User login

Large Hemorrhagic Plaque With Central Crusting

The Diagnosis: Bullous/Hemorrhagic Lichen Sclerosus et Atrophicus

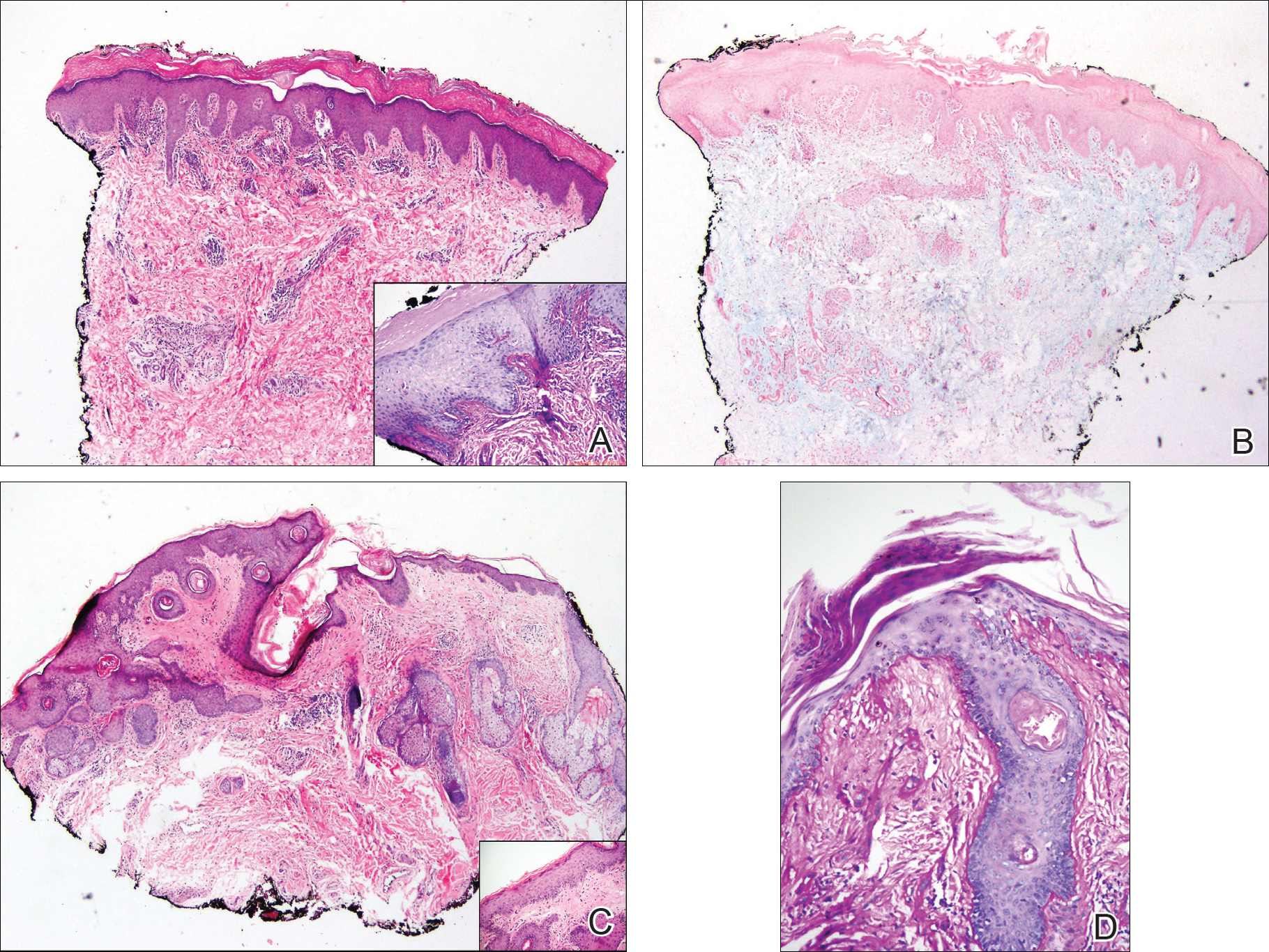

Histopathologic examination revealed hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum and thinning of the epidermis (Figure). Subepidermal edema and hemorrhage in the papillary dermis were seen. There were dilated vessels beneath the edema in the reticular dermis, as well as perivascular, perifollicular, and interstitial lymphocytic inflammation. No cytologic atypia characteristic of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and angiosarcoma or large lymphatic channels characteristic of lymphangioma were noted. Based on clinicopathologic correlation, the diagnosis of the bullous/hemorrhagic form of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A) was made. The patient was treated with high-potency topical steroids with notable symptomatic improvement and rapid resolution of the hemorrhagic lesion.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is a chronic inflammatory condition with a predilection for the anogenital region, though rare cases of extragenital involvement have been reported. It is seen in both sexes and across all age groups, with notably higher prevalence in females in the fifth and sixth decades of life.1,2 Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus can be difficult to diagnose, as these patients may present to a variety of specialists, may be embarrassed by the condition and reluctant for full evaluation, or may have asymptomatic lesions.2,3 Rare cases of isolated extragenital involvement and hemorrhagic or bullous lesions further complicate the diagnosis.1,2 Despite these difficulties, diagnosis is essential, as there is potential for cosmetically and functionally detrimental scarring as well as atrophy and development of overlying malignancies. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is not curable and rarely remits spontaneously, but appropriate treatment strategies can help control the symptoms of the condition as well as its most devastating sequelae.3

For females, classic LS&A is most common in theprepubertal, perimenopausal, or postmenopausal periods, commonly involving the vulva or perineum. Symptoms include pruritus, burning sensation, dysuria, dyspareunia, and labial stenosis, among others. For males, most cases involve the glans penis in prepubertal boys or middleaged men, and symptoms include pruritus, new-onset phimosis, decreased sensation, painful erections, dysuria, and urinary obstruction.1-3 An estimated 97% of patients have some form of genital involvement with only 2.5% showing isolated extragenital involvement, though the latter may be underdiagnosed, as this area is more likely to be asymptomatic.3-6 Extragenital LS&A most often involves the neck and shoulders. The classic appearance of LS&A includes shiny, white-red macules and papules that ultimately coalesce into atrophic plaques and can be accompanied by fissuring or scarring, especially in the genital area.2 There is an increased risk for SCC associated with genital LS&A.1

Bullous/hemorrhagic LS&A has been described as a rare phenotype. One case report cited an increased incidence of this subtype in patients with exclusively extragenital lesions, and the authors considered blister formation to be a characteristic feature of extragenital LS&A. The pathogenesis of blister formation and hemorrhage in LS&A is not completely understood, but trauma is thought to play a role due to decreased stress tolerance from atrophic skin.4 Furthermore, distortion of blood vessel architecture in LS&A has been described with loss of the capillary network and enlargement of vessels along the dermoepidermal junction, which also could play a role in hemorrhage. Differential diagnosis of the bullous/hemorrhagic type of LS&A includes bullous pemphigoid, bullous lichen planus, or bullous scleroderma.7 In our more exophytic hemorrhagic case, malignancies such as SCC or angiosarcoma also had to be considered. Unlike genital LS&A, extragenital LS&A including the bullous/hemorrhagic variant has not been linked to an increasedrisk for malignancy.1,5

