User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Multiple Firm Pink Papules and Nodules

The Diagnosis: Myeloid Leukemia Cutis

Leukemia cutis represents the infiltration of leukemic cells into the skin. It has been described in the setting of both myeloid and lymphoid leukemia. In the setting of acute myeloid leukemia, it has been reported to occur in 2% to 13% of patients overall,1,2 but it may occur in 31% of patients with the acute myelomonocytic or acute monocytic leukemia subtypes.3 Leukemia cutis is less common, with chronic myeloid leukemia occurring in 2.7% of patients in one study.4 In another study, 65% of patients with myeloid leukemia cutis had an acute myeloid leukemia.5

Myeloid leukemia cutis has been reported in patients aged 22 days to 90 years, with a median age of 62 years. There is a male predominance (1.4:1 ratio).5,6 The diagnosis of leukemia cutis is made concurrently with the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 30% of cases, subsequent to the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 60% of cases, and prior to the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 10% of cases.5

Clinically, myeloid leukemia cutis presents as an asymptomatic solitary lesion in 23% of cases or as multiple lesions in 77% of cases. Lesions consist of pink to red to violaceous papules, nodules, and macules that are occasionally purpuric and involve any cutaneous surface.5

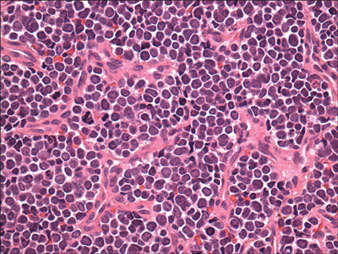

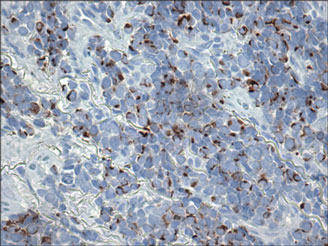

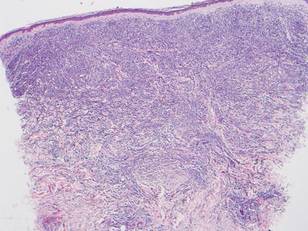

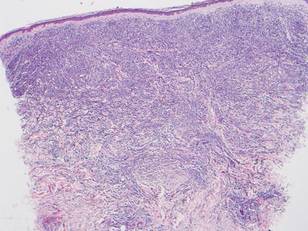

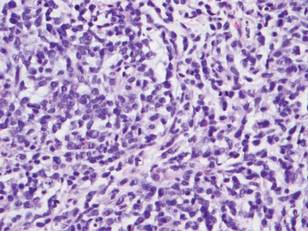

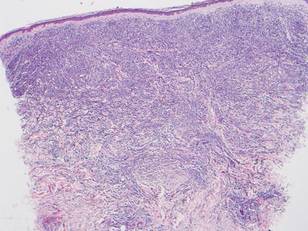

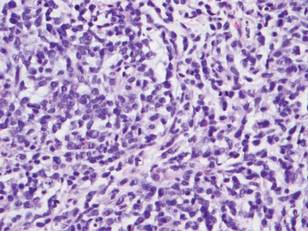

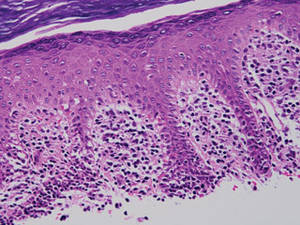

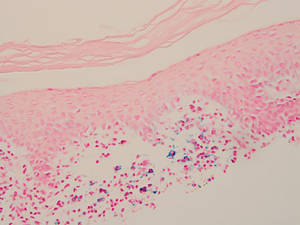

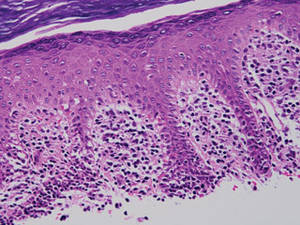

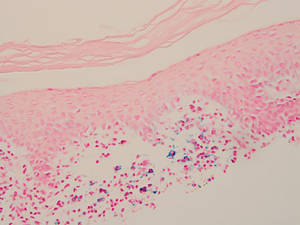

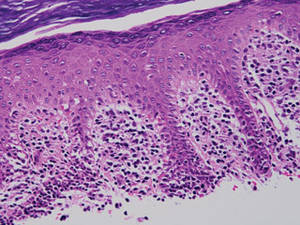

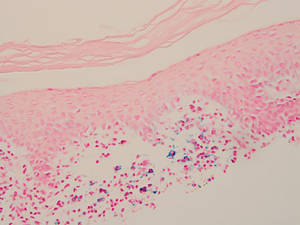

Histologically, the epidermis is unremarkable. Beneath a grenz zone within the dermis and usually extending into the subcutis there is a diffuse or nodular proliferation of neoplastic cells, often with perivascular and periadnexal accentuation and sometimes single filing of cells between collagen bundles (Figure 1). The cells are immature myeloid cells with irregular nuclear contours that may be indented or reniform (Figure 2). Nuclei contain finely dispersed chromatin with variably prominent nucleoli.5,6 Immunohistochemically, CD68 is positive in approximately 97% of cases, myeloperoxidase in 62%, and lysozyme in 85%. CD168, CD14, CD4, CD33, CD117, CD34, CD56, CD123, and CD303 are variably positive. CD3 and CD20, markers of lymphoid leukemia, are negative.5-8

Leukemia cutis in the setting of a myeloid leukemia portends a grave prognosis. In a series of 18 patients, 16 had additional extramedullary leukemia, including meningeal leukemia in 6 patients.2 Most patients with myeloid leukemia cutis die within an average of 1 to 8 months of diagnosis.9

- Boggs DR, Wintrobe MM, Cartwright GE. The acute leukemias. analysis of 322 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1962;41:163-225.

- Baer MR, Barcos M, Farrell H, et al. Acute myelogenous leukemia with leukemia cutis. eighteen cases seen between 1969 and 1986. Cancer. 1989;63:2192-2200.

- Straus DJ, Mertelsmann R, Koziner B, et al. The acute monocytic leukemias: multidisciplinary studies in 45 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1980;59:409-425.

- Rosenthal S, Canellos GP, DeVita VT Jr, et al. Characteristics of blast crisis in chronic granulocytic leukemia. Blood. 1977;49:705-714.

- Bénet C, Gomez A, Aguilar C, et al. Histologic and immunohistologic characterization of skin localization of myeloid disorders: a study of 173 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:278-290.

- Cronin DM, George TI, Sundram UN. An updated approach to the diagnosis of myeloid leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:101-110.

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142.

- Kaddu S, Zenahlik P, Beham-Schmid C, et al. Specific cutaneous infiltrates in patients with myelogenous leukemia: a clinicopathologic study of 26 patients with assessment of diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:966-978.

- Su WP, Buechner SA, Li CY. Clinicopathologic correlations in leukemia cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:121-128.

The Diagnosis: Myeloid Leukemia Cutis

Leukemia cutis represents the infiltration of leukemic cells into the skin. It has been described in the setting of both myeloid and lymphoid leukemia. In the setting of acute myeloid leukemia, it has been reported to occur in 2% to 13% of patients overall,1,2 but it may occur in 31% of patients with the acute myelomonocytic or acute monocytic leukemia subtypes.3 Leukemia cutis is less common, with chronic myeloid leukemia occurring in 2.7% of patients in one study.4 In another study, 65% of patients with myeloid leukemia cutis had an acute myeloid leukemia.5

Myeloid leukemia cutis has been reported in patients aged 22 days to 90 years, with a median age of 62 years. There is a male predominance (1.4:1 ratio).5,6 The diagnosis of leukemia cutis is made concurrently with the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 30% of cases, subsequent to the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 60% of cases, and prior to the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 10% of cases.5

Clinically, myeloid leukemia cutis presents as an asymptomatic solitary lesion in 23% of cases or as multiple lesions in 77% of cases. Lesions consist of pink to red to violaceous papules, nodules, and macules that are occasionally purpuric and involve any cutaneous surface.5

