User login

Neurology Reviews covers innovative and emerging news in neurology and neuroscience every month, with a focus on practical approaches to treating Parkinson's disease, epilepsy, headache, stroke, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer's disease, and other neurologic disorders.

PML

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

Rituxan

The leading independent newspaper covering neurology news and commentary.

Migraine after concussion linked to worse outcomes

researchers have found.

“Early assessment of headache – and whether it has migraine features – after concussion can be helpful in predicting which children are at risk for poor outcomes and identifying children who require targeted intervention,” said senior author Keith Owen Yeates, PhD, the Ronald and Irene Ward Chair in Pediatric Brain Injury Professor and head of the department of psychology at the University of Calgary (Alta.). “Posttraumatic headache, especially when it involves migraine features, is a strong predictor of persisting symptoms and poorer quality of life after childhood concussion.”

Approximately 840,000 children per year visit an emergency department in the United States after having a traumatic brain injury. As many as 90% of those visits are considered to involve a concussion, according to the investigators. Although most children recover quickly, approximately one-third continue to report symptoms a month after the event.

Posttraumatic headache occurs in up to 90% of children, most commonly with features of migraine.

The new study, published in JAMA Network Open, was a secondary analysis of the Advancing Concussion Assessment in Pediatrics (A-CAP) prospective cohort study. The study was conducted at five emergency departments in Canada from September 2016 to July 2019 and included children and adolescents aged 8-17 years who presented with acute concussion or an orthopedic injury.

Children were included in the concussion group if they had a history of blunt head trauma resulting in at least one of three criteria consistent with the World Health Organization definition of mild traumatic brain injury. The criteria include loss of consciousness for less than 30 minutes, a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 13 or 14, or at least one acute sign or symptom of concussion, as noted by emergency clinicians.

Patients were excluded from the concussion group if they had deteriorating neurologic status, underwent neurosurgical intervention, had posttraumatic amnesia that lasted more than 24 hours, or had a score higher than 4 on the Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS). The orthopedic injury group included patients without symptoms of concussion and with blunt trauma associated with an AIS 13 score of 4 or less. Patients were excluded from both groups if they had an overnight hospitalization for traumatic brain injury, a concussion within the past 3 months, or a neurodevelopmental disorder.

The researchers analyzed data from 928 children of 967 enrolled in the study. The median age was 12.2 years, and 41.3% were female. The final study cohort included 239 children with orthopedic injuries but no headache, 160 with a concussion and no headache, 134 with a concussion and nonmigraine headaches, and 254 with a concussion and migraine headaches.

Children with posttraumatic migraines 10 days after a concussion had the most severe symptoms and worst quality of life 3 months following their head trauma, the researchers found. Children without headaches within 10 days after concussion had the best 3-month outcomes, comparable to those with orthopedic injuries alone.

The researchers said the strengths of their study included its large population and its inclusion of various causes of head trauma, not just sports-related concussions. Limitations included self-reports of headaches instead of a physician diagnosis and lack of control for clinical interventions that might have affected the outcomes.

Charles Tator, MD, PhD, director of the Canadian Concussion Centre at Toronto Western Hospital, said the findings were unsurprising.

“Headaches are the most common symptom after concussion,” Dr. Tator, who was not involved in the latest research, told this news organization. “In my practice and research with concussed kids 11 and up and with adults, those with preconcussion history of migraine are the most difficult to treat because their headaches don’t improve unless specific measures are taken.”

Dr. Tator, who also is a professor of neurosurgery at the University of Toronto, said clinicians who treat concussions must determine which type of headaches children are experiencing – and refer as early as possible for migraine prevention or treatment and medication, as warranted.

“Early recognition after concussion that migraine headaches are occurring will save kids a lot of suffering,” he said.

The study was supported by a Canadian Institute of Health Research Foundation Grant and by funds from the Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation and the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute. Dr. Tator has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

researchers have found.

“Early assessment of headache – and whether it has migraine features – after concussion can be helpful in predicting which children are at risk for poor outcomes and identifying children who require targeted intervention,” said senior author Keith Owen Yeates, PhD, the Ronald and Irene Ward Chair in Pediatric Brain Injury Professor and head of the department of psychology at the University of Calgary (Alta.). “Posttraumatic headache, especially when it involves migraine features, is a strong predictor of persisting symptoms and poorer quality of life after childhood concussion.”

Approximately 840,000 children per year visit an emergency department in the United States after having a traumatic brain injury. As many as 90% of those visits are considered to involve a concussion, according to the investigators. Although most children recover quickly, approximately one-third continue to report symptoms a month after the event.

Posttraumatic headache occurs in up to 90% of children, most commonly with features of migraine.

The new study, published in JAMA Network Open, was a secondary analysis of the Advancing Concussion Assessment in Pediatrics (A-CAP) prospective cohort study. The study was conducted at five emergency departments in Canada from September 2016 to July 2019 and included children and adolescents aged 8-17 years who presented with acute concussion or an orthopedic injury.

Children were included in the concussion group if they had a history of blunt head trauma resulting in at least one of three criteria consistent with the World Health Organization definition of mild traumatic brain injury. The criteria include loss of consciousness for less than 30 minutes, a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 13 or 14, or at least one acute sign or symptom of concussion, as noted by emergency clinicians.

Patients were excluded from the concussion group if they had deteriorating neurologic status, underwent neurosurgical intervention, had posttraumatic amnesia that lasted more than 24 hours, or had a score higher than 4 on the Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS). The orthopedic injury group included patients without symptoms of concussion and with blunt trauma associated with an AIS 13 score of 4 or less. Patients were excluded from both groups if they had an overnight hospitalization for traumatic brain injury, a concussion within the past 3 months, or a neurodevelopmental disorder.

The researchers analyzed data from 928 children of 967 enrolled in the study. The median age was 12.2 years, and 41.3% were female. The final study cohort included 239 children with orthopedic injuries but no headache, 160 with a concussion and no headache, 134 with a concussion and nonmigraine headaches, and 254 with a concussion and migraine headaches.

Children with posttraumatic migraines 10 days after a concussion had the most severe symptoms and worst quality of life 3 months following their head trauma, the researchers found. Children without headaches within 10 days after concussion had the best 3-month outcomes, comparable to those with orthopedic injuries alone.

The researchers said the strengths of their study included its large population and its inclusion of various causes of head trauma, not just sports-related concussions. Limitations included self-reports of headaches instead of a physician diagnosis and lack of control for clinical interventions that might have affected the outcomes.

Charles Tator, MD, PhD, director of the Canadian Concussion Centre at Toronto Western Hospital, said the findings were unsurprising.

“Headaches are the most common symptom after concussion,” Dr. Tator, who was not involved in the latest research, told this news organization. “In my practice and research with concussed kids 11 and up and with adults, those with preconcussion history of migraine are the most difficult to treat because their headaches don’t improve unless specific measures are taken.”

Dr. Tator, who also is a professor of neurosurgery at the University of Toronto, said clinicians who treat concussions must determine which type of headaches children are experiencing – and refer as early as possible for migraine prevention or treatment and medication, as warranted.

“Early recognition after concussion that migraine headaches are occurring will save kids a lot of suffering,” he said.

The study was supported by a Canadian Institute of Health Research Foundation Grant and by funds from the Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation and the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute. Dr. Tator has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

researchers have found.

“Early assessment of headache – and whether it has migraine features – after concussion can be helpful in predicting which children are at risk for poor outcomes and identifying children who require targeted intervention,” said senior author Keith Owen Yeates, PhD, the Ronald and Irene Ward Chair in Pediatric Brain Injury Professor and head of the department of psychology at the University of Calgary (Alta.). “Posttraumatic headache, especially when it involves migraine features, is a strong predictor of persisting symptoms and poorer quality of life after childhood concussion.”

