User login

FDA approves first duodenoscope with disposable distal cap

, according to an FDA press release.

A disposable distal cap will improve the ability to clean and reprocess the duodenoscope. Without being thoroughly cleaned and disinfected, contaminated tissue can remain and potentially can be transmitted to other patients.

A previous version of the Pentax duodenoscope, the ED-3490TK, was subject to a January 2017 FDA Safety Alert, because of the potential for cracks and gaps to develop in the adhesive sealing the duodenoscope’s distal cap.

“Since the issue of duodenoscope-associated transmission of infections first received widespread attention in 2015, the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology has been working closely with regulators and endoscope manufacturers to identify and address problems in scope design and develop a path forward to ensure zero device-associated infections,” said V. Raman Muthusamy, MD, AGAF, FACG, FASGE, chair, AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology. “We applaud Pentax for answering our call for innovation to improve patient safety for this common and life-saving GI procedure. We encourage all device manufacturers to continue on a path of innovation to better support gastroenterologists and, most importantly, the patients we serve.”

, according to an FDA press release.

A disposable distal cap will improve the ability to clean and reprocess the duodenoscope. Without being thoroughly cleaned and disinfected, contaminated tissue can remain and potentially can be transmitted to other patients.

A previous version of the Pentax duodenoscope, the ED-3490TK, was subject to a January 2017 FDA Safety Alert, because of the potential for cracks and gaps to develop in the adhesive sealing the duodenoscope’s distal cap.

“Since the issue of duodenoscope-associated transmission of infections first received widespread attention in 2015, the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology has been working closely with regulators and endoscope manufacturers to identify and address problems in scope design and develop a path forward to ensure zero device-associated infections,” said V. Raman Muthusamy, MD, AGAF, FACG, FASGE, chair, AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology. “We applaud Pentax for answering our call for innovation to improve patient safety for this common and life-saving GI procedure. We encourage all device manufacturers to continue on a path of innovation to better support gastroenterologists and, most importantly, the patients we serve.”

, according to an FDA press release.

A disposable distal cap will improve the ability to clean and reprocess the duodenoscope. Without being thoroughly cleaned and disinfected, contaminated tissue can remain and potentially can be transmitted to other patients.

A previous version of the Pentax duodenoscope, the ED-3490TK, was subject to a January 2017 FDA Safety Alert, because of the potential for cracks and gaps to develop in the adhesive sealing the duodenoscope’s distal cap.

“Since the issue of duodenoscope-associated transmission of infections first received widespread attention in 2015, the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology has been working closely with regulators and endoscope manufacturers to identify and address problems in scope design and develop a path forward to ensure zero device-associated infections,” said V. Raman Muthusamy, MD, AGAF, FACG, FASGE, chair, AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology. “We applaud Pentax for answering our call for innovation to improve patient safety for this common and life-saving GI procedure. We encourage all device manufacturers to continue on a path of innovation to better support gastroenterologists and, most importantly, the patients we serve.”

Caffeine offers no perks for Parkinson’s patients

Caffeine consumption has no significant impact on motor skills in patients with Parkinson’s disease, based on data from a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 121 adults. The findings were published online Sept. 27 in Neurology.

Data from previous studies have suggested a link between caffeine consumption and reduced risk of Parkinson’s disease, wrote Ronald B. Postuma, MD, of McGill University in Montreal, and his colleagues (Neurology. 2017 Sep 27. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004568). In addition, Dr. Postuma and his coauthors found a small impact of caffeine on motor skills in patients with existing Parkinson’s as a secondary outcome in a 2012 study on the role of caffeine on daytime sleepiness. Based on these findings, they designed a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of 121 adults with Parkinson’s to assess the impact of caffeine. The average age of the patients was 62 years and the average disease duration was 4 years.

Motor skills worsened in the caffeine group by an average of 0.16 points on the Movement Disorder Society–sponsored Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) part III during patients’ “on” state and by 0.64 points in the placebo group; the difference was not significant.

The researchers found no differences between groups in the clinical global impression of change based on both patient and examiner assessment. In addition, no differences appeared in depression or anxiety, or in quality of life.

The study findings included long-term follow up data from 88 patients assessed at 12 months and 66 patients assessed at 18 months. The results were similar to the 6-month results, and the study was stopped, although the original design included a 4-year extension.

A total of 29 patients in the caffeine group and 31 patients in the placebo group reported adverse events, and 7 patients in the caffeine group and 5 in the placebo group discontinued the study because of side effects. A serious adverse event was reported by one patient in each group, but neither was deemed related to the interventions.

The findings contrast with the effects of caffeine in the 6-week study in 2012 that showed a significant, 3.2-point improvement in motor skills on the MDS-UPDRS part III with caffeine use, as well as reduced daytime sleepiness, the researchers said (Neurology. 2012;79:651-8). Interpretations of the different findings between the trials may be constrained by factors including differences in the study populations, speed of dose escalation, and trial duration and the possible short-term nature of caffeine’s impact, they noted. “Regardless, our core finding is that caffeine cannot be recommended as symptomatic therapy for parkinsonism.” However, “since caffeine is safe and generally well tolerated, it seems reasonable to empirically try intermittent moderate doses of caffeine for somnolence, and repeat if improvement is seen,” they added.

Dr. Postuma disclosed grant funding from the Canadian Institute of Health Research, the Webster Foundation, and Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Santé for this study.

The appeal of an inexpensive, well-tolerated intervention such as caffeine to improve motor symptoms in Parkinson’s patients gave Dr. Postuma and his associates a good reason to try to replicate the positive results they found in an earlier study of caffeine.

The investigators found no benefit from caffeine, although their study was designed to have more than four times as many participants as the pilot study, was adequately powered to detect the same level of improvement as before, and was planned to have an extended follow-up period to look for persistent effects. The trial ended early and enrolled approximately half of its intended total, but was well run and did not suffer from differential compliance or loss to follow-up.

Although the small number of participants resulted in a wide confidence interval and cannot exclude a small effect, this trial suggests that caffeine does not significantly improve Parkinson’s disease symptoms and that it should not be a priority for future Parkinson’s disease intervention studies.

Charles B. Hall, PhD, is affiliated with the department of epidemiology and population health at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York. He disclosed salary support from the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, National Institute of Aging, National Cancer Institute, and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. His comments are derived from an editorial that accompanied Dr. Postuma and colleagues’ study (Neurology. 2017 Sep 27. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004584).

The appeal of an inexpensive, well-tolerated intervention such as caffeine to improve motor symptoms in Parkinson’s patients gave Dr. Postuma and his associates a good reason to try to replicate the positive results they found in an earlier study of caffeine.

The investigators found no benefit from caffeine, although their study was designed to have more than four times as many participants as the pilot study, was adequately powered to detect the same level of improvement as before, and was planned to have an extended follow-up period to look for persistent effects. The trial ended early and enrolled approximately half of its intended total, but was well run and did not suffer from differential compliance or loss to follow-up.

Although the small number of participants resulted in a wide confidence interval and cannot exclude a small effect, this trial suggests that caffeine does not significantly improve Parkinson’s disease symptoms and that it should not be a priority for future Parkinson’s disease intervention studies.

Charles B. Hall, PhD, is affiliated with the department of epidemiology and population health at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York. He disclosed salary support from the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, National Institute of Aging, National Cancer Institute, and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. His comments are derived from an editorial that accompanied Dr. Postuma and colleagues’ study (Neurology. 2017 Sep 27. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004584).

The appeal of an inexpensive, well-tolerated intervention such as caffeine to improve motor symptoms in Parkinson’s patients gave Dr. Postuma and his associates a good reason to try to replicate the positive results they found in an earlier study of caffeine.

The investigators found no benefit from caffeine, although their study was designed to have more than four times as many participants as the pilot study, was adequately powered to detect the same level of improvement as before, and was planned to have an extended follow-up period to look for persistent effects. The trial ended early and enrolled approximately half of its intended total, but was well run and did not suffer from differential compliance or loss to follow-up.

Although the small number of participants resulted in a wide confidence interval and cannot exclude a small effect, this trial suggests that caffeine does not significantly improve Parkinson’s disease symptoms and that it should not be a priority for future Parkinson’s disease intervention studies.