The mainstay of treatment of all forms of LS&A is high-potency topical steroids, but topical retinoids, tacrolimus, and UVA phototherapy also have been used. Bullous/hemorrhagic lesions often resolve quickly with topical steroids, leaving behind more classic plaques in their place, which can be more refractory to treatment.5,7

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:393-416.

- Pugliese JM, Morey AF, Peterson AC. Lichen sclerosus: review of the literature and current recommendations for management. J Urol. 2007;178:2268-2276.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Kimura A, Kambe N, Satoh T, et al. Follicular keratosis and bullous formation are typical signs of extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:834-836.

- Khatu S, Vasani R. Isolated, localised extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus et atrophicus: a rare entity. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:409.

- Luzar B, Neil SM, Calonje E. Angiokeratoma-like changes in extragenital and genital lichen sclerosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:540-542.

- Lima RS, Maquine GA, Schettini AP, et al. Bullous and hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90 (3 suppl 1):118-120.

The Diagnosis: Bullous/Hemorrhagic Lichen Sclerosus et Atrophicus

Histopathologic examination revealed hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum and thinning of the epidermis (Figure). Subepidermal edema and hemorrhage in the papillary dermis were seen. There were dilated vessels beneath the edema in the reticular dermis, as well as perivascular, perifollicular, and interstitial lymphocytic inflammation. No cytologic atypia characteristic of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and angiosarcoma or large lymphatic channels characteristic of lymphangioma were noted. Based on clinicopathologic correlation, the diagnosis of the bullous/hemorrhagic form of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A) was made. The patient was treated with high-potency topical steroids with notable symptomatic improvement and rapid resolution of the hemorrhagic lesion.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is a chronic inflammatory condition with a predilection for the anogenital region, though rare cases of extragenital involvement have been reported. It is seen in both sexes and across all age groups, with notably higher prevalence in females in the fifth and sixth decades of life.1,2 Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus can be difficult to diagnose, as these patients may present to a variety of specialists, may be embarrassed by the condition and reluctant for full evaluation, or may have asymptomatic lesions.2,3 Rare cases of isolated extragenital involvement and hemorrhagic or bullous lesions further complicate the diagnosis.1,2 Despite these difficulties, diagnosis is essential, as there is potential for cosmetically and functionally detrimental scarring as well as atrophy and development of overlying malignancies. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is not curable and rarely remits spontaneously, but appropriate treatment strategies can help control the symptoms of the condition as well as its most devastating sequelae.3

