User login

Anticoagulation Hub contains news and clinical review articles for physicians seeking the most up-to-date information on the rapidly evolving treatment options for preventing stroke, acute coronary events, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism in at-risk patients. The Anticoagulation Hub is powered by Frontline Medical Communications.

Compelling case for NOACs in VTE

SNOWMASS, COLO. – All four Food and Drug Administration–approved novel oral anticoagulants offer impressive safety advantages over the traditional strategy of low-molecular-weight heparin bridging to warfarin for treatment of acute venous thromboembolism, Dr. Patrick T. O’Gara observed at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

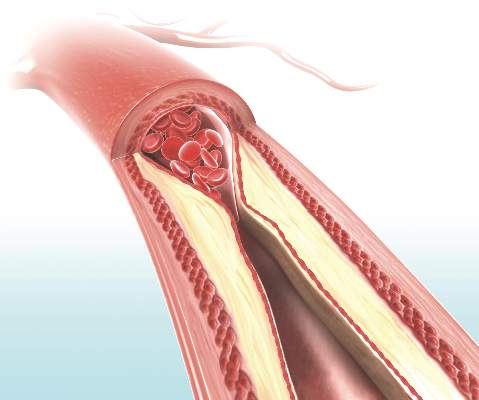

He highlighted a European analysis of six phase III clinical trials totaling more than 27,000 patients with venous thromboembolism (VTE) in which dabigatran (Pradaxa), rivaroxaban(Xarelto), apixaban (Eliquis), or edoxaban (Savaysa) was compared to the traditional strategy of unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) bridging to warfarin or another vitamin K antagonist. All four NOACs proved statistically noninferior to the traditional strategy in terms of efficacy as defined by prevention of recurrent VTE. Efficacy of NOACs and warfarin was similar regardless of body weight, chronic kidney disease, age, cancer, and pulmonary embolism versus deep venous thrombosis.

In terms of safety, it was no contest: The NOACs were collectively associated with a 39% lower risk of major bleeding, a 64% lower risk of fatal bleeding, and a 63% reduction in intracranial bleeding compared to LMWH/warfarin (Blood 2014 Sep 18;124[12]:1968-75).

“This is a big-ticket winner for the novel oral anticoagulants in the longer-term management of patients who have venous thromboembolic disease – not inferior to a strategy of low-molecular-weight heparin bridging to warfarin and much better with respect to serious consequences of a safety nature,” said Dr. O’Gara, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of clinical cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

The pivotal trials for NOACs in VTE were generally structured statistically as noninferiority trials, with one exception: edoxaban has been shown to be superior to warfarin in a prespecified subgroup with submassive pulmonary embolism.

Further strengthening the case for routine use of NOACs in treating acute VTE is the emergence of fast-acting antidotes to the drugs in the event a patient develops a bleeding complication. Idarucizumab (Praxbind) received FDA approval last October as a reversal agent for dabigatran. Many experts think andexanet alpha will likely receive regulatory approval later this year as a universal antidote to all the factor Xa inhibitors, he noted.

It’s estimated that 70% of patients with pulmonary embolism can be classified as low risk and thus eligible for consideration for early hospital discharge and home treatment, provided their social situation is suitable. Pulmonary embolism patients are categorized as low risk if they are hemodynamically stable, don’t require supplemental oxygen, don’t show right ventricular dilatation on CT imaging in the emergency department, and lack serum biomarker evidence of right ventricular strain or injury.

In making decisions about outpatient therapy for VTE, a point worth considering is that two NOACs, rivaroxaban and apixaban, possess the practical advantage of being single-agent therapy. That is, they don’t require a heparin bridge prior to their introduction, as established in the EINSTEIN trial for rivaroxaban and in the AMPLIFY study for apixaban. However, a loading dose is necessary. Rivaroxaban is given at 15 mg b.i.d. for 3 weeks before dropping down to 20 mg once daily. Apixaban has a loading dose of 10 mg b.i.d. for the first 7 days followed by 5 mg b.i.d. thereafter.

“You’ll note that you give a higher loading dose for these particular agents for events that occur on the venous side of the circulation compared with the management of patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation,” Dr. O’Gara said.

In contrast, both dabigatran and edoxaban require either unfractionated or LMWH as bridge before switching to oral therapy.

Dr. O’Gara reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – All four Food and Drug Administration–approved novel oral anticoagulants offer impressive safety advantages over the traditional strategy of low-molecular-weight heparin bridging to warfarin for treatment of acute venous thromboembolism, Dr. Patrick T. O’Gara observed at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

He highlighted a European analysis of six phase III clinical trials totaling more than 27,000 patients with venous thromboembolism (VTE) in which dabigatran (Pradaxa), rivaroxaban(Xarelto), apixaban (Eliquis), or edoxaban (Savaysa) was compared to the traditional strategy of unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) bridging to warfarin or another vitamin K antagonist. All four NOACs proved statistically noninferior to the traditional strategy in terms of efficacy as defined by prevention of recurrent VTE. Efficacy of NOACs and warfarin was similar regardless of body weight, chronic kidney disease, age, cancer, and pulmonary embolism versus deep venous thrombosis.

In terms of safety, it was no contest: The NOACs were collectively associated with a 39% lower risk of major bleeding, a 64% lower risk of fatal bleeding, and a 63% reduction in intracranial bleeding compared to LMWH/warfarin (Blood 2014 Sep 18;124[12]:1968-75).

“This is a big-ticket winner for the novel oral anticoagulants in the longer-term management of patients who have venous thromboembolic disease – not inferior to a strategy of low-molecular-weight heparin bridging to warfarin and much better with respect to serious consequences of a safety nature,” said Dr. O’Gara, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of clinical cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

The pivotal trials for NOACs in VTE were generally structured statistically as noninferiority trials, with one exception: edoxaban has been shown to be superior to warfarin in a prespecified subgroup with submassive pulmonary embolism.

Further strengthening the case for routine use of NOACs in treating acute VTE is the emergence of fast-acting antidotes to the drugs in the event a patient develops a bleeding complication. Idarucizumab (Praxbind) received FDA approval last October as a reversal agent for dabigatran. Many experts think andexanet alpha will likely receive regulatory approval later this year as a universal antidote to all the factor Xa inhibitors, he noted.

It’s estimated that 70% of patients with pulmonary embolism can be classified as low risk and thus eligible for consideration for early hospital discharge and home treatment, provided their social situation is suitable. Pulmonary embolism patients are categorized as low risk if they are hemodynamically stable, don’t require supplemental oxygen, don’t show right ventricular dilatation on CT imaging in the emergency department, and lack serum biomarker evidence of right ventricular strain or injury.

In making decisions about outpatient therapy for VTE, a point worth considering is that two NOACs, rivaroxaban and apixaban, possess the practical advantage of being single-agent therapy. That is, they don’t require a heparin bridge prior to their introduction, as established in the EINSTEIN trial for rivaroxaban and in the AMPLIFY study for apixaban. However, a loading dose is necessary. Rivaroxaban is given at 15 mg b.i.d. for 3 weeks before dropping down to 20 mg once daily. Apixaban has a loading dose of 10 mg b.i.d. for the first 7 days followed by 5 mg b.i.d. thereafter.

“You’ll note that you give a higher loading dose for these particular agents for events that occur on the venous side of the circulation compared with the management of patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation,” Dr. O’Gara said.

In contrast, both dabigatran and edoxaban require either unfractionated or LMWH as bridge before switching to oral therapy.

Dr. O’Gara reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – All four Food and Drug Administration–approved novel oral anticoagulants offer impressive safety advantages over the traditional strategy of low-molecular-weight heparin bridging to warfarin for treatment of acute venous thromboembolism, Dr. Patrick T. O’Gara observed at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

He highlighted a European analysis of six phase III clinical trials totaling more than 27,000 patients with venous thromboembolism (VTE) in which dabigatran (Pradaxa), rivaroxaban(Xarelto), apixaban (Eliquis), or edoxaban (Savaysa) was compared to the traditional strategy of unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) bridging to warfarin or another vitamin K antagonist. All four NOACs proved statistically noninferior to the traditional strategy in terms of efficacy as defined by prevention of recurrent VTE. Efficacy of NOACs and warfarin was similar regardless of body weight, chronic kidney disease, age, cancer, and pulmonary embolism versus deep venous thrombosis.