Charles B. Hall, PhD, is affiliated with the department of epidemiology and population health at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York. He disclosed salary support from the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, National Institute of Aging, National Cancer Institute, and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. His comments are derived from an editorial that accompanied Dr. Postuma and colleagues’ study (Neurology. 2017 Sep 27. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004584).

Caffeine consumption has no significant impact on motor skills in patients with Parkinson’s disease, based on data from a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 121 adults. The findings were published online Sept. 27 in Neurology.

Data from previous studies have suggested a link between caffeine consumption and reduced risk of Parkinson’s disease, wrote Ronald B. Postuma, MD, of McGill University in Montreal, and his colleagues (Neurology. 2017 Sep 27. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004568). In addition, Dr. Postuma and his coauthors found a small impact of caffeine on motor skills in patients with existing Parkinson’s as a secondary outcome in a 2012 study on the role of caffeine on daytime sleepiness. Based on these findings, they designed a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of 121 adults with Parkinson’s to assess the impact of caffeine. The average age of the patients was 62 years and the average disease duration was 4 years.

Motor skills worsened in the caffeine group by an average of 0.16 points on the Movement Disorder Society–sponsored Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) part III during patients’ “on” state and by 0.64 points in the placebo group; the difference was not significant.

The researchers found no differences between groups in the clinical global impression of change based on both patient and examiner assessment. In addition, no differences appeared in depression or anxiety, or in quality of life.

The study findings included long-term follow up data from 88 patients assessed at 12 months and 66 patients assessed at 18 months. The results were similar to the 6-month results, and the study was stopped, although the original design included a 4-year extension.

A total of 29 patients in the caffeine group and 31 patients in the placebo group reported adverse events, and 7 patients in the caffeine group and 5 in the placebo group discontinued the study because of side effects. A serious adverse event was reported by one patient in each group, but neither was deemed related to the interventions.

The findings contrast with the effects of caffeine in the 6-week study in 2012 that showed a significant, 3.2-point improvement in motor skills on the MDS-UPDRS part III with caffeine use, as well as reduced daytime sleepiness, the researchers said (Neurology. 2012;79:651-8). Interpretations of the different findings between the trials may be constrained by factors including differences in the study populations, speed of dose escalation, and trial duration and the possible short-term nature of caffeine’s impact, they noted. “Regardless, our core finding is that caffeine cannot be recommended as symptomatic therapy for parkinsonism.” However, “since caffeine is safe and generally well tolerated, it seems reasonable to empirically try intermittent moderate doses of caffeine for somnolence, and repeat if improvement is seen,” they added.

Dr. Postuma disclosed grant funding from the Canadian Institute of Health Research, the Webster Foundation, and Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Santé for this study.

Caffeine consumption has no significant impact on motor skills in patients with Parkinson’s disease, based on data from a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 121 adults. The findings were published online Sept. 27 in Neurology.

Data from previous studies have suggested a link between caffeine consumption and reduced risk of Parkinson’s disease, wrote Ronald B. Postuma, MD, of McGill University in Montreal, and his colleagues (Neurology. 2017 Sep 27. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004568). In addition, Dr. Postuma and his coauthors found a small impact of caffeine on motor skills in patients with existing Parkinson’s as a secondary outcome in a 2012 study on the role of caffeine on daytime sleepiness. Based on these findings, they designed a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of 121 adults with Parkinson’s to assess the impact of caffeine. The average age of the patients was 62 years and the average disease duration was 4 years.

Motor skills worsened in the caffeine group by an average of 0.16 points on the Movement Disorder Society–sponsored Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) part III during patients’ “on” state and by 0.64 points in the placebo group; the difference was not significant.

The researchers found no differences between groups in the clinical global impression of change based on both patient and examiner assessment. In addition, no differences appeared in depression or anxiety, or in quality of life.

The study findings included long-term follow up data from 88 patients assessed at 12 months and 66 patients assessed at 18 months. The results were similar to the 6-month results, and the study was stopped, although the original design included a 4-year extension.

A total of 29 patients in the caffeine group and 31 patients in the placebo group reported adverse events, and 7 patients in the caffeine group and 5 in the placebo group discontinued the study because of side effects. A serious adverse event was reported by one patient in each group, but neither was deemed related to the interventions.

The findings contrast with the effects of caffeine in the 6-week study in 2012 that showed a significant, 3.2-point improvement in motor skills on the MDS-UPDRS part III with caffeine use, as well as reduced daytime sleepiness, the researchers said (Neurology. 2012;79:651-8). Interpretations of the different findings between the trials may be constrained by factors including differences in the study populations, speed of dose escalation, and trial duration and the possible short-term nature of caffeine’s impact, they noted. “Regardless, our core finding is that caffeine cannot be recommended as symptomatic therapy for parkinsonism.” However, “since caffeine is safe and generally well tolerated, it seems reasonable to empirically try intermittent moderate doses of caffeine for somnolence, and repeat if improvement is seen,” they added.

Dr. Postuma disclosed grant funding from the Canadian Institute of Health Research, the Webster Foundation, and Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Santé for this study.

FROM NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Motor skills declined by an average of 0.16 points in the caffeine group and 0.64 points in the placebo group; the difference was not significant.

Data source: A double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial of 121 adults with Parkinson’s.

Disclosures: Dr. Postuma disclosed grant funding from the Canadian Institute of Health Research, the Webster Foundation, and Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Santé for this study.

LUME-Mesa trial: Nintedanib improves PFS in mesothelioma

CHICAGO – Adding the oral kinase inhibitor nintedanib to pemetrexed/cisplatin resulted in substantial improvements in outcomes in patients with unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma in phase 2 of the randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2/3 LUME-Meso study.

The effects were particularly pronounced among those with epithelioid histology, Jose Barrueco, PhD, of Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Ridgefield, Conn., reported at the Chicago Multidisciplinary Symposium in Thoracic Oncology.

Progression-free survival – the primary endpoint of the study – was improved in 44 patients randomized to receive up to six cycles of pemetrexed/cisplatin plus nintedanib, compared with 43 patients who received pemetrexed/cisplatin plus placebo (median 9.4 vs. 5.7 months; hazard ratio, 0.54), Dr. Barrueco said.

In the 89% of patients with epithelioid malignant pleural mesothelioma, progression-free survival was a median of 9.7 vs. 5.7 months with nintedanib vs. placebo (HR, 0.49).

There was a trend toward improved overall survival in the nintedanib group vs. the placebo group, (median 18.3 vs. 14.2 months; HR, 0.77; P = .319), and overall survival was slightly better in those with epithelioid histology (median 20.6 vs. 15.2 months ; HR, 0.70; P = .197).

Consistent with these results, the adjusted mean change in forced vital capacity at cycle eight also favored nintedanib over placebo (+10.0 vs. +2.8 for a mean treatment difference of 7.2 overall, and +14.1 vs. +4.2 for a mean treatment difference of 9.9 in those with epithelioid histology).

“Overall frequency of adverse events was consistent with the known safety profile of nintedanib,” Dr. Barrueco said, noting that most adverse events were reversible with dose reduction.

Study participants were chemotherapy-naive patients with a mean age of 67 years and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0-1. They received pemetrexed at a dose of 500 mg/m2 and cisplatin at a dose of 75 mg/m2 on day 1 plus either nintedanib at a dose of 200 mg twice daily on days 2-21 or placebo, followed by monotherapy with nintedanib or placebo until progression or unacceptable toxicity.

“In conclusion, nintedanib plus pemetrexed/cisplatin demonstrated a signal for clinical benefit in the first-time treatment of patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. This was evident in all endpoints of the trial, and consistently showed benefit for the nintedanib group,” Mr. Barrueco said, noting that phase 3 of the LUME-Meso study is now recruiting.

CHICAGO – Adding the oral kinase inhibitor nintedanib to pemetrexed/cisplatin resulted in substantial improvements in outcomes in patients with unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma in phase 2 of the randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2/3 LUME-Meso study.

The effects were particularly pronounced among those with epithelioid histology, Jose Barrueco, PhD, of Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Ridgefield, Conn., reported at the Chicago Multidisciplinary Symposium in Thoracic Oncology.

