User login

A primer on cannabis for cosmeceuticals: The endocannabinoid system

In the United States, 31 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam have legalized medical marijuana, which is also permitted for recreational use in 9 states, as well as in the District of Columbia. However, marijuana, derived from Cannabis sativa and Cannabis indica, is regulated as a schedule I drug in the United States at the federal level. (Some believe that the federal status may change in the coming year as a result of the Democratic Party’s takeover in the House of Representatives.1)

Cannabis species contain hundreds of various substances, of which the cannabinoids are the most studied. More than 113 biologically active chemical compounds are found within the class of cannabinoids and their derivatives,2 which have been used for centuries in natural medicine.3 The legal status of marijuana has long hampered scientific research of cannabinoids. Nevertheless, the number of studies focusing on the therapeutic potential of these compounds has steadily risen as the legal landscape of marijuana has evolved.

Findings over the last 20 years have shown that cannabinoids present in C. sativa exhibit anti-inflammatory activity and suppress the proliferation of multiple tumorigenic cell lines, some of which are moderated through cannabinoid (CB) receptors.4 In addition to anti-inflammatory properties, .3 Recent research has demonstrated that CB receptors are present in human skin.4

The endocannabinoid system has emerged as an intriguing area of research, as we’ve come to learn about its convoluted role in human anatomy and health. It features a pervasive network of endogenous ligands, enzymes, and receptors, which exogenous substances (including phytocannabinoids and synthetic cannabinoids) can activate.5 Data from recent studies indicate that the endocannabinoid system plays a significant role in cutaneous homeostasis, as it regulates proliferation, differentiation, and inflammatory mediator release.5 Further, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, pruritus, and wound healing have been identified in recent research as cutaneous concerns in which the use of cannabinoids may be of benefit.6,7 We must also consider reports that cannabinoids can slow human hair growth and that some constituents may spur the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines.8,9This column will briefly address potential confusion over the psychoactive aspects of cannabis, which are related to particular constituents of cannabis and specific CB receptors, and focus on the endocannabinoid system.

Psychoactive or not?

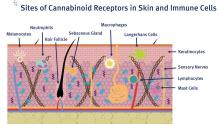

C. sativa confers biological activity through its influence on the G-protein-coupled receptor types CB1 and CB2,10 which pervade human skin epithelium.11 CB1 receptors are found in greatest supply in the central nervous system, especially the basal ganglia, cerebellum, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex, where their activation yields psychoactivity.2,5,12,13 Stimulation of CB1 receptors in the skin – where they are present in differentiated keratinocytes, hair follicle cells, immune cells, sebaceous glands, and sensory neurons14 – diminishes pain and pruritus, controls keratinocyte differentiation and proliferation, inhibits hair follicle growth, and regulates the release of damage-induced keratins and inflammatory mediators to maintain cutaneous homeostasis.11,14,15

CB2 receptors are expressed in the immune system, particularly monocytes, macrophages, as well as B and T cells, and in peripheral tissues including the spleen, tonsils, thymus gland, bone, and, notably, the skin.2,16 Stimulation of CB2 receptors in the skin – where they are found in keratinocytes, immune cells, sebaceous glands, and sensory neurons – fosters sebum production, regulates pain sensation, hinders keratinocyte differentiation and proliferation, and suppresses cutaneous inflammatory responses.14,15

The best known, or most notorious, component of exogenous cannabinoids is delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol (delta9-THC or simply THC), which is a natural psychoactive constituent in marijuana.3 In fact, of the five primary cannabinoids derived from marijuana, including cannabidiol (CBD), cannabichromene (CBC), cannabigerol (CBG), cannabinol (CBN), and THC, only THC imparts psychoactive effects.17

CBD is thought to exhibit anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities.18 THC has been found to have the capacity to induce cancer cell apoptosis and block angiogenesis,19 and is thought to have immunomodulatory potential, partly acting through the G-protein-coupled CB1 and CB2 receptors but also yielding effects not related to these receptors.20In a 2014 survey of medical cannabis users, a statistically significant preference for C. indica (which contains higher CBD and lower THC levels) was observed for pain management, sedation, and sleep, while C. sativa was associated with euphoria and improving energy.21

The endocannabinoid system and skin health

The endogenous cannabinoid or endocannabinoid system includes cannabinoid receptors, associated endogenous ligands (such as arachidonoyl ethanolamide [anandamide or AEA], 2-arachidonoyl glycerol [2-AG], and N-palmitoylethanolamide [PEA], a fatty acid amide that enhances AEA activity),2 and enzymes involved in endocannabinoid production and decay.11,15,22,23 Research in recent years appears to support the notion that the endocannabinoid system plays an important role in skin health, as its dysregulation has been linked to atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, scleroderma, and skin cancer. Data indicate that exogenous and endogenous cannabinoids influence the endocannabinoid system through cannabinoid receptors, transient receptor potential channels (TRPs), and peroxisome proliferator–activated receptors (PPARs). Río et al. suggest that the dynamism of the endocannabinoid system buttresses the targeting of multiple endpoints for therapeutic success with cannabinoids rather than the one-disease-one-target approach.24 Endogenous cannabinoids, such as arachidonoyl ethanolamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol, are now thought to be significant mediators in the skin.3 Further, endocannabinoids have been shown to deliver analgesia to the skin, at the spinal and supraspinal levels.25

Anti-inflammatory activity

In 2010, Tubaro et al. used the Croton oil mouse ear dermatitis assay to study the in vivo topical anti-inflammatory effects of seven phytocannabinoids and their related cannabivarins (nonpsychoactive cannabinoids). They found that anti-inflammatory activity was derived from the involvement of the cannabinoid receptors as well as the inflammatory endpoints that the phytocannabinoids targeted.26

In 2013, Gaffal et al. explored the anti-inflammatory activity of topical THC in dinitrofluorobenzene-mediated allergic contact dermatitis independent of CB1/2 receptors by using wild-type and CB1/2 receptor-deficient mice. The researchers found that topically applied THC reduced contact allergic ear edema and myeloid immune cell infiltration in both groups of mice. They concluded that such a decline in inflammation resulted from mitigating the keratinocyte-derived proinflammatory mediators that direct myeloid immune cell infiltration independent of CB1/2 receptors, and positions cannabinoids well for future use in treating inflammatory cutaneous conditions.20

Literature reviews

In a 2018 literature review on the uses of cannabinoids for cutaneous disorders, Eagleston et al. determined that preclinical data on cannabinoids reveal the potential to treat acne, allergic contact dermatitis, asteatotic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, hidradenitis suppurativa, Kaposi sarcoma, pruritus, psoriasis, skin cancer, and the skin symptoms of systemic sclerosis. They caution, though, that more preclinical work is necessary along with randomized, controlled trials with sufficiently large sample sizes to establish the safety and efficacy of cannabinoids to treat skin conditions.27

A literature review by Marks and Friedman published later that year on the therapeutic potential of phytocannabinoids, endocannabinoids, and synthetic cannabinoids in managing skin disorders revealed the same findings regarding the cutaneous conditions associated with these compounds. The authors noted, though, that while the preponderance of articles highlight the efficacy of cannabinoids in treating inflammatory and neoplastic cutaneous conditions, some reports indicate proinflammatory and proneoplastic activities of cannabinoids. Like Eagleston et al., they call for additional studies.28

Conclusion

As in many botanical agents that I cover in this column, cannabis is associated with numerous medical benefits. I am encouraged to see expanding legalization of medical marijuana and increased research into its reputedly broad potential to improve human health. Anecdotally, I have heard stunning reports from patients about amelioration of joint and back pain as well as relief from other inflammatory symptoms. Discovery and elucidation of the endogenous cannabinoid system is a recent development. Research on its functions and roles in cutaneous health has followed suit and is steadily increasing. Particular skin conditions for which cannabis and cannabinoids may be indicated will be the focus of the next column.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems LLC. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com