Approximately 840,000 children per year visit an emergency department in the United States after having a traumatic brain injury. As many as 90% of those visits are considered to involve a concussion, according to the investigators. Although most children recover quickly, approximately one-third continue to report symptoms a month after the event.

Posttraumatic headache occurs in up to 90% of children, most commonly with features of migraine.

The new study, published in JAMA Network Open, was a secondary analysis of the Advancing Concussion Assessment in Pediatrics (A-CAP) prospective cohort study. The study was conducted at five emergency departments in Canada from September 2016 to July 2019 and included children and adolescents aged 8-17 years who presented with acute concussion or an orthopedic injury.

Children were included in the concussion group if they had a history of blunt head trauma resulting in at least one of three criteria consistent with the World Health Organization definition of mild traumatic brain injury. The criteria include loss of consciousness for less than 30 minutes, a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 13 or 14, or at least one acute sign or symptom of concussion, as noted by emergency clinicians.

Patients were excluded from the concussion group if they had deteriorating neurologic status, underwent neurosurgical intervention, had posttraumatic amnesia that lasted more than 24 hours, or had a score higher than 4 on the Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS). The orthopedic injury group included patients without symptoms of concussion and with blunt trauma associated with an AIS 13 score of 4 or less. Patients were excluded from both groups if they had an overnight hospitalization for traumatic brain injury, a concussion within the past 3 months, or a neurodevelopmental disorder.

The researchers analyzed data from 928 children of 967 enrolled in the study. The median age was 12.2 years, and 41.3% were female. The final study cohort included 239 children with orthopedic injuries but no headache, 160 with a concussion and no headache, 134 with a concussion and nonmigraine headaches, and 254 with a concussion and migraine headaches.

Children with posttraumatic migraines 10 days after a concussion had the most severe symptoms and worst quality of life 3 months following their head trauma, the researchers found. Children without headaches within 10 days after concussion had the best 3-month outcomes, comparable to those with orthopedic injuries alone.

The researchers said the strengths of their study included its large population and its inclusion of various causes of head trauma, not just sports-related concussions. Limitations included self-reports of headaches instead of a physician diagnosis and lack of control for clinical interventions that might have affected the outcomes.

Charles Tator, MD, PhD, director of the Canadian Concussion Centre at Toronto Western Hospital, said the findings were unsurprising.

“Headaches are the most common symptom after concussion,” Dr. Tator, who was not involved in the latest research, told this news organization. “In my practice and research with concussed kids 11 and up and with adults, those with preconcussion history of migraine are the most difficult to treat because their headaches don’t improve unless specific measures are taken.”

Dr. Tator, who also is a professor of neurosurgery at the University of Toronto, said clinicians who treat concussions must determine which type of headaches children are experiencing – and refer as early as possible for migraine prevention or treatment and medication, as warranted.

“Early recognition after concussion that migraine headaches are occurring will save kids a lot of suffering,” he said.

The study was supported by a Canadian Institute of Health Research Foundation Grant and by funds from the Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation and the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute. Dr. Tator has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

We have seen the future of healthy muffins, and its name is Roselle

Get ‘em while they’re hot … for your health

Today on the Eating Channel, it’s a very special episode of “Much Ado About Muffin.”

The muffin. For some of us, it’s a good way to pretend we’re not having dessert for breakfast. A bran muffin can be loaded with calcium and fiber, and our beloved blueberry is full of yummy antioxidants and vitamins. Definitely not dessert.

Well, the muffin denial can stop there because there’s a new flavor on the scene, and research suggests it may actually be healthy. (Disclaimer: Muffin may not be considered healthy in Norway.) This new muffin has a name, Roselle, that comes from the calyx extract used in it, which is found in the Hibiscus sabdariffa plant of the same name.

Now, when it comes to new foods, especially ones that are supposed to be healthy, the No. 1 criteria is the same: It has to taste good. Researchers at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology and Amity University in India agreed, but they also set out to make it nutritionally valuable and give it a long shelf life without the addition of preservatives.

Sounds like a tall order, but they figured it out.

Not only is it tasty, but the properties of it could rival your morning multivitamin. Hibiscus extract has huge amounts of antioxidants, like phenolics, which are believed to help prevent cell membrane damage. Foods like vegetables, flax seed, and whole grains also have these antioxidants, but why not just have a Roselle muffin instead? You also get a dose of ascorbic acid without the glass of OJ in the morning.

The ascorbic acid, however, is not there just to help you. It also helps to check the researcher’s third box, shelf life. These naturally rosy-colored pastries will stay mold-free for 6 days without refrigeration at room temperature and without added preservatives.

Our guess, though, is they won’t be on the kitchen counter long enough to find out.

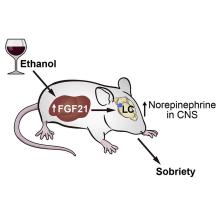

A sobering proposition

If Hollywood is to be believed, there’s no amount of drunkenness that can’t be cured with a cup of coffee or a stern slap in the face. Unfortunately, here in the real world the only thing that can make you less drunk is time. Maybe next time you’ll stop after that seventh Manhattan.

But what if we could beat time? What if there’s an actual sobriety drug out there?

Say hello to fibroblast growth factor 21. Although the liver already does good work filtering out what is essentially poison, it then goes the extra mile and produces fibroblast growth factor 21 (or, as her friends call her, FGF21), a hormone that suppresses the desire to drink, makes you desire water, and protects the liver all at the same time.

Now, FGF21 in its current role is great, but if you’ve ever seen or been a drunk person before, you’ve experienced the lack of interest in listening to reason, especially when it comes from within our own bodies. Who are you to tell us what to do, body? You’re not the boss of us! So a group of scientists decided to push the limits of FGF21. Could it do more than it already does?

First off, they genetically altered a group of mice so that they didn’t produce FGF21 on their own. Then they got them drunk. We’re going to assume they built a scale model of the bar from Cheers and had the mice filter in through the front door as they served their subjects beer out of tiny little glasses.

Once the mice were nice and liquored up, some were given a treatment of FGF21 while others were given a placebo. Lo and behold, the mice given FGF21 recovered about 50% faster than those that received the control treatment. Not exactly instant, but 50% is nothing to sniff at.

Before you bring your FGF21 supplement to the bar, though, this research only applies to mice. We don’t know if it works in people. And make sure you stick to booze. If your choice of intoxication is a bit more exotic, FGF21 isn’t going to do anything for you. Yes, the scientists tried. Yes, those mice are living a very interesting life. And yes, we are jealous of drugged-up lab mice.

Supersize your imagination, shrink your snacks

Have you ever heard of the meal-recall effect? Did you know that, in England, a biscuit is really a cookie? Did you also know that the magazine Bon Appétit is not the same as the peer-reviewed journal Appetite? We do … now.

The meal-recall effect is the subsequent reduction in snacking that comes from remembering a recent meal. It was used to great effect in a recent study conducted at the University of Cambridge, which is in England, where they feed their experimental humans cookies but, for some reason, call them biscuits.

For the first part of the study, the participants were invited to dine at Che Laboratory, where they “were given a microwave ready meal of rice and sauce and a cup of water,” according to a statement from the university. As our Uncle Ernie would say, “Gourmet all the way.”

The test subjects were instructed not to eat anything for 3 hours and “then invited back to the lab to perform imagination tasks.” Those who did come back were randomly divided into five different groups, each with a different task:

- Imagine moving their recent lunch at the lab around a plate.

- Recall eating their recent lunch in detail.

- Imagine that the lunch was twice as big and filling as it really was.