Histologically, the epidermis is unremarkable. Beneath a grenz zone within the dermis and usually extending into the subcutis there is a diffuse or nodular proliferation of neoplastic cells, often with perivascular and periadnexal accentuation and sometimes single filing of cells between collagen bundles (Figure 1). The cells are immature myeloid cells with irregular nuclear contours that may be indented or reniform (Figure 2). Nuclei contain finely dispersed chromatin with variably prominent nucleoli.5,6 Immunohistochemically, CD68 is positive in approximately 97% of cases, myeloperoxidase in 62%, and lysozyme in 85%. CD168, CD14, CD4, CD33, CD117, CD34, CD56, CD123, and CD303 are variably positive. CD3 and CD20, markers of lymphoid leukemia, are negative.5-8

Leukemia cutis in the setting of a myeloid leukemia portends a grave prognosis. In a series of 18 patients, 16 had additional extramedullary leukemia, including meningeal leukemia in 6 patients.2 Most patients with myeloid leukemia cutis die within an average of 1 to 8 months of diagnosis.9

The Diagnosis: Myeloid Leukemia Cutis

Leukemia cutis represents the infiltration of leukemic cells into the skin. It has been described in the setting of both myeloid and lymphoid leukemia. In the setting of acute myeloid leukemia, it has been reported to occur in 2% to 13% of patients overall,1,2 but it may occur in 31% of patients with the acute myelomonocytic or acute monocytic leukemia subtypes.3 Leukemia cutis is less common, with chronic myeloid leukemia occurring in 2.7% of patients in one study.4 In another study, 65% of patients with myeloid leukemia cutis had an acute myeloid leukemia.5

Myeloid leukemia cutis has been reported in patients aged 22 days to 90 years, with a median age of 62 years. There is a male predominance (1.4:1 ratio).5,6 The diagnosis of leukemia cutis is made concurrently with the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 30% of cases, subsequent to the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 60% of cases, and prior to the diagnosis of leukemia in approximately 10% of cases.5

Clinically, myeloid leukemia cutis presents as an asymptomatic solitary lesion in 23% of cases or as multiple lesions in 77% of cases. Lesions consist of pink to red to violaceous papules, nodules, and macules that are occasionally purpuric and involve any cutaneous surface.5

Histologically, the epidermis is unremarkable. Beneath a grenz zone within the dermis and usually extending into the subcutis there is a diffuse or nodular proliferation of neoplastic cells, often with perivascular and periadnexal accentuation and sometimes single filing of cells between collagen bundles (Figure 1). The cells are immature myeloid cells with irregular nuclear contours that may be indented or reniform (Figure 2). Nuclei contain finely dispersed chromatin with variably prominent nucleoli.5,6 Immunohistochemically, CD68 is positive in approximately 97% of cases, myeloperoxidase in 62%, and lysozyme in 85%. CD168, CD14, CD4, CD33, CD117, CD34, CD56, CD123, and CD303 are variably positive. CD3 and CD20, markers of lymphoid leukemia, are negative.5-8

Leukemia cutis in the setting of a myeloid leukemia portends a grave prognosis. In a series of 18 patients, 16 had additional extramedullary leukemia, including meningeal leukemia in 6 patients.2 Most patients with myeloid leukemia cutis die within an average of 1 to 8 months of diagnosis.9

- Boggs DR, Wintrobe MM, Cartwright GE. The acute leukemias. analysis of 322 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1962;41:163-225.

- Baer MR, Barcos M, Farrell H, et al. Acute myelogenous leukemia with leukemia cutis. eighteen cases seen between 1969 and 1986. Cancer. 1989;63:2192-2200.

- Straus DJ, Mertelsmann R, Koziner B, et al. The acute monocytic leukemias: multidisciplinary studies in 45 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1980;59:409-425.

- Rosenthal S, Canellos GP, DeVita VT Jr, et al. Characteristics of blast crisis in chronic granulocytic leukemia. Blood. 1977;49:705-714.

- Bénet C, Gomez A, Aguilar C, et al. Histologic and immunohistologic characterization of skin localization of myeloid disorders: a study of 173 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:278-290.

- Cronin DM, George TI, Sundram UN. An updated approach to the diagnosis of myeloid leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:101-110.

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142.

- Kaddu S, Zenahlik P, Beham-Schmid C, et al. Specific cutaneous infiltrates in patients with myelogenous leukemia: a clinicopathologic study of 26 patients with assessment of diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:966-978.

- Su WP, Buechner SA, Li CY. Clinicopathologic correlations in leukemia cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:121-128.

- Boggs DR, Wintrobe MM, Cartwright GE. The acute leukemias. analysis of 322 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 1962;41:163-225.

- Baer MR, Barcos M, Farrell H, et al. Acute myelogenous leukemia with leukemia cutis. eighteen cases seen between 1969 and 1986. Cancer. 1989;63:2192-2200.

- Straus DJ, Mertelsmann R, Koziner B, et al. The acute monocytic leukemias: multidisciplinary studies in 45 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1980;59:409-425.

- Rosenthal S, Canellos GP, DeVita VT Jr, et al. Characteristics of blast crisis in chronic granulocytic leukemia. Blood. 1977;49:705-714.

- Bénet C, Gomez A, Aguilar C, et al. Histologic and immunohistologic characterization of skin localization of myeloid disorders: a study of 173 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;135:278-290.

- Cronin DM, George TI, Sundram UN. An updated approach to the diagnosis of myeloid leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132:101-110.

- Cho-Vega JH, Medeiros LJ, Prieto VG, et al. Leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:130-142.

- Kaddu S, Zenahlik P, Beham-Schmid C, et al. Specific cutaneous infiltrates in patients with myelogenous leukemia: a clinicopathologic study of 26 patients with assessment of diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:966-978.

- Su WP, Buechner SA, Li CY. Clinicopathologic correlations in leukemia cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:121-128.

A 91-year-old man presented with numerous, scattered, asymptomatic, 3- to 9-mm, smooth, firm, pink papules and nodules involving the neck, trunk, and arms and legs of 1 week’s duration.

Manage Your Dermatology Practice: Attracting New Dermatology Patients

Attracting patients to your dermatology practice requires a multipronged approach. Dr. Gary Goldenberg discusses how technology and referrals will impact your patient base. Patient reviews also will affect your practice.

Attracting patients to your dermatology practice requires a multipronged approach. Dr. Gary Goldenberg discusses how technology and referrals will impact your patient base. Patient reviews also will affect your practice.

Attracting patients to your dermatology practice requires a multipronged approach. Dr. Gary Goldenberg discusses how technology and referrals will impact your patient base. Patient reviews also will affect your practice.

Practice Question Answers: AIDS Infectious Dermatoses

1. What is the most common treatment of invasive fungal infections in immunocompromised patients?

a. caspofungin

b. griseofulvin

c. intravenous amphotericin B

d. itraconazole

e. terbinafine

2. What mucosal infection is caused by Epstein-Barr virus and can be seen in human immunodeficiency virus and AIDS patients?

a. aphthous stomatitis

b. Kaposi sarcoma

c. median rhomboid glossitis

d. oral hairy leukoplakia

e. thrush

3. Which infection can cause thumbprint purpura and often is fatal in immunocompromised patients?

a. botryomycosis

b. coccidioidomycosis

c. invasive candidiasis

d. Kaposi sarcoma

e. strongyloidiasis

4. Which infection classically presents in advanced AIDS cases with a CD4 count less than 50 cells/mm3?

a. crusted scabies

b. giant molluscum

c. herpes zoster

d. leishmaniasis

e. Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex

5. Which antifungal medication should be avoided in patients taking protease inhibitors?

a. caspofungin

b. griseofulvin

c. itraconazole

d. micafungin

e. terbinafine

1. What is the most common treatment of invasive fungal infections in immunocompromised patients?

a. caspofungin

b. griseofulvin

c. intravenous amphotericin B

d. itraconazole

e. terbinafine

2. What mucosal infection is caused by Epstein-Barr virus and can be seen in human immunodeficiency virus and AIDS patients?

a. aphthous stomatitis

b. Kaposi sarcoma

c. median rhomboid glossitis

d. oral hairy leukoplakia

e. thrush

3. Which infection can cause thumbprint purpura and often is fatal in immunocompromised patients?

a. botryomycosis

b. coccidioidomycosis

c. invasive candidiasis

d. Kaposi sarcoma

e. strongyloidiasis

4. Which infection classically presents in advanced AIDS cases with a CD4 count less than 50 cells/mm3?

a. crusted scabies

b. giant molluscum

c. herpes zoster

d. leishmaniasis

e. Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex

5. Which antifungal medication should be avoided in patients taking protease inhibitors?

a. caspofungin

b. griseofulvin

c. itraconazole

d. micafungin

e. terbinafine

1. What is the most common treatment of invasive fungal infections in immunocompromised patients?

a. caspofungin

b. griseofulvin

c. intravenous amphotericin B

d. itraconazole

e. terbinafine

2. What mucosal infection is caused by Epstein-Barr virus and can be seen in human immunodeficiency virus and AIDS patients?

