User login

Preventing suicide: What should clinicians do differently?

“Suicide rates are increasing,” Dr. Igor Galynker said, “and I believe they will continue to rise. These are deaths of despair, and despair is increasing in our society.”

That said, I listened with interest to the May 16 MDedge Psychcast, “Approach assesses imminent suicide risk,” an interview with Igor Galynker, MD, PhD, author of “The Suicidal Crisis” and director of the Galynker Suicide Research Laboratory at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. In the podcast, Dr. Galynker talked about techniques for identifying those at risk for suicide among the patients psychiatrists see for evaluation and treatment.

“Using suicidal ideation as a risk factor is flawed,” he contended. “Asking about suicidal thoughts leaves us to miss 75% of people who go on to die by suicide.” Dr. Galynker noted that suicidal thoughts are often absent or not endorsed at all and clinicians should view other factors – such as the patient’s sense of being entrapped and the clinician’s own emotional responses to the patient – as more sensitive measures of elevated suicide risk.

This informative podcast left me with more questions, so I called Dr. Galynker. Suicide remains a rare phenomenon, and most psychiatrists will have limited experience with completed suicide during the course of a career. Dr. Galynker’s interest in suicide as an area of research began after he had a patient die the year after he finished residency training. Since then, he’s had one more patient suicide, and he’s aware of eight people who have died after leaving his care. “It can be devastating,” he said.

I wanted to know what psychiatrists should be doing differently after we have identified a patient at risk. While it seems obvious that a depressed patient should be treated for major depression, it also seems obvious that our interventions are imprecisely targeted and not fully successful.

We talked about the role of hospitalization in preventing suicide. Dr. Galynker has mixed opinions on this. He noted that suicide rates skyrocket in the time right after psychiatric hospitalization. “For women, the rate is 250 times higher at the time of hospital discharge; for men it’s 100 times higher. But hospitalization may help someone to survive a transitional period and to gather their support systems.”

Dr. Galynker noted that since the podcast in May aired, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published findings on suicide rates in the United States. He summarized some of the key points from the findings.

“Suicide rates were going down until 1999. From 2000 to 2006, suicide rates increased by 1% per year. From 2006 until 2016, rates have increased by 2% per year. Most people who die by suicide don’t have a diagnosis of a mental illness. And finally – and what has gone unnoticed – most people who die by suicide do not express suicidal intent. In fact, in that study, suicide intent was disclosed by less than a quarter of persons both with and without known mental health conditions.”

Dr. Galynker talked about safety plans and emphasized means restriction as ways to prevent suicide, including limiting access to firearms, placing netting under bridges, and providing medications in smaller containers.

“Suicidal ideation comes late; it may happen 15 minutes before a suicidal act or attempt. We need to alert people that there are certainly things that put them at risk, and we need to look at the drivers.

“Sometimes, people die for trivial reasons.” He noted instances where a susceptible person might attempt or complete suicide after an argument or perceived slight. Work is being done to look at outreach interventions to those at risk, including phone contacts and postcards.

“We don’t have a suicide-specific diagnosis ... and people die for other reasons besides mental illness. Final romantic rejection, terminal illness, and humiliating failures in business all place people at elevated risk. We need to work to change the suicidal narrative for people away from one where life has no future; we need to help them open doors.”

Dr. Miller is the coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care,” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

“Suicide rates are increasing,” Dr. Igor Galynker said, “and I believe they will continue to rise. These are deaths of despair, and despair is increasing in our society.”

That said, I listened with interest to the May 16 MDedge Psychcast, “Approach assesses imminent suicide risk,” an interview with Igor Galynker, MD, PhD, author of “The Suicidal Crisis” and director of the Galynker Suicide Research Laboratory at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. In the podcast, Dr. Galynker talked about techniques for identifying those at risk for suicide among the patients psychiatrists see for evaluation and treatment.

“Using suicidal ideation as a risk factor is flawed,” he contended. “Asking about suicidal thoughts leaves us to miss 75% of people who go on to die by suicide.” Dr. Galynker noted that suicidal thoughts are often absent or not endorsed at all and clinicians should view other factors – such as the patient’s sense of being entrapped and the clinician’s own emotional responses to the patient – as more sensitive measures of elevated suicide risk.

This informative podcast left me with more questions, so I called Dr. Galynker. Suicide remains a rare phenomenon, and most psychiatrists will have limited experience with completed suicide during the course of a career. Dr. Galynker’s interest in suicide as an area of research began after he had a patient die the year after he finished residency training. Since then, he’s had one more patient suicide, and he’s aware of eight people who have died after leaving his care. “It can be devastating,” he said.

I wanted to know what psychiatrists should be doing differently after we have identified a patient at risk. While it seems obvious that a depressed patient should be treated for major depression, it also seems obvious that our interventions are imprecisely targeted and not fully successful.

We talked about the role of hospitalization in preventing suicide. Dr. Galynker has mixed opinions on this. He noted that suicide rates skyrocket in the time right after psychiatric hospitalization. “For women, the rate is 250 times higher at the time of hospital discharge; for men it’s 100 times higher. But hospitalization may help someone to survive a transitional period and to gather their support systems.”

Dr. Galynker noted that since the podcast in May aired, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published findings on suicide rates in the United States. He summarized some of the key points from the findings.

“Suicide rates were going down until 1999. From 2000 to 2006, suicide rates increased by 1% per year. From 2006 until 2016, rates have increased by 2% per year. Most people who die by suicide don’t have a diagnosis of a mental illness. And finally – and what has gone unnoticed – most people who die by suicide do not express suicidal intent. In fact, in that study, suicide intent was disclosed by less than a quarter of persons both with and without known mental health conditions.”

Dr. Galynker talked about safety plans and emphasized means restriction as ways to prevent suicide, including limiting access to firearms, placing netting under bridges, and providing medications in smaller containers.

“Suicidal ideation comes late; it may happen 15 minutes before a suicidal act or attempt. We need to alert people that there are certainly things that put them at risk, and we need to look at the drivers.

“Sometimes, people die for trivial reasons.” He noted instances where a susceptible person might attempt or complete suicide after an argument or perceived slight. Work is being done to look at outreach interventions to those at risk, including phone contacts and postcards.

“We don’t have a suicide-specific diagnosis ... and people die for other reasons besides mental illness. Final romantic rejection, terminal illness, and humiliating failures in business all place people at elevated risk. We need to work to change the suicidal narrative for people away from one where life has no future; we need to help them open doors.”

Dr. Miller is the coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care,” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

“Suicide rates are increasing,” Dr. Igor Galynker said, “and I believe they will continue to rise. These are deaths of despair, and despair is increasing in our society.”

That said, I listened with interest to the May 16 MDedge Psychcast, “Approach assesses imminent suicide risk,” an interview with Igor Galynker, MD, PhD, author of “The Suicidal Crisis” and director of the Galynker Suicide Research Laboratory at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. In the podcast, Dr. Galynker talked about techniques for identifying those at risk for suicide among the patients psychiatrists see for evaluation and treatment.

“Using suicidal ideation as a risk factor is flawed,” he contended. “Asking about suicidal thoughts leaves us to miss 75% of people who go on to die by suicide.” Dr. Galynker noted that suicidal thoughts are often absent or not endorsed at all and clinicians should view other factors – such as the patient’s sense of being entrapped and the clinician’s own emotional responses to the patient – as more sensitive measures of elevated suicide risk.

This informative podcast left me with more questions, so I called Dr. Galynker. Suicide remains a rare phenomenon, and most psychiatrists will have limited experience with completed suicide during the course of a career. Dr. Galynker’s interest in suicide as an area of research began after he had a patient die the year after he finished residency training. Since then, he’s had one more patient suicide, and he’s aware of eight people who have died after leaving his care. “It can be devastating,” he said.

I wanted to know what psychiatrists should be doing differently after we have identified a patient at risk. While it seems obvious that a depressed patient should be treated for major depression, it also seems obvious that our interventions are imprecisely targeted and not fully successful.

