User login

Development of a VA Clinician Resource to Facilitate Care Among Veterans Experiencing Homelessness

Development of a VA Clinician Resource to Facilitate Care Among Veterans Experiencing Homelessness

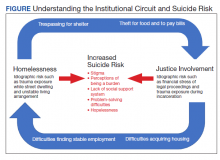

Veterans experiencing homelessness are at an elevated risk for adverse health outcomes, including suicide. This population also experiences chronic health conditions (eg, cardiovascular disease and sexually transmitted infections) and psychiatric conditions (eg, substance use disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder) with a greater propensity than veterans without history of homelessness.1,2 Similarly, veterans experiencing homelessness often report concurrent stressors, such as justice involvement and unemployment, which further impact social functioning.3

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) offers a range of health and social services to veterans experiencing homelessness. These programs are designed to respond to the multifactorial challenges faced by this population and are aimed at achieving sustained, permanent housing.4 To facilitate this effort, these programs provide targeted and tailored health (eg, primary care) and social (eg, case management and vocational rehabilitation) services to address barriers to housing stability (eg, substance use, serious mental illness, interacting with the criminal legal system, and unemployment).

Despite the availability of these programs, engaging veterans in VA services—whether in general or tailored for those experiencing or at risk for homelessness—remains challenging. Many veterans at risk for or experiencing homelessness overuse service settings that provide immediate care, such as urgent care or emergency departments (EDs).5,6 These individuals often visit an ED to augment or complement medical care they received in an outpatient setting, which can result in an elevated health care burden as well as impacted provision of treatment, especially surrounding care for chronic conditions (eg, cardiovascular health or serious mental illness).7-9

VA EDs offer urgent care and emergency services and often serve as a point of entry for veterans experiencing homelessness.10 They offer veterans expedient access to care that can address immediate needs (eg, substance use withdrawal, pain management, and suicide risk). EDs may be easier to access given they have longer hours of operation and patients can present without a scheduled appointment. VA EDs are an important point to identify homelessness and connect individuals to social service resources and outpatient health care referrals (eg, primary care and mental health).4,11

Some clinicians experience uncertainty in navigating or providing care for veterans experiencing or at risk for homelessness. A qualitative study conducted outside the VA found many clinicians did not know how to approach clinical conversations among unstably housed individuals, particularly when they discussed how to manage care for complex health conditions in the context of ongoing case management challenges, such as discharge planning.12 Another study found that clinicians working with individuals experiencing homelessness may have limited prior training or experience treating these patients.13 As a result, these clinicians may be unaware of available social services or unknowingly have biases that negatively impact care. Research remains limited surrounding beliefs about and methods of enhancing care among VA clinicians working with veterans experiencing homelessness in the ED.

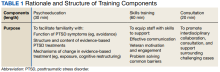

This multiphase pilot study sought to understand service delivery processes and gaps in VA ED settings. Phase 1 examined ED clinician perceptions of care, facilitators, and barriers to providing care (including suicide risk assessments) and making postdischarge outpatient referrals among VA ED clinicians who regularly work with veterans experiencing homelessness. Phase 2 used this information to develop a clinical psychoeducational resource to enhance post-ED access to care for veterans experiencing or at risk for homelessness.

QUALITATIVE INTERVIEWS

Semistructured qualitative interviews were conducted with 11 VA ED clinicians from 6 Veteran Integrated Service Networks between August 2022 and February 2023. Clinicians were eligible if they currently worked within a VA ED setting (including urgent care) and indicated that some of their patients were veterans experiencing homelessness. All health care practitioners (HCPs) participated in an interview and a postinterview self-report survey that assessed demographic and job-related characteristics. Eight HCPs identified as female and 3 identified as male. All clinicians identified as White and 3 as Hispanic or Latino. Eight clinicians were licensed clinical social workers, 2 were ED nurses, and 1 was an ED physician.

After each clinician provided informed consent, they were invited to complete a telephone or Microsoft Teams interview. All interviews were recorded and subsequently transcribed. Interviews explored clinicians’ experiences caring for veterans experiencing homelessness, with a focus on services provided within the ED, as well as mandated ED screenings such as a suicide risk assessment. Interview questions also addressed postdischarge knowledge and experiences with referrals to VA health services (eg, primary care, mental health) and social services (eg, housing programs). Interviews lasted 30 to 90 minutes.

Recruitment ended after attaining sufficient thematic data, accomplished via an information power approach to sampling. This occurred when the study aims, sample characteristics, existing theory, and depth and quality of interviews dynamically informed the decision to cease recruitment of additional participants.14,15 Given the scope of study (examining service delivery and knowledge gaps), the specificity of the targeted sample (VA ED clinicians providing care to veterans experiencing homelessness), the level of pre-existing theoretical background informing the study aims, and depth and quality of interview dialogue, this information power approach provides justification for attaining small sample sizes. Following the interview, HCPs completed a demographic questionnaire. Participants were not compensated.

Data Analysis

Directed content analysis was used to analyze qualitative data, with the framework method employed as an analytic instrument to facilitate analysis.16-18 Analysts engaged in bracketing and discussed reflexivity before data analysis to reflect on personal subjectivities and reduce potential bias.19,20

A prototype coding framework was developed that enabled coders to meaningfully summarize and condense data within transcripts into varying domains, categories, or topics found within the interview guide. Domain examples included clinical backgrounds, suicide risk and assessment protocols among veterans experiencing homelessness, beliefs about service delivery for veterans experiencing homelessness, and barriers and facilitators that may impact their ability to provide post-ED discharge care. Coders discussed the findings and if there was a need to modify templates. All transcripts were double coded. Once complete, individual templates were merged into a unified Microsoft Excel sheet, which allowed for more discrete analyses, enabling analysts to examine trends across content areas within the dataset.

Clinical Resource Development

HCPs were queried regarding available outpatient resources for post-ED care (eg, printed discharge paperwork and best practice alerts or automated workflows within the electronic health record). Resources used by participants were examined, as well as which resources clinicians thought would help them care for veterans experiencing homelessness. Noted gaps were used to develop a tailored resource for clinicians who treat veterans experiencing homelessness in the ED. This resource was created with the intention it could inform all ED clinicians, with the option for personalization to align with the needs of local services, based on needed content areas identified (eg, emergency shelters and suicide prevention resources).

Resource development followed an information systems research (ISR) framework that used a 3-pronged process of identifying circumstances for how a tool is developed, the problems it aims to address, and the knowledge that informs its development, implementation, and evaluation.21,22 Initial wireframes of the resource were provided via email to 10 subject matter experts (SMEs) in veteran suicide prevention, emergency medicine, and homeless programs. SMEs were identified via professional listservs, VA program office leadership, literature searches of similar research, and snowball sampling. Solicited feedback on the resource from the SMEs included its design, language, tone, flow, format, and content (ideation and prototyping). The feedback was collated and used to revise the resource. SMEs then reviewed and provided feedback on the revised resource. This iterative cycle (prototype review, commentary, ideation, prototype review) continued until the SMEs offered no additional edits to the resource. In total, 7 iterations of the resource were developed, critiqued, and revised.

INTERVIEW RESULTS

Compassion Fatigue

Many participants expressed concerns about compassion fatigue among VA ED clinicians. Those interviewed indicated that treating veterans experiencing homelessness sometimes led to the development of what they described as a “callus,” a “sixth sense,” or an inherent sense of “suspicion” or distrust. These feelings resulted from concerns about an individual’s secondary gain or potential hidden agenda (eg, a veteran reporting suicidal ideation to attain shelter on a cold night), with clinicians not wanting to feel as if they were taken advantage of or deceived.

Many clinicians noted that compassion fatigue resulted from witnessing the same veterans experiencing homelessness routinely use emergency services for nonemergent or nonmedical needs. Some also expressed that over time this may result in them becoming less empathetic when caring for veterans experiencing homelessness. They hypothesized that clinicians may experience burnout, which could potentially result in a lack of curiosity and concern about a veteran’s risk for suicide or need for social services. Others may “take things for granted,” leading them to discount stressors that are “very real to the patient, this person.”

Clinicians indicated that such sentiments may impact overall care. Potential negative consequences included stigmatization of veterans experiencing homelessness, incomplete or partial suicide risk screenings with this population, inattentive or impersonal care, and expedited discharge from the ED without appropriate safety planning or social service referrals. Clinicians interviewed intended to find ways to combat compassion fatigue and maintain a commitment to provide comprehensive care to all veterans, including those experiencing homelessness. They felt conflict between a lack of empathy for individuals experiencing homelessness and becoming numb to the problem due to overexposure. However, these clinicians remained committed to providing care to these veterans and fighting to maintain the purpose of recovery-focused care.

Knowledge Gaps on Available Services

While many clinicians knew of general resources available to veterans experiencing homelessness, few had detailed information on where to seek consults for other homeless programs, who to contact regarding these services, when they were available, or how to refer to them. Many reported feeling uneasy when discharging veterans experiencing homelessness from care, often being unable to provide local, comprehensive referrals to support their needs and ensure their well-being. These sentiments were compounded when the veteran reported suicidal thoughts or recent suicidal behavior; clinicians felt concerned about the methods to engage these individuals into evidence-based mental health care within the context of unstable housing arrangements.

