User login

Considerations for Psoriasis in Pregnancy

1. Trivedi MK, Vaughn AR, Murase JE. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2018;10:109-115.

2. Kondo RN, Araújo FM, Pereira AM, et al. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (impetigo herpetiformis)—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):186-189.

3. Oumeish OY, Farraj SE, Bataineh AS. Some aspects of impetigo herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:103-105.

4. Flynn A, Burke N, Byrne B, et al. Two case reports of generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: different outcomes. Obstet Med. 2016;9:55-59.

5. Shaw CJ, Wu P, Sriemevan A. First trimester impetigo herpetiformis in multiparous female successfully treated with oral cyclosporine. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0220113915.

6. Pitch M, Somers K, Scott G, et al. A case of pustular psoriasis of pregnancy with positive maternal-fetal outcomes. Cutis. 2018;101:278-280.

7. Namazi N, Dadkhahfar S. Impetigo herpetiformis: review of pathogenesis, complication, and treatment [published April 4, 2018]. Dermatol Res Pract. 2018;2018:5801280. doi:10.1155/2018/5801280. eCollection 2018.

8. Lehrhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

9. Ulubay M, Keskin U, Fidan U, et al. Case report of a rare dermatosis in pregnancy: impetigo herpetiformis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41:301-303.

10. Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288.

11. Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

12. Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

13. Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrow¬band UVB [published online January 20, 2012]. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

1. Trivedi MK, Vaughn AR, Murase JE. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2018;10:109-115.

2. Kondo RN, Araújo FM, Pereira AM, et al. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (impetigo herpetiformis)—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):186-189.

3. Oumeish OY, Farraj SE, Bataineh AS. Some aspects of impetigo herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:103-105.

4. Flynn A, Burke N, Byrne B, et al. Two case reports of generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: different outcomes. Obstet Med. 2016;9:55-59.

5. Shaw CJ, Wu P, Sriemevan A. First trimester impetigo herpetiformis in multiparous female successfully treated with oral cyclosporine. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0220113915.

6. Pitch M, Somers K, Scott G, et al. A case of pustular psoriasis of pregnancy with positive maternal-fetal outcomes. Cutis. 2018;101:278-280.

7. Namazi N, Dadkhahfar S. Impetigo herpetiformis: review of pathogenesis, complication, and treatment [published April 4, 2018]. Dermatol Res Pract. 2018;2018:5801280. doi:10.1155/2018/5801280. eCollection 2018.

8. Lehrhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

9. Ulubay M, Keskin U, Fidan U, et al. Case report of a rare dermatosis in pregnancy: impetigo herpetiformis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41:301-303.

10. Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288.

11. Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

12. Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

13. Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrow¬band UVB [published online January 20, 2012]. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

1. Trivedi MK, Vaughn AR, Murase JE. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2018;10:109-115.

2. Kondo RN, Araújo FM, Pereira AM, et al. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (impetigo herpetiformis)—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):186-189.

3. Oumeish OY, Farraj SE, Bataineh AS. Some aspects of impetigo herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:103-105.

4. Flynn A, Burke N, Byrne B, et al. Two case reports of generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: different outcomes. Obstet Med. 2016;9:55-59.

5. Shaw CJ, Wu P, Sriemevan A. First trimester impetigo herpetiformis in multiparous female successfully treated with oral cyclosporine. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0220113915.

6. Pitch M, Somers K, Scott G, et al. A case of pustular psoriasis of pregnancy with positive maternal-fetal outcomes. Cutis. 2018;101:278-280.

7. Namazi N, Dadkhahfar S. Impetigo herpetiformis: review of pathogenesis, complication, and treatment [published April 4, 2018]. Dermatol Res Pract. 2018;2018:5801280. doi:10.1155/2018/5801280. eCollection 2018.

8. Lehrhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

9. Ulubay M, Keskin U, Fidan U, et al. Case report of a rare dermatosis in pregnancy: impetigo herpetiformis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41:301-303.

10. Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288.

11. Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

12. Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

13. Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrow¬band UVB [published online January 20, 2012]. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

Psoriasis in Pregnancy

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (PPP) is a rare but potentially serious dermatosis of pregnancy. Left untreated, PPP can be fatal for both the mother and the fetus.1,2 Contrary to many other pregnancy dermatoses, which are typically limited to the skin, systemic signs and symptoms often accompany PPP, including fatigue, fever, diarrhea, delirium, elevated markers of inflammation such as an increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and increased white blood cell counts.1,3,4 Progression of the rash to erythroderma with subsequent dangerous fluid and electrolyte imbalances, loss of thermoregulation in the skin, and the risk for secondary infection and sepsis can occur in severe cases.1,5

Increasing evidence suggests that PPP is likely a variant of generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP), which can be vulnerable to a variety of triggers, including metabolic disturbances, systemic steroid withdrawals, and pregnancy; however, classification of the disease as either a variant of disease or a distinct disease state remains controversial.1,6 Early recognition and prompt treatment are critically important given the potential for fetal and maternal morbidity and mortality that is associated with PPP.1,6,7

Clinical Presentation

Most cases of PPP involve presentation in the early part of the third trimester of pregnancy; postpartum PPP has been reported but is exceedingly rare.1 Typically, lesions develop in the skin folds and spread centrifugally.2,6 The lesions usually begin as erythematous plaques with a pustular ring with a central erosion. The face, palms, and soles of the feet usually are spared; occasionally, involvement of oral and esophageal mucosae is seen. Biopsy findings usually comprise spongiform pustules with neutrophil invasion into the epidermis. Characteristic laboratory findings include electrolyte derangements with elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and leukocytosis.2,8

As was seen in the case presentation, PPP largely resolves following childbirth; however, there is a significant risk for recurrence in subsequent pregnancies, which may be more severe and present earlier.1,6 Menstrual cycle changes and the use of oral contraceptives, particularly those containing progesterone, also have been associated with PPP flares.1,6 Although its pathophysiology is not entirely understood, the development of PPP is believed to be associated with the hormonal changes that occur in the third trimester, in particular elevated progesterone levels.6

Treatment

Oral corticosteroids remain the mainstay of treatment for PPP.6 Lower dosages ranging from 15 to 30 mg daily can be used for mild cases.1 More severe cases usually are treated with an initial trial of prednisone or prednisolone with dosages ranging from 30 mg daily to as high as 60 to 80 mg daily. Higher doses should be used with caution, however, as they may result in reduced fetal reactivity on fetal monitoring.1,9 Treatment at least throughout the remainder of a patient’s pregnancy usually is required, with subsequent gradual tapering of the medication.1

Although it was once reserved for severe or refractory PPP, in 2012, a task force from the National Psoriasis Foundation categorized cyclosporine as an appropriate first-line therapy for PPP.10 Published case reports have documented the successful treatment of PPP with cyclosporine in cases that did not respond to systemic steroids.6,11

Several case reports have documented the safe use of anti–tumor necrosis factors (TNFs), primarily infliximab, for PPP.12 Infliximab and other TNF-α antibodies are pregnancy category B, but limited controlled human data exist regarding their safety in pregnancy.1

Finally, the addition of narrowband UVB light therapy to oral corticosteroids also has been proposed as a safe treatment of refractory disease.6,13 Unlike psoralen plus UVA, which is usually reserved for postpartum use, narrowband UVB light therapy has been shown to be safe for use during pregnancy.1

Future Directions

Genetic and pathogenesis studies have described involvement of IL-1 and IL-36 cytokines in GPP.1 These interleukins are important in neutrophil chemotaxis leading to pustule formation. In addition, as in other psoriasis variants, TNF-α and IL-17α are important. Such findings may help to pave the way for the development of future therapies for both GPP and PPP.

Bottom Line

Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for PPP in pregnant women who present with widespread cutaneous eruptions. Presently, oral corticosteroids paired with close involvement of obstetric care remains the cornerstone of treatment for PPP. As the case report illustrates, effective diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring are essential for safe outcomes for both mother and baby.

- Trivedi MK, Vaughn AR, Murase JE. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2018;10:109-115.

- Kondo RN, Araújo FM, Pereira AM, et al. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (impetigo herpetiformis)—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):186-189.

- Oumeish OY, Farraj SE, Bataineh AS. Some aspects of impetigo herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:103-105.

- Flynn A, Burke N, Byrne B, et al. Two case reports of generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: different outcomes. Obstet Med. 2016;9:55-59.

- Shaw CJ, Wu P, Sriemevan A. First trimester impetigo herpetiformis in multiparous female successfully treated with oral cyclosporine. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0220113915.

- Pitch M, Somers K, Scott G, et al. A case of pustular psoriasis of pregnancy with positive maternal-fetal outcomes. Cutis. 2018;101:278-280.

- Namazi N, Dadkhahfar S. Impetigo herpetiformis: review of pathogenesis, complication, and treatment [published April 4, 2018]. Dermatol Res Pract. 2018;2018:5801280. doi:10.1155/2018/5801280. eCollection 2018.

- Lehrhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

- Ulubay M, Keskin U, Fidan U, et al. Case report of a rare dermatosis in pregnancy: impetigo herpetiformis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41:301-303.

- Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288.

- Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

- Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

- Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrowband UVB [published online January 20, 2012]. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (PPP) is a rare but potentially serious dermatosis of pregnancy. Left untreated, PPP can be fatal for both the mother and the fetus.1,2 Contrary to many other pregnancy dermatoses, which are typically limited to the skin, systemic signs and symptoms often accompany PPP, including fatigue, fever, diarrhea, delirium, elevated markers of inflammation such as an increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and increased white blood cell counts.1,3,4 Progression of the rash to erythroderma with subsequent dangerous fluid and electrolyte imbalances, loss of thermoregulation in the skin, and the risk for secondary infection and sepsis can occur in severe cases.1,5

Increasing evidence suggests that PPP is likely a variant of generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP), which can be vulnerable to a variety of triggers, including metabolic disturbances, systemic steroid withdrawals, and pregnancy; however, classification of the disease as either a variant of disease or a distinct disease state remains controversial.1,6 Early recognition and prompt treatment are critically important given the potential for fetal and maternal morbidity and mortality that is associated with PPP.1,6,7

Clinical Presentation

Most cases of PPP involve presentation in the early part of the third trimester of pregnancy; postpartum PPP has been reported but is exceedingly rare.1 Typically, lesions develop in the skin folds and spread centrifugally.2,6 The lesions usually begin as erythematous plaques with a pustular ring with a central erosion. The face, palms, and soles of the feet usually are spared; occasionally, involvement of oral and esophageal mucosae is seen. Biopsy findings usually comprise spongiform pustules with neutrophil invasion into the epidermis. Characteristic laboratory findings include electrolyte derangements with elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and leukocytosis.2,8

As was seen in the case presentation, PPP largely resolves following childbirth; however, there is a significant risk for recurrence in subsequent pregnancies, which may be more severe and present earlier.1,6 Menstrual cycle changes and the use of oral contraceptives, particularly those containing progesterone, also have been associated with PPP flares.1,6 Although its pathophysiology is not entirely understood, the development of PPP is believed to be associated with the hormonal changes that occur in the third trimester, in particular elevated progesterone levels.6

Treatment

Oral corticosteroids remain the mainstay of treatment for PPP.6 Lower dosages ranging from 15 to 30 mg daily can be used for mild cases.1 More severe cases usually are treated with an initial trial of prednisone or prednisolone with dosages ranging from 30 mg daily to as high as 60 to 80 mg daily. Higher doses should be used with caution, however, as they may result in reduced fetal reactivity on fetal monitoring.1,9 Treatment at least throughout the remainder of a patient’s pregnancy usually is required, with subsequent gradual tapering of the medication.1

Although it was once reserved for severe or refractory PPP, in 2012, a task force from the National Psoriasis Foundation categorized cyclosporine as an appropriate first-line therapy for PPP.10 Published case reports have documented the successful treatment of PPP with cyclosporine in cases that did not respond to systemic steroids.6,11

Several case reports have documented the safe use of anti–tumor necrosis factors (TNFs), primarily infliximab, for PPP.12 Infliximab and other TNF-α antibodies are pregnancy category B, but limited controlled human data exist regarding their safety in pregnancy.1

Finally, the addition of narrowband UVB light therapy to oral corticosteroids also has been proposed as a safe treatment of refractory disease.6,13 Unlike psoralen plus UVA, which is usually reserved for postpartum use, narrowband UVB light therapy has been shown to be safe for use during pregnancy.1

Future Directions

Genetic and pathogenesis studies have described involvement of IL-1 and IL-36 cytokines in GPP.1 These interleukins are important in neutrophil chemotaxis leading to pustule formation. In addition, as in other psoriasis variants, TNF-α and IL-17α are important. Such findings may help to pave the way for the development of future therapies for both GPP and PPP.

Bottom Line

Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for PPP in pregnant women who present with widespread cutaneous eruptions. Presently, oral corticosteroids paired with close involvement of obstetric care remains the cornerstone of treatment for PPP. As the case report illustrates, effective diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring are essential for safe outcomes for both mother and baby.

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (PPP) is a rare but potentially serious dermatosis of pregnancy. Left untreated, PPP can be fatal for both the mother and the fetus.1,2 Contrary to many other pregnancy dermatoses, which are typically limited to the skin, systemic signs and symptoms often accompany PPP, including fatigue, fever, diarrhea, delirium, elevated markers of inflammation such as an increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and increased white blood cell counts.1,3,4 Progression of the rash to erythroderma with subsequent dangerous fluid and electrolyte imbalances, loss of thermoregulation in the skin, and the risk for secondary infection and sepsis can occur in severe cases.1,5

Increasing evidence suggests that PPP is likely a variant of generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP), which can be vulnerable to a variety of triggers, including metabolic disturbances, systemic steroid withdrawals, and pregnancy; however, classification of the disease as either a variant of disease or a distinct disease state remains controversial.1,6 Early recognition and prompt treatment are critically important given the potential for fetal and maternal morbidity and mortality that is associated with PPP.1,6,7

Clinical Presentation

Most cases of PPP involve presentation in the early part of the third trimester of pregnancy; postpartum PPP has been reported but is exceedingly rare.1 Typically, lesions develop in the skin folds and spread centrifugally.2,6 The lesions usually begin as erythematous plaques with a pustular ring with a central erosion. The face, palms, and soles of the feet usually are spared; occasionally, involvement of oral and esophageal mucosae is seen. Biopsy findings usually comprise spongiform pustules with neutrophil invasion into the epidermis. Characteristic laboratory findings include electrolyte derangements with elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate and leukocytosis.2,8

As was seen in the case presentation, PPP largely resolves following childbirth; however, there is a significant risk for recurrence in subsequent pregnancies, which may be more severe and present earlier.1,6 Menstrual cycle changes and the use of oral contraceptives, particularly those containing progesterone, also have been associated with PPP flares.1,6 Although its pathophysiology is not entirely understood, the development of PPP is believed to be associated with the hormonal changes that occur in the third trimester, in particular elevated progesterone levels.6

Treatment

Oral corticosteroids remain the mainstay of treatment for PPP.6 Lower dosages ranging from 15 to 30 mg daily can be used for mild cases.1 More severe cases usually are treated with an initial trial of prednisone or prednisolone with dosages ranging from 30 mg daily to as high as 60 to 80 mg daily. Higher doses should be used with caution, however, as they may result in reduced fetal reactivity on fetal monitoring.1,9 Treatment at least throughout the remainder of a patient’s pregnancy usually is required, with subsequent gradual tapering of the medication.1

Although it was once reserved for severe or refractory PPP, in 2012, a task force from the National Psoriasis Foundation categorized cyclosporine as an appropriate first-line therapy for PPP.10 Published case reports have documented the successful treatment of PPP with cyclosporine in cases that did not respond to systemic steroids.6,11

Several case reports have documented the safe use of anti–tumor necrosis factors (TNFs), primarily infliximab, for PPP.12 Infliximab and other TNF-α antibodies are pregnancy category B, but limited controlled human data exist regarding their safety in pregnancy.1

Finally, the addition of narrowband UVB light therapy to oral corticosteroids also has been proposed as a safe treatment of refractory disease.6,13 Unlike psoralen plus UVA, which is usually reserved for postpartum use, narrowband UVB light therapy has been shown to be safe for use during pregnancy.1

Future Directions

Genetic and pathogenesis studies have described involvement of IL-1 and IL-36 cytokines in GPP.1 These interleukins are important in neutrophil chemotaxis leading to pustule formation. In addition, as in other psoriasis variants, TNF-α and IL-17α are important. Such findings may help to pave the way for the development of future therapies for both GPP and PPP.

Bottom Line

Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for PPP in pregnant women who present with widespread cutaneous eruptions. Presently, oral corticosteroids paired with close involvement of obstetric care remains the cornerstone of treatment for PPP. As the case report illustrates, effective diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring are essential for safe outcomes for both mother and baby.

- Trivedi MK, Vaughn AR, Murase JE. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2018;10:109-115.

- Kondo RN, Araújo FM, Pereira AM, et al. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (impetigo herpetiformis)—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):186-189.

- Oumeish OY, Farraj SE, Bataineh AS. Some aspects of impetigo herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:103-105.

- Flynn A, Burke N, Byrne B, et al. Two case reports of generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: different outcomes. Obstet Med. 2016;9:55-59.

- Shaw CJ, Wu P, Sriemevan A. First trimester impetigo herpetiformis in multiparous female successfully treated with oral cyclosporine. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0220113915.

- Pitch M, Somers K, Scott G, et al. A case of pustular psoriasis of pregnancy with positive maternal-fetal outcomes. Cutis. 2018;101:278-280.

- Namazi N, Dadkhahfar S. Impetigo herpetiformis: review of pathogenesis, complication, and treatment [published April 4, 2018]. Dermatol Res Pract. 2018;2018:5801280. doi:10.1155/2018/5801280. eCollection 2018.

- Lehrhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

- Ulubay M, Keskin U, Fidan U, et al. Case report of a rare dermatosis in pregnancy: impetigo herpetiformis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41:301-303.

- Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288.

- Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

- Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

- Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrowband UVB [published online January 20, 2012]. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

- Trivedi MK, Vaughn AR, Murase JE. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2018;10:109-115.

- Kondo RN, Araújo FM, Pereira AM, et al. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (impetigo herpetiformis)—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):186-189.

- Oumeish OY, Farraj SE, Bataineh AS. Some aspects of impetigo herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:103-105.

- Flynn A, Burke N, Byrne B, et al. Two case reports of generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: different outcomes. Obstet Med. 2016;9:55-59.

- Shaw CJ, Wu P, Sriemevan A. First trimester impetigo herpetiformis in multiparous female successfully treated with oral cyclosporine. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0220113915.

- Pitch M, Somers K, Scott G, et al. A case of pustular psoriasis of pregnancy with positive maternal-fetal outcomes. Cutis. 2018;101:278-280.

- Namazi N, Dadkhahfar S. Impetigo herpetiformis: review of pathogenesis, complication, and treatment [published April 4, 2018]. Dermatol Res Pract. 2018;2018:5801280. doi:10.1155/2018/5801280. eCollection 2018.

- Lehrhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

- Ulubay M, Keskin U, Fidan U, et al. Case report of a rare dermatosis in pregnancy: impetigo herpetiformis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41:301-303.

- Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288.

- Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

- Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

- Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrowband UVB [published online January 20, 2012]. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

The Case

An otherwise healthy 29-year-old woman at 32 weeks’ gestation presented to the emergency department with a 1-week history of a pruritic burning rash that began on the thighs and then spread diffusely. She denied any similar rash in her prior pregnancy. The patient was not taking any medications except for prenatal vitamins, and she denied any systemic symptoms. Three days prior, treatment with methylprednisolone 50 mg once daily was initiated by the patient’s obstetrician for the rash, but the patient reported no improvement in symptoms. Physical examination revealed edematous pink plaques studded with 1- to 2-mm collarettes of scaling and sparse 1-mm pustules involving the arms, chest, abdomen, back, groin, buttocks, and legs (Figure 1). A peripheral rim of desquamative scaling was noted on the plaques on the back and inner thighs. There were pink macules on the palms, and superficial desquamation was noted on the lips; no other involvement of the oral mucosa was noted.

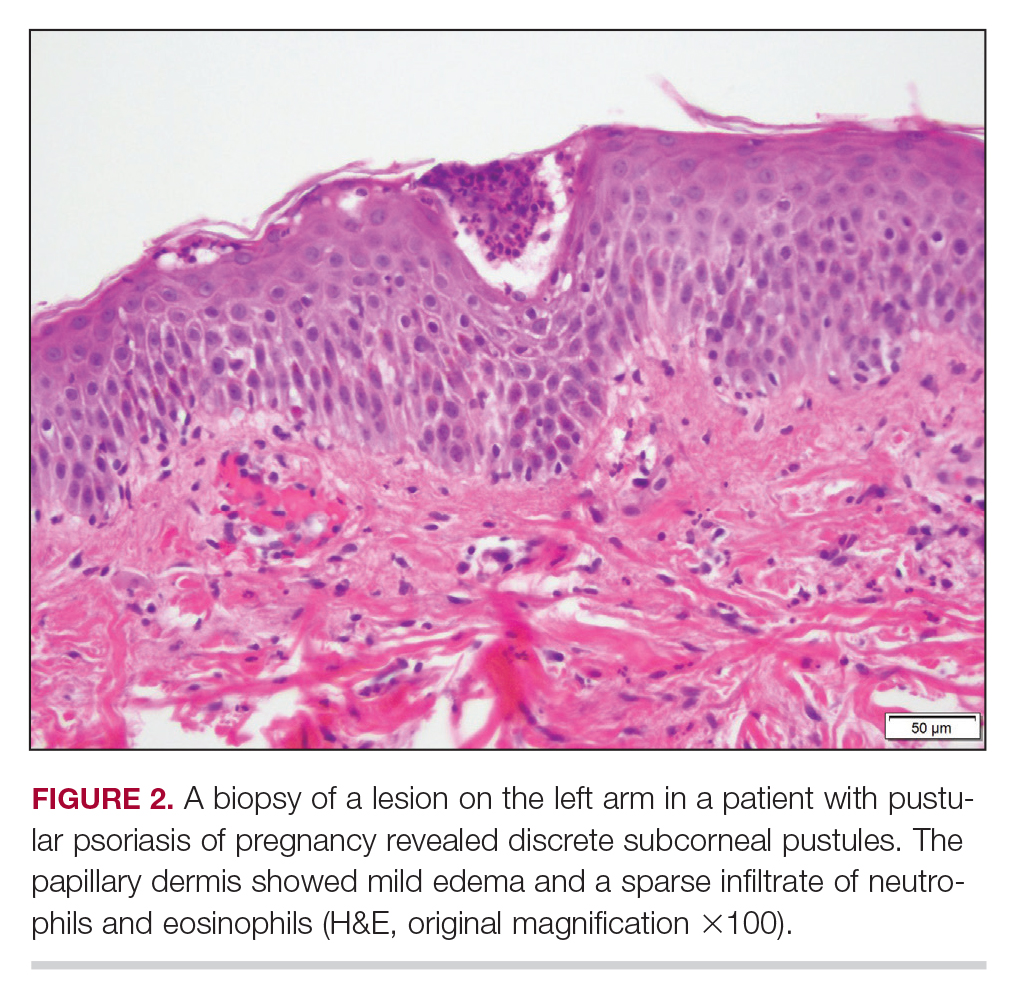

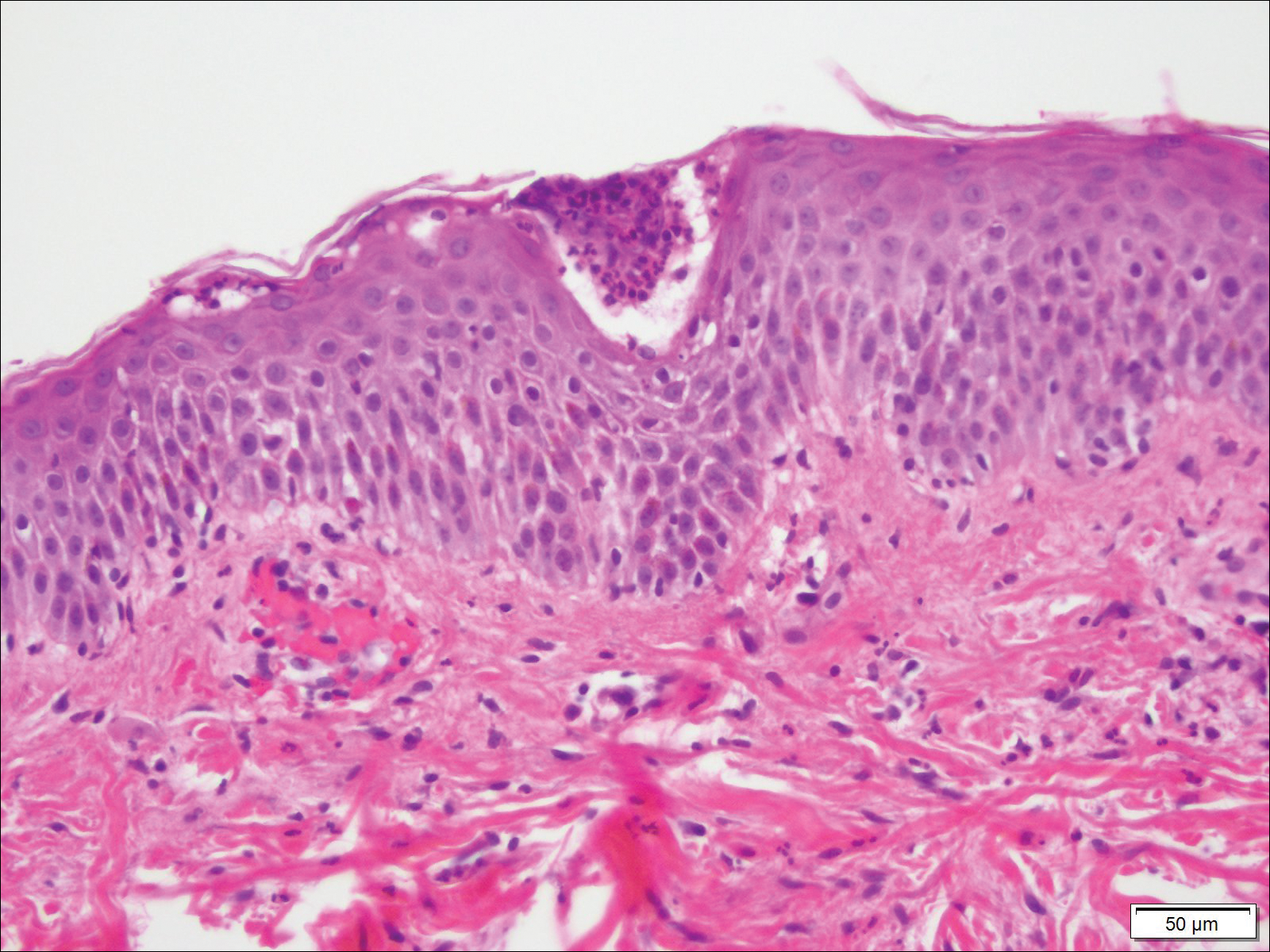

Biopsy specimens from the left arm revealed discrete subcorneal pustules with mild acanthosis of the epidermis with spongiosis (Figure 2). The papillary dermis showed a sparse infiltrate of neutrophils with numerous marginated neutrophils within vessels. Direct immunofluorescence was negative for human IgG, IgA, IgM, complement component 3, and fibrinogen. Laboratory workup revealed leukocytosis of 21.5×109/L (reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L) with neutrophilic predominance of 73.6% (reference range, 56%), an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 40 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h), and normal calcium of 8.6 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL).

