User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Black HFrEF patients get more empagliflozin benefit in EMPEROR analyses

CHICAGO – Black patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) may receive more benefit from treatment with a sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor than do White patients, according to a new report.

A secondary analysis of data collected from the pivotal trials that assessed the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin in patients with HFrEF, EMPEROR-Reduced, and in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), EMPEROR-Preserved, was presented by Subodh Verma, MD, PhD, at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The “hypothesis-generating” analysis of data from EMPEROR-Reduced showed “a suggestion of a greater benefit of empagliflozin” in Black, compared with White patients, for the study’s primary endpoint (cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure) as well as for first and total hospitalizations for heart failure, he reported.

However, a similar but separate analysis that compared Black and White patients with heart failure who received treatment with a second agent, dapagliflozin, from the same SGLT2-inhibitor class did not show any suggestion of heterogeneity in the drug’s effect based on race.

Race-linked heterogeneity in empagliflozin’s effect

In EMPEROR-Reduced, which randomized 3,730 patients with heart failure and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 40% or less, treatment of White patients with empagliflozin (Jardiance) produced a nonsignificant 16% relative reduction in the rate of the primary endpoint, compared with placebo, during a median 16-month follow-up.

By contrast, among Black patients, treatment with empagliflozin produced a significant 56% reduction in the primary endpoint, compared with placebo-treated patients, a significant heterogeneity (P = .02) in effect between the two race subgroups, said Dr. Verma, a cardiac surgeon and professor at the University of Toronto.

The analysis he reported used combined data from EMPEROR-Reduced and the companion trial EMPEROR-Preserved, which randomized 5,988 patients with heart failure and a left ventricular ejection fraction greater than 40% to treatment with either empagliflozin or placebo and followed them for a median of 26 months.

To assess the effects of the randomized treatments in the two racial subgroups, Dr. Verma and associates used pooled data from both trials, but only from the 3,502 patients enrolled in the Americas, which included 3,024 White patients and 478 Black patients. Analysis of the patients in this subgroup who were randomized to placebo showed a significantly excess rate of the primary outcome among Blacks, who tallied 49% more of the primary outcome events during follow-up than did White patients, Dr. Verma reported. The absolute rate of the primary outcome without empagliflozin treatment was 13.15 events/100 patient-years of follow-up in White patients and 20.83 events/100 patient-years in Black patients.

The impact of empagliflozin was not statistically heterogeneous in the total pool of patients that included both those with HFrEF and those with HFpEF. The drug reduced the primary outcome incidence by a significant 20% in White patients, and by a significant 44% among Black patients.

But this point-estimate difference in efficacy, when coupled with the underlying difference in risk for an event between the two racial groups, meant that the number-needed-to-treat to prevent one primary outcome event was 42 among White patients and 12 among Black patients.

Race-linked treatment responses only in HFrEF

This suggestion of an imbalance in treatment efficacy was especially apparent among patients with HFrEF. In addition to the heterogeneity for the primary outcome, the Black and White subgroups also showed significantly divergent results for the outcomes of first hospitalization for heart failure, with a nonsignificant 21% relative reduction with empagliflozin treatment in Whites but a significant 65% relative cut in this endpoint with empagliflozin in Blacks, and for total hospitalizations for heart failure, which showed a similar level of significant heterogeneity between the two race subgroups.

In contrast, the patients with HFpEF showed no signal at all for heterogeneous outcome rates between Black and White subgroups.

One other study outcome, change in symptom burden measured by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), also showed suggestion of a race-based imbalance. The adjusted mean difference from baseline in the KCCQ clinical summary score was 1.50 points higher with empagliflozin treatment, compared with placebo among all White patients (those with HFrEF and those with HFpEF), and compared with a 5.25-point increase with empagliflozin over placebo among all Black patients with heart failure in the pooled American EMPEROR dataset, a difference between White and Black patients that just missed significance (P = .06). Again, this difference was especially notable and significant among the patients with HFrEF, where the adjusted mean difference in KCCQ was a 0.77-point increase in White patients and a 6.71-point increase among Black patients (P = .043),

These results also appeared in a report published simultaneously with Dr. Verma’s talk.

But two other analyses that assessed a possible race-based difference in empagliflozin’s effect on renal protection and on functional status showed no suggestion of heterogeneity.

Dr. Verma stressed caution about the limitations of these analyses because they involved a relatively small number of Black patients, and were possibly subject to unadjusted confounding from differences in baseline characteristics between the Black and White patients.

Black patients also had a number-needed-to-treat advantage with dapagliflozin

The finding that Black patients with heart failure potentially get more bang for the buck from treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor by having a lower number needed to treat also showed up in a separate report at the meeting that assessed the treatment effect from dapagliflozin (Farxiga) in Black and White patients in a pooled analysis of the DAPA-HF pivotal trial of patients with HFrEF and the DELIVER pivotal trial of patients with HFpEF. The pooled cohort included a total of 11,007, but for the analysis by race the investigators also limited their focus to patients from the Americas with 2,626 White patients and 381 Black patients.

Assessment of the effect of dapagliflozin on the primary outcome of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure among all patients, both those with HFrEF and those with HFpEF, again showed that event rates among patients treated with placebo were significantly higher in Black, compared with White patients, and this led to a difference in the number needed to treat to prevent one primary outcome event of 12 in Blacks and 17 in Whites, Jawad H. Butt, MD said in a talk at the meeting.

Although treatment with dapagliflozin reduced the rate of the primary outcome in this subgroup of patients from the DAPA-HF trial and the DELIVER trial by similar rates in Black and White patients, event rates were higher in the Black patients resulting in “greater benefit in absolute terms” for Black patients, explained Dr. Butt, a cardiologist at Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen.

But in contrast to the empagliflozin findings reported by Dr. Verma, the combined data from the dapagliflozin trials showed no suggestion of heterogeneity in the beneficial effect of dapagliflozin based on left ventricular ejection fraction. In the Black patients, for example, the relative benefit from dapagliflozin on the primary outcome was consistent across the full spectrum of patients with HFrEF and HFpEF.

EMPEROR-Reduced and EMPEROR-Preserved were sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Lilly, the companies that jointly market empagliflozin (Jardiance). The DAPA-HF and DELIVER trials were sponsored by AstraZeneca, the company that markets dapagliflozin (Farxiga). Dr. Verma has received honoraria, research support, or both from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Lilly, and from numerous other companies. Dr. Butt has been a consultant to and received travel grants from AstraZeneca, honoraria from Novartis, and has been an adviser to Bayer.

CHICAGO – Black patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) may receive more benefit from treatment with a sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor than do White patients, according to a new report.

A secondary analysis of data collected from the pivotal trials that assessed the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin in patients with HFrEF, EMPEROR-Reduced, and in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), EMPEROR-Preserved, was presented by Subodh Verma, MD, PhD, at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The “hypothesis-generating” analysis of data from EMPEROR-Reduced showed “a suggestion of a greater benefit of empagliflozin” in Black, compared with White patients, for the study’s primary endpoint (cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure) as well as for first and total hospitalizations for heart failure, he reported.

However, a similar but separate analysis that compared Black and White patients with heart failure who received treatment with a second agent, dapagliflozin, from the same SGLT2-inhibitor class did not show any suggestion of heterogeneity in the drug’s effect based on race.

Race-linked heterogeneity in empagliflozin’s effect

In EMPEROR-Reduced, which randomized 3,730 patients with heart failure and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 40% or less, treatment of White patients with empagliflozin (Jardiance) produced a nonsignificant 16% relative reduction in the rate of the primary endpoint, compared with placebo, during a median 16-month follow-up.

By contrast, among Black patients, treatment with empagliflozin produced a significant 56% reduction in the primary endpoint, compared with placebo-treated patients, a significant heterogeneity (P = .02) in effect between the two race subgroups, said Dr. Verma, a cardiac surgeon and professor at the University of Toronto.

The analysis he reported used combined data from EMPEROR-Reduced and the companion trial EMPEROR-Preserved, which randomized 5,988 patients with heart failure and a left ventricular ejection fraction greater than 40% to treatment with either empagliflozin or placebo and followed them for a median of 26 months.

