User login

Triple therapy in question

Clinical question: In patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), is dabigatran plus a P2Y12 inhibitor safer than, and as efficacious as, triple therapy with warfarin?

Background: Recent studies have shown that patients on long-term anticoagulation who undergo PCI can be managed on oral anticoagulants and P2Y12 inhibitors with lower bleeding rates than do those who receive triple therapy.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: 414 sites in 41 countries.

Synopsis: In 2,725 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI, low-dose (110 mg, twice daily) and high-dose (150 mg, twice daily) dabigatran plus a P2Y12 inhibitor lowered absolute bleeding risk by 11.5% and 5.5%, respectively, compared with triple therapy. Rates of thrombosis, death, and unexpected revascularization as a composite endpoint were noninferior to triple therapy for both dabigatran doses studied. In patients on dabigatran for atrial fibrillation, it is reasonable to continue dabigatran and add a single P2Y12 inhibitor (clopidogrel or ticagrelor) but not aspirin after PCI. In patients at high risk for bleeding complications, it may be reasonable to dose reduce the dabigatran from 150 mg twice daily to 110 mg twice daily before starting antiplatelet therapy, although the study was underpowered to examine this.

Bottom line: In patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI, dabigatran plus clopidogrel or ticagrelor had lower bleeding rates and was noninferior with respect to the risk of thromboembolic events when compared with triple therapy with warfarin.

Citation: Cannon CP et al. Dual antithrombotic therapy with dabigatran after PCI in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708454.

Dr. Theobald is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Clinical question: In patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), is dabigatran plus a P2Y12 inhibitor safer than, and as efficacious as, triple therapy with warfarin?

Background: Recent studies have shown that patients on long-term anticoagulation who undergo PCI can be managed on oral anticoagulants and P2Y12 inhibitors with lower bleeding rates than do those who receive triple therapy.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: 414 sites in 41 countries.

Synopsis: In 2,725 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI, low-dose (110 mg, twice daily) and high-dose (150 mg, twice daily) dabigatran plus a P2Y12 inhibitor lowered absolute bleeding risk by 11.5% and 5.5%, respectively, compared with triple therapy. Rates of thrombosis, death, and unexpected revascularization as a composite endpoint were noninferior to triple therapy for both dabigatran doses studied. In patients on dabigatran for atrial fibrillation, it is reasonable to continue dabigatran and add a single P2Y12 inhibitor (clopidogrel or ticagrelor) but not aspirin after PCI. In patients at high risk for bleeding complications, it may be reasonable to dose reduce the dabigatran from 150 mg twice daily to 110 mg twice daily before starting antiplatelet therapy, although the study was underpowered to examine this.

Bottom line: In patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI, dabigatran plus clopidogrel or ticagrelor had lower bleeding rates and was noninferior with respect to the risk of thromboembolic events when compared with triple therapy with warfarin.

Citation: Cannon CP et al. Dual antithrombotic therapy with dabigatran after PCI in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708454.

Dr. Theobald is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Clinical question: In patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), is dabigatran plus a P2Y12 inhibitor safer than, and as efficacious as, triple therapy with warfarin?

Background: Recent studies have shown that patients on long-term anticoagulation who undergo PCI can be managed on oral anticoagulants and P2Y12 inhibitors with lower bleeding rates than do those who receive triple therapy.

Study design: Randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: 414 sites in 41 countries.

Synopsis: In 2,725 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI, low-dose (110 mg, twice daily) and high-dose (150 mg, twice daily) dabigatran plus a P2Y12 inhibitor lowered absolute bleeding risk by 11.5% and 5.5%, respectively, compared with triple therapy. Rates of thrombosis, death, and unexpected revascularization as a composite endpoint were noninferior to triple therapy for both dabigatran doses studied. In patients on dabigatran for atrial fibrillation, it is reasonable to continue dabigatran and add a single P2Y12 inhibitor (clopidogrel or ticagrelor) but not aspirin after PCI. In patients at high risk for bleeding complications, it may be reasonable to dose reduce the dabigatran from 150 mg twice daily to 110 mg twice daily before starting antiplatelet therapy, although the study was underpowered to examine this.

Bottom line: In patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI, dabigatran plus clopidogrel or ticagrelor had lower bleeding rates and was noninferior with respect to the risk of thromboembolic events when compared with triple therapy with warfarin.

Citation: Cannon CP et al. Dual antithrombotic therapy with dabigatran after PCI in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct 19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708454.

Dr. Theobald is a hospitalist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

The Frontier of Transition Medicine: A Unique Inpatient Model for Transitions of Care

The transition of care from pediatric to adult providers has drawn increased national attention to the survival of patients with chronic childhood conditions into adulthood.ttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11432/ While survival outcomes have improved due to advances in care, many of these patients experience gaps in medical care when they move from pediatric to adult healthcare systems, resulting in age-inappropriate and fragmented care in adulthood.4 Many youth with chronic childhood conditions are not prepared to move into adult healthcare, and this lack of transition preparation is associated with poorer health outcomes, including elevated glycosylated hemoglobin and loss of transplanted organs.5-7 National transition efforts have largely focused on the outpatient setting and there remains a paucity of literature on inpatient transitions of care.8,9 Although transition-age patients represent a small percentage of patients at children’s hospitals, they accumulate more hospital days and have higher resource utilization compared to their pediatric cohorts.10 In this issue, Coller et al.11 characterize the current state of pediatric to adult inpatient transitions of care among general pediatric services at US children’s hospitals. Over 50% of children’s hospitals did not have a specific adult-oriented hospital identified to receive transitioning patients. Fewer than half of hospitals (38%) had an explicit inpatient transition policy. Notably only 2% of hospitals could track patient outcomes through transitions; however, 41% had systems in place to address insurance issues. Institutions with combined internal medicine-pediatric (Med-Peds) providers more frequently had inpatient transition initiatives (P = .04). It is clear from Coller et al.11 that the adoption of transition initiatives has been delayed since its introduction at the US Surgeon’s conference in 1989, and much work is needed to bridge this gap.12

Coller et al.11 spearhead establishing standardized transition programs using the multidisciplinary Six Core Elements framework and highlight effective techniques from existing inpatient transition processes.13 While we encourage providers to utilize existing partnerships in the outpatient community to bridge the gap for this at-risk population, shifting to adult care continues to be disorganized in the face of some key barriers including challenges in addressing psychosocial needs, gaps in insurance, and poor care coordination between pediatric and adult healthcare systems.4

We propose several inpatient activities to improve transitions. First, we suggest the development of an inpatient transition or Med-Peds consult service across all hospitals. The Med-Peds consult service would implement the Six Core Elements, including transition readiness, transition planning, and providing insurance and referral resources. A Med-Peds consult service has been well received at our institution as it identifies clear leaders with expertise in transition. Coller et al.11 report only 11% of children’s hospitals surveyed had transition policies that referenced inpatient transitions of care. For those institutions without Med-Peds providers, we recommend establishing a hospital-wide transition policy, and identifying hospitalists trained in transitions, with multidisciplinary approaches to staff their transition consult service.

Tracking and monitoring youth in the inpatient transition process occurred in only 2% of hospitals surveyed. We urge for automatic consults to the transition service for adult aged patients admitted to children’s hospitals. With current electronic health records (EHRs), admission order sets with built-in transition consults for adolescents and young adults would improve the identification and tracking of youths. Assuming care of a pediatric patient with multiple comorbidities can be overwhelming for providers.14 The transition consult service could alleviate some of this anxiety with clear and concise documentation using standardized, readily available transition templates. These templates would summarize the patient’s past medical history and outline current medical problems, necessary subspecialty referrals, insurance status, limitations in activities of daily living, ancillary services (including physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, transportation services), and current level of readiness and independence.

