User login

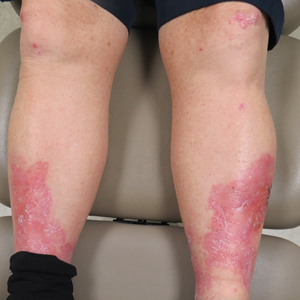

Erythema, Blisters, and Scars on the Elbows, Knees, and Legs

The Diagnosis: Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita

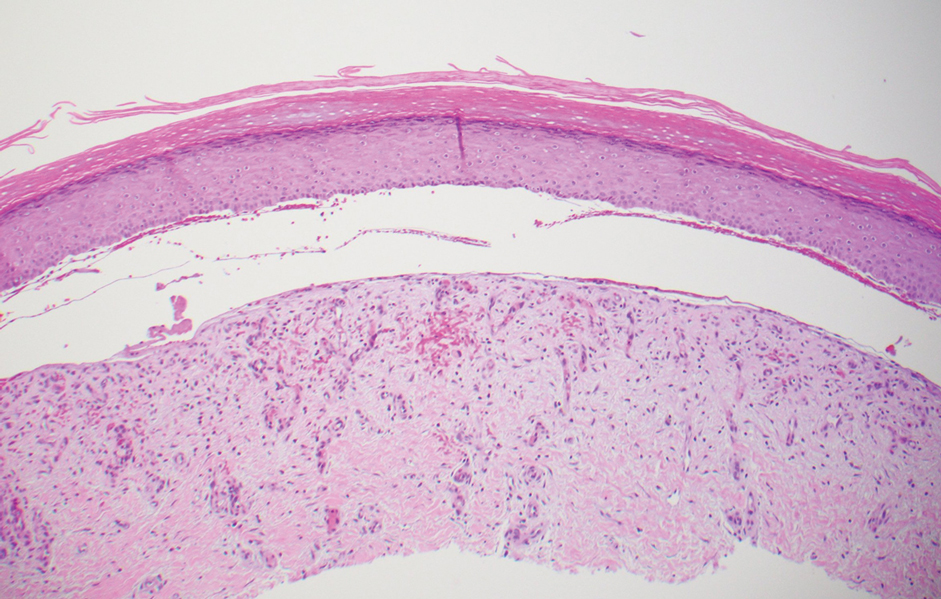

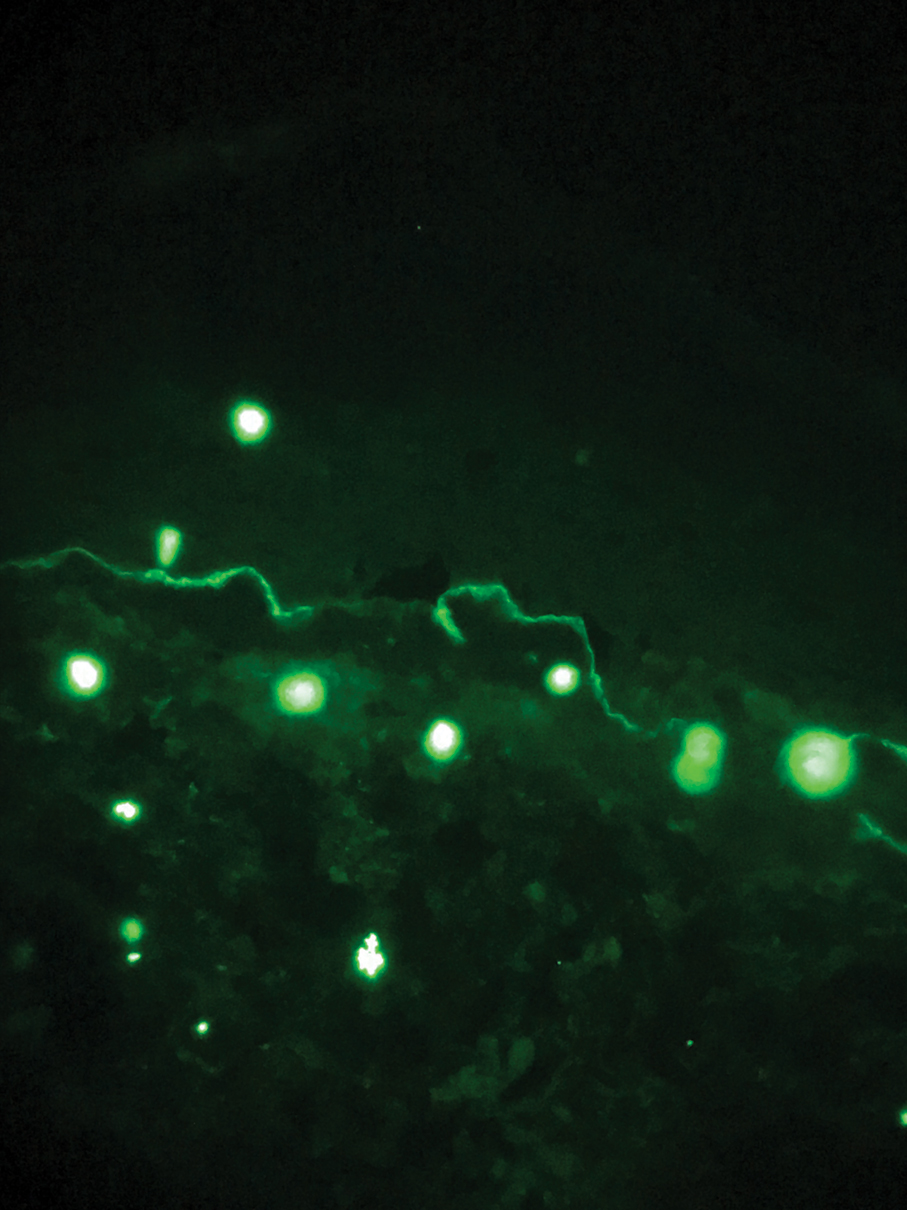

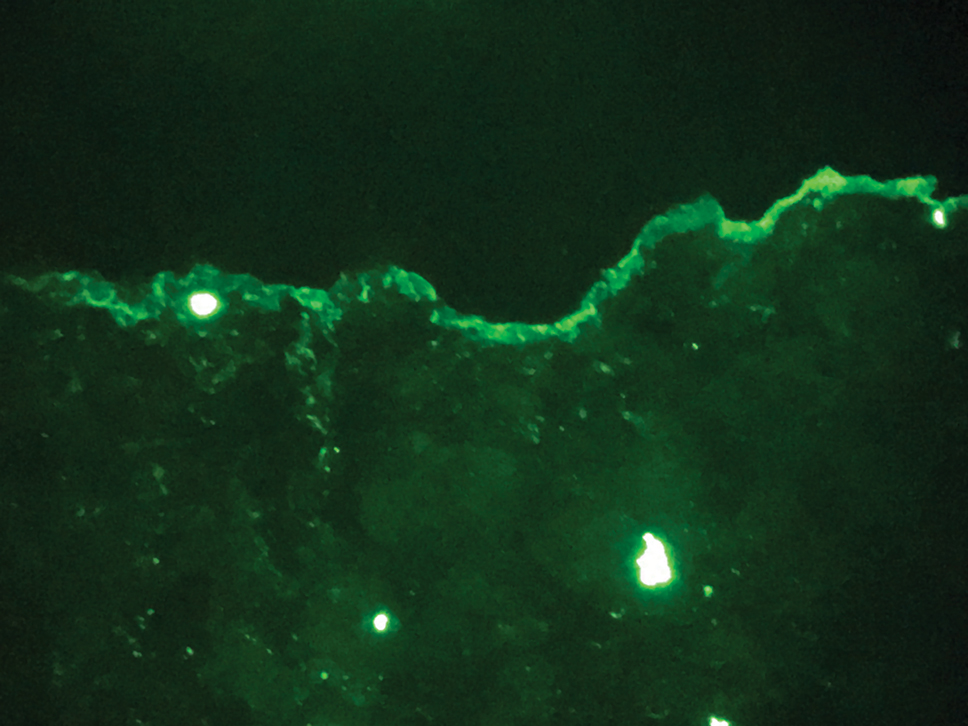

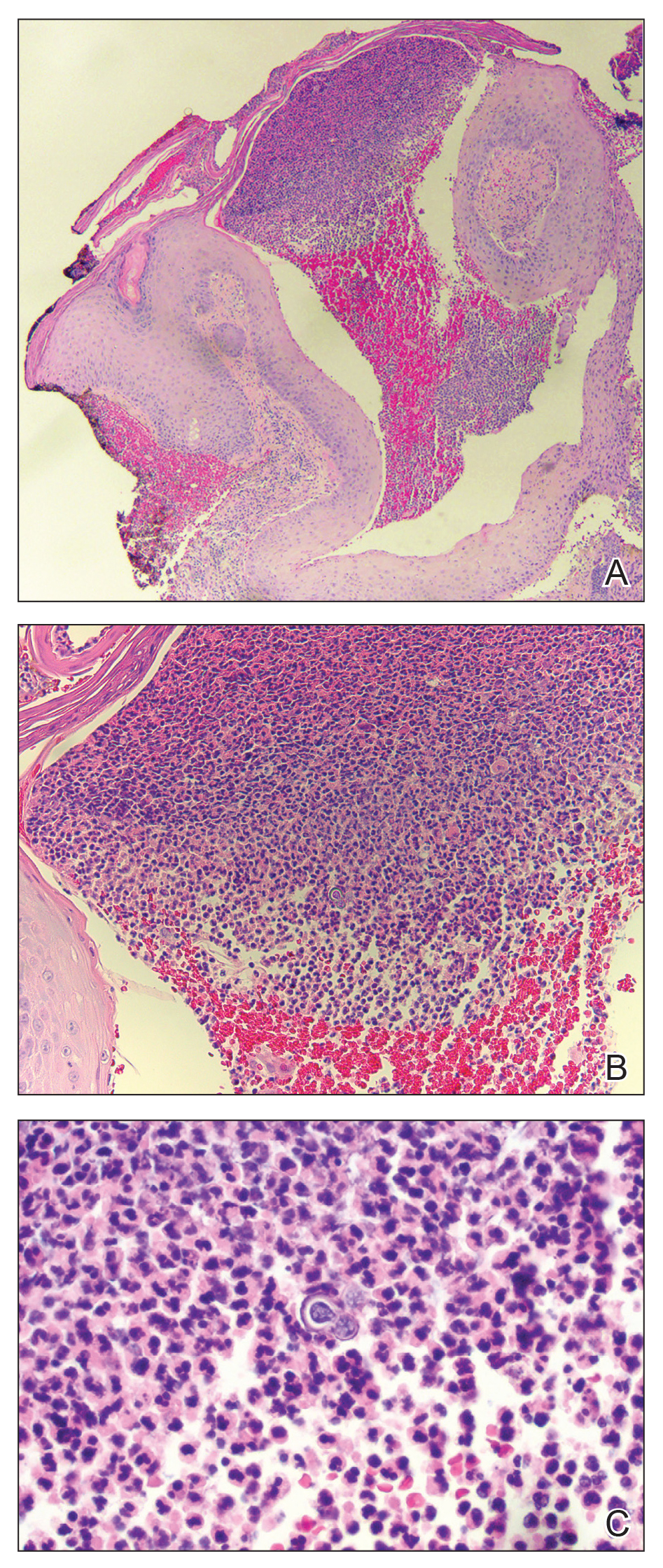

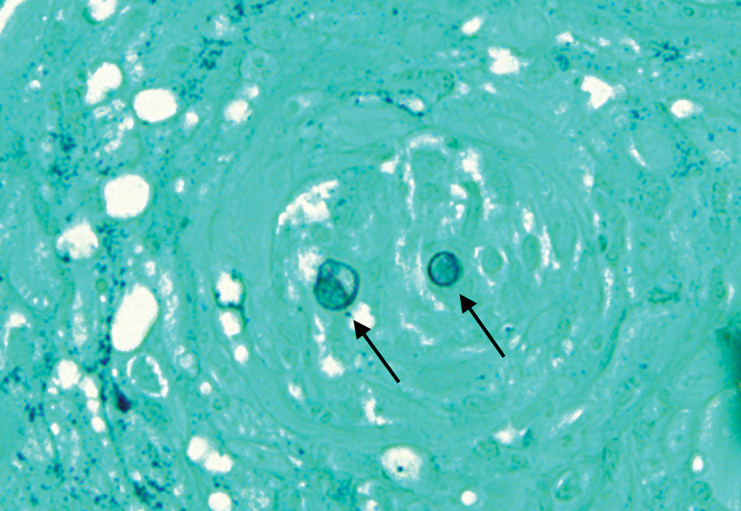

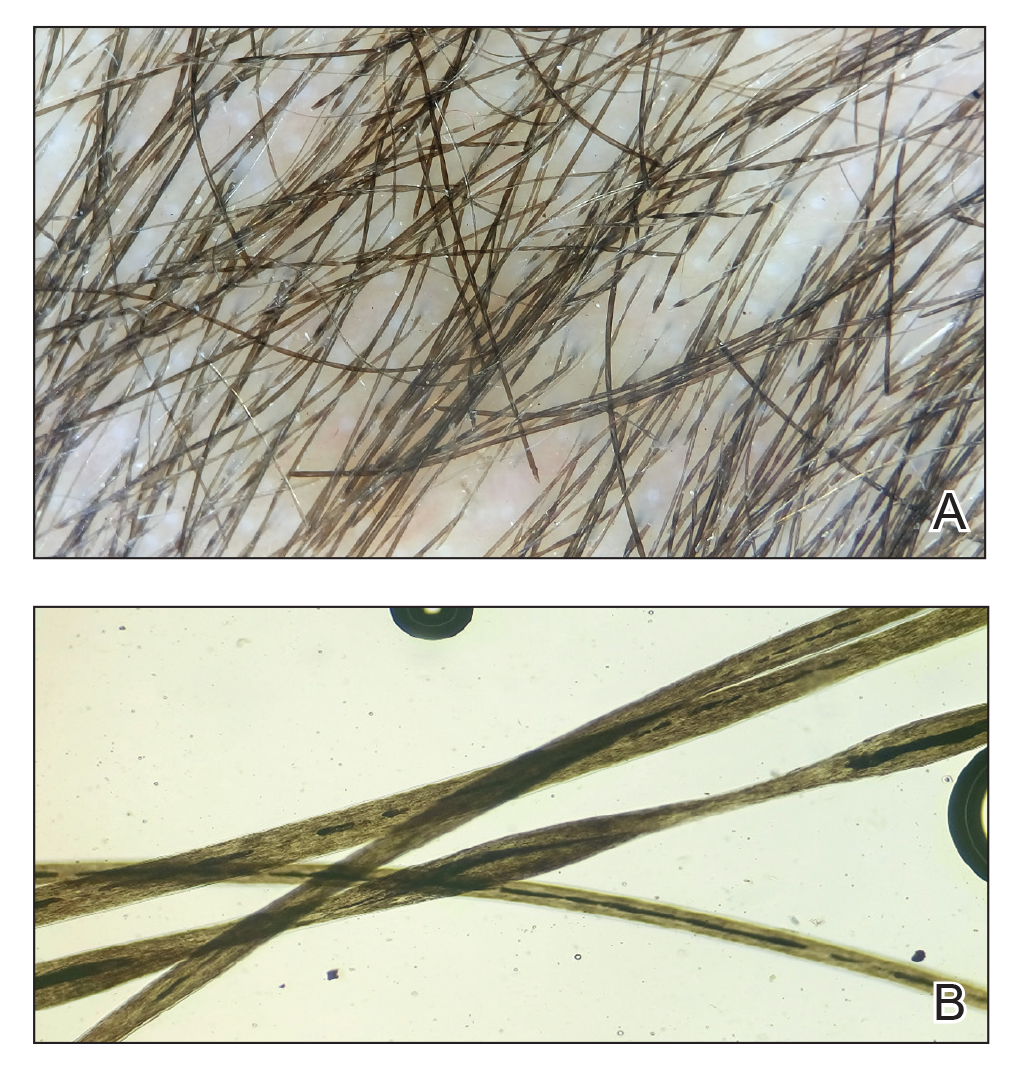

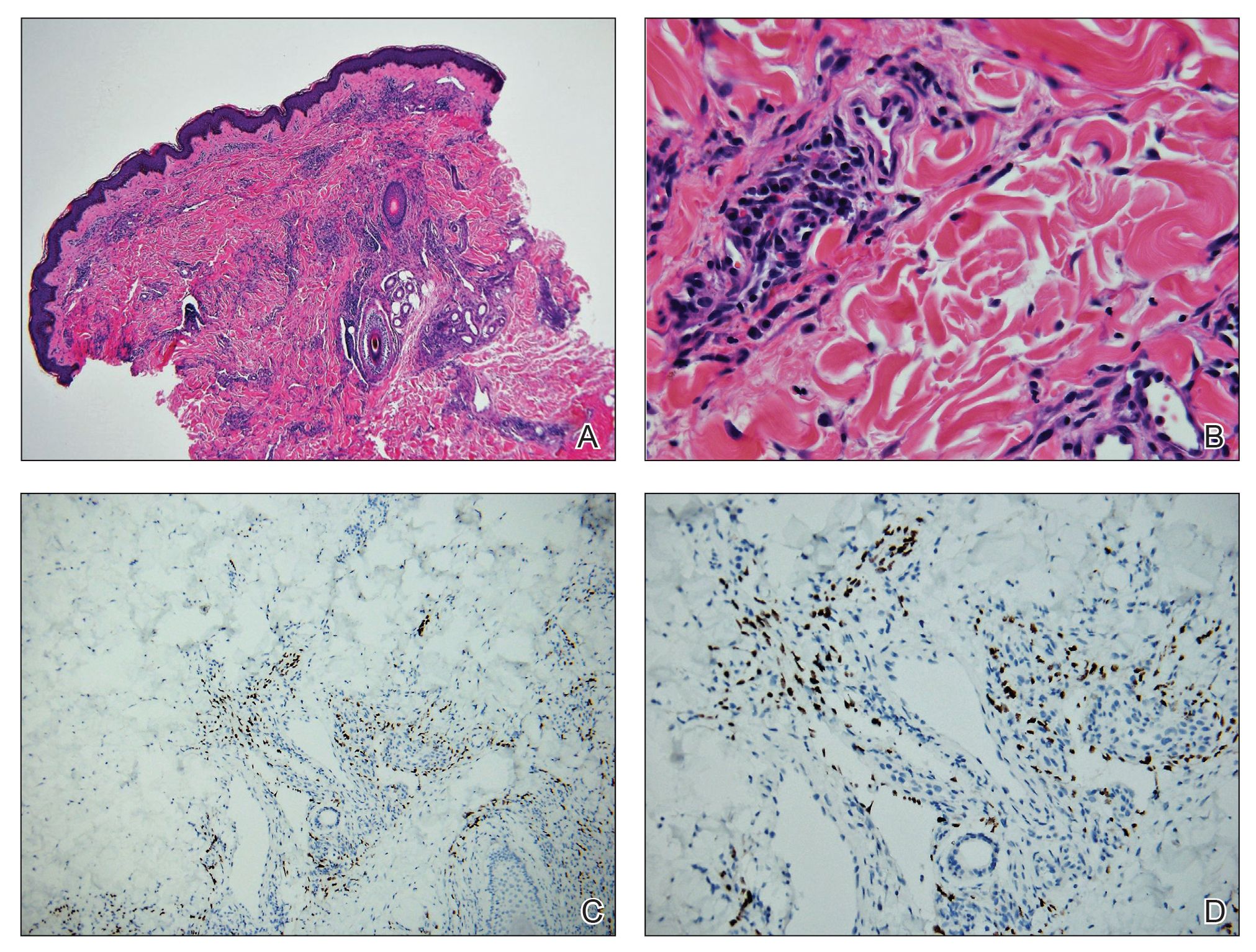

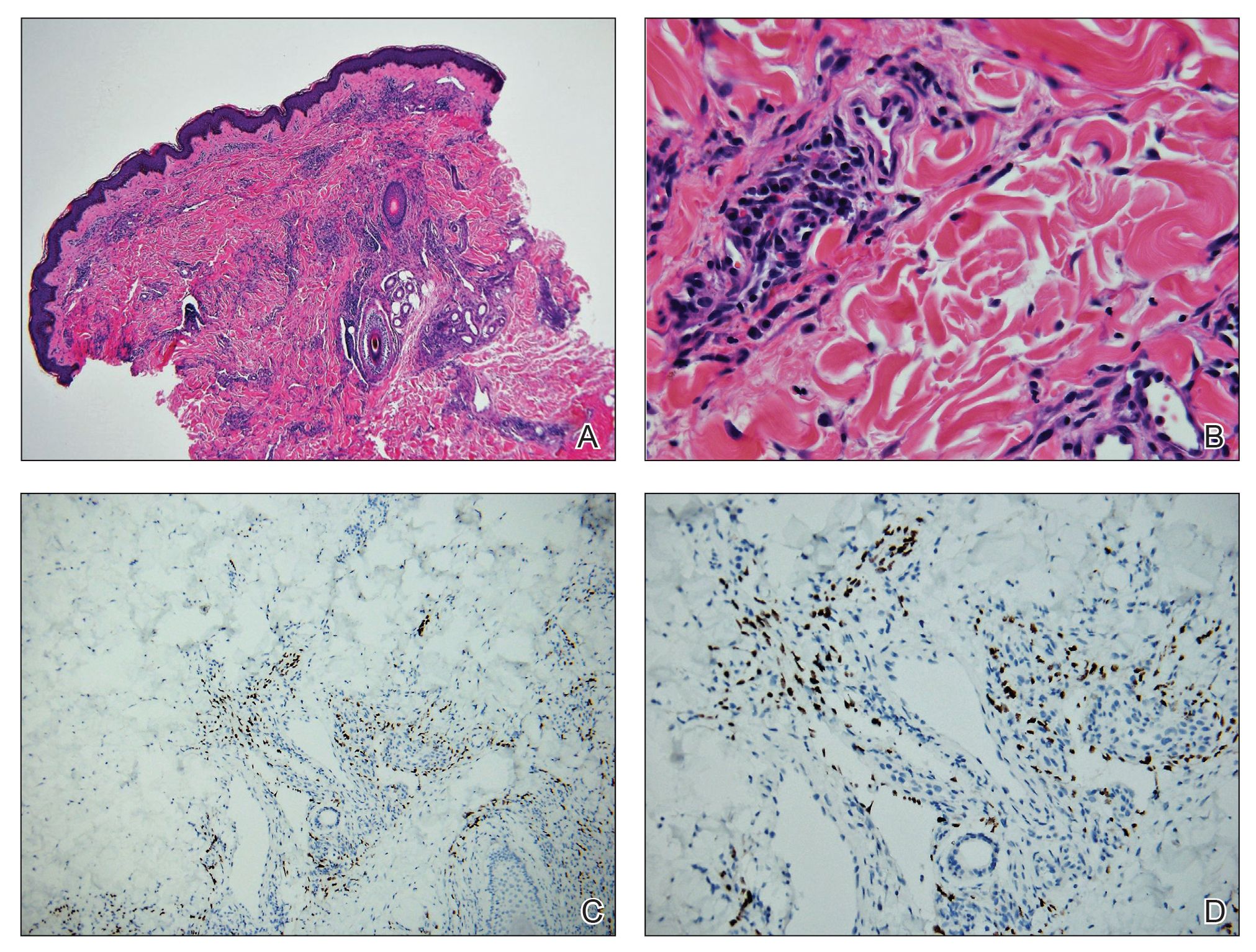

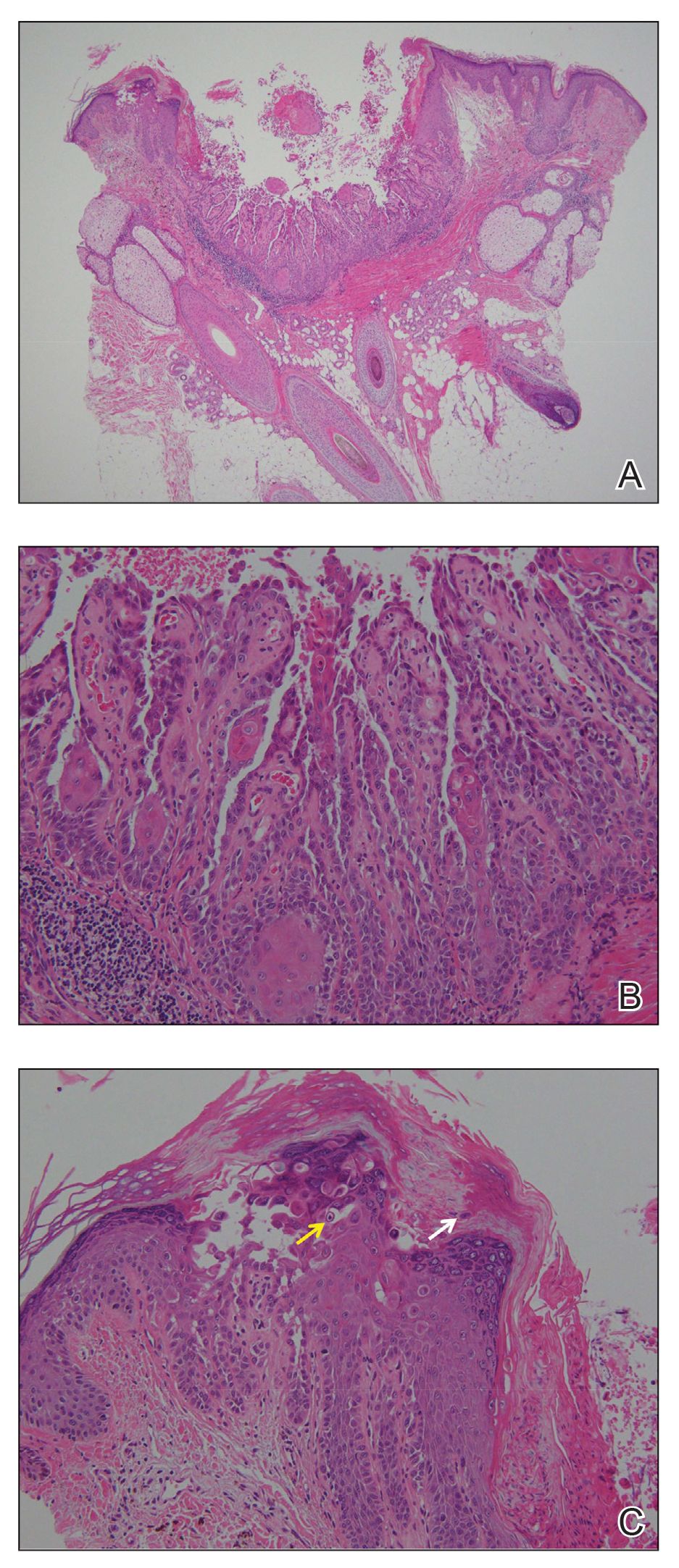

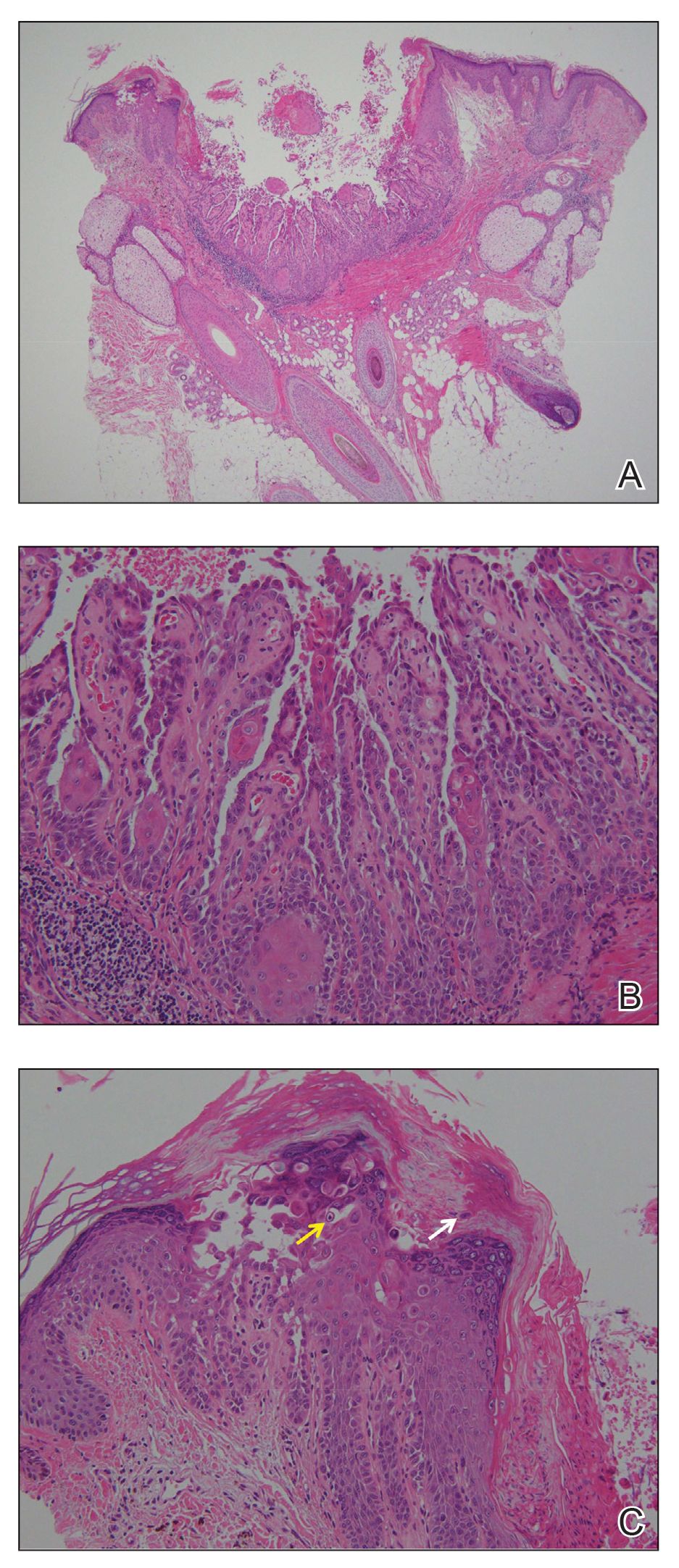

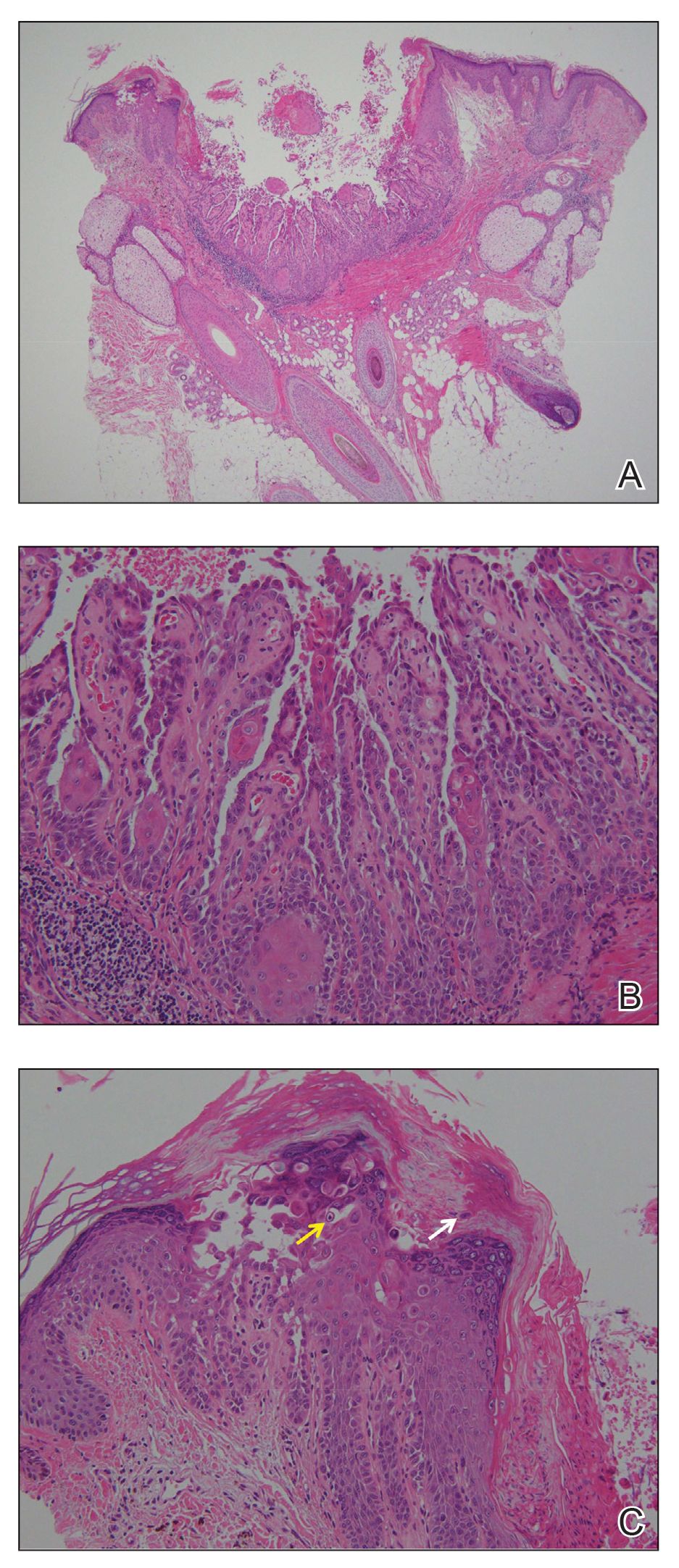

The diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) was made based on the clinical and pathologic findings. A blistering disorder that resolves with milia is characteristic of EBA. Hematoxylin and eosin staining demonstrated a pauci-inflammatory separation between the epidermis and dermis (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence studies showed linear IgG deposition along the basement membrane zone while C3 was negative (Figure 2). Salt-split skin was essential, as it revealed IgG deposition to the floor of the split (Figure 3), a pattern seen in EBA and not bullous pemphigoid (BP).1

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is an acquired autoimmune bullous disorder that results from antibodies to type VII collagen, an anchoring fibril that attaches the lamina densa to the dermis. The epidemiology and etiology of the trigger that leads to antibody production are not well known, but an association between EBA and inflammatory bowel disease has been described.2 Although this disease may present in childhood, EBA most commonly is a disorder seen in adults and the elderly. A classic noninflammatory mechanobullous form as well as an inflammatory BP-like form are the most commonly encountered presentations. Light microscopy demonstrates subepidermal cleavage without acantholysis. In the inflammatory BP-like subtype, an inflammatory infiltrate may be present. Direct immunofluorescence is remarkable for a linear band of IgG deposits along the basement membrane zone, with or without C3 deposition in a similar pattern.1

Bullous pemphigoid is within the differential of EBA. It can be difficult to differentiate clinically, especially when a patient has the BP-like variant of EBA because, as the name implies, it mimics BP. Patients with BP often will report a pruritic patch that will then develop into an urticarial plaque. Scarring and milia rarely are seen in BP but can be observed in the multiple presentations of EBA. Hematoxylin and eosin staining and direct immunofluorescence may be almost identical, and differentiating between the 2 disorders can be a challenge. Immunodeposition in EBA occurs in a U-shaped, serrated pattern, while the pattern in BP is N-shaped and serrated.3 Although the U-shaped, serrated pattern is relatively specific, it is not always easy to interpret and requires a high-quality biopsy specimen, which can be difficult to discern with certainty in suboptimal preparations. Another way to differentiate between the 2 entities is to utilize the salt-split skin technique, as performed in our patient. With salt-split skin, the biopsy is placed into a solution of 1 mol/L sodium chloride and incubated at 4 °C (39 °F) for 18 to 24 hours. A blister is then produced at the level of the lamina lucida, which allows for the staining of immunoreactants to occur either above or below that split (commonly referred to as staining on the roof or floor of the blister cavity). With EBA, there is immunoreactant deposition on the floor of the blister, while the opposite occurs in BP.4