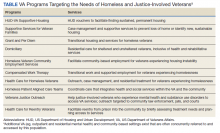

Some clinicians appeared to lack awareness of the wide array of VA homeless programming. Most could acknowledge at least some aspects of available programming (eg, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development– VA Supportive Housing program), while others were unaware of services tailored to the needs of those experiencing homelessness (eg, homeless patient aligned care teams), or of services targeting concurrent psychosocial stressors (eg, Veterans Justice Programs). Interviewees hypothesized this as being particularly notable among clinicians who are new to the VA or those who work in VA settings as part of their graduate or medical school training. Those aware of the services were uncertain of the referral process, relying on a single social worker or nurse to connect individuals experiencing homelessness to health and social services.

Interviewed clinicians noted that suicide risk screening of veterans experiencing homelessness was only performed by a limited number of individuals within the ED. Some did not feel sufficiently trained, comfortable, or knowledgeable about how to navigate care for veterans experiencing homelessness and at risk of suicide. Clinicians described “an uncomfortableness about suicidal ideation, where people just freeze up” and “don’t know what to do and don’t know what to say.”

Lack of Tangible Resources, Trainings, and Referrals

HCPs reported occasionally lacking the necessary clinical resources and information in the ED to properly support veterans experiencing homelessness and suicidal ideation. Common concerns included case management and discharge planning, as well as navigating health factors, such as elevated suicide risk. Some HCPs felt the local resources they do have access to—discharge packets or other forms of patient information—were not always tailored for the needs (eg, transportation) or abilities of veterans experiencing homelessness. One noted: “We give them a sheet of paper with some resources, which they don’t have the skills to follow up [with] anyway.”

Many interviewees wished for additional training in working with veterans experiencing homelessness. They reported that prior training from the VA Talent Management System or through unit-based programming could assist in educating clinicians on homeless services and suicide risk assessment. When queried on what training they had received, many noted there was “no formal training on what the VA offers homeless vets,” leading many to describe it as on-the-job training. This appeared especially among newer clinicians, who reported they were reliant upon learning from other, more senior staff within the ED.

The absence of training further illustrates the issue of institutional knowledge on these services and referrals, which was often confined to a single individual or team. Not having readily accessible resources, training, or information appropriate for all skill levels and positions within the ED hindered the ability of HCPs to connect veterans experiencing homelessness with social services to ensure their health and safety postdischarge: “If we had a better knowledge base of what the VA offers and the steps to go through in order to get the veteran set up for those things, it would be helpful.”

