User login

Occult HCV infection is correlated to unfavorable genotypes in hemophilia patients

The presence of occult hepatitis C virus infection is determined by finding HCV RNA in the liver and peripheral blood mononuclear cells, with no HCV RNA in the serum. Researchers have shown that the presence of occult HCV infection (OCI) was correlated with unfavorable polymorphisms near interferon lambda-3/4 (IFNL3/4), which has been associated with spontaneous HCV clearance.

This study was conducted to assess the frequency of OCI in 450 hemophilia patients in Iran with negative HCV markers, and to evaluate the association of three IFNL3 single nucleotide polymorphisms (rs8099917, rs12979860, and rs12980275) and the IFNL4 ss469415590 SNP with OCI positivity.

The estimated OCI rate was 10.2%. Among the 46 OCI patients, 56.5%, 23.9%, and 19.6% were infected with HCV-1b, HCV-1a, and HCV-3a, respectively. The researchers found that, compared with patients without OCI, unfavorable IFNL3 rs12979860, IFNL3 rs8099917, IFNL3 rs12980275, and IFNL4 ss469415590 genotypes were more frequently found in OCI patients. Multivariate analysis showed that ALT, cholesterol, triglyceride, as well as the aforementioned unfavorable interferon SNP geneotypes were associated with OCI positivity.

“10.2% of anti-HCV seronegative Iranian patients with hemophilia had OCI in our study; therefore, risk of this infection should be taken into consideration. We also showed that patients with unfavorable IFNL3 SNPs and IFNL4 ss469415590 genotypes were exposed to a higher risk of OCI, compared to hemophilia patients with other genotypes,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Nafari AH et al. Infect Genet Evol. 2019 Dec 13. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2019.104144.

The presence of occult hepatitis C virus infection is determined by finding HCV RNA in the liver and peripheral blood mononuclear cells, with no HCV RNA in the serum. Researchers have shown that the presence of occult HCV infection (OCI) was correlated with unfavorable polymorphisms near interferon lambda-3/4 (IFNL3/4), which has been associated with spontaneous HCV clearance.

This study was conducted to assess the frequency of OCI in 450 hemophilia patients in Iran with negative HCV markers, and to evaluate the association of three IFNL3 single nucleotide polymorphisms (rs8099917, rs12979860, and rs12980275) and the IFNL4 ss469415590 SNP with OCI positivity.

The estimated OCI rate was 10.2%. Among the 46 OCI patients, 56.5%, 23.9%, and 19.6% were infected with HCV-1b, HCV-1a, and HCV-3a, respectively. The researchers found that, compared with patients without OCI, unfavorable IFNL3 rs12979860, IFNL3 rs8099917, IFNL3 rs12980275, and IFNL4 ss469415590 genotypes were more frequently found in OCI patients. Multivariate analysis showed that ALT, cholesterol, triglyceride, as well as the aforementioned unfavorable interferon SNP geneotypes were associated with OCI positivity.

“10.2% of anti-HCV seronegative Iranian patients with hemophilia had OCI in our study; therefore, risk of this infection should be taken into consideration. We also showed that patients with unfavorable IFNL3 SNPs and IFNL4 ss469415590 genotypes were exposed to a higher risk of OCI, compared to hemophilia patients with other genotypes,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Nafari AH et al. Infect Genet Evol. 2019 Dec 13. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2019.104144.

The presence of occult hepatitis C virus infection is determined by finding HCV RNA in the liver and peripheral blood mononuclear cells, with no HCV RNA in the serum. Researchers have shown that the presence of occult HCV infection (OCI) was correlated with unfavorable polymorphisms near interferon lambda-3/4 (IFNL3/4), which has been associated with spontaneous HCV clearance.

This study was conducted to assess the frequency of OCI in 450 hemophilia patients in Iran with negative HCV markers, and to evaluate the association of three IFNL3 single nucleotide polymorphisms (rs8099917, rs12979860, and rs12980275) and the IFNL4 ss469415590 SNP with OCI positivity.

The estimated OCI rate was 10.2%. Among the 46 OCI patients, 56.5%, 23.9%, and 19.6% were infected with HCV-1b, HCV-1a, and HCV-3a, respectively. The researchers found that, compared with patients without OCI, unfavorable IFNL3 rs12979860, IFNL3 rs8099917, IFNL3 rs12980275, and IFNL4 ss469415590 genotypes were more frequently found in OCI patients. Multivariate analysis showed that ALT, cholesterol, triglyceride, as well as the aforementioned unfavorable interferon SNP geneotypes were associated with OCI positivity.

“10.2% of anti-HCV seronegative Iranian patients with hemophilia had OCI in our study; therefore, risk of this infection should be taken into consideration. We also showed that patients with unfavorable IFNL3 SNPs and IFNL4 ss469415590 genotypes were exposed to a higher risk of OCI, compared to hemophilia patients with other genotypes,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Nafari AH et al. Infect Genet Evol. 2019 Dec 13. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2019.104144.

FROM INFECTION, GENETICS AND EVOLUTION

ID Blog: Wuhan coronavirus – just a stop on the zoonotic highway

Emerging viruses that spread to humans from an animal host are commonplace and represent some of the deadliest diseases known. Given the details of the Wuhan coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak, including the genetic profile of the disease agent, the hypothesis of a snake origin was the first raised in the peer-reviewed literature.

It is a highly controversial origin story, however, given that mammals have been the sources of all other such zoonotic coronaviruses, as well as a host of other zoonotic diseases.

An animal source for emerging infections such as the 2019-nCoV is the default hypothesis, because “around 60% of all infectious diseases in humans are zoonotic, as are 75% of all emerging infectious diseases,” according to a United Nations report. The report goes on to say that, “on average, one new infectious disease emerges in humans every 4 months.”

To appreciate the emergence and nature of 2019-nCoV, it is important to examine the history of zoonotic outbreaks of other such diseases, especially with regard to the “mixing-vessel” phenomenon, which has been noted in closely related coronaviruses, including SARS and MERS, as well as the widely disparate HIV, Ebola, and influenza viruses.

Mutants in the mixing vessel

The mixing-vessel phenomenon is conceptually easy but molecularly complex. A single animal is coinfected with two related viruses; the virus genomes recombine together (virus “sex”) in that animal to form a new variant of virus. Such new mutant viruses can be more or less infective, more or less deadly, and more or less able to jump the species or even genus barrier. An emerging viral zoonosis can occur when a human being is exposed to one of these new viruses (either from the origin species or another species intermediate) that is capable of also infecting a human cell. Such exposure can occur from close proximity to animal waste or body fluids, as in the farm environment, or from wildlife pets or the capturing and slaughtering of wildlife for food, as is proposed in the case of the Wuhan seafood market scenario. In fact, the scientists who postulated a snake intermediary as the potential mixing vessel also stated that 2019‐nCoV appears to be a recombinant virus between a bat coronavirus and an origin‐unknown coronavirus.

Coronaviruses in particular have a history of moving from animal to human hosts (and even back again), and their detailed genetic pattern and taxonomy can reveal the animal origin of these diseases.

Going batty

Bats, in particular, have been shown to be a reservoir species for both alphacoronaviruses and betacoronaviruses. Given their ecology and behavior, they have been found to play a key role in transmitting coronaviruses between species. A highly pertinent example of this is the SARS coronavirus, which was shown to have likely originated in Chinese horseshoe bats. The SARS virus, which is genetically closely related to the new Wuhan coronavirus, first infected humans in the Guangdong province of southern China in 2002.

Scientists speculate that the virus was then either transmitted directly to humans from bats, or passed through an intermediate host species, with SARS-like viruses isolated from Himalayan palm civets found in a live-animal market in Guangdong. The virus infection was also detected in other animals (including a raccoon dog, Nyctereutes procyonoides) and in humans working at the market.

The MERS coronavirus is a betacoronavirus that was first reported in Saudi Arabia in 2012. It turned out to be far more deadly than either SARS or the Wuhan virus (at least as far as current estimates of the new coronavirus’s behavior). The MERS genotype was found to be closely related to MERS-like viruses in bats in Saudi Arabia, Africa, Europe, and Asia. Studies done on the cell receptor for MERS showed an apparently conserved viral receptor in both bats and humans. And an identical strain of MERS was found in bats in a nearby cave and near the workplace of the first known human patient.

