User login

Genetic testing and the future of cerebral palsy malpractice cases

CASE Mixed CP diagnosed at age 6 months

After learning that the statute of limitations was to run out in the near future, the parents of a 17-year-old with cerebral palsy (CP) initiated a lawsuit. At the time of her pregnancy, the mother (G2P2002) was age 39 and first sought prenatal care at 14 weeks.

Her past medical history was largely noncontributory to her current pregnancy, except for that she had hypothyroidism that was being treated with levothyroxine. She also had a history of asthma, but had had no acute episodes for years. During the course of the pregnancy there was evidence of polyhydramnios; her initial thyroid studies were abnormal (thyroid-stimulating hormone levels, 7.1 mIU/L), in part due to lack of adherence with prescribed medications. She was noted to have elevated blood pressure (BP) 150/100 mm Hg but no proteinuria, with BP monitoring during her last trimester.

The patient went into labor at 40 3/7 weeks, after spontaneous rupture of membranes. In labor and delivery she was placed on a monitor, and irregular contractions were noted. The initial vaginal examination was noted as 1-cm cervical dilation, 90% effaced, and station zero. The obstetrician evaluated the patient and ordered Pitocin augmentation. The next vaginal exam several hours later noted 3-cm dilation and 100% effacement. The Pitocin was continued. Several early decelerations, moderate variability, and better contraction pattern was noted. Eight hours into the Pitocin, there were repetitive late decelerations; the obstetrician was not notified. The nursing staff proceeded with vaginal examination, and the patient was fully dilated at station +1. Again, the doctor was not informed of the patient’s status. At 10 hours post-Pitocin initiation, the patient felt the urge to push. The obstetrician was notified, and he promptly arrived to the unit and patient’s bedside. His decision was to use forceps for the delivery, feeling this would be the most expedient way to proceed, although cesarean delivery (CD) was a definite consideration. Forceps were applied, and as the nursing staff noted,” the doctor really had to pull to deliver the head.” A male baby, 8 lb 8 oz, was delivered. A second-degree tear was noted and easily repaired following delivery of the placenta. Apgar scores were 5 and 7 at 1 and 5 minutes after birth, respectively.

The patient’s postpartum course was uneventful. The patient and baby were discharged on the third day postpartum.

As the child was evaluated by the pediatrician, the mother noted at 6 months that the child’s head lagged behind when he was picked up. He appeared stiff at times and floppy at other times according to the parents. As the child progressed he had problems with hand-to-mouth coordination, and when he would crawl he seemed to “scoot his butt,” as they stated.

The child was tested and a diagnosis of mixed cerebral palsy was made, implying a combination of spastic CP and dyskinetic CP. He is wheelchair bound. The parents filed a lawsuit against the obstetrician and the hospital, focused on hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) due to labor and delivery management being below the standard of care. They claimed that the obstetrician should have been informed by the hospital staff during the course of labor, and the obstetrician should have been more proactive in monitoring the deteriorating circumstances. This included performing a CD based on “the Category III fetal heart tracing.”

At trial, the plaintiff expert argued that failure of nursing staff to properly communicate with the obstetrician led to mismanagement. Furthermore, the obstetrician used poor judgement (ie, below the standard of care) in not performing a CD. The defense expert argued that, overall, the fetal heart tracing was Category II, and the events occurred in utero, in part reflected by the mother having polyhydramnios and hypothyroidism that was not well controlled due to lack of adherence with prescribed medications. The child in his wheelchair was brought into the courtroom. The trial went on for more than 1 week, and the jury deliberated for several hours. (Note: This case is a composite of several different events and claims.)

Continue to: WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

The jury returns a verdict for the defense.

Should anything have been done differently in this trial?

Medical considerations

Cerebral palsy is a neurodevelopmental disorder affecting 1 in 500 children.1 Other prevalence data (from a European study) indicate an incidence of 1.3–1.9 cases per 1,000 livebirths.1 The controversy continues with respect to the disorder’s etiology, especially when the infant’s magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) does not identify specific pathology. The finger is then pointed at HIE and thus the fault of the obstetrician and labor and delivery staff. In reality, HIE accounts for less than 10% of all cases of CP.2 Overall, CP is a condition focused on progressive motor impairments, many times associated with specific MRI findings.3 In addition, “MRI-negative” CP is a more vague diagnosis as discussed among neurologists.

