User login

Taming or teaching the tiger? Myths and management of childhood aggression

How to deal with aggression delivered by a child’s peers is a common concern and social dilemma for both parents and children. How does a child ward off aggressive peers without getting hurt or in trouble while also not looking weak or whiny? What can parents do to stop their child from being hurt or frightened but also not humiliate them or interfere with their learning important life skills by being over protective?

Children do not want to fight, but they do want to be treated fairly. Frustration, with its associated feelings of anger, is the most common reason for aggression. Being a child is certainly full of its frustrations because, while autonomy and desires are increasing, opportunities expand at a slower rate, particularly for children with developmental weaknesses or economic disadvantage. Fear and a lack of coping skills are other major reasons for resorting to aggressive responses.

Physical bullying affects 21% of students in grades 3-12 and is a risk factor for aggression at all ages. A full one-third of 9th-12th graders report having been in a physical fight in the last year. In grade school age and adolescence, factors known to be associated with peer aggression include the humiliation of school failure, substance use, and anger from experiencing parental or sibling aggression.

One would think a universal goal of parents would be to raise their children to get along with others without fighting. Unfortunately, some parents actually espouse childrearing methods that directly or indirectly make fighting more likely.

Essentially all toddlers and preschoolers can be aggressive at times to get things they want (instrumental) or when angry in the beginning of their second year of life; this peaks in the third year and typically declines after age 3 years. But for some 10% of children, aggression remains high. What parent and child factors set children up for such persistent aggression?

Parents have many reasons for how they raise their children, but some myths about parenting that persist promote aggression.

“My child will love me more if I am more permissive.”

Infants and toddlers develop self-regulation skills better when it is gradually expected of them with encouragement and support from their parents. Parents may feel that they are showing love to their toddler by having a “relaxed” home with few limits and no specific bedtime or rules. These parents also may “rescue” their child from frustrating situations by giving in to their demands or removing them from even mildly stressful situations.

These strategies can interfere with the progressive development of frustration tolerance, a key life skill. A lack of routines, inadequate sleep or food, overstimulation by noise, frightening experiences (including fighting in the home or neighborhood), or violent media exposure sets toddlers up to be out of control and thereby increases dysregulation. In addition, the dysregulated child may then act up, which can invoke punishment from that same parent.

Frustrating toddlers with inconsistent expectations and arbitrary punishment, a common result of low structure, makes the child feel insecure and leads to aggression. Instead, children need small doses of frustration appropriate to their age and encouragement from a supportive adult to problem solve. You can praise (or model), cheering on a child with words such as “Are you stuck? You can do it! Try again,” instead of instantly solving problems for them.

“Spare the rod and spoil the child.”

Parents may feel that they are promoting obedience when they use corporal punishment, thinking this will keep the child out of trouble in society. Instead, corporal punishment is associated with increased aggression toward peers, as well as defiance toward parents. These effects are especially strong when mothers are distant emotionally. As pediatricians, we can educate people on the importance of warm parenting, redirection instead of punishment for younger children, and using small, logical consequences or time out when needed for aggression.

“Just ignore bullies.”

It is a rare child who can follow the command to “ignore” a bully without turning red or getting tears in his or her eyes – making them appealing targets. We can coach parents and kids how to disarm bullies by standing tall, putting hands on hips, making eye contact, and asking the peer a question such as “I do not understand what you’re trying to accomplish.” Learning martial arts also teaches children that they are powerful (but not to fight outside the class) so they can present themselves in this way. Programs that encourage children to get together to confront bullies supported by a school administration that uses comprehensive assessment and habilitation strategies for aggressive students are most effective in reducing aggression in schools. Anonymous reporting (for example, by using a cell phone app, such as STOPit) empowers students to report bullying or fights to school staff without risking later retribution from the peer.

“Tough teachers help kids fall in line.”

While peer fights generally increase from 2nd to 4th grade before declining, student fighting progressively increases when teachers use reprimands, rather than praise, to manage their classes. Children look to teachers to learn more than what is in books – how to be respectful and in control without putting others down. The most effective classroom management includes clear, fair rules; any correction should be done privately to avoid shaming students. Students dealt with this way are less likely to be angry and take it out on others. Of course, appropriate services helping every child experience success in learning is the foundation of positive behavior in school.

“Children with ADHD won’t learn self-regulation if they are treated with medicine.”

Children who show “low effortful control” or higher “dysregulation” are both more aggressive and also less likely to decline in aggression in early childhood. ADHD is a neurological condition characterized by such dysregulation and low effortful control. Children with ADHD often have higher and more persistent aggression. These tendencies also result in impulsive behaviors that can irritate peers and adults and can result in correction and criticism, further increasing aggression. Children with ADHD who are better controlled, often with the help of medication, have more positive interactions at school and at home, receive more praise and less correction, and develop more reasoned interaction patterns.

“I am the parent, and my child should do what I say.”

When adults step in to stop a fight, they are rarely in a position to know what actually happened between the kids. Children may quickly learn how to entrap a sibling or peer to look like the perpetrator in order to get them in trouble and/or avoid consequences for themselves, especially if large or harsh punishments are being used.

While it can seem tricky to treat children who are very different in age or development equally, having parents elicit or at least verbalize each child’s point of view is part of how children learn respect and mediation skills. Parents who refrain from taking sides or dictating how disputes should be resolved leave the chance for the children to acquire these component skills of negotiation. This does not mean there are no consequences, just that a brief discussion comes first.

When fighting is a pediatric complaint, you have a great opportunity to educate families in evidence-based ways that can both prevent and reduce their child’s use of aggression.

In one effective 90-minute training program, parents were taught basic mediation principles: to give ground rules and ask their children to agree to them, to ask each child to describe what happened and identify their disagreements and common ground, to encourage the children to discuss their goals in the fight and feelings about the issues, and to encourage the children to come up with suggestions to resolve their disputes and help them assess the practical aspects of their ideas. Praise should be used each time a child uses even some of these skills. Parents in this program also were given communication strategies, such as active listening, reflecting, and reframing, to help children learn to take the others’ perspective. In a follow up survey a month later, children of parents in the intervention group were seen to use these skills in real situations that might otherwise have been fights.

When aggression persists, mindfulness training, cognitive-behavioral techniques, social-emotional approaches, or peer mentoring programs delivered through individual counseling or school programs are all ways of teaching kids important interaction skills to reduce peer aggression. Remember, 40% of severe adult aggression begins before age 8 years, so preventive education or early referral to mental health services is key.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News. E-mail her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

How to deal with aggression delivered by a child’s peers is a common concern and social dilemma for both parents and children. How does a child ward off aggressive peers without getting hurt or in trouble while also not looking weak or whiny? What can parents do to stop their child from being hurt or frightened but also not humiliate them or interfere with their learning important life skills by being over protective?

Children do not want to fight, but they do want to be treated fairly. Frustration, with its associated feelings of anger, is the most common reason for aggression. Being a child is certainly full of its frustrations because, while autonomy and desires are increasing, opportunities expand at a slower rate, particularly for children with developmental weaknesses or economic disadvantage. Fear and a lack of coping skills are other major reasons for resorting to aggressive responses.

Physical bullying affects 21% of students in grades 3-12 and is a risk factor for aggression at all ages. A full one-third of 9th-12th graders report having been in a physical fight in the last year. In grade school age and adolescence, factors known to be associated with peer aggression include the humiliation of school failure, substance use, and anger from experiencing parental or sibling aggression.

One would think a universal goal of parents would be to raise their children to get along with others without fighting. Unfortunately, some parents actually espouse childrearing methods that directly or indirectly make fighting more likely.