References

1. Higdon J. Why 2019 could be marijuana’s biggest year yet. Politico Magazine. Jan 21, 2019.

2. Singh D et al. Clin Dermatol. 2018 May-Jun;36(3):399-419.

3. Kupczyk P et al. Exp Dermatol. 2009 Aug;18(8):669-79.

4. Wilkinson JD et al. J Dermatol Sci. 2007 Feb;45(2):87-92.

5. Milando R et al. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019 April;20(2):167-80.

6. Robinson E et al. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018 Dec 1;17(12):1273-8.

7. Mounessa JS et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jul;77(1):188-90.

8. Liszewski W et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Sep;77(3):e87-e88.

9. Telek A et al. FASEB J. 2007 Nov;21(13):3534-41.

10. Wollenberg A et al. Br J Dermatol. 2014 Jul;170 Suppl 1:7-11.

11. Ramot Y et al. PeerJ. 2013 Feb 19;1:e40.

12. Schlicker E et al. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001 Nov;22(11):565-72.

13. Christie MJ et al. Nature. 2001 Mar 29;410(6828):527-30.

14. Ibid.

15. Bíró T et al. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009 Aug;30(8):411-20.

16. Pacher P et al. Pharmacol Rev. 2006 Sep;58(3):389-462.

17. Shalaby M et al. Pract Dermatol. 2018 Jan;68-70.

18. Chelliah MP et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jul;35(4):e224-e227.

19. Glodde N et al. Life Sci. 2015 Oct 1;138:35-40.

20. Gaffal E et al. Allergy. 2013 Aug;68(8):994-1000.

21. Pearce DD et al. J Altern Complement Med. 2014 Oct;20(10):787:91.

22. Leonti M et al. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010 Jun 15;79(12):1815-26.

23. Trusler AR et al. Dermatitis. 2017 Jan/Feb;28(1):22-32.

24. Río CD et al. Biochem Pharmacol. 2018 Nov;157:122-133.

25. Chuquilin M et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Feb;74(2):197-212.

26. Tubaro A et al. Fitoterapia. 2010 Oct;81(7):816-9.

27. Eagleston LRM et al. Dermatol Online J. 2018 Jun 15;24(6).

28. Marks DH et al. Skin Therapy Lett. 2018 Nov;23(6):1-5.

In the United States, 31 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam have legalized medical marijuana, which is also permitted for recreational use in 9 states, as well as in the District of Columbia. However, marijuana, derived from Cannabis sativa and Cannabis indica, is regulated as a schedule I drug in the United States at the federal level. (Some believe that the federal status may change in the coming year as a result of the Democratic Party’s takeover in the House of Representatives.1)

Cannabis species contain hundreds of various substances, of which the cannabinoids are the most studied. More than 113 biologically active chemical compounds are found within the class of cannabinoids and their derivatives,2 which have been used for centuries in natural medicine.3 The legal status of marijuana has long hampered scientific research of cannabinoids. Nevertheless, the number of studies focusing on the therapeutic potential of these compounds has steadily risen as the legal landscape of marijuana has evolved.

Findings over the last 20 years have shown that cannabinoids present in C. sativa exhibit anti-inflammatory activity and suppress the proliferation of multiple tumorigenic cell lines, some of which are moderated through cannabinoid (CB) receptors.4 In addition to anti-inflammatory properties, .3 Recent research has demonstrated that CB receptors are present in human skin.4

The endocannabinoid system has emerged as an intriguing area of research, as we’ve come to learn about its convoluted role in human anatomy and health. It features a pervasive network of endogenous ligands, enzymes, and receptors, which exogenous substances (including phytocannabinoids and synthetic cannabinoids) can activate.5 Data from recent studies indicate that the endocannabinoid system plays a significant role in cutaneous homeostasis, as it regulates proliferation, differentiation, and inflammatory mediator release.5 Further, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, pruritus, and wound healing have been identified in recent research as cutaneous concerns in which the use of cannabinoids may be of benefit.6,7 We must also consider reports that cannabinoids can slow human hair growth and that some constituents may spur the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines.8,9This column will briefly address potential confusion over the psychoactive aspects of cannabis, which are related to particular constituents of cannabis and specific CB receptors, and focus on the endocannabinoid system.

Psychoactive or not?

C. sativa confers biological activity through its influence on the G-protein-coupled receptor types CB1 and CB2,10 which pervade human skin epithelium.11 CB1 receptors are found in greatest supply in the central nervous system, especially the basal ganglia, cerebellum, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex, where their activation yields psychoactivity.2,5,12,13 Stimulation of CB1 receptors in the skin – where they are present in differentiated keratinocytes, hair follicle cells, immune cells, sebaceous glands, and sensory neurons14 – diminishes pain and pruritus, controls keratinocyte differentiation and proliferation, inhibits hair follicle growth, and regulates the release of damage-induced keratins and inflammatory mediators to maintain cutaneous homeostasis.11,14,15

CB2 receptors are expressed in the immune system, particularly monocytes, macrophages, as well as B and T cells, and in peripheral tissues including the spleen, tonsils, thymus gland, bone, and, notably, the skin.2,16 Stimulation of CB2 receptors in the skin – where they are found in keratinocytes, immune cells, sebaceous glands, and sensory neurons – fosters sebum production, regulates pain sensation, hinders keratinocyte differentiation and proliferation, and suppresses cutaneous inflammatory responses.14,15

The best known, or most notorious, component of exogenous cannabinoids is delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol (delta9-THC or simply THC), which is a natural psychoactive constituent in marijuana.3 In fact, of the five primary cannabinoids derived from marijuana, including cannabidiol (CBD), cannabichromene (CBC), cannabigerol (CBG), cannabinol (CBN), and THC, only THC imparts psychoactive effects.17

CBD is thought to exhibit anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities.18 THC has been found to have the capacity to induce cancer cell apoptosis and block angiogenesis,19 and is thought to have immunomodulatory potential, partly acting through the G-protein-coupled CB1 and CB2 receptors but also yielding effects not related to these receptors.20In a 2014 survey of medical cannabis users, a statistically significant preference for C. indica (which contains higher CBD and lower THC levels) was observed for pain management, sedation, and sleep, while C. sativa was associated with euphoria and improving energy.21

The endocannabinoid system and skin health

The endogenous cannabinoid or endocannabinoid system includes cannabinoid receptors, associated endogenous ligands (such as arachidonoyl ethanolamide [anandamide or AEA], 2-arachidonoyl glycerol [2-AG], and N-palmitoylethanolamide [PEA], a fatty acid amide that enhances AEA activity),2 and enzymes involved in endocannabinoid production and decay.11,15,22,23 Research in recent years appears to support the notion that the endocannabinoid system plays an important role in skin health, as its dysregulation has been linked to atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, scleroderma, and skin cancer. Data indicate that exogenous and endogenous cannabinoids influence the endocannabinoid system through cannabinoid receptors, transient receptor potential channels (TRPs), and peroxisome proliferator–activated receptors (PPARs). Río et al. suggest that the dynamism of the endocannabinoid system buttresses the targeting of multiple endpoints for therapeutic success with cannabinoids rather than the one-disease-one-target approach.24 Endogenous cannabinoids, such as arachidonoyl ethanolamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol, are now thought to be significant mediators in the skin.3 Further, endocannabinoids have been shown to deliver analgesia to the skin, at the spinal and supraspinal levels.25

Anti-inflammatory activity

In 2010, Tubaro et al. used the Croton oil mouse ear dermatitis assay to study the in vivo topical anti-inflammatory effects of seven phytocannabinoids and their related cannabivarins (nonpsychoactive cannabinoids). They found that anti-inflammatory activity was derived from the involvement of the cannabinoid receptors as well as the inflammatory endpoints that the phytocannabinoids targeted.26

In 2013, Gaffal et al. explored the anti-inflammatory activity of topical THC in dinitrofluorobenzene-mediated allergic contact dermatitis independent of CB1/2 receptors by using wild-type and CB1/2 receptor-deficient mice. The researchers found that topically applied THC reduced contact allergic ear edema and myeloid immune cell infiltration in both groups of mice. They concluded that such a decline in inflammation resulted from mitigating the keratinocyte-derived proinflammatory mediators that direct myeloid immune cell infiltration independent of CB1/2 receptors, and positions cannabinoids well for future use in treating inflammatory cutaneous conditions.20

