User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

NORD Unveils “Do Your Share for Rare” Year-Long Awareness Campaign

On Rare Disease Day 2017 (Feb. 28th) NORD launched a year-long public awareness campaign featuring the voices and stories of children and adults living with rare diseases. The purpose is to promote greater public awareness. The campaign includes a public service announcement and supporting website where those living with rare diseases may share their stories.

On Rare Disease Day 2017 (Feb. 28th) NORD launched a year-long public awareness campaign featuring the voices and stories of children and adults living with rare diseases. The purpose is to promote greater public awareness. The campaign includes a public service announcement and supporting website where those living with rare diseases may share their stories.

On Rare Disease Day 2017 (Feb. 28th) NORD launched a year-long public awareness campaign featuring the voices and stories of children and adults living with rare diseases. The purpose is to promote greater public awareness. The campaign includes a public service announcement and supporting website where those living with rare diseases may share their stories.

NORD Submits Letter to Congress on Pre-Existing Conditions

In its efforts to protect health care coverage of patients with rare diseases, NORD has submitted a letter to Congress emphasizing the importance of health insurance protection for patients with rare diseases in any legislation drafted to replace the Affordable Care Act.

In its efforts to protect health care coverage of patients with rare diseases, NORD has submitted a letter to Congress emphasizing the importance of health insurance protection for patients with rare diseases in any legislation drafted to replace the Affordable Care Act.

In its efforts to protect health care coverage of patients with rare diseases, NORD has submitted a letter to Congress emphasizing the importance of health insurance protection for patients with rare diseases in any legislation drafted to replace the Affordable Care Act.

NORD Publishes Basic Principles for Health Coverage Reform

Before the Affordable Care Act was enacted in 2010, many patients with rare diseases could not access health care coverage due to various discriminatory insurance practices, limited Medicaid eligibility, and debilitating cost-sharing. As the administration and Congress discuss repealing and/or replacing the ACA, NORD has published a Principles for Health Coverage Reform document outlining basic principles that must be maintained to protect health care coverage for rare disease patients.

Before the Affordable Care Act was enacted in 2010, many patients with rare diseases could not access health care coverage due to various discriminatory insurance practices, limited Medicaid eligibility, and debilitating cost-sharing. As the administration and Congress discuss repealing and/or replacing the ACA, NORD has published a Principles for Health Coverage Reform document outlining basic principles that must be maintained to protect health care coverage for rare disease patients.

Before the Affordable Care Act was enacted in 2010, many patients with rare diseases could not access health care coverage due to various discriminatory insurance practices, limited Medicaid eligibility, and debilitating cost-sharing. As the administration and Congress discuss repealing and/or replacing the ACA, NORD has published a Principles for Health Coverage Reform document outlining basic principles that must be maintained to protect health care coverage for rare disease patients.

NORD Awards Grants for Rare Disease Research

The National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) has awarded seven new research grants to fund rare disease research. These grants are in response to NORD’s 2016 Requests for Proposals. The 2017 Requests for Proposals will be published soon on the NORD website, where funding opportunities from NORD member organizations also are posted.

The new grant recipients are:

For the study of Alveolar Capillary Dysplasia with Misalignment of the Pulmonary Veins (ACD/MPV), with support funding raised by the David Ashwell Foundation and the Alveolar Capillary Dysplasia Association

- Przemyslaw Szafranski PhD, Baylor College of Medicine

For the study of Appendix Cancer and Pseudomyxoma Peritonei (PMP), with support funding raised by the Appendix Cancer Pseudomyxoma Peritonei Research Foundation

- Venkatesh Govindarajan PhD, Creighton University

- David L. Morris MD PhD, St. George Hospital, Australia

For the study of Autoimmune Polyglandular Syndrome Type 1 (APS Type 1), with support funding raised by the APS Type 1 Foundation

- Maureen A. Su MD, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

For the study of Homocystinuria due to Cystathionine Beta-Synthase Deficiency, with support funding raised from public donations

- Warren D. Kruger PhD, The Research Institute of Fox Chase Cancer Center

For the study of Malonic Aciduria, with support funding raised by the Hope Fund, Lundbeck “Raise Your Hand” campaign, and public donations

- Michael J. Wolfgang PhD, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

For the study of Stiff Person Syndrome, with support funding raised by the Lundbeck “Raise Your Hand” campaign and public donations

- Sarah Crisp PhD, University College, London

Grants are made possible by donations to NORD research funds and the assistance of rare disease medical experts who serve on NORD’s Medical Advisory Committee.

The National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) has awarded seven new research grants to fund rare disease research. These grants are in response to NORD’s 2016 Requests for Proposals. The 2017 Requests for Proposals will be published soon on the NORD website, where funding opportunities from NORD member organizations also are posted.

The new grant recipients are:

For the study of Alveolar Capillary Dysplasia with Misalignment of the Pulmonary Veins (ACD/MPV), with support funding raised by the David Ashwell Foundation and the Alveolar Capillary Dysplasia Association

- Przemyslaw Szafranski PhD, Baylor College of Medicine

For the study of Appendix Cancer and Pseudomyxoma Peritonei (PMP), with support funding raised by the Appendix Cancer Pseudomyxoma Peritonei Research Foundation

- Venkatesh Govindarajan PhD, Creighton University

- David L. Morris MD PhD, St. George Hospital, Australia

For the study of Autoimmune Polyglandular Syndrome Type 1 (APS Type 1), with support funding raised by the APS Type 1 Foundation

- Maureen A. Su MD, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

For the study of Homocystinuria due to Cystathionine Beta-Synthase Deficiency, with support funding raised from public donations

- Warren D. Kruger PhD, The Research Institute of Fox Chase Cancer Center

For the study of Malonic Aciduria, with support funding raised by the Hope Fund, Lundbeck “Raise Your Hand” campaign, and public donations

- Michael J. Wolfgang PhD, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

For the study of Stiff Person Syndrome, with support funding raised by the Lundbeck “Raise Your Hand” campaign and public donations

- Sarah Crisp PhD, University College, London

Grants are made possible by donations to NORD research funds and the assistance of rare disease medical experts who serve on NORD’s Medical Advisory Committee.

The National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) has awarded seven new research grants to fund rare disease research. These grants are in response to NORD’s 2016 Requests for Proposals. The 2017 Requests for Proposals will be published soon on the NORD website, where funding opportunities from NORD member organizations also are posted.

The new grant recipients are:

For the study of Alveolar Capillary Dysplasia with Misalignment of the Pulmonary Veins (ACD/MPV), with support funding raised by the David Ashwell Foundation and the Alveolar Capillary Dysplasia Association

- Przemyslaw Szafranski PhD, Baylor College of Medicine

For the study of Appendix Cancer and Pseudomyxoma Peritonei (PMP), with support funding raised by the Appendix Cancer Pseudomyxoma Peritonei Research Foundation

- Venkatesh Govindarajan PhD, Creighton University

- David L. Morris MD PhD, St. George Hospital, Australia

For the study of Autoimmune Polyglandular Syndrome Type 1 (APS Type 1), with support funding raised by the APS Type 1 Foundation

- Maureen A. Su MD, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

For the study of Homocystinuria due to Cystathionine Beta-Synthase Deficiency, with support funding raised from public donations

- Warren D. Kruger PhD, The Research Institute of Fox Chase Cancer Center

For the study of Malonic Aciduria, with support funding raised by the Hope Fund, Lundbeck “Raise Your Hand” campaign, and public donations

- Michael J. Wolfgang PhD, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

For the study of Stiff Person Syndrome, with support funding raised by the Lundbeck “Raise Your Hand” campaign and public donations

- Sarah Crisp PhD, University College, London

Grants are made possible by donations to NORD research funds and the assistance of rare disease medical experts who serve on NORD’s Medical Advisory Committee.

Cosmetic Corner: Dermatologists Weigh in on Products for Dry Cuticles

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on dry cuticle products. Consideration must be given to:

- Aquaphor Healing Ointment

Beiersdorf Inc.

“Using this product several times daily works great.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Elon Lanolin-Rich Nail Conditioner

Dartmouth Pharmaceuticals

“Dry cuticles often are accompanied by splitting, cracking, and peeling of the nails. I have found that with regular use of this product, the condition of the nail as well as the cuticle can improve dramatically, leading to smoother, stronger cuticles and nails.”—Jeannette Graf, MD, New York, New York

- Petrolatum or Olive Oil

Manufacturers vary

“Apply petrolatum or olive oil to the fingertips after soaking for 5 to 10 minutes in lukewarm water, then wear nitrile gloves for an hour. Patients should then wipe off the excess and put on cotton gloves overnight.”—Larisa Ravitskiy, MD, Gahanna, Ohio

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Athlete’s foot treatments, as well as products for dry cuticles, hyperhidrosis, and sensitive skin will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

[polldaddy:9711250]

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on dry cuticle products. Consideration must be given to:

- Aquaphor Healing Ointment

Beiersdorf Inc.

“Using this product several times daily works great.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Elon Lanolin-Rich Nail Conditioner

Dartmouth Pharmaceuticals

“Dry cuticles often are accompanied by splitting, cracking, and peeling of the nails. I have found that with regular use of this product, the condition of the nail as well as the cuticle can improve dramatically, leading to smoother, stronger cuticles and nails.”—Jeannette Graf, MD, New York, New York

- Petrolatum or Olive Oil

Manufacturers vary

“Apply petrolatum or olive oil to the fingertips after soaking for 5 to 10 minutes in lukewarm water, then wear nitrile gloves for an hour. Patients should then wipe off the excess and put on cotton gloves overnight.”—Larisa Ravitskiy, MD, Gahanna, Ohio

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Athlete’s foot treatments, as well as products for dry cuticles, hyperhidrosis, and sensitive skin will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

[polldaddy:9711250]

To improve patient care and outcomes, leading dermatologists offered their recommendations on dry cuticle products. Consideration must be given to:

- Aquaphor Healing Ointment

Beiersdorf Inc.

“Using this product several times daily works great.”—Gary Goldenberg, MD, New York, New York

- Elon Lanolin-Rich Nail Conditioner

Dartmouth Pharmaceuticals

“Dry cuticles often are accompanied by splitting, cracking, and peeling of the nails. I have found that with regular use of this product, the condition of the nail as well as the cuticle can improve dramatically, leading to smoother, stronger cuticles and nails.”—Jeannette Graf, MD, New York, New York

- Petrolatum or Olive Oil

Manufacturers vary

“Apply petrolatum or olive oil to the fingertips after soaking for 5 to 10 minutes in lukewarm water, then wear nitrile gloves for an hour. Patients should then wipe off the excess and put on cotton gloves overnight.”—Larisa Ravitskiy, MD, Gahanna, Ohio

Cutis invites readers to send us their recommendations. Athlete’s foot treatments, as well as products for dry cuticles, hyperhidrosis, and sensitive skin will be featured in upcoming editions of Cosmetic Corner. Please e-mail your recommendation(s) to the Editorial Office.

Disclaimer: Opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. and shall not be used for product endorsement purposes. Any reference made to a specific commercial product does not indicate or imply that Cutis or Frontline Medical Communications Inc. endorses, recommends, or favors the product mentioned. No guarantee is given to the effects of recommended products.

[polldaddy:9711250]

Collagenous and Elastotic Marginal Plaques of the Hands

To the Editor:

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands (CEMPHs) has several names including degenerative collagenous plaques of the hands, keratoelastoidosis marginalis, and digital papular calcific elastosis. This rare disorder is an acquired, slowly progressive, asymptomatic, dermal connective tissue abnormality that is underrecognized and underdiagnosed. Clinical presentation includes hyperkeratotic translucent papules arranged linearly on the radial aspect of the hands.