a. aphthous stomatitis

b. Kaposi sarcoma

c. median rhomboid glossitis

d. oral hairy leukoplakia

e. thrush

3. Which infection can cause thumbprint purpura and often is fatal in immunocompromised patients?

a. botryomycosis

b. coccidioidomycosis

c. invasive candidiasis

d. Kaposi sarcoma

e. strongyloidiasis

4. Which infection classically presents in advanced AIDS cases with a CD4 count less than 50 cells/mm3?

a. crusted scabies

b. giant molluscum

c. herpes zoster

d. leishmaniasis

e. Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex

5. Which antifungal medication should be avoided in patients taking protease inhibitors?

a. caspofungin

b. griseofulvin

c. itraconazole

d. micafungin

e. terbinafine

AIDS Infectious Dermatoses

Erythematous Nodular Plaque Encircling the Lower Leg

The Diagnosis: Merkel Cell Carcinoma

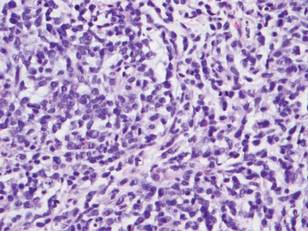

Histopathology showed small round cells (Figure 1) that stained positive for cytokeratin 20 in a paranuclear dotlike pattern (Figure 2). The tumor stained negative for lymphoma (CD45) marker. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography showed focally increased activity at cutaneous sites corresponding to the nodules, but lymph nodes and visceral sites did not show areas of increased metabolic activity. She underwent an above-knee amputation. She was started on a chemotherapy regimen of etoposide and carboplatin given that the pathology of the excised limb demonstrated vascular and lymphatic invasion by the tumor cells in the proximal skin margin. After 4 months she presented with gangrenous changes of the amputated limb and evidence of metastasis to the region of the skin flap. Similar tumors presented on the ipsilateral hip. Given her general poor condition and aggressive nature of the tumor, the patient decided to pursue hospice care 6 months after her diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC).

Figure 1. The tumor was composed of sheets of cells with a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio and fine chromatin without nucleoli (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Figure 2. Immunohistochemical staining for cytokera-tin 20 showed positivity in a paranuclear dotlike pattern (original magnification ×40). |

Merkel cell carcinoma usually presents as firm, red to purple papules on sun-exposed skin in older patients with light skin. Factors strongly associated with the development of MCC are age (>65 years), lighter skin types, history of extensive sun exposure, and chronic immune suppression (eg, kidney or heart transplantation, human immunodeficiency virus).1 The rate of MCC has increased 3-fold between 1986 and 2001; the rate of MCC was 0.15 cases per 100,000 individuals in 1986, climbing up to 0.44 cases per 100,000 individuals in 2001.2 Our patient had been on immunosuppressants—prednisone, cyclosporine, and sirolimus—for nearly a decade following kidney transplants, which had been discontinued 2 years prior to presentation.

Heath et al3 defined an acronym AEIOU (asymptomatic/lack of tenderness, expanding rapidly, immune suppression, older than 50 years, UV-exposed site on a person with fair skin) for MCC features derived from 195 patients. They advised that a biopsy is warranted if the patient presents with more than 3 of these features.3

The 1991 MCC staging system was revised in 1999 and 2005 based on experience at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (New York, New York).4 In 2010 the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging was introduced for MCC, which follows other skin malignancies.5 Using this TNM staging system for primary tumors, regional lymph nodes, and distant metastasis, our patient at the time of presentation was stage IIB (T3N0M0), with tumor size greater than 5 cm, nodes negative by clinical examination, and no distant metastasis. In a span of 3 months, she had metastasis to the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and distant lymph nodes, which resulted in classification as stage IV, proving the aggressive nature of the tumor.

The newly discovered Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) is found integrating into the Merkel cell genome. Merkel cell polyomavirus is present in 80% of cancers and is expressed in a clonal pattern, while 90% of MCC patients are seropositive for the same. Unlike antibodies to MCPyV VP1 protein, antibodies to the T antigen for MCPyV track disease burden and may be a useful biomarker for MCC in the future.6

A study of 251 patients in 1970-2002 showed that pathologic nodal staging identifies a group of patients with excellent long-term survival.1 Our patient preferred to undergo positron emission tomography rather than a sentinel lymph node biopsy prior to surgery. Also, after margin-negative excision and pathologic nodal staging, local and nodal recurrence rates were low. Adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III patients showed a trend (P=.08) to decreased survival compared with stage II patients who did not receive chemotherapy.7 A multidisciplinary approach to treatment including surgery, radiation,8 and chemotherapy needs to be created for each individual patient. Merkel cell carcinoma is the cause of death in 35% of patients within 3 years of diagnosis.9

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare orphan tumor with rapidly increasing incidence in an era of immunosuppression. It has a grave prognosis, as demonstrated in our case, if not detected early. People at increased risk for MCC must have regular skin checks. Unfortunately, our patient was a nursing home resident and had not had a skin check for 2 years prior to presentation.

1. Allen PJ, Bowne WB, Jaques DP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2300-2309.

2. Hodgson NC. Merkel cell carcinoma: changing incidence trends. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:1-4.

3. Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

4. Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. New York, NY: Springer; 2010.

5. Assouline A, Tai P, Joseph K, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of skin-current controversies and recommendations.Rare Tumors. 2011;4:e23.

6. Paulson KG, Carter JJ, Johnson LG, et al. Antibodies to Merkel cell polyomavirus T-antigen oncoproteins reflect tumor burden in Merkel cell carcinoma patients. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8388-8397.

7. Poulsen M, Rischin D, Walpole E, et al; Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group. High-risk Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin treated with synchronous carboplatin/etoposide and radiation: a Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group Study—TROG 96:07. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4371-4376.

8. Lewis KG, Weinstock MA, Weaver AL, et al. Adjuvant local irradiation for Merkel cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:693-700.

9. Agelli M, Clegg LX. Epidemiology of primary Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:832-841.

The Diagnosis: Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Histopathology showed small round cells (Figure 1) that stained positive for cytokeratin 20 in a paranuclear dotlike pattern (Figure 2). The tumor stained negative for lymphoma (CD45) marker. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography showed focally increased activity at cutaneous sites corresponding to the nodules, but lymph nodes and visceral sites did not show areas of increased metabolic activity. She underwent an above-knee amputation. She was started on a chemotherapy regimen of etoposide and carboplatin given that the pathology of the excised limb demonstrated vascular and lymphatic invasion by the tumor cells in the proximal skin margin. After 4 months she presented with gangrenous changes of the amputated limb and evidence of metastasis to the region of the skin flap. Similar tumors presented on the ipsilateral hip. Given her general poor condition and aggressive nature of the tumor, the patient decided to pursue hospice care 6 months after her diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC).

Figure 1. The tumor was composed of sheets of cells with a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio and fine chromatin without nucleoli (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Figure 2. Immunohistochemical staining for cytokera-tin 20 showed positivity in a paranuclear dotlike pattern (original magnification ×40). |

Merkel cell carcinoma usually presents as firm, red to purple papules on sun-exposed skin in older patients with light skin. Factors strongly associated with the development of MCC are age (>65 years), lighter skin types, history of extensive sun exposure, and chronic immune suppression (eg, kidney or heart transplantation, human immunodeficiency virus).1 The rate of MCC has increased 3-fold between 1986 and 2001; the rate of MCC was 0.15 cases per 100,000 individuals in 1986, climbing up to 0.44 cases per 100,000 individuals in 2001.2 Our patient had been on immunosuppressants—prednisone, cyclosporine, and sirolimus—for nearly a decade following kidney transplants, which had been discontinued 2 years prior to presentation.

