User login

Obesity: Are shared medical appointments part of the answer?

Obesity is a major health problem in the United States. The facts are well known:

- Its prevalence has almost tripled since the early 1960s1

- More than 35% of US adults are obese (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 30 kg/m2)2

- It increases the risk of comorbid conditions including type 2 diabetes mellitus, heart disease, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, certain cancers, asthma, and osteoarthritis3,4

- It decreases life expectancy5

- Medical costs are up to 6 times higher per patient.6

Moreover, obesity is often not appropriately managed, owing to a variety of factors. In this article, we describe use of shared medical appointments as a strategy to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of treating patients with obesity.

Big benefits from small changes in weight

As little as 3% to 5% weight loss is associated with significant clinical benefits, such as improved glycemic control, reduced blood pressure, and reduced cholesterol levels.7,8 However, many patients are unable to reach this modest goal using current approaches to obesity management.

This failure is partially related to the complexity and chronic nature of obesity, which requires continued medical management from a multidisciplinary team. We believe this is an area of care that can be appropriately addressed through shared medical appointments.

CURRENT APPROACHES

Interventions for obesity have increased along with the prevalence of the disease. Hundreds of diets, exercise plans, natural products, and behavioral interventions are marketed, all claiming to be successful. More-intense treatment options include antiobesity medications, intra-abdominal weight loss devices, and bariatric surgery. Despite the availability of treatments, rates of obesity have not declined.

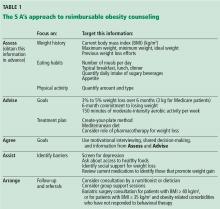

Counseling is important, but underused

Lifestyle modifications that encompass nutrition, physical activity, and behavioral interventions are the mainstay of obesity treatment.

Intensive interventions work better than less-intensive ones. In large clinical trials in overweight patients with diabetes, those who received intensive lifestyle interventions lost 3 to 5 kg more (3% to 8% of body weight) than those who received brief diet and nutrition counseling, as is often performed in a physician’s office.9–12 The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends that patients whose BMI is 30 kg/m2 or higher be offered intensive lifestyle intervention consisting of at least 12 sessions in 1 year.13

But fewer than half of primary care practitioners consistently provide specific guidance on diet, exercise, or weight control to patients with obesity, including those with a weight-related comorbidity.14 The rate has decreased since the 1990s despite the increase in obesity.15

One reason for the underuse is that many primary care practitioners do not have the training or time to deliver the recommended high-intensity obesity treatment.14 Plus, evidence does not clearly show a weight loss benefit from low-intensity interventions. Even when patients lose weight, most regain it, and only 20% are able to maintain their weight loss 1 year after treatment ends.16

Drugs and surgery also underused

Antiobesity medications and bariatric surgery are effective when added to lifestyle interventions, but they are also underused.

Bariatric surgery provides the greatest and most durable weight loss—15% to 30% of body weight—along with improvement in comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes, and its benefits are sustained for at least 10 years.17 However, fewer than 1% of eligible patients undergo bariatric surgery because of its limited availability, invasive nature, potential complications, limited insurance coverage, and high cost.17

The story is similar for antiobesity drugs. They are useful adjuncts to lifestyle interventions, providing an additional 3% to 7% weight loss,18 but fewer than 2% of eligible patients receive them.19 This may be attributed to their modest effectiveness, weight regain after discontinuation, potential adverse effects, and expense due to lack of insurance coverage.

ARE SHARED MEDICAL APPOINTMEMNTS AN ANSWER?

Although treatments have shown some effectiveness at producing weight loss, none has had a widespread impact on obesity. Lifestyle interventions, drugs, and bariatric surgery continue to be underused. Current treatment models are not providing patients with the intensive interventions needed.

Providers often find themselves offering repetitive advice to patients with obesity regarding nutrition and exercise, while simultaneously trying to manage obesity-related comorbidities, all in a 20-minute appointment. Too often, a patient returns home with prescriptions for hypertension or diabetes but no clear plan for weight management.

What can a shared medical appointment do?

A shared medical appointment is a group medical visit in which several patients with a similar clinical diagnosis, such as obesity, see a multidisciplinary team of healthcare providers. Typically, 5 to 10 patients have consultations with providers during a 60- to 90-minute appointment.20

Part of the session is dedicated to education on the patients’ common medical condition with the goal of improving their self-management, but most of the time is spent addressing individual patient concerns.

Each patient takes a turn consulting with a provider, as in a traditional medical appointment, but in a group setting. This allows others in the group to observe and learn from their peers’ experiences. During this consultation, the patient’s concerns are addressed, medications are managed, necessary tests are ordered, and a treatment plan is made.

Patients can continue to receive follow-up care through shared medical appointments at predetermined times, instead of traditional individual medical appointments.

BENEFITS OF SHARED APPOINTMENTS

Shared medical appointments could improve patient access, clinical outcomes, and patient and provider satisfaction and decrease costs.20,21 Since being introduced in the 1990s, their use has dramatically increased. For example, in the first 2 years of conducting shared medical appointments at Cleveland Clinic (2002–2004), there were just 385 shared medical appointments,21 but in 2017 there were approximately 12,300. They are used in a variety of medical and surgical specialties, and have been studied most for treating diabetes.22–24

Increased face time and access

Individual patient follow-up visits typically last 15 to 20 minutes, limiting the provider to seeing a maximum of 6 patients in 90 minutes. In that same time in the setting of a shared appointment, a multidisciplinary team can see up to 10 patients, and the patients receive up to 90 minutes of time with multiple providers.

Additionally, shared medical appointments can improve patient access to timely appointments. In a busy bariatric surgery practice, implementing shared medical appointments reduced patients’ wait time for an appointment by more than half.25 This is particularly important for patients with obesity, who usually require 12 to 26 appointments per year.

Improved patient outcomes

Use of shared medical appointments has improved clinical outcomes compared with traditional care. Patients with type 2 diabetes who attend shared medical appointments are more likely to reach target hemoglobin A1c and blood pressure levels.22−24 These benefits may be attributed to increased access to care, improved self-management skills, more frequent visits, peer support of the group, and the synergistic knowledge of multiple providers on the shared medical appointment team.

Although some trials reported patient retention rates of 75% to 90% in shared medical appointments, many trials did not report their rates. It is likely that some patients declined randomization to avoid shared medical appointments, which could have led to potential attrition and selection biases.23

Increased patient and provider satisfaction

Both patients and providers report high satisfaction with shared medical appointments.22,26 Although patients may initially hesitate to participate, their opinions significantly improve after attending 1 session.26 From 85% to 90% of patients who attend a shared medical appointment schedule their next follow-up appointment as a shared appointment as well.21,25

In comparative studies, patients who attended shared medical appointments had satisfaction rates equal to or higher than rates in patients who participated in usual care,22 noting better access to care and more sensitivity to their needs.27 Providers report greater satisfaction from working more directly with a team of providers, clearing up a backlogged schedule, and adding variety to their practice.21,24

Decreased costs

Data on the cost-effectiveness of shared medical appointments are mixed; however, some studies have shown that they are associated with a decrease in hospital admissions and emergency department visits.22 It seems reasonable to assume that, in an appropriate patient population, shared medical appointments can be cost-effective owing to increased provider productivity, but more research is needed to verify this.

CHALLENGES TO STARTING SHARED APPOINTMENTS FOR OBESITY

Despite their potential to provide comprehensive care to patients, shared medical appointments have limitations. These need to be addressed before implementing a shared medical appointment program.