Treatment

The patient was started on methylprednisone 40 mg once daily with a plan to taper the dose by 8 mg every 5 days.

Patient Outcomes

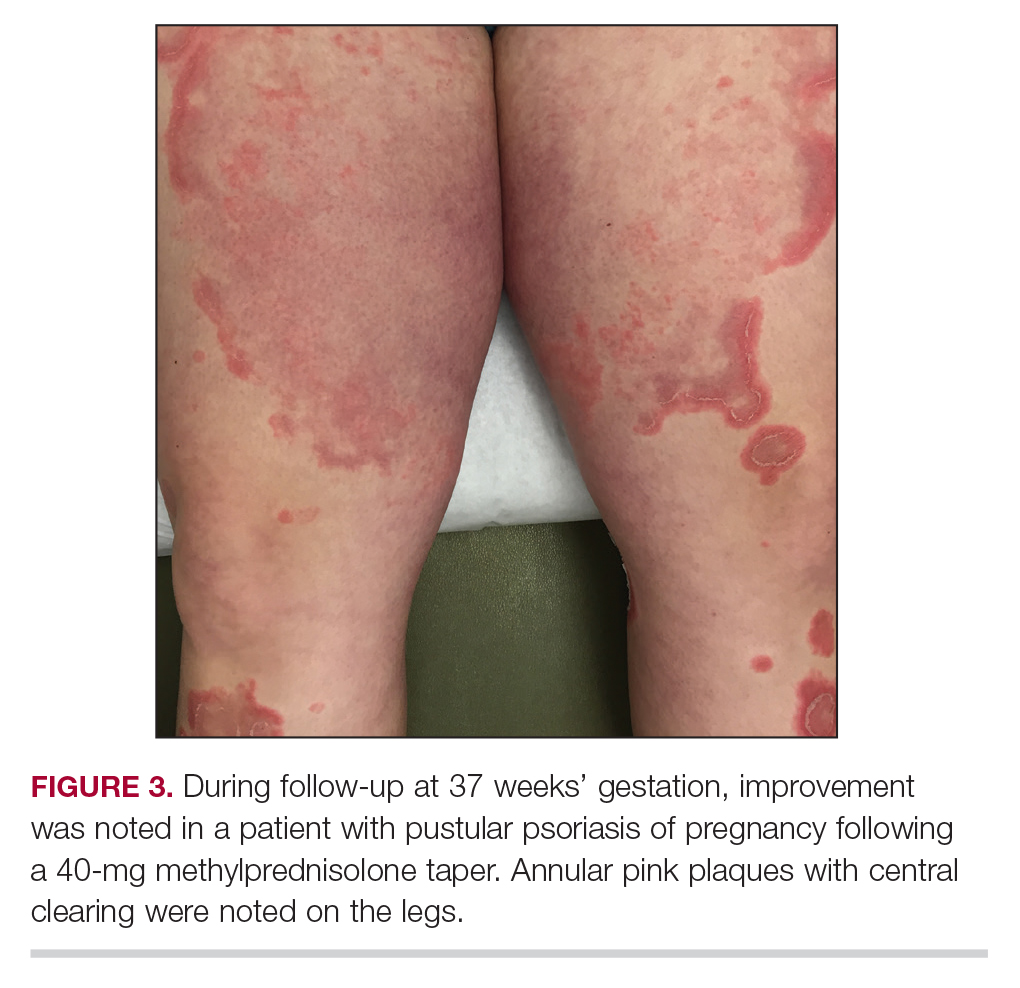

Three weeks following the initial presentation (35 weeks’ gestation), the patient continued to report pruritus and burning in the areas where the rash had developed. The morphology of the rash had changed considerably, as she now had prominent, annular, pink plaques with central clearing, trailing scaling, and a border of subtle pustules on the legs. Rings of desquamative scaling also were noted on the palms. During follow-up at 37 weeks’ gestation, the back, chest, and abdomen were improved from the initial presentation, and annular pink plaques with central clearing were noted on the legs (Figure 3). Given the clinical features and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (PPP) was made. Increased fetal surveillance with close obstetric follow-up was recommended. Weekly office visits with obstetrics and twice-weekly Doppler ultrasounds and fetal nonstress tests were deemed appropriate management. Given the risk for potential harm to the fetus PPP conveys, the patient was scheduled for induction at 39 weeks’ gestation. She was maintained on low-dose methylprednisolone 4 mg once daily for the duration of the pregnancy, and gradual improvement of the rash continued to be noted at the low treatment dose.

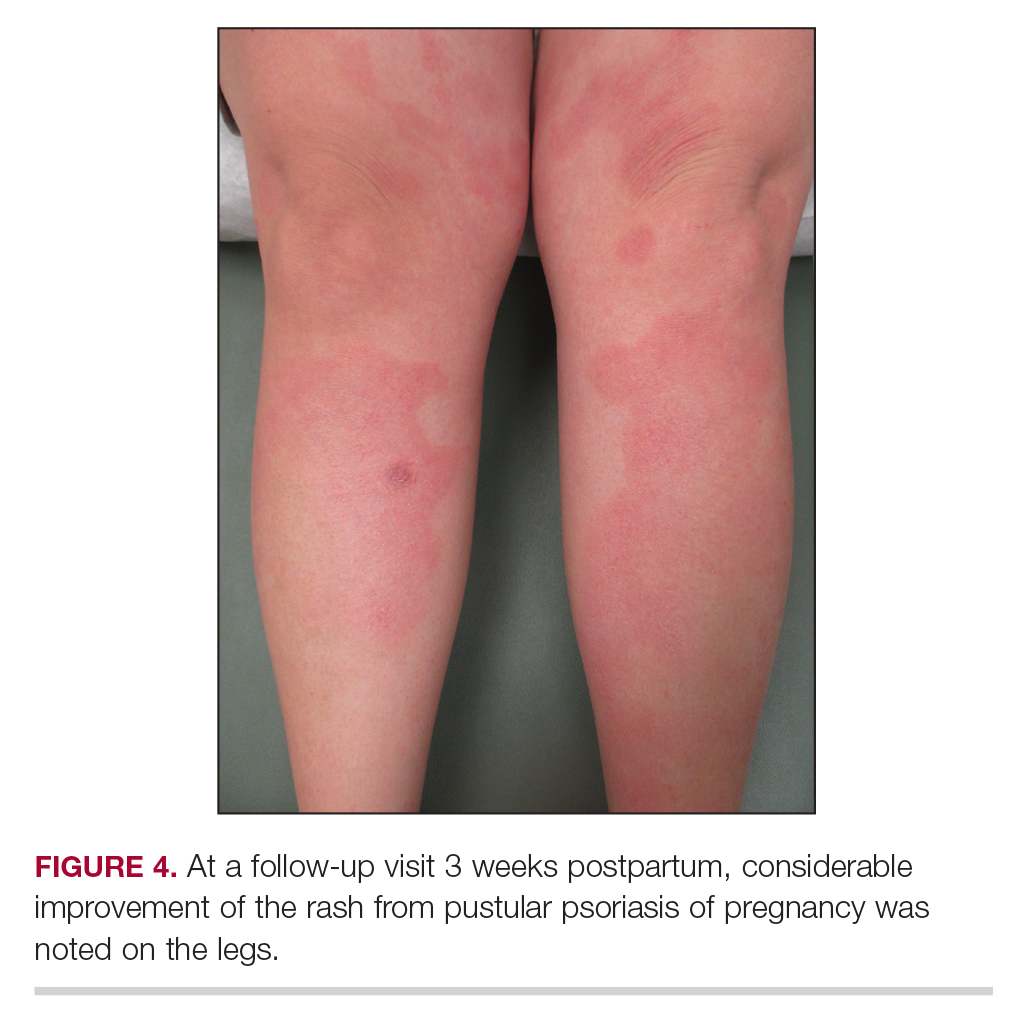

Following induction at 39 weeks’ gestation, the patient vaginally delivered a healthy, 6-lb male child at an outside hospital. She reported that the burning sensation improved within hours of delivery, and systemic steroids were stopped after delivery. At a follow-up visit 3 weeks postpartum, considerable improvement of the rash was noted with no evidence of pustules. Fading pink patches with a superficial scaling were noted on the back, chest, abdomen, arms, legs (Figure 4), and fingertips. The patient was counseled that PPP could recur in subsequent pregnancies and that she should be aware of the potential risks to the fetus.

