User login

Welcome to Day 3 of HM19

We have reached the final day of another SHM annual conference. What a spectacular ride it has been! On the first day, we heard about the success of the first National Hospitalist Day and how hospital medicine continues to evolve with the health care landscape in the United States and beyond. Throughout the course of the meeting, you have learned about critical updates in our specialty that will support hospitalists’ quest to lead the change. As health care transforms, we are well positioned to innovate in support of our peers and patients.

The importance of high-value care has been a theme of HM19, balanced with the high value of physician well-being. With inspiring keynotes from Marc Harrison, MD, on influencing lives more effectively and more affordably to approaches to fighting burnout from Tait Shanafelt, MD, hospital medicine as a specialty has the power to transform health care for patients and providers alike. I hope you also had the chance to attend the sessions on clinical updates, diagnostic reasoning, practice management, and career development, to name just a few.

The final day of the meeting is no exception when it comes to impactful topics and memorable sessions. Beginning at 7:30 a.m., you’ll find a number of sessions and workshops to round out your conference experience. Our popular “Stump the Professor” series is back, focused on challenging clinical unknowns. In addition, “Medical Jeopardy,” tips on being a successful teaching attending, best practices for promoting diversity in HMGs, the history of hospitals, and updates on LGBTQ health are just a few of the topics you’ll have a chance to immerse yourself in today.

Because of the proximity to the nation’s capital, we also are looking forward to Hill Day today, when hospitalists will travel to Capitol Hill to meet with legislators to discuss issues and policy affecting hospital medicine. This is yet another example of how hospitalists and SHM are partnering to be a voice for clinicians in important health care policy conversations.

As the conference concludes, I thank you for joining us and being a part of the hospital medicine movement. We hope you will continue to engage with SHM throughout the year as you further connect with colleagues via special interest groups, chapters, and committees. If you’re new to SHM, we invite you to discover all the options that your membership offers. We look forward to seeing you next year at Hospital Medicine 2020 (HM20) in San Diego, from April 15-18!

Dr. Frost is the incoming president of the Society of Hospital Medicine and the national medical director of hospital-based services at LifePoint Health in Brentwood, Tennessee.

We have reached the final day of another SHM annual conference. What a spectacular ride it has been! On the first day, we heard about the success of the first National Hospitalist Day and how hospital medicine continues to evolve with the health care landscape in the United States and beyond. Throughout the course of the meeting, you have learned about critical updates in our specialty that will support hospitalists’ quest to lead the change. As health care transforms, we are well positioned to innovate in support of our peers and patients.

The importance of high-value care has been a theme of HM19, balanced with the high value of physician well-being. With inspiring keynotes from Marc Harrison, MD, on influencing lives more effectively and more affordably to approaches to fighting burnout from Tait Shanafelt, MD, hospital medicine as a specialty has the power to transform health care for patients and providers alike. I hope you also had the chance to attend the sessions on clinical updates, diagnostic reasoning, practice management, and career development, to name just a few.

The final day of the meeting is no exception when it comes to impactful topics and memorable sessions. Beginning at 7:30 a.m., you’ll find a number of sessions and workshops to round out your conference experience. Our popular “Stump the Professor” series is back, focused on challenging clinical unknowns. In addition, “Medical Jeopardy,” tips on being a successful teaching attending, best practices for promoting diversity in HMGs, the history of hospitals, and updates on LGBTQ health are just a few of the topics you’ll have a chance to immerse yourself in today.

Because of the proximity to the nation’s capital, we also are looking forward to Hill Day today, when hospitalists will travel to Capitol Hill to meet with legislators to discuss issues and policy affecting hospital medicine. This is yet another example of how hospitalists and SHM are partnering to be a voice for clinicians in important health care policy conversations.

As the conference concludes, I thank you for joining us and being a part of the hospital medicine movement. We hope you will continue to engage with SHM throughout the year as you further connect with colleagues via special interest groups, chapters, and committees. If you’re new to SHM, we invite you to discover all the options that your membership offers. We look forward to seeing you next year at Hospital Medicine 2020 (HM20) in San Diego, from April 15-18!

Dr. Frost is the incoming president of the Society of Hospital Medicine and the national medical director of hospital-based services at LifePoint Health in Brentwood, Tennessee.

We have reached the final day of another SHM annual conference. What a spectacular ride it has been! On the first day, we heard about the success of the first National Hospitalist Day and how hospital medicine continues to evolve with the health care landscape in the United States and beyond. Throughout the course of the meeting, you have learned about critical updates in our specialty that will support hospitalists’ quest to lead the change. As health care transforms, we are well positioned to innovate in support of our peers and patients.

The importance of high-value care has been a theme of HM19, balanced with the high value of physician well-being. With inspiring keynotes from Marc Harrison, MD, on influencing lives more effectively and more affordably to approaches to fighting burnout from Tait Shanafelt, MD, hospital medicine as a specialty has the power to transform health care for patients and providers alike. I hope you also had the chance to attend the sessions on clinical updates, diagnostic reasoning, practice management, and career development, to name just a few.

The final day of the meeting is no exception when it comes to impactful topics and memorable sessions. Beginning at 7:30 a.m., you’ll find a number of sessions and workshops to round out your conference experience. Our popular “Stump the Professor” series is back, focused on challenging clinical unknowns. In addition, “Medical Jeopardy,” tips on being a successful teaching attending, best practices for promoting diversity in HMGs, the history of hospitals, and updates on LGBTQ health are just a few of the topics you’ll have a chance to immerse yourself in today.

Because of the proximity to the nation’s capital, we also are looking forward to Hill Day today, when hospitalists will travel to Capitol Hill to meet with legislators to discuss issues and policy affecting hospital medicine. This is yet another example of how hospitalists and SHM are partnering to be a voice for clinicians in important health care policy conversations.

As the conference concludes, I thank you for joining us and being a part of the hospital medicine movement. We hope you will continue to engage with SHM throughout the year as you further connect with colleagues via special interest groups, chapters, and committees. If you’re new to SHM, we invite you to discover all the options that your membership offers. We look forward to seeing you next year at Hospital Medicine 2020 (HM20) in San Diego, from April 15-18!

Dr. Frost is the incoming president of the Society of Hospital Medicine and the national medical director of hospital-based services at LifePoint Health in Brentwood, Tennessee.

Adopting the patient’s perspective

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” provides readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that can positively impact patients’ experience of care. In the current series of columns, physicians share how their experiences as patients have shaped their professional approach.

I have been fortunate to have had very few major health issues throughout my life. I have, however, had three major surgical procedures in the last 10 years – two total hip arthroplasties and a cataract removal with lens implant in between. The most recent THA was October 2017. Going through each procedure helped me see things from a patient’s perspective, and that showed me how important little things are to a patient, things which we may not think are all that big a deal as a provider.

Almost all of the medical personnel who came to care for me during my stays identified themselves and why they were there, and that made me feel comfortable, knowing who they were and their role. However, there were a few who did not do this, and that made me uncomfortable, not knowing who they were and why they were in my room. Not knowing is an uncomfortable feeling for a patient.

Almost every registered nurse who came to me with medication explained what the medicine was and why they were administering it, with the exception of one preop RN I met before to my cataract procedure. She walked up to me, told me to open my eye wide, held the affected eye open, and started dripping cold drops into my eye without explanation. She then said she would be back every 10 minutes to repeat the process. I had to inquire as to what the medication was and why there was a need for this process. It was a jolting experience, and she showed no compassion toward me as a patient or a person, even after I inquired.