Epidermolysis bullosa simplex is the most common type of epidermolysis bullosa, with keratin genes KRT5 and KRT14 as frequent mutations. Patients develop blisters, vesicles, bullae, and milia on traumatized areas of the body such as the hands, elbows, knees, and feet. This disease presents early in childhood. Histology exhibits a cell-poor subepidermal blister.5 With porphyria cutanea tarda, reduced activity of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, a major enzyme in the heme synthesis pathway, leads to blisters with erosions and milia on sun-exposed areas of the body. Histologic evaluation reveals a subepidermal pauci-inflammatory vesicle with festooning of the dermal papillae and amphophilic basement membrane within the epidermis. Direct immunofluorescence of porphyria cutanea tarda demonstrates IgM and C3 in the vessels.6 Sweet syndrome is a neutrophilic dermatosis that presents as erythematous, edematous, hot, and tender plaques along with fever and leukocytosis. It is associated with myeloproliferative disorders. Biopsy demonstrates papillary dermal edema along with diffuse neutrophilic infiltrate.7

Numerous medications have been recommended for the treatment of EBA, ranging from steroids to steroid-sparing drugs such as colchicine and dapsone.8,9 Our patient was educated on physical precautions and was started on dapsone alone due to comorbid diabetes mellitus and renal disease. Within a few weeks of initiating dapsone, he observed a reduction in erythema, and within months he experienced a decrease in blister eruption frequency.

- Vorobyev A, Ludwig RJ, Schmidt E. Clinical features and diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13:157-169.

- Reddy H, Shipman AR, Wojnarowska F. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita and inflammatory bowel disease: a review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:225-230.

- Vodegel RM, Jonkman MF, Pas HH, et al. U-serrated immunodeposition pattern differentiates type VII collagen targeting bullous diseases from other subepidermal bullous autoimmune diseases. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:112-118.

- Gardner KM, Crawford RI. Distinguishing epidermolysis bullosa acquisita from bullous pemphigoid without direct immunofluorescence. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22:22-24.

- Sprecher E. Epidermolysis bullosa simplex. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:23-32.

- Maynard B, Peters MS. Histologic and immunofluorescence study of cutaneous porphyrias. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:40-47.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018:79:987-1006.

- Kirtschig G, Murrell D, Wojnarowska F, et al. Interventions for mucous membrane pemphigoid and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;1:CD004056

- Gürcan HM, Ahmed AR. Current concepts in the treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011;12:1259-1268.

The Diagnosis: Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita

The diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) was made based on the clinical and pathologic findings. A blistering disorder that resolves with milia is characteristic of EBA. Hematoxylin and eosin staining demonstrated a pauci-inflammatory separation between the epidermis and dermis (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence studies showed linear IgG deposition along the basement membrane zone while C3 was negative (Figure 2). Salt-split skin was essential, as it revealed IgG deposition to the floor of the split (Figure 3), a pattern seen in EBA and not bullous pemphigoid (BP).1

