User login

It’s been about 15 years since the last surge of interest in primary care as a career, when U.S. medical graduates temporarily reversed a long decline by flocking to family medicine, general internal medicine, and pediatrics. Newly minted doctors responded enthusiastically to a widely held perception in the mid-1990s that primary care would be central to a brave new paradigm of managed healthcare delivery.

That profound change never materialized, and the primary-care workforce has since resumed a downward slide that is sounding alarm bells throughout the country. Even more distressing, the medical profession’s recent misfortunes have spread far beyond the doctor’s office.

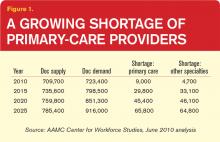

“What we’re looking at now is that there’s a shortage of somewhere around 90,000 physicians in the next 10 years, increasing in the five years beyond that to 125,000 or more,” says Atul Grover, MD, PhD, chief public policy officer of the Association of American Medical Colleges. The association’s estimates suggest that the 10- and 15-year shortfalls will be split nearly evenly between primary care and other specialties.

Hospitalists could feel that widening gap as well. With increasing numbers of aging baby boomers reaching Medicare eligibility and 32 million Americans set to join the ranks of the insured by 2019 through the Affordable Care Act, primary care’s difficulties arguably are the closest to a full-blown crisis. “Primary care in the United States needs a lifeline,” began a 2009 editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine.1 And that was before an estimate suggesting that new insurance mandates will require an additional 4,307 to 6,940 primary-care physicians to meet demand before the end of the decade contributing about 15% to the expected shortfall.2

Why should hospitalists care about the fate of their counterparts? For starters, what’s good for outpatient providers is good for a sound healthcare system. Researchers have linked strong

primary care to lower overall spending, fewer health disparities, and higher quality of care.3

Hospitalists and primary-care physicians (PCPs) also are inexorably linked. They follow similar training and education pathways, and need each other to ensure safe transitions of care. And despite the evidence pointing to a slew of contributing factors, HM regularly is blamed for many of primary care’s mounting woes.

Based on well-functioning healthcare systems around the world, analysts say the ideal primary-care-to-specialty-care-provider ratio should be roughly 40:60 or 50:50. According to Kathleen Klink, MD, director of the Division of Medicine and Dentistry in the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), only about 32% of physicians in the U.S. are practicing primary care. Unless something changes, that percentage will erode even further. “We’re going in the wrong direction,” Dr. Klink says.

Opinions differ on the extent of the current PCP shortage. Nevertheless, there is clearly a “huge maldistribution problem,” says Robert Phillips, MD, MSPH, director of the Washington, D.C.-based Robert Graham Center, a primary-care research center. Rural and underserved areas already are being shortchanged as more doctors locate in more affluent and desirable areas, he says.

That phenomenon is hardly unique to primary care, but Dr. Phillips says the deficit in frontline doctors could cause disproportionately more hardships in rural and underserved communities given the shrinking pipeline for medical trainees. A decade ago, almost a third of all medical graduates were placed into primary-care residency training slots. Now, he says, that figure is a bit less than 22%. “We can’t even replace the primary-care workforce we have now with that kind of output,” Dr. Phillips says.

Already, many doctors are no longer accepting new Medicaid or Medicare patients because their practices are losing money from low reimbursement rates. The Affordable Care Act’s significant expansion of insurance benefits, Dr. Grover says, will effectively accelerate the timetable of growing imbalances between supply and demand. “I think the challenge you face is, Will the ACA efforts to expand access fail because you’re giving people an insurance card but you have nobody there to take care of them?”

Reasons Aplenty

Some medical students simply aren’t interested in primary care. For the rest, however, interviews with doctors, analysts, and federal officials suggest that the pipeline has been battered throughout its length. Of all the contributing factors, Dr. Phillips says, the main one might be income disparity. In a 2009 study, the center found that the growing gulf in salaries between primary care and subspecialty medicine “cuts in half the likelihood that a student will choose to go into primary care,” he says. Over a career, that gap translates into a difference of $3.5 million. “It dissuades them strongly,” Dr. Phillips says.