We talked about the role of hospitalization in preventing suicide. Dr. Galynker has mixed opinions on this. He noted that suicide rates skyrocket in the time right after psychiatric hospitalization. “For women, the rate is 250 times higher at the time of hospital discharge; for men it’s 100 times higher. But hospitalization may help someone to survive a transitional period and to gather their support systems.”

Dr. Galynker noted that since the podcast in May aired, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published findings on suicide rates in the United States. He summarized some of the key points from the findings.

“Suicide rates were going down until 1999. From 2000 to 2006, suicide rates increased by 1% per year. From 2006 until 2016, rates have increased by 2% per year. Most people who die by suicide don’t have a diagnosis of a mental illness. And finally – and what has gone unnoticed – most people who die by suicide do not express suicidal intent. In fact, in that study, suicide intent was disclosed by less than a quarter of persons both with and without known mental health conditions.”

Dr. Galynker talked about safety plans and emphasized means restriction as ways to prevent suicide, including limiting access to firearms, placing netting under bridges, and providing medications in smaller containers.

“Suicidal ideation comes late; it may happen 15 minutes before a suicidal act or attempt. We need to alert people that there are certainly things that put them at risk, and we need to look at the drivers.

“Sometimes, people die for trivial reasons.” He noted instances where a susceptible person might attempt or complete suicide after an argument or perceived slight. Work is being done to look at outreach interventions to those at risk, including phone contacts and postcards.

“We don’t have a suicide-specific diagnosis ... and people die for other reasons besides mental illness. Final romantic rejection, terminal illness, and humiliating failures in business all place people at elevated risk. We need to work to change the suicidal narrative for people away from one where life has no future; we need to help them open doors.”

Dr. Miller is the coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care,” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

Universal depression screening for adolescents not without controversy

When 14-year-old Ryan saw his pediatrician for his annual physical this past August, he was asked a few quick questions about whether he was having any problems, if he was feeling depressed or anxious, and if there was anything he wanted to discuss. Ryan said no to each question, then the doctor examined him, reminded him to get a flu shot, and signed off on the forms he needed to play team sports in high school. The doctor assured Ryan’s mother that he was healthy, and the visit was over. Next August, Ryan’s exam will likely include a more detailed look at his mental health.

In February 2018, the American Academy of Pediatrics updated its guidelines on screening for depression in adolescents in primary care settings. The guidelines address the problem of undiagnosed and untreated psychiatric illness in children over the age of 10 years, the shortage of available mental health professionals, and techniques primary care physicians might use to address psychiatric needs in adolescents. The AAP guidelines include a new recommendation for universal screening with an assessment tool: “Adolescent patients ages 12 years and older should be screened annually for depression [MDD or depressive disorders] with a formal self-report screening tool either on paper or electronically.”

Dr. Liu noted that some of his patients drive 4-5 hours each way to see him in Omaha, then spend the night before making the return trip. “There is a dire shortage of pediatric mental health services in every state. This shifts the responsibility for care to pediatricians, teachers, and parents who often lack the resources to keep kids safe and well. It’s an unconscionable gap in care.”

Dr. Doran’s practice has not yet implemented the use of a written screening tool for all adolescents. He anticipates doing this soon because of the new guidelines, but he was not enthusiastic about the prospect. “ We are already loaded down with administrative tasks and screening requirements.” Of note, in Dr. Doran’s 35 years in clinical practice, no child under his care has died of suicide.

Dr. Miller is the coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care,” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

When 14-year-old Ryan saw his pediatrician for his annual physical this past August, he was asked a few quick questions about whether he was having any problems, if he was feeling depressed or anxious, and if there was anything he wanted to discuss. Ryan said no to each question, then the doctor examined him, reminded him to get a flu shot, and signed off on the forms he needed to play team sports in high school. The doctor assured Ryan’s mother that he was healthy, and the visit was over. Next August, Ryan’s exam will likely include a more detailed look at his mental health.

In February 2018, the American Academy of Pediatrics updated its guidelines on screening for depression in adolescents in primary care settings. The guidelines address the problem of undiagnosed and untreated psychiatric illness in children over the age of 10 years, the shortage of available mental health professionals, and techniques primary care physicians might use to address psychiatric needs in adolescents. The AAP guidelines include a new recommendation for universal screening with an assessment tool: “Adolescent patients ages 12 years and older should be screened annually for depression [MDD or depressive disorders] with a formal self-report screening tool either on paper or electronically.”

Dr. Liu noted that some of his patients drive 4-5 hours each way to see him in Omaha, then spend the night before making the return trip. “There is a dire shortage of pediatric mental health services in every state. This shifts the responsibility for care to pediatricians, teachers, and parents who often lack the resources to keep kids safe and well. It’s an unconscionable gap in care.”

Dr. Doran’s practice has not yet implemented the use of a written screening tool for all adolescents. He anticipates doing this soon because of the new guidelines, but he was not enthusiastic about the prospect. “ We are already loaded down with administrative tasks and screening requirements.” Of note, in Dr. Doran’s 35 years in clinical practice, no child under his care has died of suicide.

Dr. Miller is the coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care,” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

When 14-year-old Ryan saw his pediatrician for his annual physical this past August, he was asked a few quick questions about whether he was having any problems, if he was feeling depressed or anxious, and if there was anything he wanted to discuss. Ryan said no to each question, then the doctor examined him, reminded him to get a flu shot, and signed off on the forms he needed to play team sports in high school. The doctor assured Ryan’s mother that he was healthy, and the visit was over. Next August, Ryan’s exam will likely include a more detailed look at his mental health.

In February 2018, the American Academy of Pediatrics updated its guidelines on screening for depression in adolescents in primary care settings. The guidelines address the problem of undiagnosed and untreated psychiatric illness in children over the age of 10 years, the shortage of available mental health professionals, and techniques primary care physicians might use to address psychiatric needs in adolescents. The AAP guidelines include a new recommendation for universal screening with an assessment tool: “Adolescent patients ages 12 years and older should be screened annually for depression [MDD or depressive disorders] with a formal self-report screening tool either on paper or electronically.”

Dr. Liu noted that some of his patients drive 4-5 hours each way to see him in Omaha, then spend the night before making the return trip. “There is a dire shortage of pediatric mental health services in every state. This shifts the responsibility for care to pediatricians, teachers, and parents who often lack the resources to keep kids safe and well. It’s an unconscionable gap in care.”

Dr. Doran’s practice has not yet implemented the use of a written screening tool for all adolescents. He anticipates doing this soon because of the new guidelines, but he was not enthusiastic about the prospect. “ We are already loaded down with administrative tasks and screening requirements.” Of note, in Dr. Doran’s 35 years in clinical practice, no child under his care has died of suicide.

Dr. Miller is the coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care,” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

Experts explore issues, controversies around medical marijuana use

I live and work in Maryland, where medical marijuana dispensaries are just beginning to open. So far, my patients have been content to smoke illegal marijuana, even after my admonishments. Last week, however, a patient who suffers from chronic pain told me that one of her doctors suggested she try medical marijuana. What did I think? The patient is in her 70s, and she has not tolerated opiates. She lives an active life, and she drives. I didn’t know what to think and was left to tell her that I had no experience and would not object if she wanted to try it. The timing was right for “Issues and Controversies Around Marijuana Use: What’s the Buzz?” at the American Psychiatric Association’s annual meeting in New York this week.

William Iacono, PhD, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, started with a session called “Does Adolescent Marijuana Use Cause Cognitive Decline?” Dr. Iacono and all the speakers who followed him pointed out how difficult it is to research these issues. The research is largely retrospective, and the questions are complex. The degree of use is determined by self-report, and there are questions about acute versus chronic use, whether cognitive decline is temporary or permanent, whether the age of initiating drug use is important, and finally, which tests are used to measure cognitive abilities. Dr. Iacono noted that results are inconsistent and mentioned a large population study done in Dunedin, New Zealand, which measured a decrease in verbal IQ and vocabulary measures at age 38 years if the user began smoking cannabis as an adolescent. Dr. Iacono’s twin studies showed that marijuana users scored lower on these measures in childhood, well before they began smoking, and poor academic performance predisposes to marijuana use.