This was not a good experience. Although cataract surgery was a totally new experience for me, she had obviously done this many times before and had to do it many times that day. However, she acted as if I should have known what she was going to do and as if she need not explain herself to anyone – which she did not, even after being queried.

Everyone during the admission process for all three procedures was solicitous and warm except for one person. Unfortunately, this individual was the first person to greet my wife and me when we arrived for my last total hip arthroplasty. She was seated at the welcome desk with her head down. After we arrived, she kept her head down and asked “How can I help you?” without ever looking up. I did not realize how unwelcome I would feel when the first person I encountered in the surgical preop admissions area failed to make eye contact with me. Her demeanor was nice enough, but she did not even attempt to make a personal connection with me – and she was at the welcome desk!

Overall, I had tremendously good experiences at three facilities in three different parts of the United States, but as we all know, it is the things that do not go well that stand out. I choose to use those things, along with some of the good things, as “reinforcers” for many of the patient-experience behaviors we identify as best practices.

What I say and do

During each patient encounter, I make eye contact with the patient and each person in the room and identify who I am and why I am there. I sit down during each visit unless there is simply no place for me to do so. I explain the procedures that are to take place, set expectations for those procedures, and then use “teachback” to ensure that my discussion with the patient has been effective. Setting expectations is very important to me: If you do not ensure that patients have appropriate expectations, their expectations will never be met and they will never have a good experience. I explain any new medication I am ordering, what it is for, and any possible significant side effects and again use teachback. The last thing I do is ask “What questions do you have for me today?” giving the patient permission to have questions, and then I respond to those questions with plain talk and teachback.

Why I do it

Not knowing what was going on and feeling marginalized were the most uncomfortable things I experienced as a patient. Using best practices for patient experience shows courtesy and respect. These practices show a willingness to take time with the patient and demonstrate my concern that I am effectively communicating my message for that visit. All of these behaviors decrease uncertainty and/or raise the patient’s feelings of importance, thereby decreasing marginalization.

How I do it

I remind myself each day I am on a clinical shift that my goal is to treat each patient like I would want my family (or myself) to be treated, and then I go out and do it. After “forcing” myself to put these behaviors into my rounding routine, they have become second nature, and I feel better for providing this level of care because it made me feel so good when I was cared for in this manner.

Dr. Sharp is chief hospitalist with Sound Physicians at University of Florida Health in Jacksonville, Fla.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” provides readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that can positively impact patients’ experience of care. In the current series of columns, physicians share how their experiences as patients have shaped their professional approach.

I have been fortunate to have had very few major health issues throughout my life. I have, however, had three major surgical procedures in the last 10 years – two total hip arthroplasties and a cataract removal with lens implant in between. The most recent THA was October 2017. Going through each procedure helped me see things from a patient’s perspective, and that showed me how important little things are to a patient, things which we may not think are all that big a deal as a provider.

Almost all of the medical personnel who came to care for me during my stays identified themselves and why they were there, and that made me feel comfortable, knowing who they were and their role. However, there were a few who did not do this, and that made me uncomfortable, not knowing who they were and why they were in my room. Not knowing is an uncomfortable feeling for a patient.

Almost every registered nurse who came to me with medication explained what the medicine was and why they were administering it, with the exception of one preop RN I met before to my cataract procedure. She walked up to me, told me to open my eye wide, held the affected eye open, and started dripping cold drops into my eye without explanation. She then said she would be back every 10 minutes to repeat the process. I had to inquire as to what the medication was and why there was a need for this process. It was a jolting experience, and she showed no compassion toward me as a patient or a person, even after I inquired.

This was not a good experience. Although cataract surgery was a totally new experience for me, she had obviously done this many times before and had to do it many times that day. However, she acted as if I should have known what she was going to do and as if she need not explain herself to anyone – which she did not, even after being queried.

Everyone during the admission process for all three procedures was solicitous and warm except for one person. Unfortunately, this individual was the first person to greet my wife and me when we arrived for my last total hip arthroplasty. She was seated at the welcome desk with her head down. After we arrived, she kept her head down and asked “How can I help you?” without ever looking up. I did not realize how unwelcome I would feel when the first person I encountered in the surgical preop admissions area failed to make eye contact with me. Her demeanor was nice enough, but she did not even attempt to make a personal connection with me – and she was at the welcome desk!

Overall, I had tremendously good experiences at three facilities in three different parts of the United States, but as we all know, it is the things that do not go well that stand out. I choose to use those things, along with some of the good things, as “reinforcers” for many of the patient-experience behaviors we identify as best practices.

What I say and do

During each patient encounter, I make eye contact with the patient and each person in the room and identify who I am and why I am there. I sit down during each visit unless there is simply no place for me to do so. I explain the procedures that are to take place, set expectations for those procedures, and then use “teachback” to ensure that my discussion with the patient has been effective. Setting expectations is very important to me: If you do not ensure that patients have appropriate expectations, their expectations will never be met and they will never have a good experience. I explain any new medication I am ordering, what it is for, and any possible significant side effects and again use teachback. The last thing I do is ask “What questions do you have for me today?” giving the patient permission to have questions, and then I respond to those questions with plain talk and teachback.

Why I do it

Not knowing what was going on and feeling marginalized were the most uncomfortable things I experienced as a patient. Using best practices for patient experience shows courtesy and respect. These practices show a willingness to take time with the patient and demonstrate my concern that I am effectively communicating my message for that visit. All of these behaviors decrease uncertainty and/or raise the patient’s feelings of importance, thereby decreasing marginalization.

How I do it

I remind myself each day I am on a clinical shift that my goal is to treat each patient like I would want my family (or myself) to be treated, and then I go out and do it. After “forcing” myself to put these behaviors into my rounding routine, they have become second nature, and I feel better for providing this level of care because it made me feel so good when I was cared for in this manner.

Dr. Sharp is chief hospitalist with Sound Physicians at University of Florida Health in Jacksonville, Fla.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” provides readers with thoughtful and actionable communication tactics that can positively impact patients’ experience of care. In the current series of columns, physicians share how their experiences as patients have shaped their professional approach.

I have been fortunate to have had very few major health issues throughout my life. I have, however, had three major surgical procedures in the last 10 years – two total hip arthroplasties and a cataract removal with lens implant in between. The most recent THA was October 2017. Going through each procedure helped me see things from a patient’s perspective, and that showed me how important little things are to a patient, things which we may not think are all that big a deal as a provider.

Almost all of the medical personnel who came to care for me during my stays identified themselves and why they were there, and that made me feel comfortable, knowing who they were and their role. However, there were a few who did not do this, and that made me uncomfortable, not knowing who they were and why they were in my room. Not knowing is an uncomfortable feeling for a patient.

Almost every registered nurse who came to me with medication explained what the medicine was and why they were administering it, with the exception of one preop RN I met before to my cataract procedure. She walked up to me, told me to open my eye wide, held the affected eye open, and started dripping cold drops into my eye without explanation. She then said she would be back every 10 minutes to repeat the process. I had to inquire as to what the medication was and why there was a need for this process. It was a jolting experience, and she showed no compassion toward me as a patient or a person, even after I inquired.

This was not a good experience. Although cataract surgery was a totally new experience for me, she had obviously done this many times before and had to do it many times that day. However, she acted as if I should have known what she was going to do and as if she need not explain herself to anyone – which she did not, even after being queried.