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is an acquired autoimmune bullous disorder that results from antibodies to type VII collagen, an anchoring fibril that attaches the lamina densa to the dermis. The epidemiology and etiology of the trigger that leads to antibody production are not well known, but an association between EBA and inflammatory bowel disease has been described.2 Although this disease may present in childhood, EBA most commonly is a disorder seen in adults and the elderly. A classic noninflammatory mechanobullous form as well as an inflammatory BP-like form are the most commonly encountered presentations. Light microscopy demonstrates subepidermal cleavage without acantholysis. In the inflammatory BP-like subtype, an inflammatory infiltrate may be present. Direct immunofluorescence is remarkable for a linear band of IgG deposits along the basement membrane zone, with or without C3 deposition in a similar pattern.1

Bullous pemphigoid is within the differential of EBA. It can be difficult to differentiate clinically, especially when a patient has the BP-like variant of EBA because, as the name implies, it mimics BP. Patients with BP often will report a pruritic patch that will then develop into an urticarial plaque. Scarring and milia rarely are seen in BP but can be observed in the multiple presentations of EBA. Hematoxylin and eosin staining and direct immunofluorescence may be almost identical, and differentiating between the 2 disorders can be a challenge. Immunodeposition in EBA occurs in a U-shaped, serrated pattern, while the pattern in BP is N-shaped and serrated.3 Although the U-shaped, serrated pattern is relatively specific, it is not always easy to interpret and requires a high-quality biopsy specimen, which can be difficult to discern with certainty in suboptimal preparations. Another way to differentiate between the 2 entities is to utilize the salt-split skin technique, as performed in our patient. With salt-split skin, the biopsy is placed into a solution of 1 mol/L sodium chloride and incubated at 4 °C (39 °F) for 18 to 24 hours. A blister is then produced at the level of the lamina lucida, which allows for the staining of immunoreactants to occur either above or below that split (commonly referred to as staining on the roof or floor of the blister cavity). With EBA, there is immunoreactant deposition on the floor of the blister, while the opposite occurs in BP.4

Epidermolysis bullosa simplex is the most common type of epidermolysis bullosa, with keratin genes KRT5 and KRT14 as frequent mutations. Patients develop blisters, vesicles, bullae, and milia on traumatized areas of the body such as the hands, elbows, knees, and feet. This disease presents early in childhood. Histology exhibits a cell-poor subepidermal blister.5 With porphyria cutanea tarda, reduced activity of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, a major enzyme in the heme synthesis pathway, leads to blisters with erosions and milia on sun-exposed areas of the body. Histologic evaluation reveals a subepidermal pauci-inflammatory vesicle with festooning of the dermal papillae and amphophilic basement membrane within the epidermis. Direct immunofluorescence of porphyria cutanea tarda demonstrates IgM and C3 in the vessels.6 Sweet syndrome is a neutrophilic dermatosis that presents as erythematous, edematous, hot, and tender plaques along with fever and leukocytosis. It is associated with myeloproliferative disorders. Biopsy demonstrates papillary dermal edema along with diffuse neutrophilic infiltrate.7

Numerous medications have been recommended for the treatment of EBA, ranging from steroids to steroid-sparing drugs such as colchicine and dapsone.8,9 Our patient was educated on physical precautions and was started on dapsone alone due to comorbid diabetes mellitus and renal disease. Within a few weeks of initiating dapsone, he observed a reduction in erythema, and within months he experienced a decrease in blister eruption frequency.

