User login

Shifting Culture Toward Age-Friendly Care: Lessons From VHA Early Adopters

Nearly 50% of living US veterans are aged ≥ 65 years compared with 18.3% of the general population.1,2 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the largest integrated health care system in the US, has a vested interest in improving the quality and effectiveness of care for older veterans.3

Health care systems are often unprepared to care for the complex needs of older adults. There are roughly 7300 certified geriatricians practicing in the US, and about 250 new geriatricians are trained each year while the American Geriatrics Society expects > 12,000 geriatricians will be required by 2030.4,5 More geriatricians are needed to serve as the primary health care professionals (HCPs) for older adults.4,6 Health care systems like the VHA must find ways to increase geriatrics skills, knowledge, and practices among their entire health care workforce. A culture shift toward age-friendly care for older adults across care settings and inclusive of all HCPs may help meet this escalating workforce need.7

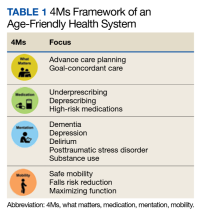

The Age-Friendly Health System (AFHS) is an initiative of the John A. Hartford Foundation and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) in partnership with the American Hospital Association and the Catholic Health Association of the United States.8,9 AFHS uses a what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility (4Ms) framework to ensure reliable, evidence-based care for older adults (Table 1).10,11 In an AFHS, the 4Ms are integrated into every discipline and care setting for older adults.11 The 4Ms neither replace formal training in geriatrics nor create the level of expertise needed for geriatrics teachers, researchers, and program leaders. However, the systematic approach of AFHS to assess and act on each of the 4Ms offers one solution to expand geriatrics skills and knowledge beyond geriatric care settings in all disciplines by engaging each HCP to meet the needs of older adults.12 To act on what matters, HCPs need to align the care plan with what is important to the older adult.

Hospitals and health care systems are encouraged to begin implementing the 4Ms in ≥ 1 care setting.13 Care settings may get started on a do-it-yourself track or by joining an IHI Action Community, which provides a series of webinars to help adopt the 4Ms over 7 months.14 By creating a plan for how each M will be assessed, documented, and acted on, care settings may earn level 1 recognition from the IHI.14 As of July 2023, there are at least 3100 AFHS participants and > 1900 have achieved level 2 recognition, which requires 3 months of clinical data to demonstrate the impact of the 4Ms.13,14

The main cultural shift of the AFHS movement is to focus on what matters to older adults by prioritizing each older adult’s personal health goals and care preferences across all care settings.9,11 Medication addresses age-appropropriate prescribing, making dose adjustments, if needed, and avoiding/deprescribing high-risk medications that may interfere with what matters, mentation, or mobility. The Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults is often used as a guide and includes lists of medications that are potentially harmful for older adults.11 Mentation focuses on preventing, identifying, treating, and managing dementia, depression, and delirium across care settings. Mobility includes assisting or encouraging older adults to move safely every day to maintain functional ability and do what matters.15,16 Each of the 4Ms has the potential to improve health outcomes for older adults, reduce waste from low-quality services, and increase the use of cost-effective services.11,17

In March 2020, the VHA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care (GEC) set the goal for the VHA to be recognized by the IHI as an AFHS.18,19 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities that joined the AFHS movement in 2020 are considered early adopters. We describe early adopter AFHS implementation at Birmingham VA Health Care System (BVAHCS) hospital, geriatrics assessment clinic (GAC), and Home Based Primary Care (HBPC) and at the Atlanta VA Medical Center (AVAMC) HBPC.

Implementing 4Ms Care

The IHI identifies 6 steps in the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle to reliably practice the 4Ms. eAppendix 1 provides a side-by-side comparison of the steps over a 9-month timeline independently taken by BVAHCS and AVAMC to achieve both levels of AFHS recognition.

Step 1: Understand the Current State

In March 2020 the BVAHCS enrolled in the IHI Action Community. Three BVAHCS care settings were identified for the Action Community: the inpatient hospital, GAC (an outpatient clinic), and HBPC. The AVAMC HBPC enrolled in the IHI Action Community in March 2021.

Before joining the AFHS movement, the BVAHCS implemented a hospital-wide delirium standard operating procedure (SOP) whereby every veteran admitted to the 313-bed hospital is screened for delirium risk, with positive screens linked to nursing-led interventions. Nursing leadership supported AFHS due to its recognized value and an exemplary process in place to assess mentation/delirium and background understanding for screening and acting on medication, mobility, and what matters most to the veteran. The BVAHCS GAC, which was led by a single geriatrician, integrated the 4Ms into all geriatrics assessment appointments.

For the BVAHCS HBPC, the 4Ms supported key performance measures, such as fall prevention, patient satisfaction, decreasing medication errors, and identification of cognition and mood disorders. For the AVAMC HBPC, joining the AFHS movement represented an opportunity to improve performance measures, interdisciplinary teamwork, and care coordination for patients. For both HBPC sites, the shift to virtual meeting modalities due to the COVID-19 pandemic enabled HBPC team members to garner support for AFHS and collectively develop a 4Ms plan.

Step 2: Describe 4Ms Care

In March 2020 as guided by the Action Community, BVAHCS created a plan for each of its 3 care settings that described assessment tools, frequency, documentation, and responsible team members. All BVAHCS care settings achieved level 1 recognition in April 2020. Of the approximately 300 veterans served by the AVAMC HBPC, 83% are aged > 65 years. They achieved level 1 recognition in August 2021.

Step 3: Design and Adapt Workflows

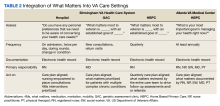

From April to August 2020, BVAHCS implemented its 4Ms plans. In the hospital, a 4Ms overview was provided with education on the delirium SOP at nursing meetings. Updates were requested to the electronic health record (EHR) templates for the GAC to streamline documentation. For the BVAHCS HBPC, 4Ms assessments were added to the EHR quarterly care plan template, which was updated by all team members (Table 2).

From April through June 2021, the AVAMC HBPC formed teams led by 4Ms champions: what matters was led by a nurse care manager, medication by a nurse practitioner and pharmacist, mentation by a social worker, and mobility by a physical therapist. The champions initially focused on a plan for each M, incorporating all 4Ms as a set for optimal effectiveness into their quarterly care plan meeting using what matters to drive the entire care plan.

Step 4: Provide Care

Each of the 4Ms was to be assessed, documented, and acted on for each veteran within a short period, such as a hospitalization or 1 or 2 outpatient visits. BVAHCS implemented 4Ms care in each care setting from August to October 2020. The AVAMC HBPC implemented 4Ms from July to September 2021.

Step 5: Study Performance

The IHI identifies 3 methods for measuring older adults who receive 4Ms care: real-time observation, chart review, or EHR report. For chart review, the IHI recommends using a random sample to calculate the number of patients who received 4Ms in 1 month, which provides evidence of progress toward reliable practice.

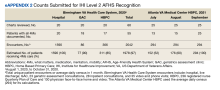

Both facilities used chart review with random sampling. Each setting estimated the number of veterans receiving 4Ms care by multiplying the percentage of sampled charts with documented 4Ms care by unique patient encounters (eAppendix 2).

From August through October 2020, BVAHCS sites reached an estimated 97% of older veterans with complete 4Ms care: hospital, 100%; GAC, 90%; and HBPC, 85%. AVAMC HBPC increased 4Ms care from 52% to 100% between July and September 2021. Both teams demonstrated the feasibility of reliably providing 4Ms care to > 85% of older veterans in these care settings and earned level 2 recognition. Through satisfaction surveys and informal feedback, notable positive changes were evident to veterans, their families, and the VA staff providing 4Ms age-friendly care.

Step 6: Improve and Sustain Care

Each site acknowledged barriers and facilitators for adopting the 4Ms. The COVID-19 pandemic was an ongoing barrier for both sites, with teams transitioning to virtual modalities for telehealth visits and team meetings, and higher staff turnover. However, the greater use of technology facilitated 4Ms adoption by allowing physically distant team members to collaborate.

