User login

Cardiology News is an independent news source that provides cardiologists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on cardiology and the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is the online destination and multimedia properties of Cardiology News, the independent news publication for cardiologists. Cardiology news is the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in cardiology as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

A Portrait of the Patient

Most of my writing starts on paper. I’ve stacks of Docket Gold legal pads, yellow and college ruled, filled with Sharpie S-Gel black ink. There are many scratch-outs and arrows, but no doodles. I’m genetically not a doodler. The draft of this essay however was interrupted by a graphic. It is a round figure with stick arms and legs. Somewhat centered are two intense scribbles, which represent eyes. A few loopy curls rest on top. It looks like a Mr. Potato Head, with owl eyes.

“Ah, art!” I say when I flip up the page and discover this spontaneous self-portrait of my 4-year-old. Using the media she had on hand, she let free her stored creative energy, an energy we all seem to have. “Tell me about what you’ve drawn here,” I say. She’s eager to share. Art is a natural way to connect.

My patients have shown me many similar self-portraits. Last week, the artist was a 71-year-old woman. She came with her friend, a 73-year-old woman, who is also my patient. They accompany each other on all their visits. She chose a small realtor pad with a color photo of a blonde with her arms folded and back against a graphic of a house. My patient managed to fit her sketch on the small, lined space, noting with tiny scribbles the lesions she wanted me to check. Although unnecessary, she added eyes, nose, and mouth.

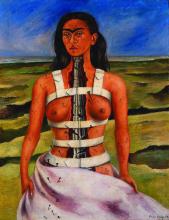

Another drawing was from a middle-aged white man. He has a look that suggests he rises early. His was on white printer paper, which he withdrew from a folder. He drew both a front and back view indicating with precision where I might find the spots he had mapped on his portrait. A retired teacher brought hers with a notably proportional anatomy and uniform tick marks on her face, arms, and legs. It reminded me of a self-portrait by the artist Frida Kahlo’s “The Broken Column.”

Kahlo was born with polio and suffered a severe bus accident as a young woman. She is one of many artists who shared their suffering through their art. “The Broken Column” depicts her with nails running from her face down her right short, weak leg. They look like the ticks my patient had added to her own self-portrait.

I remember in my neurology rotation asking patients to draw a clock. Stroke patients leave a whole half missing. Patients with dementia often crunch all the numbers into a little corner of the circle or forget to add the hands. Some of my dermatology patient self-portraits looked like that. I sometimes wonder if they also need a neurologist.

These pieces of patient art are utilitarian, drawn to narrate the story of what brought them to see me. Yet patients often add superfluous detail, demonstrating that utility and aesthetics are inseparable. I hold their drawings in the best light and notice the features and attributes. It helps me see their concerns from their point of view and primes me to notice other details during the physical exam. Viewing patients’ drawings can help build something called narrative competence the “ability to acknowledge, absorb, interpret, and act on the stories and plights of others.” Like Kahlo, patients are trying to share something with us, universal and recognizable. Art is how we connect to each other.

A few months ago, I walked in a room to see a consult. A white man in his 30s, he had prematurely graying hair and 80s-hip frames for glasses. He explained he was there for a skin screening and stood without warning, taking a step toward me. Like Michelangelo on wet plaster, he had grabbed a purple surgical marker to draw a self-portrait on the exam paper, the table set to just the right height and pitch to be an easel. It was the ginger-bread-man-type portrait with thick arms and legs and frosting-like dots marking the spots of concern. He marked L and R on the sheet, which were opposite what they would be if he was sitting facing me. But this was a self-portrait and he was drawing as it was with him facing the canvas, of course. “Ah, art!” I thought, and said, “Delightful! Tell me about what you’ve drawn here.” And so he did. A faint shadow of his portrait remains on that exam table to this day for every patient to see.

Benabio is chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Most of my writing starts on paper. I’ve stacks of Docket Gold legal pads, yellow and college ruled, filled with Sharpie S-Gel black ink. There are many scratch-outs and arrows, but no doodles. I’m genetically not a doodler. The draft of this essay however was interrupted by a graphic. It is a round figure with stick arms and legs. Somewhat centered are two intense scribbles, which represent eyes. A few loopy curls rest on top. It looks like a Mr. Potato Head, with owl eyes.

“Ah, art!” I say when I flip up the page and discover this spontaneous self-portrait of my 4-year-old. Using the media she had on hand, she let free her stored creative energy, an energy we all seem to have. “Tell me about what you’ve drawn here,” I say. She’s eager to share. Art is a natural way to connect.

My patients have shown me many similar self-portraits. Last week, the artist was a 71-year-old woman. She came with her friend, a 73-year-old woman, who is also my patient. They accompany each other on all their visits. She chose a small realtor pad with a color photo of a blonde with her arms folded and back against a graphic of a house. My patient managed to fit her sketch on the small, lined space, noting with tiny scribbles the lesions she wanted me to check. Although unnecessary, she added eyes, nose, and mouth.

Another drawing was from a middle-aged white man. He has a look that suggests he rises early. His was on white printer paper, which he withdrew from a folder. He drew both a front and back view indicating with precision where I might find the spots he had mapped on his portrait. A retired teacher brought hers with a notably proportional anatomy and uniform tick marks on her face, arms, and legs. It reminded me of a self-portrait by the artist Frida Kahlo’s “The Broken Column.”

Kahlo was born with polio and suffered a severe bus accident as a young woman. She is one of many artists who shared their suffering through their art. “The Broken Column” depicts her with nails running from her face down her right short, weak leg. They look like the ticks my patient had added to her own self-portrait.

I remember in my neurology rotation asking patients to draw a clock. Stroke patients leave a whole half missing. Patients with dementia often crunch all the numbers into a little corner of the circle or forget to add the hands. Some of my dermatology patient self-portraits looked like that. I sometimes wonder if they also need a neurologist.

These pieces of patient art are utilitarian, drawn to narrate the story of what brought them to see me. Yet patients often add superfluous detail, demonstrating that utility and aesthetics are inseparable. I hold their drawings in the best light and notice the features and attributes. It helps me see their concerns from their point of view and primes me to notice other details during the physical exam. Viewing patients’ drawings can help build something called narrative competence the “ability to acknowledge, absorb, interpret, and act on the stories and plights of others.” Like Kahlo, patients are trying to share something with us, universal and recognizable. Art is how we connect to each other.

A few months ago, I walked in a room to see a consult. A white man in his 30s, he had prematurely graying hair and 80s-hip frames for glasses. He explained he was there for a skin screening and stood without warning, taking a step toward me. Like Michelangelo on wet plaster, he had grabbed a purple surgical marker to draw a self-portrait on the exam paper, the table set to just the right height and pitch to be an easel. It was the ginger-bread-man-type portrait with thick arms and legs and frosting-like dots marking the spots of concern. He marked L and R on the sheet, which were opposite what they would be if he was sitting facing me. But this was a self-portrait and he was drawing as it was with him facing the canvas, of course. “Ah, art!” I thought, and said, “Delightful! Tell me about what you’ve drawn here.” And so he did. A faint shadow of his portrait remains on that exam table to this day for every patient to see.

Benabio is chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Most of my writing starts on paper. I’ve stacks of Docket Gold legal pads, yellow and college ruled, filled with Sharpie S-Gel black ink. There are many scratch-outs and arrows, but no doodles. I’m genetically not a doodler. The draft of this essay however was interrupted by a graphic. It is a round figure with stick arms and legs. Somewhat centered are two intense scribbles, which represent eyes. A few loopy curls rest on top. It looks like a Mr. Potato Head, with owl eyes.

“Ah, art!” I say when I flip up the page and discover this spontaneous self-portrait of my 4-year-old. Using the media she had on hand, she let free her stored creative energy, an energy we all seem to have. “Tell me about what you’ve drawn here,” I say. She’s eager to share. Art is a natural way to connect.

