User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Velvety Plaques on the Abdomen and Extremities

The Diagnosis: Dermatitis Neglecta

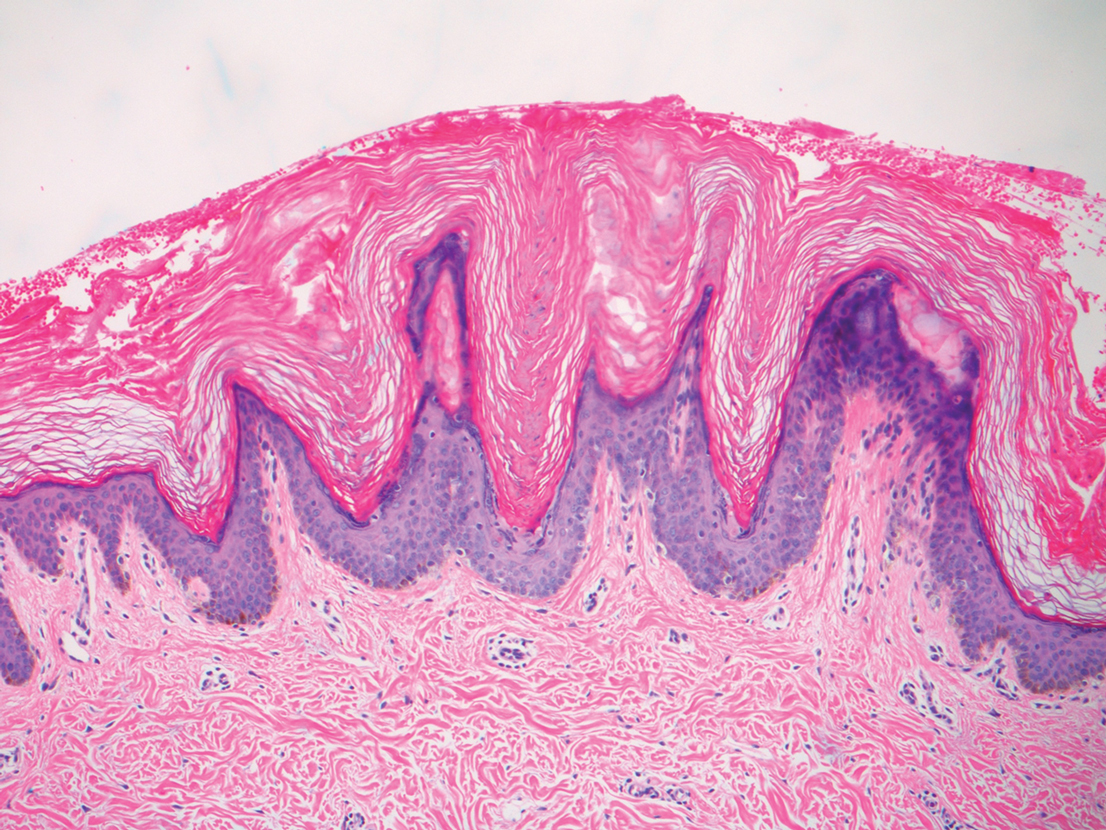

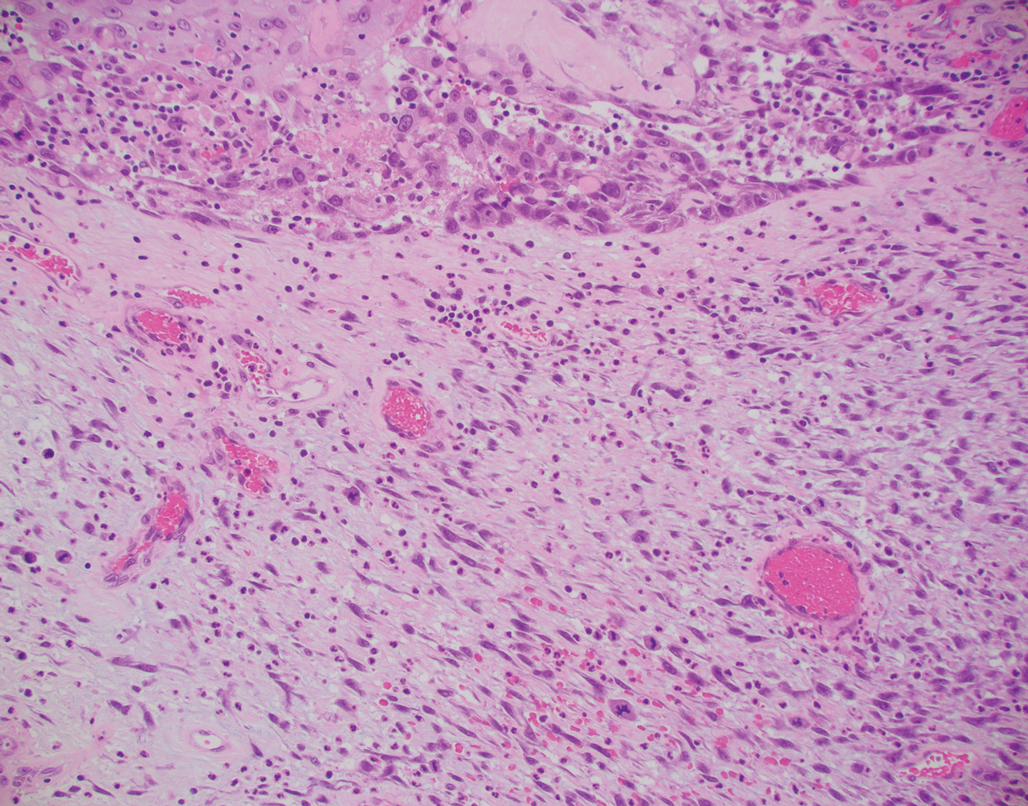

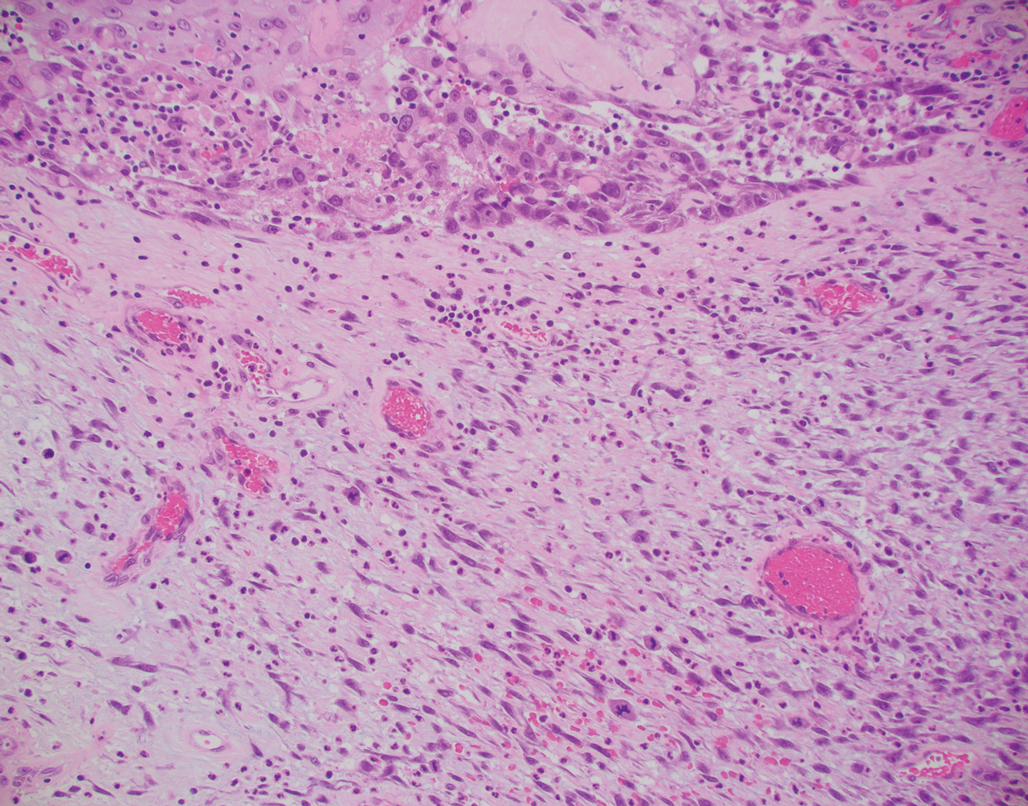

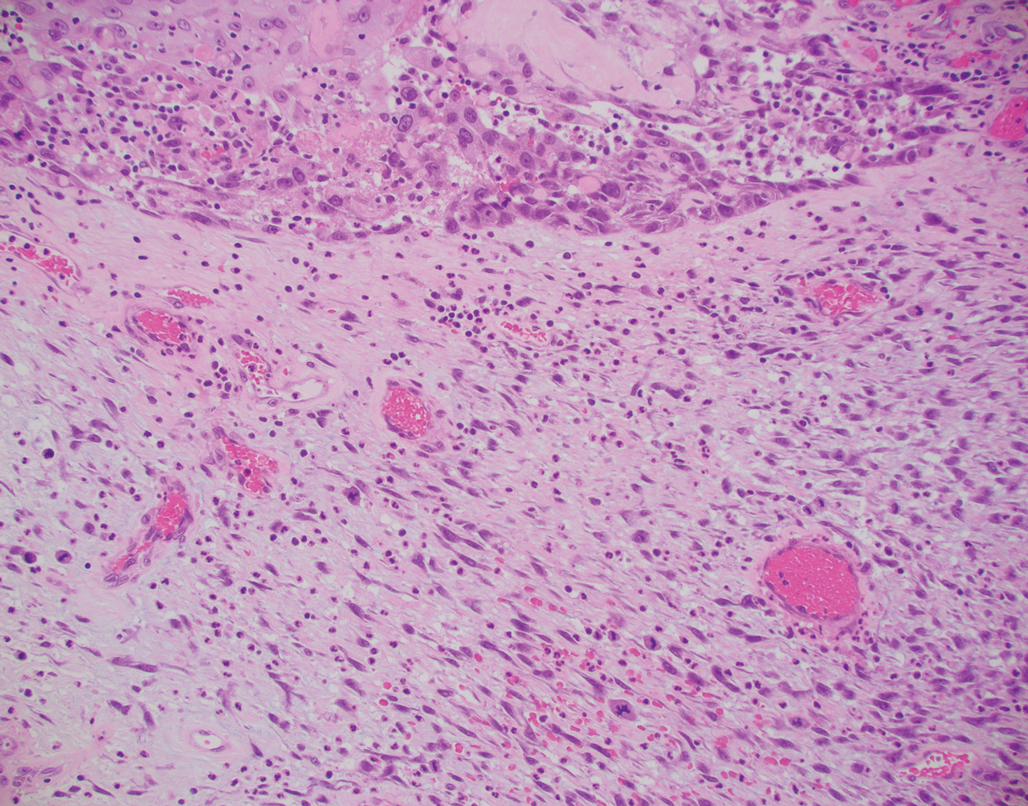

A punch biopsy of the abdomen revealed hyperkeratosis and mild papillomatosis (Figure), which can be seen in dermatitis neglecta (DN) and acanthosis nigricans (AN) as well as confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CARP). Due to the patient’s history of mood and psychotic disorders, collateral information was obtained from the patient’s family, who reported that the patient had a depressed mood in the last few months and was not showering or caring for herself during this period. There was no additional personal or family history of skin disease. Clinical and histopathologic findings led to a diagnosis of DN. Following recommendations for daily cleansing with soap and water along with topical ammonium lactate, near-complete resolution of the rash was achieved in 3 weeks.

Dermatitis neglecta, or unwashed dermatosis, is a skin condition that occurs secondary to poor hygiene, which was first reported in 1995 by Poskitt et al.1 Avoidance of washing in affected areas can be due to physical disability, pain after injury, neurological deficit, or psychologically induced fear or neglect. Sebum, sweat, corneocytes, and bacteria combine into compact adherent crusts of dirt, which appear as hyperkeratotic plaques with cornflakelike scale.2,3 Despite its innate simplicity, DN is a diagnostic challenge, as it clinically and histologically mimics other dermatoses including AN, terra firmaforme dermatosis, and CARP.2,4 Ultimately, the diagnosis of DN can be made when a history of poor hygiene is probable or elicited, and lesions can be removed with soap and water. Treatment of DN includes daily cleansing with soap and water; however, resistant lesions or extensive disease may require keratolytic agents, as in our patient.2-4 In contrast, terra firma-forme dermatosis, which may look similar, is not due to poor hygiene, and the lesions typically are resistant to soap and water, classically requiring isopropyl alcohol for removal. Overall, maintained awareness of DN is imperative, as early diagnosis can avoid unnecessary biopsies and more complex treatment measures as well as facilitate coordination of care when additional medical or psychiatric concerns are present.

