User login

Pedunculated gluteal mass

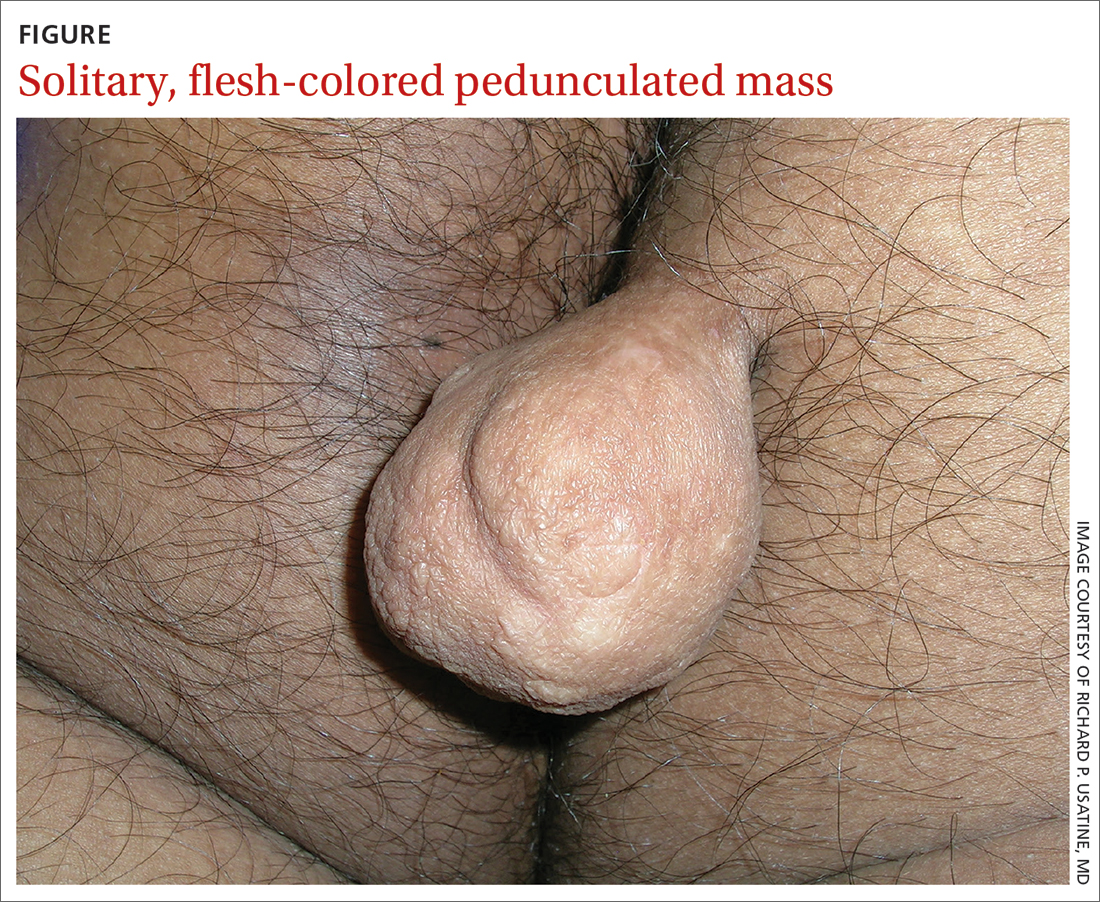

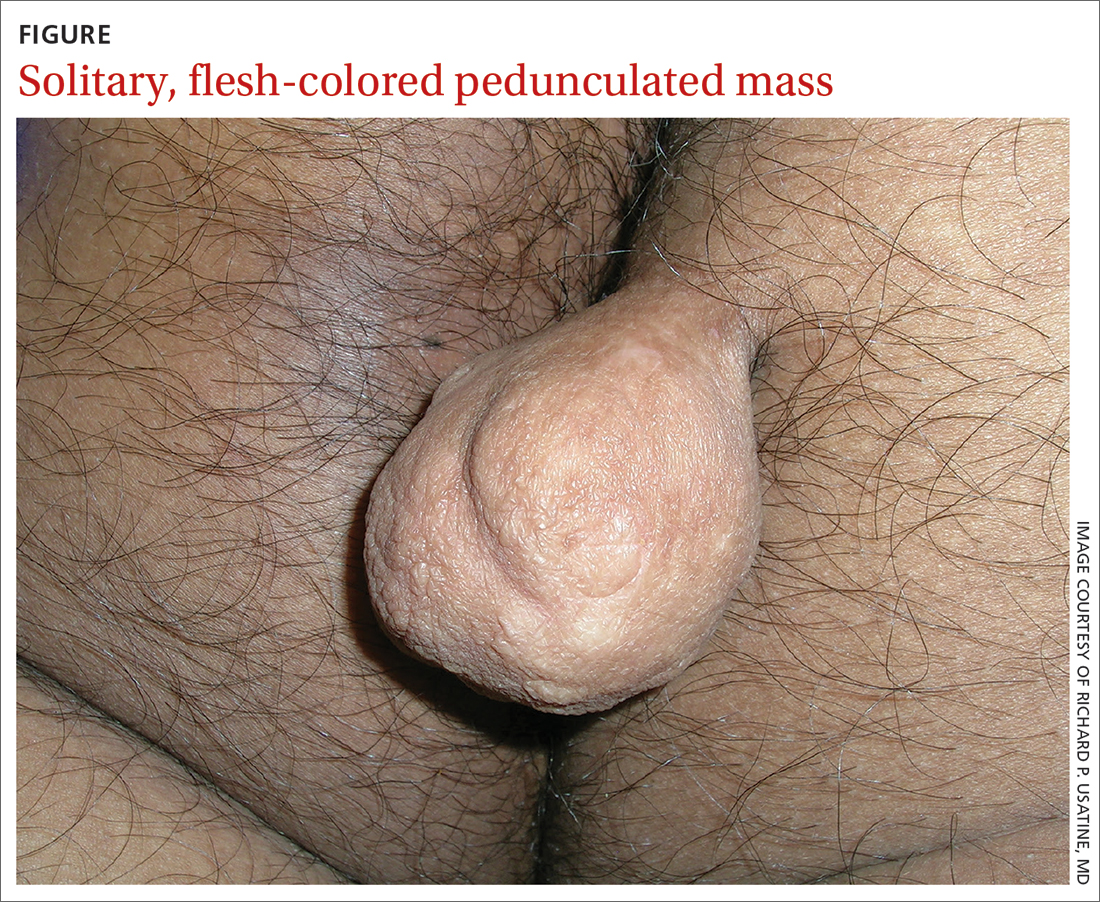

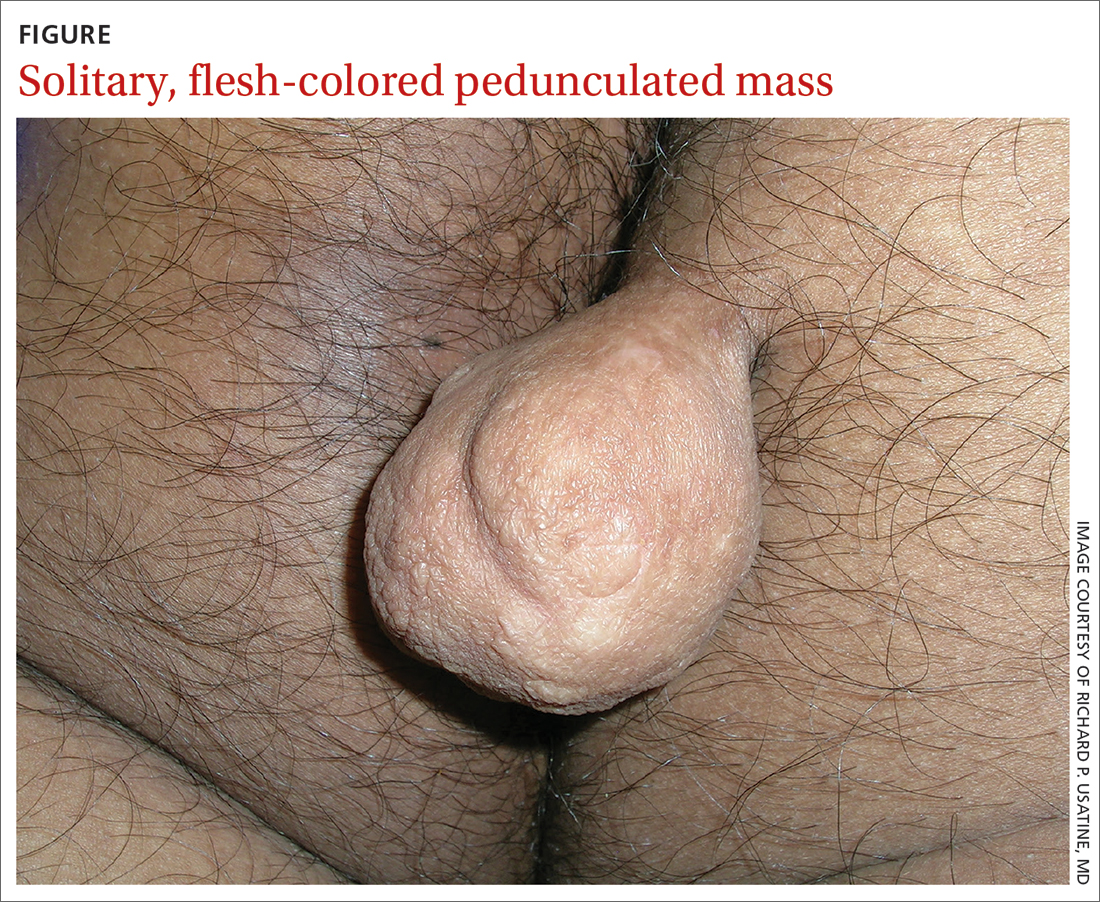

A 30-YEAR-OLD MAN presented for evaluation of a solitary, flesh-colored, pedunculated mass on his right inner gluteal area (FIGURE) that had gradually enlarged over the previous 18 months. The lesion had manifested 4 years prior as a small papule that was stable for many years. It began to grow steadily after the patient compressed the papule forcefully. Activities of daily living, such as sitting, were now uncomfortable, so he sought treatment. He denied pain, pruritis, and bleeding and reported no history of trauma or surgery in the area of the mass.

