User login

6 ‘D’s: Next steps after an insufficient antipsychotic response

There are a lack of research on, and strategies for dealing with, an insufficient response to antipsychotics. Treatment often is guided by what is described in published case reports or anecdotal evidence, rather than the findings of systematic studies.

We propose that a patient be considered “difficult-to-treat” or “treatment-resistant” after experiencing limited or negative responses to 3 different antipsychotics—with ≥1 being a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA)—that the patient has taken for at least 6 to 8 weeks at the maximum recommended dosage. Furthermore, switching to clozapine is an important strategy; do not consider it solely a last resort.

These 6 ‘D’s can remind you of other problems to consider when evaluating a treatment-resistant patient.

Diagnosis. Is the diagnosis, including the presence of comorbid conditions, accurate? Are significant psychosocial stressors undermining treatment response? Treat any comorbid conditions and consider instituting adjunctive psychosocial interventions, including cognitive-behavioral therapy.

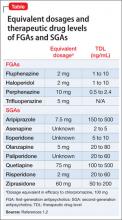

Dosage. Have the patient try the maximum recommended dosage if he (she) can tolerate it. Equivalent dosages of antipsychotics are shown in the Table,1,2 and can guide off-label use of higher dosages. Research does not support use of chlorpromazine equivalents >1,000 mg/d, and usually should not be employed. If using a higher than normal dosage, perform an ECG before the increase.3

Beneficial and adverse effects should be monitored carefully. Reduce the dosage after 3 months if the risk-benefit ratio does not justify the higher dosage.3

Duration. Try a treatment for at least 6 weeks at the maximum tolerated

dosage—even extending it to 12 weeks—before considering abandoning it because of insufficient response.

Drug interactions. Use a drug interaction tool to ensure drug-drug interactions are not reducing antipsychotic levels. A recent increase in smoking or decrease in caffeine intake can reduce the blood level of olanzapine and clozapine.4 Ultra-rapid metabolizers of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes may have a lower blood level of antipsychotic.

Consider pharmacogenetic testing in patients in whom you observe an unexpected lack of efficacy or adverse effects at customary dosages.

Double up. You might need to add another medication to the antipsychotic. Symptoms might help determine which medication to add:

- a combination of an SGA and a first-generation antipsychotic may be more effective than antipsychotic monotherapy5

- for prominent negative symptoms, consider using 2 SGAs of different potency together. Use caution when prescribing ziprasidone with another antipsychotic because this could prolong the QTc interval

- if a mood stabilizer is appropriate, consider lamotrigine because of its possible potentiating effect on SGAs6

- benzodiazepines can be used to reduce agitation or anxiety but are ineffective for psychosis.7

Drug levels. Measurement of the blood level of the drug is most useful when administering clozapine; focus on the clozapine, not on the norclozapine level that also is reported. Ensure a clozapine level of 350 to 600 ng/mL.

Therapeutic levels have been established for most antipsychotics (Table).1,2 Occasionally, knowing these levels can be helpful in evaluating patients for potential problems with absorption and metabolism of the drug, and with nonadherence.

Disclosures

Drs. Faden and Pinninti report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. Dr. Mago receives grant/research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest Institute, Genomind, and Shire.

1. Gardner DM, Murphy AL, O’Donnell H, et al. International consensus study of antipsychotic dosing. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6):686-693.

2. Hiemke C, Baumann P, Bergemann N, et al. AGNP consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in psychiatry: update 2011. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;44(6):195-235.

3. Royal College of Psychiatrists. Consensus statement on high-dose antipsychotic medication. http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/files/pdfversion/CR138.pdf. Published May 2006. Accessed March 26, 2013.

4. Pinninti NR, Mago R, de Leon J. Coffee, cigarettes and meds: what are the metabolic effects? Psychiatric Times. 2005;22(6):20-23.

5. Correll CU, Rummel-Kluge C, Corves C, et al. Antipsychotic combinations vs monotherapy in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(2):443-457.

6. Citrome L. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia: what can we do about it? Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(6):52-58.

7. Volz A, Khorsand V, Gillies D, et al. Benzodiazepines for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1): CD006391.

There are a lack of research on, and strategies for dealing with, an insufficient response to antipsychotics. Treatment often is guided by what is described in published case reports or anecdotal evidence, rather than the findings of systematic studies.

We propose that a patient be considered “difficult-to-treat” or “treatment-resistant” after experiencing limited or negative responses to 3 different antipsychotics—with ≥1 being a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA)—that the patient has taken for at least 6 to 8 weeks at the maximum recommended dosage. Furthermore, switching to clozapine is an important strategy; do not consider it solely a last resort.

These 6 ‘D’s can remind you of other problems to consider when evaluating a treatment-resistant patient.

Diagnosis. Is the diagnosis, including the presence of comorbid conditions, accurate? Are significant psychosocial stressors undermining treatment response? Treat any comorbid conditions and consider instituting adjunctive psychosocial interventions, including cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Dosage. Have the patient try the maximum recommended dosage if he (she) can tolerate it. Equivalent dosages of antipsychotics are shown in the Table,1,2 and can guide off-label use of higher dosages. Research does not support use of chlorpromazine equivalents >1,000 mg/d, and usually should not be employed. If using a higher than normal dosage, perform an ECG before the increase.3

Beneficial and adverse effects should be monitored carefully. Reduce the dosage after 3 months if the risk-benefit ratio does not justify the higher dosage.3

Duration. Try a treatment for at least 6 weeks at the maximum tolerated

dosage—even extending it to 12 weeks—before considering abandoning it because of insufficient response.

Drug interactions. Use a drug interaction tool to ensure drug-drug interactions are not reducing antipsychotic levels. A recent increase in smoking or decrease in caffeine intake can reduce the blood level of olanzapine and clozapine.4 Ultra-rapid metabolizers of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes may have a lower blood level of antipsychotic.

Consider pharmacogenetic testing in patients in whom you observe an unexpected lack of efficacy or adverse effects at customary dosages.

Double up. You might need to add another medication to the antipsychotic. Symptoms might help determine which medication to add:

- a combination of an SGA and a first-generation antipsychotic may be more effective than antipsychotic monotherapy5

- for prominent negative symptoms, consider using 2 SGAs of different potency together. Use caution when prescribing ziprasidone with another antipsychotic because this could prolong the QTc interval

- if a mood stabilizer is appropriate, consider lamotrigine because of its possible potentiating effect on SGAs6

- benzodiazepines can be used to reduce agitation or anxiety but are ineffective for psychosis.7

Drug levels. Measurement of the blood level of the drug is most useful when administering clozapine; focus on the clozapine, not on the norclozapine level that also is reported. Ensure a clozapine level of 350 to 600 ng/mL.

Therapeutic levels have been established for most antipsychotics (Table).1,2 Occasionally, knowing these levels can be helpful in evaluating patients for potential problems with absorption and metabolism of the drug, and with nonadherence.

Disclosures

Drs. Faden and Pinninti report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. Dr. Mago receives grant/research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest Institute, Genomind, and Shire.

There are a lack of research on, and strategies for dealing with, an insufficient response to antipsychotics. Treatment often is guided by what is described in published case reports or anecdotal evidence, rather than the findings of systematic studies.

We propose that a patient be considered “difficult-to-treat” or “treatment-resistant” after experiencing limited or negative responses to 3 different antipsychotics—with ≥1 being a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA)—that the patient has taken for at least 6 to 8 weeks at the maximum recommended dosage. Furthermore, switching to clozapine is an important strategy; do not consider it solely a last resort.

These 6 ‘D’s can remind you of other problems to consider when evaluating a treatment-resistant patient.