Literature reviews

In a 2018 literature review on the uses of cannabinoids for cutaneous disorders, Eagleston et al. determined that preclinical data on cannabinoids reveal the potential to treat acne, allergic contact dermatitis, asteatotic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, hidradenitis suppurativa, Kaposi sarcoma, pruritus, psoriasis, skin cancer, and the skin symptoms of systemic sclerosis. They caution, though, that more preclinical work is necessary along with randomized, controlled trials with sufficiently large sample sizes to establish the safety and efficacy of cannabinoids to treat skin conditions.27

A literature review by Marks and Friedman published later that year on the therapeutic potential of phytocannabinoids, endocannabinoids, and synthetic cannabinoids in managing skin disorders revealed the same findings regarding the cutaneous conditions associated with these compounds. The authors noted, though, that while the preponderance of articles highlight the efficacy of cannabinoids in treating inflammatory and neoplastic cutaneous conditions, some reports indicate proinflammatory and proneoplastic activities of cannabinoids. Like Eagleston et al., they call for additional studies.28

Conclusion

As in many botanical agents that I cover in this column, cannabis is associated with numerous medical benefits. I am encouraged to see expanding legalization of medical marijuana and increased research into its reputedly broad potential to improve human health. Anecdotally, I have heard stunning reports from patients about amelioration of joint and back pain as well as relief from other inflammatory symptoms. Discovery and elucidation of the endogenous cannabinoid system is a recent development. Research on its functions and roles in cutaneous health has followed suit and is steadily increasing. Particular skin conditions for which cannabis and cannabinoids may be indicated will be the focus of the next column.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems LLC. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com

References

1. Higdon J. Why 2019 could be marijuana’s biggest year yet. Politico Magazine. Jan 21, 2019.

2. Singh D et al. Clin Dermatol. 2018 May-Jun;36(3):399-419.

3. Kupczyk P et al. Exp Dermatol. 2009 Aug;18(8):669-79.

4. Wilkinson JD et al. J Dermatol Sci. 2007 Feb;45(2):87-92.

5. Milando R et al. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019 April;20(2):167-80.

6. Robinson E et al. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018 Dec 1;17(12):1273-8.

7. Mounessa JS et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jul;77(1):188-90.

8. Liszewski W et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Sep;77(3):e87-e88.

9. Telek A et al. FASEB J. 2007 Nov;21(13):3534-41.

10. Wollenberg A et al. Br J Dermatol. 2014 Jul;170 Suppl 1:7-11.

11. Ramot Y et al. PeerJ. 2013 Feb 19;1:e40.

12. Schlicker E et al. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001 Nov;22(11):565-72.

13. Christie MJ et al. Nature. 2001 Mar 29;410(6828):527-30.

14. Ibid.

15. Bíró T et al. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009 Aug;30(8):411-20.

16. Pacher P et al. Pharmacol Rev. 2006 Sep;58(3):389-462.

17. Shalaby M et al. Pract Dermatol. 2018 Jan;68-70.

18. Chelliah MP et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jul;35(4):e224-e227.

19. Glodde N et al. Life Sci. 2015 Oct 1;138:35-40.

20. Gaffal E et al. Allergy. 2013 Aug;68(8):994-1000.

21. Pearce DD et al. J Altern Complement Med. 2014 Oct;20(10):787:91.

22. Leonti M et al. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010 Jun 15;79(12):1815-26.

23. Trusler AR et al. Dermatitis. 2017 Jan/Feb;28(1):22-32.

24. Río CD et al. Biochem Pharmacol. 2018 Nov;157:122-133.

25. Chuquilin M et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Feb;74(2):197-212.

26. Tubaro A et al. Fitoterapia. 2010 Oct;81(7):816-9.

27. Eagleston LRM et al. Dermatol Online J. 2018 Jun 15;24(6).

28. Marks DH et al. Skin Therapy Lett. 2018 Nov;23(6):1-5.

In the United States, 31 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and Guam have legalized medical marijuana, which is also permitted for recreational use in 9 states, as well as in the District of Columbia. However, marijuana, derived from Cannabis sativa and Cannabis indica, is regulated as a schedule I drug in the United States at the federal level. (Some believe that the federal status may change in the coming year as a result of the Democratic Party’s takeover in the House of Representatives.1)

Cannabis species contain hundreds of various substances, of which the cannabinoids are the most studied. More than 113 biologically active chemical compounds are found within the class of cannabinoids and their derivatives,2 which have been used for centuries in natural medicine.3 The legal status of marijuana has long hampered scientific research of cannabinoids. Nevertheless, the number of studies focusing on the therapeutic potential of these compounds has steadily risen as the legal landscape of marijuana has evolved.

Findings over the last 20 years have shown that cannabinoids present in C. sativa exhibit anti-inflammatory activity and suppress the proliferation of multiple tumorigenic cell lines, some of which are moderated through cannabinoid (CB) receptors.4 In addition to anti-inflammatory properties, .3 Recent research has demonstrated that CB receptors are present in human skin.4

The endocannabinoid system has emerged as an intriguing area of research, as we’ve come to learn about its convoluted role in human anatomy and health. It features a pervasive network of endogenous ligands, enzymes, and receptors, which exogenous substances (including phytocannabinoids and synthetic cannabinoids) can activate.5 Data from recent studies indicate that the endocannabinoid system plays a significant role in cutaneous homeostasis, as it regulates proliferation, differentiation, and inflammatory mediator release.5 Further, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, pruritus, and wound healing have been identified in recent research as cutaneous concerns in which the use of cannabinoids may be of benefit.6,7 We must also consider reports that cannabinoids can slow human hair growth and that some constituents may spur the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines.8,9This column will briefly address potential confusion over the psychoactive aspects of cannabis, which are related to particular constituents of cannabis and specific CB receptors, and focus on the endocannabinoid system.

Psychoactive or not?

C. sativa confers biological activity through its influence on the G-protein-coupled receptor types CB1 and CB2,10 which pervade human skin epithelium.11 CB1 receptors are found in greatest supply in the central nervous system, especially the basal ganglia, cerebellum, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex, where their activation yields psychoactivity.2,5,12,13 Stimulation of CB1 receptors in the skin – where they are present in differentiated keratinocytes, hair follicle cells, immune cells, sebaceous glands, and sensory neurons14 – diminishes pain and pruritus, controls keratinocyte differentiation and proliferation, inhibits hair follicle growth, and regulates the release of damage-induced keratins and inflammatory mediators to maintain cutaneous homeostasis.11,14,15

CB2 receptors are expressed in the immune system, particularly monocytes, macrophages, as well as B and T cells, and in peripheral tissues including the spleen, tonsils, thymus gland, bone, and, notably, the skin.2,16 Stimulation of CB2 receptors in the skin – where they are found in keratinocytes, immune cells, sebaceous glands, and sensory neurons – fosters sebum production, regulates pain sensation, hinders keratinocyte differentiation and proliferation, and suppresses cutaneous inflammatory responses.14,15

The best known, or most notorious, component of exogenous cannabinoids is delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol (delta9-THC or simply THC), which is a natural psychoactive constituent in marijuana.3 In fact, of the five primary cannabinoids derived from marijuana, including cannabidiol (CBD), cannabichromene (CBC), cannabigerol (CBG), cannabinol (CBN), and THC, only THC imparts psychoactive effects.17

CBD is thought to exhibit anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities.18 THC has been found to have the capacity to induce cancer cell apoptosis and block angiogenesis,19 and is thought to have immunomodulatory potential, partly acting through the G-protein-coupled CB1 and CB2 receptors but also yielding effects not related to these receptors.20In a 2014 survey of medical cannabis users, a statistically significant preference for C. indica (which contains higher CBD and lower THC levels) was observed for pain management, sedation, and sleep, while C. sativa was associated with euphoria and improving energy.21