On physical examination, the mass measured 3.5 × 4.5 cm with a 1.2-cm base. It was smooth, soft, nontender, and compressible—but nonfluctuant. There were no signs of ulceration or bleeding. No regional lymphadenopathy was noted. An excisional biopsy was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Fibrolipoma

The biopsy confirmed a diagnosis of fibrolipoma—a rare variant of lipoma composed of a mixture of adipocytes and thick bands of fibrous connective tissues.1 Etiology for fibrolipomas is unknown. Blunt trauma rupture of the fibrous septa that prevent fat migration may result in a proliferation of adipose tissue and thereby enlargement of fibrolipomas and other lipoma variants.2 In this case, the patient’s compression of the original papule likely served as the trauma that led to its enlargement. Malignant change has not been reported with fibrolipomas.

What you’ll see—and on whom. Fibrolipomas typically are flesh-colored, pedunculated, compressible, and relatively asymptomatic.3 They have been reported on the face, neck, back, and pubic areas, among other locations. Size is variable; they can be as small as 1 cm in diameter and as large as 10 cm in diameter.4 However, fibrolipomas can grow to be “giant” if they exceed 10 cm (or 1000 g).2

Men and women are affected equally by fibrolipomas. Prevalence does not differ by race or ethnicity.

The differential include sother lipomas and skin tags

The differential for a mass such as this one includes lipomas, acrochordons (also known as skin tags), and fibrokeratomas.

Lipomas are the most common benign soft-tissue tumors and are composed of adipocytes.5 The fibrolipoma is just one variant of lipoma; others include the myxolipoma, myolipoma, spindle cell lipoma, angiolipoma, osteolipoma, and chondrolipoma.2 Lipomas typically are subcutaneous and located over the scalp, neck, and upper trunk area but can occur anywhere on the body. They are mobile and typically well circumscribed. Lipomas have a broad base with well-demarcated swelling; fibrolipomas are usually pedunculated.

Continue to: Acrochordons ("skin tags")

Acrochordons (“skin tags”) usually contain a peduncle but may be sessile. They range from 1 mm to 1 cm in diameter and typically are located in skin folds, especially in the neck, axillae, and inguinal areas.6 Obesity, older

Fibrokeratomas typically are benign, solitary, fibrous tissue tumors that are found on fingers and seldom are pedunculated. They are flesh-colored and conical or nodular, with a hyperkeratotic collar. Fibrokeratomas are smaller and thicker than fibromas, as well as firm in consistency. They are acquired tumors that have been shown to be related to repetitive trauma.6

Treatment involves surgical excision

The preferred treatment for fibrolipoma is complete surgical excision, although cryotherapy is another option for lesions < 1 cm.4 Without surgical excision, the mass will continue to grow, albeit slowly.

This patient’s mass was excised successfully in its entirety; there were no complications. Follow-up is usually unnecessary.

1. Kim YT, Kim WS, Park YL, et al. A case of fibrolipoma. Korean J Dermatol. 2003;41:939-941.

2. Mazzocchi M, Onesti MG, Pasquini P, et al. Giant fibrolipoma in the leg—a case report. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:3649-3654.

3. Shin SJ. Subcutaneous fibrolipoma on the back. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24:1051-1053. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182802517

4. Suleiman J, Suleman M, Amsi P, et al. Giant pedunculated lipofibroma of the thigh. J Surg Case Rep. 2023;2023(3):rjad153. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjad153

5. Dai X-M, Li Y-S, Liu H, et al. Giant pedunculated fibrolipoma arising from right facial and cervical region. J Oral and Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:1323-1326. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.12.037

6. Lee JA, Khodaee M. Enlarging, pedunculated skin lesion. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:1191-1192.

7. Banik R, Lubach D. Skin tags: localization and frequencies according to sex and age. Dermatologica. 1987;174:180-183. doi: 10.1159/000249169

A 30-YEAR-OLD MAN presented for evaluation of a solitary, flesh-colored, pedunculated mass on his right inner gluteal area (FIGURE) that had gradually enlarged over the previous 18 months. The lesion had manifested 4 years prior as a small papule that was stable for many years. It began to grow steadily after the patient compressed the papule forcefully. Activities of daily living, such as sitting, were now uncomfortable, so he sought treatment. He denied pain, pruritis, and bleeding and reported no history of trauma or surgery in the area of the mass.

On physical examination, the mass measured 3.5 × 4.5 cm with a 1.2-cm base. It was smooth, soft, nontender, and compressible—but nonfluctuant. There were no signs of ulceration or bleeding. No regional lymphadenopathy was noted. An excisional biopsy was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Fibrolipoma

The biopsy confirmed a diagnosis of fibrolipoma—a rare variant of lipoma composed of a mixture of adipocytes and thick bands of fibrous connective tissues.1 Etiology for fibrolipomas is unknown. Blunt trauma rupture of the fibrous septa that prevent fat migration may result in a proliferation of adipose tissue and thereby enlargement of fibrolipomas and other lipoma variants.2 In this case, the patient’s compression of the original papule likely served as the trauma that led to its enlargement. Malignant change has not been reported with fibrolipomas.

What you’ll see—and on whom. Fibrolipomas typically are flesh-colored, pedunculated, compressible, and relatively asymptomatic.3 They have been reported on the face, neck, back, and pubic areas, among other locations. Size is variable; they can be as small as 1 cm in diameter and as large as 10 cm in diameter.4 However, fibrolipomas can grow to be “giant” if they exceed 10 cm (or 1000 g).2

Men and women are affected equally by fibrolipomas. Prevalence does not differ by race or ethnicity.

The differential include sother lipomas and skin tags

The differential for a mass such as this one includes lipomas, acrochordons (also known as skin tags), and fibrokeratomas.

Lipomas are the most common benign soft-tissue tumors and are composed of adipocytes.5 The fibrolipoma is just one variant of lipoma; others include the myxolipoma, myolipoma, spindle cell lipoma, angiolipoma, osteolipoma, and chondrolipoma.2 Lipomas typically are subcutaneous and located over the scalp, neck, and upper trunk area but can occur anywhere on the body. They are mobile and typically well circumscribed. Lipomas have a broad base with well-demarcated swelling; fibrolipomas are usually pedunculated.

Continue to: Acrochordons ("skin tags")

Acrochordons (“skin tags”) usually contain a peduncle but may be sessile. They range from 1 mm to 1 cm in diameter and typically are located in skin folds, especially in the neck, axillae, and inguinal areas.6 Obesity, older

Fibrokeratomas typically are benign, solitary, fibrous tissue tumors that are found on fingers and seldom are pedunculated. They are flesh-colored and conical or nodular, with a hyperkeratotic collar. Fibrokeratomas are smaller and thicker than fibromas, as well as firm in consistency. They are acquired tumors that have been shown to be related to repetitive trauma.6

Treatment involves surgical excision

The preferred treatment for fibrolipoma is complete surgical excision, although cryotherapy is another option for lesions < 1 cm.4 Without surgical excision, the mass will continue to grow, albeit slowly.

This patient’s mass was excised successfully in its entirety; there were no complications. Follow-up is usually unnecessary.

A 30-YEAR-OLD MAN presented for evaluation of a solitary, flesh-colored, pedunculated mass on his right inner gluteal area (FIGURE) that had gradually enlarged over the previous 18 months. The lesion had manifested 4 years prior as a small papule that was stable for many years. It began to grow steadily after the patient compressed the papule forcefully. Activities of daily living, such as sitting, were now uncomfortable, so he sought treatment. He denied pain, pruritis, and bleeding and reported no history of trauma or surgery in the area of the mass.

On physical examination, the mass measured 3.5 × 4.5 cm with a 1.2-cm base. It was smooth, soft, nontender, and compressible—but nonfluctuant. There were no signs of ulceration or bleeding. No regional lymphadenopathy was noted. An excisional biopsy was performed.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Fibrolipoma

The biopsy confirmed a diagnosis of fibrolipoma—a rare variant of lipoma composed of a mixture of adipocytes and thick bands of fibrous connective tissues.1 Etiology for fibrolipomas is unknown. Blunt trauma rupture of the fibrous septa that prevent fat migration may result in a proliferation of adipose tissue and thereby enlargement of fibrolipomas and other lipoma variants.2 In this case, the patient’s compression of the original papule likely served as the trauma that led to its enlargement. Malignant change has not been reported with fibrolipomas.

What you’ll see—and on whom. Fibrolipomas typically are flesh-colored, pedunculated, compressible, and relatively asymptomatic.3 They have been reported on the face, neck, back, and pubic areas, among other locations. Size is variable; they can be as small as 1 cm in diameter and as large as 10 cm in diameter.4 However, fibrolipomas can grow to be “giant” if they exceed 10 cm (or 1000 g).2

Men and women are affected equally by fibrolipomas. Prevalence does not differ by race or ethnicity.

The differential include sother lipomas and skin tags

The differential for a mass such as this one includes lipomas, acrochordons (also known as skin tags), and fibrokeratomas.

Lipomas are the most common benign soft-tissue tumors and are composed of adipocytes.5 The fibrolipoma is just one variant of lipoma; others include the myxolipoma, myolipoma, spindle cell lipoma, angiolipoma, osteolipoma, and chondrolipoma.2 Lipomas typically are subcutaneous and located over the scalp, neck, and upper trunk area but can occur anywhere on the body. They are mobile and typically well circumscribed. Lipomas have a broad base with well-demarcated swelling; fibrolipomas are usually pedunculated.

Continue to: Acrochordons ("skin tags")

Acrochordons (“skin tags”) usually contain a peduncle but may be sessile. They range from 1 mm to 1 cm in diameter and typically are located in skin folds, especially in the neck, axillae, and inguinal areas.6 Obesity, older

Fibrokeratomas typically are benign, solitary, fibrous tissue tumors that are found on fingers and seldom are pedunculated. They are flesh-colored and conical or nodular, with a hyperkeratotic collar. Fibrokeratomas are smaller and thicker than fibromas, as well as firm in consistency. They are acquired tumors that have been shown to be related to repetitive trauma.6

Treatment involves surgical excision

The preferred treatment for fibrolipoma is complete surgical excision, although cryotherapy is another option for lesions < 1 cm.4 Without surgical excision, the mass will continue to grow, albeit slowly.

This patient’s mass was excised successfully in its entirety; there were no complications. Follow-up is usually unnecessary.

1. Kim YT, Kim WS, Park YL, et al. A case of fibrolipoma. Korean J Dermatol. 2003;41:939-941.

2. Mazzocchi M, Onesti MG, Pasquini P, et al. Giant fibrolipoma in the leg—a case report. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:3649-3654.