Diagnosis. Is the diagnosis, including the presence of comorbid conditions, accurate? Are significant psychosocial stressors undermining treatment response? Treat any comorbid conditions and consider instituting adjunctive psychosocial interventions, including cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Dosage. Have the patient try the maximum recommended dosage if he (she) can tolerate it. Equivalent dosages of antipsychotics are shown in the Table,1,2 and can guide off-label use of higher dosages. Research does not support use of chlorpromazine equivalents >1,000 mg/d, and usually should not be employed. If using a higher than normal dosage, perform an ECG before the increase.3

Beneficial and adverse effects should be monitored carefully. Reduce the dosage after 3 months if the risk-benefit ratio does not justify the higher dosage.3

Duration. Try a treatment for at least 6 weeks at the maximum tolerated

dosage—even extending it to 12 weeks—before considering abandoning it because of insufficient response.

Drug interactions. Use a drug interaction tool to ensure drug-drug interactions are not reducing antipsychotic levels. A recent increase in smoking or decrease in caffeine intake can reduce the blood level of olanzapine and clozapine.4 Ultra-rapid metabolizers of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes may have a lower blood level of antipsychotic.

Consider pharmacogenetic testing in patients in whom you observe an unexpected lack of efficacy or adverse effects at customary dosages.

Double up. You might need to add another medication to the antipsychotic. Symptoms might help determine which medication to add:

- a combination of an SGA and a first-generation antipsychotic may be more effective than antipsychotic monotherapy5

- for prominent negative symptoms, consider using 2 SGAs of different potency together. Use caution when prescribing ziprasidone with another antipsychotic because this could prolong the QTc interval

- if a mood stabilizer is appropriate, consider lamotrigine because of its possible potentiating effect on SGAs6

- benzodiazepines can be used to reduce agitation or anxiety but are ineffective for psychosis.7

Drug levels. Measurement of the blood level of the drug is most useful when administering clozapine; focus on the clozapine, not on the norclozapine level that also is reported. Ensure a clozapine level of 350 to 600 ng/mL.

Therapeutic levels have been established for most antipsychotics (Table).1,2 Occasionally, knowing these levels can be helpful in evaluating patients for potential problems with absorption and metabolism of the drug, and with nonadherence.

Disclosures

Drs. Faden and Pinninti report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. Dr. Mago receives grant/research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest Institute, Genomind, and Shire.

1. Gardner DM, Murphy AL, O’Donnell H, et al. International consensus study of antipsychotic dosing. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6):686-693.

2. Hiemke C, Baumann P, Bergemann N, et al. AGNP consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in psychiatry: update 2011. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;44(6):195-235.

3. Royal College of Psychiatrists. Consensus statement on high-dose antipsychotic medication. http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/files/pdfversion/CR138.pdf. Published May 2006. Accessed March 26, 2013.

4. Pinninti NR, Mago R, de Leon J. Coffee, cigarettes and meds: what are the metabolic effects? Psychiatric Times. 2005;22(6):20-23.

5. Correll CU, Rummel-Kluge C, Corves C, et al. Antipsychotic combinations vs monotherapy in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(2):443-457.

6. Citrome L. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia: what can we do about it? Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(6):52-58.

7. Volz A, Khorsand V, Gillies D, et al. Benzodiazepines for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1): CD006391.

1. Gardner DM, Murphy AL, O’Donnell H, et al. International consensus study of antipsychotic dosing. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6):686-693.

2. Hiemke C, Baumann P, Bergemann N, et al. AGNP consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in psychiatry: update 2011. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;44(6):195-235.

3. Royal College of Psychiatrists. Consensus statement on high-dose antipsychotic medication. http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/files/pdfversion/CR138.pdf. Published May 2006. Accessed March 26, 2013.

4. Pinninti NR, Mago R, de Leon J. Coffee, cigarettes and meds: what are the metabolic effects? Psychiatric Times. 2005;22(6):20-23.

5. Correll CU, Rummel-Kluge C, Corves C, et al. Antipsychotic combinations vs monotherapy in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(2):443-457.

6. Citrome L. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia: what can we do about it? Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(6):52-58.

7. Volz A, Khorsand V, Gillies D, et al. Benzodiazepines for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1): CD006391.

Ending a physician/patient relationship: 8 tips for writing a termination letter

For many valid reasons, a physician-patient relationship may need to end before treatment is completed. When terminating a clinical relationship, send a letter to the patient, even if the patient initiated the termination. Here are 8 tips for writing and sending a termination letter:

1. Don’t send a form letter. Start with a standard letter but personalize it for each patient. Address the patient by name and, if possible, allude to specifics of the patient’s situation.

2. Wish the patient well, but avoid hyperbole, such as “It truly has been an honor and a privilege to participate in your treatment.” Also, be unambiguous in stating that the treatment relationship is terminated.

3. Don’t mention confidential information. Because someone other than the patient may open the letter, do not include confidential information.

4. Provide appropriate notice. Specify a date after which you can no longer provide care. A reasonable period is 30 days from the date of the letter, but if you expect the patient will need more time to find an appropriate clinician, a longer period may be necessary.1,2 Occasionally, a patient’s care may need to be terminated immediately because of a serious problem such as actual or threatened violence. Even in these cases, communicate and document how the patient can obtain emergency psychiatric care.

5. State the reason for termination. Although you are not required legally to do so, briefly state the reason for terminating the relationship, although you should never use emotional or harshly critical language. Use nonjudgmental language and avoid referring to your “policy,” which can imply unthinking application of rigid rules.

6. Recommend continued treatment. Make a clear recommendation that the patient continue treatment elsewhere. Provide a list of mental health professionals with whom the patient could continue treatment or offer to provide referrals. Offer to send a copy of your records to the patient’s new clinician. Consider enclosing a blank copy of the release form you use so that the patient can mail it to you to request his or her records.

7. Sign the letter yourself. Don’t have a staff member sign the letter or use a stamp.

8. Send the letter by certified mail. Request a return receipt and put a copy of the letter, along with the certified mail form, in the patient’s chart. When the return receipt is received, put it in the chart. If a certified letter is returned to you, put the undelivered letter and envelope in the chart, then send a copy of the letter through regular mail and document that you did so.

If the patient requests an appointment after the notice period is over, including saying that he or she did not receive the letter, you are not legally obligated to resume his or her care.2

1. The Psychiatrist’s Program. Termination of the psychiatrist-patient relationship dos and donts. http://www.psychprogram.com/risk-management/tip-termination.html. Accessed February 1, 2013.

2. Willis DR, Zerr A. Terminating a patient: is it time to part ways? Fam Pract Manag. 2005;12(8):34-38.

For many valid reasons, a physician-patient relationship may need to end before treatment is completed. When terminating a clinical relationship, send a letter to the patient, even if the patient initiated the termination. Here are 8 tips for writing and sending a termination letter:

1. Don’t send a form letter. Start with a standard letter but personalize it for each patient. Address the patient by name and, if possible, allude to specifics of the patient’s situation.

2. Wish the patient well, but avoid hyperbole, such as “It truly has been an honor and a privilege to participate in your treatment.” Also, be unambiguous in stating that the treatment relationship is terminated.

3. Don’t mention confidential information. Because someone other than the patient may open the letter, do not include confidential information.

4. Provide appropriate notice. Specify a date after which you can no longer provide care. A reasonable period is 30 days from the date of the letter, but if you expect the patient will need more time to find an appropriate clinician, a longer period may be necessary.1,2 Occasionally, a patient’s care may need to be terminated immediately because of a serious problem such as actual or threatened violence. Even in these cases, communicate and document how the patient can obtain emergency psychiatric care.

5. State the reason for termination. Although you are not required legally to do so, briefly state the reason for terminating the relationship, although you should never use emotional or harshly critical language. Use nonjudgmental language and avoid referring to your “policy,” which can imply unthinking application of rigid rules.