At the same time, medical school tuitions have increased at a rate far outstripping the consumer price index. “What we found is that when you hit somewhere between $200,000 and $250,000 in debt, that’s where you see the dropoff really happen,” he says. “Because it becomes almost unfathomable that you can, on a primary-care income, pay off your debts without it severely cutting into your lifestyle.”

Lori Heim, MD, former president of the American Academy of Family Physicians and a hospitalist at Scotland Memorial Hospital in Laurinburg, N.C., says the prevailing fee-for-service payment model has failed primary-care providers, requiring them to work more to meet soaring outpatient demand but reimbursing them less. “People talk about the hamster wheel,” she says. “And that has created more workplace dissatisfaction. Not only does it impact students, but it also impacts the number of primary-care physicians who want to stay in the community, practicing.”

Frederick Chen, MD, MPH, associate professor of family medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle, can relate. “I came from community practice, where you’re seeing 30 to 35 patients a day, and the pressure was entirely on your productivity, and that’s not fun,” he says. “So we’re burning out a lot of primary-care physicians, and students are seeing that very easily.”

The larger theme, several doctors say, is one of perceived worth. Leora Horwitz, MD, assistant professor of internal medicine at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., says she has to think holistically about her patients’ symptoms, medication lists, family history, home situation, and other factors during her limited time with them. She bristles at the notion that specialists might spend their time considering only one aspect of her patients’ care yet bill twice as much.

“Realistically, I am providing better value to the healthcare system than a specialist does, and yet we pay specialists much more,” she says. “And until that’s different, people go where the money is and they also go where the respect is, and I think it’s going to be very hard to recruit more people to primary care.”

Despite research pointing to financial concerns, lifestyle perceptions, and training inadequacies as key factors in the decline of primary care, perceptions that HM is poaching young talent have been hard to shake. A recent article in The Atlantic asserts that HM might be a “rational choice” given the profession’s more favorable training, lifestyle, and financial considerations.4 The author, a general internist, contrasts those enticements “to the realities of office practice: Fifteen-minute visits with patients on multiple medications, oodles of paperwork that cause office docs to run a gauntlet just to get through their day, and more documentation and regulatory burdens than ever before.”

Nevertheless, the article describes PCPs who resist hospitals’ calls to move to a hospitalist system as honorable “holdouts” who are committed to being directly involved in their patients’ care.

In her blog post at KevinMD.com, “Hospitalists are Killing Primary Care, and other Myths Debunked,” Vineet Arora, MD, MPP, FHM, a hospitalist at the University of Chicago, addresses those perceptions head-on. “If hospitalists did not exist, there would still be declining interest in primary care among medical students and residents,” she writes.

In a subsequent interview, Dr. Arora contends that both primary care and HM instead might be losing out to higher-paying subspecialties, especially the “ROAD” quartet of radiology, ophthalmology, anesthesiology, and dermatology. She also questions the notion that the professions draw from the same talent pool. “Anecdotally, I can tell you that I don’t see a lot of people choosing between primary care and hospital medicine,” she says. “They’re thinking, ‘Do I want to do critical care, hospital medicine, or cardiology?’ Because the type of person who does hospital medicine is more attracted to that inpatient, acute environment.”

Dr. Horwitz agrees that the choice between a career in primary care and HM might not be as clear-cut as some detractors have suggested. Even so, she describes hospitalists as a “double-edged sword” for PCPs. “On the one hand, primary-care docs get paid so little for their outpatient visits that most need to see a high volume of patients in a day just to break even. So they have less and less time to go to the hospital to see hospitalizations,” Dr. Horwitz says. “The hospitalist movement was really a godsend in that respect, because it allowed primary-care docs to focus on their outpatient practice and not spend all that travel time going to the hospital.”

Other PCPs have lamented the erosion of their inpatient roles while recognizing that current economic realities are gradually pushing them out of the hospital. In fact, Dr. Horwitz says, PCPs often don’t know when their patients have been hospitalized, leading to a breakdown in the continuity of care. A weak primary-care infrastructure in a community, hospitalists say, can likewise imperil safe transitions. With the partitioning of inpatient and outpatient responsibilities, the potential for such miscommunications and lapses has clearly grown.