Although the diagnoses of DN and terra firma-forme dermatosis can be distinguished based on the patient’s clinical history and response to simple cleansing measures alone, the alternate diagnoses can be excluded based on different clinical distributions and response to other treatment modalities but sometimes may require clinicopathologic correlation for definitive diagnosis. Our patient had a biopsy diagnosis of psoriasiform dermatitis from an outside provider, but neither her clinical disease nor repeated histopathologic findings supported a diagnosis of psoriasis or other classic psoriasiform dermatoses such as contact dermatitis, dermatophyte/ candidal infection, seborrheic dermatitis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, pityriasis rosea, scabies, or syphilis.

It is imperative to exclude alternative diagnoses because they can have systemic implications and can misguide treatment, as was done initially with our patient. Psoriasis vulgaris in its classic form is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that manifests as sharply demarcated, erythematous plaques with overlying thick silvery scale; it has the additional histologic findings of neutrophilic spongiform pustules in the epidermis, tortuous blood vessels in the papillary dermis, and neutrophils and parakeratosis in the stratum corneum. In its benign form, AN is associated with endocrinopathies, most commonly obesity and insulin-resistant diabetes mellitus, and presents as hyperkeratotic, velvety, hyperpigmented plaques typically limited to the neck and axillae. Malignant AN spontaneously arises in association with systemic malignancy and can be extensive and generalized.5 Treatment of AN primarily focuses on resolution of the underlying systemic disease; however, cosmetic treatment with topical or oral retinoids may hasten resolution of cutaneous disease.6 Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is characterized by reticulated hyperkeratotic plaques with a common distribution over the central and upper trunk. Unlike DN and AN, which may occur at any age, CARP typically is seen in adolescents and young adults.7 There is no evidence-based gold standard for the management of CARP; however, the successful use of various antibiotics, antifungals, and retinoids—alone or in combination—has been reported.8 Overall, compared to the other entities in the differential diagnosis, DN easily can be prevented with consistent use of soap and water and may be underreported given the asymptomatic nature of the disease and the typical patient population.

- Poskitt L, Wayte J, Wojnarowska F, et al. ‘Dermatitis neglecta’: unwashed dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:827-829.

- Perez-Rodriguez IM, Munoz-Garza FZ, Ocampo-Candiani J. An unusually severe case of dermatosis neglecta: a diagnostic challenge. Case Rep Dermatol. 2014;6:194-199.

- Park JM, Roh MR, Kwon JE, et al. A case of generalized dermatitis neglecta mimicking psoriasis vulgaris. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1050-1051.

- Lopes S, Vide J, Antunes I, et al. Dermatitis neglecta: a challenging diagnosis in psychodermatology. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2018;27:109-110.

- Shah KR, Boland CR, Patel M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:189. e1-21; quiz 210.

- Patel NU, Roach C, Alinia H, et al. Current treatment options for acanthosis nigricans. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018; 11:407-413.

- Kurtyka DJ, Burke KT, DeKlotz CMC. Use of topical sirolimus (rapamycin) for treating confluent and reticulated papillomatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:121-123.

- Mufti A, Sachdeva M, Maliyar K, et al. Treatment outcomes in confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:825-829.

The Diagnosis: Dermatitis Neglecta

A punch biopsy of the abdomen revealed hyperkeratosis and mild papillomatosis (Figure), which can be seen in dermatitis neglecta (DN) and acanthosis nigricans (AN) as well as confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CARP). Due to the patient’s history of mood and psychotic disorders, collateral information was obtained from the patient’s family, who reported that the patient had a depressed mood in the last few months and was not showering or caring for herself during this period. There was no additional personal or family history of skin disease. Clinical and histopathologic findings led to a diagnosis of DN. Following recommendations for daily cleansing with soap and water along with topical ammonium lactate, near-complete resolution of the rash was achieved in 3 weeks.

Dermatitis neglecta, or unwashed dermatosis, is a skin condition that occurs secondary to poor hygiene, which was first reported in 1995 by Poskitt et al.1 Avoidance of washing in affected areas can be due to physical disability, pain after injury, neurological deficit, or psychologically induced fear or neglect. Sebum, sweat, corneocytes, and bacteria combine into compact adherent crusts of dirt, which appear as hyperkeratotic plaques with cornflakelike scale.2,3 Despite its innate simplicity, DN is a diagnostic challenge, as it clinically and histologically mimics other dermatoses including AN, terra firmaforme dermatosis, and CARP.2,4 Ultimately, the diagnosis of DN can be made when a history of poor hygiene is probable or elicited, and lesions can be removed with soap and water. Treatment of DN includes daily cleansing with soap and water; however, resistant lesions or extensive disease may require keratolytic agents, as in our patient.2-4 In contrast, terra firma-forme dermatosis, which may look similar, is not due to poor hygiene, and the lesions typically are resistant to soap and water, classically requiring isopropyl alcohol for removal. Overall, maintained awareness of DN is imperative, as early diagnosis can avoid unnecessary biopsies and more complex treatment measures as well as facilitate coordination of care when additional medical or psychiatric concerns are present.

Although the diagnoses of DN and terra firma-forme dermatosis can be distinguished based on the patient’s clinical history and response to simple cleansing measures alone, the alternate diagnoses can be excluded based on different clinical distributions and response to other treatment modalities but sometimes may require clinicopathologic correlation for definitive diagnosis. Our patient had a biopsy diagnosis of psoriasiform dermatitis from an outside provider, but neither her clinical disease nor repeated histopathologic findings supported a diagnosis of psoriasis or other classic psoriasiform dermatoses such as contact dermatitis, dermatophyte/ candidal infection, seborrheic dermatitis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, pityriasis rosea, scabies, or syphilis.

It is imperative to exclude alternative diagnoses because they can have systemic implications and can misguide treatment, as was done initially with our patient. Psoriasis vulgaris in its classic form is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that manifests as sharply demarcated, erythematous plaques with overlying thick silvery scale; it has the additional histologic findings of neutrophilic spongiform pustules in the epidermis, tortuous blood vessels in the papillary dermis, and neutrophils and parakeratosis in the stratum corneum. In its benign form, AN is associated with endocrinopathies, most commonly obesity and insulin-resistant diabetes mellitus, and presents as hyperkeratotic, velvety, hyperpigmented plaques typically limited to the neck and axillae. Malignant AN spontaneously arises in association with systemic malignancy and can be extensive and generalized.5 Treatment of AN primarily focuses on resolution of the underlying systemic disease; however, cosmetic treatment with topical or oral retinoids may hasten resolution of cutaneous disease.6 Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is characterized by reticulated hyperkeratotic plaques with a common distribution over the central and upper trunk. Unlike DN and AN, which may occur at any age, CARP typically is seen in adolescents and young adults.7 There is no evidence-based gold standard for the management of CARP; however, the successful use of various antibiotics, antifungals, and retinoids—alone or in combination—has been reported.8 Overall, compared to the other entities in the differential diagnosis, DN easily can be prevented with consistent use of soap and water and may be underreported given the asymptomatic nature of the disease and the typical patient population.

The Diagnosis: Dermatitis Neglecta

A punch biopsy of the abdomen revealed hyperkeratosis and mild papillomatosis (Figure), which can be seen in dermatitis neglecta (DN) and acanthosis nigricans (AN) as well as confluent and reticulated papillomatosis (CARP). Due to the patient’s history of mood and psychotic disorders, collateral information was obtained from the patient’s family, who reported that the patient had a depressed mood in the last few months and was not showering or caring for herself during this period. There was no additional personal or family history of skin disease. Clinical and histopathologic findings led to a diagnosis of DN. Following recommendations for daily cleansing with soap and water along with topical ammonium lactate, near-complete resolution of the rash was achieved in 3 weeks.

Dermatitis neglecta, or unwashed dermatosis, is a skin condition that occurs secondary to poor hygiene, which was first reported in 1995 by Poskitt et al.1 Avoidance of washing in affected areas can be due to physical disability, pain after injury, neurological deficit, or psychologically induced fear or neglect. Sebum, sweat, corneocytes, and bacteria combine into compact adherent crusts of dirt, which appear as hyperkeratotic plaques with cornflakelike scale.2,3 Despite its innate simplicity, DN is a diagnostic challenge, as it clinically and histologically mimics other dermatoses including AN, terra firmaforme dermatosis, and CARP.2,4 Ultimately, the diagnosis of DN can be made when a history of poor hygiene is probable or elicited, and lesions can be removed with soap and water. Treatment of DN includes daily cleansing with soap and water; however, resistant lesions or extensive disease may require keratolytic agents, as in our patient.2-4 In contrast, terra firma-forme dermatosis, which may look similar, is not due to poor hygiene, and the lesions typically are resistant to soap and water, classically requiring isopropyl alcohol for removal. Overall, maintained awareness of DN is imperative, as early diagnosis can avoid unnecessary biopsies and more complex treatment measures as well as facilitate coordination of care when additional medical or psychiatric concerns are present.

Although the diagnoses of DN and terra firma-forme dermatosis can be distinguished based on the patient’s clinical history and response to simple cleansing measures alone, the alternate diagnoses can be excluded based on different clinical distributions and response to other treatment modalities but sometimes may require clinicopathologic correlation for definitive diagnosis. Our patient had a biopsy diagnosis of psoriasiform dermatitis from an outside provider, but neither her clinical disease nor repeated histopathologic findings supported a diagnosis of psoriasis or other classic psoriasiform dermatoses such as contact dermatitis, dermatophyte/ candidal infection, seborrheic dermatitis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, pityriasis rosea, scabies, or syphilis.

It is imperative to exclude alternative diagnoses because they can have systemic implications and can misguide treatment, as was done initially with our patient. Psoriasis vulgaris in its classic form is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that manifests as sharply demarcated, erythematous plaques with overlying thick silvery scale; it has the additional histologic findings of neutrophilic spongiform pustules in the epidermis, tortuous blood vessels in the papillary dermis, and neutrophils and parakeratosis in the stratum corneum. In its benign form, AN is associated with endocrinopathies, most commonly obesity and insulin-resistant diabetes mellitus, and presents as hyperkeratotic, velvety, hyperpigmented plaques typically limited to the neck and axillae. Malignant AN spontaneously arises in association with systemic malignancy and can be extensive and generalized.5 Treatment of AN primarily focuses on resolution of the underlying systemic disease; however, cosmetic treatment with topical or oral retinoids may hasten resolution of cutaneous disease.6 Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis is characterized by reticulated hyperkeratotic plaques with a common distribution over the central and upper trunk. Unlike DN and AN, which may occur at any age, CARP typically is seen in adolescents and young adults.7 There is no evidence-based gold standard for the management of CARP; however, the successful use of various antibiotics, antifungals, and retinoids—alone or in combination—has been reported.8 Overall, compared to the other entities in the differential diagnosis, DN easily can be prevented with consistent use of soap and water and may be underreported given the asymptomatic nature of the disease and the typical patient population.

- Poskitt L, Wayte J, Wojnarowska F, et al. ‘Dermatitis neglecta’: unwashed dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:827-829.

- Perez-Rodriguez IM, Munoz-Garza FZ, Ocampo-Candiani J. An unusually severe case of dermatosis neglecta: a diagnostic challenge. Case Rep Dermatol. 2014;6:194-199.

- Park JM, Roh MR, Kwon JE, et al. A case of generalized dermatitis neglecta mimicking psoriasis vulgaris. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1050-1051.

- Lopes S, Vide J, Antunes I, et al. Dermatitis neglecta: a challenging diagnosis in psychodermatology. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2018;27:109-110.

- Shah KR, Boland CR, Patel M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:189. e1-21; quiz 210.

- Patel NU, Roach C, Alinia H, et al. Current treatment options for acanthosis nigricans. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018; 11:407-413.

- Kurtyka DJ, Burke KT, DeKlotz CMC. Use of topical sirolimus (rapamycin) for treating confluent and reticulated papillomatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:121-123.

- Mufti A, Sachdeva M, Maliyar K, et al. Treatment outcomes in confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:825-829.

- Poskitt L, Wayte J, Wojnarowska F, et al. ‘Dermatitis neglecta’: unwashed dermatosis. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:827-829.

- Perez-Rodriguez IM, Munoz-Garza FZ, Ocampo-Candiani J. An unusually severe case of dermatosis neglecta: a diagnostic challenge. Case Rep Dermatol. 2014;6:194-199.