- Look at a photograph of spaghetti hoops in tomato sauce and write a description of it before imagining moving the food around a plate.

- Look at a photo of paper clips and rubber bands and imagine moving them around.

Now, at last, we get to the biscuits/cookies, which were the subject of a taste test that “was simply a rouse for covertly assessing snacking,” the investigators explained. As part of that test, participants were told they could eat as many biscuits as they wanted.

When the tables were cleared and the leftovers examined, the group that imagined spaghetti hoops had eaten the most biscuits (75.9 g), followed by the group that imagined paper clips (75.5 g), the moving-their-lunch-around-the-plate group (72.0 g), and the group that relived eating their lunch (70.0 g).

In a victory for the meal-recall effect, the people who imagined their meal being twice as big ate the fewest biscuits (51.1 g). “Your mind can be more powerful than your stomach in dictating how much you eat,” lead author Joanna Szypula, PhD, said in the university statement.

Oh! One more thing. The study appeared in Appetite, which is a peer-reviewed journal, not in Bon Appétit, which is not a peer-reviewed journal. Thanks to the fine folks at both publications for pointing that out to us.

Get ‘em while they’re hot … for your health

Today on the Eating Channel, it’s a very special episode of “Much Ado About Muffin.”

The muffin. For some of us, it’s a good way to pretend we’re not having dessert for breakfast. A bran muffin can be loaded with calcium and fiber, and our beloved blueberry is full of yummy antioxidants and vitamins. Definitely not dessert.

Well, the muffin denial can stop there because there’s a new flavor on the scene, and research suggests it may actually be healthy. (Disclaimer: Muffin may not be considered healthy in Norway.) This new muffin has a name, Roselle, that comes from the calyx extract used in it, which is found in the Hibiscus sabdariffa plant of the same name.

Now, when it comes to new foods, especially ones that are supposed to be healthy, the No. 1 criteria is the same: It has to taste good. Researchers at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology and Amity University in India agreed, but they also set out to make it nutritionally valuable and give it a long shelf life without the addition of preservatives.

Sounds like a tall order, but they figured it out.

Not only is it tasty, but the properties of it could rival your morning multivitamin. Hibiscus extract has huge amounts of antioxidants, like phenolics, which are believed to help prevent cell membrane damage. Foods like vegetables, flax seed, and whole grains also have these antioxidants, but why not just have a Roselle muffin instead? You also get a dose of ascorbic acid without the glass of OJ in the morning.

The ascorbic acid, however, is not there just to help you. It also helps to check the researcher’s third box, shelf life. These naturally rosy-colored pastries will stay mold-free for 6 days without refrigeration at room temperature and without added preservatives.

Our guess, though, is they won’t be on the kitchen counter long enough to find out.

A sobering proposition

If Hollywood is to be believed, there’s no amount of drunkenness that can’t be cured with a cup of coffee or a stern slap in the face. Unfortunately, here in the real world the only thing that can make you less drunk is time. Maybe next time you’ll stop after that seventh Manhattan.

But what if we could beat time? What if there’s an actual sobriety drug out there?

Say hello to fibroblast growth factor 21. Although the liver already does good work filtering out what is essentially poison, it then goes the extra mile and produces fibroblast growth factor 21 (or, as her friends call her, FGF21), a hormone that suppresses the desire to drink, makes you desire water, and protects the liver all at the same time.

Now, FGF21 in its current role is great, but if you’ve ever seen or been a drunk person before, you’ve experienced the lack of interest in listening to reason, especially when it comes from within our own bodies. Who are you to tell us what to do, body? You’re not the boss of us! So a group of scientists decided to push the limits of FGF21. Could it do more than it already does?

First off, they genetically altered a group of mice so that they didn’t produce FGF21 on their own. Then they got them drunk. We’re going to assume they built a scale model of the bar from Cheers and had the mice filter in through the front door as they served their subjects beer out of tiny little glasses.

Once the mice were nice and liquored up, some were given a treatment of FGF21 while others were given a placebo. Lo and behold, the mice given FGF21 recovered about 50% faster than those that received the control treatment. Not exactly instant, but 50% is nothing to sniff at.

Before you bring your FGF21 supplement to the bar, though, this research only applies to mice. We don’t know if it works in people. And make sure you stick to booze. If your choice of intoxication is a bit more exotic, FGF21 isn’t going to do anything for you. Yes, the scientists tried. Yes, those mice are living a very interesting life. And yes, we are jealous of drugged-up lab mice.

Supersize your imagination, shrink your snacks

Have you ever heard of the meal-recall effect? Did you know that, in England, a biscuit is really a cookie? Did you also know that the magazine Bon Appétit is not the same as the peer-reviewed journal Appetite? We do … now.

The meal-recall effect is the subsequent reduction in snacking that comes from remembering a recent meal. It was used to great effect in a recent study conducted at the University of Cambridge, which is in England, where they feed their experimental humans cookies but, for some reason, call them biscuits.

For the first part of the study, the participants were invited to dine at Che Laboratory, where they “were given a microwave ready meal of rice and sauce and a cup of water,” according to a statement from the university. As our Uncle Ernie would say, “Gourmet all the way.”

The test subjects were instructed not to eat anything for 3 hours and “then invited back to the lab to perform imagination tasks.” Those who did come back were randomly divided into five different groups, each with a different task:

- Imagine moving their recent lunch at the lab around a plate.

- Recall eating their recent lunch in detail.

- Imagine that the lunch was twice as big and filling as it really was.

- Look at a photograph of spaghetti hoops in tomato sauce and write a description of it before imagining moving the food around a plate.

- Look at a photo of paper clips and rubber bands and imagine moving them around.

Now, at last, we get to the biscuits/cookies, which were the subject of a taste test that “was simply a rouse for covertly assessing snacking,” the investigators explained. As part of that test, participants were told they could eat as many biscuits as they wanted.

When the tables were cleared and the leftovers examined, the group that imagined spaghetti hoops had eaten the most biscuits (75.9 g), followed by the group that imagined paper clips (75.5 g), the moving-their-lunch-around-the-plate group (72.0 g), and the group that relived eating their lunch (70.0 g).

In a victory for the meal-recall effect, the people who imagined their meal being twice as big ate the fewest biscuits (51.1 g). “Your mind can be more powerful than your stomach in dictating how much you eat,” lead author Joanna Szypula, PhD, said in the university statement.

Oh! One more thing. The study appeared in Appetite, which is a peer-reviewed journal, not in Bon Appétit, which is not a peer-reviewed journal. Thanks to the fine folks at both publications for pointing that out to us.

Get ‘em while they’re hot … for your health

Today on the Eating Channel, it’s a very special episode of “Much Ado About Muffin.”

The muffin. For some of us, it’s a good way to pretend we’re not having dessert for breakfast. A bran muffin can be loaded with calcium and fiber, and our beloved blueberry is full of yummy antioxidants and vitamins. Definitely not dessert.

Well, the muffin denial can stop there because there’s a new flavor on the scene, and research suggests it may actually be healthy. (Disclaimer: Muffin may not be considered healthy in Norway.) This new muffin has a name, Roselle, that comes from the calyx extract used in it, which is found in the Hibiscus sabdariffa plant of the same name.

Now, when it comes to new foods, especially ones that are supposed to be healthy, the No. 1 criteria is the same: It has to taste good. Researchers at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology and Amity University in India agreed, but they also set out to make it nutritionally valuable and give it a long shelf life without the addition of preservatives.

Sounds like a tall order, but they figured it out.