My patients have shown me many similar self-portraits. Last week, the artist was a 71-year-old woman. She came with her friend, a 73-year-old woman, who is also my patient. They accompany each other on all their visits. She chose a small realtor pad with a color photo of a blonde with her arms folded and back against a graphic of a house. My patient managed to fit her sketch on the small, lined space, noting with tiny scribbles the lesions she wanted me to check. Although unnecessary, she added eyes, nose, and mouth.

Another drawing was from a middle-aged white man. He has a look that suggests he rises early. His was on white printer paper, which he withdrew from a folder. He drew both a front and back view indicating with precision where I might find the spots he had mapped on his portrait. A retired teacher brought hers with a notably proportional anatomy and uniform tick marks on her face, arms, and legs. It reminded me of a self-portrait by the artist Frida Kahlo’s “The Broken Column.”

Kahlo was born with polio and suffered a severe bus accident as a young woman. She is one of many artists who shared their suffering through their art. “The Broken Column” depicts her with nails running from her face down her right short, weak leg. They look like the ticks my patient had added to her own self-portrait.

I remember in my neurology rotation asking patients to draw a clock. Stroke patients leave a whole half missing. Patients with dementia often crunch all the numbers into a little corner of the circle or forget to add the hands. Some of my dermatology patient self-portraits looked like that. I sometimes wonder if they also need a neurologist.

These pieces of patient art are utilitarian, drawn to narrate the story of what brought them to see me. Yet patients often add superfluous detail, demonstrating that utility and aesthetics are inseparable. I hold their drawings in the best light and notice the features and attributes. It helps me see their concerns from their point of view and primes me to notice other details during the physical exam. Viewing patients’ drawings can help build something called narrative competence the “ability to acknowledge, absorb, interpret, and act on the stories and plights of others.” Like Kahlo, patients are trying to share something with us, universal and recognizable. Art is how we connect to each other.

A few months ago, I walked in a room to see a consult. A white man in his 30s, he had prematurely graying hair and 80s-hip frames for glasses. He explained he was there for a skin screening and stood without warning, taking a step toward me. Like Michelangelo on wet plaster, he had grabbed a purple surgical marker to draw a self-portrait on the exam paper, the table set to just the right height and pitch to be an easel. It was the ginger-bread-man-type portrait with thick arms and legs and frosting-like dots marking the spots of concern. He marked L and R on the sheet, which were opposite what they would be if he was sitting facing me. But this was a self-portrait and he was drawing as it was with him facing the canvas, of course. “Ah, art!” I thought, and said, “Delightful! Tell me about what you’ve drawn here.” And so he did. A faint shadow of his portrait remains on that exam table to this day for every patient to see.

Benabio is chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on X. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Post COVID-19, Long-term Risk for Autoimmune, Autoinflammatory Skin Disorders Increased, Study Finds

In addition, the authors reported that COVID-19 vaccination appears to reduce these risks.

The study was published in JAMA Dermatology.

‘Compelling Evidence’

“This well-executed study by Heo et al provides compelling evidence to support an association between COVID-19 infection and the development of subsequent autoimmune and autoinflammatory skin diseases,” wrote authors led by Lisa M. Arkin, MD, of the Department of Dermatology, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison, in an accompanying editorial.

Using databases from Korea’s National Health Insurance Service and the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, investigators led by Yeon-Woo Heo, MD, a dermatology resident at Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Republic of Korea, compared 3.1 million people who had COVID-19 with 3.8 million controls, all with at least 180 days’ follow-up through December 31, 2022.

At a mean follow-up of 287 days in both cohorts, authors found significantly elevated risks for AA and vitiligo (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.11 for both), AT (aHR, 1.24), Behçet disease (aHR, 1.45), and BP (aHR, 1.62) in the post–COVID-19 cohort. The infection also raised the risk for other conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus (aHR, 1.14) and Crohn’s disease (aHR, 1.35).

In subgroup analyses, demographic factors were associated with diverse effects: COVID-19 infection was associated with significantly higher odds of developing AA (for both men and women), vitiligo (men), Behçet disease (men and women), Crohn’s disease (men), ulcerative colitis (men), rheumatoid arthritis (men and women), systemic lupus erythematosus (men), ankylosing spondylitis (men), AT (women), and BP (women) than controls.

Those aged under 40 years were more likely to develop AA, primary cicatricial alopecia, Behçet disease, and ulcerative colitis, while those aged 40 years or older were more likely to develop AA, AT, vitiligo, Behçet disease, Crohn’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome, ankylosing spondylitis, and BP.

Additionally, severe COVID-19 requiring intensive care unit admission was associated with a significantly increased risk for autoimmune diseases, including AA, psoriasis, BP, and sarcoidosis. By timeframe, risks for AA, AT, and psoriasis were significantly higher during the initial Delta-dominant period.

Vaccination Effect

Moreover, vaccinated individuals were less likely to develop AA, AT, psoriasis, Behçet disease, and various nondermatologic conditions than were those who were unvaccinated. This finding, wrote Heo and colleagues, “may provide evidence to support the hypothesis that COVID-19 vaccines can help prevent autoimmune diseases.”

“That’s the part we all need to take into our offices tomorrow,” said Brett King, MD, PhD, a Fairfield, Connecticut–based dermatologist in private practice. He was not involved with the study but was asked to comment.

Overall, King said, the study carries two main messages. “The first is that COVID-19 infection increases the likelihood of developing an autoimmune or autoinflammatory disease in a large population.” The second and very important message is that being vaccinated against COVID-19 provides protection against developing an autoimmune or autoinflammatory disease.

“My concern is that the popular media highlights the first part,” said King, “and everybody who develops alopecia areata, vitiligo, or sarcoidosis blames COVID-19. That’s not what this work says.”

The foregoing distinction is especially important during the fall and winter, he added, when people getting influenza vaccines are routinely offered COVID-19 vaccines. “Many patients have said, ‘I got the COVID vaccine and developed alopecia areata 6 months later.’ Nearly everybody who has developed a new or worsening health condition in the last almost 5 years has had the perfect fall guy — the COVID vaccine or infection.”

With virtually all patients asking if they should get an updated COVID-19 vaccine or booster, he added, many report having heard that such vaccines cause AA, vitiligo, or other diseases. “To anchor these conversations in real data and not just anecdotes from a blog or Facebook is very useful,” said King, “and now we have very good data saying that the COVID vaccine is protective against these disorders.”

George Han, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology at the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, New York, applauds investigators’ use of a large, robust database but suggests interpreting results cautiously. He was not involved with the study but was asked to comment.

“You could do a large, well-done study,” Han said, “but it could still not necessarily be generalizable. These autoimmune conditions they’re looking at have clear ethnic and racial biases.” Heo and colleagues acknowledged shortcomings including their study population’s monomorphic nature.

Additional issues that limit the study’s impact, said Han, include the difficulty of conceptualizing a 10%-20% increase in conditions that at baseline are rare. And many of the findings reflected natural patterns, he said. For instance, BP more commonly affects older people, COVID-19 notwithstanding.

Han said that for him, the study’s main value going forward is helping to explain a rash of worsening inflammatory skin disease that many dermatologists saw early in the pandemic. “We would regularly see patients who were well controlled with, for example, psoriasis or eczema. But after COVID-19 infection or a vaccine (usually mRNA-type), in some cases they would come in flaring badly.” This happened at least a dozen times during the first year of post-shutdown appointments, he said.

“We’ve seen patients who have flared multiple times — they get the booster, then flare again,” Han added. Similar patterns occurred with pyoderma gangrenosum and other inflammatory skin diseases, he said.

Given the modest effect sizes of the associations reported in the Korean study, Arkin and colleagues wrote in their JAMA Dermatology editorial that surveillance for autoimmune disease is probably not warranted without new examination findings or symptoms. “For certain,” King said, “we should not go hunting for things that aren’t obviously there.”

