User login

6 ‘D’s: Next steps after an insufficient antipsychotic response

There are a lack of research on, and strategies for dealing with, an insufficient response to antipsychotics. Treatment often is guided by what is described in published case reports or anecdotal evidence, rather than the findings of systematic studies.

We propose that a patient be considered “difficult-to-treat” or “treatment-resistant” after experiencing limited or negative responses to 3 different antipsychotics—with ≥1 being a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA)—that the patient has taken for at least 6 to 8 weeks at the maximum recommended dosage. Furthermore, switching to clozapine is an important strategy; do not consider it solely a last resort.

These 6 ‘D’s can remind you of other problems to consider when evaluating a treatment-resistant patient.

Diagnosis. Is the diagnosis, including the presence of comorbid conditions, accurate? Are significant psychosocial stressors undermining treatment response? Treat any comorbid conditions and consider instituting adjunctive psychosocial interventions, including cognitive-behavioral therapy.

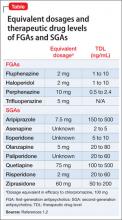

Dosage. Have the patient try the maximum recommended dosage if he (she) can tolerate it. Equivalent dosages of antipsychotics are shown in the Table,1,2 and can guide off-label use of higher dosages. Research does not support use of chlorpromazine equivalents >1,000 mg/d, and usually should not be employed. If using a higher than normal dosage, perform an ECG before the increase.3

Beneficial and adverse effects should be monitored carefully. Reduce the dosage after 3 months if the risk-benefit ratio does not justify the higher dosage.3

Duration. Try a treatment for at least 6 weeks at the maximum tolerated

dosage—even extending it to 12 weeks—before considering abandoning it because of insufficient response.

Drug interactions. Use a drug interaction tool to ensure drug-drug interactions are not reducing antipsychotic levels. A recent increase in smoking or decrease in caffeine intake can reduce the blood level of olanzapine and clozapine.4 Ultra-rapid metabolizers of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes may have a lower blood level of antipsychotic.

Consider pharmacogenetic testing in patients in whom you observe an unexpected lack of efficacy or adverse effects at customary dosages.

Double up. You might need to add another medication to the antipsychotic. Symptoms might help determine which medication to add:

- a combination of an SGA and a first-generation antipsychotic may be more effective than antipsychotic monotherapy5

- for prominent negative symptoms, consider using 2 SGAs of different potency together. Use caution when prescribing ziprasidone with another antipsychotic because this could prolong the QTc interval

- if a mood stabilizer is appropriate, consider lamotrigine because of its possible potentiating effect on SGAs6

- benzodiazepines can be used to reduce agitation or anxiety but are ineffective for psychosis.7

Drug levels. Measurement of the blood level of the drug is most useful when administering clozapine; focus on the clozapine, not on the norclozapine level that also is reported. Ensure a clozapine level of 350 to 600 ng/mL.

Therapeutic levels have been established for most antipsychotics (Table).1,2 Occasionally, knowing these levels can be helpful in evaluating patients for potential problems with absorption and metabolism of the drug, and with nonadherence.

Disclosures

Drs. Faden and Pinninti report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. Dr. Mago receives grant/research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest Institute, Genomind, and Shire.

1. Gardner DM, Murphy AL, O’Donnell H, et al. International consensus study of antipsychotic dosing. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6):686-693.

2. Hiemke C, Baumann P, Bergemann N, et al. AGNP consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in psychiatry: update 2011. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;44(6):195-235.

3. Royal College of Psychiatrists. Consensus statement on high-dose antipsychotic medication. http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/files/pdfversion/CR138.pdf. Published May 2006. Accessed March 26, 2013.

4. Pinninti NR, Mago R, de Leon J. Coffee, cigarettes and meds: what are the metabolic effects? Psychiatric Times. 2005;22(6):20-23.

5. Correll CU, Rummel-Kluge C, Corves C, et al. Antipsychotic combinations vs monotherapy in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(2):443-457.