To assess the effects of the randomized treatments in the two racial subgroups, Dr. Verma and associates used pooled data from both trials, but only from the 3,502 patients enrolled in the Americas, which included 3,024 White patients and 478 Black patients. Analysis of the patients in this subgroup who were randomized to placebo showed a significantly excess rate of the primary outcome among Blacks, who tallied 49% more of the primary outcome events during follow-up than did White patients, Dr. Verma reported. The absolute rate of the primary outcome without empagliflozin treatment was 13.15 events/100 patient-years of follow-up in White patients and 20.83 events/100 patient-years in Black patients.

The impact of empagliflozin was not statistically heterogeneous in the total pool of patients that included both those with HFrEF and those with HFpEF. The drug reduced the primary outcome incidence by a significant 20% in White patients, and by a significant 44% among Black patients.

But this point-estimate difference in efficacy, when coupled with the underlying difference in risk for an event between the two racial groups, meant that the number-needed-to-treat to prevent one primary outcome event was 42 among White patients and 12 among Black patients.

Race-linked treatment responses only in HFrEF

This suggestion of an imbalance in treatment efficacy was especially apparent among patients with HFrEF. In addition to the heterogeneity for the primary outcome, the Black and White subgroups also showed significantly divergent results for the outcomes of first hospitalization for heart failure, with a nonsignificant 21% relative reduction with empagliflozin treatment in Whites but a significant 65% relative cut in this endpoint with empagliflozin in Blacks, and for total hospitalizations for heart failure, which showed a similar level of significant heterogeneity between the two race subgroups.

In contrast, the patients with HFpEF showed no signal at all for heterogeneous outcome rates between Black and White subgroups.

One other study outcome, change in symptom burden measured by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), also showed suggestion of a race-based imbalance. The adjusted mean difference from baseline in the KCCQ clinical summary score was 1.50 points higher with empagliflozin treatment, compared with placebo among all White patients (those with HFrEF and those with HFpEF), and compared with a 5.25-point increase with empagliflozin over placebo among all Black patients with heart failure in the pooled American EMPEROR dataset, a difference between White and Black patients that just missed significance (P = .06). Again, this difference was especially notable and significant among the patients with HFrEF, where the adjusted mean difference in KCCQ was a 0.77-point increase in White patients and a 6.71-point increase among Black patients (P = .043),

These results also appeared in a report published simultaneously with Dr. Verma’s talk.

But two other analyses that assessed a possible race-based difference in empagliflozin’s effect on renal protection and on functional status showed no suggestion of heterogeneity.

Dr. Verma stressed caution about the limitations of these analyses because they involved a relatively small number of Black patients, and were possibly subject to unadjusted confounding from differences in baseline characteristics between the Black and White patients.

Black patients also had a number-needed-to-treat advantage with dapagliflozin

The finding that Black patients with heart failure potentially get more bang for the buck from treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor by having a lower number needed to treat also showed up in a separate report at the meeting that assessed the treatment effect from dapagliflozin (Farxiga) in Black and White patients in a pooled analysis of the DAPA-HF pivotal trial of patients with HFrEF and the DELIVER pivotal trial of patients with HFpEF. The pooled cohort included a total of 11,007, but for the analysis by race the investigators also limited their focus to patients from the Americas with 2,626 White patients and 381 Black patients.

Assessment of the effect of dapagliflozin on the primary outcome of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure among all patients, both those with HFrEF and those with HFpEF, again showed that event rates among patients treated with placebo were significantly higher in Black, compared with White patients, and this led to a difference in the number needed to treat to prevent one primary outcome event of 12 in Blacks and 17 in Whites, Jawad H. Butt, MD said in a talk at the meeting.

Although treatment with dapagliflozin reduced the rate of the primary outcome in this subgroup of patients from the DAPA-HF trial and the DELIVER trial by similar rates in Black and White patients, event rates were higher in the Black patients resulting in “greater benefit in absolute terms” for Black patients, explained Dr. Butt, a cardiologist at Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen.

But in contrast to the empagliflozin findings reported by Dr. Verma, the combined data from the dapagliflozin trials showed no suggestion of heterogeneity in the beneficial effect of dapagliflozin based on left ventricular ejection fraction. In the Black patients, for example, the relative benefit from dapagliflozin on the primary outcome was consistent across the full spectrum of patients with HFrEF and HFpEF.

EMPEROR-Reduced and EMPEROR-Preserved were sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Lilly, the companies that jointly market empagliflozin (Jardiance). The DAPA-HF and DELIVER trials were sponsored by AstraZeneca, the company that markets dapagliflozin (Farxiga). Dr. Verma has received honoraria, research support, or both from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Lilly, and from numerous other companies. Dr. Butt has been a consultant to and received travel grants from AstraZeneca, honoraria from Novartis, and has been an adviser to Bayer.

CHICAGO – Black patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) may receive more benefit from treatment with a sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor than do White patients, according to a new report.

A secondary analysis of data collected from the pivotal trials that assessed the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin in patients with HFrEF, EMPEROR-Reduced, and in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), EMPEROR-Preserved, was presented by Subodh Verma, MD, PhD, at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

The “hypothesis-generating” analysis of data from EMPEROR-Reduced showed “a suggestion of a greater benefit of empagliflozin” in Black, compared with White patients, for the study’s primary endpoint (cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure) as well as for first and total hospitalizations for heart failure, he reported.

However, a similar but separate analysis that compared Black and White patients with heart failure who received treatment with a second agent, dapagliflozin, from the same SGLT2-inhibitor class did not show any suggestion of heterogeneity in the drug’s effect based on race.

Race-linked heterogeneity in empagliflozin’s effect

In EMPEROR-Reduced, which randomized 3,730 patients with heart failure and a left ventricular ejection fraction of 40% or less, treatment of White patients with empagliflozin (Jardiance) produced a nonsignificant 16% relative reduction in the rate of the primary endpoint, compared with placebo, during a median 16-month follow-up.

By contrast, among Black patients, treatment with empagliflozin produced a significant 56% reduction in the primary endpoint, compared with placebo-treated patients, a significant heterogeneity (P = .02) in effect between the two race subgroups, said Dr. Verma, a cardiac surgeon and professor at the University of Toronto.

The analysis he reported used combined data from EMPEROR-Reduced and the companion trial EMPEROR-Preserved, which randomized 5,988 patients with heart failure and a left ventricular ejection fraction greater than 40% to treatment with either empagliflozin or placebo and followed them for a median of 26 months.

To assess the effects of the randomized treatments in the two racial subgroups, Dr. Verma and associates used pooled data from both trials, but only from the 3,502 patients enrolled in the Americas, which included 3,024 White patients and 478 Black patients. Analysis of the patients in this subgroup who were randomized to placebo showed a significantly excess rate of the primary outcome among Blacks, who tallied 49% more of the primary outcome events during follow-up than did White patients, Dr. Verma reported. The absolute rate of the primary outcome without empagliflozin treatment was 13.15 events/100 patient-years of follow-up in White patients and 20.83 events/100 patient-years in Black patients.

The impact of empagliflozin was not statistically heterogeneous in the total pool of patients that included both those with HFrEF and those with HFpEF. The drug reduced the primary outcome incidence by a significant 20% in White patients, and by a significant 44% among Black patients.

But this point-estimate difference in efficacy, when coupled with the underlying difference in risk for an event between the two racial groups, meant that the number-needed-to-treat to prevent one primary outcome event was 42 among White patients and 12 among Black patients.

Race-linked treatment responses only in HFrEF

This suggestion of an imbalance in treatment efficacy was especially apparent among patients with HFrEF. In addition to the heterogeneity for the primary outcome, the Black and White subgroups also showed significantly divergent results for the outcomes of first hospitalization for heart failure, with a nonsignificant 21% relative reduction with empagliflozin treatment in Whites but a significant 65% relative cut in this endpoint with empagliflozin in Blacks, and for total hospitalizations for heart failure, which showed a similar level of significant heterogeneity between the two race subgroups.

In contrast, the patients with HFpEF showed no signal at all for heterogeneous outcome rates between Black and White subgroups.

One other study outcome, change in symptom burden measured by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), also showed suggestion of a race-based imbalance. The adjusted mean difference from baseline in the KCCQ clinical summary score was 1.50 points higher with empagliflozin treatment, compared with placebo among all White patients (those with HFrEF and those with HFpEF), and compared with a 5.25-point increase with empagliflozin over placebo among all Black patients with heart failure in the pooled American EMPEROR dataset, a difference between White and Black patients that just missed significance (P = .06). Again, this difference was especially notable and significant among the patients with HFrEF, where the adjusted mean difference in KCCQ was a 0.77-point increase in White patients and a 6.71-point increase among Black patients (P = .043),

These results also appeared in a report published simultaneously with Dr. Verma’s talk.

