User login

California bans “Pay for Delay,” promotes black maternal health, PrEP access

AB 824, the Pay for Delay bill, bans pharmaceutical companies from keeping cheaper generic drugs off the market. The bill prohibits agreements between brand name and generic drug manufacturers to delay the release of generic drugs, defining them as presumptively anticompetitive. A Federal Trade Commission study found that “these anticompetitive deals cost consumers and taxpayers $3.5 billion in higher drug costs every year,” according to a statement from the governor’s office.

The second bill, SB 464, is intended to improve black maternal health care. The bill is designed to reduce preventable maternal mortality among black women by requiring all perinatal health care providers to undergo implicit bias training to curb the effects of bias on maternal health and by improving data collection at the California Department of Public Health to better understand pregnancy-related deaths. “We know that black women have been dying at alarming rates during and after giving birth. The disproportionate effect of the maternal mortality rate on this community is a public health crisis and a major health equity issue. We must do everything in our power to take implicit bias out of the medical system – it is literally a matter of life and death,” said Gov. Newsom.

The third bill, SB 159, aims to facilitate the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis and postexposure prophylaxis against HIV infection. The bill allows pharmacists in the state to dispense PrEP and PEP without a physician’s prescription and prohibits insurance companies from requiring prior authorization for patients to obtain PrEP coverage. “All Californians deserve access to PrEP and PEP, two treatments that have transformed our fight against HIV and AIDS,” Gov. Newsom said in a statement.

AB 824, the Pay for Delay bill, bans pharmaceutical companies from keeping cheaper generic drugs off the market. The bill prohibits agreements between brand name and generic drug manufacturers to delay the release of generic drugs, defining them as presumptively anticompetitive. A Federal Trade Commission study found that “these anticompetitive deals cost consumers and taxpayers $3.5 billion in higher drug costs every year,” according to a statement from the governor’s office.

The second bill, SB 464, is intended to improve black maternal health care. The bill is designed to reduce preventable maternal mortality among black women by requiring all perinatal health care providers to undergo implicit bias training to curb the effects of bias on maternal health and by improving data collection at the California Department of Public Health to better understand pregnancy-related deaths. “We know that black women have been dying at alarming rates during and after giving birth. The disproportionate effect of the maternal mortality rate on this community is a public health crisis and a major health equity issue. We must do everything in our power to take implicit bias out of the medical system – it is literally a matter of life and death,” said Gov. Newsom.

The third bill, SB 159, aims to facilitate the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis and postexposure prophylaxis against HIV infection. The bill allows pharmacists in the state to dispense PrEP and PEP without a physician’s prescription and prohibits insurance companies from requiring prior authorization for patients to obtain PrEP coverage. “All Californians deserve access to PrEP and PEP, two treatments that have transformed our fight against HIV and AIDS,” Gov. Newsom said in a statement.

AB 824, the Pay for Delay bill, bans pharmaceutical companies from keeping cheaper generic drugs off the market. The bill prohibits agreements between brand name and generic drug manufacturers to delay the release of generic drugs, defining them as presumptively anticompetitive. A Federal Trade Commission study found that “these anticompetitive deals cost consumers and taxpayers $3.5 billion in higher drug costs every year,” according to a statement from the governor’s office.

The second bill, SB 464, is intended to improve black maternal health care. The bill is designed to reduce preventable maternal mortality among black women by requiring all perinatal health care providers to undergo implicit bias training to curb the effects of bias on maternal health and by improving data collection at the California Department of Public Health to better understand pregnancy-related deaths. “We know that black women have been dying at alarming rates during and after giving birth. The disproportionate effect of the maternal mortality rate on this community is a public health crisis and a major health equity issue. We must do everything in our power to take implicit bias out of the medical system – it is literally a matter of life and death,” said Gov. Newsom.

The third bill, SB 159, aims to facilitate the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis and postexposure prophylaxis against HIV infection. The bill allows pharmacists in the state to dispense PrEP and PEP without a physician’s prescription and prohibits insurance companies from requiring prior authorization for patients to obtain PrEP coverage. “All Californians deserve access to PrEP and PEP, two treatments that have transformed our fight against HIV and AIDS,” Gov. Newsom said in a statement.

HCV+ kidney transplants: Similar outcomes to HCV- regardless of recipient serostatus

Kidneys from donors with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection function well despite adverse quality assessment and are a valuable resource for transplantation candidates independent of HCV status, according to the findings of a large U.S. registry study.

A total of 260 HCV-viremic kidneys were transplanted in the first quarter of 2019, with 105 additional viremic kidneys being discarded, according to a report in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology by Vishnu S. Potluri, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues.

Donor HCV viremia was defined as an HCV nucleic acid test–positive result reported to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). Donors who were HCV negative in this test were labeled as HCV nonviremic. Kidney transplantation recipients were defined as either HCV seropositive or seronegative based on HCV antibody testing.

During the first quarter of 2019, 74% of HCV-viremic kidneys were transplanted into seronegative recipients, which is a major change from how HCV-viremic kidneys were allocated a few years ago, according to the researchers. The results of small trials showing the benefits of such transplantations and the success of direct-acting antiviral therapy (DAA) on clearing HCV infections were indicated as likely responsible for the change.

HCV-viremic kidneys had similar function, compared with HCV-nonviremic kidneys, when matched on the donor elements included in the Kidney Profile Donor Index (KDPI), excluding HCV, they added. In addition, the 12-month estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was similar between the seropositive and seronegative recipients, respectively 65.4 and 71.1 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (P = .05), which suggests that recipient HCV serostatus does not negatively affect 1-year graft function using HCV-viremic kidneys in the era of DAA treatments, according to the authors.

Also, among HCV-seropositive recipients of HCV-viremic kidneys, seven (3.4%) died by 1 year post transplantation, while none of the HCV-seronegative recipients of HCV-viremic kidneys experienced graft failure or death.

“These striking results provide important additional evidence that the KDPI, with its current negative weighting for HCV status, does not accurately assess the quality of kidneys from HCV-viremic donors,” the authors wrote.

“HCV-viremic kidneys are a valuable resource for transplantation. Disincentives for accepting these organs should be addressed by the transplantation community,” Dr. Potluri and colleagues concluded.

This work was supported in part by the Health Resources and Services Administration of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. The various authors reported grant funding and advisory board participation with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Potluri VS et al. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30:1939-51.

Kidneys from donors with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection function well despite adverse quality assessment and are a valuable resource for transplantation candidates independent of HCV status, according to the findings of a large U.S. registry study.

A total of 260 HCV-viremic kidneys were transplanted in the first quarter of 2019, with 105 additional viremic kidneys being discarded, according to a report in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology by Vishnu S. Potluri, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues.

Donor HCV viremia was defined as an HCV nucleic acid test–positive result reported to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). Donors who were HCV negative in this test were labeled as HCV nonviremic. Kidney transplantation recipients were defined as either HCV seropositive or seronegative based on HCV antibody testing.

During the first quarter of 2019, 74% of HCV-viremic kidneys were transplanted into seronegative recipients, which is a major change from how HCV-viremic kidneys were allocated a few years ago, according to the researchers. The results of small trials showing the benefits of such transplantations and the success of direct-acting antiviral therapy (DAA) on clearing HCV infections were indicated as likely responsible for the change.

HCV-viremic kidneys had similar function, compared with HCV-nonviremic kidneys, when matched on the donor elements included in the Kidney Profile Donor Index (KDPI), excluding HCV, they added. In addition, the 12-month estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was similar between the seropositive and seronegative recipients, respectively 65.4 and 71.1 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (P = .05), which suggests that recipient HCV serostatus does not negatively affect 1-year graft function using HCV-viremic kidneys in the era of DAA treatments, according to the authors.

Also, among HCV-seropositive recipients of HCV-viremic kidneys, seven (3.4%) died by 1 year post transplantation, while none of the HCV-seronegative recipients of HCV-viremic kidneys experienced graft failure or death.

“These striking results provide important additional evidence that the KDPI, with its current negative weighting for HCV status, does not accurately assess the quality of kidneys from HCV-viremic donors,” the authors wrote.

“HCV-viremic kidneys are a valuable resource for transplantation. Disincentives for accepting these organs should be addressed by the transplantation community,” Dr. Potluri and colleagues concluded.

This work was supported in part by the Health Resources and Services Administration of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. The various authors reported grant funding and advisory board participation with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Potluri VS et al. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30:1939-51.

Kidneys from donors with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection function well despite adverse quality assessment and are a valuable resource for transplantation candidates independent of HCV status, according to the findings of a large U.S. registry study.