For females, classic LS&A is most common in theprepubertal, perimenopausal, or postmenopausal periods, commonly involving the vulva or perineum. Symptoms include pruritus, burning sensation, dysuria, dyspareunia, and labial stenosis, among others. For males, most cases involve the glans penis in prepubertal boys or middleaged men, and symptoms include pruritus, new-onset phimosis, decreased sensation, painful erections, dysuria, and urinary obstruction.1-3 An estimated 97% of patients have some form of genital involvement with only 2.5% showing isolated extragenital involvement, though the latter may be underdiagnosed, as this area is more likely to be asymptomatic.3-6 Extragenital LS&A most often involves the neck and shoulders. The classic appearance of LS&A includes shiny, white-red macules and papules that ultimately coalesce into atrophic plaques and can be accompanied by fissuring or scarring, especially in the genital area.2 There is an increased risk for SCC associated with genital LS&A.1

Bullous/hemorrhagic LS&A has been described as a rare phenotype. One case report cited an increased incidence of this subtype in patients with exclusively extragenital lesions, and the authors considered blister formation to be a characteristic feature of extragenital LS&A. The pathogenesis of blister formation and hemorrhage in LS&A is not completely understood, but trauma is thought to play a role due to decreased stress tolerance from atrophic skin.4 Furthermore, distortion of blood vessel architecture in LS&A has been described with loss of the capillary network and enlargement of vessels along the dermoepidermal junction, which also could play a role in hemorrhage. Differential diagnosis of the bullous/hemorrhagic type of LS&A includes bullous pemphigoid, bullous lichen planus, or bullous scleroderma.7 In our more exophytic hemorrhagic case, malignancies such as SCC or angiosarcoma also had to be considered. Unlike genital LS&A, extragenital LS&A including the bullous/hemorrhagic variant has not been linked to an increasedrisk for malignancy.1,5

The mainstay of treatment of all forms of LS&A is high-potency topical steroids, but topical retinoids, tacrolimus, and UVA phototherapy also have been used. Bullous/hemorrhagic lesions often resolve quickly with topical steroids, leaving behind more classic plaques in their place, which can be more refractory to treatment.5,7

The Diagnosis: Bullous/Hemorrhagic Lichen Sclerosus et Atrophicus

Histopathologic examination revealed hyperkeratosis of the stratum corneum and thinning of the epidermis (Figure). Subepidermal edema and hemorrhage in the papillary dermis were seen. There were dilated vessels beneath the edema in the reticular dermis, as well as perivascular, perifollicular, and interstitial lymphocytic inflammation. No cytologic atypia characteristic of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and angiosarcoma or large lymphatic channels characteristic of lymphangioma were noted. Based on clinicopathologic correlation, the diagnosis of the bullous/hemorrhagic form of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LS&A) was made. The patient was treated with high-potency topical steroids with notable symptomatic improvement and rapid resolution of the hemorrhagic lesion.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is a chronic inflammatory condition with a predilection for the anogenital region, though rare cases of extragenital involvement have been reported. It is seen in both sexes and across all age groups, with notably higher prevalence in females in the fifth and sixth decades of life.1,2 Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus can be difficult to diagnose, as these patients may present to a variety of specialists, may be embarrassed by the condition and reluctant for full evaluation, or may have asymptomatic lesions.2,3 Rare cases of isolated extragenital involvement and hemorrhagic or bullous lesions further complicate the diagnosis.1,2 Despite these difficulties, diagnosis is essential, as there is potential for cosmetically and functionally detrimental scarring as well as atrophy and development of overlying malignancies. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is not curable and rarely remits spontaneously, but appropriate treatment strategies can help control the symptoms of the condition as well as its most devastating sequelae.3

