User login

Heard of ApoB Testing? New Guidelines

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I've been hearing a lot about apolipoprotein B (apoB) lately. It keeps popping up, but I've not been sure where it fits in or what I should do about it. The new Expert Clinical Consensus from the National Lipid Association now finally gives us clear guidance.

ApoB is the main protein that is found on all atherogenic lipoproteins. It is found on low-density lipoprotein (LDL) but also on other atherogenic lipoprotein particles. Because it is a part of all atherogenic particles, it predicts cardiovascular (CV) risk more accurately than does LDL cholesterol (LDL-C).

ApoB and LDL-C tend to run together, but not always. While they are correlated fairly well on a population level, for a given individual they can diverge; and when they do, apoB is the better predictor of future CV outcomes. This divergence occurs frequently, and it can occur even more frequently after treatment with statins. When LDL decreases to reach the LDL threshold for treatment, but apoB remains elevated, there is the potential for misclassification of CV risk and essentially the risk for undertreatment of someone whose CV risk is actually higher than it appears to be if we only look at their LDL-C. The consensus statement says, "Where there is discordance between apoB and LDL-C, risk follows apoB."

This understanding leads to the places where measurement of apoB may be helpful:

In patients with borderline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in whom a shared decision about statin therapy is being determined and the patient prefers not to start a statin, apoB can be useful for further risk stratification. If apoB suggests low risk, then statin therapy could be withheld, and if apoB is high, that would favor starting statin therapy. Certain common conditions, such as obesity and insulin resistance, can lead to smaller cholesterol-depleted LDL particles that result in lower LDL-C, but elevated apoB levels in this circumstance may drive the decision to treat with a statin.

In patients already treated with statins, but a decision must be made about whether treatment intensification is warranted. If the LDL-C is to goal and apoB is above threshold, treatment intensification may be considered. In patients who are not yet to goal, based on an elevated apoB, the first step is intensification of statin therapy. After that, intensification would be the same as has already been addressed in my review of the 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Role of Nonstatin Therapies for LDL-Cholesterol Lowering.

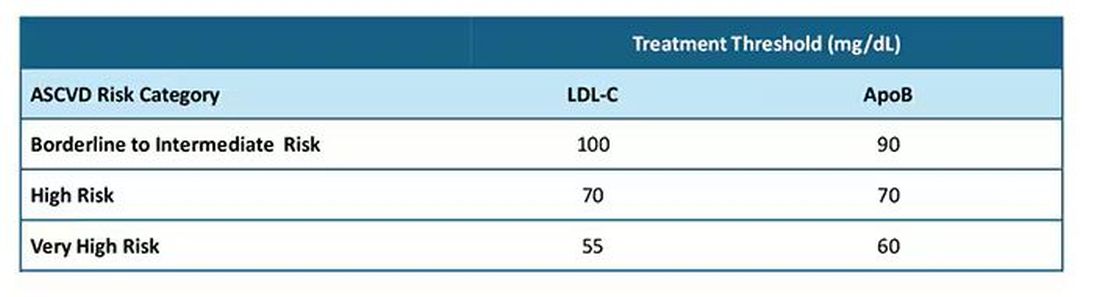

After clarifying the importance of apoB in providing additional discrimination of CV risk, the consensus statement clarifies the treatment thresholds, or goals for treatment, for apoB that correlate with established LDL-C thresholds, as shown in this table:

Let me be really clear: The consensus statement does not say that we need to measure apoB in all patients or that such measurement is the standard of care. It is not. It says, and I'll quote, "At present, the use of apoB to assess the effectiveness of lipid-lowering therapies remains a matter of clinical judgment." This guideline is helpful in pointing out the patients most likely to benefit from this additional measurement, including those with hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes, visceral adiposity, insulin resistance/metabolic syndrome, low HDL-C, or very low LDL-C levels.

In summary, measurement of apoB can be helpful for further risk stratification in patients with borderline or intermediate LDL-C levels, and for deciding whether further intensification of lipid-lowering therapy may be warranted when the LDL threshold has been reached.

Lipid management is something that we do every day in the office. This is new information, or at least clarifying information, for most of us. Hopefully it is helpful. I'm interested in your thoughts on this topic, including whether and how you plan to use apoB measurements.

Dr. Skolnik, Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia; Associate Director, Department of Family Medicine, Abington Jefferson Health, Abington, Pennsylvania, disclosed ties with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I've been hearing a lot about apolipoprotein B (apoB) lately. It keeps popping up, but I've not been sure where it fits in or what I should do about it. The new Expert Clinical Consensus from the National Lipid Association now finally gives us clear guidance.

ApoB is the main protein that is found on all atherogenic lipoproteins. It is found on low-density lipoprotein (LDL) but also on other atherogenic lipoprotein particles. Because it is a part of all atherogenic particles, it predicts cardiovascular (CV) risk more accurately than does LDL cholesterol (LDL-C).

ApoB and LDL-C tend to run together, but not always. While they are correlated fairly well on a population level, for a given individual they can diverge; and when they do, apoB is the better predictor of future CV outcomes. This divergence occurs frequently, and it can occur even more frequently after treatment with statins. When LDL decreases to reach the LDL threshold for treatment, but apoB remains elevated, there is the potential for misclassification of CV risk and essentially the risk for undertreatment of someone whose CV risk is actually higher than it appears to be if we only look at their LDL-C. The consensus statement says, "Where there is discordance between apoB and LDL-C, risk follows apoB."

This understanding leads to the places where measurement of apoB may be helpful:

In patients with borderline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in whom a shared decision about statin therapy is being determined and the patient prefers not to start a statin, apoB can be useful for further risk stratification. If apoB suggests low risk, then statin therapy could be withheld, and if apoB is high, that would favor starting statin therapy. Certain common conditions, such as obesity and insulin resistance, can lead to smaller cholesterol-depleted LDL particles that result in lower LDL-C, but elevated apoB levels in this circumstance may drive the decision to treat with a statin.

In patients already treated with statins, but a decision must be made about whether treatment intensification is warranted. If the LDL-C is to goal and apoB is above threshold, treatment intensification may be considered. In patients who are not yet to goal, based on an elevated apoB, the first step is intensification of statin therapy. After that, intensification would be the same as has already been addressed in my review of the 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Role of Nonstatin Therapies for LDL-Cholesterol Lowering.

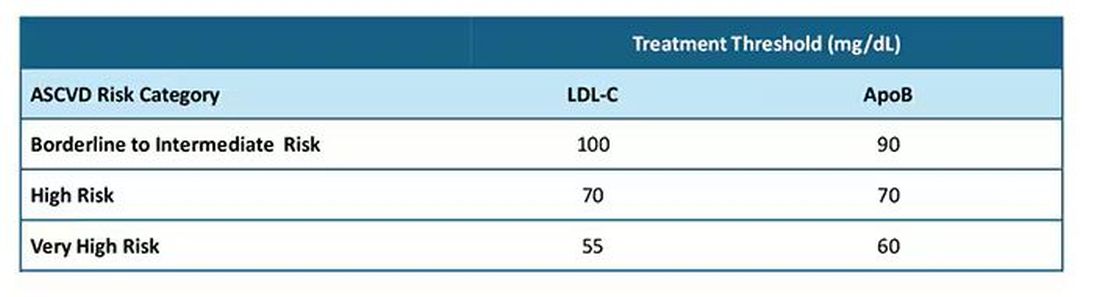

After clarifying the importance of apoB in providing additional discrimination of CV risk, the consensus statement clarifies the treatment thresholds, or goals for treatment, for apoB that correlate with established LDL-C thresholds, as shown in this table:

Let me be really clear: The consensus statement does not say that we need to measure apoB in all patients or that such measurement is the standard of care. It is not. It says, and I'll quote, "At present, the use of apoB to assess the effectiveness of lipid-lowering therapies remains a matter of clinical judgment." This guideline is helpful in pointing out the patients most likely to benefit from this additional measurement, including those with hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes, visceral adiposity, insulin resistance/metabolic syndrome, low HDL-C, or very low LDL-C levels.

