User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Bluish Gray Hyperpigmentation on the Face and Neck

The Diagnosis: Erythema Dyschromicum Perstans

Erythema dyschromicum perstans (EDP), also referred to as ashy dermatosis, was first described by Ramirez1 in 1957 who labeled the patients los cenicientos (the ashen ones). It preferentially affects women in the second decade of life; however, patients of all ages can be affected, with reported cases occurring in children as young as 2 years of age.2 Most patients have Fitzpatrick skin type IV, mainly Amerindian, Hispanic South Asian, and Southwest Asian; however, there are cases reported worldwide.3 A genetic predisposition is proposed, as major histocompatibility complex genes associated with HLA-DR4⁎0407 are frequent in Mexican patients with ashy dermatosis and in the Amerindian population.4

The etiology of EDP is unknown. Various contributing factors have been reported including alimentary, occupational, and climatic factors,5,6 yet none have been conclusively demonstrated. High expression of CD36 (thrombospondin receptor not found in normal skin) in spinous and granular layers, CD94 (cytotoxic cell marker) in the basal cell layer and in the inflammatory dermal infiltrate,7 and focal keratinocytic expression of intercellular adhesion molecule I (CD54) in the active lesions of EDP, as well as the absence of these findings in normal skin, suggests an immunologic role in the development of the disease.8

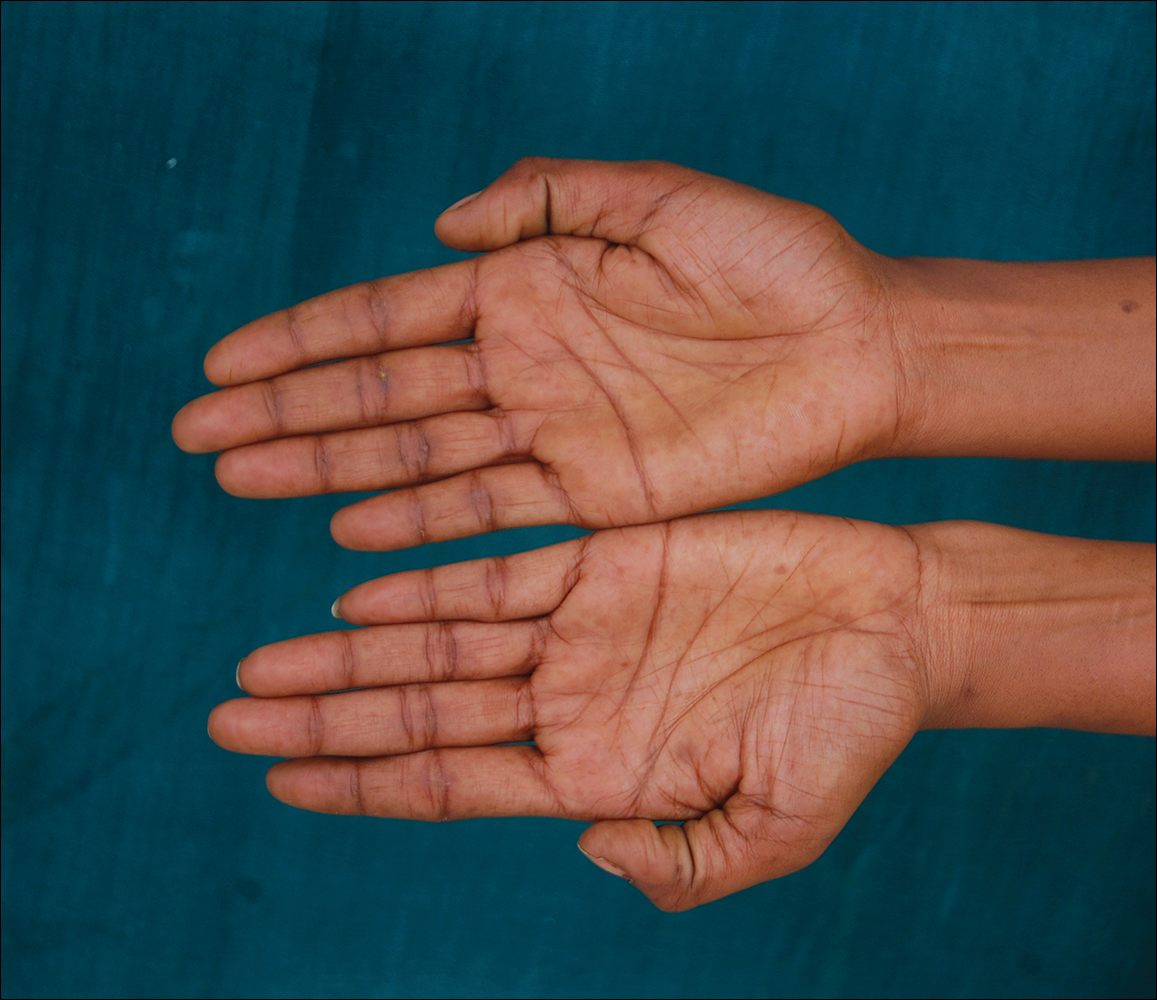

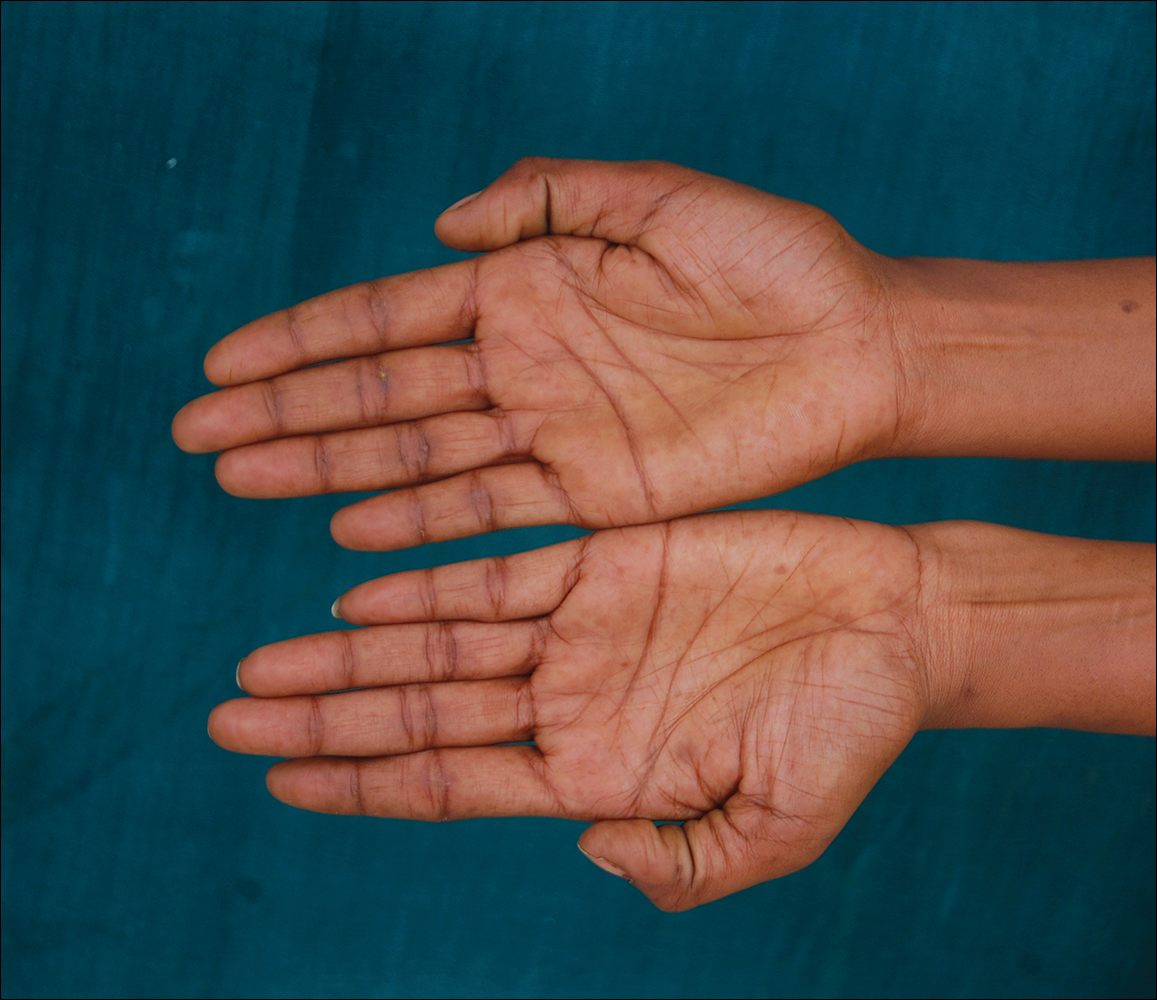

Erythema dyschromicum perstans presents clinically with blue-gray hyperpigmented macules varying in size and shape and developing symmetrically in both sun-exposed and sun-protected areas of the face, neck, trunk, arms, and sometimes the dorsal hands (Figures 1 and 2). Notable sparing of the palms, soles, scalp, and mucous membranes occurs.

Occasionally, in the early active stage of the disease, elevated erythematous borders are noted surrounding the hyperpigmented macules. Eventually a hypopigmented halo develops after a prolonged duration of disease.9 The eruption typically is chronic and asymptomatic, though some cases may be pruritic.10

