 1988 as a therapeutic alternative for patients with neurogenic bladder and has been approved in Europe since 1994. As a minimally invasive therapy for urge incontinence, idiopathic pelvic pain, and for nonobstructive urinary retention, SNS can now be used to treat a wide spectrum of conditions in urology and urogynecology. After the successful stimulation treatment of fecal incontinence was first described in 1995, the procedure has also been used in coloproctology.

Tested before implantation

In SNS, sacral nerve roots (S3 and S4) are permanently stimulated via a percutaneously implanted electrode. At first, the effect is reviewed using a test electrode and an external impulse generator over a period of a few weeks. Only if the test stimulation significantly alleviates symptoms can the indication for full implantation be issued, wrote the authors.

The positive effects on sexual function could be seen, even in the early years of stimulation therapy, when it was used for urinary and fecal incontinence as well as for idiopathic pelvic pain, they added. They have now summarized and discussed the current state of research on the potential effects of SNS on women’s sexual function in a literature review.

Systematic study analysis

To do this, they analyzed 16 studies, which included a total of 662 women, that reviewed the effect of SNS on sexual function when the treatment was being used in other indications. The overwhelming majority of data relates to urologic indications for SNS (such as overactive bladder, chronic retention, and idiopathic pelvic pain). In contrast, the SNS indication was rarely issued for fecal incontinence (9.1% of SNS indications or 61 patients). The most often used tool to assess the effect is the validated Female Sexual Function Index. The indicators covered in this index are “desire,” “arousal,” “lubrication,” “orgasm,” and “satisfaction.”

According to Dr. Allemeyer and coauthors, the analysis revealed evidence of significantly improved sexual function. It was unclear, however, whether this improvement was a primary or secondary effect of the SNS. All the original works and reviews expressly indicated that there was no proof of a primary effect of SNS on sexual function.

The mode of action of SNS and the immediate anatomic and physiologic link between the functions of urination, urinary incontinence, pelvic pain, fecal incontinence, and sexual function suggest a possible primary effect of SNS on sexual function, wrote the authors. However, no investigations use sexual function as the primary outcome parameter of SNS. This outcome should be reviewed in high-quality studies with sexual function as the primary endpoint.

An experimental therapy

According to Dr. Allemeyer and colleagues, two practical conclusions can be drawn from the study data available to date:

A possible primary effect of SNS on sexual function should be reviewed in high-quality, prospective studies that include detailed analyses of the different aspects of sexual dysfunction in both sexes.

An offer for trial-based SNS for sexual dysfunction should be made only at experienced sites with a multidisciplinary team of sex therapists and medical specialists and only after available therapy options have been exhausted and initially only within systematic studies.

This article was translated from Univadis Germany and a version appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM DIE GYNÄKOLOGIE

Postpartum sexual enjoyment: Does mode of delivery matter?

For some parents, resuming sexual intimacy after having a baby is a top priority. For others, not so much – and late-night feedings and diaper changes may not be the only hang-ups.

Dyspareunia – pain during sex – occurs in a substantial number of women after childbirth, and recent research sheds light on how psychological and biomedical factors relate to this condition.

Mode of delivery, for instance, may have less of an effect on sexual well-being than some people suspect.

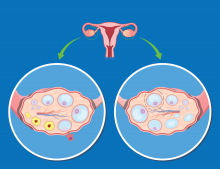

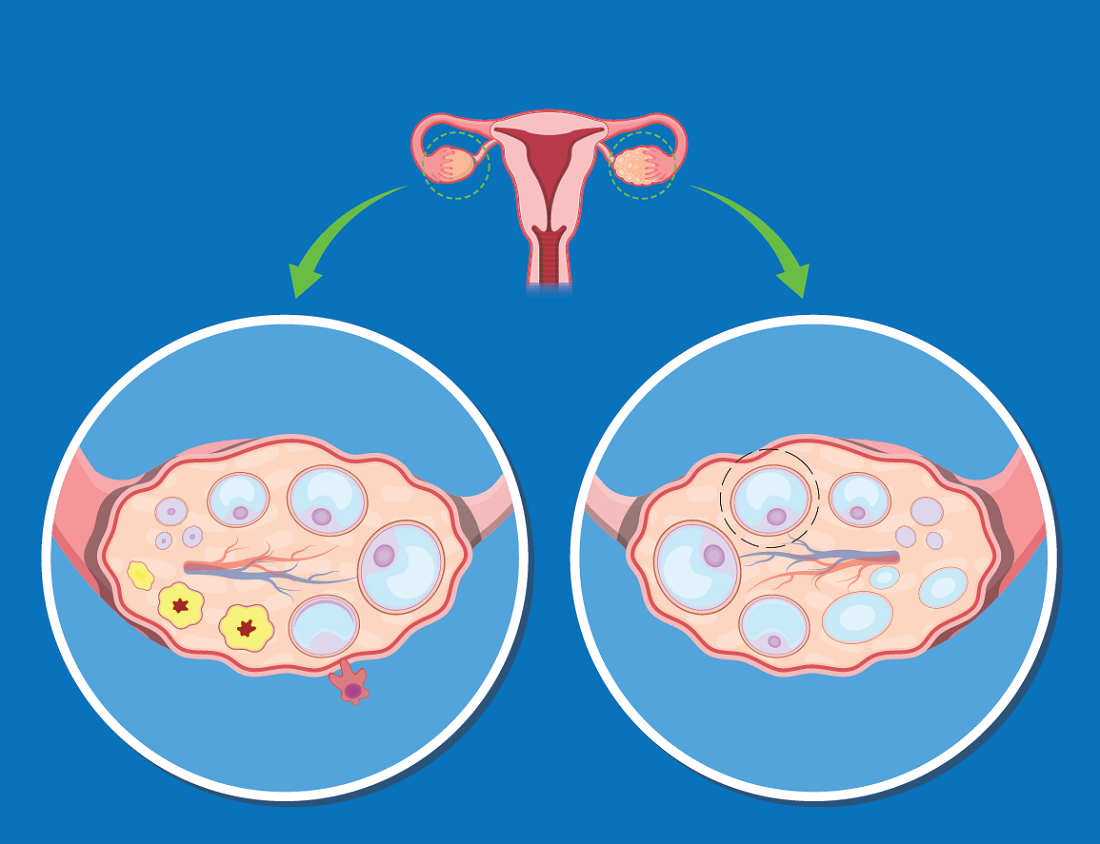

Despite a perception that cesarean delivery might affect sexual function less than vaginal delivery does, how mothers delivered did not affect how often they had sex postpartum or the amount of enjoyment they got from it, according to research published in BJOG.

Eleven years after delivery, however, cesarean delivery was associated with a 74% increased likelihood of pain in the vagina during sex, compared with vaginal delivery, the researchers found (odds ratio, 1.74; 95% confidence interval, 1.46-2.08).

The results suggest that cesarean delivery “may not help protect against sexual dysfunction, as previously thought,” Flo Martin, a PhD student in epidemiology at the University of Bristol, United Kingdom, and lead author of the study, said in a news release.

For their study, Ms. Martin and her colleagues analyzed data from more than 10,300 participants in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, which recruited women in the United Kingdom who were pregnant in 1991 and 1992.

