User login

Inspection of Deep Tumor Margins for Accurate Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Staging

To the Editor:

Histopathologic analysis of debulk specimens in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) may augment identification of high-risk factors in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC), which may warrant tumor upstaging.1 Intratumor location has not been studied when looking at these high-risk factors. Herein, we report 4 cSCCs initially categorized as well differentiated that were reclassified as moderate to poorly differentiated on analysis of debulk specimens obtained via shave removal.

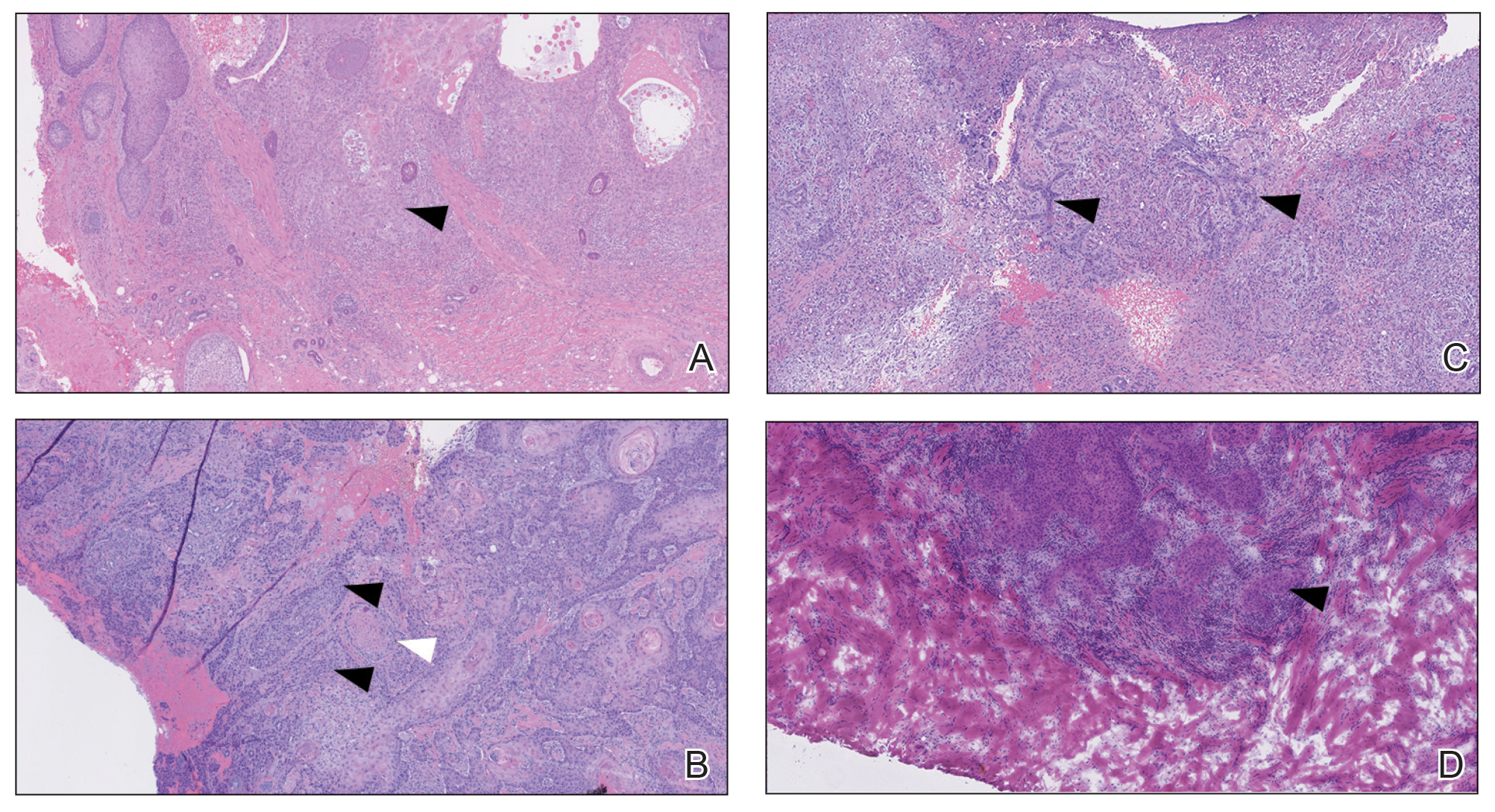

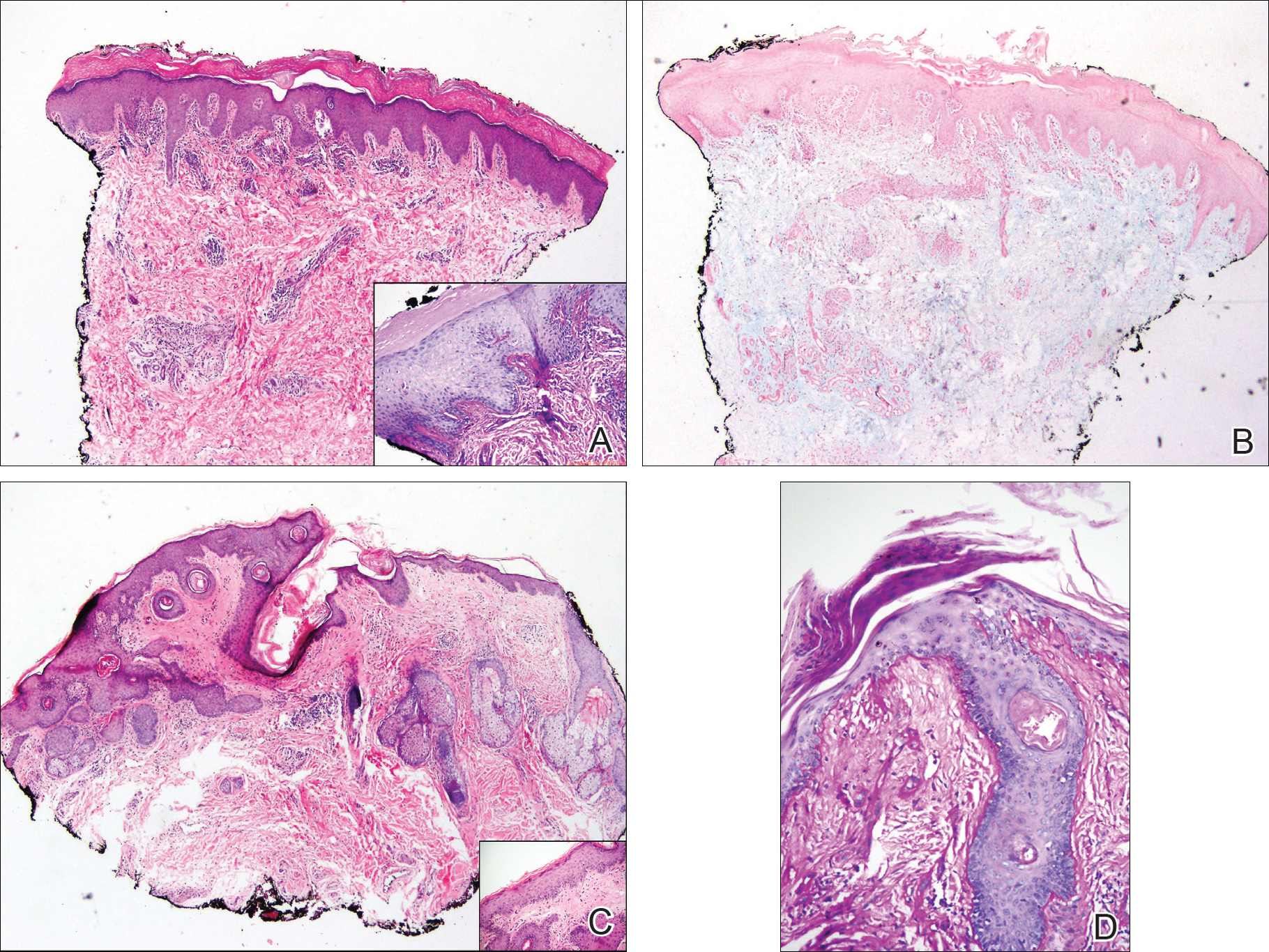

An 80-year-old man (patient 1) presented with a tender 2-cm erythematous plaque with dried hemorrhagic crusting on the frontal scalp. He had a history of nonmelanoma skin cancers. A biopsy revealed a well-differentiated cSCC, which was upgraded from a T2a tumor to T2b during MMS due to galea involvement. Debulk analysis revealed moderate to poorly differentiated cSCC, with the least-differentiated cells at the deep margin (Figure 1A). Given T2b staging, baseline imaging and radiation therapy were recommended.

