User login

Inspection of Deep Tumor Margins for Accurate Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Staging

To the Editor:

Histopathologic analysis of debulk specimens in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) may augment identification of high-risk factors in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC), which may warrant tumor upstaging.1 Intratumor location has not been studied when looking at these high-risk factors. Herein, we report 4 cSCCs initially categorized as well differentiated that were reclassified as moderate to poorly differentiated on analysis of debulk specimens obtained via shave removal.

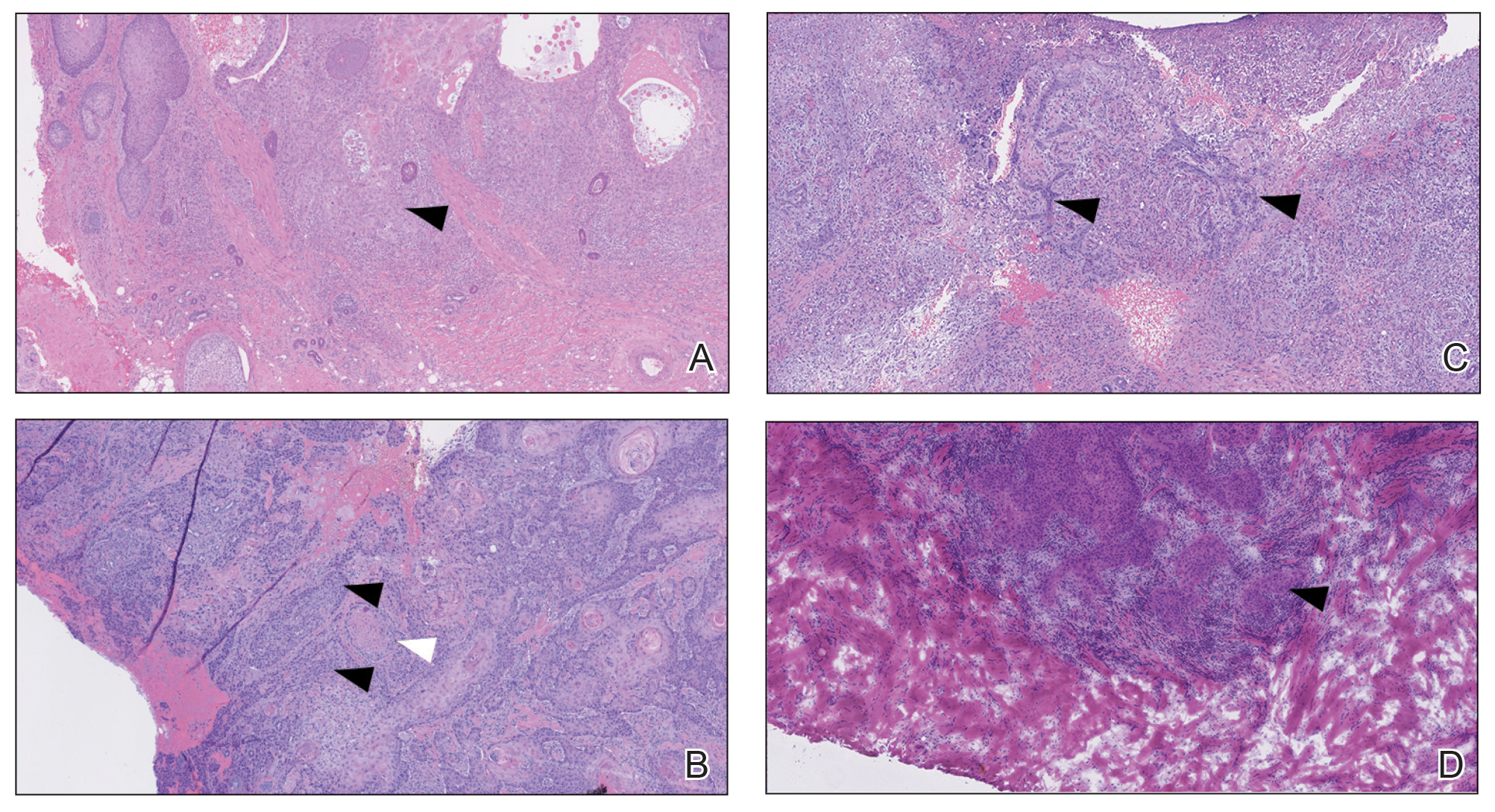

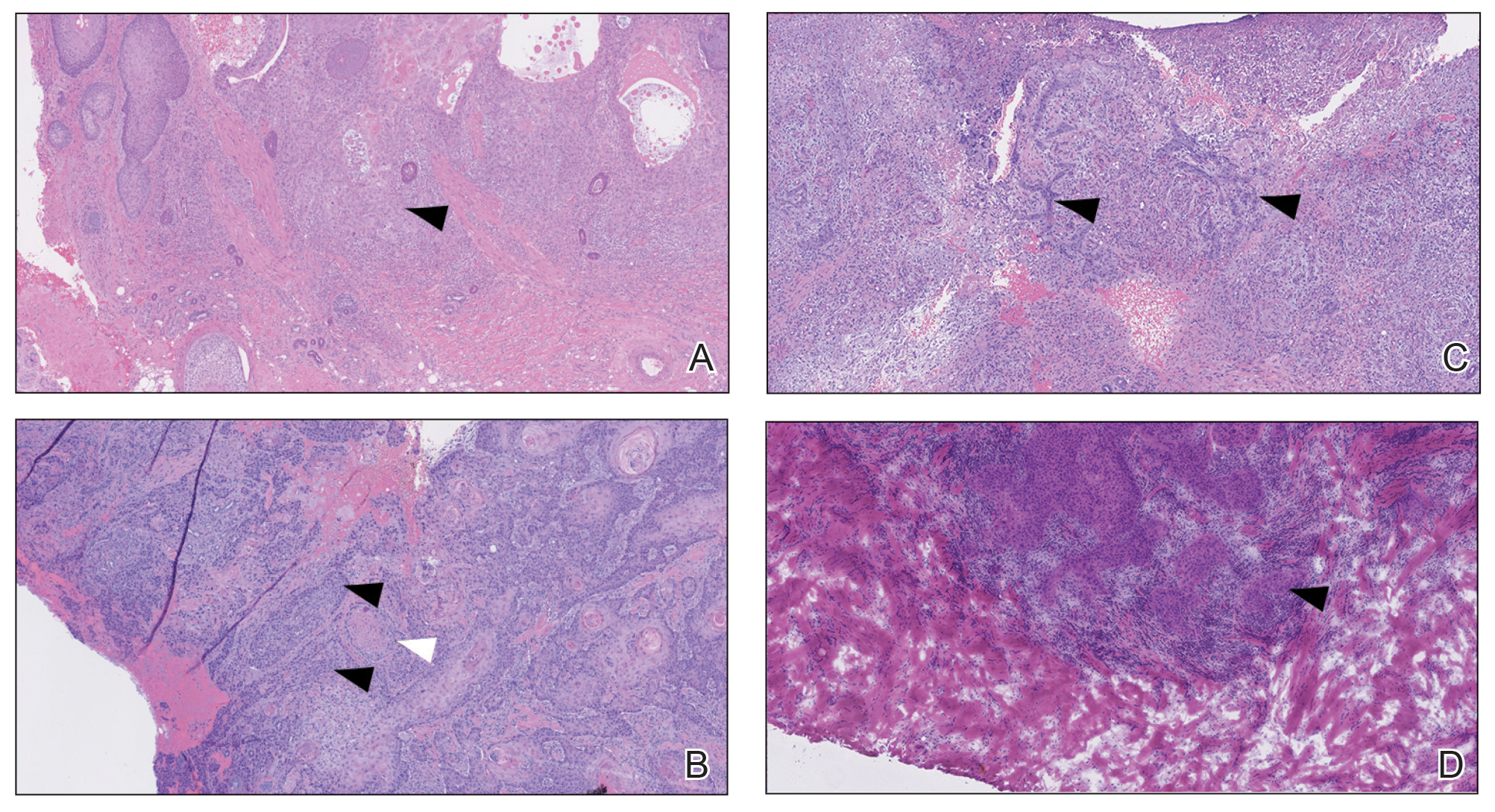

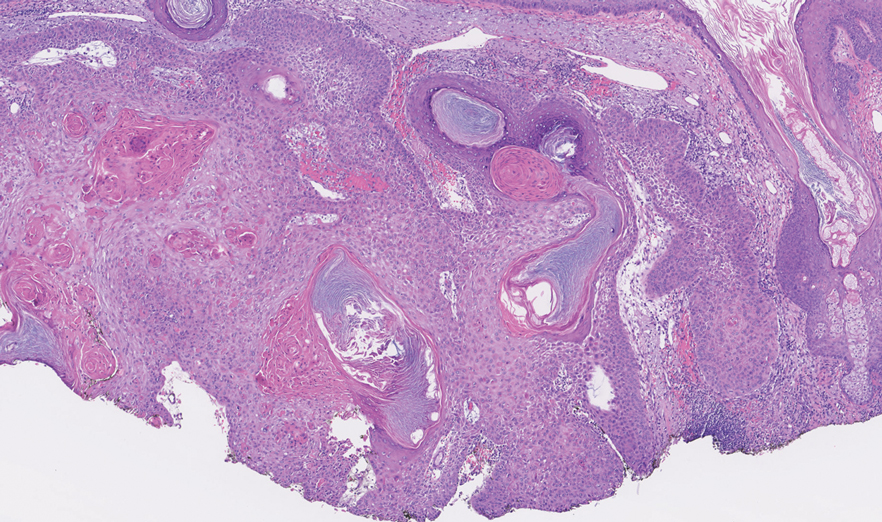

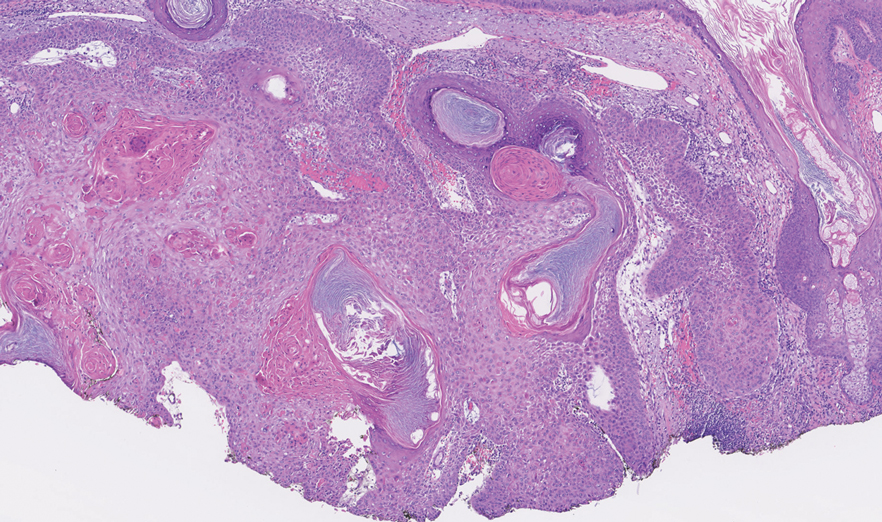

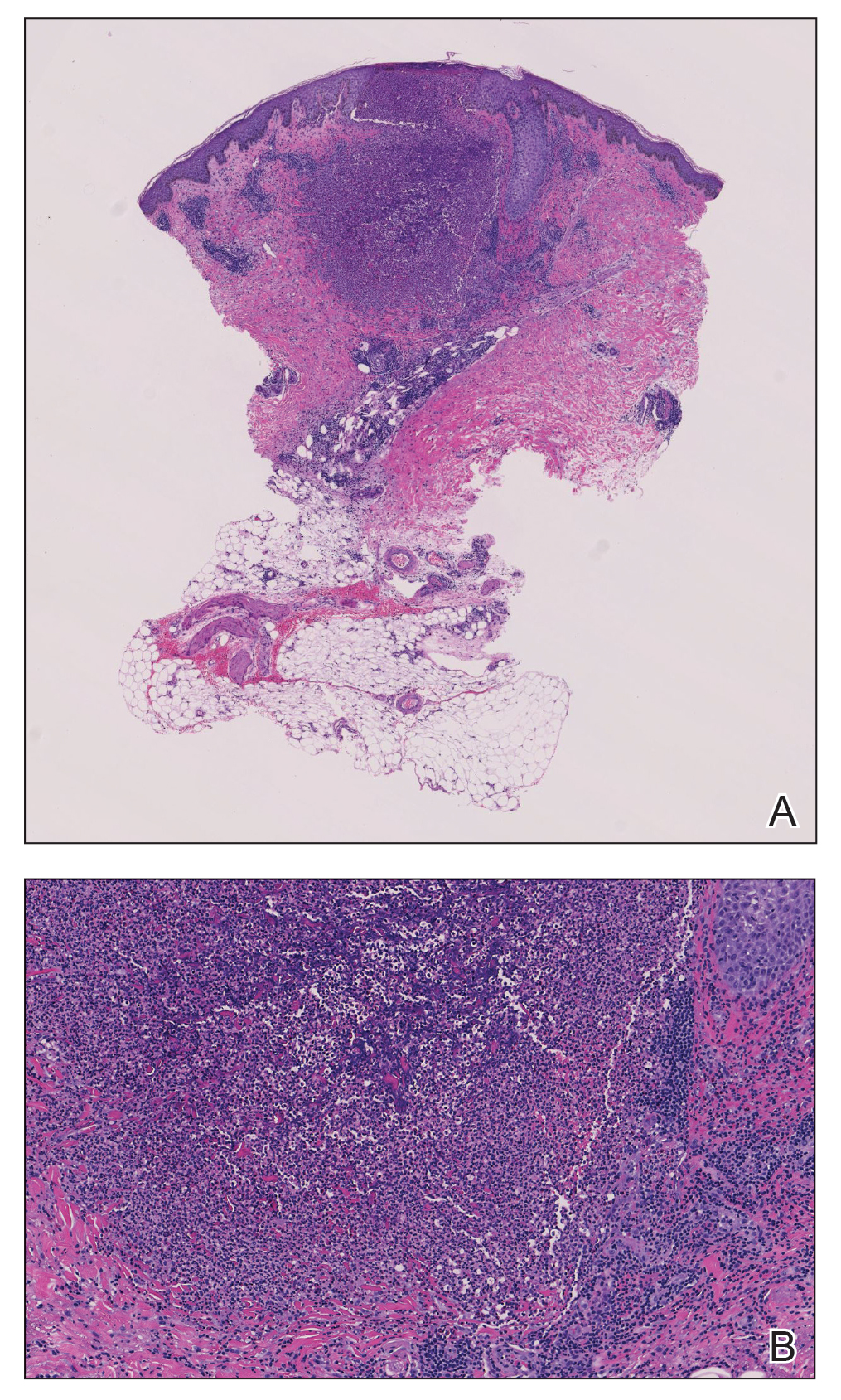

An 80-year-old man (patient 1) presented with a tender 2-cm erythematous plaque with dried hemorrhagic crusting on the frontal scalp. He had a history of nonmelanoma skin cancers. A biopsy revealed a well-differentiated cSCC, which was upgraded from a T2a tumor to T2b during MMS due to galea involvement. Debulk analysis revealed moderate to poorly differentiated cSCC, with the least-differentiated cells at the deep margin (Figure 1A). Given T2b staging, baseline imaging and radiation therapy were recommended.

A 75-year-old man (patient 2) presented with a 2-cm erythematous plaque on the left vertex scalp with hemorrhagic crusting, yellow scale, and purulent drainage. He had a history of cSCCs. A biopsy revealed well-differentiated invasive cSCC, which was upgraded from a T2a tumor to T2b during MMS due to tumor extension beyond the subcutaneous fat. Examination of the second Mohs stage revealed moderately differentiated cSCC, with the least-differentiated cells at the deep margin, infiltration beyond the subcutaneous fat, and perineural invasion (Figure 1B). Given T2b staging, baseline imaging and radiation therapy were recommended.