6. Recommend continued treatment. Make a clear recommendation that the patient continue treatment elsewhere. Provide a list of mental health professionals with whom the patient could continue treatment or offer to provide referrals. Offer to send a copy of your records to the patient’s new clinician. Consider enclosing a blank copy of the release form you use so that the patient can mail it to you to request his or her records.

7. Sign the letter yourself. Don’t have a staff member sign the letter or use a stamp.

8. Send the letter by certified mail. Request a return receipt and put a copy of the letter, along with the certified mail form, in the patient’s chart. When the return receipt is received, put it in the chart. If a certified letter is returned to you, put the undelivered letter and envelope in the chart, then send a copy of the letter through regular mail and document that you did so.

If the patient requests an appointment after the notice period is over, including saying that he or she did not receive the letter, you are not legally obligated to resume his or her care.2

For many valid reasons, a physician-patient relationship may need to end before treatment is completed. When terminating a clinical relationship, send a letter to the patient, even if the patient initiated the termination. Here are 8 tips for writing and sending a termination letter:

1. Don’t send a form letter. Start with a standard letter but personalize it for each patient. Address the patient by name and, if possible, allude to specifics of the patient’s situation.

2. Wish the patient well, but avoid hyperbole, such as “It truly has been an honor and a privilege to participate in your treatment.” Also, be unambiguous in stating that the treatment relationship is terminated.

3. Don’t mention confidential information. Because someone other than the patient may open the letter, do not include confidential information.

4. Provide appropriate notice. Specify a date after which you can no longer provide care. A reasonable period is 30 days from the date of the letter, but if you expect the patient will need more time to find an appropriate clinician, a longer period may be necessary.1,2 Occasionally, a patient’s care may need to be terminated immediately because of a serious problem such as actual or threatened violence. Even in these cases, communicate and document how the patient can obtain emergency psychiatric care.

5. State the reason for termination. Although you are not required legally to do so, briefly state the reason for terminating the relationship, although you should never use emotional or harshly critical language. Use nonjudgmental language and avoid referring to your “policy,” which can imply unthinking application of rigid rules.

6. Recommend continued treatment. Make a clear recommendation that the patient continue treatment elsewhere. Provide a list of mental health professionals with whom the patient could continue treatment or offer to provide referrals. Offer to send a copy of your records to the patient’s new clinician. Consider enclosing a blank copy of the release form you use so that the patient can mail it to you to request his or her records.

7. Sign the letter yourself. Don’t have a staff member sign the letter or use a stamp.

8. Send the letter by certified mail. Request a return receipt and put a copy of the letter, along with the certified mail form, in the patient’s chart. When the return receipt is received, put it in the chart. If a certified letter is returned to you, put the undelivered letter and envelope in the chart, then send a copy of the letter through regular mail and document that you did so.

If the patient requests an appointment after the notice period is over, including saying that he or she did not receive the letter, you are not legally obligated to resume his or her care.2

1. The Psychiatrist’s Program. Termination of the psychiatrist-patient relationship dos and donts. http://www.psychprogram.com/risk-management/tip-termination.html. Accessed February 1, 2013.

2. Willis DR, Zerr A. Terminating a patient: is it time to part ways? Fam Pract Manag. 2005;12(8):34-38.

1. The Psychiatrist’s Program. Termination of the psychiatrist-patient relationship dos and donts. http://www.psychprogram.com/risk-management/tip-termination.html. Accessed February 1, 2013.

2. Willis DR, Zerr A. Terminating a patient: is it time to part ways? Fam Pract Manag. 2005;12(8):34-38.

Ending a physician/patient relationship

Reducing CYP450 drug interactions caused by antidepressants

Most psychiatrists are aware that some antidepressants can cause clinically significant drug interactions, especially through the cytochrome P450 (CYP450) hepatic enzyme system. Antidepressants’ potential for drug interactions is especially important for patients who take >1 other medication, including cardiovascular agents.1

Unfortunately, drug interactions can be difficult to remember and are commonly missed. One strategy to help remember a list of antidepressants with a relatively low potential for CYP450 drug interactions is to use the mnemonic Various Medicines Definitely Commingle Very Easily (VMDCVE) to recall venlafaxine, mirtazapine, desvenlafaxine,2 citalopram, vilazodone,3 and escitalopram. The order in which these medications are listed does not indicate a preference for any of the 6 antidepressants. Bupropion and duloxetine are not included in this list because they are moderately potent inhibitors of the 2D6 isoenzyme.4,5

A few caveats

There are some important caveats in using this mnemonic:

- None of these antidepressants is completely devoid of effects on the CYP450 system. However, compared with the antidepressants included in this mnemonic, fluoxetine, paroxetine, fluvoxamine, duloxetine, bupropion, and nefazodone are more likely to have clinically significant effects on CYP450.4,5

- Although sertraline has a lower potential for CYP450-mediated drug interactions at low doses, it is not included in this mnemonic because it may have greater effects on 2D6 inhibition in some patients, especially at higher doses, such as ≥150 mg/d.5 Also, sertraline may significantly increase lamotrigine levels through a different mechanism: inhibition of uridine 5’-diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase 1A4.4

- Antidepressants also may be the substrates for CYP450 drug interactions caused by other medications.

- This mnemonic refers only to CYP450-mediated drug interactions. Antidepressants included in this mnemonic may have a high potential for drug interactions mediated by displacement from carrier proteins— eg, with digoxin or warfarin.

- Pharmacodynamic drug interactions also are possible—eg, serotonin syndrome as a result of combining a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor with another serotonergic medication.

To remain vigilant for drug-drug interactions, routinely use a drug interaction software, in addition to this mnemonic.

Disclosure

Dr. Mago receives grant/research, support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, and NARSAD.

1. Williams S, Wynn G, Cozza K, et al. Cardiovascular medications. Psychosomatics. 2007;48(6):537-547.

2. Nichols AI, Tourian KA, Tse SY, et al. Desvenlafaxine for major depressive disorder: incremental clinical benefits from a second-generation serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2010;6(12):1565-1574.

3. Laughren TP, Gobburu J, Temple RJ, et al. Vilazodone: clinical basis for the US Food and Drug Administration’s approval of a new antidepressant. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(9):1166-1173.

4. Sandson NB, Armstrong SC, Cozza KL. An overview of psychotropic drug-drug interactions. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(5):464-494.

5. Spina E, Santoro V, D’Arrigo C. Clinically relevant pharmacokinetic drug interactions with second-generation antidepressants: an update. Clin Ther. 2008;30(7):1206-1227.

Most psychiatrists are aware that some antidepressants can cause clinically significant drug interactions, especially through the cytochrome P450 (CYP450) hepatic enzyme system. Antidepressants’ potential for drug interactions is especially important for patients who take >1 other medication, including cardiovascular agents.1

Unfortunately, drug interactions can be difficult to remember and are commonly missed. One strategy to help remember a list of antidepressants with a relatively low potential for CYP450 drug interactions is to use the mnemonic Various Medicines Definitely Commingle Very Easily (VMDCVE) to recall venlafaxine, mirtazapine, desvenlafaxine,2 citalopram, vilazodone,3 and escitalopram. The order in which these medications are listed does not indicate a preference for any of the 6 antidepressants. Bupropion and duloxetine are not included in this list because they are moderately potent inhibitors of the 2D6 isoenzyme.4,5

A few caveats

There are some important caveats in using this mnemonic:

- None of these antidepressants is completely devoid of effects on the CYP450 system. However, compared with the antidepressants included in this mnemonic, fluoxetine, paroxetine, fluvoxamine, duloxetine, bupropion, and nefazodone are more likely to have clinically significant effects on CYP450.4,5

- Although sertraline has a lower potential for CYP450-mediated drug interactions at low doses, it is not included in this mnemonic because it may have greater effects on 2D6 inhibition in some patients, especially at higher doses, such as ≥150 mg/d.5 Also, sertraline may significantly increase lamotrigine levels through a different mechanism: inhibition of uridine 5’-diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase 1A4.4

- Antidepressants also may be the substrates for CYP450 drug interactions caused by other medications.

