User login

Widespread Necrotizing Purpura and Lucio Phenomenon as the First Diagnostic Presentation of Diffuse Nonnodular Lepromatous Leprosy

Case Report

A 70-year-old man living in Esna, Luxor, Egypt presented to the Department of Rheumatology and Rehabilitation with widespread gangrenous skin lesions associated with ulcers of 2 weeks’ duration. One year prior, the patient had an insidious onset of nocturnal fever, bilateral leg edema, and numbness and a tingling sensation in both hands. He presented some laboratory and radiologic investigations that were performed at another hospital prior to the current presentation, which revealed thrombocytopenia, mild splenomegaly, and generalized lymphadenopathy. An excisional left axillary lymph node biopsy was performed at another hospital prior to the current presentation, and the pathology report provided by the patient described a reactive, foamy, histiocyte-rich lesion, suggesting a diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. The patient had no diabetes or hypertension and no history of deep vein thrombosis, stroke, or unintentional weight loss. No medications were taken prior to the onset of the skin lesions, and his family history was irrelevant.

General examination at the current presentation revealed a fever (temperature, 101.3 °F [38.5 °C]), a normal heart rate (90 beats per minute), normal blood pressure (120/80 mmHg), normal respiratory rate (14 breaths per minute), accentuated heart sounds, and normal vesicular breathing without adventitious sounds. He had saddle nose, loss of the outer third of the eyebrows, and marked reduction in the density of the eyelashes (madarosis). Bilateral pitting edema of the legs also was present. Neurologic examination revealed hypoesthesia in a glove-and-stocking pattern, thickened peripheral nerves, and trophic changes over both hands; however, he had normal muscle power and deep reflexes. Joint examination revealed no abnormalities. Skin examination revealed widespread, reticulated, necrotizing, purpuric lesions on the arms, legs, abdomen, and ears, some associated with gangrenous ulcerations and hemorrhagic blisters. Scattered vasculitic ulcers and gangrenous patches were seen on the fingers. A gangrenous ulcer mimicking Fournier gangrene was seen involving the scrotal skin in addition to a gangrenous lesion on the glans penis (Figure 1–3). Unaffected skin appeared smooth, shiny, and edematous and showed no nodular lesions. Peripheral pulsations were intact.

Positive findings from a wide panel of laboratory investigations included an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (103 mm for the first hour [reference range, 0–22 mm]), high C-reactive protein (50.7 mg/L [reference range, up to 6 mg/L]), anemia (hemoglobin count, 7.3 g/dL [reference range, 13.5–17.5 g/dL]), thrombocytopenia (45×103/mm3 [reference range, 150×103/mm3), low serum albumin (2.3 g/dL [reference range, 3.4–5.4 g/dL]), elevated IgG and IgM anticardiolipin antibodies (IgG, 21.4 IgG phospholipid [GPL] units [reference range, <10 IgG phospholipid (GPL) units]; IgM, 59.4 IgM phospholipid (MPL) units [reference range, <7 IgM phospholipid (MPL) units]), positive lupus anticoagulant panel test, elevated anti-β2 glycoprotein antibodies (IgG, 17.5

Nerve conduction velocity showed axonal sensory polyneuropathy. Motor nerve conduction studies for median and ulnar nerves were within normal range. Lower-limb nerves assessment was limited by the ulcerated areas and marked edema. Echocardiography was unremarkable. Arterial Doppler studies were only available for the upper limbs and were unremarkable.