An 86-year-old woman (patient 3) presented with a tender 2.4-cm plum-colored nodule on the right lower leg. She had a history of basal cell carcinoma. A biopsy revealed a well-differentiated invasive cSCC staged at T2a. Debulk analysis revealed moderately differentiated cSCC, with the least-differentiated cells at the deep margin, though the staging remained the same (Figure 1C).

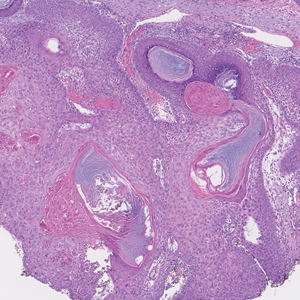

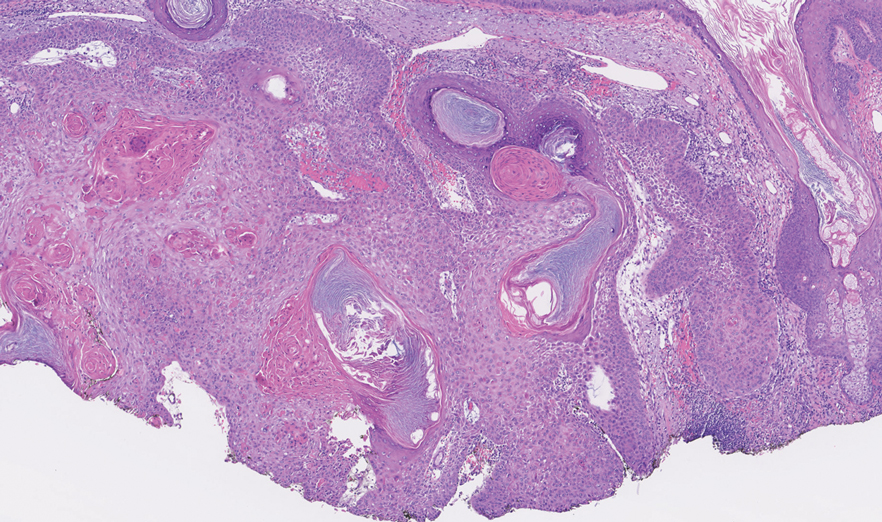

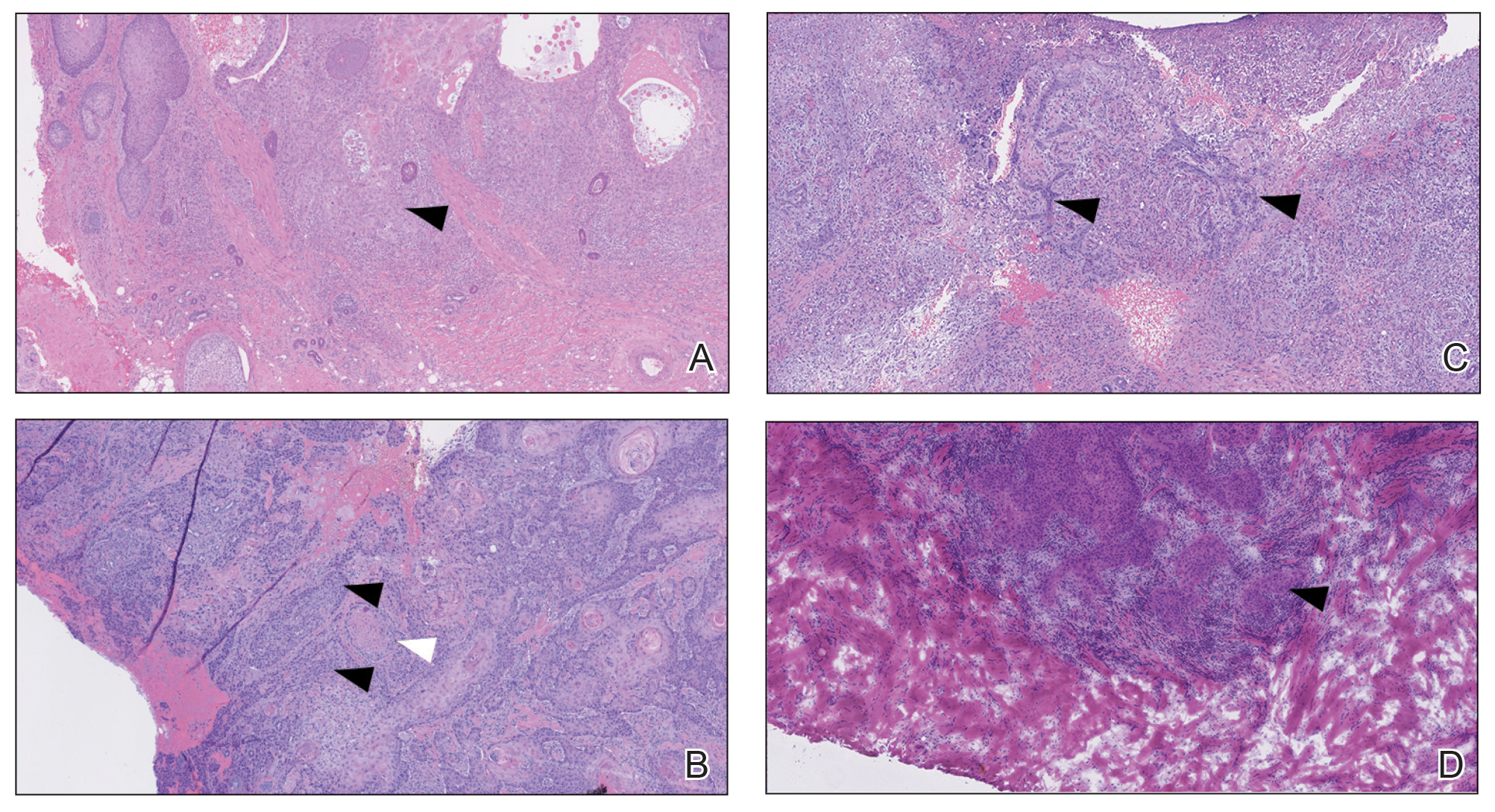

An 82-year-old man (patient 4) presented with a 2.7-cm ulcerated nodule with adjacent scaling on the vertex scalp. He had no history of skin cancer. A biopsy revealed a well-differentiated cSCC (Figure 2) that was upgraded from a T2a tumor to T2b during MMS due to tumor extension beyond the subcutaneous fat. Debulk analysis revealed moderate to poorly differentiated cSCC, with the least-differentiated cells with single-cell extension at the deep margin in the galea (Figure 1D). Given T2b staging, baseline imaging and radiation therapy were recommended.

Tumor differentiation is a factor included in the Brigham and Women’s Hospital staging system, and intratumor variability can be clinically relevant for tumor staging.1 Specifically, cSCCs may exhibit intratumor heterogeneity in which predominantly well-differentiated tumors contain focal areas of poorer differentiation.2 This intratumor heterogeneity complicates estimation of tumor risk, as a well-differentiated tumor on biopsy may exhibit poor differentiation at a deeper margin. Our cases highlight that the cells at the deeper margin indeed can show poorer differentiation or other higher-risk tumor features. Thus, the most clinically relevant cells for tumor staging and prognostication may not be visible on initial biopsy, underscoring the utility of close examination of the deep layer of the debulk specimen and Mohs layer for comprehensive staging.

Genetic studies have attempted to identify gene expression patterns in cSCCs that predispose to invasion.3 Three of the top 6 genes in this “invasion signature gene set” were matrix metalloproteases; additionally, IL-24 messenger RNA was upregulated in both the cSCC invasion front and in situ cSCCs. IL-24 has been shown to upregulate the expression of matrix metalloprotease 7 in vitro, suggesting that it may influence tumor progression.3 Although gene expression was not included in this series, the identification of genetic variability in the most poorly differentiated cells residing in the deep margins is of great interest and may reveal mutations contributing to irregular cell morphology and cSCC invasiveness.

Prior studies have indicated that a proportion of cSCCs are histopathologically upgraded from the initial biopsy during MMS due to evidence of perineural invasion, bony invasion, or lesser differentiation noted during MMS stages or debulk analysis.1,4 However, the majority of Mohs surgeons report immediately discarding debulk specimens without further evaluation.5 Herein, we highlight 4 cSCC cases in which the deep margins of the debulk specimen contained the most dedifferentiated cells. Our findings emphasize the importance of thoroughly examining deep tumor margins for complete staging yet also highlight that identifying cells at these margins may not change patient management when high-risk criteria are already met.