- Park JM, Roh MR, Kwon JE, et al. A case of generalized dermatitis neglecta mimicking psoriasis vulgaris. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1050-1051.

- Lopes S, Vide J, Antunes I, et al. Dermatitis neglecta: a challenging diagnosis in psychodermatology. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2018;27:109-110.

- Shah KR, Boland CR, Patel M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease: part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:189. e1-21; quiz 210.

- Patel NU, Roach C, Alinia H, et al. Current treatment options for acanthosis nigricans. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018; 11:407-413.

- Kurtyka DJ, Burke KT, DeKlotz CMC. Use of topical sirolimus (rapamycin) for treating confluent and reticulated papillomatosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:121-123.

- Mufti A, Sachdeva M, Maliyar K, et al. Treatment outcomes in confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:825-829.

A 28-year-old woman was admitted to the medicine service with bilateral pedal numbness and ataxia, as well as an asymptomatic rash on the neck, chest, abdomen, and extremities of a few months’ duration. The patient was seen by an outside dermatologist for the same rash 1 month prior, at which time a punch biopsy of the right forearm was suggestive of psoriasiform dermatitis; however, the rash failed to improve with topical ammonium lactate and corticosteroids. During the current admission, the patient was found to have low methylmalonic acid and vitamin B1 levels; however, vitamin B12, thyroid studies, rapid plasma reagin test, and inflammatory markers, as well as central and peripheral imaging and nerve conduction studies were normal.

Dermatology was consulted. Physical examination revealed retention hyperkeratosis on the neck that was wipeable with 70% isopropyl alcohol, as well as nonwipeable, thin, reticulated plaques on the mid chest and thick velvety plaques on the abdomen and bilateral extremities. There was notable sparing of areas with natural occlusion such as the back and body folds. A punch biopsy of the abdomen was performed.

Acne Vulgaris

THE COMPARISON

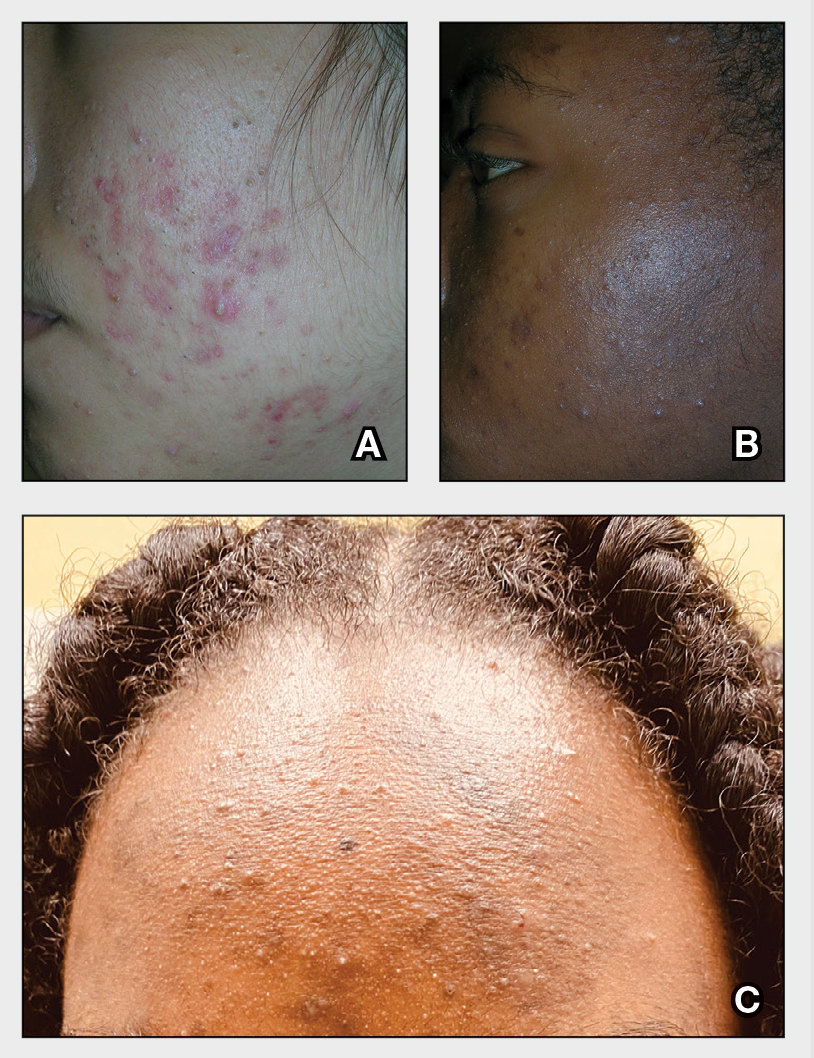

A A 27-year-old Hispanic woman with comedonal and inflammatory acne. Erythema is prominent around the inflammatory lesions. Note the pustule on the cheek surrounded by pink color.

B A teenaged Black boy with acne papules and pustules on the face. There are comedones, hyperpigmented macules, and pustules on the cheek.

C A teenaged Black girl with pomade acne. The patient used various hair care products, which obstructed the pilosebaceous units on the forehead.

Epidemiology

Acne is a leading dermatologic condition in individuals with skin of color in the United States.1

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones include:

- erythematous or hyperpigmented papules or comedones

- hyperpigmented macules and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH)

- increased risk for keloidal scars.2

Worth noting

- Patients with darker skin tones may be more concerned with the dark marks (also referred to as scars or manchas in Spanish) than the acne itself. This PIH may be viewed by patients as the major problem.

- Acne medications such as azelaic acid and some retinoids (when applied appropriately) can treat both acne and PIH.3

- Irritation from topical acne medications, including retinoid dermatitis, may lead to more PIH. Using noncomedogenic moisturizers and applying medication appropriately (ie, a pea-sized amount of topical retinoid per application) may help limit irritation.4,5

- One type of acne seen more commonly, although not exclusively, in Black patients is pomade acne, which principally appears on the forehead and is associated with use of hair care and styling products (Figure, C).

Health disparity highlight

Disparities in access to health care exist for those with dermatologic concerns. According to one study, African American (28.5%) and Hispanic patients (23.9%) were less likely to be seen by a dermatologist solely for the diagnosis of a dermatologic condition compared to Asian and Pacific Islander patients (36.7%) or White patients (43.2%).1

Noting that isotretinoin is the most potent systemic therapy for severe cystic acne vulgaris, Bell et al6 reported that Black patients had lower odds of receiving isotretinoin compared to White patients. Hispanic patients had lower odds of receiving a topical retinoid, tretinoin, than non-Hispanic patients.6

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Alexis AF, Woolery-Lloyd H, Williams K, et al. Racial/ethnic variations in acne: implications for treatment and skin care recommendations for acne patients with skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:716-725.

- Woolery-Lloyd HC, Keri J, Doig S. Retinoids and azelaic acid to treat acne and hyperpigmentation in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:434-437.

- Grayson C, Heath C. Tips for addressing common conditions affecting pediatric and adolescent patients with skin of color [published online March 2, 2021]. Pediatr Dermatol. doi:10.1111/pde.14525

- Alexis AD, Harper JC, Stein Gold L, et al. Treating acne in patients with skin of color. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37(suppl 3):S71-S73.

- Bell MA, Whang KA, Thomas J, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in access to emerging and frontline therapies in common dermatological conditions: a cross-sectional study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112:650-653.

THE COMPARISON

A A 27-year-old Hispanic woman with comedonal and inflammatory acne. Erythema is prominent around the inflammatory lesions. Note the pustule on the cheek surrounded by pink color.

B A teenaged Black boy with acne papules and pustules on the face. There are comedones, hyperpigmented macules, and pustules on the cheek.

C A teenaged Black girl with pomade acne. The patient used various hair care products, which obstructed the pilosebaceous units on the forehead.

Epidemiology

Acne is a leading dermatologic condition in individuals with skin of color in the United States.1

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones include:

- erythematous or hyperpigmented papules or comedones

- hyperpigmented macules and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH)

- increased risk for keloidal scars.2

Worth noting

- Patients with darker skin tones may be more concerned with the dark marks (also referred to as scars or manchas in Spanish) than the acne itself. This PIH may be viewed by patients as the major problem.

- Acne medications such as azelaic acid and some retinoids (when applied appropriately) can treat both acne and PIH.3

- Irritation from topical acne medications, including retinoid dermatitis, may lead to more PIH. Using noncomedogenic moisturizers and applying medication appropriately (ie, a pea-sized amount of topical retinoid per application) may help limit irritation.4,5

- One type of acne seen more commonly, although not exclusively, in Black patients is pomade acne, which principally appears on the forehead and is associated with use of hair care and styling products (Figure, C).

Health disparity highlight

Disparities in access to health care exist for those with dermatologic concerns. According to one study, African American (28.5%) and Hispanic patients (23.9%) were less likely to be seen by a dermatologist solely for the diagnosis of a dermatologic condition compared to Asian and Pacific Islander patients (36.7%) or White patients (43.2%).1

Noting that isotretinoin is the most potent systemic therapy for severe cystic acne vulgaris, Bell et al6 reported that Black patients had lower odds of receiving isotretinoin compared to White patients. Hispanic patients had lower odds of receiving a topical retinoid, tretinoin, than non-Hispanic patients.6

THE COMPARISON

A A 27-year-old Hispanic woman with comedonal and inflammatory acne. Erythema is prominent around the inflammatory lesions. Note the pustule on the cheek surrounded by pink color.

B A teenaged Black boy with acne papules and pustules on the face. There are comedones, hyperpigmented macules, and pustules on the cheek.

C A teenaged Black girl with pomade acne. The patient used various hair care products, which obstructed the pilosebaceous units on the forehead.

Epidemiology

Acne is a leading dermatologic condition in individuals with skin of color in the United States.1

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones include:

- erythematous or hyperpigmented papules or comedones

- hyperpigmented macules and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH)

- increased risk for keloidal scars.2

Worth noting

- Patients with darker skin tones may be more concerned with the dark marks (also referred to as scars or manchas in Spanish) than the acne itself. This PIH may be viewed by patients as the major problem.

- Acne medications such as azelaic acid and some retinoids (when applied appropriately) can treat both acne and PIH.3

- Irritation from topical acne medications, including retinoid dermatitis, may lead to more PIH. Using noncomedogenic moisturizers and applying medication appropriately (ie, a pea-sized amount of topical retinoid per application) may help limit irritation.4,5

- One type of acne seen more commonly, although not exclusively, in Black patients is pomade acne, which principally appears on the forehead and is associated with use of hair care and styling products (Figure, C).

Health disparity highlight

Disparities in access to health care exist for those with dermatologic concerns. According to one study, African American (28.5%) and Hispanic patients (23.9%) were less likely to be seen by a dermatologist solely for the diagnosis of a dermatologic condition compared to Asian and Pacific Islander patients (36.7%) or White patients (43.2%).1

Noting that isotretinoin is the most potent systemic therapy for severe cystic acne vulgaris, Bell et al6 reported that Black patients had lower odds of receiving isotretinoin compared to White patients. Hispanic patients had lower odds of receiving a topical retinoid, tretinoin, than non-Hispanic patients.6

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Alexis AF, Woolery-Lloyd H, Williams K, et al. Racial/ethnic variations in acne: implications for treatment and skin care recommendations for acne patients with skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:716-725.

- Woolery-Lloyd HC, Keri J, Doig S. Retinoids and azelaic acid to treat acne and hyperpigmentation in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:434-437.

- Grayson C, Heath C. Tips for addressing common conditions affecting pediatric and adolescent patients with skin of color [published online March 2, 2021]. Pediatr Dermatol. doi:10.1111/pde.14525

- Alexis AD, Harper JC, Stein Gold L, et al. Treating acne in patients with skin of color. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37(suppl 3):S71-S73.

- Bell MA, Whang KA, Thomas J, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in access to emerging and frontline therapies in common dermatological conditions: a cross-sectional study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112:650-653.

- Davis SA, Narahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Alexis AF, Woolery-Lloyd H, Williams K, et al. Racial/ethnic variations in acne: implications for treatment and skin care recommendations for acne patients with skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:716-725.

- Woolery-Lloyd HC, Keri J, Doig S. Retinoids and azelaic acid to treat acne and hyperpigmentation in skin of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:434-437.

- Grayson C, Heath C. Tips for addressing common conditions affecting pediatric and adolescent patients with skin of color [published online March 2, 2021]. Pediatr Dermatol. doi:10.1111/pde.14525

- Alexis AD, Harper JC, Stein Gold L, et al. Treating acne in patients with skin of color. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2018;37(suppl 3):S71-S73.

