User login

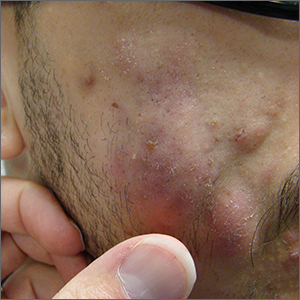

Fluctuant facial lesions

This patient had more than cystic acne; he had acne conglobata. AC is a severe form of inflammatory acne leading to coalescing lesions with purulent sinus tracts under the skin. It can be seen as part of the follicular tetrad syndrome of cystic acne, hidradenitis suppurativa, dissecting cellulitis, and pilonidal disease. AC is thought to be an elevated tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha response to Propionibacterium acnes (now known as Cutibacterium acnes) that leads to excessive inflammation and sterile abscesses.1 Acne fulminans (AF) can also manifest as a purulent form of acne, but AF has associated systemic signs and symptoms that include fevers, chills, and malaise.

Due to the depth of the inflammation, AC is treated with systemic medications, most commonly isotretinoin. Isotretinoin can be started at 0.5 mg/kg (divided twice daily to enhance tolerability) and then increased to 1 mg/kg (divided twice daily) for 5 months. There is some variation in dosing regimens in practice; the target goal is 120 to 150 mg/kg over the course of treatment. In AF, the patient is pretreated with systemic steroids, and in AC, some clinicians will even prescribe systemic steroids (prednisone 0.5 mg/kg daily for the first month) along with isotretinoin.

Second-line medications include dapsone (50-150 mg/d).2 Case reports describe the successful use of the TNF-alpha antagonist adalimumab, although this is not a usual practice in AC treatment.1 Note that all of these medications have the potential for severe adverse effects and require laboratory evaluation prior to initiation.

This patient was counseled, prescribed isotretinoin (dose as above), and enrolled in the IPledge prescribing and monitoring system for isotretinoin. At 20 weeks of use, the purulent drainage ceased. The pus-filled sinus tracts and redness had resolved, although he still had thickened tissue and scarring where the tracts had been. In time, the scars will usually get flatter and softer.

If the patient’s AC were to flare, another 20-week course of isotretinoin could be prescribed after a 2-month hiatus or he could be switched to a second-line medication. Referral for any cosmetic therapy is typically delayed for another 6 months in case there is a need to treat a recurrence.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Yiu ZZ, Madan V, Griffiths CE. Acne conglobata and adalimumab: use of tumour necrosis factor-α antagonists in treatment-resistant acne conglobata, and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:383-386. doi: 10.1111/ced.12540

2. Hafsi W, Arnold DL, Kassardjian M. Acne Conglobata. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

This patient had more than cystic acne; he had acne conglobata. AC is a severe form of inflammatory acne leading to coalescing lesions with purulent sinus tracts under the skin. It can be seen as part of the follicular tetrad syndrome of cystic acne, hidradenitis suppurativa, dissecting cellulitis, and pilonidal disease. AC is thought to be an elevated tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha response to Propionibacterium acnes (now known as Cutibacterium acnes) that leads to excessive inflammation and sterile abscesses.1 Acne fulminans (AF) can also manifest as a purulent form of acne, but AF has associated systemic signs and symptoms that include fevers, chills, and malaise.

Due to the depth of the inflammation, AC is treated with systemic medications, most commonly isotretinoin. Isotretinoin can be started at 0.5 mg/kg (divided twice daily to enhance tolerability) and then increased to 1 mg/kg (divided twice daily) for 5 months. There is some variation in dosing regimens in practice; the target goal is 120 to 150 mg/kg over the course of treatment. In AF, the patient is pretreated with systemic steroids, and in AC, some clinicians will even prescribe systemic steroids (prednisone 0.5 mg/kg daily for the first month) along with isotretinoin.

Second-line medications include dapsone (50-150 mg/d).2 Case reports describe the successful use of the TNF-alpha antagonist adalimumab, although this is not a usual practice in AC treatment.1 Note that all of these medications have the potential for severe adverse effects and require laboratory evaluation prior to initiation.

This patient was counseled, prescribed isotretinoin (dose as above), and enrolled in the IPledge prescribing and monitoring system for isotretinoin. At 20 weeks of use, the purulent drainage ceased. The pus-filled sinus tracts and redness had resolved, although he still had thickened tissue and scarring where the tracts had been. In time, the scars will usually get flatter and softer.

If the patient’s AC were to flare, another 20-week course of isotretinoin could be prescribed after a 2-month hiatus or he could be switched to a second-line medication. Referral for any cosmetic therapy is typically delayed for another 6 months in case there is a need to treat a recurrence.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

This patient had more than cystic acne; he had acne conglobata. AC is a severe form of inflammatory acne leading to coalescing lesions with purulent sinus tracts under the skin. It can be seen as part of the follicular tetrad syndrome of cystic acne, hidradenitis suppurativa, dissecting cellulitis, and pilonidal disease. AC is thought to be an elevated tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha response to Propionibacterium acnes (now known as Cutibacterium acnes) that leads to excessive inflammation and sterile abscesses.1 Acne fulminans (AF) can also manifest as a purulent form of acne, but AF has associated systemic signs and symptoms that include fevers, chills, and malaise.

Due to the depth of the inflammation, AC is treated with systemic medications, most commonly isotretinoin. Isotretinoin can be started at 0.5 mg/kg (divided twice daily to enhance tolerability) and then increased to 1 mg/kg (divided twice daily) for 5 months. There is some variation in dosing regimens in practice; the target goal is 120 to 150 mg/kg over the course of treatment. In AF, the patient is pretreated with systemic steroids, and in AC, some clinicians will even prescribe systemic steroids (prednisone 0.5 mg/kg daily for the first month) along with isotretinoin.

Second-line medications include dapsone (50-150 mg/d).2 Case reports describe the successful use of the TNF-alpha antagonist adalimumab, although this is not a usual practice in AC treatment.1 Note that all of these medications have the potential for severe adverse effects and require laboratory evaluation prior to initiation.

This patient was counseled, prescribed isotretinoin (dose as above), and enrolled in the IPledge prescribing and monitoring system for isotretinoin. At 20 weeks of use, the purulent drainage ceased. The pus-filled sinus tracts and redness had resolved, although he still had thickened tissue and scarring where the tracts had been. In time, the scars will usually get flatter and softer.

If the patient’s AC were to flare, another 20-week course of isotretinoin could be prescribed after a 2-month hiatus or he could be switched to a second-line medication. Referral for any cosmetic therapy is typically delayed for another 6 months in case there is a need to treat a recurrence.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Yiu ZZ, Madan V, Griffiths CE. Acne conglobata and adalimumab: use of tumour necrosis factor-α antagonists in treatment-resistant acne conglobata, and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:383-386. doi: 10.1111/ced.12540

2. Hafsi W, Arnold DL, Kassardjian M. Acne Conglobata. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

1. Yiu ZZ, Madan V, Griffiths CE. Acne conglobata and adalimumab: use of tumour necrosis factor-α antagonists in treatment-resistant acne conglobata, and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:383-386. doi: 10.1111/ced.12540

2. Hafsi W, Arnold DL, Kassardjian M. Acne Conglobata. StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

Leathery plaque on thigh

The necrotic eschar on this patient’s thigh is calciphylaxis, also known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy (CUA). Most cases are seen in ESRD and start as painful erythematous, firm lesions that progress to necrotic eschars. Up to 4% of patients with ESRD who are on dialysis develop CUA.1

The exact pathology of CUA is unknown. Calcification of the arterioles leads to ischemia and necrosis of tissue, which is not limited to the skin and can affect tissue elsewhere (eg, muscles, central nervous system, internal organs).2

Morbidity and mortality of CUA is often due to bacterial infections and sepsis related to the necrotic tissue. CUA can be treated with sodium thiosulfate (25 g in 100 mL of normal saline) infused intravenously during the last 30 minutes of dialysis treatment 3 times per week.3 Sodium thiosulfate (which acts as a calcium binder) and cinacalcet (a calcimimetic that leads to lower parathyroid hormone levels) have been used, but evidence of efficacy is limited. In a multicenter observational study involving 89 patients with chronic kidney disease and CUA, 17% of patients experienced complete wound healing, while 56% died over a median follow-up period of 5.8 months.1 (No cause of death data were available; sodium thiosulfate and a calcimimetic were the most widely used treatment strategies.) This extrapolated to a mortality rate of 72 patients per 100 individuals over the course of 1 year (the 100 patient-years rate).1

This patient continued her dialysis regimen and general care. She was seen by the wound care team and treated with topical wound care, including moist dressings for her open lesions. The eschars were not debrided because they showed no sign of active infection. Unfortunately, she was in extremely frail condition and died 1 month after evaluation.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Chinnadurai R, Huckle A, Hegarty J, et al. Calciphylaxis in end-stage kidney disease: outcome data from the United Kingdom Calciphylaxis Study. J Nephrol. 2021;34:1537-1545. doi: 10.1007/s40620-020-00908-9

2. Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133-146. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.034

3. Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133-146. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.034

The necrotic eschar on this patient’s thigh is calciphylaxis, also known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy (CUA). Most cases are seen in ESRD and start as painful erythematous, firm lesions that progress to necrotic eschars. Up to 4% of patients with ESRD who are on dialysis develop CUA.1

The exact pathology of CUA is unknown. Calcification of the arterioles leads to ischemia and necrosis of tissue, which is not limited to the skin and can affect tissue elsewhere (eg, muscles, central nervous system, internal organs).2

Morbidity and mortality of CUA is often due to bacterial infections and sepsis related to the necrotic tissue. CUA can be treated with sodium thiosulfate (25 g in 100 mL of normal saline) infused intravenously during the last 30 minutes of dialysis treatment 3 times per week.3 Sodium thiosulfate (which acts as a calcium binder) and cinacalcet (a calcimimetic that leads to lower parathyroid hormone levels) have been used, but evidence of efficacy is limited. In a multicenter observational study involving 89 patients with chronic kidney disease and CUA, 17% of patients experienced complete wound healing, while 56% died over a median follow-up period of 5.8 months.1 (No cause of death data were available; sodium thiosulfate and a calcimimetic were the most widely used treatment strategies.) This extrapolated to a mortality rate of 72 patients per 100 individuals over the course of 1 year (the 100 patient-years rate).1

