User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Cutaneous Cholesterol Embolization to the Lower Trunk: An Underrecognized Presentation

To the Editor:

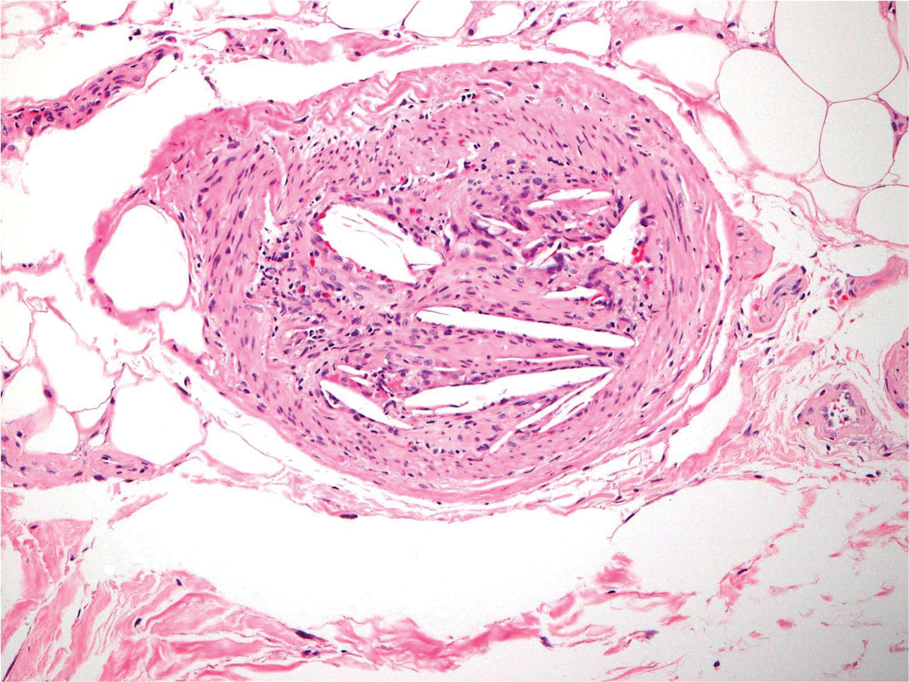

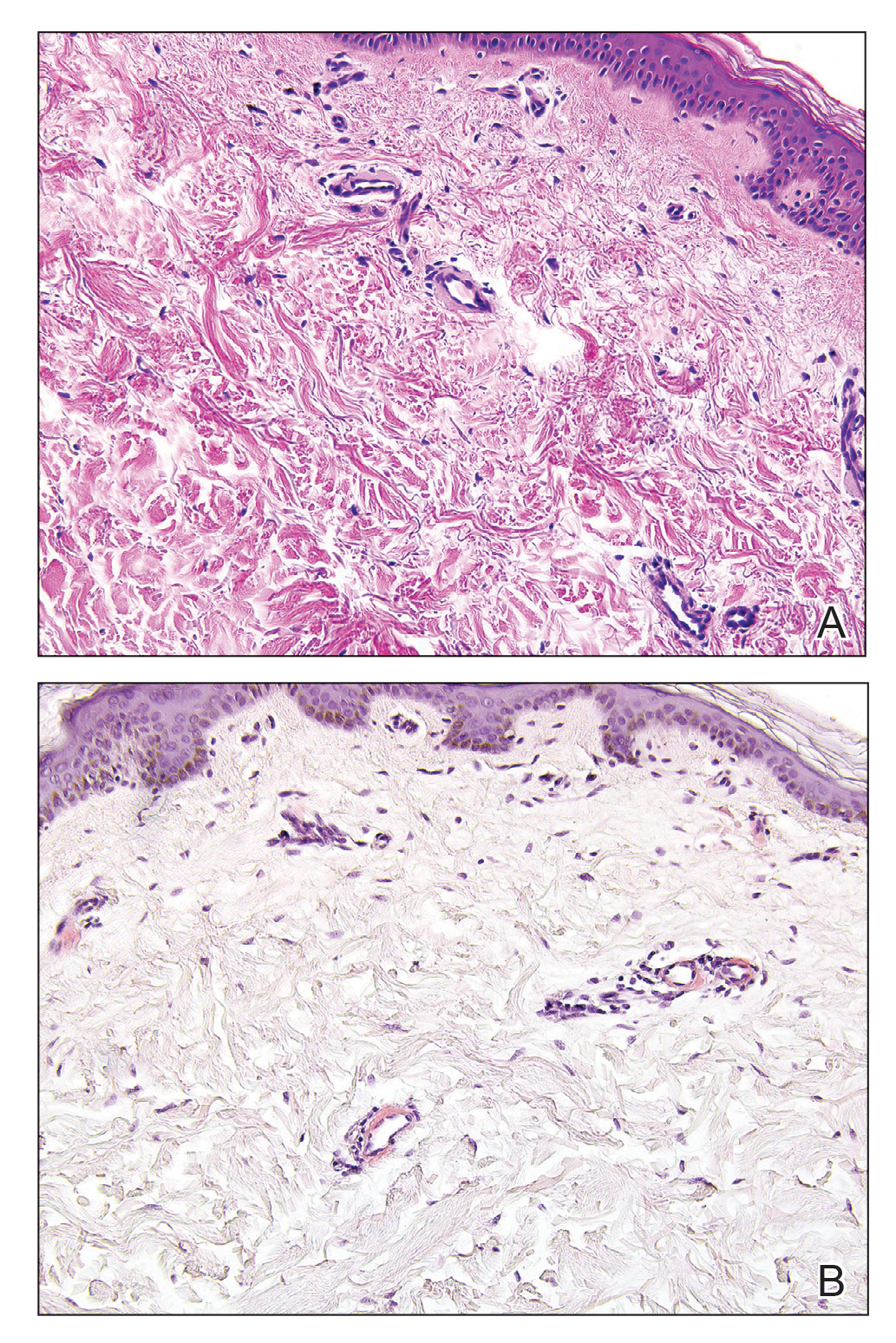

A 65-year-old man with severe atherosclerotic disease developed multiple painful eschars on the lower abdomen, thighs, sacrum, and perineum. He initially presented with myocardial ischemia and claudication and underwent 3 cardiac catheterizations as well as stenting of the superficial femoral artery. Within 2 weeks, he developed exquisitely tender nodules on the lower abdomen, clinically presumed to be sites of enoxaparin injections. These lesions gradually expanded and ulcerated to involve the sacrum, buttock, perineum, and upper thighs (Figure 1). Two punch biopsies from ulcerated skin taken 10 days apart demonstrated necrosis of skin and subcutaneous fat without evidence of vasculitis, vasculopathy, emboli, or notable inflammation despite examination of multiple levels of all submitted tissue. A definitive cause for the ulcerations remained elusive with development of new lesions. A third incisional biopsy of a newly developed, nonulcerated, subcutaneous nodule performed 8 weeks after presentation revealed multiple cholesterol emboli (Figure 2). He was treated with warfarin and clopidogrel bisulfate as well as local wound care. The lesions slowly resolved over the next 4 to 6 months.

Cholesterol embolization syndrome occurs when disrupted atherosclerotic plaques embolize from large proximal arteries to more distal arterioles, resulting in ischemic damage to 1 or more organ systems.1 It can occur spontaneously but often is a consequence of thrombolytic therapy, anticoagulation, and angioinvasive procedures.2,3 Cutaneous manifestations include livedo reticularis, retiform purpura, nodules, and gangrene. Although livedo reticularis may extend from the legs to the trunk, gangrenous lesions predominantly involve the distal digits.

This case illustrates the challenge in diagnosis of cholesterol emboli, both clinically and histologically. Cutaneous lesions are morphologically variable and often occur with systemic manifestations, mimicking numerous conditions.1 Lower extremity involvement is a well-known occurrence in cholesterol embolization (ie, blue toe syndrome); however, periumbilical and lumbosacral lesions have not been emphasized in the dermatologic or peripheral vascular literature. Our patient’s initial diagnosis was enoxaparin necrosis at abdominal injection sites; however, this unusual distribution of lesions was ultimately determined to be the consequence of cholesterol embolization from the inferior epigastric and superficial external pudendal arteries at the time of stenting of the superficial femoral artery. Proximal truncal involvement should be recognized as an atypical but important cutaneous manifestation to facilitate timely diagnosis and treatment.4,5

Our patient’s course also highlights the potential need for multiple biopsies. Although the gold standard for diagnosis is histologic confirmation, a negative biopsy does not always exclude cholesterol emboli, and one should have a low threshold to perform additional biopsies in the appropriate clinical setting.

- Fine MJ, Kapoor W, Falanga V. Cholesterol crystal embolization: a review of 221 cases in the English literature. Angiology. 1987;38:769-784.

- Fukumoto Y, Tsutsui H, Tsuchihashi M, et al. The incidence and risk factors of cholesterol embolization syndrome, a complication of cardiac catheterization: a prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:211-216.

- Karalis DG, Chandrasekaran K, Victor MF, et al. Recognition and embolic potential of intraaortic atherosclerotic debris. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:73.

- Zaytsev P, Miller K, Pellettiere EV. Cutaneous cholesterol emboli with infarction clinically mimicking heparin necrosis—a case report. Angiology. 1986;37:471-476.

- Erdim M, Tezel E, Biskin N. A case of skin necrosis as a result of cholesterol crystal embolisation. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:429-432.

To the Editor:

A 65-year-old man with severe atherosclerotic disease developed multiple painful eschars on the lower abdomen, thighs, sacrum, and perineum. He initially presented with myocardial ischemia and claudication and underwent 3 cardiac catheterizations as well as stenting of the superficial femoral artery. Within 2 weeks, he developed exquisitely tender nodules on the lower abdomen, clinically presumed to be sites of enoxaparin injections. These lesions gradually expanded and ulcerated to involve the sacrum, buttock, perineum, and upper thighs (Figure 1). Two punch biopsies from ulcerated skin taken 10 days apart demonstrated necrosis of skin and subcutaneous fat without evidence of vasculitis, vasculopathy, emboli, or notable inflammation despite examination of multiple levels of all submitted tissue. A definitive cause for the ulcerations remained elusive with development of new lesions. A third incisional biopsy of a newly developed, nonulcerated, subcutaneous nodule performed 8 weeks after presentation revealed multiple cholesterol emboli (Figure 2). He was treated with warfarin and clopidogrel bisulfate as well as local wound care. The lesions slowly resolved over the next 4 to 6 months.

