User login

Idiopathic Livedo Racemosa Presenting With Splenomegaly and Diffuse Lymphadenopathy

Sneddon syndrome (SS) was first described in 1965 in patients with persistent livedo racemosa and neurological events.1 Because the other manifestations of SS are nonspecific (eg, hypertension, cardiac valvulopathy, arterial and venous occlusion), the diagnosis often is delayed. Many patients who experience prodromal neurologic symptoms such as headaches, depression, anxiety, dizziness, and neuropathy often present to a physician prior to developing ischemic brain manifestations2 but seldom receive the correct diagnosis. Onset of cerebral occlusive events typically occurs in patients younger than 45 years and may present as a transient ischemic attack, stroke, or intracranial hemorrhage.3 The disease is more prevalent in females than males (2:1 ratio). The exact pathogenesis of SS is still unknown, and although it has been thought of as a separate entity from systemic lupus erythematosus and other antiphospholipid disorders, it has been postulated that an immunological dysfunction damages vessel walls leading to thrombosis.

Cutaneous findings associated with SS involve small- to medium-sized dermal-subdermal arteries. Histopathology in some patients demonstrates proliferation of the endothelium and fibrin deposits with subsequent obliteration of involved arteries.4 In many patients including our patient, histopathologic examination of involved skin fails to show specific abnormalities.1 Zelger et al5 reported the sequence of histopathologic skin events in a series of antiphospholipid-negative SS patients. The authors reported that only small arteries at the dermis-subcutis junction were involved and a progression of endothelial dysfunction was observed. The authors believed there were several nonspecific stages prior to fibrin occlusion of involved arteries.5 Stage I involved loosening of endothelial cells with nonspecific perivascular lymphocytic infiltration with perivascular inflammation and lymphocytic infiltration representing the prime mover of the disease.5,6 This stage is thought to be short lived, thus the reason why it has gone undetected for many years in SS patients. Stages II to IV progress through fibrin deposition and occlusion.5 Histological features of stages I to II have not been reported because of late diagnosis of SS. Stage I patients typically present with an average duration of symptoms of 6 months with few neurologic symptoms, the most common being paresthesia of the legs.5

Case Report

A 37-year-old woman with epigastric tenderness on the left side and splenomegaly seen on computed tomography was referred by a hematologist for evaluation of a reticular rash on the left side of the flank of 9 months’ duration with a presumed diagnosis of focal melanoderma. Her medical history was remarkable for a congenital ventricular septal defect and coarctation of the aorta, as well as endometriosis, myalgia, and joint stiffness that had all developed over the last year. Her medical history also was remarkable for nephrolithiasis, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic sinusitis, as well as psychiatric depression and anxiety disorders. She recently had been diagnosed with moderate hypertension and had experienced difficulty getting pregnant for the last several years with 3 consecutive miscarriages in the first trimester. Neurologic symptoms included neuropathy involving the feet, intermittent paresthesia of the legs, and a history of chronic migraine headaches for several months.

Dermatologic examination revealed a slightly overweight woman with a 25×30-cm dusky, erythematous, irregular, netlike pattern on the left side of the upper and lower trunk (Figure 1). Extensive livedo racemosa was not altered by changes in temperature and had been unchanged for more than 9 months. There were no signs of pruritus or ulcerations, and areas of livedo racemosa were slightly tender to palpation.

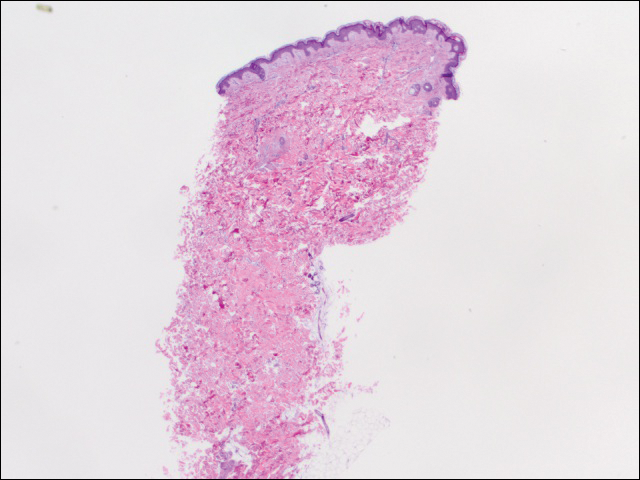

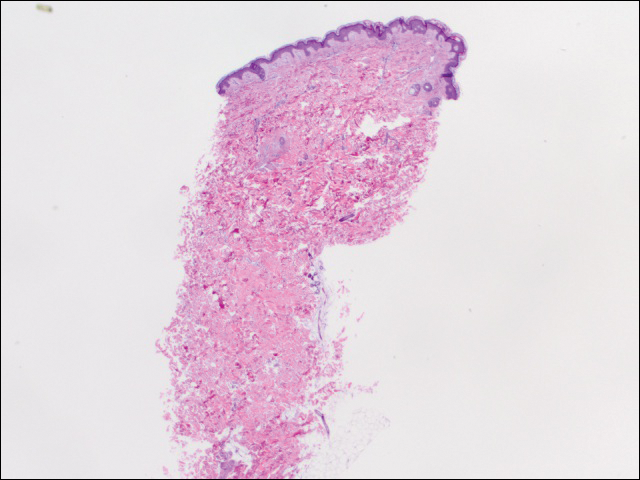

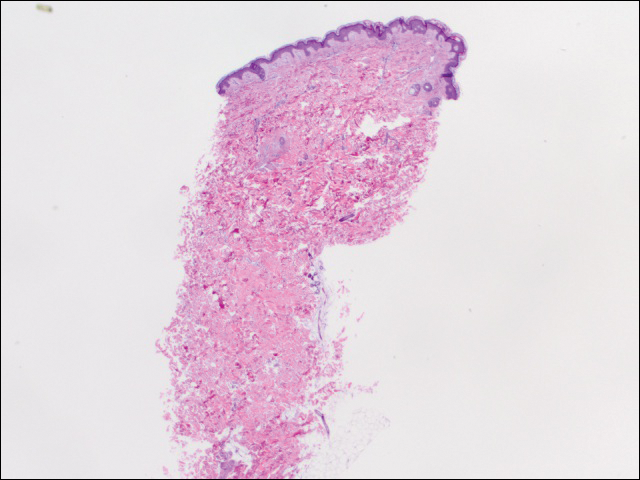

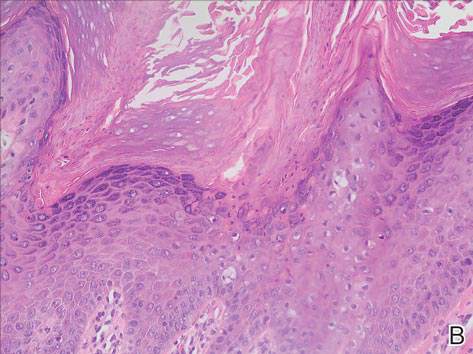

We performed 2 sets of three 4-mm biopsies. The first set targeted areas within the violaceous pattern, while the second set targeted areas of normal tissue between the mottled areas. All 6 specimens demonstrated superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with no evidence of vasculitis or connective tissue disease. The vessels showed no microthrombi or surrounding fibrosis. No eosinophils were identified within the epidermis. There was no evidence of increased dermal mucin. Both the superficial and deep vascular plexuses were unremarkable and showed no evidence of damage to the walls (Figure 2).

To rule out other possible causes of livedo racemosa, complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, coagulation profile, lipase test, urinalysis, serologic testing, and immunologic workup were performed. Lipase was within reference range. The complete blood cell count revealed mild anemia, while the rest of the values were within reference range. An immunologic workup included Sjögren syndrome antigen A, Sjögren syndrome antigen B, anticardiolipin antibodies, and antinuclear antibody, which were all negative. Family history was remarkable for first-degree relatives with systemic lupus erythematosus and Crohn disease.

Computed tomography revealed enlargement of the spleen, as well as periaortic, portacaval, and porta hepatis lymphadenopathy. Based on the laboratory findings and clinical presentation as well as the patient’s medical history, the diagnosis of exclusion was idiopathic livedo racemosa with unknown progression to full-blown SS. The patient did not meet the current diagnostic criteria for SS, and her immunologic studies failed to confirm any present antibodies, but involvement of the reticuloendothelial system pointed to production of antibodies that were not yet detectable on laboratory testing.

Comment

More than 50 years after the first case of SS was diagnosed, better laboratory workup is available and more information is known about the pathophysiology. Sneddon syndrome is a rare disorder, affecting only approximately 4 patients per million each year worldwide. Seronegative antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (SNAPS) describes patients with clinical presentations of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) without detectable serological markers.7 Antiphospholipid-negative SS, which was seen in our patient, would be categorized under SNAPS. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms livedo racemosa, Sneddon syndrome, and SNAPS and splenomegaly revealed there currently are no known cases of SNAPS that have been reported with splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy. Our patient presented with the following clinical features of SS: livedo racemosa, history of miscarriage, psychiatric disturbances, and hypertension. Surprisingly, biopsies from affected skin did not show any fibrin deposition or microthrombi but did reveal perivascular lymphocytic infiltrations. Magnetic resonance imaging did not show any pathological lesions or vascular changes.

Sneddon syndrome and APS share a common pathway to occlusive arteriolopathy for which 4 stages have been described by Zelger et al.5 Stage I involves a nonspecific Langerhans cell infiltrate with polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The tunica media and elastic lamina usually are unaltered at this early stage, while the surrounding connective tissue may appear edematous.5 This early stage of histopathology has not been evaluated in SS patients, primarily because of delay of diagnosis. Late stages III and IV will show fibrin deposition and shrinkage of affected vessels.7

A PubMed search using the terms Sneddon syndrome, lymphadenopathy and livedo racemosa, and Sneddon syndrome and lymphadenopathy revealed that splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy have not been reported in patients with SS. In patients with antiphospholipid-negative SS, one can assume that antibodies to other phospholipids not tested must exist because of striking similarities between APS and antiphospholipid-negative SS.8 Although our patient did not test positive for any of these antibodies, she did present with lymphadenopathy and splenic enlargement, leading us to believe that involvement of the reticuloendothelial system may be a feature of SS that has not been previously reported. Further studies are required to name specific antigens responsible for clinical manifestations in SS.

Currently, no single diagnostic test for SS exists, thus delaying both diagnosis and initiation of treatment. Histopathologic examination may be helpful, but in many cases it is nonspecific, as are serologic markers. Neuroradiological confirmation of involvement usually is the confirmatory feature in many patients with late-stage diagnosis.2 A diagnostic schematic for SS, which was first described by Daoud et al,2 illustrates classification of symptoms and aids in diagnosis. A working diagnosis of idiopathic livedo racemosa is made after ruling out other causes of SS in a patient with nonspecific biopsy findings and negative magnetic resonance imaging results with prodromal symptoms. The prognosis for such patients progressing to full SS is unknown with or without management using anticoagulant therapy.

Conclusion

Early diagnosis of livedo racemosa and SS is essential, as prevention of cerebrovascular accidents, myocardial infarction, and other thromboembolic diseases can be minimized by attacking risk factors such as smoking, taking oral contraceptive pills, becoming pregnant,9 and by initiating either antiplatelet or anticoagulation treatments. These treatments have been shown to delay the development of neurovascular damage and early-onset dementia. We present this case to demonstrate the variability of early-presenting symptoms in idiopathic livedo racemosa. Recognizing some of the early manifestations can lead to early diagnosis and initiation of treatment.

- Sneddon IB. Cerebro-vascular lesions and livedo reticularis. Br J Dermatol. 1965;77:180-185.

- Daoud MS, Wilmoth GJ, Su WP, et al. Sneddon syndrome. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:166-172.

