User login

Age-Friendly Health Systems and Meeting the Principles of High Reliability Organizations in the VHA

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest integrated health care system in the US, providing care to more than 9 million enrolled veterans at 1298 facilities.1 In February 2019, the VHA identified key action steps to become a high reliability organization (HRO), transforming how employees think about patient safety and care quality.2 The VHA is also working toward becoming the largest age-friendly health system in the US to be recognized by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) for its commitment to providing care guided by the 4Ms (what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility), causing no harm, and aligning care with what matters to older veterans.3 In this article, we describe how the Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS) movement supports the culture shift observed in HROs.

Age-Friendly Veteran Care

By 2060, the US population of adults aged ≥ 65 years is projected to increase to about 95 million.3 In the VHA, nearly half of veteran enrollees are aged ≥ 65 years, necessitating evidence-based models of care, such as the 4Ms, to meet their complex care needs.3 Historically, the VHA has been a leader in caring for older adults, recognizing the value of age-friendly care for veterans.4 In 1975, the VHA established the Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Centers (GRECCs) to serve as catalysts for developing, implementing, and refining enduring models of geriatric care.4 For 5 decades, GRECCs have driven innovations related to the 4Ms.

The VHA is well positioned to be a leader in the AFHS movement, building on decades of GRECC innovations and geriatric programs that align with the 4Ms and providing specialized geriatric training for health care professionals to expand age-friendly care to new settings and health systems.4 The AFHS movement organizes the 4Ms into a simple framework for frontline staff, and the VHA has recently begun tracking 4Ms care in the electronic health record (EHR) to facilitate evaluation and continuous improvement.

AFHS use the 4Ms as a framework to be implemented in every care setting, from the emergency department to inpatient units, outpatient settings, and postacute and long-term care. By assessing and acting on each M and practicing the 4Ms collectively, all members of the care team work to improve health outcomes and prevent avoidable harm.5

The 4Ms

What matters, is the driver of this person-centered approach. Any member of the care team may initiate a what matters conversation with the older adult to understand their personal values, health goals, and care preferences. When compared with usual care, care aligned with the older adult’s health priorities has been shown to decrease the use of high-risk medications and reduce treatment burden.6 The VHA has adopted Whole Health principles of care and the Patient Priorities Care approach to identify and support what matters to veterans.7,8

Addressing polypharmacy and identifying and deprescribing potentially inappropriate medications are essential in preventing adverse drug events, drug-drug interactions, and medication nonadherence.9 In the VHA, VIONE (Vital, Important, Optional, Not indicated, Every medication has an indication) is a rapidly expanding medication deprescribing program that exemplifies HRO principles.9 VIONE provides medication management that supports shared decision making, reducing risk and improving patient safety and quality of life.9 As of June 2023, > 600,000 unique veterans have benefited from VIONE, with an average of 2.2 medications deprescribed per patient with an annual cost avoidance of > $100 million.10

Assessing and acting on mentation includes preventing, identifying, and managing depression and dementia in outpatient settings and delirium in hospital and long-term care settings.5 There are many tools and clinical reminders available in the EHR so that interdisciplinary teams can document changes to mentation and identify opportunities for continuous improvement.

Closely aligned with mentation is mobility, with evidence suggesting that regular physical activity reduces the risk of falls (preventing associated complications), maintains physical functioning, and lowers the risk of cognitive impairment and depression.5 Ensuring early, frequent, and safe mobility helps patients achieve better health outcomes and prevent injury.5 Mobility programs within the VHA include the STRIDE program for the inpatient setting and Gerofit for outpatient settings.11,12

HRO Principles

An HRO is a complex environment of care that experiences fewer than anticipated accidents or adverse events by (1) establishing trust among leaders and staff by balancing individual accountability with systems thinking; (2) empowering staff to lead continuous process improvements; and (3) creating an environment where employees feel safe to report harm or near misses, focusing on the reasons errors occur.13 The work of AFHS incorporates HRO principles with an emphasis on 3 elements. First, it involves interactive systems and processes needed to support 4Ms care across care settings. Second, AFHS acknowledge the complexity of age-friendly work and deference to the expertise of interdisciplinary team members. Finally, AFHS are committed to resilience by overcoming failures and challenges to implementation and long-term sustainment as a standard of practice.

Case study

The names and details in this case have been modified to protect patient privacy. It is representative of many Community Living Centers (CLCs) involved in AFHS that work to create a safe, person-centered environment for veterans.

In a CLC team workroom, 2 nurses were discussing a long-term care resident. The nurses approached the attending physician and explained that they were worried about Sgt Johnson, who seemed depressed and sometimes combative. They had noticed a change in his behavior when they helped him clean up after an episode of incontinence and were concerned that he would try to get out of bed on his own and fall. The attending physician thanked them for sharing their concerns. Sgt Johnson was a retired Army veteran who had a long, decorated military career. His chronic health conditions had led to muscle weakness, and he fell and broke a hip before this admission. He had an uneventful hip replacement but was showing signs of depression due to his limited mobility, loss of independence, and inability to live at home without additional support.

The attending physician knocked on the door of his room, sat down next to the bed, and asked, “How are you feeling today?” Sgt Johnson tersely replied, “About the same.” The physician asked, “Sgt Johnson, what matters most to you related to your recovery? What is important to you?” Sgt Johnson responded, “Feeling like a man!” The doctor replied, “So what makes you feel ‘not like a man’?” The Sgt replied, “Having to be cleaned up by the nurses and not being able to use the toilet on my own.” The physician surmised that his decline in physical functioning had a connection to his worsening depression and combativeness and said to the Sgt, “Let’s get the team together and work out a plan to get you strong enough to use a bedside commode by yourself. Let’s make that the first goal in our plan to get you back to using the toilet independently. Can you work with us on that?” He smiled and said, “Sir, yes Sir!”

At the weekly interdisciplinary team meeting, the team discussed Sgt Johnson’s wishes and the nurses’ safety concerns. The physician reported to the team what mattered to the veteran. The nurses arranged for a bedside commode and supplies to be placed in his room, encouraged and assisted him, and provided a privacy screen. The physical therapist continued to support his mobility needs, concentrating on transfers, small steps like standing and turning with a walker to get in position to use the bedside commode, and later the bathroom toilet. The psychologist addressed what matters to Sgt Johnson and his mentation, health goals, and coping strategies. The social worker provided support and counseling for the veteran and his family. The pharmacist checked his medications to be sure that none were affecting his gastrointestinal tract and his ability to move safely and do what matters to him. Knowing what mattered to Sgt Johnson was the driver of the interdisciplinary care plan to provide 4Ms care.

The team worked collaboratively with the veteran to develop and set attainable goals around toileting and regaining his dignity. This improved his overall recovery. As Sgt Johnson became more independent, his mood gradually improved and he began to participate in other activities and interact with other residents on the unit, and he did not experience any falls. By addressing the 4Ms, the interdisciplinary team coordinated efforts to provide high-quality, person-centered care. They built trust with the veteran, shared accountability, and followed HRO principles to keep the veteran safe.

Becoming an Age-Friendly HRO

Becoming an HRO is a dynamic, ever-changing process to maintain high standards, improve care quality, and cause no harm. There are 3 pillars and 5 principles that guide an HRO. The pillars are critical areas of focus and include leadership commitment, culture of safety, and continuous process improvement.14 The first of 5 HRO principles is sensitivity to operations. This is defined as an awareness of how processes and systems impact the entire organization, the downstream impact.15 Focusing on the 4Ms helps develop the capability of frontline staff to provide high-quality care for older adults while ensuring that processes are in place to support the work. The 4Ms provide an efficient way to organize interdisciplinary team meetings, provide warm handoffs using Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation, and standardize documentation. Involvement in the AFHS movement improves communication, care quality, and patient and staff satisfaction to meet this HRO principle.15

The second HRO principle, reluctance to simplify, ensures that direct care staff and leaders delve further into issues to find solutions.15 AFHS use the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle to put the 4Ms into practice; this cycle helps teams test small increments of change, study their performance, and act to ensure that all 4Ms are being practiced as a set. AFHS teams are encouraged to review at least 3 months of data after implementation of the 4Ms, working to find solutions if there are gaps or issues identified.