Cholesterol embolization syndrome occurs when disrupted atherosclerotic plaques embolize from large proximal arteries to more distal arterioles, resulting in ischemic damage to 1 or more organ systems.1 It can occur spontaneously but often is a consequence of thrombolytic therapy, anticoagulation, and angioinvasive procedures.2,3 Cutaneous manifestations include livedo reticularis, retiform purpura, nodules, and gangrene. Although livedo reticularis may extend from the legs to the trunk, gangrenous lesions predominantly involve the distal digits.

This case illustrates the challenge in diagnosis of cholesterol emboli, both clinically and histologically. Cutaneous lesions are morphologically variable and often occur with systemic manifestations, mimicking numerous conditions.1 Lower extremity involvement is a well-known occurrence in cholesterol embolization (ie, blue toe syndrome); however, periumbilical and lumbosacral lesions have not been emphasized in the dermatologic or peripheral vascular literature. Our patient’s initial diagnosis was enoxaparin necrosis at abdominal injection sites; however, this unusual distribution of lesions was ultimately determined to be the consequence of cholesterol embolization from the inferior epigastric and superficial external pudendal arteries at the time of stenting of the superficial femoral artery. Proximal truncal involvement should be recognized as an atypical but important cutaneous manifestation to facilitate timely diagnosis and treatment.4,5

Our patient’s course also highlights the potential need for multiple biopsies. Although the gold standard for diagnosis is histologic confirmation, a negative biopsy does not always exclude cholesterol emboli, and one should have a low threshold to perform additional biopsies in the appropriate clinical setting.

To the Editor:

A 65-year-old man with severe atherosclerotic disease developed multiple painful eschars on the lower abdomen, thighs, sacrum, and perineum. He initially presented with myocardial ischemia and claudication and underwent 3 cardiac catheterizations as well as stenting of the superficial femoral artery. Within 2 weeks, he developed exquisitely tender nodules on the lower abdomen, clinically presumed to be sites of enoxaparin injections. These lesions gradually expanded and ulcerated to involve the sacrum, buttock, perineum, and upper thighs (Figure 1). Two punch biopsies from ulcerated skin taken 10 days apart demonstrated necrosis of skin and subcutaneous fat without evidence of vasculitis, vasculopathy, emboli, or notable inflammation despite examination of multiple levels of all submitted tissue. A definitive cause for the ulcerations remained elusive with development of new lesions. A third incisional biopsy of a newly developed, nonulcerated, subcutaneous nodule performed 8 weeks after presentation revealed multiple cholesterol emboli (Figure 2). He was treated with warfarin and clopidogrel bisulfate as well as local wound care. The lesions slowly resolved over the next 4 to 6 months.

Cholesterol embolization syndrome occurs when disrupted atherosclerotic plaques embolize from large proximal arteries to more distal arterioles, resulting in ischemic damage to 1 or more organ systems.1 It can occur spontaneously but often is a consequence of thrombolytic therapy, anticoagulation, and angioinvasive procedures.2,3 Cutaneous manifestations include livedo reticularis, retiform purpura, nodules, and gangrene. Although livedo reticularis may extend from the legs to the trunk, gangrenous lesions predominantly involve the distal digits.

This case illustrates the challenge in diagnosis of cholesterol emboli, both clinically and histologically. Cutaneous lesions are morphologically variable and often occur with systemic manifestations, mimicking numerous conditions.1 Lower extremity involvement is a well-known occurrence in cholesterol embolization (ie, blue toe syndrome); however, periumbilical and lumbosacral lesions have not been emphasized in the dermatologic or peripheral vascular literature. Our patient’s initial diagnosis was enoxaparin necrosis at abdominal injection sites; however, this unusual distribution of lesions was ultimately determined to be the consequence of cholesterol embolization from the inferior epigastric and superficial external pudendal arteries at the time of stenting of the superficial femoral artery. Proximal truncal involvement should be recognized as an atypical but important cutaneous manifestation to facilitate timely diagnosis and treatment.4,5

Our patient’s course also highlights the potential need for multiple biopsies. Although the gold standard for diagnosis is histologic confirmation, a negative biopsy does not always exclude cholesterol emboli, and one should have a low threshold to perform additional biopsies in the appropriate clinical setting.

- Fine MJ, Kapoor W, Falanga V. Cholesterol crystal embolization: a review of 221 cases in the English literature. Angiology. 1987;38:769-784.

- Fukumoto Y, Tsutsui H, Tsuchihashi M, et al. The incidence and risk factors of cholesterol embolization syndrome, a complication of cardiac catheterization: a prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:211-216.

- Karalis DG, Chandrasekaran K, Victor MF, et al. Recognition and embolic potential of intraaortic atherosclerotic debris. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:73.

- Zaytsev P, Miller K, Pellettiere EV. Cutaneous cholesterol emboli with infarction clinically mimicking heparin necrosis—a case report. Angiology. 1986;37:471-476.

- Erdim M, Tezel E, Biskin N. A case of skin necrosis as a result of cholesterol crystal embolisation. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:429-432.

- Fine MJ, Kapoor W, Falanga V. Cholesterol crystal embolization: a review of 221 cases in the English literature. Angiology. 1987;38:769-784.

- Fukumoto Y, Tsutsui H, Tsuchihashi M, et al. The incidence and risk factors of cholesterol embolization syndrome, a complication of cardiac catheterization: a prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:211-216.

- Karalis DG, Chandrasekaran K, Victor MF, et al. Recognition and embolic potential of intraaortic atherosclerotic debris. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:73.

- Zaytsev P, Miller K, Pellettiere EV. Cutaneous cholesterol emboli with infarction clinically mimicking heparin necrosis—a case report. Angiology. 1986;37:471-476.

- Erdim M, Tezel E, Biskin N. A case of skin necrosis as a result of cholesterol crystal embolisation. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2006;59:429-432.

Practice Points

- Cholesterol embolization may occur in proximal locations, and index of suspicion should be high in patients who are at risk.

- Several biopsies may be necessary to make a diagnosis of cholesterol emboli.

Candida Esophagitis Associated With Adalimumab for Hidradenitis Suppurativa

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by the development of painful abscesses, fistulous tracts, and scars. It most commonly affects the apocrine gland–bearing areas of the body such as the axillary, inguinal, and anogenital regions. With a prevalence of approximately 1%, HS can lead to notable morbidity.1 The pathogenesis is thought to be due to occlusion of terminal hair follicles that subsequently stimulates release of proinflammatory cytokines from nearby keratinocytes. The mechanism of initial occlusion is not well understood but may be due to friction or trauma. An inflammatory mechanism of disease also has been hypothesized; however, the exact cytokine profile is not known. Treatment of HS consists of several different modalities, including oral retinoids, antibiotics, antiandrogenic therapy, and surgery.1,2 Adalimumab is a well-known biologic that has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HS.

Adalimumab is a human monoclonal antibody against tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α and is thought to improve HS by several mechanisms. Inhibition of TNF-α and other proinflammatory cytokines found in inflammatory lesions and apocrine glands directly decreases the severity of lesion size and the frequency of recurrence.3 Adalimumab also is thought to downregulate expression of keratin 6 and prevent the hyperkeratinization seen in HS.4 Additionally, TNF-α inhibition decreases production of IL-1, which has been shown to cause hypercornification of follicles and perpetuate HS pathogenesis.5

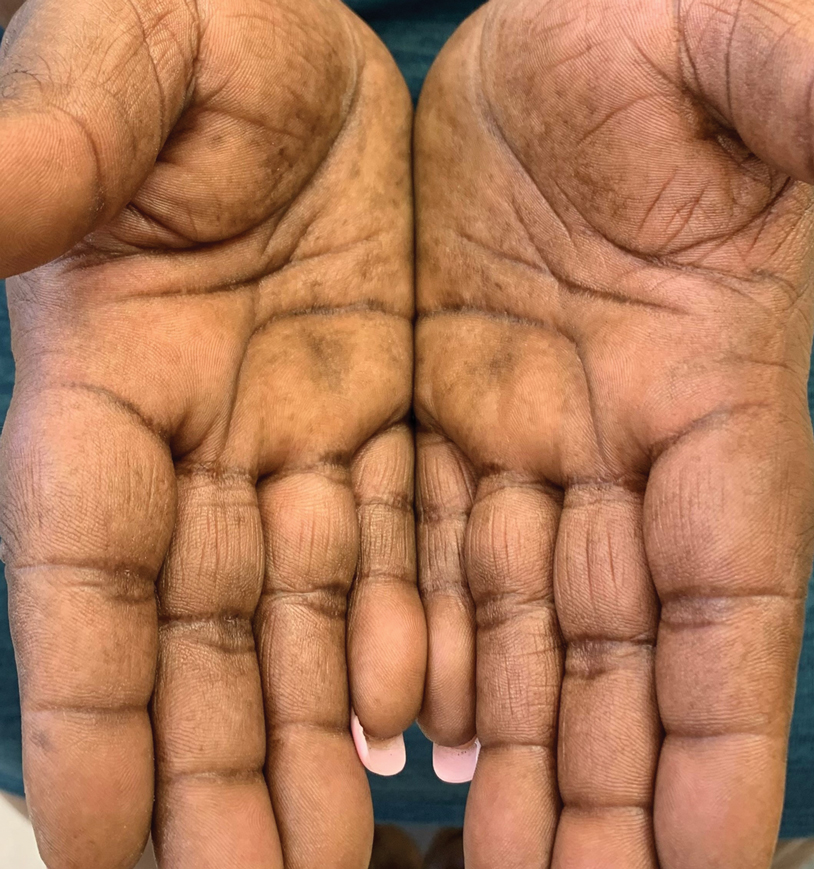

A 41-year-old woman with a history of endometriosis, adenomyosis, polycystic ovary syndrome, interstitial cystitis, asthma, fibromyalgia, depression, and Hashimoto thyroiditis presented to our dermatology clinic with active draining lesions and sinus tracts in the perivaginal area that were consistent with HS, which initially was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. She experienced minimal improvement of the HS lesions at 2-month follow-up.