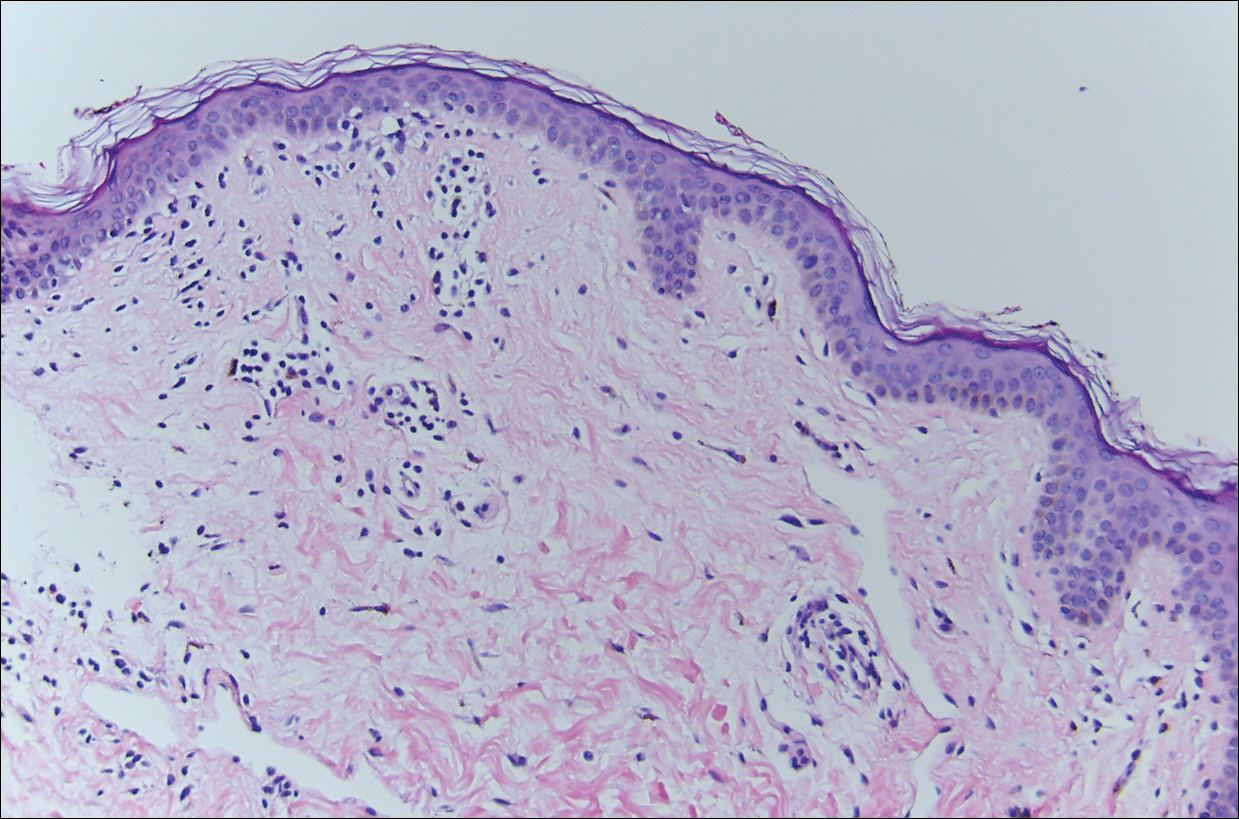

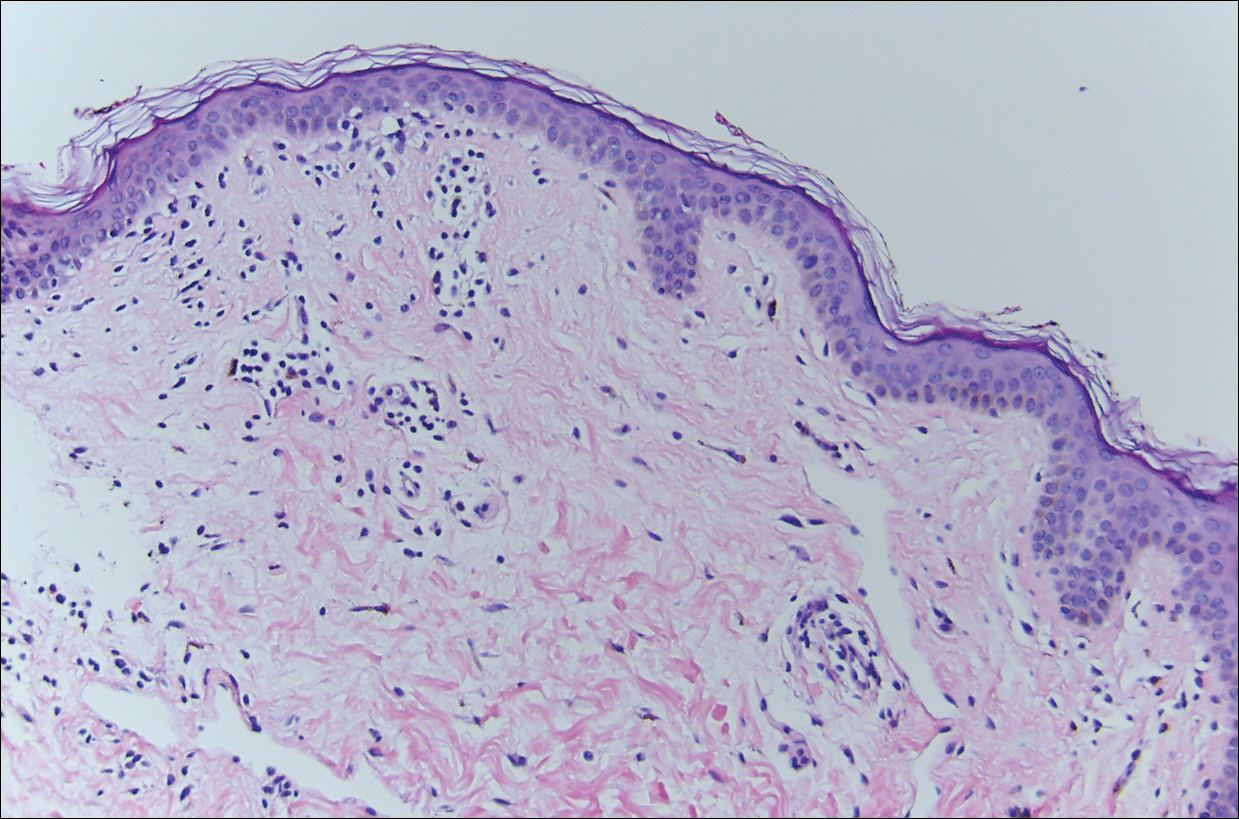

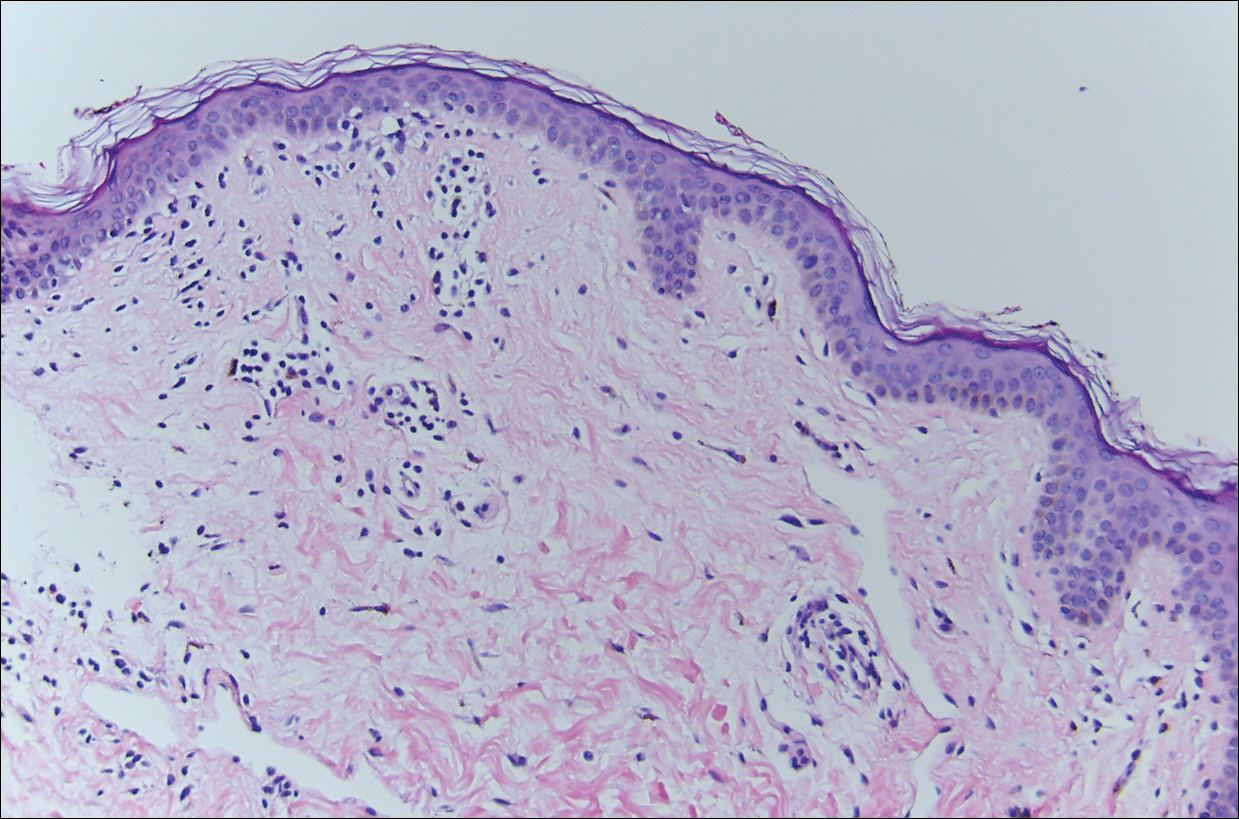

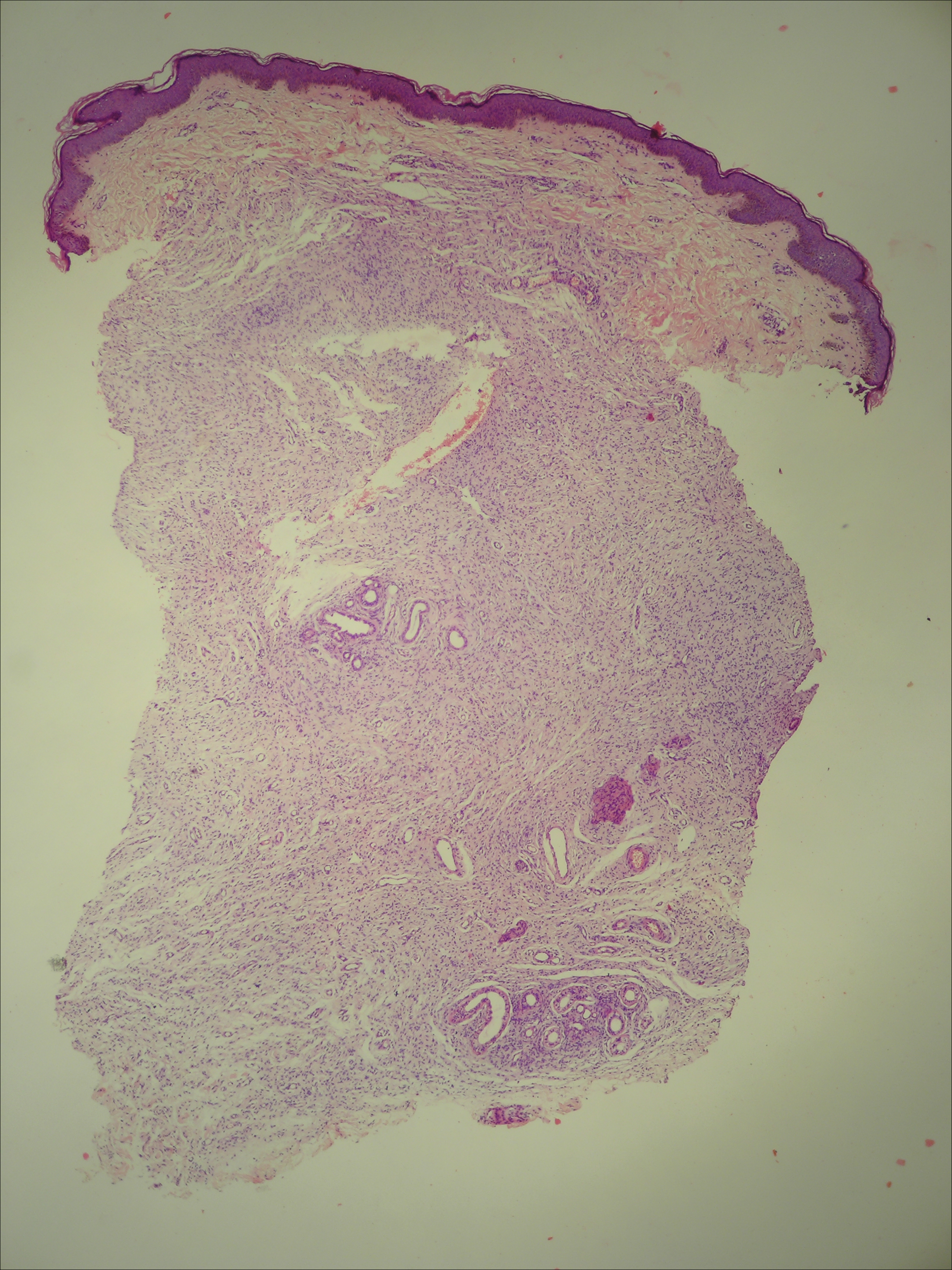

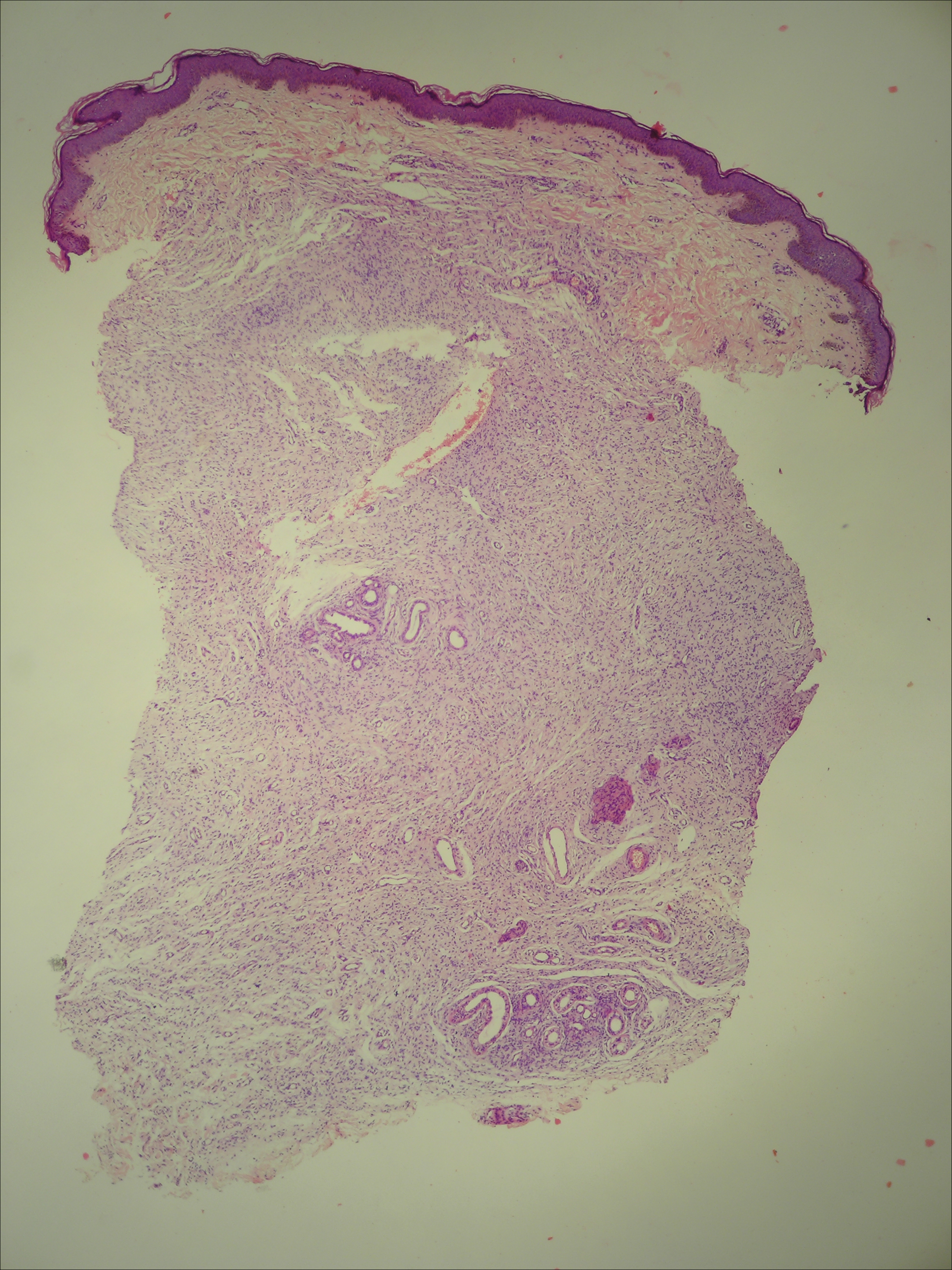

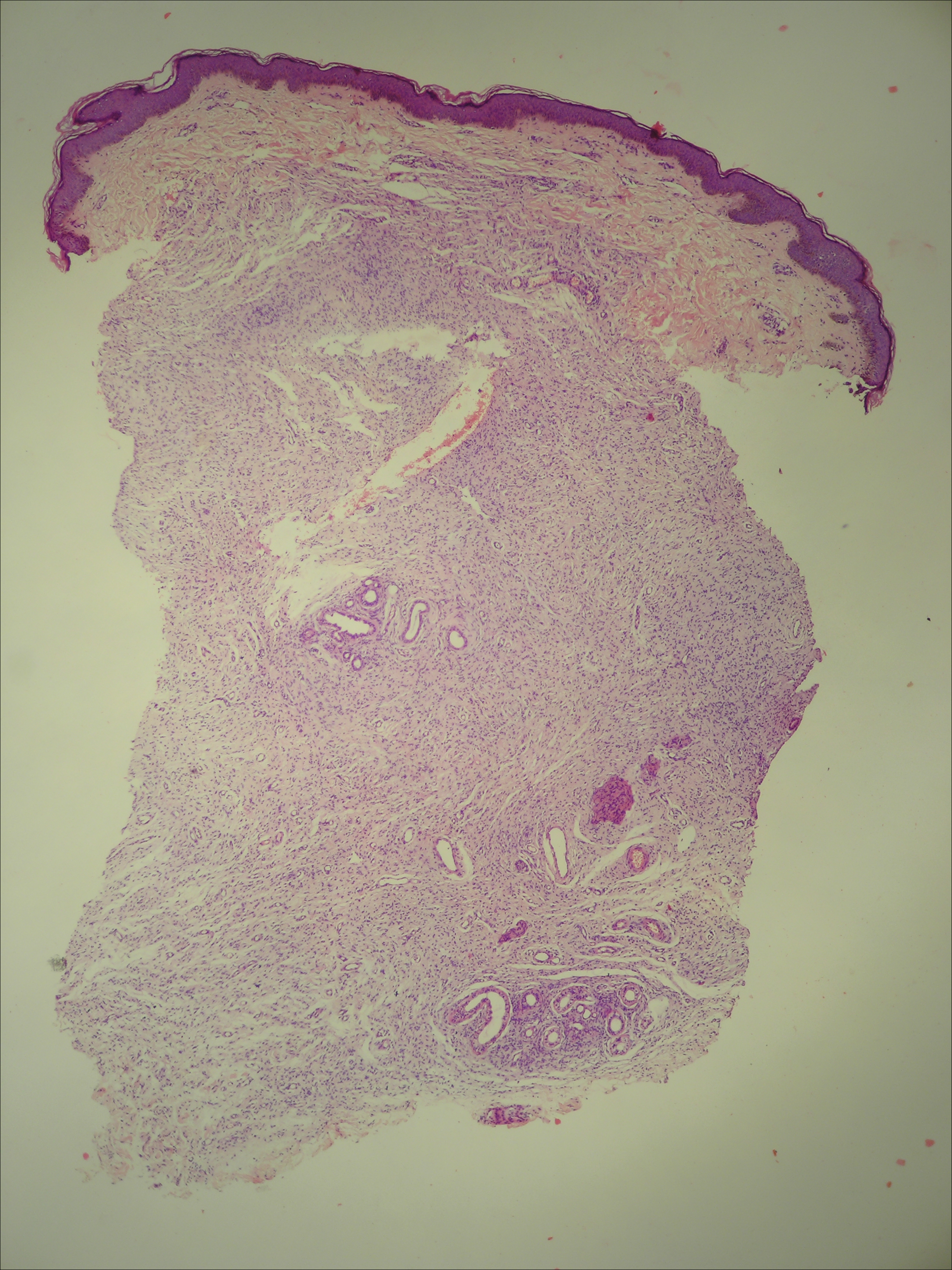

Histopathologically, the early lesions of EDP with an erythematous active border reveal lichenoid dermatitis with basal vacuolar change and occasional Civatte bodies. A mild to moderate perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate admixed with melanophages can be seen in the papillary dermis (Figure 3). In older lesions, the inflammatory infiltrate is sparse, and pigment incontinence consistent with postinflammatory pigmentation is prominent, though melanophages extending deep into the reticular dermis may aid in distinguishing EDP from other causes of postinflammatory pigment alteration.7,11

Erythema dyschromicum perstans and lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) may be indistinguishable histopathologically and may both be variants of lichen planus actinicus. Lichen planus pigmentosus often differs from EDP in that it presents with brown-black macules and patches often on the face and flexural areas. A subset of cases of LPP also may have mucous membrane involvement. The erythematous border that characterizes the active lesion of EDP is characteristically absent in LPP. In addition, pruritus often is reported with LPP. Direct immunofluorescence is not a beneficial tool in distinguishing the entities.12

Other differential diagnoses of predominantly facial hyperpigmentation include a lichenoid drug eruption; drug-induced hyperpigmentation (deposition disorder); postinflammatory hyperpigmentation following atopic dermatitis; contact dermatitis or photosensitivity reaction; early pinta; and cutaneous findings of systemic diseases manifesting with diffuse hyperpigmentation such as lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, hemochromatosis, and Addison disease. A detailed history including medication use, thorough clinical examination, and careful histopathologic evaluation will help distinguish these conditions.

Chrysiasis is a rare bluish to slate gray discoloration of the skin that predominantly occurs in sun-exposed areas. It is caused by chronic use of gold salts, which have been used to treat rheumatoid arthritis. UV light may contribute to induce the uptake of gold and subsequently stimulate tyrosinase activity.13 Histologic features of chrysiasis include dermal and perivascular gold deposition within the macrophages and endothelial cells as well as extracellular granules. It demonstrates an orange-red birefringence on fluorescent microscopy.14,15

Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation is a well-recognized side effect of this drug. It is dose dependent and appears as a blue-black pigmentation that most frequently affects the shins, ankles, and arms.16 Three distinct types were documented: abnormal discoloration of the skin that has been linked to deposition of pigmented metabolites of minocycline producing blue-black pigmentation at the site of scarring or prior inflammation (type 1); blue-gray pigmentation affecting normal skin, mainly the legs (type 2); and elevated levels of melanin on the sun-exposed areas producing dirty skin syndrome (type 3).17,18

Topical and systemic corticosteroids, UV light therapy, oral dapsone, griseofulvin, retinoids, and clofazimine are reported as treatment options for ashy dermatosis, though results typically are disappointing.7

- Ramirez CO. Los cenicientos: problema clinica. In: Memoria del Primer Congresso Centroamericano de Dermatologica, December 5-8, 1957. San Salvador, El Salvador; 1957:122-130.

- Lee SJ, Chung KY. Erythema dyschromicum perstans in early childhood. J Dermatol. 1999;26:119-121.

- Homez-Chacin, Barroso C. On the etiopathogenic of the erythema dyschromicum perstans: possibility of a melanosis neurocutaneous. Dermatol Venez. 1996;4:149-151.

- Correa MC, Memije EV, Vargas-Alarcon G, et al. HLA-DR association with the genetic susceptibility to develop ashy dermatosis in Mexican Mestizo patients [published online November 20, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:617-620.

- Jablonska S. Ingestion of ammonium nitrate as a possible cause of erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatosis). Dermatologica. 1975;150:287-291.

- Stevenson JR, Miura M. Erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatosis). Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:196-199.

- Baranda L, Torres-Alvarez B, Cortes-Franco R, et al. Involvement of cell adhesion and activation molecules in the pathogenesis of erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatitis). the effect of clofazimine therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:325-329.

- Vasquez-Ochoa LA, Isaza-Guzman DM, Orozco-Mora B, et al. Immunopathologic study of erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatosis). Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:937-941.

- Convit J, Kerdel-Vegas F, Roderiguez G. Erythema dyschromicum perstans: a hiltherto undescribed skin disease. J Invest Dermatol. 1961;36:457-462.

- Ono S, Miyachi Y, Kabashima K. Ashy dermatosis with prior pruritic and scaling skin lesions. J Dermatol. 2012;39:1103-1104.

- Sanchez NP, Pathak MA, Sato SS, et al. Circumscribed dermal melaninoses: classification, light, histochemical, and electron microscopic studies on three patients with the erythema dyschromicum perstans type. Int J Dermatol. 1982;21:25-32.

- Vega ME, Waxtein L, Arenas R, et al. Ashy dermatosis and lichen planus pigmentosus: a clinicopathologic study of 31 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:90-94.

- Ahmed SV, Sajjan R. Chrysiasis: a gold "curse!" [published online May 21, 2009]. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009.

- Fiscus V, Hankinson A, Alweis R. Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2014;4. doi:10.3402/jchimp.v4.24063.

- Cox AJ, Marich KW. Gold in the dermis following gold therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Dermatol. 1973;108:655-657.

- al-Talib RK, Wright DH, Theaker JM. Orange-red birefringence of gold particles in paraffin wax embedded sections: an aid to the diagnosis of chrysiasis. Histopathology. 1994;24:176-178.

- Meyer AJ, Nahass GT. Hyperpigmented patches on the dorsa of the feet. minocycline pigmentation. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1447-1450.

- Bayne-Poorman M, Shubrook J. Bluish pigmentation of face and sclera. J Fam Pract. 2010;59:519-522.

The Diagnosis: Erythema Dyschromicum Perstans

Erythema dyschromicum perstans (EDP), also referred to as ashy dermatosis, was first described by Ramirez1 in 1957 who labeled the patients los cenicientos (the ashen ones). It preferentially affects women in the second decade of life; however, patients of all ages can be affected, with reported cases occurring in children as young as 2 years of age.2 Most patients have Fitzpatrick skin type IV, mainly Amerindian, Hispanic South Asian, and Southwest Asian; however, there are cases reported worldwide.3 A genetic predisposition is proposed, as major histocompatibility complex genes associated with HLA-DR4⁎0407 are frequent in Mexican patients with ashy dermatosis and in the Amerindian population.4

The etiology of EDP is unknown. Various contributing factors have been reported including alimentary, occupational, and climatic factors,5,6 yet none have been conclusively demonstrated. High expression of CD36 (thrombospondin receptor not found in normal skin) in spinous and granular layers, CD94 (cytotoxic cell marker) in the basal cell layer and in the inflammatory dermal infiltrate,7 and focal keratinocytic expression of intercellular adhesion molecule I (CD54) in the active lesions of EDP, as well as the absence of these findings in normal skin, suggests an immunologic role in the development of the disease.8

