User login

Nails falling off in a 3-year-old

When the nails peel off from the proximal nail folds, the clinical term is onychomadesis and it is important to ask about recent infections or severe metabolic stressors. In children and adults, onychomadesis on multiple fingers may occur after infections and has been associated with hand-foot-mouth disease caused by common viral infections—especially strains of coxsackievirus.1

Because shed nails show evidence of viral infection, one hypothesis for their peeling off is that the tissue of the nail matrix is infected, leading to metabolic changes. As the nail matrix returns to normal function, a new nail is made and ultimately will replace the nail that has come off. In healthy US adults, fingernails grow 3.47 mm per month on average while toenails grow 1.62 mm per month on average.2

Sometimes it’s hard to elicit a history of a very mild viral illness weeks or months after it has resolved. Asking specifically about mouth ulcers may help. If there is a history of a viral illness, no specific work-up or treatment is necessary. Patients may be reassured that nails will improve over several months without lasting effects.

In this case, the patient and her family were given reassurance and the nails returned to normal within a few months.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Kim EJ, Park HS, Yoon HS, et al. Four cases of onychomadesis after hand-foot-mouth disease. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:777-778. doi: 10.5021/ad.2014.26.6.777

2. Yaemsiri S, Hou N, Slining MM, et al. Growth rate of human fingernails and toenails in healthy American young adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:420-423. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03426.x

When the nails peel off from the proximal nail folds, the clinical term is onychomadesis and it is important to ask about recent infections or severe metabolic stressors. In children and adults, onychomadesis on multiple fingers may occur after infections and has been associated with hand-foot-mouth disease caused by common viral infections—especially strains of coxsackievirus.1

Because shed nails show evidence of viral infection, one hypothesis for their peeling off is that the tissue of the nail matrix is infected, leading to metabolic changes. As the nail matrix returns to normal function, a new nail is made and ultimately will replace the nail that has come off. In healthy US adults, fingernails grow 3.47 mm per month on average while toenails grow 1.62 mm per month on average.2

Sometimes it’s hard to elicit a history of a very mild viral illness weeks or months after it has resolved. Asking specifically about mouth ulcers may help. If there is a history of a viral illness, no specific work-up or treatment is necessary. Patients may be reassured that nails will improve over several months without lasting effects.

In this case, the patient and her family were given reassurance and the nails returned to normal within a few months.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

When the nails peel off from the proximal nail folds, the clinical term is onychomadesis and it is important to ask about recent infections or severe metabolic stressors. In children and adults, onychomadesis on multiple fingers may occur after infections and has been associated with hand-foot-mouth disease caused by common viral infections—especially strains of coxsackievirus.1

Because shed nails show evidence of viral infection, one hypothesis for their peeling off is that the tissue of the nail matrix is infected, leading to metabolic changes. As the nail matrix returns to normal function, a new nail is made and ultimately will replace the nail that has come off. In healthy US adults, fingernails grow 3.47 mm per month on average while toenails grow 1.62 mm per month on average.2

Sometimes it’s hard to elicit a history of a very mild viral illness weeks or months after it has resolved. Asking specifically about mouth ulcers may help. If there is a history of a viral illness, no specific work-up or treatment is necessary. Patients may be reassured that nails will improve over several months without lasting effects.

In this case, the patient and her family were given reassurance and the nails returned to normal within a few months.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Kim EJ, Park HS, Yoon HS, et al. Four cases of onychomadesis after hand-foot-mouth disease. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:777-778. doi: 10.5021/ad.2014.26.6.777

2. Yaemsiri S, Hou N, Slining MM, et al. Growth rate of human fingernails and toenails in healthy American young adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:420-423. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03426.x

1. Kim EJ, Park HS, Yoon HS, et al. Four cases of onychomadesis after hand-foot-mouth disease. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:777-778. doi: 10.5021/ad.2014.26.6.777

2. Yaemsiri S, Hou N, Slining MM, et al. Growth rate of human fingernails and toenails in healthy American young adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:420-423. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03426.x

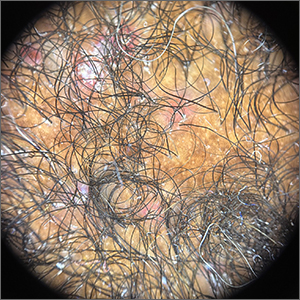

Fade haircut or something else?

The areas of hair loss and different length hairs in a patient with otherwise normal-density hair was consistent with a diagnosis of trichotillomania. The physician initially thought the patient had a “fade” hairstyle, but then observed him twirling his hair. Further queries confirmed a history of hair pulling (trichotillomania) and ingesting the hair (trichophagia).

In adulthood, trichotillomania affects females about 4 times more than males, although in childhood, the sex distribution appears about equal.1 The typical age of onset is between 10 to 13 years. Several mental health conditions are associated with trichotillomania, such as major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, and substance use disorder, with trichotillomania generally preceding these comorbid disorders. It is important to rule out obsessive compulsive disorder and consider body dysmorphic disorder when making a diagnosis of trichotillomania.1

It is common to see androgenetic alopecia precipitated by hormone therapy in FTM individuals. This would usually cause thinning of the hair rather than the irregular hair lengths and pattern seen in this patient. Tinea capitis is also part of the differential diagnosis in a case such as this. It can be diagnosed by potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations in the setting of friable and broken hair shafts (and sometimes erythema and inflammation).

Patients with trichotillomania may have hair with blunt or tapered ends; hair may also look like uneven stubble.2 The scalp is the most commonly involved site (72.8%), followed by eyebrows (50.7%), and the pubic region (50.7%).1 Useful diagnostic clues include an unusual shape of the affected area, accessible location, and a changing pattern from visit to visit.2 If trichotillomania is suspected, it might be useful to ask about hair-playing activities, such as twirling or twisting, or playing with the ends of eyelashes or eyebrows.2

Unwanted medical consequences of trichotillomania include skin damage (if sharp instruments are used for hair pulling), and the formation of gastrointestinal trichobezoars (hairballs) if trichophagia is present. Trichobezoars that cause bowel obstructions may need surgical intervention.1

Behavioral therapy is the first-line treatment for trichotillomania in all age groups.1,3 Treating any coexisting mental health disorders is also essential. There are currently no FDA-approved medications for treatment; however, there is evidence that N-acetylcysteine may be useful in treating adults with trichotillomania and other repetitive skin disorders.3 Antipsychotics and cannabinoid agonists also may be beneficial.1

This patient was continued on his current lithium, naltrexone, and bupropion regimen (rather than adding additional psychiatric medicines) as he was doing better than his previous baseline. He was advised to continue with his cognitive behavioral therapy. His hormone replacement therapy also was continued because it was not thought to be contributory. He was provided with education about symptoms of trichobezoar and red flag symptoms (eg, worsening nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain) that would necessitate emergency follow-up. His GERD symptoms were thought not to be related to his trichophagia. He was scheduled to follow up for routine primary care in 6 months.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Sarasawati Keeni, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Grant JE and Chamberlain SR. Trichotillomania. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:868-874. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15111432

2. Sah DE, Koo J, Price VH. Trichotillomania. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:13-21. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00165.x

3. Henkel ED, Jaquez SD, Diaz LZ. Pediatric trichotillomania: review of management. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:803-807. doi: 10.1111/pde.13954

The areas of hair loss and different length hairs in a patient with otherwise normal-density hair was consistent with a diagnosis of trichotillomania. The physician initially thought the patient had a “fade” hairstyle, but then observed him twirling his hair. Further queries confirmed a history of hair pulling (trichotillomania) and ingesting the hair (trichophagia).

In adulthood, trichotillomania affects females about 4 times more than males, although in childhood, the sex distribution appears about equal.1 The typical age of onset is between 10 to 13 years. Several mental health conditions are associated with trichotillomania, such as major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, and substance use disorder, with trichotillomania generally preceding these comorbid disorders. It is important to rule out obsessive compulsive disorder and consider body dysmorphic disorder when making a diagnosis of trichotillomania.1

It is common to see androgenetic alopecia precipitated by hormone therapy in FTM individuals. This would usually cause thinning of the hair rather than the irregular hair lengths and pattern seen in this patient. Tinea capitis is also part of the differential diagnosis in a case such as this. It can be diagnosed by potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations in the setting of friable and broken hair shafts (and sometimes erythema and inflammation).

Patients with trichotillomania may have hair with blunt or tapered ends; hair may also look like uneven stubble.2 The scalp is the most commonly involved site (72.8%), followed by eyebrows (50.7%), and the pubic region (50.7%).1 Useful diagnostic clues include an unusual shape of the affected area, accessible location, and a changing pattern from visit to visit.2 If trichotillomania is suspected, it might be useful to ask about hair-playing activities, such as twirling or twisting, or playing with the ends of eyelashes or eyebrows.2

Unwanted medical consequences of trichotillomania include skin damage (if sharp instruments are used for hair pulling), and the formation of gastrointestinal trichobezoars (hairballs) if trichophagia is present. Trichobezoars that cause bowel obstructions may need surgical intervention.1

Behavioral therapy is the first-line treatment for trichotillomania in all age groups.1,3 Treating any coexisting mental health disorders is also essential. There are currently no FDA-approved medications for treatment; however, there is evidence that N-acetylcysteine may be useful in treating adults with trichotillomania and other repetitive skin disorders.3 Antipsychotics and cannabinoid agonists also may be beneficial.1

This patient was continued on his current lithium, naltrexone, and bupropion regimen (rather than adding additional psychiatric medicines) as he was doing better than his previous baseline. He was advised to continue with his cognitive behavioral therapy. His hormone replacement therapy also was continued because it was not thought to be contributory. He was provided with education about symptoms of trichobezoar and red flag symptoms (eg, worsening nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain) that would necessitate emergency follow-up. His GERD symptoms were thought not to be related to his trichophagia. He was scheduled to follow up for routine primary care in 6 months.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Sarasawati Keeni, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

The areas of hair loss and different length hairs in a patient with otherwise normal-density hair was consistent with a diagnosis of trichotillomania. The physician initially thought the patient had a “fade” hairstyle, but then observed him twirling his hair. Further queries confirmed a history of hair pulling (trichotillomania) and ingesting the hair (trichophagia).