In terms of safety, it was no contest: The NOACs were collectively associated with a 39% lower risk of major bleeding, a 64% lower risk of fatal bleeding, and a 63% reduction in intracranial bleeding compared to LMWH/warfarin (Blood 2014 Sep 18;124[12]:1968-75).

“This is a big-ticket winner for the novel oral anticoagulants in the longer-term management of patients who have venous thromboembolic disease – not inferior to a strategy of low-molecular-weight heparin bridging to warfarin and much better with respect to serious consequences of a safety nature,” said Dr. O’Gara, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of clinical cardiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

The pivotal trials for NOACs in VTE were generally structured statistically as noninferiority trials, with one exception: edoxaban has been shown to be superior to warfarin in a prespecified subgroup with submassive pulmonary embolism.

Further strengthening the case for routine use of NOACs in treating acute VTE is the emergence of fast-acting antidotes to the drugs in the event a patient develops a bleeding complication. Idarucizumab (Praxbind) received FDA approval last October as a reversal agent for dabigatran. Many experts think andexanet alpha will likely receive regulatory approval later this year as a universal antidote to all the factor Xa inhibitors, he noted.

It’s estimated that 70% of patients with pulmonary embolism can be classified as low risk and thus eligible for consideration for early hospital discharge and home treatment, provided their social situation is suitable. Pulmonary embolism patients are categorized as low risk if they are hemodynamically stable, don’t require supplemental oxygen, don’t show right ventricular dilatation on CT imaging in the emergency department, and lack serum biomarker evidence of right ventricular strain or injury.

In making decisions about outpatient therapy for VTE, a point worth considering is that two NOACs, rivaroxaban and apixaban, possess the practical advantage of being single-agent therapy. That is, they don’t require a heparin bridge prior to their introduction, as established in the EINSTEIN trial for rivaroxaban and in the AMPLIFY study for apixaban. However, a loading dose is necessary. Rivaroxaban is given at 15 mg b.i.d. for 3 weeks before dropping down to 20 mg once daily. Apixaban has a loading dose of 10 mg b.i.d. for the first 7 days followed by 5 mg b.i.d. thereafter.

“You’ll note that you give a higher loading dose for these particular agents for events that occur on the venous side of the circulation compared with the management of patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation,” Dr. O’Gara said.

In contrast, both dabigatran and edoxaban require either unfractionated or LMWH as bridge before switching to oral therapy.

Dr. O’Gara reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding his presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

In refractory AF, think weight loss before ablation

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Don’t be in a rush to refer a patient with drug-refractory, symptomatic atrial fibrillation (AF) for catheter ablation of the arrhythmia, a prominent electrophysiologist advised at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

“AF ablation is not salvation – and that’s coming from somebody who does these procedures. One really needs to be very selective in referring patients for this,” said Dr. N.A. Mark Estes III, professor of medicine and director of cardiac arrhythmia services at Tufts University, Boston.

Misconceptions about AF catheter ablation outcomes abound among nonelectrophysiologists. Results have often been overstated, Dr. Estes continued. And there’s a far more attractive alternative treatment option for those AF patients who are overweight or obese: weight loss.

In the Australian LEGACY study, which he considers practice changing, patients with AF who had a body mass index of at least 27 kg/m2 who participated in a simple structured weight management program and achieved a sustained loss of at least 10% of their body weight had a 65% reduction in their AF burden as objectively documented by repeated 7-day ambulatory monitoring over 5 years of follow-up. Moreover, 46% of patients who maintained that degree of weight reduction were totally free of AF without use of drugs or ablation procedures (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 May 26;65[20]:2159-69).

In a related study, the Australian investigators, led by Dr. Rajeev K. Pathak of the University of Adelaide, showed in the same study population that participation in a tailored exercise program paid added dividends on top of the weight loss. Patients who achieved at least a 2-MET increase in cardiorespiratory fitness had a significantly greater rate of freedom from AF than those who didn’t reach that fitness threshold (J Am Coll Cardiol. Sep 1;66[9]:985-96).

“The data are compelling for improved outcomes, including reduced AF burden, with lifestyle modification in obese patients with AF. This is first-line therapy. You can bet it will be in the guidelines soon. It should be in your practice now,” Dr. Estes declared.

“The starting point is weight reduction, even before sending patients to an electrophysiologist for ablation,” he continued. “And if you’ve got patients on drugs who’ve had ablation in whom there continues to be AF, weight reduction – particularly reaching that 10% threshold – results in a dramatic decline in the burden of AF,” he said.

One of the common misconceptions about catheter ablation for AF is that if the pulmonary vein isolation procedure is successful in eliminating the arrhythmia, then the patient can discontinue oral anticoagulant therapy.

“That rationale, while logical, doesn’t really hold up. In many of the ablation trials, including the AFFIRM trial, if you discontinue anticoagulation in patients in sinus rhythm the stroke rate goes back to the same as in patients with AF,” according to the cardiologist.

In a meta-analysis of prospective studies published through 2007, the single-procedure success rate for radiofrequency ablation in achieving sinus rhythm without the use of antiarrhythmic drugs was 57%, climbing to 71% with multiple ablation procedures. In contrast, antiarrhythmic drugs were substantially less successful, with about a 50% success rate as compared with a 25% placebo response (Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009 Aug;2[4]:349-61).

“It’s notable that antiarrhythmic drug development has almost been stopped because the drugs don’t work, with the possible exception of amiodarone, which requires an individualized risk/benefit assessment,” according to Dr. Estes.

There is a major caveat regarding the ablation studies: They’ve mainly enrolled patients who are in their 50s, when AF is far less common than in later decades.

“Whether these results are going to hold up long-term in elderly patients who are hypertensive, diabetic, and may have sleep apnea really remains an unanswered question,” Dr. Estes observed.

Also, significant periprocedural complications occur in roughly 1 in 20 patients undergoing radiofrequency catheter ablation, although the safety data for cryoablation look somewhat better, he continued.

Dr. Estes predicted that the future of catheter ablation of AF hangs on three major ongoing rigorous randomized clinical trials comparing it to drug therapy with hard endpoints including all-cause mortality and cardiovascular hospitalizations. These are CASTLE-AF, with 420 patients; CABANA, with 2,200; and the German EAST study, with roughly 3,000 patients. Results are expected in 2018-2019.

Dr. Estes reported serving as a consultant to Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and St. Jude Medical.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Don’t be in a rush to refer a patient with drug-refractory, symptomatic atrial fibrillation (AF) for catheter ablation of the arrhythmia, a prominent electrophysiologist advised at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

“AF ablation is not salvation – and that’s coming from somebody who does these procedures. One really needs to be very selective in referring patients for this,” said Dr. N.A. Mark Estes III, professor of medicine and director of cardiac arrhythmia services at Tufts University, Boston.

Misconceptions about AF catheter ablation outcomes abound among nonelectrophysiologists. Results have often been overstated, Dr. Estes continued. And there’s a far more attractive alternative treatment option for those AF patients who are overweight or obese: weight loss.

In the Australian LEGACY study, which he considers practice changing, patients with AF who had a body mass index of at least 27 kg/m2 who participated in a simple structured weight management program and achieved a sustained loss of at least 10% of their body weight had a 65% reduction in their AF burden as objectively documented by repeated 7-day ambulatory monitoring over 5 years of follow-up. Moreover, 46% of patients who maintained that degree of weight reduction were totally free of AF without use of drugs or ablation procedures (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 May 26;65[20]:2159-69).

In a related study, the Australian investigators, led by Dr. Rajeev K. Pathak of the University of Adelaide, showed in the same study population that participation in a tailored exercise program paid added dividends on top of the weight loss. Patients who achieved at least a 2-MET increase in cardiorespiratory fitness had a significantly greater rate of freedom from AF than those who didn’t reach that fitness threshold (J Am Coll Cardiol. Sep 1;66[9]:985-96).