For females, classic LS&A is most common in theprepubertal, perimenopausal, or postmenopausal periods, commonly involving the vulva or perineum. Symptoms include pruritus, burning sensation, dysuria, dyspareunia, and labial stenosis, among others. For males, most cases involve the glans penis in prepubertal boys or middleaged men, and symptoms include pruritus, new-onset phimosis, decreased sensation, painful erections, dysuria, and urinary obstruction.1-3 An estimated 97% of patients have some form of genital involvement with only 2.5% showing isolated extragenital involvement, though the latter may be underdiagnosed, as this area is more likely to be asymptomatic.3-6 Extragenital LS&A most often involves the neck and shoulders. The classic appearance of LS&A includes shiny, white-red macules and papules that ultimately coalesce into atrophic plaques and can be accompanied by fissuring or scarring, especially in the genital area.2 There is an increased risk for SCC associated with genital LS&A.1

Bullous/hemorrhagic LS&A has been described as a rare phenotype. One case report cited an increased incidence of this subtype in patients with exclusively extragenital lesions, and the authors considered blister formation to be a characteristic feature of extragenital LS&A. The pathogenesis of blister formation and hemorrhage in LS&A is not completely understood, but trauma is thought to play a role due to decreased stress tolerance from atrophic skin.4 Furthermore, distortion of blood vessel architecture in LS&A has been described with loss of the capillary network and enlargement of vessels along the dermoepidermal junction, which also could play a role in hemorrhage. Differential diagnosis of the bullous/hemorrhagic type of LS&A includes bullous pemphigoid, bullous lichen planus, or bullous scleroderma.7 In our more exophytic hemorrhagic case, malignancies such as SCC or angiosarcoma also had to be considered. Unlike genital LS&A, extragenital LS&A including the bullous/hemorrhagic variant has not been linked to an increasedrisk for malignancy.1,5

The mainstay of treatment of all forms of LS&A is high-potency topical steroids, but topical retinoids, tacrolimus, and UVA phototherapy also have been used. Bullous/hemorrhagic lesions often resolve quickly with topical steroids, leaving behind more classic plaques in their place, which can be more refractory to treatment.5,7

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:393-416.

- Pugliese JM, Morey AF, Peterson AC. Lichen sclerosus: review of the literature and current recommendations for management. J Urol. 2007;178:2268-2276.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Kimura A, Kambe N, Satoh T, et al. Follicular keratosis and bullous formation are typical signs of extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:834-836.

- Khatu S, Vasani R. Isolated, localised extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus et atrophicus: a rare entity. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:409.

- Luzar B, Neil SM, Calonje E. Angiokeratoma-like changes in extragenital and genital lichen sclerosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:540-542.

- Lima RS, Maquine GA, Schettini AP, et al. Bullous and hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90 (3 suppl 1):118-120.

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:393-416.

- Pugliese JM, Morey AF, Peterson AC. Lichen sclerosus: review of the literature and current recommendations for management. J Urol. 2007;178:2268-2276.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Kimura A, Kambe N, Satoh T, et al. Follicular keratosis and bullous formation are typical signs of extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:834-836.

- Khatu S, Vasani R. Isolated, localised extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus et atrophicus: a rare entity. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:409.

- Luzar B, Neil SM, Calonje E. Angiokeratoma-like changes in extragenital and genital lichen sclerosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:540-542.

- Lima RS, Maquine GA, Schettini AP, et al. Bullous and hemorrhagic lichen sclerosus—case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90 (3 suppl 1):118-120.

A 54-year-old woman with no notable medical history was referred to dermatology by her primary care provider for evaluation of a hematoma on the posterior neck that had developed gradually over 5 months. The lesion initially was asymptomatic but more recently had started to be painful and bleed intermittently. The patient denied any personal or family history of skin cancer. Physical examination revealed a large hemorrhagic plaque on the left side of the posterior neck with central brown-yellow crusting. There were few smaller, white, thin, sclerotic plaques with crinkling atrophy at the periphery of and inferolateral to the lesion. A punch biopsy specimen was obtained from the hemorrhagic plaque.

Gottron Papules Mimicking Dermatomyositis: An Unusual Manifestation of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

To the Editor:

An 11-year-old girl presented to the dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic rash on the bilateral forearms, dorsal hands, and ears of 1 month’s duration. Recent history was notable for persistent low-grade fevers, dizziness, headaches, arthralgia, and swelling of multiple joints, as well as difficulty ambulating due to the joint pain. A thorough review of systems revealed no photosensitivity, oral sores, weight loss, pulmonary symptoms, Raynaud phenomenon, or dysphagia.