“We’re all in the same workforce; we’re all trying to take care of patients,” Dr. Heim says. “The discussion needs to be on how do we coordinate, not over turf wars.”

Signs of Life

Experts are focusing more on team-based approaches among the few potential short-term solutions, a common theme in HM circles. Advanced-practice registered nurses, physician assistants, and other providers can be trained more quickly than doctors, potentially extending the reach of primary care. In turn, the concept of team-based care could be beefed up during medical residencies.

Primary-care advocates say more equitable reimbursements also could help to ease the crisis, as would more federal support of residency training. But with many politicians focused on deficit reduction, new government incentives are debuting even as existing programs are being threatened or dismantled.

The Affordable Care Act, for example, more than doubled the capacity of the well-regarded National Health Service Corps, which provides scholarships and loan repayments to doctors who agree to practice in underserved communities. The law also created primary-care incentive payments that added $500 million to physician incomes in 2011. “So that’s a pretty strong message of value, and it’s some real value, too,” Dr. Phillips says.

—Atul Grover, MD, PhD, chief public policy officer, Association of American Medical Colleges

The Affordable Care Act, however, cuts $155 billion to hospital payments over 10 years, adding to the downward pressure on reimbursements. And President Obama’s fiscal-year 2013 budget proposal trims an additional $1 billion, or 10%, from Medicare’s annual payments for patient care, which could impact graduate medical education as hospitals seek to balance out the cuts.

Amid the challenges, primary care is showing some encouraging signs of life. Medical school enrollments are on pace to increase by 30% over their 2002 levels within the next three to five years. In both 2010 and 2011, the number of U.S. medical graduates going into family medicine increased by roughly 10% (followed by a more modest increase of 1% this year). Residency matches in general internal medicine also have been climbing. Dr. Heim and others say it’s no coincidence that students’ interest in primary care began rising again amid public discussions on healthcare reform that focused on the value of primary care.

In the end, the profession’s fate could depend in large part on whether the affirmations continue this time around. “There are some rock stars and heroes of primary care that are not as well-known to medical students as they should be,” says Elbert Huang, MD, associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago. Highlighting some of those individual leaders, Dr. Huang believes, might significantly improve the profession’s standing among students.

“We need a Michael Jordan of primary care,” he says.

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

References

- Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K, Berenson RA. A lifeline for primary care. New Engl J Med. 2009;360(26):2693-2696.

- Hofer AN, Abraham JM, Moscovice I. Expansion of coverage under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and primary care utilization. Milbank Q. 2011;89(1):69-89.

- Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457-502.

- Henning Schumann, J. The doctor is out: young talent is turning away from primary care. The Atlantic; March 12, 2012.

It’s been about 15 years since the last surge of interest in primary care as a career, when U.S. medical graduates temporarily reversed a long decline by flocking to family medicine, general internal medicine, and pediatrics. Newly minted doctors responded enthusiastically to a widely held perception in the mid-1990s that primary care would be central to a brave new paradigm of managed healthcare delivery.

That profound change never materialized, and the primary-care workforce has since resumed a downward slide that is sounding alarm bells throughout the country. Even more distressing, the medical profession’s recent misfortunes have spread far beyond the doctor’s office.

“What we’re looking at now is that there’s a shortage of somewhere around 90,000 physicians in the next 10 years, increasing in the five years beyond that to 125,000 or more,” says Atul Grover, MD, PhD, chief public policy officer of the Association of American Medical Colleges. The association’s estimates suggest that the 10- and 15-year shortfalls will be split nearly evenly between primary care and other specialties.