Not only is it tasty, but the properties of it could rival your morning multivitamin. Hibiscus extract has huge amounts of antioxidants, like phenolics, which are believed to help prevent cell membrane damage. Foods like vegetables, flax seed, and whole grains also have these antioxidants, but why not just have a Roselle muffin instead? You also get a dose of ascorbic acid without the glass of OJ in the morning.

The ascorbic acid, however, is not there just to help you. It also helps to check the researcher’s third box, shelf life. These naturally rosy-colored pastries will stay mold-free for 6 days without refrigeration at room temperature and without added preservatives.

Our guess, though, is they won’t be on the kitchen counter long enough to find out.

A sobering proposition

If Hollywood is to be believed, there’s no amount of drunkenness that can’t be cured with a cup of coffee or a stern slap in the face. Unfortunately, here in the real world the only thing that can make you less drunk is time. Maybe next time you’ll stop after that seventh Manhattan.

But what if we could beat time? What if there’s an actual sobriety drug out there?

Say hello to fibroblast growth factor 21. Although the liver already does good work filtering out what is essentially poison, it then goes the extra mile and produces fibroblast growth factor 21 (or, as her friends call her, FGF21), a hormone that suppresses the desire to drink, makes you desire water, and protects the liver all at the same time.

Now, FGF21 in its current role is great, but if you’ve ever seen or been a drunk person before, you’ve experienced the lack of interest in listening to reason, especially when it comes from within our own bodies. Who are you to tell us what to do, body? You’re not the boss of us! So a group of scientists decided to push the limits of FGF21. Could it do more than it already does?

First off, they genetically altered a group of mice so that they didn’t produce FGF21 on their own. Then they got them drunk. We’re going to assume they built a scale model of the bar from Cheers and had the mice filter in through the front door as they served their subjects beer out of tiny little glasses.

Once the mice were nice and liquored up, some were given a treatment of FGF21 while others were given a placebo. Lo and behold, the mice given FGF21 recovered about 50% faster than those that received the control treatment. Not exactly instant, but 50% is nothing to sniff at.

Before you bring your FGF21 supplement to the bar, though, this research only applies to mice. We don’t know if it works in people. And make sure you stick to booze. If your choice of intoxication is a bit more exotic, FGF21 isn’t going to do anything for you. Yes, the scientists tried. Yes, those mice are living a very interesting life. And yes, we are jealous of drugged-up lab mice.

Supersize your imagination, shrink your snacks

Have you ever heard of the meal-recall effect? Did you know that, in England, a biscuit is really a cookie? Did you also know that the magazine Bon Appétit is not the same as the peer-reviewed journal Appetite? We do … now.

The meal-recall effect is the subsequent reduction in snacking that comes from remembering a recent meal. It was used to great effect in a recent study conducted at the University of Cambridge, which is in England, where they feed their experimental humans cookies but, for some reason, call them biscuits.

For the first part of the study, the participants were invited to dine at Che Laboratory, where they “were given a microwave ready meal of rice and sauce and a cup of water,” according to a statement from the university. As our Uncle Ernie would say, “Gourmet all the way.”

The test subjects were instructed not to eat anything for 3 hours and “then invited back to the lab to perform imagination tasks.” Those who did come back were randomly divided into five different groups, each with a different task:

- Imagine moving their recent lunch at the lab around a plate.

- Recall eating their recent lunch in detail.

- Imagine that the lunch was twice as big and filling as it really was.

- Look at a photograph of spaghetti hoops in tomato sauce and write a description of it before imagining moving the food around a plate.

- Look at a photo of paper clips and rubber bands and imagine moving them around.

Now, at last, we get to the biscuits/cookies, which were the subject of a taste test that “was simply a rouse for covertly assessing snacking,” the investigators explained. As part of that test, participants were told they could eat as many biscuits as they wanted.

When the tables were cleared and the leftovers examined, the group that imagined spaghetti hoops had eaten the most biscuits (75.9 g), followed by the group that imagined paper clips (75.5 g), the moving-their-lunch-around-the-plate group (72.0 g), and the group that relived eating their lunch (70.0 g).

In a victory for the meal-recall effect, the people who imagined their meal being twice as big ate the fewest biscuits (51.1 g). “Your mind can be more powerful than your stomach in dictating how much you eat,” lead author Joanna Szypula, PhD, said in the university statement.

Oh! One more thing. The study appeared in Appetite, which is a peer-reviewed journal, not in Bon Appétit, which is not a peer-reviewed journal. Thanks to the fine folks at both publications for pointing that out to us.

Physical activity is a growing priority for patients with MS

SAN DIEGO – As , researchers have developed a mobile app to encourage young patients with the disease to become more active. The smartphone-based app provides tailored physical activity information, coaching advice, and tools to increase social connectedness.

A pilot study examining whether the intervention changes activity, depression, and fatigue levels should be wrapped up later this year, but it looks as though the app is succeeding.

“The feedback we’ve gotten so far from our coaches is that the kids seem highly motivated,” said one of the creators, E. Ann Yeh, MD, professor in the faculty of medicine at the University of Toronto and director of the pediatric MS and neuroinflammatory disorders program at the Hospital for Sick Children.

Preliminary work showed that use of the app was associated with a 31% increase in physical activity.

They discussed this and other studies of the role of exercise in MS at the annual meeting of the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

Higher levels of depression and fatigue

Studies show that youths with MS who are less physically active are more likely to experience higher levels of fatigue and depression. Evidence suggests just 15-30 more minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) makes a clinical difference in terms of improved depression and fatigue scores, said Dr. Yeh.

With moderate physical activity (for example, a brisk walk or raking the yard), the maximal heart rate (HRmax) reaches 64%-76%, while with vigorous physical activity (which includes jogging/running or participating in a strenuous fitness class), the HRmax reaches 77%-93%.

Dr. Yeh described vigorous physical activity as “the stuff that makes you sweat, makes your heart rate go up, and makes you not be able to talk when you’re moving.”

As it stands, kids get very little MVPA – 9.5 min/day, which is well below the recommended 60 min/day. Adults do a bit better – 18.7 min/day of MVPA – but this is still below the recommended 30 min/day.

Being physically active improves fatigue for adults as well as kids, said Dr. Yeh. She referred to a network meta-analysis of 27 studies involving 1,470 participants that evaluated 10 types of exercise interventions, including yoga, resistance training, dance, and aquatic activities. It found that exercise “does move the needle,” she said. “Regardless of the kind of activity that was studied, fatigue seemed to improve.”

The authors of that study ranked aquatic exercise as the most effective intervention. “It’s possible that aquatics worked better because people who can’t move well feel more comfortable in the water,” Dr. Yeh said.

But she cautioned that the one study in the meta-analysis that found a “quite strong” effect of aquatic exercise was “very small.”

With regard to depression, which affects about 30% of people with MS, Dr. Yeh told meeting attendees, “unfortunately, the data are less clear” when it comes to physical activity for adults. One meta-analysis of 15 randomized controlled trials involving 331 exercising participants and 260 control persons found that only a few studies showed positive effects of exercise on depressive symptoms.

However, Dr. Yeh noted that in this review, the baseline depressive symptoms of participants were “above the cutoff level,” which makes it more difficult to demonstrate change in depression levels.

Clear structural effects

Researchers have also described clear brain structural and functional effects from being physically active. For example, MVPA has been shown to affect brain volume, and it has been associated with better optical coherence tomography (OCT) metrics, which measures retinal thinning.

As for the impact of exercise on memory deficits, which is of interest, given the current focus on Alzheimer’s disease, “the jury is still out,” said Dr. Yeh. One 24-week randomized controlled trial found no difference in results on the Brief Repeatable Battery of Neuropsychological tests between participants who engaged in progressive aerobic exercise and control persons.

However, said Dr. Yeh, “the problem may not be with the intervention but with the outcome measures” and potentially with the populations studied.