The third principle, preoccupation with failure, refers to shared attentiveness—being prepared for the unexpected and learning from mistakes.15 The entire AFHS team shares responsibility for providing 4Ms care, where staff are empowered to report any safety concerns or close calls. The fourth principle of deference to expertise includes listening to staff who have the most knowledge for the task at hand, which aligns with the collaborative interdisciplinary teamwork of age-friendly teams.15

The final HRO principle, commitment to resilience, includes continuous learning, interdisciplinary team training, and sharing of lessons learned.15 Although IHI offers 2 levels of AFHS recognition, teams are continuously learning to improve and sustain care beyond level 2, Committed to Care Excellence recognition.16

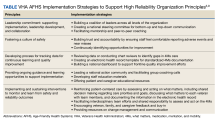

The Table shows the VHA’s AFHS implementation strategies and the HRO principles adapted from the Joint Commission’s High Reliability Health Care Maturity Model and the IHI’s Framework for Safe, Reliable, and Effective Care. The VHA is developing a national dashboard to capture age-friendly processes and health outcome measures that address patient safety and care quality.

Conclusions

AFHS empowers VHA teams to honor veterans’ care preferences and values, supporting their independence, dignity, and quality of life across care settings. The adoption of AFHS brings evidence-based practices to the point of care by addressing common pitfalls in the care of older adults, drawing attention to, and calling for action on inappropriate medication use, physical inactivity, and assessment of the vulnerable brain. The 4Ms also serve as a framework to continuously improve care and cause zero harm, reinforcing HRO pillars and principles across the VHA, and ensuring that older adults reliably receive the evidence-based, high-quality care they deserve.

1. Veterans Health Administration. Providing healthcare for veterans. Updated June 20, 2023. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.va.gov/health

2. Veazie S, Peterson K, Bourne D. Evidence brief: implementation of high reliability organization principles. Washington, DC: Evidence Synthesis Program, Health Services Research and Development Service, Office of Research and Development, Department of Veterans Affairs. VA ESP Project #09-199; 2019. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/high-reliability-org.cfm

3. Church K, Munro S, Shaughnessy M, Clancy C. Age-Friendly Health Systems: improving care for older adults in the Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv Res. 2023;58(suppl 1):5-8. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14110

4. Farrell TW, Volden TA, Butler JM, et al. Age-friendly care in the Veterans Health Administration: past, present, and future. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(1):18-25. doi:10.1111/jgs.18070

5. Mate K, Fulmer T, Pelton L, et al. Evidence for the 4Ms: interactions and outcomes across the care continuum. J Aging Health. 2021;33(7-8):469-481. doi:10.1177/0898264321991658

6. Tinetti ME, Naik AD, Dindo L, et al. Association of patient priorities-aligned decision-making with patient outcomes and ambulatory health care burden among older adults with multiple chronic conditions: A nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(12):1688-1697. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4235

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs. What is whole health? Updated: October 31, 2023. November 30, 2023. https://www.va.gov/wholehealth

8. Patient Priorities Care. Updated 2019. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://patientprioritiescare.org

9. Battar S, Watson Dickerson KR, Sedgwick C, Cmelik T. Understanding principles of high reliability organizations through the eyes of VIONE: a clinical program to improve patient safety by deprescribing potentially inappropriate medications and reducing polypharmacy. Fed Pract. 2019;36(12):564-568.

10. VA Diffusion Marketplace. VIONE- medication optimization and polypharmacy reduction initiative. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://marketplace.va.gov/innovations/vione

11. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. STRIDE program to keep hospitalized veterans mobile. Updated November 6, 2018. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.research.va.gov/research_in_action/STRIDE-program-to-keep-hospitalized-Veterans-mobile.cfm

12. US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Geriatrics and Extended Care. Gerofit: a program promoting exercise and health for older veterans. Updated August 2, 2023. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.va.gov/GERIATRICS/pages/gerofit_Home.asp

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development. VHA’s vision for a high reliability organization. Updated August 14, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/forum/summer20/default.cfm?ForumMenu=summer20-1

14. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development. Three HRO evaluation priorities. Updated August 14, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/forum/summer20/default.cfm?ForumMenu=summer20-2

15. Oster CA, Deakins S. Practical application of high-reliability principles in healthcare to optimize quality and safety outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2018;48(1):50-55. doi:10.1097/NNA.0000000000000570

16. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Age-Friendly Health Systems recognitions. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/Recognition.aspx

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest integrated health care system in the US, providing care to more than 9 million enrolled veterans at 1298 facilities.1 In February 2019, the VHA identified key action steps to become a high reliability organization (HRO), transforming how employees think about patient safety and care quality.2 The VHA is also working toward becoming the largest age-friendly health system in the US to be recognized by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) for its commitment to providing care guided by the 4Ms (what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility), causing no harm, and aligning care with what matters to older veterans.3 In this article, we describe how the Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS) movement supports the culture shift observed in HROs.

Age-Friendly Veteran Care

By 2060, the US population of adults aged ≥ 65 years is projected to increase to about 95 million.3 In the VHA, nearly half of veteran enrollees are aged ≥ 65 years, necessitating evidence-based models of care, such as the 4Ms, to meet their complex care needs.3 Historically, the VHA has been a leader in caring for older adults, recognizing the value of age-friendly care for veterans.4 In 1975, the VHA established the Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Centers (GRECCs) to serve as catalysts for developing, implementing, and refining enduring models of geriatric care.4 For 5 decades, GRECCs have driven innovations related to the 4Ms.

The VHA is well positioned to be a leader in the AFHS movement, building on decades of GRECC innovations and geriatric programs that align with the 4Ms and providing specialized geriatric training for health care professionals to expand age-friendly care to new settings and health systems.4 The AFHS movement organizes the 4Ms into a simple framework for frontline staff, and the VHA has recently begun tracking 4Ms care in the electronic health record (EHR) to facilitate evaluation and continuous improvement.

AFHS use the 4Ms as a framework to be implemented in every care setting, from the emergency department to inpatient units, outpatient settings, and postacute and long-term care. By assessing and acting on each M and practicing the 4Ms collectively, all members of the care team work to improve health outcomes and prevent avoidable harm.5

The 4Ms

What matters, is the driver of this person-centered approach. Any member of the care team may initiate a what matters conversation with the older adult to understand their personal values, health goals, and care preferences. When compared with usual care, care aligned with the older adult’s health priorities has been shown to decrease the use of high-risk medications and reduce treatment burden.6 The VHA has adopted Whole Health principles of care and the Patient Priorities Care approach to identify and support what matters to veterans.7,8

Addressing polypharmacy and identifying and deprescribing potentially inappropriate medications are essential in preventing adverse drug events, drug-drug interactions, and medication nonadherence.9 In the VHA, VIONE (Vital, Important, Optional, Not indicated, Every medication has an indication) is a rapidly expanding medication deprescribing program that exemplifies HRO principles.9 VIONE provides medication management that supports shared decision making, reducing risk and improving patient safety and quality of life.9 As of June 2023, > 600,000 unique veterans have benefited from VIONE, with an average of 2.2 medications deprescribed per patient with an annual cost avoidance of > $100 million.10

Assessing and acting on mentation includes preventing, identifying, and managing depression and dementia in outpatient settings and delirium in hospital and long-term care settings.5 There are many tools and clinical reminders available in the EHR so that interdisciplinary teams can document changes to mentation and identify opportunities for continuous improvement.