- McIlwee BE, Abidi NY, Ravi M, et al. Utility of debulk specimens during Mohs micrographic surgery for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:599-604.

- Ramón y Cajal S, Sesé M, Capdevila C, et al. Clinical implications of intratumor heterogeneity: challenges and opportunities. J Mol Med. 2020;98:161-177.

- Mitsui H, Suárez-Fariñas M, Gulati N, et al. Gene expression profiling of the leading edge of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: IL-24-driven MMP-7. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1418-1427.

- Chung E, Hoang S, McEvoy AM, et al. Histopathologic upgrading of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas during Mohs micrographic surgery: a retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:923-930.

- Alniemi DT, Swanson AM, Lasarev M, et al. Tumor debulking trends for keratinocyte carcinomas among Mohs surgeons. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1660-1661.

To the Editor:

Histopathologic analysis of debulk specimens in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) may augment identification of high-risk factors in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC), which may warrant tumor upstaging.1 Intratumor location has not been studied when looking at these high-risk factors. Herein, we report 4 cSCCs initially categorized as well differentiated that were reclassified as moderate to poorly differentiated on analysis of debulk specimens obtained via shave removal.

An 80-year-old man (patient 1) presented with a tender 2-cm erythematous plaque with dried hemorrhagic crusting on the frontal scalp. He had a history of nonmelanoma skin cancers. A biopsy revealed a well-differentiated cSCC, which was upgraded from a T2a tumor to T2b during MMS due to galea involvement. Debulk analysis revealed moderate to poorly differentiated cSCC, with the least-differentiated cells at the deep margin (Figure 1A). Given T2b staging, baseline imaging and radiation therapy were recommended.

A 75-year-old man (patient 2) presented with a 2-cm erythematous plaque on the left vertex scalp with hemorrhagic crusting, yellow scale, and purulent drainage. He had a history of cSCCs. A biopsy revealed well-differentiated invasive cSCC, which was upgraded from a T2a tumor to T2b during MMS due to tumor extension beyond the subcutaneous fat. Examination of the second Mohs stage revealed moderately differentiated cSCC, with the least-differentiated cells at the deep margin, infiltration beyond the subcutaneous fat, and perineural invasion (Figure 1B). Given T2b staging, baseline imaging and radiation therapy were recommended.

An 86-year-old woman (patient 3) presented with a tender 2.4-cm plum-colored nodule on the right lower leg. She had a history of basal cell carcinoma. A biopsy revealed a well-differentiated invasive cSCC staged at T2a. Debulk analysis revealed moderately differentiated cSCC, with the least-differentiated cells at the deep margin, though the staging remained the same (Figure 1C).

An 82-year-old man (patient 4) presented with a 2.7-cm ulcerated nodule with adjacent scaling on the vertex scalp. He had no history of skin cancer. A biopsy revealed a well-differentiated cSCC (Figure 2) that was upgraded from a T2a tumor to T2b during MMS due to tumor extension beyond the subcutaneous fat. Debulk analysis revealed moderate to poorly differentiated cSCC, with the least-differentiated cells with single-cell extension at the deep margin in the galea (Figure 1D). Given T2b staging, baseline imaging and radiation therapy were recommended.

Tumor differentiation is a factor included in the Brigham and Women’s Hospital staging system, and intratumor variability can be clinically relevant for tumor staging.1 Specifically, cSCCs may exhibit intratumor heterogeneity in which predominantly well-differentiated tumors contain focal areas of poorer differentiation.2 This intratumor heterogeneity complicates estimation of tumor risk, as a well-differentiated tumor on biopsy may exhibit poor differentiation at a deeper margin. Our cases highlight that the cells at the deeper margin indeed can show poorer differentiation or other higher-risk tumor features. Thus, the most clinically relevant cells for tumor staging and prognostication may not be visible on initial biopsy, underscoring the utility of close examination of the deep layer of the debulk specimen and Mohs layer for comprehensive staging.

Genetic studies have attempted to identify gene expression patterns in cSCCs that predispose to invasion.3 Three of the top 6 genes in this “invasion signature gene set” were matrix metalloproteases; additionally, IL-24 messenger RNA was upregulated in both the cSCC invasion front and in situ cSCCs. IL-24 has been shown to upregulate the expression of matrix metalloprotease 7 in vitro, suggesting that it may influence tumor progression.3 Although gene expression was not included in this series, the identification of genetic variability in the most poorly differentiated cells residing in the deep margins is of great interest and may reveal mutations contributing to irregular cell morphology and cSCC invasiveness.

Prior studies have indicated that a proportion of cSCCs are histopathologically upgraded from the initial biopsy during MMS due to evidence of perineural invasion, bony invasion, or lesser differentiation noted during MMS stages or debulk analysis.1,4 However, the majority of Mohs surgeons report immediately discarding debulk specimens without further evaluation.5 Herein, we highlight 4 cSCC cases in which the deep margins of the debulk specimen contained the most dedifferentiated cells. Our findings emphasize the importance of thoroughly examining deep tumor margins for complete staging yet also highlight that identifying cells at these margins may not change patient management when high-risk criteria are already met.

To the Editor:

Histopathologic analysis of debulk specimens in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) may augment identification of high-risk factors in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC), which may warrant tumor upstaging.1 Intratumor location has not been studied when looking at these high-risk factors. Herein, we report 4 cSCCs initially categorized as well differentiated that were reclassified as moderate to poorly differentiated on analysis of debulk specimens obtained via shave removal.

An 80-year-old man (patient 1) presented with a tender 2-cm erythematous plaque with dried hemorrhagic crusting on the frontal scalp. He had a history of nonmelanoma skin cancers. A biopsy revealed a well-differentiated cSCC, which was upgraded from a T2a tumor to T2b during MMS due to galea involvement. Debulk analysis revealed moderate to poorly differentiated cSCC, with the least-differentiated cells at the deep margin (Figure 1A). Given T2b staging, baseline imaging and radiation therapy were recommended.

A 75-year-old man (patient 2) presented with a 2-cm erythematous plaque on the left vertex scalp with hemorrhagic crusting, yellow scale, and purulent drainage. He had a history of cSCCs. A biopsy revealed well-differentiated invasive cSCC, which was upgraded from a T2a tumor to T2b during MMS due to tumor extension beyond the subcutaneous fat. Examination of the second Mohs stage revealed moderately differentiated cSCC, with the least-differentiated cells at the deep margin, infiltration beyond the subcutaneous fat, and perineural invasion (Figure 1B). Given T2b staging, baseline imaging and radiation therapy were recommended.

An 86-year-old woman (patient 3) presented with a tender 2.4-cm plum-colored nodule on the right lower leg. She had a history of basal cell carcinoma. A biopsy revealed a well-differentiated invasive cSCC staged at T2a. Debulk analysis revealed moderately differentiated cSCC, with the least-differentiated cells at the deep margin, though the staging remained the same (Figure 1C).

An 82-year-old man (patient 4) presented with a 2.7-cm ulcerated nodule with adjacent scaling on the vertex scalp. He had no history of skin cancer. A biopsy revealed a well-differentiated cSCC (Figure 2) that was upgraded from a T2a tumor to T2b during MMS due to tumor extension beyond the subcutaneous fat. Debulk analysis revealed moderate to poorly differentiated cSCC, with the least-differentiated cells with single-cell extension at the deep margin in the galea (Figure 1D). Given T2b staging, baseline imaging and radiation therapy were recommended.

Tumor differentiation is a factor included in the Brigham and Women’s Hospital staging system, and intratumor variability can be clinically relevant for tumor staging.1 Specifically, cSCCs may exhibit intratumor heterogeneity in which predominantly well-differentiated tumors contain focal areas of poorer differentiation.2 This intratumor heterogeneity complicates estimation of tumor risk, as a well-differentiated tumor on biopsy may exhibit poor differentiation at a deeper margin. Our cases highlight that the cells at the deeper margin indeed can show poorer differentiation or other higher-risk tumor features. Thus, the most clinically relevant cells for tumor staging and prognostication may not be visible on initial biopsy, underscoring the utility of close examination of the deep layer of the debulk specimen and Mohs layer for comprehensive staging.