- This mnemonic refers only to CYP450-mediated drug interactions. Antidepressants included in this mnemonic may have a high potential for drug interactions mediated by displacement from carrier proteins— eg, with digoxin or warfarin.

- Pharmacodynamic drug interactions also are possible—eg, serotonin syndrome as a result of combining a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor with another serotonergic medication.

To remain vigilant for drug-drug interactions, routinely use a drug interaction software, in addition to this mnemonic.

Disclosure

Dr. Mago receives grant/research, support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, and NARSAD.

Most psychiatrists are aware that some antidepressants can cause clinically significant drug interactions, especially through the cytochrome P450 (CYP450) hepatic enzyme system. Antidepressants’ potential for drug interactions is especially important for patients who take >1 other medication, including cardiovascular agents.1

Unfortunately, drug interactions can be difficult to remember and are commonly missed. One strategy to help remember a list of antidepressants with a relatively low potential for CYP450 drug interactions is to use the mnemonic Various Medicines Definitely Commingle Very Easily (VMDCVE) to recall venlafaxine, mirtazapine, desvenlafaxine,2 citalopram, vilazodone,3 and escitalopram. The order in which these medications are listed does not indicate a preference for any of the 6 antidepressants. Bupropion and duloxetine are not included in this list because they are moderately potent inhibitors of the 2D6 isoenzyme.4,5

A few caveats

There are some important caveats in using this mnemonic:

- None of these antidepressants is completely devoid of effects on the CYP450 system. However, compared with the antidepressants included in this mnemonic, fluoxetine, paroxetine, fluvoxamine, duloxetine, bupropion, and nefazodone are more likely to have clinically significant effects on CYP450.4,5

- Although sertraline has a lower potential for CYP450-mediated drug interactions at low doses, it is not included in this mnemonic because it may have greater effects on 2D6 inhibition in some patients, especially at higher doses, such as ≥150 mg/d.5 Also, sertraline may significantly increase lamotrigine levels through a different mechanism: inhibition of uridine 5’-diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase 1A4.4

- Antidepressants also may be the substrates for CYP450 drug interactions caused by other medications.

- This mnemonic refers only to CYP450-mediated drug interactions. Antidepressants included in this mnemonic may have a high potential for drug interactions mediated by displacement from carrier proteins— eg, with digoxin or warfarin.

- Pharmacodynamic drug interactions also are possible—eg, serotonin syndrome as a result of combining a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor with another serotonergic medication.

To remain vigilant for drug-drug interactions, routinely use a drug interaction software, in addition to this mnemonic.

Disclosure

Dr. Mago receives grant/research, support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, and NARSAD.

1. Williams S, Wynn G, Cozza K, et al. Cardiovascular medications. Psychosomatics. 2007;48(6):537-547.

2. Nichols AI, Tourian KA, Tse SY, et al. Desvenlafaxine for major depressive disorder: incremental clinical benefits from a second-generation serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2010;6(12):1565-1574.

3. Laughren TP, Gobburu J, Temple RJ, et al. Vilazodone: clinical basis for the US Food and Drug Administration’s approval of a new antidepressant. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(9):1166-1173.

4. Sandson NB, Armstrong SC, Cozza KL. An overview of psychotropic drug-drug interactions. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(5):464-494.

5. Spina E, Santoro V, D’Arrigo C. Clinically relevant pharmacokinetic drug interactions with second-generation antidepressants: an update. Clin Ther. 2008;30(7):1206-1227.

1. Williams S, Wynn G, Cozza K, et al. Cardiovascular medications. Psychosomatics. 2007;48(6):537-547.

2. Nichols AI, Tourian KA, Tse SY, et al. Desvenlafaxine for major depressive disorder: incremental clinical benefits from a second-generation serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2010;6(12):1565-1574.

3. Laughren TP, Gobburu J, Temple RJ, et al. Vilazodone: clinical basis for the US Food and Drug Administration’s approval of a new antidepressant. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(9):1166-1173.

4. Sandson NB, Armstrong SC, Cozza KL. An overview of psychotropic drug-drug interactions. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(5):464-494.

5. Spina E, Santoro V, D’Arrigo C. Clinically relevant pharmacokinetic drug interactions with second-generation antidepressants: an update. Clin Ther. 2008;30(7):1206-1227.

12 best Web sites for clinical needs

Nearly 1 in 4 Internet users has searched the Web for mental health information,1 but finding reliable sources is challenging. Wading through poorly organized, variable quality sites to find information you need can be time-consuming and frustrating.2 Also, without your guidance, patients may consult disreputable Web sites and follow advice that is contrary to standard psychiatric care.3

Because less is more when using the Internet, we recommend 1 good Web site for each of the following clinical needs. Each may be useful to you and to recommend to your patients.

Patient education

Medlineplus.gov from the National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is an authoritative source for reliable, unbiased information on medications and illnesses. You will find valuable information on all psychotropic and nonpsychotropic medications and most common psychiatric disorders, including information in Spanish.

You can print out medication information and give it to patients, though we recommend asking patients to visit the Web site to introduce them to this resource. Most important, Medlineplus.gov provides links to other trusted medical Web pages. For consumers, this site provides a variety of information including an illustrated medical encyclopedia and a guide to finding reputable health information on the Web. Medlineplus.gov is an enormous site that alone could satisfy most of your patient education needs.

Formulary information

When prescribing, you often need to know if a patient’s insurance will cover the cost of the drug or if preauthorization is necessary. Fingertipformulary.com, a free and user-friendly site, allows you to select a medication, your patient’s state, and insurance plan to find out if the drug will be covered. This site also tells you authorization requirements, quantity limits, and the medication’s “tier” classification, which specifies the patient’s copayment level.

Patient assistance programs

Needymeds.org is a nonprofit resource center of patient assistance programs (PAP) administered by pharmaceutical companies for individuals who cannot afford their medications. The site links to these programs’ Web sites, application forms, and groups that can help patients fill out necessary paperwork. With this Web site, patients no longer have to request or retain PAP paperwork.

Drug interactions

Enter a drug name into the search box at Epocrates.com to learn about possible drug interactions as well as dosing information, contraindications, black-box warnings, and adverse effects. This free, continually updated Web site is invaluable when treating patients who take a large number of medications.

Clinical trials

When you want to know what clinical trials are being conducted on a particular medication or disorder, visit clinicaltrials.gov. All federally and privately supported clinical trials now must be registered with the NIH and posted at clinicaltrials.gov. The site lists ongoing and completed trials, allows you to search by medication, disorder, and geographic area, and indicates which trials are recruiting volunteers.

Information on drug abuse

The National Institute on Drug Abuse’s Drugabuse.gov provides information about substance abuse for clinicians, patients, parents, and teachers. In addition, the site features new research findings, information in Spanish, and links related to substance abuse. Click on the link for parents and teachers to access a searchable index of substance abuse treatment facilities, with information about insurance plans accepted, available treatments, and contact information.

Medication pricing

When you pull out your prescription pad, patients may ask how much a drug costs or if there is a cheaper way to buy the medication. Visit the pharmacy section of Costco.com to quickly check prices and out-of-pocket expenses, even if the patient does not buy medications from this retailer. Search by drug name to find out how much a formulation of a drug costs and if generic alternatives are available. Often this exercise will help you prescribe tablet strengths or formulations that can save the patient money.

