User login

International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH): XXIV Congress

Acute pulmonary embolism doesn’t always require hospitalization

AMSTERDAM – Two-thirds of patients who presented to the emergency department of a U.S. tertiary care hospital with an acute pulmonary embolism had no acute deterioration and required no short-term hospital-based interventions, in an analysis of 298 patients seen over a 2-year period.

The finding "supports the assertion that outpatient treatment of patients with pulmonary embolism [PE] is safe," said Dr. Christopher Kabrhel at the 24th Congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

"We want to identify patients for whom nothing bad will happen. We showed that two-thirds of patients did well and didn’t need anything from the hospital and didn’t benefit from being in the hospital. We need to identify some of these patients," soon after they present in the emergency department, said Dr. Kabrhel, a surgeon and emergency-medicine physician at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston. If reliable risk markers can be found with further research, "perhaps we can identify half of the two-thirds—a third of all patients who come to the emergency department with a PE—who we know will be safe with outpatient treatment so we can send those patients home from the emergency department and not admit them."

Most symptomatic U.S. patients who come to an emergency department, and are diagnosed with a PE are immediately admitted to the hospital. In the current study, the hospitalization rate was 92% with a median length of stay of 3 days. "We need a better rule to decide whether a patient needs hospitalization. We need to find which patients benefit from hospitalization," Dr. Kabrhel said in an interview.

He and his associates reviewed 298 adults 18 years or older who presented to the Massachusetts General Hospital emergency department during October 2009 through December 2011 with a radiographically proven PE diagnosed within 24 hours of arrival. They averaged 59 years old, half were women, and the most common comorbidity was malignancy in 107 patients (36%).

The study’s primary outcome was any clinical deterioration or need for hospital-based intervention during the 5 days following presentation at the emergency department, including the need for advanced cardiac life support, the development of a new cardiac dysrhythmia, the development of hypoxia or hypotension, the need for thrombolysis or thrombectomy, recurrent PE, or death. These events occurred in 99 patients (33%); of these, 28 patients (9% of the total group) had "severe" deterioration or required a "major" intervention. Twelve patients (4%) died within 30 days of their initial emergency presentation. The most common acute complication was the need for respiratory support, in about 55 patients, followed by hypotension, in about 34.

A multivariate analysis identified five baseline factors that significantly correlated with the primary outcome. Patients who had normal vital signs at baseline had a 79% reduced rate of significant deterioration or need for hospital-based intervention. The other four factors were linked with increased rates of deterioration and need for intervention: Right heart strain caused by the PE and identified by an echocardiogram boosted the risk of a bad outcome more than fourfold, coronary disease and cerebrovascular disease each were tied to a more than threefold increased rate, and residual deep vein thrombosis was linked with a more than doubled rate of bad outcomes.

The subset of patients with the most severe outcomes had only one direct correlation with bad outcomes, right heart strain on echo. This subset of patients also showed a protective link against bad outcomes when their systolic blood pressure never fell below 90 mm Hg.

In contrast to these factors linked to 5-day outcomes, two different types of patient factors were significantly linked with 30-day mortality: having a malignancy and having chronic lung disease.

"Previously validated clinical prediction rules that looked at outcomes after PE were primarily validated based on 30-day mortality or recurrent PE, and included factors like having cancer, heart failure, or chronic lung disease. But these scores are only able to predict the outcomes we examined with 70% sensitivity," Dr. Kabrhel said. He found this out by running the numbers he collected through three validated scores for predicting PE outcome: the Geneva Prediction Score (Ann. Intern. Med. 2006;144:165-71), the Severity Index (Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2005; 172:1041-6), and the Simplified Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (Arch. Intern. Med. 2010;170:1383-9). "Predictors of all-cause 30-day mortality are different than predictors of short-term outcomes" in PE patients, he said.

"We found that echo is a very good predictor of short-term outcomes, and also abnormal vital signs. The key point is we need to look at outcomes that are relevant to the decisions made" in the emergency department, Dr. Kabrhel said. "Looking at 30-day mortality in patients who are only hospitalized for 3 days doesn’t really inform the decision on who should be in the hospital. I would suggest caution on using [prediction] tools validated against 30-day mortality and recurrent PE to determine what to do acutely. We need better rules to decide which PE patients need hospitalization."

Dr. Kabrhel said he has been a consultant to Diagnostica Stago, and is an officer for LitPulse.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AMSTERDAM – Two-thirds of patients who presented to the emergency department of a U.S. tertiary care hospital with an acute pulmonary embolism had no acute deterioration and required no short-term hospital-based interventions, in an analysis of 298 patients seen over a 2-year period.

The finding "supports the assertion that outpatient treatment of patients with pulmonary embolism [PE] is safe," said Dr. Christopher Kabrhel at the 24th Congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

"We want to identify patients for whom nothing bad will happen. We showed that two-thirds of patients did well and didn’t need anything from the hospital and didn’t benefit from being in the hospital. We need to identify some of these patients," soon after they present in the emergency department, said Dr. Kabrhel, a surgeon and emergency-medicine physician at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston. If reliable risk markers can be found with further research, "perhaps we can identify half of the two-thirds—a third of all patients who come to the emergency department with a PE—who we know will be safe with outpatient treatment so we can send those patients home from the emergency department and not admit them."

Most symptomatic U.S. patients who come to an emergency department, and are diagnosed with a PE are immediately admitted to the hospital. In the current study, the hospitalization rate was 92% with a median length of stay of 3 days. "We need a better rule to decide whether a patient needs hospitalization. We need to find which patients benefit from hospitalization," Dr. Kabrhel said in an interview.

He and his associates reviewed 298 adults 18 years or older who presented to the Massachusetts General Hospital emergency department during October 2009 through December 2011 with a radiographically proven PE diagnosed within 24 hours of arrival. They averaged 59 years old, half were women, and the most common comorbidity was malignancy in 107 patients (36%).

The study’s primary outcome was any clinical deterioration or need for hospital-based intervention during the 5 days following presentation at the emergency department, including the need for advanced cardiac life support, the development of a new cardiac dysrhythmia, the development of hypoxia or hypotension, the need for thrombolysis or thrombectomy, recurrent PE, or death. These events occurred in 99 patients (33%); of these, 28 patients (9% of the total group) had "severe" deterioration or required a "major" intervention. Twelve patients (4%) died within 30 days of their initial emergency presentation. The most common acute complication was the need for respiratory support, in about 55 patients, followed by hypotension, in about 34.

A multivariate analysis identified five baseline factors that significantly correlated with the primary outcome. Patients who had normal vital signs at baseline had a 79% reduced rate of significant deterioration or need for hospital-based intervention. The other four factors were linked with increased rates of deterioration and need for intervention: Right heart strain caused by the PE and identified by an echocardiogram boosted the risk of a bad outcome more than fourfold, coronary disease and cerebrovascular disease each were tied to a more than threefold increased rate, and residual deep vein thrombosis was linked with a more than doubled rate of bad outcomes.

The subset of patients with the most severe outcomes had only one direct correlation with bad outcomes, right heart strain on echo. This subset of patients also showed a protective link against bad outcomes when their systolic blood pressure never fell below 90 mm Hg.

In contrast to these factors linked to 5-day outcomes, two different types of patient factors were significantly linked with 30-day mortality: having a malignancy and having chronic lung disease.

"Previously validated clinical prediction rules that looked at outcomes after PE were primarily validated based on 30-day mortality or recurrent PE, and included factors like having cancer, heart failure, or chronic lung disease. But these scores are only able to predict the outcomes we examined with 70% sensitivity," Dr. Kabrhel said. He found this out by running the numbers he collected through three validated scores for predicting PE outcome: the Geneva Prediction Score (Ann. Intern. Med. 2006;144:165-71), the Severity Index (Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2005; 172:1041-6), and the Simplified Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (Arch. Intern. Med. 2010;170:1383-9). "Predictors of all-cause 30-day mortality are different than predictors of short-term outcomes" in PE patients, he said.