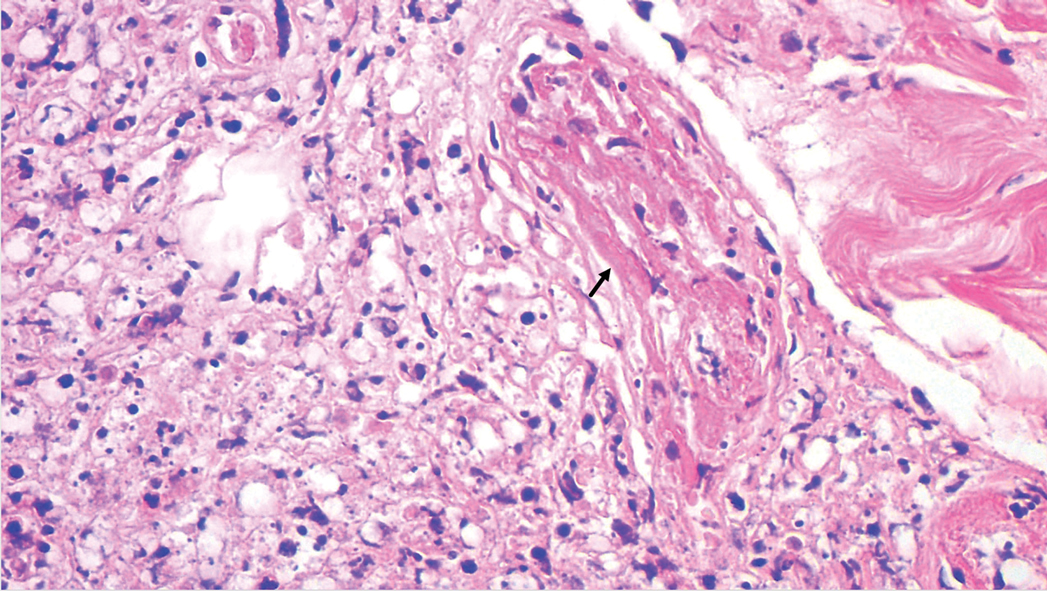

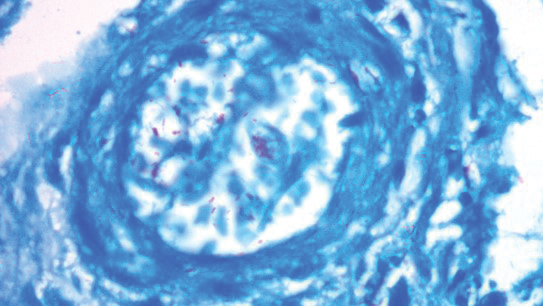

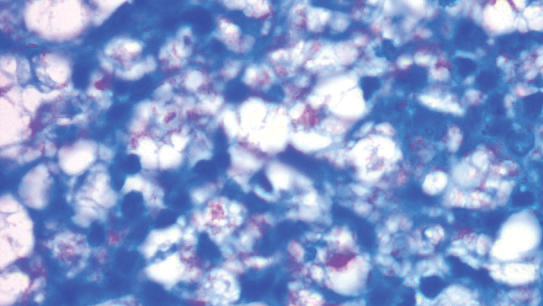

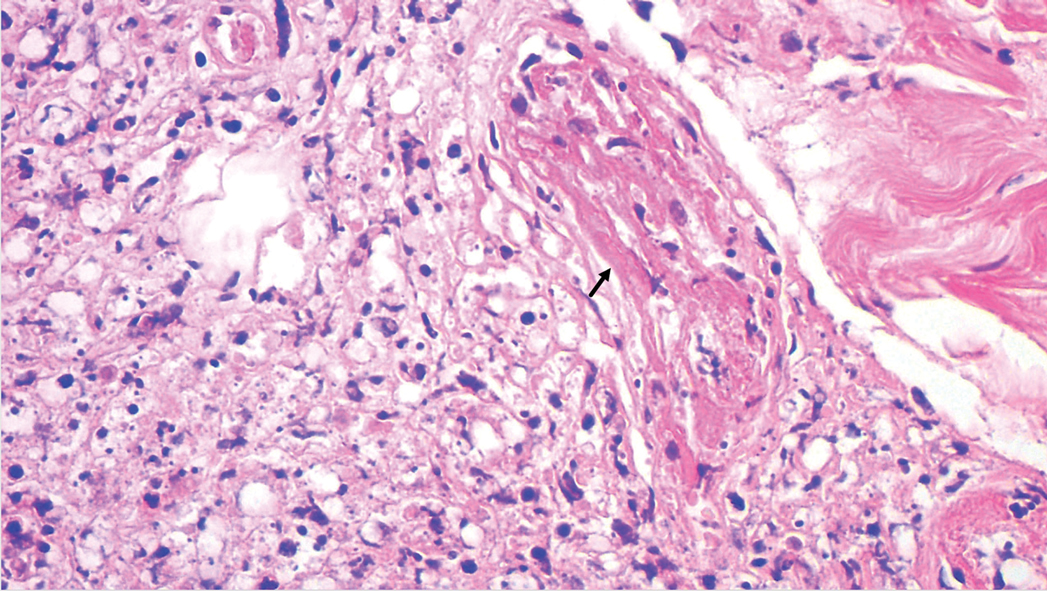

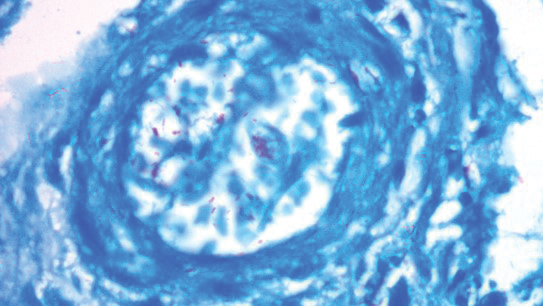

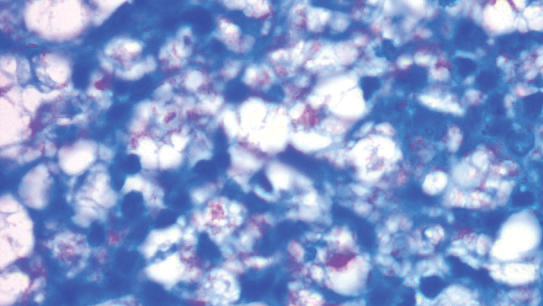

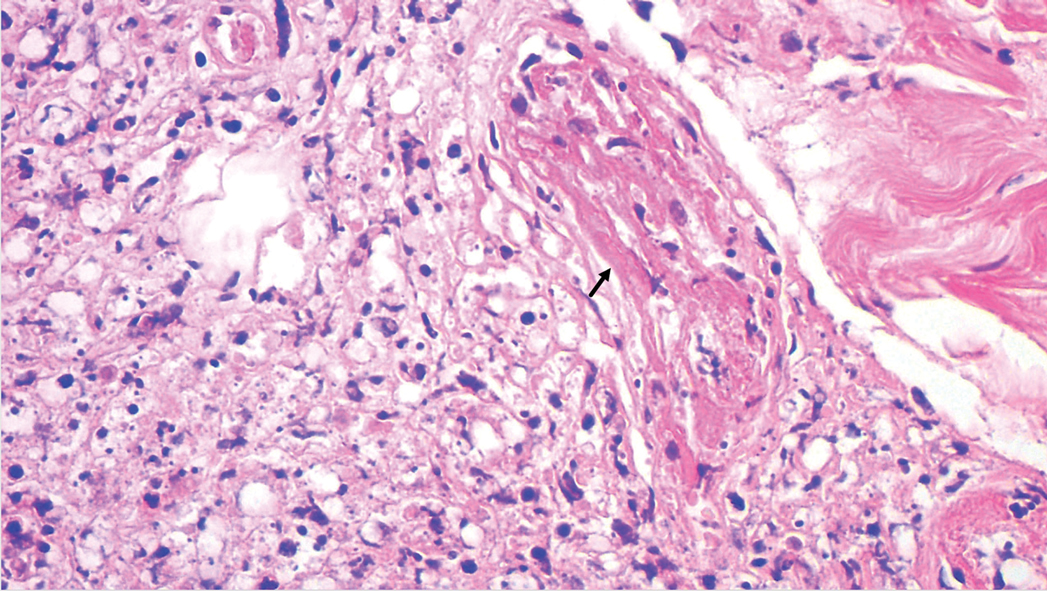

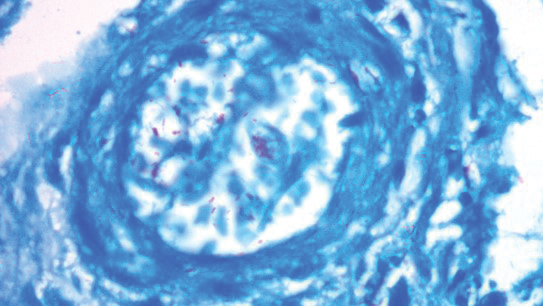

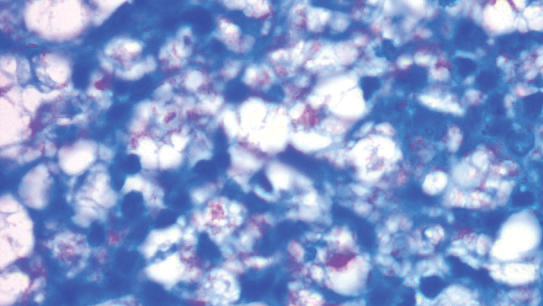

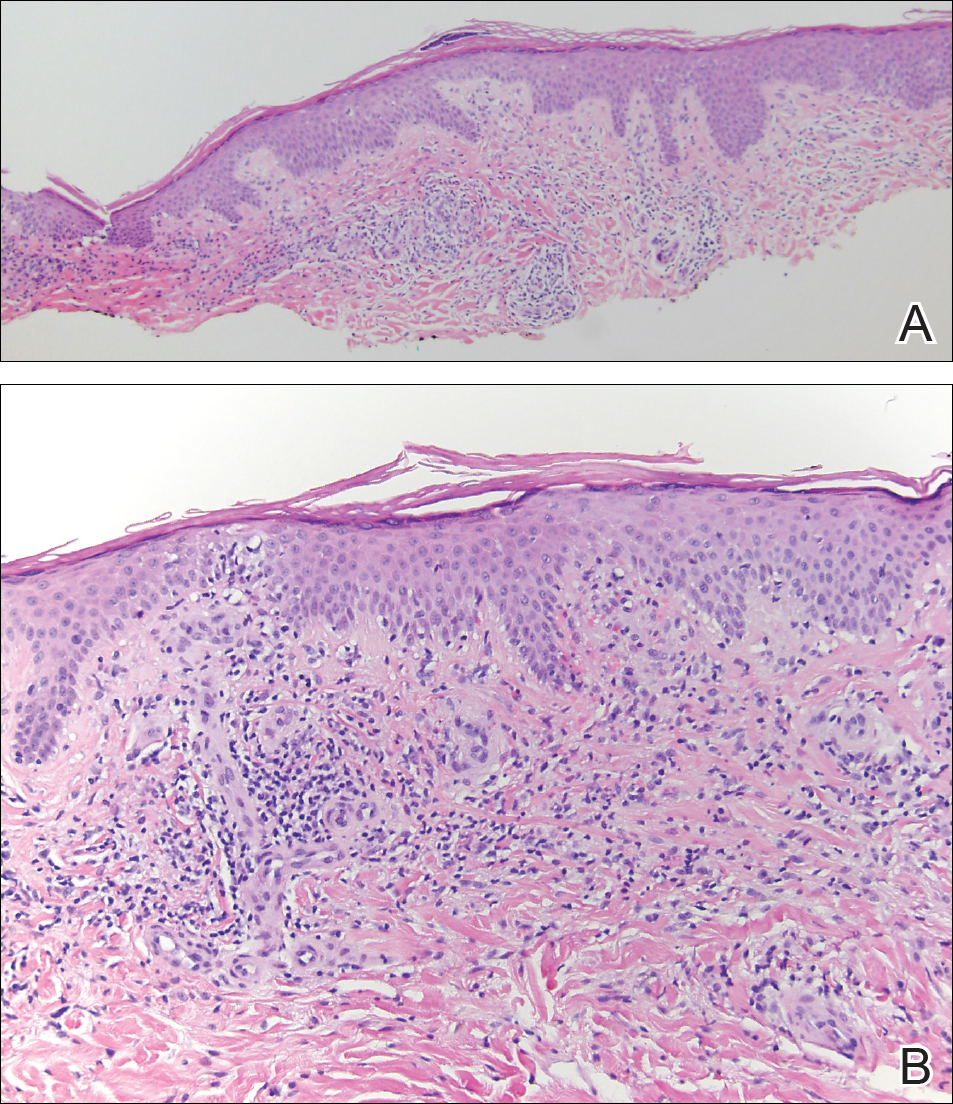

A punch biopsy was taken from one of the necrotizing purpuric lesions on the legs, and histopathologic examination revealed foci of epidermal necrosis and subepidermal separation and superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal infiltrates extending into the fat lobules. The infiltrates were mainly made up of foamy macrophages, and some contained globi (lepra cells), in addition to lymphocytes and many neutrophils with nuclear dust. Blood vessels in the superficial and deep dermis and in the subcutaneous fat showed fibrinoid necrosis in their walls with neutrophils infiltrating the walls and thrombi in the lumens (Figure 4). Modified Ziehl-Neelsen staining revealed clumps of acid-fast lepra bacilli inside vascular lumina and endothelial cell lining and within the foamy macrophages (Figure 5). Slit-skin smear examination was performed twice and yielded negative results. The slide and paraffin block of the already performed lymph node biopsy were retrieved. Examination revealed aggregates of foamy histiocytes surrounded by lymphocytes and plasma cells replacing normal lymphoid follicles. Modified Ziehl-Neelsen stain was performed, and clusters of acid-fast bacilli were detected within the foamy histiocytic infiltrate (Figure 6).

According to the results of the skin biopsy, the revised result of the lymph node biopsy, and the pattern of neurologic deficit together with clinical and laboratory correlation, the patient was diagnosed with diffuse nonnodular lepromatous leprosy presenting with Lucio phenomenon (Lucio leprosy) and associated with lepromatous lymphadenitis.

The patient received the following treatment: methylprednisolone 500 mg (intravenous pulse therapy) followed by daily oral administration of prednisolone 10 mg, rifampicin 300 mg, dapsone 100 mg, clofazimine 100 mg, acetylsalicylic acid 150 mg, and enoxaparin sodium 80 mg. In addition, the scrotal Fournier gangrene–like lesion was treated by surgical debridement followed by vacuum therapy. By the second week after treatment, the gangrenous lesions of the fingers developed a line of demarcation, and the skin infarctions started to recede.

Comment

Despite a decrease in its prevalence through a World Health Organization (WHO)–empowered eradication program, leprosy still represents a health problem in endemic areas.1,2 It is characterized by a wide range of immune responses to Mycobacterium leprae, displaying a spectrum of clinical and histopathologic manifestations that vary from the tuberculoid or paucibacillary pole with a strong cell-mediated immune response and fewer organisms to the lepromatous or multibacillary pole with weaker cell-mediated immune response and higher loads of organisms.3 In addition to its well-known cutaneous and neurologic manifestations, leprosy can present with a variety of manifestations, including constitutional symptoms, musculoskeletal manifestations, and serologic abnormalities; thus, leprosy can mimic rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis, and vasculitis—a pitfall that may result in misdiagnosis as a rheumatologic disorder.3-7

The chronic course of leprosy can be disrupted by acute, immunologically mediated reactions known as lepra reactions, of which there are 3 types.8 Type I lepra reactions are cell mediated and occur mainly in patients with borderline disease, often representing an upgrade toward the tuberculoid pole; less often they represent a downgrade reaction. Nerves become painful and swollen with possible loss of function, and skin lesions become edematous and tender; sometimes arthritis develops.9 Type II lepra reactions, also known as erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL), occur in borderline lepromatous and lepromatous patients with a high bacillary load. They are characterized by fever, body aches, tender cutaneous/subcutaneous nodules that may ulcerate, possible bullous lesions, painful nerve swellings, swollen joints, iritis, lymphadenitis, glomerulonephritis, epididymo-orchitis, and hepatic affection. Both immune-complex and delayed hypersensitivity reactions play a role in ENL.8,10 The third reaction is a rare aggressive type known as Lucio phenomenon or Lucio leprosy, which presents with irregular-shaped, angulated, or stellar necrotizing purpuric lesions (hemorrhagic infacrtions) developing mainly on the extremities. The lesions evolve into ulcers that heal with atrophic scarring.2,11 Lucio phenomenon develops as a result of thrombotic vascular occlusion secondary to massive invasion of vascular endothelial cells by lepra bacilli.2,11-14 Involvement of the scrotal skin, such as in our patient, is rare.

Lucio phenomenon mainly is seen in Mexico and Central America, and few cases have been documented in Cuba, South America, the United States, India, Polynesia, South Africa, and Southeast Asia.15-17 It specifically occurs in patients with untreated, diffuse, nonnodular lepromatous leprosy (pure and primitive diffuse lepromatous leprosy (DLL)/diffuse leprosy of Lucio and Latapí). This type of leprosy was first described by Lucio and Alvarado18 in 1852 as a distinct form of lepromatous leprosy characterized by widespread and dense infiltration of the whole skin by lepra bacilli without the typical nodular lesions of leprosy, rendering its diagnosis challenging, especially in sporadic cases. Other manifestations of DLL include complete alopecia of the eyebrows and eyelashes, destructive rhinitis, and areas of anhidrosis and dyesthesia.2

Latapí and Chévez-Zomora19 defined Lucio phenomenon in 1948 as a form of histopathologic vasculitis restricted to patients with DLL. Histopathologically, in addition to the infiltration of the skin with acid-fast bacilli–laden foamy histiocytes, lesions of Lucio phenomenon show features of necrotizing (leukocytoclastic) vasculitis with fibrinoid necrosis20 or vascular thrombi with minimal perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and no evidence of vasculitis.11 Medium to large vessels in the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue show infiltration of their walls with a large number of macrophages laden with acid-fast bacilli.11 Cases with histopathologic features mimicking antiphospholipid syndrome with endothelial cell proliferation, thrombosis, and mild mononuclear cell infiltrate also may be seen.20 In all cases, ischemic epidermal necrosis is seen, as well as acid-fast bacilli, both singly and in clusters (globi) within endothelial cells and inside blood vessel lumina.

Although Lucio phenomenon initially was thought to be immune-complex mediated like ENL, it has been suggested that the main trigger is thrombotic vascular occlusion secondary to massive invasion of the vascular endothelial cells by the lepra bacilli, resulting in necrosis.14 Bacterial lipopolysaccharides promote the release of IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor α, which in turn stimulate the production of prostaglandins, IL-6, and coagulation factor III, leading to vascular thrombosis and tissue necrosis.21,22 Moreover, antiphospholipid antibodies, which have been found to be induced in response to certain infectious agents in genetically predisposed individuals,23 have been reported in patients with leprosy, mainly in association with lepromatous leprosy. The reported prevalence of anticardiolipin antibodies ranged from 37% to 98%, whereas anti-β2-glycoprotein I antibodies ranged from 3% to 19%, and antiprothrombin antibodies ranged from 6% to 45%.24,25 Antiphospholipid antibodies have been reported to play a role in the pathogenesis of Lucio phenomenon.11,13,15,26 Our case supports this hypothesis with positive anticardiolipin antibodies, anti-β2 glycoprotein antibodies, and positive lupus anticoagulant.

In accordance with Curi et al,2 who reported 5 cases of DLL with Lucio phenomenon, our patient showed a similar presentation with positive inflammatory markers in association with a negative autoimmune profile (ANA, ANCA-C&P) and negative venereal disease research laboratory test. It is important to mention that a positive autoimmune profile (ANA, ANCA-C&P) can be present in leprotic patients, causing possible diagnostic confusion with collagen diseases.27,28

An interesting finding in our case was the negative slit-skin smear results. Although the specificity of slit-skin smear is 100%, as it directly demonstrates the presence of acid-fast bacilli,29 its sensitivity is low and varies from 10% to 50%.30 The detection of acid-fast bacilli in tissue sections is reported to be a better method for confirming the diagnosis of leprosy.31

The provisional impression of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in the lymph node biopsy in our patient was excluded upon detection of acid-fast bacilli in the foamy histiocytes infiltrating the lymph node; moreover, the normal serum lipids and serum ferritin argued against this diagnosis.32 Leprosy tends to involve the lymph nodes, particularly in borderline, borderline lepromatous, and lepromatous forms.33 The incidence of lymph node involvement accompanied by skin lesions with the presence of acid-fast bacilli in the lymph nodes is 92.2%.34

Our patient showed an excellent response to antileprotic treatment, which was administered according to the WHO multidrug therapy guidelines for multibacillary leprosy,35 combined with low-dose prednisolone, acetylsalicylic acid, and anticoagulant treatment. Thalidomide and high-dose prednisolone (60 mg/d) combined with antileprotic treatment also have been reported to be successful in managing recurrent infarctions in leprosy.36 The Fournier-like gangrenous ulcer of the scrotum was managed by surgical debridement and vacuum therapy.

It is noteworthy that the WHO elimination goal for leprosy was to reduce the prevalence to less than 1 case per 10,000 population. Egypt is among the first countries in North Africa and the Middle East regions to achieve this target supervised by the National Leprosy Control Program as early as 1994; this was further reduced to 0.33 cases per 10,000 population in 2004, and reduced again in 2009; however, certain foci showed a prevalence rate more than the elimination target, particularly in the cities of Qena (1.12) and Sohag (2.47).37 Esna, where our patient is from, is an endemic area in Egypt.38

Conclusion

1. World Health Organization. World Health Statistics: 2011. World Health Organization; 2011. https://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/EN_WHS2011_Full.pdf

2. Curi PF, Villaroel JS, Migliore N, et al. Lucio’s phenomenon: report of five cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:1397-1401.

3. Shrestha B, Li YQ, Fu P. Leprosy mimics adult onset Still’s disease in a Chinese patient. Egypt Rheumatol. 2018;40:217-220.

4. Prasad S, Misra R, Aggarwal A, et al. Leprosy revealed in a rheumatology clinic: a case series. Int J Rheum Dis. 2013;16:129-133.