3. Shin SJ. Subcutaneous fibrolipoma on the back. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24:1051-1053. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182802517

4. Suleiman J, Suleman M, Amsi P, et al. Giant pedunculated lipofibroma of the thigh. J Surg Case Rep. 2023;2023(3):rjad153. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjad153

5. Dai X-M, Li Y-S, Liu H, et al. Giant pedunculated fibrolipoma arising from right facial and cervical region. J Oral and Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:1323-1326. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.12.037

6. Lee JA, Khodaee M. Enlarging, pedunculated skin lesion. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:1191-1192.

7. Banik R, Lubach D. Skin tags: localization and frequencies according to sex and age. Dermatologica. 1987;174:180-183. doi: 10.1159/000249169

1. Kim YT, Kim WS, Park YL, et al. A case of fibrolipoma. Korean J Dermatol. 2003;41:939-941.

2. Mazzocchi M, Onesti MG, Pasquini P, et al. Giant fibrolipoma in the leg—a case report. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:3649-3654.

3. Shin SJ. Subcutaneous fibrolipoma on the back. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24:1051-1053. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182802517

4. Suleiman J, Suleman M, Amsi P, et al. Giant pedunculated lipofibroma of the thigh. J Surg Case Rep. 2023;2023(3):rjad153. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjad153

5. Dai X-M, Li Y-S, Liu H, et al. Giant pedunculated fibrolipoma arising from right facial and cervical region. J Oral and Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:1323-1326. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.12.037

6. Lee JA, Khodaee M. Enlarging, pedunculated skin lesion. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85:1191-1192.

7. Banik R, Lubach D. Skin tags: localization and frequencies according to sex and age. Dermatologica. 1987;174:180-183. doi: 10.1159/000249169

Generalized pruritic blisters and bullous lesions

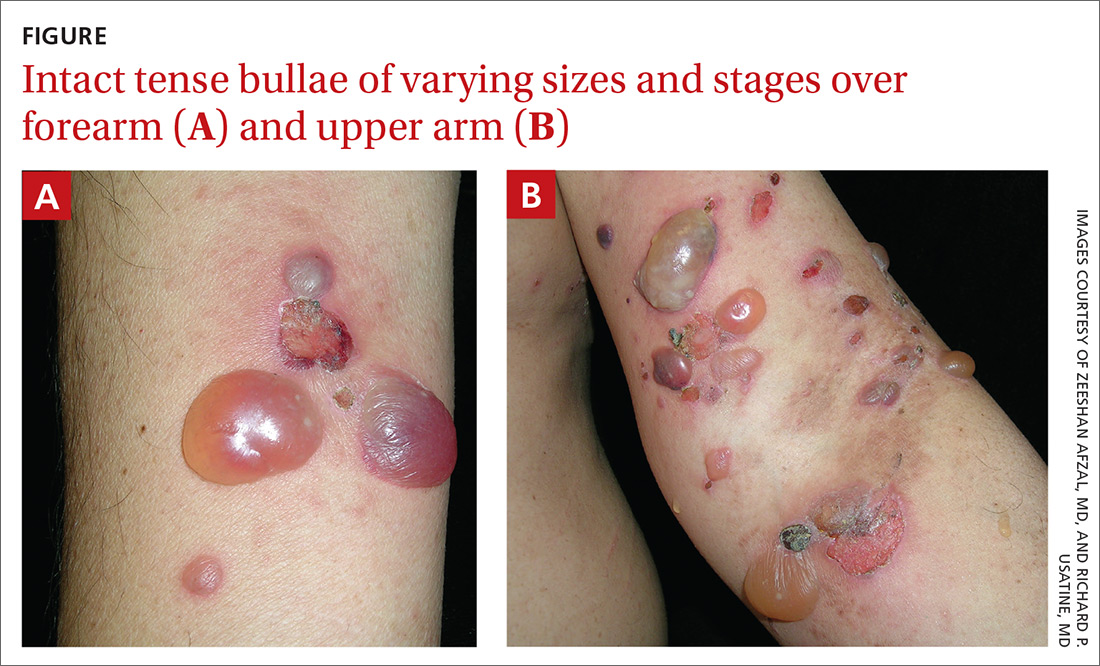

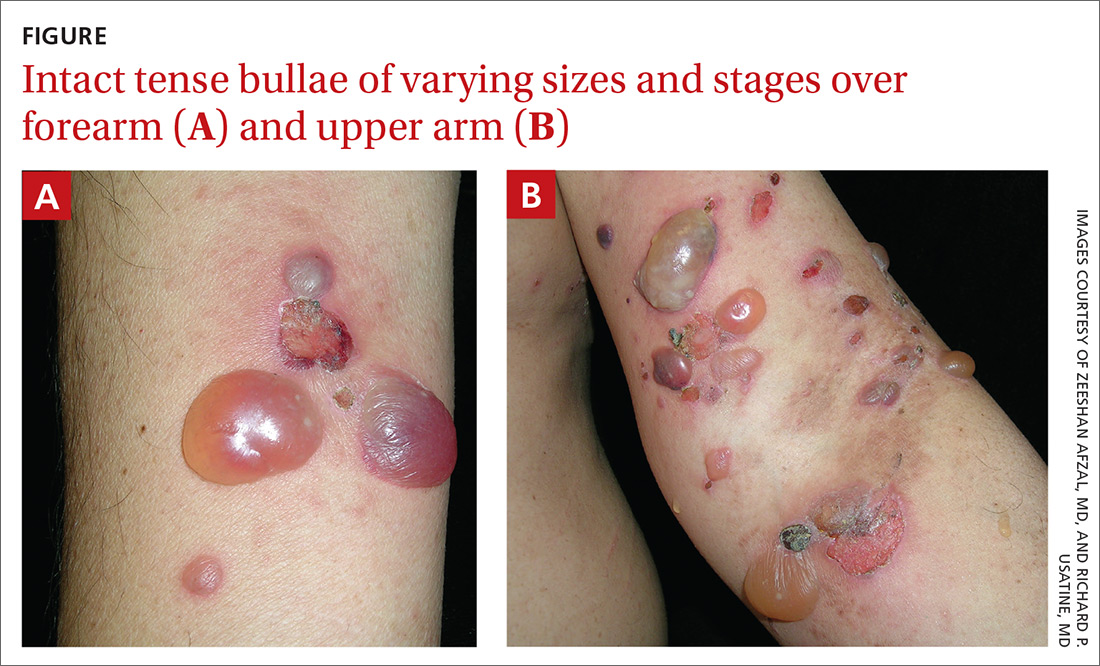

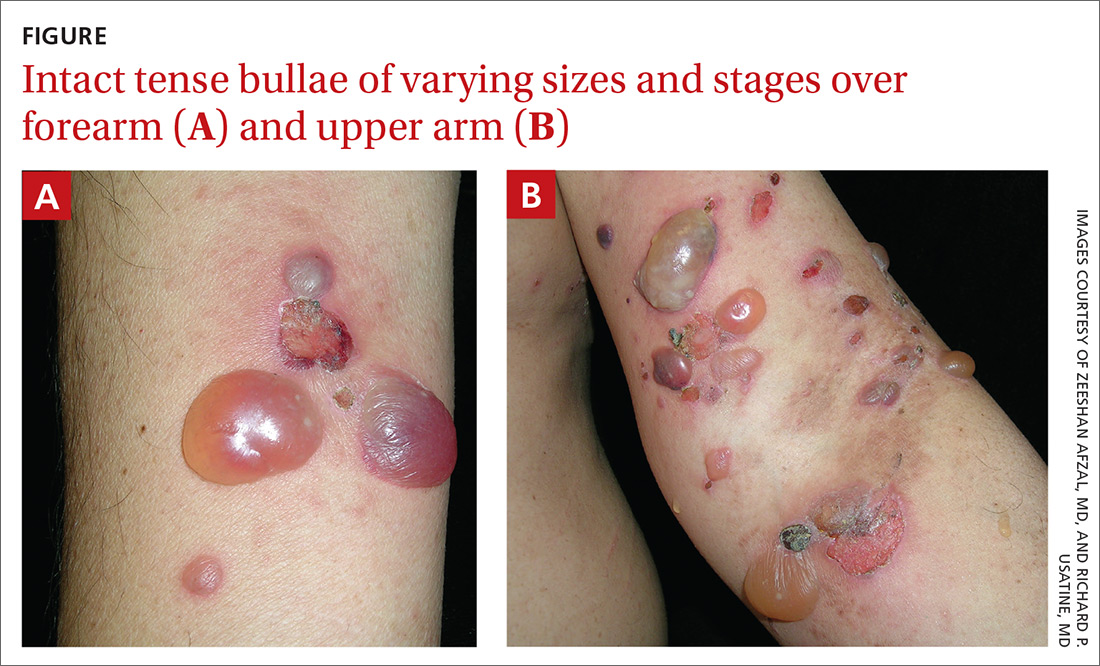

A 62-year-old man presented to our skin clinic with multiple pruritic, tense, bullous lesions that manifested on his arms, abdomen, back, and upper thighs over a 1-month period. There were no lesions in his oral cavity or around his eyes, nose, or penile region. He denied dysphagia.

The patient had multiple comorbidities, including diabetes, hypertension, recent stroke, and end-stage renal disease. He was being prepared for dialysis. His medications included torsemide, warfarin, amiodarone, metoprolol, pantoprozole, atorvastatin, and nifedipine. About 3 months prior to this presentation, he was started on oral linaglipton 5 mg/d, an oral antihyperglycemic medication. He had no history of skin disease or cancer, and his family history was not significant.

Physical examination showed multiple 5-mm to 2-cm blisters and bullae on the flexural surface of both of his arms (FIGURE), back, lower abdomen, and upper thighs. His palms and soles were not involved. The lesions were nontender, tense, and filled with clear fluid. Some were intact and others were rupturing. There was no mucocutaneous involvement. Nikolsky sign was negative. There were no signs of bleeding.