"We found that echo is a very good predictor of short-term outcomes, and also abnormal vital signs. The key point is we need to look at outcomes that are relevant to the decisions made" in the emergency department, Dr. Kabrhel said. "Looking at 30-day mortality in patients who are only hospitalized for 3 days doesn’t really inform the decision on who should be in the hospital. I would suggest caution on using [prediction] tools validated against 30-day mortality and recurrent PE to determine what to do acutely. We need better rules to decide which PE patients need hospitalization."

Dr. Kabrhel said he has been a consultant to Diagnostica Stago, and is an officer for LitPulse.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AMSTERDAM – Two-thirds of patients who presented to the emergency department of a U.S. tertiary care hospital with an acute pulmonary embolism had no acute deterioration and required no short-term hospital-based interventions, in an analysis of 298 patients seen over a 2-year period.

The finding "supports the assertion that outpatient treatment of patients with pulmonary embolism [PE] is safe," said Dr. Christopher Kabrhel at the 24th Congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

"We want to identify patients for whom nothing bad will happen. We showed that two-thirds of patients did well and didn’t need anything from the hospital and didn’t benefit from being in the hospital. We need to identify some of these patients," soon after they present in the emergency department, said Dr. Kabrhel, a surgeon and emergency-medicine physician at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston. If reliable risk markers can be found with further research, "perhaps we can identify half of the two-thirds—a third of all patients who come to the emergency department with a PE—who we know will be safe with outpatient treatment so we can send those patients home from the emergency department and not admit them."

Most symptomatic U.S. patients who come to an emergency department, and are diagnosed with a PE are immediately admitted to the hospital. In the current study, the hospitalization rate was 92% with a median length of stay of 3 days. "We need a better rule to decide whether a patient needs hospitalization. We need to find which patients benefit from hospitalization," Dr. Kabrhel said in an interview.

He and his associates reviewed 298 adults 18 years or older who presented to the Massachusetts General Hospital emergency department during October 2009 through December 2011 with a radiographically proven PE diagnosed within 24 hours of arrival. They averaged 59 years old, half were women, and the most common comorbidity was malignancy in 107 patients (36%).

The study’s primary outcome was any clinical deterioration or need for hospital-based intervention during the 5 days following presentation at the emergency department, including the need for advanced cardiac life support, the development of a new cardiac dysrhythmia, the development of hypoxia or hypotension, the need for thrombolysis or thrombectomy, recurrent PE, or death. These events occurred in 99 patients (33%); of these, 28 patients (9% of the total group) had "severe" deterioration or required a "major" intervention. Twelve patients (4%) died within 30 days of their initial emergency presentation. The most common acute complication was the need for respiratory support, in about 55 patients, followed by hypotension, in about 34.

A multivariate analysis identified five baseline factors that significantly correlated with the primary outcome. Patients who had normal vital signs at baseline had a 79% reduced rate of significant deterioration or need for hospital-based intervention. The other four factors were linked with increased rates of deterioration and need for intervention: Right heart strain caused by the PE and identified by an echocardiogram boosted the risk of a bad outcome more than fourfold, coronary disease and cerebrovascular disease each were tied to a more than threefold increased rate, and residual deep vein thrombosis was linked with a more than doubled rate of bad outcomes.

The subset of patients with the most severe outcomes had only one direct correlation with bad outcomes, right heart strain on echo. This subset of patients also showed a protective link against bad outcomes when their systolic blood pressure never fell below 90 mm Hg.

In contrast to these factors linked to 5-day outcomes, two different types of patient factors were significantly linked with 30-day mortality: having a malignancy and having chronic lung disease.

"Previously validated clinical prediction rules that looked at outcomes after PE were primarily validated based on 30-day mortality or recurrent PE, and included factors like having cancer, heart failure, or chronic lung disease. But these scores are only able to predict the outcomes we examined with 70% sensitivity," Dr. Kabrhel said. He found this out by running the numbers he collected through three validated scores for predicting PE outcome: the Geneva Prediction Score (Ann. Intern. Med. 2006;144:165-71), the Severity Index (Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2005; 172:1041-6), and the Simplified Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (Arch. Intern. Med. 2010;170:1383-9). "Predictors of all-cause 30-day mortality are different than predictors of short-term outcomes" in PE patients, he said.

"We found that echo is a very good predictor of short-term outcomes, and also abnormal vital signs. The key point is we need to look at outcomes that are relevant to the decisions made" in the emergency department, Dr. Kabrhel said. "Looking at 30-day mortality in patients who are only hospitalized for 3 days doesn’t really inform the decision on who should be in the hospital. I would suggest caution on using [prediction] tools validated against 30-day mortality and recurrent PE to determine what to do acutely. We need better rules to decide which PE patients need hospitalization."

Dr. Kabrhel said he has been a consultant to Diagnostica Stago, and is an officer for LitPulse.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT ISTH 2013

Major finding: Among patients newly diagnosed with acute pulmonary embolism, 67% had no acute complication and didn’t require a hospital-based intervention.

Data source: A review of 298 patients diagnosed in the emergency department with acute pulmonary embolism at one U.S. center during 2009-2011.

Disclosures: Dr. Kabrhel said that he has been a consultant to Diagnostica Stago, and is an officer for LitPulse.

Dalteparin safely used for 12 months to prevent VTE recurrence in cancer patients

AMSTERDAM – Cancer patients who start dalteparin to prevent a recurrence of venous thromboembolism can continue on the drug for as long as a year without an increase in bleeding risk and with stable control against another venous thromboembolism.

But the high underlying mortality risk from cancer that many of these patients face makes it hard to judge which patients will benefit from continued prophylaxis with the low-molecular-weight heparin, Dr. Ajay K. Kakkar said at the congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

A third of the patients enrolled in the trial died before the yearlong study ended, and the vast majority of the deaths were due to cancer.

"One of the most important competing risks besides thrombosis that these cancer patients face is the risk of dying from their underlying malignancy. That’s an important determinant in trying to understand whether we should continue anticoagulant treatment," said Dr. Kakkar, a professor of surgery at University College London. "It requires clinical judgment to balance the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism against the risk of bleeding [as an adverse effect of antithrombotic treatment] in patients with deteriorating health because of their progressive cancer," he said.

About 10 years ago, a 6-month course of treatment with a low-molecular-weight heparin became standard for cancer patients with a venous thromboembolism (VTE). Results from the CLOT (Randomized Comparison of Low Molecular Weight Heparin versus Oral Anticoagulant Therapy for the Prevention of Recurrent Venous Thromboembolism in Patients with Cancer) trial showed that dalteparin (Fragmin) was more effective than warfarin or another oral anticoagulant for preventing recurrent VTE without increasing the risk of bleeding during 6 months of treatment (New Engl. J. Med. 2003;349:146-53).

To examine the impact of dalteparin treatment during months 7-12 following VTE, Dr. Kakkar and his associates conducted an open-label, phase IV study in 334 cancer patients who had a VTE. Trial participants received dalteparin for up to 12 months at 50 centers in the United States, Europe, and Canada. The patients averaged 64 years old, half were women, 92% had a solid tumor, and almost two-thirds had metastatic disease. The most common tumor type was lung cancer, followed by colorectal cancer, and breast and pancreatic cancer. Patients began the regimen by receiving 200 IU/kg dalteparin subcutaneously daily for the first 30 days, and then they received a reduced dosage of 150 IU/kg daily for the balance of their treatment.

The study’s primary endpoint was the rate of major bleeds during months 7-12 compared with months 2-6. Major bleeding occurred in 4.6% of the patients during months 2-6, and in 4.2% of the patients who received treatment during months 7-12. The highest rate of bleeding occurred during the first month of treatment, a 3.6% rate during the first 30 days on dalteparin, the time when the dosage was at its highest.

The incidence of all bleeding events was 13.2% during the first month on treatment, 17.3% during months 2-6, and 14.8% during months 7-12.

