User login

Bryn Nelson is a former PhD microbiologist who decided he’d much rather write about microbes than mutate them. After seven years at the science desk of Newsday in New York, Nelson relocated to Seattle as a freelancer, where he has consumed far too much coffee and written features and stories for The Hospitalist, The New York Times, Nature, Scientific American, Science News for Students, Mosaic and many other print and online publications. In addition, he contributed a chapter to The Science Writers’ Handbook and edited two chapters for the six-volume Modernist Cuisine: The Art and Science of Cooking.

Debate Rages Over Hospitalists' Role in ICU Physician Shortage

The long-simmering debate over whether and how hospitalists might help solve the worsening shortage of critical-care physicians is beginning to boil over.

In June, SHM and the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) issued a joint position paper proposing an expedited, one-year, critical-care fellowship for hospitalists with at least three years of clinical job experience, in lieu of the two-year fellowship now required for board certification.1

“Bringing qualified hospitalists into the critical-care workforce through rigorous sanctioned and accredited one-year training programs,” the paper asserted, “will open a new intensivist training pipeline and potentially offer more critically ill patients the benefits of providers who are unequivocally qualified to care for them.”

The backlash was swift and sharp. In a strongly worded editorial response published in July, the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) declared that one year of fellowship training is inadequate for HM physicians to achieve competence in critical-care medicine.2 “No, the perfect should not be the enemy of the good in our efforts to craft solutions,” the editorial stated. “But the current imperfect SCCM/SHM proposal is an enemy of the existing good training processes already in place.”

HM leaders counter that the current strategies for bolstering the ranks of board-certified intensivists simply aren’t working, and that creative, outside-the-box thinking is required to solve the dilemma.

“Hospitalists are rapidly becoming a dominant, if not the dominant, block of physicians who are providing critical care in the United States. You can decide, if you want, whether that’s good or bad, but that’s the reality,” says Eric Siegal, MD, SFHM, lead author of the SHM/SCCM position paper, director of critical-care medicine at Aurora St. Luke’s Medical Center in Milwaukee, and an SHM board member. Given the escalating shortage of intensivists, he says, he believes that concerned stakeholders can either try to help develop the skills and knowledge of those hospitalists already in the ICU or “hope that a whole bunch of hospitalists suddenly decide to abandon their practices and complete two-year medical

critical-care fellowships.”

Intensivist leaders say that less training will do nothing to improve patient outcomes. “The reality is that hospitalists are doing it. The question should be, ‘Are they doing it well or at the detriment of the patient?’” asks Michael Baumann, MD, MS, FCCP, professor of medicine in the division of pulmonary, critical-care, and sleep medicine at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson. “The patient is the one who loses if we have somebody pinch-hitting, which is really what we’re talking about here,” adds Dr. Baumann, lead author of the ACCP/AACN editorial.

Staffing Shortfall

Despite the heated rhetoric, interviews with leaders on both sides suggest an eagerness to move forward in trying to collectively solve a problem that has vexed the entire medical community.

In 2000, the Leapfrog Group, a Washington, D.C.-based consortium of major healthcare purchasers focused on improving the safety, quality, and value of care, recommended that all ICUs should be staffed with physicians certified in critical-care medicine.3 As part of its rationale, the group cited research suggesting that greater intensivist use can yield better patient outcomes.

But a seminal study published the same year hinted at just how difficult meeting Leapfrog’s ambitious goal might be. Based on the trajectory of supply and demand, the authors forecast a 22% shortfall in intensivist hours by 2020, and a 35% shortfall by 2030, mainly due to a surge in demand from an aging U.S. population.4 A follow-up report in 2006 estimated that 53% of the nation’s ICU units had no intensivist coverage at all, and that only 4% of adult ICUs were meeting the full Leapfrog standards of high-intensity ICU staffing, dedicated attending physician coverage during the day, and dedicated coverage by any physician at night.5

—Timothy Buchman, PhD, MD, director, Emory University Center for Critical Care, Atlanta

Given the recent push for more outpatient treatment of less-critically-ill patients, many observers say the increased acuity of hospitalized patients—with more comorbidities—only exacerbates the mismatch between supply and demand. Making matters worse, providers are not evenly distributed throughout the country, with many smaller and rural hospitals already facing an acute shortage of intensivist services.

As a result, many hospitalists have been forced to step into the breach. According to SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine survey, 83.5% of responding nonacademic adult medicine groups said they routinely provide care for patients in an ICU setting, along with 27.9% of academic HM groups.

“So we have hospitalists who, either by choice or by default, care for patients who they may or may not be fully qualified to manage,” Dr. Siegal says. Practically speaking, he and his coauthors assert, the question of whether hospitalists should be in the ICU is now moot. The real question is how to ensure that those providers can deliver safe and effective care.

Experience vs. Training

Currently, internists who have completed fellowships in such specialties as pulmonary medicine, nephrology, and infectious disease can complete a one-year critical-care fellowship to obtain board certification. Experienced hospitalists have questioned the requirement that they instead complete a two-year fellowship, with no consideration given to the relevant clinical experience and maturity gained after years of hospitalist practice. In addition, they argue, it is logistically and financially unrealistic to expect a large cadre of experienced hospitalists to abandon their practices for two years to pursue critical-care training.

But Dr. Baumann says subpar internal-medicine residency requirements deserve much of the blame for offering inadequate training. “Critical care is a blend of critical thinking skills and procedural skills. Both of those are diminished tremendously in the current programs for internal medicine,” he says. “It’s really an indictment of our current training of internal-medicine residents now.”

SCCM, for its part, is sticking to its guns, albeit more quietly. When asked for comment, a spokesman issued a carefully worded statement that reads, “The paper reflects the society’s concerns regarding workforce shortages and the realities of today’s environment.”

The SHM/SCCM proposal makes sense provided that hospitalists are realistic about the types of patients they’ll see, says Timothy Buchman, PhD, MD, director of Emory University’s Center for Critical Care in Atlanta. “No one in their right mind will say one year is as good as two years. That would be folly,” he says. “On the other hand, that’s not the question. The question is, ‘Can we structure training that is competency-focused, so that the majority of people who enter the training will achieve the necessary levels of competency within a year?’”

Derek Angus, MD, chair of critical-care medicine at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and lead author of the 2000 study chronicling the intensivist shortfall, is more ambivalent. “Hospitalists and intensivists have to work hand in hand. In many ways, they are the two groups that run inpatient hospital medicine,” he says. In that respect, sorting out and streamlining training pathways might be a good idea.

“On the other hand, all of intensive-care training in the United States is a little thin in comparison to what goes on in many other countries,” Dr. Angus adds. “If anything, I would like to be seeing more vigorous training. So creating one more pathway that helps reinforce pretty light training feels like accreditation, in general, may be moving slightly in the wrong direction.”

Dr. Buchman and other observers view the debate as a difference in opinion among well-meaning people who are passionate about patient care. And they concede that no one knows yet who may be right.

“We do know that advanced training is required. We do know that it should be competency-focused,” Dr. Buchman says. “But what we don’t know is how long it’s really going to take to get to the competency levels that we believe are necessary to care for the patients.”

That point may provide one important opening for further discussions. Dr. Baumann agrees that the real issues are how to define critical-care competencies, how to measure them, and how to ensure that trainees prove their mettle as competent providers. “It really shouldn’t be time-based; it should be outcome-based,” he says.

The SHM/SCCM proposal, Dr. Siegal says, should be viewed as a conversation-starter. The true test will be whether everyone can reach an agreement on how to evaluate whether an ICU caregiver has attained the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes—and how relevant professional experience should factor into discussions over the length of training required for intensivist certification.