Adequate resources and staff training

To be successful, a shared medical appointment program needs to have intensive physical and staffing resources. You need a space large enough to accommodate the group and access to the necessary equipment (eg, projector, whiteboard) for educational sessions. Larger or armless chairs may better accommodate patients with obesity. Facilitators need training in how to lead the group sessions, including time management and handling conflicts between patients. Schedulers and clinical intake staff need training in answering patient questions regarding these appointments.

Maintaining patient attendance

The benefits of provider efficiency rest on having an adequate number of patients attend the shared appointments.21 Patient cancellations and no-shows decrease both the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of this model, and they detract from the peer support and group learning that occurs in the group dynamic. To help minimize patient dropout, a discussion of patient expectations should take place prior to enrollment in shared medical appointments. This should include information on the concept of shared appointments, frequency and duration of appointments, and realistic weight loss goals.

Logistical challenges

A shared medical appointment requires a longer patient time slot and is usually less flexible than an individual appointment. Not all patients can take the time for a prescheduled 60- to 90-minute appointment. However, reduced waiting-room time and increased face time with a provider offset some of these challenges.

Recruiting patients

A shared medical appointment is a novel experience for some, and concerns about it may make it a challenge to recruit patients. Patients might worry that the presence of the group will compromise the patient-doctor relationship. Other concerns include potential irrelevance of other patients’ medical issues and reluctance to participate because of body image and the stigma of obesity.

One solution is to select patients from your existing practice so that the individual patient-provider relationship is established before introducing the concept of shared appointments. You will need to explain how shared appointments work, discuss their pros and cons, stress your expectations about attendance and confidentiality, and address any concerns of the patient. It is also important to emphasize that nearly all patients find shared medical appointments useful.

Once a group is established, it may be a challenge to keep a constant group membership to promote positive group dynamics. In practice, patients may drop out or be added, and facilitators need to be able to integrate new members into the group. It is important to emphasize to the group that obesity is chronic and that patients at all stages and levels of treatment can contribute to group learning.

Despite the advantages of shared medical appointments, some patients may not find them useful, even after attending several sessions. These patients should be offered individual follow-up visits. Also, shared appointments may not be suitable for patients who cannot speak English very well, are hearing-impaired, have significant cognitive impairment, or have acute medical issues.

Maintaining patient confidentiality

Maintaining confidentiality of personal and health information in a shared medical appointment is an important concern for patients but can be appropriately managed. In a survey of patients attending pulmonary hypertension shared medical appointments, 24% had concerns about confidentiality before participating, but after a few sessions, this rate was cut in half.28

Patients have reported initially withholding some information, but over time, they usually become more comfortable with the group and disclose more helpful information.29 Strategies to ensure confidentiality include having patients sign a confidentiality agreement at each appointment, providing specific instruction on what characterizes confidentiality breaches, and allowing patients the opportunity to schedule individual appointments as needed.

Ensuring insurance coverage

A shared medical appointment should be billed as an individual medical appointment for level of care, rather than time spent with the provider. This ensures that insurance coverage and copayments are the same as for individual medical appointments.

Lack of insurance coverage is a major barrier to obesity treatment in general. The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services reimburses intensive behavioral obesity treatment delivered by a primary care practitioner, but limits it to 1 year of treatment and requires patients to meet weight loss goals. Some individual and employer-based healthcare plans do not cover dietitian visits, weight management programs, or antiobesity prescriptions.

EVIDENCE OF EFFECTIVENESS IN OBESITY

Few studies have investigated the use of shared medical appointments in obesity treatment. In the pediatric population, these programs significantly decreased BMI and some other anthropometric measurements,30–32 but they did not consistently involve a prescribing provider. This means they did not manage medications or comorbidities as would be expected in a shared medical appointment.

In adults, reported effects have been encouraging, although the studies are not particularly robust. In a 2-year observational study of a single physician conducting biweekly weight management shared medical appointments, participants lost 1% of their baseline weight, while those continuing with usual care gained 0.8%, a statistically significant difference.33 However, participation rates were low, with patients attending an average of only 3 shared medical appointments during the study.

In a meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials of shared medical appointments for patients with type 2 diabetes, only 3 studies reported weight outcomes.23 These results indicated a trend toward weight loss among patients attending shared appointments, but they were not statistically significant.

Positive results also were reported by the Veterans Administration’s MOVE! (Managing Overweight/obesity for Veterans Everywhere) program.34 Participants in shared medical appointments reported that they felt empowered to make positive lifestyle changes, gained knowledge about obesity, were held accountable by their peers, and appreciated the individualized care they received from the multidisciplinary healthcare teams.

A systematic review involving 336 participants in group-based obesity interventions found group treatment produced more robust weight loss than individual treatment.35 However, shared medical appointments are different from weight loss groups in that they combine an educational session and a medical appointment in a peer-group setting, which requires a provider with prescribing privileges to be present. Thus, shared medical appointments can manage medications as well as weight-related comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and hyperlipidemia.

One more point is that continued attendance at shared medical appointments, even after successful weight loss, may help to maintain the weight loss, which has otherwise been found to be extremely challenging using traditional medical approaches.

WHO SHOULD BE ON THE TEAM?

Because obesity is multifactorial, it requires a comprehensive treatment approach that can be difficult to deliver given the limited time of an individual appointment. In a shared appointment, providers across multiple specialties can meet with patients at the same time to coordinate approaches to obesity treatment.

A multidisciplinary team for shared medical appointments for obesity needs a physician or a nurse practitioner—or ideally, both— who specializes in obesity to facilitate the session. Other key providers include a registered dietitian, an exercise physiologist, a behavioral health specialist, a sleep specialist, and a social worker to participate as needed in the educational component of the appointment or act as outside consultants.

WHAT ARE REALISTIC TARGETS?

- Nutrition

- Physical activity

- Appetite control

- Sleep

- Stress and mood disorders.

Nutrition

A calorie deficit of 500 to 750 calories per day is recommended for weight loss.7,8 Although there is no consensus on the best nutritional content of a diet, adherence to a diet is a significant predictor of weight loss.36 One reason diets fail to bring about weight loss is that patients tend to underestimate their caloric intake by almost 50%.37 Thus, they may benefit from a structured and supervised diet plan.

A dietitian can help patients develop an individualized diet plan that will promote adherence, which includes specific information on food choices, portion sizes, and timing of meals.

Physical activity

At least 150 minutes of physical activity per week is recommended for weight loss, and 200 to 300 minutes per week is recommended for long-term weight maintenance.7,8

An exercise physiologist can help patients design a personalized exercise plan to help achieve these goals. This plan should take into account the patient’s cardiac status, activity level, degree of mobility, and lifestyle.

Most patients are not able to achieve the recommended physical activity goals initially, and activity levels need to be gradually increased over a period of weeks to months. Patients who were previously inactive or have evidence of cardiovascular, renal, or metabolic disease may require a cardiopulmonary assessment, including an electrocardiogram and cardiac stress test, before starting an exercise program.

Appetite control

It is very difficult for patients to lose weight without appetite control. Weight loss that results from diet and exercise is often accompanied by a change in weight-regulating hormones (eg, leptin, ghrelin, peptide YY, and cholecystokinin) that promote weight regain.38 Thus, multiple compensatory mechanisms promote weight regain through increases in appetite and decreases in energy expenditure, resisting weight loss efforts.

Antiobesity drugs can help mitigate these adaptive weight-promoting responses through several mechanisms. They are indicated for use with lifestyle interventions for patients with a BMI of at least 30 mg/kg2 or a BMI of at least 27 kg/m2 with an obesity-related comorbidity.