One of the largest barriers was the lack of 4Ms documentation in the EHR, which could not be implemented in the BVAHCS inpatient hospital due to existing standardized nursing templates. Both sites recognized that 4Ms documentation in the EHR for all care settings would facilitate achieving level 2 recognition and tracking and reporting 4Ms care in the future.

Discussion

The AFHS 4Ms approach offers a method to impart geriatrics knowledge, skills, and practice throughout an entire health care system in a short time. The AFHS framework provides a structured pathway to the often daunting challenge of care for complex, multimorbid, and highly heterogeneous older adults. The 4Ms approach promotes the provision of evidence-based care that is reliable, efficient, patient centered, and avoids unwanted care: worthy goals not only for geriatrics but for all members of a high-reliability organization.

Through the implementation of the 4Ms framework, consistent use of AFHS practices, measurement, and feedback, the staff in each VA care setting reported here reached a level of reliability in which at least 85% of patients had all 4Ms addressed. Notably, adoption was strong and improvements in reliably addressing all 4Ms were observed in both geriatrics (HBPC and outpatient clinics) and nongeriatrics (inpatient medicine) settings. Although one might expect that high-functioning interdisciplinary teams in geriatrics-focused VA settings were routinely addressing all 4Ms for most of their patients, our experience was consistent with prior teams indicating that this is often not the case. Although many of these teams were addressing some of the 4Ms in their usual practice, the 4Ms framework facilitated addressing all 4Ms as a set with input from all team members. Most importantly, it fostered a culture of asking the older adult what matters most and documenting, sharing, and aligning this with the care plan. Within 6 months, all VA care settings achieved level 1 recognition, and within 9 months, all achieved level 2 recognition.

Lessons Learned

Key lessons learned include the importance of identifying, preparing, and supporting a champion to lead this effort; garnering facility and system leadership support at the outset; and integration with the EHR for reliable and efficient data capture, reporting, and feedback. Preparing and supporting champions was achieved through national and individual calls and peer support. Guidance was provided on garnering leadership support, including local needs assessment and data analysis, meeting with leadership to first understand their key challenges and priorities and provide information on the AFHS movement, requesting a follow-up meeting to discuss local needs and data, and exploring how an AFHS might help address one or more of their priorities.

In September 2022, an AFHS 4Ms note template was introduced into the EHR for all VA sites for data capture and reporting, to standardize and facilitate documentation across all age-friendly VA sites, and decrease the reporting burden for staff. This effort is critically important: The ability to document, track, and analyze 4Ms measures, provide feedback, and synergize efforts across systems is vital to design studies to determine whether the AFHS 4Ms approach to care achieves substantive improvements in patient care across settings.

Limitations

Limitations of this analysis include the small sample of care settings, which did not include a skilled nursing or long-term care facility, nor general primary care. Although the short timeframe assessed did not allow us to report on the anticipated clinical outcomes of 4Ms care, it does set up a foundation for evaluation of the 4Ms and EHR integration and dashboard development.

Conclusions

The VHA provides a comprehensive spectrum of geriatrics services and innovative models of care that often serve as exemplars to other health care systems. Implementing the AFHS framework to assess and act on the 4Ms provides a structure for confronting the HCP shortage with geriatrics expertise by infusing geriatrics knowledge, skills, and practices throughout all care settings and disciplines. Enhancing patient-centered care to older veterans through AFHS implementation exemplifies the VHA as a learning health care system.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Veterans Health Administration Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care and the clinical staff from the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Healthcare System and the Birmingham Veterans Affairs Health Care System for assisting us in this work.

1. US Census Bureau. Older Americans month: May 2023. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/stories/older-americans-month.html

2. Vespa J. Aging veterans: America’s veteran population in later life. July 2023. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2023/acs/acs-54.pdf

3. O’Hanlon C, Huang C, Sloss E, et al. Comparing VA and non-VA quality of care: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(1):105-121. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3775-2

4. Fulmer T, Reuben DB, Auerbach J, Fick DM, Galambos C, Johnson KS. Actualizing better health and health care for older adults: commentary describes six vital directions to improve the care and quality of life for all older Americans. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(2):219-225. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01470

5. ChenMed. The physician shortage in geriatrics. March 18, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.chenmed.com/blog/physician-shortage-geriatrics

6. American Geriatrics Society. Projected future need for geriatricians. Updated May 2016. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.americangeriatrics.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/Projected-Future-Need-for-Geriatricians.pdf 7. Carmody J, Black K, Bonner A, Wolfe M, Fulmer T. Advancing gerontological nursing at the intersection of age-friendly communities, health systems, and public health. J Gerontol Nurs. 2021;47(3):13-17. doi:10.3928/00989134-20210125-01

8. Lesser S, Zakharkin S, Louie C, Escobedo MR, Whyte J, Fulmer T. Clinician knowledge and behaviors related to the 4Ms framework of Age‐Friendly Health Systems. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(3):789-800. doi:10.1111/jgs.17571

9. Edelman LS, Drost J, Moone RP, et al. Applying the Age-Friendly Health System framework to long term care settings. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25(2):141-145. doi:10.1007/s12603-020-1558-2

10. Emery-Tiburcio EE, Mack L, Zonsius MC, Carbonell E, Newman M. The 4Ms of an Age-Friendly Health System: an evidence-based framework to ensure older adults receive the highest quality care. Home Healthc Now. 2022;40(5):252-257. doi:10.1097/NHH.0000000000001113

11. Mate K, Fulmer T, Pelton L, et al. Evidence for the 4Ms: interactions and outcomes across the care continuum. J Aging Health. 2021;33(7-8):469-481. doi:10.1177/0898264321991658

12. Mate KS, Berman A, Laderman M, Kabcenell A, Fulmer T. Creating age-friendly health systems – a vision for better care of older adults. Healthc (Amst). 2018;6(1):4-6. doi:10.1016/j.hjdsi.2017.05.005

13. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. What is an Age-Friendly Health System? Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/default.aspx

14. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Health systems recognized by IHI. Updated September 2023. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/recognized-systems.aspx

15. Burke RE, Ashcraft LE, Manges K, et al. What matters when it comes to measuring Age‐Friendly Health System transformation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(10):2775-2785. doi:10.1111/jgs.18002

16. Wang J, Shen JY, Conwell Y, et al. How “age-friendly” are deprescribing interventions? A scoping review of deprescribing trials. Health Serv Res. 202;58(suppl 1):123-138. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14083

17. Pohnert AM, Schiltz NK, Pino L, et al. Achievement of age‐friendly health systems committed to care excellence designation in a convenient care health care system. Health Serv Res. 2023;58 (suppl 1):89-99. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14071

18. Church K, Munro S, Shaughnessy M, Clancy C. Age-Friendly Health Systems: improving care for older adults in the Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv Res. 2022;58(suppl 1):5-8. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14110

19. Farrell TW, Volden TA, Butler JM, et al. Age‐friendly care in the Veterans Health Administration: past, present, and future. J Am Geriatr Soc. doi:10.1111/jgs.18070

Nearly 50% of living US veterans are aged ≥ 65 years compared with 18.3% of the general population.1,2 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the largest integrated health care system in the US, has a vested interest in improving the quality and effectiveness of care for older veterans.3

Health care systems are often unprepared to care for the complex needs of older adults. There are roughly 7300 certified geriatricians practicing in the US, and about 250 new geriatricians are trained each year while the American Geriatrics Society expects > 12,000 geriatricians will be required by 2030.4,5 More geriatricians are needed to serve as the primary health care professionals (HCPs) for older adults.4,6 Health care systems like the VHA must find ways to increase geriatrics skills, knowledge, and practices among their entire health care workforce. A culture shift toward age-friendly care for older adults across care settings and inclusive of all HCPs may help meet this escalating workforce need.7

The Age-Friendly Health System (AFHS) is an initiative of the John A. Hartford Foundation and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) in partnership with the American Hospital Association and the Catholic Health Association of the United States.8,9 AFHS uses a what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility (4Ms) framework to ensure reliable, evidence-based care for older adults (Table 1).10,11 In an AFHS, the 4Ms are integrated into every discipline and care setting for older adults.11 The 4Ms neither replace formal training in geriatrics nor create the level of expertise needed for geriatrics teachers, researchers, and program leaders. However, the systematic approach of AFHS to assess and act on each of the 4Ms offers one solution to expand geriatrics skills and knowledge beyond geriatric care settings in all disciplines by engaging each HCP to meet the needs of older adults.12 To act on what matters, HCPs need to align the care plan with what is important to the older adult.