A Tiered Solution

The concept of tiered ICU care—already used in neonatal ICUs—might offer another opening for productive debate. “Can patients who are not that critically ill be managed by someone who hasn’t done that much critical-care training?” Dr. Angus asks. He believes it’s possible, provided patients are properly sorted and that hospitalists aren’t put in the uncomfortable position of managing medical conditions that they see only rarely. He has no problem, though, envisioning a tiered system in which fully trained intensivists spend most of their time managing the sickest patients, while other providers—including hospitalists—care for patients at intermediate risk.

Hospitalists have greeted the idea cautiously, noting that a two-tiered model might be difficult to define and standardize, and that it could present logistical challenges around transferring patients. However, Daniel D. Dressler, MD, MSc, SFHM, FACP, associate professor of internal medicine at Emory University School of Medicine and coauthor of the SHM/SCCM position paper, led a recent study that offers at least some support for a risk-based system.6

Overall, the study found no statistically significant difference in the length of stay or inpatient mortality rates for ICU patients cared for by hospitalist-led or intensivist-led teams. Among mechanically ventilated patients with intermediate illness severity, though, the study suggested that intensivist-led care resulted in a lower length of stay in both the hospital and ICU, as well as in a trend toward reduced inpatient mortality. “There may be some value in designing or developing a stratification system,” Dr. Dressler says, “but it definitely needs more study.”

In the meantime, Dr. Dressler says, more rapid solutions are needed. And although he says he understands and respects many of the doubts expressed about the SHM/SCCM proposal, he also believes some of the fear might be based on anecdotes about individual hospitalists who were deemed unlikely to thrive in an ICU environment. “For each person like that, we also know 10 or 20 people who might do really well” with just a year of additional training, says Dr. Dressler, a former SHM board member.

Now that both sides clearly have the attention of the other, leaders say they hope the opening salvos give way to more temperate discussions about how to move more skilled providers to the front lines.

“Health professionals are a smart and clever lot,” says Mary Stahl, RN, MSN, ACNS-BC, CCNS-CMC, CCRN, immediate past president of AACN and a clinical nurse specialist at the Mid America Heart Institute at Saint Luke’s Hospital in Kansas City, Mo. “I’m confident we’ll develop an effective solution—maybe several—by focusing on the fundamental belief that patients’ needs must drive caregivers’ knowledge and skills.”

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

References

- Siegal EM, Dressler DD, Dichter JR, Gorman MJ, Lipsett PA. Training a hospitalist workforce to address the intensivist shortage in American hospitals: a position paper from the Society of Hospital Medicine and the Society of Critical Care Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:359-364.

- Baumann MH, Simpson SQ, Stahl M, et al. First, do no harm: less training ≠ quality care. Chest. 2012;142:5-7.

- Milstein A, Galvin RS, Delbanco SF, et al. Improving the safety of health care: the Leapfrog initiative. Eff Clin Pract. 2000;3:313-316.

- Angus DC, Kelley MA, Schmitz RJ, et al. Caring for the critically ill patient. Current and projected workforce requirements for care of the critically ill and patients with pulmonary disease: can we meet the requirements of an aging population? JAMA. 2000;284:2762-2770.

- Angus DC, Shorr AF, White A, et al. Critical care delivery in the United States: distribution of services and compliance with Leapfrog recommendations. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1016-1024.

- Wise KR, Akopov VA, Williams BR Jr., Ido MS, Leeper KV, Dressler DD. Hospitalists and intensivists in the medical ICU: a prospective observational study comparing mortality and length of stay between two staffing models. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:183-189.

The long-simmering debate over whether and how hospitalists might help solve the worsening shortage of critical-care physicians is beginning to boil over.

In June, SHM and the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) issued a joint position paper proposing an expedited, one-year, critical-care fellowship for hospitalists with at least three years of clinical job experience, in lieu of the two-year fellowship now required for board certification.1

“Bringing qualified hospitalists into the critical-care workforce through rigorous sanctioned and accredited one-year training programs,” the paper asserted, “will open a new intensivist training pipeline and potentially offer more critically ill patients the benefits of providers who are unequivocally qualified to care for them.”

The backlash was swift and sharp. In a strongly worded editorial response published in July, the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) declared that one year of fellowship training is inadequate for HM physicians to achieve competence in critical-care medicine.2 “No, the perfect should not be the enemy of the good in our efforts to craft solutions,” the editorial stated. “But the current imperfect SCCM/SHM proposal is an enemy of the existing good training processes already in place.”

HM leaders counter that the current strategies for bolstering the ranks of board-certified intensivists simply aren’t working, and that creative, outside-the-box thinking is required to solve the dilemma.

“Hospitalists are rapidly becoming a dominant, if not the dominant, block of physicians who are providing critical care in the United States. You can decide, if you want, whether that’s good or bad, but that’s the reality,” says Eric Siegal, MD, SFHM, lead author of the SHM/SCCM position paper, director of critical-care medicine at Aurora St. Luke’s Medical Center in Milwaukee, and an SHM board member. Given the escalating shortage of intensivists, he says, he believes that concerned stakeholders can either try to help develop the skills and knowledge of those hospitalists already in the ICU or “hope that a whole bunch of hospitalists suddenly decide to abandon their practices and complete two-year medical

critical-care fellowships.”

Intensivist leaders say that less training will do nothing to improve patient outcomes. “The reality is that hospitalists are doing it. The question should be, ‘Are they doing it well or at the detriment of the patient?’” asks Michael Baumann, MD, MS, FCCP, professor of medicine in the division of pulmonary, critical-care, and sleep medicine at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson. “The patient is the one who loses if we have somebody pinch-hitting, which is really what we’re talking about here,” adds Dr. Baumann, lead author of the ACCP/AACN editorial.

Staffing Shortfall

Despite the heated rhetoric, interviews with leaders on both sides suggest an eagerness to move forward in trying to collectively solve a problem that has vexed the entire medical community.

In 2000, the Leapfrog Group, a Washington, D.C.-based consortium of major healthcare purchasers focused on improving the safety, quality, and value of care, recommended that all ICUs should be staffed with physicians certified in critical-care medicine.3 As part of its rationale, the group cited research suggesting that greater intensivist use can yield better patient outcomes.

But a seminal study published the same year hinted at just how difficult meeting Leapfrog’s ambitious goal might be. Based on the trajectory of supply and demand, the authors forecast a 22% shortfall in intensivist hours by 2020, and a 35% shortfall by 2030, mainly due to a surge in demand from an aging U.S. population.4 A follow-up report in 2006 estimated that 53% of the nation’s ICU units had no intensivist coverage at all, and that only 4% of adult ICUs were meeting the full Leapfrog standards of high-intensity ICU staffing, dedicated attending physician coverage during the day, and dedicated coverage by any physician at night.5

—Timothy Buchman, PhD, MD, director, Emory University Center for Critical Care, Atlanta

Given the recent push for more outpatient treatment of less-critically-ill patients, many observers say the increased acuity of hospitalized patients—with more comorbidities—only exacerbates the mismatch between supply and demand. Making matters worse, providers are not evenly distributed throughout the country, with many smaller and rural hospitals already facing an acute shortage of intensivist services.

As a result, many hospitalists have been forced to step into the breach. According to SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine survey, 83.5% of responding nonacademic adult medicine groups said they routinely provide care for patients in an ICU setting, along with 27.9% of academic HM groups.

“So we have hospitalists who, either by choice or by default, care for patients who they may or may not be fully qualified to manage,” Dr. Siegal says. Practically speaking, he and his coauthors assert, the question of whether hospitalists should be in the ICU is now moot. The real question is how to ensure that those providers can deliver safe and effective care.