Medical history was notable for presumed viral pancreatitis and transaminitis requiring inpatient hospitalization 1 year prior to presentation. The patient underwent extensive workup at that time, which was notable for a positive antinuclear antibody level of 1:2560, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate level of 75 mm/h (reference range, 0–22 mm/h), hemolytic anemia with a hemoglobin of 10.9 g/dL (14.0–17.5 g/dL), and leukopenia with a white blood cell count of 3700/µL (4500–11,000/µL). Additional laboratory tests were performed and were found to be within reference range, including creatine kinase, aldolase, complete metabolic panel, extractable nuclear antigen, complement levels, C-reactive protein level, antiphospholipid antibodies,partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, anti–double-stranded DNA, rheumatoid factor, β2-glycoprotein, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody tests. Skin purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test and chest radiograph also were unremarkable. The patient also was evaluated and found negative for Wilson disease, hemochromatosis, α1-antitrypsin disease, and autoimmune hepatitis.

Physical examination revealed erythematous plaques with crusted hyperpigmented erosions and central hypopigmentation on the bilateral conchal bowls and antihelices, findings characteristic of discoid lupus erythematosus (Figure 1A). On the bilateral elbows, metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, there were firm, erythematous to violaceous, keratotic papules that were clinically suggestive of Gottron-like papules (Figures 1B and 1C). However, there were no lesions on the skin between the MCP, PIP, and distal interphalangeal joints. The MCP joints were associated with swelling and were tender to palpation. Examination of the fingernails showed dilated telangiectasia of the proximal nail folds and ragged hyperkeratotic cuticles of all 10 digits (Figure 1D). On the extensor aspects of the bilateral forearms, there were erythematous excoriated papules and papulovesicular lesions with central hemorrhagic crusting. The patient showed no shawl sign, heliotrope rash, calcinosis, malar rash, oral lesions, or hair loss.

Additional physical examinations performed by the neufigrology and rheumatology departments revealed no impairment of muscle strength, soreness of muscles, and muscular atrophy. Joint examination was notable for restriction in range of motion of the hands, hips, and ankles due to swelling and pain of the joints. Radiographs and ultrasound of the feet showed fluid accumulation and synovial thickening of the metatarsal phalangeal joints and one of the PIP joints of the right hand without erosion.

The patient did not undergo magnetic resonance imaging of muscles due to the lack of muscular symptoms and normal myositis laboratory markers. Dermatomyositis-specific antibody testing, such as anti–Jo-1 and anti–Mi-2, also was not performed.

After reviewing the biopsy results, laboratory findings, and clinical presentation, the patient was diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), as she met American College of Rheumatology criteria1 with the following: discoid rash, hemolytic anemia, positive antinuclear antibodies, and nonerosive arthritis. Due to her abnormal constellation of laboratory values and symptoms, she was evaluated by 2 pediatric rheumatologists at 2 different medical centers who agreed with a primary diagnosis of SLE rather than dermatomyositis sine myositis. The hemolytic anemia was attributed to underlying connective tissue disease, as the hemoglobin levels were found to be persistently low for 1 year prior to the diagnosis of systemic lupus, and there was no alternative cause of the hematologic disorder.

A punch biopsy obtained from a Gottron-like papule on the dorsal aspect of the left hand revealed lymphocytic interface dermatitis and slight thickening of the basement membrane zone (Figure 2A). There was a dense superficial and deep periadnexal and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation as well as increased dermal mucin, which can be seen in both lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis (Figure 2B). Perniosis also was considered from histologic findings but was excluded based on clinical history and physical findings. A second biopsy of the left conchal bowl showed hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, interface changes, follicular plugging, and basement membrane thickening. These findings can be seen in dermatomyositis, but when considered together with the clinical appearance of the patient’s eruption on the ears, they were more consistent with discoid lupus erythematosus (Figures 2C and 2D).

Finally, although ragged cuticles and proximal nail fold telangiectasia typically are seen in dermatomyositis, nail fold hyperkeratosis, ragged cuticles, and nail bed telangiectasia also have been reported in lupus erythematosus.2,3 Therefore, the findings overlying our patient’s knuckles and elbows can be considered Gottron-like papules in the setting of SLE.

Dermatomyositis has several characteristic dermatologic manifestations, including Gottron papules, shawl sign, facial heliotrope rash, periungual telangiectasia, and mechanic’s hands. Of them, Gottron papules have been the most pathognomonic, while the other skin findings are less specific and can be seen in other disease entities.4,5

The pathogenesis of Gottron papules in dermatomyositis remains largely unknown. Prior molecular studies have proposed that stretch CD44 variant 7 and abnormal osteopontin levels may contribute to the pathogenesis of Gottron papules by increasing local inflammation.6 Studies also have linked abnormal osteopontin levels and CD44 variant 7 expression with other diseases of autoimmunity, including lupus erythematosus.7 Because lupus erythematosus can have a large variety of cutaneous findings, Gottron-like papules may be considered a rare dermatologic presentation of lupus erythematosus.