Hospitals and health care systems are encouraged to begin implementing the 4Ms in ≥ 1 care setting.13 Care settings may get started on a do-it-yourself track or by joining an IHI Action Community, which provides a series of webinars to help adopt the 4Ms over 7 months.14 By creating a plan for how each M will be assessed, documented, and acted on, care settings may earn level 1 recognition from the IHI.14 As of July 2023, there are at least 3100 AFHS participants and > 1900 have achieved level 2 recognition, which requires 3 months of clinical data to demonstrate the impact of the 4Ms.13,14

The main cultural shift of the AFHS movement is to focus on what matters to older adults by prioritizing each older adult’s personal health goals and care preferences across all care settings.9,11 Medication addresses age-appropropriate prescribing, making dose adjustments, if needed, and avoiding/deprescribing high-risk medications that may interfere with what matters, mentation, or mobility. The Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults is often used as a guide and includes lists of medications that are potentially harmful for older adults.11 Mentation focuses on preventing, identifying, treating, and managing dementia, depression, and delirium across care settings. Mobility includes assisting or encouraging older adults to move safely every day to maintain functional ability and do what matters.15,16 Each of the 4Ms has the potential to improve health outcomes for older adults, reduce waste from low-quality services, and increase the use of cost-effective services.11,17

In March 2020, the VHA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care (GEC) set the goal for the VHA to be recognized by the IHI as an AFHS.18,19 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities that joined the AFHS movement in 2020 are considered early adopters. We describe early adopter AFHS implementation at Birmingham VA Health Care System (BVAHCS) hospital, geriatrics assessment clinic (GAC), and Home Based Primary Care (HBPC) and at the Atlanta VA Medical Center (AVAMC) HBPC.

Implementing 4Ms Care

The IHI identifies 6 steps in the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle to reliably practice the 4Ms. eAppendix 1 provides a side-by-side comparison of the steps over a 9-month timeline independently taken by BVAHCS and AVAMC to achieve both levels of AFHS recognition.

Step 1: Understand the Current State

In March 2020 the BVAHCS enrolled in the IHI Action Community. Three BVAHCS care settings were identified for the Action Community: the inpatient hospital, GAC (an outpatient clinic), and HBPC. The AVAMC HBPC enrolled in the IHI Action Community in March 2021.

Before joining the AFHS movement, the BVAHCS implemented a hospital-wide delirium standard operating procedure (SOP) whereby every veteran admitted to the 313-bed hospital is screened for delirium risk, with positive screens linked to nursing-led interventions. Nursing leadership supported AFHS due to its recognized value and an exemplary process in place to assess mentation/delirium and background understanding for screening and acting on medication, mobility, and what matters most to the veteran. The BVAHCS GAC, which was led by a single geriatrician, integrated the 4Ms into all geriatrics assessment appointments.

For the BVAHCS HBPC, the 4Ms supported key performance measures, such as fall prevention, patient satisfaction, decreasing medication errors, and identification of cognition and mood disorders. For the AVAMC HBPC, joining the AFHS movement represented an opportunity to improve performance measures, interdisciplinary teamwork, and care coordination for patients. For both HBPC sites, the shift to virtual meeting modalities due to the COVID-19 pandemic enabled HBPC team members to garner support for AFHS and collectively develop a 4Ms plan.

Step 2: Describe 4Ms Care

In March 2020 as guided by the Action Community, BVAHCS created a plan for each of its 3 care settings that described assessment tools, frequency, documentation, and responsible team members. All BVAHCS care settings achieved level 1 recognition in April 2020. Of the approximately 300 veterans served by the AVAMC HBPC, 83% are aged > 65 years. They achieved level 1 recognition in August 2021.

Step 3: Design and Adapt Workflows

From April to August 2020, BVAHCS implemented its 4Ms plans. In the hospital, a 4Ms overview was provided with education on the delirium SOP at nursing meetings. Updates were requested to the electronic health record (EHR) templates for the GAC to streamline documentation. For the BVAHCS HBPC, 4Ms assessments were added to the EHR quarterly care plan template, which was updated by all team members (Table 2).

From April through June 2021, the AVAMC HBPC formed teams led by 4Ms champions: what matters was led by a nurse care manager, medication by a nurse practitioner and pharmacist, mentation by a social worker, and mobility by a physical therapist. The champions initially focused on a plan for each M, incorporating all 4Ms as a set for optimal effectiveness into their quarterly care plan meeting using what matters to drive the entire care plan.

Step 4: Provide Care

Each of the 4Ms was to be assessed, documented, and acted on for each veteran within a short period, such as a hospitalization or 1 or 2 outpatient visits. BVAHCS implemented 4Ms care in each care setting from August to October 2020. The AVAMC HBPC implemented 4Ms from July to September 2021.

Step 5: Study Performance

The IHI identifies 3 methods for measuring older adults who receive 4Ms care: real-time observation, chart review, or EHR report. For chart review, the IHI recommends using a random sample to calculate the number of patients who received 4Ms in 1 month, which provides evidence of progress toward reliable practice.

Both facilities used chart review with random sampling. Each setting estimated the number of veterans receiving 4Ms care by multiplying the percentage of sampled charts with documented 4Ms care by unique patient encounters (eAppendix 2).

From August through October 2020, BVAHCS sites reached an estimated 97% of older veterans with complete 4Ms care: hospital, 100%; GAC, 90%; and HBPC, 85%. AVAMC HBPC increased 4Ms care from 52% to 100% between July and September 2021. Both teams demonstrated the feasibility of reliably providing 4Ms care to > 85% of older veterans in these care settings and earned level 2 recognition. Through satisfaction surveys and informal feedback, notable positive changes were evident to veterans, their families, and the VA staff providing 4Ms age-friendly care.

Step 6: Improve and Sustain Care

Each site acknowledged barriers and facilitators for adopting the 4Ms. The COVID-19 pandemic was an ongoing barrier for both sites, with teams transitioning to virtual modalities for telehealth visits and team meetings, and higher staff turnover. However, the greater use of technology facilitated 4Ms adoption by allowing physically distant team members to collaborate.

One of the largest barriers was the lack of 4Ms documentation in the EHR, which could not be implemented in the BVAHCS inpatient hospital due to existing standardized nursing templates. Both sites recognized that 4Ms documentation in the EHR for all care settings would facilitate achieving level 2 recognition and tracking and reporting 4Ms care in the future.

Discussion

The AFHS 4Ms approach offers a method to impart geriatrics knowledge, skills, and practice throughout an entire health care system in a short time. The AFHS framework provides a structured pathway to the often daunting challenge of care for complex, multimorbid, and highly heterogeneous older adults. The 4Ms approach promotes the provision of evidence-based care that is reliable, efficient, patient centered, and avoids unwanted care: worthy goals not only for geriatrics but for all members of a high-reliability organization.

Through the implementation of the 4Ms framework, consistent use of AFHS practices, measurement, and feedback, the staff in each VA care setting reported here reached a level of reliability in which at least 85% of patients had all 4Ms addressed. Notably, adoption was strong and improvements in reliably addressing all 4Ms were observed in both geriatrics (HBPC and outpatient clinics) and nongeriatrics (inpatient medicine) settings. Although one might expect that high-functioning interdisciplinary teams in geriatrics-focused VA settings were routinely addressing all 4Ms for most of their patients, our experience was consistent with prior teams indicating that this is often not the case. Although many of these teams were addressing some of the 4Ms in their usual practice, the 4Ms framework facilitated addressing all 4Ms as a set with input from all team members. Most importantly, it fostered a culture of asking the older adult what matters most and documenting, sharing, and aligning this with the care plan. Within 6 months, all VA care settings achieved level 1 recognition, and within 9 months, all achieved level 2 recognition.