Searching MEDLINE

You can search the National Library of Medicine’s MEDLINE bibliographic database for free by visiting Pubmed.gov. You can read abstracts of all journal articles in the database and full-text of some articles. The number of free full-text articles will increase because all articles based on research funded by the NIH must now be posted on Pubmed.gov.

Support groups

We recommend support groups to most of our psychiatric patients and their families. To find support groups in your area visit:

- Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance (dbsalliance.org) for patients with mood disorders

- Alcoholics Anonymous (aa.org) and Narcotics Anonymous (na.org) for patients with alcohol and other substance abuse problems

- National Alliance on Mental Illness (nami.org) for general support related to severe mental illness.

1. Fox S. Online health search 2006. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/pdfs/PIP_Online_Health_2006.pdf. Accessed July 29, 2008.

2. Christensen H, Griffiths K. The Internet and mental health practice. Evid Based Ment Health 2003;6(3):66-9.

3. Montgomery R. Are irreputable health sites hurting your patients? Current Psychiatry 2006;5(12):98-100

Nearly 1 in 4 Internet users has searched the Web for mental health information,1 but finding reliable sources is challenging. Wading through poorly organized, variable quality sites to find information you need can be time-consuming and frustrating.2 Also, without your guidance, patients may consult disreputable Web sites and follow advice that is contrary to standard psychiatric care.3

Because less is more when using the Internet, we recommend 1 good Web site for each of the following clinical needs. Each may be useful to you and to recommend to your patients.

Patient education

Medlineplus.gov from the National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is an authoritative source for reliable, unbiased information on medications and illnesses. You will find valuable information on all psychotropic and nonpsychotropic medications and most common psychiatric disorders, including information in Spanish.

You can print out medication information and give it to patients, though we recommend asking patients to visit the Web site to introduce them to this resource. Most important, Medlineplus.gov provides links to other trusted medical Web pages. For consumers, this site provides a variety of information including an illustrated medical encyclopedia and a guide to finding reputable health information on the Web. Medlineplus.gov is an enormous site that alone could satisfy most of your patient education needs.

Formulary information

When prescribing, you often need to know if a patient’s insurance will cover the cost of the drug or if preauthorization is necessary. Fingertipformulary.com, a free and user-friendly site, allows you to select a medication, your patient’s state, and insurance plan to find out if the drug will be covered. This site also tells you authorization requirements, quantity limits, and the medication’s “tier” classification, which specifies the patient’s copayment level.

Patient assistance programs

Needymeds.org is a nonprofit resource center of patient assistance programs (PAP) administered by pharmaceutical companies for individuals who cannot afford their medications. The site links to these programs’ Web sites, application forms, and groups that can help patients fill out necessary paperwork. With this Web site, patients no longer have to request or retain PAP paperwork.

Drug interactions

Enter a drug name into the search box at Epocrates.com to learn about possible drug interactions as well as dosing information, contraindications, black-box warnings, and adverse effects. This free, continually updated Web site is invaluable when treating patients who take a large number of medications.

Clinical trials

When you want to know what clinical trials are being conducted on a particular medication or disorder, visit clinicaltrials.gov. All federally and privately supported clinical trials now must be registered with the NIH and posted at clinicaltrials.gov. The site lists ongoing and completed trials, allows you to search by medication, disorder, and geographic area, and indicates which trials are recruiting volunteers.

Information on drug abuse

The National Institute on Drug Abuse’s Drugabuse.gov provides information about substance abuse for clinicians, patients, parents, and teachers. In addition, the site features new research findings, information in Spanish, and links related to substance abuse. Click on the link for parents and teachers to access a searchable index of substance abuse treatment facilities, with information about insurance plans accepted, available treatments, and contact information.

Medication pricing

When you pull out your prescription pad, patients may ask how much a drug costs or if there is a cheaper way to buy the medication. Visit the pharmacy section of Costco.com to quickly check prices and out-of-pocket expenses, even if the patient does not buy medications from this retailer. Search by drug name to find out how much a formulation of a drug costs and if generic alternatives are available. Often this exercise will help you prescribe tablet strengths or formulations that can save the patient money.

Searching MEDLINE

You can search the National Library of Medicine’s MEDLINE bibliographic database for free by visiting Pubmed.gov. You can read abstracts of all journal articles in the database and full-text of some articles. The number of free full-text articles will increase because all articles based on research funded by the NIH must now be posted on Pubmed.gov.

Support groups

We recommend support groups to most of our psychiatric patients and their families. To find support groups in your area visit:

- Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance (dbsalliance.org) for patients with mood disorders

- Alcoholics Anonymous (aa.org) and Narcotics Anonymous (na.org) for patients with alcohol and other substance abuse problems

- National Alliance on Mental Illness (nami.org) for general support related to severe mental illness.

Nearly 1 in 4 Internet users has searched the Web for mental health information,1 but finding reliable sources is challenging. Wading through poorly organized, variable quality sites to find information you need can be time-consuming and frustrating.2 Also, without your guidance, patients may consult disreputable Web sites and follow advice that is contrary to standard psychiatric care.3

Because less is more when using the Internet, we recommend 1 good Web site for each of the following clinical needs. Each may be useful to you and to recommend to your patients.

Patient education

Medlineplus.gov from the National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is an authoritative source for reliable, unbiased information on medications and illnesses. You will find valuable information on all psychotropic and nonpsychotropic medications and most common psychiatric disorders, including information in Spanish.

You can print out medication information and give it to patients, though we recommend asking patients to visit the Web site to introduce them to this resource. Most important, Medlineplus.gov provides links to other trusted medical Web pages. For consumers, this site provides a variety of information including an illustrated medical encyclopedia and a guide to finding reputable health information on the Web. Medlineplus.gov is an enormous site that alone could satisfy most of your patient education needs.

Formulary information

When prescribing, you often need to know if a patient’s insurance will cover the cost of the drug or if preauthorization is necessary. Fingertipformulary.com, a free and user-friendly site, allows you to select a medication, your patient’s state, and insurance plan to find out if the drug will be covered. This site also tells you authorization requirements, quantity limits, and the medication’s “tier” classification, which specifies the patient’s copayment level.

Patient assistance programs

Needymeds.org is a nonprofit resource center of patient assistance programs (PAP) administered by pharmaceutical companies for individuals who cannot afford their medications. The site links to these programs’ Web sites, application forms, and groups that can help patients fill out necessary paperwork. With this Web site, patients no longer have to request or retain PAP paperwork.

Drug interactions

Enter a drug name into the search box at Epocrates.com to learn about possible drug interactions as well as dosing information, contraindications, black-box warnings, and adverse effects. This free, continually updated Web site is invaluable when treating patients who take a large number of medications.

Clinical trials

When you want to know what clinical trials are being conducted on a particular medication or disorder, visit clinicaltrials.gov. All federally and privately supported clinical trials now must be registered with the NIH and posted at clinicaltrials.gov. The site lists ongoing and completed trials, allows you to search by medication, disorder, and geographic area, and indicates which trials are recruiting volunteers.

Information on drug abuse

The National Institute on Drug Abuse’s Drugabuse.gov provides information about substance abuse for clinicians, patients, parents, and teachers. In addition, the site features new research findings, information in Spanish, and links related to substance abuse. Click on the link for parents and teachers to access a searchable index of substance abuse treatment facilities, with information about insurance plans accepted, available treatments, and contact information.

Medication pricing

When you pull out your prescription pad, patients may ask how much a drug costs or if there is a cheaper way to buy the medication. Visit the pharmacy section of Costco.com to quickly check prices and out-of-pocket expenses, even if the patient does not buy medications from this retailer. Search by drug name to find out how much a formulation of a drug costs and if generic alternatives are available. Often this exercise will help you prescribe tablet strengths or formulations that can save the patient money.