The family physician (FP) obtained a 4-mm punch biopsy at the edge of a 6-mm blister for light microscopy and a 3-mm perilesional punch biopsy for direct immunofluorescence (DIF) microscopy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Bullous pemphigoid secondary to linagliptin use

DIF of the biopsy sample demonstrated linear deposition of complement 3 (C3) and immunoglobulin (Ig) G along the basement membrane zone. Indirect immunofluorescence on salt-split skin demonstrated linear deposition of IgG and C3 on both the roof and floor of the induced blisters. These findings and the patient’s clinical presentation met the criteria for bullous pemphigoid (BP), which is the most common autoimmune skin-blistering disease.1

BP is associated with subepidermal blistering, which can occur in reaction to a variety of triggers. Pathogenesis of this condition involves IgG anti-basement membrane autoantibody complex formation with the hemidesmosomal antigens BP230 and BP180—a process that activates C3 and the release of proteases that can be destructive to tissue along the dermo-epidermal junction.1

Growing incidence. BP usually occurs in patients > 60 years, with no racial or gender preference.1 The incidence rate of BP ranges from 2.4 to 21.7 new cases per 1 million individuals among various worldwide populations.2 The incidence appears to have increased 1.9- to 4.3-fold over the past 2 decades.2

What you’ll see, who’s at risk

Symptoms of BP include localized areas of erythema or pruritic urticarial plaques that gradually become more extensive. A patient may have pruritis alone for an extended period prior to developing blisters and bullae. The bullae are tense and normally 1 to 7 cm in size.1 Eruption is generalized, mostly affecting the lower abdomen, as well as the flexural parts of the extremities. The palms and soles also can be affected.

FPs should be aware of the atypical clinical variants of BP. In a review by Kridin and Ludwig, variants can be prurigo-like, eczema-like, urticaria-like, dyshidrosiform type, erosive type, and erythema annulare centrifugum–like type.2 At-risk populations, such as elderly patients (> 70 years), whose pruritis manifests with or without bullous formation, should be screened for BP.3,4

Continue to: Risk factors for BP

Risk factors for BP. Certain conditions linked to developing BP include neurologic disorders (dementia and Parkinson disease) and psychiatric disorders (unipolar and bipolar disorder).4 Further, it is important to note any medications that could be the cause of a patient’s BP, including dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, psychotropic medications, spironolactone, furosemide, beta-blockers, and antibiotics.3 This patient was taking a beta-blocker (metoprolol) and a DPP-4 inhibitor (linagliptin). Because he was most recently started on linagliptin, we suspected it may have had a causal role in the development of BP.

The association of DPP-4 inhibitors and BP

FPs are increasingly using DPP-4 inhibitors—including sitagliptin, vildagliptin, and linagliptin—as oral antihyperglycemic agents for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Therefore, it’s important to recognize this medication class’s association with BP.5 In a case-control study of 165 patients with BP, Benzaquen et al reported that 28 patients who were taking DPP-4 inhibitors had an associated increased risk for BP (adjusted odds ratio = 2.64; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.19-5.85).3

The pathophysiology of BP associated with DPP-4 inhibitors remains unclear, but mechanisms have been proposed. The DPP-4 enzyme is expressed on many cells, including keratinocytes, T cells, and endothelial cells.3 It is possible that DPP-4 inhibition at these cells could stimulate activity of inflammatory cytokines, which can lead to enhanced local eosinophil activation and trigger bullous formation. DPP-4 enzymes are also involved in forming plasmin, which is a protease that cleaves BP180.3 Inhibition of this process can affect proper cleavage of BP180, impacting its function and antigenicity.3,6

Other conditions that also exhibit blisters

There are some skin conditions with similar presentations that need to be ruled out in the work-up.

Bullous diabeticorum is a rare, spontaneous, noninflammatory condition found in patients with diabetes.1 Blisters usually manifest as large, tense, asymmetrical, mildly tender lesions that commonly affect the feet and lower legs but can involve the trunk. These usually develop overnight without preceding trauma. Biopsy would show both intra-epidermal and subepidermal bulla with normal DIF findings.1 This condition usually has an excellent prognosis.

Continue to: Pemphigus vulgaris

Pemphigus vulgaris is characterized by nonpruritic, flaccid, painful blisters. This condition usually begins with manifestation of painful oral lesions that evolve into skin blisters. Some patients can develop mucocutaneous lesions.1 Nikolsky sign is positive in these cases. Light microscopy would show intra-epidermal bullae.

Dermatitis herpetiformis. This condition—usually affecting middle-age patients—is associated with severe pruritis and burning. It may start with a few pruritic papules or vesicles that later evolve into urticarial papules, vesicles, or bullae. Dermatitis herpetiformis can resemble herpes simplex virus. It can also be associated with gluten-sensitive enteropathy and small bowel lymphoma.1 DIF of a biopsy sample would show granular deposition of IgA within the tips of the dermal papillae and along the basement membrane of perilesional skin.1

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is a rare, severe, chronic condition with subepidermal mucocutaneous blistering.1 It is associated with skin fragility and spontaneous trauma-induced blisters that heal with scar formation and milia. IgG autoantibodies reacting to proteins in the basement membrane zone can cause the disease. It is also associated with Crohn disease.1 DIF findings are similar in BP, but they are differentiated by location of IgG deposits; they can be found on the dermal side of separation in epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, as compared with the epidermal side in BP.1

How to make the Dx in 3 steps

To effectively diagnose and classify BP, use the following 3-step method:

- Establish the presence of 3 of 4 clinical characteristics: patient’s age > 60 years, absence of atrophic scars, absence of mucosal involvement, and absence of bullous lesions on the head and neck.

- Order light microscopy. Findings should be consistent with eosinophils and neutrophils containing subepidermal bullae.

- Order a punch biopsy to obtain a perilesional specimen. DIF of the biopsy findings should feature linear deposits of IgG with or without C3 along the dermo-epidermal junction. This step is essential for an accurate diagnosis.

There also is benefit in ordering supplemental studies, such as an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of anti-BP180 or anti-BP230 IgG autoantibodies.7 However, for this patient, we did not order this study.

Continue to: Management focuses on steroids

Management focuses on steroids

The offending agent should be discontinued immediately. Depending on the severity of disease, treatment can include the use of potent topical corticosteroids alone or in combination with systemic corticosteroids and anti-inflammatory antibiotics (eg, doxycycline, minocycline, erythromycin).1,7 For patients with resistant or refractory disease, consider azathioprine, methotrexate, dapsone, and chlorambucil.1,7 Exceptional cases may benefit from the use of mycophenolate mofetil, intravenous immunoglobulin, or plasmapheresis.1,7

For this patient, initial treatment included discontinuation of linagliption and introduction of topical clobetasol 0.05% and oral prednisone 40 mg/d for 7 days, followed by prednisone 20 mg for 7 days. He was also started on oral doxycycline 100 mg bid and oral nicotinamide 500 mg bid.

1. Habif TP. Vesicular and bullous diseases. In: Habif TP, ed. Clinical Dermatology: a Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2016:635-666.

2. Kridin K, Ludwig RJ. The growing incidence of bullous pemphigoid: overview and potential explanations. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:220.

3. Benzaquen M, Borradori L, Berbis P, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors, a risk factor for bullous pemphigoid: retrospective multicenter case-control study from France and Switzerland. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;78:1090-1096.

4. Bastuji-Garin S, Joly P, Lemordant P, et al. Risk factors for bullous pemphigoid in the elderly: a prospective case-control study. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:637-643.

5. Kridin K, Bergman R. Association of bullous pemphigoid with dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 inhibitors in patients with diabetes: estimating the risk of the new agents and characterizing the patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1152-1158.

6. Haber R, Fayad AM, Stephan F, et al. Bullous pemphigoid associated with linagliptin treatment. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:224-226.Management of bullous pemphigoid: the European Dermatology Forum consensus in collaboration with the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:867-877.

A 62-year-old man presented to our skin clinic with multiple pruritic, tense, bullous lesions that manifested on his arms, abdomen, back, and upper thighs over a 1-month period. There were no lesions in his oral cavity or around his eyes, nose, or penile region. He denied dysphagia.

The patient had multiple comorbidities, including diabetes, hypertension, recent stroke, and end-stage renal disease. He was being prepared for dialysis. His medications included torsemide, warfarin, amiodarone, metoprolol, pantoprozole, atorvastatin, and nifedipine. About 3 months prior to this presentation, he was started on oral linaglipton 5 mg/d, an oral antihyperglycemic medication. He had no history of skin disease or cancer, and his family history was not significant.

Physical examination showed multiple 5-mm to 2-cm blisters and bullae on the flexural surface of both of his arms (FIGURE), back, lower abdomen, and upper thighs. His palms and soles were not involved. The lesions were nontender, tense, and filled with clear fluid. Some were intact and others were rupturing. There was no mucocutaneous involvement. Nikolsky sign was negative. There were no signs of bleeding.

The family physician (FP) obtained a 4-mm punch biopsy at the edge of a 6-mm blister for light microscopy and a 3-mm perilesional punch biopsy for direct immunofluorescence (DIF) microscopy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Bullous pemphigoid secondary to linagliptin use

DIF of the biopsy sample demonstrated linear deposition of complement 3 (C3) and immunoglobulin (Ig) G along the basement membrane zone. Indirect immunofluorescence on salt-split skin demonstrated linear deposition of IgG and C3 on both the roof and floor of the induced blisters. These findings and the patient’s clinical presentation met the criteria for bullous pemphigoid (BP), which is the most common autoimmune skin-blistering disease.1

BP is associated with subepidermal blistering, which can occur in reaction to a variety of triggers. Pathogenesis of this condition involves IgG anti-basement membrane autoantibody complex formation with the hemidesmosomal antigens BP230 and BP180—a process that activates C3 and the release of proteases that can be destructive to tissue along the dermo-epidermal junction.1

Growing incidence. BP usually occurs in patients > 60 years, with no racial or gender preference.1 The incidence rate of BP ranges from 2.4 to 21.7 new cases per 1 million individuals among various worldwide populations.2 The incidence appears to have increased 1.9- to 4.3-fold over the past 2 decades.2

What you’ll see, who’s at risk

Symptoms of BP include localized areas of erythema or pruritic urticarial plaques that gradually become more extensive. A patient may have pruritis alone for an extended period prior to developing blisters and bullae. The bullae are tense and normally 1 to 7 cm in size.1 Eruption is generalized, mostly affecting the lower abdomen, as well as the flexural parts of the extremities. The palms and soles also can be affected.