A 75-year-old man (patient 2) presented with a 2-cm erythematous plaque on the left vertex scalp with hemorrhagic crusting, yellow scale, and purulent drainage. He had a history of cSCCs. A biopsy revealed well-differentiated invasive cSCC, which was upgraded from a T2a tumor to T2b during MMS due to tumor extension beyond the subcutaneous fat. Examination of the second Mohs stage revealed moderately differentiated cSCC, with the least-differentiated cells at the deep margin, infiltration beyond the subcutaneous fat, and perineural invasion (Figure 1B). Given T2b staging, baseline imaging and radiation therapy were recommended.

An 86-year-old woman (patient 3) presented with a tender 2.4-cm plum-colored nodule on the right lower leg. She had a history of basal cell carcinoma. A biopsy revealed a well-differentiated invasive cSCC staged at T2a. Debulk analysis revealed moderately differentiated cSCC, with the least-differentiated cells at the deep margin, though the staging remained the same (Figure 1C).

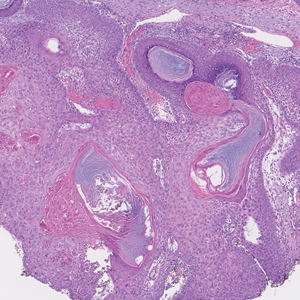

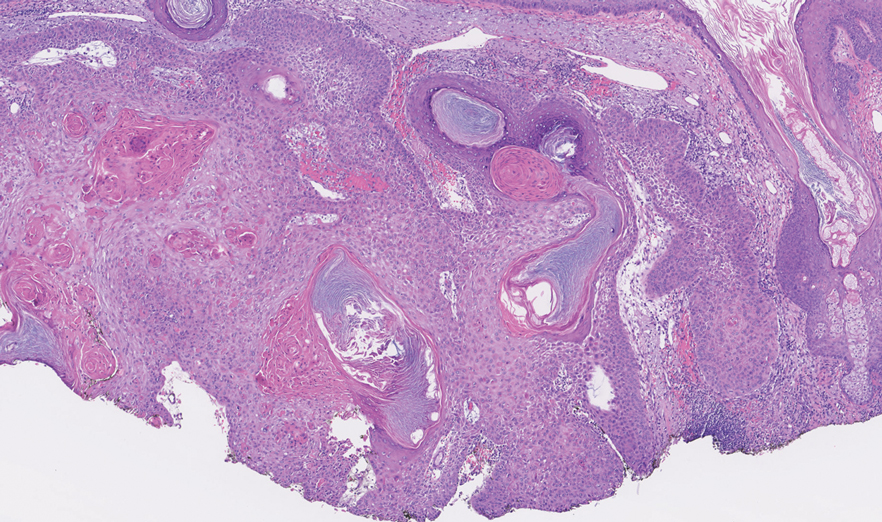

An 82-year-old man (patient 4) presented with a 2.7-cm ulcerated nodule with adjacent scaling on the vertex scalp. He had no history of skin cancer. A biopsy revealed a well-differentiated cSCC (Figure 2) that was upgraded from a T2a tumor to T2b during MMS due to tumor extension beyond the subcutaneous fat. Debulk analysis revealed moderate to poorly differentiated cSCC, with the least-differentiated cells with single-cell extension at the deep margin in the galea (Figure 1D). Given T2b staging, baseline imaging and radiation therapy were recommended.

Tumor differentiation is a factor included in the Brigham and Women’s Hospital staging system, and intratumor variability can be clinically relevant for tumor staging.1 Specifically, cSCCs may exhibit intratumor heterogeneity in which predominantly well-differentiated tumors contain focal areas of poorer differentiation.2 This intratumor heterogeneity complicates estimation of tumor risk, as a well-differentiated tumor on biopsy may exhibit poor differentiation at a deeper margin. Our cases highlight that the cells at the deeper margin indeed can show poorer differentiation or other higher-risk tumor features. Thus, the most clinically relevant cells for tumor staging and prognostication may not be visible on initial biopsy, underscoring the utility of close examination of the deep layer of the debulk specimen and Mohs layer for comprehensive staging.

Genetic studies have attempted to identify gene expression patterns in cSCCs that predispose to invasion.3 Three of the top 6 genes in this “invasion signature gene set” were matrix metalloproteases; additionally, IL-24 messenger RNA was upregulated in both the cSCC invasion front and in situ cSCCs. IL-24 has been shown to upregulate the expression of matrix metalloprotease 7 in vitro, suggesting that it may influence tumor progression.3 Although gene expression was not included in this series, the identification of genetic variability in the most poorly differentiated cells residing in the deep margins is of great interest and may reveal mutations contributing to irregular cell morphology and cSCC invasiveness.

Prior studies have indicated that a proportion of cSCCs are histopathologically upgraded from the initial biopsy during MMS due to evidence of perineural invasion, bony invasion, or lesser differentiation noted during MMS stages or debulk analysis.1,4 However, the majority of Mohs surgeons report immediately discarding debulk specimens without further evaluation.5 Herein, we highlight 4 cSCC cases in which the deep margins of the debulk specimen contained the most dedifferentiated cells. Our findings emphasize the importance of thoroughly examining deep tumor margins for complete staging yet also highlight that identifying cells at these margins may not change patient management when high-risk criteria are already met.

- McIlwee BE, Abidi NY, Ravi M, et al. Utility of debulk specimens during Mohs micrographic surgery for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:599-604.

- Ramón y Cajal S, Sesé M, Capdevila C, et al. Clinical implications of intratumor heterogeneity: challenges and opportunities. J Mol Med. 2020;98:161-177.

- Mitsui H, Suárez-Fariñas M, Gulati N, et al. Gene expression profiling of the leading edge of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: IL-24-driven MMP-7. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1418-1427.

- Chung E, Hoang S, McEvoy AM, et al. Histopathologic upgrading of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas during Mohs micrographic surgery: a retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:923-930.

- Alniemi DT, Swanson AM, Lasarev M, et al. Tumor debulking trends for keratinocyte carcinomas among Mohs surgeons. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1660-1661.

To the Editor:

Histopathologic analysis of debulk specimens in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) may augment identification of high-risk factors in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC), which may warrant tumor upstaging.1 Intratumor location has not been studied when looking at these high-risk factors. Herein, we report 4 cSCCs initially categorized as well differentiated that were reclassified as moderate to poorly differentiated on analysis of debulk specimens obtained via shave removal.

An 80-year-old man (patient 1) presented with a tender 2-cm erythematous plaque with dried hemorrhagic crusting on the frontal scalp. He had a history of nonmelanoma skin cancers. A biopsy revealed a well-differentiated cSCC, which was upgraded from a T2a tumor to T2b during MMS due to galea involvement. Debulk analysis revealed moderate to poorly differentiated cSCC, with the least-differentiated cells at the deep margin (Figure 1A). Given T2b staging, baseline imaging and radiation therapy were recommended.

A 75-year-old man (patient 2) presented with a 2-cm erythematous plaque on the left vertex scalp with hemorrhagic crusting, yellow scale, and purulent drainage. He had a history of cSCCs. A biopsy revealed well-differentiated invasive cSCC, which was upgraded from a T2a tumor to T2b during MMS due to tumor extension beyond the subcutaneous fat. Examination of the second Mohs stage revealed moderately differentiated cSCC, with the least-differentiated cells at the deep margin, infiltration beyond the subcutaneous fat, and perineural invasion (Figure 1B). Given T2b staging, baseline imaging and radiation therapy were recommended.

An 86-year-old woman (patient 3) presented with a tender 2.4-cm plum-colored nodule on the right lower leg. She had a history of basal cell carcinoma. A biopsy revealed a well-differentiated invasive cSCC staged at T2a. Debulk analysis revealed moderately differentiated cSCC, with the least-differentiated cells at the deep margin, though the staging remained the same (Figure 1C).

An 82-year-old man (patient 4) presented with a 2.7-cm ulcerated nodule with adjacent scaling on the vertex scalp. He had no history of skin cancer. A biopsy revealed a well-differentiated cSCC (Figure 2) that was upgraded from a T2a tumor to T2b during MMS due to tumor extension beyond the subcutaneous fat. Debulk analysis revealed moderate to poorly differentiated cSCC, with the least-differentiated cells with single-cell extension at the deep margin in the galea (Figure 1D). Given T2b staging, baseline imaging and radiation therapy were recommended.

Tumor differentiation is a factor included in the Brigham and Women’s Hospital staging system, and intratumor variability can be clinically relevant for tumor staging.1 Specifically, cSCCs may exhibit intratumor heterogeneity in which predominantly well-differentiated tumors contain focal areas of poorer differentiation.2 This intratumor heterogeneity complicates estimation of tumor risk, as a well-differentiated tumor on biopsy may exhibit poor differentiation at a deeper margin. Our cases highlight that the cells at the deeper margin indeed can show poorer differentiation or other higher-risk tumor features. Thus, the most clinically relevant cells for tumor staging and prognostication may not be visible on initial biopsy, underscoring the utility of close examination of the deep layer of the debulk specimen and Mohs layer for comprehensive staging.