The researchers had data about pain during sex at 11 years. They had data about sexual enjoyment and frequency at 33 months, 5 years, 12 years, and 18 years after delivery.

If women experienced pain during sex years after cesarean delivery, uterine scarring might have been a cause, Ms. Martin and colleagues suggested. Alternatively, women with dyspareunia before delivery may be more likely to have cesarean surgery, which also could explain the association.

Other studies have likewise found that different modes of delivery generally lead to similar outcomes of sexual well-being after birth.

“Several of my own longitudinal studies have shown limited associations between mode of delivery and various aspects of sexual well-being, including sexual satisfaction, sexual function, and sexual desire,” said Natalie O. Rosen, PhD, director of the Couples and Sexual Health Laboratory at Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S.

Nevertheless, other published studies have yielded conflicting results, so the question warrants further study, she said.

Pain catastrophizing

One study by Dr. Rosen’s group, published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, tracked sexual pain in 582 people from mid-pregnancy to 2 years postpartum.

About 21% of participants experienced moderate pain during sex, as determined by an average pain score greater than 4 on scale of 0-10 points. The rest were classified as having “minimal dyspareunia.”

Pain tended to peak at 3 months postpartum and then steadily decrease in both the moderate and minimal pain groups.

Mode of delivery did not affect the odds that a participant would have moderate dyspareunia. Neither did breastfeeding or prior chronic pain.

“But we did find one key thing to look out for: Those who reported a lot of negative thoughts and feelings about pain, something called pain catastrophizing, were more likely to experience moderate persistent pain during sex,” the researchers said in a video about their findings.

Pain catastrophizing 3 months after delivery was associated with significantly increased odds of following a moderate pain trajectory (odds ratio, 1.09; 95% confidence interval, 1.04-1.15).

Let’s talk about #postbabyhankypanky

Caring for a newborn while maintaining a romantic relationship can be challenging, and “there is a lack of evidence-based research aimed at helping couples prevent and navigate changes to their sexual well-being postpartum,” Dr. Rosen said.

During the 2-year study, a growing number of participants reported having sex less often over time. The percentage of women who had engaged in sexual activity in the past 4 weeks was 99% at baseline (20-24 weeks of gestation), 83.5% at 32 weeks of gestation, 73.9% at 3 months postpartum, and 69.6% at 2 years postpartum.

“One crucial way that couples sustain their connection is through their sexuality,” Dr. Rosen said. “Unfortunately, most new parents experience significant disruptions to their sexual function,” such as lower sexual desire or more pain during intercourse.

Dr. Rosen’s group has created a series of videos related to this topic dubbed #postbabyhankypanky to facilitate communication about sex postpartum. She encourages women with dyspareunia to talk with a health care provider because treatments such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, pelvic floor physical therapy, and topical medications can help manage pain.

‘Reassuring’ data

Veronica Gillispie-Bell, MD, MAS, director of quality for women’s services at the Ochsner Health System, New Orleans, said that she sees patients with postpartum sexual pain frequently.

Patients typically are instructed to have pelvic rest from delivery until 6 weeks after.

At the 6-week appointment, she tells patients to make sure that they are using lots of lubrication, because vaginal dryness related to hormonal changes during pregnancy and breastfeeding can make sex more painful, regardless of mode of delivery.

For many patients, she also recommends pelvic floor physical therapy.

As the medical director for the Louisiana Perinatal Quality Collaborative – a network of care providers, public health officials, and advocates that aims to improve outcomes for birthing persons, families, and newborns – Dr. Gillispie-Bell also is focused on reducing the rate of cesarean deliveries in the state. The BJOG study showing an increased risk for dyspareunia after a cesarean surgery serves as a reminder that there may be “long-term effects of having a C-section that may not be as obvious,” she said.

“C-sections are life-saving procedures, but they are not without risk,” Dr. Gillispie-Bell said.

Leila Frodsham, MBChB, a spokesperson for the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, told Medscape UK that it was “reassuring” to see “no difference in sexual enjoyment or sexual frequency at any time point postpartum between women who gave birth via cesarean section and those who delivered vaginally.”

“Women should be supported to make informed decisions about how they plan to give birth, and it is vital that health care professionals respect their preferences,” Dr. Frodsham added.

Clinicians should also remain aware that sexual pain is also common during periods of subfertility, perimenopause, and initiation of sexual activity.

Combinations of biological, psychological, and social factors can influence pain during sex, and there is an interpersonal element to keep in mind as well, Dr. Rosen noted.

“Pain during sex is typically elicited in the context of a partnered relationship,” Dr. Rosen said. “This means that this is an inherently interpersonal issue – let’s not forget about the partner who is both impacted by and can impact the pain through their own responses.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For some parents, resuming sexual intimacy after having a baby is a top priority. For others, not so much – and late-night feedings and diaper changes may not be the only hang-ups.

Dyspareunia – pain during sex – occurs in a substantial number of women after childbirth, and recent research sheds light on how psychological and biomedical factors relate to this condition.

Mode of delivery, for instance, may have less of an effect on sexual well-being than some people suspect.

Despite a perception that cesarean delivery might affect sexual function less than vaginal delivery does, how mothers delivered did not affect how often they had sex postpartum or the amount of enjoyment they got from it, according to research published in BJOG.

Eleven years after delivery, however, cesarean delivery was associated with a 74% increased likelihood of pain in the vagina during sex, compared with vaginal delivery, the researchers found (odds ratio, 1.74; 95% confidence interval, 1.46-2.08).

The results suggest that cesarean delivery “may not help protect against sexual dysfunction, as previously thought,” Flo Martin, a PhD student in epidemiology at the University of Bristol, United Kingdom, and lead author of the study, said in a news release.

For their study, Ms. Martin and her colleagues analyzed data from more than 10,300 participants in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, which recruited women in the United Kingdom who were pregnant in 1991 and 1992.

The researchers had data about pain during sex at 11 years. They had data about sexual enjoyment and frequency at 33 months, 5 years, 12 years, and 18 years after delivery.

If women experienced pain during sex years after cesarean delivery, uterine scarring might have been a cause, Ms. Martin and colleagues suggested. Alternatively, women with dyspareunia before delivery may be more likely to have cesarean surgery, which also could explain the association.

Other studies have likewise found that different modes of delivery generally lead to similar outcomes of sexual well-being after birth.

“Several of my own longitudinal studies have shown limited associations between mode of delivery and various aspects of sexual well-being, including sexual satisfaction, sexual function, and sexual desire,” said Natalie O. Rosen, PhD, director of the Couples and Sexual Health Laboratory at Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S.

Nevertheless, other published studies have yielded conflicting results, so the question warrants further study, she said.

Pain catastrophizing

One study by Dr. Rosen’s group, published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, tracked sexual pain in 582 people from mid-pregnancy to 2 years postpartum.

About 21% of participants experienced moderate pain during sex, as determined by an average pain score greater than 4 on scale of 0-10 points. The rest were classified as having “minimal dyspareunia.”

Pain tended to peak at 3 months postpartum and then steadily decrease in both the moderate and minimal pain groups.

Mode of delivery did not affect the odds that a participant would have moderate dyspareunia. Neither did breastfeeding or prior chronic pain.

“But we did find one key thing to look out for: Those who reported a lot of negative thoughts and feelings about pain, something called pain catastrophizing, were more likely to experience moderate persistent pain during sex,” the researchers said in a video about their findings.