The Diagnosis: Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita

The diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita (EBA) was made based on the clinical and pathologic findings. A blistering disorder that resolves with milia is characteristic of EBA. Hematoxylin and eosin staining demonstrated a pauci-inflammatory separation between the epidermis and dermis (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence studies showed linear IgG deposition along the basement membrane zone while C3 was negative (Figure 2). Salt-split skin was essential, as it revealed IgG deposition to the floor of the split (Figure 3), a pattern seen in EBA and not bullous pemphigoid (BP).1

Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita is an acquired autoimmune bullous disorder that results from antibodies to type VII collagen, an anchoring fibril that attaches the lamina densa to the dermis. The epidemiology and etiology of the trigger that leads to antibody production are not well known, but an association between EBA and inflammatory bowel disease has been described.2 Although this disease may present in childhood, EBA most commonly is a disorder seen in adults and the elderly. A classic noninflammatory mechanobullous form as well as an inflammatory BP-like form are the most commonly encountered presentations. Light microscopy demonstrates subepidermal cleavage without acantholysis. In the inflammatory BP-like subtype, an inflammatory infiltrate may be present. Direct immunofluorescence is remarkable for a linear band of IgG deposits along the basement membrane zone, with or without C3 deposition in a similar pattern.1

Bullous pemphigoid is within the differential of EBA. It can be difficult to differentiate clinically, especially when a patient has the BP-like variant of EBA because, as the name implies, it mimics BP. Patients with BP often will report a pruritic patch that will then develop into an urticarial plaque. Scarring and milia rarely are seen in BP but can be observed in the multiple presentations of EBA. Hematoxylin and eosin staining and direct immunofluorescence may be almost identical, and differentiating between the 2 disorders can be a challenge. Immunodeposition in EBA occurs in a U-shaped, serrated pattern, while the pattern in BP is N-shaped and serrated.3 Although the U-shaped, serrated pattern is relatively specific, it is not always easy to interpret and requires a high-quality biopsy specimen, which can be difficult to discern with certainty in suboptimal preparations. Another way to differentiate between the 2 entities is to utilize the salt-split skin technique, as performed in our patient. With salt-split skin, the biopsy is placed into a solution of 1 mol/L sodium chloride and incubated at 4 °C (39 °F) for 18 to 24 hours. A blister is then produced at the level of the lamina lucida, which allows for the staining of immunoreactants to occur either above or below that split (commonly referred to as staining on the roof or floor of the blister cavity). With EBA, there is immunoreactant deposition on the floor of the blister, while the opposite occurs in BP.4

Epidermolysis bullosa simplex is the most common type of epidermolysis bullosa, with keratin genes KRT5 and KRT14 as frequent mutations. Patients develop blisters, vesicles, bullae, and milia on traumatized areas of the body such as the hands, elbows, knees, and feet. This disease presents early in childhood. Histology exhibits a cell-poor subepidermal blister.5 With porphyria cutanea tarda, reduced activity of uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase, a major enzyme in the heme synthesis pathway, leads to blisters with erosions and milia on sun-exposed areas of the body. Histologic evaluation reveals a subepidermal pauci-inflammatory vesicle with festooning of the dermal papillae and amphophilic basement membrane within the epidermis. Direct immunofluorescence of porphyria cutanea tarda demonstrates IgM and C3 in the vessels.6 Sweet syndrome is a neutrophilic dermatosis that presents as erythematous, edematous, hot, and tender plaques along with fever and leukocytosis. It is associated with myeloproliferative disorders. Biopsy demonstrates papillary dermal edema along with diffuse neutrophilic infiltrate.7

Numerous medications have been recommended for the treatment of EBA, ranging from steroids to steroid-sparing drugs such as colchicine and dapsone.8,9 Our patient was educated on physical precautions and was started on dapsone alone due to comorbid diabetes mellitus and renal disease. Within a few weeks of initiating dapsone, he observed a reduction in erythema, and within months he experienced a decrease in blister eruption frequency.

- Vorobyev A, Ludwig RJ, Schmidt E. Clinical features and diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13:157-169.

- Reddy H, Shipman AR, Wojnarowska F. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita and inflammatory bowel disease: a review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:225-230.

- Vodegel RM, Jonkman MF, Pas HH, et al. U-serrated immunodeposition pattern differentiates type VII collagen targeting bullous diseases from other subepidermal bullous autoimmune diseases. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:112-118.

- Gardner KM, Crawford RI. Distinguishing epidermolysis bullosa acquisita from bullous pemphigoid without direct immunofluorescence. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22:22-24.

- Sprecher E. Epidermolysis bullosa simplex. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:23-32.

- Maynard B, Peters MS. Histologic and immunofluorescence study of cutaneous porphyrias. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:40-47.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018:79:987-1006.

- Kirtschig G, Murrell D, Wojnarowska F, et al. Interventions for mucous membrane pemphigoid and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;1:CD004056

- Gürcan HM, Ahmed AR. Current concepts in the treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011;12:1259-1268.

- Vorobyev A, Ludwig RJ, Schmidt E. Clinical features and diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13:157-169.

- Reddy H, Shipman AR, Wojnarowska F. Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita and inflammatory bowel disease: a review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:225-230.

- Vodegel RM, Jonkman MF, Pas HH, et al. U-serrated immunodeposition pattern differentiates type VII collagen targeting bullous diseases from other subepidermal bullous autoimmune diseases. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:112-118.

- Gardner KM, Crawford RI. Distinguishing epidermolysis bullosa acquisita from bullous pemphigoid without direct immunofluorescence. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22:22-24.

- Sprecher E. Epidermolysis bullosa simplex. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:23-32.

- Maynard B, Peters MS. Histologic and immunofluorescence study of cutaneous porphyrias. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:40-47.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pathogenesis, Sweet syndrome, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and Behçet disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018:79:987-1006.

- Kirtschig G, Murrell D, Wojnarowska F, et al. Interventions for mucous membrane pemphigoid and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;1:CD004056

- Gürcan HM, Ahmed AR. Current concepts in the treatment of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011;12:1259-1268.

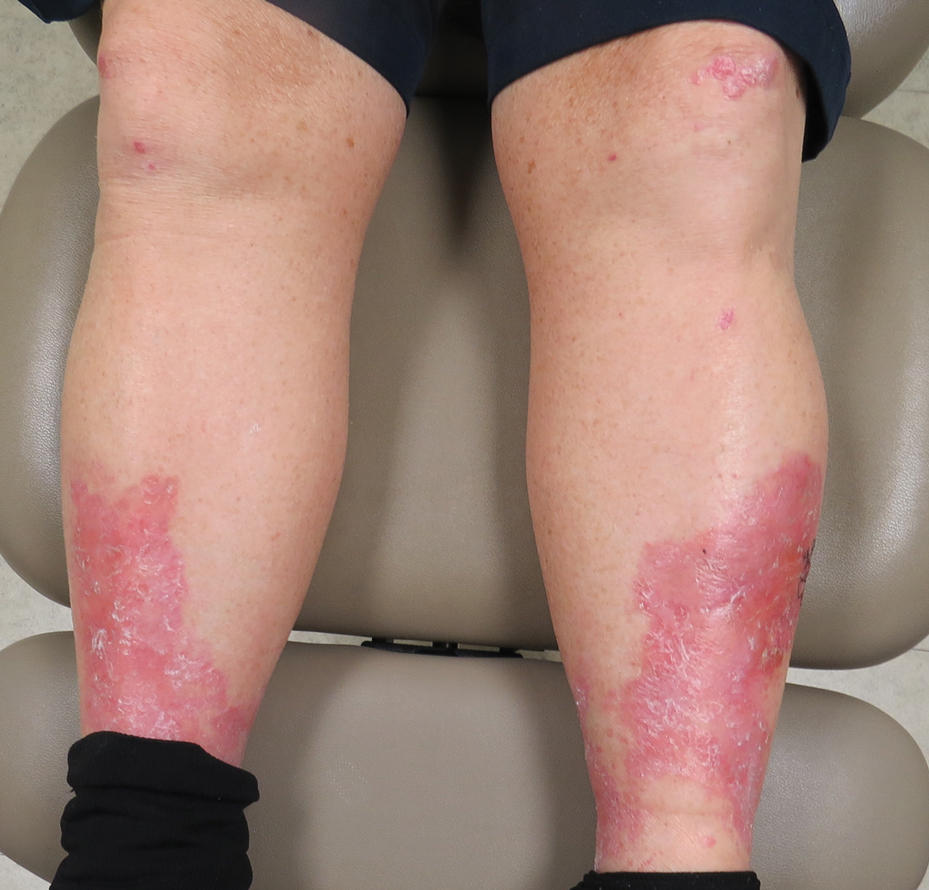

A 69-year-old man presented with an asymptomatic rash on the extensor surfaces of 2 years' duration. He reported recurrent blisters that would then scar over. The lesions did not occur in relation to any known trauma. The patient's medical history revealed dialysis-dependent end-stage renal disease secondary to type 2 diabetes mellitus. His medications were noncontributory, and there was no family history of blistering disorders. He had tried triamcinolone cream without any improvement. Physical examination was remarkable for erythematous blisters and bullae with scales and milia on the elbows, knees, and lower legs. The oral mucosa was unremarkable. Shave biopsies of the skin for direct immunofluorescence and salt-split skin studies were obtained.

Atrophic Lesion on the Abdomen

The Diagnosis: Anetoderma of Prematurity

Anetoderma is a rare benign cutaneous disorder characterized by atrophic patches of skin due to dermal thinning. The term anetoderma is derived from the Greek words anetos (relaxed) and derma (skin).1 The physical appearance of the skin is associated with a reduction or loss of elastic tissue in the dermal layer, as seen on histolopathology.2

Two forms of anetoderma have been described. Primary anetoderma is an idiopathic form with no preceding inflammatory lesions. Secondary anetoderma is a reactive process linked to a known preceding inflammatory, infectious, autoimmune, or drug-induced condition.3 On histopathology, both primary and secondary anetoderma are characterized by a loss of elastic tissue or elastin fibers in the superficial to mid dermis.2

Anetoderma of prematurity was first described in 1996 by Prizant et al4 in 9 extremely premature (24-29 weeks' gestation) infants in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). Although the exact mechanism behind anetoderma of prematurity is still unknown, Prizant et al4 and other investigators5 postulated that application of adhesive monitoring leads in the NICU played a role in the development of the lesions.

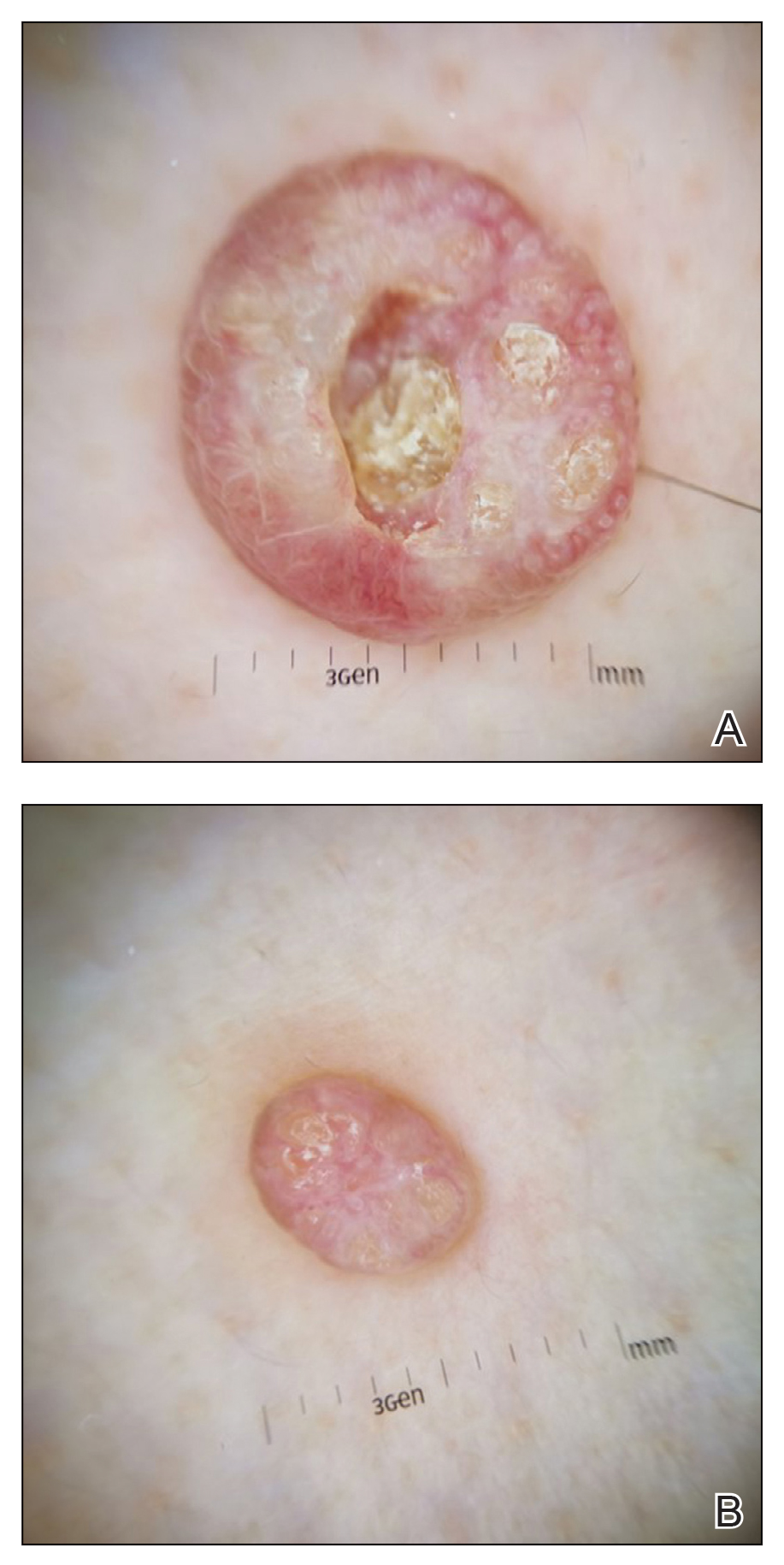

Iatrogenic anetoderma of prematurity is clinically characterized by circumscribed areas of either wrinkled macular depression or pouchlike herniations, ranging from flesh-colored to violaceous hues. Lesion size varies from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter, and they often are oval or round in shape.2 Although not common, it is possible for the atrophic patches to be preceded by an area of ecchymosis without necrosis or atrophy and, if present, they usually evolve within a few days to the characteristic appearance of anetoderma.3 They are found at discrete sites where monitoring leads or other medical devices are commonly placed, such as the forehead, abdomen, chest, and proximal limbs.

Lesions of anetoderma of prematurity are not present at birth, which distinguishes them from congenital anetoderma.6 It is unclear if the lesions are associated with the degree of prematurity, extremely low birth weight, or other associated factors of preterm birth. Although often clinically diagnosed, the diagnosis can be confirmed by a loss of elastic fibers on histopathology when stained with Verhoeff-van Gieson stain.1 Over time, the atrophic patches have the potential to evolve into herniated forms of anetoderma. Self-healing or improvement of the lesions often does not occur. Although the lesion is benign, it often requires surgical correction later in life for cosmesis.