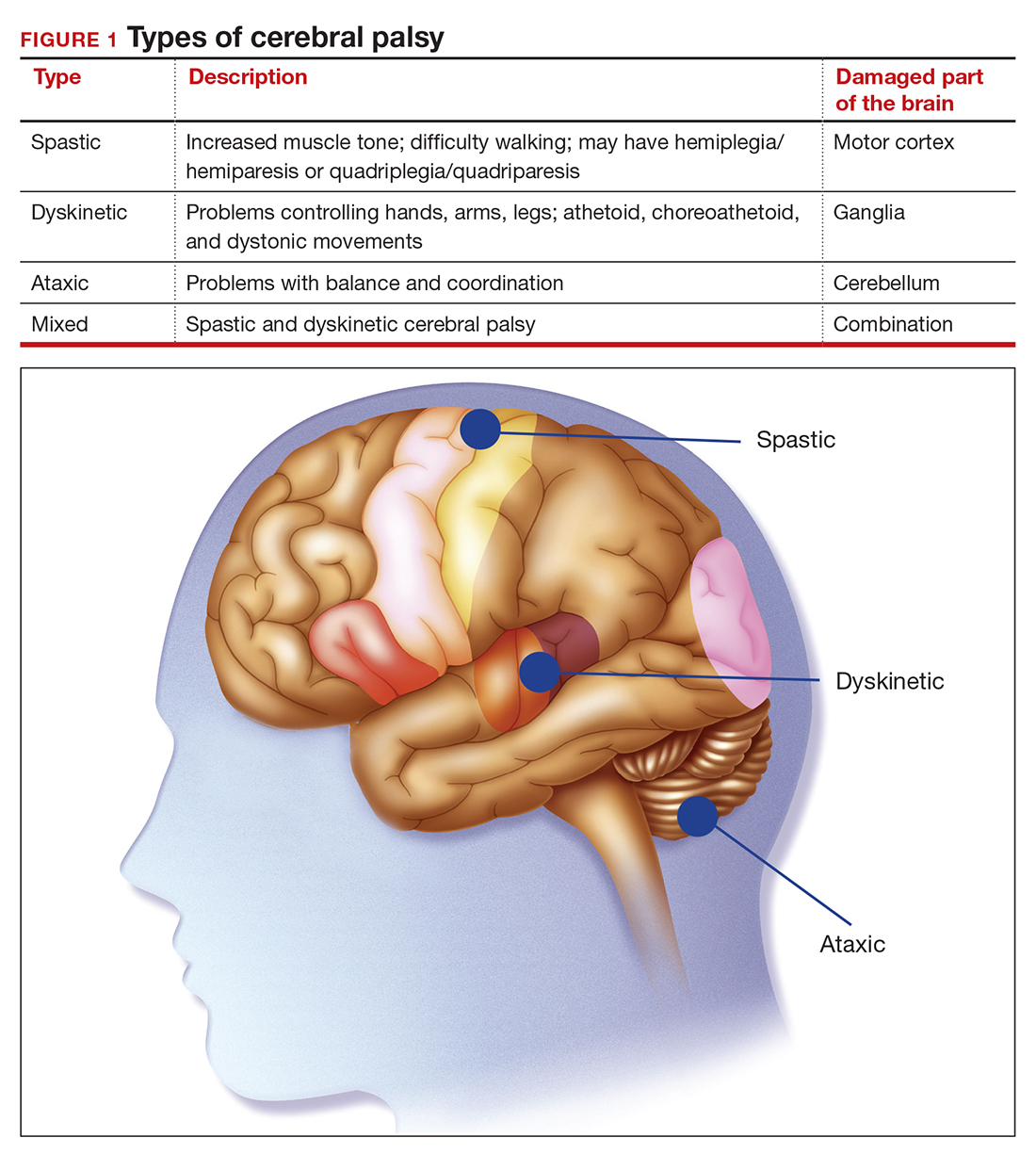

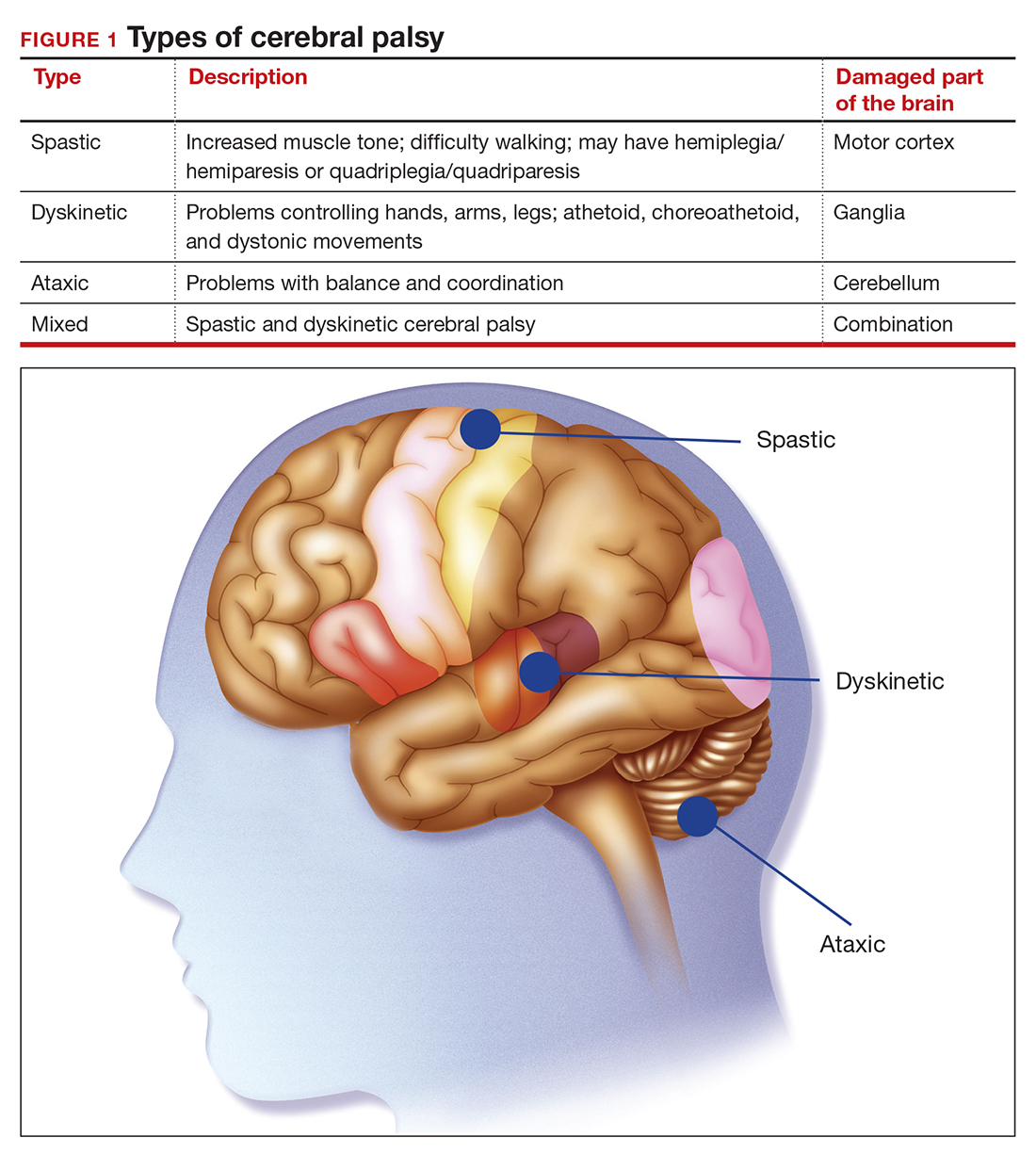

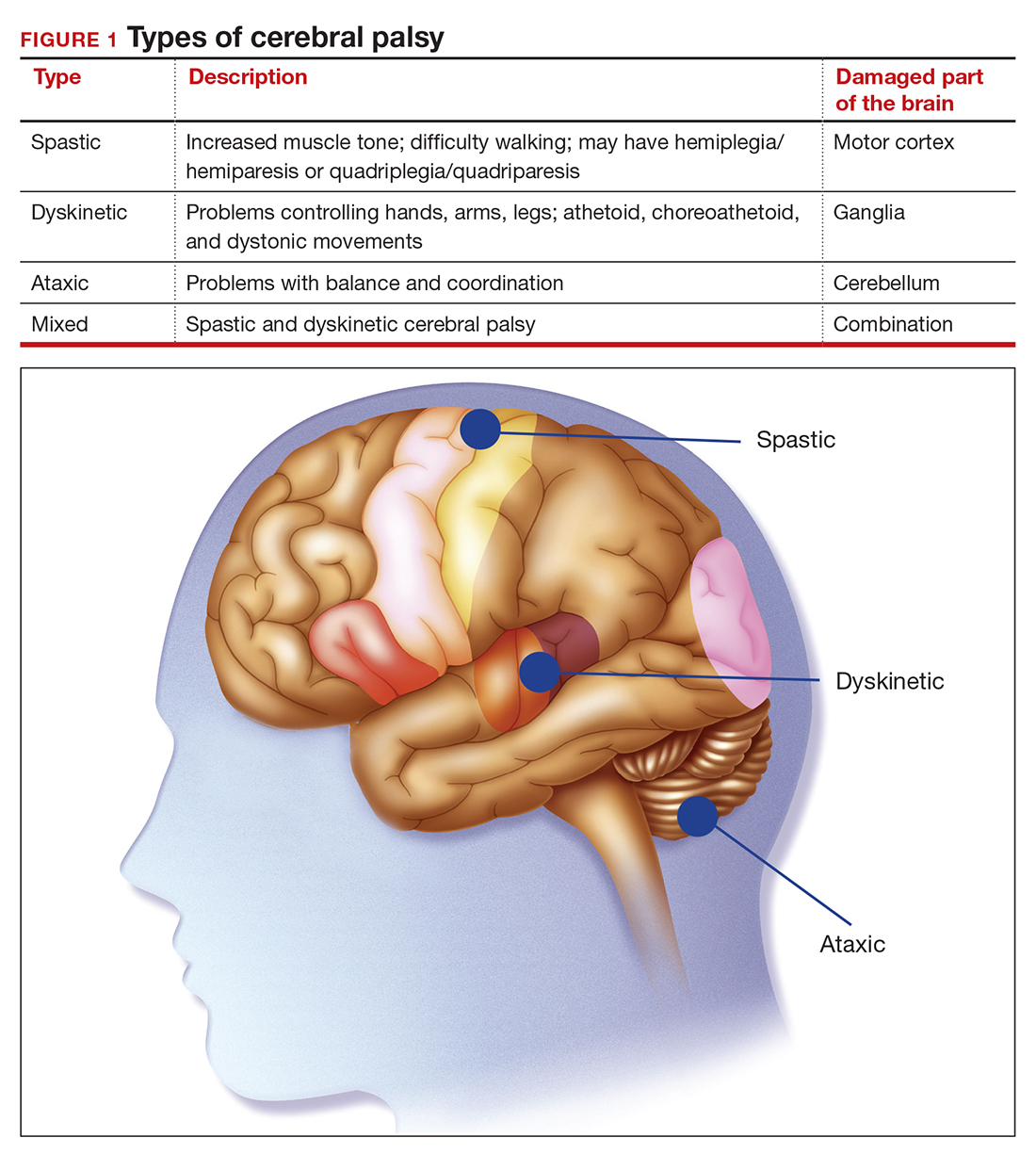

The International Consensus Definition of CP is “a group of permanent disorders of the development of movement and posture, causing activity limitations, that are attributed to nonprogressive disturbances that occurred in the developing fetal or infant brain.”4 The International Cerebral Palsy Genomics Consortium have provided a consensus statement that defines CP based upon clinical type as opposed to etiology.5 Many times, however, ascribing an HIE cause to CP is “barking up the wrong tree,” in that we now know there are clear cut genetic causes of CP, and etiology attributed to perinatal causes, in reality, are genetic in up to 80% of cases.3 Types of CP are addressed in FIGURE 1. Overall, the pathophysiology of the disorder remains unknown. Some affected children have intellectual disabilities, as well as visual, hearing, and/or speech impairment.

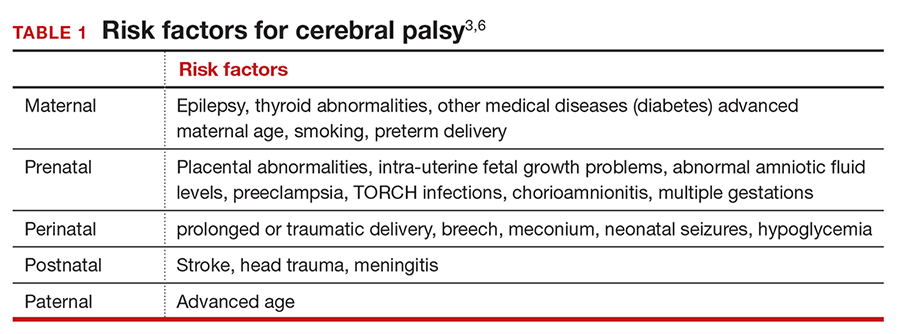

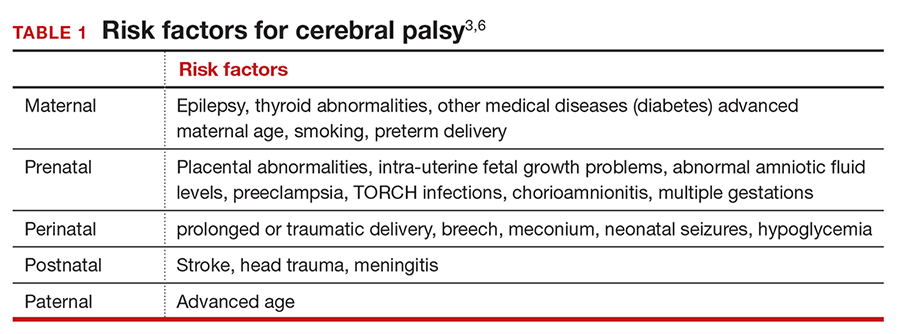

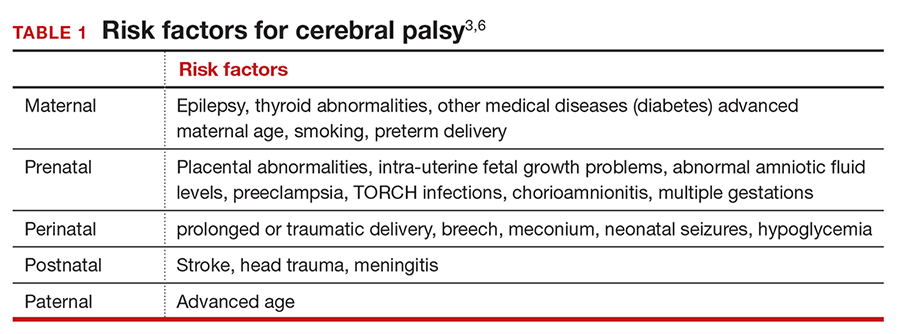

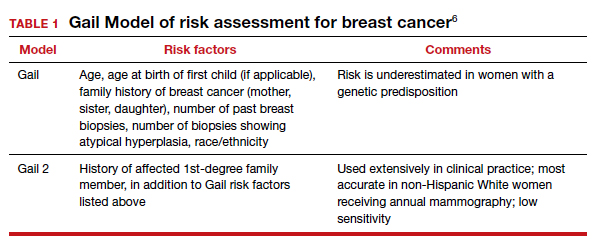

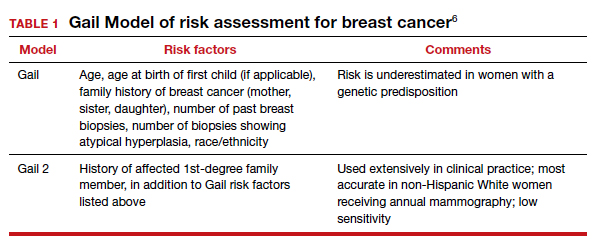

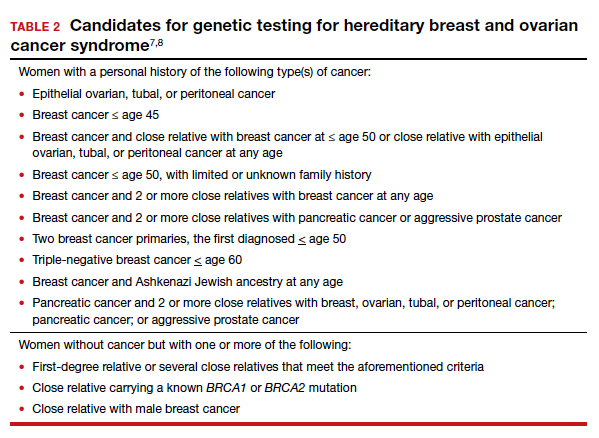

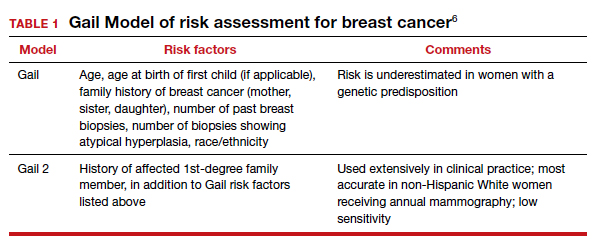

A number of risk factors have been associated with CP (TABLE 1),3,6 which contribute to cell death in the brain or altered maturation of neurons and glia, resulting in abnormal white matter tracts and smaller central nervous system (CNS) volume or cerebellar hypoxia.6 One very important aspect of assessment for CP is specific gene mutations, which may vary in part dependent upon the presence or absence of environmental factors (insults).1 Mutations can lead to profound adverse effects with resultant CNS ischemia and neuromotor disability. In fact, genetics play a major role in determining the etiology of CP.1 Of interest, animal models who are subject to HIE induction have CNS effects resulting in permanent motor impairment.7

DNA sequencing

The DNA story continues to unfold with the concept that DNA variants alter susceptibility to environmental influences. These insults are, for example, thrombosis or hemorrhage, all of which affect motor function.1 Duplications or deletions of portions of a chromosome, related to copy number variants (CNVs) as well as advances in human-genome sequencing, can identify a single gene mutation leading to CP.1 Microdeletions, microduplications, and single nucleotide variants (SNVs) are to be included in genetic-related problems causing CP.3

A number of candidate genes have been considered and include “de novo heterozygous mutations in known Online Mendelian Inheritance (OMIM).” TIBA1A and SCN8A genes are highly associated with CP.8 Genetic assessment, as it evolves and more recently with the advent of exome sequencing, appears to provide a new and unprecedented level of understanding of CP. Specifically, exome sequencing provides a diagnostic tool with which to identify the prevalence of pathogenic and pathogenic variants (the latter encompassing genomic variants) with CP.9 A retrospective study assessed a cohort of patients with CP and noted that 32.7% of the pediatric-aged patients who underwent exome sequencing had pathogenic and pathogenic variants in the sequencing.9 Thus, we have a tool to identify underlying genetic pathogenesis with CP. This theoretically can change the outcome of lawsuits initiated for CP that ascribe an HIE etiology. Clinicians need to stay tuned as the genetic repertoire continues to unfold.

Continue to: Legal considerations...