This case was adapted from Pitch M, Somers K, Scott G, et al. A case of pustular psoriasis of pregnancy with positive maternal-fetal outcomes. Cutis. 2018;101:278-280.

A Case of Pustular Psoriasis of Pregnancy With Positive Maternal-Fetal Outcomes

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (PPP), also known as impetigo herpetiformis, is a relatively rare cutaneous disorder of pregnancy wherein lesions typically appear in the third trimester and resolve after delivery; however, lesions may persist through the postpartum period. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy may be considered a fifth dermatosis of pregnancy, alongside the classic dermatoses of atopic eruption of pregnancy, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, pemphigoid gestationis, and pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy.1

As PPP is a rare disease, its effects on maternal-fetal health outcomes and management remain to be elucidated. Though maternal mortality is rare in PPP, it is a unique dermatosis of pregnancy because it may be associated with severe systemic maternal symptoms.2 Fetal morbidity and mortality are less predictable in PPP, with reported cases of stillbirth, fetal anomalies, and neonatal death thought to be due largely to placental insufficiency, even with control of symptoms.1,3 Given the risk of serious harm to the fetus, reporting of cases and discussion of PPP management is critical.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 29-year-old G2P1 woman at 32 weeks’ gestation presented to our emergency department with a 1-week history of a pruritic, burning rash that started on the thighs then spread diffusely. She denied any similar rash in her prior pregnancy. She was not currently taking any medications except for prenatal vitamins and denied any systemic symptoms. The patient’s obstetrician initiated treatment with methylprednisolone 50 mg once daily for the rash 3 days prior to the current presentation, which had not seemed to help. On physical examination, edematous pink plaques studded with 1- to 2-mm collarettes of scaling and sparse 1-mm pustules involving the arms, chest, abdomen, back, groin, buttocks, and legs were noted. The plaques on the back and inner thighs had a peripheral rim of desquamative scaling. There were pink macules on the palms, and superficial desquamation was noted on the lips. The oral mucosa was otherwise spared (Figure 1).

Biopsy specimens from the left arm revealed discrete subcorneal pustules with mild acanthosis of the epidermis with spongiosis (Figure 2). The papillary dermis showed a sparse infiltrate of neutrophils with many marginated neutrophils within vessels. Direct immunofluorescence was negative for human IgG, IgA, IgM, complement component 3, and fibrinogen. Laboratory workup revealed leukocytosis of 21.5×109/L (reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L) with neutrophilic predominance of 73.6% (reference range, 56%), an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 40 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h), and a mild hypocalcemia of 8.6 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL). The patient was started on methylprednisone 40 mg once daily with a plan to taper the dose by 8 mg every 5 days.

At 35 weeks’ gestation, the patient continued to report pruritus and burning in the areas where the rash had developed. The morphology of the rash had changed considerably, as she now had prominent, annular, pink plaques with central clearing, trailing scaling, and a border of subtle pustules on the legs. There also were rings of desquamative scaling on the palms. During follow-up at 37 weeks’ gestation, the back, chest, and abdomen were improved from the initial presentation, and annular pink plaques with central clearing were noted on the legs (Figure 3). Given the clinical and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of PPP was made. It was recommended that she undergo increased fetal surveillance with close obstetric follow-up. Weekly office visits with obstetrics and twice-weekly Doppler ultrasounds and fetal nonstress tests were deemed appropriate management. The patient was scheduled for induction at 39 weeks’ gestation given the risk for potential harm to the fetus. She was maintained on low-dose methylprednisolone 4 mg once daily for the duration of the pregnancy. The patient continued to have gradual improvement of the rash at the low treatment dose.

Following induction at 39 weeks’ gestation, the patient vaginally delivered a healthy, 6-lb male neonate at an outside hospital. She reported that the burning sensation improved within hours of delivery, and systemic steroids were stopped after delivery. At a follow-up visit 3 weeks postpartum, considerable improvement of the rash was noted with no evidence of pustules. Fading pink patches with a superficial scaling were noted on the back, chest, abdomen, arms, legs (Figure 4), and fingertips. The patient was counseled that PPP could recur in subsequent pregnancies and that she should be aware of the potential risks to the fetus.

Comment

In our patient, the diagnosis of PPP was supported by the presence of erythematous, coalescent plaques with small pustules at the margins and central erosions as well as the histologic findings of subcorneal pustules with mild acanthosis of the epidermis with spongiosis and a sparse neutrophilic infiltrate into the dermis.

The typical presentation of PPP is characterized by lesions that initially develop in skin folds with centrifugal spread.3 The lesions usually begin as erythematous plaques with a pustular ring with a central erosion. The face, palms, and soles of the feet typically are spared with occasional involvement of oral and esophageal mucosae. Biopsy findings typically include spongiform pustules with neutrophil invasion into the epidermis. Typical laboratory findings include electrolyte derangements with elevated ESR and leukocytosis.1

Diagnosis of PPP is critical given the potential for associated fetal morbidity and mortality.4 Anticipatory guidance for the patient also is necessary, as PPP can recur with subsequent pregnancies or even use of oral contraceptive pills (OCPs). Notably, a patient with recurrences of PPP with each of 9 pregnancies also experienced a recurrence when taking a combination estrogen/progesterone OCP, but not with an estrogen-only diethylstilbestrol OCP.5 Although the pathophysiology is not entirely understood, the development of PPP is thought to be related to the hormonal changes that occur in the third trimester, most notably due to elevated progesterone levels.2 The presence of progesterone in OCPs and recurrences associated with their use supports this altered hormonal state, contributing to the underlying pathophysiology of PPP.

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy can occur in women without any personal or family history of psoriasis, and as such, it is unclear whether PPP is a separate entity or a hormonally induced variation of generalized pustular psoriasis. Recent evidence included reports of women with PPP who had a mutation in the IL-36 receptor antagonist, leading to a relative abundance of IL-36 inflammatory cytokines.6

The mainstay of treatment for PPP is oral corticosteroids. Cases of PPP that are unresponsive to systemic steroids have been documented, requiring treatment with cyclosporine.9 Antitumor necrosis factors also have been used safely during pregnancy.10 Narrowband UVB phototherapy also has been proposed as a treatment alternative for patients who do not respond to oral corticosteroids.11

Conclusion

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy is a rare dermatosis of pregnancy that, unlike most other common dermatoses of pregnancy, is associated with adverse fetal outcomes. Diagnosis and management of PPP are critical to ensure the best care and outcomes for the patient and fetus and for a successful delivery of a healthy neonate. Our patient with PPP presented with involvement of the body, palms, and oral mucosa in the absence of systemic symptoms. Close follow-up and comanagement with the patient’s obstetrician ensured safe outcomes for the patient and the neonate.

- Lehrhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

- Kar S, Krishnan A, Shivkumar PV. Pregnancy and skin [published online August 28, 2012]. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2012;62:268-275.

- Kondo RN, Araújo FM, Pereira AM, et al. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (impetigo herpetiformis)—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):186-189.

- Oumeish OY, Parish JL. Impetigo herpetiformis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:101-104.

- Oumeish OY, Farraj SE, Bataineh AS. Some aspects of impetigo herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:103-105.

- Sugiura K, Oiso N, Iinuma S, et al. IL36RN mutations underlie impetigo herpetiformis. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:2472-2474.

- Sugiura K. The genetic background of generalized pustular psoriasis: IL36RN mutations and CARD14 gain-of-function variants [published online March 5, 2014]. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;74:187-192.

- Li X, Chen M, Fu X, et al. Mutation analysis of the IL36RN gene in Chinese patients with generalized pustular psoriasis with/without psoriasis vulgaris. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;76:132-138.

- Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

- Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

- Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrowband UVB [published online January 20, 2012]. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (PPP), also known as impetigo herpetiformis, is a relatively rare cutaneous disorder of pregnancy wherein lesions typically appear in the third trimester and resolve after delivery; however, lesions may persist through the postpartum period. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy may be considered a fifth dermatosis of pregnancy, alongside the classic dermatoses of atopic eruption of pregnancy, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, pemphigoid gestationis, and pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy.1

As PPP is a rare disease, its effects on maternal-fetal health outcomes and management remain to be elucidated. Though maternal mortality is rare in PPP, it is a unique dermatosis of pregnancy because it may be associated with severe systemic maternal symptoms.2 Fetal morbidity and mortality are less predictable in PPP, with reported cases of stillbirth, fetal anomalies, and neonatal death thought to be due largely to placental insufficiency, even with control of symptoms.1,3 Given the risk of serious harm to the fetus, reporting of cases and discussion of PPP management is critical.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 29-year-old G2P1 woman at 32 weeks’ gestation presented to our emergency department with a 1-week history of a pruritic, burning rash that started on the thighs then spread diffusely. She denied any similar rash in her prior pregnancy. She was not currently taking any medications except for prenatal vitamins and denied any systemic symptoms. The patient’s obstetrician initiated treatment with methylprednisolone 50 mg once daily for the rash 3 days prior to the current presentation, which had not seemed to help. On physical examination, edematous pink plaques studded with 1- to 2-mm collarettes of scaling and sparse 1-mm pustules involving the arms, chest, abdomen, back, groin, buttocks, and legs were noted. The plaques on the back and inner thighs had a peripheral rim of desquamative scaling. There were pink macules on the palms, and superficial desquamation was noted on the lips. The oral mucosa was otherwise spared (Figure 1).

