User login

Patients With Stable Lupus May Be Safely Weaned Off MMF

Patients with quiescent systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) who are on maintenance therapy with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) may be able to be safely weaned off the drug with the understanding that disease flare may occur and may require restarting immunosuppressive therapy.

That’s the conclusion of investigators in a multicenter randomized trial conducted at 19 US centers and published in The Lancet Rheumatology. They found that among 100 patients with stable SLE who were on MMF for at least 2 years for renal indications or at least 1 year for nonrenal indications, MMF withdrawal was not significantly inferior to MMF maintenance in terms of clinically significant disease reactivation within at least 1 year.

“Our findings suggest that mycophenolate mofetil could be safely withdrawn in patients with stable SLE. However, larger studies with a longer follow-up are still needed,” wrote Eliza F. Chakravarty, MD, MS, from the University of Oklahoma College of Medicine in Oklahoma City, and colleagues.

“Our study was only for 60 weeks, so we don’t have long-term data on what happens when patients taper off, but my recommendation — and I think the data support this — is that even if you do have a history of lupus nephritis, if you had stable disease or very little to no activity for a year or 2, then I think it’s worth stopping the medication and following for any signs of disease flare,” Dr. Chakravarty said in an interview with this news organization.

She added that “in clinical practice, we would follow patients regularly no matter what they’re on, even if they’re in remission, looking for clinical signs or laboratory evidence of flare, and then if they look like they might be having flare, treat them accordingly.”

Toxicities a Concern

Although MMF is effective for inducing prolonged disease quiescence, it is a known teratogen and has significant toxicities, and it’s desirable to wean patients off the drug if it can be done safely, Dr. Chakravarty said.

The optimal duration of maintenance therapy with MMF is not known, however, which prompted the researchers to conduct the open-label study.

Patients aged 18-70 years who met the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 1997 SLE criteria and had a clinical SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) score ≤ 4 at screening and who also had been on stable or tapering MMF therapy for 2 or more years for renal indications or 1 or more year for nonrenal indications were eligible. All patients were on a background regimen of hydroxychloroquine.

Patients were randomly assigned on an equal basis to either withdrawal with a 12-week taper or to continued maintenance at their baseline dose, ranging from 1 to 3 g/day for 60 weeks.

The investigators used an adaptive random-allocation strategy to ensure that the groups were balanced for study site, renal vs nonrenal disease, and baseline MMF dose (≥ 2 g/day vs < 2 g/day).

A total of 100 patients with an average age of 42 years were included in a modified intention-to-treat analysis: 49 were randomly assigned to maintenance and 51 to withdrawal.

Overall, 84% of patients were women, 40% were White, and 41% were Black. Most patients, 76%, had a history of lupus nephritis.

Significant disease reactivation, the primary endpoints, was defined as the need to increase prednisone to ≥ 15 mg/day for 4 weeks, the need for two or more short steroid bursts, or the need to resume MMF or start patients on another immunosuppressive therapy.

By week 60, 18% of patients in the withdrawal group had clinically significant disease reactivation compared with 10% of patients in the maintenance group.

“Although the differences were not significant, this study used an estimation-based design to determine estimated increases in clinically significant disease reactivation risk with 75%, 85%, and 95% confidence limits to assist clinicians and patients in making informed treatment decisions. We found a 6%-8% increase with upper 85% confidence limits of 11%-19% in clinically significant disease reactivation and flare risk following mycophenolate mofetil withdrawal,” the investigators wrote.

Rates of adverse events were similar between the groups, occurring in 90% of patients in the maintenance arm and 88% of those in the withdrawal arm. Infections occurred more frequently among patients in the maintenance group, at 64% vs 46%.

Encouraging Data

In an accompanying editorial, Noémie Jourde-Chiche, MD, PhD, from Aix-Marseille University in Marseille, France, and Laurent Chiche, MD, from Hopital Europeen de Marseille, wrote that the study data “were clearly encouraging.” They noted that the results show that it’s feasible to wean select patients off immunosuppressive therapy and keep SLE in check and that the quantified risk assessment strategy will allow shared decision-making for each patient.

“Overall, the prospect of a time-limited (versus lifelong) treatment may favor compliance, as observed in other disease fields, which might consolidate remission and reduce the risk of subsequent relapse, using sequentially treat-to-target and think-to-untreat strategies for a win-wean era in SLE,” they wrote.

“We’ve been awaiting the results of this trial for quite a while, and so it is nice to see it out,” commented Karen H. Costenbader, MD, MPH, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, and chair of the division of rheumatology and director of the Lupus Program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

“It does provide some data to address a question that comes up in discussions with patients all the time: A person with lupus has been doing really well, in what we call low disease activity state or remission, but on mycophenolate, possibly for several years,” she said in a reply to a request for objective commentary.

“The question is how and when to taper and can MMF be safely discontinued,” she said. “Personally, I always review the severity of the underlying disease and indication for the MMF in the first place. Really active SLE with rapidly progressing kidney or other organ damage has to be treated with tremendous respect and no one wants to go back there. I also think about how long it has been, which other medications are still being taken (hydroxychloroquine, belimumab [Benlysta], etc.) and whether the labs and symptoms have really returned to completely normal. Then I have discussions about all this with my patient and we often try a long, slow, gingerly taper with a lot of interim monitoring.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Chakravarty and Dr. Costenbader report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Jourde-Chiche declares personal consulting fees from Otsuka and AstraZeneca, personal speaking fees from GlaxoSmithKline and Otsuka, and personal payment for expert testimony from Otsuka. Dr. Chiche declares research grants paid to his institution from AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline, personal consulting fees from Novartis and AstraZeneca, and personal speaking fees from GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Patients with quiescent systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) who are on maintenance therapy with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) may be able to be safely weaned off the drug with the understanding that disease flare may occur and may require restarting immunosuppressive therapy.

That’s the conclusion of investigators in a multicenter randomized trial conducted at 19 US centers and published in The Lancet Rheumatology. They found that among 100 patients with stable SLE who were on MMF for at least 2 years for renal indications or at least 1 year for nonrenal indications, MMF withdrawal was not significantly inferior to MMF maintenance in terms of clinically significant disease reactivation within at least 1 year.

“Our findings suggest that mycophenolate mofetil could be safely withdrawn in patients with stable SLE. However, larger studies with a longer follow-up are still needed,” wrote Eliza F. Chakravarty, MD, MS, from the University of Oklahoma College of Medicine in Oklahoma City, and colleagues.

“Our study was only for 60 weeks, so we don’t have long-term data on what happens when patients taper off, but my recommendation — and I think the data support this — is that even if you do have a history of lupus nephritis, if you had stable disease or very little to no activity for a year or 2, then I think it’s worth stopping the medication and following for any signs of disease flare,” Dr. Chakravarty said in an interview with this news organization.

She added that “in clinical practice, we would follow patients regularly no matter what they’re on, even if they’re in remission, looking for clinical signs or laboratory evidence of flare, and then if they look like they might be having flare, treat them accordingly.”

Toxicities a Concern

Although MMF is effective for inducing prolonged disease quiescence, it is a known teratogen and has significant toxicities, and it’s desirable to wean patients off the drug if it can be done safely, Dr. Chakravarty said.

The optimal duration of maintenance therapy with MMF is not known, however, which prompted the researchers to conduct the open-label study.

Patients aged 18-70 years who met the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 1997 SLE criteria and had a clinical SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) score ≤ 4 at screening and who also had been on stable or tapering MMF therapy for 2 or more years for renal indications or 1 or more year for nonrenal indications were eligible. All patients were on a background regimen of hydroxychloroquine.

Patients were randomly assigned on an equal basis to either withdrawal with a 12-week taper or to continued maintenance at their baseline dose, ranging from 1 to 3 g/day for 60 weeks.

The investigators used an adaptive random-allocation strategy to ensure that the groups were balanced for study site, renal vs nonrenal disease, and baseline MMF dose (≥ 2 g/day vs < 2 g/day).

A total of 100 patients with an average age of 42 years were included in a modified intention-to-treat analysis: 49 were randomly assigned to maintenance and 51 to withdrawal.

Overall, 84% of patients were women, 40% were White, and 41% were Black. Most patients, 76%, had a history of lupus nephritis.

Significant disease reactivation, the primary endpoints, was defined as the need to increase prednisone to ≥ 15 mg/day for 4 weeks, the need for two or more short steroid bursts, or the need to resume MMF or start patients on another immunosuppressive therapy.

By week 60, 18% of patients in the withdrawal group had clinically significant disease reactivation compared with 10% of patients in the maintenance group.

“Although the differences were not significant, this study used an estimation-based design to determine estimated increases in clinically significant disease reactivation risk with 75%, 85%, and 95% confidence limits to assist clinicians and patients in making informed treatment decisions. We found a 6%-8% increase with upper 85% confidence limits of 11%-19% in clinically significant disease reactivation and flare risk following mycophenolate mofetil withdrawal,” the investigators wrote.

Rates of adverse events were similar between the groups, occurring in 90% of patients in the maintenance arm and 88% of those in the withdrawal arm. Infections occurred more frequently among patients in the maintenance group, at 64% vs 46%.

Encouraging Data

In an accompanying editorial, Noémie Jourde-Chiche, MD, PhD, from Aix-Marseille University in Marseille, France, and Laurent Chiche, MD, from Hopital Europeen de Marseille, wrote that the study data “were clearly encouraging.” They noted that the results show that it’s feasible to wean select patients off immunosuppressive therapy and keep SLE in check and that the quantified risk assessment strategy will allow shared decision-making for each patient.

“Overall, the prospect of a time-limited (versus lifelong) treatment may favor compliance, as observed in other disease fields, which might consolidate remission and reduce the risk of subsequent relapse, using sequentially treat-to-target and think-to-untreat strategies for a win-wean era in SLE,” they wrote.

“We’ve been awaiting the results of this trial for quite a while, and so it is nice to see it out,” commented Karen H. Costenbader, MD, MPH, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, and chair of the division of rheumatology and director of the Lupus Program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

“It does provide some data to address a question that comes up in discussions with patients all the time: A person with lupus has been doing really well, in what we call low disease activity state or remission, but on mycophenolate, possibly for several years,” she said in a reply to a request for objective commentary.

