User login

Yes, by using a pre-visit questionnaire that zeroes in on weight history, eating habits, and level of physical activity. This information will lay the foundation for effective weight loss counseling and interventions consistent with intensive behavioral therapy for obesity, reimbursable by Medicare.1

More than one-third of US adults are obese.3 And even though the rate of obesity in adults has leveled off since 2009,3 more needs to be done to bend the arc of the national obesity trend. Clinicians tend to focus on the complications of obesity (coronary artery disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia) rather than on early identification and intervention of obesity itself.4–6 A national study of outpatient visits showed that only 29% of visits by patients who were obese according to their body mass index (BMI) had a documented diagnosis of obesity, suggesting a profound underdiagnosis of obesity.7 According to one study, primary care doctors lack the level of comfort and counseling experience needed to provide obesity and weight loss counseling.8 Yet recent changes to Medicare reimbursement encourage obesity screening and management by covering up to 20 visits for intensive behavioral therapy to treat obesity.1

We offer the following targeted approach to counseling, achievable within the context of a primary care visit and based on recent evidence, including the 2013 joint guidelines for the treatment of obesity of the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the Obesity Society.2

START WITH SCREENING

Measure the patient’s height and weight with the patient wearing light clothing and no shoes, and calculate the BMI as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters. A BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater defines obesity.

OBTAIN AN OBESITY HISTORY

According to the 2013 joint guidelines,2 when obtaining a thorough obesity history, the physician should do the following:

- Obtain information about weight the patient has gained and lost over time and previous weight loss efforts

- Ask the patient about eating habits, including number of meals per day, and the contents of a typical breakfast, lunch, and dinner; we recommend also asking about the number of daily beverages high in sugar

- Quantify the type and amount of physical activity performed within a specific time period.

This information can be obtained in advance of an office visit through either an electronic medical record portal or a pre-visit questionnaire (eg, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1038/oby.2002.205/full).

Also assess the patient’s risk of cardiovascular and obesity-related comorbidities. The waist circumference for patients with a BMI between 25 and 35 kg/m2 provides additional information on risk: eg, a waist circumference greater than 88 cm for women and greater than 102 cm for men indicates increased cardiometabolic risk.2

SUGGEST SPECIFIC GOALS

Use a shared decision-making process to arrive at a set of incremental goals centered around the following evidence-based targets2:

- Weight loss: 3% to 5% of baseline weight within 6 months

- 6-month commitment to a weight loss intervention

- Exercise: at least 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity per week

- More vegetables, fewer carbohydrates, and less protein, according to the American Diabetes Association’s “Create your plate” plan9

- Mediterranean diet.10

Use motivational interviewing techniques along with the obesity history to negotiate goals. Exercise-related goals should consider the patient’s cardiovascular and musculoskeletal comorbidities.

CO-DEVELOP A TREATMENT PLAN AND ADDRESS POTENTIAL BARRIERS

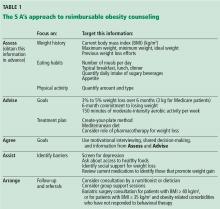

The most effective weight loss treatment consists of in-person consultations in which comprehensive lifestyle interventions are included. The components of an effective intervention (Table 1) include a reduced-calorie diet, aerobic physical activity, and behavioral strategies to meaningfully support these changes.2

We recommend addressing potential barriers to initiating and maintaining weight-loss interventions, and revisiting them during follow-up visits. Barriers include the following:

Depression

Adults with depression are more likely to be obese than adults without depression, and the age-adjusted percentage of adults who are obese increases as depression severity increases.11

Access to healthy foods

Limited access to healthy food choices can lead to poor diets and higher levels of obesity.12 Local grocery store websites and nutrition specialists can help identify a range of healthy and affordable food to sustain a dietary intervention.

Medications associated with weight gain

Certain diabetic medications, contraceptives, tricyclic antidepressants, atypical antipsychotics, antiseizure drugs, and glucocorticoids promote weight gain and may have alternatives that do not promote weight gain.13

ARRANGE FOLLOW-UP AND REFERRALS

The literature supports frequent in-person sessions as the basis for a successful weight loss intervention (ie, ≥ 14 sessions in 6 months).2 Medicare beneficiaries are eligible for 14 covered visits in the first 6 months and become eligible for an additional monthly visit over the course of 6 subsequent months if a weight loss goal of 3 kg is met in the first 6-month period.