Everyone during the admission process for all three procedures was solicitous and warm except for one person. Unfortunately, this individual was the first person to greet my wife and me when we arrived for my last total hip arthroplasty. She was seated at the welcome desk with her head down. After we arrived, she kept her head down and asked “How can I help you?” without ever looking up. I did not realize how unwelcome I would feel when the first person I encountered in the surgical preop admissions area failed to make eye contact with me. Her demeanor was nice enough, but she did not even attempt to make a personal connection with me – and she was at the welcome desk!

Overall, I had tremendously good experiences at three facilities in three different parts of the United States, but as we all know, it is the things that do not go well that stand out. I choose to use those things, along with some of the good things, as “reinforcers” for many of the patient-experience behaviors we identify as best practices.

What I say and do

During each patient encounter, I make eye contact with the patient and each person in the room and identify who I am and why I am there. I sit down during each visit unless there is simply no place for me to do so. I explain the procedures that are to take place, set expectations for those procedures, and then use “teachback” to ensure that my discussion with the patient has been effective. Setting expectations is very important to me: If you do not ensure that patients have appropriate expectations, their expectations will never be met and they will never have a good experience. I explain any new medication I am ordering, what it is for, and any possible significant side effects and again use teachback. The last thing I do is ask “What questions do you have for me today?” giving the patient permission to have questions, and then I respond to those questions with plain talk and teachback.

Why I do it

Not knowing what was going on and feeling marginalized were the most uncomfortable things I experienced as a patient. Using best practices for patient experience shows courtesy and respect. These practices show a willingness to take time with the patient and demonstrate my concern that I am effectively communicating my message for that visit. All of these behaviors decrease uncertainty and/or raise the patient’s feelings of importance, thereby decreasing marginalization.

How I do it

I remind myself each day I am on a clinical shift that my goal is to treat each patient like I would want my family (or myself) to be treated, and then I go out and do it. After “forcing” myself to put these behaviors into my rounding routine, they have become second nature, and I feel better for providing this level of care because it made me feel so good when I was cared for in this manner.

Dr. Sharp is chief hospitalist with Sound Physicians at University of Florida Health in Jacksonville, Fla.

Is Hospitalist Proficiency in Bedside Procedures in Decline?

It’s 3:30 p.m. You’ve seen your old patients, holdovers, and an admission, but you haven’t finished your notes yet. Lunch was an afterthought between emails about schedule changes for the upcoming year. Two pages ring happily from your belt, the first from you-know-who in the ED, and the next from a nurse: “THORA SUPPLIES AT BEDSIDE SINCE THIS AM—WHEN WILL THIS HAPPEN?” The phone number on the wall for the on-call radiologist beckons...

An all-too-familiar situation for hospitalists across the country, this awkward moment raises a series of difficult questions:

Should I set aside time from my day to perform a procedure that could be time-consuming?

- Do I feel confident I can perform this procedure safely?

- Am I really the best physician to provide this service?

- As hospitalists are tasked with an ever-increasing array of responsibilities, answering the call of duty for bedside procedures is becoming more difficult for some.

A Core Competency

“The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine,” authored by a group of HM thought leaders, was published as a supplement to the January/February 2006 issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine. The core competencies include such bedside procedures as arthrocentesis, paracentesis, thoracentesis, lumbar puncture, and vascular (arterial and central venous) access (see “Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: Procedures,” below). Although the authors stressed that the core competencies are to be viewed as a resource rather than as a set of requirements, the inclusion of bedside procedures emphasized the importance of procedural skills for future hospitalists.

“[Hospitalists] are in a perfect spot to continue to perform procedures in a structured manner,” says Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, FHM, associate director of the University of Miami-Jackson Memorial Hospital (UM-JMH) Center for Patient Safety. “As agents of quality and safety, hospitalists should continue to perform this clinically necessary service.”

Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, FHM, associate professor of medicine at Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago and an academic hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital (NMH), not only agrees that bedside procedures should be a core competency, but he also says hospitalists are the most appropriate providers of these services.

“I think this is part of hospital medicine. We’re in the hospital, [and] that’s what we do,” Dr. Barsuk says. Other providers, such as interventional radiologists, “really don’t understand why I’m doing [a procedure]. They understand it’s safe to do it, but they might not understand all the indications for it, and they certainly don’t understand the interpretation of the tests they’re sending.”

Despite the goals set forth by the core competencies and authorities in procedural safety, the reality of who actually performs bedside procedures is somewhat murky and varies greatly by institution. Many point to HM program setting (urban vs. rural) or structure (academic vs. community) to explain variance, but often it is other factors that determine whether hospitalists are actually preforming bedside procedures regularly.

Where Does HM Perform Procedures?

Community hospitalists, with strong support from interventional radiologists and subspecialists, often find it more efficient—even necessary, considering their patient volumes—to leave procedures to others. Community hospitalists with ICU admitting privileges, intensivists, and other HM subgroups say that being able to perform procedures should be a prerequisite for employment. Hospitalists in rural communities say they are doing procedures because they are “the only game in town.”

“Sometimes you are the only one available, and you are called upon to stretch your abilities,” says Beatrice Szantyr, MD, FAAP, a community hospitalist and pediatrician in Lincoln, Maine, who has practiced most of her career in rural settings.

Academic hospitalists in large, research-based HM programs can, paradoxically, find themselves performing fewer procedures as residents often take the lead on the majority of such cases. Conversely, academic hospitalists in large, nonteaching programs often find themselves called on to perform more bedside procedures.

No matter the setting, the simplicity of being the physician to recognize the need for a procedure, perform it, and interpret the results is undeniably efficient and “clean,” according to authorities on inpatient bedside procedures. Having to consult other physicians, optimize the patient’s lab values to their standards (a common issue with interventional radiologists), and adhere to their work schedules can often delay procedures unnecessarily.

—Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, FHM, associate director, University of Miami-Jackson Memorial Hospital (UM-JMH) Center for Patient Safety

“Hospitalists care for floor and ICU patients in many hospitals, and the inability to perform bedside procedures delays patient care,” says Dr. Nilam Soni, an academic hospitalist at the University of Chicago and a recognized expert on procedural safety.

Dr. Soni notes that when it comes to current techniques, many hospitalists suffer from a knowledge deficit. “The introduction of ultrasound for guidance of bedside procedures has been shown to improve the success and safety of certain procedures,” he says, “but the majority of practicing hospitalists did not learn how to use ultrasound for procedure guidance during residency.”

Heterogeneity of Training, Experience, and Skill

While all hospitalists draw upon different bases of training and experience, the heterogeneity of training, confidence, and inherent skill is greatest when it comes to bedside procedures. Mirroring the heterogeneity at the individual level, hospitalist programs vary greatly on the requirements placed on their staffs in regards to procedural skill and privileging.

Such research-driven programs as Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) in Boston often find requiring maintenance of privileges in bedside procedures to be difficult, says Sally Wang, MD, FHM, director of procedural education at BWH. In fact, a new procedure service being created there will be staffed mainly with ED physicians. On the flipside, most community hospitalist programs leave the task of procedural “policing” to the hospital’s medical staff affairs office.

At the University of California at San Diego (UCSD) Medical Center, the HM group is instituting a division standard in which hospitalists maintain privileging and proficiency in a core group of bedside procedures. Other large hospitalist groups have created “proceduralist” subgroups that shoulder the burden of trainee education, as well as provide a resource for less skilled or less experienced inpatient providers.