This patient continued her dialysis regimen and general care. She was seen by the wound care team and treated with topical wound care, including moist dressings for her open lesions. The eschars were not debrided because they showed no sign of active infection. Unfortunately, she was in extremely frail condition and died 1 month after evaluation.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

The necrotic eschar on this patient’s thigh is calciphylaxis, also known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy (CUA). Most cases are seen in ESRD and start as painful erythematous, firm lesions that progress to necrotic eschars. Up to 4% of patients with ESRD who are on dialysis develop CUA.1

The exact pathology of CUA is unknown. Calcification of the arterioles leads to ischemia and necrosis of tissue, which is not limited to the skin and can affect tissue elsewhere (eg, muscles, central nervous system, internal organs).2

Morbidity and mortality of CUA is often due to bacterial infections and sepsis related to the necrotic tissue. CUA can be treated with sodium thiosulfate (25 g in 100 mL of normal saline) infused intravenously during the last 30 minutes of dialysis treatment 3 times per week.3 Sodium thiosulfate (which acts as a calcium binder) and cinacalcet (a calcimimetic that leads to lower parathyroid hormone levels) have been used, but evidence of efficacy is limited. In a multicenter observational study involving 89 patients with chronic kidney disease and CUA, 17% of patients experienced complete wound healing, while 56% died over a median follow-up period of 5.8 months.1 (No cause of death data were available; sodium thiosulfate and a calcimimetic were the most widely used treatment strategies.) This extrapolated to a mortality rate of 72 patients per 100 individuals over the course of 1 year (the 100 patient-years rate).1

This patient continued her dialysis regimen and general care. She was seen by the wound care team and treated with topical wound care, including moist dressings for her open lesions. The eschars were not debrided because they showed no sign of active infection. Unfortunately, she was in extremely frail condition and died 1 month after evaluation.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Chinnadurai R, Huckle A, Hegarty J, et al. Calciphylaxis in end-stage kidney disease: outcome data from the United Kingdom Calciphylaxis Study. J Nephrol. 2021;34:1537-1545. doi: 10.1007/s40620-020-00908-9

2. Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133-146. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.034

3. Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133-146. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.034

1. Chinnadurai R, Huckle A, Hegarty J, et al. Calciphylaxis in end-stage kidney disease: outcome data from the United Kingdom Calciphylaxis Study. J Nephrol. 2021;34:1537-1545. doi: 10.1007/s40620-020-00908-9

2. Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133-146. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.034

3. Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:133-146. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.01.034

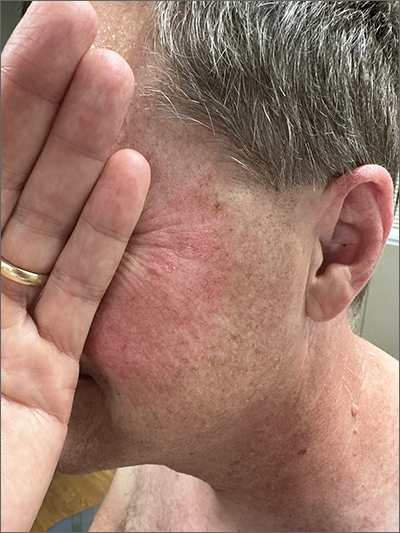

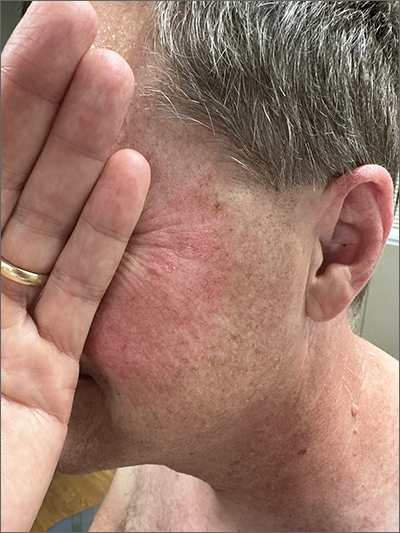

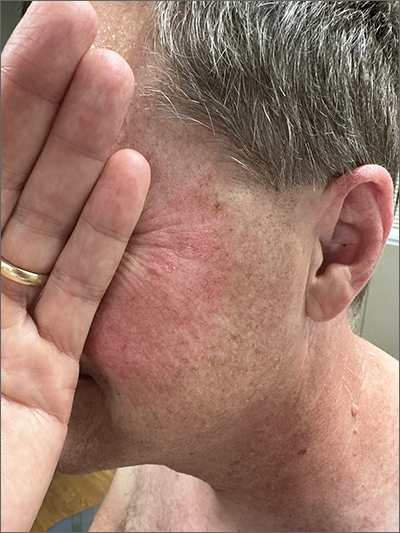

Rosacea look-alike

Although it’s easy to jump to the conclusion that facial erythema is rosacea, there are multiple other conditions that can lead to reddening of the face. In this case, excessive sun exposure had resulted in a diffuse actinic change of the malar and lateral aspects of this patient’s face. The palpably rough lesions were actinic keratoses.

Actinic keratoses are caused by exposure to ultraviolet radiation. These lesions are premalignant and common. Areas of the body at greatest risk include those not typically covered by clothing (eg, face, hands, arms, ears, forehead, and top of the scalp—especially in individuals with hair loss). There is a range of estimates regarding the percentage of actinic keratoses that will progress to squamous cell carcinoma in situ, and then invasive squamous cell carcinoma. One study determined that 10% of actinic keratoses progress to squamous cell carcinoma over the course of 2 years.1

In patients with broad areas of multiple clinically palpable lesions with rough sandpapery texture or visible white scale, there are likely preclinical lesions in the same areas. With so many lesions, field therapy of the entire region is often performed instead of treating the lesions 1 at a time.

There are multiple topical agents for field therapy, including 5-fluorouracil, diclofenac gel, and imiquimod gel.2 Since significant erythema and inflammation usually follow application of the topical agent, clinicians may want to have patients treat in segments to make the process more tolerable.

5-fluorouracil has a complete clearance rate (CCR) of 75% to 90% and is usually applied twice daily for 2 weeks, although there are multiple different protocols. Diclofenac has a CCR of 58% over a 60- to 90-day course, and imiquimod has a CCR of 54% after a 120-day course. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has the advantage of a single treatment but a CCR of 38%. PDT may be advantageous for a patient who has difficulty applying topical medication over a period of weeks.

Niacinamide has been shown to help with skin repair and reduce the risk of additional nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSC) by 23% and additional actinic keratoses by about 15% in individuals with a history of actinic keratoses or NMSC.3 In contrast to niacin, niacinamide does not cause flushing. Niacinamide is used long term; if discontinued, it no longer confers benefit in helping the skin repair itself.

The patient in this case was prescribed topical 5% fluorouracil cream to be applied twice daily to the malar regions bilaterally for 2 weeks and, if not inflamed by 2 weeks, to extend the treatment until there is robust inflammation (but not to exceed 3 weeks). He was scheduled to follow up in 3 months for reexamination. He was also advised to start taking niacinamide 500 mg twice daily to reduce his risk of additional precancerous and cancerous skin lesions and counseled on the importance of sunscreen, hats, and sun-protective clothing.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

- Fuchs A, Marmur E. The kinetics of skin cancer: progression of actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1099-1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33224.x

- Jansen MHE, Kessels JPHM, Nelemans PJ, et al. Randomized trial of four treatment approaches for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:935-946. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1811850

- Starr P. Oral nicotinamide prevents common skin cancers in high-risk patients, reduces costs. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8(spec issue):13-14.

Although it’s easy to jump to the conclusion that facial erythema is rosacea, there are multiple other conditions that can lead to reddening of the face. In this case, excessive sun exposure had resulted in a diffuse actinic change of the malar and lateral aspects of this patient’s face. The palpably rough lesions were actinic keratoses.

Actinic keratoses are caused by exposure to ultraviolet radiation. These lesions are premalignant and common. Areas of the body at greatest risk include those not typically covered by clothing (eg, face, hands, arms, ears, forehead, and top of the scalp—especially in individuals with hair loss). There is a range of estimates regarding the percentage of actinic keratoses that will progress to squamous cell carcinoma in situ, and then invasive squamous cell carcinoma. One study determined that 10% of actinic keratoses progress to squamous cell carcinoma over the course of 2 years.1

In patients with broad areas of multiple clinically palpable lesions with rough sandpapery texture or visible white scale, there are likely preclinical lesions in the same areas. With so many lesions, field therapy of the entire region is often performed instead of treating the lesions 1 at a time.

There are multiple topical agents for field therapy, including 5-fluorouracil, diclofenac gel, and imiquimod gel.2 Since significant erythema and inflammation usually follow application of the topical agent, clinicians may want to have patients treat in segments to make the process more tolerable.

5-fluorouracil has a complete clearance rate (CCR) of 75% to 90% and is usually applied twice daily for 2 weeks, although there are multiple different protocols. Diclofenac has a CCR of 58% over a 60- to 90-day course, and imiquimod has a CCR of 54% after a 120-day course. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has the advantage of a single treatment but a CCR of 38%. PDT may be advantageous for a patient who has difficulty applying topical medication over a period of weeks.

Niacinamide has been shown to help with skin repair and reduce the risk of additional nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSC) by 23% and additional actinic keratoses by about 15% in individuals with a history of actinic keratoses or NMSC.3 In contrast to niacin, niacinamide does not cause flushing. Niacinamide is used long term; if discontinued, it no longer confers benefit in helping the skin repair itself.

The patient in this case was prescribed topical 5% fluorouracil cream to be applied twice daily to the malar regions bilaterally for 2 weeks and, if not inflamed by 2 weeks, to extend the treatment until there is robust inflammation (but not to exceed 3 weeks). He was scheduled to follow up in 3 months for reexamination. He was also advised to start taking niacinamide 500 mg twice daily to reduce his risk of additional precancerous and cancerous skin lesions and counseled on the importance of sunscreen, hats, and sun-protective clothing.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

Although it’s easy to jump to the conclusion that facial erythema is rosacea, there are multiple other conditions that can lead to reddening of the face. In this case, excessive sun exposure had resulted in a diffuse actinic change of the malar and lateral aspects of this patient’s face. The palpably rough lesions were actinic keratoses.