Legal considerations

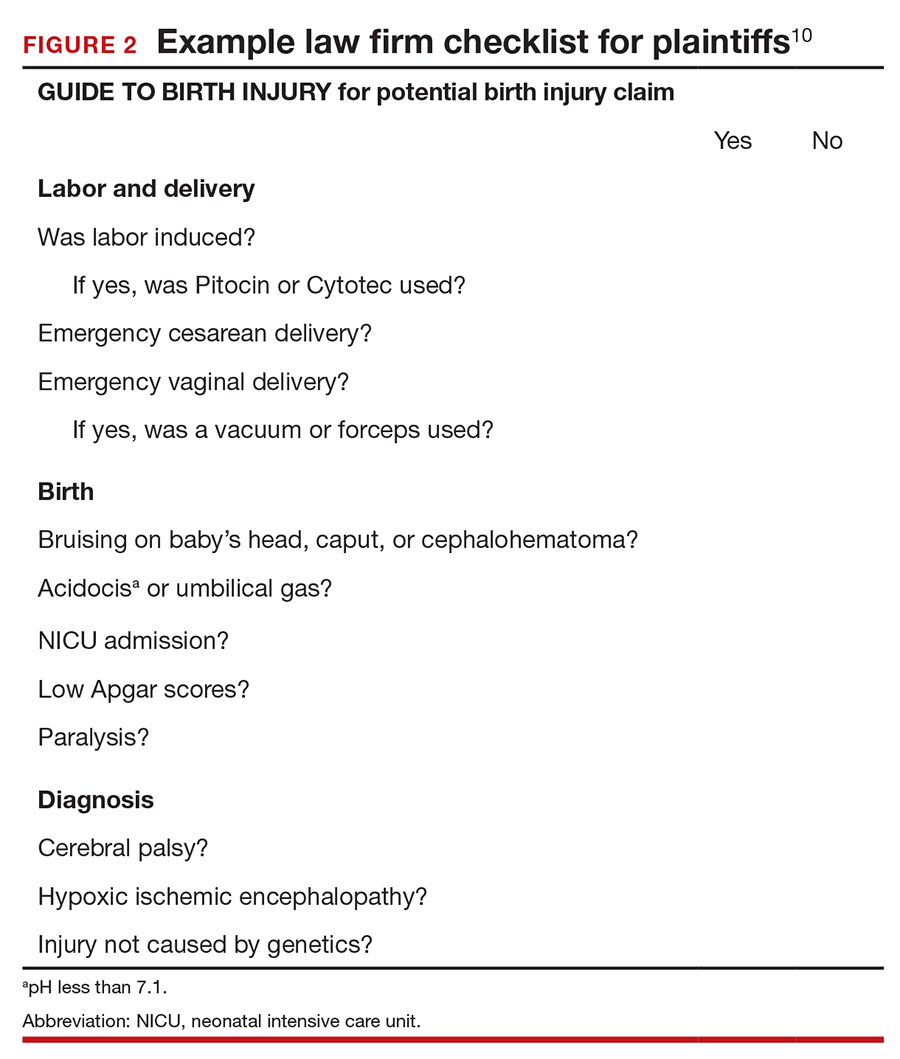

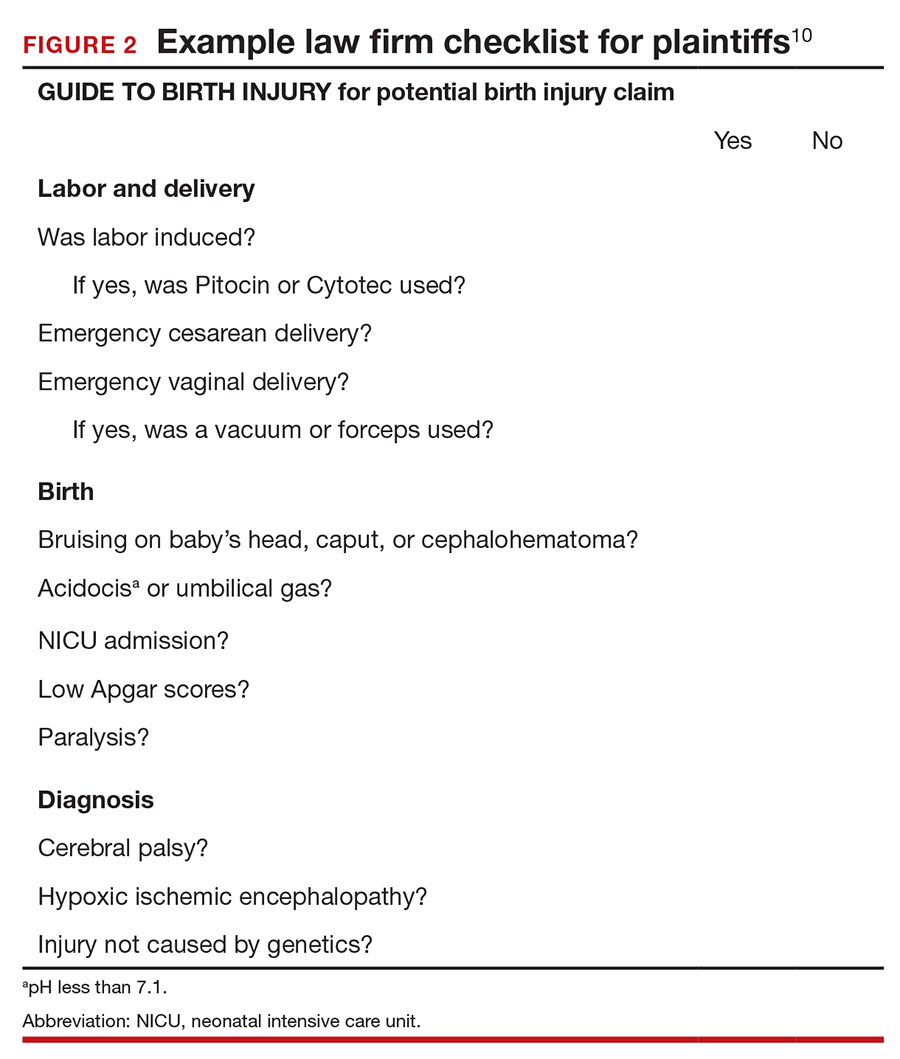

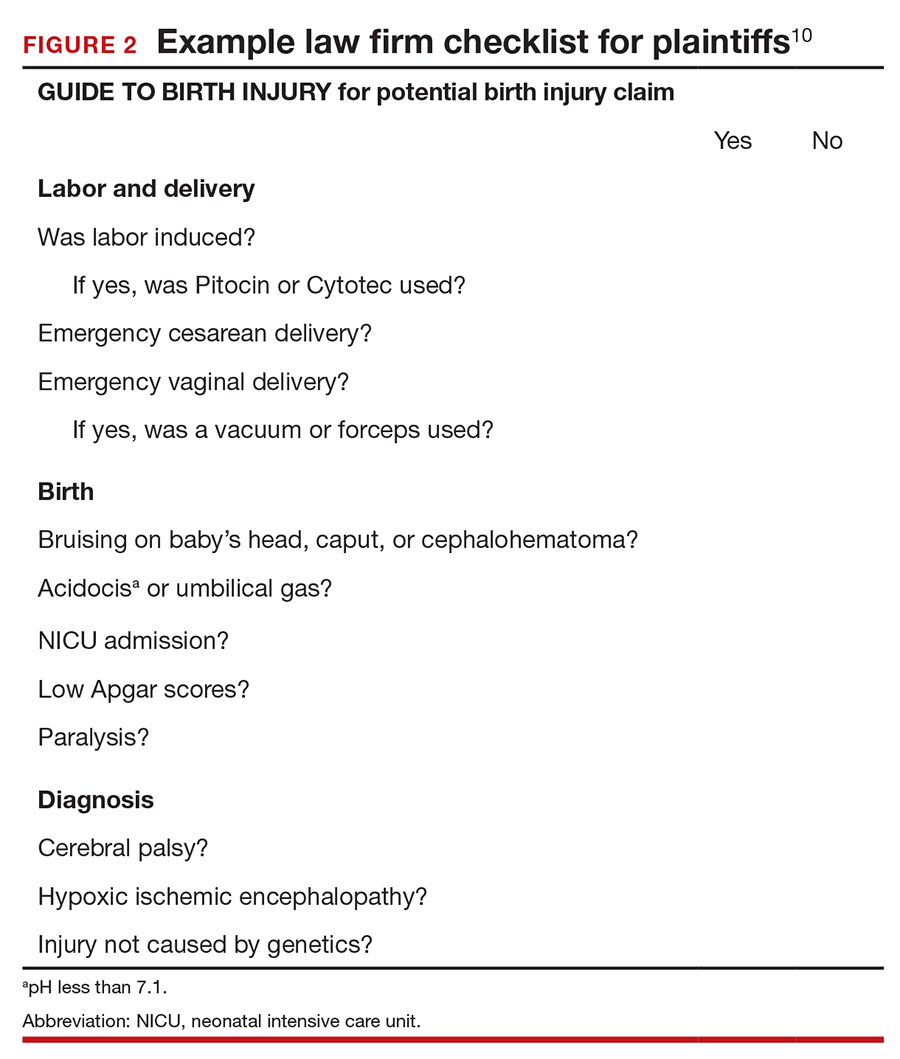

Although CP is not a common event, it has been a major factor in the total malpractice payments for ObGyns, neonatologists, and related medical disciplines. That is because the per-event liability can be staggering. Some law firms provide a “checklist” for plaintiffs early on in assessing a potential case (FIGURE 2).10