5. Chao G, Fang L, Lu C. Leprosy with ANA positive mistaken for connective tissue disease. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:645-648.

6. Chauhan S, Wakhlu A, Agarwal V. Arthritis in leprosy. Rheumatology. 2010;49:2237-2242.

7. Rath D, Bhargava S, Kundu BK. Leprosy mimicking common rheumatologic entities: a trial for the clinician in the era of biologics. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2014;2014:429698.

8. Cuevas J, Rodríguez-Peralto JL, Carrillo R, et al. Erythema nodosum leprosum: reactional leprosy. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:126-130.

9. Henriques CC, Lopéz B, Mestre T, et al. Leprosy and rheumatoid arthritis: consequence or association? BMJ Case Rep. 2012;13:1-4.

10. Vázquez-Botet M, Sánchez JL. Erythema nodosum leprosum. Int J Dermatol. 1987;26:436-437.

11. Nunzie E, Ortega Cabrera LV, Macanchi Moncayo FM, et al. Lucio leprosy with Lucio’s phenomenon, digital gangrene and anticardiolipin antibodies. Lepr Rev. 2014;85:194-200.

12. Salvi S, Chopra A. Leprosy in a rheumatology setting: a challenging mimic to expose. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:1557-1563.

13. Azulay-Abulafia L, Pereira SL, Hardmann D, et al. Lucio phenomenon. vasculitis or occlusive vasculopathy? Hautarzt. 2006;57:1101-1105.

14. Benard G, Sakai-Valente NY, Bianconcini Trindade MA. Concomittant Lucio phenomenon and erythema nodosum in a leprosy patient: clues for their distinct pathogenesis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:288-292.

15. Rocha RH, Emerich PS, Diniz LM, et al. Lucio’s phenomenon: exuberant case report and review of Brazilian cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(suppl 5):S60-S63.

16. Costa IM, Kawano LB, Pereira CP, et al. Lucio’s phenomenon: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:566-571.

17. Kumari R, Thappa DM, Basu D. A fatal case of Lucio phenomenon from India. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:10.

18. Lucio R, Alvarado I. Opúsculo Sobre el Mal de San Lázaro o Elefantiasis de los Griegos. M. Murguía; 1852.

19. Latapí F, Chévez-Zamora A. The “spotted” leprosy of Lucio: an introduction to its clinical and histological study. Int J Lepr. 1948;16:421-437.

20. Vargas OF. Diffuse leprosy of Lucio and Latapí: a histologic study. Lepr Rev. 2007;78:248-260.

21. Latapí FR, Chevez-Zamora A. La lepra manchada de Lucio. Rev Dermatol Mex. 1978;22:102-107.

22. Monteiro R, Abreu MA, Tiezzi MG, et al. Fenômeno de Lúcio: mais um caso relatado no Brasil. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:296-300.

23. Gharavi EE, Chaimovich H, Cucucrull E, et al. Induction of antiphospholipid antibodies by immunization with synthetic bacterial & viral peptides. Lupus. 1999;8:449-455.

24. de Larrañaga GF, Forastiero RR, Martinuzzo ME, et al. High prevalence of antiphospholipid antibodies in leprosy: evaluation of antigen reactivity. Lupus. 2000;9:594-600.

25. Loizou S, Singh S, Wypkema E, et al. Anticardiolipin, anti-beta(2)-glycoprotein I and antiprothrombin antibodies in black South African patients with infectious disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:1106-1111.

26. Akerkar SM, Bichile LS. Leprosy & gangrene: a rare association; role of antiphospholipid antibodies. BMC Infect Dis. 2005,5:74.

27. Horta-Baas G, Hernández-Cabrera MF, Barile-Fabris LA, et al. Multibacillary leprosy mimicking systemic lupus erythematosus: case report and literature review. Lupus. 2015;24:1095-1102.

28. Pradhan V, Badakere SS, Shankar KU. Increased incidence of cytoplasmic ANCA (cANCA) and other auto antibodies in leprosy patients from western India. Lepr Rev. 2004;75:50-56.

29. Oskam L. Diagnosis and classification of leprosy. Lepr Rev. 2002;73:17-26.

30. Rao PN. Recent advances in the control programs and therapy of leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:269-276.

31. Rao PN, Pratap D, Ramana Reddy AV, et al. Evaluation of leprosy patients with 1 to 5 skin lesions with relevance to their grouping into paucibacillary or multibacillary disease. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:207-210.

32. Rosado FGN, Kim AS. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. an update on diagnosis and pathogenesis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:713-727.

33. Kar HK, Mohanty HC, Mohanty GN, et al. Clinicopathological study of lymph node involvement in leprosy. Lepr India. 1983;55:725-738.

34. Gupta JC, Panda PK, Shrivastava KK, et al. A histopathologic study of lymph nodes in 43 cases of leprosy. Lepr India. 1978;50:196-203.

35. WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy. Seventh Report. World Health Organization; 1998. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42060/WHO_TRS_874.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

36. Misra DP, Parida JR, Chowdhury AC, et al. Lepra reaction with Lucio phenomenon mimicking cutaneous vasculitis. Case Rep Immunol. 2014;2014:641989.

37. Amer A, Mansour A. Epidemiological study of leprosy in Egypt: 2005-2009. Egypt J Dermatol Venereol. 2014;34:70-73.

38. World Health Organization. Screening campaign aims to eliminate leprosy in Egypt. Published May 9, 2018. Accessed September 8, 2021. http://www.emro.who.int/egy/egypt-events/last-miless-activities-on-eliminating-leprosy-from-egypt.html

Case Report

A 70-year-old man living in Esna, Luxor, Egypt presented to the Department of Rheumatology and Rehabilitation with widespread gangrenous skin lesions associated with ulcers of 2 weeks’ duration. One year prior, the patient had an insidious onset of nocturnal fever, bilateral leg edema, and numbness and a tingling sensation in both hands. He presented some laboratory and radiologic investigations that were performed at another hospital prior to the current presentation, which revealed thrombocytopenia, mild splenomegaly, and generalized lymphadenopathy. An excisional left axillary lymph node biopsy was performed at another hospital prior to the current presentation, and the pathology report provided by the patient described a reactive, foamy, histiocyte-rich lesion, suggesting a diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. The patient had no diabetes or hypertension and no history of deep vein thrombosis, stroke, or unintentional weight loss. No medications were taken prior to the onset of the skin lesions, and his family history was irrelevant.

General examination at the current presentation revealed a fever (temperature, 101.3 °F [38.5 °C]), a normal heart rate (90 beats per minute), normal blood pressure (120/80 mmHg), normal respiratory rate (14 breaths per minute), accentuated heart sounds, and normal vesicular breathing without adventitious sounds. He had saddle nose, loss of the outer third of the eyebrows, and marked reduction in the density of the eyelashes (madarosis). Bilateral pitting edema of the legs also was present. Neurologic examination revealed hypoesthesia in a glove-and-stocking pattern, thickened peripheral nerves, and trophic changes over both hands; however, he had normal muscle power and deep reflexes. Joint examination revealed no abnormalities. Skin examination revealed widespread, reticulated, necrotizing, purpuric lesions on the arms, legs, abdomen, and ears, some associated with gangrenous ulcerations and hemorrhagic blisters. Scattered vasculitic ulcers and gangrenous patches were seen on the fingers. A gangrenous ulcer mimicking Fournier gangrene was seen involving the scrotal skin in addition to a gangrenous lesion on the glans penis (Figure 1–3). Unaffected skin appeared smooth, shiny, and edematous and showed no nodular lesions. Peripheral pulsations were intact.

Positive findings from a wide panel of laboratory investigations included an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (103 mm for the first hour [reference range, 0–22 mm]), high C-reactive protein (50.7 mg/L [reference range, up to 6 mg/L]), anemia (hemoglobin count, 7.3 g/dL [reference range, 13.5–17.5 g/dL]), thrombocytopenia (45×103/mm3 [reference range, 150×103/mm3), low serum albumin (2.3 g/dL [reference range, 3.4–5.4 g/dL]), elevated IgG and IgM anticardiolipin antibodies (IgG, 21.4 IgG phospholipid [GPL] units [reference range, <10 IgG phospholipid (GPL) units]; IgM, 59.4 IgM phospholipid (MPL) units [reference range, <7 IgM phospholipid (MPL) units]), positive lupus anticoagulant panel test, elevated anti-β2 glycoprotein antibodies (IgG, 17.5

Nerve conduction velocity showed axonal sensory polyneuropathy. Motor nerve conduction studies for median and ulnar nerves were within normal range. Lower-limb nerves assessment was limited by the ulcerated areas and marked edema. Echocardiography was unremarkable. Arterial Doppler studies were only available for the upper limbs and were unremarkable.

A punch biopsy was taken from one of the necrotizing purpuric lesions on the legs, and histopathologic examination revealed foci of epidermal necrosis and subepidermal separation and superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal infiltrates extending into the fat lobules. The infiltrates were mainly made up of foamy macrophages, and some contained globi (lepra cells), in addition to lymphocytes and many neutrophils with nuclear dust. Blood vessels in the superficial and deep dermis and in the subcutaneous fat showed fibrinoid necrosis in their walls with neutrophils infiltrating the walls and thrombi in the lumens (Figure 4). Modified Ziehl-Neelsen staining revealed clumps of acid-fast lepra bacilli inside vascular lumina and endothelial cell lining and within the foamy macrophages (Figure 5). Slit-skin smear examination was performed twice and yielded negative results. The slide and paraffin block of the already performed lymph node biopsy were retrieved. Examination revealed aggregates of foamy histiocytes surrounded by lymphocytes and plasma cells replacing normal lymphoid follicles. Modified Ziehl-Neelsen stain was performed, and clusters of acid-fast bacilli were detected within the foamy histiocytic infiltrate (Figure 6).

According to the results of the skin biopsy, the revised result of the lymph node biopsy, and the pattern of neurologic deficit together with clinical and laboratory correlation, the patient was diagnosed with diffuse nonnodular lepromatous leprosy presenting with Lucio phenomenon (Lucio leprosy) and associated with lepromatous lymphadenitis.

The patient received the following treatment: methylprednisolone 500 mg (intravenous pulse therapy) followed by daily oral administration of prednisolone 10 mg, rifampicin 300 mg, dapsone 100 mg, clofazimine 100 mg, acetylsalicylic acid 150 mg, and enoxaparin sodium 80 mg. In addition, the scrotal Fournier gangrene–like lesion was treated by surgical debridement followed by vacuum therapy. By the second week after treatment, the gangrenous lesions of the fingers developed a line of demarcation, and the skin infarctions started to recede.

Comment

Despite a decrease in its prevalence through a World Health Organization (WHO)–empowered eradication program, leprosy still represents a health problem in endemic areas.1,2 It is characterized by a wide range of immune responses to Mycobacterium leprae, displaying a spectrum of clinical and histopathologic manifestations that vary from the tuberculoid or paucibacillary pole with a strong cell-mediated immune response and fewer organisms to the lepromatous or multibacillary pole with weaker cell-mediated immune response and higher loads of organisms.3 In addition to its well-known cutaneous and neurologic manifestations, leprosy can present with a variety of manifestations, including constitutional symptoms, musculoskeletal manifestations, and serologic abnormalities; thus, leprosy can mimic rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis, and vasculitis—a pitfall that may result in misdiagnosis as a rheumatologic disorder.3-7

The chronic course of leprosy can be disrupted by acute, immunologically mediated reactions known as lepra reactions, of which there are 3 types.8 Type I lepra reactions are cell mediated and occur mainly in patients with borderline disease, often representing an upgrade toward the tuberculoid pole; less often they represent a downgrade reaction. Nerves become painful and swollen with possible loss of function, and skin lesions become edematous and tender; sometimes arthritis develops.9 Type II lepra reactions, also known as erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL), occur in borderline lepromatous and lepromatous patients with a high bacillary load. They are characterized by fever, body aches, tender cutaneous/subcutaneous nodules that may ulcerate, possible bullous lesions, painful nerve swellings, swollen joints, iritis, lymphadenitis, glomerulonephritis, epididymo-orchitis, and hepatic affection. Both immune-complex and delayed hypersensitivity reactions play a role in ENL.8,10 The third reaction is a rare aggressive type known as Lucio phenomenon or Lucio leprosy, which presents with irregular-shaped, angulated, or stellar necrotizing purpuric lesions (hemorrhagic infacrtions) developing mainly on the extremities. The lesions evolve into ulcers that heal with atrophic scarring.2,11 Lucio phenomenon develops as a result of thrombotic vascular occlusion secondary to massive invasion of vascular endothelial cells by lepra bacilli.2,11-14 Involvement of the scrotal skin, such as in our patient, is rare.