The endocannabinoid system and skin health

The endogenous cannabinoid or endocannabinoid system includes cannabinoid receptors, associated endogenous ligands (such as arachidonoyl ethanolamide [anandamide or AEA], 2-arachidonoyl glycerol [2-AG], and N-palmitoylethanolamide [PEA], a fatty acid amide that enhances AEA activity),2 and enzymes involved in endocannabinoid production and decay.11,15,22,23 Research in recent years appears to support the notion that the endocannabinoid system plays an important role in skin health, as its dysregulation has been linked to atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, scleroderma, and skin cancer. Data indicate that exogenous and endogenous cannabinoids influence the endocannabinoid system through cannabinoid receptors, transient receptor potential channels (TRPs), and peroxisome proliferator–activated receptors (PPARs). Río et al. suggest that the dynamism of the endocannabinoid system buttresses the targeting of multiple endpoints for therapeutic success with cannabinoids rather than the one-disease-one-target approach.24 Endogenous cannabinoids, such as arachidonoyl ethanolamide and 2-arachidonoylglycerol, are now thought to be significant mediators in the skin.3 Further, endocannabinoids have been shown to deliver analgesia to the skin, at the spinal and supraspinal levels.25

Anti-inflammatory activity

In 2010, Tubaro et al. used the Croton oil mouse ear dermatitis assay to study the in vivo topical anti-inflammatory effects of seven phytocannabinoids and their related cannabivarins (nonpsychoactive cannabinoids). They found that anti-inflammatory activity was derived from the involvement of the cannabinoid receptors as well as the inflammatory endpoints that the phytocannabinoids targeted.26

In 2013, Gaffal et al. explored the anti-inflammatory activity of topical THC in dinitrofluorobenzene-mediated allergic contact dermatitis independent of CB1/2 receptors by using wild-type and CB1/2 receptor-deficient mice. The researchers found that topically applied THC reduced contact allergic ear edema and myeloid immune cell infiltration in both groups of mice. They concluded that such a decline in inflammation resulted from mitigating the keratinocyte-derived proinflammatory mediators that direct myeloid immune cell infiltration independent of CB1/2 receptors, and positions cannabinoids well for future use in treating inflammatory cutaneous conditions.20

Literature reviews

In a 2018 literature review on the uses of cannabinoids for cutaneous disorders, Eagleston et al. determined that preclinical data on cannabinoids reveal the potential to treat acne, allergic contact dermatitis, asteatotic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, hidradenitis suppurativa, Kaposi sarcoma, pruritus, psoriasis, skin cancer, and the skin symptoms of systemic sclerosis. They caution, though, that more preclinical work is necessary along with randomized, controlled trials with sufficiently large sample sizes to establish the safety and efficacy of cannabinoids to treat skin conditions.27

A literature review by Marks and Friedman published later that year on the therapeutic potential of phytocannabinoids, endocannabinoids, and synthetic cannabinoids in managing skin disorders revealed the same findings regarding the cutaneous conditions associated with these compounds. The authors noted, though, that while the preponderance of articles highlight the efficacy of cannabinoids in treating inflammatory and neoplastic cutaneous conditions, some reports indicate proinflammatory and proneoplastic activities of cannabinoids. Like Eagleston et al., they call for additional studies.28

Conclusion

As in many botanical agents that I cover in this column, cannabis is associated with numerous medical benefits. I am encouraged to see expanding legalization of medical marijuana and increased research into its reputedly broad potential to improve human health. Anecdotally, I have heard stunning reports from patients about amelioration of joint and back pain as well as relief from other inflammatory symptoms. Discovery and elucidation of the endogenous cannabinoid system is a recent development. Research on its functions and roles in cutaneous health has followed suit and is steadily increasing. Particular skin conditions for which cannabis and cannabinoids may be indicated will be the focus of the next column.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems LLC. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com

References

1. Higdon J. Why 2019 could be marijuana’s biggest year yet. Politico Magazine. Jan 21, 2019.

2. Singh D et al. Clin Dermatol. 2018 May-Jun;36(3):399-419.

3. Kupczyk P et al. Exp Dermatol. 2009 Aug;18(8):669-79.

4. Wilkinson JD et al. J Dermatol Sci. 2007 Feb;45(2):87-92.

5. Milando R et al. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019 April;20(2):167-80.

6. Robinson E et al. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018 Dec 1;17(12):1273-8.

7. Mounessa JS et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Jul;77(1):188-90.

8. Liszewski W et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Sep;77(3):e87-e88.

9. Telek A et al. FASEB J. 2007 Nov;21(13):3534-41.

10. Wollenberg A et al. Br J Dermatol. 2014 Jul;170 Suppl 1:7-11.

11. Ramot Y et al. PeerJ. 2013 Feb 19;1:e40.

12. Schlicker E et al. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001 Nov;22(11):565-72.

13. Christie MJ et al. Nature. 2001 Mar 29;410(6828):527-30.

14. Ibid.

15. Bíró T et al. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009 Aug;30(8):411-20.

16. Pacher P et al. Pharmacol Rev. 2006 Sep;58(3):389-462.

17. Shalaby M et al. Pract Dermatol. 2018 Jan;68-70.

18. Chelliah MP et al. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018 Jul;35(4):e224-e227.

19. Glodde N et al. Life Sci. 2015 Oct 1;138:35-40.

20. Gaffal E et al. Allergy. 2013 Aug;68(8):994-1000.

21. Pearce DD et al. J Altern Complement Med. 2014 Oct;20(10):787:91.

22. Leonti M et al. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010 Jun 15;79(12):1815-26.

23. Trusler AR et al. Dermatitis. 2017 Jan/Feb;28(1):22-32.

24. Río CD et al. Biochem Pharmacol. 2018 Nov;157:122-133.

25. Chuquilin M et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Feb;74(2):197-212.

26. Tubaro A et al. Fitoterapia. 2010 Oct;81(7):816-9.

27. Eagleston LRM et al. Dermatol Online J. 2018 Jun 15;24(6).

28. Marks DH et al. Skin Therapy Lett. 2018 Nov;23(6):1-5.

Lactobionic acid

Lactobionic acid (4-O-beta-galactopyranosyl-D-gluconic acid), a disaccharide formed from gluconic acid and galactose, has been established as a potent antioxidant well suited for use in solutions intended to preserve organs stored for transplantation.1,2 This polyhydroxy bionic acid is used as an excipient agent in some pharmaceutical products and has been the object of increasing interest and use in cosmetics and cosmeceuticals.3 It is included in skin care formulations for its strong humectant and antiaging effects.3,4 Lactobionic acid has been shown to suppress the synthesis of hydroxyl radicals by dint of iron-chelating activity and hinders the production of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which promote photoaging.2,3,5 It may also present an advantage over the class of alpha-hydroxy acids used to treat photoaging by engendering less or no irritation, because of its larger molecular size and corresponding slower penetration rate.6 This column will focus on some recent research on the application of this strong antioxidant in dermatologic practice.

Lactobionic acid as an ingredient and vehicle

In 2010, Tasic-Kostov et al. compared the efficacy and irritation potential of lactobionic and glycolic acids (in gel and emulsion vehicles). In 77 healthy volunteers, the investigators found that , insofar as the former caused no irritation or skin barrier damage. In a second part to the study, they determined that efficacy of the acids was improved through the use of vehicles based on the natural emulsifier, alkyl polyglucoside (APG). They concluded that lactobionic acid in a 6% concentration in an APG vehicle warranted consideration as a low-molecular option in cosmeceutical products.6

In a subsequent study, the same team found supportive evidence that APG-based emulsions are safe cosmetic/dermopharmaceutical vehicles and carriers for extremely acidic and hygroscopic AHAs, particularly lactobionic acid. They did note, however, that lactobionic acid markedly affected the colloidal structure of the emulsion and fostered the development of lamellar structures, which could influence water distribution within the cream. They concluded, therefore, that such an emulsion, which was stabilized by lamellar liquid crystalline structures, would not be a viable carrier for the hygroscopic actives to achieve optimal moisturizing potential.7More recently, Tasic-Kostov et al. investigated the antioxidant and moisturizing traits of lactobionic acid in solution as well as in a natural APG emulsifier–based system using 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl free radical scavenging and lipid peroxidation inhibition assays. The researchers found that lactobionic acid exhibited suitable physical stability (though it exerted notable impact on the colloidal structure of the vehicle) as well as antioxidant activity in both formats, suggesting its application as a versatile cosmeceutical agent for treating photoaged skin.2