Actinic keratoses are caused by exposure to ultraviolet radiation. These lesions are premalignant and common. Areas of the body at greatest risk include those not typically covered by clothing (eg, face, hands, arms, ears, forehead, and top of the scalp—especially in individuals with hair loss). There is a range of estimates regarding the percentage of actinic keratoses that will progress to squamous cell carcinoma in situ, and then invasive squamous cell carcinoma. One study determined that 10% of actinic keratoses progress to squamous cell carcinoma over the course of 2 years.1

In patients with broad areas of multiple clinically palpable lesions with rough sandpapery texture or visible white scale, there are likely preclinical lesions in the same areas. With so many lesions, field therapy of the entire region is often performed instead of treating the lesions 1 at a time.

There are multiple topical agents for field therapy, including 5-fluorouracil, diclofenac gel, and imiquimod gel.2 Since significant erythema and inflammation usually follow application of the topical agent, clinicians may want to have patients treat in segments to make the process more tolerable.

5-fluorouracil has a complete clearance rate (CCR) of 75% to 90% and is usually applied twice daily for 2 weeks, although there are multiple different protocols. Diclofenac has a CCR of 58% over a 60- to 90-day course, and imiquimod has a CCR of 54% after a 120-day course. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has the advantage of a single treatment but a CCR of 38%. PDT may be advantageous for a patient who has difficulty applying topical medication over a period of weeks.

Niacinamide has been shown to help with skin repair and reduce the risk of additional nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSC) by 23% and additional actinic keratoses by about 15% in individuals with a history of actinic keratoses or NMSC.3 In contrast to niacin, niacinamide does not cause flushing. Niacinamide is used long term; if discontinued, it no longer confers benefit in helping the skin repair itself.

The patient in this case was prescribed topical 5% fluorouracil cream to be applied twice daily to the malar regions bilaterally for 2 weeks and, if not inflamed by 2 weeks, to extend the treatment until there is robust inflammation (but not to exceed 3 weeks). He was scheduled to follow up in 3 months for reexamination. He was also advised to start taking niacinamide 500 mg twice daily to reduce his risk of additional precancerous and cancerous skin lesions and counseled on the importance of sunscreen, hats, and sun-protective clothing.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

- Fuchs A, Marmur E. The kinetics of skin cancer: progression of actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1099-1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33224.x

- Jansen MHE, Kessels JPHM, Nelemans PJ, et al. Randomized trial of four treatment approaches for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:935-946. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1811850

- Starr P. Oral nicotinamide prevents common skin cancers in high-risk patients, reduces costs. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8(spec issue):13-14.

- Fuchs A, Marmur E. The kinetics of skin cancer: progression of actinic keratosis to squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33:1099-1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.33224.x

- Jansen MHE, Kessels JPHM, Nelemans PJ, et al. Randomized trial of four treatment approaches for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:935-946. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1811850

- Starr P. Oral nicotinamide prevents common skin cancers in high-risk patients, reduces costs. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8(spec issue):13-14.

Foot rash during self-treatment

The patient’s toenail thickening appeared consistent with possible onychomycosis—but in addition, there was a marked inflammatory and vesicular eruption consistent with an allergic contact dermatitis.

TTO, also known as melaleuca oil, is a popular product used to treat many disorders including alopecia, seborrheic dermatitis, and onychomycosis.1 Unfortunately, it is a complex compound, and the rate of positive reactions to patch testing ranges from 0.1% to 3.5%.2

There are 2 types of contact dermatitis: irritant and allergic. Irritant contact dermatitis results from an irritating or relatively caustic substance causing direct damage and inflammation to the skin. In allergic contact dermatitis, as occurred here, there is sensitization to a substance that causes a type IV delayed cell-mediated immune response. Although radioallergosorbent blood testing will usually show immunoglobulin E antibodies to the inciting substance, patch testing is more specific and will show a reaction to the imputed substance on direct skin application. This usually is performed as a panel of antigens tested at the same time.

The mainstay of treatment is to identify, stop use of, and then avoid the sensitizing substance. Topical steroids (triamcinolone 0.1% ointment or clobetasol 0.05% ointment twice daily) are helpful in most cases. If the condition is severe or does not respond to initial therapy, systemic steroids (prednisone 40 mg/d for 5 days for most cases or a 2- to 3-week taper for Rhus dermatitis [eg, poison ivy]) are often effective.3

This patient was instructed to stop using TTO and counseled to avoid it in the future. She was told that her nails might fall off due to the inflammation, which might cure her onychomycosis, and that it takes 12 to 18 months to grow new toenails. She was advised to return for evaluation if the new nails developed any abnormalities or if her onychomycosis recurred. Oral terbinafine 250 mg/d for 90 days is usually a safe and effective therapy.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Pazyar N, Yaghoobi R, Bagherani N, et al. A review of applications of tea tree oil in dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:784-790. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05654.x

2. de Groot AC, Schmidt E. Tea tree oil: contact allergy and chemical composition. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75:129-143. doi: 10.1111/cod.12591

3. Usatine RP, Riojas M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:249-255.

The patient’s toenail thickening appeared consistent with possible onychomycosis—but in addition, there was a marked inflammatory and vesicular eruption consistent with an allergic contact dermatitis.

TTO, also known as melaleuca oil, is a popular product used to treat many disorders including alopecia, seborrheic dermatitis, and onychomycosis.1 Unfortunately, it is a complex compound, and the rate of positive reactions to patch testing ranges from 0.1% to 3.5%.2

There are 2 types of contact dermatitis: irritant and allergic. Irritant contact dermatitis results from an irritating or relatively caustic substance causing direct damage and inflammation to the skin. In allergic contact dermatitis, as occurred here, there is sensitization to a substance that causes a type IV delayed cell-mediated immune response. Although radioallergosorbent blood testing will usually show immunoglobulin E antibodies to the inciting substance, patch testing is more specific and will show a reaction to the imputed substance on direct skin application. This usually is performed as a panel of antigens tested at the same time.

The mainstay of treatment is to identify, stop use of, and then avoid the sensitizing substance. Topical steroids (triamcinolone 0.1% ointment or clobetasol 0.05% ointment twice daily) are helpful in most cases. If the condition is severe or does not respond to initial therapy, systemic steroids (prednisone 40 mg/d for 5 days for most cases or a 2- to 3-week taper for Rhus dermatitis [eg, poison ivy]) are often effective.3

This patient was instructed to stop using TTO and counseled to avoid it in the future. She was told that her nails might fall off due to the inflammation, which might cure her onychomycosis, and that it takes 12 to 18 months to grow new toenails. She was advised to return for evaluation if the new nails developed any abnormalities or if her onychomycosis recurred. Oral terbinafine 250 mg/d for 90 days is usually a safe and effective therapy.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

The patient’s toenail thickening appeared consistent with possible onychomycosis—but in addition, there was a marked inflammatory and vesicular eruption consistent with an allergic contact dermatitis.

TTO, also known as melaleuca oil, is a popular product used to treat many disorders including alopecia, seborrheic dermatitis, and onychomycosis.1 Unfortunately, it is a complex compound, and the rate of positive reactions to patch testing ranges from 0.1% to 3.5%.2

There are 2 types of contact dermatitis: irritant and allergic. Irritant contact dermatitis results from an irritating or relatively caustic substance causing direct damage and inflammation to the skin. In allergic contact dermatitis, as occurred here, there is sensitization to a substance that causes a type IV delayed cell-mediated immune response. Although radioallergosorbent blood testing will usually show immunoglobulin E antibodies to the inciting substance, patch testing is more specific and will show a reaction to the imputed substance on direct skin application. This usually is performed as a panel of antigens tested at the same time.

The mainstay of treatment is to identify, stop use of, and then avoid the sensitizing substance. Topical steroids (triamcinolone 0.1% ointment or clobetasol 0.05% ointment twice daily) are helpful in most cases. If the condition is severe or does not respond to initial therapy, systemic steroids (prednisone 40 mg/d for 5 days for most cases or a 2- to 3-week taper for Rhus dermatitis [eg, poison ivy]) are often effective.3

This patient was instructed to stop using TTO and counseled to avoid it in the future. She was told that her nails might fall off due to the inflammation, which might cure her onychomycosis, and that it takes 12 to 18 months to grow new toenails. She was advised to return for evaluation if the new nails developed any abnormalities or if her onychomycosis recurred. Oral terbinafine 250 mg/d for 90 days is usually a safe and effective therapy.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Pazyar N, Yaghoobi R, Bagherani N, et al. A review of applications of tea tree oil in dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:784-790. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05654.x

2. de Groot AC, Schmidt E. Tea tree oil: contact allergy and chemical composition. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75:129-143. doi: 10.1111/cod.12591

3. Usatine RP, Riojas M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:249-255.

1. Pazyar N, Yaghoobi R, Bagherani N, et al. A review of applications of tea tree oil in dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:784-790. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05654.x

2. de Groot AC, Schmidt E. Tea tree oil: contact allergy and chemical composition. Contact Dermatitis. 2016;75:129-143. doi: 10.1111/cod.12591

3. Usatine RP, Riojas M. Diagnosis and management of contact dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:249-255.