FPs should be aware of the atypical clinical variants of BP. In a review by Kridin and Ludwig, variants can be prurigo-like, eczema-like, urticaria-like, dyshidrosiform type, erosive type, and erythema annulare centrifugum–like type.2 At-risk populations, such as elderly patients (> 70 years), whose pruritis manifests with or without bullous formation, should be screened for BP.3,4

Continue to: Risk factors for BP

Risk factors for BP. Certain conditions linked to developing BP include neurologic disorders (dementia and Parkinson disease) and psychiatric disorders (unipolar and bipolar disorder).4 Further, it is important to note any medications that could be the cause of a patient’s BP, including dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, psychotropic medications, spironolactone, furosemide, beta-blockers, and antibiotics.3 This patient was taking a beta-blocker (metoprolol) and a DPP-4 inhibitor (linagliptin). Because he was most recently started on linagliptin, we suspected it may have had a causal role in the development of BP.

The association of DPP-4 inhibitors and BP

FPs are increasingly using DPP-4 inhibitors—including sitagliptin, vildagliptin, and linagliptin—as oral antihyperglycemic agents for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Therefore, it’s important to recognize this medication class’s association with BP.5 In a case-control study of 165 patients with BP, Benzaquen et al reported that 28 patients who were taking DPP-4 inhibitors had an associated increased risk for BP (adjusted odds ratio = 2.64; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.19-5.85).3

The pathophysiology of BP associated with DPP-4 inhibitors remains unclear, but mechanisms have been proposed. The DPP-4 enzyme is expressed on many cells, including keratinocytes, T cells, and endothelial cells.3 It is possible that DPP-4 inhibition at these cells could stimulate activity of inflammatory cytokines, which can lead to enhanced local eosinophil activation and trigger bullous formation. DPP-4 enzymes are also involved in forming plasmin, which is a protease that cleaves BP180.3 Inhibition of this process can affect proper cleavage of BP180, impacting its function and antigenicity.3,6

Other conditions that also exhibit blisters

There are some skin conditions with similar presentations that need to be ruled out in the work-up.

Bullous diabeticorum is a rare, spontaneous, noninflammatory condition found in patients with diabetes.1 Blisters usually manifest as large, tense, asymmetrical, mildly tender lesions that commonly affect the feet and lower legs but can involve the trunk. These usually develop overnight without preceding trauma. Biopsy would show both intra-epidermal and subepidermal bulla with normal DIF findings.1 This condition usually has an excellent prognosis.

Continue to: Pemphigus vulgaris

Pemphigus vulgaris is characterized by nonpruritic, flaccid, painful blisters. This condition usually begins with manifestation of painful oral lesions that evolve into skin blisters. Some patients can develop mucocutaneous lesions.1 Nikolsky sign is positive in these cases. Light microscopy would show intra-epidermal bullae.

Dermatitis herpetiformis. This condition—usually affecting middle-age patients—is associated with severe pruritis and burning. It may start with a few pruritic papules or vesicles that later evolve into urticarial papules, vesicles, or bullae. Dermatitis herpetiformis can resemble herpes simplex virus. It can also be associated with gluten-sensitive enteropathy and small bowel lymphoma.1 DIF of a biopsy sample would show granular deposition of IgA within the tips of the dermal papillae and along the basement membrane of perilesional skin.1

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is a rare, severe, chronic condition with subepidermal mucocutaneous blistering.1 It is associated with skin fragility and spontaneous trauma-induced blisters that heal with scar formation and milia. IgG autoantibodies reacting to proteins in the basement membrane zone can cause the disease. It is also associated with Crohn disease.1 DIF findings are similar in BP, but they are differentiated by location of IgG deposits; they can be found on the dermal side of separation in epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, as compared with the epidermal side in BP.1

How to make the Dx in 3 steps

To effectively diagnose and classify BP, use the following 3-step method:

- Establish the presence of 3 of 4 clinical characteristics: patient’s age > 60 years, absence of atrophic scars, absence of mucosal involvement, and absence of bullous lesions on the head and neck.

- Order light microscopy. Findings should be consistent with eosinophils and neutrophils containing subepidermal bullae.

- Order a punch biopsy to obtain a perilesional specimen. DIF of the biopsy findings should feature linear deposits of IgG with or without C3 along the dermo-epidermal junction. This step is essential for an accurate diagnosis.

There also is benefit in ordering supplemental studies, such as an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of anti-BP180 or anti-BP230 IgG autoantibodies.7 However, for this patient, we did not order this study.

Continue to: Management focuses on steroids

Management focuses on steroids

The offending agent should be discontinued immediately. Depending on the severity of disease, treatment can include the use of potent topical corticosteroids alone or in combination with systemic corticosteroids and anti-inflammatory antibiotics (eg, doxycycline, minocycline, erythromycin).1,7 For patients with resistant or refractory disease, consider azathioprine, methotrexate, dapsone, and chlorambucil.1,7 Exceptional cases may benefit from the use of mycophenolate mofetil, intravenous immunoglobulin, or plasmapheresis.1,7

For this patient, initial treatment included discontinuation of linagliption and introduction of topical clobetasol 0.05% and oral prednisone 40 mg/d for 7 days, followed by prednisone 20 mg for 7 days. He was also started on oral doxycycline 100 mg bid and oral nicotinamide 500 mg bid.

A 62-year-old man presented to our skin clinic with multiple pruritic, tense, bullous lesions that manifested on his arms, abdomen, back, and upper thighs over a 1-month period. There were no lesions in his oral cavity or around his eyes, nose, or penile region. He denied dysphagia.

The patient had multiple comorbidities, including diabetes, hypertension, recent stroke, and end-stage renal disease. He was being prepared for dialysis. His medications included torsemide, warfarin, amiodarone, metoprolol, pantoprozole, atorvastatin, and nifedipine. About 3 months prior to this presentation, he was started on oral linaglipton 5 mg/d, an oral antihyperglycemic medication. He had no history of skin disease or cancer, and his family history was not significant.

Physical examination showed multiple 5-mm to 2-cm blisters and bullae on the flexural surface of both of his arms (FIGURE), back, lower abdomen, and upper thighs. His palms and soles were not involved. The lesions were nontender, tense, and filled with clear fluid. Some were intact and others were rupturing. There was no mucocutaneous involvement. Nikolsky sign was negative. There were no signs of bleeding.

The family physician (FP) obtained a 4-mm punch biopsy at the edge of a 6-mm blister for light microscopy and a 3-mm perilesional punch biopsy for direct immunofluorescence (DIF) microscopy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Bullous pemphigoid secondary to linagliptin use

DIF of the biopsy sample demonstrated linear deposition of complement 3 (C3) and immunoglobulin (Ig) G along the basement membrane zone. Indirect immunofluorescence on salt-split skin demonstrated linear deposition of IgG and C3 on both the roof and floor of the induced blisters. These findings and the patient’s clinical presentation met the criteria for bullous pemphigoid (BP), which is the most common autoimmune skin-blistering disease.1

BP is associated with subepidermal blistering, which can occur in reaction to a variety of triggers. Pathogenesis of this condition involves IgG anti-basement membrane autoantibody complex formation with the hemidesmosomal antigens BP230 and BP180—a process that activates C3 and the release of proteases that can be destructive to tissue along the dermo-epidermal junction.1

Growing incidence. BP usually occurs in patients > 60 years, with no racial or gender preference.1 The incidence rate of BP ranges from 2.4 to 21.7 new cases per 1 million individuals among various worldwide populations.2 The incidence appears to have increased 1.9- to 4.3-fold over the past 2 decades.2

What you’ll see, who’s at risk

Symptoms of BP include localized areas of erythema or pruritic urticarial plaques that gradually become more extensive. A patient may have pruritis alone for an extended period prior to developing blisters and bullae. The bullae are tense and normally 1 to 7 cm in size.1 Eruption is generalized, mostly affecting the lower abdomen, as well as the flexural parts of the extremities. The palms and soles also can be affected.

FPs should be aware of the atypical clinical variants of BP. In a review by Kridin and Ludwig, variants can be prurigo-like, eczema-like, urticaria-like, dyshidrosiform type, erosive type, and erythema annulare centrifugum–like type.2 At-risk populations, such as elderly patients (> 70 years), whose pruritis manifests with or without bullous formation, should be screened for BP.3,4

Continue to: Risk factors for BP

Risk factors for BP. Certain conditions linked to developing BP include neurologic disorders (dementia and Parkinson disease) and psychiatric disorders (unipolar and bipolar disorder).4 Further, it is important to note any medications that could be the cause of a patient’s BP, including dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors, psychotropic medications, spironolactone, furosemide, beta-blockers, and antibiotics.3 This patient was taking a beta-blocker (metoprolol) and a DPP-4 inhibitor (linagliptin). Because he was most recently started on linagliptin, we suspected it may have had a causal role in the development of BP.

The association of DPP-4 inhibitors and BP

FPs are increasingly using DPP-4 inhibitors—including sitagliptin, vildagliptin, and linagliptin—as oral antihyperglycemic agents for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Therefore, it’s important to recognize this medication class’s association with BP.5 In a case-control study of 165 patients with BP, Benzaquen et al reported that 28 patients who were taking DPP-4 inhibitors had an associated increased risk for BP (adjusted odds ratio = 2.64; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.19-5.85).3

The pathophysiology of BP associated with DPP-4 inhibitors remains unclear, but mechanisms have been proposed. The DPP-4 enzyme is expressed on many cells, including keratinocytes, T cells, and endothelial cells.3 It is possible that DPP-4 inhibition at these cells could stimulate activity of inflammatory cytokines, which can lead to enhanced local eosinophil activation and trigger bullous formation. DPP-4 enzymes are also involved in forming plasmin, which is a protease that cleaves BP180.3 Inhibition of this process can affect proper cleavage of BP180, impacting its function and antigenicity.3,6

Other conditions that also exhibit blisters

There are some skin conditions with similar presentations that need to be ruled out in the work-up.

Bullous diabeticorum is a rare, spontaneous, noninflammatory condition found in patients with diabetes.1 Blisters usually manifest as large, tense, asymmetrical, mildly tender lesions that commonly affect the feet and lower legs but can involve the trunk. These usually develop overnight without preceding trauma. Biopsy would show both intra-epidermal and subepidermal bulla with normal DIF findings.1 This condition usually has an excellent prognosis.

Continue to: Pemphigus vulgaris

Pemphigus vulgaris is characterized by nonpruritic, flaccid, painful blisters. This condition usually begins with manifestation of painful oral lesions that evolve into skin blisters. Some patients can develop mucocutaneous lesions.1 Nikolsky sign is positive in these cases. Light microscopy would show intra-epidermal bullae.

