User login

An 80-year-old female developed a painful purulent nodule a day after gardening

. There are more than 100 species of dematiaceous fungi that can cause phaeohyphomycosis, including Alternaria, Exophiala, Phialophora, Wangiella, Bipolaris, Curvularia, and Exserohilum.1,2 The causative fungi are found in plants and soil, so they are commonly seen after activities such as gardening or walking barefoot. Trauma, such as a splinter, typically incites the infection. Infections can present with superficial, cutaneous and subcutaneous involvement.

Sporotrichosis, also called Rose gardener’s disease, is a mycosis caused by Sporothrix schenckii. A typical presentation is when a gardener gets pricked by a rose thorn. Classically, a pustule will develop at the site of inoculation, with additional lesions forming along the path of lymphatic drainage (called a “sporotrichoid” pattern) weeks later. Atypical mycobacterial infections, mainly Mycobacterium marinum, may also present in this way. Histopathology and tissue cultures help to differentiate the two.

An incision and drainage with pathology was performed in the office. Upon opening the nodule, a large wood splinter was extracted. Both the foreign body and a punch biopsy of skin were sent in for examination. Pathology revealed polarizable foreign material in association with suppurative inflammation and dematiaceous fungi. PAS (Periodic-acid Schiff) and GMS (Grocott methenamine silver) stain highlighted fungal forms. Cultures were negative.

Local disease may be treated with excision alone. Oral antifungals, such as itraconazole, fluconazole, or ketoconazole may be used, although may require long treatment courses for months. Amphotericin B and flucytosine may be required in systemic cases. Almost all cases of disseminated disease occur in immunocompromised patients. Our patient’s hand resolved after removal of the causative thorn.

This case and these photos were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Kradin R. Diagnostic Pathology of Infectious Disease, 1st edition (Saunders, Feb. 2, 2010).

2. Bolognia J et al. Dermatology (St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008).

. There are more than 100 species of dematiaceous fungi that can cause phaeohyphomycosis, including Alternaria, Exophiala, Phialophora, Wangiella, Bipolaris, Curvularia, and Exserohilum.1,2 The causative fungi are found in plants and soil, so they are commonly seen after activities such as gardening or walking barefoot. Trauma, such as a splinter, typically incites the infection. Infections can present with superficial, cutaneous and subcutaneous involvement.

Sporotrichosis, also called Rose gardener’s disease, is a mycosis caused by Sporothrix schenckii. A typical presentation is when a gardener gets pricked by a rose thorn. Classically, a pustule will develop at the site of inoculation, with additional lesions forming along the path of lymphatic drainage (called a “sporotrichoid” pattern) weeks later. Atypical mycobacterial infections, mainly Mycobacterium marinum, may also present in this way. Histopathology and tissue cultures help to differentiate the two.

An incision and drainage with pathology was performed in the office. Upon opening the nodule, a large wood splinter was extracted. Both the foreign body and a punch biopsy of skin were sent in for examination. Pathology revealed polarizable foreign material in association with suppurative inflammation and dematiaceous fungi. PAS (Periodic-acid Schiff) and GMS (Grocott methenamine silver) stain highlighted fungal forms. Cultures were negative.

Local disease may be treated with excision alone. Oral antifungals, such as itraconazole, fluconazole, or ketoconazole may be used, although may require long treatment courses for months. Amphotericin B and flucytosine may be required in systemic cases. Almost all cases of disseminated disease occur in immunocompromised patients. Our patient’s hand resolved after removal of the causative thorn.

This case and these photos were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Kradin R. Diagnostic Pathology of Infectious Disease, 1st edition (Saunders, Feb. 2, 2010).

2. Bolognia J et al. Dermatology (St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008).

. There are more than 100 species of dematiaceous fungi that can cause phaeohyphomycosis, including Alternaria, Exophiala, Phialophora, Wangiella, Bipolaris, Curvularia, and Exserohilum.1,2 The causative fungi are found in plants and soil, so they are commonly seen after activities such as gardening or walking barefoot. Trauma, such as a splinter, typically incites the infection. Infections can present with superficial, cutaneous and subcutaneous involvement.

Sporotrichosis, also called Rose gardener’s disease, is a mycosis caused by Sporothrix schenckii. A typical presentation is when a gardener gets pricked by a rose thorn. Classically, a pustule will develop at the site of inoculation, with additional lesions forming along the path of lymphatic drainage (called a “sporotrichoid” pattern) weeks later. Atypical mycobacterial infections, mainly Mycobacterium marinum, may also present in this way. Histopathology and tissue cultures help to differentiate the two.

An incision and drainage with pathology was performed in the office. Upon opening the nodule, a large wood splinter was extracted. Both the foreign body and a punch biopsy of skin were sent in for examination. Pathology revealed polarizable foreign material in association with suppurative inflammation and dematiaceous fungi. PAS (Periodic-acid Schiff) and GMS (Grocott methenamine silver) stain highlighted fungal forms. Cultures were negative.

Local disease may be treated with excision alone. Oral antifungals, such as itraconazole, fluconazole, or ketoconazole may be used, although may require long treatment courses for months. Amphotericin B and flucytosine may be required in systemic cases. Almost all cases of disseminated disease occur in immunocompromised patients. Our patient’s hand resolved after removal of the causative thorn.

This case and these photos were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Kradin R. Diagnostic Pathology of Infectious Disease, 1st edition (Saunders, Feb. 2, 2010).