Closely aligned with mentation is mobility, with evidence suggesting that regular physical activity reduces the risk of falls (preventing associated complications), maintains physical functioning, and lowers the risk of cognitive impairment and depression.5 Ensuring early, frequent, and safe mobility helps patients achieve better health outcomes and prevent injury.5 Mobility programs within the VHA include the STRIDE program for the inpatient setting and Gerofit for outpatient settings.11,12

HRO Principles

An HRO is a complex environment of care that experiences fewer than anticipated accidents or adverse events by (1) establishing trust among leaders and staff by balancing individual accountability with systems thinking; (2) empowering staff to lead continuous process improvements; and (3) creating an environment where employees feel safe to report harm or near misses, focusing on the reasons errors occur.13 The work of AFHS incorporates HRO principles with an emphasis on 3 elements. First, it involves interactive systems and processes needed to support 4Ms care across care settings. Second, AFHS acknowledge the complexity of age-friendly work and deference to the expertise of interdisciplinary team members. Finally, AFHS are committed to resilience by overcoming failures and challenges to implementation and long-term sustainment as a standard of practice.

Case study

The names and details in this case have been modified to protect patient privacy. It is representative of many Community Living Centers (CLCs) involved in AFHS that work to create a safe, person-centered environment for veterans.

In a CLC team workroom, 2 nurses were discussing a long-term care resident. The nurses approached the attending physician and explained that they were worried about Sgt Johnson, who seemed depressed and sometimes combative. They had noticed a change in his behavior when they helped him clean up after an episode of incontinence and were concerned that he would try to get out of bed on his own and fall. The attending physician thanked them for sharing their concerns. Sgt Johnson was a retired Army veteran who had a long, decorated military career. His chronic health conditions had led to muscle weakness, and he fell and broke a hip before this admission. He had an uneventful hip replacement but was showing signs of depression due to his limited mobility, loss of independence, and inability to live at home without additional support.

The attending physician knocked on the door of his room, sat down next to the bed, and asked, “How are you feeling today?” Sgt Johnson tersely replied, “About the same.” The physician asked, “Sgt Johnson, what matters most to you related to your recovery? What is important to you?” Sgt Johnson responded, “Feeling like a man!” The doctor replied, “So what makes you feel ‘not like a man’?” The Sgt replied, “Having to be cleaned up by the nurses and not being able to use the toilet on my own.” The physician surmised that his decline in physical functioning had a connection to his worsening depression and combativeness and said to the Sgt, “Let’s get the team together and work out a plan to get you strong enough to use a bedside commode by yourself. Let’s make that the first goal in our plan to get you back to using the toilet independently. Can you work with us on that?” He smiled and said, “Sir, yes Sir!”

At the weekly interdisciplinary team meeting, the team discussed Sgt Johnson’s wishes and the nurses’ safety concerns. The physician reported to the team what mattered to the veteran. The nurses arranged for a bedside commode and supplies to be placed in his room, encouraged and assisted him, and provided a privacy screen. The physical therapist continued to support his mobility needs, concentrating on transfers, small steps like standing and turning with a walker to get in position to use the bedside commode, and later the bathroom toilet. The psychologist addressed what matters to Sgt Johnson and his mentation, health goals, and coping strategies. The social worker provided support and counseling for the veteran and his family. The pharmacist checked his medications to be sure that none were affecting his gastrointestinal tract and his ability to move safely and do what matters to him. Knowing what mattered to Sgt Johnson was the driver of the interdisciplinary care plan to provide 4Ms care.

The team worked collaboratively with the veteran to develop and set attainable goals around toileting and regaining his dignity. This improved his overall recovery. As Sgt Johnson became more independent, his mood gradually improved and he began to participate in other activities and interact with other residents on the unit, and he did not experience any falls. By addressing the 4Ms, the interdisciplinary team coordinated efforts to provide high-quality, person-centered care. They built trust with the veteran, shared accountability, and followed HRO principles to keep the veteran safe.

Becoming an Age-Friendly HRO

Becoming an HRO is a dynamic, ever-changing process to maintain high standards, improve care quality, and cause no harm. There are 3 pillars and 5 principles that guide an HRO. The pillars are critical areas of focus and include leadership commitment, culture of safety, and continuous process improvement.14 The first of 5 HRO principles is sensitivity to operations. This is defined as an awareness of how processes and systems impact the entire organization, the downstream impact.15 Focusing on the 4Ms helps develop the capability of frontline staff to provide high-quality care for older adults while ensuring that processes are in place to support the work. The 4Ms provide an efficient way to organize interdisciplinary team meetings, provide warm handoffs using Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation, and standardize documentation. Involvement in the AFHS movement improves communication, care quality, and patient and staff satisfaction to meet this HRO principle.15

The second HRO principle, reluctance to simplify, ensures that direct care staff and leaders delve further into issues to find solutions.15 AFHS use the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle to put the 4Ms into practice; this cycle helps teams test small increments of change, study their performance, and act to ensure that all 4Ms are being practiced as a set. AFHS teams are encouraged to review at least 3 months of data after implementation of the 4Ms, working to find solutions if there are gaps or issues identified.

The third principle, preoccupation with failure, refers to shared attentiveness—being prepared for the unexpected and learning from mistakes.15 The entire AFHS team shares responsibility for providing 4Ms care, where staff are empowered to report any safety concerns or close calls. The fourth principle of deference to expertise includes listening to staff who have the most knowledge for the task at hand, which aligns with the collaborative interdisciplinary teamwork of age-friendly teams.15

The final HRO principle, commitment to resilience, includes continuous learning, interdisciplinary team training, and sharing of lessons learned.15 Although IHI offers 2 levels of AFHS recognition, teams are continuously learning to improve and sustain care beyond level 2, Committed to Care Excellence recognition.16

The Table shows the VHA’s AFHS implementation strategies and the HRO principles adapted from the Joint Commission’s High Reliability Health Care Maturity Model and the IHI’s Framework for Safe, Reliable, and Effective Care. The VHA is developing a national dashboard to capture age-friendly processes and health outcome measures that address patient safety and care quality.

Conclusions

AFHS empowers VHA teams to honor veterans’ care preferences and values, supporting their independence, dignity, and quality of life across care settings. The adoption of AFHS brings evidence-based practices to the point of care by addressing common pitfalls in the care of older adults, drawing attention to, and calling for action on inappropriate medication use, physical inactivity, and assessment of the vulnerable brain. The 4Ms also serve as a framework to continuously improve care and cause zero harm, reinforcing HRO pillars and principles across the VHA, and ensuring that older adults reliably receive the evidence-based, high-quality care they deserve.

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the largest integrated health care system in the US, providing care to more than 9 million enrolled veterans at 1298 facilities.1 In February 2019, the VHA identified key action steps to become a high reliability organization (HRO), transforming how employees think about patient safety and care quality.2 The VHA is also working toward becoming the largest age-friendly health system in the US to be recognized by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) for its commitment to providing care guided by the 4Ms (what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility), causing no harm, and aligning care with what matters to older veterans.3 In this article, we describe how the Age-Friendly Health Systems (AFHS) movement supports the culture shift observed in HROs.

Age-Friendly Veteran Care

By 2060, the US population of adults aged ≥ 65 years is projected to increase to about 95 million.3 In the VHA, nearly half of veteran enrollees are aged ≥ 65 years, necessitating evidence-based models of care, such as the 4Ms, to meet their complex care needs.3 Historically, the VHA has been a leader in caring for older adults, recognizing the value of age-friendly care for veterans.4 In 1975, the VHA established the Geriatric Research, Education, and Clinical Centers (GRECCs) to serve as catalysts for developing, implementing, and refining enduring models of geriatric care.4 For 5 decades, GRECCs have driven innovations related to the 4Ms.

The VHA is well positioned to be a leader in the AFHS movement, building on decades of GRECC innovations and geriatric programs that align with the 4Ms and providing specialized geriatric training for health care professionals to expand age-friendly care to new settings and health systems.4 The AFHS movement organizes the 4Ms into a simple framework for frontline staff, and the VHA has recently begun tracking 4Ms care in the electronic health record (EHR) to facilitate evaluation and continuous improvement.