Rather, Arkin and colleagues wrote, the higher autoimmunity rates seen among the unvaccinated, as well as during the Delta phase (when patients were sicker and hospitalizations were more likely) and in patients requiring intensive care, suggest that “interventions that reduce disease severity could also potentially reduce long-term risk of subsequent autoimmune sequelae.”

Future research addressing whether people with preexisting autoimmune conditions are at greater risk for flares or developing new autoimmune diseases following COVID-19 infection “would help to frame an evidence-based approach for patients with autoimmune disorders who develop COVID-19 infection, including the role for antiviral treatments,” they added.

The study was supported by grants from the Research Program of the Korea Medical Institute, the Korea Health Industry Development Institute, and the National Research Foundation of Korea. Han and King reported no relevant financial relationships. Arkin disclosed receiving research grants to her institution from Amgen and Eli Lilly, personal fees from Sanofi/Regeneron for consulting, and personal consulting fees from Merck outside the submitted work. Another author reported personal consulting fees from Dexcel Pharma and Honeydew outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

In addition, the authors reported that COVID-19 vaccination appears to reduce these risks.

The study was published in JAMA Dermatology.

‘Compelling Evidence’

“This well-executed study by Heo et al provides compelling evidence to support an association between COVID-19 infection and the development of subsequent autoimmune and autoinflammatory skin diseases,” wrote authors led by Lisa M. Arkin, MD, of the Department of Dermatology, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison, in an accompanying editorial.

Using databases from Korea’s National Health Insurance Service and the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, investigators led by Yeon-Woo Heo, MD, a dermatology resident at Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Republic of Korea, compared 3.1 million people who had COVID-19 with 3.8 million controls, all with at least 180 days’ follow-up through December 31, 2022.

At a mean follow-up of 287 days in both cohorts, authors found significantly elevated risks for AA and vitiligo (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.11 for both), AT (aHR, 1.24), Behçet disease (aHR, 1.45), and BP (aHR, 1.62) in the post–COVID-19 cohort. The infection also raised the risk for other conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus (aHR, 1.14) and Crohn’s disease (aHR, 1.35).

In subgroup analyses, demographic factors were associated with diverse effects: COVID-19 infection was associated with significantly higher odds of developing AA (for both men and women), vitiligo (men), Behçet disease (men and women), Crohn’s disease (men), ulcerative colitis (men), rheumatoid arthritis (men and women), systemic lupus erythematosus (men), ankylosing spondylitis (men), AT (women), and BP (women) than controls.

Those aged under 40 years were more likely to develop AA, primary cicatricial alopecia, Behçet disease, and ulcerative colitis, while those aged 40 years or older were more likely to develop AA, AT, vitiligo, Behçet disease, Crohn’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome, ankylosing spondylitis, and BP.

Additionally, severe COVID-19 requiring intensive care unit admission was associated with a significantly increased risk for autoimmune diseases, including AA, psoriasis, BP, and sarcoidosis. By timeframe, risks for AA, AT, and psoriasis were significantly higher during the initial Delta-dominant period.

Vaccination Effect

Moreover, vaccinated individuals were less likely to develop AA, AT, psoriasis, Behçet disease, and various nondermatologic conditions than were those who were unvaccinated. This finding, wrote Heo and colleagues, “may provide evidence to support the hypothesis that COVID-19 vaccines can help prevent autoimmune diseases.”

“That’s the part we all need to take into our offices tomorrow,” said Brett King, MD, PhD, a Fairfield, Connecticut–based dermatologist in private practice. He was not involved with the study but was asked to comment.

Overall, King said, the study carries two main messages. “The first is that COVID-19 infection increases the likelihood of developing an autoimmune or autoinflammatory disease in a large population.” The second and very important message is that being vaccinated against COVID-19 provides protection against developing an autoimmune or autoinflammatory disease.

“My concern is that the popular media highlights the first part,” said King, “and everybody who develops alopecia areata, vitiligo, or sarcoidosis blames COVID-19. That’s not what this work says.”

The foregoing distinction is especially important during the fall and winter, he added, when people getting influenza vaccines are routinely offered COVID-19 vaccines. “Many patients have said, ‘I got the COVID vaccine and developed alopecia areata 6 months later.’ Nearly everybody who has developed a new or worsening health condition in the last almost 5 years has had the perfect fall guy — the COVID vaccine or infection.”

With virtually all patients asking if they should get an updated COVID-19 vaccine or booster, he added, many report having heard that such vaccines cause AA, vitiligo, or other diseases. “To anchor these conversations in real data and not just anecdotes from a blog or Facebook is very useful,” said King, “and now we have very good data saying that the COVID vaccine is protective against these disorders.”

George Han, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology at the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, New York, applauds investigators’ use of a large, robust database but suggests interpreting results cautiously. He was not involved with the study but was asked to comment.

“You could do a large, well-done study,” Han said, “but it could still not necessarily be generalizable. These autoimmune conditions they’re looking at have clear ethnic and racial biases.” Heo and colleagues acknowledged shortcomings including their study population’s monomorphic nature.

Additional issues that limit the study’s impact, said Han, include the difficulty of conceptualizing a 10%-20% increase in conditions that at baseline are rare. And many of the findings reflected natural patterns, he said. For instance, BP more commonly affects older people, COVID-19 notwithstanding.

Han said that for him, the study’s main value going forward is helping to explain a rash of worsening inflammatory skin disease that many dermatologists saw early in the pandemic. “We would regularly see patients who were well controlled with, for example, psoriasis or eczema. But after COVID-19 infection or a vaccine (usually mRNA-type), in some cases they would come in flaring badly.” This happened at least a dozen times during the first year of post-shutdown appointments, he said.

“We’ve seen patients who have flared multiple times — they get the booster, then flare again,” Han added. Similar patterns occurred with pyoderma gangrenosum and other inflammatory skin diseases, he said.

Given the modest effect sizes of the associations reported in the Korean study, Arkin and colleagues wrote in their JAMA Dermatology editorial that surveillance for autoimmune disease is probably not warranted without new examination findings or symptoms. “For certain,” King said, “we should not go hunting for things that aren’t obviously there.”

Rather, Arkin and colleagues wrote, the higher autoimmunity rates seen among the unvaccinated, as well as during the Delta phase (when patients were sicker and hospitalizations were more likely) and in patients requiring intensive care, suggest that “interventions that reduce disease severity could also potentially reduce long-term risk of subsequent autoimmune sequelae.”

Future research addressing whether people with preexisting autoimmune conditions are at greater risk for flares or developing new autoimmune diseases following COVID-19 infection “would help to frame an evidence-based approach for patients with autoimmune disorders who develop COVID-19 infection, including the role for antiviral treatments,” they added.

The study was supported by grants from the Research Program of the Korea Medical Institute, the Korea Health Industry Development Institute, and the National Research Foundation of Korea. Han and King reported no relevant financial relationships. Arkin disclosed receiving research grants to her institution from Amgen and Eli Lilly, personal fees from Sanofi/Regeneron for consulting, and personal consulting fees from Merck outside the submitted work. Another author reported personal consulting fees from Dexcel Pharma and Honeydew outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

In addition, the authors reported that COVID-19 vaccination appears to reduce these risks.

The study was published in JAMA Dermatology.

‘Compelling Evidence’

“This well-executed study by Heo et al provides compelling evidence to support an association between COVID-19 infection and the development of subsequent autoimmune and autoinflammatory skin diseases,” wrote authors led by Lisa M. Arkin, MD, of the Department of Dermatology, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison, in an accompanying editorial.

Using databases from Korea’s National Health Insurance Service and the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, investigators led by Yeon-Woo Heo, MD, a dermatology resident at Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Republic of Korea, compared 3.1 million people who had COVID-19 with 3.8 million controls, all with at least 180 days’ follow-up through December 31, 2022.