Essentially all toddlers and preschoolers can be aggressive at times to get things they want (instrumental) or when angry in the beginning of their second year of life; this peaks in the third year and typically declines after age 3 years. But for some 10% of children, aggression remains high. What parent and child factors set children up for such persistent aggression?

Parents have many reasons for how they raise their children, but some myths about parenting that persist promote aggression.

“My child will love me more if I am more permissive.”

Infants and toddlers develop self-regulation skills better when it is gradually expected of them with encouragement and support from their parents. Parents may feel that they are showing love to their toddler by having a “relaxed” home with few limits and no specific bedtime or rules. These parents also may “rescue” their child from frustrating situations by giving in to their demands or removing them from even mildly stressful situations.

These strategies can interfere with the progressive development of frustration tolerance, a key life skill. A lack of routines, inadequate sleep or food, overstimulation by noise, frightening experiences (including fighting in the home or neighborhood), or violent media exposure sets toddlers up to be out of control and thereby increases dysregulation. In addition, the dysregulated child may then act up, which can invoke punishment from that same parent.

Frustrating toddlers with inconsistent expectations and arbitrary punishment, a common result of low structure, makes the child feel insecure and leads to aggression. Instead, children need small doses of frustration appropriate to their age and encouragement from a supportive adult to problem solve. You can praise (or model), cheering on a child with words such as “Are you stuck? You can do it! Try again,” instead of instantly solving problems for them.

“Spare the rod and spoil the child.”

Parents may feel that they are promoting obedience when they use corporal punishment, thinking this will keep the child out of trouble in society. Instead, corporal punishment is associated with increased aggression toward peers, as well as defiance toward parents. These effects are especially strong when mothers are distant emotionally. As pediatricians, we can educate people on the importance of warm parenting, redirection instead of punishment for younger children, and using small, logical consequences or time out when needed for aggression.

“Just ignore bullies.”

It is a rare child who can follow the command to “ignore” a bully without turning red or getting tears in his or her eyes – making them appealing targets. We can coach parents and kids how to disarm bullies by standing tall, putting hands on hips, making eye contact, and asking the peer a question such as “I do not understand what you’re trying to accomplish.” Learning martial arts also teaches children that they are powerful (but not to fight outside the class) so they can present themselves in this way. Programs that encourage children to get together to confront bullies supported by a school administration that uses comprehensive assessment and habilitation strategies for aggressive students are most effective in reducing aggression in schools. Anonymous reporting (for example, by using a cell phone app, such as STOPit) empowers students to report bullying or fights to school staff without risking later retribution from the peer.

“Tough teachers help kids fall in line.”

While peer fights generally increase from 2nd to 4th grade before declining, student fighting progressively increases when teachers use reprimands, rather than praise, to manage their classes. Children look to teachers to learn more than what is in books – how to be respectful and in control without putting others down. The most effective classroom management includes clear, fair rules; any correction should be done privately to avoid shaming students. Students dealt with this way are less likely to be angry and take it out on others. Of course, appropriate services helping every child experience success in learning is the foundation of positive behavior in school.

“Children with ADHD won’t learn self-regulation if they are treated with medicine.”

Children who show “low effortful control” or higher “dysregulation” are both more aggressive and also less likely to decline in aggression in early childhood. ADHD is a neurological condition characterized by such dysregulation and low effortful control. Children with ADHD often have higher and more persistent aggression. These tendencies also result in impulsive behaviors that can irritate peers and adults and can result in correction and criticism, further increasing aggression. Children with ADHD who are better controlled, often with the help of medication, have more positive interactions at school and at home, receive more praise and less correction, and develop more reasoned interaction patterns.

“I am the parent, and my child should do what I say.”

When adults step in to stop a fight, they are rarely in a position to know what actually happened between the kids. Children may quickly learn how to entrap a sibling or peer to look like the perpetrator in order to get them in trouble and/or avoid consequences for themselves, especially if large or harsh punishments are being used.

While it can seem tricky to treat children who are very different in age or development equally, having parents elicit or at least verbalize each child’s point of view is part of how children learn respect and mediation skills. Parents who refrain from taking sides or dictating how disputes should be resolved leave the chance for the children to acquire these component skills of negotiation. This does not mean there are no consequences, just that a brief discussion comes first.

When fighting is a pediatric complaint, you have a great opportunity to educate families in evidence-based ways that can both prevent and reduce their child’s use of aggression.

In one effective 90-minute training program, parents were taught basic mediation principles: to give ground rules and ask their children to agree to them, to ask each child to describe what happened and identify their disagreements and common ground, to encourage the children to discuss their goals in the fight and feelings about the issues, and to encourage the children to come up with suggestions to resolve their disputes and help them assess the practical aspects of their ideas. Praise should be used each time a child uses even some of these skills. Parents in this program also were given communication strategies, such as active listening, reflecting, and reframing, to help children learn to take the others’ perspective. In a follow up survey a month later, children of parents in the intervention group were seen to use these skills in real situations that might otherwise have been fights.

When aggression persists, mindfulness training, cognitive-behavioral techniques, social-emotional approaches, or peer mentoring programs delivered through individual counseling or school programs are all ways of teaching kids important interaction skills to reduce peer aggression. Remember, 40% of severe adult aggression begins before age 8 years, so preventive education or early referral to mental health services is key.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News. E-mail her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

How to deal with aggression delivered by a child’s peers is a common concern and social dilemma for both parents and children. How does a child ward off aggressive peers without getting hurt or in trouble while also not looking weak or whiny? What can parents do to stop their child from being hurt or frightened but also not humiliate them or interfere with their learning important life skills by being over protective?

Children do not want to fight, but they do want to be treated fairly. Frustration, with its associated feelings of anger, is the most common reason for aggression. Being a child is certainly full of its frustrations because, while autonomy and desires are increasing, opportunities expand at a slower rate, particularly for children with developmental weaknesses or economic disadvantage. Fear and a lack of coping skills are other major reasons for resorting to aggressive responses.

Physical bullying affects 21% of students in grades 3-12 and is a risk factor for aggression at all ages. A full one-third of 9th-12th graders report having been in a physical fight in the last year. In grade school age and adolescence, factors known to be associated with peer aggression include the humiliation of school failure, substance use, and anger from experiencing parental or sibling aggression.

One would think a universal goal of parents would be to raise their children to get along with others without fighting. Unfortunately, some parents actually espouse childrearing methods that directly or indirectly make fighting more likely.

Essentially all toddlers and preschoolers can be aggressive at times to get things they want (instrumental) or when angry in the beginning of their second year of life; this peaks in the third year and typically declines after age 3 years. But for some 10% of children, aggression remains high. What parent and child factors set children up for such persistent aggression?

Parents have many reasons for how they raise their children, but some myths about parenting that persist promote aggression.

“My child will love me more if I am more permissive.”

Infants and toddlers develop self-regulation skills better when it is gradually expected of them with encouragement and support from their parents. Parents may feel that they are showing love to their toddler by having a “relaxed” home with few limits and no specific bedtime or rules. These parents also may “rescue” their child from frustrating situations by giving in to their demands or removing them from even mildly stressful situations.

These strategies can interfere with the progressive development of frustration tolerance, a key life skill. A lack of routines, inadequate sleep or food, overstimulation by noise, frightening experiences (including fighting in the home or neighborhood), or violent media exposure sets toddlers up to be out of control and thereby increases dysregulation. In addition, the dysregulated child may then act up, which can invoke punishment from that same parent.