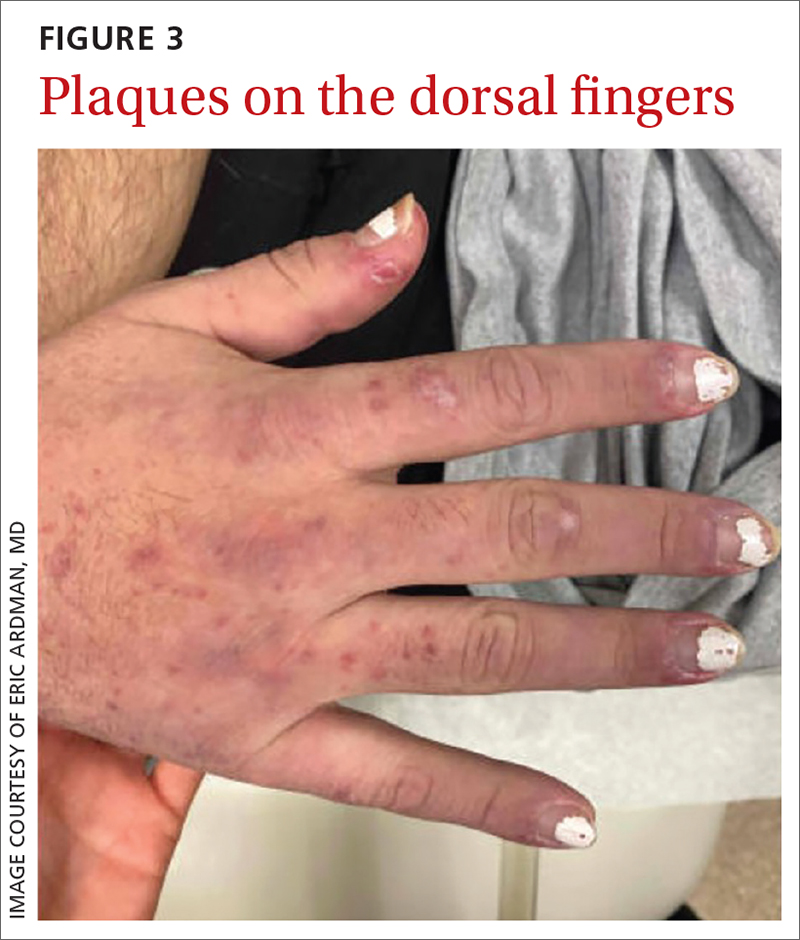

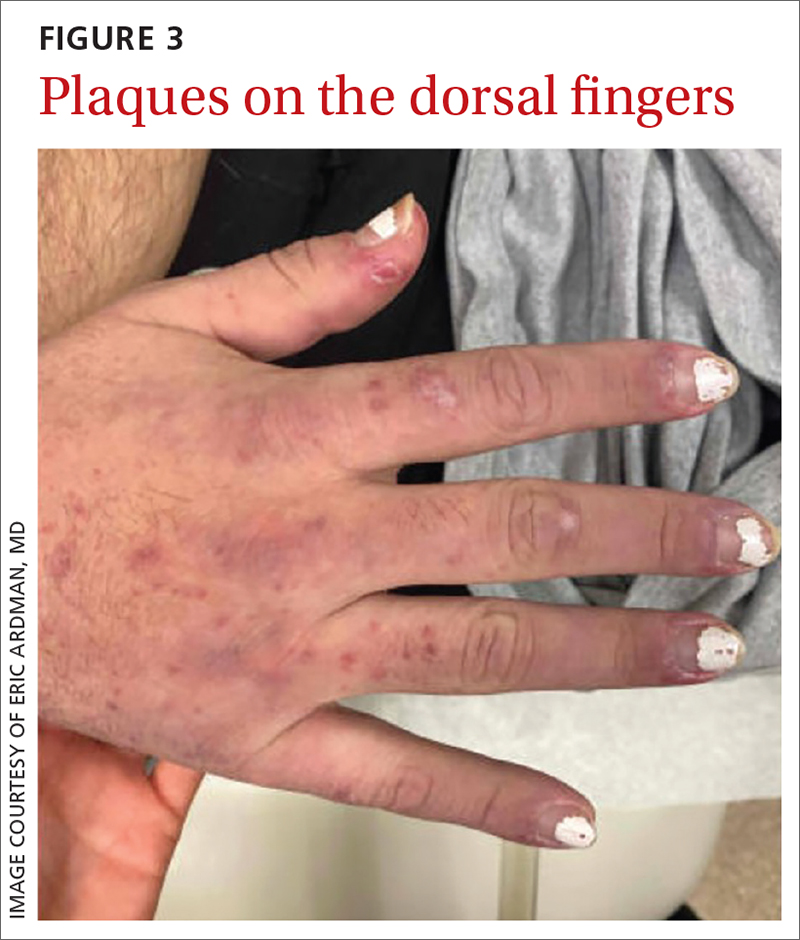

Generalized maculopapular rash and fever

A 29-YEAR-OLD MAN was referred to the emergency department for fever and rash. Two months prior, he had noticed painful spots on his toes (FIGURE 1). Soon after, a rash of different morphology appeared on his chest and upper extremities. Associated symptoms included hair loss, generalized arthralgias, chills, trouble with balance, and photophobia. The patient denied genital lesions but reported 3 recent cold sores.

On exam, the patient was febrile (102 °F). Skin exam revealed a generalized maculopapular rash on the trunk, arms, and legs with scattered lesions on the palms (FIGURE 2). There were tender purpuric macules on the tips of his toes with areas of blanching. His hands had pink plaques on the dorsal fingers (FIGURE 3). Additionally, there was an erythematous papular rash with scale on his cheeks and nasal bridge, patchy areas of hair loss, and a single oral ulcer.

A neurologic exam was notable for mildly unstable gait, an abnormal Babinski reflex on the left side, and a positive Romberg sign. Musculoskeletal exam revealed joint tenderness in his shoulders, elbows, and wrists. Lymphadenopathy was present bilaterally in the axilla.

Lab work was ordered, including a VDRL test and a treponemal antibodies test. Skin biopsies also were taken from lesions on his arm and chest.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Systemic lupus erythematosus

Our patient’s fever and rash were highly suggestive of either systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or secondary syphilis (the “great masquerader”).

In addition to the joint tenderness revealed during the musculoskeletal exam, our patient had several nonspecific lupus findings on skin exam: malar rash, discoid rash on hands, subacute vasculitis (generalized rash), alopecia, and an oral ulcer; he also had the specific finding of chilblains vasculitis of the toes. Lab work and pathology results made the diagnosis clear. Lab work revealed leukopenia, an antinuclear antibody (ANA) result of 1:2560 with speckled appearance, and positive anti-SM antibodies. A dipstick was negative for protein; VDRL and treponemal antibodies tests were also negative. Histopathology showed perivascular lymph histiocytic vacuolar dermatitis with a differential of connective tissue disease, including lupus.

Our patient met the criteria

SLE is a systemic autoimmune disease resulting in chronic inflammation in multiple organ systems; it commonly manifests with vague symptoms of fatigue, fever, and weight loss. The prevalence of SLE in the United States has been reported as high as 241 per 100,000 people. 1 Women are more likely to be affected, and the incidence is highest among Black people and lowest among Caucasians.1,2 Risk factors include cigarette smoking and exposure to silica particulate air pollution.

The 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology criteria for a diagnosis of SLE require that a patient have a positive ANA and some, but not all, additive lab, clinical, and organ-specific findings.3 Findings that clinicians should look for include3,4

- elevated ANA (≥ 1:80)

- constitutional symptoms (fever)

- hematologic findings (leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, autoimmune hemolysis)

- neuropsychiatric findings (delirium, psychosis, seizure)

- mucocutaneous findings (alopecia, oral ulcers, others)

- serosal findings (effusion, acute pericarditis)

- musculoskeletal findings (joint involvement)

- renal findings (proteinuria)

- antiphospholipid antibodies

- decreased complement proteins

- SLE-specific antibodies.

Dermatologic findings occur in more than 70% of patients with SLE.5 They can be nonspecific—eg, classic discoid rash, malar rash, alopecia, maculopapular rash (most commonly on sun-exposed areas, mimicking polymorphous light eruption)—or specific (eg, chilblains

Continue to: The differential for rash and fever is broad

The differential for rash and fever is broad

Syphilis also can manifest with rash and fever. The rash of syphilis is nonpainful and affects the torso and face, with concentration on the palms and soles.6,7

Dermatomyositis is a rare disorder of inflammation in both the skin and muscles. Symptoms include rash, muscle aches, and weakness. Lab abnormalities include elevated creatine kinase levels

Erythema multiforme is an immunologic-mediated rash consisting of firm targetoid erythematous papules distributed symmetrically on the extremities, including palms/soles. It typically appears after a viral infection, immunization, or new medications (eg, antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or phenothiazines) initiated 1 to 3 weeks prior to the appearance of the rash. History and appearance inform the diagnosis.

Polymorphic light eruption is a rash of variable appearance on sun-exposed areas that results from a sensitivity to sunlight after lack of exposure for a period of time. Symptoms include burning and itching.

Treat patients with SLE with hydroxychloroquine (200-400 mg/d) to suppress inflammation and with low-dose oral steroids such as prednisone (7.5 mg/d) for intermittent exacerbations. Higher steroid doses are sometimes needed for signs of organ inflammation. Patients with increased disease activity will require immunosuppressive therapy with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs,

Our patient was admitted for further evaluation. A lumbar puncture was performed because of his balance issues; it showed an elevated protein level, but further work-up did not find an infectious or malignant source. Balance improved with hydration. The patient remained hospitalized for 9 days, during which his fever subsided. His pain improved after initiation of hydroxychloroquine 400 mg/d. Follow-up with Rheumatology was arranged for further care.

1. Rees F, Doherty M, Grainge MJ, et al. The worldwide incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56:1945-1961. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex260

2. CDC. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Updated July 5, 2022. Accessed April 11, 2023. www.cdc.gov/lupus/facts/detailed.html

3. Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1400-1412. doi: 10.1002/art.40930

4. Lam NV, Brown JA, Sharma R. Systemic lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2023;107:383-395.

5. Albrecht J, Berlin JA, Braverman IM, et al. Dermatology position paper on revision of the 1982 ACR criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2004;13:839-849. doi: 10.1191/0961203304lu2020oa

6. Dylewski J, Duong M. The rash of secondary syphilis. CMAJ. 2007;176:33-35. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060665

7. Lautenschlager S. Cutaneous manifestations of syphilis: recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:291-304. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200607050-00003:

8. Brown DL, Frank JE. Diagnosis and management of syphilis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:283-290.

9. Ricco J, Westby A. Syphilis: far from ancient history. Am Fam Physician. 2020;102:91-98.

A 29-YEAR-OLD MAN was referred to the emergency department for fever and rash. Two months prior, he had noticed painful spots on his toes (FIGURE 1). Soon after, a rash of different morphology appeared on his chest and upper extremities. Associated symptoms included hair loss, generalized arthralgias, chills, trouble with balance, and photophobia. The patient denied genital lesions but reported 3 recent cold sores.

On exam, the patient was febrile (102 °F). Skin exam revealed a generalized maculopapular rash on the trunk, arms, and legs with scattered lesions on the palms (FIGURE 2). There were tender purpuric macules on the tips of his toes with areas of blanching. His hands had pink plaques on the dorsal fingers (FIGURE 3). Additionally, there was an erythematous papular rash with scale on his cheeks and nasal bridge, patchy areas of hair loss, and a single oral ulcer.