Dermatitis herpetiformis. This condition—usually affecting middle-age patients—is associated with severe pruritis and burning. It may start with a few pruritic papules or vesicles that later evolve into urticarial papules, vesicles, or bullae. Dermatitis herpetiformis can resemble herpes simplex virus. It can also be associated with gluten-sensitive enteropathy and small bowel lymphoma.1 DIF of a biopsy sample would show granular deposition of IgA within the tips of the dermal papillae and along the basement membrane of perilesional skin.1

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is a rare, severe, chronic condition with subepidermal mucocutaneous blistering.1 It is associated with skin fragility and spontaneous trauma-induced blisters that heal with scar formation and milia. IgG autoantibodies reacting to proteins in the basement membrane zone can cause the disease. It is also associated with Crohn disease.1 DIF findings are similar in BP, but they are differentiated by location of IgG deposits; they can be found on the dermal side of separation in epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, as compared with the epidermal side in BP.1

How to make the Dx in 3 steps

To effectively diagnose and classify BP, use the following 3-step method:

- Establish the presence of 3 of 4 clinical characteristics: patient’s age > 60 years, absence of atrophic scars, absence of mucosal involvement, and absence of bullous lesions on the head and neck.

- Order light microscopy. Findings should be consistent with eosinophils and neutrophils containing subepidermal bullae.

- Order a punch biopsy to obtain a perilesional specimen. DIF of the biopsy findings should feature linear deposits of IgG with or without C3 along the dermo-epidermal junction. This step is essential for an accurate diagnosis.

There also is benefit in ordering supplemental studies, such as an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of anti-BP180 or anti-BP230 IgG autoantibodies.7 However, for this patient, we did not order this study.

Continue to: Management focuses on steroids

Management focuses on steroids

The offending agent should be discontinued immediately. Depending on the severity of disease, treatment can include the use of potent topical corticosteroids alone or in combination with systemic corticosteroids and anti-inflammatory antibiotics (eg, doxycycline, minocycline, erythromycin).1,7 For patients with resistant or refractory disease, consider azathioprine, methotrexate, dapsone, and chlorambucil.1,7 Exceptional cases may benefit from the use of mycophenolate mofetil, intravenous immunoglobulin, or plasmapheresis.1,7

For this patient, initial treatment included discontinuation of linagliption and introduction of topical clobetasol 0.05% and oral prednisone 40 mg/d for 7 days, followed by prednisone 20 mg for 7 days. He was also started on oral doxycycline 100 mg bid and oral nicotinamide 500 mg bid.

1. Habif TP. Vesicular and bullous diseases. In: Habif TP, ed. Clinical Dermatology: a Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2016:635-666.

2. Kridin K, Ludwig RJ. The growing incidence of bullous pemphigoid: overview and potential explanations. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:220.

3. Benzaquen M, Borradori L, Berbis P, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors, a risk factor for bullous pemphigoid: retrospective multicenter case-control study from France and Switzerland. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;78:1090-1096.

4. Bastuji-Garin S, Joly P, Lemordant P, et al. Risk factors for bullous pemphigoid in the elderly: a prospective case-control study. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:637-643.

5. Kridin K, Bergman R. Association of bullous pemphigoid with dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 inhibitors in patients with diabetes: estimating the risk of the new agents and characterizing the patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1152-1158.

6. Haber R, Fayad AM, Stephan F, et al. Bullous pemphigoid associated with linagliptin treatment. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:224-226.Management of bullous pemphigoid: the European Dermatology Forum consensus in collaboration with the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:867-877.

1. Habif TP. Vesicular and bullous diseases. In: Habif TP, ed. Clinical Dermatology: a Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2016:635-666.

2. Kridin K, Ludwig RJ. The growing incidence of bullous pemphigoid: overview and potential explanations. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:220.

3. Benzaquen M, Borradori L, Berbis P, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors, a risk factor for bullous pemphigoid: retrospective multicenter case-control study from France and Switzerland. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;78:1090-1096.

4. Bastuji-Garin S, Joly P, Lemordant P, et al. Risk factors for bullous pemphigoid in the elderly: a prospective case-control study. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:637-643.

5. Kridin K, Bergman R. Association of bullous pemphigoid with dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 inhibitors in patients with diabetes: estimating the risk of the new agents and characterizing the patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154:1152-1158.

6. Haber R, Fayad AM, Stephan F, et al. Bullous pemphigoid associated with linagliptin treatment. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:224-226.Management of bullous pemphigoid: the European Dermatology Forum consensus in collaboration with the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:867-877.

Painful, slow-growing recurrent nodules

A 67-year-old woman presented with multiple painful nodules that had developed on her scalp, face, and neck over the course of 1 year. She also had a few nodules on her trunk and hip. There was no associated bleeding, ulceration, or drainage from the lesions. She had no systemic symptoms. The patient reported that she’d had a similar lesion on her frontal scalp about 15 years earlier, and it was excised completely. (She was not aware of the diagnosis.) She indicated that her mother and son had similar lesions in the past.

Her medical history was remarkable for diabetes and hypertension, which were well controlled on metformin and lisinopril, respectively. The patient had cancer of the left breast that was treated with mastectomy and chemotherapy 3 years prior.

On physical examination, the patient had multiple firm, rubbery, tender nodules with tan or pink hue, measuring 1 to 1.5 cm. The nodules were located on the left side of her chin and right preauricular area (FIGURE 1), as well as the right sides of her neck and hip. Most of the nodules were solitary; the preauricular area had 2 clustered pink lesions. The largest nodule was located on the patient’s chin and had overlying telangiectasias.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Cylindroma