- Besnier R, Francès C, Ankri A, et al. Factor V Leiden mutation in Sneddon syndrome. Lupus. 2003;12:406-408.

- K aragülle AT, Karadağ D, Erden A, et al. Sneddon’s syndrome: MR imaging findings. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:144-146.

- Zelg er B, Sepp N, Schmid KW, et al. Life-history of cutaneous vascular-lesions in Sneddon’s syndrome. Hum Pathol. 1992;23:668-675.

- Ayoub N, Esposito G, Barete S, et al. Protein Z deficiency in antiphospholipid-negative Sneddon’s syndrome. Stroke. 2004;35:1329-1332.

- Duva l A, Darnige L, Glowacki F, et al. Livedo, dementia, thrombocytopenia, and endotheliitis without antiphospholipid antibodies: seronegative antiphospholipid-like syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1076-1078.

- Kala shnikova LA, Nasonov EL, Kushekbaeva AE, et al. Anticardiolipin antibodies in Sneddon’s syndrome. Neurology. 1990;40:464-467.

- Wohl rab J, Fischer M, Wolter M, et al. Diagnostic impact and sensitivity of skin biopsies in Sneddon’s syndrome. a report of 15 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:285-288.

Sneddon syndrome (SS) was first described in 1965 in patients with persistent livedo racemosa and neurological events.1 Because the other manifestations of SS are nonspecific (eg, hypertension, cardiac valvulopathy, arterial and venous occlusion), the diagnosis often is delayed. Many patients who experience prodromal neurologic symptoms such as headaches, depression, anxiety, dizziness, and neuropathy often present to a physician prior to developing ischemic brain manifestations2 but seldom receive the correct diagnosis. Onset of cerebral occlusive events typically occurs in patients younger than 45 years and may present as a transient ischemic attack, stroke, or intracranial hemorrhage.3 The disease is more prevalent in females than males (2:1 ratio). The exact pathogenesis of SS is still unknown, and although it has been thought of as a separate entity from systemic lupus erythematosus and other antiphospholipid disorders, it has been postulated that an immunological dysfunction damages vessel walls leading to thrombosis.

Cutaneous findings associated with SS involve small- to medium-sized dermal-subdermal arteries. Histopathology in some patients demonstrates proliferation of the endothelium and fibrin deposits with subsequent obliteration of involved arteries.4 In many patients including our patient, histopathologic examination of involved skin fails to show specific abnormalities.1 Zelger et al5 reported the sequence of histopathologic skin events in a series of antiphospholipid-negative SS patients. The authors reported that only small arteries at the dermis-subcutis junction were involved and a progression of endothelial dysfunction was observed. The authors believed there were several nonspecific stages prior to fibrin occlusion of involved arteries.5 Stage I involved loosening of endothelial cells with nonspecific perivascular lymphocytic infiltration with perivascular inflammation and lymphocytic infiltration representing the prime mover of the disease.5,6 This stage is thought to be short lived, thus the reason why it has gone undetected for many years in SS patients. Stages II to IV progress through fibrin deposition and occlusion.5 Histological features of stages I to II have not been reported because of late diagnosis of SS. Stage I patients typically present with an average duration of symptoms of 6 months with few neurologic symptoms, the most common being paresthesia of the legs.5

Case Report

A 37-year-old woman with epigastric tenderness on the left side and splenomegaly seen on computed tomography was referred by a hematologist for evaluation of a reticular rash on the left side of the flank of 9 months’ duration with a presumed diagnosis of focal melanoderma. Her medical history was remarkable for a congenital ventricular septal defect and coarctation of the aorta, as well as endometriosis, myalgia, and joint stiffness that had all developed over the last year. Her medical history also was remarkable for nephrolithiasis, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic sinusitis, as well as psychiatric depression and anxiety disorders. She recently had been diagnosed with moderate hypertension and had experienced difficulty getting pregnant for the last several years with 3 consecutive miscarriages in the first trimester. Neurologic symptoms included neuropathy involving the feet, intermittent paresthesia of the legs, and a history of chronic migraine headaches for several months.

Dermatologic examination revealed a slightly overweight woman with a 25×30-cm dusky, erythematous, irregular, netlike pattern on the left side of the upper and lower trunk (Figure 1). Extensive livedo racemosa was not altered by changes in temperature and had been unchanged for more than 9 months. There were no signs of pruritus or ulcerations, and areas of livedo racemosa were slightly tender to palpation.

We performed 2 sets of three 4-mm biopsies. The first set targeted areas within the violaceous pattern, while the second set targeted areas of normal tissue between the mottled areas. All 6 specimens demonstrated superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with no evidence of vasculitis or connective tissue disease. The vessels showed no microthrombi or surrounding fibrosis. No eosinophils were identified within the epidermis. There was no evidence of increased dermal mucin. Both the superficial and deep vascular plexuses were unremarkable and showed no evidence of damage to the walls (Figure 2).

To rule out other possible causes of livedo racemosa, complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, coagulation profile, lipase test, urinalysis, serologic testing, and immunologic workup were performed. Lipase was within reference range. The complete blood cell count revealed mild anemia, while the rest of the values were within reference range. An immunologic workup included Sjögren syndrome antigen A, Sjögren syndrome antigen B, anticardiolipin antibodies, and antinuclear antibody, which were all negative. Family history was remarkable for first-degree relatives with systemic lupus erythematosus and Crohn disease.

Computed tomography revealed enlargement of the spleen, as well as periaortic, portacaval, and porta hepatis lymphadenopathy. Based on the laboratory findings and clinical presentation as well as the patient’s medical history, the diagnosis of exclusion was idiopathic livedo racemosa with unknown progression to full-blown SS. The patient did not meet the current diagnostic criteria for SS, and her immunologic studies failed to confirm any present antibodies, but involvement of the reticuloendothelial system pointed to production of antibodies that were not yet detectable on laboratory testing.

Comment

More than 50 years after the first case of SS was diagnosed, better laboratory workup is available and more information is known about the pathophysiology. Sneddon syndrome is a rare disorder, affecting only approximately 4 patients per million each year worldwide. Seronegative antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (SNAPS) describes patients with clinical presentations of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) without detectable serological markers.7 Antiphospholipid-negative SS, which was seen in our patient, would be categorized under SNAPS. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms livedo racemosa, Sneddon syndrome, and SNAPS and splenomegaly revealed there currently are no known cases of SNAPS that have been reported with splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy. Our patient presented with the following clinical features of SS: livedo racemosa, history of miscarriage, psychiatric disturbances, and hypertension. Surprisingly, biopsies from affected skin did not show any fibrin deposition or microthrombi but did reveal perivascular lymphocytic infiltrations. Magnetic resonance imaging did not show any pathological lesions or vascular changes.

Sneddon syndrome and APS share a common pathway to occlusive arteriolopathy for which 4 stages have been described by Zelger et al.5 Stage I involves a nonspecific Langerhans cell infiltrate with polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The tunica media and elastic lamina usually are unaltered at this early stage, while the surrounding connective tissue may appear edematous.5 This early stage of histopathology has not been evaluated in SS patients, primarily because of delay of diagnosis. Late stages III and IV will show fibrin deposition and shrinkage of affected vessels.7

A PubMed search using the terms Sneddon syndrome, lymphadenopathy and livedo racemosa, and Sneddon syndrome and lymphadenopathy revealed that splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy have not been reported in patients with SS. In patients with antiphospholipid-negative SS, one can assume that antibodies to other phospholipids not tested must exist because of striking similarities between APS and antiphospholipid-negative SS.8 Although our patient did not test positive for any of these antibodies, she did present with lymphadenopathy and splenic enlargement, leading us to believe that involvement of the reticuloendothelial system may be a feature of SS that has not been previously reported. Further studies are required to name specific antigens responsible for clinical manifestations in SS.

Currently, no single diagnostic test for SS exists, thus delaying both diagnosis and initiation of treatment. Histopathologic examination may be helpful, but in many cases it is nonspecific, as are serologic markers. Neuroradiological confirmation of involvement usually is the confirmatory feature in many patients with late-stage diagnosis.2 A diagnostic schematic for SS, which was first described by Daoud et al,2 illustrates classification of symptoms and aids in diagnosis. A working diagnosis of idiopathic livedo racemosa is made after ruling out other causes of SS in a patient with nonspecific biopsy findings and negative magnetic resonance imaging results with prodromal symptoms. The prognosis for such patients progressing to full SS is unknown with or without management using anticoagulant therapy.

Conclusion

Early diagnosis of livedo racemosa and SS is essential, as prevention of cerebrovascular accidents, myocardial infarction, and other thromboembolic diseases can be minimized by attacking risk factors such as smoking, taking oral contraceptive pills, becoming pregnant,9 and by initiating either antiplatelet or anticoagulation treatments. These treatments have been shown to delay the development of neurovascular damage and early-onset dementia. We present this case to demonstrate the variability of early-presenting symptoms in idiopathic livedo racemosa. Recognizing some of the early manifestations can lead to early diagnosis and initiation of treatment.

Sneddon syndrome (SS) was first described in 1965 in patients with persistent livedo racemosa and neurological events.1 Because the other manifestations of SS are nonspecific (eg, hypertension, cardiac valvulopathy, arterial and venous occlusion), the diagnosis often is delayed. Many patients who experience prodromal neurologic symptoms such as headaches, depression, anxiety, dizziness, and neuropathy often present to a physician prior to developing ischemic brain manifestations2 but seldom receive the correct diagnosis. Onset of cerebral occlusive events typically occurs in patients younger than 45 years and may present as a transient ischemic attack, stroke, or intracranial hemorrhage.3 The disease is more prevalent in females than males (2:1 ratio). The exact pathogenesis of SS is still unknown, and although it has been thought of as a separate entity from systemic lupus erythematosus and other antiphospholipid disorders, it has been postulated that an immunological dysfunction damages vessel walls leading to thrombosis.

Cutaneous findings associated with SS involve small- to medium-sized dermal-subdermal arteries. Histopathology in some patients demonstrates proliferation of the endothelium and fibrin deposits with subsequent obliteration of involved arteries.4 In many patients including our patient, histopathologic examination of involved skin fails to show specific abnormalities.1 Zelger et al5 reported the sequence of histopathologic skin events in a series of antiphospholipid-negative SS patients. The authors reported that only small arteries at the dermis-subcutis junction were involved and a progression of endothelial dysfunction was observed. The authors believed there were several nonspecific stages prior to fibrin occlusion of involved arteries.5 Stage I involved loosening of endothelial cells with nonspecific perivascular lymphocytic infiltration with perivascular inflammation and lymphocytic infiltration representing the prime mover of the disease.5,6 This stage is thought to be short lived, thus the reason why it has gone undetected for many years in SS patients. Stages II to IV progress through fibrin deposition and occlusion.5 Histological features of stages I to II have not been reported because of late diagnosis of SS. Stage I patients typically present with an average duration of symptoms of 6 months with few neurologic symptoms, the most common being paresthesia of the legs.5

Case Report

A 37-year-old woman with epigastric tenderness on the left side and splenomegaly seen on computed tomography was referred by a hematologist for evaluation of a reticular rash on the left side of the flank of 9 months’ duration with a presumed diagnosis of focal melanoderma. Her medical history was remarkable for a congenital ventricular septal defect and coarctation of the aorta, as well as endometriosis, myalgia, and joint stiffness that had all developed over the last year. Her medical history also was remarkable for nephrolithiasis, irritable bowel syndrome, and chronic sinusitis, as well as psychiatric depression and anxiety disorders. She recently had been diagnosed with moderate hypertension and had experienced difficulty getting pregnant for the last several years with 3 consecutive miscarriages in the first trimester. Neurologic symptoms included neuropathy involving the feet, intermittent paresthesia of the legs, and a history of chronic migraine headaches for several months.