Genetic studies have attempted to identify gene expression patterns in cSCCs that predispose to invasion.3 Three of the top 6 genes in this “invasion signature gene set” were matrix metalloproteases; additionally, IL-24 messenger RNA was upregulated in both the cSCC invasion front and in situ cSCCs. IL-24 has been shown to upregulate the expression of matrix metalloprotease 7 in vitro, suggesting that it may influence tumor progression.3 Although gene expression was not included in this series, the identification of genetic variability in the most poorly differentiated cells residing in the deep margins is of great interest and may reveal mutations contributing to irregular cell morphology and cSCC invasiveness.

Prior studies have indicated that a proportion of cSCCs are histopathologically upgraded from the initial biopsy during MMS due to evidence of perineural invasion, bony invasion, or lesser differentiation noted during MMS stages or debulk analysis.1,4 However, the majority of Mohs surgeons report immediately discarding debulk specimens without further evaluation.5 Herein, we highlight 4 cSCC cases in which the deep margins of the debulk specimen contained the most dedifferentiated cells. Our findings emphasize the importance of thoroughly examining deep tumor margins for complete staging yet also highlight that identifying cells at these margins may not change patient management when high-risk criteria are already met.

To the Editor:

Histopathologic analysis of debulk specimens in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) may augment identification of high-risk factors in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC), which may warrant tumor upstaging.1 Intratumor location has not been studied when looking at these high-risk factors. Herein, we report 4 cSCCs initially categorized as well differentiated that were reclassified as moderate to poorly differentiated on analysis of debulk specimens obtained via shave removal.

An 80-year-old man (patient 1) presented with a tender 2-cm erythematous plaque with dried hemorrhagic crusting on the frontal scalp. He had a history of nonmelanoma skin cancers. A biopsy revealed a well-differentiated cSCC, which was upgraded from a T2a tumor to T2b during MMS due to galea involvement. Debulk analysis revealed moderate to poorly differentiated cSCC, with the least-differentiated cells at the deep margin (Figure 1A). Given T2b staging, baseline imaging and radiation therapy were recommended.

A 75-year-old man (patient 2) presented with a 2-cm erythematous plaque on the left vertex scalp with hemorrhagic crusting, yellow scale, and purulent drainage. He had a history of cSCCs. A biopsy revealed well-differentiated invasive cSCC, which was upgraded from a T2a tumor to T2b during MMS due to tumor extension beyond the subcutaneous fat. Examination of the second Mohs stage revealed moderately differentiated cSCC, with the least-differentiated cells at the deep margin, infiltration beyond the subcutaneous fat, and perineural invasion (Figure 1B). Given T2b staging, baseline imaging and radiation therapy were recommended.

An 86-year-old woman (patient 3) presented with a tender 2.4-cm plum-colored nodule on the right lower leg. She had a history of basal cell carcinoma. A biopsy revealed a well-differentiated invasive cSCC staged at T2a. Debulk analysis revealed moderately differentiated cSCC, with the least-differentiated cells at the deep margin, though the staging remained the same (Figure 1C).

An 82-year-old man (patient 4) presented with a 2.7-cm ulcerated nodule with adjacent scaling on the vertex scalp. He had no history of skin cancer. A biopsy revealed a well-differentiated cSCC (Figure 2) that was upgraded from a T2a tumor to T2b during MMS due to tumor extension beyond the subcutaneous fat. Debulk analysis revealed moderate to poorly differentiated cSCC, with the least-differentiated cells with single-cell extension at the deep margin in the galea (Figure 1D). Given T2b staging, baseline imaging and radiation therapy were recommended.

Tumor differentiation is a factor included in the Brigham and Women’s Hospital staging system, and intratumor variability can be clinically relevant for tumor staging.1 Specifically, cSCCs may exhibit intratumor heterogeneity in which predominantly well-differentiated tumors contain focal areas of poorer differentiation.2 This intratumor heterogeneity complicates estimation of tumor risk, as a well-differentiated tumor on biopsy may exhibit poor differentiation at a deeper margin. Our cases highlight that the cells at the deeper margin indeed can show poorer differentiation or other higher-risk tumor features. Thus, the most clinically relevant cells for tumor staging and prognostication may not be visible on initial biopsy, underscoring the utility of close examination of the deep layer of the debulk specimen and Mohs layer for comprehensive staging.

Genetic studies have attempted to identify gene expression patterns in cSCCs that predispose to invasion.3 Three of the top 6 genes in this “invasion signature gene set” were matrix metalloproteases; additionally, IL-24 messenger RNA was upregulated in both the cSCC invasion front and in situ cSCCs. IL-24 has been shown to upregulate the expression of matrix metalloprotease 7 in vitro, suggesting that it may influence tumor progression.3 Although gene expression was not included in this series, the identification of genetic variability in the most poorly differentiated cells residing in the deep margins is of great interest and may reveal mutations contributing to irregular cell morphology and cSCC invasiveness.

Prior studies have indicated that a proportion of cSCCs are histopathologically upgraded from the initial biopsy during MMS due to evidence of perineural invasion, bony invasion, or lesser differentiation noted during MMS stages or debulk analysis.1,4 However, the majority of Mohs surgeons report immediately discarding debulk specimens without further evaluation.5 Herein, we highlight 4 cSCC cases in which the deep margins of the debulk specimen contained the most dedifferentiated cells. Our findings emphasize the importance of thoroughly examining deep tumor margins for complete staging yet also highlight that identifying cells at these margins may not change patient management when high-risk criteria are already met.

- McIlwee BE, Abidi NY, Ravi M, et al. Utility of debulk specimens during Mohs micrographic surgery for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:599-604.

- Ramón y Cajal S, Sesé M, Capdevila C, et al. Clinical implications of intratumor heterogeneity: challenges and opportunities. J Mol Med. 2020;98:161-177.

- Mitsui H, Suárez-Fariñas M, Gulati N, et al. Gene expression profiling of the leading edge of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: IL-24-driven MMP-7. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1418-1427.

- Chung E, Hoang S, McEvoy AM, et al. Histopathologic upgrading of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas during Mohs micrographic surgery: a retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:923-930.

- Alniemi DT, Swanson AM, Lasarev M, et al. Tumor debulking trends for keratinocyte carcinomas among Mohs surgeons. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1660-1661.

- McIlwee BE, Abidi NY, Ravi M, et al. Utility of debulk specimens during Mohs micrographic surgery for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:599-604.

- Ramón y Cajal S, Sesé M, Capdevila C, et al. Clinical implications of intratumor heterogeneity: challenges and opportunities. J Mol Med. 2020;98:161-177.

- Mitsui H, Suárez-Fariñas M, Gulati N, et al. Gene expression profiling of the leading edge of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: IL-24-driven MMP-7. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1418-1427.

- Chung E, Hoang S, McEvoy AM, et al. Histopathologic upgrading of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas during Mohs micrographic surgery: a retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:923-930.

- Alniemi DT, Swanson AM, Lasarev M, et al. Tumor debulking trends for keratinocyte carcinomas among Mohs surgeons. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1660-1661.

Practice Points

- A proportion of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas are upgraded from the initial biopsy during Mohs micrographic surgery due to evidence of perineural invasion, bony invasion, or lesser differentiation noted on Mohs stages or debulk analysis.

- Thorough inspection of the deep tumor margins may be required for accurate tumor staging and evaluation of metastatic risk. Cells at the deep margin of the tumor may demonstrate poorer differentiation and/or other higher-risk tumor features than those closer to the surface.

- Tumor staging may be incomplete until the deep margins are assessed to find the most dysplastic and likely clinically relevant cells, which may be missed without evaluation of the debulked tumor.

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type II After a Brachial Plexus and C6 Nerve Root Injury

To the Editor:

A 62-year-old man presented with an atrophied painful left arm of 17 years’ duration that began when he was hit by a car as a pedestrian. He sustained severe multisystem injuries from the accident, including left brachial plexus and C6 nerve root avulsion injury. When he regained consciousness after 6 weeks in the intensive care unit, he immediately noted diffuse pain throughout the body, especially in the left arm. Since the accident, the patient continued to have diminished sensation to touch and temperature in the left arm. He also had burning, throbbing, and electrical pain in the left arm with light touch as well as spontaneously. He was thoroughly evaluated by a neurologist and was diagnosed with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) type II. For the treatment of pain, dorsal column stimulation and hemilaminectomy with exploration of the avulsed nerve root were attempted, both of which had minimal effect. He was maintained on hydromorphone, methadone, and oxazepam. He reported that for many years he was unable move out of bed due to the unbearable pain. With pain medications, he was able to regain most of his independence in his daily life, though the pain and other clinical aspects of CRPS still completely limited his use of the left arm.