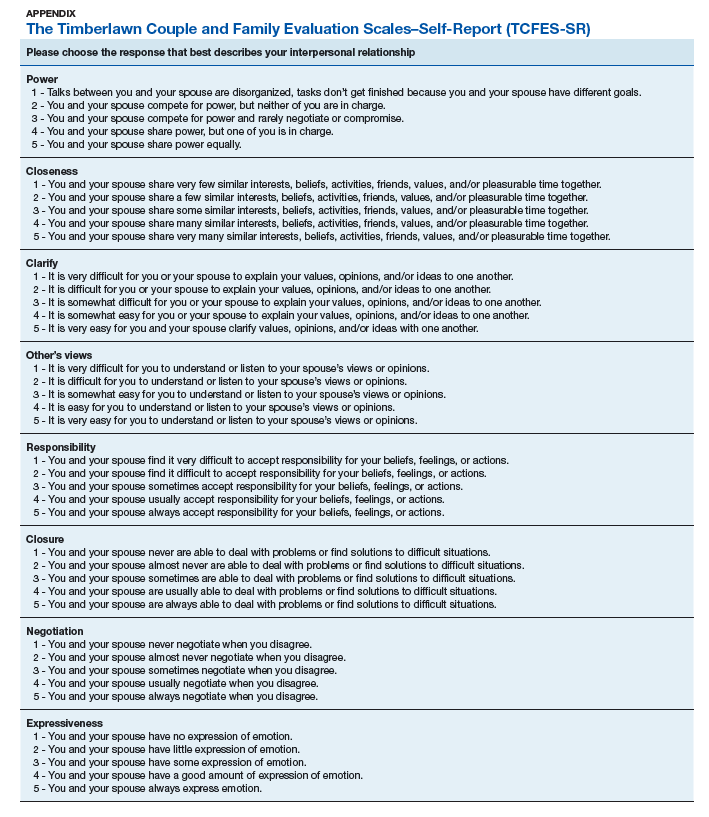

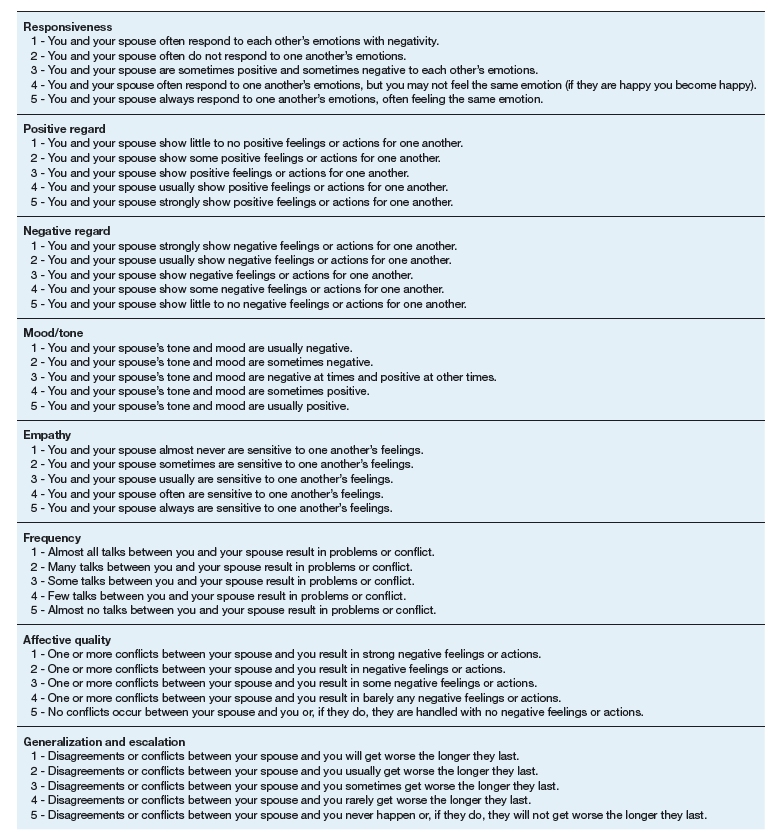

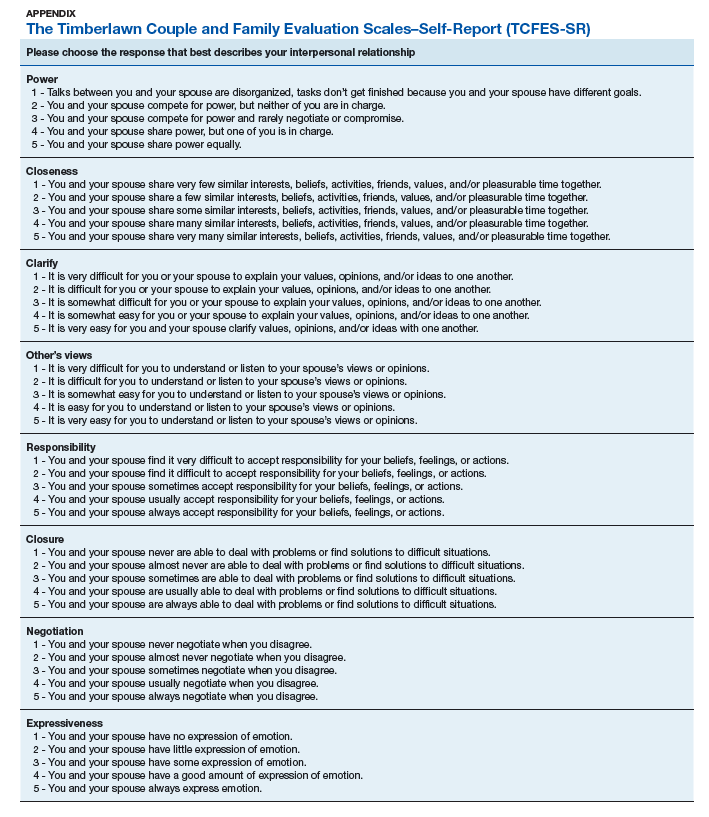

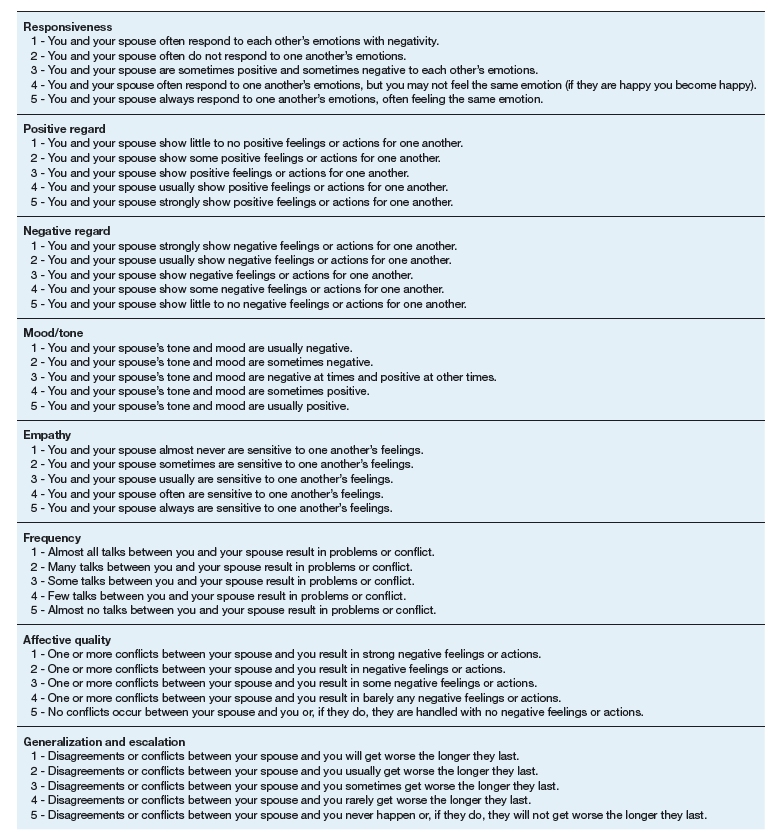

CLINICAL RESOURCE

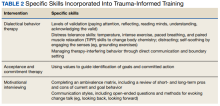

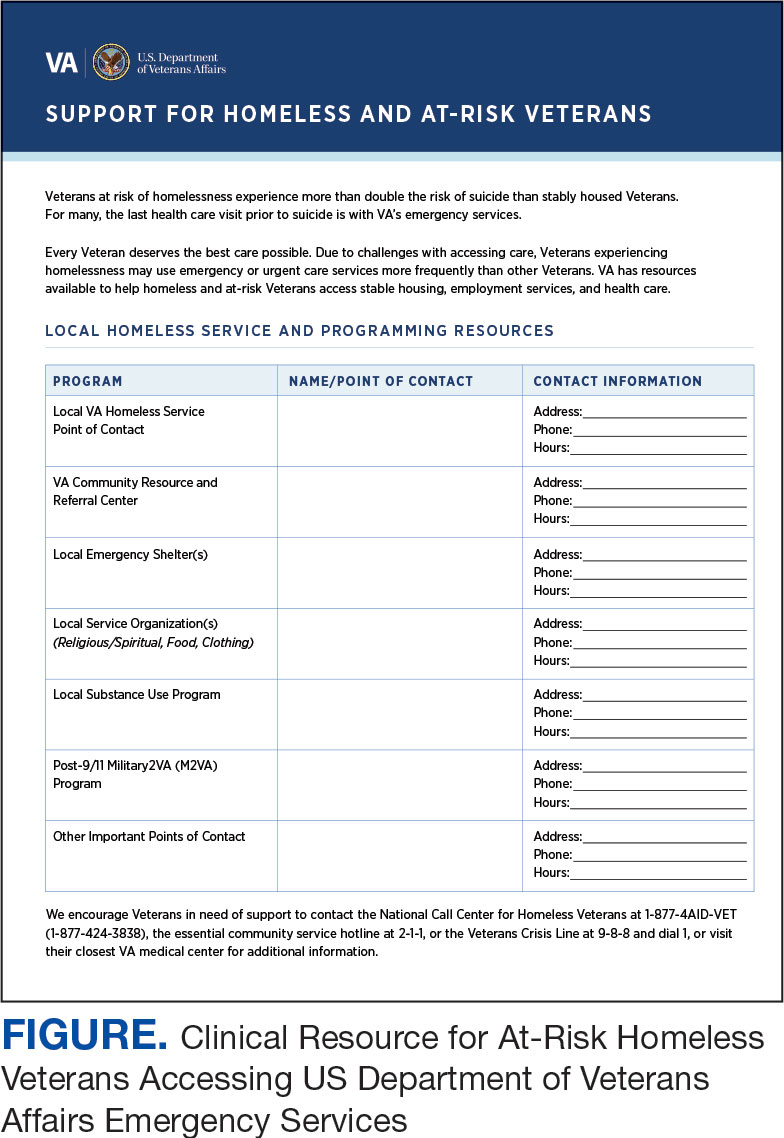

A psychoeducational resource was developed for HCPs treating veterans experiencing homelessness (Figure). The resource was designed to mitigate compassion fatigue and recenter attention on the VA commitment to care while emphasizing the need to be responsive to the concerns of these individuals. Initial wireframes of the resource were developed by a small group of authors in review and appraisal of qualitative findings (EP, RH). These wireframes were developed to broadly illustrate the arrangement/structure of content, range of resources to potentially include (eg, available VA homeless programs or consultation resources), and to draft initial wording and phrasing. Subject matter expert feedback refined these wireframes, providing commentary on specific programs to include or exclude, changes and alterations to the design and flow of the resource, and edits to language, word choice, and tone over numerous iterations.

Given that many ED HCPs presented concerns surrounding secondary gain in the context of suicide risk, this resource focused on suicide risk. At the top of the resource, it states “Veterans at risk for homelessness experience more than double the risk for suicide than stably housed veterans.”23 Also at the top, the resource states: “For many, the last health care visit prior to suicide is often with VA emergency services."24 The goal of these statements was to educate users on the elevated risk for suicide in veterans experiencing homelessness and their role in preventing such deaths.

Text in this section emphasizes that every veteran deserves the best care possible and recenters HCP attention on providing quality, comprehensive care regardless of housing status. The inclusion of this material was prioritized given the concerns expressed regarding compassion fatigue and suspicions of secondary gain (eg, a veteran reporting suicidal ideation to attain shelter or respite from outside conditions).

The resource also attempts to address high rates of emergency service by veterans experiencing homelessness: “Due to challenges with accessing care, Veterans experiencing homelessness may use emergency or urgent care services more frequently than other Veterans.”25 The resource also indicates that VA resources are available to help homeless and at-risk veterans to acquire stable housing, employment, and engage in healthcare, which are outlined with specific contact information. Given the breadth of local and VA services, a portion of the resource is dedicated to local health and social services available for veterans experiencing homelessness. HCPs complete the first page, which is devoted to local homeless service and program resources.

Following SME consultation, the list of programs provided underwent a series of iterations. The program types listed are deemed to be of greatest benefit to veterans experiencing homelessness and most consulted by HCPs. Including VA and non-VA emergency shelters allows clinicians flexible options if a particular shelter is full, closed, or would not meet the veteran’s needs or preference (eg, lack of childcare or does not allow pets). The second column of this section is left intentionally blank; here, the HCP is to list a local point-of- contact at each program. This encourages clinical teams to seek out and make direct contact with these programs and establish (in)formal relationships with them. The HCP then completes the third column with contact information.

Once completed, the resource acts as a living document. Clinicians and SMEs consulted for this study expressed the desire to have an easily accessible resource that can be updated based on necessary changes (eg, emergency shelter address or hours of operation). The resource can be housed within each local VA emergency or urgent care service setting alongside other available clinical tools.

While local resources are the primary focus, interviewees also suggested that some HCPs are not aware of the available VA services . This material, found on the back of the resource, provides a general overview of services available through VA homeless programs. SME consultation and discussion led to selecting the 5 listed categories: housing services, health care services, case management, employment services, and justice-related programming, each with a brief description.

Information for the National Call Center for Homeless Veterans, community service hotline, and Veterans Crisis Line are included on the front page. These hotlines and phone numbers are always available for veterans experiencing homelessness, enabling them to make these connections themselves, if desired. Additionally, given the challenges noted by some HCPs in performing suicide risk screening, evaluation, and intervention, a prompt for the VA Suicide Risk Management Consultation service was also included on the back page.

Creating a Shared and Local Resource

This clinical resource was developed to establish a centralized, shared, local resource available to VA ED HCPs who lacked knowledge of available services or reported discomfort conducting suicide risk screening for veterans experiencing homelessness. In many cases, ED referrals to homeless programs and suicide prevention care was assigned to a single individual, often a nurse or social worker. As a result, an undue amount of work and strain was placed on these individuals, as this forced them to act as the sole bridge between care in the ED and postdischarge social (eg, homeless programs) and mental health (eg, suicide prevention) services. The creation of a unified, easily accessible document aimed to distribute this responsibility more equitably across ED staff.

DISCUSSION

This project intended to develop a clinician resource to support VA ED clinicians caring for veterans experiencing homelessness and their access to services postdischarge. Qualitative interviews provided insights into the burnout and compassion fatigue present in these settings, as well as the challenges and needs regarding knowledge of local and VA services. Emphasis was placed on leveraging extant resources and subject matter expertise to develop a resource capable of providing brief and informative guidance.

This resource is particularly relevant for HCPs new to the VA, including trainees and new hires, who may be less aware of VA and local social services. It has the potential to reduce the burden on VA ED staff to provide guidance and recommendations surrounding postdischarge social services. The resource acknowledges homeless programming focused on social determinants of health that can destabilize housing (eg, legal or occupational challenges). This can incentivize clinicians to discuss these programs with veterans to facilitate their ability to navigate complex health and psychosocial challenges.

HCPs interviewed for this study indicated their apprehension regarding suicide risk screening and evaluation, a process currently mandated within VA ED settings.26 This may be compounded among HCPs with minimal mental health training or those who have worked in community-based settings where such screening and evaluation efforts are not required. The resource reminds clinicians of available VA consultation services, which can provide additional training, clinical guidance, and review of existing local ED processes.

While the resource was directly informed by qualitative interviews conducted with VA emergency service HCPs and developed through an iterative process with SMEs, further research is necessary to determine its effectiveness at increasing access to health and social services among veterans experiencing homelessness. The resource has not been used by HCPs working in these settings to examine uptake or sustained use, nor clinicians’ perceptions of its utility, including acceptability and feasibility; these are important next steps to understand if the resource is functioning as intended.