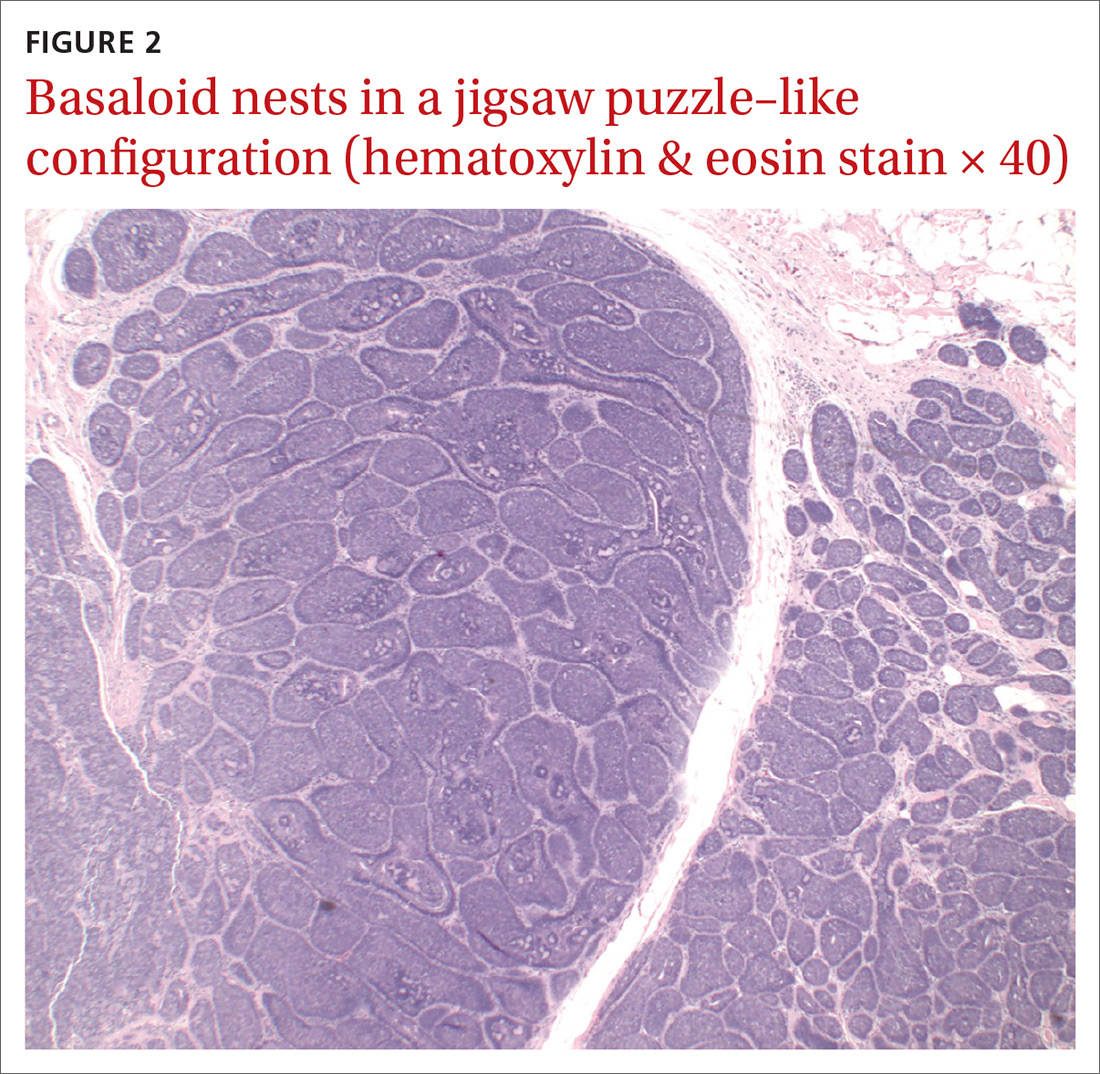

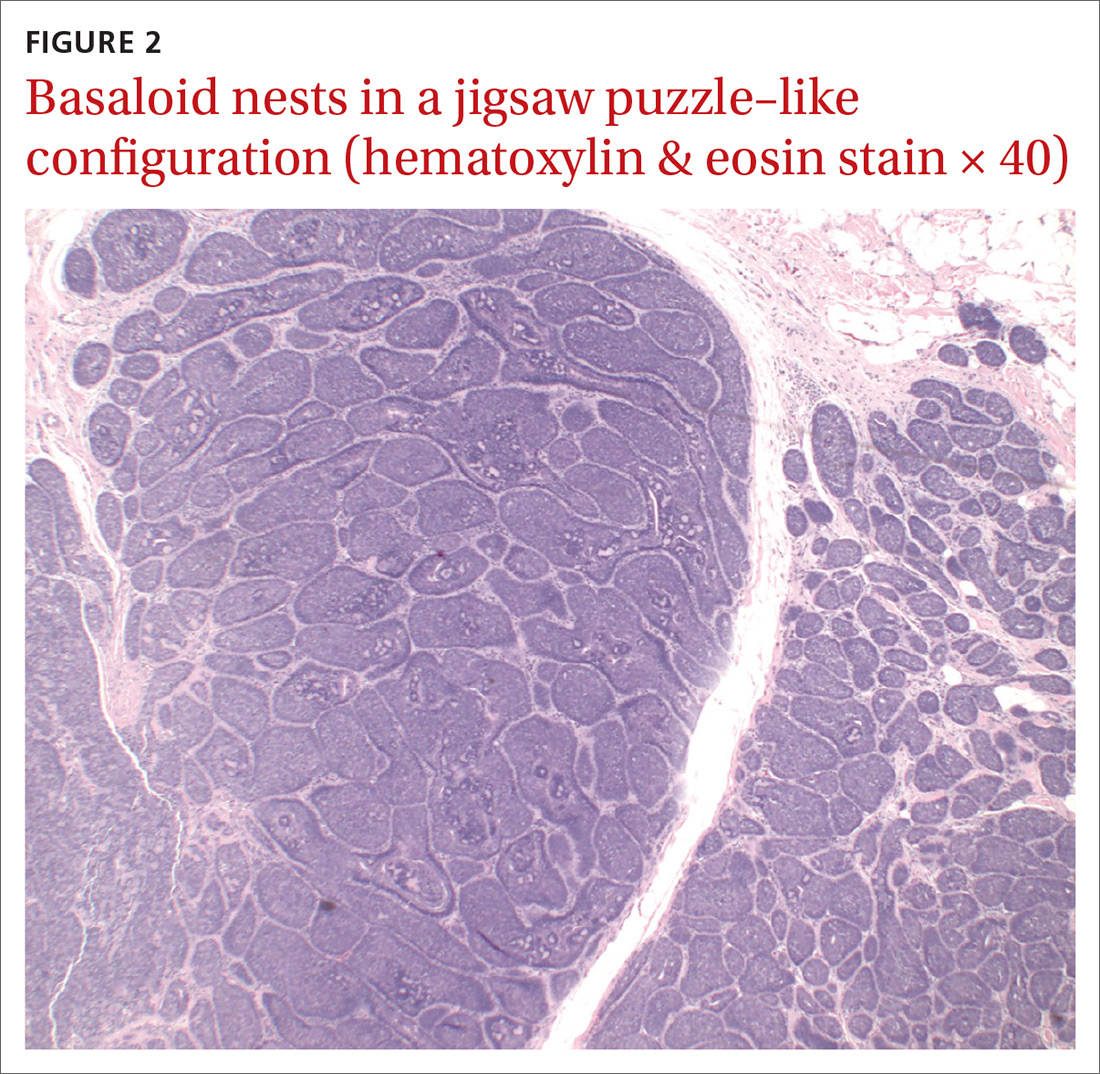

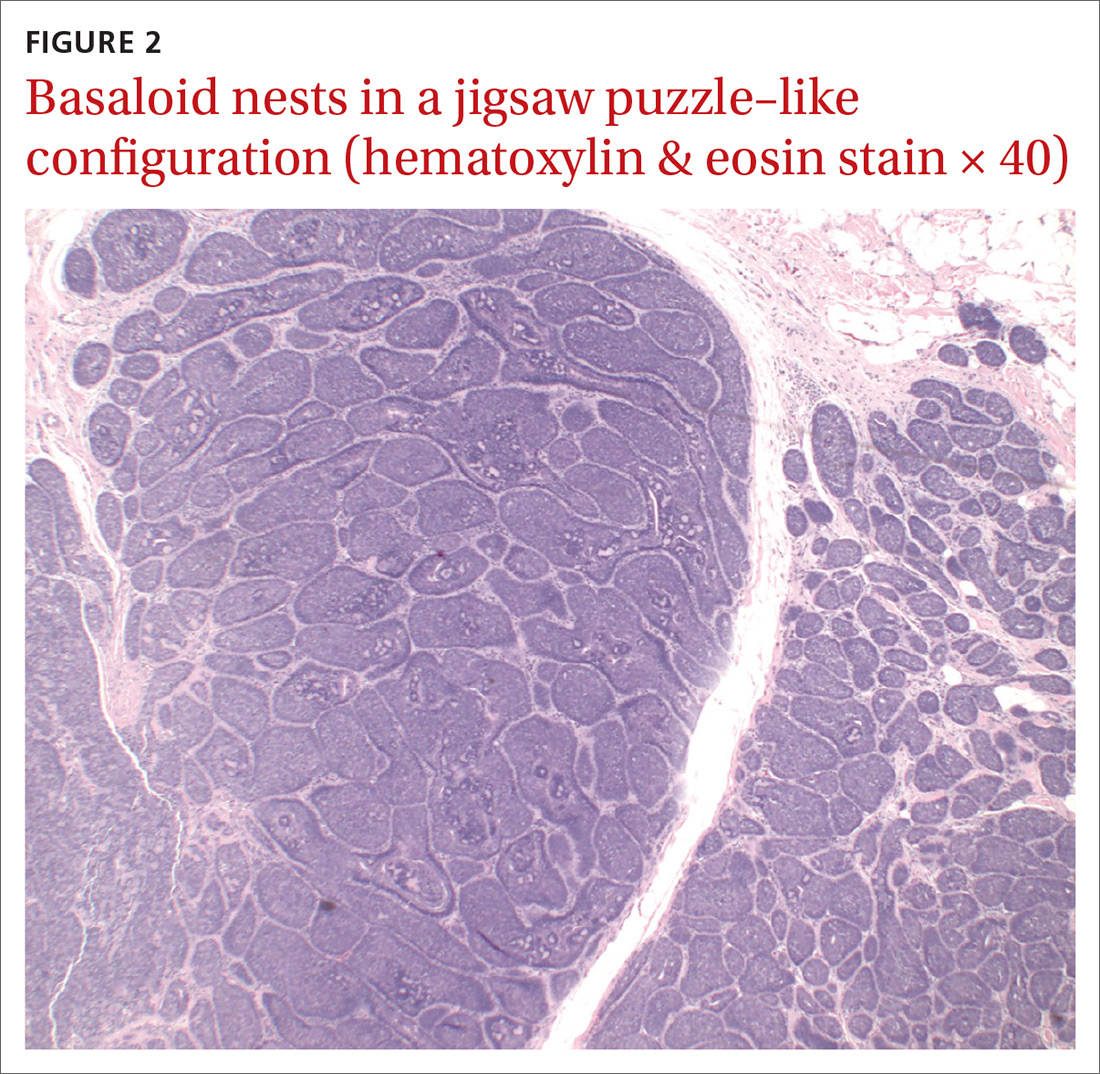

Definitive diagnosis was made by shave biopsy of the left hip lesion. Histopathology demonstrated various-sized discrete aggregates of basaloid cell nests in a jigsaw puzzle–like configuration (FIGURE 2), surrounded by rims of homogenous eosinophilic material. Histologic findings were consistent with cylindroma.1

Rare with a female predominance. Solitary cylindromas occur sporadically and usually affect middle-aged and elderly patients. Incidence is rare, but there is a female predominance of 6 to 9:1.2 Clinical appearance shows a slow-growing, firm mass that can range from a few millimeters to a few centimeters in diameter. The masses can have a pink or blue hue and usually are nontender unless there is nerve impingement.2

If multiple tumors are present or the patient has a family history of similar lesions, the disorder is likely inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern (with variable expression), which can be associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. This syndrome is related to a mutation of the cylindromatosis gene on chromosome 16. This is a tumor suppressor gene, inactivation of which can lead to uninhibited action of NF-

Rarely, cylindromas can undergo malignant transformation; signs include ulceration, bleeding, rapid growth, or color change.2 In these cases, appropriate imaging such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or positron emission tomography should be sought as there have been case reports of cylindroma extension to bone, as well as metastases to sites including the lymph nodes, thyroid, liver, lungs, bones, and meninges.4

Lipomas and pilar cysts comprise the differential

Lipomas are soft, painless, flesh-colored masses that typically appear on the trunk and arms but are uncommon on the face. Telangiectasias are not seen.

Continue to: Pilar cysts

Pilar cysts can mimic cylindromas in clinical presentation. Derived from the root sheath of hair follicles, they typically appear on the scalp but rarely on the face. Pilar cysts are slow growing, firm, and whitish in color5; several cysts can appear at a time.

Pilomatricomas are firm skin masses—usually < 3 cm in size—that can vary in color. There may be an extrusion of calcified material within the nodules, which does not occur in cylindromas.

Sebaceous adenomas are yellowish papules, usually < 1 cm in size, that appear on the head and neck area.6

Making the diagnosis. The clinical appearance of cylindromas and their location will point to the diagnosis, as will a family history of similar lesions. Ultimately, the diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy.

Treatment mainstay includes excision

Complete excision of all lesions is key due to the possibility of malignant transformation and metastasis. Options for removal include electrodesiccation, curettage, cryosurgery,3 high-dose radiation, and the use of a CO2 laser.2 For multiple large tumors, or ones in cosmetically sensitive areas, consider referral to Dermatology or Plastic Surgery. Further imaging should be sought to rule out extension to bone or metastasis. Patients with multiple cylindromas and Brooke-Spiegler syndrome need lifelong follow-up to monitor for recurrence and malignant transformation.3,7,8

Continue to: Our patient...

Our patient underwent complete excision of the left hip lesion. Other trunk lesions were excised serially. The patient was referred to a surgeon specializing in Mohs micrographic surgery for excision of the facial lesions. The patient and her family members were referred for genetic testing.

CORRESPONDENCE

Zeeshan Afzal, MD, McAllen Family Medicine Residency Program, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, 205 E Toronto Ave, McAllen, TX 78503; Drzeeshanafzal@gmail.com

1. Elder D, Elenitsas R, Jaworsky CH, et al. Tumors of the epidermal appendages. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:775-777.

2. Singh DD, Naujoks C, Depprich R, et al. Cylindroma of head and neck: Review of the literature and report of two rare cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2013;41:516-521.

3. Sicinska J, Rakowska A, Czuwara-Ladykowska J, et al. Cylindroma transforming into basal cell carcinoma in a patient with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2007;1:4-9.

4. Jordão C, de Magalhães TC, Cuzzi T, et al. Cylindroma: an update. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:275-278.

5. Stone M. Cysts. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1920.

6. McCalmont T, Pincus L. Adnexal neoplasms. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1938-1942.

7. Gerretsen AL, Van der Putte SC, Deenstra W, et al. Cutaneous cylindroma with malignant transformation. Cancer. 1993;72:1618-1623.