In adulthood, trichotillomania affects females about 4 times more than males, although in childhood, the sex distribution appears about equal.1 The typical age of onset is between 10 to 13 years. Several mental health conditions are associated with trichotillomania, such as major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, and substance use disorder, with trichotillomania generally preceding these comorbid disorders. It is important to rule out obsessive compulsive disorder and consider body dysmorphic disorder when making a diagnosis of trichotillomania.1

It is common to see androgenetic alopecia precipitated by hormone therapy in FTM individuals. This would usually cause thinning of the hair rather than the irregular hair lengths and pattern seen in this patient. Tinea capitis is also part of the differential diagnosis in a case such as this. It can be diagnosed by potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparations in the setting of friable and broken hair shafts (and sometimes erythema and inflammation).

Patients with trichotillomania may have hair with blunt or tapered ends; hair may also look like uneven stubble.2 The scalp is the most commonly involved site (72.8%), followed by eyebrows (50.7%), and the pubic region (50.7%).1 Useful diagnostic clues include an unusual shape of the affected area, accessible location, and a changing pattern from visit to visit.2 If trichotillomania is suspected, it might be useful to ask about hair-playing activities, such as twirling or twisting, or playing with the ends of eyelashes or eyebrows.2

Unwanted medical consequences of trichotillomania include skin damage (if sharp instruments are used for hair pulling), and the formation of gastrointestinal trichobezoars (hairballs) if trichophagia is present. Trichobezoars that cause bowel obstructions may need surgical intervention.1

Behavioral therapy is the first-line treatment for trichotillomania in all age groups.1,3 Treating any coexisting mental health disorders is also essential. There are currently no FDA-approved medications for treatment; however, there is evidence that N-acetylcysteine may be useful in treating adults with trichotillomania and other repetitive skin disorders.3 Antipsychotics and cannabinoid agonists also may be beneficial.1

This patient was continued on his current lithium, naltrexone, and bupropion regimen (rather than adding additional psychiatric medicines) as he was doing better than his previous baseline. He was advised to continue with his cognitive behavioral therapy. His hormone replacement therapy also was continued because it was not thought to be contributory. He was provided with education about symptoms of trichobezoar and red flag symptoms (eg, worsening nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain) that would necessitate emergency follow-up. His GERD symptoms were thought not to be related to his trichophagia. He was scheduled to follow up for routine primary care in 6 months.

Photo courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD. Text courtesy of Sarasawati Keeni, MD, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Grant JE and Chamberlain SR. Trichotillomania. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:868-874. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15111432

2. Sah DE, Koo J, Price VH. Trichotillomania. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:13-21. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00165.x

3. Henkel ED, Jaquez SD, Diaz LZ. Pediatric trichotillomania: review of management. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:803-807. doi: 10.1111/pde.13954

1. Grant JE and Chamberlain SR. Trichotillomania. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:868-874. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15111432

2. Sah DE, Koo J, Price VH. Trichotillomania. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:13-21. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00165.x

3. Henkel ED, Jaquez SD, Diaz LZ. Pediatric trichotillomania: review of management. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:803-807. doi: 10.1111/pde.13954

Crusted scalp rash

Dermoscopy showed not only the erythema, inflammation, and crusting visible during the initial examination, but it also revealed that each lesion had a hair growing through it. This pointed to a diagnosis of superficial folliculitis of the scalp.

The physician ruled out tinea capitis, acne keloidalis nuchae, and scarring alopecia based on the dermoscopic exam. There were no broken hairs that one would expect with tinea capitis. Also, there was no polytrichia (multiple hairs pushed into a single follicular opening due to scarring of the skin) that would be expected with acne keloidalis nuchae and scarring alopecias.

There are multiple types of scalp folliculitis. This patient had superficial folliculitis, in which pustules develop at the ostium of the hair follicles. Deep folliculitis is more severe and includes furuncles and carbuncles.1

Folliculitis is usually caused by a bacterial infection and, less commonly, fungal infection. In addition to superficial and deep folliculitis, inflammation with scarring of the follicles occurs with folliculitis decalvans, which is one of the scarring alopecias.1

Mild cases of superficial bacterial folliculitis are treated with topical antibiotics (eg, topical clindamycin 1% applied twice daily). Depending on the severity, oral antibiotics including doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 7 days or trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole 160 mg/800 mg (double strength) twice daily for 7 days may be used. There is also a chronic nonscarring form of scalp folliculitis that often responds initially to antibiotics but then recurs. This has been treated with longer courses of oral antibiotics and, if the lesions don’t respond or continue to recur, with low-dose isotretinoin.2

Due to the amount of scalp involvement, crusting, and inflammation seen on this patient’s scalp, he was treated with trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole 160 mg/800 mg twice daily for 7 days. After 1 week, he reported that he was doing much better and that the lesions had nearly resolved. He was told to return for reevaluation if the lesions did not completely resolve.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Lugović-Mihić L, Barisić F, Bulat V, et al. Differential diagnosis of the scalp hair folliculitis. Acta Clin Croat. 2011;50:395-402.

2. Romero-Maté A, Arias-Palomo D, Hernández-Núñez A, et al. Chronic nonscarring scalp folliculitis: retrospective case series study of 34 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:1023-1024. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.065

Dermoscopy showed not only the erythema, inflammation, and crusting visible during the initial examination, but it also revealed that each lesion had a hair growing through it. This pointed to a diagnosis of superficial folliculitis of the scalp.

The physician ruled out tinea capitis, acne keloidalis nuchae, and scarring alopecia based on the dermoscopic exam. There were no broken hairs that one would expect with tinea capitis. Also, there was no polytrichia (multiple hairs pushed into a single follicular opening due to scarring of the skin) that would be expected with acne keloidalis nuchae and scarring alopecias.

There are multiple types of scalp folliculitis. This patient had superficial folliculitis, in which pustules develop at the ostium of the hair follicles. Deep folliculitis is more severe and includes furuncles and carbuncles.1

Folliculitis is usually caused by a bacterial infection and, less commonly, fungal infection. In addition to superficial and deep folliculitis, inflammation with scarring of the follicles occurs with folliculitis decalvans, which is one of the scarring alopecias.1

Mild cases of superficial bacterial folliculitis are treated with topical antibiotics (eg, topical clindamycin 1% applied twice daily). Depending on the severity, oral antibiotics including doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 7 days or trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole 160 mg/800 mg (double strength) twice daily for 7 days may be used. There is also a chronic nonscarring form of scalp folliculitis that often responds initially to antibiotics but then recurs. This has been treated with longer courses of oral antibiotics and, if the lesions don’t respond or continue to recur, with low-dose isotretinoin.2

Due to the amount of scalp involvement, crusting, and inflammation seen on this patient’s scalp, he was treated with trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole 160 mg/800 mg twice daily for 7 days. After 1 week, he reported that he was doing much better and that the lesions had nearly resolved. He was told to return for reevaluation if the lesions did not completely resolve.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

Dermoscopy showed not only the erythema, inflammation, and crusting visible during the initial examination, but it also revealed that each lesion had a hair growing through it. This pointed to a diagnosis of superficial folliculitis of the scalp.

The physician ruled out tinea capitis, acne keloidalis nuchae, and scarring alopecia based on the dermoscopic exam. There were no broken hairs that one would expect with tinea capitis. Also, there was no polytrichia (multiple hairs pushed into a single follicular opening due to scarring of the skin) that would be expected with acne keloidalis nuchae and scarring alopecias.

There are multiple types of scalp folliculitis. This patient had superficial folliculitis, in which pustules develop at the ostium of the hair follicles. Deep folliculitis is more severe and includes furuncles and carbuncles.1

Folliculitis is usually caused by a bacterial infection and, less commonly, fungal infection. In addition to superficial and deep folliculitis, inflammation with scarring of the follicles occurs with folliculitis decalvans, which is one of the scarring alopecias.1

Mild cases of superficial bacterial folliculitis are treated with topical antibiotics (eg, topical clindamycin 1% applied twice daily). Depending on the severity, oral antibiotics including doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 7 days or trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole 160 mg/800 mg (double strength) twice daily for 7 days may be used. There is also a chronic nonscarring form of scalp folliculitis that often responds initially to antibiotics but then recurs. This has been treated with longer courses of oral antibiotics and, if the lesions don’t respond or continue to recur, with low-dose isotretinoin.2

Due to the amount of scalp involvement, crusting, and inflammation seen on this patient’s scalp, he was treated with trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole 160 mg/800 mg twice daily for 7 days. After 1 week, he reported that he was doing much better and that the lesions had nearly resolved. He was told to return for reevaluation if the lesions did not completely resolve.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Lugović-Mihić L, Barisić F, Bulat V, et al. Differential diagnosis of the scalp hair folliculitis. Acta Clin Croat. 2011;50:395-402.

2. Romero-Maté A, Arias-Palomo D, Hernández-Núñez A, et al. Chronic nonscarring scalp folliculitis: retrospective case series study of 34 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:1023-1024. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.065

1. Lugović-Mihić L, Barisić F, Bulat V, et al. Differential diagnosis of the scalp hair folliculitis. Acta Clin Croat. 2011;50:395-402.

2. Romero-Maté A, Arias-Palomo D, Hernández-Núñez A, et al. Chronic nonscarring scalp folliculitis: retrospective case series study of 34 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:1023-1024. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.065

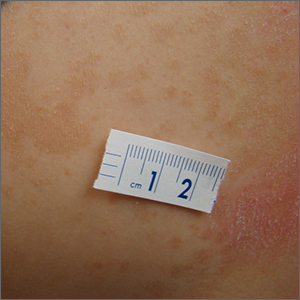

Persistent scaling rash

The clinical pattern of a scaly herald patch predating the eruption of multiple scaly macules is the hallmark of pityriasis rosea (PR). This patient’s severe itching is also classic for PR.