It might be a different story for high-intensity exercise, though. A study by Danish researchers assessed the effects of a 24-week high-intensity intervention among 84 adult patients with mild-severe impairment.

The primary outcome of that study, which was the percentage of brain volume change, was not met, possibly because the study was too short. There were significant results for some secondary endpoints, including improved cardiorespiratory fitness and lower relapse rate.

“Even though on the face of it, it sounds like a negative study, there were important outcomes,” said Dr. Yeh.

Research into the possible mechanisms behind positive effects of physical activity is limited with regard to patients with MS, said Dr. Yeh. Some studies have implicated certain circulating factors, such as the cytokine irisin and brain-derived neurotrophic factor, but more work is needed, she said.

“There is need for further mechanistic knowledge related to exercise in MS, and this must be accomplished through prospective, randomized studies.”

While exercise likely makes some difference for MS patients, the problem is in getting them to be more active. “You can’t just write a prescription,” said Dr. Yeh.

“Patients should be doing whatever they can, but gradually, and should not go crazy at the beginning because they’ll just burn out,” she said.

She stressed that patients need to find what works for them personally. It’s also important for them to find ways to be active with a friend who can be “a motivator” to help sustain physical activity goals, said Dr. Yeh.

Patients can also look online for remote physical activity programs geared to people with MS, which popped up during the pandemic.

Improved mood, cognition, pain, sleep

In a comment, Marwa Kaisey, MD, assistant professor of neurology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, in Los Angeles, who cochaired the session highlighting the presentation, praised Dr. Yeh’s “excellent talk,” which highlighted the “strong benefit” of exercise for patients with MS.

“As a clinician, I often talk to my patients about the importance of physical exercise and have heard countless anecdotes of how their workout programs helped improve mood, cognition, pain, or sleep.”

However, she agreed there are several areas “where we need more data-driven solutions and a mechanistic understanding of the benefits of physical exercise.”

The pilot study was funded by the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. The MS Society of Canada funded early work on the app, and the National MS Society is funding the trial of the app. Dr. Yeh receives support from the MS Society of Canada. Dr. Kaisey reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO – As , researchers have developed a mobile app to encourage young patients with the disease to become more active. The smartphone-based app provides tailored physical activity information, coaching advice, and tools to increase social connectedness.

A pilot study examining whether the intervention changes activity, depression, and fatigue levels should be wrapped up later this year, but it looks as though the app is succeeding.

“The feedback we’ve gotten so far from our coaches is that the kids seem highly motivated,” said one of the creators, E. Ann Yeh, MD, professor in the faculty of medicine at the University of Toronto and director of the pediatric MS and neuroinflammatory disorders program at the Hospital for Sick Children.

Preliminary work showed that use of the app was associated with a 31% increase in physical activity.

They discussed this and other studies of the role of exercise in MS at the annual meeting of the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

Higher levels of depression and fatigue

Studies show that youths with MS who are less physically active are more likely to experience higher levels of fatigue and depression. Evidence suggests just 15-30 more minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) makes a clinical difference in terms of improved depression and fatigue scores, said Dr. Yeh.

With moderate physical activity (for example, a brisk walk or raking the yard), the maximal heart rate (HRmax) reaches 64%-76%, while with vigorous physical activity (which includes jogging/running or participating in a strenuous fitness class), the HRmax reaches 77%-93%.

Dr. Yeh described vigorous physical activity as “the stuff that makes you sweat, makes your heart rate go up, and makes you not be able to talk when you’re moving.”

As it stands, kids get very little MVPA – 9.5 min/day, which is well below the recommended 60 min/day. Adults do a bit better – 18.7 min/day of MVPA – but this is still below the recommended 30 min/day.

Being physically active improves fatigue for adults as well as kids, said Dr. Yeh. She referred to a network meta-analysis of 27 studies involving 1,470 participants that evaluated 10 types of exercise interventions, including yoga, resistance training, dance, and aquatic activities. It found that exercise “does move the needle,” she said. “Regardless of the kind of activity that was studied, fatigue seemed to improve.”

The authors of that study ranked aquatic exercise as the most effective intervention. “It’s possible that aquatics worked better because people who can’t move well feel more comfortable in the water,” Dr. Yeh said.

But she cautioned that the one study in the meta-analysis that found a “quite strong” effect of aquatic exercise was “very small.”

With regard to depression, which affects about 30% of people with MS, Dr. Yeh told meeting attendees, “unfortunately, the data are less clear” when it comes to physical activity for adults. One meta-analysis of 15 randomized controlled trials involving 331 exercising participants and 260 control persons found that only a few studies showed positive effects of exercise on depressive symptoms.

However, Dr. Yeh noted that in this review, the baseline depressive symptoms of participants were “above the cutoff level,” which makes it more difficult to demonstrate change in depression levels.

Clear structural effects

Researchers have also described clear brain structural and functional effects from being physically active. For example, MVPA has been shown to affect brain volume, and it has been associated with better optical coherence tomography (OCT) metrics, which measures retinal thinning.

As for the impact of exercise on memory deficits, which is of interest, given the current focus on Alzheimer’s disease, “the jury is still out,” said Dr. Yeh. One 24-week randomized controlled trial found no difference in results on the Brief Repeatable Battery of Neuropsychological tests between participants who engaged in progressive aerobic exercise and control persons.

However, said Dr. Yeh, “the problem may not be with the intervention but with the outcome measures” and potentially with the populations studied.

It might be a different story for high-intensity exercise, though. A study by Danish researchers assessed the effects of a 24-week high-intensity intervention among 84 adult patients with mild-severe impairment.

The primary outcome of that study, which was the percentage of brain volume change, was not met, possibly because the study was too short. There were significant results for some secondary endpoints, including improved cardiorespiratory fitness and lower relapse rate.

“Even though on the face of it, it sounds like a negative study, there were important outcomes,” said Dr. Yeh.

Research into the possible mechanisms behind positive effects of physical activity is limited with regard to patients with MS, said Dr. Yeh. Some studies have implicated certain circulating factors, such as the cytokine irisin and brain-derived neurotrophic factor, but more work is needed, she said.

“There is need for further mechanistic knowledge related to exercise in MS, and this must be accomplished through prospective, randomized studies.”

While exercise likely makes some difference for MS patients, the problem is in getting them to be more active. “You can’t just write a prescription,” said Dr. Yeh.

“Patients should be doing whatever they can, but gradually, and should not go crazy at the beginning because they’ll just burn out,” she said.

She stressed that patients need to find what works for them personally. It’s also important for them to find ways to be active with a friend who can be “a motivator” to help sustain physical activity goals, said Dr. Yeh.

Patients can also look online for remote physical activity programs geared to people with MS, which popped up during the pandemic.

Improved mood, cognition, pain, sleep

In a comment, Marwa Kaisey, MD, assistant professor of neurology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, in Los Angeles, who cochaired the session highlighting the presentation, praised Dr. Yeh’s “excellent talk,” which highlighted the “strong benefit” of exercise for patients with MS.

“As a clinician, I often talk to my patients about the importance of physical exercise and have heard countless anecdotes of how their workout programs helped improve mood, cognition, pain, or sleep.”

However, she agreed there are several areas “where we need more data-driven solutions and a mechanistic understanding of the benefits of physical exercise.”

The pilot study was funded by the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. The MS Society of Canada funded early work on the app, and the National MS Society is funding the trial of the app. Dr. Yeh receives support from the MS Society of Canada. Dr. Kaisey reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN DIEGO – As , researchers have developed a mobile app to encourage young patients with the disease to become more active. The smartphone-based app provides tailored physical activity information, coaching advice, and tools to increase social connectedness.