But two other analyses that assessed a possible race-based difference in empagliflozin’s effect on renal protection and on functional status showed no suggestion of heterogeneity.

Dr. Verma stressed caution about the limitations of these analyses because they involved a relatively small number of Black patients, and were possibly subject to unadjusted confounding from differences in baseline characteristics between the Black and White patients.

Black patients also had a number-needed-to-treat advantage with dapagliflozin

The finding that Black patients with heart failure potentially get more bang for the buck from treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor by having a lower number needed to treat also showed up in a separate report at the meeting that assessed the treatment effect from dapagliflozin (Farxiga) in Black and White patients in a pooled analysis of the DAPA-HF pivotal trial of patients with HFrEF and the DELIVER pivotal trial of patients with HFpEF. The pooled cohort included a total of 11,007, but for the analysis by race the investigators also limited their focus to patients from the Americas with 2,626 White patients and 381 Black patients.

Assessment of the effect of dapagliflozin on the primary outcome of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure among all patients, both those with HFrEF and those with HFpEF, again showed that event rates among patients treated with placebo were significantly higher in Black, compared with White patients, and this led to a difference in the number needed to treat to prevent one primary outcome event of 12 in Blacks and 17 in Whites, Jawad H. Butt, MD said in a talk at the meeting.

Although treatment with dapagliflozin reduced the rate of the primary outcome in this subgroup of patients from the DAPA-HF trial and the DELIVER trial by similar rates in Black and White patients, event rates were higher in the Black patients resulting in “greater benefit in absolute terms” for Black patients, explained Dr. Butt, a cardiologist at Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen.

But in contrast to the empagliflozin findings reported by Dr. Verma, the combined data from the dapagliflozin trials showed no suggestion of heterogeneity in the beneficial effect of dapagliflozin based on left ventricular ejection fraction. In the Black patients, for example, the relative benefit from dapagliflozin on the primary outcome was consistent across the full spectrum of patients with HFrEF and HFpEF.

EMPEROR-Reduced and EMPEROR-Preserved were sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim and Lilly, the companies that jointly market empagliflozin (Jardiance). The DAPA-HF and DELIVER trials were sponsored by AstraZeneca, the company that markets dapagliflozin (Farxiga). Dr. Verma has received honoraria, research support, or both from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Lilly, and from numerous other companies. Dr. Butt has been a consultant to and received travel grants from AstraZeneca, honoraria from Novartis, and has been an adviser to Bayer.

AT AHA 2022

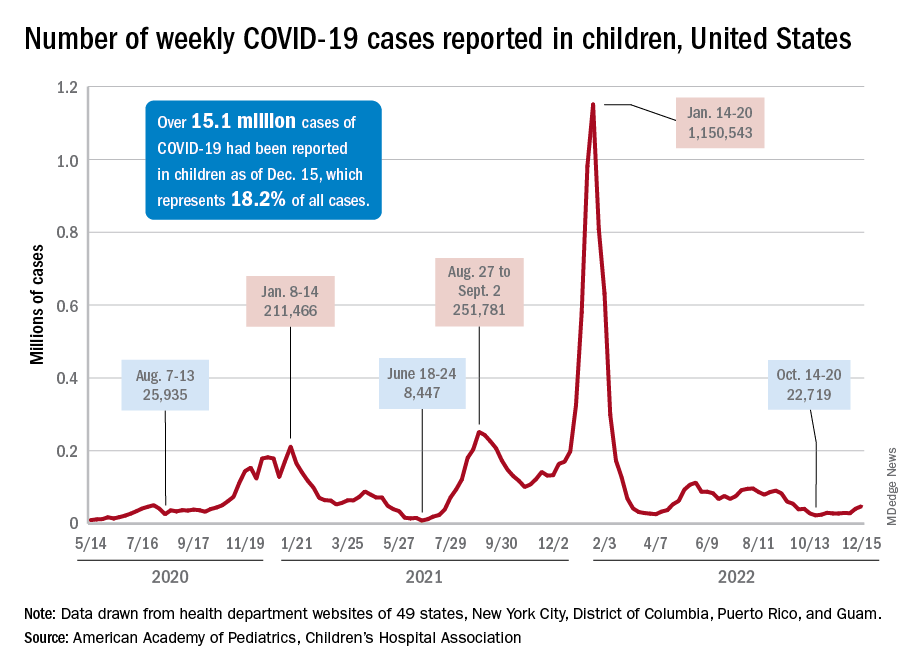

Children and COVID: New-case counts offer dueling narratives

New COVID-19 cases in children jumped by 66% during the first 2 weeks of December after an 8-week steady period lasting through October and November, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

and totaling less than 29,000 for the week of Nov. 25 to Dec. 1. That increase of almost 19,000 cases is the largest over a 2-week period since late July, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report based on data collected from state and territorial health department websites.

[This publication has been following the AAP/CHA report since the summer of 2020 and continues to share the data for the sake of consistency, but it must be noted that a number of states are no longer updating their public COVID dashboards. As a result, there is now a considerable discrepancy between the AAP/CHA weekly figures and those reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which has no such limitations on state data.]

The situation involving new cases over the last 2 weeks is quite different from the CDC’s perspective. The agency does not publish a weekly count, instead offering cumulative cases, which stood at almost 16.1 million as of Dec. 14. Calculating a 2-week total puts the new-case count for Dec. 1-14 at 113,572 among children aged 0-17 years. That is higher than the AAP/CHA count (88,629) for roughly the same period, but it is actually lower than the CDC’s figure (161,832) for the last 2 weeks of November.

The CDC data, in other words, suggest that new cases have gone down in the last 2 weeks, while the AAP and CHA, with their somewhat limited perspective, announced that new cases have gone up.

One COVID-related measure from the CDC that is not contradicted by other sources is hospitalization rates, which had climbed from 0.16 new admissions in children aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID per 100,000 population on Oct. 22 to 0.29 per 100,000 on Dec. 9. Visits to the emergency department with diagnosed COVID, meanwhile, have been fairly steady so far through December in children, according to the CDC.

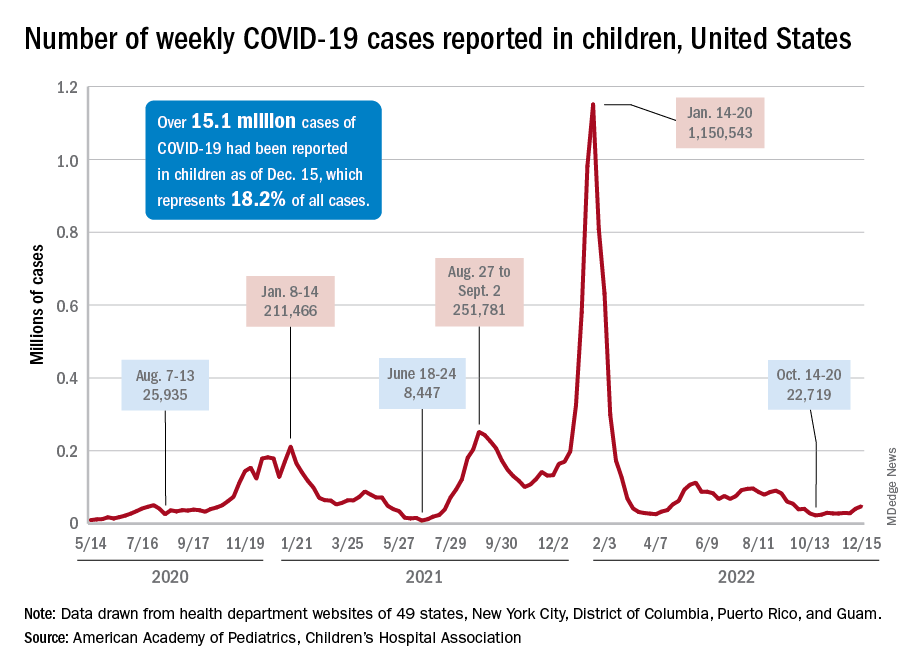

New COVID-19 cases in children jumped by 66% during the first 2 weeks of December after an 8-week steady period lasting through October and November, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

and totaling less than 29,000 for the week of Nov. 25 to Dec. 1. That increase of almost 19,000 cases is the largest over a 2-week period since late July, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report based on data collected from state and territorial health department websites.