Infants in the NICU are at risk for iatrogenic cutaneous injuries, which rarely may include anetoderma. Anetoderma of prematurity has been linked to the use of monitoring leads, adhesive tape, and other medical devices placed on the skin. Prizant et al4 postulated that the cause of anetoderma in these infants was irritants such as skin cleansers, urine, or sweat that may be trapped under the electrodes. Other hypotheses include local hypoxemia due to prolonged pressure from the electrodes on immature skin or excessive traction used when removing adhesive tape from the skin.7,8 Premature infants may be more susceptible to these lesions because of the reduced epidermal thickness of premature skin; immaturity of skin structure; or functional immaturity of elastin deposition regulators, such as elastase, lysyl oxidase, the complement system, and decay-accelerating factor.3 The diagnosis should be differentiated from congenital anetoderma, which also has been described in premature neonates but is characterized by lesions that are present at birth. Its origins are still unclear, despite having histopathologic features similar to iatrogenic anetoderma.9

Focal dermal hypoplasia (FDH) is the hallmark cutaneous finding in Goltz syndrome, a rare set of congenital abnormalities of the skin, oral structures, musculoskeletal system, and central nervous system. Similar to congenital anetoderma, FDH also is characterized by atrophic cutaneous lesions; however, the cutaneous lesions in FDH appear as linear, streaky atrophic lesions often with telangiectasias that follow Blaschko lines.10 The cutaneous lesions in FDH often are associated with other noncutaneous signs such as polydactyly or asymmetric limbs.10 Cutis laxa is caused by an abnormality in the elastic tissue resulting in a loose sagging appearance of the skin and frequently results in an aged facial appearance. There are both acquired and inherited forms that can be either solely cutaneous or present with extracutaneous features, such as cardiac abnormalities or emphysema.11

In contrast to the atrophic appearance of anetodermas, connective tissue nevi and nevus lipomatosus superficialis present as hamartomas that either can be present at birth or arise in infancy. Connective tissue nevi are hamartomas of dermal connective tissue that consist of excessive production of collagen, elastin, or glycosaminoglycans and appear as slightly elevated, flesh-colored to yellow nodules or plaques.12 Connective tissue nevi often are described in association with other diseases, most commonly tuberous sclerosis (shagreen patches) or familial cutaneous collagenoma. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis is an asymptomatic connective tissue hamartoma composed of mature adipocytes in the dermis. The lesions consist of clusters of flesh-colored to yellow, soft, rubbery papules or nodules with a smooth or verrucoid surface that do not cross the midline and may follow Blaschko lines.11

With advances in neonatal infant medical care, survival of extremely premature infants is increasing, and it is possible that this rare cutaneous disorder may become more prevalent. Care should be taken to avoid unnecessary pressure on surfaces where electrodes are placed and tightly applied adhesive tape. When electrodes are placed on the ventral side, the child should be placed supine; similarly, place electrodes on the dorsal side when the child is lying prone.5 A diagnosis of anetoderma of prematurity later in childhood may be difficult, so knowledge and awareness can help guide pediatricians and dermatologists to a correct diagnosis and prevent unnecessary evaluations and/or concerns.

- Misch KJ, Rhodes EL, Allen J, et al. Anetoderma of Jadassohn. J R Soc Med.1988;81:734-736.

- Venencie PY, Winkelmann RK. Histopathologic findings in anetoderma. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1040-1044.

- Maffeis L, Pugni L, Pietrasanta C, et al. Case report iatrogenic anetoderma of prematurity: a case report and review of the literature. 2014;2014:781493.

- Prizant TL, Lucky AW, Frieden IJ, et al. Spontaneous atrophic patches in extremely premature infants: anetoderma of prematurity. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:671-674.

- Goujon E, Beer F, Gay S, et al. Anetoderma of prematurity: an iatrogenic consequence of neonatal intensive care anetoderma of prematurity from NICU. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:565-567.

- Wain EM, Mellerio JE, Robson A, et al. Congenital anetoderma in a preterm infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:626-629.

- Colditz PB, Dunster KR, Joy GJ, et al. Anetoderma of prematurity in association with electrocardiographic electrodes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:479-481.

- Goujan E, Beer F, Gay S, et al. Study supervision. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:565-567.

- Aberer E, Weissenbacher G. Congenital anetoderma induced by intrauterine infection? Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:526-527.

- Mallory SB, Krafchik BR, Moore DJ, et al. Goltz syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 1989;6:251-253.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L. Dermatology. Elsevier Saunders; 2017.

- Uitto J, Santa Cruz DJ, Eisen AZ. Connective tissue nevi of the skin. clinical, genetic, and histopathologic classification of hamartomas of the collagen, elastin, and proteoglycan type. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:441-461.

The Diagnosis: Anetoderma of Prematurity

Anetoderma is a rare benign cutaneous disorder characterized by atrophic patches of skin due to dermal thinning. The term anetoderma is derived from the Greek words anetos (relaxed) and derma (skin).1 The physical appearance of the skin is associated with a reduction or loss of elastic tissue in the dermal layer, as seen on histolopathology.2

Two forms of anetoderma have been described. Primary anetoderma is an idiopathic form with no preceding inflammatory lesions. Secondary anetoderma is a reactive process linked to a known preceding inflammatory, infectious, autoimmune, or drug-induced condition.3 On histopathology, both primary and secondary anetoderma are characterized by a loss of elastic tissue or elastin fibers in the superficial to mid dermis.2

Anetoderma of prematurity was first described in 1996 by Prizant et al4 in 9 extremely premature (24-29 weeks' gestation) infants in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). Although the exact mechanism behind anetoderma of prematurity is still unknown, Prizant et al4 and other investigators5 postulated that application of adhesive monitoring leads in the NICU played a role in the development of the lesions.

Iatrogenic anetoderma of prematurity is clinically characterized by circumscribed areas of either wrinkled macular depression or pouchlike herniations, ranging from flesh-colored to violaceous hues. Lesion size varies from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter, and they often are oval or round in shape.2 Although not common, it is possible for the atrophic patches to be preceded by an area of ecchymosis without necrosis or atrophy and, if present, they usually evolve within a few days to the characteristic appearance of anetoderma.3 They are found at discrete sites where monitoring leads or other medical devices are commonly placed, such as the forehead, abdomen, chest, and proximal limbs.

Lesions of anetoderma of prematurity are not present at birth, which distinguishes them from congenital anetoderma.6 It is unclear if the lesions are associated with the degree of prematurity, extremely low birth weight, or other associated factors of preterm birth. Although often clinically diagnosed, the diagnosis can be confirmed by a loss of elastic fibers on histopathology when stained with Verhoeff-van Gieson stain.1 Over time, the atrophic patches have the potential to evolve into herniated forms of anetoderma. Self-healing or improvement of the lesions often does not occur. Although the lesion is benign, it often requires surgical correction later in life for cosmesis.

Infants in the NICU are at risk for iatrogenic cutaneous injuries, which rarely may include anetoderma. Anetoderma of prematurity has been linked to the use of monitoring leads, adhesive tape, and other medical devices placed on the skin. Prizant et al4 postulated that the cause of anetoderma in these infants was irritants such as skin cleansers, urine, or sweat that may be trapped under the electrodes. Other hypotheses include local hypoxemia due to prolonged pressure from the electrodes on immature skin or excessive traction used when removing adhesive tape from the skin.7,8 Premature infants may be more susceptible to these lesions because of the reduced epidermal thickness of premature skin; immaturity of skin structure; or functional immaturity of elastin deposition regulators, such as elastase, lysyl oxidase, the complement system, and decay-accelerating factor.3 The diagnosis should be differentiated from congenital anetoderma, which also has been described in premature neonates but is characterized by lesions that are present at birth. Its origins are still unclear, despite having histopathologic features similar to iatrogenic anetoderma.9

Focal dermal hypoplasia (FDH) is the hallmark cutaneous finding in Goltz syndrome, a rare set of congenital abnormalities of the skin, oral structures, musculoskeletal system, and central nervous system. Similar to congenital anetoderma, FDH also is characterized by atrophic cutaneous lesions; however, the cutaneous lesions in FDH appear as linear, streaky atrophic lesions often with telangiectasias that follow Blaschko lines.10 The cutaneous lesions in FDH often are associated with other noncutaneous signs such as polydactyly or asymmetric limbs.10 Cutis laxa is caused by an abnormality in the elastic tissue resulting in a loose sagging appearance of the skin and frequently results in an aged facial appearance. There are both acquired and inherited forms that can be either solely cutaneous or present with extracutaneous features, such as cardiac abnormalities or emphysema.11

In contrast to the atrophic appearance of anetodermas, connective tissue nevi and nevus lipomatosus superficialis present as hamartomas that either can be present at birth or arise in infancy. Connective tissue nevi are hamartomas of dermal connective tissue that consist of excessive production of collagen, elastin, or glycosaminoglycans and appear as slightly elevated, flesh-colored to yellow nodules or plaques.12 Connective tissue nevi often are described in association with other diseases, most commonly tuberous sclerosis (shagreen patches) or familial cutaneous collagenoma. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis is an asymptomatic connective tissue hamartoma composed of mature adipocytes in the dermis. The lesions consist of clusters of flesh-colored to yellow, soft, rubbery papules or nodules with a smooth or verrucoid surface that do not cross the midline and may follow Blaschko lines.11

With advances in neonatal infant medical care, survival of extremely premature infants is increasing, and it is possible that this rare cutaneous disorder may become more prevalent. Care should be taken to avoid unnecessary pressure on surfaces where electrodes are placed and tightly applied adhesive tape. When electrodes are placed on the ventral side, the child should be placed supine; similarly, place electrodes on the dorsal side when the child is lying prone.5 A diagnosis of anetoderma of prematurity later in childhood may be difficult, so knowledge and awareness can help guide pediatricians and dermatologists to a correct diagnosis and prevent unnecessary evaluations and/or concerns.

The Diagnosis: Anetoderma of Prematurity

Anetoderma is a rare benign cutaneous disorder characterized by atrophic patches of skin due to dermal thinning. The term anetoderma is derived from the Greek words anetos (relaxed) and derma (skin).1 The physical appearance of the skin is associated with a reduction or loss of elastic tissue in the dermal layer, as seen on histolopathology.2

Two forms of anetoderma have been described. Primary anetoderma is an idiopathic form with no preceding inflammatory lesions. Secondary anetoderma is a reactive process linked to a known preceding inflammatory, infectious, autoimmune, or drug-induced condition.3 On histopathology, both primary and secondary anetoderma are characterized by a loss of elastic tissue or elastin fibers in the superficial to mid dermis.2

Anetoderma of prematurity was first described in 1996 by Prizant et al4 in 9 extremely premature (24-29 weeks' gestation) infants in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). Although the exact mechanism behind anetoderma of prematurity is still unknown, Prizant et al4 and other investigators5 postulated that application of adhesive monitoring leads in the NICU played a role in the development of the lesions.

Iatrogenic anetoderma of prematurity is clinically characterized by circumscribed areas of either wrinkled macular depression or pouchlike herniations, ranging from flesh-colored to violaceous hues. Lesion size varies from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter, and they often are oval or round in shape.2 Although not common, it is possible for the atrophic patches to be preceded by an area of ecchymosis without necrosis or atrophy and, if present, they usually evolve within a few days to the characteristic appearance of anetoderma.3 They are found at discrete sites where monitoring leads or other medical devices are commonly placed, such as the forehead, abdomen, chest, and proximal limbs.

Lesions of anetoderma of prematurity are not present at birth, which distinguishes them from congenital anetoderma.6 It is unclear if the lesions are associated with the degree of prematurity, extremely low birth weight, or other associated factors of preterm birth. Although often clinically diagnosed, the diagnosis can be confirmed by a loss of elastic fibers on histopathology when stained with Verhoeff-van Gieson stain.1 Over time, the atrophic patches have the potential to evolve into herniated forms of anetoderma. Self-healing or improvement of the lesions often does not occur. Although the lesion is benign, it often requires surgical correction later in life for cosmesis.

Infants in the NICU are at risk for iatrogenic cutaneous injuries, which rarely may include anetoderma. Anetoderma of prematurity has been linked to the use of monitoring leads, adhesive tape, and other medical devices placed on the skin. Prizant et al4 postulated that the cause of anetoderma in these infants was irritants such as skin cleansers, urine, or sweat that may be trapped under the electrodes. Other hypotheses include local hypoxemia due to prolonged pressure from the electrodes on immature skin or excessive traction used when removing adhesive tape from the skin.7,8 Premature infants may be more susceptible to these lesions because of the reduced epidermal thickness of premature skin; immaturity of skin structure; or functional immaturity of elastin deposition regulators, such as elastase, lysyl oxidase, the complement system, and decay-accelerating factor.3 The diagnosis should be differentiated from congenital anetoderma, which also has been described in premature neonates but is characterized by lesions that are present at birth. Its origins are still unclear, despite having histopathologic features similar to iatrogenic anetoderma.9

Focal dermal hypoplasia (FDH) is the hallmark cutaneous finding in Goltz syndrome, a rare set of congenital abnormalities of the skin, oral structures, musculoskeletal system, and central nervous system. Similar to congenital anetoderma, FDH also is characterized by atrophic cutaneous lesions; however, the cutaneous lesions in FDH appear as linear, streaky atrophic lesions often with telangiectasias that follow Blaschko lines.10 The cutaneous lesions in FDH often are associated with other noncutaneous signs such as polydactyly or asymmetric limbs.10 Cutis laxa is caused by an abnormality in the elastic tissue resulting in a loose sagging appearance of the skin and frequently results in an aged facial appearance. There are both acquired and inherited forms that can be either solely cutaneous or present with extracutaneous features, such as cardiac abnormalities or emphysema.11

In contrast to the atrophic appearance of anetodermas, connective tissue nevi and nevus lipomatosus superficialis present as hamartomas that either can be present at birth or arise in infancy. Connective tissue nevi are hamartomas of dermal connective tissue that consist of excessive production of collagen, elastin, or glycosaminoglycans and appear as slightly elevated, flesh-colored to yellow nodules or plaques.12 Connective tissue nevi often are described in association with other diseases, most commonly tuberous sclerosis (shagreen patches) or familial cutaneous collagenoma. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis is an asymptomatic connective tissue hamartoma composed of mature adipocytes in the dermis. The lesions consist of clusters of flesh-colored to yellow, soft, rubbery papules or nodules with a smooth or verrucoid surface that do not cross the midline and may follow Blaschko lines.11

With advances in neonatal infant medical care, survival of extremely premature infants is increasing, and it is possible that this rare cutaneous disorder may become more prevalent. Care should be taken to avoid unnecessary pressure on surfaces where electrodes are placed and tightly applied adhesive tape. When electrodes are placed on the ventral side, the child should be placed supine; similarly, place electrodes on the dorsal side when the child is lying prone.5 A diagnosis of anetoderma of prematurity later in childhood may be difficult, so knowledge and awareness can help guide pediatricians and dermatologists to a correct diagnosis and prevent unnecessary evaluations and/or concerns.

- Misch KJ, Rhodes EL, Allen J, et al. Anetoderma of Jadassohn. J R Soc Med.1988;81:734-736.

- Venencie PY, Winkelmann RK. Histopathologic findings in anetoderma. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1040-1044.

- Maffeis L, Pugni L, Pietrasanta C, et al. Case report iatrogenic anetoderma of prematurity: a case report and review of the literature. 2014;2014:781493.

- Prizant TL, Lucky AW, Frieden IJ, et al. Spontaneous atrophic patches in extremely premature infants: anetoderma of prematurity. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:671-674.

- Goujon E, Beer F, Gay S, et al. Anetoderma of prematurity: an iatrogenic consequence of neonatal intensive care anetoderma of prematurity from NICU. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:565-567.

- Wain EM, Mellerio JE, Robson A, et al. Congenital anetoderma in a preterm infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:626-629.

- Colditz PB, Dunster KR, Joy GJ, et al. Anetoderma of prematurity in association with electrocardiographic electrodes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:479-481.

- Goujan E, Beer F, Gay S, et al. Study supervision. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:565-567.

- Aberer E, Weissenbacher G. Congenital anetoderma induced by intrauterine infection? Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:526-527.