Nutritionists, dieticians, and behavioral psychologists are often instrumental in comprehensive weight loss interventions. Antiobesity drugs help curb appetite, promote weight loss, help enhance adherence to lifestyle modifications, and make it easier for patients to start a program of physical activity.14

The joint 2013 guidelines2 recommend referral for bariatric surgery for adults with a BMI 40 kg/m2 or higher, or for adults with a BMI 35 kg/m2 or higher and obesity-related comorbidities who have not responded to behavioral treatment (with or without pharmacotherapy).

A growing body of evidence promotes the use of group support sessions such as shared medical appointments to encourage healthy eating and physical activity.15

OBESITY COUNSELING IS ACHIEVABLE AND REIMBURSABLE

To receive reimbursement from Medicare for obesity counseling, the information listed under “assess” and “advise” in Table 1 should be obtained in the initial visit; and follow-up visits should be used to address items under “agree,” “assist,” and “arrange.” Up to 20 visits are eligible for reimbursement when patients meet the goal of a 3-kg weight loss in the first 6 months (or 14 visits).

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Decision memo for intensive behavioral therapy for obesity (CAG-00423N). www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?&NcaName=Intensive%20Behavioral%20Therapy%20for%20Obesity&bc=ACAAAAAAIAAA&NCAId=253. Accessed June 5, 2017.

- Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Obesity Society. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63:2985–3023.

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity among adults: United States, 2011-2012. NCHS Data Brief 2013; 131:1–8.

- Potter MB, Vu JD, Croughan-Minihane M. Weight management: what patients want from their primary care physicians. J Fam Pract 2001; 50:513–518.

- Galuska D, Will J, Serdula M, Ford E. Are health care professionals advising obese patients to lose weight? JAMA 1999; 282:1576–1578.

- Nawaz H, Adams ML, Katz DL. Weight loss counseling by health care providers. Am J Public Health 1999; 89:764–767.

- Ma J, Xiao L, Stafford R. Underdiagnosis of obesity in adults in US outpatient settings. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169:313–314.

- Huang J, Yu H, Marin E, Brock S, Carden D, Davis T. Physicians’ weight loss counseling in two public hospital primary care clinics. Acad Med 2004; 79:156–161.

- American Diabetes Association. Create your plate. www.diabetes.org/food-and-fitness/food/planning-meals/create-your-plate. Accessed May 19, 2017.

- Serra-Majem L, Roman B, Estruch R. Scientific evidence of interventions using the Mediterranean diet: a systematic review. Nutr Rev 2006; 64:S27–S47.

- Pratt LA, Brody DJ. Depression and obesity in the US adult household population, 2005-2010. NCHS Data Brief 2014; 167:1–8.

- Gordon-Larsen P. Food availability/convenience and obesity. Adv Nutr 2014; 5:809–817.

- Malone M. Medications associated with weight gain. Ann Pharmacother 2005; 39:2046–2055.

- Patel D. Pharmacotherapy for the management of obesity. Metabolism 2015; 64:1376–1385.

- Guthrie GE, Bogue RJ. Impact of a shared medical appointment lifestyle intervention on weight and lipid parameters in individuals with type 2 diabetes: a clinical pilot. J Am Coll Nutr 2015; 34:300–309.

Yes, by using a pre-visit questionnaire that zeroes in on weight history, eating habits, and level of physical activity. This information will lay the foundation for effective weight loss counseling and interventions consistent with intensive behavioral therapy for obesity, reimbursable by Medicare.1

More than one-third of US adults are obese.3 And even though the rate of obesity in adults has leveled off since 2009,3 more needs to be done to bend the arc of the national obesity trend. Clinicians tend to focus on the complications of obesity (coronary artery disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia) rather than on early identification and intervention of obesity itself.4–6 A national study of outpatient visits showed that only 29% of visits by patients who were obese according to their body mass index (BMI) had a documented diagnosis of obesity, suggesting a profound underdiagnosis of obesity.7 According to one study, primary care doctors lack the level of comfort and counseling experience needed to provide obesity and weight loss counseling.8 Yet recent changes to Medicare reimbursement encourage obesity screening and management by covering up to 20 visits for intensive behavioral therapy to treat obesity.1

We offer the following targeted approach to counseling, achievable within the context of a primary care visit and based on recent evidence, including the 2013 joint guidelines for the treatment of obesity of the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the Obesity Society.2

START WITH SCREENING

Measure the patient’s height and weight with the patient wearing light clothing and no shoes, and calculate the BMI as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters. A BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater defines obesity.

