User login

Cardiology News is an independent news source that provides cardiologists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on cardiology and the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is the online destination and multimedia properties of Cardiology News, the independent news publication for cardiologists. Cardiology news is the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in cardiology as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the cardiologist's practice. Cardiology News Digital Network is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

What Would ‘Project 2025’ Mean for Health and Healthcare?

The Heritage Foundation sponsored and developed Project 2025 for the explicit, stated purpose of building a conservative victory through policy, personnel, and training with a 180-day game plan after a sympathetic new President of the United States takes office. To date, Project 2025 has not been formally endorsed by any presidential campaign.

Chapter 14 of the “Mandate for Leadership” is an exhaustive proposed overhaul of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), one of the major existing arms of the executive branch of the US government.

The mandate’s sweeping recommendations, if implemented, would impact the lives of all Americans and all healthcare workers, as outlined in the following excerpts.

Healthcare-Related Excerpts From Project 2025

- “From the moment of conception, every human being possesses inherent dignity and worth, and our humanity does not depend on our age, stage of development, race, or abilities. The Secretary must ensure that all HHS programs and activities are rooted in a deep respect for innocent human life from day one until natural death: Abortion and euthanasia are not health care.”

- “Unfortunately, family policies and programs under President Biden’s HHS are fraught with agenda items focusing on ‘LGBTQ+ equity,’ subsidizing single motherhood, disincentivizing work, and penalizing marriage. These policies should be repealed and replaced by policies that support the formation of stable, married, nuclear families.”

- “The next Administration should guard against the regulatory capture of our public health agencies by pharmaceutical companies, insurers, hospital conglomerates, and related economic interests that these agencies are meant to regulate. We must erect robust firewalls to mitigate these obvious financial conflicts of interest.”

- “All National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Food and Drug Administration regulators should be entirely free from private biopharmaceutical funding. In this realm, ‘public–private partnerships’ is a euphemism for agency capture, a thin veneer for corporatism. Funding for agencies and individual government researchers must come directly from the government with robust congressional oversight.”

- “The CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] operates several programs related to vaccine safety including the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS); Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD); and Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Project. Those functions and their associated funding should be transferred to the FDA [Food and Drug Administration], which is responsible for post-market surveillance and evaluation of all other drugs and biological products.”

- “Because liberal states have now become sanctuaries for abortion tourism, HHS should use every available tool, including the cutting of funds, to ensure that every state reports exactly how many abortions take place within its borders, at what gestational age of the child, for what reason, the mother’s state of residence, and by what method. It should also ensure that statistics are separated by category: spontaneous miscarriage; treatments that incidentally result in the death of a child (such as chemotherapy); stillbirths; and induced abortion. In addition, CDC should require monitoring and reporting for complications due to abortion and every instance of children being born alive after an abortion.”

- “The CDC should immediately end its collection of data on gender identity, which legitimizes the unscientific notion that men can become women (and vice versa) and encourages the phenomenon of ever-multiplying subjective identities.”

- “A test developed by a lab in accordance with the protocols developed by another lab (non-commercial sharing) currently constitutes a ‘new’ laboratory-developed test because the lab in which it will be used is different from the initial developing lab. To encourage interlaboratory collaboration and discourage duplicative test creation (and associated regulatory and logistical burdens), the FDA should introduce mechanisms through which laboratory-developed tests can easily be shared with other laboratories without the current regulatory burdens.”

- “[FDA should] Reverse its approval of chemical abortion drugs because the politicized approval process was illegal from the start. The FDA failed to abide by its legal obligations to protect the health, safety, and welfare of girls and women.”

- “[FDA should] Stop promoting or approving mail-order abortions in violation of long-standing federal laws that prohibit the mailing and interstate carriage of abortion drugs.”

- “[HHS should] Promptly restore the ethics advisory committee to oversee abortion-derived fetal tissue research, and Congress should prohibit such research altogether.”

- “[HHS should] End intramural research projects using tissue from aborted children within the NIH, which should end its human embryonic stem cell registry.”

- “Under Francis Collins, NIH became so focused on the #MeToo movement that it refused to sponsor scientific conferences unless there were a certain number of women panelists, which violates federal civil rights law against sex discrimination. This quota practice should be ended, and the NIH Office of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion, which pushes such unlawful actions, should be abolished.”

- “Make Medicare Advantage [MA] the default enrollment option.”

- “[Legislation reforming legacy (non-MA) Medicare should] Repeal harmful health policies enacted under the Obama and Biden Administrations such as the Medicare Shared Savings Program and Inflation Reduction Act.”

- “…the next Administration should] Add work requirements and match Medicaid benefits to beneficiary needs. Because Medicaid serves a broad and diverse group of individuals, it should be flexible enough to accommodate different designs for different groups.”

- “The No Surprises Act should scrap the dispute resolution process in favor of a truth-in-advertising approach that will protect consumers and free doctors, insurers, and arbiters from confused and conflicting standards for resolving disputes that the disputing parties can best resolve themselves.”

- “Prohibit abortion travel funding. Providing funding for abortions increases the number of abortions and violates the conscience and religious freedom rights of Americans who object to subsidizing the taking of life.”

- “Prohibit Planned Parenthood from receiving Medicaid funds. During the 2020–2021 reporting period, Planned Parenthood performed more than 383,000 abortions.”

- “Protect faith-based grant recipients from religious liberty violations and maintain a biblically based, social science–reinforced definition of marriage and family. Social science reports that assess the objective outcomes for children raised in homes aside from a heterosexual, intact marriage are clear.”

- “Allocate funding to strategy programs promoting father involvement or terminate parental rights quickly.”

- “Eliminate the Head Start program.”

- “Support palliative care. Physician-assisted suicide (PAS) is legal in 10 states and the District of Columbia. Legalizing PAS is a grave mistake that endangers the weak and vulnerable, corrupts the practice of medicine and the doctor–patient relationship, compromises the family and intergenerational commitments, and betrays human dignity and equality before the law.”

- “Eliminate men’s preventive services from the women’s preventive services mandate. In December 2021, HRSA [Health Resources and Services Administration] updated its women’s preventive services guidelines to include male condoms.”

- “Prioritize funding for home-based childcare, not universal day care.”

- “ The Office of the Secretary should eliminate the HHS Reproductive Healthcare Access Task Force and install a pro-life task force to ensure that all of the department’s divisions seek to use their authority to promote the life and health of women and their unborn children.”

- “The ASH [Assistant Secretary for Health] and SG [Surgeon General] positions should be combined into one four-star position with the rank, responsibilities, and authority of the ASH retained but with the title of Surgeon General.”

- “OCR [Office for Civil Rights] should withdraw its Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) guidance on abortion.”

Dr. Lundberg is Editor in Chief, Cancer Commons, and has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Heritage Foundation sponsored and developed Project 2025 for the explicit, stated purpose of building a conservative victory through policy, personnel, and training with a 180-day game plan after a sympathetic new President of the United States takes office. To date, Project 2025 has not been formally endorsed by any presidential campaign.

Chapter 14 of the “Mandate for Leadership” is an exhaustive proposed overhaul of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), one of the major existing arms of the executive branch of the US government.

The mandate’s sweeping recommendations, if implemented, would impact the lives of all Americans and all healthcare workers, as outlined in the following excerpts.

Healthcare-Related Excerpts From Project 2025

- “From the moment of conception, every human being possesses inherent dignity and worth, and our humanity does not depend on our age, stage of development, race, or abilities. The Secretary must ensure that all HHS programs and activities are rooted in a deep respect for innocent human life from day one until natural death: Abortion and euthanasia are not health care.”

- “Unfortunately, family policies and programs under President Biden’s HHS are fraught with agenda items focusing on ‘LGBTQ+ equity,’ subsidizing single motherhood, disincentivizing work, and penalizing marriage. These policies should be repealed and replaced by policies that support the formation of stable, married, nuclear families.”

- “The next Administration should guard against the regulatory capture of our public health agencies by pharmaceutical companies, insurers, hospital conglomerates, and related economic interests that these agencies are meant to regulate. We must erect robust firewalls to mitigate these obvious financial conflicts of interest.”

- “All National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Food and Drug Administration regulators should be entirely free from private biopharmaceutical funding. In this realm, ‘public–private partnerships’ is a euphemism for agency capture, a thin veneer for corporatism. Funding for agencies and individual government researchers must come directly from the government with robust congressional oversight.”

- “The CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] operates several programs related to vaccine safety including the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS); Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD); and Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Project. Those functions and their associated funding should be transferred to the FDA [Food and Drug Administration], which is responsible for post-market surveillance and evaluation of all other drugs and biological products.”