AFHS use the 4Ms as a framework to be implemented in every care setting, from the emergency department to inpatient units, outpatient settings, and postacute and long-term care. By assessing and acting on each M and practicing the 4Ms collectively, all members of the care team work to improve health outcomes and prevent avoidable harm.5

The 4Ms

What matters, is the driver of this person-centered approach. Any member of the care team may initiate a what matters conversation with the older adult to understand their personal values, health goals, and care preferences. When compared with usual care, care aligned with the older adult’s health priorities has been shown to decrease the use of high-risk medications and reduce treatment burden.6 The VHA has adopted Whole Health principles of care and the Patient Priorities Care approach to identify and support what matters to veterans.7,8

Addressing polypharmacy and identifying and deprescribing potentially inappropriate medications are essential in preventing adverse drug events, drug-drug interactions, and medication nonadherence.9 In the VHA, VIONE (Vital, Important, Optional, Not indicated, Every medication has an indication) is a rapidly expanding medication deprescribing program that exemplifies HRO principles.9 VIONE provides medication management that supports shared decision making, reducing risk and improving patient safety and quality of life.9 As of June 2023, > 600,000 unique veterans have benefited from VIONE, with an average of 2.2 medications deprescribed per patient with an annual cost avoidance of > $100 million.10

Assessing and acting on mentation includes preventing, identifying, and managing depression and dementia in outpatient settings and delirium in hospital and long-term care settings.5 There are many tools and clinical reminders available in the EHR so that interdisciplinary teams can document changes to mentation and identify opportunities for continuous improvement.

Closely aligned with mentation is mobility, with evidence suggesting that regular physical activity reduces the risk of falls (preventing associated complications), maintains physical functioning, and lowers the risk of cognitive impairment and depression.5 Ensuring early, frequent, and safe mobility helps patients achieve better health outcomes and prevent injury.5 Mobility programs within the VHA include the STRIDE program for the inpatient setting and Gerofit for outpatient settings.11,12

HRO Principles

An HRO is a complex environment of care that experiences fewer than anticipated accidents or adverse events by (1) establishing trust among leaders and staff by balancing individual accountability with systems thinking; (2) empowering staff to lead continuous process improvements; and (3) creating an environment where employees feel safe to report harm or near misses, focusing on the reasons errors occur.13 The work of AFHS incorporates HRO principles with an emphasis on 3 elements. First, it involves interactive systems and processes needed to support 4Ms care across care settings. Second, AFHS acknowledge the complexity of age-friendly work and deference to the expertise of interdisciplinary team members. Finally, AFHS are committed to resilience by overcoming failures and challenges to implementation and long-term sustainment as a standard of practice.

Case study

The names and details in this case have been modified to protect patient privacy. It is representative of many Community Living Centers (CLCs) involved in AFHS that work to create a safe, person-centered environment for veterans.

In a CLC team workroom, 2 nurses were discussing a long-term care resident. The nurses approached the attending physician and explained that they were worried about Sgt Johnson, who seemed depressed and sometimes combative. They had noticed a change in his behavior when they helped him clean up after an episode of incontinence and were concerned that he would try to get out of bed on his own and fall. The attending physician thanked them for sharing their concerns. Sgt Johnson was a retired Army veteran who had a long, decorated military career. His chronic health conditions had led to muscle weakness, and he fell and broke a hip before this admission. He had an uneventful hip replacement but was showing signs of depression due to his limited mobility, loss of independence, and inability to live at home without additional support.

The attending physician knocked on the door of his room, sat down next to the bed, and asked, “How are you feeling today?” Sgt Johnson tersely replied, “About the same.” The physician asked, “Sgt Johnson, what matters most to you related to your recovery? What is important to you?” Sgt Johnson responded, “Feeling like a man!” The doctor replied, “So what makes you feel ‘not like a man’?” The Sgt replied, “Having to be cleaned up by the nurses and not being able to use the toilet on my own.” The physician surmised that his decline in physical functioning had a connection to his worsening depression and combativeness and said to the Sgt, “Let’s get the team together and work out a plan to get you strong enough to use a bedside commode by yourself. Let’s make that the first goal in our plan to get you back to using the toilet independently. Can you work with us on that?” He smiled and said, “Sir, yes Sir!”

At the weekly interdisciplinary team meeting, the team discussed Sgt Johnson’s wishes and the nurses’ safety concerns. The physician reported to the team what mattered to the veteran. The nurses arranged for a bedside commode and supplies to be placed in his room, encouraged and assisted him, and provided a privacy screen. The physical therapist continued to support his mobility needs, concentrating on transfers, small steps like standing and turning with a walker to get in position to use the bedside commode, and later the bathroom toilet. The psychologist addressed what matters to Sgt Johnson and his mentation, health goals, and coping strategies. The social worker provided support and counseling for the veteran and his family. The pharmacist checked his medications to be sure that none were affecting his gastrointestinal tract and his ability to move safely and do what matters to him. Knowing what mattered to Sgt Johnson was the driver of the interdisciplinary care plan to provide 4Ms care.

The team worked collaboratively with the veteran to develop and set attainable goals around toileting and regaining his dignity. This improved his overall recovery. As Sgt Johnson became more independent, his mood gradually improved and he began to participate in other activities and interact with other residents on the unit, and he did not experience any falls. By addressing the 4Ms, the interdisciplinary team coordinated efforts to provide high-quality, person-centered care. They built trust with the veteran, shared accountability, and followed HRO principles to keep the veteran safe.

Becoming an Age-Friendly HRO

Becoming an HRO is a dynamic, ever-changing process to maintain high standards, improve care quality, and cause no harm. There are 3 pillars and 5 principles that guide an HRO. The pillars are critical areas of focus and include leadership commitment, culture of safety, and continuous process improvement.14 The first of 5 HRO principles is sensitivity to operations. This is defined as an awareness of how processes and systems impact the entire organization, the downstream impact.15 Focusing on the 4Ms helps develop the capability of frontline staff to provide high-quality care for older adults while ensuring that processes are in place to support the work. The 4Ms provide an efficient way to organize interdisciplinary team meetings, provide warm handoffs using Situation-Background-Assessment-Recommendation, and standardize documentation. Involvement in the AFHS movement improves communication, care quality, and patient and staff satisfaction to meet this HRO principle.15

The second HRO principle, reluctance to simplify, ensures that direct care staff and leaders delve further into issues to find solutions.15 AFHS use the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle to put the 4Ms into practice; this cycle helps teams test small increments of change, study their performance, and act to ensure that all 4Ms are being practiced as a set. AFHS teams are encouraged to review at least 3 months of data after implementation of the 4Ms, working to find solutions if there are gaps or issues identified.

The third principle, preoccupation with failure, refers to shared attentiveness—being prepared for the unexpected and learning from mistakes.15 The entire AFHS team shares responsibility for providing 4Ms care, where staff are empowered to report any safety concerns or close calls. The fourth principle of deference to expertise includes listening to staff who have the most knowledge for the task at hand, which aligns with the collaborative interdisciplinary teamwork of age-friendly teams.15

The final HRO principle, commitment to resilience, includes continuous learning, interdisciplinary team training, and sharing of lessons learned.15 Although IHI offers 2 levels of AFHS recognition, teams are continuously learning to improve and sustain care beyond level 2, Committed to Care Excellence recognition.16

The Table shows the VHA’s AFHS implementation strategies and the HRO principles adapted from the Joint Commission’s High Reliability Health Care Maturity Model and the IHI’s Framework for Safe, Reliable, and Effective Care. The VHA is developing a national dashboard to capture age-friendly processes and health outcome measures that address patient safety and care quality.