Biopsy specimens from the left arm revealed discrete subcorneal pustules with mild acanthosis of the epidermis with spongiosis (Figure 2). The papillary dermis showed a sparse infiltrate of neutrophils with many marginated neutrophils within vessels. Direct immunofluorescence was negative for human IgG, IgA, IgM, complement component 3, and fibrinogen. Laboratory workup revealed leukocytosis of 21.5×109/L (reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L) with neutrophilic predominance of 73.6% (reference range, 56%), an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 40 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h), and a mild hypocalcemia of 8.6 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL). The patient was started on methylprednisone 40 mg once daily with a plan to taper the dose by 8 mg every 5 days.

At 35 weeks’ gestation, the patient continued to report pruritus and burning in the areas where the rash had developed. The morphology of the rash had changed considerably, as she now had prominent, annular, pink plaques with central clearing, trailing scaling, and a border of subtle pustules on the legs. There also were rings of desquamative scaling on the palms. During follow-up at 37 weeks’ gestation, the back, chest, and abdomen were improved from the initial presentation, and annular pink plaques with central clearing were noted on the legs (Figure 3). Given the clinical and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of PPP was made. It was recommended that she undergo increased fetal surveillance with close obstetric follow-up. Weekly office visits with obstetrics and twice-weekly Doppler ultrasounds and fetal nonstress tests were deemed appropriate management. The patient was scheduled for induction at 39 weeks’ gestation given the risk for potential harm to the fetus. She was maintained on low-dose methylprednisolone 4 mg once daily for the duration of the pregnancy. The patient continued to have gradual improvement of the rash at the low treatment dose.

Following induction at 39 weeks’ gestation, the patient vaginally delivered a healthy, 6-lb male neonate at an outside hospital. She reported that the burning sensation improved within hours of delivery, and systemic steroids were stopped after delivery. At a follow-up visit 3 weeks postpartum, considerable improvement of the rash was noted with no evidence of pustules. Fading pink patches with a superficial scaling were noted on the back, chest, abdomen, arms, legs (Figure 4), and fingertips. The patient was counseled that PPP could recur in subsequent pregnancies and that she should be aware of the potential risks to the fetus.

Comment

In our patient, the diagnosis of PPP was supported by the presence of erythematous, coalescent plaques with small pustules at the margins and central erosions as well as the histologic findings of subcorneal pustules with mild acanthosis of the epidermis with spongiosis and a sparse neutrophilic infiltrate into the dermis.

The typical presentation of PPP is characterized by lesions that initially develop in skin folds with centrifugal spread.3 The lesions usually begin as erythematous plaques with a pustular ring with a central erosion. The face, palms, and soles of the feet typically are spared with occasional involvement of oral and esophageal mucosae. Biopsy findings typically include spongiform pustules with neutrophil invasion into the epidermis. Typical laboratory findings include electrolyte derangements with elevated ESR and leukocytosis.1

Diagnosis of PPP is critical given the potential for associated fetal morbidity and mortality.4 Anticipatory guidance for the patient also is necessary, as PPP can recur with subsequent pregnancies or even use of oral contraceptive pills (OCPs). Notably, a patient with recurrences of PPP with each of 9 pregnancies also experienced a recurrence when taking a combination estrogen/progesterone OCP, but not with an estrogen-only diethylstilbestrol OCP.5 Although the pathophysiology is not entirely understood, the development of PPP is thought to be related to the hormonal changes that occur in the third trimester, most notably due to elevated progesterone levels.2 The presence of progesterone in OCPs and recurrences associated with their use supports this altered hormonal state, contributing to the underlying pathophysiology of PPP.

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy can occur in women without any personal or family history of psoriasis, and as such, it is unclear whether PPP is a separate entity or a hormonally induced variation of generalized pustular psoriasis. Recent evidence included reports of women with PPP who had a mutation in the IL-36 receptor antagonist, leading to a relative abundance of IL-36 inflammatory cytokines.6

The mainstay of treatment for PPP is oral corticosteroids. Cases of PPP that are unresponsive to systemic steroids have been documented, requiring treatment with cyclosporine.9 Antitumor necrosis factors also have been used safely during pregnancy.10 Narrowband UVB phototherapy also has been proposed as a treatment alternative for patients who do not respond to oral corticosteroids.11

Conclusion

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy is a rare dermatosis of pregnancy that, unlike most other common dermatoses of pregnancy, is associated with adverse fetal outcomes. Diagnosis and management of PPP are critical to ensure the best care and outcomes for the patient and fetus and for a successful delivery of a healthy neonate. Our patient with PPP presented with involvement of the body, palms, and oral mucosa in the absence of systemic symptoms. Close follow-up and comanagement with the patient’s obstetrician ensured safe outcomes for the patient and the neonate.

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (PPP), also known as impetigo herpetiformis, is a relatively rare cutaneous disorder of pregnancy wherein lesions typically appear in the third trimester and resolve after delivery; however, lesions may persist through the postpartum period. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy may be considered a fifth dermatosis of pregnancy, alongside the classic dermatoses of atopic eruption of pregnancy, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, pemphigoid gestationis, and pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy.1

As PPP is a rare disease, its effects on maternal-fetal health outcomes and management remain to be elucidated. Though maternal mortality is rare in PPP, it is a unique dermatosis of pregnancy because it may be associated with severe systemic maternal symptoms.2 Fetal morbidity and mortality are less predictable in PPP, with reported cases of stillbirth, fetal anomalies, and neonatal death thought to be due largely to placental insufficiency, even with control of symptoms.1,3 Given the risk of serious harm to the fetus, reporting of cases and discussion of PPP management is critical.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 29-year-old G2P1 woman at 32 weeks’ gestation presented to our emergency department with a 1-week history of a pruritic, burning rash that started on the thighs then spread diffusely. She denied any similar rash in her prior pregnancy. She was not currently taking any medications except for prenatal vitamins and denied any systemic symptoms. The patient’s obstetrician initiated treatment with methylprednisolone 50 mg once daily for the rash 3 days prior to the current presentation, which had not seemed to help. On physical examination, edematous pink plaques studded with 1- to 2-mm collarettes of scaling and sparse 1-mm pustules involving the arms, chest, abdomen, back, groin, buttocks, and legs were noted. The plaques on the back and inner thighs had a peripheral rim of desquamative scaling. There were pink macules on the palms, and superficial desquamation was noted on the lips. The oral mucosa was otherwise spared (Figure 1).

Biopsy specimens from the left arm revealed discrete subcorneal pustules with mild acanthosis of the epidermis with spongiosis (Figure 2). The papillary dermis showed a sparse infiltrate of neutrophils with many marginated neutrophils within vessels. Direct immunofluorescence was negative for human IgG, IgA, IgM, complement component 3, and fibrinogen. Laboratory workup revealed leukocytosis of 21.5×109/L (reference range, 4.5–11.0×109/L) with neutrophilic predominance of 73.6% (reference range, 56%), an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 40 mm/h (reference range, 0–20 mm/h), and a mild hypocalcemia of 8.6 mg/dL (reference range, 8.2–10.2 mg/dL). The patient was started on methylprednisone 40 mg once daily with a plan to taper the dose by 8 mg every 5 days.

At 35 weeks’ gestation, the patient continued to report pruritus and burning in the areas where the rash had developed. The morphology of the rash had changed considerably, as she now had prominent, annular, pink plaques with central clearing, trailing scaling, and a border of subtle pustules on the legs. There also were rings of desquamative scaling on the palms. During follow-up at 37 weeks’ gestation, the back, chest, and abdomen were improved from the initial presentation, and annular pink plaques with central clearing were noted on the legs (Figure 3). Given the clinical and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of PPP was made. It was recommended that she undergo increased fetal surveillance with close obstetric follow-up. Weekly office visits with obstetrics and twice-weekly Doppler ultrasounds and fetal nonstress tests were deemed appropriate management. The patient was scheduled for induction at 39 weeks’ gestation given the risk for potential harm to the fetus. She was maintained on low-dose methylprednisolone 4 mg once daily for the duration of the pregnancy. The patient continued to have gradual improvement of the rash at the low treatment dose.