Pain catastrophizing 3 months after delivery was associated with significantly increased odds of following a moderate pain trajectory (odds ratio, 1.09; 95% confidence interval, 1.04-1.15).

Let’s talk about #postbabyhankypanky

Caring for a newborn while maintaining a romantic relationship can be challenging, and “there is a lack of evidence-based research aimed at helping couples prevent and navigate changes to their sexual well-being postpartum,” Dr. Rosen said.

During the 2-year study, a growing number of participants reported having sex less often over time. The percentage of women who had engaged in sexual activity in the past 4 weeks was 99% at baseline (20-24 weeks of gestation), 83.5% at 32 weeks of gestation, 73.9% at 3 months postpartum, and 69.6% at 2 years postpartum.

“One crucial way that couples sustain their connection is through their sexuality,” Dr. Rosen said. “Unfortunately, most new parents experience significant disruptions to their sexual function,” such as lower sexual desire or more pain during intercourse.

Dr. Rosen’s group has created a series of videos related to this topic dubbed #postbabyhankypanky to facilitate communication about sex postpartum. She encourages women with dyspareunia to talk with a health care provider because treatments such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, pelvic floor physical therapy, and topical medications can help manage pain.

‘Reassuring’ data

Veronica Gillispie-Bell, MD, MAS, director of quality for women’s services at the Ochsner Health System, New Orleans, said that she sees patients with postpartum sexual pain frequently.

Patients typically are instructed to have pelvic rest from delivery until 6 weeks after.

At the 6-week appointment, she tells patients to make sure that they are using lots of lubrication, because vaginal dryness related to hormonal changes during pregnancy and breastfeeding can make sex more painful, regardless of mode of delivery.

For many patients, she also recommends pelvic floor physical therapy.

As the medical director for the Louisiana Perinatal Quality Collaborative – a network of care providers, public health officials, and advocates that aims to improve outcomes for birthing persons, families, and newborns – Dr. Gillispie-Bell also is focused on reducing the rate of cesarean deliveries in the state. The BJOG study showing an increased risk for dyspareunia after a cesarean surgery serves as a reminder that there may be “long-term effects of having a C-section that may not be as obvious,” she said.

“C-sections are life-saving procedures, but they are not without risk,” Dr. Gillispie-Bell said.

Leila Frodsham, MBChB, a spokesperson for the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, told Medscape UK that it was “reassuring” to see “no difference in sexual enjoyment or sexual frequency at any time point postpartum between women who gave birth via cesarean section and those who delivered vaginally.”

“Women should be supported to make informed decisions about how they plan to give birth, and it is vital that health care professionals respect their preferences,” Dr. Frodsham added.

Clinicians should also remain aware that sexual pain is also common during periods of subfertility, perimenopause, and initiation of sexual activity.

Combinations of biological, psychological, and social factors can influence pain during sex, and there is an interpersonal element to keep in mind as well, Dr. Rosen noted.

“Pain during sex is typically elicited in the context of a partnered relationship,” Dr. Rosen said. “This means that this is an inherently interpersonal issue – let’s not forget about the partner who is both impacted by and can impact the pain through their own responses.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For some parents, resuming sexual intimacy after having a baby is a top priority. For others, not so much – and late-night feedings and diaper changes may not be the only hang-ups.

Dyspareunia – pain during sex – occurs in a substantial number of women after childbirth, and recent research sheds light on how psychological and biomedical factors relate to this condition.

Mode of delivery, for instance, may have less of an effect on sexual well-being than some people suspect.

Despite a perception that cesarean delivery might affect sexual function less than vaginal delivery does, how mothers delivered did not affect how often they had sex postpartum or the amount of enjoyment they got from it, according to research published in BJOG.

Eleven years after delivery, however, cesarean delivery was associated with a 74% increased likelihood of pain in the vagina during sex, compared with vaginal delivery, the researchers found (odds ratio, 1.74; 95% confidence interval, 1.46-2.08).

The results suggest that cesarean delivery “may not help protect against sexual dysfunction, as previously thought,” Flo Martin, a PhD student in epidemiology at the University of Bristol, United Kingdom, and lead author of the study, said in a news release.

For their study, Ms. Martin and her colleagues analyzed data from more than 10,300 participants in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, which recruited women in the United Kingdom who were pregnant in 1991 and 1992.

The researchers had data about pain during sex at 11 years. They had data about sexual enjoyment and frequency at 33 months, 5 years, 12 years, and 18 years after delivery.

If women experienced pain during sex years after cesarean delivery, uterine scarring might have been a cause, Ms. Martin and colleagues suggested. Alternatively, women with dyspareunia before delivery may be more likely to have cesarean surgery, which also could explain the association.

Other studies have likewise found that different modes of delivery generally lead to similar outcomes of sexual well-being after birth.

“Several of my own longitudinal studies have shown limited associations between mode of delivery and various aspects of sexual well-being, including sexual satisfaction, sexual function, and sexual desire,” said Natalie O. Rosen, PhD, director of the Couples and Sexual Health Laboratory at Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S.

Nevertheless, other published studies have yielded conflicting results, so the question warrants further study, she said.

Pain catastrophizing

One study by Dr. Rosen’s group, published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, tracked sexual pain in 582 people from mid-pregnancy to 2 years postpartum.

About 21% of participants experienced moderate pain during sex, as determined by an average pain score greater than 4 on scale of 0-10 points. The rest were classified as having “minimal dyspareunia.”

Pain tended to peak at 3 months postpartum and then steadily decrease in both the moderate and minimal pain groups.

Mode of delivery did not affect the odds that a participant would have moderate dyspareunia. Neither did breastfeeding or prior chronic pain.

“But we did find one key thing to look out for: Those who reported a lot of negative thoughts and feelings about pain, something called pain catastrophizing, were more likely to experience moderate persistent pain during sex,” the researchers said in a video about their findings.

Pain catastrophizing 3 months after delivery was associated with significantly increased odds of following a moderate pain trajectory (odds ratio, 1.09; 95% confidence interval, 1.04-1.15).

Let’s talk about #postbabyhankypanky

Caring for a newborn while maintaining a romantic relationship can be challenging, and “there is a lack of evidence-based research aimed at helping couples prevent and navigate changes to their sexual well-being postpartum,” Dr. Rosen said.

During the 2-year study, a growing number of participants reported having sex less often over time. The percentage of women who had engaged in sexual activity in the past 4 weeks was 99% at baseline (20-24 weeks of gestation), 83.5% at 32 weeks of gestation, 73.9% at 3 months postpartum, and 69.6% at 2 years postpartum.

“One crucial way that couples sustain their connection is through their sexuality,” Dr. Rosen said. “Unfortunately, most new parents experience significant disruptions to their sexual function,” such as lower sexual desire or more pain during intercourse.

Dr. Rosen’s group has created a series of videos related to this topic dubbed #postbabyhankypanky to facilitate communication about sex postpartum. She encourages women with dyspareunia to talk with a health care provider because treatments such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, pelvic floor physical therapy, and topical medications can help manage pain.

‘Reassuring’ data

Veronica Gillispie-Bell, MD, MAS, director of quality for women’s services at the Ochsner Health System, New Orleans, said that she sees patients with postpartum sexual pain frequently.