A total of 260 HCV-viremic kidneys were transplanted in the first quarter of 2019, with 105 additional viremic kidneys being discarded, according to a report in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology by Vishnu S. Potluri, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, and colleagues.

Donor HCV viremia was defined as an HCV nucleic acid test–positive result reported to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). Donors who were HCV negative in this test were labeled as HCV nonviremic. Kidney transplantation recipients were defined as either HCV seropositive or seronegative based on HCV antibody testing.

During the first quarter of 2019, 74% of HCV-viremic kidneys were transplanted into seronegative recipients, which is a major change from how HCV-viremic kidneys were allocated a few years ago, according to the researchers. The results of small trials showing the benefits of such transplantations and the success of direct-acting antiviral therapy (DAA) on clearing HCV infections were indicated as likely responsible for the change.

HCV-viremic kidneys had similar function, compared with HCV-nonviremic kidneys, when matched on the donor elements included in the Kidney Profile Donor Index (KDPI), excluding HCV, they added. In addition, the 12-month estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was similar between the seropositive and seronegative recipients, respectively 65.4 and 71.1 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (P = .05), which suggests that recipient HCV serostatus does not negatively affect 1-year graft function using HCV-viremic kidneys in the era of DAA treatments, according to the authors.

Also, among HCV-seropositive recipients of HCV-viremic kidneys, seven (3.4%) died by 1 year post transplantation, while none of the HCV-seronegative recipients of HCV-viremic kidneys experienced graft failure or death.

“These striking results provide important additional evidence that the KDPI, with its current negative weighting for HCV status, does not accurately assess the quality of kidneys from HCV-viremic donors,” the authors wrote.

“HCV-viremic kidneys are a valuable resource for transplantation. Disincentives for accepting these organs should be addressed by the transplantation community,” Dr. Potluri and colleagues concluded.

This work was supported in part by the Health Resources and Services Administration of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. The various authors reported grant funding and advisory board participation with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Potluri VS et al. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;30:1939-51.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF NEPHROLOGY

IDWeek examined hot topics in the clinical treatment of infectious diseases

WASHINGTON – The top existential threats to health today are climate change and overpopulation, but third in this list is antimicrobial resistance, according to Helen Boucher, MD, of Tufts Medical Center, Boston. In her talk at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases, however, she focused on the last, presenting the hottest developments in the clinical science of treating and identifying disease-causing agents.

In particular, she discussed two of the most important developments in the area of rapid diagnostics: cell-free microbial DNA in plasma and the use of next-generation gene sequencing for determining disease etiology.

Using a meta-genomics test, cell-free microbial DNA can be identified in plasma from more than 1,000 relevant bacteria, DNA viruses, fungi, and parasites. Though importantly, RNA viruses are not detectable using this technology, she added. Although current sampling is of plasma, this might expand to the ability to use urine in the future. She discussed its particular use in sepsis, as outlined in a paper in Nature Microbiology (2019;4[4]:663-74). The researchers examined 350 suspected sepsis patients and they found a 93% sensitivity, compared with reference standards, using this new test. The main issue with the test was a high incidence of false positives.

Another test Dr. Boucher discussed was the use of meta-genomic next-generation sequencing. She referred to a 2019 paper in the New England Journal of Medicine, which discussed the use of clinical meta-genomic next-generation sequencing of cerebrospinal fluid for the diagnosis of meningitis and encephalitis (2019;380[27]:2327-40). Next-generation sequencing identified 13% of patients positive who were missed using standard screening. However, a number of patients were not diagnosed using the new test, showing that this technique was an improvement over current methods, but not 100% successful.

Dr. Boucher stressed the need for “diagnostic stewardship” to identify the correct microbial agent causing disease, allowing for the use of appropriate treatment rather than shotgun approaches to prevent the development of antibiotic resistance. This practice requires collaboration between the clinical laboratory, pharmacists, and infectious disease specialists.

Dr. Boucher then switched to the area of therapeutics, focusing on the introduction of new antibiotics and other innovations in disease treatment methodologies, especially in the field of transplant ID.

“We have new drugs. That is the good news,” with the goals of the 10 x ’20 initiative to develop 10 new systemic antibiotics by 2020, having “been met and then some,” said Dr. Boucher.

“We now have 13 new drugs, systemically available antibiotics, available by August 2019,” she added, discussing several of the new drugs.

In addition, she pointed out several studies that have indicated that shorter courses of antibiotics are better than longer, and that, in many cases, oral therapy is better than intravenous.

In the burgeoning area of transplant ID studies, Dr. Boucher discussed new research showing that vaccinations in transplanted patients can be advised in several instances, though may require higher dosing, and how the use of hepatitis C virus–positive organs for transplant is showing good results and increasing the availability of organs for transplant.

Dr. Boucher has served on data review committees for Actelion and Medtronix and has served as a consultant/advisor for Cerexa, Durata Therapeutics, Merck (adjudication committee), Rib-X, and Wyeth/Pfizer (data safety monitoring committee).

WASHINGTON – The top existential threats to health today are climate change and overpopulation, but third in this list is antimicrobial resistance, according to Helen Boucher, MD, of Tufts Medical Center, Boston. In her talk at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases, however, she focused on the last, presenting the hottest developments in the clinical science of treating and identifying disease-causing agents.

In particular, she discussed two of the most important developments in the area of rapid diagnostics: cell-free microbial DNA in plasma and the use of next-generation gene sequencing for determining disease etiology.

Using a meta-genomics test, cell-free microbial DNA can be identified in plasma from more than 1,000 relevant bacteria, DNA viruses, fungi, and parasites. Though importantly, RNA viruses are not detectable using this technology, she added. Although current sampling is of plasma, this might expand to the ability to use urine in the future. She discussed its particular use in sepsis, as outlined in a paper in Nature Microbiology (2019;4[4]:663-74). The researchers examined 350 suspected sepsis patients and they found a 93% sensitivity, compared with reference standards, using this new test. The main issue with the test was a high incidence of false positives.

Another test Dr. Boucher discussed was the use of meta-genomic next-generation sequencing. She referred to a 2019 paper in the New England Journal of Medicine, which discussed the use of clinical meta-genomic next-generation sequencing of cerebrospinal fluid for the diagnosis of meningitis and encephalitis (2019;380[27]:2327-40). Next-generation sequencing identified 13% of patients positive who were missed using standard screening. However, a number of patients were not diagnosed using the new test, showing that this technique was an improvement over current methods, but not 100% successful.

Dr. Boucher stressed the need for “diagnostic stewardship” to identify the correct microbial agent causing disease, allowing for the use of appropriate treatment rather than shotgun approaches to prevent the development of antibiotic resistance. This practice requires collaboration between the clinical laboratory, pharmacists, and infectious disease specialists.

Dr. Boucher then switched to the area of therapeutics, focusing on the introduction of new antibiotics and other innovations in disease treatment methodologies, especially in the field of transplant ID.

“We have new drugs. That is the good news,” with the goals of the 10 x ’20 initiative to develop 10 new systemic antibiotics by 2020, having “been met and then some,” said Dr. Boucher.

“We now have 13 new drugs, systemically available antibiotics, available by August 2019,” she added, discussing several of the new drugs.

In addition, she pointed out several studies that have indicated that shorter courses of antibiotics are better than longer, and that, in many cases, oral therapy is better than intravenous.

In the burgeoning area of transplant ID studies, Dr. Boucher discussed new research showing that vaccinations in transplanted patients can be advised in several instances, though may require higher dosing, and how the use of hepatitis C virus–positive organs for transplant is showing good results and increasing the availability of organs for transplant.

Dr. Boucher has served on data review committees for Actelion and Medtronix and has served as a consultant/advisor for Cerexa, Durata Therapeutics, Merck (adjudication committee), Rib-X, and Wyeth/Pfizer (data safety monitoring committee).

WASHINGTON – The top existential threats to health today are climate change and overpopulation, but third in this list is antimicrobial resistance, according to Helen Boucher, MD, of Tufts Medical Center, Boston. In her talk at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases, however, she focused on the last, presenting the hottest developments in the clinical science of treating and identifying disease-causing agents.

In particular, she discussed two of the most important developments in the area of rapid diagnostics: cell-free microbial DNA in plasma and the use of next-generation gene sequencing for determining disease etiology.

Using a meta-genomics test, cell-free microbial DNA can be identified in plasma from more than 1,000 relevant bacteria, DNA viruses, fungi, and parasites. Though importantly, RNA viruses are not detectable using this technology, she added. Although current sampling is of plasma, this might expand to the ability to use urine in the future. She discussed its particular use in sepsis, as outlined in a paper in Nature Microbiology (2019;4[4]:663-74). The researchers examined 350 suspected sepsis patients and they found a 93% sensitivity, compared with reference standards, using this new test. The main issue with the test was a high incidence of false positives.