Progression-free survival – the primary endpoint of the study – was improved in 44 patients randomized to receive up to six cycles of pemetrexed/cisplatin plus nintedanib, compared with 43 patients who received pemetrexed/cisplatin plus placebo (median 9.4 vs. 5.7 months; hazard ratio, 0.54), Dr. Barrueco said.

In the 89% of patients with epithelioid malignant pleural mesothelioma, progression-free survival was a median of 9.7 vs. 5.7 months with nintedanib vs. placebo (HR, 0.49).

There was a trend toward improved overall survival in the nintedanib group vs. the placebo group, (median 18.3 vs. 14.2 months; HR, 0.77; P = .319), and overall survival was slightly better in those with epithelioid histology (median 20.6 vs. 15.2 months ; HR, 0.70; P = .197).

Consistent with these results, the adjusted mean change in forced vital capacity at cycle eight also favored nintedanib over placebo (+10.0 vs. +2.8 for a mean treatment difference of 7.2 overall, and +14.1 vs. +4.2 for a mean treatment difference of 9.9 in those with epithelioid histology).

“Overall frequency of adverse events was consistent with the known safety profile of nintedanib,” Dr. Barrueco said, noting that most adverse events were reversible with dose reduction.

Study participants were chemotherapy-naive patients with a mean age of 67 years and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0-1. They received pemetrexed at a dose of 500 mg/m2 and cisplatin at a dose of 75 mg/m2 on day 1 plus either nintedanib at a dose of 200 mg twice daily on days 2-21 or placebo, followed by monotherapy with nintedanib or placebo until progression or unacceptable toxicity.

“In conclusion, nintedanib plus pemetrexed/cisplatin demonstrated a signal for clinical benefit in the first-time treatment of patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. This was evident in all endpoints of the trial, and consistently showed benefit for the nintedanib group,” Mr. Barrueco said, noting that phase 3 of the LUME-Meso study is now recruiting.

CHICAGO – Adding the oral kinase inhibitor nintedanib to pemetrexed/cisplatin resulted in substantial improvements in outcomes in patients with unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma in phase 2 of the randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2/3 LUME-Meso study.

The effects were particularly pronounced among those with epithelioid histology, Jose Barrueco, PhD, of Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Ridgefield, Conn., reported at the Chicago Multidisciplinary Symposium in Thoracic Oncology.

Progression-free survival – the primary endpoint of the study – was improved in 44 patients randomized to receive up to six cycles of pemetrexed/cisplatin plus nintedanib, compared with 43 patients who received pemetrexed/cisplatin plus placebo (median 9.4 vs. 5.7 months; hazard ratio, 0.54), Dr. Barrueco said.

In the 89% of patients with epithelioid malignant pleural mesothelioma, progression-free survival was a median of 9.7 vs. 5.7 months with nintedanib vs. placebo (HR, 0.49).

There was a trend toward improved overall survival in the nintedanib group vs. the placebo group, (median 18.3 vs. 14.2 months; HR, 0.77; P = .319), and overall survival was slightly better in those with epithelioid histology (median 20.6 vs. 15.2 months ; HR, 0.70; P = .197).

Consistent with these results, the adjusted mean change in forced vital capacity at cycle eight also favored nintedanib over placebo (+10.0 vs. +2.8 for a mean treatment difference of 7.2 overall, and +14.1 vs. +4.2 for a mean treatment difference of 9.9 in those with epithelioid histology).

“Overall frequency of adverse events was consistent with the known safety profile of nintedanib,” Dr. Barrueco said, noting that most adverse events were reversible with dose reduction.

Study participants were chemotherapy-naive patients with a mean age of 67 years and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0-1. They received pemetrexed at a dose of 500 mg/m2 and cisplatin at a dose of 75 mg/m2 on day 1 plus either nintedanib at a dose of 200 mg twice daily on days 2-21 or placebo, followed by monotherapy with nintedanib or placebo until progression or unacceptable toxicity.

“In conclusion, nintedanib plus pemetrexed/cisplatin demonstrated a signal for clinical benefit in the first-time treatment of patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. This was evident in all endpoints of the trial, and consistently showed benefit for the nintedanib group,” Mr. Barrueco said, noting that phase 3 of the LUME-Meso study is now recruiting.

AT A SYMPOSIUM IN THORACIC ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Overall median PFS with nintedanib vs. placebo was 9.4 vs. 5.7 months (HR, 0.54).

Data source: Phase 2 of the LUME-Meso trial with 87 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Barrueco is an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim.

Risk of Osteoporotic Fracture After Steroid Injections in Patients With Medicare

Take-Home Points

Analysis of patients in the Medicare database showed that each successive ESI decreased the risk of an osteoporotic spine fracture by 2%, and that each successive LJSI decreases it by 4%.

Although statistically significant, this may not be clinically relevant.

Successive ESI did not influence the risk of developing an osteoporotic hip or wrist fracture, but that each additional LJSI reduced the risk.

Prolonged steroid exposure was found to increase the risk of spine fracture for ESI and LJSI patients.

Acute exposure to exogenous steroids via the epidural space, transforaminal space, or large joints does not seem to increase the risk of an osteoporotic fracture of the spine, hip, or wrist.

Epidural steroid injections (ESIs) are widely used in the nonoperative treatment of low back pain, radicular leg pain, and spinal stenosis. The treatment rationale is that locally injected anti-inflammatory drugs, such as steroids, reduce inflammation by inhibiting formation and release of inflammatory cytokines, leading to pain reduction.1,2 According to 4 systematic reviews, the best available evidence of the efficacy of ESIs is less than robust.3-6 These reviews were limited by the heterogeneity of patient selection, delivery mode, type and dose of steroid used, number and frequency of ESIs, and outcome measures.

The association of chronic oral steroid use and the development of osteoporosis was previously established.7,8 One concern is that acute exposure to steroids in the form of lumbar ESIs may also lead to osteoporosis and then a pathologic fracture of the vertebra. Several studies have found no association between bone mineral density and cumulative steroid dose,9,10 mean number of ESIs, or duration of ESIs,10 though other studies have found lower bone mineral density in postmenopausal women treated with ESIs.11-13

In a study of 3000 ESI patients propensity-matched to a non-ESI cohort, Mandel and colleagues14 found that each successive ESI increased the risk of osteoporotic spine fracture by 21%. This clinically relevant 21% increased risk might lead physicians to stop prescribing or using this intervention. However, the association between osteoporotic fractures and other types of steroid injections remains poorly understood and underinvestigated.

To further evaluate the relationship between steroid injections and osteoporotic fracture risk, we analyzed Medicare administrative claims data on both large-joint steroid injections (LJSIs) into knee and hip and transforaminal steroid injections (TSIs), as well as osteoporotic hip and wrist fractures. Our hypothesis was that a systemic effect of steroid injections would increase fracture risk in all skeletal locations regardless of injection site, whereas a local effect would produce a disproportionate increased risk of spine fracture with spine injection.

Materials and Methods

Medicare is a publicly funded US health insurance program for people 65 years old or older, people under age 65 years with certain disabilities, and people (any age) with end-stage renal disease or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. The 5% Medicare Part B (physician, carrier) dataset contains individual claims records for a random sample of Medicare beneficiaries (~2.4 million enrollees). Patients who received steroid injections were identified from 5% Medicare claims made between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2011. LJSIs were identified by Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 20610 and any of 16 other CPT codes: J0702, J1020, J1030, J1040, J1094, J1100, J1700, J1710, J1720, J2650, J2920, J2930, J3300, J3301, J3302, and J3303. ESIs were identified by CPT code 62310, 62311, 62318, or 62319, and TSIs by CPT code 64479, 64480, 64483, or 64484. Patients were followed in their initial injection cohort. For example, a patient who received an ESI initially and later received an LJSI remained in the ESI cohort.

Several groups of patients were excluded from the study: those who received Medicare coverage because of their age (under 65 years) and disabilities; those who received Medicare health benefits through health maintenance organizations (healthcare expenses were not submitted to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for payment, and therefore claims were not in the database or were incomplete); those with a prior claim history of <12 months (incomplete comorbidity history); and those who received a diagnosis of osteoporotic fracture (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code 733.1x) before the initial steroid injection.