2. Bolognia J et al. Dermatology (St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008).

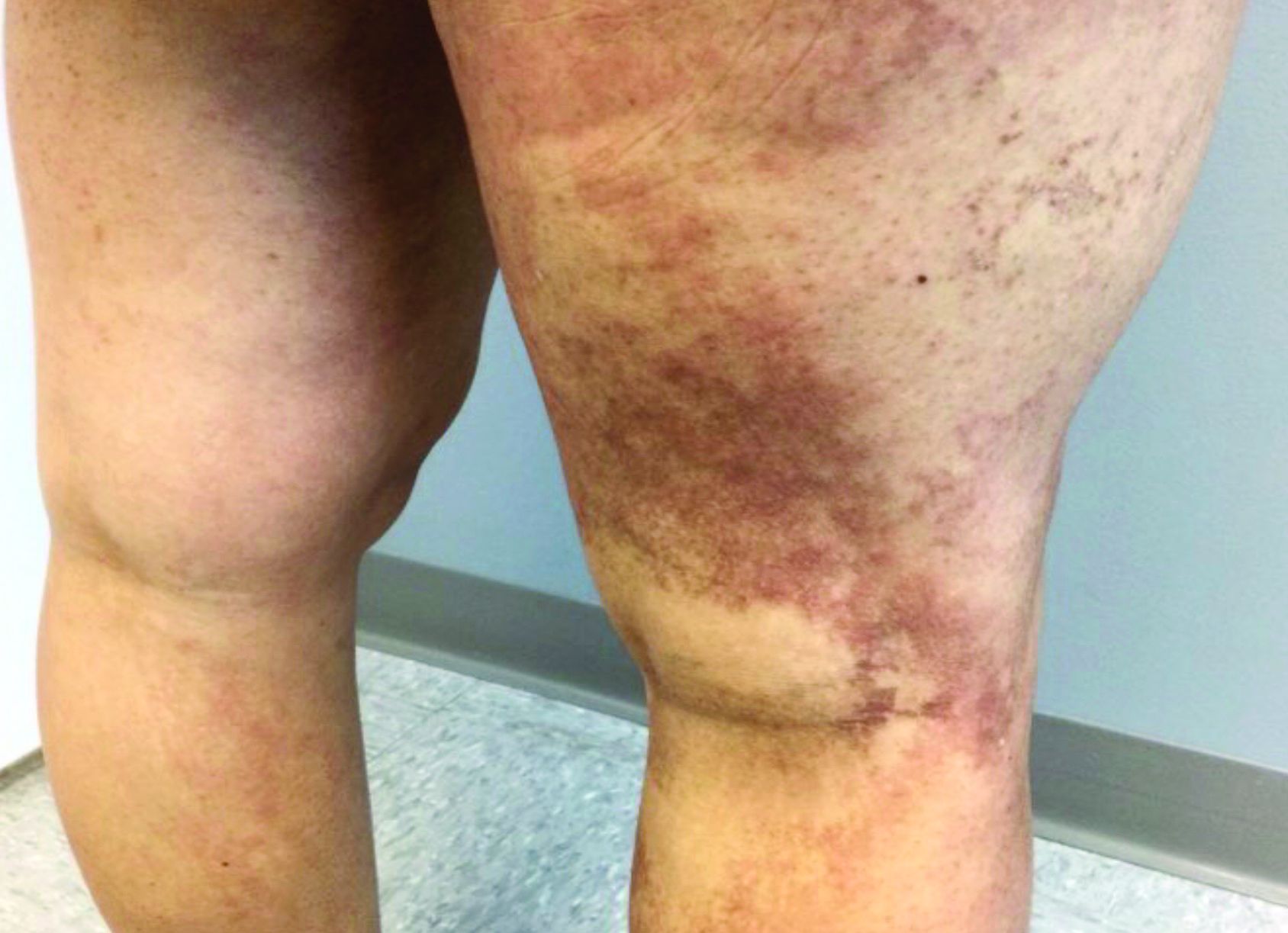

A 35-year-old with erythematous, dusky patches on both lower extremities

Zinc deficiency may be inherited or acquired. Acrodermatitis enteropathica is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder caused by a mutation in the gene that encodes a zinc transporter. It presents in infancy with the classic triad of diarrhea, dermatitis, and alopecia. Acquired zinc deficiency is due to causes such as alcoholism, malabsorption disorders like cystic fibrosis, inflammatory disease, gastrointestinal surgery, metabolic stress following general surgery, eating disorders, infections, malignancy, or occasionally in pregnancy. Classically, the face, groin, and extremities are affected (often acral), with erythematous, scaly patches. Pustules and bullae may be present. Angular cheilitis is often seen.

Necrolytic migratory erythema, or glucagonoma syndrome, is a very rare syndrome that presents as annular, erythematous patches with blisters that erode on the lower extremities and groin. The condition results from a cancerous tumor in the alpha cells of the pancreas called a glucagonoma, which secretes the hormone glucagon. It is often associated with diabetes and hyperglycemia.

Necrolytic acral erythema resembles acrodermatitis enteropathica and necrolytic migratory erythema clinically, however, it is associated with hepatitis C infection. Lesions are plaques with well defined borders distributed acrally. Treatment of the hepatitis C often improves the dermatitis.

Our patient’s blood work was consistent with nutritional deficiency and revealed low levels of zinc, vitamin A, ceruloplasmin, albumin and prealbumin, total protein, calcium, selenium, vitamin E, vitamin K, and vitamin C. Her hemoglobin A1C was under 4. Her hepatitis serologies were negative. The patient received total parenteral nutrition with subsequent complete resolution of her rash. Follow up for gastric bypass patients should be performed long term as they are at risk for nutritional deficiencies.

Dr. Bilu Martin, and Andrew Harris, DO, Mount Sinai Medical Center, Aventura, Fla., provided the case and photos.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

Dermatol Online J. 2016 Nov 15; 22(11):13030.

Andrews’ Disease of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2006.

Bolognia et al. Dermatology. St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008.

Zinc deficiency may be inherited or acquired. Acrodermatitis enteropathica is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder caused by a mutation in the gene that encodes a zinc transporter. It presents in infancy with the classic triad of diarrhea, dermatitis, and alopecia. Acquired zinc deficiency is due to causes such as alcoholism, malabsorption disorders like cystic fibrosis, inflammatory disease, gastrointestinal surgery, metabolic stress following general surgery, eating disorders, infections, malignancy, or occasionally in pregnancy. Classically, the face, groin, and extremities are affected (often acral), with erythematous, scaly patches. Pustules and bullae may be present. Angular cheilitis is often seen.

Necrolytic migratory erythema, or glucagonoma syndrome, is a very rare syndrome that presents as annular, erythematous patches with blisters that erode on the lower extremities and groin. The condition results from a cancerous tumor in the alpha cells of the pancreas called a glucagonoma, which secretes the hormone glucagon. It is often associated with diabetes and hyperglycemia.

Necrolytic acral erythema resembles acrodermatitis enteropathica and necrolytic migratory erythema clinically, however, it is associated with hepatitis C infection. Lesions are plaques with well defined borders distributed acrally. Treatment of the hepatitis C often improves the dermatitis.

Our patient’s blood work was consistent with nutritional deficiency and revealed low levels of zinc, vitamin A, ceruloplasmin, albumin and prealbumin, total protein, calcium, selenium, vitamin E, vitamin K, and vitamin C. Her hemoglobin A1C was under 4. Her hepatitis serologies were negative. The patient received total parenteral nutrition with subsequent complete resolution of her rash. Follow up for gastric bypass patients should be performed long term as they are at risk for nutritional deficiencies.

Dr. Bilu Martin, and Andrew Harris, DO, Mount Sinai Medical Center, Aventura, Fla., provided the case and photos.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

Dermatol Online J. 2016 Nov 15; 22(11):13030.

Andrews’ Disease of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2006.

Bolognia et al. Dermatology. St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008.

Zinc deficiency may be inherited or acquired. Acrodermatitis enteropathica is an autosomal recessive genetic disorder caused by a mutation in the gene that encodes a zinc transporter. It presents in infancy with the classic triad of diarrhea, dermatitis, and alopecia. Acquired zinc deficiency is due to causes such as alcoholism, malabsorption disorders like cystic fibrosis, inflammatory disease, gastrointestinal surgery, metabolic stress following general surgery, eating disorders, infections, malignancy, or occasionally in pregnancy. Classically, the face, groin, and extremities are affected (often acral), with erythematous, scaly patches. Pustules and bullae may be present. Angular cheilitis is often seen.

Necrolytic migratory erythema, or glucagonoma syndrome, is a very rare syndrome that presents as annular, erythematous patches with blisters that erode on the lower extremities and groin. The condition results from a cancerous tumor in the alpha cells of the pancreas called a glucagonoma, which secretes the hormone glucagon. It is often associated with diabetes and hyperglycemia.

Necrolytic acral erythema resembles acrodermatitis enteropathica and necrolytic migratory erythema clinically, however, it is associated with hepatitis C infection. Lesions are plaques with well defined borders distributed acrally. Treatment of the hepatitis C often improves the dermatitis.

Our patient’s blood work was consistent with nutritional deficiency and revealed low levels of zinc, vitamin A, ceruloplasmin, albumin and prealbumin, total protein, calcium, selenium, vitamin E, vitamin K, and vitamin C. Her hemoglobin A1C was under 4. Her hepatitis serologies were negative. The patient received total parenteral nutrition with subsequent complete resolution of her rash. Follow up for gastric bypass patients should be performed long term as they are at risk for nutritional deficiencies.

Dr. Bilu Martin, and Andrew Harris, DO, Mount Sinai Medical Center, Aventura, Fla., provided the case and photos.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

Dermatol Online J. 2016 Nov 15; 22(11):13030.

Andrews’ Disease of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2006.