Hospitalists could feel that widening gap as well. With increasing numbers of aging baby boomers reaching Medicare eligibility and 32 million Americans set to join the ranks of the insured by 2019 through the Affordable Care Act, primary care’s difficulties arguably are the closest to a full-blown crisis. “Primary care in the United States needs a lifeline,” began a 2009 editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine.1 And that was before an estimate suggesting that new insurance mandates will require an additional 4,307 to 6,940 primary-care physicians to meet demand before the end of the decade contributing about 15% to the expected shortfall.2

Why should hospitalists care about the fate of their counterparts? For starters, what’s good for outpatient providers is good for a sound healthcare system. Researchers have linked strong

primary care to lower overall spending, fewer health disparities, and higher quality of care.3

Hospitalists and primary-care physicians (PCPs) also are inexorably linked. They follow similar training and education pathways, and need each other to ensure safe transitions of care. And despite the evidence pointing to a slew of contributing factors, HM regularly is blamed for many of primary care’s mounting woes.

Based on well-functioning healthcare systems around the world, analysts say the ideal primary-care-to-specialty-care-provider ratio should be roughly 40:60 or 50:50. According to Kathleen Klink, MD, director of the Division of Medicine and Dentistry in the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), only about 32% of physicians in the U.S. are practicing primary care. Unless something changes, that percentage will erode even further. “We’re going in the wrong direction,” Dr. Klink says.

Opinions differ on the extent of the current PCP shortage. Nevertheless, there is clearly a “huge maldistribution problem,” says Robert Phillips, MD, MSPH, director of the Washington, D.C.-based Robert Graham Center, a primary-care research center. Rural and underserved areas already are being shortchanged as more doctors locate in more affluent and desirable areas, he says.

That phenomenon is hardly unique to primary care, but Dr. Phillips says the deficit in frontline doctors could cause disproportionately more hardships in rural and underserved communities given the shrinking pipeline for medical trainees. A decade ago, almost a third of all medical graduates were placed into primary-care residency training slots. Now, he says, that figure is a bit less than 22%. “We can’t even replace the primary-care workforce we have now with that kind of output,” Dr. Phillips says.

Already, many doctors are no longer accepting new Medicaid or Medicare patients because their practices are losing money from low reimbursement rates. The Affordable Care Act’s significant expansion of insurance benefits, Dr. Grover says, will effectively accelerate the timetable of growing imbalances between supply and demand. “I think the challenge you face is, Will the ACA efforts to expand access fail because you’re giving people an insurance card but you have nobody there to take care of them?”

Reasons Aplenty

Some medical students simply aren’t interested in primary care. For the rest, however, interviews with doctors, analysts, and federal officials suggest that the pipeline has been battered throughout its length. Of all the contributing factors, Dr. Phillips says, the main one might be income disparity. In a 2009 study, the center found that the growing gulf in salaries between primary care and subspecialty medicine “cuts in half the likelihood that a student will choose to go into primary care,” he says. Over a career, that gap translates into a difference of $3.5 million. “It dissuades them strongly,” Dr. Phillips says.

At the same time, medical school tuitions have increased at a rate far outstripping the consumer price index. “What we found is that when you hit somewhere between $200,000 and $250,000 in debt, that’s where you see the dropoff really happen,” he says. “Because it becomes almost unfathomable that you can, on a primary-care income, pay off your debts without it severely cutting into your lifestyle.”

Lori Heim, MD, former president of the American Academy of Family Physicians and a hospitalist at Scotland Memorial Hospital in Laurinburg, N.C., says the prevailing fee-for-service payment model has failed primary-care providers, requiring them to work more to meet soaring outpatient demand but reimbursing them less. “People talk about the hamster wheel,” she says. “And that has created more workplace dissatisfaction. Not only does it impact students, but it also impacts the number of primary-care physicians who want to stay in the community, practicing.”

Frederick Chen, MD, MPH, associate professor of family medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle, can relate. “I came from community practice, where you’re seeing 30 to 35 patients a day, and the pressure was entirely on your productivity, and that’s not fun,” he says. “So we’re burning out a lot of primary-care physicians, and students are seeing that very easily.”

The larger theme, several doctors say, is one of perceived worth. Leora Horwitz, MD, assistant professor of internal medicine at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., says she has to think holistically about her patients’ symptoms, medication lists, family history, home situation, and other factors during her limited time with them. She bristles at the notion that specialists might spend their time considering only one aspect of her patients’ care yet bill twice as much.