Physical examination revealed glossy, cold, hairless skin with hypohidrosis of the left arm, forearm, and hand (Figures 1 and 2A). The left arm was conspicuously atrophied, with the forearm and hand erythematous. The fingers were taut, contracted, and edematous (Figure 2B), and the skin was unable to be pinched. The fingernails on the left hand had dystrophic changes including yellow color and brittleness with longitudinal ridges (Figure 3). The patient could activate the left bicep and tricep muscles against gravity but had minimal function of the deltoid muscle. He also had minimal movement of the left index finger and was unable to move any other digits of the left hand. The patient was continued on pain management treatments and physical therapy for his condition.

Complex regional pain syndrome is a neuropathic disorder of the extremities characterized by pain and a variety of autonomic and motor disturbances such as local edema, limited active range of motion, and vasomotor and trophic skin changes. There are 2 types of CRPS: type II is marked by explicit nerve injury and type I is not. The pathophysiology of CRPS is unknown.1-3

There is no definite set of diagnostic criteria for CRPS. The lack of any gold-standard diagnostic test for CRPS has made arriving at one valid, widely accepted set of diagnostic criteria impossible.1 There are 4 widely used sets of diagnostic criteria. One is the International Association for the Study of Pain diagnostic criteria defined in 1994.4 However, the criteria rely entirely on subjective symptoms and have been under great scrutiny due to their questionable validity.2 Veldman et al5 presented other widely used CRPS diagnostic criteria in their prospective study of 829 reflex sympathetic dystrophy patients, which paid particular attention to the early clinical manifestations of CRPS. In 1999, Bruehl et al2 proposed their own modified diagnostic criteria, which required physician-assessed signs in 2 of 4 categories to avoid the practice of exclusively relying on subjective symptoms. In addition, during a consensus meeting in Budapest, Hungary, a modified version of the Bruehl criteria was proposed.6 All 4 criteria rely solely on detailed history and physical examination, and the choice of diagnostic criteria remains subjective.

The pathophysiology of CRPS also remains unclear. There are several proposed mechanisms such as sympathetic nervous system dysfunction, abnormal inflammatory response, and central nervous system involvement.1 Psychologic factors, sequelae of nerve injury, and genetic predisposition also have been implicated in the pathophysiology of CRPS.1 It is likely that several mechanisms variably contribute to each presentation of CRPS.

Many dermatologic findings, in addition to neuromuscular symptoms, accompany CRPS and serve as important clues to making the clinical diagnosis. Complex regional pain syndrome has been thought to have 3 distinct sequential stages of CRPS.1,3,7 Stage 1—the acute stage—is marked by hyperalgesia, allodynia, sudomotor disturbances, and prominent edema. Stage 2—the dystrophic stage—is characterized by more marked pain and sensory dysfunction, vasomotor dysfunction, development of motor dysfunction, soft tissue edema, skin and articular soft tissue thickening, and development of dystrophic nail changes. Stage 3—the atrophic stage—is marked by decreased pain and sensory disturbances, markedly increased motor dysfunction, waxy atrophic skin changes, progression of dystrophic nail changes, and skeletal cystic and subchondral erosions with diffuse osteoporosis.1,3,7

The staging model, however, has been called into question.3 In a cluster analysis, Bruehl et al3 arrived at 3 relatively consistent CRPS patient subgroups that did not have notably different pain duration, suggesting the existence of 3 CRPS subtypes, not stages. Their study found that one of the subgroups best represented the clinical presentation of CRPS type II. This subgroup had the greatest pain and sensory abnormalities and the least vasomotor dysfunction of all 3 subgroups. Nonetheless, this study has not settled the discussion, as it only included 113 patients.3 Thus, with future studies, our understanding of CRPS in stages may change, which likely will impact how the clinical diagnosis is made.

There is a lack of high-quality evidence for most treatment interventions for CRPS8; however, the current practice is to use an interdisciplinary approach.1,9,10 The main therapeutic arm of this approach is rehabilitation; physical and occupational therapy can help improve range of motion, contracture, and atrophy. The other 2 arms of the approach are psychologic therapy to improve quality of life and pain management with pharmacologic therapy and/or invasive interventions. The choice of therapy remains empirical; trial and error should be expected in developing an adequate treatment plan for each individual patient.

Many aspects of CRPS remain unclear, and even our current understanding of the disease will inevitably change over time. The syndrome can cause life-changing morbidities in patients, and late diagnosis and treatment are associated with poor prognosis. Because there are many dermatologic findings associated with the disorder, it is crucial for dermatologists to clinically recognize the disorder and to refer patients to appropriate channels so that treatment can be started as soon as possible.

- Borchers A, Gershwin M. Complex regional pain syndrome: a comprehensive and critical review. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:242-265.

- Bruehl S, Harden RN, Galer BS, et al. External validation of IASP diagnostic criteria for complex regional pain syndrome and proposed research diagnostic criteria. International Association for the Study of Pain. Pain. 1999;81:147-154.

- Bruehl S, Harden RN, Gaker BS, et al. Complex regional pain syndrome: are there distinct subtypes and sequential stages of the syndrome? Pain. 2002;95:119-124.

- Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of Chronic Pain: Descriptions of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of Pain Terms. 2nd ed. Seattle, WA: IASP Press; 1994.

- Veldman PH, Reynen HM, Arntz IE, et al. Signs and symptoms of reflex sympathetic dystrophy: prospective study of 829 patients. Lancet. 1993;342:1012-1016.

- Harden RN, Bruehl S, Perez RS, et al. Validation of proposed diagnostic criteria (the “Budapest Criteria”) for complex regional pain syndrome. Pain. 2010;150:268-274.

- Sebastin SJ. Complex regional pain syndrome. Indian J Plast Surg. 2011;44:298-307.

- O’Connell NE, Wand BM, McAuley J, et al. Interventions for treating pain and disability in adults with complex regional pain syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;4:CD009416.

- Hsu ES. Practical management of complex regional pain syndrome. Am J Ther. 2009;16:147-154.

- Stanton-Hicks MD, Burton AW, Bruehl SP, et al. An updated interdisciplinary clinical pathway for CRPS: report of an expert panel. Pain Pract. 2002;2:1-16.

To the Editor:

A 62-year-old man presented with an atrophied painful left arm of 17 years’ duration that began when he was hit by a car as a pedestrian. He sustained severe multisystem injuries from the accident, including left brachial plexus and C6 nerve root avulsion injury. When he regained consciousness after 6 weeks in the intensive care unit, he immediately noted diffuse pain throughout the body, especially in the left arm. Since the accident, the patient continued to have diminished sensation to touch and temperature in the left arm. He also had burning, throbbing, and electrical pain in the left arm with light touch as well as spontaneously. He was thoroughly evaluated by a neurologist and was diagnosed with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) type II. For the treatment of pain, dorsal column stimulation and hemilaminectomy with exploration of the avulsed nerve root were attempted, both of which had minimal effect. He was maintained on hydromorphone, methadone, and oxazepam. He reported that for many years he was unable move out of bed due to the unbearable pain. With pain medications, he was able to regain most of his independence in his daily life, though the pain and other clinical aspects of CRPS still completely limited his use of the left arm.

Physical examination revealed glossy, cold, hairless skin with hypohidrosis of the left arm, forearm, and hand (Figures 1 and 2A). The left arm was conspicuously atrophied, with the forearm and hand erythematous. The fingers were taut, contracted, and edematous (Figure 2B), and the skin was unable to be pinched. The fingernails on the left hand had dystrophic changes including yellow color and brittleness with longitudinal ridges (Figure 3). The patient could activate the left bicep and tricep muscles against gravity but had minimal function of the deltoid muscle. He also had minimal movement of the left index finger and was unable to move any other digits of the left hand. The patient was continued on pain management treatments and physical therapy for his condition.

Complex regional pain syndrome is a neuropathic disorder of the extremities characterized by pain and a variety of autonomic and motor disturbances such as local edema, limited active range of motion, and vasomotor and trophic skin changes. There are 2 types of CRPS: type II is marked by explicit nerve injury and type I is not. The pathophysiology of CRPS is unknown.1-3

There is no definite set of diagnostic criteria for CRPS. The lack of any gold-standard diagnostic test for CRPS has made arriving at one valid, widely accepted set of diagnostic criteria impossible.1 There are 4 widely used sets of diagnostic criteria. One is the International Association for the Study of Pain diagnostic criteria defined in 1994.4 However, the criteria rely entirely on subjective symptoms and have been under great scrutiny due to their questionable validity.2 Veldman et al5 presented other widely used CRPS diagnostic criteria in their prospective study of 829 reflex sympathetic dystrophy patients, which paid particular attention to the early clinical manifestations of CRPS. In 1999, Bruehl et al2 proposed their own modified diagnostic criteria, which required physician-assessed signs in 2 of 4 categories to avoid the practice of exclusively relying on subjective symptoms. In addition, during a consensus meeting in Budapest, Hungary, a modified version of the Bruehl criteria was proposed.6 All 4 criteria rely solely on detailed history and physical examination, and the choice of diagnostic criteria remains subjective.