A neurologic exam was notable for mildly unstable gait, an abnormal Babinski reflex on the left side, and a positive Romberg sign. Musculoskeletal exam revealed joint tenderness in his shoulders, elbows, and wrists. Lymphadenopathy was present bilaterally in the axilla.

Lab work was ordered, including a VDRL test and a treponemal antibodies test. Skin biopsies also were taken from lesions on his arm and chest.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Systemic lupus erythematosus

Our patient’s fever and rash were highly suggestive of either systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or secondary syphilis (the “great masquerader”).

In addition to the joint tenderness revealed during the musculoskeletal exam, our patient had several nonspecific lupus findings on skin exam: malar rash, discoid rash on hands, subacute vasculitis (generalized rash), alopecia, and an oral ulcer; he also had the specific finding of chilblains vasculitis of the toes. Lab work and pathology results made the diagnosis clear. Lab work revealed leukopenia, an antinuclear antibody (ANA) result of 1:2560 with speckled appearance, and positive anti-SM antibodies. A dipstick was negative for protein; VDRL and treponemal antibodies tests were also negative. Histopathology showed perivascular lymph histiocytic vacuolar dermatitis with a differential of connective tissue disease, including lupus.

Our patient met the criteria

SLE is a systemic autoimmune disease resulting in chronic inflammation in multiple organ systems; it commonly manifests with vague symptoms of fatigue, fever, and weight loss. The prevalence of SLE in the United States has been reported as high as 241 per 100,000 people. 1 Women are more likely to be affected, and the incidence is highest among Black people and lowest among Caucasians.1,2 Risk factors include cigarette smoking and exposure to silica particulate air pollution.

The 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology criteria for a diagnosis of SLE require that a patient have a positive ANA and some, but not all, additive lab, clinical, and organ-specific findings.3 Findings that clinicians should look for include3,4

- elevated ANA (≥ 1:80)

- constitutional symptoms (fever)

- hematologic findings (leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, autoimmune hemolysis)

- neuropsychiatric findings (delirium, psychosis, seizure)

- mucocutaneous findings (alopecia, oral ulcers, others)

- serosal findings (effusion, acute pericarditis)

- musculoskeletal findings (joint involvement)

- renal findings (proteinuria)

- antiphospholipid antibodies

- decreased complement proteins

- SLE-specific antibodies.

Dermatologic findings occur in more than 70% of patients with SLE.5 They can be nonspecific—eg, classic discoid rash, malar rash, alopecia, maculopapular rash (most commonly on sun-exposed areas, mimicking polymorphous light eruption)—or specific (eg, chilblains

Continue to: The differential for rash and fever is broad

The differential for rash and fever is broad

Syphilis also can manifest with rash and fever. The rash of syphilis is nonpainful and affects the torso and face, with concentration on the palms and soles.6,7

Dermatomyositis is a rare disorder of inflammation in both the skin and muscles. Symptoms include rash, muscle aches, and weakness. Lab abnormalities include elevated creatine kinase levels

Erythema multiforme is an immunologic-mediated rash consisting of firm targetoid erythematous papules distributed symmetrically on the extremities, including palms/soles. It typically appears after a viral infection, immunization, or new medications (eg, antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or phenothiazines) initiated 1 to 3 weeks prior to the appearance of the rash. History and appearance inform the diagnosis.

Polymorphic light eruption is a rash of variable appearance on sun-exposed areas that results from a sensitivity to sunlight after lack of exposure for a period of time. Symptoms include burning and itching.

Treat patients with SLE with hydroxychloroquine (200-400 mg/d) to suppress inflammation and with low-dose oral steroids such as prednisone (7.5 mg/d) for intermittent exacerbations. Higher steroid doses are sometimes needed for signs of organ inflammation. Patients with increased disease activity will require immunosuppressive therapy with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs,

Our patient was admitted for further evaluation. A lumbar puncture was performed because of his balance issues; it showed an elevated protein level, but further work-up did not find an infectious or malignant source. Balance improved with hydration. The patient remained hospitalized for 9 days, during which his fever subsided. His pain improved after initiation of hydroxychloroquine 400 mg/d. Follow-up with Rheumatology was arranged for further care.

A 29-YEAR-OLD MAN was referred to the emergency department for fever and rash. Two months prior, he had noticed painful spots on his toes (FIGURE 1). Soon after, a rash of different morphology appeared on his chest and upper extremities. Associated symptoms included hair loss, generalized arthralgias, chills, trouble with balance, and photophobia. The patient denied genital lesions but reported 3 recent cold sores.

On exam, the patient was febrile (102 °F). Skin exam revealed a generalized maculopapular rash on the trunk, arms, and legs with scattered lesions on the palms (FIGURE 2). There were tender purpuric macules on the tips of his toes with areas of blanching. His hands had pink plaques on the dorsal fingers (FIGURE 3). Additionally, there was an erythematous papular rash with scale on his cheeks and nasal bridge, patchy areas of hair loss, and a single oral ulcer.

A neurologic exam was notable for mildly unstable gait, an abnormal Babinski reflex on the left side, and a positive Romberg sign. Musculoskeletal exam revealed joint tenderness in his shoulders, elbows, and wrists. Lymphadenopathy was present bilaterally in the axilla.

Lab work was ordered, including a VDRL test and a treponemal antibodies test. Skin biopsies also were taken from lesions on his arm and chest.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Systemic lupus erythematosus

Our patient’s fever and rash were highly suggestive of either systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or secondary syphilis (the “great masquerader”).

In addition to the joint tenderness revealed during the musculoskeletal exam, our patient had several nonspecific lupus findings on skin exam: malar rash, discoid rash on hands, subacute vasculitis (generalized rash), alopecia, and an oral ulcer; he also had the specific finding of chilblains vasculitis of the toes. Lab work and pathology results made the diagnosis clear. Lab work revealed leukopenia, an antinuclear antibody (ANA) result of 1:2560 with speckled appearance, and positive anti-SM antibodies. A dipstick was negative for protein; VDRL and treponemal antibodies tests were also negative. Histopathology showed perivascular lymph histiocytic vacuolar dermatitis with a differential of connective tissue disease, including lupus.

Our patient met the criteria

SLE is a systemic autoimmune disease resulting in chronic inflammation in multiple organ systems; it commonly manifests with vague symptoms of fatigue, fever, and weight loss. The prevalence of SLE in the United States has been reported as high as 241 per 100,000 people. 1 Women are more likely to be affected, and the incidence is highest among Black people and lowest among Caucasians.1,2 Risk factors include cigarette smoking and exposure to silica particulate air pollution.

The 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology criteria for a diagnosis of SLE require that a patient have a positive ANA and some, but not all, additive lab, clinical, and organ-specific findings.3 Findings that clinicians should look for include3,4

- elevated ANA (≥ 1:80)

- constitutional symptoms (fever)

- hematologic findings (leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, autoimmune hemolysis)

- neuropsychiatric findings (delirium, psychosis, seizure)

- mucocutaneous findings (alopecia, oral ulcers, others)

- serosal findings (effusion, acute pericarditis)

- musculoskeletal findings (joint involvement)

- renal findings (proteinuria)

- antiphospholipid antibodies

- decreased complement proteins

- SLE-specific antibodies.

Dermatologic findings occur in more than 70% of patients with SLE.5 They can be nonspecific—eg, classic discoid rash, malar rash, alopecia, maculopapular rash (most commonly on sun-exposed areas, mimicking polymorphous light eruption)—or specific (eg, chilblains

Continue to: The differential for rash and fever is broad

The differential for rash and fever is broad

Syphilis also can manifest with rash and fever. The rash of syphilis is nonpainful and affects the torso and face, with concentration on the palms and soles.6,7

Dermatomyositis is a rare disorder of inflammation in both the skin and muscles. Symptoms include rash, muscle aches, and weakness. Lab abnormalities include elevated creatine kinase levels

Erythema multiforme is an immunologic-mediated rash consisting of firm targetoid erythematous papules distributed symmetrically on the extremities, including palms/soles. It typically appears after a viral infection, immunization, or new medications (eg, antibiotics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or phenothiazines) initiated 1 to 3 weeks prior to the appearance of the rash. History and appearance inform the diagnosis.

Polymorphic light eruption is a rash of variable appearance on sun-exposed areas that results from a sensitivity to sunlight after lack of exposure for a period of time. Symptoms include burning and itching.

Treat patients with SLE with hydroxychloroquine (200-400 mg/d) to suppress inflammation and with low-dose oral steroids such as prednisone (7.5 mg/d) for intermittent exacerbations. Higher steroid doses are sometimes needed for signs of organ inflammation. Patients with increased disease activity will require immunosuppressive therapy with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs,

Our patient was admitted for further evaluation. A lumbar puncture was performed because of his balance issues; it showed an elevated protein level, but further work-up did not find an infectious or malignant source. Balance improved with hydration. The patient remained hospitalized for 9 days, during which his fever subsided. His pain improved after initiation of hydroxychloroquine 400 mg/d. Follow-up with Rheumatology was arranged for further care.

1. Rees F, Doherty M, Grainge MJ, et al. The worldwide incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56:1945-1961. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex260

2. CDC. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Updated July 5, 2022. Accessed April 11, 2023. www.cdc.gov/lupus/facts/detailed.html

3. Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1400-1412. doi: 10.1002/art.40930

4. Lam NV, Brown JA, Sharma R. Systemic lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2023;107:383-395.

5. Albrecht J, Berlin JA, Braverman IM, et al. Dermatology position paper on revision of the 1982 ACR criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2004;13:839-849. doi: 10.1191/0961203304lu2020oa

6. Dylewski J, Duong M. The rash of secondary syphilis. CMAJ. 2007;176:33-35. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060665

7. Lautenschlager S. Cutaneous manifestations of syphilis: recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:291-304. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200607050-00003:

8. Brown DL, Frank JE. Diagnosis and management of syphilis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:283-290.