- Bell MA, Whang KA, Thomas J, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in access to emerging and frontline therapies in common dermatological conditions: a cross-sectional study. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112:650-653.

Erythematous and Ulcerated Plaque on the Left Temple

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Carcinosarcoma

The immunohistochemical findings supported an epithelial component consistent with moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and a mesenchymal component with features consistent with a sarcoma. Consequently, the lesion was diagnosed as a primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma (PCCS).

Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma is a rare biphasic neoplasm consisting of malignant epithelial (carcinoma) and mesenchymal (sarcoma) components.1 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas are uncommon, poorly understood, primary cutaneous tumors.2,3 Characteristic of this tumor, cytokeratins highlight the epithelial component while vimentin highlights the mesenchymal component.4 Histologically, the sarcomatous components of PCCS often are highly variable, with an absence of transitional areas within the epithelial component, which frequently resembles basal cell carcinoma and/ or SCC.5-7 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma favors areas of chronic UV radiation exposure, particularly on the head and neck. Most tumors present with a slowly growing, polypoid, flesh-colored to erythematous nodule due to the infiltrative mesenchymal component.7 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma primarily is diagnosed in elderly patients, with the majority of cases diagnosed in the eighth or ninth decades of life (range, 32–98 years).1,8 Men appear to be twice as likely to be diagnosed with a PCCS compared to women.1 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas are recognized as aggressive tumors with a high propensity to metastasize and recur locally, necessitating early diagnosis and treatment.4 Accurate diagnosis of PCCSs can be challenging due to the biphasic nature of the neoplasm as well as poor differentiation or unequal proportions of the epithelial and mesenchymal components.5 Additionally, overlapping diagnostic criteria coupled with vague demarcation between soft-tissue sarcomas and distinct carcinomas also may contribute to a delay in diagnosis.9 Treatment is achieved surgically by complete wide resection, with no evidence to support the use of adjuvant or neoadjuvant external beam radiation therapy. Due to the small number of reported cases, no treatment recommendations currently exist.1

Surgical management with wide local excision has been disappointing, with recurrence rates reported as high as 33%.6 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma has an estimated overall recurrence rate of 19% and a 5-year disease-free rate of 50%.10 Risk factors associated with poorer prognosis include tumors with adnexal subtype, age less than 65 years, rapid tumor growth, a tumor greater than 20 mm at presentation, and a long-standing tumor lasting up to 30 years.2,4 Although wide local excision and Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) both have been utilized successfully, MMS has been shown to result in a cure rate of greater than 98%.6

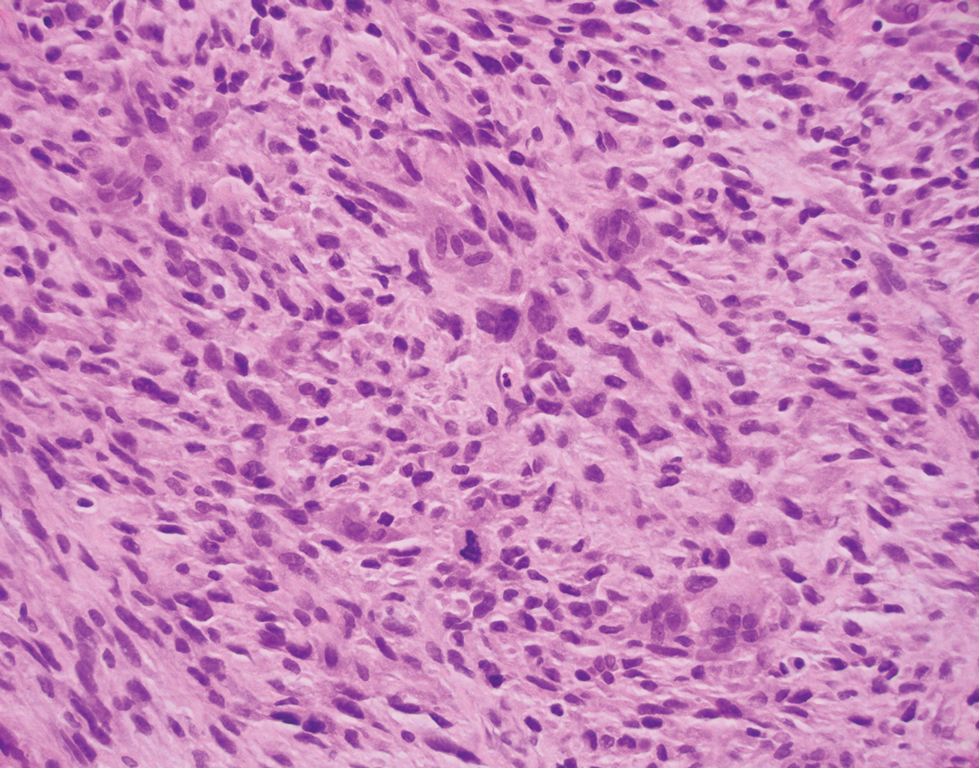

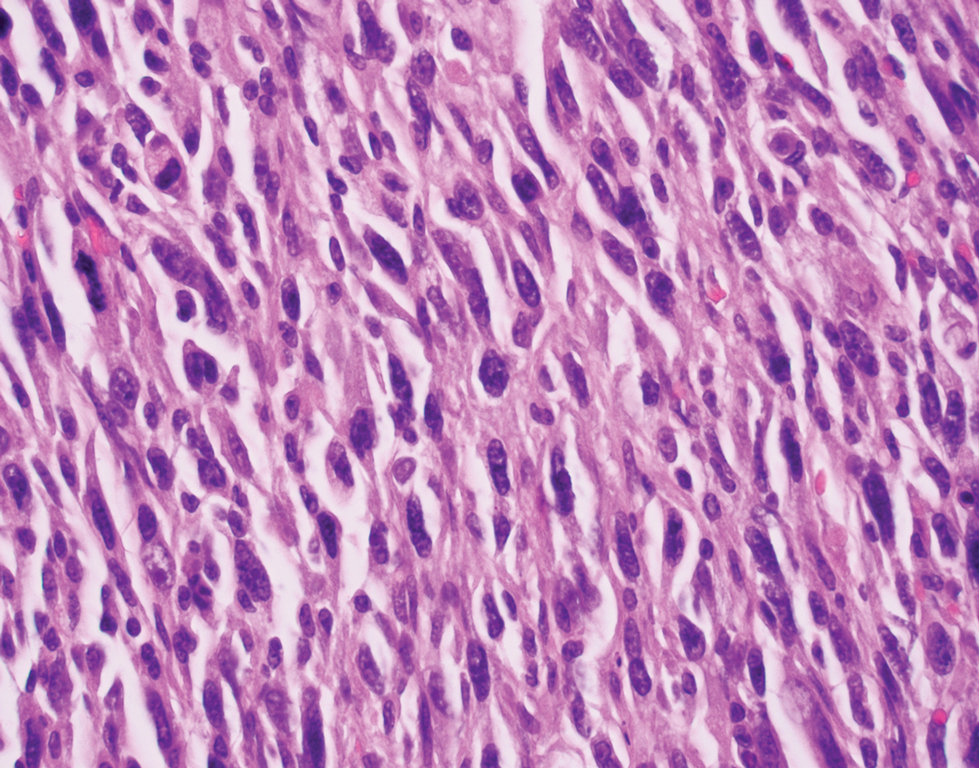

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) is a cutaneous tumor of fibrohistiocytic mesenchymal origin that typically manifests on sun-damaged skin in elderly individuals. Clinically, it presents as a rapidly growing neoplasm that often ulcerates and bleeds. These heterogenous neoplasms have several distinct characteristics, including dense cellularity with disorganized, large, pleomorphic, and atypical-appearing spindle-shaped cells arising in the upper layers of the dermis, often disseminating into the reticular dermis and occasionally into the subcutaneous fat (Figure 1). The neoplastic cells often exhibit hyperchromic and irregular nuclei, multinucleated giant cells, and atypical mitotic figures. In most cases, negative immunohistochemical staining with SOX-10, S-100, cytokeratins, desmin, and caldesmon will allow pathologists to differentiate between AFX and other common tumors on the differential diagnosis, such as SCC, melanoma, and leiomyosarcoma. CD10 and procollagen type 1 are positive antigenic markers in AFX, but they are not specific. The standard treatment of AFX includes wide local excision or MMS for superior margin control.11

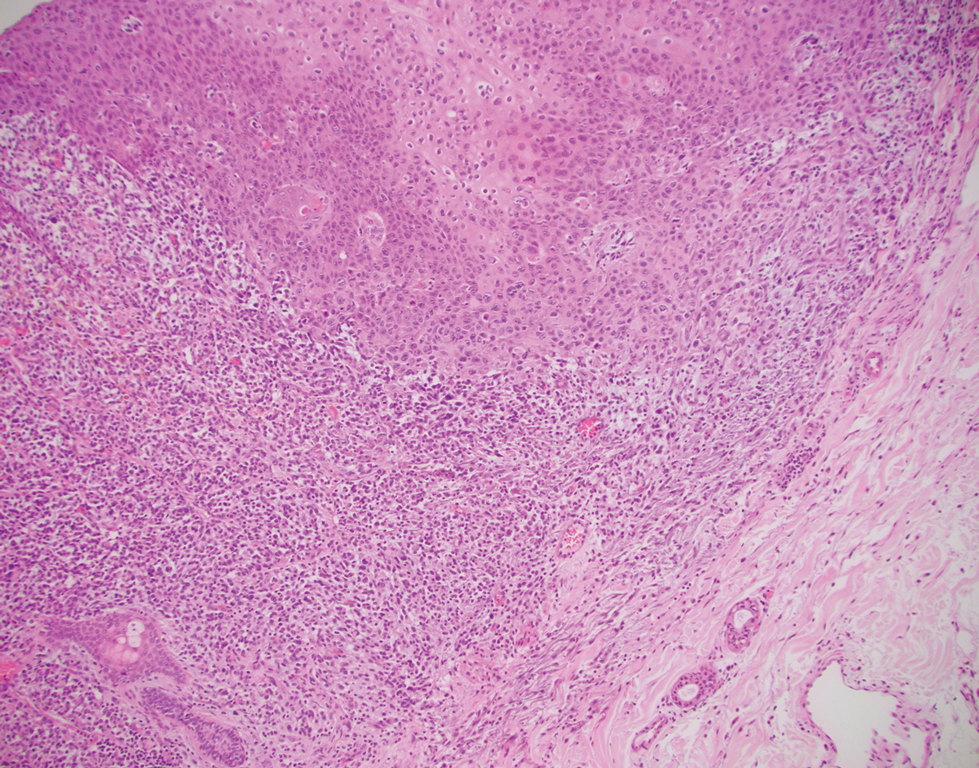

Spindle cell SCC presents as a raised or exophytic nodule, often with spontaneous bleeding and central ulceration. It usually presents on sun-damaged skin or in individuals with a history of ionizing radiation. Histologically, it is characterized by atypical spindleshaped keratinocytes in the dermis existing as single cells or cohesive nests along with keratin pearls (Figure 2). The atypical spindle cells may comprise the entire tumor or only a small portion. The use of immunohistochemical markers often is required to establish a definitive diagnosis. Spindle cell SCC stains positively, albeit frequently focally, for p63, p40, and high-molecular-weight cytokeratins such as cytokeratin 5/6, while S-100 protein, SOX-10, MART-1/Melan-A, and muscle-specific actin stains typically are negative. Wide local excision or MMS is recommended for treatment of these lesions.12