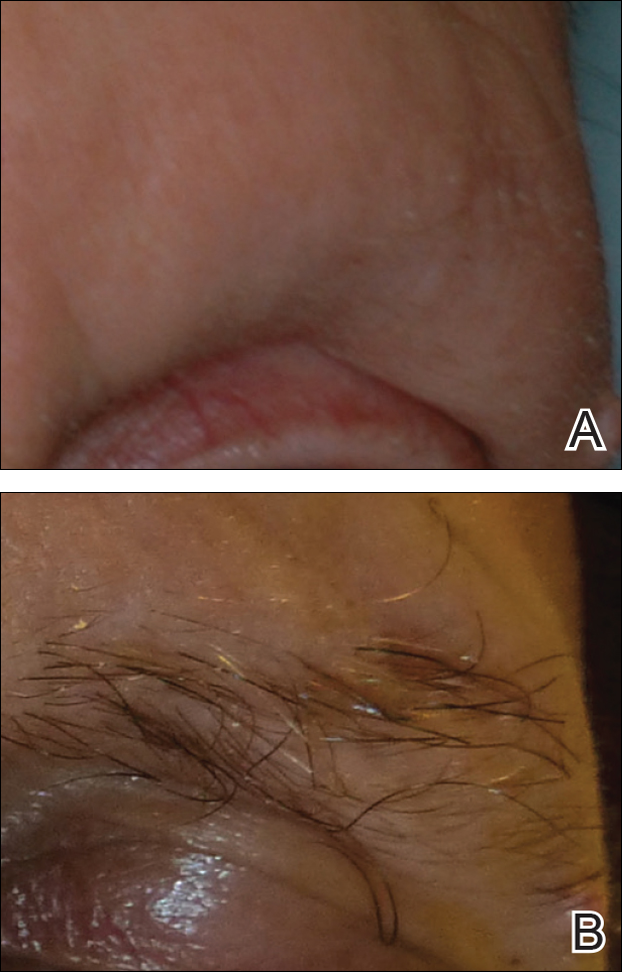

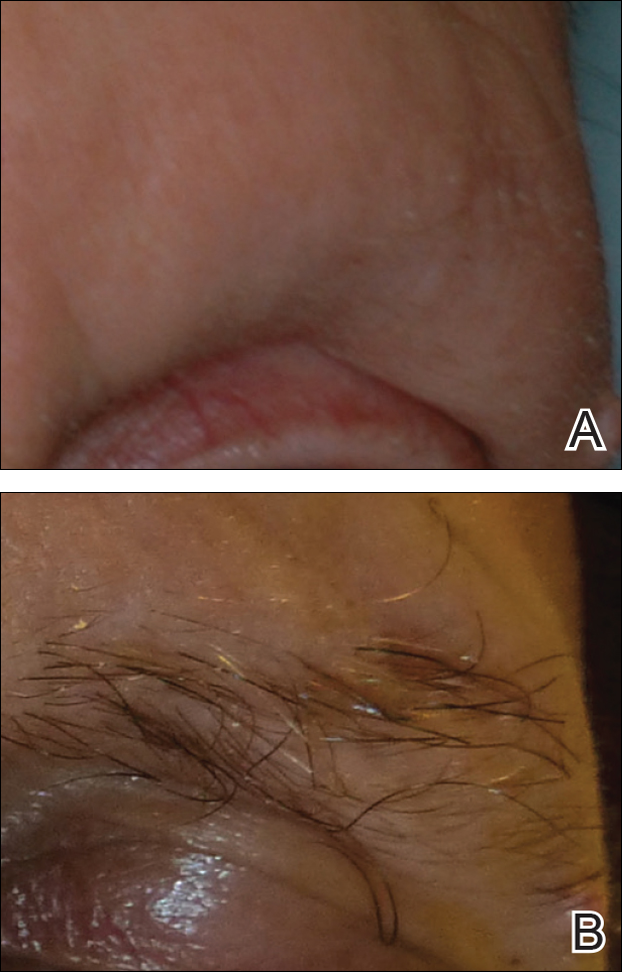

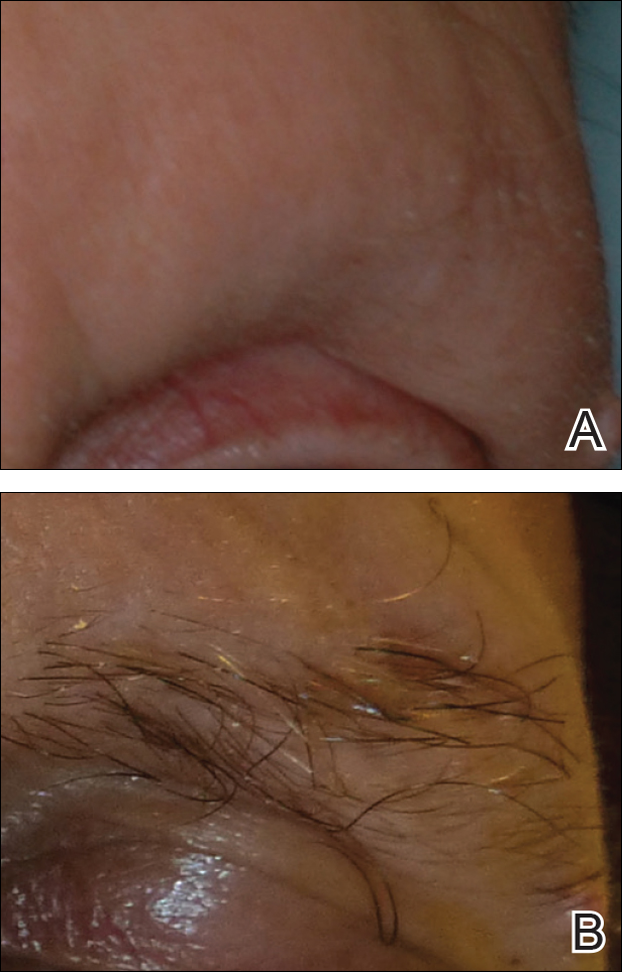

A 74-year-old woman described having "rough hands" of more than 20 years' duration. She presented with 4-cm wide longitudinal, erythematous, firm, depressed plaques along the lateral edge of the second finger and extending to the medial thumb in both hands (Figure 1). She had attempted multiple treatments by her primary care physician, including topical and oral medications unknown to the patient and light therapy, all without benefit over a period of several years. We have attempted salicylic acid 40%, clobetasol cream 0.05%, and emollient creams containing α-hydroxy acid. At best the condition fluctuated between a subtle raised scale at the edge to smooth and occasionally more red-pink, seemingly unrelated to any treatments.

The patient did not have plaques elsewhere on the body, and notably, the feet were clear. She did not have a history of repeated trauma to the hands and did not engage in manual labor. She denied excessive sun exposure, though she had Fitzpatrick skin type III and a history of multiple precancers and nonmelanoma skin cancers 7 years prior to presentation.