In summary, the transition of care from pediatric to adult providers is a particularly vulnerable time for young adults with chronic medical conditions, and efforts focused on inpatient transitions of medical care have overall been limited. Crucial barriers include addressing psychosocial needs, gaps in insurance, and poor communication between pediatric and adult providers.4 Coller et al.11 have identified several gaps in inpatient transitions of care as well as multiple areas of focus to improve the patient experience. Based on the findings of this study, we urge children’s hospitals caring for adult patients to identify transition leaders, partner with an adult hospital to foster effective transitions, and to protocolize inpatient and outpatient models of transition. Perhaps the most concerning finding of this study was the widespread inability to track transition outcomes. Our group’s experience has led us to believe that coupling an inpatient transition consult team with EHR-based interventions to identify patients and follow outcomes has the most potential to improve inpatient transitions of care from pediatric to adult providers.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interests or financial disclosures.

1. Elborn JS, Shale DJ, Britton JR. Cystic fibrosis: current survival and population estimates to the year 2000. Thorax. 1991;46(12):881-885.

2. Reid GJ, Webb GD, Barzel M, McCrindle BW, Irvine MJ, Siu SC. Estimates of life expectancy by adolescents and young adults with congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(2):349-355. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.041.

3. Ferris ME, Gipson DS, Kimmel PL, Eggers PW. Trends in treatment and outcomes of survival of adolescents initiating end-stage renal disease care in the United States of America. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21(7):1020-1026. doi:10.1007/s00467-006-0059-9.

4. Sharma N, O’Hare K, Antonelli RC, Sawicki GS. Transition care: future directions in education, health policy, and outcomes research. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14(2):120-127. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2013.11.007.

5. Harden PN, Walsh G, Bandler N, et al. Bridging the gap: an integrated paediatric to adult clinical service for young adults with kidney failure. BMJ. 2012;344:e3718. doi:10.1136/bmj.e3718.

6. Watson AR. Non-compliance and transfer from paediatric to adult transplant unit. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;14(6):469-472.

7. Lotstein DS, Seid M, Klingensmith G, et al. Transition from pediatric to adult care for youth diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in adolescence. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):e1062-1070. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-1450.

8. Scal P. Transition for youth with chronic conditions: primary care physicians’ approaches. Pediatrics. 2002;110(6 Pt 2):1315-1321.

9. Kelly AM, Kratz B, Bielski M, Rinehart PM. Implementing transitions for youth with complex chronic conditions using the medical home model. Pediatrics. 2002;110(6 Pt 2):1322-1327.

10. Goodman DM, Hall M, Levin A, et al. Adults with chronic health conditions originating in childhood: inpatient experience in children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):5-13. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-2037.

11. Coller RJ, Ahrens S, Ehlenbach M, et al. Transitioning from General Pediatric to Adult-Oriented Inpatient Care: National Survey of US Children’s Hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(1):13-20.

12. Olson D. Health Care Transitions for Young People. In Field MJ, Jette AM, Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Disability in America, editors. The Future of Disability in America. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2007. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11432/.

13. GotTransition.org. http://www.gottransition.org/. Accessed September 15, 2017.

14. Okumura MJ, Kerr EA, Cabana MD, Davis MM, Demonner S, Heisler M. Physician views on barriers to primary care for young adults with childhood-onset chronic disease. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):e748-754. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-3451.

The transition of care from pediatric to adult providers has drawn increased national attention to the survival of patients with chronic childhood conditions into adulthood.ttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11432/ While survival outcomes have improved due to advances in care, many of these patients experience gaps in medical care when they move from pediatric to adult healthcare systems, resulting in age-inappropriate and fragmented care in adulthood.4 Many youth with chronic childhood conditions are not prepared to move into adult healthcare, and this lack of transition preparation is associated with poorer health outcomes, including elevated glycosylated hemoglobin and loss of transplanted organs.5-7 National transition efforts have largely focused on the outpatient setting and there remains a paucity of literature on inpatient transitions of care.8,9 Although transition-age patients represent a small percentage of patients at children’s hospitals, they accumulate more hospital days and have higher resource utilization compared to their pediatric cohorts.10 In this issue, Coller et al.11 characterize the current state of pediatric to adult inpatient transitions of care among general pediatric services at US children’s hospitals. Over 50% of children’s hospitals did not have a specific adult-oriented hospital identified to receive transitioning patients. Fewer than half of hospitals (38%) had an explicit inpatient transition policy. Notably only 2% of hospitals could track patient outcomes through transitions; however, 41% had systems in place to address insurance issues. Institutions with combined internal medicine-pediatric (Med-Peds) providers more frequently had inpatient transition initiatives (P = .04). It is clear from Coller et al.11 that the adoption of transition initiatives has been delayed since its introduction at the US Surgeon’s conference in 1989, and much work is needed to bridge this gap.12

Coller et al.11 spearhead establishing standardized transition programs using the multidisciplinary Six Core Elements framework and highlight effective techniques from existing inpatient transition processes.13 While we encourage providers to utilize existing partnerships in the outpatient community to bridge the gap for this at-risk population, shifting to adult care continues to be disorganized in the face of some key barriers including challenges in addressing psychosocial needs, gaps in insurance, and poor care coordination between pediatric and adult healthcare systems.4

We propose several inpatient activities to improve transitions. First, we suggest the development of an inpatient transition or Med-Peds consult service across all hospitals. The Med-Peds consult service would implement the Six Core Elements, including transition readiness, transition planning, and providing insurance and referral resources. A Med-Peds consult service has been well received at our institution as it identifies clear leaders with expertise in transition. Coller et al.11 report only 11% of children’s hospitals surveyed had transition policies that referenced inpatient transitions of care. For those institutions without Med-Peds providers, we recommend establishing a hospital-wide transition policy, and identifying hospitalists trained in transitions, with multidisciplinary approaches to staff their transition consult service.

Tracking and monitoring youth in the inpatient transition process occurred in only 2% of hospitals surveyed. We urge for automatic consults to the transition service for adult aged patients admitted to children’s hospitals. With current electronic health records (EHRs), admission order sets with built-in transition consults for adolescents and young adults would improve the identification and tracking of youths. Assuming care of a pediatric patient with multiple comorbidities can be overwhelming for providers.14 The transition consult service could alleviate some of this anxiety with clear and concise documentation using standardized, readily available transition templates. These templates would summarize the patient’s past medical history and outline current medical problems, necessary subspecialty referrals, insurance status, limitations in activities of daily living, ancillary services (including physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, transportation services), and current level of readiness and independence.

In summary, the transition of care from pediatric to adult providers is a particularly vulnerable time for young adults with chronic medical conditions, and efforts focused on inpatient transitions of medical care have overall been limited. Crucial barriers include addressing psychosocial needs, gaps in insurance, and poor communication between pediatric and adult providers.4 Coller et al.11 have identified several gaps in inpatient transitions of care as well as multiple areas of focus to improve the patient experience. Based on the findings of this study, we urge children’s hospitals caring for adult patients to identify transition leaders, partner with an adult hospital to foster effective transitions, and to protocolize inpatient and outpatient models of transition. Perhaps the most concerning finding of this study was the widespread inability to track transition outcomes. Our group’s experience has led us to believe that coupling an inpatient transition consult team with EHR-based interventions to identify patients and follow outcomes has the most potential to improve inpatient transitions of care from pediatric to adult providers.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interests or financial disclosures.