These drugs promote an additional 3% to 7% weight loss when added to lifestyle interventions.18 But their effects are limited without appropriate lifestyle interventions.

Sleep

Adequate sleep is an often-overlooked component of obesity treatment. Inadequate sleep is associated with weight gain and an appetite-inducing hormone profile.39 Just 2 days of sleep deprivation in healthy normal-weight adult men was associated with a 70% increase in the ghrelin-to-leptin ratio, which showed a linear relationship with self-reported increased hunger.39 Sleep disorders, especially obstructive sleep apnea, are common in patients with obesity but are often underdiagnosed and undertreated.40

Healthy sleep habits and sleep quality should be addressed in shared medical appointments for obesity, as patients may be unaware of the impact that sleep may be having on their obesity treatment. The STOP-BANG questionnaire (snoring, tiredness, observed apnea, high blood pressure, BMI, age, neck circumference, and male sex) is a simple and reliable tool to screen for obstructive sleep apnea.41 Patients with symptoms of a sleep disorder should be referred to a sleep specialist for diagnosis and management.

Stress management and mood disorders

Stress and psychiatric disorders are underappreciated contributors to obesity. All patients receiving obesity treatment need to be screened for mood disorders and suicidal ideation.8

Chronic stress promotes weight gain through activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis, whereby increased cortisol levels enhance appetite and accumulation of visceral fat.42 In addition, obesity is associated with a 25% increased risk of mood disorders, although the mechanism and direction of this association are unclear.43 Weight gain as a side effect of antidepressant or other psychiatric medications is another important consideration.

Management of stress and psychiatric disorders through goal-setting, self-monitoring, and patient education is vital to help patients fully participate in lifestyle changes and maximize weight loss. Patients participating in shared medical appointments usually benefit from consultations with psychiatrists or psychologists to manage psychiatric comorbidities and assist with adherence to behavior modification.

IN FAVOR OF SHARED MEDICAL APPOINTMENTS FOR OBESITY

Shared medical appointments can be an effective method of addressing the challenges of treating patients with obesity, using a multidisciplinary approach that combines nutrition, physical activity, appetite suppression, sleep improvement, and stress management. In addition, shared appointments allow practitioners to treat the primary problem of excess weight, rather than just its comorbidities, recognizing that obesity is a chronic disease that requires long-term, individualized treatment. Satisfaction rates are high for both patients and providers. Overall, education is essential to implementing and maintaining a successful shared medical appointment program.

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD. National Center for Health Statistics. Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and extreme obesity among adults: United States, trends 1960-62 through 2007–2008. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity_adult_07_08/obesity_adult_07_08.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2018.

- Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA 2016; 315(21):2284–2291. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.6458

- Pantalone KM, Hobbs TM, Chagin KM, et al. Prevalence and recognition of obesity and its associated comorbidities: cross-sectional analysis of electronic health record data from a large US integrated health system. BMJ Open 2017; 7(11):e017583. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017583

- Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL, Anis AH. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2009;9:88. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-88

- Fontaine KR, Redden DT, Wang C, Westfall AO, Allison DB. Years of life lost due to obesity. JAMA 2003; 289(2):187–193. pmid:12517229

- Tsai AG, Williamson DF, Glick HA. Direct medical cost of overweight and obesity in the United States: a quantitative systematic review. Int Assoc Study Obes Rev 2011; 12(1):50–61. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00708.x

- Jensen MD. Notice of duplicate publication of Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Obesity Society. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation 2014; 129(25 suppl 2):S102–S138. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63(25 Pt B):2985–3023. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.004

- Garvey WT, Mechanick JI, Brett EM, et al; Reviewers of the AACE/ACE Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity: executive summary. Endocr Pract 2016; 22(7):842–884. doi:10.4158/EP161356.ESGL

- Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al; Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002; 346(6):393–403. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa012512

- Eriksson J, Lindstrom J, Valle T, et al. Prevention of type II diabetes in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance: The Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS) in Finland. Study design and 1-year interim report on the feasibility of the lifestyle intervention programme. Diabetologia 1999; 42(7):793–801. pmid:10440120

- Look AHEAD Research Group; Pi-Sunyer X, Blackburn G, Brancati FL, et al. Reduction in weight and cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes: one-year results of the look AHEAD trial. Diabetes Care 2007; 30(6):1374–1383. doi:10.2337/dc07-0048

- Burguera B, Jesús Tur J, Escudero AJ, et al. An intensive lifestyle intervention is an effective treatment of morbid obesity: the TRAMOMTANA study—a two-year randomized controlled clinical trial. Int J Endocrinol 2015; 2015:194696. doi:10.1155/2015/194696

- Moyer VA; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for and management of obesity in adults: US Preventative Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157(5):373–378. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-5-201209040-00475

- Smith AW, Borowski LA, Liu B, et al. US primary care physicians’ diet-, physical activity-, and weight-related care of adult patients. Am J Prev Med 2011; 41(1):33–42. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.03.017

- Kraschnewski JL, Sciamanna CN, Stuckey HL, et al. A silent response to the obesity epidemic: decline in US physician weight counseling. Med Care 2013; 51(2):186–192. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182726c33

- Wing RR, Hill JO. Successful weight loss maintenance. Annu Rev Nutr 2001; 21:323–341. doi:10.1146/annurev.nutr.21.1.323

- Nguyen NT, Varela JE. Bariatric surgery for obesity and metabolic disorders: state of the art. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 14(3):160–169. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2016.170

- Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Long-term drug treatment for obesity: a systematic and clinical review. JAMA 2014; 311(1):74–86. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.281361

- Xia Y, Kelton CM, Guo JJ, Bian B, Heaton PC. Treatment of obesity: pharmacotherapy trends in the United States from 1999 to 2010. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015; 23(8):1721–1728. doi:10.1002/oby.21136

- Ramdas K, Darzi A. Adopting innovations in care delivery—the care of shared medical appointments. N Engl J Med 2017; 376(12):1105–1107. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1612803

- Bronson DL, Maxwell RA. Shared medical appointments: increasing patient access without increasing physician hours. Cleve Clin J Med 2004; 71(5):369–377. pmid:15195773

- Edelman D, McDuffie JR, Oddone E, et al. Shared Medical Appointments for Chronic Medical Conditions: A Systematic Review. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2012.

- Housden L, Wong ST, Dawes M. Effectiveness of group medical visits for improving diabetes care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2013; 185(13):E635–E644. doi:10.1503/cmaj.130053

- Housden LM, Wong ST. Using group medical visits with those who have diabetes: examining the evidence. Curr Diab Rep 2016; 16(12):134. doi:10.1007/s11892-016-0817-4

- Kaidar-Person O, Swartz EW, Lefkowitz M, et al. Shared medical appointments: new concept for high-volume follow-up for bariatric patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2006; 2(5):509–512. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2006.05.010

- Seager MJ, Egan RJ, Meredith HE, Bates SE, Norton SA, Morgan JD. Shared medical appointments for bariatric surgery follow-up: a patient satisfaction questionnaire. Obes Surg 2012; 22(4):641–645. doi:10.1007/s11695-012-0603-6

- Heyworth L, Rozenblum R, Burgess JF Jr, et al. Influence of shared medical appointments on patient satisfaction: a retrospective 3-year study. Ann Fam Med 2014; 12(4):324–330. doi:10.1370/afm.1660

- Rahaghi FF, Chastain VL, Benavides R, et al. Shared medical appointments in pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ 2014; 4(1):53–60. doi:10.1086/674883

- Wong ST, Lavoie JG, Browne AJ, Macleod ML, Chongo M. Patient confidentiality within the context of group medical visits: Is there cause for concern? Health Expect 2015; 18(5):727–739. doi:10.1111/hex.12156