“Adolescents who use cannabis are not the same as those who don’t,” Dr. Iacono said, “and heavy or daily use does not cause cognitive decline in those who begin smoking as adults.”

Dr. Pearlson introduced the second speaker by saying, “It’s easier to get funding to show the ill effects of cannabis than to show medicinal effects.” Sue Sisley, MD, director of Midtown Roots, a medical marijuana dispensary in Phoenix, conducts cannabis trials for the treatment of PTSD in veterans and noted that she has had a long and difficult road with marijuana research, and hers is the only controlled trial on cannabis for PTSD. When her Schedule I license was approved by the Food and Drug Administration, she was able to receive marijuana from the National Institute on Drug Abuse that was grown by the University of Mississippi in Oxford – the only federal growing facility. The marijuana was delivered by FedEx, and the drug was the consistency of talcum powder. It was a challenge to find a lab that could verify the components of the test drug, and when she did, she found the tetrahydrocannabinol content was considerably lower than marijuana sold on the black market. Also, the product contained both mold and lead. “As a physician, how do you hand out mold weed to our veterans?”

Her trials are still in progress, and more veterans are needed. Anecdotally, she says, a decrease has been seen in the use of both opiates and Viagra by the research subjects.

Michael Stevens, PhD, adjunct professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., discussed the risk of motor vehicle accidents in marijuana smokers and the logistical issues enforcement poses for law enforcement officials. “There is evidence that marijuana increases the risk for accidents.” Dr. Stevens went on to say that the elevated risk is notably less than that associated with the use of alcohol or stimulants. Studying the effects of marijuana on driving is difficult, as driving simulators do not necessarily reflect on-road experiences, and cognitive testing does not always translate into impairment. “We can’t give marijuana to teens and test them, and you can’t tell people who smoke every day that you’ll check in with them in a few years and check their driving records.”

In terms of law enforcement issues, roadside sobriety tests have not been validated for marijuana use, and plasma levels of the drug drop within minutes of use. “The alcohol model works well with alcohol, but cannabis is not alcohol.”

Deborah Hasin, PhD, professor of epidemiology (psychiatry) at Columbia University, New York, talked about trends of cannabis use in the United States. “Looking at states before and after legalization, we see that there is an increase in both cannabis use and cannabis disorders in adults.” Adolescents, however, are not smoking more, and “Kids are just not socializing; they are in their bedrooms with their smartphones. Depression is increasing in teens, but substance abuse is not.”

The last speaker was Deepak Cyril D’Souza, MD, a professor of psychiatry at Yale University, who talked about cannabis and psychosis. He defined three distinct relationships: acute transient psychosis that resolves fairly quickly, acute persistent psychosis that takes days or weeks to resolve, and psychotic reactions that are associated with recurrent psychotic symptoms. Studies suggest that those who have a psychotic reaction to marijuana are at elevated risk of being diagnosed with schizophrenia later, and that timing of exposure to marijuana may be important.

With regard to the important question of whether marijuana causes schizophrenia, Dr. D’Souza noted that “it’s neither a necessary nor sufficient component, but it does appear it hastens psychosis in schizophrenia and earlier symptoms are associated with a worse prognosis.”

I’ll see what happens with my patient. A Canadian physician in the audience noted that he has treated thousands of patients, and most find medical marijuana to be helpful. In our country, marijuana continues to be a controversial topic with strong opinions about its usefulness and a conversation that is limited by our lack of research.

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care,” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She practices in Baltimore.

I live and work in Maryland, where medical marijuana dispensaries are just beginning to open. So far, my patients have been content to smoke illegal marijuana, even after my admonishments. Last week, however, a patient who suffers from chronic pain told me that one of her doctors suggested she try medical marijuana. What did I think? The patient is in her 70s, and she has not tolerated opiates. She lives an active life, and she drives. I didn’t know what to think and was left to tell her that I had no experience and would not object if she wanted to try it. The timing was right for “Issues and Controversies Around Marijuana Use: What’s the Buzz?” at the American Psychiatric Association’s annual meeting in New York this week.

William Iacono, PhD, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, started with a session called “Does Adolescent Marijuana Use Cause Cognitive Decline?” Dr. Iacono and all the speakers who followed him pointed out how difficult it is to research these issues. The research is largely retrospective, and the questions are complex. The degree of use is determined by self-report, and there are questions about acute versus chronic use, whether cognitive decline is temporary or permanent, whether the age of initiating drug use is important, and finally, which tests are used to measure cognitive abilities. Dr. Iacono noted that results are inconsistent and mentioned a large population study done in Dunedin, New Zealand, which measured a decrease in verbal IQ and vocabulary measures at age 38 years if the user began smoking cannabis as an adolescent. Dr. Iacono’s twin studies showed that marijuana users scored lower on these measures in childhood, well before they began smoking, and poor academic performance predisposes to marijuana use.

“Adolescents who use cannabis are not the same as those who don’t,” Dr. Iacono said, “and heavy or daily use does not cause cognitive decline in those who begin smoking as adults.”

Dr. Pearlson introduced the second speaker by saying, “It’s easier to get funding to show the ill effects of cannabis than to show medicinal effects.” Sue Sisley, MD, director of Midtown Roots, a medical marijuana dispensary in Phoenix, conducts cannabis trials for the treatment of PTSD in veterans and noted that she has had a long and difficult road with marijuana research, and hers is the only controlled trial on cannabis for PTSD. When her Schedule I license was approved by the Food and Drug Administration, she was able to receive marijuana from the National Institute on Drug Abuse that was grown by the University of Mississippi in Oxford – the only federal growing facility. The marijuana was delivered by FedEx, and the drug was the consistency of talcum powder. It was a challenge to find a lab that could verify the components of the test drug, and when she did, she found the tetrahydrocannabinol content was considerably lower than marijuana sold on the black market. Also, the product contained both mold and lead. “As a physician, how do you hand out mold weed to our veterans?”

Her trials are still in progress, and more veterans are needed. Anecdotally, she says, a decrease has been seen in the use of both opiates and Viagra by the research subjects.

Michael Stevens, PhD, adjunct professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., discussed the risk of motor vehicle accidents in marijuana smokers and the logistical issues enforcement poses for law enforcement officials. “There is evidence that marijuana increases the risk for accidents.” Dr. Stevens went on to say that the elevated risk is notably less than that associated with the use of alcohol or stimulants. Studying the effects of marijuana on driving is difficult, as driving simulators do not necessarily reflect on-road experiences, and cognitive testing does not always translate into impairment. “We can’t give marijuana to teens and test them, and you can’t tell people who smoke every day that you’ll check in with them in a few years and check their driving records.”

In terms of law enforcement issues, roadside sobriety tests have not been validated for marijuana use, and plasma levels of the drug drop within minutes of use. “The alcohol model works well with alcohol, but cannabis is not alcohol.”

Deborah Hasin, PhD, professor of epidemiology (psychiatry) at Columbia University, New York, talked about trends of cannabis use in the United States. “Looking at states before and after legalization, we see that there is an increase in both cannabis use and cannabis disorders in adults.” Adolescents, however, are not smoking more, and “Kids are just not socializing; they are in their bedrooms with their smartphones. Depression is increasing in teens, but substance abuse is not.”

The last speaker was Deepak Cyril D’Souza, MD, a professor of psychiatry at Yale University, who talked about cannabis and psychosis. He defined three distinct relationships: acute transient psychosis that resolves fairly quickly, acute persistent psychosis that takes days or weeks to resolve, and psychotic reactions that are associated with recurrent psychotic symptoms. Studies suggest that those who have a psychotic reaction to marijuana are at elevated risk of being diagnosed with schizophrenia later, and that timing of exposure to marijuana may be important.

With regard to the important question of whether marijuana causes schizophrenia, Dr. D’Souza noted that “it’s neither a necessary nor sufficient component, but it does appear it hastens psychosis in schizophrenia and earlier symptoms are associated with a worse prognosis.”