Due to disease severity, adalimumab was started. The patient received a loading dose of 4 injections totaling 160 mg and 80 mg on day 15, followed by a maintenance dose of 40 mg/0.4 mL weekly. The patient reported substantial improvement of pain, and complete resolution of active lesions was noted on physical examination after 4 weeks of treatment with adalimumab.

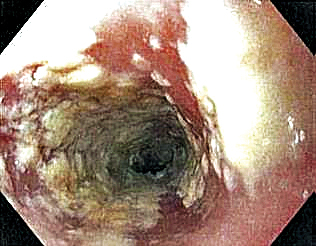

Six weeks after adalimumab was started, the patient developed severe dysphagia. She was evaluated by a gastroenterologist and underwent endoscopy (Figure), which led to a diagnosis of esophageal candidiasis. Adalimumab was discontinued immediately thereafter. The patient started treatment with nystatin oral rinse 4 times daily and oral fluconazole 200 mg daily. The candidiasis resolved within 2 weeks; however, she experienced recurrence of HS with draining lesions in the perivaginal area approximately 8 weeks after discontinuation of adalimumab. The patient requested to restart adalimumab treatment despite the recent history of esophagitis. Adalimumab 40 mg/0.4 mL weekly was restarted along with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice weekly and nystatin oral rinse 4 times daily. This regimen resulted in complete resolution of HS symptoms within 6 weeks with no recurrence of esophageal candidiasis during 6 months of follow-up.

Although the side effect of Candida esophagitis associated with adalimumab treatment in our patient may be logical given the medication’s mechanism of action and side-effect profile, this case warrants additional attention. An increase in fungal infections occurs from treatment with adalimumab because TNF-α is involved in many immune regulatory steps that counteract infection. Candida typically activates the innate immune system through macrophages via pathogen-associated molecular pattern stimulation, subsequently stimulating the release of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α. The cellular immune system also is activated. Helper T cells (TH1) release TNF-α along with other proinflammatory cytokines to increase phagocytosis in polymorphonuclear cells and macrophages.6 Thus, inhibition of TNF-α compromises innate and cellular immunity, thereby increasing susceptibility to fungal organisms.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Candida, candidiasis, esophageal, adalimumab, anti-TNF, and TNF revealed no reports of esophageal candidiasis in patients receiving adalimumab or any of the TNF inhibitors. Candida laryngitis was reported in a patient receiving adalimumab for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.7 Other studies have demonstrated an incidence of mucocutaneous candidiasis, most notably oropharyngeal and vaginal candidiasis.8-10 One study found that anti-TNF medications were associated with an increased risk for candidiasis by a hazard ratio of 2.7 in patients with Crohn disease.8 Other studies have shown that the highest incidence of fungal infection is seen with the use of infliximab, while adalimumab is associated with lower rates of fungal infection.9,10 Although it is known that anti-TNF therapy predisposes patients to fungal infection, the dose of medication known to preclude the highest risk has not been studied. Furthermore, most studies assess rates of Candida infection in individuals receiving anti-TNF therapy in addition to several other immunosuppressant agents (ie, corticosteroids), which confounds the interpretation of results. Additional studies assessing rates of Candida and other opportunistic infections associated with use of adalimumab alone are needed to better guide clinical practices in dermatology.

Patients receiving adalimumab for dermatologic or other conditions should be closely monitored for opportunistic infections. Although immunomodulatory medications offer promising therapeutic benefits in patients with HS, larger studies regarding treatment with anti-TNF agents in HS are warranted to prevent complications from treatment and promote long-term efficacy and safety.

- Kurayev A, Ashkar H, Saraiya A, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: review of the pathogenesis and treatment. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:1107-1022.

- Rambhatla PV, Lim HW, Hamzavi I. A systematic review of treatments for hidradenitis suppurativa. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:439-446.

- van der Zee HH, de Ruiter L, van den Broecke DG, et al. Elevated levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, interleukin (IL)-1beta and IL-10 in hidradenitis suppurativa skin: a rationale for targeting TNF-alpha and IL-1beta. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1292-1298.

- Shuja F, Chan CS, Rosen T. Biologic drugs for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: an evidence-based review. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:511-521, 523-514.

- Kutsch CL, Norris DA, Arend WP. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces interleukin-1 alpha and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist production by cultured human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101:79-85.

- Senet JM. Risk factors and physiopathology of candidiasis. Rev Iberoam Micol. 1997;14:6-13.

- Kobak S, Yilmaz H, Guclu O, et al. Severe candida laryngitis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis treated with adalimumab. Eur J Rheumatol. 2014;1:167-169.

- Marehbian J, Arrighi HM, Hass S, et al. Adverse events associated with common therapy regimens for moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2524-2533.

- Tsiodras S, Samonis G, Boumpas DT, et al. Fungal infections complicating tumor necrosis factor alpha blockade therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:181-194.

- Aikawa NE, Rosa DT, Del Negro GM, et al. Systemic and localized infection by Candida species in patients with rheumatic diseases receiving anti-TNF therapy [in Portuguese]. Rev Bras Reumatol. doi:10.1016/j.rbr.2015.03.010

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by the development of painful abscesses, fistulous tracts, and scars. It most commonly affects the apocrine gland–bearing areas of the body such as the axillary, inguinal, and anogenital regions. With a prevalence of approximately 1%, HS can lead to notable morbidity.1 The pathogenesis is thought to be due to occlusion of terminal hair follicles that subsequently stimulates release of proinflammatory cytokines from nearby keratinocytes. The mechanism of initial occlusion is not well understood but may be due to friction or trauma. An inflammatory mechanism of disease also has been hypothesized; however, the exact cytokine profile is not known. Treatment of HS consists of several different modalities, including oral retinoids, antibiotics, antiandrogenic therapy, and surgery.1,2 Adalimumab is a well-known biologic that has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HS.

Adalimumab is a human monoclonal antibody against tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α and is thought to improve HS by several mechanisms. Inhibition of TNF-α and other proinflammatory cytokines found in inflammatory lesions and apocrine glands directly decreases the severity of lesion size and the frequency of recurrence.3 Adalimumab also is thought to downregulate expression of keratin 6 and prevent the hyperkeratinization seen in HS.4 Additionally, TNF-α inhibition decreases production of IL-1, which has been shown to cause hypercornification of follicles and perpetuate HS pathogenesis.5

A 41-year-old woman with a history of endometriosis, adenomyosis, polycystic ovary syndrome, interstitial cystitis, asthma, fibromyalgia, depression, and Hashimoto thyroiditis presented to our dermatology clinic with active draining lesions and sinus tracts in the perivaginal area that were consistent with HS, which initially was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. She experienced minimal improvement of the HS lesions at 2-month follow-up.

Due to disease severity, adalimumab was started. The patient received a loading dose of 4 injections totaling 160 mg and 80 mg on day 15, followed by a maintenance dose of 40 mg/0.4 mL weekly. The patient reported substantial improvement of pain, and complete resolution of active lesions was noted on physical examination after 4 weeks of treatment with adalimumab.

Six weeks after adalimumab was started, the patient developed severe dysphagia. She was evaluated by a gastroenterologist and underwent endoscopy (Figure), which led to a diagnosis of esophageal candidiasis. Adalimumab was discontinued immediately thereafter. The patient started treatment with nystatin oral rinse 4 times daily and oral fluconazole 200 mg daily. The candidiasis resolved within 2 weeks; however, she experienced recurrence of HS with draining lesions in the perivaginal area approximately 8 weeks after discontinuation of adalimumab. The patient requested to restart adalimumab treatment despite the recent history of esophagitis. Adalimumab 40 mg/0.4 mL weekly was restarted along with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice weekly and nystatin oral rinse 4 times daily. This regimen resulted in complete resolution of HS symptoms within 6 weeks with no recurrence of esophageal candidiasis during 6 months of follow-up.

Although the side effect of Candida esophagitis associated with adalimumab treatment in our patient may be logical given the medication’s mechanism of action and side-effect profile, this case warrants additional attention. An increase in fungal infections occurs from treatment with adalimumab because TNF-α is involved in many immune regulatory steps that counteract infection. Candida typically activates the innate immune system through macrophages via pathogen-associated molecular pattern stimulation, subsequently stimulating the release of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α. The cellular immune system also is activated. Helper T cells (TH1) release TNF-α along with other proinflammatory cytokines to increase phagocytosis in polymorphonuclear cells and macrophages.6 Thus, inhibition of TNF-α compromises innate and cellular immunity, thereby increasing susceptibility to fungal organisms.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Candida, candidiasis, esophageal, adalimumab, anti-TNF, and TNF revealed no reports of esophageal candidiasis in patients receiving adalimumab or any of the TNF inhibitors. Candida laryngitis was reported in a patient receiving adalimumab for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.7 Other studies have demonstrated an incidence of mucocutaneous candidiasis, most notably oropharyngeal and vaginal candidiasis.8-10 One study found that anti-TNF medications were associated with an increased risk for candidiasis by a hazard ratio of 2.7 in patients with Crohn disease.8 Other studies have shown that the highest incidence of fungal infection is seen with the use of infliximab, while adalimumab is associated with lower rates of fungal infection.9,10 Although it is known that anti-TNF therapy predisposes patients to fungal infection, the dose of medication known to preclude the highest risk has not been studied. Furthermore, most studies assess rates of Candida infection in individuals receiving anti-TNF therapy in addition to several other immunosuppressant agents (ie, corticosteroids), which confounds the interpretation of results. Additional studies assessing rates of Candida and other opportunistic infections associated with use of adalimumab alone are needed to better guide clinical practices in dermatology.

Patients receiving adalimumab for dermatologic or other conditions should be closely monitored for opportunistic infections. Although immunomodulatory medications offer promising therapeutic benefits in patients with HS, larger studies regarding treatment with anti-TNF agents in HS are warranted to prevent complications from treatment and promote long-term efficacy and safety.

To the Editor:

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by the development of painful abscesses, fistulous tracts, and scars. It most commonly affects the apocrine gland–bearing areas of the body such as the axillary, inguinal, and anogenital regions. With a prevalence of approximately 1%, HS can lead to notable morbidity.1 The pathogenesis is thought to be due to occlusion of terminal hair follicles that subsequently stimulates release of proinflammatory cytokines from nearby keratinocytes. The mechanism of initial occlusion is not well understood but may be due to friction or trauma. An inflammatory mechanism of disease also has been hypothesized; however, the exact cytokine profile is not known. Treatment of HS consists of several different modalities, including oral retinoids, antibiotics, antiandrogenic therapy, and surgery.1,2 Adalimumab is a well-known biologic that has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of HS.