The pathophysiology of CRPS also remains unclear. There are several proposed mechanisms such as sympathetic nervous system dysfunction, abnormal inflammatory response, and central nervous system involvement.1 Psychologic factors, sequelae of nerve injury, and genetic predisposition also have been implicated in the pathophysiology of CRPS.1 It is likely that several mechanisms variably contribute to each presentation of CRPS.

Many dermatologic findings, in addition to neuromuscular symptoms, accompany CRPS and serve as important clues to making the clinical diagnosis. Complex regional pain syndrome has been thought to have 3 distinct sequential stages of CRPS.1,3,7 Stage 1—the acute stage—is marked by hyperalgesia, allodynia, sudomotor disturbances, and prominent edema. Stage 2—the dystrophic stage—is characterized by more marked pain and sensory dysfunction, vasomotor dysfunction, development of motor dysfunction, soft tissue edema, skin and articular soft tissue thickening, and development of dystrophic nail changes. Stage 3—the atrophic stage—is marked by decreased pain and sensory disturbances, markedly increased motor dysfunction, waxy atrophic skin changes, progression of dystrophic nail changes, and skeletal cystic and subchondral erosions with diffuse osteoporosis.1,3,7

The staging model, however, has been called into question.3 In a cluster analysis, Bruehl et al3 arrived at 3 relatively consistent CRPS patient subgroups that did not have notably different pain duration, suggesting the existence of 3 CRPS subtypes, not stages. Their study found that one of the subgroups best represented the clinical presentation of CRPS type II. This subgroup had the greatest pain and sensory abnormalities and the least vasomotor dysfunction of all 3 subgroups. Nonetheless, this study has not settled the discussion, as it only included 113 patients.3 Thus, with future studies, our understanding of CRPS in stages may change, which likely will impact how the clinical diagnosis is made.

There is a lack of high-quality evidence for most treatment interventions for CRPS8; however, the current practice is to use an interdisciplinary approach.1,9,10 The main therapeutic arm of this approach is rehabilitation; physical and occupational therapy can help improve range of motion, contracture, and atrophy. The other 2 arms of the approach are psychologic therapy to improve quality of life and pain management with pharmacologic therapy and/or invasive interventions. The choice of therapy remains empirical; trial and error should be expected in developing an adequate treatment plan for each individual patient.

Many aspects of CRPS remain unclear, and even our current understanding of the disease will inevitably change over time. The syndrome can cause life-changing morbidities in patients, and late diagnosis and treatment are associated with poor prognosis. Because there are many dermatologic findings associated with the disorder, it is crucial for dermatologists to clinically recognize the disorder and to refer patients to appropriate channels so that treatment can be started as soon as possible.

To the Editor:

A 62-year-old man presented with an atrophied painful left arm of 17 years’ duration that began when he was hit by a car as a pedestrian. He sustained severe multisystem injuries from the accident, including left brachial plexus and C6 nerve root avulsion injury. When he regained consciousness after 6 weeks in the intensive care unit, he immediately noted diffuse pain throughout the body, especially in the left arm. Since the accident, the patient continued to have diminished sensation to touch and temperature in the left arm. He also had burning, throbbing, and electrical pain in the left arm with light touch as well as spontaneously. He was thoroughly evaluated by a neurologist and was diagnosed with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) type II. For the treatment of pain, dorsal column stimulation and hemilaminectomy with exploration of the avulsed nerve root were attempted, both of which had minimal effect. He was maintained on hydromorphone, methadone, and oxazepam. He reported that for many years he was unable move out of bed due to the unbearable pain. With pain medications, he was able to regain most of his independence in his daily life, though the pain and other clinical aspects of CRPS still completely limited his use of the left arm.

Physical examination revealed glossy, cold, hairless skin with hypohidrosis of the left arm, forearm, and hand (Figures 1 and 2A). The left arm was conspicuously atrophied, with the forearm and hand erythematous. The fingers were taut, contracted, and edematous (Figure 2B), and the skin was unable to be pinched. The fingernails on the left hand had dystrophic changes including yellow color and brittleness with longitudinal ridges (Figure 3). The patient could activate the left bicep and tricep muscles against gravity but had minimal function of the deltoid muscle. He also had minimal movement of the left index finger and was unable to move any other digits of the left hand. The patient was continued on pain management treatments and physical therapy for his condition.

Complex regional pain syndrome is a neuropathic disorder of the extremities characterized by pain and a variety of autonomic and motor disturbances such as local edema, limited active range of motion, and vasomotor and trophic skin changes. There are 2 types of CRPS: type II is marked by explicit nerve injury and type I is not. The pathophysiology of CRPS is unknown.1-3

There is no definite set of diagnostic criteria for CRPS. The lack of any gold-standard diagnostic test for CRPS has made arriving at one valid, widely accepted set of diagnostic criteria impossible.1 There are 4 widely used sets of diagnostic criteria. One is the International Association for the Study of Pain diagnostic criteria defined in 1994.4 However, the criteria rely entirely on subjective symptoms and have been under great scrutiny due to their questionable validity.2 Veldman et al5 presented other widely used CRPS diagnostic criteria in their prospective study of 829 reflex sympathetic dystrophy patients, which paid particular attention to the early clinical manifestations of CRPS. In 1999, Bruehl et al2 proposed their own modified diagnostic criteria, which required physician-assessed signs in 2 of 4 categories to avoid the practice of exclusively relying on subjective symptoms. In addition, during a consensus meeting in Budapest, Hungary, a modified version of the Bruehl criteria was proposed.6 All 4 criteria rely solely on detailed history and physical examination, and the choice of diagnostic criteria remains subjective.

The pathophysiology of CRPS also remains unclear. There are several proposed mechanisms such as sympathetic nervous system dysfunction, abnormal inflammatory response, and central nervous system involvement.1 Psychologic factors, sequelae of nerve injury, and genetic predisposition also have been implicated in the pathophysiology of CRPS.1 It is likely that several mechanisms variably contribute to each presentation of CRPS.

Many dermatologic findings, in addition to neuromuscular symptoms, accompany CRPS and serve as important clues to making the clinical diagnosis. Complex regional pain syndrome has been thought to have 3 distinct sequential stages of CRPS.1,3,7 Stage 1—the acute stage—is marked by hyperalgesia, allodynia, sudomotor disturbances, and prominent edema. Stage 2—the dystrophic stage—is characterized by more marked pain and sensory dysfunction, vasomotor dysfunction, development of motor dysfunction, soft tissue edema, skin and articular soft tissue thickening, and development of dystrophic nail changes. Stage 3—the atrophic stage—is marked by decreased pain and sensory disturbances, markedly increased motor dysfunction, waxy atrophic skin changes, progression of dystrophic nail changes, and skeletal cystic and subchondral erosions with diffuse osteoporosis.1,3,7

The staging model, however, has been called into question.3 In a cluster analysis, Bruehl et al3 arrived at 3 relatively consistent CRPS patient subgroups that did not have notably different pain duration, suggesting the existence of 3 CRPS subtypes, not stages. Their study found that one of the subgroups best represented the clinical presentation of CRPS type II. This subgroup had the greatest pain and sensory abnormalities and the least vasomotor dysfunction of all 3 subgroups. Nonetheless, this study has not settled the discussion, as it only included 113 patients.3 Thus, with future studies, our understanding of CRPS in stages may change, which likely will impact how the clinical diagnosis is made.

There is a lack of high-quality evidence for most treatment interventions for CRPS8; however, the current practice is to use an interdisciplinary approach.1,9,10 The main therapeutic arm of this approach is rehabilitation; physical and occupational therapy can help improve range of motion, contracture, and atrophy. The other 2 arms of the approach are psychologic therapy to improve quality of life and pain management with pharmacologic therapy and/or invasive interventions. The choice of therapy remains empirical; trial and error should be expected in developing an adequate treatment plan for each individual patient.

Many aspects of CRPS remain unclear, and even our current understanding of the disease will inevitably change over time. The syndrome can cause life-changing morbidities in patients, and late diagnosis and treatment are associated with poor prognosis. Because there are many dermatologic findings associated with the disorder, it is crucial for dermatologists to clinically recognize the disorder and to refer patients to appropriate channels so that treatment can be started as soon as possible.

- Borchers A, Gershwin M. Complex regional pain syndrome: a comprehensive and critical review. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:242-265.