I’ll see what happens with my patient. A Canadian physician in the audience noted that he has treated thousands of patients, and most find medical marijuana to be helpful. In our country, marijuana continues to be a controversial topic with strong opinions about its usefulness and a conversation that is limited by our lack of research.

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care,” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She practices in Baltimore.

I live and work in Maryland, where medical marijuana dispensaries are just beginning to open. So far, my patients have been content to smoke illegal marijuana, even after my admonishments. Last week, however, a patient who suffers from chronic pain told me that one of her doctors suggested she try medical marijuana. What did I think? The patient is in her 70s, and she has not tolerated opiates. She lives an active life, and she drives. I didn’t know what to think and was left to tell her that I had no experience and would not object if she wanted to try it. The timing was right for “Issues and Controversies Around Marijuana Use: What’s the Buzz?” at the American Psychiatric Association’s annual meeting in New York this week.

William Iacono, PhD, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, started with a session called “Does Adolescent Marijuana Use Cause Cognitive Decline?” Dr. Iacono and all the speakers who followed him pointed out how difficult it is to research these issues. The research is largely retrospective, and the questions are complex. The degree of use is determined by self-report, and there are questions about acute versus chronic use, whether cognitive decline is temporary or permanent, whether the age of initiating drug use is important, and finally, which tests are used to measure cognitive abilities. Dr. Iacono noted that results are inconsistent and mentioned a large population study done in Dunedin, New Zealand, which measured a decrease in verbal IQ and vocabulary measures at age 38 years if the user began smoking cannabis as an adolescent. Dr. Iacono’s twin studies showed that marijuana users scored lower on these measures in childhood, well before they began smoking, and poor academic performance predisposes to marijuana use.

“Adolescents who use cannabis are not the same as those who don’t,” Dr. Iacono said, “and heavy or daily use does not cause cognitive decline in those who begin smoking as adults.”

Dr. Pearlson introduced the second speaker by saying, “It’s easier to get funding to show the ill effects of cannabis than to show medicinal effects.” Sue Sisley, MD, director of Midtown Roots, a medical marijuana dispensary in Phoenix, conducts cannabis trials for the treatment of PTSD in veterans and noted that she has had a long and difficult road with marijuana research, and hers is the only controlled trial on cannabis for PTSD. When her Schedule I license was approved by the Food and Drug Administration, she was able to receive marijuana from the National Institute on Drug Abuse that was grown by the University of Mississippi in Oxford – the only federal growing facility. The marijuana was delivered by FedEx, and the drug was the consistency of talcum powder. It was a challenge to find a lab that could verify the components of the test drug, and when she did, she found the tetrahydrocannabinol content was considerably lower than marijuana sold on the black market. Also, the product contained both mold and lead. “As a physician, how do you hand out mold weed to our veterans?”

Her trials are still in progress, and more veterans are needed. Anecdotally, she says, a decrease has been seen in the use of both opiates and Viagra by the research subjects.

Michael Stevens, PhD, adjunct professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., discussed the risk of motor vehicle accidents in marijuana smokers and the logistical issues enforcement poses for law enforcement officials. “There is evidence that marijuana increases the risk for accidents.” Dr. Stevens went on to say that the elevated risk is notably less than that associated with the use of alcohol or stimulants. Studying the effects of marijuana on driving is difficult, as driving simulators do not necessarily reflect on-road experiences, and cognitive testing does not always translate into impairment. “We can’t give marijuana to teens and test them, and you can’t tell people who smoke every day that you’ll check in with them in a few years and check their driving records.”

In terms of law enforcement issues, roadside sobriety tests have not been validated for marijuana use, and plasma levels of the drug drop within minutes of use. “The alcohol model works well with alcohol, but cannabis is not alcohol.”

Deborah Hasin, PhD, professor of epidemiology (psychiatry) at Columbia University, New York, talked about trends of cannabis use in the United States. “Looking at states before and after legalization, we see that there is an increase in both cannabis use and cannabis disorders in adults.” Adolescents, however, are not smoking more, and “Kids are just not socializing; they are in their bedrooms with their smartphones. Depression is increasing in teens, but substance abuse is not.”

The last speaker was Deepak Cyril D’Souza, MD, a professor of psychiatry at Yale University, who talked about cannabis and psychosis. He defined three distinct relationships: acute transient psychosis that resolves fairly quickly, acute persistent psychosis that takes days or weeks to resolve, and psychotic reactions that are associated with recurrent psychotic symptoms. Studies suggest that those who have a psychotic reaction to marijuana are at elevated risk of being diagnosed with schizophrenia later, and that timing of exposure to marijuana may be important.

With regard to the important question of whether marijuana causes schizophrenia, Dr. D’Souza noted that “it’s neither a necessary nor sufficient component, but it does appear it hastens psychosis in schizophrenia and earlier symptoms are associated with a worse prognosis.”

I’ll see what happens with my patient. A Canadian physician in the audience noted that he has treated thousands of patients, and most find medical marijuana to be helpful. In our country, marijuana continues to be a controversial topic with strong opinions about its usefulness and a conversation that is limited by our lack of research.

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care,” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016). She practices in Baltimore.

Why isn’t smart gun technology on Parkland activists’ agenda?

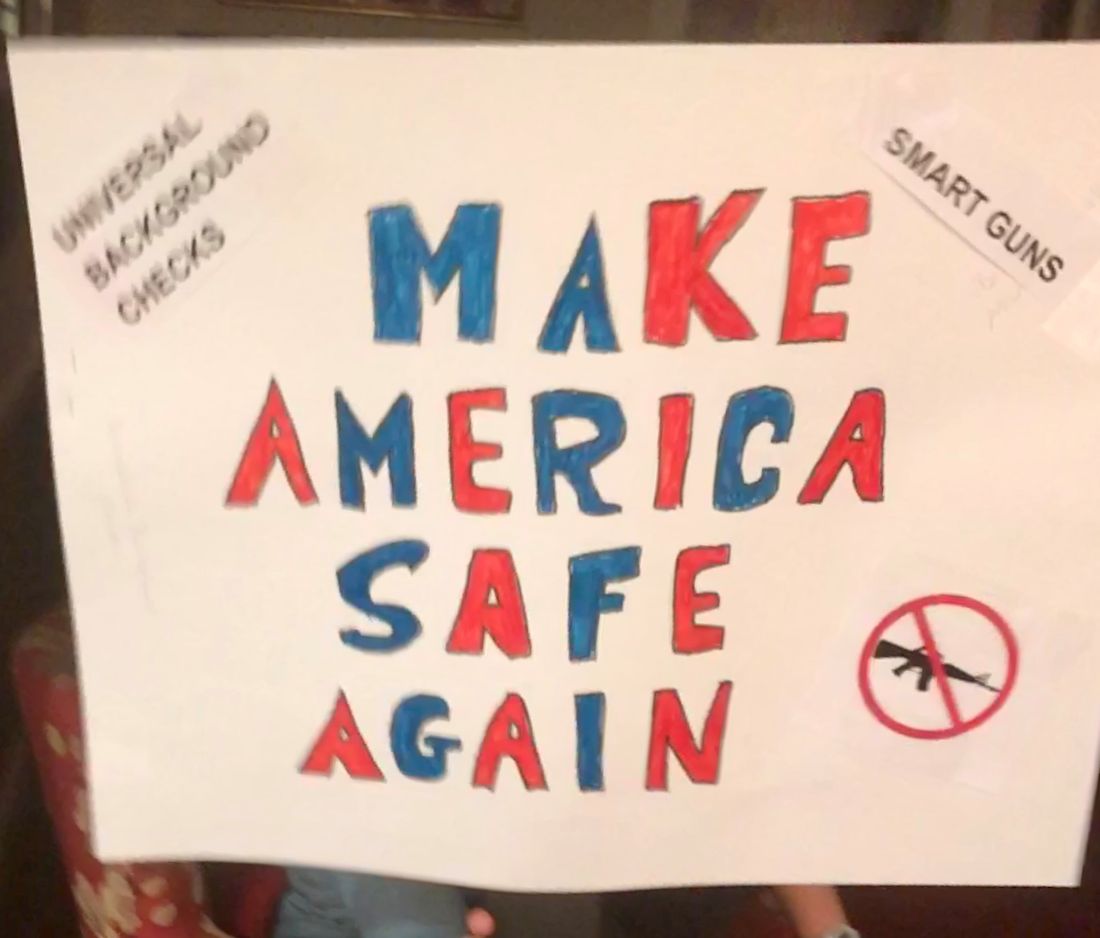

The evening before the March For Our Lives rally in Washington, I was hard at work on my sign. Making a statement is important, but at the Women’s March last January, I discovered that a sign was invaluable for keeping friends together in a crowd. Since my Women’s March sign read “Make America Kind Again,” I opted to keep with the theme, and I created a “Make America Safe Again” sign for gun control. My daughter looked at my sign skeptically. “It’s too vague and nondirective,” she declared. Now challenged, I added the following directives: “Universal Background Checks,” “Ban Assault Weapons,” and “Smart Guns.” My sign was now complete.