At a mean follow-up of 287 days in both cohorts, authors found significantly elevated risks for AA and vitiligo (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 1.11 for both), AT (aHR, 1.24), Behçet disease (aHR, 1.45), and BP (aHR, 1.62) in the post–COVID-19 cohort. The infection also raised the risk for other conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus (aHR, 1.14) and Crohn’s disease (aHR, 1.35).

In subgroup analyses, demographic factors were associated with diverse effects: COVID-19 infection was associated with significantly higher odds of developing AA (for both men and women), vitiligo (men), Behçet disease (men and women), Crohn’s disease (men), ulcerative colitis (men), rheumatoid arthritis (men and women), systemic lupus erythematosus (men), ankylosing spondylitis (men), AT (women), and BP (women) than controls.

Those aged under 40 years were more likely to develop AA, primary cicatricial alopecia, Behçet disease, and ulcerative colitis, while those aged 40 years or older were more likely to develop AA, AT, vitiligo, Behçet disease, Crohn’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome, ankylosing spondylitis, and BP.

Additionally, severe COVID-19 requiring intensive care unit admission was associated with a significantly increased risk for autoimmune diseases, including AA, psoriasis, BP, and sarcoidosis. By timeframe, risks for AA, AT, and psoriasis were significantly higher during the initial Delta-dominant period.

Vaccination Effect

Moreover, vaccinated individuals were less likely to develop AA, AT, psoriasis, Behçet disease, and various nondermatologic conditions than were those who were unvaccinated. This finding, wrote Heo and colleagues, “may provide evidence to support the hypothesis that COVID-19 vaccines can help prevent autoimmune diseases.”

“That’s the part we all need to take into our offices tomorrow,” said Brett King, MD, PhD, a Fairfield, Connecticut–based dermatologist in private practice. He was not involved with the study but was asked to comment.

Overall, King said, the study carries two main messages. “The first is that COVID-19 infection increases the likelihood of developing an autoimmune or autoinflammatory disease in a large population.” The second and very important message is that being vaccinated against COVID-19 provides protection against developing an autoimmune or autoinflammatory disease.

“My concern is that the popular media highlights the first part,” said King, “and everybody who develops alopecia areata, vitiligo, or sarcoidosis blames COVID-19. That’s not what this work says.”

The foregoing distinction is especially important during the fall and winter, he added, when people getting influenza vaccines are routinely offered COVID-19 vaccines. “Many patients have said, ‘I got the COVID vaccine and developed alopecia areata 6 months later.’ Nearly everybody who has developed a new or worsening health condition in the last almost 5 years has had the perfect fall guy — the COVID vaccine or infection.”

With virtually all patients asking if they should get an updated COVID-19 vaccine or booster, he added, many report having heard that such vaccines cause AA, vitiligo, or other diseases. “To anchor these conversations in real data and not just anecdotes from a blog or Facebook is very useful,” said King, “and now we have very good data saying that the COVID vaccine is protective against these disorders.”

George Han, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology at the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, New York, applauds investigators’ use of a large, robust database but suggests interpreting results cautiously. He was not involved with the study but was asked to comment.

“You could do a large, well-done study,” Han said, “but it could still not necessarily be generalizable. These autoimmune conditions they’re looking at have clear ethnic and racial biases.” Heo and colleagues acknowledged shortcomings including their study population’s monomorphic nature.

Additional issues that limit the study’s impact, said Han, include the difficulty of conceptualizing a 10%-20% increase in conditions that at baseline are rare. And many of the findings reflected natural patterns, he said. For instance, BP more commonly affects older people, COVID-19 notwithstanding.

Han said that for him, the study’s main value going forward is helping to explain a rash of worsening inflammatory skin disease that many dermatologists saw early in the pandemic. “We would regularly see patients who were well controlled with, for example, psoriasis or eczema. But after COVID-19 infection or a vaccine (usually mRNA-type), in some cases they would come in flaring badly.” This happened at least a dozen times during the first year of post-shutdown appointments, he said.

“We’ve seen patients who have flared multiple times — they get the booster, then flare again,” Han added. Similar patterns occurred with pyoderma gangrenosum and other inflammatory skin diseases, he said.

Given the modest effect sizes of the associations reported in the Korean study, Arkin and colleagues wrote in their JAMA Dermatology editorial that surveillance for autoimmune disease is probably not warranted without new examination findings or symptoms. “For certain,” King said, “we should not go hunting for things that aren’t obviously there.”

Rather, Arkin and colleagues wrote, the higher autoimmunity rates seen among the unvaccinated, as well as during the Delta phase (when patients were sicker and hospitalizations were more likely) and in patients requiring intensive care, suggest that “interventions that reduce disease severity could also potentially reduce long-term risk of subsequent autoimmune sequelae.”

Future research addressing whether people with preexisting autoimmune conditions are at greater risk for flares or developing new autoimmune diseases following COVID-19 infection “would help to frame an evidence-based approach for patients with autoimmune disorders who develop COVID-19 infection, including the role for antiviral treatments,” they added.

The study was supported by grants from the Research Program of the Korea Medical Institute, the Korea Health Industry Development Institute, and the National Research Foundation of Korea. Han and King reported no relevant financial relationships. Arkin disclosed receiving research grants to her institution from Amgen and Eli Lilly, personal fees from Sanofi/Regeneron for consulting, and personal consulting fees from Merck outside the submitted work. Another author reported personal consulting fees from Dexcel Pharma and Honeydew outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Sitting for More Than 10 Hours Daily Ups Heart Disease Risk

TOPLINE:

Sedentary time exceeding 10.6 h/d is linked to an increased risk for atrial fibrillation, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular (CV) mortality, researchers found. The risk persists even in individuals who meet recommended physical activity levels.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers used a validated machine learning approach to investigate the relationships between sedentary behavior and the future risks for CV illness and mortality in 89,530 middle-aged and older adults (mean age, 62 years; 56% women) from the UK Biobank.

- Participants provided data from a wrist-worn triaxial accelerometer that recorded their movements over a period of 7 days.

- Machine learning algorithms classified accelerometer signals into four classes of activities: Sleep, sedentary behavior, light physical activity, and moderate to vigorous physical activity.

- Participants were followed up for a median of 8 years through linkage to national health-related datasets in England, Scotland, and Wales.

- The median sedentary time was 9.4 h/d.

TAKEAWAY:

- During the follow-up period, 3638 individuals (4.9%) experienced incident atrial fibrillation, 1854 (2.09%) developed incident heart failure, 1610 (1.84%) experienced incident myocardial infarction, and 846 (0.94%) died from cardiovascular causes.

- The risks for atrial fibrillation and myocardial infarction increased steadily with an increase in sedentary time, with sedentary time greater than 10.6 h/d showing a modest increase in risk for atrial fibrillation (hazard ratio [HR], 1.11; 95% CI, 1.01-1.21).

- The risks for heart failure and CV mortality were low until sedentary time surpassed approximately 10.6 h/d, after which they rose by 45% (HR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.28-1.65) and 62% (HR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.34-1.96), respectively.

- The associations were attenuated but remained significant for CV mortality (HR, 1.33; 95% CI: 1.07-1.64) in individuals who met the recommended levels for physical activity yet were sedentary for more than 10.6 h/d. Reallocating 30 minutes of sedentary time to other activities reduced the risk for heart failure (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.90-0.96) among those who were sedentary more than 10.6 h/d.

IN PRACTICE:

The study “highlights a complex interplay between sedentary behavior and physical activity, ultimately suggesting that sedentary behavior remains relevant for CV disease risk even among individuals meeting sufficient” levels of activity, the researchers reported.