The incidence of new or recurrent VTEs was 5.7% during the first month on treatment, 3.4% during months 2-6, and 4.1% during months 7-12. The results suggest that dalteparin continued to suppress thrombosis during extended treatment. The overall VTE rate during the first 6 months was about 9%, which matched the 9% VTE rate on 6 months of dalteparin treatment reported in the CLOT study results in 2003. A logistic regression analysis failed to identify any patient factors that were significantly linked to the development of a new or recurrent VTE.

The study was sponsored by Eisai, the company that markets dalteparin (Fragmin). Dr. Kakkar said that he has been a consultant to and has received honoraria from Eisai as well as from several other drug companies.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AMSTERDAM – Cancer patients who start dalteparin to prevent a recurrence of venous thromboembolism can continue on the drug for as long as a year without an increase in bleeding risk and with stable control against another venous thromboembolism.

But the high underlying mortality risk from cancer that many of these patients face makes it hard to judge which patients will benefit from continued prophylaxis with the low-molecular-weight heparin, Dr. Ajay K. Kakkar said at the congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

A third of the patients enrolled in the trial died before the yearlong study ended, and the vast majority of the deaths were due to cancer.

"One of the most important competing risks besides thrombosis that these cancer patients face is the risk of dying from their underlying malignancy. That’s an important determinant in trying to understand whether we should continue anticoagulant treatment," said Dr. Kakkar, a professor of surgery at University College London. "It requires clinical judgment to balance the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism against the risk of bleeding [as an adverse effect of antithrombotic treatment] in patients with deteriorating health because of their progressive cancer," he said.

About 10 years ago, a 6-month course of treatment with a low-molecular-weight heparin became standard for cancer patients with a venous thromboembolism (VTE). Results from the CLOT (Randomized Comparison of Low Molecular Weight Heparin versus Oral Anticoagulant Therapy for the Prevention of Recurrent Venous Thromboembolism in Patients with Cancer) trial showed that dalteparin (Fragmin) was more effective than warfarin or another oral anticoagulant for preventing recurrent VTE without increasing the risk of bleeding during 6 months of treatment (New Engl. J. Med. 2003;349:146-53).

To examine the impact of dalteparin treatment during months 7-12 following VTE, Dr. Kakkar and his associates conducted an open-label, phase IV study in 334 cancer patients who had a VTE. Trial participants received dalteparin for up to 12 months at 50 centers in the United States, Europe, and Canada. The patients averaged 64 years old, half were women, 92% had a solid tumor, and almost two-thirds had metastatic disease. The most common tumor type was lung cancer, followed by colorectal cancer, and breast and pancreatic cancer. Patients began the regimen by receiving 200 IU/kg dalteparin subcutaneously daily for the first 30 days, and then they received a reduced dosage of 150 IU/kg daily for the balance of their treatment.

The study’s primary endpoint was the rate of major bleeds during months 7-12 compared with months 2-6. Major bleeding occurred in 4.6% of the patients during months 2-6, and in 4.2% of the patients who received treatment during months 7-12. The highest rate of bleeding occurred during the first month of treatment, a 3.6% rate during the first 30 days on dalteparin, the time when the dosage was at its highest.

The incidence of all bleeding events was 13.2% during the first month on treatment, 17.3% during months 2-6, and 14.8% during months 7-12.

The incidence of new or recurrent VTEs was 5.7% during the first month on treatment, 3.4% during months 2-6, and 4.1% during months 7-12. The results suggest that dalteparin continued to suppress thrombosis during extended treatment. The overall VTE rate during the first 6 months was about 9%, which matched the 9% VTE rate on 6 months of dalteparin treatment reported in the CLOT study results in 2003. A logistic regression analysis failed to identify any patient factors that were significantly linked to the development of a new or recurrent VTE.

The study was sponsored by Eisai, the company that markets dalteparin (Fragmin). Dr. Kakkar said that he has been a consultant to and has received honoraria from Eisai as well as from several other drug companies.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AMSTERDAM – Cancer patients who start dalteparin to prevent a recurrence of venous thromboembolism can continue on the drug for as long as a year without an increase in bleeding risk and with stable control against another venous thromboembolism.

But the high underlying mortality risk from cancer that many of these patients face makes it hard to judge which patients will benefit from continued prophylaxis with the low-molecular-weight heparin, Dr. Ajay K. Kakkar said at the congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

A third of the patients enrolled in the trial died before the yearlong study ended, and the vast majority of the deaths were due to cancer.

"One of the most important competing risks besides thrombosis that these cancer patients face is the risk of dying from their underlying malignancy. That’s an important determinant in trying to understand whether we should continue anticoagulant treatment," said Dr. Kakkar, a professor of surgery at University College London. "It requires clinical judgment to balance the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism against the risk of bleeding [as an adverse effect of antithrombotic treatment] in patients with deteriorating health because of their progressive cancer," he said.

About 10 years ago, a 6-month course of treatment with a low-molecular-weight heparin became standard for cancer patients with a venous thromboembolism (VTE). Results from the CLOT (Randomized Comparison of Low Molecular Weight Heparin versus Oral Anticoagulant Therapy for the Prevention of Recurrent Venous Thromboembolism in Patients with Cancer) trial showed that dalteparin (Fragmin) was more effective than warfarin or another oral anticoagulant for preventing recurrent VTE without increasing the risk of bleeding during 6 months of treatment (New Engl. J. Med. 2003;349:146-53).

To examine the impact of dalteparin treatment during months 7-12 following VTE, Dr. Kakkar and his associates conducted an open-label, phase IV study in 334 cancer patients who had a VTE. Trial participants received dalteparin for up to 12 months at 50 centers in the United States, Europe, and Canada. The patients averaged 64 years old, half were women, 92% had a solid tumor, and almost two-thirds had metastatic disease. The most common tumor type was lung cancer, followed by colorectal cancer, and breast and pancreatic cancer. Patients began the regimen by receiving 200 IU/kg dalteparin subcutaneously daily for the first 30 days, and then they received a reduced dosage of 150 IU/kg daily for the balance of their treatment.

The study’s primary endpoint was the rate of major bleeds during months 7-12 compared with months 2-6. Major bleeding occurred in 4.6% of the patients during months 2-6, and in 4.2% of the patients who received treatment during months 7-12. The highest rate of bleeding occurred during the first month of treatment, a 3.6% rate during the first 30 days on dalteparin, the time when the dosage was at its highest.

The incidence of all bleeding events was 13.2% during the first month on treatment, 17.3% during months 2-6, and 14.8% during months 7-12.

The incidence of new or recurrent VTEs was 5.7% during the first month on treatment, 3.4% during months 2-6, and 4.1% during months 7-12. The results suggest that dalteparin continued to suppress thrombosis during extended treatment. The overall VTE rate during the first 6 months was about 9%, which matched the 9% VTE rate on 6 months of dalteparin treatment reported in the CLOT study results in 2003. A logistic regression analysis failed to identify any patient factors that were significantly linked to the development of a new or recurrent VTE.

The study was sponsored by Eisai, the company that markets dalteparin (Fragmin). Dr. Kakkar said that he has been a consultant to and has received honoraria from Eisai as well as from several other drug companies.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE 2013 ISTH CONGRESS

Major finding: Major bleeding occurred in 4.6% of the patients during months 2-6, and in 4.2% of the patients who received treatment during months 7-12.

Data source: Data came from a multicenter, open-label, phase IV study of dalteparin in 334 cancer patients following an index venous thromboembolism.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by Eisai, the company that markets dalteparin (Fragmin). Dr. Kakkar said that he has been a consultant to and has received honoraria from Eisai as well as from several other drug companies.

Estrogen-related VTE shows low recurrence rate

AMSTERDAM – Women with an unprovoked index venous thromboembolism while they are on estrogen treatment have a low recurrence risk as long as they stop estrogen, and therefore don’t need prolonged anticoagulant treatment, based on a review of 630 cases.

Women whose index venous thromboembolism (VTE) occurred while on estrogen had 4 recurrences for every 10 among the women who had unprovoked VTE and were not on estrogen during an average follow-up of more than 6 years, Dr. Lisbeth Eischer said at the 24th Congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

"We propose that these women [whose index VTE occurred while on estrogen] should receive anticoagulant treatment for no longer than 3 months," said Dr. Eischer of the division of hematology and hemostasis at the Medical University of Vienna.