“The question is how and when to taper and can MMF be safely discontinued,” she said. “Personally, I always review the severity of the underlying disease and indication for the MMF in the first place. Really active SLE with rapidly progressing kidney or other organ damage has to be treated with tremendous respect and no one wants to go back there. I also think about how long it has been, which other medications are still being taken (hydroxychloroquine, belimumab [Benlysta], etc.) and whether the labs and symptoms have really returned to completely normal. Then I have discussions about all this with my patient and we often try a long, slow, gingerly taper with a lot of interim monitoring.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Chakravarty and Dr. Costenbader report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Jourde-Chiche declares personal consulting fees from Otsuka and AstraZeneca, personal speaking fees from GlaxoSmithKline and Otsuka, and personal payment for expert testimony from Otsuka. Dr. Chiche declares research grants paid to his institution from AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline, personal consulting fees from Novartis and AstraZeneca, and personal speaking fees from GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Patients with quiescent systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) who are on maintenance therapy with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) may be able to be safely weaned off the drug with the understanding that disease flare may occur and may require restarting immunosuppressive therapy.

That’s the conclusion of investigators in a multicenter randomized trial conducted at 19 US centers and published in The Lancet Rheumatology. They found that among 100 patients with stable SLE who were on MMF for at least 2 years for renal indications or at least 1 year for nonrenal indications, MMF withdrawal was not significantly inferior to MMF maintenance in terms of clinically significant disease reactivation within at least 1 year.

“Our findings suggest that mycophenolate mofetil could be safely withdrawn in patients with stable SLE. However, larger studies with a longer follow-up are still needed,” wrote Eliza F. Chakravarty, MD, MS, from the University of Oklahoma College of Medicine in Oklahoma City, and colleagues.

“Our study was only for 60 weeks, so we don’t have long-term data on what happens when patients taper off, but my recommendation — and I think the data support this — is that even if you do have a history of lupus nephritis, if you had stable disease or very little to no activity for a year or 2, then I think it’s worth stopping the medication and following for any signs of disease flare,” Dr. Chakravarty said in an interview with this news organization.

She added that “in clinical practice, we would follow patients regularly no matter what they’re on, even if they’re in remission, looking for clinical signs or laboratory evidence of flare, and then if they look like they might be having flare, treat them accordingly.”

Toxicities a Concern

Although MMF is effective for inducing prolonged disease quiescence, it is a known teratogen and has significant toxicities, and it’s desirable to wean patients off the drug if it can be done safely, Dr. Chakravarty said.

The optimal duration of maintenance therapy with MMF is not known, however, which prompted the researchers to conduct the open-label study.

Patients aged 18-70 years who met the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 1997 SLE criteria and had a clinical SLE Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) score ≤ 4 at screening and who also had been on stable or tapering MMF therapy for 2 or more years for renal indications or 1 or more year for nonrenal indications were eligible. All patients were on a background regimen of hydroxychloroquine.

Patients were randomly assigned on an equal basis to either withdrawal with a 12-week taper or to continued maintenance at their baseline dose, ranging from 1 to 3 g/day for 60 weeks.

The investigators used an adaptive random-allocation strategy to ensure that the groups were balanced for study site, renal vs nonrenal disease, and baseline MMF dose (≥ 2 g/day vs < 2 g/day).

A total of 100 patients with an average age of 42 years were included in a modified intention-to-treat analysis: 49 were randomly assigned to maintenance and 51 to withdrawal.

Overall, 84% of patients were women, 40% were White, and 41% were Black. Most patients, 76%, had a history of lupus nephritis.

Significant disease reactivation, the primary endpoints, was defined as the need to increase prednisone to ≥ 15 mg/day for 4 weeks, the need for two or more short steroid bursts, or the need to resume MMF or start patients on another immunosuppressive therapy.

By week 60, 18% of patients in the withdrawal group had clinically significant disease reactivation compared with 10% of patients in the maintenance group.

“Although the differences were not significant, this study used an estimation-based design to determine estimated increases in clinically significant disease reactivation risk with 75%, 85%, and 95% confidence limits to assist clinicians and patients in making informed treatment decisions. We found a 6%-8% increase with upper 85% confidence limits of 11%-19% in clinically significant disease reactivation and flare risk following mycophenolate mofetil withdrawal,” the investigators wrote.

Rates of adverse events were similar between the groups, occurring in 90% of patients in the maintenance arm and 88% of those in the withdrawal arm. Infections occurred more frequently among patients in the maintenance group, at 64% vs 46%.

Encouraging Data

In an accompanying editorial, Noémie Jourde-Chiche, MD, PhD, from Aix-Marseille University in Marseille, France, and Laurent Chiche, MD, from Hopital Europeen de Marseille, wrote that the study data “were clearly encouraging.” They noted that the results show that it’s feasible to wean select patients off immunosuppressive therapy and keep SLE in check and that the quantified risk assessment strategy will allow shared decision-making for each patient.

“Overall, the prospect of a time-limited (versus lifelong) treatment may favor compliance, as observed in other disease fields, which might consolidate remission and reduce the risk of subsequent relapse, using sequentially treat-to-target and think-to-untreat strategies for a win-wean era in SLE,” they wrote.

“We’ve been awaiting the results of this trial for quite a while, and so it is nice to see it out,” commented Karen H. Costenbader, MD, MPH, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, and chair of the division of rheumatology and director of the Lupus Program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

“It does provide some data to address a question that comes up in discussions with patients all the time: A person with lupus has been doing really well, in what we call low disease activity state or remission, but on mycophenolate, possibly for several years,” she said in a reply to a request for objective commentary.

“The question is how and when to taper and can MMF be safely discontinued,” she said. “Personally, I always review the severity of the underlying disease and indication for the MMF in the first place. Really active SLE with rapidly progressing kidney or other organ damage has to be treated with tremendous respect and no one wants to go back there. I also think about how long it has been, which other medications are still being taken (hydroxychloroquine, belimumab [Benlysta], etc.) and whether the labs and symptoms have really returned to completely normal. Then I have discussions about all this with my patient and we often try a long, slow, gingerly taper with a lot of interim monitoring.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Chakravarty and Dr. Costenbader report no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Jourde-Chiche declares personal consulting fees from Otsuka and AstraZeneca, personal speaking fees from GlaxoSmithKline and Otsuka, and personal payment for expert testimony from Otsuka. Dr. Chiche declares research grants paid to his institution from AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline, personal consulting fees from Novartis and AstraZeneca, and personal speaking fees from GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

FROM THE LANCET RHEUMATOLOGY

New Findings on Vitamin D, Omega-3 Supplements for Preventing Autoimmune Diseases

Two years after the end of a randomized trial that showed a benefit of daily vitamin D and omega-3 fatty acid (n-3 FA) supplementation for reducing risk for autoimmune diseases, the salubrious effects of daily vitamin D appear to have waned after the supplement was discontinued, while the protection from n-3 lived on for at least 2 additional years.

As previously reported, the randomized VITAL, which was designed primarily to study the effects of vitamin D and n-3 supplementation on incident cancer and cardiovascular disease, also showed that 5 years of vitamin D supplementation was associated with a 22% reduction in risk for confirmed autoimmune diseases, and 5 years of n-3 FA supplementation was associated with an 18% reduction in confirmed and probable incident autoimmune diseases.

Now, investigators Karen H. Costenbader, MD, MPH, of Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, and colleagues reported that among 21,592 participants in VITAL who agreed to be followed for an additional 2 years after discontinuation, the protection against autoimmune diseases from daily vitamin D (cholecalciferol; 2000 IU/d) was no longer statistically significant, but the benefits of daily marine n-3 FAs (1 g/d as a fish-oil capsule containing 460 mg of eicosapentaenoic acid and 380 mg of docosahexaenoic acid) remained significant.

“VITAL observational extension results suggest that vitamin D supplementation should be given on a continuous basis for long-term prevention of [autoimmune diseases]. The beneficial effects of n-3 fatty acids, however, may be prolonged for at least 2 years after discontinuation,” they wrote in an article published in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

Dr. Costenbader told this news organization that the results of the observational extension study suggest that the benefits of vitamin D “wear off more quickly, and it should be continued for a longer period of time or indefinitely, rather than only for 5 years.”

In addition to the disparity in the duration of the protective effect, the investigators also saw differences in the effects across different autoimmune diseases.

“The protective effect of vitamin D seemed strongest for psoriasis, while for omega-3 fatty acids, the protective effects were strongest for rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease,” she said.

Mixed Effects

In an interview with this news organization, Janet Funk, MD, MS, vice chair of research in the Department of Medicine and professor in the School of Nutritional Science and Wellness at the University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, who was not involved in the study, saidthat the results suggest that while each supplement may offer protection against autoimmune diseases, the effects are inconsistent and may not apply to all patients.

“I think the VITAL extension results suggest that either supplement (or both together) may have benefits in reducing risk of autoimmune diseases, including possible persistent effects posttreatment, but that these effects are nuanced (ie, only in normal weight post-vitamin D treatment) and possibly not uniform across all autoimmune diseases (including possible adverse effects for some — eg, inverse association between prior omega-3 and psoriasis and tendency for increased autoimmune thyroid disease for vitamin D), although the study was not powered sufficiently to draw disease-specific conclusions,” she said.

In an editorial accompanying the study, rheumatologist Joel M. Kremer, MD, of Albany Medical College and the Corrona Research Foundation in Delray Beach, Florida, wrote that “[T]he studies by Dr. Costenbader, et al. have shed new light on the possibility that dietary supplements of n-3 FA [fatty acid] may prevent the onset of [autoimmune disease]. The sustained benefits they describe for as long as 2 years after the supplements are discontinued are consistent with the chronicity of FA species in cellular plasma membranes where they serve as substrates for a diverse array of salient metabolic and inflammatory pathways.”

VITAL Then

To test whether vitamin D or marine-derived long-chain n-3 FA supplementation could protect against autoimmune disease over time, Dr. Costenbader and colleagues piggybacked an ancillary study onto the VITAL trial, which had primary outcomes of cancer and cardiovascular disease incidence.

A total of 25,871 participants were enrolled, including 12,786 men aged 50 and older and 13,085 women aged 55 and older. The study had a 2 × 2 factorial design, with patients randomly assigned to vitamin D 2000 IU/d or placebo and then further randomized to either 1 g/d n-3 FAs or placebo in both the vitamin D and placebo primary randomization arms.

In multivariate analysis adjusted for age, sex, race, and other supplement arm, vitamin D alone was associated with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.68 (P = .02) for incident autoimmune disease, n-3 alone was associated with a nonsignificant HR of 0.74, and the combination was associated with an HR of 0.69 (P = .03). However, when probable incident autoimmune disease cases were included, the effect of n-3 became significant, with an HR of 0.82.

VITAL Now

In the current analysis, Dr. Costenbader and colleagues reported observational data on 21,592 VITAL participants, a sample representing 83.5% of those who were initially randomized, and 87.9% of those who were alive and could be contacted at the end of the study.

As in the initial trial, the investigators used annual questionnaires to assess incident autoimmune diseases during the randomized follow-up. Participants were asked about new-onset, doctor-diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis, polymyalgia rheumatica, psoriasis, autoimmune thyroid disease, and inflammatory bowel disease. Participants could also write in any other new autoimmune disease diagnoses.