However, in many of the other locations of the outbreak in the Middle East, there appeared to be limited contact between bats and humans, so scientists looked for another vector species, perhaps one that was acting as an intermediate. A high seroprevalence of MERS-CoV or a closely related virus was found in camels across the Arabian Peninsula and parts of eastern and northern Africa, while tests for MERS antibodies were negative in the most-likely other species of livestock or pet animals, including chickens, cows, goats, horses, and sheep.

In addition, the MERS-related CoV carried by camels was genetically highly similar to that detected in humans, as demonstrated in one particular outbreak on a farm in Qatar where the genetic sequences of MERS-CoV in the nasal swabs from 3 of 14 seropositive camels were similar to those of 2 human cases on the same farm. Similar genomic results were found in MERS-CoV from nasal swabs from camels in Saudi Arabia.

Other mixing-vessel zoonoses

HIV, the viral cause of AIDS, provides an almost-textbook origin story of the rise of a zoonotic supervillain. The virus was genetically traced to have a chimpanzee-to-human origin, but it was found to be more complicated than that. The virus first emerged in the 1920s in Africa in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, well before its rise to a global pandemic in the 1980s.

Researchers believe the chimpanzee virus is a hybrid of the simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs) naturally infecting two different monkey species: the red-capped mangabey (Cercocebus torquatus) and the greater spot-nosed monkey (Cercopithecus nictitans). Chimpanzees kill and eat monkeys, which is likely how they acquired the monkey viruses. The viruses hybridized in a chimpanzee; the hybrid virus then spread through the chimpanzee population and was later transmitted to humans who captured and slaughtered chimps for meat (becoming exposed to their blood). This was the most likely origin of HIV-1.

HIV-1 also shows one of the major risks of zoonotic infections. They can continue to mutate in its human host, increasing the risk of greater virulence, but also interfering with the production of a universally effective vaccine. Since its transmission to humans, for example, many subtypes of the HIV-1 strain have developed, with genetic differences even in the same subtypes found to be up to 20%.

Ebolavirus, first detected in 1976, is another case of bats being the potential culprit. Genetic analysis has shown that African fruit bats are likely involved in the spread of the virus and may be its reservoir host. Further evidence of this was found in the most recent human-infecting Bombali variant of the virus, which was identified in samples from bats collected from Sierra Leone.

It was also found that pigs can also become infected with Zaire ebolavirus, leading to the fear that pigs could serve as a mixing vessel for it and other filoviruses. Pigs have their own forms of Ebola-like disease viruses, which are not currently transmissible to humans, but could provide a potential mixing-vessel reservoir.

Emergent influenzas

The Western world has been most affected by these highly mutable, multispecies zoonotic viruses. The 1957 and 1968 flu pandemics contained a mixture of gene segments from human and avian influenza viruses. “What is clear from genetic analysis of the viruses that caused these past pandemics is that reassortment (gene swapping) occurred to produce novel influenza viruses that caused the pandemics. In both of these cases, the new viruses that emerged showed major differences from the parent viruses,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Influenza is, however, a good example that all zoonoses are not the result of a mixing-vessel phenomenon, with evidence showing that the origin of the catastrophic 1918 virus pandemic likely resulted from a bird influenza virus directly infecting humans and pigs at about the same time without reassortment, according to the CDC.

Building a protective infrastructure

The first 2 decades of the 21st century saw a huge increase in efforts to develop an infrastructure to monitor and potentially prevent the spread of new zoonoses. As part of a global effort led by the United Nations, the U.S. Agency for International AID developed the PREDICT program in 2009 “to strengthen global capacity for detection and discovery of zoonotic viruses with pandemic potential. Those include coronaviruses, the family to which SARS and MERS belong; paramyxoviruses, like Nipah virus; influenza viruses; and filoviruses, like the ebolavirus.”

PREDICT funding to the EcoHealth Alliance led to discovery of the likely bat origins of the Zaire ebolavirus during the 2013-2016 outbreak. And throughout the existence of PREDICT, more than 145,000 animals and people were surveyed in areas of likely zoonotic outbreaks, leading to the detection of more than “1,100 unique viruses, including zoonotic diseases of public health concern such as Bombali ebolavirus, Zaire ebolavirus, Marburg virus, and MERS- and SARS-like coronaviruses,” according to PREDICT partner, the University of California, Davis.

PREDICT-2 was launched in 2014 with the continuing goals of “identifying and better characterizing pathogens of known epidemic and unknown pandemic potential; recognizing animal reservoirs and amplification hosts of human-infectious viruses; and efficiently targeting intervention action at human behaviors which amplify disease transmission at critical animal-animal and animal-human interfaces in hotspots of viral evolution, spillover, amplification, and spread.”

However, in October 2019, the Trump administration cut all funding to the PREDICT program, leading to its shutdown. In a New York Times interview, Peter Daszak, president of the EcoHealth Alliance, stated: “PREDICT was an approach to heading off pandemics, instead of sitting there waiting for them to emerge and then mobilizing.”

Ultimately, in addition to its human cost, the current Wuhan coronavirus outbreak can be looked at an object lesson – a test of the pandemic surveillance and control systems currently in place, and a practice run for the next and potentially deadlier zoonotic outbreaks to come. Perhaps it is also a reminder that cutting resources to detect zoonoses at their source in their animal hosts – before they enter the human chain– is perhaps not the most prudent of ideas.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor of the department of biochemistry and molecular & celluar biology at Georgetown University, Washington.

Emerging viruses that spread to humans from an animal host are commonplace and represent some of the deadliest diseases known. Given the details of the Wuhan coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak, including the genetic profile of the disease agent, the hypothesis of a snake origin was the first raised in the peer-reviewed literature.

It is a highly controversial origin story, however, given that mammals have been the sources of all other such zoonotic coronaviruses, as well as a host of other zoonotic diseases.

An animal source for emerging infections such as the 2019-nCoV is the default hypothesis, because “around 60% of all infectious diseases in humans are zoonotic, as are 75% of all emerging infectious diseases,” according to a United Nations report. The report goes on to say that, “on average, one new infectious disease emerges in humans every 4 months.”

To appreciate the emergence and nature of 2019-nCoV, it is important to examine the history of zoonotic outbreaks of other such diseases, especially with regard to the “mixing-vessel” phenomenon, which has been noted in closely related coronaviruses, including SARS and MERS, as well as the widely disparate HIV, Ebola, and influenza viruses.

Mutants in the mixing vessel

The mixing-vessel phenomenon is conceptually easy but molecularly complex. A single animal is coinfected with two related viruses; the virus genomes recombine together (virus “sex”) in that animal to form a new variant of virus. Such new mutant viruses can be more or less infective, more or less deadly, and more or less able to jump the species or even genus barrier. An emerging viral zoonosis can occur when a human being is exposed to one of these new viruses (either from the origin species or another species intermediate) that is capable of also infecting a human cell. Such exposure can occur from close proximity to animal waste or body fluids, as in the farm environment, or from wildlife pets or the capturing and slaughtering of wildlife for food, as is proposed in the case of the Wuhan seafood market scenario. In fact, the scientists who postulated a snake intermediary as the potential mixing vessel also stated that 2019‐nCoV appears to be a recombinant virus between a bat coronavirus and an origin‐unknown coronavirus.

Coronaviruses in particular have a history of moving from animal to human hosts (and even back again), and their detailed genetic pattern and taxonomy can reveal the animal origin of these diseases.

Going batty

Bats, in particular, have been shown to be a reservoir species for both alphacoronaviruses and betacoronaviruses. Given their ecology and behavior, they have been found to play a key role in transmitting coronaviruses between species. A highly pertinent example of this is the SARS coronavirus, which was shown to have likely originated in Chinese horseshoe bats. The SARS virus, which is genetically closely related to the new Wuhan coronavirus, first infected humans in the Guangdong province of southern China in 2002.

Scientists speculate that the virus was then either transmitted directly to humans from bats, or passed through an intermediate host species, with SARS-like viruses isolated from Himalayan palm civets found in a live-animal market in Guangdong. The virus infection was also detected in other animals (including a raccoon dog, Nyctereutes procyonoides) and in humans working at the market.