9. Ricco J, Westby A. Syphilis: far from ancient history. Am Fam Physician. 2020;102:91-98.

1. Rees F, Doherty M, Grainge MJ, et al. The worldwide incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56:1945-1961. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex260

2. CDC. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Updated July 5, 2022. Accessed April 11, 2023. www.cdc.gov/lupus/facts/detailed.html

3. Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71:1400-1412. doi: 10.1002/art.40930

4. Lam NV, Brown JA, Sharma R. Systemic lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2023;107:383-395.

5. Albrecht J, Berlin JA, Braverman IM, et al. Dermatology position paper on revision of the 1982 ACR criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2004;13:839-849. doi: 10.1191/0961203304lu2020oa

6. Dylewski J, Duong M. The rash of secondary syphilis. CMAJ. 2007;176:33-35. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060665

7. Lautenschlager S. Cutaneous manifestations of syphilis: recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2006;7:291-304. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200607050-00003:

8. Brown DL, Frank JE. Diagnosis and management of syphilis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:283-290.

9. Ricco J, Westby A. Syphilis: far from ancient history. Am Fam Physician. 2020;102:91-98.

Rapid-onset ulcerative hand nodule

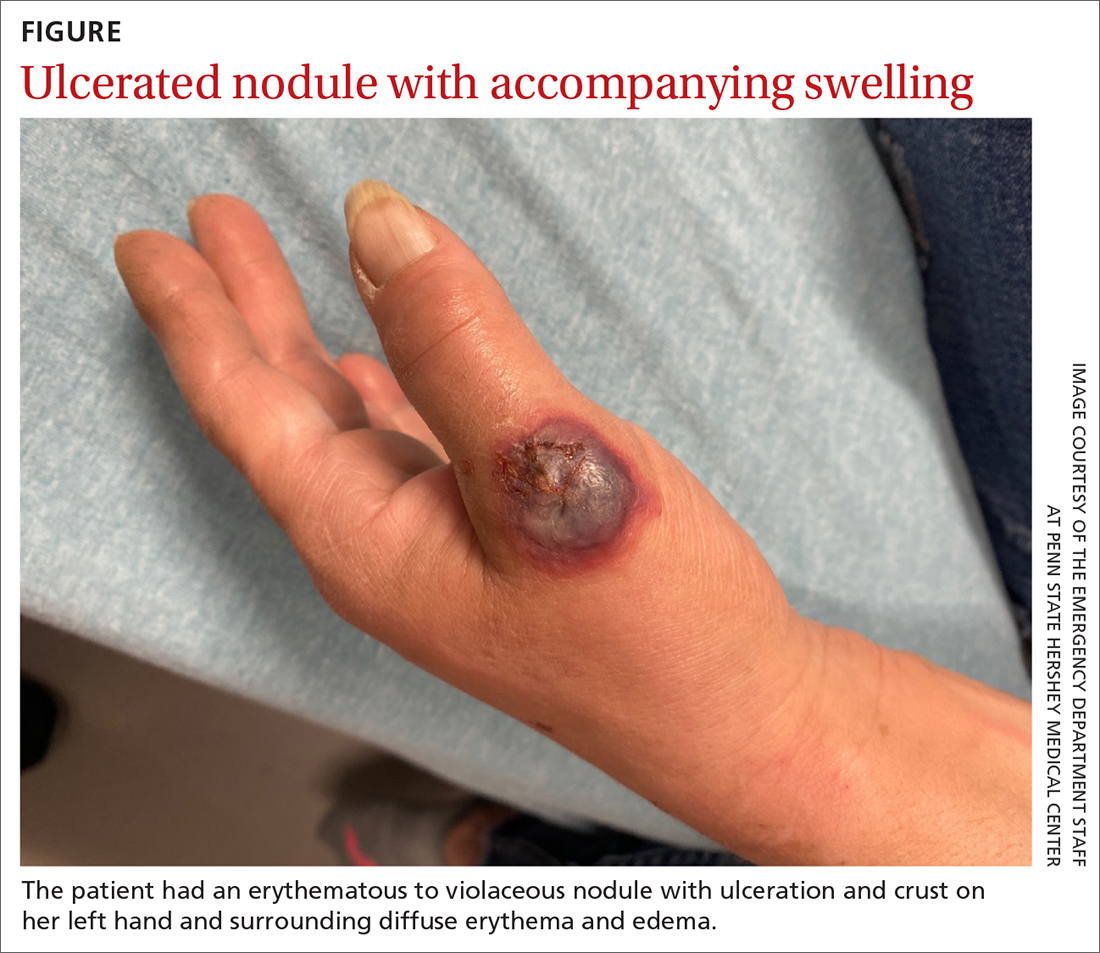

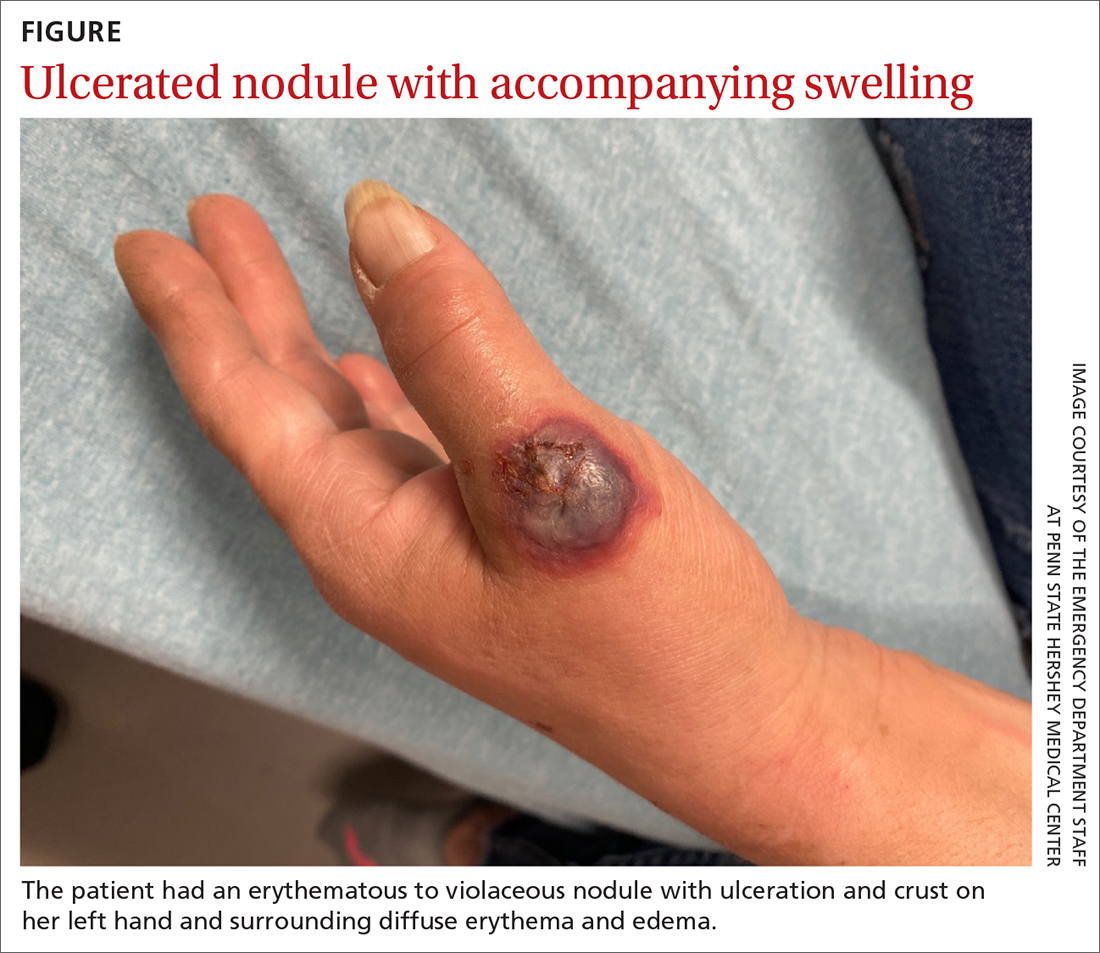

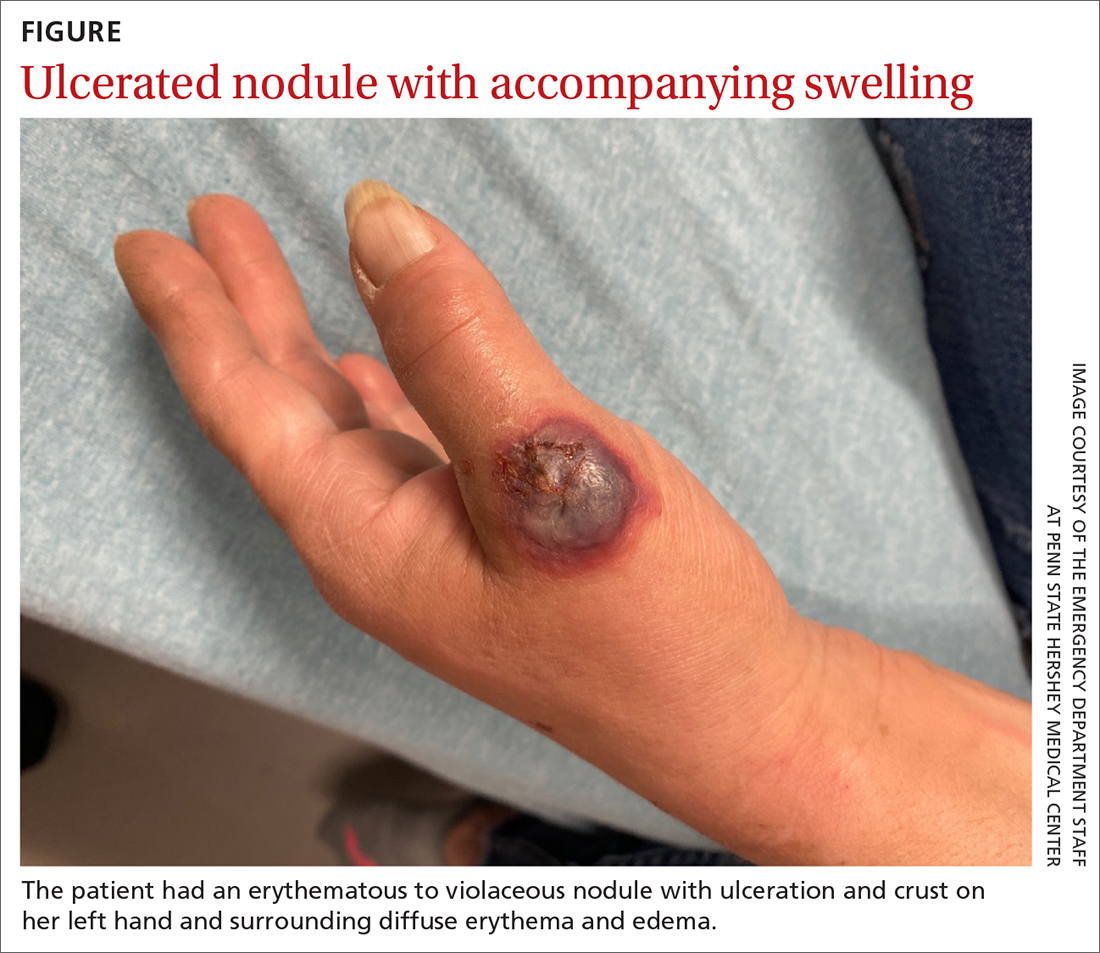

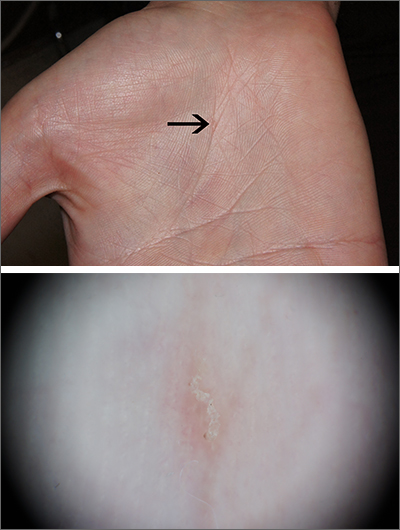

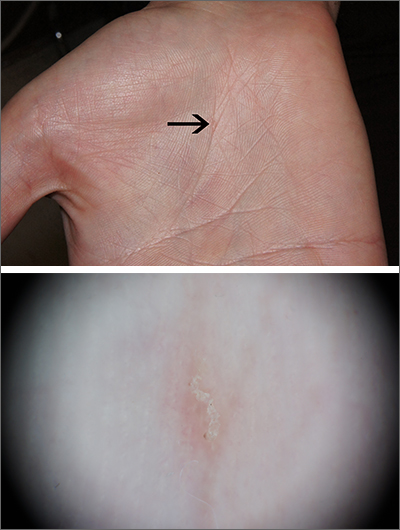

A 55-YEAR-OLD WOMAN developed a small red papule on her left hand that, over the course of a week, progressed rapidly into an ulcerated nodule with accompanying swelling and pain. She reported concomitant fatigue, unintentional weight loss, and swollen axillary lymph nodes. Past medical history included rheumatoid arthritis.

A physical examination of her left hand revealed a tender, erythematous to violaceous nodule with ulceration and crust and surrounding diffuse erythema and edema (FIGURE). She also had several enlarged, nontender right axillary lymph nodes. Initial lab evaluation was significant for leukocytosis (13.8 K/uL) with increased neutrophils, lymphocytes, and eosinophils. Two punch biopsies were performed and the samples submitted for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and tissue culture.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands

The results of H&E were consistent with neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands (NDDH). Tissue culture was negative for fungus, bacteria, and atypical mycobacteria, confirming the diagnosis.

NDDH is a neutrophilic dermatosis and considered a localized variant of Sweet syndrome, manifesting on the dorsal hands as suppurative, erythematous to violaceous papules, plaques, or nodules that often undergo necrosis, blistering, and ulceration. The diagnosis can be made clinically, although a biopsy is usually performed for confirmation. It is characterized histologically by a dense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate along with dermal edema.1

The pathogenesis of NDDH is not fully known.2 It is often preceded by trauma and may be associated with recent infection (respiratory, gastrointestinal), inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune disease (eg, rheumatoid arthritis), or malignancy.1 The most common associated malignancies are hematologic, such as myelodysplastic syndrome, leukemia, or lymphoma, although solid tumors also can be seen.1,3 Therefore, patients who receive a diagnosis of NDDH typically require further work-up to rule out these associated conditions. NDDH is a rare enough entity that incidence/prevalence data aren’t available or likely to be accurate.

The differential includes infection and neoplastic processes

NDDH often is mistaken for an infectious abscess and unsuccessfully treated with antimicrobial agents, such as those commonly used for staphylococcus and streptococcus skin and soft-tissue infections. Thus, wound or tissue culture may be considered to exclude infection from the differential diagnosis. In addition to infectious processes such as sporotrichosis or an atypical mycobacterial infection, the differential includes other neutrophilic dermatoses and neoplastic processes such as lymphoma or leukemia cutis.

Sporotrichosis is caused by Sporothrix schenckii and usually spreads proximally after entering through a wound or cut. Special stains on histology and culture are needed to make the diagnosis.

Continue to: Atypical mycobacterial infections

Atypical mycobacterial infections usually enter through an area of trauma and spread proximally after inoculation. Atypical mycobacterial infections can be diagnosed via biopsy with special stains, culture, and polymerase chain reaction of the tissue.

Neutrophilic dermatoses are a broad category of dermatoses that include NDDH, pyoderma gangrenosum, and Sweet syndrome. This category of dermatoses is differentiated by morphology and distribution of lesions.

Lymphoma can be primary cutaneous or secondary to a systemic lymphoma. A biopsy will show a collection of atypical lymphocytes.

Treatment begins with steroids

Treatment with topical (eg, 0.05% clobetasol ointment bid), intralesional (10 to 40 mg/mL triamcinolone acetonide), or systemic (eg, prednisone 0.5 to 1 mg/kg tapered over the course of 1-2 months) steroids is considered first-line therapy and often results in rapid clinical improvement. Agents such as dapsone (25 to 150 mg/d) and/or colchicine (0.6 mg bid to tid) may be used in recalcitrant cases or in patients for whom steroids are contraindicated.2