A pilot study examining whether the intervention changes activity, depression, and fatigue levels should be wrapped up later this year, but it looks as though the app is succeeding.

“The feedback we’ve gotten so far from our coaches is that the kids seem highly motivated,” said one of the creators, E. Ann Yeh, MD, professor in the faculty of medicine at the University of Toronto and director of the pediatric MS and neuroinflammatory disorders program at the Hospital for Sick Children.

Preliminary work showed that use of the app was associated with a 31% increase in physical activity.

They discussed this and other studies of the role of exercise in MS at the annual meeting of the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

Higher levels of depression and fatigue

Studies show that youths with MS who are less physically active are more likely to experience higher levels of fatigue and depression. Evidence suggests just 15-30 more minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) makes a clinical difference in terms of improved depression and fatigue scores, said Dr. Yeh.

With moderate physical activity (for example, a brisk walk or raking the yard), the maximal heart rate (HRmax) reaches 64%-76%, while with vigorous physical activity (which includes jogging/running or participating in a strenuous fitness class), the HRmax reaches 77%-93%.

Dr. Yeh described vigorous physical activity as “the stuff that makes you sweat, makes your heart rate go up, and makes you not be able to talk when you’re moving.”

As it stands, kids get very little MVPA – 9.5 min/day, which is well below the recommended 60 min/day. Adults do a bit better – 18.7 min/day of MVPA – but this is still below the recommended 30 min/day.

Being physically active improves fatigue for adults as well as kids, said Dr. Yeh. She referred to a network meta-analysis of 27 studies involving 1,470 participants that evaluated 10 types of exercise interventions, including yoga, resistance training, dance, and aquatic activities. It found that exercise “does move the needle,” she said. “Regardless of the kind of activity that was studied, fatigue seemed to improve.”

The authors of that study ranked aquatic exercise as the most effective intervention. “It’s possible that aquatics worked better because people who can’t move well feel more comfortable in the water,” Dr. Yeh said.

But she cautioned that the one study in the meta-analysis that found a “quite strong” effect of aquatic exercise was “very small.”

With regard to depression, which affects about 30% of people with MS, Dr. Yeh told meeting attendees, “unfortunately, the data are less clear” when it comes to physical activity for adults. One meta-analysis of 15 randomized controlled trials involving 331 exercising participants and 260 control persons found that only a few studies showed positive effects of exercise on depressive symptoms.

However, Dr. Yeh noted that in this review, the baseline depressive symptoms of participants were “above the cutoff level,” which makes it more difficult to demonstrate change in depression levels.

Clear structural effects

Researchers have also described clear brain structural and functional effects from being physically active. For example, MVPA has been shown to affect brain volume, and it has been associated with better optical coherence tomography (OCT) metrics, which measures retinal thinning.

As for the impact of exercise on memory deficits, which is of interest, given the current focus on Alzheimer’s disease, “the jury is still out,” said Dr. Yeh. One 24-week randomized controlled trial found no difference in results on the Brief Repeatable Battery of Neuropsychological tests between participants who engaged in progressive aerobic exercise and control persons.

However, said Dr. Yeh, “the problem may not be with the intervention but with the outcome measures” and potentially with the populations studied.

It might be a different story for high-intensity exercise, though. A study by Danish researchers assessed the effects of a 24-week high-intensity intervention among 84 adult patients with mild-severe impairment.

The primary outcome of that study, which was the percentage of brain volume change, was not met, possibly because the study was too short. There were significant results for some secondary endpoints, including improved cardiorespiratory fitness and lower relapse rate.

“Even though on the face of it, it sounds like a negative study, there were important outcomes,” said Dr. Yeh.

Research into the possible mechanisms behind positive effects of physical activity is limited with regard to patients with MS, said Dr. Yeh. Some studies have implicated certain circulating factors, such as the cytokine irisin and brain-derived neurotrophic factor, but more work is needed, she said.

“There is need for further mechanistic knowledge related to exercise in MS, and this must be accomplished through prospective, randomized studies.”

While exercise likely makes some difference for MS patients, the problem is in getting them to be more active. “You can’t just write a prescription,” said Dr. Yeh.

“Patients should be doing whatever they can, but gradually, and should not go crazy at the beginning because they’ll just burn out,” she said.

She stressed that patients need to find what works for them personally. It’s also important for them to find ways to be active with a friend who can be “a motivator” to help sustain physical activity goals, said Dr. Yeh.

Patients can also look online for remote physical activity programs geared to people with MS, which popped up during the pandemic.

Improved mood, cognition, pain, sleep

In a comment, Marwa Kaisey, MD, assistant professor of neurology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, in Los Angeles, who cochaired the session highlighting the presentation, praised Dr. Yeh’s “excellent talk,” which highlighted the “strong benefit” of exercise for patients with MS.

“As a clinician, I often talk to my patients about the importance of physical exercise and have heard countless anecdotes of how their workout programs helped improve mood, cognition, pain, or sleep.”

However, she agreed there are several areas “where we need more data-driven solutions and a mechanistic understanding of the benefits of physical exercise.”

The pilot study was funded by the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers. The MS Society of Canada funded early work on the app, and the National MS Society is funding the trial of the app. Dr. Yeh receives support from the MS Society of Canada. Dr. Kaisey reports no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ACTRIMS FORUM 2023

Focused ultrasound ablation reduces dyskinesia in Parkinson’s disease

, new research shows.

The technique requires no sedation or brain implants. Surgeons use MRI to identify the globus pallidus internus, a part of the basal ganglia involved in movement disorders, and a focused ultrasound beam to heat and destroy the tissue.

Investigators performed the procedure with a device called Exablate Neuro, which was first approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2016 to treat essential tremor.

On the basis of the results of a multicenter, randomized, sham-controlled trial, the agency expanded the indication in 2021 to include unilateral pallidotomy to treat advanced Parkinson’s disease for patients with mobility, rigidity, or dyskinesia symptoms.

“In some patients with Parkinson’s disease, you get dyskinesias, and ablation of the globus pallidus significantly reduces those dyskinesias and motor impairment,” said lead investigator Vibhor Krishna, MD, associate professor of neurosurgery at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “It could be used to treat patients when other surgical procedures can’t be applied.”

The study was published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Strong response

For the study, 94 patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease who had dyskinesias or motor fluctuations and motor impairment in the off-medication state wore transducer helmets while lying in an MRI scanner. Patients were awake during the entire procedure.

The treatment group received unilateral FUSA on the side of the brain with the greatest motor impairment. The device initially delivered target temperatures of 40°-45° C. Ablative temperatures were gradually increased following evaluations to test for improvement of motor symptoms. The maximum temperature used was 54.3° C.

Patients in the control group underwent an identical procedure with the sonication energy disabled.

The primary outcome was a response to therapy at 3 months, defined as a decrease of at least three points from baseline either in the score on the Movement Disorders Society–Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS), part III, while off medication or in the score on the Unified Dyskinesia Rating Scale (UDRS) while on medication.

At 3 months, 69% of the treatment group reported a response, compared with 32% of the control group (P = .003).

When researchers analyzed MDS-UPDRS scores, they found that 29% of the treatment group and 27% of the control group showed improvement. For UDRS scores, 12% of the treatment group demonstrated improvement. In the control group, there was no improvement on this score. Improvements in both scores were reported in 28% of the treatment group and 5% of the control group.

Among those who reported a response at 3 months, 77% continued to show a response at 12 months.

‘Unforgiving’ area of the brain

While the response rate was a promising sign of this finding, it was not what interested Dr. Krishna the most. “The most surprising finding of this trial is how safe focused ultrasound pallidotomy is in treating patients with Parkinson’s disease,” he said.