Patients typically are instructed to have pelvic rest from delivery until 6 weeks after.

At the 6-week appointment, she tells patients to make sure that they are using lots of lubrication, because vaginal dryness related to hormonal changes during pregnancy and breastfeeding can make sex more painful, regardless of mode of delivery.

For many patients, she also recommends pelvic floor physical therapy.

As the medical director for the Louisiana Perinatal Quality Collaborative – a network of care providers, public health officials, and advocates that aims to improve outcomes for birthing persons, families, and newborns – Dr. Gillispie-Bell also is focused on reducing the rate of cesarean deliveries in the state. The BJOG study showing an increased risk for dyspareunia after a cesarean surgery serves as a reminder that there may be “long-term effects of having a C-section that may not be as obvious,” she said.

“C-sections are life-saving procedures, but they are not without risk,” Dr. Gillispie-Bell said.

Leila Frodsham, MBChB, a spokesperson for the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, told Medscape UK that it was “reassuring” to see “no difference in sexual enjoyment or sexual frequency at any time point postpartum between women who gave birth via cesarean section and those who delivered vaginally.”

“Women should be supported to make informed decisions about how they plan to give birth, and it is vital that health care professionals respect their preferences,” Dr. Frodsham added.

Clinicians should also remain aware that sexual pain is also common during periods of subfertility, perimenopause, and initiation of sexual activity.

Combinations of biological, psychological, and social factors can influence pain during sex, and there is an interpersonal element to keep in mind as well, Dr. Rosen noted.

“Pain during sex is typically elicited in the context of a partnered relationship,” Dr. Rosen said. “This means that this is an inherently interpersonal issue – let’s not forget about the partner who is both impacted by and can impact the pain through their own responses.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Below the belt: sexual dysfunction overlooked in women with diabetes

Among patients with diabetes, women are just as likely as men to suffer from sexual dysfunction, but their issues are overlooked, with the narrative focusing mainly on the impact of this issue on men, say experts.

Women with diabetes can experience reduced sexual desire, painful sex, reduced lubrication, and sexual distress, increasing the risk of depression, and such issues often go unnoticed despite treatments being available, said Kirsty Winkley, PhD, diabetes nurse and health psychologist, King’s College London.

There is also the “embarrassment factor” on the side of both the health care professional and the patient, she said in a session she chaired at the Diabetes UK Professional Conference 2022. Many women with diabetes “wouldn’t necessarily know” that their sexual dysfunction “is related to their diabetes,” she told this news organization.

For women, sexual health conversations are “often about contraception and pregnancy,” as well as menstrual disorders, genital infections, and hormone replacement therapy. “As health care professionals, you’re trained to focus on those things, and you’re not really considering there might be sexual dysfunction. If women aren’t aware that it’s related to diabetes, you’ve got the perfect situation where it goes under the radar.”

However, cochair Debbie Cooke, PhD, health psychologist at the University of Surrey in Guildford, explained that having psychotherapy embedded within the diabetes team and “integrated throughout the whole service” means that the problem can be identified and treatment offered.

The issue is that such integration is “very uncommon” and access needs to be improved, Dr. Cooke said in an interview.

Sexual dysfunction major predictor of depression in women

Jacqueline Fosbury, psychotherapy lead at Diabetes Care for You, Sussex Community NHS Foundation Trust, said that “intimate activity is clearly beneficial for emotional and physical health,” as it is associated with increased oxytocin release, the burning of calories, better immunity, and improved sleep.

Sexual dysfunction is common in people with diabetes, she noted. Poor glycemic control can “damage” blood vessels and nerves, causing reduced blood flow and loss of sensation in sexual organs.

A recent study led by Belgian researchers found that among more than 750 adults with diabetes, 36% of men and 33% of women reported sexual dysfunction.

Sexual dysfunction was more common in women with type 1 diabetes, at 36%, compared with 26% for those with type 2 diabetes. The most commonly reported issues were decreased sexual desire, lubrication problems, orgasmic dysfunction, and pain. Body image problems and fear of hypoglycemia also affect sexuality and intimacy, leading to “sexual distress.”

Moreover, Ms. Fosbury said female sexual dysfunction has been identified as a “major predictor” of depression, which in turn reduces libido.

Treatments for women can include lubricants, local estrogen, and medications that are prescribed off-label, such as sildenafil. The same is true of testosterone therapy, which can be used to boost libido.

Couples therapy?

Next, Trudy Hannington, a psychosexual therapist with Leger Clinic, Doncaster, U.K., talked about how to use an integrated approach to address sexuality overall in people with diabetes.

She said this should be seen in a biopsychosocial context, with emphasis on the couple, on sensation and communication, and sexual growth, as well as changes in daily routines.

There should be a move away from “penetrative sex,” Ms. Hannington said, with the goal being “enjoyment, not orgasm.” Pleasure should be facilitated and the opportunities for “performance pressure and/or anxiety” reduced.

She discussed the case of Marie, a 27-year-old woman with type 1 diabetes who had been referred with painful sex and vaginal dryness. Marie had “never experienced orgasm,” despite being in a same-sex relationship with Emily.

Marie’s treatment involved a sexual growth program, to which Emily was invited, as well as recommendations to use lubricants, vibrators, and to try sildenafil.

Prioritize women

Ms. Fosbury reiterated that, in men, sexual dysfunction is “readily identified as a complication of diabetes” and is described as “traumatic” and “crucial to well-being.” It is also seen as “easy to treat” with medication, such as that for erectile dysfunction.

It is therefore crucial to talk to women with diabetes about possible sexual dysfunction, and the scene must be set before the appointment to explain that the subject will be broached. In addition, handouts and leaflets should be available for patients in the clinic so they can read about female sexual health and to lower the stigma around discussing it.

“Cultural stereotypes diminish the importance of female sexuality and prevent us from providing equal consideration to the sexual difficulties of our patients,” she concluded.

No funding declared. No relevant financial relationships declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Among patients with diabetes, women are just as likely as men to suffer from sexual dysfunction, but their issues are overlooked, with the narrative focusing mainly on the impact of this issue on men, say experts.

Women with diabetes can experience reduced sexual desire, painful sex, reduced lubrication, and sexual distress, increasing the risk of depression, and such issues often go unnoticed despite treatments being available, said Kirsty Winkley, PhD, diabetes nurse and health psychologist, King’s College London.

There is also the “embarrassment factor” on the side of both the health care professional and the patient, she said in a session she chaired at the Diabetes UK Professional Conference 2022. Many women with diabetes “wouldn’t necessarily know” that their sexual dysfunction “is related to their diabetes,” she told this news organization.

For women, sexual health conversations are “often about contraception and pregnancy,” as well as menstrual disorders, genital infections, and hormone replacement therapy. “As health care professionals, you’re trained to focus on those things, and you’re not really considering there might be sexual dysfunction. If women aren’t aware that it’s related to diabetes, you’ve got the perfect situation where it goes under the radar.”

However, cochair Debbie Cooke, PhD, health psychologist at the University of Surrey in Guildford, explained that having psychotherapy embedded within the diabetes team and “integrated throughout the whole service” means that the problem can be identified and treatment offered.

The issue is that such integration is “very uncommon” and access needs to be improved, Dr. Cooke said in an interview.