Frustrating toddlers with inconsistent expectations and arbitrary punishment, a common result of low structure, makes the child feel insecure and leads to aggression. Instead, children need small doses of frustration appropriate to their age and encouragement from a supportive adult to problem solve. You can praise (or model), cheering on a child with words such as “Are you stuck? You can do it! Try again,” instead of instantly solving problems for them.

“Spare the rod and spoil the child.”

Parents may feel that they are promoting obedience when they use corporal punishment, thinking this will keep the child out of trouble in society. Instead, corporal punishment is associated with increased aggression toward peers, as well as defiance toward parents. These effects are especially strong when mothers are distant emotionally. As pediatricians, we can educate people on the importance of warm parenting, redirection instead of punishment for younger children, and using small, logical consequences or time out when needed for aggression.

“Just ignore bullies.”

It is a rare child who can follow the command to “ignore” a bully without turning red or getting tears in his or her eyes – making them appealing targets. We can coach parents and kids how to disarm bullies by standing tall, putting hands on hips, making eye contact, and asking the peer a question such as “I do not understand what you’re trying to accomplish.” Learning martial arts also teaches children that they are powerful (but not to fight outside the class) so they can present themselves in this way. Programs that encourage children to get together to confront bullies supported by a school administration that uses comprehensive assessment and habilitation strategies for aggressive students are most effective in reducing aggression in schools. Anonymous reporting (for example, by using a cell phone app, such as STOPit) empowers students to report bullying or fights to school staff without risking later retribution from the peer.

“Tough teachers help kids fall in line.”

While peer fights generally increase from 2nd to 4th grade before declining, student fighting progressively increases when teachers use reprimands, rather than praise, to manage their classes. Children look to teachers to learn more than what is in books – how to be respectful and in control without putting others down. The most effective classroom management includes clear, fair rules; any correction should be done privately to avoid shaming students. Students dealt with this way are less likely to be angry and take it out on others. Of course, appropriate services helping every child experience success in learning is the foundation of positive behavior in school.

“Children with ADHD won’t learn self-regulation if they are treated with medicine.”

Children who show “low effortful control” or higher “dysregulation” are both more aggressive and also less likely to decline in aggression in early childhood. ADHD is a neurological condition characterized by such dysregulation and low effortful control. Children with ADHD often have higher and more persistent aggression. These tendencies also result in impulsive behaviors that can irritate peers and adults and can result in correction and criticism, further increasing aggression. Children with ADHD who are better controlled, often with the help of medication, have more positive interactions at school and at home, receive more praise and less correction, and develop more reasoned interaction patterns.

“I am the parent, and my child should do what I say.”

When adults step in to stop a fight, they are rarely in a position to know what actually happened between the kids. Children may quickly learn how to entrap a sibling or peer to look like the perpetrator in order to get them in trouble and/or avoid consequences for themselves, especially if large or harsh punishments are being used.

While it can seem tricky to treat children who are very different in age or development equally, having parents elicit or at least verbalize each child’s point of view is part of how children learn respect and mediation skills. Parents who refrain from taking sides or dictating how disputes should be resolved leave the chance for the children to acquire these component skills of negotiation. This does not mean there are no consequences, just that a brief discussion comes first.

When fighting is a pediatric complaint, you have a great opportunity to educate families in evidence-based ways that can both prevent and reduce their child’s use of aggression.

In one effective 90-minute training program, parents were taught basic mediation principles: to give ground rules and ask their children to agree to them, to ask each child to describe what happened and identify their disagreements and common ground, to encourage the children to discuss their goals in the fight and feelings about the issues, and to encourage the children to come up with suggestions to resolve their disputes and help them assess the practical aspects of their ideas. Praise should be used each time a child uses even some of these skills. Parents in this program also were given communication strategies, such as active listening, reflecting, and reframing, to help children learn to take the others’ perspective. In a follow up survey a month later, children of parents in the intervention group were seen to use these skills in real situations that might otherwise have been fights.

When aggression persists, mindfulness training, cognitive-behavioral techniques, social-emotional approaches, or peer mentoring programs delivered through individual counseling or school programs are all ways of teaching kids important interaction skills to reduce peer aggression. Remember, 40% of severe adult aggression begins before age 8 years, so preventive education or early referral to mental health services is key.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News. E-mail her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Sleepless in adolescence

One thing that constantly surprises me about adolescent sleep is that neither the teen nor the parent is as concerned about it as I am. Instead, they complain about irritability, dropping grades, anxiety, depression, obesity, oppositionality, fatigue, and even substance use – all documented effects of sleep debt.

Inadequate sleep changes the brain, resulting in thinner gray matter, less neuroplasticity, poorer higher-level cognitive abilities (attention, working memory, inhibition, judgment, decision-making), lower motivation, and poorer academic functioning. None of these are losses teens can afford!

While sleep problems are more common in those with mental health disorders, poor sleep precedes anxiety and depression more than the reverse. Sleep problems increase the risk of depression, and depression relapses. Insomnia predicts risk behaviors – drinking and driving, smoking, delinquency. Getting less than 8 hours of sleep is associated with a threefold higher risk of suicide attempts.

Despite these pervasive threats to health and development, instead of concern, I find a lot of resistance in families and teens to taking action to improve sleep.

Teens don’t believe in problems from inadequate sleep. After all, they say, their peers are “all” getting the same amount of sleep. And they are largely correct – 75% of U.S. 12th graders get less than 8 hours of sleep. But the data are clear that children aged 12-18 years need 8.25-9.25 hours of sleep.

Parents generally are not aware of how little sleep their teens are getting because they go to bed on their own. If parents do check, any teenagers worth the label can growl their way out of supervision, “promise” to shut off the lights, or feign sleep. Having the house, pantry, and electronics to themselves at night is worth the risk of a consequence, especially for those who would rather avoid interacting.

The social forces keeping teens up at night are their “life”: the hours required for homework can be the reason for inadequate sleep. In subgroups of teens, sports practices, employment, or family responsibilities may extend the day past a bedtime needed for optimal sleep.