In summary, measurement of apoB can be helpful for further risk stratification in patients with borderline or intermediate LDL-C levels, and for deciding whether further intensification of lipid-lowering therapy may be warranted when the LDL threshold has been reached.

Lipid management is something that we do every day in the office. This is new information, or at least clarifying information, for most of us. Hopefully it is helpful. I'm interested in your thoughts on this topic, including whether and how you plan to use apoB measurements.

Dr. Skolnik, Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia; Associate Director, Department of Family Medicine, Abington Jefferson Health, Abington, Pennsylvania, disclosed ties with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I've been hearing a lot about apolipoprotein B (apoB) lately. It keeps popping up, but I've not been sure where it fits in or what I should do about it. The new Expert Clinical Consensus from the National Lipid Association now finally gives us clear guidance.

ApoB is the main protein that is found on all atherogenic lipoproteins. It is found on low-density lipoprotein (LDL) but also on other atherogenic lipoprotein particles. Because it is a part of all atherogenic particles, it predicts cardiovascular (CV) risk more accurately than does LDL cholesterol (LDL-C).

ApoB and LDL-C tend to run together, but not always. While they are correlated fairly well on a population level, for a given individual they can diverge; and when they do, apoB is the better predictor of future CV outcomes. This divergence occurs frequently, and it can occur even more frequently after treatment with statins. When LDL decreases to reach the LDL threshold for treatment, but apoB remains elevated, there is the potential for misclassification of CV risk and essentially the risk for undertreatment of someone whose CV risk is actually higher than it appears to be if we only look at their LDL-C. The consensus statement says, "Where there is discordance between apoB and LDL-C, risk follows apoB."

This understanding leads to the places where measurement of apoB may be helpful:

In patients with borderline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in whom a shared decision about statin therapy is being determined and the patient prefers not to start a statin, apoB can be useful for further risk stratification. If apoB suggests low risk, then statin therapy could be withheld, and if apoB is high, that would favor starting statin therapy. Certain common conditions, such as obesity and insulin resistance, can lead to smaller cholesterol-depleted LDL particles that result in lower LDL-C, but elevated apoB levels in this circumstance may drive the decision to treat with a statin.

In patients already treated with statins, but a decision must be made about whether treatment intensification is warranted. If the LDL-C is to goal and apoB is above threshold, treatment intensification may be considered. In patients who are not yet to goal, based on an elevated apoB, the first step is intensification of statin therapy. After that, intensification would be the same as has already been addressed in my review of the 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Role of Nonstatin Therapies for LDL-Cholesterol Lowering.

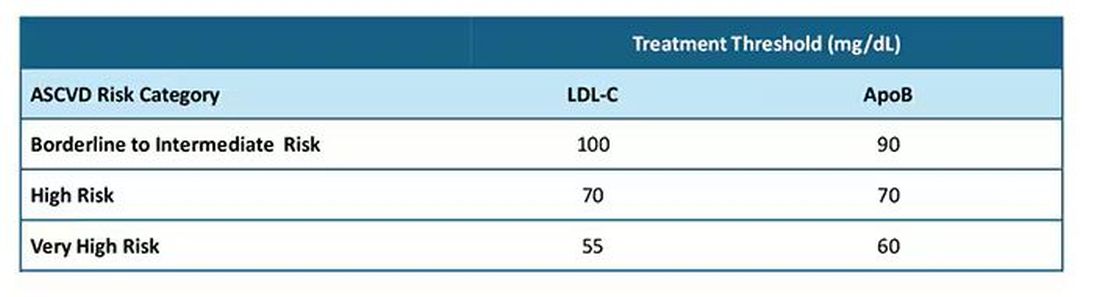

After clarifying the importance of apoB in providing additional discrimination of CV risk, the consensus statement clarifies the treatment thresholds, or goals for treatment, for apoB that correlate with established LDL-C thresholds, as shown in this table:

Let me be really clear: The consensus statement does not say that we need to measure apoB in all patients or that such measurement is the standard of care. It is not. It says, and I'll quote, "At present, the use of apoB to assess the effectiveness of lipid-lowering therapies remains a matter of clinical judgment." This guideline is helpful in pointing out the patients most likely to benefit from this additional measurement, including those with hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes, visceral adiposity, insulin resistance/metabolic syndrome, low HDL-C, or very low LDL-C levels.

In summary, measurement of apoB can be helpful for further risk stratification in patients with borderline or intermediate LDL-C levels, and for deciding whether further intensification of lipid-lowering therapy may be warranted when the LDL threshold has been reached.

Lipid management is something that we do every day in the office. This is new information, or at least clarifying information, for most of us. Hopefully it is helpful. I'm interested in your thoughts on this topic, including whether and how you plan to use apoB measurements.

Dr. Skolnik, Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia; Associate Director, Department of Family Medicine, Abington Jefferson Health, Abington, Pennsylvania, disclosed ties with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Meaningful Use Criteria: What's Missing

Since the passage of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act in February of 2009, there has been a tremendous amount of discussion about the idea of “meaningful use.” Associated with the meaningful use criteria are financial incentives for those who adopt an electronic health record and care for Medicare and Medicaid patients. Such incentives may total more than $40k-60k per provider. Those who fail to meet the criteria will find their reimbursements reduced beginning in 2016.

Despite the abundance of commentary and speculation over meaningful use, until recently the term had not actually been defined. And now that the full set of rules for meaningful use is available, it might surprise some to know what has actually been excluded from the criteria.

In explaining the meaningful use concept at the beginning of this year, the Department of Health and Human Services laid out a number of objectives and priorities centered on improving the quality, safety, efficiency, and accessibility of care. Any aspects of electronic health record (EHR) implementation that do not meet those goals have been specifically left out of the criteria. In doing so, the intent is to challenge health care providers to move forward toward the goal of EHR implementation, while acknowledging the limitations of the technology currently available.

The first and most fascinating exclusion is any requirement for encounter note generation. The criteria specifically state that it will not be necessary for providers to document their encounter notes using the EHR, commenting that proper documentation is “a medical-legal requirement and a component of basic EHR functionality, [but] is not directly related to advanced processes of care or improvements in quality, safety, or efficiency,” according to the report (Federal Register 2010;75:1843-2010).

In other words, while most EHR products emphasize electronic note generation, the authors feel this does not provide a significant benefit over handwritten charting in meeting the goals of HITECH.

Many might disagree with this statement, but others may be breathing a sigh of relief. The challenge of typing office notes has long been among the most feared by physicians with limited computer skills. These providers may rest assured, knowing that—for now—holding onto pen and paper for documenting patient encounters will not preclude them from the financial incentives under the HITECH act. Still, it might be difficult to implement an EHR without this piece, as once an office becomes dependent on the technology, workflow can be significantly hindered by searching for documentation that is not in the electronic record.

To address this, some practices have chosen to scan in handwritten notes. Unfortunately, this might preclude critical data points from being captured by the system, and make it impossible to meet some of the quality reporting goals laid out elsewhere in HITECH.