Lucio phenomenon mainly is seen in Mexico and Central America, and few cases have been documented in Cuba, South America, the United States, India, Polynesia, South Africa, and Southeast Asia.15-17 It specifically occurs in patients with untreated, diffuse, nonnodular lepromatous leprosy (pure and primitive diffuse lepromatous leprosy (DLL)/diffuse leprosy of Lucio and Latapí). This type of leprosy was first described by Lucio and Alvarado18 in 1852 as a distinct form of lepromatous leprosy characterized by widespread and dense infiltration of the whole skin by lepra bacilli without the typical nodular lesions of leprosy, rendering its diagnosis challenging, especially in sporadic cases. Other manifestations of DLL include complete alopecia of the eyebrows and eyelashes, destructive rhinitis, and areas of anhidrosis and dyesthesia.2

Latapí and Chévez-Zomora19 defined Lucio phenomenon in 1948 as a form of histopathologic vasculitis restricted to patients with DLL. Histopathologically, in addition to the infiltration of the skin with acid-fast bacilli–laden foamy histiocytes, lesions of Lucio phenomenon show features of necrotizing (leukocytoclastic) vasculitis with fibrinoid necrosis20 or vascular thrombi with minimal perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and no evidence of vasculitis.11 Medium to large vessels in the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue show infiltration of their walls with a large number of macrophages laden with acid-fast bacilli.11 Cases with histopathologic features mimicking antiphospholipid syndrome with endothelial cell proliferation, thrombosis, and mild mononuclear cell infiltrate also may be seen.20 In all cases, ischemic epidermal necrosis is seen, as well as acid-fast bacilli, both singly and in clusters (globi) within endothelial cells and inside blood vessel lumina.

Although Lucio phenomenon initially was thought to be immune-complex mediated like ENL, it has been suggested that the main trigger is thrombotic vascular occlusion secondary to massive invasion of the vascular endothelial cells by the lepra bacilli, resulting in necrosis.14 Bacterial lipopolysaccharides promote the release of IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor α, which in turn stimulate the production of prostaglandins, IL-6, and coagulation factor III, leading to vascular thrombosis and tissue necrosis.21,22 Moreover, antiphospholipid antibodies, which have been found to be induced in response to certain infectious agents in genetically predisposed individuals,23 have been reported in patients with leprosy, mainly in association with lepromatous leprosy. The reported prevalence of anticardiolipin antibodies ranged from 37% to 98%, whereas anti-β2-glycoprotein I antibodies ranged from 3% to 19%, and antiprothrombin antibodies ranged from 6% to 45%.24,25 Antiphospholipid antibodies have been reported to play a role in the pathogenesis of Lucio phenomenon.11,13,15,26 Our case supports this hypothesis with positive anticardiolipin antibodies, anti-β2 glycoprotein antibodies, and positive lupus anticoagulant.

In accordance with Curi et al,2 who reported 5 cases of DLL with Lucio phenomenon, our patient showed a similar presentation with positive inflammatory markers in association with a negative autoimmune profile (ANA, ANCA-C&P) and negative venereal disease research laboratory test. It is important to mention that a positive autoimmune profile (ANA, ANCA-C&P) can be present in leprotic patients, causing possible diagnostic confusion with collagen diseases.27,28

An interesting finding in our case was the negative slit-skin smear results. Although the specificity of slit-skin smear is 100%, as it directly demonstrates the presence of acid-fast bacilli,29 its sensitivity is low and varies from 10% to 50%.30 The detection of acid-fast bacilli in tissue sections is reported to be a better method for confirming the diagnosis of leprosy.31

The provisional impression of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in the lymph node biopsy in our patient was excluded upon detection of acid-fast bacilli in the foamy histiocytes infiltrating the lymph node; moreover, the normal serum lipids and serum ferritin argued against this diagnosis.32 Leprosy tends to involve the lymph nodes, particularly in borderline, borderline lepromatous, and lepromatous forms.33 The incidence of lymph node involvement accompanied by skin lesions with the presence of acid-fast bacilli in the lymph nodes is 92.2%.34

Our patient showed an excellent response to antileprotic treatment, which was administered according to the WHO multidrug therapy guidelines for multibacillary leprosy,35 combined with low-dose prednisolone, acetylsalicylic acid, and anticoagulant treatment. Thalidomide and high-dose prednisolone (60 mg/d) combined with antileprotic treatment also have been reported to be successful in managing recurrent infarctions in leprosy.36 The Fournier-like gangrenous ulcer of the scrotum was managed by surgical debridement and vacuum therapy.

It is noteworthy that the WHO elimination goal for leprosy was to reduce the prevalence to less than 1 case per 10,000 population. Egypt is among the first countries in North Africa and the Middle East regions to achieve this target supervised by the National Leprosy Control Program as early as 1994; this was further reduced to 0.33 cases per 10,000 population in 2004, and reduced again in 2009; however, certain foci showed a prevalence rate more than the elimination target, particularly in the cities of Qena (1.12) and Sohag (2.47).37 Esna, where our patient is from, is an endemic area in Egypt.38

Conclusion

Case Report

A 70-year-old man living in Esna, Luxor, Egypt presented to the Department of Rheumatology and Rehabilitation with widespread gangrenous skin lesions associated with ulcers of 2 weeks’ duration. One year prior, the patient had an insidious onset of nocturnal fever, bilateral leg edema, and numbness and a tingling sensation in both hands. He presented some laboratory and radiologic investigations that were performed at another hospital prior to the current presentation, which revealed thrombocytopenia, mild splenomegaly, and generalized lymphadenopathy. An excisional left axillary lymph node biopsy was performed at another hospital prior to the current presentation, and the pathology report provided by the patient described a reactive, foamy, histiocyte-rich lesion, suggesting a diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. The patient had no diabetes or hypertension and no history of deep vein thrombosis, stroke, or unintentional weight loss. No medications were taken prior to the onset of the skin lesions, and his family history was irrelevant.

General examination at the current presentation revealed a fever (temperature, 101.3 °F [38.5 °C]), a normal heart rate (90 beats per minute), normal blood pressure (120/80 mmHg), normal respiratory rate (14 breaths per minute), accentuated heart sounds, and normal vesicular breathing without adventitious sounds. He had saddle nose, loss of the outer third of the eyebrows, and marked reduction in the density of the eyelashes (madarosis). Bilateral pitting edema of the legs also was present. Neurologic examination revealed hypoesthesia in a glove-and-stocking pattern, thickened peripheral nerves, and trophic changes over both hands; however, he had normal muscle power and deep reflexes. Joint examination revealed no abnormalities. Skin examination revealed widespread, reticulated, necrotizing, purpuric lesions on the arms, legs, abdomen, and ears, some associated with gangrenous ulcerations and hemorrhagic blisters. Scattered vasculitic ulcers and gangrenous patches were seen on the fingers. A gangrenous ulcer mimicking Fournier gangrene was seen involving the scrotal skin in addition to a gangrenous lesion on the glans penis (Figure 1–3). Unaffected skin appeared smooth, shiny, and edematous and showed no nodular lesions. Peripheral pulsations were intact.

Positive findings from a wide panel of laboratory investigations included an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (103 mm for the first hour [reference range, 0–22 mm]), high C-reactive protein (50.7 mg/L [reference range, up to 6 mg/L]), anemia (hemoglobin count, 7.3 g/dL [reference range, 13.5–17.5 g/dL]), thrombocytopenia (45×103/mm3 [reference range, 150×103/mm3), low serum albumin (2.3 g/dL [reference range, 3.4–5.4 g/dL]), elevated IgG and IgM anticardiolipin antibodies (IgG, 21.4 IgG phospholipid [GPL] units [reference range, <10 IgG phospholipid (GPL) units]; IgM, 59.4 IgM phospholipid (MPL) units [reference range, <7 IgM phospholipid (MPL) units]), positive lupus anticoagulant panel test, elevated anti-β2 glycoprotein antibodies (IgG, 17.5

Nerve conduction velocity showed axonal sensory polyneuropathy. Motor nerve conduction studies for median and ulnar nerves were within normal range. Lower-limb nerves assessment was limited by the ulcerated areas and marked edema. Echocardiography was unremarkable. Arterial Doppler studies were only available for the upper limbs and were unremarkable.

A punch biopsy was taken from one of the necrotizing purpuric lesions on the legs, and histopathologic examination revealed foci of epidermal necrosis and subepidermal separation and superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal infiltrates extending into the fat lobules. The infiltrates were mainly made up of foamy macrophages, and some contained globi (lepra cells), in addition to lymphocytes and many neutrophils with nuclear dust. Blood vessels in the superficial and deep dermis and in the subcutaneous fat showed fibrinoid necrosis in their walls with neutrophils infiltrating the walls and thrombi in the lumens (Figure 4). Modified Ziehl-Neelsen staining revealed clumps of acid-fast lepra bacilli inside vascular lumina and endothelial cell lining and within the foamy macrophages (Figure 5). Slit-skin smear examination was performed twice and yielded negative results. The slide and paraffin block of the already performed lymph node biopsy were retrieved. Examination revealed aggregates of foamy histiocytes surrounded by lymphocytes and plasma cells replacing normal lymphoid follicles. Modified Ziehl-Neelsen stain was performed, and clusters of acid-fast bacilli were detected within the foamy histiocytic infiltrate (Figure 6).

According to the results of the skin biopsy, the revised result of the lymph node biopsy, and the pattern of neurologic deficit together with clinical and laboratory correlation, the patient was diagnosed with diffuse nonnodular lepromatous leprosy presenting with Lucio phenomenon (Lucio leprosy) and associated with lepromatous lymphadenitis.

The patient received the following treatment: methylprednisolone 500 mg (intravenous pulse therapy) followed by daily oral administration of prednisolone 10 mg, rifampicin 300 mg, dapsone 100 mg, clofazimine 100 mg, acetylsalicylic acid 150 mg, and enoxaparin sodium 80 mg. In addition, the scrotal Fournier gangrene–like lesion was treated by surgical debridement followed by vacuum therapy. By the second week after treatment, the gangrenous lesions of the fingers developed a line of demarcation, and the skin infarctions started to recede.

Comment

Despite a decrease in its prevalence through a World Health Organization (WHO)–empowered eradication program, leprosy still represents a health problem in endemic areas.1,2 It is characterized by a wide range of immune responses to Mycobacterium leprae, displaying a spectrum of clinical and histopathologic manifestations that vary from the tuberculoid or paucibacillary pole with a strong cell-mediated immune response and fewer organisms to the lepromatous or multibacillary pole with weaker cell-mediated immune response and higher loads of organisms.3 In addition to its well-known cutaneous and neurologic manifestations, leprosy can present with a variety of manifestations, including constitutional symptoms, musculoskeletal manifestations, and serologic abnormalities; thus, leprosy can mimic rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis, and vasculitis—a pitfall that may result in misdiagnosis as a rheumatologic disorder.3-7

The chronic course of leprosy can be disrupted by acute, immunologically mediated reactions known as lepra reactions, of which there are 3 types.8 Type I lepra reactions are cell mediated and occur mainly in patients with borderline disease, often representing an upgrade toward the tuberculoid pole; less often they represent a downgrade reaction. Nerves become painful and swollen with possible loss of function, and skin lesions become edematous and tender; sometimes arthritis develops.9 Type II lepra reactions, also known as erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL), occur in borderline lepromatous and lepromatous patients with a high bacillary load. They are characterized by fever, body aches, tender cutaneous/subcutaneous nodules that may ulcerate, possible bullous lesions, painful nerve swellings, swollen joints, iritis, lymphadenitis, glomerulonephritis, epididymo-orchitis, and hepatic affection. Both immune-complex and delayed hypersensitivity reactions play a role in ENL.8,10 The third reaction is a rare aggressive type known as Lucio phenomenon or Lucio leprosy, which presents with irregular-shaped, angulated, or stellar necrotizing purpuric lesions (hemorrhagic infacrtions) developing mainly on the extremities. The lesions evolve into ulcers that heal with atrophic scarring.2,11 Lucio phenomenon develops as a result of thrombotic vascular occlusion secondary to massive invasion of vascular endothelial cells by lepra bacilli.2,11-14 Involvement of the scrotal skin, such as in our patient, is rare.

Lucio phenomenon mainly is seen in Mexico and Central America, and few cases have been documented in Cuba, South America, the United States, India, Polynesia, South Africa, and Southeast Asia.15-17 It specifically occurs in patients with untreated, diffuse, nonnodular lepromatous leprosy (pure and primitive diffuse lepromatous leprosy (DLL)/diffuse leprosy of Lucio and Latapí). This type of leprosy was first described by Lucio and Alvarado18 in 1852 as a distinct form of lepromatous leprosy characterized by widespread and dense infiltration of the whole skin by lepra bacilli without the typical nodular lesions of leprosy, rendering its diagnosis challenging, especially in sporadic cases. Other manifestations of DLL include complete alopecia of the eyebrows and eyelashes, destructive rhinitis, and areas of anhidrosis and dyesthesia.2

Latapí and Chévez-Zomora19 defined Lucio phenomenon in 1948 as a form of histopathologic vasculitis restricted to patients with DLL. Histopathologically, in addition to the infiltration of the skin with acid-fast bacilli–laden foamy histiocytes, lesions of Lucio phenomenon show features of necrotizing (leukocytoclastic) vasculitis with fibrinoid necrosis20 or vascular thrombi with minimal perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate and no evidence of vasculitis.11 Medium to large vessels in the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue show infiltration of their walls with a large number of macrophages laden with acid-fast bacilli.11 Cases with histopathologic features mimicking antiphospholipid syndrome with endothelial cell proliferation, thrombosis, and mild mononuclear cell infiltrate also may be seen.20 In all cases, ischemic epidermal necrosis is seen, as well as acid-fast bacilli, both singly and in clusters (globi) within endothelial cells and inside blood vessel lumina.