"I think the recommendation [for duration of anticoagulation] should be comparable to women who have undergone surgery, not more than 3 months," she said. In the review she presented, which included 630 women treated for a VTE since 1992, the average duration of anticoagulant treatment was 7 months among women whose VTE occurred when on estrogen as well as those not on estrogen at the time of their VTE.

Dr. Eischer and her associates studied women enrolled in the prospective Austrian Study on Recurrent Venous Thromboembolism (AUREC). The group of 630 included women aged 18 years or older who had a first VTE and received at least 3 months of anticoagulant treatment. The study excluded women with another identifiable cause of VTE, such as surgery, trauma, pregnancy, cancer, or significant thrombophilia. Women were not excluded if they were heterozygous for a factor V Leiden mutation. They averaged 46 years old; 361 (57%) had deep vein thrombosis as their index case, and 269 (43%) had pulmonary embolism as their index case. The average length of follow-up was 76 months (6.3 years).

Three hundred thirty-three (53%) women were on estrogen treatment at the time of their VTE. These women were significantly younger, averaging 38 years compared with an average of 55 among the women not receiving estrogen at the time of their VTE. The prevalence of women with a single factor V Leiden mutation was 48 (16%) among those not on estrogen and 98 (28%) among those on estrogen, a statistically significant difference.

During follow-up, the incidence of recurrent VTE was 22 (7%) among the 333 women whose index VTE occurred while on estrogen, and 49 (16%) among the 297 with an unprovoked index VTE. In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for age, location of the VTE (pulmonary or deep vein), and presence of a factor V Leiden mutation, women whose index VTE occurred while they were taking estrogen had a statistically significant 60% reduced rate of having a recurrent VTE during follow-up compared with the women whose index VTE occurred when they were not on estrogen.

Dr. Eischer said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AMSTERDAM – Women with an unprovoked index venous thromboembolism while they are on estrogen treatment have a low recurrence risk as long as they stop estrogen, and therefore don’t need prolonged anticoagulant treatment, based on a review of 630 cases.

Women whose index venous thromboembolism (VTE) occurred while on estrogen had 4 recurrences for every 10 among the women who had unprovoked VTE and were not on estrogen during an average follow-up of more than 6 years, Dr. Lisbeth Eischer said at the 24th Congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

"We propose that these women [whose index VTE occurred while on estrogen] should receive anticoagulant treatment for no longer than 3 months," said Dr. Eischer of the division of hematology and hemostasis at the Medical University of Vienna.

"I think the recommendation [for duration of anticoagulation] should be comparable to women who have undergone surgery, not more than 3 months," she said. In the review she presented, which included 630 women treated for a VTE since 1992, the average duration of anticoagulant treatment was 7 months among women whose VTE occurred when on estrogen as well as those not on estrogen at the time of their VTE.

Dr. Eischer and her associates studied women enrolled in the prospective Austrian Study on Recurrent Venous Thromboembolism (AUREC). The group of 630 included women aged 18 years or older who had a first VTE and received at least 3 months of anticoagulant treatment. The study excluded women with another identifiable cause of VTE, such as surgery, trauma, pregnancy, cancer, or significant thrombophilia. Women were not excluded if they were heterozygous for a factor V Leiden mutation. They averaged 46 years old; 361 (57%) had deep vein thrombosis as their index case, and 269 (43%) had pulmonary embolism as their index case. The average length of follow-up was 76 months (6.3 years).

Three hundred thirty-three (53%) women were on estrogen treatment at the time of their VTE. These women were significantly younger, averaging 38 years compared with an average of 55 among the women not receiving estrogen at the time of their VTE. The prevalence of women with a single factor V Leiden mutation was 48 (16%) among those not on estrogen and 98 (28%) among those on estrogen, a statistically significant difference.

During follow-up, the incidence of recurrent VTE was 22 (7%) among the 333 women whose index VTE occurred while on estrogen, and 49 (16%) among the 297 with an unprovoked index VTE. In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for age, location of the VTE (pulmonary or deep vein), and presence of a factor V Leiden mutation, women whose index VTE occurred while they were taking estrogen had a statistically significant 60% reduced rate of having a recurrent VTE during follow-up compared with the women whose index VTE occurred when they were not on estrogen.

Dr. Eischer said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AMSTERDAM – Women with an unprovoked index venous thromboembolism while they are on estrogen treatment have a low recurrence risk as long as they stop estrogen, and therefore don’t need prolonged anticoagulant treatment, based on a review of 630 cases.

Women whose index venous thromboembolism (VTE) occurred while on estrogen had 4 recurrences for every 10 among the women who had unprovoked VTE and were not on estrogen during an average follow-up of more than 6 years, Dr. Lisbeth Eischer said at the 24th Congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

"We propose that these women [whose index VTE occurred while on estrogen] should receive anticoagulant treatment for no longer than 3 months," said Dr. Eischer of the division of hematology and hemostasis at the Medical University of Vienna.

"I think the recommendation [for duration of anticoagulation] should be comparable to women who have undergone surgery, not more than 3 months," she said. In the review she presented, which included 630 women treated for a VTE since 1992, the average duration of anticoagulant treatment was 7 months among women whose VTE occurred when on estrogen as well as those not on estrogen at the time of their VTE.

Dr. Eischer and her associates studied women enrolled in the prospective Austrian Study on Recurrent Venous Thromboembolism (AUREC). The group of 630 included women aged 18 years or older who had a first VTE and received at least 3 months of anticoagulant treatment. The study excluded women with another identifiable cause of VTE, such as surgery, trauma, pregnancy, cancer, or significant thrombophilia. Women were not excluded if they were heterozygous for a factor V Leiden mutation. They averaged 46 years old; 361 (57%) had deep vein thrombosis as their index case, and 269 (43%) had pulmonary embolism as their index case. The average length of follow-up was 76 months (6.3 years).

Three hundred thirty-three (53%) women were on estrogen treatment at the time of their VTE. These women were significantly younger, averaging 38 years compared with an average of 55 among the women not receiving estrogen at the time of their VTE. The prevalence of women with a single factor V Leiden mutation was 48 (16%) among those not on estrogen and 98 (28%) among those on estrogen, a statistically significant difference.

During follow-up, the incidence of recurrent VTE was 22 (7%) among the 333 women whose index VTE occurred while on estrogen, and 49 (16%) among the 297 with an unprovoked index VTE. In a multivariate analysis that adjusted for age, location of the VTE (pulmonary or deep vein), and presence of a factor V Leiden mutation, women whose index VTE occurred while they were taking estrogen had a statistically significant 60% reduced rate of having a recurrent VTE during follow-up compared with the women whose index VTE occurred when they were not on estrogen.

Dr. Eischer said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT ISTH 2013

Major finding: Women whose otherwise unprovoked venous thromboembolism occurred while they were on estrogen had 60% fewer recurrences than did women not on estrogen.

Data source: A review of 630 women followed after a first-time VTE at one Austrian center.

Disclosures: Dr. Eischer said she had no relevant financial disclosures.

Sickle cell disease linked to VTE risk

AMSTERDAM – Adult patients who become hospitalized and have sickle cell disease have about a sixfold increased risk of developing venous thromboembolism during the following weeks and months, compared with hospitalized patients without sickle cell disease, in a case-control study of more than 25,000 people admitted to or seen at California hospitals during 1990-2010.

Since 46% of the venous thromboembolism (VTE) episodes in patients with sickle cell disease happened within 30 days of a hospitalization or emergency department visit, the painful, inflammatory episodes that often drive patients with sickle cell disease to seek hospitalization may also provoke VTE said Dr. Ted Wun and his associates in a poster presented at a congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Relative immobilization during hospitalization may also play a role in triggering VTE in these patients, suggesting that "robust" thromboprophylaxis be applied to patients with sickle cell disease who enter a hospital, said Dr. Wun, professor of medicine and chief of hematology and oncology at the University of California, Davis, in Sacramento.