Sexual dysfunction major predictor of depression in women

Jacqueline Fosbury, psychotherapy lead at Diabetes Care for You, Sussex Community NHS Foundation Trust, said that “intimate activity is clearly beneficial for emotional and physical health,” as it is associated with increased oxytocin release, the burning of calories, better immunity, and improved sleep.

Sexual dysfunction is common in people with diabetes, she noted. Poor glycemic control can “damage” blood vessels and nerves, causing reduced blood flow and loss of sensation in sexual organs.

A recent study led by Belgian researchers found that among more than 750 adults with diabetes, 36% of men and 33% of women reported sexual dysfunction.

Sexual dysfunction was more common in women with type 1 diabetes, at 36%, compared with 26% for those with type 2 diabetes. The most commonly reported issues were decreased sexual desire, lubrication problems, orgasmic dysfunction, and pain. Body image problems and fear of hypoglycemia also affect sexuality and intimacy, leading to “sexual distress.”

Moreover, Ms. Fosbury said female sexual dysfunction has been identified as a “major predictor” of depression, which in turn reduces libido.

Treatments for women can include lubricants, local estrogen, and medications that are prescribed off-label, such as sildenafil. The same is true of testosterone therapy, which can be used to boost libido.

Couples therapy?

Next, Trudy Hannington, a psychosexual therapist with Leger Clinic, Doncaster, U.K., talked about how to use an integrated approach to address sexuality overall in people with diabetes.

She said this should be seen in a biopsychosocial context, with emphasis on the couple, on sensation and communication, and sexual growth, as well as changes in daily routines.

There should be a move away from “penetrative sex,” Ms. Hannington said, with the goal being “enjoyment, not orgasm.” Pleasure should be facilitated and the opportunities for “performance pressure and/or anxiety” reduced.

She discussed the case of Marie, a 27-year-old woman with type 1 diabetes who had been referred with painful sex and vaginal dryness. Marie had “never experienced orgasm,” despite being in a same-sex relationship with Emily.

Marie’s treatment involved a sexual growth program, to which Emily was invited, as well as recommendations to use lubricants, vibrators, and to try sildenafil.

Prioritize women

Ms. Fosbury reiterated that, in men, sexual dysfunction is “readily identified as a complication of diabetes” and is described as “traumatic” and “crucial to well-being.” It is also seen as “easy to treat” with medication, such as that for erectile dysfunction.

It is therefore crucial to talk to women with diabetes about possible sexual dysfunction, and the scene must be set before the appointment to explain that the subject will be broached. In addition, handouts and leaflets should be available for patients in the clinic so they can read about female sexual health and to lower the stigma around discussing it.

“Cultural stereotypes diminish the importance of female sexuality and prevent us from providing equal consideration to the sexual difficulties of our patients,” she concluded.

No funding declared. No relevant financial relationships declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Among patients with diabetes, women are just as likely as men to suffer from sexual dysfunction, but their issues are overlooked, with the narrative focusing mainly on the impact of this issue on men, say experts.

Women with diabetes can experience reduced sexual desire, painful sex, reduced lubrication, and sexual distress, increasing the risk of depression, and such issues often go unnoticed despite treatments being available, said Kirsty Winkley, PhD, diabetes nurse and health psychologist, King’s College London.

There is also the “embarrassment factor” on the side of both the health care professional and the patient, she said in a session she chaired at the Diabetes UK Professional Conference 2022. Many women with diabetes “wouldn’t necessarily know” that their sexual dysfunction “is related to their diabetes,” she told this news organization.

For women, sexual health conversations are “often about contraception and pregnancy,” as well as menstrual disorders, genital infections, and hormone replacement therapy. “As health care professionals, you’re trained to focus on those things, and you’re not really considering there might be sexual dysfunction. If women aren’t aware that it’s related to diabetes, you’ve got the perfect situation where it goes under the radar.”

However, cochair Debbie Cooke, PhD, health psychologist at the University of Surrey in Guildford, explained that having psychotherapy embedded within the diabetes team and “integrated throughout the whole service” means that the problem can be identified and treatment offered.

The issue is that such integration is “very uncommon” and access needs to be improved, Dr. Cooke said in an interview.

Sexual dysfunction major predictor of depression in women

Jacqueline Fosbury, psychotherapy lead at Diabetes Care for You, Sussex Community NHS Foundation Trust, said that “intimate activity is clearly beneficial for emotional and physical health,” as it is associated with increased oxytocin release, the burning of calories, better immunity, and improved sleep.

Sexual dysfunction is common in people with diabetes, she noted. Poor glycemic control can “damage” blood vessels and nerves, causing reduced blood flow and loss of sensation in sexual organs.

A recent study led by Belgian researchers found that among more than 750 adults with diabetes, 36% of men and 33% of women reported sexual dysfunction.

Sexual dysfunction was more common in women with type 1 diabetes, at 36%, compared with 26% for those with type 2 diabetes. The most commonly reported issues were decreased sexual desire, lubrication problems, orgasmic dysfunction, and pain. Body image problems and fear of hypoglycemia also affect sexuality and intimacy, leading to “sexual distress.”

Moreover, Ms. Fosbury said female sexual dysfunction has been identified as a “major predictor” of depression, which in turn reduces libido.

Treatments for women can include lubricants, local estrogen, and medications that are prescribed off-label, such as sildenafil. The same is true of testosterone therapy, which can be used to boost libido.

Couples therapy?

Next, Trudy Hannington, a psychosexual therapist with Leger Clinic, Doncaster, U.K., talked about how to use an integrated approach to address sexuality overall in people with diabetes.

She said this should be seen in a biopsychosocial context, with emphasis on the couple, on sensation and communication, and sexual growth, as well as changes in daily routines.

There should be a move away from “penetrative sex,” Ms. Hannington said, with the goal being “enjoyment, not orgasm.” Pleasure should be facilitated and the opportunities for “performance pressure and/or anxiety” reduced.

She discussed the case of Marie, a 27-year-old woman with type 1 diabetes who had been referred with painful sex and vaginal dryness. Marie had “never experienced orgasm,” despite being in a same-sex relationship with Emily.

Marie’s treatment involved a sexual growth program, to which Emily was invited, as well as recommendations to use lubricants, vibrators, and to try sildenafil.

Prioritize women

Ms. Fosbury reiterated that, in men, sexual dysfunction is “readily identified as a complication of diabetes” and is described as “traumatic” and “crucial to well-being.” It is also seen as “easy to treat” with medication, such as that for erectile dysfunction.

It is therefore crucial to talk to women with diabetes about possible sexual dysfunction, and the scene must be set before the appointment to explain that the subject will be broached. In addition, handouts and leaflets should be available for patients in the clinic so they can read about female sexual health and to lower the stigma around discussing it.

“Cultural stereotypes diminish the importance of female sexuality and prevent us from providing equal consideration to the sexual difficulties of our patients,” she concluded.

No funding declared. No relevant financial relationships declared.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pill not enough for ‘sexual problems’ female cancer patients face

The antidepressant bupropion failed to improve sexual dysfunction in female cancer survivors, according to new findings published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Using the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) as a measurement tool, investigators found that desire scores were not significantly different for participants who received bupropion versus a placebo over the 9-week study period.