OBTAIN AN OBESITY HISTORY

According to the 2013 joint guidelines,2 when obtaining a thorough obesity history, the physician should do the following:

- Obtain information about weight the patient has gained and lost over time and previous weight loss efforts

- Ask the patient about eating habits, including number of meals per day, and the contents of a typical breakfast, lunch, and dinner; we recommend also asking about the number of daily beverages high in sugar

- Quantify the type and amount of physical activity performed within a specific time period.

This information can be obtained in advance of an office visit through either an electronic medical record portal or a pre-visit questionnaire (eg, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1038/oby.2002.205/full).

Also assess the patient’s risk of cardiovascular and obesity-related comorbidities. The waist circumference for patients with a BMI between 25 and 35 kg/m2 provides additional information on risk: eg, a waist circumference greater than 88 cm for women and greater than 102 cm for men indicates increased cardiometabolic risk.2

SUGGEST SPECIFIC GOALS

Use a shared decision-making process to arrive at a set of incremental goals centered around the following evidence-based targets2:

- Weight loss: 3% to 5% of baseline weight within 6 months

- 6-month commitment to a weight loss intervention

- Exercise: at least 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity per week

- More vegetables, fewer carbohydrates, and less protein, according to the American Diabetes Association’s “Create your plate” plan9

- Mediterranean diet.10

Use motivational interviewing techniques along with the obesity history to negotiate goals. Exercise-related goals should consider the patient’s cardiovascular and musculoskeletal comorbidities.

CO-DEVELOP A TREATMENT PLAN AND ADDRESS POTENTIAL BARRIERS

The most effective weight loss treatment consists of in-person consultations in which comprehensive lifestyle interventions are included. The components of an effective intervention (Table 1) include a reduced-calorie diet, aerobic physical activity, and behavioral strategies to meaningfully support these changes.2

We recommend addressing potential barriers to initiating and maintaining weight-loss interventions, and revisiting them during follow-up visits. Barriers include the following:

Depression

Adults with depression are more likely to be obese than adults without depression, and the age-adjusted percentage of adults who are obese increases as depression severity increases.11

Access to healthy foods

Limited access to healthy food choices can lead to poor diets and higher levels of obesity.12 Local grocery store websites and nutrition specialists can help identify a range of healthy and affordable food to sustain a dietary intervention.

Medications associated with weight gain

Certain diabetic medications, contraceptives, tricyclic antidepressants, atypical antipsychotics, antiseizure drugs, and glucocorticoids promote weight gain and may have alternatives that do not promote weight gain.13

ARRANGE FOLLOW-UP AND REFERRALS

The literature supports frequent in-person sessions as the basis for a successful weight loss intervention (ie, ≥ 14 sessions in 6 months).2 Medicare beneficiaries are eligible for 14 covered visits in the first 6 months and become eligible for an additional monthly visit over the course of 6 subsequent months if a weight loss goal of 3 kg is met in the first 6-month period.

Nutritionists, dieticians, and behavioral psychologists are often instrumental in comprehensive weight loss interventions. Antiobesity drugs help curb appetite, promote weight loss, help enhance adherence to lifestyle modifications, and make it easier for patients to start a program of physical activity.14

The joint 2013 guidelines2 recommend referral for bariatric surgery for adults with a BMI 40 kg/m2 or higher, or for adults with a BMI 35 kg/m2 or higher and obesity-related comorbidities who have not responded to behavioral treatment (with or without pharmacotherapy).

A growing body of evidence promotes the use of group support sessions such as shared medical appointments to encourage healthy eating and physical activity.15

OBESITY COUNSELING IS ACHIEVABLE AND REIMBURSABLE

To receive reimbursement from Medicare for obesity counseling, the information listed under “assess” and “advise” in Table 1 should be obtained in the initial visit; and follow-up visits should be used to address items under “agree,” “assist,” and “arrange.” Up to 20 visits are eligible for reimbursement when patients meet the goal of a 3-kg weight loss in the first 6 months (or 14 visits).