There were 236 new cases of confirmed autoimmune disease that occurred since the initial publication of the trial results, as well as 65 probable cases identified during the median 5.3 years of the randomized portion, and 42 probable cases diagnosed during the 2-year observational phase.

The investigators found that after the 2-year observation period, 255 participants initially randomized to receive vitamin D had a newly developed confirmed autoimmune disease, compared with 259 of those initially randomized to a vitamin D placebo. This translated into a nonsignificant HR of 0.98.

Adding probable autoimmune cases to the confirmed cases made little difference, resulting in a nonsignificant adjusted HR of 0.95.

In contrast, there were 234 confirmed autoimmune disease cases among patients initially assigned to n-3, compared with 280 among patients randomized to the n-3 placebo, translating into a statistically significant HR of 0.83 for new-onset autoimmune disease with n-3.

Dr. Costenbader and colleagues acknowledged that the study was limited by the use of doses intended to prevent cancer or cardiovascular disease and that higher doses intended for high-risk or nutritionally deficient populations might reveal larger effects of supplementation. In addition, they noted the difficulty of identifying the timing and onset of incident disease, and that the small number of cases that occurred during the 2-year observational period precluded detailed analyses of individual autoimmune diseases.

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Costenbader, Dr. Funk, and Dr. Kremer reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Two years after the end of a randomized trial that showed a benefit of daily vitamin D and omega-3 fatty acid (n-3 FA) supplementation for reducing risk for autoimmune diseases, the salubrious effects of daily vitamin D appear to have waned after the supplement was discontinued, while the protection from n-3 lived on for at least 2 additional years.

As previously reported, the randomized VITAL, which was designed primarily to study the effects of vitamin D and n-3 supplementation on incident cancer and cardiovascular disease, also showed that 5 years of vitamin D supplementation was associated with a 22% reduction in risk for confirmed autoimmune diseases, and 5 years of n-3 FA supplementation was associated with an 18% reduction in confirmed and probable incident autoimmune diseases.

Now, investigators Karen H. Costenbader, MD, MPH, of Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, and colleagues reported that among 21,592 participants in VITAL who agreed to be followed for an additional 2 years after discontinuation, the protection against autoimmune diseases from daily vitamin D (cholecalciferol; 2000 IU/d) was no longer statistically significant, but the benefits of daily marine n-3 FAs (1 g/d as a fish-oil capsule containing 460 mg of eicosapentaenoic acid and 380 mg of docosahexaenoic acid) remained significant.

“VITAL observational extension results suggest that vitamin D supplementation should be given on a continuous basis for long-term prevention of [autoimmune diseases]. The beneficial effects of n-3 fatty acids, however, may be prolonged for at least 2 years after discontinuation,” they wrote in an article published in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

Dr. Costenbader told this news organization that the results of the observational extension study suggest that the benefits of vitamin D “wear off more quickly, and it should be continued for a longer period of time or indefinitely, rather than only for 5 years.”

In addition to the disparity in the duration of the protective effect, the investigators also saw differences in the effects across different autoimmune diseases.

“The protective effect of vitamin D seemed strongest for psoriasis, while for omega-3 fatty acids, the protective effects were strongest for rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease,” she said.

Mixed Effects

In an interview with this news organization, Janet Funk, MD, MS, vice chair of research in the Department of Medicine and professor in the School of Nutritional Science and Wellness at the University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, who was not involved in the study, saidthat the results suggest that while each supplement may offer protection against autoimmune diseases, the effects are inconsistent and may not apply to all patients.

“I think the VITAL extension results suggest that either supplement (or both together) may have benefits in reducing risk of autoimmune diseases, including possible persistent effects posttreatment, but that these effects are nuanced (ie, only in normal weight post-vitamin D treatment) and possibly not uniform across all autoimmune diseases (including possible adverse effects for some — eg, inverse association between prior omega-3 and psoriasis and tendency for increased autoimmune thyroid disease for vitamin D), although the study was not powered sufficiently to draw disease-specific conclusions,” she said.

In an editorial accompanying the study, rheumatologist Joel M. Kremer, MD, of Albany Medical College and the Corrona Research Foundation in Delray Beach, Florida, wrote that “[T]he studies by Dr. Costenbader, et al. have shed new light on the possibility that dietary supplements of n-3 FA [fatty acid] may prevent the onset of [autoimmune disease]. The sustained benefits they describe for as long as 2 years after the supplements are discontinued are consistent with the chronicity of FA species in cellular plasma membranes where they serve as substrates for a diverse array of salient metabolic and inflammatory pathways.”

VITAL Then

To test whether vitamin D or marine-derived long-chain n-3 FA supplementation could protect against autoimmune disease over time, Dr. Costenbader and colleagues piggybacked an ancillary study onto the VITAL trial, which had primary outcomes of cancer and cardiovascular disease incidence.

A total of 25,871 participants were enrolled, including 12,786 men aged 50 and older and 13,085 women aged 55 and older. The study had a 2 × 2 factorial design, with patients randomly assigned to vitamin D 2000 IU/d or placebo and then further randomized to either 1 g/d n-3 FAs or placebo in both the vitamin D and placebo primary randomization arms.

In multivariate analysis adjusted for age, sex, race, and other supplement arm, vitamin D alone was associated with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.68 (P = .02) for incident autoimmune disease, n-3 alone was associated with a nonsignificant HR of 0.74, and the combination was associated with an HR of 0.69 (P = .03). However, when probable incident autoimmune disease cases were included, the effect of n-3 became significant, with an HR of 0.82.

VITAL Now

In the current analysis, Dr. Costenbader and colleagues reported observational data on 21,592 VITAL participants, a sample representing 83.5% of those who were initially randomized, and 87.9% of those who were alive and could be contacted at the end of the study.

As in the initial trial, the investigators used annual questionnaires to assess incident autoimmune diseases during the randomized follow-up. Participants were asked about new-onset, doctor-diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis, polymyalgia rheumatica, psoriasis, autoimmune thyroid disease, and inflammatory bowel disease. Participants could also write in any other new autoimmune disease diagnoses.

There were 236 new cases of confirmed autoimmune disease that occurred since the initial publication of the trial results, as well as 65 probable cases identified during the median 5.3 years of the randomized portion, and 42 probable cases diagnosed during the 2-year observational phase.

The investigators found that after the 2-year observation period, 255 participants initially randomized to receive vitamin D had a newly developed confirmed autoimmune disease, compared with 259 of those initially randomized to a vitamin D placebo. This translated into a nonsignificant HR of 0.98.

Adding probable autoimmune cases to the confirmed cases made little difference, resulting in a nonsignificant adjusted HR of 0.95.

In contrast, there were 234 confirmed autoimmune disease cases among patients initially assigned to n-3, compared with 280 among patients randomized to the n-3 placebo, translating into a statistically significant HR of 0.83 for new-onset autoimmune disease with n-3.

Dr. Costenbader and colleagues acknowledged that the study was limited by the use of doses intended to prevent cancer or cardiovascular disease and that higher doses intended for high-risk or nutritionally deficient populations might reveal larger effects of supplementation. In addition, they noted the difficulty of identifying the timing and onset of incident disease, and that the small number of cases that occurred during the 2-year observational period precluded detailed analyses of individual autoimmune diseases.

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Costenbader, Dr. Funk, and Dr. Kremer reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Two years after the end of a randomized trial that showed a benefit of daily vitamin D and omega-3 fatty acid (n-3 FA) supplementation for reducing risk for autoimmune diseases, the salubrious effects of daily vitamin D appear to have waned after the supplement was discontinued, while the protection from n-3 lived on for at least 2 additional years.

As previously reported, the randomized VITAL, which was designed primarily to study the effects of vitamin D and n-3 supplementation on incident cancer and cardiovascular disease, also showed that 5 years of vitamin D supplementation was associated with a 22% reduction in risk for confirmed autoimmune diseases, and 5 years of n-3 FA supplementation was associated with an 18% reduction in confirmed and probable incident autoimmune diseases.

Now, investigators Karen H. Costenbader, MD, MPH, of Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, and colleagues reported that among 21,592 participants in VITAL who agreed to be followed for an additional 2 years after discontinuation, the protection against autoimmune diseases from daily vitamin D (cholecalciferol; 2000 IU/d) was no longer statistically significant, but the benefits of daily marine n-3 FAs (1 g/d as a fish-oil capsule containing 460 mg of eicosapentaenoic acid and 380 mg of docosahexaenoic acid) remained significant.

“VITAL observational extension results suggest that vitamin D supplementation should be given on a continuous basis for long-term prevention of [autoimmune diseases]. The beneficial effects of n-3 fatty acids, however, may be prolonged for at least 2 years after discontinuation,” they wrote in an article published in Arthritis & Rheumatology.

Dr. Costenbader told this news organization that the results of the observational extension study suggest that the benefits of vitamin D “wear off more quickly, and it should be continued for a longer period of time or indefinitely, rather than only for 5 years.”

In addition to the disparity in the duration of the protective effect, the investigators also saw differences in the effects across different autoimmune diseases.

“The protective effect of vitamin D seemed strongest for psoriasis, while for omega-3 fatty acids, the protective effects were strongest for rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease,” she said.

Mixed Effects

In an interview with this news organization, Janet Funk, MD, MS, vice chair of research in the Department of Medicine and professor in the School of Nutritional Science and Wellness at the University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, who was not involved in the study, saidthat the results suggest that while each supplement may offer protection against autoimmune diseases, the effects are inconsistent and may not apply to all patients.

“I think the VITAL extension results suggest that either supplement (or both together) may have benefits in reducing risk of autoimmune diseases, including possible persistent effects posttreatment, but that these effects are nuanced (ie, only in normal weight post-vitamin D treatment) and possibly not uniform across all autoimmune diseases (including possible adverse effects for some — eg, inverse association between prior omega-3 and psoriasis and tendency for increased autoimmune thyroid disease for vitamin D), although the study was not powered sufficiently to draw disease-specific conclusions,” she said.

In an editorial accompanying the study, rheumatologist Joel M. Kremer, MD, of Albany Medical College and the Corrona Research Foundation in Delray Beach, Florida, wrote that “[T]he studies by Dr. Costenbader, et al. have shed new light on the possibility that dietary supplements of n-3 FA [fatty acid] may prevent the onset of [autoimmune disease]. The sustained benefits they describe for as long as 2 years after the supplements are discontinued are consistent with the chronicity of FA species in cellular plasma membranes where they serve as substrates for a diverse array of salient metabolic and inflammatory pathways.”

VITAL Then

To test whether vitamin D or marine-derived long-chain n-3 FA supplementation could protect against autoimmune disease over time, Dr. Costenbader and colleagues piggybacked an ancillary study onto the VITAL trial, which had primary outcomes of cancer and cardiovascular disease incidence.