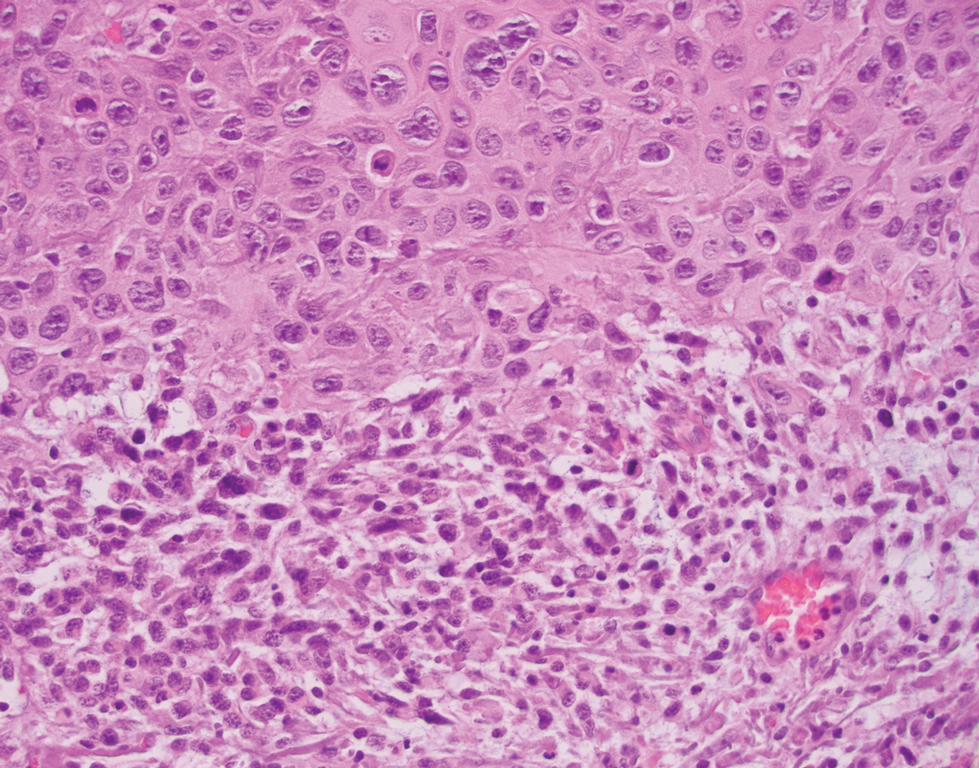

Primary cutaneous myoepithelial carcinomas are uncommon neoplasms of myoepithelial differentiation. Clinically, they often arise as soft nodular lesions on the head, neck, and lower extremities with a bimodal age distribution (50 years). Histologically cutaneous myoepithelial tumors are well-differentiated, dermal-based nodules without connection to the overlying epidermis (Figure 3). The myoepithelial cells can exhibit spindled, epithelioid, plasmacytoid, or clear cell morphologic features and show variability in cell growth patterns. One of the most common growth patterns is oval to round cells forming cords and chains in a chondromyxoid stroma. Most cases display an immunophenotyped co-expression of an epithelial cytokeratin and S-100 protein. Myoepithelial markers also may be present, including keratins, smooth muscle actin, calponin, glial fibrillary acidic protein, p63, and desmin. Surgical removal with wide local excision or MMS is essential.13

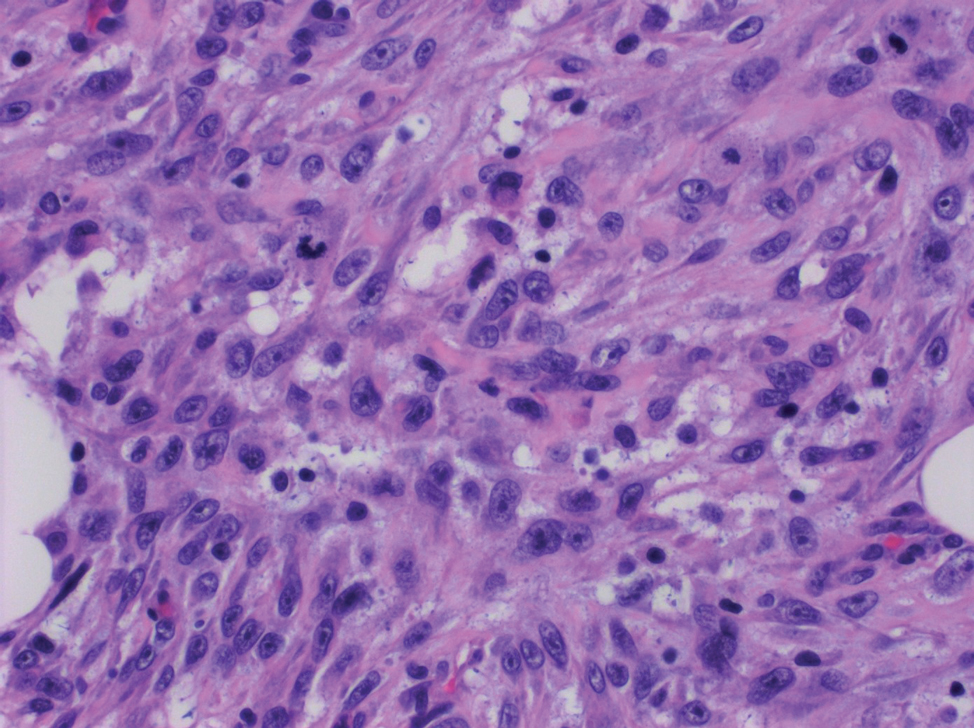

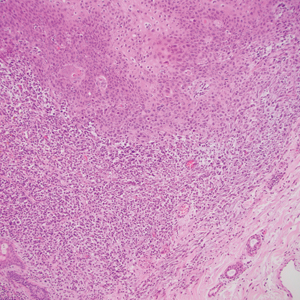

Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is a tumor that originates from smooth muscle and rarely develops in the dermis.14 Pleomorphic LMS is a morphologic variant of LMS that has a low propensity to metastasize but commonly exhibits local recurrence.15 Leiomyosarcoma can present in any age group but most commonly manifests in individuals aged 50 to 70 years. Clinically, LMS presents as a firm solitary nodule with a smooth pink surface or a more exophytic tumor with a reddish or brown color on the extensor surface of the lower limbs; it is less common on the scalp and face.14 Histologically, most cases of pleomorphic LMS show small foci of fascicles consisting of smooth muscle tumor cells in addition to cellular pleomorphism (Figure 4).15 Many of these cells demonstrate a clear perinuclear vacuole that generally is appreciated in neoplastic smooth muscle cells.14 Pleomorphic LMS typically stains positively for at least one smooth muscle marker including desmin, h-caldesmon, muscle-specific actin, α-smooth muscle actin, or smooth muscle myosin in the leiomyosarcomatous fascicular areas.16 Complete surgical excision is the treatment of choice, and the best results are obtained with MMS.14

- Syme-Grant J, Syme-Grant NJ, Motta L, et al. Are primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas underdiagnosed? five cases and a review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:1402-1408.

- Bourgeault E, Alain J, Gagne E. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma of the basal cell subtype should be treated as a high-risk basal cell carcinoma. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:407-411.

- West L, Srivastava D. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma of the medial canthus discovered on Mohs debulk analysis. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1700-1702.

- Kwan JM, Satter EK. Carcinosarcoma: a primary cutaneous tumor with biphasic differentiation. Cutis. 2013;92:247-249.

- Suh KY, Lacouture M, Gerami P. p63 in primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:374‐377.

- Ruiz-Villaverde R, Aneiros-Fernandez J. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma: a cutaneous neoplasm with an exceptional presentation. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2018;18:E114-E115.

- Smart CN, Pucci RA, Binder SW, et al. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma with myoepithelial differentiation: immunohistochemical and cytogenetic analysis of a case presenting in an unusual location. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:715‐717.

- Clark JJ, Bowen AR, Bowen GM, et al. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma: a series of six cases and a review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:34‐44.

- Müller CS, Pföhler C, Schiekofer C, et al. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas: a morphological histogenetic concept revisited. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:328‐339.

- Bellew S, Del Rosso JQ, Mobini N. Primary carcinosarcoma of the ear: case report and review of the literature. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:33‐35.

- Hong SH, Hong SJ, Lee Y, et al. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma of the shoulder: case report with literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:338-340.

- Soleymani T, Aasi SZ, Novoa R, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: updates on classification and management. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:253-259.

- Parekh V, Seykora JT. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:503-525.

- Johnson GE, Stevens K, Morrison AO, et al. Cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma with disseminated metastases. Cutis. 2017;99:E19-E26.

- Llombart B, Serra-Guillén C, Requena C, et al. Leiomyosarcoma and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019;110:4-11.

- Oda Y, Miyajima K, Kawaguchi K, et al. Pleomorphic leiomyosarcoma: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study with special emphasis on its distinction from ordinary leiomyosarcoma and malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1030-1038.

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Carcinosarcoma

The immunohistochemical findings supported an epithelial component consistent with moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and a mesenchymal component with features consistent with a sarcoma. Consequently, the lesion was diagnosed as a primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma (PCCS).

Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma is a rare biphasic neoplasm consisting of malignant epithelial (carcinoma) and mesenchymal (sarcoma) components.1 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas are uncommon, poorly understood, primary cutaneous tumors.2,3 Characteristic of this tumor, cytokeratins highlight the epithelial component while vimentin highlights the mesenchymal component.4 Histologically, the sarcomatous components of PCCS often are highly variable, with an absence of transitional areas within the epithelial component, which frequently resembles basal cell carcinoma and/ or SCC.5-7 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma favors areas of chronic UV radiation exposure, particularly on the head and neck. Most tumors present with a slowly growing, polypoid, flesh-colored to erythematous nodule due to the infiltrative mesenchymal component.7 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma primarily is diagnosed in elderly patients, with the majority of cases diagnosed in the eighth or ninth decades of life (range, 32–98 years).1,8 Men appear to be twice as likely to be diagnosed with a PCCS compared to women.1 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas are recognized as aggressive tumors with a high propensity to metastasize and recur locally, necessitating early diagnosis and treatment.4 Accurate diagnosis of PCCSs can be challenging due to the biphasic nature of the neoplasm as well as poor differentiation or unequal proportions of the epithelial and mesenchymal components.5 Additionally, overlapping diagnostic criteria coupled with vague demarcation between soft-tissue sarcomas and distinct carcinomas also may contribute to a delay in diagnosis.9 Treatment is achieved surgically by complete wide resection, with no evidence to support the use of adjuvant or neoadjuvant external beam radiation therapy. Due to the small number of reported cases, no treatment recommendations currently exist.1

Surgical management with wide local excision has been disappointing, with recurrence rates reported as high as 33%.6 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma has an estimated overall recurrence rate of 19% and a 5-year disease-free rate of 50%.10 Risk factors associated with poorer prognosis include tumors with adnexal subtype, age less than 65 years, rapid tumor growth, a tumor greater than 20 mm at presentation, and a long-standing tumor lasting up to 30 years.2,4 Although wide local excision and Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) both have been utilized successfully, MMS has been shown to result in a cure rate of greater than 98%.6

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) is a cutaneous tumor of fibrohistiocytic mesenchymal origin that typically manifests on sun-damaged skin in elderly individuals. Clinically, it presents as a rapidly growing neoplasm that often ulcerates and bleeds. These heterogenous neoplasms have several distinct characteristics, including dense cellularity with disorganized, large, pleomorphic, and atypical-appearing spindle-shaped cells arising in the upper layers of the dermis, often disseminating into the reticular dermis and occasionally into the subcutaneous fat (Figure 1). The neoplastic cells often exhibit hyperchromic and irregular nuclei, multinucleated giant cells, and atypical mitotic figures. In most cases, negative immunohistochemical staining with SOX-10, S-100, cytokeratins, desmin, and caldesmon will allow pathologists to differentiate between AFX and other common tumors on the differential diagnosis, such as SCC, melanoma, and leiomyosarcoma. CD10 and procollagen type 1 are positive antigenic markers in AFX, but they are not specific. The standard treatment of AFX includes wide local excision or MMS for superior margin control.11

Spindle cell SCC presents as a raised or exophytic nodule, often with spontaneous bleeding and central ulceration. It usually presents on sun-damaged skin or in individuals with a history of ionizing radiation. Histologically, it is characterized by atypical spindleshaped keratinocytes in the dermis existing as single cells or cohesive nests along with keratin pearls (Figure 2). The atypical spindle cells may comprise the entire tumor or only a small portion. The use of immunohistochemical markers often is required to establish a definitive diagnosis. Spindle cell SCC stains positively, albeit frequently focally, for p63, p40, and high-molecular-weight cytokeratins such as cytokeratin 5/6, while S-100 protein, SOX-10, MART-1/Melan-A, and muscle-specific actin stains typically are negative. Wide local excision or MMS is recommended for treatment of these lesions.12

Primary cutaneous myoepithelial carcinomas are uncommon neoplasms of myoepithelial differentiation. Clinically, they often arise as soft nodular lesions on the head, neck, and lower extremities with a bimodal age distribution (50 years). Histologically cutaneous myoepithelial tumors are well-differentiated, dermal-based nodules without connection to the overlying epidermis (Figure 3). The myoepithelial cells can exhibit spindled, epithelioid, plasmacytoid, or clear cell morphologic features and show variability in cell growth patterns. One of the most common growth patterns is oval to round cells forming cords and chains in a chondromyxoid stroma. Most cases display an immunophenotyped co-expression of an epithelial cytokeratin and S-100 protein. Myoepithelial markers also may be present, including keratins, smooth muscle actin, calponin, glial fibrillary acidic protein, p63, and desmin. Surgical removal with wide local excision or MMS is essential.13

Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is a tumor that originates from smooth muscle and rarely develops in the dermis.14 Pleomorphic LMS is a morphologic variant of LMS that has a low propensity to metastasize but commonly exhibits local recurrence.15 Leiomyosarcoma can present in any age group but most commonly manifests in individuals aged 50 to 70 years. Clinically, LMS presents as a firm solitary nodule with a smooth pink surface or a more exophytic tumor with a reddish or brown color on the extensor surface of the lower limbs; it is less common on the scalp and face.14 Histologically, most cases of pleomorphic LMS show small foci of fascicles consisting of smooth muscle tumor cells in addition to cellular pleomorphism (Figure 4).15 Many of these cells demonstrate a clear perinuclear vacuole that generally is appreciated in neoplastic smooth muscle cells.14 Pleomorphic LMS typically stains positively for at least one smooth muscle marker including desmin, h-caldesmon, muscle-specific actin, α-smooth muscle actin, or smooth muscle myosin in the leiomyosarcomatous fascicular areas.16 Complete surgical excision is the treatment of choice, and the best results are obtained with MMS.14

The Diagnosis: Primary Cutaneous Carcinosarcoma

The immunohistochemical findings supported an epithelial component consistent with moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and a mesenchymal component with features consistent with a sarcoma. Consequently, the lesion was diagnosed as a primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma (PCCS).

Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma is a rare biphasic neoplasm consisting of malignant epithelial (carcinoma) and mesenchymal (sarcoma) components.1 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas are uncommon, poorly understood, primary cutaneous tumors.2,3 Characteristic of this tumor, cytokeratins highlight the epithelial component while vimentin highlights the mesenchymal component.4 Histologically, the sarcomatous components of PCCS often are highly variable, with an absence of transitional areas within the epithelial component, which frequently resembles basal cell carcinoma and/ or SCC.5-7 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma favors areas of chronic UV radiation exposure, particularly on the head and neck. Most tumors present with a slowly growing, polypoid, flesh-colored to erythematous nodule due to the infiltrative mesenchymal component.7 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma primarily is diagnosed in elderly patients, with the majority of cases diagnosed in the eighth or ninth decades of life (range, 32–98 years).1,8 Men appear to be twice as likely to be diagnosed with a PCCS compared to women.1 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas are recognized as aggressive tumors with a high propensity to metastasize and recur locally, necessitating early diagnosis and treatment.4 Accurate diagnosis of PCCSs can be challenging due to the biphasic nature of the neoplasm as well as poor differentiation or unequal proportions of the epithelial and mesenchymal components.5 Additionally, overlapping diagnostic criteria coupled with vague demarcation between soft-tissue sarcomas and distinct carcinomas also may contribute to a delay in diagnosis.9 Treatment is achieved surgically by complete wide resection, with no evidence to support the use of adjuvant or neoadjuvant external beam radiation therapy. Due to the small number of reported cases, no treatment recommendations currently exist.1

Surgical management with wide local excision has been disappointing, with recurrence rates reported as high as 33%.6 Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma has an estimated overall recurrence rate of 19% and a 5-year disease-free rate of 50%.10 Risk factors associated with poorer prognosis include tumors with adnexal subtype, age less than 65 years, rapid tumor growth, a tumor greater than 20 mm at presentation, and a long-standing tumor lasting up to 30 years.2,4 Although wide local excision and Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) both have been utilized successfully, MMS has been shown to result in a cure rate of greater than 98%.6

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) is a cutaneous tumor of fibrohistiocytic mesenchymal origin that typically manifests on sun-damaged skin in elderly individuals. Clinically, it presents as a rapidly growing neoplasm that often ulcerates and bleeds. These heterogenous neoplasms have several distinct characteristics, including dense cellularity with disorganized, large, pleomorphic, and atypical-appearing spindle-shaped cells arising in the upper layers of the dermis, often disseminating into the reticular dermis and occasionally into the subcutaneous fat (Figure 1). The neoplastic cells often exhibit hyperchromic and irregular nuclei, multinucleated giant cells, and atypical mitotic figures. In most cases, negative immunohistochemical staining with SOX-10, S-100, cytokeratins, desmin, and caldesmon will allow pathologists to differentiate between AFX and other common tumors on the differential diagnosis, such as SCC, melanoma, and leiomyosarcoma. CD10 and procollagen type 1 are positive antigenic markers in AFX, but they are not specific. The standard treatment of AFX includes wide local excision or MMS for superior margin control.11

Spindle cell SCC presents as a raised or exophytic nodule, often with spontaneous bleeding and central ulceration. It usually presents on sun-damaged skin or in individuals with a history of ionizing radiation. Histologically, it is characterized by atypical spindleshaped keratinocytes in the dermis existing as single cells or cohesive nests along with keratin pearls (Figure 2). The atypical spindle cells may comprise the entire tumor or only a small portion. The use of immunohistochemical markers often is required to establish a definitive diagnosis. Spindle cell SCC stains positively, albeit frequently focally, for p63, p40, and high-molecular-weight cytokeratins such as cytokeratin 5/6, while S-100 protein, SOX-10, MART-1/Melan-A, and muscle-specific actin stains typically are negative. Wide local excision or MMS is recommended for treatment of these lesions.12

Primary cutaneous myoepithelial carcinomas are uncommon neoplasms of myoepithelial differentiation. Clinically, they often arise as soft nodular lesions on the head, neck, and lower extremities with a bimodal age distribution (50 years). Histologically cutaneous myoepithelial tumors are well-differentiated, dermal-based nodules without connection to the overlying epidermis (Figure 3). The myoepithelial cells can exhibit spindled, epithelioid, plasmacytoid, or clear cell morphologic features and show variability in cell growth patterns. One of the most common growth patterns is oval to round cells forming cords and chains in a chondromyxoid stroma. Most cases display an immunophenotyped co-expression of an epithelial cytokeratin and S-100 protein. Myoepithelial markers also may be present, including keratins, smooth muscle actin, calponin, glial fibrillary acidic protein, p63, and desmin. Surgical removal with wide local excision or MMS is essential.13

Leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is a tumor that originates from smooth muscle and rarely develops in the dermis.14 Pleomorphic LMS is a morphologic variant of LMS that has a low propensity to metastasize but commonly exhibits local recurrence.15 Leiomyosarcoma can present in any age group but most commonly manifests in individuals aged 50 to 70 years. Clinically, LMS presents as a firm solitary nodule with a smooth pink surface or a more exophytic tumor with a reddish or brown color on the extensor surface of the lower limbs; it is less common on the scalp and face.14 Histologically, most cases of pleomorphic LMS show small foci of fascicles consisting of smooth muscle tumor cells in addition to cellular pleomorphism (Figure 4).15 Many of these cells demonstrate a clear perinuclear vacuole that generally is appreciated in neoplastic smooth muscle cells.14 Pleomorphic LMS typically stains positively for at least one smooth muscle marker including desmin, h-caldesmon, muscle-specific actin, α-smooth muscle actin, or smooth muscle myosin in the leiomyosarcomatous fascicular areas.16 Complete surgical excision is the treatment of choice, and the best results are obtained with MMS.14

- Syme-Grant J, Syme-Grant NJ, Motta L, et al. Are primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas underdiagnosed? five cases and a review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:1402-1408.

- Bourgeault E, Alain J, Gagne E. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma of the basal cell subtype should be treated as a high-risk basal cell carcinoma. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:407-411.

- West L, Srivastava D. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma of the medial canthus discovered on Mohs debulk analysis. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1700-1702.

- Kwan JM, Satter EK. Carcinosarcoma: a primary cutaneous tumor with biphasic differentiation. Cutis. 2013;92:247-249.

- Suh KY, Lacouture M, Gerami P. p63 in primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:374‐377.

- Ruiz-Villaverde R, Aneiros-Fernandez J. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma: a cutaneous neoplasm with an exceptional presentation. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2018;18:E114-E115.

- Smart CN, Pucci RA, Binder SW, et al. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma with myoepithelial differentiation: immunohistochemical and cytogenetic analysis of a case presenting in an unusual location. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:715‐717.

- Clark JJ, Bowen AR, Bowen GM, et al. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma: a series of six cases and a review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:34‐44.

- Müller CS, Pföhler C, Schiekofer C, et al. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas: a morphological histogenetic concept revisited. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:328‐339.

- Bellew S, Del Rosso JQ, Mobini N. Primary carcinosarcoma of the ear: case report and review of the literature. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:33‐35.

- Hong SH, Hong SJ, Lee Y, et al. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma of the shoulder: case report with literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:338-340.

- Soleymani T, Aasi SZ, Novoa R, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: updates on classification and management. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:253-259.

- Parekh V, Seykora JT. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:503-525.

- Johnson GE, Stevens K, Morrison AO, et al. Cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma with disseminated metastases. Cutis. 2017;99:E19-E26.

- Llombart B, Serra-Guillén C, Requena C, et al. Leiomyosarcoma and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019;110:4-11.

- Oda Y, Miyajima K, Kawaguchi K, et al. Pleomorphic leiomyosarcoma: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study with special emphasis on its distinction from ordinary leiomyosarcoma and malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1030-1038.

- Syme-Grant J, Syme-Grant NJ, Motta L, et al. Are primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas underdiagnosed? five cases and a review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:1402-1408.

- Bourgeault E, Alain J, Gagne E. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma of the basal cell subtype should be treated as a high-risk basal cell carcinoma. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:407-411.

- West L, Srivastava D. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma of the medial canthus discovered on Mohs debulk analysis. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:1700-1702.

- Kwan JM, Satter EK. Carcinosarcoma: a primary cutaneous tumor with biphasic differentiation. Cutis. 2013;92:247-249.

- Suh KY, Lacouture M, Gerami P. p63 in primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:374‐377.

- Ruiz-Villaverde R, Aneiros-Fernandez J. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma: a cutaneous neoplasm with an exceptional presentation. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2018;18:E114-E115.

- Smart CN, Pucci RA, Binder SW, et al. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma with myoepithelial differentiation: immunohistochemical and cytogenetic analysis of a case presenting in an unusual location. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:715‐717.

- Clark JJ, Bowen AR, Bowen GM, et al. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma: a series of six cases and a review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:34‐44.

- Müller CS, Pföhler C, Schiekofer C, et al. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcomas: a morphological histogenetic concept revisited. Am J Dermatopathol. 2014;36:328‐339.

- Bellew S, Del Rosso JQ, Mobini N. Primary carcinosarcoma of the ear: case report and review of the literature. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:33‐35.

- Hong SH, Hong SJ, Lee Y, et al. Primary cutaneous carcinosarcoma of the shoulder: case report with literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:338-340.

- Soleymani T, Aasi SZ, Novoa R, et al. Atypical fibroxanthoma and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: updates on classification and management. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:253-259.

- Parekh V, Seykora JT. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Lab Med. 2017;37:503-525.

- Johnson GE, Stevens K, Morrison AO, et al. Cutaneous myoepithelial carcinoma with disseminated metastases. Cutis. 2017;99:E19-E26.

- Llombart B, Serra-Guillén C, Requena C, et al. Leiomyosarcoma and pleomorphic dermal sarcoma: guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019;110:4-11.

- Oda Y, Miyajima K, Kawaguchi K, et al. Pleomorphic leiomyosarcoma: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study with special emphasis on its distinction from ordinary leiomyosarcoma and malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1030-1038.

A 72-year-old man with a history of nonmelanoma skin cancer and lung transplant maintained on stable doses of prednisone and tacrolimus presented with a 1.3×1.8-cm, slow-growing, well-demarcated, ulcerated, erythematous plaque with overlying serous crust on the left temple of 6 months’ duration. No cervical or axillary lymphadenopathy was appreciated on physical examination. A biopsy was performed followed by Mohs micrographic surgery. Microscopic examination of the debulking specimen revealed atypical spindle cells in the papillary and reticular dermis radiating from a central focus of a moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma. The squamous cells stained positive for cytokeratin 5/6, pankeratin, and p40, while the spindle cells stained positive only for vimentin.