We determined the incidence of osteoporotic wrist, hip, and spine fractures within 1, 2, and 8 years after LJSI, ESI, and TSI. Wrist, hip, and spine fractures were identified by ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes 733.12, 733.13, and 733.14, respectively. We also determined the number of steroid injections given before wrist, hip, or spine fracture or, if no fracture occurred, before death or the end of the data period.

Statistical Analysis

Multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to evaluate the risk factors for wrist, spine, and hip fractures. The covariates in this model included age, sex, race, census region, Medicare buy-in status, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI),15 year, and number of steroid injections before fracture, death, or end of data period. Medicare buy-in status, which indicates whether the beneficiary received financial assistance in paying insurance premiums, was used as a proxy for socioeconomic status. CCI is used as a composite score of a patient’s general health status in terms of comorbidities.15,16 Four previously established categories17 were used to group CCIs in this study: 0 (none), 1 to 2 (low), 3 to 4 (moderate), and 5 or more (high). In addition, several diagnoses made within the 12 months before initial steroid injection were considered: osteoporosis (ICD-9-CM codes 733.0x, V82.81), Cushing syndrome (ICD-9-CM code 255.0), long-term (current) use of bisphosphonates (ICD-9-CM code V58.68), asymptomatic postmenopausal status (ICD-9-CM code V49.81), postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy (ICD-9-CM code V07.4), and long-term (current) use of steroids (ICD-9-CM code V58.65). The comparison of relative risk between any groups was reported as the adjusted hazard ratio (AHR), which is the ratio of the hazard rates of that particular outcome, taking into account inherent patient characteristics such as age, sex, and race as covariates. AHR of 1 corresponds to equivalent risk, AHR of >1 to elevated risk, and AHR of <1 to reduced risk.

Results

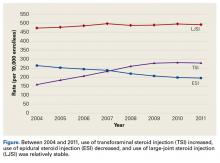

Using the 5% Medicare data for 2004 to 2011, we identified 275,999 Medicare beneficiaries who underwent LJSI, 93,943 who underwent ESI, and 32,311 who underwent TSI. During this period, TSI use increased, ESI use decreased, and LJSI use was relatively stable (Figure).

The risk for osteoporotic spine fracture 1, 2, and 8 years after ESI, TSI, or LJSI was affected by age, race, sex, and CCI (P < .001 for all; Tables 2-4).

The risk for osteoporotic hip fracture after 1 and 2 years was affected by age and number of LJSIs and TSIs but not by number of ESIs. Sex and CCI were also risk factors for hip fracture at 1 and 2 years for ESI and LJSI patients, as was race for LJSI patients. Risk for osteoporotic wrist fracture at 1 and 2 years was affected by sex and race for ESI and LJSI patients; age, race, CCI, and long-term steroid use were risk factors for TSI patients at all time points. Higher number of LJSIs, but not ESIs or TSIs, was associated with lower wrist fracture risk.

Discussion

ESIs continue to be used in the nonoperative treatment of low back pain, radicular leg pain, and spinal stenosis. Although the present study found ESI use increased in the Medicare population between 1994 and 2001,18 the trend is reversing, decreasing by 25%, with rates of 264 per 10,000 Medicare enrollees in 2004 and 194 per 10,000 enrollees in 2011. ESI use may have changed after systematic reviews revealed there was no clear evidence of the efficacy of ESIs in managing low back pain and radicular leg pain3,5,6 or spinal stenosis.4

Nevertheless, ESIs are widely used because of the perceived benefit balanced against the perceived rarity of adverse events.6 Even if patients recognize a low likelihood of significant benefit, they may accept ESI as preferable to surgery. In addition, most private payers require extensive nonoperative treatment before they will approve surgery as a treatment option.

In a study by Mandel and colleagues,14 ESI increased the risk of vertebral compression fractures by 21%, which in turn increased the risk of death.19 If accurate, these findings obviously would challenge the perception that ESI is a low-risk intervention. In contrast to the Mandel study,14 the present analysis of the Medicare population revealed no clinically relevant change in risk of osteoporotic spine fracture with each successive ESI after the initial injection. After the initial injection, each successive ESI decreased the relative risk of osteoporotic spine fracture by 2%, and each successive LJSI decreased it by 4%. Although statistically significant, the small change in relative risk may not be clinically relevant. However, taken cumulatively over a number of successive injections, these effects may be clinically relevant.

The data also showed that, after the initial injection, each successive ESI had no effect on risk of osteoporotic hip or wrist fracture, and each successive LJSI reduced the risk. Similar to earlier findings,20,21 long-term steroid use increased the risk of spine fracture in ESI and LJSI patients. Prolonged exposure to steroids may be necessary to reduce bone formation and increase bone breakdown.12

Although the study by Mandel and colleagues14 and our study both used administrative databases and survival analysis methods, conclusions differed. First, Mandel and colleagues14 used a study inclusion criterion of spine-related steroid injections, whereas we used a criterion of any steroid injection. Second, they used 50 years as the lower age for study inclusion, and we used 65 years. Third, to control for patients who had osteoporosis before study entry, they excluded those who had a fracture in an adjacent vertebra after kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty. It is unclear if patients who had osteoporotic fractures at other sites were excluded as well. Thus, the 2 cohorts may not be directly comparable.

Whereas Mandel and colleagues14 based their definition of osteoporotic spine fracture on a keyword search of a radiology database, we used a specific reportable ICD-9-CM diagnosis code. As a result, they may have overreported osteoporotic spine fractures, and we may have underreported. Finally, our sample was much larger than theirs. Given the relative rarity of osteoporotic fractures, a study with a larger sample may have more power to detect differences. In addition, unlike Mandel and colleagues,14 we focused on an injection cohort. We did not include or make comparisons with a no-injection cohort because our study hypothesis involved the potential systemic effects of steroid injections based on injection site. Although chronic steroid use was found to have a significant effect in our study, it is unclear to what extent the diagnosis code was used, during the comorbidity assessment or only in the event of steroid-related complications.

Our study also found that, after the initial injection, each successive LJSI decreased the risk of osteoporotic wrist fracture by 10%, and each successive TSI decreased the risk of osteoporotic hip fracture by 5%. It is plausible these injections allowed improved mobility, mitigating the effects of osteoporosis induced by inactivity and lack of resistance training. It is also possible that improved mobility limited falls.

In summary, this analysis of the Medicare claims database revealed that ESI, TSI, and LJSI decreased osteoporotic spine fracture risk. However, the effect was small and may not be clinically meaningful. After the initial injection, successive ESIs had no effect on the risk of osteoporotic hip or wrist fracture, and successive LJSIs reduced the risk of osteoporotic wrist fracture, perhaps because of improved mobility. Prolonged oral steroid use increased spine fracture risk in ESI and LJSI patients. More studies are needed to evaluate the risk-benefit profile of steroid injections.

1. Pethö G, Reeh PW. Sensory and signaling mechanisms of bradykinin, eicosanoids, platelet-activating factor, and nitric oxide in peripheral nociceptors. Physiol Rev. 2012;92(4):1699-1775.

2. Saal J. The role of inflammation in lumbar pain. Spine. 1995;20(16):1821-1827.

3. Choi HJ, Hahn S, Kim CH, et al. Epidural steroid injection therapy for low back pain: a meta-analysis. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2013;29(3):244-253.

4. Chou R, Loeser JD, Owens DK, et al; American Pain Society Low Back Pain Guideline Panel. Interventional therapies, surgery, and interdisciplinary rehabilitation for low back pain: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society. Spine. 2009;34(10):1066-1077.

5. Savigny P, Watson P, Underwood M; Guideline Development Group. Early management of persistent non-specific low back pain: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2009;338:b1805.

6. Staal JB, de Bie RA, de Vet HC, Hildebrandt J, Nelemans P. Injection therapy for subacute and chronic low back pain: an updated Cochrane review. Spine. 2009;34(1):49-59.

7. Angeli A, Guglielmi G, Dovio A, et al. High prevalence of asymptomatic vertebral fractures in post-menopausal women receiving chronic glucocorticoid therapy: a cross-sectional outpatient study. Bone. 2006;39(2):253-259.

8. Donnan PT, Libby G, Boyter AC, Thompson P. The population risk of fractures attributable to oral corticosteroids. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14(3):177-186.