A total of 25,871 participants were enrolled, including 12,786 men aged 50 and older and 13,085 women aged 55 and older. The study had a 2 × 2 factorial design, with patients randomly assigned to vitamin D 2000 IU/d or placebo and then further randomized to either 1 g/d n-3 FAs or placebo in both the vitamin D and placebo primary randomization arms.

In multivariate analysis adjusted for age, sex, race, and other supplement arm, vitamin D alone was associated with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.68 (P = .02) for incident autoimmune disease, n-3 alone was associated with a nonsignificant HR of 0.74, and the combination was associated with an HR of 0.69 (P = .03). However, when probable incident autoimmune disease cases were included, the effect of n-3 became significant, with an HR of 0.82.

VITAL Now

In the current analysis, Dr. Costenbader and colleagues reported observational data on 21,592 VITAL participants, a sample representing 83.5% of those who were initially randomized, and 87.9% of those who were alive and could be contacted at the end of the study.

As in the initial trial, the investigators used annual questionnaires to assess incident autoimmune diseases during the randomized follow-up. Participants were asked about new-onset, doctor-diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis, polymyalgia rheumatica, psoriasis, autoimmune thyroid disease, and inflammatory bowel disease. Participants could also write in any other new autoimmune disease diagnoses.

There were 236 new cases of confirmed autoimmune disease that occurred since the initial publication of the trial results, as well as 65 probable cases identified during the median 5.3 years of the randomized portion, and 42 probable cases diagnosed during the 2-year observational phase.

The investigators found that after the 2-year observation period, 255 participants initially randomized to receive vitamin D had a newly developed confirmed autoimmune disease, compared with 259 of those initially randomized to a vitamin D placebo. This translated into a nonsignificant HR of 0.98.

Adding probable autoimmune cases to the confirmed cases made little difference, resulting in a nonsignificant adjusted HR of 0.95.

In contrast, there were 234 confirmed autoimmune disease cases among patients initially assigned to n-3, compared with 280 among patients randomized to the n-3 placebo, translating into a statistically significant HR of 0.83 for new-onset autoimmune disease with n-3.

Dr. Costenbader and colleagues acknowledged that the study was limited by the use of doses intended to prevent cancer or cardiovascular disease and that higher doses intended for high-risk or nutritionally deficient populations might reveal larger effects of supplementation. In addition, they noted the difficulty of identifying the timing and onset of incident disease, and that the small number of cases that occurred during the 2-year observational period precluded detailed analyses of individual autoimmune diseases.

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Costenbader, Dr. Funk, and Dr. Kremer reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Success with Sirolimus in Treating Skin Sarcoidosis Could Spur Studies in Other Organs

Sirolimus may be an effective treatment for patients with persistent cutaneous sarcoidosis.

In a small clinical trial, 7 of 10 patients treated with sirolimus via oral solution had improvements in skin lesions after 4 months, which was sustained for up to 2 years after the study concluded.

The results suggested that mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibition is a potential therapeutic avenue for sarcoidosis, which the authors said should be explored in larger clinical trials.

In the past decade, there has been a growing amount of evidence suggesting mTOR’s role in sarcoidosis. In 2017, researchers showed that activation of mTOR in macrophages could cause progressive sarcoidosis in mice. In additional studies, high levels of mTOR activity were detected in human sarcoidosis granulomas in various organs, including the skin, lung, and heart.

Three case reports also documented using the mTOR inhibitor sirolimus to effectively treat systemic sarcoidosis.

“Although all reports observed improvement of the disease following the treatment, no clinical trial investigating the efficacy and safety of sirolimus in patients with sarcoidosis had been published” prior to this study, wrote senior author Georg Stary, MD, of the Medical University of Vienna and the Research Center for Molecular Medicine of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna, Austria, and colleagues.

The findings were published in the The Lancet Rheumatology.

For the study, researchers recruited 16 individuals with persistent and glucocorticoid-refractory cutaneous sarcoidosis between September 2019 and June 2021. A total of 14 participants were randomly assigned to the topical phase of the study, whereas two immediately received systemic treatment. All treatment was conducted at Vienna General Hospital.

In the placebo-controlled, double-blinded topical treatment arm, patients received either 0.1% topical sirolimus in Vaseline or Vaseline alone (placebo) twice daily for 2 months. After a 1-month washout period, participants were switched to the alternate treatment arm for an additional 2 months.

Following this topical phase and an additional 1-month washout period, all remaining participants received systemic sirolimus via a 1-mg/mL solution, starting with a 6-mg loading dose and continuing with 2 mg once daily for 4 months. The primary outcome was change in Cutaneous Sarcoidosis Activity and Morphology Index (CSAMI) from baseline, with decrease of more than five points representing a response to treatment.

A total of 10 patients completed the trial.

There was no change in CSAMI in either topical treatment groups. In the systemic group, 70% of patients had clinical improvement in skin lesions, with three responders in this group having complete resolution of skin lesions. The median change in CSAMI was −7.0 points (P = .018).

This improvement persisted for 2 months following study conclusion, with more pronounced improvement from baseline after 2 years of drug-free follow-up (−11.5 points).

There were no serious adverse events reported during the study, but 42% of patients treated with systemic sirolimus reported mild skin reactions, such as acne and eczema. Other related adverse events were hypertriglyceridemia (17%), hyperglycemia (17%), and proteinuria (8%).

Compared with clinical outcomes with tofacitinib and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, “the strength of our study lies in the sustained treatment effect after drug withdrawal among all responders. This prolonged effect has not yet been explored with tofacitinib, whereas with TNF inhibitors disease relapse was seen in more than 50% of patients at 3-8 months,” the authors wrote.

The researchers also analyzed participants’ skin biopsies to gain a better understanding of how mTOR inhibition affected granuloma structures. They found that, at baseline, mTOR activity was significantly lower in the fibroblasts of treatment nonresponders than in responders. They speculated that lower expression of mTOR could make these granuloma-associated cells resistant to systemic sirolimus.

These promising findings combine “clinical response with a molecular analysis,” Avrom Caplan, MD, co-director of the Sarcoidosis Program at NYU Langone in New York City, told this news organization. He was not involved with the research. Adding molecular information to clinical outcome data “helps solidify that [the mTOR] pathway has relevance in the sarcoid granuloma formation.”

The study had a limited sample size — a challenge for many clinical trials of rare diseases, Dr. Caplan said. Larger clinical trials are necessary to explore mTOR inhibition in sarcoidosis, both he and the authors agreed. A larger trial could also include greater heterogeneity of patients, including varied sarcoid presentation and demographics, Dr. Caplan noted. In this study, all but one participants were White individuals, and 63% of participants were female.

Larger studies could also address important questions on ideal length of therapy, dosing, and where this therapy “would fall within the therapeutic step ladder,” Dr. Caplan continued.

Whether mTOR inhibition could be effective at treating individuals with sarcoidosis in other organs beyond the skin is also unknown.

“If the pathogenesis of sarcoid granuloma formation does include mTOR upregulation, which they are showing here…then you could hypothesize that, yes, using this therapy could benefit other organs,” he said. “But that has to be investigated in larger trials.”

The study was funded in part by a Vienna Science and Technology Fund project. Several authors report receiving grants from the Austrian Science Fund and one from the Ann Theodore Foundation Breakthrough Sarcoidosis Initiative. Dr. Caplan reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Sirolimus may be an effective treatment for patients with persistent cutaneous sarcoidosis.

In a small clinical trial, 7 of 10 patients treated with sirolimus via oral solution had improvements in skin lesions after 4 months, which was sustained for up to 2 years after the study concluded.

The results suggested that mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibition is a potential therapeutic avenue for sarcoidosis, which the authors said should be explored in larger clinical trials.

In the past decade, there has been a growing amount of evidence suggesting mTOR’s role in sarcoidosis. In 2017, researchers showed that activation of mTOR in macrophages could cause progressive sarcoidosis in mice. In additional studies, high levels of mTOR activity were detected in human sarcoidosis granulomas in various organs, including the skin, lung, and heart.

Three case reports also documented using the mTOR inhibitor sirolimus to effectively treat systemic sarcoidosis.

“Although all reports observed improvement of the disease following the treatment, no clinical trial investigating the efficacy and safety of sirolimus in patients with sarcoidosis had been published” prior to this study, wrote senior author Georg Stary, MD, of the Medical University of Vienna and the Research Center for Molecular Medicine of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna, Austria, and colleagues.

The findings were published in the The Lancet Rheumatology.

For the study, researchers recruited 16 individuals with persistent and glucocorticoid-refractory cutaneous sarcoidosis between September 2019 and June 2021. A total of 14 participants were randomly assigned to the topical phase of the study, whereas two immediately received systemic treatment. All treatment was conducted at Vienna General Hospital.

In the placebo-controlled, double-blinded topical treatment arm, patients received either 0.1% topical sirolimus in Vaseline or Vaseline alone (placebo) twice daily for 2 months. After a 1-month washout period, participants were switched to the alternate treatment arm for an additional 2 months.

Following this topical phase and an additional 1-month washout period, all remaining participants received systemic sirolimus via a 1-mg/mL solution, starting with a 6-mg loading dose and continuing with 2 mg once daily for 4 months. The primary outcome was change in Cutaneous Sarcoidosis Activity and Morphology Index (CSAMI) from baseline, with decrease of more than five points representing a response to treatment.

A total of 10 patients completed the trial.

There was no change in CSAMI in either topical treatment groups. In the systemic group, 70% of patients had clinical improvement in skin lesions, with three responders in this group having complete resolution of skin lesions. The median change in CSAMI was −7.0 points (P = .018).

This improvement persisted for 2 months following study conclusion, with more pronounced improvement from baseline after 2 years of drug-free follow-up (−11.5 points).

There were no serious adverse events reported during the study, but 42% of patients treated with systemic sirolimus reported mild skin reactions, such as acne and eczema. Other related adverse events were hypertriglyceridemia (17%), hyperglycemia (17%), and proteinuria (8%).

Compared with clinical outcomes with tofacitinib and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, “the strength of our study lies in the sustained treatment effect after drug withdrawal among all responders. This prolonged effect has not yet been explored with tofacitinib, whereas with TNF inhibitors disease relapse was seen in more than 50% of patients at 3-8 months,” the authors wrote.

The researchers also analyzed participants’ skin biopsies to gain a better understanding of how mTOR inhibition affected granuloma structures. They found that, at baseline, mTOR activity was significantly lower in the fibroblasts of treatment nonresponders than in responders. They speculated that lower expression of mTOR could make these granuloma-associated cells resistant to systemic sirolimus.