- Bruehl S, Harden RN, Galer BS, et al. External validation of IASP diagnostic criteria for complex regional pain syndrome and proposed research diagnostic criteria. International Association for the Study of Pain. Pain. 1999;81:147-154.

- Bruehl S, Harden RN, Gaker BS, et al. Complex regional pain syndrome: are there distinct subtypes and sequential stages of the syndrome? Pain. 2002;95:119-124.

- Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of Chronic Pain: Descriptions of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of Pain Terms. 2nd ed. Seattle, WA: IASP Press; 1994.

- Veldman PH, Reynen HM, Arntz IE, et al. Signs and symptoms of reflex sympathetic dystrophy: prospective study of 829 patients. Lancet. 1993;342:1012-1016.

- Harden RN, Bruehl S, Perez RS, et al. Validation of proposed diagnostic criteria (the “Budapest Criteria”) for complex regional pain syndrome. Pain. 2010;150:268-274.

- Sebastin SJ. Complex regional pain syndrome. Indian J Plast Surg. 2011;44:298-307.

- O’Connell NE, Wand BM, McAuley J, et al. Interventions for treating pain and disability in adults with complex regional pain syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;4:CD009416.

- Hsu ES. Practical management of complex regional pain syndrome. Am J Ther. 2009;16:147-154.

- Stanton-Hicks MD, Burton AW, Bruehl SP, et al. An updated interdisciplinary clinical pathway for CRPS: report of an expert panel. Pain Pract. 2002;2:1-16.

- Borchers A, Gershwin M. Complex regional pain syndrome: a comprehensive and critical review. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:242-265.

- Bruehl S, Harden RN, Galer BS, et al. External validation of IASP diagnostic criteria for complex regional pain syndrome and proposed research diagnostic criteria. International Association for the Study of Pain. Pain. 1999;81:147-154.

- Bruehl S, Harden RN, Gaker BS, et al. Complex regional pain syndrome: are there distinct subtypes and sequential stages of the syndrome? Pain. 2002;95:119-124.

- Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of Chronic Pain: Descriptions of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of Pain Terms. 2nd ed. Seattle, WA: IASP Press; 1994.

- Veldman PH, Reynen HM, Arntz IE, et al. Signs and symptoms of reflex sympathetic dystrophy: prospective study of 829 patients. Lancet. 1993;342:1012-1016.

- Harden RN, Bruehl S, Perez RS, et al. Validation of proposed diagnostic criteria (the “Budapest Criteria”) for complex regional pain syndrome. Pain. 2010;150:268-274.

- Sebastin SJ. Complex regional pain syndrome. Indian J Plast Surg. 2011;44:298-307.

- O’Connell NE, Wand BM, McAuley J, et al. Interventions for treating pain and disability in adults with complex regional pain syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;4:CD009416.

- Hsu ES. Practical management of complex regional pain syndrome. Am J Ther. 2009;16:147-154.

- Stanton-Hicks MD, Burton AW, Bruehl SP, et al. An updated interdisciplinary clinical pathway for CRPS: report of an expert panel. Pain Pract. 2002;2:1-16.

Practice Points

- Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a neuropathic disorder of the extremities characterized by pain, a variety of autonomic and motor disturbances, and dermatologic findings.

- Early recognition of CRPS is critical, as it presents life-changing morbidities to patients.

- A multidisciplinary treatment approach with physical therapy, occupational therapy, psychological support, and pain control is needed for the management of CRPS.

Gottron Papules Mimicking Dermatomyositis: An Unusual Manifestation of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

To the Editor:

An 11-year-old girl presented to the dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic rash on the bilateral forearms, dorsal hands, and ears of 1 month’s duration. Recent history was notable for persistent low-grade fevers, dizziness, headaches, arthralgia, and swelling of multiple joints, as well as difficulty ambulating due to the joint pain. A thorough review of systems revealed no photosensitivity, oral sores, weight loss, pulmonary symptoms, Raynaud phenomenon, or dysphagia.

Medical history was notable for presumed viral pancreatitis and transaminitis requiring inpatient hospitalization 1 year prior to presentation. The patient underwent extensive workup at that time, which was notable for a positive antinuclear antibody level of 1:2560, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate level of 75 mm/h (reference range, 0–22 mm/h), hemolytic anemia with a hemoglobin of 10.9 g/dL (14.0–17.5 g/dL), and leukopenia with a white blood cell count of 3700/µL (4500–11,000/µL). Additional laboratory tests were performed and were found to be within reference range, including creatine kinase, aldolase, complete metabolic panel, extractable nuclear antigen, complement levels, C-reactive protein level, antiphospholipid antibodies,partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, anti–double-stranded DNA, rheumatoid factor, β2-glycoprotein, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody tests. Skin purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test and chest radiograph also were unremarkable. The patient also was evaluated and found negative for Wilson disease, hemochromatosis, α1-antitrypsin disease, and autoimmune hepatitis.

Physical examination revealed erythematous plaques with crusted hyperpigmented erosions and central hypopigmentation on the bilateral conchal bowls and antihelices, findings characteristic of discoid lupus erythematosus (Figure 1A). On the bilateral elbows, metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, there were firm, erythematous to violaceous, keratotic papules that were clinically suggestive of Gottron-like papules (Figures 1B and 1C). However, there were no lesions on the skin between the MCP, PIP, and distal interphalangeal joints. The MCP joints were associated with swelling and were tender to palpation. Examination of the fingernails showed dilated telangiectasia of the proximal nail folds and ragged hyperkeratotic cuticles of all 10 digits (Figure 1D). On the extensor aspects of the bilateral forearms, there were erythematous excoriated papules and papulovesicular lesions with central hemorrhagic crusting. The patient showed no shawl sign, heliotrope rash, calcinosis, malar rash, oral lesions, or hair loss.

Additional physical examinations performed by the neufigrology and rheumatology departments revealed no impairment of muscle strength, soreness of muscles, and muscular atrophy. Joint examination was notable for restriction in range of motion of the hands, hips, and ankles due to swelling and pain of the joints. Radiographs and ultrasound of the feet showed fluid accumulation and synovial thickening of the metatarsal phalangeal joints and one of the PIP joints of the right hand without erosion.

The patient did not undergo magnetic resonance imaging of muscles due to the lack of muscular symptoms and normal myositis laboratory markers. Dermatomyositis-specific antibody testing, such as anti–Jo-1 and anti–Mi-2, also was not performed.

After reviewing the biopsy results, laboratory findings, and clinical presentation, the patient was diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), as she met American College of Rheumatology criteria1 with the following: discoid rash, hemolytic anemia, positive antinuclear antibodies, and nonerosive arthritis. Due to her abnormal constellation of laboratory values and symptoms, she was evaluated by 2 pediatric rheumatologists at 2 different medical centers who agreed with a primary diagnosis of SLE rather than dermatomyositis sine myositis. The hemolytic anemia was attributed to underlying connective tissue disease, as the hemoglobin levels were found to be persistently low for 1 year prior to the diagnosis of systemic lupus, and there was no alternative cause of the hematologic disorder.