Bolognia et al. Dermatology. St. Louis: Mosby/Elsevier, 2008.

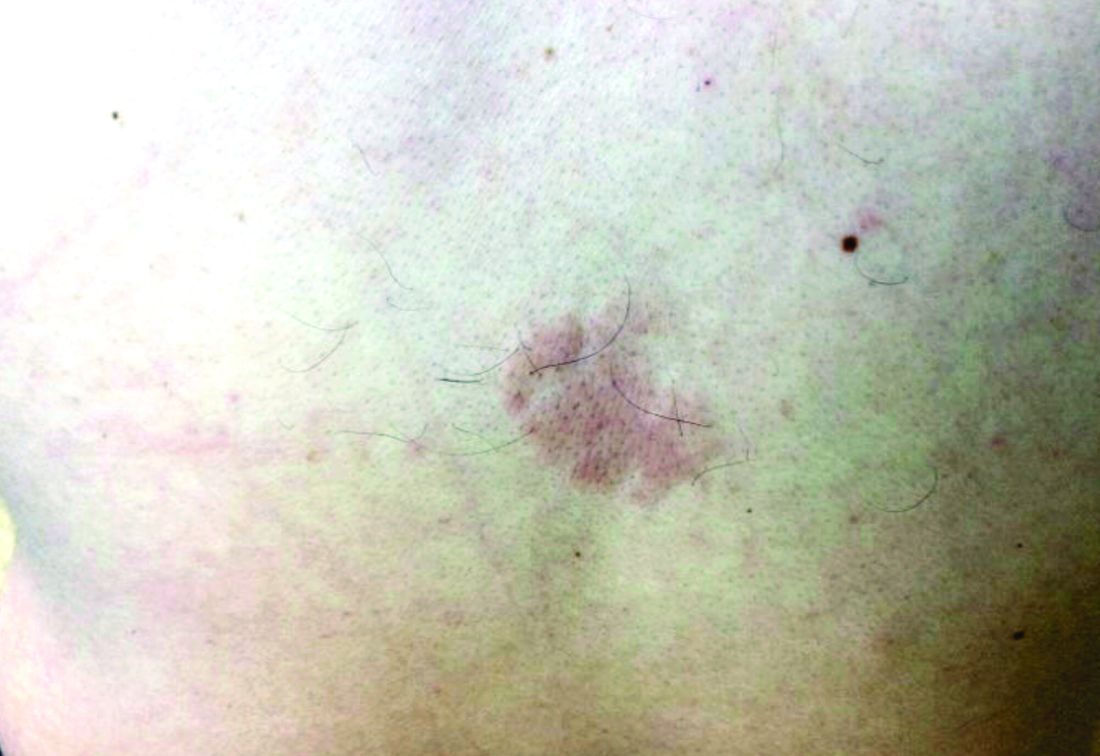

A male with pruritic scaling and bumps in the red area of a tattoo placed months earlier

, photoallergic reactions, infectious processes because of contaminated ink or a nonsterile environment, or as a Koebner response.

Dermatitis is commonly seen in patients with a sensitivity to certain pigments. Mercury sulfide or cinnabar in red, chromium in green, and cobalt in blue are common offenders. Cadmium, which is used for yellow, may cause a photoallergic reaction following exposure to ultraviolet light. Other inorganic salts of metals used for tattooing include ferric hydrate for ochre, ferric oxide for brown, manganese salts for purple. Reactions may be seen within a few weeks up to years after the tattoo is placed.

Reactions are often confined to the tattoo and may present as erythematous papules or plaques, although lesions may also present as scaly and eczematous patches. Psoriasis, vitiligo, and lichen planus may Koebnerize and appear in the tattoo. Sarcoidosis may occur in tattoos and can be seen upon histopathologic examination. Allergic contact dermatitis may also be seen in people who receive temporary henna tattoos in which the henna dye is mixed with paraphenylenediamine (PPD).

Histologically, granulomatous, sarcoidal, and lichenoid patterns may be seen. A punch biopsy was performed in this patient that revealed a lichenoid and interstitial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with red tattoo pigment. Special stains for PAS, GMS, FITE, and AFB were negative. There was no polarizable foreign material identified.

Treatment includes topical steroids, which may be ineffective, intralesional kenalog, and surgical excision. Laser must be used with caution, as it may aggravate the allergic reaction and cause a systemic reaction.

This case and photo were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

, photoallergic reactions, infectious processes because of contaminated ink or a nonsterile environment, or as a Koebner response.

Dermatitis is commonly seen in patients with a sensitivity to certain pigments. Mercury sulfide or cinnabar in red, chromium in green, and cobalt in blue are common offenders. Cadmium, which is used for yellow, may cause a photoallergic reaction following exposure to ultraviolet light. Other inorganic salts of metals used for tattooing include ferric hydrate for ochre, ferric oxide for brown, manganese salts for purple. Reactions may be seen within a few weeks up to years after the tattoo is placed.

Reactions are often confined to the tattoo and may present as erythematous papules or plaques, although lesions may also present as scaly and eczematous patches. Psoriasis, vitiligo, and lichen planus may Koebnerize and appear in the tattoo. Sarcoidosis may occur in tattoos and can be seen upon histopathologic examination. Allergic contact dermatitis may also be seen in people who receive temporary henna tattoos in which the henna dye is mixed with paraphenylenediamine (PPD).

Histologically, granulomatous, sarcoidal, and lichenoid patterns may be seen. A punch biopsy was performed in this patient that revealed a lichenoid and interstitial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with red tattoo pigment. Special stains for PAS, GMS, FITE, and AFB were negative. There was no polarizable foreign material identified.

Treatment includes topical steroids, which may be ineffective, intralesional kenalog, and surgical excision. Laser must be used with caution, as it may aggravate the allergic reaction and cause a systemic reaction.

This case and photo were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

, photoallergic reactions, infectious processes because of contaminated ink or a nonsterile environment, or as a Koebner response.

Dermatitis is commonly seen in patients with a sensitivity to certain pigments. Mercury sulfide or cinnabar in red, chromium in green, and cobalt in blue are common offenders. Cadmium, which is used for yellow, may cause a photoallergic reaction following exposure to ultraviolet light. Other inorganic salts of metals used for tattooing include ferric hydrate for ochre, ferric oxide for brown, manganese salts for purple. Reactions may be seen within a few weeks up to years after the tattoo is placed.

Reactions are often confined to the tattoo and may present as erythematous papules or plaques, although lesions may also present as scaly and eczematous patches. Psoriasis, vitiligo, and lichen planus may Koebnerize and appear in the tattoo. Sarcoidosis may occur in tattoos and can be seen upon histopathologic examination. Allergic contact dermatitis may also be seen in people who receive temporary henna tattoos in which the henna dye is mixed with paraphenylenediamine (PPD).

Histologically, granulomatous, sarcoidal, and lichenoid patterns may be seen. A punch biopsy was performed in this patient that revealed a lichenoid and interstitial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with red tattoo pigment. Special stains for PAS, GMS, FITE, and AFB were negative. There was no polarizable foreign material identified.

Treatment includes topical steroids, which may be ineffective, intralesional kenalog, and surgical excision. Laser must be used with caution, as it may aggravate the allergic reaction and cause a systemic reaction.

This case and photo were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

A woman with scaling, and painful, crusted, erythematous papules and pustules on her face

Biopsy for this patient revealed folliculitis with Demodex mites visualized on histology. Direct immunofluorescence was negative. A KOH preparation was performed and was positive for large numbers of Demodex. Bacterial cultures were negative. The patient was started on a course of submicrobial doxycycline and ivermectin and showed marked improvement 1 month following treatment.

Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis (collectively referred to as Demodex) are microscopic parasitic mites that commonly live on human skin.1 Typically, the mite remains asymptomatic. However, in higher numbers, the infestation may cause dermatoses, called demodicosis. Lesions often present as itchy papules, pustules, and erythematous scaling on the face, ears, and scalp. Blepharitis may be present. Demodex folliculitis is more common in immunocompromised patients.2

Demodex may have a causative role in rosacea and present similarly, with a key difference being that Demodex-type rosacea is more scaly/dry and pustular than common rosacea.1 In Demodex folliculitis, bacterial cultures are often negative. A skin scraping for KOH will reveal increased mite colonization. The Demodex mite may also be seen in histologic slides.

Treatment of Demodex folliculitis includes crotamiton cream, permethrin cream, oral tetracyclines, topical or systemic metronidazole, and topical or oral ivermectin.

This case and photos were submitted by Susannah McClain, MD, Three Rivers Dermatology, Pittsburgh.

References

1. Rather PA and Hassan I. Indian J Dermatol. 2014 Jan;59(1):60-6.

2. Bachmeyer C and Moreno-Sabater A. CMAJ. 2017 Jun 26;189(25):E865.

Biopsy for this patient revealed folliculitis with Demodex mites visualized on histology. Direct immunofluorescence was negative. A KOH preparation was performed and was positive for large numbers of Demodex. Bacterial cultures were negative. The patient was started on a course of submicrobial doxycycline and ivermectin and showed marked improvement 1 month following treatment.

Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis (collectively referred to as Demodex) are microscopic parasitic mites that commonly live on human skin.1 Typically, the mite remains asymptomatic. However, in higher numbers, the infestation may cause dermatoses, called demodicosis. Lesions often present as itchy papules, pustules, and erythematous scaling on the face, ears, and scalp. Blepharitis may be present. Demodex folliculitis is more common in immunocompromised patients.2

Demodex may have a causative role in rosacea and present similarly, with a key difference being that Demodex-type rosacea is more scaly/dry and pustular than common rosacea.1 In Demodex folliculitis, bacterial cultures are often negative. A skin scraping for KOH will reveal increased mite colonization. The Demodex mite may also be seen in histologic slides.

Treatment of Demodex folliculitis includes crotamiton cream, permethrin cream, oral tetracyclines, topical or systemic metronidazole, and topical or oral ivermectin.

This case and photos were submitted by Susannah McClain, MD, Three Rivers Dermatology, Pittsburgh.

References

1. Rather PA and Hassan I. Indian J Dermatol. 2014 Jan;59(1):60-6.

2. Bachmeyer C and Moreno-Sabater A. CMAJ. 2017 Jun 26;189(25):E865.

Biopsy for this patient revealed folliculitis with Demodex mites visualized on histology. Direct immunofluorescence was negative. A KOH preparation was performed and was positive for large numbers of Demodex. Bacterial cultures were negative. The patient was started on a course of submicrobial doxycycline and ivermectin and showed marked improvement 1 month following treatment.

Demodex folliculorum and Demodex brevis (collectively referred to as Demodex) are microscopic parasitic mites that commonly live on human skin.1 Typically, the mite remains asymptomatic. However, in higher numbers, the infestation may cause dermatoses, called demodicosis. Lesions often present as itchy papules, pustules, and erythematous scaling on the face, ears, and scalp. Blepharitis may be present. Demodex folliculitis is more common in immunocompromised patients.2

Demodex may have a causative role in rosacea and present similarly, with a key difference being that Demodex-type rosacea is more scaly/dry and pustular than common rosacea.1 In Demodex folliculitis, bacterial cultures are often negative. A skin scraping for KOH will reveal increased mite colonization. The Demodex mite may also be seen in histologic slides.

Treatment of Demodex folliculitis includes crotamiton cream, permethrin cream, oral tetracyclines, topical or systemic metronidazole, and topical or oral ivermectin.

This case and photos were submitted by Susannah McClain, MD, Three Rivers Dermatology, Pittsburgh.

References

1. Rather PA and Hassan I. Indian J Dermatol. 2014 Jan;59(1):60-6.

2. Bachmeyer C and Moreno-Sabater A. CMAJ. 2017 Jun 26;189(25):E865.

A woman with a history of diabetes, and plaques on both shins

. Women are often more affected than men. Patients often present in their 30s and 40s. The cause of NLD is unknown. Twenty percent of patients with NLD will have glucose intolerance or a family history of diabetes.1 The percentage of patients with NLD who have diabetes varies in reports from 11% to 65%.2 NLD may progress despite the diabetes treatment. Only 0.03% of patient with diabetes will have NLD.3

Lesions most commonly occur on the extremities, with shins being affected in most cases. They vary from asymptomatic to painful. Typically, lesions begin as small, firm erythematous papules that evolve into shiny, well-defined plaques. In older plaques, the center will often appear yellow, depressed, and atrophic, with telangiectasias. The periphery appears pink to violaceous to brown. Ulceration may be present, particularly after trauma, and there may be decreased sensation in the plaques. NLD is clinically distinct from diabetic dermopathy, which appear as brown macules, often in older patients with diabetes.

Ideally, biopsy should be taken at the edge of a lesion. Histologically, the epidermis appears normal or atrophic. A diffuse palisaded and interstitial granulomatous dermatitis consisting of histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes, and plasma cells is seen in the dermis. Granulomas are often oriented parallel to the epidermis. There is no mucin at the center of the granulomas (as seen in granuloma annulare). Inflammation may extend into the subcutaneous fat. Asteroid bodies (as seen in sarcoid) are absent.

Unfortunately, treatment of NLD is often unsuccessful. Treatment includes potent topical corticosteroids for early lesions and intralesional triamcinolone to the leading edge of lesions. Care should be taken to avoid injecting centrally where atrophy and ulceration may result. Systemic steroids may be helpful in some cases, but can elevate glucose levels. Other reported medical treatments include pentoxifylline, cyclosporine, and niacinamide. Some lesions may spontaneously resolve. Ulcerations may require surgical excision with grafting.

This case and photo are provided by Dr. Bilu Martin, who is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. James WD et al. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2006.

2. Hashemi D et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Apr 1;155(4):455-9.

3. Bolognia JL et al. Dermatology. St. Louis, Mo.: Mosby Elsevier, 2008.

. Women are often more affected than men. Patients often present in their 30s and 40s. The cause of NLD is unknown. Twenty percent of patients with NLD will have glucose intolerance or a family history of diabetes.1 The percentage of patients with NLD who have diabetes varies in reports from 11% to 65%.2 NLD may progress despite the diabetes treatment. Only 0.03% of patient with diabetes will have NLD.3

Lesions most commonly occur on the extremities, with shins being affected in most cases. They vary from asymptomatic to painful. Typically, lesions begin as small, firm erythematous papules that evolve into shiny, well-defined plaques. In older plaques, the center will often appear yellow, depressed, and atrophic, with telangiectasias. The periphery appears pink to violaceous to brown. Ulceration may be present, particularly after trauma, and there may be decreased sensation in the plaques. NLD is clinically distinct from diabetic dermopathy, which appear as brown macules, often in older patients with diabetes.

Ideally, biopsy should be taken at the edge of a lesion. Histologically, the epidermis appears normal or atrophic. A diffuse palisaded and interstitial granulomatous dermatitis consisting of histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes, and plasma cells is seen in the dermis. Granulomas are often oriented parallel to the epidermis. There is no mucin at the center of the granulomas (as seen in granuloma annulare). Inflammation may extend into the subcutaneous fat. Asteroid bodies (as seen in sarcoid) are absent.