I was surprised when my daughter – our family Jeopardy! whiz – asked, “What’s a smart gun?” When we arrived to join friends, their daughter – a doctoral student – also looked at the sign and asked me what a smart gun is. I explained to both young women that a smart gun – like an iPhone – relies on a biometric such as a fingerprint so that it can be used only by authorized users. This technology would reduce the flow of firearms to illegal owners, prevent accidental discharge by children, protect rightful owners and law enforcement officers from having their own weapons used against them by criminals, and decrease the number of suicides by family members of gun owners. In my state of Maryland, there have been two school shootings, one as recently as March 20, and both were committed by boys who took a parent’s firearm to school.

We arrived at the rally and found a spot in front of the Newseum, with two jumbotrons in sight, right in the middle of the crowd. The young people who spoke were inspirational. Regardless of one’s political views or thoughts on gun control, they were bright, articulate, fearless, passionate, and determined. The show was stolen by Naomi Wadler, a precocious 11-year-old girl who is destined to be a member of Congress (if not president) one day, and by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s 9-year-old granddaughter, Yolanda Renee King.

The rest of the speakers were teenagers, all of whom had lost someone to gunfire. There were speakers from Parkland, Fla., who talked about the raw losses they were feeling, and the student who wasn’t celebrating his 18th birthday on March 24. Matthew Soto from Newtown, Conn., talked about losing his sister, a first-grade teacher, in the Sandy Hook shooting.

But the rally wasn’t just about mass murders and school shootings: Zion Kelly talked about the death of his twin, a teen who was killed when he stopped at a convenience store on the way home from school in Washington, only to have his promising life snuffed out during a holdup. We heard about shootings in the bullet-riddled streets of Chicago and Los Angeles and the toll they have taken. The losses to gun violence have been felt most strongly in communities of color. While it was mentioned that the majority of gun deaths are suicides, there were no speakers from families of people who died from suicide. The final speaker was Emma Gonzalez, a young woman from Parkland who took the stage for 6 minutes and 20 seconds - the duration of the shooter’s rampage - and closed with a powerful moment of silence.* The rally closed with a performance of Bob Dylan’s “The Times They Are a-Changin’ ” by Jennifer Hudson, whose mother, brother, and nephew were murdered by a gunman.

The teens talked about what changes they wanted to see enacted. They talked about closing loopholes to background checks, and I was pleased that one young man specifically mentioned keeping guns from those who are violent, but did not mention mental illness as a reason to block gun ownership. A call to resume a ban on assault weapons was made repeatedly as was a call to raise the age (to 21) at which an individual can purchase a gun. Military-style weapons are not necessary for hunting or self-defense, and they enable the rapid-fire assassinations we have seen in mass shootings, so they remain an easy target of gun control advocacy. But in terms of numbers, these firearms are responsible for a small fraction of gun deaths. I was surprised, but the teens did not mention “smart gun” legislation as a way to reduce gun deaths.

Guns, and gun deaths, are a part of American society. While the majority of Americans favor stronger regulation of gun ownership, legislation that would end gun ownership is not likely to go anywhere. Smart guns, however, are different. Forty percent of polled gun owners have said they would swap their firearm for a smart firearm. So given the appeal of a firearm that can’t be diverted or stolen, used against the owner, discharged accidentally by a child, or used for suicide or homicide by a distressed family member, why don’t these weapons exist for use by the American people? . People want these guns and the protections they offer, yet they have never been produced and made available to either the American public or to our law enforcement officers.

So where are these firearms, and why aren’t our Parkland teens asking for them? The answer to the first part of that question lies with the National Rifle Association (NRA) and the state of New Jersey. In 2003, New Jersey passed the Childproof Handgun bill, which requires that all guns sold in the state be smart guns within 3 years of their availability. The NRA has vigorously opposed any legislation that would require all guns to be smart guns. Because the availability of these weapons would trigger the New Jersey bill, California and Maryland have been prevented from importing smart firearms from a German company. Perhaps, however, New Jersey does not need to bear all the blame; in 1999, 4 years before the passage of the bill, the NRA and its members boycotted Smith & Wesson when the gun manufacturer revealed plans to develop a smart gun for the government. The NRA’s public stance is that it does not oppose smart guns for those who want them, but it opposes legislation that would eliminate the sale of conventional firearms. The organization has voiced concerns that technology fails and that it potentially slows down firing the weapon. It doesn’t talk about dead toddlers, or about police officers who’ve been killed when their weapons were taken from them.

As for the Parkland students, I don’t know why they aren’t asking for smart gun technology while they have the attention of the country. Perhaps they, like the young women I was with, don’t know it’s an option. Perhaps it’s too removed from the issue of mass murders and an assault weapon ban feels more attainable. Or perhaps the NRA’s mission has too much of a stronghold in Florida. I don’t know why they aren’t asking for smart gun production, but I know they should be.

*Correction, 3/27/2018: An earlier version of this story misstated the duration of Emma Gonzalez's moment of silence.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press), 2016. She practices in Baltimore.

The evening before the March For Our Lives rally in Washington, I was hard at work on my sign. Making a statement is important, but at the Women’s March last January, I discovered that a sign was invaluable for keeping friends together in a crowd. Since my Women’s March sign read “Make America Kind Again,” I opted to keep with the theme, and I created a “Make America Safe Again” sign for gun control. My daughter looked at my sign skeptically. “It’s too vague and nondirective,” she declared. Now challenged, I added the following directives: “Universal Background Checks,” “Ban Assault Weapons,” and “Smart Guns.” My sign was now complete.

I was surprised when my daughter – our family Jeopardy! whiz – asked, “What’s a smart gun?” When we arrived to join friends, their daughter – a doctoral student – also looked at the sign and asked me what a smart gun is. I explained to both young women that a smart gun – like an iPhone – relies on a biometric such as a fingerprint so that it can be used only by authorized users. This technology would reduce the flow of firearms to illegal owners, prevent accidental discharge by children, protect rightful owners and law enforcement officers from having their own weapons used against them by criminals, and decrease the number of suicides by family members of gun owners. In my state of Maryland, there have been two school shootings, one as recently as March 20, and both were committed by boys who took a parent’s firearm to school.

We arrived at the rally and found a spot in front of the Newseum, with two jumbotrons in sight, right in the middle of the crowd. The young people who spoke were inspirational. Regardless of one’s political views or thoughts on gun control, they were bright, articulate, fearless, passionate, and determined. The show was stolen by Naomi Wadler, a precocious 11-year-old girl who is destined to be a member of Congress (if not president) one day, and by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s 9-year-old granddaughter, Yolanda Renee King.

The rest of the speakers were teenagers, all of whom had lost someone to gunfire. There were speakers from Parkland, Fla., who talked about the raw losses they were feeling, and the student who wasn’t celebrating his 18th birthday on March 24. Matthew Soto from Newtown, Conn., talked about losing his sister, a first-grade teacher, in the Sandy Hook shooting.