Experience vs. Training

Currently, internists who have completed fellowships in such specialties as pulmonary medicine, nephrology, and infectious disease can complete a one-year critical-care fellowship to obtain board certification. Experienced hospitalists have questioned the requirement that they instead complete a two-year fellowship, with no consideration given to the relevant clinical experience and maturity gained after years of hospitalist practice. In addition, they argue, it is logistically and financially unrealistic to expect a large cadre of experienced hospitalists to abandon their practices for two years to pursue critical-care training.

But Dr. Baumann says subpar internal-medicine residency requirements deserve much of the blame for offering inadequate training. “Critical care is a blend of critical thinking skills and procedural skills. Both of those are diminished tremendously in the current programs for internal medicine,” he says. “It’s really an indictment of our current training of internal-medicine residents now.”

SCCM, for its part, is sticking to its guns, albeit more quietly. When asked for comment, a spokesman issued a carefully worded statement that reads, “The paper reflects the society’s concerns regarding workforce shortages and the realities of today’s environment.”

The SHM/SCCM proposal makes sense provided that hospitalists are realistic about the types of patients they’ll see, says Timothy Buchman, PhD, MD, director of Emory University’s Center for Critical Care in Atlanta. “No one in their right mind will say one year is as good as two years. That would be folly,” he says. “On the other hand, that’s not the question. The question is, ‘Can we structure training that is competency-focused, so that the majority of people who enter the training will achieve the necessary levels of competency within a year?’”

Derek Angus, MD, chair of critical-care medicine at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and lead author of the 2000 study chronicling the intensivist shortfall, is more ambivalent. “Hospitalists and intensivists have to work hand in hand. In many ways, they are the two groups that run inpatient hospital medicine,” he says. In that respect, sorting out and streamlining training pathways might be a good idea.

“On the other hand, all of intensive-care training in the United States is a little thin in comparison to what goes on in many other countries,” Dr. Angus adds. “If anything, I would like to be seeing more vigorous training. So creating one more pathway that helps reinforce pretty light training feels like accreditation, in general, may be moving slightly in the wrong direction.”

Dr. Buchman and other observers view the debate as a difference in opinion among well-meaning people who are passionate about patient care. And they concede that no one knows yet who may be right.

“We do know that advanced training is required. We do know that it should be competency-focused,” Dr. Buchman says. “But what we don’t know is how long it’s really going to take to get to the competency levels that we believe are necessary to care for the patients.”

That point may provide one important opening for further discussions. Dr. Baumann agrees that the real issues are how to define critical-care competencies, how to measure them, and how to ensure that trainees prove their mettle as competent providers. “It really shouldn’t be time-based; it should be outcome-based,” he says.

The SHM/SCCM proposal, Dr. Siegal says, should be viewed as a conversation-starter. The true test will be whether everyone can reach an agreement on how to evaluate whether an ICU caregiver has attained the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes—and how relevant professional experience should factor into discussions over the length of training required for intensivist certification.

A Tiered Solution

The concept of tiered ICU care—already used in neonatal ICUs—might offer another opening for productive debate. “Can patients who are not that critically ill be managed by someone who hasn’t done that much critical-care training?” Dr. Angus asks. He believes it’s possible, provided patients are properly sorted and that hospitalists aren’t put in the uncomfortable position of managing medical conditions that they see only rarely. He has no problem, though, envisioning a tiered system in which fully trained intensivists spend most of their time managing the sickest patients, while other providers—including hospitalists—care for patients at intermediate risk.

Hospitalists have greeted the idea cautiously, noting that a two-tiered model might be difficult to define and standardize, and that it could present logistical challenges around transferring patients. However, Daniel D. Dressler, MD, MSc, SFHM, FACP, associate professor of internal medicine at Emory University School of Medicine and coauthor of the SHM/SCCM position paper, led a recent study that offers at least some support for a risk-based system.6

Overall, the study found no statistically significant difference in the length of stay or inpatient mortality rates for ICU patients cared for by hospitalist-led or intensivist-led teams. Among mechanically ventilated patients with intermediate illness severity, though, the study suggested that intensivist-led care resulted in a lower length of stay in both the hospital and ICU, as well as in a trend toward reduced inpatient mortality. “There may be some value in designing or developing a stratification system,” Dr. Dressler says, “but it definitely needs more study.”

In the meantime, Dr. Dressler says, more rapid solutions are needed. And although he says he understands and respects many of the doubts expressed about the SHM/SCCM proposal, he also believes some of the fear might be based on anecdotes about individual hospitalists who were deemed unlikely to thrive in an ICU environment. “For each person like that, we also know 10 or 20 people who might do really well” with just a year of additional training, says Dr. Dressler, a former SHM board member.

Now that both sides clearly have the attention of the other, leaders say they hope the opening salvos give way to more temperate discussions about how to move more skilled providers to the front lines.

“Health professionals are a smart and clever lot,” says Mary Stahl, RN, MSN, ACNS-BC, CCNS-CMC, CCRN, immediate past president of AACN and a clinical nurse specialist at the Mid America Heart Institute at Saint Luke’s Hospital in Kansas City, Mo. “I’m confident we’ll develop an effective solution—maybe several—by focusing on the fundamental belief that patients’ needs must drive caregivers’ knowledge and skills.”

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

References

- Siegal EM, Dressler DD, Dichter JR, Gorman MJ, Lipsett PA. Training a hospitalist workforce to address the intensivist shortage in American hospitals: a position paper from the Society of Hospital Medicine and the Society of Critical Care Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:359-364.

- Baumann MH, Simpson SQ, Stahl M, et al. First, do no harm: less training ≠ quality care. Chest. 2012;142:5-7.

- Milstein A, Galvin RS, Delbanco SF, et al. Improving the safety of health care: the Leapfrog initiative. Eff Clin Pract. 2000;3:313-316.

- Angus DC, Kelley MA, Schmitz RJ, et al. Caring for the critically ill patient. Current and projected workforce requirements for care of the critically ill and patients with pulmonary disease: can we meet the requirements of an aging population? JAMA. 2000;284:2762-2770.

- Angus DC, Shorr AF, White A, et al. Critical care delivery in the United States: distribution of services and compliance with Leapfrog recommendations. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1016-1024.

- Wise KR, Akopov VA, Williams BR Jr., Ido MS, Leeper KV, Dressler DD. Hospitalists and intensivists in the medical ICU: a prospective observational study comparing mortality and length of stay between two staffing models. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:183-189.

The long-simmering debate over whether and how hospitalists might help solve the worsening shortage of critical-care physicians is beginning to boil over.

In June, SHM and the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) issued a joint position paper proposing an expedited, one-year, critical-care fellowship for hospitalists with at least three years of clinical job experience, in lieu of the two-year fellowship now required for board certification.1

“Bringing qualified hospitalists into the critical-care workforce through rigorous sanctioned and accredited one-year training programs,” the paper asserted, “will open a new intensivist training pipeline and potentially offer more critically ill patients the benefits of providers who are unequivocally qualified to care for them.”

The backlash was swift and sharp. In a strongly worded editorial response published in July, the American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) declared that one year of fellowship training is inadequate for HM physicians to achieve competence in critical-care medicine.2 “No, the perfect should not be the enemy of the good in our efforts to craft solutions,” the editorial stated. “But the current imperfect SCCM/SHM proposal is an enemy of the existing good training processes already in place.”

HM leaders counter that the current strategies for bolstering the ranks of board-certified intensivists simply aren’t working, and that creative, outside-the-box thinking is required to solve the dilemma.

“Hospitalists are rapidly becoming a dominant, if not the dominant, block of physicians who are providing critical care in the United States. You can decide, if you want, whether that’s good or bad, but that’s the reality,” says Eric Siegal, MD, SFHM, lead author of the SHM/SCCM position paper, director of critical-care medicine at Aurora St. Luke’s Medical Center in Milwaukee, and an SHM board member. Given the escalating shortage of intensivists, he says, he believes that concerned stakeholders can either try to help develop the skills and knowledge of those hospitalists already in the ICU or “hope that a whole bunch of hospitalists suddenly decide to abandon their practices and complete two-year medical

critical-care fellowships.”