[This publication has been following the AAP/CHA report since the summer of 2020 and continues to share the data for the sake of consistency, but it must be noted that a number of states are no longer updating their public COVID dashboards. As a result, there is now a considerable discrepancy between the AAP/CHA weekly figures and those reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which has no such limitations on state data.]

The situation involving new cases over the last 2 weeks is quite different from the CDC’s perspective. The agency does not publish a weekly count, instead offering cumulative cases, which stood at almost 16.1 million as of Dec. 14. Calculating a 2-week total puts the new-case count for Dec. 1-14 at 113,572 among children aged 0-17 years. That is higher than the AAP/CHA count (88,629) for roughly the same period, but it is actually lower than the CDC’s figure (161,832) for the last 2 weeks of November.

The CDC data, in other words, suggest that new cases have gone down in the last 2 weeks, while the AAP and CHA, with their somewhat limited perspective, announced that new cases have gone up.

One COVID-related measure from the CDC that is not contradicted by other sources is hospitalization rates, which had climbed from 0.16 new admissions in children aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID per 100,000 population on Oct. 22 to 0.29 per 100,000 on Dec. 9. Visits to the emergency department with diagnosed COVID, meanwhile, have been fairly steady so far through December in children, according to the CDC.

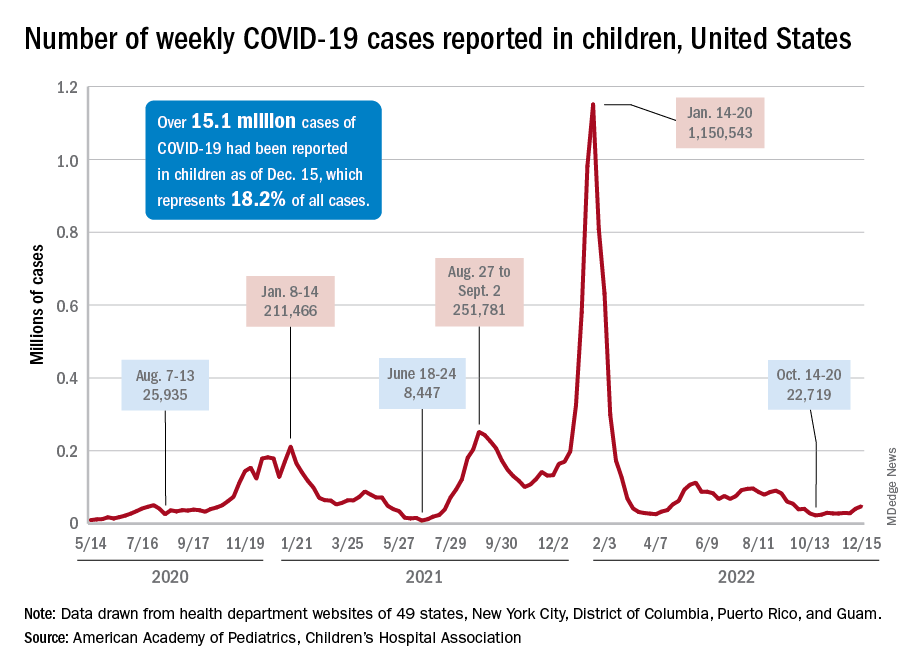

New COVID-19 cases in children jumped by 66% during the first 2 weeks of December after an 8-week steady period lasting through October and November, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

and totaling less than 29,000 for the week of Nov. 25 to Dec. 1. That increase of almost 19,000 cases is the largest over a 2-week period since late July, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report based on data collected from state and territorial health department websites.

[This publication has been following the AAP/CHA report since the summer of 2020 and continues to share the data for the sake of consistency, but it must be noted that a number of states are no longer updating their public COVID dashboards. As a result, there is now a considerable discrepancy between the AAP/CHA weekly figures and those reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which has no such limitations on state data.]

The situation involving new cases over the last 2 weeks is quite different from the CDC’s perspective. The agency does not publish a weekly count, instead offering cumulative cases, which stood at almost 16.1 million as of Dec. 14. Calculating a 2-week total puts the new-case count for Dec. 1-14 at 113,572 among children aged 0-17 years. That is higher than the AAP/CHA count (88,629) for roughly the same period, but it is actually lower than the CDC’s figure (161,832) for the last 2 weeks of November.

The CDC data, in other words, suggest that new cases have gone down in the last 2 weeks, while the AAP and CHA, with their somewhat limited perspective, announced that new cases have gone up.

One COVID-related measure from the CDC that is not contradicted by other sources is hospitalization rates, which had climbed from 0.16 new admissions in children aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID per 100,000 population on Oct. 22 to 0.29 per 100,000 on Dec. 9. Visits to the emergency department with diagnosed COVID, meanwhile, have been fairly steady so far through December in children, according to the CDC.

High lipoprotein(a) levels plus hypertension add to CVD risk

High levels of lipoprotein(a) increase the risk for incident cardiovascular disease (CVD) for hypertensive individuals but not for those without hypertension, a new MESA analysis suggests.

There are ways to test for statistical interaction, “in this case, multiplicative interaction between Lp(a) and hypertension, which suggests that Lp(a) is actually modifying the effect between blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. It’s not simply additive,” senior author Michael D. Shapiro, DO, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., told this news organization.

“So that’s new and I don’t think anybody’s looked at that before.”

Although Lp(a) is recognized as an independent cause of atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD), the significance of Lp(a) in hypertension has been “virtually untapped,” he noted. A recent prospective study reported that elevated CVD risk was present only in individuals with Lp(a) ≥ 30 mg/dL and hypertension but it included only Chinese participants with stable coronary artery disease.

The current analysis, published online in the journal Hypertension, included 6,674 participants in the ongoing Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), all free of baseline ASCVD, who were recruited from six communities in the United States and had measured baseline Lp(a), blood pressure, and CVD events data over follow-up from 2000 to 2018.

Participants were stratified into four groups based on the presence or absence of hypertension (defined as 140/90 mm Hg or higher or the use of antihypertensive drugs) and an Lp(a) threshold of 50 mg/dL, as recommended by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol guideline for consideration as an ASCVD risk-enhancing factor.

Slightly more than half of participants were female (52.8%), 38.6% were White, 27.5% were African American, 22.1% were Hispanic, and 11.9% were Chinese American.

According to the researchers, 809 participants had a CVD event over an average follow-up of 13.9 years, including 7.7% of group 1 with Lp(a) < 50 mg/dL and no hypertension, 8.0% of group 2 with Lp(a) ≥ 50 mg/dL and no hypertension, 16.2% of group 3 with Lp(a) < 50 mg/dL and hypertension, and 18.8% of group 4 with Lp(a) ≥ 50 mg/dL and hypertension.

When compared with group 1 in a fully adjusted Cox proportional model, participants with elevated Lp(a) and no hypertension (group 2) did not have an increased risk of CVD events (hazard ratio [HR], 1.09; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.79-1.50).

CVD risk, however, was significantly higher in group 3 with normal Lp(a) and hypertension (HR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.39-1.98) and group 4 with elevated Lp(a) and hypertension (HR, 2.07, 95% CI, 1.63-2.62).

Among all participants with hypertension (groups 3 and 4), Lp(a) was associated with a significant increase in CVD risk (HR, 1.24, 95% CI, 1.01-1.53).

“What I think is interesting here is that in the absence of hypertension, we didn’t really see an increased risk despite having an elevated Lp(a),” said Dr. Shapiro. “What it may indicate is that really for Lp(a) to be associated with risk, there may already need to be some kind of arterial damage that allows the Lp(a) to have its atherogenic impact.

“In other words, in individuals who have totally normal arterial walls, potentially, maybe that is protective enough against Lp(a) that in the absence of any other injurious factor, maybe it’s not an issue,” he said. “That’s a big hypothesis-generating [statement], but hypertension is certainly one of those risk factors that’s known to cause endothelial injury and endothelial dysfunction.”

Dr. Shapiro pointed out that when first measured in MESA, Lp(a) was measured in 4,600 participants who were not on statins, which is important because statins can increase Lp(a) levels.

“When you look just at those participants, those 4,600, you actually do see a relationship between Lp(a) and cardiovascular disease,” he said. “When you look at the whole population, including the 17% who are baseline populations, even when you adjust for statin therapy, we fail to see that, at least in the long-term follow up.”