The globus pallidus internus is an area of the brain that Dr. Krishna calls “unforgiving.”

“One side is motor fibers, and any problem with that can paralyze the patient, and just below that is the optic tract, and any problem there, you would lose vision,” Dr. Krishna said. “It is a very tough neighborhood to be in.”

By using MRI-guided ultrasound, surgeons can change the target and temperature of the ultrasound beam during the procedure to allow more precise treatment.

Pallidotomy-related adverse events in the treatment group included dysarthria, gait disturbance, loss of taste, visual disturbance, and facial weakness. All were mild to moderate, Dr. Krishna said.

More study is needed

Dyskinesia is a challenge in the management of Parkinson’s disease. Patients need antiparkinsonian medications to slow deterioration of motor function, but those medications can cause the involuntary movements that are a hallmark of dyskinesia.

The most common treatment for this complication, deep-brain stimulation (DBS), has its own drawbacks. It’s an open procedure, and there is a low-level risk for intracranial bleeding and infection. In addition, the electrode implants require ongoing maintenance and adjustment.

But the findings of this study show that, for patients who aren’t candidates for other therapies, such as DBS and ablative radiofrequency, FUSA may be an alternative, wrote Anette Schrag, PhD, professor of clinical neurosciences at University College London, in an accompanying commentary.

“The results confirm that it is effective in reducing motor complications of Parkinson’s disease, at least in the short term,” Dr. Schrag wrote. However, more long-term studies are needed, she added.

One-third of patients in the treatment group had no response to the treatment, and investigators aren’t sure why. Dr. Krishna noted that the benefits of the procedure waned in about a quarter of patients within a year of treatment.

Investigators plan to probe these questions in future trials.

“The results of this trial are promising,” Dr. Schrag wrote, “but given the nonreversible nature of the intervention and the progressive nature of the disease, it will be important to establish whether improvements in motor complications are maintained over longer periods and whether treatment results in improved overall functioning and quality of life for patients.”

The study was funded by Insightec. Disclosure forms for Dr. Krishna and Dr. Schrag are provided on the journal’s website.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows.

The technique requires no sedation or brain implants. Surgeons use MRI to identify the globus pallidus internus, a part of the basal ganglia involved in movement disorders, and a focused ultrasound beam to heat and destroy the tissue.

Investigators performed the procedure with a device called Exablate Neuro, which was first approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2016 to treat essential tremor.

On the basis of the results of a multicenter, randomized, sham-controlled trial, the agency expanded the indication in 2021 to include unilateral pallidotomy to treat advanced Parkinson’s disease for patients with mobility, rigidity, or dyskinesia symptoms.

“In some patients with Parkinson’s disease, you get dyskinesias, and ablation of the globus pallidus significantly reduces those dyskinesias and motor impairment,” said lead investigator Vibhor Krishna, MD, associate professor of neurosurgery at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “It could be used to treat patients when other surgical procedures can’t be applied.”

The study was published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Strong response

For the study, 94 patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease who had dyskinesias or motor fluctuations and motor impairment in the off-medication state wore transducer helmets while lying in an MRI scanner. Patients were awake during the entire procedure.

The treatment group received unilateral FUSA on the side of the brain with the greatest motor impairment. The device initially delivered target temperatures of 40°-45° C. Ablative temperatures were gradually increased following evaluations to test for improvement of motor symptoms. The maximum temperature used was 54.3° C.

Patients in the control group underwent an identical procedure with the sonication energy disabled.

The primary outcome was a response to therapy at 3 months, defined as a decrease of at least three points from baseline either in the score on the Movement Disorders Society–Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS), part III, while off medication or in the score on the Unified Dyskinesia Rating Scale (UDRS) while on medication.

At 3 months, 69% of the treatment group reported a response, compared with 32% of the control group (P = .003).

When researchers analyzed MDS-UPDRS scores, they found that 29% of the treatment group and 27% of the control group showed improvement. For UDRS scores, 12% of the treatment group demonstrated improvement. In the control group, there was no improvement on this score. Improvements in both scores were reported in 28% of the treatment group and 5% of the control group.

Among those who reported a response at 3 months, 77% continued to show a response at 12 months.

‘Unforgiving’ area of the brain

While the response rate was a promising sign of this finding, it was not what interested Dr. Krishna the most. “The most surprising finding of this trial is how safe focused ultrasound pallidotomy is in treating patients with Parkinson’s disease,” he said.

The globus pallidus internus is an area of the brain that Dr. Krishna calls “unforgiving.”

“One side is motor fibers, and any problem with that can paralyze the patient, and just below that is the optic tract, and any problem there, you would lose vision,” Dr. Krishna said. “It is a very tough neighborhood to be in.”

By using MRI-guided ultrasound, surgeons can change the target and temperature of the ultrasound beam during the procedure to allow more precise treatment.

Pallidotomy-related adverse events in the treatment group included dysarthria, gait disturbance, loss of taste, visual disturbance, and facial weakness. All were mild to moderate, Dr. Krishna said.

More study is needed

Dyskinesia is a challenge in the management of Parkinson’s disease. Patients need antiparkinsonian medications to slow deterioration of motor function, but those medications can cause the involuntary movements that are a hallmark of dyskinesia.

The most common treatment for this complication, deep-brain stimulation (DBS), has its own drawbacks. It’s an open procedure, and there is a low-level risk for intracranial bleeding and infection. In addition, the electrode implants require ongoing maintenance and adjustment.

But the findings of this study show that, for patients who aren’t candidates for other therapies, such as DBS and ablative radiofrequency, FUSA may be an alternative, wrote Anette Schrag, PhD, professor of clinical neurosciences at University College London, in an accompanying commentary.

“The results confirm that it is effective in reducing motor complications of Parkinson’s disease, at least in the short term,” Dr. Schrag wrote. However, more long-term studies are needed, she added.

One-third of patients in the treatment group had no response to the treatment, and investigators aren’t sure why. Dr. Krishna noted that the benefits of the procedure waned in about a quarter of patients within a year of treatment.

Investigators plan to probe these questions in future trials.

“The results of this trial are promising,” Dr. Schrag wrote, “but given the nonreversible nature of the intervention and the progressive nature of the disease, it will be important to establish whether improvements in motor complications are maintained over longer periods and whether treatment results in improved overall functioning and quality of life for patients.”

The study was funded by Insightec. Disclosure forms for Dr. Krishna and Dr. Schrag are provided on the journal’s website.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows.

The technique requires no sedation or brain implants. Surgeons use MRI to identify the globus pallidus internus, a part of the basal ganglia involved in movement disorders, and a focused ultrasound beam to heat and destroy the tissue.

Investigators performed the procedure with a device called Exablate Neuro, which was first approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2016 to treat essential tremor.

On the basis of the results of a multicenter, randomized, sham-controlled trial, the agency expanded the indication in 2021 to include unilateral pallidotomy to treat advanced Parkinson’s disease for patients with mobility, rigidity, or dyskinesia symptoms.

“In some patients with Parkinson’s disease, you get dyskinesias, and ablation of the globus pallidus significantly reduces those dyskinesias and motor impairment,” said lead investigator Vibhor Krishna, MD, associate professor of neurosurgery at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “It could be used to treat patients when other surgical procedures can’t be applied.”

The study was published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Strong response

For the study, 94 patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease who had dyskinesias or motor fluctuations and motor impairment in the off-medication state wore transducer helmets while lying in an MRI scanner. Patients were awake during the entire procedure.

The treatment group received unilateral FUSA on the side of the brain with the greatest motor impairment. The device initially delivered target temperatures of 40°-45° C. Ablative temperatures were gradually increased following evaluations to test for improvement of motor symptoms. The maximum temperature used was 54.3° C.