In 2017, Chaouat et al. found that lactobionic acid was a key component in a green microparticle carrier system for cosmetics also containing chitosan and linoleic acid (as the skin penetration–enhancing constituent). Chitosan and lactobionic acid made up the shell surrounding the linoleic acid core. The carrier system, in an aqueous solution, was found to be stable and able to encapsulate the hydrophobic skin lightener phenylethyl resorcinol.8

Potential in atopic dermatitis treatment

Using an oxazolone-induced, atopic dermatitis–like murine dermatitis model, Sakai et al. demonstrated in 2016 that the coapplication of a PAR2 inhibitor and lactobionic acid, which maintained stratum corneum acidity, could target skin barrier abnormality and allergic inflammation, the key mechanisms in atopic dermatitis etiology.9

Lactobionic acid in chemical peels

Early this year, Algiert-Zielinska et al. reported on the results of a split-face study with 20 white women in which the effects of a 20% lactobionic acid peel were compared with those of the 20% peel combined with aluminum oxide crystal microdermabrasion. Treatments were administered weekly over 6 weeks, with the peel alone performed on the left side and the combination therapy on the right. The combination was found to achieve a significantly higher hydration level as well as skin elasticity measurements. There were no statistically significant differences between the tested therapies in transepidermal water loss, which decreased for both approaches. Both the lactobionic acid peel and combination procedure delivered notable moisturizing effects.10

Previously, this team performed a comparative evaluation of the skin-moisturizing activities of lactobionic acid in 10% and 30% concentrations in 10 white subjects between 26 and 73 years old. In this split-face study, 10% lactobionic acid was applied on the left side and 30% on the right on a weekly basis through eight treatments. A 5% lactobionic acid cream was supplied for overnight use. Skin hydration levels were measured before each weekly treatment. Although any differences between cutaneous hydration between the lactobionic acid preparations could not be ascertained, the investigators identified a statistically significant enhancement of hydration levels for both concentrations after the full series of treatments. They concluded that lactobionic is a potent moisturizing compound.11The same authors also conducted a literature review on the moisturizing properties of lactobionic and lactic acids, noting that both acids are capable of binding copious amounts of water and display robust chelating characteristics, as well as antioxidant activity, by suppressing MMPs. The authors added that both act as strong moisturizing substances, helping to maintain epidermal barrier integrity, and are suitable for sensitive skin.3

Conclusion

Greater capacity to moisturize and deliver antiaging benefits while causing less or no irritation are desirable qualities in a dermatologic agent. Evidence is limited, but the data available seem to suggest that lactobionic acid exhibits such qualities in comparison to alpha-hydroxy acids. Much more research is needed, though, to determine the most appropriate ways to use this promising compound.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems LLC. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Annu Rev Med. 1995;46:235-47.

2. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2012 Oct;34(5):424-34.

3. Int J Dermatol. 2019 Mar;58(3):374-79.

4. Clin Dermatol. 2009 Sep-Oct;27(5):495-501.

5.The next generation hydroxy acids, in “Cosmeceuticals” (New York: Elsevier Saunders, 2005, pp. 205-11).

6. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2010 Mar;9(1):3-10.

7. Pharmazie. 2011 Nov;66(11):862-70.

8. J Microencapsul. 2017 Mar;34(2):162-70.

9. J Invest Dermatol. 2016 Feb;136(2):538-41.

10. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019 Jan 20. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12859. [Epub ahead of print].

11. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018 Dec;17(6):1096-1100.

Lactobionic acid (4-O-beta-galactopyranosyl-D-gluconic acid), a disaccharide formed from gluconic acid and galactose, has been established as a potent antioxidant well suited for use in solutions intended to preserve organs stored for transplantation.1,2 This polyhydroxy bionic acid is used as an excipient agent in some pharmaceutical products and has been the object of increasing interest and use in cosmetics and cosmeceuticals.3 It is included in skin care formulations for its strong humectant and antiaging effects.3,4 Lactobionic acid has been shown to suppress the synthesis of hydroxyl radicals by dint of iron-chelating activity and hinders the production of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which promote photoaging.2,3,5 It may also present an advantage over the class of alpha-hydroxy acids used to treat photoaging by engendering less or no irritation, because of its larger molecular size and corresponding slower penetration rate.6 This column will focus on some recent research on the application of this strong antioxidant in dermatologic practice.

Lactobionic acid as an ingredient and vehicle

In 2010, Tasic-Kostov et al. compared the efficacy and irritation potential of lactobionic and glycolic acids (in gel and emulsion vehicles). In 77 healthy volunteers, the investigators found that , insofar as the former caused no irritation or skin barrier damage. In a second part to the study, they determined that efficacy of the acids was improved through the use of vehicles based on the natural emulsifier, alkyl polyglucoside (APG). They concluded that lactobionic acid in a 6% concentration in an APG vehicle warranted consideration as a low-molecular option in cosmeceutical products.6

In a subsequent study, the same team found supportive evidence that APG-based emulsions are safe cosmetic/dermopharmaceutical vehicles and carriers for extremely acidic and hygroscopic AHAs, particularly lactobionic acid. They did note, however, that lactobionic acid markedly affected the colloidal structure of the emulsion and fostered the development of lamellar structures, which could influence water distribution within the cream. They concluded, therefore, that such an emulsion, which was stabilized by lamellar liquid crystalline structures, would not be a viable carrier for the hygroscopic actives to achieve optimal moisturizing potential.7More recently, Tasic-Kostov et al. investigated the antioxidant and moisturizing traits of lactobionic acid in solution as well as in a natural APG emulsifier–based system using 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl free radical scavenging and lipid peroxidation inhibition assays. The researchers found that lactobionic acid exhibited suitable physical stability (though it exerted notable impact on the colloidal structure of the vehicle) as well as antioxidant activity in both formats, suggesting its application as a versatile cosmeceutical agent for treating photoaged skin.2

In 2017, Chaouat et al. found that lactobionic acid was a key component in a green microparticle carrier system for cosmetics also containing chitosan and linoleic acid (as the skin penetration–enhancing constituent). Chitosan and lactobionic acid made up the shell surrounding the linoleic acid core. The carrier system, in an aqueous solution, was found to be stable and able to encapsulate the hydrophobic skin lightener phenylethyl resorcinol.8

Potential in atopic dermatitis treatment

Using an oxazolone-induced, atopic dermatitis–like murine dermatitis model, Sakai et al. demonstrated in 2016 that the coapplication of a PAR2 inhibitor and lactobionic acid, which maintained stratum corneum acidity, could target skin barrier abnormality and allergic inflammation, the key mechanisms in atopic dermatitis etiology.9

Lactobionic acid in chemical peels

Early this year, Algiert-Zielinska et al. reported on the results of a split-face study with 20 white women in which the effects of a 20% lactobionic acid peel were compared with those of the 20% peel combined with aluminum oxide crystal microdermabrasion. Treatments were administered weekly over 6 weeks, with the peel alone performed on the left side and the combination therapy on the right. The combination was found to achieve a significantly higher hydration level as well as skin elasticity measurements. There were no statistically significant differences between the tested therapies in transepidermal water loss, which decreased for both approaches. Both the lactobionic acid peel and combination procedure delivered notable moisturizing effects.10

Previously, this team performed a comparative evaluation of the skin-moisturizing activities of lactobionic acid in 10% and 30% concentrations in 10 white subjects between 26 and 73 years old. In this split-face study, 10% lactobionic acid was applied on the left side and 30% on the right on a weekly basis through eight treatments. A 5% lactobionic acid cream was supplied for overnight use. Skin hydration levels were measured before each weekly treatment. Although any differences between cutaneous hydration between the lactobionic acid preparations could not be ascertained, the investigators identified a statistically significant enhancement of hydration levels for both concentrations after the full series of treatments. They concluded that lactobionic is a potent moisturizing compound.11The same authors also conducted a literature review on the moisturizing properties of lactobionic and lactic acids, noting that both acids are capable of binding copious amounts of water and display robust chelating characteristics, as well as antioxidant activity, by suppressing MMPs. The authors added that both act as strong moisturizing substances, helping to maintain epidermal barrier integrity, and are suitable for sensitive skin.3

Conclusion

Greater capacity to moisturize and deliver antiaging benefits while causing less or no irritation are desirable qualities in a dermatologic agent. Evidence is limited, but the data available seem to suggest that lactobionic acid exhibits such qualities in comparison to alpha-hydroxy acids. Much more research is needed, though, to determine the most appropriate ways to use this promising compound.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems LLC. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Annu Rev Med. 1995;46:235-47.

2. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2012 Oct;34(5):424-34.

3. Int J Dermatol. 2019 Mar;58(3):374-79.

4. Clin Dermatol. 2009 Sep-Oct;27(5):495-501.

5.The next generation hydroxy acids, in “Cosmeceuticals” (New York: Elsevier Saunders, 2005, pp. 205-11).

6. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2010 Mar;9(1):3-10.

7. Pharmazie. 2011 Nov;66(11):862-70.

8. J Microencapsul. 2017 Mar;34(2):162-70.

9. J Invest Dermatol. 2016 Feb;136(2):538-41.

10. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019 Jan 20. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12859. [Epub ahead of print].

11. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018 Dec;17(6):1096-1100.

Lactobionic acid (4-O-beta-galactopyranosyl-D-gluconic acid), a disaccharide formed from gluconic acid and galactose, has been established as a potent antioxidant well suited for use in solutions intended to preserve organs stored for transplantation.1,2 This polyhydroxy bionic acid is used as an excipient agent in some pharmaceutical products and has been the object of increasing interest and use in cosmetics and cosmeceuticals.3 It is included in skin care formulations for its strong humectant and antiaging effects.3,4 Lactobionic acid has been shown to suppress the synthesis of hydroxyl radicals by dint of iron-chelating activity and hinders the production of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which promote photoaging.2,3,5 It may also present an advantage over the class of alpha-hydroxy acids used to treat photoaging by engendering less or no irritation, because of its larger molecular size and corresponding slower penetration rate.6 This column will focus on some recent research on the application of this strong antioxidant in dermatologic practice.

Lactobionic acid as an ingredient and vehicle

In 2010, Tasic-Kostov et al. compared the efficacy and irritation potential of lactobionic and glycolic acids (in gel and emulsion vehicles). In 77 healthy volunteers, the investigators found that , insofar as the former caused no irritation or skin barrier damage. In a second part to the study, they determined that efficacy of the acids was improved through the use of vehicles based on the natural emulsifier, alkyl polyglucoside (APG). They concluded that lactobionic acid in a 6% concentration in an APG vehicle warranted consideration as a low-molecular option in cosmeceutical products.6

In a subsequent study, the same team found supportive evidence that APG-based emulsions are safe cosmetic/dermopharmaceutical vehicles and carriers for extremely acidic and hygroscopic AHAs, particularly lactobionic acid. They did note, however, that lactobionic acid markedly affected the colloidal structure of the emulsion and fostered the development of lamellar structures, which could influence water distribution within the cream. They concluded, therefore, that such an emulsion, which was stabilized by lamellar liquid crystalline structures, would not be a viable carrier for the hygroscopic actives to achieve optimal moisturizing potential.7More recently, Tasic-Kostov et al. investigated the antioxidant and moisturizing traits of lactobionic acid in solution as well as in a natural APG emulsifier–based system using 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl free radical scavenging and lipid peroxidation inhibition assays. The researchers found that lactobionic acid exhibited suitable physical stability (though it exerted notable impact on the colloidal structure of the vehicle) as well as antioxidant activity in both formats, suggesting its application as a versatile cosmeceutical agent for treating photoaged skin.2

In 2017, Chaouat et al. found that lactobionic acid was a key component in a green microparticle carrier system for cosmetics also containing chitosan and linoleic acid (as the skin penetration–enhancing constituent). Chitosan and lactobionic acid made up the shell surrounding the linoleic acid core. The carrier system, in an aqueous solution, was found to be stable and able to encapsulate the hydrophobic skin lightener phenylethyl resorcinol.8

Potential in atopic dermatitis treatment

Using an oxazolone-induced, atopic dermatitis–like murine dermatitis model, Sakai et al. demonstrated in 2016 that the coapplication of a PAR2 inhibitor and lactobionic acid, which maintained stratum corneum acidity, could target skin barrier abnormality and allergic inflammation, the key mechanisms in atopic dermatitis etiology.9

Lactobionic acid in chemical peels

Early this year, Algiert-Zielinska et al. reported on the results of a split-face study with 20 white women in which the effects of a 20% lactobionic acid peel were compared with those of the 20% peel combined with aluminum oxide crystal microdermabrasion. Treatments were administered weekly over 6 weeks, with the peel alone performed on the left side and the combination therapy on the right. The combination was found to achieve a significantly higher hydration level as well as skin elasticity measurements. There were no statistically significant differences between the tested therapies in transepidermal water loss, which decreased for both approaches. Both the lactobionic acid peel and combination procedure delivered notable moisturizing effects.10

Previously, this team performed a comparative evaluation of the skin-moisturizing activities of lactobionic acid in 10% and 30% concentrations in 10 white subjects between 26 and 73 years old. In this split-face study, 10% lactobionic acid was applied on the left side and 30% on the right on a weekly basis through eight treatments. A 5% lactobionic acid cream was supplied for overnight use. Skin hydration levels were measured before each weekly treatment. Although any differences between cutaneous hydration between the lactobionic acid preparations could not be ascertained, the investigators identified a statistically significant enhancement of hydration levels for both concentrations after the full series of treatments. They concluded that lactobionic is a potent moisturizing compound.11The same authors also conducted a literature review on the moisturizing properties of lactobionic and lactic acids, noting that both acids are capable of binding copious amounts of water and display robust chelating characteristics, as well as antioxidant activity, by suppressing MMPs. The authors added that both act as strong moisturizing substances, helping to maintain epidermal barrier integrity, and are suitable for sensitive skin.3

Conclusion

Greater capacity to moisturize and deliver antiaging benefits while causing less or no irritation are desirable qualities in a dermatologic agent. Evidence is limited, but the data available seem to suggest that lactobionic acid exhibits such qualities in comparison to alpha-hydroxy acids. Much more research is needed, though, to determine the most appropriate ways to use this promising compound.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems LLC. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Annu Rev Med. 1995;46:235-47.

2. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2012 Oct;34(5):424-34.

3. Int J Dermatol. 2019 Mar;58(3):374-79.

4. Clin Dermatol. 2009 Sep-Oct;27(5):495-501.

5.The next generation hydroxy acids, in “Cosmeceuticals” (New York: Elsevier Saunders, 2005, pp. 205-11).

6. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2010 Mar;9(1):3-10.

7. Pharmazie. 2011 Nov;66(11):862-70.

8. J Microencapsul. 2017 Mar;34(2):162-70.

9. J Invest Dermatol. 2016 Feb;136(2):538-41.

10. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019 Jan 20. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12859. [Epub ahead of print].

11. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018 Dec;17(6):1096-1100.