- Geller JS, Dube ET, Cruz GA, Stevens J, Keating Bench K. Pediatric Obesity Empowerment Model Group Medical Visits (POEM-GMV) as treatment for pediatric obesity in an underserved community. Child Obes 2015; 11(5):638–646. doi:10.1089/chi.2014.0163

- Weigel C, Kokocinski K, Lederer P, Dötsch J, Rascher W, Knerr I. Childhood obesity: concept, feasibility, and interim results of a local group-based, long-term treatment program. J Nutr Educ Behav 2008; 40(6):369–373. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2007.07.009

- Hinchman J, Beno L, Mims A. Kaiser Permanente Georgia’s experience with operation zero: a group medical appointment to address pediatric overweight. Perm J 2006; 10(3):66–71. pmid:21519478

- Palaniappan LP, Muzaffar AL, Wang EJ, Wong EC, Orchard TJ, Mbbch M. Shared medical appointments: promoting weight loss in a clinical setting. J Am Board Fam Med 2011; 24(3):326–328. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2011.03.100220

- Cohen S, Hartley S, Mavi J, Vest B, Wilson M. Veteran experiences related to participation in shared medical appointments. Mil Med 2012; 177(11):1287–1292. pmid:23198503

- Paul-Ebhohimhen V, Avenell A. A systematic review of the effectiveness of group versus individual treatments for adult obesity. Obes Facts 2009; 2(1):17–24. doi:10.1159/000186144

- Sacks FM, Bray GA, Carey VJ, et al. Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. N Engl J Med 2009; 360(9):859–873. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0804748

- Lichtman SW, Pisarska K, Berman ER, et al. Discrepancy between self-reported and actual caloric intake and exercise in obese subjects. N Engl J Med 1992; 327(27):1893–1898. doi:10.1056/NEJM199212313272701

- Sumithran P, Prendergast LA, Delbridge E, et al. Long-term persistence of hormonal adaptations to weight loss. N Engl J Med 2011; 365(17):1597–1604. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1105816

- Spiegel K, Tasali E, Penev P, Van Cauter E. Brief communication: sleep curtailment in healthy young men is associated with decreased leptin levels, elevated ghrelin levels, and increased hunger and appetite. Ann Intern Med 2004; 141(11):846–850. pmid:15583226

- Kapur V, Strohl KP, Redline S, Iber C, O’Connor G, Nieto J. Underdiagnosis of sleep apnea syndrome in US communities. Sleep Breath 2002; 6(2):49–54. doi:10.1007/s11325-002-0049-5

- Chung F, Yegneswaran B, Liao P, et al. STOP questionnaire: a tool to screen patients for obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology 2008; 108(5):812–821. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e31816d83e4

- Charmandari E, Tsigos C, Chrousos G. Endocrinology of the stress response. Annu Rev Physiol 2005; 67:259–284. doi:10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.040403.120816

- Simon GE, Von Korff M, Saunders K, et al. Association between obesity and psychiatric disorders in the US adult population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63(7):824-830. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.824

Obesity is a major health problem in the United States. The facts are well known:

- Its prevalence has almost tripled since the early 1960s1

- More than 35% of US adults are obese (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 30 kg/m2)2

- It increases the risk of comorbid conditions including type 2 diabetes mellitus, heart disease, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, certain cancers, asthma, and osteoarthritis3,4

- It decreases life expectancy5

- Medical costs are up to 6 times higher per patient.6

Moreover, obesity is often not appropriately managed, owing to a variety of factors. In this article, we describe use of shared medical appointments as a strategy to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of treating patients with obesity.

Big benefits from small changes in weight

As little as 3% to 5% weight loss is associated with significant clinical benefits, such as improved glycemic control, reduced blood pressure, and reduced cholesterol levels.7,8 However, many patients are unable to reach this modest goal using current approaches to obesity management.

This failure is partially related to the complexity and chronic nature of obesity, which requires continued medical management from a multidisciplinary team. We believe this is an area of care that can be appropriately addressed through shared medical appointments.

CURRENT APPROACHES

Interventions for obesity have increased along with the prevalence of the disease. Hundreds of diets, exercise plans, natural products, and behavioral interventions are marketed, all claiming to be successful. More-intense treatment options include antiobesity medications, intra-abdominal weight loss devices, and bariatric surgery. Despite the availability of treatments, rates of obesity have not declined.

Counseling is important, but underused

Lifestyle modifications that encompass nutrition, physical activity, and behavioral interventions are the mainstay of obesity treatment.

Intensive interventions work better than less-intensive ones. In large clinical trials in overweight patients with diabetes, those who received intensive lifestyle interventions lost 3 to 5 kg more (3% to 8% of body weight) than those who received brief diet and nutrition counseling, as is often performed in a physician’s office.9–12 The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends that patients whose BMI is 30 kg/m2 or higher be offered intensive lifestyle intervention consisting of at least 12 sessions in 1 year.13

But fewer than half of primary care practitioners consistently provide specific guidance on diet, exercise, or weight control to patients with obesity, including those with a weight-related comorbidity.14 The rate has decreased since the 1990s despite the increase in obesity.15

One reason for the underuse is that many primary care practitioners do not have the training or time to deliver the recommended high-intensity obesity treatment.14 Plus, evidence does not clearly show a weight loss benefit from low-intensity interventions. Even when patients lose weight, most regain it, and only 20% are able to maintain their weight loss 1 year after treatment ends.16

Drugs and surgery also underused

Antiobesity medications and bariatric surgery are effective when added to lifestyle interventions, but they are also underused.

Bariatric surgery provides the greatest and most durable weight loss—15% to 30% of body weight—along with improvement in comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes, and its benefits are sustained for at least 10 years.17 However, fewer than 1% of eligible patients undergo bariatric surgery because of its limited availability, invasive nature, potential complications, limited insurance coverage, and high cost.17

The story is similar for antiobesity drugs. They are useful adjuncts to lifestyle interventions, providing an additional 3% to 7% weight loss,18 but fewer than 2% of eligible patients receive them.19 This may be attributed to their modest effectiveness, weight regain after discontinuation, potential adverse effects, and expense due to lack of insurance coverage.

ARE SHARED MEDICAL APPOINTMEMNTS AN ANSWER?

Although treatments have shown some effectiveness at producing weight loss, none has had a widespread impact on obesity. Lifestyle interventions, drugs, and bariatric surgery continue to be underused. Current treatment models are not providing patients with the intensive interventions needed.

Providers often find themselves offering repetitive advice to patients with obesity regarding nutrition and exercise, while simultaneously trying to manage obesity-related comorbidities, all in a 20-minute appointment. Too often, a patient returns home with prescriptions for hypertension or diabetes but no clear plan for weight management.

What can a shared medical appointment do?

A shared medical appointment is a group medical visit in which several patients with a similar clinical diagnosis, such as obesity, see a multidisciplinary team of healthcare providers. Typically, 5 to 10 patients have consultations with providers during a 60- to 90-minute appointment.20

Part of the session is dedicated to education on the patients’ common medical condition with the goal of improving their self-management, but most of the time is spent addressing individual patient concerns.

Each patient takes a turn consulting with a provider, as in a traditional medical appointment, but in a group setting. This allows others in the group to observe and learn from their peers’ experiences. During this consultation, the patient’s concerns are addressed, medications are managed, necessary tests are ordered, and a treatment plan is made.

Patients can continue to receive follow-up care through shared medical appointments at predetermined times, instead of traditional individual medical appointments.