Lessons Learned

Key lessons learned include the importance of identifying, preparing, and supporting a champion to lead this effort; garnering facility and system leadership support at the outset; and integration with the EHR for reliable and efficient data capture, reporting, and feedback. Preparing and supporting champions was achieved through national and individual calls and peer support. Guidance was provided on garnering leadership support, including local needs assessment and data analysis, meeting with leadership to first understand their key challenges and priorities and provide information on the AFHS movement, requesting a follow-up meeting to discuss local needs and data, and exploring how an AFHS might help address one or more of their priorities.

In September 2022, an AFHS 4Ms note template was introduced into the EHR for all VA sites for data capture and reporting, to standardize and facilitate documentation across all age-friendly VA sites, and decrease the reporting burden for staff. This effort is critically important: The ability to document, track, and analyze 4Ms measures, provide feedback, and synergize efforts across systems is vital to design studies to determine whether the AFHS 4Ms approach to care achieves substantive improvements in patient care across settings.

Limitations

Limitations of this analysis include the small sample of care settings, which did not include a skilled nursing or long-term care facility, nor general primary care. Although the short timeframe assessed did not allow us to report on the anticipated clinical outcomes of 4Ms care, it does set up a foundation for evaluation of the 4Ms and EHR integration and dashboard development.

Conclusions

The VHA provides a comprehensive spectrum of geriatrics services and innovative models of care that often serve as exemplars to other health care systems. Implementing the AFHS framework to assess and act on the 4Ms provides a structure for confronting the HCP shortage with geriatrics expertise by infusing geriatrics knowledge, skills, and practices throughout all care settings and disciplines. Enhancing patient-centered care to older veterans through AFHS implementation exemplifies the VHA as a learning health care system.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Veterans Health Administration Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care and the clinical staff from the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Healthcare System and the Birmingham Veterans Affairs Health Care System for assisting us in this work.

Nearly 50% of living US veterans are aged ≥ 65 years compared with 18.3% of the general population.1,2 The Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the largest integrated health care system in the US, has a vested interest in improving the quality and effectiveness of care for older veterans.3

Health care systems are often unprepared to care for the complex needs of older adults. There are roughly 7300 certified geriatricians practicing in the US, and about 250 new geriatricians are trained each year while the American Geriatrics Society expects > 12,000 geriatricians will be required by 2030.4,5 More geriatricians are needed to serve as the primary health care professionals (HCPs) for older adults.4,6 Health care systems like the VHA must find ways to increase geriatrics skills, knowledge, and practices among their entire health care workforce. A culture shift toward age-friendly care for older adults across care settings and inclusive of all HCPs may help meet this escalating workforce need.7

The Age-Friendly Health System (AFHS) is an initiative of the John A. Hartford Foundation and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) in partnership with the American Hospital Association and the Catholic Health Association of the United States.8,9 AFHS uses a what matters, medication, mentation, and mobility (4Ms) framework to ensure reliable, evidence-based care for older adults (Table 1).10,11 In an AFHS, the 4Ms are integrated into every discipline and care setting for older adults.11 The 4Ms neither replace formal training in geriatrics nor create the level of expertise needed for geriatrics teachers, researchers, and program leaders. However, the systematic approach of AFHS to assess and act on each of the 4Ms offers one solution to expand geriatrics skills and knowledge beyond geriatric care settings in all disciplines by engaging each HCP to meet the needs of older adults.12 To act on what matters, HCPs need to align the care plan with what is important to the older adult.

Hospitals and health care systems are encouraged to begin implementing the 4Ms in ≥ 1 care setting.13 Care settings may get started on a do-it-yourself track or by joining an IHI Action Community, which provides a series of webinars to help adopt the 4Ms over 7 months.14 By creating a plan for how each M will be assessed, documented, and acted on, care settings may earn level 1 recognition from the IHI.14 As of July 2023, there are at least 3100 AFHS participants and > 1900 have achieved level 2 recognition, which requires 3 months of clinical data to demonstrate the impact of the 4Ms.13,14

The main cultural shift of the AFHS movement is to focus on what matters to older adults by prioritizing each older adult’s personal health goals and care preferences across all care settings.9,11 Medication addresses age-appropropriate prescribing, making dose adjustments, if needed, and avoiding/deprescribing high-risk medications that may interfere with what matters, mentation, or mobility. The Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults is often used as a guide and includes lists of medications that are potentially harmful for older adults.11 Mentation focuses on preventing, identifying, treating, and managing dementia, depression, and delirium across care settings. Mobility includes assisting or encouraging older adults to move safely every day to maintain functional ability and do what matters.15,16 Each of the 4Ms has the potential to improve health outcomes for older adults, reduce waste from low-quality services, and increase the use of cost-effective services.11,17

In March 2020, the VHA Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care (GEC) set the goal for the VHA to be recognized by the IHI as an AFHS.18,19 US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities that joined the AFHS movement in 2020 are considered early adopters. We describe early adopter AFHS implementation at Birmingham VA Health Care System (BVAHCS) hospital, geriatrics assessment clinic (GAC), and Home Based Primary Care (HBPC) and at the Atlanta VA Medical Center (AVAMC) HBPC.

Implementing 4Ms Care

The IHI identifies 6 steps in the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle to reliably practice the 4Ms. eAppendix 1 provides a side-by-side comparison of the steps over a 9-month timeline independently taken by BVAHCS and AVAMC to achieve both levels of AFHS recognition.

Step 1: Understand the Current State

In March 2020 the BVAHCS enrolled in the IHI Action Community. Three BVAHCS care settings were identified for the Action Community: the inpatient hospital, GAC (an outpatient clinic), and HBPC. The AVAMC HBPC enrolled in the IHI Action Community in March 2021.

Before joining the AFHS movement, the BVAHCS implemented a hospital-wide delirium standard operating procedure (SOP) whereby every veteran admitted to the 313-bed hospital is screened for delirium risk, with positive screens linked to nursing-led interventions. Nursing leadership supported AFHS due to its recognized value and an exemplary process in place to assess mentation/delirium and background understanding for screening and acting on medication, mobility, and what matters most to the veteran. The BVAHCS GAC, which was led by a single geriatrician, integrated the 4Ms into all geriatrics assessment appointments.

For the BVAHCS HBPC, the 4Ms supported key performance measures, such as fall prevention, patient satisfaction, decreasing medication errors, and identification of cognition and mood disorders. For the AVAMC HBPC, joining the AFHS movement represented an opportunity to improve performance measures, interdisciplinary teamwork, and care coordination for patients. For both HBPC sites, the shift to virtual meeting modalities due to the COVID-19 pandemic enabled HBPC team members to garner support for AFHS and collectively develop a 4Ms plan.

Step 2: Describe 4Ms Care

In March 2020 as guided by the Action Community, BVAHCS created a plan for each of its 3 care settings that described assessment tools, frequency, documentation, and responsible team members. All BVAHCS care settings achieved level 1 recognition in April 2020. Of the approximately 300 veterans served by the AVAMC HBPC, 83% are aged > 65 years. They achieved level 1 recognition in August 2021.

Step 3: Design and Adapt Workflows

From April to August 2020, BVAHCS implemented its 4Ms plans. In the hospital, a 4Ms overview was provided with education on the delirium SOP at nursing meetings. Updates were requested to the electronic health record (EHR) templates for the GAC to streamline documentation. For the BVAHCS HBPC, 4Ms assessments were added to the EHR quarterly care plan template, which was updated by all team members (Table 2).

From April through June 2021, the AVAMC HBPC formed teams led by 4Ms champions: what matters was led by a nurse care manager, medication by a nurse practitioner and pharmacist, mentation by a social worker, and mobility by a physical therapist. The champions initially focused on a plan for each M, incorporating all 4Ms as a set for optimal effectiveness into their quarterly care plan meeting using what matters to drive the entire care plan.

Step 4: Provide Care

Each of the 4Ms was to be assessed, documented, and acted on for each veteran within a short period, such as a hospitalization or 1 or 2 outpatient visits. BVAHCS implemented 4Ms care in each care setting from August to October 2020. The AVAMC HBPC implemented 4Ms from July to September 2021.