Melatonin update, Part 2

Recall that melatonin displays multiple biological functions, acting as an antioxidant, cytokine, neurotransmitter, and global regulator of the circadian clock, the latter for which it is best known.1-3 At the cutaneous level, melatonin exhibits antioxidant (direct, as a radical scavenger; indirect, through upregulating antioxidant enzymes), anti-inflammatory, photoprotective, tissue regenerative, and cytoprotective activity, particularly in its capacity to preserve mitochondrial function.4-8

Melatonin also protects skin homeostasis,6 and, consequently, is believed to act against carcinogenesis and potentially other deleterious dysfunctions such as hyperproliferative/inflammatory conditions.5 Notably, , further buttressing the critical role that melatonin plays in skin health.5 Melatonin also displays immunomodulatory, thermoregulatory, and antitumor functions.9 The topical application of melatonin has been demonstrated to diminish markers of reactive oxygen species as well as reverse manifestations of cutaneous aging.5

Melatonin is both produced by and metabolized in the skin. The hormone and its metabolites (6-hydroxymelatonin, N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine [AFMK], N-acetyl-serotonin, and 5-methoxytryptamine) reduce UVB-induced oxidative cell damage in human keratinocytes and melanocytes, and also act as radioprotectors.6

Melatonin has been shown to protect human dermal fibroblasts from UVA- and UVB-induced damage.9 In addition, melatonin and its metabolites have been demonstrated to suppress the growth of cultured human melanomas, and high doses of melatonin used in clinical trials in late metastatic melanoma stages have enhanced the efficacy of or diminished the side effects of chemotherapy/chemo-immunotherapy.9

UVB and melatonin in the lab

In a 2018 hairless mouse study in which animals were irradiated by UVB for 8 weeks, Park et al. showed that melatonin displays anti-wrinkle activity by suppressing reactive oxygen species- and sonic hedgehog-mediated inflammatory proteins. Melatonin also protected against transepidermal water loss and prevented epidermal thickness as well as dermal collagen degradation.10

Also that year, Skobowiat et al. found that the topical application of melatonin and its active derivatives (N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynurenine and N-acetylserotonin) yielded photoprotective effects pre- and post-UVB treatment in human and porcine skin ex vivo. They concluded that their results justify additional investigation of the clinical applications of melatonin and its metabolites for its potential to exert protective effects against UVB in human subjects.8

Although the preponderance of previous work identifies melatonin as a strong antioxidant, Kocyigit et al. reported in 2018 on new in vitro studies suggesting that melatonin dose-dependently exerts cytotoxic and apoptotic activity on several cell types, including both human epidermoid carcinoma and normal skin fibroblasts. Their findings showed that melatonin exhibited proliferative effects on cancerous and normal cells at low doses and cytotoxic effects at high doses.11

Melatonin as a sunscreen ingredient

Further supporting its use in the topical armamentarium for skin health, melatonin is a key ingredient in a sunscreen formulation, the creation of which was driven by the need to protect the skin of military personnel facing lengthy UV exposure. Specifically, the formulation containing avobenzone, octinoxate, oxybenzone, and titanium dioxide along with melatonin and pumpkin seed oil underwent a preclinical safety evaluation in 2017, as reported by Bora et al. The formulation was found to be nonmutagenic, nontoxic, and safe in animal models and is deemed ready to test for its efficacy in humans.12 Melatonin is also among a host of systemic treatment options for skin lightening.13

Oral and topical melatonin in human studies

In a 2017 study on the impact of melatonin treatment on the skin of former smokers, Sagan et al. assessed oxidative damage to membrane lipids in blood serum and in epidermis exfoliated during microdermabrasion (at baseline, 2 weeks after, and 4 weeks after treatment) in postmenopausal women. Never smokers (n = 44) and former smokers (n = 46) were divided into control, melatonin topical, antioxidant topical, and melatonin oral treatment groups. The investigators found that after only 2 weeks, melatonin oral treatment significantly reversed the elevated serum lipid peroxidation in former smokers. Oral melatonin increased elasticity, moisture, and sebum levels after 4 weeks of treatment and topical melatonin increased sebum level. They concluded that the use of exogenous melatonin reverses the effects of oxidative damage to membrane lipids and ameliorates cutaneous biophysical traits in postmenopausal women who once smoked. The researchers added that melatonin use for all former smokers is warranted and that topically applied melatonin merits consideration for improving the effects of facial microdermabrasion.14

In a systematic literature review in 2017, Scheuer identified 20 studies (4 human and 16 experimental) indicating that melatonin exerts a protective effect against artificial UV-induced erythema when applied pre-exposure.7 Also that year, Scheuer and colleagues conducted randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled work demonstrating that topical melatonin (12.5%) significantly reduced erythema resulting from natural sunlight, and in a separate randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study that the same concentration of a full body application of melatonin exhibited no significant impact on cognition and should be considered safe for dermal application.7 Scheuer added that additional longitudinal research is needed to ascertain effects of topical melatonin usage over time.

Early in 2018, Milani and Sparavigna reported on a randomized, split-face, assessor-blinded, prospective 3-month study of 22 women (mean age 55 years) with moderate to severe facial skin aging; the study was designed to test the efficacy of melatonin-based day and night creams. All of the women completed the proof-of-concept trial in which crow’s feet were found to be significantly diminished on the sides of the face treated with the creams compared with the nontreated skin.

Both well-tolerated melatonin formulations were associated with significant improvements in surface microrelief, skin profilometry, tonicity, and dryness. With marked enhancement of skin hydration and reduction of roughness noted, the investigators concluded that their results supported the notion that the tested melatonin topical formulations yielded antiaging effects.4

Conclusion

The majority of research on the potent hormone melatonin over nearly the last quarter century indicates that this dynamic substance provides multifaceted benefits in performing several biological functions. Topical melatonin is available over the counter. Its expanded use in skin care warrants greater attention as we learn more about this versatile endogenous substance.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems LLC. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Zmijewski MA et al. Dermatoendocrinol. 2011 Jan;3(1):3-10.

2. Slominski A et al. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Jan;19(1):17-24.

3. Slominski A et al. J Cell Physiol. 2003 Jul;196(1):144-53.

4. Milani M et al. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018 Jan 24;11:51-7.

5. Day D et al. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018 Sep 1;17(9):966-9.

6. Slominski AT et al. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017 Nov;74(21):3913-25.

7. Scheuer C. Dan Med J. 2017 Jun;64(6). pii:B5358.

8. Skobowiat C et al. J Pineal Res. 2018 Sep;65(2):e12501.

9. Slominski AT et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2018 Mar;138(3):490-9.

10. Park EK et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2018 Jul 8;19(7). pii: E1995.

11. Kocyigit A et al. Mutat Res. 2018 May-Jun;829-30:50-60.

12. Bora NS et al. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2017 Oct;89:1-12.

13. Juhasz MLW et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018 Dec;17(6):1144-57.

14. Sagan D et al. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2017 Dec 23;24(4):659-66.

Recall that melatonin displays multiple biological functions, acting as an antioxidant, cytokine, neurotransmitter, and global regulator of the circadian clock, the latter for which it is best known.1-3 At the cutaneous level, melatonin exhibits antioxidant (direct, as a radical scavenger; indirect, through upregulating antioxidant enzymes), anti-inflammatory, photoprotective, tissue regenerative, and cytoprotective activity, particularly in its capacity to preserve mitochondrial function.4-8

Melatonin also protects skin homeostasis,6 and, consequently, is believed to act against carcinogenesis and potentially other deleterious dysfunctions such as hyperproliferative/inflammatory conditions.5 Notably, , further buttressing the critical role that melatonin plays in skin health.5 Melatonin also displays immunomodulatory, thermoregulatory, and antitumor functions.9 The topical application of melatonin has been demonstrated to diminish markers of reactive oxygen species as well as reverse manifestations of cutaneous aging.5

Melatonin is both produced by and metabolized in the skin. The hormone and its metabolites (6-hydroxymelatonin, N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine [AFMK], N-acetyl-serotonin, and 5-methoxytryptamine) reduce UVB-induced oxidative cell damage in human keratinocytes and melanocytes, and also act as radioprotectors.6

Melatonin has been shown to protect human dermal fibroblasts from UVA- and UVB-induced damage.9 In addition, melatonin and its metabolites have been demonstrated to suppress the growth of cultured human melanomas, and high doses of melatonin used in clinical trials in late metastatic melanoma stages have enhanced the efficacy of or diminished the side effects of chemotherapy/chemo-immunotherapy.9

UVB and melatonin in the lab

In a 2018 hairless mouse study in which animals were irradiated by UVB for 8 weeks, Park et al. showed that melatonin displays anti-wrinkle activity by suppressing reactive oxygen species- and sonic hedgehog-mediated inflammatory proteins. Melatonin also protected against transepidermal water loss and prevented epidermal thickness as well as dermal collagen degradation.10