Erythema dyschromicum perstans presents clinically with blue-gray hyperpigmented macules varying in size and shape and developing symmetrically in both sun-exposed and sun-protected areas of the face, neck, trunk, arms, and sometimes the dorsal hands (Figures 1 and 2). Notable sparing of the palms, soles, scalp, and mucous membranes occurs.

Occasionally, in the early active stage of the disease, elevated erythematous borders are noted surrounding the hyperpigmented macules. Eventually a hypopigmented halo develops after a prolonged duration of disease.9 The eruption typically is chronic and asymptomatic, though some cases may be pruritic.10

Histopathologically, the early lesions of EDP with an erythematous active border reveal lichenoid dermatitis with basal vacuolar change and occasional Civatte bodies. A mild to moderate perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate admixed with melanophages can be seen in the papillary dermis (Figure 3). In older lesions, the inflammatory infiltrate is sparse, and pigment incontinence consistent with postinflammatory pigmentation is prominent, though melanophages extending deep into the reticular dermis may aid in distinguishing EDP from other causes of postinflammatory pigment alteration.7,11

Erythema dyschromicum perstans and lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) may be indistinguishable histopathologically and may both be variants of lichen planus actinicus. Lichen planus pigmentosus often differs from EDP in that it presents with brown-black macules and patches often on the face and flexural areas. A subset of cases of LPP also may have mucous membrane involvement. The erythematous border that characterizes the active lesion of EDP is characteristically absent in LPP. In addition, pruritus often is reported with LPP. Direct immunofluorescence is not a beneficial tool in distinguishing the entities.12

Other differential diagnoses of predominantly facial hyperpigmentation include a lichenoid drug eruption; drug-induced hyperpigmentation (deposition disorder); postinflammatory hyperpigmentation following atopic dermatitis; contact dermatitis or photosensitivity reaction; early pinta; and cutaneous findings of systemic diseases manifesting with diffuse hyperpigmentation such as lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, hemochromatosis, and Addison disease. A detailed history including medication use, thorough clinical examination, and careful histopathologic evaluation will help distinguish these conditions.

Chrysiasis is a rare bluish to slate gray discoloration of the skin that predominantly occurs in sun-exposed areas. It is caused by chronic use of gold salts, which have been used to treat rheumatoid arthritis. UV light may contribute to induce the uptake of gold and subsequently stimulate tyrosinase activity.13 Histologic features of chrysiasis include dermal and perivascular gold deposition within the macrophages and endothelial cells as well as extracellular granules. It demonstrates an orange-red birefringence on fluorescent microscopy.14,15

Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation is a well-recognized side effect of this drug. It is dose dependent and appears as a blue-black pigmentation that most frequently affects the shins, ankles, and arms.16 Three distinct types were documented: abnormal discoloration of the skin that has been linked to deposition of pigmented metabolites of minocycline producing blue-black pigmentation at the site of scarring or prior inflammation (type 1); blue-gray pigmentation affecting normal skin, mainly the legs (type 2); and elevated levels of melanin on the sun-exposed areas producing dirty skin syndrome (type 3).17,18

Topical and systemic corticosteroids, UV light therapy, oral dapsone, griseofulvin, retinoids, and clofazimine are reported as treatment options for ashy dermatosis, though results typically are disappointing.7

The Diagnosis: Erythema Dyschromicum Perstans

Erythema dyschromicum perstans (EDP), also referred to as ashy dermatosis, was first described by Ramirez1 in 1957 who labeled the patients los cenicientos (the ashen ones). It preferentially affects women in the second decade of life; however, patients of all ages can be affected, with reported cases occurring in children as young as 2 years of age.2 Most patients have Fitzpatrick skin type IV, mainly Amerindian, Hispanic South Asian, and Southwest Asian; however, there are cases reported worldwide.3 A genetic predisposition is proposed, as major histocompatibility complex genes associated with HLA-DR4⁎0407 are frequent in Mexican patients with ashy dermatosis and in the Amerindian population.4

The etiology of EDP is unknown. Various contributing factors have been reported including alimentary, occupational, and climatic factors,5,6 yet none have been conclusively demonstrated. High expression of CD36 (thrombospondin receptor not found in normal skin) in spinous and granular layers, CD94 (cytotoxic cell marker) in the basal cell layer and in the inflammatory dermal infiltrate,7 and focal keratinocytic expression of intercellular adhesion molecule I (CD54) in the active lesions of EDP, as well as the absence of these findings in normal skin, suggests an immunologic role in the development of the disease.8

Erythema dyschromicum perstans presents clinically with blue-gray hyperpigmented macules varying in size and shape and developing symmetrically in both sun-exposed and sun-protected areas of the face, neck, trunk, arms, and sometimes the dorsal hands (Figures 1 and 2). Notable sparing of the palms, soles, scalp, and mucous membranes occurs.

Occasionally, in the early active stage of the disease, elevated erythematous borders are noted surrounding the hyperpigmented macules. Eventually a hypopigmented halo develops after a prolonged duration of disease.9 The eruption typically is chronic and asymptomatic, though some cases may be pruritic.10

Histopathologically, the early lesions of EDP with an erythematous active border reveal lichenoid dermatitis with basal vacuolar change and occasional Civatte bodies. A mild to moderate perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate admixed with melanophages can be seen in the papillary dermis (Figure 3). In older lesions, the inflammatory infiltrate is sparse, and pigment incontinence consistent with postinflammatory pigmentation is prominent, though melanophages extending deep into the reticular dermis may aid in distinguishing EDP from other causes of postinflammatory pigment alteration.7,11

Erythema dyschromicum perstans and lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) may be indistinguishable histopathologically and may both be variants of lichen planus actinicus. Lichen planus pigmentosus often differs from EDP in that it presents with brown-black macules and patches often on the face and flexural areas. A subset of cases of LPP also may have mucous membrane involvement. The erythematous border that characterizes the active lesion of EDP is characteristically absent in LPP. In addition, pruritus often is reported with LPP. Direct immunofluorescence is not a beneficial tool in distinguishing the entities.12

Other differential diagnoses of predominantly facial hyperpigmentation include a lichenoid drug eruption; drug-induced hyperpigmentation (deposition disorder); postinflammatory hyperpigmentation following atopic dermatitis; contact dermatitis or photosensitivity reaction; early pinta; and cutaneous findings of systemic diseases manifesting with diffuse hyperpigmentation such as lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, hemochromatosis, and Addison disease. A detailed history including medication use, thorough clinical examination, and careful histopathologic evaluation will help distinguish these conditions.