But the rally wasn’t just about mass murders and school shootings: Zion Kelly talked about the death of his twin, a teen who was killed when he stopped at a convenience store on the way home from school in Washington, only to have his promising life snuffed out during a holdup. We heard about shootings in the bullet-riddled streets of Chicago and Los Angeles and the toll they have taken. The losses to gun violence have been felt most strongly in communities of color. While it was mentioned that the majority of gun deaths are suicides, there were no speakers from families of people who died from suicide. The final speaker was Emma Gonzalez, a young woman from Parkland who took the stage for 6 minutes and 20 seconds - the duration of the shooter’s rampage - and closed with a powerful moment of silence.* The rally closed with a performance of Bob Dylan’s “The Times They Are a-Changin’ ” by Jennifer Hudson, whose mother, brother, and nephew were murdered by a gunman.

The teens talked about what changes they wanted to see enacted. They talked about closing loopholes to background checks, and I was pleased that one young man specifically mentioned keeping guns from those who are violent, but did not mention mental illness as a reason to block gun ownership. A call to resume a ban on assault weapons was made repeatedly as was a call to raise the age (to 21) at which an individual can purchase a gun. Military-style weapons are not necessary for hunting or self-defense, and they enable the rapid-fire assassinations we have seen in mass shootings, so they remain an easy target of gun control advocacy. But in terms of numbers, these firearms are responsible for a small fraction of gun deaths. I was surprised, but the teens did not mention “smart gun” legislation as a way to reduce gun deaths.

Guns, and gun deaths, are a part of American society. While the majority of Americans favor stronger regulation of gun ownership, legislation that would end gun ownership is not likely to go anywhere. Smart guns, however, are different. Forty percent of polled gun owners have said they would swap their firearm for a smart firearm. So given the appeal of a firearm that can’t be diverted or stolen, used against the owner, discharged accidentally by a child, or used for suicide or homicide by a distressed family member, why don’t these weapons exist for use by the American people? . People want these guns and the protections they offer, yet they have never been produced and made available to either the American public or to our law enforcement officers.

So where are these firearms, and why aren’t our Parkland teens asking for them? The answer to the first part of that question lies with the National Rifle Association (NRA) and the state of New Jersey. In 2003, New Jersey passed the Childproof Handgun bill, which requires that all guns sold in the state be smart guns within 3 years of their availability. The NRA has vigorously opposed any legislation that would require all guns to be smart guns. Because the availability of these weapons would trigger the New Jersey bill, California and Maryland have been prevented from importing smart firearms from a German company. Perhaps, however, New Jersey does not need to bear all the blame; in 1999, 4 years before the passage of the bill, the NRA and its members boycotted Smith & Wesson when the gun manufacturer revealed plans to develop a smart gun for the government. The NRA’s public stance is that it does not oppose smart guns for those who want them, but it opposes legislation that would eliminate the sale of conventional firearms. The organization has voiced concerns that technology fails and that it potentially slows down firing the weapon. It doesn’t talk about dead toddlers, or about police officers who’ve been killed when their weapons were taken from them.

As for the Parkland students, I don’t know why they aren’t asking for smart gun technology while they have the attention of the country. Perhaps they, like the young women I was with, don’t know it’s an option. Perhaps it’s too removed from the issue of mass murders and an assault weapon ban feels more attainable. Or perhaps the NRA’s mission has too much of a stronghold in Florida. I don’t know why they aren’t asking for smart gun production, but I know they should be.

*Correction, 3/27/2018: An earlier version of this story misstated the duration of Emma Gonzalez's moment of silence.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press), 2016. She practices in Baltimore.

The evening before the March For Our Lives rally in Washington, I was hard at work on my sign. Making a statement is important, but at the Women’s March last January, I discovered that a sign was invaluable for keeping friends together in a crowd. Since my Women’s March sign read “Make America Kind Again,” I opted to keep with the theme, and I created a “Make America Safe Again” sign for gun control. My daughter looked at my sign skeptically. “It’s too vague and nondirective,” she declared. Now challenged, I added the following directives: “Universal Background Checks,” “Ban Assault Weapons,” and “Smart Guns.” My sign was now complete.

I was surprised when my daughter – our family Jeopardy! whiz – asked, “What’s a smart gun?” When we arrived to join friends, their daughter – a doctoral student – also looked at the sign and asked me what a smart gun is. I explained to both young women that a smart gun – like an iPhone – relies on a biometric such as a fingerprint so that it can be used only by authorized users. This technology would reduce the flow of firearms to illegal owners, prevent accidental discharge by children, protect rightful owners and law enforcement officers from having their own weapons used against them by criminals, and decrease the number of suicides by family members of gun owners. In my state of Maryland, there have been two school shootings, one as recently as March 20, and both were committed by boys who took a parent’s firearm to school.

We arrived at the rally and found a spot in front of the Newseum, with two jumbotrons in sight, right in the middle of the crowd. The young people who spoke were inspirational. Regardless of one’s political views or thoughts on gun control, they were bright, articulate, fearless, passionate, and determined. The show was stolen by Naomi Wadler, a precocious 11-year-old girl who is destined to be a member of Congress (if not president) one day, and by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s 9-year-old granddaughter, Yolanda Renee King.

The rest of the speakers were teenagers, all of whom had lost someone to gunfire. There were speakers from Parkland, Fla., who talked about the raw losses they were feeling, and the student who wasn’t celebrating his 18th birthday on March 24. Matthew Soto from Newtown, Conn., talked about losing his sister, a first-grade teacher, in the Sandy Hook shooting.

But the rally wasn’t just about mass murders and school shootings: Zion Kelly talked about the death of his twin, a teen who was killed when he stopped at a convenience store on the way home from school in Washington, only to have his promising life snuffed out during a holdup. We heard about shootings in the bullet-riddled streets of Chicago and Los Angeles and the toll they have taken. The losses to gun violence have been felt most strongly in communities of color. While it was mentioned that the majority of gun deaths are suicides, there were no speakers from families of people who died from suicide. The final speaker was Emma Gonzalez, a young woman from Parkland who took the stage for 6 minutes and 20 seconds - the duration of the shooter’s rampage - and closed with a powerful moment of silence.* The rally closed with a performance of Bob Dylan’s “The Times They Are a-Changin’ ” by Jennifer Hudson, whose mother, brother, and nephew were murdered by a gunman.

The teens talked about what changes they wanted to see enacted. They talked about closing loopholes to background checks, and I was pleased that one young man specifically mentioned keeping guns from those who are violent, but did not mention mental illness as a reason to block gun ownership. A call to resume a ban on assault weapons was made repeatedly as was a call to raise the age (to 21) at which an individual can purchase a gun. Military-style weapons are not necessary for hunting or self-defense, and they enable the rapid-fire assassinations we have seen in mass shootings, so they remain an easy target of gun control advocacy. But in terms of numbers, these firearms are responsible for a small fraction of gun deaths. I was surprised, but the teens did not mention “smart gun” legislation as a way to reduce gun deaths.

Guns, and gun deaths, are a part of American society. While the majority of Americans favor stronger regulation of gun ownership, legislation that would end gun ownership is not likely to go anywhere. Smart guns, however, are different. Forty percent of polled gun owners have said they would swap their firearm for a smart firearm. So given the appeal of a firearm that can’t be diverted or stolen, used against the owner, discharged accidentally by a child, or used for suicide or homicide by a distressed family member, why don’t these weapons exist for use by the American people? . People want these guns and the protections they offer, yet they have never been produced and made available to either the American public or to our law enforcement officers.

So where are these firearms, and why aren’t our Parkland teens asking for them? The answer to the first part of that question lies with the National Rifle Association (NRA) and the state of New Jersey. In 2003, New Jersey passed the Childproof Handgun bill, which requires that all guns sold in the state be smart guns within 3 years of their availability. The NRA has vigorously opposed any legislation that would require all guns to be smart guns. Because the availability of these weapons would trigger the New Jersey bill, California and Maryland have been prevented from importing smart firearms from a German company. Perhaps, however, New Jersey does not need to bear all the blame; in 1999, 4 years before the passage of the bill, the NRA and its members boycotted Smith & Wesson when the gun manufacturer revealed plans to develop a smart gun for the government. The NRA’s public stance is that it does not oppose smart guns for those who want them, but it opposes legislation that would eliminate the sale of conventional firearms. The organization has voiced concerns that technology fails and that it potentially slows down firing the weapon. It doesn’t talk about dead toddlers, or about police officers who’ve been killed when their weapons were taken from them.