PR’s etiology is believed to be a reactivation of infection from human herpes viruses 6 and 7.1 Prodromal viral symptoms of malaise, sore throat, myalgias, and fever are common.2 Along with the prodromal symptoms, there is often a several-centimeter herald patch that occurs on the trunk. It is often confused with eczema or tinea due to its erythema and scale. (Secondary syphilis is also in the differential.) Sometimes PR can be differentiated by the scale pattern being a collarette instead of diffuse. The diagnosis becomes clearer 1 to 2 weeks later with the onset of multiple small scaly macules across the trunk following the Langer’s skin lines. The course is self-limited but takes several weeks to months to resolve.

If severe, PR may be treated with acyclovir 800 mg orally 5 times daily for 5 days; this is the same regimen for treating varicella zoster (shingles).1,2 Estimated recurrence rates are 4% to 24%.1,3

At age 49 years, this woman was older than the average patient with PR, as the usual age range is 10 to 35 years.1 Her physician advised her that the outbreak might recur. She was also given a prescription for oral hydroxyzine 25 mg to be taken at bedtime if the itching was interfering with her sleep. Her physician told her to return for reevaluation if the rash did not resolve in 3 months. She did not return for reevaluation.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Drago F, Ciccarese G, Parodi A. Commentary on: "pityriasis rosea recurrence is much higher than previously known: a prospective study." Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:1053-1054. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3265

2. Villalon-Gomez JM. Pityriasis rosea: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97:38-44.

3. Yüksel M. Pityriasis rosea recurrence is much higher than previously known: a prospective study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:664-667. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3169

The clinical pattern of a scaly herald patch predating the eruption of multiple scaly macules is the hallmark of pityriasis rosea (PR). This patient’s severe itching is also classic for PR.

PR’s etiology is believed to be a reactivation of infection from human herpes viruses 6 and 7.1 Prodromal viral symptoms of malaise, sore throat, myalgias, and fever are common.2 Along with the prodromal symptoms, there is often a several-centimeter herald patch that occurs on the trunk. It is often confused with eczema or tinea due to its erythema and scale. (Secondary syphilis is also in the differential.) Sometimes PR can be differentiated by the scale pattern being a collarette instead of diffuse. The diagnosis becomes clearer 1 to 2 weeks later with the onset of multiple small scaly macules across the trunk following the Langer’s skin lines. The course is self-limited but takes several weeks to months to resolve.

If severe, PR may be treated with acyclovir 800 mg orally 5 times daily for 5 days; this is the same regimen for treating varicella zoster (shingles).1,2 Estimated recurrence rates are 4% to 24%.1,3

At age 49 years, this woman was older than the average patient with PR, as the usual age range is 10 to 35 years.1 Her physician advised her that the outbreak might recur. She was also given a prescription for oral hydroxyzine 25 mg to be taken at bedtime if the itching was interfering with her sleep. Her physician told her to return for reevaluation if the rash did not resolve in 3 months. She did not return for reevaluation.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

The clinical pattern of a scaly herald patch predating the eruption of multiple scaly macules is the hallmark of pityriasis rosea (PR). This patient’s severe itching is also classic for PR.

PR’s etiology is believed to be a reactivation of infection from human herpes viruses 6 and 7.1 Prodromal viral symptoms of malaise, sore throat, myalgias, and fever are common.2 Along with the prodromal symptoms, there is often a several-centimeter herald patch that occurs on the trunk. It is often confused with eczema or tinea due to its erythema and scale. (Secondary syphilis is also in the differential.) Sometimes PR can be differentiated by the scale pattern being a collarette instead of diffuse. The diagnosis becomes clearer 1 to 2 weeks later with the onset of multiple small scaly macules across the trunk following the Langer’s skin lines. The course is self-limited but takes several weeks to months to resolve.

If severe, PR may be treated with acyclovir 800 mg orally 5 times daily for 5 days; this is the same regimen for treating varicella zoster (shingles).1,2 Estimated recurrence rates are 4% to 24%.1,3

At age 49 years, this woman was older than the average patient with PR, as the usual age range is 10 to 35 years.1 Her physician advised her that the outbreak might recur. She was also given a prescription for oral hydroxyzine 25 mg to be taken at bedtime if the itching was interfering with her sleep. Her physician told her to return for reevaluation if the rash did not resolve in 3 months. She did not return for reevaluation.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Drago F, Ciccarese G, Parodi A. Commentary on: "pityriasis rosea recurrence is much higher than previously known: a prospective study." Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:1053-1054. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3265

2. Villalon-Gomez JM. Pityriasis rosea: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97:38-44.

3. Yüksel M. Pityriasis rosea recurrence is much higher than previously known: a prospective study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:664-667. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3169

1. Drago F, Ciccarese G, Parodi A. Commentary on: "pityriasis rosea recurrence is much higher than previously known: a prospective study." Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:1053-1054. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3265

2. Villalon-Gomez JM. Pityriasis rosea: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97:38-44.

3. Yüksel M. Pityriasis rosea recurrence is much higher than previously known: a prospective study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:664-667. doi: 10.2340/00015555-3169