The analysis also showed the impact of VTE episodes. After 10 years of follow-up, cumulative mortality was just under 20% in patients with sickle cell disease who did not have a VTE, and more than 40% in patients who had a VTE, a statistically significant difference in an actuarial analysis.

The risk for VTE posed by sickle cell disease was even higher in the 42% of patients with severe sickle cell disease, defined as patients who had three or more hospitalizations or emergency department visits during the prior year. Patients in the severe subgroup had a 9.5-fold higher rate of VTE, compared with controls who had no sickle cell disease. Among the 58% of sickle cell patients without severe disease, the incidence of VTE was fourfold greater than among those without sickle cell disease.

Dr. Wun and his associates used data collected in the California Patient Discharge Dataset and in California’s Emergency Department Utilization database. They identified 4,280 patients 18-65 years old with sickle cell disease who were either hospitalized or seen at an emergency department during 1990-2010. They matched each of these sickle cell patients with five patients hospitalized or seen at emergency departments who did not have sickle cell disease. Matching included age, sex, race, ethnicity, and year of index event. The researchers could track each of the more than 25,000 total patients through subsequent hospitalizations and emergency-department visits by their unique identifier codes.

The patients with sickle cell disease averaged 28 years old, 91% were black, and during follow-up they had an 8% incidence of VTE.

The analysis also showed that comorbidities increased the risk for VTE, although not as strongly as sickle cell disease. For the entire group of more than 25,000 patients having three or more comorbidities linked with a threefold higher rate of VTEs, compared with those without any comorbidities. Among only patients with sickle cell disease, having three or more comorbidities boosted the VTE rate by a statistically-significant 67%, compared with sickle cell patients without any comorbidities. Female sex also significantly linked with a boosted VTE rate among patients with sickle cell disease. Women with sickle cell disease had 43% more VTE episodes than did men with sickle cell disease in the adjusted analysis.

Dr. Wun had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AMSTERDAM – Adult patients who become hospitalized and have sickle cell disease have about a sixfold increased risk of developing venous thromboembolism during the following weeks and months, compared with hospitalized patients without sickle cell disease, in a case-control study of more than 25,000 people admitted to or seen at California hospitals during 1990-2010.

Since 46% of the venous thromboembolism (VTE) episodes in patients with sickle cell disease happened within 30 days of a hospitalization or emergency department visit, the painful, inflammatory episodes that often drive patients with sickle cell disease to seek hospitalization may also provoke VTE said Dr. Ted Wun and his associates in a poster presented at a congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Relative immobilization during hospitalization may also play a role in triggering VTE in these patients, suggesting that "robust" thromboprophylaxis be applied to patients with sickle cell disease who enter a hospital, said Dr. Wun, professor of medicine and chief of hematology and oncology at the University of California, Davis, in Sacramento.

The analysis also showed the impact of VTE episodes. After 10 years of follow-up, cumulative mortality was just under 20% in patients with sickle cell disease who did not have a VTE, and more than 40% in patients who had a VTE, a statistically significant difference in an actuarial analysis.

The risk for VTE posed by sickle cell disease was even higher in the 42% of patients with severe sickle cell disease, defined as patients who had three or more hospitalizations or emergency department visits during the prior year. Patients in the severe subgroup had a 9.5-fold higher rate of VTE, compared with controls who had no sickle cell disease. Among the 58% of sickle cell patients without severe disease, the incidence of VTE was fourfold greater than among those without sickle cell disease.

Dr. Wun and his associates used data collected in the California Patient Discharge Dataset and in California’s Emergency Department Utilization database. They identified 4,280 patients 18-65 years old with sickle cell disease who were either hospitalized or seen at an emergency department during 1990-2010. They matched each of these sickle cell patients with five patients hospitalized or seen at emergency departments who did not have sickle cell disease. Matching included age, sex, race, ethnicity, and year of index event. The researchers could track each of the more than 25,000 total patients through subsequent hospitalizations and emergency-department visits by their unique identifier codes.

The patients with sickle cell disease averaged 28 years old, 91% were black, and during follow-up they had an 8% incidence of VTE.

The analysis also showed that comorbidities increased the risk for VTE, although not as strongly as sickle cell disease. For the entire group of more than 25,000 patients having three or more comorbidities linked with a threefold higher rate of VTEs, compared with those without any comorbidities. Among only patients with sickle cell disease, having three or more comorbidities boosted the VTE rate by a statistically-significant 67%, compared with sickle cell patients without any comorbidities. Female sex also significantly linked with a boosted VTE rate among patients with sickle cell disease. Women with sickle cell disease had 43% more VTE episodes than did men with sickle cell disease in the adjusted analysis.

Dr. Wun had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AMSTERDAM – Adult patients who become hospitalized and have sickle cell disease have about a sixfold increased risk of developing venous thromboembolism during the following weeks and months, compared with hospitalized patients without sickle cell disease, in a case-control study of more than 25,000 people admitted to or seen at California hospitals during 1990-2010.

Since 46% of the venous thromboembolism (VTE) episodes in patients with sickle cell disease happened within 30 days of a hospitalization or emergency department visit, the painful, inflammatory episodes that often drive patients with sickle cell disease to seek hospitalization may also provoke VTE said Dr. Ted Wun and his associates in a poster presented at a congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Relative immobilization during hospitalization may also play a role in triggering VTE in these patients, suggesting that "robust" thromboprophylaxis be applied to patients with sickle cell disease who enter a hospital, said Dr. Wun, professor of medicine and chief of hematology and oncology at the University of California, Davis, in Sacramento.

The analysis also showed the impact of VTE episodes. After 10 years of follow-up, cumulative mortality was just under 20% in patients with sickle cell disease who did not have a VTE, and more than 40% in patients who had a VTE, a statistically significant difference in an actuarial analysis.

The risk for VTE posed by sickle cell disease was even higher in the 42% of patients with severe sickle cell disease, defined as patients who had three or more hospitalizations or emergency department visits during the prior year. Patients in the severe subgroup had a 9.5-fold higher rate of VTE, compared with controls who had no sickle cell disease. Among the 58% of sickle cell patients without severe disease, the incidence of VTE was fourfold greater than among those without sickle cell disease.

Dr. Wun and his associates used data collected in the California Patient Discharge Dataset and in California’s Emergency Department Utilization database. They identified 4,280 patients 18-65 years old with sickle cell disease who were either hospitalized or seen at an emergency department during 1990-2010. They matched each of these sickle cell patients with five patients hospitalized or seen at emergency departments who did not have sickle cell disease. Matching included age, sex, race, ethnicity, and year of index event. The researchers could track each of the more than 25,000 total patients through subsequent hospitalizations and emergency-department visits by their unique identifier codes.

The patients with sickle cell disease averaged 28 years old, 91% were black, and during follow-up they had an 8% incidence of VTE.

The analysis also showed that comorbidities increased the risk for VTE, although not as strongly as sickle cell disease. For the entire group of more than 25,000 patients having three or more comorbidities linked with a threefold higher rate of VTEs, compared with those without any comorbidities. Among only patients with sickle cell disease, having three or more comorbidities boosted the VTE rate by a statistically-significant 67%, compared with sickle cell patients without any comorbidities. Female sex also significantly linked with a boosted VTE rate among patients with sickle cell disease. Women with sickle cell disease had 43% more VTE episodes than did men with sickle cell disease in the adjusted analysis.

Dr. Wun had no disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT ISTH 2013

Khorana score tracks risk of cancer death

AMSTERDAM – A score routinely used to quantify cancer patients’ risk for developing venous thromboembolism also can be used to gauge their risk of death, according to an analysis of data from more than 1,500 patients.

The new findings are only exploratory, but they suggest that the well-established risk calculator known as the Khorana score "may support clinical decision making not only for VTE prophylaxis but also for anticancer treatment strategies," Dr. Cihan Ay said at the Congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

The link between higher Khorana scores and an increased rate of death over the following 2 years was independent of VTE occurrence, suggesting that the Khorana score identifies susceptibilities in addition to VTE than can cause death, said Dr. Ay, a hematologist-oncologist at the Medical University of Vienna.