6. Citrome L. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia: what can we do about it? Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(6):52-58.

7. Volz A, Khorsand V, Gillies D, et al. Benzodiazepines for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1): CD006391.

There are a lack of research on, and strategies for dealing with, an insufficient response to antipsychotics. Treatment often is guided by what is described in published case reports or anecdotal evidence, rather than the findings of systematic studies.

We propose that a patient be considered “difficult-to-treat” or “treatment-resistant” after experiencing limited or negative responses to 3 different antipsychotics—with ≥1 being a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA)—that the patient has taken for at least 6 to 8 weeks at the maximum recommended dosage. Furthermore, switching to clozapine is an important strategy; do not consider it solely a last resort.

These 6 ‘D’s can remind you of other problems to consider when evaluating a treatment-resistant patient.

Diagnosis. Is the diagnosis, including the presence of comorbid conditions, accurate? Are significant psychosocial stressors undermining treatment response? Treat any comorbid conditions and consider instituting adjunctive psychosocial interventions, including cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Dosage. Have the patient try the maximum recommended dosage if he (she) can tolerate it. Equivalent dosages of antipsychotics are shown in the Table,1,2 and can guide off-label use of higher dosages. Research does not support use of chlorpromazine equivalents >1,000 mg/d, and usually should not be employed. If using a higher than normal dosage, perform an ECG before the increase.3

Beneficial and adverse effects should be monitored carefully. Reduce the dosage after 3 months if the risk-benefit ratio does not justify the higher dosage.3

Duration. Try a treatment for at least 6 weeks at the maximum tolerated

dosage—even extending it to 12 weeks—before considering abandoning it because of insufficient response.

Drug interactions. Use a drug interaction tool to ensure drug-drug interactions are not reducing antipsychotic levels. A recent increase in smoking or decrease in caffeine intake can reduce the blood level of olanzapine and clozapine.4 Ultra-rapid metabolizers of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes may have a lower blood level of antipsychotic.

Consider pharmacogenetic testing in patients in whom you observe an unexpected lack of efficacy or adverse effects at customary dosages.

Double up. You might need to add another medication to the antipsychotic. Symptoms might help determine which medication to add:

- a combination of an SGA and a first-generation antipsychotic may be more effective than antipsychotic monotherapy5

- for prominent negative symptoms, consider using 2 SGAs of different potency together. Use caution when prescribing ziprasidone with another antipsychotic because this could prolong the QTc interval

- if a mood stabilizer is appropriate, consider lamotrigine because of its possible potentiating effect on SGAs6

- benzodiazepines can be used to reduce agitation or anxiety but are ineffective for psychosis.7

Drug levels. Measurement of the blood level of the drug is most useful when administering clozapine; focus on the clozapine, not on the norclozapine level that also is reported. Ensure a clozapine level of 350 to 600 ng/mL.

Therapeutic levels have been established for most antipsychotics (Table).1,2 Occasionally, knowing these levels can be helpful in evaluating patients for potential problems with absorption and metabolism of the drug, and with nonadherence.

Disclosures

Drs. Faden and Pinninti report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. Dr. Mago receives grant/research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest Institute, Genomind, and Shire.

There are a lack of research on, and strategies for dealing with, an insufficient response to antipsychotics. Treatment often is guided by what is described in published case reports or anecdotal evidence, rather than the findings of systematic studies.

We propose that a patient be considered “difficult-to-treat” or “treatment-resistant” after experiencing limited or negative responses to 3 different antipsychotics—with ≥1 being a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA)—that the patient has taken for at least 6 to 8 weeks at the maximum recommended dosage. Furthermore, switching to clozapine is an important strategy; do not consider it solely a last resort.

These 6 ‘D’s can remind you of other problems to consider when evaluating a treatment-resistant patient.