Genetic studies have attempted to identify gene expression patterns in cSCCs that predispose to invasion.3 Three of the top 6 genes in this “invasion signature gene set” were matrix metalloproteases; additionally, IL-24 messenger RNA was upregulated in both the cSCC invasion front and in situ cSCCs. IL-24 has been shown to upregulate the expression of matrix metalloprotease 7 in vitro, suggesting that it may influence tumor progression.3 Although gene expression was not included in this series, the identification of genetic variability in the most poorly differentiated cells residing in the deep margins is of great interest and may reveal mutations contributing to irregular cell morphology and cSCC invasiveness.

Prior studies have indicated that a proportion of cSCCs are histopathologically upgraded from the initial biopsy during MMS due to evidence of perineural invasion, bony invasion, or lesser differentiation noted during MMS stages or debulk analysis.1,4 However, the majority of Mohs surgeons report immediately discarding debulk specimens without further evaluation.5 Herein, we highlight 4 cSCC cases in which the deep margins of the debulk specimen contained the most dedifferentiated cells. Our findings emphasize the importance of thoroughly examining deep tumor margins for complete staging yet also highlight that identifying cells at these margins may not change patient management when high-risk criteria are already met.

- McIlwee BE, Abidi NY, Ravi M, et al. Utility of debulk specimens during Mohs micrographic surgery for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:599-604.

- Ramón y Cajal S, Sesé M, Capdevila C, et al. Clinical implications of intratumor heterogeneity: challenges and opportunities. J Mol Med. 2020;98:161-177.

- Mitsui H, Suárez-Fariñas M, Gulati N, et al. Gene expression profiling of the leading edge of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: IL-24-driven MMP-7. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1418-1427.

- Chung E, Hoang S, McEvoy AM, et al. Histopathologic upgrading of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas during Mohs micrographic surgery: a retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:923-930.

- Alniemi DT, Swanson AM, Lasarev M, et al. Tumor debulking trends for keratinocyte carcinomas among Mohs surgeons. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1660-1661.

- McIlwee BE, Abidi NY, Ravi M, et al. Utility of debulk specimens during Mohs micrographic surgery for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:599-604.

- Ramón y Cajal S, Sesé M, Capdevila C, et al. Clinical implications of intratumor heterogeneity: challenges and opportunities. J Mol Med. 2020;98:161-177.

- Mitsui H, Suárez-Fariñas M, Gulati N, et al. Gene expression profiling of the leading edge of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: IL-24-driven MMP-7. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1418-1427.

- Chung E, Hoang S, McEvoy AM, et al. Histopathologic upgrading of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas during Mohs micrographic surgery: a retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:923-930.

- Alniemi DT, Swanson AM, Lasarev M, et al. Tumor debulking trends for keratinocyte carcinomas among Mohs surgeons. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:1660-1661.

Practice Points

- A proportion of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas are upgraded from the initial biopsy during Mohs micrographic surgery due to evidence of perineural invasion, bony invasion, or lesser differentiation noted on Mohs stages or debulk analysis.

- Thorough inspection of the deep tumor margins may be required for accurate tumor staging and evaluation of metastatic risk. Cells at the deep margin of the tumor may demonstrate poorer differentiation and/or other higher-risk tumor features than those closer to the surface.

- Tumor staging may be incomplete until the deep margins are assessed to find the most dysplastic and likely clinically relevant cells, which may be missed without evaluation of the debulked tumor.

Eosinophilic Pustular Folliculitis in the Setting of Untreated Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

To the Editor:

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (EPF) is a noninfectious dermatosis that typically manifests as recurrent follicular papulopustules that generally affect the face and occasionally the trunk and arms. There are several subtypes of EPF: classic EPF (Ofuji disease), infancy-associated EPF, and immunosuppression-associated EPF.1,2 We report a rare case of EPF in the setting of untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), a subtype of immunosuppression-associated EPF that has been associated with hematologic malignancy EPF (HM-EPF).3-5

A 69-year-old woman presented with diffusely scattered, pruritic, erythematous, erosive lesions on the back, arms, legs, and forehead (Figure 1) of 4 months’ duration, as well as an ulcerative lesion on the left third toe due to a suspected insect bite. She had a history of untreated CLL that was diagnosed 2 years prior. The patient was empirically started on clindamycin for presumed infection of the toe. A punch biopsy of the left wrist revealed superficial and deep dermal perivascular and interstitial inflammatory infiltrates composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous eosinophils in association with edema and necrosis. Histopathology was overall most consistent with an exuberant arthropod reaction; however, at 2-week follow-up, the patient reported that the pustular lesions improved upon starting antibiotics, which raised concerns for a bacterial process. The patient initially was continued on clindamycin given subjective improvement but was later switched to daptomycin, as she developed clindamycin-resistant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis from the necrotic toe.