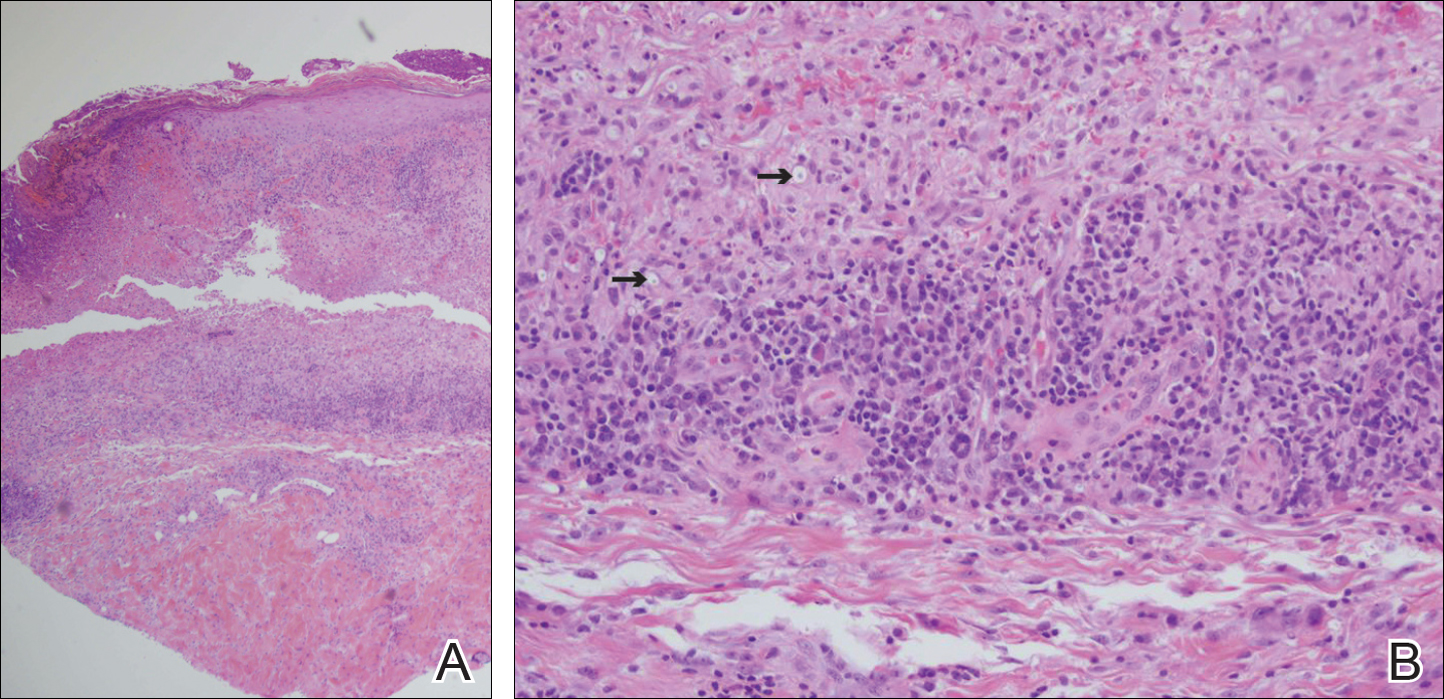

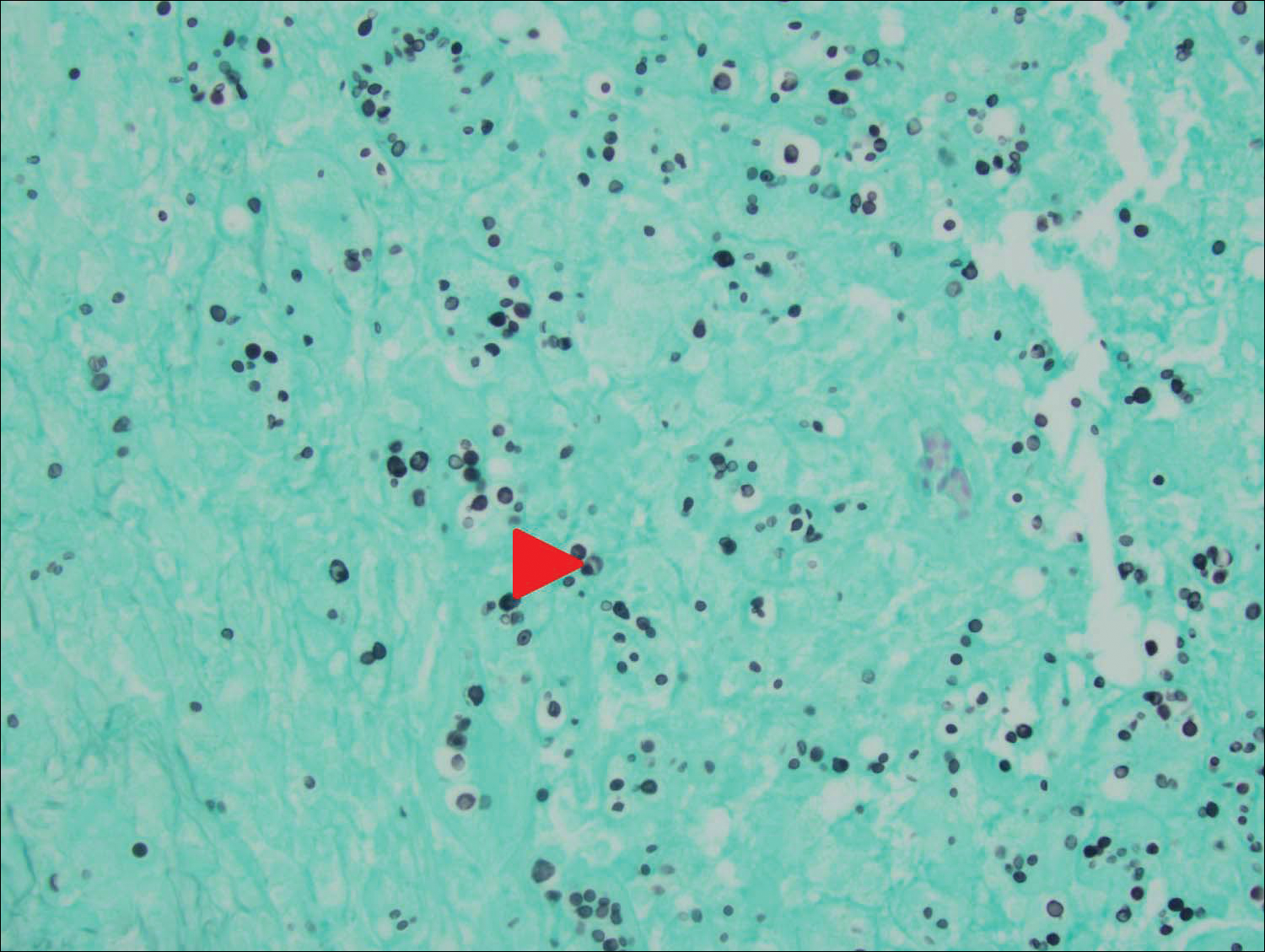

Histology of CEMPH reveals a hyperkeratotic epidermis with an avascular and acellular replacement of the superficial reticular dermis by haphazardly arranged, thickened collagen fibers (Figure 2A-2C). Collagen fibers were oriented perpendicularly to the epidermal surface. Intervening amorphous basophilic elastotic masses were present in the upper dermis with occasional calcification and degenerative elastic fibers (Figure 2D).

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands is a chronic, asymptomatic, sclerotic skin disorder described in a 1960 case series of 5 patients reported by Burks et al.1 Although it has many names, the most common is CEMPH. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands most often presents in white men aged 50 to 60 years.2 Patients typically are asymptomatic with plaques limited to the junction of the palmar and dorsal surfaces of the hands with only minimal intermittent stiffness around the flexor creases. Lesions begin as discrete yellow papules that coalesce to form hyperkeratotic linear plaques with occasional telangiectasia.3

The etiology of CEMPH is attributed to collagen and elastin degeneration by chronic actinic damage, pressure, or trauma.4,5 The 3 stages of degeneration include an initial linear padded stage, an intermediate padded plaque stage, and an advanced padded hyperkeratotic plaque stage.4 Vascular compromise is seen from the enlarged and fused thickened collagen and elastic fibers that in turn lead to ischemic changes, hyperkeratosis with epidermal atrophy, and papillary dermis telangiectasia. Absence or weak expression of keratins 14 and 10 and strong expression of keratin 16 have been reported in the epidermis of CEMPH patients.4

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands do not have a specific treatment, as it is a benign, slowly progressive condition. Several treatments such as laser therapy, high-potency topical corticosteroids, topical tazarotene and tretinoin, oral isotretinoin, and cryotherapy have been tried with little long-term success.4 Moisturizing may help reduce fissuring, and patients are advised to avoid the sun and repeated trauma to the hands.

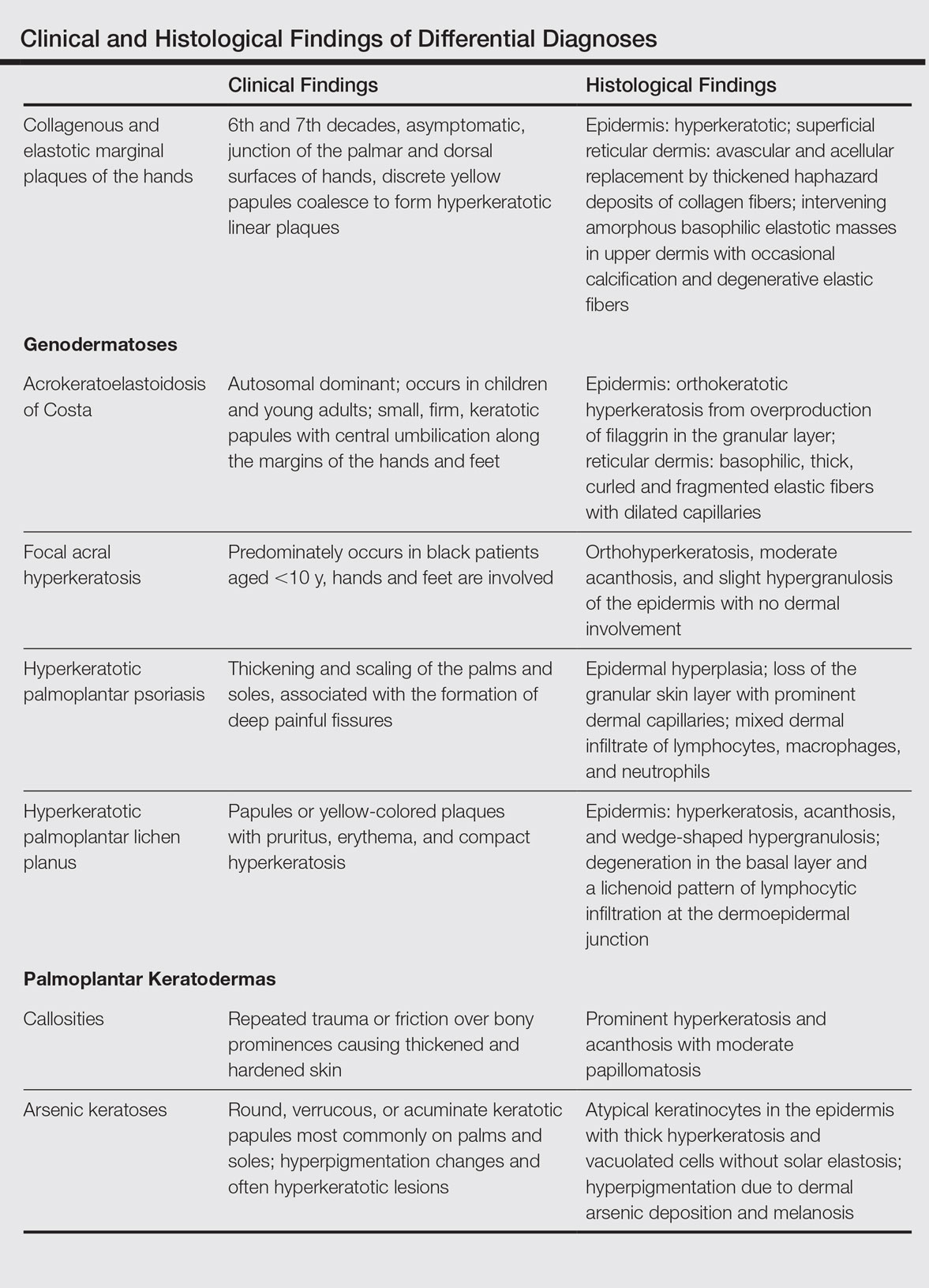

The differential diagnosis of CEMPH is summarized in the Table. Two genodermatoses—acrokeratoelastoidosis of Costa and focal acral hyperkeratosis—clinically resemble CEMPH. Acrokeratoelastoidosis of Costa is an autosomal-dominant condition that occurs without trauma in children and young adults. Histopathology shows orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis due to an overproduction of filaggrin in the granular layer of the epidermis. The reticular dermis shows basophilic, thick, curled and fragmented elastic fibers with dilated capillaries that can be seen with Weigert elastic, Verhoeff-van Gieson, or orcein stains. Focal acral hyperkeratosis occurs on the hands and feet, predominantly in black patients. On histology, the epidermis shows a characteristic orthohyperkeratosis, moderate acanthosis, and slight hypergranulosis with no dermal involvment.6

Chronic hyperkeratotic eczematous dermatitis is another common entity in the differential characterized by hyperkeratotic plaques that scale and fissure. Biopsy demonstrates a spongiotic acanthotic epidermis.7,8

Psoriasis of the hands, specifically hyperkeratotic palmoplantar psoriasis, is associated with manual labor, similar to CEMPH. Histology shows epidermal hyperplasia; regular acanthosis; loss of the granular skin layer with prominent dermal capillaries; and a mixed dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils.9 Hyperkeratotic palmoplantar lichen planus presents with pruritic papules in the third and fifth decades of life. Histologically, hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and wedge-shaped hypergranulosis with a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltration at the dermoepidermal junction is seen.10

Palmoplantar keratodermas due to inflammatory reactive dermatoses include callosities that develop in response to repeated trauma or friction on the skin. On histology, there is prominent hyperkeratosis and acanthosis with moderate papillomatosis.11 Drug-related palmoplantar keratodermas such as those from arsenic exposure can lead to multiple, irregular, verrucous, keratotic, and pigmented lesions on the palms and soles. Histologically, atypical keratinocytes are seen in the epidermis with thick hyperkeratosis and vacuolated cells without solar elastosis.12

In conclusion, CEMPH is an underdiagnosed and underrecognized condition characterized by asymptomatic hyperkeratotic linear plaques along the medial aspect of the thumb and radial aspect of the index finger. It is important to keep CEMPH in mind when dealing with occupational cases of repeated long-term trauma or pressure to the hands as well as excessive sun exposure. It also is imperative to separate it from other diseases and avoid misdiagnosing this degenerative collagenous and elastotic disease as a malignant lesion.

- Burks JW, Wise LJ, Clark WH. Degenerative collagenous plaques of the hands. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:362-366.

- Jordaan HF, Rossouw DJ. Digital papular calcific elastosis: a histopathological, histochemical and ultrastructural study of 20 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 1990;17:358-370.

- Mortimore RJ, Conrad RJ. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:211-213.

- Tieu KD, Satter EK. Thickened plaques on the hands. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands (CEMPH). Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:499-504.

- Todd D, Al-Aboosi M, Hameed O, et al. The role of UV light in the pathogenesis of digital papular calcific elastosis. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:379-381.

- Mengesha YM, Kayal JD, Swerlick RA. Keratoelastoidosis marginalis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:23-25.

- MacKee MG, Lewis MG. Keratolysis exfoliativa and the mosaic fungus. Arch Dermatol. 1931;23:445-447.

- Walling HW, Swick BL, Storrs FJ, et al. Frictional hyperkeratotic hand dermatitis responding to Grenz ray therapy. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;58:49-51.

- Farley E, Masrour S, McKey J, et al. Palmoplantar psoriasis: a phenotypical and clinical review with introduction of a new quality-of-life assessment tool. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1024-1031.