The MERS coronavirus is a betacoronavirus that was first reported in Saudi Arabia in 2012. It turned out to be far more deadly than either SARS or the Wuhan virus (at least as far as current estimates of the new coronavirus’s behavior). The MERS genotype was found to be closely related to MERS-like viruses in bats in Saudi Arabia, Africa, Europe, and Asia. Studies done on the cell receptor for MERS showed an apparently conserved viral receptor in both bats and humans. And an identical strain of MERS was found in bats in a nearby cave and near the workplace of the first known human patient.

However, in many of the other locations of the outbreak in the Middle East, there appeared to be limited contact between bats and humans, so scientists looked for another vector species, perhaps one that was acting as an intermediate. A high seroprevalence of MERS-CoV or a closely related virus was found in camels across the Arabian Peninsula and parts of eastern and northern Africa, while tests for MERS antibodies were negative in the most-likely other species of livestock or pet animals, including chickens, cows, goats, horses, and sheep.

In addition, the MERS-related CoV carried by camels was genetically highly similar to that detected in humans, as demonstrated in one particular outbreak on a farm in Qatar where the genetic sequences of MERS-CoV in the nasal swabs from 3 of 14 seropositive camels were similar to those of 2 human cases on the same farm. Similar genomic results were found in MERS-CoV from nasal swabs from camels in Saudi Arabia.

Other mixing-vessel zoonoses

HIV, the viral cause of AIDS, provides an almost-textbook origin story of the rise of a zoonotic supervillain. The virus was genetically traced to have a chimpanzee-to-human origin, but it was found to be more complicated than that. The virus first emerged in the 1920s in Africa in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, well before its rise to a global pandemic in the 1980s.

Researchers believe the chimpanzee virus is a hybrid of the simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs) naturally infecting two different monkey species: the red-capped mangabey (Cercocebus torquatus) and the greater spot-nosed monkey (Cercopithecus nictitans). Chimpanzees kill and eat monkeys, which is likely how they acquired the monkey viruses. The viruses hybridized in a chimpanzee; the hybrid virus then spread through the chimpanzee population and was later transmitted to humans who captured and slaughtered chimps for meat (becoming exposed to their blood). This was the most likely origin of HIV-1.

HIV-1 also shows one of the major risks of zoonotic infections. They can continue to mutate in its human host, increasing the risk of greater virulence, but also interfering with the production of a universally effective vaccine. Since its transmission to humans, for example, many subtypes of the HIV-1 strain have developed, with genetic differences even in the same subtypes found to be up to 20%.

Ebolavirus, first detected in 1976, is another case of bats being the potential culprit. Genetic analysis has shown that African fruit bats are likely involved in the spread of the virus and may be its reservoir host. Further evidence of this was found in the most recent human-infecting Bombali variant of the virus, which was identified in samples from bats collected from Sierra Leone.

It was also found that pigs can also become infected with Zaire ebolavirus, leading to the fear that pigs could serve as a mixing vessel for it and other filoviruses. Pigs have their own forms of Ebola-like disease viruses, which are not currently transmissible to humans, but could provide a potential mixing-vessel reservoir.

Emergent influenzas

The Western world has been most affected by these highly mutable, multispecies zoonotic viruses. The 1957 and 1968 flu pandemics contained a mixture of gene segments from human and avian influenza viruses. “What is clear from genetic analysis of the viruses that caused these past pandemics is that reassortment (gene swapping) occurred to produce novel influenza viruses that caused the pandemics. In both of these cases, the new viruses that emerged showed major differences from the parent viruses,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Influenza is, however, a good example that all zoonoses are not the result of a mixing-vessel phenomenon, with evidence showing that the origin of the catastrophic 1918 virus pandemic likely resulted from a bird influenza virus directly infecting humans and pigs at about the same time without reassortment, according to the CDC.

Building a protective infrastructure

The first 2 decades of the 21st century saw a huge increase in efforts to develop an infrastructure to monitor and potentially prevent the spread of new zoonoses. As part of a global effort led by the United Nations, the U.S. Agency for International AID developed the PREDICT program in 2009 “to strengthen global capacity for detection and discovery of zoonotic viruses with pandemic potential. Those include coronaviruses, the family to which SARS and MERS belong; paramyxoviruses, like Nipah virus; influenza viruses; and filoviruses, like the ebolavirus.”

PREDICT funding to the EcoHealth Alliance led to discovery of the likely bat origins of the Zaire ebolavirus during the 2013-2016 outbreak. And throughout the existence of PREDICT, more than 145,000 animals and people were surveyed in areas of likely zoonotic outbreaks, leading to the detection of more than “1,100 unique viruses, including zoonotic diseases of public health concern such as Bombali ebolavirus, Zaire ebolavirus, Marburg virus, and MERS- and SARS-like coronaviruses,” according to PREDICT partner, the University of California, Davis.

PREDICT-2 was launched in 2014 with the continuing goals of “identifying and better characterizing pathogens of known epidemic and unknown pandemic potential; recognizing animal reservoirs and amplification hosts of human-infectious viruses; and efficiently targeting intervention action at human behaviors which amplify disease transmission at critical animal-animal and animal-human interfaces in hotspots of viral evolution, spillover, amplification, and spread.”

However, in October 2019, the Trump administration cut all funding to the PREDICT program, leading to its shutdown. In a New York Times interview, Peter Daszak, president of the EcoHealth Alliance, stated: “PREDICT was an approach to heading off pandemics, instead of sitting there waiting for them to emerge and then mobilizing.”

Ultimately, in addition to its human cost, the current Wuhan coronavirus outbreak can be looked at an object lesson – a test of the pandemic surveillance and control systems currently in place, and a practice run for the next and potentially deadlier zoonotic outbreaks to come. Perhaps it is also a reminder that cutting resources to detect zoonoses at their source in their animal hosts – before they enter the human chain– is perhaps not the most prudent of ideas.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor of the department of biochemistry and molecular & celluar biology at Georgetown University, Washington.

Emerging viruses that spread to humans from an animal host are commonplace and represent some of the deadliest diseases known. Given the details of the Wuhan coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak, including the genetic profile of the disease agent, the hypothesis of a snake origin was the first raised in the peer-reviewed literature.

It is a highly controversial origin story, however, given that mammals have been the sources of all other such zoonotic coronaviruses, as well as a host of other zoonotic diseases.

An animal source for emerging infections such as the 2019-nCoV is the default hypothesis, because “around 60% of all infectious diseases in humans are zoonotic, as are 75% of all emerging infectious diseases,” according to a United Nations report. The report goes on to say that, “on average, one new infectious disease emerges in humans every 4 months.”

To appreciate the emergence and nature of 2019-nCoV, it is important to examine the history of zoonotic outbreaks of other such diseases, especially with regard to the “mixing-vessel” phenomenon, which has been noted in closely related coronaviruses, including SARS and MERS, as well as the widely disparate HIV, Ebola, and influenza viruses.

Mutants in the mixing vessel

The mixing-vessel phenomenon is conceptually easy but molecularly complex. A single animal is coinfected with two related viruses; the virus genomes recombine together (virus “sex”) in that animal to form a new variant of virus. Such new mutant viruses can be more or less infective, more or less deadly, and more or less able to jump the species or even genus barrier. An emerging viral zoonosis can occur when a human being is exposed to one of these new viruses (either from the origin species or another species intermediate) that is capable of also infecting a human cell. Such exposure can occur from close proximity to animal waste or body fluids, as in the farm environment, or from wildlife pets or the capturing and slaughtering of wildlife for food, as is proposed in the case of the Wuhan seafood market scenario. In fact, the scientists who postulated a snake intermediary as the potential mixing vessel also stated that 2019‐nCoV appears to be a recombinant virus between a bat coronavirus and an origin‐unknown coronavirus.

Coronaviruses in particular have a history of moving from animal to human hosts (and even back again), and their detailed genetic pattern and taxonomy can reveal the animal origin of these diseases.

Going batty

Bats, in particular, have been shown to be a reservoir species for both alphacoronaviruses and betacoronaviruses. Given their ecology and behavior, they have been found to play a key role in transmitting coronaviruses between species. A highly pertinent example of this is the SARS coronavirus, which was shown to have likely originated in Chinese horseshoe bats. The SARS virus, which is genetically closely related to the new Wuhan coronavirus, first infected humans in the Guangdong province of southern China in 2002.