Intensivist leaders say that less training will do nothing to improve patient outcomes. “The reality is that hospitalists are doing it. The question should be, ‘Are they doing it well or at the detriment of the patient?’” asks Michael Baumann, MD, MS, FCCP, professor of medicine in the division of pulmonary, critical-care, and sleep medicine at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Jackson. “The patient is the one who loses if we have somebody pinch-hitting, which is really what we’re talking about here,” adds Dr. Baumann, lead author of the ACCP/AACN editorial.

Staffing Shortfall

Despite the heated rhetoric, interviews with leaders on both sides suggest an eagerness to move forward in trying to collectively solve a problem that has vexed the entire medical community.

In 2000, the Leapfrog Group, a Washington, D.C.-based consortium of major healthcare purchasers focused on improving the safety, quality, and value of care, recommended that all ICUs should be staffed with physicians certified in critical-care medicine.3 As part of its rationale, the group cited research suggesting that greater intensivist use can yield better patient outcomes.

But a seminal study published the same year hinted at just how difficult meeting Leapfrog’s ambitious goal might be. Based on the trajectory of supply and demand, the authors forecast a 22% shortfall in intensivist hours by 2020, and a 35% shortfall by 2030, mainly due to a surge in demand from an aging U.S. population.4 A follow-up report in 2006 estimated that 53% of the nation’s ICU units had no intensivist coverage at all, and that only 4% of adult ICUs were meeting the full Leapfrog standards of high-intensity ICU staffing, dedicated attending physician coverage during the day, and dedicated coverage by any physician at night.5

—Timothy Buchman, PhD, MD, director, Emory University Center for Critical Care, Atlanta

Given the recent push for more outpatient treatment of less-critically-ill patients, many observers say the increased acuity of hospitalized patients—with more comorbidities—only exacerbates the mismatch between supply and demand. Making matters worse, providers are not evenly distributed throughout the country, with many smaller and rural hospitals already facing an acute shortage of intensivist services.

As a result, many hospitalists have been forced to step into the breach. According to SHM’s 2012 State of Hospital Medicine survey, 83.5% of responding nonacademic adult medicine groups said they routinely provide care for patients in an ICU setting, along with 27.9% of academic HM groups.

“So we have hospitalists who, either by choice or by default, care for patients who they may or may not be fully qualified to manage,” Dr. Siegal says. Practically speaking, he and his coauthors assert, the question of whether hospitalists should be in the ICU is now moot. The real question is how to ensure that those providers can deliver safe and effective care.

Experience vs. Training

Currently, internists who have completed fellowships in such specialties as pulmonary medicine, nephrology, and infectious disease can complete a one-year critical-care fellowship to obtain board certification. Experienced hospitalists have questioned the requirement that they instead complete a two-year fellowship, with no consideration given to the relevant clinical experience and maturity gained after years of hospitalist practice. In addition, they argue, it is logistically and financially unrealistic to expect a large cadre of experienced hospitalists to abandon their practices for two years to pursue critical-care training.

But Dr. Baumann says subpar internal-medicine residency requirements deserve much of the blame for offering inadequate training. “Critical care is a blend of critical thinking skills and procedural skills. Both of those are diminished tremendously in the current programs for internal medicine,” he says. “It’s really an indictment of our current training of internal-medicine residents now.”

SCCM, for its part, is sticking to its guns, albeit more quietly. When asked for comment, a spokesman issued a carefully worded statement that reads, “The paper reflects the society’s concerns regarding workforce shortages and the realities of today’s environment.”

The SHM/SCCM proposal makes sense provided that hospitalists are realistic about the types of patients they’ll see, says Timothy Buchman, PhD, MD, director of Emory University’s Center for Critical Care in Atlanta. “No one in their right mind will say one year is as good as two years. That would be folly,” he says. “On the other hand, that’s not the question. The question is, ‘Can we structure training that is competency-focused, so that the majority of people who enter the training will achieve the necessary levels of competency within a year?’”

Derek Angus, MD, chair of critical-care medicine at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and lead author of the 2000 study chronicling the intensivist shortfall, is more ambivalent. “Hospitalists and intensivists have to work hand in hand. In many ways, they are the two groups that run inpatient hospital medicine,” he says. In that respect, sorting out and streamlining training pathways might be a good idea.

“On the other hand, all of intensive-care training in the United States is a little thin in comparison to what goes on in many other countries,” Dr. Angus adds. “If anything, I would like to be seeing more vigorous training. So creating one more pathway that helps reinforce pretty light training feels like accreditation, in general, may be moving slightly in the wrong direction.”

Dr. Buchman and other observers view the debate as a difference in opinion among well-meaning people who are passionate about patient care. And they concede that no one knows yet who may be right.

“We do know that advanced training is required. We do know that it should be competency-focused,” Dr. Buchman says. “But what we don’t know is how long it’s really going to take to get to the competency levels that we believe are necessary to care for the patients.”

That point may provide one important opening for further discussions. Dr. Baumann agrees that the real issues are how to define critical-care competencies, how to measure them, and how to ensure that trainees prove their mettle as competent providers. “It really shouldn’t be time-based; it should be outcome-based,” he says.

The SHM/SCCM proposal, Dr. Siegal says, should be viewed as a conversation-starter. The true test will be whether everyone can reach an agreement on how to evaluate whether an ICU caregiver has attained the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes—and how relevant professional experience should factor into discussions over the length of training required for intensivist certification.

A Tiered Solution

The concept of tiered ICU care—already used in neonatal ICUs—might offer another opening for productive debate. “Can patients who are not that critically ill be managed by someone who hasn’t done that much critical-care training?” Dr. Angus asks. He believes it’s possible, provided patients are properly sorted and that hospitalists aren’t put in the uncomfortable position of managing medical conditions that they see only rarely. He has no problem, though, envisioning a tiered system in which fully trained intensivists spend most of their time managing the sickest patients, while other providers—including hospitalists—care for patients at intermediate risk.

Hospitalists have greeted the idea cautiously, noting that a two-tiered model might be difficult to define and standardize, and that it could present logistical challenges around transferring patients. However, Daniel D. Dressler, MD, MSc, SFHM, FACP, associate professor of internal medicine at Emory University School of Medicine and coauthor of the SHM/SCCM position paper, led a recent study that offers at least some support for a risk-based system.6

Overall, the study found no statistically significant difference in the length of stay or inpatient mortality rates for ICU patients cared for by hospitalist-led or intensivist-led teams. Among mechanically ventilated patients with intermediate illness severity, though, the study suggested that intensivist-led care resulted in a lower length of stay in both the hospital and ICU, as well as in a trend toward reduced inpatient mortality. “There may be some value in designing or developing a stratification system,” Dr. Dressler says, “but it definitely needs more study.”

In the meantime, Dr. Dressler says, more rapid solutions are needed. And although he says he understands and respects many of the doubts expressed about the SHM/SCCM proposal, he also believes some of the fear might be based on anecdotes about individual hospitalists who were deemed unlikely to thrive in an ICU environment. “For each person like that, we also know 10 or 20 people who might do really well” with just a year of additional training, says Dr. Dressler, a former SHM board member.

Now that both sides clearly have the attention of the other, leaders say they hope the opening salvos give way to more temperate discussions about how to move more skilled providers to the front lines.

“Health professionals are a smart and clever lot,” says Mary Stahl, RN, MSN, ACNS-BC, CCNS-CMC, CCRN, immediate past president of AACN and a clinical nurse specialist at the Mid America Heart Institute at Saint Luke’s Hospital in Kansas City, Mo. “I’m confident we’ll develop an effective solution—maybe several—by focusing on the fundamental belief that patients’ needs must drive caregivers’ knowledge and skills.”