Yes, by using a pre-visit questionnaire that zeroes in on weight history, eating habits, and level of physical activity. This information will lay the foundation for effective weight loss counseling and interventions consistent with intensive behavioral therapy for obesity, reimbursable by Medicare.1

More than one-third of US adults are obese.3 And even though the rate of obesity in adults has leveled off since 2009,3 more needs to be done to bend the arc of the national obesity trend. Clinicians tend to focus on the complications of obesity (coronary artery disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia) rather than on early identification and intervention of obesity itself.4–6 A national study of outpatient visits showed that only 29% of visits by patients who were obese according to their body mass index (BMI) had a documented diagnosis of obesity, suggesting a profound underdiagnosis of obesity.7 According to one study, primary care doctors lack the level of comfort and counseling experience needed to provide obesity and weight loss counseling.8 Yet recent changes to Medicare reimbursement encourage obesity screening and management by covering up to 20 visits for intensive behavioral therapy to treat obesity.1

We offer the following targeted approach to counseling, achievable within the context of a primary care visit and based on recent evidence, including the 2013 joint guidelines for the treatment of obesity of the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the Obesity Society.2

START WITH SCREENING

Measure the patient’s height and weight with the patient wearing light clothing and no shoes, and calculate the BMI as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters. A BMI of 30 kg/m2 or greater defines obesity.

OBTAIN AN OBESITY HISTORY

According to the 2013 joint guidelines,2 when obtaining a thorough obesity history, the physician should do the following:

- Obtain information about weight the patient has gained and lost over time and previous weight loss efforts

- Ask the patient about eating habits, including number of meals per day, and the contents of a typical breakfast, lunch, and dinner; we recommend also asking about the number of daily beverages high in sugar

- Quantify the type and amount of physical activity performed within a specific time period.

This information can be obtained in advance of an office visit through either an electronic medical record portal or a pre-visit questionnaire (eg, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1038/oby.2002.205/full).

Also assess the patient’s risk of cardiovascular and obesity-related comorbidities. The waist circumference for patients with a BMI between 25 and 35 kg/m2 provides additional information on risk: eg, a waist circumference greater than 88 cm for women and greater than 102 cm for men indicates increased cardiometabolic risk.2

SUGGEST SPECIFIC GOALS

Use a shared decision-making process to arrive at a set of incremental goals centered around the following evidence-based targets2:

- Weight loss: 3% to 5% of baseline weight within 6 months

- 6-month commitment to a weight loss intervention

- Exercise: at least 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity per week

- More vegetables, fewer carbohydrates, and less protein, according to the American Diabetes Association’s “Create your plate” plan9

- Mediterranean diet.10

Use motivational interviewing techniques along with the obesity history to negotiate goals. Exercise-related goals should consider the patient’s cardiovascular and musculoskeletal comorbidities.

CO-DEVELOP A TREATMENT PLAN AND ADDRESS POTENTIAL BARRIERS

The most effective weight loss treatment consists of in-person consultations in which comprehensive lifestyle interventions are included. The components of an effective intervention (Table 1) include a reduced-calorie diet, aerobic physical activity, and behavioral strategies to meaningfully support these changes.2

We recommend addressing potential barriers to initiating and maintaining weight-loss interventions, and revisiting them during follow-up visits. Barriers include the following:

Depression

Adults with depression are more likely to be obese than adults without depression, and the age-adjusted percentage of adults who are obese increases as depression severity increases.11

Access to healthy foods

Limited access to healthy food choices can lead to poor diets and higher levels of obesity.12 Local grocery store websites and nutrition specialists can help identify a range of healthy and affordable food to sustain a dietary intervention.

Medications associated with weight gain

Certain diabetic medications, contraceptives, tricyclic antidepressants, atypical antipsychotics, antiseizure drugs, and glucocorticoids promote weight gain and may have alternatives that do not promote weight gain.13

ARRANGE FOLLOW-UP AND REFERRALS

The literature supports frequent in-person sessions as the basis for a successful weight loss intervention (ie, ≥ 14 sessions in 6 months).2 Medicare beneficiaries are eligible for 14 covered visits in the first 6 months and become eligible for an additional monthly visit over the course of 6 subsequent months if a weight loss goal of 3 kg is met in the first 6-month period.

Nutritionists, dieticians, and behavioral psychologists are often instrumental in comprehensive weight loss interventions. Antiobesity drugs help curb appetite, promote weight loss, help enhance adherence to lifestyle modifications, and make it easier for patients to start a program of physical activity.14

The joint 2013 guidelines2 recommend referral for bariatric surgery for adults with a BMI 40 kg/m2 or higher, or for adults with a BMI 35 kg/m2 or higher and obesity-related comorbidities who have not responded to behavioral treatment (with or without pharmacotherapy).

A growing body of evidence promotes the use of group support sessions such as shared medical appointments to encourage healthy eating and physical activity.15

OBESITY COUNSELING IS ACHIEVABLE AND REIMBURSABLE

To receive reimbursement from Medicare for obesity counseling, the information listed under “assess” and “advise” in Table 1 should be obtained in the initial visit; and follow-up visits should be used to address items under “agree,” “assist,” and “arrange.” Up to 20 visits are eligible for reimbursement when patients meet the goal of a 3-kg weight loss in the first 6 months (or 14 visits).