Also that year, Skobowiat et al. found that the topical application of melatonin and its active derivatives (N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynurenine and N-acetylserotonin) yielded photoprotective effects pre- and post-UVB treatment in human and porcine skin ex vivo. They concluded that their results justify additional investigation of the clinical applications of melatonin and its metabolites for its potential to exert protective effects against UVB in human subjects.8

Although the preponderance of previous work identifies melatonin as a strong antioxidant, Kocyigit et al. reported in 2018 on new in vitro studies suggesting that melatonin dose-dependently exerts cytotoxic and apoptotic activity on several cell types, including both human epidermoid carcinoma and normal skin fibroblasts. Their findings showed that melatonin exhibited proliferative effects on cancerous and normal cells at low doses and cytotoxic effects at high doses.11

Melatonin as a sunscreen ingredient

Further supporting its use in the topical armamentarium for skin health, melatonin is a key ingredient in a sunscreen formulation, the creation of which was driven by the need to protect the skin of military personnel facing lengthy UV exposure. Specifically, the formulation containing avobenzone, octinoxate, oxybenzone, and titanium dioxide along with melatonin and pumpkin seed oil underwent a preclinical safety evaluation in 2017, as reported by Bora et al. The formulation was found to be nonmutagenic, nontoxic, and safe in animal models and is deemed ready to test for its efficacy in humans.12 Melatonin is also among a host of systemic treatment options for skin lightening.13

Oral and topical melatonin in human studies

In a 2017 study on the impact of melatonin treatment on the skin of former smokers, Sagan et al. assessed oxidative damage to membrane lipids in blood serum and in epidermis exfoliated during microdermabrasion (at baseline, 2 weeks after, and 4 weeks after treatment) in postmenopausal women. Never smokers (n = 44) and former smokers (n = 46) were divided into control, melatonin topical, antioxidant topical, and melatonin oral treatment groups. The investigators found that after only 2 weeks, melatonin oral treatment significantly reversed the elevated serum lipid peroxidation in former smokers. Oral melatonin increased elasticity, moisture, and sebum levels after 4 weeks of treatment and topical melatonin increased sebum level. They concluded that the use of exogenous melatonin reverses the effects of oxidative damage to membrane lipids and ameliorates cutaneous biophysical traits in postmenopausal women who once smoked. The researchers added that melatonin use for all former smokers is warranted and that topically applied melatonin merits consideration for improving the effects of facial microdermabrasion.14

In a systematic literature review in 2017, Scheuer identified 20 studies (4 human and 16 experimental) indicating that melatonin exerts a protective effect against artificial UV-induced erythema when applied pre-exposure.7 Also that year, Scheuer and colleagues conducted randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled work demonstrating that topical melatonin (12.5%) significantly reduced erythema resulting from natural sunlight, and in a separate randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study that the same concentration of a full body application of melatonin exhibited no significant impact on cognition and should be considered safe for dermal application.7 Scheuer added that additional longitudinal research is needed to ascertain effects of topical melatonin usage over time.

Early in 2018, Milani and Sparavigna reported on a randomized, split-face, assessor-blinded, prospective 3-month study of 22 women (mean age 55 years) with moderate to severe facial skin aging; the study was designed to test the efficacy of melatonin-based day and night creams. All of the women completed the proof-of-concept trial in which crow’s feet were found to be significantly diminished on the sides of the face treated with the creams compared with the nontreated skin.

Both well-tolerated melatonin formulations were associated with significant improvements in surface microrelief, skin profilometry, tonicity, and dryness. With marked enhancement of skin hydration and reduction of roughness noted, the investigators concluded that their results supported the notion that the tested melatonin topical formulations yielded antiaging effects.4

Conclusion

The majority of research on the potent hormone melatonin over nearly the last quarter century indicates that this dynamic substance provides multifaceted benefits in performing several biological functions. Topical melatonin is available over the counter. Its expanded use in skin care warrants greater attention as we learn more about this versatile endogenous substance.

Dr. Baumann is a private practice dermatologist, researcher, author, and entrepreneur who practices in Miami. She founded the Cosmetic Dermatology Center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote two textbooks: “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), and “Cosmeceuticals and Cosmetic Ingredients,” (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2014), and a New York Times Best Sellers book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (New York: Bantam Dell, 2006). Dr. Baumann has received funding for advisory boards and/or clinical research trials from Allergan, Evolus, Galderma, and Revance. She is the founder and CEO of Skin Type Solutions Franchise Systems LLC. Write to her at dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Zmijewski MA et al. Dermatoendocrinol. 2011 Jan;3(1):3-10.

2. Slominski A et al. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Jan;19(1):17-24.

3. Slominski A et al. J Cell Physiol. 2003 Jul;196(1):144-53.

4. Milani M et al. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2018 Jan 24;11:51-7.

5. Day D et al. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018 Sep 1;17(9):966-9.

6. Slominski AT et al. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017 Nov;74(21):3913-25.

7. Scheuer C. Dan Med J. 2017 Jun;64(6). pii:B5358.

8. Skobowiat C et al. J Pineal Res. 2018 Sep;65(2):e12501.

9. Slominski AT et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2018 Mar;138(3):490-9.

10. Park EK et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2018 Jul 8;19(7). pii: E1995.

11. Kocyigit A et al. Mutat Res. 2018 May-Jun;829-30:50-60.

12. Bora NS et al. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2017 Oct;89:1-12.

13. Juhasz MLW et al. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018 Dec;17(6):1144-57.

14. Sagan D et al. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2017 Dec 23;24(4):659-66.

Recall that melatonin displays multiple biological functions, acting as an antioxidant, cytokine, neurotransmitter, and global regulator of the circadian clock, the latter for which it is best known.1-3 At the cutaneous level, melatonin exhibits antioxidant (direct, as a radical scavenger; indirect, through upregulating antioxidant enzymes), anti-inflammatory, photoprotective, tissue regenerative, and cytoprotective activity, particularly in its capacity to preserve mitochondrial function.4-8

Melatonin also protects skin homeostasis,6 and, consequently, is believed to act against carcinogenesis and potentially other deleterious dysfunctions such as hyperproliferative/inflammatory conditions.5 Notably, , further buttressing the critical role that melatonin plays in skin health.5 Melatonin also displays immunomodulatory, thermoregulatory, and antitumor functions.9 The topical application of melatonin has been demonstrated to diminish markers of reactive oxygen species as well as reverse manifestations of cutaneous aging.5

Melatonin is both produced by and metabolized in the skin. The hormone and its metabolites (6-hydroxymelatonin, N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine [AFMK], N-acetyl-serotonin, and 5-methoxytryptamine) reduce UVB-induced oxidative cell damage in human keratinocytes and melanocytes, and also act as radioprotectors.6

Melatonin has been shown to protect human dermal fibroblasts from UVA- and UVB-induced damage.9 In addition, melatonin and its metabolites have been demonstrated to suppress the growth of cultured human melanomas, and high doses of melatonin used in clinical trials in late metastatic melanoma stages have enhanced the efficacy of or diminished the side effects of chemotherapy/chemo-immunotherapy.9

UVB and melatonin in the lab

In a 2018 hairless mouse study in which animals were irradiated by UVB for 8 weeks, Park et al. showed that melatonin displays anti-wrinkle activity by suppressing reactive oxygen species- and sonic hedgehog-mediated inflammatory proteins. Melatonin also protected against transepidermal water loss and prevented epidermal thickness as well as dermal collagen degradation.10

Also that year, Skobowiat et al. found that the topical application of melatonin and its active derivatives (N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynurenine and N-acetylserotonin) yielded photoprotective effects pre- and post-UVB treatment in human and porcine skin ex vivo. They concluded that their results justify additional investigation of the clinical applications of melatonin and its metabolites for its potential to exert protective effects against UVB in human subjects.8

Although the preponderance of previous work identifies melatonin as a strong antioxidant, Kocyigit et al. reported in 2018 on new in vitro studies suggesting that melatonin dose-dependently exerts cytotoxic and apoptotic activity on several cell types, including both human epidermoid carcinoma and normal skin fibroblasts. Their findings showed that melatonin exhibited proliferative effects on cancerous and normal cells at low doses and cytotoxic effects at high doses.11

Melatonin as a sunscreen ingredient