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

References

- Siegal EM, Dressler DD, Dichter JR, Gorman MJ, Lipsett PA. Training a hospitalist workforce to address the intensivist shortage in American hospitals: a position paper from the Society of Hospital Medicine and the Society of Critical Care Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:359-364.

- Baumann MH, Simpson SQ, Stahl M, et al. First, do no harm: less training ≠ quality care. Chest. 2012;142:5-7.

- Milstein A, Galvin RS, Delbanco SF, et al. Improving the safety of health care: the Leapfrog initiative. Eff Clin Pract. 2000;3:313-316.

- Angus DC, Kelley MA, Schmitz RJ, et al. Caring for the critically ill patient. Current and projected workforce requirements for care of the critically ill and patients with pulmonary disease: can we meet the requirements of an aging population? JAMA. 2000;284:2762-2770.

- Angus DC, Shorr AF, White A, et al. Critical care delivery in the United States: distribution of services and compliance with Leapfrog recommendations. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1016-1024.

- Wise KR, Akopov VA, Williams BR Jr., Ido MS, Leeper KV, Dressler DD. Hospitalists and intensivists in the medical ICU: a prospective observational study comparing mortality and length of stay between two staffing models. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:183-189.

Alternative Healthcare Models Aim to Boost Sagging Critical-Care Workforce

Amid the struggle to boost the country’s sagging critical-care workforce, experts have most commonly proposed creating a tiered or regionalized model of care, investing more in tele-ICU services, and augmenting the role of midlevel providers.

The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, with 20 hospitals and roughly 500 ICU beds throughout its network, is adopting a regionalized healthcare delivery system. Some of the center’s most high-risk services, such as its big transplant programs, are centralized within the main university campus hospitals, as are about half of the ICU beds.

“In those hospitals, we’ve decided that we need 24/7 in-house, intensive-care attendings,” says Derek Angus, MD, the center’s chair of critical-care medicine. The doctors work with fellows and a rapidly growing expansion of midlevel providers.

In some of the smaller hospitals, however, some ICU patients are seen and managed by hospitalists. The medical center’s eventual goal is to be more systematic about the kinds of patients managed by intensivists as well as those managed by hospitalists. It’s a task made easier by the specialists’ close working relationship within the same department.

Dr. Angus believes telemedicine could help by providing a sort of mission control that can help track critically ill patients and those at risk of being admitted to ICUs across all 20 hospitals. He concedes, however, that telemedicine for ICU assistance has had mixed results in the medical literature, suggesting that a major key is working out the proper roles and responsibilities of those using the technology.

To improve the consistency of its own frontline providers, the Emory University Center for Critical Care in Atlanta developed a competency-based, critical-care training program for nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs).

“It’s very clear that if you have a group of NP and PA providers who can do 90 percent of what the physician does, it really begins to unload the physician to focus on what I call the big-picture pieces of critical care,” says center director Timothy Buchman, PhD, MD.

That attending physician can be trained as a care executive to ensure well-coordinated care and to focus on any process that isn’t working well. “At a big academic health sciences center, that should probably be a critical-care physician,” Dr. Buchman notes. “But for the smaller community and regional hospitals that have a relatively less sick population, the person who will be well-positioned to oversee this nonphysician provider staff could well be a hospitalist who’s received additional guidance and training in critical care.”

For mild or moderate complexity of care, he says, the added training need not necessarily include a traditional two-year fellowship. Under a value-based system, sicker patients could be rapidly transferred to a higher level of care, and telemedicine could provide a “backstop” for providers in smaller hospitals who lack the training and experience of someone with a full critical-care fellowship.

Amid the struggle to boost the country’s sagging critical-care workforce, experts have most commonly proposed creating a tiered or regionalized model of care, investing more in tele-ICU services, and augmenting the role of midlevel providers.

The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, with 20 hospitals and roughly 500 ICU beds throughout its network, is adopting a regionalized healthcare delivery system. Some of the center’s most high-risk services, such as its big transplant programs, are centralized within the main university campus hospitals, as are about half of the ICU beds.

“In those hospitals, we’ve decided that we need 24/7 in-house, intensive-care attendings,” says Derek Angus, MD, the center’s chair of critical-care medicine. The doctors work with fellows and a rapidly growing expansion of midlevel providers.

In some of the smaller hospitals, however, some ICU patients are seen and managed by hospitalists. The medical center’s eventual goal is to be more systematic about the kinds of patients managed by intensivists as well as those managed by hospitalists. It’s a task made easier by the specialists’ close working relationship within the same department.

Dr. Angus believes telemedicine could help by providing a sort of mission control that can help track critically ill patients and those at risk of being admitted to ICUs across all 20 hospitals. He concedes, however, that telemedicine for ICU assistance has had mixed results in the medical literature, suggesting that a major key is working out the proper roles and responsibilities of those using the technology.

To improve the consistency of its own frontline providers, the Emory University Center for Critical Care in Atlanta developed a competency-based, critical-care training program for nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs).

“It’s very clear that if you have a group of NP and PA providers who can do 90 percent of what the physician does, it really begins to unload the physician to focus on what I call the big-picture pieces of critical care,” says center director Timothy Buchman, PhD, MD.

That attending physician can be trained as a care executive to ensure well-coordinated care and to focus on any process that isn’t working well. “At a big academic health sciences center, that should probably be a critical-care physician,” Dr. Buchman notes. “But for the smaller community and regional hospitals that have a relatively less sick population, the person who will be well-positioned to oversee this nonphysician provider staff could well be a hospitalist who’s received additional guidance and training in critical care.”

For mild or moderate complexity of care, he says, the added training need not necessarily include a traditional two-year fellowship. Under a value-based system, sicker patients could be rapidly transferred to a higher level of care, and telemedicine could provide a “backstop” for providers in smaller hospitals who lack the training and experience of someone with a full critical-care fellowship.

Amid the struggle to boost the country’s sagging critical-care workforce, experts have most commonly proposed creating a tiered or regionalized model of care, investing more in tele-ICU services, and augmenting the role of midlevel providers.

The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, with 20 hospitals and roughly 500 ICU beds throughout its network, is adopting a regionalized healthcare delivery system. Some of the center’s most high-risk services, such as its big transplant programs, are centralized within the main university campus hospitals, as are about half of the ICU beds.

“In those hospitals, we’ve decided that we need 24/7 in-house, intensive-care attendings,” says Derek Angus, MD, the center’s chair of critical-care medicine. The doctors work with fellows and a rapidly growing expansion of midlevel providers.

In some of the smaller hospitals, however, some ICU patients are seen and managed by hospitalists. The medical center’s eventual goal is to be more systematic about the kinds of patients managed by intensivists as well as those managed by hospitalists. It’s a task made easier by the specialists’ close working relationship within the same department.

Dr. Angus believes telemedicine could help by providing a sort of mission control that can help track critically ill patients and those at risk of being admitted to ICUs across all 20 hospitals. He concedes, however, that telemedicine for ICU assistance has had mixed results in the medical literature, suggesting that a major key is working out the proper roles and responsibilities of those using the technology.

To improve the consistency of its own frontline providers, the Emory University Center for Critical Care in Atlanta developed a competency-based, critical-care training program for nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs).

“It’s very clear that if you have a group of NP and PA providers who can do 90 percent of what the physician does, it really begins to unload the physician to focus on what I call the big-picture pieces of critical care,” says center director Timothy Buchman, PhD, MD.