Another test Dr. Boucher discussed was the use of meta-genomic next-generation sequencing. She referred to a 2019 paper in the New England Journal of Medicine, which discussed the use of clinical meta-genomic next-generation sequencing of cerebrospinal fluid for the diagnosis of meningitis and encephalitis (2019;380[27]:2327-40). Next-generation sequencing identified 13% of patients positive who were missed using standard screening. However, a number of patients were not diagnosed using the new test, showing that this technique was an improvement over current methods, but not 100% successful.

Dr. Boucher stressed the need for “diagnostic stewardship” to identify the correct microbial agent causing disease, allowing for the use of appropriate treatment rather than shotgun approaches to prevent the development of antibiotic resistance. This practice requires collaboration between the clinical laboratory, pharmacists, and infectious disease specialists.

Dr. Boucher then switched to the area of therapeutics, focusing on the introduction of new antibiotics and other innovations in disease treatment methodologies, especially in the field of transplant ID.

“We have new drugs. That is the good news,” with the goals of the 10 x ’20 initiative to develop 10 new systemic antibiotics by 2020, having “been met and then some,” said Dr. Boucher.

“We now have 13 new drugs, systemically available antibiotics, available by August 2019,” she added, discussing several of the new drugs.

In addition, she pointed out several studies that have indicated that shorter courses of antibiotics are better than longer, and that, in many cases, oral therapy is better than intravenous.

In the burgeoning area of transplant ID studies, Dr. Boucher discussed new research showing that vaccinations in transplanted patients can be advised in several instances, though may require higher dosing, and how the use of hepatitis C virus–positive organs for transplant is showing good results and increasing the availability of organs for transplant.

Dr. Boucher has served on data review committees for Actelion and Medtronix and has served as a consultant/advisor for Cerexa, Durata Therapeutics, Merck (adjudication committee), Rib-X, and Wyeth/Pfizer (data safety monitoring committee).

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM IDWEEK 2019

FDA approves Descovy as HIV PrEP for men and transgender women who have sex with men

The decision, backing the earlier recommendation of the FDA’s Antimicrobial Drugs Advisory Committee, was based upon results from DISCOVER, a pivotal, multiyear, global phase 3 clinical trial that evaluated the safety and efficacy of Descovy (emtricitabine 200 mg and tenofovir alafenamide 25-mg tablets for PrEP, compared with Truvada (emtricitabine 200 mg and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 300-mg tablets).

DISCOVER included more than 5,300 adult cisgender men who have sex with men or transgender women who have sex with men.

In the trial, Descovy achieved noninferiority to Truvada.

Descovy has a Boxed Warning in its U.S. product label regarding the risk of posttreatment acute exacerbation of hepatitis B, according to the company.

The Descovy label also includes a Boxed Warning regarding the risk of drug resistance with PrEP use in undiagnosed early HIV-1 infection. The effectiveness of Descovy for PrEP in individuals at risk of HIV-1 from receptive vaginal sex was not tested, and thus cisgender women at risk for infection from vaginal sex were not included in the population for which the drug was approved.

The Descovy label and safety information is available here.

The FDA version of the announcement is available here.

The decision, backing the earlier recommendation of the FDA’s Antimicrobial Drugs Advisory Committee, was based upon results from DISCOVER, a pivotal, multiyear, global phase 3 clinical trial that evaluated the safety and efficacy of Descovy (emtricitabine 200 mg and tenofovir alafenamide 25-mg tablets for PrEP, compared with Truvada (emtricitabine 200 mg and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 300-mg tablets).

DISCOVER included more than 5,300 adult cisgender men who have sex with men or transgender women who have sex with men.

In the trial, Descovy achieved noninferiority to Truvada.

Descovy has a Boxed Warning in its U.S. product label regarding the risk of posttreatment acute exacerbation of hepatitis B, according to the company.

The Descovy label also includes a Boxed Warning regarding the risk of drug resistance with PrEP use in undiagnosed early HIV-1 infection. The effectiveness of Descovy for PrEP in individuals at risk of HIV-1 from receptive vaginal sex was not tested, and thus cisgender women at risk for infection from vaginal sex were not included in the population for which the drug was approved.

The Descovy label and safety information is available here.

The FDA version of the announcement is available here.

The decision, backing the earlier recommendation of the FDA’s Antimicrobial Drugs Advisory Committee, was based upon results from DISCOVER, a pivotal, multiyear, global phase 3 clinical trial that evaluated the safety and efficacy of Descovy (emtricitabine 200 mg and tenofovir alafenamide 25-mg tablets for PrEP, compared with Truvada (emtricitabine 200 mg and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 300-mg tablets).

DISCOVER included more than 5,300 adult cisgender men who have sex with men or transgender women who have sex with men.

In the trial, Descovy achieved noninferiority to Truvada.

Descovy has a Boxed Warning in its U.S. product label regarding the risk of posttreatment acute exacerbation of hepatitis B, according to the company.

The Descovy label also includes a Boxed Warning regarding the risk of drug resistance with PrEP use in undiagnosed early HIV-1 infection. The effectiveness of Descovy for PrEP in individuals at risk of HIV-1 from receptive vaginal sex was not tested, and thus cisgender women at risk for infection from vaginal sex were not included in the population for which the drug was approved.

The Descovy label and safety information is available here.

The FDA version of the announcement is available here.

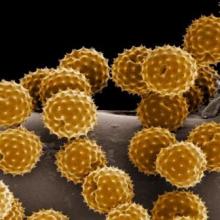

Allergy immunotherapy may modify asthma severity progression

The use of a grass-based allergy immunotherapy (AIT) lowered the risk of progression from milder to more severe asthma, according to the results of a large, real-world, industry-sponsored, observational study.

The researchers analyzed a cohort of 1,739,440 patients aged 12 years and older using 2005-2014 data from a statutory health insurance database in Germany. From this population, 39,167 individuals aged 14 years or older were classified as having incident asthma during the observation period and were included in the study.

The severity of asthma was classified according to the treatment steps recommended by the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA).

Among these, 4,111 patients (10.5%) received AIT. AIT use was associated with a significantly decreased likelihood of asthma progression from GINA step 1 to step 3 (hazard ratio, 0.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.80‐0.95) and GINA step 3 to step 4 (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.60‐0.74).

Medications for GINA step 2 (3.5%) and GINA step 5 (0.03%) were rarely prescribed, so the researchers could not analyze the transition between GINA steps 1 and 2, step 2 and 3, and step 4 and 5.

A total of 8,726 patients had at least one transition between GINA steps 1, 3, or 4, and 1,085 had two transitions, though not all 39,167 patients were under risk of severity progression into all GINA steps, according to the authors.

The findings are consistent with earlier studies that indicate grass-based immunotherapy can effectively treat asthma symptoms and potentially asthma progression (J Allergy Clin Immuno. 2012;129[3];717-25; J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141[2]:529‐38).

“This study indicates that AIT may modify the course of asthma. Our study supports the assumption that treatment with AIT may prevent the progression from mild to more severe asthma,” the authors concluded.

The study was financially supported by ALK‐Abelló; several of the authors were also employees of or received funding from the company.

SOURCE: Schmitt J et al. Allergy. 2019. doi: 10.1111/all.14020.

The use of a grass-based allergy immunotherapy (AIT) lowered the risk of progression from milder to more severe asthma, according to the results of a large, real-world, industry-sponsored, observational study.

The researchers analyzed a cohort of 1,739,440 patients aged 12 years and older using 2005-2014 data from a statutory health insurance database in Germany. From this population, 39,167 individuals aged 14 years or older were classified as having incident asthma during the observation period and were included in the study.

The severity of asthma was classified according to the treatment steps recommended by the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA).

Among these, 4,111 patients (10.5%) received AIT. AIT use was associated with a significantly decreased likelihood of asthma progression from GINA step 1 to step 3 (hazard ratio, 0.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.80‐0.95) and GINA step 3 to step 4 (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.60‐0.74).

Medications for GINA step 2 (3.5%) and GINA step 5 (0.03%) were rarely prescribed, so the researchers could not analyze the transition between GINA steps 1 and 2, step 2 and 3, and step 4 and 5.

A total of 8,726 patients had at least one transition between GINA steps 1, 3, or 4, and 1,085 had two transitions, though not all 39,167 patients were under risk of severity progression into all GINA steps, according to the authors.

The findings are consistent with earlier studies that indicate grass-based immunotherapy can effectively treat asthma symptoms and potentially asthma progression (J Allergy Clin Immuno. 2012;129[3];717-25; J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141[2]:529‐38).