Chrysiasis is a rare bluish to slate gray discoloration of the skin that predominantly occurs in sun-exposed areas. It is caused by chronic use of gold salts, which have been used to treat rheumatoid arthritis. UV light may contribute to induce the uptake of gold and subsequently stimulate tyrosinase activity.13 Histologic features of chrysiasis include dermal and perivascular gold deposition within the macrophages and endothelial cells as well as extracellular granules. It demonstrates an orange-red birefringence on fluorescent microscopy.14,15

Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation is a well-recognized side effect of this drug. It is dose dependent and appears as a blue-black pigmentation that most frequently affects the shins, ankles, and arms.16 Three distinct types were documented: abnormal discoloration of the skin that has been linked to deposition of pigmented metabolites of minocycline producing blue-black pigmentation at the site of scarring or prior inflammation (type 1); blue-gray pigmentation affecting normal skin, mainly the legs (type 2); and elevated levels of melanin on the sun-exposed areas producing dirty skin syndrome (type 3).17,18

Topical and systemic corticosteroids, UV light therapy, oral dapsone, griseofulvin, retinoids, and clofazimine are reported as treatment options for ashy dermatosis, though results typically are disappointing.7

- Ramirez CO. Los cenicientos: problema clinica. In: Memoria del Primer Congresso Centroamericano de Dermatologica, December 5-8, 1957. San Salvador, El Salvador; 1957:122-130.

- Lee SJ, Chung KY. Erythema dyschromicum perstans in early childhood. J Dermatol. 1999;26:119-121.

- Homez-Chacin, Barroso C. On the etiopathogenic of the erythema dyschromicum perstans: possibility of a melanosis neurocutaneous. Dermatol Venez. 1996;4:149-151.

- Correa MC, Memije EV, Vargas-Alarcon G, et al. HLA-DR association with the genetic susceptibility to develop ashy dermatosis in Mexican Mestizo patients [published online November 20, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:617-620.

- Jablonska S. Ingestion of ammonium nitrate as a possible cause of erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatosis). Dermatologica. 1975;150:287-291.

- Stevenson JR, Miura M. Erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatosis). Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:196-199.

- Baranda L, Torres-Alvarez B, Cortes-Franco R, et al. Involvement of cell adhesion and activation molecules in the pathogenesis of erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatitis). the effect of clofazimine therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:325-329.

- Vasquez-Ochoa LA, Isaza-Guzman DM, Orozco-Mora B, et al. Immunopathologic study of erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatosis). Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:937-941.

- Convit J, Kerdel-Vegas F, Roderiguez G. Erythema dyschromicum perstans: a hiltherto undescribed skin disease. J Invest Dermatol. 1961;36:457-462.

- Ono S, Miyachi Y, Kabashima K. Ashy dermatosis with prior pruritic and scaling skin lesions. J Dermatol. 2012;39:1103-1104.

- Sanchez NP, Pathak MA, Sato SS, et al. Circumscribed dermal melaninoses: classification, light, histochemical, and electron microscopic studies on three patients with the erythema dyschromicum perstans type. Int J Dermatol. 1982;21:25-32.

- Vega ME, Waxtein L, Arenas R, et al. Ashy dermatosis and lichen planus pigmentosus: a clinicopathologic study of 31 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:90-94.

- Ahmed SV, Sajjan R. Chrysiasis: a gold "curse!" [published online May 21, 2009]. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009.

- Fiscus V, Hankinson A, Alweis R. Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2014;4. doi:10.3402/jchimp.v4.24063.

- Cox AJ, Marich KW. Gold in the dermis following gold therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Dermatol. 1973;108:655-657.

- al-Talib RK, Wright DH, Theaker JM. Orange-red birefringence of gold particles in paraffin wax embedded sections: an aid to the diagnosis of chrysiasis. Histopathology. 1994;24:176-178.

- Meyer AJ, Nahass GT. Hyperpigmented patches on the dorsa of the feet. minocycline pigmentation. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1447-1450.

- Bayne-Poorman M, Shubrook J. Bluish pigmentation of face and sclera. J Fam Pract. 2010;59:519-522.

- Ramirez CO. Los cenicientos: problema clinica. In: Memoria del Primer Congresso Centroamericano de Dermatologica, December 5-8, 1957. San Salvador, El Salvador; 1957:122-130.

- Lee SJ, Chung KY. Erythema dyschromicum perstans in early childhood. J Dermatol. 1999;26:119-121.

- Homez-Chacin, Barroso C. On the etiopathogenic of the erythema dyschromicum perstans: possibility of a melanosis neurocutaneous. Dermatol Venez. 1996;4:149-151.

- Correa MC, Memije EV, Vargas-Alarcon G, et al. HLA-DR association with the genetic susceptibility to develop ashy dermatosis in Mexican Mestizo patients [published online November 20, 2006]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:617-620.

- Jablonska S. Ingestion of ammonium nitrate as a possible cause of erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatosis). Dermatologica. 1975;150:287-291.

- Stevenson JR, Miura M. Erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatosis). Arch Dermatol. 1966;94:196-199.

- Baranda L, Torres-Alvarez B, Cortes-Franco R, et al. Involvement of cell adhesion and activation molecules in the pathogenesis of erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatitis). the effect of clofazimine therapy. Arch Dermatol. 1997;133:325-329.

- Vasquez-Ochoa LA, Isaza-Guzman DM, Orozco-Mora B, et al. Immunopathologic study of erythema dyschromicum perstans (ashy dermatosis). Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:937-941.

- Convit J, Kerdel-Vegas F, Roderiguez G. Erythema dyschromicum perstans: a hiltherto undescribed skin disease. J Invest Dermatol. 1961;36:457-462.

- Ono S, Miyachi Y, Kabashima K. Ashy dermatosis with prior pruritic and scaling skin lesions. J Dermatol. 2012;39:1103-1104.

- Sanchez NP, Pathak MA, Sato SS, et al. Circumscribed dermal melaninoses: classification, light, histochemical, and electron microscopic studies on three patients with the erythema dyschromicum perstans type. Int J Dermatol. 1982;21:25-32.

- Vega ME, Waxtein L, Arenas R, et al. Ashy dermatosis and lichen planus pigmentosus: a clinicopathologic study of 31 cases. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:90-94.

- Ahmed SV, Sajjan R. Chrysiasis: a gold "curse!" [published online May 21, 2009]. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009.

- Fiscus V, Hankinson A, Alweis R. Minocycline-induced hyperpigmentation. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2014;4. doi:10.3402/jchimp.v4.24063.

- Cox AJ, Marich KW. Gold in the dermis following gold therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Dermatol. 1973;108:655-657.

- al-Talib RK, Wright DH, Theaker JM. Orange-red birefringence of gold particles in paraffin wax embedded sections: an aid to the diagnosis of chrysiasis. Histopathology. 1994;24:176-178.

- Meyer AJ, Nahass GT. Hyperpigmented patches on the dorsa of the feet. minocycline pigmentation. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1447-1450.

- Bayne-Poorman M, Shubrook J. Bluish pigmentation of face and sclera. J Fam Pract. 2010;59:519-522.

A middle-aged woman with Fitzpatrick skin type IV was evaluated for progressive hyperpigmentation of several months' duration involving the neck, jawline, both sides of the face, and forehead. The lesions were mildly pruritic. She denied contact with any new substance and there was no history of an eruption preceding the hyperpigmentation. Medical history included chronic anemia that was managed with iron supplementation. On physical examination, blue-gray nonscaly macules and patches were observed distributed symmetrically on the neck, jawline, sides of the face, and forehead. Microscopic examination of 2 shave biopsies revealed subtle vacuolar interface dermatitis with mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and dermal melanophages (inset).

Postoperative Henoch-Schönlein Purpura

To the Editor:

A 57-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension was hospitalized for heart disease resulting in an aortic valve replacement and multiple-vessel bypass grafting. He experienced a stormy septic postoperative course during which he developed numerous palpable purplish plaques (Figure 1). The lesions were bilateral and more heavily involved the lower legs and buttocks. The head and neck remained free of skin lesions. Additionally, the patient reported a bilateral burning sensation from the knees to the feet.