That attending physician can be trained as a care executive to ensure well-coordinated care and to focus on any process that isn’t working well. “At a big academic health sciences center, that should probably be a critical-care physician,” Dr. Buchman notes. “But for the smaller community and regional hospitals that have a relatively less sick population, the person who will be well-positioned to oversee this nonphysician provider staff could well be a hospitalist who’s received additional guidance and training in critical care.”

For mild or moderate complexity of care, he says, the added training need not necessarily include a traditional two-year fellowship. Under a value-based system, sicker patients could be rapidly transferred to a higher level of care, and telemedicine could provide a “backstop” for providers in smaller hospitals who lack the training and experience of someone with a full critical-care fellowship.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Budget Cuts Threaten Doctor-Aid Programs

Just as the federal government is introducing several new programs to promote the recruitment, training, and placement of more primary-care providers, other efforts are being threatened with funding decreases or elimination.

One, the Children’s Hospitals Graduate Medical Education program, distributed $268 million in pediatric training funds to 55 freestanding children’s teaching hospitals in fiscal-year 2012. The program, however, was zeroed out in President Obama’s initial budget proposal last year, and the president’s fiscal-year 2013 budget proposal recommends slashing the program’s annual funding by two-thirds to $88 million.

—Robert Phillips, MD, MSPH, director, Robert Graham Center, a primary-care research center in Washington, D.C.

Kathleen Klink, MD, director of the Division of Medicine and Dentistry in the federal Health Resources and Services Administration, also points to the Title VII Area Health Education Center program as an example of government-funded assistance. The competitive grant process supports innovation and access to care for vulnerable populations, in part by improving the primary-care workforce’s geographic and ethnic distribution. Some of the grantees introduce high school students to medical careers, while others recruit and train minorities or place providers in underserved communities, effectively targeting both ends of the pipeline.

Robert Phillips, MD, MSPH, director of the Washington, D.C.-based Robert Graham Center, a primary-care research center, has high regard for the Title VII program. But making an impact requires a long-term investment, he cautions. “In the states that do this well, like Arkansas and North Carolina, it pays off,” he says. “But they can’t prove it sufficiently to save their budget.” The federal program received $233 million in fiscal-year 2012. Under the president’s fiscal-year 2013 budget proposal, however, the funding is likewise eliminated.

Other programs have debuted in recent legislation. One program, introduced under the Affordable Care Act, provides $230 million over five years to expand residency training slots within ambulatory primary-care settings. Dr. Klink says the Teaching Health Center Graduate Medical Education program, as it is known, has so far supported 22 health centers and 150 enrolled residents. “It’s just the beginning,” she adds.

Another program, the Primary Care Residency Expansion, likewise initiated under the Affordable Care Act, will distribute $167 million to train an estimated 700 primary-care physicians (PCPs), 900 physician assistants, and 600 nurse practitioners and nurse midwives over five years. Glen Stream, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, recently told The Washington Post, “It’s good, but it’s also a drop in the bucket.”

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

Just as the federal government is introducing several new programs to promote the recruitment, training, and placement of more primary-care providers, other efforts are being threatened with funding decreases or elimination.

One, the Children’s Hospitals Graduate Medical Education program, distributed $268 million in pediatric training funds to 55 freestanding children’s teaching hospitals in fiscal-year 2012. The program, however, was zeroed out in President Obama’s initial budget proposal last year, and the president’s fiscal-year 2013 budget proposal recommends slashing the program’s annual funding by two-thirds to $88 million.

—Robert Phillips, MD, MSPH, director, Robert Graham Center, a primary-care research center in Washington, D.C.

Kathleen Klink, MD, director of the Division of Medicine and Dentistry in the federal Health Resources and Services Administration, also points to the Title VII Area Health Education Center program as an example of government-funded assistance. The competitive grant process supports innovation and access to care for vulnerable populations, in part by improving the primary-care workforce’s geographic and ethnic distribution. Some of the grantees introduce high school students to medical careers, while others recruit and train minorities or place providers in underserved communities, effectively targeting both ends of the pipeline.

Robert Phillips, MD, MSPH, director of the Washington, D.C.-based Robert Graham Center, a primary-care research center, has high regard for the Title VII program. But making an impact requires a long-term investment, he cautions. “In the states that do this well, like Arkansas and North Carolina, it pays off,” he says. “But they can’t prove it sufficiently to save their budget.” The federal program received $233 million in fiscal-year 2012. Under the president’s fiscal-year 2013 budget proposal, however, the funding is likewise eliminated.

Other programs have debuted in recent legislation. One program, introduced under the Affordable Care Act, provides $230 million over five years to expand residency training slots within ambulatory primary-care settings. Dr. Klink says the Teaching Health Center Graduate Medical Education program, as it is known, has so far supported 22 health centers and 150 enrolled residents. “It’s just the beginning,” she adds.

Another program, the Primary Care Residency Expansion, likewise initiated under the Affordable Care Act, will distribute $167 million to train an estimated 700 primary-care physicians (PCPs), 900 physician assistants, and 600 nurse practitioners and nurse midwives over five years. Glen Stream, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, recently told The Washington Post, “It’s good, but it’s also a drop in the bucket.”

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

Just as the federal government is introducing several new programs to promote the recruitment, training, and placement of more primary-care providers, other efforts are being threatened with funding decreases or elimination.

One, the Children’s Hospitals Graduate Medical Education program, distributed $268 million in pediatric training funds to 55 freestanding children’s teaching hospitals in fiscal-year 2012. The program, however, was zeroed out in President Obama’s initial budget proposal last year, and the president’s fiscal-year 2013 budget proposal recommends slashing the program’s annual funding by two-thirds to $88 million.

—Robert Phillips, MD, MSPH, director, Robert Graham Center, a primary-care research center in Washington, D.C.

Kathleen Klink, MD, director of the Division of Medicine and Dentistry in the federal Health Resources and Services Administration, also points to the Title VII Area Health Education Center program as an example of government-funded assistance. The competitive grant process supports innovation and access to care for vulnerable populations, in part by improving the primary-care workforce’s geographic and ethnic distribution. Some of the grantees introduce high school students to medical careers, while others recruit and train minorities or place providers in underserved communities, effectively targeting both ends of the pipeline.

Robert Phillips, MD, MSPH, director of the Washington, D.C.-based Robert Graham Center, a primary-care research center, has high regard for the Title VII program. But making an impact requires a long-term investment, he cautions. “In the states that do this well, like Arkansas and North Carolina, it pays off,” he says. “But they can’t prove it sufficiently to save their budget.” The federal program received $233 million in fiscal-year 2012. Under the president’s fiscal-year 2013 budget proposal, however, the funding is likewise eliminated.

Other programs have debuted in recent legislation. One program, introduced under the Affordable Care Act, provides $230 million over five years to expand residency training slots within ambulatory primary-care settings. Dr. Klink says the Teaching Health Center Graduate Medical Education program, as it is known, has so far supported 22 health centers and 150 enrolled residents. “It’s just the beginning,” she adds.

Another program, the Primary Care Residency Expansion, likewise initiated under the Affordable Care Act, will distribute $167 million to train an estimated 700 primary-care physicians (PCPs), 900 physician assistants, and 600 nurse practitioners and nurse midwives over five years. Glen Stream, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, recently told The Washington Post, “It’s good, but it’s also a drop in the bucket.”

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Elbert Huang discusses primary care's role in providing access and value

Click here to listen to Dr. Huang

Click here to listen to Dr. Huang

Click here to listen to Dr. Huang

Workforce Shortages, Increased Patient Populations, and Funding Woes Pressure U.S. Primary-Care System

It’s been about 15 years since the last surge of interest in primary care as a career, when U.S. medical graduates temporarily reversed a long decline by flocking to family medicine, general internal medicine, and pediatrics. Newly minted doctors responded enthusiastically to a widely held perception in the mid-1990s that primary care would be central to a brave new paradigm of managed healthcare delivery.