Step 5: Study Performance

The IHI identifies 3 methods for measuring older adults who receive 4Ms care: real-time observation, chart review, or EHR report. For chart review, the IHI recommends using a random sample to calculate the number of patients who received 4Ms in 1 month, which provides evidence of progress toward reliable practice.

Both facilities used chart review with random sampling. Each setting estimated the number of veterans receiving 4Ms care by multiplying the percentage of sampled charts with documented 4Ms care by unique patient encounters (eAppendix 2).

From August through October 2020, BVAHCS sites reached an estimated 97% of older veterans with complete 4Ms care: hospital, 100%; GAC, 90%; and HBPC, 85%. AVAMC HBPC increased 4Ms care from 52% to 100% between July and September 2021. Both teams demonstrated the feasibility of reliably providing 4Ms care to > 85% of older veterans in these care settings and earned level 2 recognition. Through satisfaction surveys and informal feedback, notable positive changes were evident to veterans, their families, and the VA staff providing 4Ms age-friendly care.

Step 6: Improve and Sustain Care

Each site acknowledged barriers and facilitators for adopting the 4Ms. The COVID-19 pandemic was an ongoing barrier for both sites, with teams transitioning to virtual modalities for telehealth visits and team meetings, and higher staff turnover. However, the greater use of technology facilitated 4Ms adoption by allowing physically distant team members to collaborate.

One of the largest barriers was the lack of 4Ms documentation in the EHR, which could not be implemented in the BVAHCS inpatient hospital due to existing standardized nursing templates. Both sites recognized that 4Ms documentation in the EHR for all care settings would facilitate achieving level 2 recognition and tracking and reporting 4Ms care in the future.

Discussion

The AFHS 4Ms approach offers a method to impart geriatrics knowledge, skills, and practice throughout an entire health care system in a short time. The AFHS framework provides a structured pathway to the often daunting challenge of care for complex, multimorbid, and highly heterogeneous older adults. The 4Ms approach promotes the provision of evidence-based care that is reliable, efficient, patient centered, and avoids unwanted care: worthy goals not only for geriatrics but for all members of a high-reliability organization.

Through the implementation of the 4Ms framework, consistent use of AFHS practices, measurement, and feedback, the staff in each VA care setting reported here reached a level of reliability in which at least 85% of patients had all 4Ms addressed. Notably, adoption was strong and improvements in reliably addressing all 4Ms were observed in both geriatrics (HBPC and outpatient clinics) and nongeriatrics (inpatient medicine) settings. Although one might expect that high-functioning interdisciplinary teams in geriatrics-focused VA settings were routinely addressing all 4Ms for most of their patients, our experience was consistent with prior teams indicating that this is often not the case. Although many of these teams were addressing some of the 4Ms in their usual practice, the 4Ms framework facilitated addressing all 4Ms as a set with input from all team members. Most importantly, it fostered a culture of asking the older adult what matters most and documenting, sharing, and aligning this with the care plan. Within 6 months, all VA care settings achieved level 1 recognition, and within 9 months, all achieved level 2 recognition.

Lessons Learned

Key lessons learned include the importance of identifying, preparing, and supporting a champion to lead this effort; garnering facility and system leadership support at the outset; and integration with the EHR for reliable and efficient data capture, reporting, and feedback. Preparing and supporting champions was achieved through national and individual calls and peer support. Guidance was provided on garnering leadership support, including local needs assessment and data analysis, meeting with leadership to first understand their key challenges and priorities and provide information on the AFHS movement, requesting a follow-up meeting to discuss local needs and data, and exploring how an AFHS might help address one or more of their priorities.

In September 2022, an AFHS 4Ms note template was introduced into the EHR for all VA sites for data capture and reporting, to standardize and facilitate documentation across all age-friendly VA sites, and decrease the reporting burden for staff. This effort is critically important: The ability to document, track, and analyze 4Ms measures, provide feedback, and synergize efforts across systems is vital to design studies to determine whether the AFHS 4Ms approach to care achieves substantive improvements in patient care across settings.

Limitations

Limitations of this analysis include the small sample of care settings, which did not include a skilled nursing or long-term care facility, nor general primary care. Although the short timeframe assessed did not allow us to report on the anticipated clinical outcomes of 4Ms care, it does set up a foundation for evaluation of the 4Ms and EHR integration and dashboard development.

Conclusions

The VHA provides a comprehensive spectrum of geriatrics services and innovative models of care that often serve as exemplars to other health care systems. Implementing the AFHS framework to assess and act on the 4Ms provides a structure for confronting the HCP shortage with geriatrics expertise by infusing geriatrics knowledge, skills, and practices throughout all care settings and disciplines. Enhancing patient-centered care to older veterans through AFHS implementation exemplifies the VHA as a learning health care system.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Veterans Health Administration Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care and the clinical staff from the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Healthcare System and the Birmingham Veterans Affairs Health Care System for assisting us in this work.

1. US Census Bureau. Older Americans month: May 2023. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/stories/older-americans-month.html

2. Vespa J. Aging veterans: America’s veteran population in later life. July 2023. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2023/acs/acs-54.pdf

3. O’Hanlon C, Huang C, Sloss E, et al. Comparing VA and non-VA quality of care: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(1):105-121. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3775-2

4. Fulmer T, Reuben DB, Auerbach J, Fick DM, Galambos C, Johnson KS. Actualizing better health and health care for older adults: commentary describes six vital directions to improve the care and quality of life for all older Americans. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(2):219-225. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01470

5. ChenMed. The physician shortage in geriatrics. March 18, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.chenmed.com/blog/physician-shortage-geriatrics

6. American Geriatrics Society. Projected future need for geriatricians. Updated May 2016. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.americangeriatrics.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/Projected-Future-Need-for-Geriatricians.pdf 7. Carmody J, Black K, Bonner A, Wolfe M, Fulmer T. Advancing gerontological nursing at the intersection of age-friendly communities, health systems, and public health. J Gerontol Nurs. 2021;47(3):13-17. doi:10.3928/00989134-20210125-01

8. Lesser S, Zakharkin S, Louie C, Escobedo MR, Whyte J, Fulmer T. Clinician knowledge and behaviors related to the 4Ms framework of Age‐Friendly Health Systems. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(3):789-800. doi:10.1111/jgs.17571

9. Edelman LS, Drost J, Moone RP, et al. Applying the Age-Friendly Health System framework to long term care settings. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25(2):141-145. doi:10.1007/s12603-020-1558-2

10. Emery-Tiburcio EE, Mack L, Zonsius MC, Carbonell E, Newman M. The 4Ms of an Age-Friendly Health System: an evidence-based framework to ensure older adults receive the highest quality care. Home Healthc Now. 2022;40(5):252-257. doi:10.1097/NHH.0000000000001113

11. Mate K, Fulmer T, Pelton L, et al. Evidence for the 4Ms: interactions and outcomes across the care continuum. J Aging Health. 2021;33(7-8):469-481. doi:10.1177/0898264321991658

12. Mate KS, Berman A, Laderman M, Kabcenell A, Fulmer T. Creating age-friendly health systems – a vision for better care of older adults. Healthc (Amst). 2018;6(1):4-6. doi:10.1016/j.hjdsi.2017.05.005

13. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. What is an Age-Friendly Health System? Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/default.aspx

14. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Health systems recognized by IHI. Updated September 2023. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/recognized-systems.aspx

15. Burke RE, Ashcraft LE, Manges K, et al. What matters when it comes to measuring Age‐Friendly Health System transformation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(10):2775-2785. doi:10.1111/jgs.18002

16. Wang J, Shen JY, Conwell Y, et al. How “age-friendly” are deprescribing interventions? A scoping review of deprescribing trials. Health Serv Res. 202;58(suppl 1):123-138. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14083

17. Pohnert AM, Schiltz NK, Pino L, et al. Achievement of age‐friendly health systems committed to care excellence designation in a convenient care health care system. Health Serv Res. 2023;58 (suppl 1):89-99. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14071