“If you have a big group, you could have a dedicated procedure service and have a core group of hospitalists who are experts in procedure,” Dr. Barsuk says. “But it needs to be self-sustaining.” Once started, Dr. Barsuk says, proceduralist groups would continue to provide hospitals with ongoing return-on-investment (ROI) benefit.

Variability in procedure volume and payor mix, however, can make it hard for HM groups to demonstrate to hospital leadership a satisfactory ROI for a proceduralist program. Financial backing from grant support or a high-volume procedure—such as paracentesis in hospitals with large hepatology programs—can nurture starting proceduralist programs until all procedural revenues can justify the costs. Lower ROI can also be justified by showing improvement in quality indices—such as CLABSI rates—reduced time to procedures, and reduced costs compared to other subspecialists offering similar services.

“I’m of the firm belief that we can reduce costs by doing the procedures at the bedside rather than referring them to departments such as interventional radiology (IR),” Dr. Barsuk says. “What you would have to do is show the institution that it costs more money to have IR do [bedside procedures].”

National Response

—Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, MS, FHM, associate professor of medicine, Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine, academic hospitalist, Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago

Filling in the procedural training gaps found on the local level, such national organizations as SHM have stepped in to provide education and support for hospitalists yearning for training. Since its inception, an SHM annual meeting pre-course that focuses on hand-held ultrasound and invasive procedures has consistently been one of the first to sell out. Other national organizations, such as ACP and its annual meeting, have seen similar interest in their courses on ultrasound-guided procedures.

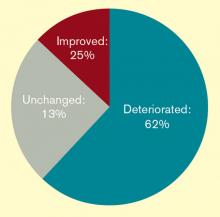

The popularity of this continuing education bears out a worrisome trend: Hospitalists feel they are losing their procedural skills. An online survey conducted by The Hospitalist in May 2011 found that a majority of respondents (62%) had experienced deterioration of their procedural skills in the past five years; only 25% said they experienced improvement over the same period.

Historically, general internists have claimed bedside procedures as their domain. As stated dispassionately in the 1978 book The House of God, “There is no body cavity that cannot be reached with a #14G needle and a good strong arm.”1 Yet much has changed since Samuel Shem’s apocryphal description of medical residency training.

Most notably, the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has not only progressively restricted inpatient hours and patient loads for residents, but also increased the requirements for outpatient training. Some feel the balance of inpatient and outpatient training has tipped too far toward the latter in medicine residency programs, especially in light of the growing popularity of the hospitalist career path amongst new residency program graduates. This stands in contrast to ED training programs, which have embraced focused procedures training more readily.

“Adult care appears to be diverging into two career tacks as a result of external forces, of which we have limited control over, “ says Michael Beck, MD, a pediatric and adult hospitalist at Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pa. “With new career choices emerging for graduates, the same square-peg, round-hole residency training should not exist.”

Dr. Beck advocates continuing an ongoing trend of “track” creation in residency programs, which allow trainees to focus training on their planned career path. Hospitalist tracks already exist in many medicine programs, including those at Cleveland Clinic and Northwestern. But many other factors limit the opportunity for trainees to obtain experience with bedside procedures, including competition with nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Even the increasing availability of ancillary phlebotomy and IV-start teams can increase a resident’s anxiety about procedures.

“By the time my residency was over [in 1993] and the work restrictions were beginning, hospital employees were doing all these tasks, making the residents less comfortable with hurting a patient when it was therapeutically necessary,” says Katharine Deiss, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine at the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York. Interns who came from medical schools without extensive ancillary services in their teaching hospitals, she adds, were more comfortable with invasive procedures.

ACGME has sent a subtle message by decreasing emphasis on procedural skills by eradicating the requirement of showing manual proficiency in most bedside procedures as a requirement for certification. The omission has left individual residency programs and hospitalist groups to determine training and proficiency requirements for more invasive bedside procedures without a national standard.

In an editorial in the March 2007 issue of the Annals of Internal Medicine, F. Daniel Duffy, MD, and Eric Holmboe, MD, wrote that the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) could only give a “qualified ‘yes’” to the question of whether residents should be trained in procedures they may not perform in practice. Although the authors asserted that the relaxed ABIM policy was “an important but small step toward revamping procedure skill training during residency,” others say it portrays an image of the ABIM de-emphasizing the importance of procedural training.

In addition, the recently established Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM) pathway to ABIM Maintenance of Certification (MOC) has no requirement to show proficiency in bedside procedures.

“The absence of the procedural requirement in no way constitutes a statement that procedural skills are not important,” says Jeff Wiese, MD, FACP, SFHM, associate professor of medicine and residency program director at Tulane University Health Sciences Center in New Orleans, chair of the ABIM Hospital Medicine MOC Question Writing Committee, and former SHM president. “Rather, it is merely a practical issue with respect to making the MOC process applicable to all physicians engaged in hospital medicine (i.e. many hospitalists do not do procedures) while still making the MOC focused on the skill sets that are common for physicians doing hospital medicine.”

Once released into the world, even if trained well in residency, hospitalists can find it difficult to maintain their skills. In community and nonteaching settings, the pressure to admit and discharge in a timely manner can make procedures seem like the easiest corner to cut. Before long, it has been months since they have laid eyes on a needle of any sort. Many begin to develop performance anxiety.

In teaching hospitals, academic hospitalists often are called upon to participate in quality improvement (QI) and research efforts, which take time away from clinical rotations. Once there, it can be easy for a ward attending to rely upon a well-trained resident to supervise interns doing procedures. The lack of first-hand or even supervisory experience can lead to many academic hospitalists losing facility with procedures, with potentially disastrous results.

“In order to supervise a group of residents, the attending needs to be technically proficient and able to salvage a botched, or failed, procedure,” UM-JMH’s Dr. Lenchus says. “To this end, we strictly limit who can attend on the service.”

So what’s a residency or HM program director to do in the face of wavering support nationally, and sometimes locally, for maintaining procedural skills for hospitalists and trainees? Many hospitalists in teaching hospitals say it’s critical for clinicians to “get their own house in order,” to maintain procedural standards of proficiency with ongoing training, education, and verification.

“The profession now needs to redesign procedural training across the continuum of education and a lifetime of practice,” Drs. Duffy and Holmboe editorialized in the March 2007 Annals paper. “This approach would recognize the varied settings of internal-medicine practice and offer manual skills training to those whose practice settings require such skills.” Hospitalists can partner with medicine residency program leaders to provide procedural education and training to residents, either as a standalone elective or as a more general resource.

Hospitalists in such teaching hospitals as UCSD, Brigham and Women’s, UM-JMH, and Northwestern are leading efforts to provide procedural education to medical students, residents, and attendings. Training takes many forms, including formal procedural electives, required procedure rotations, or even brief one- or two-day courses in procedural skills at a simulation center.

Utilizing simulation training has been shown in many studies to be helpful in establishing procedural skills in learners of all training levels. Dr. Barsuk and his colleagues at Northwestern published studies in the Journal of Hospital Medicine in 2008 and 2009 showing that simulation training of residents was effective in improving skills in thoracentesis and central venous catheterization, respectively.3,4

In the community hospital setting, requirements for procedural skills can vary greatly based on the institution. For those community programs requiring procedural skills of their hospitalists, the clear definition of procedural training and requirements at the time of hiring is critical. Even after vetting a hospitalist’s procedural skills at hire, however, community programs should consider monitoring procedural skills and provide ongoing time and money for CME focused on procedural skills.