Diagnosis. Is the diagnosis, including the presence of comorbid conditions, accurate? Are significant psychosocial stressors undermining treatment response? Treat any comorbid conditions and consider instituting adjunctive psychosocial interventions, including cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Dosage. Have the patient try the maximum recommended dosage if he (she) can tolerate it. Equivalent dosages of antipsychotics are shown in the Table,1,2 and can guide off-label use of higher dosages. Research does not support use of chlorpromazine equivalents >1,000 mg/d, and usually should not be employed. If using a higher than normal dosage, perform an ECG before the increase.3

Beneficial and adverse effects should be monitored carefully. Reduce the dosage after 3 months if the risk-benefit ratio does not justify the higher dosage.3

Duration. Try a treatment for at least 6 weeks at the maximum tolerated

dosage—even extending it to 12 weeks—before considering abandoning it because of insufficient response.

Drug interactions. Use a drug interaction tool to ensure drug-drug interactions are not reducing antipsychotic levels. A recent increase in smoking or decrease in caffeine intake can reduce the blood level of olanzapine and clozapine.4 Ultra-rapid metabolizers of cytochrome P450 isoenzymes may have a lower blood level of antipsychotic.

Consider pharmacogenetic testing in patients in whom you observe an unexpected lack of efficacy or adverse effects at customary dosages.

Double up. You might need to add another medication to the antipsychotic. Symptoms might help determine which medication to add:

- a combination of an SGA and a first-generation antipsychotic may be more effective than antipsychotic monotherapy5

- for prominent negative symptoms, consider using 2 SGAs of different potency together. Use caution when prescribing ziprasidone with another antipsychotic because this could prolong the QTc interval

- if a mood stabilizer is appropriate, consider lamotrigine because of its possible potentiating effect on SGAs6

- benzodiazepines can be used to reduce agitation or anxiety but are ineffective for psychosis.7

Drug levels. Measurement of the blood level of the drug is most useful when administering clozapine; focus on the clozapine, not on the norclozapine level that also is reported. Ensure a clozapine level of 350 to 600 ng/mL.

Therapeutic levels have been established for most antipsychotics (Table).1,2 Occasionally, knowing these levels can be helpful in evaluating patients for potential problems with absorption and metabolism of the drug, and with nonadherence.

Disclosures

Drs. Faden and Pinninti report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products. Dr. Mago receives grant/research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest Institute, Genomind, and Shire.

1. Gardner DM, Murphy AL, O’Donnell H, et al. International consensus study of antipsychotic dosing. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6):686-693.

2. Hiemke C, Baumann P, Bergemann N, et al. AGNP consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in psychiatry: update 2011. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;44(6):195-235.

3. Royal College of Psychiatrists. Consensus statement on high-dose antipsychotic medication. http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/files/pdfversion/CR138.pdf. Published May 2006. Accessed March 26, 2013.

4. Pinninti NR, Mago R, de Leon J. Coffee, cigarettes and meds: what are the metabolic effects? Psychiatric Times. 2005;22(6):20-23.

5. Correll CU, Rummel-Kluge C, Corves C, et al. Antipsychotic combinations vs monotherapy in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(2):443-457.

6. Citrome L. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia: what can we do about it? Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(6):52-58.

7. Volz A, Khorsand V, Gillies D, et al. Benzodiazepines for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1): CD006391.

1. Gardner DM, Murphy AL, O’Donnell H, et al. International consensus study of antipsychotic dosing. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6):686-693.

2. Hiemke C, Baumann P, Bergemann N, et al. AGNP consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in psychiatry: update 2011. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2011;44(6):195-235.

3. Royal College of Psychiatrists. Consensus statement on high-dose antipsychotic medication. http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/files/pdfversion/CR138.pdf. Published May 2006. Accessed March 26, 2013.

4. Pinninti NR, Mago R, de Leon J. Coffee, cigarettes and meds: what are the metabolic effects? Psychiatric Times. 2005;22(6):20-23.