“Realistically, I am providing better value to the healthcare system than a specialist does, and yet we pay specialists much more,” she says. “And until that’s different, people go where the money is and they also go where the respect is, and I think it’s going to be very hard to recruit more people to primary care.”

Despite research pointing to financial concerns, lifestyle perceptions, and training inadequacies as key factors in the decline of primary care, perceptions that HM is poaching young talent have been hard to shake. A recent article in The Atlantic asserts that HM might be a “rational choice” given the profession’s more favorable training, lifestyle, and financial considerations.4 The author, a general internist, contrasts those enticements “to the realities of office practice: Fifteen-minute visits with patients on multiple medications, oodles of paperwork that cause office docs to run a gauntlet just to get through their day, and more documentation and regulatory burdens than ever before.”

Nevertheless, the article describes PCPs who resist hospitals’ calls to move to a hospitalist system as honorable “holdouts” who are committed to being directly involved in their patients’ care.

In her blog post at KevinMD.com, “Hospitalists are Killing Primary Care, and other Myths Debunked,” Vineet Arora, MD, MPP, FHM, a hospitalist at the University of Chicago, addresses those perceptions head-on. “If hospitalists did not exist, there would still be declining interest in primary care among medical students and residents,” she writes.

In a subsequent interview, Dr. Arora contends that both primary care and HM instead might be losing out to higher-paying subspecialties, especially the “ROAD” quartet of radiology, ophthalmology, anesthesiology, and dermatology. She also questions the notion that the professions draw from the same talent pool. “Anecdotally, I can tell you that I don’t see a lot of people choosing between primary care and hospital medicine,” she says. “They’re thinking, ‘Do I want to do critical care, hospital medicine, or cardiology?’ Because the type of person who does hospital medicine is more attracted to that inpatient, acute environment.”

Dr. Horwitz agrees that the choice between a career in primary care and HM might not be as clear-cut as some detractors have suggested. Even so, she describes hospitalists as a “double-edged sword” for PCPs. “On the one hand, primary-care docs get paid so little for their outpatient visits that most need to see a high volume of patients in a day just to break even. So they have less and less time to go to the hospital to see hospitalizations,” Dr. Horwitz says. “The hospitalist movement was really a godsend in that respect, because it allowed primary-care docs to focus on their outpatient practice and not spend all that travel time going to the hospital.”

Other PCPs have lamented the erosion of their inpatient roles while recognizing that current economic realities are gradually pushing them out of the hospital. In fact, Dr. Horwitz says, PCPs often don’t know when their patients have been hospitalized, leading to a breakdown in the continuity of care. A weak primary-care infrastructure in a community, hospitalists say, can likewise imperil safe transitions. With the partitioning of inpatient and outpatient responsibilities, the potential for such miscommunications and lapses has clearly grown.

“We’re all in the same workforce; we’re all trying to take care of patients,” Dr. Heim says. “The discussion needs to be on how do we coordinate, not over turf wars.”

Signs of Life

Experts are focusing more on team-based approaches among the few potential short-term solutions, a common theme in HM circles. Advanced-practice registered nurses, physician assistants, and other providers can be trained more quickly than doctors, potentially extending the reach of primary care. In turn, the concept of team-based care could be beefed up during medical residencies.

Primary-care advocates say more equitable reimbursements also could help to ease the crisis, as would more federal support of residency training. But with many politicians focused on deficit reduction, new government incentives are debuting even as existing programs are being threatened or dismantled.

The Affordable Care Act, for example, more than doubled the capacity of the well-regarded National Health Service Corps, which provides scholarships and loan repayments to doctors who agree to practice in underserved communities. The law also created primary-care incentive payments that added $500 million to physician incomes in 2011. “So that’s a pretty strong message of value, and it’s some real value, too,” Dr. Phillips says.

—Atul Grover, MD, PhD, chief public policy officer, Association of American Medical Colleges

The Affordable Care Act, however, cuts $155 billion to hospital payments over 10 years, adding to the downward pressure on reimbursements. And President Obama’s fiscal-year 2013 budget proposal trims an additional $1 billion, or 10%, from Medicare’s annual payments for patient care, which could impact graduate medical education as hospitals seek to balance out the cuts.