18. Church K, Munro S, Shaughnessy M, Clancy C. Age-Friendly Health Systems: improving care for older adults in the Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv Res. 2022;58(suppl 1):5-8. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14110

19. Farrell TW, Volden TA, Butler JM, et al. Age‐friendly care in the Veterans Health Administration: past, present, and future. J Am Geriatr Soc. doi:10.1111/jgs.18070

1. US Census Bureau. Older Americans month: May 2023. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/stories/older-americans-month.html

2. Vespa J. Aging veterans: America’s veteran population in later life. July 2023. Accessed September 11, 2023. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2023/acs/acs-54.pdf

3. O’Hanlon C, Huang C, Sloss E, et al. Comparing VA and non-VA quality of care: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(1):105-121. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3775-2

4. Fulmer T, Reuben DB, Auerbach J, Fick DM, Galambos C, Johnson KS. Actualizing better health and health care for older adults: commentary describes six vital directions to improve the care and quality of life for all older Americans. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(2):219-225. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01470

5. ChenMed. The physician shortage in geriatrics. March 18, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.chenmed.com/blog/physician-shortage-geriatrics

6. American Geriatrics Society. Projected future need for geriatricians. Updated May 2016. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.americangeriatrics.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/Projected-Future-Need-for-Geriatricians.pdf 7. Carmody J, Black K, Bonner A, Wolfe M, Fulmer T. Advancing gerontological nursing at the intersection of age-friendly communities, health systems, and public health. J Gerontol Nurs. 2021;47(3):13-17. doi:10.3928/00989134-20210125-01

8. Lesser S, Zakharkin S, Louie C, Escobedo MR, Whyte J, Fulmer T. Clinician knowledge and behaviors related to the 4Ms framework of Age‐Friendly Health Systems. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(3):789-800. doi:10.1111/jgs.17571

9. Edelman LS, Drost J, Moone RP, et al. Applying the Age-Friendly Health System framework to long term care settings. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25(2):141-145. doi:10.1007/s12603-020-1558-2

10. Emery-Tiburcio EE, Mack L, Zonsius MC, Carbonell E, Newman M. The 4Ms of an Age-Friendly Health System: an evidence-based framework to ensure older adults receive the highest quality care. Home Healthc Now. 2022;40(5):252-257. doi:10.1097/NHH.0000000000001113

11. Mate K, Fulmer T, Pelton L, et al. Evidence for the 4Ms: interactions and outcomes across the care continuum. J Aging Health. 2021;33(7-8):469-481. doi:10.1177/0898264321991658

12. Mate KS, Berman A, Laderman M, Kabcenell A, Fulmer T. Creating age-friendly health systems – a vision for better care of older adults. Healthc (Amst). 2018;6(1):4-6. doi:10.1016/j.hjdsi.2017.05.005

13. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. What is an Age-Friendly Health System? Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/default.aspx

14. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Health systems recognized by IHI. Updated September 2023. Accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/recognized-systems.aspx

15. Burke RE, Ashcraft LE, Manges K, et al. What matters when it comes to measuring Age‐Friendly Health System transformation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(10):2775-2785. doi:10.1111/jgs.18002

16. Wang J, Shen JY, Conwell Y, et al. How “age-friendly” are deprescribing interventions? A scoping review of deprescribing trials. Health Serv Res. 202;58(suppl 1):123-138. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14083

17. Pohnert AM, Schiltz NK, Pino L, et al. Achievement of age‐friendly health systems committed to care excellence designation in a convenient care health care system. Health Serv Res. 2023;58 (suppl 1):89-99. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14071

18. Church K, Munro S, Shaughnessy M, Clancy C. Age-Friendly Health Systems: improving care for older adults in the Veterans Health Administration. Health Serv Res. 2022;58(suppl 1):5-8. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.14110

19. Farrell TW, Volden TA, Butler JM, et al. Age‐friendly care in the Veterans Health Administration: past, present, and future. J Am Geriatr Soc. doi:10.1111/jgs.18070

Polypharmacy Review of Vulnerable Elders: Can We IMPROVE Outcomes?

Investigators at the Atlanta site of the Birmingham/Atlanta VA Geriatric Research and Education Clinical Center (GRECC) developed the Integrated Management and Polypharmacy Review of Vulnerable Elders (IMPROVE) clinical demonstration project to enhance medication management and quality of prescribing for vulnerable older veterans. Poor quality prescribing in older adults is common and can result in adverse drug reactions (ADRs); increased emergency department, hospital, and primary care provider (PCP) use; and death. The ADRs alone, which are strongly correlated with multiple medication use, account for at least 10% of hospitalizations in older persons.1

Many factors contributing to poor quality prescribing in older persons include time constraints on health professionals, multiple providers, patient-driven prescribing, patients with low health literacy, and frequent transitions in care between home, hospital, and postacute care. Older veterans may be harmed by taking medications with no clear benefit, duplication of therapy, and omission of beneficial medications. Prescribing medications with known high risk for ADRs, inadequate monitoring, and limited patient education on how and why to take a medication can further increase the risk for adverse outcomes. Prescribing for multimorbid older veterans requires comprehensive, individualized care plans that take into account patients’ goals of care and quality of life, as well as evidence-based practice standards.

Clinical trials have repeatedly shown that individualized pharmacy review can reduce polypharmacy in older patients. Positive outcomes have included reduced ADRs, improved measures of prescribing quality, appropriate medication use, compliance with care recommendations, and reduction in the total number of medications.2-5 Optimal use of medications is achieved when a pharmacist works with other care team members to implement and oversee a care plan, as opposed to each provider working alone.2,5

In 2011, the VHA Geriatrics Pharmacy Taskforce recommended that facilities offer “individualized pharmacy review for high-risk patients on multiple medications.”6 This recommendation was in line with the increasingly integrated role of the clinical pharmacist in the patient aligned care team (PACT) and the recent requirement that Medicare Part D medication therapy management programs offer this service to select patients with chronic disease.

The IMPROVE Model

Given the high and growing numbers of older veterans enrolled in VA primary care who are at risk for ADRs, the Atlanta VA IMPROVE team implemented a GRECC-funded clinical demonstration project. The project supported the VA’s focus on PACTs in combination with existing best practice standards to improve medication management in high-risk older veterans. The Emory University Institutional Review Board ruled that IMPROVE was a quality improvement project, and therefore was exempt from review and VA research oversight.

For this clinical demonstration, IMPROVE targeted noninstitutionalized veterans aged ≥ 85 years taking 10 or more medications who received care in the VA primary care clinic and used the VA pharmacy for medications. This cohort represented the top 5% of medication users enrolled in the clinic. While age and number of medications are independently associated with increased risk for ADRs, other factors common in this cohort, including higher levels of comorbid disease, frequent care transitions, and cognitive impairment are also associated with higher ADR risk.7The IMPROVE model was designed to promote fully engaged partnerships among veterans, family caregivers, and the PACT with input from all parties in the design of the model. The IMPROVE team conducted individual, qualitative, semistructured interviews with 5 clinical pharmacists, 5 geriatricians, and 1 geriatric nurse practitioner on the challenges faced in the management of medications for older patients, individual needs/barriers to meet these challenges, the clinical pharmacist role in providing recommendations to providers, and attitudes and preferences for team communication.

Challenges discovered included time constraints during clinic visits, a need for joint decision making, and limited competency with principles of health literacy. The IMPROVE team also conducted focus groups with veterans (n = 4) and caregivers (n = 7) to determine medication management needs, values, preferences, and barriers to self-management. Key findings from these sessions included poor recognition of limitations in medication self-management, problems related to health literacy, and misunderstanding the role of the clinical pharmacist.8

Using the information gained from patients, family caregivers, and PACT members, the model was tailored to address concerns. The IMPROVE model engaged a PACT clinical pharmacist skilled in medication management and patient education to perform a face-to-face clinical consult with selected patients and their caregivers.5 Making veterans, families, and PACT members collaborators in IMPROVE’s design helped establish active partnerships that enabled effective execution of the project and promoted sustained culture and system change over time.