That profound change never materialized, and the primary-care workforce has since resumed a downward slide that is sounding alarm bells throughout the country. Even more distressing, the medical profession’s recent misfortunes have spread far beyond the doctor’s office.

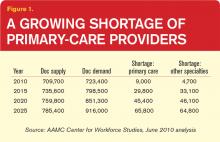

“What we’re looking at now is that there’s a shortage of somewhere around 90,000 physicians in the next 10 years, increasing in the five years beyond that to 125,000 or more,” says Atul Grover, MD, PhD, chief public policy officer of the Association of American Medical Colleges. The association’s estimates suggest that the 10- and 15-year shortfalls will be split nearly evenly between primary care and other specialties.

Hospitalists could feel that widening gap as well. With increasing numbers of aging baby boomers reaching Medicare eligibility and 32 million Americans set to join the ranks of the insured by 2019 through the Affordable Care Act, primary care’s difficulties arguably are the closest to a full-blown crisis. “Primary care in the United States needs a lifeline,” began a 2009 editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine.1 And that was before an estimate suggesting that new insurance mandates will require an additional 4,307 to 6,940 primary-care physicians to meet demand before the end of the decade contributing about 15% to the expected shortfall.2

Why should hospitalists care about the fate of their counterparts? For starters, what’s good for outpatient providers is good for a sound healthcare system. Researchers have linked strong

primary care to lower overall spending, fewer health disparities, and higher quality of care.3

Hospitalists and primary-care physicians (PCPs) also are inexorably linked. They follow similar training and education pathways, and need each other to ensure safe transitions of care. And despite the evidence pointing to a slew of contributing factors, HM regularly is blamed for many of primary care’s mounting woes.

Based on well-functioning healthcare systems around the world, analysts say the ideal primary-care-to-specialty-care-provider ratio should be roughly 40:60 or 50:50. According to Kathleen Klink, MD, director of the Division of Medicine and Dentistry in the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), only about 32% of physicians in the U.S. are practicing primary care. Unless something changes, that percentage will erode even further. “We’re going in the wrong direction,” Dr. Klink says.

Opinions differ on the extent of the current PCP shortage. Nevertheless, there is clearly a “huge maldistribution problem,” says Robert Phillips, MD, MSPH, director of the Washington, D.C.-based Robert Graham Center, a primary-care research center. Rural and underserved areas already are being shortchanged as more doctors locate in more affluent and desirable areas, he says.

That phenomenon is hardly unique to primary care, but Dr. Phillips says the deficit in frontline doctors could cause disproportionately more hardships in rural and underserved communities given the shrinking pipeline for medical trainees. A decade ago, almost a third of all medical graduates were placed into primary-care residency training slots. Now, he says, that figure is a bit less than 22%. “We can’t even replace the primary-care workforce we have now with that kind of output,” Dr. Phillips says.

Already, many doctors are no longer accepting new Medicaid or Medicare patients because their practices are losing money from low reimbursement rates. The Affordable Care Act’s significant expansion of insurance benefits, Dr. Grover says, will effectively accelerate the timetable of growing imbalances between supply and demand. “I think the challenge you face is, Will the ACA efforts to expand access fail because you’re giving people an insurance card but you have nobody there to take care of them?”

Reasons Aplenty

Some medical students simply aren’t interested in primary care. For the rest, however, interviews with doctors, analysts, and federal officials suggest that the pipeline has been battered throughout its length. Of all the contributing factors, Dr. Phillips says, the main one might be income disparity. In a 2009 study, the center found that the growing gulf in salaries between primary care and subspecialty medicine “cuts in half the likelihood that a student will choose to go into primary care,” he says. Over a career, that gap translates into a difference of $3.5 million. “It dissuades them strongly,” Dr. Phillips says.

At the same time, medical school tuitions have increased at a rate far outstripping the consumer price index. “What we found is that when you hit somewhere between $200,000 and $250,000 in debt, that’s where you see the dropoff really happen,” he says. “Because it becomes almost unfathomable that you can, on a primary-care income, pay off your debts without it severely cutting into your lifestyle.”

Lori Heim, MD, former president of the American Academy of Family Physicians and a hospitalist at Scotland Memorial Hospital in Laurinburg, N.C., says the prevailing fee-for-service payment model has failed primary-care providers, requiring them to work more to meet soaring outpatient demand but reimbursing them less. “People talk about the hamster wheel,” she says. “And that has created more workplace dissatisfaction. Not only does it impact students, but it also impacts the number of primary-care physicians who want to stay in the community, practicing.”

Frederick Chen, MD, MPH, associate professor of family medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle, can relate. “I came from community practice, where you’re seeing 30 to 35 patients a day, and the pressure was entirely on your productivity, and that’s not fun,” he says. “So we’re burning out a lot of primary-care physicians, and students are seeing that very easily.”

The larger theme, several doctors say, is one of perceived worth. Leora Horwitz, MD, assistant professor of internal medicine at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., says she has to think holistically about her patients’ symptoms, medication lists, family history, home situation, and other factors during her limited time with them. She bristles at the notion that specialists might spend their time considering only one aspect of her patients’ care yet bill twice as much.

“Realistically, I am providing better value to the healthcare system than a specialist does, and yet we pay specialists much more,” she says. “And until that’s different, people go where the money is and they also go where the respect is, and I think it’s going to be very hard to recruit more people to primary care.”

Despite research pointing to financial concerns, lifestyle perceptions, and training inadequacies as key factors in the decline of primary care, perceptions that HM is poaching young talent have been hard to shake. A recent article in The Atlantic asserts that HM might be a “rational choice” given the profession’s more favorable training, lifestyle, and financial considerations.4 The author, a general internist, contrasts those enticements “to the realities of office practice: Fifteen-minute visits with patients on multiple medications, oodles of paperwork that cause office docs to run a gauntlet just to get through their day, and more documentation and regulatory burdens than ever before.”

Nevertheless, the article describes PCPs who resist hospitals’ calls to move to a hospitalist system as honorable “holdouts” who are committed to being directly involved in their patients’ care.

In her blog post at KevinMD.com, “Hospitalists are Killing Primary Care, and other Myths Debunked,” Vineet Arora, MD, MPP, FHM, a hospitalist at the University of Chicago, addresses those perceptions head-on. “If hospitalists did not exist, there would still be declining interest in primary care among medical students and residents,” she writes.

In a subsequent interview, Dr. Arora contends that both primary care and HM instead might be losing out to higher-paying subspecialties, especially the “ROAD” quartet of radiology, ophthalmology, anesthesiology, and dermatology. She also questions the notion that the professions draw from the same talent pool. “Anecdotally, I can tell you that I don’t see a lot of people choosing between primary care and hospital medicine,” she says. “They’re thinking, ‘Do I want to do critical care, hospital medicine, or cardiology?’ Because the type of person who does hospital medicine is more attracted to that inpatient, acute environment.”

Dr. Horwitz agrees that the choice between a career in primary care and HM might not be as clear-cut as some detractors have suggested. Even so, she describes hospitalists as a “double-edged sword” for PCPs. “On the one hand, primary-care docs get paid so little for their outpatient visits that most need to see a high volume of patients in a day just to break even. So they have less and less time to go to the hospital to see hospitalizations,” Dr. Horwitz says. “The hospitalist movement was really a godsend in that respect, because it allowed primary-care docs to focus on their outpatient practice and not spend all that travel time going to the hospital.”

Other PCPs have lamented the erosion of their inpatient roles while recognizing that current economic realities are gradually pushing them out of the hospital. In fact, Dr. Horwitz says, PCPs often don’t know when their patients have been hospitalized, leading to a breakdown in the continuity of care. A weak primary-care infrastructure in a community, hospitalists say, can likewise imperil safe transitions. With the partitioning of inpatient and outpatient responsibilities, the potential for such miscommunications and lapses has clearly grown.