Adalimumab is a human monoclonal antibody against tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α and is thought to improve HS by several mechanisms. Inhibition of TNF-α and other proinflammatory cytokines found in inflammatory lesions and apocrine glands directly decreases the severity of lesion size and the frequency of recurrence.3 Adalimumab also is thought to downregulate expression of keratin 6 and prevent the hyperkeratinization seen in HS.4 Additionally, TNF-α inhibition decreases production of IL-1, which has been shown to cause hypercornification of follicles and perpetuate HS pathogenesis.5

A 41-year-old woman with a history of endometriosis, adenomyosis, polycystic ovary syndrome, interstitial cystitis, asthma, fibromyalgia, depression, and Hashimoto thyroiditis presented to our dermatology clinic with active draining lesions and sinus tracts in the perivaginal area that were consistent with HS, which initially was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily. She experienced minimal improvement of the HS lesions at 2-month follow-up.

Due to disease severity, adalimumab was started. The patient received a loading dose of 4 injections totaling 160 mg and 80 mg on day 15, followed by a maintenance dose of 40 mg/0.4 mL weekly. The patient reported substantial improvement of pain, and complete resolution of active lesions was noted on physical examination after 4 weeks of treatment with adalimumab.

Six weeks after adalimumab was started, the patient developed severe dysphagia. She was evaluated by a gastroenterologist and underwent endoscopy (Figure), which led to a diagnosis of esophageal candidiasis. Adalimumab was discontinued immediately thereafter. The patient started treatment with nystatin oral rinse 4 times daily and oral fluconazole 200 mg daily. The candidiasis resolved within 2 weeks; however, she experienced recurrence of HS with draining lesions in the perivaginal area approximately 8 weeks after discontinuation of adalimumab. The patient requested to restart adalimumab treatment despite the recent history of esophagitis. Adalimumab 40 mg/0.4 mL weekly was restarted along with oral fluconazole 200 mg twice weekly and nystatin oral rinse 4 times daily. This regimen resulted in complete resolution of HS symptoms within 6 weeks with no recurrence of esophageal candidiasis during 6 months of follow-up.

Although the side effect of Candida esophagitis associated with adalimumab treatment in our patient may be logical given the medication’s mechanism of action and side-effect profile, this case warrants additional attention. An increase in fungal infections occurs from treatment with adalimumab because TNF-α is involved in many immune regulatory steps that counteract infection. Candida typically activates the innate immune system through macrophages via pathogen-associated molecular pattern stimulation, subsequently stimulating the release of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α. The cellular immune system also is activated. Helper T cells (TH1) release TNF-α along with other proinflammatory cytokines to increase phagocytosis in polymorphonuclear cells and macrophages.6 Thus, inhibition of TNF-α compromises innate and cellular immunity, thereby increasing susceptibility to fungal organisms.

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Candida, candidiasis, esophageal, adalimumab, anti-TNF, and TNF revealed no reports of esophageal candidiasis in patients receiving adalimumab or any of the TNF inhibitors. Candida laryngitis was reported in a patient receiving adalimumab for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.7 Other studies have demonstrated an incidence of mucocutaneous candidiasis, most notably oropharyngeal and vaginal candidiasis.8-10 One study found that anti-TNF medications were associated with an increased risk for candidiasis by a hazard ratio of 2.7 in patients with Crohn disease.8 Other studies have shown that the highest incidence of fungal infection is seen with the use of infliximab, while adalimumab is associated with lower rates of fungal infection.9,10 Although it is known that anti-TNF therapy predisposes patients to fungal infection, the dose of medication known to preclude the highest risk has not been studied. Furthermore, most studies assess rates of Candida infection in individuals receiving anti-TNF therapy in addition to several other immunosuppressant agents (ie, corticosteroids), which confounds the interpretation of results. Additional studies assessing rates of Candida and other opportunistic infections associated with use of adalimumab alone are needed to better guide clinical practices in dermatology.

Patients receiving adalimumab for dermatologic or other conditions should be closely monitored for opportunistic infections. Although immunomodulatory medications offer promising therapeutic benefits in patients with HS, larger studies regarding treatment with anti-TNF agents in HS are warranted to prevent complications from treatment and promote long-term efficacy and safety.

- Kurayev A, Ashkar H, Saraiya A, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: review of the pathogenesis and treatment. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:1107-1022.

- Rambhatla PV, Lim HW, Hamzavi I. A systematic review of treatments for hidradenitis suppurativa. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:439-446.

- van der Zee HH, de Ruiter L, van den Broecke DG, et al. Elevated levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, interleukin (IL)-1beta and IL-10 in hidradenitis suppurativa skin: a rationale for targeting TNF-alpha and IL-1beta. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1292-1298.

- Shuja F, Chan CS, Rosen T. Biologic drugs for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: an evidence-based review. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:511-521, 523-514.

- Kutsch CL, Norris DA, Arend WP. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces interleukin-1 alpha and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist production by cultured human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101:79-85.

- Senet JM. Risk factors and physiopathology of candidiasis. Rev Iberoam Micol. 1997;14:6-13.

- Kobak S, Yilmaz H, Guclu O, et al. Severe candida laryngitis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis treated with adalimumab. Eur J Rheumatol. 2014;1:167-169.

- Marehbian J, Arrighi HM, Hass S, et al. Adverse events associated with common therapy regimens for moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2524-2533.

- Tsiodras S, Samonis G, Boumpas DT, et al. Fungal infections complicating tumor necrosis factor alpha blockade therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:181-194.

- Aikawa NE, Rosa DT, Del Negro GM, et al. Systemic and localized infection by Candida species in patients with rheumatic diseases receiving anti-TNF therapy [in Portuguese]. Rev Bras Reumatol. doi:10.1016/j.rbr.2015.03.010

- Kurayev A, Ashkar H, Saraiya A, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: review of the pathogenesis and treatment. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:1107-1022.

- Rambhatla PV, Lim HW, Hamzavi I. A systematic review of treatments for hidradenitis suppurativa. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:439-446.

- van der Zee HH, de Ruiter L, van den Broecke DG, et al. Elevated levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, interleukin (IL)-1beta and IL-10 in hidradenitis suppurativa skin: a rationale for targeting TNF-alpha and IL-1beta. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1292-1298.

- Shuja F, Chan CS, Rosen T. Biologic drugs for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: an evidence-based review. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:511-521, 523-514.

- Kutsch CL, Norris DA, Arend WP. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces interleukin-1 alpha and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist production by cultured human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 1993;101:79-85.

- Senet JM. Risk factors and physiopathology of candidiasis. Rev Iberoam Micol. 1997;14:6-13.

- Kobak S, Yilmaz H, Guclu O, et al. Severe candida laryngitis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis treated with adalimumab. Eur J Rheumatol. 2014;1:167-169.

- Marehbian J, Arrighi HM, Hass S, et al. Adverse events associated with common therapy regimens for moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2524-2533.

- Tsiodras S, Samonis G, Boumpas DT, et al. Fungal infections complicating tumor necrosis factor alpha blockade therapy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:181-194.

- Aikawa NE, Rosa DT, Del Negro GM, et al. Systemic and localized infection by Candida species in patients with rheumatic diseases receiving anti-TNF therapy [in Portuguese]. Rev Bras Reumatol. doi:10.1016/j.rbr.2015.03.010

Practice Points

- Adalimumab is an effective treatment for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa.

- There is risk for opportunistic infections with adalimumab, and patients should be monitored closely.

Treatment of Generalized Pustular Psoriasis of Pregnancy With Infliximab

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (GPPP), formerly known as impetigo herpetiformis, is a rare dermatosis that causes maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. It is characterized by widespread, circular, erythematous plaques with pustules at the periphery.1 Conventional first-line treatment includes systemic corticosteroids and cyclosporine. The National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board also has included infliximab among the first-line treatment options for GPPP.2 Herein, we report a case of GPPP treated with infliximab at 30 weeks’ gestation and during the postpartum period.

Case Report

A 22-year-old woman was admitted to our inpatient clinic at 20 weeks’ gestation in her second pregnancy for evaluation of cutaneous eruptions covering the entire body. The lesions first appeared 3 to 4 days prior to her admission and dramatically progressed. She had a history of psoriasis vulgaris diagnosed during her first pregnancy 2 years prior that was treated with topical steroids throughout the pregnancy and methotrexate during lactation for a total of 11 months. She then was started on cyclosporine, which she used for 6 months due to ineffectiveness of the methotrexate, but she stopped treatment 4 months before the second pregnancy.