“This study indicates that AIT may modify the course of asthma. Our study supports the assumption that treatment with AIT may prevent the progression from mild to more severe asthma,” the authors concluded.

The study was financially supported by ALK‐Abelló; several of the authors were also employees of or received funding from the company.

SOURCE: Schmitt J et al. Allergy. 2019. doi: 10.1111/all.14020.

The use of a grass-based allergy immunotherapy (AIT) lowered the risk of progression from milder to more severe asthma, according to the results of a large, real-world, industry-sponsored, observational study.

The researchers analyzed a cohort of 1,739,440 patients aged 12 years and older using 2005-2014 data from a statutory health insurance database in Germany. From this population, 39,167 individuals aged 14 years or older were classified as having incident asthma during the observation period and were included in the study.

The severity of asthma was classified according to the treatment steps recommended by the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA).

Among these, 4,111 patients (10.5%) received AIT. AIT use was associated with a significantly decreased likelihood of asthma progression from GINA step 1 to step 3 (hazard ratio, 0.87; 95% confidence interval, 0.80‐0.95) and GINA step 3 to step 4 (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.60‐0.74).

Medications for GINA step 2 (3.5%) and GINA step 5 (0.03%) were rarely prescribed, so the researchers could not analyze the transition between GINA steps 1 and 2, step 2 and 3, and step 4 and 5.

A total of 8,726 patients had at least one transition between GINA steps 1, 3, or 4, and 1,085 had two transitions, though not all 39,167 patients were under risk of severity progression into all GINA steps, according to the authors.

The findings are consistent with earlier studies that indicate grass-based immunotherapy can effectively treat asthma symptoms and potentially asthma progression (J Allergy Clin Immuno. 2012;129[3];717-25; J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141[2]:529‐38).

“This study indicates that AIT may modify the course of asthma. Our study supports the assumption that treatment with AIT may prevent the progression from mild to more severe asthma,” the authors concluded.

The study was financially supported by ALK‐Abelló; several of the authors were also employees of or received funding from the company.

SOURCE: Schmitt J et al. Allergy. 2019. doi: 10.1111/all.14020.

FROM ALLERGY

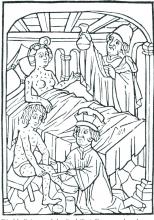

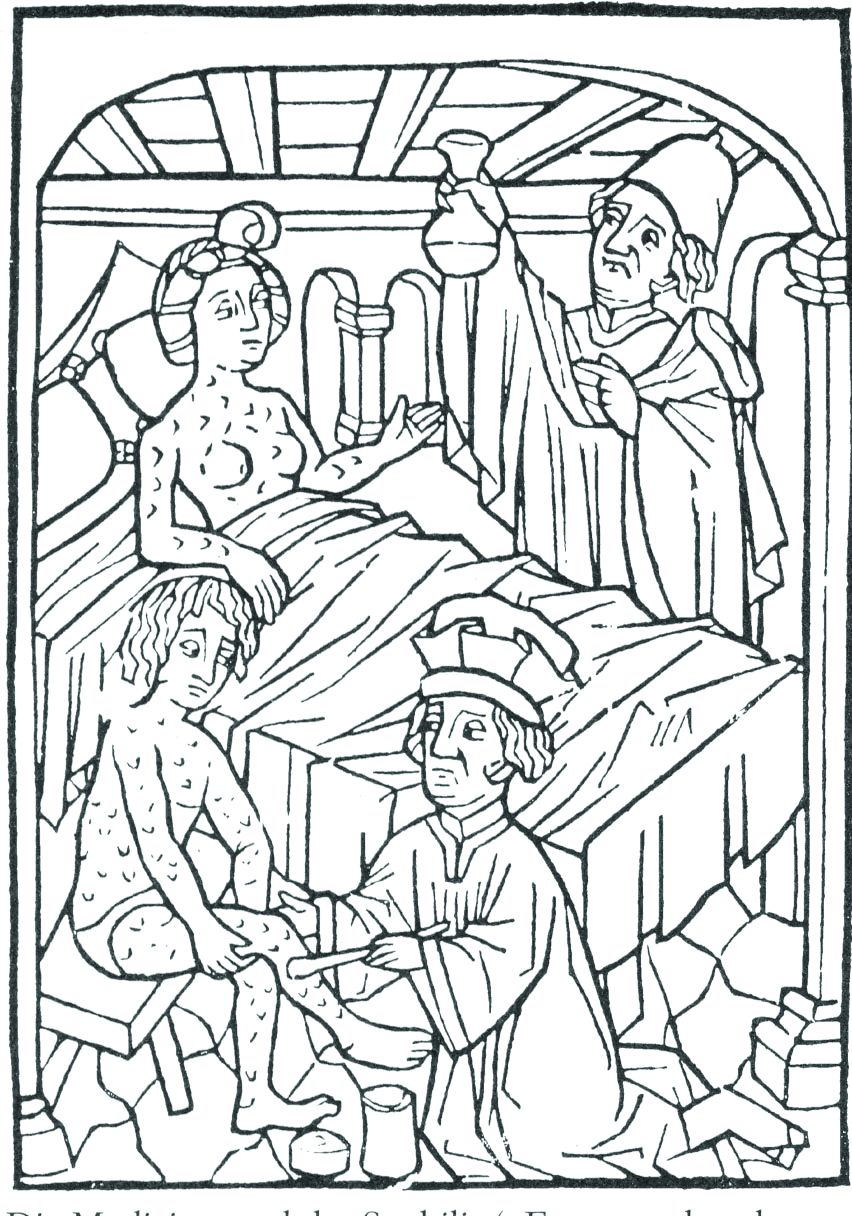

ID Blog: The story of syphilis, part II

From epidemic to endemic curse

Evolution is an amazing thing, and its more fascinating aspects are never more apparent than in the endless genetic dance between host and pathogen. And certainly, our fascination with the dance is not merely an intellectual exercise. The evolution of disease is perhaps one of the starkest examples of human misery writ large across the pages of recorded history.

In particular, the evolution of syphilis from dramatically visible, epidemic terror to silent, endemic, and long-term killer is one of the most striking examples of host-pathogen evolution. It is an example noteworthy not only for the profound transformation that occurred, but for the speed of the change, beginning so fast that it was noticed and detailed by physicians at the time as occurring over less than a human generation rather than centuries.

This very speed of the change makes it relatively certain that it was not the human species that evolved resistance, but rather that the syphilis-causing spirochetes transformed in virulence within almost the blink of an evolutionary eye – an epidemiologic mystery of profound importance to the countless lives involved.

Syphilis was a dramatic new phenomenon in the Old World of the late 15th and early 16th centuries – a hitherto unknown disease of terrible guise and rapid dissemination. It was noted and discussed throughout many of the writings of the time, so much so that one of the first detailed patient accounts in recorded history of the experience of a disease was written in response to a syphilis infection.

In 1498, Tommaso di Silvestro, an Italian notary, described his symptoms in depth: “I remember how I, Ser Tomaso, during the day 27th of April 1498, coming back from the fair in Foligno, started to feel pain in the virga [a contemporary euphemism for penis]. And then the pain grew in intensity. Then in June I started to feel the pains of the French disease. And all my body filled with pustules and crusts. I had pains in the right and left arms, in the entire arm, from the shoulder to the hand, I was filled with pain to the bones and I never found peace. And then I had pains in the right knee and all my body got full of boils, at the back at the front and behind.”

Alessandro Benedetti (1450-1512), a military surgeon and chronicler of the expedition of Charles VIII, wrote in 1497 that sufferers lost hands, feet, eyes, and noses to the disease, such that it made “the entire body so repulsive to look at and causes such great suffering.”Another common characteristic was a foul smell typical of the infected.

Careful analysis by historians has shown that, according to records from the time period, 10-15 years after the start of the epidemic in the late 15th century, there was a noticeable decline in disease virulence.

As one historian put it: “Many physicians and contemporary observers noticed the progressive decline in the severity of the disease. Many symptoms were less severe, and the rash, of a reddish color, did not cause itching.” Girolamo Fracastoro writes about some of these transformations, stating that “in the first epidemic periods the pustules were filthier,’ while they were ‘harder and drier’ afterwards.” Similarly, the historian and scholar Bernardino Cirillo dell’Aquila (1500-1575), writing in the 1530s, stated: “This horrible disease in different periods (1494) till the present had different alterations and different effects depending on the complications, and now many people just lose their hair and nothing else.”