These promising findings combine “clinical response with a molecular analysis,” Avrom Caplan, MD, co-director of the Sarcoidosis Program at NYU Langone in New York City, told this news organization. He was not involved with the research. Adding molecular information to clinical outcome data “helps solidify that [the mTOR] pathway has relevance in the sarcoid granuloma formation.”

The study had a limited sample size — a challenge for many clinical trials of rare diseases, Dr. Caplan said. Larger clinical trials are necessary to explore mTOR inhibition in sarcoidosis, both he and the authors agreed. A larger trial could also include greater heterogeneity of patients, including varied sarcoid presentation and demographics, Dr. Caplan noted. In this study, all but one participants were White individuals, and 63% of participants were female.

Larger studies could also address important questions on ideal length of therapy, dosing, and where this therapy “would fall within the therapeutic step ladder,” Dr. Caplan continued.

Whether mTOR inhibition could be effective at treating individuals with sarcoidosis in other organs beyond the skin is also unknown.

“If the pathogenesis of sarcoid granuloma formation does include mTOR upregulation, which they are showing here…then you could hypothesize that, yes, using this therapy could benefit other organs,” he said. “But that has to be investigated in larger trials.”

The study was funded in part by a Vienna Science and Technology Fund project. Several authors report receiving grants from the Austrian Science Fund and one from the Ann Theodore Foundation Breakthrough Sarcoidosis Initiative. Dr. Caplan reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Sirolimus may be an effective treatment for patients with persistent cutaneous sarcoidosis.

In a small clinical trial, 7 of 10 patients treated with sirolimus via oral solution had improvements in skin lesions after 4 months, which was sustained for up to 2 years after the study concluded.

The results suggested that mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibition is a potential therapeutic avenue for sarcoidosis, which the authors said should be explored in larger clinical trials.

In the past decade, there has been a growing amount of evidence suggesting mTOR’s role in sarcoidosis. In 2017, researchers showed that activation of mTOR in macrophages could cause progressive sarcoidosis in mice. In additional studies, high levels of mTOR activity were detected in human sarcoidosis granulomas in various organs, including the skin, lung, and heart.

Three case reports also documented using the mTOR inhibitor sirolimus to effectively treat systemic sarcoidosis.

“Although all reports observed improvement of the disease following the treatment, no clinical trial investigating the efficacy and safety of sirolimus in patients with sarcoidosis had been published” prior to this study, wrote senior author Georg Stary, MD, of the Medical University of Vienna and the Research Center for Molecular Medicine of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna, Austria, and colleagues.

The findings were published in the The Lancet Rheumatology.

For the study, researchers recruited 16 individuals with persistent and glucocorticoid-refractory cutaneous sarcoidosis between September 2019 and June 2021. A total of 14 participants were randomly assigned to the topical phase of the study, whereas two immediately received systemic treatment. All treatment was conducted at Vienna General Hospital.

In the placebo-controlled, double-blinded topical treatment arm, patients received either 0.1% topical sirolimus in Vaseline or Vaseline alone (placebo) twice daily for 2 months. After a 1-month washout period, participants were switched to the alternate treatment arm for an additional 2 months.

Following this topical phase and an additional 1-month washout period, all remaining participants received systemic sirolimus via a 1-mg/mL solution, starting with a 6-mg loading dose and continuing with 2 mg once daily for 4 months. The primary outcome was change in Cutaneous Sarcoidosis Activity and Morphology Index (CSAMI) from baseline, with decrease of more than five points representing a response to treatment.

A total of 10 patients completed the trial.

There was no change in CSAMI in either topical treatment groups. In the systemic group, 70% of patients had clinical improvement in skin lesions, with three responders in this group having complete resolution of skin lesions. The median change in CSAMI was −7.0 points (P = .018).

This improvement persisted for 2 months following study conclusion, with more pronounced improvement from baseline after 2 years of drug-free follow-up (−11.5 points).

There were no serious adverse events reported during the study, but 42% of patients treated with systemic sirolimus reported mild skin reactions, such as acne and eczema. Other related adverse events were hypertriglyceridemia (17%), hyperglycemia (17%), and proteinuria (8%).

Compared with clinical outcomes with tofacitinib and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, “the strength of our study lies in the sustained treatment effect after drug withdrawal among all responders. This prolonged effect has not yet been explored with tofacitinib, whereas with TNF inhibitors disease relapse was seen in more than 50% of patients at 3-8 months,” the authors wrote.

The researchers also analyzed participants’ skin biopsies to gain a better understanding of how mTOR inhibition affected granuloma structures. They found that, at baseline, mTOR activity was significantly lower in the fibroblasts of treatment nonresponders than in responders. They speculated that lower expression of mTOR could make these granuloma-associated cells resistant to systemic sirolimus.

These promising findings combine “clinical response with a molecular analysis,” Avrom Caplan, MD, co-director of the Sarcoidosis Program at NYU Langone in New York City, told this news organization. He was not involved with the research. Adding molecular information to clinical outcome data “helps solidify that [the mTOR] pathway has relevance in the sarcoid granuloma formation.”

The study had a limited sample size — a challenge for many clinical trials of rare diseases, Dr. Caplan said. Larger clinical trials are necessary to explore mTOR inhibition in sarcoidosis, both he and the authors agreed. A larger trial could also include greater heterogeneity of patients, including varied sarcoid presentation and demographics, Dr. Caplan noted. In this study, all but one participants were White individuals, and 63% of participants were female.

Larger studies could also address important questions on ideal length of therapy, dosing, and where this therapy “would fall within the therapeutic step ladder,” Dr. Caplan continued.

Whether mTOR inhibition could be effective at treating individuals with sarcoidosis in other organs beyond the skin is also unknown.

“If the pathogenesis of sarcoid granuloma formation does include mTOR upregulation, which they are showing here…then you could hypothesize that, yes, using this therapy could benefit other organs,” he said. “But that has to be investigated in larger trials.”

The study was funded in part by a Vienna Science and Technology Fund project. Several authors report receiving grants from the Austrian Science Fund and one from the Ann Theodore Foundation Breakthrough Sarcoidosis Initiative. Dr. Caplan reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

FROM THE LANCET RHEUMATOLOGY

Impact of Ketogenic and Low-Glycemic Diets on Inflammatory Skin Conditions

Inflammatory skin conditions often have a relapsing and remitting course and represent a large proportion of chronic skin diseases. Common inflammatory skin disorders include acne, psoriasis, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), atopic dermatitis (AD), and seborrheic dermatitis (SD).1 Although each of these conditions has a unique pathogenesis, they all are driven by a background of chronic inflammation. It has been reported that diets with high levels of refined carbohydrates and saturated or trans-fatty acids may exacerbate existing inflammation.2 Consequently, dietary interventions, such as the ketogenic and low-glycemic diets, have potential anti-inflammatory and metabolic effects that are being assessed as stand-alone or adjunctive therapies for dermatologic diseases.

Diet may partially influence systemic inflammation through its effect on weight. Higher body mass index and obesity are linked to a low-grade inflammatory state and higher levels of circulating inflammatory markers. Therefore, weight loss leads to decreases in inflammatory cytokines, including C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor α, and IL-6.3 These cytokines and metabolic effects overlap with inflammatory skin condition pathways. It also is posited that decreased insulin release associated with weight loss results in decreased sebaceous lipogenesis and androgens, which drive keratinocyte proliferation and acne development.4,5 For instance, in a 2015 meta-analysis of 5 randomized controlled trials on psoriasis, patients in the weight loss intervention group had more substantial reductions in psoriasis area and severity index (PASI) scores compared with controls receiving usual care (P=.004).6 However, in a systematic review of 35 studies on acne vulgaris, overweight and obese patients (defined by a body mass index of ≥23 kg/m2) had similar odds of having acne compared with normal-weight individuals (P=.671).7