- “Because liberal states have now become sanctuaries for abortion tourism, HHS should use every available tool, including the cutting of funds, to ensure that every state reports exactly how many abortions take place within its borders, at what gestational age of the child, for what reason, the mother’s state of residence, and by what method. It should also ensure that statistics are separated by category: spontaneous miscarriage; treatments that incidentally result in the death of a child (such as chemotherapy); stillbirths; and induced abortion. In addition, CDC should require monitoring and reporting for complications due to abortion and every instance of children being born alive after an abortion.”

- “The CDC should immediately end its collection of data on gender identity, which legitimizes the unscientific notion that men can become women (and vice versa) and encourages the phenomenon of ever-multiplying subjective identities.”

- “A test developed by a lab in accordance with the protocols developed by another lab (non-commercial sharing) currently constitutes a ‘new’ laboratory-developed test because the lab in which it will be used is different from the initial developing lab. To encourage interlaboratory collaboration and discourage duplicative test creation (and associated regulatory and logistical burdens), the FDA should introduce mechanisms through which laboratory-developed tests can easily be shared with other laboratories without the current regulatory burdens.”

- “[FDA should] Reverse its approval of chemical abortion drugs because the politicized approval process was illegal from the start. The FDA failed to abide by its legal obligations to protect the health, safety, and welfare of girls and women.”

- “[FDA should] Stop promoting or approving mail-order abortions in violation of long-standing federal laws that prohibit the mailing and interstate carriage of abortion drugs.”

- “[HHS should] Promptly restore the ethics advisory committee to oversee abortion-derived fetal tissue research, and Congress should prohibit such research altogether.”

- “[HHS should] End intramural research projects using tissue from aborted children within the NIH, which should end its human embryonic stem cell registry.”

- “Under Francis Collins, NIH became so focused on the #MeToo movement that it refused to sponsor scientific conferences unless there were a certain number of women panelists, which violates federal civil rights law against sex discrimination. This quota practice should be ended, and the NIH Office of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion, which pushes such unlawful actions, should be abolished.”

- “Make Medicare Advantage [MA] the default enrollment option.”

- “[Legislation reforming legacy (non-MA) Medicare should] Repeal harmful health policies enacted under the Obama and Biden Administrations such as the Medicare Shared Savings Program and Inflation Reduction Act.”

- “…the next Administration should] Add work requirements and match Medicaid benefits to beneficiary needs. Because Medicaid serves a broad and diverse group of individuals, it should be flexible enough to accommodate different designs for different groups.”

- “The No Surprises Act should scrap the dispute resolution process in favor of a truth-in-advertising approach that will protect consumers and free doctors, insurers, and arbiters from confused and conflicting standards for resolving disputes that the disputing parties can best resolve themselves.”

- “Prohibit abortion travel funding. Providing funding for abortions increases the number of abortions and violates the conscience and religious freedom rights of Americans who object to subsidizing the taking of life.”

- “Prohibit Planned Parenthood from receiving Medicaid funds. During the 2020–2021 reporting period, Planned Parenthood performed more than 383,000 abortions.”

- “Protect faith-based grant recipients from religious liberty violations and maintain a biblically based, social science–reinforced definition of marriage and family. Social science reports that assess the objective outcomes for children raised in homes aside from a heterosexual, intact marriage are clear.”

- “Allocate funding to strategy programs promoting father involvement or terminate parental rights quickly.”

- “Eliminate the Head Start program.”

- “Support palliative care. Physician-assisted suicide (PAS) is legal in 10 states and the District of Columbia. Legalizing PAS is a grave mistake that endangers the weak and vulnerable, corrupts the practice of medicine and the doctor–patient relationship, compromises the family and intergenerational commitments, and betrays human dignity and equality before the law.”

- “Eliminate men’s preventive services from the women’s preventive services mandate. In December 2021, HRSA [Health Resources and Services Administration] updated its women’s preventive services guidelines to include male condoms.”

- “Prioritize funding for home-based childcare, not universal day care.”

- “ The Office of the Secretary should eliminate the HHS Reproductive Healthcare Access Task Force and install a pro-life task force to ensure that all of the department’s divisions seek to use their authority to promote the life and health of women and their unborn children.”

- “The ASH [Assistant Secretary for Health] and SG [Surgeon General] positions should be combined into one four-star position with the rank, responsibilities, and authority of the ASH retained but with the title of Surgeon General.”

- “OCR [Office for Civil Rights] should withdraw its Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) guidance on abortion.”

Dr. Lundberg is Editor in Chief, Cancer Commons, and has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Heritage Foundation sponsored and developed Project 2025 for the explicit, stated purpose of building a conservative victory through policy, personnel, and training with a 180-day game plan after a sympathetic new President of the United States takes office. To date, Project 2025 has not been formally endorsed by any presidential campaign.

Chapter 14 of the “Mandate for Leadership” is an exhaustive proposed overhaul of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), one of the major existing arms of the executive branch of the US government.

The mandate’s sweeping recommendations, if implemented, would impact the lives of all Americans and all healthcare workers, as outlined in the following excerpts.

Healthcare-Related Excerpts From Project 2025

- “From the moment of conception, every human being possesses inherent dignity and worth, and our humanity does not depend on our age, stage of development, race, or abilities. The Secretary must ensure that all HHS programs and activities are rooted in a deep respect for innocent human life from day one until natural death: Abortion and euthanasia are not health care.”

- “Unfortunately, family policies and programs under President Biden’s HHS are fraught with agenda items focusing on ‘LGBTQ+ equity,’ subsidizing single motherhood, disincentivizing work, and penalizing marriage. These policies should be repealed and replaced by policies that support the formation of stable, married, nuclear families.”

- “The next Administration should guard against the regulatory capture of our public health agencies by pharmaceutical companies, insurers, hospital conglomerates, and related economic interests that these agencies are meant to regulate. We must erect robust firewalls to mitigate these obvious financial conflicts of interest.”

- “All National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Food and Drug Administration regulators should be entirely free from private biopharmaceutical funding. In this realm, ‘public–private partnerships’ is a euphemism for agency capture, a thin veneer for corporatism. Funding for agencies and individual government researchers must come directly from the government with robust congressional oversight.”

- “The CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] operates several programs related to vaccine safety including the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS); Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD); and Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Project. Those functions and their associated funding should be transferred to the FDA [Food and Drug Administration], which is responsible for post-market surveillance and evaluation of all other drugs and biological products.”

- “Because liberal states have now become sanctuaries for abortion tourism, HHS should use every available tool, including the cutting of funds, to ensure that every state reports exactly how many abortions take place within its borders, at what gestational age of the child, for what reason, the mother’s state of residence, and by what method. It should also ensure that statistics are separated by category: spontaneous miscarriage; treatments that incidentally result in the death of a child (such as chemotherapy); stillbirths; and induced abortion. In addition, CDC should require monitoring and reporting for complications due to abortion and every instance of children being born alive after an abortion.”

- “The CDC should immediately end its collection of data on gender identity, which legitimizes the unscientific notion that men can become women (and vice versa) and encourages the phenomenon of ever-multiplying subjective identities.”

- “A test developed by a lab in accordance with the protocols developed by another lab (non-commercial sharing) currently constitutes a ‘new’ laboratory-developed test because the lab in which it will be used is different from the initial developing lab. To encourage interlaboratory collaboration and discourage duplicative test creation (and associated regulatory and logistical burdens), the FDA should introduce mechanisms through which laboratory-developed tests can easily be shared with other laboratories without the current regulatory burdens.”

- “[FDA should] Reverse its approval of chemical abortion drugs because the politicized approval process was illegal from the start. The FDA failed to abide by its legal obligations to protect the health, safety, and welfare of girls and women.”

- “[FDA should] Stop promoting or approving mail-order abortions in violation of long-standing federal laws that prohibit the mailing and interstate carriage of abortion drugs.”

- “[HHS should] Promptly restore the ethics advisory committee to oversee abortion-derived fetal tissue research, and Congress should prohibit such research altogether.”

- “[HHS should] End intramural research projects using tissue from aborted children within the NIH, which should end its human embryonic stem cell registry.”

- “Under Francis Collins, NIH became so focused on the #MeToo movement that it refused to sponsor scientific conferences unless there were a certain number of women panelists, which violates federal civil rights law against sex discrimination. This quota practice should be ended, and the NIH Office of Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion, which pushes such unlawful actions, should be abolished.”

- “Make Medicare Advantage [MA] the default enrollment option.”