Heath et al3 defined an acronym AEIOU (asymptomatic/lack of tenderness, expanding rapidly, immune suppression, older than 50 years, UV-exposed site on a person with fair skin) for MCC features derived from 195 patients. They advised that a biopsy is warranted if the patient presents with more than 3 of these features.3

The 1991 MCC staging system was revised in 1999 and 2005 based on experience at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (New York, New York).4 In 2010 the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging was introduced for MCC, which follows other skin malignancies.5 Using this TNM staging system for primary tumors, regional lymph nodes, and distant metastasis, our patient at the time of presentation was stage IIB (T3N0M0), with tumor size greater than 5 cm, nodes negative by clinical examination, and no distant metastasis. In a span of 3 months, she had metastasis to the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and distant lymph nodes, which resulted in classification as stage IV, proving the aggressive nature of the tumor.

The newly discovered Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) is found integrating into the Merkel cell genome. Merkel cell polyomavirus is present in 80% of cancers and is expressed in a clonal pattern, while 90% of MCC patients are seropositive for the same. Unlike antibodies to MCPyV VP1 protein, antibodies to the T antigen for MCPyV track disease burden and may be a useful biomarker for MCC in the future.6

A study of 251 patients in 1970-2002 showed that pathologic nodal staging identifies a group of patients with excellent long-term survival.1 Our patient preferred to undergo positron emission tomography rather than a sentinel lymph node biopsy prior to surgery. Also, after margin-negative excision and pathologic nodal staging, local and nodal recurrence rates were low. Adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III patients showed a trend (P=.08) to decreased survival compared with stage II patients who did not receive chemotherapy.7 A multidisciplinary approach to treatment including surgery, radiation,8 and chemotherapy needs to be created for each individual patient. Merkel cell carcinoma is the cause of death in 35% of patients within 3 years of diagnosis.9

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare orphan tumor with rapidly increasing incidence in an era of immunosuppression. It has a grave prognosis, as demonstrated in our case, if not detected early. People at increased risk for MCC must have regular skin checks. Unfortunately, our patient was a nursing home resident and had not had a skin check for 2 years prior to presentation.

The Diagnosis: Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Histopathology showed small round cells (Figure 1) that stained positive for cytokeratin 20 in a paranuclear dotlike pattern (Figure 2). The tumor stained negative for lymphoma (CD45) marker. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography showed focally increased activity at cutaneous sites corresponding to the nodules, but lymph nodes and visceral sites did not show areas of increased metabolic activity. She underwent an above-knee amputation. She was started on a chemotherapy regimen of etoposide and carboplatin given that the pathology of the excised limb demonstrated vascular and lymphatic invasion by the tumor cells in the proximal skin margin. After 4 months she presented with gangrenous changes of the amputated limb and evidence of metastasis to the region of the skin flap. Similar tumors presented on the ipsilateral hip. Given her general poor condition and aggressive nature of the tumor, the patient decided to pursue hospice care 6 months after her diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC).

Figure 1. The tumor was composed of sheets of cells with a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio and fine chromatin without nucleoli (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

Figure 2. Immunohistochemical staining for cytokera-tin 20 showed positivity in a paranuclear dotlike pattern (original magnification ×40). |

Merkel cell carcinoma usually presents as firm, red to purple papules on sun-exposed skin in older patients with light skin. Factors strongly associated with the development of MCC are age (>65 years), lighter skin types, history of extensive sun exposure, and chronic immune suppression (eg, kidney or heart transplantation, human immunodeficiency virus).1 The rate of MCC has increased 3-fold between 1986 and 2001; the rate of MCC was 0.15 cases per 100,000 individuals in 1986, climbing up to 0.44 cases per 100,000 individuals in 2001.2 Our patient had been on immunosuppressants—prednisone, cyclosporine, and sirolimus—for nearly a decade following kidney transplants, which had been discontinued 2 years prior to presentation.

Heath et al3 defined an acronym AEIOU (asymptomatic/lack of tenderness, expanding rapidly, immune suppression, older than 50 years, UV-exposed site on a person with fair skin) for MCC features derived from 195 patients. They advised that a biopsy is warranted if the patient presents with more than 3 of these features.3

The 1991 MCC staging system was revised in 1999 and 2005 based on experience at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (New York, New York).4 In 2010 the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging was introduced for MCC, which follows other skin malignancies.5 Using this TNM staging system for primary tumors, regional lymph nodes, and distant metastasis, our patient at the time of presentation was stage IIB (T3N0M0), with tumor size greater than 5 cm, nodes negative by clinical examination, and no distant metastasis. In a span of 3 months, she had metastasis to the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and distant lymph nodes, which resulted in classification as stage IV, proving the aggressive nature of the tumor.

The newly discovered Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) is found integrating into the Merkel cell genome. Merkel cell polyomavirus is present in 80% of cancers and is expressed in a clonal pattern, while 90% of MCC patients are seropositive for the same. Unlike antibodies to MCPyV VP1 protein, antibodies to the T antigen for MCPyV track disease burden and may be a useful biomarker for MCC in the future.6

A study of 251 patients in 1970-2002 showed that pathologic nodal staging identifies a group of patients with excellent long-term survival.1 Our patient preferred to undergo positron emission tomography rather than a sentinel lymph node biopsy prior to surgery. Also, after margin-negative excision and pathologic nodal staging, local and nodal recurrence rates were low. Adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III patients showed a trend (P=.08) to decreased survival compared with stage II patients who did not receive chemotherapy.7 A multidisciplinary approach to treatment including surgery, radiation,8 and chemotherapy needs to be created for each individual patient. Merkel cell carcinoma is the cause of death in 35% of patients within 3 years of diagnosis.9

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare orphan tumor with rapidly increasing incidence in an era of immunosuppression. It has a grave prognosis, as demonstrated in our case, if not detected early. People at increased risk for MCC must have regular skin checks. Unfortunately, our patient was a nursing home resident and had not had a skin check for 2 years prior to presentation.

1. Allen PJ, Bowne WB, Jaques DP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2300-2309.

2. Hodgson NC. Merkel cell carcinoma: changing incidence trends. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:1-4.

3. Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

4. Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. New York, NY: Springer; 2010.

5. Assouline A, Tai P, Joseph K, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of skin-current controversies and recommendations.Rare Tumors. 2011;4:e23.

6. Paulson KG, Carter JJ, Johnson LG, et al. Antibodies to Merkel cell polyomavirus T-antigen oncoproteins reflect tumor burden in Merkel cell carcinoma patients. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8388-8397.

7. Poulsen M, Rischin D, Walpole E, et al; Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group. High-risk Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin treated with synchronous carboplatin/etoposide and radiation: a Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group Study—TROG 96:07. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4371-4376.

8. Lewis KG, Weinstock MA, Weaver AL, et al. Adjuvant local irradiation for Merkel cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:693-700.

9. Agelli M, Clegg LX. Epidemiology of primary Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:832-841.

1. Allen PJ, Bowne WB, Jaques DP, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2300-2309.

2. Hodgson NC. Merkel cell carcinoma: changing incidence trends. J Surg Oncol. 2005;89:1-4.

3. Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al. Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:375-381.

4. Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. New York, NY: Springer; 2010.

5. Assouline A, Tai P, Joseph K, et al. Merkel cell carcinoma of skin-current controversies and recommendations.Rare Tumors. 2011;4:e23.

6. Paulson KG, Carter JJ, Johnson LG, et al. Antibodies to Merkel cell polyomavirus T-antigen oncoproteins reflect tumor burden in Merkel cell carcinoma patients. Cancer Res. 2010;70:8388-8397.

7. Poulsen M, Rischin D, Walpole E, et al; Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group. High-risk Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin treated with synchronous carboplatin/etoposide and radiation: a Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group Study—TROG 96:07. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4371-4376.

8. Lewis KG, Weinstock MA, Weaver AL, et al. Adjuvant local irradiation for Merkel cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:693-700.

9. Agelli M, Clegg LX. Epidemiology of primary Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:832-841.

A 66-year-old woman presented with red to violaceous, rapidly growing nodules on the skin. Her medical history was remarkable for diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and renal failure. She had 2 rejected kidney transplants and was on hemodialysis at the time of presentation. She noticed asymptomatic nodules present on the left lower leg that progressively coalesced, finally encroaching the whole girth of the limb, spreading from the foot to the knee in a short duration of 3 months. The regional lymph nodes were not clinically palpable.