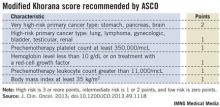

Following the Khorana score’s introduction in 2008 by Dr. Alok Khorana and his associates (Blood 2008;111:4902-7) to assess a patient’s risk for VTE and need for anticoagulant prophylaxis, the score underwent several validations. Earlier this year, the score was adopted in a slightly modified form as part of the VTE management guidelines of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (J. Clin. Onc. 2013 [doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.1118]).

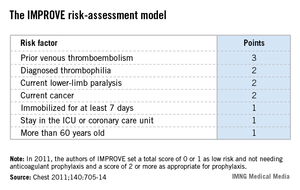

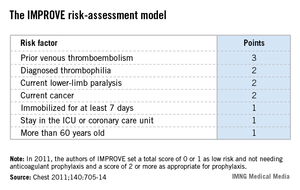

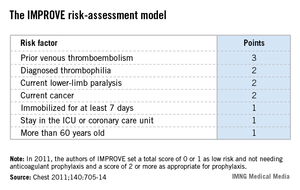

The ASCO guidelines say that "the Panel recommends that patients with cancer be assessed for VTE risk at the time of chemotherapy initiation and periodically thereafter" using the slightly modified form of the Khorana score (see box). The 2013 formula from the ASCO Panel revised the original 2008 version of the Khorana score by adding primary brain tumors to the 2-point category and renal tumors to the 1-point category.

"The Khorana score is used to identify patients for primary thromboprophylaxis. My idea is to also use it to get information on general prognosis," Dr. Ay said in an interview. "There is often a discussion of the patient’s prognosis and how far to go with treatment, how intensive treatment should be. If patients have a poor prognosis, some treatments may not be worth trying."

Dr. Ay and his associates applied their own slight modification of the Khorana score to 1,544 patients with a variety of cancers enrolled in the Vienna Cancer and Thrombosis Study. The patients averaged 62 years old, about 45% were women, and they were followed for a mean of about 19 months, during which overall, all-cause mortality was 42%. The most common tumor type was lung cancer, in about 250 patients, followed by lymphoma, breast cancer, and brain tumors, which each affected more than 200 patients. The researchers modified the Khorana score by adding melanoma to the 1-point group of cancers and removing gynecologic, bladder, and testicular cancer from being assigned any points.

The analysis showed a strong link between patients’ Khorana scores at baseline, before treatment began, and their survival over the next 2 years of follow-up. The 466 patients (30%) with a score of 0 had a 27% mortality rate; the 489 patients (32%) with a score of 1 had a 38% mortality rate (adjusted hazard ratio, 61% compared with patients with a score of 0). The 405 patients (26%) with a score of 2 had a 51% mortality rate, a 2.8-fold increased mortality rate after adjustment, and the 184 patients (12%) with a score of 3 or more had a 63% mortality rate, a fourfold higher mortality rate after adjustment compared with patients with a score of 0. Between-group differences in mortality were all statistically significant. The hazard model adjusted for age, sex, and incident VTE.

Overall in the adjusted model, every 1-point increase in modified Khorana score linked with a statistically significant 56% increase in mortality, Dr. Ay said.

Dr. Ay said that he had no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AMSTERDAM – A score routinely used to quantify cancer patients’ risk for developing venous thromboembolism also can be used to gauge their risk of death, according to an analysis of data from more than 1,500 patients.

The new findings are only exploratory, but they suggest that the well-established risk calculator known as the Khorana score "may support clinical decision making not only for VTE prophylaxis but also for anticancer treatment strategies," Dr. Cihan Ay said at the Congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

The link between higher Khorana scores and an increased rate of death over the following 2 years was independent of VTE occurrence, suggesting that the Khorana score identifies susceptibilities in addition to VTE than can cause death, said Dr. Ay, a hematologist-oncologist at the Medical University of Vienna.

Following the Khorana score’s introduction in 2008 by Dr. Alok Khorana and his associates (Blood 2008;111:4902-7) to assess a patient’s risk for VTE and need for anticoagulant prophylaxis, the score underwent several validations. Earlier this year, the score was adopted in a slightly modified form as part of the VTE management guidelines of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (J. Clin. Onc. 2013 [doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.1118]).

The ASCO guidelines say that "the Panel recommends that patients with cancer be assessed for VTE risk at the time of chemotherapy initiation and periodically thereafter" using the slightly modified form of the Khorana score (see box). The 2013 formula from the ASCO Panel revised the original 2008 version of the Khorana score by adding primary brain tumors to the 2-point category and renal tumors to the 1-point category.

"The Khorana score is used to identify patients for primary thromboprophylaxis. My idea is to also use it to get information on general prognosis," Dr. Ay said in an interview. "There is often a discussion of the patient’s prognosis and how far to go with treatment, how intensive treatment should be. If patients have a poor prognosis, some treatments may not be worth trying."

Dr. Ay and his associates applied their own slight modification of the Khorana score to 1,544 patients with a variety of cancers enrolled in the Vienna Cancer and Thrombosis Study. The patients averaged 62 years old, about 45% were women, and they were followed for a mean of about 19 months, during which overall, all-cause mortality was 42%. The most common tumor type was lung cancer, in about 250 patients, followed by lymphoma, breast cancer, and brain tumors, which each affected more than 200 patients. The researchers modified the Khorana score by adding melanoma to the 1-point group of cancers and removing gynecologic, bladder, and testicular cancer from being assigned any points.

The analysis showed a strong link between patients’ Khorana scores at baseline, before treatment began, and their survival over the next 2 years of follow-up. The 466 patients (30%) with a score of 0 had a 27% mortality rate; the 489 patients (32%) with a score of 1 had a 38% mortality rate (adjusted hazard ratio, 61% compared with patients with a score of 0). The 405 patients (26%) with a score of 2 had a 51% mortality rate, a 2.8-fold increased mortality rate after adjustment, and the 184 patients (12%) with a score of 3 or more had a 63% mortality rate, a fourfold higher mortality rate after adjustment compared with patients with a score of 0. Between-group differences in mortality were all statistically significant. The hazard model adjusted for age, sex, and incident VTE.

Overall in the adjusted model, every 1-point increase in modified Khorana score linked with a statistically significant 56% increase in mortality, Dr. Ay said.

Dr. Ay said that he had no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AMSTERDAM – A score routinely used to quantify cancer patients’ risk for developing venous thromboembolism also can be used to gauge their risk of death, according to an analysis of data from more than 1,500 patients.

The new findings are only exploratory, but they suggest that the well-established risk calculator known as the Khorana score "may support clinical decision making not only for VTE prophylaxis but also for anticancer treatment strategies," Dr. Cihan Ay said at the Congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

The link between higher Khorana scores and an increased rate of death over the following 2 years was independent of VTE occurrence, suggesting that the Khorana score identifies susceptibilities in addition to VTE than can cause death, said Dr. Ay, a hematologist-oncologist at the Medical University of Vienna.

Following the Khorana score’s introduction in 2008 by Dr. Alok Khorana and his associates (Blood 2008;111:4902-7) to assess a patient’s risk for VTE and need for anticoagulant prophylaxis, the score underwent several validations. Earlier this year, the score was adopted in a slightly modified form as part of the VTE management guidelines of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (J. Clin. Onc. 2013 [doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.1118]).

The ASCO guidelines say that "the Panel recommends that patients with cancer be assessed for VTE risk at the time of chemotherapy initiation and periodically thereafter" using the slightly modified form of the Khorana score (see box). The 2013 formula from the ASCO Panel revised the original 2008 version of the Khorana score by adding primary brain tumors to the 2-point category and renal tumors to the 1-point category.

"The Khorana score is used to identify patients for primary thromboprophylaxis. My idea is to also use it to get information on general prognosis," Dr. Ay said in an interview. "There is often a discussion of the patient’s prognosis and how far to go with treatment, how intensive treatment should be. If patients have a poor prognosis, some treatments may not be worth trying."