BENEFITS OF SHARED APPOINTMENTS

Shared medical appointments could improve patient access, clinical outcomes, and patient and provider satisfaction and decrease costs.20,21 Since being introduced in the 1990s, their use has dramatically increased. For example, in the first 2 years of conducting shared medical appointments at Cleveland Clinic (2002–2004), there were just 385 shared medical appointments,21 but in 2017 there were approximately 12,300. They are used in a variety of medical and surgical specialties, and have been studied most for treating diabetes.22–24

Increased face time and access

Individual patient follow-up visits typically last 15 to 20 minutes, limiting the provider to seeing a maximum of 6 patients in 90 minutes. In that same time in the setting of a shared appointment, a multidisciplinary team can see up to 10 patients, and the patients receive up to 90 minutes of time with multiple providers.

Additionally, shared medical appointments can improve patient access to timely appointments. In a busy bariatric surgery practice, implementing shared medical appointments reduced patients’ wait time for an appointment by more than half.25 This is particularly important for patients with obesity, who usually require 12 to 26 appointments per year.

Improved patient outcomes

Use of shared medical appointments has improved clinical outcomes compared with traditional care. Patients with type 2 diabetes who attend shared medical appointments are more likely to reach target hemoglobin A1c and blood pressure levels.22−24 These benefits may be attributed to increased access to care, improved self-management skills, more frequent visits, peer support of the group, and the synergistic knowledge of multiple providers on the shared medical appointment team.

Although some trials reported patient retention rates of 75% to 90% in shared medical appointments, many trials did not report their rates. It is likely that some patients declined randomization to avoid shared medical appointments, which could have led to potential attrition and selection biases.23

Increased patient and provider satisfaction

Both patients and providers report high satisfaction with shared medical appointments.22,26 Although patients may initially hesitate to participate, their opinions significantly improve after attending 1 session.26 From 85% to 90% of patients who attend a shared medical appointment schedule their next follow-up appointment as a shared appointment as well.21,25

In comparative studies, patients who attended shared medical appointments had satisfaction rates equal to or higher than rates in patients who participated in usual care,22 noting better access to care and more sensitivity to their needs.27 Providers report greater satisfaction from working more directly with a team of providers, clearing up a backlogged schedule, and adding variety to their practice.21,24

Decreased costs

Data on the cost-effectiveness of shared medical appointments are mixed; however, some studies have shown that they are associated with a decrease in hospital admissions and emergency department visits.22 It seems reasonable to assume that, in an appropriate patient population, shared medical appointments can be cost-effective owing to increased provider productivity, but more research is needed to verify this.

CHALLENGES TO STARTING SHARED APPOINTMENTS FOR OBESITY

Despite their potential to provide comprehensive care to patients, shared medical appointments have limitations. These need to be addressed before implementing a shared medical appointment program.

Adequate resources and staff training

To be successful, a shared medical appointment program needs to have intensive physical and staffing resources. You need a space large enough to accommodate the group and access to the necessary equipment (eg, projector, whiteboard) for educational sessions. Larger or armless chairs may better accommodate patients with obesity. Facilitators need training in how to lead the group sessions, including time management and handling conflicts between patients. Schedulers and clinical intake staff need training in answering patient questions regarding these appointments.

Maintaining patient attendance

The benefits of provider efficiency rest on having an adequate number of patients attend the shared appointments.21 Patient cancellations and no-shows decrease both the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of this model, and they detract from the peer support and group learning that occurs in the group dynamic. To help minimize patient dropout, a discussion of patient expectations should take place prior to enrollment in shared medical appointments. This should include information on the concept of shared appointments, frequency and duration of appointments, and realistic weight loss goals.

Logistical challenges

A shared medical appointment requires a longer patient time slot and is usually less flexible than an individual appointment. Not all patients can take the time for a prescheduled 60- to 90-minute appointment. However, reduced waiting-room time and increased face time with a provider offset some of these challenges.

Recruiting patients

A shared medical appointment is a novel experience for some, and concerns about it may make it a challenge to recruit patients. Patients might worry that the presence of the group will compromise the patient-doctor relationship. Other concerns include potential irrelevance of other patients’ medical issues and reluctance to participate because of body image and the stigma of obesity.

One solution is to select patients from your existing practice so that the individual patient-provider relationship is established before introducing the concept of shared appointments. You will need to explain how shared appointments work, discuss their pros and cons, stress your expectations about attendance and confidentiality, and address any concerns of the patient. It is also important to emphasize that nearly all patients find shared medical appointments useful.

Once a group is established, it may be a challenge to keep a constant group membership to promote positive group dynamics. In practice, patients may drop out or be added, and facilitators need to be able to integrate new members into the group. It is important to emphasize to the group that obesity is chronic and that patients at all stages and levels of treatment can contribute to group learning.

Despite the advantages of shared medical appointments, some patients may not find them useful, even after attending several sessions. These patients should be offered individual follow-up visits. Also, shared appointments may not be suitable for patients who cannot speak English very well, are hearing-impaired, have significant cognitive impairment, or have acute medical issues.

Maintaining patient confidentiality

Maintaining confidentiality of personal and health information in a shared medical appointment is an important concern for patients but can be appropriately managed. In a survey of patients attending pulmonary hypertension shared medical appointments, 24% had concerns about confidentiality before participating, but after a few sessions, this rate was cut in half.28

Patients have reported initially withholding some information, but over time, they usually become more comfortable with the group and disclose more helpful information.29 Strategies to ensure confidentiality include having patients sign a confidentiality agreement at each appointment, providing specific instruction on what characterizes confidentiality breaches, and allowing patients the opportunity to schedule individual appointments as needed.

Ensuring insurance coverage

A shared medical appointment should be billed as an individual medical appointment for level of care, rather than time spent with the provider. This ensures that insurance coverage and copayments are the same as for individual medical appointments.

Lack of insurance coverage is a major barrier to obesity treatment in general. The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services reimburses intensive behavioral obesity treatment delivered by a primary care practitioner, but limits it to 1 year of treatment and requires patients to meet weight loss goals. Some individual and employer-based healthcare plans do not cover dietitian visits, weight management programs, or antiobesity prescriptions.

EVIDENCE OF EFFECTIVENESS IN OBESITY

Few studies have investigated the use of shared medical appointments in obesity treatment. In the pediatric population, these programs significantly decreased BMI and some other anthropometric measurements,30–32 but they did not consistently involve a prescribing provider. This means they did not manage medications or comorbidities as would be expected in a shared medical appointment.

In adults, reported effects have been encouraging, although the studies are not particularly robust. In a 2-year observational study of a single physician conducting biweekly weight management shared medical appointments, participants lost 1% of their baseline weight, while those continuing with usual care gained 0.8%, a statistically significant difference.33 However, participation rates were low, with patients attending an average of only 3 shared medical appointments during the study.

In a meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials of shared medical appointments for patients with type 2 diabetes, only 3 studies reported weight outcomes.23 These results indicated a trend toward weight loss among patients attending shared appointments, but they were not statistically significant.

Positive results also were reported by the Veterans Administration’s MOVE! (Managing Overweight/obesity for Veterans Everywhere) program.34 Participants in shared medical appointments reported that they felt empowered to make positive lifestyle changes, gained knowledge about obesity, were held accountable by their peers, and appreciated the individualized care they received from the multidisciplinary healthcare teams.

A systematic review involving 336 participants in group-based obesity interventions found group treatment produced more robust weight loss than individual treatment.35 However, shared medical appointments are different from weight loss groups in that they combine an educational session and a medical appointment in a peer-group setting, which requires a provider with prescribing privileges to be present. Thus, shared medical appointments can manage medications as well as weight-related comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and hyperlipidemia.