- Rotunda AM, Craft N, Haley JC. Hyperkeratotic plaques on the palms and soles. palmoplantar lichen planus, hyperkeratotic variant. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1275-1280.

- Unal VS, Sevin A, Dayican A. Palmar callus formation as a result of mechanical trauma during sailing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:2161-2162.

- Cöl M, Cöl C, Soran A, et al. Arsenic-related Bowen's disease, palmar keratosis, and skin cancer. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107:687-689.

To the Editor:

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands (CEMPHs) has several names including degenerative collagenous plaques of the hands, keratoelastoidosis marginalis, and digital papular calcific elastosis. This rare disorder is an acquired, slowly progressive, asymptomatic, dermal connective tissue abnormality that is underrecognized and underdiagnosed. Clinical presentation includes hyperkeratotic translucent papules arranged linearly on the radial aspect of the hands.

A 74-year-old woman described having "rough hands" of more than 20 years' duration. She presented with 4-cm wide longitudinal, erythematous, firm, depressed plaques along the lateral edge of the second finger and extending to the medial thumb in both hands (Figure 1). She had attempted multiple treatments by her primary care physician, including topical and oral medications unknown to the patient and light therapy, all without benefit over a period of several years. We have attempted salicylic acid 40%, clobetasol cream 0.05%, and emollient creams containing α-hydroxy acid. At best the condition fluctuated between a subtle raised scale at the edge to smooth and occasionally more red-pink, seemingly unrelated to any treatments.

The patient did not have plaques elsewhere on the body, and notably, the feet were clear. She did not have a history of repeated trauma to the hands and did not engage in manual labor. She denied excessive sun exposure, though she had Fitzpatrick skin type III and a history of multiple precancers and nonmelanoma skin cancers 7 years prior to presentation.

Histology of CEMPH reveals a hyperkeratotic epidermis with an avascular and acellular replacement of the superficial reticular dermis by haphazardly arranged, thickened collagen fibers (Figure 2A-2C). Collagen fibers were oriented perpendicularly to the epidermal surface. Intervening amorphous basophilic elastotic masses were present in the upper dermis with occasional calcification and degenerative elastic fibers (Figure 2D).

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands is a chronic, asymptomatic, sclerotic skin disorder described in a 1960 case series of 5 patients reported by Burks et al.1 Although it has many names, the most common is CEMPH. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands most often presents in white men aged 50 to 60 years.2 Patients typically are asymptomatic with plaques limited to the junction of the palmar and dorsal surfaces of the hands with only minimal intermittent stiffness around the flexor creases. Lesions begin as discrete yellow papules that coalesce to form hyperkeratotic linear plaques with occasional telangiectasia.3

The etiology of CEMPH is attributed to collagen and elastin degeneration by chronic actinic damage, pressure, or trauma.4,5 The 3 stages of degeneration include an initial linear padded stage, an intermediate padded plaque stage, and an advanced padded hyperkeratotic plaque stage.4 Vascular compromise is seen from the enlarged and fused thickened collagen and elastic fibers that in turn lead to ischemic changes, hyperkeratosis with epidermal atrophy, and papillary dermis telangiectasia. Absence or weak expression of keratins 14 and 10 and strong expression of keratin 16 have been reported in the epidermis of CEMPH patients.4

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands do not have a specific treatment, as it is a benign, slowly progressive condition. Several treatments such as laser therapy, high-potency topical corticosteroids, topical tazarotene and tretinoin, oral isotretinoin, and cryotherapy have been tried with little long-term success.4 Moisturizing may help reduce fissuring, and patients are advised to avoid the sun and repeated trauma to the hands.

The differential diagnosis of CEMPH is summarized in the Table. Two genodermatoses—acrokeratoelastoidosis of Costa and focal acral hyperkeratosis—clinically resemble CEMPH. Acrokeratoelastoidosis of Costa is an autosomal-dominant condition that occurs without trauma in children and young adults. Histopathology shows orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis due to an overproduction of filaggrin in the granular layer of the epidermis. The reticular dermis shows basophilic, thick, curled and fragmented elastic fibers with dilated capillaries that can be seen with Weigert elastic, Verhoeff-van Gieson, or orcein stains. Focal acral hyperkeratosis occurs on the hands and feet, predominantly in black patients. On histology, the epidermis shows a characteristic orthohyperkeratosis, moderate acanthosis, and slight hypergranulosis with no dermal involvment.6

Chronic hyperkeratotic eczematous dermatitis is another common entity in the differential characterized by hyperkeratotic plaques that scale and fissure. Biopsy demonstrates a spongiotic acanthotic epidermis.7,8

Psoriasis of the hands, specifically hyperkeratotic palmoplantar psoriasis, is associated with manual labor, similar to CEMPH. Histology shows epidermal hyperplasia; regular acanthosis; loss of the granular skin layer with prominent dermal capillaries; and a mixed dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils.9 Hyperkeratotic palmoplantar lichen planus presents with pruritic papules in the third and fifth decades of life. Histologically, hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and wedge-shaped hypergranulosis with a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltration at the dermoepidermal junction is seen.10

Palmoplantar keratodermas due to inflammatory reactive dermatoses include callosities that develop in response to repeated trauma or friction on the skin. On histology, there is prominent hyperkeratosis and acanthosis with moderate papillomatosis.11 Drug-related palmoplantar keratodermas such as those from arsenic exposure can lead to multiple, irregular, verrucous, keratotic, and pigmented lesions on the palms and soles. Histologically, atypical keratinocytes are seen in the epidermis with thick hyperkeratosis and vacuolated cells without solar elastosis.12

In conclusion, CEMPH is an underdiagnosed and underrecognized condition characterized by asymptomatic hyperkeratotic linear plaques along the medial aspect of the thumb and radial aspect of the index finger. It is important to keep CEMPH in mind when dealing with occupational cases of repeated long-term trauma or pressure to the hands as well as excessive sun exposure. It also is imperative to separate it from other diseases and avoid misdiagnosing this degenerative collagenous and elastotic disease as a malignant lesion.

To the Editor:

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands (CEMPHs) has several names including degenerative collagenous plaques of the hands, keratoelastoidosis marginalis, and digital papular calcific elastosis. This rare disorder is an acquired, slowly progressive, asymptomatic, dermal connective tissue abnormality that is underrecognized and underdiagnosed. Clinical presentation includes hyperkeratotic translucent papules arranged linearly on the radial aspect of the hands.

A 74-year-old woman described having "rough hands" of more than 20 years' duration. She presented with 4-cm wide longitudinal, erythematous, firm, depressed plaques along the lateral edge of the second finger and extending to the medial thumb in both hands (Figure 1). She had attempted multiple treatments by her primary care physician, including topical and oral medications unknown to the patient and light therapy, all without benefit over a period of several years. We have attempted salicylic acid 40%, clobetasol cream 0.05%, and emollient creams containing α-hydroxy acid. At best the condition fluctuated between a subtle raised scale at the edge to smooth and occasionally more red-pink, seemingly unrelated to any treatments.

The patient did not have plaques elsewhere on the body, and notably, the feet were clear. She did not have a history of repeated trauma to the hands and did not engage in manual labor. She denied excessive sun exposure, though she had Fitzpatrick skin type III and a history of multiple precancers and nonmelanoma skin cancers 7 years prior to presentation.

Histology of CEMPH reveals a hyperkeratotic epidermis with an avascular and acellular replacement of the superficial reticular dermis by haphazardly arranged, thickened collagen fibers (Figure 2A-2C). Collagen fibers were oriented perpendicularly to the epidermal surface. Intervening amorphous basophilic elastotic masses were present in the upper dermis with occasional calcification and degenerative elastic fibers (Figure 2D).

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands is a chronic, asymptomatic, sclerotic skin disorder described in a 1960 case series of 5 patients reported by Burks et al.1 Although it has many names, the most common is CEMPH. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands most often presents in white men aged 50 to 60 years.2 Patients typically are asymptomatic with plaques limited to the junction of the palmar and dorsal surfaces of the hands with only minimal intermittent stiffness around the flexor creases. Lesions begin as discrete yellow papules that coalesce to form hyperkeratotic linear plaques with occasional telangiectasia.3

The etiology of CEMPH is attributed to collagen and elastin degeneration by chronic actinic damage, pressure, or trauma.4,5 The 3 stages of degeneration include an initial linear padded stage, an intermediate padded plaque stage, and an advanced padded hyperkeratotic plaque stage.4 Vascular compromise is seen from the enlarged and fused thickened collagen and elastic fibers that in turn lead to ischemic changes, hyperkeratosis with epidermal atrophy, and papillary dermis telangiectasia. Absence or weak expression of keratins 14 and 10 and strong expression of keratin 16 have been reported in the epidermis of CEMPH patients.4

Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands do not have a specific treatment, as it is a benign, slowly progressive condition. Several treatments such as laser therapy, high-potency topical corticosteroids, topical tazarotene and tretinoin, oral isotretinoin, and cryotherapy have been tried with little long-term success.4 Moisturizing may help reduce fissuring, and patients are advised to avoid the sun and repeated trauma to the hands.

The differential diagnosis of CEMPH is summarized in the Table. Two genodermatoses—acrokeratoelastoidosis of Costa and focal acral hyperkeratosis—clinically resemble CEMPH. Acrokeratoelastoidosis of Costa is an autosomal-dominant condition that occurs without trauma in children and young adults. Histopathology shows orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis due to an overproduction of filaggrin in the granular layer of the epidermis. The reticular dermis shows basophilic, thick, curled and fragmented elastic fibers with dilated capillaries that can be seen with Weigert elastic, Verhoeff-van Gieson, or orcein stains. Focal acral hyperkeratosis occurs on the hands and feet, predominantly in black patients. On histology, the epidermis shows a characteristic orthohyperkeratosis, moderate acanthosis, and slight hypergranulosis with no dermal involvment.6

Chronic hyperkeratotic eczematous dermatitis is another common entity in the differential characterized by hyperkeratotic plaques that scale and fissure. Biopsy demonstrates a spongiotic acanthotic epidermis.7,8

Psoriasis of the hands, specifically hyperkeratotic palmoplantar psoriasis, is associated with manual labor, similar to CEMPH. Histology shows epidermal hyperplasia; regular acanthosis; loss of the granular skin layer with prominent dermal capillaries; and a mixed dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes, macrophages, and neutrophils.9 Hyperkeratotic palmoplantar lichen planus presents with pruritic papules in the third and fifth decades of life. Histologically, hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and wedge-shaped hypergranulosis with a lichenoid lymphocytic infiltration at the dermoepidermal junction is seen.10

Palmoplantar keratodermas due to inflammatory reactive dermatoses include callosities that develop in response to repeated trauma or friction on the skin. On histology, there is prominent hyperkeratosis and acanthosis with moderate papillomatosis.11 Drug-related palmoplantar keratodermas such as those from arsenic exposure can lead to multiple, irregular, verrucous, keratotic, and pigmented lesions on the palms and soles. Histologically, atypical keratinocytes are seen in the epidermis with thick hyperkeratosis and vacuolated cells without solar elastosis.12

In conclusion, CEMPH is an underdiagnosed and underrecognized condition characterized by asymptomatic hyperkeratotic linear plaques along the medial aspect of the thumb and radial aspect of the index finger. It is important to keep CEMPH in mind when dealing with occupational cases of repeated long-term trauma or pressure to the hands as well as excessive sun exposure. It also is imperative to separate it from other diseases and avoid misdiagnosing this degenerative collagenous and elastotic disease as a malignant lesion.

- Burks JW, Wise LJ, Clark WH. Degenerative collagenous plaques of the hands. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:362-366.