“The data are compelling for improved outcomes, including reduced AF burden, with lifestyle modification in obese patients with AF. This is first-line therapy. You can bet it will be in the guidelines soon. It should be in your practice now,” Dr. Estes declared.

“The starting point is weight reduction, even before sending patients to an electrophysiologist for ablation,” he continued. “And if you’ve got patients on drugs who’ve had ablation in whom there continues to be AF, weight reduction – particularly reaching that 10% threshold – results in a dramatic decline in the burden of AF,” he said.

One of the common misconceptions about catheter ablation for AF is that if the pulmonary vein isolation procedure is successful in eliminating the arrhythmia, then the patient can discontinue oral anticoagulant therapy.

“That rationale, while logical, doesn’t really hold up. In many of the ablation trials, including the AFFIRM trial, if you discontinue anticoagulation in patients in sinus rhythm the stroke rate goes back to the same as in patients with AF,” according to the cardiologist.

In a meta-analysis of prospective studies published through 2007, the single-procedure success rate for radiofrequency ablation in achieving sinus rhythm without the use of antiarrhythmic drugs was 57%, climbing to 71% with multiple ablation procedures. In contrast, antiarrhythmic drugs were substantially less successful, with about a 50% success rate as compared with a 25% placebo response (Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009 Aug;2[4]:349-61).

“It’s notable that antiarrhythmic drug development has almost been stopped because the drugs don’t work, with the possible exception of amiodarone, which requires an individualized risk/benefit assessment,” according to Dr. Estes.

There is a major caveat regarding the ablation studies: They’ve mainly enrolled patients who are in their 50s, when AF is far less common than in later decades.

“Whether these results are going to hold up long-term in elderly patients who are hypertensive, diabetic, and may have sleep apnea really remains an unanswered question,” Dr. Estes observed.

Also, significant periprocedural complications occur in roughly 1 in 20 patients undergoing radiofrequency catheter ablation, although the safety data for cryoablation look somewhat better, he continued.

Dr. Estes predicted that the future of catheter ablation of AF hangs on three major ongoing rigorous randomized clinical trials comparing it to drug therapy with hard endpoints including all-cause mortality and cardiovascular hospitalizations. These are CASTLE-AF, with 420 patients; CABANA, with 2,200; and the German EAST study, with roughly 3,000 patients. Results are expected in 2018-2019.

Dr. Estes reported serving as a consultant to Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and St. Jude Medical.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Don’t be in a rush to refer a patient with drug-refractory, symptomatic atrial fibrillation (AF) for catheter ablation of the arrhythmia, a prominent electrophysiologist advised at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

“AF ablation is not salvation – and that’s coming from somebody who does these procedures. One really needs to be very selective in referring patients for this,” said Dr. N.A. Mark Estes III, professor of medicine and director of cardiac arrhythmia services at Tufts University, Boston.

Misconceptions about AF catheter ablation outcomes abound among nonelectrophysiologists. Results have often been overstated, Dr. Estes continued. And there’s a far more attractive alternative treatment option for those AF patients who are overweight or obese: weight loss.

In the Australian LEGACY study, which he considers practice changing, patients with AF who had a body mass index of at least 27 kg/m2 who participated in a simple structured weight management program and achieved a sustained loss of at least 10% of their body weight had a 65% reduction in their AF burden as objectively documented by repeated 7-day ambulatory monitoring over 5 years of follow-up. Moreover, 46% of patients who maintained that degree of weight reduction were totally free of AF without use of drugs or ablation procedures (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 May 26;65[20]:2159-69).

In a related study, the Australian investigators, led by Dr. Rajeev K. Pathak of the University of Adelaide, showed in the same study population that participation in a tailored exercise program paid added dividends on top of the weight loss. Patients who achieved at least a 2-MET increase in cardiorespiratory fitness had a significantly greater rate of freedom from AF than those who didn’t reach that fitness threshold (J Am Coll Cardiol. Sep 1;66[9]:985-96).

“The data are compelling for improved outcomes, including reduced AF burden, with lifestyle modification in obese patients with AF. This is first-line therapy. You can bet it will be in the guidelines soon. It should be in your practice now,” Dr. Estes declared.

“The starting point is weight reduction, even before sending patients to an electrophysiologist for ablation,” he continued. “And if you’ve got patients on drugs who’ve had ablation in whom there continues to be AF, weight reduction – particularly reaching that 10% threshold – results in a dramatic decline in the burden of AF,” he said.

One of the common misconceptions about catheter ablation for AF is that if the pulmonary vein isolation procedure is successful in eliminating the arrhythmia, then the patient can discontinue oral anticoagulant therapy.

“That rationale, while logical, doesn’t really hold up. In many of the ablation trials, including the AFFIRM trial, if you discontinue anticoagulation in patients in sinus rhythm the stroke rate goes back to the same as in patients with AF,” according to the cardiologist.

In a meta-analysis of prospective studies published through 2007, the single-procedure success rate for radiofrequency ablation in achieving sinus rhythm without the use of antiarrhythmic drugs was 57%, climbing to 71% with multiple ablation procedures. In contrast, antiarrhythmic drugs were substantially less successful, with about a 50% success rate as compared with a 25% placebo response (Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009 Aug;2[4]:349-61).

“It’s notable that antiarrhythmic drug development has almost been stopped because the drugs don’t work, with the possible exception of amiodarone, which requires an individualized risk/benefit assessment,” according to Dr. Estes.

There is a major caveat regarding the ablation studies: They’ve mainly enrolled patients who are in their 50s, when AF is far less common than in later decades.

“Whether these results are going to hold up long-term in elderly patients who are hypertensive, diabetic, and may have sleep apnea really remains an unanswered question,” Dr. Estes observed.

Also, significant periprocedural complications occur in roughly 1 in 20 patients undergoing radiofrequency catheter ablation, although the safety data for cryoablation look somewhat better, he continued.

Dr. Estes predicted that the future of catheter ablation of AF hangs on three major ongoing rigorous randomized clinical trials comparing it to drug therapy with hard endpoints including all-cause mortality and cardiovascular hospitalizations. These are CASTLE-AF, with 420 patients; CABANA, with 2,200; and the German EAST study, with roughly 3,000 patients. Results are expected in 2018-2019.

Dr. Estes reported serving as a consultant to Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and St. Jude Medical.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

Warfarin is best for anticoagulation in prosthetic heart valve pregnancies

SNOWMASS, COLO. – How would you manage anticoagulation in a newly pregnant 23-year-old with a mechanical heart valve who has been on warfarin at 3 mg/day?

A) Weight-adjusted low-molecular-weight heparin during the first trimester, then warfarin in the second and third until switching to unfractionated heparin for delivery.

B) Low-molecular-weight heparin throughout pregnancy.

C) Warfarin throughout pregnancy.

D) Unfractionated heparin in the first trimester, warfarin in the second and third until returning to unfractionated heparin peridelivery.

The correct answer, according to both the ACC/AHA guidelines (Circulation. 2014 Jun 10;129[23]:e521-643) and European Society of Cardiology guidelines (Eur Heart J. 2011 Dec;32[24]:3147-97), is C in women who are on 5 mg/day of warfarin or less.

“Oral anticoagulants throughout pregnancy are much better for the mother, and this is where the guidelines have moved,” Dr. Carole A. Warnes said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

Both sets of guidelines give a class I recommendation to warfarin during the second and third trimesters, because the risk of warfarin embryopathy is confined to weeks 6-12. During the first trimester, warfarin at 5 mg/day or less gets a class IIa rating – making it preferable to unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin – because heparin is a far less effective anticoagulant. Plus, multiple small studies indicate the risk of embryopathy is low – roughly 1%-2% – when the mother is on warfarin at 5 mg/day or less.

In a woman on more than 5 mg/day of warfarin, the risk of warfarin embryopathy is about 6%, so the guidelines recommend replacing the drug with heparin during weeks 6-12.

“It’s not a walk in the park,” said Dr. Warnes, director of the Snowmass conference and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

The major concern in using heparin for anticoagulation in pregnancy is valve thrombosis. It doubles the risk.