Compassion fatigue, as well as associated sequelae (eg, burnout, distress, and psychiatric symptoms), is well-documented among individuals working with individuals experiencing homelessness, including VA HCPs.27-30 Such experiences are likely driven by several factors, including the clinical complexity and service needs of this veteran population. Although compassion fatigue was noted by many clinicians interviewed for this study, it is unclear if the resource alone would address factors driving compassion fatigue, or if additional programming or services may be necessary.

Limitations

The resource requires local HCPs to routinely update its content (eg, establishment of a new emergency shelter in the community or change in hours or contact information of an existing one), which may be challenging. This is especially true as it relates to community resources, which may be more likely to change than national VA programming.

This resource was initially developed following qualitative interviews with a small sample of VA HCPs (explicitly those working within ED settings) and may not be representative of all HCPs engaged in VA care with veterans experiencing homelessness. The perspectives and experiences of those interviewed do not represent the views of all VA ED HCPs and may differ from the perspectives of those in regions with unique cultural and regional considerations.31

Given that most of the interviewees were social workers in EDs engaged in care for veterans experiencing homelessness, these findings and informational needs may differ among other types of HCPs who provide services for veterans experiencing homelessness in other settings. Content in the resource was included based on clinician input, and may not reflect the perspectives of veterans, who may perceive some resources as more important (eg, access to primary care or dental services).28

CONCLUSIONS

This project represents the culmination of qualitative interviews and SME input to develop a free-to-use clinician resource to facilitate service delivery and connection to services following discharge from VA EDs for veterans experiencing homelessness. Serving as a template, this resource can be customized to increase knowledge of local VA and community resources to support these individuals. Continued refinement and piloting of this resource to evaluate acceptability, implementation barriers, and use remains warranted.

- Holliday R, Kinney AR, Smith AA, et al. A latent class analysis to identify subgroups of VHA using homeless veterans at greater risk for suicide mortality. J Affect Disord. 2022;315:162-167. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2022.07.062

- Weber J, Lee RC, Martsolf D. Understanding the health of veterans who are homeless: a review of the literature. Public Health Nurs. 2017;34(5):505-511. doi:10.1111/phn.12338

- Holliday R, Desai A, Stimmel M, Liu S, Monteith LL, Stewart KE. Meeting the health and social service needs of veterans who interact with the criminal justice system and experience homelessness: a holistic conceptualization and recommendations for tailoring care. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry. 2022;9(3):174-185. doi:10.1007/s40501-022-00275-1

- Holliday R, Desai A, Gerard G, Liu S, Stimmel M. Understanding the intersection of homelessness and justice involvement: enhancing veteran suicide prevention through VA programming. Fed Pract. 2022;39(1):8-11. doi:10.12788/fp.0216

- Kushel MB, Perry S, Bangsberg D, Clark R, Moss AR. Emergency department use among the homeless and marginally housed: results from a community-based study. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):778-784. doi:10.2105/ajph.92.5.778

- Tsai J, Doran KM, Rosenheck RA. When health insurance is not a factor: national comparison of homeless and nonhomeless US veterans who use Veterans Affairs emergency departments. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(Suppl 2):S225-S231. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301307

- Doran KM, Raven MC, Rosenheck RA. What drives frequent emergency department use in an integrated health system? National data from the Veterans Health Administration. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(2):151-159. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.02.016

- Tsai J, Rosenheck RA. Risk factors for ED use among homeless veterans. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(5):855-858. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2013.02.046

- Nelson RE, Suo Y, Pettey W, et al. Costs associated with health care services accessed through VA and in the community through Medicare for veterans experiencing homelessness. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(Suppl 3):5352-5374. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13054

- Gabrielian S, Yuan AH, Andersen RM, Rubenstein LV, Gelberg L. VA health service utilization for homeless and low-income veterans: a spotlight on the VA Supportive Housing (VASH) program in greater Los Angeles. Med Care. 2014;52(5):454-461. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000112

- Larkin GL, Beautrais AL. Emergency departments are underutilized sites for suicide prevention. Crisis. 2010;31(1):1- 6. doi:10.1027/0227-5910/a000001

- Decker H, Raguram M, Kanzaria HK, Duke M, Wick E. Provider perceptions of challenges and facilitators to surgical care in unhoused patients: a qualitative analysis. Surgery. 2024;175(4):1095-1102. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2023.11.009

- Panushka KA, Kozlowski Z, Dalessandro C, Sanders JN, Millar MM, Gawron LM. “It’s not a top priority”: a qualitative analysis of provider views on barriers to reproductive healthcare provision for homeless women in the United States. Soc Work Public Health. 2023;38(5 -8):428-436. doi:10.1080/19371918.2024.2315180

- Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52:1893-1907. doi:10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

- Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753-1760. doi:10.1177/1049732315617444

- Assarroudi A, Heshmati Nabavi F, Armat MR, Ebadi A, Vaismoradi M. Directed qualitative content analysis: the description and elaboration of its underpinning methods and data analysis process. J Res Nurs. 2018;23(1):42-55. doi:10.1177/1744987117741667

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277-1288.

- Goldsmith LJ. Using Framework Analysis in Applied Qualitative Research. Qual Rep. 2021;26(6):2061-2076. doi:10.46743/2160-3715/2021.5011

- Tufford L, Newman P. Bracketing in qualitative research. Qual Soc Work. 2012;11(1):80-96.

- Dodgson JE. Reflexivity in Qualitative Research. J Hum Lact. 2019;35(2):220-222. doi:10.1177/0890334419830990

- Hevner AR. A three cycle view of design science research. Scand J Inf Syst. 2007;19(2):4.

- Farao J, Malila B, Conrad N, Mutsvangwa T, Rangaka MX, Douglas TS. A user-centred design frame work for mHealth. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(8):e0237910. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0237910

- Hoffberg AS, Spitzer E, Mackelprang JL, Farro SA, Brenner LA. Suicidal Self-Directed Violence Among Homeless US Veterans: A Systematic Review. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2018;48(4):481-498. doi:10.1111/sltb.12369

- Larkin GL, Beautrais AL. Emergency departments are underutilized sites for suicide prevention. Crisis. 2010;31(1):1- 6. doi:10.1027/0227-5910/a000001

- Gabrielian S, Yuan AH, Andersen RM, Rubenstein LV, Gelberg L. VA health service utilization for homeless and lowincome Veterans: a spotlight on the VA Supportive Housing (VASH) program in greater Los Angeles. Med Care. 2014;52(5):454-461. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000112

- Holliday R, Hostetter T, Brenner LA, Bahraini N, Tsai J. Suicide risk screening and evaluation among patients accessing VHA services and identified as being newly homeless. Health Serv Res. 2024;59(5):e14301. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14301

- Waegemakers Schiff J, Lane AM. PTSD symptoms, vicarious traumatization, and burnout in front line workers in the homeless sector. Community Ment Health J. 2019;55(3):454-462. doi:10.1007/s10597-018-00364-7

- Steenekamp BL, Barker SL. Exploring the experiences of compassion fatigue amongst peer support workers in homelessness services. Community Ment Health J. 2024;60(4):772-783. doi:10.1007/s10597-024-01234-1

- Perez S, Kerman N, Dej E, et al. When I can’t help, I suffer: a scoping review of moral distress in service providers working with persons experiencing homelessness. J Ment Health. Published online 2024:1-16. doi:10.1080/09638237.2024.2426986

- Monteith LL, Holliday R, Christe’An DI, Sherrill A, Brenner LA, Hoffmire CA. Suicide risk and prevention in Guam: clinical and research considerations and a call to action. Asian J Psychiatry. 2023;83:103546. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2023.103546

- Surís A, Holliday R, Hooshyar D, et al. Development and implementation of a homeless mobile medical/mental veteran intervention. Fed Pract. 2017;34(9):18.

Veterans experiencing homelessness are at an elevated risk for adverse health outcomes, including suicide. This population also experiences chronic health conditions (eg, cardiovascular disease and sexually transmitted infections) and psychiatric conditions (eg, substance use disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder) with a greater propensity than veterans without history of homelessness.1,2 Similarly, veterans experiencing homelessness often report concurrent stressors, such as justice involvement and unemployment, which further impact social functioning.3

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) offers a range of health and social services to veterans experiencing homelessness. These programs are designed to respond to the multifactorial challenges faced by this population and are aimed at achieving sustained, permanent housing.4 To facilitate this effort, these programs provide targeted and tailored health (eg, primary care) and social (eg, case management and vocational rehabilitation) services to address barriers to housing stability (eg, substance use, serious mental illness, interacting with the criminal legal system, and unemployment).

Despite the availability of these programs, engaging veterans in VA services—whether in general or tailored for those experiencing or at risk for homelessness—remains challenging. Many veterans at risk for or experiencing homelessness overuse service settings that provide immediate care, such as urgent care or emergency departments (EDs).5,6 These individuals often visit an ED to augment or complement medical care they received in an outpatient setting, which can result in an elevated health care burden as well as impacted provision of treatment, especially surrounding care for chronic conditions (eg, cardiovascular health or serious mental illness).7-9

VA EDs offer urgent care and emergency services and often serve as a point of entry for veterans experiencing homelessness.10 They offer veterans expedient access to care that can address immediate needs (eg, substance use withdrawal, pain management, and suicide risk). EDs may be easier to access given they have longer hours of operation and patients can present without a scheduled appointment. VA EDs are an important point to identify homelessness and connect individuals to social service resources and outpatient health care referrals (eg, primary care and mental health).4,11

Some clinicians experience uncertainty in navigating or providing care for veterans experiencing or at risk for homelessness. A qualitative study conducted outside the VA found many clinicians did not know how to approach clinical conversations among unstably housed individuals, particularly when they discussed how to manage care for complex health conditions in the context of ongoing case management challenges, such as discharge planning.12 Another study found that clinicians working with individuals experiencing homelessness may have limited prior training or experience treating these patients.13 As a result, these clinicians may be unaware of available social services or unknowingly have biases that negatively impact care. Research remains limited surrounding beliefs about and methods of enhancing care among VA clinicians working with veterans experiencing homelessness in the ED.