Patients in the control group underwent an identical procedure with the sonication energy disabled.

The primary outcome was a response to therapy at 3 months, defined as a decrease of at least three points from baseline either in the score on the Movement Disorders Society–Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS), part III, while off medication or in the score on the Unified Dyskinesia Rating Scale (UDRS) while on medication.

At 3 months, 69% of the treatment group reported a response, compared with 32% of the control group (P = .003).

When researchers analyzed MDS-UPDRS scores, they found that 29% of the treatment group and 27% of the control group showed improvement. For UDRS scores, 12% of the treatment group demonstrated improvement. In the control group, there was no improvement on this score. Improvements in both scores were reported in 28% of the treatment group and 5% of the control group.

Among those who reported a response at 3 months, 77% continued to show a response at 12 months.

‘Unforgiving’ area of the brain

While the response rate was a promising sign of this finding, it was not what interested Dr. Krishna the most. “The most surprising finding of this trial is how safe focused ultrasound pallidotomy is in treating patients with Parkinson’s disease,” he said.

The globus pallidus internus is an area of the brain that Dr. Krishna calls “unforgiving.”

“One side is motor fibers, and any problem with that can paralyze the patient, and just below that is the optic tract, and any problem there, you would lose vision,” Dr. Krishna said. “It is a very tough neighborhood to be in.”

By using MRI-guided ultrasound, surgeons can change the target and temperature of the ultrasound beam during the procedure to allow more precise treatment.

Pallidotomy-related adverse events in the treatment group included dysarthria, gait disturbance, loss of taste, visual disturbance, and facial weakness. All were mild to moderate, Dr. Krishna said.

More study is needed

Dyskinesia is a challenge in the management of Parkinson’s disease. Patients need antiparkinsonian medications to slow deterioration of motor function, but those medications can cause the involuntary movements that are a hallmark of dyskinesia.

The most common treatment for this complication, deep-brain stimulation (DBS), has its own drawbacks. It’s an open procedure, and there is a low-level risk for intracranial bleeding and infection. In addition, the electrode implants require ongoing maintenance and adjustment.

But the findings of this study show that, for patients who aren’t candidates for other therapies, such as DBS and ablative radiofrequency, FUSA may be an alternative, wrote Anette Schrag, PhD, professor of clinical neurosciences at University College London, in an accompanying commentary.

“The results confirm that it is effective in reducing motor complications of Parkinson’s disease, at least in the short term,” Dr. Schrag wrote. However, more long-term studies are needed, she added.

One-third of patients in the treatment group had no response to the treatment, and investigators aren’t sure why. Dr. Krishna noted that the benefits of the procedure waned in about a quarter of patients within a year of treatment.

Investigators plan to probe these questions in future trials.

“The results of this trial are promising,” Dr. Schrag wrote, “but given the nonreversible nature of the intervention and the progressive nature of the disease, it will be important to establish whether improvements in motor complications are maintained over longer periods and whether treatment results in improved overall functioning and quality of life for patients.”

The study was funded by Insightec. Disclosure forms for Dr. Krishna and Dr. Schrag are provided on the journal’s website.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Specialty and age may contribute to suicidal thoughts among physicians

A physician’s specialty can make a difference when it comes to having suicidal thoughts. Doctors who specialize in family medicine, obstetrics-gynecology, and psychiatry reported double the rates of suicidal thoughts than doctors in oncology, rheumatology, and pulmonary medicine, according to Doctors’ Burden: Medscape Physician Suicide Report 2023.

“The specialties with the highest reporting of physician suicidal thoughts are also those with the greatest physician shortages, based on the number of job openings posted by recruiting sites,” said Peter Yellowlees, MD, professor of psychiatry and chief wellness officer at UC Davis Health.

Doctors in those specialties are overworked, which can lead to burnout, he said.

There’s also a generational divide among physicians who reported suicidal thoughts. Millennials (age 27-41) and Gen-X physicians (age 42-56) were more likely to report these thoughts than were Baby Boomers (age 57-75) and the Silent Generation (age 76-95).

“Younger physicians are more burned out – they may have less control over their lives and less meaning than some older doctors who can do what they want,” said Dr. Yellowlees.

One millennial respondent commented that being on call and being required to chart detailed notes in the EHR has contributed to her burnout. “I’m more impatient and make less time and effort to see my friends and family.”

One Silent Generation respondent commented, “I am semi-retired, I take no call, I work no weekends, I provide anesthesia care in my area of special expertise, I work clinically about 46 days a year. Life is good, particularly compared to my younger colleagues who are working 60-plus hours a week with evening work, weekend work, and call. I feel really sorry for them.”

When young people enter medical school, they’re quite healthy, with low rates of depression and burnout, said Dr. Yellowlees. Yet, studies have shown that rates of burnout and suicidal thoughts increased within 2 years. “That reflects what happens when a group of idealistic young people hit a horrible system,” he said.

Who’s responsible?

Millennials were three times as likely as baby boomers to say that a medical school or health care organization should be responsible when a student or physician commits suicide.

“Young physicians may expect more of their employers than my generation did, which we see in residency programs that have unionized,” said Dr. Yellowlees, a Baby Boomer.

“As more young doctors are employed by health care organizations, they also may expect more resources to be available to them, such as wellness programs,” he added.

Younger doctors also focus more on work-life balance than older doctors, including time off and having hobbies, he said. “They are much more rational in terms of their overall beliefs and expectations than the older generation.”

Whom doctors confide in

Nearly 60% of physician-respondents with suicidal thoughts said they confided in a professional or someone they knew. Men were just as likely as women to reach out to a therapist (38%), whereas men were slightly more likely to confide in a family member and women were slightly more likely to confide in a colleague.

“It’s interesting that women are more active in seeking support at work – they often have developed a network of colleagues to support each other’s careers and whom they can confide in,” said Dr. Yellowlees.

He emphasized that 40% of physicians said they didn’t confide in anyone when they had suicidal thoughts. Of those, just over half said they could cope without professional help.

One respondent commented, “It’s just a thought; nothing I would actually do.” Another commented, “Mental health professionals can’t fix the underlying reason for the problem.”

Many doctors were concerned about risking disclosure to their medical boards (42%); that it would show up on their insurance records (33%); and that their colleagues would find out (25%), according to the report.

One respondent commented, “I don’t trust doctors to keep it to themselves.”

Another barrier doctors mentioned was a lack of time to seek help. One commented, “Time. I have none, when am I supposed to find an hour for counseling?”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A physician’s specialty can make a difference when it comes to having suicidal thoughts. Doctors who specialize in family medicine, obstetrics-gynecology, and psychiatry reported double the rates of suicidal thoughts than doctors in oncology, rheumatology, and pulmonary medicine, according to Doctors’ Burden: Medscape Physician Suicide Report 2023.

“The specialties with the highest reporting of physician suicidal thoughts are also those with the greatest physician shortages, based on the number of job openings posted by recruiting sites,” said Peter Yellowlees, MD, professor of psychiatry and chief wellness officer at UC Davis Health.

Doctors in those specialties are overworked, which can lead to burnout, he said.

There’s also a generational divide among physicians who reported suicidal thoughts. Millennials (age 27-41) and Gen-X physicians (age 42-56) were more likely to report these thoughts than were Baby Boomers (age 57-75) and the Silent Generation (age 76-95).

“Younger physicians are more burned out – they may have less control over their lives and less meaning than some older doctors who can do what they want,” said Dr. Yellowlees.

One millennial respondent commented that being on call and being required to chart detailed notes in the EHR has contributed to her burnout. “I’m more impatient and make less time and effort to see my friends and family.”