- Jordaan HF, Rossouw DJ. Digital papular calcific elastosis: a histopathological, histochemical and ultrastructural study of 20 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 1990;17:358-370.

- Mortimore RJ, Conrad RJ. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:211-213.

- Tieu KD, Satter EK. Thickened plaques on the hands. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands (CEMPH). Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:499-504.

- Todd D, Al-Aboosi M, Hameed O, et al. The role of UV light in the pathogenesis of digital papular calcific elastosis. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:379-381.

- Mengesha YM, Kayal JD, Swerlick RA. Keratoelastoidosis marginalis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:23-25.

- MacKee MG, Lewis MG. Keratolysis exfoliativa and the mosaic fungus. Arch Dermatol. 1931;23:445-447.

- Walling HW, Swick BL, Storrs FJ, et al. Frictional hyperkeratotic hand dermatitis responding to Grenz ray therapy. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;58:49-51.

- Farley E, Masrour S, McKey J, et al. Palmoplantar psoriasis: a phenotypical and clinical review with introduction of a new quality-of-life assessment tool. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1024-1031.

- Rotunda AM, Craft N, Haley JC. Hyperkeratotic plaques on the palms and soles. palmoplantar lichen planus, hyperkeratotic variant. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1275-1280.

- Unal VS, Sevin A, Dayican A. Palmar callus formation as a result of mechanical trauma during sailing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:2161-2162.

- Cöl M, Cöl C, Soran A, et al. Arsenic-related Bowen's disease, palmar keratosis, and skin cancer. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107:687-689.

- Burks JW, Wise LJ, Clark WH. Degenerative collagenous plaques of the hands. Arch Dermatol. 1960;82:362-366.

- Jordaan HF, Rossouw DJ. Digital papular calcific elastosis: a histopathological, histochemical and ultrastructural study of 20 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 1990;17:358-370.

- Mortimore RJ, Conrad RJ. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands. Australas J Dermatol. 2001;42:211-213.

- Tieu KD, Satter EK. Thickened plaques on the hands. Collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands (CEMPH). Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:499-504.

- Todd D, Al-Aboosi M, Hameed O, et al. The role of UV light in the pathogenesis of digital papular calcific elastosis. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:379-381.

- Mengesha YM, Kayal JD, Swerlick RA. Keratoelastoidosis marginalis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002;6:23-25.

- MacKee MG, Lewis MG. Keratolysis exfoliativa and the mosaic fungus. Arch Dermatol. 1931;23:445-447.

- Walling HW, Swick BL, Storrs FJ, et al. Frictional hyperkeratotic hand dermatitis responding to Grenz ray therapy. Contact Dermatitis. 2008;58:49-51.

- Farley E, Masrour S, McKey J, et al. Palmoplantar psoriasis: a phenotypical and clinical review with introduction of a new quality-of-life assessment tool. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:1024-1031.

- Rotunda AM, Craft N, Haley JC. Hyperkeratotic plaques on the palms and soles. palmoplantar lichen planus, hyperkeratotic variant. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1275-1280.

- Unal VS, Sevin A, Dayican A. Palmar callus formation as a result of mechanical trauma during sailing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:2161-2162.

- Cöl M, Cöl C, Soran A, et al. Arsenic-related Bowen's disease, palmar keratosis, and skin cancer. Environ Health Perspect. 1999;107:687-689.

Practice Points

- The etiology of collagenous and elastotic marginal plaques of the hands (CEMPHs) is attributed to collagen and elastin degeneration by chronic actinic damage, pressure, or trauma.

- It is important to keep CEMPH in mind when dealing with occupational cases of repeated long-term trauma or pressure to the hands as well as excessive sun exposure. It should be separated from other diseases and avoid being misdiagnosed as a malignant lesion.

Successful Treatment of Ota Nevus With the 532-nm Solid-State Picosecond Laser

Ota nevus is a dermal melanocytosis that is typically characterized by blue, gray, or brown pigmented patches in the periorbital region.1 The condition has a prevalence of 0.04% in a Philadelphia study of 6915 patients and is most notable in patients with skin of color, affecting up to 0.6% of Asians,2 0.038% of white individuals, and 0.014% of black individuals.3,4 The appearance of an Ota nevus often imparts a negative psychosocial impact on the patient, prompting requests for treatment and/or removal.5Laser treatment of Ota nevi must be carefully implemented, especially in Fitzpatrick skin types IV through VI. Although 532- and 755-nm Q-switched nanosecond lasers have been used to treat Ota nevi,5,6 typically only moderate improvement is seen; further treatment at higher fluences will only increase the risk for dyspigmentation and scarring.6

We report a case of successful treatment of an Ota nevus following 2 treatment sessions with the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser, which is a novel application in patients with skin of color (Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI). The Q-switched nanosecond laser has been shown to be moderately effective at treating Ota nevi.6