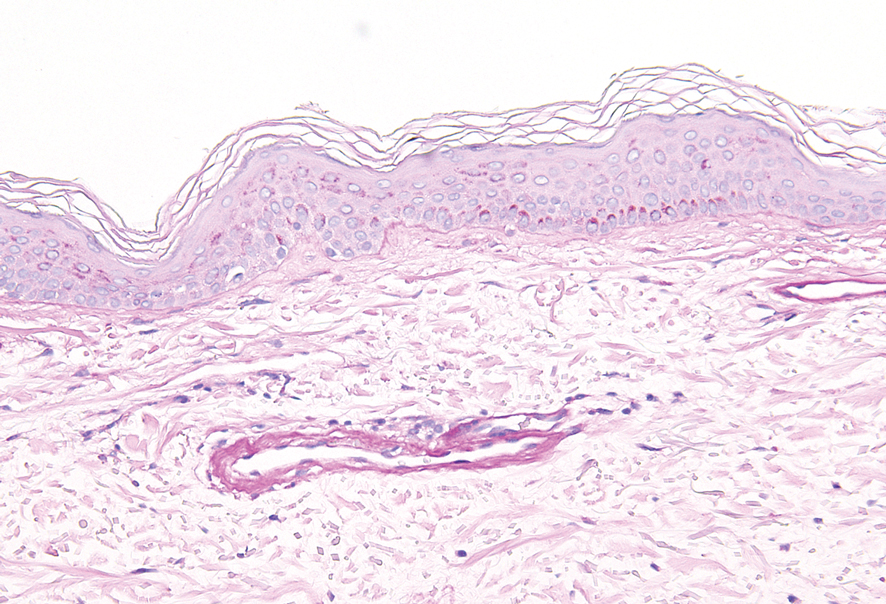

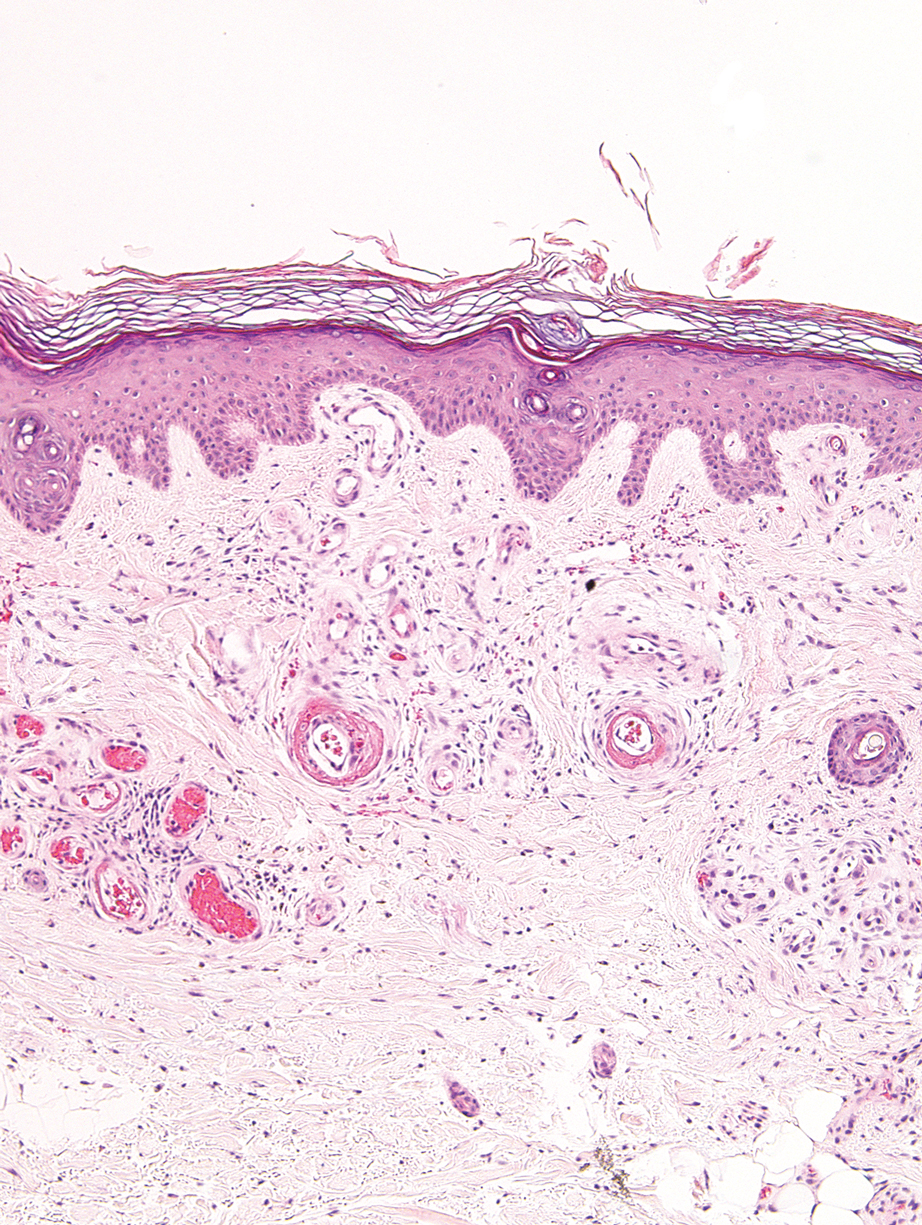

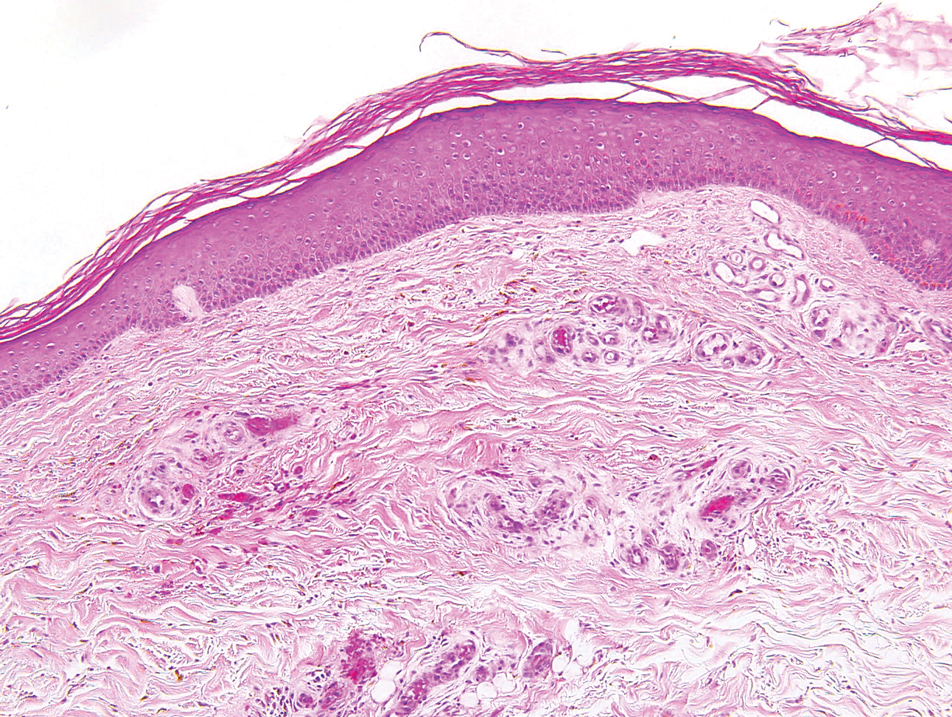

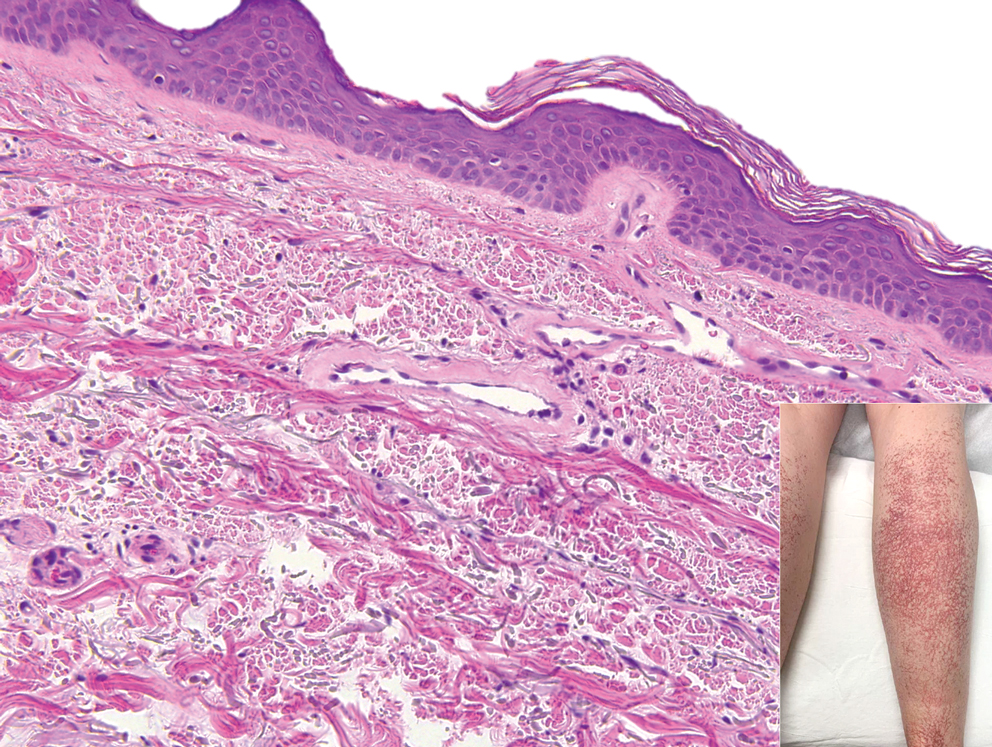

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed erythroderma and widespread pustules on the chest, abdomen, arms, and legs, including the intertriginous regions, that tended to coalesce and form lakes of pus over an erythematous base (Figure 1). The mucosae were normal. She exhibited a low blood pressure (85/50 mmHg) and high body temperature (102 °F [38.9 °C]). Routine laboratory examination revealed anemia and a normal leukocyte count. Her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (57 mm/h [reference range, <20 mm/h]) and C-reactive protein level (102 mg/L [reference range, <6 mg/L]) were elevated, whereas total calcium (8.11 mg/dL [reference range, 8.2–10.6 mg/dL]) and albumin (3.15 g/dL [reference range, >4.0 g/dL]) levels were low.

Empirical intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam was started due to hypotension, high fever, and elevated C-reactive protein levels; however, treatment was stopped after 4 days when microbiological cultures taken from blood and pustules revealed no bacterial growth, and therefore the fever was assumed to be caused by erythroderma. A skin biopsy before the start of topical and systemic treatment revealed changes consistent with GPPP.

Because her disease was extensive, systemic methylprednisolone 1.5 mg/kg once daily was started, and the dose was increased up to 2.5 mg/kg once daily on the tenth day of treatment to control new crops of eruptions. The dose was tapered to 2 mg/kg once daily when the lesions subsided 4 weeks into the treatment. The patient was discharged after 7 weeks at 27 weeks’ gestation.

Twelve days later, the patient was readmitted to the clinic in an erythrodermic state. The lesions were not controlled with increased doses of systemic corticosteroids. Treatment with cyclosporine was considered, but the patient refused; thus, infliximab treatment was planned. Isoniazid 300 mg once daily was started due to a risk of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection revealed by a tuberculosis blood test. Other evaluations revealed no contraindications, and an infusion of infliximab 300 mg (5 mg/kg) was administered at 30 weeks’ gestation. There was visible improvement in the erythroderma and pustular lesions within the same day of treatment, and the lesions were completely cleared within 2 days of the infusion. The methylprednisolone dose was reduced to 1.5 mg/kg once daily.