“Individuals should move more and be less sedentary to reduce CV risk. ... Being a ‘weekend warrior’ and meeting guideline levels of [moderate to vigorous physical activity] of 150 minutes/week will not completely abolish the deleterious effects of extended sedentary time of > 10.6 hours per day,” Charles B. Eaton, MD, MS, of the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, wrote in an editorial accompanying the journal article.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Ezimamaka Ajufo, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. It was published online on November 15, 2024, in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

Wrist-based accelerometers cannot assess specific contexts for sedentary behavior and may misclassify standing time as sedentary time, and these limitations may have affected the findings. Physical activity was measured for 1 week only, which might not have fully represented habitual activity patterns. The sample included predominantly White participants and was enriched for health and socioeconomic status, which may have limited the generalizability of the findings.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors disclosed receiving research support, grants, and research fellowships and collaborations from various institutions and pharmaceutical companies, as well as serving on their advisory boards.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Sedentary time exceeding 10.6 h/d is linked to an increased risk for atrial fibrillation, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular (CV) mortality, researchers found. The risk persists even in individuals who meet recommended physical activity levels.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers used a validated machine learning approach to investigate the relationships between sedentary behavior and the future risks for CV illness and mortality in 89,530 middle-aged and older adults (mean age, 62 years; 56% women) from the UK Biobank.

- Participants provided data from a wrist-worn triaxial accelerometer that recorded their movements over a period of 7 days.

- Machine learning algorithms classified accelerometer signals into four classes of activities: Sleep, sedentary behavior, light physical activity, and moderate to vigorous physical activity.

- Participants were followed up for a median of 8 years through linkage to national health-related datasets in England, Scotland, and Wales.

- The median sedentary time was 9.4 h/d.

TAKEAWAY:

- During the follow-up period, 3638 individuals (4.9%) experienced incident atrial fibrillation, 1854 (2.09%) developed incident heart failure, 1610 (1.84%) experienced incident myocardial infarction, and 846 (0.94%) died from cardiovascular causes.

- The risks for atrial fibrillation and myocardial infarction increased steadily with an increase in sedentary time, with sedentary time greater than 10.6 h/d showing a modest increase in risk for atrial fibrillation (hazard ratio [HR], 1.11; 95% CI, 1.01-1.21).

- The risks for heart failure and CV mortality were low until sedentary time surpassed approximately 10.6 h/d, after which they rose by 45% (HR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.28-1.65) and 62% (HR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.34-1.96), respectively.

- The associations were attenuated but remained significant for CV mortality (HR, 1.33; 95% CI: 1.07-1.64) in individuals who met the recommended levels for physical activity yet were sedentary for more than 10.6 h/d. Reallocating 30 minutes of sedentary time to other activities reduced the risk for heart failure (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.90-0.96) among those who were sedentary more than 10.6 h/d.

IN PRACTICE:

The study “highlights a complex interplay between sedentary behavior and physical activity, ultimately suggesting that sedentary behavior remains relevant for CV disease risk even among individuals meeting sufficient” levels of activity, the researchers reported.

“Individuals should move more and be less sedentary to reduce CV risk. ... Being a ‘weekend warrior’ and meeting guideline levels of [moderate to vigorous physical activity] of 150 minutes/week will not completely abolish the deleterious effects of extended sedentary time of > 10.6 hours per day,” Charles B. Eaton, MD, MS, of the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, wrote in an editorial accompanying the journal article.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Ezimamaka Ajufo, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. It was published online on November 15, 2024, in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

Wrist-based accelerometers cannot assess specific contexts for sedentary behavior and may misclassify standing time as sedentary time, and these limitations may have affected the findings. Physical activity was measured for 1 week only, which might not have fully represented habitual activity patterns. The sample included predominantly White participants and was enriched for health and socioeconomic status, which may have limited the generalizability of the findings.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors disclosed receiving research support, grants, and research fellowships and collaborations from various institutions and pharmaceutical companies, as well as serving on their advisory boards.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Sedentary time exceeding 10.6 h/d is linked to an increased risk for atrial fibrillation, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular (CV) mortality, researchers found. The risk persists even in individuals who meet recommended physical activity levels.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers used a validated machine learning approach to investigate the relationships between sedentary behavior and the future risks for CV illness and mortality in 89,530 middle-aged and older adults (mean age, 62 years; 56% women) from the UK Biobank.

- Participants provided data from a wrist-worn triaxial accelerometer that recorded their movements over a period of 7 days.

- Machine learning algorithms classified accelerometer signals into four classes of activities: Sleep, sedentary behavior, light physical activity, and moderate to vigorous physical activity.

- Participants were followed up for a median of 8 years through linkage to national health-related datasets in England, Scotland, and Wales.

- The median sedentary time was 9.4 h/d.

TAKEAWAY:

- During the follow-up period, 3638 individuals (4.9%) experienced incident atrial fibrillation, 1854 (2.09%) developed incident heart failure, 1610 (1.84%) experienced incident myocardial infarction, and 846 (0.94%) died from cardiovascular causes.

- The risks for atrial fibrillation and myocardial infarction increased steadily with an increase in sedentary time, with sedentary time greater than 10.6 h/d showing a modest increase in risk for atrial fibrillation (hazard ratio [HR], 1.11; 95% CI, 1.01-1.21).

- The risks for heart failure and CV mortality were low until sedentary time surpassed approximately 10.6 h/d, after which they rose by 45% (HR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.28-1.65) and 62% (HR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.34-1.96), respectively.

- The associations were attenuated but remained significant for CV mortality (HR, 1.33; 95% CI: 1.07-1.64) in individuals who met the recommended levels for physical activity yet were sedentary for more than 10.6 h/d. Reallocating 30 minutes of sedentary time to other activities reduced the risk for heart failure (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.90-0.96) among those who were sedentary more than 10.6 h/d.

IN PRACTICE:

The study “highlights a complex interplay between sedentary behavior and physical activity, ultimately suggesting that sedentary behavior remains relevant for CV disease risk even among individuals meeting sufficient” levels of activity, the researchers reported.

“Individuals should move more and be less sedentary to reduce CV risk. ... Being a ‘weekend warrior’ and meeting guideline levels of [moderate to vigorous physical activity] of 150 minutes/week will not completely abolish the deleterious effects of extended sedentary time of > 10.6 hours per day,” Charles B. Eaton, MD, MS, of the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, wrote in an editorial accompanying the journal article.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Ezimamaka Ajufo, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. It was published online on November 15, 2024, in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

Wrist-based accelerometers cannot assess specific contexts for sedentary behavior and may misclassify standing time as sedentary time, and these limitations may have affected the findings. Physical activity was measured for 1 week only, which might not have fully represented habitual activity patterns. The sample included predominantly White participants and was enriched for health and socioeconomic status, which may have limited the generalizability of the findings.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors disclosed receiving research support, grants, and research fellowships and collaborations from various institutions and pharmaceutical companies, as well as serving on their advisory boards.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In IBD Patients, No Increased Risk for MACE Seen for JAK Inhibitors vs Anti-TNF

PHILADELPHIA — according to a study presented at the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) 2024 Annual Scientific Meeting.

In particular, 1.76% of patients taking JAKi and 1.94% of patients taking anti-TNF developed MACE. There also weren’t significant differences when comparing ulcerative colitis with Crohn’s disease, upadacitinib with tofacitinib, or JAKi with infliximab.

“IBD is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, and with the emergence of JAK inhibitors and anti-TNF therapies, there is a concern about the increased risk of MACE,” said lead author Saqr Alsakarneh, MD, an internal medicine resident at the University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Medicine.

Previous randomized controlled trials have indicated increased risks of MACE with JAKi and anti-TNF agents, compared with placebo, but researchers haven’t conducted a head-to-head comparison, he said.

“A potential explanation for previous associations could be linked to immune modulation and inflammation that can increase coagulation risk, as well as fluctuation in disease severity while patients are on the medications, which can impact cardiovascular risk factors,” he added.