9. Dubois EF, Wagemans MF, Verdouw BC, et al. Lack of relationships between cumulative methylprednisolone dose and bone mineral density in healthy men and postmenopausal women with chronic low back pain. Clin Rheumatol. 2003;22(1):12-17.

10. Yi Y, Hwang B, Son H, Cheong I. Low bone mineral density, but not epidural steroid injection, is associated with fracture in postmenopausal women with low back pain. Pain Physician. 2012;15(6):441-449.

11. Al-Shoha A, Rao DS, Schilling J, Peterson E, Mandel S. Effect of epidural steroid injection on bone mineral density and markers of bone turnover in postmenopausal women. Spine. 2012;37(25):E1567-E1571.

12. Kang SS, Hwang BM, Son H, Cheong IY, Lee SJ, Chung TY. Changes in bone mineral density in postmenopausal women treated with epidural steroid injections for lower back pain. Pain Physician. 2012;15(3):229-236.

13. Kim S, Hwang B. Relationship between bone mineral density and the frequent administration of epidural steroid injections in postmenopausal women with low back pain. Pain Res Manag. 2014;19(1):30-34.

14. Mandel S, Schilling J, Peterson E, Rao DS, Sanders W. A retrospective analysis of vertebral body fractures following epidural steroid injections. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(11):961-964.

15. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383.

16. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613-619.

17. Murray SB, Bates DW, Ngo L, Ufberg JW, Shapiro NI. Charlson index is associated with one-year mortality in emergency department patients with suspected infection. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(5):530-536.

18. Friedly J, Chan L, Deyo R. Increases in lumbosacral injections in the Medicare population: 1994 to 2001. Spine. 2007;32(16):1754-1760.

19. Puisto V, Rissanen H, Heliövaara M, et al. Vertebral fracture and cause-specific mortality: a prospective population study of 3,210 men and 3,730 women with 30 years of follow-up. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(12):2181-2186.

20. Lee YH, Woo JH, Choi SJ, Ji JD, Song GG. Effects of low-dose corticosteroids on the bone mineral density of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis. J Investig Med. 2008;56(8):1011-1018.

21. Lukert BP, Raisz LG. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1994;20(3):629-650.

Take-Home Points

Analysis of patients in the Medicare database showed that each successive ESI decreased the risk of an osteoporotic spine fracture by 2%, and that each successive LJSI decreases it by 4%.

Although statistically significant, this may not be clinically relevant.

Successive ESI did not influence the risk of developing an osteoporotic hip or wrist fracture, but that each additional LJSI reduced the risk.

Prolonged steroid exposure was found to increase the risk of spine fracture for ESI and LJSI patients.

Acute exposure to exogenous steroids via the epidural space, transforaminal space, or large joints does not seem to increase the risk of an osteoporotic fracture of the spine, hip, or wrist.

Epidural steroid injections (ESIs) are widely used in the nonoperative treatment of low back pain, radicular leg pain, and spinal stenosis. The treatment rationale is that locally injected anti-inflammatory drugs, such as steroids, reduce inflammation by inhibiting formation and release of inflammatory cytokines, leading to pain reduction.1,2 According to 4 systematic reviews, the best available evidence of the efficacy of ESIs is less than robust.3-6 These reviews were limited by the heterogeneity of patient selection, delivery mode, type and dose of steroid used, number and frequency of ESIs, and outcome measures.

The association of chronic oral steroid use and the development of osteoporosis was previously established.7,8 One concern is that acute exposure to steroids in the form of lumbar ESIs may also lead to osteoporosis and then a pathologic fracture of the vertebra. Several studies have found no association between bone mineral density and cumulative steroid dose,9,10 mean number of ESIs, or duration of ESIs,10 though other studies have found lower bone mineral density in postmenopausal women treated with ESIs.11-13

In a study of 3000 ESI patients propensity-matched to a non-ESI cohort, Mandel and colleagues14 found that each successive ESI increased the risk of osteoporotic spine fracture by 21%. This clinically relevant 21% increased risk might lead physicians to stop prescribing or using this intervention. However, the association between osteoporotic fractures and other types of steroid injections remains poorly understood and underinvestigated.

To further evaluate the relationship between steroid injections and osteoporotic fracture risk, we analyzed Medicare administrative claims data on both large-joint steroid injections (LJSIs) into knee and hip and transforaminal steroid injections (TSIs), as well as osteoporotic hip and wrist fractures. Our hypothesis was that a systemic effect of steroid injections would increase fracture risk in all skeletal locations regardless of injection site, whereas a local effect would produce a disproportionate increased risk of spine fracture with spine injection.

Materials and Methods

Medicare is a publicly funded US health insurance program for people 65 years old or older, people under age 65 years with certain disabilities, and people (any age) with end-stage renal disease or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. The 5% Medicare Part B (physician, carrier) dataset contains individual claims records for a random sample of Medicare beneficiaries (~2.4 million enrollees). Patients who received steroid injections were identified from 5% Medicare claims made between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2011. LJSIs were identified by Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 20610 and any of 16 other CPT codes: J0702, J1020, J1030, J1040, J1094, J1100, J1700, J1710, J1720, J2650, J2920, J2930, J3300, J3301, J3302, and J3303. ESIs were identified by CPT code 62310, 62311, 62318, or 62319, and TSIs by CPT code 64479, 64480, 64483, or 64484. Patients were followed in their initial injection cohort. For example, a patient who received an ESI initially and later received an LJSI remained in the ESI cohort.

Several groups of patients were excluded from the study: those who received Medicare coverage because of their age (under 65 years) and disabilities; those who received Medicare health benefits through health maintenance organizations (healthcare expenses were not submitted to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for payment, and therefore claims were not in the database or were incomplete); those with a prior claim history of <12 months (incomplete comorbidity history); and those who received a diagnosis of osteoporotic fracture (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code 733.1x) before the initial steroid injection.

We determined the incidence of osteoporotic wrist, hip, and spine fractures within 1, 2, and 8 years after LJSI, ESI, and TSI. Wrist, hip, and spine fractures were identified by ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes 733.12, 733.13, and 733.14, respectively. We also determined the number of steroid injections given before wrist, hip, or spine fracture or, if no fracture occurred, before death or the end of the data period.

Statistical Analysis

Multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to evaluate the risk factors for wrist, spine, and hip fractures. The covariates in this model included age, sex, race, census region, Medicare buy-in status, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI),15 year, and number of steroid injections before fracture, death, or end of data period. Medicare buy-in status, which indicates whether the beneficiary received financial assistance in paying insurance premiums, was used as a proxy for socioeconomic status. CCI is used as a composite score of a patient’s general health status in terms of comorbidities.15,16 Four previously established categories17 were used to group CCIs in this study: 0 (none), 1 to 2 (low), 3 to 4 (moderate), and 5 or more (high). In addition, several diagnoses made within the 12 months before initial steroid injection were considered: osteoporosis (ICD-9-CM codes 733.0x, V82.81), Cushing syndrome (ICD-9-CM code 255.0), long-term (current) use of bisphosphonates (ICD-9-CM code V58.68), asymptomatic postmenopausal status (ICD-9-CM code V49.81), postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy (ICD-9-CM code V07.4), and long-term (current) use of steroids (ICD-9-CM code V58.65). The comparison of relative risk between any groups was reported as the adjusted hazard ratio (AHR), which is the ratio of the hazard rates of that particular outcome, taking into account inherent patient characteristics such as age, sex, and race as covariates. AHR of 1 corresponds to equivalent risk, AHR of >1 to elevated risk, and AHR of <1 to reduced risk.

Results

Using the 5% Medicare data for 2004 to 2011, we identified 275,999 Medicare beneficiaries who underwent LJSI, 93,943 who underwent ESI, and 32,311 who underwent TSI. During this period, TSI use increased, ESI use decreased, and LJSI use was relatively stable (Figure).

The risk for osteoporotic spine fracture 1, 2, and 8 years after ESI, TSI, or LJSI was affected by age, race, sex, and CCI (P < .001 for all; Tables 2-4).