Dr. Ay and his associates applied their own slight modification of the Khorana score to 1,544 patients with a variety of cancers enrolled in the Vienna Cancer and Thrombosis Study. The patients averaged 62 years old, about 45% were women, and they were followed for a mean of about 19 months, during which overall, all-cause mortality was 42%. The most common tumor type was lung cancer, in about 250 patients, followed by lymphoma, breast cancer, and brain tumors, which each affected more than 200 patients. The researchers modified the Khorana score by adding melanoma to the 1-point group of cancers and removing gynecologic, bladder, and testicular cancer from being assigned any points.

The analysis showed a strong link between patients’ Khorana scores at baseline, before treatment began, and their survival over the next 2 years of follow-up. The 466 patients (30%) with a score of 0 had a 27% mortality rate; the 489 patients (32%) with a score of 1 had a 38% mortality rate (adjusted hazard ratio, 61% compared with patients with a score of 0). The 405 patients (26%) with a score of 2 had a 51% mortality rate, a 2.8-fold increased mortality rate after adjustment, and the 184 patients (12%) with a score of 3 or more had a 63% mortality rate, a fourfold higher mortality rate after adjustment compared with patients with a score of 0. Between-group differences in mortality were all statistically significant. The hazard model adjusted for age, sex, and incident VTE.

Overall in the adjusted model, every 1-point increase in modified Khorana score linked with a statistically significant 56% increase in mortality, Dr. Ay said.

Dr. Ay said that he had no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE 2013 ISTH CONGRESS

Major finding: In the adjusted model, every 1-point increase in modified Khorana score linked with a statistically significant 56% increase in mortality.

Data source: An analysis of 1,544 cancer patients followed prospectively at an Austrian center.

Disclosures: Dr. Ay said that he had no relevant disclosures.

Will a novel antibody fix the anticoagulant-bleeding problem?

It seems inescapable: If patients are made less able to form blood clots, they bleed more.

Bleeding is the perennial problem for anticoagulants. Whether it’s the traditional anticoagulants (heparin, warfarin, and the low-molecular-weight heparins) or new drugs (fondaparinux, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban), as the anticoagulant’s potency or dosage increases to stop blood clots from forming, the inevitable downside is increased bleeding.

Maybe not.

A newly developed, synthetic human IgG antibody appears, in animal and in vitro models, to allow normal clotting to occur and stop bleeding at vessel tears and cuts, while short-circuiting pathologic clotting in intravascular spaces – the sorts of clots that cause venous thromboembolisms, myocardial infarctions, and strokes.

"It seems too good to be true. It’s beyond comprehension," said Dr. Trevor Baglin, the University of Cambridge, England, hematologist who discovered the first identified, naturally occurring example of this antibody, in IgA form, in a patient he initially saw in 2008. "All we can do is go forward and see if it genuinely is as good as it seems," he said while presenting his group’s initial animal findings with the antibody at the Congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis in Amsterdam earlier this month.

The antibody – which has been patented, synthesized, and is in extensive preclinical testing – has been named ichorcumab. In Greek mythology, "ichor" was the blood factor in gods that made them immortal.

The secret behind ichorcumab is that it binds to and inactivates exosite 1, the part of the thrombin molecule that cleaves fibrinogen into fibrin, an effective brake on clotting. Study results suggest that whether the exosite 1 portion of thrombin is exposed or hidden at various body sites accounts for ichorcumab’s varied effects.

"Our hypothesis is that exosite 1 is protected from the antibody [when a thrombin molecule sits] on a cell or clot surface, so hemostasis is unaffected, but thrombosis occurs in the luminal space, where exosite 1 is exposed an available to the antibody," Dr. Baglin explained.

"While before we thought of just one type of clot, [the work with ichorcumab so far] suggests there is not one clotting mechanism but two," he noted, one that leads to clot formation that stops bleeding, and a second mechanism that produces clots that cause thrombosis. Ichorcumab blocks the bad clots but not the good ones, because the clots form at different locations that affect the way that exosite 1 on thrombin is exposed.

It may sound farfetched, but it’s a way for the researchers to explain the curious patient whom Dr. Baglin first met in 2008, a 53-year old woman who spontaneously makes and carries the IgA prototype of ichorcumab in her blood.

Dr. Baglin said that he consulted on her case after a preprocedural clotting screen revealed that her blood was unclottable by standard tests, yet she had no history of any bleeding disorder. In fact, her history showed that she had undergone knee surgery (when no clotting screen had been done) 5 months before Dr. Baglin first saw her without any hint of a bleeding incident. She subsequently cut the tip of a finger while slicing with a mandolin, but her bleeding stopped spontaneously.

The patient goes through life with this antibody in her blood at a level of about 3 g/L with no bleeding problems whatsoever; yet in a mouse model, a substantially lower level of the mimic antibody, ichorcumab, effectively blocked thrombosis. In the mouse model, this effective dose of ichorcumab does not cause bleeding if the mouse’s tail is cut.

Dr. Baglin and his associates started a company in Cambridge, XO1, to fund the preclinical work and eventually commercialize ichorcumab. They believe it will be another 2 years before any person receives a dose of the antibody.

–BY MITCHEL L. ZOLER

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

It seems inescapable: If patients are made less able to form blood clots, they bleed more.

Bleeding is the perennial problem for anticoagulants. Whether it’s the traditional anticoagulants (heparin, warfarin, and the low-molecular-weight heparins) or new drugs (fondaparinux, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban), as the anticoagulant’s potency or dosage increases to stop blood clots from forming, the inevitable downside is increased bleeding.

Maybe not.

A newly developed, synthetic human IgG antibody appears, in animal and in vitro models, to allow normal clotting to occur and stop bleeding at vessel tears and cuts, while short-circuiting pathologic clotting in intravascular spaces – the sorts of clots that cause venous thromboembolisms, myocardial infarctions, and strokes.

"It seems too good to be true. It’s beyond comprehension," said Dr. Trevor Baglin, the University of Cambridge, England, hematologist who discovered the first identified, naturally occurring example of this antibody, in IgA form, in a patient he initially saw in 2008. "All we can do is go forward and see if it genuinely is as good as it seems," he said while presenting his group’s initial animal findings with the antibody at the Congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis in Amsterdam earlier this month.

The antibody – which has been patented, synthesized, and is in extensive preclinical testing – has been named ichorcumab. In Greek mythology, "ichor" was the blood factor in gods that made them immortal.

The secret behind ichorcumab is that it binds to and inactivates exosite 1, the part of the thrombin molecule that cleaves fibrinogen into fibrin, an effective brake on clotting. Study results suggest that whether the exosite 1 portion of thrombin is exposed or hidden at various body sites accounts for ichorcumab’s varied effects.

"Our hypothesis is that exosite 1 is protected from the antibody [when a thrombin molecule sits] on a cell or clot surface, so hemostasis is unaffected, but thrombosis occurs in the luminal space, where exosite 1 is exposed an available to the antibody," Dr. Baglin explained.

"While before we thought of just one type of clot, [the work with ichorcumab so far] suggests there is not one clotting mechanism but two," he noted, one that leads to clot formation that stops bleeding, and a second mechanism that produces clots that cause thrombosis. Ichorcumab blocks the bad clots but not the good ones, because the clots form at different locations that affect the way that exosite 1 on thrombin is exposed.

It may sound farfetched, but it’s a way for the researchers to explain the curious patient whom Dr. Baglin first met in 2008, a 53-year old woman who spontaneously makes and carries the IgA prototype of ichorcumab in her blood.

Dr. Baglin said that he consulted on her case after a preprocedural clotting screen revealed that her blood was unclottable by standard tests, yet she had no history of any bleeding disorder. In fact, her history showed that she had undergone knee surgery (when no clotting screen had been done) 5 months before Dr. Baglin first saw her without any hint of a bleeding incident. She subsequently cut the tip of a finger while slicing with a mandolin, but her bleeding stopped spontaneously.