One more point is that continued attendance at shared medical appointments, even after successful weight loss, may help to maintain the weight loss, which has otherwise been found to be extremely challenging using traditional medical approaches.

WHO SHOULD BE ON THE TEAM?

Because obesity is multifactorial, it requires a comprehensive treatment approach that can be difficult to deliver given the limited time of an individual appointment. In a shared appointment, providers across multiple specialties can meet with patients at the same time to coordinate approaches to obesity treatment.

A multidisciplinary team for shared medical appointments for obesity needs a physician or a nurse practitioner—or ideally, both— who specializes in obesity to facilitate the session. Other key providers include a registered dietitian, an exercise physiologist, a behavioral health specialist, a sleep specialist, and a social worker to participate as needed in the educational component of the appointment or act as outside consultants.

WHAT ARE REALISTIC TARGETS?

- Nutrition

- Physical activity

- Appetite control

- Sleep

- Stress and mood disorders.

Nutrition

A calorie deficit of 500 to 750 calories per day is recommended for weight loss.7,8 Although there is no consensus on the best nutritional content of a diet, adherence to a diet is a significant predictor of weight loss.36 One reason diets fail to bring about weight loss is that patients tend to underestimate their caloric intake by almost 50%.37 Thus, they may benefit from a structured and supervised diet plan.

A dietitian can help patients develop an individualized diet plan that will promote adherence, which includes specific information on food choices, portion sizes, and timing of meals.

Physical activity

At least 150 minutes of physical activity per week is recommended for weight loss, and 200 to 300 minutes per week is recommended for long-term weight maintenance.7,8

An exercise physiologist can help patients design a personalized exercise plan to help achieve these goals. This plan should take into account the patient’s cardiac status, activity level, degree of mobility, and lifestyle.

Most patients are not able to achieve the recommended physical activity goals initially, and activity levels need to be gradually increased over a period of weeks to months. Patients who were previously inactive or have evidence of cardiovascular, renal, or metabolic disease may require a cardiopulmonary assessment, including an electrocardiogram and cardiac stress test, before starting an exercise program.

Appetite control

It is very difficult for patients to lose weight without appetite control. Weight loss that results from diet and exercise is often accompanied by a change in weight-regulating hormones (eg, leptin, ghrelin, peptide YY, and cholecystokinin) that promote weight regain.38 Thus, multiple compensatory mechanisms promote weight regain through increases in appetite and decreases in energy expenditure, resisting weight loss efforts.

Antiobesity drugs can help mitigate these adaptive weight-promoting responses through several mechanisms. They are indicated for use with lifestyle interventions for patients with a BMI of at least 30 mg/kg2 or a BMI of at least 27 kg/m2 with an obesity-related comorbidity.

These drugs promote an additional 3% to 7% weight loss when added to lifestyle interventions.18 But their effects are limited without appropriate lifestyle interventions.

Sleep

Adequate sleep is an often-overlooked component of obesity treatment. Inadequate sleep is associated with weight gain and an appetite-inducing hormone profile.39 Just 2 days of sleep deprivation in healthy normal-weight adult men was associated with a 70% increase in the ghrelin-to-leptin ratio, which showed a linear relationship with self-reported increased hunger.39 Sleep disorders, especially obstructive sleep apnea, are common in patients with obesity but are often underdiagnosed and undertreated.40

Healthy sleep habits and sleep quality should be addressed in shared medical appointments for obesity, as patients may be unaware of the impact that sleep may be having on their obesity treatment. The STOP-BANG questionnaire (snoring, tiredness, observed apnea, high blood pressure, BMI, age, neck circumference, and male sex) is a simple and reliable tool to screen for obstructive sleep apnea.41 Patients with symptoms of a sleep disorder should be referred to a sleep specialist for diagnosis and management.

Stress management and mood disorders

Stress and psychiatric disorders are underappreciated contributors to obesity. All patients receiving obesity treatment need to be screened for mood disorders and suicidal ideation.8

Chronic stress promotes weight gain through activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis, whereby increased cortisol levels enhance appetite and accumulation of visceral fat.42 In addition, obesity is associated with a 25% increased risk of mood disorders, although the mechanism and direction of this association are unclear.43 Weight gain as a side effect of antidepressant or other psychiatric medications is another important consideration.

Management of stress and psychiatric disorders through goal-setting, self-monitoring, and patient education is vital to help patients fully participate in lifestyle changes and maximize weight loss. Patients participating in shared medical appointments usually benefit from consultations with psychiatrists or psychologists to manage psychiatric comorbidities and assist with adherence to behavior modification.

IN FAVOR OF SHARED MEDICAL APPOINTMENTS FOR OBESITY

Shared medical appointments can be an effective method of addressing the challenges of treating patients with obesity, using a multidisciplinary approach that combines nutrition, physical activity, appetite suppression, sleep improvement, and stress management. In addition, shared appointments allow practitioners to treat the primary problem of excess weight, rather than just its comorbidities, recognizing that obesity is a chronic disease that requires long-term, individualized treatment. Satisfaction rates are high for both patients and providers. Overall, education is essential to implementing and maintaining a successful shared medical appointment program.

Obesity is a major health problem in the United States. The facts are well known:

- Its prevalence has almost tripled since the early 1960s1

- More than 35% of US adults are obese (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 30 kg/m2)2

- It increases the risk of comorbid conditions including type 2 diabetes mellitus, heart disease, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, certain cancers, asthma, and osteoarthritis3,4

- It decreases life expectancy5

- Medical costs are up to 6 times higher per patient.6

Moreover, obesity is often not appropriately managed, owing to a variety of factors. In this article, we describe use of shared medical appointments as a strategy to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of treating patients with obesity.

Big benefits from small changes in weight

As little as 3% to 5% weight loss is associated with significant clinical benefits, such as improved glycemic control, reduced blood pressure, and reduced cholesterol levels.7,8 However, many patients are unable to reach this modest goal using current approaches to obesity management.

This failure is partially related to the complexity and chronic nature of obesity, which requires continued medical management from a multidisciplinary team. We believe this is an area of care that can be appropriately addressed through shared medical appointments.

CURRENT APPROACHES

Interventions for obesity have increased along with the prevalence of the disease. Hundreds of diets, exercise plans, natural products, and behavioral interventions are marketed, all claiming to be successful. More-intense treatment options include antiobesity medications, intra-abdominal weight loss devices, and bariatric surgery. Despite the availability of treatments, rates of obesity have not declined.

Counseling is important, but underused

Lifestyle modifications that encompass nutrition, physical activity, and behavioral interventions are the mainstay of obesity treatment.

Intensive interventions work better than less-intensive ones. In large clinical trials in overweight patients with diabetes, those who received intensive lifestyle interventions lost 3 to 5 kg more (3% to 8% of body weight) than those who received brief diet and nutrition counseling, as is often performed in a physician’s office.9–12 The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends that patients whose BMI is 30 kg/m2 or higher be offered intensive lifestyle intervention consisting of at least 12 sessions in 1 year.13

But fewer than half of primary care practitioners consistently provide specific guidance on diet, exercise, or weight control to patients with obesity, including those with a weight-related comorbidity.14 The rate has decreased since the 1990s despite the increase in obesity.15

One reason for the underuse is that many primary care practitioners do not have the training or time to deliver the recommended high-intensity obesity treatment.14 Plus, evidence does not clearly show a weight loss benefit from low-intensity interventions. Even when patients lose weight, most regain it, and only 20% are able to maintain their weight loss 1 year after treatment ends.16

Drugs and surgery also underused

Antiobesity medications and bariatric surgery are effective when added to lifestyle interventions, but they are also underused.