A second intentional omission in the criteria is the requirement that providers make educational resources available to patients. In spite of a clear objective to involve patients more in their care, the authors are reluctant to make this a necessity. They admit that proper information and education are “a critical component of patient engagement and empowerment,” but acknowledge that “there is currently a paucity of knowledge resources that are integrated within EHRs, that are widely available, and that meet [our] criteria, particularly in multiple languages.”

As it turns out, many EHR products do include patient education resources, but these often are limited in quality and come at an additional fee. As an alternative, online resources available through Web sites such as familydoctor.orgemedicine.com

Another anticipated requirement that's been excluded from the criteria is the necessity for orders to be transmitted electronically from care provider to testing, diagnostic imaging, or treatment facilities. It should be noted that computerized physician order entry (CPOE) is greatly emphasized under HITECH, with the objective that 80% of orders be entered through the EHR. CPOE is defined as “the provider's use of computer assistance to directly enter medical orders (for example, medications, consultations with other providers, laboratory services, imaging studies, and other auxiliary services) from a computer or mobile device.” But in the criteria released so far, the requirements “will not include the electronic transmittal of [those orders] to the pharmacy, laboratory, or diagnostic imaging center.” Since the guidelines do require e-prescribing to meet criteria, further clarification is needed to determine which orders must be sent electronically and which do not.

A review of these exclusions makes it apparent that no one is completely sure how the meaningful use criteria will affect day-to-day practice. The authors of the legislation have attempted to challenge the status-quo and yet maintain a practical perspective on what is possible with the resources at hand. Many physicians will remain skeptical of any government intervention in health care but can at least now be assured that the financial incentives are attached to a fairly practical set of requirements.

Since the passage of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act in February of 2009, there has been a tremendous amount of discussion about the idea of “meaningful use.” Associated with the meaningful use criteria are financial incentives for those who adopt an electronic health record and care for Medicare and Medicaid patients. Such incentives may total more than $40k-60k per provider. Those who fail to meet the criteria will find their reimbursements reduced beginning in 2016.

Despite the abundance of commentary and speculation over meaningful use, until recently the term had not actually been defined. And now that the full set of rules for meaningful use is available, it might surprise some to know what has actually been excluded from the criteria.

In explaining the meaningful use concept at the beginning of this year, the Department of Health and Human Services laid out a number of objectives and priorities centered on improving the quality, safety, efficiency, and accessibility of care. Any aspects of electronic health record (EHR) implementation that do not meet those goals have been specifically left out of the criteria. In doing so, the intent is to challenge health care providers to move forward toward the goal of EHR implementation, while acknowledging the limitations of the technology currently available.

The first and most fascinating exclusion is any requirement for encounter note generation. The criteria specifically state that it will not be necessary for providers to document their encounter notes using the EHR, commenting that proper documentation is “a medical-legal requirement and a component of basic EHR functionality, [but] is not directly related to advanced processes of care or improvements in quality, safety, or efficiency,” according to the report (Federal Register 2010;75:1843-2010).

In other words, while most EHR products emphasize electronic note generation, the authors feel this does not provide a significant benefit over handwritten charting in meeting the goals of HITECH.

Many might disagree with this statement, but others may be breathing a sigh of relief. The challenge of typing office notes has long been among the most feared by physicians with limited computer skills. These providers may rest assured, knowing that—for now—holding onto pen and paper for documenting patient encounters will not preclude them from the financial incentives under the HITECH act. Still, it might be difficult to implement an EHR without this piece, as once an office becomes dependent on the technology, workflow can be significantly hindered by searching for documentation that is not in the electronic record.

To address this, some practices have chosen to scan in handwritten notes. Unfortunately, this might preclude critical data points from being captured by the system, and make it impossible to meet some of the quality reporting goals laid out elsewhere in HITECH.

A second intentional omission in the criteria is the requirement that providers make educational resources available to patients. In spite of a clear objective to involve patients more in their care, the authors are reluctant to make this a necessity. They admit that proper information and education are “a critical component of patient engagement and empowerment,” but acknowledge that “there is currently a paucity of knowledge resources that are integrated within EHRs, that are widely available, and that meet [our] criteria, particularly in multiple languages.”

As it turns out, many EHR products do include patient education resources, but these often are limited in quality and come at an additional fee. As an alternative, online resources available through Web sites such as familydoctor.orgemedicine.com

Another anticipated requirement that's been excluded from the criteria is the necessity for orders to be transmitted electronically from care provider to testing, diagnostic imaging, or treatment facilities. It should be noted that computerized physician order entry (CPOE) is greatly emphasized under HITECH, with the objective that 80% of orders be entered through the EHR. CPOE is defined as “the provider's use of computer assistance to directly enter medical orders (for example, medications, consultations with other providers, laboratory services, imaging studies, and other auxiliary services) from a computer or mobile device.” But in the criteria released so far, the requirements “will not include the electronic transmittal of [those orders] to the pharmacy, laboratory, or diagnostic imaging center.” Since the guidelines do require e-prescribing to meet criteria, further clarification is needed to determine which orders must be sent electronically and which do not.

A review of these exclusions makes it apparent that no one is completely sure how the meaningful use criteria will affect day-to-day practice. The authors of the legislation have attempted to challenge the status-quo and yet maintain a practical perspective on what is possible with the resources at hand. Many physicians will remain skeptical of any government intervention in health care but can at least now be assured that the financial incentives are attached to a fairly practical set of requirements.

Since the passage of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act in February of 2009, there has been a tremendous amount of discussion about the idea of “meaningful use.” Associated with the meaningful use criteria are financial incentives for those who adopt an electronic health record and care for Medicare and Medicaid patients. Such incentives may total more than $40k-60k per provider. Those who fail to meet the criteria will find their reimbursements reduced beginning in 2016.

Despite the abundance of commentary and speculation over meaningful use, until recently the term had not actually been defined. And now that the full set of rules for meaningful use is available, it might surprise some to know what has actually been excluded from the criteria.

In explaining the meaningful use concept at the beginning of this year, the Department of Health and Human Services laid out a number of objectives and priorities centered on improving the quality, safety, efficiency, and accessibility of care. Any aspects of electronic health record (EHR) implementation that do not meet those goals have been specifically left out of the criteria. In doing so, the intent is to challenge health care providers to move forward toward the goal of EHR implementation, while acknowledging the limitations of the technology currently available.

The first and most fascinating exclusion is any requirement for encounter note generation. The criteria specifically state that it will not be necessary for providers to document their encounter notes using the EHR, commenting that proper documentation is “a medical-legal requirement and a component of basic EHR functionality, [but] is not directly related to advanced processes of care or improvements in quality, safety, or efficiency,” according to the report (Federal Register 2010;75:1843-2010).

In other words, while most EHR products emphasize electronic note generation, the authors feel this does not provide a significant benefit over handwritten charting in meeting the goals of HITECH.

Many might disagree with this statement, but others may be breathing a sigh of relief. The challenge of typing office notes has long been among the most feared by physicians with limited computer skills. These providers may rest assured, knowing that—for now—holding onto pen and paper for documenting patient encounters will not preclude them from the financial incentives under the HITECH act. Still, it might be difficult to implement an EHR without this piece, as once an office becomes dependent on the technology, workflow can be significantly hindered by searching for documentation that is not in the electronic record.

To address this, some practices have chosen to scan in handwritten notes. Unfortunately, this might preclude critical data points from being captured by the system, and make it impossible to meet some of the quality reporting goals laid out elsewhere in HITECH.