Our patient’s NDDH was treated with prednisone (~1.0 mg/kg daily tapered over the course of 6 weeks). She was referred to Hematology/Oncology for further work-up of her constitutional symptoms, lymphadenopathy, and leukocytosis. Ultimately, she received a diagnosis of concomitant chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. The patient required no immediate treatment for her indolent lymphoma and was advised that she would need to get blood work done on a regular basis and have annual check-ups.

1. Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

2. Micallef D, Bonnici M, Pisani D, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands: a review of 123 Cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;S0190-9622(19)32678-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.070

3. Mobini N, Sadrolashrafi K, Michaels S. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands: report of a case and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2019;2019:8301585. doi: 10.1155/2019/8301585

A 55-YEAR-OLD WOMAN developed a small red papule on her left hand that, over the course of a week, progressed rapidly into an ulcerated nodule with accompanying swelling and pain. She reported concomitant fatigue, unintentional weight loss, and swollen axillary lymph nodes. Past medical history included rheumatoid arthritis.

A physical examination of her left hand revealed a tender, erythematous to violaceous nodule with ulceration and crust and surrounding diffuse erythema and edema (FIGURE). She also had several enlarged, nontender right axillary lymph nodes. Initial lab evaluation was significant for leukocytosis (13.8 K/uL) with increased neutrophils, lymphocytes, and eosinophils. Two punch biopsies were performed and the samples submitted for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and tissue culture.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands

The results of H&E were consistent with neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands (NDDH). Tissue culture was negative for fungus, bacteria, and atypical mycobacteria, confirming the diagnosis.

NDDH is a neutrophilic dermatosis and considered a localized variant of Sweet syndrome, manifesting on the dorsal hands as suppurative, erythematous to violaceous papules, plaques, or nodules that often undergo necrosis, blistering, and ulceration. The diagnosis can be made clinically, although a biopsy is usually performed for confirmation. It is characterized histologically by a dense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate along with dermal edema.1

The pathogenesis of NDDH is not fully known.2 It is often preceded by trauma and may be associated with recent infection (respiratory, gastrointestinal), inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune disease (eg, rheumatoid arthritis), or malignancy.1 The most common associated malignancies are hematologic, such as myelodysplastic syndrome, leukemia, or lymphoma, although solid tumors also can be seen.1,3 Therefore, patients who receive a diagnosis of NDDH typically require further work-up to rule out these associated conditions. NDDH is a rare enough entity that incidence/prevalence data aren’t available or likely to be accurate.

The differential includes infection and neoplastic processes

NDDH often is mistaken for an infectious abscess and unsuccessfully treated with antimicrobial agents, such as those commonly used for staphylococcus and streptococcus skin and soft-tissue infections. Thus, wound or tissue culture may be considered to exclude infection from the differential diagnosis. In addition to infectious processes such as sporotrichosis or an atypical mycobacterial infection, the differential includes other neutrophilic dermatoses and neoplastic processes such as lymphoma or leukemia cutis.

Sporotrichosis is caused by Sporothrix schenckii and usually spreads proximally after entering through a wound or cut. Special stains on histology and culture are needed to make the diagnosis.

Continue to: Atypical mycobacterial infections

Atypical mycobacterial infections usually enter through an area of trauma and spread proximally after inoculation. Atypical mycobacterial infections can be diagnosed via biopsy with special stains, culture, and polymerase chain reaction of the tissue.

Neutrophilic dermatoses are a broad category of dermatoses that include NDDH, pyoderma gangrenosum, and Sweet syndrome. This category of dermatoses is differentiated by morphology and distribution of lesions.

Lymphoma can be primary cutaneous or secondary to a systemic lymphoma. A biopsy will show a collection of atypical lymphocytes.

Treatment begins with steroids

Treatment with topical (eg, 0.05% clobetasol ointment bid), intralesional (10 to 40 mg/mL triamcinolone acetonide), or systemic (eg, prednisone 0.5 to 1 mg/kg tapered over the course of 1-2 months) steroids is considered first-line therapy and often results in rapid clinical improvement. Agents such as dapsone (25 to 150 mg/d) and/or colchicine (0.6 mg bid to tid) may be used in recalcitrant cases or in patients for whom steroids are contraindicated.2

Our patient’s NDDH was treated with prednisone (~1.0 mg/kg daily tapered over the course of 6 weeks). She was referred to Hematology/Oncology for further work-up of her constitutional symptoms, lymphadenopathy, and leukocytosis. Ultimately, she received a diagnosis of concomitant chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. The patient required no immediate treatment for her indolent lymphoma and was advised that she would need to get blood work done on a regular basis and have annual check-ups.