Alsakarneh and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study using the TriNetX database to identify adult patients with IBD who were treated with JAKi or anti-TNF therapy after diagnosis. After matching patients in the JAKi cohort with patients in the anti-TNF cohort, the research team looked for MACE and VTE within a year of medication initiation, as well as associations by age, sex, and IBD type.

Overall, 3740 patients in the JAKi cohort had a mean age of 43.1 and were 48.9% women and 75.3% White individuals, while 3,740 patients in the anti-TNF cohort had a mean age of 43 and were 48.9% women and 75.3% White individuals.

After excluding those with a history of a prior cardiovascular event, 57 patients (1.76%) in the JAKi cohort developed MACE, compared with 63 patients (1.94%) in the anti-TNF cohort. There weren’t significant differences between the groups in MACE (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.99) or VTE (aHR, 0.9).

Among patients aged ≥ 65, 25 patients (5.3%) in the JAKi cohort developed MACE, as compared with 30 patients (6.4%) in the anti-TNF cohort. There weren’t significant differences between the groups in MACE (aHR, 0.83) or VTE (aHR, 0.77).

In addition, there were no differences when comparing Crohn’s disease with ulcerative colitis for MACE (aHR, 1.69) or VTE (aHR, 0.85); upadacitinib with tofacitinib for MACE (aHR, 1.1) or VTE (aHR, 1.13); or JAKi medications with infliximab for MACE (aHR, 0.85) or VTE (aHR, 0.8).

Patients in the JAKi group were more likely to undergo intestinal resection surgery (aHR, 1.32), but there wasn’t a statistically significant difference in systematic corticosteroid use (aHR, 0.99).

The study limitations included the inability to assess for disease severity, dose-dependent risk for MACE or VTE, or long-term outcomes among the two cohorts, Alsakarneh said. Prospective controlled trials are needed to confirm findings.

“This is a wonderful study and nice to see. We presented the same thing at Digestive Disease Week that’s being confirmed in this data,” said Miguel Regueiro, MD, AGAF, chief of Cleveland Clinic’s Digestive Disease Institute in Ohio. Regueiro, who wasn’t involved with the study, attended the conference session.

“Looking ahead, all of us are wondering if the regulatory guidance by the FDA [Food and Drug Administration] is going to change the label so we don’t need to step through a TNF,” he said. “I think we’re seeing study after study showing safety or at least not an increased risk with JAK.”

The study was awarded an ACG Noteworthy Abstract. Alsakarneh and Regueiro reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

PHILADELPHIA — according to a study presented at the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) 2024 Annual Scientific Meeting.

In particular, 1.76% of patients taking JAKi and 1.94% of patients taking anti-TNF developed MACE. There also weren’t significant differences when comparing ulcerative colitis with Crohn’s disease, upadacitinib with tofacitinib, or JAKi with infliximab.

“IBD is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, and with the emergence of JAK inhibitors and anti-TNF therapies, there is a concern about the increased risk of MACE,” said lead author Saqr Alsakarneh, MD, an internal medicine resident at the University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Medicine.

Previous randomized controlled trials have indicated increased risks of MACE with JAKi and anti-TNF agents, compared with placebo, but researchers haven’t conducted a head-to-head comparison, he said.

“A potential explanation for previous associations could be linked to immune modulation and inflammation that can increase coagulation risk, as well as fluctuation in disease severity while patients are on the medications, which can impact cardiovascular risk factors,” he added.

Alsakarneh and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study using the TriNetX database to identify adult patients with IBD who were treated with JAKi or anti-TNF therapy after diagnosis. After matching patients in the JAKi cohort with patients in the anti-TNF cohort, the research team looked for MACE and VTE within a year of medication initiation, as well as associations by age, sex, and IBD type.

Overall, 3740 patients in the JAKi cohort had a mean age of 43.1 and were 48.9% women and 75.3% White individuals, while 3,740 patients in the anti-TNF cohort had a mean age of 43 and were 48.9% women and 75.3% White individuals.

After excluding those with a history of a prior cardiovascular event, 57 patients (1.76%) in the JAKi cohort developed MACE, compared with 63 patients (1.94%) in the anti-TNF cohort. There weren’t significant differences between the groups in MACE (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.99) or VTE (aHR, 0.9).

Among patients aged ≥ 65, 25 patients (5.3%) in the JAKi cohort developed MACE, as compared with 30 patients (6.4%) in the anti-TNF cohort. There weren’t significant differences between the groups in MACE (aHR, 0.83) or VTE (aHR, 0.77).

In addition, there were no differences when comparing Crohn’s disease with ulcerative colitis for MACE (aHR, 1.69) or VTE (aHR, 0.85); upadacitinib with tofacitinib for MACE (aHR, 1.1) or VTE (aHR, 1.13); or JAKi medications with infliximab for MACE (aHR, 0.85) or VTE (aHR, 0.8).

Patients in the JAKi group were more likely to undergo intestinal resection surgery (aHR, 1.32), but there wasn’t a statistically significant difference in systematic corticosteroid use (aHR, 0.99).

The study limitations included the inability to assess for disease severity, dose-dependent risk for MACE or VTE, or long-term outcomes among the two cohorts, Alsakarneh said. Prospective controlled trials are needed to confirm findings.

“This is a wonderful study and nice to see. We presented the same thing at Digestive Disease Week that’s being confirmed in this data,” said Miguel Regueiro, MD, AGAF, chief of Cleveland Clinic’s Digestive Disease Institute in Ohio. Regueiro, who wasn’t involved with the study, attended the conference session.

“Looking ahead, all of us are wondering if the regulatory guidance by the FDA [Food and Drug Administration] is going to change the label so we don’t need to step through a TNF,” he said. “I think we’re seeing study after study showing safety or at least not an increased risk with JAK.”

The study was awarded an ACG Noteworthy Abstract. Alsakarneh and Regueiro reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

PHILADELPHIA — according to a study presented at the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) 2024 Annual Scientific Meeting.

In particular, 1.76% of patients taking JAKi and 1.94% of patients taking anti-TNF developed MACE. There also weren’t significant differences when comparing ulcerative colitis with Crohn’s disease, upadacitinib with tofacitinib, or JAKi with infliximab.

“IBD is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases, and with the emergence of JAK inhibitors and anti-TNF therapies, there is a concern about the increased risk of MACE,” said lead author Saqr Alsakarneh, MD, an internal medicine resident at the University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Medicine.

Previous randomized controlled trials have indicated increased risks of MACE with JAKi and anti-TNF agents, compared with placebo, but researchers haven’t conducted a head-to-head comparison, he said.

“A potential explanation for previous associations could be linked to immune modulation and inflammation that can increase coagulation risk, as well as fluctuation in disease severity while patients are on the medications, which can impact cardiovascular risk factors,” he added.

Alsakarneh and colleagues conducted a retrospective cohort study using the TriNetX database to identify adult patients with IBD who were treated with JAKi or anti-TNF therapy after diagnosis. After matching patients in the JAKi cohort with patients in the anti-TNF cohort, the research team looked for MACE and VTE within a year of medication initiation, as well as associations by age, sex, and IBD type.

Overall, 3740 patients in the JAKi cohort had a mean age of 43.1 and were 48.9% women and 75.3% White individuals, while 3,740 patients in the anti-TNF cohort had a mean age of 43 and were 48.9% women and 75.3% White individuals.

After excluding those with a history of a prior cardiovascular event, 57 patients (1.76%) in the JAKi cohort developed MACE, compared with 63 patients (1.94%) in the anti-TNF cohort. There weren’t significant differences between the groups in MACE (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.99) or VTE (aHR, 0.9).

Among patients aged ≥ 65, 25 patients (5.3%) in the JAKi cohort developed MACE, as compared with 30 patients (6.4%) in the anti-TNF cohort. There weren’t significant differences between the groups in MACE (aHR, 0.83) or VTE (aHR, 0.77).