5. Correll CU, Rummel-Kluge C, Corves C, et al. Antipsychotic combinations vs monotherapy in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(2):443-457.

6. Citrome L. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia: what can we do about it? Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(6):52-58.

7. Volz A, Khorsand V, Gillies D, et al. Benzodiazepines for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1): CD006391.

5 Ways to quiet auditory hallucinations

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) can help patients cope with auditory hallucinations and reshape delusional beliefs to make the voices less frequent.1 Use the following CBT methods alone or with medication.

1. Engage the patient by showing interest in the voices. Ask: “When did the voices start? Where are they coming from? Can you bring them on or stop them? Do they tell you to do things? What happens when you ignore them?”

2. Normalize the hallucination. List scientifically plausible “reasons for hearing voices,”2 including sleep deprivation, isolation, dehydration and/or starvation, extreme stress, strong thoughts or emotions, fever and illness, and drug/alcohol use.

Ask which reasons might apply. Patients often agree with several explanations and begin questioning their delusional interpretations. Your list should include the possibility that the voices are real, but only if the patient initially believes this.

3. Suggest coping strategies, such as:

- humming or singing a song several times

- listening to music

- reading (forwards and backwards)

- talking with others

- exercise

- ignoring the voices

- medication (important to include).

Ask which methods worked previously and have patients build on that list, if possible.

If a patient hears command hallucinations, assess their acuity and decide whether he or she is likely to act on them before starting CBT.

4. Use in-session voices to teach coping strategies. Ask the patient to hum a song with you (“Happy Birthday” works well). If unsuccessful, try reading a paragraph together forwards or backwards. If the voices stop—even for 2 minutes—tell the patient that he or she has begun to control them.3 Have the patient practice these exercises at home and notice if the voices stop for longer periods.

5. Briefly explain the neurology behind the voices. PET scans have shown that auditory hallucinations activate brain areas that regulate hearing and speaking,4 suggesting that people talk or think to themselves while hearing voices.

When patients ask why they hear strange voices, explain that many voices are buried inside our memory. When people hear voices, the brain’s speech, hearing, and memory centers interact.5

That said, calling auditory hallucinations “voice-thoughts,” rather than “voices,” reduces stigma and reinforces an alternate explanation behind the delusion. As the patient begins to understand that hallucinations are related to dysfunctional thoughts, we can help correct them.

1. Rector NA, Beck AT. A clinical review of cognitive therapy for schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2002;4:284-292.

2. Kingdon DG, Turkington D. Cognitive-behavioral therapy of schizophrenia. New York: Guilford Press; 1994.

3. Beck AT. E-mail communication.

4. McGuire PK, Shah GMS, Murray RM. Increased blood flow in Broca’s area during auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia. Lancet. 1993;342:703-706.

5. Sosland MD, Deibler MW. Temple University Psychosis Group. 2003.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) can help patients cope with auditory hallucinations and reshape delusional beliefs to make the voices less frequent.1 Use the following CBT methods alone or with medication.

1. Engage the patient by showing interest in the voices. Ask: “When did the voices start? Where are they coming from? Can you bring them on or stop them? Do they tell you to do things? What happens when you ignore them?”

2. Normalize the hallucination. List scientifically plausible “reasons for hearing voices,”2 including sleep deprivation, isolation, dehydration and/or starvation, extreme stress, strong thoughts or emotions, fever and illness, and drug/alcohol use.

Ask which reasons might apply. Patients often agree with several explanations and begin questioning their delusional interpretations. Your list should include the possibility that the voices are real, but only if the patient initially believes this.

3. Suggest coping strategies, such as:

- humming or singing a song several times

- listening to music

- reading (forwards and backwards)

- talking with others

- exercise

- ignoring the voices

- medication (important to include).

Ask which methods worked previously and have patients build on that list, if possible.

If a patient hears command hallucinations, assess their acuity and decide whether he or she is likely to act on them before starting CBT.