The financial risks and incentives

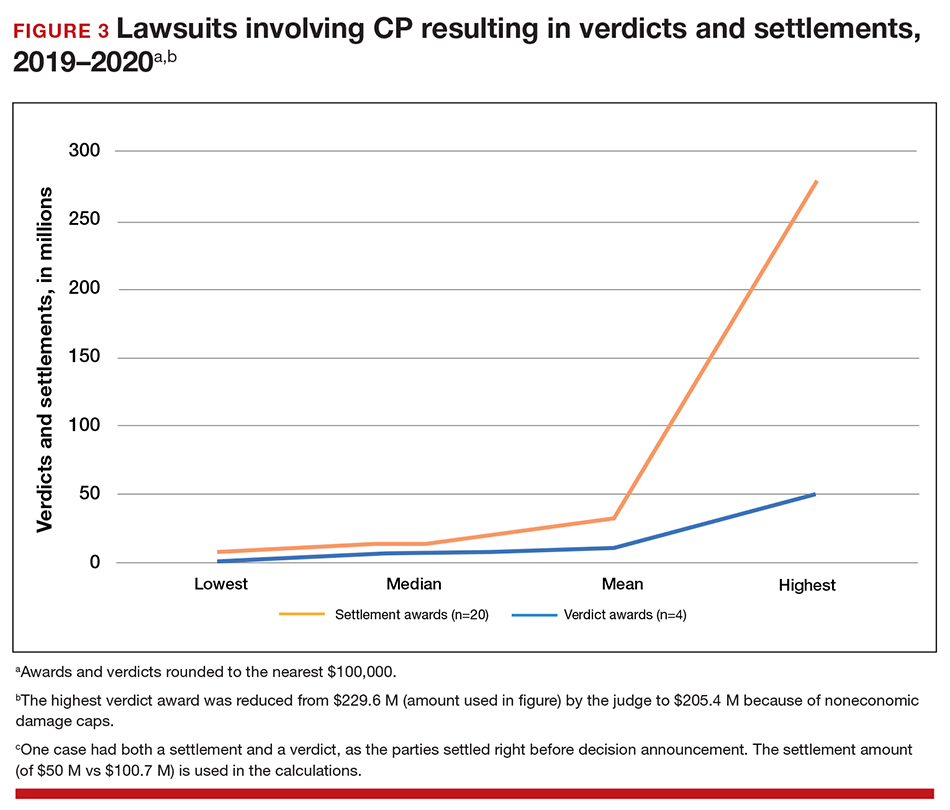

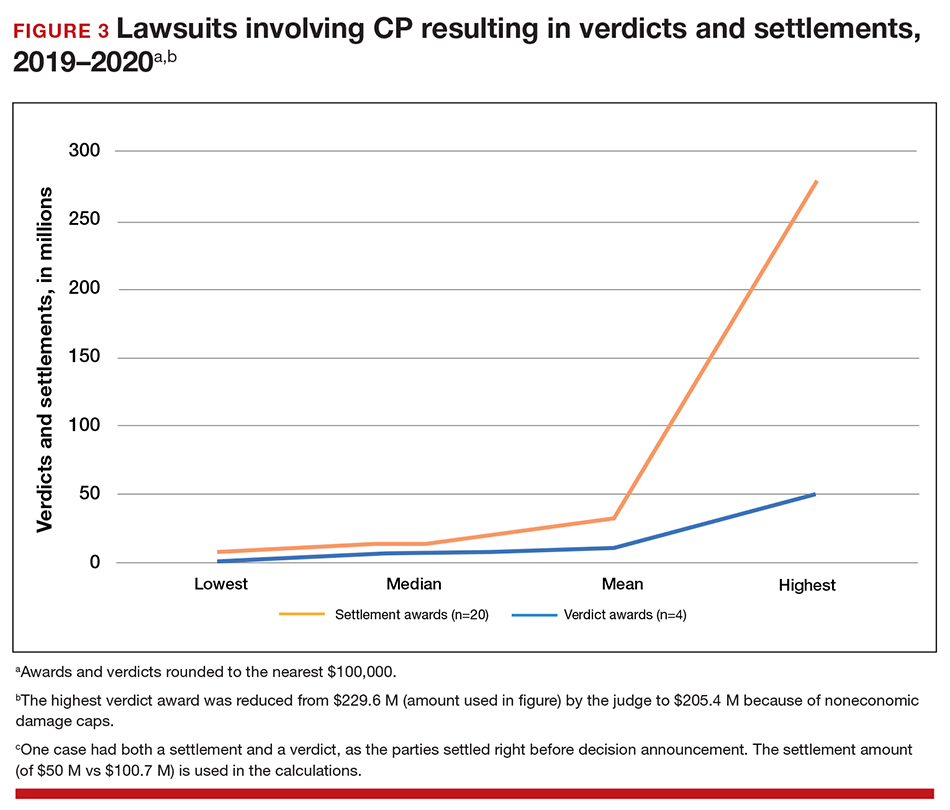

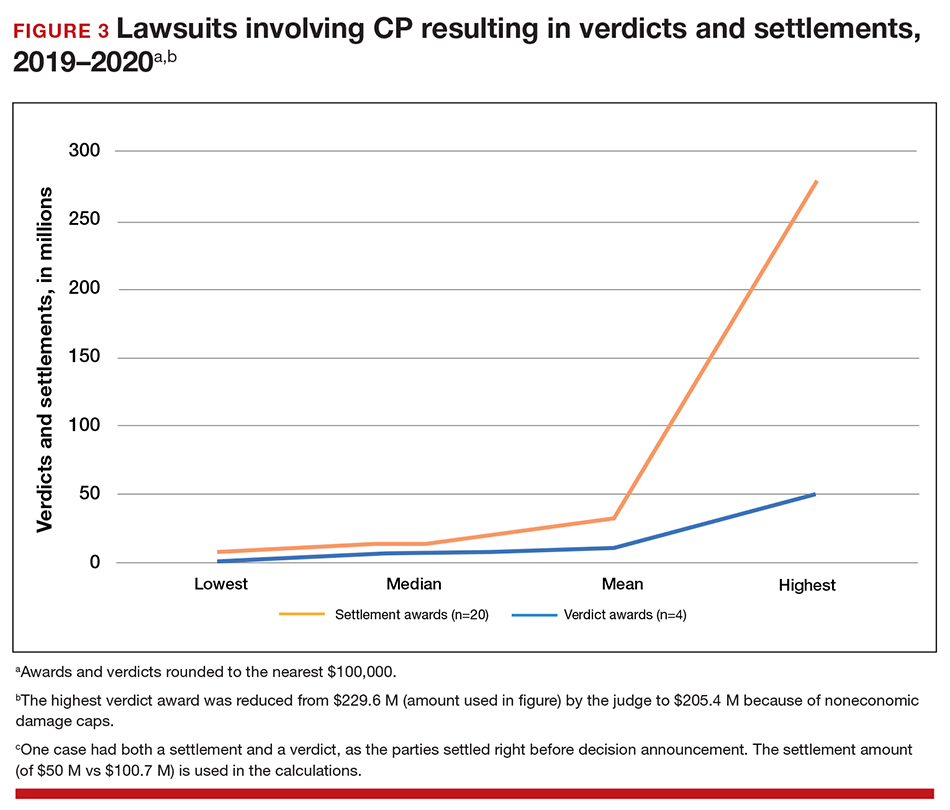

To understand what the current settlements and verdicts are in birth-related CP cases, a search of Lexis files revealed the reported outcomes of cases in 2019 and 2020 (FIGURE 3). Taking into account that the pandemic limited legal activity, 23 unduplicated cases were described with a reported settlement or verdict. Four cases resulted in verdicts for the injured patients, with the mean of these awards substantially higher than the settlements ($88.3 million vs $11.1 million, respectively).

These numbers are a glimpse at some of the very high settlements and verdicts that are common in CP cases. Notably, these are not a random sample of CP cases, but only those with the amount of the verdict or settlement reported. Potentially tried cases that may have been simply abandoned or dismissed are not reported. Furthermore, most settlements include confidentiality clauses, which may preclude the release of the financial value of the settlement. Cases in which the defense won (for example, a jury verdict in favor of the physician) are not included.

The high monetary awards in some CP cases are indirectly backed by Google search results for “cerebral palsy and liability” or “cerebral palsy and malpractice.” A very large number of results for law firms seeking clients with CP injuries is produced. Some of the websites note that only 10% (or 20% on some sites) of CP cases are caused by medical negligence, offering a “free legal case review” and a phone number for callers to “ask a legal question.” In the fine print one site notes that, “if you request any information you may receive a phone call or email from a partner law firm.”11 US physicians may be interested to note that a recent study of CP-based malpractice cases in China found that, although nearly 90% of the claims resulted in compensation, the mean damage award was $73,500.12 This was compared with a mean actual loss to the family of $128,200.

The interest by law firms in CP cases may be generated in part by the opportunity to assist a settlement or judgement that may be in the tens of millions of dollars. It is financially sensible to take a substantial risk on a contingency fee in a CP case compared with many other malpractice areas or claims where the likely damages are much lower. In addition, the vast majority of the damages in CP cases are for economic damages (cost of care and treatment and lost earning capacity), not noneconomic damages (pain and suffering). Therefore, the cap on noneconomic damages available in many states would not reduce the damages by a significant percentage.

CP cases are a significant part of the malpractice costs for ObGyns. Nearly one-third of obstetric claims are for neurologic injuries, including CP.13,14 These cases are often very complex and difficult, meaning that, in addition to the payments to the injured, there are considerable litigation costs associated with defending the cases. Perhaps as much as 60% of malpractice costs in obstetrics are in some way related to CP claims.15,16

Continue to: Negligence...

Negligence

Malpractice cases require not only damages (which clearly there are with CP) but also negligence and causation. (A more complete discussion of the elements of professional liability are included in a recent “What’s the Verdict?” column within

Several areas of negligence are common in CP related to delivery, including failure to monitor properly or ignoring, or not responding to, fetal heart rate (FHR) monitoring.18,19 For FHR monitoring, the claim is that problems can lead to asphyxia, resulting in HIE. Electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) has been an especially contentious matter. On one hand, the evidence of its efficacy is doubtful, but it has remained a standard practice, and it is often a centerpiece of delivery.20 Attorney Thomas Sartwelle has been prolific in suggesting that it not only has created legal problems for physicians but also results in unnecessary cesarean deliveries (CDs), which carry attendant risks for mother and infant.21 (It should be noted that other attorneys have expressed quite different views.22) He has argued that experts relying on EFM should be excluded from testifying because the technology is not based on sufficient science to meet the standard criteria used to determine the admissibility of expert witness (the Daubert standard).23 This argument is a difficult one so long as EFM is standard practice. Other claims of negligence include improper use of instruments at delivery, resulting in physical damage to the baby’s head, neck, or shoulders or internal hemorrhage. In addition, failure to deal with neonatal infection may be the basis for negligence.24

Causation

The question of whether or not the negligence (no matter how bad it was) caused the CP still needs to be addressed. Because a number of factors may cause CP, it has often been difficult to determine for any individual what the cause, or contributing causes, were. This fact would ordinarily work to the advantage of defendant-physicians and hospitals because the plaintiff in a malpractice case must prove by a preponderance of the evidence that the defendant’s negligence caused the CP. “Caused” is a term of art in the law; at the most basic level it means that the harm would not have occurred (or would have been less severe) but for the negligence.

In most CP cases the real cause is unknowable. It is, therefore, important to understand the difference between the certainty required in negligence cases and the certainty required in scientific studies (eg, 95% confidence). Negligence and causation in civil cases (including malpractice) must only be demonstrated by a preponderance of the evidence, which means “more likely than not.” For recovery in malpractice cases, states may require only that negligence be a “substantial factor.”

The theory that this lack of knowledge means that the plaintiff cannot prove causation, however, does not always hold.25 The following is what a jury might see: a child who will have a lifetime of medical, social, and financial burdens. Clear negligent practice by the physician coupled with severe injury can create considerable sympathy for the family. Then there are experts on both sides claiming that it is reasonably certain, in their opinions, that the injury was/was not caused by the negligence of the physician and health care team. The plaintiff’s witnesses will start eliminating other causes of CP in a form of differential diagnosis, stating that the remaining possibilities of causation clearly point to malpractice as the cause of CP. At some point, the elimination of alternative explanations for CP makes malpractice more likely than not to be a substantial factor in causing CP. On the other hand, the defense witnesses will stress that CP occurs most often without any negligence, and that, in this case, there are remaining, perhaps unknown, possible causes that are more likely than malpractice.

In this trial mix, it is not unthinkable that a jury or judge might find the plaintiff’s opinions more appealing. As a practical matter, and contrary to the technical rules, the burden of proof can seem to shift. The defendant clinician may, in effect, have to prove that the CP was caused by something other than the clinician’s negligence.

The role of insurance in award amounts

One reason that malpractice insurance companies settle CP cases for millions of dollars is that they face the possibility of judgements in the tens of millions. We saw even more than $100 million, in the 2019-2020 CP cases reported above. Another risk for malpractice insurance companies is that, if they do not settle, they may have liability beyond the policy limits. (Policy limits are the maximum an insurance policy is obligated to pay for any occurrence, or the total for all claims for the time covered by the premium.) For example, assume a malpractice policy has a $5 million policy limit covering Dr. Defendant, who has been sued for CP resulting from malpractice. There was apparently negligence during delivery in monitoring the fetus, but on the issue of causation the best estimate is that there is a 75% probability a jury would find no causal link between the negligence and the CP. If there is liability, damages would likely range from $5 to $25 million. Assume that the plaintiff has signaled it would settle for the policy limits ($5 million). Based purely on the odds and the policy limits, the insurance company should go to trial as opposed to settling for $5 million. That is because the physician personally (as opposed to the insurance company) is responsible for that part of a verdict that exceeds $5 million.

To prevent just such abuse (or bad faith), in most states, if the insurance company declines to settle the case for $5 million, it may become liable for the excess verdict above the policy limits. One reason that the cases that result in a verdict on damages—the 4 cases reported above for 2019‒2020—are interesting is that they help establish the risk of failing to settle a CP case.

Genetic understanding of causation

Given the importance of defendant-clinicians to be able to find a cause other than negligence to explain CP, the recent research of Moreno-De-Luca and colleagues may be especially meaningful.9 Using exome sequencing, the researchers found that 32.7% of pediatric-aged CP patients had pathogenic variance in the sequencing. In theory, this might mean that for about one-third of the CP plaintiffs, there may be genomic (rather than malpractice) explanations for CP, which might ultimately result in fewer cases of CP.

As significant as these findings are, caution is warranted. As the authors note, “this was an observational study and a causal relationship between detected gene variants and phenotypes in participants was not definitively established.”9 Until the causal relationship is established, it is not clear how much influence such a study would have in CP malpractice cases. Another caveat is that, at most, the genetic variants accounted for less than a third of CP cases studied, leaving many cases in which the cause remains unknown. In those cases in which a genomic association was not found, the case may be stronger for the “malpractice was the cause” claim. The follow-up research will likely shed light on some of these issues. Of course, if the genetic research demonstrates that in some proportion of cases there are genetic factors that contribute to the probability of CP, then the search will be for other triggering elements, which could possibly include poor care (that might well be a substantial factor for malpractice). Therefore, the preliminary genetic research likely represents only a part of the CP puzzle in malpractice cases.

Continue to: Why the opening case outcome was for the defense...

Why the opening case outcome was for the defense

Juries, of course, do not write opinions, so the basis for the jury’s decision in the example case is somewhat speculative. It seems most likely that causation had not been established. That is, the plaintiff-patient did not demonstrate that any malpractice was the likely, or substantial contributing, cause of the CP. The case illustrates several important issues.