Conclusions

AFHS empowers VHA teams to honor veterans’ care preferences and values, supporting their independence, dignity, and quality of life across care settings. The adoption of AFHS brings evidence-based practices to the point of care by addressing common pitfalls in the care of older adults, drawing attention to, and calling for action on inappropriate medication use, physical inactivity, and assessment of the vulnerable brain. The 4Ms also serve as a framework to continuously improve care and cause zero harm, reinforcing HRO pillars and principles across the VHA, and ensuring that older adults reliably receive the evidence-based, high-quality care they deserve.

1. Veterans Health Administration. Providing healthcare for veterans. Updated June 20, 2023. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.va.gov/health

2. Veazie S, Peterson K, Bourne D. Evidence brief: implementation of high reliability organization principles. Washington, DC: Evidence Synthesis Program, Health Services Research and Development Service, Office of Research and Development, Department of Veterans Affairs. VA ESP Project #09-199; 2019. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/high-reliability-org.cfm

3. Church K, Munro S, Shaughnessy M, Clancy C. Age-Friendly Health Systems: improving care for older adults in the Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv Res. 2023;58(suppl 1):5-8. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14110

4. Farrell TW, Volden TA, Butler JM, et al. Age-friendly care in the Veterans Health Administration: past, present, and future. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(1):18-25. doi:10.1111/jgs.18070

5. Mate K, Fulmer T, Pelton L, et al. Evidence for the 4Ms: interactions and outcomes across the care continuum. J Aging Health. 2021;33(7-8):469-481. doi:10.1177/0898264321991658

6. Tinetti ME, Naik AD, Dindo L, et al. Association of patient priorities-aligned decision-making with patient outcomes and ambulatory health care burden among older adults with multiple chronic conditions: A nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(12):1688-1697. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4235

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs. What is whole health? Updated: October 31, 2023. November 30, 2023. https://www.va.gov/wholehealth

8. Patient Priorities Care. Updated 2019. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://patientprioritiescare.org

9. Battar S, Watson Dickerson KR, Sedgwick C, Cmelik T. Understanding principles of high reliability organizations through the eyes of VIONE: a clinical program to improve patient safety by deprescribing potentially inappropriate medications and reducing polypharmacy. Fed Pract. 2019;36(12):564-568.

10. VA Diffusion Marketplace. VIONE- medication optimization and polypharmacy reduction initiative. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://marketplace.va.gov/innovations/vione

11. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. STRIDE program to keep hospitalized veterans mobile. Updated November 6, 2018. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.research.va.gov/research_in_action/STRIDE-program-to-keep-hospitalized-Veterans-mobile.cfm

12. US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Geriatrics and Extended Care. Gerofit: a program promoting exercise and health for older veterans. Updated August 2, 2023. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.va.gov/GERIATRICS/pages/gerofit_Home.asp

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development. VHA’s vision for a high reliability organization. Updated August 14, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/forum/summer20/default.cfm?ForumMenu=summer20-1

14. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development. Three HRO evaluation priorities. Updated August 14, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/forum/summer20/default.cfm?ForumMenu=summer20-2

15. Oster CA, Deakins S. Practical application of high-reliability principles in healthcare to optimize quality and safety outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2018;48(1):50-55. doi:10.1097/NNA.0000000000000570

16. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Age-Friendly Health Systems recognitions. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/Recognition.aspx

1. Veterans Health Administration. Providing healthcare for veterans. Updated June 20, 2023. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.va.gov/health

2. Veazie S, Peterson K, Bourne D. Evidence brief: implementation of high reliability organization principles. Washington, DC: Evidence Synthesis Program, Health Services Research and Development Service, Office of Research and Development, Department of Veterans Affairs. VA ESP Project #09-199; 2019. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/high-reliability-org.cfm

3. Church K, Munro S, Shaughnessy M, Clancy C. Age-Friendly Health Systems: improving care for older adults in the Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv Res. 2023;58(suppl 1):5-8. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14110

4. Farrell TW, Volden TA, Butler JM, et al. Age-friendly care in the Veterans Health Administration: past, present, and future. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(1):18-25. doi:10.1111/jgs.18070

5. Mate K, Fulmer T, Pelton L, et al. Evidence for the 4Ms: interactions and outcomes across the care continuum. J Aging Health. 2021;33(7-8):469-481. doi:10.1177/0898264321991658

6. Tinetti ME, Naik AD, Dindo L, et al. Association of patient priorities-aligned decision-making with patient outcomes and ambulatory health care burden among older adults with multiple chronic conditions: A nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(12):1688-1697. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4235

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs. What is whole health? Updated: October 31, 2023. November 30, 2023. https://www.va.gov/wholehealth

8. Patient Priorities Care. Updated 2019. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://patientprioritiescare.org

9. Battar S, Watson Dickerson KR, Sedgwick C, Cmelik T. Understanding principles of high reliability organizations through the eyes of VIONE: a clinical program to improve patient safety by deprescribing potentially inappropriate medications and reducing polypharmacy. Fed Pract. 2019;36(12):564-568.

10. VA Diffusion Marketplace. VIONE- medication optimization and polypharmacy reduction initiative. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://marketplace.va.gov/innovations/vione

11. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development. STRIDE program to keep hospitalized veterans mobile. Updated November 6, 2018. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.research.va.gov/research_in_action/STRIDE-program-to-keep-hospitalized-Veterans-mobile.cfm

12. US Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Geriatrics and Extended Care. Gerofit: a program promoting exercise and health for older veterans. Updated August 2, 2023. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.va.gov/GERIATRICS/pages/gerofit_Home.asp

13. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development. VHA’s vision for a high reliability organization. Updated August 14, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/forum/summer20/default.cfm?ForumMenu=summer20-1

14. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research and Development. Three HRO evaluation priorities. Updated August 14, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/forum/summer20/default.cfm?ForumMenu=summer20-2

15. Oster CA, Deakins S. Practical application of high-reliability principles in healthcare to optimize quality and safety outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2018;48(1):50-55. doi:10.1097/NNA.0000000000000570

16. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Age-Friendly Health Systems recognitions. Accessed November 30, 2023. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/Recognition.aspx

Shifting Culture Toward Age-Friendly Care: Lessons From VHA Early Adopters

Nearly 50% of living US veterans are aged ≥ 65 years compared with 18.3% of the general population.1,2 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the largest integrated health care system in the US, has a vested interest in improving the quality and effectiveness of care for older veterans.3

Health care systems are often unprepared to care for the complex needs of older adults. There are roughly 7300 certified geriatricians practicing in the US, and about 250 new geriatricians are trained each year while the American Geriatrics Society expects > 12,000 geriatricians will be required by 2030.4,5 More geriatricians are needed to serve as the primary health care professionals (HCPs) for older adults.4,6 Health care systems like the VHA must find ways to increase geriatrics skills, knowledge, and practices among their entire health care workforce. A culture shift toward age-friendly care for older adults across care settings and inclusive of all HCPs may help meet this escalating workforce need.7

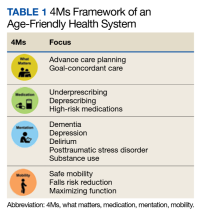

The Age-Friendly Health System (AFHS) is an initiative of the John A. Hartford Foundation and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) in partnership with the American Hospital Association and the Catholic Health Association of the United States.8,9 AFHS uses a what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility (4Ms) framework to ensure reliable, evidence-based care for older adults (Table 1).10,11 In an AFHS, the 4Ms are integrated into every discipline and care setting for older adults.11 The 4Ms neither replace formal training in geriatrics nor create the level of expertise needed for geriatrics teachers, researchers, and program leaders. However, the systematic approach of AFHS to assess and act on each of the 4Ms offers one solution to expand geriatrics skills and knowledge beyond geriatric care settings in all disciplines by engaging each HCP to meet the needs of older adults.12 To act on what matters, HCPs need to align the care plan with what is important to the older adult.