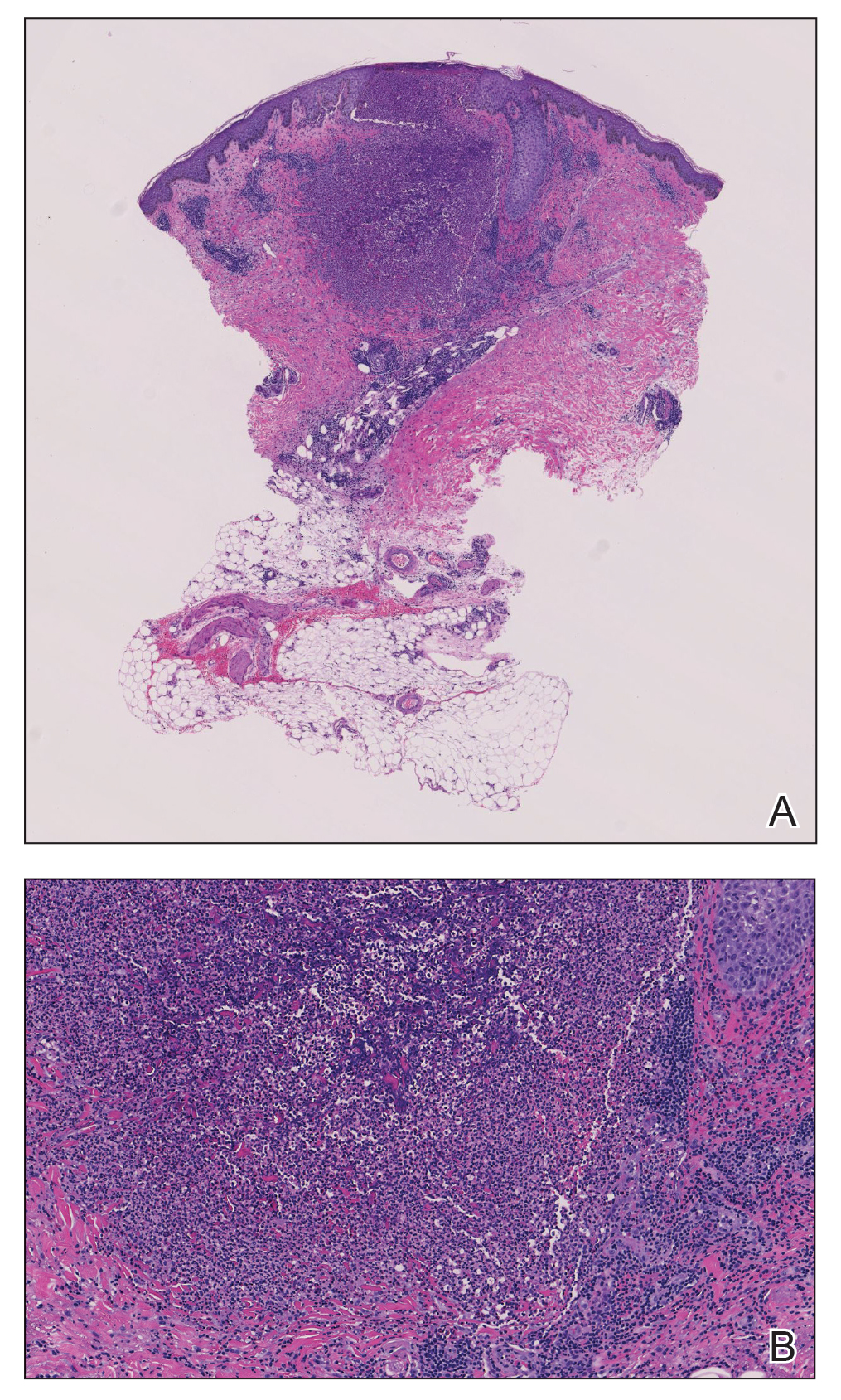

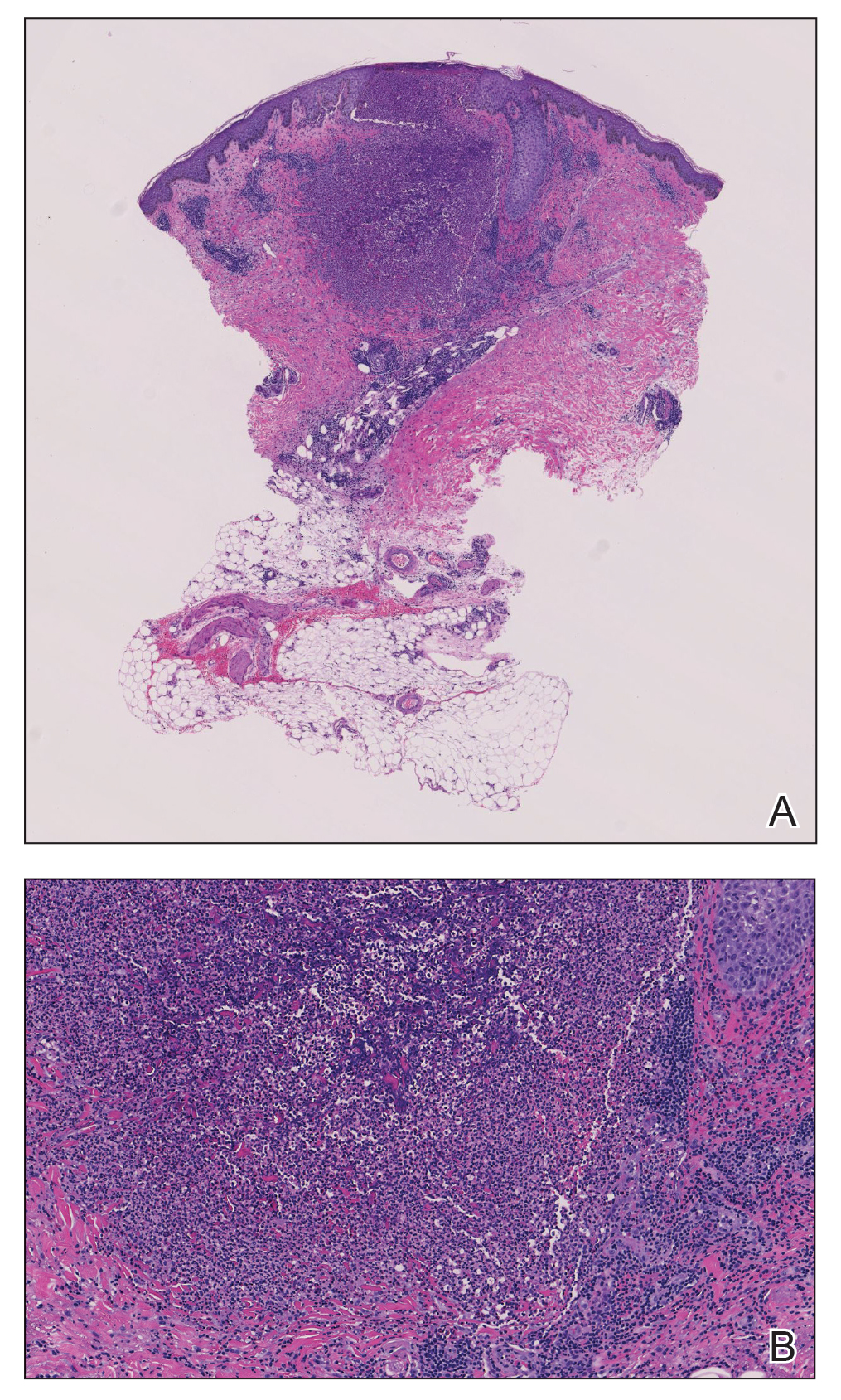

A month later, the patient returned with new papules and pustules on the arms and trunk. A repeat biopsy showed notable dermal collections comprised predominantly of neutrophils and eosinophils as well as involvement of follicular structures by dense inflammation (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated a predominant population of small CD3+ T cells, which raised concern for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. However, retention of CD5 expression made this less likely. Few scattered CD20+ B cells with limited CD23 reactivity and without CD5 co-expression were detected, which ruled out cutaneous involvement of the patient’s CLL. Bacterial culture and Grocott methenamine-silver, Gram, acid-fast bacilli, and periodic acid-Schiff stains were negative. Polymerase chain reaction testing for varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus also were negative. Thus, a diagnosis of EPF secondary to CLL was favored, as an infectious process also was unlikely. The patient was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1% with gradual improvement.

Cases of HM-EPF predominantly have been reported in patients who have undergone chemotherapy, bone marrow transplantation, or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Furthermore, a vast majority of these cases have been reported in older males.3-16 In a retrospective study of more than 750 patients with established CLL, Agnew et al7 identified 125 different skin complications in 40 patients. Of this subset, only a small number (2/40) were associated with eosinophilic folliculitis, with 1 case noted in a middle-aged woman with a history of CLL treatment.7 Moreover, Motaparthi et al4 reported 3 additional cases of HM-EPF, with all patients identified as middle-aged men who were treated with chemotherapy for underlying CLL. Our patient represents a case of EPF in the context of untreated CLL in a woman.

Although topical corticosteroids remain the first-line treatment for EPF, a survey study conducted across 67 hospitals in Japan indicated that antibiotics were moderately or highly effective in 79% of EPF patients (n=143).17 This association may explain the subjective improvement reported by our patient upon starting clindamycin. Furthermore, in HIV-associated EPF, high-dose cetirizine, itraconazole, and metronidazole have been successful when topical therapies have failed.18 Although the precise pathogenesis of EPF is unknown, histopathologic features, clinical appearance, and identification of the accurate EPF subtype can still prove valuable in informing empiric treatment strategies. Consequently, the initial histopathologic diagnosis of an arthropod bite reaction in our patient highlights the importance of clinical correlation and additional ancillary studies in the determination of EPF vs other inflammatory dermatoses that manifest microscopically with lymphocytic infiltrates, prominent eosinophils, and follicular involvement.4 The histopathologic features of EPF demonstrate considerable overlap with eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy (also known as eosinophilic dermatosis of myeloproliferative disease). It is suspected that eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy and EPF may exist on a spectrum, and additional cases may improve categorization of these entities.19

In conclusion, this report adds to the medical practitioner’s awareness of EPF manifestations in patients with underlying CLL, an infrequently reported subtype of HM-EPF.