“Pregnancy is the most prothrombotic state there is,” she said. “It’s not like managing a patient through a hip replacement or prostate surgery. Women with a mechanical prosthetic valve should be managed by a heart valve team with expertise in treatment during pregnancy.”

The alternatives to warfarin are adjusted-dose unfractionated heparin, which must be given in a continuous intravenous infusion with meticulous monitoring of activated partial thromboplastin time, or twice-daily low-molecular-weight heparin with dose adjustment by weight and maintenance of a target anti–Factor Xa level of 1.0-1.2 IU/mL.

“If you use low-molecular-weight heparin, you’re going to be seeing that patient every week to monitor anti–Factor Xa 4-6 hours post injection. You’ll find it’s not that easy to stay in the sweet spot, with excellent anticoagulation without an increased risk of maternal thromboembolism, or at the other extreme, fetal bleeding. What might look initially as a relatively easy strategy with a lot of appeal turns out to entail considerable risk,” Dr. Warnes said.

This was underscored in a cautionary report by highly experienced University of Toronto investigators. In their series of 23 pregnancies in 17 women with mechanical heart valves on low-molecular-weight heparin throughout pregnancy with careful monitoring, there was one maternal thromboembolic event resulting in maternal and fetal death despite a documented therapeutic anti–Factor Xa level (Am J Cardiol. 2009 Nov 1;104[9]:1259-63).

Although warfarin is clearly the better anticoagulant for the mother, the fetus pays the price. This was highlighted in a recent report from the ESC Registry of Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease (ROPAC) that compared pregnancy outcomes in 212 patients with a mechanical heart valve, 134 with a tissue valve, and 2,620 women without a prosthetic heart valve. Use of warfarin or another vitamin K antagonist in the first trimester was associated with a higher rate of miscarriage than heparin – 28.6% vs. 9.2% – as well as a 7.1% incidence of late fetal death, compared with just 0.7% with heparin.

On the other hand, the mechanical valve thrombosis rate was 4.7%, with half of those serious events occurring during the first trimester in patients after they’d been switched to heparin (Circulation. 2015 Jul 14;132[2]:132-42).

Hemorrhagic events occurred in 23.1% of mothers with a mechanical heart valve, 5.1% of those with a bioprosthetic valve, and 4.9% of patients without a prosthetic valve. A point worth incorporating into prepregnancy patient counseling, Dr. Warnes noted, is that only 58% of ROPAC participants with a mechanical heart valve had an uncomplicated pregnancy with a live birth, in contrast to 79% of those with a tissue valve and 78% of controls.

Because warfarin crosses the placenta, and it takes about a week for the fetus to eliminate the drug following maternal discontinuation, the guidelines recommend stopping warfarin at about week 36 and changing to a continuous infusion of dose-adjusted unfractionated heparin peridelivery. The heparin should be stopped for as short a time as possible before delivery and resumed 6-12 hours post delivery in order to protect against valve thrombosis.

Of course, opting for a bioprosthetic rather than a mechanical heart valve avoids all these difficult anticoagulation-related issues. But it poses a different serious problem: The younger the patient at the time of tissue valve implantation, the greater the risk of rapid calcification and structural valve deterioration. Indeed, among patients who are age 16-39 when they receive a bioprosthetic valve, the rate of structural valve deterioration is 50% at 10 years and 90% at 15 years.

“There is no ideal valve prosthesis. If you elect a tissue prosthesis, you have to discuss the risk of reoperation in that young woman,” Dr. Warnes advised.

Recent data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons database indicate the mortality associated with redo elective aortic valve replacement in a 35-year-old woman with no comorbidities averages 1.63%, with a 2% mortality rate for redo mitral valve replacement.

Dr. Warnes reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – How would you manage anticoagulation in a newly pregnant 23-year-old with a mechanical heart valve who has been on warfarin at 3 mg/day?

A) Weight-adjusted low-molecular-weight heparin during the first trimester, then warfarin in the second and third until switching to unfractionated heparin for delivery.

B) Low-molecular-weight heparin throughout pregnancy.

C) Warfarin throughout pregnancy.

D) Unfractionated heparin in the first trimester, warfarin in the second and third until returning to unfractionated heparin peridelivery.

The correct answer, according to both the ACC/AHA guidelines (Circulation. 2014 Jun 10;129[23]:e521-643) and European Society of Cardiology guidelines (Eur Heart J. 2011 Dec;32[24]:3147-97), is C in women who are on 5 mg/day of warfarin or less.

“Oral anticoagulants throughout pregnancy are much better for the mother, and this is where the guidelines have moved,” Dr. Carole A. Warnes said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

Both sets of guidelines give a class I recommendation to warfarin during the second and third trimesters, because the risk of warfarin embryopathy is confined to weeks 6-12. During the first trimester, warfarin at 5 mg/day or less gets a class IIa rating – making it preferable to unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin – because heparin is a far less effective anticoagulant. Plus, multiple small studies indicate the risk of embryopathy is low – roughly 1%-2% – when the mother is on warfarin at 5 mg/day or less.

In a woman on more than 5 mg/day of warfarin, the risk of warfarin embryopathy is about 6%, so the guidelines recommend replacing the drug with heparin during weeks 6-12.

“It’s not a walk in the park,” said Dr. Warnes, director of the Snowmass conference and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

The major concern in using heparin for anticoagulation in pregnancy is valve thrombosis. It doubles the risk.

“Pregnancy is the most prothrombotic state there is,” she said. “It’s not like managing a patient through a hip replacement or prostate surgery. Women with a mechanical prosthetic valve should be managed by a heart valve team with expertise in treatment during pregnancy.”

The alternatives to warfarin are adjusted-dose unfractionated heparin, which must be given in a continuous intravenous infusion with meticulous monitoring of activated partial thromboplastin time, or twice-daily low-molecular-weight heparin with dose adjustment by weight and maintenance of a target anti–Factor Xa level of 1.0-1.2 IU/mL.

“If you use low-molecular-weight heparin, you’re going to be seeing that patient every week to monitor anti–Factor Xa 4-6 hours post injection. You’ll find it’s not that easy to stay in the sweet spot, with excellent anticoagulation without an increased risk of maternal thromboembolism, or at the other extreme, fetal bleeding. What might look initially as a relatively easy strategy with a lot of appeal turns out to entail considerable risk,” Dr. Warnes said.

This was underscored in a cautionary report by highly experienced University of Toronto investigators. In their series of 23 pregnancies in 17 women with mechanical heart valves on low-molecular-weight heparin throughout pregnancy with careful monitoring, there was one maternal thromboembolic event resulting in maternal and fetal death despite a documented therapeutic anti–Factor Xa level (Am J Cardiol. 2009 Nov 1;104[9]:1259-63).

Although warfarin is clearly the better anticoagulant for the mother, the fetus pays the price. This was highlighted in a recent report from the ESC Registry of Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease (ROPAC) that compared pregnancy outcomes in 212 patients with a mechanical heart valve, 134 with a tissue valve, and 2,620 women without a prosthetic heart valve. Use of warfarin or another vitamin K antagonist in the first trimester was associated with a higher rate of miscarriage than heparin – 28.6% vs. 9.2% – as well as a 7.1% incidence of late fetal death, compared with just 0.7% with heparin.

On the other hand, the mechanical valve thrombosis rate was 4.7%, with half of those serious events occurring during the first trimester in patients after they’d been switched to heparin (Circulation. 2015 Jul 14;132[2]:132-42).

Hemorrhagic events occurred in 23.1% of mothers with a mechanical heart valve, 5.1% of those with a bioprosthetic valve, and 4.9% of patients without a prosthetic valve. A point worth incorporating into prepregnancy patient counseling, Dr. Warnes noted, is that only 58% of ROPAC participants with a mechanical heart valve had an uncomplicated pregnancy with a live birth, in contrast to 79% of those with a tissue valve and 78% of controls.

Because warfarin crosses the placenta, and it takes about a week for the fetus to eliminate the drug following maternal discontinuation, the guidelines recommend stopping warfarin at about week 36 and changing to a continuous infusion of dose-adjusted unfractionated heparin peridelivery. The heparin should be stopped for as short a time as possible before delivery and resumed 6-12 hours post delivery in order to protect against valve thrombosis.