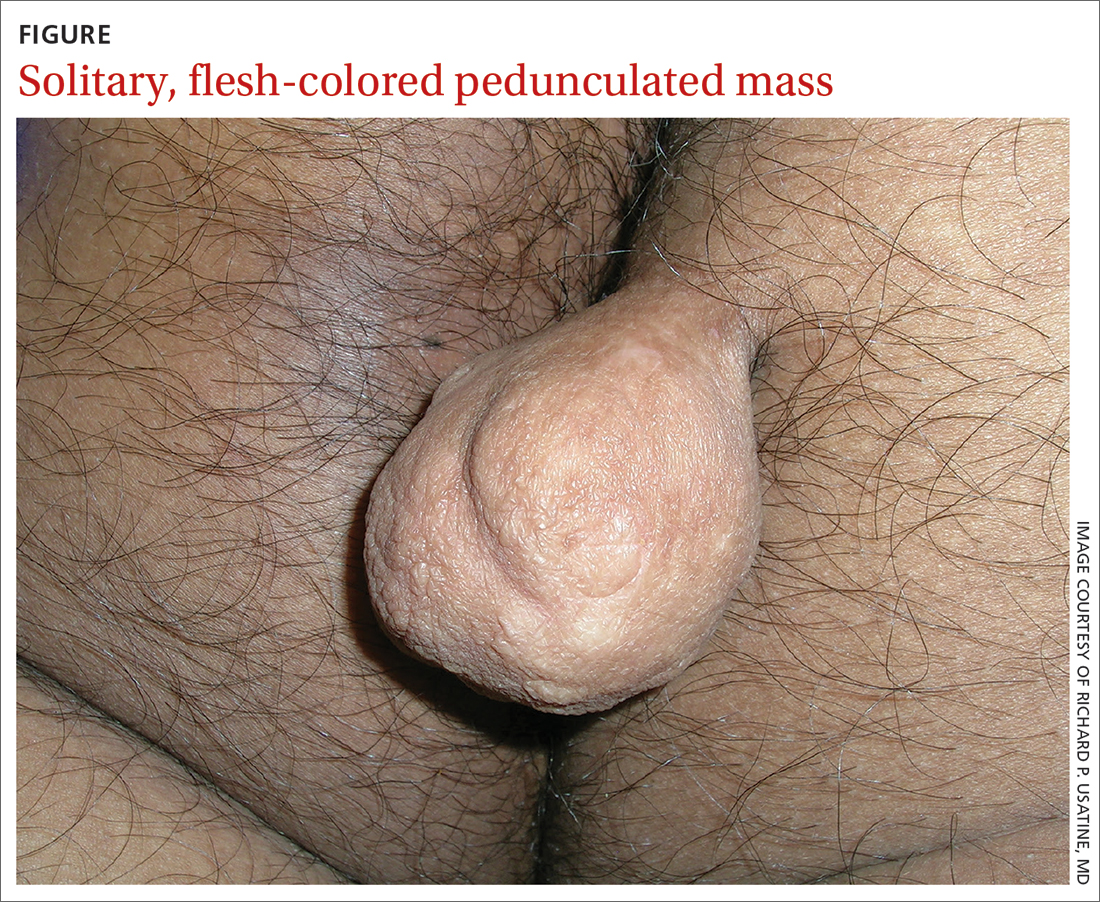

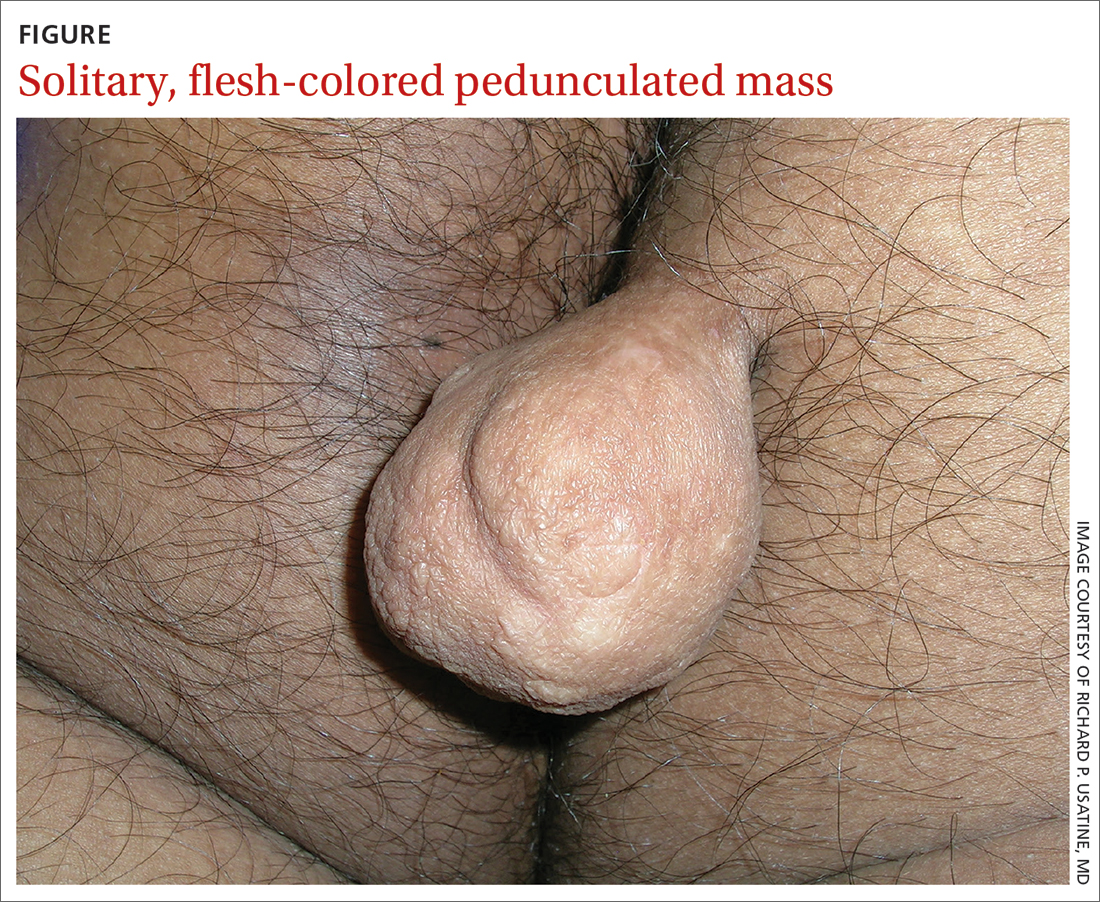

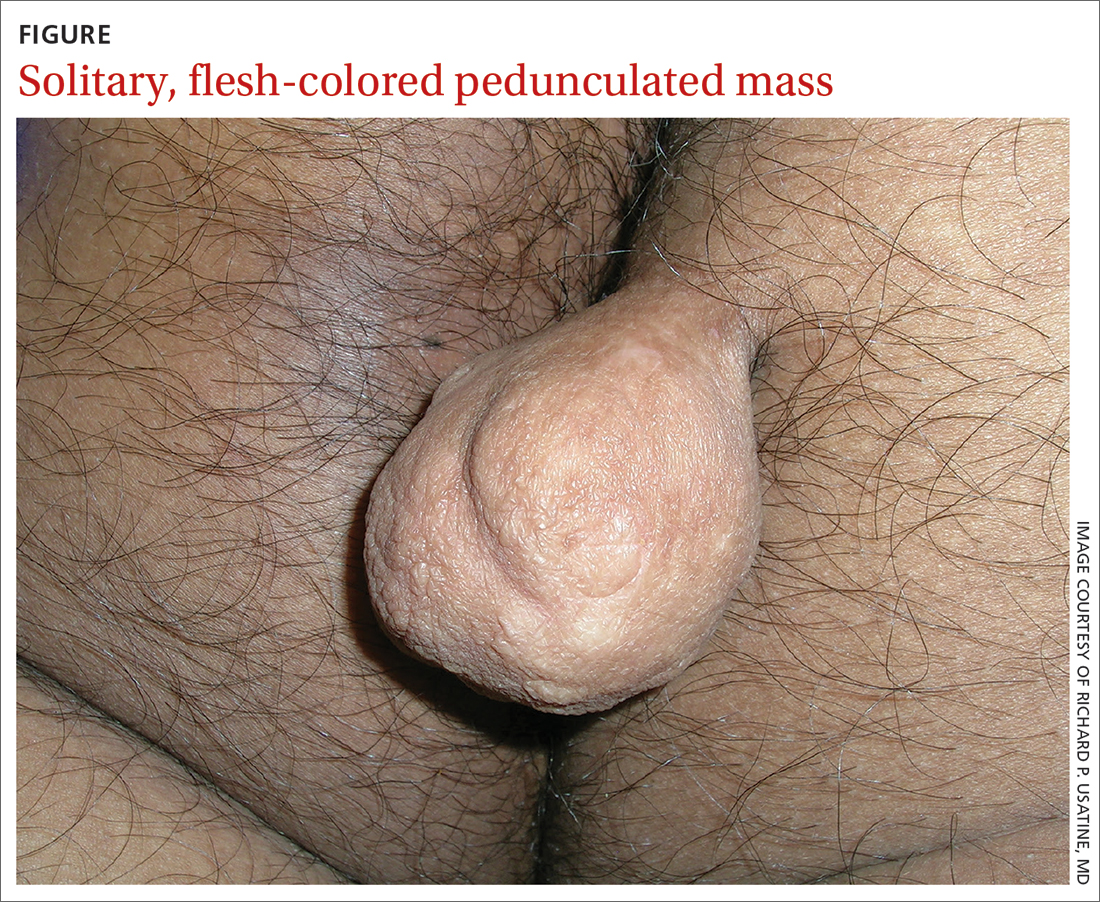

Pedunculated gluteal mass

A 30-YEAR-OLD MAN presented for evaluation of a solitary, flesh-colored, pedunculated mass on his right inner gluteal area (FIGURE) that had gradually enlarged over the previous 18 months. The lesion had manifested 4 years prior as a small papule that was stable for many years. It began to grow steadily after the patient compressed the papule forcefully. Activities of daily living, such as sitting, were now uncomfortable, so he sought treatment. He denied pain, pruritis, and bleeding and reported no history of trauma or surgery in the area of the mass.

On physical examination, the mass measured 3.5 × 4.5 cm with a 1.2-cm base. It was smooth, soft, nontender, and compressible—but nonfluctuant. There were no signs of ulceration or bleeding. No regional lymphadenopathy was noted. An excisional biopsy was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Fibrolipoma

The biopsy confirmed a diagnosis of fibrolipoma—a rare variant of lipoma composed of a mixture of adipocytes and thick bands of fibrous connective tissues.1 Etiology for fibrolipomas is unknown. Blunt trauma rupture of the fibrous septa that prevent fat migration may result in a proliferation of adipose tissue and thereby enlargement of fibrolipomas and other lipoma variants.2 In this case, the patient’s compression of the original papule likely served as the trauma that led to its enlargement. Malignant change has not been reported with fibrolipomas.

What you’ll see—and on whom. Fibrolipomas typically are flesh-colored, pedunculated, compressible, and relatively asymptomatic.3 They have been reported on the face, neck, back, and pubic areas, among other locations. Size is variable; they can be as small as 1 cm in diameter and as large as 10 cm in diameter.4 However, fibrolipomas can grow to be “giant” if they exceed 10 cm (or 1000 g).2

Men and women are affected equally by fibrolipomas. Prevalence does not differ by race or ethnicity.

The differential include sother lipomas and skin tags

The differential for a mass such as this one includes lipomas, acrochordons (also known as skin tags), and fibrokeratomas.

Lipomas are the most common benign soft-tissue tumors and are composed of adipocytes.5 The fibrolipoma is just one variant of lipoma; others include the myxolipoma, myolipoma, spindle cell lipoma, angiolipoma, osteolipoma, and chondrolipoma.2 Lipomas typically are subcutaneous and located over the scalp, neck, and upper trunk area but can occur anywhere on the body. They are mobile and typically well circumscribed. Lipomas have a broad base with well-demarcated swelling; fibrolipomas are usually pedunculated.

Continue to: Acrochordons ("skin tags")

Acrochordons (“skin tags”) usually contain a peduncle but may be sessile. They range from 1 mm to 1 cm in diameter and typically are located in skin folds, especially in the neck, axillae, and inguinal areas.6 Obesity, older

Fibrokeratomas typically are benign, solitary, fibrous tissue tumors that are found on fingers and seldom are pedunculated. They are flesh-colored and conical or nodular, with a hyperkeratotic collar. Fibrokeratomas are smaller and thicker than fibromas, as well as firm in consistency. They are acquired tumors that have been shown to be related to repetitive trauma.6

Treatment involves surgical excision

The preferred treatment for fibrolipoma is complete surgical excision, although cryotherapy is another option for lesions < 1 cm.4 Without surgical excision, the mass will continue to grow, albeit slowly.

This patient’s mass was excised successfully in its entirety; there were no complications. Follow-up is usually unnecessary.

1. Kim YT, Kim WS, Park YL, et al. A case of fibrolipoma. Korean J Dermatol. 2003;41:939-941.

2. Mazzocchi M, Onesti MG, Pasquini P, et al. Giant fibrolipoma in the leg—a case report. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:3649-3654.

3. Shin SJ. Subcutaneous fibrolipoma on the back. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24:1051-1053. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182802517

4. Suleiman J, Suleman M, Amsi P, et al. Giant pedunculated lipofibroma of the thigh. J Surg Case Rep. 2023;2023(3):rjad153. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjad153

5. Dai X-M, Li Y-S, Liu H, et al. Giant pedunculated fibrolipoma arising from right facial and cervical region. J Oral and Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:1323-1326. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.12.037

6. Lee JA, Khodaee M. Enlarging, pedunculated skin lesion. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:1191-1192.

7. Banik R, Lubach D. Skin tags: localization and frequencies according to sex and age. Dermatologica. 1987;174:180-183. doi: 10.1159/000249169

A 30-YEAR-OLD MAN presented for evaluation of a solitary, flesh-colored, pedunculated mass on his right inner gluteal area (FIGURE) that had gradually enlarged over the previous 18 months. The lesion had manifested 4 years prior as a small papule that was stable for many years. It began to grow steadily after the patient compressed the papule forcefully. Activities of daily living, such as sitting, were now uncomfortable, so he sought treatment. He denied pain, pruritis, and bleeding and reported no history of trauma or surgery in the area of the mass.

On physical examination, the mass measured 3.5 × 4.5 cm with a 1.2-cm base. It was smooth, soft, nontender, and compressible—but nonfluctuant. There were no signs of ulceration or bleeding. No regional lymphadenopathy was noted. An excisional biopsy was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Fibrolipoma

The biopsy confirmed a diagnosis of fibrolipoma—a rare variant of lipoma composed of a mixture of adipocytes and thick bands of fibrous connective tissues.1 Etiology for fibrolipomas is unknown. Blunt trauma rupture of the fibrous septa that prevent fat migration may result in a proliferation of adipose tissue and thereby enlargement of fibrolipomas and other lipoma variants.2 In this case, the patient’s compression of the original papule likely served as the trauma that led to its enlargement. Malignant change has not been reported with fibrolipomas.