Dermatologic examination revealed a slightly overweight woman with a 25×30-cm dusky, erythematous, irregular, netlike pattern on the left side of the upper and lower trunk (Figure 1). Extensive livedo racemosa was not altered by changes in temperature and had been unchanged for more than 9 months. There were no signs of pruritus or ulcerations, and areas of livedo racemosa were slightly tender to palpation.

We performed 2 sets of three 4-mm biopsies. The first set targeted areas within the violaceous pattern, while the second set targeted areas of normal tissue between the mottled areas. All 6 specimens demonstrated superficial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with no evidence of vasculitis or connective tissue disease. The vessels showed no microthrombi or surrounding fibrosis. No eosinophils were identified within the epidermis. There was no evidence of increased dermal mucin. Both the superficial and deep vascular plexuses were unremarkable and showed no evidence of damage to the walls (Figure 2).

To rule out other possible causes of livedo racemosa, complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, coagulation profile, lipase test, urinalysis, serologic testing, and immunologic workup were performed. Lipase was within reference range. The complete blood cell count revealed mild anemia, while the rest of the values were within reference range. An immunologic workup included Sjögren syndrome antigen A, Sjögren syndrome antigen B, anticardiolipin antibodies, and antinuclear antibody, which were all negative. Family history was remarkable for first-degree relatives with systemic lupus erythematosus and Crohn disease.

Computed tomography revealed enlargement of the spleen, as well as periaortic, portacaval, and porta hepatis lymphadenopathy. Based on the laboratory findings and clinical presentation as well as the patient’s medical history, the diagnosis of exclusion was idiopathic livedo racemosa with unknown progression to full-blown SS. The patient did not meet the current diagnostic criteria for SS, and her immunologic studies failed to confirm any present antibodies, but involvement of the reticuloendothelial system pointed to production of antibodies that were not yet detectable on laboratory testing.

Comment

More than 50 years after the first case of SS was diagnosed, better laboratory workup is available and more information is known about the pathophysiology. Sneddon syndrome is a rare disorder, affecting only approximately 4 patients per million each year worldwide. Seronegative antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (SNAPS) describes patients with clinical presentations of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) without detectable serological markers.7 Antiphospholipid-negative SS, which was seen in our patient, would be categorized under SNAPS. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms livedo racemosa, Sneddon syndrome, and SNAPS and splenomegaly revealed there currently are no known cases of SNAPS that have been reported with splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy. Our patient presented with the following clinical features of SS: livedo racemosa, history of miscarriage, psychiatric disturbances, and hypertension. Surprisingly, biopsies from affected skin did not show any fibrin deposition or microthrombi but did reveal perivascular lymphocytic infiltrations. Magnetic resonance imaging did not show any pathological lesions or vascular changes.

Sneddon syndrome and APS share a common pathway to occlusive arteriolopathy for which 4 stages have been described by Zelger et al.5 Stage I involves a nonspecific Langerhans cell infiltrate with polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The tunica media and elastic lamina usually are unaltered at this early stage, while the surrounding connective tissue may appear edematous.5 This early stage of histopathology has not been evaluated in SS patients, primarily because of delay of diagnosis. Late stages III and IV will show fibrin deposition and shrinkage of affected vessels.7

A PubMed search using the terms Sneddon syndrome, lymphadenopathy and livedo racemosa, and Sneddon syndrome and lymphadenopathy revealed that splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy have not been reported in patients with SS. In patients with antiphospholipid-negative SS, one can assume that antibodies to other phospholipids not tested must exist because of striking similarities between APS and antiphospholipid-negative SS.8 Although our patient did not test positive for any of these antibodies, she did present with lymphadenopathy and splenic enlargement, leading us to believe that involvement of the reticuloendothelial system may be a feature of SS that has not been previously reported. Further studies are required to name specific antigens responsible for clinical manifestations in SS.

Currently, no single diagnostic test for SS exists, thus delaying both diagnosis and initiation of treatment. Histopathologic examination may be helpful, but in many cases it is nonspecific, as are serologic markers. Neuroradiological confirmation of involvement usually is the confirmatory feature in many patients with late-stage diagnosis.2 A diagnostic schematic for SS, which was first described by Daoud et al,2 illustrates classification of symptoms and aids in diagnosis. A working diagnosis of idiopathic livedo racemosa is made after ruling out other causes of SS in a patient with nonspecific biopsy findings and negative magnetic resonance imaging results with prodromal symptoms. The prognosis for such patients progressing to full SS is unknown with or without management using anticoagulant therapy.

Conclusion

Early diagnosis of livedo racemosa and SS is essential, as prevention of cerebrovascular accidents, myocardial infarction, and other thromboembolic diseases can be minimized by attacking risk factors such as smoking, taking oral contraceptive pills, becoming pregnant,9 and by initiating either antiplatelet or anticoagulation treatments. These treatments have been shown to delay the development of neurovascular damage and early-onset dementia. We present this case to demonstrate the variability of early-presenting symptoms in idiopathic livedo racemosa. Recognizing some of the early manifestations can lead to early diagnosis and initiation of treatment.

- Sneddon IB. Cerebro-vascular lesions and livedo reticularis. Br J Dermatol. 1965;77:180-185.

- Daoud MS, Wilmoth GJ, Su WP, et al. Sneddon syndrome. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:166-172.

- Besnier R, Francès C, Ankri A, et al. Factor V Leiden mutation in Sneddon syndrome. Lupus. 2003;12:406-408.

- K aragülle AT, Karadağ D, Erden A, et al. Sneddon’s syndrome: MR imaging findings. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:144-146.

- Zelg er B, Sepp N, Schmid KW, et al. Life-history of cutaneous vascular-lesions in Sneddon’s syndrome. Hum Pathol. 1992;23:668-675.

- Ayoub N, Esposito G, Barete S, et al. Protein Z deficiency in antiphospholipid-negative Sneddon’s syndrome. Stroke. 2004;35:1329-1332.

- Duva l A, Darnige L, Glowacki F, et al. Livedo, dementia, thrombocytopenia, and endotheliitis without antiphospholipid antibodies: seronegative antiphospholipid-like syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1076-1078.

- Kala shnikova LA, Nasonov EL, Kushekbaeva AE, et al. Anticardiolipin antibodies in Sneddon’s syndrome. Neurology. 1990;40:464-467.

- Wohl rab J, Fischer M, Wolter M, et al. Diagnostic impact and sensitivity of skin biopsies in Sneddon’s syndrome. a report of 15 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:285-288.

- Sneddon IB. Cerebro-vascular lesions and livedo reticularis. Br J Dermatol. 1965;77:180-185.

- Daoud MS, Wilmoth GJ, Su WP, et al. Sneddon syndrome. Semin Dermatol. 1995;14:166-172.

- Besnier R, Francès C, Ankri A, et al. Factor V Leiden mutation in Sneddon syndrome. Lupus. 2003;12:406-408.

- K aragülle AT, Karadağ D, Erden A, et al. Sneddon’s syndrome: MR imaging findings. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:144-146.

- Zelg er B, Sepp N, Schmid KW, et al. Life-history of cutaneous vascular-lesions in Sneddon’s syndrome. Hum Pathol. 1992;23:668-675.

- Ayoub N, Esposito G, Barete S, et al. Protein Z deficiency in antiphospholipid-negative Sneddon’s syndrome. Stroke. 2004;35:1329-1332.

- Duva l A, Darnige L, Glowacki F, et al. Livedo, dementia, thrombocytopenia, and endotheliitis without antiphospholipid antibodies: seronegative antiphospholipid-like syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:1076-1078.

- Kala shnikova LA, Nasonov EL, Kushekbaeva AE, et al. Anticardiolipin antibodies in Sneddon’s syndrome. Neurology. 1990;40:464-467.

- Wohl rab J, Fischer M, Wolter M, et al. Diagnostic impact and sensitivity of skin biopsies in Sneddon’s syndrome. a report of 15 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:285-288.

Practice Points

- The classic physical diagnostic finding of Sneddon syndrome (SS) is livedo racemosa.

- Early identification and treatment of SS can prevent serious morbidity due to stroke, myocardial infarction, and other thrombotic events.

- Preventive care in SS should include antiplatelet therapy or anticoagulants and smoking cessation along with avoidance of birth control pills.

Nevus Spilus: Is the Presence of Hair Associated With an Increased Risk for Melanoma?

The term nevus spilus (NS), also known as speckled lentiginous nevus, was first used in the 19th century to describe lesions with background café au lait–like lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia speckled with small, 1- to 3-mm, darker foci. The dark spots reflect lentigines; junctional, compound, and intradermal nevus cell nests; and more rarely Spitz and blue nevi. Both macular and papular subtypes have been described.1 This birthmark is quite common, occurring in 1.3% to 2.3% of the adult population worldwide.2 Hypertrichosis has been described in NS.3-9 Two subsequent cases of malignant melanoma in hairy NS suggested that lesions may be particularly prone to malignant degeneration.4,8 We report an additional case of hairy NS that was not associated with melanoma and consider whether dermatologists should warn their patients about this association.

Case Report

A 26-year-old woman presented with a stable 7×8-cm, tan-brown, macular, pigmented birthmark studded with darker 1- to 2-mm, irregular, brown-black and blue, confettilike macules on the left proximal lateral thigh that had been present since birth (Figure 1). Dark terminal hairs were present, arising from both the darker and lighter pigmented areas but not the surrounding normal skin.

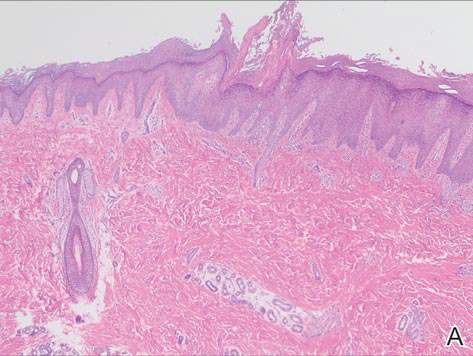

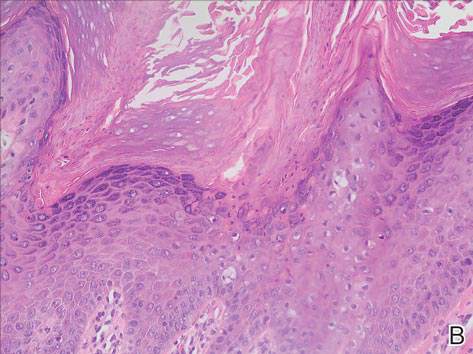

A 4-mm punch biopsy from one of the dark blue macules demonstrated uniform lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia and nevus cell nests adjacent to the sweat glands extending into the mid dermis (Figure 2). No clinical evidence of malignant degeneration was present.

Comment

The risk for melanoma is increased in classic nonspeckled congenital nevi and the risk correlates with the size of the lesion and most probably the number of nevus cells in the lesion that increase the risk for a random mutation.8,10,11 It is likely that NS with or without hair presages a small increased risk for melanoma,6,9,12 which is not surprising because NS is a subtype of congenital melanocytic nevus (CMN), a condition that is present at birth and results from a proliferation of melanocytes.6 Nevus spilus, however, appears to have a notably lower risk for malignant degeneration than other classic CMN of the same size. The following support for this hypothesis is offered: First, CMN have nevus cells broadly filling the dermis that extend more deeply into the dermis than NS (Figure 2A).10 In our estimation, CMN have at least 100 times the number of nevus cells per square centimeter compared to NS. The potential for malignant degeneration of any one melanocyte is greater when more are present. Second, although some NS lesions evolve, classic CMN are universally more proliferative than NS.10,13 The involved skin in CMN thickens over time with increased numbers of melanocytes and marked overgrowth of adjacent tissue. Melanocytes in a proliferative phase may be more likely to undergo malignant degeneration.10

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term nevus spilus and melanoma yielded 2 cases4,8 of melanoma arising among 15 cases of hairy NS in the literature, which led to the suggestion that the presence of hair could be associated with an increased risk for malignant degeneration in NS (Table). This apparent high incidence of melanoma most likely reflects referral/publication bias rather than a statistically significant association. In fact, the clinical lesion most clinically similar to hairy NS is Becker nevus, with tan macules demonstrating lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia associated with numerous coarse terminal hairs. There is no indication that Becker nevi have a considerable premalignant potential, though one case of melanoma arising in a Becker nevus has been reported.9 There is no evidence to suggest that classic CMN with hypertrichosis has a greater premalignant potential than similar lesions without hypertrichosis.