- “[Legislation reforming legacy (non-MA) Medicare should] Repeal harmful health policies enacted under the Obama and Biden Administrations such as the Medicare Shared Savings Program and Inflation Reduction Act.”

- “…the next Administration should] Add work requirements and match Medicaid benefits to beneficiary needs. Because Medicaid serves a broad and diverse group of individuals, it should be flexible enough to accommodate different designs for different groups.”

- “The No Surprises Act should scrap the dispute resolution process in favor of a truth-in-advertising approach that will protect consumers and free doctors, insurers, and arbiters from confused and conflicting standards for resolving disputes that the disputing parties can best resolve themselves.”

- “Prohibit abortion travel funding. Providing funding for abortions increases the number of abortions and violates the conscience and religious freedom rights of Americans who object to subsidizing the taking of life.”

- “Prohibit Planned Parenthood from receiving Medicaid funds. During the 2020–2021 reporting period, Planned Parenthood performed more than 383,000 abortions.”

- “Protect faith-based grant recipients from religious liberty violations and maintain a biblically based, social science–reinforced definition of marriage and family. Social science reports that assess the objective outcomes for children raised in homes aside from a heterosexual, intact marriage are clear.”

- “Allocate funding to strategy programs promoting father involvement or terminate parental rights quickly.”

- “Eliminate the Head Start program.”

- “Support palliative care. Physician-assisted suicide (PAS) is legal in 10 states and the District of Columbia. Legalizing PAS is a grave mistake that endangers the weak and vulnerable, corrupts the practice of medicine and the doctor–patient relationship, compromises the family and intergenerational commitments, and betrays human dignity and equality before the law.”

- “Eliminate men’s preventive services from the women’s preventive services mandate. In December 2021, HRSA [Health Resources and Services Administration] updated its women’s preventive services guidelines to include male condoms.”

- “Prioritize funding for home-based childcare, not universal day care.”

- “ The Office of the Secretary should eliminate the HHS Reproductive Healthcare Access Task Force and install a pro-life task force to ensure that all of the department’s divisions seek to use their authority to promote the life and health of women and their unborn children.”

- “The ASH [Assistant Secretary for Health] and SG [Surgeon General] positions should be combined into one four-star position with the rank, responsibilities, and authority of the ASH retained but with the title of Surgeon General.”

- “OCR [Office for Civil Rights] should withdraw its Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) guidance on abortion.”

Dr. Lundberg is Editor in Chief, Cancer Commons, and has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A Racing Heart Signals Trouble in Chronic Kidney Disease

TOPLINE:

A higher resting heart rate, even within the normal range, is linked to an increased risk for mortality and cardiovascular events in patients with non–dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease (CKD).

METHODOLOGY:

- An elevated resting heart rate is an independent risk factor for all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in the general population; however, the correlation between heart rate and mortality in patients with CKD is unclear.

- Researchers analyzed the longitudinal data of patients with non–dialysis-dependent CKD enrolled in the Fukushima CKD Cohort Study to investigate the association between resting heart rate and adverse clinical outcomes.

- The patient cohort was stratified into four groups on the basis of resting heart rates: < 70, 70-79, 80-89, and ≥ 90 beats/min.

- The primary and secondary outcomes were all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events, respectively, the latter category including myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, and heart failure.

TAKEAWAY:

- Researchers enrolled 1353 patients with non–dialysis-dependent CKD (median age, 65 years; 56.7% men; median estimated glomerular filtration rate, 52.2 mL/min/1.73 m2) who had a median heart rate of 76 beats/min.

- During the median observation period of 4.9 years, 123 patients died and 163 developed cardiovascular events.

- Compared with patients with a resting heart rate < 70 beats/min, those with a resting heart rate of 80-89 and ≥ 90 beats/min had an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.74 and 2.61 for all-cause mortality, respectively.

- Similarly, the risk for cardiovascular events was higher in patients with a heart rate of 80-89 beats/min than in those with a heart rate < 70 beats/min (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.70).

IN PRACTICE:

“The present study supported the idea that reducing heart rate might be effective for CKD patients with a heart rate ≥ 70/min, since the lowest risk of mortality was seen in patients with heart rate < 70/min,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Hirotaka Saito, Department of Nephrology and Hypertension, Fukushima Medical University, Fukushima City, Japan. It was published online in Scientific Reports.

LIMITATIONS:

Heart rate was measured using a standard sphygmomanometer or an automated device, rather than an electrocardiograph, which may have introduced measurement variability. The observational nature of the study precluded the establishment of cause-and-effect relationships between heart rate and clinical outcomes. Additionally, variables such as lifestyle factors, underlying health conditions, and socioeconomic factors were not measured, which could have affected the results.

DISCLOSURES:

Some authors received research funding from Chugai Pharmaceutical, Kowa Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, and other sources. They declared having no competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

A higher resting heart rate, even within the normal range, is linked to an increased risk for mortality and cardiovascular events in patients with non–dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease (CKD).

METHODOLOGY:

- An elevated resting heart rate is an independent risk factor for all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in the general population; however, the correlation between heart rate and mortality in patients with CKD is unclear.

- Researchers analyzed the longitudinal data of patients with non–dialysis-dependent CKD enrolled in the Fukushima CKD Cohort Study to investigate the association between resting heart rate and adverse clinical outcomes.

- The patient cohort was stratified into four groups on the basis of resting heart rates: < 70, 70-79, 80-89, and ≥ 90 beats/min.

- The primary and secondary outcomes were all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events, respectively, the latter category including myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, and heart failure.

TAKEAWAY:

- Researchers enrolled 1353 patients with non–dialysis-dependent CKD (median age, 65 years; 56.7% men; median estimated glomerular filtration rate, 52.2 mL/min/1.73 m2) who had a median heart rate of 76 beats/min.

- During the median observation period of 4.9 years, 123 patients died and 163 developed cardiovascular events.

- Compared with patients with a resting heart rate < 70 beats/min, those with a resting heart rate of 80-89 and ≥ 90 beats/min had an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.74 and 2.61 for all-cause mortality, respectively.

- Similarly, the risk for cardiovascular events was higher in patients with a heart rate of 80-89 beats/min than in those with a heart rate < 70 beats/min (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.70).

IN PRACTICE:

“The present study supported the idea that reducing heart rate might be effective for CKD patients with a heart rate ≥ 70/min, since the lowest risk of mortality was seen in patients with heart rate < 70/min,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Hirotaka Saito, Department of Nephrology and Hypertension, Fukushima Medical University, Fukushima City, Japan. It was published online in Scientific Reports.

LIMITATIONS:

Heart rate was measured using a standard sphygmomanometer or an automated device, rather than an electrocardiograph, which may have introduced measurement variability. The observational nature of the study precluded the establishment of cause-and-effect relationships between heart rate and clinical outcomes. Additionally, variables such as lifestyle factors, underlying health conditions, and socioeconomic factors were not measured, which could have affected the results.

DISCLOSURES:

Some authors received research funding from Chugai Pharmaceutical, Kowa Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, and other sources. They declared having no competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

A higher resting heart rate, even within the normal range, is linked to an increased risk for mortality and cardiovascular events in patients with non–dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease (CKD).

METHODOLOGY:

- An elevated resting heart rate is an independent risk factor for all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in the general population; however, the correlation between heart rate and mortality in patients with CKD is unclear.

- Researchers analyzed the longitudinal data of patients with non–dialysis-dependent CKD enrolled in the Fukushima CKD Cohort Study to investigate the association between resting heart rate and adverse clinical outcomes.

- The patient cohort was stratified into four groups on the basis of resting heart rates: < 70, 70-79, 80-89, and ≥ 90 beats/min.

- The primary and secondary outcomes were all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events, respectively, the latter category including myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, and heart failure.

TAKEAWAY:

- Researchers enrolled 1353 patients with non–dialysis-dependent CKD (median age, 65 years; 56.7% men; median estimated glomerular filtration rate, 52.2 mL/min/1.73 m2) who had a median heart rate of 76 beats/min.

- During the median observation period of 4.9 years, 123 patients died and 163 developed cardiovascular events.

- Compared with patients with a resting heart rate < 70 beats/min, those with a resting heart rate of 80-89 and ≥ 90 beats/min had an adjusted hazard ratio of 1.74 and 2.61 for all-cause mortality, respectively.

- Similarly, the risk for cardiovascular events was higher in patients with a heart rate of 80-89 beats/min than in those with a heart rate < 70 beats/min (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.70).