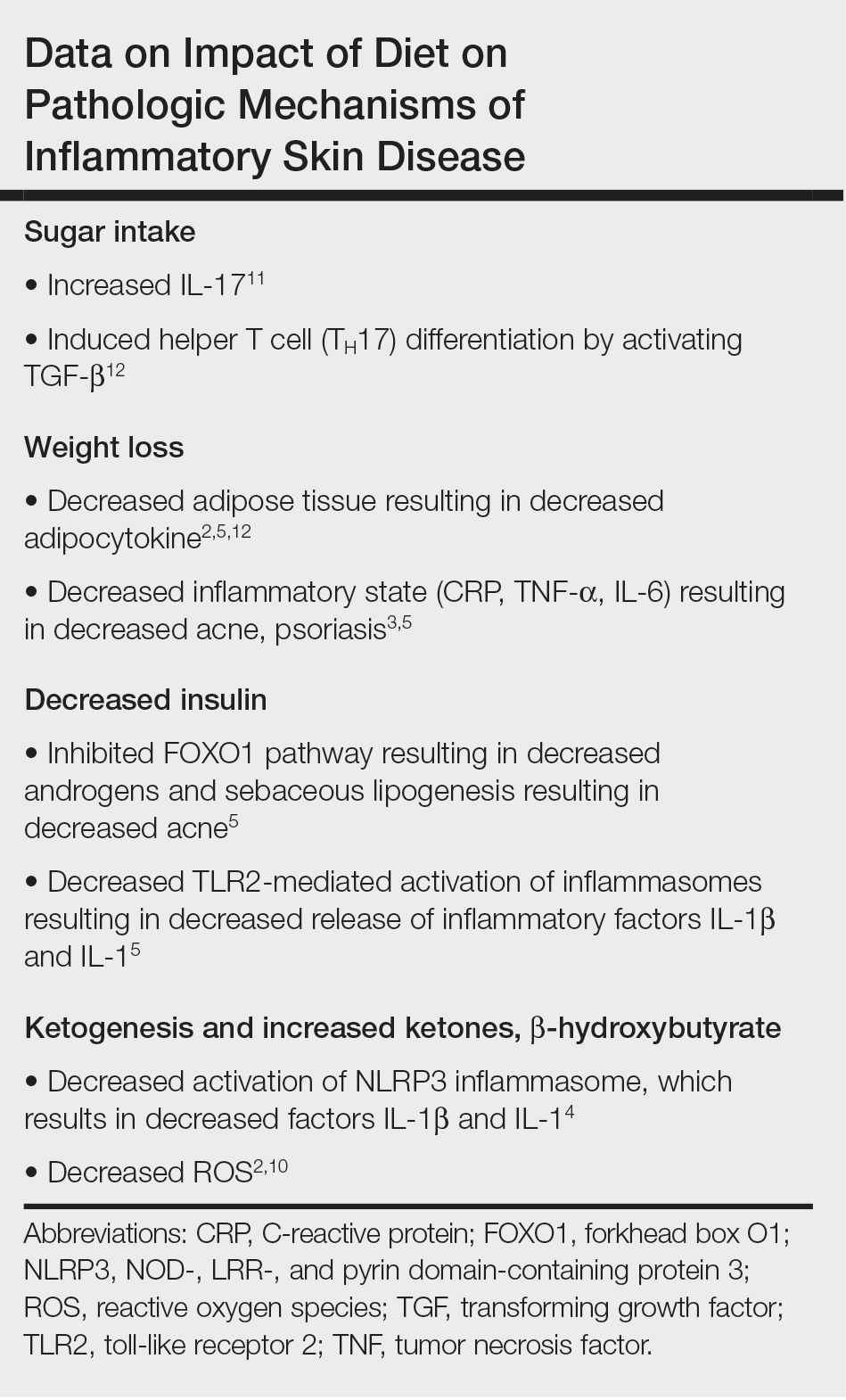

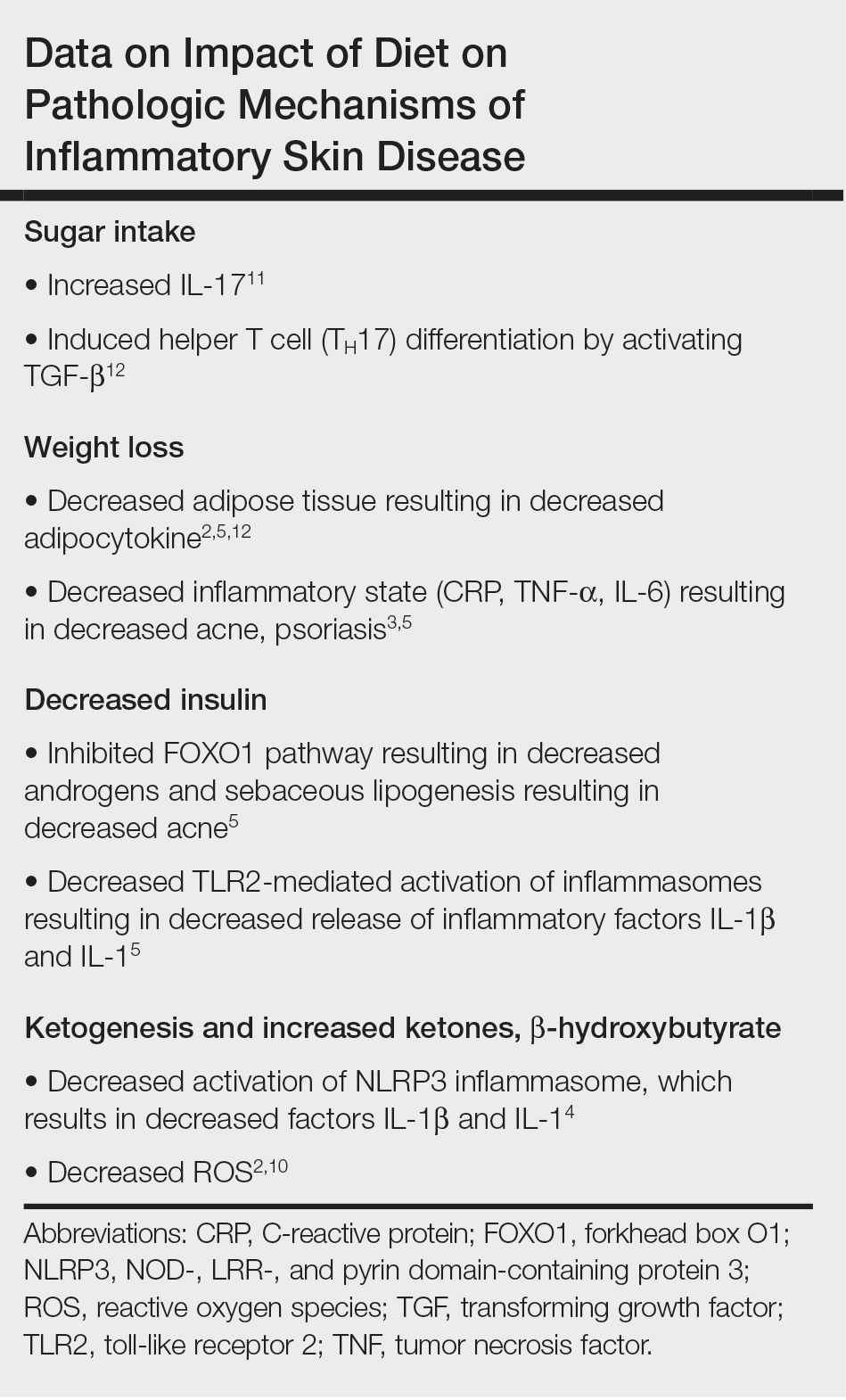

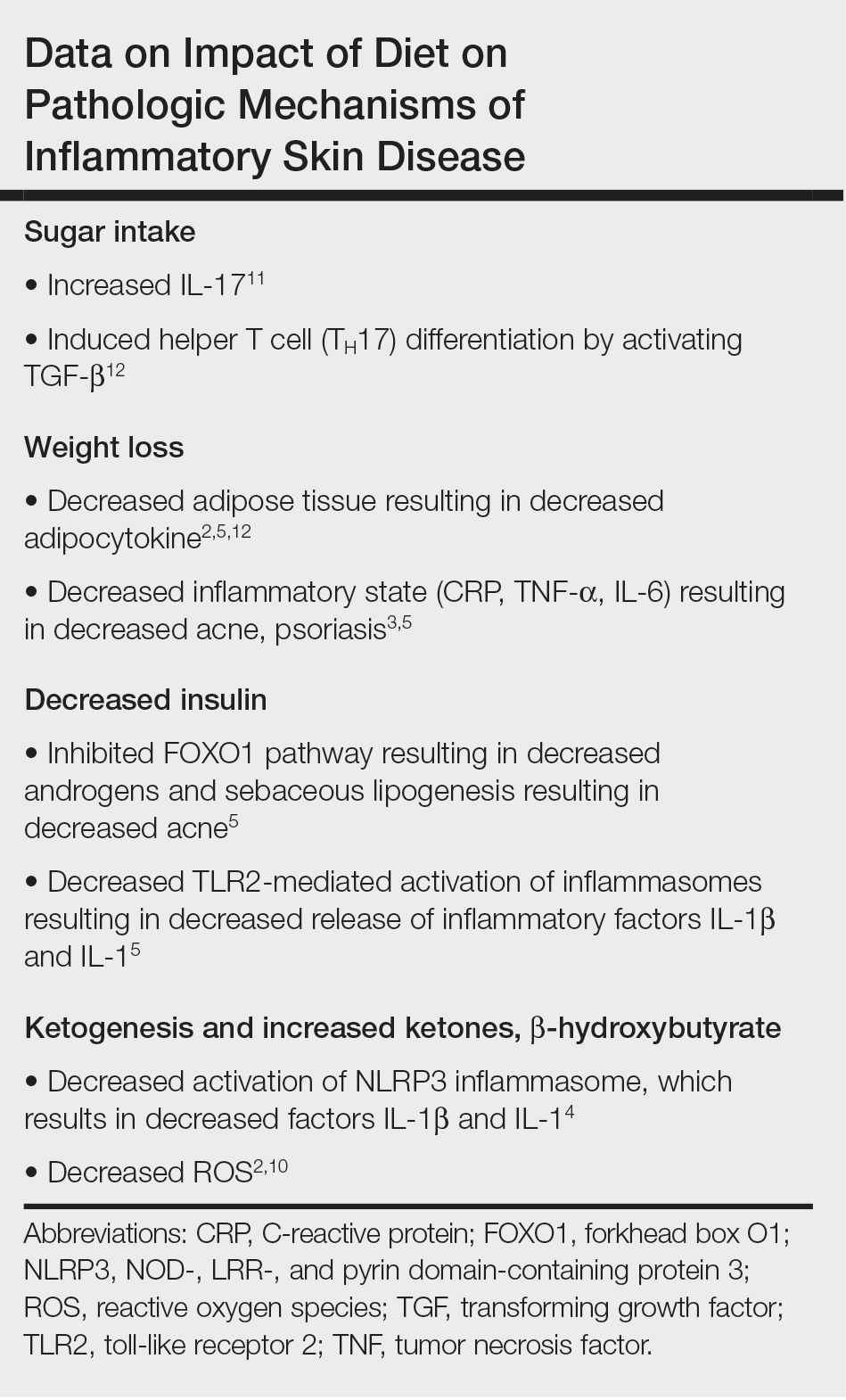

Similar to weight loss, ketogenesis acts as a negative feedback mechanism to reduce insulin release, leading to decreased inflammation and androgens that often exacerbate inflammatory skin diseases.8 Ketogenesis ensues when daily carbohydrate intake is limited to less than 50 g, and long-term adherence to a ketogenic diet results in metabolic reliance on ketone bodies such as acetoacetate, β-hydroxybutyrate, and acetone.9 These metabolites may decrease free radical damage and consequently improve signs and symptoms of acne, psoriasis, and other inflammatory skin diseases.10-12 Similarly, increased ketones also may decrease activation of the NLRP3 (NOD-, LRR-, and Pyrin domain-containing protein 3) inflammasome and therefore reduce inflammatory markers such as IL-1β and IL-1.4,13 Several proposed mechanisms are outlined in the Table.

Collectively, low-glycemic and ketogenic diets have been proposed as potential interventions for reducing inflammatory skin conditions. These dietary approaches are hypothesized to exert their effects by facilitating weight loss, elevating ketone levels, and reducing systemic inflammation. The current review summarizes the existing evidence on ketogenic and low-glycemic diets as treatments for inflammatory skin conditions and evaluates the potential benefits of these dietary interventions in managing and improving outcomes for individuals with inflammatory skin conditions.

Methods

Using PubMed for articles indexed for MEDLINE and Google Scholar, a review of the literature was conducted with a combination of the following search terms: low-glycemic diet, inflammatory, dermatologic, ketogenic diet, inflammation, dermatology, acne, psoriasis, eczema, seborrheic dermatitis, and hidradenitis suppurativa. Reference citations in identified works also were reviewed. Interventional (experimental studies or clinical trials), survey-based, and observational studies that investigated the effects of low-glycemic or ketogenic diets for the treatment of inflammatory skin conditions were included. Inclusion criteria were studies assessing acne, psoriasis, SD, AD, and HS. Exclusion criteria were studies published before 1965; those written in languages other than English; and those analyzing other diets, such as the Mediterranean or low-fat diets. The search yielded a total of 11 observational studies and 4 controlled studies published between 1966 and January 2023. Because this analysis utilized publicly available data and did not qualify as human subject research, institutional review board approval was not required.