We noticed the presence of hair in our patient’s lesion only after reports in the literature caused us to look for this phenomenon.9 This occurrence may actually be quite common. We do not recommend prophylactic excision of NS and believe the risk for malignant degeneration is low in NS with or without hair, though larger NS (>4 cm), especially giant, zosteriform, or segmental lesions, may have a greater risk.1,6,9,10 It is prudent for physicians to carefully examine NS and sample suspicious foci, especially when patients describe a lesion as changing.

- Vidaurri-de la Cruz H, Happle R. Two distinct types of speckled lentiginous nevi characterized by macular versus papular speckles. Dermatology. 2006;212:53-58.

- Ly L, Christie M, Swain S, et al. Melanoma(s) arising in large segmental speckled lentiginous nevi: a case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1190-1193.

- Prose NS, Heilman E, Felman YM, et al. Multiple benign juvenile melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:236-242.

- Grinspan D, Casala A, Abulafia J, et al. Melanoma on dysplastic nevus spilus. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:499-502 .

- Langenbach N, Pfau A, Landthaler M, et al. Naevi spili, café-au-lait spots and melanocytic naevi aggregated alongside Blaschko’s lines, with a review of segmental melanocytic lesions. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:378-380.

- Schaffer JV, Orlow SJ, Lazova R, et al. Speckled lentiginous nevus: within the spectrum of congenital melanocytic nevi. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:172-178.

- Saraswat A, Dogra S, Bansali A, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica associated with hypophosphataemic vitamin D–resistant rickets: improvement in phosphate homeostasis after partial laser ablation. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:1074-1076.

- Zeren-Bilgin

i , Gür S, Aydın O, et al. Melanoma arising in a hairy nevus spilus. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1362-1364. - Singh S, Jain N, Khanna N, et al. Hairy nevus spilus: a case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:100-104.

- Price HN, Schaffer JV. Congenital melanocytic nevi—when to worry and how to treat: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:293-302.

- Alikhan Ali, Ibrahimi OA, Eisen DB. Congenital melanocytic nevi: where are we now? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:495.e1-495.e17.

- Haenssle HA, Kaune KM, Buhl T, et al. Melanoma arising in segmental nevus spilus: detection by sequential digital dermatoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:337-341.

- Cohen LM. Nevus spilus: congenital or acquired? Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:215-216.

The term nevus spilus (NS), also known as speckled lentiginous nevus, was first used in the 19th century to describe lesions with background café au lait–like lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia speckled with small, 1- to 3-mm, darker foci. The dark spots reflect lentigines; junctional, compound, and intradermal nevus cell nests; and more rarely Spitz and blue nevi. Both macular and papular subtypes have been described.1 This birthmark is quite common, occurring in 1.3% to 2.3% of the adult population worldwide.2 Hypertrichosis has been described in NS.3-9 Two subsequent cases of malignant melanoma in hairy NS suggested that lesions may be particularly prone to malignant degeneration.4,8 We report an additional case of hairy NS that was not associated with melanoma and consider whether dermatologists should warn their patients about this association.

Case Report

A 26-year-old woman presented with a stable 7×8-cm, tan-brown, macular, pigmented birthmark studded with darker 1- to 2-mm, irregular, brown-black and blue, confettilike macules on the left proximal lateral thigh that had been present since birth (Figure 1). Dark terminal hairs were present, arising from both the darker and lighter pigmented areas but not the surrounding normal skin.

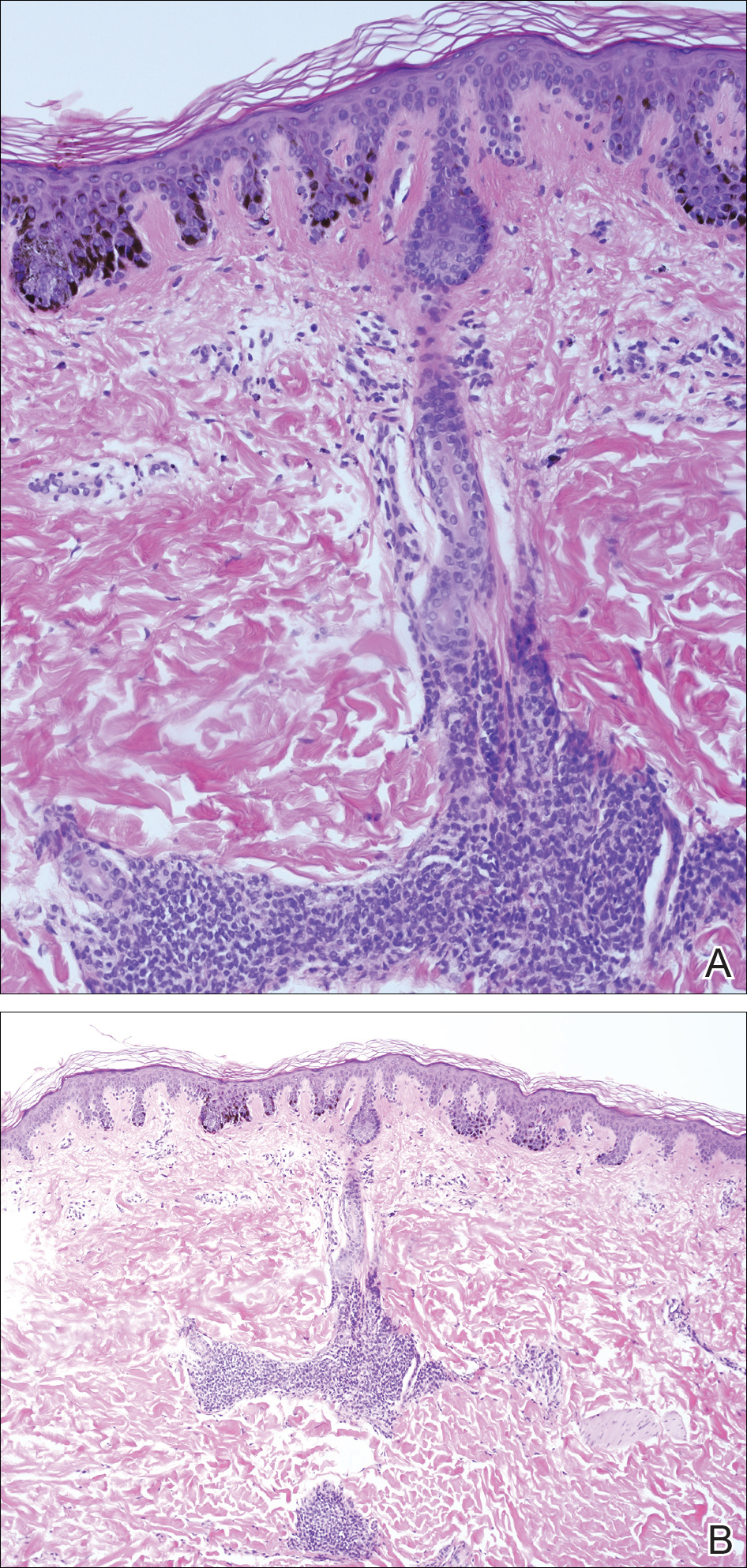

A 4-mm punch biopsy from one of the dark blue macules demonstrated uniform lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia and nevus cell nests adjacent to the sweat glands extending into the mid dermis (Figure 2). No clinical evidence of malignant degeneration was present.

Comment

The risk for melanoma is increased in classic nonspeckled congenital nevi and the risk correlates with the size of the lesion and most probably the number of nevus cells in the lesion that increase the risk for a random mutation.8,10,11 It is likely that NS with or without hair presages a small increased risk for melanoma,6,9,12 which is not surprising because NS is a subtype of congenital melanocytic nevus (CMN), a condition that is present at birth and results from a proliferation of melanocytes.6 Nevus spilus, however, appears to have a notably lower risk for malignant degeneration than other classic CMN of the same size. The following support for this hypothesis is offered: First, CMN have nevus cells broadly filling the dermis that extend more deeply into the dermis than NS (Figure 2A).10 In our estimation, CMN have at least 100 times the number of nevus cells per square centimeter compared to NS. The potential for malignant degeneration of any one melanocyte is greater when more are present. Second, although some NS lesions evolve, classic CMN are universally more proliferative than NS.10,13 The involved skin in CMN thickens over time with increased numbers of melanocytes and marked overgrowth of adjacent tissue. Melanocytes in a proliferative phase may be more likely to undergo malignant degeneration.10

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term nevus spilus and melanoma yielded 2 cases4,8 of melanoma arising among 15 cases of hairy NS in the literature, which led to the suggestion that the presence of hair could be associated with an increased risk for malignant degeneration in NS (Table). This apparent high incidence of melanoma most likely reflects referral/publication bias rather than a statistically significant association. In fact, the clinical lesion most clinically similar to hairy NS is Becker nevus, with tan macules demonstrating lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia associated with numerous coarse terminal hairs. There is no indication that Becker nevi have a considerable premalignant potential, though one case of melanoma arising in a Becker nevus has been reported.9 There is no evidence to suggest that classic CMN with hypertrichosis has a greater premalignant potential than similar lesions without hypertrichosis.

We noticed the presence of hair in our patient’s lesion only after reports in the literature caused us to look for this phenomenon.9 This occurrence may actually be quite common. We do not recommend prophylactic excision of NS and believe the risk for malignant degeneration is low in NS with or without hair, though larger NS (>4 cm), especially giant, zosteriform, or segmental lesions, may have a greater risk.1,6,9,10 It is prudent for physicians to carefully examine NS and sample suspicious foci, especially when patients describe a lesion as changing.

The term nevus spilus (NS), also known as speckled lentiginous nevus, was first used in the 19th century to describe lesions with background café au lait–like lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia speckled with small, 1- to 3-mm, darker foci. The dark spots reflect lentigines; junctional, compound, and intradermal nevus cell nests; and more rarely Spitz and blue nevi. Both macular and papular subtypes have been described.1 This birthmark is quite common, occurring in 1.3% to 2.3% of the adult population worldwide.2 Hypertrichosis has been described in NS.3-9 Two subsequent cases of malignant melanoma in hairy NS suggested that lesions may be particularly prone to malignant degeneration.4,8 We report an additional case of hairy NS that was not associated with melanoma and consider whether dermatologists should warn their patients about this association.

Case Report

A 26-year-old woman presented with a stable 7×8-cm, tan-brown, macular, pigmented birthmark studded with darker 1- to 2-mm, irregular, brown-black and blue, confettilike macules on the left proximal lateral thigh that had been present since birth (Figure 1). Dark terminal hairs were present, arising from both the darker and lighter pigmented areas but not the surrounding normal skin.

A 4-mm punch biopsy from one of the dark blue macules demonstrated uniform lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia and nevus cell nests adjacent to the sweat glands extending into the mid dermis (Figure 2). No clinical evidence of malignant degeneration was present.