Although Lucio phenomenon initially was thought to be immune-complex mediated like ENL, it has been suggested that the main trigger is thrombotic vascular occlusion secondary to massive invasion of the vascular endothelial cells by the lepra bacilli, resulting in necrosis.14 Bacterial lipopolysaccharides promote the release of IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor α, which in turn stimulate the production of prostaglandins, IL-6, and coagulation factor III, leading to vascular thrombosis and tissue necrosis.21,22 Moreover, antiphospholipid antibodies, which have been found to be induced in response to certain infectious agents in genetically predisposed individuals,23 have been reported in patients with leprosy, mainly in association with lepromatous leprosy. The reported prevalence of anticardiolipin antibodies ranged from 37% to 98%, whereas anti-β2-glycoprotein I antibodies ranged from 3% to 19%, and antiprothrombin antibodies ranged from 6% to 45%.24,25 Antiphospholipid antibodies have been reported to play a role in the pathogenesis of Lucio phenomenon.11,13,15,26 Our case supports this hypothesis with positive anticardiolipin antibodies, anti-β2 glycoprotein antibodies, and positive lupus anticoagulant.

In accordance with Curi et al,2 who reported 5 cases of DLL with Lucio phenomenon, our patient showed a similar presentation with positive inflammatory markers in association with a negative autoimmune profile (ANA, ANCA-C&P) and negative venereal disease research laboratory test. It is important to mention that a positive autoimmune profile (ANA, ANCA-C&P) can be present in leprotic patients, causing possible diagnostic confusion with collagen diseases.27,28

An interesting finding in our case was the negative slit-skin smear results. Although the specificity of slit-skin smear is 100%, as it directly demonstrates the presence of acid-fast bacilli,29 its sensitivity is low and varies from 10% to 50%.30 The detection of acid-fast bacilli in tissue sections is reported to be a better method for confirming the diagnosis of leprosy.31

The provisional impression of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in the lymph node biopsy in our patient was excluded upon detection of acid-fast bacilli in the foamy histiocytes infiltrating the lymph node; moreover, the normal serum lipids and serum ferritin argued against this diagnosis.32 Leprosy tends to involve the lymph nodes, particularly in borderline, borderline lepromatous, and lepromatous forms.33 The incidence of lymph node involvement accompanied by skin lesions with the presence of acid-fast bacilli in the lymph nodes is 92.2%.34

Our patient showed an excellent response to antileprotic treatment, which was administered according to the WHO multidrug therapy guidelines for multibacillary leprosy,35 combined with low-dose prednisolone, acetylsalicylic acid, and anticoagulant treatment. Thalidomide and high-dose prednisolone (60 mg/d) combined with antileprotic treatment also have been reported to be successful in managing recurrent infarctions in leprosy.36 The Fournier-like gangrenous ulcer of the scrotum was managed by surgical debridement and vacuum therapy.

It is noteworthy that the WHO elimination goal for leprosy was to reduce the prevalence to less than 1 case per 10,000 population. Egypt is among the first countries in North Africa and the Middle East regions to achieve this target supervised by the National Leprosy Control Program as early as 1994; this was further reduced to 0.33 cases per 10,000 population in 2004, and reduced again in 2009; however, certain foci showed a prevalence rate more than the elimination target, particularly in the cities of Qena (1.12) and Sohag (2.47).37 Esna, where our patient is from, is an endemic area in Egypt.38

Conclusion

1. World Health Organization. World Health Statistics: 2011. World Health Organization; 2011. https://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/EN_WHS2011_Full.pdf

2. Curi PF, Villaroel JS, Migliore N, et al. Lucio’s phenomenon: report of five cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:1397-1401.

3. Shrestha B, Li YQ, Fu P. Leprosy mimics adult onset Still’s disease in a Chinese patient. Egypt Rheumatol. 2018;40:217-220.

4. Prasad S, Misra R, Aggarwal A, et al. Leprosy revealed in a rheumatology clinic: a case series. Int J Rheum Dis. 2013;16:129-133.

5. Chao G, Fang L, Lu C. Leprosy with ANA positive mistaken for connective tissue disease. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:645-648.

6. Chauhan S, Wakhlu A, Agarwal V. Arthritis in leprosy. Rheumatology. 2010;49:2237-2242.

7. Rath D, Bhargava S, Kundu BK. Leprosy mimicking common rheumatologic entities: a trial for the clinician in the era of biologics. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2014;2014:429698.

8. Cuevas J, Rodríguez-Peralto JL, Carrillo R, et al. Erythema nodosum leprosum: reactional leprosy. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:126-130.

9. Henriques CC, Lopéz B, Mestre T, et al. Leprosy and rheumatoid arthritis: consequence or association? BMJ Case Rep. 2012;13:1-4.

10. Vázquez-Botet M, Sánchez JL. Erythema nodosum leprosum. Int J Dermatol. 1987;26:436-437.

11. Nunzie E, Ortega Cabrera LV, Macanchi Moncayo FM, et al. Lucio leprosy with Lucio’s phenomenon, digital gangrene and anticardiolipin antibodies. Lepr Rev. 2014;85:194-200.

12. Salvi S, Chopra A. Leprosy in a rheumatology setting: a challenging mimic to expose. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:1557-1563.

13. Azulay-Abulafia L, Pereira SL, Hardmann D, et al. Lucio phenomenon. vasculitis or occlusive vasculopathy? Hautarzt. 2006;57:1101-1105.

14. Benard G, Sakai-Valente NY, Bianconcini Trindade MA. Concomittant Lucio phenomenon and erythema nodosum in a leprosy patient: clues for their distinct pathogenesis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:288-292.

15. Rocha RH, Emerich PS, Diniz LM, et al. Lucio’s phenomenon: exuberant case report and review of Brazilian cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(suppl 5):S60-S63.

16. Costa IM, Kawano LB, Pereira CP, et al. Lucio’s phenomenon: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:566-571.

17. Kumari R, Thappa DM, Basu D. A fatal case of Lucio phenomenon from India. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:10.

18. Lucio R, Alvarado I. Opúsculo Sobre el Mal de San Lázaro o Elefantiasis de los Griegos. M. Murguía; 1852.

19. Latapí F, Chévez-Zamora A. The “spotted” leprosy of Lucio: an introduction to its clinical and histological study. Int J Lepr. 1948;16:421-437.

20. Vargas OF. Diffuse leprosy of Lucio and Latapí: a histologic study. Lepr Rev. 2007;78:248-260.

21. Latapí FR, Chevez-Zamora A. La lepra manchada de Lucio. Rev Dermatol Mex. 1978;22:102-107.

22. Monteiro R, Abreu MA, Tiezzi MG, et al. Fenômeno de Lúcio: mais um caso relatado no Brasil. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:296-300.

23. Gharavi EE, Chaimovich H, Cucucrull E, et al. Induction of antiphospholipid antibodies by immunization with synthetic bacterial & viral peptides. Lupus. 1999;8:449-455.

24. de Larrañaga GF, Forastiero RR, Martinuzzo ME, et al. High prevalence of antiphospholipid antibodies in leprosy: evaluation of antigen reactivity. Lupus. 2000;9:594-600.

25. Loizou S, Singh S, Wypkema E, et al. Anticardiolipin, anti-beta(2)-glycoprotein I and antiprothrombin antibodies in black South African patients with infectious disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:1106-1111.

26. Akerkar SM, Bichile LS. Leprosy & gangrene: a rare association; role of antiphospholipid antibodies. BMC Infect Dis. 2005,5:74.

27. Horta-Baas G, Hernández-Cabrera MF, Barile-Fabris LA, et al. Multibacillary leprosy mimicking systemic lupus erythematosus: case report and literature review. Lupus. 2015;24:1095-1102.

28. Pradhan V, Badakere SS, Shankar KU. Increased incidence of cytoplasmic ANCA (cANCA) and other auto antibodies in leprosy patients from western India. Lepr Rev. 2004;75:50-56.

29. Oskam L. Diagnosis and classification of leprosy. Lepr Rev. 2002;73:17-26.

30. Rao PN. Recent advances in the control programs and therapy of leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:269-276.

31. Rao PN, Pratap D, Ramana Reddy AV, et al. Evaluation of leprosy patients with 1 to 5 skin lesions with relevance to their grouping into paucibacillary or multibacillary disease. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:207-210.

32. Rosado FGN, Kim AS. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. an update on diagnosis and pathogenesis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:713-727.

33. Kar HK, Mohanty HC, Mohanty GN, et al. Clinicopathological study of lymph node involvement in leprosy. Lepr India. 1983;55:725-738.

34. Gupta JC, Panda PK, Shrivastava KK, et al. A histopathologic study of lymph nodes in 43 cases of leprosy. Lepr India. 1978;50:196-203.

35. WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy. Seventh Report. World Health Organization; 1998. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42060/WHO_TRS_874.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

36. Misra DP, Parida JR, Chowdhury AC, et al. Lepra reaction with Lucio phenomenon mimicking cutaneous vasculitis. Case Rep Immunol. 2014;2014:641989.

37. Amer A, Mansour A. Epidemiological study of leprosy in Egypt: 2005-2009. Egypt J Dermatol Venereol. 2014;34:70-73.

38. World Health Organization. Screening campaign aims to eliminate leprosy in Egypt. Published May 9, 2018. Accessed September 8, 2021. http://www.emro.who.int/egy/egypt-events/last-miless-activities-on-eliminating-leprosy-from-egypt.html

1. World Health Organization. World Health Statistics: 2011. World Health Organization; 2011. https://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/EN_WHS2011_Full.pdf

2. Curi PF, Villaroel JS, Migliore N, et al. Lucio’s phenomenon: report of five cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:1397-1401.

3. Shrestha B, Li YQ, Fu P. Leprosy mimics adult onset Still’s disease in a Chinese patient. Egypt Rheumatol. 2018;40:217-220.

4. Prasad S, Misra R, Aggarwal A, et al. Leprosy revealed in a rheumatology clinic: a case series. Int J Rheum Dis. 2013;16:129-133.

5. Chao G, Fang L, Lu C. Leprosy with ANA positive mistaken for connective tissue disease. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:645-648.

6. Chauhan S, Wakhlu A, Agarwal V. Arthritis in leprosy. Rheumatology. 2010;49:2237-2242.

7. Rath D, Bhargava S, Kundu BK. Leprosy mimicking common rheumatologic entities: a trial for the clinician in the era of biologics. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2014;2014:429698.

8. Cuevas J, Rodríguez-Peralto JL, Carrillo R, et al. Erythema nodosum leprosum: reactional leprosy. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2007;26:126-130.

9. Henriques CC, Lopéz B, Mestre T, et al. Leprosy and rheumatoid arthritis: consequence or association? BMJ Case Rep. 2012;13:1-4.

10. Vázquez-Botet M, Sánchez JL. Erythema nodosum leprosum. Int J Dermatol. 1987;26:436-437.

11. Nunzie E, Ortega Cabrera LV, Macanchi Moncayo FM, et al. Lucio leprosy with Lucio’s phenomenon, digital gangrene and anticardiolipin antibodies. Lepr Rev. 2014;85:194-200.

12. Salvi S, Chopra A. Leprosy in a rheumatology setting: a challenging mimic to expose. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32:1557-1563.

13. Azulay-Abulafia L, Pereira SL, Hardmann D, et al. Lucio phenomenon. vasculitis or occlusive vasculopathy? Hautarzt. 2006;57:1101-1105.

14. Benard G, Sakai-Valente NY, Bianconcini Trindade MA. Concomittant Lucio phenomenon and erythema nodosum in a leprosy patient: clues for their distinct pathogenesis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:288-292.

15. Rocha RH, Emerich PS, Diniz LM, et al. Lucio’s phenomenon: exuberant case report and review of Brazilian cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(suppl 5):S60-S63.

16. Costa IM, Kawano LB, Pereira CP, et al. Lucio’s phenomenon: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:566-571.

17. Kumari R, Thappa DM, Basu D. A fatal case of Lucio phenomenon from India. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:10.