Cosmetic Corner: Dermatologists Weigh in on Mineral Makeup

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on the top mineral makeup products. Consideration must be given to:

- bareMinerals

Bare Escentuals Beauty, Inc

“I recommend bareMinerals everyday to patients with various facial blemishes, acne, and dermatoses. This brand has products for patients of all skin types and colors.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

Recommended by Elizabeth K. Hale, MD, New York, New York

“Very light and noncomedogenic and does not cake up.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- Jane Iredale

Iredale Mineral Cosmetics, Ltd

“My patients and staff love this brand as a whole. They find the options are terrific for various skin types and the company support is very strong, which is a huge part of the equation. The brush-on sunscreen is terrific.”—Joel Schlessinger, MD, Omaha, Nebraska

- Météorites Powder

Guerlain

“Adds brightness but does not dry the skin.”—Antonella Tosti, MD, Miami, Florida

- Sheer Cover Studio

Guthy-Renker

“It provides very effective coverage without appearing heavy.”—Whitney Bowe, MD, Brooklyn, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Skin care products for babies, eyelash enhancers, and cleansing pads will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on the top mineral makeup products. Consideration must be given to:

- bareMinerals

Bare Escentuals Beauty, Inc

“I recommend bareMinerals everyday to patients with various facial blemishes, acne, and dermatoses. This brand has products for patients of all skin types and colors.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

Recommended by Elizabeth K. Hale, MD, New York, New York

“Very light and noncomedogenic and does not cake up.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- Jane Iredale

Iredale Mineral Cosmetics, Ltd

“My patients and staff love this brand as a whole. They find the options are terrific for various skin types and the company support is very strong, which is a huge part of the equation. The brush-on sunscreen is terrific.”—Joel Schlessinger, MD, Omaha, Nebraska

- Météorites Powder

Guerlain

“Adds brightness but does not dry the skin.”—Antonella Tosti, MD, Miami, Florida

- Sheer Cover Studio

Guthy-Renker

“It provides very effective coverage without appearing heavy.”—Whitney Bowe, MD, Brooklyn, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Skin care products for babies, eyelash enhancers, and cleansing pads will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on the top mineral makeup products. Consideration must be given to:

- bareMinerals

Bare Escentuals Beauty, Inc

“I recommend bareMinerals everyday to patients with various facial blemishes, acne, and dermatoses. This brand has products for patients of all skin types and colors.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

Recommended by Elizabeth K. Hale, MD, New York, New York

“Very light and noncomedogenic and does not cake up.”—Anthony M. Rossi, MD, New York, New York

- Jane Iredale

Iredale Mineral Cosmetics, Ltd

“My patients and staff love this brand as a whole. They find the options are terrific for various skin types and the company support is very strong, which is a huge part of the equation. The brush-on sunscreen is terrific.”—Joel Schlessinger, MD, Omaha, Nebraska

- Météorites Powder

Guerlain

“Adds brightness but does not dry the skin.”—Antonella Tosti, MD, Miami, Florida

- Sheer Cover Studio

Guthy-Renker

“It provides very effective coverage without appearing heavy.”—Whitney Bowe, MD, Brooklyn, New York

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Skin care products for babies, eyelash enhancers, and cleansing pads will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

Nailing Down the Data: Topicals for Onychomycosis

In summer 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved 2 new topical medications for onychomycosis. In recent months, the Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology (2014;7:10-18) and Medscape provided review materials to assist in sifting through this topic. In summary, efinaconazole, a triazole antifungal in a 10% solution recommended for daily application for 48 weeks, exhibited 17.8% complete and 55.2% mycological cure rates compared to vehicle (5.5% and 16.9%, respectively). Tavaborole, an oxaborole antifungal in a 5% solution recommended for daily application for 48 weeks, displayed 9.1% complete and 35.9% mycological cure rates versus vehicle (1.5% and 12.2%, respectively). To complete the discussion, ciclopirox nail lacquer, FDA approved in 1999 for onychomycosis for daily application for 48 weeks, heralded 8.5% complete and 36% mycological cure rates compared to vehicle (0% and 9%, respectively). Ciclopirox requires nail debridement periodically, and the newer agents do not.

What’s the issue?

Do you agree that nary a day goes by without an e-mailed article or continuing medical education opportunity tasked at “getting to know” new topical onychomycosis therapies? That being said, how often have you summarily deleted them, assuming that topicals just don’t work? I know I have, though I paused this week after thinking to myself, “How often have I written a prescription for ciclopirox nail lacquer to appease a patient who would prefer nonsystemic therapy?” And then I read on. Based on the data above, perhaps these medications, particularly efinaconazole, at least deserve perusal compared to our current meager topical and systemic options. What has your experience been with these novel topicals, their insurance coverage, and their tolerability and efficacy in your practice?

In summer 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved 2 new topical medications for onychomycosis. In recent months, the Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology (2014;7:10-18) and Medscape provided review materials to assist in sifting through this topic. In summary, efinaconazole, a triazole antifungal in a 10% solution recommended for daily application for 48 weeks, exhibited 17.8% complete and 55.2% mycological cure rates compared to vehicle (5.5% and 16.9%, respectively). Tavaborole, an oxaborole antifungal in a 5% solution recommended for daily application for 48 weeks, displayed 9.1% complete and 35.9% mycological cure rates versus vehicle (1.5% and 12.2%, respectively). To complete the discussion, ciclopirox nail lacquer, FDA approved in 1999 for onychomycosis for daily application for 48 weeks, heralded 8.5% complete and 36% mycological cure rates compared to vehicle (0% and 9%, respectively). Ciclopirox requires nail debridement periodically, and the newer agents do not.

What’s the issue?

Do you agree that nary a day goes by without an e-mailed article or continuing medical education opportunity tasked at “getting to know” new topical onychomycosis therapies? That being said, how often have you summarily deleted them, assuming that topicals just don’t work? I know I have, though I paused this week after thinking to myself, “How often have I written a prescription for ciclopirox nail lacquer to appease a patient who would prefer nonsystemic therapy?” And then I read on. Based on the data above, perhaps these medications, particularly efinaconazole, at least deserve perusal compared to our current meager topical and systemic options. What has your experience been with these novel topicals, their insurance coverage, and their tolerability and efficacy in your practice?

In summer 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved 2 new topical medications for onychomycosis. In recent months, the Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology (2014;7:10-18) and Medscape provided review materials to assist in sifting through this topic. In summary, efinaconazole, a triazole antifungal in a 10% solution recommended for daily application for 48 weeks, exhibited 17.8% complete and 55.2% mycological cure rates compared to vehicle (5.5% and 16.9%, respectively). Tavaborole, an oxaborole antifungal in a 5% solution recommended for daily application for 48 weeks, displayed 9.1% complete and 35.9% mycological cure rates versus vehicle (1.5% and 12.2%, respectively). To complete the discussion, ciclopirox nail lacquer, FDA approved in 1999 for onychomycosis for daily application for 48 weeks, heralded 8.5% complete and 36% mycological cure rates compared to vehicle (0% and 9%, respectively). Ciclopirox requires nail debridement periodically, and the newer agents do not.

What’s the issue?

Do you agree that nary a day goes by without an e-mailed article or continuing medical education opportunity tasked at “getting to know” new topical onychomycosis therapies? That being said, how often have you summarily deleted them, assuming that topicals just don’t work? I know I have, though I paused this week after thinking to myself, “How often have I written a prescription for ciclopirox nail lacquer to appease a patient who would prefer nonsystemic therapy?” And then I read on. Based on the data above, perhaps these medications, particularly efinaconazole, at least deserve perusal compared to our current meager topical and systemic options. What has your experience been with these novel topicals, their insurance coverage, and their tolerability and efficacy in your practice?

Stains and Smears: Resident Guide to Bedside Diagnostic Testing

Dermatologists are fortunate to specialize in the organ that is most accessible to evaluation. Although we use the physical examination to formulate the initial differential diagnosis, at times we must rely on ancillary tests to narrow down the diagnosis. Various bedside testing modalities—potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, Tzanck smear, mineral oil preparation, and Gram stain—are most useful in diagnosing infectious causes of cutaneous disease. This guide serves as a useful reference for residents on how to perform these tests and which conditions they can help diagnose. Several of these procedures have no standard protocol for performing them; the literature is littered with various methodologies, fixatives, and stains, and as such, this article will attempt to describe a technique that is convenient and quick to perform with readily available materials while still offering high diagnostic utility.