The transition of care from pediatric to adult providers has drawn increased national attention to the survival of patients with chronic childhood conditions into adulthood.ttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11432/ While survival outcomes have improved due to advances in care, many of these patients experience gaps in medical care when they move from pediatric to adult healthcare systems, resulting in age-inappropriate and fragmented care in adulthood.4 Many youth with chronic childhood conditions are not prepared to move into adult healthcare, and this lack of transition preparation is associated with poorer health outcomes, including elevated glycosylated hemoglobin and loss of transplanted organs.5-7 National transition efforts have largely focused on the outpatient setting and there remains a paucity of literature on inpatient transitions of care.8,9 Although transition-age patients represent a small percentage of patients at children’s hospitals, they accumulate more hospital days and have higher resource utilization compared to their pediatric cohorts.10 In this issue, Coller et al.11 characterize the current state of pediatric to adult inpatient transitions of care among general pediatric services at US children’s hospitals. Over 50% of children’s hospitals did not have a specific adult-oriented hospital identified to receive transitioning patients. Fewer than half of hospitals (38%) had an explicit inpatient transition policy. Notably only 2% of hospitals could track patient outcomes through transitions; however, 41% had systems in place to address insurance issues. Institutions with combined internal medicine-pediatric (Med-Peds) providers more frequently had inpatient transition initiatives (P = .04). It is clear from Coller et al.11 that the adoption of transition initiatives has been delayed since its introduction at the US Surgeon’s conference in 1989, and much work is needed to bridge this gap.12

Coller et al.11 spearhead establishing standardized transition programs using the multidisciplinary Six Core Elements framework and highlight effective techniques from existing inpatient transition processes.13 While we encourage providers to utilize existing partnerships in the outpatient community to bridge the gap for this at-risk population, shifting to adult care continues to be disorganized in the face of some key barriers including challenges in addressing psychosocial needs, gaps in insurance, and poor care coordination between pediatric and adult healthcare systems.4

We propose several inpatient activities to improve transitions. First, we suggest the development of an inpatient transition or Med-Peds consult service across all hospitals. The Med-Peds consult service would implement the Six Core Elements, including transition readiness, transition planning, and providing insurance and referral resources. A Med-Peds consult service has been well received at our institution as it identifies clear leaders with expertise in transition. Coller et al.11 report only 11% of children’s hospitals surveyed had transition policies that referenced inpatient transitions of care. For those institutions without Med-Peds providers, we recommend establishing a hospital-wide transition policy, and identifying hospitalists trained in transitions, with multidisciplinary approaches to staff their transition consult service.

Tracking and monitoring youth in the inpatient transition process occurred in only 2% of hospitals surveyed. We urge for automatic consults to the transition service for adult aged patients admitted to children’s hospitals. With current electronic health records (EHRs), admission order sets with built-in transition consults for adolescents and young adults would improve the identification and tracking of youths. Assuming care of a pediatric patient with multiple comorbidities can be overwhelming for providers.14 The transition consult service could alleviate some of this anxiety with clear and concise documentation using standardized, readily available transition templates. These templates would summarize the patient’s past medical history and outline current medical problems, necessary subspecialty referrals, insurance status, limitations in activities of daily living, ancillary services (including physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, transportation services), and current level of readiness and independence.

In summary, the transition of care from pediatric to adult providers is a particularly vulnerable time for young adults with chronic medical conditions, and efforts focused on inpatient transitions of medical care have overall been limited. Crucial barriers include addressing psychosocial needs, gaps in insurance, and poor communication between pediatric and adult providers.4 Coller et al.11 have identified several gaps in inpatient transitions of care as well as multiple areas of focus to improve the patient experience. Based on the findings of this study, we urge children’s hospitals caring for adult patients to identify transition leaders, partner with an adult hospital to foster effective transitions, and to protocolize inpatient and outpatient models of transition. Perhaps the most concerning finding of this study was the widespread inability to track transition outcomes. Our group’s experience has led us to believe that coupling an inpatient transition consult team with EHR-based interventions to identify patients and follow outcomes has the most potential to improve inpatient transitions of care from pediatric to adult providers.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interests or financial disclosures.

1. Elborn JS, Shale DJ, Britton JR. Cystic fibrosis: current survival and population estimates to the year 2000. Thorax. 1991;46(12):881-885.

2. Reid GJ, Webb GD, Barzel M, McCrindle BW, Irvine MJ, Siu SC. Estimates of life expectancy by adolescents and young adults with congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(2):349-355. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.041.

3. Ferris ME, Gipson DS, Kimmel PL, Eggers PW. Trends in treatment and outcomes of survival of adolescents initiating end-stage renal disease care in the United States of America. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21(7):1020-1026. doi:10.1007/s00467-006-0059-9.

4. Sharma N, O’Hare K, Antonelli RC, Sawicki GS. Transition care: future directions in education, health policy, and outcomes research. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14(2):120-127. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2013.11.007.

5. Harden PN, Walsh G, Bandler N, et al. Bridging the gap: an integrated paediatric to adult clinical service for young adults with kidney failure. BMJ. 2012;344:e3718. doi:10.1136/bmj.e3718.

6. Watson AR. Non-compliance and transfer from paediatric to adult transplant unit. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;14(6):469-472.

7. Lotstein DS, Seid M, Klingensmith G, et al. Transition from pediatric to adult care for youth diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in adolescence. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):e1062-1070. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-1450.

8. Scal P. Transition for youth with chronic conditions: primary care physicians’ approaches. Pediatrics. 2002;110(6 Pt 2):1315-1321.

9. Kelly AM, Kratz B, Bielski M, Rinehart PM. Implementing transitions for youth with complex chronic conditions using the medical home model. Pediatrics. 2002;110(6 Pt 2):1322-1327.

10. Goodman DM, Hall M, Levin A, et al. Adults with chronic health conditions originating in childhood: inpatient experience in children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):5-13. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-2037.

11. Coller RJ, Ahrens S, Ehlenbach M, et al. Transitioning from General Pediatric to Adult-Oriented Inpatient Care: National Survey of US Children’s Hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(1):13-20.

12. Olson D. Health Care Transitions for Young People. In Field MJ, Jette AM, Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Disability in America, editors. The Future of Disability in America. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2007. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11432/.

13. GotTransition.org. http://www.gottransition.org/. Accessed September 15, 2017.

14. Okumura MJ, Kerr EA, Cabana MD, Davis MM, Demonner S, Heisler M. Physician views on barriers to primary care for young adults with childhood-onset chronic disease. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):e748-754. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-3451.

1. Elborn JS, Shale DJ, Britton JR. Cystic fibrosis: current survival and population estimates to the year 2000. Thorax. 1991;46(12):881-885.

2. Reid GJ, Webb GD, Barzel M, McCrindle BW, Irvine MJ, Siu SC. Estimates of life expectancy by adolescents and young adults with congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(2):349-355. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.041.

3. Ferris ME, Gipson DS, Kimmel PL, Eggers PW. Trends in treatment and outcomes of survival of adolescents initiating end-stage renal disease care in the United States of America. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21(7):1020-1026. doi:10.1007/s00467-006-0059-9.

4. Sharma N, O’Hare K, Antonelli RC, Sawicki GS. Transition care: future directions in education, health policy, and outcomes research. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14(2):120-127. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2013.11.007.

5. Harden PN, Walsh G, Bandler N, et al. Bridging the gap: an integrated paediatric to adult clinical service for young adults with kidney failure. BMJ. 2012;344:e3718. doi:10.1136/bmj.e3718.

6. Watson AR. Non-compliance and transfer from paediatric to adult transplant unit. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;14(6):469-472.

7. Lotstein DS, Seid M, Klingensmith G, et al. Transition from pediatric to adult care for youth diagnosed with type 1 diabetes in adolescence. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):e1062-1070. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-1450.

8. Scal P. Transition for youth with chronic conditions: primary care physicians’ approaches. Pediatrics. 2002;110(6 Pt 2):1315-1321.