Of course, opting for a bioprosthetic rather than a mechanical heart valve avoids all these difficult anticoagulation-related issues. But it poses a different serious problem: The younger the patient at the time of tissue valve implantation, the greater the risk of rapid calcification and structural valve deterioration. Indeed, among patients who are age 16-39 when they receive a bioprosthetic valve, the rate of structural valve deterioration is 50% at 10 years and 90% at 15 years.

“There is no ideal valve prosthesis. If you elect a tissue prosthesis, you have to discuss the risk of reoperation in that young woman,” Dr. Warnes advised.

Recent data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons database indicate the mortality associated with redo elective aortic valve replacement in a 35-year-old woman with no comorbidities averages 1.63%, with a 2% mortality rate for redo mitral valve replacement.

Dr. Warnes reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – How would you manage anticoagulation in a newly pregnant 23-year-old with a mechanical heart valve who has been on warfarin at 3 mg/day?

A) Weight-adjusted low-molecular-weight heparin during the first trimester, then warfarin in the second and third until switching to unfractionated heparin for delivery.

B) Low-molecular-weight heparin throughout pregnancy.

C) Warfarin throughout pregnancy.

D) Unfractionated heparin in the first trimester, warfarin in the second and third until returning to unfractionated heparin peridelivery.

The correct answer, according to both the ACC/AHA guidelines (Circulation. 2014 Jun 10;129[23]:e521-643) and European Society of Cardiology guidelines (Eur Heart J. 2011 Dec;32[24]:3147-97), is C in women who are on 5 mg/day of warfarin or less.

“Oral anticoagulants throughout pregnancy are much better for the mother, and this is where the guidelines have moved,” Dr. Carole A. Warnes said at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

Both sets of guidelines give a class I recommendation to warfarin during the second and third trimesters, because the risk of warfarin embryopathy is confined to weeks 6-12. During the first trimester, warfarin at 5 mg/day or less gets a class IIa rating – making it preferable to unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin – because heparin is a far less effective anticoagulant. Plus, multiple small studies indicate the risk of embryopathy is low – roughly 1%-2% – when the mother is on warfarin at 5 mg/day or less.

In a woman on more than 5 mg/day of warfarin, the risk of warfarin embryopathy is about 6%, so the guidelines recommend replacing the drug with heparin during weeks 6-12.

“It’s not a walk in the park,” said Dr. Warnes, director of the Snowmass conference and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

The major concern in using heparin for anticoagulation in pregnancy is valve thrombosis. It doubles the risk.

“Pregnancy is the most prothrombotic state there is,” she said. “It’s not like managing a patient through a hip replacement or prostate surgery. Women with a mechanical prosthetic valve should be managed by a heart valve team with expertise in treatment during pregnancy.”

The alternatives to warfarin are adjusted-dose unfractionated heparin, which must be given in a continuous intravenous infusion with meticulous monitoring of activated partial thromboplastin time, or twice-daily low-molecular-weight heparin with dose adjustment by weight and maintenance of a target anti–Factor Xa level of 1.0-1.2 IU/mL.

“If you use low-molecular-weight heparin, you’re going to be seeing that patient every week to monitor anti–Factor Xa 4-6 hours post injection. You’ll find it’s not that easy to stay in the sweet spot, with excellent anticoagulation without an increased risk of maternal thromboembolism, or at the other extreme, fetal bleeding. What might look initially as a relatively easy strategy with a lot of appeal turns out to entail considerable risk,” Dr. Warnes said.

This was underscored in a cautionary report by highly experienced University of Toronto investigators. In their series of 23 pregnancies in 17 women with mechanical heart valves on low-molecular-weight heparin throughout pregnancy with careful monitoring, there was one maternal thromboembolic event resulting in maternal and fetal death despite a documented therapeutic anti–Factor Xa level (Am J Cardiol. 2009 Nov 1;104[9]:1259-63).

Although warfarin is clearly the better anticoagulant for the mother, the fetus pays the price. This was highlighted in a recent report from the ESC Registry of Pregnancy and Cardiac Disease (ROPAC) that compared pregnancy outcomes in 212 patients with a mechanical heart valve, 134 with a tissue valve, and 2,620 women without a prosthetic heart valve. Use of warfarin or another vitamin K antagonist in the first trimester was associated with a higher rate of miscarriage than heparin – 28.6% vs. 9.2% – as well as a 7.1% incidence of late fetal death, compared with just 0.7% with heparin.

On the other hand, the mechanical valve thrombosis rate was 4.7%, with half of those serious events occurring during the first trimester in patients after they’d been switched to heparin (Circulation. 2015 Jul 14;132[2]:132-42).

Hemorrhagic events occurred in 23.1% of mothers with a mechanical heart valve, 5.1% of those with a bioprosthetic valve, and 4.9% of patients without a prosthetic valve. A point worth incorporating into prepregnancy patient counseling, Dr. Warnes noted, is that only 58% of ROPAC participants with a mechanical heart valve had an uncomplicated pregnancy with a live birth, in contrast to 79% of those with a tissue valve and 78% of controls.

Because warfarin crosses the placenta, and it takes about a week for the fetus to eliminate the drug following maternal discontinuation, the guidelines recommend stopping warfarin at about week 36 and changing to a continuous infusion of dose-adjusted unfractionated heparin peridelivery. The heparin should be stopped for as short a time as possible before delivery and resumed 6-12 hours post delivery in order to protect against valve thrombosis.

Of course, opting for a bioprosthetic rather than a mechanical heart valve avoids all these difficult anticoagulation-related issues. But it poses a different serious problem: The younger the patient at the time of tissue valve implantation, the greater the risk of rapid calcification and structural valve deterioration. Indeed, among patients who are age 16-39 when they receive a bioprosthetic valve, the rate of structural valve deterioration is 50% at 10 years and 90% at 15 years.

“There is no ideal valve prosthesis. If you elect a tissue prosthesis, you have to discuss the risk of reoperation in that young woman,” Dr. Warnes advised.

Recent data from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons database indicate the mortality associated with redo elective aortic valve replacement in a 35-year-old woman with no comorbidities averages 1.63%, with a 2% mortality rate for redo mitral valve replacement.

Dr. Warnes reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

Experts say abandon aspirin for stroke prevention in atrial fib

SNOWMASS, COLO. – It’s time to eliminate the practice of prescribing aspirin for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation and a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1, two eminent cardiologists agreed at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

“The European guidelines have done away with aspirin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. It barely made it into our current U.S. guidelines. I don’t think aspirin should be in there and I don’t think it will be there in the next guidelines. The role of aspirin will fall away,” predicted Dr. Bernard J. Gersh, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“It’s not that aspirin is less effective than the oral anticoagulants, it’s that there’s no role for it. There are no good data to support aspirin in the prevention of stroke in atrial fibrillation,” he declared.

Dr. N.A. Mark Estes III agreed the aspirin evidence is seriously flawed.

“The use of aspirin has probably been misguided, based upon a single trial which showed a profound effect and was probably just an anomaly,” according to Dr. Estes, a past president of the Heart Rhythm Society who is professor of medicine and director of the New England Cardiac Arrhythmia Center at Tufts University, Boston.

The sole positive clinical trial of aspirin versus placebo, the 25-year-old Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation (SPAF) study (Circulation. 1991 Aug;84[2]:527-39), found an unrealistically high stroke protection benefit for aspirin, a result made implausible by multiple other randomized trials showing no benefit, the cardiologists agreed.

“In our current guidelines for atrial fibrillation (Circulation. 2014 Dec 2;130[23]:2071-104), aspirin can be considered as a Class IIb level of evidence C recommendation in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 1. But I would just take it off of your clinical armamentarium because the best available data indicates that it doesn’t prevent strokes. I’m certainly not using it in my patients. Increasingly in my patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 1, I’m discussing the risks and benefits of a NOAC [novel oral anticoagulant],” Dr. Estes said.

Dr. Gersh was also critical of another common practice in stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: concomitant use of aspirin with an oral anticoagulant.