- Mallory SB, Krafchik BR, Moore DJ, et al. Goltz syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 1989;6:251-253.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L. Dermatology. Elsevier Saunders; 2017.

- Uitto J, Santa Cruz DJ, Eisen AZ. Connective tissue nevi of the skin. clinical, genetic, and histopathologic classification of hamartomas of the collagen, elastin, and proteoglycan type. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:441-461.

- Misch KJ, Rhodes EL, Allen J, et al. Anetoderma of Jadassohn. J R Soc Med.1988;81:734-736.

- Venencie PY, Winkelmann RK. Histopathologic findings in anetoderma. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1040-1044.

- Maffeis L, Pugni L, Pietrasanta C, et al. Case report iatrogenic anetoderma of prematurity: a case report and review of the literature. 2014;2014:781493.

- Prizant TL, Lucky AW, Frieden IJ, et al. Spontaneous atrophic patches in extremely premature infants: anetoderma of prematurity. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:671-674.

- Goujon E, Beer F, Gay S, et al. Anetoderma of prematurity: an iatrogenic consequence of neonatal intensive care anetoderma of prematurity from NICU. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:565-567.

- Wain EM, Mellerio JE, Robson A, et al. Congenital anetoderma in a preterm infant. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:626-629.

- Colditz PB, Dunster KR, Joy GJ, et al. Anetoderma of prematurity in association with electrocardiographic electrodes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:479-481.

- Goujan E, Beer F, Gay S, et al. Study supervision. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:565-567.

- Aberer E, Weissenbacher G. Congenital anetoderma induced by intrauterine infection? Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:526-527.

- Mallory SB, Krafchik BR, Moore DJ, et al. Goltz syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 1989;6:251-253.

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L. Dermatology. Elsevier Saunders; 2017.

- Uitto J, Santa Cruz DJ, Eisen AZ. Connective tissue nevi of the skin. clinical, genetic, and histopathologic classification of hamartomas of the collagen, elastin, and proteoglycan type. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1980;3:441-461.

An 18-month-old child presented with a 4-cm, atrophic, flesh-colored plaque on the left lateral aspect of the abdomen with overlying wrinkling of the skin. There was no outpouching of the skin or pain associated with the lesion. No other skin abnormalities were noted. The child was born premature at 30 weeks’ gestation (birth weight, 1400 g). The postnatal course was complicated by respiratory distress syndrome requiring prolonged ventilator support. The infant was in the neonatal intensive care unit for 5 months. The atrophic lesion first developed at 5 months of life and remained stable. Although the lesion was not present at birth, the parents noted that it was preceded by an ecchymotic lesion without necrosis that was first noticed at 2 months of life while the patient was in the neonatal intensive care unit.

Expanding Verrucous Plaque on the Face

The Diagnosis: Blastomycosis

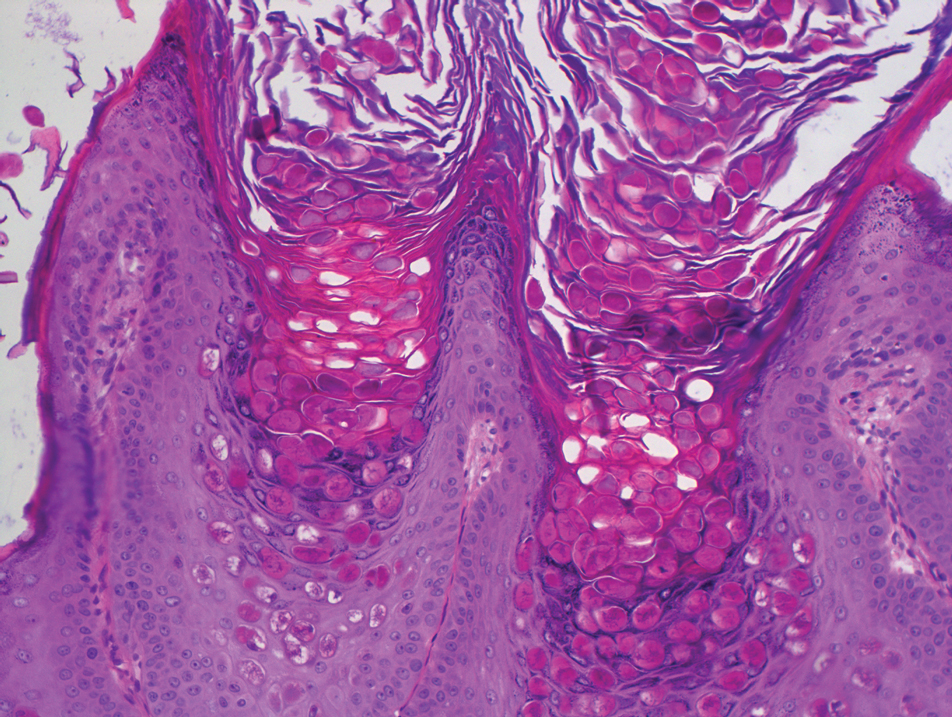

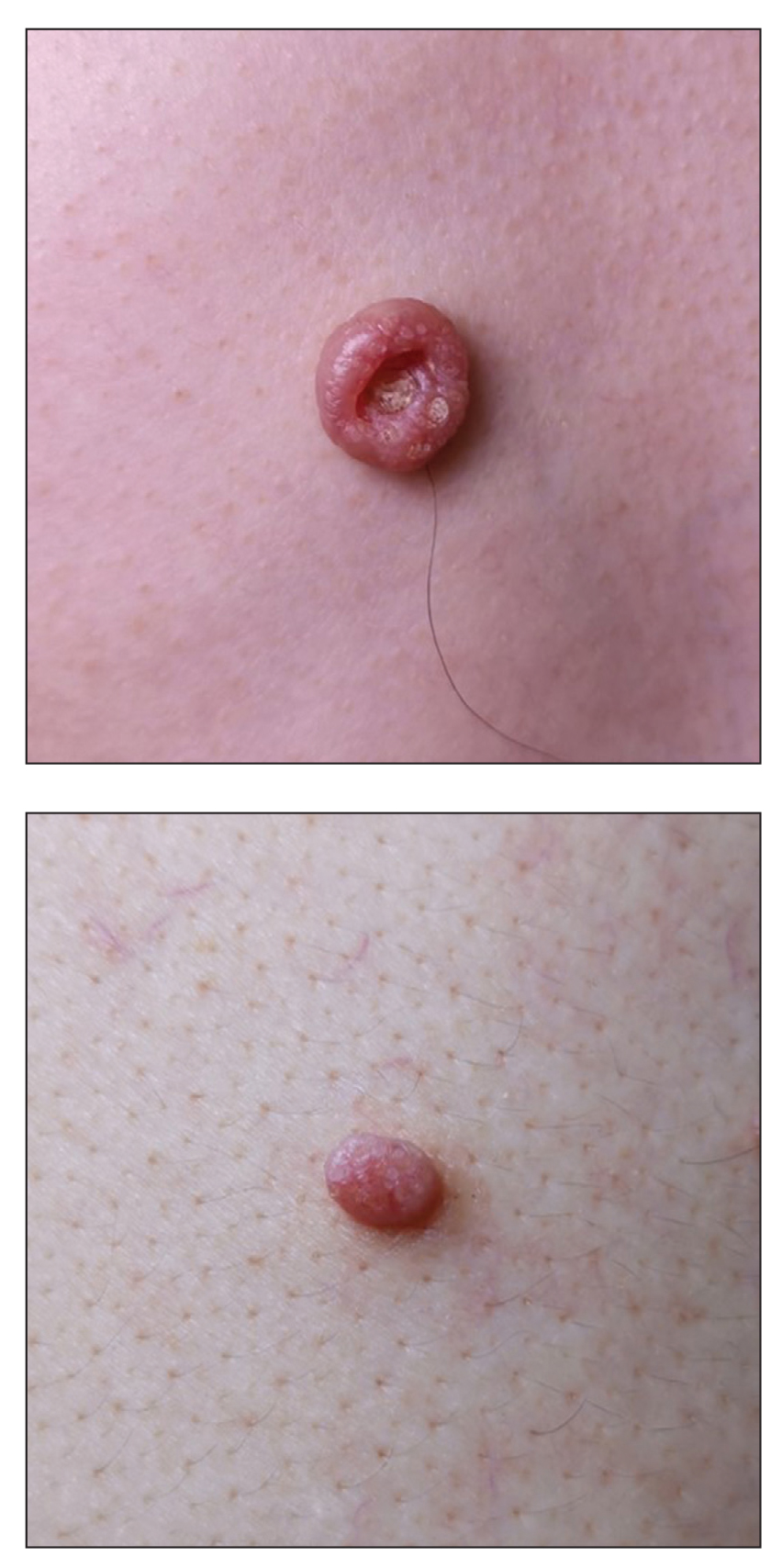

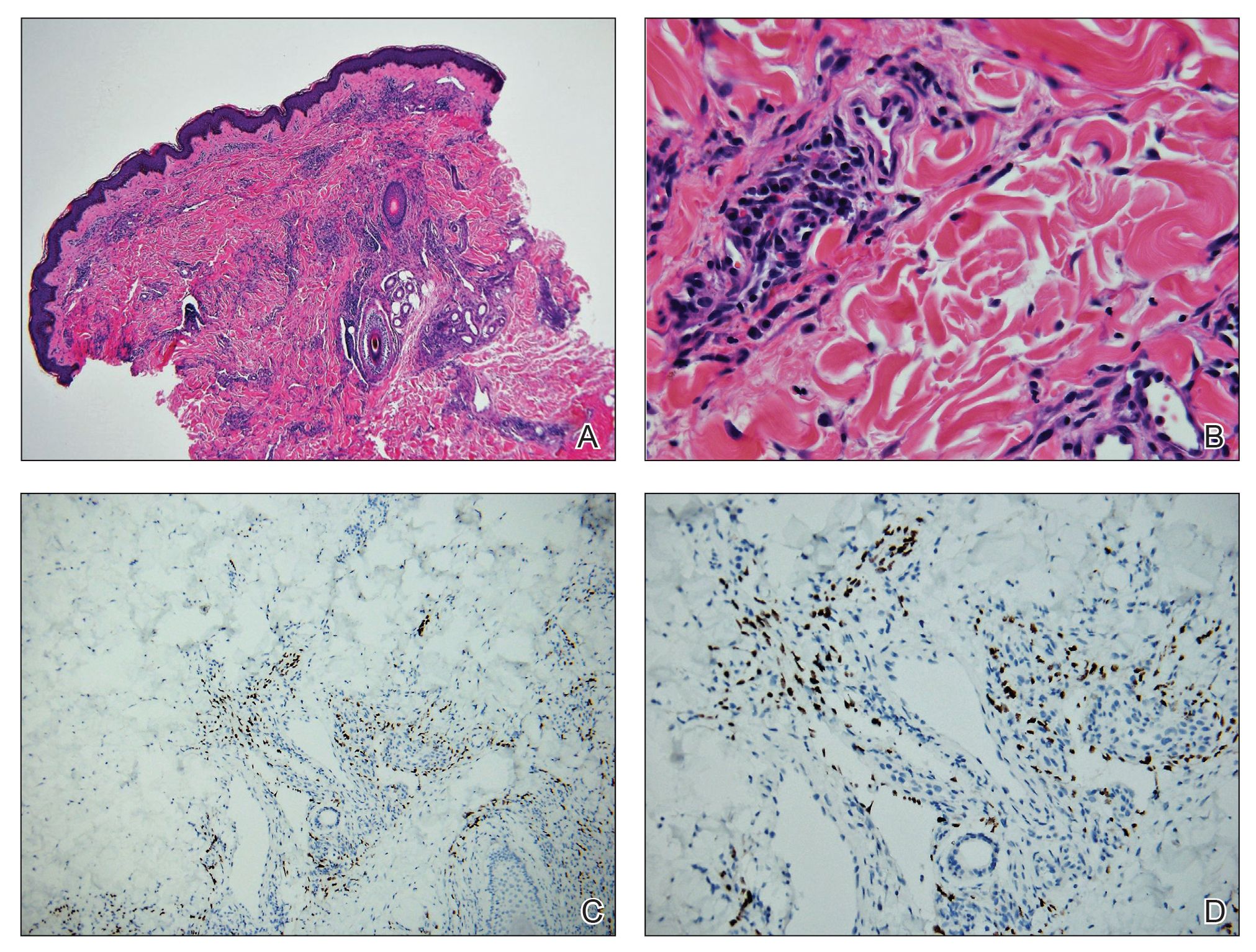

Histopathologic examination of 3 punch biopsies from the left side of the upper lip showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal microabscesses and dermal suppurative granulomatous inflammation (Figure 1A). Stains were negative for periodic acid-Schiff, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus. Direct and indirect immunofluorescence for skin autoantibodies were negative. Two separate tissue culture specimens showed no bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial growth. Leishmania polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing were negative. An additional punch biopsy revealed yeast forms with broad-based budding and refractile walls (Figures 1B and 1C) that were highlighted with Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain of the tissue (Figure 2). Chest radiography demonstrated no pulmonary involvement. In collaboration with an infectious disease specialist, the patient was started on itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for a total of 6 months.

Blastomycosis is a fungal infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus endemic in the soils of the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys and southeastern United States.1 It most commonly manifests as a pulmonary infection following inhalation of spores that are transformed into thick-walled yeasts capable of evading the host's immune system. Unlike other deep fungal infections, blastomycosis occurs in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Extrapulmonary disease after hematogenous dissemination from the lungs occurs in approximately 25% to 30% of patients, with the skin as the most common site of dissemination.2 Clinically, cutaneous blastomycosis typically starts as papules that evolve into crusted vegetative plaques, often with central clearing or ulceration. Primary cutaneous blastomycosis is rare and occurs due to direct inoculation after trauma to the skin via an infected animal bite, direct inoculation in laboratory settings, or due to injury during outdoor activities involving contact with soil.3 Given our patient's horticultural hobbies, lack of pulmonary symptoms, and negative radiologic examination, primary cutaneous blastomycosis infection due to direct inoculation from contaminated soil was a possibility; however, definite confirmation was difficult, as the primary pulmonary infection of blastomycosis can be asymptomatic and therefore often goes undetected.