As for the Parkland students, I don’t know why they aren’t asking for smart gun technology while they have the attention of the country. Perhaps they, like the young women I was with, don’t know it’s an option. Perhaps it’s too removed from the issue of mass murders and an assault weapon ban feels more attainable. Or perhaps the NRA’s mission has too much of a stronghold in Florida. I don’t know why they aren’t asking for smart gun production, but I know they should be.

*Correction, 3/27/2018: An earlier version of this story misstated the duration of Emma Gonzalez's moment of silence.

Dr. Miller is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press), 2016. She practices in Baltimore.

Trauma surgeon shares story of involuntary commitment, redemption

Over the last few years, I have spoken to many people about their experiences with involuntary psychiatric hospitalizations. While the stories I’ve heard are anecdotes, often from people who have reached out to me, and not randomized, controlled studies, I’ve taken the liberty of coming to a few conclusions. First, involuntary hospitalizations help people. Most people say that they left the hospital with fewer symptoms than they had when they entered. Second, many of those people, helped though they may have been, are angry about the treatment they received. An unknown percentage feel traumatized by their psychiatric treatment, and years later they dwell on a perception of injustice and injury.

It’s perplexing that this negative residue remains given that involuntary psychiatric care often helps people to escape from the torment of psychosis or from soul-crushing depressions. While many feel it should be easier to involuntarily treat psychiatric disorders, there are no groups of patients asking for easier access to involuntary care. One group, Mad in America – formed by journalist Robert Whitaker – takes the position that psychiatric medications don’t just harm people, but that psychotropic medications actually cause psychiatric disorders in people who would have fared better without them. It now offers CME activities through its conferences and website!

“In the middle of elective inpatient electroconvulsive therapy for treatment-resistant depression, he had become profoundly depressed, delirious, and hopeless. He’d lost faith in treatment and in reasons to live. He withdrew to bed and would not get up or eat. He had to be committed for his own safety. Several security guards had to forcefully remove him from his bed.”

The patient, he noted, was injected with haloperidol and placed in restraints in a seclusion room. By the third paragraph, Weinstein switches to a first-person narrative and reveals that he is that patient. He goes on to talk about the stresses of life as a trauma surgeon, and describes both classic physician burnout and severe major depression. The essay includes an element of catharsis. The author shares his painful story, with all the gore of amputating the limbs of others to the agony of feeling that those he loves might be better off without him. Post-hospitalization, Weinstein’s message is clear: He wants to help others break free from the stigma of silent shame and let them know that help is available. “You would not be reading this today were it not for the love of my wife, my children, my mother and sister, and so many others, including the guards and doctors who ‘locked me up’ against my will. They kept me from crossing into the abyss,” he writes.

The essay (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:793-5) surprised me, because I have never heard a patient who has been forcibly medicated and placed in restraints and seclusion talk about the experience with gratitude. I contacted Dr. Weinstein and asked if he would speak with me about his experiences as a committed patient back in early 2016. In fact, he said that he had only recently begun to speak of his experiences with his therapist, and he spoke openly about what he remembered of those events.

Dr. Weinstein told me his story in more detail – it was a long and tumultuous journey from the depth of depression to where he is now. “I’m in a much better place than I’ve ever been. I’ve developed tools for resilience and I’ve found joy.” His gratitude was real, and his purpose in sharing his story remains a positive and hopeful vision for others who suffer. Clearly, he was not traumatized by his treatment. I approached him with the question of what psychiatrists could learn from his experiences. The story that followed had the texture of those I was used to hearing from people who had been involuntarily treated.

Like many people I’ve spoken with, Dr. Weinstein assumed he was officially committed to the locked unit, but he did not recall a legal hearing. In fact, many of those I’ve talked with had actually signed themselves in, and Dr. Weinstein thought that was possible.

“When I wrote the New England Journal piece, it originated from a place of anger. I was voluntarily admitted to a private, self-pay psychiatric unit, and I was getting ECT. I was getting worse, not better. I was in a scary place, and I was deeply depressed. The day before, I had gone for a walk without telling the staff or following the sign-out procedure. They decided I needed to be in a locked unit, and when they told me, I was lying in bed.”

Upon hearing that he would be transferred, Dr. Weinstein became combative. He was medicated and taken to a locked unit in the hospital, placed in restraints, and put into a seclusion room.

“I’ve wondered if this could have been done another way. Maybe if they had given me a chance to process the information, perhaps I would have gone more willingly without guards carrying me through the facility. I wondered if the way the information was delivered didn’t escalate things, if it could have been done differently.” Listening to him, I wondered as well, though Dr. Weinstein was well aware that the actions of his treatment team came with the best of intentions to help him. I pointed out that the treatment team may have felt fearful when he disappeared from the unit, and as they watched him decline further, they may well have felt a bit desperate and fearful of their ability to keep him safe on an unlocked unit. None of this surprised him.

Was Dr. Weinstein open to returning to a psychiatric unit if his depression recurs?

“A few months after I left, I became even more depressed and suicidal. I didn’t go back, and I really hope I’ll never have to be in a hospital again.” Instead,. “They changed my perspective.”

Dr. Weinstein also questions if he should have agreed to ECT. “I was better when I left the hospital, but the treatment itself was crude, and I still wonder if it affects my memory now.”

I wanted to know what psychiatrists might learn from his experiences with involuntary care. Weinstein hesitated. “It wasn’t the best experience, and I felt there had to be a better way, but I know everyone was trying to help me, and I want my overall message to be one of hope. I don’t want to complain, because I’ve ended up in a much better place, I’m back at work, enjoying my family, and I feel joy now.”

For psychiatrists, this is the best outcome from a story such as Dr. Weinstein’s. He’s much better, in a scenario where he could have just as easily have died, and he wasn’t traumatized by his care. However, he avoided returning to inpatient care at a precarious time, and he’s left asking if there weren’t a gentler way this could have transpired. These questions are easier to look at from the perspective of a Monday morning quarterback than they are to look at from the perspective of a treatment team dealing with a very sick and combative patient. Still, I hope we all continue to question patients about their experiences and ask if there might be better ways.

Dr. Miller, who practices in Baltimore, is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

Over the last few years, I have spoken to many people about their experiences with involuntary psychiatric hospitalizations. While the stories I’ve heard are anecdotes, often from people who have reached out to me, and not randomized, controlled studies, I’ve taken the liberty of coming to a few conclusions. First, involuntary hospitalizations help people. Most people say that they left the hospital with fewer symptoms than they had when they entered. Second, many of those people, helped though they may have been, are angry about the treatment they received. An unknown percentage feel traumatized by their psychiatric treatment, and years later they dwell on a perception of injustice and injury.

It’s perplexing that this negative residue remains given that involuntary psychiatric care often helps people to escape from the torment of psychosis or from soul-crushing depressions. While many feel it should be easier to involuntarily treat psychiatric disorders, there are no groups of patients asking for easier access to involuntary care. One group, Mad in America – formed by journalist Robert Whitaker – takes the position that psychiatric medications don’t just harm people, but that psychotropic medications actually cause psychiatric disorders in people who would have fared better without them. It now offers CME activities through its conferences and website!

“In the middle of elective inpatient electroconvulsive therapy for treatment-resistant depression, he had become profoundly depressed, delirious, and hopeless. He’d lost faith in treatment and in reasons to live. He withdrew to bed and would not get up or eat. He had to be committed for his own safety. Several security guards had to forcefully remove him from his bed.”

The patient, he noted, was injected with haloperidol and placed in restraints in a seclusion room. By the third paragraph, Weinstein switches to a first-person narrative and reveals that he is that patient. He goes on to talk about the stresses of life as a trauma surgeon, and describes both classic physician burnout and severe major depression. The essay includes an element of catharsis. The author shares his painful story, with all the gore of amputating the limbs of others to the agony of feeling that those he loves might be better off without him. Post-hospitalization, Weinstein’s message is clear: He wants to help others break free from the stigma of silent shame and let them know that help is available. “You would not be reading this today were it not for the love of my wife, my children, my mother and sister, and so many others, including the guards and doctors who ‘locked me up’ against my will. They kept me from crossing into the abyss,” he writes.