Case Report

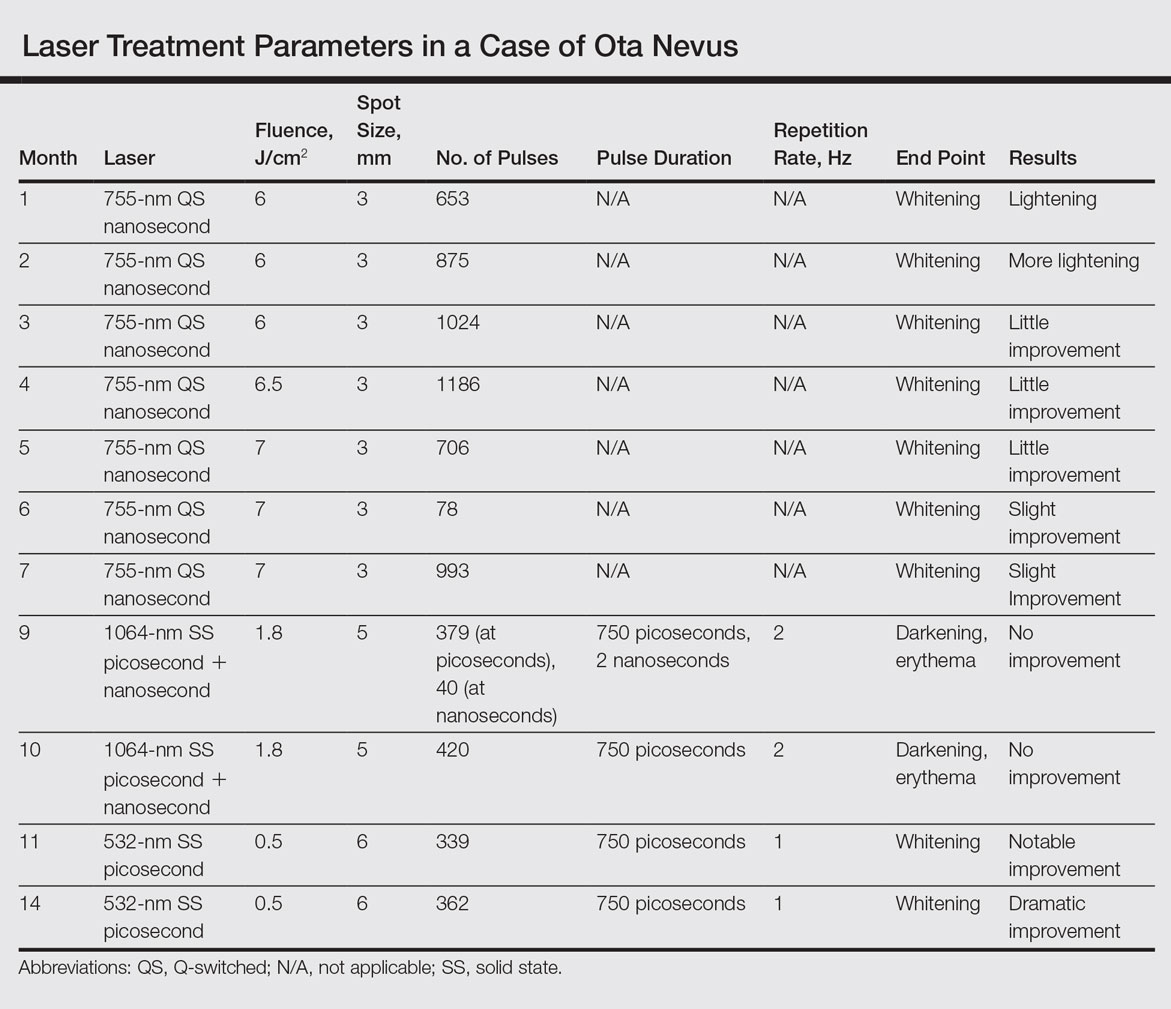

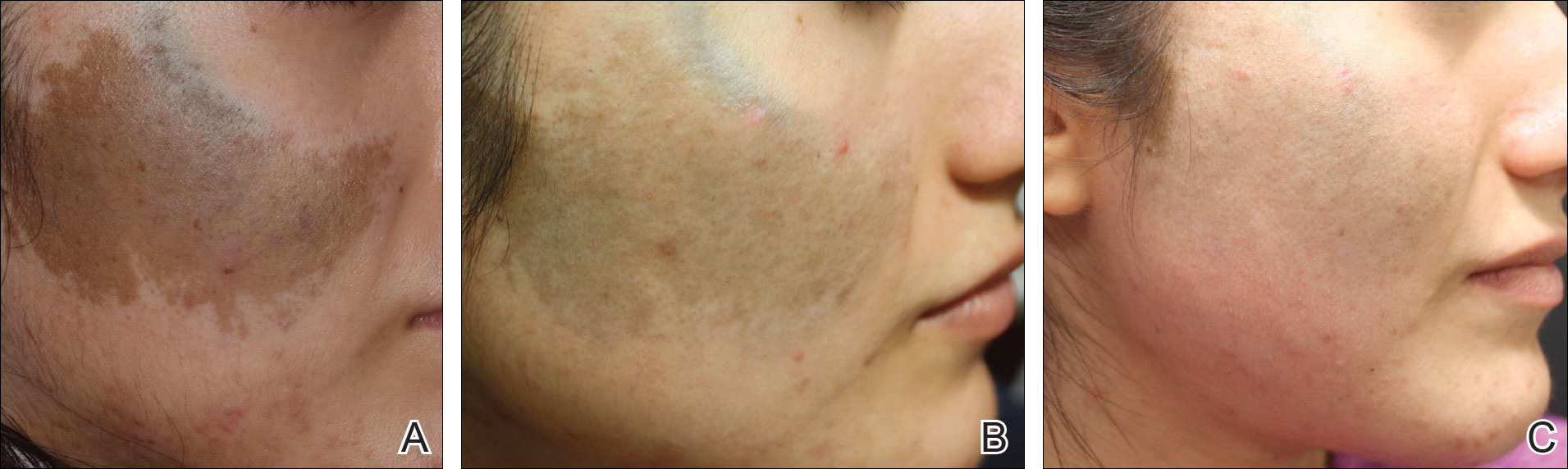

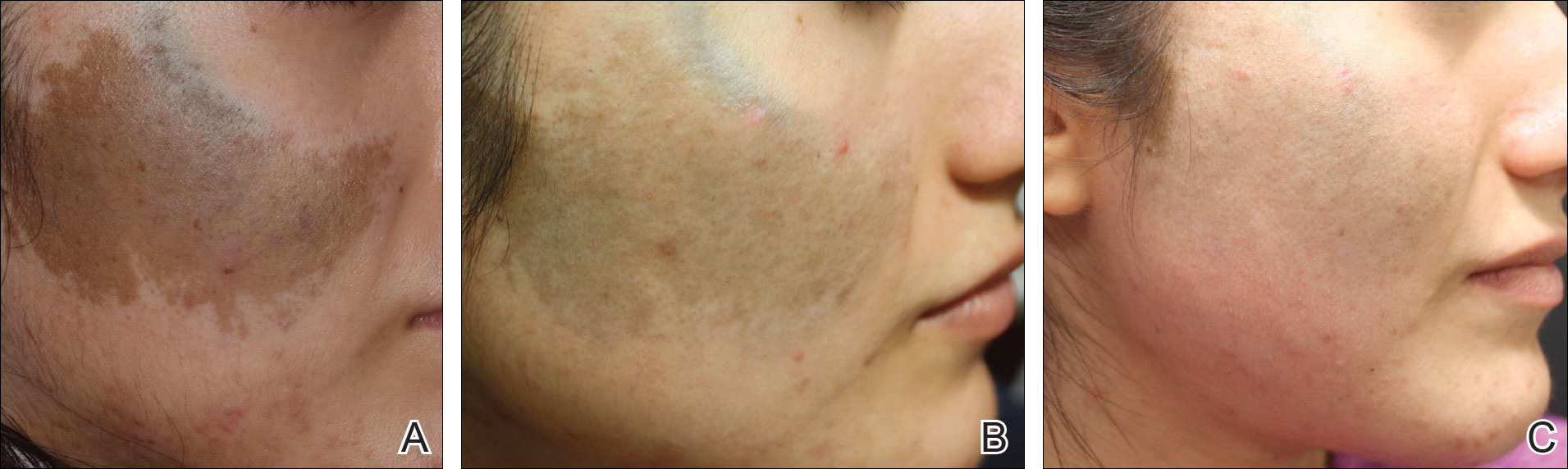

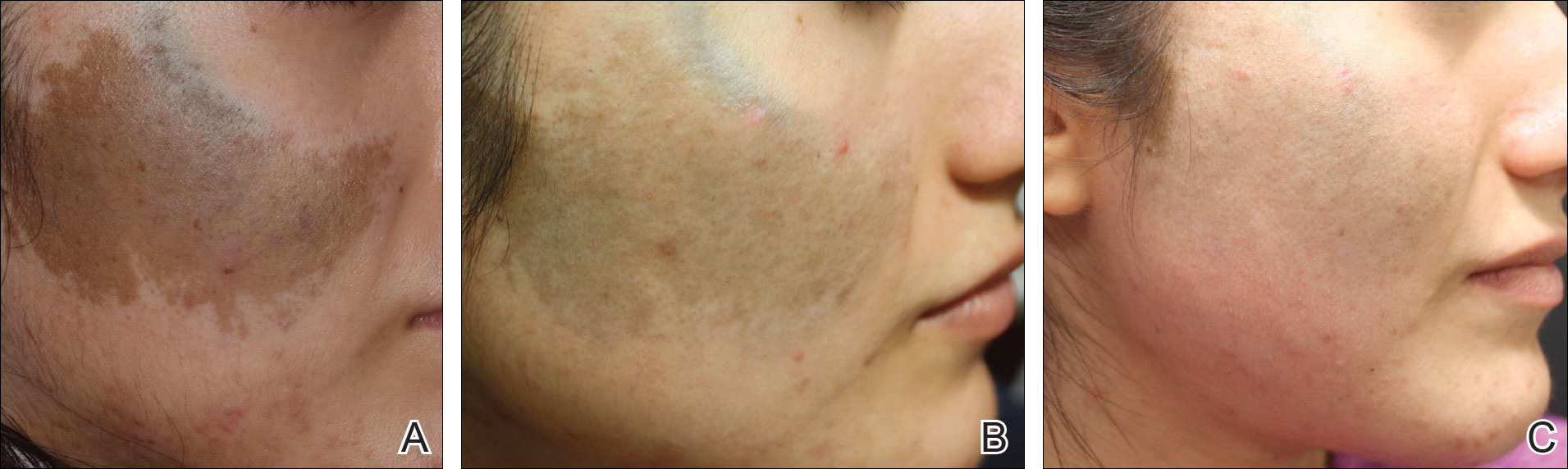

An 18-year-old woman with Fitzpatrick skin type IV presented for cosmetic removal of an 8×5-cm dark brown-blue patch on the right temple and malar and buccal cheek present since birth that had failed to respond to an unknown laser treatment that was administered outside of the United States (Figure, A). To ascertain the diagnosis, a biopsy was performed, showing histology consistent with Ota nevus. Initially, the 755-nm Q-switched nanosecond laser was recommended for treatment. Over the course of 7 months (1 treatment session per month [Table]), the patient saw improvement but not to the desired extent. The patient then underwent 2 treatments at 4-week intervals with the 1064-nm solid-state picosecond and nanosecond lasers; however, no improvement was seen following these 2 sessions (Table).

The next month the patient received treatment with a novel 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser using the following parameters: fluence, 0.5 J/cm2; spot size, 6 mm; repetition rate, 1 Hz; pulse duration, 750 picoseconds; 339 pulses. The end point was whitening. A remarkable clinical response was demonstrated 6 weeks later (Figure, B). A second treatment with the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser was then performed at 14 months. On a return visit 2 months after the second treatment, the patient showed dramatic improvement, almost to the degree of complete resolution (Figure, C).

Comment

Pigmentation disorders are more common in patients with skin of color, and those affected may experience psychological effects secondary to these dermatoses, prompting requests for treatment and/or removal.7 Although the 532- and 755-nm Q-switched nanosecond lasers have been used to treat Ota nevi,3 the challenge remains for patients with skin of color, as these lasers work through photothermolysis, which generates heat and may cause thermal damage by targeting melanin. Because more melanin is present in skin of color patients, the threshold for too much heat is lower and these patients are at a higher risk for adverse events such as scarring and hyperpigmentation.6,8

By delivering energy in shorter pulses, the novel 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser shows greater fragmentation of melanosomes into melanin particles that are eventually phagocytosed.8 In our patient, dramatic improvement was noted after only 2 treatments, as evidenced by other picosecond treatments on Ota nevi,6,8 suggesting that fewer treatments are necessary when using the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser for Ota nevi.

Although the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser was cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration for tattoo removal, this laser shows potential use in other pigmentary disorders, particularly in patients with skin of color, as demonstrated in our case. With continued understanding through further studies, this picosecond laser with a shorter pulse duration may prove to be a safer and more effective alternative to the Q-switched nanosecond laser.

Conclusion

As shown in our case, the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser appears to be a safe and effective modality for treating Ota nevi. This case demonstrates the potential utility of this laser in patients desiring more complete clearing, as it removes pigment more rapidly with lower risk for serious adverse effects. The 9th Cosmetic Surgery Forum will be held November 29-December 2, 2017, in Las Vegas, Nevada. Get more information at www.cosmeticsurgeryforum.com.

- Kim JY, Lee HG, Kim MJ, et al. The efficacy and safety of episcleral pigmentation removal from pig eyes: using a 532-nm quality-switched Nd: YAG laser. Cornea. 2012;31:1449-1454.

- Watanabe S, Takahashi H. Treatment of nevus of Ota with the Q-switched ruby laser. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1745-1750.

- Yates B, Que SK, D'Souza L, et al. Laser treatment of periocular skin conditions. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:197-206.

- Gonder JR, Ezell PC, Shields JA, et al. Ocular melanocytosis. a study to determine the prevalence rate of ocular melanocytosis. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:950-952.

- Chesnut C, Diehl J, Lask G. Treatment of nevus of Ota with a picosecond 755-nm alexandrite laser. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:508-510.

- Moreno-Arias GA, Camps-Fresneda A. Treatment of nevus of Ota with the Q-switched alexandrite laser. Lasers Surg Med. 2001;28:451-455.

- Manuskiatti W, Eimpunth S, Wanitphakdeedecha R. Effect of cold air cooling on the incidence of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation after Q-switched Nd:YAG laser treatment of acquired bilateral nevus of Ota like macules. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1139-1143.

- Levin MK, Ng E, Bae YS, et al. Treatment of pigmentary disorders in patients with skin of color with a novel 755 nm picosecond, Q-switched ruby, and Q-switched Nd:YAG nanosecond lasers: a retrospective photographic review. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:181-187.

Ota nevus is a dermal melanocytosis that is typically characterized by blue, gray, or brown pigmented patches in the periorbital region.1 The condition has a prevalence of 0.04% in a Philadelphia study of 6915 patients and is most notable in patients with skin of color, affecting up to 0.6% of Asians,2 0.038% of white individuals, and 0.014% of black individuals.3,4 The appearance of an Ota nevus often imparts a negative psychosocial impact on the patient, prompting requests for treatment and/or removal.5Laser treatment of Ota nevi must be carefully implemented, especially in Fitzpatrick skin types IV through VI. Although 532- and 755-nm Q-switched nanosecond lasers have been used to treat Ota nevi,5,6 typically only moderate improvement is seen; further treatment at higher fluences will only increase the risk for dyspigmentation and scarring.6

We report a case of successful treatment of an Ota nevus following 2 treatment sessions with the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser, which is a novel application in patients with skin of color (Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI). The Q-switched nanosecond laser has been shown to be moderately effective at treating Ota nevi.6

Case Report

An 18-year-old woman with Fitzpatrick skin type IV presented for cosmetic removal of an 8×5-cm dark brown-blue patch on the right temple and malar and buccal cheek present since birth that had failed to respond to an unknown laser treatment that was administered outside of the United States (Figure, A). To ascertain the diagnosis, a biopsy was performed, showing histology consistent with Ota nevus. Initially, the 755-nm Q-switched nanosecond laser was recommended for treatment. Over the course of 7 months (1 treatment session per month [Table]), the patient saw improvement but not to the desired extent. The patient then underwent 2 treatments at 4-week intervals with the 1064-nm solid-state picosecond and nanosecond lasers; however, no improvement was seen following these 2 sessions (Table).

The next month the patient received treatment with a novel 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser using the following parameters: fluence, 0.5 J/cm2; spot size, 6 mm; repetition rate, 1 Hz; pulse duration, 750 picoseconds; 339 pulses. The end point was whitening. A remarkable clinical response was demonstrated 6 weeks later (Figure, B). A second treatment with the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser was then performed at 14 months. On a return visit 2 months after the second treatment, the patient showed dramatic improvement, almost to the degree of complete resolution (Figure, C).

Comment

Pigmentation disorders are more common in patients with skin of color, and those affected may experience psychological effects secondary to these dermatoses, prompting requests for treatment and/or removal.7 Although the 532- and 755-nm Q-switched nanosecond lasers have been used to treat Ota nevi,3 the challenge remains for patients with skin of color, as these lasers work through photothermolysis, which generates heat and may cause thermal damage by targeting melanin. Because more melanin is present in skin of color patients, the threshold for too much heat is lower and these patients are at a higher risk for adverse events such as scarring and hyperpigmentation.6,8

By delivering energy in shorter pulses, the novel 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser shows greater fragmentation of melanosomes into melanin particles that are eventually phagocytosed.8 In our patient, dramatic improvement was noted after only 2 treatments, as evidenced by other picosecond treatments on Ota nevi,6,8 suggesting that fewer treatments are necessary when using the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser for Ota nevi.

Although the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser was cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration for tattoo removal, this laser shows potential use in other pigmentary disorders, particularly in patients with skin of color, as demonstrated in our case. With continued understanding through further studies, this picosecond laser with a shorter pulse duration may prove to be a safer and more effective alternative to the Q-switched nanosecond laser.