A second intentional omission in the criteria is the requirement that providers make educational resources available to patients. In spite of a clear objective to involve patients more in their care, the authors are reluctant to make this a necessity. They admit that proper information and education are “a critical component of patient engagement and empowerment,” but acknowledge that “there is currently a paucity of knowledge resources that are integrated within EHRs, that are widely available, and that meet [our] criteria, particularly in multiple languages.”

As it turns out, many EHR products do include patient education resources, but these often are limited in quality and come at an additional fee. As an alternative, online resources available through Web sites such as familydoctor.orgemedicine.com

Another anticipated requirement that's been excluded from the criteria is the necessity for orders to be transmitted electronically from care provider to testing, diagnostic imaging, or treatment facilities. It should be noted that computerized physician order entry (CPOE) is greatly emphasized under HITECH, with the objective that 80% of orders be entered through the EHR. CPOE is defined as “the provider's use of computer assistance to directly enter medical orders (for example, medications, consultations with other providers, laboratory services, imaging studies, and other auxiliary services) from a computer or mobile device.” But in the criteria released so far, the requirements “will not include the electronic transmittal of [those orders] to the pharmacy, laboratory, or diagnostic imaging center.” Since the guidelines do require e-prescribing to meet criteria, further clarification is needed to determine which orders must be sent electronically and which do not.

A review of these exclusions makes it apparent that no one is completely sure how the meaningful use criteria will affect day-to-day practice. The authors of the legislation have attempted to challenge the status-quo and yet maintain a practical perspective on what is possible with the resources at hand. Many physicians will remain skeptical of any government intervention in health care but can at least now be assured that the financial incentives are attached to a fairly practical set of requirements.

Teamwork Is Key to a Successful Transition

The failure of EHR implementations is often due to productivity loss, and nothing is more detrimental to productivity than discouraged employees. Before taking the giant leap, it is critical to solidify support from all members of a practice staff and build enthusiasm for the transition. The only proven way to do this is to create a transition team to effectively guide the process and allay fears about the changes to office workflow.

The first team-member role that should be defined is the “physician champion,” who will communicate with fellow providers and foster an environment that is excited about change. No matter how big or small a practice, there will always be naysayers, and that means the champion will need to have strong staff rapport and be effective at communicating the goals of the transition.

This person will have a significant impact on how the new technology will affect patient care, so the other providers must trust the champion to act in their best interests. He or she will act as a “superuser” of the EHR software, possessing a firm grasp on most aspects of its operation, and be available to help the staff with technical questions.

Next, identify the team manager. This may be the office manager or another staff member with good organizational and communication skills.

With the primary responsibility of overseeing the transition team, this person must clearly understand the needs of the practice and keep the process moving forward according to the established timeline. He or she will be the go-between for the EHR vendor and the transition team to ensure that all concerns are addressed and will keep track of information related to the process. Together with the physician champion, the team manager will select the rest of the transition committee.

It is typically beneficial to select one individual from each department—including members of the front, back, and clinical office staff—so that all aspects of office workflow can be considered. It can be invaluable to choose influential individuals who are excited about the new technology. Be sure to spend some time assessing the strengths and relationships of individual staff members prior to making the choice.

Once the team members are identified, the real work begins. The first step is to establish a common vision. Early on, presentations providing a preview of the EHR software can be helpful to ensure that the team members are all on board with the same objectives.

Ask the EHR vendor to provide a demonstration to the entire office that highlights the features of the product and allows them to interact with it. Often, this demo will raise questions and concerns that can then be addressed by the transition team. This leads to the next—and perhaps the most important—step to implementation success: Create buy-in from the staff.

Medical professionals have a reputation, whether deserved or not, of disliking change. After all, routine in the workplace is often the source of efficiency, and disrupting the routine can significantly impact workflow. There is no question that introducing information technologies into an office will be disruptive. For those employees with limited technical skill, the mere idea of spending any more time interacting with computers may be daunting. For others, it may feel like an unnecessary inconvenience.

To address these concerns, highlight ways in which the EHR implementation may save time and make life easier: automating appointment reminders and refill requests, simplifying repetitive office processes, and increasing the legibility of progress notes. What once was handwritten and clipped onto a paper chart can now be documented electronically. This is not only more secure, but also makes it easier to search for notes and other documents later. Charge capture can be dramatically improved with more accurate coding and billing, and staff time can be optimized by avoiding chart pulls and streamlining quality data reporting.

If the technology is used to its full potential, every office process will be affected by the transition. The hope is that ultimately it will provide an opportunity to examine current workflow procedures and improve on them. This can be achieved if the leadership communicates the vision and reason for the change and addresses employee concerns.

The failure of EHR implementations is often due to productivity loss, and nothing is more detrimental to productivity than discouraged employees. Before taking the giant leap, it is critical to solidify support from all members of a practice staff and build enthusiasm for the transition. The only proven way to do this is to create a transition team to effectively guide the process and allay fears about the changes to office workflow.

The first team-member role that should be defined is the “physician champion,” who will communicate with fellow providers and foster an environment that is excited about change. No matter how big or small a practice, there will always be naysayers, and that means the champion will need to have strong staff rapport and be effective at communicating the goals of the transition.

This person will have a significant impact on how the new technology will affect patient care, so the other providers must trust the champion to act in their best interests. He or she will act as a “superuser” of the EHR software, possessing a firm grasp on most aspects of its operation, and be available to help the staff with technical questions.

Next, identify the team manager. This may be the office manager or another staff member with good organizational and communication skills.

With the primary responsibility of overseeing the transition team, this person must clearly understand the needs of the practice and keep the process moving forward according to the established timeline. He or she will be the go-between for the EHR vendor and the transition team to ensure that all concerns are addressed and will keep track of information related to the process. Together with the physician champion, the team manager will select the rest of the transition committee.

It is typically beneficial to select one individual from each department—including members of the front, back, and clinical office staff—so that all aspects of office workflow can be considered. It can be invaluable to choose influential individuals who are excited about the new technology. Be sure to spend some time assessing the strengths and relationships of individual staff members prior to making the choice.

Once the team members are identified, the real work begins. The first step is to establish a common vision. Early on, presentations providing a preview of the EHR software can be helpful to ensure that the team members are all on board with the same objectives.

Ask the EHR vendor to provide a demonstration to the entire office that highlights the features of the product and allows them to interact with it. Often, this demo will raise questions and concerns that can then be addressed by the transition team. This leads to the next—and perhaps the most important—step to implementation success: Create buy-in from the staff.

Medical professionals have a reputation, whether deserved or not, of disliking change. After all, routine in the workplace is often the source of efficiency, and disrupting the routine can significantly impact workflow. There is no question that introducing information technologies into an office will be disruptive. For those employees with limited technical skill, the mere idea of spending any more time interacting with computers may be daunting. For others, it may feel like an unnecessary inconvenience.

To address these concerns, highlight ways in which the EHR implementation may save time and make life easier: automating appointment reminders and refill requests, simplifying repetitive office processes, and increasing the legibility of progress notes. What once was handwritten and clipped onto a paper chart can now be documented electronically. This is not only more secure, but also makes it easier to search for notes and other documents later. Charge capture can be dramatically improved with more accurate coding and billing, and staff time can be optimized by avoiding chart pulls and streamlining quality data reporting.

If the technology is used to its full potential, every office process will be affected by the transition. The hope is that ultimately it will provide an opportunity to examine current workflow procedures and improve on them. This can be achieved if the leadership communicates the vision and reason for the change and addresses employee concerns.