As added documentation of the change, the chaplain of the infamous conquistador Hernàn Cortés reported that syphilis was less severe in his time than earlier. He wrote that: “at the beginning this disease was very violent, dirty and indecent; now it is no longer so severe and so indecent.”

The medical literature of the time confirmed that the fever, characteristic of the second stage of the disease, “was less violent, while even the rashes were just a ‘reddening.’ Moreover, the gummy tumors appeared only in a limited number of cases.”

According to another historian, “By the middle of the 16th century, the generation of physicians born between the end of the 15th century and the first decades of the 16th century considered the exceptional virulence manifested by syphilis when it first appeared to be ancient history.”

And Ambroise Paré (1510-1590), a renowned French surgeon, stated: “Today it is much less serious and easier to heal than it was in the past... It is obviously becoming much milder … so that it seems it should disappear in the future.”

Lacking detailed genetic analysis of the changing pathogen, if one were to speculate on why the virulence of syphilis decreased so rapidly, I suggest, in a Just-So story fashion, that one might merely speculate on the evolutionary wisdom of an STD that commonly turned its victims into foul-smelling, scabrous, agonized, and lethargic individuals who lost body parts, including their genitals, according to some reports. None of these outcomes, of course, would be conducive to the natural spread of the disease. In addition, this is a good case for sexual selection as well as early death of the host, which are two main engineers of evolutionary change.

But for whatever reason, the presentation of syphilis changed dramatically over a relatively short period of time, and as the disease was still spreading through a previously unexposed population, a change in pathogenicity rather than host immunity seems the most logical explanation.

As syphilis evolved from its initial onslaught, it showed new and hitherto unseen symptoms, including the aforementioned hair loss, and other manifestations such as tinnitus. Soon it was presenting so many systemic phenotypes similar to the effects of other diseases that Sir William Osler (1849-1919) ultimately proposed that syphilis should be described as the “Great Imitator.”

The evolution of syphilis from epidemic to endemic does not diminish the horrors of those afflicted with active tertiary syphilis, but as the disease transformed, these effects were greatly postponed and occurred less commonly, compared with their relatively rapid onset in an earlier era and in a greater proportion of the infected individuals.

Although still lethal, especially in its congenital form, by the end of the 16th century, syphilis had completed its rapid evolution from a devastating, highly visible plague to the covert disease “so sinful that it could not be discussed by name.” It would remain so until the rise of modern antibiotics finally provided a reliable cure. Active tertiary syphilis remained a severe affliction, but the effects were postponed from their relatively rapid onset in an earlier era and in a greater proportion of the infected individuals.

So, syphilis remains a unique example of host-pathogen evolution, an endemic part of the global human condition, battled by physicians in mostly futile efforts for nearly 500 years, and a disease tracking closely with the rise of modern medicine.

References

Frith J. 2012. Syphilis – Its Early History and Treatment Until Penicillin and the Debate on its Origins. J Military and Veteran’s Health. 20(4):49-58.

Tognoti B. 2009. The Rise and Fall of Syphilis in Renaissance Italy. J Med Humanit. 30(2):99-113.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor of the department of biochemistry and molecular & celluar biology at Georgetown University, Washington, D.C.

From epidemic to endemic curse

From epidemic to endemic curse

Evolution is an amazing thing, and its more fascinating aspects are never more apparent than in the endless genetic dance between host and pathogen. And certainly, our fascination with the dance is not merely an intellectual exercise. The evolution of disease is perhaps one of the starkest examples of human misery writ large across the pages of recorded history.

In particular, the evolution of syphilis from dramatically visible, epidemic terror to silent, endemic, and long-term killer is one of the most striking examples of host-pathogen evolution. It is an example noteworthy not only for the profound transformation that occurred, but for the speed of the change, beginning so fast that it was noticed and detailed by physicians at the time as occurring over less than a human generation rather than centuries.

This very speed of the change makes it relatively certain that it was not the human species that evolved resistance, but rather that the syphilis-causing spirochetes transformed in virulence within almost the blink of an evolutionary eye – an epidemiologic mystery of profound importance to the countless lives involved.

Syphilis was a dramatic new phenomenon in the Old World of the late 15th and early 16th centuries – a hitherto unknown disease of terrible guise and rapid dissemination. It was noted and discussed throughout many of the writings of the time, so much so that one of the first detailed patient accounts in recorded history of the experience of a disease was written in response to a syphilis infection.

In 1498, Tommaso di Silvestro, an Italian notary, described his symptoms in depth: “I remember how I, Ser Tomaso, during the day 27th of April 1498, coming back from the fair in Foligno, started to feel pain in the virga [a contemporary euphemism for penis]. And then the pain grew in intensity. Then in June I started to feel the pains of the French disease. And all my body filled with pustules and crusts. I had pains in the right and left arms, in the entire arm, from the shoulder to the hand, I was filled with pain to the bones and I never found peace. And then I had pains in the right knee and all my body got full of boils, at the back at the front and behind.”

Alessandro Benedetti (1450-1512), a military surgeon and chronicler of the expedition of Charles VIII, wrote in 1497 that sufferers lost hands, feet, eyes, and noses to the disease, such that it made “the entire body so repulsive to look at and causes such great suffering.”Another common characteristic was a foul smell typical of the infected.

Careful analysis by historians has shown that, according to records from the time period, 10-15 years after the start of the epidemic in the late 15th century, there was a noticeable decline in disease virulence.

As one historian put it: “Many physicians and contemporary observers noticed the progressive decline in the severity of the disease. Many symptoms were less severe, and the rash, of a reddish color, did not cause itching.” Girolamo Fracastoro writes about some of these transformations, stating that “in the first epidemic periods the pustules were filthier,’ while they were ‘harder and drier’ afterwards.” Similarly, the historian and scholar Bernardino Cirillo dell’Aquila (1500-1575), writing in the 1530s, stated: “This horrible disease in different periods (1494) till the present had different alterations and different effects depending on the complications, and now many people just lose their hair and nothing else.”

As added documentation of the change, the chaplain of the infamous conquistador Hernàn Cortés reported that syphilis was less severe in his time than earlier. He wrote that: “at the beginning this disease was very violent, dirty and indecent; now it is no longer so severe and so indecent.”

The medical literature of the time confirmed that the fever, characteristic of the second stage of the disease, “was less violent, while even the rashes were just a ‘reddening.’ Moreover, the gummy tumors appeared only in a limited number of cases.”

According to another historian, “By the middle of the 16th century, the generation of physicians born between the end of the 15th century and the first decades of the 16th century considered the exceptional virulence manifested by syphilis when it first appeared to be ancient history.”

And Ambroise Paré (1510-1590), a renowned French surgeon, stated: “Today it is much less serious and easier to heal than it was in the past... It is obviously becoming much milder … so that it seems it should disappear in the future.”

Lacking detailed genetic analysis of the changing pathogen, if one were to speculate on why the virulence of syphilis decreased so rapidly, I suggest, in a Just-So story fashion, that one might merely speculate on the evolutionary wisdom of an STD that commonly turned its victims into foul-smelling, scabrous, agonized, and lethargic individuals who lost body parts, including their genitals, according to some reports. None of these outcomes, of course, would be conducive to the natural spread of the disease. In addition, this is a good case for sexual selection as well as early death of the host, which are two main engineers of evolutionary change.

But for whatever reason, the presentation of syphilis changed dramatically over a relatively short period of time, and as the disease was still spreading through a previously unexposed population, a change in pathogenicity rather than host immunity seems the most logical explanation.

As syphilis evolved from its initial onslaught, it showed new and hitherto unseen symptoms, including the aforementioned hair loss, and other manifestations such as tinnitus. Soon it was presenting so many systemic phenotypes similar to the effects of other diseases that Sir William Osler (1849-1919) ultimately proposed that syphilis should be described as the “Great Imitator.”

The evolution of syphilis from epidemic to endemic does not diminish the horrors of those afflicted with active tertiary syphilis, but as the disease transformed, these effects were greatly postponed and occurred less commonly, compared with their relatively rapid onset in an earlier era and in a greater proportion of the infected individuals.

Although still lethal, especially in its congenital form, by the end of the 16th century, syphilis had completed its rapid evolution from a devastating, highly visible plague to the covert disease “so sinful that it could not be discussed by name.” It would remain so until the rise of modern antibiotics finally provided a reliable cure. Active tertiary syphilis remained a severe affliction, but the effects were postponed from their relatively rapid onset in an earlier era and in a greater proportion of the infected individuals.

So, syphilis remains a unique example of host-pathogen evolution, an endemic part of the global human condition, battled by physicians in mostly futile efforts for nearly 500 years, and a disease tracking closely with the rise of modern medicine.