4. Use in-session voices to teach coping strategies. Ask the patient to hum a song with you (“Happy Birthday” works well). If unsuccessful, try reading a paragraph together forwards or backwards. If the voices stop—even for 2 minutes—tell the patient that he or she has begun to control them.3 Have the patient practice these exercises at home and notice if the voices stop for longer periods.

5. Briefly explain the neurology behind the voices. PET scans have shown that auditory hallucinations activate brain areas that regulate hearing and speaking,4 suggesting that people talk or think to themselves while hearing voices.

When patients ask why they hear strange voices, explain that many voices are buried inside our memory. When people hear voices, the brain’s speech, hearing, and memory centers interact.5

That said, calling auditory hallucinations “voice-thoughts,” rather than “voices,” reduces stigma and reinforces an alternate explanation behind the delusion. As the patient begins to understand that hallucinations are related to dysfunctional thoughts, we can help correct them.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) can help patients cope with auditory hallucinations and reshape delusional beliefs to make the voices less frequent.1 Use the following CBT methods alone or with medication.

1. Engage the patient by showing interest in the voices. Ask: “When did the voices start? Where are they coming from? Can you bring them on or stop them? Do they tell you to do things? What happens when you ignore them?”

2. Normalize the hallucination. List scientifically plausible “reasons for hearing voices,”2 including sleep deprivation, isolation, dehydration and/or starvation, extreme stress, strong thoughts or emotions, fever and illness, and drug/alcohol use.

Ask which reasons might apply. Patients often agree with several explanations and begin questioning their delusional interpretations. Your list should include the possibility that the voices are real, but only if the patient initially believes this.

3. Suggest coping strategies, such as:

- humming or singing a song several times

- listening to music

- reading (forwards and backwards)

- talking with others

- exercise

- ignoring the voices

- medication (important to include).

Ask which methods worked previously and have patients build on that list, if possible.

If a patient hears command hallucinations, assess their acuity and decide whether he or she is likely to act on them before starting CBT.

4. Use in-session voices to teach coping strategies. Ask the patient to hum a song with you (“Happy Birthday” works well). If unsuccessful, try reading a paragraph together forwards or backwards. If the voices stop—even for 2 minutes—tell the patient that he or she has begun to control them.3 Have the patient practice these exercises at home and notice if the voices stop for longer periods.

5. Briefly explain the neurology behind the voices. PET scans have shown that auditory hallucinations activate brain areas that regulate hearing and speaking,4 suggesting that people talk or think to themselves while hearing voices.

When patients ask why they hear strange voices, explain that many voices are buried inside our memory. When people hear voices, the brain’s speech, hearing, and memory centers interact.5

That said, calling auditory hallucinations “voice-thoughts,” rather than “voices,” reduces stigma and reinforces an alternate explanation behind the delusion. As the patient begins to understand that hallucinations are related to dysfunctional thoughts, we can help correct them.

1. Rector NA, Beck AT. A clinical review of cognitive therapy for schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2002;4:284-292.

2. Kingdon DG, Turkington D. Cognitive-behavioral therapy of schizophrenia. New York: Guilford Press; 1994.

3. Beck AT. E-mail communication.

4. McGuire PK, Shah GMS, Murray RM. Increased blood flow in Broca’s area during auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia. Lancet. 1993;342:703-706.

5. Sosland MD, Deibler MW. Temple University Psychosis Group. 2003.

1. Rector NA, Beck AT. A clinical review of cognitive therapy for schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2002;4:284-292.

2. Kingdon DG, Turkington D. Cognitive-behavioral therapy of schizophrenia. New York: Guilford Press; 1994.

3. Beck AT. E-mail communication.

4. McGuire PK, Shah GMS, Murray RM. Increased blood flow in Broca’s area during auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia. Lancet. 1993;342:703-706.

5. Sosland MD, Deibler MW. Temple University Psychosis Group. 2003.