Amid the challenges, primary care is showing some encouraging signs of life. Medical school enrollments are on pace to increase by 30% over their 2002 levels within the next three to five years. In both 2010 and 2011, the number of U.S. medical graduates going into family medicine increased by roughly 10% (followed by a more modest increase of 1% this year). Residency matches in general internal medicine also have been climbing. Dr. Heim and others say it’s no coincidence that students’ interest in primary care began rising again amid public discussions on healthcare reform that focused on the value of primary care.

In the end, the profession’s fate could depend in large part on whether the affirmations continue this time around. “There are some rock stars and heroes of primary care that are not as well-known to medical students as they should be,” says Elbert Huang, MD, associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago. Highlighting some of those individual leaders, Dr. Huang believes, might significantly improve the profession’s standing among students.

“We need a Michael Jordan of primary care,” he says.

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

References

- Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K, Berenson RA. A lifeline for primary care. New Engl J Med. 2009;360(26):2693-2696.

- Hofer AN, Abraham JM, Moscovice I. Expansion of coverage under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and primary care utilization. Milbank Q. 2011;89(1):69-89.

- Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457-502.

- Henning Schumann, J. The doctor is out: young talent is turning away from primary care. The Atlantic; March 12, 2012.

It’s been about 15 years since the last surge of interest in primary care as a career, when U.S. medical graduates temporarily reversed a long decline by flocking to family medicine, general internal medicine, and pediatrics. Newly minted doctors responded enthusiastically to a widely held perception in the mid-1990s that primary care would be central to a brave new paradigm of managed healthcare delivery.

That profound change never materialized, and the primary-care workforce has since resumed a downward slide that is sounding alarm bells throughout the country. Even more distressing, the medical profession’s recent misfortunes have spread far beyond the doctor’s office.

“What we’re looking at now is that there’s a shortage of somewhere around 90,000 physicians in the next 10 years, increasing in the five years beyond that to 125,000 or more,” says Atul Grover, MD, PhD, chief public policy officer of the Association of American Medical Colleges. The association’s estimates suggest that the 10- and 15-year shortfalls will be split nearly evenly between primary care and other specialties.

Hospitalists could feel that widening gap as well. With increasing numbers of aging baby boomers reaching Medicare eligibility and 32 million Americans set to join the ranks of the insured by 2019 through the Affordable Care Act, primary care’s difficulties arguably are the closest to a full-blown crisis. “Primary care in the United States needs a lifeline,” began a 2009 editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine.1 And that was before an estimate suggesting that new insurance mandates will require an additional 4,307 to 6,940 primary-care physicians to meet demand before the end of the decade contributing about 15% to the expected shortfall.2

Why should hospitalists care about the fate of their counterparts? For starters, what’s good for outpatient providers is good for a sound healthcare system. Researchers have linked strong

primary care to lower overall spending, fewer health disparities, and higher quality of care.3

Hospitalists and primary-care physicians (PCPs) also are inexorably linked. They follow similar training and education pathways, and need each other to ensure safe transitions of care. And despite the evidence pointing to a slew of contributing factors, HM regularly is blamed for many of primary care’s mounting woes.

Based on well-functioning healthcare systems around the world, analysts say the ideal primary-care-to-specialty-care-provider ratio should be roughly 40:60 or 50:50. According to Kathleen Klink, MD, director of the Division of Medicine and Dentistry in the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), only about 32% of physicians in the U.S. are practicing primary care. Unless something changes, that percentage will erode even further. “We’re going in the wrong direction,” Dr. Klink says.

Opinions differ on the extent of the current PCP shortage. Nevertheless, there is clearly a “huge maldistribution problem,” says Robert Phillips, MD, MSPH, director of the Washington, D.C.-based Robert Graham Center, a primary-care research center. Rural and underserved areas already are being shortchanged as more doctors locate in more affluent and desirable areas, he says.