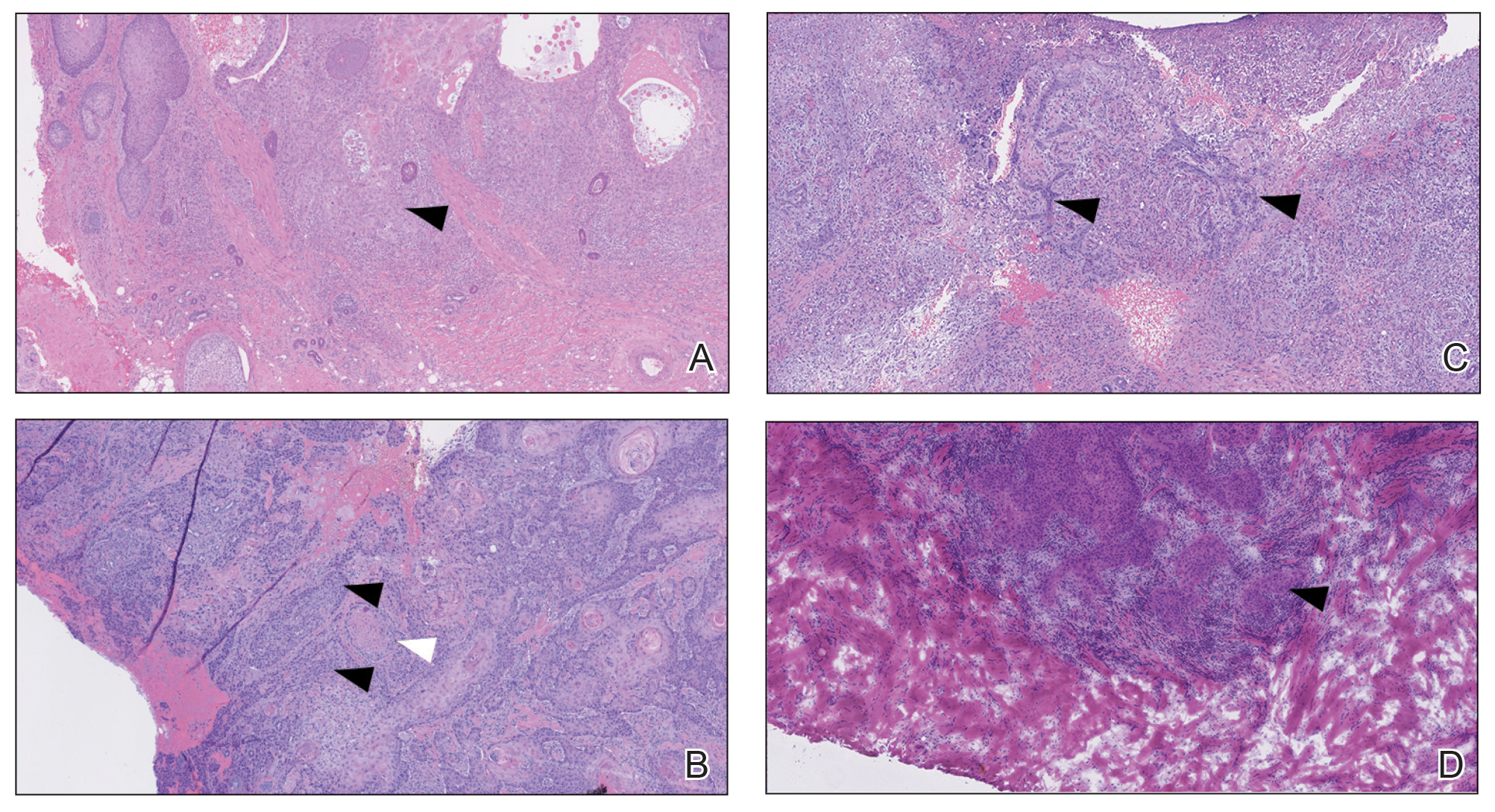

A punch biopsy obtained from a Gottron-like papule on the dorsal aspect of the left hand revealed lymphocytic interface dermatitis and slight thickening of the basement membrane zone (Figure 2A). There was a dense superficial and deep periadnexal and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation as well as increased dermal mucin, which can be seen in both lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis (Figure 2B). Perniosis also was considered from histologic findings but was excluded based on clinical history and physical findings. A second biopsy of the left conchal bowl showed hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, interface changes, follicular plugging, and basement membrane thickening. These findings can be seen in dermatomyositis, but when considered together with the clinical appearance of the patient’s eruption on the ears, they were more consistent with discoid lupus erythematosus (Figures 2C and 2D).

Finally, although ragged cuticles and proximal nail fold telangiectasia typically are seen in dermatomyositis, nail fold hyperkeratosis, ragged cuticles, and nail bed telangiectasia also have been reported in lupus erythematosus.2,3 Therefore, the findings overlying our patient’s knuckles and elbows can be considered Gottron-like papules in the setting of SLE.

Dermatomyositis has several characteristic dermatologic manifestations, including Gottron papules, shawl sign, facial heliotrope rash, periungual telangiectasia, and mechanic’s hands. Of them, Gottron papules have been the most pathognomonic, while the other skin findings are less specific and can be seen in other disease entities.4,5

The pathogenesis of Gottron papules in dermatomyositis remains largely unknown. Prior molecular studies have proposed that stretch CD44 variant 7 and abnormal osteopontin levels may contribute to the pathogenesis of Gottron papules by increasing local inflammation.6 Studies also have linked abnormal osteopontin levels and CD44 variant 7 expression with other diseases of autoimmunity, including lupus erythematosus.7 Because lupus erythematosus can have a large variety of cutaneous findings, Gottron-like papules may be considered a rare dermatologic presentation of lupus erythematosus.

We present a case of Gottron-like papules as an unusual dermatologic manifestation of SLE, challenging the concept of Gottron papules as a pathognomonic finding of dermatomyositis.

- Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725.

- Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74.

- Trüeb RM. Hair and nail involvement in lupus erythematosus. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:139-147.

- Koler RA, Montemarano A. Dermatomyositis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:1565-1572.

- Muro Y, Sugiura K, Akiyama M. Cutaneous manifestations in dermatomyositis: key clinical and serological features—a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51:293-302.

- Kim JS, Bashir MM, Werth VP. Gottron’s papules exhibit dermal accumulation of CD44 variant 7 (CD44v7) and its binding partner osteopontin: a unique molecular signature. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1825-1832.

- Kim JS, Werth VP. Identification of specific chondroitin sulfate species in cutaneous autoimmune disease. J Histochem Cytochem. 2011;59:780-790.

To the Editor:

An 11-year-old girl presented to the dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic rash on the bilateral forearms, dorsal hands, and ears of 1 month’s duration. Recent history was notable for persistent low-grade fevers, dizziness, headaches, arthralgia, and swelling of multiple joints, as well as difficulty ambulating due to the joint pain. A thorough review of systems revealed no photosensitivity, oral sores, weight loss, pulmonary symptoms, Raynaud phenomenon, or dysphagia.

Medical history was notable for presumed viral pancreatitis and transaminitis requiring inpatient hospitalization 1 year prior to presentation. The patient underwent extensive workup at that time, which was notable for a positive antinuclear antibody level of 1:2560, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate level of 75 mm/h (reference range, 0–22 mm/h), hemolytic anemia with a hemoglobin of 10.9 g/dL (14.0–17.5 g/dL), and leukopenia with a white blood cell count of 3700/µL (4500–11,000/µL). Additional laboratory tests were performed and were found to be within reference range, including creatine kinase, aldolase, complete metabolic panel, extractable nuclear antigen, complement levels, C-reactive protein level, antiphospholipid antibodies,partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, anti–double-stranded DNA, rheumatoid factor, β2-glycoprotein, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody tests. Skin purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test and chest radiograph also were unremarkable. The patient also was evaluated and found negative for Wilson disease, hemochromatosis, α1-antitrypsin disease, and autoimmune hepatitis.

Physical examination revealed erythematous plaques with crusted hyperpigmented erosions and central hypopigmentation on the bilateral conchal bowls and antihelices, findings characteristic of discoid lupus erythematosus (Figure 1A). On the bilateral elbows, metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, there were firm, erythematous to violaceous, keratotic papules that were clinically suggestive of Gottron-like papules (Figures 1B and 1C). However, there were no lesions on the skin between the MCP, PIP, and distal interphalangeal joints. The MCP joints were associated with swelling and were tender to palpation. Examination of the fingernails showed dilated telangiectasia of the proximal nail folds and ragged hyperkeratotic cuticles of all 10 digits (Figure 1D). On the extensor aspects of the bilateral forearms, there were erythematous excoriated papules and papulovesicular lesions with central hemorrhagic crusting. The patient showed no shawl sign, heliotrope rash, calcinosis, malar rash, oral lesions, or hair loss.

Additional physical examinations performed by the neufigrology and rheumatology departments revealed no impairment of muscle strength, soreness of muscles, and muscular atrophy. Joint examination was notable for restriction in range of motion of the hands, hips, and ankles due to swelling and pain of the joints. Radiographs and ultrasound of the feet showed fluid accumulation and synovial thickening of the metatarsal phalangeal joints and one of the PIP joints of the right hand without erosion.

The patient did not undergo magnetic resonance imaging of muscles due to the lack of muscular symptoms and normal myositis laboratory markers. Dermatomyositis-specific antibody testing, such as anti–Jo-1 and anti–Mi-2, also was not performed.

After reviewing the biopsy results, laboratory findings, and clinical presentation, the patient was diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), as she met American College of Rheumatology criteria1 with the following: discoid rash, hemolytic anemia, positive antinuclear antibodies, and nonerosive arthritis. Due to her abnormal constellation of laboratory values and symptoms, she was evaluated by 2 pediatric rheumatologists at 2 different medical centers who agreed with a primary diagnosis of SLE rather than dermatomyositis sine myositis. The hemolytic anemia was attributed to underlying connective tissue disease, as the hemoglobin levels were found to be persistently low for 1 year prior to the diagnosis of systemic lupus, and there was no alternative cause of the hematologic disorder.

A punch biopsy obtained from a Gottron-like papule on the dorsal aspect of the left hand revealed lymphocytic interface dermatitis and slight thickening of the basement membrane zone (Figure 2A). There was a dense superficial and deep periadnexal and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation as well as increased dermal mucin, which can be seen in both lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis (Figure 2B). Perniosis also was considered from histologic findings but was excluded based on clinical history and physical findings. A second biopsy of the left conchal bowl showed hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, interface changes, follicular plugging, and basement membrane thickening. These findings can be seen in dermatomyositis, but when considered together with the clinical appearance of the patient’s eruption on the ears, they were more consistent with discoid lupus erythematosus (Figures 2C and 2D).