Nevertheless, he cautioned that hypertension is just one of many traditional cardiovascular risk factors that could affect the relationship between Lp(a) and CVD risk. “I don’t want to suggest that we believe there’s something specifically magical about hypertension and Lp(a). If we chose, say, diabetes or smoking or another traditional risk factor, we may or may not have seen kind of similar results.”

When the investigators stratified the analyses by sex and race/ethnicity, they found that Lp(a) was not associated with CVD risk, regardless of hypertension status. In Black participants, however, greater CVD risk was seen when both elevated Lp(a) and hypertension were present (HR, 2.07, 95% CI, 1.34-3.21; P = .001).

Asked whether the results support one-time universal screening for Lp(a), which is almost exclusively genetically determined, Dr. Shapiro said he supports screening but that this was a secondary analysis and its numbers were modest. He added that median Lp(a) level is higher in African Americans than any other racial/ethnic group but the “most recent data has clarified that, per any absolute level of Lp(a), it appears to confer the same absolute risk in any racial or ethnic group.”

The authors acknowledge that differential loss to follow-up could have resulted in selection bias in the study and that there were relatively few CVD events in group 2, which may have limited the ability to detect differences in groups without hypertension, particularly in the subgroup analyses. Other limitations are the potential for residual confounding and participants may have developed hypertension during follow-up, resulting in misclassification bias.

Further research is needed to better understand the mechanistic link between Lp(a), hypertension, and CVD, Dr. Shapiro said. Further insights also should be provided by the ongoing phase 3 Lp(a) HORIZON trial evaluating the effect of Lp(a) lowering with the investigational antisense drug, pelacarsen, on cardiovascular events in 8,324 patients with established CVD and elevated Lp(a). The study is expected to be completed in May 2025.

The study was supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and by grants from the National Center for Advanced Translational Sciences. Dr. Shapiro reports participating in scientific advisory boards with Amgen, Novartis, and Novo Nordisk, and consulting for Regeneron.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

High levels of lipoprotein(a) increase the risk for incident cardiovascular disease (CVD) for hypertensive individuals but not for those without hypertension, a new MESA analysis suggests.

There are ways to test for statistical interaction, “in this case, multiplicative interaction between Lp(a) and hypertension, which suggests that Lp(a) is actually modifying the effect between blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. It’s not simply additive,” senior author Michael D. Shapiro, DO, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., told this news organization.

“So that’s new and I don’t think anybody’s looked at that before.”

Although Lp(a) is recognized as an independent cause of atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD), the significance of Lp(a) in hypertension has been “virtually untapped,” he noted. A recent prospective study reported that elevated CVD risk was present only in individuals with Lp(a) ≥ 30 mg/dL and hypertension but it included only Chinese participants with stable coronary artery disease.

The current analysis, published online in the journal Hypertension, included 6,674 participants in the ongoing Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), all free of baseline ASCVD, who were recruited from six communities in the United States and had measured baseline Lp(a), blood pressure, and CVD events data over follow-up from 2000 to 2018.

Participants were stratified into four groups based on the presence or absence of hypertension (defined as 140/90 mm Hg or higher or the use of antihypertensive drugs) and an Lp(a) threshold of 50 mg/dL, as recommended by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol guideline for consideration as an ASCVD risk-enhancing factor.

Slightly more than half of participants were female (52.8%), 38.6% were White, 27.5% were African American, 22.1% were Hispanic, and 11.9% were Chinese American.

According to the researchers, 809 participants had a CVD event over an average follow-up of 13.9 years, including 7.7% of group 1 with Lp(a) < 50 mg/dL and no hypertension, 8.0% of group 2 with Lp(a) ≥ 50 mg/dL and no hypertension, 16.2% of group 3 with Lp(a) < 50 mg/dL and hypertension, and 18.8% of group 4 with Lp(a) ≥ 50 mg/dL and hypertension.

When compared with group 1 in a fully adjusted Cox proportional model, participants with elevated Lp(a) and no hypertension (group 2) did not have an increased risk of CVD events (hazard ratio [HR], 1.09; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.79-1.50).

CVD risk, however, was significantly higher in group 3 with normal Lp(a) and hypertension (HR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.39-1.98) and group 4 with elevated Lp(a) and hypertension (HR, 2.07, 95% CI, 1.63-2.62).

Among all participants with hypertension (groups 3 and 4), Lp(a) was associated with a significant increase in CVD risk (HR, 1.24, 95% CI, 1.01-1.53).

“What I think is interesting here is that in the absence of hypertension, we didn’t really see an increased risk despite having an elevated Lp(a),” said Dr. Shapiro. “What it may indicate is that really for Lp(a) to be associated with risk, there may already need to be some kind of arterial damage that allows the Lp(a) to have its atherogenic impact.

“In other words, in individuals who have totally normal arterial walls, potentially, maybe that is protective enough against Lp(a) that in the absence of any other injurious factor, maybe it’s not an issue,” he said. “That’s a big hypothesis-generating [statement], but hypertension is certainly one of those risk factors that’s known to cause endothelial injury and endothelial dysfunction.”

Dr. Shapiro pointed out that when first measured in MESA, Lp(a) was measured in 4,600 participants who were not on statins, which is important because statins can increase Lp(a) levels.

“When you look just at those participants, those 4,600, you actually do see a relationship between Lp(a) and cardiovascular disease,” he said. “When you look at the whole population, including the 17% who are baseline populations, even when you adjust for statin therapy, we fail to see that, at least in the long-term follow up.”

Nevertheless, he cautioned that hypertension is just one of many traditional cardiovascular risk factors that could affect the relationship between Lp(a) and CVD risk. “I don’t want to suggest that we believe there’s something specifically magical about hypertension and Lp(a). If we chose, say, diabetes or smoking or another traditional risk factor, we may or may not have seen kind of similar results.”

When the investigators stratified the analyses by sex and race/ethnicity, they found that Lp(a) was not associated with CVD risk, regardless of hypertension status. In Black participants, however, greater CVD risk was seen when both elevated Lp(a) and hypertension were present (HR, 2.07, 95% CI, 1.34-3.21; P = .001).

Asked whether the results support one-time universal screening for Lp(a), which is almost exclusively genetically determined, Dr. Shapiro said he supports screening but that this was a secondary analysis and its numbers were modest. He added that median Lp(a) level is higher in African Americans than any other racial/ethnic group but the “most recent data has clarified that, per any absolute level of Lp(a), it appears to confer the same absolute risk in any racial or ethnic group.”

The authors acknowledge that differential loss to follow-up could have resulted in selection bias in the study and that there were relatively few CVD events in group 2, which may have limited the ability to detect differences in groups without hypertension, particularly in the subgroup analyses. Other limitations are the potential for residual confounding and participants may have developed hypertension during follow-up, resulting in misclassification bias.

Further research is needed to better understand the mechanistic link between Lp(a), hypertension, and CVD, Dr. Shapiro said. Further insights also should be provided by the ongoing phase 3 Lp(a) HORIZON trial evaluating the effect of Lp(a) lowering with the investigational antisense drug, pelacarsen, on cardiovascular events in 8,324 patients with established CVD and elevated Lp(a). The study is expected to be completed in May 2025.

The study was supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and by grants from the National Center for Advanced Translational Sciences. Dr. Shapiro reports participating in scientific advisory boards with Amgen, Novartis, and Novo Nordisk, and consulting for Regeneron.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

High levels of lipoprotein(a) increase the risk for incident cardiovascular disease (CVD) for hypertensive individuals but not for those without hypertension, a new MESA analysis suggests.

There are ways to test for statistical interaction, “in this case, multiplicative interaction between Lp(a) and hypertension, which suggests that Lp(a) is actually modifying the effect between blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. It’s not simply additive,” senior author Michael D. Shapiro, DO, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, N.C., told this news organization.

“So that’s new and I don’t think anybody’s looked at that before.”

Although Lp(a) is recognized as an independent cause of atherosclerotic CVD (ASCVD), the significance of Lp(a) in hypertension has been “virtually untapped,” he noted. A recent prospective study reported that elevated CVD risk was present only in individuals with Lp(a) ≥ 30 mg/dL and hypertension but it included only Chinese participants with stable coronary artery disease.

The current analysis, published online in the journal Hypertension, included 6,674 participants in the ongoing Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), all free of baseline ASCVD, who were recruited from six communities in the United States and had measured baseline Lp(a), blood pressure, and CVD events data over follow-up from 2000 to 2018.