That phenomenon is hardly unique to primary care, but Dr. Phillips says the deficit in frontline doctors could cause disproportionately more hardships in rural and underserved communities given the shrinking pipeline for medical trainees. A decade ago, almost a third of all medical graduates were placed into primary-care residency training slots. Now, he says, that figure is a bit less than 22%. “We can’t even replace the primary-care workforce we have now with that kind of output,” Dr. Phillips says.

Already, many doctors are no longer accepting new Medicaid or Medicare patients because their practices are losing money from low reimbursement rates. The Affordable Care Act’s significant expansion of insurance benefits, Dr. Grover says, will effectively accelerate the timetable of growing imbalances between supply and demand. “I think the challenge you face is, Will the ACA efforts to expand access fail because you’re giving people an insurance card but you have nobody there to take care of them?”

Reasons Aplenty

Some medical students simply aren’t interested in primary care. For the rest, however, interviews with doctors, analysts, and federal officials suggest that the pipeline has been battered throughout its length. Of all the contributing factors, Dr. Phillips says, the main one might be income disparity. In a 2009 study, the center found that the growing gulf in salaries between primary care and subspecialty medicine “cuts in half the likelihood that a student will choose to go into primary care,” he says. Over a career, that gap translates into a difference of $3.5 million. “It dissuades them strongly,” Dr. Phillips says.

At the same time, medical school tuitions have increased at a rate far outstripping the consumer price index. “What we found is that when you hit somewhere between $200,000 and $250,000 in debt, that’s where you see the dropoff really happen,” he says. “Because it becomes almost unfathomable that you can, on a primary-care income, pay off your debts without it severely cutting into your lifestyle.”

Lori Heim, MD, former president of the American Academy of Family Physicians and a hospitalist at Scotland Memorial Hospital in Laurinburg, N.C., says the prevailing fee-for-service payment model has failed primary-care providers, requiring them to work more to meet soaring outpatient demand but reimbursing them less. “People talk about the hamster wheel,” she says. “And that has created more workplace dissatisfaction. Not only does it impact students, but it also impacts the number of primary-care physicians who want to stay in the community, practicing.”

Frederick Chen, MD, MPH, associate professor of family medicine at the University of Washington in Seattle, can relate. “I came from community practice, where you’re seeing 30 to 35 patients a day, and the pressure was entirely on your productivity, and that’s not fun,” he says. “So we’re burning out a lot of primary-care physicians, and students are seeing that very easily.”

The larger theme, several doctors say, is one of perceived worth. Leora Horwitz, MD, assistant professor of internal medicine at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Conn., says she has to think holistically about her patients’ symptoms, medication lists, family history, home situation, and other factors during her limited time with them. She bristles at the notion that specialists might spend their time considering only one aspect of her patients’ care yet bill twice as much.

“Realistically, I am providing better value to the healthcare system than a specialist does, and yet we pay specialists much more,” she says. “And until that’s different, people go where the money is and they also go where the respect is, and I think it’s going to be very hard to recruit more people to primary care.”

Despite research pointing to financial concerns, lifestyle perceptions, and training inadequacies as key factors in the decline of primary care, perceptions that HM is poaching young talent have been hard to shake. A recent article in The Atlantic asserts that HM might be a “rational choice” given the profession’s more favorable training, lifestyle, and financial considerations.4 The author, a general internist, contrasts those enticements “to the realities of office practice: Fifteen-minute visits with patients on multiple medications, oodles of paperwork that cause office docs to run a gauntlet just to get through their day, and more documentation and regulatory burdens than ever before.”

Nevertheless, the article describes PCPs who resist hospitals’ calls to move to a hospitalist system as honorable “holdouts” who are committed to being directly involved in their patients’ care.

In her blog post at KevinMD.com, “Hospitalists are Killing Primary Care, and other Myths Debunked,” Vineet Arora, MD, MPP, FHM, a hospitalist at the University of Chicago, addresses those perceptions head-on. “If hospitalists did not exist, there would still be declining interest in primary care among medical students and residents,” she writes.