“We use too much aspirin in patients on oral anticoagulation. Aspirin is perhaps the major cause of bleeding in patients on an oral anticoagulant. Other than in people with a drug-eluting stent, there’s no role at all for aspirin in stroke prevention,” he asserted.

He was coauthor of an analysis of 7,347 participants in the Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (ORBIT-AF) who were on an oral anticoagulant. Fully 35% of them were also on aspirin. In a multivariate analysis, concomitant aspirin and oral anticoagulation was independently associated with a 53% increased risk of major bleeding and a 52% increase in hospitalization for bleeding, compared with atrial fibrillation patients on an oral anticoagulant alone (Circulation. 2013 Aug 13;128[7]:721-8).

Moreover, the widespread use of dual therapy in this real-world registry didn’t appear to be rational. Thirty-nine percent of those on aspirin plus an oral anticoagulant had no history of atherosclerotic disease, the presence of which would be an indication for considering aspirin. And 17% of dual therapy patients had an elevated Anticoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) risk score of 5 or more, making dual therapy particularly risky.

This clinically important interaction between aspirin and oral anticoagulation was recently underscored in an analysis of rivaroxaban-treated patients in the ROCKET AF trial, Dr. Gersh observed. Long-term use of aspirin at entry into this pivotal randomized trial of rivaroxaban (Xarelto) versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation proved to be an independent predictor of a 47% increase in the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, compared with patients on rivaroxaban alone (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Dec 1;66[21]:2271-81).

He added that there is no evidence that combining aspirin and oral anticoagulation enhances stroke prevention beyond the marked benefit achieved with oral anticoagulation alone.

Dr. Gersh reported serving on the leadership of the ORBIT-AF Registry, which was sponsored by Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Estes reported having no financial conflicts relevant to this discussion.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – It’s time to eliminate the practice of prescribing aspirin for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation and a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1, two eminent cardiologists agreed at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

“The European guidelines have done away with aspirin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. It barely made it into our current U.S. guidelines. I don’t think aspirin should be in there and I don’t think it will be there in the next guidelines. The role of aspirin will fall away,” predicted Dr. Bernard J. Gersh, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“It’s not that aspirin is less effective than the oral anticoagulants, it’s that there’s no role for it. There are no good data to support aspirin in the prevention of stroke in atrial fibrillation,” he declared.

Dr. N.A. Mark Estes III agreed the aspirin evidence is seriously flawed.

“The use of aspirin has probably been misguided, based upon a single trial which showed a profound effect and was probably just an anomaly,” according to Dr. Estes, a past president of the Heart Rhythm Society who is professor of medicine and director of the New England Cardiac Arrhythmia Center at Tufts University, Boston.

The sole positive clinical trial of aspirin versus placebo, the 25-year-old Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation (SPAF) study (Circulation. 1991 Aug;84[2]:527-39), found an unrealistically high stroke protection benefit for aspirin, a result made implausible by multiple other randomized trials showing no benefit, the cardiologists agreed.

“In our current guidelines for atrial fibrillation (Circulation. 2014 Dec 2;130[23]:2071-104), aspirin can be considered as a Class IIb level of evidence C recommendation in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 1. But I would just take it off of your clinical armamentarium because the best available data indicates that it doesn’t prevent strokes. I’m certainly not using it in my patients. Increasingly in my patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 1, I’m discussing the risks and benefits of a NOAC [novel oral anticoagulant],” Dr. Estes said.

Dr. Gersh was also critical of another common practice in stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: concomitant use of aspirin with an oral anticoagulant.

“We use too much aspirin in patients on oral anticoagulation. Aspirin is perhaps the major cause of bleeding in patients on an oral anticoagulant. Other than in people with a drug-eluting stent, there’s no role at all for aspirin in stroke prevention,” he asserted.

He was coauthor of an analysis of 7,347 participants in the Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (ORBIT-AF) who were on an oral anticoagulant. Fully 35% of them were also on aspirin. In a multivariate analysis, concomitant aspirin and oral anticoagulation was independently associated with a 53% increased risk of major bleeding and a 52% increase in hospitalization for bleeding, compared with atrial fibrillation patients on an oral anticoagulant alone (Circulation. 2013 Aug 13;128[7]:721-8).

Moreover, the widespread use of dual therapy in this real-world registry didn’t appear to be rational. Thirty-nine percent of those on aspirin plus an oral anticoagulant had no history of atherosclerotic disease, the presence of which would be an indication for considering aspirin. And 17% of dual therapy patients had an elevated Anticoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) risk score of 5 or more, making dual therapy particularly risky.

This clinically important interaction between aspirin and oral anticoagulation was recently underscored in an analysis of rivaroxaban-treated patients in the ROCKET AF trial, Dr. Gersh observed. Long-term use of aspirin at entry into this pivotal randomized trial of rivaroxaban (Xarelto) versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation proved to be an independent predictor of a 47% increase in the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, compared with patients on rivaroxaban alone (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Dec 1;66[21]:2271-81).

He added that there is no evidence that combining aspirin and oral anticoagulation enhances stroke prevention beyond the marked benefit achieved with oral anticoagulation alone.

Dr. Gersh reported serving on the leadership of the ORBIT-AF Registry, which was sponsored by Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Estes reported having no financial conflicts relevant to this discussion.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – It’s time to eliminate the practice of prescribing aspirin for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation and a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1, two eminent cardiologists agreed at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass.

“The European guidelines have done away with aspirin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. It barely made it into our current U.S. guidelines. I don’t think aspirin should be in there and I don’t think it will be there in the next guidelines. The role of aspirin will fall away,” predicted Dr. Bernard J. Gersh, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“It’s not that aspirin is less effective than the oral anticoagulants, it’s that there’s no role for it. There are no good data to support aspirin in the prevention of stroke in atrial fibrillation,” he declared.

Dr. N.A. Mark Estes III agreed the aspirin evidence is seriously flawed.

“The use of aspirin has probably been misguided, based upon a single trial which showed a profound effect and was probably just an anomaly,” according to Dr. Estes, a past president of the Heart Rhythm Society who is professor of medicine and director of the New England Cardiac Arrhythmia Center at Tufts University, Boston.

The sole positive clinical trial of aspirin versus placebo, the 25-year-old Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation (SPAF) study (Circulation. 1991 Aug;84[2]:527-39), found an unrealistically high stroke protection benefit for aspirin, a result made implausible by multiple other randomized trials showing no benefit, the cardiologists agreed.

“In our current guidelines for atrial fibrillation (Circulation. 2014 Dec 2;130[23]:2071-104), aspirin can be considered as a Class IIb level of evidence C recommendation in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 1. But I would just take it off of your clinical armamentarium because the best available data indicates that it doesn’t prevent strokes. I’m certainly not using it in my patients. Increasingly in my patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 1, I’m discussing the risks and benefits of a NOAC [novel oral anticoagulant],” Dr. Estes said.

Dr. Gersh was also critical of another common practice in stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: concomitant use of aspirin with an oral anticoagulant.

“We use too much aspirin in patients on oral anticoagulation. Aspirin is perhaps the major cause of bleeding in patients on an oral anticoagulant. Other than in people with a drug-eluting stent, there’s no role at all for aspirin in stroke prevention,” he asserted.

He was coauthor of an analysis of 7,347 participants in the Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (ORBIT-AF) who were on an oral anticoagulant. Fully 35% of them were also on aspirin. In a multivariate analysis, concomitant aspirin and oral anticoagulation was independently associated with a 53% increased risk of major bleeding and a 52% increase in hospitalization for bleeding, compared with atrial fibrillation patients on an oral anticoagulant alone (Circulation. 2013 Aug 13;128[7]:721-8).

Moreover, the widespread use of dual therapy in this real-world registry didn’t appear to be rational. Thirty-nine percent of those on aspirin plus an oral anticoagulant had no history of atherosclerotic disease, the presence of which would be an indication for considering aspirin. And 17% of dual therapy patients had an elevated Anticoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) risk score of 5 or more, making dual therapy particularly risky.