Currently, most hospitals depend on the honesty of individual physicians during the privileging process for bedside procedures. Even when the skills of physicians begin to wane, most are reluctant to voluntarily give up their procedure privileges.

“I think it would be pretty unusual for a hospitalist to relinquish their privileges,” Dr. Barsuk admits. But ideally, physicians who relinquish their privileges due to lack of experience could get retrained in simulation centers, then reproctored in order to regain their privileges. Northwestern established the Center for Simulation Technology and Immersive Learning as a resource for simulation training both locally and nationally.

Establishing an environment that supports hospitalists performing bedside procedures is critical. This includes the need to limit hospitalist workload to ensure adequate time to meet the procedural needs of patients. Providing easy access to the tools necessary to perform bedside procedures (e.g. portable ultrasound and pre-packaged procedure trays) helps avoid additional hurdles.

Academic hospitalist programs can serve as a regional resource by developing ongoing procedure mastery programs for hospitalists in their communities, as many smaller institutions do not have the resources to provide ongoing training in bedside procedures. This process can be tedious, but it should not be humiliating.

If the popularity of the SHM pre-course in bedside ultrasound and procedures is any indication, when given the opportunity to receive protected time for procedure training, most hospitalists will likely jump at the chance.

Dr. Chang is an associate clinical professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Diego Medical Center. He is also a member of Team Hospitalist.

References

- Shem S. The House of God. New York: Dell Publishing; 1978.

- Duffy FD, Holmboe ES. What procedures should internists do? Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(5):392-393.

- Wayne DB, Barsuk JH, O’Leary KJ, Fudala MJ, McGaghie WC. Mastery learning of thoracentesis skills by internal medicine residents using simulation technology and deliberate practice. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(1):48-54.

- Barsuk JH, McGaghie WC, Cohen ER, Balachandran JS, Wayne DB. Use of simulation-based mastery learning to improve the quality of central venous catheter placement in a medical intensive care unit. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(7):397–403.

It’s 3:30 p.m. You’ve seen your old patients, holdovers, and an admission, but you haven’t finished your notes yet. Lunch was an afterthought between emails about schedule changes for the upcoming year. Two pages ring happily from your belt, the first from you-know-who in the ED, and the next from a nurse: “THORA SUPPLIES AT BEDSIDE SINCE THIS AM—WHEN WILL THIS HAPPEN?” The phone number on the wall for the on-call radiologist beckons...

An all-too-familiar situation for hospitalists across the country, this awkward moment raises a series of difficult questions:

Should I set aside time from my day to perform a procedure that could be time-consuming?

- Do I feel confident I can perform this procedure safely?

- Am I really the best physician to provide this service?

- As hospitalists are tasked with an ever-increasing array of responsibilities, answering the call of duty for bedside procedures is becoming more difficult for some.

A Core Competency

“The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine,” authored by a group of HM thought leaders, was published as a supplement to the January/February 2006 issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine. The core competencies include such bedside procedures as arthrocentesis, paracentesis, thoracentesis, lumbar puncture, and vascular (arterial and central venous) access (see “Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: Procedures,” below). Although the authors stressed that the core competencies are to be viewed as a resource rather than as a set of requirements, the inclusion of bedside procedures emphasized the importance of procedural skills for future hospitalists.

“[Hospitalists] are in a perfect spot to continue to perform procedures in a structured manner,” says Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, FHM, associate director of the University of Miami-Jackson Memorial Hospital (UM-JMH) Center for Patient Safety. “As agents of quality and safety, hospitalists should continue to perform this clinically necessary service.”

Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, FHM, associate professor of medicine at Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago and an academic hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital (NMH), not only agrees that bedside procedures should be a core competency, but he also says hospitalists are the most appropriate providers of these services.

“I think this is part of hospital medicine. We’re in the hospital, [and] that’s what we do,” Dr. Barsuk says. Other providers, such as interventional radiologists, “really don’t understand why I’m doing [a procedure]. They understand it’s safe to do it, but they might not understand all the indications for it, and they certainly don’t understand the interpretation of the tests they’re sending.”

Despite the goals set forth by the core competencies and authorities in procedural safety, the reality of who actually performs bedside procedures is somewhat murky and varies greatly by institution. Many point to HM program setting (urban vs. rural) or structure (academic vs. community) to explain variance, but often it is other factors that determine whether hospitalists are actually preforming bedside procedures regularly.

Where Does HM Perform Procedures?

Community hospitalists, with strong support from interventional radiologists and subspecialists, often find it more efficient—even necessary, considering their patient volumes—to leave procedures to others. Community hospitalists with ICU admitting privileges, intensivists, and other HM subgroups say that being able to perform procedures should be a prerequisite for employment. Hospitalists in rural communities say they are doing procedures because they are “the only game in town.”

“Sometimes you are the only one available, and you are called upon to stretch your abilities,” says Beatrice Szantyr, MD, FAAP, a community hospitalist and pediatrician in Lincoln, Maine, who has practiced most of her career in rural settings.

Academic hospitalists in large, research-based HM programs can, paradoxically, find themselves performing fewer procedures as residents often take the lead on the majority of such cases. Conversely, academic hospitalists in large, nonteaching programs often find themselves called on to perform more bedside procedures.

No matter the setting, the simplicity of being the physician to recognize the need for a procedure, perform it, and interpret the results is undeniably efficient and “clean,” according to authorities on inpatient bedside procedures. Having to consult other physicians, optimize the patient’s lab values to their standards (a common issue with interventional radiologists), and adhere to their work schedules can often delay procedures unnecessarily.

—Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, FHM, associate director, University of Miami-Jackson Memorial Hospital (UM-JMH) Center for Patient Safety

“Hospitalists care for floor and ICU patients in many hospitals, and the inability to perform bedside procedures delays patient care,” says Dr. Nilam Soni, an academic hospitalist at the University of Chicago and a recognized expert on procedural safety.

Dr. Soni notes that when it comes to current techniques, many hospitalists suffer from a knowledge deficit. “The introduction of ultrasound for guidance of bedside procedures has been shown to improve the success and safety of certain procedures,” he says, “but the majority of practicing hospitalists did not learn how to use ultrasound for procedure guidance during residency.”

Heterogeneity of Training, Experience, and Skill

While all hospitalists draw upon different bases of training and experience, the heterogeneity of training, confidence, and inherent skill is greatest when it comes to bedside procedures. Mirroring the heterogeneity at the individual level, hospitalist programs vary greatly on the requirements placed on their staffs in regards to procedural skill and privileging.

Such research-driven programs as Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) in Boston often find requiring maintenance of privileges in bedside procedures to be difficult, says Sally Wang, MD, FHM, director of procedural education at BWH. In fact, a new procedure service being created there will be staffed mainly with ED physicians. On the flipside, most community hospitalist programs leave the task of procedural “policing” to the hospital’s medical staff affairs office.

At the University of California at San Diego (UCSD) Medical Center, the HM group is instituting a division standard in which hospitalists maintain privileging and proficiency in a core group of bedside procedures. Other large hospitalist groups have created “proceduralist” subgroups that shoulder the burden of trainee education, as well as provide a resource for less skilled or less experienced inpatient providers.

“If you have a big group, you could have a dedicated procedure service and have a core group of hospitalists who are experts in procedure,” Dr. Barsuk says. “But it needs to be self-sustaining.” Once started, Dr. Barsuk says, proceduralist groups would continue to provide hospitals with ongoing return-on-investment (ROI) benefit.