Statute of limitations. This issue is common in CP cases because the condition may not be diagnosed for some time after birth. The statute of limitations can vary by state for medical malpractice cases “from 2 years to 22 years.”26 Many states begin with a 2-year statute but extend it if the injury or harm is not discovered. The extension is sometimes referred to as a statute of repose because, after that time, there is no extension even if the harm is discovered only later. In some states the statute does not run until the plaintiff is at or near the time of majority (usually age 18).27

Establishing negligence. The information provided about the presented case is mixed on the question of negligence, both regarding the hospital (through its nursing staff) for not properly contacting the obstetrician over the 10 hours, or the physician for inadequate monitoring. In addition, the reference to “really had to pull to deliver the head” may be the basis for claiming excessive, and potentially harmful use of force, which may have caused injury. In addition, the question remains whether the combination of these factors, including the Category III fetal heart tracing, made a cesarean delivery the appropriate standard of care.

Addressing causation. Assuming negligence, there is still a question of causation. It is far from clear that what the clinician did, or did not do, in terms of monitoring caused the CP injury. There is, however, no alternative causation that appeared in the case record, and this may be because of dueling expert witnesses.

The plaintiff sued both the obstetrician and the hospital, which is common among CP cases. While the legal interest of the two parties are aligned in some areas (causation), they may be in conflict in others (the failure of the hospital staff to keep the obstetrician informed). These potential conflicts are not for the clinicians to try to work out on their own. There is the potential for their actions to be misunderstood. When such a case is filed or threatened, the obstetrician should immediately discuss these matters with their attorney. In malpractice cases, malpractice insurance companies often select the attorneys who are experienced in such conflicts. If clinicians are not entirely comfortable that the appointed attorney is representing their interest and preserving a relationship with the hospital or other institution, however, they may engage their own legal counsel to protect their interests.

Practical considerations for avoiding malpractice claims

Good practices for avoiding malpractice claims apply with special force as it relates to CP.28,29

Uphold practice standards and good patient records. The causation element of these legal cases will remain problematic in the foreseeable future. But causation does not matter if negligent practice is not demonstrated. Therefore, maintaining best practices and continuous efforts at quality assurance and following all relevant professional practice guidelines is a good start. More than good intentions, it is essential that policies are implemented and reviewed. Among the areas of ongoing concern is the failure to monitor patients sufficiently. The long period of labor—where perhaps no physician is present for many hours—can introduce problems, as laypersons may have the impression that medical personnel were not on top of the situation.

Maintaining excellent records is also key for clinicians. The more complete the record, the fewer opportunities there are for faulty memories of parties and caregivers to fill in the gaps (especially when causation is so difficult to establish). Under absolutely no circumstances should records be changed or modified to eliminate damaging or an otherwise unfortunate notation. Few things are as harmful to credibility as discovered record tampering.

Inform patients of what is to come. Expectations are an important part of patient satisfaction. While not unduly frightening pregnant patients or eliminating reassurance, the informed consent process and patient counseling should be opportunities to avoid unreasonable expectations.

Stay alert to early genetic counseling, which is becoming increasingly available and important. Maintaining currency with what early testing can be done will become a critical part of ObGyn practice. For CP cases, in the near future, genetic testing may become part of determining causation. In the longer term, it will be part of counseling women and couples in deciding whether to have children, or potentially to end a pregnancy.

Expect the unexpected, and plan for it. Sometimes things just go wrong—there is a bad outcome, mistakes are made, patients are upset. It is important that any practice or institution have a clear plan for when such things happen. Some organizations have used apologies when appropriate,30 others have more complex plans for dealing with bad outcomes.31 Implement developed plans when they are needed. Individual practitioners also should consult with their attorney, who is familiar with their practice and who can help them maintain adherence to legal requirements and good legal problem prevention. ●

During a trial, all parties generally present evidence on negligence, causation, and damages. They do so without knowing whether a jury will find negligence and causation. The question of what the damages should be in cerebral palsy (CP) cases is also quite complex and expensive, but neither the defense nor the plaintiff can afford to ignore it. Past economic damages are relatively easy to calculate. Damages, for instance, includes medical care (pharmaceuticals and supplies, tests and procedures) and personal care (physical, occupational, and psychological therapy; long-term care; special educational costs; assistive equipment; and home modifications) that would have been avoided if it were not for CP. Future and personal care costs are more speculative, and must be estimated with the help of experts. In addition to future costs for the medical and personal care suggested above, depending on the state, the cost of lost future earnings (or earning capacity) may be additional economic damages. The cost of such intensive care, over a lifetime, accounts for many of the large verdicts and settlements.

Noneconomic damages are also available for such things as pain and suffering and diminished quality of life, both past and future. A number of states cap these noneconomic damages.

The wide range of damages correctly suggests that experts from several disciplines must be engaged to cover the damages landscape. This fact accounts for some of the costs of litigating these cases, and also for why damage calculations can be so complex.

- Fahey M, Macleenan A, Kretzschmar D, et al. The genetic basis of cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59:462-469. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13363.

- Ellenberg J, Nelson, K. The association of cerebral palsy with birth asphyxia: a definitional quagmire. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55:210-216. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12016.

- Emrick L, DiCarlo S. The expanding role of genetics in cerebral palsy. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2020;31:15-24. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2019.09.006.

- Rosenbaum P, Paneth N, Leviton A, et al. A report: the definition and classification of cerebral palsy [published correction appears in Dev Med Child Neurol. 2007;49:480]. Dev Med Child Neuro. 2007;109(suppl):8-14.

- MacLenan A, Lewis S, Moreno-DeLuca A, et al. Genetic or other causation should not change the clinical diagnosis of cerebral palsy. J Child Neurol. 2019;34:472-476. doi: 10.1177/0883073819840449.

- Lewis S, Shetty S, Wilson B, et al. Insights from genetic studies of cerebral palsy. Front Neurol. 2021;11:1-10. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.625428.

- Derick M, Drobyshevsky A, Ji X. A model of cerebral palsy from fetal hypoxia-ischemia. Stroke. 2007;38:731-735. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000251445.94697.64.

- McMichael G, Bainbridge M, Haan E, et al. Whole exome sequencing points to considerable genetic heterogeneity of cerebral palsy. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:176-182. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.189.

- Moreno-DeLuca A, Milan F, Pesacreta D, et al. Molecular diagnostic yield of exome sequencing in patients with cerebral palsy. JAMA. 2021;325:467-475. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.26148.

- Helping disabled children across Maryland & throughout the U.S. The Law Firm of Michael H. Bereston, Inc. website. https://www.berestonlaw.com/birth-injury/. Accessed April 26, 2021.

- Cerebral palsy lawsuits explained. Cerebral Palsy Guide website. https://www.cerebralpalsyguide.com/legal/. Accessed March 22, 2021.

- Zhou L, Li H, Li C, et al. Risk management and provider liabilities in infantile cerebral palsy based on malpractice litigation cases. J Forensic Leg Med. 2019;61:82-88. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2018.11.010.

- Cavanaugh MA. Bad cures for bad babies: policy challenges to the statutory removal of the common law claim for birth-related neurological injuries. Case West Res L Rev. 1992;43:1299-1346.

- Kain ZN, Caldwell-Andrews AA. What pediatricians should know about child-related malpractice payments in the United States. Pediatrics. 2006;118:464-468. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-3112.

- Tabarrok A, Agan A. Medical malpractice awards, insurance, and negligence: which are related? Manhattan Institute Policy Research. Civil Justice Report; 2006. https://media4.manhattan-institute.org/pdf/cjr_10.pdf. Accessed April 27, 2021.

- Freeman AD, Freeman JM. No-fault cerebral palsy insurance: an alternative to the obstetrical malpractice lottery. J Health Politics Policy Law. 1989;14:707-718. doi: 10.1215/03616878-14-4-707.

- Sanfilippo JS, Smith SR. Is there liability if you don’t test for BRCA? OBG Manag. 2021;33:39-46. doi: 10.12788/obgm.0077.

- Fanaroff JM, Goldsmith JP. The most common patient safety issues resulting in legal action against neonatologists. Semin Perinatol. 2019;43:151181-1-9. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2019.08.010.

- Sartwelle TP, Johnston, JC. Cerebral palsy litigation: change course or abandon ship. J Child Neurol. 2015;30:828-841. doi: 10.1177/0883073814543306.

- Roth LM. The Business of Birth. NYU Press: New York, NY; 2021.

- Sartwelle TP. Electronic fetal monitoring: a bridge too far. J Legal Med. 2012;33:313-379. doi: 10.1080/01947648.2012.714321.

- Reiter JM, Walsh RS, Thomas EG. Best practices in birth injury litigation: timing hypoxic-ischemic fetal brain injury. Michigan Bar J. 2018;97:42-44.

- Sartwelle TP. Defending a neurologic birth injury: asphyxia neonatorum redux. J Legal Med. 2009;30:181-247. doi: 10.1080/01947640902936522.

- Daubert v Merrell Dow Pharm, Inc. 509 U.S. 579 (1993).

- Jha S. The factors making Americans litigious. J Am College Radiology. 2019;17:551-553. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2019.10.011.

- Salvi S, Pritchard PC. Statute of limitations on cerebral palsy cases. Personal Injury Lawyers website. https://www.salvilaw.com/birth-injury-lawyers/cerebral-palsy/time-limits/. Accessed March 24, 2021.

- Wharton R. Cerebral palsy statute of limitations. Cerebral Palsy Guidance website. October 16, 2020. https://www.cerebralpalsyguidance.com/cerebral-palsy-lawyer/statute-of-limitations/. Accessed March 24, 2021.

- Kassim PJ, Ushiro S, Najid KM. Compensating cerebral palsy cases: problems in court litigation and the no-fault alternative. Med Law. 2015;34:335-355.

- Williams D. Practice patterns to decrease the risk of malpractice suit. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;51:680-687. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181899bc7.

- McMichael BJ, Van Horn RL, Viscusi WK. “Sorry” is never enough: how state apology laws fail to reduce medical malpractice liability risk. Stanford Law Rev. 2019;71:341-409.

- Kachalia A, Kaufman SR, Boothman R, et al. Liability claims and costs before and after implementation of a medical error disclosure program. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:213-221. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-4-201008170-00002.

CASE Mixed CP diagnosed at age 6 months

After learning that the statute of limitations was to run out in the near future, the parents of a 17-year-old with cerebral palsy (CP) initiated a lawsuit. At the time of her pregnancy, the mother (G2P2002) was age 39 and first sought prenatal care at 14 weeks.

Her past medical history was largely noncontributory to her current pregnancy, except for that she had hypothyroidism that was being treated with levothyroxine. She also had a history of asthma, but had had no acute episodes for years. During the course of the pregnancy there was evidence of polyhydramnios; her initial thyroid studies were abnormal (thyroid-stimulating hormone levels, 7.1 mIU/L), in part due to lack of adherence with prescribed medications. She was noted to have elevated blood pressure (BP) 150/100 mm Hg but no proteinuria, with BP monitoring during her last trimester.

The patient went into labor at 40 3/7 weeks, after spontaneous rupture of membranes. In labor and delivery she was placed on a monitor, and irregular contractions were noted. The initial vaginal examination was noted as 1-cm cervical dilation, 90% effaced, and station zero. The obstetrician evaluated the patient and ordered Pitocin augmentation. The next vaginal exam several hours later noted 3-cm dilation and 100% effacement. The Pitocin was continued. Several early decelerations, moderate variability, and better contraction pattern was noted. Eight hours into the Pitocin, there were repetitive late decelerations; the obstetrician was not notified. The nursing staff proceeded with vaginal examination, and the patient was fully dilated at station +1. Again, the doctor was not informed of the patient’s status. At 10 hours post-Pitocin initiation, the patient felt the urge to push. The obstetrician was notified, and he promptly arrived to the unit and patient’s bedside. His decision was to use forceps for the delivery, feeling this would be the most expedient way to proceed, although cesarean delivery (CD) was a definite consideration. Forceps were applied, and as the nursing staff noted,” the doctor really had to pull to deliver the head.” A male baby, 8 lb 8 oz, was delivered. A second-degree tear was noted and easily repaired following delivery of the placenta. Apgar scores were 5 and 7 at 1 and 5 minutes after birth, respectively.

The patient’s postpartum course was uneventful. The patient and baby were discharged on the third day postpartum.

As the child was evaluated by the pediatrician, the mother noted at 6 months that the child’s head lagged behind when he was picked up. He appeared stiff at times and floppy at other times according to the parents. As the child progressed he had problems with hand-to-mouth coordination, and when he would crawl he seemed to “scoot his butt,” as they stated.