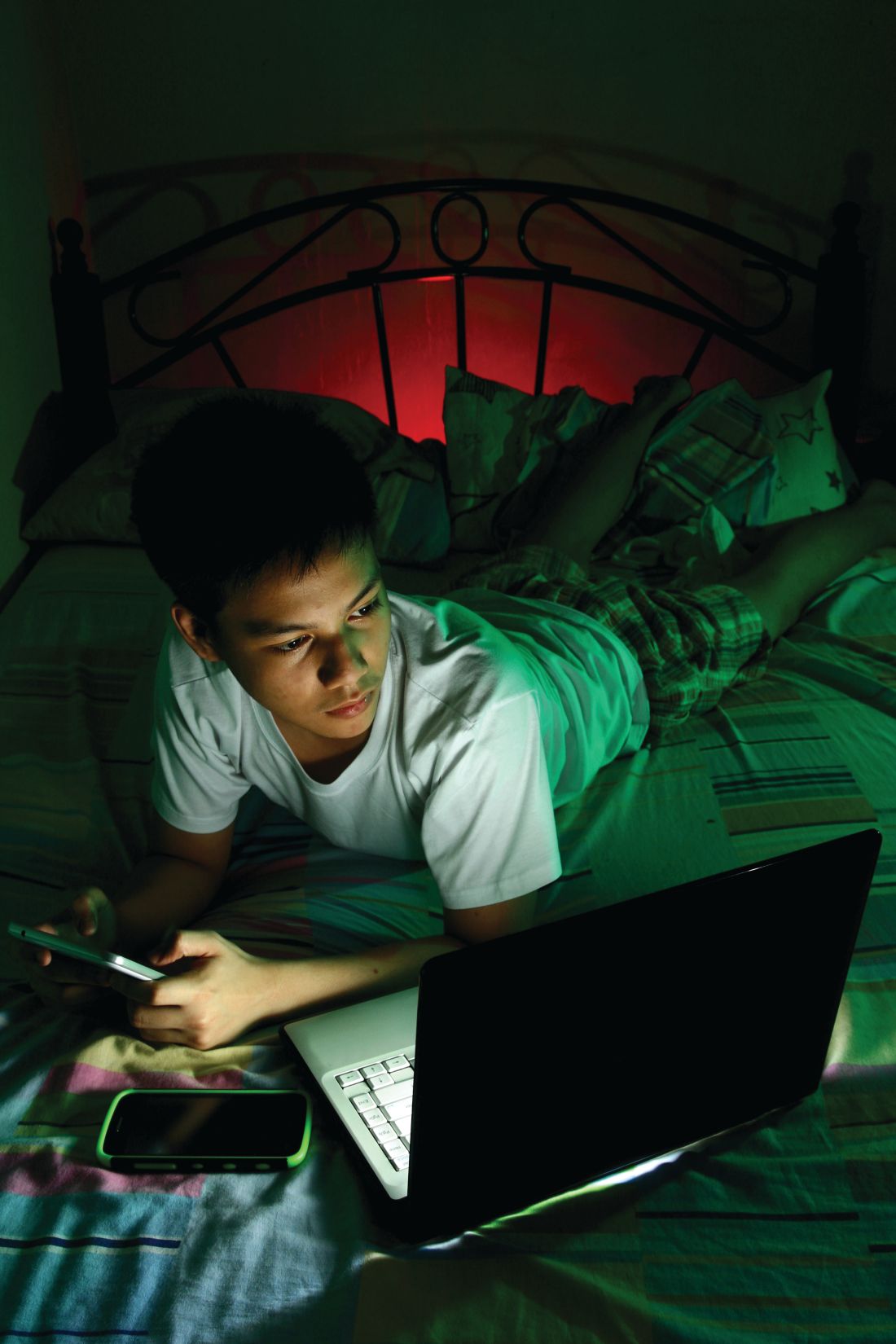

But use of electronics – the lifeline of adolescents – is responsible for much of their sleep debt. Electronic devices both delay sleep onset and reduce sleep duration. After 9:00 p.m., 34% of children aged older than 12 years are text messaging, 44% are talking, 55% are online, and 24% are playing computer games. Use of a TV or tablet at bedtime results in reduced sleep, and increased poor quality of sleep. Three or more hours of TV result not only in difficulty falling asleep and frequent awakenings, but also sleep issues later as adults. Shooter video games result in lower sleepiness, longer sleep latency, and shorter REM sleep. Even the low level light from electronic devices alters circadian rhythm and suppresses nocturnal melatonin secretion.

Keep in mind the biological reasons teens go to bed later. One is the typical emotional hyperarousal of being a teen. But other biological forces are at work in adolescence, such as reduction in the accumulation of sleep pressure during wakefulness and delaying the melatonin release that produces sleepiness. Teens (and parents) think sleeping in on weekends takes care of inadequate weekday sleep, but this so-called “recovery sleep” tends to occur at an inappropriate time in the circadian phase and further delays melatonin production, as well as reducing sleep pressure, making it even harder to fall asleep.

In some cases, medications we prescribe – such as stimulants, theophylline, antihistamines, or anticonvulsants – are at fault for delaying or disturbing sleep. But more often it is self-administered substances that are part of the teen’s attempt to stay awake – including nicotine, alcohol, and caffeine – that produce shorter sleep duration, increased latency to sleep, more wake time during sleep, and increased daytime sleepiness; it results in a vicious cycle. Sleep disruption may explain the association of these substances with less memory consolidation, poorer academic performance, and higher rates of risk behaviors.

We adults also are a cause of teen sleep debt. We are the ones allowing the early school start times for teens, primarily to allow for after school sports programs that glorify the school and bring kudos to some at the expense of all the students. A 65-minute earlier start in 10th grade resulted in less than half of students getting 7 hours of sleep or more. The level of resulting sleepiness is equal to that of narcolepsy.

As primary care clinicians, we can and need to detect, educate about, and treat sleep debt and sleep disorders. Sleep questionnaires can help. Treatment of sleep includes coaching for: having a cool, dark room used mainly for sleep; a regular schedule 7 days per week; avoiding exercise within 2 hours of bedtime; avoiding stimulants such as caffeine, tea, nicotine, and medications at least 3 hours before bedtime; keeping to a routine with no daytime naps; and especially no media in the bedroom! For teens already not able to sleep until early morning, you can recommend that they work bedtime back or forward by 1 hour per day until hitting a time that will allow 9 hours of sleep. Alternatively, have them stay up all night to reset their biological clock. Subsequently, the sleep schedule has to stay within 1 hour for sleep and waking 7 days per week. Anxious teens, besides needing therapy, may need a soothing routine, no visible clock, and a plan to get back up for 1 hour every time it takes longer than 10 minutes to fall asleep.

If sleepy teens report adequate time in bed, then we need to understand pathologies such as obstructive sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, menstruation-related or primary hypersomnias, and narcolepsy to diagnose and resolve the problem.

Parents may have given up protecting their teens from inadequate sleep so we as health providers need to do so.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News. E-mail her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

One thing that constantly surprises me about adolescent sleep is that neither the teen nor the parent is as concerned about it as I am. Instead, they complain about irritability, dropping grades, anxiety, depression, obesity, oppositionality, fatigue, and even substance use – all documented effects of sleep debt.

Inadequate sleep changes the brain, resulting in thinner gray matter, less neuroplasticity, poorer higher-level cognitive abilities (attention, working memory, inhibition, judgment, decision-making), lower motivation, and poorer academic functioning. None of these are losses teens can afford!

While sleep problems are more common in those with mental health disorders, poor sleep precedes anxiety and depression more than the reverse. Sleep problems increase the risk of depression, and depression relapses. Insomnia predicts risk behaviors – drinking and driving, smoking, delinquency. Getting less than 8 hours of sleep is associated with a threefold higher risk of suicide attempts.

Despite these pervasive threats to health and development, instead of concern, I find a lot of resistance in families and teens to taking action to improve sleep.

Teens don’t believe in problems from inadequate sleep. After all, they say, their peers are “all” getting the same amount of sleep. And they are largely correct – 75% of U.S. 12th graders get less than 8 hours of sleep. But the data are clear that children aged 12-18 years need 8.25-9.25 hours of sleep.

Parents generally are not aware of how little sleep their teens are getting because they go to bed on their own. If parents do check, any teenagers worth the label can growl their way out of supervision, “promise” to shut off the lights, or feign sleep. Having the house, pantry, and electronics to themselves at night is worth the risk of a consequence, especially for those who would rather avoid interacting.

The social forces keeping teens up at night are their “life”: the hours required for homework can be the reason for inadequate sleep. In subgroups of teens, sports practices, employment, or family responsibilities may extend the day past a bedtime needed for optimal sleep.

But use of electronics – the lifeline of adolescents – is responsible for much of their sleep debt. Electronic devices both delay sleep onset and reduce sleep duration. After 9:00 p.m., 34% of children aged older than 12 years are text messaging, 44% are talking, 55% are online, and 24% are playing computer games. Use of a TV or tablet at bedtime results in reduced sleep, and increased poor quality of sleep. Three or more hours of TV result not only in difficulty falling asleep and frequent awakenings, but also sleep issues later as adults. Shooter video games result in lower sleepiness, longer sleep latency, and shorter REM sleep. Even the low level light from electronic devices alters circadian rhythm and suppresses nocturnal melatonin secretion.