This clinically important interaction between aspirin and oral anticoagulation was recently underscored in an analysis of rivaroxaban-treated patients in the ROCKET AF trial, Dr. Gersh observed. Long-term use of aspirin at entry into this pivotal randomized trial of rivaroxaban (Xarelto) versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation proved to be an independent predictor of a 47% increase in the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, compared with patients on rivaroxaban alone (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Dec 1;66[21]:2271-81).

He added that there is no evidence that combining aspirin and oral anticoagulation enhances stroke prevention beyond the marked benefit achieved with oral anticoagulation alone.

Dr. Gersh reported serving on the leadership of the ORBIT-AF Registry, which was sponsored by Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Estes reported having no financial conflicts relevant to this discussion.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE CARDIOVASCULAR CONFERENCE AT SNOWMASS

AHA: Bariatric surgery slashes heart failure exacerbations

ORLANDO – Bariatric surgery in obese patients with heart failure was associated with a marked decrease in the subsequent rate of ED visits and hospitalizations for heart failure in a large, real-world, case-control study presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“This decline in the rate of heart failure morbidity was rapid in onset and sustained for at least 2 years after bariatric surgery,” according to Dr. Yuichi J. Shimada of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

In a separate study, however, he found that bariatric surgery for obesity in patients with atrial fibrillation didn’t produce a reduction in ED visits and hospitalizations for the arrhythmia.

The heart failure study was a case-control study of 1,664 consecutive obese patients with heart failure who underwent a single bariatric surgical procedure in California, Florida, or Nebraska. Their median age was 49 years. Women accounted for 70% of the participants. Drawing upon federal Healthcare Cost and Utility Project databases on ED visits and hospital admissions in those three states, Dr. Shimada and coinvestigators compared the group’s rates of ED visits and hospitalizations for heart failure for 2 years before and 2 years after bariatric surgery. Thus, the subjects served as their own controls.

During the reference period, which lasted from months 13-24 presurgery, the group’s combined rate of ED visits and hospital admission for heart failure exacerbation was 14.4%. The rate wasn’t significantly different during the 12 months immediately prior to surgery, at 13.3%.

The rate dropped to 8.7% during the first 12 months after bariatric surgery and remained rock solid at 8.7% during months 13-24 postsurgery. In a logistic regression analysis, this translated to a 44% reduction in the risk of ED visits or hospital admission for heart failure during the first 2 years following bariatric surgery.

These findings are consistent with previous work by other investigators showing a link between obesity and heart failure exacerbations. The new data advance the field by providing the best evidence to date of the effectiveness of substantial weight loss on heart failure morbidity, Dr. Shimada observed.

Nonbariatric surgeries such as hysterectomy or cholecysectomy in the study population had no effect on the rate of heart failure exacerbations.

Dr. Shimada’s atrial fibrillation study was structured in the same way. It included 1,056 patients with atrial fibrillation who underwent bariatric surgery for obesity in the same three states. The rate of ED visits or hospitalization for heart failure was 12.1% in months 13-24 prior to bariatric surgery, 12.6% in presurgical months 1-12, 14.2% in the first 12 months post-bariatric surgery, and 13.4% during postsurgical months 13-24. These rates weren’t statistically different.

Dr. Shimada reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding the two studies.

ORLANDO – Bariatric surgery in obese patients with heart failure was associated with a marked decrease in the subsequent rate of ED visits and hospitalizations for heart failure in a large, real-world, case-control study presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“This decline in the rate of heart failure morbidity was rapid in onset and sustained for at least 2 years after bariatric surgery,” according to Dr. Yuichi J. Shimada of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

In a separate study, however, he found that bariatric surgery for obesity in patients with atrial fibrillation didn’t produce a reduction in ED visits and hospitalizations for the arrhythmia.

The heart failure study was a case-control study of 1,664 consecutive obese patients with heart failure who underwent a single bariatric surgical procedure in California, Florida, or Nebraska. Their median age was 49 years. Women accounted for 70% of the participants. Drawing upon federal Healthcare Cost and Utility Project databases on ED visits and hospital admissions in those three states, Dr. Shimada and coinvestigators compared the group’s rates of ED visits and hospitalizations for heart failure for 2 years before and 2 years after bariatric surgery. Thus, the subjects served as their own controls.

During the reference period, which lasted from months 13-24 presurgery, the group’s combined rate of ED visits and hospital admission for heart failure exacerbation was 14.4%. The rate wasn’t significantly different during the 12 months immediately prior to surgery, at 13.3%.

The rate dropped to 8.7% during the first 12 months after bariatric surgery and remained rock solid at 8.7% during months 13-24 postsurgery. In a logistic regression analysis, this translated to a 44% reduction in the risk of ED visits or hospital admission for heart failure during the first 2 years following bariatric surgery.

These findings are consistent with previous work by other investigators showing a link between obesity and heart failure exacerbations. The new data advance the field by providing the best evidence to date of the effectiveness of substantial weight loss on heart failure morbidity, Dr. Shimada observed.

Nonbariatric surgeries such as hysterectomy or cholecysectomy in the study population had no effect on the rate of heart failure exacerbations.

Dr. Shimada’s atrial fibrillation study was structured in the same way. It included 1,056 patients with atrial fibrillation who underwent bariatric surgery for obesity in the same three states. The rate of ED visits or hospitalization for heart failure was 12.1% in months 13-24 prior to bariatric surgery, 12.6% in presurgical months 1-12, 14.2% in the first 12 months post-bariatric surgery, and 13.4% during postsurgical months 13-24. These rates weren’t statistically different.

Dr. Shimada reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding the two studies.

ORLANDO – Bariatric surgery in obese patients with heart failure was associated with a marked decrease in the subsequent rate of ED visits and hospitalizations for heart failure in a large, real-world, case-control study presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“This decline in the rate of heart failure morbidity was rapid in onset and sustained for at least 2 years after bariatric surgery,” according to Dr. Yuichi J. Shimada of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

In a separate study, however, he found that bariatric surgery for obesity in patients with atrial fibrillation didn’t produce a reduction in ED visits and hospitalizations for the arrhythmia.

The heart failure study was a case-control study of 1,664 consecutive obese patients with heart failure who underwent a single bariatric surgical procedure in California, Florida, or Nebraska. Their median age was 49 years. Women accounted for 70% of the participants. Drawing upon federal Healthcare Cost and Utility Project databases on ED visits and hospital admissions in those three states, Dr. Shimada and coinvestigators compared the group’s rates of ED visits and hospitalizations for heart failure for 2 years before and 2 years after bariatric surgery. Thus, the subjects served as their own controls.

During the reference period, which lasted from months 13-24 presurgery, the group’s combined rate of ED visits and hospital admission for heart failure exacerbation was 14.4%. The rate wasn’t significantly different during the 12 months immediately prior to surgery, at 13.3%.

The rate dropped to 8.7% during the first 12 months after bariatric surgery and remained rock solid at 8.7% during months 13-24 postsurgery. In a logistic regression analysis, this translated to a 44% reduction in the risk of ED visits or hospital admission for heart failure during the first 2 years following bariatric surgery.

These findings are consistent with previous work by other investigators showing a link between obesity and heart failure exacerbations. The new data advance the field by providing the best evidence to date of the effectiveness of substantial weight loss on heart failure morbidity, Dr. Shimada observed.

Nonbariatric surgeries such as hysterectomy or cholecysectomy in the study population had no effect on the rate of heart failure exacerbations.

Dr. Shimada’s atrial fibrillation study was structured in the same way. It included 1,056 patients with atrial fibrillation who underwent bariatric surgery for obesity in the same three states. The rate of ED visits or hospitalization for heart failure was 12.1% in months 13-24 prior to bariatric surgery, 12.6% in presurgical months 1-12, 14.2% in the first 12 months post-bariatric surgery, and 13.4% during postsurgical months 13-24. These rates weren’t statistically different.

Dr. Shimada reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding the two studies.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Bariatric surgery in obese patients with heart failure results in a dramatic reduction in ED visits and hospital admission for heart failure.

Major finding: The combined rate of ED visits and hospital admissions for heart failure dropped by 44% during the 2 years after a large group of patients with heart failure underwent bariatric surgery for obesity.