9. Kelly AM, Kratz B, Bielski M, Rinehart PM. Implementing transitions for youth with complex chronic conditions using the medical home model. Pediatrics. 2002;110(6 Pt 2):1322-1327.

10. Goodman DM, Hall M, Levin A, et al. Adults with chronic health conditions originating in childhood: inpatient experience in children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):5-13. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-2037.

11. Coller RJ, Ahrens S, Ehlenbach M, et al. Transitioning from General Pediatric to Adult-Oriented Inpatient Care: National Survey of US Children’s Hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(1):13-20.

12. Olson D. Health Care Transitions for Young People. In Field MJ, Jette AM, Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Disability in America, editors. The Future of Disability in America. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2007. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11432/.

13. GotTransition.org. http://www.gottransition.org/. Accessed September 15, 2017.

14. Okumura MJ, Kerr EA, Cabana MD, Davis MM, Demonner S, Heisler M. Physician views on barriers to primary care for young adults with childhood-onset chronic disease. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):e748-754. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-3451.

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Penalizing Physicians for Low-Value Care in Hospital Medicine: A Randomized Survey

Reducing low-value care—services for which there is little to no benefit, little benefit relative to cost, or outsized potential harm compared with benefit—is an essential step toward maintaining or improving quality while lowering cost. Unfortunately, low-value services persist widelydespite professional consensus, guidelines, and national campaigns aimed to reduce them.1-3 In turn, policy makers are beginning to consider financially penalizing physicians in order to deter low-value services.4,5 Physician support for such penalties remains unknown. In this study, we used a randomized survey experiment to evaluate how the framing of harms from low-value care—in terms of those to patients, healthcare institutions, or society—influenced physician support of financial penalties for low-value care services.

METHODS

Study Sample

By using a stratified random sample maintained by the American College of Physicians, we conducted a web-based survey among 484 physicians who were either internal medicine residents or internists practicing hospital medicine.

Instrument Design and Administration

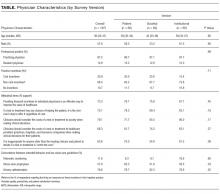

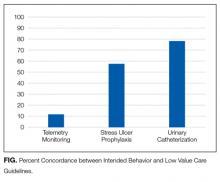

Our study focused on 3 low-value services relevant to inpatient medicine: (1) placing, and leaving in, urinary catheters for urine output monitoring in noncritically ill patients; (2) ordering continuous telemetry monitoring for nonintensive care unit (non-ICU) patients without a protocol governing continuation; and (3) prescribing stress ulcer prophylaxis for medical patients not at a high risk for gastrointestinal (GI) complications. Although the nature and trade-offs between costs, harms, and benefits vary by individual service, all 3 are promulgated through the Choosing Wisely® guidelines as low value based on existing data and professional consensus from the Society of Hospital Medicine.6

To evaluate intended behavior related to these 3 low-value services, respondents were first presented with 3 clinical vignettes focused on the care of patients hospitalized for pneumonia, congestive heart failure, and alcohol withdrawal, which were selected to reflect common inpatient medicine scenarios. Respondents were asked to use a 4-point scale (very likely to very unlikely) to estimate how likely they were to recommend various tests or treatments, including the low-value services noted above. Respondents who were “somewhat unlikely” and “very unlikely” to recommend low-value services were considered concordant with low-value care guidelines.

Following the vignettes, respondents then used a 5-point scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree) to indicate their agreement with a policy that financially penalizes physicians for prescribing each service. Support was defined as “somewhat or strongly” agreeing with the policy. Respondents were randomized to receive 1 of 3 versions of this question (supplementary Appendix).

All versions stated that, “According to research and expert opinion, certain aspects of inpatient care provide little benefit to patients” and listed the 3 low-value services noted above. The “patient harm” version also described the harm of low-value care as costs to patients and risk for clinical harms and complications. The “societal harm” version described the harms as costs to society and utilization of limited healthcare resources. The “institutional harm” version described harms as costs to hospitals and insurers.

Other survey items were adapted from existing literature7-9 and evaluated respondent beliefs about the effectiveness of physician incentives in improving the value of care, as well as the appropriateness of including cost considerations in clinical decision-making.

The instrument was pilot tested among study team members and several independent internists affiliated with the University of Pennsylvania. After incorporating feedback into the final instrument, the web-based survey was distributed to eligible physicians via e-mail. Responses were anonymous and respondents received a $15 gift card for participation. The protocol was reviewed and deemed exempt by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Statistical Analysis

Respondent characteristics (sociodemographic, intended clinical behavior, and cost control attitudes) were described by using percentages for categorical variables and medians and interquartile ranges for continuous variables. Balance in respondent characteristics across survey versions was evaluated using χ2 and Kruskal-Wallis tests. Multivariable logistic regression, adjusted for characteristics in the Table, was used to evaluate the association between survey version and policy support. All tests of significance were 2-tailed with significance level alpha = 0.05. Analyses were performed using STATA version 14.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, http://www.stata.com).

RESULTS

Of 484 eligible respondents, 187 (39%) completed the survey. Compared with nonrespondents, respondents were more likely to be female (30% vs 26%, P = 0.001), older (mean age 41 vs 36 years, P < 0.001), and practicing clinicians rather than internal medicine residents (87% vs 69%, P < 0.001). Physician characteristics were similar across the 3 survey versions (Table). Most respondents agreed that financial incentives for individual physicians is an effective way to improve the value of healthcare (73.3%) and that physicians should consider the costs of a test or treatment to society when making clinical decisions for patients (79.1%). The majority also felt that clinicians have a duty to offer a test or treatment to a patient if it has any chance of helping them (70.1%) and that it is inappropriate for anyone beyond the clinician and patient to decide if a test or treatment is “worth the cost” (63.6%).

Overall, policy support rate was 39.6% and was the highest for the “societal harm” version (48.4%), followed by the “institutional harm” (36.9%) and “patient harm” (33.3%) versions. Compared with respondents receiving the “patient harm” version, those receiving the “societal harm” version (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 2.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.20-6.69), but not the “institutional harm” framing (adjusted OR 1.53; 95% CI, 0.66-3.53), were more likely to report policy support. Policy support was also higher among those who agreed that providing financial incentives to individual physicians is an effective way to improve the value of healthcare (adjusted OR 4.61; 95% CI, 1.80-11.80).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to prospectively evaluate physician support of financial penalties for low-value services relevant to hospital medicine. It has 2 main findings.

First, although overall policy support was relatively low (39.6%), it varied significantly on the basis of how the harms of low-value care were framed. Support was highest in the “societal harm” version, suggesting that emphasizing these harms may increase acceptability of financial penalties among physicians and contribute to the larger effort to decrease low-value care in hospital settings. The comparatively low support for the “patient harm” version is somewhat surprising but may reflect variation in the nature of harm, benefit, and cost trade-offs for individual low-value services, as noted above, and physician belief that some low-value services do not in fact produce significant clinical harms.

For example, whereas evidence demonstrates that stress ulcer prophylaxis in non-ICU patients can harm patients through nosocomial infections and adverse drug effects,10,11 the clinical harms of telemetry are less obvious. Telemetry’s low value derives more from its high cost relative to benefit, rather than its potential for clinical harm.6 The many paths to “low value” underscore the need to examine attitudes and uptake toward these services separately and may explain the wide range in concordance between intended clinical behavior and low-value care guidelines (11.8% to 78.6%).

Reinforcing policies could more effectively deter low-value care. For example, multiple forces, including Medicare payment reform and national accreditation policies,12,13 have converged to discourage low-value use of urinary catheters in hospitalized patients. In contrast, there has been little reinforcement beyond consensus guidelines to reduce low-value use of telemetric monitoring. Given questions about whether consensus methods alone can deter low-value care beyond obvious “low hanging fruit,”14 policy makers could coordinate policies to accelerate progress within other priority areas.