The failure of EHR implementations is often due to productivity loss, and nothing is more detrimental to productivity than discouraged employees. Before taking the giant leap, it is critical to solidify support from all members of a practice staff and build enthusiasm for the transition. The only proven way to do this is to create a transition team to effectively guide the process and allay fears about the changes to office workflow.

The first team-member role that should be defined is the “physician champion,” who will communicate with fellow providers and foster an environment that is excited about change. No matter how big or small a practice, there will always be naysayers, and that means the champion will need to have strong staff rapport and be effective at communicating the goals of the transition.

This person will have a significant impact on how the new technology will affect patient care, so the other providers must trust the champion to act in their best interests. He or she will act as a “superuser” of the EHR software, possessing a firm grasp on most aspects of its operation, and be available to help the staff with technical questions.

Next, identify the team manager. This may be the office manager or another staff member with good organizational and communication skills.

With the primary responsibility of overseeing the transition team, this person must clearly understand the needs of the practice and keep the process moving forward according to the established timeline. He or she will be the go-between for the EHR vendor and the transition team to ensure that all concerns are addressed and will keep track of information related to the process. Together with the physician champion, the team manager will select the rest of the transition committee.

It is typically beneficial to select one individual from each department—including members of the front, back, and clinical office staff—so that all aspects of office workflow can be considered. It can be invaluable to choose influential individuals who are excited about the new technology. Be sure to spend some time assessing the strengths and relationships of individual staff members prior to making the choice.

Once the team members are identified, the real work begins. The first step is to establish a common vision. Early on, presentations providing a preview of the EHR software can be helpful to ensure that the team members are all on board with the same objectives.

Ask the EHR vendor to provide a demonstration to the entire office that highlights the features of the product and allows them to interact with it. Often, this demo will raise questions and concerns that can then be addressed by the transition team. This leads to the next—and perhaps the most important—step to implementation success: Create buy-in from the staff.

Medical professionals have a reputation, whether deserved or not, of disliking change. After all, routine in the workplace is often the source of efficiency, and disrupting the routine can significantly impact workflow. There is no question that introducing information technologies into an office will be disruptive. For those employees with limited technical skill, the mere idea of spending any more time interacting with computers may be daunting. For others, it may feel like an unnecessary inconvenience.

To address these concerns, highlight ways in which the EHR implementation may save time and make life easier: automating appointment reminders and refill requests, simplifying repetitive office processes, and increasing the legibility of progress notes. What once was handwritten and clipped onto a paper chart can now be documented electronically. This is not only more secure, but also makes it easier to search for notes and other documents later. Charge capture can be dramatically improved with more accurate coding and billing, and staff time can be optimized by avoiding chart pulls and streamlining quality data reporting.

If the technology is used to its full potential, every office process will be affected by the transition. The hope is that ultimately it will provide an opportunity to examine current workflow procedures and improve on them. This can be achieved if the leadership communicates the vision and reason for the change and addresses employee concerns.

EHRs Get a Failing Grade on Usability

Despite the federal government's pledges of financial incentives and eventual penalties, adoption rates of electronic health record (EHR) systems remain stubbornly low. When a product or service is still underutilized, even after being subsidized by public funds, we have to ask ourselves why.

Many vendors advise physicians that extensive training is needed to learn how to document a note using their system and that they should be prepared to reduce their patient volume throughout the EHR adoption period. This lost patient volume is the direct result of data collection gone awry.

Instead of focusing data collection on key elements required for interaction—checking and billing, for example—most EHR systems require users to codify all data. This means physicians and their staff will spend time navigating through multiple windows, drop-down menus, and check box lists to record something as simple as “3 days of productive cough.” Multiply that effort by all the data collected during a brief encounter and you have a note that takes more time to document than the visit itself. The very fact that vendors require extensive training is proof that these EHRs are neither intuitively designed nor easy to use.

The concept of “usability” is defined as the ease with which people can use a particular product to accomplish defined goals. The lack of usability has been a major cause of dissatisfaction with EHR systems. It has been estimated that one in every three EHR adoptions fail, with poor usability likely a major contributing factor.

Unfortunately, the true experience of an EHR's usability only occurs well after an EHR contract is signed, training has completed, and the light patient load has ended. That is when the seriousness of poor EHR usability becomes apparent.

To compensate, many physicians end up using templates, macros, and preset lists. This may help alleviate the slowdown caused by an EHR's poor design, and the resulting patient notes may be full of data, but they often lack any real substance. The real story in each patient encounter is frequently lost. This is a common complaint reported by physicians attempting to use notes generated by an EHR.

To add insult to injury, there is an ever-growing list of horror stories reported by physicians who have given up on their EHRs. Unfortunately, many EHR vendors do not allow dissatisfied users out of their long-term contracts. Or if a vendor does allow a physician out of the contract at a reduced cost, there are often stipulations. One of the physicians we interviewed for this article said that he was negotiating an early termination of his contract, but to do so he had to sign a nondisclosure statement saying he would never comment on his poor experience with that EHR.

So how can a physician avoid ending up with an EHR that may be unusable? It is essential to review the experience of those who have already purchased an EHR. The American Academy of Family Physicians' Center for Health IT provides a Web site through which members can rate their own EHR based on a five-point scale measuring quality, price, support, ease of use, and impact on productivity. Sorting the available list of 93 EHR systems by rating provides a clear look at overall user satisfaction (www.centerforhit.org

User satisfaction studies are another indispensable resource. An October 2009 survey of over 3,700 EHR users published by Medscape.comwww.medscape.com/viewarticle/709856

Similarly, “The 2009 EHR User Satisfaction Survey,” published in the November/December 2009 issue of Family Practice Management, provides a troubling look at how physicians rate many of the best-known EHRs. This survey's final question asked 2,012 family physicians if they agreed or disagreed with the following statement, “I am highly satisfied with this EHR system.” Astoundingly, nearly 50% of all respondents said that they would not agree.

With the current rate of physician dissatisfaction, EHR adoption rates will likely remain low despite the government incentives. Perhaps most ironic is that federal financial incentives to adopt EHR systems may contribute to delays in improvements in EHR usability. Rather than allowing competition to reward vendors who produce better software at lower prices, the stimulus money encourages physicians to purchase mediocre software at inflated prices.

As physicians recognize the perils of signing EHR contracts before they truly know if an EHR is usable, they will begin to demand usable, intuitive EHRs.

Increasingly, physicians will come to appreciate how financial incentives and initial system costs are dwarfed by the potential reduction in productivity and revenue when a system proves difficult to use.

As they gain more exposure to the EHR market, physicians will start to ask the important questions and demand answers about the critical issue of usability, which ultimately makes or breaks their EHR experience.

Despite the federal government's pledges of financial incentives and eventual penalties, adoption rates of electronic health record (EHR) systems remain stubbornly low. When a product or service is still underutilized, even after being subsidized by public funds, we have to ask ourselves why.

Many vendors advise physicians that extensive training is needed to learn how to document a note using their system and that they should be prepared to reduce their patient volume throughout the EHR adoption period. This lost patient volume is the direct result of data collection gone awry.

Instead of focusing data collection on key elements required for interaction—checking and billing, for example—most EHR systems require users to codify all data. This means physicians and their staff will spend time navigating through multiple windows, drop-down menus, and check box lists to record something as simple as “3 days of productive cough.” Multiply that effort by all the data collected during a brief encounter and you have a note that takes more time to document than the visit itself. The very fact that vendors require extensive training is proof that these EHRs are neither intuitively designed nor easy to use.