Comment

The risk for melanoma is increased in classic nonspeckled congenital nevi and the risk correlates with the size of the lesion and most probably the number of nevus cells in the lesion that increase the risk for a random mutation.8,10,11 It is likely that NS with or without hair presages a small increased risk for melanoma,6,9,12 which is not surprising because NS is a subtype of congenital melanocytic nevus (CMN), a condition that is present at birth and results from a proliferation of melanocytes.6 Nevus spilus, however, appears to have a notably lower risk for malignant degeneration than other classic CMN of the same size. The following support for this hypothesis is offered: First, CMN have nevus cells broadly filling the dermis that extend more deeply into the dermis than NS (Figure 2A).10 In our estimation, CMN have at least 100 times the number of nevus cells per square centimeter compared to NS. The potential for malignant degeneration of any one melanocyte is greater when more are present. Second, although some NS lesions evolve, classic CMN are universally more proliferative than NS.10,13 The involved skin in CMN thickens over time with increased numbers of melanocytes and marked overgrowth of adjacent tissue. Melanocytes in a proliferative phase may be more likely to undergo malignant degeneration.10

A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term nevus spilus and melanoma yielded 2 cases4,8 of melanoma arising among 15 cases of hairy NS in the literature, which led to the suggestion that the presence of hair could be associated with an increased risk for malignant degeneration in NS (Table). This apparent high incidence of melanoma most likely reflects referral/publication bias rather than a statistically significant association. In fact, the clinical lesion most clinically similar to hairy NS is Becker nevus, with tan macules demonstrating lentiginous melanocytic hyperplasia associated with numerous coarse terminal hairs. There is no indication that Becker nevi have a considerable premalignant potential, though one case of melanoma arising in a Becker nevus has been reported.9 There is no evidence to suggest that classic CMN with hypertrichosis has a greater premalignant potential than similar lesions without hypertrichosis.

We noticed the presence of hair in our patient’s lesion only after reports in the literature caused us to look for this phenomenon.9 This occurrence may actually be quite common. We do not recommend prophylactic excision of NS and believe the risk for malignant degeneration is low in NS with or without hair, though larger NS (>4 cm), especially giant, zosteriform, or segmental lesions, may have a greater risk.1,6,9,10 It is prudent for physicians to carefully examine NS and sample suspicious foci, especially when patients describe a lesion as changing.

- Vidaurri-de la Cruz H, Happle R. Two distinct types of speckled lentiginous nevi characterized by macular versus papular speckles. Dermatology. 2006;212:53-58.

- Ly L, Christie M, Swain S, et al. Melanoma(s) arising in large segmental speckled lentiginous nevi: a case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1190-1193.

- Prose NS, Heilman E, Felman YM, et al. Multiple benign juvenile melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:236-242.

- Grinspan D, Casala A, Abulafia J, et al. Melanoma on dysplastic nevus spilus. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:499-502 .

- Langenbach N, Pfau A, Landthaler M, et al. Naevi spili, café-au-lait spots and melanocytic naevi aggregated alongside Blaschko’s lines, with a review of segmental melanocytic lesions. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:378-380.

- Schaffer JV, Orlow SJ, Lazova R, et al. Speckled lentiginous nevus: within the spectrum of congenital melanocytic nevi. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:172-178.

- Saraswat A, Dogra S, Bansali A, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica associated with hypophosphataemic vitamin D–resistant rickets: improvement in phosphate homeostasis after partial laser ablation. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:1074-1076.

- Zeren-Bilgin

i , Gür S, Aydın O, et al. Melanoma arising in a hairy nevus spilus. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1362-1364. - Singh S, Jain N, Khanna N, et al. Hairy nevus spilus: a case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:100-104.

- Price HN, Schaffer JV. Congenital melanocytic nevi—when to worry and how to treat: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:293-302.

- Alikhan Ali, Ibrahimi OA, Eisen DB. Congenital melanocytic nevi: where are we now? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:495.e1-495.e17.

- Haenssle HA, Kaune KM, Buhl T, et al. Melanoma arising in segmental nevus spilus: detection by sequential digital dermatoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:337-341.

- Cohen LM. Nevus spilus: congenital or acquired? Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:215-216.

- Vidaurri-de la Cruz H, Happle R. Two distinct types of speckled lentiginous nevi characterized by macular versus papular speckles. Dermatology. 2006;212:53-58.

- Ly L, Christie M, Swain S, et al. Melanoma(s) arising in large segmental speckled lentiginous nevi: a case series. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1190-1193.

- Prose NS, Heilman E, Felman YM, et al. Multiple benign juvenile melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:236-242.

- Grinspan D, Casala A, Abulafia J, et al. Melanoma on dysplastic nevus spilus. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:499-502 .

- Langenbach N, Pfau A, Landthaler M, et al. Naevi spili, café-au-lait spots and melanocytic naevi aggregated alongside Blaschko’s lines, with a review of segmental melanocytic lesions. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:378-380.

- Schaffer JV, Orlow SJ, Lazova R, et al. Speckled lentiginous nevus: within the spectrum of congenital melanocytic nevi. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:172-178.

- Saraswat A, Dogra S, Bansali A, et al. Phakomatosis pigmentokeratotica associated with hypophosphataemic vitamin D–resistant rickets: improvement in phosphate homeostasis after partial laser ablation. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:1074-1076.

- Zeren-Bilgin

i , Gür S, Aydın O, et al. Melanoma arising in a hairy nevus spilus. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1362-1364. - Singh S, Jain N, Khanna N, et al. Hairy nevus spilus: a case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:100-104.

- Price HN, Schaffer JV. Congenital melanocytic nevi—when to worry and how to treat: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:293-302.

- Alikhan Ali, Ibrahimi OA, Eisen DB. Congenital melanocytic nevi: where are we now? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:495.e1-495.e17.

- Haenssle HA, Kaune KM, Buhl T, et al. Melanoma arising in segmental nevus spilus: detection by sequential digital dermatoscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:337-341.

- Cohen LM. Nevus spilus: congenital or acquired? Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:215-216.

Practice Points

- Nevus spilus (NS) appears as a café au lait macule studded with darker brown “moles.”

- Although melanoma has been described in NS, it is rare.

- There is no evidence that hairy NS are predisposed to melanoma.

Diagnosing Porokeratosis of Mibelli Every Time: A Novel Biopsy Technique to Maximize Histopathologic Confirmation

Porokeratosis of Mibelli (PM) is a lesion characterized by a surrounding cornoid lamella with variable nonspecific findings (eg, atrophy, acanthosis, verrucous hyperplasia) in the center of the lesion that typically presents in infancy to early childhood.1 We report a case of PM in which a prior biopsy from the center of the lesion demonstrated papulosquamous dermatitis. We propose a 3-step technique to ensure proper orientation of a punch biopsy in cases of suspected PM.

Case Report

A 3-year-old girl presented with an erythematous, hypopigmented, scaling plaque on the posterior aspect of the left ankle surrounded by a hard rim. The plaque was first noted at 12 months of age and had slowly enlarged as the patient grew. Six months prior, a biopsy from the center of the lesion performed at another facility demonstrated a papulosquamous dermatitis.

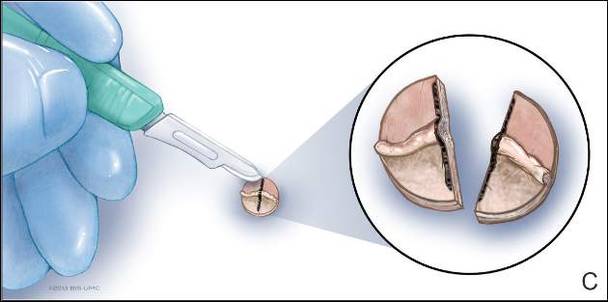

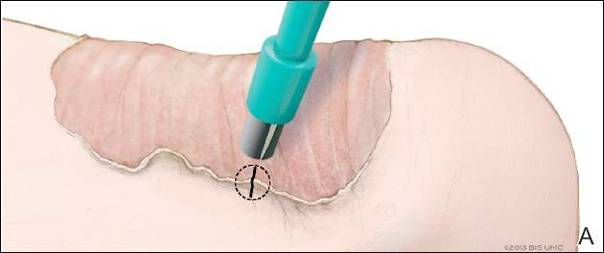

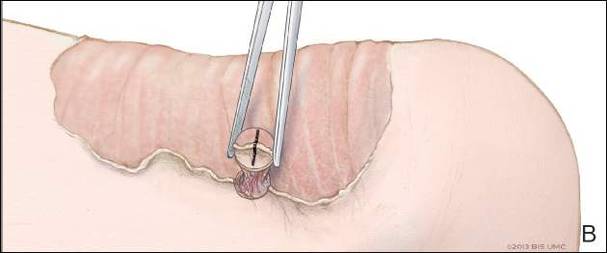

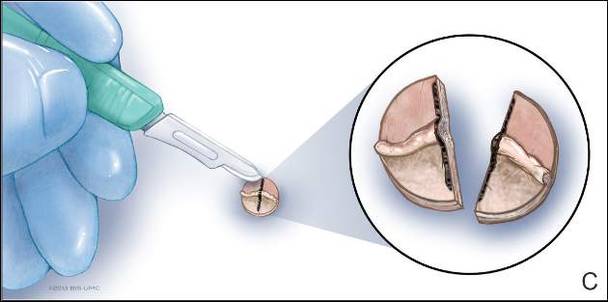

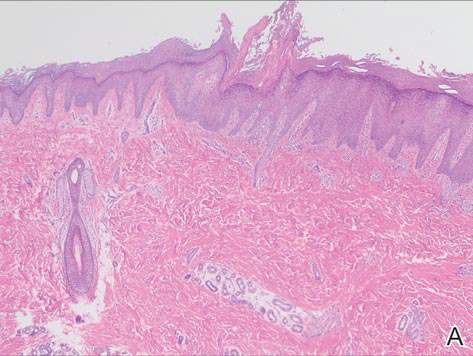

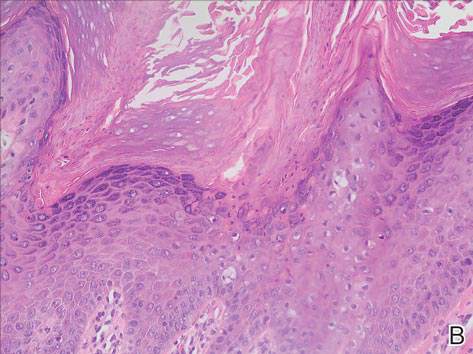

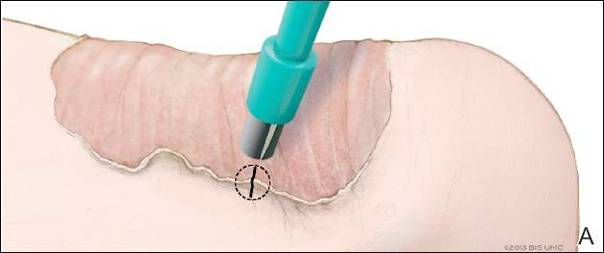

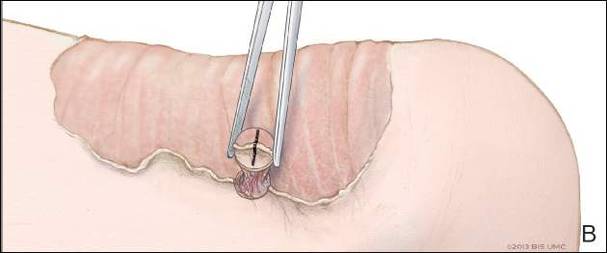

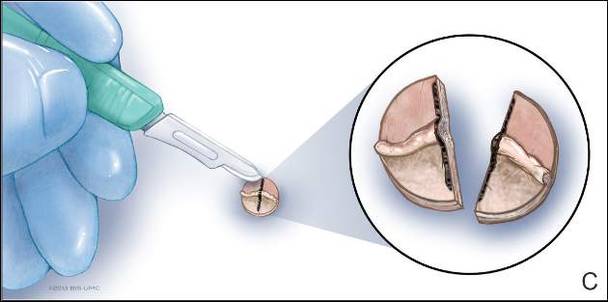

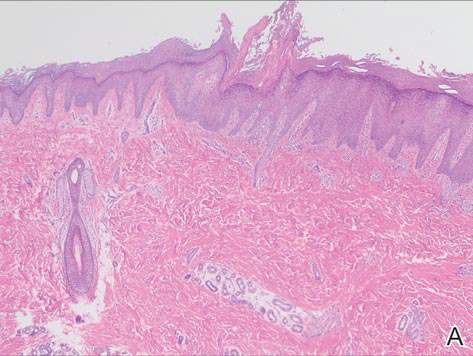

Physical examination revealed a lesion that was 4.2-cm long, 2.2-cm wide at the superior pole, and 3.5-cm wide at the inferior pole (Figure 1). A line was drawn with a skin marker perpendicular to the rim of the lesion (Figure 2A) and a 6-mm punch biopsy was performed, centered at the intersection of the drawn line and the cornoid lamella (Figure 2B). The tissue was then bisected at the bedside along the skin marker line with a #15 blade (Figure 2C) and submitted in formalin for histologic processing. Histologic examination revealed an invagination of the epidermis producing a tier of parakeratotic cells with its apex pointed away from the center of the lesion. Dyskeratotic cells were noted at the base of the parakeratosis (Figure 3). Verrucous hyperplasia was present in the central portion of the specimen adjacent to the cornoid lamella. Based on these histopathologic findings, the correct diagnosis of PM was made.