The risk for osteoporotic hip fracture after 1 and 2 years was affected by age and number of LJSIs and TSIs but not by number of ESIs. Sex and CCI were also risk factors for hip fracture at 1 and 2 years for ESI and LJSI patients, as was race for LJSI patients. Risk for osteoporotic wrist fracture at 1 and 2 years was affected by sex and race for ESI and LJSI patients; age, race, CCI, and long-term steroid use were risk factors for TSI patients at all time points. Higher number of LJSIs, but not ESIs or TSIs, was associated with lower wrist fracture risk.

Discussion

ESIs continue to be used in the nonoperative treatment of low back pain, radicular leg pain, and spinal stenosis. Although the present study found ESI use increased in the Medicare population between 1994 and 2001,18 the trend is reversing, decreasing by 25%, with rates of 264 per 10,000 Medicare enrollees in 2004 and 194 per 10,000 enrollees in 2011. ESI use may have changed after systematic reviews revealed there was no clear evidence of the efficacy of ESIs in managing low back pain and radicular leg pain3,5,6 or spinal stenosis.4

Nevertheless, ESIs are widely used because of the perceived benefit balanced against the perceived rarity of adverse events.6 Even if patients recognize a low likelihood of significant benefit, they may accept ESI as preferable to surgery. In addition, most private payers require extensive nonoperative treatment before they will approve surgery as a treatment option.

In a study by Mandel and colleagues,14 ESI increased the risk of vertebral compression fractures by 21%, which in turn increased the risk of death.19 If accurate, these findings obviously would challenge the perception that ESI is a low-risk intervention. In contrast to the Mandel study,14 the present analysis of the Medicare population revealed no clinically relevant change in risk of osteoporotic spine fracture with each successive ESI after the initial injection. After the initial injection, each successive ESI decreased the relative risk of osteoporotic spine fracture by 2%, and each successive LJSI decreased it by 4%. Although statistically significant, the small change in relative risk may not be clinically relevant. However, taken cumulatively over a number of successive injections, these effects may be clinically relevant.

The data also showed that, after the initial injection, each successive ESI had no effect on risk of osteoporotic hip or wrist fracture, and each successive LJSI reduced the risk. Similar to earlier findings,20,21 long-term steroid use increased the risk of spine fracture in ESI and LJSI patients. Prolonged exposure to steroids may be necessary to reduce bone formation and increase bone breakdown.12

Although the study by Mandel and colleagues14 and our study both used administrative databases and survival analysis methods, conclusions differed. First, Mandel and colleagues14 used a study inclusion criterion of spine-related steroid injections, whereas we used a criterion of any steroid injection. Second, they used 50 years as the lower age for study inclusion, and we used 65 years. Third, to control for patients who had osteoporosis before study entry, they excluded those who had a fracture in an adjacent vertebra after kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty. It is unclear if patients who had osteoporotic fractures at other sites were excluded as well. Thus, the 2 cohorts may not be directly comparable.

Whereas Mandel and colleagues14 based their definition of osteoporotic spine fracture on a keyword search of a radiology database, we used a specific reportable ICD-9-CM diagnosis code. As a result, they may have overreported osteoporotic spine fractures, and we may have underreported. Finally, our sample was much larger than theirs. Given the relative rarity of osteoporotic fractures, a study with a larger sample may have more power to detect differences. In addition, unlike Mandel and colleagues,14 we focused on an injection cohort. We did not include or make comparisons with a no-injection cohort because our study hypothesis involved the potential systemic effects of steroid injections based on injection site. Although chronic steroid use was found to have a significant effect in our study, it is unclear to what extent the diagnosis code was used, during the comorbidity assessment or only in the event of steroid-related complications.

Our study also found that, after the initial injection, each successive LJSI decreased the risk of osteoporotic wrist fracture by 10%, and each successive TSI decreased the risk of osteoporotic hip fracture by 5%. It is plausible these injections allowed improved mobility, mitigating the effects of osteoporosis induced by inactivity and lack of resistance training. It is also possible that improved mobility limited falls.

In summary, this analysis of the Medicare claims database revealed that ESI, TSI, and LJSI decreased osteoporotic spine fracture risk. However, the effect was small and may not be clinically meaningful. After the initial injection, successive ESIs had no effect on the risk of osteoporotic hip or wrist fracture, and successive LJSIs reduced the risk of osteoporotic wrist fracture, perhaps because of improved mobility. Prolonged oral steroid use increased spine fracture risk in ESI and LJSI patients. More studies are needed to evaluate the risk-benefit profile of steroid injections.

Take-Home Points

Analysis of patients in the Medicare database showed that each successive ESI decreased the risk of an osteoporotic spine fracture by 2%, and that each successive LJSI decreases it by 4%.

Although statistically significant, this may not be clinically relevant.

Successive ESI did not influence the risk of developing an osteoporotic hip or wrist fracture, but that each additional LJSI reduced the risk.

Prolonged steroid exposure was found to increase the risk of spine fracture for ESI and LJSI patients.

Acute exposure to exogenous steroids via the epidural space, transforaminal space, or large joints does not seem to increase the risk of an osteoporotic fracture of the spine, hip, or wrist.

Epidural steroid injections (ESIs) are widely used in the nonoperative treatment of low back pain, radicular leg pain, and spinal stenosis. The treatment rationale is that locally injected anti-inflammatory drugs, such as steroids, reduce inflammation by inhibiting formation and release of inflammatory cytokines, leading to pain reduction.1,2 According to 4 systematic reviews, the best available evidence of the efficacy of ESIs is less than robust.3-6 These reviews were limited by the heterogeneity of patient selection, delivery mode, type and dose of steroid used, number and frequency of ESIs, and outcome measures.

The association of chronic oral steroid use and the development of osteoporosis was previously established.7,8 One concern is that acute exposure to steroids in the form of lumbar ESIs may also lead to osteoporosis and then a pathologic fracture of the vertebra. Several studies have found no association between bone mineral density and cumulative steroid dose,9,10 mean number of ESIs, or duration of ESIs,10 though other studies have found lower bone mineral density in postmenopausal women treated with ESIs.11-13

In a study of 3000 ESI patients propensity-matched to a non-ESI cohort, Mandel and colleagues14 found that each successive ESI increased the risk of osteoporotic spine fracture by 21%. This clinically relevant 21% increased risk might lead physicians to stop prescribing or using this intervention. However, the association between osteoporotic fractures and other types of steroid injections remains poorly understood and underinvestigated.

To further evaluate the relationship between steroid injections and osteoporotic fracture risk, we analyzed Medicare administrative claims data on both large-joint steroid injections (LJSIs) into knee and hip and transforaminal steroid injections (TSIs), as well as osteoporotic hip and wrist fractures. Our hypothesis was that a systemic effect of steroid injections would increase fracture risk in all skeletal locations regardless of injection site, whereas a local effect would produce a disproportionate increased risk of spine fracture with spine injection.

Materials and Methods

Medicare is a publicly funded US health insurance program for people 65 years old or older, people under age 65 years with certain disabilities, and people (any age) with end-stage renal disease or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. The 5% Medicare Part B (physician, carrier) dataset contains individual claims records for a random sample of Medicare beneficiaries (~2.4 million enrollees). Patients who received steroid injections were identified from 5% Medicare claims made between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2011. LJSIs were identified by Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 20610 and any of 16 other CPT codes: J0702, J1020, J1030, J1040, J1094, J1100, J1700, J1710, J1720, J2650, J2920, J2930, J3300, J3301, J3302, and J3303. ESIs were identified by CPT code 62310, 62311, 62318, or 62319, and TSIs by CPT code 64479, 64480, 64483, or 64484. Patients were followed in their initial injection cohort. For example, a patient who received an ESI initially and later received an LJSI remained in the ESI cohort.

Several groups of patients were excluded from the study: those who received Medicare coverage because of their age (under 65 years) and disabilities; those who received Medicare health benefits through health maintenance organizations (healthcare expenses were not submitted to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for payment, and therefore claims were not in the database or were incomplete); those with a prior claim history of <12 months (incomplete comorbidity history); and those who received a diagnosis of osteoporotic fracture (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code 733.1x) before the initial steroid injection.

We determined the incidence of osteoporotic wrist, hip, and spine fractures within 1, 2, and 8 years after LJSI, ESI, and TSI. Wrist, hip, and spine fractures were identified by ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes 733.12, 733.13, and 733.14, respectively. We also determined the number of steroid injections given before wrist, hip, or spine fracture or, if no fracture occurred, before death or the end of the data period.