The concept of “usability” is defined as the ease with which people can use a particular product to accomplish defined goals. The lack of usability has been a major cause of dissatisfaction with EHR systems. It has been estimated that one in every three EHR adoptions fail, with poor usability likely a major contributing factor.

Unfortunately, the true experience of an EHR's usability only occurs well after an EHR contract is signed, training has completed, and the light patient load has ended. That is when the seriousness of poor EHR usability becomes apparent.

To compensate, many physicians end up using templates, macros, and preset lists. This may help alleviate the slowdown caused by an EHR's poor design, and the resulting patient notes may be full of data, but they often lack any real substance. The real story in each patient encounter is frequently lost. This is a common complaint reported by physicians attempting to use notes generated by an EHR.

To add insult to injury, there is an ever-growing list of horror stories reported by physicians who have given up on their EHRs. Unfortunately, many EHR vendors do not allow dissatisfied users out of their long-term contracts. Or if a vendor does allow a physician out of the contract at a reduced cost, there are often stipulations. One of the physicians we interviewed for this article said that he was negotiating an early termination of his contract, but to do so he had to sign a nondisclosure statement saying he would never comment on his poor experience with that EHR.

So how can a physician avoid ending up with an EHR that may be unusable? It is essential to review the experience of those who have already purchased an EHR. The American Academy of Family Physicians' Center for Health IT provides a Web site through which members can rate their own EHR based on a five-point scale measuring quality, price, support, ease of use, and impact on productivity. Sorting the available list of 93 EHR systems by rating provides a clear look at overall user satisfaction (www.centerforhit.org

User satisfaction studies are another indispensable resource. An October 2009 survey of over 3,700 EHR users published by Medscape.comwww.medscape.com/viewarticle/709856

Similarly, “The 2009 EHR User Satisfaction Survey,” published in the November/December 2009 issue of Family Practice Management, provides a troubling look at how physicians rate many of the best-known EHRs. This survey's final question asked 2,012 family physicians if they agreed or disagreed with the following statement, “I am highly satisfied with this EHR system.” Astoundingly, nearly 50% of all respondents said that they would not agree.

With the current rate of physician dissatisfaction, EHR adoption rates will likely remain low despite the government incentives. Perhaps most ironic is that federal financial incentives to adopt EHR systems may contribute to delays in improvements in EHR usability. Rather than allowing competition to reward vendors who produce better software at lower prices, the stimulus money encourages physicians to purchase mediocre software at inflated prices.

As physicians recognize the perils of signing EHR contracts before they truly know if an EHR is usable, they will begin to demand usable, intuitive EHRs.

Increasingly, physicians will come to appreciate how financial incentives and initial system costs are dwarfed by the potential reduction in productivity and revenue when a system proves difficult to use.

As they gain more exposure to the EHR market, physicians will start to ask the important questions and demand answers about the critical issue of usability, which ultimately makes or breaks their EHR experience.

Despite the federal government's pledges of financial incentives and eventual penalties, adoption rates of electronic health record (EHR) systems remain stubbornly low. When a product or service is still underutilized, even after being subsidized by public funds, we have to ask ourselves why.

Many vendors advise physicians that extensive training is needed to learn how to document a note using their system and that they should be prepared to reduce their patient volume throughout the EHR adoption period. This lost patient volume is the direct result of data collection gone awry.

Instead of focusing data collection on key elements required for interaction—checking and billing, for example—most EHR systems require users to codify all data. This means physicians and their staff will spend time navigating through multiple windows, drop-down menus, and check box lists to record something as simple as “3 days of productive cough.” Multiply that effort by all the data collected during a brief encounter and you have a note that takes more time to document than the visit itself. The very fact that vendors require extensive training is proof that these EHRs are neither intuitively designed nor easy to use.

The concept of “usability” is defined as the ease with which people can use a particular product to accomplish defined goals. The lack of usability has been a major cause of dissatisfaction with EHR systems. It has been estimated that one in every three EHR adoptions fail, with poor usability likely a major contributing factor.

Unfortunately, the true experience of an EHR's usability only occurs well after an EHR contract is signed, training has completed, and the light patient load has ended. That is when the seriousness of poor EHR usability becomes apparent.

To compensate, many physicians end up using templates, macros, and preset lists. This may help alleviate the slowdown caused by an EHR's poor design, and the resulting patient notes may be full of data, but they often lack any real substance. The real story in each patient encounter is frequently lost. This is a common complaint reported by physicians attempting to use notes generated by an EHR.

To add insult to injury, there is an ever-growing list of horror stories reported by physicians who have given up on their EHRs. Unfortunately, many EHR vendors do not allow dissatisfied users out of their long-term contracts. Or if a vendor does allow a physician out of the contract at a reduced cost, there are often stipulations. One of the physicians we interviewed for this article said that he was negotiating an early termination of his contract, but to do so he had to sign a nondisclosure statement saying he would never comment on his poor experience with that EHR.

So how can a physician avoid ending up with an EHR that may be unusable? It is essential to review the experience of those who have already purchased an EHR. The American Academy of Family Physicians' Center for Health IT provides a Web site through which members can rate their own EHR based on a five-point scale measuring quality, price, support, ease of use, and impact on productivity. Sorting the available list of 93 EHR systems by rating provides a clear look at overall user satisfaction (www.centerforhit.org

User satisfaction studies are another indispensable resource. An October 2009 survey of over 3,700 EHR users published by Medscape.comwww.medscape.com/viewarticle/709856

Similarly, “The 2009 EHR User Satisfaction Survey,” published in the November/December 2009 issue of Family Practice Management, provides a troubling look at how physicians rate many of the best-known EHRs. This survey's final question asked 2,012 family physicians if they agreed or disagreed with the following statement, “I am highly satisfied with this EHR system.” Astoundingly, nearly 50% of all respondents said that they would not agree.

With the current rate of physician dissatisfaction, EHR adoption rates will likely remain low despite the government incentives. Perhaps most ironic is that federal financial incentives to adopt EHR systems may contribute to delays in improvements in EHR usability. Rather than allowing competition to reward vendors who produce better software at lower prices, the stimulus money encourages physicians to purchase mediocre software at inflated prices.

As physicians recognize the perils of signing EHR contracts before they truly know if an EHR is usable, they will begin to demand usable, intuitive EHRs.

Increasingly, physicians will come to appreciate how financial incentives and initial system costs are dwarfed by the potential reduction in productivity and revenue when a system proves difficult to use.

As they gain more exposure to the EHR market, physicians will start to ask the important questions and demand answers about the critical issue of usability, which ultimately makes or breaks their EHR experience.

Going Paperless

As medical practices grow, so does the number of charts occupying space on their shelves. Most physicians look forward to the day when they can dispense with paper charts completely and reclaim precious office space. Unfortunately, the goal of a paperless office is a very difficult one to achieve. It can take years to get there and, even with the best EHR software, the process of adding old data into the system can be arduous.

There are two basic methods to input old paper records. Historical information such as diagnoses, medication lists, and allergies can be manually entered by the physician or staff. More detailed information, such as reports of procedures or correspondence from other physicians, will need to be scanned into the record. Either way, it will take a significant amount of work to enter even a small number of charts. This can be both time consuming and costly. There are many pitfalls that may not be obvious initially, so it can be helpful to consider the following tips:

Begin by Looking Forward

Typically, it is most beneficial to work forward from the point of installation and ensure that all new patient information is immediately entered into the EHR to avoid creating a paper chart entirely. One way to do this is to “scan forward”—that is, to scan documents received only after the EHR is in place. Such scanned documents can immediately be digitized and attached to the patient's electronic chart. The original can then be shredded instead of adding it to the paper record. By doing so, there will be a single date marking the end of information available on paper. After that date, all staff members will know to look in the EHR to find the data they need.

