User login

One thing that constantly surprises me about adolescent sleep is that neither the teen nor the parent is as concerned about it as I am. Instead, they complain about irritability, dropping grades, anxiety, depression, obesity, oppositionality, fatigue, and even substance use – all documented effects of sleep debt.

Inadequate sleep changes the brain, resulting in thinner gray matter, less neuroplasticity, poorer higher-level cognitive abilities (attention, working memory, inhibition, judgment, decision-making), lower motivation, and poorer academic functioning. None of these are losses teens can afford!

While sleep problems are more common in those with mental health disorders, poor sleep precedes anxiety and depression more than the reverse. Sleep problems increase the risk of depression, and depression relapses. Insomnia predicts risk behaviors – drinking and driving, smoking, delinquency. Getting less than 8 hours of sleep is associated with a threefold higher risk of suicide attempts.

Despite these pervasive threats to health and development, instead of concern, I find a lot of resistance in families and teens to taking action to improve sleep.

Teens don’t believe in problems from inadequate sleep. After all, they say, their peers are “all” getting the same amount of sleep. And they are largely correct – 75% of U.S. 12th graders get less than 8 hours of sleep. But the data are clear that children aged 12-18 years need 8.25-9.25 hours of sleep.

Parents generally are not aware of how little sleep their teens are getting because they go to bed on their own. If parents do check, any teenagers worth the label can growl their way out of supervision, “promise” to shut off the lights, or feign sleep. Having the house, pantry, and electronics to themselves at night is worth the risk of a consequence, especially for those who would rather avoid interacting.

The social forces keeping teens up at night are their “life”: the hours required for homework can be the reason for inadequate sleep. In subgroups of teens, sports practices, employment, or family responsibilities may extend the day past a bedtime needed for optimal sleep.