Participants were stratified into four groups based on the presence or absence of hypertension (defined as 140/90 mm Hg or higher or the use of antihypertensive drugs) and an Lp(a) threshold of 50 mg/dL, as recommended by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol guideline for consideration as an ASCVD risk-enhancing factor.

Slightly more than half of participants were female (52.8%), 38.6% were White, 27.5% were African American, 22.1% were Hispanic, and 11.9% were Chinese American.

According to the researchers, 809 participants had a CVD event over an average follow-up of 13.9 years, including 7.7% of group 1 with Lp(a) < 50 mg/dL and no hypertension, 8.0% of group 2 with Lp(a) ≥ 50 mg/dL and no hypertension, 16.2% of group 3 with Lp(a) < 50 mg/dL and hypertension, and 18.8% of group 4 with Lp(a) ≥ 50 mg/dL and hypertension.

When compared with group 1 in a fully adjusted Cox proportional model, participants with elevated Lp(a) and no hypertension (group 2) did not have an increased risk of CVD events (hazard ratio [HR], 1.09; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.79-1.50).

CVD risk, however, was significantly higher in group 3 with normal Lp(a) and hypertension (HR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.39-1.98) and group 4 with elevated Lp(a) and hypertension (HR, 2.07, 95% CI, 1.63-2.62).

Among all participants with hypertension (groups 3 and 4), Lp(a) was associated with a significant increase in CVD risk (HR, 1.24, 95% CI, 1.01-1.53).

“What I think is interesting here is that in the absence of hypertension, we didn’t really see an increased risk despite having an elevated Lp(a),” said Dr. Shapiro. “What it may indicate is that really for Lp(a) to be associated with risk, there may already need to be some kind of arterial damage that allows the Lp(a) to have its atherogenic impact.

“In other words, in individuals who have totally normal arterial walls, potentially, maybe that is protective enough against Lp(a) that in the absence of any other injurious factor, maybe it’s not an issue,” he said. “That’s a big hypothesis-generating [statement], but hypertension is certainly one of those risk factors that’s known to cause endothelial injury and endothelial dysfunction.”

Dr. Shapiro pointed out that when first measured in MESA, Lp(a) was measured in 4,600 participants who were not on statins, which is important because statins can increase Lp(a) levels.

“When you look just at those participants, those 4,600, you actually do see a relationship between Lp(a) and cardiovascular disease,” he said. “When you look at the whole population, including the 17% who are baseline populations, even when you adjust for statin therapy, we fail to see that, at least in the long-term follow up.”

Nevertheless, he cautioned that hypertension is just one of many traditional cardiovascular risk factors that could affect the relationship between Lp(a) and CVD risk. “I don’t want to suggest that we believe there’s something specifically magical about hypertension and Lp(a). If we chose, say, diabetes or smoking or another traditional risk factor, we may or may not have seen kind of similar results.”

When the investigators stratified the analyses by sex and race/ethnicity, they found that Lp(a) was not associated with CVD risk, regardless of hypertension status. In Black participants, however, greater CVD risk was seen when both elevated Lp(a) and hypertension were present (HR, 2.07, 95% CI, 1.34-3.21; P = .001).

Asked whether the results support one-time universal screening for Lp(a), which is almost exclusively genetically determined, Dr. Shapiro said he supports screening but that this was a secondary analysis and its numbers were modest. He added that median Lp(a) level is higher in African Americans than any other racial/ethnic group but the “most recent data has clarified that, per any absolute level of Lp(a), it appears to confer the same absolute risk in any racial or ethnic group.”

The authors acknowledge that differential loss to follow-up could have resulted in selection bias in the study and that there were relatively few CVD events in group 2, which may have limited the ability to detect differences in groups without hypertension, particularly in the subgroup analyses. Other limitations are the potential for residual confounding and participants may have developed hypertension during follow-up, resulting in misclassification bias.

Further research is needed to better understand the mechanistic link between Lp(a), hypertension, and CVD, Dr. Shapiro said. Further insights also should be provided by the ongoing phase 3 Lp(a) HORIZON trial evaluating the effect of Lp(a) lowering with the investigational antisense drug, pelacarsen, on cardiovascular events in 8,324 patients with established CVD and elevated Lp(a). The study is expected to be completed in May 2025.

The study was supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and by grants from the National Center for Advanced Translational Sciences. Dr. Shapiro reports participating in scientific advisory boards with Amgen, Novartis, and Novo Nordisk, and consulting for Regeneron.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM HYPERTENSION

Systematic review supports preferred drugs for HIV in youths

A systematic review of observational studies and clinical trials found dolutegravir and raltegravir to be safe and effective for treating teens and children living with HIV.

Effectiveness was higher across dolutegravir studies, the authors reported. After 12 months of treatment and observation, viral suppression levels were greater than 70% in most studies assessing dolutegravir. Viral suppression with raltegravir after 12 months varied between 42% and 83%.

“Our findings support the use of these two integrase inhibitors as part of WHO-recommended regimens for treating HIV,” said lead study author Claire Townsend, PhD, an epidemiologist and consultant to the World Health Organization HIV department in Geneva. “They were in line with what has been reported in adults and provide reassurance for the continued use of these two drugs in children and adolescents.”

The study was published in the Journal of the International AIDS Society.

Tracking outcomes for WHO guidelines

Integrase inhibitors, including dolutegravir and raltegravir, have become leading first- and second-line treatments in patients with HIV, largely owing to their effectiveness and fewer side effects, compared with other antiretroviral treatments.

Monitoring short- and long-term health outcomes of these widely used drugs is critical, the authors wrote. This is especially the case for dolutegravir, which has recently been approved in pediatric formulations. The review supported the development of the 2021 WHO consolidated HIV guidelines.

Dr. Townsend and colleagues searched the literature and screened trial registries for relevant studies conducted from January 2009 to March 2021. Among more than 4,000 published papers and abstracts, they identified 19 studies that met their review criteria relating to dolutegravir or raltegravir in children or adolescents aged 0-19 years who are living with HIV, including two studies that reported data on both agents.

Data on dolutegravir were extracted from 11 studies that included 2,330 children and adolescents in 1 randomized controlled trial, 1 single-arm trial, and 9 cohort studies. Data on raltegravir were extracted from 10 studies that included 649 children and adolescents in 1 randomized controlled trial, 1 single-arm trial, and 8 cohort studies.

The median follow-up in the dolutegravir studies was 6-36 months. Six studies recruited participants from Europe, three studies were based in sub-Saharan Africa, and two studies included persons from multiple geographic regions.

Across all studies, grade 3/4 adverse events were reported in 0%-50% of cases. Of these adverse events, very few were drug related, and no deaths were attributed to either dolutegravir or raltegravir.

However, Dr. Townsend cautioned that future research is needed to fill in evidence gaps “on longer-term safety and effectiveness of dolutegravir and raltegravir in children and adolescents,” including “research into adverse outcomes such as weight gain, potential metabolic changes, and neuropsychiatric adverse events, which have been reported in adults.”

The researchers noted that the small sample size of many of the studies contributed to variability in the findings and that most studies were observational, providing important real-world data but making their results less robust compared with data from randomized controlled studies with large sample sizes. They also noted that there was a high risk of bias (4 studies) and unclear risk of bias (5 studies) among the 15 observational studies included in their analysis.

“This research is particularly important because it supports the WHO recommendation that dolutegravir, which has a particularly high barrier of resistance to the HIV virus, be synchronized in adults and children as the preferred first-line and second-line treatment against HIV,” said Natella Rakhmanina, MD, PhD, director of HIV Services & Special Immunology at the Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C. Dr. Rakhmanina was not associated with the study.

Dr. Rakhmanina agreed that the safety profile of both drugs is “very good.” The lack of serious adverse events was meaningful, she highlighted, because “good tolerability is very important, particularly in children” as it means that drug compliance and viral suppression are achievable.

Two authors reported their authorship on two studies included in the review, as well as grant funding from ViiV Healthcare/GlaxoSmithKline, the marketing authorization holder for dolutegravir.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A systematic review of observational studies and clinical trials found dolutegravir and raltegravir to be safe and effective for treating teens and children living with HIV.

Effectiveness was higher across dolutegravir studies, the authors reported. After 12 months of treatment and observation, viral suppression levels were greater than 70% in most studies assessing dolutegravir. Viral suppression with raltegravir after 12 months varied between 42% and 83%.