IN PRACTICE:

“The present study supported the idea that reducing heart rate might be effective for CKD patients with a heart rate ≥ 70/min, since the lowest risk of mortality was seen in patients with heart rate < 70/min,” the authors concluded.

SOURCE:

This study was led by Hirotaka Saito, Department of Nephrology and Hypertension, Fukushima Medical University, Fukushima City, Japan. It was published online in Scientific Reports.

LIMITATIONS:

Heart rate was measured using a standard sphygmomanometer or an automated device, rather than an electrocardiograph, which may have introduced measurement variability. The observational nature of the study precluded the establishment of cause-and-effect relationships between heart rate and clinical outcomes. Additionally, variables such as lifestyle factors, underlying health conditions, and socioeconomic factors were not measured, which could have affected the results.

DISCLOSURES:

Some authors received research funding from Chugai Pharmaceutical, Kowa Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, and other sources. They declared having no competing interests.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Remission or Not, Biologics May Mitigate Cardiovascular Risks of RA

TOPLINE:

, suggesting that biologics may reduce cardiovascular risk in RA even if remission is not achieved.

METHODOLOGY:

- Studies reported reduced cardiovascular risk in patients with RA who respond to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors but not in nonresponders, highlighting the importance of controlling inflammation for cardiovascular protection.

- Researchers assessed whether bDMARDs modify the impact of disease activity and systemic inflammation on cardiovascular risk in 4370 patients (mean age, 55 years) with RA without cardiovascular disease from a 10-country observational cohort.

- The severity of RA disease activity was assessed using C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on CRP (DAS28-CRP).

- Endpoints were time to first MACE — a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke — and time to first ischemic cardiovascular event (iCVE) — a composite of MACE plus revascularization, angina, transient ischemic attack, and peripheral arterial disease.

TAKEAWAY:

- The interaction between use of bDMARD and DAS28-CRP (P = .017) or CRP (P = .011) was significant for MACE.

- Each unit increase in DAS28-CRP increased the risk for MACE in bDMARD nonusers (hazard ratio [HR], 1.21; P = .002) but not in users.

- The per log unit increase in CRP was associated with a risk for MACE in bDMARD nonusers (HR, 1.16; P = .009) but not in users.

- No interaction was observed between bDMARD use and DAS28-CRP or CRP for the iCVE risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“This may indicate additional bDMARD-specific benefits directly on arterial wall inflammation and atherosclerotic plaque anatomy, stability, and biology, independently of systemic inflammation,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by George Athanasios Karpouzas, MD, The Lundquist Institute, Torrance, California, was published online in RMD Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Patients with a particular interest in RA-associated cardiovascular disease were included, which may have introduced referral bias and affected the generalizability of the findings. Standard definitions were used for selected outcomes; however, differences in the reporting of outcomes may be plausible. Some patients were evaluated prospectively, while others were evaluated retrospectively, leading to differences in surveillance.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by Pfizer. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, suggesting that biologics may reduce cardiovascular risk in RA even if remission is not achieved.

METHODOLOGY:

- Studies reported reduced cardiovascular risk in patients with RA who respond to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors but not in nonresponders, highlighting the importance of controlling inflammation for cardiovascular protection.

- Researchers assessed whether bDMARDs modify the impact of disease activity and systemic inflammation on cardiovascular risk in 4370 patients (mean age, 55 years) with RA without cardiovascular disease from a 10-country observational cohort.

- The severity of RA disease activity was assessed using C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on CRP (DAS28-CRP).

- Endpoints were time to first MACE — a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke — and time to first ischemic cardiovascular event (iCVE) — a composite of MACE plus revascularization, angina, transient ischemic attack, and peripheral arterial disease.

TAKEAWAY:

- The interaction between use of bDMARD and DAS28-CRP (P = .017) or CRP (P = .011) was significant for MACE.

- Each unit increase in DAS28-CRP increased the risk for MACE in bDMARD nonusers (hazard ratio [HR], 1.21; P = .002) but not in users.

- The per log unit increase in CRP was associated with a risk for MACE in bDMARD nonusers (HR, 1.16; P = .009) but not in users.

- No interaction was observed between bDMARD use and DAS28-CRP or CRP for the iCVE risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“This may indicate additional bDMARD-specific benefits directly on arterial wall inflammation and atherosclerotic plaque anatomy, stability, and biology, independently of systemic inflammation,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by George Athanasios Karpouzas, MD, The Lundquist Institute, Torrance, California, was published online in RMD Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Patients with a particular interest in RA-associated cardiovascular disease were included, which may have introduced referral bias and affected the generalizability of the findings. Standard definitions were used for selected outcomes; however, differences in the reporting of outcomes may be plausible. Some patients were evaluated prospectively, while others were evaluated retrospectively, leading to differences in surveillance.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by Pfizer. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

, suggesting that biologics may reduce cardiovascular risk in RA even if remission is not achieved.

METHODOLOGY:

- Studies reported reduced cardiovascular risk in patients with RA who respond to tumor necrosis factor inhibitors but not in nonresponders, highlighting the importance of controlling inflammation for cardiovascular protection.

- Researchers assessed whether bDMARDs modify the impact of disease activity and systemic inflammation on cardiovascular risk in 4370 patients (mean age, 55 years) with RA without cardiovascular disease from a 10-country observational cohort.

- The severity of RA disease activity was assessed using C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and 28-joint Disease Activity Score based on CRP (DAS28-CRP).

- Endpoints were time to first MACE — a composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke — and time to first ischemic cardiovascular event (iCVE) — a composite of MACE plus revascularization, angina, transient ischemic attack, and peripheral arterial disease.

TAKEAWAY:

- The interaction between use of bDMARD and DAS28-CRP (P = .017) or CRP (P = .011) was significant for MACE.

- Each unit increase in DAS28-CRP increased the risk for MACE in bDMARD nonusers (hazard ratio [HR], 1.21; P = .002) but not in users.

- The per log unit increase in CRP was associated with a risk for MACE in bDMARD nonusers (HR, 1.16; P = .009) but not in users.

- No interaction was observed between bDMARD use and DAS28-CRP or CRP for the iCVE risk.

IN PRACTICE:

“This may indicate additional bDMARD-specific benefits directly on arterial wall inflammation and atherosclerotic plaque anatomy, stability, and biology, independently of systemic inflammation,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, led by George Athanasios Karpouzas, MD, The Lundquist Institute, Torrance, California, was published online in RMD Open.

LIMITATIONS:

Patients with a particular interest in RA-associated cardiovascular disease were included, which may have introduced referral bias and affected the generalizability of the findings. Standard definitions were used for selected outcomes; however, differences in the reporting of outcomes may be plausible. Some patients were evaluated prospectively, while others were evaluated retrospectively, leading to differences in surveillance.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by Pfizer. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

These Four Factors Account for 18 Years of Life Expectancy

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Two individuals in the United States are celebrating their 30th birthdays. It’s a good day. They are entering the prime of their lives. One is a married White woman with a university degree. The other is a never-married White man with a high school diploma.

How many more years of life can these two individuals look forward to?

There’s a fairly dramatic difference. The man can expect 37.1 more years of life on average, living to be about 67. The woman can expect to live to age 85. That’s a life-expectancy discrepancy of 18 years based solely on gender, education, and marital status.

I’m using these cases to illustrate the extremes of life expectancy across four key social determinants of health: sex, race, marital status, and education. We all have some sense of how these factors play out in terms of health, but a new study suggests that it’s actually quite a bit more complicated than we thought.

Let me start by acknowledging my own bias here. As a clinical researcher, I sometimes find it hard to appreciate the value of actuarial-type studies that look at life expectancy (or any metric, really) between groups defined by marital status, for example. I’m never quite sure what to do with the conclusion. Married people live longer, the headline says. Okay, but as a doctor, what am I supposed to do about that? Encourage my patients to settle down and commit? Studies showing that women live longer than men or that White people live longer than Black people are also hard for me to incorporate into my practice. These are not easily changeable states.

But studies examining these groups are a reasonable starting point to ask more relevant questions. Why do women live longer than men? Is it behavioral (men take more risks and are less likely to see doctors)? Or is it hormonal (estrogen has a lot of protective effects that testosterone does not)? Or is it something else?

Integrating these social determinants of health into a cohesive story is a bit harder than it might seem, as this study, appearing in BMJ Open, illustrates.