KOH Preparation

A standard in the armamentarium of a dermatologist, the KOH preparation is invaluable to diagnose fungal and yeast infections. Although there are many available preparations including varying concentrations of KOH, dimethyl sulfoxide, and various inks, the procedure is similar for all of them.1 The first step involves collecting the specimen, which can be scale from an active border of suspected cutaneous dermatophyte or Malassezia infection, debris from suspected candidiasis, or hair shafts plucked from an area of alopecia of presumed tinea capitis. A no. 15 blade can be used to scrape the specimen onto a microscope slide, though a second microscope slide can be used in lieu of a blade in patients who will not remain still, and then a coverslip is placed. Two drops of the KOH solution of your choice are then placed on opposite ends of the coverslip, allowing capillary action to spread the stain evenly. A paper towel can be folded in half and pushed down on the surface of the coverslip to spread the stain and soak up any excess, and this pressure also can help the KOH solution digest the keratin in the specimen. Briefly heating the underside of the slide (below boiling point) will help digest the keratin; this step is not necessary when you are using a KOH preparation with dimethyl sulfoxide. Although many dermatologists view the slide almost immediately, ideally at least 5 minutes should pass before it is read. Particularly thick specimens may require additional digestion time, so setting them aside for later review may help visualize infectious agents. In a busy clinic where an immediate diagnosis may not be requisite and a prescription can be called in pending the result, waiting to review the slide may be feasible.

Tzanck Smear

The Tzanck smear is a useful cytopathologic test in the rapid diagnosis of herpetic lesions, though it cannot differentiate between herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2, and varicella-zoster virus. It also has shown utility for rapid diagnosis of protean other dermatologic conditions including autoimmune blistering disorders, cutaneous malignancies, and other infectious processes, though it has been superseded by histopathology in most cases.2 An ideal sample is collected by scraping the base of a fresh blister with a no. 15 blade or a second microscope slide. The scrapings then are smeared onto another microscope slide and allowed to air-dry briefly. Then, Wright-Giemsa stain is dispensed to cover the sample and allowed to sit for 15 minutes before being washed off with sterile water. After air-drying, the sample is examined for the presence of clumped multinucleated giant cells, a feature that confirms herpetic infection and allows rapid initiation of antiviral medication.3

Mineral Oil Preparation

A mineral oil preparation has utility in diagnosing ectoparasitic infestation. In the case of scabies, a positive microscopic examination is diagnostic and requires no further testing, allowing for rapid initiation of therapy. This technique also is useful in diagnosing rosacea related to Demodex, which requires a treatment algorithm that differs from the classic papulopustular rosacea which it mimics.4

Mineral oil preparations can be rapidly performed and interpreted. Several drops of mineral oil are placed onto a microscope slide and a no. 15 blade is dipped into this oil prior to scraping the sample lesion. For scabies, a burrow is scraped repeatedly with the blade, and the debris is collected in the mineral oil. Occasionally, the mite can be dermoscopically visualized as a jet plane or arrowhead at the leading edge of a burrow; scraping should be focused in the vicinity of the mite.5 A coverslip is applied to the microscope slide and examination for the mite, egg casings, and scybala can be performed with microscopy.6 For Demodex infestation, a facial pustule can be expressed or several eyelash hairs can be plucked and suspended in mineral oil. Examination of this specimen is identical to scabies.

Gram Stain

The Gram stain is invaluable in classifying bacteria, and a properly performed test can narrow the identification of a causative organism based on cellular morphology. Although it is more technically complex than other bedside diagnostic maneuvers, it can be rapidly performed once the sequence of stains is mastered. The collected sample is smeared onto a glass slide and then briefly passed over a flame several times to heat-fix the specimen. Caution should be taken to avoid direct or prolonged flame contact with the underside of the slide. After fixation, the staining can be performed. First, crystal violet is instilled onto the slide and remains on for 30 seconds before being rinsed off with sink water. Then, Gram iodine is used for 30 seconds, followed by another rinse in water. Next, pour the decolorizer solution over the slide until the runoff is clear, and then rinse in water. Finally, flood with safranin counterstain for 30 seconds and give the slide a final rinse. After air-drying, it is ready to be interpreted.7

Final Thoughts

Although the modern dermatologist has access to biopsies, cultures, and sophisticated diagnostic techniques, it is important to remember these useful bedside tests. The ability to rapidly pin a diagnosis is particularly useful on the consultative service where critically ill patients can benefit from identification of a causative pathogen sooner rather than later. Residents should master these stains in their training, as this knowledge may prove to be invaluable in their careers.

1. Trozak DJ, Tennenhouse DJ, Russell JJ. Dermatology Skills for Primary Care: An Illustrated Guide. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2006.

2. Kelly B, Shimoni T. Reintroducing the Tzanck smear. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:141-152.

3. Singhi M, Gupta L. Tzanck smear: a useful diagnostic tool. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:295.

4. Elston DM. Demodex mites: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:502-504.

5. Dupuy A, Dehen L, Bourrat E, et al. Accuracy of standard dermoscopy for diagnosing scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:53-62.

6. Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Duncan K, et al. Dermatology Essentials. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

7. Ruocco E, Baroni A, Donnarumma G, et al. Diagnostic procedures in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:548-556.

Dermatologists are fortunate to specialize in the organ that is most accessible to evaluation. Although we use the physical examination to formulate the initial differential diagnosis, at times we must rely on ancillary tests to narrow down the diagnosis. Various bedside testing modalities—potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, Tzanck smear, mineral oil preparation, and Gram stain—are most useful in diagnosing infectious causes of cutaneous disease. This guide serves as a useful reference for residents on how to perform these tests and which conditions they can help diagnose. Several of these procedures have no standard protocol for performing them; the literature is littered with various methodologies, fixatives, and stains, and as such, this article will attempt to describe a technique that is convenient and quick to perform with readily available materials while still offering high diagnostic utility.

KOH Preparation

A standard in the armamentarium of a dermatologist, the KOH preparation is invaluable to diagnose fungal and yeast infections. Although there are many available preparations including varying concentrations of KOH, dimethyl sulfoxide, and various inks, the procedure is similar for all of them.1 The first step involves collecting the specimen, which can be scale from an active border of suspected cutaneous dermatophyte or Malassezia infection, debris from suspected candidiasis, or hair shafts plucked from an area of alopecia of presumed tinea capitis. A no. 15 blade can be used to scrape the specimen onto a microscope slide, though a second microscope slide can be used in lieu of a blade in patients who will not remain still, and then a coverslip is placed. Two drops of the KOH solution of your choice are then placed on opposite ends of the coverslip, allowing capillary action to spread the stain evenly. A paper towel can be folded in half and pushed down on the surface of the coverslip to spread the stain and soak up any excess, and this pressure also can help the KOH solution digest the keratin in the specimen. Briefly heating the underside of the slide (below boiling point) will help digest the keratin; this step is not necessary when you are using a KOH preparation with dimethyl sulfoxide. Although many dermatologists view the slide almost immediately, ideally at least 5 minutes should pass before it is read. Particularly thick specimens may require additional digestion time, so setting them aside for later review may help visualize infectious agents. In a busy clinic where an immediate diagnosis may not be requisite and a prescription can be called in pending the result, waiting to review the slide may be feasible.

Tzanck Smear

The Tzanck smear is a useful cytopathologic test in the rapid diagnosis of herpetic lesions, though it cannot differentiate between herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2, and varicella-zoster virus. It also has shown utility for rapid diagnosis of protean other dermatologic conditions including autoimmune blistering disorders, cutaneous malignancies, and other infectious processes, though it has been superseded by histopathology in most cases.2 An ideal sample is collected by scraping the base of a fresh blister with a no. 15 blade or a second microscope slide. The scrapings then are smeared onto another microscope slide and allowed to air-dry briefly. Then, Wright-Giemsa stain is dispensed to cover the sample and allowed to sit for 15 minutes before being washed off with sterile water. After air-drying, the sample is examined for the presence of clumped multinucleated giant cells, a feature that confirms herpetic infection and allows rapid initiation of antiviral medication.3

Mineral Oil Preparation

A mineral oil preparation has utility in diagnosing ectoparasitic infestation. In the case of scabies, a positive microscopic examination is diagnostic and requires no further testing, allowing for rapid initiation of therapy. This technique also is useful in diagnosing rosacea related to Demodex, which requires a treatment algorithm that differs from the classic papulopustular rosacea which it mimics.4

Mineral oil preparations can be rapidly performed and interpreted. Several drops of mineral oil are placed onto a microscope slide and a no. 15 blade is dipped into this oil prior to scraping the sample lesion. For scabies, a burrow is scraped repeatedly with the blade, and the debris is collected in the mineral oil. Occasionally, the mite can be dermoscopically visualized as a jet plane or arrowhead at the leading edge of a burrow; scraping should be focused in the vicinity of the mite.5 A coverslip is applied to the microscope slide and examination for the mite, egg casings, and scybala can be performed with microscopy.6 For Demodex infestation, a facial pustule can be expressed or several eyelash hairs can be plucked and suspended in mineral oil. Examination of this specimen is identical to scabies.