Searching MEDLINE

You can search the National Library of Medicine’s MEDLINE bibliographic database for free by visiting Pubmed.gov. You can read abstracts of all journal articles in the database and full-text of some articles. The number of free full-text articles will increase because all articles based on research funded by the NIH must now be posted on Pubmed.gov.

Support groups

We recommend support groups to most of our psychiatric patients and their families. To find support groups in your area visit:

- Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance (dbsalliance.org) for patients with mood disorders

- Alcoholics Anonymous (aa.org) and Narcotics Anonymous (na.org) for patients with alcohol and other substance abuse problems

- National Alliance on Mental Illness (nami.org) for general support related to severe mental illness.

1. Fox S. Online health search 2006. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/pdfs/PIP_Online_Health_2006.pdf. Accessed July 29, 2008.

2. Christensen H, Griffiths K. The Internet and mental health practice. Evid Based Ment Health 2003;6(3):66-9.

3. Montgomery R. Are irreputable health sites hurting your patients? Current Psychiatry 2006;5(12):98-100

1. Fox S. Online health search 2006. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/pdfs/PIP_Online_Health_2006.pdf. Accessed July 29, 2008.

2. Christensen H, Griffiths K. The Internet and mental health practice. Evid Based Ment Health 2003;6(3):66-9.

3. Montgomery R. Are irreputable health sites hurting your patients? Current Psychiatry 2006;5(12):98-100

Help your patients keep appointments

Patients’ failure to keep appointments is a common problem. On average, patients miss approximately 15% of follow-up psychiatric appointments,1 but the percentage is much higher in some patient populations, such as patients with significant socioeconomic difficulties. Those who miss appointments often have worse outcomes and even a higher likelihood of psychiatric readmission.2

We present strategies to help patients keep appointments and to handle occasional and repeated absences. Although the problem of missed appointments will never go away, following these suggestions could help minimize it.

Prevent the problem

Explain to the patient why regular appointments are important. The most important point is that clinician and patient must agree that—to best help the patient—treatment requires that all appointments be kept, barring emergencies.

Communicate clearly. Avoid emphasizing rules, such as that patients must keep 80% of appointments, give 48-hours’ notice for cancellations, or pay a no-show fee. These suggest that patients may miss appointments as long as they follow the rules.

Fix structural problems in your practice that may be barriers to making, rescheduling, or cancelling appointments. Be clear with patients about:

- the phone number they should call for appointments

- if they or you must cancel, that person is to reschedule at the earliest opportunity.

If the patient is missing appointments because the frequency is too burdensome, in many cases less frequent but more regular visits may be better.

During your early sessions with patients, be sure they understand that you reserve specific times for them. Make sure, however, that patients don’t interpret this to mean that attending every appointment is for your benefit, rather than important for their treatment.

Emphasize responsibility. At the end of each session, set a goal with patients for the next appointment. With a patient who has missed appointments, ask for a commitment that he or she will come to the next session. We have found that stating that you are concerned the patient might not come to the next session can paradoxically be helpful.

Having your receptionist call and remind patients the day before their visits might not be a good idea in many cases. Patients might think these calls relieve them of the responsibility for remembering to keep appointments.

With patients you think might miss appointments—especially those on a medication that requires careful monitoring—consider writing prescriptions to last no longer than the next appointment.

Occasional missed appointments

Don’t just let it go when patients occasionally miss appointments without adequate reason. Ignoring the problem lets it progress.

Resist the temptation to be courteous and say, “That’s all right” when patients apologize or give a reason for missing the session. Doing so gives a subtle message that missing appointments is acceptable.

Discussing the patients’ reasons for missing appointments might solve the problem at times. For example, patients might not mention transportation or child care problems.

Note in the chart when a patient does not come to an appointment so you can calculate how many have been missed. This notation also will remind you to address these missed appointments during the next visit. Because discussing missed appointments at the start of the session might seem confrontational or punitive, inquire about the reasons for missing the previous appointment in a gentle manner and later in the session.

Remind patients that therapy is the tool to solve their emotional problems and thus has a special place in their lives. If patients want to solve other problems, they must start by regularly attending therapy.

Repeatedly missed appointments

When a patient misses appointments repeatedly, take 1 or more sessions to discuss it. This has to be done before therapy can proceed effectively (of course you might need to postpone this discussion if the patient has experienced major stressful events or has other pressing clinical issues).

When doing this, resist the temptation to become sidetracked by other issues the patient brings up. You can let the patient vent for a few minutes, but don’t let most of the session go by before addressing the missed appointments.

1. Mitchell AJ, Selmes T. A comparative survey of missed initial and follow-up appointments to psychiatric specialties in the United Kingdom. Psychiatr Serv 2007;58(6):868-71.

2. Killaspy H, Banerjee S, King M, Lloyd M. Prospective controlled study of psychiatric out-patient non-attendance. Characteristics and outcome. Br J Psychiatry 2000;176:160-5.

Dr. Mago is assistant professor of psychiatry and director of the mood disorders program; Dr. Mahajan is a research volunteer; and Dr. McFadden is an instructor and associate director of adult outpatient services, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia.

Patients’ failure to keep appointments is a common problem. On average, patients miss approximately 15% of follow-up psychiatric appointments,1 but the percentage is much higher in some patient populations, such as patients with significant socioeconomic difficulties. Those who miss appointments often have worse outcomes and even a higher likelihood of psychiatric readmission.2

We present strategies to help patients keep appointments and to handle occasional and repeated absences. Although the problem of missed appointments will never go away, following these suggestions could help minimize it.

Prevent the problem

Explain to the patient why regular appointments are important. The most important point is that clinician and patient must agree that—to best help the patient—treatment requires that all appointments be kept, barring emergencies.

Communicate clearly. Avoid emphasizing rules, such as that patients must keep 80% of appointments, give 48-hours’ notice for cancellations, or pay a no-show fee. These suggest that patients may miss appointments as long as they follow the rules.

Fix structural problems in your practice that may be barriers to making, rescheduling, or cancelling appointments. Be clear with patients about:

- the phone number they should call for appointments

- if they or you must cancel, that person is to reschedule at the earliest opportunity.

If the patient is missing appointments because the frequency is too burdensome, in many cases less frequent but more regular visits may be better.

During your early sessions with patients, be sure they understand that you reserve specific times for them. Make sure, however, that patients don’t interpret this to mean that attending every appointment is for your benefit, rather than important for their treatment.

Emphasize responsibility. At the end of each session, set a goal with patients for the next appointment. With a patient who has missed appointments, ask for a commitment that he or she will come to the next session. We have found that stating that you are concerned the patient might not come to the next session can paradoxically be helpful.

Having your receptionist call and remind patients the day before their visits might not be a good idea in many cases. Patients might think these calls relieve them of the responsibility for remembering to keep appointments.

With patients you think might miss appointments—especially those on a medication that requires careful monitoring—consider writing prescriptions to last no longer than the next appointment.

Occasional missed appointments

Don’t just let it go when patients occasionally miss appointments without adequate reason. Ignoring the problem lets it progress.

Resist the temptation to be courteous and say, “That’s all right” when patients apologize or give a reason for missing the session. Doing so gives a subtle message that missing appointments is acceptable.

Discussing the patients’ reasons for missing appointments might solve the problem at times. For example, patients might not mention transportation or child care problems.

Note in the chart when a patient does not come to an appointment so you can calculate how many have been missed. This notation also will remind you to address these missed appointments during the next visit. Because discussing missed appointments at the start of the session might seem confrontational or punitive, inquire about the reasons for missing the previous appointment in a gentle manner and later in the session.