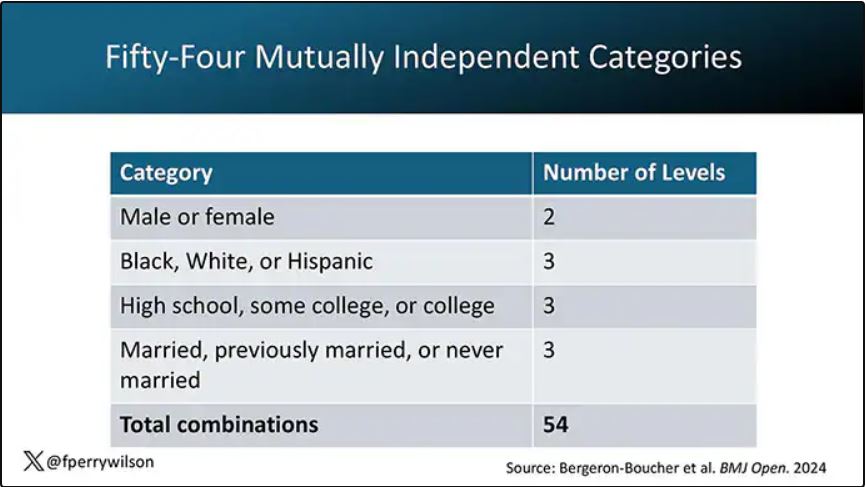

In the context of this study, every person in America can be placed into one of 54 mutually exclusive groups. You can be male or female. You can be Black, White, or Hispanic. You can have a high school diploma or less, an associate degree, or a college degree; and you can be married, previously married, or never married.

Of course, this does not capture the beautiful tapestry that is American life, but let’s give them a pass. They are working with data from the American Community Survey, which contains 8634 people — the statistics would run into trouble with more granular divisions. This survey can be population weighted, so you can scale up the results to reasonably represent the population of the United States.

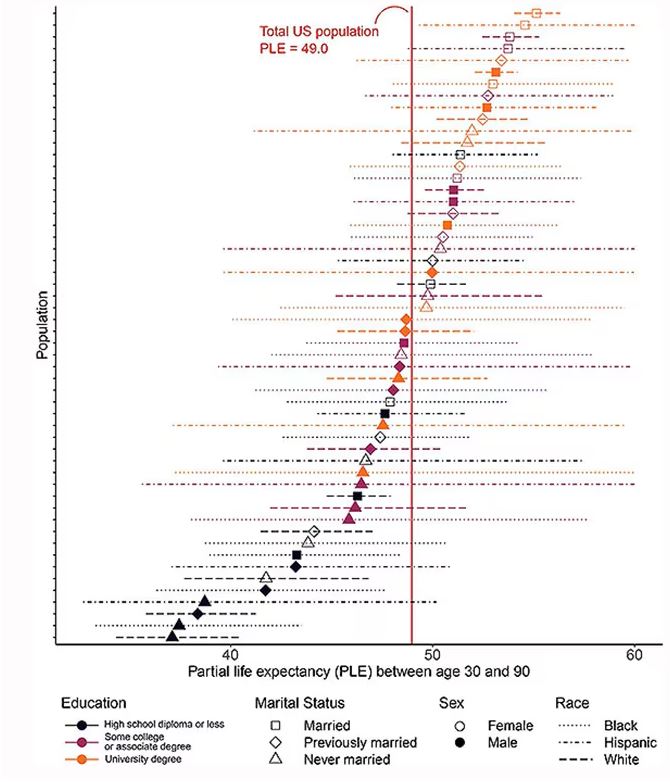

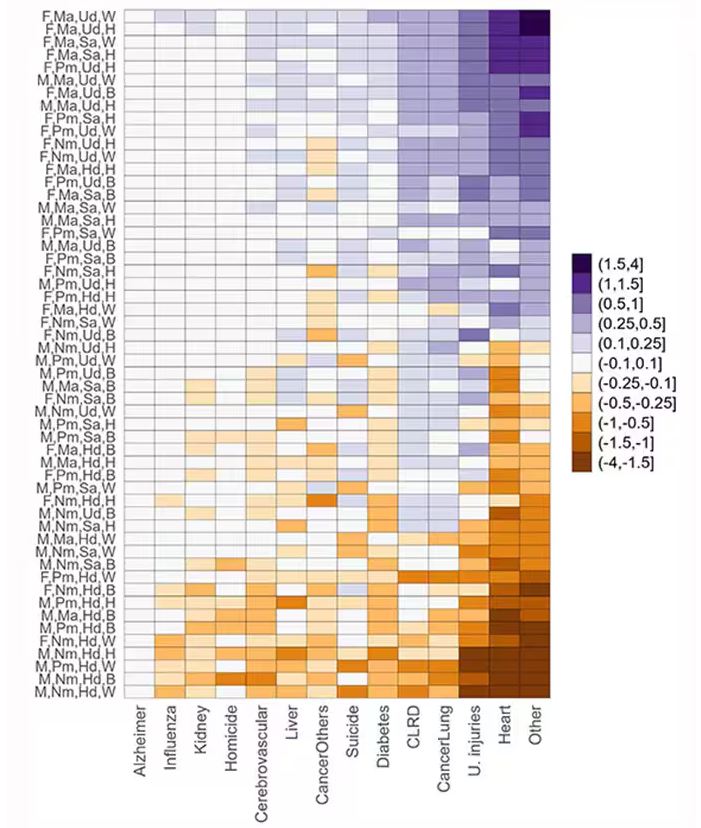

The survey collected data on the four broad categories of sex, race, education, and marital status and linked those survey results to the Multiple Cause of Death dataset from the CDC. From there, it’s a pretty simple task to rank the 54 categories in order from longest to shortest life expectancy, as you can see here.

But that’s not really the interesting part of this study. Sure, there is a lot of variation; it’s interesting that these four factors explain about 18 years’ difference in life expectancy in this country. What strikes me here, actually, is the lack of an entirely consistent message across this spectrum.

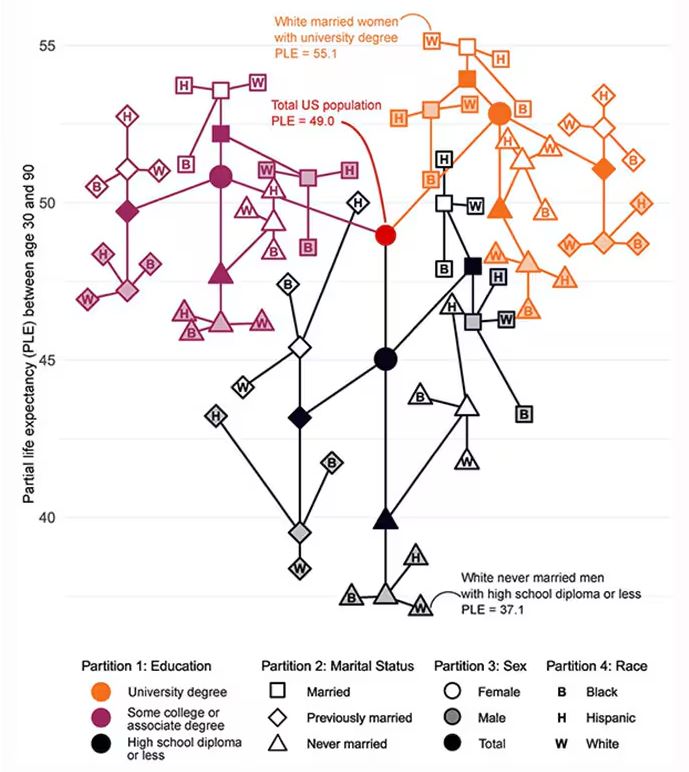

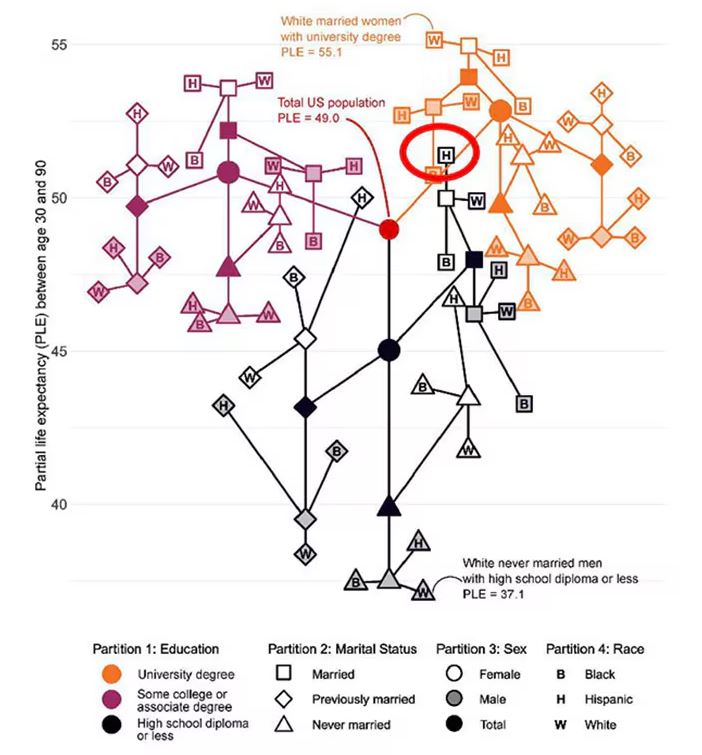

Let me walk you through the second figure in this paper, because this nicely illustrates the surprising heterogeneity that exists here.