Unfortunately, treatment of NLD is often unsuccessful. Treatment includes potent topical corticosteroids for early lesions and intralesional triamcinolone to the leading edge of lesions. Care should be taken to avoid injecting centrally where atrophy and ulceration may result. Systemic steroids may be helpful in some cases, but can elevate glucose levels. Other reported medical treatments include pentoxifylline, cyclosporine, and niacinamide. Some lesions may spontaneously resolve. Ulcerations may require surgical excision with grafting.

This case and photo are provided by Dr. Bilu Martin, who is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. James WD et al. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2006.

2. Hashemi D et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Apr 1;155(4):455-9.

3. Bolognia JL et al. Dermatology. St. Louis, Mo.: Mosby Elsevier, 2008.

. Women are often more affected than men. Patients often present in their 30s and 40s. The cause of NLD is unknown. Twenty percent of patients with NLD will have glucose intolerance or a family history of diabetes.1 The percentage of patients with NLD who have diabetes varies in reports from 11% to 65%.2 NLD may progress despite the diabetes treatment. Only 0.03% of patient with diabetes will have NLD.3

Lesions most commonly occur on the extremities, with shins being affected in most cases. They vary from asymptomatic to painful. Typically, lesions begin as small, firm erythematous papules that evolve into shiny, well-defined plaques. In older plaques, the center will often appear yellow, depressed, and atrophic, with telangiectasias. The periphery appears pink to violaceous to brown. Ulceration may be present, particularly after trauma, and there may be decreased sensation in the plaques. NLD is clinically distinct from diabetic dermopathy, which appear as brown macules, often in older patients with diabetes.

Ideally, biopsy should be taken at the edge of a lesion. Histologically, the epidermis appears normal or atrophic. A diffuse palisaded and interstitial granulomatous dermatitis consisting of histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes, and plasma cells is seen in the dermis. Granulomas are often oriented parallel to the epidermis. There is no mucin at the center of the granulomas (as seen in granuloma annulare). Inflammation may extend into the subcutaneous fat. Asteroid bodies (as seen in sarcoid) are absent.

Unfortunately, treatment of NLD is often unsuccessful. Treatment includes potent topical corticosteroids for early lesions and intralesional triamcinolone to the leading edge of lesions. Care should be taken to avoid injecting centrally where atrophy and ulceration may result. Systemic steroids may be helpful in some cases, but can elevate glucose levels. Other reported medical treatments include pentoxifylline, cyclosporine, and niacinamide. Some lesions may spontaneously resolve. Ulcerations may require surgical excision with grafting.

This case and photo are provided by Dr. Bilu Martin, who is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. James WD et al. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier, 2006.

2. Hashemi D et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Apr 1;155(4):455-9.

3. Bolognia JL et al. Dermatology. St. Louis, Mo.: Mosby Elsevier, 2008.

An 80-year-old patient presents with an asymptomatic firm pink plaque on his shoulder

Melanoma is a type of skin cancer that arises from melanocytes. According to the American Cancer Society, about 106,110 new melanomas will be diagnosed in the United States in 2021.The risk for developing melanoma increases with age. There are multiple clinical forms of cutaneous melanoma. The four main types are superficial spreading melanoma, nodular melanoma, melanoma in situ (lentigo maligna), and acral lentiginous melanoma. Rare variants include amelanotic melanoma, nevoid melanoma, spitzoid melanoma, and desmoplastic melanoma (DM). Melanoma can also rarely affect parts of the eye and mucosa.

, according to the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. It typically presents as a subtle pigmented, pink, red, or skin colored patch, papule or plaque on sun-exposed skin (head and neck most frequently). Chronic UV exposure has been linked to DM. It may be mistaken for a scar or dermatofibroma. DM tends to grow locally and has less risk for nodal metastasis.1

Histologic diagnosis may be challenging. Two histologic variants in desmoplastic melanoma have been described: pure and mixed, depending on the degree of desmoplasia and cellularity present in the tumor.1 Pure DM tends to have a less aggressive course. Melanocytes can appear spindled in a fibrotic stroma. Patchy lymphocyte aggregates may be seen. Perineural invasion is more common in desmoplastic melanoma. Histologically, the differential includes spindle cell carcinoma and sarcoma. Immunostaining is helpful in differentiation.

Our patient had no lymphadenopathy on physical examination. Biopsy revealed a desmoplastic melanoma, 3.6 mm in depth, no ulceration, no regression, mitotic rate 1/mm2. He was referred to surgical oncology. The patient underwent wide excision. Sentinel lymph node biopsy was deferred.

It is imperative for dermatologists to be cognizant of this challenging subtype of melanoma when evaluating patients.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Chen L et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 May;68(5):825-33.

Melanoma is a type of skin cancer that arises from melanocytes. According to the American Cancer Society, about 106,110 new melanomas will be diagnosed in the United States in 2021.The risk for developing melanoma increases with age. There are multiple clinical forms of cutaneous melanoma. The four main types are superficial spreading melanoma, nodular melanoma, melanoma in situ (lentigo maligna), and acral lentiginous melanoma. Rare variants include amelanotic melanoma, nevoid melanoma, spitzoid melanoma, and desmoplastic melanoma (DM). Melanoma can also rarely affect parts of the eye and mucosa.

, according to the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. It typically presents as a subtle pigmented, pink, red, or skin colored patch, papule or plaque on sun-exposed skin (head and neck most frequently). Chronic UV exposure has been linked to DM. It may be mistaken for a scar or dermatofibroma. DM tends to grow locally and has less risk for nodal metastasis.1

Histologic diagnosis may be challenging. Two histologic variants in desmoplastic melanoma have been described: pure and mixed, depending on the degree of desmoplasia and cellularity present in the tumor.1 Pure DM tends to have a less aggressive course. Melanocytes can appear spindled in a fibrotic stroma. Patchy lymphocyte aggregates may be seen. Perineural invasion is more common in desmoplastic melanoma. Histologically, the differential includes spindle cell carcinoma and sarcoma. Immunostaining is helpful in differentiation.

Our patient had no lymphadenopathy on physical examination. Biopsy revealed a desmoplastic melanoma, 3.6 mm in depth, no ulceration, no regression, mitotic rate 1/mm2. He was referred to surgical oncology. The patient underwent wide excision. Sentinel lymph node biopsy was deferred.

It is imperative for dermatologists to be cognizant of this challenging subtype of melanoma when evaluating patients.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Chen L et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 May;68(5):825-33.

Melanoma is a type of skin cancer that arises from melanocytes. According to the American Cancer Society, about 106,110 new melanomas will be diagnosed in the United States in 2021.The risk for developing melanoma increases with age. There are multiple clinical forms of cutaneous melanoma. The four main types are superficial spreading melanoma, nodular melanoma, melanoma in situ (lentigo maligna), and acral lentiginous melanoma. Rare variants include amelanotic melanoma, nevoid melanoma, spitzoid melanoma, and desmoplastic melanoma (DM). Melanoma can also rarely affect parts of the eye and mucosa.

, according to the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. It typically presents as a subtle pigmented, pink, red, or skin colored patch, papule or plaque on sun-exposed skin (head and neck most frequently). Chronic UV exposure has been linked to DM. It may be mistaken for a scar or dermatofibroma. DM tends to grow locally and has less risk for nodal metastasis.1

Histologic diagnosis may be challenging. Two histologic variants in desmoplastic melanoma have been described: pure and mixed, depending on the degree of desmoplasia and cellularity present in the tumor.1 Pure DM tends to have a less aggressive course. Melanocytes can appear spindled in a fibrotic stroma. Patchy lymphocyte aggregates may be seen. Perineural invasion is more common in desmoplastic melanoma. Histologically, the differential includes spindle cell carcinoma and sarcoma. Immunostaining is helpful in differentiation.