Remind patients that therapy is the tool to solve their emotional problems and thus has a special place in their lives. If patients want to solve other problems, they must start by regularly attending therapy.

Repeatedly missed appointments

When a patient misses appointments repeatedly, take 1 or more sessions to discuss it. This has to be done before therapy can proceed effectively (of course you might need to postpone this discussion if the patient has experienced major stressful events or has other pressing clinical issues).

When doing this, resist the temptation to become sidetracked by other issues the patient brings up. You can let the patient vent for a few minutes, but don’t let most of the session go by before addressing the missed appointments.

Patients’ failure to keep appointments is a common problem. On average, patients miss approximately 15% of follow-up psychiatric appointments,1 but the percentage is much higher in some patient populations, such as patients with significant socioeconomic difficulties. Those who miss appointments often have worse outcomes and even a higher likelihood of psychiatric readmission.2

We present strategies to help patients keep appointments and to handle occasional and repeated absences. Although the problem of missed appointments will never go away, following these suggestions could help minimize it.

Prevent the problem

Explain to the patient why regular appointments are important. The most important point is that clinician and patient must agree that—to best help the patient—treatment requires that all appointments be kept, barring emergencies.

Communicate clearly. Avoid emphasizing rules, such as that patients must keep 80% of appointments, give 48-hours’ notice for cancellations, or pay a no-show fee. These suggest that patients may miss appointments as long as they follow the rules.

Fix structural problems in your practice that may be barriers to making, rescheduling, or cancelling appointments. Be clear with patients about:

- the phone number they should call for appointments

- if they or you must cancel, that person is to reschedule at the earliest opportunity.

If the patient is missing appointments because the frequency is too burdensome, in many cases less frequent but more regular visits may be better.

During your early sessions with patients, be sure they understand that you reserve specific times for them. Make sure, however, that patients don’t interpret this to mean that attending every appointment is for your benefit, rather than important for their treatment.

Emphasize responsibility. At the end of each session, set a goal with patients for the next appointment. With a patient who has missed appointments, ask for a commitment that he or she will come to the next session. We have found that stating that you are concerned the patient might not come to the next session can paradoxically be helpful.

Having your receptionist call and remind patients the day before their visits might not be a good idea in many cases. Patients might think these calls relieve them of the responsibility for remembering to keep appointments.

With patients you think might miss appointments—especially those on a medication that requires careful monitoring—consider writing prescriptions to last no longer than the next appointment.

Occasional missed appointments

Don’t just let it go when patients occasionally miss appointments without adequate reason. Ignoring the problem lets it progress.

Resist the temptation to be courteous and say, “That’s all right” when patients apologize or give a reason for missing the session. Doing so gives a subtle message that missing appointments is acceptable.

Discussing the patients’ reasons for missing appointments might solve the problem at times. For example, patients might not mention transportation or child care problems.

Note in the chart when a patient does not come to an appointment so you can calculate how many have been missed. This notation also will remind you to address these missed appointments during the next visit. Because discussing missed appointments at the start of the session might seem confrontational or punitive, inquire about the reasons for missing the previous appointment in a gentle manner and later in the session.

Remind patients that therapy is the tool to solve their emotional problems and thus has a special place in their lives. If patients want to solve other problems, they must start by regularly attending therapy.

Repeatedly missed appointments

When a patient misses appointments repeatedly, take 1 or more sessions to discuss it. This has to be done before therapy can proceed effectively (of course you might need to postpone this discussion if the patient has experienced major stressful events or has other pressing clinical issues).

When doing this, resist the temptation to become sidetracked by other issues the patient brings up. You can let the patient vent for a few minutes, but don’t let most of the session go by before addressing the missed appointments.

1. Mitchell AJ, Selmes T. A comparative survey of missed initial and follow-up appointments to psychiatric specialties in the United Kingdom. Psychiatr Serv 2007;58(6):868-71.

2. Killaspy H, Banerjee S, King M, Lloyd M. Prospective controlled study of psychiatric out-patient non-attendance. Characteristics and outcome. Br J Psychiatry 2000;176:160-5.

Dr. Mago is assistant professor of psychiatry and director of the mood disorders program; Dr. Mahajan is a research volunteer; and Dr. McFadden is an instructor and associate director of adult outpatient services, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia.

1. Mitchell AJ, Selmes T. A comparative survey of missed initial and follow-up appointments to psychiatric specialties in the United Kingdom. Psychiatr Serv 2007;58(6):868-71.

2. Killaspy H, Banerjee S, King M, Lloyd M. Prospective controlled study of psychiatric out-patient non-attendance. Characteristics and outcome. Br J Psychiatry 2000;176:160-5.

Dr. Mago is assistant professor of psychiatry and director of the mood disorders program; Dr. Mahajan is a research volunteer; and Dr. McFadden is an instructor and associate director of adult outpatient services, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia.

7 steps to a successful antipsychotic switch

Patient education and timing are crucial to promoting a positive outcome after switching antipsychotics. Although little empiric evidence is available to guide these medication switches,1-3 we find the following process helpful based on our clinical experience.

Think Before You Switch

Before switching antipsychotics, ask:

- Did the first antipsychotic have some effect on psychosis or mood or on associated symptoms, such as sleep, anxiety, or agitation? If so, anticipate and manage the benefits that will be lost while tapering off the antipsychotic.

- How stable is the patient?

- How much external monitoring or support is available? If the patient has limited external support, make the switch slowly and monitor the patient more closely.

- How urgent is the medication switch?

- Is the patient suffering severe adverse effects from the first antipsychotic?

- Is a high dosage of the new antipsychotic needed to manage positive symptoms?

Dos and Don’Ts Of Switching

If switching antipsychotics is necessary, follow these seven steps:

- Don’t switch while the patient is unstable, particularly if you are switching because of side effects or for administrative reasons such as formulary restrictions or cost. Delay the switch until the patient is stable, if possible. For unstable patients who are inadequately controlled on the first antipsychotic, consider temporarily adding another antipsychotic and deferring the switch until the patient is more stable.

- Explain the switch’s risks and benefits to the patient. Mention how long before the new drug begins to work and when side effects could surface. Also, give the patient a choice regarding alternate medications, when to switch, and how gradual the switch should be. A collaborative approach is more likely to be successful.

- Make sure the patient’s family, case managers, or group home operators understand why you are switching antipsychotics. Instruct them to watch for worsening symptoms after the patient starts the new medication.

- Stay in touch with the patient—by phone and in person—during and after the switch. Numerous factors—including the patient’s stability and whether family or friends are monitoring him—should guide frequency of contact.

- Tell the patient to call you if a problem arises. Counsel the patient through minor or temporary side effects with the new antipsychotic.

- Do not switch multiple medications at once, if possible, as this can destabilize the patient and make it difficult to assess the new medications’ benefits and adverse effects.

- An adjuvant medication can reduce pharmacodynamic changes resulting from the switch. For example, consider adding a hypnotic and/or an anxiolytic when switching from a sedating to a nonsedating antipsychotic. When switching from an antipsychotic with significant anticholinergic properties—such as olanzapine or quetiapine—consider adding an anticholinergic that may be tapered off later.

- Don’t switch while the patient is unstable

- Explain the switch’s risks and benefits

- Discuss the change with family, case managers, or group home operators

- Stay in touch with the patient

- Tell the patient to call you if a problem arises

- Don’t switch multiple medications at once

- Consider an adjuvant medication

1. Remington G, Chue P, Stip E, et al. The crossover approach to switching antipsychotics: what is the evidence? Schizophr Res 2005;76:267-72.