This multiphase pilot study sought to understand service delivery processes and gaps in VA ED settings. Phase 1 examined ED clinician perceptions of care, facilitators, and barriers to providing care (including suicide risk assessments) and making postdischarge outpatient referrals among VA ED clinicians who regularly work with veterans experiencing homelessness. Phase 2 used this information to develop a clinical psychoeducational resource to enhance post-ED access to care for veterans experiencing or at risk for homelessness.

QUALITATIVE INTERVIEWS

Semistructured qualitative interviews were conducted with 11 VA ED clinicians from 6 Veteran Integrated Service Networks between August 2022 and February 2023. Clinicians were eligible if they currently worked within a VA ED setting (including urgent care) and indicated that some of their patients were veterans experiencing homelessness. All health care practitioners (HCPs) participated in an interview and a postinterview self-report survey that assessed demographic and job-related characteristics. Eight HCPs identified as female and 3 identified as male. All clinicians identified as White and 3 as Hispanic or Latino. Eight clinicians were licensed clinical social workers, 2 were ED nurses, and 1 was an ED physician.

After each clinician provided informed consent, they were invited to complete a telephone or Microsoft Teams interview. All interviews were recorded and subsequently transcribed. Interviews explored clinicians’ experiences caring for veterans experiencing homelessness, with a focus on services provided within the ED, as well as mandated ED screenings such as a suicide risk assessment. Interview questions also addressed postdischarge knowledge and experiences with referrals to VA health services (eg, primary care, mental health) and social services (eg, housing programs). Interviews lasted 30 to 90 minutes.

Recruitment ended after attaining sufficient thematic data, accomplished via an information power approach to sampling. This occurred when the study aims, sample characteristics, existing theory, and depth and quality of interviews dynamically informed the decision to cease recruitment of additional participants.14,15 Given the scope of study (examining service delivery and knowledge gaps), the specificity of the targeted sample (VA ED clinicians providing care to veterans experiencing homelessness), the level of pre-existing theoretical background informing the study aims, and depth and quality of interview dialogue, this information power approach provides justification for attaining small sample sizes. Following the interview, HCPs completed a demographic questionnaire. Participants were not compensated.

Data Analysis

Directed content analysis was used to analyze qualitative data, with the framework method employed as an analytic instrument to facilitate analysis.16-18 Analysts engaged in bracketing and discussed reflexivity before data analysis to reflect on personal subjectivities and reduce potential bias.19,20

A prototype coding framework was developed that enabled coders to meaningfully summarize and condense data within transcripts into varying domains, categories, or topics found within the interview guide. Domain examples included clinical backgrounds, suicide risk and assessment protocols among veterans experiencing homelessness, beliefs about service delivery for veterans experiencing homelessness, and barriers and facilitators that may impact their ability to provide post-ED discharge care. Coders discussed the findings and if there was a need to modify templates. All transcripts were double coded. Once complete, individual templates were merged into a unified Microsoft Excel sheet, which allowed for more discrete analyses, enabling analysts to examine trends across content areas within the dataset.

Clinical Resource Development

HCPs were queried regarding available outpatient resources for post-ED care (eg, printed discharge paperwork and best practice alerts or automated workflows within the electronic health record). Resources used by participants were examined, as well as which resources clinicians thought would help them care for veterans experiencing homelessness. Noted gaps were used to develop a tailored resource for clinicians who treat veterans experiencing homelessness in the ED. This resource was created with the intention it could inform all ED clinicians, with the option for personalization to align with the needs of local services, based on needed content areas identified (eg, emergency shelters and suicide prevention resources).

Resource development followed an information systems research (ISR) framework that used a 3-pronged process of identifying circumstances for how a tool is developed, the problems it aims to address, and the knowledge that informs its development, implementation, and evaluation.21,22 Initial wireframes of the resource were provided via email to 10 subject matter experts (SMEs) in veteran suicide prevention, emergency medicine, and homeless programs. SMEs were identified via professional listservs, VA program office leadership, literature searches of similar research, and snowball sampling. Solicited feedback on the resource from the SMEs included its design, language, tone, flow, format, and content (ideation and prototyping). The feedback was collated and used to revise the resource. SMEs then reviewed and provided feedback on the revised resource. This iterative cycle (prototype review, commentary, ideation, prototype review) continued until the SMEs offered no additional edits to the resource. In total, 7 iterations of the resource were developed, critiqued, and revised.

INTERVIEW RESULTS

Compassion Fatigue

Many participants expressed concerns about compassion fatigue among VA ED clinicians. Those interviewed indicated that treating veterans experiencing homelessness sometimes led to the development of what they described as a “callus,” a “sixth sense,” or an inherent sense of “suspicion” or distrust. These feelings resulted from concerns about an individual’s secondary gain or potential hidden agenda (eg, a veteran reporting suicidal ideation to attain shelter on a cold night), with clinicians not wanting to feel as if they were taken advantage of or deceived.

Many clinicians noted that compassion fatigue resulted from witnessing the same veterans experiencing homelessness routinely use emergency services for nonemergent or nonmedical needs. Some also expressed that over time this may result in them becoming less empathetic when caring for veterans experiencing homelessness. They hypothesized that clinicians may experience burnout, which could potentially result in a lack of curiosity and concern about a veteran’s risk for suicide or need for social services. Others may “take things for granted,” leading them to discount stressors that are “very real to the patient, this person.”

Clinicians indicated that such sentiments may impact overall care. Potential negative consequences included stigmatization of veterans experiencing homelessness, incomplete or partial suicide risk screenings with this population, inattentive or impersonal care, and expedited discharge from the ED without appropriate safety planning or social service referrals. Clinicians interviewed intended to find ways to combat compassion fatigue and maintain a commitment to provide comprehensive care to all veterans, including those experiencing homelessness. They felt conflict between a lack of empathy for individuals experiencing homelessness and becoming numb to the problem due to overexposure. However, these clinicians remained committed to providing care to these veterans and fighting to maintain the purpose of recovery-focused care.

Knowledge Gaps on Available Services

While many clinicians knew of general resources available to veterans experiencing homelessness, few had detailed information on where to seek consults for other homeless programs, who to contact regarding these services, when they were available, or how to refer to them. Many reported feeling uneasy when discharging veterans experiencing homelessness from care, often being unable to provide local, comprehensive referrals to support their needs and ensure their well-being. These sentiments were compounded when the veteran reported suicidal thoughts or recent suicidal behavior; clinicians felt concerned about the methods to engage these individuals into evidence-based mental health care within the context of unstable housing arrangements.

Some clinicians appeared to lack awareness of the wide array of VA homeless programming. Most could acknowledge at least some aspects of available programming (eg, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development– VA Supportive Housing program), while others were unaware of services tailored to the needs of those experiencing homelessness (eg, homeless patient aligned care teams), or of services targeting concurrent psychosocial stressors (eg, Veterans Justice Programs). Interviewees hypothesized this as being particularly notable among clinicians who are new to the VA or those who work in VA settings as part of their graduate or medical school training. Those aware of the services were uncertain of the referral process, relying on a single social worker or nurse to connect individuals experiencing homelessness to health and social services.

Interviewed clinicians noted that suicide risk screening of veterans experiencing homelessness was only performed by a limited number of individuals within the ED. Some did not feel sufficiently trained, comfortable, or knowledgeable about how to navigate care for veterans experiencing homelessness and at risk of suicide. Clinicians described “an uncomfortableness about suicidal ideation, where people just freeze up” and “don’t know what to do and don’t know what to say.”

Lack of Tangible Resources, Trainings, and Referrals

HCPs reported occasionally lacking the necessary clinical resources and information in the ED to properly support veterans experiencing homelessness and suicidal ideation. Common concerns included case management and discharge planning, as well as navigating health factors, such as elevated suicide risk. Some HCPs felt the local resources they do have access to—discharge packets or other forms of patient information—were not always tailored for the needs (eg, transportation) or abilities of veterans experiencing homelessness. One noted: “We give them a sheet of paper with some resources, which they don’t have the skills to follow up [with] anyway.”

Many interviewees wished for additional training in working with veterans experiencing homelessness. They reported that prior training from the VA Talent Management System or through unit-based programming could assist in educating clinicians on homeless services and suicide risk assessment. When queried on what training they had received, many noted there was “no formal training on what the VA offers homeless vets,” leading many to describe it as on-the-job training. This appeared especially among newer clinicians, who reported they were reliant upon learning from other, more senior staff within the ED.

The absence of training further illustrates the issue of institutional knowledge on these services and referrals, which was often confined to a single individual or team. Not having readily accessible resources, training, or information appropriate for all skill levels and positions within the ED hindered the ability of HCPs to connect veterans experiencing homelessness with social services to ensure their health and safety postdischarge: “If we had a better knowledge base of what the VA offers and the steps to go through in order to get the veteran set up for those things, it would be helpful.”