Gram Stain

The Gram stain is invaluable in classifying bacteria, and a properly performed test can narrow the identification of a causative organism based on cellular morphology. Although it is more technically complex than other bedside diagnostic maneuvers, it can be rapidly performed once the sequence of stains is mastered. The collected sample is smeared onto a glass slide and then briefly passed over a flame several times to heat-fix the specimen. Caution should be taken to avoid direct or prolonged flame contact with the underside of the slide. After fixation, the staining can be performed. First, crystal violet is instilled onto the slide and remains on for 30 seconds before being rinsed off with sink water. Then, Gram iodine is used for 30 seconds, followed by another rinse in water. Next, pour the decolorizer solution over the slide until the runoff is clear, and then rinse in water. Finally, flood with safranin counterstain for 30 seconds and give the slide a final rinse. After air-drying, it is ready to be interpreted.7

Final Thoughts

Although the modern dermatologist has access to biopsies, cultures, and sophisticated diagnostic techniques, it is important to remember these useful bedside tests. The ability to rapidly pin a diagnosis is particularly useful on the consultative service where critically ill patients can benefit from identification of a causative pathogen sooner rather than later. Residents should master these stains in their training, as this knowledge may prove to be invaluable in their careers.

Dermatologists are fortunate to specialize in the organ that is most accessible to evaluation. Although we use the physical examination to formulate the initial differential diagnosis, at times we must rely on ancillary tests to narrow down the diagnosis. Various bedside testing modalities—potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation, Tzanck smear, mineral oil preparation, and Gram stain—are most useful in diagnosing infectious causes of cutaneous disease. This guide serves as a useful reference for residents on how to perform these tests and which conditions they can help diagnose. Several of these procedures have no standard protocol for performing them; the literature is littered with various methodologies, fixatives, and stains, and as such, this article will attempt to describe a technique that is convenient and quick to perform with readily available materials while still offering high diagnostic utility.

KOH Preparation

A standard in the armamentarium of a dermatologist, the KOH preparation is invaluable to diagnose fungal and yeast infections. Although there are many available preparations including varying concentrations of KOH, dimethyl sulfoxide, and various inks, the procedure is similar for all of them.1 The first step involves collecting the specimen, which can be scale from an active border of suspected cutaneous dermatophyte or Malassezia infection, debris from suspected candidiasis, or hair shafts plucked from an area of alopecia of presumed tinea capitis. A no. 15 blade can be used to scrape the specimen onto a microscope slide, though a second microscope slide can be used in lieu of a blade in patients who will not remain still, and then a coverslip is placed. Two drops of the KOH solution of your choice are then placed on opposite ends of the coverslip, allowing capillary action to spread the stain evenly. A paper towel can be folded in half and pushed down on the surface of the coverslip to spread the stain and soak up any excess, and this pressure also can help the KOH solution digest the keratin in the specimen. Briefly heating the underside of the slide (below boiling point) will help digest the keratin; this step is not necessary when you are using a KOH preparation with dimethyl sulfoxide. Although many dermatologists view the slide almost immediately, ideally at least 5 minutes should pass before it is read. Particularly thick specimens may require additional digestion time, so setting them aside for later review may help visualize infectious agents. In a busy clinic where an immediate diagnosis may not be requisite and a prescription can be called in pending the result, waiting to review the slide may be feasible.

Tzanck Smear

The Tzanck smear is a useful cytopathologic test in the rapid diagnosis of herpetic lesions, though it cannot differentiate between herpes simplex virus type 1, herpes simplex virus type 2, and varicella-zoster virus. It also has shown utility for rapid diagnosis of protean other dermatologic conditions including autoimmune blistering disorders, cutaneous malignancies, and other infectious processes, though it has been superseded by histopathology in most cases.2 An ideal sample is collected by scraping the base of a fresh blister with a no. 15 blade or a second microscope slide. The scrapings then are smeared onto another microscope slide and allowed to air-dry briefly. Then, Wright-Giemsa stain is dispensed to cover the sample and allowed to sit for 15 minutes before being washed off with sterile water. After air-drying, the sample is examined for the presence of clumped multinucleated giant cells, a feature that confirms herpetic infection and allows rapid initiation of antiviral medication.3

Mineral Oil Preparation

A mineral oil preparation has utility in diagnosing ectoparasitic infestation. In the case of scabies, a positive microscopic examination is diagnostic and requires no further testing, allowing for rapid initiation of therapy. This technique also is useful in diagnosing rosacea related to Demodex, which requires a treatment algorithm that differs from the classic papulopustular rosacea which it mimics.4

Mineral oil preparations can be rapidly performed and interpreted. Several drops of mineral oil are placed onto a microscope slide and a no. 15 blade is dipped into this oil prior to scraping the sample lesion. For scabies, a burrow is scraped repeatedly with the blade, and the debris is collected in the mineral oil. Occasionally, the mite can be dermoscopically visualized as a jet plane or arrowhead at the leading edge of a burrow; scraping should be focused in the vicinity of the mite.5 A coverslip is applied to the microscope slide and examination for the mite, egg casings, and scybala can be performed with microscopy.6 For Demodex infestation, a facial pustule can be expressed or several eyelash hairs can be plucked and suspended in mineral oil. Examination of this specimen is identical to scabies.

Gram Stain

The Gram stain is invaluable in classifying bacteria, and a properly performed test can narrow the identification of a causative organism based on cellular morphology. Although it is more technically complex than other bedside diagnostic maneuvers, it can be rapidly performed once the sequence of stains is mastered. The collected sample is smeared onto a glass slide and then briefly passed over a flame several times to heat-fix the specimen. Caution should be taken to avoid direct or prolonged flame contact with the underside of the slide. After fixation, the staining can be performed. First, crystal violet is instilled onto the slide and remains on for 30 seconds before being rinsed off with sink water. Then, Gram iodine is used for 30 seconds, followed by another rinse in water. Next, pour the decolorizer solution over the slide until the runoff is clear, and then rinse in water. Finally, flood with safranin counterstain for 30 seconds and give the slide a final rinse. After air-drying, it is ready to be interpreted.7

Final Thoughts

Although the modern dermatologist has access to biopsies, cultures, and sophisticated diagnostic techniques, it is important to remember these useful bedside tests. The ability to rapidly pin a diagnosis is particularly useful on the consultative service where critically ill patients can benefit from identification of a causative pathogen sooner rather than later. Residents should master these stains in their training, as this knowledge may prove to be invaluable in their careers.

1. Trozak DJ, Tennenhouse DJ, Russell JJ. Dermatology Skills for Primary Care: An Illustrated Guide. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2006.

2. Kelly B, Shimoni T. Reintroducing the Tzanck smear. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:141-152.

3. Singhi M, Gupta L. Tzanck smear: a useful diagnostic tool. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:295.

4. Elston DM. Demodex mites: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:502-504.

5. Dupuy A, Dehen L, Bourrat E, et al. Accuracy of standard dermoscopy for diagnosing scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:53-62.

6. Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Duncan K, et al. Dermatology Essentials. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

7. Ruocco E, Baroni A, Donnarumma G, et al. Diagnostic procedures in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:548-556.

1. Trozak DJ, Tennenhouse DJ, Russell JJ. Dermatology Skills for Primary Care: An Illustrated Guide. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2006.

2. Kelly B, Shimoni T. Reintroducing the Tzanck smear. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:141-152.

3. Singhi M, Gupta L. Tzanck smear: a useful diagnostic tool. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71:295.