References

Frith J. 2012. Syphilis – Its Early History and Treatment Until Penicillin and the Debate on its Origins. J Military and Veteran’s Health. 20(4):49-58.

Tognoti B. 2009. The Rise and Fall of Syphilis in Renaissance Italy. J Med Humanit. 30(2):99-113.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor of the department of biochemistry and molecular & celluar biology at Georgetown University, Washington, D.C.

Evolution is an amazing thing, and its more fascinating aspects are never more apparent than in the endless genetic dance between host and pathogen. And certainly, our fascination with the dance is not merely an intellectual exercise. The evolution of disease is perhaps one of the starkest examples of human misery writ large across the pages of recorded history.

In particular, the evolution of syphilis from dramatically visible, epidemic terror to silent, endemic, and long-term killer is one of the most striking examples of host-pathogen evolution. It is an example noteworthy not only for the profound transformation that occurred, but for the speed of the change, beginning so fast that it was noticed and detailed by physicians at the time as occurring over less than a human generation rather than centuries.

This very speed of the change makes it relatively certain that it was not the human species that evolved resistance, but rather that the syphilis-causing spirochetes transformed in virulence within almost the blink of an evolutionary eye – an epidemiologic mystery of profound importance to the countless lives involved.

Syphilis was a dramatic new phenomenon in the Old World of the late 15th and early 16th centuries – a hitherto unknown disease of terrible guise and rapid dissemination. It was noted and discussed throughout many of the writings of the time, so much so that one of the first detailed patient accounts in recorded history of the experience of a disease was written in response to a syphilis infection.

In 1498, Tommaso di Silvestro, an Italian notary, described his symptoms in depth: “I remember how I, Ser Tomaso, during the day 27th of April 1498, coming back from the fair in Foligno, started to feel pain in the virga [a contemporary euphemism for penis]. And then the pain grew in intensity. Then in June I started to feel the pains of the French disease. And all my body filled with pustules and crusts. I had pains in the right and left arms, in the entire arm, from the shoulder to the hand, I was filled with pain to the bones and I never found peace. And then I had pains in the right knee and all my body got full of boils, at the back at the front and behind.”

Alessandro Benedetti (1450-1512), a military surgeon and chronicler of the expedition of Charles VIII, wrote in 1497 that sufferers lost hands, feet, eyes, and noses to the disease, such that it made “the entire body so repulsive to look at and causes such great suffering.”Another common characteristic was a foul smell typical of the infected.

Careful analysis by historians has shown that, according to records from the time period, 10-15 years after the start of the epidemic in the late 15th century, there was a noticeable decline in disease virulence.

As one historian put it: “Many physicians and contemporary observers noticed the progressive decline in the severity of the disease. Many symptoms were less severe, and the rash, of a reddish color, did not cause itching.” Girolamo Fracastoro writes about some of these transformations, stating that “in the first epidemic periods the pustules were filthier,’ while they were ‘harder and drier’ afterwards.” Similarly, the historian and scholar Bernardino Cirillo dell’Aquila (1500-1575), writing in the 1530s, stated: “This horrible disease in different periods (1494) till the present had different alterations and different effects depending on the complications, and now many people just lose their hair and nothing else.”

As added documentation of the change, the chaplain of the infamous conquistador Hernàn Cortés reported that syphilis was less severe in his time than earlier. He wrote that: “at the beginning this disease was very violent, dirty and indecent; now it is no longer so severe and so indecent.”

The medical literature of the time confirmed that the fever, characteristic of the second stage of the disease, “was less violent, while even the rashes were just a ‘reddening.’ Moreover, the gummy tumors appeared only in a limited number of cases.”

According to another historian, “By the middle of the 16th century, the generation of physicians born between the end of the 15th century and the first decades of the 16th century considered the exceptional virulence manifested by syphilis when it first appeared to be ancient history.”

And Ambroise Paré (1510-1590), a renowned French surgeon, stated: “Today it is much less serious and easier to heal than it was in the past... It is obviously becoming much milder … so that it seems it should disappear in the future.”

Lacking detailed genetic analysis of the changing pathogen, if one were to speculate on why the virulence of syphilis decreased so rapidly, I suggest, in a Just-So story fashion, that one might merely speculate on the evolutionary wisdom of an STD that commonly turned its victims into foul-smelling, scabrous, agonized, and lethargic individuals who lost body parts, including their genitals, according to some reports. None of these outcomes, of course, would be conducive to the natural spread of the disease. In addition, this is a good case for sexual selection as well as early death of the host, which are two main engineers of evolutionary change.

But for whatever reason, the presentation of syphilis changed dramatically over a relatively short period of time, and as the disease was still spreading through a previously unexposed population, a change in pathogenicity rather than host immunity seems the most logical explanation.

As syphilis evolved from its initial onslaught, it showed new and hitherto unseen symptoms, including the aforementioned hair loss, and other manifestations such as tinnitus. Soon it was presenting so many systemic phenotypes similar to the effects of other diseases that Sir William Osler (1849-1919) ultimately proposed that syphilis should be described as the “Great Imitator.”

The evolution of syphilis from epidemic to endemic does not diminish the horrors of those afflicted with active tertiary syphilis, but as the disease transformed, these effects were greatly postponed and occurred less commonly, compared with their relatively rapid onset in an earlier era and in a greater proportion of the infected individuals.

Although still lethal, especially in its congenital form, by the end of the 16th century, syphilis had completed its rapid evolution from a devastating, highly visible plague to the covert disease “so sinful that it could not be discussed by name.” It would remain so until the rise of modern antibiotics finally provided a reliable cure. Active tertiary syphilis remained a severe affliction, but the effects were postponed from their relatively rapid onset in an earlier era and in a greater proportion of the infected individuals.

So, syphilis remains a unique example of host-pathogen evolution, an endemic part of the global human condition, battled by physicians in mostly futile efforts for nearly 500 years, and a disease tracking closely with the rise of modern medicine.

References

Frith J. 2012. Syphilis – Its Early History and Treatment Until Penicillin and the Debate on its Origins. J Military and Veteran’s Health. 20(4):49-58.

Tognoti B. 2009. The Rise and Fall of Syphilis in Renaissance Italy. J Med Humanit. 30(2):99-113.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor of the department of biochemistry and molecular & celluar biology at Georgetown University, Washington, D.C.

New engineered HIV-1 vaccine candidate shows improved immunogenicity in early trial

ALVAC-HIV vaccine showed immunogenicity across several HIV clades in an early trial involving 100 healthy patients at low risk of HIV infection, according to a study by Glenda E. Gray, MBBCH, FCPaed, of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, and colleagues that was published online in the Sep. 18 issue of Science Translational Medicine.

ALVAC-HIV (vCP1521) is a live attenuated recombinant canarypox-derived virus that expresses gene products from the HIV-1 gp120 (92TH023/clade E), Gag (clade B), and Pro (clade B) that is cultured in chicken embryo fibroblast cells.

Four injections of ALVAC-HIV were given at months 0, 1, 3, and 6. At months 3 and 6, two booster injections were given of AIDSVAX/BE, a bivalent HIV glycoprotein 120 (gp120) that was previously studied in the RV144 trial. The HVTN 097 trial examined primary immunogenicity endpoints including the frequency and magnitude of IgG and IgG3 antibody binding, measured in serum specimens obtained at baseline, at a peak time point (2 weeks after second ALVAC/AIDSVAX vaccination), a durability time point (6 months after second ALVAC/AIDSVAX vaccination), and the response rates and magnitudes of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses at the baseline, peak, and durability time points. One hundred healthy adults at low risk for HIV infection were randomized in 3:1:1 ratio to group T1 (HIV vaccines, tetanus vaccine, and hepatitis B vaccine), group T2 (HIV vaccine only), and the placebo group T3 (tetanus vaccine and hepatitis B vaccine). There were no meaningful differences in HIV immune responses between the HIV vaccine recipients with or without the tetanus and hepatitis B vaccines, so the researchers pooled the data from groups T1 and T2 in their analysis.

At the peak immunogenicity time point, the vaccine schedule predominantly induced CD4+ T cells directed to HIV-1 Env; this was measured by expression of interleukin-2 and/or interferon-gamma. The Env-specific CD4+ T-cell response rate was significantly higher in HVTN 097 vaccine recipients than it was in those in the RV144 trial (51.9% vs. 36.4%; P = .043). The HVTN 097 trial also showed significantly higher response rates for CD40L(59.3% for HVTN 097 vs. 33.7% for RV144; P less than .001) and for interferon-gamma (42.6% in HVTN 097 vs. 19.5% in RV144; P = .001).