What you’ll see—and on whom. Fibrolipomas typically are flesh-colored, pedunculated, compressible, and relatively asymptomatic.3 They have been reported on the face, neck, back, and pubic areas, among other locations. Size is variable; they can be as small as 1 cm in diameter and as large as 10 cm in diameter.4 However, fibrolipomas can grow to be “giant” if they exceed 10 cm (or 1000 g).2

Men and women are affected equally by fibrolipomas. Prevalence does not differ by race or ethnicity.

The differential include sother lipomas and skin tags

The differential for a mass such as this one includes lipomas, acrochordons (also known as skin tags), and fibrokeratomas.

Lipomas are the most common benign soft-tissue tumors and are composed of adipocytes.5 The fibrolipoma is just one variant of lipoma; others include the myxolipoma, myolipoma, spindle cell lipoma, angiolipoma, osteolipoma, and chondrolipoma.2 Lipomas typically are subcutaneous and located over the scalp, neck, and upper trunk area but can occur anywhere on the body. They are mobile and typically well circumscribed. Lipomas have a broad base with well-demarcated swelling; fibrolipomas are usually pedunculated.

Continue to: Acrochordons ("skin tags")

Acrochordons (“skin tags”) usually contain a peduncle but may be sessile. They range from 1 mm to 1 cm in diameter and typically are located in skin folds, especially in the neck, axillae, and inguinal areas.6 Obesity, older

Fibrokeratomas typically are benign, solitary, fibrous tissue tumors that are found on fingers and seldom are pedunculated. They are flesh-colored and conical or nodular, with a hyperkeratotic collar. Fibrokeratomas are smaller and thicker than fibromas, as well as firm in consistency. They are acquired tumors that have been shown to be related to repetitive trauma.6

Treatment involves surgical excision

The preferred treatment for fibrolipoma is complete surgical excision, although cryotherapy is another option for lesions < 1 cm.4 Without surgical excision, the mass will continue to grow, albeit slowly.

This patient’s mass was excised successfully in its entirety; there were no complications. Follow-up is usually unnecessary.

A 30-YEAR-OLD MAN presented for evaluation of a solitary, flesh-colored, pedunculated mass on his right inner gluteal area (FIGURE) that had gradually enlarged over the previous 18 months. The lesion had manifested 4 years prior as a small papule that was stable for many years. It began to grow steadily after the patient compressed the papule forcefully. Activities of daily living, such as sitting, were now uncomfortable, so he sought treatment. He denied pain, pruritis, and bleeding and reported no history of trauma or surgery in the area of the mass.

On physical examination, the mass measured 3.5 × 4.5 cm with a 1.2-cm base. It was smooth, soft, nontender, and compressible—but nonfluctuant. There were no signs of ulceration or bleeding. No regional lymphadenopathy was noted. An excisional biopsy was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Fibrolipoma

The biopsy confirmed a diagnosis of fibrolipoma—a rare variant of lipoma composed of a mixture of adipocytes and thick bands of fibrous connective tissues.1 Etiology for fibrolipomas is unknown. Blunt trauma rupture of the fibrous septa that prevent fat migration may result in a proliferation of adipose tissue and thereby enlargement of fibrolipomas and other lipoma variants.2 In this case, the patient’s compression of the original papule likely served as the trauma that led to its enlargement. Malignant change has not been reported with fibrolipomas.

What you’ll see—and on whom. Fibrolipomas typically are flesh-colored, pedunculated, compressible, and relatively asymptomatic.3 They have been reported on the face, neck, back, and pubic areas, among other locations. Size is variable; they can be as small as 1 cm in diameter and as large as 10 cm in diameter.4 However, fibrolipomas can grow to be “giant” if they exceed 10 cm (or 1000 g).2

Men and women are affected equally by fibrolipomas. Prevalence does not differ by race or ethnicity.

The differential include sother lipomas and skin tags

The differential for a mass such as this one includes lipomas, acrochordons (also known as skin tags), and fibrokeratomas.

Lipomas are the most common benign soft-tissue tumors and are composed of adipocytes.5 The fibrolipoma is just one variant of lipoma; others include the myxolipoma, myolipoma, spindle cell lipoma, angiolipoma, osteolipoma, and chondrolipoma.2 Lipomas typically are subcutaneous and located over the scalp, neck, and upper trunk area but can occur anywhere on the body. They are mobile and typically well circumscribed. Lipomas have a broad base with well-demarcated swelling; fibrolipomas are usually pedunculated.

Continue to: Acrochordons ("skin tags")

Acrochordons (“skin tags”) usually contain a peduncle but may be sessile. They range from 1 mm to 1 cm in diameter and typically are located in skin folds, especially in the neck, axillae, and inguinal areas.6 Obesity, older

Fibrokeratomas typically are benign, solitary, fibrous tissue tumors that are found on fingers and seldom are pedunculated. They are flesh-colored and conical or nodular, with a hyperkeratotic collar. Fibrokeratomas are smaller and thicker than fibromas, as well as firm in consistency. They are acquired tumors that have been shown to be related to repetitive trauma.6

Treatment involves surgical excision

The preferred treatment for fibrolipoma is complete surgical excision, although cryotherapy is another option for lesions < 1 cm.4 Without surgical excision, the mass will continue to grow, albeit slowly.

This patient’s mass was excised successfully in its entirety; there were no complications. Follow-up is usually unnecessary.

1. Kim YT, Kim WS, Park YL, et al. A case of fibrolipoma. Korean J Dermatol. 2003;41:939-941.

2. Mazzocchi M, Onesti MG, Pasquini P, et al. Giant fibrolipoma in the leg—a case report. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:3649-3654.

3. Shin SJ. Subcutaneous fibrolipoma on the back. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24:1051-1053. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182802517

4. Suleiman J, Suleman M, Amsi P, et al. Giant pedunculated lipofibroma of the thigh. J Surg Case Rep. 2023;2023(3):rjad153. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjad153

5. Dai X-M, Li Y-S, Liu H, et al. Giant pedunculated fibrolipoma arising from right facial and cervical region. J Oral and Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:1323-1326. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.12.037

6. Lee JA, Khodaee M. Enlarging, pedunculated skin lesion. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:1191-1192.

7. Banik R, Lubach D. Skin tags: localization and frequencies according to sex and age. Dermatologica. 1987;174:180-183. doi: 10.1159/000249169

1. Kim YT, Kim WS, Park YL, et al. A case of fibrolipoma. Korean J Dermatol. 2003;41:939-941.

2. Mazzocchi M, Onesti MG, Pasquini P, et al. Giant fibrolipoma in the leg—a case report. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:3649-3654.

3. Shin SJ. Subcutaneous fibrolipoma on the back. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24:1051-1053. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182802517

4. Suleiman J, Suleman M, Amsi P, et al. Giant pedunculated lipofibroma of the thigh. J Surg Case Rep. 2023;2023(3):rjad153. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjad153

5. Dai X-M, Li Y-S, Liu H, et al. Giant pedunculated fibrolipoma arising from right facial and cervical region. J Oral and Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:1323-1326. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.12.037

6. Lee JA, Khodaee M. Enlarging, pedunculated skin lesion. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:1191-1192.

7. Banik R, Lubach D. Skin tags: localization and frequencies according to sex and age. Dermatologica. 1987;174:180-183. doi: 10.1159/000249169