Hospitals and health care systems are encouraged to begin implementing the 4Ms in ≥ 1 care setting.13 Care settings may get started on a do-it-yourself track or by joining an IHI Action Community, which provides a series of webinars to help adopt the 4Ms over 7 months.14 By creating a plan for how each M will be assessed, documented, and acted on, care settings may earn level 1 recognition from the IHI.14 As of July 2023, there are at least 3100 AFHS participants and > 1900 have achieved level 2 recognition, which requires 3 months of clinical data to demonstrate the impact of the 4Ms.13,14

The main cultural shift of the AFHS movement is to focus on what matters to older adults by prioritizing each older adult’s personal health goals and care preferences across all care settings.9,11 Medication addresses age-appropropriate prescribing, making dose adjustments, if needed, and avoiding/deprescribing high-risk medications that may interfere with what matters, mentation, or mobility. The Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults is often used as a guide and includes lists of medications that are potentially harmful for older adults.11 Mentation focuses on preventing, identifying, treating, and managing dementia, depression, and delirium across care settings. Mobility includes assisting or encouraging older adults to move safely every day to maintain functional ability and do what matters.15,16 Each of the 4Ms has the potential to improve health outcomes for older adults, reduce waste from low-quality services, and increase the use of cost-effective services.11,17

In March 2020, the VHA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care (GEC) set the goal for the VHA to be recognized by the IHI as an AFHS.18,19 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities that joined the AFHS movement in 2020 are considered early adopters. We describe early adopter AFHS implementation at Birmingham VA Health Care System (BVAHCS) hospital, geriatrics assessment clinic (GAC), and Home Based Primary Care (HBPC) and at the Atlanta VA Medical Center (AVAMC) HBPC.

Implementing 4Ms Care

The IHI identifies 6 steps in the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle to reliably practice the 4Ms. eAppendix 1 provides a side-by-side comparison of the steps over a 9-month timeline independently taken by BVAHCS and AVAMC to achieve both levels of AFHS recognition.

Step 1: Understand the Current State

In March 2020 the BVAHCS enrolled in the IHI Action Community. Three BVAHCS care settings were identified for the Action Community: the inpatient hospital, GAC (an outpatient clinic), and HBPC. The AVAMC HBPC enrolled in the IHI Action Community in March 2021.

Before joining the AFHS movement, the BVAHCS implemented a hospital-wide delirium standard operating procedure (SOP) whereby every veteran admitted to the 313-bed hospital is screened for delirium risk, with positive screens linked to nursing-led interventions. Nursing leadership supported AFHS due to its recognized value and an exemplary process in place to assess mentation/delirium and background understanding for screening and acting on medication, mobility, and what matters most to the veteran. The BVAHCS GAC, which was led by a single geriatrician, integrated the 4Ms into all geriatrics assessment appointments.

For the BVAHCS HBPC, the 4Ms supported key performance measures, such as fall prevention, patient satisfaction, decreasing medication errors, and identification of cognition and mood disorders. For the AVAMC HBPC, joining the AFHS movement represented an opportunity to improve performance measures, interdisciplinary teamwork, and care coordination for patients. For both HBPC sites, the shift to virtual meeting modalities due to the COVID-19 pandemic enabled HBPC team members to garner support for AFHS and collectively develop a 4Ms plan.

Step 2: Describe 4Ms Care

In March 2020 as guided by the Action Community, BVAHCS created a plan for each of its 3 care settings that described assessment tools, frequency, documentation, and responsible team members. All BVAHCS care settings achieved level 1 recognition in April 2020. Of the approximately 300 veterans served by the AVAMC HBPC, 83% are aged > 65 years. They achieved level 1 recognition in August 2021.

Step 3: Design and Adapt Workflows

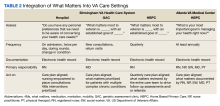

From April to August 2020, BVAHCS implemented its 4Ms plans. In the hospital, a 4Ms overview was provided with education on the delirium SOP at nursing meetings. Updates were requested to the electronic health record (EHR) templates for the GAC to streamline documentation. For the BVAHCS HBPC, 4Ms assessments were added to the EHR quarterly care plan template, which was updated by all team members (Table 2).

From April through June 2021, the AVAMC HBPC formed teams led by 4Ms champions: what matters was led by a nurse care manager, medication by a nurse practitioner and pharmacist, mentation by a social worker, and mobility by a physical therapist. The champions initially focused on a plan for each M, incorporating all 4Ms as a set for optimal effectiveness into their quarterly care plan meeting using what matters to drive the entire care plan.

Step 4: Provide Care

Each of the 4Ms was to be assessed, documented, and acted on for each veteran within a short period, such as a hospitalization or 1 or 2 outpatient visits. BVAHCS implemented 4Ms care in each care setting from August to October 2020. The AVAMC HBPC implemented 4Ms from July to September 2021.

Step 5: Study Performance

The IHI identifies 3 methods for measuring older adults who receive 4Ms care: real-time observation, chart review, or EHR report. For chart review, the IHI recommends using a random sample to calculate the number of patients who received 4Ms in 1 month, which provides evidence of progress toward reliable practice.

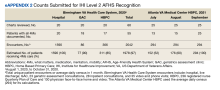

Both facilities used chart review with random sampling. Each setting estimated the number of veterans receiving 4Ms care by multiplying the percentage of sampled charts with documented 4Ms care by unique patient encounters (eAppendix 2).

From August through October 2020, BVAHCS sites reached an estimated 97% of older veterans with complete 4Ms care: hospital, 100%; GAC, 90%; and HBPC, 85%. AVAMC HBPC increased 4Ms care from 52% to 100% between July and September 2021. Both teams demonstrated the feasibility of reliably providing 4Ms care to > 85% of older veterans in these care settings and earned level 2 recognition. Through satisfaction surveys and informal feedback, notable positive changes were evident to veterans, their families, and the VA staff providing 4Ms age-friendly care.

Step 6: Improve and Sustain Care

Each site acknowledged barriers and facilitators for adopting the 4Ms. The COVID-19 pandemic was an ongoing barrier for both sites, with teams transitioning to virtual modalities for telehealth visits and team meetings, and higher staff turnover. However, the greater use of technology facilitated 4Ms adoption by allowing physically distant team members to collaborate.

One of the largest barriers was the lack of 4Ms documentation in the EHR, which could not be implemented in the BVAHCS inpatient hospital due to existing standardized nursing templates. Both sites recognized that 4Ms documentation in the EHR for all care settings would facilitate achieving level 2 recognition and tracking and reporting 4Ms care in the future.

Discussion

The AFHS 4Ms approach offers a method to impart geriatrics knowledge, skills, and practice throughout an entire health care system in a short time. The AFHS framework provides a structured pathway to the often daunting challenge of care for complex, multimorbid, and highly heterogeneous older adults. The 4Ms approach promotes the provision of evidence-based care that is reliable, efficient, patient centered, and avoids unwanted care: worthy goals not only for geriatrics but for all members of a high-reliability organization.

Through the implementation of the 4Ms framework, consistent use of AFHS practices, measurement, and feedback, the staff in each VA care setting reported here reached a level of reliability in which at least 85% of patients had all 4Ms addressed. Notably, adoption was strong and improvements in reliably addressing all 4Ms were observed in both geriatrics (HBPC and outpatient clinics) and nongeriatrics (inpatient medicine) settings. Although one might expect that high-functioning interdisciplinary teams in geriatrics-focused VA settings were routinely addressing all 4Ms for most of their patients, our experience was consistent with prior teams indicating that this is often not the case. Although many of these teams were addressing some of the 4Ms in their usual practice, the 4Ms framework facilitated addressing all 4Ms as a set with input from all team members. Most importantly, it fostered a culture of asking the older adult what matters most and documenting, sharing, and aligning this with the care plan. Within 6 months, all VA care settings achieved level 1 recognition, and within 9 months, all achieved level 2 recognition.