18. Lucio R, Alvarado I. Opúsculo Sobre el Mal de San Lázaro o Elefantiasis de los Griegos. M. Murguía; 1852.

19. Latapí F, Chévez-Zamora A. The “spotted” leprosy of Lucio: an introduction to its clinical and histological study. Int J Lepr. 1948;16:421-437.

20. Vargas OF. Diffuse leprosy of Lucio and Latapí: a histologic study. Lepr Rev. 2007;78:248-260.

21. Latapí FR, Chevez-Zamora A. La lepra manchada de Lucio. Rev Dermatol Mex. 1978;22:102-107.

22. Monteiro R, Abreu MA, Tiezzi MG, et al. Fenômeno de Lúcio: mais um caso relatado no Brasil. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:296-300.

23. Gharavi EE, Chaimovich H, Cucucrull E, et al. Induction of antiphospholipid antibodies by immunization with synthetic bacterial & viral peptides. Lupus. 1999;8:449-455.

24. de Larrañaga GF, Forastiero RR, Martinuzzo ME, et al. High prevalence of antiphospholipid antibodies in leprosy: evaluation of antigen reactivity. Lupus. 2000;9:594-600.

25. Loizou S, Singh S, Wypkema E, et al. Anticardiolipin, anti-beta(2)-glycoprotein I and antiprothrombin antibodies in black South African patients with infectious disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:1106-1111.

26. Akerkar SM, Bichile LS. Leprosy & gangrene: a rare association; role of antiphospholipid antibodies. BMC Infect Dis. 2005,5:74.

27. Horta-Baas G, Hernández-Cabrera MF, Barile-Fabris LA, et al. Multibacillary leprosy mimicking systemic lupus erythematosus: case report and literature review. Lupus. 2015;24:1095-1102.

28. Pradhan V, Badakere SS, Shankar KU. Increased incidence of cytoplasmic ANCA (cANCA) and other auto antibodies in leprosy patients from western India. Lepr Rev. 2004;75:50-56.

29. Oskam L. Diagnosis and classification of leprosy. Lepr Rev. 2002;73:17-26.

30. Rao PN. Recent advances in the control programs and therapy of leprosy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:269-276.

31. Rao PN, Pratap D, Ramana Reddy AV, et al. Evaluation of leprosy patients with 1 to 5 skin lesions with relevance to their grouping into paucibacillary or multibacillary disease. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:207-210.

32. Rosado FGN, Kim AS. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. an update on diagnosis and pathogenesis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:713-727.

33. Kar HK, Mohanty HC, Mohanty GN, et al. Clinicopathological study of lymph node involvement in leprosy. Lepr India. 1983;55:725-738.

34. Gupta JC, Panda PK, Shrivastava KK, et al. A histopathologic study of lymph nodes in 43 cases of leprosy. Lepr India. 1978;50:196-203.

35. WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy. Seventh Report. World Health Organization; 1998. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42060/WHO_TRS_874.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

36. Misra DP, Parida JR, Chowdhury AC, et al. Lepra reaction with Lucio phenomenon mimicking cutaneous vasculitis. Case Rep Immunol. 2014;2014:641989.

37. Amer A, Mansour A. Epidemiological study of leprosy in Egypt: 2005-2009. Egypt J Dermatol Venereol. 2014;34:70-73.

38. World Health Organization. Screening campaign aims to eliminate leprosy in Egypt. Published May 9, 2018. Accessed September 8, 2021. http://www.emro.who.int/egy/egypt-events/last-miless-activities-on-eliminating-leprosy-from-egypt.html

Practice Points

- Leprosy is a great mimicker of many connective tissue diseases, including vasculitis.

- Antiphospholipid antibodies are involved in Lucio phenomenon.

- Prompt treatment is important in Lucio phenomenon to avoid morbidity and mortality.