Scientists speculate that the virus was then either transmitted directly to humans from bats, or passed through an intermediate host species, with SARS-like viruses isolated from Himalayan palm civets found in a live-animal market in Guangdong. The virus infection was also detected in other animals (including a raccoon dog, Nyctereutes procyonoides) and in humans working at the market.

The MERS coronavirus is a betacoronavirus that was first reported in Saudi Arabia in 2012. It turned out to be far more deadly than either SARS or the Wuhan virus (at least as far as current estimates of the new coronavirus’s behavior). The MERS genotype was found to be closely related to MERS-like viruses in bats in Saudi Arabia, Africa, Europe, and Asia. Studies done on the cell receptor for MERS showed an apparently conserved viral receptor in both bats and humans. And an identical strain of MERS was found in bats in a nearby cave and near the workplace of the first known human patient.

However, in many of the other locations of the outbreak in the Middle East, there appeared to be limited contact between bats and humans, so scientists looked for another vector species, perhaps one that was acting as an intermediate. A high seroprevalence of MERS-CoV or a closely related virus was found in camels across the Arabian Peninsula and parts of eastern and northern Africa, while tests for MERS antibodies were negative in the most-likely other species of livestock or pet animals, including chickens, cows, goats, horses, and sheep.

In addition, the MERS-related CoV carried by camels was genetically highly similar to that detected in humans, as demonstrated in one particular outbreak on a farm in Qatar where the genetic sequences of MERS-CoV in the nasal swabs from 3 of 14 seropositive camels were similar to those of 2 human cases on the same farm. Similar genomic results were found in MERS-CoV from nasal swabs from camels in Saudi Arabia.

Other mixing-vessel zoonoses

HIV, the viral cause of AIDS, provides an almost-textbook origin story of the rise of a zoonotic supervillain. The virus was genetically traced to have a chimpanzee-to-human origin, but it was found to be more complicated than that. The virus first emerged in the 1920s in Africa in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, well before its rise to a global pandemic in the 1980s.

Researchers believe the chimpanzee virus is a hybrid of the simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs) naturally infecting two different monkey species: the red-capped mangabey (Cercocebus torquatus) and the greater spot-nosed monkey (Cercopithecus nictitans). Chimpanzees kill and eat monkeys, which is likely how they acquired the monkey viruses. The viruses hybridized in a chimpanzee; the hybrid virus then spread through the chimpanzee population and was later transmitted to humans who captured and slaughtered chimps for meat (becoming exposed to their blood). This was the most likely origin of HIV-1.

HIV-1 also shows one of the major risks of zoonotic infections. They can continue to mutate in its human host, increasing the risk of greater virulence, but also interfering with the production of a universally effective vaccine. Since its transmission to humans, for example, many subtypes of the HIV-1 strain have developed, with genetic differences even in the same subtypes found to be up to 20%.

Ebolavirus, first detected in 1976, is another case of bats being the potential culprit. Genetic analysis has shown that African fruit bats are likely involved in the spread of the virus and may be its reservoir host. Further evidence of this was found in the most recent human-infecting Bombali variant of the virus, which was identified in samples from bats collected from Sierra Leone.

It was also found that pigs can also become infected with Zaire ebolavirus, leading to the fear that pigs could serve as a mixing vessel for it and other filoviruses. Pigs have their own forms of Ebola-like disease viruses, which are not currently transmissible to humans, but could provide a potential mixing-vessel reservoir.

Emergent influenzas

The Western world has been most affected by these highly mutable, multispecies zoonotic viruses. The 1957 and 1968 flu pandemics contained a mixture of gene segments from human and avian influenza viruses. “What is clear from genetic analysis of the viruses that caused these past pandemics is that reassortment (gene swapping) occurred to produce novel influenza viruses that caused the pandemics. In both of these cases, the new viruses that emerged showed major differences from the parent viruses,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Influenza is, however, a good example that all zoonoses are not the result of a mixing-vessel phenomenon, with evidence showing that the origin of the catastrophic 1918 virus pandemic likely resulted from a bird influenza virus directly infecting humans and pigs at about the same time without reassortment, according to the CDC.

Building a protective infrastructure

The first 2 decades of the 21st century saw a huge increase in efforts to develop an infrastructure to monitor and potentially prevent the spread of new zoonoses. As part of a global effort led by the United Nations, the U.S. Agency for International AID developed the PREDICT program in 2009 “to strengthen global capacity for detection and discovery of zoonotic viruses with pandemic potential. Those include coronaviruses, the family to which SARS and MERS belong; paramyxoviruses, like Nipah virus; influenza viruses; and filoviruses, like the ebolavirus.”

PREDICT funding to the EcoHealth Alliance led to discovery of the likely bat origins of the Zaire ebolavirus during the 2013-2016 outbreak. And throughout the existence of PREDICT, more than 145,000 animals and people were surveyed in areas of likely zoonotic outbreaks, leading to the detection of more than “1,100 unique viruses, including zoonotic diseases of public health concern such as Bombali ebolavirus, Zaire ebolavirus, Marburg virus, and MERS- and SARS-like coronaviruses,” according to PREDICT partner, the University of California, Davis.

PREDICT-2 was launched in 2014 with the continuing goals of “identifying and better characterizing pathogens of known epidemic and unknown pandemic potential; recognizing animal reservoirs and amplification hosts of human-infectious viruses; and efficiently targeting intervention action at human behaviors which amplify disease transmission at critical animal-animal and animal-human interfaces in hotspots of viral evolution, spillover, amplification, and spread.”

However, in October 2019, the Trump administration cut all funding to the PREDICT program, leading to its shutdown. In a New York Times interview, Peter Daszak, president of the EcoHealth Alliance, stated: “PREDICT was an approach to heading off pandemics, instead of sitting there waiting for them to emerge and then mobilizing.”

Ultimately, in addition to its human cost, the current Wuhan coronavirus outbreak can be looked at an object lesson – a test of the pandemic surveillance and control systems currently in place, and a practice run for the next and potentially deadlier zoonotic outbreaks to come. Perhaps it is also a reminder that cutting resources to detect zoonoses at their source in their animal hosts – before they enter the human chain– is perhaps not the most prudent of ideas.

Mark Lesney is the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has served as an adjunct assistant professor of the department of biochemistry and molecular & celluar biology at Georgetown University, Washington.

HCV a risk in HIV-negative MSM who use PrEP

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is known to be a common sexually transmitted infection (STI) among HIV-positive men who have sex with men (MSM). To examine this relationship in HIV-negative MSM, researchers in the Amsterdam PrEP Project team in the HIV Transmission Elimination AMsterdam (H-TEAM) Initiative evaluated HCV-incidence and its risk-factors in this population, who were using pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Participants in the Amsterdam PrEP project were tested for HCV antibodies or HCV-RNA every 6 months. During the period, participants used daily or event-driven PrEP and could switch regimens during follow-up, according to the report by published in the Journal of Hepatology.

HIV-negative MSM on PrEP are at risk for incident HCV-infection, while identified risk-factors are similar to those in HIV-positive MSM.

Among 350 participants, they detected 15 HCV infections in 14 participants, finding 8 primary infections and 7 reinfections. The researchers found that the factors associated with incident HCV-infection were higher number of receptive condomless anal sex acts with casual partners, anal STI, injecting drug use, and sharing straws when snorting drugs. These are similar risk-factors to those found among in HIV-positive MSM.

They concluded that, because HIV-negative MSM on PrEP are at risk for incident HCV-infection, regular HCV-testing was needed, especially for those with a previous HCV-infection.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is known to be a common sexually transmitted infection (STI) among HIV-positive men who have sex with men (MSM). To examine this relationship in HIV-negative MSM, researchers in the Amsterdam PrEP Project team in the HIV Transmission Elimination AMsterdam (H-TEAM) Initiative evaluated HCV-incidence and its risk-factors in this population, who were using pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Participants in the Amsterdam PrEP project were tested for HCV antibodies or HCV-RNA every 6 months. During the period, participants used daily or event-driven PrEP and could switch regimens during follow-up, according to the report by published in the Journal of Hepatology.