Our patient had no lymphadenopathy on physical examination. Biopsy revealed a desmoplastic melanoma, 3.6 mm in depth, no ulceration, no regression, mitotic rate 1/mm2. He was referred to surgical oncology. The patient underwent wide excision. Sentinel lymph node biopsy was deferred.

It is imperative for dermatologists to be cognizant of this challenging subtype of melanoma when evaluating patients.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Chen L et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 May;68(5):825-33.

A 35-year-old male who takes antiseizure medications, has asymptomatic lesions on his nose and cheeks, present since birth

although up to 75% of cases may be caused by a spontaneous mutation. It is caused by mutations in the TSC1 gene on chromosome 9q34–encoding hamartin or the TSC2 gene on chromosome I6pl3–encoding tuberin. Patients present at birth and males and females are affected equally.

There are multiple skin findings in TS that may herald the diagnosis. The earliest findings are hypopigmented macules, found in 85% of patients. They may be in an ash-leaf shape or confetti pattern. Adenoma sebaceum, or angiofibromas, are present on the forehead, nose, and cheeks, and often present in childhood. Periungual angiofibromas called Koenen tumors tend to occur at puberty. Connective-tissue nevi called Shagreen plaques, or collagenomas, may be present, which is what our patient exhibits on his back. The lumbosacral region is the most common area for these to appear in the first decade of life.

TS can affect other organ systems in the body. Seizures, neuropsychiatric diseases, and mental deficiency are common. Cortical tumors, gliomas, and astrocytomas may develop in the brain. Congenital retinal hamartomas (phakomas) occur. Renal cysts and angiomyolipomas may occur in the kidneys. In the lungs, patients may develop lymphangiomyomatosis. Rhabdomyomas can occur in the heart in infancy and may regress spontaneously over time. Bony changes such as cysts and sclerosis may occur.

Treatment and monitoring of TS requires a multidisciplinary approach with neurology, pulmonology, cardiology, ophthalmology, orthopedics, and dermatology. Cosmetic treatment for angiofibromas includes CO2 laser, shaving, and dermabrasion. Topical rapamycin use has been described in the literature to improve the appearance of angiofibromas. Our patient has been using rapamycin 1% cream for more than 5 years and has had a substantial reduction in the size and number of angiofibromas.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References:

Spitz J. Genodermatoses. A Clinical Guide to Genetic Skin Disorders. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

James W et al. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2006.

Bolognia JL et al. Dermatology. London: Mosby Elsevier, 2008.

although up to 75% of cases may be caused by a spontaneous mutation. It is caused by mutations in the TSC1 gene on chromosome 9q34–encoding hamartin or the TSC2 gene on chromosome I6pl3–encoding tuberin. Patients present at birth and males and females are affected equally.

There are multiple skin findings in TS that may herald the diagnosis. The earliest findings are hypopigmented macules, found in 85% of patients. They may be in an ash-leaf shape or confetti pattern. Adenoma sebaceum, or angiofibromas, are present on the forehead, nose, and cheeks, and often present in childhood. Periungual angiofibromas called Koenen tumors tend to occur at puberty. Connective-tissue nevi called Shagreen plaques, or collagenomas, may be present, which is what our patient exhibits on his back. The lumbosacral region is the most common area for these to appear in the first decade of life.

TS can affect other organ systems in the body. Seizures, neuropsychiatric diseases, and mental deficiency are common. Cortical tumors, gliomas, and astrocytomas may develop in the brain. Congenital retinal hamartomas (phakomas) occur. Renal cysts and angiomyolipomas may occur in the kidneys. In the lungs, patients may develop lymphangiomyomatosis. Rhabdomyomas can occur in the heart in infancy and may regress spontaneously over time. Bony changes such as cysts and sclerosis may occur.

Treatment and monitoring of TS requires a multidisciplinary approach with neurology, pulmonology, cardiology, ophthalmology, orthopedics, and dermatology. Cosmetic treatment for angiofibromas includes CO2 laser, shaving, and dermabrasion. Topical rapamycin use has been described in the literature to improve the appearance of angiofibromas. Our patient has been using rapamycin 1% cream for more than 5 years and has had a substantial reduction in the size and number of angiofibromas.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References:

Spitz J. Genodermatoses. A Clinical Guide to Genetic Skin Disorders. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

James W et al. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2006.

Bolognia JL et al. Dermatology. London: Mosby Elsevier, 2008.

although up to 75% of cases may be caused by a spontaneous mutation. It is caused by mutations in the TSC1 gene on chromosome 9q34–encoding hamartin or the TSC2 gene on chromosome I6pl3–encoding tuberin. Patients present at birth and males and females are affected equally.

There are multiple skin findings in TS that may herald the diagnosis. The earliest findings are hypopigmented macules, found in 85% of patients. They may be in an ash-leaf shape or confetti pattern. Adenoma sebaceum, or angiofibromas, are present on the forehead, nose, and cheeks, and often present in childhood. Periungual angiofibromas called Koenen tumors tend to occur at puberty. Connective-tissue nevi called Shagreen plaques, or collagenomas, may be present, which is what our patient exhibits on his back. The lumbosacral region is the most common area for these to appear in the first decade of life.

TS can affect other organ systems in the body. Seizures, neuropsychiatric diseases, and mental deficiency are common. Cortical tumors, gliomas, and astrocytomas may develop in the brain. Congenital retinal hamartomas (phakomas) occur. Renal cysts and angiomyolipomas may occur in the kidneys. In the lungs, patients may develop lymphangiomyomatosis. Rhabdomyomas can occur in the heart in infancy and may regress spontaneously over time. Bony changes such as cysts and sclerosis may occur.

Treatment and monitoring of TS requires a multidisciplinary approach with neurology, pulmonology, cardiology, ophthalmology, orthopedics, and dermatology. Cosmetic treatment for angiofibromas includes CO2 laser, shaving, and dermabrasion. Topical rapamycin use has been described in the literature to improve the appearance of angiofibromas. Our patient has been using rapamycin 1% cream for more than 5 years and has had a substantial reduction in the size and number of angiofibromas.

This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References:

Spitz J. Genodermatoses. A Clinical Guide to Genetic Skin Disorders. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

James W et al. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2006.

Bolognia JL et al. Dermatology. London: Mosby Elsevier, 2008.

A 67-year-old White woman presented with 2 weeks of bullae on her lower feet

Bullous arthropod assault

Insect-bite reactions are commonly seen in dermatology practice. Most often, they present as pruritic papules. Vesicles and bullae can be seen as well but are less common. Flea bites are the most likely to cause blisters.1 Lesions may be grouped or in a linear pattern. Children tend to have more severe reactions than adults. Body temperature and odor may make some people more susceptible than others to bites. Of note, patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia tend to have more severe, bullous reactions.2 The differential diagnosis includes bullous pemphigoid, bullous impetigo, bullous tinea, bullous fixed drug, and bullous diabeticorum.

In general, bullous arthropod reactions begin as intraepidermal vesicles that can progress to subepidermal blisters. Eosinophils can be present. Flame figures are often seen in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.3 Histopathology in this patient revealed a subepidermal vesicular dermatitis with minimal inflammation. Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain was negative. Direct immunofluorescence was negative for IgG, C3, IgA, IgM, and fibrinogen. Of note, systemic steroids may alter histologic and immunologic findings.

Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune blistering disorder where patients develop widespread tense bullae. Histopathology revealed a subepidermal blister with numerous eosinophils. Direct immunofluorescence study of perilesional skin showed linear IgG and C3 deposits at the basal membrane level. Systemic steroids, tetracyclines, and immunosuppressive medications are a mainstay of treatment. In bullous impetigo, the toxin of Staphylococcus aureus causes blister formation. It is treated with antistaphylococcal antibiotics. Bullous tinea reveals hyphae with PAS staining. Topical or systemic antifungals are used for treatment.

In severe cases, systemic steroids can be used as well. Bacterial culture was negative in this patient. The patient was treated with 1 week of oral prednisone prior to biopsy and topical betamethasone ointment. Her lesions subsequently resolved with no recurrence.

This case and photo were submitted by Brooke Resh Sateesh, MD, San Diego Family Dermatology.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1-3. “Dermatology” 2nd ed. (Maryland Heights, Mo.: Mosby, 2008).

Bullous arthropod assault

Insect-bite reactions are commonly seen in dermatology practice. Most often, they present as pruritic papules. Vesicles and bullae can be seen as well but are less common. Flea bites are the most likely to cause blisters.1 Lesions may be grouped or in a linear pattern. Children tend to have more severe reactions than adults. Body temperature and odor may make some people more susceptible than others to bites. Of note, patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia tend to have more severe, bullous reactions.2 The differential diagnosis includes bullous pemphigoid, bullous impetigo, bullous tinea, bullous fixed drug, and bullous diabeticorum.

In general, bullous arthropod reactions begin as intraepidermal vesicles that can progress to subepidermal blisters. Eosinophils can be present. Flame figures are often seen in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.3 Histopathology in this patient revealed a subepidermal vesicular dermatitis with minimal inflammation. Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain was negative. Direct immunofluorescence was negative for IgG, C3, IgA, IgM, and fibrinogen. Of note, systemic steroids may alter histologic and immunologic findings.

Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune blistering disorder where patients develop widespread tense bullae. Histopathology revealed a subepidermal blister with numerous eosinophils. Direct immunofluorescence study of perilesional skin showed linear IgG and C3 deposits at the basal membrane level. Systemic steroids, tetracyclines, and immunosuppressive medications are a mainstay of treatment. In bullous impetigo, the toxin of Staphylococcus aureus causes blister formation. It is treated with antistaphylococcal antibiotics. Bullous tinea reveals hyphae with PAS staining. Topical or systemic antifungals are used for treatment.

In severe cases, systemic steroids can be used as well. Bacterial culture was negative in this patient. The patient was treated with 1 week of oral prednisone prior to biopsy and topical betamethasone ointment. Her lesions subsequently resolved with no recurrence.

This case and photo were submitted by Brooke Resh Sateesh, MD, San Diego Family Dermatology.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1-3. “Dermatology” 2nd ed. (Maryland Heights, Mo.: Mosby, 2008).

Bullous arthropod assault

Insect-bite reactions are commonly seen in dermatology practice. Most often, they present as pruritic papules. Vesicles and bullae can be seen as well but are less common. Flea bites are the most likely to cause blisters.1 Lesions may be grouped or in a linear pattern. Children tend to have more severe reactions than adults. Body temperature and odor may make some people more susceptible than others to bites. Of note, patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia tend to have more severe, bullous reactions.2 The differential diagnosis includes bullous pemphigoid, bullous impetigo, bullous tinea, bullous fixed drug, and bullous diabeticorum.

In general, bullous arthropod reactions begin as intraepidermal vesicles that can progress to subepidermal blisters. Eosinophils can be present. Flame figures are often seen in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia.3 Histopathology in this patient revealed a subepidermal vesicular dermatitis with minimal inflammation. Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain was negative. Direct immunofluorescence was negative for IgG, C3, IgA, IgM, and fibrinogen. Of note, systemic steroids may alter histologic and immunologic findings.

Bullous pemphigoid is an autoimmune blistering disorder where patients develop widespread tense bullae. Histopathology revealed a subepidermal blister with numerous eosinophils. Direct immunofluorescence study of perilesional skin showed linear IgG and C3 deposits at the basal membrane level. Systemic steroids, tetracyclines, and immunosuppressive medications are a mainstay of treatment. In bullous impetigo, the toxin of Staphylococcus aureus causes blister formation. It is treated with antistaphylococcal antibiotics. Bullous tinea reveals hyphae with PAS staining. Topical or systemic antifungals are used for treatment.

In severe cases, systemic steroids can be used as well. Bacterial culture was negative in this patient. The patient was treated with 1 week of oral prednisone prior to biopsy and topical betamethasone ointment. Her lesions subsequently resolved with no recurrence.

This case and photo were submitted by Brooke Resh Sateesh, MD, San Diego Family Dermatology.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1-3. “Dermatology” 2nd ed. (Maryland Heights, Mo.: Mosby, 2008).

A 70-year-old presented with a 3-week history of asymptomatic violaceous papules on his feet

and named the condition multiple benign pigmented hemorrhagic sarcoma. The disease emerged again at the onset of the AIDS epidemic among homosexual men. There are five variants: HIV/AIDS–related KS, classic KS, African cutaneous KS, African lymphadenopathic KS, and immunosuppression-associated KS (from immunosuppressive therapy or malignancies such as lymphoma).

KS is caused by human herpes virus type 8 (HHV-8). Patients with KS have an increased risk of developing other malignancies such as lymphomas, leukemia, and myeloma. This patient exhibited classic KS.

The various forms of KS may appear different clinically. The lesions may appear as erythematous macules, small violaceous papules, large plaques, or ulcerated nodules. In classic KS, violaceous to bluish-black macules evolve to papules or plaques. Lesions are generally asymptomatic. The most common locations are the toes and soles, although other areas may be affected. Any mucocutaneous surface can be involved. The most common areas of internal involvement are the gastrointestinal system and lymphatics.

Histology reveals angular vessels lined by atypical cells. An associated inflammatory infiltrate containing plasma cells may be present in the upper dermis and perivascular areas. Nodules and plaques reveal a spindle cell neoplasm pattern. Lesions will stain positive for HHV-8.

In patients with HIV/AIDS–related KS, highly active antiretroviral therapy is the most important and beneficial treatment. Since the introduction of HAART, the incidence of KS has greatly decreased. However, there are a proportion of HIV/AIDS–associated Kaposi’s sarcoma patients with well-controlled HIV and undetectable viral loads who require further treatment.

Lesions may spontaneously resolve on their own. Other treatment methods include: cryotherapy, topical alitretinoin (9-cis-retinoic acid), intralesional interferon-alpha or vinblastine, superficial radiotherapy, liposomal doxorubicin, daunorubicin or paclitaxel. Small lesions that are asymptomatic may be monitored.

This patient had no internal involvement and responded well to cryotherapy.

This case and photo were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

and named the condition multiple benign pigmented hemorrhagic sarcoma. The disease emerged again at the onset of the AIDS epidemic among homosexual men. There are five variants: HIV/AIDS–related KS, classic KS, African cutaneous KS, African lymphadenopathic KS, and immunosuppression-associated KS (from immunosuppressive therapy or malignancies such as lymphoma).

KS is caused by human herpes virus type 8 (HHV-8). Patients with KS have an increased risk of developing other malignancies such as lymphomas, leukemia, and myeloma. This patient exhibited classic KS.

The various forms of KS may appear different clinically. The lesions may appear as erythematous macules, small violaceous papules, large plaques, or ulcerated nodules. In classic KS, violaceous to bluish-black macules evolve to papules or plaques. Lesions are generally asymptomatic. The most common locations are the toes and soles, although other areas may be affected. Any mucocutaneous surface can be involved. The most common areas of internal involvement are the gastrointestinal system and lymphatics.