Take It One Day at a Time

One way to feasibly address the problem of entering old information into the EHR is to do a limited but consistent amount every day. But where to start? Many practices select charts to scan by reviewing the following day's patient schedule. By “preloading” charts, important data are available at the time of an appointment, and the charts of so-called “frequent flyer” patients are usually among the first to be entered. Once the chart has been inputted, it can be archived off-site or properly disposed of.

To Scan or Not to Scan

Commonly, patient charts are filled with a tremendous amount of irrelevant information. Amidst the radiology reports, notes, and letters are likely to be dozens of sticky notes, blank pages, fax cover sheets, and antiquated data. For a couple of reasons, it behooves a practice to spend time prepping charts before scanning them.

First, every page that is scanned will need to be indexed for the EHR to properly file it. It would be extremely cumbersome, when searching for an old lab result, to have to wade through dozens of papers at random. Indexing allows all documents to be sorted by type and date, but this process is extremely time consuming. Each page scanned needs to be individually addressed. To minimize the amount of indexing, a practice may decide to only sort information of a certain age or type. Everything else can be then placed into a general, unsorted electronic file. In this way, the most important data are easy to find, yet even less valuable documents can be located with a bit of effort if necessary.

The second compelling reason is cost, both in staff hours and in storage. Many offices choose EHR solutions that are hosted off-site. All data exist on an external server and, depending on the nature of the storage agreement, every page scanned into the system may incur an additional charge. In most cases the rate is about a penny a page. One need not take a very long look at the chart rack to realize how quickly the price will add up. Choosing to electronically archive only the most important items can help minimize the economic impact and make the overall process much more efficient.

When to Say Good-Bye to Paper

There are a few commonly cited reasons why practices hesitate to finally eliminate paper charts. First is the fear of unintentionally losing critical patient data. This is reasonable, and data security should be a primary consideration when designing an electronic storage solution. All EHR vendors have set specifications for storage focused on security and reliability. If the data are to be maintained on-site, one way to ensure safety is through continuous backup. Higher standards are typically maintained at off-site storage facilities with multiple levels of redundancy. A well-chosen storage method should alleviate any fears of data loss.

The second reason practices hold on to paper records is concern about the need to produce the chart for possible malpractice proceedings. This represents a misunderstanding about the legality of electronic media. Regardless of where the chart is stored—on paper or in cyberspace—it is acceptable in a court of law. The length of time the data must be maintained varies from state to state, but is typically about 7 years for adults or 7 years after turning age 18 for minors. Fortunately, once all the charts are archived, they can be safely and securely maintained indefinitely without the ever-growing need for a bigger office to store them.

As medical practices grow, so does the number of charts occupying space on their shelves. Most physicians look forward to the day when they can dispense with paper charts completely and reclaim precious office space. Unfortunately, the goal of a paperless office is a very difficult one to achieve. It can take years to get there and, even with the best EHR software, the process of adding old data into the system can be arduous.

There are two basic methods to input old paper records. Historical information such as diagnoses, medication lists, and allergies can be manually entered by the physician or staff. More detailed information, such as reports of procedures or correspondence from other physicians, will need to be scanned into the record. Either way, it will take a significant amount of work to enter even a small number of charts. This can be both time consuming and costly. There are many pitfalls that may not be obvious initially, so it can be helpful to consider the following tips:

Begin by Looking Forward

Typically, it is most beneficial to work forward from the point of installation and ensure that all new patient information is immediately entered into the EHR to avoid creating a paper chart entirely. One way to do this is to “scan forward”—that is, to scan documents received only after the EHR is in place. Such scanned documents can immediately be digitized and attached to the patient's electronic chart. The original can then be shredded instead of adding it to the paper record. By doing so, there will be a single date marking the end of information available on paper. After that date, all staff members will know to look in the EHR to find the data they need.

Take It One Day at a Time

One way to feasibly address the problem of entering old information into the EHR is to do a limited but consistent amount every day. But where to start? Many practices select charts to scan by reviewing the following day's patient schedule. By “preloading” charts, important data are available at the time of an appointment, and the charts of so-called “frequent flyer” patients are usually among the first to be entered. Once the chart has been inputted, it can be archived off-site or properly disposed of.

To Scan or Not to Scan

Commonly, patient charts are filled with a tremendous amount of irrelevant information. Amidst the radiology reports, notes, and letters are likely to be dozens of sticky notes, blank pages, fax cover sheets, and antiquated data. For a couple of reasons, it behooves a practice to spend time prepping charts before scanning them.

First, every page that is scanned will need to be indexed for the EHR to properly file it. It would be extremely cumbersome, when searching for an old lab result, to have to wade through dozens of papers at random. Indexing allows all documents to be sorted by type and date, but this process is extremely time consuming. Each page scanned needs to be individually addressed. To minimize the amount of indexing, a practice may decide to only sort information of a certain age or type. Everything else can be then placed into a general, unsorted electronic file. In this way, the most important data are easy to find, yet even less valuable documents can be located with a bit of effort if necessary.

The second compelling reason is cost, both in staff hours and in storage. Many offices choose EHR solutions that are hosted off-site. All data exist on an external server and, depending on the nature of the storage agreement, every page scanned into the system may incur an additional charge. In most cases the rate is about a penny a page. One need not take a very long look at the chart rack to realize how quickly the price will add up. Choosing to electronically archive only the most important items can help minimize the economic impact and make the overall process much more efficient.

When to Say Good-Bye to Paper

There are a few commonly cited reasons why practices hesitate to finally eliminate paper charts. First is the fear of unintentionally losing critical patient data. This is reasonable, and data security should be a primary consideration when designing an electronic storage solution. All EHR vendors have set specifications for storage focused on security and reliability. If the data are to be maintained on-site, one way to ensure safety is through continuous backup. Higher standards are typically maintained at off-site storage facilities with multiple levels of redundancy. A well-chosen storage method should alleviate any fears of data loss.

The second reason practices hold on to paper records is concern about the need to produce the chart for possible malpractice proceedings. This represents a misunderstanding about the legality of electronic media. Regardless of where the chart is stored—on paper or in cyberspace—it is acceptable in a court of law. The length of time the data must be maintained varies from state to state, but is typically about 7 years for adults or 7 years after turning age 18 for minors. Fortunately, once all the charts are archived, they can be safely and securely maintained indefinitely without the ever-growing need for a bigger office to store them.

As medical practices grow, so does the number of charts occupying space on their shelves. Most physicians look forward to the day when they can dispense with paper charts completely and reclaim precious office space. Unfortunately, the goal of a paperless office is a very difficult one to achieve. It can take years to get there and, even with the best EHR software, the process of adding old data into the system can be arduous.

There are two basic methods to input old paper records. Historical information such as diagnoses, medication lists, and allergies can be manually entered by the physician or staff. More detailed information, such as reports of procedures or correspondence from other physicians, will need to be scanned into the record. Either way, it will take a significant amount of work to enter even a small number of charts. This can be both time consuming and costly. There are many pitfalls that may not be obvious initially, so it can be helpful to consider the following tips:

Begin by Looking Forward

Typically, it is most beneficial to work forward from the point of installation and ensure that all new patient information is immediately entered into the EHR to avoid creating a paper chart entirely. One way to do this is to “scan forward”—that is, to scan documents received only after the EHR is in place. Such scanned documents can immediately be digitized and attached to the patient's electronic chart. The original can then be shredded instead of adding it to the paper record. By doing so, there will be a single date marking the end of information available on paper. After that date, all staff members will know to look in the EHR to find the data they need.