Pilot Program

High-risk veterans and their caregivers were recruited by letter, followed by a phone call to schedule an appointment for those interested, and a reminder to bring all their medications to the appointment. Twenty-eight male veterans participated in the pilot. The average age was 89 years; 52% were white; 53% had a diagnosis of dementia; 78% reported assistance with medication management; and patients took an average of 16 medications daily. Recruited high-risk veterans and their caregivers were seen in a 1 hour in-person visit with the clinical pharmacist.

To maximize the benefit of the session, the pharmacist was provided with several tools to assist in a systematic evaluation of medication management concerns and quality of prescribing. Tools included a quick reference card citing potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) per the published 2012 Beers Criteria and a reference for potentially beneficial medications based on the START-STOPP criteria.9,10

A Computerized Patient Record System template was developed to guide the pharmacist visit. The template included medication reconciliation, a systematic review of all medications to verify indication and check for redundancies, drug interactions, PIMs, and proper therapeutic monitoring. The template also included assessments for level of medication assistance available, goals of care, health literacy, and barriers to adherence.

A collaborative review of the medication regimen was conducted with the veteran, caregiver, and pharmacist, resulting in individualized recommendations, education, strategies, and tools to improve the quality and safety of the medication regimen as well as patient adherence. When necessary, pill boxes, illustrated medication schedules, low vision aids, and other adaptive devices were provided.

Communication of recommendations with the PCP occurred by cosignature on the note. Same-day consultation with the PCP was also available for any urgent concerns or significant changes to the regimen. At the discretion of the pharmacist, a face-to-face follow-up visit with the pharmacist or a follow-up phone call was conducted.

Results

Both qualitative and quantitative outcomes measures were used to evaluate the IMPROVE model. Semi-structured postpilot interviews with PCPs showed that the model had high satisfaction, acceptability, and feasibility. Providers reported that the model helped them and their patients in an area that takes considerable time (medication review and education) and is not always feasible in a short clinic visit. Providers were willing to accept pharmacist recommendations, which was likely fostered by pre-intervention strategies to keep communication open about proposed medication changes. In a survey, 93% of patients and caregivers found the IMPROVE model helpful; 100% recommended the clinic to others.

Objective measures found 79% of patients in the pilot had at least 1 medication discontinued, 75% had ≥ 1 dosing or timing adjustments made, and PIMs were reduced 14%. Comparing the 6-month period before the pilot and the 6 months after, pharmacy cost savings averaged $64 per veteran per month. Health care use showed a decreasing trend in phone calls and visits to the PCP.7 Cost savings were comparable or greater than those previously reported for similar interventions.4

Conclusions

The results of the IMPROVE pilot suggest that an integrated model involving both pharmacists and PCPs in managing medications and empowering the patient and family caregivers as stakeholders in their own care can lead to improved quality of medication management and cost savings. Based on the success of the pilot, the IMPROVE model received VA Office of Rural Health funding to translate this model to target rural older veterans in community based outpatient clinics.

The success of the IMPROVE model was undoubtedly enhanced by engaged PACT members at the pilot site and a clinical pharmacist who championed the model. The effort involved in recruiting, scheduling, and assessing participants may limit generalizability to settings without such a champion and without dedicated time available with a pharmacist. Determining which groups of older veterans benefit most from individualized medication management and optimal methods to translate the program to other primary care settings are ongoing endeavors for the Atlanta GRECC IMPROVE team.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a VA Transformation-21 grant awarded through the Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care. The authors thank Christine Jasien, MS; for data management, Aaron Bozzorg, MS; for interview transcription, Joette Lowe, PharmD; for general consultation; and the VISN 7 leadership for their support.

1. Marcum ZA, Amuan ME, Hanlon JT, et al. Prevalence of unplanned hospitalizations caused by adverse drug reactions in older veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(1):34-41.

2. Schmader KE, Hanlon JT, Pieper CF, et al. Effects of geriatric evaluation and management on adverse drug reactions and suboptimal prescribing in the frail elderly. Am J Med. 2004;116(6):394-401.

3. Krska J, Cromarty JA, Arris F, et al. Pharmacist‐led medication review in patients over 65: a randomized, controlled trial in primary care. Age Ageing. 2001;30(3):205-211.

4. Chumney EC, Robinson LC. The effects of pharmacist interventions on patients with polypharmacy. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2006;4(3):103-109.

5. Lee JK, Slack MK, Martin J, Ehrman C, Chrisholm-Burns M. Geriatric patient care by U.S. pharmacists in healthcare teams: systematic review and meta-analyses. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(7):1119-1127.

6. Veterans Health Administration Geriatrics Pharmacy Taskforce. Improving Patient-Centered Medication Management for Elderly Veterans: VHA Geriatrics Pharmacy Taskforce Report and Recommendations. August 2010.

7. Spinewine A, Schmader KE, Barber N, et al. Appropriate prescribing in elderly people: how well can it be measured and optimised? Lancet. 2007;370(9582):173-184.

8. Mirk A, Kemp L, Echt KV, Perkins MM. Integrated management and polypharmacy review of vulnerable elders: Can we IMPROVE outcomes? [abstract]. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(suppl 1):S92.

9. American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616-613.

10. Barry P, Gallagher P, Ryan C, O'Mahony D. START (screening tool to alert doctors to the right treatment)--an evidence-based screening tool to detect prescribing omissions in elderly patients. Age Ageing. 2007;36(6):632-638.

Investigators at the Atlanta site of the Birmingham/Atlanta VA Geriatric Research and Education Clinical Center (GRECC) developed the Integrated Management and Polypharmacy Review of Vulnerable Elders (IMPROVE) clinical demonstration project to enhance medication management and quality of prescribing for vulnerable older veterans. Poor quality prescribing in older adults is common and can result in adverse drug reactions (ADRs); increased emergency department, hospital, and primary care provider (PCP) use; and death. The ADRs alone, which are strongly correlated with multiple medication use, account for at least 10% of hospitalizations in older persons.1

Many factors contributing to poor quality prescribing in older persons include time constraints on health professionals, multiple providers, patient-driven prescribing, patients with low health literacy, and frequent transitions in care between home, hospital, and postacute care. Older veterans may be harmed by taking medications with no clear benefit, duplication of therapy, and omission of beneficial medications. Prescribing medications with known high risk for ADRs, inadequate monitoring, and limited patient education on how and why to take a medication can further increase the risk for adverse outcomes. Prescribing for multimorbid older veterans requires comprehensive, individualized care plans that take into account patients’ goals of care and quality of life, as well as evidence-based practice standards.

Clinical trials have repeatedly shown that individualized pharmacy review can reduce polypharmacy in older patients. Positive outcomes have included reduced ADRs, improved measures of prescribing quality, appropriate medication use, compliance with care recommendations, and reduction in the total number of medications.2-5 Optimal use of medications is achieved when a pharmacist works with other care team members to implement and oversee a care plan, as opposed to each provider working alone.2,5

In 2011, the VHA Geriatrics Pharmacy Taskforce recommended that facilities offer “individualized pharmacy review for high-risk patients on multiple medications.”6 This recommendation was in line with the increasingly integrated role of the clinical pharmacist in the patient aligned care team (PACT) and the recent requirement that Medicare Part D medication therapy management programs offer this service to select patients with chronic disease.

The IMPROVE Model

Given the high and growing numbers of older veterans enrolled in VA primary care who are at risk for ADRs, the Atlanta VA IMPROVE team implemented a GRECC-funded clinical demonstration project. The project supported the VA’s focus on PACTs in combination with existing best practice standards to improve medication management in high-risk older veterans. The Emory University Institutional Review Board ruled that IMPROVE was a quality improvement project, and therefore was exempt from review and VA research oversight.