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Decision memo for intensive behavioral therapy for obesity (CAG-00423N). www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?&NcaName=Intensive%20Behavioral%20Therapy%20for%20Obesity&bc=ACAAAAAAIAAA&NCAId=253. Accessed June 5, 2017.

- Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Obesity Society. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63:2985–3023.

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity among adults: United States, 2011-2012. NCHS Data Brief 2013; 131:1–8.

- Potter MB, Vu JD, Croughan-Minihane M. Weight management: what patients want from their primary care physicians. J Fam Pract 2001; 50:513–518.

- Galuska D, Will J, Serdula M, Ford E. Are health care professionals advising obese patients to lose weight? JAMA 1999; 282:1576–1578.

- Nawaz H, Adams ML, Katz DL. Weight loss counseling by health care providers. Am J Public Health 1999; 89:764–767.

- Ma J, Xiao L, Stafford R. Underdiagnosis of obesity in adults in US outpatient settings. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169:313–314.

- Huang J, Yu H, Marin E, Brock S, Carden D, Davis T. Physicians’ weight loss counseling in two public hospital primary care clinics. Acad Med 2004; 79:156–161.

- American Diabetes Association. Create your plate. www.diabetes.org/food-and-fitness/food/planning-meals/create-your-plate. Accessed May 19, 2017.

- Serra-Majem L, Roman B, Estruch R. Scientific evidence of interventions using the Mediterranean diet: a systematic review. Nutr Rev 2006; 64:S27–S47.

- Pratt LA, Brody DJ. Depression and obesity in the US adult household population, 2005-2010. NCHS Data Brief 2014; 167:1–8.

- Gordon-Larsen P. Food availability/convenience and obesity. Adv Nutr 2014; 5:809–817.

- Malone M. Medications associated with weight gain. Ann Pharmacother 2005; 39:2046–2055.

- Patel D. Pharmacotherapy for the management of obesity. Metabolism 2015; 64:1376–1385.

- Guthrie GE, Bogue RJ. Impact of a shared medical appointment lifestyle intervention on weight and lipid parameters in individuals with type 2 diabetes: a clinical pilot. J Am Coll Nutr 2015; 34:300–309.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Decision memo for intensive behavioral therapy for obesity (CAG-00423N). www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?&NcaName=Intensive%20Behavioral%20Therapy%20for%20Obesity&bc=ACAAAAAAIAAA&NCAId=253. Accessed June 5, 2017.

- Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines; Obesity Society. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Obesity Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63:2985–3023.

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity among adults: United States, 2011-2012. NCHS Data Brief 2013; 131:1–8.

- Potter MB, Vu JD, Croughan-Minihane M. Weight management: what patients want from their primary care physicians. J Fam Pract 2001; 50:513–518.

- Galuska D, Will J, Serdula M, Ford E. Are health care professionals advising obese patients to lose weight? JAMA 1999; 282:1576–1578.

- Nawaz H, Adams ML, Katz DL. Weight loss counseling by health care providers. Am J Public Health 1999; 89:764–767.

- Ma J, Xiao L, Stafford R. Underdiagnosis of obesity in adults in US outpatient settings. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169:313–314.

- Huang J, Yu H, Marin E, Brock S, Carden D, Davis T. Physicians’ weight loss counseling in two public hospital primary care clinics. Acad Med 2004; 79:156–161.

- American Diabetes Association. Create your plate. www.diabetes.org/food-and-fitness/food/planning-meals/create-your-plate. Accessed May 19, 2017.

- Serra-Majem L, Roman B, Estruch R. Scientific evidence of interventions using the Mediterranean diet: a systematic review. Nutr Rev 2006; 64:S27–S47.

- Pratt LA, Brody DJ. Depression and obesity in the US adult household population, 2005-2010. NCHS Data Brief 2014; 167:1–8.

- Gordon-Larsen P. Food availability/convenience and obesity. Adv Nutr 2014; 5:809–817.

- Malone M. Medications associated with weight gain. Ann Pharmacother 2005; 39:2046–2055.

- Patel D. Pharmacotherapy for the management of obesity. Metabolism 2015; 64:1376–1385.

- Guthrie GE, Bogue RJ. Impact of a shared medical appointment lifestyle intervention on weight and lipid parameters in individuals with type 2 diabetes: a clinical pilot. J Am Coll Nutr 2015; 34:300–309.