CLINICAL RESOURCE

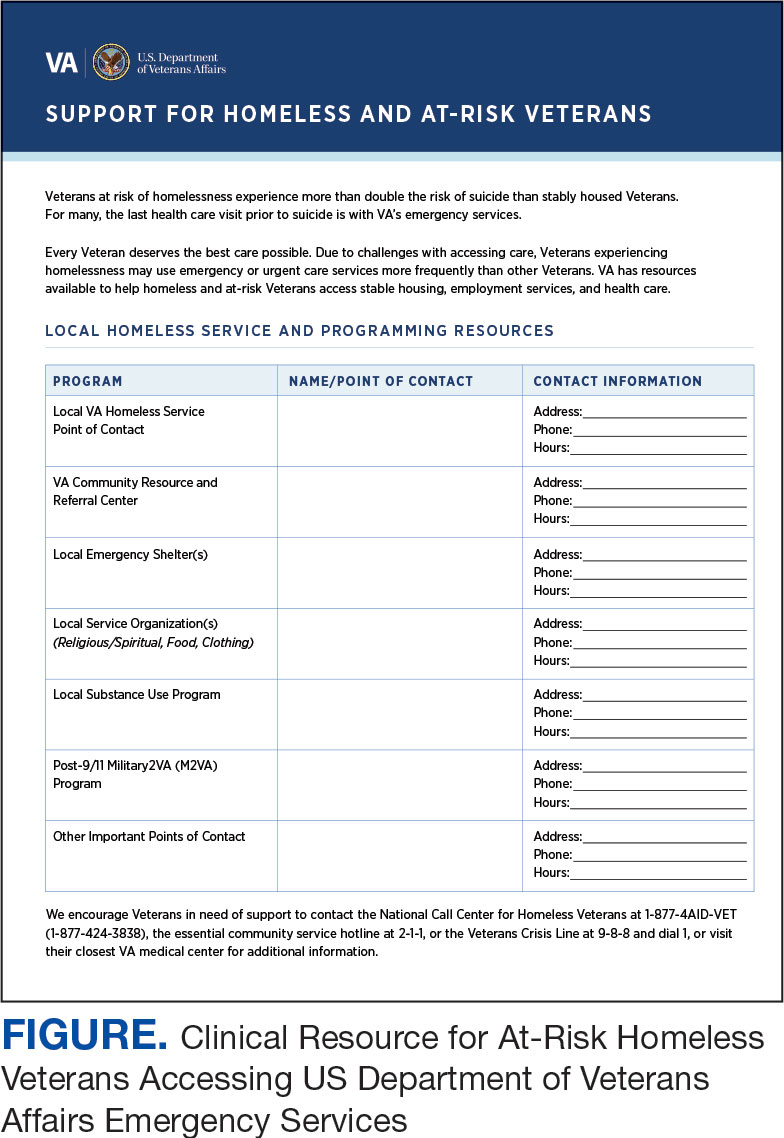

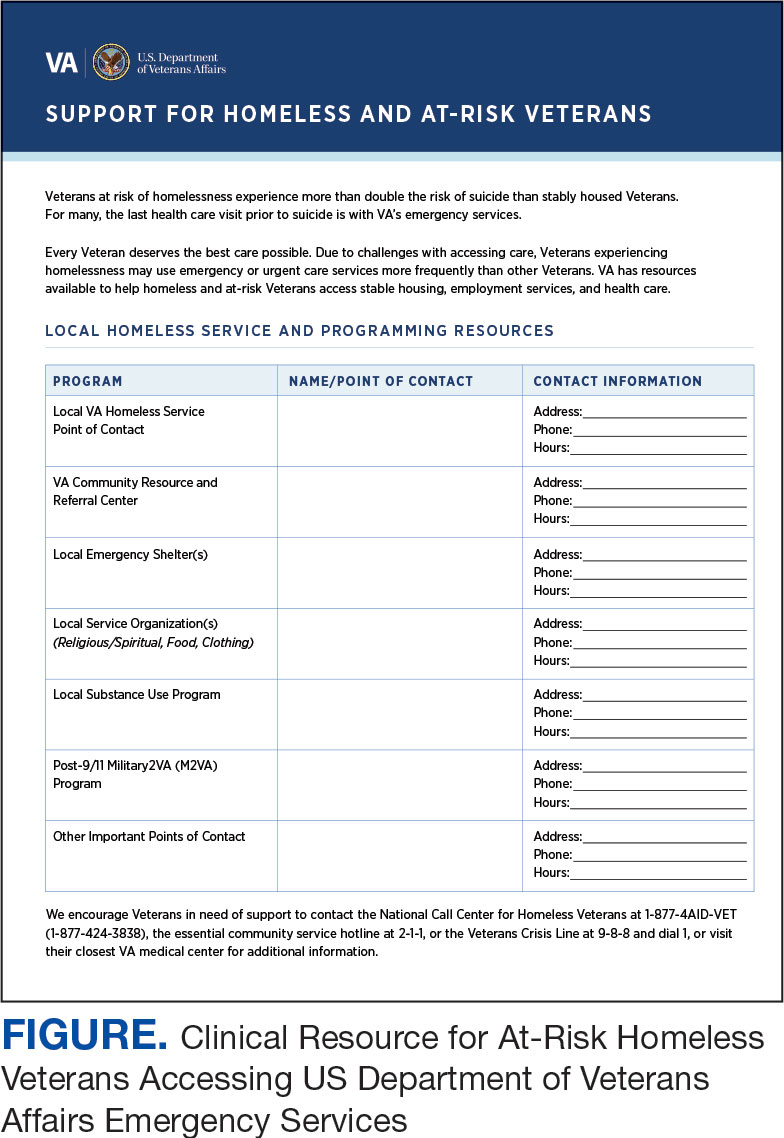

A psychoeducational resource was developed for HCPs treating veterans experiencing homelessness (Figure). The resource was designed to mitigate compassion fatigue and recenter attention on the VA commitment to care while emphasizing the need to be responsive to the concerns of these individuals. Initial wireframes of the resource were developed by a small group of authors in review and appraisal of qualitative findings (EP, RH). These wireframes were developed to broadly illustrate the arrangement/structure of content, range of resources to potentially include (eg, available VA homeless programs or consultation resources), and to draft initial wording and phrasing. Subject matter expert feedback refined these wireframes, providing commentary on specific programs to include or exclude, changes and alterations to the design and flow of the resource, and edits to language, word choice, and tone over numerous iterations.

Given that many ED HCPs presented concerns surrounding secondary gain in the context of suicide risk, this resource focused on suicide risk. At the top of the resource, it states “Veterans at risk for homelessness experience more than double the risk for suicide than stably housed veterans.”23 Also at the top, the resource states: “For many, the last health care visit prior to suicide is often with VA emergency services."24 The goal of these statements was to educate users on the elevated risk for suicide in veterans experiencing homelessness and their role in preventing such deaths.

Text in this section emphasizes that every veteran deserves the best care possible and recenters HCP attention on providing quality, comprehensive care regardless of housing status. The inclusion of this material was prioritized given the concerns expressed regarding compassion fatigue and suspicions of secondary gain (eg, a veteran reporting suicidal ideation to attain shelter or respite from outside conditions).

The resource also attempts to address high rates of emergency service by veterans experiencing homelessness: “Due to challenges with accessing care, Veterans experiencing homelessness may use emergency or urgent care services more frequently than other Veterans.”25 The resource also indicates that VA resources are available to help homeless and at-risk veterans to acquire stable housing, employment, and engage in healthcare, which are outlined with specific contact information. Given the breadth of local and VA services, a portion of the resource is dedicated to local health and social services available for veterans experiencing homelessness. HCPs complete the first page, which is devoted to local homeless service and program resources.

Following SME consultation, the list of programs provided underwent a series of iterations. The program types listed are deemed to be of greatest benefit to veterans experiencing homelessness and most consulted by HCPs. Including VA and non-VA emergency shelters allows clinicians flexible options if a particular shelter is full, closed, or would not meet the veteran’s needs or preference (eg, lack of childcare or does not allow pets). The second column of this section is left intentionally blank; here, the HCP is to list a local point-of- contact at each program. This encourages clinical teams to seek out and make direct contact with these programs and establish (in)formal relationships with them. The HCP then completes the third column with contact information.

Once completed, the resource acts as a living document. Clinicians and SMEs consulted for this study expressed the desire to have an easily accessible resource that can be updated based on necessary changes (eg, emergency shelter address or hours of operation). The resource can be housed within each local VA emergency or urgent care service setting alongside other available clinical tools.

While local resources are the primary focus, interviewees also suggested that some HCPs are not aware of the available VA services . This material, found on the back of the resource, provides a general overview of services available through VA homeless programs. SME consultation and discussion led to selecting the 5 listed categories: housing services, health care services, case management, employment services, and justice-related programming, each with a brief description.

Information for the National Call Center for Homeless Veterans, community service hotline, and Veterans Crisis Line are included on the front page. These hotlines and phone numbers are always available for veterans experiencing homelessness, enabling them to make these connections themselves, if desired. Additionally, given the challenges noted by some HCPs in performing suicide risk screening, evaluation, and intervention, a prompt for the VA Suicide Risk Management Consultation service was also included on the back page.

Creating a Shared and Local Resource

This clinical resource was developed to establish a centralized, shared, local resource available to VA ED HCPs who lacked knowledge of available services or reported discomfort conducting suicide risk screening for veterans experiencing homelessness. In many cases, ED referrals to homeless programs and suicide prevention care was assigned to a single individual, often a nurse or social worker. As a result, an undue amount of work and strain was placed on these individuals, as this forced them to act as the sole bridge between care in the ED and postdischarge social (eg, homeless programs) and mental health (eg, suicide prevention) services. The creation of a unified, easily accessible document aimed to distribute this responsibility more equitably across ED staff.