HIV-negative MSM on PrEP are at risk for incident HCV-infection, while identified risk-factors are similar to those in HIV-positive MSM.

Among 350 participants, they detected 15 HCV infections in 14 participants, finding 8 primary infections and 7 reinfections. The researchers found that the factors associated with incident HCV-infection were higher number of receptive condomless anal sex acts with casual partners, anal STI, injecting drug use, and sharing straws when snorting drugs. These are similar risk-factors to those found among in HIV-positive MSM.

They concluded that, because HIV-negative MSM on PrEP are at risk for incident HCV-infection, regular HCV-testing was needed, especially for those with a previous HCV-infection.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is known to be a common sexually transmitted infection (STI) among HIV-positive men who have sex with men (MSM). To examine this relationship in HIV-negative MSM, researchers in the Amsterdam PrEP Project team in the HIV Transmission Elimination AMsterdam (H-TEAM) Initiative evaluated HCV-incidence and its risk-factors in this population, who were using pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Participants in the Amsterdam PrEP project were tested for HCV antibodies or HCV-RNA every 6 months. During the period, participants used daily or event-driven PrEP and could switch regimens during follow-up, according to the report by published in the Journal of Hepatology.

HIV-negative MSM on PrEP are at risk for incident HCV-infection, while identified risk-factors are similar to those in HIV-positive MSM.

Among 350 participants, they detected 15 HCV infections in 14 participants, finding 8 primary infections and 7 reinfections. The researchers found that the factors associated with incident HCV-infection were higher number of receptive condomless anal sex acts with casual partners, anal STI, injecting drug use, and sharing straws when snorting drugs. These are similar risk-factors to those found among in HIV-positive MSM.

They concluded that, because HIV-negative MSM on PrEP are at risk for incident HCV-infection, regular HCV-testing was needed, especially for those with a previous HCV-infection.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF HEPATOLOGY

The rise of U.S. dermatology: A brief history from the 1800s to 1970

As Dermatology News (formerly Skin and Allergy News) reaches its 50th-year milestone, a reflection on the history of the discipline, especially in the United States, up to the time of the launch of this publication is in order. Such an overview must, of course, be cursory in this context. Yet, for those who want to learn more, a large body of historical references and research has been created to fill in the gaps, as modern dermatology has always been cognizant of the importance of its history, with many individuals and groups drawn to the subject.

Two excellent sources for the history of the field can be found in work by William Allen Pusey, MD (1865-1940), and Herbert Rattner, MD (1900-1962), “The History of Dermatology” published in 1933 and research by members of the History of Dermatology Society, founded in 1973 in New York.

Modern dermatology

The development of the field of modern dermatology can be traced back to the early to mid-19th century. During the first half of the 19th century, England and France dominated the study of dermatology, but by the middle of the century, the German revolution in microparasitology shifted that focus “with remarkable German discoveries,” according to Bernard S. Potter, MD, in his review of bibliographic landmarks of the history of dermatology (J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;48:919-32). For example, Johann Lucas Schoenlein (1793-1864) in 1839 discovered the fungal origin of favus, and in 1841 Jacob Henle (1809-1885) discovered Demodex folliculorum. Karl Ferdinand Eichstedt (1816-1892) in 1846 followed with the discovery of the causative agent of pityriasis versicolor, and Friedrich Wilhelm Felix von Barensprung (1822-1864) in 1862 coined the term erythrasma and named the organism responsible for this condition Microsporum minutissimum.

Dr. Potter described how American dermatology originated in New York City in 1836 when Henry Daggett Bulkley, MD, (1803-1872) opened the first dispensary for skin diseases, the Broome Street Infirmary for Diseases of the Skin, thus creating the first institution in the United States for the treatment of cutaneous disease. As the first American dermatologist, he was also the first in the United States to lecture on and to exclusively practice dermatology.

The rise of interest in the importance of dermatology led to the organization of the early American Dermatological Association in 1886.

However, the state of dermatology as a science in the 19th century was not always looked upon favorably, even by its practitioners, especially in the United States. In 1871, in a “Review on Modern Dermatology,” given as a series of lectures on skin disease at Harvard University, James C. White, MD (1833-1916) of Massachusetts General Hospital, stated that: “Were the literature of skin diseases previous to that of the last half-century absolutely annihilated, and with it, the influence it has exercised upon that of the present day, it would be an immense gain to dermatology, although much of real value would perish.” He lamented that America had contributed little so far to the study of dermatology, and that the discipline was only taught in some of its largest schools, and he urged that this be changed. He also lamented that The American Journal of Syphilography and Dermatology, established the year before, had so far proved itself heavy on syphilis, but light on dermatology, a situation he also hoped would change dramatically.

By the late-19th century, the conviction that diseases of the skin needed to be connected to the overall metabolism and physiology of the patient as a whole was becoming more mainstream.

“It has been, and still is, too much the custom to study diseases of the skin in the light of pathological pictures, to name the local manifestation and to so label it as disease. It is much easier to give the disease name and to label it than it is to comprehend the process at work. The former is comparatively unimportant for the patient, the latter point upon which recovery may depend. The nature and meaning of the process in connection with the cutaneous symptoms has not received enough attention, and I believe this to be one reason why the treatment of many of these diseases in the past has been so notoriously unsatisfactory,” Louis A. Duhring, MD (1845-1913) chided his colleagues in the Section of Dermatology and Syphilography, at the Forty-fourth Annual Meeting of the American Medical Association in 1894. (collections.nlm.nih.gov/ext/dw/101489447/PDF/101489447.pdf)

In the early-20th century, German dermatology influenced American dermatology more than any other, according to Karl Holubar, MD, of the Institute for the History of Medicine, University of Vienna, in his lecture on the history of European dermatopathology.

He stated that, with regard to dermatopathology, it was Oscar Gans, MD (1888-1983) who brought the latest knowledge into the United States by delivering a series of lectures at Mayo Clinic in the late 1920s upon the invitation of Paul A. O’Leary, MD, (1891-1955) who then headed the Mayo section of dermatology.

By the 1930s, a flurry of organizational activity overtook American dermatology. In 1932, the American Board of Dermatology was established, with its first exams given in 1933 (20 students passed, 7 failed). The Society for Investigative Dermatology was founded in 1937, and the American Academy of Dermatology and Syphilology (now the American Academy of Dermatology), founded in 1938.

The 1930s also saw a major influx of German and other European Jews fleeing Nazi oppression who would forever change the face of American dermatology. “Between 1933 and 1938, a series of repressive measures eliminated them from the practice of medicine in Germany and other countries. Although some died in concentration camps and others committed suicide, many were able to emigrate from Europe. Dermatology in the United States particularly benefited from the influx of several stellar Jewish dermatologists who were major contributors to the subsequent flowering of academic dermatology in the United States” (JAMA Derm. 2013;149[9]:1090-4).

“The overtures of the holocaust and the rising power of Hitler in Europe finally brought over to the United States the flower of dermatologists and investigators of the German School, e.g., Alexander and Walter Lever, Felix and Hermann Pinkus, the Epsteins, Erich Auerbach, Stephen Rothman, to name just a few. With this exodus and transfer of brain power, Europe lost its leading role to never again regain it,” according to Dr. Holubar. Walter F. Lever, MD (1909-1992) was especially well-known for his landmark textbook on dermatology, “Histopathology of the Skin,” published in the United States in 1949.

The therapeutic era

Throughout the 19th century, a variety of soaps and patent medicines were touted as cure-alls for a host of skin diseases. Other than their benefits to surface cleanliness and their antiseptic properties, however, they were of little effect.

It wasn’t until the 20th century that truly effective therapeutics entered the dermatologic pharmacopoeia. In their 1989 review, Diane Quintal, MD, and Robert Jackson, MD, discussed the origins of the most important of these drugs and pointed out that, “Until this century, the essence of dermatology resided in the realm of morphology. Early contributors largely confined their activities to the classification of skin diseases and to the elaboration of clinical dermatologic entities based on morphologic features. ... but “in the last 50 years, there have been significant scientific discoveries in the field of therapeutics that have revolutionized the practice of dermatology.“ (Clin Dermatol. 1989;7[3]38-47).