“Sexual health is a complex phenomenon and [our results suggest that] no one intervention is going to solve the broader issue,” lead author Debra Barton, RN, PhD, FAAN, professor in the School of Nursing at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, told this news organization.

Sexual dysfunction is common among cancer survivors and experienced across multiple cancer types and stages of disease. Research shows that as many as 70% of female cancer survivors report loss of desire, compared with up to one-third of the general population.

Common sexual concerns among female cancer survivors include low desire, arousal issues, lack of appropriate lubrication, difficulty in achieving orgasm, and pain with penetrative sexual activity. Additionally, these women may experience significant overlap of symptoms, and often encounter multiple sexual issues that are exacerbated by a range of cancer treatments.

“It’s a huge problem,” Maryam B. Lustberg, MD, MPH, from Yale Cancer Center, New Haven, Conn., and colleagues wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Despite the prevalence of sexual dysfunction among cancer survivors, effective treatments remain elusive. Preliminary evidence suggests that bupropion, already approved for seasonal affective disorder, major depressive disorder, and smoking cessation, may also enhance libido.

Dr. Barton and colleagues conducted this phase 2 trial to determine whether bupropion can improve sexual desire in female cancer survivors without undesirable side effects.

In the study, Dr. Barton and colleagues compared two dose levels of extended-release bupropion in a cohort of 230 postmenopausal women diagnosed with breast or gynecologic cancer and low baseline FSFI desire scores (<3.3), who had completed definitive cancer therapy.

Participants were randomized to receive either 150 mg (79 patients) or 300 mg (74 patients) once daily of extended-release bupropion, or placebo (77 patients).

Barton and colleagues then evaluated whether sexual desire significantly improved over the 9-week study period comparing the bupropion arms and the placebo group.

Overall, the authors found no significant differences (mean between-arm change for 150 mg once daily and placebo of 0.02; P = .93; mean between-arm change for 300 mg once daily and placebo of –0.02; P = .92). Mean scores at 9 weeks on the desire subscale were 2.17, 2.27, and 2.30 for 150 mg, 300 mg, and the placebo group, respectively.

In addition, none of the subscales – which included arousal, lubrication, and orgasm – or the total score showed a significant difference between arms at either 5 or 9 weeks.

Bupropion did, however, appear to be well tolerated. No grade 4-5 treatment-related adverse events occurred. In the 150-mg bupropion arm, two patients (2.6%) experienced a grade 3 event (insomnia and headache) and one patient in the 300-mg bupropion arm (1.4%) and placebo arm (1.3%) experienced a grade 3 event related to treatment (hypertension and headache, respectively).

In the accompanying editorial, Dr. Lustberg and colleagues “applaud the authors for conducting a study in this population of cancer survivors,” noting that “evidenced-based approaches have not been extensively studied.”

Dr. Lustberg and colleagues also commented that other randomized controlled clinical trials evaluating sexual desire disorder assessed outcomes using additional metrics, such as the Female Sexual Distress Scale–Revised questionnaire, which measures distress related to sexual dysfunction and low desire, in particular.

“The use of specific validated instruments for libido in place of the FSFI might have helped determine the effect of the study intervention in this reported trial,” they wrote.

Overall, according to Dr. Lustberg and colleagues, the negative results of this study indicate that a multidisciplinary clinical approach may be needed.

“As much as we would like to have one intervention that addresses this prominent issue, the evidence strongly suggests that cancer-related sexual problems may need an integrative biopsychosocial model that intervenes on biologic, psychologic, interpersonal, and social-cultural factors, not just on one factor, such as libido,” they wrote. “Such work may require access to multidisciplinary care with specialists in women’s health, pelvic floor rehabilitation, and psychosocial oncology.”

Dr. Barton said she has been developing a multicomponent approach to addressing sexual health in female cancer survivors.

However, she noted, “there is still much we do not fully understand about the broader impact of the degree of hormone deprivation in the population of female cancer survivors. A better understanding would provide clearer targets for interventions.”

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute and Breast Cancer Research Foundation. Dr. Barton has disclosed research funding from Merck. Dr. Lustberg reported receiving honoraria from Novartis and Biotheranostics; consulting or advising with PledPharma, Disarm Therapeutics, Pfizer; and other relationships with Cynosure/Hologic.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The antidepressant bupropion failed to improve sexual dysfunction in female cancer survivors, according to new findings published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Using the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) as a measurement tool, investigators found that desire scores were not significantly different for participants who received bupropion versus a placebo over the 9-week study period.

“Sexual health is a complex phenomenon and [our results suggest that] no one intervention is going to solve the broader issue,” lead author Debra Barton, RN, PhD, FAAN, professor in the School of Nursing at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, told this news organization.

Sexual dysfunction is common among cancer survivors and experienced across multiple cancer types and stages of disease. Research shows that as many as 70% of female cancer survivors report loss of desire, compared with up to one-third of the general population.

Common sexual concerns among female cancer survivors include low desire, arousal issues, lack of appropriate lubrication, difficulty in achieving orgasm, and pain with penetrative sexual activity. Additionally, these women may experience significant overlap of symptoms, and often encounter multiple sexual issues that are exacerbated by a range of cancer treatments.

“It’s a huge problem,” Maryam B. Lustberg, MD, MPH, from Yale Cancer Center, New Haven, Conn., and colleagues wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Despite the prevalence of sexual dysfunction among cancer survivors, effective treatments remain elusive. Preliminary evidence suggests that bupropion, already approved for seasonal affective disorder, major depressive disorder, and smoking cessation, may also enhance libido.

Dr. Barton and colleagues conducted this phase 2 trial to determine whether bupropion can improve sexual desire in female cancer survivors without undesirable side effects.

In the study, Dr. Barton and colleagues compared two dose levels of extended-release bupropion in a cohort of 230 postmenopausal women diagnosed with breast or gynecologic cancer and low baseline FSFI desire scores (<3.3), who had completed definitive cancer therapy.

Participants were randomized to receive either 150 mg (79 patients) or 300 mg (74 patients) once daily of extended-release bupropion, or placebo (77 patients).

Barton and colleagues then evaluated whether sexual desire significantly improved over the 9-week study period comparing the bupropion arms and the placebo group.

Overall, the authors found no significant differences (mean between-arm change for 150 mg once daily and placebo of 0.02; P = .93; mean between-arm change for 300 mg once daily and placebo of –0.02; P = .92). Mean scores at 9 weeks on the desire subscale were 2.17, 2.27, and 2.30 for 150 mg, 300 mg, and the placebo group, respectively.

In addition, none of the subscales – which included arousal, lubrication, and orgasm – or the total score showed a significant difference between arms at either 5 or 9 weeks.

Bupropion did, however, appear to be well tolerated. No grade 4-5 treatment-related adverse events occurred. In the 150-mg bupropion arm, two patients (2.6%) experienced a grade 3 event (insomnia and headache) and one patient in the 300-mg bupropion arm (1.4%) and placebo arm (1.3%) experienced a grade 3 event related to treatment (hypertension and headache, respectively).

In the accompanying editorial, Dr. Lustberg and colleagues “applaud the authors for conducting a study in this population of cancer survivors,” noting that “evidenced-based approaches have not been extensively studied.”