Results

Acne Vulgaris—Acne vulgaris is a disease of chronic pilosebaceous inflammation and follicular epithelial proliferation associated with Propionibacterium acnes. The association between acne and low-glycemic diets has been examined in several studies. Diet quality is measured and assessed using the glycemic index (GI), which is the effect of a single food on postprandial blood glucose, and the glycemic load, which is the GI adjusted for carbohydrates per serving.14 High levels of GI and glycemic load are associated with hyperinsulinemia and an increase in insulinlike growth factor 1 concentration that promotes

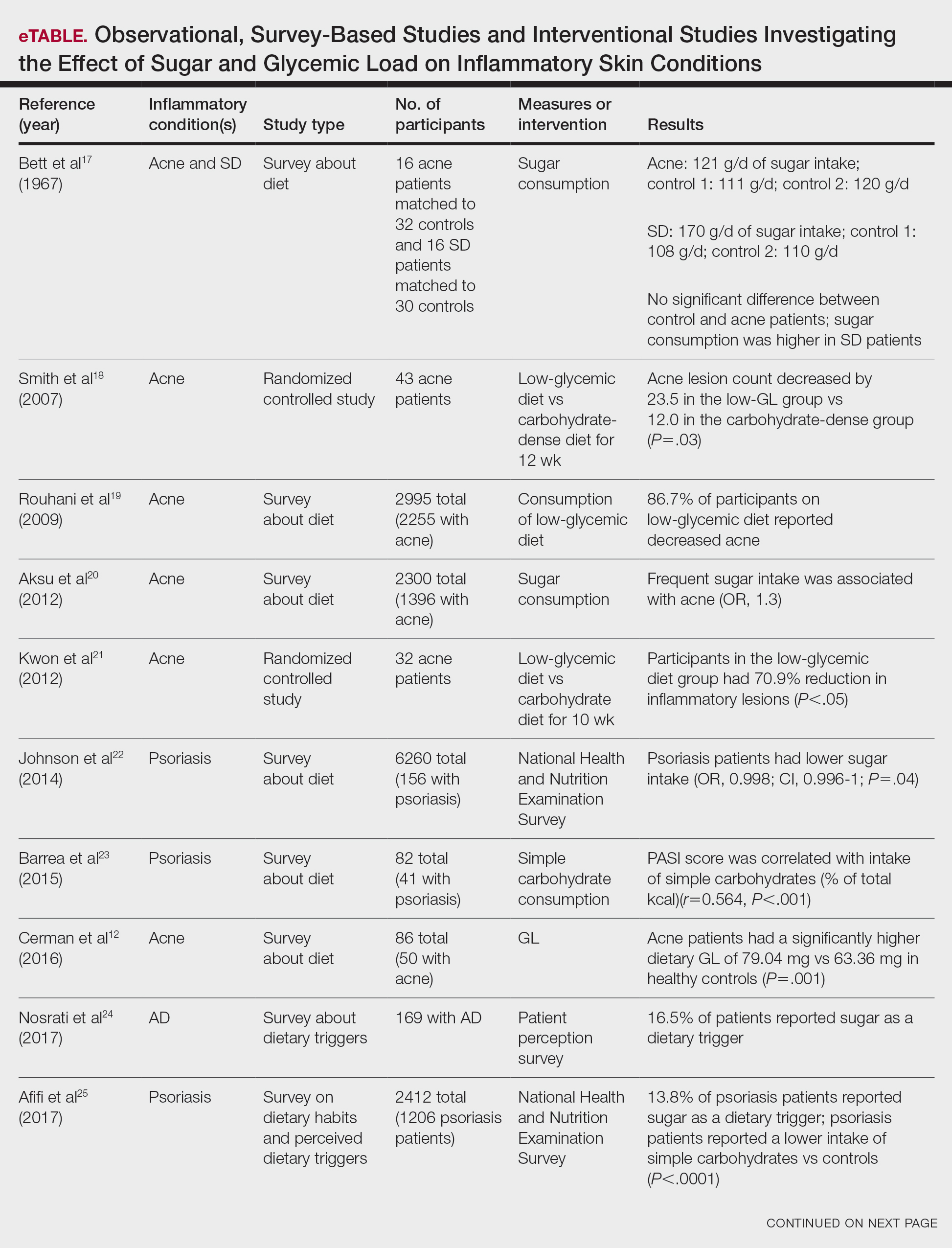

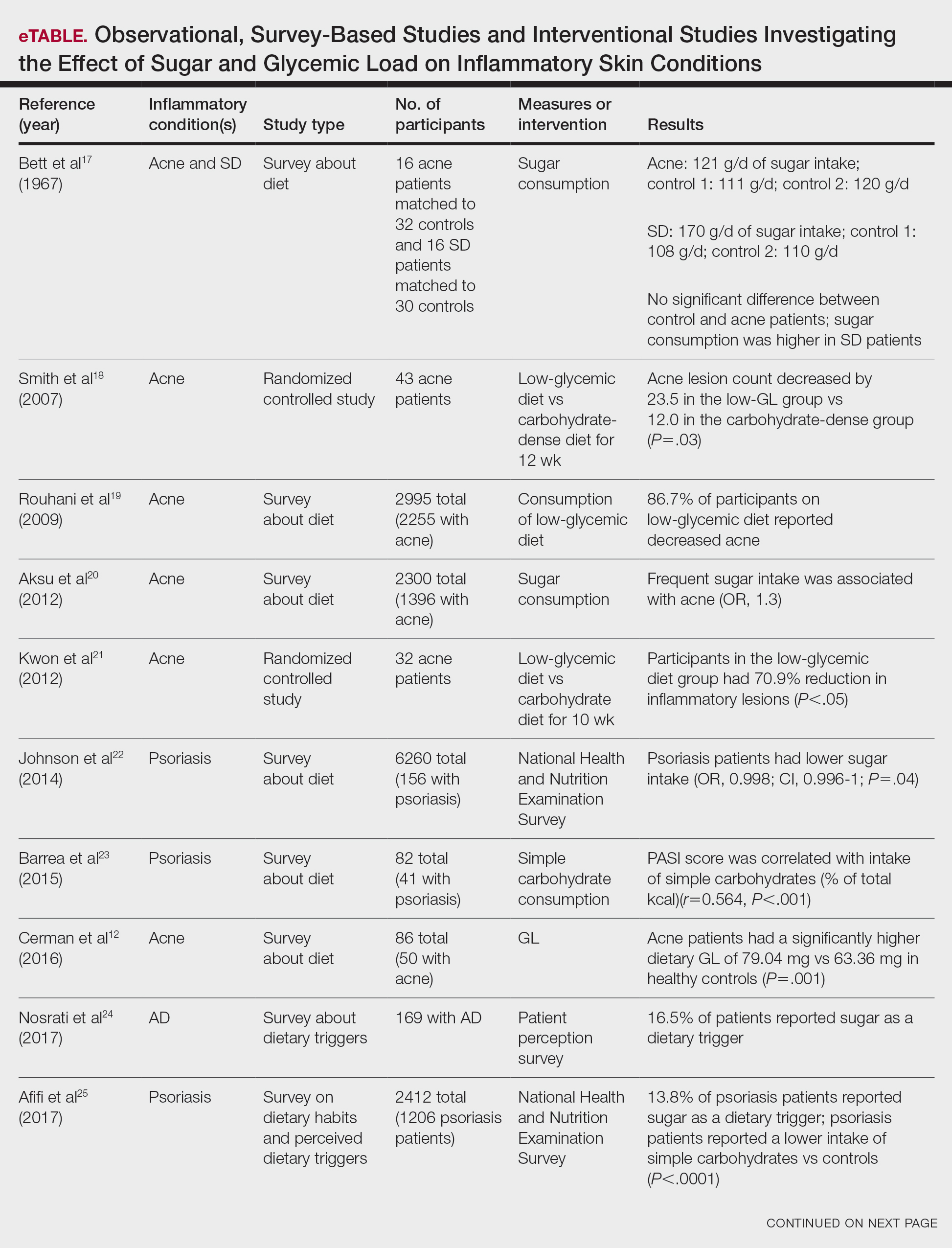

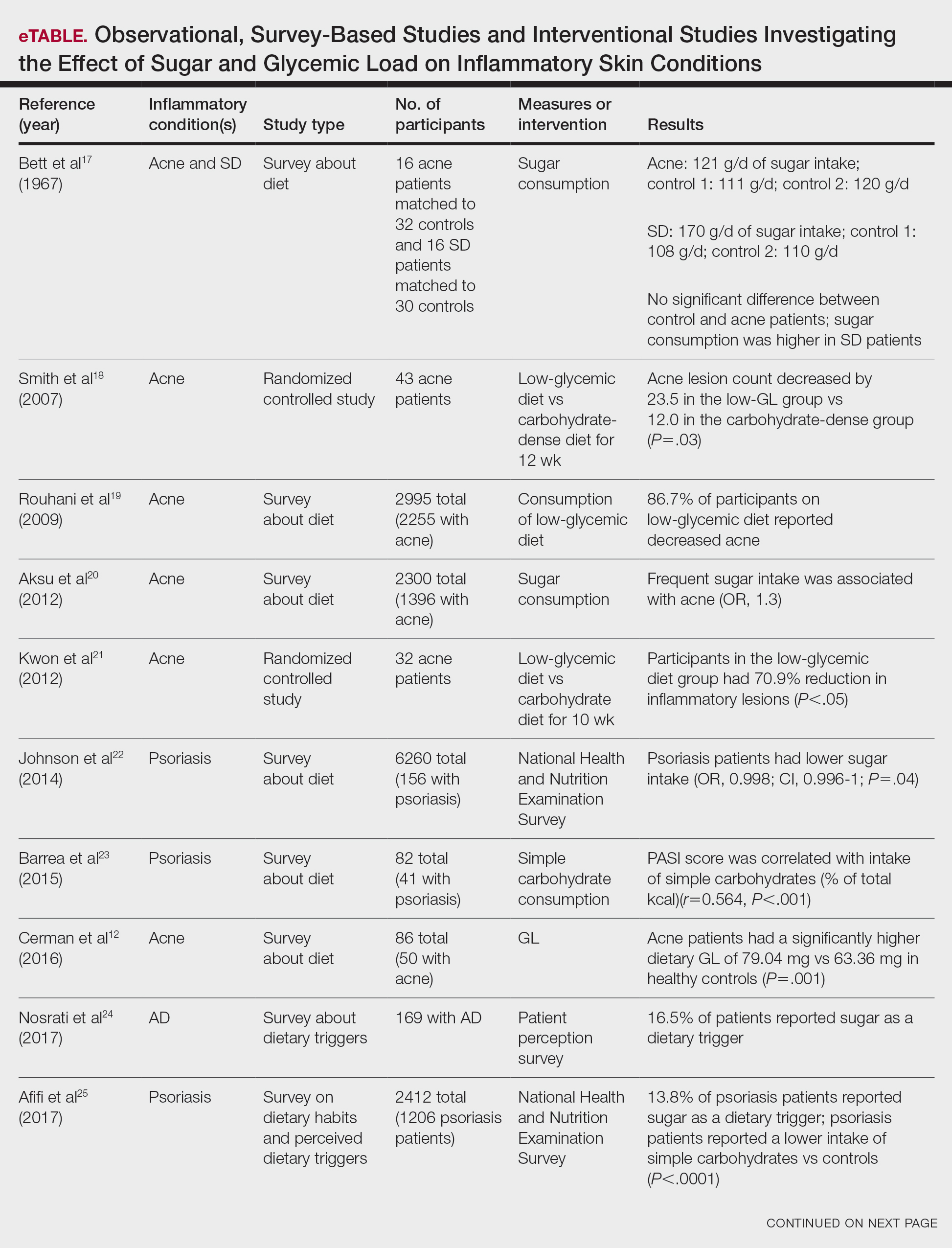

Six survey-based studies evaluated sugar intake in patients with acne compared to healthy matched controls (eTable). Among these studies, 5 reported higher glycemic loads or daily sugar intake in acne patients compared to individuals without acne.12,19,20,26,28 The remaining study was conducted in 1967 and enrolled 16 acne patients and 32 matched controls. It reported no significant difference in sugar intake between the groups (P>.05).17