Variability in procedure volume and payor mix, however, can make it hard for HM groups to demonstrate to hospital leadership a satisfactory ROI for a proceduralist program. Financial backing from grant support or a high-volume procedure—such as paracentesis in hospitals with large hepatology programs—can nurture starting proceduralist programs until all procedural revenues can justify the costs. Lower ROI can also be justified by showing improvement in quality indices—such as CLABSI rates—reduced time to procedures, and reduced costs compared to other subspecialists offering similar services.

“I’m of the firm belief that we can reduce costs by doing the procedures at the bedside rather than referring them to departments such as interventional radiology (IR),” Dr. Barsuk says. “What you would have to do is show the institution that it costs more money to have IR do [bedside procedures].”

National Response

—Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, MS, FHM, associate professor of medicine, Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine, academic hospitalist, Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago

Filling in the procedural training gaps found on the local level, such national organizations as SHM have stepped in to provide education and support for hospitalists yearning for training. Since its inception, an SHM annual meeting pre-course that focuses on hand-held ultrasound and invasive procedures has consistently been one of the first to sell out. Other national organizations, such as ACP and its annual meeting, have seen similar interest in their courses on ultrasound-guided procedures.

The popularity of this continuing education bears out a worrisome trend: Hospitalists feel they are losing their procedural skills. An online survey conducted by The Hospitalist in May 2011 found that a majority of respondents (62%) had experienced deterioration of their procedural skills in the past five years; only 25% said they experienced improvement over the same period.

Historically, general internists have claimed bedside procedures as their domain. As stated dispassionately in the 1978 book The House of God, “There is no body cavity that cannot be reached with a #14G needle and a good strong arm.”1 Yet much has changed since Samuel Shem’s apocryphal description of medical residency training.

Most notably, the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has not only progressively restricted inpatient hours and patient loads for residents, but also increased the requirements for outpatient training. Some feel the balance of inpatient and outpatient training has tipped too far toward the latter in medicine residency programs, especially in light of the growing popularity of the hospitalist career path amongst new residency program graduates. This stands in contrast to ED training programs, which have embraced focused procedures training more readily.

“Adult care appears to be diverging into two career tacks as a result of external forces, of which we have limited control over, “ says Michael Beck, MD, a pediatric and adult hospitalist at Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pa. “With new career choices emerging for graduates, the same square-peg, round-hole residency training should not exist.”

Dr. Beck advocates continuing an ongoing trend of “track” creation in residency programs, which allow trainees to focus training on their planned career path. Hospitalist tracks already exist in many medicine programs, including those at Cleveland Clinic and Northwestern. But many other factors limit the opportunity for trainees to obtain experience with bedside procedures, including competition with nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Even the increasing availability of ancillary phlebotomy and IV-start teams can increase a resident’s anxiety about procedures.

“By the time my residency was over [in 1993] and the work restrictions were beginning, hospital employees were doing all these tasks, making the residents less comfortable with hurting a patient when it was therapeutically necessary,” says Katharine Deiss, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine at the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York. Interns who came from medical schools without extensive ancillary services in their teaching hospitals, she adds, were more comfortable with invasive procedures.

ACGME has sent a subtle message by decreasing emphasis on procedural skills by eradicating the requirement of showing manual proficiency in most bedside procedures as a requirement for certification. The omission has left individual residency programs and hospitalist groups to determine training and proficiency requirements for more invasive bedside procedures without a national standard.

In an editorial in the March 2007 issue of the Annals of Internal Medicine, F. Daniel Duffy, MD, and Eric Holmboe, MD, wrote that the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) could only give a “qualified ‘yes’” to the question of whether residents should be trained in procedures they may not perform in practice. Although the authors asserted that the relaxed ABIM policy was “an important but small step toward revamping procedure skill training during residency,” others say it portrays an image of the ABIM de-emphasizing the importance of procedural training.

In addition, the recently established Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM) pathway to ABIM Maintenance of Certification (MOC) has no requirement to show proficiency in bedside procedures.

“The absence of the procedural requirement in no way constitutes a statement that procedural skills are not important,” says Jeff Wiese, MD, FACP, SFHM, associate professor of medicine and residency program director at Tulane University Health Sciences Center in New Orleans, chair of the ABIM Hospital Medicine MOC Question Writing Committee, and former SHM president. “Rather, it is merely a practical issue with respect to making the MOC process applicable to all physicians engaged in hospital medicine (i.e. many hospitalists do not do procedures) while still making the MOC focused on the skill sets that are common for physicians doing hospital medicine.”

Once released into the world, even if trained well in residency, hospitalists can find it difficult to maintain their skills. In community and nonteaching settings, the pressure to admit and discharge in a timely manner can make procedures seem like the easiest corner to cut. Before long, it has been months since they have laid eyes on a needle of any sort. Many begin to develop performance anxiety.

In teaching hospitals, academic hospitalists often are called upon to participate in quality improvement (QI) and research efforts, which take time away from clinical rotations. Once there, it can be easy for a ward attending to rely upon a well-trained resident to supervise interns doing procedures. The lack of first-hand or even supervisory experience can lead to many academic hospitalists losing facility with procedures, with potentially disastrous results.

“In order to supervise a group of residents, the attending needs to be technically proficient and able to salvage a botched, or failed, procedure,” UM-JMH’s Dr. Lenchus says. “To this end, we strictly limit who can attend on the service.”

So what’s a residency or HM program director to do in the face of wavering support nationally, and sometimes locally, for maintaining procedural skills for hospitalists and trainees? Many hospitalists in teaching hospitals say it’s critical for clinicians to “get their own house in order,” to maintain procedural standards of proficiency with ongoing training, education, and verification.

“The profession now needs to redesign procedural training across the continuum of education and a lifetime of practice,” Drs. Duffy and Holmboe editorialized in the March 2007 Annals paper. “This approach would recognize the varied settings of internal-medicine practice and offer manual skills training to those whose practice settings require such skills.” Hospitalists can partner with medicine residency program leaders to provide procedural education and training to residents, either as a standalone elective or as a more general resource.

Hospitalists in such teaching hospitals as UCSD, Brigham and Women’s, UM-JMH, and Northwestern are leading efforts to provide procedural education to medical students, residents, and attendings. Training takes many forms, including formal procedural electives, required procedure rotations, or even brief one- or two-day courses in procedural skills at a simulation center.

Utilizing simulation training has been shown in many studies to be helpful in establishing procedural skills in learners of all training levels. Dr. Barsuk and his colleagues at Northwestern published studies in the Journal of Hospital Medicine in 2008 and 2009 showing that simulation training of residents was effective in improving skills in thoracentesis and central venous catheterization, respectively.3,4

In the community hospital setting, requirements for procedural skills can vary greatly based on the institution. For those community programs requiring procedural skills of their hospitalists, the clear definition of procedural training and requirements at the time of hiring is critical. Even after vetting a hospitalist’s procedural skills at hire, however, community programs should consider monitoring procedural skills and provide ongoing time and money for CME focused on procedural skills.

Currently, most hospitals depend on the honesty of individual physicians during the privileging process for bedside procedures. Even when the skills of physicians begin to wane, most are reluctant to voluntarily give up their procedure privileges.