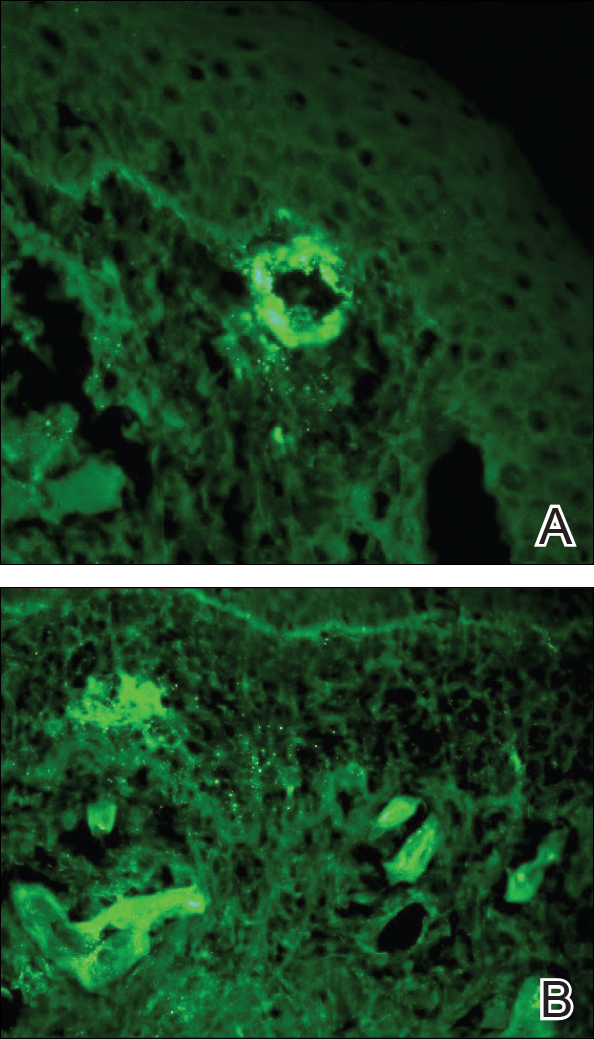

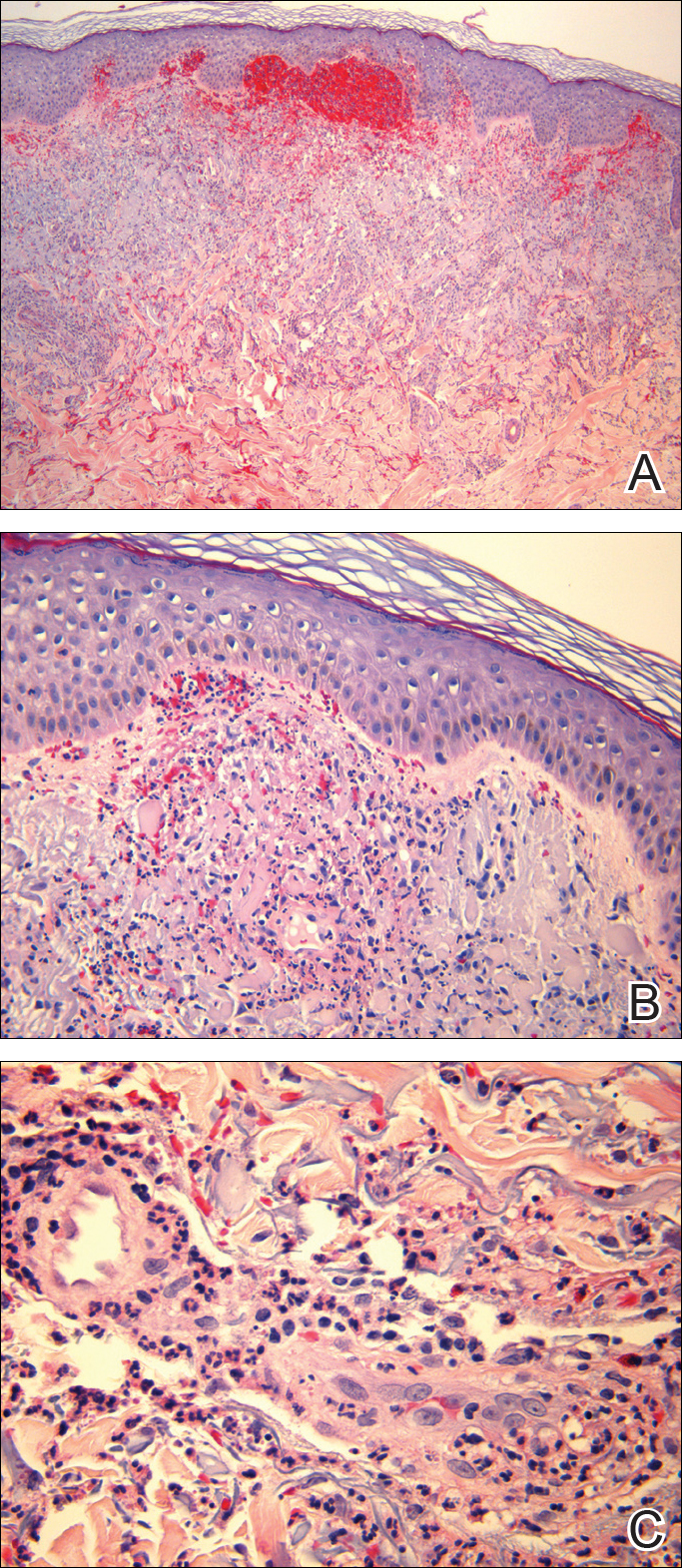

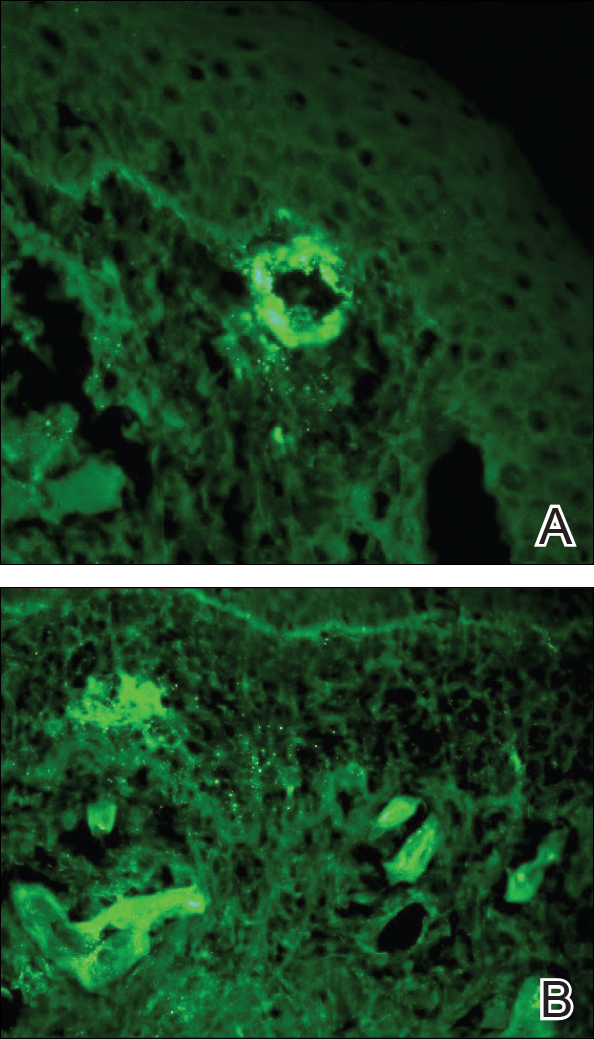

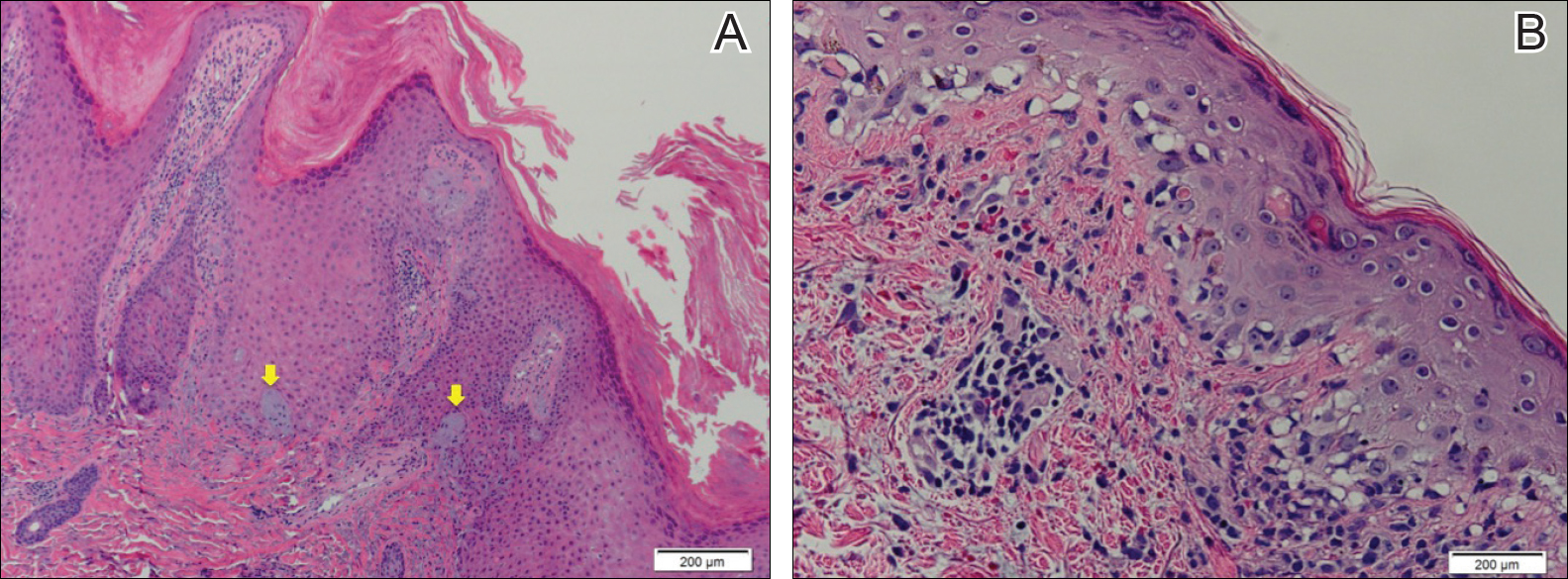

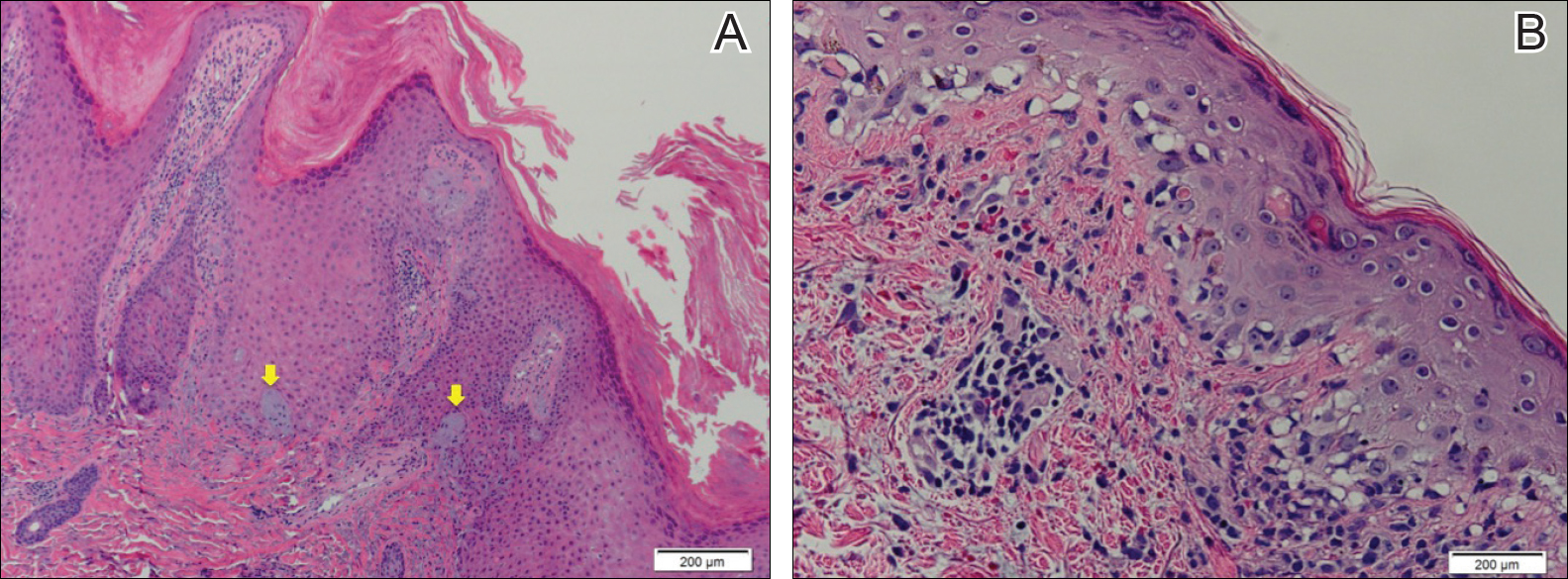

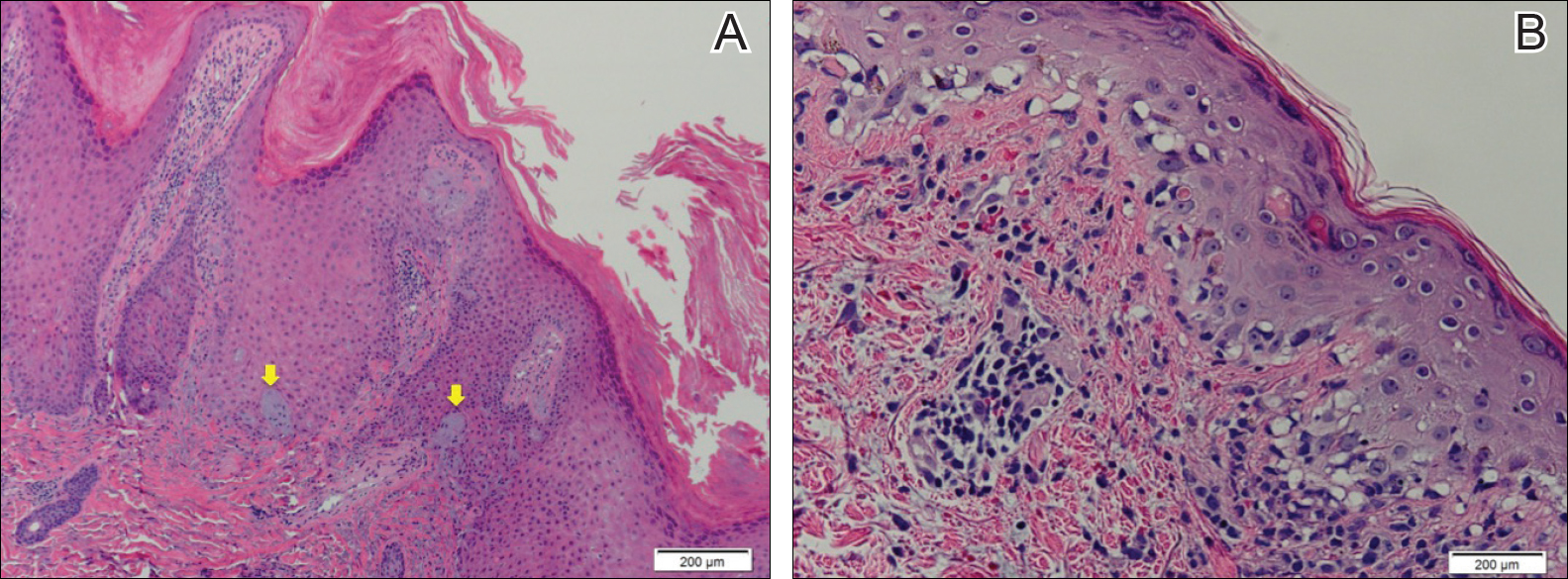

Punch biopsies of lesions from the right upper arm were obtained. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed neutrophilic-predominant small vessel vasculitis (Figure 2A) with the upper dermal location more heavily involved, as demonstrated by involvement of a superficial vascular plexus (Figures 2B and 2C) that was consistent with Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP). The diagnosis later was confirmed with immunofluorescence. Direct immunofluorescence revealed granular IgA deposition around the superficial vascular plexus (Figure 3). No IgG, IgM, C3, C5b-9 complement complex, or fibrinogen deposition was seen. Additionally, periodic acid-Schiff staining failed to show microorganisms, thrombi, or intravascular hyaline material.

At our initial consultation, we observed an ill-appearing afebrile man with purplish plaques. Our impression was that he had vasculitis and not warfarin necrosis, which had been suspected by the cardiovascular team. The burning sensation noted by the patient lent credence to our vasculitic diagnosis. Proteinuria and hematuria were present; however, the values for blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and glomerular filtration rate all remained within reference range. His signs and symptoms responded dramatically to prednisone. He remains on 1 mg of prednisone daily and a nephrologist continues to monitor renal function as an outpatient.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura is a systemic leukocytoclastic vasculitis involving small vessels. The small vessel vasculitis is associated with IgA antigen-antibody complex deposition in areas throughout the body. Palpable purpura typically is seen on the skin, which characteristically involves dependent areas such as the legs and the buttocks. Lesions normally are present bilaterally in a symmetric distribution. Initially, the lesions develop as erythematous macules that progress to purple, nonblanching, palpable, and purpuric plaques.1 Henoch-Schönlein purpura most commonly involves the skin; however, other locations for the immune complexes include the gastrointestinal tract, joints, and kidneys.2 The cause for the body's immunogenic deposition response is unknown in a majority of cases.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura most commonly is seen in the pediatric population with a predilection for males.3 The incidence in the pediatric population is 13.5 to 20 per 100,000 children per year; HSP is more rare in adults.4-6 Henoch-Schönlein purpura most often is a self-limiting disease that requires only supportive treatment. The signs and symptoms last 4 to 6 weeks in most patients and resolve completely in 94% of children and 89% of adults.7 Renal involvement carries a worse prognosis. Adult patients have a higher incidence of renal involvement, renal insufficiency, and subsequent progression to end-stage renal disease.3,8-10 In a study by Hung et al8 of 65 children and 22 adult HSP patients, 12 adults presented with renal involvement in which hematuria or proteinuria were present. Of them, 6 progressed to renal insufficiency (defined as having a plasma creatinine concentration>1.2 mg/dL).8 Fogazzi et al11 reported similar findings; 8 of 16 patients affected with HSP progressed to renal insufficiency with creatinine clearances ranging from 31 to 60 mL/min, and 3 patients required chronic dialysis. Pillebout et al9 evaluated 250 adults with HSP and 32% reached renal insufficiency with creatinine clearances of less than 50 mL/min, with 11% of patients developing end-stage renal disease. The degree of hematuria and/or proteinuria has been shown to be an effective prognostic indicator.9,10 Coppo et al10 found a similar prognosis among children and adults with HSP-related nephritis.

Our patient described the burning sensation as occurring bilaterally from the knees down to the feet, which provided an additional clue that small vessel vasculitis was involved, as occluded blood vessels can cause ischemia to nerves and perivascular involvement can affect nearby neural structures. Sais et al12 demonstrated that paresthesia in the setting of HSP was a risk factor for systemic involvement. Of note, our patient's paresthesia lasted only several days.

The cause of HSP is not always as evident in the adult population as in the pediatric population. Early diagnosis of HSP in adults may allow for the proper instatement of treatment to deter long-term renal complications. Follow-up with urinalysis is recommended because a small percentage of patients have a late progression to renal failure.13,14

Because the dermatologists involved in this case knew where and what types of biopsies to perform, a correct diagnosis was obtained quickly, allowing for the correct therapeutic intervention. After the diagnosis of HSP is made in an adult, nephrology should be consulted early in the treatment course.