In a subsequent interview, Dr. Arora contends that both primary care and HM instead might be losing out to higher-paying subspecialties, especially the “ROAD” quartet of radiology, ophthalmology, anesthesiology, and dermatology. She also questions the notion that the professions draw from the same talent pool. “Anecdotally, I can tell you that I don’t see a lot of people choosing between primary care and hospital medicine,” she says. “They’re thinking, ‘Do I want to do critical care, hospital medicine, or cardiology?’ Because the type of person who does hospital medicine is more attracted to that inpatient, acute environment.”

Dr. Horwitz agrees that the choice between a career in primary care and HM might not be as clear-cut as some detractors have suggested. Even so, she describes hospitalists as a “double-edged sword” for PCPs. “On the one hand, primary-care docs get paid so little for their outpatient visits that most need to see a high volume of patients in a day just to break even. So they have less and less time to go to the hospital to see hospitalizations,” Dr. Horwitz says. “The hospitalist movement was really a godsend in that respect, because it allowed primary-care docs to focus on their outpatient practice and not spend all that travel time going to the hospital.”

Other PCPs have lamented the erosion of their inpatient roles while recognizing that current economic realities are gradually pushing them out of the hospital. In fact, Dr. Horwitz says, PCPs often don’t know when their patients have been hospitalized, leading to a breakdown in the continuity of care. A weak primary-care infrastructure in a community, hospitalists say, can likewise imperil safe transitions. With the partitioning of inpatient and outpatient responsibilities, the potential for such miscommunications and lapses has clearly grown.

“We’re all in the same workforce; we’re all trying to take care of patients,” Dr. Heim says. “The discussion needs to be on how do we coordinate, not over turf wars.”

Signs of Life

Experts are focusing more on team-based approaches among the few potential short-term solutions, a common theme in HM circles. Advanced-practice registered nurses, physician assistants, and other providers can be trained more quickly than doctors, potentially extending the reach of primary care. In turn, the concept of team-based care could be beefed up during medical residencies.

Primary-care advocates say more equitable reimbursements also could help to ease the crisis, as would more federal support of residency training. But with many politicians focused on deficit reduction, new government incentives are debuting even as existing programs are being threatened or dismantled.

The Affordable Care Act, for example, more than doubled the capacity of the well-regarded National Health Service Corps, which provides scholarships and loan repayments to doctors who agree to practice in underserved communities. The law also created primary-care incentive payments that added $500 million to physician incomes in 2011. “So that’s a pretty strong message of value, and it’s some real value, too,” Dr. Phillips says.

—Atul Grover, MD, PhD, chief public policy officer, Association of American Medical Colleges

The Affordable Care Act, however, cuts $155 billion to hospital payments over 10 years, adding to the downward pressure on reimbursements. And President Obama’s fiscal-year 2013 budget proposal trims an additional $1 billion, or 10%, from Medicare’s annual payments for patient care, which could impact graduate medical education as hospitals seek to balance out the cuts.

Amid the challenges, primary care is showing some encouraging signs of life. Medical school enrollments are on pace to increase by 30% over their 2002 levels within the next three to five years. In both 2010 and 2011, the number of U.S. medical graduates going into family medicine increased by roughly 10% (followed by a more modest increase of 1% this year). Residency matches in general internal medicine also have been climbing. Dr. Heim and others say it’s no coincidence that students’ interest in primary care began rising again amid public discussions on healthcare reform that focused on the value of primary care.

In the end, the profession’s fate could depend in large part on whether the affirmations continue this time around. “There are some rock stars and heroes of primary care that are not as well-known to medical students as they should be,” says Elbert Huang, MD, associate professor of medicine at the University of Chicago. Highlighting some of those individual leaders, Dr. Huang believes, might significantly improve the profession’s standing among students.

“We need a Michael Jordan of primary care,” he says.

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

References

- Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K, Berenson RA. A lifeline for primary care. New Engl J Med. 2009;360(26):2693-2696.

- Hofer AN, Abraham JM, Moscovice I. Expansion of coverage under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and primary care utilization. Milbank Q. 2011;89(1):69-89.

- Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457-502.

- Henning Schumann, J. The doctor is out: young talent is turning away from primary care. The Atlantic; March 12, 2012.