Comment

Porokeratosis of Mibelli is a rare condition that typically presents in infancy to early childhood.1 It may appear as small keratotic papules or larger plaques that reach several centimeters in diameter.2 There is a 7.5% risk for malignant transformation (eg, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, Bowen disease).3 Variable nonspecific findings (eg, atrophy, acanthosis, verrucous hyperplasia) typically are present in the center of the lesion. In our case, a biopsy from the center of the plaque demonstrated verrucous hyperplasia. The incorrect diagnosis of PM as psoriasis also has been reported.4

We propose a 3-step technique to ensure proper orientation of a punch biopsy in cases of suspected PM. First, draw a line perpendicular to the rim of the lesion to mark the biopsy site (Figure 2A). Second, perform a punch biopsy centered at the intersection of the drawn line and the cornoid lamella (Figure 2B). Third, section the biopsied tissue with a #15 blade along the perpendicular line at the bedside (Figure 2C). The surgical pathology requisition should mention that the specimen has been transected and the cut edges should be placed down in the cassette, ensuring that the cornoid lamella will be present in cross-section on the slides.

If the punch biopsy specimen is not bisected, it can be difficult to orient it in the pathology laboratory, especially if the cornoid lamellae are not prominent. Furthermore, the technician processing the tissue may not be aware of the importance of sectioning the specimen perpendicular to the cornoid lamella. Following this procedure, diagnosis can be confirmed in virtually every case of PM.

- Richard G, Irvine A, Traupe H, et al. Ichthyosis and disorders of other conification. In: Schachner L, Hansen R, Krafchik B, et al, eds. Pediatric Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011:640-643.

- Pierson D, Bandel C, Ehrig, et al. Benign epidermal tumors and proliferations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, et al, eds. Dermatology. 1st ed. Vol 2. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier; 2003:1707-1709.

- Cort DF, Abdel-Aziz AH. Epithelioma arising in porokeratosis of Mibelli. Br J Plast Surg. 1972;25:318-328.

- De Simone C, Paradisi A, Massi G, et al. Giant verrucous porokeratosis of Mibelli mimicking psoriasis in a patient with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:665-668.

Porokeratosis of Mibelli (PM) is a lesion characterized by a surrounding cornoid lamella with variable nonspecific findings (eg, atrophy, acanthosis, verrucous hyperplasia) in the center of the lesion that typically presents in infancy to early childhood.1 We report a case of PM in which a prior biopsy from the center of the lesion demonstrated papulosquamous dermatitis. We propose a 3-step technique to ensure proper orientation of a punch biopsy in cases of suspected PM.

Case Report

A 3-year-old girl presented with an erythematous, hypopigmented, scaling plaque on the posterior aspect of the left ankle surrounded by a hard rim. The plaque was first noted at 12 months of age and had slowly enlarged as the patient grew. Six months prior, a biopsy from the center of the lesion performed at another facility demonstrated a papulosquamous dermatitis.

Physical examination revealed a lesion that was 4.2-cm long, 2.2-cm wide at the superior pole, and 3.5-cm wide at the inferior pole (Figure 1). A line was drawn with a skin marker perpendicular to the rim of the lesion (Figure 2A) and a 6-mm punch biopsy was performed, centered at the intersection of the drawn line and the cornoid lamella (Figure 2B). The tissue was then bisected at the bedside along the skin marker line with a #15 blade (Figure 2C) and submitted in formalin for histologic processing. Histologic examination revealed an invagination of the epidermis producing a tier of parakeratotic cells with its apex pointed away from the center of the lesion. Dyskeratotic cells were noted at the base of the parakeratosis (Figure 3). Verrucous hyperplasia was present in the central portion of the specimen adjacent to the cornoid lamella. Based on these histopathologic findings, the correct diagnosis of PM was made.

Comment

Porokeratosis of Mibelli is a rare condition that typically presents in infancy to early childhood.1 It may appear as small keratotic papules or larger plaques that reach several centimeters in diameter.2 There is a 7.5% risk for malignant transformation (eg, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, Bowen disease).3 Variable nonspecific findings (eg, atrophy, acanthosis, verrucous hyperplasia) typically are present in the center of the lesion. In our case, a biopsy from the center of the plaque demonstrated verrucous hyperplasia. The incorrect diagnosis of PM as psoriasis also has been reported.4

We propose a 3-step technique to ensure proper orientation of a punch biopsy in cases of suspected PM. First, draw a line perpendicular to the rim of the lesion to mark the biopsy site (Figure 2A). Second, perform a punch biopsy centered at the intersection of the drawn line and the cornoid lamella (Figure 2B). Third, section the biopsied tissue with a #15 blade along the perpendicular line at the bedside (Figure 2C). The surgical pathology requisition should mention that the specimen has been transected and the cut edges should be placed down in the cassette, ensuring that the cornoid lamella will be present in cross-section on the slides.

If the punch biopsy specimen is not bisected, it can be difficult to orient it in the pathology laboratory, especially if the cornoid lamellae are not prominent. Furthermore, the technician processing the tissue may not be aware of the importance of sectioning the specimen perpendicular to the cornoid lamella. Following this procedure, diagnosis can be confirmed in virtually every case of PM.

Porokeratosis of Mibelli (PM) is a lesion characterized by a surrounding cornoid lamella with variable nonspecific findings (eg, atrophy, acanthosis, verrucous hyperplasia) in the center of the lesion that typically presents in infancy to early childhood.1 We report a case of PM in which a prior biopsy from the center of the lesion demonstrated papulosquamous dermatitis. We propose a 3-step technique to ensure proper orientation of a punch biopsy in cases of suspected PM.

Case Report

A 3-year-old girl presented with an erythematous, hypopigmented, scaling plaque on the posterior aspect of the left ankle surrounded by a hard rim. The plaque was first noted at 12 months of age and had slowly enlarged as the patient grew. Six months prior, a biopsy from the center of the lesion performed at another facility demonstrated a papulosquamous dermatitis.

Physical examination revealed a lesion that was 4.2-cm long, 2.2-cm wide at the superior pole, and 3.5-cm wide at the inferior pole (Figure 1). A line was drawn with a skin marker perpendicular to the rim of the lesion (Figure 2A) and a 6-mm punch biopsy was performed, centered at the intersection of the drawn line and the cornoid lamella (Figure 2B). The tissue was then bisected at the bedside along the skin marker line with a #15 blade (Figure 2C) and submitted in formalin for histologic processing. Histologic examination revealed an invagination of the epidermis producing a tier of parakeratotic cells with its apex pointed away from the center of the lesion. Dyskeratotic cells were noted at the base of the parakeratosis (Figure 3). Verrucous hyperplasia was present in the central portion of the specimen adjacent to the cornoid lamella. Based on these histopathologic findings, the correct diagnosis of PM was made.

Comment

Porokeratosis of Mibelli is a rare condition that typically presents in infancy to early childhood.1 It may appear as small keratotic papules or larger plaques that reach several centimeters in diameter.2 There is a 7.5% risk for malignant transformation (eg, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, Bowen disease).3 Variable nonspecific findings (eg, atrophy, acanthosis, verrucous hyperplasia) typically are present in the center of the lesion. In our case, a biopsy from the center of the plaque demonstrated verrucous hyperplasia. The incorrect diagnosis of PM as psoriasis also has been reported.4

We propose a 3-step technique to ensure proper orientation of a punch biopsy in cases of suspected PM. First, draw a line perpendicular to the rim of the lesion to mark the biopsy site (Figure 2A). Second, perform a punch biopsy centered at the intersection of the drawn line and the cornoid lamella (Figure 2B). Third, section the biopsied tissue with a #15 blade along the perpendicular line at the bedside (Figure 2C). The surgical pathology requisition should mention that the specimen has been transected and the cut edges should be placed down in the cassette, ensuring that the cornoid lamella will be present in cross-section on the slides.

If the punch biopsy specimen is not bisected, it can be difficult to orient it in the pathology laboratory, especially if the cornoid lamellae are not prominent. Furthermore, the technician processing the tissue may not be aware of the importance of sectioning the specimen perpendicular to the cornoid lamella. Following this procedure, diagnosis can be confirmed in virtually every case of PM.

- Richard G, Irvine A, Traupe H, et al. Ichthyosis and disorders of other conification. In: Schachner L, Hansen R, Krafchik B, et al, eds. Pediatric Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011:640-643.

- Pierson D, Bandel C, Ehrig, et al. Benign epidermal tumors and proliferations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, et al, eds. Dermatology. 1st ed. Vol 2. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier; 2003:1707-1709.

- Cort DF, Abdel-Aziz AH. Epithelioma arising in porokeratosis of Mibelli. Br J Plast Surg. 1972;25:318-328.

- De Simone C, Paradisi A, Massi G, et al. Giant verrucous porokeratosis of Mibelli mimicking psoriasis in a patient with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:665-668.

- Richard G, Irvine A, Traupe H, et al. Ichthyosis and disorders of other conification. In: Schachner L, Hansen R, Krafchik B, et al, eds. Pediatric Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011:640-643.

- Pierson D, Bandel C, Ehrig, et al. Benign epidermal tumors and proliferations. In: Bolognia J, Jorizzo J, Rapini R, et al, eds. Dermatology. 1st ed. Vol 2. Edinburgh, Scotland: Elsevier; 2003:1707-1709.

- Cort DF, Abdel-Aziz AH. Epithelioma arising in porokeratosis of Mibelli. Br J Plast Surg. 1972;25:318-328.

- De Simone C, Paradisi A, Massi G, et al. Giant verrucous porokeratosis of Mibelli mimicking psoriasis in a patient with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:665-668.

Practice Points

- A biopsy from the center of a plaque of porokeratosis will produce nonspecific findings.

- Bisecting the punch specimen at the bedside along a line drawn perpendicular to the cornoid lamella guarantees proper orientation of the specimen.

The Clinical Learning Environment Review as a Model for Impactful Self-directed Quality Control Initiatives in Clinical Practice

As part of its Next Accreditation System, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has introduced the Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) program, designed to assess the learning environment of institutions that have ACGME residency and fellowship programs.1 The CLER program emphasizes the responsibility of these hospitals, multispecialty groups, and other organizations to focus on quality and safety in the health care environment of resident learning and patient care. The expectation is that emphasis on quality of care in a residency training program will influence these physicians’ approach to quality of care after graduation.2,3 The Department of Dermatology at the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC)(Jackson, Mississippi) saw CLER as an opportunity to demonstrate leadership in the patient safety movement.