Following induction at 39 weeks’ gestation, the patient vaginally delivered a healthy, 6-lb male neonate at an outside hospital. She reported that the burning sensation improved within hours of delivery, and systemic steroids were stopped after delivery. At a follow-up visit 3 weeks postpartum, considerable improvement of the rash was noted with no evidence of pustules. Fading pink patches with a superficial scaling were noted on the back, chest, abdomen, arms, legs (Figure 4), and fingertips. The patient was counseled that PPP could recur in subsequent pregnancies and that she should be aware of the potential risks to the fetus.

Comment

In our patient, the diagnosis of PPP was supported by the presence of erythematous, coalescent plaques with small pustules at the margins and central erosions as well as the histologic findings of subcorneal pustules with mild acanthosis of the epidermis with spongiosis and a sparse neutrophilic infiltrate into the dermis.

The typical presentation of PPP is characterized by lesions that initially develop in skin folds with centrifugal spread.3 The lesions usually begin as erythematous plaques with a pustular ring with a central erosion. The face, palms, and soles of the feet typically are spared with occasional involvement of oral and esophageal mucosae. Biopsy findings typically include spongiform pustules with neutrophil invasion into the epidermis. Typical laboratory findings include electrolyte derangements with elevated ESR and leukocytosis.1

Diagnosis of PPP is critical given the potential for associated fetal morbidity and mortality.4 Anticipatory guidance for the patient also is necessary, as PPP can recur with subsequent pregnancies or even use of oral contraceptive pills (OCPs). Notably, a patient with recurrences of PPP with each of 9 pregnancies also experienced a recurrence when taking a combination estrogen/progesterone OCP, but not with an estrogen-only diethylstilbestrol OCP.5 Although the pathophysiology is not entirely understood, the development of PPP is thought to be related to the hormonal changes that occur in the third trimester, most notably due to elevated progesterone levels.2 The presence of progesterone in OCPs and recurrences associated with their use supports this altered hormonal state, contributing to the underlying pathophysiology of PPP.

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy can occur in women without any personal or family history of psoriasis, and as such, it is unclear whether PPP is a separate entity or a hormonally induced variation of generalized pustular psoriasis. Recent evidence included reports of women with PPP who had a mutation in the IL-36 receptor antagonist, leading to a relative abundance of IL-36 inflammatory cytokines.6

The mainstay of treatment for PPP is oral corticosteroids. Cases of PPP that are unresponsive to systemic steroids have been documented, requiring treatment with cyclosporine.9 Antitumor necrosis factors also have been used safely during pregnancy.10 Narrowband UVB phototherapy also has been proposed as a treatment alternative for patients who do not respond to oral corticosteroids.11

Conclusion

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy is a rare dermatosis of pregnancy that, unlike most other common dermatoses of pregnancy, is associated with adverse fetal outcomes. Diagnosis and management of PPP are critical to ensure the best care and outcomes for the patient and fetus and for a successful delivery of a healthy neonate. Our patient with PPP presented with involvement of the body, palms, and oral mucosa in the absence of systemic symptoms. Close follow-up and comanagement with the patient’s obstetrician ensured safe outcomes for the patient and the neonate.

- Lehrhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

- Kar S, Krishnan A, Shivkumar PV. Pregnancy and skin [published online August 28, 2012]. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2012;62:268-275.

- Kondo RN, Araújo FM, Pereira AM, et al. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (impetigo herpetiformis)—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):186-189.

- Oumeish OY, Parish JL. Impetigo herpetiformis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:101-104.

- Oumeish OY, Farraj SE, Bataineh AS. Some aspects of impetigo herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:103-105.

- Sugiura K, Oiso N, Iinuma S, et al. IL36RN mutations underlie impetigo herpetiformis. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:2472-2474.

- Sugiura K. The genetic background of generalized pustular psoriasis: IL36RN mutations and CARD14 gain-of-function variants [published online March 5, 2014]. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;74:187-192.

- Li X, Chen M, Fu X, et al. Mutation analysis of the IL36RN gene in Chinese patients with generalized pustular psoriasis with/without psoriasis vulgaris. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;76:132-138.

- Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

- Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

- Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrowband UVB [published online January 20, 2012]. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

- Lehrhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

- Kar S, Krishnan A, Shivkumar PV. Pregnancy and skin [published online August 28, 2012]. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2012;62:268-275.

- Kondo RN, Araújo FM, Pereira AM, et al. Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (impetigo herpetiformis)—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(6 suppl 1):186-189.

- Oumeish OY, Parish JL. Impetigo herpetiformis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:101-104.

- Oumeish OY, Farraj SE, Bataineh AS. Some aspects of impetigo herpetiformis. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:103-105.

- Sugiura K, Oiso N, Iinuma S, et al. IL36RN mutations underlie impetigo herpetiformis. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:2472-2474.

- Sugiura K. The genetic background of generalized pustular psoriasis: IL36RN mutations and CARD14 gain-of-function variants [published online March 5, 2014]. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;74:187-192.

- Li X, Chen M, Fu X, et al. Mutation analysis of the IL36RN gene in Chinese patients with generalized pustular psoriasis with/without psoriasis vulgaris. J Dermatol Sci. 2014;76:132-138.

- Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

- Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

- Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrowband UVB [published online January 20, 2012]. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

Practice Points

- Given its association with maternal and fetal morbidity/mortality, it is important for physicians to have a high suspicion for pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (PPP) in pregnant women with widespread cutaneous eruptions.

- Oral corticosteroids and close involvement of obstetric care is the mainstay of treatment for PPP.

Primary Cutaneous Cryptococcosis Presenting as an Extensive Eroded Plaque

To the Editor:

Primary cutaneous cryptococcal infection is rare. Cryptococcal skin infections, either primary or disseminated, can be highly pleomorphic and mimic entities such as basal cell carcinoma or even severe dermatitis, as in our case.

An 80-year-old woman who was residing in a nursing facility presented to the emergency department with an itchy nontender rash on the left arm of 2 to 3 weeks' duration that gradually spread. The patient had not started any new topical or oral medications and was otherwise healthy. A review of symptoms was negative for fever, weight loss, or new cough. Her medical history was notable for congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring chronic low-dose prednisone, hypothyroidism, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and dementia. On physical examination the patient had a large, well-demarcated, pink, scaly plaque with areas of ulceration extending from the dorsal aspect of the hand and fingers to the mid upper arm. There was minimal overlying yellow-brown crust (Figure 1). A potassium hydroxide preparation from a superficial scraping was negative. A punch biopsy specimen was obtained from the lesion and microscopic examination revealed histiocytes with innumerable intracytoplasmic yeast forms demonstrating small buds (Figure 2). The organisms were highlighted by periodic acid-Schiff and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains (Figure 3), while acid-fast bacillus and Fite stains were negative. The presumptive diagnosis of cutaneous cryptococcosis was made, and subsequent culture and latex agglutination test was positive for Cryptococcus neoformans. A chest radiograph showed no evidence of active disease. Infectious disease specialists were consulted and ordered additional laboratory studies, which were negative for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis, and fungemia. The patient had a low CD4 count of 119 cells/μL (reference range, 496-2186 cells/μL). Workup for systemic Cryptococcus, including head computed tomography, cerebral spinal fluid analysis, and bone marrow biopsy were all negative. Epstein-Barr virus and human T lymphotropic virus tests were both negative. The source of the patient's low CD4 count was never discovered. She gradually began to improve with diligent wound care and continued fluconazole 400 mg daily. The patient's history did reveal working on a chicken farm as an adult many years ago.

Cryptococcus is a yeast that causes infection primarily through airborne spores that lead to pulmonary infection. Cryptococcus neoformans is the most common pathogenic strain, though infection with other strains such as Cryptococcus albidus1 and Cryptococcus laurentii2 have been reported. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis is an exceedingly rare entity, with the majority of cases of cutaneous cryptococcosis originating from primary pulmonary infection with hematogenous dissemination to the skin. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis rarely can be caused by inoculation in nonimmunosuppressed hosts and infection of nonimmunosuppressed hosts is more common in men than in women.3 Manifestations of cutaneous cryptococcosis can be incredibly varied and diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion along with appropriate histological and serological confirmation. Cutaneous cryptococcosis can present in various clinical ways, including molluscumlike lesions, which are more common in patients with AIDS; acneform lesions; vesicles; dermal plaques or nodules; and rarely cellulitis with ulcerations, as in our patient. Cryptococcosis also can imitate basal cell carcinoma, nummular and follicular eczema, and Kaposi sarcoma.4

Histologic examination reveals either a gelatinous or granulomatous pattern based on the number of organisms present. The gelatinous pattern is characterized by little inflammation and a large number of phagocytosed organisms floating in mucin. The granulomatous pattern shows prominent inflammation with lymphocytes, histiocytes, and giant cells, as well as associated necrosis.

Treatment depends on the type of infection and host immunological status. Immunocompetent hosts with cutaneous infection may spontaneously heal. Treatment consists of surgical excision, if possible, followed by fluconazole or itraconazole. For disseminated cryptococcal infections in immunosuppressed hosts, the standard of care is amphotericin B with or without flucytosine.3

- Hoang JK, Burruss J. Localized cutaneous Cryptococcus albidus infection in a 14-year-old boy on etanercept therapy [published online June 5, 2007]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:285-288. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00404.x.