These key drugs comprised:

- Quinacrine was introduced in 1932 by Walter Kikuth, MD, as an antimalarial drug. But it was not until 1940, that A.J. Prokoptchouksi, MD, reported on its effectiveness 35 patients with lupus erythematosus.

- Para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) came into prominence in 1942, when Stephen Rothman, MD, and Jack Rubin, MD, at the University of Chicago, published the results of their experiment, showing that when PABA was incorporated in an ointment base and applied to the skin, it could protect against sunburn.

- Dapsone. The effectiveness of sulfapyridine was demonstrated in 1947 by M.J. Costello, MD, who reported its usefulness in a patient with dermatitis herpetiformis, which he believed to be caused by a bacterial allergy. Sulfapyridine controlled the disease, but gastrointestinal intolerance and sulfonamide sensitivity were side effects. Ultimately, in 1951, Theodore Cornbleet, MD, introduced the use of sulfoxones in his article entitled “Sulfoxone (diasones) sodium for dermatitis herpetiformis,” considered more effective than sulfapyridine. Dapsone is the active principal ingredient.

- Hydrocortisone. In August 1952, Marion Sulzberger, MD, and Victor H. Witten, MD (both members of the first Skin & Allergy News editorial advisory board), described use of Compound F (17-hydroxycorticosterone-21-acetate, hydrocortisone) in seven cases of atopic dermatitis and one case of discoid or subacute lupus erythematosus, reporting improvement in all of these cases.

- Benzoyl peroxide. Canadian dermatologist William E. Pace, MD, reported on the beneficial effects of benzoyl peroxide on acne in 1953. The product had originally been used for chronic Staphylococcus aureus folliculitis of the beard.

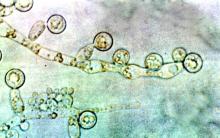

- Griseofulvin, a metabolic byproduct of a number of species of Penicillium, was first isolated in 1939. But in 1958, Harvey Blank, MD, at the University of Miami (also on the first Skin & Allergy News editorial advisory board), and Stanley I. Cullen, MD, administered the drug to a patient with Trichophyton rubrum granuloma, in the first human trial. In 1959, they reported the drug’s benefits on 31 patients with various fungal infections.

- Methotrexate. In 1951, R. Gubner, MD, and colleagues noticed the rapid clearing of skin lesions in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis who had been treated with the folic acid antagonist, aminopterin. And in 1958, W.F. Edmundson, MD, and W.B. Guy, MD, reported on the oral use of the folic acid antagonist, methotrexate. This was followed by multiple reports on the successful use of methotrexate in psoriasis.

- 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). In 1957, 5-FU, an antimetabolite of uracil, was first synthesized. In 1962, G. Falkson, MD, and E.J. Schulz, MD, reported on skin changes observed in 85 patients being treated with systemic 5-FU for advanced carcinomatosis. They found that 31 of the 85 patients developed sensitivity to sunlight and subsequent disappearance of actinic keratoses in these same patients.

Technology in skin care also was developing in the era just before the launch of Skin & Allergy News. For example, Leon Goldman, MD, then chairman of the department of dermatology at the University of Cincinnati, was the first physician to use a laser for tattoo removal. His publication in 1965 helped to solidify its use, leading him to be “regarded by many in the dermatologic community as the ‘godfather of lasers in medicine and surgery’ ” (Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:434-42).

So, by 1970, dermatology as a field had established itself fully with a strong societal infrastructure, a vibrant base of journals and books, and an evolving set of scientific and technical tools. The launch of Skin & Allergy News (now Dermatology News) that year would chronicle dermatology’s commitment to the development of new therapeutics and technologies in service of patient needs – the stories of which would grace the newspaper’s pages for 5 decades and counting.

As Dermatology News (formerly Skin and Allergy News) reaches its 50th-year milestone, a reflection on the history of the discipline, especially in the United States, up to the time of the launch of this publication is in order. Such an overview must, of course, be cursory in this context. Yet, for those who want to learn more, a large body of historical references and research has been created to fill in the gaps, as modern dermatology has always been cognizant of the importance of its history, with many individuals and groups drawn to the subject.

Two excellent sources for the history of the field can be found in work by William Allen Pusey, MD (1865-1940), and Herbert Rattner, MD (1900-1962), “The History of Dermatology” published in 1933 and research by members of the History of Dermatology Society, founded in 1973 in New York.

Modern dermatology

The development of the field of modern dermatology can be traced back to the early to mid-19th century. During the first half of the 19th century, England and France dominated the study of dermatology, but by the middle of the century, the German revolution in microparasitology shifted that focus “with remarkable German discoveries,” according to Bernard S. Potter, MD, in his review of bibliographic landmarks of the history of dermatology (J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;48:919-32). For example, Johann Lucas Schoenlein (1793-1864) in 1839 discovered the fungal origin of favus, and in 1841 Jacob Henle (1809-1885) discovered Demodex folliculorum. Karl Ferdinand Eichstedt (1816-1892) in 1846 followed with the discovery of the causative agent of pityriasis versicolor, and Friedrich Wilhelm Felix von Barensprung (1822-1864) in 1862 coined the term erythrasma and named the organism responsible for this condition Microsporum minutissimum.

Dr. Potter described how American dermatology originated in New York City in 1836 when Henry Daggett Bulkley, MD, (1803-1872) opened the first dispensary for skin diseases, the Broome Street Infirmary for Diseases of the Skin, thus creating the first institution in the United States for the treatment of cutaneous disease. As the first American dermatologist, he was also the first in the United States to lecture on and to exclusively practice dermatology.

The rise of interest in the importance of dermatology led to the organization of the early American Dermatological Association in 1886.

However, the state of dermatology as a science in the 19th century was not always looked upon favorably, even by its practitioners, especially in the United States. In 1871, in a “Review on Modern Dermatology,” given as a series of lectures on skin disease at Harvard University, James C. White, MD (1833-1916) of Massachusetts General Hospital, stated that: “Were the literature of skin diseases previous to that of the last half-century absolutely annihilated, and with it, the influence it has exercised upon that of the present day, it would be an immense gain to dermatology, although much of real value would perish.” He lamented that America had contributed little so far to the study of dermatology, and that the discipline was only taught in some of its largest schools, and he urged that this be changed. He also lamented that The American Journal of Syphilography and Dermatology, established the year before, had so far proved itself heavy on syphilis, but light on dermatology, a situation he also hoped would change dramatically.

By the late-19th century, the conviction that diseases of the skin needed to be connected to the overall metabolism and physiology of the patient as a whole was becoming more mainstream.

“It has been, and still is, too much the custom to study diseases of the skin in the light of pathological pictures, to name the local manifestation and to so label it as disease. It is much easier to give the disease name and to label it than it is to comprehend the process at work. The former is comparatively unimportant for the patient, the latter point upon which recovery may depend. The nature and meaning of the process in connection with the cutaneous symptoms has not received enough attention, and I believe this to be one reason why the treatment of many of these diseases in the past has been so notoriously unsatisfactory,” Louis A. Duhring, MD (1845-1913) chided his colleagues in the Section of Dermatology and Syphilography, at the Forty-fourth Annual Meeting of the American Medical Association in 1894. (collections.nlm.nih.gov/ext/dw/101489447/PDF/101489447.pdf)

In the early-20th century, German dermatology influenced American dermatology more than any other, according to Karl Holubar, MD, of the Institute for the History of Medicine, University of Vienna, in his lecture on the history of European dermatopathology.

He stated that, with regard to dermatopathology, it was Oscar Gans, MD (1888-1983) who brought the latest knowledge into the United States by delivering a series of lectures at Mayo Clinic in the late 1920s upon the invitation of Paul A. O’Leary, MD, (1891-1955) who then headed the Mayo section of dermatology.

By the 1930s, a flurry of organizational activity overtook American dermatology. In 1932, the American Board of Dermatology was established, with its first exams given in 1933 (20 students passed, 7 failed). The Society for Investigative Dermatology was founded in 1937, and the American Academy of Dermatology and Syphilology (now the American Academy of Dermatology), founded in 1938.

The 1930s also saw a major influx of German and other European Jews fleeing Nazi oppression who would forever change the face of American dermatology. “Between 1933 and 1938, a series of repressive measures eliminated them from the practice of medicine in Germany and other countries. Although some died in concentration camps and others committed suicide, many were able to emigrate from Europe. Dermatology in the United States particularly benefited from the influx of several stellar Jewish dermatologists who were major contributors to the subsequent flowering of academic dermatology in the United States” (JAMA Derm. 2013;149[9]:1090-4).