Cutaneous blastomycosis can be mistaken for pemphigus vegetans, leishmaniasis, herpes vegetans, bacterial pyoderma, and other deep fungal infections that also display pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with pyogranulomatous inflammation on histopathology. Direct visualization of the characteristic yeast forms in a histologic specimen or the growth of fungus in culture is essential for a definitive diagnosis. The yeasts are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with thick, double-contoured walls and characteristically display broad-based budding.4 This budding pattern aids in differentiating blastomycosis from other entities with a similar histopathologic appearance. Chromoblastomycosis would show brown, thick-walled fungal cells inside giant cells, while coccidioidomycosis displays large spherules containing endospores, and leishmaniasis demonstrates amastigotes (small oval organisms with a bar-shaped kinetoplast) highlighted with Giemsa staining. Pemphigus vegetans would show intercellular deposition of IgG on direct immunofluorescence. Blastomyces dermatitidis can be difficult to visualize with routine hematoxylin and eosin stains, and it is important to note that a negative result does not exclude the possibility of blastomycosis, as demonstrated in our case.4 Special stains including Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff can aid in examining tissue for the presence of fungal elements, which typically can be found within histiocytes or abscesses in the dermis. Culture is the most sensitive method for detecting and diagnosing blastomycosis. Growth typically is detected in 5 to 10 days but can take up to 30 days if few organisms are present in the specimen.1

Although spontaneous remission can occur, it is recommended that all patients with cutaneous blastomycosis be treated to avoid dissemination and recurrence. Itraconazole currently is the treatment of choice.5 Doses typically are 200 to 400 mg/d for 8 to 12 months.6 Itraconazole-related side effects experienced by our patient during his 6-month treatment course included leg edema, 20-lb weight gain, gastrointestinal upset, blurred vision, and a transient increase in blood pressure, all resolving once the medication was discontinued. Complete resolution of the lesion was noted at the completion of the treatment course. At a 6-month posttreatment follow-up, residual scarring and alopecia were noted in parts of the previously affected areas of the upper cutaneous lip and nasolabial fold.

- Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-831.

- Chapman SW, Lin AC, Hendricks KA, et al. Endemic blastomycosis in Mississippi: epidemiological and clinical studies. Semin Respir Infect. 1997;12:219-228.

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Patel AJ, Gattuso P, Reddy VB. Diagnosis of blastomycosis in surgical pathology and cytopathology: correlation with microbiologic culture. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:256-261.

- Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801-1812.

- Lomaestro, BM, Piatek MA. Update on drug interactions with azole antifungal agents. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32:915-928.

The Diagnosis: Blastomycosis

Histopathologic examination of 3 punch biopsies from the left side of the upper lip showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal microabscesses and dermal suppurative granulomatous inflammation (Figure 1A). Stains were negative for periodic acid-Schiff, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus. Direct and indirect immunofluorescence for skin autoantibodies were negative. Two separate tissue culture specimens showed no bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial growth. Leishmania polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing were negative. An additional punch biopsy revealed yeast forms with broad-based budding and refractile walls (Figures 1B and 1C) that were highlighted with Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain of the tissue (Figure 2). Chest radiography demonstrated no pulmonary involvement. In collaboration with an infectious disease specialist, the patient was started on itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for a total of 6 months.

Blastomycosis is a fungal infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus endemic in the soils of the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys and southeastern United States.1 It most commonly manifests as a pulmonary infection following inhalation of spores that are transformed into thick-walled yeasts capable of evading the host's immune system. Unlike other deep fungal infections, blastomycosis occurs in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Extrapulmonary disease after hematogenous dissemination from the lungs occurs in approximately 25% to 30% of patients, with the skin as the most common site of dissemination.2 Clinically, cutaneous blastomycosis typically starts as papules that evolve into crusted vegetative plaques, often with central clearing or ulceration. Primary cutaneous blastomycosis is rare and occurs due to direct inoculation after trauma to the skin via an infected animal bite, direct inoculation in laboratory settings, or due to injury during outdoor activities involving contact with soil.3 Given our patient's horticultural hobbies, lack of pulmonary symptoms, and negative radiologic examination, primary cutaneous blastomycosis infection due to direct inoculation from contaminated soil was a possibility; however, definite confirmation was difficult, as the primary pulmonary infection of blastomycosis can be asymptomatic and therefore often goes undetected.

Cutaneous blastomycosis can be mistaken for pemphigus vegetans, leishmaniasis, herpes vegetans, bacterial pyoderma, and other deep fungal infections that also display pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with pyogranulomatous inflammation on histopathology. Direct visualization of the characteristic yeast forms in a histologic specimen or the growth of fungus in culture is essential for a definitive diagnosis. The yeasts are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with thick, double-contoured walls and characteristically display broad-based budding.4 This budding pattern aids in differentiating blastomycosis from other entities with a similar histopathologic appearance. Chromoblastomycosis would show brown, thick-walled fungal cells inside giant cells, while coccidioidomycosis displays large spherules containing endospores, and leishmaniasis demonstrates amastigotes (small oval organisms with a bar-shaped kinetoplast) highlighted with Giemsa staining. Pemphigus vegetans would show intercellular deposition of IgG on direct immunofluorescence. Blastomyces dermatitidis can be difficult to visualize with routine hematoxylin and eosin stains, and it is important to note that a negative result does not exclude the possibility of blastomycosis, as demonstrated in our case.4 Special stains including Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff can aid in examining tissue for the presence of fungal elements, which typically can be found within histiocytes or abscesses in the dermis. Culture is the most sensitive method for detecting and diagnosing blastomycosis. Growth typically is detected in 5 to 10 days but can take up to 30 days if few organisms are present in the specimen.1

Although spontaneous remission can occur, it is recommended that all patients with cutaneous blastomycosis be treated to avoid dissemination and recurrence. Itraconazole currently is the treatment of choice.5 Doses typically are 200 to 400 mg/d for 8 to 12 months.6 Itraconazole-related side effects experienced by our patient during his 6-month treatment course included leg edema, 20-lb weight gain, gastrointestinal upset, blurred vision, and a transient increase in blood pressure, all resolving once the medication was discontinued. Complete resolution of the lesion was noted at the completion of the treatment course. At a 6-month posttreatment follow-up, residual scarring and alopecia were noted in parts of the previously affected areas of the upper cutaneous lip and nasolabial fold.

The Diagnosis: Blastomycosis

Histopathologic examination of 3 punch biopsies from the left side of the upper lip showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal microabscesses and dermal suppurative granulomatous inflammation (Figure 1A). Stains were negative for periodic acid-Schiff, herpes simplex virus, and varicella-zoster virus. Direct and indirect immunofluorescence for skin autoantibodies were negative. Two separate tissue culture specimens showed no bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial growth. Leishmania polymerase chain reaction and DNA sequencing were negative. An additional punch biopsy revealed yeast forms with broad-based budding and refractile walls (Figures 1B and 1C) that were highlighted with Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain of the tissue (Figure 2). Chest radiography demonstrated no pulmonary involvement. In collaboration with an infectious disease specialist, the patient was started on itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for a total of 6 months.

Blastomycosis is a fungal infection caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a thermally dimorphic fungus endemic in the soils of the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys and southeastern United States.1 It most commonly manifests as a pulmonary infection following inhalation of spores that are transformed into thick-walled yeasts capable of evading the host's immune system. Unlike other deep fungal infections, blastomycosis occurs in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised hosts. Extrapulmonary disease after hematogenous dissemination from the lungs occurs in approximately 25% to 30% of patients, with the skin as the most common site of dissemination.2 Clinically, cutaneous blastomycosis typically starts as papules that evolve into crusted vegetative plaques, often with central clearing or ulceration. Primary cutaneous blastomycosis is rare and occurs due to direct inoculation after trauma to the skin via an infected animal bite, direct inoculation in laboratory settings, or due to injury during outdoor activities involving contact with soil.3 Given our patient's horticultural hobbies, lack of pulmonary symptoms, and negative radiologic examination, primary cutaneous blastomycosis infection due to direct inoculation from contaminated soil was a possibility; however, definite confirmation was difficult, as the primary pulmonary infection of blastomycosis can be asymptomatic and therefore often goes undetected.

Cutaneous blastomycosis can be mistaken for pemphigus vegetans, leishmaniasis, herpes vegetans, bacterial pyoderma, and other deep fungal infections that also display pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with pyogranulomatous inflammation on histopathology. Direct visualization of the characteristic yeast forms in a histologic specimen or the growth of fungus in culture is essential for a definitive diagnosis. The yeasts are 8 to 15 µm in diameter with thick, double-contoured walls and characteristically display broad-based budding.4 This budding pattern aids in differentiating blastomycosis from other entities with a similar histopathologic appearance. Chromoblastomycosis would show brown, thick-walled fungal cells inside giant cells, while coccidioidomycosis displays large spherules containing endospores, and leishmaniasis demonstrates amastigotes (small oval organisms with a bar-shaped kinetoplast) highlighted with Giemsa staining. Pemphigus vegetans would show intercellular deposition of IgG on direct immunofluorescence. Blastomyces dermatitidis can be difficult to visualize with routine hematoxylin and eosin stains, and it is important to note that a negative result does not exclude the possibility of blastomycosis, as demonstrated in our case.4 Special stains including Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver and periodic acid-Schiff can aid in examining tissue for the presence of fungal elements, which typically can be found within histiocytes or abscesses in the dermis. Culture is the most sensitive method for detecting and diagnosing blastomycosis. Growth typically is detected in 5 to 10 days but can take up to 30 days if few organisms are present in the specimen.1

Although spontaneous remission can occur, it is recommended that all patients with cutaneous blastomycosis be treated to avoid dissemination and recurrence. Itraconazole currently is the treatment of choice.5 Doses typically are 200 to 400 mg/d for 8 to 12 months.6 Itraconazole-related side effects experienced by our patient during his 6-month treatment course included leg edema, 20-lb weight gain, gastrointestinal upset, blurred vision, and a transient increase in blood pressure, all resolving once the medication was discontinued. Complete resolution of the lesion was noted at the completion of the treatment course. At a 6-month posttreatment follow-up, residual scarring and alopecia were noted in parts of the previously affected areas of the upper cutaneous lip and nasolabial fold.

- Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-831.

- Chapman SW, Lin AC, Hendricks KA, et al. Endemic blastomycosis in Mississippi: epidemiological and clinical studies. Semin Respir Infect. 1997;12:219-228.

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Patel AJ, Gattuso P, Reddy VB. Diagnosis of blastomycosis in surgical pathology and cytopathology: correlation with microbiologic culture. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:256-261.

- Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801-1812.

- Lomaestro, BM, Piatek MA. Update on drug interactions with azole antifungal agents. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32:915-928.

- Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-831.

- Chapman SW, Lin AC, Hendricks KA, et al. Endemic blastomycosis in Mississippi: epidemiological and clinical studies. Semin Respir Infect. 1997;12:219-228.

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Patel AJ, Gattuso P, Reddy VB. Diagnosis of blastomycosis in surgical pathology and cytopathology: correlation with microbiologic culture. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:256-261.

- Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801-1812.

- Lomaestro, BM, Piatek MA. Update on drug interactions with azole antifungal agents. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32:915-928.

A 69-year-old man presented with a slowly expanding, verrucous plaque on the left side of the upper cutaneous lip of 4 months’ duration. The lesion reportedly began as an abscess and had undergone incision and drainage followed by multiple courses of oral antibiotics that were unsuccessful prior to presentation to our clinic. The patient’s hobbies included gardening near his summer home in the mountains of western North Carolina, where he resided when the lesion appeared. Physical examination revealed an approximately 6×4-cm verrucous plaque with central ulceration on the left side of the upper cutaneous and vermilion lip extending to the nasolabial fold. A review of systems was negative for any systemic symptoms. Routine laboratory tests and computed tomography of the head and neck were normal.

Unilateral Alar Ulceration

The Diagnosis: Trigeminal Trophic Syndrome (Self-induced Trauma)

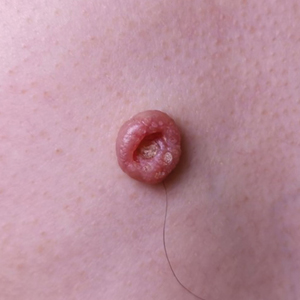

The patient admitted to manipulation of the ala in response to persistent pain despite resolution of the herpes zoster, for which he recently had completed a course of oral acyclovir. A preliminary diagnosis of trigeminal trophic syndrome (TTS) was made, and a subsequent punch biopsy revealed no evidence of malignancy. Topical antibiotic prophylaxis was prescribed, and he was instructed to avoid manipulation of the affected area. Treatment was initiated in consultation with pain specialists, and over the following 3 years our patient experienced a waxing and waning course of persistent pain complicated by new scalp and oral ulcers as well as alar impetigo. His condition eventually stabilized with tolerable pain on oral gabapentin and doxepin cream 5% applied up to 4 times daily. The alar lesion healed following sufficient abstinence from manipulation, leaving a crescent-shaped rim defect.

Trigeminal trophic syndrome classically is characterized by a triad of cutaneous anesthesia, paresthesia and/or pain, and ulceration secondary to pathology of trigeminal nerve sensory branches. Ulceration arises primarily through excoriation in response to paresthetic pruritus or pain. The differential diagnosis for TTS includes ulcerating cutaneous neoplasms (eg, basal cell carcinoma); mycobacterial, fungal, and viral infections (especially herpetic lesions); and cutaneous involvement of systemic vasculitides (eg, granulomatosis with polyangiitis).1 Biopsy is necessary to exclude malignancy, and ulcers may be scraped for viral diagnosis. Complete blood cell count and serologic testing also may help to exclude immunodeficiencies or disorders. Apart from viral neuropathy, common etiologies of TTS include iatrogenic trigeminal injury (eg, in ablation treatment for trigeminal neuralgia) and stroke (eg, lateral medullary syndrome).

- Khan AU, Khachemoune A. Trigeminal trophic syndrome: an updated review. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:530-537.

The Diagnosis: Trigeminal Trophic Syndrome (Self-induced Trauma)

The patient admitted to manipulation of the ala in response to persistent pain despite resolution of the herpes zoster, for which he recently had completed a course of oral acyclovir. A preliminary diagnosis of trigeminal trophic syndrome (TTS) was made, and a subsequent punch biopsy revealed no evidence of malignancy. Topical antibiotic prophylaxis was prescribed, and he was instructed to avoid manipulation of the affected area. Treatment was initiated in consultation with pain specialists, and over the following 3 years our patient experienced a waxing and waning course of persistent pain complicated by new scalp and oral ulcers as well as alar impetigo. His condition eventually stabilized with tolerable pain on oral gabapentin and doxepin cream 5% applied up to 4 times daily. The alar lesion healed following sufficient abstinence from manipulation, leaving a crescent-shaped rim defect.

Trigeminal trophic syndrome classically is characterized by a triad of cutaneous anesthesia, paresthesia and/or pain, and ulceration secondary to pathology of trigeminal nerve sensory branches. Ulceration arises primarily through excoriation in response to paresthetic pruritus or pain. The differential diagnosis for TTS includes ulcerating cutaneous neoplasms (eg, basal cell carcinoma); mycobacterial, fungal, and viral infections (especially herpetic lesions); and cutaneous involvement of systemic vasculitides (eg, granulomatosis with polyangiitis).1 Biopsy is necessary to exclude malignancy, and ulcers may be scraped for viral diagnosis. Complete blood cell count and serologic testing also may help to exclude immunodeficiencies or disorders. Apart from viral neuropathy, common etiologies of TTS include iatrogenic trigeminal injury (eg, in ablation treatment for trigeminal neuralgia) and stroke (eg, lateral medullary syndrome).