Broad policies should also be paired with local initiatives to influence physician behavior. For example, health systems have begun successfully leveraging the electronic medical record and utilizing behavioral economics principles to design interventions to reduce inappropriate overuse of antibiotics for upper respiratory infections in primary care clinics.15 Organizations are also redesigning care processes in response to resource utilization imperatives under ongoing value-based care payment reform. Care redesign and behavioral interventions embedded at the point of care can both help deter low-value services in inpatient settings.

Study limitations include a relatively low response rate, which limits generalizability. However, all 3 randomized groups were similar on measured characteristics, and experimental randomization reduces the nonresponse bias concerns accompanying descriptive surveys. Additionally, although we evaluated intended clinical behavior in a national sample, our results may not reflect actual behavior among all physicians practicing hospital medicine. Future work could include assessments of actual or self-reported practices or examine additional factors, including site, years of practice, knowledge about guidelines, and other possible determinants of guideline-concordant behaviors.

Despite these limitations, our study provides important early evidence about physician support of financial penalties for low-value care relevant to hospital medicine. As policy makers design and organizational leaders implement financial incentive policies, this information can help increase their acceptability among physicians and more effectively reduce low-value care within hospitals.

Disclosure

Drs. Liao, Schapira, Mitra, and Weissman have no conflicts to disclose. Dr. Navathe serves as advisor to Navvis and Company, Navigant Inc, Lynx Medical, Indegene Inc, and Sutherland Global Services and receives an honorarium from Elsevier Press, none of which have relationship to this manuscript. Dr. Asch is a partner and part owner of VAL Health, which has no relationship to this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by The Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania, which had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of results.

1. The MedPAC blog. Use of low-value care in Medicare is substantial. http://www.medpac.gov/-blog-/medpacblog/2015/05/21/use-of-low-value-care-in-medicare-is-substantial. Accessed on September 18, 2017.

2. American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. Choosing Wisely. http://www.choosingwisely.org/. Accessed on September 18, 2017.

3. Rosenberg A, Agiro A, Gottlieb M, et al. Early Trends Among Seven Recommendations From the Choosing Wisely Campaign. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1913-1920. PubMed

4. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS Response to Public Comments on Non-Recommended PSA-Based Screening Measure. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/MMS/Downloads/eCQM-Development-and-Maintenance-for-Eligible-Professionals_CMS_PSA_Response_Public-Comment.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2017.

5. Berwick DM. Avoiding overuse-the next quality frontier. Lancet. 2017;390(10090):102-104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32570-3. PubMed

6. Society of Hospital Medicine. Choosing Wisely. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/choosingwisely. Accessed on September 18, 2017.

7. Tilburt JC, Wynia MK, Sheeler RD, et al. Views of US Physicians About Controlling Health Care Costs. JAMA. 2013;310(4):380-388. PubMed

8. Ginsburg ME, Kravitz RL, Sandberg WA. A survey of physician attitudes and practices concerning cost-effectiveness in patient care. West J Med. 2000;173(6):309-394. PubMed

9. Colla CH, Kinsella EA, Morden NE, Meyers DJ, Rosenthal MB, Sequist TD. Physician perceptions of Choosing Wisely and drivers of overuse. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(5):337-343. PubMed

10. Herzig SJ, Vaughn BP, Howell MD, Ngo LH, Marcantonio ER. Acid-suppressive medication use and the risk for nosocomial gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(11):991-997. PubMed

11. Pappas M, Jolly S, Vijan S. Defining Appropriate Use of Proton-Pump Inhibitors Among Medical Inpatients. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(4):364-371. PubMed

12. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS’ Value-Based Programs. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/Value-Based-Programs.html. Accessed September 18, 2017.

13. The Joint Commission. Requirements for the Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections (CAUTI) National Patient Safety Goal for Hospitals. https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/R3_Cauti_HAP.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2017 .

14. Beaudin-Seiler B, Ciarametaro M, Dubois R, Lee J, Fendrick AM. Reducing Low-Value Care. Health Affairs Blog. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2016/09/20/reducing-low-value-care/. Accessed on September 18, 2017.

15. Meeker D, Linder JA, Fox CR, et al. Effect of Behavioral Interventions on Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescribing Among Primary Care Practices: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315(6):562-570. PubMed

Reducing low-value care—services for which there is little to no benefit, little benefit relative to cost, or outsized potential harm compared with benefit—is an essential step toward maintaining or improving quality while lowering cost. Unfortunately, low-value services persist widelydespite professional consensus, guidelines, and national campaigns aimed to reduce them.1-3 In turn, policy makers are beginning to consider financially penalizing physicians in order to deter low-value services.4,5 Physician support for such penalties remains unknown. In this study, we used a randomized survey experiment to evaluate how the framing of harms from low-value care—in terms of those to patients, healthcare institutions, or society—influenced physician support of financial penalties for low-value care services.

METHODS

Study Sample

By using a stratified random sample maintained by the American College of Physicians, we conducted a web-based survey among 484 physicians who were either internal medicine residents or internists practicing hospital medicine.

Instrument Design and Administration

Our study focused on 3 low-value services relevant to inpatient medicine: (1) placing, and leaving in, urinary catheters for urine output monitoring in noncritically ill patients; (2) ordering continuous telemetry monitoring for nonintensive care unit (non-ICU) patients without a protocol governing continuation; and (3) prescribing stress ulcer prophylaxis for medical patients not at a high risk for gastrointestinal (GI) complications. Although the nature and trade-offs between costs, harms, and benefits vary by individual service, all 3 are promulgated through the Choosing Wisely® guidelines as low value based on existing data and professional consensus from the Society of Hospital Medicine.6

To evaluate intended behavior related to these 3 low-value services, respondents were first presented with 3 clinical vignettes focused on the care of patients hospitalized for pneumonia, congestive heart failure, and alcohol withdrawal, which were selected to reflect common inpatient medicine scenarios. Respondents were asked to use a 4-point scale (very likely to very unlikely) to estimate how likely they were to recommend various tests or treatments, including the low-value services noted above. Respondents who were “somewhat unlikely” and “very unlikely” to recommend low-value services were considered concordant with low-value care guidelines.

Following the vignettes, respondents then used a 5-point scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree) to indicate their agreement with a policy that financially penalizes physicians for prescribing each service. Support was defined as “somewhat or strongly” agreeing with the policy. Respondents were randomized to receive 1 of 3 versions of this question (supplementary Appendix).

All versions stated that, “According to research and expert opinion, certain aspects of inpatient care provide little benefit to patients” and listed the 3 low-value services noted above. The “patient harm” version also described the harm of low-value care as costs to patients and risk for clinical harms and complications. The “societal harm” version described the harms as costs to society and utilization of limited healthcare resources. The “institutional harm” version described harms as costs to hospitals and insurers.

Other survey items were adapted from existing literature7-9 and evaluated respondent beliefs about the effectiveness of physician incentives in improving the value of care, as well as the appropriateness of including cost considerations in clinical decision-making.

The instrument was pilot tested among study team members and several independent internists affiliated with the University of Pennsylvania. After incorporating feedback into the final instrument, the web-based survey was distributed to eligible physicians via e-mail. Responses were anonymous and respondents received a $15 gift card for participation. The protocol was reviewed and deemed exempt by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Statistical Analysis

Respondent characteristics (sociodemographic, intended clinical behavior, and cost control attitudes) were described by using percentages for categorical variables and medians and interquartile ranges for continuous variables. Balance in respondent characteristics across survey versions was evaluated using χ2 and Kruskal-Wallis tests. Multivariable logistic regression, adjusted for characteristics in the Table, was used to evaluate the association between survey version and policy support. All tests of significance were 2-tailed with significance level alpha = 0.05. Analyses were performed using STATA version 14.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, http://www.stata.com).