Hyperpigmented Patch on the Leg

The Diagnosis: Lichen Aureus

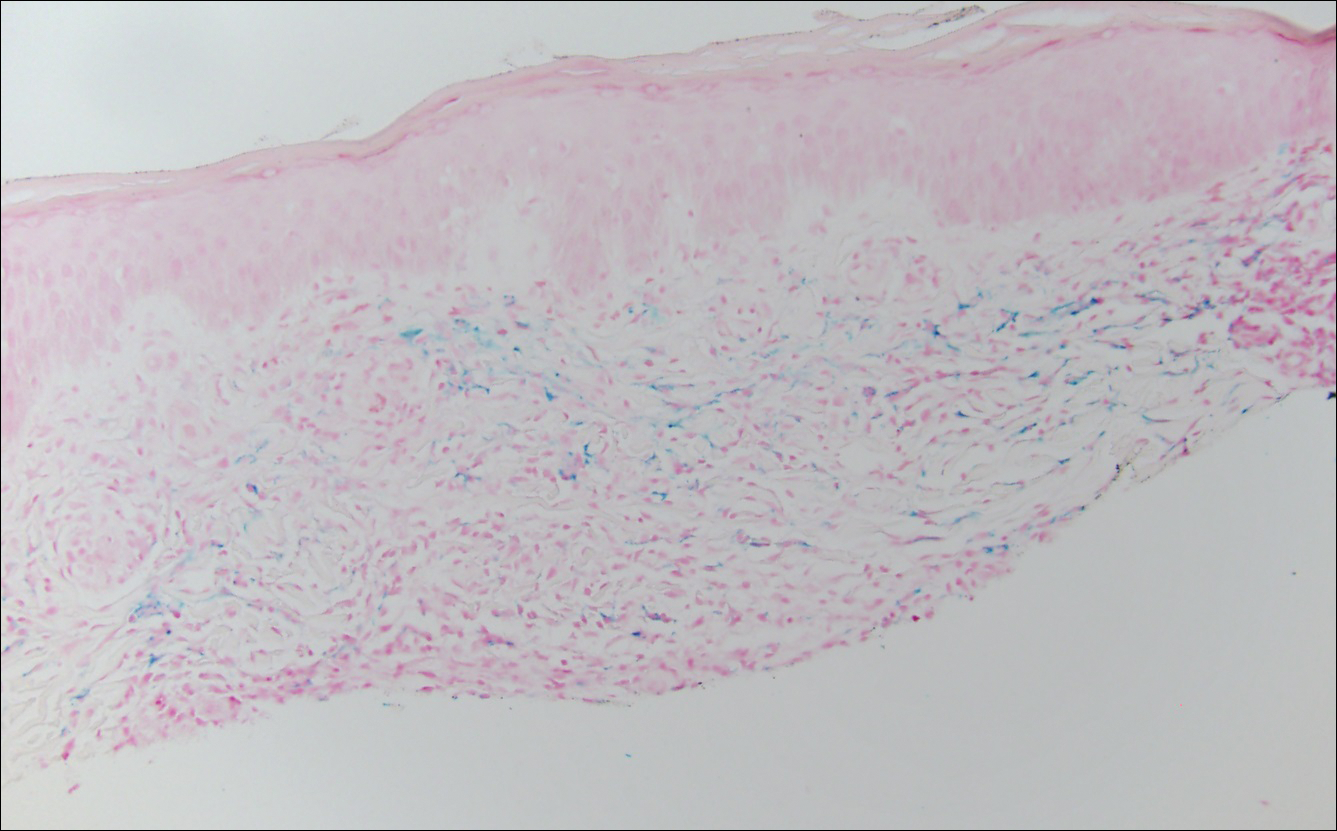

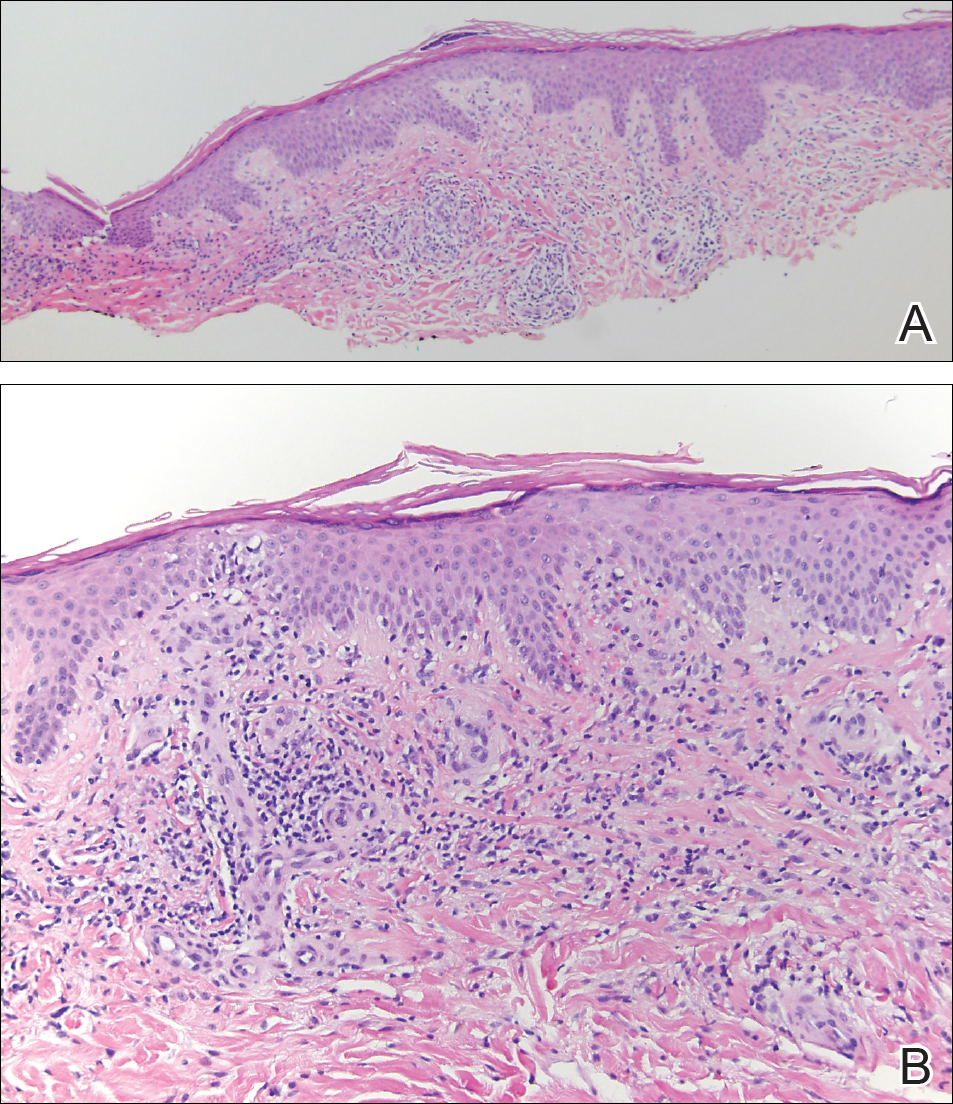

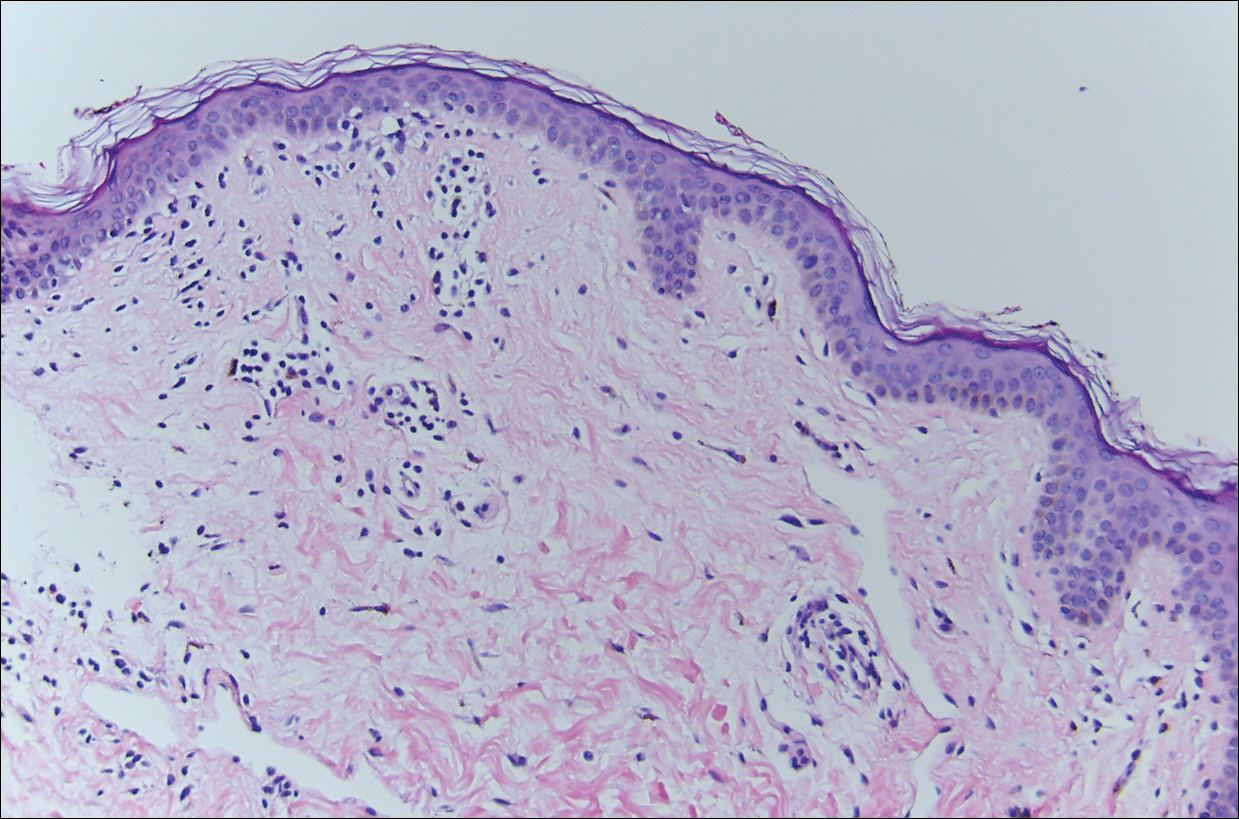

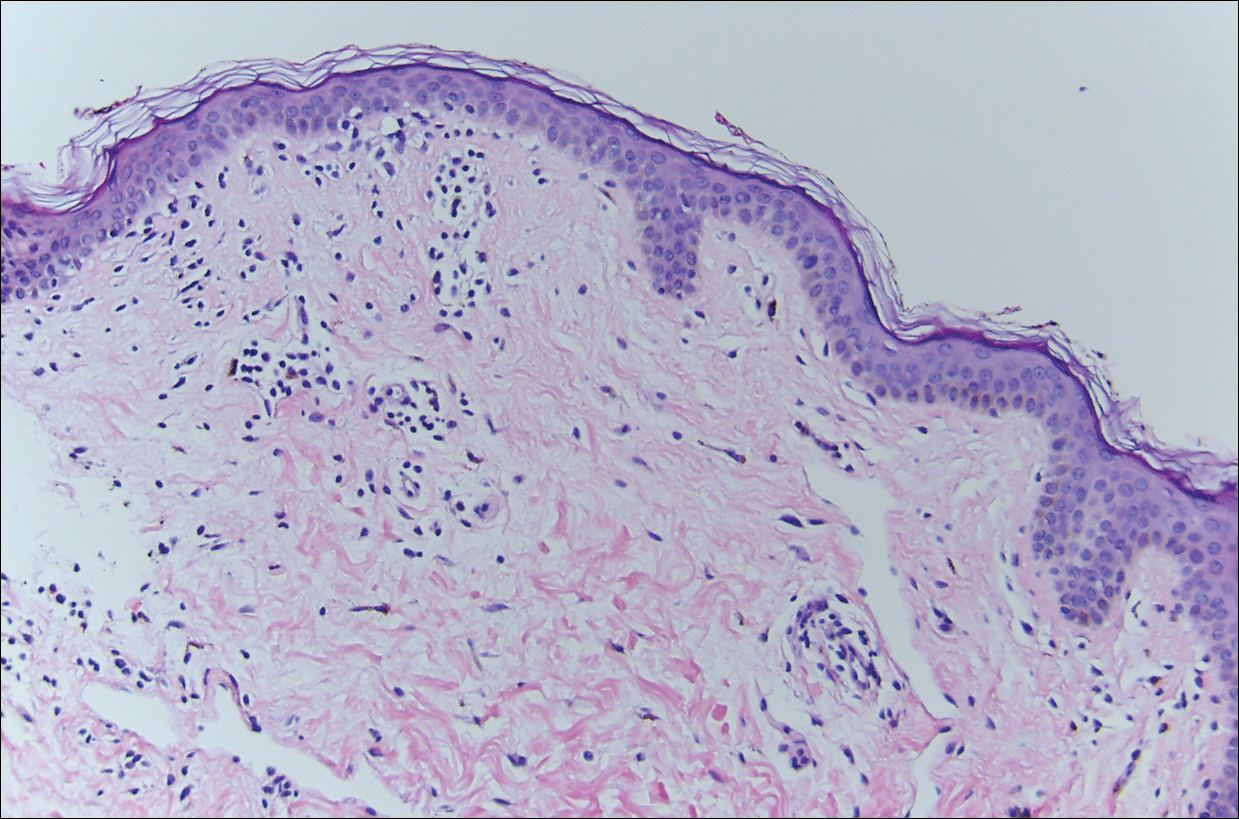

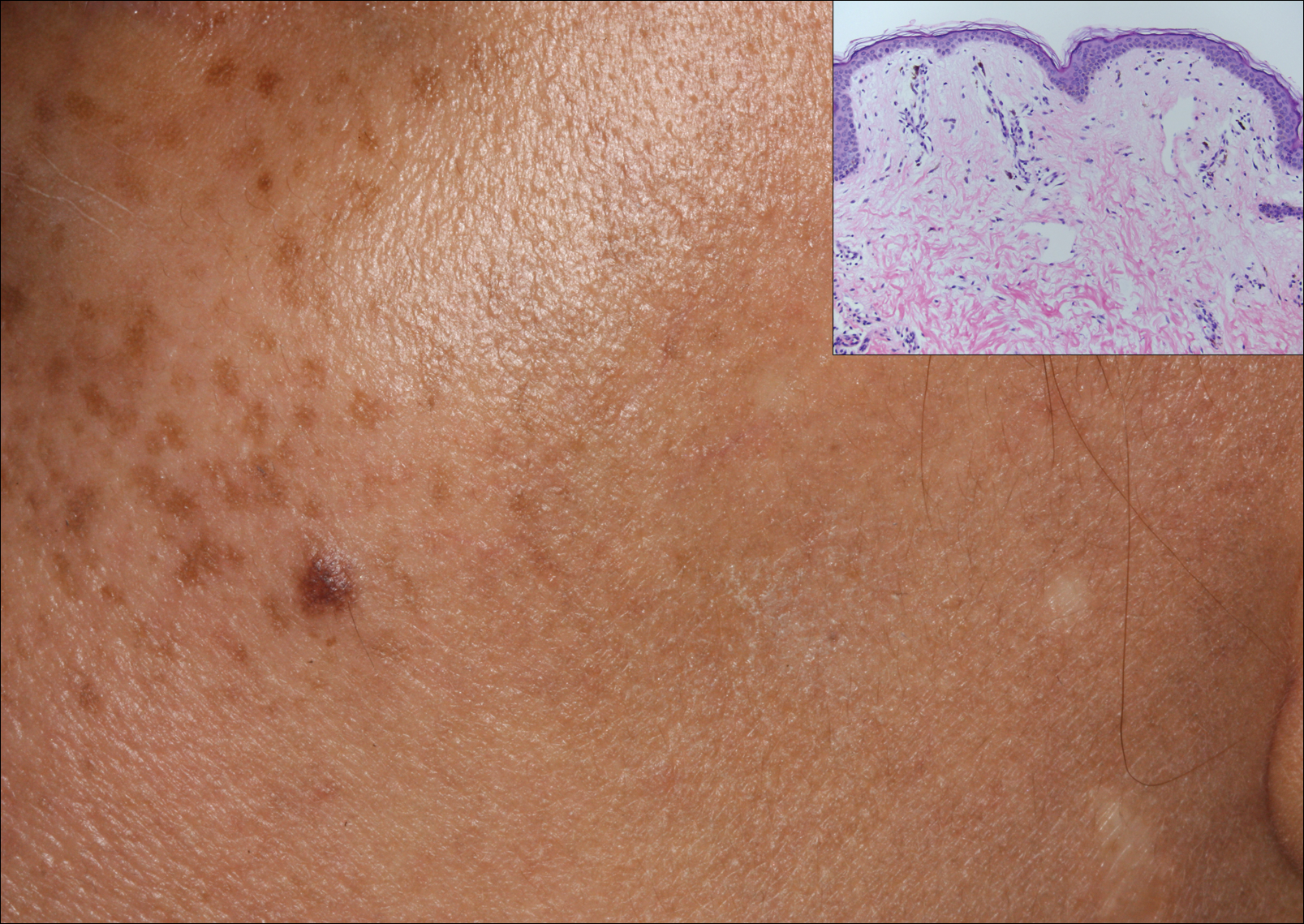

The clinicopathological findings were diagnostic of lichen aureus (LA). Microscopic examination revealed a relatively sparse, superficial, perivascular and interstitial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with scattered siderophages in the upper dermis. Extravasation of red blood cells also was noted (Figure 1). An immunohistochemical stain for Melan-A highlighted a normal number and distribution of single melanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction with no evidence of pagetoid scatter. A Perls Prussian blue stain for iron demonstrated abundant hemosiderin in the dermis (Figure 2).

Pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD) describes a group of cutaneous lesions that are characterized by petechiae and pigmentary changes. These lesions most commonly present on the lower limbs; however, other sites have been reported.1 This group includes several major clinical forms such as Schamberg disease, LA, purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi, eczematidlike purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis, and lichenoid PPD of Gougerot and Blum. Lesions typically demonstrate a striking golden brown color clinically and by definition occur in the absence of platelet defects or vasculitis.1

Factors implicated in the pathogenesis of pigmented purpura include gravitational dependency, venous stasis, infection, and drugs.2 It is suggested that cellular immunity may play a role in the development of the disease based on the presence of CD4+ T lymphocytes in the infiltrate and the expression of HLA-DR by these lymphocytes and the keratinocytes.3 Lichen aureus differs in that it relates to increased intravascular pressure from an incompetent valve in an underlying perforating vein.4

Lichen aureus, also referred to as lichen purpuricus, is one major variant of PPD. The name reflects both the characteristic golden brown color and the histopathologic pattern of inflammation.1 Lichen aureus usually presents as a unilateral, asymptomatic, confined single lesion located mainly on the leg,1 though it can develop at other sites or as a localized group of lesions. Extensive lesions have been reported5 and cases with a segmental distribution have been described.6 In contrast, Schamberg disease demonstrates pinhead-sized reddish lesions giving the characteristic cayenne pepper pigmentation. These lesions coalesce to form thumbprint patches that progress proximally.1 Majocchi purpura is annular and telangiectatic, while lichenoid purpura of Gougerot and Blum presents with flat-topped, polygonal, violaceous papules that turn brown over time.

Some authors have championed a role for dermoscopy in diagnosis of LA.7 By dermoscopy, LA demonstrates a diffuse copper background reflecting the lymphohistiocytic dermal infiltrate, red dots and globules representing the extravasated red blood cells and the dilated swollen vessels, and grey dots that reflect the hemosiderin present in the dermis.8

Histologically, LA demonstrates a superficial perivascular infiltrate composed mainly of CD4+ lymphocytes surrounding the superficial capillaries. Over time, red cell extravasation leads to the formation of hemosiderin-laden macrophages, which can be highlighted with Perls Prussian blue stain. A bandlike infiltrate with thin strands of collagen separating it from the epidermis also may be noted.9

An important consideration in the differential diagnosis of PPD is mycosis fungoides (MF). Mycosis fungoides is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that clinically presents as a single or multiple hypopigmented or hyperpigmented patches or as erythematous scaly lesions in the patch or plaque stage. These lesions eventually may evolve into tumor stage.10 Mycosis fungoides may mimic PPD clinically and/or histopathologically, and rarely PPD also may precede MF.11 Involvement of the trunk, especially the lower abdomen and buttock region, favors a diagnosis of MF. Typically, histopathologic examination of MF demonstrates an epidermotropic lymphocytic infiltrate composed of atypical cerebriform lymphocytes overlying papillary dermal fibrosis. Although classic MF would be difficult to confuse with PPD, the atrophic lichenoid pattern of MF may show remarkable overlap with PPD.12 Such cases require clinicopathologic correlation, immunophenotyping of the epidermotropic lymphocytes, and occasionally T-cell clonality studies.

Lichen aureus is a chronic persistent disease unless the underlying incompetent perforator vessel is ligated. Various treatments have been used for other forms of pigmented purpura including topical corticosteroids, topical tacrolimus, systemic vasodilators such as prostacyclin and pentoxifylline, and phototherapy.1 Clinical follow-up is recommended for lesions that show some clinical or histopathological overlap with MF. Additional biopsies also may prove useful in establishing a definitive diagnosis in ambiguous cases.

- Sardana K, Sarkar R, Sehgal VN. Pigmented purpuric dermatoses: an overview. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:482-488.

- Newton RC, Raimer SS. Pigmented purpuric eruptions. Dermatol Clin. 1985;3:165-169.

- Aiba S, Tagami H. Immunohistologic studies in Schamberg's disease. evidence for cellular immune reaction in lesional skin. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1058-1062.

- English J. Lichen aureus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12(2, pt 1):377-379.

- Duhra P, Tan CY. Lichen aureus. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:395.