“I think it would be pretty unusual for a hospitalist to relinquish their privileges,” Dr. Barsuk admits. But ideally, physicians who relinquish their privileges due to lack of experience could get retrained in simulation centers, then reproctored in order to regain their privileges. Northwestern established the Center for Simulation Technology and Immersive Learning as a resource for simulation training both locally and nationally.

Establishing an environment that supports hospitalists performing bedside procedures is critical. This includes the need to limit hospitalist workload to ensure adequate time to meet the procedural needs of patients. Providing easy access to the tools necessary to perform bedside procedures (e.g. portable ultrasound and pre-packaged procedure trays) helps avoid additional hurdles.

Academic hospitalist programs can serve as a regional resource by developing ongoing procedure mastery programs for hospitalists in their communities, as many smaller institutions do not have the resources to provide ongoing training in bedside procedures. This process can be tedious, but it should not be humiliating.

If the popularity of the SHM pre-course in bedside ultrasound and procedures is any indication, when given the opportunity to receive protected time for procedure training, most hospitalists will likely jump at the chance.

Dr. Chang is an associate clinical professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine at Diego Medical Center. He is also a member of Team Hospitalist.

References

- Shem S. The House of God. New York: Dell Publishing; 1978.

- Duffy FD, Holmboe ES. What procedures should internists do? Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(5):392-393.

- Wayne DB, Barsuk JH, O’Leary KJ, Fudala MJ, McGaghie WC. Mastery learning of thoracentesis skills by internal medicine residents using simulation technology and deliberate practice. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(1):48-54.

- Barsuk JH, McGaghie WC, Cohen ER, Balachandran JS, Wayne DB. Use of simulation-based mastery learning to improve the quality of central venous catheter placement in a medical intensive care unit. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(7):397–403.

It’s 3:30 p.m. You’ve seen your old patients, holdovers, and an admission, but you haven’t finished your notes yet. Lunch was an afterthought between emails about schedule changes for the upcoming year. Two pages ring happily from your belt, the first from you-know-who in the ED, and the next from a nurse: “THORA SUPPLIES AT BEDSIDE SINCE THIS AM—WHEN WILL THIS HAPPEN?” The phone number on the wall for the on-call radiologist beckons...

An all-too-familiar situation for hospitalists across the country, this awkward moment raises a series of difficult questions:

Should I set aside time from my day to perform a procedure that could be time-consuming?

- Do I feel confident I can perform this procedure safely?

- Am I really the best physician to provide this service?

- As hospitalists are tasked with an ever-increasing array of responsibilities, answering the call of duty for bedside procedures is becoming more difficult for some.

A Core Competency

“The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine,” authored by a group of HM thought leaders, was published as a supplement to the January/February 2006 issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine. The core competencies include such bedside procedures as arthrocentesis, paracentesis, thoracentesis, lumbar puncture, and vascular (arterial and central venous) access (see “Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: Procedures,” below). Although the authors stressed that the core competencies are to be viewed as a resource rather than as a set of requirements, the inclusion of bedside procedures emphasized the importance of procedural skills for future hospitalists.

“[Hospitalists] are in a perfect spot to continue to perform procedures in a structured manner,” says Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, FHM, associate director of the University of Miami-Jackson Memorial Hospital (UM-JMH) Center for Patient Safety. “As agents of quality and safety, hospitalists should continue to perform this clinically necessary service.”

Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, FHM, associate professor of medicine at Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago and an academic hospitalist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital (NMH), not only agrees that bedside procedures should be a core competency, but he also says hospitalists are the most appropriate providers of these services.

“I think this is part of hospital medicine. We’re in the hospital, [and] that’s what we do,” Dr. Barsuk says. Other providers, such as interventional radiologists, “really don’t understand why I’m doing [a procedure]. They understand it’s safe to do it, but they might not understand all the indications for it, and they certainly don’t understand the interpretation of the tests they’re sending.”

Despite the goals set forth by the core competencies and authorities in procedural safety, the reality of who actually performs bedside procedures is somewhat murky and varies greatly by institution. Many point to HM program setting (urban vs. rural) or structure (academic vs. community) to explain variance, but often it is other factors that determine whether hospitalists are actually preforming bedside procedures regularly.

Where Does HM Perform Procedures?

Community hospitalists, with strong support from interventional radiologists and subspecialists, often find it more efficient—even necessary, considering their patient volumes—to leave procedures to others. Community hospitalists with ICU admitting privileges, intensivists, and other HM subgroups say that being able to perform procedures should be a prerequisite for employment. Hospitalists in rural communities say they are doing procedures because they are “the only game in town.”

“Sometimes you are the only one available, and you are called upon to stretch your abilities,” says Beatrice Szantyr, MD, FAAP, a community hospitalist and pediatrician in Lincoln, Maine, who has practiced most of her career in rural settings.

Academic hospitalists in large, research-based HM programs can, paradoxically, find themselves performing fewer procedures as residents often take the lead on the majority of such cases. Conversely, academic hospitalists in large, nonteaching programs often find themselves called on to perform more bedside procedures.

No matter the setting, the simplicity of being the physician to recognize the need for a procedure, perform it, and interpret the results is undeniably efficient and “clean,” according to authorities on inpatient bedside procedures. Having to consult other physicians, optimize the patient’s lab values to their standards (a common issue with interventional radiologists), and adhere to their work schedules can often delay procedures unnecessarily.

—Joshua Lenchus, DO, RPh, FACP, FHM, associate director, University of Miami-Jackson Memorial Hospital (UM-JMH) Center for Patient Safety

“Hospitalists care for floor and ICU patients in many hospitals, and the inability to perform bedside procedures delays patient care,” says Dr. Nilam Soni, an academic hospitalist at the University of Chicago and a recognized expert on procedural safety.

Dr. Soni notes that when it comes to current techniques, many hospitalists suffer from a knowledge deficit. “The introduction of ultrasound for guidance of bedside procedures has been shown to improve the success and safety of certain procedures,” he says, “but the majority of practicing hospitalists did not learn how to use ultrasound for procedure guidance during residency.”

Heterogeneity of Training, Experience, and Skill

While all hospitalists draw upon different bases of training and experience, the heterogeneity of training, confidence, and inherent skill is greatest when it comes to bedside procedures. Mirroring the heterogeneity at the individual level, hospitalist programs vary greatly on the requirements placed on their staffs in regards to procedural skill and privileging.

Such research-driven programs as Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) in Boston often find requiring maintenance of privileges in bedside procedures to be difficult, says Sally Wang, MD, FHM, director of procedural education at BWH. In fact, a new procedure service being created there will be staffed mainly with ED physicians. On the flipside, most community hospitalist programs leave the task of procedural “policing” to the hospital’s medical staff affairs office.

At the University of California at San Diego (UCSD) Medical Center, the HM group is instituting a division standard in which hospitalists maintain privileging and proficiency in a core group of bedside procedures. Other large hospitalist groups have created “proceduralist” subgroups that shoulder the burden of trainee education, as well as provide a resource for less skilled or less experienced inpatient providers.

“If you have a big group, you could have a dedicated procedure service and have a core group of hospitalists who are experts in procedure,” Dr. Barsuk says. “But it needs to be self-sustaining.” Once started, Dr. Barsuk says, proceduralist groups would continue to provide hospitals with ongoing return-on-investment (ROI) benefit.