“Our findings support the use of these two integrase inhibitors as part of WHO-recommended regimens for treating HIV,” said lead study author Claire Townsend, PhD, an epidemiologist and consultant to the World Health Organization HIV department in Geneva. “They were in line with what has been reported in adults and provide reassurance for the continued use of these two drugs in children and adolescents.”

The study was published in the Journal of the International AIDS Society.

Tracking outcomes for WHO guidelines

Integrase inhibitors, including dolutegravir and raltegravir, have become leading first- and second-line treatments in patients with HIV, largely owing to their effectiveness and fewer side effects, compared with other antiretroviral treatments.

Monitoring short- and long-term health outcomes of these widely used drugs is critical, the authors wrote. This is especially the case for dolutegravir, which has recently been approved in pediatric formulations. The review supported the development of the 2021 WHO consolidated HIV guidelines.

Dr. Townsend and colleagues searched the literature and screened trial registries for relevant studies conducted from January 2009 to March 2021. Among more than 4,000 published papers and abstracts, they identified 19 studies that met their review criteria relating to dolutegravir or raltegravir in children or adolescents aged 0-19 years who are living with HIV, including two studies that reported data on both agents.

Data on dolutegravir were extracted from 11 studies that included 2,330 children and adolescents in 1 randomized controlled trial, 1 single-arm trial, and 9 cohort studies. Data on raltegravir were extracted from 10 studies that included 649 children and adolescents in 1 randomized controlled trial, 1 single-arm trial, and 8 cohort studies.

The median follow-up in the dolutegravir studies was 6-36 months. Six studies recruited participants from Europe, three studies were based in sub-Saharan Africa, and two studies included persons from multiple geographic regions.

Across all studies, grade 3/4 adverse events were reported in 0%-50% of cases. Of these adverse events, very few were drug related, and no deaths were attributed to either dolutegravir or raltegravir.

However, Dr. Townsend cautioned that future research is needed to fill in evidence gaps “on longer-term safety and effectiveness of dolutegravir and raltegravir in children and adolescents,” including “research into adverse outcomes such as weight gain, potential metabolic changes, and neuropsychiatric adverse events, which have been reported in adults.”

The researchers noted that the small sample size of many of the studies contributed to variability in the findings and that most studies were observational, providing important real-world data but making their results less robust compared with data from randomized controlled studies with large sample sizes. They also noted that there was a high risk of bias (4 studies) and unclear risk of bias (5 studies) among the 15 observational studies included in their analysis.

“This research is particularly important because it supports the WHO recommendation that dolutegravir, which has a particularly high barrier of resistance to the HIV virus, be synchronized in adults and children as the preferred first-line and second-line treatment against HIV,” said Natella Rakhmanina, MD, PhD, director of HIV Services & Special Immunology at the Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C. Dr. Rakhmanina was not associated with the study.

Dr. Rakhmanina agreed that the safety profile of both drugs is “very good.” The lack of serious adverse events was meaningful, she highlighted, because “good tolerability is very important, particularly in children” as it means that drug compliance and viral suppression are achievable.

Two authors reported their authorship on two studies included in the review, as well as grant funding from ViiV Healthcare/GlaxoSmithKline, the marketing authorization holder for dolutegravir.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A systematic review of observational studies and clinical trials found dolutegravir and raltegravir to be safe and effective for treating teens and children living with HIV.

Effectiveness was higher across dolutegravir studies, the authors reported. After 12 months of treatment and observation, viral suppression levels were greater than 70% in most studies assessing dolutegravir. Viral suppression with raltegravir after 12 months varied between 42% and 83%.

“Our findings support the use of these two integrase inhibitors as part of WHO-recommended regimens for treating HIV,” said lead study author Claire Townsend, PhD, an epidemiologist and consultant to the World Health Organization HIV department in Geneva. “They were in line with what has been reported in adults and provide reassurance for the continued use of these two drugs in children and adolescents.”

The study was published in the Journal of the International AIDS Society.

Tracking outcomes for WHO guidelines

Integrase inhibitors, including dolutegravir and raltegravir, have become leading first- and second-line treatments in patients with HIV, largely owing to their effectiveness and fewer side effects, compared with other antiretroviral treatments.

Monitoring short- and long-term health outcomes of these widely used drugs is critical, the authors wrote. This is especially the case for dolutegravir, which has recently been approved in pediatric formulations. The review supported the development of the 2021 WHO consolidated HIV guidelines.

Dr. Townsend and colleagues searched the literature and screened trial registries for relevant studies conducted from January 2009 to March 2021. Among more than 4,000 published papers and abstracts, they identified 19 studies that met their review criteria relating to dolutegravir or raltegravir in children or adolescents aged 0-19 years who are living with HIV, including two studies that reported data on both agents.

Data on dolutegravir were extracted from 11 studies that included 2,330 children and adolescents in 1 randomized controlled trial, 1 single-arm trial, and 9 cohort studies. Data on raltegravir were extracted from 10 studies that included 649 children and adolescents in 1 randomized controlled trial, 1 single-arm trial, and 8 cohort studies.

The median follow-up in the dolutegravir studies was 6-36 months. Six studies recruited participants from Europe, three studies were based in sub-Saharan Africa, and two studies included persons from multiple geographic regions.

Across all studies, grade 3/4 adverse events were reported in 0%-50% of cases. Of these adverse events, very few were drug related, and no deaths were attributed to either dolutegravir or raltegravir.

However, Dr. Townsend cautioned that future research is needed to fill in evidence gaps “on longer-term safety and effectiveness of dolutegravir and raltegravir in children and adolescents,” including “research into adverse outcomes such as weight gain, potential metabolic changes, and neuropsychiatric adverse events, which have been reported in adults.”

The researchers noted that the small sample size of many of the studies contributed to variability in the findings and that most studies were observational, providing important real-world data but making their results less robust compared with data from randomized controlled studies with large sample sizes. They also noted that there was a high risk of bias (4 studies) and unclear risk of bias (5 studies) among the 15 observational studies included in their analysis.

“This research is particularly important because it supports the WHO recommendation that dolutegravir, which has a particularly high barrier of resistance to the HIV virus, be synchronized in adults and children as the preferred first-line and second-line treatment against HIV,” said Natella Rakhmanina, MD, PhD, director of HIV Services & Special Immunology at the Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C. Dr. Rakhmanina was not associated with the study.

Dr. Rakhmanina agreed that the safety profile of both drugs is “very good.” The lack of serious adverse events was meaningful, she highlighted, because “good tolerability is very important, particularly in children” as it means that drug compliance and viral suppression are achievable.

Two authors reported their authorship on two studies included in the review, as well as grant funding from ViiV Healthcare/GlaxoSmithKline, the marketing authorization holder for dolutegravir.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL AIDS SOCIETY

Dispatching volunteer responders may not increase AED use in OHCA

Dispatching trained volunteer responders via smartphones to retrieve automated external defibrillators for patients in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) did not significantly increase bystander AED use in a randomized clinical trial in Sweden.

Most patients in OHCA can be saved if cardiopulmonary resuscitation and defibrillation are initiated within minutes, but despite the “substantial” public availability of AEDs and widespread CPR training among the Swedish public, use rates of both are low, Mattias Ringh, MD, PhD, of Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, and colleagues wrote.

A previous study by the team showed that dispatching volunteer responders via a smartphone app significantly increased bystander CPR. The current study, called the Swedish AED and Mobile Bystander Activation (SAMBA) trial, aimed to see whether dispatching volunteer responders to collect a nearby AED would increase bystander AED use. A control group of volunteer responders was instructed to go straight to the scene and start CPR.

“The results showed that the volunteer responders were first to provide treatment with both CPR and AEDs in a large proportion of cases in both groups, thereby creating a ‘statistical’ dilutional effect,” Dr. Ringh said in an interview. In effect, the control arm also became an active arm.

“But if we agree that treatment with AEDs and CPR is saving lives, then dispatching volunteer responders is doing just that, although we could not fully measure the effect in our study,” he added.

The study was published online in JAMA Cardiology.

No significant differences

The SAMBA trial assessed outcomes of the smartphone dispatch system (Heartrunner), which is triggered at emergency dispatch centers in response to suspected OHCAs at the same time that an ambulance with advanced life support equipment is dispatched.