Finally, although ragged cuticles and proximal nail fold telangiectasia typically are seen in dermatomyositis, nail fold hyperkeratosis, ragged cuticles, and nail bed telangiectasia also have been reported in lupus erythematosus.2,3 Therefore, the findings overlying our patient’s knuckles and elbows can be considered Gottron-like papules in the setting of SLE.

Dermatomyositis has several characteristic dermatologic manifestations, including Gottron papules, shawl sign, facial heliotrope rash, periungual telangiectasia, and mechanic’s hands. Of them, Gottron papules have been the most pathognomonic, while the other skin findings are less specific and can be seen in other disease entities.4,5

The pathogenesis of Gottron papules in dermatomyositis remains largely unknown. Prior molecular studies have proposed that stretch CD44 variant 7 and abnormal osteopontin levels may contribute to the pathogenesis of Gottron papules by increasing local inflammation.6 Studies also have linked abnormal osteopontin levels and CD44 variant 7 expression with other diseases of autoimmunity, including lupus erythematosus.7 Because lupus erythematosus can have a large variety of cutaneous findings, Gottron-like papules may be considered a rare dermatologic presentation of lupus erythematosus.

We present a case of Gottron-like papules as an unusual dermatologic manifestation of SLE, challenging the concept of Gottron papules as a pathognomonic finding of dermatomyositis.

To the Editor:

An 11-year-old girl presented to the dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic rash on the bilateral forearms, dorsal hands, and ears of 1 month’s duration. Recent history was notable for persistent low-grade fevers, dizziness, headaches, arthralgia, and swelling of multiple joints, as well as difficulty ambulating due to the joint pain. A thorough review of systems revealed no photosensitivity, oral sores, weight loss, pulmonary symptoms, Raynaud phenomenon, or dysphagia.

Medical history was notable for presumed viral pancreatitis and transaminitis requiring inpatient hospitalization 1 year prior to presentation. The patient underwent extensive workup at that time, which was notable for a positive antinuclear antibody level of 1:2560, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate level of 75 mm/h (reference range, 0–22 mm/h), hemolytic anemia with a hemoglobin of 10.9 g/dL (14.0–17.5 g/dL), and leukopenia with a white blood cell count of 3700/µL (4500–11,000/µL). Additional laboratory tests were performed and were found to be within reference range, including creatine kinase, aldolase, complete metabolic panel, extractable nuclear antigen, complement levels, C-reactive protein level, antiphospholipid antibodies,partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, anti–double-stranded DNA, rheumatoid factor, β2-glycoprotein, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody tests. Skin purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test and chest radiograph also were unremarkable. The patient also was evaluated and found negative for Wilson disease, hemochromatosis, α1-antitrypsin disease, and autoimmune hepatitis.

Physical examination revealed erythematous plaques with crusted hyperpigmented erosions and central hypopigmentation on the bilateral conchal bowls and antihelices, findings characteristic of discoid lupus erythematosus (Figure 1A). On the bilateral elbows, metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, there were firm, erythematous to violaceous, keratotic papules that were clinically suggestive of Gottron-like papules (Figures 1B and 1C). However, there were no lesions on the skin between the MCP, PIP, and distal interphalangeal joints. The MCP joints were associated with swelling and were tender to palpation. Examination of the fingernails showed dilated telangiectasia of the proximal nail folds and ragged hyperkeratotic cuticles of all 10 digits (Figure 1D). On the extensor aspects of the bilateral forearms, there were erythematous excoriated papules and papulovesicular lesions with central hemorrhagic crusting. The patient showed no shawl sign, heliotrope rash, calcinosis, malar rash, oral lesions, or hair loss.

Additional physical examinations performed by the neufigrology and rheumatology departments revealed no impairment of muscle strength, soreness of muscles, and muscular atrophy. Joint examination was notable for restriction in range of motion of the hands, hips, and ankles due to swelling and pain of the joints. Radiographs and ultrasound of the feet showed fluid accumulation and synovial thickening of the metatarsal phalangeal joints and one of the PIP joints of the right hand without erosion.

The patient did not undergo magnetic resonance imaging of muscles due to the lack of muscular symptoms and normal myositis laboratory markers. Dermatomyositis-specific antibody testing, such as anti–Jo-1 and anti–Mi-2, also was not performed.

After reviewing the biopsy results, laboratory findings, and clinical presentation, the patient was diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), as she met American College of Rheumatology criteria1 with the following: discoid rash, hemolytic anemia, positive antinuclear antibodies, and nonerosive arthritis. Due to her abnormal constellation of laboratory values and symptoms, she was evaluated by 2 pediatric rheumatologists at 2 different medical centers who agreed with a primary diagnosis of SLE rather than dermatomyositis sine myositis. The hemolytic anemia was attributed to underlying connective tissue disease, as the hemoglobin levels were found to be persistently low for 1 year prior to the diagnosis of systemic lupus, and there was no alternative cause of the hematologic disorder.

A punch biopsy obtained from a Gottron-like papule on the dorsal aspect of the left hand revealed lymphocytic interface dermatitis and slight thickening of the basement membrane zone (Figure 2A). There was a dense superficial and deep periadnexal and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation as well as increased dermal mucin, which can be seen in both lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis (Figure 2B). Perniosis also was considered from histologic findings but was excluded based on clinical history and physical findings. A second biopsy of the left conchal bowl showed hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, interface changes, follicular plugging, and basement membrane thickening. These findings can be seen in dermatomyositis, but when considered together with the clinical appearance of the patient’s eruption on the ears, they were more consistent with discoid lupus erythematosus (Figures 2C and 2D).

Finally, although ragged cuticles and proximal nail fold telangiectasia typically are seen in dermatomyositis, nail fold hyperkeratosis, ragged cuticles, and nail bed telangiectasia also have been reported in lupus erythematosus.2,3 Therefore, the findings overlying our patient’s knuckles and elbows can be considered Gottron-like papules in the setting of SLE.

Dermatomyositis has several characteristic dermatologic manifestations, including Gottron papules, shawl sign, facial heliotrope rash, periungual telangiectasia, and mechanic’s hands. Of them, Gottron papules have been the most pathognomonic, while the other skin findings are less specific and can be seen in other disease entities.4,5

The pathogenesis of Gottron papules in dermatomyositis remains largely unknown. Prior molecular studies have proposed that stretch CD44 variant 7 and abnormal osteopontin levels may contribute to the pathogenesis of Gottron papules by increasing local inflammation.6 Studies also have linked abnormal osteopontin levels and CD44 variant 7 expression with other diseases of autoimmunity, including lupus erythematosus.7 Because lupus erythematosus can have a large variety of cutaneous findings, Gottron-like papules may be considered a rare dermatologic presentation of lupus erythematosus.

We present a case of Gottron-like papules as an unusual dermatologic manifestation of SLE, challenging the concept of Gottron papules as a pathognomonic finding of dermatomyositis.

- Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725.

- Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74.

- Trüeb RM. Hair and nail involvement in lupus erythematosus. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:139-147.

- Koler RA, Montemarano A. Dermatomyositis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:1565-1572.

- Muro Y, Sugiura K, Akiyama M. Cutaneous manifestations in dermatomyositis: key clinical and serological features—a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51:293-302.

- Kim JS, Bashir MM, Werth VP. Gottron’s papules exhibit dermal accumulation of CD44 variant 7 (CD44v7) and its binding partner osteopontin: a unique molecular signature. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1825-1832.

- Kim JS, Werth VP. Identification of specific chondroitin sulfate species in cutaneous autoimmune disease. J Histochem Cytochem. 2011;59:780-790.

- Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725.

- Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74.

- Trüeb RM. Hair and nail involvement in lupus erythematosus. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:139-147.

- Koler RA, Montemarano A. Dermatomyositis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:1565-1572.

- Muro Y, Sugiura K, Akiyama M. Cutaneous manifestations in dermatomyositis: key clinical and serological features—a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51:293-302.

- Kim JS, Bashir MM, Werth VP. Gottron’s papules exhibit dermal accumulation of CD44 variant 7 (CD44v7) and its binding partner osteopontin: a unique molecular signature. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1825-1832.

- Kim JS, Werth VP. Identification of specific chondroitin sulfate species in cutaneous autoimmune disease. J Histochem Cytochem. 2011;59:780-790.

Practice Points

- Gottron-like papules can be a dermatologic presentation of lupus erythematosus.

- When present along with other findings of lupus erythematosus without any clinical manifestations of dermatomyositis, Gottron-like papules can be thought of as a manifestation of lupus erythematosus rather than dermatomyositis.