4. Elston DM. Demodex mites: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:502-504.

5. Dupuy A, Dehen L, Bourrat E, et al. Accuracy of standard dermoscopy for diagnosing scabies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:53-62.

6. Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Duncan K, et al. Dermatology Essentials. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; 2014.

7. Ruocco E, Baroni A, Donnarumma G, et al. Diagnostic procedures in dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:548-556.

Erythematous Plaques on the Hand and Wrist

The Diagnosis: Lichen Aureus

Lichen aureus (LA) is classified as a pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD), a collection of conditions that are characterized by petechiae, pigmentation, and occasionally telangiectasia without a causative underlying disorder. As in our case, the lesions of LA are usually asymptomatic. They appear as circumscribed areas of discrete or confluent macules and papules that can range in color from gold or copper to purple (Figure 1). The lesions typically occur unilaterally on the lower extremities but can occur on all body regions. The etiology is unknown, but explanations such as venous insufficiency,1 contact allergens,2 and drugs3,4 have been proposed. Unlike other PPDs, LA tends to occur abruptly and then either stabilizes or progresses slowly over years. Studies have reported resolution in 2 to 7 years.5 The average age of onset is in the 20s and 30s, with pediatric cases accounting for only 17%.6 Pediatric cases are more likely to be self-limited and occur in uncommon sites such as the trunk and arms.7

Lichen aureus is characterized histopathologically by a dense, bandlike, dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2). Additionally, there is variable exocytosis of lymphocytes and marked accumulation of siderotic macrophages (Figure 3). These qualities in the proper clinical setting help differentiate LA from other PPDs that share findings of capillaritis, hemosiderin deposition, and erythrocyte extravasation near dermal vessels. An iron stain assists in the diagnosis of LA (Figure 3), as it differentiates the disease from other lichenoid conditions such as lichen planus. Zaballos et al8 also demonstrated a role for dermoscopy to clinically differentiate LA from other similar-appearing lesions such as lichen planus.

The lesions of LA are benign. Because the predominantly T-cell infiltrate is monoclonal in approximately 50% of cases,2,9-11 authors have suggested the possibility of progression to cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.9,12 Guitart and Magro13 classified LA as a T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia with potential for progression. Despite these reports, the general consensus is that LA is a benign, self-limiting condition. The benign nature of LA is supported by Fink-Puches et al2 who followed 23 patients for a mean 102.1 months and did not observe a single case of progression to malignancy.

There have been many treatment regimens attempted for patients with LA. Topical corticosteroids have not been found to be beneficial14; however, there have been isolated cases reporting its efficacy in children.7,15 Other medications that have been effective in small trials include psoralen plus UVA,16 topical pimecrolimus,5 calcium dobesilate,17 and combination therapy with pentoxifylline and prostacyclin.18 Despite some reported benefit, the use of potent immunomodulating medications is not indicated due to the benign nature of the disease. Alternative supplements including oral bioflavonoids and ascorbic acid have also been explored with modest benefit.19

1. Reinhardt L, Wilkin JK, Tausend R. Vascular abnormalities in lichen aureus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:417-420.

2. Fink-Puches R, Wolf P, Kerl H, et al. Lichen aureus: clinicopathologic features, natural history, and relationship to mycosis fungoides. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1169-1173.

3. Nishioka K, Katayama I, Masuzawa M, et al. Drug-induced chronic pigmented purpura. J Dermatol. 1989;16:220-222.

4. Yazdi AS, Mayser P, Sander CA. Lichen aureus with clonal T cells in a child possibly induced by regular consumption of an energy drink. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:960-962.

5. Bohm M, Bonsmann G, Luger TA. Resolution of lichen aureus in a 10-year-old child after topical pimecrolimus. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:519-520.

6. Gelmetti C, Cerri D, Grimalt R. Lichen aureus in childhood. Pediatr Dermatol. 1991;8:280-283.

7. Kim MJ, Kim BY, Park KC, et al. A case of childhood lichen aureus. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:393-395.

8. Zaballos P, Puig S, Malvehy J. Dermoscopy of pigmented purpuric dermatoses (lichen aureus): a useful tool for clinical diagnosis. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1290-1291.

9. Toro JR, Sander CA, LeBoit PE. Persistent pigmented purpuric dermatitis and mycosis fungoides: simulant, precursor, or both? a study by light microscopy and molecular methods. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:108-118.

10. Magro CM, Schaefer JT, Crowson AN, et al. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis: classification by phenotypic and molecular profiles. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:218-229.

11. Crowson AN, Magro CM, Zahorchak R. Atypical pigmentary purpura: a clinical, histopathologic, and genotypic study. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:1004-1012.

12. Barnhill RL, Braverman IM. Progression of pigmented purpura-like eruptions to mycosis fungoides: report of three cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;19(1, pt 1):25-31.

13. Guitart J, Magro C. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia: a unifying term for idiopathic chronic dermatoses with persistent T-cell clones. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:921-932.

14. Graham RM, English JS, Emmerson RW. Lichen aureus—a study of twelve cases. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1984;9:393-401.

15. Fujita H, Iguchi M, Ikari Y, et al. Lichen aureus on the back in a 6-year-old girl. J Dermatol. 2007;34:148-149.

16. Ling TC, Goulden V, Goodfield MJ. PUVA therapy in lichen aureus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:145-146.

17. Agrawal SK, Gandhi V, Bhattacharya SN. Calcium dobesilate (Cd) in pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD): a pilot evaluation. J Dermatol. 2004;31:98-103.

18. Lee HW, Lee DK, Chang SE, et al. Segmental lichen aureus: combination therapy with pentoxifylline and prostacyclin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1378-1380.

19. Reinhold U, Seiter S, Ugurel S, et al. Treatment of progressive pigmented purpura with oral bioflavonoids and ascorbic acid: an open pilot study in 3 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;4(2, pt 1):207-208.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Aureus

Lichen aureus (LA) is classified as a pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD), a collection of conditions that are characterized by petechiae, pigmentation, and occasionally telangiectasia without a causative underlying disorder. As in our case, the lesions of LA are usually asymptomatic. They appear as circumscribed areas of discrete or confluent macules and papules that can range in color from gold or copper to purple (Figure 1). The lesions typically occur unilaterally on the lower extremities but can occur on all body regions. The etiology is unknown, but explanations such as venous insufficiency,1 contact allergens,2 and drugs3,4 have been proposed. Unlike other PPDs, LA tends to occur abruptly and then either stabilizes or progresses slowly over years. Studies have reported resolution in 2 to 7 years.5 The average age of onset is in the 20s and 30s, with pediatric cases accounting for only 17%.6 Pediatric cases are more likely to be self-limited and occur in uncommon sites such as the trunk and arms.7

Lichen aureus is characterized histopathologically by a dense, bandlike, dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2). Additionally, there is variable exocytosis of lymphocytes and marked accumulation of siderotic macrophages (Figure 3). These qualities in the proper clinical setting help differentiate LA from other PPDs that share findings of capillaritis, hemosiderin deposition, and erythrocyte extravasation near dermal vessels. An iron stain assists in the diagnosis of LA (Figure 3), as it differentiates the disease from other lichenoid conditions such as lichen planus. Zaballos et al8 also demonstrated a role for dermoscopy to clinically differentiate LA from other similar-appearing lesions such as lichen planus.

The lesions of LA are benign. Because the predominantly T-cell infiltrate is monoclonal in approximately 50% of cases,2,9-11 authors have suggested the possibility of progression to cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.9,12 Guitart and Magro13 classified LA as a T-cell lymphoid dyscrasia with potential for progression. Despite these reports, the general consensus is that LA is a benign, self-limiting condition. The benign nature of LA is supported by Fink-Puches et al2 who followed 23 patients for a mean 102.1 months and did not observe a single case of progression to malignancy.

There have been many treatment regimens attempted for patients with LA. Topical corticosteroids have not been found to be beneficial14; however, there have been isolated cases reporting its efficacy in children.7,15 Other medications that have been effective in small trials include psoralen plus UVA,16 topical pimecrolimus,5 calcium dobesilate,17 and combination therapy with pentoxifylline and prostacyclin.18 Despite some reported benefit, the use of potent immunomodulating medications is not indicated due to the benign nature of the disease. Alternative supplements including oral bioflavonoids and ascorbic acid have also been explored with modest benefit.19

The Diagnosis: Lichen Aureus