Conclusion

As shown in our case, the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser appears to be a safe and effective modality for treating Ota nevi. This case demonstrates the potential utility of this laser in patients desiring more complete clearing, as it removes pigment more rapidly with lower risk for serious adverse effects. The 9th Cosmetic Surgery Forum will be held November 29-December 2, 2017, in Las Vegas, Nevada. Get more information at www.cosmeticsurgeryforum.com.

Ota nevus is a dermal melanocytosis that is typically characterized by blue, gray, or brown pigmented patches in the periorbital region.1 The condition has a prevalence of 0.04% in a Philadelphia study of 6915 patients and is most notable in patients with skin of color, affecting up to 0.6% of Asians,2 0.038% of white individuals, and 0.014% of black individuals.3,4 The appearance of an Ota nevus often imparts a negative psychosocial impact on the patient, prompting requests for treatment and/or removal.5Laser treatment of Ota nevi must be carefully implemented, especially in Fitzpatrick skin types IV through VI. Although 532- and 755-nm Q-switched nanosecond lasers have been used to treat Ota nevi,5,6 typically only moderate improvement is seen; further treatment at higher fluences will only increase the risk for dyspigmentation and scarring.6

We report a case of successful treatment of an Ota nevus following 2 treatment sessions with the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser, which is a novel application in patients with skin of color (Fitzpatrick skin types IV-VI). The Q-switched nanosecond laser has been shown to be moderately effective at treating Ota nevi.6

Case Report

An 18-year-old woman with Fitzpatrick skin type IV presented for cosmetic removal of an 8×5-cm dark brown-blue patch on the right temple and malar and buccal cheek present since birth that had failed to respond to an unknown laser treatment that was administered outside of the United States (Figure, A). To ascertain the diagnosis, a biopsy was performed, showing histology consistent with Ota nevus. Initially, the 755-nm Q-switched nanosecond laser was recommended for treatment. Over the course of 7 months (1 treatment session per month [Table]), the patient saw improvement but not to the desired extent. The patient then underwent 2 treatments at 4-week intervals with the 1064-nm solid-state picosecond and nanosecond lasers; however, no improvement was seen following these 2 sessions (Table).

The next month the patient received treatment with a novel 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser using the following parameters: fluence, 0.5 J/cm2; spot size, 6 mm; repetition rate, 1 Hz; pulse duration, 750 picoseconds; 339 pulses. The end point was whitening. A remarkable clinical response was demonstrated 6 weeks later (Figure, B). A second treatment with the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser was then performed at 14 months. On a return visit 2 months after the second treatment, the patient showed dramatic improvement, almost to the degree of complete resolution (Figure, C).

Comment

Pigmentation disorders are more common in patients with skin of color, and those affected may experience psychological effects secondary to these dermatoses, prompting requests for treatment and/or removal.7 Although the 532- and 755-nm Q-switched nanosecond lasers have been used to treat Ota nevi,3 the challenge remains for patients with skin of color, as these lasers work through photothermolysis, which generates heat and may cause thermal damage by targeting melanin. Because more melanin is present in skin of color patients, the threshold for too much heat is lower and these patients are at a higher risk for adverse events such as scarring and hyperpigmentation.6,8

By delivering energy in shorter pulses, the novel 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser shows greater fragmentation of melanosomes into melanin particles that are eventually phagocytosed.8 In our patient, dramatic improvement was noted after only 2 treatments, as evidenced by other picosecond treatments on Ota nevi,6,8 suggesting that fewer treatments are necessary when using the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser for Ota nevi.

Although the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser was cleared by the US Food and Drug Administration for tattoo removal, this laser shows potential use in other pigmentary disorders, particularly in patients with skin of color, as demonstrated in our case. With continued understanding through further studies, this picosecond laser with a shorter pulse duration may prove to be a safer and more effective alternative to the Q-switched nanosecond laser.

Conclusion

As shown in our case, the 532-nm solid-state picosecond laser appears to be a safe and effective modality for treating Ota nevi. This case demonstrates the potential utility of this laser in patients desiring more complete clearing, as it removes pigment more rapidly with lower risk for serious adverse effects. The 9th Cosmetic Surgery Forum will be held November 29-December 2, 2017, in Las Vegas, Nevada. Get more information at www.cosmeticsurgeryforum.com.

- Kim JY, Lee HG, Kim MJ, et al. The efficacy and safety of episcleral pigmentation removal from pig eyes: using a 532-nm quality-switched Nd: YAG laser. Cornea. 2012;31:1449-1454.

- Watanabe S, Takahashi H. Treatment of nevus of Ota with the Q-switched ruby laser. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1745-1750.

- Yates B, Que SK, D'Souza L, et al. Laser treatment of periocular skin conditions. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:197-206.

- Gonder JR, Ezell PC, Shields JA, et al. Ocular melanocytosis. a study to determine the prevalence rate of ocular melanocytosis. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:950-952.

- Chesnut C, Diehl J, Lask G. Treatment of nevus of Ota with a picosecond 755-nm alexandrite laser. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:508-510.

- Moreno-Arias GA, Camps-Fresneda A. Treatment of nevus of Ota with the Q-switched alexandrite laser. Lasers Surg Med. 2001;28:451-455.

- Manuskiatti W, Eimpunth S, Wanitphakdeedecha R. Effect of cold air cooling on the incidence of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation after Q-switched Nd:YAG laser treatment of acquired bilateral nevus of Ota like macules. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1139-1143.

- Levin MK, Ng E, Bae YS, et al. Treatment of pigmentary disorders in patients with skin of color with a novel 755 nm picosecond, Q-switched ruby, and Q-switched Nd:YAG nanosecond lasers: a retrospective photographic review. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:181-187.

- Kim JY, Lee HG, Kim MJ, et al. The efficacy and safety of episcleral pigmentation removal from pig eyes: using a 532-nm quality-switched Nd: YAG laser. Cornea. 2012;31:1449-1454.

- Watanabe S, Takahashi H. Treatment of nevus of Ota with the Q-switched ruby laser. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1745-1750.

- Yates B, Que SK, D'Souza L, et al. Laser treatment of periocular skin conditions. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:197-206.

- Gonder JR, Ezell PC, Shields JA, et al. Ocular melanocytosis. a study to determine the prevalence rate of ocular melanocytosis. Ophthalmology. 1982;89:950-952.

- Chesnut C, Diehl J, Lask G. Treatment of nevus of Ota with a picosecond 755-nm alexandrite laser. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:508-510.

- Moreno-Arias GA, Camps-Fresneda A. Treatment of nevus of Ota with the Q-switched alexandrite laser. Lasers Surg Med. 2001;28:451-455.

- Manuskiatti W, Eimpunth S, Wanitphakdeedecha R. Effect of cold air cooling on the incidence of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation after Q-switched Nd:YAG laser treatment of acquired bilateral nevus of Ota like macules. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1139-1143.

- Levin MK, Ng E, Bae YS, et al. Treatment of pigmentary disorders in patients with skin of color with a novel 755 nm picosecond, Q-switched ruby, and Q-switched Nd:YAG nanosecond lasers: a retrospective photographic review. Lasers Surg Med. 2016;48:181-187.

Resident Pearl

The Q-switched 532-nm picosecond laser delivers energy in short pulses, creating fragmentation of melanosomes into melanin particles that eventually become phagocytosed. This process may be safer for patients with Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI, as it decreases the risk for dyschromia and scarring.

Antiphospholipid Syndrome in a Patient With Rheumatoid Arthritis

Case Report

A 39-year-old woman with a 20-year history of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) presented to a university-affiliated tertiary care hospital with painful ulcerations on the bilateral dorsal feet that started as bullae 16 weeks prior to presentation. Initial skin biopsy performed by an outside dermatologist 8 weeks prior to presentation showed vasculitis and culture was positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. She was started on a prednisone taper and cephalexin, which did not improve the lower extremity ulcerations and the pain became progressively worse. At the time of presentation to our dermatology department, the patient was taking prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, hydrocodone-acetaminophen, and gabapentin. Prior therapy with sulfasalazine failed; etanercept and methotrexate were discontinued years prior due to side effects. The patient had no history of deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or miscarriage.

At presentation, the patient was afebrile and her vital signs were stable. Physical examination showed multiple ulcers and erosions on the bilateral dorsal feet with a few scattered retiform red-purple patches (Figure). One bulla was present on the right dorsal foot. All lesions were tender to the touch and edema was present on the bilateral feet. No oral ulcerations were present and no focal neuropathies or palpable cords were appreciated in the lower extremities. There were no other cutaneous abnormalities.

Laboratory studies showed a white blood cell count of 9.54×103/µL (reference range, 4.16-9.95×103/µL), hemoglobin count of 12.4 g/dL (reference range, 11.6-15.2 g/dL), and a platelet count of 175×103/µL (reference range, 143-398×103/µL). A basic metabolic panel was normal except for an elevated glucose level of 185 mg/dL (reference range, 65-100 mg/dL). Urinalysis was normal. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level were not elevated. Antinuclear antibodies and double-stranded DNA antibodies were normal. Prothrombin time was 10.4 seconds (reference range, 9.2-11.5 seconds) and dilute viper's venom time was negative. Rheumatoid factor level was elevated at 76 IU/mL (reference range, <25 IU/mL) and anti-citrullinated peptide antibody was moderately elevated at 42 U/mL (negative, <20 U/mL; weak positive, 20-39 U/mL; moderate positive, 40-59 U/mL; strong positive, >59 U/mL). The cardiolipin antibodies IgG, IgM, and IgA were within reference range. Results of β2-glycoprotein I IgG and IgM antibody tests were normal, but IgA was elevated at 34 µg/mL (reference range, <20 µg/mL). Wound cultures grew moderate Enterobacter cloacae and Staphylococcus lugdunensis.

Slides from 2 prior punch biopsies obtained by an outside hospital approximately 8 weeks prior from the right and left dorsal foot lesions were reviewed. Both biopsies were histologically similar. Postcapillary venules showed extensive vasculitis with numerous fibrin thrombi in the lumens in both biopsy specimens. The biopsy from the right foot showed prominent ulceration of the epidermis, with a few of the affected vessels showing minimal accompanying nuclear dust; however, the predominant pattern was not that of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Biopsy from the left foot showed prominent epidermal necrosis with focal reepithelialization and scattered eosinophils. The pathologist felt that a vasculitis secondary to coagulopathy was most likely but that a drug reaction and rheumatoid vasculitis would be other entities to consider in the differential. A review of the laboratory findings from the outside hospital from approximately 12 weeks prior to presentation showed IgM was normal but IgG was elevated at 28 U/mL (reference range, 0-15 U/mL) and IgA was elevated at 8 U/mL (reference range, 0-7 U/mL); β2-glycoprotein I IgG antibodies were elevated at 37 mg/dL (reference range, 0-25.0 mg/dL) and β2-glycoprotein I IgA antibodies were elevated at 5 mg/dL (reference range, 0-4.0 mg/dL).

The clinical suspicion of a thrombotic event on the dorsal feet, which was confirmed histologically, and the persistently positive antiphospholipid (aPL) antibody titers helped to establish the diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) in the setting of RA. The dose of prednisone was increased from 10 mg daily on admission to 40 mg daily. The patient was started on enoxaparin 60 mg subcutaneously twice daily at initial presentation and was bridged to oral warfarin 2 mg daily after the diagnosis of APS was established. Oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily was started for wound infection. The ulcerations gradually improved over the course of her 7-day hospitalization. She was continued on prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, and warfarin as an outpatient and has had no recurrence of lesions after 3 years of follow-up on this regimen.