DISCUSSION

This project intended to develop a clinician resource to support VA ED clinicians caring for veterans experiencing homelessness and their access to services postdischarge. Qualitative interviews provided insights into the burnout and compassion fatigue present in these settings, as well as the challenges and needs regarding knowledge of local and VA services. Emphasis was placed on leveraging extant resources and subject matter expertise to develop a resource capable of providing brief and informative guidance.

This resource is particularly relevant for HCPs new to the VA, including trainees and new hires, who may be less aware of VA and local social services. It has the potential to reduce the burden on VA ED staff to provide guidance and recommendations surrounding postdischarge social services. The resource acknowledges homeless programming focused on social determinants of health that can destabilize housing (eg, legal or occupational challenges). This can incentivize clinicians to discuss these programs with veterans to facilitate their ability to navigate complex health and psychosocial challenges.

HCPs interviewed for this study indicated their apprehension regarding suicide risk screening and evaluation, a process currently mandated within VA ED settings.26 This may be compounded among HCPs with minimal mental health training or those who have worked in community-based settings where such screening and evaluation efforts are not required. The resource reminds clinicians of available VA consultation services, which can provide additional training, clinical guidance, and review of existing local ED processes.

While the resource was directly informed by qualitative interviews conducted with VA emergency service HCPs and developed through an iterative process with SMEs, further research is necessary to determine its effectiveness at increasing access to health and social services among veterans experiencing homelessness. The resource has not been used by HCPs working in these settings to examine uptake or sustained use, nor clinicians’ perceptions of its utility, including acceptability and feasibility; these are important next steps to understand if the resource is functioning as intended.

Compassion fatigue, as well as associated sequelae (eg, burnout, distress, and psychiatric symptoms), is well-documented among individuals working with individuals experiencing homelessness, including VA HCPs.27-30 Such experiences are likely driven by several factors, including the clinical complexity and service needs of this veteran population. Although compassion fatigue was noted by many clinicians interviewed for this study, it is unclear if the resource alone would address factors driving compassion fatigue, or if additional programming or services may be necessary.

Limitations

The resource requires local HCPs to routinely update its content (eg, establishment of a new emergency shelter in the community or change in hours or contact information of an existing one), which may be challenging. This is especially true as it relates to community resources, which may be more likely to change than national VA programming.

This resource was initially developed following qualitative interviews with a small sample of VA HCPs (explicitly those working within ED settings) and may not be representative of all HCPs engaged in VA care with veterans experiencing homelessness. The perspectives and experiences of those interviewed do not represent the views of all VA ED HCPs and may differ from the perspectives of those in regions with unique cultural and regional considerations.31

Given that most of the interviewees were social workers in EDs engaged in care for veterans experiencing homelessness, these findings and informational needs may differ among other types of HCPs who provide services for veterans experiencing homelessness in other settings. Content in the resource was included based on clinician input, and may not reflect the perspectives of veterans, who may perceive some resources as more important (eg, access to primary care or dental services).28

CONCLUSIONS

This project represents the culmination of qualitative interviews and SME input to develop a free-to-use clinician resource to facilitate service delivery and connection to services following discharge from VA EDs for veterans experiencing homelessness. Serving as a template, this resource can be customized to increase knowledge of local VA and community resources to support these individuals. Continued refinement and piloting of this resource to evaluate acceptability, implementation barriers, and use remains warranted.

Veterans experiencing homelessness are at an elevated risk for adverse health outcomes, including suicide. This population also experiences chronic health conditions (eg, cardiovascular disease and sexually transmitted infections) and psychiatric conditions (eg, substance use disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder) with a greater propensity than veterans without history of homelessness.1,2 Similarly, veterans experiencing homelessness often report concurrent stressors, such as justice involvement and unemployment, which further impact social functioning.3

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) offers a range of health and social services to veterans experiencing homelessness. These programs are designed to respond to the multifactorial challenges faced by this population and are aimed at achieving sustained, permanent housing.4 To facilitate this effort, these programs provide targeted and tailored health (eg, primary care) and social (eg, case management and vocational rehabilitation) services to address barriers to housing stability (eg, substance use, serious mental illness, interacting with the criminal legal system, and unemployment).

Despite the availability of these programs, engaging veterans in VA services—whether in general or tailored for those experiencing or at risk for homelessness—remains challenging. Many veterans at risk for or experiencing homelessness overuse service settings that provide immediate care, such as urgent care or emergency departments (EDs).5,6 These individuals often visit an ED to augment or complement medical care they received in an outpatient setting, which can result in an elevated health care burden as well as impacted provision of treatment, especially surrounding care for chronic conditions (eg, cardiovascular health or serious mental illness).7-9

VA EDs offer urgent care and emergency services and often serve as a point of entry for veterans experiencing homelessness.10 They offer veterans expedient access to care that can address immediate needs (eg, substance use withdrawal, pain management, and suicide risk). EDs may be easier to access given they have longer hours of operation and patients can present without a scheduled appointment. VA EDs are an important point to identify homelessness and connect individuals to social service resources and outpatient health care referrals (eg, primary care and mental health).4,11

Some clinicians experience uncertainty in navigating or providing care for veterans experiencing or at risk for homelessness. A qualitative study conducted outside the VA found many clinicians did not know how to approach clinical conversations among unstably housed individuals, particularly when they discussed how to manage care for complex health conditions in the context of ongoing case management challenges, such as discharge planning.12 Another study found that clinicians working with individuals experiencing homelessness may have limited prior training or experience treating these patients.13 As a result, these clinicians may be unaware of available social services or unknowingly have biases that negatively impact care. Research remains limited surrounding beliefs about and methods of enhancing care among VA clinicians working with veterans experiencing homelessness in the ED.

This multiphase pilot study sought to understand service delivery processes and gaps in VA ED settings. Phase 1 examined ED clinician perceptions of care, facilitators, and barriers to providing care (including suicide risk assessments) and making postdischarge outpatient referrals among VA ED clinicians who regularly work with veterans experiencing homelessness. Phase 2 used this information to develop a clinical psychoeducational resource to enhance post-ED access to care for veterans experiencing or at risk for homelessness.

QUALITATIVE INTERVIEWS

Semistructured qualitative interviews were conducted with 11 VA ED clinicians from 6 Veteran Integrated Service Networks between August 2022 and February 2023. Clinicians were eligible if they currently worked within a VA ED setting (including urgent care) and indicated that some of their patients were veterans experiencing homelessness. All health care practitioners (HCPs) participated in an interview and a postinterview self-report survey that assessed demographic and job-related characteristics. Eight HCPs identified as female and 3 identified as male. All clinicians identified as White and 3 as Hispanic or Latino. Eight clinicians were licensed clinical social workers, 2 were ED nurses, and 1 was an ED physician.

After each clinician provided informed consent, they were invited to complete a telephone or Microsoft Teams interview. All interviews were recorded and subsequently transcribed. Interviews explored clinicians’ experiences caring for veterans experiencing homelessness, with a focus on services provided within the ED, as well as mandated ED screenings such as a suicide risk assessment. Interview questions also addressed postdischarge knowledge and experiences with referrals to VA health services (eg, primary care, mental health) and social services (eg, housing programs). Interviews lasted 30 to 90 minutes.

Recruitment ended after attaining sufficient thematic data, accomplished via an information power approach to sampling. This occurred when the study aims, sample characteristics, existing theory, and depth and quality of interviews dynamically informed the decision to cease recruitment of additional participants.14,15 Given the scope of study (examining service delivery and knowledge gaps), the specificity of the targeted sample (VA ED clinicians providing care to veterans experiencing homelessness), the level of pre-existing theoretical background informing the study aims, and depth and quality of interview dialogue, this information power approach provides justification for attaining small sample sizes. Following the interview, HCPs completed a demographic questionnaire. Participants were not compensated.

Data Analysis

Directed content analysis was used to analyze qualitative data, with the framework method employed as an analytic instrument to facilitate analysis.16-18 Analysts engaged in bracketing and discussed reflexivity before data analysis to reflect on personal subjectivities and reduce potential bias.19,20

A prototype coding framework was developed that enabled coders to meaningfully summarize and condense data within transcripts into varying domains, categories, or topics found within the interview guide. Domain examples included clinical backgrounds, suicide risk and assessment protocols among veterans experiencing homelessness, beliefs about service delivery for veterans experiencing homelessness, and barriers and facilitators that may impact their ability to provide post-ED discharge care. Coders discussed the findings and if there was a need to modify templates. All transcripts were double coded. Once complete, individual templates were merged into a unified Microsoft Excel sheet, which allowed for more discrete analyses, enabling analysts to examine trends across content areas within the dataset.

Clinical Resource Development

HCPs were queried regarding available outpatient resources for post-ED care (eg, printed discharge paperwork and best practice alerts or automated workflows within the electronic health record). Resources used by participants were examined, as well as which resources clinicians thought would help them care for veterans experiencing homelessness. Noted gaps were used to develop a tailored resource for clinicians who treat veterans experiencing homelessness in the ED. This resource was created with the intention it could inform all ED clinicians, with the option for personalization to align with the needs of local services, based on needed content areas identified (eg, emergency shelters and suicide prevention resources).