In addition, there were no differences when comparing Crohn’s disease with ulcerative colitis for MACE (aHR, 1.69) or VTE (aHR, 0.85); upadacitinib with tofacitinib for MACE (aHR, 1.1) or VTE (aHR, 1.13); or JAKi medications with infliximab for MACE (aHR, 0.85) or VTE (aHR, 0.8).

Patients in the JAKi group were more likely to undergo intestinal resection surgery (aHR, 1.32), but there wasn’t a statistically significant difference in systematic corticosteroid use (aHR, 0.99).

The study limitations included the inability to assess for disease severity, dose-dependent risk for MACE or VTE, or long-term outcomes among the two cohorts, Alsakarneh said. Prospective controlled trials are needed to confirm findings.

“This is a wonderful study and nice to see. We presented the same thing at Digestive Disease Week that’s being confirmed in this data,” said Miguel Regueiro, MD, AGAF, chief of Cleveland Clinic’s Digestive Disease Institute in Ohio. Regueiro, who wasn’t involved with the study, attended the conference session.

“Looking ahead, all of us are wondering if the regulatory guidance by the FDA [Food and Drug Administration] is going to change the label so we don’t need to step through a TNF,” he said. “I think we’re seeing study after study showing safety or at least not an increased risk with JAK.”

The study was awarded an ACG Noteworthy Abstract. Alsakarneh and Regueiro reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ACG 2024

New Pill Successfully Lowers Lp(a) Levels

Concentrations of Lp(a) cholesterol are genetically determined and remain steady throughout life. Levels of 125 nmol/L or higher promote clotting and inflammation, significantly increasing the risk for heart attack, stroke, aortic stenosis, and peripheral artery disease. This affects about 20% of the population, particularly people of Black African and South Asian descent.

There are currently no approved therapies that lower Lp(a), said study author Stephen Nicholls, MBBS, PhD, director of the Victorian Heart Institute at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. Several injectable therapies are currently in clinical trials, but muvalaplin is the only oral option. The new drug lowers Lp(a) levels by disrupting the bond between the two parts of the Lp(a) particle.

The KRAKEN Trial

In the KRAKEN trial, 233 adults from around the world with very high Lp(a) levels (> 175 nmol/L) were randomized either to one of three daily doses of muvalaplin — 10, 60, or 240 mg — or to placebo for 12 weeks.

The researchers measured Lp(a) levels with a standard blood test and with a novel test designed to specifically measure levels of intact Lp(a) particles in the blood. In addition to Lp(a), the standard test detects one of its components, apolipoprotein A particles, that are bound to the drug, which can lead to an underestimation of Lp(a) reductions.

Lp(a) levels were up to 70.0% lower in the muvalaplin group than in the placebo group when measured with the traditional blood test and by up to 85.5% lower when measured with the new test. Approximately 82% of participants achieved an Lp(a) level lower than 125 nmol/L when measured with the traditional blood test, and 97% achieved that level when the new test was used. Patients who received either 60 or 240 mg of muvalaplin had similar reductions in Lp(a) levels, which were greater than the reductions seen in the 10 mg group. The drug was safe and generally well tolerated.

“This is a very reassuring phase 2 result,” Nicholls said when he presented the KRAKEN findings at the American Heart Association (AHA) Scientific Sessions 2024 in Chicago, which were simultaneously published online in JAMA. “It encourages the ongoing development of this agent.”

Lp(a) levels are not affected by changes in lifestyle or diet or by traditional lipid-lowering treatments like statins, said Erin Michos, MD, a cardiologist at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland, who was not involved in the study.

And high Lp(a) levels confer significant cardiovascular risk even when other risks are reduced. So muvalaplin is “a highly promising approach to treat a previously untreatable disorder,” she explained.

Larger and longer studies, with more diverse patient populations, are needed to confirm the results and to determine whether reducing Lp(a) also improves cardiovascular outcomes, Michos pointed out.

“While muvalaplin appears to be an effective approach to lowering Lp(a) levels, we still need to study whether Lp(a) lowering will result in fewer heart attacks and strokes,” Nicholls added.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Concentrations of Lp(a) cholesterol are genetically determined and remain steady throughout life. Levels of 125 nmol/L or higher promote clotting and inflammation, significantly increasing the risk for heart attack, stroke, aortic stenosis, and peripheral artery disease. This affects about 20% of the population, particularly people of Black African and South Asian descent.

There are currently no approved therapies that lower Lp(a), said study author Stephen Nicholls, MBBS, PhD, director of the Victorian Heart Institute at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. Several injectable therapies are currently in clinical trials, but muvalaplin is the only oral option. The new drug lowers Lp(a) levels by disrupting the bond between the two parts of the Lp(a) particle.

The KRAKEN Trial

In the KRAKEN trial, 233 adults from around the world with very high Lp(a) levels (> 175 nmol/L) were randomized either to one of three daily doses of muvalaplin — 10, 60, or 240 mg — or to placebo for 12 weeks.

The researchers measured Lp(a) levels with a standard blood test and with a novel test designed to specifically measure levels of intact Lp(a) particles in the blood. In addition to Lp(a), the standard test detects one of its components, apolipoprotein A particles, that are bound to the drug, which can lead to an underestimation of Lp(a) reductions.

Lp(a) levels were up to 70.0% lower in the muvalaplin group than in the placebo group when measured with the traditional blood test and by up to 85.5% lower when measured with the new test. Approximately 82% of participants achieved an Lp(a) level lower than 125 nmol/L when measured with the traditional blood test, and 97% achieved that level when the new test was used. Patients who received either 60 or 240 mg of muvalaplin had similar reductions in Lp(a) levels, which were greater than the reductions seen in the 10 mg group. The drug was safe and generally well tolerated.

“This is a very reassuring phase 2 result,” Nicholls said when he presented the KRAKEN findings at the American Heart Association (AHA) Scientific Sessions 2024 in Chicago, which were simultaneously published online in JAMA. “It encourages the ongoing development of this agent.”

Lp(a) levels are not affected by changes in lifestyle or diet or by traditional lipid-lowering treatments like statins, said Erin Michos, MD, a cardiologist at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland, who was not involved in the study.

And high Lp(a) levels confer significant cardiovascular risk even when other risks are reduced. So muvalaplin is “a highly promising approach to treat a previously untreatable disorder,” she explained.

Larger and longer studies, with more diverse patient populations, are needed to confirm the results and to determine whether reducing Lp(a) also improves cardiovascular outcomes, Michos pointed out.

“While muvalaplin appears to be an effective approach to lowering Lp(a) levels, we still need to study whether Lp(a) lowering will result in fewer heart attacks and strokes,” Nicholls added.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Concentrations of Lp(a) cholesterol are genetically determined and remain steady throughout life. Levels of 125 nmol/L or higher promote clotting and inflammation, significantly increasing the risk for heart attack, stroke, aortic stenosis, and peripheral artery disease. This affects about 20% of the population, particularly people of Black African and South Asian descent.

There are currently no approved therapies that lower Lp(a), said study author Stephen Nicholls, MBBS, PhD, director of the Victorian Heart Institute at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. Several injectable therapies are currently in clinical trials, but muvalaplin is the only oral option. The new drug lowers Lp(a) levels by disrupting the bond between the two parts of the Lp(a) particle.

The KRAKEN Trial

In the KRAKEN trial, 233 adults from around the world with very high Lp(a) levels (> 175 nmol/L) were randomized either to one of three daily doses of muvalaplin — 10, 60, or 240 mg — or to placebo for 12 weeks.

The researchers measured Lp(a) levels with a standard blood test and with a novel test designed to specifically measure levels of intact Lp(a) particles in the blood. In addition to Lp(a), the standard test detects one of its components, apolipoprotein A particles, that are bound to the drug, which can lead to an underestimation of Lp(a) reductions.