Histology reveals angular vessels lined by atypical cells. An associated inflammatory infiltrate containing plasma cells may be present in the upper dermis and perivascular areas. Nodules and plaques reveal a spindle cell neoplasm pattern. Lesions will stain positive for HHV-8.

In patients with HIV/AIDS–related KS, highly active antiretroviral therapy is the most important and beneficial treatment. Since the introduction of HAART, the incidence of KS has greatly decreased. However, there are a proportion of HIV/AIDS–associated Kaposi’s sarcoma patients with well-controlled HIV and undetectable viral loads who require further treatment.

Lesions may spontaneously resolve on their own. Other treatment methods include: cryotherapy, topical alitretinoin (9-cis-retinoic acid), intralesional interferon-alpha or vinblastine, superficial radiotherapy, liposomal doxorubicin, daunorubicin or paclitaxel. Small lesions that are asymptomatic may be monitored.

This patient had no internal involvement and responded well to cryotherapy.

This case and photo were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

and named the condition multiple benign pigmented hemorrhagic sarcoma. The disease emerged again at the onset of the AIDS epidemic among homosexual men. There are five variants: HIV/AIDS–related KS, classic KS, African cutaneous KS, African lymphadenopathic KS, and immunosuppression-associated KS (from immunosuppressive therapy or malignancies such as lymphoma).

KS is caused by human herpes virus type 8 (HHV-8). Patients with KS have an increased risk of developing other malignancies such as lymphomas, leukemia, and myeloma. This patient exhibited classic KS.

The various forms of KS may appear different clinically. The lesions may appear as erythematous macules, small violaceous papules, large plaques, or ulcerated nodules. In classic KS, violaceous to bluish-black macules evolve to papules or plaques. Lesions are generally asymptomatic. The most common locations are the toes and soles, although other areas may be affected. Any mucocutaneous surface can be involved. The most common areas of internal involvement are the gastrointestinal system and lymphatics.

Histology reveals angular vessels lined by atypical cells. An associated inflammatory infiltrate containing plasma cells may be present in the upper dermis and perivascular areas. Nodules and plaques reveal a spindle cell neoplasm pattern. Lesions will stain positive for HHV-8.

In patients with HIV/AIDS–related KS, highly active antiretroviral therapy is the most important and beneficial treatment. Since the introduction of HAART, the incidence of KS has greatly decreased. However, there are a proportion of HIV/AIDS–associated Kaposi’s sarcoma patients with well-controlled HIV and undetectable viral loads who require further treatment.

Lesions may spontaneously resolve on their own. Other treatment methods include: cryotherapy, topical alitretinoin (9-cis-retinoic acid), intralesional interferon-alpha or vinblastine, superficial radiotherapy, liposomal doxorubicin, daunorubicin or paclitaxel. Small lesions that are asymptomatic may be monitored.

This patient had no internal involvement and responded well to cryotherapy.

This case and photo were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

April 2020

Shiitake mushroom flagellate dermatitis

that resemble whiplash marks. The lesions may be extremely pruritic, and petechiae may be present in the streaks. The trunk is most commonly affected, although lesions can occur on the limbs. Mucosa is not affected. Sun exposure may exacerbate the condition. The dermatitis has been described in all ages and races, and males seem to be more affected than females.

Shiitake mushroom flagellate dermatitis typically occurs following the ingestion of raw or undercooked shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes). The mushrooms contain a polysaccharide called lentinan. Ingestion of lentinan activates interleukin-1 (IL-1), resulting in vasodilation and the subsequent dermatitis that can occur within a few hours and up to 5 days post ingestion. Associated gastrointestinal symptoms, fever, and localized swelling have been reported. The rash will resolve spontaneously over a few days to weeks.

Flagellate erythema has been described with bleomycin treatment. Other reported associations include peplomycin (a bleomycin derivative) and docetaxel. The rash may appear following administration of bleomycin by any route and has been shown to be dose independent. Onset occurs anywhere from 1 day to several months after exposure. Over time, the erythema will develop into postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Dermatomyositis may present with flagellate erythema. Other symptoms include muscle weakness and an inflammatory myopathy. A heliotrope rash on the eyelids, Gottron’s papules on the hands, ragged cuticles with prominent vessels on nail folds may be seen. Blood work may reveal elevated antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti–Mi-2 and anti–Jo-1. Adult-onset Still disease is characterized by fever, arthritis, and salmon-colored patches.

Our patient’s dermatitis resolved spontaneously without treatment.

This case and photo were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

Shiitake mushroom flagellate dermatitis

that resemble whiplash marks. The lesions may be extremely pruritic, and petechiae may be present in the streaks. The trunk is most commonly affected, although lesions can occur on the limbs. Mucosa is not affected. Sun exposure may exacerbate the condition. The dermatitis has been described in all ages and races, and males seem to be more affected than females.

Shiitake mushroom flagellate dermatitis typically occurs following the ingestion of raw or undercooked shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes). The mushrooms contain a polysaccharide called lentinan. Ingestion of lentinan activates interleukin-1 (IL-1), resulting in vasodilation and the subsequent dermatitis that can occur within a few hours and up to 5 days post ingestion. Associated gastrointestinal symptoms, fever, and localized swelling have been reported. The rash will resolve spontaneously over a few days to weeks.

Flagellate erythema has been described with bleomycin treatment. Other reported associations include peplomycin (a bleomycin derivative) and docetaxel. The rash may appear following administration of bleomycin by any route and has been shown to be dose independent. Onset occurs anywhere from 1 day to several months after exposure. Over time, the erythema will develop into postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Dermatomyositis may present with flagellate erythema. Other symptoms include muscle weakness and an inflammatory myopathy. A heliotrope rash on the eyelids, Gottron’s papules on the hands, ragged cuticles with prominent vessels on nail folds may be seen. Blood work may reveal elevated antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti–Mi-2 and anti–Jo-1. Adult-onset Still disease is characterized by fever, arthritis, and salmon-colored patches.

Our patient’s dermatitis resolved spontaneously without treatment.

This case and photo were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

Shiitake mushroom flagellate dermatitis

that resemble whiplash marks. The lesions may be extremely pruritic, and petechiae may be present in the streaks. The trunk is most commonly affected, although lesions can occur on the limbs. Mucosa is not affected. Sun exposure may exacerbate the condition. The dermatitis has been described in all ages and races, and males seem to be more affected than females.

Shiitake mushroom flagellate dermatitis typically occurs following the ingestion of raw or undercooked shiitake mushrooms (Lentinula edodes). The mushrooms contain a polysaccharide called lentinan. Ingestion of lentinan activates interleukin-1 (IL-1), resulting in vasodilation and the subsequent dermatitis that can occur within a few hours and up to 5 days post ingestion. Associated gastrointestinal symptoms, fever, and localized swelling have been reported. The rash will resolve spontaneously over a few days to weeks.

Flagellate erythema has been described with bleomycin treatment. Other reported associations include peplomycin (a bleomycin derivative) and docetaxel. The rash may appear following administration of bleomycin by any route and has been shown to be dose independent. Onset occurs anywhere from 1 day to several months after exposure. Over time, the erythema will develop into postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Dermatomyositis may present with flagellate erythema. Other symptoms include muscle weakness and an inflammatory myopathy. A heliotrope rash on the eyelids, Gottron’s papules on the hands, ragged cuticles with prominent vessels on nail folds may be seen. Blood work may reveal elevated antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti–Mi-2 and anti–Jo-1. Adult-onset Still disease is characterized by fever, arthritis, and salmon-colored patches.

Our patient’s dermatitis resolved spontaneously without treatment.

This case and photo were provided by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.