Statistical Analysis

Multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to evaluate the risk factors for wrist, spine, and hip fractures. The covariates in this model included age, sex, race, census region, Medicare buy-in status, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI),15 year, and number of steroid injections before fracture, death, or end of data period. Medicare buy-in status, which indicates whether the beneficiary received financial assistance in paying insurance premiums, was used as a proxy for socioeconomic status. CCI is used as a composite score of a patient’s general health status in terms of comorbidities.15,16 Four previously established categories17 were used to group CCIs in this study: 0 (none), 1 to 2 (low), 3 to 4 (moderate), and 5 or more (high). In addition, several diagnoses made within the 12 months before initial steroid injection were considered: osteoporosis (ICD-9-CM codes 733.0x, V82.81), Cushing syndrome (ICD-9-CM code 255.0), long-term (current) use of bisphosphonates (ICD-9-CM code V58.68), asymptomatic postmenopausal status (ICD-9-CM code V49.81), postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy (ICD-9-CM code V07.4), and long-term (current) use of steroids (ICD-9-CM code V58.65). The comparison of relative risk between any groups was reported as the adjusted hazard ratio (AHR), which is the ratio of the hazard rates of that particular outcome, taking into account inherent patient characteristics such as age, sex, and race as covariates. AHR of 1 corresponds to equivalent risk, AHR of >1 to elevated risk, and AHR of <1 to reduced risk.

Results

Using the 5% Medicare data for 2004 to 2011, we identified 275,999 Medicare beneficiaries who underwent LJSI, 93,943 who underwent ESI, and 32,311 who underwent TSI. During this period, TSI use increased, ESI use decreased, and LJSI use was relatively stable (Figure).

The risk for osteoporotic spine fracture 1, 2, and 8 years after ESI, TSI, or LJSI was affected by age, race, sex, and CCI (P < .001 for all; Tables 2-4).

The risk for osteoporotic hip fracture after 1 and 2 years was affected by age and number of LJSIs and TSIs but not by number of ESIs. Sex and CCI were also risk factors for hip fracture at 1 and 2 years for ESI and LJSI patients, as was race for LJSI patients. Risk for osteoporotic wrist fracture at 1 and 2 years was affected by sex and race for ESI and LJSI patients; age, race, CCI, and long-term steroid use were risk factors for TSI patients at all time points. Higher number of LJSIs, but not ESIs or TSIs, was associated with lower wrist fracture risk.

Discussion

ESIs continue to be used in the nonoperative treatment of low back pain, radicular leg pain, and spinal stenosis. Although the present study found ESI use increased in the Medicare population between 1994 and 2001,18 the trend is reversing, decreasing by 25%, with rates of 264 per 10,000 Medicare enrollees in 2004 and 194 per 10,000 enrollees in 2011. ESI use may have changed after systematic reviews revealed there was no clear evidence of the efficacy of ESIs in managing low back pain and radicular leg pain3,5,6 or spinal stenosis.4

Nevertheless, ESIs are widely used because of the perceived benefit balanced against the perceived rarity of adverse events.6 Even if patients recognize a low likelihood of significant benefit, they may accept ESI as preferable to surgery. In addition, most private payers require extensive nonoperative treatment before they will approve surgery as a treatment option.

In a study by Mandel and colleagues,14 ESI increased the risk of vertebral compression fractures by 21%, which in turn increased the risk of death.19 If accurate, these findings obviously would challenge the perception that ESI is a low-risk intervention. In contrast to the Mandel study,14 the present analysis of the Medicare population revealed no clinically relevant change in risk of osteoporotic spine fracture with each successive ESI after the initial injection. After the initial injection, each successive ESI decreased the relative risk of osteoporotic spine fracture by 2%, and each successive LJSI decreased it by 4%. Although statistically significant, the small change in relative risk may not be clinically relevant. However, taken cumulatively over a number of successive injections, these effects may be clinically relevant.

The data also showed that, after the initial injection, each successive ESI had no effect on risk of osteoporotic hip or wrist fracture, and each successive LJSI reduced the risk. Similar to earlier findings,20,21 long-term steroid use increased the risk of spine fracture in ESI and LJSI patients. Prolonged exposure to steroids may be necessary to reduce bone formation and increase bone breakdown.12

Although the study by Mandel and colleagues14 and our study both used administrative databases and survival analysis methods, conclusions differed. First, Mandel and colleagues14 used a study inclusion criterion of spine-related steroid injections, whereas we used a criterion of any steroid injection. Second, they used 50 years as the lower age for study inclusion, and we used 65 years. Third, to control for patients who had osteoporosis before study entry, they excluded those who had a fracture in an adjacent vertebra after kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty. It is unclear if patients who had osteoporotic fractures at other sites were excluded as well. Thus, the 2 cohorts may not be directly comparable.

Whereas Mandel and colleagues14 based their definition of osteoporotic spine fracture on a keyword search of a radiology database, we used a specific reportable ICD-9-CM diagnosis code. As a result, they may have overreported osteoporotic spine fractures, and we may have underreported. Finally, our sample was much larger than theirs. Given the relative rarity of osteoporotic fractures, a study with a larger sample may have more power to detect differences. In addition, unlike Mandel and colleagues,14 we focused on an injection cohort. We did not include or make comparisons with a no-injection cohort because our study hypothesis involved the potential systemic effects of steroid injections based on injection site. Although chronic steroid use was found to have a significant effect in our study, it is unclear to what extent the diagnosis code was used, during the comorbidity assessment or only in the event of steroid-related complications.

Our study also found that, after the initial injection, each successive LJSI decreased the risk of osteoporotic wrist fracture by 10%, and each successive TSI decreased the risk of osteoporotic hip fracture by 5%. It is plausible these injections allowed improved mobility, mitigating the effects of osteoporosis induced by inactivity and lack of resistance training. It is also possible that improved mobility limited falls.

In summary, this analysis of the Medicare claims database revealed that ESI, TSI, and LJSI decreased osteoporotic spine fracture risk. However, the effect was small and may not be clinically meaningful. After the initial injection, successive ESIs had no effect on the risk of osteoporotic hip or wrist fracture, and successive LJSIs reduced the risk of osteoporotic wrist fracture, perhaps because of improved mobility. Prolonged oral steroid use increased spine fracture risk in ESI and LJSI patients. More studies are needed to evaluate the risk-benefit profile of steroid injections.

1. Pethö G, Reeh PW. Sensory and signaling mechanisms of bradykinin, eicosanoids, platelet-activating factor, and nitric oxide in peripheral nociceptors. Physiol Rev. 2012;92(4):1699-1775.

2. Saal J. The role of inflammation in lumbar pain. Spine. 1995;20(16):1821-1827.

3. Choi HJ, Hahn S, Kim CH, et al. Epidural steroid injection therapy for low back pain: a meta-analysis. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2013;29(3):244-253.

4. Chou R, Loeser JD, Owens DK, et al; American Pain Society Low Back Pain Guideline Panel. Interventional therapies, surgery, and interdisciplinary rehabilitation for low back pain: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society. Spine. 2009;34(10):1066-1077.

5. Savigny P, Watson P, Underwood M; Guideline Development Group. Early management of persistent non-specific low back pain: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2009;338:b1805.

6. Staal JB, de Bie RA, de Vet HC, Hildebrandt J, Nelemans P. Injection therapy for subacute and chronic low back pain: an updated Cochrane review. Spine. 2009;34(1):49-59.

7. Angeli A, Guglielmi G, Dovio A, et al. High prevalence of asymptomatic vertebral fractures in post-menopausal women receiving chronic glucocorticoid therapy: a cross-sectional outpatient study. Bone. 2006;39(2):253-259.

8. Donnan PT, Libby G, Boyter AC, Thompson P. The population risk of fractures attributable to oral corticosteroids. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14(3):177-186.

9. Dubois EF, Wagemans MF, Verdouw BC, et al. Lack of relationships between cumulative methylprednisolone dose and bone mineral density in healthy men and postmenopausal women with chronic low back pain. Clin Rheumatol. 2003;22(1):12-17.