Keep in mind the biological reasons teens go to bed later. One is the typical emotional hyperarousal of being a teen. But other biological forces are at work in adolescence, such as reduction in the accumulation of sleep pressure during wakefulness and delaying the melatonin release that produces sleepiness. Teens (and parents) think sleeping in on weekends takes care of inadequate weekday sleep, but this so-called “recovery sleep” tends to occur at an inappropriate time in the circadian phase and further delays melatonin production, as well as reducing sleep pressure, making it even harder to fall asleep.

In some cases, medications we prescribe – such as stimulants, theophylline, antihistamines, or anticonvulsants – are at fault for delaying or disturbing sleep. But more often it is self-administered substances that are part of the teen’s attempt to stay awake – including nicotine, alcohol, and caffeine – that produce shorter sleep duration, increased latency to sleep, more wake time during sleep, and increased daytime sleepiness; it results in a vicious cycle. Sleep disruption may explain the association of these substances with less memory consolidation, poorer academic performance, and higher rates of risk behaviors.

We adults also are a cause of teen sleep debt. We are the ones allowing the early school start times for teens, primarily to allow for after school sports programs that glorify the school and bring kudos to some at the expense of all the students. A 65-minute earlier start in 10th grade resulted in less than half of students getting 7 hours of sleep or more. The level of resulting sleepiness is equal to that of narcolepsy.

As primary care clinicians, we can and need to detect, educate about, and treat sleep debt and sleep disorders. Sleep questionnaires can help. Treatment of sleep includes coaching for: having a cool, dark room used mainly for sleep; a regular schedule 7 days per week; avoiding exercise within 2 hours of bedtime; avoiding stimulants such as caffeine, tea, nicotine, and medications at least 3 hours before bedtime; keeping to a routine with no daytime naps; and especially no media in the bedroom! For teens already not able to sleep until early morning, you can recommend that they work bedtime back or forward by 1 hour per day until hitting a time that will allow 9 hours of sleep. Alternatively, have them stay up all night to reset their biological clock. Subsequently, the sleep schedule has to stay within 1 hour for sleep and waking 7 days per week. Anxious teens, besides needing therapy, may need a soothing routine, no visible clock, and a plan to get back up for 1 hour every time it takes longer than 10 minutes to fall asleep.

If sleepy teens report adequate time in bed, then we need to understand pathologies such as obstructive sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, menstruation-related or primary hypersomnias, and narcolepsy to diagnose and resolve the problem.

Parents may have given up protecting their teens from inadequate sleep so we as health providers need to do so.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News. E-mail her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

One thing that constantly surprises me about adolescent sleep is that neither the teen nor the parent is as concerned about it as I am. Instead, they complain about irritability, dropping grades, anxiety, depression, obesity, oppositionality, fatigue, and even substance use – all documented effects of sleep debt.

Inadequate sleep changes the brain, resulting in thinner gray matter, less neuroplasticity, poorer higher-level cognitive abilities (attention, working memory, inhibition, judgment, decision-making), lower motivation, and poorer academic functioning. None of these are losses teens can afford!

While sleep problems are more common in those with mental health disorders, poor sleep precedes anxiety and depression more than the reverse. Sleep problems increase the risk of depression, and depression relapses. Insomnia predicts risk behaviors – drinking and driving, smoking, delinquency. Getting less than 8 hours of sleep is associated with a threefold higher risk of suicide attempts.

Despite these pervasive threats to health and development, instead of concern, I find a lot of resistance in families and teens to taking action to improve sleep.

Teens don’t believe in problems from inadequate sleep. After all, they say, their peers are “all” getting the same amount of sleep. And they are largely correct – 75% of U.S. 12th graders get less than 8 hours of sleep. But the data are clear that children aged 12-18 years need 8.25-9.25 hours of sleep.

Parents generally are not aware of how little sleep their teens are getting because they go to bed on their own. If parents do check, any teenagers worth the label can growl their way out of supervision, “promise” to shut off the lights, or feign sleep. Having the house, pantry, and electronics to themselves at night is worth the risk of a consequence, especially for those who would rather avoid interacting.

The social forces keeping teens up at night are their “life”: the hours required for homework can be the reason for inadequate sleep. In subgroups of teens, sports practices, employment, or family responsibilities may extend the day past a bedtime needed for optimal sleep.

But use of electronics – the lifeline of adolescents – is responsible for much of their sleep debt. Electronic devices both delay sleep onset and reduce sleep duration. After 9:00 p.m., 34% of children aged older than 12 years are text messaging, 44% are talking, 55% are online, and 24% are playing computer games. Use of a TV or tablet at bedtime results in reduced sleep, and increased poor quality of sleep. Three or more hours of TV result not only in difficulty falling asleep and frequent awakenings, but also sleep issues later as adults. Shooter video games result in lower sleepiness, longer sleep latency, and shorter REM sleep. Even the low level light from electronic devices alters circadian rhythm and suppresses nocturnal melatonin secretion.

Keep in mind the biological reasons teens go to bed later. One is the typical emotional hyperarousal of being a teen. But other biological forces are at work in adolescence, such as reduction in the accumulation of sleep pressure during wakefulness and delaying the melatonin release that produces sleepiness. Teens (and parents) think sleeping in on weekends takes care of inadequate weekday sleep, but this so-called “recovery sleep” tends to occur at an inappropriate time in the circadian phase and further delays melatonin production, as well as reducing sleep pressure, making it even harder to fall asleep.

In some cases, medications we prescribe – such as stimulants, theophylline, antihistamines, or anticonvulsants – are at fault for delaying or disturbing sleep. But more often it is self-administered substances that are part of the teen’s attempt to stay awake – including nicotine, alcohol, and caffeine – that produce shorter sleep duration, increased latency to sleep, more wake time during sleep, and increased daytime sleepiness; it results in a vicious cycle. Sleep disruption may explain the association of these substances with less memory consolidation, poorer academic performance, and higher rates of risk behaviors.

We adults also are a cause of teen sleep debt. We are the ones allowing the early school start times for teens, primarily to allow for after school sports programs that glorify the school and bring kudos to some at the expense of all the students. A 65-minute earlier start in 10th grade resulted in less than half of students getting 7 hours of sleep or more. The level of resulting sleepiness is equal to that of narcolepsy.

As primary care clinicians, we can and need to detect, educate about, and treat sleep debt and sleep disorders. Sleep questionnaires can help. Treatment of sleep includes coaching for: having a cool, dark room used mainly for sleep; a regular schedule 7 days per week; avoiding exercise within 2 hours of bedtime; avoiding stimulants such as caffeine, tea, nicotine, and medications at least 3 hours before bedtime; keeping to a routine with no daytime naps; and especially no media in the bedroom! For teens already not able to sleep until early morning, you can recommend that they work bedtime back or forward by 1 hour per day until hitting a time that will allow 9 hours of sleep. Alternatively, have them stay up all night to reset their biological clock. Subsequently, the sleep schedule has to stay within 1 hour for sleep and waking 7 days per week. Anxious teens, besides needing therapy, may need a soothing routine, no visible clock, and a plan to get back up for 1 hour every time it takes longer than 10 minutes to fall asleep.

If sleepy teens report adequate time in bed, then we need to understand pathologies such as obstructive sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, menstruation-related or primary hypersomnias, and narcolepsy to diagnose and resolve the problem.

Parents may have given up protecting their teens from inadequate sleep so we as health providers need to do so.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News. E-mail her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

You can help with behavior of children with autism spectrum disorder

There are lots of reasons you may be eager to refer children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) to specialty agencies. You want the fastest possible entry for the child into intervention and the families into a support system. , as well as the general health care, of their children.