The child was tested and a diagnosis of mixed cerebral palsy was made, implying a combination of spastic CP and dyskinetic CP. He is wheelchair bound. The parents filed a lawsuit against the obstetrician and the hospital, focused on hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) due to labor and delivery management being below the standard of care. They claimed that the obstetrician should have been informed by the hospital staff during the course of labor, and the obstetrician should have been more proactive in monitoring the deteriorating circumstances. This included performing a CD based on “the Category III fetal heart tracing.”

At trial, the plaintiff expert argued that failure of nursing staff to properly communicate with the obstetrician led to mismanagement. Furthermore, the obstetrician used poor judgement (ie, below the standard of care) in not performing a CD. The defense expert argued that, overall, the fetal heart tracing was Category II, and the events occurred in utero, in part reflected by the mother having polyhydramnios and hypothyroidism that was not well controlled due to lack of adherence with prescribed medications. The child in his wheelchair was brought into the courtroom. The trial went on for more than 1 week, and the jury deliberated for several hours. (Note: This case is a composite of several different events and claims.)

Continue to: WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

The jury returns a verdict for the defense.

Should anything have been done differently in this trial?

Medical considerations

Cerebral palsy is a neurodevelopmental disorder affecting 1 in 500 children.1 Other prevalence data (from a European study) indicate an incidence of 1.3–1.9 cases per 1,000 livebirths.1 The controversy continues with respect to the disorder’s etiology, especially when the infant’s magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) does not identify specific pathology. The finger is then pointed at HIE and thus the fault of the obstetrician and labor and delivery staff. In reality, HIE accounts for less than 10% of all cases of CP.2 Overall, CP is a condition focused on progressive motor impairments, many times associated with specific MRI findings.3 In addition, “MRI-negative” CP is a more vague diagnosis as discussed among neurologists.

The International Consensus Definition of CP is “a group of permanent disorders of the development of movement and posture, causing activity limitations, that are attributed to nonprogressive disturbances that occurred in the developing fetal or infant brain.”4 The International Cerebral Palsy Genomics Consortium have provided a consensus statement that defines CP based upon clinical type as opposed to etiology.5 Many times, however, ascribing an HIE cause to CP is “barking up the wrong tree,” in that we now know there are clear cut genetic causes of CP, and etiology attributed to perinatal causes, in reality, are genetic in up to 80% of cases.3 Types of CP are addressed in FIGURE 1. Overall, the pathophysiology of the disorder remains unknown. Some affected children have intellectual disabilities, as well as visual, hearing, and/or speech impairment.

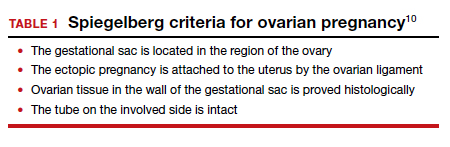

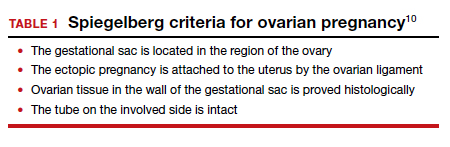

A number of risk factors have been associated with CP (TABLE 1),3,6 which contribute to cell death in the brain or altered maturation of neurons and glia, resulting in abnormal white matter tracts and smaller central nervous system (CNS) volume or cerebellar hypoxia.6 One very important aspect of assessment for CP is specific gene mutations, which may vary in part dependent upon the presence or absence of environmental factors (insults).1 Mutations can lead to profound adverse effects with resultant CNS ischemia and neuromotor disability. In fact, genetics play a major role in determining the etiology of CP.1 Of interest, animal models who are subject to HIE induction have CNS effects resulting in permanent motor impairment.7

DNA sequencing

The DNA story continues to unfold with the concept that DNA variants alter susceptibility to environmental influences. These insults are, for example, thrombosis or hemorrhage, all of which affect motor function.1 Duplications or deletions of portions of a chromosome, related to copy number variants (CNVs) as well as advances in human-genome sequencing, can identify a single gene mutation leading to CP.1 Microdeletions, microduplications, and single nucleotide variants (SNVs) are to be included in genetic-related problems causing CP.3

A number of candidate genes have been considered and include “de novo heterozygous mutations in known Online Mendelian Inheritance (OMIM).” TIBA1A and SCN8A genes are highly associated with CP.8 Genetic assessment, as it evolves and more recently with the advent of exome sequencing, appears to provide a new and unprecedented level of understanding of CP. Specifically, exome sequencing provides a diagnostic tool with which to identify the prevalence of pathogenic and pathogenic variants (the latter encompassing genomic variants) with CP.9 A retrospective study assessed a cohort of patients with CP and noted that 32.7% of the pediatric-aged patients who underwent exome sequencing had pathogenic and pathogenic variants in the sequencing.9 Thus, we have a tool to identify underlying genetic pathogenesis with CP. This theoretically can change the outcome of lawsuits initiated for CP that ascribe an HIE etiology. Clinicians need to stay tuned as the genetic repertoire continues to unfold.

Continue to: Legal considerations...

Legal considerations

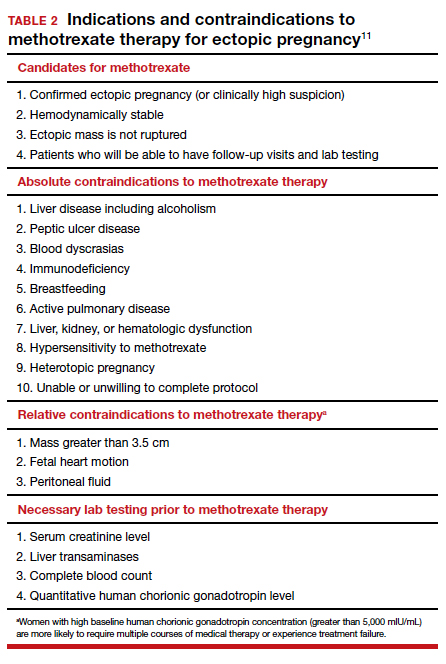

Although CP is not a common event, it has been a major factor in the total malpractice payments for ObGyns, neonatologists, and related medical disciplines. That is because the per-event liability can be staggering. Some law firms provide a “checklist” for plaintiffs early on in assessing a potential case (FIGURE 2).10

The financial risks and incentives

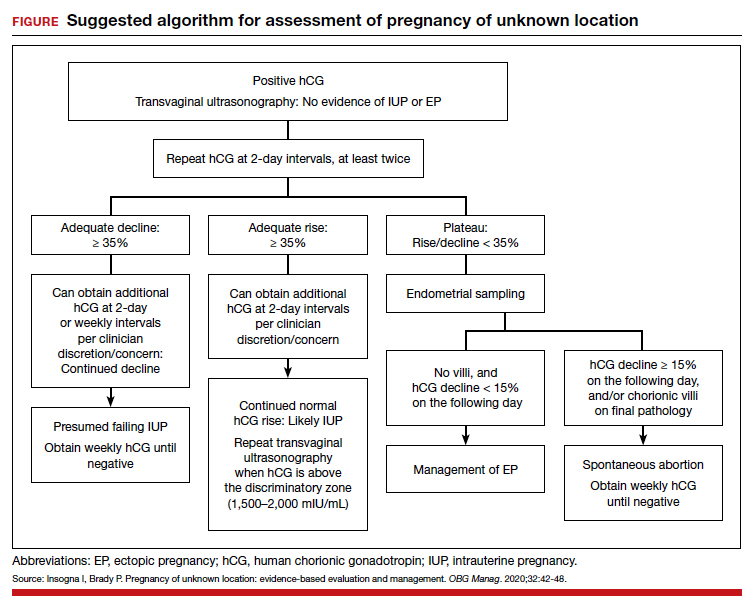

To understand what the current settlements and verdicts are in birth-related CP cases, a search of Lexis files revealed the reported outcomes of cases in 2019 and 2020 (FIGURE 3). Taking into account that the pandemic limited legal activity, 23 unduplicated cases were described with a reported settlement or verdict. Four cases resulted in verdicts for the injured patients, with the mean of these awards substantially higher than the settlements ($88.3 million vs $11.1 million, respectively).

These numbers are a glimpse at some of the very high settlements and verdicts that are common in CP cases. Notably, these are not a random sample of CP cases, but only those with the amount of the verdict or settlement reported. Potentially tried cases that may have been simply abandoned or dismissed are not reported. Furthermore, most settlements include confidentiality clauses, which may preclude the release of the financial value of the settlement. Cases in which the defense won (for example, a jury verdict in favor of the physician) are not included.

The high monetary awards in some CP cases are indirectly backed by Google search results for “cerebral palsy and liability” or “cerebral palsy and malpractice.” A very large number of results for law firms seeking clients with CP injuries is produced. Some of the websites note that only 10% (or 20% on some sites) of CP cases are caused by medical negligence, offering a “free legal case review” and a phone number for callers to “ask a legal question.” In the fine print one site notes that, “if you request any information you may receive a phone call or email from a partner law firm.”11 US physicians may be interested to note that a recent study of CP-based malpractice cases in China found that, although nearly 90% of the claims resulted in compensation, the mean damage award was $73,500.12 This was compared with a mean actual loss to the family of $128,200.

The interest by law firms in CP cases may be generated in part by the opportunity to assist a settlement or judgement that may be in the tens of millions of dollars. It is financially sensible to take a substantial risk on a contingency fee in a CP case compared with many other malpractice areas or claims where the likely damages are much lower. In addition, the vast majority of the damages in CP cases are for economic damages (cost of care and treatment and lost earning capacity), not noneconomic damages (pain and suffering). Therefore, the cap on noneconomic damages available in many states would not reduce the damages by a significant percentage.

CP cases are a significant part of the malpractice costs for ObGyns. Nearly one-third of obstetric claims are for neurologic injuries, including CP.13,14 These cases are often very complex and difficult, meaning that, in addition to the payments to the injured, there are considerable litigation costs associated with defending the cases. Perhaps as much as 60% of malpractice costs in obstetrics are in some way related to CP claims.15,16

Continue to: Negligence...

Negligence

Malpractice cases require not only damages (which clearly there are with CP) but also negligence and causation. (A more complete discussion of the elements of professional liability are included in a recent “What’s the Verdict?” column within

Several areas of negligence are common in CP related to delivery, including failure to monitor properly or ignoring, or not responding to, fetal heart rate (FHR) monitoring.18,19 For FHR monitoring, the claim is that problems can lead to asphyxia, resulting in HIE. Electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) has been an especially contentious matter. On one hand, the evidence of its efficacy is doubtful, but it has remained a standard practice, and it is often a centerpiece of delivery.20 Attorney Thomas Sartwelle has been prolific in suggesting that it not only has created legal problems for physicians but also results in unnecessary cesarean deliveries (CDs), which carry attendant risks for mother and infant.21 (It should be noted that other attorneys have expressed quite different views.22) He has argued that experts relying on EFM should be excluded from testifying because the technology is not based on sufficient science to meet the standard criteria used to determine the admissibility of expert witness (the Daubert standard).23 This argument is a difficult one so long as EFM is standard practice. Other claims of negligence include improper use of instruments at delivery, resulting in physical damage to the baby’s head, neck, or shoulders or internal hemorrhage. In addition, failure to deal with neonatal infection may be the basis for negligence.24

Causation

The question of whether or not the negligence (no matter how bad it was) caused the CP still needs to be addressed. Because a number of factors may cause CP, it has often been difficult to determine for any individual what the cause, or contributing causes, were. This fact would ordinarily work to the advantage of defendant-physicians and hospitals because the plaintiff in a malpractice case must prove by a preponderance of the evidence that the defendant’s negligence caused the CP. “Caused” is a term of art in the law; at the most basic level it means that the harm would not have occurred (or would have been less severe) but for the negligence.

In most CP cases the real cause is unknowable. It is, therefore, important to understand the difference between the certainty required in negligence cases and the certainty required in scientific studies (eg, 95% confidence). Negligence and causation in civil cases (including malpractice) must only be demonstrated by a preponderance of the evidence, which means “more likely than not.” For recovery in malpractice cases, states may require only that negligence be a “substantial factor.”