This may seem overwhelming, but basically, shapes that are higher up on the Y-axis represent the groups with longer life expectancy.

You can tell, for example, that shapes that are black in color (groups with high school educations or less) are generally lower. But not universally so. This box represents married, Hispanic females who do quite well in terms of life expectancy, even at that lower educational level.

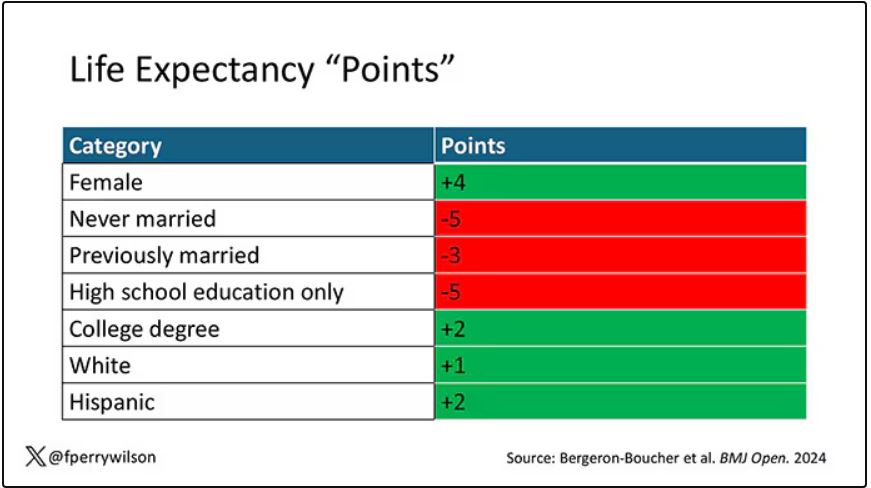

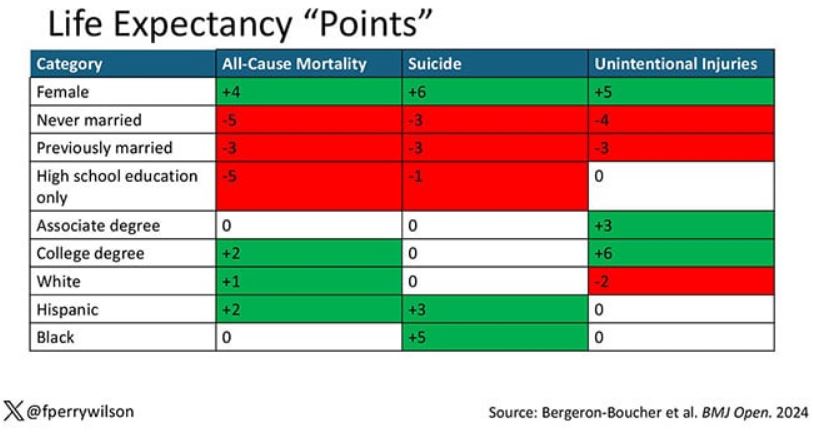

The authors quantify this phenomenon by creating a mortality risk score that integrates these findings. It looks something like this, with 0 being average morality for the United States.

As you can see, you get a bunch of points for being female, but you lose a bunch for not being married. Education plays a large role, with a big hit for those who have a high school diploma or less, and a bonus for those with a college degree. Race plays a relatively more minor role.

This is all very interesting, but as I said at the beginning, this isn’t terribly useful to me as a physician. More important is figuring out why these differences exist. And there are some clues in the study data, particularly when we examine causes of death. This figure ranks those 54 groups again, from the married, White, college-educated females down to the never-married, White, high school–educated males. The boxes show how much more or less likely this group is to die of a given condition than the general population.

Looking at the bottom groups, you can see a dramatically increased risk for death from unintentional injuries, heart disease, and lung cancer. You see an increased risk for suicide as well. In the upper tiers, the only place where risk seems higher than expected is for the category of “other cancers,” reminding us that many types of cancer do not respect definitions of socioeconomic status.

You can even update the risk-scoring system to reflect the risk for different causes of death. You can see here how White people, for example, are at higher risk for death from unintentional injuries relative to other populations, despite having a lower mortality overall.

So maybe, through cause of death, we get a little closer to the answer of why. But this paper is really just a start. Its primary effect should be to surprise us — that in a country as wealthy as the United States, such dramatic variation exists based on factors that, with the exception of sex, I suppose, are not really biological. Which means that to find the why, we may need to turn from physiology to sociology.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Two individuals in the United States are celebrating their 30th birthdays. It’s a good day. They are entering the prime of their lives. One is a married White woman with a university degree. The other is a never-married White man with a high school diploma.

How many more years of life can these two individuals look forward to?

There’s a fairly dramatic difference. The man can expect 37.1 more years of life on average, living to be about 67. The woman can expect to live to age 85. That’s a life-expectancy discrepancy of 18 years based solely on gender, education, and marital status.

I’m using these cases to illustrate the extremes of life expectancy across four key social determinants of health: sex, race, marital status, and education. We all have some sense of how these factors play out in terms of health, but a new study suggests that it’s actually quite a bit more complicated than we thought.

Let me start by acknowledging my own bias here. As a clinical researcher, I sometimes find it hard to appreciate the value of actuarial-type studies that look at life expectancy (or any metric, really) between groups defined by marital status, for example. I’m never quite sure what to do with the conclusion. Married people live longer, the headline says. Okay, but as a doctor, what am I supposed to do about that? Encourage my patients to settle down and commit? Studies showing that women live longer than men or that White people live longer than Black people are also hard for me to incorporate into my practice. These are not easily changeable states.

But studies examining these groups are a reasonable starting point to ask more relevant questions. Why do women live longer than men? Is it behavioral (men take more risks and are less likely to see doctors)? Or is it hormonal (estrogen has a lot of protective effects that testosterone does not)? Or is it something else?

Integrating these social determinants of health into a cohesive story is a bit harder than it might seem, as this study, appearing in BMJ Open, illustrates.

In the context of this study, every person in America can be placed into one of 54 mutually exclusive groups. You can be male or female. You can be Black, White, or Hispanic. You can have a high school diploma or less, an associate degree, or a college degree; and you can be married, previously married, or never married.

Of course, this does not capture the beautiful tapestry that is American life, but let’s give them a pass. They are working with data from the American Community Survey, which contains 8634 people — the statistics would run into trouble with more granular divisions. This survey can be population weighted, so you can scale up the results to reasonably represent the population of the United States.

The survey collected data on the four broad categories of sex, race, education, and marital status and linked those survey results to the Multiple Cause of Death dataset from the CDC. From there, it’s a pretty simple task to rank the 54 categories in order from longest to shortest life expectancy, as you can see here.

But that’s not really the interesting part of this study. Sure, there is a lot of variation; it’s interesting that these four factors explain about 18 years’ difference in life expectancy in this country. What strikes me here, actually, is the lack of an entirely consistent message across this spectrum.

Let me walk you through the second figure in this paper, because this nicely illustrates the surprising heterogeneity that exists here.

This may seem overwhelming, but basically, shapes that are higher up on the Y-axis represent the groups with longer life expectancy.

You can tell, for example, that shapes that are black in color (groups with high school educations or less) are generally lower. But not universally so. This box represents married, Hispanic females who do quite well in terms of life expectancy, even at that lower educational level.

The authors quantify this phenomenon by creating a mortality risk score that integrates these findings. It looks something like this, with 0 being average morality for the United States.

As you can see, you get a bunch of points for being female, but you lose a bunch for not being married. Education plays a large role, with a big hit for those who have a high school diploma or less, and a bonus for those with a college degree. Race plays a relatively more minor role.