A 55-YEAR-OLD WOMAN developed a small red papule on her left hand that, over the course of a week, progressed rapidly into an ulcerated nodule with accompanying swelling and pain. She reported concomitant fatigue, unintentional weight loss, and swollen axillary lymph nodes. Past medical history included rheumatoid arthritis.

A physical examination of her left hand revealed a tender, erythematous to violaceous nodule with ulceration and crust and surrounding diffuse erythema and edema (FIGURE). She also had several enlarged, nontender right axillary lymph nodes. Initial lab evaluation was significant for leukocytosis (13.8 K/uL) with increased neutrophils, lymphocytes, and eosinophils. Two punch biopsies were performed and the samples submitted for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and tissue culture.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands

The results of H&E were consistent with neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands (NDDH). Tissue culture was negative for fungus, bacteria, and atypical mycobacteria, confirming the diagnosis.

NDDH is a neutrophilic dermatosis and considered a localized variant of Sweet syndrome, manifesting on the dorsal hands as suppurative, erythematous to violaceous papules, plaques, or nodules that often undergo necrosis, blistering, and ulceration. The diagnosis can be made clinically, although a biopsy is usually performed for confirmation. It is characterized histologically by a dense dermal neutrophilic infiltrate along with dermal edema.1

The pathogenesis of NDDH is not fully known.2 It is often preceded by trauma and may be associated with recent infection (respiratory, gastrointestinal), inflammatory bowel disease, autoimmune disease (eg, rheumatoid arthritis), or malignancy.1 The most common associated malignancies are hematologic, such as myelodysplastic syndrome, leukemia, or lymphoma, although solid tumors also can be seen.1,3 Therefore, patients who receive a diagnosis of NDDH typically require further work-up to rule out these associated conditions. NDDH is a rare enough entity that incidence/prevalence data aren’t available or likely to be accurate.

The differential includes infection and neoplastic processes

NDDH often is mistaken for an infectious abscess and unsuccessfully treated with antimicrobial agents, such as those commonly used for staphylococcus and streptococcus skin and soft-tissue infections. Thus, wound or tissue culture may be considered to exclude infection from the differential diagnosis. In addition to infectious processes such as sporotrichosis or an atypical mycobacterial infection, the differential includes other neutrophilic dermatoses and neoplastic processes such as lymphoma or leukemia cutis.

Sporotrichosis is caused by Sporothrix schenckii and usually spreads proximally after entering through a wound or cut. Special stains on histology and culture are needed to make the diagnosis.

Continue to: Atypical mycobacterial infections

Atypical mycobacterial infections usually enter through an area of trauma and spread proximally after inoculation. Atypical mycobacterial infections can be diagnosed via biopsy with special stains, culture, and polymerase chain reaction of the tissue.

Neutrophilic dermatoses are a broad category of dermatoses that include NDDH, pyoderma gangrenosum, and Sweet syndrome. This category of dermatoses is differentiated by morphology and distribution of lesions.

Lymphoma can be primary cutaneous or secondary to a systemic lymphoma. A biopsy will show a collection of atypical lymphocytes.

Treatment begins with steroids

Treatment with topical (eg, 0.05% clobetasol ointment bid), intralesional (10 to 40 mg/mL triamcinolone acetonide), or systemic (eg, prednisone 0.5 to 1 mg/kg tapered over the course of 1-2 months) steroids is considered first-line therapy and often results in rapid clinical improvement. Agents such as dapsone (25 to 150 mg/d) and/or colchicine (0.6 mg bid to tid) may be used in recalcitrant cases or in patients for whom steroids are contraindicated.2

Our patient’s NDDH was treated with prednisone (~1.0 mg/kg daily tapered over the course of 6 weeks). She was referred to Hematology/Oncology for further work-up of her constitutional symptoms, lymphadenopathy, and leukocytosis. Ultimately, she received a diagnosis of concomitant chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. The patient required no immediate treatment for her indolent lymphoma and was advised that she would need to get blood work done on a regular basis and have annual check-ups.

1. Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

2. Micallef D, Bonnici M, Pisani D, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands: a review of 123 Cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;S0190-9622(19)32678-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.070

3. Mobini N, Sadrolashrafi K, Michaels S. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands: report of a case and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2019;2019:8301585. doi: 10.1155/2019/8301585

1. Walling HW, Snipes CJ, Gerami P, et al. The relationship between neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands and Sweet syndrome: report of 9 cases and comparison to atypical pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:57-63.

2. Micallef D, Bonnici M, Pisani D, et al. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands: a review of 123 Cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;S0190-9622(19)32678-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.070

3. Mobini N, Sadrolashrafi K, Michaels S. Neutrophilic dermatosis of the dorsal hands: report of a case and review of the literature. Case Rep Dermatol Med. 2019;2019:8301585. doi: 10.1155/2019/8301585

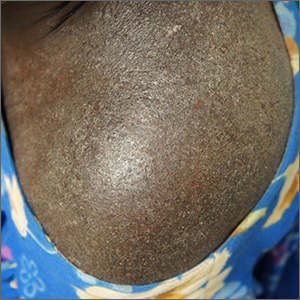

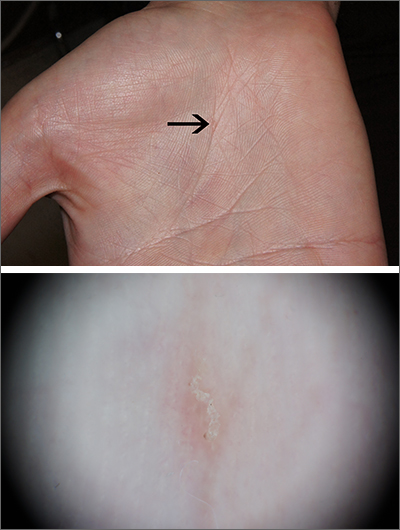

Clothing provides Dx clue

A close examination of the patient’s scalp and hair was unhelpful, but a close look at the weave and seams of her dress revealed multiple nits and lice, consistent with a diagnosis of body lice.

Head lice and body lice are 2 different ecotypes of the species Pediculus humanus and occupy different environments on the body. They differ slightly in body shape caused by variable expression of the same genes.1 Body lice primarily live and lay eggs on clothing, especially along seams and within knit weaves. They travel to the skin to feed, causing significant itching in the host from the inflammatory and allergic effects of their saliva and feces. Additionally, body lice are vectors of several serious diseases including epidemic typhus (Rickettsia prowasekii), trench fever (Bartonella quintana), and relapsing fever (Borrelia recurrentis).1

A diagnosis of body lice is a sign of severe lack of access to basic human needs—uncrowded shelter, clean clothes, and clean water for bathing. A patient who has been given this diagnosis should be offered and receive a bath or shower with generous soap and warm water. Clothes should be cleaned with hot water (up to 149 °F) or discarded. Patients also may be treated once with topical permethrin 5% cream applied from the top of the neck to the toes in the event that mites survived bathing by attaching to body hairs. Any systemic illness or fever should be evaluated for the above epidemic pathogens. Patients should also be put in touch with social services and mental health services, as appropriate.

This patient received all of the above treatments and had already accessed social services. That said, she continued to struggle with housing instability.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Veracx A, Raoult D. Biology and genetics of human head and body lice. Trends Parasitol. 2012;28:563-571. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2012.09.003

A close examination of the patient’s scalp and hair was unhelpful, but a close look at the weave and seams of her dress revealed multiple nits and lice, consistent with a diagnosis of body lice.

Head lice and body lice are 2 different ecotypes of the species Pediculus humanus and occupy different environments on the body. They differ slightly in body shape caused by variable expression of the same genes.1 Body lice primarily live and lay eggs on clothing, especially along seams and within knit weaves. They travel to the skin to feed, causing significant itching in the host from the inflammatory and allergic effects of their saliva and feces. Additionally, body lice are vectors of several serious diseases including epidemic typhus (Rickettsia prowasekii), trench fever (Bartonella quintana), and relapsing fever (Borrelia recurrentis).1

A diagnosis of body lice is a sign of severe lack of access to basic human needs—uncrowded shelter, clean clothes, and clean water for bathing. A patient who has been given this diagnosis should be offered and receive a bath or shower with generous soap and warm water. Clothes should be cleaned with hot water (up to 149 °F) or discarded. Patients also may be treated once with topical permethrin 5% cream applied from the top of the neck to the toes in the event that mites survived bathing by attaching to body hairs. Any systemic illness or fever should be evaluated for the above epidemic pathogens. Patients should also be put in touch with social services and mental health services, as appropriate.

This patient received all of the above treatments and had already accessed social services. That said, she continued to struggle with housing instability.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

A close examination of the patient’s scalp and hair was unhelpful, but a close look at the weave and seams of her dress revealed multiple nits and lice, consistent with a diagnosis of body lice.

Head lice and body lice are 2 different ecotypes of the species Pediculus humanus and occupy different environments on the body. They differ slightly in body shape caused by variable expression of the same genes.1 Body lice primarily live and lay eggs on clothing, especially along seams and within knit weaves. They travel to the skin to feed, causing significant itching in the host from the inflammatory and allergic effects of their saliva and feces. Additionally, body lice are vectors of several serious diseases including epidemic typhus (Rickettsia prowasekii), trench fever (Bartonella quintana), and relapsing fever (Borrelia recurrentis).1

A diagnosis of body lice is a sign of severe lack of access to basic human needs—uncrowded shelter, clean clothes, and clean water for bathing. A patient who has been given this diagnosis should be offered and receive a bath or shower with generous soap and warm water. Clothes should be cleaned with hot water (up to 149 °F) or discarded. Patients also may be treated once with topical permethrin 5% cream applied from the top of the neck to the toes in the event that mites survived bathing by attaching to body hairs. Any systemic illness or fever should be evaluated for the above epidemic pathogens. Patients should also be put in touch with social services and mental health services, as appropriate.

This patient received all of the above treatments and had already accessed social services. That said, she continued to struggle with housing instability.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Veracx A, Raoult D. Biology and genetics of human head and body lice. Trends Parasitol. 2012;28:563-571. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2012.09.003

1. Veracx A, Raoult D. Biology and genetics of human head and body lice. Trends Parasitol. 2012;28:563-571. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2012.09.003

Intensely itchy normal skin