We present a case of Gottron-like papules as an unusual dermatologic manifestation of SLE, challenging the concept of Gottron papules as a pathognomonic finding of dermatomyositis.

- Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725.

- Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74.

- Trüeb RM. Hair and nail involvement in lupus erythematosus. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:139-147.

- Koler RA, Montemarano A. Dermatomyositis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:1565-1572.

- Muro Y, Sugiura K, Akiyama M. Cutaneous manifestations in dermatomyositis: key clinical and serological features—a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51:293-302.

- Kim JS, Bashir MM, Werth VP. Gottron’s papules exhibit dermal accumulation of CD44 variant 7 (CD44v7) and its binding partner osteopontin: a unique molecular signature. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1825-1832.

- Kim JS, Werth VP. Identification of specific chondroitin sulfate species in cutaneous autoimmune disease. J Histochem Cytochem. 2011;59:780-790.

To the Editor:

An 11-year-old girl presented to the dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic rash on the bilateral forearms, dorsal hands, and ears of 1 month’s duration. Recent history was notable for persistent low-grade fevers, dizziness, headaches, arthralgia, and swelling of multiple joints, as well as difficulty ambulating due to the joint pain. A thorough review of systems revealed no photosensitivity, oral sores, weight loss, pulmonary symptoms, Raynaud phenomenon, or dysphagia.

Medical history was notable for presumed viral pancreatitis and transaminitis requiring inpatient hospitalization 1 year prior to presentation. The patient underwent extensive workup at that time, which was notable for a positive antinuclear antibody level of 1:2560, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate level of 75 mm/h (reference range, 0–22 mm/h), hemolytic anemia with a hemoglobin of 10.9 g/dL (14.0–17.5 g/dL), and leukopenia with a white blood cell count of 3700/µL (4500–11,000/µL). Additional laboratory tests were performed and were found to be within reference range, including creatine kinase, aldolase, complete metabolic panel, extractable nuclear antigen, complement levels, C-reactive protein level, antiphospholipid antibodies,partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, anti–double-stranded DNA, rheumatoid factor, β2-glycoprotein, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody tests. Skin purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test and chest radiograph also were unremarkable. The patient also was evaluated and found negative for Wilson disease, hemochromatosis, α1-antitrypsin disease, and autoimmune hepatitis.

Physical examination revealed erythematous plaques with crusted hyperpigmented erosions and central hypopigmentation on the bilateral conchal bowls and antihelices, findings characteristic of discoid lupus erythematosus (Figure 1A). On the bilateral elbows, metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, there were firm, erythematous to violaceous, keratotic papules that were clinically suggestive of Gottron-like papules (Figures 1B and 1C). However, there were no lesions on the skin between the MCP, PIP, and distal interphalangeal joints. The MCP joints were associated with swelling and were tender to palpation. Examination of the fingernails showed dilated telangiectasia of the proximal nail folds and ragged hyperkeratotic cuticles of all 10 digits (Figure 1D). On the extensor aspects of the bilateral forearms, there were erythematous excoriated papules and papulovesicular lesions with central hemorrhagic crusting. The patient showed no shawl sign, heliotrope rash, calcinosis, malar rash, oral lesions, or hair loss.

Additional physical examinations performed by the neufigrology and rheumatology departments revealed no impairment of muscle strength, soreness of muscles, and muscular atrophy. Joint examination was notable for restriction in range of motion of the hands, hips, and ankles due to swelling and pain of the joints. Radiographs and ultrasound of the feet showed fluid accumulation and synovial thickening of the metatarsal phalangeal joints and one of the PIP joints of the right hand without erosion.

The patient did not undergo magnetic resonance imaging of muscles due to the lack of muscular symptoms and normal myositis laboratory markers. Dermatomyositis-specific antibody testing, such as anti–Jo-1 and anti–Mi-2, also was not performed.

After reviewing the biopsy results, laboratory findings, and clinical presentation, the patient was diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), as she met American College of Rheumatology criteria1 with the following: discoid rash, hemolytic anemia, positive antinuclear antibodies, and nonerosive arthritis. Due to her abnormal constellation of laboratory values and symptoms, she was evaluated by 2 pediatric rheumatologists at 2 different medical centers who agreed with a primary diagnosis of SLE rather than dermatomyositis sine myositis. The hemolytic anemia was attributed to underlying connective tissue disease, as the hemoglobin levels were found to be persistently low for 1 year prior to the diagnosis of systemic lupus, and there was no alternative cause of the hematologic disorder.