Lessons Learned

Key lessons learned include the importance of identifying, preparing, and supporting a champion to lead this effort; garnering facility and system leadership support at the outset; and integration with the EHR for reliable and efficient data capture, reporting, and feedback. Preparing and supporting champions was achieved through national and individual calls and peer support. Guidance was provided on garnering leadership support, including local needs assessment and data analysis, meeting with leadership to first understand their key challenges and priorities and provide information on the AFHS movement, requesting a follow-up meeting to discuss local needs and data, and exploring how an AFHS might help address one or more of their priorities.

In September 2022, an AFHS 4Ms note template was introduced into the EHR for all VA sites for data capture and reporting, to standardize and facilitate documentation across all age-friendly VA sites, and decrease the reporting burden for staff. This effort is critically important: The ability to document, track, and analyze 4Ms measures, provide feedback, and synergize efforts across systems is vital to design studies to determine whether the AFHS 4Ms approach to care achieves substantive improvements in patient care across settings.

Limitations

Limitations of this analysis include the small sample of care settings, which did not include a skilled nursing or long-term care facility, nor general primary care. Although the short timeframe assessed did not allow us to report on the anticipated clinical outcomes of 4Ms care, it does set up a foundation for evaluation of the 4Ms and EHR integration and dashboard development.

Conclusions

The VHA provides a comprehensive spectrum of geriatrics services and innovative models of care that often serve as exemplars to other health care systems. Implementing the AFHS framework to assess and act on the 4Ms provides a structure for confronting the HCP shortage with geriatrics expertise by infusing geriatrics knowledge, skills, and practices throughout all care settings and disciplines. Enhancing patient-centered care to older veterans through AFHS implementation exemplifies the VHA as a learning health care system.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Veterans Health Administration Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care and the clinical staff from the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Healthcare System and the Birmingham Veterans Affairs Health Care System for assisting us in this work.

1. US Census Bureau. Older Americans month: May 2023. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/stories/older-americans-month.html

2. Vespa J. Aging veterans: America’s veteran population in later life. July 2023. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2023/acs/acs-54.pdf

3. O’Hanlon C, Huang C, Sloss E, et al. Comparing VA and non-VA quality of care: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(1):105-121. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3775-2

4. Fulmer T, Reuben DB, Auerbach J, Fick DM, Galambos C, Johnson KS. Actualizing better health and health care for older adults: commentary describes six vital directions to improve the care and quality of life for all older Americans. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(2):219-225. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01470

5. ChenMed. The physician shortage in geriatrics. March 18, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.chenmed.com/blog/physician-shortage-geriatrics

6. American Geriatrics Society. Projected future need for geriatricians. Updated May 2016. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.americangeriatrics.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/Projected-Future-Need-for-Geriatricians.pdf 7. Carmody J, Black K, Bonner A, Wolfe M, Fulmer T. Advancing gerontological nursing at the intersection of age-friendly communities, health systems, and public health. J Gerontol Nurs. 2021;47(3):13-17. doi:10.3928/00989134-20210125-01

8. Lesser S, Zakharkin S, Louie C, Escobedo MR, Whyte J, Fulmer T. Clinician knowledge and behaviors related to the 4Ms framework of Age‐Friendly Health Systems. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(3):789-800. doi:10.1111/jgs.17571

9. Edelman LS, Drost J, Moone RP, et al. Applying the Age-Friendly Health System framework to long term care settings. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25(2):141-145. doi:10.1007/s12603-020-1558-2

10. Emery-Tiburcio EE, Mack L, Zonsius MC, Carbonell E, Newman M. The 4Ms of an Age-Friendly Health System: an evidence-based framework to ensure older adults receive the highest quality care. Home Healthc Now. 2022;40(5):252-257. doi:10.1097/NHH.0000000000001113

11. Mate K, Fulmer T, Pelton L, et al. Evidence for the 4Ms: interactions and outcomes across the care continuum. J Aging Health. 2021;33(7-8):469-481. doi:10.1177/0898264321991658

12. Mate KS, Berman A, Laderman M, Kabcenell A, Fulmer T. Creating age-friendly health systems – a vision for better care of older adults. Healthc (Amst). 2018;6(1):4-6. doi:10.1016/j.hjdsi.2017.05.005

13. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. What is an Age-Friendly Health System? Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/default.aspx

14. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Health systems recognized by IHI. Updated September 2023. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/recognized-systems.aspx

15. Burke RE, Ashcraft LE, Manges K, et al. What matters when it comes to measuring Age‐Friendly Health System transformation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(10):2775-2785. doi:10.1111/jgs.18002

16. Wang J, Shen JY, Conwell Y, et al. How “age-friendly” are deprescribing interventions? A scoping review of deprescribing trials. Health Serv Res. 202;58(suppl 1):123-138. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14083

17. Pohnert AM, Schiltz NK, Pino L, et al. Achievement of age‐friendly health systems committed to care excellence designation in a convenient care health care system. Health Serv Res. 2023;58 (suppl 1):89-99. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14071

18. Church K, Munro S, Shaughnessy M, Clancy C. Age-Friendly Health Systems: improving care for older adults in the Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv Res. 2022;58(suppl 1):5-8. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14110

19. Farrell TW, Volden TA, Butler JM, et al. Age‐friendly care in the Veterans Health Administration: past, present, and future. J Am Geriatr Soc. doi:10.1111/jgs.18070

Nearly 50% of living US veterans are aged ≥ 65 years compared with 18.3% of the general population.1,2 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the largest integrated health care system in the US, has a vested interest in improving the quality and effectiveness of care for older veterans.3

Health care systems are often unprepared to care for the complex needs of older adults. There are roughly 7300 certified geriatricians practicing in the US, and about 250 new geriatricians are trained each year while the American Geriatrics Society expects > 12,000 geriatricians will be required by 2030.4,5 More geriatricians are needed to serve as the primary health care professionals (HCPs) for older adults.4,6 Health care systems like the VHA must find ways to increase geriatrics skills, knowledge, and practices among their entire health care workforce. A culture shift toward age-friendly care for older adults across care settings and inclusive of all HCPs may help meet this escalating workforce need.7

The Age-Friendly Health System (AFHS) is an initiative of the John A. Hartford Foundation and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) in partnership with the American Hospital Association and the Catholic Health Association of the United States.8,9 AFHS uses a what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility (4Ms) framework to ensure reliable, evidence-based care for older adults (Table 1).10,11 In an AFHS, the 4Ms are integrated into every discipline and care setting for older adults.11 The 4Ms neither replace formal training in geriatrics nor create the level of expertise needed for geriatrics teachers, researchers, and program leaders. However, the systematic approach of AFHS to assess and act on each of the 4Ms offers one solution to expand geriatrics skills and knowledge beyond geriatric care settings in all disciplines by engaging each HCP to meet the needs of older adults.12 To act on what matters, HCPs need to align the care plan with what is important to the older adult.

Hospitals and health care systems are encouraged to begin implementing the 4Ms in ≥ 1 care setting.13 Care settings may get started on a do-it-yourself track or by joining an IHI Action Community, which provides a series of webinars to help adopt the 4Ms over 7 months.14 By creating a plan for how each M will be assessed, documented, and acted on, care settings may earn level 1 recognition from the IHI.14 As of July 2023, there are at least 3100 AFHS participants and > 1900 have achieved level 2 recognition, which requires 3 months of clinical data to demonstrate the impact of the 4Ms.13,14

The main cultural shift of the AFHS movement is to focus on what matters to older adults by prioritizing each older adult’s personal health goals and care preferences across all care settings.9,11 Medication addresses age-appropropriate prescribing, making dose adjustments, if needed, and avoiding/deprescribing high-risk medications that may interfere with what matters, mentation, or mobility. The Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults is often used as a guide and includes lists of medications that are potentially harmful for older adults.11 Mentation focuses on preventing, identifying, treating, and managing dementia, depression, and delirium across care settings. Mobility includes assisting or encouraging older adults to move safely every day to maintain functional ability and do what matters.15,16 Each of the 4Ms has the potential to improve health outcomes for older adults, reduce waste from low-quality services, and increase the use of cost-effective services.11,17

In March 2020, the VHA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care (GEC) set the goal for the VHA to be recognized by the IHI as an AFHS.18,19 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities that joined the AFHS movement in 2020 are considered early adopters. We describe early adopter AFHS implementation at Birmingham VA Health Care System (BVAHCS) hospital, geriatrics assessment clinic (GAC), and Home Based Primary Care (HBPC) and at the Atlanta VA Medical Center (AVAMC) HBPC.