CLER Program at UMMC

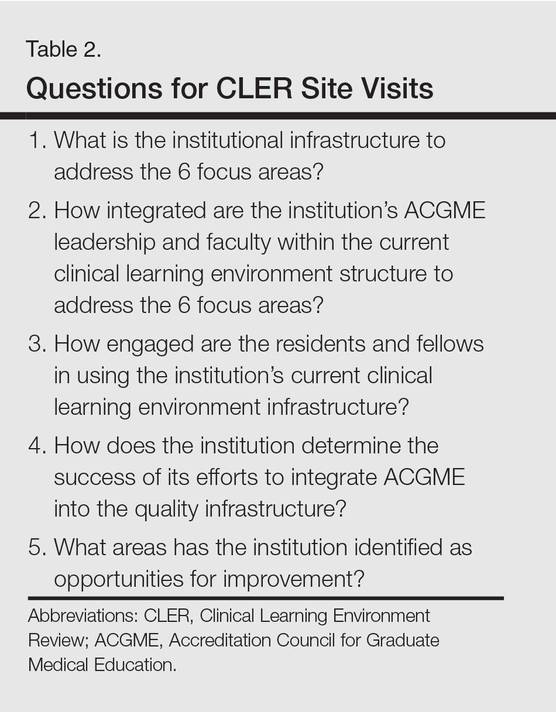

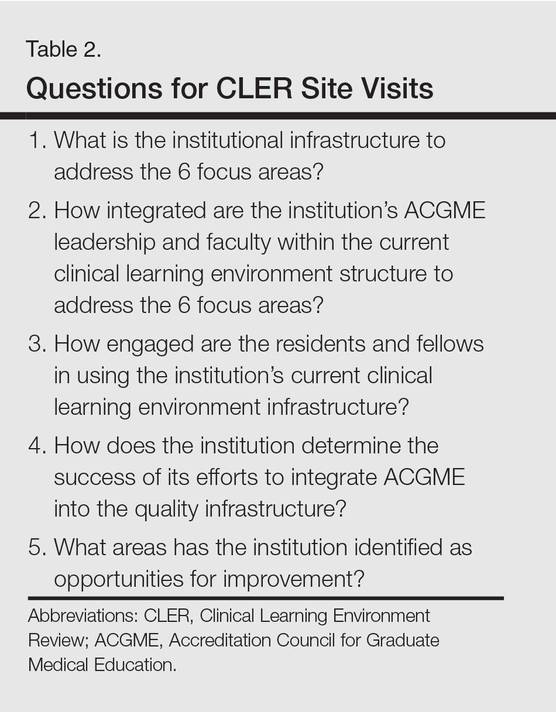

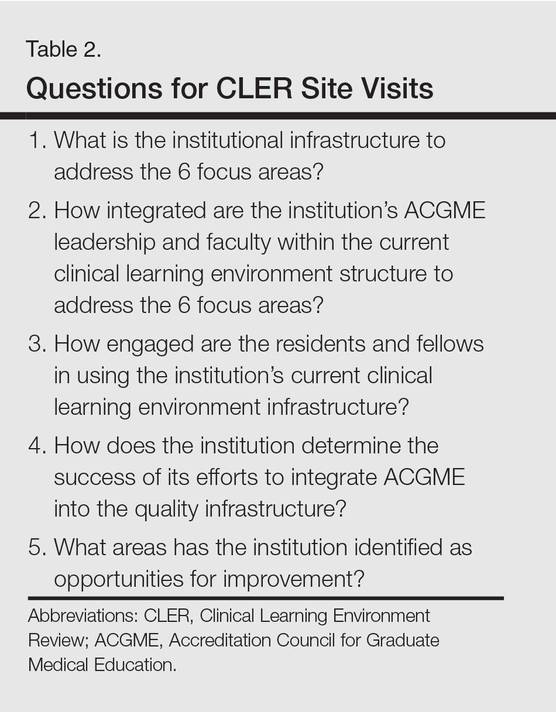

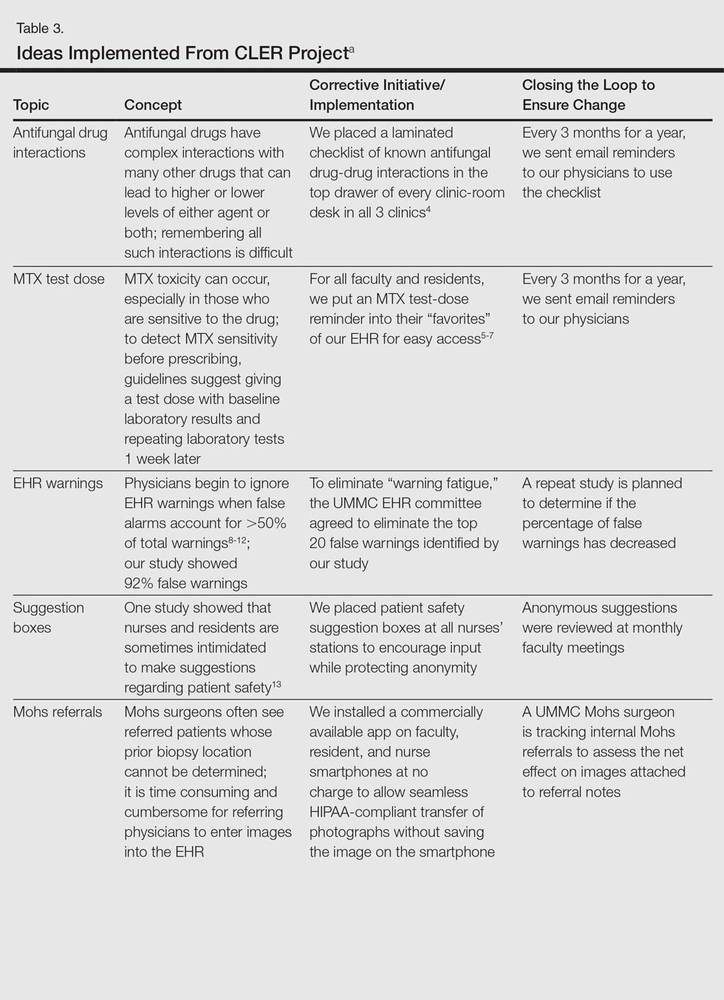

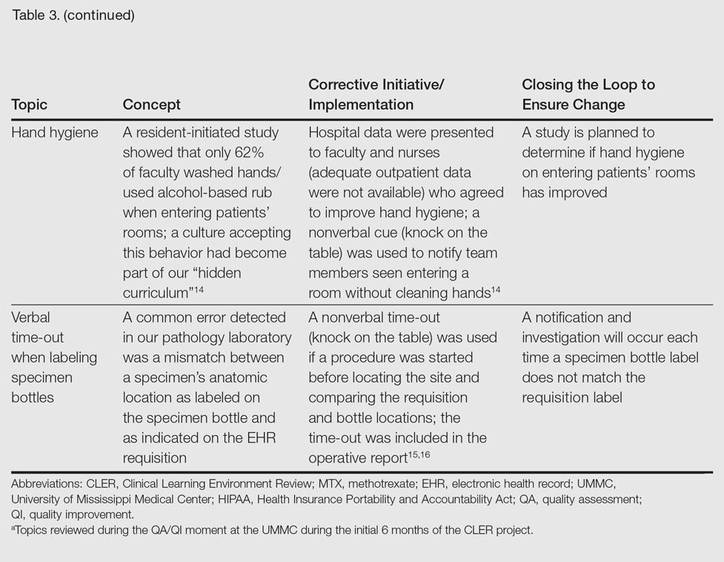

As a model CLER program at our institution, our project at the outset concentrated resident efforts on the focus areas specified by the ACGME (Table 1). We also were aware that our ACGME committee would need to answer questions during CLER site visits (Table 2). Because the data generated would not be used for accreditation decisions, there was no concern that exposing errors would jeopardize our postgraduate training certification.

The first 15 minutes of monthly faculty meetings were devoted to the presentation of a resident project, called a QA/QI (quality assurance/quality improvement) moment, that addressed ACGME focus areas 1, 2, 3, or 6 (Table 1). (Transitions in care [focus area 4] and work hours and fatigue [focus area 5] generally are less important issues in a predominantly outpatient specialty such as dermatology.) The residents were encouraged to identify areas where patient harm could occur due to poorly designed systems and to report situations in which patients actually were harmed.

Each project had to be approved by the department chairperson based on the following 4 requirements: First, the initiative must have the potential to notably impact patient safety and reduce harm. Second, residents with faculty support had to design methods to assess the identified problem. Third, participants had to design (to the best of their abilities) cost-effective and achievable interventions in a manner that would not produce unintended consequences. Fourth, residents were asked to devise a system to close the loop, ensuring that the effort put into the process was not wasted.

Findings From the CLER Program

The CLER program generates data on program and institutional attributes that have a salutatory effect on quality and safety, specifically involving 6 focus areas highlighted in Table 1. Putting residents at the center of efforts to improve the quality of care in our department proved critical to improving patient safety.

Involving residents in a series of QA/QI initiatives was logical because they rotate with faculty members. They also are in a position to view inconsistencies and to work to establish consistent patterns of patient care. In addition, our busy faculty members are charged with a variety of other clinical, educational, and administrative duties complicated by requirements in the design of a new residency training program. Faculty and residents working together were able to find problem areas in our department and devise solutions to improve those problems.