Smith et al18 randomized 43 male patients aged 15 to 25 years with facial acne into 2 cohorts for 12 weeks, each consuming either a low-glycemic diet (25% protein, 45% low-glycemic food [fruits, whole grains], and 30% fat) or a carbohydrate-dense diet of foods with medium to high GI based on prior documentation of the original diet. Patients were instructed to use a noncomedogenic cleanser as their only acne treatment. At 12 weeks, patients consuming the low-glycemic diet had an average of 23.5 fewer inflammatory lesions, while those in the intervention group had 12.0 fewer lesions (P=.03).18

In another controlled study by Kwon et al,21 32 male and female acne patients were randomized to a low-glycemic diet (25% protein, 45% low-glycemic food, and 30% fat) or a standard diet for 10 weeks. Patients on the low-glycemic diet experienced a 70.9% reduction in inflammatory lesions (P<.05). Hematoxylin and eosin staining and image analysis were performed to measure sebaceous gland surface area in the low-glycemic diet group, which decreased from 0.32 to 0.24 mm2 (P=.03). The sebaceous gland surface area in the control group was not reported. Moreover, patients on the low-glycemic diet had reduced IL-8 immunohistochemical staining (decreasing from 2.9 to 1.7 [P=.03]) and sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 levels (decreasing from 2.6 to 1.3 [P=.03]), suggesting suppression of ongoing inflammation. Patients on the low-glycemic diet had no significant difference in transforming growth factor β1(P=.83). In the control group, there was no difference in IL-8, sterol regulatory element binding protein 1, or transforming growth factor β1 (P>.05) on immunohistochemical staining.21

Psoriasis—Psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory disease characterized by hyperproliferation and aberrant keratinocyte plaque formation. The innate immune response of keratinocytes in response to epidermal damage or infection begins with neutrophil recruitment and dendritic cell activation. Dendritic cell secretion of IL-23 promotes T-cell differentiation into helper T cells (TH1) that subsequently secrete IL-17 and IL-22, thereby stimulating keratinocyte proliferation and eventual plaque formation. The relationship between diet and psoriasis is poorly understood; however, hyperinsulinemia is associated with greater severity of psoriasis.31

Four observational studies examined sugar intake in psoriasis patients. Barrea et al23 conducted a survey-based study of 82 male participants (41 with psoriasis and 41 healthy controls), reporting that PASI score was correlated with intake of simple carbohydrates (percentage of total kilocalorie)(r=0.564, P<.001). Another study by Yamashita et al27 found higher sugar intake in psoriasis patients than controls (P=.003) based on surveys from 70 patients with psoriasis and 70 matched healthy controls.

These findings contrast with 2 survey-based studies by Johnson et al22 and Afifi et al25 of sugar intake in psoriasis patients using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Johnson et al22 reported reduced sugar intake among 156 psoriasis patients compared with 6104 unmatched controls (odds ratio, 0.998; CI, 0.996-1 [P=.04]) from 2003 to 2006. Similarly, Afifi et al25 reported decreased sugar intake in 1206 psoriasis patients compared with sex- and age-matched controls (P<.0001) in 2009 and 2010. When patients were asked about dietary triggers, 13.8% of psoriasis patients reported sugar as the most common trigger, which was more frequent than alcohol (13.6%), gluten (7.2%), and dairy (6%).25

Castaldo et al29,30 published 2 nonrandomized clinical intervention studies in 2020 and 2021 evaluating the impact of the ketogenic diet on psoriasis. In the first study, 37 psoriasis patients followed a 10-week diet consisting of 4 weeks on a ketogenic diet (500 kcal/d) followed by 6 weeks on a low-caloric Mediterranean diet.29 At the end of the intervention, there was a 17.4% reduction in PASI score, a 33.2-point reduction in itch severity score, and a 13.4-point reduction in the dermatology life quality index score; however, this study did not include a control diet group for comparison.29 The second study included 30 psoriasis patients on a ketogenic diet and 30 control patients without psoriasis on a regular diet.30 The ketogenic diet consisted of 400 to 500 g of vegetables, 20 to 30 g of fat, and a proportion of protein based on body weight with at least 12 g of whey protein and various amino acids. Patients on the ketogenic diet had significant reduction in PASI scores (value relative to clinical features, 1.4916 [P=.007]). Furthermore, concentrations of cytokines IL-2 (P=.04) and IL-1β (P=.006) decreased following the ketogenic diet but were not measured in the control group.30

Seborrheic Dermatitis—Seborrheic dermatitis is associated with overcolonization of Malassezia species near lipid-rich sebaceous glands. Malassezia hydrolyzes free fatty acids, yielding oleic acids and leading to T-cell release of IL-8 and IL-17.32 Literature is sparse regarding how dietary modifications may play a role in disease severity. In a survey study, Bett et al17 compared 16 SD patients to 1:2 matched controls (N=29) to investigate the relationship between sugar consumption and presence of disease. Two control cohorts were selected, 1 from clinic patients diagnosed with verruca and 1 matched by age and sex from a survey-based study at a facility in London, England. Sugar intake was measured both in total grams per day and in “beverage sugar” per day, defined as sugar taken in tea and coffee. There was higher total sugar and higher beverage sugar intake among the SD group compared with both control groups (P<.05).17

Atopic Dermatitis—Atopic dermatitis is a disease of epidermal barrier dysfunction and IgE-mediated allergic sensitization.33 There are several mechanisms by which skin structure may be disrupted. It is well established that filaggrin mutations inhibit stratum corneum maturation and lamellar matrix deposition.34 Upregulation of IL-4–, IL-13–, and IL-17–secreting TH2 cells also is associated with disruption of tight junctions and reduction of filaggrin.35,36 Given that a T cell–mediated inflammatory response is involved in disease pathogenesis, glycemic control is hypothesized to have therapeutic potential.

Nosrati et al24 surveyed 169 AD patients about their perceived dietary triggers through a 61-question survey based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Respondents were queried about their perceptions and dietary changes, such as removal or addition of specific food groups and trial of specific diets. Overall, 16.5% of patients reported sugar being a trigger, making it the fourth most common among those surveyed and less common than dairy (24.8%), gluten (18.3%), and alcohol (17.1%).24

Hidradenitis Suppurativa—Hidradenitis suppurativa is driven by hyperkeratosis, dilatation, and occlusion of pilosebaceous follicular ducts, whose eventual rupture evokes a local acute inflammatory response.37 The inciting event for both acne and HS involves mTOR complex–mediated follicular hyperproliferation andinsulinlike growth factor 1 stimulation of androgen receptors in pilosebaceous glands. Given the similarities between the pathogenesis of acne and HS, it is hypothesized that lifestyle changes, including diet modification, may have a beneficial effect on HS.38-40

Comment

Acne—Overall, there is strong evidence supporting the efficacy of a low-glycemic diet in the treatment of acne. Notably, among the 6 observational studies identified, there was 1 conflicting study by Bett et al17 that did not find a statistically significant difference in glucose intake between acne and control patients. However, this study included only 16 acne patients, whereas the other 5 observational studies included 32 to 2255 patients.17 The strongest evidence supporting low-glycemic dietary interventions in acne treatment is from 2 rigorous randomized clinical trials by Kwon et al21 and Smith et al.18 These trials used intention-to-treat models and maintained consistency in gender, age, and acne treatment protocols across both control and treatment groups. To ensure compliance with dietary interventions, daily telephone calls, food logs, and 24-hour urea sampling were utilized. Acne outcomes were assessed by a dermatologist who remained blinded with well-defined outcome measures. An important limitation of these studies is the difficulty in attributing the observed results solely to reduced glucose intake, as low-glycemic diets often lead to other dietary changes, including reduced fat intake and increased nutrient consumption.18,21

A 2022 systematic review of acne by Meixiong et al41 further reinforced the beneficial effects of low-glycemic diets in the management of acne patients. The group reviewed 6 interventional studies and 28 observational studies to investigate the relationship among acne, dairy, and glycemic content and found an association between decreased glucose and dairy on reduction of acne.41

It is likely that the ketogenic diet, which limits glucose, would be beneficial for acne patients. There may be added benefit through elevated ketone bodies and substantially reduced insulin secretion. However, because there are no observational or interventional studies, further research is needed to draw firm conclusions regarding diet for acne treatment. A randomized clinical trial investigating the effects of the ketogenic diet compared to the low-glycemic diet compared to a regular diet would be valuable.

Psoriasis—Among psoriasis studies, there was a lack of consensus regarding glucose intake and correlation with disease. Among the 4 observational studies, 2 reported increased glucose intake among psoriasis patients and 2 reported decreased glucose intake. It is plausible that the variability in studies is due to differences in sample size and diet heterogeneity among study populations. More specifically, Johnson et al22 and Afifi et al25 analyzed large sample sizes of 6260 and 2412 US participants, respectively, and found decreased sugar intake among psoriasis patients compared to controls. In comparison, Barrea et al23 and Yamashita et al27 analyzed substantially smaller and more specific populations consisting of 82 Italian and 140 Japanese participants, respectively; both reported increased glucose intake among psoriasis patients compared to controls. These seemingly antithetical results may be explained by regional dietary differences, with varying proportions of meats, vegetables, antioxidants, and vitamins.