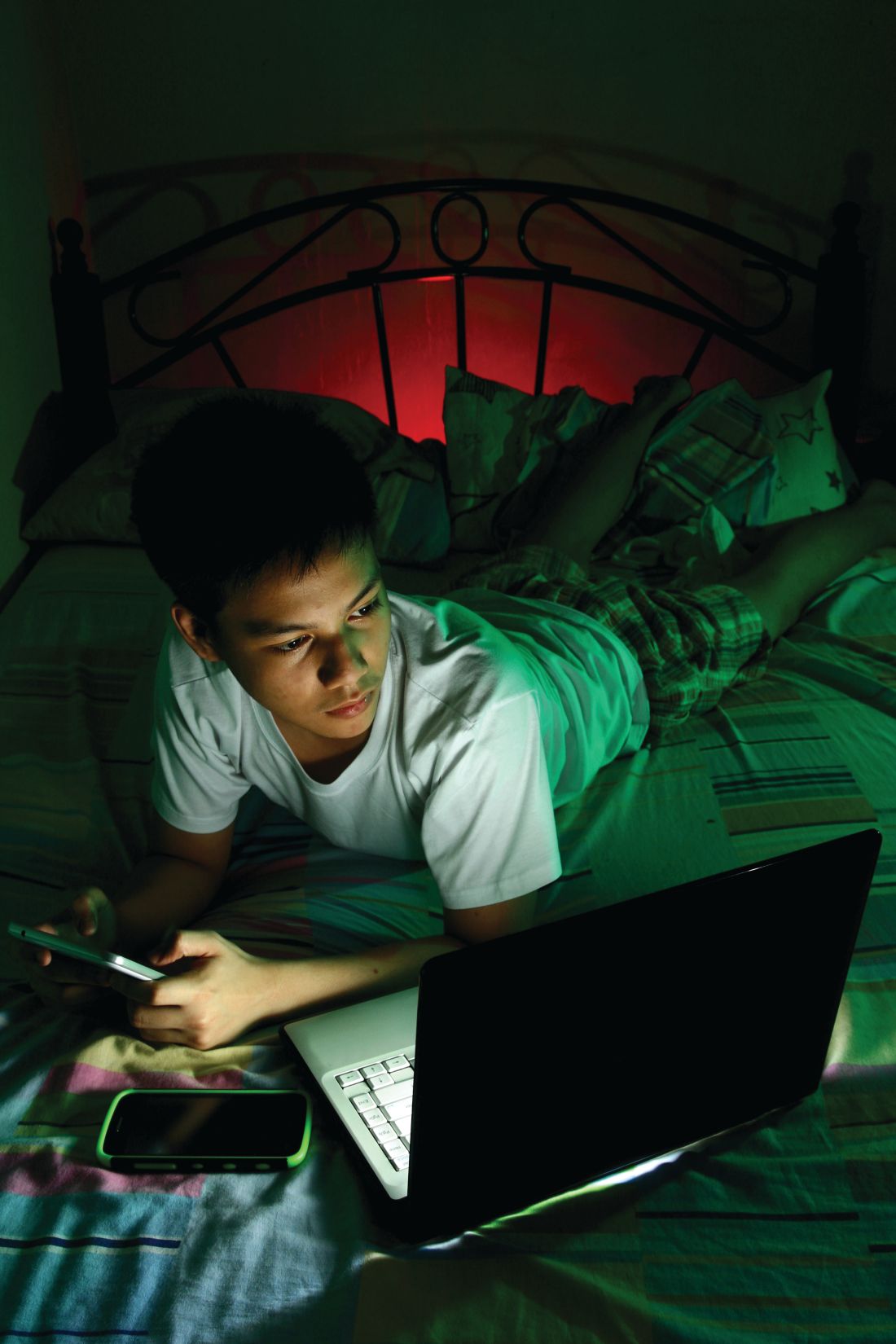

But use of electronics – the lifeline of adolescents – is responsible for much of their sleep debt. Electronic devices both delay sleep onset and reduce sleep duration. After 9:00 p.m., 34% of children aged older than 12 years are text messaging, 44% are talking, 55% are online, and 24% are playing computer games. Use of a TV or tablet at bedtime results in reduced sleep, and increased poor quality of sleep. Three or more hours of TV result not only in difficulty falling asleep and frequent awakenings, but also sleep issues later as adults. Shooter video games result in lower sleepiness, longer sleep latency, and shorter REM sleep. Even the low level light from electronic devices alters circadian rhythm and suppresses nocturnal melatonin secretion.

Keep in mind the biological reasons teens go to bed later. One is the typical emotional hyperarousal of being a teen. But other biological forces are at work in adolescence, such as reduction in the accumulation of sleep pressure during wakefulness and delaying the melatonin release that produces sleepiness. Teens (and parents) think sleeping in on weekends takes care of inadequate weekday sleep, but this so-called “recovery sleep” tends to occur at an inappropriate time in the circadian phase and further delays melatonin production, as well as reducing sleep pressure, making it even harder to fall asleep.

In some cases, medications we prescribe – such as stimulants, theophylline, antihistamines, or anticonvulsants – are at fault for delaying or disturbing sleep. But more often it is self-administered substances that are part of the teen’s attempt to stay awake – including nicotine, alcohol, and caffeine – that produce shorter sleep duration, increased latency to sleep, more wake time during sleep, and increased daytime sleepiness; it results in a vicious cycle. Sleep disruption may explain the association of these substances with less memory consolidation, poorer academic performance, and higher rates of risk behaviors.

We adults also are a cause of teen sleep debt. We are the ones allowing the early school start times for teens, primarily to allow for after school sports programs that glorify the school and bring kudos to some at the expense of all the students. A 65-minute earlier start in 10th grade resulted in less than half of students getting 7 hours of sleep or more. The level of resulting sleepiness is equal to that of narcolepsy.

As primary care clinicians, we can and need to detect, educate about, and treat sleep debt and sleep disorders. Sleep questionnaires can help. Treatment of sleep includes coaching for: having a cool, dark room used mainly for sleep; a regular schedule 7 days per week; avoiding exercise within 2 hours of bedtime; avoiding stimulants such as caffeine, tea, nicotine, and medications at least 3 hours before bedtime; keeping to a routine with no daytime naps; and especially no media in the bedroom! For teens already not able to sleep until early morning, you can recommend that they work bedtime back or forward by 1 hour per day until hitting a time that will allow 9 hours of sleep. Alternatively, have them stay up all night to reset their biological clock. Subsequently, the sleep schedule has to stay within 1 hour for sleep and waking 7 days per week. Anxious teens, besides needing therapy, may need a soothing routine, no visible clock, and a plan to get back up for 1 hour every time it takes longer than 10 minutes to fall asleep.

If sleepy teens report adequate time in bed, then we need to understand pathologies such as obstructive sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, menstruation-related or primary hypersomnias, and narcolepsy to diagnose and resolve the problem.

Parents may have given up protecting their teens from inadequate sleep so we as health providers need to do so.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News. E-mail her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

One thing that constantly surprises me about adolescent sleep is that neither the teen nor the parent is as concerned about it as I am. Instead, they complain about irritability, dropping grades, anxiety, depression, obesity, oppositionality, fatigue, and even substance use – all documented effects of sleep debt.

Inadequate sleep changes the brain, resulting in thinner gray matter, less neuroplasticity, poorer higher-level cognitive abilities (attention, working memory, inhibition, judgment, decision-making), lower motivation, and poorer academic functioning. None of these are losses teens can afford!