The volunteer responder system locates a maximum of 30 volunteer responders within a 1.3-km radius from the suspected out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, the researchers explained in their report. Volunteer responders are requested via their smartphone application to accept or decline the alert. If they accept an alert, the volunteer responders receive map-aided route directions to the location of the suspected arrest.

In patients allocated to intervention in this study, four of five of all volunteer responders who accepted the alert received instructions to collect the nearest available AED and then go directly to the patient with suspected out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, the authors noted. Route directions to the scene of the cardiac arrest and the AED were displayed on their smartphones. One of the 5 volunteer responders, closest to the arrest, was dispatched to go directly to initiate CPR.

In patients allocated to the control group, all volunteer responders who accepted the alert were instructed to go directly to the patient with suspected out-of-hospital cardiac arrest to perform CPR. No route directions to or locations of AEDs were displayed.

The study was conducted in Stockholm and in Västra Götaland from 2018 to 2020. At the start of the study, there were 3,123 AEDs and 24,493 volunteer responders in Stockholm and 3,195 AEDs and 19,117 volunteer responders in Västra Götaland.

Post-randomization exclusions included patients without OHCA, those with OHCAs not treated by emergency medical services, and those with OHCAs witnessed by EMS.

The primary outcome was overall bystander AED attachment before the arrival of EMS, including those attached by the volunteer responders but also by lay volunteers who did not use the smartphone app.

Volunteer responders were activated for 947 individuals with OHCA; 461 patients were randomized to the intervention group and 486 to the control group. In both groups, the patients’ median age was 73 and about 65% were men.

Attachment of the AED before the arrival of EMS or first responders occurred in 61 patients (13.2%) in the intervention group versus 46 (9.5%) in the control group (P = .08). However, the majority of all AEDs were attached by lay volunteers who were not volunteer responders using the smartphone app (37 in the intervention arm vs. 28 in the control arm), the researchers noted.

No significant differences were seen in secondary outcomes, which included bystander CPR (69% vs. 71.6%, respectively) and defibrillation before EMS arrival (3.7% vs. 3.9%) between groups.

Among the volunteer responders using the app, crossover was 11% and compliance to instructions was 31%. Overall, volunteer responders attached 38% of all bystander-attached AEDs and provided 45% of all bystander defibrillations and 43% of all bystander CPR.

Going forward, Dr. Ringh and colleagues will be further analyzing the results to understand how to better optimize the logistical challenges involved with smartphone dispatch to OHCA patients. “In the longer term, investigating the impact on survival is also warranted,” he concluded.

U.S. in worse shape

In a comment, Christopher Calandrella, DO, chair of emergency medicine at Long Island Jewish Forest Hills,, New York, part of Northwell Health, said: “Significant data are available to support the importance of prompt initiation of CPR and defibrillation for OHCA, and although this study did not demonstrate a meaningful increase in use of AEDs with the trial system, layperson CPR was initiated in approximately 70% of cases in the cohort as a whole. Because of this, I believe it is evident that patients still benefit from a system that encourages bystanders to provide aid prior to the arrival of EMS.”

Nevertheless, he noted, “despite the training of volunteers in applying an AED, overall, only a small percentage of patients in either group had placement and use of the device. While the reasons likely are multifactorial, it may be in part due to the significant stress and anxiety associated with OHCA.”

Additional research would be helpful, he said. “Future studies focusing on more rural areas with lower population density and limited availability of AEDs may be beneficial. Expanding the research outside of Europe to other countries would be useful. Next-phase trials looking at 30-day survival in these patients would also be important.”

Currently in the United States, research is underway to evaluate the use of smartphones to improve in-hospital cardiac arrests, he added, “but no nationwide programs are in place for OHCA.”

Similarly, Kevin G. Volpp, MD, PhD, and Benjamin S. Abella, MD, MPhil, both of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, wrote in a related editorial: “It is sobering to recognize that, in the U.S., it may be nearly impossible to even test an idea like this, given the lack of a supporting data infrastructure.”

Although there is an app in the United States to link OHCA events to bystander response, they noted, less than half of eligible 911 centers have linked to it.

“Furthermore, the bystander CPR rate in the U.S. is less than 35%, only about half of the Swedish rate, indicating far fewer people are trained in CPR and comfortable performing it in the U.S.,” they wrote. “A wealthy country like the U.S. should be able to develop a far more effective approach to preventing millions of ... families from having a loved one die of OHCA in the decade to come.”

The study was funded by unrestricted grant from the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation and Stockholm County. The authors, editorialists, and Dr. Calandrella disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Dispatching trained volunteer responders via smartphones to retrieve automated external defibrillators for patients in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) did not significantly increase bystander AED use in a randomized clinical trial in Sweden.

Most patients in OHCA can be saved if cardiopulmonary resuscitation and defibrillation are initiated within minutes, but despite the “substantial” public availability of AEDs and widespread CPR training among the Swedish public, use rates of both are low, Mattias Ringh, MD, PhD, of Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, and colleagues wrote.

A previous study by the team showed that dispatching volunteer responders via a smartphone app significantly increased bystander CPR. The current study, called the Swedish AED and Mobile Bystander Activation (SAMBA) trial, aimed to see whether dispatching volunteer responders to collect a nearby AED would increase bystander AED use. A control group of volunteer responders was instructed to go straight to the scene and start CPR.

“The results showed that the volunteer responders were first to provide treatment with both CPR and AEDs in a large proportion of cases in both groups, thereby creating a ‘statistical’ dilutional effect,” Dr. Ringh said in an interview. In effect, the control arm also became an active arm.

“But if we agree that treatment with AEDs and CPR is saving lives, then dispatching volunteer responders is doing just that, although we could not fully measure the effect in our study,” he added.

The study was published online in JAMA Cardiology.

No significant differences

The SAMBA trial assessed outcomes of the smartphone dispatch system (Heartrunner), which is triggered at emergency dispatch centers in response to suspected OHCAs at the same time that an ambulance with advanced life support equipment is dispatched.

The volunteer responder system locates a maximum of 30 volunteer responders within a 1.3-km radius from the suspected out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, the researchers explained in their report. Volunteer responders are requested via their smartphone application to accept or decline the alert. If they accept an alert, the volunteer responders receive map-aided route directions to the location of the suspected arrest.

In patients allocated to intervention in this study, four of five of all volunteer responders who accepted the alert received instructions to collect the nearest available AED and then go directly to the patient with suspected out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, the authors noted. Route directions to the scene of the cardiac arrest and the AED were displayed on their smartphones. One of the 5 volunteer responders, closest to the arrest, was dispatched to go directly to initiate CPR.

In patients allocated to the control group, all volunteer responders who accepted the alert were instructed to go directly to the patient with suspected out-of-hospital cardiac arrest to perform CPR. No route directions to or locations of AEDs were displayed.

The study was conducted in Stockholm and in Västra Götaland from 2018 to 2020. At the start of the study, there were 3,123 AEDs and 24,493 volunteer responders in Stockholm and 3,195 AEDs and 19,117 volunteer responders in Västra Götaland.

Post-randomization exclusions included patients without OHCA, those with OHCAs not treated by emergency medical services, and those with OHCAs witnessed by EMS.

The primary outcome was overall bystander AED attachment before the arrival of EMS, including those attached by the volunteer responders but also by lay volunteers who did not use the smartphone app.

Volunteer responders were activated for 947 individuals with OHCA; 461 patients were randomized to the intervention group and 486 to the control group. In both groups, the patients’ median age was 73 and about 65% were men.

Attachment of the AED before the arrival of EMS or first responders occurred in 61 patients (13.2%) in the intervention group versus 46 (9.5%) in the control group (P = .08). However, the majority of all AEDs were attached by lay volunteers who were not volunteer responders using the smartphone app (37 in the intervention arm vs. 28 in the control arm), the researchers noted.

No significant differences were seen in secondary outcomes, which included bystander CPR (69% vs. 71.6%, respectively) and defibrillation before EMS arrival (3.7% vs. 3.9%) between groups.

Among the volunteer responders using the app, crossover was 11% and compliance to instructions was 31%. Overall, volunteer responders attached 38% of all bystander-attached AEDs and provided 45% of all bystander defibrillations and 43% of all bystander CPR.

Going forward, Dr. Ringh and colleagues will be further analyzing the results to understand how to better optimize the logistical challenges involved with smartphone dispatch to OHCA patients. “In the longer term, investigating the impact on survival is also warranted,” he concluded.

U.S. in worse shape