User login

AMSTERDAM – A score routinely used to quantify cancer patients’ risk for developing venous thromboembolism also can be used to gauge their risk of death, according to an analysis of data from more than 1,500 patients.

The new findings are only exploratory, but they suggest that the well-established risk calculator known as the Khorana score "may support clinical decision making not only for VTE prophylaxis but also for anticancer treatment strategies," Dr. Cihan Ay said at the Congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

The link between higher Khorana scores and an increased rate of death over the following 2 years was independent of VTE occurrence, suggesting that the Khorana score identifies susceptibilities in addition to VTE than can cause death, said Dr. Ay, a hematologist-oncologist at the Medical University of Vienna.

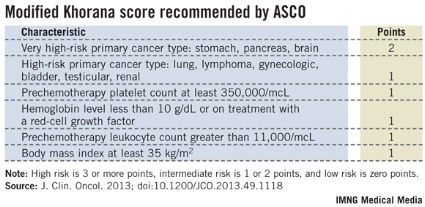

Following the Khorana score’s introduction in 2008 by Dr. Alok Khorana and his associates (Blood 2008;111:4902-7) to assess a patient’s risk for VTE and need for anticoagulant prophylaxis, the score underwent several validations. Earlier this year, the score was adopted in a slightly modified form as part of the VTE management guidelines of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (J. Clin. Onc. 2013 [doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.1118]).

The ASCO guidelines say that "the Panel recommends that patients with cancer be assessed for VTE risk at the time of chemotherapy initiation and periodically thereafter" using the slightly modified form of the Khorana score (see box). The 2013 formula from the ASCO Panel revised the original 2008 version of the Khorana score by adding primary brain tumors to the 2-point category and renal tumors to the 1-point category.

"The Khorana score is used to identify patients for primary thromboprophylaxis. My idea is to also use it to get information on general prognosis," Dr. Ay said in an interview. "There is often a discussion of the patient’s prognosis and how far to go with treatment, how intensive treatment should be. If patients have a poor prognosis, some treatments may not be worth trying."

Dr. Ay and his associates applied their own slight modification of the Khorana score to 1,544 patients with a variety of cancers enrolled in the Vienna Cancer and Thrombosis Study. The patients averaged 62 years old, about 45% were women, and they were followed for a mean of about 19 months, during which overall, all-cause mortality was 42%. The most common tumor type was lung cancer, in about 250 patients, followed by lymphoma, breast cancer, and brain tumors, which each affected more than 200 patients. The researchers modified the Khorana score by adding melanoma to the 1-point group of cancers and removing gynecologic, bladder, and testicular cancer from being assigned any points.

The analysis showed a strong link between patients’ Khorana scores at baseline, before treatment began, and their survival over the next 2 years of follow-up. The 466 patients (30%) with a score of 0 had a 27% mortality rate; the 489 patients (32%) with a score of 1 had a 38% mortality rate (adjusted hazard ratio, 61% compared with patients with a score of 0). The 405 patients (26%) with a score of 2 had a 51% mortality rate, a 2.8-fold increased mortality rate after adjustment, and the 184 patients (12%) with a score of 3 or more had a 63% mortality rate, a fourfold higher mortality rate after adjustment compared with patients with a score of 0. Between-group differences in mortality were all statistically significant. The hazard model adjusted for age, sex, and incident VTE.

Overall in the adjusted model, every 1-point increase in modified Khorana score linked with a statistically significant 56% increase in mortality, Dr. Ay said.

Dr. Ay said that he had no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AMSTERDAM – A score routinely used to quantify cancer patients’ risk for developing venous thromboembolism also can be used to gauge their risk of death, according to an analysis of data from more than 1,500 patients.

The new findings are only exploratory, but they suggest that the well-established risk calculator known as the Khorana score "may support clinical decision making not only for VTE prophylaxis but also for anticancer treatment strategies," Dr. Cihan Ay said at the Congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

The link between higher Khorana scores and an increased rate of death over the following 2 years was independent of VTE occurrence, suggesting that the Khorana score identifies susceptibilities in addition to VTE than can cause death, said Dr. Ay, a hematologist-oncologist at the Medical University of Vienna.

Following the Khorana score’s introduction in 2008 by Dr. Alok Khorana and his associates (Blood 2008;111:4902-7) to assess a patient’s risk for VTE and need for anticoagulant prophylaxis, the score underwent several validations. Earlier this year, the score was adopted in a slightly modified form as part of the VTE management guidelines of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (J. Clin. Onc. 2013 [doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.1118]).

The ASCO guidelines say that "the Panel recommends that patients with cancer be assessed for VTE risk at the time of chemotherapy initiation and periodically thereafter" using the slightly modified form of the Khorana score (see box). The 2013 formula from the ASCO Panel revised the original 2008 version of the Khorana score by adding primary brain tumors to the 2-point category and renal tumors to the 1-point category.

"The Khorana score is used to identify patients for primary thromboprophylaxis. My idea is to also use it to get information on general prognosis," Dr. Ay said in an interview. "There is often a discussion of the patient’s prognosis and how far to go with treatment, how intensive treatment should be. If patients have a poor prognosis, some treatments may not be worth trying."