The essay (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:793-5) surprised me, because I have never heard a patient who has been forcibly medicated and placed in restraints and seclusion talk about the experience with gratitude. I contacted Dr. Weinstein and asked if he would speak with me about his experiences as a committed patient back in early 2016. In fact, he said that he had only recently begun to speak of his experiences with his therapist, and he spoke openly about what he remembered of those events.

Dr. Weinstein told me his story in more detail – it was a long and tumultuous journey from the depth of depression to where he is now. “I’m in a much better place than I’ve ever been. I’ve developed tools for resilience and I’ve found joy.” His gratitude was real, and his purpose in sharing his story remains a positive and hopeful vision for others who suffer. Clearly, he was not traumatized by his treatment. I approached him with the question of what psychiatrists could learn from his experiences. The story that followed had the texture of those I was used to hearing from people who had been involuntarily treated.

Like many people I’ve spoken with, Dr. Weinstein assumed he was officially committed to the locked unit, but he did not recall a legal hearing. In fact, many of those I’ve talked with had actually signed themselves in, and Dr. Weinstein thought that was possible.

“When I wrote the New England Journal piece, it originated from a place of anger. I was voluntarily admitted to a private, self-pay psychiatric unit, and I was getting ECT. I was getting worse, not better. I was in a scary place, and I was deeply depressed. The day before, I had gone for a walk without telling the staff or following the sign-out procedure. They decided I needed to be in a locked unit, and when they told me, I was lying in bed.”

Upon hearing that he would be transferred, Dr. Weinstein became combative. He was medicated and taken to a locked unit in the hospital, placed in restraints, and put into a seclusion room.

“I’ve wondered if this could have been done another way. Maybe if they had given me a chance to process the information, perhaps I would have gone more willingly without guards carrying me through the facility. I wondered if the way the information was delivered didn’t escalate things, if it could have been done differently.” Listening to him, I wondered as well, though Dr. Weinstein was well aware that the actions of his treatment team came with the best of intentions to help him. I pointed out that the treatment team may have felt fearful when he disappeared from the unit, and as they watched him decline further, they may well have felt a bit desperate and fearful of their ability to keep him safe on an unlocked unit. None of this surprised him.

Was Dr. Weinstein open to returning to a psychiatric unit if his depression recurs?

“A few months after I left, I became even more depressed and suicidal. I didn’t go back, and I really hope I’ll never have to be in a hospital again.” Instead,. “They changed my perspective.”

Dr. Weinstein also questions if he should have agreed to ECT. “I was better when I left the hospital, but the treatment itself was crude, and I still wonder if it affects my memory now.”

I wanted to know what psychiatrists might learn from his experiences with involuntary care. Weinstein hesitated. “It wasn’t the best experience, and I felt there had to be a better way, but I know everyone was trying to help me, and I want my overall message to be one of hope. I don’t want to complain, because I’ve ended up in a much better place, I’m back at work, enjoying my family, and I feel joy now.”

For psychiatrists, this is the best outcome from a story such as Dr. Weinstein’s. He’s much better, in a scenario where he could have just as easily have died, and he wasn’t traumatized by his care. However, he avoided returning to inpatient care at a precarious time, and he’s left asking if there weren’t a gentler way this could have transpired. These questions are easier to look at from the perspective of a Monday morning quarterback than they are to look at from the perspective of a treatment team dealing with a very sick and combative patient. Still, I hope we all continue to question patients about their experiences and ask if there might be better ways.

Dr. Miller, who practices in Baltimore, is coauthor with Annette Hanson, MD, of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

Over the last few years, I have spoken to many people about their experiences with involuntary psychiatric hospitalizations. While the stories I’ve heard are anecdotes, often from people who have reached out to me, and not randomized, controlled studies, I’ve taken the liberty of coming to a few conclusions. First, involuntary hospitalizations help people. Most people say that they left the hospital with fewer symptoms than they had when they entered. Second, many of those people, helped though they may have been, are angry about the treatment they received. An unknown percentage feel traumatized by their psychiatric treatment, and years later they dwell on a perception of injustice and injury.

It’s perplexing that this negative residue remains given that involuntary psychiatric care often helps people to escape from the torment of psychosis or from soul-crushing depressions. While many feel it should be easier to involuntarily treat psychiatric disorders, there are no groups of patients asking for easier access to involuntary care. One group, Mad in America – formed by journalist Robert Whitaker – takes the position that psychiatric medications don’t just harm people, but that psychotropic medications actually cause psychiatric disorders in people who would have fared better without them. It now offers CME activities through its conferences and website!

“In the middle of elective inpatient electroconvulsive therapy for treatment-resistant depression, he had become profoundly depressed, delirious, and hopeless. He’d lost faith in treatment and in reasons to live. He withdrew to bed and would not get up or eat. He had to be committed for his own safety. Several security guards had to forcefully remove him from his bed.”

The patient, he noted, was injected with haloperidol and placed in restraints in a seclusion room. By the third paragraph, Weinstein switches to a first-person narrative and reveals that he is that patient. He goes on to talk about the stresses of life as a trauma surgeon, and describes both classic physician burnout and severe major depression. The essay includes an element of catharsis. The author shares his painful story, with all the gore of amputating the limbs of others to the agony of feeling that those he loves might be better off without him. Post-hospitalization, Weinstein’s message is clear: He wants to help others break free from the stigma of silent shame and let them know that help is available. “You would not be reading this today were it not for the love of my wife, my children, my mother and sister, and so many others, including the guards and doctors who ‘locked me up’ against my will. They kept me from crossing into the abyss,” he writes.

The essay (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:793-5) surprised me, because I have never heard a patient who has been forcibly medicated and placed in restraints and seclusion talk about the experience with gratitude. I contacted Dr. Weinstein and asked if he would speak with me about his experiences as a committed patient back in early 2016. In fact, he said that he had only recently begun to speak of his experiences with his therapist, and he spoke openly about what he remembered of those events.

Dr. Weinstein told me his story in more detail – it was a long and tumultuous journey from the depth of depression to where he is now. “I’m in a much better place than I’ve ever been. I’ve developed tools for resilience and I’ve found joy.” His gratitude was real, and his purpose in sharing his story remains a positive and hopeful vision for others who suffer. Clearly, he was not traumatized by his treatment. I approached him with the question of what psychiatrists could learn from his experiences. The story that followed had the texture of those I was used to hearing from people who had been involuntarily treated.

Like many people I’ve spoken with, Dr. Weinstein assumed he was officially committed to the locked unit, but he did not recall a legal hearing. In fact, many of those I’ve talked with had actually signed themselves in, and Dr. Weinstein thought that was possible.

“When I wrote the New England Journal piece, it originated from a place of anger. I was voluntarily admitted to a private, self-pay psychiatric unit, and I was getting ECT. I was getting worse, not better. I was in a scary place, and I was deeply depressed. The day before, I had gone for a walk without telling the staff or following the sign-out procedure. They decided I needed to be in a locked unit, and when they told me, I was lying in bed.”

Upon hearing that he would be transferred, Dr. Weinstein became combative. He was medicated and taken to a locked unit in the hospital, placed in restraints, and put into a seclusion room.

“I’ve wondered if this could have been done another way. Maybe if they had given me a chance to process the information, perhaps I would have gone more willingly without guards carrying me through the facility. I wondered if the way the information was delivered didn’t escalate things, if it could have been done differently.” Listening to him, I wondered as well, though Dr. Weinstein was well aware that the actions of his treatment team came with the best of intentions to help him. I pointed out that the treatment team may have felt fearful when he disappeared from the unit, and as they watched him decline further, they may well have felt a bit desperate and fearful of their ability to keep him safe on an unlocked unit. None of this surprised him.

Was Dr. Weinstein open to returning to a psychiatric unit if his depression recurs?