Three days after treatment with infliximab, lesions with yellow encrustation appeared in the perioral region and on the oral mucosa and left ear. She was diagnosed with an oral herpes infection. Oral valacyclovir 1 g twice daily and topical mupirocin were started and the lesions subsided within 1 week. Twelve days after the infliximab infusion, new pustular lesions appeared, and a second infusion of infliximab was administered 13 days after the first, which cleared all lesions within 48 hours.

The patient’s methylprednisolone dose was tapered and stopped prior to delivery at 34 weeks’ gestation—2 weeks after the second dose of infliximab—as she did not have any new skin eruptions. A third infliximab infusion that normally would have occurred 4 weeks after the second treatment was postponed for a Cesarean section scheduled at 36 weeks’ gestation due to suspected intrauterine growth retardation. The patient stayed at the hospital until delivery without any new skin lesions. The gross and histopathologic examination of the placenta was normal. The neonate weighed 4.8 lb at birth and had neonatal jaundice that resolved spontaneously within 10 days but was otherwise healthy.

The patient returned to the clinic 3 weeks postpartum with a few pustules on erythematous plaques on the chest, abdomen, and back. At this time, she received a third infusion of infliximab 8 weeks after the second dose. For the past 5 years, the patient has been undergoing infliximab maintenance treatment, which she receives at the hospital every 8 weeks with excellent response. She has had no further pregnancies to date.

Comment

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy is a rare condition that typically occurs in the third trimester but also can start in the first and second trimesters. It may result in maternal and fetal morbidity by causing fluid and electrolyte imbalance and/or placental insufficiency, resulting in an increased risk for fetal abnormalities, stillbirth, and neonatal death.3 In subsequent pregnancies, GPPP has been observed to recur at an earlier gestational age with a more severe presentation.1,3

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy usually involves an eruption that begins symmetrically in the intertriginous areas and spreads to the rest of the body. The lesions present as erythematous annular plaques with pustules on the periphery and desquamation in the center due to older pustules.1,3 The mucous membranes also may be involved with erosive and exfoliative plaques, and there may be nail involvement. Patients often present with systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, diarrhea, and vomiting.1 Laboratory investigations may reveal neutrophilic leukocytosis, high erythrocyte sedimentation rate, hypocalcemia, and hypoalbuminemia.4 Cultures from blood and pustules show no bacterial growth. A skin biopsy is helpful in diagnosis, with features similar to generalized pustular psoriasis, demonstrating spongiform pustules containing neutrophils, lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrates in the papillary dermis, and negative direct immunofluorescence.3

The differential diagnosis of GPPP includes subcorneal pustular dermatosis, dermatitis herpetiformis, herpes gestationis, impetigo, and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis.1,3 Due to concerns of fetal implications, treatment options in GPPP are somewhat limited; however, the condition requires treatment because it may result in unfavorable pregnancy outcomes. Topical corticosteroids may be an option for limited disease.5,6 Systemic corticosteroids (eg, prednisone 60–80 mg/d) were previously considered as first-line agents, although they have shown limited efficacy in our case as well as in other case reports.7 Their ineffectiveness and risk for flare-up after dose tapering should be kept in mind when starting GPPP patients on systemic corticosteroids. Systemic cyclosporine (2–3 mg/kg/d) may be added to increase the efficacy of systemic steroids, which was done in several cases in literature.1,6,8 Although cyclosporine has been classified as a pregnancy category C drug, an analysis of pregnancy outcomes of 629 renal transplant patients revealed no association with adverse pregnancy outcomes compared to the general population and no increase in fetal malformations.9 Therefore, cyclosporine is a safe treatment option and was classified as a first-line drug for GPPP in a 2012 review by the National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board.2 Narrowband UVB also has been reported to be used for the treatment of GPPP.10 Methotrexate and retinoids have been used in cases with lesions that persisted postpartum.1

Anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α agents are another effective option for treatment of GPPP. Anti-TNF agents are classified as pregnancy category B due to results showing that anti-mouse TNF-α monoclonal antibodies did not cause embryotoxicity or teratogenicity in pregnant mice.11 Although Carter et al12 published a review of US Food and Drug Administration data on pregnant women receiving anti-TNF treatment and concluded that these agents were associated with the VACTERL group of malformations (vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defect, tracheoesophageal fistula with esophageal atresia, cardiac defects, renal and limb anomalies), no such association was found in further studies. A 2014 study showed no difference in the rate of major malformations in infants born to women who were treated with anti-TNF drugs compared to the disease-matched group not treated with these agents and pregnant women counselled for nonteratogenic exposure.13 The same study detected an increase in preterm and low-birth-weight deliveries and suggested this might be caused by the increased severity of disease in patients requiring anti-TNF medication. The British Society of Rheumatology Biologics Register published data on pregnancy outcomes in 130 rheumatoid arthritis patients who had been exposed to anti-TNF agents.14 The results suggested an increased rate of spontaneous abortions in women exposed to anti-TNF treatment around the time of conception, especially in those taking these medications together with methotrexate or leflunomide; however, results also indicated that disease activity may have had an impact on the rate of spontaneous abortions in these patients. In a 2013 review of 462 women with inflammatory bowel disease who had been exposed to anti-TNF agents during pregnancy, the investigators concluded that pregnancy outcomes and the rate of congenital anomalies did not significantly differ from other inflammatory bowel disease patients not receiving anti-TNF drugs or the general population.15

In 2012, the National Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation put infliximab amongst the first-line treatment modalities for GPPP.2 In one case of GPPP in which the eruption persisted after delivery, the patient was treated with infliximab 7 weeks postpartum due to failure to control the disease with prednisolone 60 mg daily and cyclosporine 7.5 mg/kg daily. Unlike our patient, this patient was only started on an infliximab regimen after delivery.16 In another case reported in 2010, the patient was started on infliximab during the postpartum period of her first pregnancy following a pustular flare of previously diagnosed plaque psoriasis (not a generalized pustular psoriasis, as in our case).17 As a good response was obtained, infliximab treatment was continued in the patient throughout her second pregnancy.

Our case is unique in that infliximab was started during pregnancy because of intractable disease leading to systemic symptoms. Our patient showed an excellent response to infliximab after a 10-week disease course with repeated flare-ups and impairment to her overall condition. Delivery occurred at 36 weeks’ gestation due to suspected intrauterine growth retardation; however, the neonate was born with a 5-minute APGAR score of 10 and required no special medical care, which suggests that the low birth weight was constitutional due to the patient’s small frame (her height was 4 ft 11 in). The breast milk of patients with inflammatory bowel disease has been detected to contain very small amounts of infliximab (101 ng/mL, about 1/200 of the therapeutic blood level).18 Considering the large molecular weight of this agent and possible proteolysis in the stomach and intestines, infliximab is unlikely to affect the neonate.15 Thus, we encouraged our patient to breastfeed her baby. A case of fatal disseminated Bacille-Calmette-Guérin infection in an infant whose mother received infliximab treatment during pregnancy has been reported.19 It has been suggested that live vaccines should be avoided in neonates exposed to anti-TNF agents at least for the first 6 months of life or until the agent is no longer detectable in their blood.15 We therefore informed our patient’s family practitioner about this data.

Conclusion

We report a case of infliximab treatment for GPPP that was continued during the postpartum period. Infliximab was an effective treatment option in our patient with no detected serious adverse events and may be considered in other cases of GPPP that are not responsive to systemic steroids. However, further studies are warranted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of infliximab treatment for GPPP and psoriasis in pregnancy.

- Lerhoff S, Pomeranz MK. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy and their treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2013;26:274-284.

- Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:279-288.

- Oumeish OY, Parish JL. Impetigo herpetiformis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:101-104.

- Gao QQ, Xi MR, Yao Q. Impetigo herpetiformis during pregnancy: a case report and literature review. Dermatology. 2013;226:35-40.

- Bae YS, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, et al. Review of treatment options for psoriasis in pregnant or lactating women: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:459-477.

- Shaw CJ, Wu P, Sriemevan A. First trimester impetigo herpetiformis in multiparous female successfully treated with oral cyclosporine [published May 12, 2011]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr.02.2011.3915

- Hazarika D. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy successfully treated with cyclosporine. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:638.

- Luan L, Han S, Zhang Z, et al. Personal treatment experience for severe generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy: two case reports. Dermatol Ther. 2014;27:174-177.

- Lamarque V, Leleu MF, Monka C, et al. Analysis of 629 pregnancy outcomes in transplant recipients treated with Sandimmun. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:2480.

- Bozdag K, Ozturk S, Ermete M. A case of recurrent impetigo herpetiformis treated with systemic corticosteroids and narrowband UVB. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2012;31:67-69.

- Treacy G. Using an analogous monoclonal antibody to evaluate the reproductive and chronic toxicity potential for a humanized anti-TNF alpha monoclonal antibody. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2000;19:226-228.

- Carter JD, Ladhani A, Ricca LR, et al. A safety assessment of tumor necrosis factor antagonists during pregnancy: a review of the Food and Drug Administration database. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:635-641.

- Diav-Citrin O, Otcheretianski-Volodarsky A, Shechtman S, et al. Pregnancy outcome following gestational exposure to TNF-alpha-inhibitors: a prospective, comparative, observational study. Reprod Toxicol. 2014;43:78-84.

- Verstappen SM, King Y, Watson KD, et al. Anti-TNF therapies and pregnancy: outcome of 130 pregnancies in the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:823-826.

- Gisbert JP, Chaparro M. Safety of anti-TNF agents during pregnancy and breastfeeding in women with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1426-1438.

- Sheth N, Greenblatt DT, Acland K, et al. Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy treated with infliximab. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:521-522.

- Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220:71-76.

- Ben-Horin S, Yavzori M, Kopylov U, et al. Detection of infliximab in breast milk of nursing mothers with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:555-558.

- Cheent K, Nolan J, Shariq S, et al. Case report: fatal case of disseminated BCG infection in an infant born to a mother taking infliximab for Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:603-605.

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (GPPP), formerly known as impetigo herpetiformis, is a rare dermatosis that causes maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. It is characterized by widespread, circular, erythematous plaques with pustules at the periphery.1 Conventional first-line treatment includes systemic corticosteroids and cyclosporine. The National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board also has included infliximab among the first-line treatment options for GPPP.2 Herein, we report a case of GPPP treated with infliximab at 30 weeks’ gestation and during the postpartum period.