“Wait!” you say, “I do not have the special knowledge to help with behavior of children with autism! There is much you can and should do, however, as the specialist(s) may not provide such guidance, entry into behavioral services may take months, and behavior issues may feel urgent to families.

So pick an example of a behavior that is concerning to the family. One problem might be lack of cooperation with activities of daily living such as eating. In this case, the A is being asked to stop playing and sit at the table; the B may be refusing to eat what is served or even to sit very long, ending in a tantrum that disrupts the family meal; and the C could be the child being sent from the table to play on their iPad. But what is the G?

Lack of social communication skills, restrictive interests, hypersensitivity, lack of coordination, and ADHD all may be playing a role. Lack of communication skills makes the social aspect of meals uninteresting. Giving verbal reasons for joining the family may not be effective. Hypersensitivity often is associated with extremes of food selectivity. Lack of fine motor coordination makes eating soup a challenge. And ADHD makes sitting for a long time difficult!

But what about that tantrum? Tantrums that are reinforced by allowing the child to leave and play on the iPad easily can turn into a chronic escape mechanism. Instead, parents need to watch for increasing restlessness, and allow the child to signal “all done” and be “excused” before any tantrum begins. Use of the iPad (a reward) should not be allowed until the family meal is over for everyone. Such accommodations are best decided on by all caregivers in advance, ideally also involving the higher-functioning child. A caregiver who persists in thinking that the child “should” be able to behave may be in denial or grief, and deserves counseling on ASD.

But he is so rigid, the parents say! The tendency of children with ASD to like sameness can be an asset to easing behavior. The key is to design and stick to routines as much as possible, 7 days per week. If the meal is at the same time each day, in the same seat, with the same plate, with no iPad, and the child is allowed to leave only after requesting to, the entire sequence is likely to be smoother. While flexibility does not come easily, it is acquired from the natural variability in family life, but only gradually and over time.

Creating and rehearsing “social stories” is an evidence-based way to help children with ASD have acceptable behaviors. Books, storyboards, and visual schedulers can be purchased to help. But even taking photos or a video of the components of a task and posting this online (private YouTube channel) or on the refrigerator, to review before, during, and/or after the activity, builds an internal image for the child. Children with ASD often watch the same YouTube videos over and over again, and even memorize and use chunks of the speech or songs at other times. Families can capitalize on this kind of repetition by using routines and songs to improve skills.

What to do when she only cares about her iPad? It is sometimes difficult to identify reinforcers to use to strengthen desired behaviors in a child with ASD. A smile or a hug or even candy may not be valued. Help parents think about an object, song, or touch the child tends to like. Media are a strong reinforcer, but need to be used sparingly, in specific situations, and kept under parental control, or else removing them can become a major source of upsets.

When a child with ASD gets upset or even violent, the behavior may be interpreted as defiance; it may scare or upset the whole family, and is not conducive to problem solving. Siblings may start screaming or begging for the parents to stop the behavior. While this creates a crisis, you can advise parents to first ensure that everyone is safe, take deep breaths, and then think about which gap is being stressed. A subtle change from what the child expected – new furniture, a guest at the table, a day off from school, or being interrupted mid video – can cause panic, especially for anxious children. Children with ASD also may act up when uncomfortable from a headache, tooth pain, constipation, hunger, or lack of sleep, but often are unable to vocalize the reason, even if they are verbal. Having parents make a few notes about the As, Bs, Cs, and Gs of each event (the essence of a functional behavioral assessment) to review with the child, each other, the teacher, or you is key to understanding the child with ASD and successfully shifting his behavior.

Dr. Howard is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News.

There are lots of reasons you may be eager to refer children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) to specialty agencies. You want the fastest possible entry for the child into intervention and the families into a support system. , as well as the general health care, of their children.

“Wait!” you say, “I do not have the special knowledge to help with behavior of children with autism! There is much you can and should do, however, as the specialist(s) may not provide such guidance, entry into behavioral services may take months, and behavior issues may feel urgent to families.

So pick an example of a behavior that is concerning to the family. One problem might be lack of cooperation with activities of daily living such as eating. In this case, the A is being asked to stop playing and sit at the table; the B may be refusing to eat what is served or even to sit very long, ending in a tantrum that disrupts the family meal; and the C could be the child being sent from the table to play on their iPad. But what is the G?

Lack of social communication skills, restrictive interests, hypersensitivity, lack of coordination, and ADHD all may be playing a role. Lack of communication skills makes the social aspect of meals uninteresting. Giving verbal reasons for joining the family may not be effective. Hypersensitivity often is associated with extremes of food selectivity. Lack of fine motor coordination makes eating soup a challenge. And ADHD makes sitting for a long time difficult!

But what about that tantrum? Tantrums that are reinforced by allowing the child to leave and play on the iPad easily can turn into a chronic escape mechanism. Instead, parents need to watch for increasing restlessness, and allow the child to signal “all done” and be “excused” before any tantrum begins. Use of the iPad (a reward) should not be allowed until the family meal is over for everyone. Such accommodations are best decided on by all caregivers in advance, ideally also involving the higher-functioning child. A caregiver who persists in thinking that the child “should” be able to behave may be in denial or grief, and deserves counseling on ASD.

But he is so rigid, the parents say! The tendency of children with ASD to like sameness can be an asset to easing behavior. The key is to design and stick to routines as much as possible, 7 days per week. If the meal is at the same time each day, in the same seat, with the same plate, with no iPad, and the child is allowed to leave only after requesting to, the entire sequence is likely to be smoother. While flexibility does not come easily, it is acquired from the natural variability in family life, but only gradually and over time.

Creating and rehearsing “social stories” is an evidence-based way to help children with ASD have acceptable behaviors. Books, storyboards, and visual schedulers can be purchased to help. But even taking photos or a video of the components of a task and posting this online (private YouTube channel) or on the refrigerator, to review before, during, and/or after the activity, builds an internal image for the child. Children with ASD often watch the same YouTube videos over and over again, and even memorize and use chunks of the speech or songs at other times. Families can capitalize on this kind of repetition by using routines and songs to improve skills.

What to do when she only cares about her iPad? It is sometimes difficult to identify reinforcers to use to strengthen desired behaviors in a child with ASD. A smile or a hug or even candy may not be valued. Help parents think about an object, song, or touch the child tends to like. Media are a strong reinforcer, but need to be used sparingly, in specific situations, and kept under parental control, or else removing them can become a major source of upsets.

When a child with ASD gets upset or even violent, the behavior may be interpreted as defiance; it may scare or upset the whole family, and is not conducive to problem solving. Siblings may start screaming or begging for the parents to stop the behavior. While this creates a crisis, you can advise parents to first ensure that everyone is safe, take deep breaths, and then think about which gap is being stressed. A subtle change from what the child expected – new furniture, a guest at the table, a day off from school, or being interrupted mid video – can cause panic, especially for anxious children. Children with ASD also may act up when uncomfortable from a headache, tooth pain, constipation, hunger, or lack of sleep, but often are unable to vocalize the reason, even if they are verbal. Having parents make a few notes about the As, Bs, Cs, and Gs of each event (the essence of a functional behavioral assessment) to review with the child, each other, the teacher, or you is key to understanding the child with ASD and successfully shifting his behavior.

Dr. Howard is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News.

There are lots of reasons you may be eager to refer children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) to specialty agencies. You want the fastest possible entry for the child into intervention and the families into a support system. , as well as the general health care, of their children.

“Wait!” you say, “I do not have the special knowledge to help with behavior of children with autism! There is much you can and should do, however, as the specialist(s) may not provide such guidance, entry into behavioral services may take months, and behavior issues may feel urgent to families.