- Moche J, Glassman S, Modi D, et al. Segmental lichen aureus: a report of two cases treated with methylprednisolone aceponate. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:E15-E18.

- Zaballos P, Puig S, Malvehy J. Dermoscopy of pigmented purpuric dermatoses (lichen aureus): a useful tool for clinical diagnosis. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1290-1291.

- Portela PS, Melo DF, Ormiga P, et al. Dermoscopy of lichen aureus. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:253-255.

- Smoller BR, Kamel OW. Pigmented purpuric eruptions: immunopathologic studies supportive of a common immunophenotype. J Cutan Pathol. 1991;18:423-427.

- Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Diebold J, et al. World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. a progress report. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;111(1 suppl 1):S8-S12.

- Hanna S, Walsh N, D'Intino Y, et al. Mycosis fungoides presenting as pigmented purpuric dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:350-354.

- Toro JR, Sander CA, LeBoit PE. Persistent pigmented purpuric dermatitis and mycosis fungoides: simulant, precursor, or both? a study by light microscopy and molecular methods. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:108-118.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Aureus

The clinicopathological findings were diagnostic of lichen aureus (LA). Microscopic examination revealed a relatively sparse, superficial, perivascular and interstitial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with scattered siderophages in the upper dermis. Extravasation of red blood cells also was noted (Figure 1). An immunohistochemical stain for Melan-A highlighted a normal number and distribution of single melanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction with no evidence of pagetoid scatter. A Perls Prussian blue stain for iron demonstrated abundant hemosiderin in the dermis (Figure 2).

Pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD) describes a group of cutaneous lesions that are characterized by petechiae and pigmentary changes. These lesions most commonly present on the lower limbs; however, other sites have been reported.1 This group includes several major clinical forms such as Schamberg disease, LA, purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi, eczematidlike purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis, and lichenoid PPD of Gougerot and Blum. Lesions typically demonstrate a striking golden brown color clinically and by definition occur in the absence of platelet defects or vasculitis.1

Factors implicated in the pathogenesis of pigmented purpura include gravitational dependency, venous stasis, infection, and drugs.2 It is suggested that cellular immunity may play a role in the development of the disease based on the presence of CD4+ T lymphocytes in the infiltrate and the expression of HLA-DR by these lymphocytes and the keratinocytes.3 Lichen aureus differs in that it relates to increased intravascular pressure from an incompetent valve in an underlying perforating vein.4

Lichen aureus, also referred to as lichen purpuricus, is one major variant of PPD. The name reflects both the characteristic golden brown color and the histopathologic pattern of inflammation.1 Lichen aureus usually presents as a unilateral, asymptomatic, confined single lesion located mainly on the leg,1 though it can develop at other sites or as a localized group of lesions. Extensive lesions have been reported5 and cases with a segmental distribution have been described.6 In contrast, Schamberg disease demonstrates pinhead-sized reddish lesions giving the characteristic cayenne pepper pigmentation. These lesions coalesce to form thumbprint patches that progress proximally.1 Majocchi purpura is annular and telangiectatic, while lichenoid purpura of Gougerot and Blum presents with flat-topped, polygonal, violaceous papules that turn brown over time.

Some authors have championed a role for dermoscopy in diagnosis of LA.7 By dermoscopy, LA demonstrates a diffuse copper background reflecting the lymphohistiocytic dermal infiltrate, red dots and globules representing the extravasated red blood cells and the dilated swollen vessels, and grey dots that reflect the hemosiderin present in the dermis.8

Histologically, LA demonstrates a superficial perivascular infiltrate composed mainly of CD4+ lymphocytes surrounding the superficial capillaries. Over time, red cell extravasation leads to the formation of hemosiderin-laden macrophages, which can be highlighted with Perls Prussian blue stain. A bandlike infiltrate with thin strands of collagen separating it from the epidermis also may be noted.9

An important consideration in the differential diagnosis of PPD is mycosis fungoides (MF). Mycosis fungoides is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that clinically presents as a single or multiple hypopigmented or hyperpigmented patches or as erythematous scaly lesions in the patch or plaque stage. These lesions eventually may evolve into tumor stage.10 Mycosis fungoides may mimic PPD clinically and/or histopathologically, and rarely PPD also may precede MF.11 Involvement of the trunk, especially the lower abdomen and buttock region, favors a diagnosis of MF. Typically, histopathologic examination of MF demonstrates an epidermotropic lymphocytic infiltrate composed of atypical cerebriform lymphocytes overlying papillary dermal fibrosis. Although classic MF would be difficult to confuse with PPD, the atrophic lichenoid pattern of MF may show remarkable overlap with PPD.12 Such cases require clinicopathologic correlation, immunophenotyping of the epidermotropic lymphocytes, and occasionally T-cell clonality studies.

Lichen aureus is a chronic persistent disease unless the underlying incompetent perforator vessel is ligated. Various treatments have been used for other forms of pigmented purpura including topical corticosteroids, topical tacrolimus, systemic vasodilators such as prostacyclin and pentoxifylline, and phototherapy.1 Clinical follow-up is recommended for lesions that show some clinical or histopathological overlap with MF. Additional biopsies also may prove useful in establishing a definitive diagnosis in ambiguous cases.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Aureus

The clinicopathological findings were diagnostic of lichen aureus (LA). Microscopic examination revealed a relatively sparse, superficial, perivascular and interstitial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with scattered siderophages in the upper dermis. Extravasation of red blood cells also was noted (Figure 1). An immunohistochemical stain for Melan-A highlighted a normal number and distribution of single melanocytes at the dermoepidermal junction with no evidence of pagetoid scatter. A Perls Prussian blue stain for iron demonstrated abundant hemosiderin in the dermis (Figure 2).

Pigmented purpuric dermatosis (PPD) describes a group of cutaneous lesions that are characterized by petechiae and pigmentary changes. These lesions most commonly present on the lower limbs; however, other sites have been reported.1 This group includes several major clinical forms such as Schamberg disease, LA, purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi, eczematidlike purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis, and lichenoid PPD of Gougerot and Blum. Lesions typically demonstrate a striking golden brown color clinically and by definition occur in the absence of platelet defects or vasculitis.1

Factors implicated in the pathogenesis of pigmented purpura include gravitational dependency, venous stasis, infection, and drugs.2 It is suggested that cellular immunity may play a role in the development of the disease based on the presence of CD4+ T lymphocytes in the infiltrate and the expression of HLA-DR by these lymphocytes and the keratinocytes.3 Lichen aureus differs in that it relates to increased intravascular pressure from an incompetent valve in an underlying perforating vein.4

Lichen aureus, also referred to as lichen purpuricus, is one major variant of PPD. The name reflects both the characteristic golden brown color and the histopathologic pattern of inflammation.1 Lichen aureus usually presents as a unilateral, asymptomatic, confined single lesion located mainly on the leg,1 though it can develop at other sites or as a localized group of lesions. Extensive lesions have been reported5 and cases with a segmental distribution have been described.6 In contrast, Schamberg disease demonstrates pinhead-sized reddish lesions giving the characteristic cayenne pepper pigmentation. These lesions coalesce to form thumbprint patches that progress proximally.1 Majocchi purpura is annular and telangiectatic, while lichenoid purpura of Gougerot and Blum presents with flat-topped, polygonal, violaceous papules that turn brown over time.

Some authors have championed a role for dermoscopy in diagnosis of LA.7 By dermoscopy, LA demonstrates a diffuse copper background reflecting the lymphohistiocytic dermal infiltrate, red dots and globules representing the extravasated red blood cells and the dilated swollen vessels, and grey dots that reflect the hemosiderin present in the dermis.8

Histologically, LA demonstrates a superficial perivascular infiltrate composed mainly of CD4+ lymphocytes surrounding the superficial capillaries. Over time, red cell extravasation leads to the formation of hemosiderin-laden macrophages, which can be highlighted with Perls Prussian blue stain. A bandlike infiltrate with thin strands of collagen separating it from the epidermis also may be noted.9

An important consideration in the differential diagnosis of PPD is mycosis fungoides (MF). Mycosis fungoides is a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma that clinically presents as a single or multiple hypopigmented or hyperpigmented patches or as erythematous scaly lesions in the patch or plaque stage. These lesions eventually may evolve into tumor stage.10 Mycosis fungoides may mimic PPD clinically and/or histopathologically, and rarely PPD also may precede MF.11 Involvement of the trunk, especially the lower abdomen and buttock region, favors a diagnosis of MF. Typically, histopathologic examination of MF demonstrates an epidermotropic lymphocytic infiltrate composed of atypical cerebriform lymphocytes overlying papillary dermal fibrosis. Although classic MF would be difficult to confuse with PPD, the atrophic lichenoid pattern of MF may show remarkable overlap with PPD.12 Such cases require clinicopathologic correlation, immunophenotyping of the epidermotropic lymphocytes, and occasionally T-cell clonality studies.

Lichen aureus is a chronic persistent disease unless the underlying incompetent perforator vessel is ligated. Various treatments have been used for other forms of pigmented purpura including topical corticosteroids, topical tacrolimus, systemic vasodilators such as prostacyclin and pentoxifylline, and phototherapy.1 Clinical follow-up is recommended for lesions that show some clinical or histopathological overlap with MF. Additional biopsies also may prove useful in establishing a definitive diagnosis in ambiguous cases.

- Sardana K, Sarkar R, Sehgal VN. Pigmented purpuric dermatoses: an overview. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:482-488.

- Newton RC, Raimer SS. Pigmented purpuric eruptions. Dermatol Clin. 1985;3:165-169.

- Aiba S, Tagami H. Immunohistologic studies in Schamberg's disease. evidence for cellular immune reaction in lesional skin. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1058-1062.

- English J. Lichen aureus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12(2, pt 1):377-379.

- Duhra P, Tan CY. Lichen aureus. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:395.

- Moche J, Glassman S, Modi D, et al. Segmental lichen aureus: a report of two cases treated with methylprednisolone aceponate. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:E15-E18.

- Zaballos P, Puig S, Malvehy J. Dermoscopy of pigmented purpuric dermatoses (lichen aureus): a useful tool for clinical diagnosis. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1290-1291.

- Portela PS, Melo DF, Ormiga P, et al. Dermoscopy of lichen aureus. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:253-255.

- Smoller BR, Kamel OW. Pigmented purpuric eruptions: immunopathologic studies supportive of a common immunophenotype. J Cutan Pathol. 1991;18:423-427.

- Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Diebold J, et al. World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. a progress report. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;111(1 suppl 1):S8-S12.

- Hanna S, Walsh N, D'Intino Y, et al. Mycosis fungoides presenting as pigmented purpuric dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:350-354.

- Toro JR, Sander CA, LeBoit PE. Persistent pigmented purpuric dermatitis and mycosis fungoides: simulant, precursor, or both? a study by light microscopy and molecular methods. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:108-118.

- Sardana K, Sarkar R, Sehgal VN. Pigmented purpuric dermatoses: an overview. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:482-488.

- Newton RC, Raimer SS. Pigmented purpuric eruptions. Dermatol Clin. 1985;3:165-169.

- Aiba S, Tagami H. Immunohistologic studies in Schamberg's disease. evidence for cellular immune reaction in lesional skin. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1058-1062.

- English J. Lichen aureus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12(2, pt 1):377-379.

- Duhra P, Tan CY. Lichen aureus. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:395.

- Moche J, Glassman S, Modi D, et al. Segmental lichen aureus: a report of two cases treated with methylprednisolone aceponate. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:E15-E18.

- Zaballos P, Puig S, Malvehy J. Dermoscopy of pigmented purpuric dermatoses (lichen aureus): a useful tool for clinical diagnosis. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1290-1291.

- Portela PS, Melo DF, Ormiga P, et al. Dermoscopy of lichen aureus. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:253-255.

- Smoller BR, Kamel OW. Pigmented purpuric eruptions: immunopathologic studies supportive of a common immunophenotype. J Cutan Pathol. 1991;18:423-427.

- Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Diebold J, et al. World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. a progress report. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;111(1 suppl 1):S8-S12.

- Hanna S, Walsh N, D'Intino Y, et al. Mycosis fungoides presenting as pigmented purpuric dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:350-354.

- Toro JR, Sander CA, LeBoit PE. Persistent pigmented purpuric dermatitis and mycosis fungoides: simulant, precursor, or both? a study by light microscopy and molecular methods. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997;19:108-118.

A 32-year-old man presented with an asymptomatic pigmented lesion on the left foot that developed over the course of 4 months. Physical examination revealed a 4-cm asymmetrical, deeply pigmented macule on the left foot. A shave biopsy of the lesion was performed.

Flesh-Colored Nodule With Underlying Sclerotic Plaque

The Diagnosis: Collision Tumor

Excisional biopsy and histopathological examination demonstrated a collision tumor composed of a benign intradermal melanocytic nevus, tumor of follicular infundibulum, and an underlying sclerosing epithelial neoplasm, with a differential diagnosis of desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, and microcystic adnexal carcinoma (Figure).