2. Edlinger M, Baumgartner S, Eltanaihi-Furtmuller N, et al. Switching between second-generation antipsychotics: why and how? CNS Drugs 2005;19:27-42.

3. Masand P. A review of pharmacologic strategies for switching to atypical antipsychotics. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2005;7:121-9.

Dr. Mago is assistant professor of psychiatry, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, and director of its mood disorders program.

Dr. Pinninti is associate professor of psychiatry, School of Osteopathic Medicine, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, and medical director, Steininger Behavioral Care Services, Cherry Hill, NJ.

Patient education and timing are crucial to promoting a positive outcome after switching antipsychotics. Although little empiric evidence is available to guide these medication switches,1-3 we find the following process helpful based on our clinical experience.

Think Before You Switch

Before switching antipsychotics, ask:

- Did the first antipsychotic have some effect on psychosis or mood or on associated symptoms, such as sleep, anxiety, or agitation? If so, anticipate and manage the benefits that will be lost while tapering off the antipsychotic.

- How stable is the patient?

- How much external monitoring or support is available? If the patient has limited external support, make the switch slowly and monitor the patient more closely.

- How urgent is the medication switch?

- Is the patient suffering severe adverse effects from the first antipsychotic?

- Is a high dosage of the new antipsychotic needed to manage positive symptoms?

Dos and Don’Ts Of Switching

If switching antipsychotics is necessary, follow these seven steps:

- Don’t switch while the patient is unstable, particularly if you are switching because of side effects or for administrative reasons such as formulary restrictions or cost. Delay the switch until the patient is stable, if possible. For unstable patients who are inadequately controlled on the first antipsychotic, consider temporarily adding another antipsychotic and deferring the switch until the patient is more stable.

- Explain the switch’s risks and benefits to the patient. Mention how long before the new drug begins to work and when side effects could surface. Also, give the patient a choice regarding alternate medications, when to switch, and how gradual the switch should be. A collaborative approach is more likely to be successful.

- Make sure the patient’s family, case managers, or group home operators understand why you are switching antipsychotics. Instruct them to watch for worsening symptoms after the patient starts the new medication.

- Stay in touch with the patient—by phone and in person—during and after the switch. Numerous factors—including the patient’s stability and whether family or friends are monitoring him—should guide frequency of contact.

- Tell the patient to call you if a problem arises. Counsel the patient through minor or temporary side effects with the new antipsychotic.

- Do not switch multiple medications at once, if possible, as this can destabilize the patient and make it difficult to assess the new medications’ benefits and adverse effects.

- An adjuvant medication can reduce pharmacodynamic changes resulting from the switch. For example, consider adding a hypnotic and/or an anxiolytic when switching from a sedating to a nonsedating antipsychotic. When switching from an antipsychotic with significant anticholinergic properties—such as olanzapine or quetiapine—consider adding an anticholinergic that may be tapered off later.

- Don’t switch while the patient is unstable

- Explain the switch’s risks and benefits

- Discuss the change with family, case managers, or group home operators

- Stay in touch with the patient

- Tell the patient to call you if a problem arises

- Don’t switch multiple medications at once

- Consider an adjuvant medication

Patient education and timing are crucial to promoting a positive outcome after switching antipsychotics. Although little empiric evidence is available to guide these medication switches,1-3 we find the following process helpful based on our clinical experience.

Think Before You Switch

Before switching antipsychotics, ask:

- Did the first antipsychotic have some effect on psychosis or mood or on associated symptoms, such as sleep, anxiety, or agitation? If so, anticipate and manage the benefits that will be lost while tapering off the antipsychotic.

- How stable is the patient?

- How much external monitoring or support is available? If the patient has limited external support, make the switch slowly and monitor the patient more closely.

- How urgent is the medication switch?

- Is the patient suffering severe adverse effects from the first antipsychotic?

- Is a high dosage of the new antipsychotic needed to manage positive symptoms?

Dos and Don’Ts Of Switching

If switching antipsychotics is necessary, follow these seven steps:

- Don’t switch while the patient is unstable, particularly if you are switching because of side effects or for administrative reasons such as formulary restrictions or cost. Delay the switch until the patient is stable, if possible. For unstable patients who are inadequately controlled on the first antipsychotic, consider temporarily adding another antipsychotic and deferring the switch until the patient is more stable.

- Explain the switch’s risks and benefits to the patient. Mention how long before the new drug begins to work and when side effects could surface. Also, give the patient a choice regarding alternate medications, when to switch, and how gradual the switch should be. A collaborative approach is more likely to be successful.

- Make sure the patient’s family, case managers, or group home operators understand why you are switching antipsychotics. Instruct them to watch for worsening symptoms after the patient starts the new medication.

- Stay in touch with the patient—by phone and in person—during and after the switch. Numerous factors—including the patient’s stability and whether family or friends are monitoring him—should guide frequency of contact.

- Tell the patient to call you if a problem arises. Counsel the patient through minor or temporary side effects with the new antipsychotic.

- Do not switch multiple medications at once, if possible, as this can destabilize the patient and make it difficult to assess the new medications’ benefits and adverse effects.

- An adjuvant medication can reduce pharmacodynamic changes resulting from the switch. For example, consider adding a hypnotic and/or an anxiolytic when switching from a sedating to a nonsedating antipsychotic. When switching from an antipsychotic with significant anticholinergic properties—such as olanzapine or quetiapine—consider adding an anticholinergic that may be tapered off later.

- Don’t switch while the patient is unstable

- Explain the switch’s risks and benefits

- Discuss the change with family, case managers, or group home operators

- Stay in touch with the patient

- Tell the patient to call you if a problem arises

- Don’t switch multiple medications at once

- Consider an adjuvant medication

1. Remington G, Chue P, Stip E, et al. The crossover approach to switching antipsychotics: what is the evidence? Schizophr Res 2005;76:267-72.

2. Edlinger M, Baumgartner S, Eltanaihi-Furtmuller N, et al. Switching between second-generation antipsychotics: why and how? CNS Drugs 2005;19:27-42.

3. Masand P. A review of pharmacologic strategies for switching to atypical antipsychotics. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2005;7:121-9.

Dr. Mago is assistant professor of psychiatry, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, and director of its mood disorders program.

Dr. Pinninti is associate professor of psychiatry, School of Osteopathic Medicine, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, and medical director, Steininger Behavioral Care Services, Cherry Hill, NJ.

1. Remington G, Chue P, Stip E, et al. The crossover approach to switching antipsychotics: what is the evidence? Schizophr Res 2005;76:267-72.

2. Edlinger M, Baumgartner S, Eltanaihi-Furtmuller N, et al. Switching between second-generation antipsychotics: why and how? CNS Drugs 2005;19:27-42.

3. Masand P. A review of pharmacologic strategies for switching to atypical antipsychotics. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2005;7:121-9.

Dr. Mago is assistant professor of psychiatry, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA, and director of its mood disorders program.

Dr. Pinninti is associate professor of psychiatry, School of Osteopathic Medicine, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, and medical director, Steininger Behavioral Care Services, Cherry Hill, NJ.

Suicide risk assessment: Questions that reveal what you really need to know

You can make more-informed decisions about a patient’s acute suicide risk—such as over the phone at 3 AM—if you know what to ask the psychiatry resident or crisis worker. For suicide risk assessment—especially when you have not seen the patient—you need specific, high-yield questions to draw out danger signals from large amounts of data.

We are not suggesting that a short list of questions is sufficient for this extremely difficult task. Rather—because we recognize its complexity—we offer the questions we find most useful when evaluating patients with suicidal behaviors.

American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines1 provide a comprehensive discussion of assessing suicide risk. In addition, we teach clinicians we supervise to probe for high-risk and less-commonly explored “protective” factors.

High-risk factors