- Vlchkova-Lashkoska M, Kamberova S, Starova A, et al. Cutaneous Cryptococcus laurentii infection in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative subject. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:99-100.

- Antony SA, Antony SJ. Primary cutaneous Cryptococcus in nonimmunocompromised patients. Cutis. 1995;56:96-98.

- Murakawa GJ, Kerschmann R, Berger T. Cutaneous Cryptococcus infection and AIDS. report of 12 cases and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:545-548.

To the Editor:

Primary cutaneous cryptococcal infection is rare. Cryptococcal skin infections, either primary or disseminated, can be highly pleomorphic and mimic entities such as basal cell carcinoma or even severe dermatitis, as in our case.

An 80-year-old woman who was residing in a nursing facility presented to the emergency department with an itchy nontender rash on the left arm of 2 to 3 weeks' duration that gradually spread. The patient had not started any new topical or oral medications and was otherwise healthy. A review of symptoms was negative for fever, weight loss, or new cough. Her medical history was notable for congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring chronic low-dose prednisone, hypothyroidism, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and dementia. On physical examination the patient had a large, well-demarcated, pink, scaly plaque with areas of ulceration extending from the dorsal aspect of the hand and fingers to the mid upper arm. There was minimal overlying yellow-brown crust (Figure 1). A potassium hydroxide preparation from a superficial scraping was negative. A punch biopsy specimen was obtained from the lesion and microscopic examination revealed histiocytes with innumerable intracytoplasmic yeast forms demonstrating small buds (Figure 2). The organisms were highlighted by periodic acid-Schiff and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains (Figure 3), while acid-fast bacillus and Fite stains were negative. The presumptive diagnosis of cutaneous cryptococcosis was made, and subsequent culture and latex agglutination test was positive for Cryptococcus neoformans. A chest radiograph showed no evidence of active disease. Infectious disease specialists were consulted and ordered additional laboratory studies, which were negative for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis, and fungemia. The patient had a low CD4 count of 119 cells/μL (reference range, 496-2186 cells/μL). Workup for systemic Cryptococcus, including head computed tomography, cerebral spinal fluid analysis, and bone marrow biopsy were all negative. Epstein-Barr virus and human T lymphotropic virus tests were both negative. The source of the patient's low CD4 count was never discovered. She gradually began to improve with diligent wound care and continued fluconazole 400 mg daily. The patient's history did reveal working on a chicken farm as an adult many years ago.

Cryptococcus is a yeast that causes infection primarily through airborne spores that lead to pulmonary infection. Cryptococcus neoformans is the most common pathogenic strain, though infection with other strains such as Cryptococcus albidus1 and Cryptococcus laurentii2 have been reported. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis is an exceedingly rare entity, with the majority of cases of cutaneous cryptococcosis originating from primary pulmonary infection with hematogenous dissemination to the skin. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis rarely can be caused by inoculation in nonimmunosuppressed hosts and infection of nonimmunosuppressed hosts is more common in men than in women.3 Manifestations of cutaneous cryptococcosis can be incredibly varied and diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion along with appropriate histological and serological confirmation. Cutaneous cryptococcosis can present in various clinical ways, including molluscumlike lesions, which are more common in patients with AIDS; acneform lesions; vesicles; dermal plaques or nodules; and rarely cellulitis with ulcerations, as in our patient. Cryptococcosis also can imitate basal cell carcinoma, nummular and follicular eczema, and Kaposi sarcoma.4

Histologic examination reveals either a gelatinous or granulomatous pattern based on the number of organisms present. The gelatinous pattern is characterized by little inflammation and a large number of phagocytosed organisms floating in mucin. The granulomatous pattern shows prominent inflammation with lymphocytes, histiocytes, and giant cells, as well as associated necrosis.

Treatment depends on the type of infection and host immunological status. Immunocompetent hosts with cutaneous infection may spontaneously heal. Treatment consists of surgical excision, if possible, followed by fluconazole or itraconazole. For disseminated cryptococcal infections in immunosuppressed hosts, the standard of care is amphotericin B with or without flucytosine.3

To the Editor:

Primary cutaneous cryptococcal infection is rare. Cryptococcal skin infections, either primary or disseminated, can be highly pleomorphic and mimic entities such as basal cell carcinoma or even severe dermatitis, as in our case.

An 80-year-old woman who was residing in a nursing facility presented to the emergency department with an itchy nontender rash on the left arm of 2 to 3 weeks' duration that gradually spread. The patient had not started any new topical or oral medications and was otherwise healthy. A review of symptoms was negative for fever, weight loss, or new cough. Her medical history was notable for congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring chronic low-dose prednisone, hypothyroidism, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and dementia. On physical examination the patient had a large, well-demarcated, pink, scaly plaque with areas of ulceration extending from the dorsal aspect of the hand and fingers to the mid upper arm. There was minimal overlying yellow-brown crust (Figure 1). A potassium hydroxide preparation from a superficial scraping was negative. A punch biopsy specimen was obtained from the lesion and microscopic examination revealed histiocytes with innumerable intracytoplasmic yeast forms demonstrating small buds (Figure 2). The organisms were highlighted by periodic acid-Schiff and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stains (Figure 3), while acid-fast bacillus and Fite stains were negative. The presumptive diagnosis of cutaneous cryptococcosis was made, and subsequent culture and latex agglutination test was positive for Cryptococcus neoformans. A chest radiograph showed no evidence of active disease. Infectious disease specialists were consulted and ordered additional laboratory studies, which were negative for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis, and fungemia. The patient had a low CD4 count of 119 cells/μL (reference range, 496-2186 cells/μL). Workup for systemic Cryptococcus, including head computed tomography, cerebral spinal fluid analysis, and bone marrow biopsy were all negative. Epstein-Barr virus and human T lymphotropic virus tests were both negative. The source of the patient's low CD4 count was never discovered. She gradually began to improve with diligent wound care and continued fluconazole 400 mg daily. The patient's history did reveal working on a chicken farm as an adult many years ago.

Cryptococcus is a yeast that causes infection primarily through airborne spores that lead to pulmonary infection. Cryptococcus neoformans is the most common pathogenic strain, though infection with other strains such as Cryptococcus albidus1 and Cryptococcus laurentii2 have been reported. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis is an exceedingly rare entity, with the majority of cases of cutaneous cryptococcosis originating from primary pulmonary infection with hematogenous dissemination to the skin. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis rarely can be caused by inoculation in nonimmunosuppressed hosts and infection of nonimmunosuppressed hosts is more common in men than in women.3 Manifestations of cutaneous cryptococcosis can be incredibly varied and diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion along with appropriate histological and serological confirmation. Cutaneous cryptococcosis can present in various clinical ways, including molluscumlike lesions, which are more common in patients with AIDS; acneform lesions; vesicles; dermal plaques or nodules; and rarely cellulitis with ulcerations, as in our patient. Cryptococcosis also can imitate basal cell carcinoma, nummular and follicular eczema, and Kaposi sarcoma.4

Histologic examination reveals either a gelatinous or granulomatous pattern based on the number of organisms present. The gelatinous pattern is characterized by little inflammation and a large number of phagocytosed organisms floating in mucin. The granulomatous pattern shows prominent inflammation with lymphocytes, histiocytes, and giant cells, as well as associated necrosis.

Treatment depends on the type of infection and host immunological status. Immunocompetent hosts with cutaneous infection may spontaneously heal. Treatment consists of surgical excision, if possible, followed by fluconazole or itraconazole. For disseminated cryptococcal infections in immunosuppressed hosts, the standard of care is amphotericin B with or without flucytosine.3

- Hoang JK, Burruss J. Localized cutaneous Cryptococcus albidus infection in a 14-year-old boy on etanercept therapy [published online June 5, 2007]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:285-288. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00404.x.

- Vlchkova-Lashkoska M, Kamberova S, Starova A, et al. Cutaneous Cryptococcus laurentii infection in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative subject. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:99-100.

- Antony SA, Antony SJ. Primary cutaneous Cryptococcus in nonimmunocompromised patients. Cutis. 1995;56:96-98.

- Murakawa GJ, Kerschmann R, Berger T. Cutaneous Cryptococcus infection and AIDS. report of 12 cases and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:545-548.

- Hoang JK, Burruss J. Localized cutaneous Cryptococcus albidus infection in a 14-year-old boy on etanercept therapy [published online June 5, 2007]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:285-288. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00404.x.

- Vlchkova-Lashkoska M, Kamberova S, Starova A, et al. Cutaneous Cryptococcus laurentii infection in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative subject. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:99-100.

- Antony SA, Antony SJ. Primary cutaneous Cryptococcus in nonimmunocompromised patients. Cutis. 1995;56:96-98.

- Murakawa GJ, Kerschmann R, Berger T. Cutaneous Cryptococcus infection and AIDS. report of 12 cases and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:545-548.

Practice Points

- Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis is rare in nonimmunosuppressed patients.

- Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis secondary to inoculation can have a clinical presentation similar to more common conditions, such as molluscum, acne, and dermatitis.