The theory that this lack of knowledge means that the plaintiff cannot prove causation, however, does not always hold.25 The following is what a jury might see: a child who will have a lifetime of medical, social, and financial burdens. Clear negligent practice by the physician coupled with severe injury can create considerable sympathy for the family. Then there are experts on both sides claiming that it is reasonably certain, in their opinions, that the injury was/was not caused by the negligence of the physician and health care team. The plaintiff’s witnesses will start eliminating other causes of CP in a form of differential diagnosis, stating that the remaining possibilities of causation clearly point to malpractice as the cause of CP. At some point, the elimination of alternative explanations for CP makes malpractice more likely than not to be a substantial factor in causing CP. On the other hand, the defense witnesses will stress that CP occurs most often without any negligence, and that, in this case, there are remaining, perhaps unknown, possible causes that are more likely than malpractice.

In this trial mix, it is not unthinkable that a jury or judge might find the plaintiff’s opinions more appealing. As a practical matter, and contrary to the technical rules, the burden of proof can seem to shift. The defendant clinician may, in effect, have to prove that the CP was caused by something other than the clinician’s negligence.

The role of insurance in award amounts

One reason that malpractice insurance companies settle CP cases for millions of dollars is that they face the possibility of judgements in the tens of millions. We saw even more than $100 million, in the 2019-2020 CP cases reported above. Another risk for malpractice insurance companies is that, if they do not settle, they may have liability beyond the policy limits. (Policy limits are the maximum an insurance policy is obligated to pay for any occurrence, or the total for all claims for the time covered by the premium.) For example, assume a malpractice policy has a $5 million policy limit covering Dr. Defendant, who has been sued for CP resulting from malpractice. There was apparently negligence during delivery in monitoring the fetus, but on the issue of causation the best estimate is that there is a 75% probability a jury would find no causal link between the negligence and the CP. If there is liability, damages would likely range from $5 to $25 million. Assume that the plaintiff has signaled it would settle for the policy limits ($5 million). Based purely on the odds and the policy limits, the insurance company should go to trial as opposed to settling for $5 million. That is because the physician personally (as opposed to the insurance company) is responsible for that part of a verdict that exceeds $5 million.

To prevent just such abuse (or bad faith), in most states, if the insurance company declines to settle the case for $5 million, it may become liable for the excess verdict above the policy limits. One reason that the cases that result in a verdict on damages—the 4 cases reported above for 2019‒2020—are interesting is that they help establish the risk of failing to settle a CP case.

Genetic understanding of causation

Given the importance of defendant-clinicians to be able to find a cause other than negligence to explain CP, the recent research of Moreno-De-Luca and colleagues may be especially meaningful.9 Using exome sequencing, the researchers found that 32.7% of pediatric-aged CP patients had pathogenic variance in the sequencing. In theory, this might mean that for about one-third of the CP plaintiffs, there may be genomic (rather than malpractice) explanations for CP, which might ultimately result in fewer cases of CP.

As significant as these findings are, caution is warranted. As the authors note, “this was an observational study and a causal relationship between detected gene variants and phenotypes in participants was not definitively established.”9 Until the causal relationship is established, it is not clear how much influence such a study would have in CP malpractice cases. Another caveat is that, at most, the genetic variants accounted for less than a third of CP cases studied, leaving many cases in which the cause remains unknown. In those cases in which a genomic association was not found, the case may be stronger for the “malpractice was the cause” claim. The follow-up research will likely shed light on some of these issues. Of course, if the genetic research demonstrates that in some proportion of cases there are genetic factors that contribute to the probability of CP, then the search will be for other triggering elements, which could possibly include poor care (that might well be a substantial factor for malpractice). Therefore, the preliminary genetic research likely represents only a part of the CP puzzle in malpractice cases.

Continue to: Why the opening case outcome was for the defense...

Why the opening case outcome was for the defense

Juries, of course, do not write opinions, so the basis for the jury’s decision in the example case is somewhat speculative. It seems most likely that causation had not been established. That is, the plaintiff-patient did not demonstrate that any malpractice was the likely, or substantial contributing, cause of the CP. The case illustrates several important issues.

Statute of limitations. This issue is common in CP cases because the condition may not be diagnosed for some time after birth. The statute of limitations can vary by state for medical malpractice cases “from 2 years to 22 years.”26 Many states begin with a 2-year statute but extend it if the injury or harm is not discovered. The extension is sometimes referred to as a statute of repose because, after that time, there is no extension even if the harm is discovered only later. In some states the statute does not run until the plaintiff is at or near the time of majority (usually age 18).27

Establishing negligence. The information provided about the presented case is mixed on the question of negligence, both regarding the hospital (through its nursing staff) for not properly contacting the obstetrician over the 10 hours, or the physician for inadequate monitoring. In addition, the reference to “really had to pull to deliver the head” may be the basis for claiming excessive, and potentially harmful use of force, which may have caused injury. In addition, the question remains whether the combination of these factors, including the Category III fetal heart tracing, made a cesarean delivery the appropriate standard of care.

Addressing causation. Assuming negligence, there is still a question of causation. It is far from clear that what the clinician did, or did not do, in terms of monitoring caused the CP injury. There is, however, no alternative causation that appeared in the case record, and this may be because of dueling expert witnesses.

The plaintiff sued both the obstetrician and the hospital, which is common among CP cases. While the legal interest of the two parties are aligned in some areas (causation), they may be in conflict in others (the failure of the hospital staff to keep the obstetrician informed). These potential conflicts are not for the clinicians to try to work out on their own. There is the potential for their actions to be misunderstood. When such a case is filed or threatened, the obstetrician should immediately discuss these matters with their attorney. In malpractice cases, malpractice insurance companies often select the attorneys who are experienced in such conflicts. If clinicians are not entirely comfortable that the appointed attorney is representing their interest and preserving a relationship with the hospital or other institution, however, they may engage their own legal counsel to protect their interests.

Practical considerations for avoiding malpractice claims

Good practices for avoiding malpractice claims apply with special force as it relates to CP.28,29

Uphold practice standards and good patient records. The causation element of these legal cases will remain problematic in the foreseeable future. But causation does not matter if negligent practice is not demonstrated. Therefore, maintaining best practices and continuous efforts at quality assurance and following all relevant professional practice guidelines is a good start. More than good intentions, it is essential that policies are implemented and reviewed. Among the areas of ongoing concern is the failure to monitor patients sufficiently. The long period of labor—where perhaps no physician is present for many hours—can introduce problems, as laypersons may have the impression that medical personnel were not on top of the situation.

Maintaining excellent records is also key for clinicians. The more complete the record, the fewer opportunities there are for faulty memories of parties and caregivers to fill in the gaps (especially when causation is so difficult to establish). Under absolutely no circumstances should records be changed or modified to eliminate damaging or an otherwise unfortunate notation. Few things are as harmful to credibility as discovered record tampering.

Inform patients of what is to come. Expectations are an important part of patient satisfaction. While not unduly frightening pregnant patients or eliminating reassurance, the informed consent process and patient counseling should be opportunities to avoid unreasonable expectations.

Stay alert to early genetic counseling, which is becoming increasingly available and important. Maintaining currency with what early testing can be done will become a critical part of ObGyn practice. For CP cases, in the near future, genetic testing may become part of determining causation. In the longer term, it will be part of counseling women and couples in deciding whether to have children, or potentially to end a pregnancy.

Expect the unexpected, and plan for it. Sometimes things just go wrong—there is a bad outcome, mistakes are made, patients are upset. It is important that any practice or institution have a clear plan for when such things happen. Some organizations have used apologies when appropriate,30 others have more complex plans for dealing with bad outcomes.31 Implement developed plans when they are needed. Individual practitioners also should consult with their attorney, who is familiar with their practice and who can help them maintain adherence to legal requirements and good legal problem prevention. ●

During a trial, all parties generally present evidence on negligence, causation, and damages. They do so without knowing whether a jury will find negligence and causation. The question of what the damages should be in cerebral palsy (CP) cases is also quite complex and expensive, but neither the defense nor the plaintiff can afford to ignore it. Past economic damages are relatively easy to calculate. Damages, for instance, includes medical care (pharmaceuticals and supplies, tests and procedures) and personal care (physical, occupational, and psychological therapy; long-term care; special educational costs; assistive equipment; and home modifications) that would have been avoided if it were not for CP. Future and personal care costs are more speculative, and must be estimated with the help of experts. In addition to future costs for the medical and personal care suggested above, depending on the state, the cost of lost future earnings (or earning capacity) may be additional economic damages. The cost of such intensive care, over a lifetime, accounts for many of the large verdicts and settlements.

Noneconomic damages are also available for such things as pain and suffering and diminished quality of life, both past and future. A number of states cap these noneconomic damages.

The wide range of damages correctly suggests that experts from several disciplines must be engaged to cover the damages landscape. This fact accounts for some of the costs of litigating these cases, and also for why damage calculations can be so complex.

CASE Mixed CP diagnosed at age 6 months

After learning that the statute of limitations was to run out in the near future, the parents of a 17-year-old with cerebral palsy (CP) initiated a lawsuit. At the time of her pregnancy, the mother (G2P2002) was age 39 and first sought prenatal care at 14 weeks.

Her past medical history was largely noncontributory to her current pregnancy, except for that she had hypothyroidism that was being treated with levothyroxine. She also had a history of asthma, but had had no acute episodes for years. During the course of the pregnancy there was evidence of polyhydramnios; her initial thyroid studies were abnormal (thyroid-stimulating hormone levels, 7.1 mIU/L), in part due to lack of adherence with prescribed medications. She was noted to have elevated blood pressure (BP) 150/100 mm Hg but no proteinuria, with BP monitoring during her last trimester.

The patient went into labor at 40 3/7 weeks, after spontaneous rupture of membranes. In labor and delivery she was placed on a monitor, and irregular contractions were noted. The initial vaginal examination was noted as 1-cm cervical dilation, 90% effaced, and station zero. The obstetrician evaluated the patient and ordered Pitocin augmentation. The next vaginal exam several hours later noted 3-cm dilation and 100% effacement. The Pitocin was continued. Several early decelerations, moderate variability, and better contraction pattern was noted. Eight hours into the Pitocin, there were repetitive late decelerations; the obstetrician was not notified. The nursing staff proceeded with vaginal examination, and the patient was fully dilated at station +1. Again, the doctor was not informed of the patient’s status. At 10 hours post-Pitocin initiation, the patient felt the urge to push. The obstetrician was notified, and he promptly arrived to the unit and patient’s bedside. His decision was to use forceps for the delivery, feeling this would be the most expedient way to proceed, although cesarean delivery (CD) was a definite consideration. Forceps were applied, and as the nursing staff noted,” the doctor really had to pull to deliver the head.” A male baby, 8 lb 8 oz, was delivered. A second-degree tear was noted and easily repaired following delivery of the placenta. Apgar scores were 5 and 7 at 1 and 5 minutes after birth, respectively.

The patient’s postpartum course was uneventful. The patient and baby were discharged on the third day postpartum.

As the child was evaluated by the pediatrician, the mother noted at 6 months that the child’s head lagged behind when he was picked up. He appeared stiff at times and floppy at other times according to the parents. As the child progressed he had problems with hand-to-mouth coordination, and when he would crawl he seemed to “scoot his butt,” as they stated.

The child was tested and a diagnosis of mixed cerebral palsy was made, implying a combination of spastic CP and dyskinetic CP. He is wheelchair bound. The parents filed a lawsuit against the obstetrician and the hospital, focused on hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) due to labor and delivery management being below the standard of care. They claimed that the obstetrician should have been informed by the hospital staff during the course of labor, and the obstetrician should have been more proactive in monitoring the deteriorating circumstances. This included performing a CD based on “the Category III fetal heart tracing.”

At trial, the plaintiff expert argued that failure of nursing staff to properly communicate with the obstetrician led to mismanagement. Furthermore, the obstetrician used poor judgement (ie, below the standard of care) in not performing a CD. The defense expert argued that, overall, the fetal heart tracing was Category II, and the events occurred in utero, in part reflected by the mother having polyhydramnios and hypothyroidism that was not well controlled due to lack of adherence with prescribed medications. The child in his wheelchair was brought into the courtroom. The trial went on for more than 1 week, and the jury deliberated for several hours. (Note: This case is a composite of several different events and claims.)

Continue to: WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

WHAT’S THE VERDICT?

The jury returns a verdict for the defense.

Should anything have been done differently in this trial?