RESULTS

Of 484 eligible respondents, 187 (39%) completed the survey. Compared with nonrespondents, respondents were more likely to be female (30% vs 26%, P = 0.001), older (mean age 41 vs 36 years, P < 0.001), and practicing clinicians rather than internal medicine residents (87% vs 69%, P < 0.001). Physician characteristics were similar across the 3 survey versions (Table). Most respondents agreed that financial incentives for individual physicians is an effective way to improve the value of healthcare (73.3%) and that physicians should consider the costs of a test or treatment to society when making clinical decisions for patients (79.1%). The majority also felt that clinicians have a duty to offer a test or treatment to a patient if it has any chance of helping them (70.1%) and that it is inappropriate for anyone beyond the clinician and patient to decide if a test or treatment is “worth the cost” (63.6%).

Overall, policy support rate was 39.6% and was the highest for the “societal harm” version (48.4%), followed by the “institutional harm” (36.9%) and “patient harm” (33.3%) versions. Compared with respondents receiving the “patient harm” version, those receiving the “societal harm” version (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 2.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.20-6.69), but not the “institutional harm” framing (adjusted OR 1.53; 95% CI, 0.66-3.53), were more likely to report policy support. Policy support was also higher among those who agreed that providing financial incentives to individual physicians is an effective way to improve the value of healthcare (adjusted OR 4.61; 95% CI, 1.80-11.80).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to prospectively evaluate physician support of financial penalties for low-value services relevant to hospital medicine. It has 2 main findings.

First, although overall policy support was relatively low (39.6%), it varied significantly on the basis of how the harms of low-value care were framed. Support was highest in the “societal harm” version, suggesting that emphasizing these harms may increase acceptability of financial penalties among physicians and contribute to the larger effort to decrease low-value care in hospital settings. The comparatively low support for the “patient harm” version is somewhat surprising but may reflect variation in the nature of harm, benefit, and cost trade-offs for individual low-value services, as noted above, and physician belief that some low-value services do not in fact produce significant clinical harms.

For example, whereas evidence demonstrates that stress ulcer prophylaxis in non-ICU patients can harm patients through nosocomial infections and adverse drug effects,10,11 the clinical harms of telemetry are less obvious. Telemetry’s low value derives more from its high cost relative to benefit, rather than its potential for clinical harm.6 The many paths to “low value” underscore the need to examine attitudes and uptake toward these services separately and may explain the wide range in concordance between intended clinical behavior and low-value care guidelines (11.8% to 78.6%).

Reinforcing policies could more effectively deter low-value care. For example, multiple forces, including Medicare payment reform and national accreditation policies,12,13 have converged to discourage low-value use of urinary catheters in hospitalized patients. In contrast, there has been little reinforcement beyond consensus guidelines to reduce low-value use of telemetric monitoring. Given questions about whether consensus methods alone can deter low-value care beyond obvious “low hanging fruit,”14 policy makers could coordinate policies to accelerate progress within other priority areas.

Broad policies should also be paired with local initiatives to influence physician behavior. For example, health systems have begun successfully leveraging the electronic medical record and utilizing behavioral economics principles to design interventions to reduce inappropriate overuse of antibiotics for upper respiratory infections in primary care clinics.15 Organizations are also redesigning care processes in response to resource utilization imperatives under ongoing value-based care payment reform. Care redesign and behavioral interventions embedded at the point of care can both help deter low-value services in inpatient settings.

Study limitations include a relatively low response rate, which limits generalizability. However, all 3 randomized groups were similar on measured characteristics, and experimental randomization reduces the nonresponse bias concerns accompanying descriptive surveys. Additionally, although we evaluated intended clinical behavior in a national sample, our results may not reflect actual behavior among all physicians practicing hospital medicine. Future work could include assessments of actual or self-reported practices or examine additional factors, including site, years of practice, knowledge about guidelines, and other possible determinants of guideline-concordant behaviors.

Despite these limitations, our study provides important early evidence about physician support of financial penalties for low-value care relevant to hospital medicine. As policy makers design and organizational leaders implement financial incentive policies, this information can help increase their acceptability among physicians and more effectively reduce low-value care within hospitals.

Disclosure

Drs. Liao, Schapira, Mitra, and Weissman have no conflicts to disclose. Dr. Navathe serves as advisor to Navvis and Company, Navigant Inc, Lynx Medical, Indegene Inc, and Sutherland Global Services and receives an honorarium from Elsevier Press, none of which have relationship to this manuscript. Dr. Asch is a partner and part owner of VAL Health, which has no relationship to this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by The Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania, which had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of results.

Reducing low-value care—services for which there is little to no benefit, little benefit relative to cost, or outsized potential harm compared with benefit—is an essential step toward maintaining or improving quality while lowering cost. Unfortunately, low-value services persist widelydespite professional consensus, guidelines, and national campaigns aimed to reduce them.1-3 In turn, policy makers are beginning to consider financially penalizing physicians in order to deter low-value services.4,5 Physician support for such penalties remains unknown. In this study, we used a randomized survey experiment to evaluate how the framing of harms from low-value care—in terms of those to patients, healthcare institutions, or society—influenced physician support of financial penalties for low-value care services.

METHODS

Study Sample

By using a stratified random sample maintained by the American College of Physicians, we conducted a web-based survey among 484 physicians who were either internal medicine residents or internists practicing hospital medicine.

Instrument Design and Administration

Our study focused on 3 low-value services relevant to inpatient medicine: (1) placing, and leaving in, urinary catheters for urine output monitoring in noncritically ill patients; (2) ordering continuous telemetry monitoring for nonintensive care unit (non-ICU) patients without a protocol governing continuation; and (3) prescribing stress ulcer prophylaxis for medical patients not at a high risk for gastrointestinal (GI) complications. Although the nature and trade-offs between costs, harms, and benefits vary by individual service, all 3 are promulgated through the Choosing Wisely® guidelines as low value based on existing data and professional consensus from the Society of Hospital Medicine.6

To evaluate intended behavior related to these 3 low-value services, respondents were first presented with 3 clinical vignettes focused on the care of patients hospitalized for pneumonia, congestive heart failure, and alcohol withdrawal, which were selected to reflect common inpatient medicine scenarios. Respondents were asked to use a 4-point scale (very likely to very unlikely) to estimate how likely they were to recommend various tests or treatments, including the low-value services noted above. Respondents who were “somewhat unlikely” and “very unlikely” to recommend low-value services were considered concordant with low-value care guidelines.

Following the vignettes, respondents then used a 5-point scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree) to indicate their agreement with a policy that financially penalizes physicians for prescribing each service. Support was defined as “somewhat or strongly” agreeing with the policy. Respondents were randomized to receive 1 of 3 versions of this question (supplementary Appendix).

All versions stated that, “According to research and expert opinion, certain aspects of inpatient care provide little benefit to patients” and listed the 3 low-value services noted above. The “patient harm” version also described the harm of low-value care as costs to patients and risk for clinical harms and complications. The “societal harm” version described the harms as costs to society and utilization of limited healthcare resources. The “institutional harm” version described harms as costs to hospitals and insurers.

Other survey items were adapted from existing literature7-9 and evaluated respondent beliefs about the effectiveness of physician incentives in improving the value of care, as well as the appropriateness of including cost considerations in clinical decision-making.