“The overtures of the holocaust and the rising power of Hitler in Europe finally brought over to the United States the flower of dermatologists and investigators of the German School, e.g., Alexander and Walter Lever, Felix and Hermann Pinkus, the Epsteins, Erich Auerbach, Stephen Rothman, to name just a few. With this exodus and transfer of brain power, Europe lost its leading role to never again regain it,” according to Dr. Holubar. Walter F. Lever, MD (1909-1992) was especially well-known for his landmark textbook on dermatology, “Histopathology of the Skin,” published in the United States in 1949.

The therapeutic era

Throughout the 19th century, a variety of soaps and patent medicines were touted as cure-alls for a host of skin diseases. Other than their benefits to surface cleanliness and their antiseptic properties, however, they were of little effect.

It wasn’t until the 20th century that truly effective therapeutics entered the dermatologic pharmacopoeia. In their 1989 review, Diane Quintal, MD, and Robert Jackson, MD, discussed the origins of the most important of these drugs and pointed out that, “Until this century, the essence of dermatology resided in the realm of morphology. Early contributors largely confined their activities to the classification of skin diseases and to the elaboration of clinical dermatologic entities based on morphologic features. ... but “in the last 50 years, there have been significant scientific discoveries in the field of therapeutics that have revolutionized the practice of dermatology.“ (Clin Dermatol. 1989;7[3]38-47).

These key drugs comprised:

- Quinacrine was introduced in 1932 by Walter Kikuth, MD, as an antimalarial drug. But it was not until 1940, that A.J. Prokoptchouksi, MD, reported on its effectiveness 35 patients with lupus erythematosus.

- Para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) came into prominence in 1942, when Stephen Rothman, MD, and Jack Rubin, MD, at the University of Chicago, published the results of their experiment, showing that when PABA was incorporated in an ointment base and applied to the skin, it could protect against sunburn.

- Dapsone. The effectiveness of sulfapyridine was demonstrated in 1947 by M.J. Costello, MD, who reported its usefulness in a patient with dermatitis herpetiformis, which he believed to be caused by a bacterial allergy. Sulfapyridine controlled the disease, but gastrointestinal intolerance and sulfonamide sensitivity were side effects. Ultimately, in 1951, Theodore Cornbleet, MD, introduced the use of sulfoxones in his article entitled “Sulfoxone (diasones) sodium for dermatitis herpetiformis,” considered more effective than sulfapyridine. Dapsone is the active principal ingredient.

- Hydrocortisone. In August 1952, Marion Sulzberger, MD, and Victor H. Witten, MD (both members of the first Skin & Allergy News editorial advisory board), described use of Compound F (17-hydroxycorticosterone-21-acetate, hydrocortisone) in seven cases of atopic dermatitis and one case of discoid or subacute lupus erythematosus, reporting improvement in all of these cases.

- Benzoyl peroxide. Canadian dermatologist William E. Pace, MD, reported on the beneficial effects of benzoyl peroxide on acne in 1953. The product had originally been used for chronic Staphylococcus aureus folliculitis of the beard.

- Griseofulvin, a metabolic byproduct of a number of species of Penicillium, was first isolated in 1939. But in 1958, Harvey Blank, MD, at the University of Miami (also on the first Skin & Allergy News editorial advisory board), and Stanley I. Cullen, MD, administered the drug to a patient with Trichophyton rubrum granuloma, in the first human trial. In 1959, they reported the drug’s benefits on 31 patients with various fungal infections.

- Methotrexate. In 1951, R. Gubner, MD, and colleagues noticed the rapid clearing of skin lesions in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis who had been treated with the folic acid antagonist, aminopterin. And in 1958, W.F. Edmundson, MD, and W.B. Guy, MD, reported on the oral use of the folic acid antagonist, methotrexate. This was followed by multiple reports on the successful use of methotrexate in psoriasis.

- 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). In 1957, 5-FU, an antimetabolite of uracil, was first synthesized. In 1962, G. Falkson, MD, and E.J. Schulz, MD, reported on skin changes observed in 85 patients being treated with systemic 5-FU for advanced carcinomatosis. They found that 31 of the 85 patients developed sensitivity to sunlight and subsequent disappearance of actinic keratoses in these same patients.

Technology in skin care also was developing in the era just before the launch of Skin & Allergy News. For example, Leon Goldman, MD, then chairman of the department of dermatology at the University of Cincinnati, was the first physician to use a laser for tattoo removal. His publication in 1965 helped to solidify its use, leading him to be “regarded by many in the dermatologic community as the ‘godfather of lasers in medicine and surgery’ ” (Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:434-42).

So, by 1970, dermatology as a field had established itself fully with a strong societal infrastructure, a vibrant base of journals and books, and an evolving set of scientific and technical tools. The launch of Skin & Allergy News (now Dermatology News) that year would chronicle dermatology’s commitment to the development of new therapeutics and technologies in service of patient needs – the stories of which would grace the newspaper’s pages for 5 decades and counting.

As Dermatology News (formerly Skin and Allergy News) reaches its 50th-year milestone, a reflection on the history of the discipline, especially in the United States, up to the time of the launch of this publication is in order. Such an overview must, of course, be cursory in this context. Yet, for those who want to learn more, a large body of historical references and research has been created to fill in the gaps, as modern dermatology has always been cognizant of the importance of its history, with many individuals and groups drawn to the subject.

Two excellent sources for the history of the field can be found in work by William Allen Pusey, MD (1865-1940), and Herbert Rattner, MD (1900-1962), “The History of Dermatology” published in 1933 and research by members of the History of Dermatology Society, founded in 1973 in New York.

Modern dermatology

The development of the field of modern dermatology can be traced back to the early to mid-19th century. During the first half of the 19th century, England and France dominated the study of dermatology, but by the middle of the century, the German revolution in microparasitology shifted that focus “with remarkable German discoveries,” according to Bernard S. Potter, MD, in his review of bibliographic landmarks of the history of dermatology (J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;48:919-32). For example, Johann Lucas Schoenlein (1793-1864) in 1839 discovered the fungal origin of favus, and in 1841 Jacob Henle (1809-1885) discovered Demodex folliculorum. Karl Ferdinand Eichstedt (1816-1892) in 1846 followed with the discovery of the causative agent of pityriasis versicolor, and Friedrich Wilhelm Felix von Barensprung (1822-1864) in 1862 coined the term erythrasma and named the organism responsible for this condition Microsporum minutissimum.

Dr. Potter described how American dermatology originated in New York City in 1836 when Henry Daggett Bulkley, MD, (1803-1872) opened the first dispensary for skin diseases, the Broome Street Infirmary for Diseases of the Skin, thus creating the first institution in the United States for the treatment of cutaneous disease. As the first American dermatologist, he was also the first in the United States to lecture on and to exclusively practice dermatology.

The rise of interest in the importance of dermatology led to the organization of the early American Dermatological Association in 1886.

However, the state of dermatology as a science in the 19th century was not always looked upon favorably, even by its practitioners, especially in the United States. In 1871, in a “Review on Modern Dermatology,” given as a series of lectures on skin disease at Harvard University, James C. White, MD (1833-1916) of Massachusetts General Hospital, stated that: “Were the literature of skin diseases previous to that of the last half-century absolutely annihilated, and with it, the influence it has exercised upon that of the present day, it would be an immense gain to dermatology, although much of real value would perish.” He lamented that America had contributed little so far to the study of dermatology, and that the discipline was only taught in some of its largest schools, and he urged that this be changed. He also lamented that The American Journal of Syphilography and Dermatology, established the year before, had so far proved itself heavy on syphilis, but light on dermatology, a situation he also hoped would change dramatically.

By the late-19th century, the conviction that diseases of the skin needed to be connected to the overall metabolism and physiology of the patient as a whole was becoming more mainstream.