So pick an example of a behavior that is concerning to the family. One problem might be lack of cooperation with activities of daily living such as eating. In this case, the A is being asked to stop playing and sit at the table; the B may be refusing to eat what is served or even to sit very long, ending in a tantrum that disrupts the family meal; and the C could be the child being sent from the table to play on their iPad. But what is the G?

Lack of social communication skills, restrictive interests, hypersensitivity, lack of coordination, and ADHD all may be playing a role. Lack of communication skills makes the social aspect of meals uninteresting. Giving verbal reasons for joining the family may not be effective. Hypersensitivity often is associated with extremes of food selectivity. Lack of fine motor coordination makes eating soup a challenge. And ADHD makes sitting for a long time difficult!

But what about that tantrum? Tantrums that are reinforced by allowing the child to leave and play on the iPad easily can turn into a chronic escape mechanism. Instead, parents need to watch for increasing restlessness, and allow the child to signal “all done” and be “excused” before any tantrum begins. Use of the iPad (a reward) should not be allowed until the family meal is over for everyone. Such accommodations are best decided on by all caregivers in advance, ideally also involving the higher-functioning child. A caregiver who persists in thinking that the child “should” be able to behave may be in denial or grief, and deserves counseling on ASD.

But he is so rigid, the parents say! The tendency of children with ASD to like sameness can be an asset to easing behavior. The key is to design and stick to routines as much as possible, 7 days per week. If the meal is at the same time each day, in the same seat, with the same plate, with no iPad, and the child is allowed to leave only after requesting to, the entire sequence is likely to be smoother. While flexibility does not come easily, it is acquired from the natural variability in family life, but only gradually and over time.

Creating and rehearsing “social stories” is an evidence-based way to help children with ASD have acceptable behaviors. Books, storyboards, and visual schedulers can be purchased to help. But even taking photos or a video of the components of a task and posting this online (private YouTube channel) or on the refrigerator, to review before, during, and/or after the activity, builds an internal image for the child. Children with ASD often watch the same YouTube videos over and over again, and even memorize and use chunks of the speech or songs at other times. Families can capitalize on this kind of repetition by using routines and songs to improve skills.

What to do when she only cares about her iPad? It is sometimes difficult to identify reinforcers to use to strengthen desired behaviors in a child with ASD. A smile or a hug or even candy may not be valued. Help parents think about an object, song, or touch the child tends to like. Media are a strong reinforcer, but need to be used sparingly, in specific situations, and kept under parental control, or else removing them can become a major source of upsets.

When a child with ASD gets upset or even violent, the behavior may be interpreted as defiance; it may scare or upset the whole family, and is not conducive to problem solving. Siblings may start screaming or begging for the parents to stop the behavior. While this creates a crisis, you can advise parents to first ensure that everyone is safe, take deep breaths, and then think about which gap is being stressed. A subtle change from what the child expected – new furniture, a guest at the table, a day off from school, or being interrupted mid video – can cause panic, especially for anxious children. Children with ASD also may act up when uncomfortable from a headache, tooth pain, constipation, hunger, or lack of sleep, but often are unable to vocalize the reason, even if they are verbal. Having parents make a few notes about the As, Bs, Cs, and Gs of each event (the essence of a functional behavioral assessment) to review with the child, each other, the teacher, or you is key to understanding the child with ASD and successfully shifting his behavior.

Dr. Howard is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News.

Mindfulness and child health

If you are struggling to figure out how you, as an individual pediatrician, can make a significant impact on the most common current issues in child health of anxiety, depression, sleep problems, stress, and even adverse childhood experiences, you are not alone. Many of the problems we see in the office appear to stem so much from the culture in which we live that the medical interventions we have to offer seem paltry. Yet we strive to identify and attempt to ameliorate the child’s and family’s distress.

Real physical danger aside, a lot of personal distress is due to negative thoughts about one’s past or fears for one’s future. These thoughts are very important in restraining us from repeating mistakes and preparing us for action to prevent future harm. But the thoughts themselves can be stressful; they may paralyze us with anxiety, take away pleasure, interrupt our sleep, stimulate physiologic stress responses, and have adverse impacts on health. All these effects can occur without actually changing the course of events! How can we advise our patients and their parents to work to balance the protective function of our thoughts against the cost to our well-being?

One promising method you can confidently recommend to both children and their parents to manage stressful thinking is to learn and practice mindfulness. Mindfulness refers to a state of nonreactivity, awareness, focus, attention, and nonjudgment. Noticing thoughts and feelings passing through us with a neutral mind, as if we were watching a movie, rather than taking them personally, is the goal. Jon Kabat-Zinn, PhD, learned from Buddhists, then developed and disseminated a formal program to teach this skill called mindfulness-based stress reduction; it has yielded significant benefits to the emotions and health of adult participants. While everyone can be mindful at times, the ability to enter this state at will and maintain it for a few minutes can be learned, even by preschool children.

How am I going to refer my patients to mindfulness programs, I can hear you saying, when I can’t even get them to standard therapies? Mindfulness in a less-structured format is often part of yoga or Tai Chi, meditation, art therapy, group therapy, or even religious services. Fortunately, parents and educators also can teach children mindfulness. But the first way you can start making this life skill available to your patients is by recommending it to their parents (“The Family ADHD Solution” by Mark Bertin [New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2011]).

You know that child emotional or behavior problems can cause adult stress. But adult stress also can cause or exacerbate a child’s emotional or behavior problems. Adult caregivers modeling meltdowns are shaping the minds of their children. Studies of teaching mindfulness to parents of children with developmental disabilities, autism, and ADHD, without touching the underlying disorder, show significant reductions in both adult stress and child behavior problems. Parents who can suspend emotion, take some deep breaths, and be thoughtful about the response they want to make instead of reacting impulsively act more reasonably, appear warmer and more compassionate to their children, and are often rewarded with better behavior. Such parents may feel better about themselves and their parenting, may experience less stress, and may themselves sleep better at night!

For children, having an adult simply declare moments to stop, take deep breaths, and notice the sounds, sights, feelings, and smells around them is a good start. Making a routine of taking an “awareness walk” around the block can be another lesson. Eating a food, such as a strawberry, mindfully – observing and savoring every bite – is another natural opportunity to practice increased awareness. One of my favorite tools, having a child shake a glitter globe (like a snow globe that can be made at home) and silently wait for the chaos to subside, “just like their feelings inside,” is soothing and a great metaphor! Abdominal breathing, part of many relaxation exercises, may be hard for young children to master. A parent might try having the child lie down with a stuffed animal on his or her belly and focus on watching it rise and fall while breathing as a way to learn this. For older children, keeping a “gratitude journal” helps focus on the positive, and also has some proven efficacy in relieving depression. Using the “1 Second Everyday” app to video a special moment daily may have a similar effect on sharpening awareness.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News.

If you are struggling to figure out how you, as an individual pediatrician, can make a significant impact on the most common current issues in child health of anxiety, depression, sleep problems, stress, and even adverse childhood experiences, you are not alone. Many of the problems we see in the office appear to stem so much from the culture in which we live that the medical interventions we have to offer seem paltry. Yet we strive to identify and attempt to ameliorate the child’s and family’s distress.

Real physical danger aside, a lot of personal distress is due to negative thoughts about one’s past or fears for one’s future. These thoughts are very important in restraining us from repeating mistakes and preparing us for action to prevent future harm. But the thoughts themselves can be stressful; they may paralyze us with anxiety, take away pleasure, interrupt our sleep, stimulate physiologic stress responses, and have adverse impacts on health. All these effects can occur without actually changing the course of events! How can we advise our patients and their parents to work to balance the protective function of our thoughts against the cost to our well-being?