The instrument was pilot tested among study team members and several independent internists affiliated with the University of Pennsylvania. After incorporating feedback into the final instrument, the web-based survey was distributed to eligible physicians via e-mail. Responses were anonymous and respondents received a $15 gift card for participation. The protocol was reviewed and deemed exempt by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Statistical Analysis

Respondent characteristics (sociodemographic, intended clinical behavior, and cost control attitudes) were described by using percentages for categorical variables and medians and interquartile ranges for continuous variables. Balance in respondent characteristics across survey versions was evaluated using χ2 and Kruskal-Wallis tests. Multivariable logistic regression, adjusted for characteristics in the Table, was used to evaluate the association between survey version and policy support. All tests of significance were 2-tailed with significance level alpha = 0.05. Analyses were performed using STATA version 14.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, http://www.stata.com).

RESULTS

Of 484 eligible respondents, 187 (39%) completed the survey. Compared with nonrespondents, respondents were more likely to be female (30% vs 26%, P = 0.001), older (mean age 41 vs 36 years, P < 0.001), and practicing clinicians rather than internal medicine residents (87% vs 69%, P < 0.001). Physician characteristics were similar across the 3 survey versions (Table). Most respondents agreed that financial incentives for individual physicians is an effective way to improve the value of healthcare (73.3%) and that physicians should consider the costs of a test or treatment to society when making clinical decisions for patients (79.1%). The majority also felt that clinicians have a duty to offer a test or treatment to a patient if it has any chance of helping them (70.1%) and that it is inappropriate for anyone beyond the clinician and patient to decide if a test or treatment is “worth the cost” (63.6%).

Overall, policy support rate was 39.6% and was the highest for the “societal harm” version (48.4%), followed by the “institutional harm” (36.9%) and “patient harm” (33.3%) versions. Compared with respondents receiving the “patient harm” version, those receiving the “societal harm” version (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 2.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.20-6.69), but not the “institutional harm” framing (adjusted OR 1.53; 95% CI, 0.66-3.53), were more likely to report policy support. Policy support was also higher among those who agreed that providing financial incentives to individual physicians is an effective way to improve the value of healthcare (adjusted OR 4.61; 95% CI, 1.80-11.80).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to prospectively evaluate physician support of financial penalties for low-value services relevant to hospital medicine. It has 2 main findings.

First, although overall policy support was relatively low (39.6%), it varied significantly on the basis of how the harms of low-value care were framed. Support was highest in the “societal harm” version, suggesting that emphasizing these harms may increase acceptability of financial penalties among physicians and contribute to the larger effort to decrease low-value care in hospital settings. The comparatively low support for the “patient harm” version is somewhat surprising but may reflect variation in the nature of harm, benefit, and cost trade-offs for individual low-value services, as noted above, and physician belief that some low-value services do not in fact produce significant clinical harms.

For example, whereas evidence demonstrates that stress ulcer prophylaxis in non-ICU patients can harm patients through nosocomial infections and adverse drug effects,10,11 the clinical harms of telemetry are less obvious. Telemetry’s low value derives more from its high cost relative to benefit, rather than its potential for clinical harm.6 The many paths to “low value” underscore the need to examine attitudes and uptake toward these services separately and may explain the wide range in concordance between intended clinical behavior and low-value care guidelines (11.8% to 78.6%).

Reinforcing policies could more effectively deter low-value care. For example, multiple forces, including Medicare payment reform and national accreditation policies,12,13 have converged to discourage low-value use of urinary catheters in hospitalized patients. In contrast, there has been little reinforcement beyond consensus guidelines to reduce low-value use of telemetric monitoring. Given questions about whether consensus methods alone can deter low-value care beyond obvious “low hanging fruit,”14 policy makers could coordinate policies to accelerate progress within other priority areas.

Broad policies should also be paired with local initiatives to influence physician behavior. For example, health systems have begun successfully leveraging the electronic medical record and utilizing behavioral economics principles to design interventions to reduce inappropriate overuse of antibiotics for upper respiratory infections in primary care clinics.15 Organizations are also redesigning care processes in response to resource utilization imperatives under ongoing value-based care payment reform. Care redesign and behavioral interventions embedded at the point of care can both help deter low-value services in inpatient settings.

Study limitations include a relatively low response rate, which limits generalizability. However, all 3 randomized groups were similar on measured characteristics, and experimental randomization reduces the nonresponse bias concerns accompanying descriptive surveys. Additionally, although we evaluated intended clinical behavior in a national sample, our results may not reflect actual behavior among all physicians practicing hospital medicine. Future work could include assessments of actual or self-reported practices or examine additional factors, including site, years of practice, knowledge about guidelines, and other possible determinants of guideline-concordant behaviors.

Despite these limitations, our study provides important early evidence about physician support of financial penalties for low-value care relevant to hospital medicine. As policy makers design and organizational leaders implement financial incentive policies, this information can help increase their acceptability among physicians and more effectively reduce low-value care within hospitals.

Disclosure

Drs. Liao, Schapira, Mitra, and Weissman have no conflicts to disclose. Dr. Navathe serves as advisor to Navvis and Company, Navigant Inc, Lynx Medical, Indegene Inc, and Sutherland Global Services and receives an honorarium from Elsevier Press, none of which have relationship to this manuscript. Dr. Asch is a partner and part owner of VAL Health, which has no relationship to this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by The Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics at the University of Pennsylvania, which had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of results.

1. The MedPAC blog. Use of low-value care in Medicare is substantial. http://www.medpac.gov/-blog-/medpacblog/2015/05/21/use-of-low-value-care-in-medicare-is-substantial. Accessed on September 18, 2017.

2. American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. Choosing Wisely. http://www.choosingwisely.org/. Accessed on September 18, 2017.

3. Rosenberg A, Agiro A, Gottlieb M, et al. Early Trends Among Seven Recommendations From the Choosing Wisely Campaign. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1913-1920. PubMed

4. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS Response to Public Comments on Non-Recommended PSA-Based Screening Measure. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/MMS/Downloads/eCQM-Development-and-Maintenance-for-Eligible-Professionals_CMS_PSA_Response_Public-Comment.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2017.

5. Berwick DM. Avoiding overuse-the next quality frontier. Lancet. 2017;390(10090):102-104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32570-3. PubMed

6. Society of Hospital Medicine. Choosing Wisely. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/choosingwisely. Accessed on September 18, 2017.

7. Tilburt JC, Wynia MK, Sheeler RD, et al. Views of US Physicians About Controlling Health Care Costs. JAMA. 2013;310(4):380-388. PubMed

8. Ginsburg ME, Kravitz RL, Sandberg WA. A survey of physician attitudes and practices concerning cost-effectiveness in patient care. West J Med. 2000;173(6):309-394. PubMed

9. Colla CH, Kinsella EA, Morden NE, Meyers DJ, Rosenthal MB, Sequist TD. Physician perceptions of Choosing Wisely and drivers of overuse. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(5):337-343. PubMed

10. Herzig SJ, Vaughn BP, Howell MD, Ngo LH, Marcantonio ER. Acid-suppressive medication use and the risk for nosocomial gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(11):991-997. PubMed

11. Pappas M, Jolly S, Vijan S. Defining Appropriate Use of Proton-Pump Inhibitors Among Medical Inpatients. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(4):364-371. PubMed

12. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS’ Value-Based Programs. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/Value-Based-Programs.html. Accessed September 18, 2017.

13. The Joint Commission. Requirements for the Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections (CAUTI) National Patient Safety Goal for Hospitals. https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/R3_Cauti_HAP.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2017 .

14. Beaudin-Seiler B, Ciarametaro M, Dubois R, Lee J, Fendrick AM. Reducing Low-Value Care. Health Affairs Blog. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2016/09/20/reducing-low-value-care/. Accessed on September 18, 2017.