- Rai A, Nast C, Adler S. Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2637-2644.

- Helander SD, De Castro FR, Gibson LE. Henoch-Schönlein purpura: clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous vascular IgA deposits and the relationship to leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:125-129.

- Garcia-Porrua C, Calvino MC, Llorca J, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children and adults: clinical differences in a defined population. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002;32:149-156.

- Stewart M, Savage JM, Bell B, et al. Long term renal prognosis of Henoch-Schönlein purpura in an unselected childhood population. Eur J Pediatr. 1988;147:113-115.

- Watts RA, Scott DG. Epidemiology of the vasculitides. Semin Respir Crit Care. 2004;25:455-464.

- Gardner-Medwin JM, Dolezalova P, Cummins C, et al. Incidence of Henoch-Schönlein purpura, Kawasaki disease, and rare vasculitides in children of different ethnic origins. Lancet. 2002;360:1197-1202.

- Blanco R, Martínez-Taboada VM, Rodríguez-Valverde V, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adulthood and childhood: two different expressions of the same syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:859-864.

- Hung SP, Yang YH, Lin YT, et al. Clinical manifestations and outcomes of Henoch-Schönlein purpura: comparison between adults and children. Pediatr Neonatol. 2009;50:162-168.

- Pillebout E, Thervet E, Hill G, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adults: outcomes and prognostic factors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1271-1278.

- Coppo R, Mazzucco G, Cagnoli L, et al. Long-term prognosis of Henoch-Schönlein nephritis in adults and children. Italian Group of Renal Immunopathology collaborative study on Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:2277-2283.

- Fogazzi GB, Pasquali S, Moriggi M, et al. Long-term outcome of Schönlein-Henoch nephritis in the adult. Clin Nephrol. 1989;31:60-66.

- Sais G, Vidaller A, Jucgla A. Prognostic factors in leukocytoclastic vasculitis. a clinicopathologic study of 160 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:309-315.

- Kraft DM, McKee D, Scott C. Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a review. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58:405-408.

- Narchi H. Risk of long-term renal impairment and duration of follow up recommended for Henoch-Schönlein purpura with normal or minimal urinary findings: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:916-920.

To the Editor:

A 57-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension was hospitalized for heart disease resulting in an aortic valve replacement and multiple-vessel bypass grafting. He experienced a stormy septic postoperative course during which he developed numerous palpable purplish plaques (Figure 1). The lesions were bilateral and more heavily involved the lower legs and buttocks. The head and neck remained free of skin lesions. Additionally, the patient reported a bilateral burning sensation from the knees to the feet.

Punch biopsies of lesions from the right upper arm were obtained. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed neutrophilic-predominant small vessel vasculitis (Figure 2A) with the upper dermal location more heavily involved, as demonstrated by involvement of a superficial vascular plexus (Figures 2B and 2C) that was consistent with Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP). The diagnosis later was confirmed with immunofluorescence. Direct immunofluorescence revealed granular IgA deposition around the superficial vascular plexus (Figure 3). No IgG, IgM, C3, C5b-9 complement complex, or fibrinogen deposition was seen. Additionally, periodic acid-Schiff staining failed to show microorganisms, thrombi, or intravascular hyaline material.

At our initial consultation, we observed an ill-appearing afebrile man with purplish plaques. Our impression was that he had vasculitis and not warfarin necrosis, which had been suspected by the cardiovascular team. The burning sensation noted by the patient lent credence to our vasculitic diagnosis. Proteinuria and hematuria were present; however, the values for blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and glomerular filtration rate all remained within reference range. His signs and symptoms responded dramatically to prednisone. He remains on 1 mg of prednisone daily and a nephrologist continues to monitor renal function as an outpatient.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura is a systemic leukocytoclastic vasculitis involving small vessels. The small vessel vasculitis is associated with IgA antigen-antibody complex deposition in areas throughout the body. Palpable purpura typically is seen on the skin, which characteristically involves dependent areas such as the legs and the buttocks. Lesions normally are present bilaterally in a symmetric distribution. Initially, the lesions develop as erythematous macules that progress to purple, nonblanching, palpable, and purpuric plaques.1 Henoch-Schönlein purpura most commonly involves the skin; however, other locations for the immune complexes include the gastrointestinal tract, joints, and kidneys.2 The cause for the body's immunogenic deposition response is unknown in a majority of cases.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura most commonly is seen in the pediatric population with a predilection for males.3 The incidence in the pediatric population is 13.5 to 20 per 100,000 children per year; HSP is more rare in adults.4-6 Henoch-Schönlein purpura most often is a self-limiting disease that requires only supportive treatment. The signs and symptoms last 4 to 6 weeks in most patients and resolve completely in 94% of children and 89% of adults.7 Renal involvement carries a worse prognosis. Adult patients have a higher incidence of renal involvement, renal insufficiency, and subsequent progression to end-stage renal disease.3,8-10 In a study by Hung et al8 of 65 children and 22 adult HSP patients, 12 adults presented with renal involvement in which hematuria or proteinuria were present. Of them, 6 progressed to renal insufficiency (defined as having a plasma creatinine concentration>1.2 mg/dL).8 Fogazzi et al11 reported similar findings; 8 of 16 patients affected with HSP progressed to renal insufficiency with creatinine clearances ranging from 31 to 60 mL/min, and 3 patients required chronic dialysis. Pillebout et al9 evaluated 250 adults with HSP and 32% reached renal insufficiency with creatinine clearances of less than 50 mL/min, with 11% of patients developing end-stage renal disease. The degree of hematuria and/or proteinuria has been shown to be an effective prognostic indicator.9,10 Coppo et al10 found a similar prognosis among children and adults with HSP-related nephritis.

Our patient described the burning sensation as occurring bilaterally from the knees down to the feet, which provided an additional clue that small vessel vasculitis was involved, as occluded blood vessels can cause ischemia to nerves and perivascular involvement can affect nearby neural structures. Sais et al12 demonstrated that paresthesia in the setting of HSP was a risk factor for systemic involvement. Of note, our patient's paresthesia lasted only several days.

The cause of HSP is not always as evident in the adult population as in the pediatric population. Early diagnosis of HSP in adults may allow for the proper instatement of treatment to deter long-term renal complications. Follow-up with urinalysis is recommended because a small percentage of patients have a late progression to renal failure.13,14

Because the dermatologists involved in this case knew where and what types of biopsies to perform, a correct diagnosis was obtained quickly, allowing for the correct therapeutic intervention. After the diagnosis of HSP is made in an adult, nephrology should be consulted early in the treatment course.

To the Editor:

A 57-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension was hospitalized for heart disease resulting in an aortic valve replacement and multiple-vessel bypass grafting. He experienced a stormy septic postoperative course during which he developed numerous palpable purplish plaques (Figure 1). The lesions were bilateral and more heavily involved the lower legs and buttocks. The head and neck remained free of skin lesions. Additionally, the patient reported a bilateral burning sensation from the knees to the feet.

Punch biopsies of lesions from the right upper arm were obtained. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed neutrophilic-predominant small vessel vasculitis (Figure 2A) with the upper dermal location more heavily involved, as demonstrated by involvement of a superficial vascular plexus (Figures 2B and 2C) that was consistent with Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP). The diagnosis later was confirmed with immunofluorescence. Direct immunofluorescence revealed granular IgA deposition around the superficial vascular plexus (Figure 3). No IgG, IgM, C3, C5b-9 complement complex, or fibrinogen deposition was seen. Additionally, periodic acid-Schiff staining failed to show microorganisms, thrombi, or intravascular hyaline material.

At our initial consultation, we observed an ill-appearing afebrile man with purplish plaques. Our impression was that he had vasculitis and not warfarin necrosis, which had been suspected by the cardiovascular team. The burning sensation noted by the patient lent credence to our vasculitic diagnosis. Proteinuria and hematuria were present; however, the values for blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and glomerular filtration rate all remained within reference range. His signs and symptoms responded dramatically to prednisone. He remains on 1 mg of prednisone daily and a nephrologist continues to monitor renal function as an outpatient.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura is a systemic leukocytoclastic vasculitis involving small vessels. The small vessel vasculitis is associated with IgA antigen-antibody complex deposition in areas throughout the body. Palpable purpura typically is seen on the skin, which characteristically involves dependent areas such as the legs and the buttocks. Lesions normally are present bilaterally in a symmetric distribution. Initially, the lesions develop as erythematous macules that progress to purple, nonblanching, palpable, and purpuric plaques.1 Henoch-Schönlein purpura most commonly involves the skin; however, other locations for the immune complexes include the gastrointestinal tract, joints, and kidneys.2 The cause for the body's immunogenic deposition response is unknown in a majority of cases.

Henoch-Schönlein purpura most commonly is seen in the pediatric population with a predilection for males.3 The incidence in the pediatric population is 13.5 to 20 per 100,000 children per year; HSP is more rare in adults.4-6 Henoch-Schönlein purpura most often is a self-limiting disease that requires only supportive treatment. The signs and symptoms last 4 to 6 weeks in most patients and resolve completely in 94% of children and 89% of adults.7 Renal involvement carries a worse prognosis. Adult patients have a higher incidence of renal involvement, renal insufficiency, and subsequent progression to end-stage renal disease.3,8-10 In a study by Hung et al8 of 65 children and 22 adult HSP patients, 12 adults presented with renal involvement in which hematuria or proteinuria were present. Of them, 6 progressed to renal insufficiency (defined as having a plasma creatinine concentration>1.2 mg/dL).8 Fogazzi et al11 reported similar findings; 8 of 16 patients affected with HSP progressed to renal insufficiency with creatinine clearances ranging from 31 to 60 mL/min, and 3 patients required chronic dialysis. Pillebout et al9 evaluated 250 adults with HSP and 32% reached renal insufficiency with creatinine clearances of less than 50 mL/min, with 11% of patients developing end-stage renal disease. The degree of hematuria and/or proteinuria has been shown to be an effective prognostic indicator.9,10 Coppo et al10 found a similar prognosis among children and adults with HSP-related nephritis.

Our patient described the burning sensation as occurring bilaterally from the knees down to the feet, which provided an additional clue that small vessel vasculitis was involved, as occluded blood vessels can cause ischemia to nerves and perivascular involvement can affect nearby neural structures. Sais et al12 demonstrated that paresthesia in the setting of HSP was a risk factor for systemic involvement. Of note, our patient's paresthesia lasted only several days.

The cause of HSP is not always as evident in the adult population as in the pediatric population. Early diagnosis of HSP in adults may allow for the proper instatement of treatment to deter long-term renal complications. Follow-up with urinalysis is recommended because a small percentage of patients have a late progression to renal failure.13,14

Because the dermatologists involved in this case knew where and what types of biopsies to perform, a correct diagnosis was obtained quickly, allowing for the correct therapeutic intervention. After the diagnosis of HSP is made in an adult, nephrology should be consulted early in the treatment course.

- Rai A, Nast C, Adler S. Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2637-2644.

- Helander SD, De Castro FR, Gibson LE. Henoch-Schönlein purpura: clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous vascular IgA deposits and the relationship to leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:125-129.

- Garcia-Porrua C, Calvino MC, Llorca J, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children and adults: clinical differences in a defined population. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002;32:149-156.

- Stewart M, Savage JM, Bell B, et al. Long term renal prognosis of Henoch-Schönlein purpura in an unselected childhood population. Eur J Pediatr. 1988;147:113-115.

- Watts RA, Scott DG. Epidemiology of the vasculitides. Semin Respir Crit Care. 2004;25:455-464.

- Gardner-Medwin JM, Dolezalova P, Cummins C, et al. Incidence of Henoch-Schönlein purpura, Kawasaki disease, and rare vasculitides in children of different ethnic origins. Lancet. 2002;360:1197-1202.

- Blanco R, Martínez-Taboada VM, Rodríguez-Valverde V, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adulthood and childhood: two different expressions of the same syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:859-864.

- Hung SP, Yang YH, Lin YT, et al. Clinical manifestations and outcomes of Henoch-Schönlein purpura: comparison between adults and children. Pediatr Neonatol. 2009;50:162-168.

- Pillebout E, Thervet E, Hill G, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adults: outcomes and prognostic factors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1271-1278.

- Coppo R, Mazzucco G, Cagnoli L, et al. Long-term prognosis of Henoch-Schönlein nephritis in adults and children. Italian Group of Renal Immunopathology collaborative study on Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:2277-2283.

- Fogazzi GB, Pasquali S, Moriggi M, et al. Long-term outcome of Schönlein-Henoch nephritis in the adult. Clin Nephrol. 1989;31:60-66.

- Sais G, Vidaller A, Jucgla A. Prognostic factors in leukocytoclastic vasculitis. a clinicopathologic study of 160 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:309-315.

- Kraft DM, McKee D, Scott C. Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a review. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58:405-408.

- Narchi H. Risk of long-term renal impairment and duration of follow up recommended for Henoch-Schönlein purpura with normal or minimal urinary findings: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:916-920.

- Rai A, Nast C, Adler S. Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2637-2644.

- Helander SD, De Castro FR, Gibson LE. Henoch-Schönlein purpura: clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous vascular IgA deposits and the relationship to leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:125-129.

- Garcia-Porrua C, Calvino MC, Llorca J, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children and adults: clinical differences in a defined population. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002;32:149-156.

- Stewart M, Savage JM, Bell B, et al. Long term renal prognosis of Henoch-Schönlein purpura in an unselected childhood population. Eur J Pediatr. 1988;147:113-115.

- Watts RA, Scott DG. Epidemiology of the vasculitides. Semin Respir Crit Care. 2004;25:455-464.

- Gardner-Medwin JM, Dolezalova P, Cummins C, et al. Incidence of Henoch-Schönlein purpura, Kawasaki disease, and rare vasculitides in children of different ethnic origins. Lancet. 2002;360:1197-1202.

- Blanco R, Martínez-Taboada VM, Rodríguez-Valverde V, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adulthood and childhood: two different expressions of the same syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:859-864.

- Hung SP, Yang YH, Lin YT, et al. Clinical manifestations and outcomes of Henoch-Schönlein purpura: comparison between adults and children. Pediatr Neonatol. 2009;50:162-168.

- Pillebout E, Thervet E, Hill G, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adults: outcomes and prognostic factors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1271-1278.