However, durability at 6 months after the second vaccine injection remained an issue, with the frequency of circulating Env-specific CD4+ T-cell responses among vaccine recipients declining significantly; the response rate dropped from 70.8% to 36.1%.

“These data may indicate that cross-clade immune responses, especially to non-neutralizing epitopes correlated with decreased HIV-1 risk, can be achieved for a globally effective vaccine by using unique HIV Env strains,” Dr. Gray and associates concluded.

The authors declared that they had no competing interests.

SOURCE: Gray GE et al. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019 Sep 18. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aax1880..

ALVAC-HIV vaccine showed immunogenicity across several HIV clades in an early trial involving 100 healthy patients at low risk of HIV infection, according to a study by Glenda E. Gray, MBBCH, FCPaed, of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, and colleagues that was published online in the Sep. 18 issue of Science Translational Medicine.

ALVAC-HIV (vCP1521) is a live attenuated recombinant canarypox-derived virus that expresses gene products from the HIV-1 gp120 (92TH023/clade E), Gag (clade B), and Pro (clade B) that is cultured in chicken embryo fibroblast cells.

Four injections of ALVAC-HIV were given at months 0, 1, 3, and 6. At months 3 and 6, two booster injections were given of AIDSVAX/BE, a bivalent HIV glycoprotein 120 (gp120) that was previously studied in the RV144 trial. The HVTN 097 trial examined primary immunogenicity endpoints including the frequency and magnitude of IgG and IgG3 antibody binding, measured in serum specimens obtained at baseline, at a peak time point (2 weeks after second ALVAC/AIDSVAX vaccination), a durability time point (6 months after second ALVAC/AIDSVAX vaccination), and the response rates and magnitudes of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses at the baseline, peak, and durability time points. One hundred healthy adults at low risk for HIV infection were randomized in 3:1:1 ratio to group T1 (HIV vaccines, tetanus vaccine, and hepatitis B vaccine), group T2 (HIV vaccine only), and the placebo group T3 (tetanus vaccine and hepatitis B vaccine). There were no meaningful differences in HIV immune responses between the HIV vaccine recipients with or without the tetanus and hepatitis B vaccines, so the researchers pooled the data from groups T1 and T2 in their analysis.

At the peak immunogenicity time point, the vaccine schedule predominantly induced CD4+ T cells directed to HIV-1 Env; this was measured by expression of interleukin-2 and/or interferon-gamma. The Env-specific CD4+ T-cell response rate was significantly higher in HVTN 097 vaccine recipients than it was in those in the RV144 trial (51.9% vs. 36.4%; P = .043). The HVTN 097 trial also showed significantly higher response rates for CD40L(59.3% for HVTN 097 vs. 33.7% for RV144; P less than .001) and for interferon-gamma (42.6% in HVTN 097 vs. 19.5% in RV144; P = .001).

However, durability at 6 months after the second vaccine injection remained an issue, with the frequency of circulating Env-specific CD4+ T-cell responses among vaccine recipients declining significantly; the response rate dropped from 70.8% to 36.1%.

“These data may indicate that cross-clade immune responses, especially to non-neutralizing epitopes correlated with decreased HIV-1 risk, can be achieved for a globally effective vaccine by using unique HIV Env strains,” Dr. Gray and associates concluded.

The authors declared that they had no competing interests.

SOURCE: Gray GE et al. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019 Sep 18. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aax1880..

ALVAC-HIV vaccine showed immunogenicity across several HIV clades in an early trial involving 100 healthy patients at low risk of HIV infection, according to a study by Glenda E. Gray, MBBCH, FCPaed, of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, and colleagues that was published online in the Sep. 18 issue of Science Translational Medicine.

ALVAC-HIV (vCP1521) is a live attenuated recombinant canarypox-derived virus that expresses gene products from the HIV-1 gp120 (92TH023/clade E), Gag (clade B), and Pro (clade B) that is cultured in chicken embryo fibroblast cells.

Four injections of ALVAC-HIV were given at months 0, 1, 3, and 6. At months 3 and 6, two booster injections were given of AIDSVAX/BE, a bivalent HIV glycoprotein 120 (gp120) that was previously studied in the RV144 trial. The HVTN 097 trial examined primary immunogenicity endpoints including the frequency and magnitude of IgG and IgG3 antibody binding, measured in serum specimens obtained at baseline, at a peak time point (2 weeks after second ALVAC/AIDSVAX vaccination), a durability time point (6 months after second ALVAC/AIDSVAX vaccination), and the response rates and magnitudes of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses at the baseline, peak, and durability time points. One hundred healthy adults at low risk for HIV infection were randomized in 3:1:1 ratio to group T1 (HIV vaccines, tetanus vaccine, and hepatitis B vaccine), group T2 (HIV vaccine only), and the placebo group T3 (tetanus vaccine and hepatitis B vaccine). There were no meaningful differences in HIV immune responses between the HIV vaccine recipients with or without the tetanus and hepatitis B vaccines, so the researchers pooled the data from groups T1 and T2 in their analysis.

At the peak immunogenicity time point, the vaccine schedule predominantly induced CD4+ T cells directed to HIV-1 Env; this was measured by expression of interleukin-2 and/or interferon-gamma. The Env-specific CD4+ T-cell response rate was significantly higher in HVTN 097 vaccine recipients than it was in those in the RV144 trial (51.9% vs. 36.4%; P = .043). The HVTN 097 trial also showed significantly higher response rates for CD40L(59.3% for HVTN 097 vs. 33.7% for RV144; P less than .001) and for interferon-gamma (42.6% in HVTN 097 vs. 19.5% in RV144; P = .001).

However, durability at 6 months after the second vaccine injection remained an issue, with the frequency of circulating Env-specific CD4+ T-cell responses among vaccine recipients declining significantly; the response rate dropped from 70.8% to 36.1%.

“These data may indicate that cross-clade immune responses, especially to non-neutralizing epitopes correlated with decreased HIV-1 risk, can be achieved for a globally effective vaccine by using unique HIV Env strains,” Dr. Gray and associates concluded.

The authors declared that they had no competing interests.

SOURCE: Gray GE et al. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019 Sep 18. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aax1880..

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: “These data may indicate that cross-clade immune responses ... can be achieved for a globally effective vaccine by using unique HIV Env strains.”

Major finding: At the peak immunogenicity time point, the vaccine schedule predominantly induced CD4+ T cells directed to HIV-1 Env .

Study details: A phase 1b randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to assess the safety and immunogenicity of the ALVAC-HIV vaccine in 100 healthy patients at low risk of HIV infection.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and other global health agencies. The authors declared that they had no competing interests.

Source: Gray GE et al. Sci Transl Med. 2019 Sep 18. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aax1880.

Hospital-acquired C. diff. tied to four ‘high-risk’ antibiotic classes

The use of four antibiotic classes designated “high risk” was found to be an independent predictor of hospital-acquired Clostridioides difficile (CDI), based upon an analysis of microbiologic and pharmacy data from 171 hospitals in the United States.

The high-risk antibiotic classes were second-, third-, and fourth-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, carbapenems, and lincosamides, according to a report by Ying P. Tabak, PhD, of Becton Dickinson in Franklin Lakes, N.J., and colleagues published in Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology.

Of the 171 study sites studied, 66 (39%) were teaching hospitals and 105 (61%) were nonteaching hospitals. The high-risk antibiotics most frequently used were cephalosporins (47.9%), fluoroquinolones (31.6%), carbapenems (13.0%), and lincosamides (7.6%). The sites were distributed across various regions of the United States. The hospital-level antibiotic use was measured as days of therapy (DOT) per 1,000 days present (DP).

The study was not able to determine specific links to individual antibiotic classes but to the use of high-risk antibiotics as a whole, except for cephalosporins, which were significantly correlated with hospital-acquired CDI (r = 0.23; P less than .01).

The overall correlation of high-risk antibiotic use and hospital-acquired CDI was 0.22 (P = .003). Higher correlation was observed in teaching hospitals (r = 0.38; P = .002) versus nonteaching hospitals (r = 0.19; P = .055), according to the researchers. The authors attributed this to the possibility of teaching hospitals dealing with more elderly and sicker patients.

After adjusting for significant confounders, the use of high-risk antibiotics was still independently associated with significant risk for hospital-acquired CDI. “For every 100-day increase of DOT per 1,000 DP in high-risk antibiotic use, there was a 12% increase in [hospital-acquired] CDI (RR, 1.12; 95% [confidence interval], 1.04-1.21; P = .002),” according to the authors. This translated to four additional hospital-acquired CDI cases with every 100 DOT increase per 1,000 DP.