One promising method you can confidently recommend to both children and their parents to manage stressful thinking is to learn and practice mindfulness. Mindfulness refers to a state of nonreactivity, awareness, focus, attention, and nonjudgment. Noticing thoughts and feelings passing through us with a neutral mind, as if we were watching a movie, rather than taking them personally, is the goal. Jon Kabat-Zinn, PhD, learned from Buddhists, then developed and disseminated a formal program to teach this skill called mindfulness-based stress reduction; it has yielded significant benefits to the emotions and health of adult participants. While everyone can be mindful at times, the ability to enter this state at will and maintain it for a few minutes can be learned, even by preschool children.

How am I going to refer my patients to mindfulness programs, I can hear you saying, when I can’t even get them to standard therapies? Mindfulness in a less-structured format is often part of yoga or Tai Chi, meditation, art therapy, group therapy, or even religious services. Fortunately, parents and educators also can teach children mindfulness. But the first way you can start making this life skill available to your patients is by recommending it to their parents (“The Family ADHD Solution” by Mark Bertin [New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2011]).

You know that child emotional or behavior problems can cause adult stress. But adult stress also can cause or exacerbate a child’s emotional or behavior problems. Adult caregivers modeling meltdowns are shaping the minds of their children. Studies of teaching mindfulness to parents of children with developmental disabilities, autism, and ADHD, without touching the underlying disorder, show significant reductions in both adult stress and child behavior problems. Parents who can suspend emotion, take some deep breaths, and be thoughtful about the response they want to make instead of reacting impulsively act more reasonably, appear warmer and more compassionate to their children, and are often rewarded with better behavior. Such parents may feel better about themselves and their parenting, may experience less stress, and may themselves sleep better at night!

For children, having an adult simply declare moments to stop, take deep breaths, and notice the sounds, sights, feelings, and smells around them is a good start. Making a routine of taking an “awareness walk” around the block can be another lesson. Eating a food, such as a strawberry, mindfully – observing and savoring every bite – is another natural opportunity to practice increased awareness. One of my favorite tools, having a child shake a glitter globe (like a snow globe that can be made at home) and silently wait for the chaos to subside, “just like their feelings inside,” is soothing and a great metaphor! Abdominal breathing, part of many relaxation exercises, may be hard for young children to master. A parent might try having the child lie down with a stuffed animal on his or her belly and focus on watching it rise and fall while breathing as a way to learn this. For older children, keeping a “gratitude journal” helps focus on the positive, and also has some proven efficacy in relieving depression. Using the “1 Second Everyday” app to video a special moment daily may have a similar effect on sharpening awareness.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News.

If you are struggling to figure out how you, as an individual pediatrician, can make a significant impact on the most common current issues in child health of anxiety, depression, sleep problems, stress, and even adverse childhood experiences, you are not alone. Many of the problems we see in the office appear to stem so much from the culture in which we live that the medical interventions we have to offer seem paltry. Yet we strive to identify and attempt to ameliorate the child’s and family’s distress.

Real physical danger aside, a lot of personal distress is due to negative thoughts about one’s past or fears for one’s future. These thoughts are very important in restraining us from repeating mistakes and preparing us for action to prevent future harm. But the thoughts themselves can be stressful; they may paralyze us with anxiety, take away pleasure, interrupt our sleep, stimulate physiologic stress responses, and have adverse impacts on health. All these effects can occur without actually changing the course of events! How can we advise our patients and their parents to work to balance the protective function of our thoughts against the cost to our well-being?

One promising method you can confidently recommend to both children and their parents to manage stressful thinking is to learn and practice mindfulness. Mindfulness refers to a state of nonreactivity, awareness, focus, attention, and nonjudgment. Noticing thoughts and feelings passing through us with a neutral mind, as if we were watching a movie, rather than taking them personally, is the goal. Jon Kabat-Zinn, PhD, learned from Buddhists, then developed and disseminated a formal program to teach this skill called mindfulness-based stress reduction; it has yielded significant benefits to the emotions and health of adult participants. While everyone can be mindful at times, the ability to enter this state at will and maintain it for a few minutes can be learned, even by preschool children.

How am I going to refer my patients to mindfulness programs, I can hear you saying, when I can’t even get them to standard therapies? Mindfulness in a less-structured format is often part of yoga or Tai Chi, meditation, art therapy, group therapy, or even religious services. Fortunately, parents and educators also can teach children mindfulness. But the first way you can start making this life skill available to your patients is by recommending it to their parents (“The Family ADHD Solution” by Mark Bertin [New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2011]).

You know that child emotional or behavior problems can cause adult stress. But adult stress also can cause or exacerbate a child’s emotional or behavior problems. Adult caregivers modeling meltdowns are shaping the minds of their children. Studies of teaching mindfulness to parents of children with developmental disabilities, autism, and ADHD, without touching the underlying disorder, show significant reductions in both adult stress and child behavior problems. Parents who can suspend emotion, take some deep breaths, and be thoughtful about the response they want to make instead of reacting impulsively act more reasonably, appear warmer and more compassionate to their children, and are often rewarded with better behavior. Such parents may feel better about themselves and their parenting, may experience less stress, and may themselves sleep better at night!

For children, having an adult simply declare moments to stop, take deep breaths, and notice the sounds, sights, feelings, and smells around them is a good start. Making a routine of taking an “awareness walk” around the block can be another lesson. Eating a food, such as a strawberry, mindfully – observing and savoring every bite – is another natural opportunity to practice increased awareness. One of my favorite tools, having a child shake a glitter globe (like a snow globe that can be made at home) and silently wait for the chaos to subside, “just like their feelings inside,” is soothing and a great metaphor! Abdominal breathing, part of many relaxation exercises, may be hard for young children to master. A parent might try having the child lie down with a stuffed animal on his or her belly and focus on watching it rise and fall while breathing as a way to learn this. For older children, keeping a “gratitude journal” helps focus on the positive, and also has some proven efficacy in relieving depression. Using the “1 Second Everyday” app to video a special moment daily may have a similar effect on sharpening awareness.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News.

Solving stool refusal

When parents bring in their delightful, verbal 3-year-old for refusing to poop on the potty, it may seem laughable. But with impending preschool and costs of diapers, stool refusal can be a major aggravation for families! Fortunately,

Commonly a healthy, typically developing boy stands and urinates in the toilet just fine, but sneaks off behind the sofa to poop. Parent gyrations have gone from cajoling, to punishing, to offering trips to Disney! Flaring tempers can set the stage for stool refusal to be a power play.

There are a number of reasons stool refusal may give clues to child and family tendencies and relevant intervention. We always should be alert to rare medical problems such as Hirschsprung disease or traumas (from slammed toilet lids to sexual abuse). But while learning to use the toilet for urination and defecation generally occur around the same time, there are pitfalls making pooping in the potty different. An impending stool provides stronger sensations and more advance warning than urine and tends to come at regular times, making it logical to start toilet learning with sitting on the potty after meals.

But once seated on the potty, stools can require some waiting – not a typical toddler forte! While running to sit has novelty at first and may be reinforced by celebration, this quickly becomes routine and boring. Very active or very intense children especially hate having their play interrupted by a trip to the bathroom. Oppositional children just won’t perform if they think the parent cares! And unlike for urination, everyone can inhibit defecation long enough for the urge to pass. Repeated stool retention from ignoring the urge makes stools dessicated and harder, with resulting pain when finally passed. One painful stool makes many a young child decide “Never again!” and simply refuse the toilet. A rectal fissure can both start