“We’re all in the same workforce; we’re all trying to take care of patients,” Dr. Heim says. “The discussion needs to be on how do we coordinate, not over turf wars.”

Signs of Life

Experts are focusing more on team-based approaches among the few potential short-term solutions, a common theme in HM circles. Advanced-practice registered nurses, physician assistants, and other providers can be trained more quickly than doctors, potentially extending the reach of primary care. In turn, the concept of team-based care could be beefed up during medical residencies.

Primary-care advocates say more equitable reimbursements also could help to ease the crisis, as would more federal support of residency training. But with many politicians focused on deficit reduction, new government incentives are debuting even as existing programs are being threatened or dismantled.

The Affordable Care Act, for example, more than doubled the capacity of the well-regarded National Health Service Corps, which provides scholarships and loan repayments to doctors who agree to practice in underserved communities. The law also created primary-care incentive payments that added $500 million to physician incomes in 2011. “So that’s a pretty strong message of value, and it’s some real value, too,” Dr. Phillips says.

—Atul Grover, MD, PhD, chief public policy officer, Association of American Medical Colleges

The Affordable Care Act, however, cuts $155 billion to hospital payments over 10 years, adding to the downward pressure on reimbursements. And President Obama’s fiscal-year 2013 budget proposal trims an additional $1 billion, or 10%, from Medicare’s annual payments for patient care, which could impact graduate medical education as hospitals seek to balance out the cuts.

Amid the challenges, primary care is showing some encouraging signs of life. Medical school enrollments are on pace to increase by 30% over their 2002 levels within the next three to five years. In both 2010 and 2011, the number of U.S. medical graduates going into family medicine increased by roughly 10% (followed by a more modest increase of 1% this year). Residency matches in general internal medicine also have been climbing. Dr. Heim and others say it’s no coincidence that students’ interest in primary care began rising again amid public discussions on healthcare reform that focused on the value of primary care.

In the end, the profession’s fate could depend in large part on whether the affirmations continue this time around. “There are some rock stars and heroes of primary care that are not as well-known to medical students as they should be,” says Elbert Huang, MD, associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago. Highlighting some of those individual leaders, Dr. Huang believes, might significantly improve the profession’s standing among students.

“We need a Michael Jordan of primary care,” he says.

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

References

- Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K, Berenson RA. A lifeline for primary care. New Engl J Med. 2009;360(26):2693-2696.

- Hofer AN, Abraham JM, Moscovice I. Expansion of coverage under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and primary care utilization. Milbank Q. 2011;89(1):69-89.

- Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457-502.

- Henning Schumann, J. The doctor is out: young talent is turning away from primary care. The Atlantic; March 12, 2012.

It’s been about 15 years since the last surge of interest in primary care as a career, when U.S. medical graduates temporarily reversed a long decline by flocking to family medicine, general internal medicine, and pediatrics. Newly minted doctors responded enthusiastically to a widely held perception in the mid-1990s that primary care would be central to a brave new paradigm of managed healthcare delivery.

That profound change never materialized, and the primary-care workforce has since resumed a downward slide that is sounding alarm bells throughout the country. Even more distressing, the medical profession’s recent misfortunes have spread far beyond the doctor’s office.

“What we’re looking at now is that there’s a shortage of somewhere around 90,000 physicians in the next 10 years, increasing in the five years beyond that to 125,000 or more,” says Atul Grover, MD, PhD, chief public policy officer of the Association of American Medical Colleges. The association’s estimates suggest that the 10- and 15-year shortfalls will be split nearly evenly between primary care and other specialties.

Hospitalists could feel that widening gap as well. With increasing numbers of aging baby boomers reaching Medicare eligibility and 32 million Americans set to join the ranks of the insured by 2019 through the Affordable Care Act, primary care’s difficulties arguably are the closest to a full-blown crisis. “Primary care in the United States needs a lifeline,” began a 2009 editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine.1 And that was before an estimate suggesting that new insurance mandates will require an additional 4,307 to 6,940 primary-care physicians to meet demand before the end of the decade contributing about 15% to the expected shortfall.2

Why should hospitalists care about the fate of their counterparts? For starters, what’s good for outpatient providers is good for a sound healthcare system. Researchers have linked strong

primary care to lower overall spending, fewer health disparities, and higher quality of care.3

Hospitalists and primary-care physicians (PCPs) also are inexorably linked. They follow similar training and education pathways, and need each other to ensure safe transitions of care. And despite the evidence pointing to a slew of contributing factors, HM regularly is blamed for many of primary care’s mounting woes.

Based on well-functioning healthcare systems around the world, analysts say the ideal primary-care-to-specialty-care-provider ratio should be roughly 40:60 or 50:50. According to Kathleen Klink, MD, director of the Division of Medicine and Dentistry in the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), only about 32% of physicians in the U.S. are practicing primary care. Unless something changes, that percentage will erode even further. “We’re going in the wrong direction,” Dr. Klink says.

Opinions differ on the extent of the current PCP shortage. Nevertheless, there is clearly a “huge maldistribution problem,” says Robert Phillips, MD, MSPH, director of the Washington, D.C.-based Robert Graham Center, a primary-care research center. Rural and underserved areas already are being shortchanged as more doctors locate in more affluent and desirable areas, he says.

That phenomenon is hardly unique to primary care, but Dr. Phillips says the deficit in frontline doctors could cause disproportionately more hardships in rural and underserved communities given the shrinking pipeline for medical trainees. A decade ago, almost a third of all medical graduates were placed into primary-care residency training slots. Now, he says, that figure is a bit less than 22%. “We can’t even replace the primary-care workforce we have now with that kind of output,” Dr. Phillips says.

Already, many doctors are no longer accepting new Medicaid or Medicare patients because their practices are losing money from low reimbursement rates. The Affordable Care Act’s significant expansion of insurance benefits, Dr. Grover says, will effectively accelerate the timetable of growing imbalances between supply and demand. “I think the challenge you face is, Will the ACA efforts to expand access fail because you’re giving people an insurance card but you have nobody there to take care of them?”

Reasons Aplenty

Some medical students simply aren’t interested in primary care. For the rest, however, interviews with doctors, analysts, and federal officials suggest that the pipeline has been battered throughout its length. Of all the contributing factors, Dr. Phillips says, the main one might be income disparity. In a 2009 study, the center found that the growing gulf in salaries between primary care and subspecialty medicine “cuts in half the likelihood that a student will choose to go into primary care,” he says. Over a career, that gap translates into a difference of $3.5 million. “It dissuades them strongly,” Dr. Phillips says.

At the same time, medical school tuitions have increased at a rate far outstripping the consumer price index. “What we found is that when you hit somewhere between $200,000 and $250,000 in debt, that’s where you see the dropoff really happen,” he says. “Because it becomes almost unfathomable that you can, on a primary-care income, pay off your debts without it severely cutting into your lifestyle.”

Lori Heim, MD, former president of the American Academy of Family Physicians and a hospitalist at Scotland Memorial Hospital in Laurinburg, N.C., says the prevailing fee-for-service payment model has failed primary-care providers, requiring them to work more to meet soaring outpatient demand but reimbursing them less. “People talk about the hamster wheel,” she says. “And that has created more workplace dissatisfaction. Not only does it impact students, but it also impacts the number of primary-care physicians who want to stay in the community, practicing.”

Frederick Chen, MD, MPH, associate professor of family medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle, can relate. “I came from community practice, where you’re seeing 30 to 35 patients a day, and the pressure was entirely on your productivity, and that’s not fun,” he says. “So we’re burning out a lot of primary-care physicians, and students are seeing that very easily.”