“Using a large and current dataset, we found an independent impact of hospital-level high-risk antibiotic use on [hospital-acquired] CDI even after adjusting for confounding factors such as community CDI pressure, proportion of patients aged 65 years or older, average length of stay, and hospital teaching status,” the researchers concluded.

Funding was provided by Nabriva Therapeutics, an antibiotic development company. Four of the authors are full-time employees of Becton Dickinson, which sells diagnostics for infectious diseases, including CDI, and one author was an employee of Nabriva Therapeutics.

SOURCE: Tabak YP et al. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2019 Sep 16. doi: 10.1017/ice.2019.236.

The use of four antibiotic classes designated “high risk” was found to be an independent predictor of hospital-acquired Clostridioides difficile (CDI), based upon an analysis of microbiologic and pharmacy data from 171 hospitals in the United States.

The high-risk antibiotic classes were second-, third-, and fourth-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, carbapenems, and lincosamides, according to a report by Ying P. Tabak, PhD, of Becton Dickinson in Franklin Lakes, N.J., and colleagues published in Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology.

Of the 171 study sites studied, 66 (39%) were teaching hospitals and 105 (61%) were nonteaching hospitals. The high-risk antibiotics most frequently used were cephalosporins (47.9%), fluoroquinolones (31.6%), carbapenems (13.0%), and lincosamides (7.6%). The sites were distributed across various regions of the United States. The hospital-level antibiotic use was measured as days of therapy (DOT) per 1,000 days present (DP).

The study was not able to determine specific links to individual antibiotic classes but to the use of high-risk antibiotics as a whole, except for cephalosporins, which were significantly correlated with hospital-acquired CDI (r = 0.23; P less than .01).

The overall correlation of high-risk antibiotic use and hospital-acquired CDI was 0.22 (P = .003). Higher correlation was observed in teaching hospitals (r = 0.38; P = .002) versus nonteaching hospitals (r = 0.19; P = .055), according to the researchers. The authors attributed this to the possibility of teaching hospitals dealing with more elderly and sicker patients.

After adjusting for significant confounders, the use of high-risk antibiotics was still independently associated with significant risk for hospital-acquired CDI. “For every 100-day increase of DOT per 1,000 DP in high-risk antibiotic use, there was a 12% increase in [hospital-acquired] CDI (RR, 1.12; 95% [confidence interval], 1.04-1.21; P = .002),” according to the authors. This translated to four additional hospital-acquired CDI cases with every 100 DOT increase per 1,000 DP.

“Using a large and current dataset, we found an independent impact of hospital-level high-risk antibiotic use on [hospital-acquired] CDI even after adjusting for confounding factors such as community CDI pressure, proportion of patients aged 65 years or older, average length of stay, and hospital teaching status,” the researchers concluded.

Funding was provided by Nabriva Therapeutics, an antibiotic development company. Four of the authors are full-time employees of Becton Dickinson, which sells diagnostics for infectious diseases, including CDI, and one author was an employee of Nabriva Therapeutics.

SOURCE: Tabak YP et al. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2019 Sep 16. doi: 10.1017/ice.2019.236.

The use of four antibiotic classes designated “high risk” was found to be an independent predictor of hospital-acquired Clostridioides difficile (CDI), based upon an analysis of microbiologic and pharmacy data from 171 hospitals in the United States.

The high-risk antibiotic classes were second-, third-, and fourth-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, carbapenems, and lincosamides, according to a report by Ying P. Tabak, PhD, of Becton Dickinson in Franklin Lakes, N.J., and colleagues published in Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology.

Of the 171 study sites studied, 66 (39%) were teaching hospitals and 105 (61%) were nonteaching hospitals. The high-risk antibiotics most frequently used were cephalosporins (47.9%), fluoroquinolones (31.6%), carbapenems (13.0%), and lincosamides (7.6%). The sites were distributed across various regions of the United States. The hospital-level antibiotic use was measured as days of therapy (DOT) per 1,000 days present (DP).

The study was not able to determine specific links to individual antibiotic classes but to the use of high-risk antibiotics as a whole, except for cephalosporins, which were significantly correlated with hospital-acquired CDI (r = 0.23; P less than .01).

The overall correlation of high-risk antibiotic use and hospital-acquired CDI was 0.22 (P = .003). Higher correlation was observed in teaching hospitals (r = 0.38; P = .002) versus nonteaching hospitals (r = 0.19; P = .055), according to the researchers. The authors attributed this to the possibility of teaching hospitals dealing with more elderly and sicker patients.

After adjusting for significant confounders, the use of high-risk antibiotics was still independently associated with significant risk for hospital-acquired CDI. “For every 100-day increase of DOT per 1,000 DP in high-risk antibiotic use, there was a 12% increase in [hospital-acquired] CDI (RR, 1.12; 95% [confidence interval], 1.04-1.21; P = .002),” according to the authors. This translated to four additional hospital-acquired CDI cases with every 100 DOT increase per 1,000 DP.

“Using a large and current dataset, we found an independent impact of hospital-level high-risk antibiotic use on [hospital-acquired] CDI even after adjusting for confounding factors such as community CDI pressure, proportion of patients aged 65 years or older, average length of stay, and hospital teaching status,” the researchers concluded.

Funding was provided by Nabriva Therapeutics, an antibiotic development company. Four of the authors are full-time employees of Becton Dickinson, which sells diagnostics for infectious diseases, including CDI, and one author was an employee of Nabriva Therapeutics.

SOURCE: Tabak YP et al. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2019 Sep 16. doi: 10.1017/ice.2019.236.

FROM INFECTION CONTROL & HOSPITAL EPIDEMIOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: For every 100-day increase in high-risk antibiotic therapy, there was a 12% increase in hospital-acquired C. difficile.

Study details: Microbiological and pharmacy data from 171 hospitals comparing hospitalwide use of four antibiotics classes on hospital-acquired C. difficile.

Disclosures: Funding was provided Nabriva Therapeutics, an antibiotic development company. Four of the authors are full-time employees of Becton Dickinson, which sells diagnostics for infectious diseases, including C. difficile, and one author was an employee of Nabriva Therapeutics.

Source: Tabak YP et al. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2019 Sep 16. doi: 10.1017/ice.2019.236.

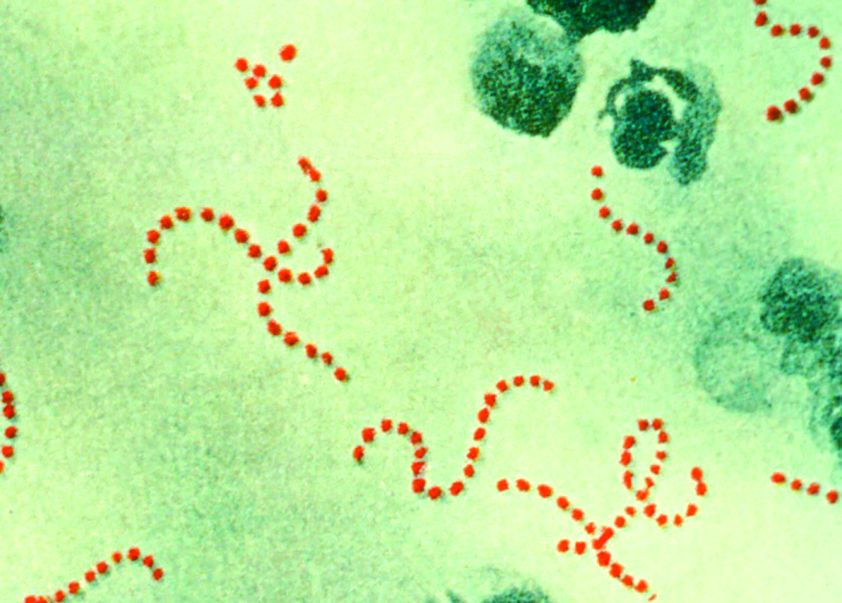

New genotype of S. pyrogenes found in rise of scarlet fever in U.K.

A new Streptococcus pyogenes genotype (designated M1UK) emerged in 2014 in England causing an increase in scarlet fever “unprecedented in modern times.” Researchers discovered that this new genotype became dominant during this increased period of scarlet fever. This new genotype was characterized by an increased production of streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin A (SpeA, also known as scarlet fever or erythrogenic toxin A) compared to previous isolates, according to a report in The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

The researchers analyzed changes in S. pyogenes emm1 genotypes sampled from scarlet fever and invasive disease cases in 2014-2016. The emm1 gene encodes the cell surface M virulence protein and is used for serotyping S. pyogenes isolates. Using regional (northwest London) and national (England and Wales) data, they compared genomes of 135 noninvasive and 552 invasive emm1 isolates from 2009-2016 with 2,800 global emm1 sequences.