Data source: This case-control study compared the rates of ED visits and hospital admissions for worsening heart failure in 1,664 patients with heart failure during the 2 years before and 2 years after they underwent bariatric surgery for obesity.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding the study, which utilized publicly available patient data.

AHA: Poor real-world adherence to NOACs

ORLANDO – Adherence to the novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) is surprisingly poor in clinical practice, Xiaoxi Yao, Ph.D., reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Her retrospective study of nearly 65,000 patients with atrial fibrillation who initiated therapy with apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or warfarin showed that during a median 1.1 years of follow-up fewer than half of all patients were treatment adherent, with adherence defined as possession of sufficient medication to cover at least 80% of days.

Adherence rates, while uniformly suboptimal, nevertheless varied considerably: lowest at 38.5% for dabigatran, followed by 40.2% for warfarin, 50.5% for rivaroxaban, and 61.9% for apixaban.

This poor adherence to NOACs in real-world clinical practice is surprising in light of the drugs’ greater convenience, with fewer drug interactions than warfarin and no need for laboratory monitoring, observed Dr. Yao of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

It’s possible, although speculative, that the NOACs’ greater convenience paradoxically contributes to the low adherence rates, since unlike warfarin, NOACs don’t require regular interactions with the health care system for INR monitoring. And then there is the hefty cost of the novel agents, she added.

The study population consisted of 3,900 patients with atrial fibrillation who initiated oral anticoagulation with apixaban (Eliquis), 10,235 who started on dabigatran (Pradaxa), 12,366 on rivaroxaban (Xarelto), and 38,190 on warfarin. The analysis utilized claims data from a large U.S. commercial insurance database.

Adherence rates were better among patients with greater stroke risk as reflected by their CHA2DS2-VASc scores. For example, at the high end of the adherence spectrum, the adherence rate for apixaban was 50% in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0-1, rising to 62% with a score of 2-3 and 64% with a score of 4 or more. The corresponding adherence rates for dabigatran were 25% in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 0-1, 40% among those with a score of 2-3, and 42% in patients with a score of 4 or higher.

Dr. Yao and coinvestigators were interested in whether lower adherence to oral anticoagulation was associated with worse outcomes. This proved to be the case with regard to stroke rate for patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more, where a clear dose-response relationship was evident between the event rate and cumulative time off oral anticoagulation during follow-up.

Among patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 2 or 3, the stroke rate was nearly twice as high among those off oral anticoagulation for a total of 3-6 months and three times greater if off therapy for more than 6 months than in those with a total time off of less than 1 week. The stroke rate was even higher in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 4 or more who had suboptimal adherence.

An unexpected finding, she continued, was that among patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more there was no significant relationship between cumulative time off oral anticoagulation and the risk of major bleeding unless they were off treatment for a total of 6 months or more; only then was the major bleeding risk lower than in patients whose total time off therapy was less than a week. Also, one would expect that when patients are off oral anticoagulation they should be at significantly lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage than when on-therapy, but this proved not to be the case.

For patients at substantial stroke risk as indicated by a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2, this finding about off-treatment bleeding risk actually constitutes a good argument for sticking to their medication, in Dr. Yao’s view.

“Physicians and patients often fear bleeding, especially intracranial hemorrhage, but we found that for patients at higher risk for stroke there is little difference in intracranial hemorrhage risk whether you’re on or off of oral anticoagulation. So higher-risk patients should definitely adhere to their medication because of the stroke prevention benefit. However, in low-risk patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 0-1, the benefits of oral anticoagulation may not always outweigh the harm,” she said.

Dr. Yao reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study.

ORLANDO – Adherence to the novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) is surprisingly poor in clinical practice, Xiaoxi Yao, Ph.D., reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Her retrospective study of nearly 65,000 patients with atrial fibrillation who initiated therapy with apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or warfarin showed that during a median 1.1 years of follow-up fewer than half of all patients were treatment adherent, with adherence defined as possession of sufficient medication to cover at least 80% of days.

Adherence rates, while uniformly suboptimal, nevertheless varied considerably: lowest at 38.5% for dabigatran, followed by 40.2% for warfarin, 50.5% for rivaroxaban, and 61.9% for apixaban.

This poor adherence to NOACs in real-world clinical practice is surprising in light of the drugs’ greater convenience, with fewer drug interactions than warfarin and no need for laboratory monitoring, observed Dr. Yao of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

It’s possible, although speculative, that the NOACs’ greater convenience paradoxically contributes to the low adherence rates, since unlike warfarin, NOACs don’t require regular interactions with the health care system for INR monitoring. And then there is the hefty cost of the novel agents, she added.

The study population consisted of 3,900 patients with atrial fibrillation who initiated oral anticoagulation with apixaban (Eliquis), 10,235 who started on dabigatran (Pradaxa), 12,366 on rivaroxaban (Xarelto), and 38,190 on warfarin. The analysis utilized claims data from a large U.S. commercial insurance database.

Adherence rates were better among patients with greater stroke risk as reflected by their CHA2DS2-VASc scores. For example, at the high end of the adherence spectrum, the adherence rate for apixaban was 50% in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0-1, rising to 62% with a score of 2-3 and 64% with a score of 4 or more. The corresponding adherence rates for dabigatran were 25% in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 0-1, 40% among those with a score of 2-3, and 42% in patients with a score of 4 or higher.

Dr. Yao and coinvestigators were interested in whether lower adherence to oral anticoagulation was associated with worse outcomes. This proved to be the case with regard to stroke rate for patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more, where a clear dose-response relationship was evident between the event rate and cumulative time off oral anticoagulation during follow-up.

Among patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 2 or 3, the stroke rate was nearly twice as high among those off oral anticoagulation for a total of 3-6 months and three times greater if off therapy for more than 6 months than in those with a total time off of less than 1 week. The stroke rate was even higher in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 4 or more who had suboptimal adherence.

An unexpected finding, she continued, was that among patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 2 or more there was no significant relationship between cumulative time off oral anticoagulation and the risk of major bleeding unless they were off treatment for a total of 6 months or more; only then was the major bleeding risk lower than in patients whose total time off therapy was less than a week. Also, one would expect that when patients are off oral anticoagulation they should be at significantly lower risk of intracranial hemorrhage than when on-therapy, but this proved not to be the case.

For patients at substantial stroke risk as indicated by a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2, this finding about off-treatment bleeding risk actually constitutes a good argument for sticking to their medication, in Dr. Yao’s view.

“Physicians and patients often fear bleeding, especially intracranial hemorrhage, but we found that for patients at higher risk for stroke there is little difference in intracranial hemorrhage risk whether you’re on or off of oral anticoagulation. So higher-risk patients should definitely adhere to their medication because of the stroke prevention benefit. However, in low-risk patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 0-1, the benefits of oral anticoagulation may not always outweigh the harm,” she said.

Dr. Yao reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding her study.

ORLANDO – Adherence to the novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) is surprisingly poor in clinical practice, Xiaoxi Yao, Ph.D., reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Her retrospective study of nearly 65,000 patients with atrial fibrillation who initiated therapy with apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or warfarin showed that during a median 1.1 years of follow-up fewer than half of all patients were treatment adherent, with adherence defined as possession of sufficient medication to cover at least 80% of days.

Adherence rates, while uniformly suboptimal, nevertheless varied considerably: lowest at 38.5% for dabigatran, followed by 40.2% for warfarin, 50.5% for rivaroxaban, and 61.9% for apixaban.

This poor adherence to NOACs in real-world clinical practice is surprising in light of the drugs’ greater convenience, with fewer drug interactions than warfarin and no need for laboratory monitoring, observed Dr. Yao of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

It’s possible, although speculative, that the NOACs’ greater convenience paradoxically contributes to the low adherence rates, since unlike warfarin, NOACs don’t require regular interactions with the health care system for INR monitoring. And then there is the hefty cost of the novel agents, she added.

The study population consisted of 3,900 patients with atrial fibrillation who initiated oral anticoagulation with apixaban (Eliquis), 10,235 who started on dabigatran (Pradaxa), 12,366 on rivaroxaban (Xarelto), and 38,190 on warfarin. The analysis utilized claims data from a large U.S. commercial insurance database.