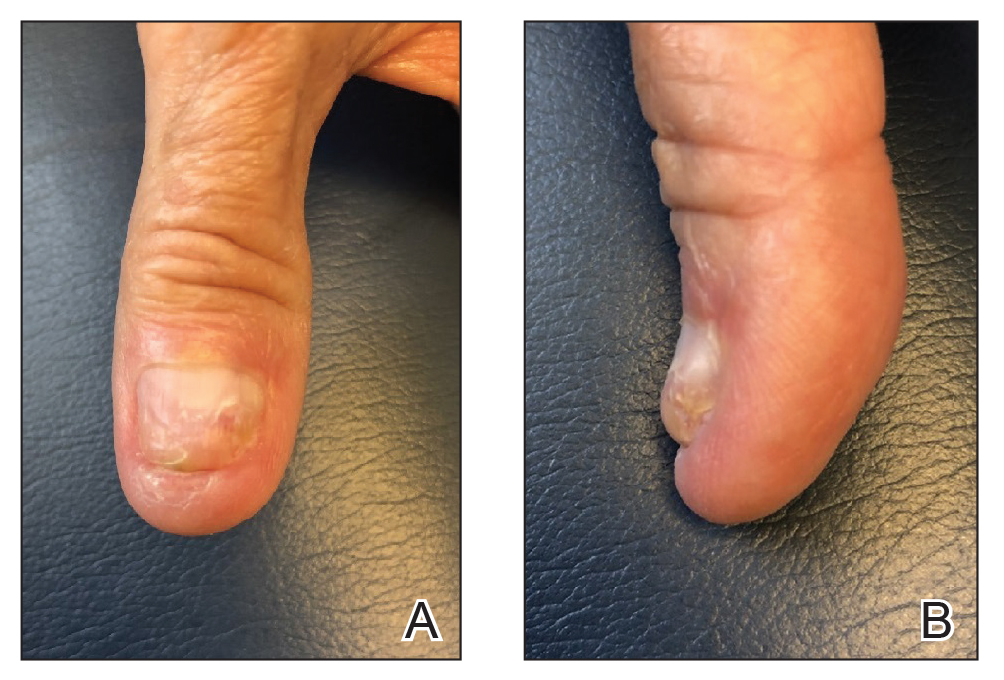

Spiral Plaque on the Left Ankle

The Diagnosis: Recurrent Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma

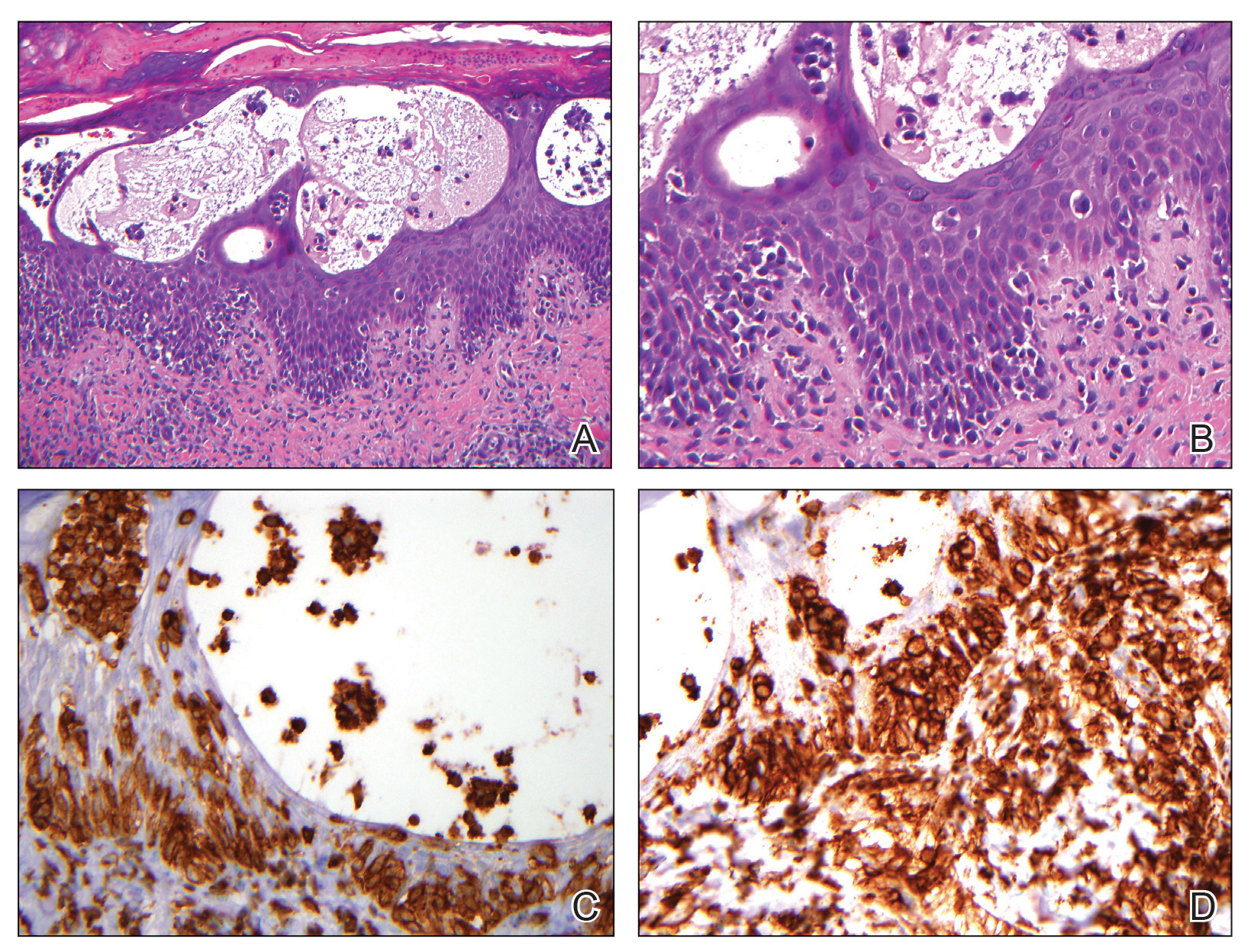

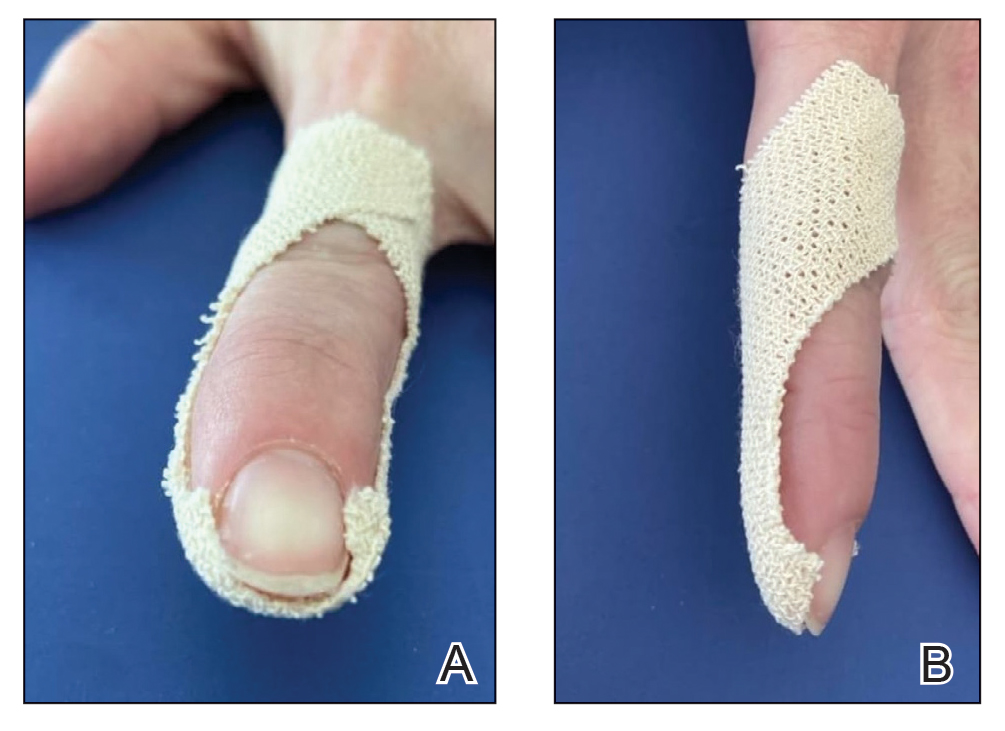

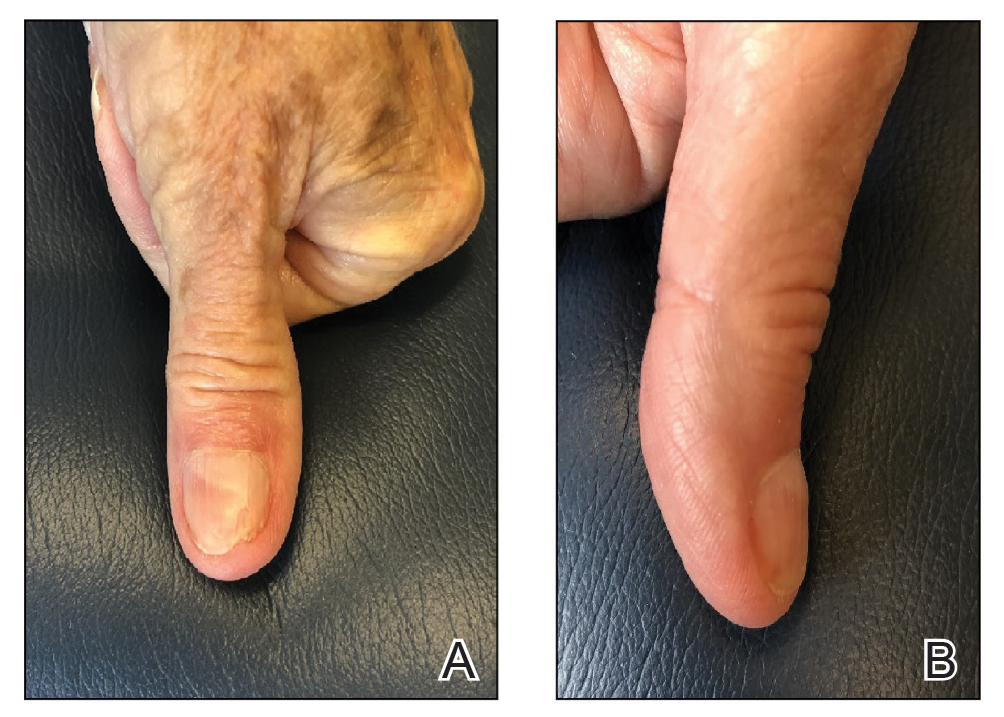

The skin biopsy revealed alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis with mild to moderate spongiosis and intraepidermal vesiculation as well as individual and nested atypical mononuclear cells with moderately enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei in the epidermis. There was a superficial interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate with occasional enlarged cells (Figure, A and B), and atypical cells in the epidermis and dermis stained with antibodies against CD3 and CD4 (Figure, C and D) but not against CD20 or CD8. These histopathologic findings were consistent with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), mycosis fungoides (MF) type. Additional application of bexarotene gel on days the patient received narrowband UVB was recommended with noted improvement of the skin.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas are a heterogenous group of diseases with monoclonal proliferation of T lymphocytes that largely are confined to the skin at the time of diagnosis.1 The incidence of CTCL rose steadily for more than 25 years, with an annual age-adjusted incidence of 6.4 to 9.6 cases per million individuals in the United States from 1973 to 2002.2 Mycosis fungoides is the most common classification of CTCL. It usually is characterized by patches or plaques of scaly erythema or poikiloderma; however, it also can present with annular, arcuate, concentrative, annular and linear morphologies. Mycosis fungoides tumor cells typically express a mature memory T helper cell phenotype of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8−, but there are different variants that have been discovered.3 Mycosis fungoides distributed in a spiral pattern is a distinctly unusual manifestation. Mechanisms of such dynamic morphologies are unknown but may represent an interplay between malignant cell proliferation and lost immune responses in temporospatial relationships.