“It has been, and still is, too much the custom to study diseases of the skin in the light of pathological pictures, to name the local manifestation and to so label it as disease. It is much easier to give the disease name and to label it than it is to comprehend the process at work. The former is comparatively unimportant for the patient, the latter point upon which recovery may depend. The nature and meaning of the process in connection with the cutaneous symptoms has not received enough attention, and I believe this to be one reason why the treatment of many of these diseases in the past has been so notoriously unsatisfactory,” Louis A. Duhring, MD (1845-1913) chided his colleagues in the Section of Dermatology and Syphilography, at the Forty-fourth Annual Meeting of the American Medical Association in 1894. (collections.nlm.nih.gov/ext/dw/101489447/PDF/101489447.pdf)

In the early-20th century, German dermatology influenced American dermatology more than any other, according to Karl Holubar, MD, of the Institute for the History of Medicine, University of Vienna, in his lecture on the history of European dermatopathology.

He stated that, with regard to dermatopathology, it was Oscar Gans, MD (1888-1983) who brought the latest knowledge into the United States by delivering a series of lectures at Mayo Clinic in the late 1920s upon the invitation of Paul A. O’Leary, MD, (1891-1955) who then headed the Mayo section of dermatology.

By the 1930s, a flurry of organizational activity overtook American dermatology. In 1932, the American Board of Dermatology was established, with its first exams given in 1933 (20 students passed, 7 failed). The Society for Investigative Dermatology was founded in 1937, and the American Academy of Dermatology and Syphilology (now the American Academy of Dermatology), founded in 1938.

The 1930s also saw a major influx of German and other European Jews fleeing Nazi oppression who would forever change the face of American dermatology. “Between 1933 and 1938, a series of repressive measures eliminated them from the practice of medicine in Germany and other countries. Although some died in concentration camps and others committed suicide, many were able to emigrate from Europe. Dermatology in the United States particularly benefited from the influx of several stellar Jewish dermatologists who were major contributors to the subsequent flowering of academic dermatology in the United States” (JAMA Derm. 2013;149[9]:1090-4).

“The overtures of the holocaust and the rising power of Hitler in Europe finally brought over to the United States the flower of dermatologists and investigators of the German School, e.g., Alexander and Walter Lever, Felix and Hermann Pinkus, the Epsteins, Erich Auerbach, Stephen Rothman, to name just a few. With this exodus and transfer of brain power, Europe lost its leading role to never again regain it,” according to Dr. Holubar. Walter F. Lever, MD (1909-1992) was especially well-known for his landmark textbook on dermatology, “Histopathology of the Skin,” published in the United States in 1949.

The therapeutic era

Throughout the 19th century, a variety of soaps and patent medicines were touted as cure-alls for a host of skin diseases. Other than their benefits to surface cleanliness and their antiseptic properties, however, they were of little effect.

It wasn’t until the 20th century that truly effective therapeutics entered the dermatologic pharmacopoeia. In their 1989 review, Diane Quintal, MD, and Robert Jackson, MD, discussed the origins of the most important of these drugs and pointed out that, “Until this century, the essence of dermatology resided in the realm of morphology. Early contributors largely confined their activities to the classification of skin diseases and to the elaboration of clinical dermatologic entities based on morphologic features. ... but “in the last 50 years, there have been significant scientific discoveries in the field of therapeutics that have revolutionized the practice of dermatology.“ (Clin Dermatol. 1989;7[3]38-47).

These key drugs comprised:

- Quinacrine was introduced in 1932 by Walter Kikuth, MD, as an antimalarial drug. But it was not until 1940, that A.J. Prokoptchouksi, MD, reported on its effectiveness 35 patients with lupus erythematosus.

- Para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) came into prominence in 1942, when Stephen Rothman, MD, and Jack Rubin, MD, at the University of Chicago, published the results of their experiment, showing that when PABA was incorporated in an ointment base and applied to the skin, it could protect against sunburn.

- Dapsone. The effectiveness of sulfapyridine was demonstrated in 1947 by M.J. Costello, MD, who reported its usefulness in a patient with dermatitis herpetiformis, which he believed to be caused by a bacterial allergy. Sulfapyridine controlled the disease, but gastrointestinal intolerance and sulfonamide sensitivity were side effects. Ultimately, in 1951, Theodore Cornbleet, MD, introduced the use of sulfoxones in his article entitled “Sulfoxone (diasones) sodium for dermatitis herpetiformis,” considered more effective than sulfapyridine. Dapsone is the active principal ingredient.

- Hydrocortisone. In August 1952, Marion Sulzberger, MD, and Victor H. Witten, MD (both members of the first Skin & Allergy News editorial advisory board), described use of Compound F (17-hydroxycorticosterone-21-acetate, hydrocortisone) in seven cases of atopic dermatitis and one case of discoid or subacute lupus erythematosus, reporting improvement in all of these cases.

- Benzoyl peroxide. Canadian dermatologist William E. Pace, MD, reported on the beneficial effects of benzoyl peroxide on acne in 1953. The product had originally been used for chronic Staphylococcus aureus folliculitis of the beard.

- Griseofulvin, a metabolic byproduct of a number of species of Penicillium, was first isolated in 1939. But in 1958, Harvey Blank, MD, at the University of Miami (also on the first Skin & Allergy News editorial advisory board), and Stanley I. Cullen, MD, administered the drug to a patient with Trichophyton rubrum granuloma, in the first human trial. In 1959, they reported the drug’s benefits on 31 patients with various fungal infections.

- Methotrexate. In 1951, R. Gubner, MD, and colleagues noticed the rapid clearing of skin lesions in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis who had been treated with the folic acid antagonist, aminopterin. And in 1958, W.F. Edmundson, MD, and W.B. Guy, MD, reported on the oral use of the folic acid antagonist, methotrexate. This was followed by multiple reports on the successful use of methotrexate in psoriasis.

- 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). In 1957, 5-FU, an antimetabolite of uracil, was first synthesized. In 1962, G. Falkson, MD, and E.J. Schulz, MD, reported on skin changes observed in 85 patients being treated with systemic 5-FU for advanced carcinomatosis. They found that 31 of the 85 patients developed sensitivity to sunlight and subsequent disappearance of actinic keratoses in these same patients.

Technology in skin care also was developing in the era just before the launch of Skin & Allergy News. For example, Leon Goldman, MD, then chairman of the department of dermatology at the University of Cincinnati, was the first physician to use a laser for tattoo removal. His publication in 1965 helped to solidify its use, leading him to be “regarded by many in the dermatologic community as the ‘godfather of lasers in medicine and surgery’ ” (Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:434-42).

So, by 1970, dermatology as a field had established itself fully with a strong societal infrastructure, a vibrant base of journals and books, and an evolving set of scientific and technical tools. The launch of Skin & Allergy News (now Dermatology News) that year would chronicle dermatology’s commitment to the development of new therapeutics and technologies in service of patient needs – the stories of which would grace the newspaper’s pages for 5 decades and counting.

ID consult for Candida bloodstream infections can reduce mortality risk

findings from a large retrospective study suggest.

Mortality attributable to Candida bloodstream infection ranges between 15% and 47%, and delay in initiation of appropriate treatment has been associated with increased mortality. Previous small studies showed that ID consultation has conferred benefits to patients with Candida bloodstream infections. Carlos Mejia-Chew, MD, and colleagues from Washington University, St. Louis, sought to explore this further by performing a retrospective, single-center cohort study of 1,691 patients aged 18 years or older with Candida bloodstream infection from 2002 to 2015. They analyzed demographics, comorbidities, predisposing factors, all-cause mortality, antifungal use, central-line removal, and ophthalmological and echocardiographic evaluation in order to compare 90-day all-cause mortality between individuals with and without an ID consultation.

They found that those patients who received an ID consult for a Candida bloodstream infection had a significantly lower 90-day mortality rate than did those who did not (29% vs. 51%).

With a model using inverse weighting by the propensity score, they found that ID consultation was associated with a hazard ratio of 0.81 for mortality (95% confidence interval, 0.73-0.91; P less than .0001). In the ID consultation group, the median duration of antifungal therapy was significantly longer (18 vs. 14 days; P less than .0001); central-line removal was significantly more common (76% vs. 59%; P less than .0001); echocardiography use was more frequent (57% vs. 33%; P less than .0001); and ophthalmological examinations were performed more often (53% vs. 17%; P less than .0001). Importantly, fewer patients in the ID consultation group were untreated (2% vs. 14%; P less than .0001).