The patient goes through life with this antibody in her blood at a level of about 3 g/L with no bleeding problems whatsoever; yet in a mouse model, a substantially lower level of the mimic antibody, ichorcumab, effectively blocked thrombosis. In the mouse model, this effective dose of ichorcumab does not cause bleeding if the mouse’s tail is cut.

Dr. Baglin and his associates started a company in Cambridge, XO1, to fund the preclinical work and eventually commercialize ichorcumab. They believe it will be another 2 years before any person receives a dose of the antibody.

–BY MITCHEL L. ZOLER

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

It seems inescapable: If patients are made less able to form blood clots, they bleed more.

Bleeding is the perennial problem for anticoagulants. Whether it’s the traditional anticoagulants (heparin, warfarin, and the low-molecular-weight heparins) or new drugs (fondaparinux, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban), as the anticoagulant’s potency or dosage increases to stop blood clots from forming, the inevitable downside is increased bleeding.

Maybe not.

A newly developed, synthetic human IgG antibody appears, in animal and in vitro models, to allow normal clotting to occur and stop bleeding at vessel tears and cuts, while short-circuiting pathologic clotting in intravascular spaces – the sorts of clots that cause venous thromboembolisms, myocardial infarctions, and strokes.

"It seems too good to be true. It’s beyond comprehension," said Dr. Trevor Baglin, the University of Cambridge, England, hematologist who discovered the first identified, naturally occurring example of this antibody, in IgA form, in a patient he initially saw in 2008. "All we can do is go forward and see if it genuinely is as good as it seems," he said while presenting his group’s initial animal findings with the antibody at the Congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis in Amsterdam earlier this month.

The antibody – which has been patented, synthesized, and is in extensive preclinical testing – has been named ichorcumab. In Greek mythology, "ichor" was the blood factor in gods that made them immortal.

The secret behind ichorcumab is that it binds to and inactivates exosite 1, the part of the thrombin molecule that cleaves fibrinogen into fibrin, an effective brake on clotting. Study results suggest that whether the exosite 1 portion of thrombin is exposed or hidden at various body sites accounts for ichorcumab’s varied effects.

"Our hypothesis is that exosite 1 is protected from the antibody [when a thrombin molecule sits] on a cell or clot surface, so hemostasis is unaffected, but thrombosis occurs in the luminal space, where exosite 1 is exposed an available to the antibody," Dr. Baglin explained.

"While before we thought of just one type of clot, [the work with ichorcumab so far] suggests there is not one clotting mechanism but two," he noted, one that leads to clot formation that stops bleeding, and a second mechanism that produces clots that cause thrombosis. Ichorcumab blocks the bad clots but not the good ones, because the clots form at different locations that affect the way that exosite 1 on thrombin is exposed.

It may sound farfetched, but it’s a way for the researchers to explain the curious patient whom Dr. Baglin first met in 2008, a 53-year old woman who spontaneously makes and carries the IgA prototype of ichorcumab in her blood.

Dr. Baglin said that he consulted on her case after a preprocedural clotting screen revealed that her blood was unclottable by standard tests, yet she had no history of any bleeding disorder. In fact, her history showed that she had undergone knee surgery (when no clotting screen had been done) 5 months before Dr. Baglin first saw her without any hint of a bleeding incident. She subsequently cut the tip of a finger while slicing with a mandolin, but her bleeding stopped spontaneously.

The patient goes through life with this antibody in her blood at a level of about 3 g/L with no bleeding problems whatsoever; yet in a mouse model, a substantially lower level of the mimic antibody, ichorcumab, effectively blocked thrombosis. In the mouse model, this effective dose of ichorcumab does not cause bleeding if the mouse’s tail is cut.

Dr. Baglin and his associates started a company in Cambridge, XO1, to fund the preclinical work and eventually commercialize ichorcumab. They believe it will be another 2 years before any person receives a dose of the antibody.

–BY MITCHEL L. ZOLER

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

VTE rate triples in pediatric cancer survivors

AMSTERDAM – Children, adolescents, and young adults who survived a diagnosis and treatment of cancer had a greater than threefold higher rate of acute venous thromboembolism during roughly 10 years of follow-up, compared with matched controls from the general population, in a study that included more than 30,000 Canadians.

The increased rate of VTE appeared to be linked to the chemotherapy and radiation treatments that patients received, because patients who were managed only by surgery had a substantially reduced rate of VTE during follow-up.

"Our working hypothesis is that VTE that develops during [initial] treatment of childhood cancers then places these patients at an increased risk" for a second VTE later in their life, Dr. Ketan P. Kulkarni said at the congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

If a first episode of VTE during or soon after the initial therapy that young cancer patients receive can be clearly established as a major risk factor for a subsequent episode of VTE, the next step would be to test whether improved prophylaxis during initial therapy can prevent a first episode and thereby also cut patients’ risk for a second VTE several months or years later. Clinicians who manage children, adolescents, and young adults with cancer need increased awareness that VTE "is a major problem" during both initial treatment and follow-up, Dr. Kulkarni said in an interview. "We think the VTEs during follow-up are recurrences of clots that first formed during treatment." He and his associates have begun to review the medical records of each survivor to better determine how many of the VTEs seen during follow-up were recurrences.

Another major finding from this analysis of people who survived at least 5 years following cancer diagnosis at age 0-24 years was that the entire range of cancers posed a VTE risk to patients, not just leukemia as some had previously though. The VTE rate during follow-up of the survivors was roughly the same regardless of whether patients had leukemia, lymphoma, carcinoma, or some other type of cancer.

"We have clearly dispelled the myth that it’s only leukemias. It’s all cancers," said Dr. Kulkarni, a pediatric hematologist-oncologist at the University of Alberta in Edmonton.

The researchers used provincial health insurance records from British Columbia during 1981-1999 to identify 2,857 patients who were aged 0-24 years at the time of their initial cancer diagnosis and then lived for at least another 5 years. The survivors averaged about 14 years old at the time of their initial cancer diagnosis. The investigators also assembled a control group matched by age and sex from the general British Columbia population, taking 10 controls for each case for a total of 28,570 controls.

During follow-up that ranged from 5 to 21 years and averaged nearly 10 years, they found that 43 survivors had an episode of VTE, a 1.5% incidence rate, compared with a 0.5% rate among the controls. In a multivariate analysis that controlled for sex, socioeconomic status, and region of residence, patients who were cancer survivors had a statistically significant, 3.4-fold increased rate of VTE compared with the controls, Dr. Kulkarni reported. Among the survivors the incidence of deep vein thrombosis was roughly 0.8%, the incidence of pulmonary embolism was roughly 0.5%, and VTE in other locations occurred in about 0.3% of the survivors (the total is 1.6% because of rounding). The incidence of VTEs was highest during the first 6 months following cancer diagnosis.

Cancer survivors who had been treated by surgery alone, without chemotherapy or radiation, had a statistically significant, 81% lower rate of developing a VTE compared with the patients treated by chemotherapy alone, radiation alone, or both.

"This supports the hypothesis that treatment by radiation or by chemotherapy increases the VTE risk," Dr. Kulkarni said.

The VTE rate was also substantially higher in survivors who had a relapse of their cancer during follow-up. Patients with relapses had a 2.5-fold higher rate of VTE compared with survivors who did not have a relapse.

Dr. Kulkarni said that he had no disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AMSTERDAM – Children, adolescents, and young adults who survived a diagnosis and treatment of cancer had a greater than threefold higher rate of acute venous thromboembolism during roughly 10 years of follow-up, compared with matched controls from the general population, in a study that included more than 30,000 Canadians.

The increased rate of VTE appeared to be linked to the chemotherapy and radiation treatments that patients received, because patients who were managed only by surgery had a substantially reduced rate of VTE during follow-up.

"Our working hypothesis is that VTE that develops during [initial] treatment of childhood cancers then places these patients at an increased risk" for a second VTE later in their life, Dr. Ketan P. Kulkarni said at the congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.