15. Meeker D, Linder JA, Fox CR, et al. Effect of Behavioral Interventions on Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescribing Among Primary Care Practices: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315(6):562-570. PubMed

1. The MedPAC blog. Use of low-value care in Medicare is substantial. http://www.medpac.gov/-blog-/medpacblog/2015/05/21/use-of-low-value-care-in-medicare-is-substantial. Accessed on September 18, 2017.

2. American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. Choosing Wisely. http://www.choosingwisely.org/. Accessed on September 18, 2017.

3. Rosenberg A, Agiro A, Gottlieb M, et al. Early Trends Among Seven Recommendations From the Choosing Wisely Campaign. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(12):1913-1920. PubMed

4. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS Response to Public Comments on Non-Recommended PSA-Based Screening Measure. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/MMS/Downloads/eCQM-Development-and-Maintenance-for-Eligible-Professionals_CMS_PSA_Response_Public-Comment.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2017.

5. Berwick DM. Avoiding overuse-the next quality frontier. Lancet. 2017;390(10090):102-104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32570-3. PubMed

6. Society of Hospital Medicine. Choosing Wisely. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/choosingwisely. Accessed on September 18, 2017.

7. Tilburt JC, Wynia MK, Sheeler RD, et al. Views of US Physicians About Controlling Health Care Costs. JAMA. 2013;310(4):380-388. PubMed

8. Ginsburg ME, Kravitz RL, Sandberg WA. A survey of physician attitudes and practices concerning cost-effectiveness in patient care. West J Med. 2000;173(6):309-394. PubMed

9. Colla CH, Kinsella EA, Morden NE, Meyers DJ, Rosenthal MB, Sequist TD. Physician perceptions of Choosing Wisely and drivers of overuse. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(5):337-343. PubMed

10. Herzig SJ, Vaughn BP, Howell MD, Ngo LH, Marcantonio ER. Acid-suppressive medication use and the risk for nosocomial gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(11):991-997. PubMed

11. Pappas M, Jolly S, Vijan S. Defining Appropriate Use of Proton-Pump Inhibitors Among Medical Inpatients. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(4):364-371. PubMed

12. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS’ Value-Based Programs. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/Value-Based-Programs.html. Accessed September 18, 2017.

13. The Joint Commission. Requirements for the Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections (CAUTI) National Patient Safety Goal for Hospitals. https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/R3_Cauti_HAP.pdf. Accessed September 18, 2017 .

14. Beaudin-Seiler B, Ciarametaro M, Dubois R, Lee J, Fendrick AM. Reducing Low-Value Care. Health Affairs Blog. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2016/09/20/reducing-low-value-care/. Accessed on September 18, 2017.

15. Meeker D, Linder JA, Fox CR, et al. Effect of Behavioral Interventions on Inappropriate Antibiotic Prescribing Among Primary Care Practices: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315(6):562-570. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Isolation precautions are associated with higher costs, longer LOS

Clinical question: What are the effects of isolation precautions on hospital outcomes and cost of care?

Background: Previous studies have found that isolation precautions negatively affect various aspects of patient care, including frequency of contact with clinicians, adverse events in the hospital, measures of patient well-being, and patient experience scores. It is not known how isolation precautions affect other hospital-based metrics, such as 30-day readmissions, length of stay (LOS), in-hospital mortality, and cost of care.

Study design: Multisite, retrospective, propensity score–matched cohort study.

Setting: Three academic tertiary care hospitals in Toronto.

Synopsis: The authors used administrative databases and propensity-score modeling to match isolated patients and nonisolated controls. Researchers included 17,649 control patients, 737 patients isolated for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (contact isolation), and 1,502 patients isolated for respiratory illnesses (contact and droplet isolation) in the study. Patients isolated for MRSA had a higher 30-day readmission rate than did controls (19% vs. 14.7%), a longer average length of stay (11.9 days vs. 9.1 days), and higher direct costs ($11,009 vs. $7,670). Patients isolated for respiratory illnesses had a longer average length of stay (8.5 days vs. 7.6 days) and higher direct costs ($7,194 vs. $6,294). No differences in adverse events rates or in-hospital mortality were observed between control patients and patients in either isolation group.

Some of the differences observed may be from illness severity rather than from the effects of isolation, especially in the MRSA group. There was no difference observed in rates of adverse outcomes, such as falls or medication errors, or in rates of formal patient complaints to the hospital. It is possible that propensity score modeling corrected for unidentified biases in prior studies that found differences in these types of outcomes.

Bottom line: Isolation precautions are associated with higher costs and longer LOS in hospitalized general medicine patients.

Citation: Tran K et al. The effect of hospital isolation precautions on patient outcomes and cost of care: A multisite, retrospective, propensity score-matched cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):262-8.

Dr. Wachter is an assistant professor of medicine at Duke University.

Clinical question: What are the effects of isolation precautions on hospital outcomes and cost of care?

Background: Previous studies have found that isolation precautions negatively affect various aspects of patient care, including frequency of contact with clinicians, adverse events in the hospital, measures of patient well-being, and patient experience scores. It is not known how isolation precautions affect other hospital-based metrics, such as 30-day readmissions, length of stay (LOS), in-hospital mortality, and cost of care.

Study design: Multisite, retrospective, propensity score–matched cohort study.

Setting: Three academic tertiary care hospitals in Toronto.

Synopsis: The authors used administrative databases and propensity-score modeling to match isolated patients and nonisolated controls. Researchers included 17,649 control patients, 737 patients isolated for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (contact isolation), and 1,502 patients isolated for respiratory illnesses (contact and droplet isolation) in the study. Patients isolated for MRSA had a higher 30-day readmission rate than did controls (19% vs. 14.7%), a longer average length of stay (11.9 days vs. 9.1 days), and higher direct costs ($11,009 vs. $7,670). Patients isolated for respiratory illnesses had a longer average length of stay (8.5 days vs. 7.6 days) and higher direct costs ($7,194 vs. $6,294). No differences in adverse events rates or in-hospital mortality were observed between control patients and patients in either isolation group.

Some of the differences observed may be from illness severity rather than from the effects of isolation, especially in the MRSA group. There was no difference observed in rates of adverse outcomes, such as falls or medication errors, or in rates of formal patient complaints to the hospital. It is possible that propensity score modeling corrected for unidentified biases in prior studies that found differences in these types of outcomes.

Bottom line: Isolation precautions are associated with higher costs and longer LOS in hospitalized general medicine patients.

Citation: Tran K et al. The effect of hospital isolation precautions on patient outcomes and cost of care: A multisite, retrospective, propensity score-matched cohort study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):262-8.

Dr. Wachter is an assistant professor of medicine at Duke University.

Clinical question: What are the effects of isolation precautions on hospital outcomes and cost of care?

Background: Previous studies have found that isolation precautions negatively affect various aspects of patient care, including frequency of contact with clinicians, adverse events in the hospital, measures of patient well-being, and patient experience scores. It is not known how isolation precautions affect other hospital-based metrics, such as 30-day readmissions, length of stay (LOS), in-hospital mortality, and cost of care.

Study design: Multisite, retrospective, propensity score–matched cohort study.

Setting: Three academic tertiary care hospitals in Toronto.

Synopsis: The authors used administrative databases and propensity-score modeling to match isolated patients and nonisolated controls. Researchers included 17,649 control patients, 737 patients isolated for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (contact isolation), and 1,502 patients isolated for respiratory illnesses (contact and droplet isolation) in the study. Patients isolated for MRSA had a higher 30-day readmission rate than did controls (19% vs. 14.7%), a longer average length of stay (11.9 days vs. 9.1 days), and higher direct costs ($11,009 vs. $7,670). Patients isolated for respiratory illnesses had a longer average length of stay (8.5 days vs. 7.6 days) and higher direct costs ($7,194 vs. $6,294). No differences in adverse events rates or in-hospital mortality were observed between control patients and patients in either isolation group.