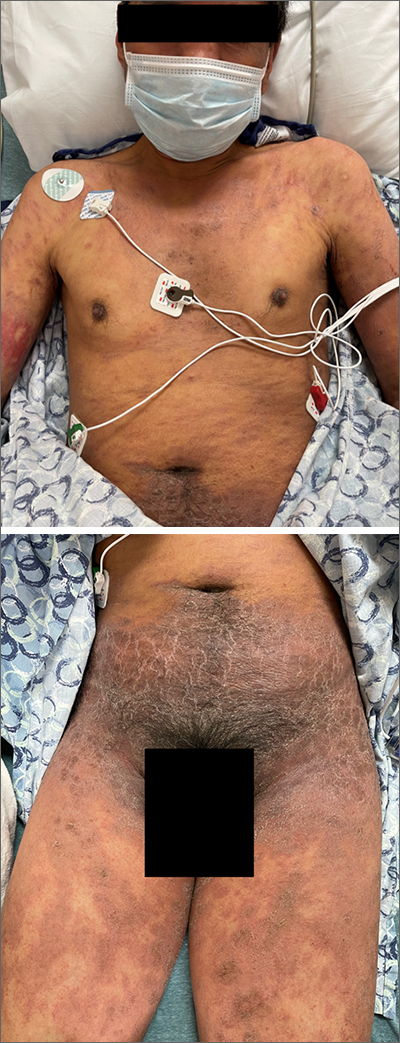

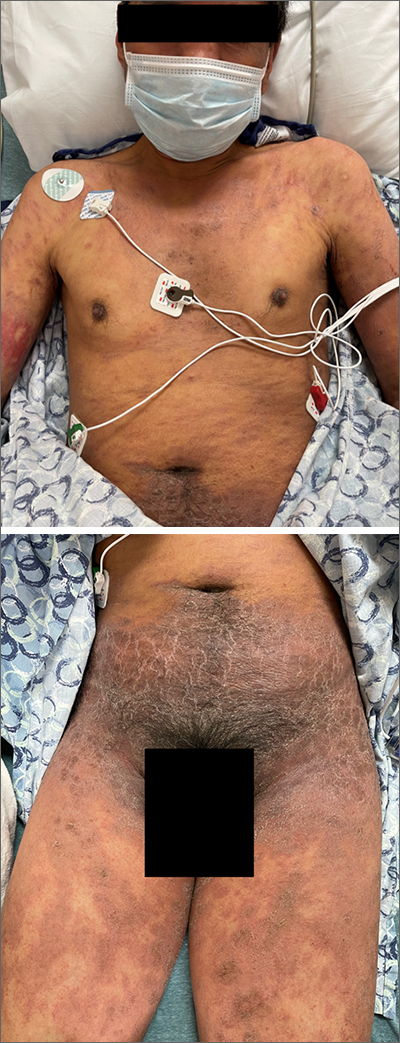

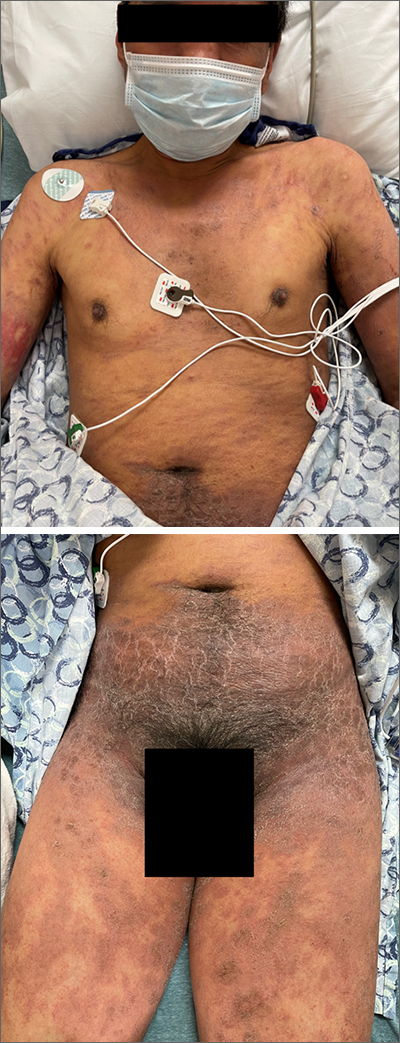

Acute diffuse rash on trunk

This patient’s diffusely erythematous and scaly rash, in association with recent antibiotic use, was a classic presentation of a drug eruption. Drug eruptions are adverse cutaneous reactions to various medications; they frequently involve antibiotics and anti-epileptics. They can manifest in a multitude of ways with different morphologies. Medication history and timing to onset of symptoms are paramount in making the diagnosis.

Classic reactions include those that are morbilliform (erythematous macules and papules), lichenoid (violaceous and hyperpigmented papules), exfoliative/erythrodermic, and/or urticarial.1 Petechiae and palpable purpura may also manifest.1 Severe reactions, while less common, must always be considered, given their significant morbidity and mortality. These include2:

- Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis with diffuse erythema and areas of denuded, necrotic epidermis,

- Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, and

- Acute, generalized, exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) consisting of confluent, nonfollicular pustules.

A general principle in the management of drug eruptions is the discontinuation of the offending drug (if known) as soon as possible. If the agent is not known, it is important to discontinue all drugs that are not deemed as essential, particularly medications that are often associated with reactions, such as antibiotics and anti-epileptics. Additionally, evaluation of the oral mucosa, eyes, and genitourinary tract is helpful to diagnose Stevens-Johnson syndrome, if indicated by symptoms or history.

Wound care with cleansing and covering of denuded skin with emollients and wet dressings should be performed. Infections are common complications in these patients due to the increased inflammation, fissuring, and excoriations that accompany the rash, with sepsis from staphylococcal bacteria being the most concerning complication of infection. Additionally, the compromised skin barrier may lead to heat loss and hypothermia, a compensatory hypermetabolism with hyperthermia, and electrolyte imbalances from insensible water losses.2

Most mild eruptions can be treated with topical corticosteroids and antihistamines. However, in severe eruptions, systemic corticosteroids, or referral for immunosuppressive and anticytokine therapies, also should be considered.1

This patient was treated with both a short course of systemic corticosteroids (prednisone 40 mg/d for 5 days, then tapered over 15 days) and topical steroids (triamcinolone 0.1% ointment bid) for symptomatic care. He also was started on an antihistamine (cetirizine 10 mg bid) for itching. Doxycycline and Augmentin were added to his allergy list. At a 1-week follow up, the patient had near resolution of his rash.

Images courtesy of Jose L. Cortez, MD. Text courtesy of Jose L. Cortez, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Riedl MA, Casillas AM. Adverse drug reactions: types and treatment options. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:1781-1790.

2. Zhang J, Lei Z, Xu C, et al. Current perspectives on severe drug eruption. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2021;61:282-298. doi: 10.1007/s12016-021-08859-0

This patient’s diffusely erythematous and scaly rash, in association with recent antibiotic use, was a classic presentation of a drug eruption. Drug eruptions are adverse cutaneous reactions to various medications; they frequently involve antibiotics and anti-epileptics. They can manifest in a multitude of ways with different morphologies. Medication history and timing to onset of symptoms are paramount in making the diagnosis.

Classic reactions include those that are morbilliform (erythematous macules and papules), lichenoid (violaceous and hyperpigmented papules), exfoliative/erythrodermic, and/or urticarial.1 Petechiae and palpable purpura may also manifest.1 Severe reactions, while less common, must always be considered, given their significant morbidity and mortality. These include2:

- Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis with diffuse erythema and areas of denuded, necrotic epidermis,

- Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, and

- Acute, generalized, exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) consisting of confluent, nonfollicular pustules.

A general principle in the management of drug eruptions is the discontinuation of the offending drug (if known) as soon as possible. If the agent is not known, it is important to discontinue all drugs that are not deemed as essential, particularly medications that are often associated with reactions, such as antibiotics and anti-epileptics. Additionally, evaluation of the oral mucosa, eyes, and genitourinary tract is helpful to diagnose Stevens-Johnson syndrome, if indicated by symptoms or history.

Wound care with cleansing and covering of denuded skin with emollients and wet dressings should be performed. Infections are common complications in these patients due to the increased inflammation, fissuring, and excoriations that accompany the rash, with sepsis from staphylococcal bacteria being the most concerning complication of infection. Additionally, the compromised skin barrier may lead to heat loss and hypothermia, a compensatory hypermetabolism with hyperthermia, and electrolyte imbalances from insensible water losses.2

Most mild eruptions can be treated with topical corticosteroids and antihistamines. However, in severe eruptions, systemic corticosteroids, or referral for immunosuppressive and anticytokine therapies, also should be considered.1

This patient was treated with both a short course of systemic corticosteroids (prednisone 40 mg/d for 5 days, then tapered over 15 days) and topical steroids (triamcinolone 0.1% ointment bid) for symptomatic care. He also was started on an antihistamine (cetirizine 10 mg bid) for itching. Doxycycline and Augmentin were added to his allergy list. At a 1-week follow up, the patient had near resolution of his rash.

Images courtesy of Jose L. Cortez, MD. Text courtesy of Jose L. Cortez, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

This patient’s diffusely erythematous and scaly rash, in association with recent antibiotic use, was a classic presentation of a drug eruption. Drug eruptions are adverse cutaneous reactions to various medications; they frequently involve antibiotics and anti-epileptics. They can manifest in a multitude of ways with different morphologies. Medication history and timing to onset of symptoms are paramount in making the diagnosis.

Classic reactions include those that are morbilliform (erythematous macules and papules), lichenoid (violaceous and hyperpigmented papules), exfoliative/erythrodermic, and/or urticarial.1 Petechiae and palpable purpura may also manifest.1 Severe reactions, while less common, must always be considered, given their significant morbidity and mortality. These include2:

- Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis with diffuse erythema and areas of denuded, necrotic epidermis,

- Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome, and

- Acute, generalized, exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) consisting of confluent, nonfollicular pustules.

A general principle in the management of drug eruptions is the discontinuation of the offending drug (if known) as soon as possible. If the agent is not known, it is important to discontinue all drugs that are not deemed as essential, particularly medications that are often associated with reactions, such as antibiotics and anti-epileptics. Additionally, evaluation of the oral mucosa, eyes, and genitourinary tract is helpful to diagnose Stevens-Johnson syndrome, if indicated by symptoms or history.

Wound care with cleansing and covering of denuded skin with emollients and wet dressings should be performed. Infections are common complications in these patients due to the increased inflammation, fissuring, and excoriations that accompany the rash, with sepsis from staphylococcal bacteria being the most concerning complication of infection. Additionally, the compromised skin barrier may lead to heat loss and hypothermia, a compensatory hypermetabolism with hyperthermia, and electrolyte imbalances from insensible water losses.2

Most mild eruptions can be treated with topical corticosteroids and antihistamines. However, in severe eruptions, systemic corticosteroids, or referral for immunosuppressive and anticytokine therapies, also should be considered.1

This patient was treated with both a short course of systemic corticosteroids (prednisone 40 mg/d for 5 days, then tapered over 15 days) and topical steroids (triamcinolone 0.1% ointment bid) for symptomatic care. He also was started on an antihistamine (cetirizine 10 mg bid) for itching. Doxycycline and Augmentin were added to his allergy list. At a 1-week follow up, the patient had near resolution of his rash.

Images courtesy of Jose L. Cortez, MD. Text courtesy of Jose L. Cortez, MD, Department of Dermatology, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Riedl MA, Casillas AM. Adverse drug reactions: types and treatment options. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:1781-1790.

2. Zhang J, Lei Z, Xu C, et al. Current perspectives on severe drug eruption. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2021;61:282-298. doi: 10.1007/s12016-021-08859-0

1. Riedl MA, Casillas AM. Adverse drug reactions: types and treatment options. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:1781-1790.