A punch biopsy obtained from a Gottron-like papule on the dorsal aspect of the left hand revealed lymphocytic interface dermatitis and slight thickening of the basement membrane zone (Figure 2A). There was a dense superficial and deep periadnexal and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation as well as increased dermal mucin, which can be seen in both lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis (Figure 2B). Perniosis also was considered from histologic findings but was excluded based on clinical history and physical findings. A second biopsy of the left conchal bowl showed hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, interface changes, follicular plugging, and basement membrane thickening. These findings can be seen in dermatomyositis, but when considered together with the clinical appearance of the patient’s eruption on the ears, they were more consistent with discoid lupus erythematosus (Figures 2C and 2D).

Finally, although ragged cuticles and proximal nail fold telangiectasia typically are seen in dermatomyositis, nail fold hyperkeratosis, ragged cuticles, and nail bed telangiectasia also have been reported in lupus erythematosus.2,3 Therefore, the findings overlying our patient’s knuckles and elbows can be considered Gottron-like papules in the setting of SLE.

Dermatomyositis has several characteristic dermatologic manifestations, including Gottron papules, shawl sign, facial heliotrope rash, periungual telangiectasia, and mechanic’s hands. Of them, Gottron papules have been the most pathognomonic, while the other skin findings are less specific and can be seen in other disease entities.4,5

The pathogenesis of Gottron papules in dermatomyositis remains largely unknown. Prior molecular studies have proposed that stretch CD44 variant 7 and abnormal osteopontin levels may contribute to the pathogenesis of Gottron papules by increasing local inflammation.6 Studies also have linked abnormal osteopontin levels and CD44 variant 7 expression with other diseases of autoimmunity, including lupus erythematosus.7 Because lupus erythematosus can have a large variety of cutaneous findings, Gottron-like papules may be considered a rare dermatologic presentation of lupus erythematosus.

We present a case of Gottron-like papules as an unusual dermatologic manifestation of SLE, challenging the concept of Gottron papules as a pathognomonic finding of dermatomyositis.

To the Editor:

An 11-year-old girl presented to the dermatology clinic with an asymptomatic rash on the bilateral forearms, dorsal hands, and ears of 1 month’s duration. Recent history was notable for persistent low-grade fevers, dizziness, headaches, arthralgia, and swelling of multiple joints, as well as difficulty ambulating due to the joint pain. A thorough review of systems revealed no photosensitivity, oral sores, weight loss, pulmonary symptoms, Raynaud phenomenon, or dysphagia.

Medical history was notable for presumed viral pancreatitis and transaminitis requiring inpatient hospitalization 1 year prior to presentation. The patient underwent extensive workup at that time, which was notable for a positive antinuclear antibody level of 1:2560, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate level of 75 mm/h (reference range, 0–22 mm/h), hemolytic anemia with a hemoglobin of 10.9 g/dL (14.0–17.5 g/dL), and leukopenia with a white blood cell count of 3700/µL (4500–11,000/µL). Additional laboratory tests were performed and were found to be within reference range, including creatine kinase, aldolase, complete metabolic panel, extractable nuclear antigen, complement levels, C-reactive protein level, antiphospholipid antibodies,partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, anti–double-stranded DNA, rheumatoid factor, β2-glycoprotein, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody tests. Skin purified protein derivative (tuberculin) test and chest radiograph also were unremarkable. The patient also was evaluated and found negative for Wilson disease, hemochromatosis, α1-antitrypsin disease, and autoimmune hepatitis.

Physical examination revealed erythematous plaques with crusted hyperpigmented erosions and central hypopigmentation on the bilateral conchal bowls and antihelices, findings characteristic of discoid lupus erythematosus (Figure 1A). On the bilateral elbows, metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, there were firm, erythematous to violaceous, keratotic papules that were clinically suggestive of Gottron-like papules (Figures 1B and 1C). However, there were no lesions on the skin between the MCP, PIP, and distal interphalangeal joints. The MCP joints were associated with swelling and were tender to palpation. Examination of the fingernails showed dilated telangiectasia of the proximal nail folds and ragged hyperkeratotic cuticles of all 10 digits (Figure 1D). On the extensor aspects of the bilateral forearms, there were erythematous excoriated papules and papulovesicular lesions with central hemorrhagic crusting. The patient showed no shawl sign, heliotrope rash, calcinosis, malar rash, oral lesions, or hair loss.

Additional physical examinations performed by the neufigrology and rheumatology departments revealed no impairment of muscle strength, soreness of muscles, and muscular atrophy. Joint examination was notable for restriction in range of motion of the hands, hips, and ankles due to swelling and pain of the joints. Radiographs and ultrasound of the feet showed fluid accumulation and synovial thickening of the metatarsal phalangeal joints and one of the PIP joints of the right hand without erosion.