- Coppo R, Mazzucco G, Cagnoli L, et al. Long-term prognosis of Henoch-Schönlein nephritis in adults and children. Italian Group of Renal Immunopathology collaborative study on Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:2277-2283.

- Fogazzi GB, Pasquali S, Moriggi M, et al. Long-term outcome of Schönlein-Henoch nephritis in the adult. Clin Nephrol. 1989;31:60-66.

- Sais G, Vidaller A, Jucgla A. Prognostic factors in leukocytoclastic vasculitis. a clinicopathologic study of 160 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:309-315.

- Kraft DM, McKee D, Scott C. Henoch-Schönlein purpura: a review. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58:405-408.

- Narchi H. Risk of long-term renal impairment and duration of follow up recommended for Henoch-Schönlein purpura with normal or minimal urinary findings: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:916-920.

Practice Points

- Henoch-Schönlein purpura is a multidisciplinary problem.

- Henoch-Schönlein purpura is an IgA-mediated disorder that is more common in children and has a more severe course in adults.

ICD-10 Update: Report From the AAD Meeting

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Hair Disorders in the Skin of Color Population: Report From the AAD Meeting

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Phacomatosis Cesioflammea in Association With von Recklinghausen Disease (Neurofibromatosis Type I)

To the Editor:

Vascular lesions associated with melanocytic nevi were first described by Ota et al1 in 1947 and given the name phacomatosis pigmentovascularis. In 2005, Happle2 reclassified phacomatosis pigmentovascularis into 3 well-defined types: (1) phacomatosis cesioflammea: blue spots (caesius means bluish gray in Latin) and nevus flammeus; (2) phacomatosis spilorosea: nevus spilus coexisting with a pale pink telangiectatic nevus; and (3) phacomatosis cesiomarmorata: blue spots and cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita. In 2011 Joshi et al3 described a case of a 31-year-old woman who had a port-wine stain in association with neurofibromatosis type I (NF-1). We present a case of phacomatosis cesioflammea in association with NF-1.

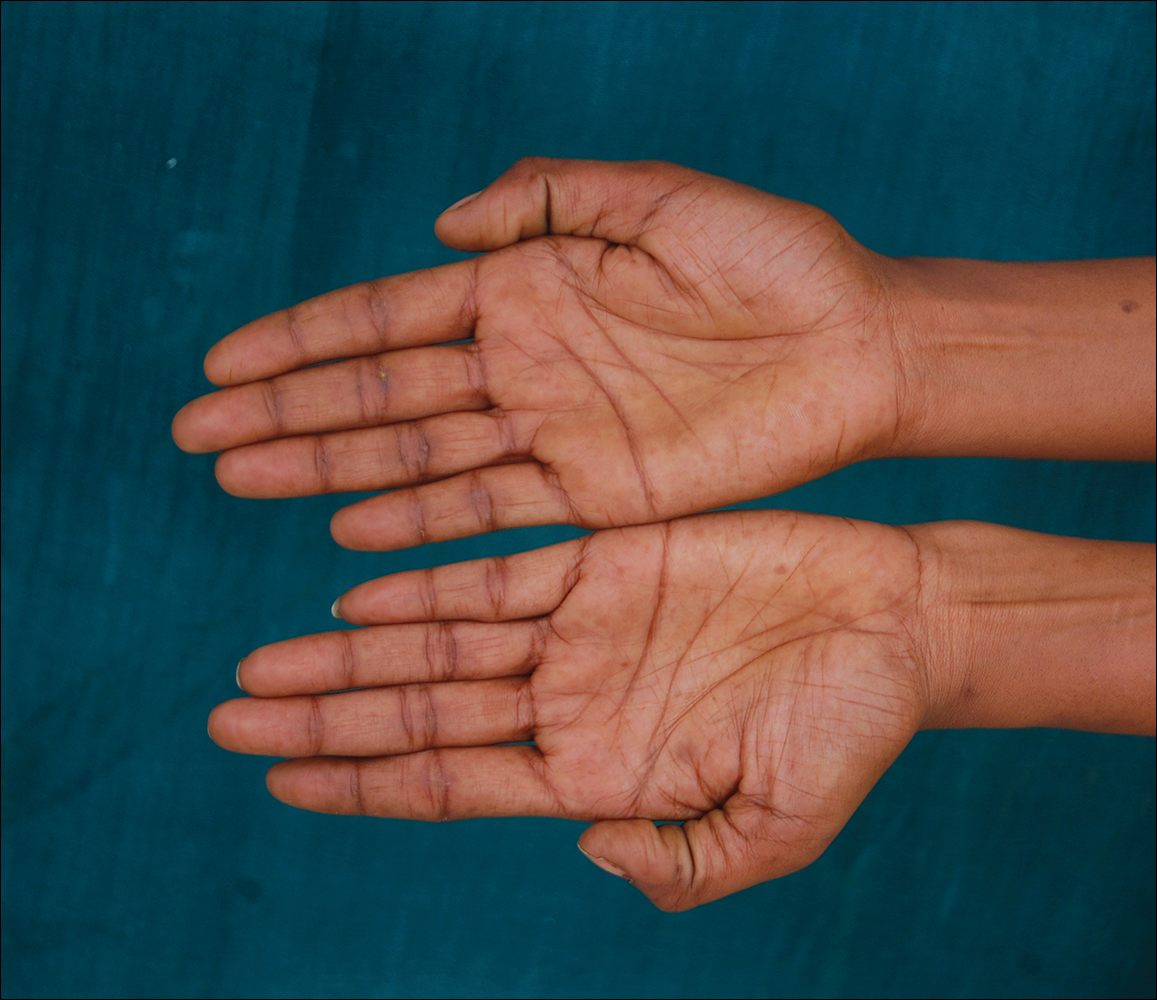

A 20-year-old woman presented to our outpatient section with a bluish black birthmark on the left side of the face since birth with the onset of multiple painless flesh-colored nodules on the trunk and arms of 1 year’s duration. She reported having occasional pruritus over the nodular lesions. Cutaneous examination showed multiple well-defined café au lait macules (0.5–3.0 cm) with regular margins. Multiple flesh-colored nodules were evident on the upper arms (Figure 1) and trunk. The nodules were firm in consistency and showed buttonholing phenomenon with some of the lesions demonstrating bag-of-worms consistency on palpation. Both palms showed multiple brownish frecklelike macules (Figure 2). A single bluish patch extended from the left ala of the nose to the sideburns. Adjoining the bluish patch was a subtle, ill-defined, nonblanchable red patch extending from the lower margin of the bluish patch to the mandibular ridge (Figure 3). Ocular examination showed melanosis bulbi of the left sclera and a few iris hamartomas (Lisch nodules) in both eyes. A biopsy of the skin nodule was obtained under local anesthesia after obtaining the patient’s informed consent; the specimen was fixed in 10% buffered formalin. A hematoxylin and eosin–stained section showed a well-circumscribed nonencapsulated tumor in the dermis composed of loosely spaced spindle cells and wavy collagenous strands (Figure 4). Routine hemogram and blood biochemistry including urinalysis were within reference range. Radiologic examination of the long bones was unremarkable. Our patient had 3 of 6 criteria defined by the National Institutes of Health for diagnosis of NF-1.4 On clinicopathological correlation we made a diagnosis of phacomatosis cesioflammea in association with NF-1. We have reassured the patient about the benign nature of vascular nevus. She was informed that the skin nodules could increase in size during pregnancy and to regularly follow-up with an eye specialist if any visual abnormalities occur.

The term phacomatosis is applied to genetically determined disorders of tissue derived from ectodermal origin (eg, skin, central nervous system, eyes) and commonly includes NF-1, tuberous sclerosis, and von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Neurofibromatosis type I was first described by German pathologist Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen.5 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis has been defined as the association of vascular nevus with a pigmentary nevus. Its pathogenesis can be explained by the twin spotting phenomenon.6 Twin spots are paired patches of mutant tissue that differ from each other and from the surrounding normal background skin. They can occur as 2 clinical types: allelic and nonallelic twin spotting. Our patient had nonallelic twin spots for 2 nevoid conditions: vascular (nevus flammeus) and pigmentary (nevus of Ota). Nevus of Ota was distributed in the V2 segment (maxillary nerve) of the fifth cranial nerve along with classical melanosis bulbi, which is considered a characteristic clinical feature of nevus of Ota (nevus cesius).7 Nevus flammeus (port-wine stain) is a vascular malformation presenting with flat lesions that persists throughout a patient’s life. The phenomenon of twin spotting, or didymosis (didymos means twin in Greek), has been proposed for co-occurrence of vascular and pigmented nevi.8 The association of NF-1 along with phacomatosis cesioflammea (a twin spot) could be explained from mosaicism of tissues derived from neuroectodermal and mesenchymal elements. Neurofibromatosis type I can occur as a mosaic disorder due to either postzygotic germ line or somatic mutations in the NF1 gene located on the proximal long arm of chromosome 17.9 Irrespective of the mutational event, a mosaic patient has a mixture of cells, some have normal copies of a particular gene and others have an abnormal copy of the same gene. Somatic mutation can lead to segmental (localized), generalized, or gonadal mosaicism. Somatic mutations occurring early during embryonic development produce generalized mosaicism, and generalized mosaics clinically appear similar to nonmosaic NF-1 cases.10,11 However, due to a lack of adequate facilities for mutation analysis and financial constraints, we were unable to confirm our case as generalized somatic mosaic for NF1 gene.

Several morphologic abnormalities have been reported with phacomatosis cesioflammea. Wu et al12 reported a single case of phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum in a 9-month-old infant. Shields et al13 suggested that a thorough ocular examination on a periodic basis is essential to rule out melanoma of ocular tissues in patients with nevus flammeus and ocular melanosis.

Phacomatosis cesioflammea can occur in association with NF-1. The exact incidence of association is not known. The nevoid condition can be treated with appropriate lasers.

- Ota M, Kawamura T, Ito N. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis (Ota). Jpn J Dermatol. 1947;52:1-3.

- Happle R. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis revisited and reclassified. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:385-388.

- Joshi A, Manchanda Y, Rijhwani M. Port-wine-stain with rare associations in two cases from Kuwait: phakomatosis pigmentovascularis redefined. Gulf J Dermatol Venereol. 2011;18:59-64.

- Neurofibromatosis. Conference Statement. National Institutes of Health Consensus. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:575-578.

- Gerber PA, Antal AS, Neumann NJ, et al. Neurofibromatosis. Eur J Med Res. 2009;14:102-105.

- Goyal T, Varshney A. Phacomatosis cesioflammea: first case report from India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:307.

- Happle R. Didymosis cesioanemica: an unusual counterpart of phakomatosis cesioflammea. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:471.

- Happle R, Steijlen PM. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis interpreted as a phenomenon of twin spots [in German]. Hautarzt. 1989;40:721-724.

- Adigun CG, Stein J. Segmental neurofibromatosis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:25.

- Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

- Boyd KP, Korf BR, Theos A. Neurofibromatosis type 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1-14.

- Wu CY, Chen PH, Chen GS. Phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:309-310.

- Shields CL, Kligman BE, Suriano M, et al. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis of cesioflammea type in 7 patients: combination of ocular pigmentation (melanocytosis or melanosis) and nevus flammeus with risk for melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:746-750.

To the Editor:

Vascular lesions associated with melanocytic nevi were first described by Ota et al1 in 1947 and given the name phacomatosis pigmentovascularis. In 2005, Happle2 reclassified phacomatosis pigmentovascularis into 3 well-defined types: (1) phacomatosis cesioflammea: blue spots (caesius means bluish gray in Latin) and nevus flammeus; (2) phacomatosis spilorosea: nevus spilus coexisting with a pale pink telangiectatic nevus; and (3) phacomatosis cesiomarmorata: blue spots and cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita. In 2011 Joshi et al3 described a case of a 31-year-old woman who had a port-wine stain in association with neurofibromatosis type I (NF-1). We present a case of phacomatosis cesioflammea in association with NF-1.

A 20-year-old woman presented to our outpatient section with a bluish black birthmark on the left side of the face since birth with the onset of multiple painless flesh-colored nodules on the trunk and arms of 1 year’s duration. She reported having occasional pruritus over the nodular lesions. Cutaneous examination showed multiple well-defined café au lait macules (0.5–3.0 cm) with regular margins. Multiple flesh-colored nodules were evident on the upper arms (Figure 1) and trunk. The nodules were firm in consistency and showed buttonholing phenomenon with some of the lesions demonstrating bag-of-worms consistency on palpation. Both palms showed multiple brownish frecklelike macules (Figure 2). A single bluish patch extended from the left ala of the nose to the sideburns. Adjoining the bluish patch was a subtle, ill-defined, nonblanchable red patch extending from the lower margin of the bluish patch to the mandibular ridge (Figure 3). Ocular examination showed melanosis bulbi of the left sclera and a few iris hamartomas (Lisch nodules) in both eyes. A biopsy of the skin nodule was obtained under local anesthesia after obtaining the patient’s informed consent; the specimen was fixed in 10% buffered formalin. A hematoxylin and eosin–stained section showed a well-circumscribed nonencapsulated tumor in the dermis composed of loosely spaced spindle cells and wavy collagenous strands (Figure 4). Routine hemogram and blood biochemistry including urinalysis were within reference range. Radiologic examination of the long bones was unremarkable. Our patient had 3 of 6 criteria defined by the National Institutes of Health for diagnosis of NF-1.4 On clinicopathological correlation we made a diagnosis of phacomatosis cesioflammea in association with NF-1. We have reassured the patient about the benign nature of vascular nevus. She was informed that the skin nodules could increase in size during pregnancy and to regularly follow-up with an eye specialist if any visual abnormalities occur.