Variability in procedure volume and payor mix, however, can make it hard for HM groups to demonstrate to hospital leadership a satisfactory ROI for a proceduralist program. Financial backing from grant support or a high-volume procedure—such as paracentesis in hospitals with large hepatology programs—can nurture starting proceduralist programs until all procedural revenues can justify the costs. Lower ROI can also be justified by showing improvement in quality indices—such as CLABSI rates—reduced time to procedures, and reduced costs compared to other subspecialists offering similar services.

“I’m of the firm belief that we can reduce costs by doing the procedures at the bedside rather than referring them to departments such as interventional radiology (IR),” Dr. Barsuk says. “What you would have to do is show the institution that it costs more money to have IR do [bedside procedures].”

National Response

—Jeffrey Barsuk, MD, MS, FHM, associate professor of medicine, Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine, academic hospitalist, Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Chicago

Filling in the procedural training gaps found on the local level, such national organizations as SHM have stepped in to provide education and support for hospitalists yearning for training. Since its inception, an SHM annual meeting pre-course that focuses on hand-held ultrasound and invasive procedures has consistently been one of the first to sell out. Other national organizations, such as ACP and its annual meeting, have seen similar interest in their courses on ultrasound-guided procedures.

The popularity of this continuing education bears out a worrisome trend: Hospitalists feel they are losing their procedural skills. An online survey conducted by The Hospitalist in May 2011 found that a majority of respondents (62%) had experienced deterioration of their procedural skills in the past five years; only 25% said they experienced improvement over the same period.

Historically, general internists have claimed bedside procedures as their domain. As stated dispassionately in the 1978 book The House of God, “There is no body cavity that cannot be reached with a #14G needle and a good strong arm.”1 Yet much has changed since Samuel Shem’s apocryphal description of medical residency training.

Most notably, the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has not only progressively restricted inpatient hours and patient loads for residents, but also increased the requirements for outpatient training. Some feel the balance of inpatient and outpatient training has tipped too far toward the latter in medicine residency programs, especially in light of the growing popularity of the hospitalist career path amongst new residency program graduates. This stands in contrast to ED training programs, which have embraced focused procedures training more readily.

“Adult care appears to be diverging into two career tacks as a result of external forces, of which we have limited control over, “ says Michael Beck, MD, a pediatric and adult hospitalist at Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pa. “With new career choices emerging for graduates, the same square-peg, round-hole residency training should not exist.”

Dr. Beck advocates continuing an ongoing trend of “track” creation in residency programs, which allow trainees to focus training on their planned career path. Hospitalist tracks already exist in many medicine programs, including those at Cleveland Clinic and Northwestern. But many other factors limit the opportunity for trainees to obtain experience with bedside procedures, including competition with nurse practitioners and physician assistants. Even the increasing availability of ancillary phlebotomy and IV-start teams can increase a resident’s anxiety about procedures.

“By the time my residency was over [in 1993] and the work restrictions were beginning, hospital employees were doing all these tasks, making the residents less comfortable with hurting a patient when it was therapeutically necessary,” says Katharine Deiss, MD, assistant clinical professor of medicine at the University of Rochester Medical Center in New York. Interns who came from medical schools without extensive ancillary services in their teaching hospitals, she adds, were more comfortable with invasive procedures.

ACGME has sent a subtle message by decreasing emphasis on procedural skills by eradicating the requirement of showing manual proficiency in most bedside procedures as a requirement for certification. The omission has left individual residency programs and hospitalist groups to determine training and proficiency requirements for more invasive bedside procedures without a national standard.

In an editorial in the March 2007 issue of the Annals of Internal Medicine, F. Daniel Duffy, MD, and Eric Holmboe, MD, wrote that the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) could only give a “qualified ‘yes’” to the question of whether residents should be trained in procedures they may not perform in practice. Although the authors asserted that the relaxed ABIM policy was “an important but small step toward revamping procedure skill training during residency,” others say it portrays an image of the ABIM de-emphasizing the importance of procedural training.

In addition, the recently established Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (FPHM) pathway to ABIM Maintenance of Certification (MOC) has no requirement to show proficiency in bedside procedures.

“The absence of the procedural requirement in no way constitutes a statement that procedural skills are not important,” says Jeff Wiese, MD, FACP, SFHM, associate professor of medicine and residency program director at Tulane University Health Sciences Center in New Orleans, chair of the ABIM Hospital Medicine MOC Question Writing Committee, and former SHM president. “Rather, it is merely a practical issue with respect to making the MOC process applicable to all physicians engaged in hospital medicine (i.e. many hospitalists do not do procedures) while still making the MOC focused on the skill sets that are common for physicians doing hospital medicine.”

Once released into the world, even if trained well in residency, hospitalists can find it difficult to maintain their skills. In community and nonteaching settings, the pressure to admit and discharge in a timely manner can make procedures seem like the easiest corner to cut. Before long, it has been months since they have laid eyes on a needle of any sort. Many begin to develop performance anxiety.

In teaching hospitals, academic hospitalists often are called upon to participate in quality improvement (QI) and research efforts, which take time away from clinical rotations. Once there, it can be easy for a ward attending to rely upon a well-trained resident to supervise interns doing procedures. The lack of first-hand or even supervisory experience can lead to many academic hospitalists losing facility with procedures, with potentially disastrous results.

“In order to supervise a group of residents, the attending needs to be technically proficient and able to salvage a botched, or failed, procedure,” UM-JMH’s Dr. Lenchus says. “To this end, we strictly limit who can attend on the service.”

So what’s a residency or HM program director to do in the face of wavering support nationally, and sometimes locally, for maintaining procedural skills for hospitalists and trainees? Many hospitalists in teaching hospitals say it’s critical for clinicians to “get their own house in order,” to maintain procedural standards of proficiency with ongoing training, education, and verification.

“The profession now needs to redesign procedural training across the continuum of education and a lifetime of practice,” Drs. Duffy and Holmboe editorialized in the March 2007 Annals paper. “This approach would recognize the varied settings of internal-medicine practice and offer manual skills training to those whose practice settings require such skills.” Hospitalists can partner with medicine residency program leaders to provide procedural education and training to residents, either as a standalone elective or as a more general resource.

Hospitalists in such teaching hospitals as UCSD, Brigham and Women’s, UM-JMH, and Northwestern are leading efforts to provide procedural education to medical students, residents, and attendings. Training takes many forms, including formal procedural electives, required procedure rotations, or even brief one- or two-day courses in procedural skills at a simulation center.

Utilizing simulation training has been shown in many studies to be helpful in establishing procedural skills in learners of all training levels. Dr. Barsuk and his colleagues at Northwestern published studies in the Journal of Hospital Medicine in 2008 and 2009 showing that simulation training of residents was effective in improving skills in thoracentesis and central venous catheterization, respectively.3,4

In the community hospital setting, requirements for procedural skills can vary greatly based on the institution. For those community programs requiring procedural skills of their hospitalists, the clear definition of procedural training and requirements at the time of hiring is critical. Even after vetting a hospitalist’s procedural skills at hire, however, community programs should consider monitoring procedural skills and provide ongoing time and money for CME focused on procedural skills.

Currently, most hospitals depend on the honesty of individual physicians during the privileging process for bedside procedures. Even when the skills of physicians begin to wane, most are reluctant to voluntarily give up their procedure privileges.

“I think it would be pretty unusual for a hospitalist to relinquish their privileges,” Dr. Barsuk admits. But ideally, physicians who relinquish their privileges due to lack of experience could get retrained in simulation centers, then reproctored in order to regain their privileges. Northwestern established the Center for Simulation Technology and Immersive Learning as a resource for simulation training both locally and nationally.