While sleep problems are more common in those with mental health disorders, poor sleep precedes anxiety and depression more than the reverse. Sleep problems increase the risk of depression, and depression relapses. Insomnia predicts risk behaviors – drinking and driving, smoking, delinquency. Getting less than 8 hours of sleep is associated with a threefold higher risk of suicide attempts.

Despite these pervasive threats to health and development, instead of concern, I find a lot of resistance in families and teens to taking action to improve sleep.

Teens don’t believe in problems from inadequate sleep. After all, they say, their peers are “all” getting the same amount of sleep. And they are largely correct – 75% of U.S. 12th graders get less than 8 hours of sleep. But the data are clear that children aged 12-18 years need 8.25-9.25 hours of sleep.

Parents generally are not aware of how little sleep their teens are getting because they go to bed on their own. If parents do check, any teenagers worth the label can growl their way out of supervision, “promise” to shut off the lights, or feign sleep. Having the house, pantry, and electronics to themselves at night is worth the risk of a consequence, especially for those who would rather avoid interacting.

The social forces keeping teens up at night are their “life”: the hours required for homework can be the reason for inadequate sleep. In subgroups of teens, sports practices, employment, or family responsibilities may extend the day past a bedtime needed for optimal sleep.

But use of electronics – the lifeline of adolescents – is responsible for much of their sleep debt. Electronic devices both delay sleep onset and reduce sleep duration. After 9:00 p.m., 34% of children aged older than 12 years are text messaging, 44% are talking, 55% are online, and 24% are playing computer games. Use of a TV or tablet at bedtime results in reduced sleep, and increased poor quality of sleep. Three or more hours of TV result not only in difficulty falling asleep and frequent awakenings, but also sleep issues later as adults. Shooter video games result in lower sleepiness, longer sleep latency, and shorter REM sleep. Even the low level light from electronic devices alters circadian rhythm and suppresses nocturnal melatonin secretion.

Keep in mind the biological reasons teens go to bed later. One is the typical emotional hyperarousal of being a teen. But other biological forces are at work in adolescence, such as reduction in the accumulation of sleep pressure during wakefulness and delaying the melatonin release that produces sleepiness. Teens (and parents) think sleeping in on weekends takes care of inadequate weekday sleep, but this so-called “recovery sleep” tends to occur at an inappropriate time in the circadian phase and further delays melatonin production, as well as reducing sleep pressure, making it even harder to fall asleep.

In some cases, medications we prescribe – such as stimulants, theophylline, antihistamines, or anticonvulsants – are at fault for delaying or disturbing sleep. But more often it is self-administered substances that are part of the teen’s attempt to stay awake – including nicotine, alcohol, and caffeine – that produce shorter sleep duration, increased latency to sleep, more wake time during sleep, and increased daytime sleepiness; it results in a vicious cycle. Sleep disruption may explain the association of these substances with less memory consolidation, poorer academic performance, and higher rates of risk behaviors.

We adults also are a cause of teen sleep debt. We are the ones allowing the early school start times for teens, primarily to allow for after school sports programs that glorify the school and bring kudos to some at the expense of all the students. A 65-minute earlier start in 10th grade resulted in less than half of students getting 7 hours of sleep or more. The level of resulting sleepiness is equal to that of narcolepsy.

As primary care clinicians, we can and need to detect, educate about, and treat sleep debt and sleep disorders. Sleep questionnaires can help. Treatment of sleep includes coaching for: having a cool, dark room used mainly for sleep; a regular schedule 7 days per week; avoiding exercise within 2 hours of bedtime; avoiding stimulants such as caffeine, tea, nicotine, and medications at least 3 hours before bedtime; keeping to a routine with no daytime naps; and especially no media in the bedroom! For teens already not able to sleep until early morning, you can recommend that they work bedtime back or forward by 1 hour per day until hitting a time that will allow 9 hours of sleep. Alternatively, have them stay up all night to reset their biological clock. Subsequently, the sleep schedule has to stay within 1 hour for sleep and waking 7 days per week. Anxious teens, besides needing therapy, may need a soothing routine, no visible clock, and a plan to get back up for 1 hour every time it takes longer than 10 minutes to fall asleep.

If sleepy teens report adequate time in bed, then we need to understand pathologies such as obstructive sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, menstruation-related or primary hypersomnias, and narcolepsy to diagnose and resolve the problem.

Parents may have given up protecting their teens from inadequate sleep so we as health providers need to do so.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News. E-mail her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

One thing that constantly surprises me about adolescent sleep is that neither the teen nor the parent is as concerned about it as I am. Instead, they complain about irritability, dropping grades, anxiety, depression, obesity, oppositionality, fatigue, and even substance use – all documented effects of sleep debt.

Inadequate sleep changes the brain, resulting in thinner gray matter, less neuroplasticity, poorer higher-level cognitive abilities (attention, working memory, inhibition, judgment, decision-making), lower motivation, and poorer academic functioning. None of these are losses teens can afford!