Resource development followed an information systems research (ISR) framework that used a 3-pronged process of identifying circumstances for how a tool is developed, the problems it aims to address, and the knowledge that informs its development, implementation, and evaluation.21,22 Initial wireframes of the resource were provided via email to 10 subject matter experts (SMEs) in veteran suicide prevention, emergency medicine, and homeless programs. SMEs were identified via professional listservs, VA program office leadership, literature searches of similar research, and snowball sampling. Solicited feedback on the resource from the SMEs included its design, language, tone, flow, format, and content (ideation and prototyping). The feedback was collated and used to revise the resource. SMEs then reviewed and provided feedback on the revised resource. This iterative cycle (prototype review, commentary, ideation, prototype review) continued until the SMEs offered no additional edits to the resource. In total, 7 iterations of the resource were developed, critiqued, and revised.

INTERVIEW RESULTS

Compassion Fatigue

Many participants expressed concerns about compassion fatigue among VA ED clinicians. Those interviewed indicated that treating veterans experiencing homelessness sometimes led to the development of what they described as a “callus,” a “sixth sense,” or an inherent sense of “suspicion” or distrust. These feelings resulted from concerns about an individual’s secondary gain or potential hidden agenda (eg, a veteran reporting suicidal ideation to attain shelter on a cold night), with clinicians not wanting to feel as if they were taken advantage of or deceived.

Many clinicians noted that compassion fatigue resulted from witnessing the same veterans experiencing homelessness routinely use emergency services for nonemergent or nonmedical needs. Some also expressed that over time this may result in them becoming less empathetic when caring for veterans experiencing homelessness. They hypothesized that clinicians may experience burnout, which could potentially result in a lack of curiosity and concern about a veteran’s risk for suicide or need for social services. Others may “take things for granted,” leading them to discount stressors that are “very real to the patient, this person.”

Clinicians indicated that such sentiments may impact overall care. Potential negative consequences included stigmatization of veterans experiencing homelessness, incomplete or partial suicide risk screenings with this population, inattentive or impersonal care, and expedited discharge from the ED without appropriate safety planning or social service referrals. Clinicians interviewed intended to find ways to combat compassion fatigue and maintain a commitment to provide comprehensive care to all veterans, including those experiencing homelessness. They felt conflict between a lack of empathy for individuals experiencing homelessness and becoming numb to the problem due to overexposure. However, these clinicians remained committed to providing care to these veterans and fighting to maintain the purpose of recovery-focused care.

Knowledge Gaps on Available Services

While many clinicians knew of general resources available to veterans experiencing homelessness, few had detailed information on where to seek consults for other homeless programs, who to contact regarding these services, when they were available, or how to refer to them. Many reported feeling uneasy when discharging veterans experiencing homelessness from care, often being unable to provide local, comprehensive referrals to support their needs and ensure their well-being. These sentiments were compounded when the veteran reported suicidal thoughts or recent suicidal behavior; clinicians felt concerned about the methods to engage these individuals into evidence-based mental health care within the context of unstable housing arrangements.

Some clinicians appeared to lack awareness of the wide array of VA homeless programming. Most could acknowledge at least some aspects of available programming (eg, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development– VA Supportive Housing program), while others were unaware of services tailored to the needs of those experiencing homelessness (eg, homeless patient aligned care teams), or of services targeting concurrent psychosocial stressors (eg, Veterans Justice Programs). Interviewees hypothesized this as being particularly notable among clinicians who are new to the VA or those who work in VA settings as part of their graduate or medical school training. Those aware of the services were uncertain of the referral process, relying on a single social worker or nurse to connect individuals experiencing homelessness to health and social services.

Interviewed clinicians noted that suicide risk screening of veterans experiencing homelessness was only performed by a limited number of individuals within the ED. Some did not feel sufficiently trained, comfortable, or knowledgeable about how to navigate care for veterans experiencing homelessness and at risk of suicide. Clinicians described “an uncomfortableness about suicidal ideation, where people just freeze up” and “don’t know what to do and don’t know what to say.”

Lack of Tangible Resources, Trainings, and Referrals

HCPs reported occasionally lacking the necessary clinical resources and information in the ED to properly support veterans experiencing homelessness and suicidal ideation. Common concerns included case management and discharge planning, as well as navigating health factors, such as elevated suicide risk. Some HCPs felt the local resources they do have access to—discharge packets or other forms of patient information—were not always tailored for the needs (eg, transportation) or abilities of veterans experiencing homelessness. One noted: “We give them a sheet of paper with some resources, which they don’t have the skills to follow up [with] anyway.”

Many interviewees wished for additional training in working with veterans experiencing homelessness. They reported that prior training from the VA Talent Management System or through unit-based programming could assist in educating clinicians on homeless services and suicide risk assessment. When queried on what training they had received, many noted there was “no formal training on what the VA offers homeless vets,” leading many to describe it as on-the-job training. This appeared especially among newer clinicians, who reported they were reliant upon learning from other, more senior staff within the ED.

The absence of training further illustrates the issue of institutional knowledge on these services and referrals, which was often confined to a single individual or team. Not having readily accessible resources, training, or information appropriate for all skill levels and positions within the ED hindered the ability of HCPs to connect veterans experiencing homelessness with social services to ensure their health and safety postdischarge: “If we had a better knowledge base of what the VA offers and the steps to go through in order to get the veteran set up for those things, it would be helpful.”

CLINICAL RESOURCE

A psychoeducational resource was developed for HCPs treating veterans experiencing homelessness (Figure). The resource was designed to mitigate compassion fatigue and recenter attention on the VA commitment to care while emphasizing the need to be responsive to the concerns of these individuals. Initial wireframes of the resource were developed by a small group of authors in review and appraisal of qualitative findings (EP, RH). These wireframes were developed to broadly illustrate the arrangement/structure of content, range of resources to potentially include (eg, available VA homeless programs or consultation resources), and to draft initial wording and phrasing. Subject matter expert feedback refined these wireframes, providing commentary on specific programs to include or exclude, changes and alterations to the design and flow of the resource, and edits to language, word choice, and tone over numerous iterations.

Given that many ED HCPs presented concerns surrounding secondary gain in the context of suicide risk, this resource focused on suicide risk. At the top of the resource, it states “Veterans at risk for homelessness experience more than double the risk for suicide than stably housed veterans.”23 Also at the top, the resource states: “For many, the last health care visit prior to suicide is often with VA emergency services."24 The goal of these statements was to educate users on the elevated risk for suicide in veterans experiencing homelessness and their role in preventing such deaths.

Text in this section emphasizes that every veteran deserves the best care possible and recenters HCP attention on providing quality, comprehensive care regardless of housing status. The inclusion of this material was prioritized given the concerns expressed regarding compassion fatigue and suspicions of secondary gain (eg, a veteran reporting suicidal ideation to attain shelter or respite from outside conditions).

The resource also attempts to address high rates of emergency service by veterans experiencing homelessness: “Due to challenges with accessing care, Veterans experiencing homelessness may use emergency or urgent care services more frequently than other Veterans.”25 The resource also indicates that VA resources are available to help homeless and at-risk veterans to acquire stable housing, employment, and engage in healthcare, which are outlined with specific contact information. Given the breadth of local and VA services, a portion of the resource is dedicated to local health and social services available for veterans experiencing homelessness. HCPs complete the first page, which is devoted to local homeless service and program resources.

Following SME consultation, the list of programs provided underwent a series of iterations. The program types listed are deemed to be of greatest benefit to veterans experiencing homelessness and most consulted by HCPs. Including VA and non-VA emergency shelters allows clinicians flexible options if a particular shelter is full, closed, or would not meet the veteran’s needs or preference (eg, lack of childcare or does not allow pets). The second column of this section is left intentionally blank; here, the HCP is to list a local point-of- contact at each program. This encourages clinical teams to seek out and make direct contact with these programs and establish (in)formal relationships with them. The HCP then completes the third column with contact information.

Once completed, the resource acts as a living document. Clinicians and SMEs consulted for this study expressed the desire to have an easily accessible resource that can be updated based on necessary changes (eg, emergency shelter address or hours of operation). The resource can be housed within each local VA emergency or urgent care service setting alongside other available clinical tools.

While local resources are the primary focus, interviewees also suggested that some HCPs are not aware of the available VA services . This material, found on the back of the resource, provides a general overview of services available through VA homeless programs. SME consultation and discussion led to selecting the 5 listed categories: housing services, health care services, case management, employment services, and justice-related programming, each with a brief description.

Information for the National Call Center for Homeless Veterans, community service hotline, and Veterans Crisis Line are included on the front page. These hotlines and phone numbers are always available for veterans experiencing homelessness, enabling them to make these connections themselves, if desired. Additionally, given the challenges noted by some HCPs in performing suicide risk screening, evaluation, and intervention, a prompt for the VA Suicide Risk Management Consultation service was also included on the back page.

Creating a Shared and Local Resource

This clinical resource was developed to establish a centralized, shared, local resource available to VA ED HCPs who lacked knowledge of available services or reported discomfort conducting suicide risk screening for veterans experiencing homelessness. In many cases, ED referrals to homeless programs and suicide prevention care was assigned to a single individual, often a nurse or social worker. As a result, an undue amount of work and strain was placed on these individuals, as this forced them to act as the sole bridge between care in the ED and postdischarge social (eg, homeless programs) and mental health (eg, suicide prevention) services. The creation of a unified, easily accessible document aimed to distribute this responsibility more equitably across ED staff.

DISCUSSION

This project intended to develop a clinician resource to support VA ED clinicians caring for veterans experiencing homelessness and their access to services postdischarge. Qualitative interviews provided insights into the burnout and compassion fatigue present in these settings, as well as the challenges and needs regarding knowledge of local and VA services. Emphasis was placed on leveraging extant resources and subject matter expertise to develop a resource capable of providing brief and informative guidance.