This is all very interesting, but as I said at the beginning, this isn’t terribly useful to me as a physician. More important is figuring out why these differences exist. And there are some clues in the study data, particularly when we examine causes of death. This figure ranks those 54 groups again, from the married, White, college-educated females down to the never-married, White, high school–educated males. The boxes show how much more or less likely this group is to die of a given condition than the general population.

Looking at the bottom groups, you can see a dramatically increased risk for death from unintentional injuries, heart disease, and lung cancer. You see an increased risk for suicide as well. In the upper tiers, the only place where risk seems higher than expected is for the category of “other cancers,” reminding us that many types of cancer do not respect definitions of socioeconomic status.

You can even update the risk-scoring system to reflect the risk for different causes of death. You can see here how White people, for example, are at higher risk for death from unintentional injuries relative to other populations, despite having a lower mortality overall.

So maybe, through cause of death, we get a little closer to the answer of why. But this paper is really just a start. Its primary effect should be to surprise us — that in a country as wealthy as the United States, such dramatic variation exists based on factors that, with the exception of sex, I suppose, are not really biological. Which means that to find the why, we may need to turn from physiology to sociology.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Two individuals in the United States are celebrating their 30th birthdays. It’s a good day. They are entering the prime of their lives. One is a married White woman with a university degree. The other is a never-married White man with a high school diploma.

How many more years of life can these two individuals look forward to?

There’s a fairly dramatic difference. The man can expect 37.1 more years of life on average, living to be about 67. The woman can expect to live to age 85. That’s a life-expectancy discrepancy of 18 years based solely on gender, education, and marital status.

I’m using these cases to illustrate the extremes of life expectancy across four key social determinants of health: sex, race, marital status, and education. We all have some sense of how these factors play out in terms of health, but a new study suggests that it’s actually quite a bit more complicated than we thought.

Let me start by acknowledging my own bias here. As a clinical researcher, I sometimes find it hard to appreciate the value of actuarial-type studies that look at life expectancy (or any metric, really) between groups defined by marital status, for example. I’m never quite sure what to do with the conclusion. Married people live longer, the headline says. Okay, but as a doctor, what am I supposed to do about that? Encourage my patients to settle down and commit? Studies showing that women live longer than men or that White people live longer than Black people are also hard for me to incorporate into my practice. These are not easily changeable states.

But studies examining these groups are a reasonable starting point to ask more relevant questions. Why do women live longer than men? Is it behavioral (men take more risks and are less likely to see doctors)? Or is it hormonal (estrogen has a lot of protective effects that testosterone does not)? Or is it something else?

Integrating these social determinants of health into a cohesive story is a bit harder than it might seem, as this study, appearing in BMJ Open, illustrates.

In the context of this study, every person in America can be placed into one of 54 mutually exclusive groups. You can be male or female. You can be Black, White, or Hispanic. You can have a high school diploma or less, an associate degree, or a college degree; and you can be married, previously married, or never married.

Of course, this does not capture the beautiful tapestry that is American life, but let’s give them a pass. They are working with data from the American Community Survey, which contains 8634 people — the statistics would run into trouble with more granular divisions. This survey can be population weighted, so you can scale up the results to reasonably represent the population of the United States.

The survey collected data on the four broad categories of sex, race, education, and marital status and linked those survey results to the Multiple Cause of Death dataset from the CDC. From there, it’s a pretty simple task to rank the 54 categories in order from longest to shortest life expectancy, as you can see here.

But that’s not really the interesting part of this study. Sure, there is a lot of variation; it’s interesting that these four factors explain about 18 years’ difference in life expectancy in this country. What strikes me here, actually, is the lack of an entirely consistent message across this spectrum.

Let me walk you through the second figure in this paper, because this nicely illustrates the surprising heterogeneity that exists here.

This may seem overwhelming, but basically, shapes that are higher up on the Y-axis represent the groups with longer life expectancy.

You can tell, for example, that shapes that are black in color (groups with high school educations or less) are generally lower. But not universally so. This box represents married, Hispanic females who do quite well in terms of life expectancy, even at that lower educational level.

The authors quantify this phenomenon by creating a mortality risk score that integrates these findings. It looks something like this, with 0 being average morality for the United States.

As you can see, you get a bunch of points for being female, but you lose a bunch for not being married. Education plays a large role, with a big hit for those who have a high school diploma or less, and a bonus for those with a college degree. Race plays a relatively more minor role.

This is all very interesting, but as I said at the beginning, this isn’t terribly useful to me as a physician. More important is figuring out why these differences exist. And there are some clues in the study data, particularly when we examine causes of death. This figure ranks those 54 groups again, from the married, White, college-educated females down to the never-married, White, high school–educated males. The boxes show how much more or less likely this group is to die of a given condition than the general population.

Looking at the bottom groups, you can see a dramatically increased risk for death from unintentional injuries, heart disease, and lung cancer. You see an increased risk for suicide as well. In the upper tiers, the only place where risk seems higher than expected is for the category of “other cancers,” reminding us that many types of cancer do not respect definitions of socioeconomic status.

You can even update the risk-scoring system to reflect the risk for different causes of death. You can see here how White people, for example, are at higher risk for death from unintentional injuries relative to other populations, despite having a lower mortality overall.

So maybe, through cause of death, we get a little closer to the answer of why. But this paper is really just a start. Its primary effect should be to surprise us — that in a country as wealthy as the United States, such dramatic variation exists based on factors that, with the exception of sex, I suppose, are not really biological. Which means that to find the why, we may need to turn from physiology to sociology.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Xanthelasma Not Linked to Heart Diseases, Study Finds

TOPLINE:

Xanthelasma palpebrarum, characterized by yellowish plaques on the eyelids, is not associated with increased rates of dyslipidemia or cardiovascular disease.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a case-control study at a single tertiary care center in Israel and analyzed data from 35,452 individuals (mean age, 52.2 years; 69% men) who underwent medical screening from 2001 to 2020.

- They compared 203 patients with xanthelasma palpebrarum with 2030 individuals without the disease (control).

- Primary outcomes were prevalence of dyslipidemia and cardiovascular disease between the two groups.

TAKEAWAY:

- Lipid profiles were similar between the two groups, with no difference in total cholesterol, high- and low-density lipoprotein, and triglyceride levels (all P > .05).

- The prevalence of dyslipidemia was similar for patients with xanthelasma palpebrarum and controls (46% vs 42%, respectively; P = .29), as was the incidence of cardiovascular disease (8.9% vs 10%, respectively; P = .56).

- The incidence of diabetes (P = .13), cerebrovascular accidents (P > .99), ischemic heart disease (P = .73), and hypertension (P = .56) were not significantly different between the two groups.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our study conducted on a large population of individuals undergoing comprehensive ophthalmic and systemic screening tests did not find a significant association between xanthelasma palpebrarum and an increased prevalence of lipid abnormalities or cardiovascular disease,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Yael Lustig, MD, of the Goldschleger Eye Institute at Sheba Medical Center, in Ramat Gan, Israel. It was published online on August 5, 2024, in Ophthalmology.

LIMITATIONS:

The retrospective nature of the study and the single-center design may have limited the generalizability of the findings. The study population was self-selected, potentially introducing selection bias. Lack of histopathologic examination could have affected the accuracy of the diagnosis.

DISCLOSURES:

No funding sources were disclosed for this study. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Xanthelasma palpebrarum, characterized by yellowish plaques on the eyelids, is not associated with increased rates of dyslipidemia or cardiovascular disease.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a case-control study at a single tertiary care center in Israel and analyzed data from 35,452 individuals (mean age, 52.2 years; 69% men) who underwent medical screening from 2001 to 2020.

- They compared 203 patients with xanthelasma palpebrarum with 2030 individuals without the disease (control).

- Primary outcomes were prevalence of dyslipidemia and cardiovascular disease between the two groups.

TAKEAWAY:

- Lipid profiles were similar between the two groups, with no difference in total cholesterol, high- and low-density lipoprotein, and triglyceride levels (all P > .05).

- The prevalence of dyslipidemia was similar for patients with xanthelasma palpebrarum and controls (46% vs 42%, respectively; P = .29), as was the incidence of cardiovascular disease (8.9% vs 10%, respectively; P = .56).

- The incidence of diabetes (P = .13), cerebrovascular accidents (P > .99), ischemic heart disease (P = .73), and hypertension (P = .56) were not significantly different between the two groups.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our study conducted on a large population of individuals undergoing comprehensive ophthalmic and systemic screening tests did not find a significant association between xanthelasma palpebrarum and an increased prevalence of lipid abnormalities or cardiovascular disease,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Yael Lustig, MD, of the Goldschleger Eye Institute at Sheba Medical Center, in Ramat Gan, Israel. It was published online on August 5, 2024, in Ophthalmology.