Implementing 4Ms Care

The IHI identifies 6 steps in the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle to reliably practice the 4Ms. eAppendix 1 provides a side-by-side comparison of the steps over a 9-month timeline independently taken by BVAHCS and AVAMC to achieve both levels of AFHS recognition.

Step 1: Understand the Current State

In March 2020 the BVAHCS enrolled in the IHI Action Community. Three BVAHCS care settings were identified for the Action Community: the inpatient hospital, GAC (an outpatient clinic), and HBPC. The AVAMC HBPC enrolled in the IHI Action Community in March 2021.

Before joining the AFHS movement, the BVAHCS implemented a hospital-wide delirium standard operating procedure (SOP) whereby every veteran admitted to the 313-bed hospital is screened for delirium risk, with positive screens linked to nursing-led interventions. Nursing leadership supported AFHS due to its recognized value and an exemplary process in place to assess mentation/delirium and background understanding for screening and acting on medication, mobility, and what matters most to the veteran. The BVAHCS GAC, which was led by a single geriatrician, integrated the 4Ms into all geriatrics assessment appointments.

For the BVAHCS HBPC, the 4Ms supported key performance measures, such as fall prevention, patient satisfaction, decreasing medication errors, and identification of cognition and mood disorders. For the AVAMC HBPC, joining the AFHS movement represented an opportunity to improve performance measures, interdisciplinary teamwork, and care coordination for patients. For both HBPC sites, the shift to virtual meeting modalities due to the COVID-19 pandemic enabled HBPC team members to garner support for AFHS and collectively develop a 4Ms plan.

Step 2: Describe 4Ms Care

In March 2020 as guided by the Action Community, BVAHCS created a plan for each of its 3 care settings that described assessment tools, frequency, documentation, and responsible team members. All BVAHCS care settings achieved level 1 recognition in April 2020. Of the approximately 300 veterans served by the AVAMC HBPC, 83% are aged > 65 years. They achieved level 1 recognition in August 2021.

Step 3: Design and Adapt Workflows

From April to August 2020, BVAHCS implemented its 4Ms plans. In the hospital, a 4Ms overview was provided with education on the delirium SOP at nursing meetings. Updates were requested to the electronic health record (EHR) templates for the GAC to streamline documentation. For the BVAHCS HBPC, 4Ms assessments were added to the EHR quarterly care plan template, which was updated by all team members (Table 2).

From April through June 2021, the AVAMC HBPC formed teams led by 4Ms champions: what matters was led by a nurse care manager, medication by a nurse practitioner and pharmacist, mentation by a social worker, and mobility by a physical therapist. The champions initially focused on a plan for each M, incorporating all 4Ms as a set for optimal effectiveness into their quarterly care plan meeting using what matters to drive the entire care plan.

Step 4: Provide Care

Each of the 4Ms was to be assessed, documented, and acted on for each veteran within a short period, such as a hospitalization or 1 or 2 outpatient visits. BVAHCS implemented 4Ms care in each care setting from August to October 2020. The AVAMC HBPC implemented 4Ms from July to September 2021.

Step 5: Study Performance

The IHI identifies 3 methods for measuring older adults who receive 4Ms care: real-time observation, chart review, or EHR report. For chart review, the IHI recommends using a random sample to calculate the number of patients who received 4Ms in 1 month, which provides evidence of progress toward reliable practice.

Both facilities used chart review with random sampling. Each setting estimated the number of veterans receiving 4Ms care by multiplying the percentage of sampled charts with documented 4Ms care by unique patient encounters (eAppendix 2).

From August through October 2020, BVAHCS sites reached an estimated 97% of older veterans with complete 4Ms care: hospital, 100%; GAC, 90%; and HBPC, 85%. AVAMC HBPC increased 4Ms care from 52% to 100% between July and September 2021. Both teams demonstrated the feasibility of reliably providing 4Ms care to > 85% of older veterans in these care settings and earned level 2 recognition. Through satisfaction surveys and informal feedback, notable positive changes were evident to veterans, their families, and the VA staff providing 4Ms age-friendly care.

Step 6: Improve and Sustain Care

Each site acknowledged barriers and facilitators for adopting the 4Ms. The COVID-19 pandemic was an ongoing barrier for both sites, with teams transitioning to virtual modalities for telehealth visits and team meetings, and higher staff turnover. However, the greater use of technology facilitated 4Ms adoption by allowing physically distant team members to collaborate.

One of the largest barriers was the lack of 4Ms documentation in the EHR, which could not be implemented in the BVAHCS inpatient hospital due to existing standardized nursing templates. Both sites recognized that 4Ms documentation in the EHR for all care settings would facilitate achieving level 2 recognition and tracking and reporting 4Ms care in the future.

Discussion

The AFHS 4Ms approach offers a method to impart geriatrics knowledge, skills, and practice throughout an entire health care system in a short time. The AFHS framework provides a structured pathway to the often daunting challenge of care for complex, multimorbid, and highly heterogeneous older adults. The 4Ms approach promotes the provision of evidence-based care that is reliable, efficient, patient centered, and avoids unwanted care: worthy goals not only for geriatrics but for all members of a high-reliability organization.

Through the implementation of the 4Ms framework, consistent use of AFHS practices, measurement, and feedback, the staff in each VA care setting reported here reached a level of reliability in which at least 85% of patients had all 4Ms addressed. Notably, adoption was strong and improvements in reliably addressing all 4Ms were observed in both geriatrics (HBPC and outpatient clinics) and nongeriatrics (inpatient medicine) settings. Although one might expect that high-functioning interdisciplinary teams in geriatrics-focused VA settings were routinely addressing all 4Ms for most of their patients, our experience was consistent with prior teams indicating that this is often not the case. Although many of these teams were addressing some of the 4Ms in their usual practice, the 4Ms framework facilitated addressing all 4Ms as a set with input from all team members. Most importantly, it fostered a culture of asking the older adult what matters most and documenting, sharing, and aligning this with the care plan. Within 6 months, all VA care settings achieved level 1 recognition, and within 9 months, all achieved level 2 recognition.

Lessons Learned

Key lessons learned include the importance of identifying, preparing, and supporting a champion to lead this effort; garnering facility and system leadership support at the outset; and integration with the EHR for reliable and efficient data capture, reporting, and feedback. Preparing and supporting champions was achieved through national and individual calls and peer support. Guidance was provided on garnering leadership support, including local needs assessment and data analysis, meeting with leadership to first understand their key challenges and priorities and provide information on the AFHS movement, requesting a follow-up meeting to discuss local needs and data, and exploring how an AFHS might help address one or more of their priorities.

In September 2022, an AFHS 4Ms note template was introduced into the EHR for all VA sites for data capture and reporting, to standardize and facilitate documentation across all age-friendly VA sites, and decrease the reporting burden for staff. This effort is critically important: The ability to document, track, and analyze 4Ms measures, provide feedback, and synergize efforts across systems is vital to design studies to determine whether the AFHS 4Ms approach to care achieves substantive improvements in patient care across settings.

Limitations

Limitations of this analysis include the small sample of care settings, which did not include a skilled nursing or long-term care facility, nor general primary care. Although the short timeframe assessed did not allow us to report on the anticipated clinical outcomes of 4Ms care, it does set up a foundation for evaluation of the 4Ms and EHR integration and dashboard development.

Conclusions