8. Manicketh I, Singh R, Ghosh PK. Eccrine cylindroma of the face and scalp. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:203-205.

A 67-year-old woman presented with multiple painful nodules that had developed on her scalp, face, and neck over the course of 1 year. She also had a few nodules on her trunk and hip. There was no associated bleeding, ulceration, or drainage from the lesions. She had no systemic symptoms. The patient reported that she’d had a similar lesion on her frontal scalp about 15 years earlier, and it was excised completely. (She was not aware of the diagnosis.) She indicated that her mother and son had similar lesions in the past.

Her medical history was remarkable for diabetes and hypertension, which were well controlled on metformin and lisinopril, respectively. The patient had cancer of the left breast that was treated with mastectomy and chemotherapy 3 years prior.

On physical examination, the patient had multiple firm, rubbery, tender nodules with tan or pink hue, measuring 1 to 1.5 cm. The nodules were located on the left side of her chin and right preauricular area (FIGURE 1), as well as the right sides of her neck and hip. Most of the nodules were solitary; the preauricular area had 2 clustered pink lesions. The largest nodule was located on the patient’s chin and had overlying telangiectasias.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Cylindroma

Definitive diagnosis was made by shave biopsy of the left hip lesion. Histopathology demonstrated various-sized discrete aggregates of basaloid cell nests in a jigsaw puzzle–like configuration (FIGURE 2), surrounded by rims of homogenous eosinophilic material. Histologic findings were consistent with cylindroma.1

Rare with a female predominance. Solitary cylindromas occur sporadically and usually affect middle-aged and elderly patients. Incidence is rare, but there is a female predominance of 6 to 9:1.2 Clinical appearance shows a slow-growing, firm mass that can range from a few millimeters to a few centimeters in diameter. The masses can have a pink or blue hue and usually are nontender unless there is nerve impingement.2

If multiple tumors are present or the patient has a family history of similar lesions, the disorder is likely inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern (with variable expression), which can be associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. This syndrome is related to a mutation of the cylindromatosis gene on chromosome 16. This is a tumor suppressor gene, inactivation of which can lead to uninhibited action of NF-

Rarely, cylindromas can undergo malignant transformation; signs include ulceration, bleeding, rapid growth, or color change.2 In these cases, appropriate imaging such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or positron emission tomography should be sought as there have been case reports of cylindroma extension to bone, as well as metastases to sites including the lymph nodes, thyroid, liver, lungs, bones, and meninges.4

Lipomas and pilar cysts comprise the differential

Lipomas are soft, painless, flesh-colored masses that typically appear on the trunk and arms but are uncommon on the face. Telangiectasias are not seen.

Continue to: Pilar cysts

Pilar cysts can mimic cylindromas in clinical presentation. Derived from the root sheath of hair follicles, they typically appear on the scalp but rarely on the face. Pilar cysts are slow growing, firm, and whitish in color5; several cysts can appear at a time.

Pilomatricomas are firm skin masses—usually < 3 cm in size—that can vary in color. There may be an extrusion of calcified material within the nodules, which does not occur in cylindromas.

Sebaceous adenomas are yellowish papules, usually < 1 cm in size, that appear on the head and neck area.6

Making the diagnosis. The clinical appearance of cylindromas and their location will point to the diagnosis, as will a family history of similar lesions. Ultimately, the diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy.

Treatment mainstay includes excision

Complete excision of all lesions is key due to the possibility of malignant transformation and metastasis. Options for removal include electrodesiccation, curettage, cryosurgery,3 high-dose radiation, and the use of a CO2 laser.2 For multiple large tumors, or ones in cosmetically sensitive areas, consider referral to Dermatology or Plastic Surgery. Further imaging should be sought to rule out extension to bone or metastasis. Patients with multiple cylindromas and Brooke-Spiegler syndrome need lifelong follow-up to monitor for recurrence and malignant transformation.3,7,8

Continue to: Our patient...

Our patient underwent complete excision of the left hip lesion. Other trunk lesions were excised serially. The patient was referred to a surgeon specializing in Mohs micrographic surgery for excision of the facial lesions. The patient and her family members were referred for genetic testing.

CORRESPONDENCE

Zeeshan Afzal, MD, McAllen Family Medicine Residency Program, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, 205 E Toronto Ave, McAllen, TX 78503; Drzeeshanafzal@gmail.com

A 67-year-old woman presented with multiple painful nodules that had developed on her scalp, face, and neck over the course of 1 year. She also had a few nodules on her trunk and hip. There was no associated bleeding, ulceration, or drainage from the lesions. She had no systemic symptoms. The patient reported that she’d had a similar lesion on her frontal scalp about 15 years earlier, and it was excised completely. (She was not aware of the diagnosis.) She indicated that her mother and son had similar lesions in the past.

Her medical history was remarkable for diabetes and hypertension, which were well controlled on metformin and lisinopril, respectively. The patient had cancer of the left breast that was treated with mastectomy and chemotherapy 3 years prior.

On physical examination, the patient had multiple firm, rubbery, tender nodules with tan or pink hue, measuring 1 to 1.5 cm. The nodules were located on the left side of her chin and right preauricular area (FIGURE 1), as well as the right sides of her neck and hip. Most of the nodules were solitary; the preauricular area had 2 clustered pink lesions. The largest nodule was located on the patient’s chin and had overlying telangiectasias.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Cylindroma

Definitive diagnosis was made by shave biopsy of the left hip lesion. Histopathology demonstrated various-sized discrete aggregates of basaloid cell nests in a jigsaw puzzle–like configuration (FIGURE 2), surrounded by rims of homogenous eosinophilic material. Histologic findings were consistent with cylindroma.1

Rare with a female predominance. Solitary cylindromas occur sporadically and usually affect middle-aged and elderly patients. Incidence is rare, but there is a female predominance of 6 to 9:1.2 Clinical appearance shows a slow-growing, firm mass that can range from a few millimeters to a few centimeters in diameter. The masses can have a pink or blue hue and usually are nontender unless there is nerve impingement.2

If multiple tumors are present or the patient has a family history of similar lesions, the disorder is likely inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern (with variable expression), which can be associated with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. This syndrome is related to a mutation of the cylindromatosis gene on chromosome 16. This is a tumor suppressor gene, inactivation of which can lead to uninhibited action of NF-

Rarely, cylindromas can undergo malignant transformation; signs include ulceration, bleeding, rapid growth, or color change.2 In these cases, appropriate imaging such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or positron emission tomography should be sought as there have been case reports of cylindroma extension to bone, as well as metastases to sites including the lymph nodes, thyroid, liver, lungs, bones, and meninges.4

Lipomas and pilar cysts comprise the differential

Lipomas are soft, painless, flesh-colored masses that typically appear on the trunk and arms but are uncommon on the face. Telangiectasias are not seen.

Continue to: Pilar cysts

Pilar cysts can mimic cylindromas in clinical presentation. Derived from the root sheath of hair follicles, they typically appear on the scalp but rarely on the face. Pilar cysts are slow growing, firm, and whitish in color5; several cysts can appear at a time.

Pilomatricomas are firm skin masses—usually < 3 cm in size—that can vary in color. There may be an extrusion of calcified material within the nodules, which does not occur in cylindromas.

Sebaceous adenomas are yellowish papules, usually < 1 cm in size, that appear on the head and neck area.6

Making the diagnosis. The clinical appearance of cylindromas and their location will point to the diagnosis, as will a family history of similar lesions. Ultimately, the diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy.

Treatment mainstay includes excision

Complete excision of all lesions is key due to the possibility of malignant transformation and metastasis. Options for removal include electrodesiccation, curettage, cryosurgery,3 high-dose radiation, and the use of a CO2 laser.2 For multiple large tumors, or ones in cosmetically sensitive areas, consider referral to Dermatology or Plastic Surgery. Further imaging should be sought to rule out extension to bone or metastasis. Patients with multiple cylindromas and Brooke-Spiegler syndrome need lifelong follow-up to monitor for recurrence and malignant transformation.3,7,8

Continue to: Our patient...

Our patient underwent complete excision of the left hip lesion. Other trunk lesions were excised serially. The patient was referred to a surgeon specializing in Mohs micrographic surgery for excision of the facial lesions. The patient and her family members were referred for genetic testing.

CORRESPONDENCE

Zeeshan Afzal, MD, McAllen Family Medicine Residency Program, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, 205 E Toronto Ave, McAllen, TX 78503; Drzeeshanafzal@gmail.com

1. Elder D, Elenitsas R, Jaworsky CH, et al. Tumors of the epidermal appendages. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:775-777.

2. Singh DD, Naujoks C, Depprich R, et al. Cylindroma of head and neck: Review of the literature and report of two rare cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2013;41:516-521.

3. Sicinska J, Rakowska A, Czuwara-Ladykowska J, et al. Cylindroma transforming into basal cell carcinoma in a patient with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2007;1:4-9.

4. Jordão C, de Magalhães TC, Cuzzi T, et al. Cylindroma: an update. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:275-278.

5. Stone M. Cysts. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1920.

6. McCalmont T, Pincus L. Adnexal neoplasms. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1938-1942.

7. Gerretsen AL, Van der Putte SC, Deenstra W, et al. Cutaneous cylindroma with malignant transformation. Cancer. 1993;72:1618-1623.

8. Manicketh I, Singh R, Ghosh PK. Eccrine cylindroma of the face and scalp. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:203-205.

1. Elder D, Elenitsas R, Jaworsky CH, et al. Tumors of the epidermal appendages. Lever’s Histopathology of the Skin. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:775-777.

2. Singh DD, Naujoks C, Depprich R, et al. Cylindroma of head and neck: Review of the literature and report of two rare cases. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2013;41:516-521.

3. Sicinska J, Rakowska A, Czuwara-Ladykowska J, et al. Cylindroma transforming into basal cell carcinoma in a patient with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2007;1:4-9.

4. Jordão C, de Magalhães TC, Cuzzi T, et al. Cylindroma: an update. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:275-278.

5. Stone M. Cysts. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1920.

6. McCalmont T, Pincus L. Adnexal neoplasms. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018:1938-1942.

7. Gerretsen AL, Van der Putte SC, Deenstra W, et al. Cutaneous cylindroma with malignant transformation. Cancer. 1993;72:1618-1623.

8. Manicketh I, Singh R, Ghosh PK. Eccrine cylindroma of the face and scalp. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:203-205.