The presence of keratotic gyrate lesions on acral surfaces should raise the possibility of pagetoid reticulosis. However, our patient had a history of MF involving areas of the body beyond the extremities, making this diagnosis less likely. Pagetoid reticulosis is categorized as an MF variant under the current World Health Organization– European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification for cutaneous lymphomas.4 Pagetoid reticulosis clinically presents as a solitary psoriasiform or hyperkeratotic patch or plaque that affects the distal extremities. Variable immunophenotypes have been shown in pagetoid reticulosis, such as CD4−/CD8+ and CD4−/CD8−, while classic MF typically shows CD4+/CD8−, as in our case.5

Tinea pedis is a superficial fungal infection usually caused by anthropophilic dermatophytes, with Trichophyton rubrum being the most common organism. Four common clinical presentations of tinea pedis have been identified: interdigital, moccasin, vesicular, and acute ulcerative. Clinical presentation ranges from macerations, ulcerations, and erosions in the toe web spaces to dry hyperkeratotic scaling and fissures on the plantar foot.6 Tinea pedis primarily affects the plantar and interdigital spaces, sparing the dorsal foot and ankle. Treatment is recommended to alleviate symptoms and limit the spread of infection; topical antifungals for 4 weeks is the treatment of choice. However, recurrence is common, and maintenance therapy often is indicated. Oral antifungals or a combination of both topical and oral medications may be needed in certain cases.7

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) is a rare dermatologic disease described as erythematous or urticarial papules that can enlarge centrifugally to form annular lesions that clear centrally. Thought to be a hypersensitivity reaction to an underlying condition, EAC has been associated with fungal infections, various cutaneous diseases, and even internal malignancies. Clinically, EAC can be divided into 2 forms: deep and superficial. Deep gyrate erythema is characterized by a firm indurated border with rare scaling and pruritus that histologically shows perivascular lymphocytic infiltration in the upper and deep dermis. Superficial gyrate erythema has minimally elevated lesions with an indistinct border and trailing scales and pruritus; histopathologic findings present a dense, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltration restricted to the upper dermis.8 Therapy for EAC is directed at relieving symptoms and treating the underlying condition if there is one associated.

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a common skin disorder classically characterized by ringed erythematous plaques, though many variants have been identified. Localized GA is the most common variant and presents with pink-red, nonscaly, annular patches or plaques, typically affecting the hands and feet. Generalized GA is characterized as diffuse annular patches or plaques classically affecting the trunk and extremities. Histology is notable for mucin with a palisading or interstitial pattern of granulomatous inflammation, which was not evident in our patient.9 Topical or intralesional corticosteroids are the first-line treatment of localized GA; however, localized GA generally is self-limited, and treatment often is not necessary. Treatment with cryosurgery, laser therapy, and topical dapsone and tacrolimus also has been described, but evidence of the efficacy of these agents is limited. For generalized GA, phototherapy currently is the most reliable therapy. Systemic therapies include antimalarials, fumaric acid esters, biologics, antimicrobials, and isotretinoin.10

Erythema gyratum repens (EGR) is a rare dermatologic disease described as erythematous concentric bands arranged in parallel rings that can be annular, figurate, or gyrate, with a fine scale trailing the leading edge. Histopathologic features of EGR are nonspecific but are characterized by a perivascular, superficial, mononuclear dermatitis. Diagnosis is based on its characteristic clinical presentation. Although EGR commonly is associated with internal malignancies such as bronchial carcinoma, it also may be associated with benign conditions.11 Improvement often is seen with successful therapy of the underlying associated malignancy.12

Treatment of MF is based on tumor-node-metastasisblood classification, prognostic factors, and clinical stage at the time of diagnosis. Early-stage MF (IA–IIA) commonly is treated with skin-directed therapies such as topical corticosteroids, topical mechlorethamine, topical retinoids, UV phototherapy, and localized radiotherapy. In late stages (IIB–IV), systemic therapy is indicated and includes systemic retinoids, interferon alfa, chemotherapy, monoclonal antibodies, and psoralen plus UVA.13 In many cases, patients may require combination therapy to achieve remission or better control of their condition, as in our patient.

The Diagnosis: Recurrent Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma

The skin biopsy revealed alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis with mild to moderate spongiosis and intraepidermal vesiculation as well as individual and nested atypical mononuclear cells with moderately enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei in the epidermis. There was a superficial interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate with occasional enlarged cells (Figure, A and B), and atypical cells in the epidermis and dermis stained with antibodies against CD3 and CD4 (Figure, C and D) but not against CD20 or CD8. These histopathologic findings were consistent with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), mycosis fungoides (MF) type. Additional application of bexarotene gel on days the patient received narrowband UVB was recommended with noted improvement of the skin.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas are a heterogenous group of diseases with monoclonal proliferation of T lymphocytes that largely are confined to the skin at the time of diagnosis.1 The incidence of CTCL rose steadily for more than 25 years, with an annual age-adjusted incidence of 6.4 to 9.6 cases per million individuals in the United States from 1973 to 2002.2 Mycosis fungoides is the most common classification of CTCL. It usually is characterized by patches or plaques of scaly erythema or poikiloderma; however, it also can present with annular, arcuate, concentrative, annular and linear morphologies. Mycosis fungoides tumor cells typically express a mature memory T helper cell phenotype of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8−, but there are different variants that have been discovered.3 Mycosis fungoides distributed in a spiral pattern is a distinctly unusual manifestation. Mechanisms of such dynamic morphologies are unknown but may represent an interplay between malignant cell proliferation and lost immune responses in temporospatial relationships.

The presence of keratotic gyrate lesions on acral surfaces should raise the possibility of pagetoid reticulosis. However, our patient had a history of MF involving areas of the body beyond the extremities, making this diagnosis less likely. Pagetoid reticulosis is categorized as an MF variant under the current World Health Organization– European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification for cutaneous lymphomas.4 Pagetoid reticulosis clinically presents as a solitary psoriasiform or hyperkeratotic patch or plaque that affects the distal extremities. Variable immunophenotypes have been shown in pagetoid reticulosis, such as CD4−/CD8+ and CD4−/CD8−, while classic MF typically shows CD4+/CD8−, as in our case.5

Tinea pedis is a superficial fungal infection usually caused by anthropophilic dermatophytes, with Trichophyton rubrum being the most common organism. Four common clinical presentations of tinea pedis have been identified: interdigital, moccasin, vesicular, and acute ulcerative. Clinical presentation ranges from macerations, ulcerations, and erosions in the toe web spaces to dry hyperkeratotic scaling and fissures on the plantar foot.6 Tinea pedis primarily affects the plantar and interdigital spaces, sparing the dorsal foot and ankle. Treatment is recommended to alleviate symptoms and limit the spread of infection; topical antifungals for 4 weeks is the treatment of choice. However, recurrence is common, and maintenance therapy often is indicated. Oral antifungals or a combination of both topical and oral medications may be needed in certain cases.7

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) is a rare dermatologic disease described as erythematous or urticarial papules that can enlarge centrifugally to form annular lesions that clear centrally. Thought to be a hypersensitivity reaction to an underlying condition, EAC has been associated with fungal infections, various cutaneous diseases, and even internal malignancies. Clinically, EAC can be divided into 2 forms: deep and superficial. Deep gyrate erythema is characterized by a firm indurated border with rare scaling and pruritus that histologically shows perivascular lymphocytic infiltration in the upper and deep dermis. Superficial gyrate erythema has minimally elevated lesions with an indistinct border and trailing scales and pruritus; histopathologic findings present a dense, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltration restricted to the upper dermis.8 Therapy for EAC is directed at relieving symptoms and treating the underlying condition if there is one associated.

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a common skin disorder classically characterized by ringed erythematous plaques, though many variants have been identified. Localized GA is the most common variant and presents with pink-red, nonscaly, annular patches or plaques, typically affecting the hands and feet. Generalized GA is characterized as diffuse annular patches or plaques classically affecting the trunk and extremities. Histology is notable for mucin with a palisading or interstitial pattern of granulomatous inflammation, which was not evident in our patient.9 Topical or intralesional corticosteroids are the first-line treatment of localized GA; however, localized GA generally is self-limited, and treatment often is not necessary. Treatment with cryosurgery, laser therapy, and topical dapsone and tacrolimus also has been described, but evidence of the efficacy of these agents is limited. For generalized GA, phototherapy currently is the most reliable therapy. Systemic therapies include antimalarials, fumaric acid esters, biologics, antimicrobials, and isotretinoin.10

Erythema gyratum repens (EGR) is a rare dermatologic disease described as erythematous concentric bands arranged in parallel rings that can be annular, figurate, or gyrate, with a fine scale trailing the leading edge. Histopathologic features of EGR are nonspecific but are characterized by a perivascular, superficial, mononuclear dermatitis. Diagnosis is based on its characteristic clinical presentation. Although EGR commonly is associated with internal malignancies such as bronchial carcinoma, it also may be associated with benign conditions.11 Improvement often is seen with successful therapy of the underlying associated malignancy.12

Treatment of MF is based on tumor-node-metastasisblood classification, prognostic factors, and clinical stage at the time of diagnosis. Early-stage MF (IA–IIA) commonly is treated with skin-directed therapies such as topical corticosteroids, topical mechlorethamine, topical retinoids, UV phototherapy, and localized radiotherapy. In late stages (IIB–IV), systemic therapy is indicated and includes systemic retinoids, interferon alfa, chemotherapy, monoclonal antibodies, and psoralen plus UVA.13 In many cases, patients may require combination therapy to achieve remission or better control of their condition, as in our patient.

The Diagnosis: Recurrent Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma

The skin biopsy revealed alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis with mild to moderate spongiosis and intraepidermal vesiculation as well as individual and nested atypical mononuclear cells with moderately enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei in the epidermis. There was a superficial interstitial lymphocytic infiltrate with occasional enlarged cells (Figure, A and B), and atypical cells in the epidermis and dermis stained with antibodies against CD3 and CD4 (Figure, C and D) but not against CD20 or CD8. These histopathologic findings were consistent with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), mycosis fungoides (MF) type. Additional application of bexarotene gel on days the patient received narrowband UVB was recommended with noted improvement of the skin.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas are a heterogenous group of diseases with monoclonal proliferation of T lymphocytes that largely are confined to the skin at the time of diagnosis.1 The incidence of CTCL rose steadily for more than 25 years, with an annual age-adjusted incidence of 6.4 to 9.6 cases per million individuals in the United States from 1973 to 2002.2 Mycosis fungoides is the most common classification of CTCL. It usually is characterized by patches or plaques of scaly erythema or poikiloderma; however, it also can present with annular, arcuate, concentrative, annular and linear morphologies. Mycosis fungoides tumor cells typically express a mature memory T helper cell phenotype of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8−, but there are different variants that have been discovered.3 Mycosis fungoides distributed in a spiral pattern is a distinctly unusual manifestation. Mechanisms of such dynamic morphologies are unknown but may represent an interplay between malignant cell proliferation and lost immune responses in temporospatial relationships.

The presence of keratotic gyrate lesions on acral surfaces should raise the possibility of pagetoid reticulosis. However, our patient had a history of MF involving areas of the body beyond the extremities, making this diagnosis less likely. Pagetoid reticulosis is categorized as an MF variant under the current World Health Organization– European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification for cutaneous lymphomas.4 Pagetoid reticulosis clinically presents as a solitary psoriasiform or hyperkeratotic patch or plaque that affects the distal extremities. Variable immunophenotypes have been shown in pagetoid reticulosis, such as CD4−/CD8+ and CD4−/CD8−, while classic MF typically shows CD4+/CD8−, as in our case.5

Tinea pedis is a superficial fungal infection usually caused by anthropophilic dermatophytes, with Trichophyton rubrum being the most common organism. Four common clinical presentations of tinea pedis have been identified: interdigital, moccasin, vesicular, and acute ulcerative. Clinical presentation ranges from macerations, ulcerations, and erosions in the toe web spaces to dry hyperkeratotic scaling and fissures on the plantar foot.6 Tinea pedis primarily affects the plantar and interdigital spaces, sparing the dorsal foot and ankle. Treatment is recommended to alleviate symptoms and limit the spread of infection; topical antifungals for 4 weeks is the treatment of choice. However, recurrence is common, and maintenance therapy often is indicated. Oral antifungals or a combination of both topical and oral medications may be needed in certain cases.7

Erythema annulare centrifugum (EAC) is a rare dermatologic disease described as erythematous or urticarial papules that can enlarge centrifugally to form annular lesions that clear centrally. Thought to be a hypersensitivity reaction to an underlying condition, EAC has been associated with fungal infections, various cutaneous diseases, and even internal malignancies. Clinically, EAC can be divided into 2 forms: deep and superficial. Deep gyrate erythema is characterized by a firm indurated border with rare scaling and pruritus that histologically shows perivascular lymphocytic infiltration in the upper and deep dermis. Superficial gyrate erythema has minimally elevated lesions with an indistinct border and trailing scales and pruritus; histopathologic findings present a dense, perivascular, lymphocytic infiltration restricted to the upper dermis.8 Therapy for EAC is directed at relieving symptoms and treating the underlying condition if there is one associated.