Bariatric surgery provides the greatest and most durable weight loss—15% to 30% of body weight—along with improvement in comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes, and its benefits are sustained for at least 10 years.17 However, fewer than 1% of eligible patients undergo bariatric surgery because of its limited availability, invasive nature, potential complications, limited insurance coverage, and high cost.17

The story is similar for antiobesity drugs. They are useful adjuncts to lifestyle interventions, providing an additional 3% to 7% weight loss,18 but fewer than 2% of eligible patients receive them.19 This may be attributed to their modest effectiveness, weight regain after discontinuation, potential adverse effects, and expense due to lack of insurance coverage.

ARE SHARED MEDICAL APPOINTMEMNTS AN ANSWER?

Although treatments have shown some effectiveness at producing weight loss, none has had a widespread impact on obesity. Lifestyle interventions, drugs, and bariatric surgery continue to be underused. Current treatment models are not providing patients with the intensive interventions needed.

Providers often find themselves offering repetitive advice to patients with obesity regarding nutrition and exercise, while simultaneously trying to manage obesity-related comorbidities, all in a 20-minute appointment. Too often, a patient returns home with prescriptions for hypertension or diabetes but no clear plan for weight management.

What can a shared medical appointment do?

A shared medical appointment is a group medical visit in which several patients with a similar clinical diagnosis, such as obesity, see a multidisciplinary team of healthcare providers. Typically, 5 to 10 patients have consultations with providers during a 60- to 90-minute appointment.20

Part of the session is dedicated to education on the patients’ common medical condition with the goal of improving their self-management, but most of the time is spent addressing individual patient concerns.

Each patient takes a turn consulting with a provider, as in a traditional medical appointment, but in a group setting. This allows others in the group to observe and learn from their peers’ experiences. During this consultation, the patient’s concerns are addressed, medications are managed, necessary tests are ordered, and a treatment plan is made.

Patients can continue to receive follow-up care through shared medical appointments at predetermined times, instead of traditional individual medical appointments.

BENEFITS OF SHARED APPOINTMENTS

Shared medical appointments could improve patient access, clinical outcomes, and patient and provider satisfaction and decrease costs.20,21 Since being introduced in the 1990s, their use has dramatically increased. For example, in the first 2 years of conducting shared medical appointments at Cleveland Clinic (2002–2004), there were just 385 shared medical appointments,21 but in 2017 there were approximately 12,300. They are used in a variety of medical and surgical specialties, and have been studied most for treating diabetes.22–24

Increased face time and access

Individual patient follow-up visits typically last 15 to 20 minutes, limiting the provider to seeing a maximum of 6 patients in 90 minutes. In that same time in the setting of a shared appointment, a multidisciplinary team can see up to 10 patients, and the patients receive up to 90 minutes of time with multiple providers.

Additionally, shared medical appointments can improve patient access to timely appointments. In a busy bariatric surgery practice, implementing shared medical appointments reduced patients’ wait time for an appointment by more than half.25 This is particularly important for patients with obesity, who usually require 12 to 26 appointments per year.

Improved patient outcomes

Use of shared medical appointments has improved clinical outcomes compared with traditional care. Patients with type 2 diabetes who attend shared medical appointments are more likely to reach target hemoglobin A1c and blood pressure levels.22−24 These benefits may be attributed to increased access to care, improved self-management skills, more frequent visits, peer support of the group, and the synergistic knowledge of multiple providers on the shared medical appointment team.

Although some trials reported patient retention rates of 75% to 90% in shared medical appointments, many trials did not report their rates. It is likely that some patients declined randomization to avoid shared medical appointments, which could have led to potential attrition and selection biases.23

Increased patient and provider satisfaction

Both patients and providers report high satisfaction with shared medical appointments.22,26 Although patients may initially hesitate to participate, their opinions significantly improve after attending 1 session.26 From 85% to 90% of patients who attend a shared medical appointment schedule their next follow-up appointment as a shared appointment as well.21,25

In comparative studies, patients who attended shared medical appointments had satisfaction rates equal to or higher than rates in patients who participated in usual care,22 noting better access to care and more sensitivity to their needs.27 Providers report greater satisfaction from working more directly with a team of providers, clearing up a backlogged schedule, and adding variety to their practice.21,24

Decreased costs

Data on the cost-effectiveness of shared medical appointments are mixed; however, some studies have shown that they are associated with a decrease in hospital admissions and emergency department visits.22 It seems reasonable to assume that, in an appropriate patient population, shared medical appointments can be cost-effective owing to increased provider productivity, but more research is needed to verify this.

CHALLENGES TO STARTING SHARED APPOINTMENTS FOR OBESITY

Despite their potential to provide comprehensive care to patients, shared medical appointments have limitations. These need to be addressed before implementing a shared medical appointment program.

Adequate resources and staff training

To be successful, a shared medical appointment program needs to have intensive physical and staffing resources. You need a space large enough to accommodate the group and access to the necessary equipment (eg, projector, whiteboard) for educational sessions. Larger or armless chairs may better accommodate patients with obesity. Facilitators need training in how to lead the group sessions, including time management and handling conflicts between patients. Schedulers and clinical intake staff need training in answering patient questions regarding these appointments.

Maintaining patient attendance

The benefits of provider efficiency rest on having an adequate number of patients attend the shared appointments.21 Patient cancellations and no-shows decrease both the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of this model, and they detract from the peer support and group learning that occurs in the group dynamic. To help minimize patient dropout, a discussion of patient expectations should take place prior to enrollment in shared medical appointments. This should include information on the concept of shared appointments, frequency and duration of appointments, and realistic weight loss goals.

Logistical challenges

A shared medical appointment requires a longer patient time slot and is usually less flexible than an individual appointment. Not all patients can take the time for a prescheduled 60- to 90-minute appointment. However, reduced waiting-room time and increased face time with a provider offset some of these challenges.

Recruiting patients

A shared medical appointment is a novel experience for some, and concerns about it may make it a challenge to recruit patients. Patients might worry that the presence of the group will compromise the patient-doctor relationship. Other concerns include potential irrelevance of other patients’ medical issues and reluctance to participate because of body image and the stigma of obesity.

One solution is to select patients from your existing practice so that the individual patient-provider relationship is established before introducing the concept of shared appointments. You will need to explain how shared appointments work, discuss their pros and cons, stress your expectations about attendance and confidentiality, and address any concerns of the patient. It is also important to emphasize that nearly all patients find shared medical appointments useful.

Once a group is established, it may be a challenge to keep a constant group membership to promote positive group dynamics. In practice, patients may drop out or be added, and facilitators need to be able to integrate new members into the group. It is important to emphasize to the group that obesity is chronic and that patients at all stages and levels of treatment can contribute to group learning.

Despite the advantages of shared medical appointments, some patients may not find them useful, even after attending several sessions. These patients should be offered individual follow-up visits. Also, shared appointments may not be suitable for patients who cannot speak English very well, are hearing-impaired, have significant cognitive impairment, or have acute medical issues.

Maintaining patient confidentiality

Maintaining confidentiality of personal and health information in a shared medical appointment is an important concern for patients but can be appropriately managed. In a survey of patients attending pulmonary hypertension shared medical appointments, 24% had concerns about confidentiality before participating, but after a few sessions, this rate was cut in half.28

Patients have reported initially withholding some information, but over time, they usually become more comfortable with the group and disclose more helpful information.29 Strategies to ensure confidentiality include having patients sign a confidentiality agreement at each appointment, providing specific instruction on what characterizes confidentiality breaches, and allowing patients the opportunity to schedule individual appointments as needed.