LIMITATIONS:

The retrospective nature of the study and the single-center design may have limited the generalizability of the findings. The study population was self-selected, potentially introducing selection bias. Lack of histopathologic examination could have affected the accuracy of the diagnosis.

DISCLOSURES:

No funding sources were disclosed for this study. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Xanthelasma palpebrarum, characterized by yellowish plaques on the eyelids, is not associated with increased rates of dyslipidemia or cardiovascular disease.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a case-control study at a single tertiary care center in Israel and analyzed data from 35,452 individuals (mean age, 52.2 years; 69% men) who underwent medical screening from 2001 to 2020.

- They compared 203 patients with xanthelasma palpebrarum with 2030 individuals without the disease (control).

- Primary outcomes were prevalence of dyslipidemia and cardiovascular disease between the two groups.

TAKEAWAY:

- Lipid profiles were similar between the two groups, with no difference in total cholesterol, high- and low-density lipoprotein, and triglyceride levels (all P > .05).

- The prevalence of dyslipidemia was similar for patients with xanthelasma palpebrarum and controls (46% vs 42%, respectively; P = .29), as was the incidence of cardiovascular disease (8.9% vs 10%, respectively; P = .56).

- The incidence of diabetes (P = .13), cerebrovascular accidents (P > .99), ischemic heart disease (P = .73), and hypertension (P = .56) were not significantly different between the two groups.

IN PRACTICE:

“Our study conducted on a large population of individuals undergoing comprehensive ophthalmic and systemic screening tests did not find a significant association between xanthelasma palpebrarum and an increased prevalence of lipid abnormalities or cardiovascular disease,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Yael Lustig, MD, of the Goldschleger Eye Institute at Sheba Medical Center, in Ramat Gan, Israel. It was published online on August 5, 2024, in Ophthalmology.

LIMITATIONS:

The retrospective nature of the study and the single-center design may have limited the generalizability of the findings. The study population was self-selected, potentially introducing selection bias. Lack of histopathologic examination could have affected the accuracy of the diagnosis.

DISCLOSURES:

No funding sources were disclosed for this study. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New Study Links Sweetener to Heart Risk: What to Know

Is going sugar free really good advice for patients with cardiometabolic risk factors?

That’s the question raised by new Cleveland Clinic research, which suggests that consuming erythritol, a sweetener widely found in sugar-free and keto food products, could spur a prothrombotic response.

In the study, published in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 10 healthy participants ate 30 grams of erythritol. Thirty minutes later, their blood showed enhanced platelet aggregation and increased markers of platelet responsiveness and activation.

Specifically, the researchers saw enhanced stimulus-dependent release of serotonin (a marker of platelet dense granules) and CXCL4 (a platelet alpha-granule marker).

“ With every single person, you see a prothrombotic effect with every single test that we did,” said study author Stanley Hazen, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Cardiovascular & Metabolic Sciences at Cleveland Clinic in Ohio. By contrast, participants who ate 30 grams of glucose saw no such effect.

The erythritol itself does not activate the platelets, Dr. Hazen said, rather it lowers the threshold for triggering a response. This could make someone more prone to clotting, raising heart attack and stroke risk over time.

Though the mechanism is unknown, Dr. Hazen has an idea.

“There appears to be a receptor on platelets that is recognizing and sensing these sugar alcohols,” Dr. Hazen said, “much in the same way your taste bud for sweet is a receptor for recognizing a glucose or sugar molecule.”

“We’re very interested in trying to figure out what the receptor is,” Dr. Hazen said, “because I think that then becomes a very interesting potential target for further investigation and study into how this is linked to causing heart disease.”

The Past and Future of Erythritol Research

In 2001, the Food and Drug Administration classified erythritol as a “generally recognized as safe” food additive. A sugar alcohol that occurs naturally in foods like melon and grapes, erythritol is also manufactured by fermenting sugars. It’s about 70% as sweet as table sugar. Humans also produce small amounts of erythritol naturally: Our blood cells make it from glucose via the pentose phosphate pathway.

Previous research from Dr. Hazen’s group linked erythritol to a risk for major adverse cardiovascular events and clotting.

“Based on their previous study, I think this was a really important study to do in healthy individuals,” said Martha Field, PhD, assistant professor in the Division of Nutritional Sciences at Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, who was not involved in the study.

The earlier paper analyzed blood samples from participants with unknown erythritol intake, including some taken before the sweetener, and it was as widespread as it is today. That made disentangling the effects of eating erythritol vs naturally producing it more difficult.

By showing that eating erythritol raises markers associated with thrombosis, the new paper reinforces the importance of thinking about and developing a deeper understanding of what we put into our bodies.

“This paper was conducted in healthy individuals — might this be particularly dangerous for individuals who are at increased risk of clotting?” asked Dr. Field. “There are lots of genetic polymorphisms that increase your risk for clotting disorders or your propensity to form thrombosis.”

Field would like to see similar analyses of xylitol and sorbitol, other sugar alcohols found in sugar-free foods. And she called for more studies on erythritol that look at lower erythritol consumption over longer time periods.

Registered dietitian nutritionist Valisa E. Hedrick, PhD, agreed: Much more work is needed in this area, particularly in higher-risk groups, such as those with prediabetes and diabetes, said Dr. Hedrick, an associate professor in the Department of Human Nutrition, Foods, and Exercise at Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, who was not involved in the study.

“Because this study was conducted in healthy individuals, the impact of a small dose of glucose was negligible, as their body can effectively regulate blood glucose levels,” she said. “Because high blood glucose concentrations have also been shown to increase platelet reactivity, and consequently increase thrombosis potential, individuals who are not able to regulate their blood glucose levels, such as those with prediabetes and diabetes, could potentially see a similar effect on the body as erythritol when consuming large amounts of sugar.”

At the same time, “individuals with diabetes or prediabetes may be more inclined to consume erythritol as an alternative to sugar,” Dr. Hedrick added. “It will be important to design studies that include these individuals to determine if erythritol has an additive adverse effect on cardiac event risk.”

Criticism and Impact

Critics have suggested the 30-gram dose of erythritol ingested by study participants is unrealistic. Dr. Hazen said that it’s not.

Erythritol is often recommended as a one-to-one sugar replacement. And you could top 30 grams with a few servings of erythritol-sweetened ice cream or soda, Dr. Hazen said.

“The dose that we used, it’s on the high end, but it’s well within a physiologically relevant level,” he said.

Still others say the results are only relevant for people with preexisting heart trouble. But Dr. Hazen said they matter for the masses.

“I think there’s a significant health concern at a population level that this work is underscoring,” he said.

After all, heart disease risk factors like obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and smoking are common and quickly add up.

“If you look at middle-aged America, most people who experience a heart attack or stroke do not know that they have coronary artery disease, and the first recognition of it is that event,” Dr. Hazen said.

For now, Dr. Hazen recommends eating real sugar in moderation. He hopes future research will reveal a nonnutritive sweetener that doesn’t activate platelets.

The Bigger Picture

The new research adds yet another piece to the puzzle of whether nonnutritive sweeteners are better than sugar.

“I think these results are concerning,” said JoAnn E. Manson, MD, chief of the Division of Preventive Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, both in Boston, Massachusetts. They “ may help explain the surprising results in some observational studies that artificial sweeteners are linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.”

Dr. Manson, who was not involved in the new study, has conducted other research linking artificial sweetener use with stroke risk.

In an upcoming randomized clinical study, her team is comparing head-to-head sugar-sweetened beverages, drinks sweetened with calorie-free substitutes, and water to determine which is best for a range of cardiometabolic outcomes.

“We need more research on this question,” she said, “because these artificial sweeteners are commonly used, and many people are assuming that their health outcomes will be better with the artificial sweeteners than with sugar-sweetened products.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Is going sugar free really good advice for patients with cardiometabolic risk factors?

That’s the question raised by new Cleveland Clinic research, which suggests that consuming erythritol, a sweetener widely found in sugar-free and keto food products, could spur a prothrombotic response.

In the study, published in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 10 healthy participants ate 30 grams of erythritol. Thirty minutes later, their blood showed enhanced platelet aggregation and increased markers of platelet responsiveness and activation.

Specifically, the researchers saw enhanced stimulus-dependent release of serotonin (a marker of platelet dense granules) and CXCL4 (a platelet alpha-granule marker).