Medical considerations

Cerebral palsy is a neurodevelopmental disorder affecting 1 in 500 children.1 Other prevalence data (from a European study) indicate an incidence of 1.3–1.9 cases per 1,000 livebirths.1 The controversy continues with respect to the disorder’s etiology, especially when the infant’s magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) does not identify specific pathology. The finger is then pointed at HIE and thus the fault of the obstetrician and labor and delivery staff. In reality, HIE accounts for less than 10% of all cases of CP.2 Overall, CP is a condition focused on progressive motor impairments, many times associated with specific MRI findings.3 In addition, “MRI-negative” CP is a more vague diagnosis as discussed among neurologists.

The International Consensus Definition of CP is “a group of permanent disorders of the development of movement and posture, causing activity limitations, that are attributed to nonprogressive disturbances that occurred in the developing fetal or infant brain.”4 The International Cerebral Palsy Genomics Consortium have provided a consensus statement that defines CP based upon clinical type as opposed to etiology.5 Many times, however, ascribing an HIE cause to CP is “barking up the wrong tree,” in that we now know there are clear cut genetic causes of CP, and etiology attributed to perinatal causes, in reality, are genetic in up to 80% of cases.3 Types of CP are addressed in FIGURE 1. Overall, the pathophysiology of the disorder remains unknown. Some affected children have intellectual disabilities, as well as visual, hearing, and/or speech impairment.

A number of risk factors have been associated with CP (TABLE 1),3,6 which contribute to cell death in the brain or altered maturation of neurons and glia, resulting in abnormal white matter tracts and smaller central nervous system (CNS) volume or cerebellar hypoxia.6 One very important aspect of assessment for CP is specific gene mutations, which may vary in part dependent upon the presence or absence of environmental factors (insults).1 Mutations can lead to profound adverse effects with resultant CNS ischemia and neuromotor disability. In fact, genetics play a major role in determining the etiology of CP.1 Of interest, animal models who are subject to HIE induction have CNS effects resulting in permanent motor impairment.7

DNA sequencing

The DNA story continues to unfold with the concept that DNA variants alter susceptibility to environmental influences. These insults are, for example, thrombosis or hemorrhage, all of which affect motor function.1 Duplications or deletions of portions of a chromosome, related to copy number variants (CNVs) as well as advances in human-genome sequencing, can identify a single gene mutation leading to CP.1 Microdeletions, microduplications, and single nucleotide variants (SNVs) are to be included in genetic-related problems causing CP.3

A number of candidate genes have been considered and include “de novo heterozygous mutations in known Online Mendelian Inheritance (OMIM).” TIBA1A and SCN8A genes are highly associated with CP.8 Genetic assessment, as it evolves and more recently with the advent of exome sequencing, appears to provide a new and unprecedented level of understanding of CP. Specifically, exome sequencing provides a diagnostic tool with which to identify the prevalence of pathogenic and pathogenic variants (the latter encompassing genomic variants) with CP.9 A retrospective study assessed a cohort of patients with CP and noted that 32.7% of the pediatric-aged patients who underwent exome sequencing had pathogenic and pathogenic variants in the sequencing.9 Thus, we have a tool to identify underlying genetic pathogenesis with CP. This theoretically can change the outcome of lawsuits initiated for CP that ascribe an HIE etiology. Clinicians need to stay tuned as the genetic repertoire continues to unfold.

Continue to: Legal considerations...

Legal considerations

Although CP is not a common event, it has been a major factor in the total malpractice payments for ObGyns, neonatologists, and related medical disciplines. That is because the per-event liability can be staggering. Some law firms provide a “checklist” for plaintiffs early on in assessing a potential case (FIGURE 2).10

The financial risks and incentives

To understand what the current settlements and verdicts are in birth-related CP cases, a search of Lexis files revealed the reported outcomes of cases in 2019 and 2020 (FIGURE 3). Taking into account that the pandemic limited legal activity, 23 unduplicated cases were described with a reported settlement or verdict. Four cases resulted in verdicts for the injured patients, with the mean of these awards substantially higher than the settlements ($88.3 million vs $11.1 million, respectively).

These numbers are a glimpse at some of the very high settlements and verdicts that are common in CP cases. Notably, these are not a random sample of CP cases, but only those with the amount of the verdict or settlement reported. Potentially tried cases that may have been simply abandoned or dismissed are not reported. Furthermore, most settlements include confidentiality clauses, which may preclude the release of the financial value of the settlement. Cases in which the defense won (for example, a jury verdict in favor of the physician) are not included.

The high monetary awards in some CP cases are indirectly backed by Google search results for “cerebral palsy and liability” or “cerebral palsy and malpractice.” A very large number of results for law firms seeking clients with CP injuries is produced. Some of the websites note that only 10% (or 20% on some sites) of CP cases are caused by medical negligence, offering a “free legal case review” and a phone number for callers to “ask a legal question.” In the fine print one site notes that, “if you request any information you may receive a phone call or email from a partner law firm.”11 US physicians may be interested to note that a recent study of CP-based malpractice cases in China found that, although nearly 90% of the claims resulted in compensation, the mean damage award was $73,500.12 This was compared with a mean actual loss to the family of $128,200.

The interest by law firms in CP cases may be generated in part by the opportunity to assist a settlement or judgement that may be in the tens of millions of dollars. It is financially sensible to take a substantial risk on a contingency fee in a CP case compared with many other malpractice areas or claims where the likely damages are much lower. In addition, the vast majority of the damages in CP cases are for economic damages (cost of care and treatment and lost earning capacity), not noneconomic damages (pain and suffering). Therefore, the cap on noneconomic damages available in many states would not reduce the damages by a significant percentage.

CP cases are a significant part of the malpractice costs for ObGyns. Nearly one-third of obstetric claims are for neurologic injuries, including CP.13,14 These cases are often very complex and difficult, meaning that, in addition to the payments to the injured, there are considerable litigation costs associated with defending the cases. Perhaps as much as 60% of malpractice costs in obstetrics are in some way related to CP claims.15,16

Continue to: Negligence...

Negligence

Malpractice cases require not only damages (which clearly there are with CP) but also negligence and causation. (A more complete discussion of the elements of professional liability are included in a recent “What’s the Verdict?” column within

Several areas of negligence are common in CP related to delivery, including failure to monitor properly or ignoring, or not responding to, fetal heart rate (FHR) monitoring.18,19 For FHR monitoring, the claim is that problems can lead to asphyxia, resulting in HIE. Electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) has been an especially contentious matter. On one hand, the evidence of its efficacy is doubtful, but it has remained a standard practice, and it is often a centerpiece of delivery.20 Attorney Thomas Sartwelle has been prolific in suggesting that it not only has created legal problems for physicians but also results in unnecessary cesarean deliveries (CDs), which carry attendant risks for mother and infant.21 (It should be noted that other attorneys have expressed quite different views.22) He has argued that experts relying on EFM should be excluded from testifying because the technology is not based on sufficient science to meet the standard criteria used to determine the admissibility of expert witness (the Daubert standard).23 This argument is a difficult one so long as EFM is standard practice. Other claims of negligence include improper use of instruments at delivery, resulting in physical damage to the baby’s head, neck, or shoulders or internal hemorrhage. In addition, failure to deal with neonatal infection may be the basis for negligence.24

Causation

The question of whether or not the negligence (no matter how bad it was) caused the CP still needs to be addressed. Because a number of factors may cause CP, it has often been difficult to determine for any individual what the cause, or contributing causes, were. This fact would ordinarily work to the advantage of defendant-physicians and hospitals because the plaintiff in a malpractice case must prove by a preponderance of the evidence that the defendant’s negligence caused the CP. “Caused” is a term of art in the law; at the most basic level it means that the harm would not have occurred (or would have been less severe) but for the negligence.

In most CP cases the real cause is unknowable. It is, therefore, important to understand the difference between the certainty required in negligence cases and the certainty required in scientific studies (eg, 95% confidence). Negligence and causation in civil cases (including malpractice) must only be demonstrated by a preponderance of the evidence, which means “more likely than not.” For recovery in malpractice cases, states may require only that negligence be a “substantial factor.”

The theory that this lack of knowledge means that the plaintiff cannot prove causation, however, does not always hold.25 The following is what a jury might see: a child who will have a lifetime of medical, social, and financial burdens. Clear negligent practice by the physician coupled with severe injury can create considerable sympathy for the family. Then there are experts on both sides claiming that it is reasonably certain, in their opinions, that the injury was/was not caused by the negligence of the physician and health care team. The plaintiff’s witnesses will start eliminating other causes of CP in a form of differential diagnosis, stating that the remaining possibilities of causation clearly point to malpractice as the cause of CP. At some point, the elimination of alternative explanations for CP makes malpractice more likely than not to be a substantial factor in causing CP. On the other hand, the defense witnesses will stress that CP occurs most often without any negligence, and that, in this case, there are remaining, perhaps unknown, possible causes that are more likely than malpractice.

In this trial mix, it is not unthinkable that a jury or judge might find the plaintiff’s opinions more appealing. As a practical matter, and contrary to the technical rules, the burden of proof can seem to shift. The defendant clinician may, in effect, have to prove that the CP was caused by something other than the clinician’s negligence.

The role of insurance in award amounts

One reason that malpractice insurance companies settle CP cases for millions of dollars is that they face the possibility of judgements in the tens of millions. We saw even more than $100 million, in the 2019-2020 CP cases reported above. Another risk for malpractice insurance companies is that, if they do not settle, they may have liability beyond the policy limits. (Policy limits are the maximum an insurance policy is obligated to pay for any occurrence, or the total for all claims for the time covered by the premium.) For example, assume a malpractice policy has a $5 million policy limit covering Dr. Defendant, who has been sued for CP resulting from malpractice. There was apparently negligence during delivery in monitoring the fetus, but on the issue of causation the best estimate is that there is a 75% probability a jury would find no causal link between the negligence and the CP. If there is liability, damages would likely range from $5 to $25 million. Assume that the plaintiff has signaled it would settle for the policy limits ($5 million). Based purely on the odds and the policy limits, the insurance company should go to trial as opposed to settling for $5 million. That is because the physician personally (as opposed to the insurance company) is responsible for that part of a verdict that exceeds $5 million.

To prevent just such abuse (or bad faith), in most states, if the insurance company declines to settle the case for $5 million, it may become liable for the excess verdict above the policy limits. One reason that the cases that result in a verdict on damages—the 4 cases reported above for 2019‒2020—are interesting is that they help establish the risk of failing to settle a CP case.

Genetic understanding of causation

Given the importance of defendant-clinicians to be able to find a cause other than negligence to explain CP, the recent research of Moreno-De-Luca and colleagues may be especially meaningful.9 Using exome sequencing, the researchers found that 32.7% of pediatric-aged CP patients had pathogenic variance in the sequencing. In theory, this might mean that for about one-third of the CP plaintiffs, there may be genomic (rather than malpractice) explanations for CP, which might ultimately result in fewer cases of CP.

As significant as these findings are, caution is warranted. As the authors note, “this was an observational study and a causal relationship between detected gene variants and phenotypes in participants was not definitively established.”9 Until the causal relationship is established, it is not clear how much influence such a study would have in CP malpractice cases. Another caveat is that, at most, the genetic variants accounted for less than a third of CP cases studied, leaving many cases in which the cause remains unknown. In those cases in which a genomic association was not found, the case may be stronger for the “malpractice was the cause” claim. The follow-up research will likely shed light on some of these issues. Of course, if the genetic research demonstrates that in some proportion of cases there are genetic factors that contribute to the probability of CP, then the search will be for other triggering elements, which could possibly include poor care (that might well be a substantial factor for malpractice). Therefore, the preliminary genetic research likely represents only a part of the CP puzzle in malpractice cases.

Continue to: Why the opening case outcome was for the defense...

Why the opening case outcome was for the defense

Juries, of course, do not write opinions, so the basis for the jury’s decision in the example case is somewhat speculative. It seems most likely that causation had not been established. That is, the plaintiff-patient did not demonstrate that any malpractice was the likely, or substantial contributing, cause of the CP. The case illustrates several important issues.

Statute of limitations. This issue is common in CP cases because the condition may not be diagnosed for some time after birth. The statute of limitations can vary by state for medical malpractice cases “from 2 years to 22 years.”26 Many states begin with a 2-year statute but extend it if the injury or harm is not discovered. The extension is sometimes referred to as a statute of repose because, after that time, there is no extension even if the harm is discovered only later. In some states the statute does not run until the plaintiff is at or near the time of majority (usually age 18).27