Lp(a) levels were up to 70.0% lower in the muvalaplin group than in the placebo group when measured with the traditional blood test and by up to 85.5% lower when measured with the new test. Approximately 82% of participants achieved an Lp(a) level lower than 125 nmol/L when measured with the traditional blood test, and 97% achieved that level when the new test was used. Patients who received either 60 or 240 mg of muvalaplin had similar reductions in Lp(a) levels, which were greater than the reductions seen in the 10 mg group. The drug was safe and generally well tolerated.

“This is a very reassuring phase 2 result,” Nicholls said when he presented the KRAKEN findings at the American Heart Association (AHA) Scientific Sessions 2024 in Chicago, which were simultaneously published online in JAMA. “It encourages the ongoing development of this agent.”

Lp(a) levels are not affected by changes in lifestyle or diet or by traditional lipid-lowering treatments like statins, said Erin Michos, MD, a cardiologist at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland, who was not involved in the study.

And high Lp(a) levels confer significant cardiovascular risk even when other risks are reduced. So muvalaplin is “a highly promising approach to treat a previously untreatable disorder,” she explained.

Larger and longer studies, with more diverse patient populations, are needed to confirm the results and to determine whether reducing Lp(a) also improves cardiovascular outcomes, Michos pointed out.

“While muvalaplin appears to be an effective approach to lowering Lp(a) levels, we still need to study whether Lp(a) lowering will result in fewer heart attacks and strokes,” Nicholls added.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Lessons Learned: What Docs Wish Med Students Knew

Despite 4 years of med school and 3-7 years in residency, when you enter the workforce as a doctor, you still have much to learn. There is only so much your professors and attending physicians can pack in. Going forward, you’ll continue to learn on the job and via continuing education.

Some of that lifelong learning will involve soft skills — how to compassionately work with your patients and their families, for instance. Other lessons will get down to the business of medicine — the paperwork, the work/life balance, and the moral dilemmas you never saw coming. And still others will involve learning how to take care of yourself in the middle of seemingly endless hours on the job.

“We all have things we wish we had known upon starting our careers,” said Daniel Opris, MD, a primary care physician at Ohio-based Executive Medical Centers.

We tapped several veteran physicians and an educator to learn what they wish med students knew as they enter the workforce. We’ve compiled them here to give you a head start on the lessons ahead.

You Won’t Know Everything, and That’s Okay

When you go through your medical training, it can feel overwhelming to absorb all the knowledge your professors and attendings impart. The bottom line, said Shoshana Ungerleider, MD, an internal medicine specialist, is that you shouldn’t worry about it.

David Lenihan, PhD, CEO at Ponce Health Sciences University, agrees. “What we’ve lost in recent years, is the ability to apply your skill set and say, ‘let me take a day and get back to you,’” he said. “Doctors love it when you do that because it shows you can pitch in and work as part of a team.”

Medicine is a collaborative field, said Ungerleider, and learning from others, whether peers, nurses, or specialists, is “not a weakness.” She recommends embracing uncertainty and getting comfortable with the unknown.

You’ll Take Your Work Home With You

Doctors enter the field because they care about their patients and want to help. Successful outcomes are never guaranteed, however, no matter how much you try. The result? Some days you’ll bring home those upsetting and haunting cases, said Lenihan.

“We often believe that we should leave our work at the office, but sometimes you need to bring it home and think it through,” he said. “It can’t overwhelm you, but you should digest what happened.”

When you do, said Lenihan, you’ll come out the other end more empathetic and that helps the healthcare system in the long run. “The more you reflect on your day, the better you’ll get at reading the room and treating your patients.”

Drew Remignanti, MD, a retired emergency medicine physician from New Hampshire, agrees, but puts a different spin on bringing work home.

“We revisit the patient care decisions we made, second-guess ourselves, and worry about our patients’ welfare and outcomes,” he said. “I think it can only lead to better outcomes down the road, however, if you learn from that bad decision, preventing you from committing a similar mistake.”

Burnout Is Real — Make Self-Care a Priority

As a retired physician who spent 40 years practicing medicine, Remignanti experienced the evolution of healthcare as it has become what he calls a “consumer-provider” model. “Productivity didn’t use to be part of the equation, but now it’s the focus,” he said.

The result is burnout, a very real threat to incoming physicians. Remignanti holds that if you are aware of the risk, you can resist it. Part of avoiding burnout is self-care, according to Ungerleider. “The sooner you prioritize your mental, emotional, and physical well-being, the better,” she said. “Balancing work and life may feel impossible at times but taking care of yourself is essential to being a better physician in the long run.”

That means carving out time for exercise, hobbies, and connections outside of the medical field. It also means making sleep and nutrition a priority, even when that feels hard to accomplish. “If you don’t take care of yourself, you can’t take care of others,” added Opris. “It’s so common to lose yourself in your career, but you need to hold onto your physical, emotional, and spiritual self.”

Avoid Relying Too Heavily on Tech

Technology is invading every aspect of our lives — often for the greater good — but in medicine, it’s important to always return to your core knowledge above all else. Case in point, said Opris, the UpToDate app. While it can be a useful tool, it’s important not to become too reliant on it. “UpToDate is expert opinion-based guidance, and it’s a fantastic resource,” he said. “But you need to use your references and knowledge in every case.”

It’s key to remember that every patient is different, and their case may not line up perfectly with the guidance presented in UpToDate or other technology source. Piggybacking on that, Ungerleider added that it’s important to remember medicine is about people, not just conditions.

“It’s easy to focus on mastering the science, but the real art of medicine comes from seeing the whole person in front of you,” she said. “Your patients are more than their diagnoses — they come with complex emotions, life stories, and needs.” Being compassionate, listening carefully, and building trust should match up to your clinical skills.

Partner With Your Patients, Even When It’s Difficult

Perhaps the most difficult lesson of all is remembering that your patients may not always agree with your recommendations and choose to ignore them. After all your years spent learning, there may be times when it feels your education is going to waste.

“Remember that the landscape today is so varied, and that bleeds into medicine,” said Opris. “We go into cases with our own biases, and it’s important to take a step back to reset, every time.”

Opris reminds himself of Sir William Osler’s famous essay, “Aequanimitas,” in which he tells graduating medical students to practice with “coolness and presence of mind under all circumstances.”

Remignanti offers this advice: “Physicians need to be able to partner with their patients and jointly decide which courses of action are most effective,” he said. “Cling to the idea that you are forming a partnership with your patients — what can we together determine is the best course?”

At the same time, the path the patient chooses may not be what’s best for them — potentially even leading to a poor outcome.

“You may not always understand their choices,” said Opris. “But they do have a choice. Think of yourself almost like a consultant.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Despite 4 years of med school and 3-7 years in residency, when you enter the workforce as a doctor, you still have much to learn. There is only so much your professors and attending physicians can pack in. Going forward, you’ll continue to learn on the job and via continuing education.

Some of that lifelong learning will involve soft skills — how to compassionately work with your patients and their families, for instance. Other lessons will get down to the business of medicine — the paperwork, the work/life balance, and the moral dilemmas you never saw coming. And still others will involve learning how to take care of yourself in the middle of seemingly endless hours on the job.

“We all have things we wish we had known upon starting our careers,” said Daniel Opris, MD, a primary care physician at Ohio-based Executive Medical Centers.

We tapped several veteran physicians and an educator to learn what they wish med students knew as they enter the workforce. We’ve compiled them here to give you a head start on the lessons ahead.

You Won’t Know Everything, and That’s Okay

When you go through your medical training, it can feel overwhelming to absorb all the knowledge your professors and attendings impart. The bottom line, said Shoshana Ungerleider, MD, an internal medicine specialist, is that you shouldn’t worry about it.