The term phacomatosis is applied to genetically determined disorders of tissue derived from ectodermal origin (eg, skin, central nervous system, eyes) and commonly includes NF-1, tuberous sclerosis, and von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Neurofibromatosis type I was first described by German pathologist Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen.5 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis has been defined as the association of vascular nevus with a pigmentary nevus. Its pathogenesis can be explained by the twin spotting phenomenon.6 Twin spots are paired patches of mutant tissue that differ from each other and from the surrounding normal background skin. They can occur as 2 clinical types: allelic and nonallelic twin spotting. Our patient had nonallelic twin spots for 2 nevoid conditions: vascular (nevus flammeus) and pigmentary (nevus of Ota). Nevus of Ota was distributed in the V2 segment (maxillary nerve) of the fifth cranial nerve along with classical melanosis bulbi, which is considered a characteristic clinical feature of nevus of Ota (nevus cesius).7 Nevus flammeus (port-wine stain) is a vascular malformation presenting with flat lesions that persists throughout a patient’s life. The phenomenon of twin spotting, or didymosis (didymos means twin in Greek), has been proposed for co-occurrence of vascular and pigmented nevi.8 The association of NF-1 along with phacomatosis cesioflammea (a twin spot) could be explained from mosaicism of tissues derived from neuroectodermal and mesenchymal elements. Neurofibromatosis type I can occur as a mosaic disorder due to either postzygotic germ line or somatic mutations in the NF1 gene located on the proximal long arm of chromosome 17.9 Irrespective of the mutational event, a mosaic patient has a mixture of cells, some have normal copies of a particular gene and others have an abnormal copy of the same gene. Somatic mutation can lead to segmental (localized), generalized, or gonadal mosaicism. Somatic mutations occurring early during embryonic development produce generalized mosaicism, and generalized mosaics clinically appear similar to nonmosaic NF-1 cases.10,11 However, due to a lack of adequate facilities for mutation analysis and financial constraints, we were unable to confirm our case as generalized somatic mosaic for NF1 gene.

Several morphologic abnormalities have been reported with phacomatosis cesioflammea. Wu et al12 reported a single case of phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum in a 9-month-old infant. Shields et al13 suggested that a thorough ocular examination on a periodic basis is essential to rule out melanoma of ocular tissues in patients with nevus flammeus and ocular melanosis.

Phacomatosis cesioflammea can occur in association with NF-1. The exact incidence of association is not known. The nevoid condition can be treated with appropriate lasers.

To the Editor:

Vascular lesions associated with melanocytic nevi were first described by Ota et al1 in 1947 and given the name phacomatosis pigmentovascularis. In 2005, Happle2 reclassified phacomatosis pigmentovascularis into 3 well-defined types: (1) phacomatosis cesioflammea: blue spots (caesius means bluish gray in Latin) and nevus flammeus; (2) phacomatosis spilorosea: nevus spilus coexisting with a pale pink telangiectatic nevus; and (3) phacomatosis cesiomarmorata: blue spots and cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita. In 2011 Joshi et al3 described a case of a 31-year-old woman who had a port-wine stain in association with neurofibromatosis type I (NF-1). We present a case of phacomatosis cesioflammea in association with NF-1.

A 20-year-old woman presented to our outpatient section with a bluish black birthmark on the left side of the face since birth with the onset of multiple painless flesh-colored nodules on the trunk and arms of 1 year’s duration. She reported having occasional pruritus over the nodular lesions. Cutaneous examination showed multiple well-defined café au lait macules (0.5–3.0 cm) with regular margins. Multiple flesh-colored nodules were evident on the upper arms (Figure 1) and trunk. The nodules were firm in consistency and showed buttonholing phenomenon with some of the lesions demonstrating bag-of-worms consistency on palpation. Both palms showed multiple brownish frecklelike macules (Figure 2). A single bluish patch extended from the left ala of the nose to the sideburns. Adjoining the bluish patch was a subtle, ill-defined, nonblanchable red patch extending from the lower margin of the bluish patch to the mandibular ridge (Figure 3). Ocular examination showed melanosis bulbi of the left sclera and a few iris hamartomas (Lisch nodules) in both eyes. A biopsy of the skin nodule was obtained under local anesthesia after obtaining the patient’s informed consent; the specimen was fixed in 10% buffered formalin. A hematoxylin and eosin–stained section showed a well-circumscribed nonencapsulated tumor in the dermis composed of loosely spaced spindle cells and wavy collagenous strands (Figure 4). Routine hemogram and blood biochemistry including urinalysis were within reference range. Radiologic examination of the long bones was unremarkable. Our patient had 3 of 6 criteria defined by the National Institutes of Health for diagnosis of NF-1.4 On clinicopathological correlation we made a diagnosis of phacomatosis cesioflammea in association with NF-1. We have reassured the patient about the benign nature of vascular nevus. She was informed that the skin nodules could increase in size during pregnancy and to regularly follow-up with an eye specialist if any visual abnormalities occur.

The term phacomatosis is applied to genetically determined disorders of tissue derived from ectodermal origin (eg, skin, central nervous system, eyes) and commonly includes NF-1, tuberous sclerosis, and von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Neurofibromatosis type I was first described by German pathologist Friedrich Daniel von Recklinghausen.5 Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis has been defined as the association of vascular nevus with a pigmentary nevus. Its pathogenesis can be explained by the twin spotting phenomenon.6 Twin spots are paired patches of mutant tissue that differ from each other and from the surrounding normal background skin. They can occur as 2 clinical types: allelic and nonallelic twin spotting. Our patient had nonallelic twin spots for 2 nevoid conditions: vascular (nevus flammeus) and pigmentary (nevus of Ota). Nevus of Ota was distributed in the V2 segment (maxillary nerve) of the fifth cranial nerve along with classical melanosis bulbi, which is considered a characteristic clinical feature of nevus of Ota (nevus cesius).7 Nevus flammeus (port-wine stain) is a vascular malformation presenting with flat lesions that persists throughout a patient’s life. The phenomenon of twin spotting, or didymosis (didymos means twin in Greek), has been proposed for co-occurrence of vascular and pigmented nevi.8 The association of NF-1 along with phacomatosis cesioflammea (a twin spot) could be explained from mosaicism of tissues derived from neuroectodermal and mesenchymal elements. Neurofibromatosis type I can occur as a mosaic disorder due to either postzygotic germ line or somatic mutations in the NF1 gene located on the proximal long arm of chromosome 17.9 Irrespective of the mutational event, a mosaic patient has a mixture of cells, some have normal copies of a particular gene and others have an abnormal copy of the same gene. Somatic mutation can lead to segmental (localized), generalized, or gonadal mosaicism. Somatic mutations occurring early during embryonic development produce generalized mosaicism, and generalized mosaics clinically appear similar to nonmosaic NF-1 cases.10,11 However, due to a lack of adequate facilities for mutation analysis and financial constraints, we were unable to confirm our case as generalized somatic mosaic for NF1 gene.

Several morphologic abnormalities have been reported with phacomatosis cesioflammea. Wu et al12 reported a single case of phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum in a 9-month-old infant. Shields et al13 suggested that a thorough ocular examination on a periodic basis is essential to rule out melanoma of ocular tissues in patients with nevus flammeus and ocular melanosis.

Phacomatosis cesioflammea can occur in association with NF-1. The exact incidence of association is not known. The nevoid condition can be treated with appropriate lasers.

- Ota M, Kawamura T, Ito N. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis (Ota). Jpn J Dermatol. 1947;52:1-3.

- Happle R. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis revisited and reclassified. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:385-388.

- Joshi A, Manchanda Y, Rijhwani M. Port-wine-stain with rare associations in two cases from Kuwait: phakomatosis pigmentovascularis redefined. Gulf J Dermatol Venereol. 2011;18:59-64.

- Neurofibromatosis. Conference Statement. National Institutes of Health Consensus. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:575-578.

- Gerber PA, Antal AS, Neumann NJ, et al. Neurofibromatosis. Eur J Med Res. 2009;14:102-105.

- Goyal T, Varshney A. Phacomatosis cesioflammea: first case report from India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:307.

- Happle R. Didymosis cesioanemica: an unusual counterpart of phakomatosis cesioflammea. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:471.

- Happle R, Steijlen PM. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis interpreted as a phenomenon of twin spots [in German]. Hautarzt. 1989;40:721-724.

- Adigun CG, Stein J. Segmental neurofibromatosis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:25.

- Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

- Boyd KP, Korf BR, Theos A. Neurofibromatosis type 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1-14.

- Wu CY, Chen PH, Chen GS. Phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:309-310.

- Shields CL, Kligman BE, Suriano M, et al. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis of cesioflammea type in 7 patients: combination of ocular pigmentation (melanocytosis or melanosis) and nevus flammeus with risk for melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:746-750.

- Ota M, Kawamura T, Ito N. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis (Ota). Jpn J Dermatol. 1947;52:1-3.

- Happle R. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis revisited and reclassified. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:385-388.

- Joshi A, Manchanda Y, Rijhwani M. Port-wine-stain with rare associations in two cases from Kuwait: phakomatosis pigmentovascularis redefined. Gulf J Dermatol Venereol. 2011;18:59-64.

- Neurofibromatosis. Conference Statement. National Institutes of Health Consensus. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:575-578.

- Gerber PA, Antal AS, Neumann NJ, et al. Neurofibromatosis. Eur J Med Res. 2009;14:102-105.

- Goyal T, Varshney A. Phacomatosis cesioflammea: first case report from India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:307.

- Happle R. Didymosis cesioanemica: an unusual counterpart of phakomatosis cesioflammea. Eur J Dermatol. 2011;21:471.

- Happle R, Steijlen PM. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis interpreted as a phenomenon of twin spots [in German]. Hautarzt. 1989;40:721-724.

- Adigun CG, Stein J. Segmental neurofibromatosis. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:25.

- Ruggieri M, Huson SM. The clinical and diagnostic implications of mosaicism in the neurofibromatoses. Neurology. 2001;56:1433-1443.

- Boyd KP, Korf BR, Theos A. Neurofibromatosis type 1. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1-14.

- Wu CY, Chen PH, Chen GS. Phacomatosis cesioflammea associated with pectus excavatum. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:309-310.

- Shields CL, Kligman BE, Suriano M, et al. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis of cesioflammea type in 7 patients: combination of ocular pigmentation (melanocytosis or melanosis) and nevus flammeus with risk for melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:746-750.

Practice Points

- Phacomatosis cesioflammea can be associated with neurofibromatosis type I.

- The port-wine stain component of phacomatosis cesioflammea may develop nodularity in long-standing cases.

- The Nd:YAG laser is beneficial for treating blue spots of phacomatosis cesioflammea.

Recalcitrant Hyperkeratotic Plaques

The Diagnosis: Hypertrophic Lupus Erythematosus

Physical examination at initial presentation revealed well-demarcated, 2- to 3-cm plaques with scale distributed most extensively on the elbows and shins with lesser involvement of the chest and abdomen. After treatment with topical steroids, adalimumab, methotrexate, and narrowband UVB phototherapy, new annular, erythematous, and edematous lesions began to appear on the chest and abdomen (Figure 1). These new lesions appeared less hyperkeratotic than the older ones.

Biopsy of a hyperkeratotic lesion from the patient's arm revealed marked hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, epidermal hyperplasia, focal vacuolar change, solar elastosis, and transepidermal elastotic elimination (Figure 2A). A second biopsy performed on a newer chest lesion revealed interface changes, degeneration of the basal layer, follicular plugging, and dermal mucin (Figure 2B). Serology revealed an antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer of 1:1280 (reference range, <1:40 dilution) and hemoglobin of 11.5 g/dL (reference range, 14.0-17.5 g/dL). On the basis of clinical, histologic, and serologic findings, hypertrophic lupus erythematosus (LE) was diagnosed. The patient was treated with oral prednisone, which resulted in rapid improvement.

Hypertrophic LE is a rare subset of chronic cutaneous lupus first described by Behcet1 in 1942. Lesions are identified as verrucous keratotic plaques with a characteristic erythematous indurated border.2 Patients predominantly are middle-aged women with lesions distributed on sun-exposed areas. Most often, hypertrophic LE is seen in association with the classic lesions of discoid LE; however, patients may present exclusively with the cutaneous manifestations of hypertrophic LE. More rarely, as seen in this case, hypertrophic LE may present in conjunction with systemic features.3 The diagnosis of systemic LE requires 4 of the following criteria be fulfilled: malar rash; discoid rash; photosensitivity; oral ulcers; arthritis; cardiopulmonary serositis; renal involvement; positive ANA titer; and neurologic, hematologic, or immunologic disorders.4 Our patient qualified for discoid rash, photosensitivity, cardiopulmonary involvement with mitral valve defects and pulmonary pleuritis, hematologic disorder (anemia), and a positive ANA titer. Furthermore, in patients with only cutaneous discoid LE, serology generally reveals negative or low-titer ANA and negative anti-Ro antibodies.5

Hypertrophic LE is characterized histologically by irregular epidermal hyperplasia in association with features of classic cutaneous LE. Distinctive features of cutaneous LE include interface changes, follicular plugging, dermal mucin, and angiocentric lymphocytic inflammation.6 Notably, additional biopsies of the less hyperkeratotic lesions on our patient's chest and abdomen were performed, which revealed classic cutaneous LE features (Figure 2B).

Hypertrophic LE has 2 histological variants: lichen planus-like and keratoacanthoma (KA)-like patterns. Most cases are described as lichen planus-like, with a dense bandlike infiltrate in association with irregular epidermal hyperplasia, vacuolar interface changes, and reactive squamous atypia.5 In contrast, the less common KA-like lesions consist of a keratinous center with vigorous squamous epithelial proliferation.6

Clinically, hypertrophic LE may resemble hypertrophic psoriasis, lichen planus, KA, or squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Due to the presence of pseudocarcinomatous hyperplasia, the histopathologic differential includes hypertrophic lichen planus, SCC, KA, and deep fungal infections. However, these other diseases lack the classic features of cutaneous LE, which include interface changes, follicular plugging, dermal mucin, and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation. Additionally, transepidermal elastotic elimination (Figure 2A) helps distinguish hypertrophic LE from other diagnoses.7 One of the most important tasks is distinguishing hypertrophic LE from SCC. Hypertrophic LE does not typically display eosinophil infiltrates, which differentiates it from SCC and KA. Additionally, studies report that CD123 positivity can be useful.6 Positive plasmacytoid dendritic cells are abundant at the dermoepidermal junction in hypertrophic LE, while only single or rare clusters of CD123+ cells are seen in SCC.8 Also, SCC has been found to arise in long-standing cutaneous LE lesions including both discoid and hypertrophic LE. Therefore, clinical and sometimes histological follow-up is required.

Hypertrophic LE often is challenging to treat and frequently is resistant to antimalarial drugs. The primary goals of treatment involve reducing inflammatory infiltrate and minimizing hyperkeratinization. Topical corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors often are inadequate as monotherapy due to reduced penetrance through the thick lesions; however, intralesional corticosteroids may be beneficial in patients with localized disease.9 Unfortunately, topical or intralesional treatments are impractical in patients with extensive lesions, as seen in our patient, in which case systemic corticosteroids can be beneficial.