- Fujiyama T, Tokura Y. Clinical and histopathological differential diagnosis of eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. J Dermatol. 2013;40:419-423. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12125

- Katoh M, Nomura T, Miyachi Y, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: a review of the Japanese published works. J Dermatol. 2013;40:15-20. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12008

- Takamura S, Teraki Y. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis associated with hematological disorders: a report of two cases and review of Japanese literature. J Dermatol. 2016;43:432-435. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.13088

- Motaparthi K, Kapil J, Hsu S. Eosinophilic folliculitis in association with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a clinicopathologic series. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:263-268. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.03.007

- Lambert J, Berneman Z, Dockx P, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis and B-cell chronic lymphatic leukaemia. Dermatology. 1994;189(suppl 2):58-59. doi:10.1159/000246994

- Patrizi A, Chieregato C, Visani G, et al. Leukaemia-associated eosinophilic folliculitis (Ofuji’s disease). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:596-598. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00982.x

- Agnew KL, Ruchlemer R, Catovsky D, et al. Cutaneous findings in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:1129-1135. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05982.x

- Zitelli K, Fernandes N, Adams BB. Eosinophilic folliculitis occurring after stem cell transplant for acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a case report and review. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:785-789. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05982.x

- Goiriz R, Guhl-Millán G, Peñas PF, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis following allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation: case report and review. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34(suppl 1):33-36. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00725.x

- Bhandare PC, Ghodge RR, Bhobe MR, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis post chemotherapy in a patient of non-Hodgkins lymphoma: a case report. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:521. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.164432

- Sugaya M, Suga H, Miyagaki T, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis associated with Sézary syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:536-538. doi:10.1111/ced.12315

- Keida T, Hayashi N, Kawashima M. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis following autologous peripheral blood stem-cell transplantation. J Dermatol. 2004;31:21-26. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2004.tb00499.x

- Ota M, Shimizu T, Hashino S, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis in a patient after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: case report and review of the literature. Am J Hematol. 2004;76:295-296. doi:10.1002/ajh.20080

- Vassallo C, Ciocca O, Arcaini L, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis occurring in a patient affected by Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:298-300. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01356_6.x

- Evans TR, Mansi JL, Bull R, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis occurring after bone marrow autograft in a patient with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Cancer. 1994;73:2512-2514. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19940515)73:10<2512::aid-cncr2820731010>3.0.co;2-s

- Patrizi A, Di Lernia V, Neri I, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (Ofuji’s disease) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 1992;72:146-147.

- Ono S, Yamamoto Y, Otsuka A, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of antibiotics against eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013;5:144-147. doi:10.1159/000351330

- Ellis E, Scheinfeld N. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:189-197. doi:10.2165/00128071-200405030-00007

- Bailey CAR, Laurain DA, Sheinbein DM, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis, eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy and acneiform follicular mucinosis: two case reports and a review of the literature highlighting the spectrum of histopathology. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:439-450. doi:10.1111/cup.13932

To the Editor:

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (EPF) is a noninfectious dermatosis that typically manifests as recurrent follicular papulopustules that generally affect the face and occasionally the trunk and arms. There are several subtypes of EPF: classic EPF (Ofuji disease), infancy-associated EPF, and immunosuppression-associated EPF.1,2 We report a rare case of EPF in the setting of untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), a subtype of immunosuppression-associated EPF that has been associated with hematologic malignancy EPF (HM-EPF).3-5

A 69-year-old woman presented with diffusely scattered, pruritic, erythematous, erosive lesions on the back, arms, legs, and forehead (Figure 1) of 4 months’ duration, as well as an ulcerative lesion on the left third toe due to a suspected insect bite. She had a history of untreated CLL that was diagnosed 2 years prior. The patient was empirically started on clindamycin for presumed infection of the toe. A punch biopsy of the left wrist revealed superficial and deep dermal perivascular and interstitial inflammatory infiltrates composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous eosinophils in association with edema and necrosis. Histopathology was overall most consistent with an exuberant arthropod reaction; however, at 2-week follow-up, the patient reported that the pustular lesions improved upon starting antibiotics, which raised concerns for a bacterial process. The patient initially was continued on clindamycin given subjective improvement but was later switched to daptomycin, as she developed clindamycin-resistant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis from the necrotic toe.

A month later, the patient returned with new papules and pustules on the arms and trunk. A repeat biopsy showed notable dermal collections comprised predominantly of neutrophils and eosinophils as well as involvement of follicular structures by dense inflammation (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated a predominant population of small CD3+ T cells, which raised concern for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. However, retention of CD5 expression made this less likely. Few scattered CD20+ B cells with limited CD23 reactivity and without CD5 co-expression were detected, which ruled out cutaneous involvement of the patient’s CLL. Bacterial culture and Grocott methenamine-silver, Gram, acid-fast bacilli, and periodic acid-Schiff stains were negative. Polymerase chain reaction testing for varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus also were negative. Thus, a diagnosis of EPF secondary to CLL was favored, as an infectious process also was unlikely. The patient was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1% with gradual improvement.

Cases of HM-EPF predominantly have been reported in patients who have undergone chemotherapy, bone marrow transplantation, or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Furthermore, a vast majority of these cases have been reported in older males.3-16 In a retrospective study of more than 750 patients with established CLL, Agnew et al7 identified 125 different skin complications in 40 patients. Of this subset, only a small number (2/40) were associated with eosinophilic folliculitis, with 1 case noted in a middle-aged woman with a history of CLL treatment.7 Moreover, Motaparthi et al4 reported 3 additional cases of HM-EPF, with all patients identified as middle-aged men who were treated with chemotherapy for underlying CLL. Our patient represents a case of EPF in the context of untreated CLL in a woman.

Although topical corticosteroids remain the first-line treatment for EPF, a survey study conducted across 67 hospitals in Japan indicated that antibiotics were moderately or highly effective in 79% of EPF patients (n=143).17 This association may explain the subjective improvement reported by our patient upon starting clindamycin. Furthermore, in HIV-associated EPF, high-dose cetirizine, itraconazole, and metronidazole have been successful when topical therapies have failed.18 Although the precise pathogenesis of EPF is unknown, histopathologic features, clinical appearance, and identification of the accurate EPF subtype can still prove valuable in informing empiric treatment strategies. Consequently, the initial histopathologic diagnosis of an arthropod bite reaction in our patient highlights the importance of clinical correlation and additional ancillary studies in the determination of EPF vs other inflammatory dermatoses that manifest microscopically with lymphocytic infiltrates, prominent eosinophils, and follicular involvement.4 The histopathologic features of EPF demonstrate considerable overlap with eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy (also known as eosinophilic dermatosis of myeloproliferative disease). It is suspected that eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy and EPF may exist on a spectrum, and additional cases may improve categorization of these entities.19

In conclusion, this report adds to the medical practitioner’s awareness of EPF manifestations in patients with underlying CLL, an infrequently reported subtype of HM-EPF.

To the Editor:

Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (EPF) is a noninfectious dermatosis that typically manifests as recurrent follicular papulopustules that generally affect the face and occasionally the trunk and arms. There are several subtypes of EPF: classic EPF (Ofuji disease), infancy-associated EPF, and immunosuppression-associated EPF.1,2 We report a rare case of EPF in the setting of untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), a subtype of immunosuppression-associated EPF that has been associated with hematologic malignancy EPF (HM-EPF).3-5

A 69-year-old woman presented with diffusely scattered, pruritic, erythematous, erosive lesions on the back, arms, legs, and forehead (Figure 1) of 4 months’ duration, as well as an ulcerative lesion on the left third toe due to a suspected insect bite. She had a history of untreated CLL that was diagnosed 2 years prior. The patient was empirically started on clindamycin for presumed infection of the toe. A punch biopsy of the left wrist revealed superficial and deep dermal perivascular and interstitial inflammatory infiltrates composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and numerous eosinophils in association with edema and necrosis. Histopathology was overall most consistent with an exuberant arthropod reaction; however, at 2-week follow-up, the patient reported that the pustular lesions improved upon starting antibiotics, which raised concerns for a bacterial process. The patient initially was continued on clindamycin given subjective improvement but was later switched to daptomycin, as she developed clindamycin-resistant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis from the necrotic toe.

A month later, the patient returned with new papules and pustules on the arms and trunk. A repeat biopsy showed notable dermal collections comprised predominantly of neutrophils and eosinophils as well as involvement of follicular structures by dense inflammation (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry demonstrated a predominant population of small CD3+ T cells, which raised concern for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. However, retention of CD5 expression made this less likely. Few scattered CD20+ B cells with limited CD23 reactivity and without CD5 co-expression were detected, which ruled out cutaneous involvement of the patient’s CLL. Bacterial culture and Grocott methenamine-silver, Gram, acid-fast bacilli, and periodic acid-Schiff stains were negative. Polymerase chain reaction testing for varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus also were negative. Thus, a diagnosis of EPF secondary to CLL was favored, as an infectious process also was unlikely. The patient was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1% with gradual improvement.