Comment

Antiphospholipid syndrome is an autoimmune condition defined by a venous and/or arterial thrombotic event and/or pregnancy morbidity in the presence of persistently elevated aPL antibody titers. The most frequently detected subgroups of aPL are anticardiolipin (aCL) antibodies, anti-β2-glycoprotein I antibodies, and lupus anticoagulants.1 Primary APS occurs as an isolated entity, whereas secondary APS occurs in the setting of a preexisting autoimmune disease, infection, malignancy, or medication.2 The diagnostic criteria for APS requires positive aPL titers at least 12 weeks apart and a clinically confirmed thrombotic event or pregnancy morbidity.3

About one-third to half of patients with APS exhibit cutaneous manifestations.4,5 Livedo reticularis is most commonly observed and represents the first clinical sign of APS in 17.5% of cases.6 Cutaneous findings of APS also include anetoderma, cutaneous ulceration and necrosis, necrotizing vasculitis, livedoid vasculitis, thrombophlebitis, purpura, ecchymoses, painful skin nodules, and subungual hemorrhages.7 The various cutaneous manifestations of APS are associated with a range of histopathologic findings, but noninflammatory thrombosis in small arteries and/or veins in the dermis and subcutaneous fat tissue is the most common histologic feature.4 Our patient exhibited cutaneous ulceration and necrosis, and biopsy clearly showed the presence of vasculitis and fibrin thrombi within postcapillary venules. These findings along with the persistently elevated β2-glycoprotein I IgA solidified the diagnosis of APS.

The most common cutaneous manifestations of RA are nodules (32%), Raynaud phenomenon (10%), and vasculitis (3%).8 The mean prevalence of aPL antibodies in patients with RA is 28%, though reports range from 5% to 75%.1 The presence of aPL or aCL does not predict the development of thrombosis and/or thrombocytopenia in RA patients9,10; however, aCL antibodies in RA patients are associated with a higher risk for developing rheumatoid nodules. It is hypothesized that the majority of aCL antibodies identified in RA patients have different specificities than those identified in other diseases that are associated with thrombotic events.1

Anticoagulation has been proven to decrease the risk for recurrent thrombotic events in patients with APS.11 Patients should discontinue the use of estrogen-containing oral contraceptives; avoid smoking cigarettes; and treat hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus, if present. The type and duration of anticoagulation therapy, especially for the treatment of the cutaneous manifestations of APS, is less well defined. Antiplatelet therapies such as low-dose aspirin or dipyridamole often are used for less severe cutaneous manifestations such as livedoid vasculopathy. Warfarin with a target international normalized ratio of 2.0 to 3.0 is most commonly used following major thrombotic events, including cutaneous necrosis and digital gangrene. The role of corticosteroids and immunosuppressants is unclear; one study showed that these therapies did not prevent further thrombotic events in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.4

Conclusion

Although aPL antibodies are most prevalent in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, an estimated 28% of patients with RA have elevated aPL titers. The aPL antibodies recognized in RA patients are thought to have a different specificity than those recognized in other APS-associated diseases because elevated aPL antibody titers are not associated with an increased incidence of thrombotic events in RA patients; however, larger studies are needed to clarify this phenomenon. It remains to be determined if this case of APS and RA represents a coincidence or a true disease association, but the recognition of the cutaneous and histological features of APS is crucial for establishing a diagnosis and initiating anticoagulation therapy to prevent further morbidity and mortality.

- Olech E, Merrill JT. The prevalence and clinical significance of antiphospholipid antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2006;8:100-108.

- Thornsberry LA, LoSicco KI, English JC. The skin and hypercoagulable states. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:450-462.

- Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:295-306.

- Asherson A, Francès C, Iaccarino FL, et al. Theantiphospholipid antibody syndrome: diagnosis, skin manifestations and current therapy. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2006;24(1 suppl 40):S46-S51.

- Cervera R, Piette JC, Font J, et al; Euro-Phospholipid Project Group. Antiphospholipid syndrome: clinical and immunologic manifestations and patterns of disease expression in a cohort of 1,000 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1019-1027.

- Francès C, Niang S, Laffitte E, et al. Dermatologic manifestations of antiphospholipid syndrome. two hundred consecutive cases. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1785-1793.

- Gibson GE, Su WP, Pittelkow MR. Antiphospholipid syndrome and the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(6, pt 1):970-982.

- Young A. Extra-articular manifestations and complications of rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007;21:907-927.

- Palomo I, Pinochet C, Alarcón M, et al. Prevalence of antiphospholipid antibodies in Chilean patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2006;20:190-194.

- Wolf P, Gretler J, Aglas F, et al. Anticardiolipin antibodies in rheumatoid arthritis: their relation to rheumatoid nodules and cutaneous vascular manifestations. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:48-51.

- Lim W, Crowther MA, Eikelboom JW. Management of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;295:1050-1057.

Case Report

A 39-year-old woman with a 20-year history of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) presented to a university-affiliated tertiary care hospital with painful ulcerations on the bilateral dorsal feet that started as bullae 16 weeks prior to presentation. Initial skin biopsy performed by an outside dermatologist 8 weeks prior to presentation showed vasculitis and culture was positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. She was started on a prednisone taper and cephalexin, which did not improve the lower extremity ulcerations and the pain became progressively worse. At the time of presentation to our dermatology department, the patient was taking prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, hydrocodone-acetaminophen, and gabapentin. Prior therapy with sulfasalazine failed; etanercept and methotrexate were discontinued years prior due to side effects. The patient had no history of deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or miscarriage.

At presentation, the patient was afebrile and her vital signs were stable. Physical examination showed multiple ulcers and erosions on the bilateral dorsal feet with a few scattered retiform red-purple patches (Figure). One bulla was present on the right dorsal foot. All lesions were tender to the touch and edema was present on the bilateral feet. No oral ulcerations were present and no focal neuropathies or palpable cords were appreciated in the lower extremities. There were no other cutaneous abnormalities.

Laboratory studies showed a white blood cell count of 9.54×103/µL (reference range, 4.16-9.95×103/µL), hemoglobin count of 12.4 g/dL (reference range, 11.6-15.2 g/dL), and a platelet count of 175×103/µL (reference range, 143-398×103/µL). A basic metabolic panel was normal except for an elevated glucose level of 185 mg/dL (reference range, 65-100 mg/dL). Urinalysis was normal. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein level were not elevated. Antinuclear antibodies and double-stranded DNA antibodies were normal. Prothrombin time was 10.4 seconds (reference range, 9.2-11.5 seconds) and dilute viper's venom time was negative. Rheumatoid factor level was elevated at 76 IU/mL (reference range, <25 IU/mL) and anti-citrullinated peptide antibody was moderately elevated at 42 U/mL (negative, <20 U/mL; weak positive, 20-39 U/mL; moderate positive, 40-59 U/mL; strong positive, >59 U/mL). The cardiolipin antibodies IgG, IgM, and IgA were within reference range. Results of β2-glycoprotein I IgG and IgM antibody tests were normal, but IgA was elevated at 34 µg/mL (reference range, <20 µg/mL). Wound cultures grew moderate Enterobacter cloacae and Staphylococcus lugdunensis.

Slides from 2 prior punch biopsies obtained by an outside hospital approximately 8 weeks prior from the right and left dorsal foot lesions were reviewed. Both biopsies were histologically similar. Postcapillary venules showed extensive vasculitis with numerous fibrin thrombi in the lumens in both biopsy specimens. The biopsy from the right foot showed prominent ulceration of the epidermis, with a few of the affected vessels showing minimal accompanying nuclear dust; however, the predominant pattern was not that of leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Biopsy from the left foot showed prominent epidermal necrosis with focal reepithelialization and scattered eosinophils. The pathologist felt that a vasculitis secondary to coagulopathy was most likely but that a drug reaction and rheumatoid vasculitis would be other entities to consider in the differential. A review of the laboratory findings from the outside hospital from approximately 12 weeks prior to presentation showed IgM was normal but IgG was elevated at 28 U/mL (reference range, 0-15 U/mL) and IgA was elevated at 8 U/mL (reference range, 0-7 U/mL); β2-glycoprotein I IgG antibodies were elevated at 37 mg/dL (reference range, 0-25.0 mg/dL) and β2-glycoprotein I IgA antibodies were elevated at 5 mg/dL (reference range, 0-4.0 mg/dL).

The clinical suspicion of a thrombotic event on the dorsal feet, which was confirmed histologically, and the persistently positive antiphospholipid (aPL) antibody titers helped to establish the diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) in the setting of RA. The dose of prednisone was increased from 10 mg daily on admission to 40 mg daily. The patient was started on enoxaparin 60 mg subcutaneously twice daily at initial presentation and was bridged to oral warfarin 2 mg daily after the diagnosis of APS was established. Oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily was started for wound infection. The ulcerations gradually improved over the course of her 7-day hospitalization. She was continued on prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, and warfarin as an outpatient and has had no recurrence of lesions after 3 years of follow-up on this regimen.

Comment

Antiphospholipid syndrome is an autoimmune condition defined by a venous and/or arterial thrombotic event and/or pregnancy morbidity in the presence of persistently elevated aPL antibody titers. The most frequently detected subgroups of aPL are anticardiolipin (aCL) antibodies, anti-β2-glycoprotein I antibodies, and lupus anticoagulants.1 Primary APS occurs as an isolated entity, whereas secondary APS occurs in the setting of a preexisting autoimmune disease, infection, malignancy, or medication.2 The diagnostic criteria for APS requires positive aPL titers at least 12 weeks apart and a clinically confirmed thrombotic event or pregnancy morbidity.3

About one-third to half of patients with APS exhibit cutaneous manifestations.4,5 Livedo reticularis is most commonly observed and represents the first clinical sign of APS in 17.5% of cases.6 Cutaneous findings of APS also include anetoderma, cutaneous ulceration and necrosis, necrotizing vasculitis, livedoid vasculitis, thrombophlebitis, purpura, ecchymoses, painful skin nodules, and subungual hemorrhages.7 The various cutaneous manifestations of APS are associated with a range of histopathologic findings, but noninflammatory thrombosis in small arteries and/or veins in the dermis and subcutaneous fat tissue is the most common histologic feature.4 Our patient exhibited cutaneous ulceration and necrosis, and biopsy clearly showed the presence of vasculitis and fibrin thrombi within postcapillary venules. These findings along with the persistently elevated β2-glycoprotein I IgA solidified the diagnosis of APS.

The most common cutaneous manifestations of RA are nodules (32%), Raynaud phenomenon (10%), and vasculitis (3%).8 The mean prevalence of aPL antibodies in patients with RA is 28%, though reports range from 5% to 75%.1 The presence of aPL or aCL does not predict the development of thrombosis and/or thrombocytopenia in RA patients9,10; however, aCL antibodies in RA patients are associated with a higher risk for developing rheumatoid nodules. It is hypothesized that the majority of aCL antibodies identified in RA patients have different specificities than those identified in other diseases that are associated with thrombotic events.1

Anticoagulation has been proven to decrease the risk for recurrent thrombotic events in patients with APS.11 Patients should discontinue the use of estrogen-containing oral contraceptives; avoid smoking cigarettes; and treat hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus, if present. The type and duration of anticoagulation therapy, especially for the treatment of the cutaneous manifestations of APS, is less well defined. Antiplatelet therapies such as low-dose aspirin or dipyridamole often are used for less severe cutaneous manifestations such as livedoid vasculopathy. Warfarin with a target international normalized ratio of 2.0 to 3.0 is most commonly used following major thrombotic events, including cutaneous necrosis and digital gangrene. The role of corticosteroids and immunosuppressants is unclear; one study showed that these therapies did not prevent further thrombotic events in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.4

Conclusion