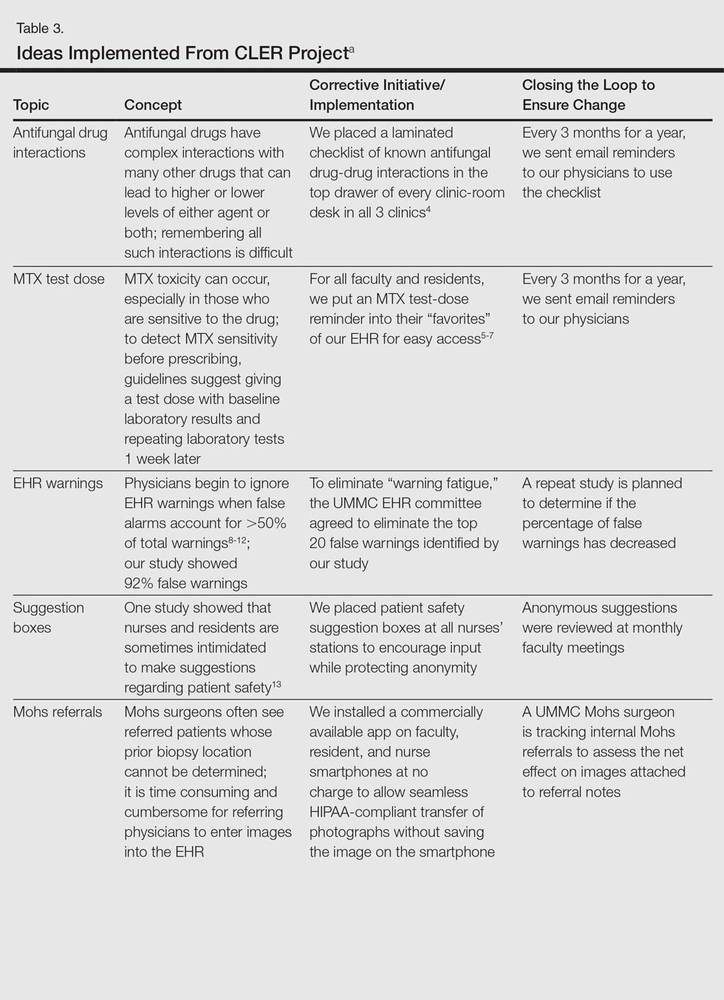

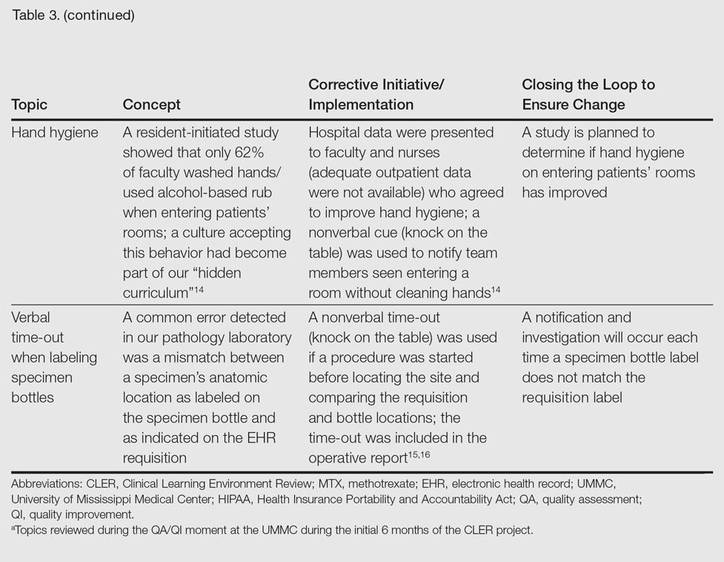

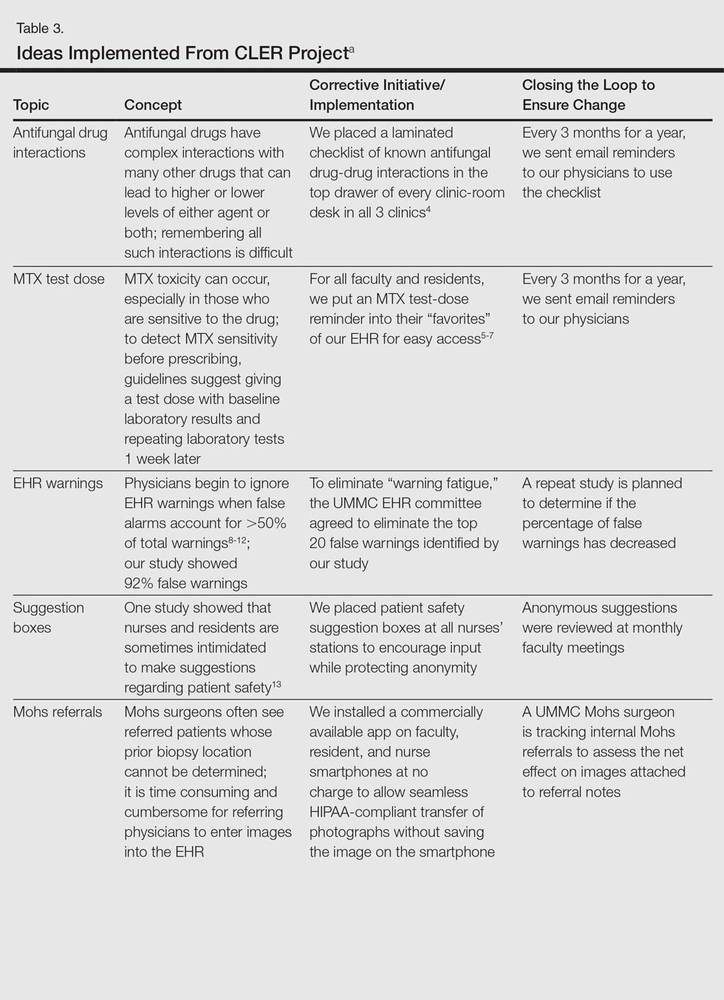

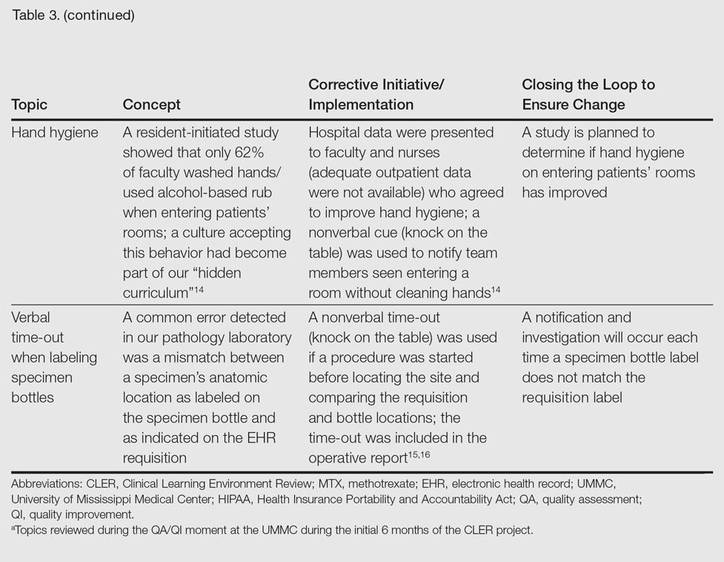

The CLER program involved a series of steps. Residents were charged with identifying errors (QA) and then devising a system to prevent similar errors from being repeated (QI)(Table 3). Efforts focused on preventing needless harm in our department. Initiatives developed by residents, who are closest to patients, have advantages over safety programs developed by the hospital’s administration. Residents became passionate about error prevention when they determined that their efforts could make a difference to patients.

Forward Thinking for Dermatology Practices

Perhaps there are lessons here that could apply to safety promotion in the practicing dermatologist’s office. The American Board of Dermatology, within the framework established by the American Board of Medical Specialties, requires physicians seeking recertification to participate in preapproved practice assessment QI exercises twice every 10 years.17 Six programs sponsored by the American Academy of Dermatology have now been approved in the areas of melanoma, biopsy follow-up measure, psoriasis, chronic urticaria, venous insufficiency, and laser- and light-based therapy for rejuvenation.18 An additional program has been approved for dermatopathologists through the American Society of Dermatopathology.19 None of these programs match the topics chosen by our residents in consultation with faculty to meet safety gaps identified in clinics at UMMC. Perhaps the next generation of performance improvement continuing medical education programs could include a pilot program for part 4 of Maintenance of Certification credit that is nonpunitive, patient focused, and allows dermatologists to design specific error-prevention solutions tailored to their individual practice in the same way residency programs are taking up this task.

- Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, et al. The Next GME accreditation system—rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1051-1056.

- Philibert I, Gonzalez del Rey JA, Lannon C, et al. Quality improvement skills for pediatric residents: from lecture to implementation and sustainability. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14:40-46.

- Vidyarthi AR, Green AL, Rosenbluth G, et al. Engaging residents and fellows to improve institution-wide quality: the first six years of a novel financial incentive program. Acad Med. 2014;89:460-468.

- Brodell RT, Elewski B. Antifungal drug interactions. avoidance requires more than memorization. Postgrad Med. 2000;107:41-43.

- Kerr IG, Jolivet J, Collin JM, et al. Test dose for predicting high-dose methotrexate infusions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1983;33:44-51.

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 4. guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with traditional systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:451-485.

- Saporito FC, Menter MA. Methotrexate and psoriasis in the era of new biologic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:301-309.

- Van Der Sijs H, Aarts J, Vulto A, et al. Overriding of drug safety alerts in computerized physician order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13:138-147.

- Hunter KM. Implementation of an electronic medication administration record and bedside verification system. Online J Nurs Inform (OJNI). 2011;15:672.

- Nanji KC, Slight SP, Seger DL, et al. Overrides of medication-related clinical decision support alerts in outpatients. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21:487-491.

- Schedlbauer A, Prasad V, Mulvaney C, et al. What evidence supports the use of computerized alerts and prompts to improve clinicians’ prescribing behavior? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16:531-538.

- Lee EK, Mejia AF, Senior T, et al. Improving patient safety through medical alert management: an automated decision tool to reduce alert fatigue. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2010;2010:417-421.

- Brenner AB. Physician and nurse relationships, a key to patient safety. J Ky Med Assoc. 2007;105:165-169.

- Rush JL, Flowers RH, Casamiquela KM, et al. Research letter: the knock: an adjunct to education opening the door to improved outpatient hand hygiene. J Am Acad Dermatol. In press.

- Lee SL. The extended surgical time-out: does it improve quality and prevent wrong-site surgery? Perm J. 2010;14:19-23.

- Altpeter T, Luckhardt K, Lewis JN, et al. Expanded surgical time out: a key to real-time data collection and quality improvement. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:527-532.

- MOC requirements. American Board of Dermatology Web site. https://www.abderm.org/diplomates/fulfilling-moc-requirements/moc-requirements.aspx#PI. Accessed January 18, 2016.

- How AAD develops measures. American Academy of Dermatology Web site. https://www.aad.org/practice-tools/quality-care/quality-measures. Accessed January 20, 2016.

- Quality assurance programs. The American Society of Dermatopathology Web site. http://www.asdp.org/education/quality-assurance-programs. Accessed January 20, 2016.

As part of its Next Accreditation System, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has introduced the Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) program, designed to assess the learning environment of institutions that have ACGME residency and fellowship programs.1 The CLER program emphasizes the responsibility of these hospitals, multispecialty groups, and other organizations to focus on quality and safety in the health care environment of resident learning and patient care. The expectation is that emphasis on quality of care in a residency training program will influence these physicians’ approach to quality of care after graduation.2,3 The Department of Dermatology at the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC)(Jackson, Mississippi) saw CLER as an opportunity to demonstrate leadership in the patient safety movement.

CLER Program at UMMC

As a model CLER program at our institution, our project at the outset concentrated resident efforts on the focus areas specified by the ACGME (Table 1). We also were aware that our ACGME committee would need to answer questions during CLER site visits (Table 2). Because the data generated would not be used for accreditation decisions, there was no concern that exposing errors would jeopardize our postgraduate training certification.

The first 15 minutes of monthly faculty meetings were devoted to the presentation of a resident project, called a QA/QI (quality assurance/quality improvement) moment, that addressed ACGME focus areas 1, 2, 3, or 6 (Table 1). (Transitions in care [focus area 4] and work hours and fatigue [focus area 5] generally are less important issues in a predominantly outpatient specialty such as dermatology.) The residents were encouraged to identify areas where patient harm could occur due to poorly designed systems and to report situations in which patients actually were harmed.

Each project had to be approved by the department chairperson based on the following 4 requirements: First, the initiative must have the potential to notably impact patient safety and reduce harm. Second, residents with faculty support had to design methods to assess the identified problem. Third, participants had to design (to the best of their abilities) cost-effective and achievable interventions in a manner that would not produce unintended consequences. Fourth, residents were asked to devise a system to close the loop, ensuring that the effort put into the process was not wasted.

Findings From the CLER Program

The CLER program generates data on program and institutional attributes that have a salutatory effect on quality and safety, specifically involving 6 focus areas highlighted in Table 1. Putting residents at the center of efforts to improve the quality of care in our department proved critical to improving patient safety.

Involving residents in a series of QA/QI initiatives was logical because they rotate with faculty members. They also are in a position to view inconsistencies and to work to establish consistent patterns of patient care. In addition, our busy faculty members are charged with a variety of other clinical, educational, and administrative duties complicated by requirements in the design of a new residency training program. Faculty and residents working together were able to find problem areas in our department and devise solutions to improve those problems.

The CLER program involved a series of steps. Residents were charged with identifying errors (QA) and then devising a system to prevent similar errors from being repeated (QI)(Table 3). Efforts focused on preventing needless harm in our department. Initiatives developed by residents, who are closest to patients, have advantages over safety programs developed by the hospital’s administration. Residents became passionate about error prevention when they determined that their efforts could make a difference to patients.

Forward Thinking for Dermatology Practices