The patient did not undergo magnetic resonance imaging of muscles due to the lack of muscular symptoms and normal myositis laboratory markers. Dermatomyositis-specific antibody testing, such as anti–Jo-1 and anti–Mi-2, also was not performed.

After reviewing the biopsy results, laboratory findings, and clinical presentation, the patient was diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), as she met American College of Rheumatology criteria1 with the following: discoid rash, hemolytic anemia, positive antinuclear antibodies, and nonerosive arthritis. Due to her abnormal constellation of laboratory values and symptoms, she was evaluated by 2 pediatric rheumatologists at 2 different medical centers who agreed with a primary diagnosis of SLE rather than dermatomyositis sine myositis. The hemolytic anemia was attributed to underlying connective tissue disease, as the hemoglobin levels were found to be persistently low for 1 year prior to the diagnosis of systemic lupus, and there was no alternative cause of the hematologic disorder.

A punch biopsy obtained from a Gottron-like papule on the dorsal aspect of the left hand revealed lymphocytic interface dermatitis and slight thickening of the basement membrane zone (Figure 2A). There was a dense superficial and deep periadnexal and perivascular lymphocytic inflammation as well as increased dermal mucin, which can be seen in both lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis (Figure 2B). Perniosis also was considered from histologic findings but was excluded based on clinical history and physical findings. A second biopsy of the left conchal bowl showed hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, interface changes, follicular plugging, and basement membrane thickening. These findings can be seen in dermatomyositis, but when considered together with the clinical appearance of the patient’s eruption on the ears, they were more consistent with discoid lupus erythematosus (Figures 2C and 2D).

Finally, although ragged cuticles and proximal nail fold telangiectasia typically are seen in dermatomyositis, nail fold hyperkeratosis, ragged cuticles, and nail bed telangiectasia also have been reported in lupus erythematosus.2,3 Therefore, the findings overlying our patient’s knuckles and elbows can be considered Gottron-like papules in the setting of SLE.

Dermatomyositis has several characteristic dermatologic manifestations, including Gottron papules, shawl sign, facial heliotrope rash, periungual telangiectasia, and mechanic’s hands. Of them, Gottron papules have been the most pathognomonic, while the other skin findings are less specific and can be seen in other disease entities.4,5

The pathogenesis of Gottron papules in dermatomyositis remains largely unknown. Prior molecular studies have proposed that stretch CD44 variant 7 and abnormal osteopontin levels may contribute to the pathogenesis of Gottron papules by increasing local inflammation.6 Studies also have linked abnormal osteopontin levels and CD44 variant 7 expression with other diseases of autoimmunity, including lupus erythematosus.7 Because lupus erythematosus can have a large variety of cutaneous findings, Gottron-like papules may be considered a rare dermatologic presentation of lupus erythematosus.

We present a case of Gottron-like papules as an unusual dermatologic manifestation of SLE, challenging the concept of Gottron papules as a pathognomonic finding of dermatomyositis.

- Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725.

- Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74.

- Trüeb RM. Hair and nail involvement in lupus erythematosus. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:139-147.

- Koler RA, Montemarano A. Dermatomyositis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:1565-1572.

- Muro Y, Sugiura K, Akiyama M. Cutaneous manifestations in dermatomyositis: key clinical and serological features—a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51:293-302.

- Kim JS, Bashir MM, Werth VP. Gottron’s papules exhibit dermal accumulation of CD44 variant 7 (CD44v7) and its binding partner osteopontin: a unique molecular signature. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1825-1832.

- Kim JS, Werth VP. Identification of specific chondroitin sulfate species in cutaneous autoimmune disease. J Histochem Cytochem. 2011;59:780-790.

- Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725.

- Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74.

- Trüeb RM. Hair and nail involvement in lupus erythematosus. Clin Dermatol. 2004;22:139-147.

- Koler RA, Montemarano A. Dermatomyositis. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64:1565-1572.

- Muro Y, Sugiura K, Akiyama M. Cutaneous manifestations in dermatomyositis: key clinical and serological features—a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;51:293-302.

- Kim JS, Bashir MM, Werth VP. Gottron’s papules exhibit dermal accumulation of CD44 variant 7 (CD44v7) and its binding partner osteopontin: a unique molecular signature. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1825-1832.

- Kim JS, Werth VP. Identification of specific chondroitin sulfate species in cutaneous autoimmune disease. J Histochem Cytochem. 2011;59:780-790.

Practice Points

- Gottron-like papules can be a dermatologic presentation of lupus erythematosus.

- When present along with other findings of lupus erythematosus without any clinical manifestations of dermatomyositis, Gottron-like papules can be thought of as a manifestation of lupus erythematosus rather than dermatomyositis.