While sleep problems are more common in those with mental health disorders, poor sleep precedes anxiety and depression more than the reverse. Sleep problems increase the risk of depression, and depression relapses. Insomnia predicts risk behaviors – drinking and driving, smoking, delinquency. Getting less than 8 hours of sleep is associated with a threefold higher risk of suicide attempts.

Despite these pervasive threats to health and development, instead of concern, I find a lot of resistance in families and teens to taking action to improve sleep.

Teens don’t believe in problems from inadequate sleep. After all, they say, their peers are “all” getting the same amount of sleep. And they are largely correct – 75% of U.S. 12th graders get less than 8 hours of sleep. But the data are clear that children aged 12-18 years need 8.25-9.25 hours of sleep.

Parents generally are not aware of how little sleep their teens are getting because they go to bed on their own. If parents do check, any teenagers worth the label can growl their way out of supervision, “promise” to shut off the lights, or feign sleep. Having the house, pantry, and electronics to themselves at night is worth the risk of a consequence, especially for those who would rather avoid interacting.

The social forces keeping teens up at night are their “life”: the hours required for homework can be the reason for inadequate sleep. In subgroups of teens, sports practices, employment, or family responsibilities may extend the day past a bedtime needed for optimal sleep.

But use of electronics – the lifeline of adolescents – is responsible for much of their sleep debt. Electronic devices both delay sleep onset and reduce sleep duration. After 9:00 p.m., 34% of children aged older than 12 years are text messaging, 44% are talking, 55% are online, and 24% are playing computer games. Use of a TV or tablet at bedtime results in reduced sleep, and increased poor quality of sleep. Three or more hours of TV result not only in difficulty falling asleep and frequent awakenings, but also sleep issues later as adults. Shooter video games result in lower sleepiness, longer sleep latency, and shorter REM sleep. Even the low level light from electronic devices alters circadian rhythm and suppresses nocturnal melatonin secretion.

Keep in mind the biological reasons teens go to bed later. One is the typical emotional hyperarousal of being a teen. But other biological forces are at work in adolescence, such as reduction in the accumulation of sleep pressure during wakefulness and delaying the melatonin release that produces sleepiness. Teens (and parents) think sleeping in on weekends takes care of inadequate weekday sleep, but this so-called “recovery sleep” tends to occur at an inappropriate time in the circadian phase and further delays melatonin production, as well as reducing sleep pressure, making it even harder to fall asleep.

In some cases, medications we prescribe – such as stimulants, theophylline, antihistamines, or anticonvulsants – are at fault for delaying or disturbing sleep. But more often it is self-administered substances that are part of the teen’s attempt to stay awake – including nicotine, alcohol, and caffeine – that produce shorter sleep duration, increased latency to sleep, more wake time during sleep, and increased daytime sleepiness; it results in a vicious cycle. Sleep disruption may explain the association of these substances with less memory consolidation, poorer academic performance, and higher rates of risk behaviors.

We adults also are a cause of teen sleep debt. We are the ones allowing the early school start times for teens, primarily to allow for after school sports programs that glorify the school and bring kudos to some at the expense of all the students. A 65-minute earlier start in 10th grade resulted in less than half of students getting 7 hours of sleep or more. The level of resulting sleepiness is equal to that of narcolepsy.

As primary care clinicians, we can and need to detect, educate about, and treat sleep debt and sleep disorders. Sleep questionnaires can help. Treatment of sleep includes coaching for: having a cool, dark room used mainly for sleep; a regular schedule 7 days per week; avoiding exercise within 2 hours of bedtime; avoiding stimulants such as caffeine, tea, nicotine, and medications at least 3 hours before bedtime; keeping to a routine with no daytime naps; and especially no media in the bedroom! For teens already not able to sleep until early morning, you can recommend that they work bedtime back or forward by 1 hour per day until hitting a time that will allow 9 hours of sleep. Alternatively, have them stay up all night to reset their biological clock. Subsequently, the sleep schedule has to stay within 1 hour for sleep and waking 7 days per week. Anxious teens, besides needing therapy, may need a soothing routine, no visible clock, and a plan to get back up for 1 hour every time it takes longer than 10 minutes to fall asleep.

If sleepy teens report adequate time in bed, then we need to understand pathologies such as obstructive sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, menstruation-related or primary hypersomnias, and narcolepsy to diagnose and resolve the problem.

Parents may have given up protecting their teens from inadequate sleep so we as health providers need to do so.

Dr. Howard is assistant professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and creator of CHADIS (www.CHADIS.com). She had no other relevant disclosures. Dr. Howard’s contribution to this publication was as a paid expert to Frontline Medical News. E-mail her at pdnews@frontlinemedcom.com.