Ensuring insurance coverage

A shared medical appointment should be billed as an individual medical appointment for level of care, rather than time spent with the provider. This ensures that insurance coverage and copayments are the same as for individual medical appointments.

Lack of insurance coverage is a major barrier to obesity treatment in general. The US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services reimburses intensive behavioral obesity treatment delivered by a primary care practitioner, but limits it to 1 year of treatment and requires patients to meet weight loss goals. Some individual and employer-based healthcare plans do not cover dietitian visits, weight management programs, or antiobesity prescriptions.

EVIDENCE OF EFFECTIVENESS IN OBESITY

Few studies have investigated the use of shared medical appointments in obesity treatment. In the pediatric population, these programs significantly decreased BMI and some other anthropometric measurements,30–32 but they did not consistently involve a prescribing provider. This means they did not manage medications or comorbidities as would be expected in a shared medical appointment.

In adults, reported effects have been encouraging, although the studies are not particularly robust. In a 2-year observational study of a single physician conducting biweekly weight management shared medical appointments, participants lost 1% of their baseline weight, while those continuing with usual care gained 0.8%, a statistically significant difference.33 However, participation rates were low, with patients attending an average of only 3 shared medical appointments during the study.

In a meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials of shared medical appointments for patients with type 2 diabetes, only 3 studies reported weight outcomes.23 These results indicated a trend toward weight loss among patients attending shared appointments, but they were not statistically significant.

Positive results also were reported by the Veterans Administration’s MOVE! (Managing Overweight/obesity for Veterans Everywhere) program.34 Participants in shared medical appointments reported that they felt empowered to make positive lifestyle changes, gained knowledge about obesity, were held accountable by their peers, and appreciated the individualized care they received from the multidisciplinary healthcare teams.

A systematic review involving 336 participants in group-based obesity interventions found group treatment produced more robust weight loss than individual treatment.35 However, shared medical appointments are different from weight loss groups in that they combine an educational session and a medical appointment in a peer-group setting, which requires a provider with prescribing privileges to be present. Thus, shared medical appointments can manage medications as well as weight-related comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and hyperlipidemia.

One more point is that continued attendance at shared medical appointments, even after successful weight loss, may help to maintain the weight loss, which has otherwise been found to be extremely challenging using traditional medical approaches.

WHO SHOULD BE ON THE TEAM?

Because obesity is multifactorial, it requires a comprehensive treatment approach that can be difficult to deliver given the limited time of an individual appointment. In a shared appointment, providers across multiple specialties can meet with patients at the same time to coordinate approaches to obesity treatment.

A multidisciplinary team for shared medical appointments for obesity needs a physician or a nurse practitioner—or ideally, both— who specializes in obesity to facilitate the session. Other key providers include a registered dietitian, an exercise physiologist, a behavioral health specialist, a sleep specialist, and a social worker to participate as needed in the educational component of the appointment or act as outside consultants.

WHAT ARE REALISTIC TARGETS?

- Nutrition

- Physical activity

- Appetite control

- Sleep

- Stress and mood disorders.

Nutrition

A calorie deficit of 500 to 750 calories per day is recommended for weight loss.7,8 Although there is no consensus on the best nutritional content of a diet, adherence to a diet is a significant predictor of weight loss.36 One reason diets fail to bring about weight loss is that patients tend to underestimate their caloric intake by almost 50%.37 Thus, they may benefit from a structured and supervised diet plan.

A dietitian can help patients develop an individualized diet plan that will promote adherence, which includes specific information on food choices, portion sizes, and timing of meals.

Physical activity

At least 150 minutes of physical activity per week is recommended for weight loss, and 200 to 300 minutes per week is recommended for long-term weight maintenance.7,8

An exercise physiologist can help patients design a personalized exercise plan to help achieve these goals. This plan should take into account the patient’s cardiac status, activity level, degree of mobility, and lifestyle.

Most patients are not able to achieve the recommended physical activity goals initially, and activity levels need to be gradually increased over a period of weeks to months. Patients who were previously inactive or have evidence of cardiovascular, renal, or metabolic disease may require a cardiopulmonary assessment, including an electrocardiogram and cardiac stress test, before starting an exercise program.

Appetite control

It is very difficult for patients to lose weight without appetite control. Weight loss that results from diet and exercise is often accompanied by a change in weight-regulating hormones (eg, leptin, ghrelin, peptide YY, and cholecystokinin) that promote weight regain.38 Thus, multiple compensatory mechanisms promote weight regain through increases in appetite and decreases in energy expenditure, resisting weight loss efforts.

Antiobesity drugs can help mitigate these adaptive weight-promoting responses through several mechanisms. They are indicated for use with lifestyle interventions for patients with a BMI of at least 30 mg/kg2 or a BMI of at least 27 kg/m2 with an obesity-related comorbidity.

These drugs promote an additional 3% to 7% weight loss when added to lifestyle interventions.18 But their effects are limited without appropriate lifestyle interventions.

Sleep

Adequate sleep is an often-overlooked component of obesity treatment. Inadequate sleep is associated with weight gain and an appetite-inducing hormone profile.39 Just 2 days of sleep deprivation in healthy normal-weight adult men was associated with a 70% increase in the ghrelin-to-leptin ratio, which showed a linear relationship with self-reported increased hunger.39 Sleep disorders, especially obstructive sleep apnea, are common in patients with obesity but are often underdiagnosed and undertreated.40

Healthy sleep habits and sleep quality should be addressed in shared medical appointments for obesity, as patients may be unaware of the impact that sleep may be having on their obesity treatment. The STOP-BANG questionnaire (snoring, tiredness, observed apnea, high blood pressure, BMI, age, neck circumference, and male sex) is a simple and reliable tool to screen for obstructive sleep apnea.41 Patients with symptoms of a sleep disorder should be referred to a sleep specialist for diagnosis and management.

Stress management and mood disorders

Stress and psychiatric disorders are underappreciated contributors to obesity. All patients receiving obesity treatment need to be screened for mood disorders and suicidal ideation.8

Chronic stress promotes weight gain through activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis, whereby increased cortisol levels enhance appetite and accumulation of visceral fat.42 In addition, obesity is associated with a 25% increased risk of mood disorders, although the mechanism and direction of this association are unclear.43 Weight gain as a side effect of antidepressant or other psychiatric medications is another important consideration.

Management of stress and psychiatric disorders through goal-setting, self-monitoring, and patient education is vital to help patients fully participate in lifestyle changes and maximize weight loss. Patients participating in shared medical appointments usually benefit from consultations with psychiatrists or psychologists to manage psychiatric comorbidities and assist with adherence to behavior modification.

IN FAVOR OF SHARED MEDICAL APPOINTMENTS FOR OBESITY

Shared medical appointments can be an effective method of addressing the challenges of treating patients with obesity, using a multidisciplinary approach that combines nutrition, physical activity, appetite suppression, sleep improvement, and stress management. In addition, shared appointments allow practitioners to treat the primary problem of excess weight, rather than just its comorbidities, recognizing that obesity is a chronic disease that requires long-term, individualized treatment. Satisfaction rates are high for both patients and providers. Overall, education is essential to implementing and maintaining a successful shared medical appointment program.

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD. National Center for Health Statistics. Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and extreme obesity among adults: United States, trends 1960-62 through 2007–2008. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/obesity_adult_07_08/obesity_adult_07_08.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2018.

- Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA 2016; 315(21):2284–2291. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.6458