Dr. Ay and his associates applied their own slight modification of the Khorana score to 1,544 patients with a variety of cancers enrolled in the Vienna Cancer and Thrombosis Study. The patients averaged 62 years old, about 45% were women, and they were followed for a mean of about 19 months, during which overall, all-cause mortality was 42%. The most common tumor type was lung cancer, in about 250 patients, followed by lymphoma, breast cancer, and brain tumors, which each affected more than 200 patients. The researchers modified the Khorana score by adding melanoma to the 1-point group of cancers and removing gynecologic, bladder, and testicular cancer from being assigned any points.

The analysis showed a strong link between patients’ Khorana scores at baseline, before treatment began, and their survival over the next 2 years of follow-up. The 466 patients (30%) with a score of 0 had a 27% mortality rate; the 489 patients (32%) with a score of 1 had a 38% mortality rate (adjusted hazard ratio, 61% compared with patients with a score of 0). The 405 patients (26%) with a score of 2 had a 51% mortality rate, a 2.8-fold increased mortality rate after adjustment, and the 184 patients (12%) with a score of 3 or more had a 63% mortality rate, a fourfold higher mortality rate after adjustment compared with patients with a score of 0. Between-group differences in mortality were all statistically significant. The hazard model adjusted for age, sex, and incident VTE.

Overall in the adjusted model, every 1-point increase in modified Khorana score linked with a statistically significant 56% increase in mortality, Dr. Ay said.

Dr. Ay said that he had no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AMSTERDAM – A score routinely used to quantify cancer patients’ risk for developing venous thromboembolism also can be used to gauge their risk of death, according to an analysis of data from more than 1,500 patients.

The new findings are only exploratory, but they suggest that the well-established risk calculator known as the Khorana score "may support clinical decision making not only for VTE prophylaxis but also for anticancer treatment strategies," Dr. Cihan Ay said at the Congress of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

The link between higher Khorana scores and an increased rate of death over the following 2 years was independent of VTE occurrence, suggesting that the Khorana score identifies susceptibilities in addition to VTE than can cause death, said Dr. Ay, a hematologist-oncologist at the Medical University of Vienna.

Following the Khorana score’s introduction in 2008 by Dr. Alok Khorana and his associates (Blood 2008;111:4902-7) to assess a patient’s risk for VTE and need for anticoagulant prophylaxis, the score underwent several validations. Earlier this year, the score was adopted in a slightly modified form as part of the VTE management guidelines of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (J. Clin. Onc. 2013 [doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.1118]).

The ASCO guidelines say that "the Panel recommends that patients with cancer be assessed for VTE risk at the time of chemotherapy initiation and periodically thereafter" using the slightly modified form of the Khorana score (see box). The 2013 formula from the ASCO Panel revised the original 2008 version of the Khorana score by adding primary brain tumors to the 2-point category and renal tumors to the 1-point category.

"The Khorana score is used to identify patients for primary thromboprophylaxis. My idea is to also use it to get information on general prognosis," Dr. Ay said in an interview. "There is often a discussion of the patient’s prognosis and how far to go with treatment, how intensive treatment should be. If patients have a poor prognosis, some treatments may not be worth trying."

Dr. Ay and his associates applied their own slight modification of the Khorana score to 1,544 patients with a variety of cancers enrolled in the Vienna Cancer and Thrombosis Study. The patients averaged 62 years old, about 45% were women, and they were followed for a mean of about 19 months, during which overall, all-cause mortality was 42%. The most common tumor type was lung cancer, in about 250 patients, followed by lymphoma, breast cancer, and brain tumors, which each affected more than 200 patients. The researchers modified the Khorana score by adding melanoma to the 1-point group of cancers and removing gynecologic, bladder, and testicular cancer from being assigned any points.

The analysis showed a strong link between patients’ Khorana scores at baseline, before treatment began, and their survival over the next 2 years of follow-up. The 466 patients (30%) with a score of 0 had a 27% mortality rate; the 489 patients (32%) with a score of 1 had a 38% mortality rate (adjusted hazard ratio, 61% compared with patients with a score of 0). The 405 patients (26%) with a score of 2 had a 51% mortality rate, a 2.8-fold increased mortality rate after adjustment, and the 184 patients (12%) with a score of 3 or more had a 63% mortality rate, a fourfold higher mortality rate after adjustment compared with patients with a score of 0. Between-group differences in mortality were all statistically significant. The hazard model adjusted for age, sex, and incident VTE.

Overall in the adjusted model, every 1-point increase in modified Khorana score linked with a statistically significant 56% increase in mortality, Dr. Ay said.

Dr. Ay said that he had no relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE 2013 ISTH CONGRESS

Major finding: In the adjusted model, every 1-point increase in modified Khorana score linked with a statistically significant 56% increase in mortality.

Data source: An analysis of 1,544 cancer patients followed prospectively at an Austrian center.

Disclosures: Dr. Ay said that he had no relevant disclosures.