10. Yi Y, Hwang B, Son H, Cheong I. Low bone mineral density, but not epidural steroid injection, is associated with fracture in postmenopausal women with low back pain. Pain Physician. 2012;15(6):441-449.

11. Al-Shoha A, Rao DS, Schilling J, Peterson E, Mandel S. Effect of epidural steroid injection on bone mineral density and markers of bone turnover in postmenopausal women. Spine. 2012;37(25):E1567-E1571.

12. Kang SS, Hwang BM, Son H, Cheong IY, Lee SJ, Chung TY. Changes in bone mineral density in postmenopausal women treated with epidural steroid injections for lower back pain. Pain Physician. 2012;15(3):229-236.

13. Kim S, Hwang B. Relationship between bone mineral density and the frequent administration of epidural steroid injections in postmenopausal women with low back pain. Pain Res Manag. 2014;19(1):30-34.

14. Mandel S, Schilling J, Peterson E, Rao DS, Sanders W. A retrospective analysis of vertebral body fractures following epidural steroid injections. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(11):961-964.

15. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383.

16. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613-619.

17. Murray SB, Bates DW, Ngo L, Ufberg JW, Shapiro NI. Charlson index is associated with one-year mortality in emergency department patients with suspected infection. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(5):530-536.

18. Friedly J, Chan L, Deyo R. Increases in lumbosacral injections in the Medicare population: 1994 to 2001. Spine. 2007;32(16):1754-1760.

19. Puisto V, Rissanen H, Heliövaara M, et al. Vertebral fracture and cause-specific mortality: a prospective population study of 3,210 men and 3,730 women with 30 years of follow-up. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(12):2181-2186.

20. Lee YH, Woo JH, Choi SJ, Ji JD, Song GG. Effects of low-dose corticosteroids on the bone mineral density of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis. J Investig Med. 2008;56(8):1011-1018.

21. Lukert BP, Raisz LG. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1994;20(3):629-650.

1. Pethö G, Reeh PW. Sensory and signaling mechanisms of bradykinin, eicosanoids, platelet-activating factor, and nitric oxide in peripheral nociceptors. Physiol Rev. 2012;92(4):1699-1775.

2. Saal J. The role of inflammation in lumbar pain. Spine. 1995;20(16):1821-1827.

3. Choi HJ, Hahn S, Kim CH, et al. Epidural steroid injection therapy for low back pain: a meta-analysis. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2013;29(3):244-253.

4. Chou R, Loeser JD, Owens DK, et al; American Pain Society Low Back Pain Guideline Panel. Interventional therapies, surgery, and interdisciplinary rehabilitation for low back pain: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society. Spine. 2009;34(10):1066-1077.

5. Savigny P, Watson P, Underwood M; Guideline Development Group. Early management of persistent non-specific low back pain: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2009;338:b1805.

6. Staal JB, de Bie RA, de Vet HC, Hildebrandt J, Nelemans P. Injection therapy for subacute and chronic low back pain: an updated Cochrane review. Spine. 2009;34(1):49-59.

7. Angeli A, Guglielmi G, Dovio A, et al. High prevalence of asymptomatic vertebral fractures in post-menopausal women receiving chronic glucocorticoid therapy: a cross-sectional outpatient study. Bone. 2006;39(2):253-259.

8. Donnan PT, Libby G, Boyter AC, Thompson P. The population risk of fractures attributable to oral corticosteroids. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14(3):177-186.

9. Dubois EF, Wagemans MF, Verdouw BC, et al. Lack of relationships between cumulative methylprednisolone dose and bone mineral density in healthy men and postmenopausal women with chronic low back pain. Clin Rheumatol. 2003;22(1):12-17.

10. Yi Y, Hwang B, Son H, Cheong I. Low bone mineral density, but not epidural steroid injection, is associated with fracture in postmenopausal women with low back pain. Pain Physician. 2012;15(6):441-449.

11. Al-Shoha A, Rao DS, Schilling J, Peterson E, Mandel S. Effect of epidural steroid injection on bone mineral density and markers of bone turnover in postmenopausal women. Spine. 2012;37(25):E1567-E1571.

12. Kang SS, Hwang BM, Son H, Cheong IY, Lee SJ, Chung TY. Changes in bone mineral density in postmenopausal women treated with epidural steroid injections for lower back pain. Pain Physician. 2012;15(3):229-236.

13. Kim S, Hwang B. Relationship between bone mineral density and the frequent administration of epidural steroid injections in postmenopausal women with low back pain. Pain Res Manag. 2014;19(1):30-34.

14. Mandel S, Schilling J, Peterson E, Rao DS, Sanders W. A retrospective analysis of vertebral body fractures following epidural steroid injections. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(11):961-964.

15. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383.

16. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613-619.

17. Murray SB, Bates DW, Ngo L, Ufberg JW, Shapiro NI. Charlson index is associated with one-year mortality in emergency department patients with suspected infection. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13(5):530-536.

18. Friedly J, Chan L, Deyo R. Increases in lumbosacral injections in the Medicare population: 1994 to 2001. Spine. 2007;32(16):1754-1760.

19. Puisto V, Rissanen H, Heliövaara M, et al. Vertebral fracture and cause-specific mortality: a prospective population study of 3,210 men and 3,730 women with 30 years of follow-up. Eur Spine J. 2011;20(12):2181-2186.

20. Lee YH, Woo JH, Choi SJ, Ji JD, Song GG. Effects of low-dose corticosteroids on the bone mineral density of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis. J Investig Med. 2008;56(8):1011-1018.

21. Lukert BP, Raisz LG. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1994;20(3):629-650.

Robot-assisted prostatectomy providing better outcomes

Robot-assisted radical prostatectomy shows better early postoperative outcomes than does laparoscopic radical prostatectomy, but the differences between the two surgical approaches disappeared by the 6-month follow-up.

Dr. Hiroyuki Koike and his colleagues at Wakayama (Japan) Medical University Hospital conducted a study of two groups of patients treated for localized prostate cancer. One group of 229 patients underwent laparoscopic radical prostatectomy (LRP) between July 2007 and July 2013. The other group of 115 patients had robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP) between December 2012 and August 2014 (J Robot Surg. 2017;11[3]:325-31).

The patients were given health-related quality of life self-assessment surveys prior to surgery and at 3, 6, and 12 months post surgery. In addition, a generic questionnaire, the eight-item Short-Form Health Survey, was used to assess a physical component summary (PCS) and a mental component summary (MCS). The Expanded Prostate Cancer Index of Prostate, which covers four domains – urinary, sexual, bowel, and hormonal – was used as a disease-specific measure, and the response rates for both LRP and RARP at each follow-up interval were over 80%.

“The RARP group showed significantly better scores in urinary summary and all urinary subscales at postoperative 3-month follow-up. However, these differences disappeared at postoperative 6 and 12-month follow-up,” the investigators wrote. For the urinary summary score, LRP significantly underperformed, compared with RARP, with scores of 63.3 vs. 75.8, respectively, after 3 months. In addition, the bowel function score was superior for RARP, compared with LRP, at 96.9 vs. 92.9, respectively. Sexual function results were similar, with RARP and LRP scores of 2.8 vs. 0.

The general measures of the PCS and MCS also favored RARP. At the 3-month follow-up, PCS (51.3 vs. 48.1) and MCS (50 vs. 47.8) scores were higher for RARP, compared with LRP.

“It is unclear why our superiority of urinary function in RARP was observed only in early period. However, we can speculate several reasons for better urinary function in RARP group. First, we were able to treat the apex area more delicately with RARP. Second, some of the new techniques which we employed after the introduction of RARP could influence the urinary continence recovery,” the investigators wrote.

The authors had no relevant financial disclosures.

Robot-assisted radical prostatectomy shows better early postoperative outcomes than does laparoscopic radical prostatectomy, but the differences between the two surgical approaches disappeared by the 6-month follow-up.

Dr. Hiroyuki Koike and his colleagues at Wakayama (Japan) Medical University Hospital conducted a study of two groups of patients treated for localized prostate cancer. One group of 229 patients underwent laparoscopic radical prostatectomy (LRP) between July 2007 and July 2013. The other group of 115 patients had robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP) between December 2012 and August 2014 (J Robot Surg. 2017;11[3]:325-31).