Dr. Lustberg and colleagues also commented that other randomized controlled clinical trials evaluating sexual desire disorder assessed outcomes using additional metrics, such as the Female Sexual Distress Scale–Revised questionnaire, which measures distress related to sexual dysfunction and low desire, in particular.

“The use of specific validated instruments for libido in place of the FSFI might have helped determine the effect of the study intervention in this reported trial,” they wrote.

Overall, according to Dr. Lustberg and colleagues, the negative results of this study indicate that a multidisciplinary clinical approach may be needed.

“As much as we would like to have one intervention that addresses this prominent issue, the evidence strongly suggests that cancer-related sexual problems may need an integrative biopsychosocial model that intervenes on biologic, psychologic, interpersonal, and social-cultural factors, not just on one factor, such as libido,” they wrote. “Such work may require access to multidisciplinary care with specialists in women’s health, pelvic floor rehabilitation, and psychosocial oncology.”

Dr. Barton said she has been developing a multicomponent approach to addressing sexual health in female cancer survivors.

However, she noted, “there is still much we do not fully understand about the broader impact of the degree of hormone deprivation in the population of female cancer survivors. A better understanding would provide clearer targets for interventions.”

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute and Breast Cancer Research Foundation. Dr. Barton has disclosed research funding from Merck. Dr. Lustberg reported receiving honoraria from Novartis and Biotheranostics; consulting or advising with PledPharma, Disarm Therapeutics, Pfizer; and other relationships with Cynosure/Hologic.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The antidepressant bupropion failed to improve sexual dysfunction in female cancer survivors, according to new findings published online in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Using the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) as a measurement tool, investigators found that desire scores were not significantly different for participants who received bupropion versus a placebo over the 9-week study period.

“Sexual health is a complex phenomenon and [our results suggest that] no one intervention is going to solve the broader issue,” lead author Debra Barton, RN, PhD, FAAN, professor in the School of Nursing at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, told this news organization.

Sexual dysfunction is common among cancer survivors and experienced across multiple cancer types and stages of disease. Research shows that as many as 70% of female cancer survivors report loss of desire, compared with up to one-third of the general population.

Common sexual concerns among female cancer survivors include low desire, arousal issues, lack of appropriate lubrication, difficulty in achieving orgasm, and pain with penetrative sexual activity. Additionally, these women may experience significant overlap of symptoms, and often encounter multiple sexual issues that are exacerbated by a range of cancer treatments.

“It’s a huge problem,” Maryam B. Lustberg, MD, MPH, from Yale Cancer Center, New Haven, Conn., and colleagues wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Despite the prevalence of sexual dysfunction among cancer survivors, effective treatments remain elusive. Preliminary evidence suggests that bupropion, already approved for seasonal affective disorder, major depressive disorder, and smoking cessation, may also enhance libido.

Dr. Barton and colleagues conducted this phase 2 trial to determine whether bupropion can improve sexual desire in female cancer survivors without undesirable side effects.

In the study, Dr. Barton and colleagues compared two dose levels of extended-release bupropion in a cohort of 230 postmenopausal women diagnosed with breast or gynecologic cancer and low baseline FSFI desire scores (<3.3), who had completed definitive cancer therapy.

Participants were randomized to receive either 150 mg (79 patients) or 300 mg (74 patients) once daily of extended-release bupropion, or placebo (77 patients).

Barton and colleagues then evaluated whether sexual desire significantly improved over the 9-week study period comparing the bupropion arms and the placebo group.

Overall, the authors found no significant differences (mean between-arm change for 150 mg once daily and placebo of 0.02; P = .93; mean between-arm change for 300 mg once daily and placebo of –0.02; P = .92). Mean scores at 9 weeks on the desire subscale were 2.17, 2.27, and 2.30 for 150 mg, 300 mg, and the placebo group, respectively.

In addition, none of the subscales – which included arousal, lubrication, and orgasm – or the total score showed a significant difference between arms at either 5 or 9 weeks.

Bupropion did, however, appear to be well tolerated. No grade 4-5 treatment-related adverse events occurred. In the 150-mg bupropion arm, two patients (2.6%) experienced a grade 3 event (insomnia and headache) and one patient in the 300-mg bupropion arm (1.4%) and placebo arm (1.3%) experienced a grade 3 event related to treatment (hypertension and headache, respectively).

In the accompanying editorial, Dr. Lustberg and colleagues “applaud the authors for conducting a study in this population of cancer survivors,” noting that “evidenced-based approaches have not been extensively studied.”

Dr. Lustberg and colleagues also commented that other randomized controlled clinical trials evaluating sexual desire disorder assessed outcomes using additional metrics, such as the Female Sexual Distress Scale–Revised questionnaire, which measures distress related to sexual dysfunction and low desire, in particular.

“The use of specific validated instruments for libido in place of the FSFI might have helped determine the effect of the study intervention in this reported trial,” they wrote.

Overall, according to Dr. Lustberg and colleagues, the negative results of this study indicate that a multidisciplinary clinical approach may be needed.

“As much as we would like to have one intervention that addresses this prominent issue, the evidence strongly suggests that cancer-related sexual problems may need an integrative biopsychosocial model that intervenes on biologic, psychologic, interpersonal, and social-cultural factors, not just on one factor, such as libido,” they wrote. “Such work may require access to multidisciplinary care with specialists in women’s health, pelvic floor rehabilitation, and psychosocial oncology.”

Dr. Barton said she has been developing a multicomponent approach to addressing sexual health in female cancer survivors.

However, she noted, “there is still much we do not fully understand about the broader impact of the degree of hormone deprivation in the population of female cancer survivors. A better understanding would provide clearer targets for interventions.”

The study was supported by the National Cancer Institute and Breast Cancer Research Foundation. Dr. Barton has disclosed research funding from Merck. Dr. Lustberg reported receiving honoraria from Novartis and Biotheranostics; consulting or advising with PledPharma, Disarm Therapeutics, Pfizer; and other relationships with Cynosure/Hologic.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

2021 Update on female sexual health

The approach to diagnosis and treatment of female sexual function continues to be a challenge for women’s health professionals. The search for a female “little blue pill” remains elusive as researchers struggle to understand the mechanisms that underlie the complex aspects of female sexual health. This Update will review the recent literature on the use of fractional CO2 laser for treatment of female sexual dysfunction and vulvovaginal symptoms. Bottom line: While the quality of the studies is poor overall, fractional CO2 laser treatment seems to temporarily improve symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). The duration of response, cost, and the overall long-term impact on sexual health remain in question.

A retrospective look at CO2 laser and postmenopausal GSM

Filippini M, Luvero D, Salvatore S, et al. Efficacy of fractional CO2 laser treatment in postmenopausal women with genitourinary syndrome: a multicenter study. Menopause. 2019;27:43-49. doi: 10.1097/GME. 0000000000001428.

Researchers conducted a retrospective, multicenter study of postmenopausal women with at least one symptom of GSM, including itching, burning, dyspareunia with penetration, and dryness.

Study details

A total of 171 of the 645 women (26.5%) were oncology patients. Women were excluded from analysis if they used any form of topical therapy within 15 days; had prolapse stage 2 or greater; or had any infection, abscess, or anatomical deformity precluding treatment with the laser.