The Diagnosis: Trigeminal Trophic Syndrome (Self-induced Trauma)

The patient admitted to manipulation of the ala in response to persistent pain despite resolution of the herpes zoster, for which he recently had completed a course of oral acyclovir. A preliminary diagnosis of trigeminal trophic syndrome (TTS) was made, and a subsequent punch biopsy revealed no evidence of malignancy. Topical antibiotic prophylaxis was prescribed, and he was instructed to avoid manipulation of the affected area. Treatment was initiated in consultation with pain specialists, and over the following 3 years our patient experienced a waxing and waning course of persistent pain complicated by new scalp and oral ulcers as well as alar impetigo. His condition eventually stabilized with tolerable pain on oral gabapentin and doxepin cream 5% applied up to 4 times daily. The alar lesion healed following sufficient abstinence from manipulation, leaving a crescent-shaped rim defect.

Trigeminal trophic syndrome classically is characterized by a triad of cutaneous anesthesia, paresthesia and/or pain, and ulceration secondary to pathology of trigeminal nerve sensory branches. Ulceration arises primarily through excoriation in response to paresthetic pruritus or pain. The differential diagnosis for TTS includes ulcerating cutaneous neoplasms (eg, basal cell carcinoma); mycobacterial, fungal, and viral infections (especially herpetic lesions); and cutaneous involvement of systemic vasculitides (eg, granulomatosis with polyangiitis).1 Biopsy is necessary to exclude malignancy, and ulcers may be scraped for viral diagnosis. Complete blood cell count and serologic testing also may help to exclude immunodeficiencies or disorders. Apart from viral neuropathy, common etiologies of TTS include iatrogenic trigeminal injury (eg, in ablation treatment for trigeminal neuralgia) and stroke (eg, lateral medullary syndrome).

- Khan AU, Khachemoune A. Trigeminal trophic syndrome: an updated review. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:530-537.

- Khan AU, Khachemoune A. Trigeminal trophic syndrome: an updated review. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:530-537.

A 68-year-old man presented with a new left nasal alar ulcer following a recent episode of primary herpes zoster. Physical examination revealed erythema, erosion, and necrosis of the left naris with partial loss of the alar rim. Additional erythema was present without vesicles around the left eye and on the forehead.

Telangiectatic Patch on the Forehead

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

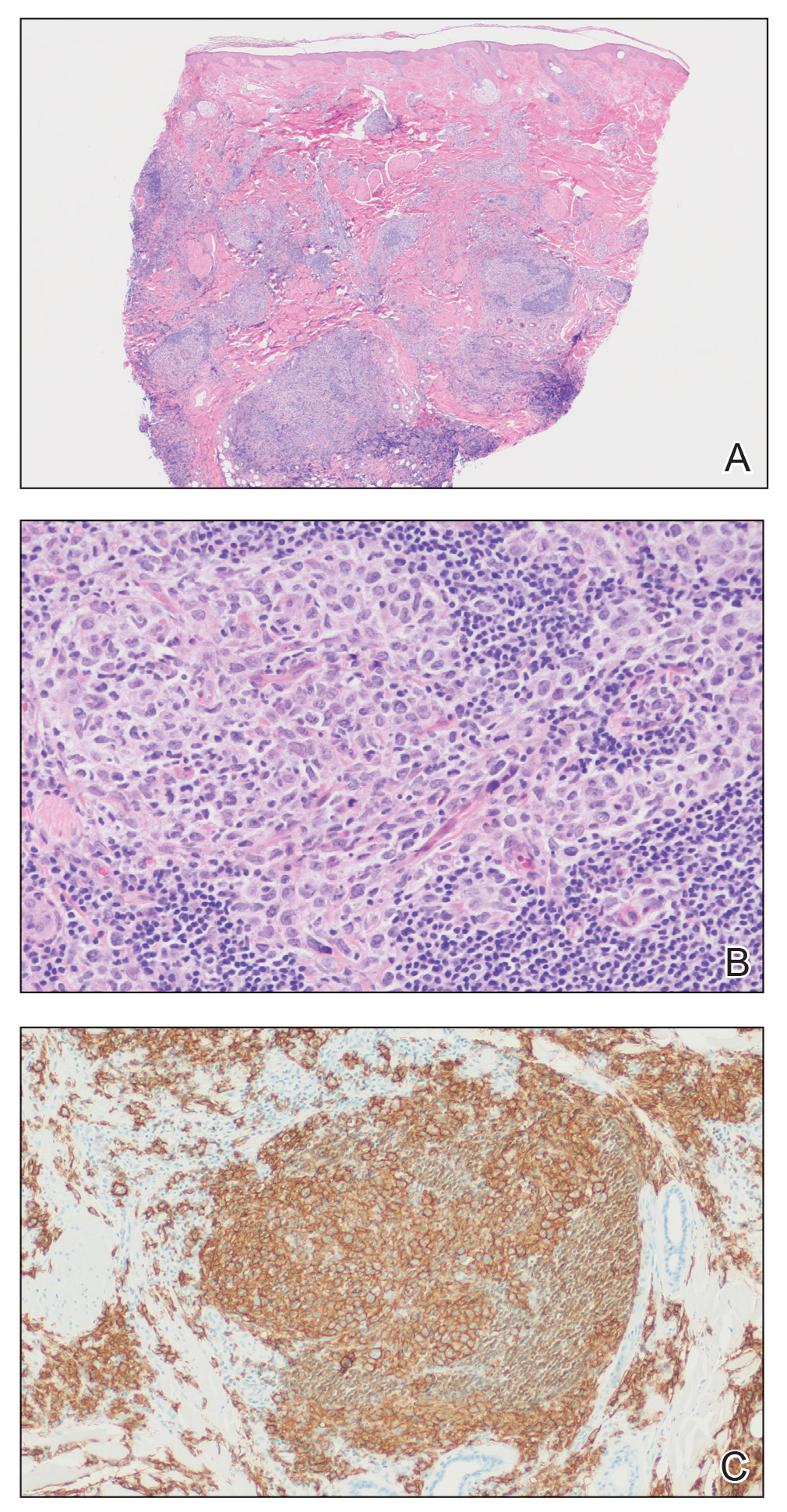

Histopathology was suggestive of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (Figure). Further immunohistochemical studies including Bcl-6 positivity and Bcl-2 negativity in the large atypical cells supported a diagnosis of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL). The designation of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma includes several different types of lymphoma, including marginal zone lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and intravascular lymphoma. To be considered a primary cutaneous lymphoma, there must be evidence of the lymphoma in the skin without concomitant evidence of systemic involvement, as determined through a full staging workup. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is an indolent lymphoma that most commonly presents as solitary or grouped, pink to plum-colored papules, plaques, nodules, and tumors on the scalp, forehead, or back.1 The lesions often are biopsied as suspected basal cell carcinomas or Merkel cell carcinomas (MCCs). Lesions on the face or scalp may easily evade diagnosis, as they initially may mimic rosacea or insect bites. Less common presentations include infiltrative lesions that cause rhinophymatous changes or scarring alopecia. Multifocal or disseminated lesions rarely can be observed. This case presentation is unique in its patchy appearance that clinically resembled angiosarcoma.2 When identified and treated, the disease-specific 5-year survival rate for PCFCL is greater than 95%.3

Merkel cell carcinoma was first described in 1972 and has been diagnosed with increasing frequency each year.4 It generally presents as an erythematous or violaceous, tender, indurated nodule on sun-exposed skin of the head or neck in elderly White men. However, other presentations have been reported, including papules, plaques, cystlike structures, pruritic tumors, pedunculated lesions, subcutaneous masses, and telangiectatic papules.5 Histopathologically, MCC is characterized by dermal nests and sheets of basaloid cells with finely granular salt and pepper-like chromatin. The histologic features can resemble other small blue cell tumors; therefore, the differential diagnosis can be broad.5 Immunohistochemistry that can confirm the diagnosis of MCC generally will be positive for cytokeratin 20 and neuroendocrine markers but negative for cytokeratin 7 and thyroid transcription factor 1. Merkel cell carcinoma is an aggressive tumor with a high risk for local recurrence and distant metastasis that carries a generally poor prognosis, especially when there is evidence of metastatic disease at presentation.5,6

Rosacea can appear as telangiectatic patches, though generally not as one discrete patch limited to the forehead, as in our patient. Histologic features vary based on the age of the lesion and clinical variant. In early lesions there is a mild perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate within the dermis, while older lesions can have a mixed infiltrate crowded around vessels and adnexal structures. Granulomas often are seen near hair follicles and interspersed throughout the dermis with ectatic vessels and dermal edema.7

Angiosarcoma is divided into 3 clinicopathological subtypes: idiopathic angiosarcoma of the head and neck, angiosarcoma in the setting of lymphedema, and postirradiation angiosarcoma.7 Idiopathic angiosarcoma most closely mimics PCFCL, as it can present as single or multifocal nodules, plaques, or patches. Histologically, the 3 groups appear similar with poorly circumscribed, infiltrative, dermal tumors. The neoplastic endothelial cells have large hyperchromatic nuclei that protrude into vascular lumens. The prognosis for idiopathic angiosarcoma of the head and neck is poor, with a 5-year survival rate of 15% to 34%, which often is due to delayed diagnosis.7

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses (PPDs) are chronic skin disorders characterized by purpura due to extravasation of blood from capillaries; the resulting hemosiderin deposition leads to pigmentation.7 There are various forms of PPD, which are classified into groups based on clinical appearance including Schamberg disease, purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi, pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum, lichen aureus, and others including eczematid and itching variants, which some consider to be distinct entities. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi is the specific PPD that should be included in the clinical differential for PCFCL because it presents as annular patches with telangiectasias. Histologically, PPDs are characterized by a CD4+ lymphocytic infiltrate in the upper dermis with extravasated red blood cells and the presence of hemosiderin mostly within macrophages and a lack of true vasculitis. Clonality of the T cells has been shown, and there is some evidence that PPD may overlap with mycosis fungoides. However, this overlap mainly has been seen in patients with widespread lesions and would not apply to this case. In general, patients with PPD can be reassured of the benign process. In cases of widespread PPD, patients should be followed clinically to assess for progression to mycosis fungoides, though the likelihood is low.7

Our patient underwent a full staging workup, which confirmed the diagnosis of PCFCL. He was treated with radiation to the forehead that resulted in clearance of the lesion. Approximately 2 years after the initial diagnosis, the patient was alive and well with no evidence of recurrence of PCFCL.

In conclusion, it is imperative to identify unusual, macular, vascular-appearing patches, especially on the head and neck in older individuals. Because the clinical presentations of PCFCL, angiosarcoma, rosacea, MCC, and PPD can overlap with one another as well as with other entities, it is necessary to have a high level of suspicion and low threshold to biopsy these types of lesions, as outcomes can be drastically different.

- Goyal A, LeBlanc RE, Carter JB. Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:149-161.

- Massone C, Fink-Puches R, Cerroni L. Atypical clinical presentation of primary and secondary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (FCL) on the head characterized by macular lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1000-1006.

- Wilcox RA. Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:1052-1055.

- Conic RRZ, Ko J, Saridakis S, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in Merkel cell carcinoma: predictors of sentinel lymph node positivity and association with overall survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:364-372

- Coggshall K, Tello TL, North JP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and review: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and staging. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:433-442.

- Tello TL, Coggshall K, Yom SS, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: an update and review: current and future therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:445-454.

- Patterson JW, Hosler GA. Weedon's Skin Pathology. 4th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous B-cell Lymphoma

Histopathology was suggestive of cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (Figure). Further immunohistochemical studies including Bcl-6 positivity and Bcl-2 negativity in the large atypical cells supported a diagnosis of primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma (PCFCL). The designation of primary cutaneous B-cell lymphoma includes several different types of lymphoma, including marginal zone lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and intravascular lymphoma. To be considered a primary cutaneous lymphoma, there must be evidence of the lymphoma in the skin without concomitant evidence of systemic involvement, as determined through a full staging workup. Primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma is an indolent lymphoma that most commonly presents as solitary or grouped, pink to plum-colored papules, plaques, nodules, and tumors on the scalp, forehead, or back.1 The lesions often are biopsied as suspected basal cell carcinomas or Merkel cell carcinomas (MCCs). Lesions on the face or scalp may easily evade diagnosis, as they initially may mimic rosacea or insect bites. Less common presentations include infiltrative lesions that cause rhinophymatous changes or scarring alopecia. Multifocal or disseminated lesions rarely can be observed. This case presentation is unique in its patchy appearance that clinically resembled angiosarcoma.2 When identified and treated, the disease-specific 5-year survival rate for PCFCL is greater than 95%.3

Merkel cell carcinoma was first described in 1972 and has been diagnosed with increasing frequency each year.4 It generally presents as an erythematous or violaceous, tender, indurated nodule on sun-exposed skin of the head or neck in elderly White men. However, other presentations have been reported, including papules, plaques, cystlike structures, pruritic tumors, pedunculated lesions, subcutaneous masses, and telangiectatic papules.5 Histopathologically, MCC is characterized by dermal nests and sheets of basaloid cells with finely granular salt and pepper-like chromatin. The histologic features can resemble other small blue cell tumors; therefore, the differential diagnosis can be broad.5 Immunohistochemistry that can confirm the diagnosis of MCC generally will be positive for cytokeratin 20 and neuroendocrine markers but negative for cytokeratin 7 and thyroid transcription factor 1. Merkel cell carcinoma is an aggressive tumor with a high risk for local recurrence and distant metastasis that carries a generally poor prognosis, especially when there is evidence of metastatic disease at presentation.5,6

Rosacea can appear as telangiectatic patches, though generally not as one discrete patch limited to the forehead, as in our patient. Histologic features vary based on the age of the lesion and clinical variant. In early lesions there is a mild perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate within the dermis, while older lesions can have a mixed infiltrate crowded around vessels and adnexal structures. Granulomas often are seen near hair follicles and interspersed throughout the dermis with ectatic vessels and dermal edema.7

Angiosarcoma is divided into 3 clinicopathological subtypes: idiopathic angiosarcoma of the head and neck, angiosarcoma in the setting of lymphedema, and postirradiation angiosarcoma.7 Idiopathic angiosarcoma most closely mimics PCFCL, as it can present as single or multifocal nodules, plaques, or patches. Histologically, the 3 groups appear similar with poorly circumscribed, infiltrative, dermal tumors. The neoplastic endothelial cells have large hyperchromatic nuclei that protrude into vascular lumens. The prognosis for idiopathic angiosarcoma of the head and neck is poor, with a 5-year survival rate of 15% to 34%, which often is due to delayed diagnosis.7