Case Report

A 22-year-old woman was admitted to our inpatient clinic at 20 weeks’ gestation in her second pregnancy for evaluation of cutaneous eruptions covering the entire body. The lesions first appeared 3 to 4 days prior to her admission and dramatically progressed. She had a history of psoriasis vulgaris diagnosed during her first pregnancy 2 years prior that was treated with topical steroids throughout the pregnancy and methotrexate during lactation for a total of 11 months. She then was started on cyclosporine, which she used for 6 months due to ineffectiveness of the methotrexate, but she stopped treatment 4 months before the second pregnancy.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed erythroderma and widespread pustules on the chest, abdomen, arms, and legs, including the intertriginous regions, that tended to coalesce and form lakes of pus over an erythematous base (Figure 1). The mucosae were normal. She exhibited a low blood pressure (85/50 mmHg) and high body temperature (102 °F [38.9 °C]). Routine laboratory examination revealed anemia and a normal leukocyte count. Her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (57 mm/h [reference range, <20 mm/h]) and C-reactive protein level (102 mg/L [reference range, <6 mg/L]) were elevated, whereas total calcium (8.11 mg/dL [reference range, 8.2–10.6 mg/dL]) and albumin (3.15 g/dL [reference range, >4.0 g/dL]) levels were low.

Empirical intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam was started due to hypotension, high fever, and elevated C-reactive protein levels; however, treatment was stopped after 4 days when microbiological cultures taken from blood and pustules revealed no bacterial growth, and therefore the fever was assumed to be caused by erythroderma. A skin biopsy before the start of topical and systemic treatment revealed changes consistent with GPPP.

Because her disease was extensive, systemic methylprednisolone 1.5 mg/kg once daily was started, and the dose was increased up to 2.5 mg/kg once daily on the tenth day of treatment to control new crops of eruptions. The dose was tapered to 2 mg/kg once daily when the lesions subsided 4 weeks into the treatment. The patient was discharged after 7 weeks at 27 weeks’ gestation.

Twelve days later, the patient was readmitted to the clinic in an erythrodermic state. The lesions were not controlled with increased doses of systemic corticosteroids. Treatment with cyclosporine was considered, but the patient refused; thus, infliximab treatment was planned. Isoniazid 300 mg once daily was started due to a risk of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection revealed by a tuberculosis blood test. Other evaluations revealed no contraindications, and an infusion of infliximab 300 mg (5 mg/kg) was administered at 30 weeks’ gestation. There was visible improvement in the erythroderma and pustular lesions within the same day of treatment, and the lesions were completely cleared within 2 days of the infusion. The methylprednisolone dose was reduced to 1.5 mg/kg once daily.

Three days after treatment with infliximab, lesions with yellow encrustation appeared in the perioral region and on the oral mucosa and left ear. She was diagnosed with an oral herpes infection. Oral valacyclovir 1 g twice daily and topical mupirocin were started and the lesions subsided within 1 week. Twelve days after the infliximab infusion, new pustular lesions appeared, and a second infusion of infliximab was administered 13 days after the first, which cleared all lesions within 48 hours.

The patient’s methylprednisolone dose was tapered and stopped prior to delivery at 34 weeks’ gestation—2 weeks after the second dose of infliximab—as she did not have any new skin eruptions. A third infliximab infusion that normally would have occurred 4 weeks after the second treatment was postponed for a Cesarean section scheduled at 36 weeks’ gestation due to suspected intrauterine growth retardation. The patient stayed at the hospital until delivery without any new skin lesions. The gross and histopathologic examination of the placenta was normal. The neonate weighed 4.8 lb at birth and had neonatal jaundice that resolved spontaneously within 10 days but was otherwise healthy.

The patient returned to the clinic 3 weeks postpartum with a few pustules on erythematous plaques on the chest, abdomen, and back. At this time, she received a third infusion of infliximab 8 weeks after the second dose. For the past 5 years, the patient has been undergoing infliximab maintenance treatment, which she receives at the hospital every 8 weeks with excellent response. She has had no further pregnancies to date.

Comment

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy is a rare condition that typically occurs in the third trimester but also can start in the first and second trimesters. It may result in maternal and fetal morbidity by causing fluid and electrolyte imbalance and/or placental insufficiency, resulting in an increased risk for fetal abnormalities, stillbirth, and neonatal death.3 In subsequent pregnancies, GPPP has been observed to recur at an earlier gestational age with a more severe presentation.1,3

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy usually involves an eruption that begins symmetrically in the intertriginous areas and spreads to the rest of the body. The lesions present as erythematous annular plaques with pustules on the periphery and desquamation in the center due to older pustules.1,3 The mucous membranes also may be involved with erosive and exfoliative plaques, and there may be nail involvement. Patients often present with systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, diarrhea, and vomiting.1 Laboratory investigations may reveal neutrophilic leukocytosis, high erythrocyte sedimentation rate, hypocalcemia, and hypoalbuminemia.4 Cultures from blood and pustules show no bacterial growth. A skin biopsy is helpful in diagnosis, with features similar to generalized pustular psoriasis, demonstrating spongiform pustules containing neutrophils, lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrates in the papillary dermis, and negative direct immunofluorescence.3

The differential diagnosis of GPPP includes subcorneal pustular dermatosis, dermatitis herpetiformis, herpes gestationis, impetigo, and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis.1,3 Due to concerns of fetal implications, treatment options in GPPP are somewhat limited; however, the condition requires treatment because it may result in unfavorable pregnancy outcomes. Topical corticosteroids may be an option for limited disease.5,6 Systemic corticosteroids (eg, prednisone 60–80 mg/d) were previously considered as first-line agents, although they have shown limited efficacy in our case as well as in other case reports.7 Their ineffectiveness and risk for flare-up after dose tapering should be kept in mind when starting GPPP patients on systemic corticosteroids. Systemic cyclosporine (2–3 mg/kg/d) may be added to increase the efficacy of systemic steroids, which was done in several cases in literature.1,6,8 Although cyclosporine has been classified as a pregnancy category C drug, an analysis of pregnancy outcomes of 629 renal transplant patients revealed no association with adverse pregnancy outcomes compared to the general population and no increase in fetal malformations.9 Therefore, cyclosporine is a safe treatment option and was classified as a first-line drug for GPPP in a 2012 review by the National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board.2 Narrowband UVB also has been reported to be used for the treatment of GPPP.10 Methotrexate and retinoids have been used in cases with lesions that persisted postpartum.1

Anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α agents are another effective option for treatment of GPPP. Anti-TNF agents are classified as pregnancy category B due to results showing that anti-mouse TNF-α monoclonal antibodies did not cause embryotoxicity or teratogenicity in pregnant mice.11 Although Carter et al12 published a review of US Food and Drug Administration data on pregnant women receiving anti-TNF treatment and concluded that these agents were associated with the VACTERL group of malformations (vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defect, tracheoesophageal fistula with esophageal atresia, cardiac defects, renal and limb anomalies), no such association was found in further studies. A 2014 study showed no difference in the rate of major malformations in infants born to women who were treated with anti-TNF drugs compared to the disease-matched group not treated with these agents and pregnant women counselled for nonteratogenic exposure.13 The same study detected an increase in preterm and low-birth-weight deliveries and suggested this might be caused by the increased severity of disease in patients requiring anti-TNF medication. The British Society of Rheumatology Biologics Register published data on pregnancy outcomes in 130 rheumatoid arthritis patients who had been exposed to anti-TNF agents.14 The results suggested an increased rate of spontaneous abortions in women exposed to anti-TNF treatment around the time of conception, especially in those taking these medications together with methotrexate or leflunomide; however, results also indicated that disease activity may have had an impact on the rate of spontaneous abortions in these patients. In a 2013 review of 462 women with inflammatory bowel disease who had been exposed to anti-TNF agents during pregnancy, the investigators concluded that pregnancy outcomes and the rate of congenital anomalies did not significantly differ from other inflammatory bowel disease patients not receiving anti-TNF drugs or the general population.15

In 2012, the National Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation put infliximab amongst the first-line treatment modalities for GPPP.2 In one case of GPPP in which the eruption persisted after delivery, the patient was treated with infliximab 7 weeks postpartum due to failure to control the disease with prednisolone 60 mg daily and cyclosporine 7.5 mg/kg daily. Unlike our patient, this patient was only started on an infliximab regimen after delivery.16 In another case reported in 2010, the patient was started on infliximab during the postpartum period of her first pregnancy following a pustular flare of previously diagnosed plaque psoriasis (not a generalized pustular psoriasis, as in our case).17 As a good response was obtained, infliximab treatment was continued in the patient throughout her second pregnancy.

Our case is unique in that infliximab was started during pregnancy because of intractable disease leading to systemic symptoms. Our patient showed an excellent response to infliximab after a 10-week disease course with repeated flare-ups and impairment to her overall condition. Delivery occurred at 36 weeks’ gestation due to suspected intrauterine growth retardation; however, the neonate was born with a 5-minute APGAR score of 10 and required no special medical care, which suggests that the low birth weight was constitutional due to the patient’s small frame (her height was 4 ft 11 in). The breast milk of patients with inflammatory bowel disease has been detected to contain very small amounts of infliximab (101 ng/mL, about 1/200 of the therapeutic blood level).18 Considering the large molecular weight of this agent and possible proteolysis in the stomach and intestines, infliximab is unlikely to affect the neonate.15 Thus, we encouraged our patient to breastfeed her baby. A case of fatal disseminated Bacille-Calmette-Guérin infection in an infant whose mother received infliximab treatment during pregnancy has been reported.19 It has been suggested that live vaccines should be avoided in neonates exposed to anti-TNF agents at least for the first 6 months of life or until the agent is no longer detectable in their blood.15 We therefore informed our patient’s family practitioner about this data.

Conclusion

We report a case of infliximab treatment for GPPP that was continued during the postpartum period. Infliximab was an effective treatment option in our patient with no detected serious adverse events and may be considered in other cases of GPPP that are not responsive to systemic steroids. However, further studies are warranted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of infliximab treatment for GPPP and psoriasis in pregnancy.