2. Zhang J, Lei Z, Xu C, et al. Current perspectives on severe drug eruption. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2021;61:282-298. doi: 10.1007/s12016-021-08859-0

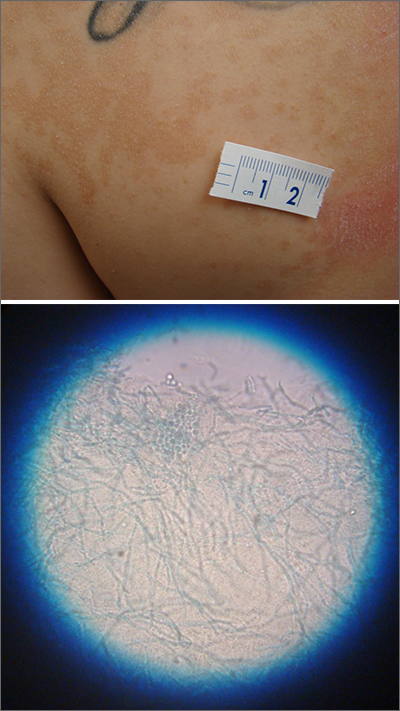

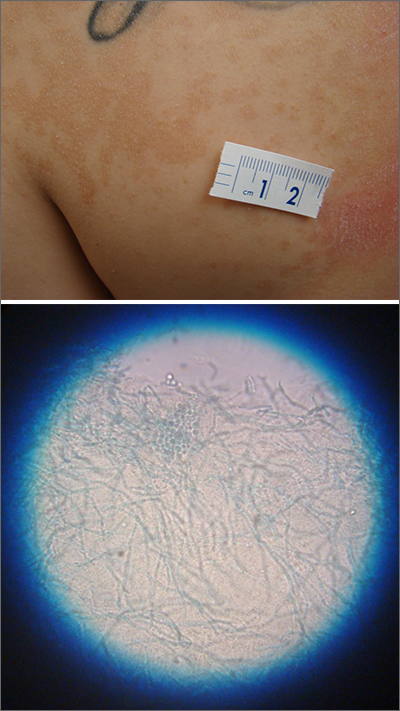

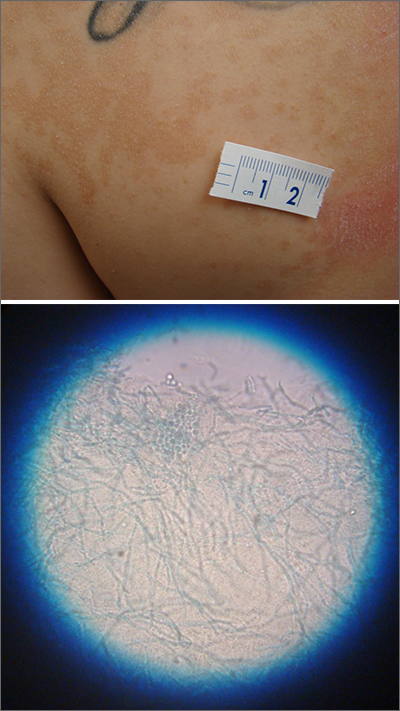

Itchy scaling rash

A waxing and waning rash with fine scale is classic for tinea versicolor (TV). A potassium hydroxide (KOH) prep with Swartz-Lamkins stain confirmed the presence of the spaghetti-and-meatballs pattern of Malassezia furfur (MF).

TV is a skin infection caused by M furfur. TF is notorious for the variety of colors that are seen clinically, including hyperpigmentation, as seen in a recent installment in this column.1 It can also appear as hypopigmented lesions or tan macules and patches with fine scale, as was seen in this patient. Hypopigmentation is often more pronounced on sun-exposed areas of the body. The MF produces azelaic acid. The azelaic acid blocks tyrosinase, which hinders melanocyte function and leads to hypopigmentation.2 As a result, areas of skin that are affected by TV do not tan as much as the surrounding skin, making the lesions more pronounced.

First line treatment of TV includes topical antifungal preparations, such as the “azoles” (eg, clotrimazole, ketoconazole, miconazole) twice daily for 2 to 4 weeks. However, the large surface areas involved would require a large amount of these antifungal preparations that come in relatively small tubes. Thus, for many years, clinicians have turned to economical over-the-counter dandruff shampoos with either selenium sulfide or zinc pyrithione that provide excellent results. These shampoos are applied to the entire trunk at full strength, allowed to dry, and then washed off later following various timed protocols. If topical therapy is not successful, or if there is a recurrence, systemic antifungal medications are used. Oral options include fluconazole 200 mg to 300 mg orally once a week for 2 weeks and itraconazole 200 mg orally once a day for 7 days.3 Ketoconazole is avoided as a systemic antifungal (except in life-threatening situations) due to its higher rate of liver dysfunction.

This patient was instructed to apply full-strength selenium sulfide shampoo to his entire trunk in the evening, allow it to dry, then wash it off the next morning and repeat in 1 week. An alternate regimen is to leave it on for 1 hour before washing and repeat daily for 1 week. At the patient’s follow-up appointment a month later, the rash and itching had resolved.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Jasser J, Stulberg D. Teen with hyperpigmented skin lesions. J Fam Pract. 2022;71. Published December 2022. Accessed May 26, 2023. www.mdedge.com/familymedicine/article/260076/dermatology/teen-hyperpigmented-skin-lesions. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0529

2. Leung AK, Barankin B, Lam JM, et al. Tinea versicolor: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2022;11:2022-9-2. doi: 10.7573/dic.2022-9-2

3. Gupta AK, Foley KA. Antifungal treatment for pityriasis versicolor. J Fungi (Basel). 2015;1:13-29. doi: 10.3390/jof1010013

A waxing and waning rash with fine scale is classic for tinea versicolor (TV). A potassium hydroxide (KOH) prep with Swartz-Lamkins stain confirmed the presence of the spaghetti-and-meatballs pattern of Malassezia furfur (MF).

TV is a skin infection caused by M furfur. TF is notorious for the variety of colors that are seen clinically, including hyperpigmentation, as seen in a recent installment in this column.1 It can also appear as hypopigmented lesions or tan macules and patches with fine scale, as was seen in this patient. Hypopigmentation is often more pronounced on sun-exposed areas of the body. The MF produces azelaic acid. The azelaic acid blocks tyrosinase, which hinders melanocyte function and leads to hypopigmentation.2 As a result, areas of skin that are affected by TV do not tan as much as the surrounding skin, making the lesions more pronounced.

First line treatment of TV includes topical antifungal preparations, such as the “azoles” (eg, clotrimazole, ketoconazole, miconazole) twice daily for 2 to 4 weeks. However, the large surface areas involved would require a large amount of these antifungal preparations that come in relatively small tubes. Thus, for many years, clinicians have turned to economical over-the-counter dandruff shampoos with either selenium sulfide or zinc pyrithione that provide excellent results. These shampoos are applied to the entire trunk at full strength, allowed to dry, and then washed off later following various timed protocols. If topical therapy is not successful, or if there is a recurrence, systemic antifungal medications are used. Oral options include fluconazole 200 mg to 300 mg orally once a week for 2 weeks and itraconazole 200 mg orally once a day for 7 days.3 Ketoconazole is avoided as a systemic antifungal (except in life-threatening situations) due to its higher rate of liver dysfunction.

This patient was instructed to apply full-strength selenium sulfide shampoo to his entire trunk in the evening, allow it to dry, then wash it off the next morning and repeat in 1 week. An alternate regimen is to leave it on for 1 hour before washing and repeat daily for 1 week. At the patient’s follow-up appointment a month later, the rash and itching had resolved.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

A waxing and waning rash with fine scale is classic for tinea versicolor (TV). A potassium hydroxide (KOH) prep with Swartz-Lamkins stain confirmed the presence of the spaghetti-and-meatballs pattern of Malassezia furfur (MF).

TV is a skin infection caused by M furfur. TF is notorious for the variety of colors that are seen clinically, including hyperpigmentation, as seen in a recent installment in this column.1 It can also appear as hypopigmented lesions or tan macules and patches with fine scale, as was seen in this patient. Hypopigmentation is often more pronounced on sun-exposed areas of the body. The MF produces azelaic acid. The azelaic acid blocks tyrosinase, which hinders melanocyte function and leads to hypopigmentation.2 As a result, areas of skin that are affected by TV do not tan as much as the surrounding skin, making the lesions more pronounced.

First line treatment of TV includes topical antifungal preparations, such as the “azoles” (eg, clotrimazole, ketoconazole, miconazole) twice daily for 2 to 4 weeks. However, the large surface areas involved would require a large amount of these antifungal preparations that come in relatively small tubes. Thus, for many years, clinicians have turned to economical over-the-counter dandruff shampoos with either selenium sulfide or zinc pyrithione that provide excellent results. These shampoos are applied to the entire trunk at full strength, allowed to dry, and then washed off later following various timed protocols. If topical therapy is not successful, or if there is a recurrence, systemic antifungal medications are used. Oral options include fluconazole 200 mg to 300 mg orally once a week for 2 weeks and itraconazole 200 mg orally once a day for 7 days.3 Ketoconazole is avoided as a systemic antifungal (except in life-threatening situations) due to its higher rate of liver dysfunction.

This patient was instructed to apply full-strength selenium sulfide shampoo to his entire trunk in the evening, allow it to dry, then wash it off the next morning and repeat in 1 week. An alternate regimen is to leave it on for 1 hour before washing and repeat daily for 1 week. At the patient’s follow-up appointment a month later, the rash and itching had resolved.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Jasser J, Stulberg D. Teen with hyperpigmented skin lesions. J Fam Pract. 2022;71. Published December 2022. Accessed May 26, 2023. www.mdedge.com/familymedicine/article/260076/dermatology/teen-hyperpigmented-skin-lesions. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0529

2. Leung AK, Barankin B, Lam JM, et al. Tinea versicolor: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2022;11:2022-9-2. doi: 10.7573/dic.2022-9-2

3. Gupta AK, Foley KA. Antifungal treatment for pityriasis versicolor. J Fungi (Basel). 2015;1:13-29. doi: 10.3390/jof1010013

1. Jasser J, Stulberg D. Teen with hyperpigmented skin lesions. J Fam Pract. 2022;71. Published December 2022. Accessed May 26, 2023. www.mdedge.com/familymedicine/article/260076/dermatology/teen-hyperpigmented-skin-lesions. doi: 10.12788/jfp.0529

2. Leung AK, Barankin B, Lam JM, et al. Tinea versicolor: an updated review. Drugs Context. 2022;11:2022-9-2. doi: 10.7573/dic.2022-9-2

3. Gupta AK, Foley KA. Antifungal treatment for pityriasis versicolor. J Fungi (Basel). 2015;1:13-29. doi: 10.3390/jof1010013

Nodule on farmer’s hand

A broad shave biopsy was performed at the base of the lesion and the results were consistent with a thick nodular melanoma with a Breslow depth of 5.5 mm.