Cases of HM-EPF predominantly have been reported in patients who have undergone chemotherapy, bone marrow transplantation, or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Furthermore, a vast majority of these cases have been reported in older males.3-16 In a retrospective study of more than 750 patients with established CLL, Agnew et al7 identified 125 different skin complications in 40 patients. Of this subset, only a small number (2/40) were associated with eosinophilic folliculitis, with 1 case noted in a middle-aged woman with a history of CLL treatment.7 Moreover, Motaparthi et al4 reported 3 additional cases of HM-EPF, with all patients identified as middle-aged men who were treated with chemotherapy for underlying CLL. Our patient represents a case of EPF in the context of untreated CLL in a woman.

Although topical corticosteroids remain the first-line treatment for EPF, a survey study conducted across 67 hospitals in Japan indicated that antibiotics were moderately or highly effective in 79% of EPF patients (n=143).17 This association may explain the subjective improvement reported by our patient upon starting clindamycin. Furthermore, in HIV-associated EPF, high-dose cetirizine, itraconazole, and metronidazole have been successful when topical therapies have failed.18 Although the precise pathogenesis of EPF is unknown, histopathologic features, clinical appearance, and identification of the accurate EPF subtype can still prove valuable in informing empiric treatment strategies. Consequently, the initial histopathologic diagnosis of an arthropod bite reaction in our patient highlights the importance of clinical correlation and additional ancillary studies in the determination of EPF vs other inflammatory dermatoses that manifest microscopically with lymphocytic infiltrates, prominent eosinophils, and follicular involvement.4 The histopathologic features of EPF demonstrate considerable overlap with eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy (also known as eosinophilic dermatosis of myeloproliferative disease). It is suspected that eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy and EPF may exist on a spectrum, and additional cases may improve categorization of these entities.19

In conclusion, this report adds to the medical practitioner’s awareness of EPF manifestations in patients with underlying CLL, an infrequently reported subtype of HM-EPF.

- Fujiyama T, Tokura Y. Clinical and histopathological differential diagnosis of eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. J Dermatol. 2013;40:419-423. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12125

- Katoh M, Nomura T, Miyachi Y, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: a review of the Japanese published works. J Dermatol. 2013;40:15-20. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12008

- Takamura S, Teraki Y. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis associated with hematological disorders: a report of two cases and review of Japanese literature. J Dermatol. 2016;43:432-435. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.13088

- Motaparthi K, Kapil J, Hsu S. Eosinophilic folliculitis in association with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a clinicopathologic series. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:263-268. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.03.007

- Lambert J, Berneman Z, Dockx P, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis and B-cell chronic lymphatic leukaemia. Dermatology. 1994;189(suppl 2):58-59. doi:10.1159/000246994

- Patrizi A, Chieregato C, Visani G, et al. Leukaemia-associated eosinophilic folliculitis (Ofuji’s disease). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:596-598. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00982.x

- Agnew KL, Ruchlemer R, Catovsky D, et al. Cutaneous findings in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:1129-1135. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05982.x

- Zitelli K, Fernandes N, Adams BB. Eosinophilic folliculitis occurring after stem cell transplant for acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a case report and review. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:785-789. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05982.x

- Goiriz R, Guhl-Millán G, Peñas PF, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis following allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation: case report and review. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34(suppl 1):33-36. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00725.x

- Bhandare PC, Ghodge RR, Bhobe MR, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis post chemotherapy in a patient of non-Hodgkins lymphoma: a case report. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:521. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.164432

- Sugaya M, Suga H, Miyagaki T, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis associated with Sézary syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:536-538. doi:10.1111/ced.12315

- Keida T, Hayashi N, Kawashima M. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis following autologous peripheral blood stem-cell transplantation. J Dermatol. 2004;31:21-26. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2004.tb00499.x

- Ota M, Shimizu T, Hashino S, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis in a patient after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: case report and review of the literature. Am J Hematol. 2004;76:295-296. doi:10.1002/ajh.20080

- Vassallo C, Ciocca O, Arcaini L, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis occurring in a patient affected by Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:298-300. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01356_6.x

- Evans TR, Mansi JL, Bull R, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis occurring after bone marrow autograft in a patient with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Cancer. 1994;73:2512-2514. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19940515)73:10<2512::aid-cncr2820731010>3.0.co;2-s

- Patrizi A, Di Lernia V, Neri I, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (Ofuji’s disease) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 1992;72:146-147.

- Ono S, Yamamoto Y, Otsuka A, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of antibiotics against eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013;5:144-147. doi:10.1159/000351330

- Ellis E, Scheinfeld N. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:189-197. doi:10.2165/00128071-200405030-00007

- Bailey CAR, Laurain DA, Sheinbein DM, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis, eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy and acneiform follicular mucinosis: two case reports and a review of the literature highlighting the spectrum of histopathology. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:439-450. doi:10.1111/cup.13932

- Fujiyama T, Tokura Y. Clinical and histopathological differential diagnosis of eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. J Dermatol. 2013;40:419-423. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12125

- Katoh M, Nomura T, Miyachi Y, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis: a review of the Japanese published works. J Dermatol. 2013;40:15-20. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12008

- Takamura S, Teraki Y. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis associated with hematological disorders: a report of two cases and review of Japanese literature. J Dermatol. 2016;43:432-435. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.13088

- Motaparthi K, Kapil J, Hsu S. Eosinophilic folliculitis in association with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a clinicopathologic series. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:263-268. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.03.007

- Lambert J, Berneman Z, Dockx P, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis and B-cell chronic lymphatic leukaemia. Dermatology. 1994;189(suppl 2):58-59. doi:10.1159/000246994

- Patrizi A, Chieregato C, Visani G, et al. Leukaemia-associated eosinophilic folliculitis (Ofuji’s disease). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:596-598. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00982.x

- Agnew KL, Ruchlemer R, Catovsky D, et al. Cutaneous findings in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150:1129-1135. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05982.x

- Zitelli K, Fernandes N, Adams BB. Eosinophilic folliculitis occurring after stem cell transplant for acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a case report and review. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:785-789. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.05982.x

- Goiriz R, Guhl-Millán G, Peñas PF, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis following allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation: case report and review. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34(suppl 1):33-36. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00725.x

- Bhandare PC, Ghodge RR, Bhobe MR, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis post chemotherapy in a patient of non-Hodgkins lymphoma: a case report. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:521. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.164432

- Sugaya M, Suga H, Miyagaki T, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis associated with Sézary syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:536-538. doi:10.1111/ced.12315

- Keida T, Hayashi N, Kawashima M. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis following autologous peripheral blood stem-cell transplantation. J Dermatol. 2004;31:21-26. doi:10.1111/j.1346-8138.2004.tb00499.x

- Ota M, Shimizu T, Hashino S, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis in a patient after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: case report and review of the literature. Am J Hematol. 2004;76:295-296. doi:10.1002/ajh.20080

- Vassallo C, Ciocca O, Arcaini L, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis occurring in a patient affected by Hodgkin lymphoma. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:298-300. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2002.01356_6.x

- Evans TR, Mansi JL, Bull R, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis occurring after bone marrow autograft in a patient with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Cancer. 1994;73:2512-2514. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19940515)73:10<2512::aid-cncr2820731010>3.0.co;2-s

- Patrizi A, Di Lernia V, Neri I, et al. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (Ofuji’s disease) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 1992;72:146-147.

- Ono S, Yamamoto Y, Otsuka A, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness of antibiotics against eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013;5:144-147. doi:10.1159/000351330

- Ellis E, Scheinfeld N. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2004;5:189-197. doi:10.2165/00128071-200405030-00007

- Bailey CAR, Laurain DA, Sheinbein DM, et al. Eosinophilic folliculitis, eosinophilic dermatosis of hematologic malignancy and acneiform follicular mucinosis: two case reports and a review of the literature highlighting the spectrum of histopathology. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:439-450. doi:10.1111/cup.13932

Practice Points

- Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (EPF) is associated with an immunosuppressed state, as in patients with underlying hematologic malignancy.

- Topical corticosteroids remain the first-line treatment for EPF; however, antimicrobial agents have been used with moderate success when topical therapies have failed.