For this clinical demonstration, IMPROVE targeted noninstitutionalized veterans aged ≥ 85 years taking 10 or more medications who received care in the VA primary care clinic and used the VA pharmacy for medications. This cohort represented the top 5% of medication users enrolled in the clinic. While age and number of medications are independently associated with increased risk for ADRs, other factors common in this cohort, including higher levels of comorbid disease, frequent care transitions, and cognitive impairment are also associated with higher ADR risk.7The IMPROVE model was designed to promote fully engaged partnerships among veterans, family caregivers, and the PACT with input from all parties in the design of the model. The IMPROVE team conducted individual, qualitative, semistructured interviews with 5 clinical pharmacists, 5 geriatricians, and 1 geriatric nurse practitioner on the challenges faced in the management of medications for older patients, individual needs/barriers to meet these challenges, the clinical pharmacist role in providing recommendations to providers, and attitudes and preferences for team communication.

Challenges discovered included time constraints during clinic visits, a need for joint decision making, and limited competency with principles of health literacy. The IMPROVE team also conducted focus groups with veterans (n = 4) and caregivers (n = 7) to determine medication management needs, values, preferences, and barriers to self-management. Key findings from these sessions included poor recognition of limitations in medication self-management, problems related to health literacy, and misunderstanding the role of the clinical pharmacist.8

Using the information gained from patients, family caregivers, and PACT members, the model was tailored to address concerns. The IMPROVE model engaged a PACT clinical pharmacist skilled in medication management and patient education to perform a face-to-face clinical consult with selected patients and their caregivers.5 Making veterans, families, and PACT members collaborators in IMPROVE’s design helped establish active partnerships that enabled effective execution of the project and promoted sustained culture and system change over time.

Pilot Program

High-risk veterans and their caregivers were recruited by letter, followed by a phone call to schedule an appointment for those interested, and a reminder to bring all their medications to the appointment. Twenty-eight male veterans participated in the pilot. The average age was 89 years; 52% were white; 53% had a diagnosis of dementia; 78% reported assistance with medication management; and patients took an average of 16 medications daily. Recruited high-risk veterans and their caregivers were seen in a 1 hour in-person visit with the clinical pharmacist.

To maximize the benefit of the session, the pharmacist was provided with several tools to assist in a systematic evaluation of medication management concerns and quality of prescribing. Tools included a quick reference card citing potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) per the published 2012 Beers Criteria and a reference for potentially beneficial medications based on the START-STOPP criteria.9,10

A Computerized Patient Record System template was developed to guide the pharmacist visit. The template included medication reconciliation, a systematic review of all medications to verify indication and check for redundancies, drug interactions, PIMs, and proper therapeutic monitoring. The template also included assessments for level of medication assistance available, goals of care, health literacy, and barriers to adherence.

A collaborative review of the medication regimen was conducted with the veteran, caregiver, and pharmacist, resulting in individualized recommendations, education, strategies, and tools to improve the quality and safety of the medication regimen as well as patient adherence. When necessary, pill boxes, illustrated medication schedules, low vision aids, and other adaptive devices were provided.

Communication of recommendations with the PCP occurred by cosignature on the note. Same-day consultation with the PCP was also available for any urgent concerns or significant changes to the regimen. At the discretion of the pharmacist, a face-to-face follow-up visit with the pharmacist or a follow-up phone call was conducted.

Results

Both qualitative and quantitative outcomes measures were used to evaluate the IMPROVE model. Semi-structured postpilot interviews with PCPs showed that the model had high satisfaction, acceptability, and feasibility. Providers reported that the model helped them and their patients in an area that takes considerable time (medication review and education) and is not always feasible in a short clinic visit. Providers were willing to accept pharmacist recommendations, which was likely fostered by pre-intervention strategies to keep communication open about proposed medication changes. In a survey, 93% of patients and caregivers found the IMPROVE model helpful; 100% recommended the clinic to others.

Objective measures found 79% of patients in the pilot had at least 1 medication discontinued, 75% had ≥ 1 dosing or timing adjustments made, and PIMs were reduced 14%. Comparing the 6-month period before the pilot and the 6 months after, pharmacy cost savings averaged $64 per veteran per month. Health care use showed a decreasing trend in phone calls and visits to the PCP.7 Cost savings were comparable or greater than those previously reported for similar interventions.4

Conclusions

The results of the IMPROVE pilot suggest that an integrated model involving both pharmacists and PCPs in managing medications and empowering the patient and family caregivers as stakeholders in their own care can lead to improved quality of medication management and cost savings. Based on the success of the pilot, the IMPROVE model received VA Office of Rural Health funding to translate this model to target rural older veterans in community based outpatient clinics.

The success of the IMPROVE model was undoubtedly enhanced by engaged PACT members at the pilot site and a clinical pharmacist who championed the model. The effort involved in recruiting, scheduling, and assessing participants may limit generalizability to settings without such a champion and without dedicated time available with a pharmacist. Determining which groups of older veterans benefit most from individualized medication management and optimal methods to translate the program to other primary care settings are ongoing endeavors for the Atlanta GRECC IMPROVE team.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a VA Transformation-21 grant awarded through the Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care. The authors thank Christine Jasien, MS; for data management, Aaron Bozzorg, MS; for interview transcription, Joette Lowe, PharmD; for general consultation; and the VISN 7 leadership for their support.

Investigators at the Atlanta site of the Birmingham/Atlanta VA Geriatric Research and Education Clinical Center (GRECC) developed the Integrated Management and Polypharmacy Review of Vulnerable Elders (IMPROVE) clinical demonstration project to enhance medication management and quality of prescribing for vulnerable older veterans. Poor quality prescribing in older adults is common and can result in adverse drug reactions (ADRs); increased emergency department, hospital, and primary care provider (PCP) use; and death. The ADRs alone, which are strongly correlated with multiple medication use, account for at least 10% of hospitalizations in older persons.1

Many factors contributing to poor quality prescribing in older persons include time constraints on health professionals, multiple providers, patient-driven prescribing, patients with low health literacy, and frequent transitions in care between home, hospital, and postacute care. Older veterans may be harmed by taking medications with no clear benefit, duplication of therapy, and omission of beneficial medications. Prescribing medications with known high risk for ADRs, inadequate monitoring, and limited patient education on how and why to take a medication can further increase the risk for adverse outcomes. Prescribing for multimorbid older veterans requires comprehensive, individualized care plans that take into account patients’ goals of care and quality of life, as well as evidence-based practice standards.

Clinical trials have repeatedly shown that individualized pharmacy review can reduce polypharmacy in older patients. Positive outcomes have included reduced ADRs, improved measures of prescribing quality, appropriate medication use, compliance with care recommendations, and reduction in the total number of medications.2-5 Optimal use of medications is achieved when a pharmacist works with other care team members to implement and oversee a care plan, as opposed to each provider working alone.2,5

In 2011, the VHA Geriatrics Pharmacy Taskforce recommended that facilities offer “individualized pharmacy review for high-risk patients on multiple medications.”6 This recommendation was in line with the increasingly integrated role of the clinical pharmacist in the patient aligned care team (PACT) and the recent requirement that Medicare Part D medication therapy management programs offer this service to select patients with chronic disease.

The IMPROVE Model

Given the high and growing numbers of older veterans enrolled in VA primary care who are at risk for ADRs, the Atlanta VA IMPROVE team implemented a GRECC-funded clinical demonstration project. The project supported the VA’s focus on PACTs in combination with existing best practice standards to improve medication management in high-risk older veterans. The Emory University Institutional Review Board ruled that IMPROVE was a quality improvement project, and therefore was exempt from review and VA research oversight.

For this clinical demonstration, IMPROVE targeted noninstitutionalized veterans aged ≥ 85 years taking 10 or more medications who received care in the VA primary care clinic and used the VA pharmacy for medications. This cohort represented the top 5% of medication users enrolled in the clinic. While age and number of medications are independently associated with increased risk for ADRs, other factors common in this cohort, including higher levels of comorbid disease, frequent care transitions, and cognitive impairment are also associated with higher ADR risk.7The IMPROVE model was designed to promote fully engaged partnerships among veterans, family caregivers, and the PACT with input from all parties in the design of the model. The IMPROVE team conducted individual, qualitative, semistructured interviews with 5 clinical pharmacists, 5 geriatricians, and 1 geriatric nurse practitioner on the challenges faced in the management of medications for older patients, individual needs/barriers to meet these challenges, the clinical pharmacist role in providing recommendations to providers, and attitudes and preferences for team communication.