Melanoma is the deadliest skin cancer in the United States with mortality risk corresponding with the depth of the tumor.1 Nodular melanomas grow faster than all other types of melanoma. For this reason, a concerning raised lesion with a risk of melanoma should not be observed for change over time; it should be biopsied promptly. In this case, a depth of 5.5 mm was cause for quick action. Patients with tumors > 1 mm in depth (and some tumors > 0.8 mm) should be offered sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) along with wide local excision to evaluate for lymphatic spread. Patients with thinner tumors may undergo wide local excision without SLNB.

In this case, National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines would dictate a 2-cm margin for a wide local incision; the patient underwent a modified version of this with Surgical Oncology to accommodate maintenance of hand function. This patient’s SLNB was negative, so the melanoma was classified as Stage IIC.

In the recent past, there were no additional treatments for patients with late Stage II disease (thick tumors without evidence of metastasis). However, in December 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the use of immunotherapy with pembrolizumab in patients with node-negative late Stage II melanoma after demonstration of improved recurrence-free survival in the KEYNOTE trial.2 Evidence of improved long-term survival is mixed with adjuvant therapy, and studies evaluating the best role of adjuvant therapy are ongoing.

This patient was started on a regimen of pembrolizumab 200 mg IV every 3 weeks, which he will continue for as long as 1 year. He has tolerated this regimen without difficulty and has no evidence of disease.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Epstein DS, Lange JR, Gruber SB, et al. Is physician detection associated with thinner melanomas? JAMA. 1999;281:640-643. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.7.640

2. Luke JJ, Rutkowski P, Queirolo P, et al; KEYNOTE-716 Investigators. Pembrolizumab versus placebo as adjuvant therapy in completely resected stage IIB or IIC melanoma (KEYNOTE-716): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;399:1718-1729. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00562-1

A broad shave biopsy was performed at the base of the lesion and the results were consistent with a thick nodular melanoma with a Breslow depth of 5.5 mm.

Melanoma is the deadliest skin cancer in the United States with mortality risk corresponding with the depth of the tumor.1 Nodular melanomas grow faster than all other types of melanoma. For this reason, a concerning raised lesion with a risk of melanoma should not be observed for change over time; it should be biopsied promptly. In this case, a depth of 5.5 mm was cause for quick action. Patients with tumors > 1 mm in depth (and some tumors > 0.8 mm) should be offered sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) along with wide local excision to evaluate for lymphatic spread. Patients with thinner tumors may undergo wide local excision without SLNB.

In this case, National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines would dictate a 2-cm margin for a wide local incision; the patient underwent a modified version of this with Surgical Oncology to accommodate maintenance of hand function. This patient’s SLNB was negative, so the melanoma was classified as Stage IIC.

In the recent past, there were no additional treatments for patients with late Stage II disease (thick tumors without evidence of metastasis). However, in December 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the use of immunotherapy with pembrolizumab in patients with node-negative late Stage II melanoma after demonstration of improved recurrence-free survival in the KEYNOTE trial.2 Evidence of improved long-term survival is mixed with adjuvant therapy, and studies evaluating the best role of adjuvant therapy are ongoing.

This patient was started on a regimen of pembrolizumab 200 mg IV every 3 weeks, which he will continue for as long as 1 year. He has tolerated this regimen without difficulty and has no evidence of disease.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

A broad shave biopsy was performed at the base of the lesion and the results were consistent with a thick nodular melanoma with a Breslow depth of 5.5 mm.

Melanoma is the deadliest skin cancer in the United States with mortality risk corresponding with the depth of the tumor.1 Nodular melanomas grow faster than all other types of melanoma. For this reason, a concerning raised lesion with a risk of melanoma should not be observed for change over time; it should be biopsied promptly. In this case, a depth of 5.5 mm was cause for quick action. Patients with tumors > 1 mm in depth (and some tumors > 0.8 mm) should be offered sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) along with wide local excision to evaluate for lymphatic spread. Patients with thinner tumors may undergo wide local excision without SLNB.

In this case, National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines would dictate a 2-cm margin for a wide local incision; the patient underwent a modified version of this with Surgical Oncology to accommodate maintenance of hand function. This patient’s SLNB was negative, so the melanoma was classified as Stage IIC.

In the recent past, there were no additional treatments for patients with late Stage II disease (thick tumors without evidence of metastasis). However, in December 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the use of immunotherapy with pembrolizumab in patients with node-negative late Stage II melanoma after demonstration of improved recurrence-free survival in the KEYNOTE trial.2 Evidence of improved long-term survival is mixed with adjuvant therapy, and studies evaluating the best role of adjuvant therapy are ongoing.

This patient was started on a regimen of pembrolizumab 200 mg IV every 3 weeks, which he will continue for as long as 1 year. He has tolerated this regimen without difficulty and has no evidence of disease.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Epstein DS, Lange JR, Gruber SB, et al. Is physician detection associated with thinner melanomas? JAMA. 1999;281:640-643. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.7.640

2. Luke JJ, Rutkowski P, Queirolo P, et al; KEYNOTE-716 Investigators. Pembrolizumab versus placebo as adjuvant therapy in completely resected stage IIB or IIC melanoma (KEYNOTE-716): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;399:1718-1729. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00562-1

1. Epstein DS, Lange JR, Gruber SB, et al. Is physician detection associated with thinner melanomas? JAMA. 1999;281:640-643. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.7.640

2. Luke JJ, Rutkowski P, Queirolo P, et al; KEYNOTE-716 Investigators. Pembrolizumab versus placebo as adjuvant therapy in completely resected stage IIB or IIC melanoma (KEYNOTE-716): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;399:1718-1729. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00562-1

Firm nodule following tick bite

The biopsy revealed abundant lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous B cell pseudolymphoma. The pseudolymphoma was caused by an exaggerated response to a tick bite.

As the name implies, B cell pseudolymphomas clinically and histologically mimic the various patterns of cutaneous lymphoma, often appearing as a firm, pink to dark violet nodule. A biopsy is mandatory to distinguish between pseudolymphoma and true lymphoma. There is an association between pseudolymphomas and Borrelia burgdorferi, the organism responsible for Lyme disease. Thus, testing for Lyme disease is recommended for patients with pseudolymphomas who live in endemic areas. Patients who test positive should be treated with doxycycline 100 mg bid for 10 days.

In the absence of Lyme disease, a pseudolymphoma may resolve spontaneously over weeks or months. Resolution can be hastened with topical superpotent steroids, intralesional steroids, or systemic steroids. Treatment can begin with topical clobetasol 0.05% bid. If the lesion does not resolve, the next step would be intralesional triamcinolone 10 mg/mL injected directly into the nodule until it blanches slightly. Injections should be repeated every 3 to 4 weeks for a total of 2 to 3 injections.

The patient in this case had negative Lyme serology and was treated with 2 injections of triamcinolone 10 mg/mL administered 3 weeks apart. She experienced complete resolution.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Mitteldorf C, Kempf W. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:455-476. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2017.01.002

The biopsy revealed abundant lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous B cell pseudolymphoma. The pseudolymphoma was caused by an exaggerated response to a tick bite.

As the name implies, B cell pseudolymphomas clinically and histologically mimic the various patterns of cutaneous lymphoma, often appearing as a firm, pink to dark violet nodule. A biopsy is mandatory to distinguish between pseudolymphoma and true lymphoma. There is an association between pseudolymphomas and Borrelia burgdorferi, the organism responsible for Lyme disease. Thus, testing for Lyme disease is recommended for patients with pseudolymphomas who live in endemic areas. Patients who test positive should be treated with doxycycline 100 mg bid for 10 days.

In the absence of Lyme disease, a pseudolymphoma may resolve spontaneously over weeks or months. Resolution can be hastened with topical superpotent steroids, intralesional steroids, or systemic steroids. Treatment can begin with topical clobetasol 0.05% bid. If the lesion does not resolve, the next step would be intralesional triamcinolone 10 mg/mL injected directly into the nodule until it blanches slightly. Injections should be repeated every 3 to 4 weeks for a total of 2 to 3 injections.

The patient in this case had negative Lyme serology and was treated with 2 injections of triamcinolone 10 mg/mL administered 3 weeks apart. She experienced complete resolution.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

The biopsy revealed abundant lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils consistent with a diagnosis of cutaneous B cell pseudolymphoma. The pseudolymphoma was caused by an exaggerated response to a tick bite.

As the name implies, B cell pseudolymphomas clinically and histologically mimic the various patterns of cutaneous lymphoma, often appearing as a firm, pink to dark violet nodule. A biopsy is mandatory to distinguish between pseudolymphoma and true lymphoma. There is an association between pseudolymphomas and Borrelia burgdorferi, the organism responsible for Lyme disease. Thus, testing for Lyme disease is recommended for patients with pseudolymphomas who live in endemic areas. Patients who test positive should be treated with doxycycline 100 mg bid for 10 days.

In the absence of Lyme disease, a pseudolymphoma may resolve spontaneously over weeks or months. Resolution can be hastened with topical superpotent steroids, intralesional steroids, or systemic steroids. Treatment can begin with topical clobetasol 0.05% bid. If the lesion does not resolve, the next step would be intralesional triamcinolone 10 mg/mL injected directly into the nodule until it blanches slightly. Injections should be repeated every 3 to 4 weeks for a total of 2 to 3 injections.

The patient in this case had negative Lyme serology and was treated with 2 injections of triamcinolone 10 mg/mL administered 3 weeks apart. She experienced complete resolution.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Mitteldorf C, Kempf W. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:455-476. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2017.01.002

1. Mitteldorf C, Kempf W. Cutaneous pseudolymphoma. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:455-476. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2017.01.002