Take It One Day at a Time

One way to feasibly address the problem of entering old information into the EHR is to do a limited but consistent amount every day. But where to start? Many practices select charts to scan by reviewing the following day's patient schedule. By “preloading” charts, important data are available at the time of an appointment, and the charts of so-called “frequent flyer” patients are usually among the first to be entered. Once the chart has been inputted, it can be archived off-site or properly disposed of.

To Scan or Not to Scan

Commonly, patient charts are filled with a tremendous amount of irrelevant information. Amidst the radiology reports, notes, and letters are likely to be dozens of sticky notes, blank pages, fax cover sheets, and antiquated data. For a couple of reasons, it behooves a practice to spend time prepping charts before scanning them.

First, every page that is scanned will need to be indexed for the EHR to properly file it. It would be extremely cumbersome, when searching for an old lab result, to have to wade through dozens of papers at random. Indexing allows all documents to be sorted by type and date, but this process is extremely time consuming. Each page scanned needs to be individually addressed. To minimize the amount of indexing, a practice may decide to only sort information of a certain age or type. Everything else can be then placed into a general, unsorted electronic file. In this way, the most important data are easy to find, yet even less valuable documents can be located with a bit of effort if necessary.

The second compelling reason is cost, both in staff hours and in storage. Many offices choose EHR solutions that are hosted off-site. All data exist on an external server and, depending on the nature of the storage agreement, every page scanned into the system may incur an additional charge. In most cases the rate is about a penny a page. One need not take a very long look at the chart rack to realize how quickly the price will add up. Choosing to electronically archive only the most important items can help minimize the economic impact and make the overall process much more efficient.

When to Say Good-Bye to Paper

There are a few commonly cited reasons why practices hesitate to finally eliminate paper charts. First is the fear of unintentionally losing critical patient data. This is reasonable, and data security should be a primary consideration when designing an electronic storage solution. All EHR vendors have set specifications for storage focused on security and reliability. If the data are to be maintained on-site, one way to ensure safety is through continuous backup. Higher standards are typically maintained at off-site storage facilities with multiple levels of redundancy. A well-chosen storage method should alleviate any fears of data loss.

The second reason practices hold on to paper records is concern about the need to produce the chart for possible malpractice proceedings. This represents a misunderstanding about the legality of electronic media. Regardless of where the chart is stored—on paper or in cyberspace—it is acceptable in a court of law. The length of time the data must be maintained varies from state to state, but is typically about 7 years for adults or 7 years after turning age 18 for minors. Fortunately, once all the charts are archived, they can be safely and securely maintained indefinitely without the ever-growing need for a bigger office to store them.

Virtual Patient Encounters

One of the greatest proposed advantages of electronic health record systems is enhanced physician-patient interaction. Most of the recommended EHR products available today include a Web-based portal that facilitates communication, allowing for the sharing of lab results, medication refill requests, and follow-up after an in-office consultation. Many questions arise, though, when implementing these services, and these issues should be considered before making the leap into electronic visits.

Are e-visits secure?

Many physicians and patients are reluctant to embrace health-related electronic communication because they question its security. Given the ever-looming shadow of HIPAA and frequent reports of personal data being stolen by hackers, this is a reasonable concern. In fact, according to SecureWorks, an Atlanta-based managed security firm, electronic attacks on health care organizations doubled in the fourth quarter of 2009. This underscores the importance of ensuring that the communication medium is designed to protect sensitive data.

Most EHR products that include an interactive portal require that both the physician and the patient log in to the same encrypted Web site to ensure that the data stay on a single server and are not mailed through cyberspace, where they can be intercepted and stolen. Such portals also allow communication to be limited to referral requests or lab result notices, which helps prevent unwanted or inappropriate messages from flooding a physician's in-box. Personal e-mail accounts should never be used by physicians or patients to communicate sensitive information. Not only do such accounts lack security, but they provide the possibility for patients to take inappropriate advantage of the professional relationship.

What are the legal aspects of e-visits?

Unfortunately, every advance in health care provides a new opportunity for litigation. With electronic medical communications, several significant legal pitfalls can arise. E-mails that are typed quickly and casually can be easily misconstrued, and once written, such electronic exchanges provide indelible documentation of every interaction. It is therefore very important to be careful when communicating health-related information electronically.

It's a good idea to set guidelines that limit what and how information is to be communicated. In 2002, the American Medical Association produced well-designed guidelines that cover not only the technical aspects of electronic communications, but also include a code of ethics that should be followed when using e-mail. For example, the AMA encourages that e-mail be supplemental to office visits and only be used after a clear discussion with the patient about privacy issues.

More recently, several AMA publications have addressed social networking media, such as Facebook and MySpace. Although these sites can present a great opportunity for marketing and sharing general practice information, they may jeopardize the physician-patient relationship by blurring the line between personal and professional communication.

How do e-visits affect the bottom line?

With an increase in virtual availability to patients, it becomes very easy to foresee a future of electronic visits eliminating the need for certain in-office consultations. Depending on an individual physician's payer mix, this can have a dramatic impact on income. It might benefit those with a high percentage of Medicaid or capitated patients, but it could be greatly detrimental to a practice with a larger share of fee-for-service patients, as it's not clear if and when insurers will begin reimbursement for electronic visits.

Currently, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services limits reimbursement for electronic patient encounters only to regions where there is limited access to health care. In light of the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act, several proposals are being considered that would expand payment opportunities to all areas of the country.

A few private insurers have begun compensating physicians for e-visits. BlueCross BlueShield of North Carolina recently started to offer reimbursement under specific CPT codes. So far, the insurer reports that only 31% of participating providers are using electronic patient communications, while 74% of members desire to interact with their physicians in this way.

As more practices adopt EHR systems and insurers expand reimbursement, the true mark of success will be better health care outcomes and improved satisfaction for both physicians and patients.

One of the greatest proposed advantages of electronic health record systems is enhanced physician-patient interaction. Most of the recommended EHR products available today include a Web-based portal that facilitates communication, allowing for the sharing of lab results, medication refill requests, and follow-up after an in-office consultation. Many questions arise, though, when implementing these services, and these issues should be considered before making the leap into electronic visits.

Are e-visits secure?

Many physicians and patients are reluctant to embrace health-related electronic communication because they question its security. Given the ever-looming shadow of HIPAA and frequent reports of personal data being stolen by hackers, this is a reasonable concern. In fact, according to SecureWorks, an Atlanta-based managed security firm, electronic attacks on health care organizations doubled in the fourth quarter of 2009. This underscores the importance of ensuring that the communication medium is designed to protect sensitive data.

Most EHR products that include an interactive portal require that both the physician and the patient log in to the same encrypted Web site to ensure that the data stay on a single server and are not mailed through cyberspace, where they can be intercepted and stolen. Such portals also allow communication to be limited to referral requests or lab result notices, which helps prevent unwanted or inappropriate messages from flooding a physician's in-box. Personal e-mail accounts should never be used by physicians or patients to communicate sensitive information. Not only do such accounts lack security, but they provide the possibility for patients to take inappropriate advantage of the professional relationship.