Patients underwent gynecologic examination and were given a questionnaire to assess vulvovaginal symptoms. Exams occurred monthly during treatment (average, 6.5 months), at 6- and 12-months posttreatment, and then annually. No topical therapy was advised during or after treatment.

Patients received either 3 or 4 fractional CO2 laser treatments to the vulva and/or vagina depending on symptom location and type. Higher power settings of the same laser were used to treat vaginal symptoms (40W; 1,000 microseconds) versus vulvar symptoms (25W; 500 microseconds). Treatment sessions were 5 to 6 minutes. The study authors used a visual analog rating scale (VAS) for “atrophy and related symptoms,” tested vaginal pH, and completed the Vaginal Health Index Score. VAS scores were obtained from the patients prior to the initial laser intervention and 1 month after the final treatment.

Results

There were statistically significant improvements in dryness, vaginal orifice pain, dyspareunia, itching, and burning for both the 3-treatment and 4-treatment cohorts. The delta of improvement was then compared for the 2 subgroups; curiously, there was greater improvement of symptoms such as dryness (65% vs 61%), itching (78% vs 72%), burning (72% vs 67%), and vaginal orifice pain (67% vs 60%) in the group that received 3 cycles than in the group that received 4 cycles.

With regard to vaginal pH improvement, the 4-cycle group performed better than the 3-cycle group (1% improvement in the 4-cycle group vs 6% in the 3-cycle group). Although vaginal pH reduction was somewhat better in the group that received 4 treatments, and the pre versus posttreatment percentages were statistically significantly different, the clinical significance of a pH difference between 5.72 and 5.53 is questionable, especially since there was a greater difference in baseline pH between the two cohorts (6.08 in the 4-cycle group vs 5.59 in the 3-cycle group).

There were no reported adverse events related to the fractional laser treatments, and 6% of the patients underwent additional laser treatments during the followup timeframe of 8 to 20 months.

This was a retrospective study with no control or comparison group and short-term follow-up. The VAS scores were obtained 1 month after the final treatment. Failure to request additional treatment at 8 to 20 months cannot be used to infer that the therapeutic improvements recorded at 1 month were enduring. In addition, although the large number of patients in this study may lead to statistical significance, clinical significance is still questionable. Given the lack of a comparison group and the very short follow-up, it is hard to draw any scientifically valid conclusions from this study.

Continue to: Randomized data on CO2 laser vs Kegels for sexual dysfunction...

Randomized data on CO2 laser vs Kegels for sexual dysfunction

Lou W, Chen F, Xu T, et al. A randomized controlled study of vaginal fractional CO2 laser therapy for female sexual dysfunction. Lasers Med Sci. March 15, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s10103-021-03260-x.

In a small randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted in China, Lou and colleagues identified premenopausal women at “high risk” for sexual dysfunction as determined by the Chinese version of the Female Sexual Function Index (CFSFI).

Details of the study

A total of 84 women (mean age, 36.5 years) were included in the study. All the participants were heterosexual and married or with a long-term partner. The domain of sexual dysfunction was not considered. Women were excluded if they had no current heterosexual partner; had genital malformation, urinary incontinence, or prolapse stage 2 or higher; a history of pelvic floor mesh treatment; current gynecologic malignancy; abnormal cervical cytology; or were currently pregnant or postpartum. In addition, women were excluded if they had been treated previously for sexual dysfunction or mental “disease.” The cohort was randomized to receive fractional CO2 laser treatments (three 15-minute treatments 1 month apart at 60W, 1,000 microseconds) or coached Kegel exercises (10 exercises repeated twice daily at least 3 times/week and monitored by physical therapists at biweekly clinic visits). Sexual distress was evaluated by using the Female Sexual Distress Scale-Revised (FSDSR). Outcomes measured were pelvic floor muscle strength and scores on the CFSFI and FSDSR. Data were obtained at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after initiation of therapy.

Both groups showed improvement

The laser cohort showed slightly more improvement in scale scores at 6 and 12 months. Specifically, the laser group had better scores on lubrication and overall satisfaction, with moderate effect size; neither group had improvements in arousal, desire, or orgasm. The Kegel group showed a significant improvement in pelvic floor strength and orgasm at 12 months, an improvement not seen in the laser cohort. Both groups showed gradual improvement in the FSDSR, with the laser group reporting a lower score (10.0) at 12 months posttreatment relative to the Kegel group (11.1). Again, these were modest effects as baseline scores for both cohorts were around 12.5. There were minimal safety signals in the laser group, with 22.5% of women reporting scant bloody discharge posttreatment and 72.5% describing mild discomfort (1 on a 1–10 VAS scale) during the procedure.

This study is problematic in several areas. Although it was a prospective, randomized trial, it was not blinded, and the therapeutic interventions were markedly different in nature and requirement for individual patient motivation. The experiences of sexual dysfunction among the participants were not stratified by type—arousal, desire, lubrication, orgasm, or pain. All patients had regular cyclic menses; however, the authors do not report on contraceptive methods, hormonal therapy, or other comorbid conditions that could impact sexual health. The cohorts may or may not have been similar in baseline types of sexual dissatisfaction.

CO2 laser for lichen sclerosus: Is it effective?

Pagano T, Conforti A, Buonfantino C, et al. Effect of rescue fractional microablative CO2 laser on symptoms and sexual dysfunction in women affected by vulvar lichen sclerosus resistant to long-term use of topic corticosteroid: a prospective longitudinal study. Menopause. 2020;27:418-422. doi: 10.1097 /GME.0000000000001482.

Burkett LS, Siddique M, Zeymo A, et al. Clobetasol compared with fractionated carbon dioxide laser for lichen sclerosus: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:968-978. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000004332.

Mitchell L, Goldstein AT, Heller D, et al. Fractionated carbon dioxide laser for the treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:979-987. doi: 10.1097 /AOG.0000000000004409.

High potency corticosteroid ointment is the current standard treatment for lichen sclerosus. Alternative options for disease that is refractory to steroids are limited. Three studies published in the past year explored the CO2 laser’s ability to treat lichen sclerosus symptoms and resultant sexual dysfunction—Pagano and colleagues conducted a small prospective study and Burkett and colleagues and Mitchell et al conducted small RCTs.

Details of the Pagano study

Three premenopausal and 37 postmenopausal women with refractory lichen sclerosus (defined as no improvement after 4 cycles of ultra-high potency steroids) were included in the study. Lichen sclerosus was uniformly biopsy confirmed. Women using topical or systemic hormones were excluded. VAS was administered prior to initial treatment and after each of 2 fractional CO2 treatments (25–30 W; 1,000 microseconds) 30 to 40 days apart to determine severity of vulvar itching, dyspareunia with penetration, vulvar dryness, sexual dysfunction, and procedure discomfort. Follow-up was conducted at 1 month after the final treatment. VAS score for the primary outcome of vulvar itching declined from 8 pretreatment to 6 after the first treatment and to 3 after the second. There was no significant treatment-related pain reported.

The authors acknowledged the limitations of their study; it was a relatively small sample size, nonrandomized and had short-term follow-up of a mixed patient population and no sham or control group. The short-term improvements reported in the study patients may not be sustained without ongoing treatment for a lifelong chronic disease, and the long-term potential for development of squamous cell carcinoma may or may not be ameliorated.

Continue to: Burkett et al: RCT study 1...

Burkett et al: RCT study 1