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (GPPP), formerly known as impetigo herpetiformis, is a rare dermatosis that causes maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. It is characterized by widespread, circular, erythematous plaques with pustules at the periphery.1 Conventional first-line treatment includes systemic corticosteroids and cyclosporine. The National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board also has included infliximab among the first-line treatment options for GPPP.2 Herein, we report a case of GPPP treated with infliximab at 30 weeks’ gestation and during the postpartum period.

Case Report

A 22-year-old woman was admitted to our inpatient clinic at 20 weeks’ gestation in her second pregnancy for evaluation of cutaneous eruptions covering the entire body. The lesions first appeared 3 to 4 days prior to her admission and dramatically progressed. She had a history of psoriasis vulgaris diagnosed during her first pregnancy 2 years prior that was treated with topical steroids throughout the pregnancy and methotrexate during lactation for a total of 11 months. She then was started on cyclosporine, which she used for 6 months due to ineffectiveness of the methotrexate, but she stopped treatment 4 months before the second pregnancy.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed erythroderma and widespread pustules on the chest, abdomen, arms, and legs, including the intertriginous regions, that tended to coalesce and form lakes of pus over an erythematous base (Figure 1). The mucosae were normal. She exhibited a low blood pressure (85/50 mmHg) and high body temperature (102 °F [38.9 °C]). Routine laboratory examination revealed anemia and a normal leukocyte count. Her erythrocyte sedimentation rate (57 mm/h [reference range, <20 mm/h]) and C-reactive protein level (102 mg/L [reference range, <6 mg/L]) were elevated, whereas total calcium (8.11 mg/dL [reference range, 8.2–10.6 mg/dL]) and albumin (3.15 g/dL [reference range, >4.0 g/dL]) levels were low.

Empirical intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam was started due to hypotension, high fever, and elevated C-reactive protein levels; however, treatment was stopped after 4 days when microbiological cultures taken from blood and pustules revealed no bacterial growth, and therefore the fever was assumed to be caused by erythroderma. A skin biopsy before the start of topical and systemic treatment revealed changes consistent with GPPP.

Because her disease was extensive, systemic methylprednisolone 1.5 mg/kg once daily was started, and the dose was increased up to 2.5 mg/kg once daily on the tenth day of treatment to control new crops of eruptions. The dose was tapered to 2 mg/kg once daily when the lesions subsided 4 weeks into the treatment. The patient was discharged after 7 weeks at 27 weeks’ gestation.

Twelve days later, the patient was readmitted to the clinic in an erythrodermic state. The lesions were not controlled with increased doses of systemic corticosteroids. Treatment with cyclosporine was considered, but the patient refused; thus, infliximab treatment was planned. Isoniazid 300 mg once daily was started due to a risk of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection revealed by a tuberculosis blood test. Other evaluations revealed no contraindications, and an infusion of infliximab 300 mg (5 mg/kg) was administered at 30 weeks’ gestation. There was visible improvement in the erythroderma and pustular lesions within the same day of treatment, and the lesions were completely cleared within 2 days of the infusion. The methylprednisolone dose was reduced to 1.5 mg/kg once daily.

Three days after treatment with infliximab, lesions with yellow encrustation appeared in the perioral region and on the oral mucosa and left ear. She was diagnosed with an oral herpes infection. Oral valacyclovir 1 g twice daily and topical mupirocin were started and the lesions subsided within 1 week. Twelve days after the infliximab infusion, new pustular lesions appeared, and a second infusion of infliximab was administered 13 days after the first, which cleared all lesions within 48 hours.

The patient’s methylprednisolone dose was tapered and stopped prior to delivery at 34 weeks’ gestation—2 weeks after the second dose of infliximab—as she did not have any new skin eruptions. A third infliximab infusion that normally would have occurred 4 weeks after the second treatment was postponed for a Cesarean section scheduled at 36 weeks’ gestation due to suspected intrauterine growth retardation. The patient stayed at the hospital until delivery without any new skin lesions. The gross and histopathologic examination of the placenta was normal. The neonate weighed 4.8 lb at birth and had neonatal jaundice that resolved spontaneously within 10 days but was otherwise healthy.

The patient returned to the clinic 3 weeks postpartum with a few pustules on erythematous plaques on the chest, abdomen, and back. At this time, she received a third infusion of infliximab 8 weeks after the second dose. For the past 5 years, the patient has been undergoing infliximab maintenance treatment, which she receives at the hospital every 8 weeks with excellent response. She has had no further pregnancies to date.

Comment

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy is a rare condition that typically occurs in the third trimester but also can start in the first and second trimesters. It may result in maternal and fetal morbidity by causing fluid and electrolyte imbalance and/or placental insufficiency, resulting in an increased risk for fetal abnormalities, stillbirth, and neonatal death.3 In subsequent pregnancies, GPPP has been observed to recur at an earlier gestational age with a more severe presentation.1,3

Generalized pustular psoriasis of pregnancy usually involves an eruption that begins symmetrically in the intertriginous areas and spreads to the rest of the body. The lesions present as erythematous annular plaques with pustules on the periphery and desquamation in the center due to older pustules.1,3 The mucous membranes also may be involved with erosive and exfoliative plaques, and there may be nail involvement. Patients often present with systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, diarrhea, and vomiting.1 Laboratory investigations may reveal neutrophilic leukocytosis, high erythrocyte sedimentation rate, hypocalcemia, and hypoalbuminemia.4 Cultures from blood and pustules show no bacterial growth. A skin biopsy is helpful in diagnosis, with features similar to generalized pustular psoriasis, demonstrating spongiform pustules containing neutrophils, lymphocytic and neutrophilic infiltrates in the papillary dermis, and negative direct immunofluorescence.3

The differential diagnosis of GPPP includes subcorneal pustular dermatosis, dermatitis herpetiformis, herpes gestationis, impetigo, and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis.1,3 Due to concerns of fetal implications, treatment options in GPPP are somewhat limited; however, the condition requires treatment because it may result in unfavorable pregnancy outcomes. Topical corticosteroids may be an option for limited disease.5,6 Systemic corticosteroids (eg, prednisone 60–80 mg/d) were previously considered as first-line agents, although they have shown limited efficacy in our case as well as in other case reports.7 Their ineffectiveness and risk for flare-up after dose tapering should be kept in mind when starting GPPP patients on systemic corticosteroids. Systemic cyclosporine (2–3 mg/kg/d) may be added to increase the efficacy of systemic steroids, which was done in several cases in literature.1,6,8 Although cyclosporine has been classified as a pregnancy category C drug, an analysis of pregnancy outcomes of 629 renal transplant patients revealed no association with adverse pregnancy outcomes compared to the general population and no increase in fetal malformations.9 Therefore, cyclosporine is a safe treatment option and was classified as a first-line drug for GPPP in a 2012 review by the National Psoriasis Foundation Medical Board.2 Narrowband UVB also has been reported to be used for the treatment of GPPP.10 Methotrexate and retinoids have been used in cases with lesions that persisted postpartum.1

Anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α agents are another effective option for treatment of GPPP. Anti-TNF agents are classified as pregnancy category B due to results showing that anti-mouse TNF-α monoclonal antibodies did not cause embryotoxicity or teratogenicity in pregnant mice.11 Although Carter et al12 published a review of US Food and Drug Administration data on pregnant women receiving anti-TNF treatment and concluded that these agents were associated with the VACTERL group of malformations (vertebral defects, anal atresia, cardiac defect, tracheoesophageal fistula with esophageal atresia, cardiac defects, renal and limb anomalies), no such association was found in further studies. A 2014 study showed no difference in the rate of major malformations in infants born to women who were treated with anti-TNF drugs compared to the disease-matched group not treated with these agents and pregnant women counselled for nonteratogenic exposure.13 The same study detected an increase in preterm and low-birth-weight deliveries and suggested this might be caused by the increased severity of disease in patients requiring anti-TNF medication. The British Society of Rheumatology Biologics Register published data on pregnancy outcomes in 130 rheumatoid arthritis patients who had been exposed to anti-TNF agents.14 The results suggested an increased rate of spontaneous abortions in women exposed to anti-TNF treatment around the time of conception, especially in those taking these medications together with methotrexate or leflunomide; however, results also indicated that disease activity may have had an impact on the rate of spontaneous abortions in these patients. In a 2013 review of 462 women with inflammatory bowel disease who had been exposed to anti-TNF agents during pregnancy, the investigators concluded that pregnancy outcomes and the rate of congenital anomalies did not significantly differ from other inflammatory bowel disease patients not receiving anti-TNF drugs or the general population.15

In 2012, the National Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation put infliximab amongst the first-line treatment modalities for GPPP.2 In one case of GPPP in which the eruption persisted after delivery, the patient was treated with infliximab 7 weeks postpartum due to failure to control the disease with prednisolone 60 mg daily and cyclosporine 7.5 mg/kg daily. Unlike our patient, this patient was only started on an infliximab regimen after delivery.16 In another case reported in 2010, the patient was started on infliximab during the postpartum period of her first pregnancy following a pustular flare of previously diagnosed plaque psoriasis (not a generalized pustular psoriasis, as in our case).17 As a good response was obtained, infliximab treatment was continued in the patient throughout her second pregnancy.

Our case is unique in that infliximab was started during pregnancy because of intractable disease leading to systemic symptoms. Our patient showed an excellent response to infliximab after a 10-week disease course with repeated flare-ups and impairment to her overall condition. Delivery occurred at 36 weeks’ gestation due to suspected intrauterine growth retardation; however, the neonate was born with a 5-minute APGAR score of 10 and required no special medical care, which suggests that the low birth weight was constitutional due to the patient’s small frame (her height was 4 ft 11 in). The breast milk of patients with inflammatory bowel disease has been detected to contain very small amounts of infliximab (101 ng/mL, about 1/200 of the therapeutic blood level).18 Considering the large molecular weight of this agent and possible proteolysis in the stomach and intestines, infliximab is unlikely to affect the neonate.15 Thus, we encouraged our patient to breastfeed her baby. A case of fatal disseminated Bacille-Calmette-Guérin infection in an infant whose mother received infliximab treatment during pregnancy has been reported.19 It has been suggested that live vaccines should be avoided in neonates exposed to anti-TNF agents at least for the first 6 months of life or until the agent is no longer detectable in their blood.15 We therefore informed our patient’s family practitioner about this data.

Conclusion